00 STILL RHYTHM

Maria Yocca, photo by JaLeel Marques Porcha

02

03

06

07

09

11

Jean Marie Wanlass & Jack Walker

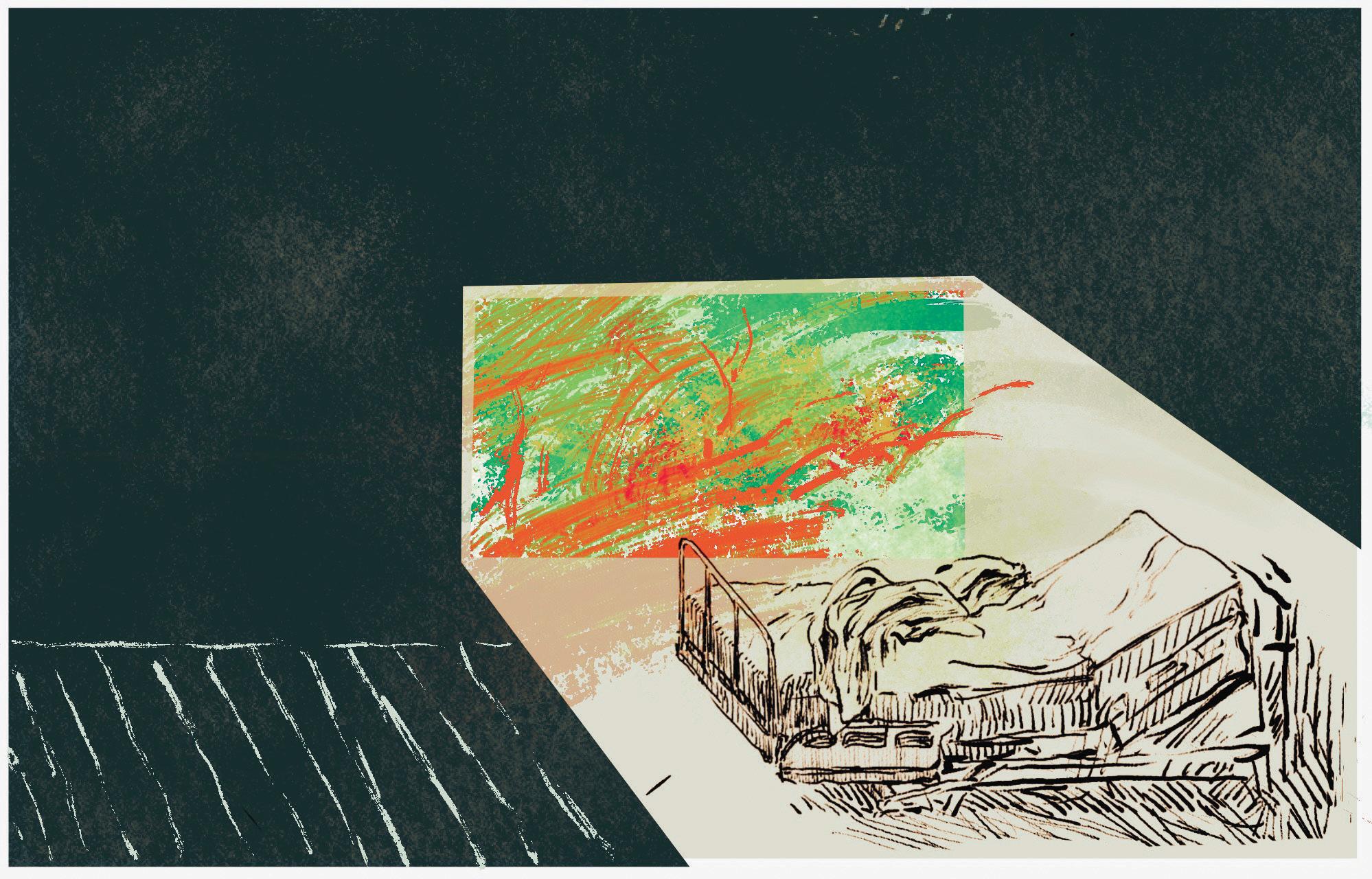

Ryan Chuang

Hyungjin Lee [이형진]

Natalie Mitchell

Graciela Batista

Angela Qian

13 GRIEF IN ‘CANCERLAND’

Catherine Jones

16 FROM ROMAN WALLS TO BATHROOM STALLS

Luca Suarez

18 THERE’S SOMETHING INDIE AIR

Annie Stein

19 BULLETIN

Mark Buckley & Kayla Morrison

In a kitchen that smells like every April for as long as I can remember (parsley, apple, horseradish, sweet wine, the bitter and the sweet, like Carole says, get it?) I feel transported not just across time but also space. It’s a comfort sometimes that every long warm table is, when you get down to it, just the same as every other long warm table. (There are many tonight—even in Conmag, to which I will deliver the holiday spirit via Manischewitz.)

These days, I can’t escape the birds. On a walk in the cemetery this weekend, after marveling at purple-blue flowers, I found myself eye-to-eye with a giant male turkey, laughably round and dangerously proud. He shook his plume of a beard at me, seemingly angry to find another living soul in his realm, and strutted over the headstone of a man named Spencer. I did as I was told and left.

That’s all to say: rituals big and small foretell a return. In any event, I’ll stick to my kitchen.

MANAGING EDITORS

Zachary Braner

Lucia Kan-Sperling

Ella Spungen

WEEK IN REVIEW

Karlos Bautista

Morgan Varnado

ARTS

Kian Braulik

Corinne Leong

Charlie Medeiros

EPHEMERA

Ayça Ülgen

Livia Weiner

FEATURES

Madeline Canfield

Jane Wang

LITERARY

Ryan Chuang

Evan Donnachie

Anabelle Johnston

METRO

Jack Doughty

Rose Houglet

Sacha Sloan

SCIENCE + TECH

Eric Guo

Angela Qian

Katherine Xiong

WORLD

Everest Maya-Tudor

Lily Seltz

X

Claire Chasse

DEAR INDY

Annie Stein

BULLETIN BOARD

Mark Buckley

Kayla Morrison

SENIOR EDITORS

Sage Jennings

Anabelle Johnston

Corinne Leong

Isaac McKenna

Sacha Sloan

Jane Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Tanvi Anand

Cecilia Barron

Graciela Bautista

Mariana Fajnzylber

Saraphina Forman

Keelin Gaughan

Sarah Goldman

Jonathan Green

Sarah Holloway

Anushka Kataruka

Roza Kavak

Nicole Konecke

Cameron Leo

Abani Neferkara

Justin Scheer

Julia Vaz

Kathy/Siqi Wang

Madeleine Young

COPY CHIEF

Addie Allen

COPY EDITORS / FACT-CHECKERS

Qiaoying Chen

Veronica Dickstein

Eleanor Dushin

Aidan Harbison

Doren Hsiao-Wecksler

Jasmine Li

Rebecca Martin-Welp

Kabir Narayanan

Eleanor Peters

Angelina Rios-Galindo

Taleen Sample

Angela Sha

Jean Wanlass

Michelle Yuan

DEVELOPMENT COORDINATOR

Angela Lian

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Kian Braulik

Angela Lian

Natalie Mitchell

WEB MANAGER

Isaac McKenna

WEB EDITORS

Hadley Dalton

Arman Deendar

Ash Ma

GAMEMAKERS

Alyscia Batista

Anna Wang

COVER COORDINATOR

Zora Gamberg

DESIGN EDITORS

Anna Brinkhuis

Sam Stewart

DESIGNERS

Nicole Ban

Brianna Cheng

Ri Choi

Ashley Guo

Kira Held

Xinyu/Sara Hu

Gina Kang

Amy/Youjin Lim

Andrew Liu

Ash Ma

Jaesun Myung

Tanya Qu

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Floria Tsui

Anna Wang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Sophie Foulkes

Izzy Roth-Dishy

ILLUSTRATORS

Sylvie Bartusek

Lucy Carpenter

Bethenie Carriaga

Julia/Shuo Yun Cheng

Avanee Dalmia

Michelle Ding

Nicholas Edwards

Jameson Enriquez

Lillyanne Fisher

Haimeng Ge

Jacob Gong

Ned Kennedy

Elisa Kim

Sarosh Nadeem

Hannah Park

Luca Suarez

Yanning Sun

Anna Wang

Camilla Watson

Iris Wright

Nor Wu

Celine Yeh

Jane Zhou

MVP

Ella

The College Hill Independent is printed by TCI in Seekonk, MA

The CollegeHillIndependent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and selfcritical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

How do you picture your relationship to your past? A tree, with rings of new growth encasing the old? A hermit crab, perpetually shrugging off last year’s shell? If you’re like me, you might suddenly see yourself—only younger—sitting across the table or staring back from the passenger seat.

And how to entertain this visitor, this child you used to be? Considering a total lack of daycares that fit the bill, you’ll need to get creative. Pack sunscreen, snacks, water, and the remnants of your curiosity and joy: It’s time for a trip to the Roger Williams Park Zoo!

Especially if you were a lot closer to the age of your miniature doppelgänger on your last visit—if it’s been a while since you wore a shirt with glow-in-the-dark monkeys, spent the whole day wiggling a loose tooth, or tried to color in your nails with Crayola markers at recess because your mom wouldn’t let you use her polish—it can be easy to forget how the whole zoo system works. You’ll get through the gate and begin to walk down the path with your usual half-urgency before remembering that you’re no longer trying to cross a college campus. But this will fail to fully sink in for a while: not until you come around the bend and, through a few driedout stalks of bamboo, lock eyes with a zebra.

At this point, some behavioral muscle memory will start kicking in, and the child beside you will pick up speed. You’ll wander by the elephants (engrossed by a suspended blue barrel full of grass) and into the giraffe pavilion, accidentally trailing a family pushing a stroller. You might briefly wonder if they will question your presence here, no visible child in tow. Yet, just as soon as you’ve wondered it, you’ll push through the doors, be met with a hot rush of air from inside, and see two giraffes, just standing there. Τhe sight will be so absurd—long eyelashes batting on long faces, mounted on even longer necks—that you’ll have to spend a moment suppressing a giggle.

Next up is Faces of the Rainforest, another indoor enclosure. Here, as your child self darts around, marveling at the free-range tropical birds and tiny, orange monkeys, you will recall that recurrent obsession of the zoo-goer: finding the actual animal. The two of you will discover giant otters curled up behind a plastic tree trunk, a giant anteater pacing back and forth in a dark den behind glass, and a (not giant) red panda asleep on the highest level of an elaborate treehouse, but the sloth and the wolves will remain elusive.

One of you will start to consider enclosure sizes. And freedom. And ethics. Why don’t the eagles (two bald, one golden) leave their openair enclosure? Can they? Do the moon bear and the snow leopards get confused if they catch a glimpse of each other through the layers of protective netting? How fast would you get bored on the other side of that glass, and are these spaces designed so intricately to engage paws and scales and talons, or just human eyes?

To get to these lines of inquiry, there’s a lot of unadulterated awe (catching a cheetah perched on a rock in the corner of your eye! hearing a kookaburra’s gravelly chuckle!) you’ll have to tamp down. Child-you cannot find a reason to question this place, and—in fact— wouldn’t even think to search for one. From that pair of eyes, a sky behind reinforced glass still looks blue. But you’ll try. Winding your way past the gift shop (which does not sell shirts in immaterial or memorial sizes), you’ll consider the wild mix of smells and sounds and sensations that pass from exhibit to exhibit. What is it like to live in such a calamitous space, surrounded by the full measure of the world’s

life and yet confined to such a tiny corner of it, positioned delicately below I-95’s roaring curve? This train of thought gets disrupted as it starts to rain. In your menagerie-minded haze, you panic: Did a toucan just poop on my head? But the sky is free from birds of any variety, so you take yourself by the hand and proceed toward the exit: half-full of wonder, half-full of wondering.

-JMW

Those of us who’ve spent some time on College Hill have likely passed the Providence Art Club. Spanning four colorful buildings on Thomas Street—a mountain of a road that takes you from the Providence riverfront to RISD’s campus—the Club brings a certain picturesque quality to an otherwise cumbersome hike uphill. (Or, alternatively, your ever-graceful stumble downhill.)

Perhaps the Club is most known for its Fleur-de-lys Studios: a yellow building whose timber-framed facade evokes a vague European ambiance standing in contrast to the understated colonial architecture that dominates the neighborhood. But have you ever wondered what lies inside these historic-looking buildings? Rest assured, my Providence peers! This week, I took on the task for both of us, trekking halfway down College Hill to find out.

Crossing the threshold of the main entryway, I was soon surrounded by a slew of black silhouettes plastered onto the walls, each representing a notable member of the Club’s past. Ah, hello gentlemen. How lovely to see you! How delightful your old-timey mustaches are! Many silhouettes were given a small detail to remind us of who exactly they represent. After all, faces tend to look similar in silhouette form. Club co-founder Edward Mitchell Bannister boasted an impressive cutout of the number one beside his profile, marking it as the first in the Club’s collection; others drew from lavish-looking tobacco pipes.

From the 216 silhouettes the Club fea tures online, I could only find two that clearly represented women, though I’m no expert on 19th-century gender expression. The Club de serves some flowers for its history of inclusivity in moments when people of color and women were excluded from most art spaces; Bannister himself was Black, and women were granted full and equal membership in the Club’s original 1880 charter. Still, I was left won dering why these particular faces were honored, and what it said about the identities I only realized were there with the help of Google.

Elaborately patterned wallpaper and dreamily dim fireplaces reveal the Club to be a work of art itself, but the whole time I was inside I couldn’t shake the feeling that if I sneezed too hard I might shatter some priceless arti fact. In my attempts to take photos, I had to angle my camera awkwardly away from folks enjoying fine New England dining or what seemed to be a whisper-only figure drawing class. In spite of the ways the Club has elevated creatives from a spectrum of identities, it still maintains a certain air of elitism treading exclusion that is baked into the culture of fine art at large.

The Club’s calendar is filled with gallery showings, dinners, socials, and artist talks.

But first crack at these opportunities, plus art classes and workshops, necessitates paid membership. Aside from initiation fees that can cost from $1760 to $2200 per person, aspiring members who aren’t professional artists must pay a minimum of $735 per year—and typically need a preexisting relationship with a current member.

To reiterate, the Club does make efforts to foster inclusivity. It exhibits the work of artists from diverse backgrounds, and will soon host its Edward Mitchell Bannister National Exhibition, which celebrates BIPOC artists across the country. It also waives initiation fees for membership applicants under the age of 35. But with the way that art has historically been built upon wealth and whiteness, I was uncertain whether the Club was doing enough to meet the art world in its current moment.

You’d be hard pressed to say the Providence Art Club isn’t impressive. Rooms brim with grand feats of creativity and furniture pulled from centuries past. Highlights for me included a ceiling painted to resemble the sky on a partially cloudy summer day, and a painting entitled “The Fiddler” in which a ginger violinist sports a snarl that could send the children of Rhode Island running.

But what struck me most about my visit was brushing past members of the wait staff in hallways. Each of them was hurrying to and from the dining room, but stood aside and allowed me to pass before continuing. For a moment, as I descended the stairs en route to the exit, I could see through a window into the kitchen, where the outlines of chefs and servers and dishwashers alike spanned a room vastly unlike others in the building. Their labor paints the Club into an image beautiful yet fleeting, and when I glance at the Club in my descent down Thomas Street, theirs are the silhou-

Idon’t remember the exact year Elijah vanished. He started to slide away the summer we turned fourteen, just around the time the tadpoles in the swamp were beginning to grow their legs and lose their tails. The algae in the swamp were green and clumpy then, congealing on all surfaces (liquid, solid) and pervasive the way God and fear are pervasive in Florida.

That summer, Elijah and I spent most of our days in the swamp, running our fingers absentmindedly through the algae, skimming the water’s surface, letting our nail beds suffuse with green. During these sessions we clung tight to the worlds we knew and fantasized adulthood: stealing each other peppermint candies from the 99 cent store, sweeping stray branches off pavement, thinking about each other when the lights went out. We discussed our future families (me: two kids, both daughters, Elijah: one) and what we would do with them (me: warm cookies and bedtime stories, Elijah: cultivate a rose garden). We had nowhere to go so we dipped into our imagination and picked out new toys to admire, silver and shiny. But to each other, Elijah and I said little about our grief; we didn’t know how to. Instead, we let the swamp heat marinate our unease in silence, allowing our angst to seep and swirl and pool, unaddressed, into muddy water.

Elijah’s favorite swamp pastime was his plank-walking act: When I wasn’t looking, he would pull himself up on a log and shout to me (pleading, grinning). Look, he would say, sticking his hands out haphazardly, waving them desperately around in exaggerated figure eights. Mar, I’ve been condemned to walk the plank I would laugh as Elijah placed his weathered yellow-laced boots step by step on wet bough, teeth clenched around his overall buckle in an attempt not to lose his footing as the branch grew thinner, looking deadly serious the whole time. Quick, come, come grab me before I fall in, he would plead, his voice sinusoidally wavering between bravado and distress, always rising, begging me to indulge in his sham fantasy. I could never tell how much trouble Elijah was really in. He had this tendency to slowly bend the lines of reality, to collapse our world until he was all you had left to hold onto, the only thing tethering you back.

“You didn’t rescue me. A real friend would have come up on the log with me and helped me back down,” Elijah would state matter-of-factly as he clambered, mucky and dripping, out of the swamp.

Elijah performed this routine every few months or so. Usually, it took place after one of his disappearances, which he always returned from with dark purple splotches below his knees and elbows. They were from crawling around the swamp for too long, Elijah had explained once, his eyes focused on the moving bog as if it might jump up and attack him.

“Of course I didn’t. The log would have snapped,” I would reply.

“Maybe, but this has nothing to do with you falling in the swamp, and everything to do with quantifying how willing you are to fall into the swamp for me. Which, as it turns out,

is less than the cost of yourself falling into the swamp,” he told me with a wobbly grin. I rolled my eyes and didn’t respond. We both knew (trusted, deduced) it wouldn’t take much for me to jump into the swamp to save Elijah, that this was also just better left unsaid, another secret to make the swamp air a little heavier.

In between plank-walkings, Elijah and I saw each other frequently, enough that we fell into a sort of routine. Most afternoons, we wandered the swamp, tracing and retracing our path through the mud. Despite our daily expeditions, the swamp remained a cartographical abyss—as soon as I set foot past the treeline, I was always swallowed entirely by the everglades, thrust tumbling into its belly, the edge of the forest instantaneously out of sight. And my sense of direction was stripped away entirely, too, like excess meat off of a wet bone.

As we walked, Elijah and I exchanged handme-down ghost stories from my grandmother for an index of details about different plants. He knew their Latin names (holy, binding), and had developed his own cataloging framework for the ecosystem. He knew what each plant or animal needed to grow, the threats to their survival, why they lived. Elijah made sense of the world in strict patterns and axioms: climbing onto a plank signifying friendship, one plant needing another to survive. The swamp was full of delicate overlapping, Elijah would profess wondrously, where everything is entirely contingent on everything else. One misstep in this world of rules, this stained glass world, and it would shatter. But these were our rules, and the swamp made more sense to us than the real world. It was safe here. It was so easy to sink in.

For me, these swamp escapades were a diversion. Mother spent the summer trading gas station cashier work for yelling at the little people in her TV, her voice hot and sticky and always rising. She was gone most days until nighttime, and would return with her face feral and plastered in desperation. That’s when the yelling usually took place—a silent, mechanized yelling, her face contorted so that you might think if she stretched it enough, she would be launched into a new life, out of the swamp. I thought it was silly to think you could escape so easily. The swamp has a habit of following a person around and pulling them back in.

Eventually, she always exhausted herself and made her way to the couch, where she would replay fuzzy Family Feud reruns, the refracted technicolor flashing backwards across her face, illuminating her narrow cheekbones (emaciated, refined). As she fell asleep, her eyes would roll back into her sockets so that they were all white, two dreamy little pearls. Mar, she would say with a sigh, her voice already warbling, Turn the volume a little higher, Mar. Be a doll. Help out mama, this one time, please sweetie? There you go, that’s right, perfect.

We would sit in silence for a while, the TV flickering in front of us until Mother, dancing on the edge of consciousness, would murmur something. Her sentences crawled out of her mouth ugly, like cockroaches.

I’m sorry, I’m so so sorry. I didn’t respond, because I didn’t really know what she was apologizing for.

Over time, Elijah started coming to the swamp less. At first, his absences had been sporadic, just a few days at a time here and there, but then they came in spades, faster and longer and more unpredictable. Elijah only offered loose accounts of family trips and mysterious illnesses. He would vanish for weeks without letting me know, and then one afternoon I would bend into a clearing and there he would be, sitting on a branch and stretching his back, as if he had never left. It was clear there was something going on, but Elijah and I let it fester.

Late that summer, out of the blue, Elijah called me suddenly over to his home to help him make tamarind paste. I had never been to his house before, and it was farther into the woods than I expected, in a clearing at the end of a long dirt road. The outside of his house was made of dark lumber, almost like an extension of the swamp, and it looked run down.

“Come in, Mar,” Elijah called, as I rang the doorbell. He was still wearing his yellow-laced boots, and some overalls. There were bags under his eyes, heavy like a carpet, and he seemed tired. I took off my shoes and lined them up by the door, neatly, underneath a framed photo of Mary Magdalene and Our Savior.

Elijah’s home was intimate and dark, with beige floor to floor carpeting. The walls were slanted inwards so the room seemed ready to collapse on itself. Elijah was in the kitchen, chopping tamarinds with a knife. He made small, precise cuts, wielding it deliberately like someone who knew the weight in a blade (fatal, revolutionary).

“How can I help?”

“Don’t worry about it. Come sit with me—I’m almost finished anyway.”

“I didn’t know you knew how to make tamarind paste,” I remarked, stepping into the kitchen.

Elijah tilted his head as if deep in thought, but didn’t respond. I watched as he emptied a bag of tamarind pods into hot water, turning away from me toward the sink (cavernous, staring). There was a long pause as the tamarinds softened in the pot, losing their shape. He seemed gooey, as if his thoughts were syrup and he was wading through them.

“Mar, did you know,” Elijah exclaimed suddenly, gazing out of the window into the swamp, “my mother once told me I had a twin in the womb.”

“A twin?”

“Yes. She thought she would give birth to two children. After I was born, she waited for another child, open and bloody, pushing out air. She lay there heaving, even after the doctor told her to go home, waiting for a miracle. She had another name, another crib, another set of tiny, knitted clothes ready—they’re all still in our house somewhere, this shell of a sister. It’s called vanishing twin syndrome, which I find strangely beautiful—the idea that people can just… vanish.”

I wasn’t able to see his face, but Elijah’s dis-

comfort reared purple and husky in the room. His posture was rigid, as if he were made of cardboard. He seemed to be somewhere else in the moment (dissociating, fantasizing).

“People can’t just vanish like that,” I supposed uncertainly, not really knowing what I was talking about.

“When a fetus is absorbed in the womb, the tissue of that fetus becomes part of the mother and the other child. Like the tamarind, whose wood, seeds, leaves, and fruit all have function, the vanishing twin is fully used, everything is repurposed. No waste. I absorbed her body—its body—she’s a part of me now.”

He paused, and nobody spoke for a while. I wasn’t sure what to say next.

“So she’s, like, haunting you?”

“I suppose so. But it’s not as much a frightening haunting, but more a lingering one—like how when you close your eyes, you know everything around you is still there, because it is, but you can’t see it. That kind of haunting.”

After a while, when the tamarind had thickened, Elijah passed it through a strainer. The paste was lumpy, like algae in a still pond. He poured it slowly into mason jars, twisting them tight and leaving them on the top shelf, pretty little treasures. As he reached up to open the cabinet, I saw the splotches again, Rorschached across his lower back.

“Why are you telling me this now?” I asked.

The truth was, I was worried about him, about what he was saying. I was concerned that he hadn’t been coming to the swamp or picking up my calls or at least walking the plank and pretending he needed saving. I was afraid that one of these days, he would disappear forever. Elijah had a dangerous tendency to erase the edges of his world and redraw them the way he wanted them to be.

Elijah shivered, his eyes far off and opaque (dilated, empty). His thoughts seemed to come out soft, like dough.

“I don’t know.”

Then with a lopsided smile, he continued, “maybe I’ve been spending too much time out here in the swamp, listening to the algae sing.”

I nodded, because I didn’t have an answer for Elijah. I tried to think, but I couldn’t get the image of algae singing out of my head. The picture inflated quickly within my mind, like a car’s airbag, until my thoughts were entirely void.

“Sometimes,” I said quietly after a few moments, “things aren’t supposed to make sense. You just have to live with them.”

Elijah looked at me confused, as if I had spoken another language.

“It seems much harder this way.”

While the sun started to set, Elijah and I sat side by side on the couch, replacing the rotten chunks in our fantasies with new parts of ourselves. After a while, I couldn’t help but feel our conversation started to stall. After exchanging brief goodbyes, I grabbed my shoes and prepared to leave.

As I opened the door, I turned back toward Elijah. He was leaning against the doorframe, illuminated by lamplight behind him. His eyes were closed, right hand dancing in u-loops in line to an imaginary rhythm.

“Do you mind if I ask you something?” I said suddenly.

“Go ahead.”

“It’s somewhat of a strange comment, but ever since you mentioned listening to the algae singing earlier, I haven’t been able to get the thought out of my head. I know this might sound foolish, but there’s an image that has been slowly forming in my mind of the swamp in full voice, everything swirling into symphony. It’s gnawing at my insides.”

Elijah remained quiet for a long time.

“The algae song, yes. If you listen too hard, you can’t hear it. It’s hollow at first, then fills you up hot and thick like a trumpet. I can even hear it now—soft, but it’s swelling.”

“Algae can’t sing,” I retorted reflexively. “Too much time in the swamp, and you start hearing things.”

Elijah seemed to be straddling the line between reality and ecstasy now. “I’m starting to understand it, but it’s hard— the words don’t quite stick, as if someone had spilled

some oil on them. And they’re heart-rending. Sometimes I get home and it’s dark out, and I realize I’ve been away all day listening. And my ears are tired from concentrating on the swamp: I feel as if I don’t have capacity for any more words.”

First his talk of vanishing, then this about the algae song. It was all starting to sound quite frightening—I felt I was now seeing a part of Elijah, ugly and growing, that I had only previously touched through a white sheet.

“So you’re saying it’s real.”

“It’s hard to say whether it’s real or fantasy,” Elijah began. “All I know is that when I sit alone in the swamp for long enough, I start to hear it. At first there’s only silence, but then time starts to twist up into knots and I can’t tell how long I’ve been sitting there. That’s when it usually starts up. It sounds crazy, but it’s true Mar, I promise. ”

Elijah’s forehead wrinkled, confused. He pushed the branch next to him, and watched its pendular arc (grieving, returning).

“That’s ridiculous,” I said.

“Perhaps,” Elijah responded.

That was the last time I saw Elijah for many months.

When school started again, I wasn’t concerned about Elijah, but I thought about him a lot, especially when teachers mentioned heterotrophy, or the Krebs cycle. Out of instinct, I looked over to his empty seat in the corner, half-expecting to see him grinning, splaying his fingers wide to simulate a brain exploding. I even called him, but the calls always went straight to voicemail. Elijah’s phone, the recording began, mired in static, I’m gone now, but I’ll listen for you later!

I went to the swamp at night to listen for the algae song a few times, too. I didn’t really believe Elijah’s story, but I hoped I might run into him alone, sitting on a riverbank and listening. There were moments when I thought I caught a glimpse of him, only to uncover an oblong shadow on a rock or a garter snake rustling in the marsh (duplicitous, doubling). I never saw him, nor did I hear the algae song. In fact, I didn’t hear a thing apart from the wind whistling through the cypress trees, and the low croaking of pig frogs.

I received a call from Elijah around Christmas time, asking to meet him at the carnival. The carnival stood alone in a wheat field right on the border of the swamp, away from the town center. I agreed to come almost immediately. I hadn’t been to the carnival in many years, but as soon as I saw it, I was smothered by its lights, alive like thousands of slot machines.

I found Elijah sitting alone on a bench by the corn maze, drawing flowers on notebook paper. He was wearing his boots, and looked gossamer thin in white moonlight, as if he might flutter away and disappear at any moment. He looked up and we hugged (tightly, desperately).

As we walked back through the crowd of carnival-goers, I saw that none of the people we passed had any distinguishing facial features. It

looked as if they had been rubbed clean with an eraser. Elijah and I discussed what colors our feelings were (me: frustration was black, Elijah: love was orange). My mind couldn’t help but drift toward Elijah’s disappearances. Eventually, I asked Elijah where he had been recently, and he smiled tragically with lopsided teeth.

“You need to stop worrying about saving me, Mar.”

“Who said I was worried?” I asked curtly, looking away.

“It was unsaid. Wanting to save someone isn’t something that you can hide easily.”

I stayed silent, letting my anger curdle.

“It takes a person in need of saving to see that someone else needs to be saved.” Elijah gestured to the carnival around him, swinging his arm in circles. “It’s like an illusion, a funhouse mirror to convince yourself you’re in control.”

I wanted to yell at Elijah. I wanted to yell into his face, force him to swallow my scream until it rolled down his esophagus into the folds of his stomach, and sat in his large intestine, indigestible, like a stone.

“You think you’ve got it all figured out, don’t you? Running off for months at a time, leaving your life behind, philosophizing on saving this and being saved that. We can play pretend all we like in the swamp but out here there are stakes and no prizes for bravado,” I said, my voice more forceful than I anticipated. “Walking the plank out here means walking the plank, not slipping into the swamp.”

I looked at Elijah but couldn’t tell what he was thinking. His face seemed covered in organs, as if all the missing facial features from the carnival-goers had been superimposed onto his. Now that I think about it, I must have been delirious. Either way, I stormed off, leaving Elijah standing alone in the crowd.

The next hours melted together. In one fragile moment, I sat at the top of the ferris wheel, almost horizontal with the swamp treeline. From my vantage point, I was confronted by a wall of trees, but just a few feet higher and I would be able to see all of the swamp. I imagined this sight would be liberating, the same way finding God in Florida is liberating because it sucks out any ambiguity through a straw. The ride, however, was already at its apex, and soon gravity (inevitable, thieving) pulled me back down.

Eventually, darkness blanketed the swamp and the carnival cleared out. The only people remaining were the few who were lost and those who had nobody to go home to. Elijah fell into both of these categories, yet I couldn’t find him anywhere.

As I was preparing to leave, however, I noticed Elijah’s yellow shoelace tied to a ring toss stand at the edge of the carnival. It was unmistakable: a shade of yellow so bright it erased all the color in the landscape. Sure enough, Elijah’s footprints were there in the mud; first faint, then deeper, outlining a path downward into the swamp. So Elijah called, and so I followed, letting the twilight eat me up as I wound my way through marshland on his trail. I’m not sure how long I was walking—time seemed to aban-

don me completely as soon as I began pursuit, twisting around itself into loops.

After a long descent, I turned around a tree and found myself standing in a clearing. Cypress trees curved over me like fingers, forming a canopy closed off from the rest of the world. As my eyes adjusted, I realized I was surrounded on all sides by shiny black water. This spot was where the footsteps ended abruptly, as if Elijah had all of a sudden disappeared. His boots were dangling, tied to a tree by the remaining yellow shoelace, but there was no sign of Elijah. It was all very mysterious.

I didn’t know what to do, or what to think. I just sat there laying in silence, letting my mind go completely blank.

That’s when I heard it. It came from all around me. Low and hollow at first, then growing, hot and thick like a trumpet, just like Elijah had said. It’s hard to describe, but it was something like a funnel, where the entirety of the swamp felt like it was pouring onto my body, not unlike a baptism.

Since that day, I have yet to see Elijah. Sometimes I’ll hear my phone ringing late at night or hear footsteps in the marsh and feel a coldness run up and down my body like a knife, but it’s never him. I even returned to his house at the end of the dirt road once, but he wasn’t there.

I still stop by the swamp at night, though. I sit by the water and watch the log, pretending for a second that Elijah is walking the plank. My toes dangle in the water, emerald-stained and wrapped in seaweed. After a while, Elijah starts to tightrope. His footsteps are lazy and precarious, and he’s waving his arms wildly in exaggerated circles. He’s ascending and it’s starting to get dangerous, and I can tell he’s shaky but he’s pretending he’s stable. When he reaches the end of the log, he stops.

He’s standing perfectly still.

RYAN CHUANG B’23 is considering taking swimming lessons

Hyungjin

My Names

Digital video, cyanotypes

I created this film in the fall of 2022, when I started going by my Korean name for the first time in eleven years. Through the voices of myself and my parents, I try to make sense of the contradictions, love, and history behind my name, Hyungjin Lee.

was vital with the return of campus life: “I knew there were talented people here. And so it was just about creating those connections, and really just creating this scene with all these people. Because I knew that if there was a space, there would be a huge demand for it.”

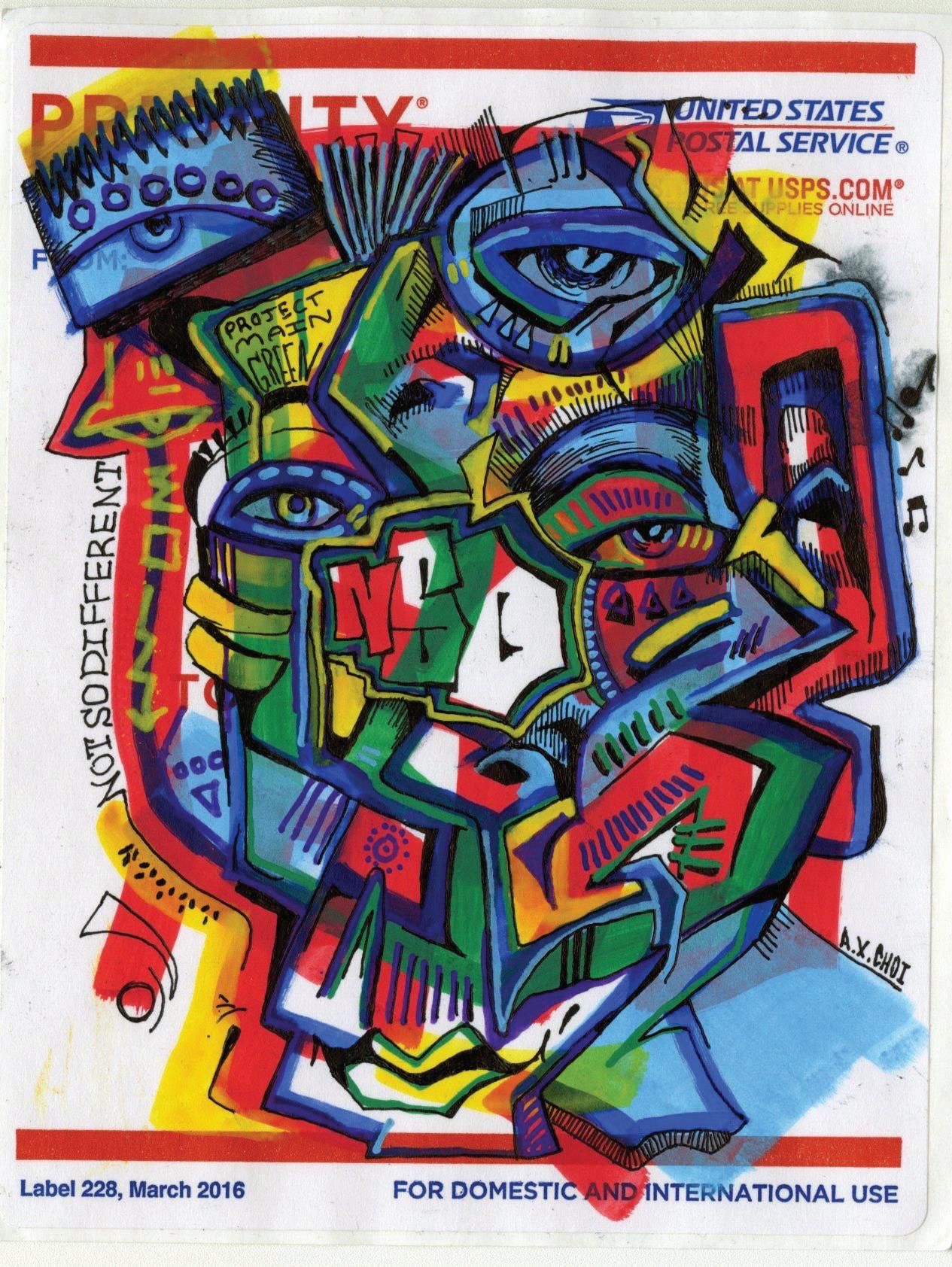

Carving out this space for music demanded an investment in the broader culture of hip hop, which is just what NSD set out to achieve. “It’s the difference between going to an open-mic night with a guitar versus if you have a beat and you’re rapping over it; you have energy, you’re hype, you’re engaging with the crowd … Hip hop is so unique and different that I think we need spaces for hip hop, and I think NSD has done a great job in doing that,” said Jordan Turman, aka rapper Sodomaybe, who began performing with the collective in some of its earliest projects. It was only after a couple of events and performances, most notably an art installation on the ceiling of Wayland Arch created by Song and “Project Main Green’’—an exhibition which presented a wreath of visual artmaking surrounding the musicians performing in the most central location on Brown’s campus—that the collective came into shape with motivated, concrete objectives. “Once I saw us all three get together, I was like, damn,” said Walendom, describing those earlier days of NOTSODIFFERENT, as he built a close personal relationship with Song and Urgent. “After Project Main Green and seeing the sum of all we could create…when that music goes, people are here for it.”

These goals manifested in the score of events that NSD has either performed in or hosted since October, through which they created diverse setlists of artists and built a consistent audience. Singer, rapper, and storyteller Jennora Blair first got involved with the collective in early November through Professor Enongo A. Lumumba-Kasongo’s Intro to Rap Songwriting class. Walendom was one of her classmates and eventually asked her if she wanted to be part of NSD’s Sounds@Brown set. “I was really drawn to NSD because of how I could think of my voice as hip hop,” Blair said. “Envisioning my voice as a part of the hip hop genre is refreshing and new to me—specifically rapping. I’d never rapped before in my life.”

She stresses the importance of the space that they have curated, especially for Black artists like herself, saying, “I think it’s the fact that the community is very diverse and it’s predominantly students of color also running it … [it’s] just such a warm atmosphere because of that collective joy of difference. It’s really generative.” +++

That Wednesday night, the vibe in the basement of the House of Ninnuog, meaning “House of the People” in Narragansett (aka Brown University’s Native House) felt, more than anything else, like a group of friends hanging out after a long day of classes. Music was emanating from a speaker as student Jordan Walendom, a rapper and DJ, queued up songs; some were familiar, while others were new mixes and beats created by the students sitting in front of me. I felt a bit starstruck.

Kalikoonāmaukūpuna Kalāhiki, a music producer, rapper, and member of the house, seamlessly began the meeting by proclaiming the space a vehicle to help people with their creative practices.

Kalāhiki is a junior at Brown and a queer māhū, from Kāneʻohe, Oʻahu—“for Hawaiians, māhū is our analog to 2Spirit…we embody both masculine and feminine energies,” they explained. They later brought in their dog, a

mini poodle named Duke, who ran around the circle of couches and bean bags, trying to steal the snacks people had brought. Throughout the rounds of introductions, creative share-outs, and invited interjections, I candidly got to know the various singers, rappers, producers, filmmakers, graphic designers, and poets that had made their way into this space—and, among them, the three founders of the hip hop collective NOTSODIFFERENT.

+++

Walendom, Namoo Song, and Elliot Urgent had long recognized a persistent drought in the hip hop and party scene on Brown’s campus post-pandemic, especially due to the lack of performance opportunities for rap artists and DJs. Urgent, a DJ himself, had studied the scene as a freshman prior to the pandemic, and provided a sense of institutional knowledge that

While the collective continued to grow and the diverse, vibrant space of NSD took shape, the need for further organization became apparent. Kalāhiki was first introduced to the founders of NSD through their best friend, who had been involved in their events and performances from the start. By meeting up on campus with Walendom over Thanksgiving break, working on beats, and writing verses, they forged their relationship to the collective, eventually coming on as an additional organizer alongside Valerie Villegas and JD Gorman. “We were very much there to provide increased capacity and help to coordinate between a lot of disparate parts of the collective,” said Kalāhiki.

Their guidance on these matters helped to facilitate the NSD events of the current spring semester, most notably the “NOTSODIFFERENT Super Bowl,” which saw several rappers facing off in team battles against

“With the artists that they’re bringing together, they’re basically like, do whatever you want, and in that sense, there’s the emphasis on ‘you don’t have to buy into the normative.’”

Gustav Hall

one another. A week prior to the event, Urgent and Kalāhiki cooked up beats, sent them off to each artist, “and then everyone would just like, hop on,” as rapper and Brown sophomore Osiris Russell-Delano described it. “The Super Bowl was honestly the coolest show I’ve ever done,” he reflected. “The performance itself wasn’t that crazy but the whole idea and the world building that took place was super dope.”

For R&B and neo-soul artist, RISD senior Rose Poyser aka DomeDekka, the event was a new challenge: “I was like, ‘Oh, shit. I’m supposed to freestyle, I can barely do a little ‘Miss Mary Mac’ situation’… but it went pretty swimmingly I think.” They were on Team Purple alongside rappers Gustav Hall and Jesse McCormick-Evans (aka “McBaller”), and the three have collaborated on tracks together since. “We’re just gonna spit whatever. And it wasn’t stressful at all,” said DomeDekka. And spit they did, with not-so-friendly fire and quick-witted back-and-forths against the competing team that had the packed living room in stitches and in awe. Like watching the actual Super Bowl, but instead, the beat is sick and the players are people you have class with every day.

Thus, my initial framing for this piece centered on the success of the Super Bowl and NSD’s social media promos leading up to the event, specifically examining the performance hype surrounding the community and what made it so special. However, when I asked the co-founders what NSD performance they had coming up next, I was surprised that Song pointed me toward the Mezcla Latin Dance showcase, an event where they would be ushering, but not performing.

At the showcase, witnessing their show of support, my attention was drawn to what I now understand as NSD’s most arduous task: building a community.

+++

To accomplish this task, NSD created a Departmental Independent Study Project (DISP), whose meeting I was attending in the The House of Ninnuog lounge that Wednesday night. Kalāhiki organized the DISP with their advisor in the Ethnic Studies Department “just for us to have the space to talk about, ‘How do we intentionally build a community for creatives, and what does that mean to have a community for creative expression?’”

They modeled the framework for the course on the book Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds by adrienne maree brown, specifically “understanding our community as fractals,” Kalāhiki explained. “Our relationships to one another on an individual level will reflect how we operate on a big scale.”

Walendom claims that “one of the molds that NOTSODIFFERENT aims to break is the dominant male hierarchy that hip hop historically has, and go beyond the conversations and personalities that songs are allowed to have.” By design, NSD highlights the art of queer and trans creatives of color within the community. “I speak from my experiences as a trans woman and I think that they give me the space to do that,” said Sodomaybe. Though “I personally just make my space,” she added. “I don’t wait for people to do it if I want space.”

But there’s still the broader question at hand—“I think NSD’s goal is to change and shift the culture and I think, implicitly, a question that they’ll have to answer for themselves is: what does it mean for them as men [to be featured at the forefront]?” asked Dori Walker, a videographer and recent collaborator with NSD on a music video for the singer Daiela. She articulated the difficulties of creative authority in spaces shared by men, and how the agency of women, especially Black women, is often neglected. “I see the people that shift and change culture most in this country to be within black femme spaces, queer black spaces, [and at] the intersections of that,” Walker said. “So I definitely would say there’s always going to be tension in masculine-dominated spaces with that reality.”

NSD, a large proportion of which is Black men, confronts both white supremacy and the complexities of Black masculinity. They have enlisted the help of Beta Omega Chi (BOX),

an all-Black, anti-hazing fraternity at Brown, in approaching this project. Walendom and Urgent are both members of BOX; Walendom is currently its President. “The emphasis that BOX places on certain things like communication and vulnerability … is really important” in NSD, Urgent explained. “[It] has really been a huge factor in how we went about trying to intentionally build our connections with all these artists, and maintain [a] space that is comfortable for everybody.”

As for Kalāhiki, they see their role within the collective as a force to work through the challenges of community building, to shape NSD not merely as a place for creativity but also a space for healing. “Because NOTSODIFFERENT is so diverse, we’re all bringing different traumas into the space to process and work through together, specifically as a majority space for people of color. So because of that we’re going to make mistakes, we’re gonna fuck up. That’s why I’m so passionate about us being held accountable … in Hawaiian we call it ho’oponopono, which means ‘to restore back to balance.’”

+++

The collective (now in its “terrible-twos,” as the co-founders and others refer to it) is trying to manage NSD’s growth—projects, events, and building a collaborative network of artists— while also sustaining this foundational sense of community care.

There is also the management of pressure from Brown’s institutions. “The fact that we are students is something that we’ve just got to accept,” Song acknowledged, explaining issues they’ve faced accessing Brown’s resources and hosting student events. “We’re really just trying to take the most out of the cards we were dealt and play into the fact that we’re just trying to be ourselves.”

Since NOTSODIFFERENT has made clear that the hip hop collective does not consider themselves a club or just some ‘rap group’ of Brown students, the question of proximity to the school’s administrative authority is complicated. “I think we’ve been able to use the resources at Brown, while keeping our distance,” as Urgent put it. “Just the restrictions that you have to deal with, when you’re under [Undergraduate Finance Board] funding and stuff like that, we don’t want to deal with it. So we make our own money. We put it back in.”

The Super Bowl was the first NSD event that charged for its tickets and was hosted at a space off campus where they did not have to worry about being shut down by DPS or needing Brown-hired security—which is partially why they’ve decided to remain lukewarm with the administration. “We’ll keep you safe, you know,” said Song. “We’ve been very lucky with the people who come, [they] understand the level of respect that people have for each other in that space.”

When it comes to diversity on Brown’s campus, students of color face a double-edged sword. Success is not always rewarded for those who achieve it, in comparison to white students; other times it is tokenized. This is visible in

how the administration praises past protests as moves toward progress while sweeping discussions of worker rights and apartheid investments under the rug. Walendom told me: “It’s kind of scary that by taking [resources] from Brown, we provide for Brown this diversity brochure, which is terrifying … it’s a double irony that we play against one another.”

NOTSODIFFERENT and its ethos can only exist in spite of the structures of this institution. “I’ve been focusing on African American literature and the Black radical tradition,” said Hall, a junior at Brown. “So a lot of the stuff that I write about has to do with Blackness and the politics of Blackness, Black youth, things like that.” For many students on Brown’s campus, critiques of the University are made possible by the legacy of protests and organizing of BIPOC students over the past 60-plus years—a legacy Brown tries to claim as its own.

+++

The collective’s goals of nurturing creative freedom have provided a necessary space for all of its artists, especially for rappers like Sodomaybe. “[In] my music, I am a bit, like, raunchy and vulgar,” she told me: “I have a whole song called ‘Pillow-Princess Paradise’… I like to be artistic in that way. [But] I’m about to apply to med school next year. And so I think my digital footprint is very important. I don’t know what that will look like and I think that’s also a reason I’ve been kind of stalling on the recording process.” For her, NSD’s focus on live performance has provided a solution to this dilemma. “NSD gives opportunities to showcase your art, and NSD has [helped] me perform and get myself out there and really put effort and time into my artistry.”

Art and its longevity is never a promise one can make, and it is impossible to think that an artist could ever be paid to create the work that they truly want to be making. But when the primary incentive for creativity is the support of a community, the art that is produced can transcend the boundaries of what we deem valuable in society. As Urgent told me, “in presenting these rappers and vocalists, I think it’s just really important to redefine what is acceptable to be presented as hip hop and as Black.”

Like fractals, these intentional steps toward artistic liberation hold power beyond measure, connecting populations of queer and trans people of color who crave this sense of community. “People don’t know the lyrics to the song at the beginning of the song, but at the end, they’re screaming the hook back at us,” said Kalāhiki. “I think that energy is what keeps people coming back and keeps our artists really engaged and wanting to work with us. It’s inexplicable. It’s NOTSODIFFERENT.”

NATALIE MITCHELL B’25 thinks that rappers sometimes have the most interesting things to say.

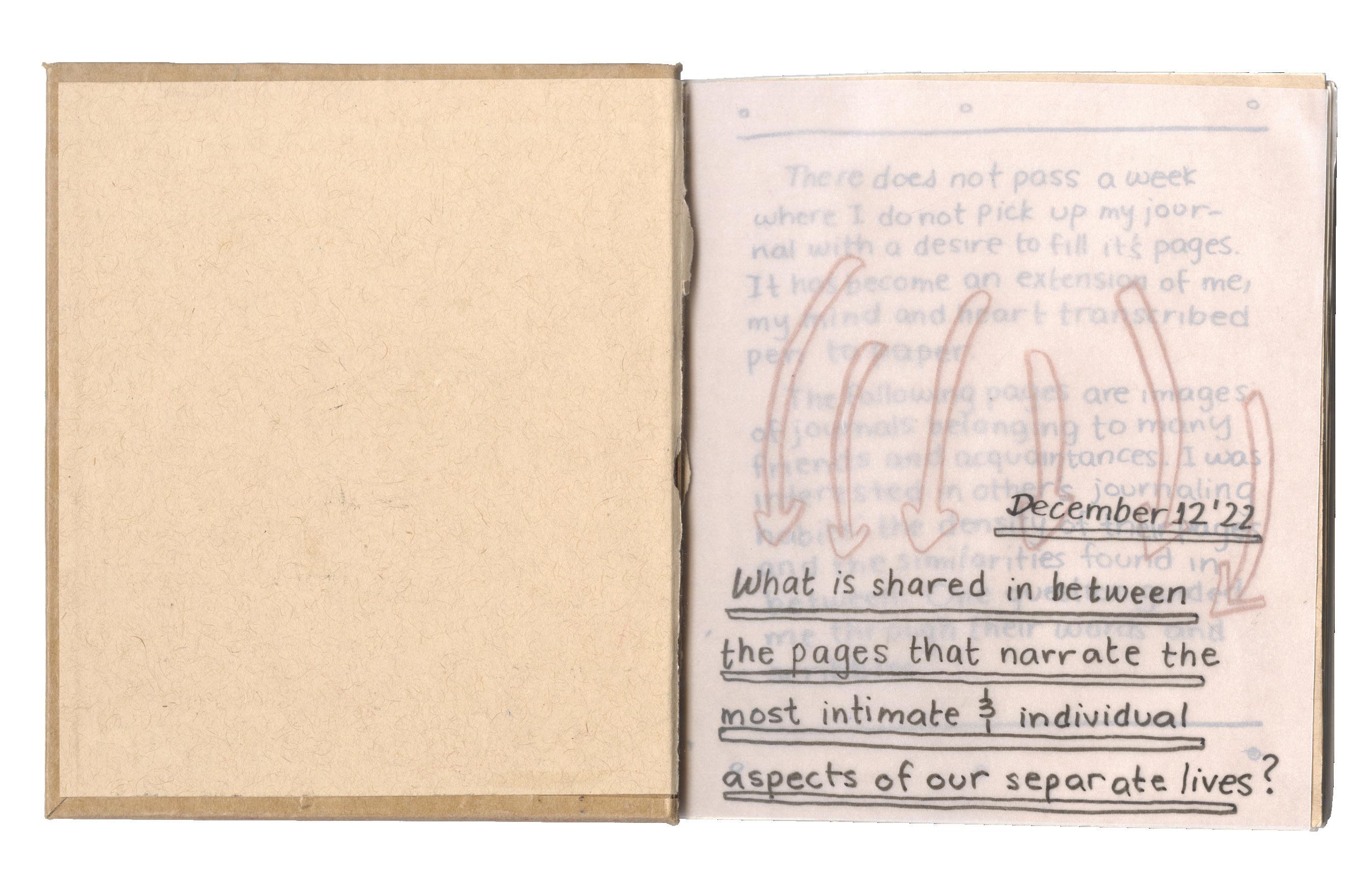

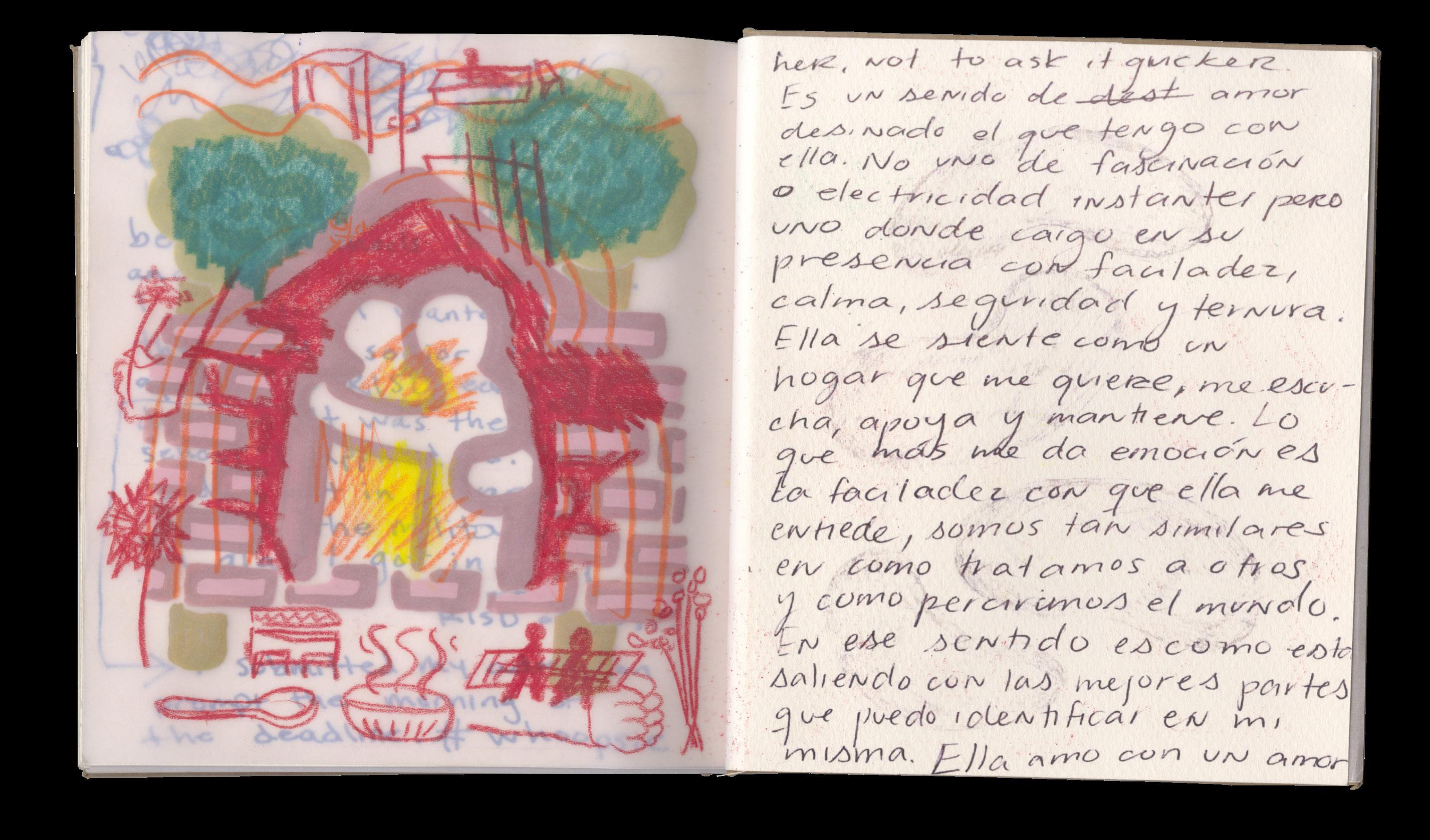

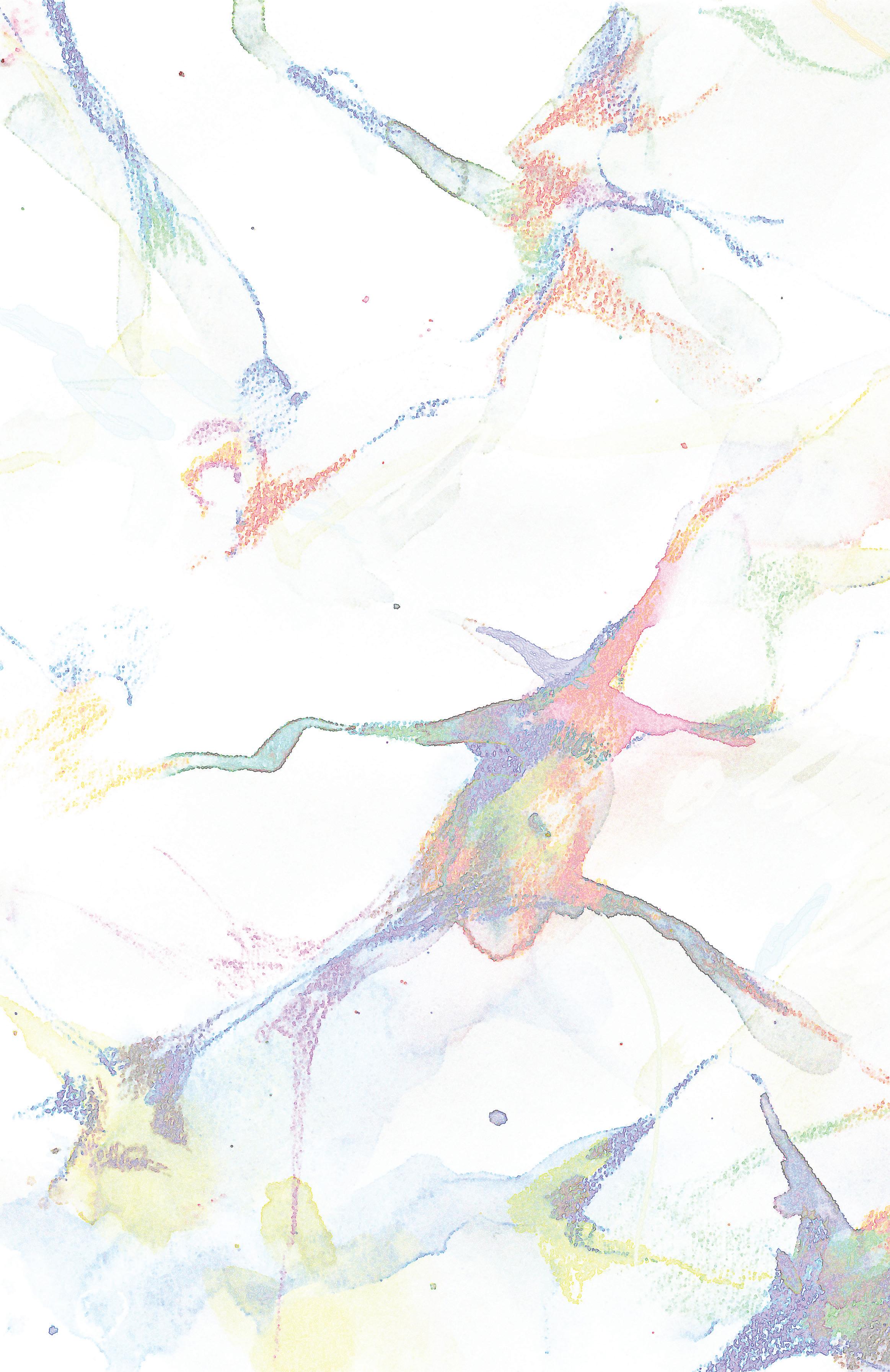

Graciela Batista R’24

December 3rd, 2022

Vellum paper, colored pencil, gouache, cardstock and book board

“December 3rd 2022” is an exploration and documentation of internal monologue found in the journals of the people around me. As an avid journaler myself, I was interested in unveiling the archived intimacy and searching for connecting threads amongst the strings of consciousness through illustrated imagery.

A burning wig.

A halo, a carcass, a curse. The wig smoldered on the cement behind my house. I recorded it on my old digital camera, zooming in, trying to capture the shapes of the tongues of fire, the intensities the wig made against the pavement as it burned. The hair resisted destruction but the wig cap was not so lucky: it began to destroy itself from the middle, leaving behind a gleaming, undamaged wreath of blonde. It melted into a fragile lattice that fell apart as we pried it from the ground.

After two years of attempting to do what was ‘practical’ in school by pursuing a degree first in Behavioral Decision Sciences and then in Public Health, I finally recognized that I wanted to spend my remaining undergraduate time as a writer. So, in addition to enrolling in a full course load of literature and writing classes, I joined the Indy. It was a forbidding campus publication my roommate helped run. We hosted an icebreaker event at our house, which was creaky, barely furnished. We hadn’t been living there for long. It was a “Medieval Bartering Party,” and someone had bartered their way into possession of a cheap wig. We were bored and out of cigarettes. We lit matches outside, and watched the wig begin to burn.

An actor going on cold.

“You can do what you’re interested in, but you have to know why,” my roommate’s mom tells her. She is a history professor in Western Massachusetts who immigrated from Germany to attend graduate school. She is skinny and direct. My roommate Lucia studies English and Modern Culture and Media, and in personality is her mother in miniature. She’s always known she wanted to concentrate in media studies. English came after: She wanted something structured, to complement the amorphous. She had taken the intro Computer Science sequence, but had decided against continuing. The style of class, the type of assessments, were not right for her. She didn’t want to take tests and be graded out of points. Instead, she was interested in using her excellent critical and literary gifts to make arguments, and be graded on the strength of those arguments.

“That’s why I’m always freaking out,” she explains. She is never freaking out. “Sure, I’m interested in what I’m studying. But why? I think in the present, not the future. Like, what do I want my thesis to be about, now? I envision graduating and being like, ‘What do I do now?’”

We’ve talked about this before: while in certain fields such as science, engineering, consulting, and finance, there’s a relatively set path for what’s ‘normal’ out of college, the

humanities offer much less certainty. Students pursuing the former must contend with a rigid set of guidelines during undergrad to achieve a more tangible end: jobs at top firms, positions in top grad schools. There’s a sense of a roadmap— albeit an often competitive, complicated, and backbreaking one. The humanities—especially literature and writing—exchange that certainty for flexibility. And, for some people, studying literature simply feels nourishing in a way that STEM does not. For Lucia, this made it worth the cost.

For me, it only heightened my sense of panic. I entered Brown intending to double concentrate in Behavioral Decision Sciences and Literary Arts: my misguided attempt to capture both certainty and nourishment. It’s an incredible privilege to be able to choose your life, especially somewhere as prestigious as here, and I was intent on fulfilling my potential. I liked science, I wanted to learn about fields we hadn’t covered in high school, and I loved to write. My goal was to write a Literary Arts thesis.

Everything seemed poised to bring about my success. But I was finding, to my dismay, that I disliked my classes. I disliked college. I began my education at Brown under the strictest COVID-19 guidelines. Every class was remote. Everybody was a freshman. We trudged up the hill to get our COVID-19 tests each week, through wet snow that turned to slush. The greatest characteristic of my COVID-19 freshman year, however, was a blinding confusion. We were isolated from the exchanges of unofficial knowledge that the university doesn’t advertise: advice from upperclassmen, integration into a wider campus culture, the day-to-day interchanges through which the most banal, important wisdom is diffused. In these years, I was often haunted by a sense of cluelessness, and its ensuing terror. Who out there would guide me? Who would show me how? Who would tell me what best to do, instruct me on how best to live my college years, before it was too late? Instead of being nourished by an existing community, we freshmen fashioned our own societies from faded images of high school. There were no geniuses. There were only socialites. It was less pressing to figure out what to do with our lives than to figure out who to waste them with.

+++

COVID-19 guidelines eased. I had been taking a literature seminar or two each semester, but now I began loading up on Behavioral Decision Science classes. I avoided thinking too much

about planning my courses over the next four years. I knew I was neglecting something important, but I didn’t know how to attend to it properly. If I probed it, something would come apart.

But even my literature classes were being spoiled under the demands of my science and economics classes, which required entirely different modes of scholarship. I was struggling to go to class. I was struggling to do everything. I was disengaging from my learning. I had forgotten what it was to be engaged.

Worse, I couldn’t dream myself out. I didn’t know what kinds of futures could be sustained on an English or Literary Arts degree. If only I knew what I was doing, if only my classes felt like I was working toward something I believed in! I neglected to pursue that knowledge. I didn’t really know how to pursue it. I didn’t even know what I didn’t know. Although some of my friends were concentrating in English, most were studying economics, and I wrote off the few as being specially gifted or else possessors of resources that I didn’t have. I couldn’t imagine a post-grad world where I, the child of two immigrant scientists, attained success and satisfaction with a literature degree. Nor could I dream of a future where I’d be happy with the fruits of an economics-adjacent degree.

More and more clearly, I was seeing my choice of concentration not as a reflection of my academic interests, but as a choice of the type of life I wanted to lead. Did I want to spend those honorable hours in the library memorizing cell structures, like my parents? Pursue vast sums of wealth in a pantsuit? Spout literary theory with the aesthetes at parties? Did I want to enjoy studying literature, and resign myself to an unknown—maybe impoverished, drifting— future? Or did I want to grit my teeth and obtain a practical degree, and the comfort of stability? I knew all of these worlds were open to me, and would welcome me, whatever I chose, but each of the worlds seemed so sweet—and so deadly— that I found it impossible to choose just one. After all, I brought the mindset from high school that had proven moderately successful thus far, that I didn’t have to choose, that, especially at Brown, it was possible to attain greatness on many fronts—even though it felt like I was actually attaining greatness nowhere. What did I want? James Baldwin wrote, “The barrier between oneself and one’s knowledge of oneself is high indeed.” In other words, I had no fucking idea.

I would talk about it any time I was given a chance, and bore everyone. People would often comment that I studied Behavioral Decision Sciences, and couldn’t make up my mind, how

How to choose a major when you have no clue what you want.

funny! In the beginning, I laughed along, but I soon began to press my lips together and quickly move on, caught by the growing feeling that someone was playing a joke on me, a joke that was insignificant to the entire world, but disastrous to my individual life. I hoped for a miracle, or a catastrophe. I desperately needed guidance, but I didn’t know how to access it institutionally—no adult figure seemed appropriate, and besides, everything was on Zoom. I couldn’t exactly lay out my history of horribly bad academic decisions and stupidity over Zoom.

I looked for the answer in books, and felt comforted and doomed. Milan Kundera’s Tomas, in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, realizes, at a juncture, that not knowing what he wants is actually quite natural. He is born from “einmal ist keinmal.” Once is never, says the German adage. Tomas interprets: human life happens once and then disappears. Since we only have one life to live, we might as well have not lived at all. It’s impossible to know what decision is better because we have no past life to compare it to or future life with which to correct it. Kundera writes, “We live everything as it comes, without warning, like an actor going on cold. And what can life be worth if the first rehearsal for life is life itself?”

A Korean spa.

At the end of my sophomore semester, I decided to drop BDS. My friends were still studying all kinds of things, but my favorites all studied English. I would maintain the double concentration—I didn’t feel ready to give up the stability. But the BDS department was too scattered. I didn’t enjoy my classes, didn’t see a path forward. I needed something to change.

That summer, I worked in entertainment in Los Angeles. I met new people—a Brown alum who majored in Development Studies but went on to make documentaries, and her daughter, who did East Asian Studies at Bard. Asia was a creature of Los Angeles, with bleached eyebrows, bitten fingernails, and a closet full of fantastic clothes inherited from her grandmother. It was my first time in LA, my first time living alone and doing whatever I wanted. I was never lonely. It seemed like Angelenos lived entirely different types of lives. I drove through the mountains. I visited Ojai. I swam in the Pacific and saw fireworks on the Fourth of July.

At one point, Asia and I visited a Korean spa: a multi-floor structure including bathhouses, saunas, and a big family-friendly floor where mats were laid in rows. She explained that there was no prescribed order of things in the spa. You could go from the hot tub, to the cold tub, to the

saunas, to the showers, and back, as many times as you wanted, and everywhere offered fresh sensations.

“Where do we go next?” I kept asking her, and the answer was always the same: “Anywhere.”

To have the freedom to go anywhere, unrestricted by what you were supposed to do, was a new variation on my concentration troubles. On one hand, I was lucky enough that freedom was the problem. On the other hand, I was still being steered by the sense that there was something I was “supposed” to do.

I spent the following semester studying Public Health. It was a rigorous education, an interest out of the blue. I had enough Literary Arts credits stored up so I could afford to spend an entire semester on something else. I told everybody I was changing majors and was happy about it for a while. But—for reasons I couldn’t then explain—I began to disengage again. I had gotten closer to following my interests, but still hadn’t struck upon the center. I missed my literature classes. I missed the community. They were really learning, it seemed, about things that were important and impenetrable. They were creating arguments from scratch. They were being graded on the strength of those arguments.

Furthermore, I had been splitting my energy so much trying to figure out my second concentration that I had given little thought to my first: thesis deliberations were coming up, and I was so out of touch with my writing practice and the workings of the department that I knew I would fail to attain my goal if I didn’t drop everything and fully commit. I experienced this clarity at the end of my semester. I like to attribute it to the misery of finals. My parents like to say that it’s the fruit of their prayers.

I knew it was time. Even if it meant closing the door on each of those other lives. So, I would enroll in an entire courseload of literature and creative writing classes, an indulgence I had never before allowed myself, so intent had I been on pragmatism. The act was deeply seductive because of its transgressiveness, made me giddy, and slightly ashamed. But I realized now that committing to my writing was pragmatic. There were futures waiting for me in fields unrelated to economics or public health. In fact, there might be many. They might be uncertain, but they could be mine.

I quit my second concentration entirely. I still liked science, but I needed to put everything I had into developing strong theoretical and literary foundations for my writing. I finally stopped trying to split my energy between two fields, and go nowhere. I would put my energy

toward one field and go somewhere.

When I was a child, I would read books about tragic characters with fatal flaws. I resolved to always stay aware of my flaws, looking out for a potentially fatal one. I understood that I might not always know them all, or which ones were fatal, but I felt it was an important task. The truth was: If someone had laid out a literary future for me in my freshman year, would I have even listened? Were my flaws lying dormant, waiting to ensnare me—pride, laziness, stubbornness? Or, could it be that it wasn’t a matter of simply having the knowledge—even of the self, even of what I wanted— but a matter of growing into the knowledge, of growing into my interests and my futures? Maybe, probably, it was a combination of the two.

An angel.

My hand holding the camera shook, and the ends of the wig curled up toward the sky, and with a start, I realized that by deciding to pursue what I enjoyed, rather than what I thought might be practical, there had been some change wrought upon my home and myself. This semester, I have been happier by far. I’ve exchanged career certainty for another kind of certainty—a lostand-found feeling of knowing I am spending my education in the best way possible, for me. While going on cold is still terrifying, and life isn’t always hopping from sauna to sauna, I have finally begun to find the freedom within einmal ist keinmal, and to take courage.

It wasn’t just a creaky Providence home. It was my home, and the world seemed like mine too. It wasn’t a world without possibility; it was a world that made space for many images, including something as absurd as a burning wig on the ground, as a child of immigrants pursuing a career in writing. It wasn’t a carcass, wasn’t a halo, wasn’t a curse. It was simply another image, an angel in lattices on the ground. It was transfiguration and high temperatures, and creation within destruction.

ANGELA QIAN B’24 likes burning things for fun.

In the 2000s, a rubber bracelet swept the nation in a frenzy of ‘awareness.’ Every prepubescent boy I knew proudly donned their “I ❤ boobies” bracelet from their local Zumiez or Tillys to show their support for people with breast cancer—until the popularity of the bracelet wore off. ‘Breast cancer awareness’ became an adolescent fashion statement coated in “pink kitsch.” It was everywhere. It still is.

In October of 2021, I remember seeing the Brown University football team’s “Bench Press for Cancer” event on the Main Green as I walked to class. It caught my attention, but I barely considered its meaning. I was only focused on the offensive lineman I was crazy about, hoping that he would look my way, maybe wave at me. But I was mad at him, and he knew that, so I didn’t put my money on it. He did wave, though, and he smiled. That mattered to me then.

In October of 2022, I was no longer thinking about him, and none of that mattered anymore. I was thinking about my dad and how I missed

him so much it hurt, and how I wished these guys weren’t heckling me to lift weights or to watch them lift weights to raise money to ‘fight’ the disease that had killed my dad just months before. I was thinking about how I watched his life leave him, and how it haunts me everyday, and how it will always be with me, and how I am fundamentally and permanently changed by it.

+++

With every raucous fundraiser, every awareness-spreading bracelet, and every pink ribbon, cancer flows almost effortlessly through American life. From a big picture perspective, the visibility and ‘awareness’ of cancer seem only positive: if more people are aware, then more people might care, and then more people will give money to fund research, and more patients will get the treatment they need or, at the very least, the encouragement necessary to ‘fight’ the disease. The notion of this positive chain of events certainly has merit, but the chain’s

effectiveness becomes suspect when it links something like a rubber bracelet to a cure for cancer.

The phrase “fight cancer” derives from America’s linguistic reliance on military metaphors in medicine and daily life. When a patient is called to ‘fight,’ there is an assumed possibility of ‘defeat’ or ‘victory.’ The patient might ‘lose’ their ‘battle’ with the ‘foreign’ thing that has ‘invaded’ their body. They might ‘succumb’ to the enemy if they don’t fight hard enough. No matter the permutation of these metaphors, they all suggest some kind of personal responsibility and moral implication for the individual living with cancer.

Not all that long ago, though, cancer was almost unspeakable in American culture, let alone constantly publicized in the media through graphic military metaphors. In her essays “Illness as Metaphor” and “AIDS and Its Metaphors,” Susan Sontag puts cancer in conversation with other culturally significant diseases, noting that in the 19th century, for instance,

while tuberculosis was the disease of the passionate and talented, cancer was the disease of the weak—of the “physically defeated.” Those with cancer were not the ‘warriors’ they are today. They had no chance at a ‘fight’ to begin with, not even metaphorically. Cancer patients were essentially less-than, and therefore, their cancer was, in a sense, justified.

Sontag traces the history of metaphor in Western medicine from its supposed beginnings in ancient Greece, where the arts highly influenced medical language. The use of the term “harmony” as a metaphor to describe the way a body’s components should operate together was criticized by Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius for implying equal importance of every organ to keep a person alive, which is a medical inaccuracy. Architecture, often infused with militaristic connotations, has also been used as a metaphor for the body, with words like “fortress” accompanied by the metaphoric ‘invasion’ or ‘siege’ to describe illness inhabiting a body. In 1627, John Donne wrote that the exanthematic typhus entering his body was a “cannon” that “batters all, overthrows all, demolishes all.” Modern medicine’s use of metaphor is highly specific and can be credited, in part, to Rudolf Virchow’s Cellular Pathology, which explores how disease functions through cellular changes specifically. This understanding of disease necessarily relies on a higher level of scrutiny in medicine, giving cellular pathology— and Western medicine in general—a new kind of credibility. Once it became accepted that diseases were caused by specific microscopic organisms, the “invader” metaphor no longer applied to the illness alone, but also to the thing that caused the illness.

It is through this specificity and new understanding of disease that the military metaphor in Western medicine gained more integrity and legitimacy. Sontag argues that Western medicine sees disease as “an invasion of alien organisms, to which the body responds by its own military operations such as the mobilizing of immunological ‘defenses,’ and medicine is ‘aggressive,’ as in the language of most chemotherapies.” This language creates a kind of “war-making,” as Sontag calls it, effectively creating the war on cancer in the public sphere, which necessarily calls for zeal in our collective battle against this enemy. When the ‘foreign body’ invades our own, we must ‘take action.’ Something like cancer is ripe for “war-making” because of its pervasiveness and, in the words of author S. Lochlann Jain, its status as a “central trauma of U.S. culture.”

The intense and militarized language used when speaking of cancer has, in part, made it possible for cancer to actually be spoken about in the United States, and, in turn, become visible. This language has given us an understanding of disease as ‘the enemy’ or a ‘foreign invader’ that we might have the power to ‘fight.’ In a country where Uncle Sam is the most important man in the family, we can better grasp this thing that is disease, or cancer specifically, if it is militarized linguistically.

It is undoubtedly a good thing that the word “cancer” can now be uttered freely and seemingly without the stigma, but the pendulum has swung so far in the other direction in American culture that the country that once shunned the word has now become its loudest, proudest, and weakest adversary. The explicit language of cancer as the disease of the “physically defeated” has been replaced with calls for the individual with cancer to ‘fight,’and ultimately win, the

‘battle’ against the disease, creating a different kind of stigma. Through the understanding of disease that this language fabricates, both having the cancer and curing the cancer is, at least in part, the patient’s responsibility. The constant visibility and the persistent “war-making” obfuscate both the experience of having the disease and the reality of what the disease might mean for the individual with it.

Today, cancer is the “biggest disease on the cultural map,” and “breast cancer has blossomed from wallflower to the most popular girl at the corporate charity prom,” argues Barbara Ehrenreich in her essay “Welcome to Cancerland,” a critique of the “pink kitsch” of breast cancer awareness that has flooded the United States. Symbols of breast cancer are everywhere, from pink ribbons to teddy bears to lingerie. In this way, the U.S. has become “Cancerland.”

BMW, one of the world’s largest automotive companies, has been a ‘champion’ of cancer research and funding for decades. In the early 2000s, the company offered test drives of sports cars to raise money for cancer (“a dollar a mile”) while imbuing their dealerships and marketing tactics in a pink hue that screams of fierce optimism. This past October, BMW hosted a raffle for the National Breast Cancer Research Institute, through which contestants could win a new BMW X1 Plugin Hybrid with the purchase of a €20 ticket. Ford, too, promotes itself as dedicated to “empower[ing]” those “touched” by cancer through an initiative called “Ford Warriors in Pink.” On their website, these words take center stage: “Ford has been active in the fight against breast cancer for 30 years and has dedicated more than $139 million to the cause… Through the sale of Ford Warriors in Pink inspirational wear and gear, Ford helps provide transportation solutions for patients in need” and “Bang the drum loudly. This is war.”

emitted through the tailpipes of gas and diesel vehicles. Creating personal responsibility for getting cancer and/or ‘beating’ it really is one of the cruelest jokes capitalism plays, and it plays it well. While BMW and Ford offer test drives and transportation to ‘fight’ cancer, their very own products actively help create it. In 2007, Jain, a former breast cancer patient, wrote: “If I die of cancer—forget burial—just drop my carcass on the steps of BMW Headquarters.” These companies promote individual action and responsibility, camouflaging their own culpability as ‘care,’ all while filling the air with militaristic language rooted in a history of stigma.

Perhaps the use of pink kitsch is an earnest attempt to bring a little light into what is, for many, an extremely dark part of their life. Perhaps there is an honest-to-goodness optimism people gain from wearing the bracelets and test driving the sports cars to ‘fight’ cancer. I am not of the mind to condemn that, especially if people with cancer find comfort in these activities. There is something missing, though, from these depictions and awareness-raising tactics that rely on pink kitsch: the presence of grief and a sincere reverence for the potential, or reality, of death. Cancer is so visible, so mediated, so metaphorized that it is almost unrecognizable as the torturous disease that it so often is.

+++

“I am not feeling very hopeful these days, about selfhood or anything else. I handle the outward motions of each day while pain fills me like a puspocket and every touch threatens to breach the taut membrane that keeps it from flowing through and poisoning my whole existence.”

– Audre Lorde, The Cancer JournalsWhen I was five years old, I was introduced to a man named Jon. He was my mom’s new boyfriend, and I was not too keen on his presence at first. I learned very quickly, though, that this strange man was more like me than anyone, and he understood me the way nobody else had. When it comes to stepparents, that sort of bond is about as lucky as it gets. I was lucky.

Before I could drive, he would take me to school in the mornings. We’d either flip through the radio or listen to the Beatles’ Anthology 2 CD he had in his car, discussing the intricacies of every little detail of every little song. We’d marvel at those crude but brilliant demos, counting our blessings because we got to hear something amazing. He would say things like, “Are you kidding me? WHAT?” and “Who writes this?” while dodging in and out of LA traffic to get me to school on time. It was a simple practice but some of the most fun I’ve ever had. It was on those drives that I finally started to understand that the man who was my stepdad was really my dad.

These seemingly generous acts of corporate care conveniently mask BMW and Ford’s own responsibility for the cancer they aim to ‘fight.’

In 2012, the World Health Organization and the International Agency for Research on Cancer published a study on diesel exhaust’s contribution to lung cancer. In 1988, diesel exhaust was understood as “probably carcinogenic” to humans; after this 2012 reevaluation, there was no longer any probability or uncertainty in the IARC’s findings. Benzene and formaldehyde, two known carcinogens, are both used in automotive manufacturing, and formaldehyde is

In 2020, my dad was diagnosed with transitional cell cancer. Then, for a couple years, the roles reversed, and I was the one behind the wheel, playing tracks like “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” and “I’m Looking Through You,” desperately trying to engage, in any way I could, with someone whose body and mind were hurting and changing to a degree that I cannot describe. Through these years of doctor’s appointments, misdiagnoses, brutal chemotherapy treatments, the ups and downs of my dad’s days became, quite literally, matters of life and death. Constantly on edge for two years, my dad ‘fought,’ like he was told he was supposed to. I hoped that if we just kept listening and

Admittedly, it is easier to grapple with something as awful as cancer if you cover it with pink and cake it in militaristic zeal. The reality of cancer, then, is not at the forefront of ‘awareness’; rather, it is the very accessible and comfortable aesthetic of pink kitsch which has made breast cancer the symbol in popular culture for cancer generally.

listening, all of it would go away. What started in 2019 in his kidney (which he had had removed) spread to his lungs, then to his knee, then to his brain. In 2022, he died.

+++