Volume Issue 05 May 2023 the 03 AN IMPERIAL ORDER 10 WHAT WOULD I DO 11 ATHENS IN RHODE ISLAND THE IRREVOCABLE ISSUE The College Hill Independent * 46 10

From the Editors

The first issue of Volume 46, Z, L, and I (E) sat in Conmag, wracked with indecision about writing our first ever FTE. We weren’t sure what we had to say, we were nervous our writing wouldn’t stand up to SJC’s excellence, and we didn’t really know each other. We each hunched over our own computers in tortured silence, and at the end produced three incredibly different pieces (soup, armadillos, ghosts). We threw them on the same document, agreed they complemented each other in their differences, and then called it a 4am day.

This evening, we’re once again sitting in Conmag, wracked with indecision about our last ever FTE. It’s different this time, though—we’re bad at saying goodbyes, allergic to sap, and have so much to say that it’s hard to know what to leave out. We’ve resorted to disjointed fragments: a HAGS here, a banana there. Though we wrote together earlier this evening, listing thank yous to our Vol. 46 stalwarts, we’ve begun to drift to our own corners of this Google Doc to craft our own answers to this impossible question. Three pages of potential issue titles (The Abalone Issue, anyone?) above me, Zach writes silly but somehow beautiful verse on our tenure. I can’t tell if he’s serious and I think neither can he. At the same time, above her compilation of special items (What’s In My ConMag?), Lucia drafts a mysterious and nocturnal goodbye.

Perhaps it couldn’t ever have been otherwise. I thought, over ten issues, we might find a unified editorial voice, but I think I like this better. In classic ZEL fashion, we’re better when we do our own thing, together.

Masthead*

MANAGING EDITORS

Zachary Braner

Lucia Kan-Sperling

Ella Spungen

WEEK IN REVIEW

Karlos Bautista

Morgan Varnado

ARTS

Kian Braulik

Corinne Leong

Charlie Medeiros

EPHEMERA

Ayça Ülgen

Livia Weiner

FEATURES

Madeline Canfield

Jane Wang

LITERARY

Ryan Chuang

Evan Donnachie

Anabelle Johnston

METRO

Jack Doughty

Rose Houglet

Sacha Sloan

SCIENCE + TECH

Eric Guo

Angela Qian

Katherine Xiong

WORLD

Everest Maya-Tudor

Lily Seltz

X

Claire Chasse

DEAR INDY

Annie Stein

BULLETIN BOARD

Mark Buckley

Kayla Morrison

SENIOR EDITORS

Sage Jennings

Anabelle Johnston

Corinne Leong

Isaac McKenna

Sacha Sloan

Jane Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Tanvi Anand

Cecilia Barron

Graciela Batista

Mariana Fajnzylber

Saraphina Forman

Keelin Gaughan

Sarah Goldman

Jonathan Green

Sarah Holloway

Anushka Kataruka

Roza Kavak

Nicole Konecke

Cameron Leo

Abani Neferkara

Justin Scheer

Julia Vaz

Kathy/Siqi Wang

Madeleine Young

COPY CHIEF

Addie Allen

COPY EDITORS / FACT-CHECKERS

Qiaoying Chen

Veronica Dickstein

Eleanor Dushin

Aidan Harbison

Doren Hsiao-Wecksler

Jasmine Li

Rebecca Martin-Welp

Kabir Narayanan

Eleanor Peters

Angelina Rios-Galindo

Taleen Sample

Angela Sha

Jean Wanlass

Michelle Yuan

DEVELOPMENT COORDINATOR

Angela Lian

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Kian Braulik

Angela Lian

Natalie Mitchell

WEB MANAGER

Isaac McKenna

WEB EDITORS

Hadley Dalton

Arman Deendar

Ash Ma

GAMEMAKERS

Alyscia Batista

Anna Wang

*Our Beloved Staff

Mission Statement

COVER COORDINATOR

Zora Gamberg

DESIGN EDITORS

Anna Brinkhuis

Sam Stewart

DESIGNERS

Nicole Ban

Ri Choi

Ashley Guo

Kira Held

Xinyu/Sara Hu

Gina Kang

Amy/Youjin Lim

Andrew Liu

Ash Ma

Tanya Qu

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Anna Wang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Sophie Foulkes

Izzy Roth-Dishy

ILLUSTRATORS

Sylvie Bartusek

Lucy Carpenter

Bethenie Carriaga

Julia/Shuo Yun Cheng

Avanee Dalmia

Michelle Ding

Nicholas Edwards

Jameson Enriquez

Lillyanne Fisher

Haimeng Ge

Jacob Gong

Ned Kennedy

Elisa Kim

Sarosh Nadeem

Hannah Park

Luca Suarez

Yanning Sun

Anna Wang

Camilla Watson

Iris Wright

Nor Wu

Celine Yeh

Jane Zhou

MVP ZEL

The College Hill Independent is printed by TCI in Seekonk, MA

The CollegeHillIndependent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and selfcritical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

01 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 00 “INFINITIES” Evelyn Tan 02 WEEK IN NIGHTS Cameron Leo & Daisy Zuckerman 03 AN IMPERIAL ORDER Tanvi Anand 05 A VISIT FROM MY BOYFRIEND Annie Stein 07 SEBALD AND ME Karlos Bautista 10 WHAT WOULD I

Leo Gordon 11 ATHENS IN RHODE ISLAND Kian Braulik 14 TOE TAGS 17 “WIGGLE YOUR TOES...” Quinn Erickson et al. 18 UP INDIE AIR Annie Stein

BULLETIN

DO

19

Mark Buckley & Kayla Morrison This Issue

46 10 05.05

- ES

Letters to the editor are welcome; scan the QR code here or email us at theindy@gmail.com!

NIGHTS

others.

WEEK IN

Directors’ Cut

I walk half-announced into the Olney House dorm room of directors Aidan Blain and Jonathan Green. They’re pacing across the floor in velvet pants and patterned button-downs and peering sporadically into their mirror. The pair’s first independent film, Tigers and Sparrows, is premiering at the Avon Cinema in two hours. The air is manic, their gazes bewitched.

“We’re trying on our outfits,” Aidan says. “We look different enough, right?” I tell them yes mostly because it is time for the interview. “Should I change into less pink socks?” Jonathan asks, glancing down as we take seats criss-cross-applesauce on the floor. “No, no, no one’s gonna see your fucking socks,” Aidan replies.

+++

When I envisioned the conception of Tigers and Sparrows, I liked to imagine the two of them, lying across from each other in matching pajamas, eating marshmallows while they exchange abstract artistic visions. When I describe my platonic ideal of the film’s genesis, the pair is insulted. “Okay, how did it happen then?” I ask.

“Well, we were biking next to each other on the west side of Manhattan. And, I don’t know, we sort of started passing ideas back and forth. It was raining,” Jonathan says.

“It was raining. That sucked,” says Aidan.

“We were like, ‘What if there was a manager of a band?’ We were like, ‘Oh, we like bands. We like music.’ ‘What happens to him?’ ‘What if he’s getting fired?’ ‘Oh, that’s interesting.’” After the ride they ended up, to my endless delight, back in a bedroom for a sleepover.

“I very much remember this moment of sitting on your bed,” Aidan said. “And we were kind of brainstorming. I remember I just started kind of, like laughing, crying, you know, when you, like, get an idea. I was like, ‘What if it’s like Boogie Nights?’ You remember that moment?”

“Yeah,” Jonathan says, eyes aglow. “I can remember exactly that moment.”

“When I first read the script, I was like, what the hell is this,” Anna Davis, who co-starred in the film with Homer Gere, reflected. “It is very Boogie Nights, I’ll give them that.” To describe the plot would be a disservice. It is music—silence—cowardice—sex—noise—fear— rebirth. A man hits rock bottom then sinks to unseen magmatic depths below. An artist seeks something more primal. A band plays.

The film was produced over seven sub-freezing night shoots spanning from October to December. They were working with no budget, a crew of 15-odd students, and gear they planned to return to Best Buy.

“In all honesty, we were drunk for a lot of it,” Anna says. “A lot of arguing was going on, especially during those first few shoots,” she adds.

Aidan recalls filming the movie’s climax: “[Jonathan] wanted to shoot it all still, like

Apocalypse Now. And I wanted to be moving around in a circle the whole time. I remember getting really snappy with each other. ‘Cause we were just like, ‘You don’t understand what I’m seeing.’” Jonathan nods.

“But the moral of that part of the story,” Aidan concludes, still cross-legged on the rug he shares with Jonathan, “is that we ended up having the beginning part be still shots and the end be moving shots. And that makes it perfect because it builds. So my idea alone wouldn’t have worked. His idea alone wouldn’t have worked. But together, they worked.”

+++

The air on Thayer buzzed frenetically. Six weeks before, the directors had secured the theater for the movie’s premiere screening in a short phone call with Avon owner Richard Dulgarian. That night, the line for entry extended down the block—over 300 people purchased tickets for the 17 minute screening. By the end of the night, the movie had raised over $1000 in donations to the Avon.

As the lights dimmed, the crew and I were restless and crazed. We giggled incessantly while the Avon’s old-fashioned concessions cartoon played, then fell to rapt silence when the film’s opening credits displayed. Then, roaring sound filled the theater—a concert filmed in the crew team’s basement showed Ian Stettner, who plays the band’s cocky lead singer, gruffly shouting lyrics from a Strokes song.

Three minutes into the film, anxiety was subdued by pride and awe. “Okay, this is really good,” I whispered to a friend. Jokes landed, laughter abounded. It was visually stunning, in no small part due to the camera work of cinematographer Izzy Roth-Dishy. The chaos that marked the film’s production had given way to a piece of art that was dynamic, offbeat, and brimming with raw energy. -CL

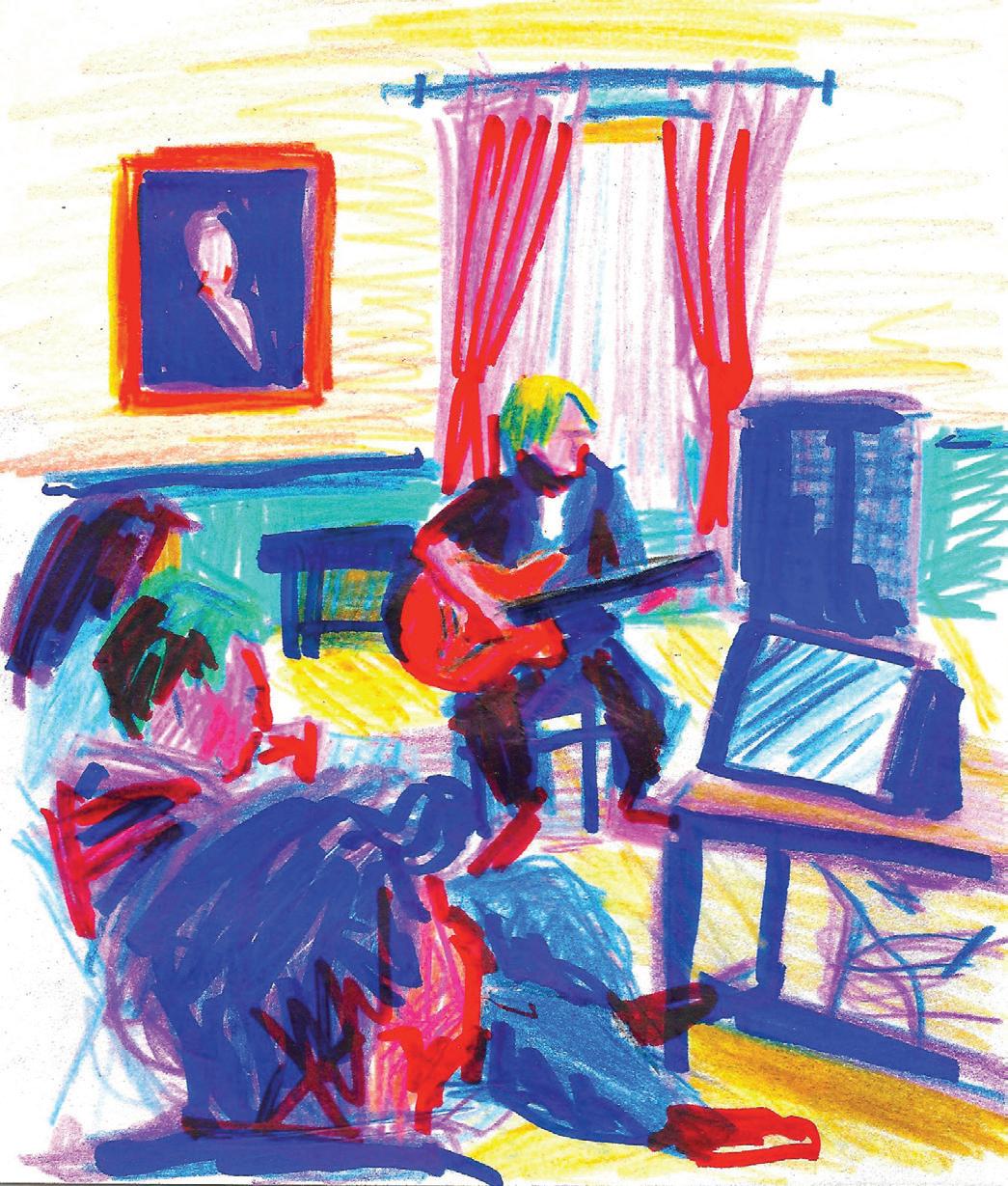

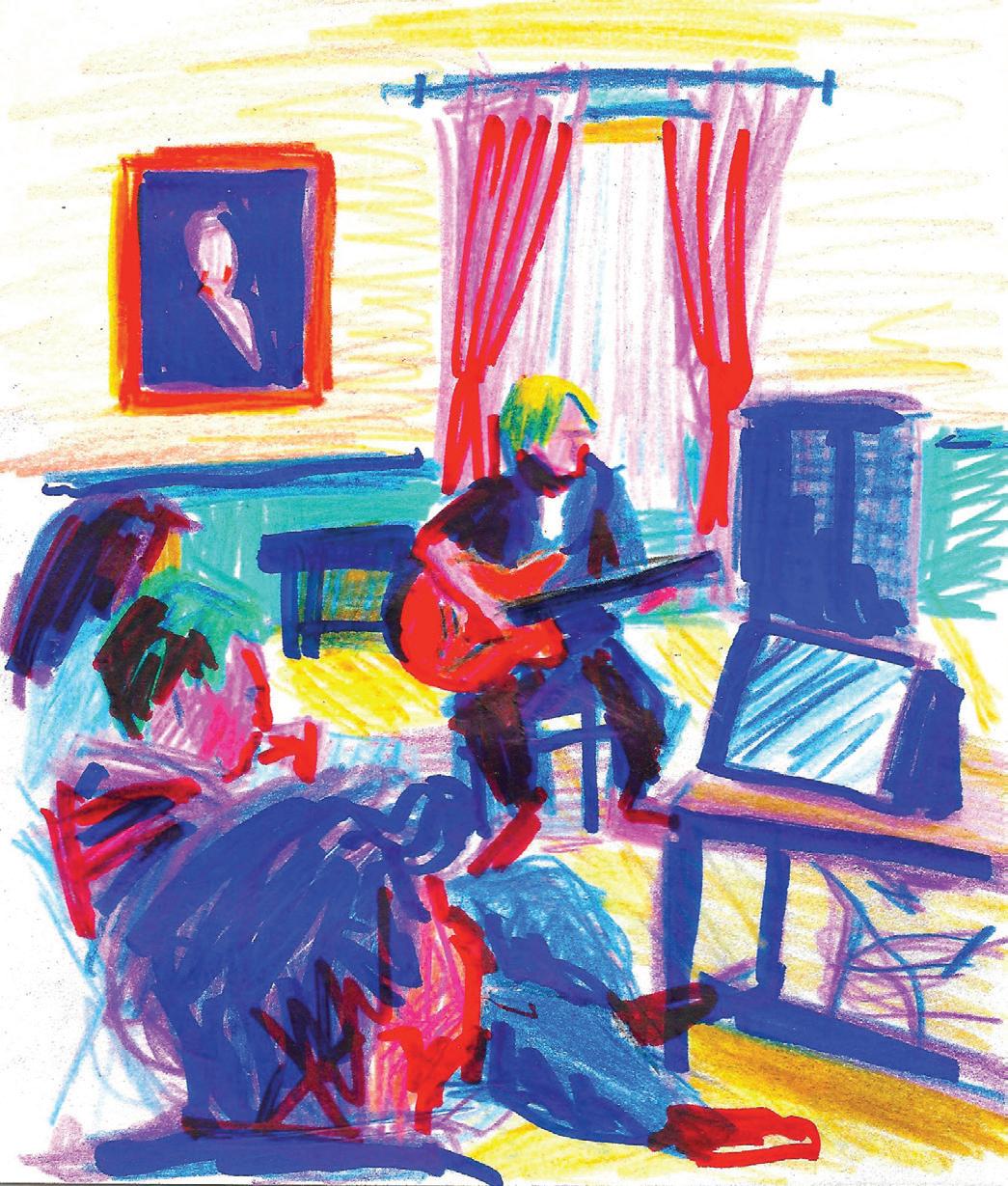

Electric Hour

Never did I expect to find myself, on a Monday evening, sitting in a plastic folding chair listening to improvisational jazz and slam poetry in a Neo-Georgian manor home. But there I was. Perched on the steep block of Meeting Street between Prospect and Congdon, the Music Mansion is a converted house originally owned by classical pianist and patron of music Mary Kimball Hail. She’d long dreamed of a home featuring a performance space, and in 1928 architect Albert Harkness brought her fantasy to life. Just before her death, Hail bequeathed the Mansion to the Providence community as a space for the public to enjoy music. Today, it’s run by a nonprofit and receives funding from The Champlin Foundation and the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts, among

One evening last spring, intrigued by the Mansion’s vine-covered stone arch and plaque, Brown sophomore Karim Zohdy wandered into a jazz concert. Soon after, he began organizing student performances in the building’s Concert Hall. Karim reached out to Brown senior Chance Emerson—a folk-rock singer-songwriter from Hong Kong and prominent figure in the campus music scene— about putting on a concert. But Chance, having performed on campus many times over the years, proposed a singer-songwriter show instead.

Cut to a roomful of Brown students spilling out the doorway of the Concert Hall. What Chance and Karim had expected to be a one- or two-time gathering turned into a six-part series. Electric Hour—“an artist showcase for busy people,” as Chance puts it—featured student musicians (and, as of April 24, poets!) from all years, many of whom had never before performed in public.

With its high, cherry-wood ceilings, turquoise wainscoting, and floral curtains, the Concert Hall is undoubtedly a warm, welcoming space. Chance hoped that the civilized yet informal environment would help musicians with minimal performance experience feel comfortable in front of an audience.

When sophomore Tabatha Hirsch took the stage on April 10, she prefaced her set by explaining that it was her first performance at Brown—saying, in other words, Please lower your expectations. But, smiling coyly, she proceeded to play two original songs, and as the performance wore on, her stage fright wore off. Strumming her guitar as she sang a folksy ballad called “Maybe Love,” she urged audience members to sing along—and, against all odds, we did.

A week later, in 10 minutes of improvisational jazz, junior Leo Major effortlessly switched between saxophone and piano while senior Gabe Toth accompanied him on drums. They seemed to communicate telepathically, seamlessly transitioning from slow, drawn-out moments to quick, staccato beats.

The following Monday, in the last show of the series, sophomore Alice Jokela shared two poems, “postbellum castles” and “therapized.” Her soft yet confident voice captivated the room as she reminisced on her childhood, invoking a “house draped in pomp and Spanish moss,” tinfoil saved from Hershey kisses, and baby teeth “[metamorphosing] into silver dollar coins.”

Reflecting on his inspiration for the series, Chance explained that “the hardest leap was going from on-campus stuff, like playing in basements, to getting off-campus and into Providence.” By working with a non-Brown-affiliated building and donating all of the money raised to AS220, a nonprofit arts center downtown, he hoped Electric Hour might begin to bridge the gap between the school’s music scene and that of the city more broadly. And while there’s still some work to be done, the audiences did include students from RISD and Johnson & Wales, Providence locals, and, says Chance, “some kid just passing through Providence who saw it in an Eventbrite.”

He and Karim plan to start the series back up in September, and they’re already brainstorming how they might continue to foster those connections. “Hopefully we’ve made it a space where people want to get involved,” Chance says. “We don’t want it to be just an extension of our bubble.”

02 VOLUME 46 ISSUE 10 WEEK IN REVIEW TEXT CAMERON LEO & DAISY ZUCKERMAN DESIGN ANNA BRINKHUIS ILLUSTRATION SYLVIE BARTUSEK

-DZ

A N I MPERIAL ORDER

America’s #1 Restaurant Is INDIAN! But Is It Authentic? is the title of Karl Rice’s viral 2022 YouTube video in which he judges the authenticity of Chai Pani, the James Beard-award-winning restaurant in Asheville, North Carolina. Rice, a YouTuber from New Zealand whose channel “Karl Rock” has almost 2.6 million subscribers, had made the journey to Asheville from Mumbai to compare the acclaimed restaurant to “the real thing.”

Karl Rice seems to be obsessed with the Indian subcontinent. Even after being blacklisted by the Indian government for almost two years due to visa agreement violations (he was partaking in commercial activity on a tourist visa) he still returned to the country in April 2022 to live there with his Indian wife. His YouTube channel revolves entirely around the region, and he has positioned himself as an ‘expert’ on the matter, even writing a book titled India Survival Guide.

He stands now in front of the restaurant in Asheville, still slightly groggy from the 26-hour journey he endured to get there from Mumbai. He shows us the inside of the building. The bare concrete walls are painted with colorful Hindi slogans and the welded-metal chairs serve a more aesthetic than practical purpose. Chai Pani’s interior cements the restaurant firmly within the milieu of millennial-chic eateries while simultaneously replicating the ambiance of an Indian canteen.

The eatery is bustling. In the video, he inserts a montage of the people lining up to eat at the restaurant, which snakes around the block. While he’s in line, a couple behind him gives him glowing reviews of the restaurant—they’re regular patrons of this establishment.

But Rice remains apprehensive. After he studies the menu, he hopes out loud that he will not encounter “whitewashed” Indian food at this restaurant. “Let’s hope that it’s authentic, let’s hope that there’s no fusion business going on here… Indian food don’t need fusion. I just want to eat authentic Indian street food,” he says.

+++

Karl Rice’s yearning for an “authentic” Indian dining experience is not a sign that he is the well-traveled, cosmopolitan white guy he portrays himself to be. Rather, he is reproducing a colonial tale, one that can be traced to the conception of Indian restaurants in the West.

The history of Indian restaurants is one defined by empire. Indian restaurants outside of India were started for (and sometimes by) those who had been to India to advance the colonial project. The first known Indian restaurant in the West opened in London in 1809. Founded by Sake Dean Mahomed, a Bengali entrepreneur, the “Hindostanee Coffee House” sought to attract English nobility “with a taste for India” after their excursions to the British colony. The restaurant’s interior was lavishly decorated so as to remind the patrons of their exotic travels. In a similar vein, the oldest surviving Indian restaurant, Veeraswamy, allowed ex-colonials to relive their Indian fantasies by calling waiters “bearers” and being called “Sahib” in return. Both restaurants emphasized the fact that they were serving the real foods from India, not a flimsy, anglicized imitation.

But there is no true ‘authentic Indian food’ from a subcontinent with dozens of regional variations where two dishes with the same name can have immensely different flavor profiles. The food that we think of now as ‘Indian’ most closely resembles the dishes served in New Delhi (in the North of India), but restaurants have always had to alter their dishes to suit British tastes. The vocabularies of Indian cuisine are dense, impossible to translate into a Western context and therefore must be homogenized into something more easily digestible. It’s a consumptive colonial fantasy; much like the spice ‘trade’ itself and the networks of colonialism that pushed British people to settle on the subcontinent, India’s resources were violently extracted and neatly repackaged for the leisure of the British elite.

In his seminal book Orientalism, Edward

Saïd introduces the reader to the Orientalist, a colonial-era “expert” on the dealings of the Orient. The Orientalist “knows how they [the people from the “Orient”] feel since he knows their history, their reliance upon such as he, and their expectations… [Those in the Orient] are a subject race, dominated by a race that knows them and what is good for them better than they could possibly know themselves.” If we understand Karl Rice as a modern-day Orientalist, his obsession with Indian culture and “authenticity” can be seen not as an eccentric yet benign fascination, but rather as revealing a more insidious reality of hegemonic power relations. Edward Saïd writes about the perverse desire of the Orientalists to capture the “true Orient.” This essentializing notion reinforces the “exotic” nature of “the Other” by implying that it is enigmatic and a worthy conquest to capture. The impulse to chase and validate an “authentic” culinary experience is thus intertwined with the desire of the Orientalists.

+++

Karl places his order. When the server repeats his order back to him, Rice remarks that the (American) staff need to “work on the pronunciation of these dishes… they’re pronouncing everything quite, quite wrong.” Rice prides himself on his command of Hindi—he sprinkles Hindi expressions throughout this video and has a whole series on his channel where he “surprises” Indians by speaking to them in Hindi.

The drink arrives. It’s mango lassi—a classic. He examines the glass in front of him, picking it up and turning it around so that he can get a comprehensive view. He samples the drink, taking small sips. He’s not the happiest. “This drink should be made by placing yogurt, fresh mango, and some sugar in a blender,” he says, “but I think they’ve just not used enough mango.”

As the starters and mains trickle through, he continues dissecting every morsel. “This

03 THE COLLEGE

INDEPENDENT WORLD

HILL

TEXT

TANVI ANAND DESIGN ANNA BRINKHUIS ILLUSTRATION JANE ZHOU

OnIndian Food, Orientalism,and ‘Authentic ity ’

spice mix is not quite right... In India, you can get this for 90 rupees—at this restaurant, the same dish is 800 rupees… This hasn’t been exactly what you’re going to taste in India…” Even though he does not certify the food as authentic (he gracefully gives us an exact figure—apparently “it’s 70 percent there”), he still claims that the food is “very tasty.”

+++

Figures such as Karl Rice have existed since the beginning of the European colonization of the subcontinent. The relationship between what is now considered “Indian cuisine” and the West is one that has transformed over time, yet has maintained the subordinate position of “the Other” relative to the Westerner.

Following the Second World War, Britain’s manufacturing industry was in disrepair. So, Britain turned to the Indian subcontinent as a source of cheap labor (mostly from the Sylhet region of what is now considered Bangladesh). A new type of “Indian restaurant” started to proliferate, serving South Asian factory workers in Northern English industrial towns instead of high-ranking colonial officials. White Britannia, facing record levels of unemployment, was frustrated by the post-war increase in migrants from former colonies working industrial jobs at low wages. They used these restaurants as a metonym for the South Asian diaspora itself: the scent of the “curry” was penetrating the “pristine” British air.

The further decline of British industry in the 1970s meant that those who had initially come to the U.K. to work in manufacturing were now displaced, and many turned to the restaurant industry as a last resort. Indian restaurants were presented as a cheap and convenient alternative to fish-and-chips shops for British families, and the notion of “going for an Indian” after a long evening at the pub became embedded in British culture. However, the imperial undercurrents fueling the initial desire for such restaurants remained. The economic uncertainty of the Brit-

ish state fueled nostalgia among the British public for the empire it once had.

As acclaimed author Salman Rushdie puts it, ’70s and ’80s Britain was in a state of “cultural psychosis, in which it begins once again to strut and posture like a great power while in fact its power diminishes every year. The jewel in the crown is made, these days, of paste.”

We are entering a new generation of Indian restaurants today, though. Corporate-hipster establishments like Chai Pani in the U.S. and Dishoom in the U.K. have given a new face to Indian restaurants, with menus mainly consisting of “street food” rather than the stereotypical curry and naan. Despite serving the dishes of the Indian working and middle classes, the ownership of this new wave of Indian restaurant is not working-class: Shamil Thakrar, founder of Dishoom (a popular Indian “street food” restaurant that seeks to replicate Irani cafés in Mumbai), graduated from Oxford and Harvard Business School before starting his business.

It’s a big departure from the small “curry houses” run primarily by working-class Bangladeshi immigrants, run instead by the Indian bourgeois. Yet, the adoption of Indian restaurants by “trendier” circles is not just a harmless form of cultural exchange, it is also a way for the white establishment to signal their elevated cultural capital.

As an “ethnic restaurant,” the Indian restaurant is a site of cultural consumption and when we talk about Indian restaurants, we are talking about race—whether knowingly or not.

As bell hooks puts it in her 1998 essay, Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance, “ethnicity becomes spice, seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is mainstream white culture.” The desire to “liven up” “mainstream white culture” reproduces the same colonizing journeys that were fueled by the spice trade, a “narrative fantasy of power and desire, of seduction by the Other.” This “fantasy” culminates in a desire to not only “make the Other over in one’s image but to become the Other.” It’s a relationship that is never decided on the terms of the Other but carefully plucked and curated when the white establishment pleases.

I discussed Karl Rice as an almost-hyperbolic figure, an extreme example of something that is ubiquitous. However, I still hear watered-down echoes of his sentiments about finding “authentic” Indian food by students on College Hill. I remember speaking to a white student at an event with catered Indian food from a local restaurant. They expressed a desire to have “authentic” Indian food instead of what was being served. I am not interested in dissecting whether the food in question was “authentic”; rather, I question what led them to assert that the food was ‘inauthentic’ in the first place—why are we so fixated with authenticity and who does it serve?

Indian restaurants have always had to perform to certain expectations of authenticity. These performances of authenticity are a form of “self-Orientalism,” which is a result of the Other’s internalization of the Orientalist images developed by the Western colonial hegemony. The Other then adopts and replicates the images. In order to appeal to the ‘tasteful’ white palette, Indian restaurants need to exaggerate their ‘otherness’ by decorating their spaces with ‘exotic’ imagery so that the restaurant is considered ‘more authentic’ to be validated by its clientele.

I’m back on YouTube, this time watching a different video. It’s a Kannada-language restaurant review for London Curry House, a restaurant in the Indian city of Bangalore that seeks to replicate the ambiance of London curry houses. The restaurant seems busy, and it’s in a posh four-star hotel. The restaurant reviewer shows us the menu: it’s shaped like a British King’s Guard, the menu items snaking around the outline of his figure. Miniature red telephone boxes are on a shelf alongside miniature reproductions of other London landmarks.

I pause the video to get a good look at the menu. It has many of the same dishes that Karl Rice ordered at Chai Pani as well as the dishes that are instantly recognizable as “Indian” in the West, including saag paneer, daal makhani, samosas, and mango lassi.

I went straight to Google reviews, eagerly awaiting the review of a well-traveled Indian claiming that the food is inauthentic and unlike the dishes they had at “real” curry houses in England. Not quite. The most scathing reviews criticized the wait times to get a table due to the restaurant’s popularity. Some also found the dishes to be too expensive.

My first instinct was to think of this ersatz English curry-and-rice establishment as a form of resistance: they are essentializing a rich Indian diasporic culinary tradition into a hodgepodge menu, much like the first Indian restaurants to open in the U.K. In reality, I see a game of broken telephone, impossible to parse. It’s a ‘British-Indian’ restaurant in South India. ‘British-Indian’ cuisine is trying to replicate food from North India, which is exotic to South Indians. ‘London Curry House’ does not label itself as a North Indian restaurant, though—its presentation is British. Among this incoherence, the impossibility of defining and demarcating the ‘authentic’ becomes glaringly apparent.

TANVI ANAND B’26 is craving garlic naan.

04 WORLD

+++

VOLUME 46 ISSUE 10

A VISIT FROM MY BOYFRIEND

to stop going through chairs and tables like this. It’ll be so nice to see his face, and to feel the hard plastic of a toothbrush so real in my hand––well, to feel my hand so real around a toothbrush––on the first try.

We’ve been together for a year and four months, and I really love him, and he loves me. The thing is that he’s a really good guy. He did this crazy thing for me on my birthday where he put together a scavenger hunt all over the city. What he did was leave a riddle in every place we really like to go together, and I had to solve them in order to figure out where to go next. Every time I’d figure it out (very quickly, because they were easy) he’d blush, and beam at me, and practically pull me by the hand all the way there. At each spot, like the concessions counter in the old-fashioned movie theater, or a specific bench in the park, he had hidden a little cardboard puzzle piece for me to find. At the very end, I put together all the pieces and it made a little square that said, in my boyfriend’s boyish, careful handwriting, ‘HAPPY BIRTHDAY. YOU ARE MY FAVORITE PLACE. I LOVE YOU.’ The only problem was that at one of the places––it was the little weird duck statue outside of the library––the little cardboard puzzle piece was missing, so the square actually said, ‘YOU ARE MY FAVORITE PLAC.’ He was really disappointed about it. I laughed, and said it added charm and that I loved it so much anyway, and I squeezed his hand and he smiled, but I could tell he really wished that piece had been there, even though he understood that I didn’t mind.

For that reason, I have not told (and will not tell) my boyfriend that I start falling through the furniture when he leaves.

He’ll be here basically first thing tomorrow, maybe before breakfast, even, which is good. Good because I obviously want to see him, and to feel his shoulder against my cheek when I hug him, as soon as possible, but also because this morning when I tried to make an egg the frying pan went right through my hand and fell on the floor and made a huge mess. When he’s here, I’m sure that won’t happen. It does make me really sad that he had to move away for his job, and I know it makes him sad, too. But beneath all of that, bigger than that, is how happy I am for him. He does really incredible work, the research he’s doing on a specific kind of cancer cell, and I’m always so proud to tell other people about it, the way he’s going to actually probably change the world. All day I think about his hands, which normally do things like gesture emphatically and rumple my hair, becoming very steady and serious while he works. I love to picture him like that. He’s really only an hour away by train. Last night I thought I might try to sit in a chair at the kitchen table. It was okay for a minute. Then my elbow went right through the table where it was propped up, and a moment later I was on the ground.

Two shattered wineglasses unfortunately compelled me to tell one of my friends about my problem. (My “corporeality problem,” my boyfriend would call it, if he knew about it, which he doesn’t.) I hadn’t seen her in a while. She sat with me on the floor so I could explain it to her. “I think it might just be you spending too much time alone here,” she said, helpfully. “Let’s go to the movies this weekend, okay?” I hugged her and it was an unwavering, solid hug. I didn’t really mention that I only had my goingthrough-things problem when my boyfriend wasn’t around, or that it happened the worst when I thought about him the most. It would have made things sound a lot more serious than they were. And what’s two shattered wineglasses, a toothbrush covered in lint, a dented frying pan, and a ripening tailbone bruise?

I’m trying to clean up, so that everything will look nice for when he gets here, but it’s proving a little bit difficult. The very hardest thing is making the bed. My fingers pass through the blankets and pillows like they’re steam––the blankets and pillows, that is, or, wait, no, my fingers. I really can’t wait to see him. He sounded a little strange on the phone this morning, actually, a little upset, not at me or anything, but just in general. Maybe about work, but I didn’t ask, because I know that sometimes it’s hard for him to talk about things that really upset him, it makes his throat start getting scratchy and he can’t look at anything, and so I didn’t want to push things. It hurt me, though, to hear his voice like that. I can’t stop thinking about him. I can’t stop thinking about this bed, either, whose pillows are all flat and uneven and whose blankets and sheets are rumpled because I just can’t touch them. I’m really trying, too.

+ + +

Things might have been a little easier if I were still in school, with lots of people and classes to think about, but all of that already feels far away. The apartment has been getting really hot this summer. I’m not exactly sure what the plan is for when I move out of here. I guess I’m waiting it out. My academic advisor really wanted me to meet with a career counselor before I graduated. I really liked my academic advisor, who was this very nice old lady who always offered me cookies, so I went and did one session with a career counselor. It went fine, or I at least acted like it was going fine for the sake of the career counselor. She sat at her desk with her hands folded so tight that I thought they might have been glued together (my boyfriend laughed when I told him that later). Her hair was trying hard to be blond, but it was limp and gray and bobbed to her chin. She was wearing a dark gray blazer but still sort of sweating through it.

She told me about multiple contacts and internships and opportunities based on what I had majored in, and gave me a piece of yellow paper listing all of those things, and I nodded and said, “Wow, great,” a lot of times, but the

truth was that I couldn’t see myself doing any of the things she was saying. If you really want to know, I couldn’t get excited about any of that stuff even close to the degree I got excited imag ining my boyfriend going to the job he loved so much. (At that point, he didn’t know he was going to have to move away for it yet. He hadn’t even gotten the job for sure, but he told me he just knew that he really aced his interview, and I could feel it––the job was his.)

I’m not hopeless, or despairing, about the world and my place in it––not at all. I walked out of the career counselors’ office smiling, and I folded the paper she gave me before shoving it in my bag.

+ + +

I did end up going to the movies with my friend, and it was really nice overall, but a few things were tough along the way, and it didn’t end so well. For one, we went to the old-fashioned movie theater, which is where my boyfriend and I love to go. We do the same thing every time, my boyfriend and I, where we guess what candy the other person is in the mood for, and we almost always get it right, and even when we don’t get it right we don’t get upset about it. When I went with my friend, I didn’t order anything because I knew what would happen. But my friend forgot about my little problem and handed me her popcorn without thinking, and for one second I really held it, and then it was a huge mess all over the floor, and I felt so terrible that I offered to help the employee clean it up, but she refused. We ended up seeing a really gritty action movie, the kind I don’t usually see, but I thought I might have liked it. I sat in the seat and everything, though I had to focus hard on the movie in order to stop my arm from going right through the armrest. It took a few tries. My friend nicely pretended not to notice, but I know she did. Before we left, I thought about how my boyfriend always holds my hand when we go to the movies, like we’re kids.

The worst part happened on the way home. Thankfully the taxi was going really, really slowly, because we had just started pulling away, when I felt myself slipping, through the seat and then through the floor of it, and then smacking into the pavement. I scraped the back of my elbow where it hit the ground. My friend looked really stricken, kind of terrified, when she opened the door and scrambled out of the taxi, which had screeched to a halt. She grabbed my hand (second try) and pulled me up. “Jesus,” she said, looking at me, and suddenly she seemed less terrified and more pitying, almost. “You have got to see someone about that.”

Even after the whole going-through-the-taxi incident, I didn’t go see anyone about my problem. I avoided the texts and calls of my friend for a little bit, too, which I’m not the proudest

05 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT

+ + +

+ + +

TEXT ANNIE STEIN DESIGN ANNA BRINKHUIS ILLUSTRATION JACOB GONG

of, but I felt like I was handling things more or less pretty well. Plus, I knew that she would start pestering me to seek some kind of treatment, and I didn’t feel like listening to some secretly condescending plea.

About a week or two after the taxi thing, I was having a pretty good day. I was repotting some of our plants, which admittedly might have been a recipe for disaster, but I had been feeling very solid recently. My boyfriend had told me that morning that he had to schedule some kind of last-minute meeting at work, so he wouldn’t have time to call during his lunch break. I was obviously sad not to be able to talk to him, but there wasn’t anything to be done about it, and I knew of course that he was okay, so I went and repotted some plants. It felt productive. It made me remember the kind of little projects I used to do a lot more of––like that bird feeder I made and hung up outside the apartment, or the sets of cloth napkins I used to embroider little flowers on, to use for things like dinner parties––when I had more focus and I could hold onto things better.

The next morning I opened my eyes, tried to sit up, and slammed my forehead into the bottom of the bed frame. I wasn’t sure how I’d managed to stay asleep while falling through my mattress and smashing into the floor in the middle of the night. The back of my head was already throbbing, and I could actually feel a really big bump forming under my hair. If it wasn’t gone by the time my boyfriend came, I’d have to make up some story of how I got it, and I really didn’t want to have to do that.

Sitting in the kitchen (on the floor), holding a bag of ice to the back of my head (you wouldn’t believe how tedious it is to gather up ice cubes, which are already slippery, even if you have no issues holding onto things), I called my mom. I didn’t want to have to do it, but I thought she might understand. “Oh, I know that feeling, I do,” she said. “God, I think it must be genetic. It happened to me when I first started going out with Dad. Such an odd thing. Your great aunt had it for a while, too, when she was younger…hers was way worse, she was going through walls and sometimes the floor, too…what was I saying? Oh. You’re not going to like this answer, but I think you should go get it treated.” I started to protest, but she inter-

rupted. “Look, I know, I know. But in my day we just sat around and waited out something like this. Now, you have ways to do something about it! And you really don’t want it to get as bad as Aunty Kathy— two broken legs and nearly divorced before hers went away, for Pete’s sake. In the long run, you know, it’ll be better to take care of this now.” She paused for a second, and then, in a giggly, conspiratorial-sounding whisper, said, “Isn’t it a little bit fun, though?”

He’s running a little late, but he’ll be here any minute now. I just swept up the remains of my two breakfast plates with the little broom and dustpan that I bought, it only took half an hour, I dumped it all into the trash and then tied up the bag and threw it (three tries) into the bin outside. I’m so excited. I always get the same feeling when I see his face for the first time in a long time. It feels warm and light and very solid, and it’s been so long since my body has remembered it, which makes me sad, but I know it’ll come back right away, any minute now. He called when his train arrived and he texted me a picture of the license plate of the car that came to pick him up, because it was a funny one, it spelled something funny, only I’ve forgotten exactly what, but I smiled when I saw it, and he said he knew that it would make me laugh. How silly is this! I’m a mess, I’m sitting on the kitchen floor waiting for my boyfriend, and he’ll be here any minute now. I have to confess something. There was only one time where I even thought about maybe going to see someone about my little problem, and it was two nights ago.

I was sitting in bed, reading, right before I planned on going to sleep, when suddenly I wasn’t there. I can’t entirely make you understand what happened to me unless it’s happened to you, but I was sitting there with my book, though not completely focusing on any of the words, and suddenly I wasn’t sure where the outlines of my body were, and I could still sense the room around me but I could tell my body wasn’t in it, but my body also wasn’t somewhere else, it was just nowhere. I breathed but I couldn’t feel anything moving. The bed was below me, but where was I? I suddenly felt like I was surrounded by a thick pocket of heavy emptiness, but it wasn’t around my body, it was instead of my body. God, how silly this all

sounds now! I’m glad I didn’t go to see anyone about it, because my body came back from wherever it had been after about three seconds (certainly it had been somewhere, it couldn’t have just stopped), and then I was back, sitting sturdily in bed. That only ever happened that one time. And I won’t have to worry about it again once he gets here.

+ + +

I think he should be here. He’ll be climbing the stairs with his bag––oh––I’ll stand up in a minute to get the door. To be honest, I’m getting used to sitting on the floor. I think I even like it. At first it made my back hurt, this dull sort of ache in my shoulders, but now I can barely feel it. Since chairs have become so unreliable, I’ve been spending more time down here, especially in the kitchen, looking around at the apartment—looking up at the apartment, I mean. Now I know what the underneath of the kitchen table looks like, and it feels like special, secret knowledge. It makes me feel grateful, or even lucky. There’s something I didn’t say about that little episode two nights ago, which was that when I felt all my outlines disappear, I was afraid, a little, but mainly what I thought was––isn’t this so beautiful? Isn’t it something so rare, so sacred, to be so tethered to the one you love? Every wineglass through your fingers and toothbrush dropped to the floor––how special, how good it all felt, to know where you truly were, and where you weren’t.

He’s knocking––oh thank god he’s here––I’m going to go get him––let me just get my fingers around the doorknob––once––twice––

06 LIT VOLUME 46 ISSUE 10

ANNIE STEIN B’24 is feeling solid.

Sebald and

Dreams, ecology, history, and The Rings of Saturn

Brooklyn. Late spring, last year. Walking toward Prospect Park, I came across a book on the crimson brick of a stoop. Yes, I absolutely judged it by its cover—aquamarine with round cutouts of Saturn, a silkworm, and (what I would later discover to be) a detail of Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson. It was W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn I decided to take it with me to the park; I also chose not to start reading it immediately. I don’t exactly remember who I was with or what I was up to. Sebald’s book is the only record of that day (on the last page I figured to write, “Found in Park Slope, May 2022”). I didn’t get to reading the book for a long time, and I lost track of it for months. I forgot about its existence almost entirely, until my roommate mentioned that he had come across it in our apartment a few months ago, and had been keeping it on his desk. Interesting photographs, he noted—but altogether a boring read. After as many months as Saturn has rings, I decided to read it. Maybe because my expectations were low, maybe because I’m a contrarian roommate at times, I was surprised by the novel—even astonished. The writing was entrancing, phantasmagoric; at the risk of sounding cliché, it felt nearly impossible to put the book down. Its ghostly quality somehow felt tangible. It follows a peculiar trajectory perhaps analogous only to the logic of dreams. Like nearly all dreams—which we usually forget soon after waking—it felt like the novel was undercutting itself. Apparently forgettable moments are put down to pen despite their unremarkability. (If you were to grill me on the exact events of the novel, I’d be as successful as I would be at recalling a dream I had a couple of weeks ago.) The occasion for Rings is itself by the by. The novel starts: “In August 1992, when the dog days were drawing to an end, I set off to walk the county of Suffolk, in the hope of dispelling the emptiness that takes hold of me whenever I have completed a long stint of work.” The moment the novel concerns itself with is an in-between respite, incidental. The kind of walk you take after a long meeting before you have to get onto the next thing, the next stint of work.

Winfried Georg (he preferred Max) Sebald was a German writer and academic. He was born near the end of the Second World War in Bavaria. His father served in the Reichswehr and the Wehrmacht under the Nazis. The Holocaust and the aftermath of the Nazi regime would become central to Sebald’s writing and fiction, leading many critics and commentators to consider him a “prime speaker” of the Holocaust. Sebald’s scholarly pursuits

Me

took him from Germany to Switzerland to England, then back to Germany, then finally back to England, specifically East Anglia, where the narrator of Rings takes his walk.

While the back cover to Rings might lead you to believe that Sebald’s novel is about a walking tour through England with “things” that “cross the path and mind” of the novel’s narrator, it’s the walk that is incidental rather than the “things.” As much as the plot of Rings—if it can be said to have one—is about an extended journey across various landscapes, Sebald’s novel takes the following as (some of) its central interests: writers and their histories; historical miscellanea; the surprising, disturbingly banal underpinnings of colonialism; socioeconomic downturns; and environmental and ecological degradation.

The Rings of Saturn pursues its interests—and maintains its function as a work of unique travel fiction—through its presentation of photographs and its quotations of other writers and their texts.

Throughout the book, Sebald intersperses photographs, diagrams, and illustrations. Broadly speaking, the photographs and visuals serve one of two purposes: (1) They are photographs of locations and views Sebald’s narrator encounters during his walk—including coastlines, garden and forest paths, and buildings in small towns and villages. (More on these photographs to come.) Or (2) they are diagrams, illustrations, etc. that supplement, as it were, the narrator’s meandering musings about (to name just a few) the fishing industry in England and Germany, silkworm production, and the earlier-mentioned Rembrandt painting.

Sebald frequently makes use of lines from other writers and their texts, including: Sir Thomas Browne, Jorge Luis Borges, Joseph Conrad, and the 19th-century French aristocrat François-René de Chateaubriand. What’s curious about these quotations is that they appear without quotation marks, making it difficult to know where Sebald’s voice ends and where the words of others start—especially when Sebald quotes for multiple lines or pages. Although Sebald will include tags (e.g., “Borges writes”) to mark to whom words may belong, these appear infrequently.

For example, near the end of the novel, Sebald’s narrator is walking around Ditchingham Park, in the English county Chateaubriand stayed during the French Revolution. Sebald’s narrator—upon making the fortuitous connection between his own walk and Chateaubriand’s sojourn—gives some summary of Chateaubriand’s life in England, and his infatuation with the daughter of a vicar, whom he tutors. “He was aware that their studies brought them closer every day,” Sebald writes,

“and, convinced that he was not fit to pick up her glove, sought to conduct himself with the utmost restraint, but nonetheless remained irresistibly drawn to her.” The next sentence is a direct quote from Chateaubriand’s memoirs without any quotation marks, but it includes a tag from Sebald: “With some dismay, as he later wrote in his Mémoires d’outre-tombe, I could foresee the moment at which I would be obliged to leave.” The next four pages of the novel, and some pages after those, are straight from the Mémoires d’outre-tombe, minimally acknowledging that they don’t belong to Sebald’s book. Even if you know that a line is straight from some other text, it becomes difficult to disentangle the original sentiment from the one Sebald produces by quoting. For example, the forlornness of Sebald’s narrator is indistinguishable from Chateaubriand’s sentiment in his sentences about leaving his father and homeland for what might be the last time: “We drove up the lane by the fishponds, and one more time I beheld the mill stream shining and the swallows swooping across the reeds. Then I looked ahead, at the broad terrain that was now opening up in front of me.” Sebald rarely marks when a citation ends. The next paragraph (“It took another hour to walk from Ilketshall St Margaret to Bungay …”) carries on as if the citation didn’t happen. The “I” that should belong to Chateaubriand just as well belongs to Sebald’s narrator.

The result of this strategy in Sebald’s work, one keen critic notes: “The more one reads W. G. Sebald, the more one gets the sense that one is reading someone else.” The blending of

S+T 07 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT

TEXT KARLOS BAUTISTA

DESIGN SAM STEWART

ILLUSTRATION CELINE YEH

voices produces “a blurring of literary modes mirroring the ceaseless repetitions which weary Sebald’s narrator, who repeatedly notes the exact resemblance—even duplication—of people, places, and events.” The Rings of Saturn, like the Chateaubriand scene I described, propels itself by the careful attention to resemblances, regardless of temporal (and even spatial) difference. Walking in Ditchingham brings Sebald’s narrator back to Chateaubriand in the 19th century. A coastline near Lowestoft in England and the nearby fishermen lead Sebald’s narrator to remember watching films about the herring industry in Germany earlier in his life and then to muse about fishing generally. And so on and so on. The divisions across time and space between Sebald’s narrator’s location, his life, other writers, art, the lives of others, and historical events are permeable, the logic of their transitions greatly resembling the logic and progression of dreams.

Entering Sebald’s novel is like entering a dream. In dreams, real persons, places, events, and things meld together in surprising relations, going so far as to cohere into “composite” images, as Freud argues in The Interpretation of Dreams. In one of Freud’s dreams, for example, multiple patients that left him with a common, negative impression appear as a single person. Your dreams can represent all the train rides you’ve ever been on as one Amtrak ride. That one uncle turns into a friend’s roommate—or your third grade crush morphs into your high school ex-girlfriend. Dreams traffic in the overlaps— one might think of the middle spaces in Venn

diagrams—of our psychic experience. So too does Rings in its use of visuals and quotations. +++

Sebald’s book is a work ostensibly about the contours of East Anglia’s landscape and history and (obliquely) about the Holocaust. But what especially fascinated me about Rings was its relation to the ecological. Unlike the earlier Romantic poets—like William Wordsworth or Percy B. Shelley—who traversed the European mountains and country in search of an encounter with the sublime, Sebald’s narrator finds himself in inexorably vanishing land and seascapes, whether they be a coastline near Lowestoft or the forests of Suffolk. The Romantic poets— arguably one of the most well-known English ecologic literary and poetic movements—took landscapes as indestructible, instilling terror or awe to suggest the power of human thought. For Wordsworth’s “Prelude,” the immensity of a “blue chasm … through which / Mounted the roar of waters, torrents, streams / Innumerable, roaring with one voice” proves durable and awe-inspiring enough to suggest itself as the place where “Nature lodged” the grandness of the human soul. A mountain for Wordsworth can appear to be “The perfect image of a mighty mind, / Of one that feeds upon infinity” and can have a touch of the “sense of God.” But Sebald’s novel underscores the ephemerality of the ecological spaces it examines instead of imagining them as mirroring back human grandeur. This contrast is most viscerally felt in the

photographs of ecological spaces and their natural features in Rings—those photographs, as I mentioned earlier, that make Sebald’s book something of a travelogue. As Sebald’s narrator continues walking through Ditchingham Park (after thinking about Chateaubriand), he goes into detail about how the English nobility set up Ditchingham, planting trees and displacing residents and violently disciplining those who resisted. There then appears in the novel a photograph of Sebald’s narrator in front of a tree. “This picture was taken at Ditchingham about ten years ago, on a Saturday afternoon,” he writes.

The Lebanese cedar which I am leaning against, unaware still of the woeful events that were to come, is one of the trees that were planted when the park was laid out, and most of which, as I have said, have already disappeared. Since the mid-Seventies there has been an ever more rapid decline in the number of trees, with heavy losses, above all amongst the species most common in England.

Using the present tense is a matter of course in describing art objects, like photographs. But the “present” within the photograph is quickly undercut—not only by the passage of time, but by the human-inflicted environmental deterioration. The rapidity of the ecological degradation Sebald’s novel points out is sharpened by its interlocking with the dissolution of temporality at work in these lines and their interaction with photographs. Although this photograph, like others throughout the book, records natural spaces and features as if you could visit them yourself if you were in the area, the locales these photographs capture are either ones that are undergoing great degradation or, like the cedar, are already gone. As much as a photograph in a travelogue would like to assert its presence, assert that the place it captures is there for you to visit too, the photographs in Rings reveal that opportunity to be impossible. Moreover, the text that follows these travelogue photographs further exacerbates that impossibility. Rather than directly responding to photographs through positive descriptions (like those on museum plaques), Sebald’s lines challenge the status of each image.

The photograph of the cedar leads Sebald’s narrator to remember a different tree (photograph not included)—and again, like a dream, the photograph points to a surprising resemblance that takes the novel elsewhere: “One of the most perfect trees I have ever seen was an almost two hundred-year-old elm that stood on its own in a field not far from our house. About one hundred feet tall, it filled an immense space.” The tree is one of the last standing near him after the spread of Dutch elm disease from the south coast and into Norfolk. The tree seems to offer

08 S+T VOLUME 46 ISSUE 10

a permanence, but that permanence is revoked. This lone tree is doomed to a fate similar to its absent contemporaries. “Finally, in the autumn of 1987, a hurricane such as no one had ever experienced before passed over the land.”

Rather than describe the hurricane, the narrator details its aftermath: “The silence of that brilliant night after the storm was followed by the revving of chainsaws during the winter months.” The landscape is irrevocably altered. “Now, in the truest sense of the word, everything was turned upside down. The forest floor, which in the spring of last year had still been carpeted with snowdrops, violets and wood anemones, ferns and cushions of moss, was now covered by a layer of barren clay. The rays of the sun, with nothing left to impede them, destroyed all the shadeloving plants so that it seemed as if we were living on the edge of an infertile plain.”

More devastating than the ravaged appearane of the terrain is the annihilation of sound. Where a short while ago, Sebald’s narrator remembers, “the dawn chorus had at times reached such a pitch that we had to close the bedroom windows, where larks had risen on the morning air above the fields and where, in the evenings, we occasionally even heard a nightingale in the thicket, its pure and penetrating song punctuated by theatrical silences, there was now not a living sound.” Sebald here masterfully displays a great virtue of literature and poetry: the ability to make the intangible tangible through language. Sebald does this in such a way that not only retains the ephemerality of the intangible, but makes it paradoxically there. What is set in writerly stone, as it were, is the looming impermanence of nature. Theodor W. Adorno praises literature and art that offer a “determinate negation of empirical reality.” With these terms, Adorno is suggesting that art should have a rigorous sense of the world it inhabits, or is made from, and in turn direct a resistance to the status quo. Adorno arrives at this notion of art from his earlier 1949 dictum that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Many readers (including Adorno himself, at a time) took this dictum to mean that there should be no more poetry—or art for that matter. But for the later Adorno, it is only through this type of negative framing that we can arrive at something else, some other positive sense of what writing poetry should achieve. Rather than being complicit in barbarism, or being barbaric itself, poetry and art, so Adorno’s later thinking perhaps suggests, should reveal the barbarism and cruelty in our world.

The Rings of Saturn constructs correspondences across historical periods, alerting us to current barbarism and how it has endured. Sebald’s novel, for example, ties the despotic origins of the production of silk in China to silk production under the Nazi regime to, in turn, obliquely consider the full implications of “that peculiar thoroughness” German fascists brought to silk starting in 1936. But the ability

to trace that strand requires a certain sense of equivalence and mutability between places and times that can blur particularity and, at worst, trivialize great trauma—one thinks of Adorno’s scorn for those who would seek to compare Auschwitz to the Dresden firebombings based on the number of those murdered. It would seem that comparing and equating comprise the order of the day. This is nothing new. As crisis follows crisis, each seems to blend and disappear. Now, our imagination resorts to asking, when looking back at the all-too-recent past, “Which forest fire?” “Which tornado?” “Which earthquake?” “Which hurricane?” The Rings of Saturn, more than resisting the condi tions behind empirical reality, shows how ecological spaces are being negated seemingly digressive citations and paradoxical travel photographs, Sebald’s novel reenacts the ongoing degradation of the ecolog ical spaces it takes interest in. In many ways, the degradation of the ecological spaces in Sebald’s and our world resembles the dissolution of our relationship to history. The logic behind our sense of history parallels the dynamics of ecological deterioration as Sebald’s novel describes them. As much as our unconscious is able to record all of our experiences and impres sions (as Freud claims) to make surprising composite images possible in dreams (and neuroses alike), as much as Sebald can weave together disparate associations into poignant narrative strands, as much as we believe that our human knowledge and power is inde structible, eternal—our efforts toward remembering, recalling, and preserving can just as well become the basis for forgetting. lenges us to consider whether or not compar ison, or metaphor, is truly barbaric. We need to use metaphor to reveal its insufficiency to account for the scale of catastrophe.

I would have been pleased to follow Sebald’s steps across East Anglia myself. Instead, earlier this winter, I found myself in Prospect Park once more. There weren’t any leaves yet. For a few moments, I decided to sit on a bench close to the one I must have sat on the summer before while I was waiting for a friend for dinner. I hadn’t remembered that summer day until I saw a water fountain and recognized the slope of the walking path by it. In the cold, streams

of runners flowing past me, I remembered how I had sat months before in glimmer and green, anxious about things I had forgotten about until now. While the concerns and worries I had harbored over the summer weren’t all that different from ones I had that day in March, they nonetheless felt alien to me. How long will this park, this place last? What I remember now about that cold day, louder than the sounds of afternoon conversation, is the chorus of birds.

KARLOS BAUTISTA B’23 wants to read the books that put you to sleep.

09 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT S+T TEXT KARLOS BAUTISTA DESIGN SAM STEWART ILLUSTRATION CELINE YEH

+++

What Would I Do

; or, how to write a speech for a friend’s funeral

The Providence mid-morning glow lit the faded white walls of the stairwell, the heavy arms that rushed to rub my back, the phone clutched to my ear, the wet spots on the gray-green-blue carpet. Pressure built until my head split wide open. They found their son on June 20. Father’s Day.

Their son, my best friend in high school, Aidan.

I sat in shock, grasping at his memory. I tried to remember the musical numbers we’d belt together—“For Good,” “How Glory Goes,” “What Would I Do”—in the company of our friends, on the stage of the Little Theater, in his backyard during lockdown. I looked back through old photos, the one where I smile over his shoulder at the handycam we used to film our games when we were both bound to the sidelines by twin knee injuries, the selfies we took in senior year while we lay laughing in a pile, waiting for the standardized tests to start. I pressed them one by one into a digital album which I sent to the friend group we’d shared in a new group chat. One without him.

Aidan and I met in freshman year through the frisbee team at our high school. Over the next four years, we’d scheme our way through a plant-growing science fair project and spend most of our lunches for a semester trying to become ambidextrous disc throwers. His love of obscure musicals began to rub off on me until, by senior year, he’d successfully convinced me to join the school production of Carrie for which he was the assistant music director.

All the while, our class of frisbee teammates grew closer, convening at each other’s houses to study before practices and playing together at beach tournaments by the Pacific. Aidan was the glue that held us together through it all, with his bear hugs, ridiculous jokes, and dreams bigger than mountains. We talked about buying a huge house when we grew up where we could all live and play Ultimate together.

But now that future felt unreachable. We had more immediate matters to attend to—a month after Aidan’s death, his father asked our friend group to speak at his funeral, “to collectively come up with some sort of story to put a spotlight on the friend part of his life.” So the nine of us, barely two decades old and scattered between coasts, began to plan our speeches for the memorial of our friend. Someone created a shared document, which, for the longest time, I couldn’t bring myself to open. I felt so distant from them, from him, for was he not still there, back in Berkeley? To see their memories, let alone write my own, would make it all too real.

What to write? What did I want to say? How would I put a spotlight on the friend part of his life? How could I communicate what he meant to me?

+++

No one teaches this kind of writing, at least not that I’ve seen, and to children least of all— grief is so often hidden; tears are shed behind closed doors, leaving only traces of the language of sorrow. Instead, my only models were the speeches my parents had given at their parents’ funerals.

I wonder how they prepared. They had time to process, time to say goodbye. They probably talked to their parents about wills and songs to play. My mom interviewed her mother a few years before she died, filling up maybe 20 tapes with stories from her childhood in Japan and immigration to the United States. I remember walking in on my mom sitting on the wood floor listening to her mother’s scratchy, warm voice on the old CD player, talking about her life. I could almost smell the mothballs in my grandparents’ apartment and the fresh husks of corn we’d shuck for sticky summer barbecues.

But at my grandmother’s funeral, my mom did not mention these domestic details; she

spoke instead of her mother’s unconditional love. We sat in rigid plastic folding chairs in the New Haven Cemetery. Rain had fallen earlier that day; it smelled of damp grass and mud. As tears began to fall from my mom’s face, my vision blurred and my sobs finally found their way into the somber air.

When I began to write my piece for Aidan, spurred by the impending deadline, I followed her lead. On the train from Providence to Boston where I’d catch my plane home for the memorial, I took out my pen and journal and scanned the document where our friends had written their speeches, many of them mentioning frisbee. They reminded me of the afternoons Aidan and I had spent throwing a disc back and forth until we could barely raise our arms.

But while those too were some of my favorite memories, I wanted to say something of my own. I rested my head against the window, the trees and rivers and towns rushing past in the fading light, my mind traveling back to an evening we’d spent together before I left the Bay to spend the rest of the summer in Providence.

+++

Less than two weeks before he passed, Aidan, a couple of our friends, and I ended up on an impromptu reunion pilgrimage to the nearest In-N-Out, a reminder of the afternoons we’d spend post-tournament recovering with fries and milkshakes. We met at my house. Aidan dropped off his bike in my backyard and our friends picked us up. Though I hadn’t seen the three of them for almost half a year, the juvenile jabs and inside jokes still flowed. Aidan sat next to me in the back, queuing songs. I requested “Good 4 U,” reached up to max out the volume, and we howled out the words into the eucalyptus breeze.

We stopped at a lookout to watch the sun glaze over the dry grass hills east of the Bay. As the soft golden light, quiet and cool, dissolved into the landscape, we talked about how our semesters had gone. Aidan loved his new friends from school, who would bring guitars to his room to accompany his keyboard and sing songs late into the night. He wanted to introduce them to us.

As the sky faded indigo blue, we got back in the car and made our winding way to the burger joint, then, after eating, drove to the marina and listened to Aidan’s eclectic mix of hard rap and musical theater while watching the twinkling lights of the bridge refract upon the black waves of the bay. When we made it home, some hours later, I retrieved Aidan’s bike and chatted with him for a few minutes about nothing in particular, then hugged him goodnight for one of the last times.

“I love you,” he said.

“I love you too, dude. I’ll see you later.”

I could analyze this story for a funeral speech with ease, talk about how free I felt to be emotionally intimate with Aidan, how I missed his sense of humor, the way he toed the line to make the most out-of-pocket jokes that would make you laugh, even when you knew you shouldn’t. Or talk about how I wish I could relive that hug again and again and again. One of the hardest things about losing Aidan has been to let go of the future I imagined with him, not just the hopes and dreams, but also the hugs and tears and laughter, the moments shared in quiet when we weren’t really doing anything at all.

Yet this was something that I wanted to process for myself. Something that I did not want to lament to an audience of folks who might wish that they, too, had had the privilege to share these simple memories, to be as close to Aidan as I was.

So I wrote in a new direction, toward the music we used to make together, in the process realizing how deeply Aidan had shaped my musical journey. I told the story of how I’d first been captivated by Aidan’s piano ability and how he coached me into a role in the school musical. I tried to make it meaningful, to find some theme, to shape it into something that an audience could understand.

It was like trying to fit a flannel into a packing cube, shoving something warm and unruly into a neat gray mesh pouch through which you can still see flashes of color—what I had thought would be cathartic instead became an exercise in performative compartmentalization. My final eulogy felt formal and forced, even though it was true.

“That’s just one thing that was so special about Aidan—he understood so deeply the power of musical theater to bring joy and wonder to others, to help others express themselves. His infectious passion helped to show me a different side of myself, a more open, joyous, and loving side, and I will spend the rest of my life thanking him for that and hoping that I can do for others just a fraction of what he did for me.”

Months after Aidan’s funeral, I ended up watching The Fault in Our Stars with some friends here at school. Hazel and Gus, the main characters who both are in cautious cancer remission, fall in love. But Gus’s cancer returns with a vengeance. On his last good day, his last lucid day before he dies, he asks Hazel and a friend to read to him what they’ve agreed to say at his funeral. Hazel walks up to the wooden pulpit to spill her emotions into the room. “You gave me a forever within numbered days, and I’m grateful,” she finishes. But at the memorial, she decides in the moment to say something entirely different, something less personal.

I think I understand why now. Funeral speeches, traditionally, are not for the dead. They are for the living. They are meant to make some sort of sense out of something so senseless, to capture the impact that someone had in your life in a snapshot of sentences and paragraphs so that other people can understand.

Any attempt to communicate what someone means to you will always fall short. All you can do is try to keep them alive for one moment longer.

+++

The Providence mid-afternoon glow washes through the bright green leaves that grace the once barren branches, dappling the stone façade of the Hay Library. Seagulls circle over the river, between the buildings downtown, higher and higher into the cloud-spotted sky, and the breeze that brushes my neck smells like the ocean, like home. It’s spring now, and almost two years have passed.

Sometimes I wish I could have had the same opportunity Hazel did. I wonder what I would have said to him had I known he was going to go, what I will never get to say. But I think of my mom, and her mother, and I know—goodbye would never be enough.

LEO GORDON B’23 wants you to try out for the school musical :P

10 FEATS TEXT LEO GORDON DESIGN ZOE RUDOLPH-LARREA ILLUSTRATION ELISA KIM

+++

VOLUME 46 ISSUE 10

CitiArt and Its Legacies

In the late 1970s, a small group of artists got together to dictate bylaws, consolidate members, and write the charter of an artist’s union in Providence. They painted the block between Empire and Snow on Westminster Street a wavy light-blue for a promotional event. Shirts off and paint rollers in hand, the first summer event for “CitiArt” got together a community of Renaissance people, excited to splatter the Creative Capital.

I first encountered CitiArt during a trawl through the Providence Public Library’s (PPL) Collections Overview webpage. I immediately sent an email to my boss, Curator Kate Wells: “Would it be alright if I used some of [my volunteer] time to research the CitiArt collection?”

A week later, I was flipping through photograph slides, DVDs, and periodicals from a bygone Providence.

Arts-union-slash-nonprofit-organization

CitiArt got its charter in 1976. Founded by a small group of Providence artists—including Andrea Hollis and Roger Birn—the organization sought to “acquire land and buildings” in downtown Providence to serve as either a center for the arts or an artist’s coffee house, win artists representation on the Rhode Island State Council for the Arts (RISCA), and facilitate networking opportunities between artists in Providence and Rhode Island.

CitiArt bylaws specifically suggest the former National Furniture Store (NFS), now the Richmond Building at 270 Weybosset Street, as a potential site for an arts center in downtown Providence. Robert Walker, a realtor and CitiArt associate, suggested that the NFS might eventually host galleries, stages, and artist’s offices, a veritable haven for Ocean State talents. As soon as CitiArt broke even, the founders planned for the NFS to become a launchpad from which the CitiArt board could “begin expanding to other buildings.” “Buy RI” was the slogan by which CitiArt vowed to revitalize downtown into a flourishing community of rough-and-tumble, loft-living tenant artist bohèmes. Despite dreaming up Athens in Rhode Island, CitiArt never even achieved its central goal to open its arts center.

Nonetheless, CitiArt isn’t dead and buried. It’s surprising how what might seem like a blip in labor history resonates with the needs of artists in Providence, 2023. But first, the ’70s.

It took until March 13, 1977 (over a year after CitiArt’s founding) for board member Johnette Isham to secure an interim office from which to conduct CitiArt’s operations. The first volume of Citiartnews, a quarterly periodical produced by the organization, optimistically reads: “Until the Art Center on Weybosset Street is open, CITIART will have use of a second floor office in the Winslow Building at 189 Mathewson Street.”

According to founding member of CitiArt and sculptor Andrea Hollis in an email correspondence with the College Hill Independent, “The gentleman who owned the National Furniture building seemed to lose interest [in the art center] and CitiArt was focused elsewhere.” It became increasingly difficult to move beyond the interim office.

Hollis also brought up now-defunct Providence hotspot Leo’s as a potential reason for

CitiArt’s difficulty establishing a new artists’ space: their proposed coffee shop. Leo’s, what Hollis called an “artist’s bar,” lasted in downtown Providence from 1974 until 1994 and already provided what many saw as an appropriate stand-in for the kind of foodie art space that CitiArt wanted downtown. No dice on that coffee shop.

A lack of space saw CitiArt without a concrete meeting place for an already-sparse membership. Hollis paints a picture of a disorganized organization in our correspondence: “I recall an initial artists’ meeting at Trinity Theatre where we spoke to maybe 80 artists.” Beyond that, Hollis additionally described only one other meeting, with a construction company in her own loft. Even to Hollis, it’s unclear whether that meeting wasn’t just to fulfill the construction workers’ “[curiosity] to see inside one of the city’s many illegal artist lofts.”

Bylaws for CitiArt confirm Hollis’ recollection of the institution’s disorganization as status quo. The bylaws only mandate that members receive “seven days’ written notice” with a “place, day, and hour” for a given CitiArt meeting. With no concrete real estate assets, it’s no wonder that Providence artists left the organization in the hands of a “small number of people,” especially since membership required a $25 due (according to the solicitation forms on back leaves of Citiartnews). (It’s unclear whether that $25 was a recurring or one-time fee.)

CitiArt sought out new members through a series of artist surveys in print volumes of Citiartnews and early promotional material. These “Economic Surveys of Rhode Island Artists” solicited information on artists’ total income by category of artist (painters, photographers, sculptors), artists’ cost of living, and their cost of studio space. In July 1977, three quarters of survey respondents could not support themselves on the basis of their artwork, with 62.5 percent of respondents earning less than $600 in monthly income for their work. On its face, both CitiArt’s lack of meeting structure and its burdensome dues presented a barrier to accessibility for working artists.

In the second volume of Citiartnews, the editors received a letter condemning the organization’s derivativeness. “Why should anyone go about duplicating certain agencies that already exist? Why is CITIART unique?” asked the litigious artist. Roger Birn responded with a heartfelt concession: “The feeling seems to be that CITIART lacks a cohesive direction, that its scope is too broad for effective realization. It is true that the scope of CITIART’s ambition is staggeringly broad, that implementation of the many varied projects which have been proposed will be difficult.”