MORE THAN SALMON

In Alaska, a small community is taking action to thwart Pebble Mine and protect an essential ecosystem.

02 / SOLAR SOLUTIONS

05 / SPOTTING JAGUARS

SPRING 2023

The Rare Sight of a Big Cat

In the winter of 2011, I got a once-in-a-lifetime call: I’d been invited to come to Nepal to help collar a young male tiger and drive him across the country as part of a relocation effort aimed at reestablishing tigers in their historical range. So I jumped on a plane in a Chicago blizzard, flew to Kathmandu, then drove west to Chitwan National Park. I’ll never forget the sound of the tiger’s roar at close range nor his massive paws, the softness of his hair, or the long journey from Chitwan to Bardia National Park.

and enforcing the country’s laws against wildlife trade. In India, the wild tiger population has more than doubled since 2008. And while those gains are sadly offset by losses elsewhere, the global tiger population is trending upward after nine decades of decline.

Our dream is to repeat Tx2 in Latin America with another apex predator, the jaguar. Found in a variety of habitats across 18 countries, from northern Mexico to Argentina, this majestic big cat is a symbol of power for many Latin American cultures. It’s

our canoes, we spied a dark shape swimming across the river toward shore, its telltale rosettes barely visible in its black fur. The jaguar hauled itself out of the water, shook itself off, then disappeared into the forest.

That rare sighting was possible because of the connectivity of the wider Amazon basin, where people have developed a massive network of parks one and a half times the size of California. The strengthening of an even larger network of Indigenous reserves, combined with the Forest Code and a soy moratorium, has driven down deforestation and, along with sustainable financing, kept the jaguar’s habitat safe.

This work was in support of a 2010 commitment by 13 tiger-range states to double the population of wild tigers by 2022, known as Tx2. Today, Nepal’s tiger population has nearly tripled a result of protecting key habitats and corridors, delivering economic benefits for local communities,

also often seen as a protector of the rain forest.

I’ve been lucky enough to cross paths with two jaguars in my life. The first was in Guatemala’s Tikal National Park. The second appeared on the Tapajós River in the southwest Amazon. As my companions and I paddled

But our work is far from done. Global and national forces now rear their ugly heads, and we need to prepare ourselves for a far bigger push. We also need success stories to capture the imagination and inspire support. A rebounding global tiger population is one such story. With determination, creativity, and partnerships, we can bend these curves. You can read more about our work with tigers, jaguars, and other big cats in the online publication of this issue.

CARTER ROBERTS PRESIDENT & CEO

PRESIDENT’S LETTER

© WWF-SWEDEN/OLA JENNERSTEN

SPRING 2023

WWF’s mission is to conserve nature and reduce the most pressing threats to the diversity of life on Earth.

WWF’s vision is to build a future in which people live in harmony with nature.

president & ceo Carter Roberts

editorial director Alex MacLennan

publications director Sarah Forrest

managing editor Ananya Bhattacharyya

editor Erin Waite

EDITORIAL

senior editor Alice Taylor

editor, digital edition Alison Henry web producers Victoria Grimme, Isabelle Willson, Ellie Yanagisawa

contributing editors

Teresa Duran, Karl Egloff, Molly M. Ginty, Brie Wilson

contributing writers

Clay Bolt, Tara Doyle, Ali Evarts, Alex Fox, Jennifer Hanna, Madeleine Janz, Kate Morgan

ART

art direction and design

Page 33 Studio

consulting art director Sharon Roberts

PRODUCTION

production manager Mick Jones

volume 11, number 1

(ISSN 2330-3077)

World Wildlife is published quarterly by World Wildlife Fund, 1250 24th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20037. Annual membership dues begin at $15. Nonprofit postage paid at Washington, DC, and additional mailing offices.

learn more

Visit worldwildlife.org to learn more about World Wildlife Fund and what you can do to help.

contact us editor@wwfus.org

© 2023 wwf. all rights reserved by world wildlife fund, inc.

wwf® and ©1986 panda symbol are owned by wwf. all rights reserved.

Current financial and other information about World Wildlife Fund, Inc.’s purpose, programs, and activities can be obtained by contacting us at 1250 24th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20037, 1-800-960-0993, or for residents of the following states, as stated below. CONTRIBUTIONS ARE DEDUCTIBLE FOR FEDERAL INCOME TAX PURPOSES IN ACCORDANCE WITH APPLICABLE LAW. REGISTRATION IN A STATE DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION OF WORLD WILDLIFE FUND BY THE STATE. Colorado: Colorado residents may obtain copies of registration and financial documents from the office of the Secretary of State, (303) 894-2680, http://www.sos. state.co.us/ re: Reg. No. 20023005803. Florida: Registration # SC No. 00294. A COPY OF THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING TOLL-FREE WITHIN THE STATE, 1-800-HELP-FLA, OR BY VISITING https:// www.fdacs.gov/ConsumerServices. Georgia: A full and fair description of the programs and activities of World Wildlife Fund and its financial statement are available upon request at the address indicated above. Maryland: For the cost of postage and copying, from the Secretary of State. Michigan: MICS No. 9377. Mississippi: The official registration and financial information of World Wildlife Fund may be obtained from the Mississippi Secretary of State’s office by calling 1-888-2366167. New Jersey: INFORMATION FILED WITH THE ATTORNEY GENERAL CONCERNING THIS CHARITABLE SOLICITATION AND THE PERCENTAGE OF CONTRIBUTIONS RECEIVED BY THE CHARITY DURING THE LAST REPORTING PERIOD THAT WERE DEDICATED TO THE CHARITABLE PURPOSE MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY BY CALLING (973) 504-6215 AND IS AVAILABLE ON THE INTERNET AT http://www.state.nj.us/lps/ca/charfrm.htm. New York: Upon request, from the charities registry on the website of the New York Attorney General, Charities Bureau, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271. Information on charitable organizations may be obtained at https://www.charitiesnys.com/ or calling (212) 416-8401. North Carolina: Financial information about this organization and a copy of its license are available from the State Solicitation Licensing Branch at 1-888-830-4989 (within North Carolina) or (919) 807-2214 (outside of North Carolina). Pennsylvania: The official registration and financial information of World Wildlife Fund, Inc. may be obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of State by calling toll-free, within Pennsylvania, 1-800-732-0999. Virginia: From the State Office of Consumer Affairs in the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, P.O. Box 1163, Richmond, VA 23218. Washington: From the Secretary of State at 1-800-332-4483. West Virginia: West Virginia residents may obtain a summary of the registration and financial documents from the Secretary of State, State Capitol, Charleston, WV 25305.

1 WORLD WILDLIFE MAGAZINE 1 FPO FPO

MIYUYU :: TANZANIA POWER UP

Youth engineers lead the charge for solar energy

It’s a warm, sunny day as Fatuma Hemed finishes assembling solar panels on a barber shop in Miyuyu Village, a small community where many buildings lack grid electricity. But, thanks to a program through which Hemed and other young people have become solar engineers, the village’s future is bright.

Leading the Charge (LTC), a program developed by WWF and partners, aims to increase access to renewable, affordable energy throughout rural Tanzania. In Miyuyu, villagers must often travel far to obtain firewood or use costly generators. By training local youth to install and maintain solar power systems, LTC is providing more reliable ways for people to light their homes and businesses.

The project has transformed daily life, allowing shops, a school, and the village market center to remain open past dark while improving access to global news and entertainment. It’s also helped diversify livelihoods and empower community members.

“The first day the lights went on in our village center was an important moment,” says Baraka Issa, who works as a solar engineer. “With the right skills,” he adds, “we have the tools to overcome poverty and help our community better manage its natural resources.”

DISPATCH

THE ISLANDS OF DISCOVERY TRAVEL

WITH WWF

Wander into the world of Darwin. The Galápagos Islands were forged from black lava and named after the giant tortoises that are among their most noted inhabitants. Six hundred miles off the coast of Ecuador, the volcanic islands that were the source of Darwin’s theory of evolution remain a priceless living laboratory for scientists today. On this small-group, ship-based adventure, you’ll be in awe of iguanas, blue-footed boobies, sea lions, porpoises, penguins, sea turtles, and more. Book with confidence, knowing that you’re directly supporting WWF’s global conservation efforts. Other South American adventures include trips to Brazil, Chile, and Peru.

WWF offers nearly 90 trips of a lifetime. Trips include

+ Jaguars & Wildlife of Brazil’s Pantanal June–September

+ Patagonia Wilderness & Wildlife Explorer

November–April

+ Discover Amazon & Machu Picchu

February, May, August, and October

GET WWF’S TRAVEL CATALOG

Contact us at 888.WWF.TOUR (888.993.8687)

wwf.travel/catalog2023

WWF’s membership travel program is operated in conjunction with Natural Habitat Adventures. They have donated more than $4.5 million to date in support of WWF’s mission and will continue to give 1% of gross sales plus $150,000 annually through 2023.

© WWF-TANZANIA

© ANTONIO BUSIELLO/WWF-US

FAST FORWARD

Bhutan for Life’s sweeping conservation commitments deliver multiple benefits

BUILDING RESILIENCE

Flash flooding in the Bumdeling Valley had washed away much-needed habitat for blacknecked cranes and other birds—and wrecked nearby paddy fields. A 2021 BFL-funded project planted native trees between wetlands and fields to save this vital home for wildlife and protect the 40 households whose livelihoods rely on the crops.

SPOTTING STRIPES

Species conservation is a primary goal of BFL. Funding from this initiative has revived water holes, created salt licks, and promoted grasslands in protected areas and biological corridors to improve tiger habitat and protect wildlife—and it seems to be working. In 2019, a camera trap photographed a tiger in a part of Bhutan where the big cats had likely been absent for 15 years.

HALTING INVADERS

When invasive grasses threatened the health of the Kanamakura grasslands in Royal Manas National Park, BFL supported clearing and replanting efforts. Since then, Kanamakura has seen an increase in wildlife.

SUPPORTING PEOPLE

MAY 2015

Our “Bhutan Rising” feature took readers to the Eastern Himalayas, rich with cultural significance and remarkable wildlife. There, the Royal Government of Bhutan and partners like WWF were busy developing Bhutan for Life (BFL), a conservation initiative that would permanently finance the protection of the country’s ecosystems while fostering economic stability for its people. Now recognized as a role model for projects around the globe, BFL offers lessons for conservation on a national scale.

To bolster ecotourism as a source of economic prosperity, BFL has funded the creation of ecotourism amenities, such as toilets, waste bins, trail maps, and a bird-spotting field guide. Some 10,000 people—over half of them women—have participated in BFL’s trainings on conservation, waste management, and hospitality.

4 WORLD WILDLIFE MAGAZINE © BERNARD CASTELEIN/NATUREPL.COM

THE PANTANAL :: BRAZIL A WETLAND WONDERLAND

Finding a wildlife paradise in Brazil’s expansive Pantanal

Most people visit the Pantanal excited to see the elusive jaguar. I would have been thrilled to see just one. But while traveling in the world’s largest tropical wetland, I was lucky to spot several, each sighting an exhilarating experience. More than the cats, though, it’s the variety and abundance of the Pantanal’s wildlife that still fill my imagination.

Capybaras, Earth’s biggest rodents, are plentiful in the Pantanal; their gentle playfulness made them a favorite. Where there’s water, caimans too are ubiquitous. Well-camouflaged and usually sedentary during the day, many more lurk in the shallow waters than are seen at first glance. And of the diverse bird species we encountered, I’ll never forget the hyacinth macaws. A brilliant cobalt blue, these birds were almost always soaring together in pairs.

Yet it is the people of the Pantanal, from lodge owners to cattle ranchers, I most remember because of their extraordinary devotion to and enthusiasm about protecting and sharing these unique natural treasures.

Karl Egloff

DISCOVER

to explore the Pantanal with WWF? Visit worldwildlife.org/ExploreBrazil2023

© LUCIANO CANDISANI Want

BY THE NUMBERS

Critical Critters

Insects get the job done: They maintain healthy soil, recycle nutrients, pollinate flowers and crops, and control pests. But by the end of the century, up to 40% of the world’s insect species may go extinct owing in part to habitat loss. Thankfully, gardeners, policy-makers, Native American nations, ranchers, and others are finding ways to protect these invaluable invertebrates, from planting native gardens to avoiding pesticides to conserving habitats. Here are just a few of the critters that help keep North America, and our planet at large, in balance.

NATURE’S UNDERTAKERS

American burying beetles form one of nature’s most efficient cleanup crews. As carrion-feeding insects that help animal carcasses decompose, they keep the North American landscape looking and smelling a lot better than it otherwise might.

1 WATER FILTERS

Insects like the giant casemaker caddisfly break down debris in aquatic ecosystems such as wetlands, ponds, creeks, and streams, contributing to cleaner water for people, wildlife, and plants.

2 FRUITS OF THEIR LABOR

North America is home to around 4,000 native bee species, many of which are in decline. Without bees, which along with other pollinators contribute billions of dollars’ worth of ecological services annually, we’d no longer have foods like blueberries and tomatoes.

3 BIRD BITES

Ninety-six percent of North American birds feed insects like yellow-jacket wasps to their young. One study estimates that, worldwide, birds consume up to 500 tons of insects each year.

2 3 6 © MUTI/WWF-US

6 WORLD WILDLIFE MAGAZINE

Only 0.5% of the world’s insect species damage crops. In fact, predatory insects such as ground beetles increase crop yields by keeping weeds and pest species in check.

By breaking down and burying animal waste, dung beetles can reduce overall methane emissions on dairy and beef farms, a 2016 study found. These species also help reduce disease, aerate the soil, disperse seeds, and promote plant growth.

Wasps such as the tarantula hawk are often feared for their stings. But wasps and other predators help prevent populations of caterpillars, spiders, and crickets from reaching pest levels, providing an estimated $416 billion in pest control each year.

7

Halloween pennants and other dragonfly species are voracious predators of mosquitoes which are vectors for various infectious diseases with some dragonflies consuming hundreds in a single day.

7 1 4 5 7

4 FARMERS’ FRIENDS

5 DIGGING IN THE DIRT

6 CROWD CONTROL

SKEETER EATERS

GLOBAL FREE FALL

A WWF report sounds the alarm about nature’s decline

In WWF’s 2022 Living Planet Report, researchers assessed how 32,000 vertebrate populations— representing more than 5,000 species—fared over the past half-century. Their findings were dire: Since 1970, the populations of birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, and amphibians in the study have declined by an average of 69%.

“This is a wake-up call,” says Rebecca Shaw, WWF’s chief scientist. “Nature is unraveling.”

But the report also highlights conservation successes that offer clear lessons. The populations that increased during the study—such as mountain gorillas in Virunga National Park and loggerhead sea turtles in North Cyprus—all shared a key factor: engaged communities of people actively participating in conservation.

It’s urgent that we use these successes as models for how to reverse nature loss, says Shaw. “We have maybe a decade to figure this out.”

UPDATE

NATURE NEEDS PARTNERS NATURE NEEDS YOU

Partners in Conservation is a community of committed people working together to create a brighter future for wildlife, people, and our planet. By pooling your contributions with those of other Partners, you ensure a greater impact as WWF works to protect the species and habitats that sustain and inspire us.

With either an annual gift of $1,000+ or a monthly commitment of $100+, you join a diverse community of Partners driving global change together.

As a Partner in Conservation, you enjoy a closer relationship with WWF through special Privileges of Partnership, including

ACCESS—Hear directly from WWF leaders and experts; have a personal liaison answer your questions.

IMPACT—Get personalized updates on how your gifts advance our shared conservation goals.

COMMUNITY—Network with your fellow Partners in Conservation at exclusive events.

Help create a healthier planet for wildlife and people.

Become a Partner in Conservation.

9 © STEPHEN FRINK/THE IMAGE BANK VIA GETTY IMAGES

© MATEUSZ PIESIAK/NATUREPL.COM CONTACT OUR PARTNERS IN CONSERVATION TEAM TODAY. 800.960.0993 partnersinfo@wwfus.org worldwildlife.org/partners

Vehicles are the single largest source of GHG emissions in San Diego, which is working to implement zero-emissions bus fleets to ensure cleaner air and healthier communities.

SUSTAINABILITY LEADER

Moriah Saldaña on engaging the community in climate action

How did you decide which issues to prioritize in the city’s Climate Action Plan?

What solutions could create a more sustainable transportation sector?

HOME

San Diego, California

CAUSE

Growing up in San Bernardino, California, a city with historically poor air quality, inspired Moriah Saldaña to pursue a master’s in public administration and to join the sustainability field. Now the program manager for San Diego’s Climate Action Plan, she works to implement climate solutions increasing energy from renewable sources, improving air quality, and partnering with underserved communities to achieve the city’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2035.

We engaged the public. When we were developing it, we heard from over 4,000 residents, many of whom live in historically underserved communities. The two issues that rose to the top were access to transportation alternatives and air pollution, so we created specific strategies to tackle those challenges.

What are the biggest opportunities for reducing GHG emissions in your city?

We have a great need, and the capacity, to reduce emissions in the building and transportation sectors. To meet our emissions goals, we must remove natural gas from our buildings and electrify new and existing buildings. We must also make it easier for San Diegans to get around using more sustainable modes of transportation while transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.

Our plan commits to shifting 50% of all trips in the city from driving to walking, bicycling, or transit by 2035. That’s why enhancing the walkability and bikeability of our streets, including making sidewalks and bike paths wider and safer, is a major focus. And we’re working with the San Diego Metro Transit System to build more bus-only lanes and encourage people to use public transit.

How do you ensure underserved communities benefit from climate initiatives?

The first step is to listen. Many people in the sustainability field assume they know what’s best for a community. But we must work to secure community input and partner with local organizations before making major decisions.

10 WORLD WILDLIFE MAGAZINE BUS IMAGE COURTESY OF SAN DIEGO MTS

LOCAL

In rural Alaska, communities are coming together to protect a way of life that revolves around salmon

story by Ananya Bhattacharyya

photography by Brian Adams

SALMON WAYS

CarolAnn Hester, who practices subsistence fishing in Naknek, stands in front of her smokehouse holding fillets of smoked salmon. Inside her home, she cans salmon to eat during the winter months, using a technique she learned from her mother.

carolann hester presides over a massive pressure cooker, surrounded by an array of small mason jars and large salmon fillets. Her sentences are short and lyrical, brimming with assertions. “The big secret to putting up good fish is to get the blood out,” she says. “Soak, soak, soak, soak, soak.”

Each summer, Hester comes to Naknek, a small village in southwestern Alaska where she has a house, and catches around 500 to 600 fish on her skiff. Some of the catch is frozen, but the rest makes its way to her smokehouse. To cure the fish, she soaks them in clean water and then in brine repeatedly. Some salmon sides are smoked for three days, then cut into small strips and packed into mason jars before being pressure cooked. “This is what we call kippers,” Hester explains.

The rest of the fish spend between a week and 10 days in the small smokehouse next to her house, glowing when sunlight touches their oily surface. In the mouth, the flesh is chewy, yielding slowly. The flavor, birch and ocean, can overwhelm the tongue. Hester’s smoked salmon is so delicious that people stop by unannounced to buy what she can spare.

Many rural Alaskans like Hester preserve their catch for an entire year by freezing, canning, or smoking it. Preserving food is part of a cultural heritage and a necessity. Food costs in Alaska are sky-high because of the state’s geography and seclusion.

13

“A packet of chicken for dinner can cost $30 in rural Alaska,” says Steve MacLean, the managing director of the WWF-US Arctic Program. “Being able to use the resources from the land is an extremely important part of living out in these parts.”

According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 75%–98% of people living in rural Alaska harvest fish and 48%–70% harvest game.

“If those resources become scarcer and more difficult to get, meeting your basic needs becomes more challenging,” says MacLean, whose hometown of Utqiagvik is at the northernmost tip of Alaska.

Hester points out that not only do humans fish, but so do bears, foxes, wolves, beavers, and otters. “Fish make this land alive,” she says. But the reality is that climate change and other human-made factors pose very real threats to fisheries in Alaska.

A Village That Fishes for the World

In summer, after the surrounding lowlands of Bristol Bay have emerged from under several feet of snow, Naknek a village with a few hundred permanent residents becomes a bustling hot spot. Thousands of people fly in for commercial, subsistence, or sports fishing.

Unlike the skiffs owned by subsistence fishers like Hester, the larger vessels bobbing like

FISH MAKE THIS LAND ALIVE.

CAROLANN HESTER

a giant maritime orchestra on the water near Naknek are commercial fishing boats. At the start of fishing season, each commercial boat signs up with a seafood processing and freezing facility. In June and July, tender boats carry huge hauls from the commercial vessels to the facilities, where seasonal migrant workers process the catch for retailers around the country.

Last year, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game reported a total run of 76 million sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay a record-breaking number of which fishers were able to harvest 58 million. Nearly half the world’s wild sockeye harvest comes from Bristol Bay. Valued at $1.5 billion, its salmon fishery supports more than 15,000 US jobs.

And while people here including commercial fishers are happy with the recent sockeye runs, they don’t take anything for granted. Clues to what local folks here are worried about abound in Naknek: “No Pebble Mine” bumper stickers and t-shirts are hard to miss.

A Mine on People’s Minds

“There’s an 800-pound gorilla in the room,” says MacLean, as he looks over Bristol Bay’s flatlands. He’s referring to the proposed Pebble Mine 100 miles northeast of Bristol Bay, the plans for which include extracting 1.5 billion tons of material from deposits there and building a huge power plant and a transportation corridor. Area residents, conservationists, and scientists fear that extracting copper, gold, and molybdenum at the proposed site, which would create up to 10.2 billion tons of waste, would wreck more than 100 miles of streams, polluting salmon spawning ground and harming the ecosystem.

Through “No Pebble Mine” stickers, Bristol Bay fishers raise their voices against the threat to the fishery they depend on. Fishing boats in Bristol Bay harvested 58 million salmon in 2022—a record-breaking year.

A ROUNDTRIP JOURNEY

Young sockeye salmon spend one to two years maturing in streams, creeks, and lakes before heading out to the ocean as small fish. They remain in the ocean for another two to three years before making an upstream journey back to their birthplaces to spawn.

In Bristol Bay, they get a little help from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Each year, the department sets certain “escapement goals” for salmon. Fishing in the bay can only begin when the desired number of salmon have escaped upriver, which increases the possibility of healthy populations of salmon returning to the bay in subsequent years.

And so, millions of sockeye salmon band together in large groups and swim miles and miles against the rushing current with unwavering determination to reach their birthplaces. As the fish near their destination, a splendid transformation takes place. Their skin turns bright red, as the red pigment in their flesh travels to their skin. This is a signal to prospective mates: They are ready for the final chapter of their lives.

When they reach the spawning grounds, females dig a few shallow cavities to create their nests. As soon as a female releases eggs, its male partner, which waits nearby, fertilizes them. The spawned-out fish their bodies already starting to decay remain near the nests for a week before dying and returning precious nutrients into the stream.

The deposits were discovered here more than 30 years ago, and the prospect of the mine has been looming ever since. From the beginning, WWF, in alignment with local communities and other environmental organizations, encouraged its members and supporters to voice their concerns. In 2018, nearly 220,000 WWF activists did so, asking the US Army Corps of Engineers to deny a permit to the mine developer.

At last, in November 2020, the Corps denied the permit. And more recently, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) indicated its intention to protect Bristol Bay by applying Clean Water Act protections to prohibit disposing of mine waste in the watershed. WWF again asked its supporters to weigh in, this time to urge the EPA to permanently protect the headwaters, and more than 20,000 supporters heeded our call. In December 2022, the regional administrator of the EPA issued a recommendation to the headquarters to veto Pebble Mine.

But no matter the victories, like a game of Whac-A-Mole, news of the mine’s proposed development keeps popping back up. “The mine rises to the top of people’s thoughts here,” says MacLean. “It has nearly been approved several times.”

Clearly, the fight to protect the bay is still not over. And an important piece of the puzzle isn’t in Bristol Bay but upriver, near Lake Iliamna, where a tiny village with only 35–40 residents has come to play an outsize role in the future of Bristol Bay.

Ready to Act

Large schools of intensely red sockeye salmon returning from Bristol Bay pulse in streams and creeks edged with clusters of fireweed blossoms near the village of Pedro Bay. It sits at the northeastern end of Lake Iliamna, not far from the proposed location of Pebble Mine. The area, with its picture-perfect beauty alder, cottonwood, spruce forests; termination dust (the first sprinkling of snow at the end of summer) on mountains; and a giant, sparkling lake forms the watershed for Kvichak River, which ultimately flows into Bristol Bay.

Pebble Mine, if it were developed, couldn’t exist in isolation. A road would have to be built for the mine to access a port, and this road would pass through land owned by the Pedro Bay Corporation, one of 200 Native village corporations that own land across Alaska.

17

“There are times when Alaska Native communities have the right to move their land into development to support their economics,” says Matt McDaniel, chief executive of Pedro Bay Corporation. But, he says, after considering the matter closely, 90% of the corporation’s shareholders decided to say no to Pebble Mine.

Sarah Thiele, treasurer of the Native Corporation board, lives in Anchorage and returns to Pedro Bay every summer to her stilt house by the lake, right next to a creek. “This is the headwater of the greatest salmon fishery,” she says. “It’s so important to keep it pristine.”

Beverly Cloud, who is now on the board of directors of the corporation, says she listened to what the Pebble Partnership had to say with an open mind. But when she visualized an industrial road and a gas pipeline being developed nearby, she realized that it would change the entire landscape. “The region is not even remotely prepared for the social changes of something like that,” she says.

So the corporation decided to offer up conservation easements on 44,000 acres of its land to The Conservation Fund, an environmental nonprofit, for $20 million. In other words, they gave away their development rights to that land in exchange for conserving it, even as the land itself remains in the hands of the corporation. The arrangement provides financial security to the Pedro Bay Corporation and its shareholders, and at the same time achieves a great conservation victory: blocking the road Pebble Mine would need.

The success of this Pedro Bay project reinforces the importance of partnerships in this region. WWF, The Conservation Fund’s partner in the project, helped raise a portion of the last $5 million needed through the Bristol Bay Victory Challenge (coordinated by the Alaska Venture Fund with 12 partners, including WWF). Other long-term goals of this five-year, $50 million effort include passing state and federal legislation to permanently protect Bristol Bay and to increase funding for Indigenous communities here.

“We are committed to protecting the terms of that conservation easement in perpetuity,” says McDaniel.

“The Bristol Bay Victory Challenge is a simple and elegant solution to a complex and

long-standing problem,” says Diane Moxness, a WWF National Council member, a longtime donor, and one of the Challenge’s generous supporters. “In supporting the Challenge, it’s my hope that we can, once and for all, put an end to Pebble Mine and permanently protect the Bristol Bay watershed and its fisheries, while also creating sustainable economic opportunities for local communities.”

The Road Ahead

Residents of Pedro Bay, conservation organizations, commercial fishers, activists, and many others joined forces to fight a very real threat to Bristol Bay’s salmon ecosystem. But there’s more work to do. Climate change is causing shifts in Alaska that are hard for communities to keep up with. For instance, salmon populations have been crashing in the Yukon, Kuskokwim, and Nushagak rivers. And threats to food security are increasing in rural Alaska.

Steve MacLean emphasizes the need to build trust as WWF moves forward with our work in Alaska. “If we can demonstrate that we showed up at this one place, worked with the community there, met their expectation, then we’ve started to earn trust. People will be willing to say, ‘All right, these people showed up and produced the results they said they would. Now let’s work with them.’ I’m so excited to see what happens with other communities.”

18 WORLD WILDLIFE MAGAZINE

IF IT WILL HELP US TO PRESERVE OUR WAY OF LIFE AND PROTECT THE SALMON FISHERIES FOR MY GRANDCHILDREN AND MY GRANDCHILDREN’S CHILDREN, THAT’S A GOOD TRADE-OFF.

KEITH JENSEN

Keith Jensen, president of the Pedro Bay Village Council and one of this area’s few year-round residents, says it costs 90 cents a pound to bring food to Pedro Bay. That’s why residents gather berries, hunt moose, and fish salmon and trout. “We smoke [salmon], salt it, freeze it, fry it,” he says.

TEL AVIV :: ISRAEL

MIDDAY FLIGHT

Discovering a new side to a misunderstood mammal

Like most of the 1,400 species of bats, Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) are nocturnal. But in Tel Aviv, you can spot a rare phenomenon: these bats flying around in broad daylight. As part of my efforts to photograph them, I headed to a local mulberry tree one May afternoon and waited patiently for this pregnant bat to finish her meal. I wanted to capture her majestic flight between the sun-dappled treetops.

I’m not the only one who’s taken with the animals. In 2020, researchers at Tel Aviv University contacted me; they’d noticed that in some of my photos the bats appeared to be smiling a sign they were echolocating. The researchers hypothesized then proved through experiments that despite having excellent vision, these bats use their eyes and echolocation during the daytime to navigate the city.

Unfortunately, bats don’t have a great reputation, especially as an animal often implicated in zoonotic diseases. But I aim to capture their grace and sweetness, giving viewers a new perspective while encouraging more research on these unique creatures.

Yuval Barkai

Yuval Barkai

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

SECURITY FOR YOU AND FOR WILDLIFE

Did you know there is an easy gift that can further your impact and benefit you in return?

It’s called a charitable gift annuity. You transfer assets to WWF to protect people and our planet, and in return you receive regular payments for life.

When you establish a charitable gift annuity with WWF, you can provide yourself or someone you designate with dependable income for life. Best of all, your gift will help guarantee a more secure future for wildlife and their habitats around the world.

CONTACT OUR GIFT PLANNING TEAM TODAY. 888.993.9455 legacygifts@wwfus.org wwf.planmylegacy.org

The information provided above is for educational purposes only and is not intended as legal or tax advice. Please consult an attorney or tax advisor before making a charitable gift.

21 © YUVAL BARKAI

© ANDY ROUSE/NATUREPL.COM

GALLERY

Ingrid Weyland

Topographies of Fragility

Argentinian photographer Ingrid Weyland began creating her Topographies of Fragility series after witnessing the effects of irresponsible tourism on one of her favorite places in Iceland. As a metaphor for “the violent damage nature suffers,” she crumples up, twists, and reshapes physical photographs of majestic landscapes, then rephotographs them atop the original prints. The resulting images parallel “the way we treat nature as though it’s disposable,” says Weyland, ultimately “conveying both beauty and decay, reminding us of what we stand to lose.”

22 WORLD WILDLIFE MAGAZINE

ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND KLOMPCHING GALLERY, NEW YORK

(Top)

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY II (2019)

(Bottom, left to right)

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY VI (2019)

(Top)

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY II (2019)

(Bottom, left to right)

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY VI (2019)

23

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY XXI (2020)

Paige Curtis

Finding Community

“I think I found a chanterelle!” I proclaimed, delighted by the prospect of having identified a choice mushroom.

“Actually, that’s a jack-o’-lantern, which you really don’t want to eat. They’re often confused with chanterelles,” Jada said.

This was my third foraging trip with the Boston chapter of Outdoor Afro, and I was starting to recognize some of the mushrooms common in New England with the occasional slipup. New to Boston and hoping to make some friends, I joined a slew of meetup groups catering to people of color.

Soon, I found myself ambling through the forest with friends, trying to identify a fruiting tree. The consensus seemed to be crabapple, and we took turns harvesting small amounts to take home. As we brainstormed recipe ideas, I remembered the stories my mom told of her childhood in Jamaica, living around tropical fruit trees.

Having grown up in the US, I never dreamed of foraging for my supper, let alone with people who shared my background. Foraging, I learned, was a deeply communal practice once outlawed for Black, Indigenous, and rural Americans.

I paused at a lookout point, in awe of the white oak leaves, now a deep auburn in late fall, and excited by the promise of acorns. Newly freed slaves foraged acorns to make butters and acorn meal while subsisting for months in the wilderness. Walking back, Jada paused to pick some wild sage, hoping to brew a tonic inspired by her aunt’s.

“Where I come from, we call that ‘bush tea,’” I said, “and my grandmother used native peppermint.”

I thought of the Black hunters, naturalists, and homesteaders who came before me, and lamented the knowledge lost to their persecution. But that day, only 30 minutes outside of Boston, what I felt most was gratitude for the kinship that foraging helped me find.

24 WORLD WILDLIFE MAGAZINE LOVE LETTER F R O M T H E D E S K O F

© LAUREN TAMAKI/WWF-US

WANT MORE?

Find expanded content from this issue of World Wildlife on our magazine website at worldwildlife.org/magazine.

to Protect Nature The Wildest Way

BREATHING ROOM

Large predators like lions and tigers require ample space to roam, mate, and hunt. But as human activity encroaches on big cats’ range, their habitats are shrinking fast. Discover how WWF is working to restore and reconnect wildlife corridors and protect critical habitats for these iconic but vulnerable species.

Register at wearitwild.org

REMOVING BARRIERS

A new internship program brings diverse perspectives to the conservation field.

DEFINING CHALLENGES

WWF’s Stephanie Roe stays grounded while taking on global climate work.

CONSERVATION CONTRIBUTORS

Brenda and Swep Davis on the importance of understanding the big picture.

WEAR IT WILD is a fun, creative fundraising challenge perfect for families, classrooms, offices, and anyone who loves animals and nature!

The challenge is easy: Set a fundraising goal, and promise that if you reach it you’ll wear a wildlife-themed outfit or accessory out somewhere in your everyday world on a specific day. Then let your friends and family know— and watch them flock to support you.

25 DIGITAL

© SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

LIONS © CHRIS SCHMID; PHOTO COLLAGE © NIKI ERNST/WWF-US; COURTESY OF STEPHANIE ROE; © WWF-US/IRENE MAGAFAN

THE MASTHEAD

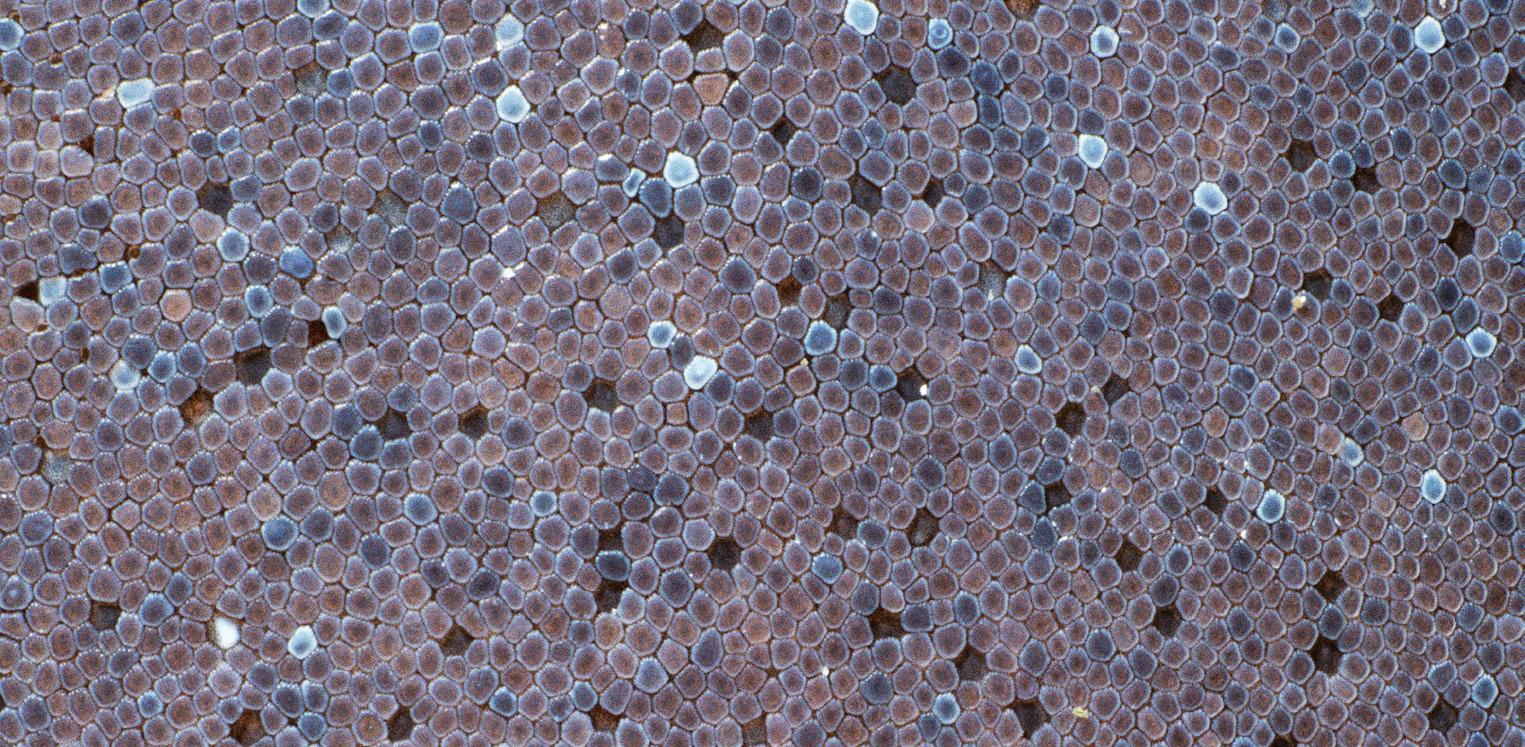

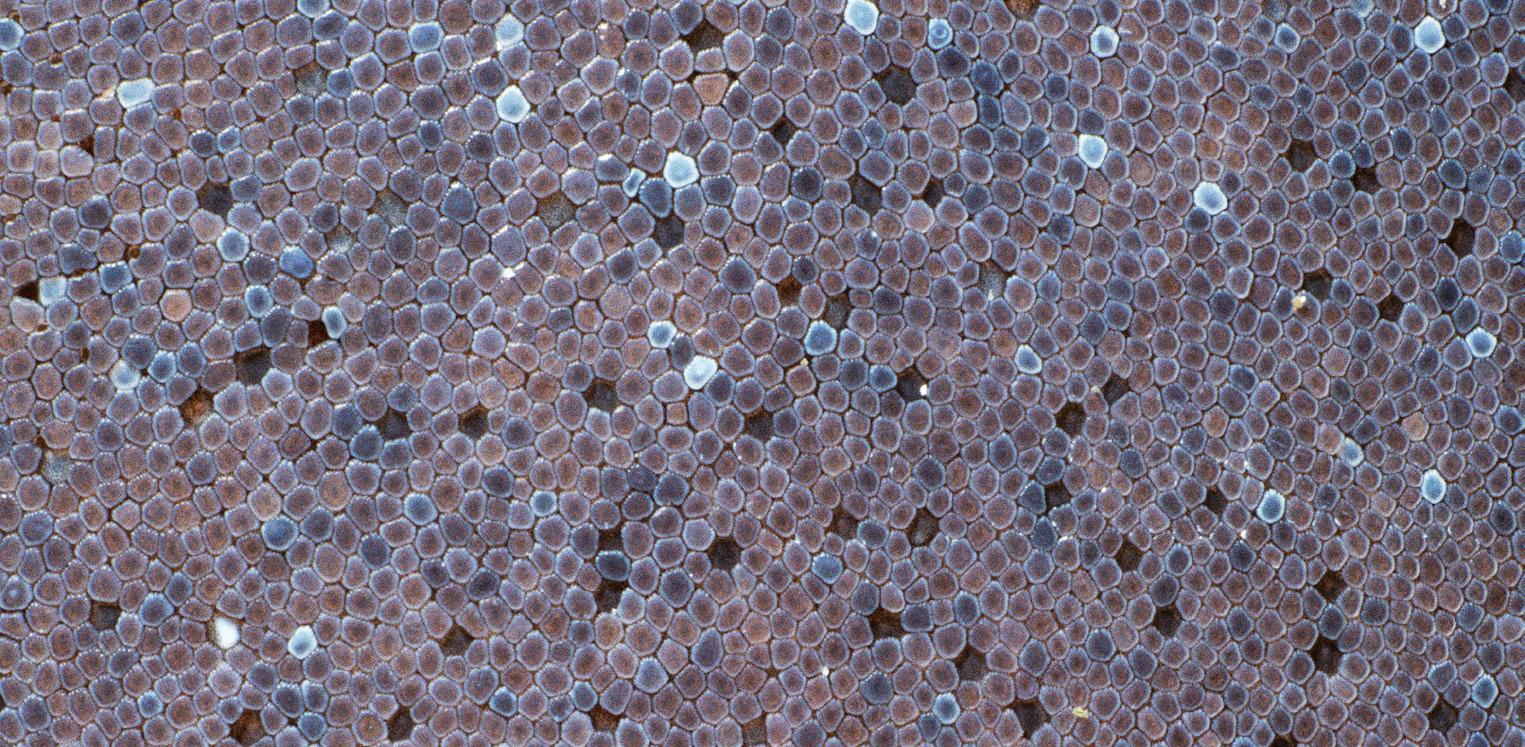

What’s on the cover?

The speckled skin of a whitetip reef shark; it’s classified as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

NORTH AMERICAN BEAVER Castor canadensis

North American beavers may be known for their sharp, tree-felling teeth, but it’s the animals’ flat, leathery tails that are their calling card and for good reason. The appendages help propel the semiaquatic mammals through the rivers, lakes, and ponds they inhabit; can sound an alarm with a loud slap against the water; and allow them to balance when carrying heavy logs. Once hunted and trapped to near extinction for their fur, these famously industrious rodents are nature’s engineers their ability to swim underwater for up to 15 minutes helps them to build homes (called lodges) and impressive dams, which create habitat for other wildlife and improve water quality. They’ve been at it for a long time, too; the North American beaver’s oldest fossil record dates back 7 million years.

SHARK SKIN © JEFF ROTMAN/NATUREPL.COM BEAVER © JOEL SARTORE/PHOTO ARK

SHARK SKIN © JEFF ROTMAN/NATUREPL.COM BEAVER © JOEL SARTORE/PHOTO ARK

Yuval Barkai

Yuval Barkai

(Top)

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY II (2019)

(Bottom, left to right)

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY VI (2019)

(Top)

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY II (2019)

(Bottom, left to right)

TOPOGRAPHIES OF FRAGILITY VI (2019)

SHARK SKIN © JEFF ROTMAN/NATUREPL.COM BEAVER © JOEL SARTORE/PHOTO ARK

SHARK SKIN © JEFF ROTMAN/NATUREPL.COM BEAVER © JOEL SARTORE/PHOTO ARK