Spring 2024 ISSUE • VOLUME 36 3

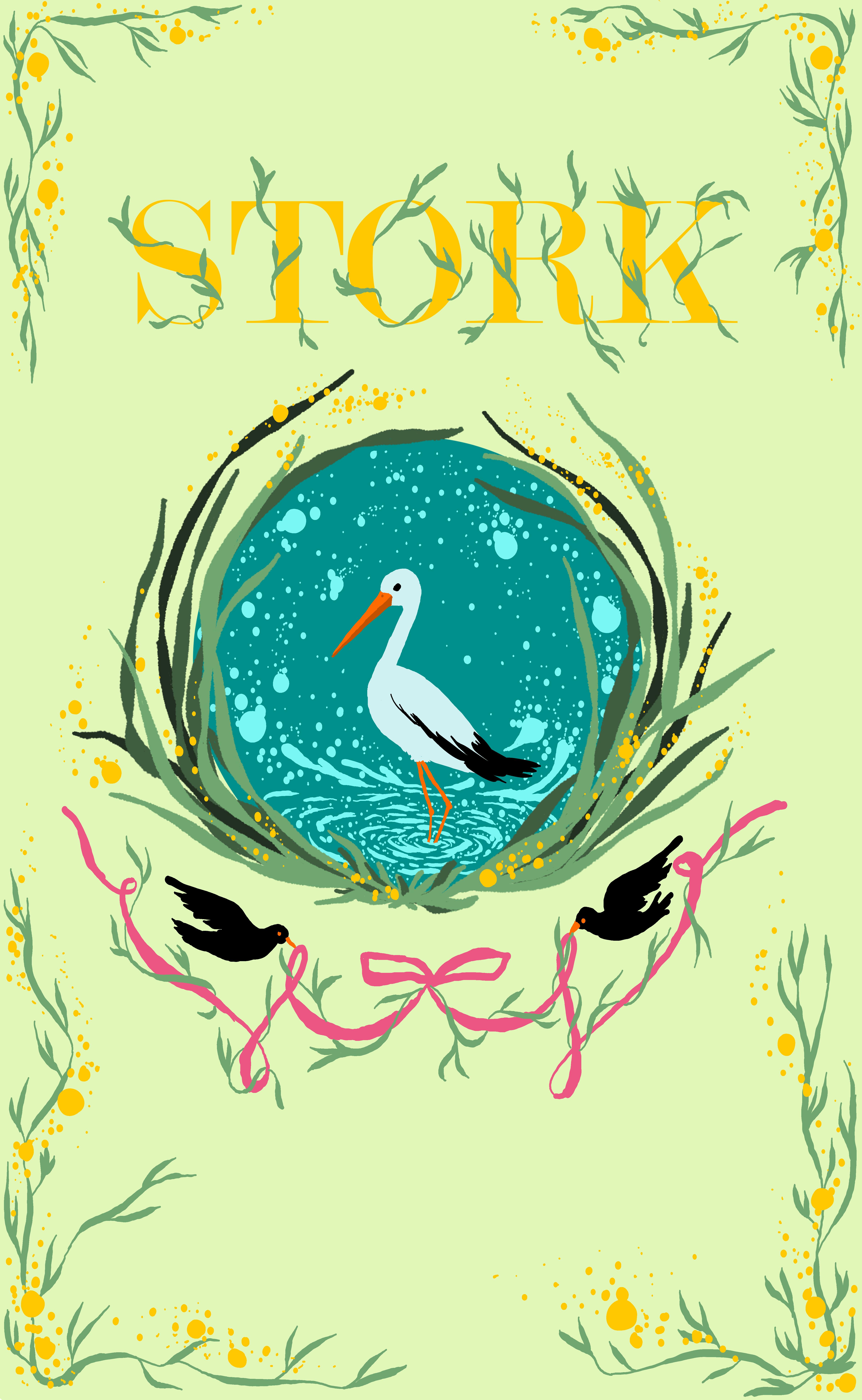

STORK

Stork Magazine is a fiction journal published by undergraduate students at Emerson College. Initial submissions are workshopped and discussed with the authors, and stories are accepted based on the quality of the author’s revisions. The process is designed to guide writers through rewriting and provide authors and staff members editorial support and an understanding of the editorial and publishing process. Stork is founded on the idea of communication between writers and editors— not a simple letter of rejection or acceptance.

We accept submissions from undergraduate and graduate Emerson students in any department. Work may be submitted at stork.submittable.com during specific submission periods. Stories should be in 12-point type, double-spaced, and must not exceed 4 pages for the “flash fiction” issue. Authors retain all rights upon publication. For questions about submissions, email storkstory@gmail.com

Stork accepts staff applications at the beginning of each fall semester. We are looking for undergraduate students who are well-read in contemporary fiction and have a good understanding of the short story form.

Copyright © 2024 Stork Magazine

Cover design done by Katherine Fitzhugh

Illustrations done by Katherine Fitzhugh and Aubrey McConnell

Typesetting done by Eden Ornstein and Aubrey McConnell

4

MASTHEAD

Editors in Chief

Hannah Meyers

Sage Liebowitz

Managing Editors

Aubrey McConnell

Gabriel Borges

Head Designer

Eden Ornstein

Design Team

Aubrey McConnell

Katherine Fitzhugh

Head Copy Editor

Anna Carson

Copy Editors

Ella Maoz

Eva Windler

Ava Belchez

Prose Editors

Roni Moser

Dana Guterman Levy

Ali Dening

Emma Winiarski

Alexander Pham

Staff Readers

Gabel Strickland

Kaya Westbrook

Mars Early

Reid Perry

Stella Lapidus

Danielle Bartholet

Patricia Smallwood

Julia Montgomery

Abigail Andrews

Maria Gil De Leon

Vanessa Jacome Barsallo

Faculty Advisor

Jon Papernick

7

Letter From The Editors

For over a decade, Stork Magazine has proudly served as Emerson College’s sole fiction-only literary publication. With a short story focus in the fall and a flash fiction focus in the spring, Stork is committed to uplifting a wide range of authorial voices. We believe in the vital role that community plays in the writing process. Through workshops, editorial feedback, and revision opportunities, we hope to provide a space where all authors— seasoned and new—feel comfortable sharing their stories.

Of course, no publication would be possible without the hard work of our wonderful staff. To our editorial and design team, thank you for your continued commitment and endless enthusiasm. It has been a pleasure to create this issue with you—we appreciate all that you do! Be proud! Stork is held up by passionate readers, editors, and designers, who all work tirelessly to put out the most meaningful content possible. We would also like to thank our faculty advisor Jon Papernick for his guidance this semester.

We finally wanted to extend a special thank you to all of our authors, including everyone who submitted. We are honored that you have trusted Stork with your stories, and it is our pleasure to share them with the Emerson community. We highly value storytellers of all backgrounds, and hope that we have been able to share your journeys in the best way we can.

This year’s collection of flash fiction takes readers on a stylistic voyage. Whether realistic and dialogue-driven or poetically surreal, these stories demonstrate the endless potential that four short pages can offer. We hope you come away as inspired as we were.

Once again, thank you to all our readers, contributors, and staff, past and present. We hope you enjoy the 36th edition!

Hannah Meyers and Sage Liebowitz Editors-in-Chief

Spring Fiction 2024

10

CONTENTS

The Painter

By Nicholas Romano

Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh

Orion

By Willow Torres

Illustration by Aubrey McConnell

The Fireplace

By Max Ardrey

Illustration by Aubrey McConnell

The Terrible Thing

By Margo Heller

Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh

The Tidepool

By Jagger van Vliet

Illustration by Aubrey McConnell

When You Swallow A Watermelon

By Grace Zhu

Illustration by Aubrey McConnell

The Caged Bird’s Lament

By Marin/Spencer Madden

Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh

13 21 27 35 41 49 53 11

12

The Painter

by Nicholas Romano

Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh

Before the tremors, George considered himself an artist. When he painted, whole worlds formed at his fingertips. He could create universes with his brush and just as easily destroy them. It was like conjuring magic for only his use, but was understood by whoever he chose to share it with. He was proud of his collection of work, ranging from vast landscapes, both imaginary and real, to portraits of friends, which he kindly did without commission.

George never sold his works, except for the time he was painting a drab landscape surrounding a mill in an old New England town. An old man discovered him on the street corner and watched him work; he finished up an hour later without a single word exchanged between the two of them aside from the occasional inscrutable hmm the old man let out every few minutes—an opinion on specific color or composition choices, maybe—but whether these were positive or negative was uncertain.

13

When George completed the painting, the man finally spoke, offering him an extraordinary sum of money in exchange for the piece. Given that George was not particularly satisfied with his work—there were slight blemishes where unexpected droplets of rain had fallen onto the canvas, and the scale of the mill and trees was all off—he weighed his options and, after a moment of silent consideration, he conceded. Perhaps the man had eye trouble, or maybe he kept a collection of failed artwork, or maybe he could relate to the scene of an ancient ruin that was once young and beautiful and useful. Whatever the reason, that day was the only occasion that George put a price on his work. But after his senior friend departed as solemnly as he had arrived, the painter simply shrugged, pulled a fresh canvas out of his bag, and patiently began again, painting the exact same landscape. This time he made sure to fix the mistakes from his previous attempt, and this time it was perfect. The Mill now rests on the wall in the painter’s kitchen. He barely noticed it above the sink this morning as he cleaned his breakfast plate and silverware, fighting against the uncontrollable shakiness of his hands that had become a challenge which was seemingly impossible to overcome. This, however, did not stop him from trying.

14

Today, George was attempting his third painting with the newfound companionship of his hand’s tremors. His first two efforts had ended in disaster, his hand shaking so much that every time he put brush to canvas what he created was indistinguishable from an abstractionist’s depiction of a train wreck caught in a mudslide.

His first attempt was a straightforward, if unusual, landscape. He sat down in his office and painted exactly that—him in his office, surrounded by paintings. It was a place he knew well, a place that he could paint to the last detail in his imagination; so why could he not do so on a canvas? Barely half of a minute passed before he tossed the painting aside. George’s frustration building, he decided to aim for a simpler task. The second canvas was meant to contain a straightforward self-portrait, but when the brush wouldn’t hold still for even the most undemanding line, something in him broke. For the first time in his life he lost all patience, and he forced his hand through the center of the painting where his face should have been. In the fire of his rage he ripped the canvas off its easel and tore the other from its place on the floor. He flung himself through the doorway and hurled the paintings to their rightful place, to become nothing but ash under flames. The connection

15

between his mind and his paintbrush had been severed. What had once been magic was gone. It was replaced by frustration—an unnecessary tool, if you ask any painter. But today there was a change.

He now sat at the bottom of a hill, positioned toward an average forest of northern hardwoods. There was nothing entirely notable about this scene, and the only thing that even remotely stuck out was George himself. But he no longer had an interest in painting a beautiful phenomenon of nature—no exceptional skies, stars, or night-lit city blocks. All he wanted to do was prove to himself that he could still paint something that was easily identifiable. And so, perched on his stool at the edge of the woods and dwarfed by the giants in his full frame of view, George’s brush caressed the canvas. The first ten minutes plodded by, and so too did the next ten, and the ten after that. At the end of an hour the painter sat back and looked in full at the paint he had applied, and he wept. The piece was made up of barely discernible brown lines that were angular and crooked, and ugly yellow-green swirls that, when combined in a singular observation, looked simply as though he had puked on the canvas. George felt his hands shaking, unable to defend against whatever demon or evil spirit had wrested

16

control of his art away from him. But as he mourned, he felt the stool on which he sat quiver and rattle, and his feet and his legs began to shake in conjunction. A loose screw in the easel in front of him vibrated in its metallic home.

George lifted his head from his hands and opened his eyes to a miracle: as the ground shook with vigor, so too did the forest. Every tree oscillated from side to side as birds and squirrels scrambled from their nests and loose foliage and acorns and sticks freed themselves from their places and emerged into the cool open air of the northern hardwood forest, which, for not quite the entire duration of the ten-second earthquake, looked briefly like George the painter’s latest artwork come to life.

George’s tears disappeared, and as he glanced between his painting and the life in front of him, he saw that he had achieved more than what he had set out to do that day. He had painted life, or rather, the life in front of him had become his painting. George decided that he would never paint another painting from this day forward. Not because of his tremors, not because his body had failed him. But because he had done what many painters hope for but few ever achieve. He had let the life in front of him take over the work for him. The trees and their quaking became the oil on his canvas, rather

17

than George, a mere human, imitating what he wanted to see. But this is impossible to control; this is only something that might occur if nature happens to do so one day. And so right then and there, on the basis of life’s greatest coincidence, George decided to quit, because he knew that he would never create a painting quite as good as this one ever again.

18

19

20

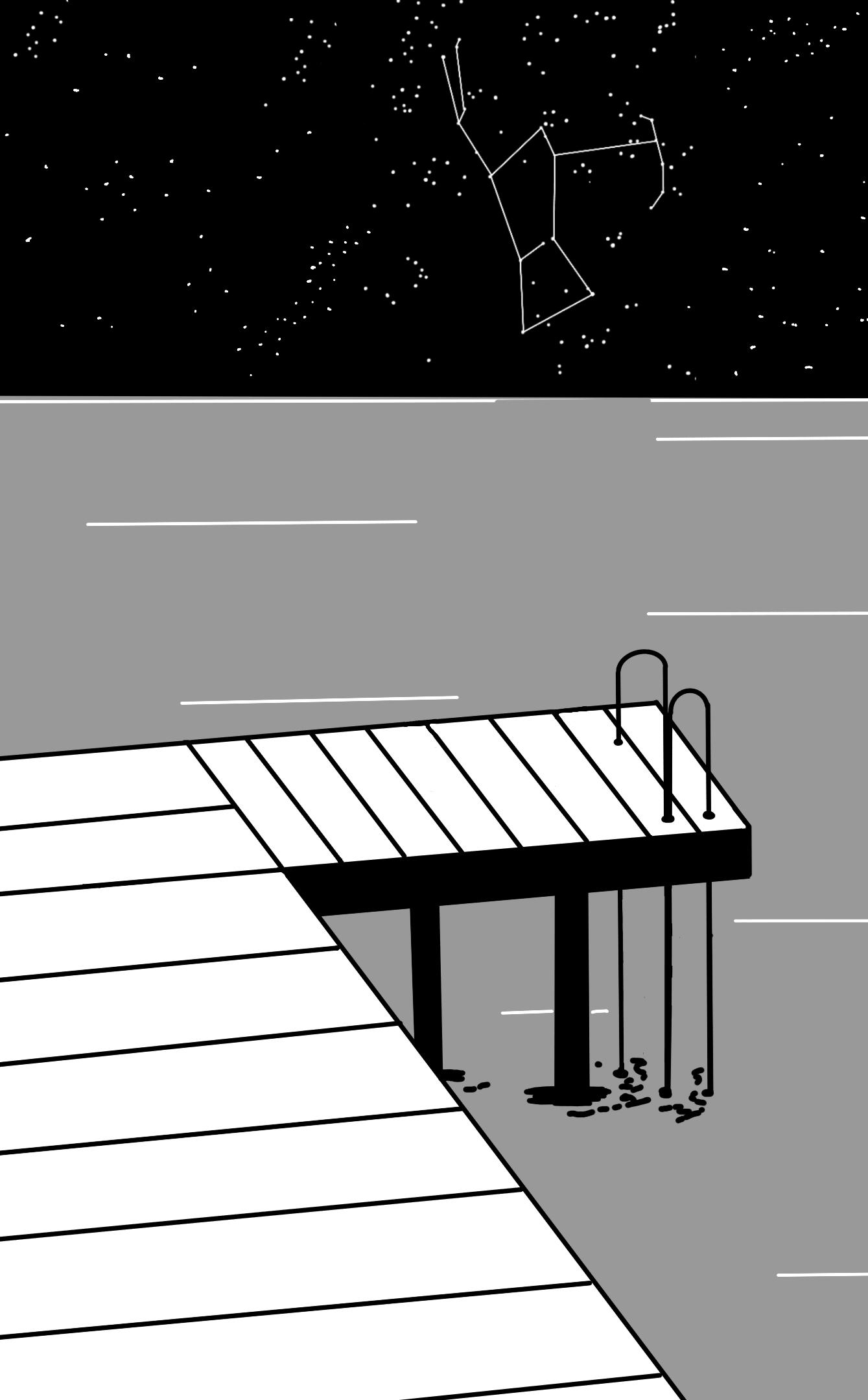

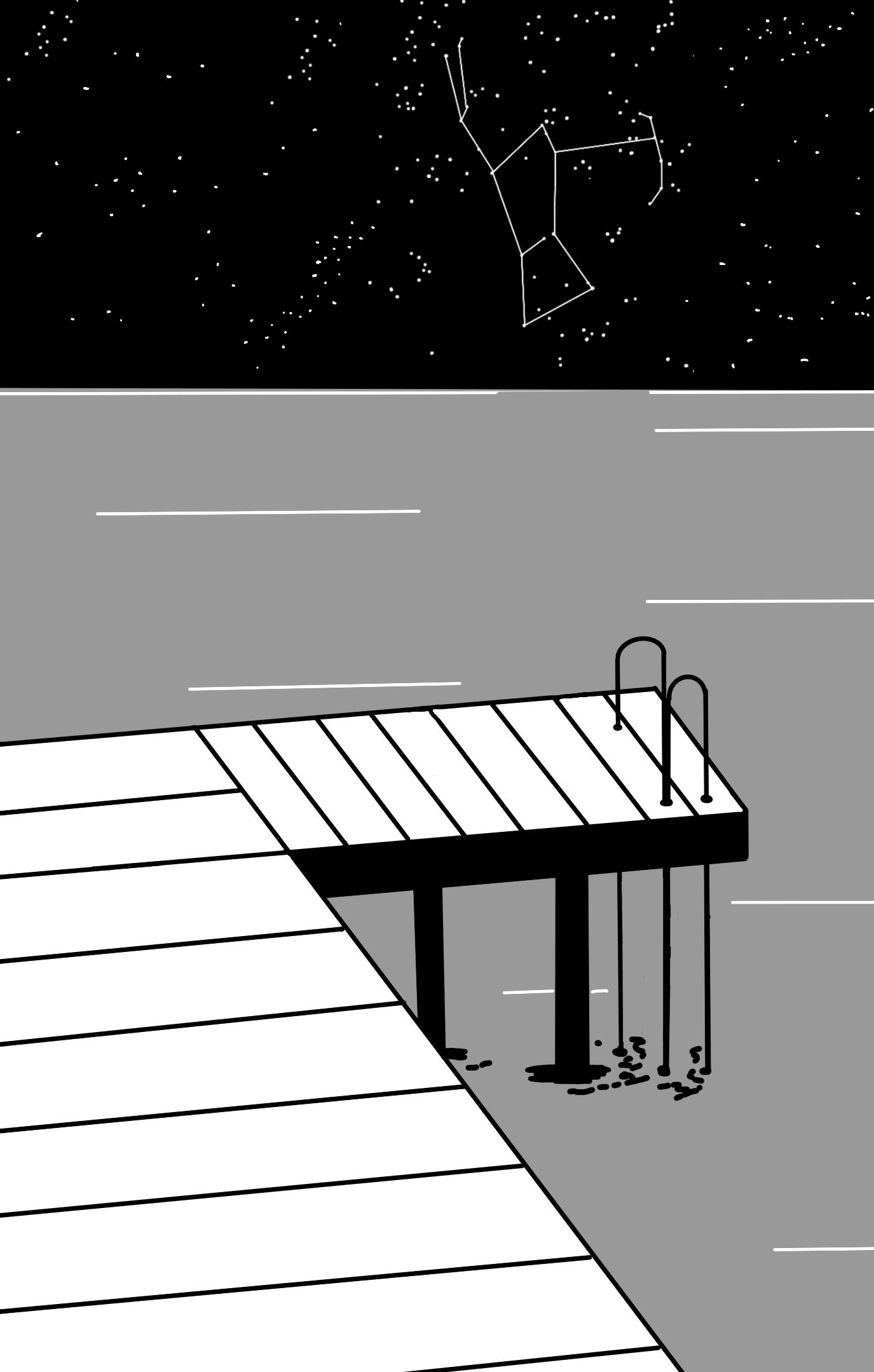

Orion

by Willow Torres

It is later than I should be out. The rest of Eliza’s quiet woodsy road is asleep at this hour and my mother doesn’t know where I am. It’s peaceful here. I can make out my favorite constellations. There is a breeze that rustles the leaves on this oppressive August night. I look at the light in the window of a house across the lake. I wonder what they’re watching, I wonder what their house smells like. I wonder what they do for a living—and my gaze shifts back to her. I’ve never been in love before, I don’t think. I watch her nervously. I stand at one end of her neighbors’ dock as she tiptoes to the other. She struts so fearlessly. Not that I’m afraid, but I don’t need to be caught by the kind of stuck-up people who live here. It’s the kind of neighborhood with those wicker star door decorations and scary-looking blond children. I’d probably say something snarky and get myself in trouble, but she would probably get us out of it. She is graceful and charismatic. She has the

Illustration by Aubrey McConnell

21

smile of someone you trust. She doesn’t take up so much space, like I do. I am so loud and clunky and every step feels wrong. Brash and abrasive, I am always too much. But I could never get tired of her; I don’t think anyone could. She waves me down to her end, and I walk over as quietly as I can. Barefoot on the weathered wood. It creaks beneath me, and I meet her, sitting at the edge. The water is still and cool as I put one foot in.

“Ready?” she says sincerely. I always like the simplicity in her voice. She doesn’t try so hard to seem a certain way. She just is.

“Yeah,” I reply.

“You have to be quiet, though,” she says back.

“So you think I’m loud?” I smile at her.

She laughs. “You can get a little excited sometimes.” The way she says it makes me like that about myself. The treatment of my flaws in her nonjudgmental eyes makes me forget about them. I slip myself off the dock and into the water before she can, like I have something to prove. She sits with a smile for a second and then follows. She always looks at me like she knows something about me that I don’t know. And she probably does. Our feet hardly touch the bottom over here. We tread.

“You know, I can’t believe we haven’t hung

22

out in so long.” She reveals the elephant in the room. It breaks from its enclosure and promptly tramples me to death, the weight heavy on my chest.

“Yeah” is all I can muster. I haven’t seen her since Christmas. I kind of can’t breathe. I might throw up. Maybe this is how I die. Maybe that wouldn’t be so bad. At Christmas we sat in a friend’s basement, warm and glowing from whatever fizzed in our mugs— mine read Nothing Like a Grandma’s Love. She and I exchanged cold glances and a few distant sentences. As though we were only acquaintances. As though we hadn’t just distanced ourselves in the last four months, but as though we had never known each other at all.

“Last time I talked to you I thought you hated me.” She is prying as gently as she can get away with and floating on her back to show me how unbothered she is. I join. I almost hate her. How she’s always teased me with her nonchalance when she knows how sick I am inside—or maybe she doesn’t. Though I imagine there’s no way you can’t tell just from looking at me that I am the type to cry when I can feel my socks in my shoes. I search for Orion’s Belt.

“That one’s Orion.” I point.

“I know, you always show me,” she says. And I do. My grandmother would point it out to me

23

when I was a kid. We would sit on the porch and look up at the sky and she would point, cigarette between her lips, and say, That one’s Orion, and I always look up to search for the belt of three bright stars. At Eliza’s sixteenth birthday party, we shared a hammock. It was August. The night air was muggy, but the sky was clear like it is tonight. My brother had forgotten to pick me up, leaving just her and I here, in her backyard, in the hammock, in the thick air with the unusually bright stars. Flustered, at a loss from our closeness, I pointed a finger to the sky. That one’s Orion. I dared not turn my face to hers. She laid unfazed. I closely monitored my own breath. Am I breathing too fast? Too slow? Too heavy? I’m being weird. I remember noticing I was holding my breath. And since then, when I look at the stars, I think of her. Like a curse.

“I’m sorry,” I admit. “I think I was jealous. You seem to have so much fun without me.” I break my float and go to hold my weight on the dock’s edge. She follows. “Well, am I supposed to just cry every day?” She is only half kidding,

“That’s what I do,” I laugh. I am almost not at all kidding.

“I missed being here,” I say. “I like how loud your house is. You have board games and siblings and nice furniture. I like looking in on your life.”

“Weirdo,” she quips, “it’s not all that.”

24

“Well, I liked it.” I smile. We share a look. Almost like I make her feel the same way she makes me. Our wet elbows touching, we are strangely close. And I swear she’s the one who moves her body closer to mine. The weight on my chest is still there.

“You know, I only went to school in the city so I wouldn’t be so far from you,” I reveal. I’m not sure if it’s the right thing to say. I keep going.

“I wanted to go across the country, but I was scared to be so far from you.” Her face drops.

“But I guess it didn’t matter anyway,” I try to joke. It was definitely the wrong thing to say.

“Why would you do that?” She is serious. “I am not at all that important.”

“I think you’re that important.” I’m trying to make it up to her. She seems embarrassed, like she did something wrong.

“But I would never want you to—” she starts, and the back porch light turns on. We duck under the dock in the small space of air between the wood and the water.

“Hello?” the neighbor calls out. The water comes just above my mouth. I pray he doesn’t see my shoes at the dock’s base. I giggle and bubbles ripple. She laughs too; I cover my mouth to stop myself from laughing. She smiles. I see the stars through the cracks. Tonight it seems like they shine brighter than usual. Our noses have never been so close.

25

26

The Fireplace

by Max Ardrey

Illustration by Aubrey McConnell

"Have you made any decisions, or do you both need a little more time?” the waiter asked with a tired yet chipper demeanor as he swapped the empty basket of bread for a filled one. Matt looked up from his menu to Diane across the table. She shrugged. He shrugged back. Though they’d been studying the menu to avoid conversation, the food listed hadn’t really been on their minds.

“If we could just take another peek, that’d be great,” said Matt. The waiter nodded and walked off towards the kitchen.

The Italian restaurant they had decided on was a longtime favorite of theirs. It was an older place in the East Village; it had been there since the two of them were kids. They usually felt comfortable there. The white tablecloths dressed up what were, in actuality, incredibly rickety, beat-up, aged tables. The pop music that played throughout the restaurant was always a little loud, but fine for when multiple conversations

27

were occurring at once. When they were with their group of friends, Matt and Diane would usually just get the same thing they always ordered. When they were with their friends, they didn’t feel the need to pay attention to the fact that the restaurant was never more than half full.

To them, it was always a cozy retreat from their hectic lives. But this time wasn’t like that.

They sat at a table for two near the back of the restaurant beside a fireplace with a dwindling flame. They had never sat by the fireplace until now, as the usual size of their party typically led to them getting placed near the door. Now, close to the kitchen, with just the two of them, the loud music became a bit more grating to the ear.

“—yeah, work’s been alright, it’s just that I can’t stand the main lady in our office. Everyone else is fine, but no one’s that interesting. They’re all pretty boring,” said Diane.

“Sounds boring,” said Matt as he meticulously tried to arrange his silverware so that they would all lay parallel in front of him.

“Yeah,” Diane said.

After some silence, Diane coughed into her napkin; she was hoping Matt would actually contribute to the conversation. A spark popped from the fireplace.

“Yeah,” she said again. “But I think I might be moving upstairs sometime in the next couple

28

weeks.”

Matt had just about finished aligning the spoon.“Like, in your apartment?”

“No, at work. I’m talking about my job.”

Matt nervously put his hands in his lap after realizing that he’d unfortunately aligned his utensils as perfectly as physically possible. “Oh, right. Yeah, sorry,” he said.

“. . .Yeah,” she said. “But at least—”

“This is completely weird, right?” said Matt, hastily interrupting her, finally making eye contact.

Diane was taken aback. She had been trying to avoid something like this. “Why?” She felt she had to be on the defensive.

He looked at her intently. “You don’t find any of this weird at all?”

Diane sighed. “Well, you know the age-old adage,” she said, rubbing her temples.

Matt thought for a moment. “It’s only weird if you make it weird?” he said. “Bingo.”

Matt looked down. “I mean, I don’t know. For me at least, it’s nice to rip that band-aid off.”

“No, because now you’ve accepted the fact that it’s weird. You’ve lost,” she said.

Matt chuckled. “It’s always a competition with you,” he said. “Remember in middle school when you used to say that Andrew from math

29

class was better friends with you than he was with me?”

Diane tried not to blush. She looked away. “I was obviously kidding.”

He gave her a smirk. The middle school thing was true. “I mean, I knew this was going to be hard. But it’s not the fact that we’re alone. We’ve hung out before. It’s just now there’s like, an underlying thing.”

“I thought we said no labels.”

“I know we said no labels. The plan was one date,” he said. “I don’t mean it’s a labels thing, it’s just that now things are . . . I don’t know, different.”

Diane took a slice of bread from the basket on the table and ripped off a small piece, tossing it in her mouth. She wasn’t all that hungry; she just wanted to briefly leave the moment. “You asked me,” she said after a few munches.

“You said yes,” he replied.

There was another moment of silence. Matt looked at the items on the table: a bottle of wine and a little rose in a jar. Yeah, this was new. He looked at her, all dolled up in her cable-knit sweater over a sleek burgundy dress. Brown mascara and cranberry lip gloss complemented her already alluring features. She never wore makeup. All of a sudden, he started to feel bad.

“I’m sorry,” he said, shuffling in his chair a little

30

bit.

“For what?” she said.

He put his hands together on the table, addressing her. “I feel like asking you out made it strange. I feel like we were, I don’t know . . . basically going out already? I mean we would hang out before this . . .”

“Right.”

“. . . But this just feels like it has completely different undertones.”

Now she started to get annoyed. “Yes, Matt, because it’s a date. We have started to date now.

Friends before, dating now. It’s not that hard.” She eyed another piece of bread. Any distraction would do.

“I guess you’re right,” he said. A subtle smile started slowly growing on his face. “But maybe it’s just that I’ve always liked you.” He averted his eyes, almost embarrassed. “And that never really went away.”

Putting down the bread, she looked at him in his dorky blue button-down and corduroy jacket.

Matt noticed her gaze. Was she staring?

“Stop that,” he said.

“Stop what?” asked Diane, still looking.

“That look. You always do that. You and your looks,” he said.

“I can’t help my looks!” she said with a smirk.

31

Matt scoffed. “That’s not—” A smile grew on his face, too. “This is what I mean. It’s all really nice until we think about what we’re doing here.”

He gave her his own look, one that had been there for a while, but that she had only started to notice recently. “I don’t want things to change.”

She returned the look and put her right hand across the table. “They will,” she affirmed. “They can get better.”

He looked at her hand. “Is that your angle?”

“I guess . . . I guess loving someone at first feels easy. Learning to understand them is the hard part,” she said, opening her hand. “I just kinda felt like I already had the latter down. So why not the former?”

He took a breath, and then her hand with his. “I just . . . worry.” He gripped her hand a little tighter, trying to get the words out right. “It just feels as if . . . as if it’s easier to lose a partner rather than a friend.” Desperation filled his gaze. “And I don’t want to lose you at all.”

Diane looked at their hands joined across the table. “Me neither.”

They sat there in their own melancholy for what seemed like ages as the fireplace’s dying flame flickered and snapped, seemingly clawing towards the sky. Locking eyes, the two of them tried to find something to mutter—anything. But as if the fire had been stealing all the air in

32

the room for itself, they merely sat there in silent asphyxiation.

Their trance was ruptured by the waiter, who briskly walked up to their table. Embarrassed, they pulled their hands away from one another. The waiter asked, “So, have you two decided on anything?”

33

34

The Terrible Thing

by Margo Heller

Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh

It was really none of my business.

A boy in the neighborhood died last December. He was sick for a while with heart issues—cardiomyopathy, if I remember correctly—and left quietly on a Tuesday morning. I was making my coffee when the ambulance pulled up outside his house, and washing my mug when his mother sat down sobbing on the porch. His little sister came out, and then his father. He was fifteen, I think. We sent them a casserole.

George, the boy, had been diagnosed at seven years old. After too many intensive surgeries, his doctors decided to put him on the list for a heart transplant. I didn’t know that then. The first time, I didn’t think anything of it. On our morning walk, my lab, Sadie, started pulling on her leash, twitching her nose to the air, whining desperately. I’ve never seen her act

35

like that; she’s a well-behaved dog. It became clear, when she dragged me off the path and down to the creek bed, that the object of her curiosity was a little gray mouse—or at least, what was left of one. With a firm hand on Sadie’s leash, I leaned down to investigate. Laying on its side in sloppy wet mud, the small body was belly up and ripped open. Its fur was smeared with dried brown blood, but the insides were red and scrambled like poorly cooked eggs. Flies buzzed past my ears and around my hair, and were landing on its open flesh to lay eggs. Maybe another animal had gotten to it, a fox or a bird. I winced at the acrid smell and pulled Sadie away, not wanting to spend a week’s paycheck on a rotten rodent in her stomach. It wasn’t long before corpses started to pile up.

There were more mice scattered around the mud, but the biggest difference was that soon we began finding them with their bellies sliced instead of ripped. Clean, careful incisions ran from their throats to their tummies, and the indiscriminate guts were replaced with the sight of distinguishable gooey pink organs. It made me think someone in the neighborhood had enrolled in a self-taught course on dissection. Weird, but whatever.

With that change, I stopped indulging Sadie

36

when she tugged on my wrist near the creek. “You know what’s down there, girl,” I mumbled once. She looked up at me with those wide, eager dog eyes, and I looked away.

I got concerned when the squirrels started showing up. It was getting colder, with vivid leaves covering the ground in a decaying carpet. I almost didn’t see it with the autumn camouflage. This time, whoever disposed of the poor thing didn’t even do a good job, lazily throwing it to the side of the path as if it were mere litter. It was tucked under some overgrown weeds, but it was visible—and smellable—without a dog needing to lead you to it. I thought of using my shoe to push it down toward the creek for some decency, but decided against it. It was probably best to keep to myself.

The rabbits were the worst. I nearly cried looking at their bloodied bodies, the creek water rushing over their limp ears and carrying rot downstream. Their long front teeth hung out of their open mouths, and their beady eyes followed us when we walked by, which was even more unsettling than the sick game of operation that had been played with their bodies. That’s a bit excessive for at-home experiments, isn’t it? I started putting Sadie inside the house with me at night. God knows what could have come next.

I was going to say something, really.

37

It was deja vu, seeing the ambulance outside their house. The pristine stonework, the manicured shrubbery. The story had been all over the news. The local channel came knocking at my door for a comment, but I couldn’t bring myself to answer. There was no casserole.

I heard from our neighbors that the boy’s little sister, Gracie, had killed herself. It was brutal. The mother found her in the garage, collapsed in front of a mirror, her torso meticulously sliced with a kitchen knife from collar to belly. Not a spot was clean of blood. Her fingers were clutched tight around her heart—her actual heart, just ripped from the muscles and tendons in her chest. Self-inflicted, they determined.

I found out later that she was a potential match for her brother. Just before George died, doctors were considering using some of her tissue to repair his. And I suppose it was just the kind of sadness that ate her alive. Poor girl.

Two months after Gracie’s death, her mother overdosed in her bed. Her father moved out, and we haven’t heard from him since. Grief is a terrible thing.

One night, I couldn’t sleep. In a fit of panic, I ran to the creek in my pajamas, bare feet slapping in the mud, and gathered all the animals I left behind. Searching through the

38

overgrowth and trudging along the creek bank, I carried their remains in my arms, decay and all, like I should have when I first saw them. I clawed out little graves with my hands under a dogwood tree and didn’t stop until they were all buried, until I could breathe again. Somehow, the mice were the hardest. I woke up to Sadie’s cool wet nose sniffing at my face with dirt under my nails and smeared across my bed sheets. A new couple moved in nine months later. They’re young and friendly. I’m not sure they know. They’ve been working out front to bring life back to the bushes, but I don’t know if it’ll ever be as green as it once was. Sadie sleeps inside at night. We don’t walk by the creek anymore.

39

40

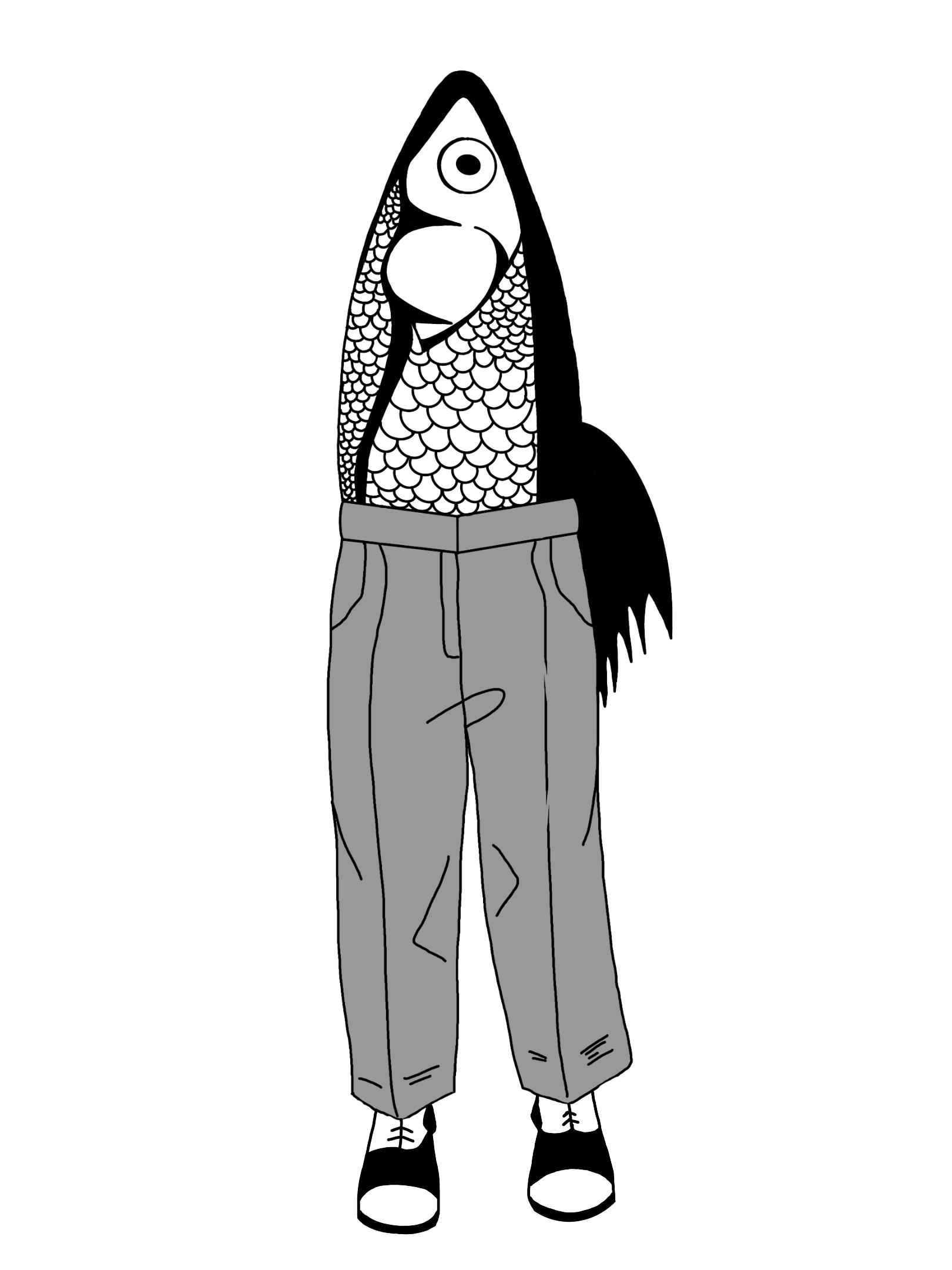

The Tidepool

by Jagger van Vliet Illustration by Aubrey McConnell

Down on the rocks where the waves have yet to lay themselves:

I was merely looking, with no particular interest, at a pool left from an old tide. It was then, to my delight, that a fish spoke out to me. “How wretched is this world,” the fish lamented.

Here, I was certainly inclined to agree, though I could see no reason for the fish to think as such. It seemed his pool was ample enough, fairly abundant, and generally spacious in footage. He, a rather small fish, had much room to swim about and live a decidedly unwretched life.

“Why, it is,” I said to the fish, “but how can it be so miserable for you?” The fish moved in a turn, and I saw that he was a leopard-spotted thing.

41

“I detest this terrible life,” the fish answered.

Now, of course, I was inclined to laugh at this. The fish was not a man, not afflicted by maladies of love, morals, or any earthly problems. As I looked at the fish, all his terrible life appeared, at once, confined to the edges of his own pool.

“Come now,” I implored the fish, “see your pool here. Is it not a lovely place to swim about?”

The fish moved again in a turn.

“This pool? Lovely?” The fish scoffed at me. “I assure you that this is a perfectly sordid place to live.”

“But look here.” I wagged my finger at the fish. “Look at all that you have. See your pool, vibrant with purple corals and algae. What extravagance! How beautiful the scene, so alight with colors and pleasant things. Or think of this! See all the creatures in your pool. Occupy yourself with the urchins just beyond you, huddled in congregation. Or what of the slugs that slip along the rocks? They seem gentle enough. Surely, they can provide solace.”

The fish swam about slowly and reflexively returned to where he’d first spoken from. “Alas, there may have been a time when I would have agreed with you, sir. But that is a time that has

42

long since gone from me. Perhaps when I was a fry and did not know anything I was blissfully happy to be here. But I have grown, and this pool has not. The urchins all clammer far too loudly for my taste, now. They click their beaks to dispense their streams of gossip. If I should ever swim too close, I would be punctured, surely, by a stray foil. Ah yes, and the slugs. So aptly named, I should say. They are as willing a conversationalist as the moon. They speak so simply that I am prone to believing they are either greatly stupid or otherwise half asleep. What business have I to go about risking my safety and sanity?”

I looked about then and noticed that the rocks near to me were growing slick with salt spray. A rare and striking sheen of water then encroached steadily on my position. “Ah! Then why don’t you leave when the water comes close to your pool?” I offered. “The waves almost stretch to this point, and I am sure with a welltimed jump, you might propel yourself into their clutches. Or else, if all is wretched, why don’t you give up entirely?”

The fish shook his head again. “No good, I'm afraid. No good at all. I’ve done this already, you see. I’ve pushed myself and sprung from within this pool. But look upon me, sir. Look at my size. In the open waters, I am a baitfish. I can hardly

43

go ten meters without dodging the maw of a great barracuda or skirting the teeth of a grouper. And to give up! Is that what you think of me? I am not something drifting aimlessly as jellyfish or a plankton. I can assure you of that.”

There was a note of asperity to the fish’s tone, and so I hastened to make him see that I really meant no offense.

“I am only offering solutions.”

“There are no solutions,” spat the fish. “And there is the same answer as before. Again and again, the same answer.” The fish looked unlike himself now, beset with agitation. Somewhere within me, I took a strange pleasure in this. An odd and heated effect had now installed itself within my chest.

“I cannot help it,” the fish said. “I meet so many creatures who won’t ever understand. They think of me as a nuisance when I am only speaking the truth. It would seem now that above solutions, I am simply in dire need of understanding.”

Still imbued with a strange heat, I felt that this was the fish’s newest mistake. Here, he had dissolved into passion and admitted it himself.

I could not show it, but this error excited me. “So it is the case that you are looking for pity?”

I offered, as though this were nothing but an innocent remark. “You won’t see any solution,

44

and you only want someone to agree that your dilemma is truly a wretched one.”

Here, I knew that I had shaken the fish’s resolve, for he was silent. There came only from him a series of bubbles made into grotesque rings as they came to the water’s surface.

“Now I have felt this way too, of course,” I went on. “It is what we all want in some regard: complete and total assurance that we are worth our weight in suffering.”

I gestured once to the pool and then to the distant, thunderous waves beyond.

“But consider that there is every chance you are simply imagining yourself as separate. You, sir, seem to labor under the weight of your own certainty. If this were all your own doing, then perhaps you are not quite as clever as you believe.”

At this moment, I began to consider myself anew. Though I’d felt excitement in triumphing over the fish, I now allowed myself some general sympathy for his troubles.

“If you must know the truth,” I said earnestly to the fish, “there is less of a difference between us than you might at first believe. I am not happy either, and life, as it happens, is passing me by. I perhaps judged you unfairly, for I did not know a fish could suffer like a man. But you should know that we are not different. I grant you that

45

this world is wretched, but there is no place free of affliction. Not that I have found, and I should hope I have traveled a great deal farther than you.”

The fish scowled, eyeing me and flexing his gills. Only after several moments of this calculated brooding did the effect fall suddenly away, replaced by a steely calm. “I believe you are a properly ungrateful fellow,” the fish concluded coldly. “You are a man, after all. You are perched quite happily atop the food chain, and yet you, too, bemoan your own circumstances. This is a world built around man, so you can eat and, travel and explore at your leisure. I have no leisure to speak of, for my every day is not filled with such opportunities. The life of man is teeming with such glories, and yet you dare to commiserate. You dare to extend a hand in friendly sympathy when you are at good odds to at least change your present affliction.”

I, admittedly quite offended, pondered the fish’s vitriol with some consideration before deciding that he was, after all, merely a fish. And what did a fish know of life? I had plenty of reasons to be miserable and plenty of reasons to be lonesome. The fish was a fool, and an illmannered fool at that.

And so I moved along, albeit sourly, to observe another pool.

46

47

48

When You Swallow A Watermelon

by Grace Zhu

Once, a girl’s mother brought home a watermelon so tender that the girl swallowed its bitter seeds one by one just to taste the sweetness again. The next morning, a watermelon sprouted in her stomach.

Delighted, the girl split her skin apart and cracked open the melon with her mother’s butcher knife, sharing slices for all her neighbors to try. Juice trickled down their fingers as they bit into the rinds; they remarked on how particularly succulent a melon it was.

The next day, the girl’s ribs were replaced by rows of shiny bananas. Once again, the neighbors swarmed and bit into the firm flesh at the girl’s cajoling.

The day after that, there was a pomegranate heart and trails of purple grape intestines to feast on. Strawberries and cherries crowded her blood, and instead of lungs, she had two perfectly formed pineapples to offer. Once her lips were a pile of raspberries, the girl could no longer

49

Illustration by Aubrey McConnell

entreat her neighbors to feast, but they made sure to savor every offering of hers down to the last. It was only when the girl’s skin turned into hollow lemon rind, and there was nothing left of her, that her particularly industrious mother thought to plant the watermelon seeds from the girl’s stomach in her spring garden. New leaves sprouted by the minute, and within hours, the vines had strangled her turnips and tomatoes and swallowed her garden gate whole.

The neighbors complained of yellow flowers biting at their cowering dogs and a vine dragging the mailman away. They told the mother that it was irresponsible of her to let her garden grow so wild if she wasn’t able to keep it under control.

Mortified, the woman picked up her garden shears and pruned a path to where the seed was planted. Cradled in the vegetation was a perfectly round and perfectly ordinary watermelon. It was green and luscious, and when she rapped her knuckles along the rind, it gave the most seductive ring. With her shears, the mother cracked open the melon, and a baby, slick with red juice, fell onto the dirt. It opened up its watermelon seed eyes and smiled, revealing a mouth of tender, red fruit flesh. It looked a little like her daughter who had been eaten down to the quick, and the baby stretched out its dripping arms to her.

50

Like any good neighbor, the mother split apart the baby and shared slices with the neighbors, who remarked that it was even sweeter than the girl had been.

51

52

The Caged Bird’s Lament

by Marin/Spencer Madden

Illustration by Katherine Fitzhugh

Here is my hand, he said. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Here is my hand that will not harm you.

— Louise Glück

I.

This will be the last time you believe that life is kind.

VII.

You run out of books. Nothing else seems to make you happy anymore, so your parents buy you dolls, and you make up your own stories for them—all full of love, all with Happily Ever Afters. You wish them all the best, and you imagine they are wishing you the same.

VIII.

You ask where babies come from. Your parents get you a book from the library. You are

53

fascinated for a few months. Afterward, you feel so dirty and horrible that you pretend it never happened. If anyone asks where your fear of growing bellies came from, you lie and say you don’t know.

XI.

You begin to bleed in gym class, and it feels like the magic’s leaking out of you. You cross your arms over your chest to hide how it’s grown. You don’t like yourself anymore. You feel greasy and sweaty and gross, like a tennis ball in a dog’s mouth. You want to go home. You want to go home all the time, even when your mom says you’re already there.

XIII.

You wake up one morning and your back hurts so bad you can’t move. When you finally drag yourself over to the mirror, there are two gaping, oozing wounds there. You go to scream but nothing comes out. You try to show your parents, but they tell you nothing’s there. You hide the scars under bras but they keep on consuming your flesh until suddenly—there they are. One black, one white. Wings as soft as clouds, and all yours. All yours.

XIV.

The day your wings heal, Sam is waiting in your

54

bedroom, reading your favorite books. He looks up when you walk in and he smiles, the smallest and sweetest of things.

“Hello,” he says. “Can you see me?”

“Hello,” you say. “Yes. Is that normal?”

Sam smiles wider. “No, not at all. I like your wings,” he says, nodding toward the hulking, demonic things on your back.

“I like yours,” you say, nodding toward the bones on his. “Are you going to stay?”

He reaches out and folds your tiny hand in both of his. “Yes,” he says. “Yes, I’m going to stay.”

XVI.

Your birthday rolls around, and Sam bakes you a cake and sings you a song that no one else can hear. You disappear into him, and him into you, and your parents don’t seem to notice you’ve been missing. They listen to you cry and rail against the world, and they tell you all teenagers feel like this, but you don’t think that’s true. You feel like you’re going to die all the time, like nothing means anything. Even when the sun’s out, the sky is always gray. You force yourself to love the rain. You drench yourself in colors so the darkness can’t swallow you. You try to fly, and you fall. But Sam is there. Sam is always there.

XVII. You leave. You take everything the world said

55

you weren’t allowed to have and you leave. You move up onto a cliff and into a yellow Victorian house, and you keep all the doors locked. You write letters to people who don’t love you, counting their names on your fingers to fall asleep. Sam wanders the house and cleans up the aftermath of your every apocalypse. He sleeps in your bed and tells you he loves your emptiness. You sit at the window all day and wonder why everybody else wants to be full when this empty life is so quiet, when this life is so good. You tell Sam you love him, and he tells you he loves you back. He is the very first friend you have, and you know, even though your parents told you otherwise, that he will also be the very last.

XVIII.

Someone calls you an adult and you have to hide under your bed for your whole birthday. Sam crawls under there with you. “Why are you hiding under here?” he asks. “Because,” you say. “This is where monsters belong.” He holds your hand. You stay there until you’re not an adult anymore.

XIX.

You don’t have any friends, so you make up your own, all with wings, just like you. You draw them over and over until they come to life, until they’re real. But they all wilt eventually like the

56

flowers in your garden. They melt into puddles that Sam has to clean off the floor while you cry into your hands. Your tears are made of blood, and you can’t wash them off your palms. They stain everything you touch, so everyone knows you have been there, even when you tell them you never were.

Sam sits down beside you on the couch and slips a doll into your hands. She has cottoncandy hair and a painted-on smile that you used to press to another doll’s smile, back when you believed in love.

“Your parents are outside,” Sam says. “They’ve been knocking for years.”

You push the doll’s face into your own face, like she’s kissing your cheek. “Are you going to stay?” you ask.

Sam takes your not-so-tiny hand in both of his. “Yes,” he says. “Yes, I’m going to stay.” You put the doll down on the couch. You shake out your wings. Then you go and open the door.

XX.

You still can’t fly. But at least Sam is still here. Sam is always here.

57

About the Authors

Nick Romano (he/him) is a freshman VMA student. After college, he wants to be involved in a currently undecided part of the process of making narrative films. But for now, if he’s not writing or editing, you will likely find him on a set or at the movies!

Willow Torres (she/her) is a junior pursuing a Visual Media Arts BFA and a minor in Narrative Nonfiction. She also has a radio show, Thrift Store Couch, on WECB and is the Lead Graphic Designer for BONK Comic Collective. This is her first time being published, so she’s super excited!

Max Ardrey (he/him) is an undergraduate Visual and Media Arts Major at Emerson College. He grew up in Westport, Connecticut, and now resides in Boston. Most recently, he has worked as a member of the EVVYs writing team. He is also set to star in the upcoming independent film And I Love Her.

Margo Heller (she/her) is a sophomore WLP major from Red Bank, New Jersey. Her work has previously appeared in Stork, Gauge, and soon Concrete! Outside of writing rather morbid things, she enjoys love, friendship, and admiring everything soft and kind in the world.

58

Born in Maine and currently living in Boston, Jagger van Vliet (he/him) is an undergraduate student at Emerson College, studying Writing, Literature, and Publishing. His other works can be found in High Tide Magazine, Index, Five Cent Sound, Sieva, and Generic Magazine. Presently, he works on the editorial team at a Boston-based fashion magazine. He primarily writes novels, novellas, and short stories, with a focus on Dadaism and the surreal.

Grace Zhu (she/her) is a first year MFA student in the fiction program at Emerson College. She is also a board member for Writers of Color, and a reader for the literary magazine Redivider.

Marin/Spencer Madden (she/him) lives in a boring town called Framingham, Massachusetts, and currently works at the local Barnes & Noble, where she spends half her paycheck before she’s earned it. When he’s not writing romances about dead gay people, he’s online window-shopping to stave off the existential dread. She’s been published in magazines like Stork and Palette, and is currently a Creative Writing student at Emerson College, Class of ‘26.

59

About the Type

The running text for this issue is set in Adobe Caslon Pro, designed for Adobe by Carol Twombly based on specimen pages by William Caslon between 1734 and 1770.

The display types for this book are Yu Gothic Pr6N designed by Morisawa Inc.

61