SAND Journal Willibald-Alexis-Str. 16 10965 Berlin Germany info@sandjournal.com www.sandjournal.com Connect with us for news and events: Facebook: SAND Journal Twitter: @sandjournal Instagram: @sandjournalberlin ISSN 2191-429X Copyright © SAND Journal, May 2019 All authors, translators, and artists retain their copyrights to the respective works.

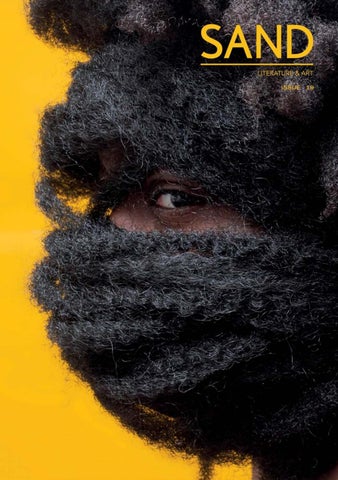

SAND e.V. is a registered nonprofit association (gemeinnütziger Verein) under German law. Designed by Bárbara Fonseca Printed in Latvia by Jelgavas Tipografija on Cyclus 90g paper Fonts: Spectral by Production Type, Sporting Grotesque by Lucas Le Bihan Cover image: “Hair Vigilante” by Vicky Charles Quotes from song lyrics contained in “Editor’s Note,” “Citizen!,” and “Lashes” fall under fair use according to German copyright law. Attributions for the relevant quotations are as follows: “Somewhere” written by Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim for West Side Story (1957). “Wave of Mutilation” first performed by The Pixies (1989), written by Black Francis. “Little Animals” first performed by The Ravonettes (2003), written by Sune Rose Wagner. “Night Drive” first performed by Jimmy Eat World (2004), written by Jim Adkins. “Mr Brightside” first performed by The Killers (2003), written by Brandon Flowers. “Soft” first performed by Kings of Leon (2004), written by Caleb Followill. “All Cats Are Grey” first performed by The Cure (1981), written by Laurence Tolhurst, Simon Gallup, and Robert Smith. “Disorder” first performed by Joy Division (1979), written by Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook, Ian Curtis, and Stephen Morris.

2

Editor’s Note

Out of Place JAKE SCHNEIDER

“All my distances point to home” — King Llanza

→ 96

From “Somewhere,” West Side Story

In this apprehensive time, the conversation keeps returning to who belongs where. In December, a multilingual poster appeared in my local Berlin U-Bahn station, courtesy of our newly renamed “Homeland” Ministry, with the tagline: “Your Country! Your Future! Now!” The former Interior Ministry was advertising a program that pays people to leave their homes in Germany and return to other “homelands.” So much for Willkommenskultur. After seven years here, I thought I already was in my country, living my future – right now. In February, Fatma Aydemir and Hengameh Yaghoobifarah released a brilliant volume of essays by a dozen prominent members of German society – who are also members of religious, ethnic, and/or sexual minorities often omitted from the national narrative.

Edito r’ s No te

The book’s German title means “Your Homeland Is Our Nightmare,” and it is dedicated, with deliberate ambiguity, to “us.” Out of their shared sense of doom, both the Homeland Ministry and its naysayers drew lines between us and you, changing the subject from diversity to place. The widespread impulse to sort like with like goes both ways. It’s not the sole province of nativists barricading their birthplaces against newcomers, who they fear could displace or “replace” them. For their own part, outliers often wall themselves in: a turtle-like defense mechanism. When I’m traveling, I find it comforting to walk into a synagogue or gay bar and to know the tunes by heart. The comforts of coming home to eccentric Berlin are less specific but no less palpable. So many of “us” supposed anomalies grew up imagining a more welcoming enclave, a zone of elseness populated by sore thumbs just like ourselves: maybe a queer mecca, an artists’ colony, or an ancestral land where our faces and names would blend into the citizenry. Then again, enclave dreams recreate the same segregation that gave us our original loneliness-in-a-crowd. They simply leave out someone else. This issue is loaded with incongruities we would be tempted to label “out of place.” Sore thumbs and misfits, hermits and dreamers, immigrants and local-born loners. Yet to say that they exist at the margins is, once again, to restrict their worlds to one page. Perhaps “out of place” doesn’t mean “in the wrong place,” after all. Perhaps it’s an invitation to leave “place” altogether, to set aside the quilt of geography and find another pattern, another set of connecting threads. Here are a few isolated examples from the issue: A ham-radio hobbyist explores their identity in Germany; some of the neighbors are tuned, tragically, to another frequency. →

40

A Bangladeshi-American essayist ponders the intersections of sex, culture, and religion.

→

→

84

A poetically censored report from Mexico gives us clues about a disastrous wrong-place/wrong-time scenario.

→

→

37

A young American man shuts himself in his bedroom for years, culturally appropriating a Japanese epidemic of self-seclusion. →

10

In a poem inspired by an article from The Journal of Molecular Biology, the surname “Okazaki” becomes a recurring genetic fragment whose function we cannot immediately place.

→

81

In another unknown dimension, we struggle to classify an “electric nosferatu.”

→

→

→

In a pharaonic, otherworldly realm, we’re the outsiders. → 47,

121 61, 120

A Brexit-era Briton explores a free-trade zone peppered with borderless brand names.

→

→

→

49

And on the cover, Vicky Charles wraps her hair around her face, locking eyes with us through her self-imposed cage. • •

What unites SAND #19 is a sense of dissonance and disconnection, whether in Greenland, Nigeria, or Iran. The place is beside the point. As usual, we haven’t announced a theme in advance – the anomalies just fell into place – so some of the works we selected might relate to this theme more than others. By that logic, the exceptions are “out of singularities. “Even on this roof, the grass trembles / in the wind” (→27). The grass has found higher ground. It isn’t going anywhere, and neither are we.

Ja k e S ch n eid er

place” themselves. Let us appreciate all of it, the universals and the

8

Carlo Andre CRTL+

+DEL

40

Florian Wacker trans. Rachel McNicholl MOUSE

10 22

Luke Muyskens ENDLESS SOAK

trans. Rebecca Ruth Gould

MOURNING THE BIRTH OF IMAGE

27

Rosaire Appel MATHEMATICAL WEATHER

trans. Rebecca Ruth Gould Kayvan Tahmasebian

WILD GRASS

48

Candice Nembhard

49

Christian Brookland

57 58

PEACHES

THE IDEA OF PERMANENCE

SUNSTROKE

CITIZEN!

Rosaire Appel WEATHER

Trace Howard DePass NEW AMERICAN CONSTITUTION (TERMS & CONDITIONS)

SOMETIMES THEY FALL FROM

61

Lisa López Smith

Marc Cohen THE INTELLIGENCE OF THE EARTH

FROM THE AYOTZINAPA INVESTIGATION REPORT

39

Marc Cohen

Jeffrey Gibbs

THE SKY

37

47

Bijan Elahi

&

28

Lindsay Costello

Bijan Elahi

& Kayvan Tahmasebian

26

46

62

Rowen Foster DON’T KNOW WHAT TO

Uma Menon

DO WITH VIOLENCE SO

SPOKEN LANGUAGE

I PICK AT MY LIP

64

Art Section VICKY CHARLES

118

Hussain Ahmed MAGHRIB

SARA ANSTIS AVANTIKA KHANNA HENRY CURCHOD

119

Marie Lundquist trans. Kristina Andersson Bicher

81

Kanika Agrawal

UNTITLED

from OKAZAKI FRAGMENTS

84

Marina Reza

96

King Llanza

120

Marc Cohen

121

Andriana Minou

SUNSET DANCE

LASHES

AN ANNIVERSARY

4TH OF NOVEMBER

97

Joshua Bohnsack

107

msw

123

MY SECOND ENCOUNTER WITH ABANDONMENT

LAZY EYE

ALLUP IN MY DREAMS, #1

Alyssa Ripley

124

Arianna Reiche

132

Marta Helm

NOTHING MACHINE

(FEATURING OCTAVIA BUTLER)

109

Rosaire Appel

110

Helena Granstrรถm

TOOLING AROUND THE KEYS

trans. Saskia Vogel WHAT ONCE WAS

POEMS ARE LOCATIONS

Po e t ry

CARLO ANDRE

CTRL+ +DEL Untethered state I music you myself . . . morphed : : the mundane meta blender : : the sky grappler the Rebelmaster spheres in : ripper of lights thrown out : equinoxes neon-grab the [+]me te quiero, amorpill regatta pulsing my deepest end f*ck it body : leave it evident a void : the real prone to Xfade being : O O O long awaited instant & drop & drop & drop: where I’m here not & the destination’s me mover : : alleye Marshall domino piece here we tumble off personal

8

9 shatter cord aboil at the fry surround like dazzlelust hear me speck the inverted eye of me to zoom center pit & spit [ignominy] hand to mouth as it rushes in

Fic t io n

Endless Soak LUKE MUYSKENS

twenty-five women. one man. five thousand bottles of champagne. There are no cameras. The girls face a dense, velveteen block of red. It doesn’t matter. Aliyah, Alex, Amberlee, Anne, Becky, Beverlee, Cari, Celine, Elisa, Jayne, Jessie, Kelly R., Kelly T., LaTonya, Liz, Martzia, Molly L., Molly R., Nicole, Penelope, Renee, Samantha, Sarah, Sara, Veronica, and Zara matter, their eyeshadow is of consequence, their dresses have weight. the next seven weeks will be spent here, in our wine country estate, where these twenty-five girls will vie for the eyes and seed of one purebred hunk. and who better to mediate than yours truly? Ty’s voice is strong and luxurious, like an oak door. His suit is Italian or French and his imposition on the world is welcome. Who better, truly? i am ready to separate cat fights and, if necessary, punish our contestants with a playful spanking or two. he delivers a charming wink. all kidding aside, we’re here to find love. aren’t we, ladies? The ones who aren’t caught preening give dutiful nods. Ty is momentarily overwhelmed by the collective glamour of these women. As a unit, they embody the verve, glitz, and polish to which all girls aspire. His eye is trained, however, to recognize defects. Small scars and blackheads fighting through foundation make the presentation of their bodies pornographic. this season’s hunk is special. some variety of doctor/marketing manager/entrepreneur whose enamel we have inspected and whose parents’ pedigree we guarantee. girls, you have so much

10

11 to lose this time. you cannot afford to let your posture go slack. The lights are hot, they blind, the candles burn, the torches burn. ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the bachelor. Fans everywhere admire Ty’s grace and poise. While the twenty-five women sweat and grind their teeth, Ty moves with the fluidity of something more natural and confident, a jet stream. The universal envy for his ease gathers in the atmosphere, condenses into rain, and pours on every nation. • •

Night. Morning. Ty folds his shirt and places it in a wicker basket. He steps out of his sweatpants and puts them on top. Covering himself with a small towel, he walks from his bedroom into the bathroom. Onsen cannot be fully accomplished outside a bathhouse, but Ty replicates the Japanese ritual to the extent he can, performing kakeyu in the shower by pouring hot water over his body with a measuring cup, something like a short prayer. He then climbs into the steaming bath. Water quiets his body, dissipating the static and stress in his joints. Uniformity, he sinks. Underwater, sense is limited to thumping noises and broad pressure on his skin. Ty dries himself with a warm towel, dresses, and returns to his room, which remains unchanged. Afternoon. Evening. Night. Morning. Afternoon. Evening. Night. Morning. Afternoon. Evening. Night. Morning. Afternoon. • •

ty? His mother, Edna. how are you doing today? A response is not expected. She is magnificent, an institution of culture and care who deserves a progeny, not a polyp. your groceries are in the bathroom. Pause. i got you some mochi from whole foods. green tea flavor. i read about it online. enjoy,

E n dles s S o a k

ty. please. The door choking her voice is impermeable, less of a portal than a continuation of the wall. It has not been opened in three years. Ty hasn’t crossed its threshold in four. Edna delivers his groceries through the bathroom, which has openings into both his room and the hall. i’m going to work now. i’ll be at the university if you need anything. A professor, an intellectual at the helm of her field with him, a useless skin tag on her legacy. Do her coworkers know? Ty assumes shame, omission. i tried the mochi. it’s good. please have some, ty. The window seems a more possible escape than the door. It’s occasionally opened to the air twelve stories over the park’s brain-crushing streets when Ty finds his energy focused and forward. goodbye. He cracks open the world and tries to find something, anything, within himself. • •

In the bathroom, Ty opens the bag his mother left and pulls out chicken stock, soy sauce, Top Ramen, sliced pork, baby spinach, eggs, dried nori, and shallots. In the medicine cabinet he finds garlic powder, ginger powder, chili powder, and five spice. The bathtub holds an electric cooking pot, in which he combines the stock, soy sauce, and seasoning. He adds pork, egg, and vegetables. Once everything has cooked, Ty tastes. No. It’s not the same, it must be the same. Sugar. He adds sugar and relaxes. The same, every day, the same, one meal at four, always. He will not eat the mochi. • •

below them is a pool of mud. they must cross the monkey bars while our audience pelts them with eggs. Ty commands a group of goonish Midwesterners who’ve won sweepstakes. They wait with fistfuls of eggs and yellow smiles, unexamined

12

13 bodies peppered with age spots and acne. The show’s participants, in contrast, are hyperaware of their myriad shortcomings. For this challenge, the girls are dressed in glittering bikinis that show off their augmented figures. The group has been whittled down to Aliyah, Alex, Beverlee, Cari, Celine, Kelly R., Kelly T., Martzia, Molly L., Nicole, Samantha, Veronica, and Zara. They shiver, nipples protruding from layers of foam and Lycra, pointing across the mud to where the bachelor lounges with a daiquiri. after this challenge, the girls will accompany our bachelor on a group date. here’s the catch – they won’t have an opportunity to clean themselves before. the girls who fall into mud will visit d’alonso’s, a five-star italian eatery, looking like pigs in slop. Ty stands in between, pleasantly realized. Only within this fantasy can he find something resembling stasis. • •

A blink is the first withdrawal, an almost immeasurably minute cloak under which you’re free from the persecution of sense and socialization. Some consider the eyes windows to the inner life, but since an early age, Ty has found them to be portals, passageways, and the eyelids their doors. The same way he toddled around the house closing every cupboard and shutter, he sat through dinner, church, school, and television commercials with his eyes shut. These small moments alone were an introduction to more total isolation. Time-consuming shits, walks along the lakeshore, evenings in his bedroom. Once, when Ty was an early teen, he didn’t leave his room for a twenty-four hour period. He found it could be done. Withdrawal offered its full then more, then he was swallowed, then now. • •

L uk e M uy sk ens

mouth, and years later, one day became two, then five, then a month,

E n dles s S o a k

Ty's avatar leaps from behind a bunker and sprints toward the ops. Headshot, headshot, headshot, headshot, to the neck, to the chest, headshot, kill streak. hikiki69 is on fire! get ʼem, bro! Endorphins bubble through Ty’s spine. to the fuckin’ dome. His headset microphone is deactivated. It’s not that Ty can’t speak – he fills the day with little vocal aphorisms, narrations – it’s that his voice has become not a tool but a compulsion serving only himself, and its volume has diminished to where he can barely be heard. After a close call in PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, he’ll sometimes make an audible sound of relief. That’s all. to the north! dude to the north! get his ass, hikiki! Change guns, sniper. Fire, reload, fire, reload, fire, reload, fire, reload. Got him. Ty is playing alongside Florida high schoolers against a team from Japan, a country that makes more sense to him. He regularly consumes anime, manga, and hentai. In high school, Ty excelled at judo, and he sometimes wears his white judogi in the morning. And, of course, Japan is home to a million compatriots – the hikikomori, confined to their rooms like Ty. The knowledge of others, a neural network of brains with similar insufficiencies elsewhere in the world, has kept Ty alive. Their message boards and newsletters are a method of deferring blame. One does not point fingers at the dead during an epidemic. kill

him! Japanese players come on the mic and chatter. 地獄へようこそ!

私はあなたのお尻を殺すつも りです! They swarm, neutralizing half the American team in moments. Ty hides in a bombed-out building. They spot him. 誰かがその dōtei を殺す! Ty only knows a handful of words picked up through osmosis, one of which is dōtei – a male

virgin. 彼を殺せ! 彼を殺せ! Their tone is playful and competitive, but Ty feels a pang. Sex and romance seem, to him, like unifying elements of life that are unfamiliar to him. Unlike the mundane experiences he’s missing, he imagines sex holds answers. Why else would everyone talk about it so much? Though he’s not technically a virgin – there was a short-lived fling his sophomore year of high school with a commanding senior – Ty is involuntarily celibate

14

and feels the word “virgin” encapsulates him. These Japanese kids have lifted a rock to watch him squirm like a pill bug. He is gunned down and chooses not to respawn. hikiki69! what’s wrong with your dumb ass? For a moment, Ty forgets where he is. The room is incidental. A crushing. • •

Ty’s fortitude of will allows his situation. Someone weaker might not withstand the monotony of meals, the frigidity of a captive body, and the spooling and unspooling of time that occurs in limitation. Hikiki are not agoraphobes. They are motivated by futility and annihilation. A regimen is critical, and as part of this, Ty only allows himself to masturbate once a week. The internet being a bottomless pit filled primarily with porn, disappearing in it would be easier than putting on a hat. With a towel and a bottle of lotion nearby, Ty steadies himself. First, he opens his email. from: edna.williams@uchicago. edu. subject: a proposition. She rarely contacts him like this. Changing mental gears, Ty clicks. dear ty, you’ve made the bathroom into such a lovely spa. i hear you soaking for hours. sometimes i worry, but mostly i’m happy you have something to do. so i’m making you an offer – i will buy you an indoor hot tub. find one you like on amazon. Ty is filled with effervescence. A real spa could bring the peace he craves. True onsen. in return, i want you to see a specialist. she practices emdr – eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. it works wonders. feel free to research

• •

L uk e M uy sk ens

on your own. love, mom.

E n dles s S o a k

He’s in a chair, lit from the side in blue, electrodes taped to his chest and forehead. Behind him is darkness filled with the static electricity of bodies. Opposite him are Aliyah, Cari, Kelly T., Molly L., Samantha, and Zara, electrodes fixed to breasts almost popping from tube tops. The lights turn pink and rise to reveal a room of squinting eyes, and in front of them, Ty, wearing an immaculate suit hewn by Tom Ford himself. He smiles. ladies and gentlemen. welcome to the hour of judgement. the hour of truth. There are murmurs. Speculation. Who will expose and embarrass themselves? What skeletons will they find? As always, Ty is not the focal point. They’re here for these girls, their desperation, the bachelor’s oblivious, gleaming abdomen. The host is simply a reference point of normalcy to compare against these maniacs. our bachelor will now interview the contestants about their families, romantic history, criminal records, fetishes, murderous impulses, physical abnormalities, and pets. if he can stomach what he unearths, they stay. Ty turns to the audience. Men, women, and those in-between only here for carnage. Why does Ty place himself in these shoes, this suit? Grace? Power? No. He’s delivering the gift of entertainment. before we begin, i have a special treat for those in our studio audience. each of you will be going home today with a brand-new sundance kingston luxury hot tub! The room explodes with enthusiasm, hands clattering, teeth beaming. Ty brings them down with a gentle smile. The role of a host is service – something Ty was born for. • •

you aren’t required to speak while the machine is activated. just look for your target and allow your mind to move freely. i’ll stop the machine after a few min-

16

17 utes and check in. how does that sound? Ty nods and squirms on the edge of the tub. They’re in his bathroom, an antechamber less precious than his bedroom, and still the intrusion pries apart his comfort. The specialist flips a switch and the nodule in Ty’s left hand clicks, like those small rubber domes you flip inside out. The right one clicks, then back to the left. Deep inside his brain is an empty suitcase. He’s trying to fill it with a target defined by the specialist – his early bouts of isolation, more than four years ago. Ty sees himself meandering through each day without spine or regimen, shuffling, drawing, crying, bored, dying, and regenerating. The clicking stops. ty? what did you find? Before speaking, Ty tries to plan the volume of his voice. Still it comes out far too quiet. not much. just regular stuff. no trauma? nothing like that. things are better now. how do those early days affect your life now? not having anything to do taught me how to do nothing, I think. The therapist sucks her teeth. She reactivates the machine. Ty returns to his internal search. She wants to find some awful happening that shocked him into isolation. She won’t like the truth – that no such event exists. maybe you’ve blocked it out? no, I don’t think so. He digs in earnest. He wants to change, maybe. were you beaten? molested? attacked? There is nothing to put inside that suitcase, it remains empty. If there were something to put inside he would – he wants that weight, that accompaniment, but there is nothing to block or protect himself from, nothing but air. • •

Before the workers come, Ty constructs a temporary wall of blankets access to both sides of the wall between his bedroom and bathroom, Edna had explained via email. He used a whole roll of tape to fix the blankets to plaster, yet the prospect of his wall coming down fills

L uk e M uy sk ens

to cordon off a corner of his bedroom. For installation, they’ll need

E n dles s S o a k

Ty with palpitations. Recovering from the specialist’s intrusion had taken hours of onsen and she was only in the bathroom. When the men come, the sound of their exertions penetrates the barrier. Water rippling, pouring, screws and hammers, a drill. Ty worries they’re fucking up his bathroom. Where, then, will he practice onsen? Where will he prepare meals? From their voices, he counts only two men. Ty leans against the wall to hear. gimme the crescent wrench. you got a tile knife? Ty is drawn to the bass and resonance of their voices. He leans a little too far and the blankets pull down. no. Ty feels penetrated, a foreign object inside his body. The men look. They look at him, two men looking at him, looking. Before panic can collect into anything of substance, one speaks. i thought you was shia labeouf for a second there, bro. • •

He will not do it for his mother, though her kindness and patience are appreciated. He will not do it for his own happiness, because his mind and body are begging him not to. Ty will leave his apartment for one reason – he is beginning to want, for the first time in years, an audience to his life, a witness. Not the scrutiny or interrogation of the specialist. Something more like the hot tub delivery men. They didn’t want to dig, they wanted only to see him. Ty is still roiling with pleasure from the case of mistaken identity. He has no illusion of potential – he’s already purchased tickets for Avengers: Infinity War at Harper Theater and will not be required to interact with anyone but a machine. Fifteen minutes to walk there, twenty minutes of previews, two hours and forty minutes of actual film, and fifteen minutes to walk back. A quick three and a half hours of being seen, no more. Ty puts on jeans that are surely out of style, a Neon Genesis Evangelion shirt, and chunky Airwalk shoes. Feeling the need for more walls, more barriers, he dons an unseasonably warm coat.

18

19 Good enough. The door is still too much so Ty leaves through the bathroom. The sparkling, boiling, untouched hot tub will be his reward upon returning. He steps through the door, a movement which for him has incredible weight, a gigaton. After four years in the hole, that step is more than pulling teeth – it’s pulling bones. The walk to Harper Theater is not so bad. He puts on headphones and blasts through. excuse me sir, can i bother you for— got good weed, good weed— morning, son— who this nerd think he is?— watch your step. A storm of sensation and proclamation scraping against his brain, taking away its protective coating, and then it’s over, and then he’s there, slumped into a scratchy plush seat before an expanse of white, waiting. The movie begins. Ty is here, doing this. The screen is unbelievably large – were they always this large? – encompassing more than his entire bedroom. Stars and heroes populate its immense space as the action begins: this is the asgardian refugee vessel. we are under assault. Ty wants to watch the movie but his mind is buzzing with thrill; he has envisioned this moment for years. A monumental accomplishment. A villain speaks to him from the screen: you may think this is suffering. no. it is salvation. universal scales tipped toward balance because of your sacrifice. smile, for even— The sound cuts out. Heroes and villains fight in silence. What is happening? The theater lights go up. Ty sinks into his seat. Exposed. Other moviegoers look at each other in confusion. Still fixed on the screen, Ty feels someone in the next row turn and look at him. The lights are not meant to be on now. He is not meant to be seen. ladies and gentlemen, we are experiencing technical difficulties. Technical difficulties? This can't be happening. Not in this moment. we apologize for the inoffice. No. It was not supposed to be this way. Order the ticket, walk to the theater, see the movie, walk home. There was a plan. Ty’s mouth has gone dry. His muscles are rigid. Box office? Refund? The

L uk e M uy sk ens

convenience. your tickets will be refunded at the box

E n dles s S o a k

others are getting up and trickling to the exit but Ty cannot move. Maybe, if he waits long enough, the movie will restart or another will begin. Waiting is something he can imagine. Something he can manage. He remains in his seat for a long time, long enough to lose track, until it’s clear there will be no more movies. Nothing will ever happen. And still he waits. • •

tonight, only two remain. kelly t. and zara compete for the devotion of our handsome bachelor. they have come so far this season – through arguments, fights, and two attempted poisonings – all for a shot at true love. by the end of this six-hour special, one will receive a rose, and – fingers crossed – live happily ever after. The monologue plays in Ty’s head as he soaks. Powerful jets massage his shoulders and back, working away the lactic acid buildup from the stress of his excursion. The temperature is a tropical 102 degrees and he will never leave. Kelly T. looks stunning in a Rosie Assoulin gown, yellow and lace framing her exquisite Pilates body. Zara looks a little ridiculous in an Alexander McQueen ruffled mesh gown, spilling out of her doll-like dress. Kelly trembles in adorable, anxious anticipation while Zara is more poised than a captain, eyes like Adamantium. Ty has no horse in the game – he’s a professional. Whoever wins, there will be another season, a fresh batch of girls will arrive, the contestant will be replaced, and the mansion will be remodeled. The only constant in this game is Ty, the dependable host. For twenty-five seasons he has ushered these fascinating specimens, and he’ll continue to do so until the world burns or the public loses interest. He sinks under, letting the uniformity of water encapsulate his skin. Ty cannot think of a single bad thing that has ever happened underwater. He opens his eyes. The room is a blue

20

21 blur, all sound is his breath, there is no smell. He is enclosed and can think of only one reason to surface. The oxygen in his lungs is expiring. as always, i’m ty williams, your dashing host. welcome to the bachelor. He fights, but it must be done. Ty

L uk e M uy sk ens

breaks the surface and breathes.

Po e t ry

BIJAN ELAHI TRANSLATED FROM THE PERSIAN BY REBECCA RUTH GOULD & KAVYAN TAHMASEBIAN

Mourning the Birth of Image 1. Time turned blue. Your fingers brought no more good news. Your fingers used to be a ladder on which plucked doves would climb to the roof. 2. Time turned blue. And in its veins there lived another time that struck his heart at the glass and tore the newborn hour in pieces.

22

23 3. Suddenly in the father’s veins, I was out of breath, a sperm who dreamed of a mother for years.1 The mother was searching for a bird in the veins of a tree. She had forgotten the bird’s empty perch on the branch. 4. Here is that bird in mirrors. Let us break the mirrors! Shall the bird die or shall it be born? An image born is a mirror broken A mirror dead is an image broken. 5. Fable A bird lived in a mirror. The mirror broke. The mirror birthed a bird.

M ounri ng the Birth o f I m a ge

The bird melted the mirror, drank the water, and became a mirror! 6. Here I am, having become the bird in the mirror.

24

Bi ja n El ah i

1. The same Persian word – mani – here denotes both the first-person pronoun “I” and sperm.

Ro s a ire A p p e l , " M a t hem at i cal Weat h er, " 2 0 1 8

26

Po et r y

27

BIJAN ELAHI TRANSLATED FROM THE PERSIAN BY REBECCA RUTH GOULD & KAVYAN TAHMASEBIAN

Wild Grass In memory of green it is green. Never say it is green. The grass greens to say it can green. Never say it greens. Never in the ruins. Never in the garden. Never say it’s trapped, never say it’s free. Even on this roof, the grass trembles in the wind. Wild grass is wild grass. Otherwise, it’s nameless.

Fic t io n

Sometimes They Fall From the Sky JEFFREY GIBBS

Anxiously, she watches the two men in wolf masks confer in front of the Burger King where she first tried to call her blind date, Aram. They scan the street, their animal heads moving in unison, snouts lifted slightly up. It’s like they’re trying to catch the scent of the fading electromagnetic waves. The masks are overly large and the features exaggerated in the manner of anime characters, but they are covered in real fur, coarse and brown, and there’s a white screen over the eye holes. Both men are slim and wear black pants with black jackets over silk dress shirts. One sports a thin black tie, the other leaves his shirt open at the collar to reveal a hairy chest. Her gaze follows them in growing alarm as they walk up the street and pause one more time in front of the ATM where she withdrew cash and texted: “Where R U?” The masked men head toward the Mavi Jeans store from which she’d sent her final frustrated “I’m outta here in 5,” and now she’s almost certain they’re coming for her. From there, they will look across to where she’s sipping coffee out of a to-go cup on the patio of one of the new hipster cafés, the five minutes not quite up. They will see her watching them, smell her fear, and know. She quietly grabs her purse, walks out the door, and ducks down a side street next to the café.

28

29 Istiklal Avenue is crowded today. Middle Eastern tourists pour in and out of the storefronts, their arms overloaded with bags labeled Gap and Zara and LC Waikiki. The malls were empty for a long time after the bombing. Locals were too afraid to leave their homes. Now the shoppers come in droves from overseas. She found Aram on Tinder late last night. It must have been after 2 a.m. when she finally surrendered to her insomnia and climbed out of bed. She’d been tossing and turning, arguing in her head with one of her male students at the university who had asked why she was staying in Istanbul. He himself had just secured a visa to the UK and he wanted her to know that when he didn’t show up in class it was because he had escaped – not that he had disappeared. “You’re just an expat,” he’d said, “Go already. You’ve no reason to stay except a paycheck.” A paycheck and my entire life, she thought. Her accidental decade-long career, the ten different apartments, the ex-husband and friendships and failed dates and two miscarriages, and the day-to-day moments that had accumulated like a mason’s stones, building houses and blocks and cities of memory. There was a gravity here that kept her rooted. And besides, at the signing of her last contract, her manager had told her she had nothing to worry about as long as she kept her nose clean. They’re not after foreigners. That’s what she told the student in the end. “I don’t do anything that matters. They’re not after foreigners.” The street ends at a gaming store, veering either right into a passage of secondhand bookstores or left beneath a banner advertising “International Shopping Week!” She stands in front of the shop window and feigns interest in the ceramic statues of dragons and aliens and wizards on display there, turning her head slightly until she can see the café she’s just left barely visible at the other end. The men in masks are crossing from the Mavi Jeans store toward where she’d been sitting. It’s then she realizes she’s still clutching her phone. She looks down at the screen in alarm – the red flame of the Tinder icon

S ometi mes T hey F al l F ro m th e S k y

is at the top of her feed. She taps the WhatsApp speech bubble, still no response from Aram. “Fuck,” she says, and hurriedly switches it off. The screen goes black. Will that be enough? I’ve got to get rid of this phone, she thinks. His profile had immediately caught her eye. Unable to fall back to sleep, she’d gone out on her balcony, taking a beer in defiance of the curfews and bans. The windows of the neighboring buildings were all dark, though she knew that didn’t mean no one was watching. The cameras on the cornices of the building moved as she did – she heard them aim at her, humming – but she’d poured the beer into a used McDonald’s cup so it would not be obvious what it was. She flipped through her messages – nothing new – skimmed her Facebook feed, then switched over to Tinder. His picture popped up third – a balding, bearded, athletic young man in a Hawaiian shirt. He was grinning boyishly and holding up a photo of the President, one of those official portraits with the waving red flag in the background, clipped from a poster or maybe from one of the oversized patriotic magazines handed out door to door by the Party women. He had defaced the President’s face, adding black-marker horns and a caveman unibrow. The bearded man’s name was Aram, and he had written, “I still dare. Want to dare with me?” in three languages – Turkish, Kurdish and English. It was like he’d spoken directly to her mood. Impulsively, she swiped right, and a notification popped up to let her know that he’d also liked her. She winds past the used bookstores, emerging at the other end of the passage and heading left. She walks quickly but tries not to look like she’s walking quickly. She thinks the vendors might notice and turn her in. She hangs a right down a large crowded alley. The left side is closed off with a wall of corrugated sheet metal and scrap wood covered in construction signs – they’re converting another old theater into something else – the right side is jammed with cafés and restaurants. The bang and clamor of jackhammers and drills make

30

31 all the diners shout. Toward the end of the alley, where it’s slightly quieter, she kneels and finds a gap between the metal and wood. She sweeps her eyes over the cafés, but no one seems to be watching. Quickly, she wedges her phone into the gap and stands, brushing the dust off her jeans. She starts to leave but then takes out her house key and scratches a small x in the wood where her phone is hidden. It had cost her over a thousand lira. Maybe they won’t find it after all. Maybe in a few days or a week, the danger will pass and she can come back and get it – if no one else finds it first. Or if it doesn’t rain, she thinks, quickening her steps, Or a street kid doesn’t steal it, or they don’t knock the wall down. She takes a right down another alley, then left at the end, then right again, winding her way downhill to lose herself in Beyoğlu’s endless backstreets. Can they track her without her phone? Everyone says they can, but it sounds paranoid, and she doesn’t want to succumb to the panic she feels poised at the center of her chest like a hand over her heart, waiting to squeeze. She’d sent him back a picture last night at 3 a.m. – the monitoring of the net would be the most lax then, she’d reasoned. She went to the bathroom to take it – there were no windows – and put on her white tank top to reveal her graceful brown neck and a hint of cleavage. She held up a vandalized picture of her own creation – something improvised on the fly – a photo of the President from one of the newspapers. She’d used a pen to draw a blue penis dangling in front of his mouth and scribbled across his forehead, “I still dare.” At the time, the only thing she’d worried about was that it was too explicit and would give the wrong message to the guy. Stupid, she berates herself now. Stupid, stupid, stupid. She imagines the faces of the patriotic boy-trolls, lit by their green LCD, taking screenshots of her makeshift artwork and forwarding spring to life. She’s so lost in this vision that she doesn’t notice the tall young man texting in the middle of the street. She crashes right

J ef fr ey Gi bbs

them to some ominous central command where figures in shadows

S ometi mes T hey F al l F ro m th e S k y

into him, the phone slipping from his long fingers and clattering over the pavement. “Çok pardon,” she mumbles. “I’m so sorry. Is it…?” They both squat down at the same time. Their fingers touch and she jerks her hand back. He grabs his phone and inspects it. “Not a scratch,” he says. “That screen protector was worth the money.” He’s at least ten years younger than her. His voice is deep and resonant. They stay crouched, smiling nervously at each other. He shows her the undamaged screen and winks. Perfect teeth, a long jaw covered in stubble. His wavy black hair is gelled on top of his head like some kind of elegant confection. She likes his smell – something about it makes her blush. He’s wearing a black concert tee of a Turkish band called Duman. Peeking out of the frayed collar she sees a tattoo arching up his slim neck – the head of a horse with a flock of pencil-thin birds flying toward his Adam’s apple. He notices her gaze. “In the old days,” he says, “they’d paint pictures like this on rocks or trees to mark where they left their valuables.” “Oh,” she says, nodding, and starts to stand. He puts a hand on her arm. The heat of it sends tingles over her skin. “But there was never anyone left to go back and find them,” he continues. “It’s all still there, waiting to be taken.” The pupils in his dark eyes seem to expand – perfect black circles reflect her own face. She notices a red light blinking on his phone. She glances down and sees the words “terror alert.” “Again, sorry,” she says. “I wasn’t looking.” He lets go and taps his phone. The red light goes away, and they both stand. “Don’t worry about it.” He gives her a wink and then waves. “Stay safe.” As he walks away, she wonders, “Now why would he say that?” She steps in front of an abandoned ramshackle Greek house – one

32

33 of the few left intact. It’s a crumbling wooden skeleton of what was once a glamorous mansion, standing four stories tall – a slender building with filigree and gingerbread railing. Its former courtyard is closed off from the street with a brick wall covered in shards of stained glass. Bramble, weeds, and street garbage thrown in from the street fill the garden, and right in the middle stands a persimmon tree. Swells of orange fruit crowd the bare black branches. Imagine, she thinks, it’s still alive in there after all these years. There seems to be something between the street and house, something besides the wall, an invisible barrier like aquarium glass that holds everything in – the older time and history, the somber dignity of the ruined facade, the quiet abandonment of the shadowed rooms and bright autumn fruit. The house calms her, somehow, and so she sits down at a döner shop across the way to decide what to do. “A chicken wrap and a Coke,” she tells the teenage boy who approaches her table. It’s a rickety plastic fold-out that wobbles when she puts her purse on it. The boy shoves a broken piece of wood under one leg to keep it steady and murmurs an apology. The moustached man in white who tends the rotisseries of meat says he’s sorry too, then orders the boy to bring her a complimentary tea. Is this the best idea? Sitting so close to where she ditched her phone? Her first thought is that they will expect her to put as much distance between herself and the evidence as possible, so this might be the smartest place to hide. A Turkish friend had said that the other day at lunch, “Don’t run. Just find a crowd and try to blend in.” The men in the masks are just boys right out of high school, apparently, loyal stooges too stupid to think much about strategy. They’ve played too many video games and long for car chases and shootouts on the street. But what if they’ve gotten her picture from Aram’s phone? The boy sets a tea down in front of her and a small plastic bowl of “Your wrap will be up soon,” he says. Her heart is pounding. As long as you keep your nose clean, she

J ef fr ey Gi bbs

sugar. He also gives her the Coke.

S ometi mes T hey F al l F ro m th e S k y

thinks. Why had she so deliberately put herself at risk by responding to someone as blatantly obvious as Aram? The feeling had been building for years – that feeling they all felt, of being caged in – and she’d wanted to strike a blow, however small and personal. But now they had him, and they will take everyone he’s contacted. Or maybe she’s jumping the gun and they haven’t gotten him yet at all. Maybe they’re going to catch him by tracking her. Or maybe it’s her they want. He was just a ruse, a setup, and she’d sent that damn picture, which they’ll use as an excuse to parade her in front of the news cameras as a perverse foreign terrorist. Or maybe it’s because of something else she’s done. Something careless, something she didn’t know was illegal or something newly banned. Did they overhear her conversation with the student yesterday? Would that matter? She watches the people pass in front of her – groups of young boys smoking cigarettes in one hand and flipping prayer beads with the other, pairs of schoolgirls walking arm in arm, middle-aged women loaded down with groceries, a group of Kurdish musicians hurrying toward the main street. The rich shoppers don’t seem to come down these back streets where a different Istanbul still hangs on. Everything seems so mundane and rundown, the same as it’s been for decades. A movement catches her eye, like a shadow of wings crossing the sun. Her gaze falls on the ruins of the Greek house. The roof is gone on the right side and the third floor is missing the back wall. The two front windows look like the eye sockets of a skull, long emptied – the bleached bones of a murder victim found among the weeds of a deserted field. The silhouette of a grandfather clock stands like a sentinel in the frame of the window on the right, lit from behind by a white sky. On the second floor the windows are black, the panes cracked and coated with dust. The ones on the ground floor are boarded up, blindfolded, and a doorway stands between them without a door. It looks like a gaping mouth. She notices a gate in the brick wall. Had there been one before? It’s rusted and open to the street.

34

35 She sips her tea and her stomach growls. She turns around to check on the progress of her wrap but the shop is now empty. The meat still sizzles over the fire, the refrigerator with the drinks still hums, but the boy and the man at the rotisserie have both disappeared. There’s a short hallway in the back of the shop, painted all white. A door at the end has a sign that says “Employees Only.” Have they gone in there? When she turns back around there’s something different about the house, something liquid, as if it has all been painted secretly on a curtain and she’s caught a ripple moving through as the wind passes by. The clock on the third floor is gone. On the first floor, from the window on the right, she sees a long leg kick out one of the boards. Fragments of wood splinter onto the ground until there’s room enough for a man to emerge into what was once the front garden. He’s slim, wearing black pants and a black jacket and the wolf mask over his face. From the black doorway comes the one with the collar open at the throat. He casually steps out sideways and pirouettes to face where she sits, as if completing a dance step. He offers a little bow and then the two of them move forward to stand on either side of the persimmon tree. They regard one another from across the narrow street – she and the men in the masks. The people passing between them quickly thin out – they have learned when to disappear – until the space between the ruined house and the döner shop is completely emptied and ready. “I’m sorry,” she whispers. She knows everything she has touched will be implicated. Her landlord, the university, her ex-husband, the student she talked to yesterday who might still escape, even the boy and the man at the döner shop – all in an instant. Their footsteps are steady and rhythmic, the soles crunching first on glass and pieces of pavement and into the store.

J ef fr ey Gi bbs

plastic and then moving like a slow, thudding heartbeat across the

S ometi mes T hey F al l F ro m th e S k y

The white screens across the eyeholes of the wolf heads flicker as they close in on her. She sees a dream from many weeks before appear on their surface: it’s winter. She’s in a taxi driving along a ridge that overlooks the Bosphorus. The driver stops at a traffic light and she notices a park on the right with a small lake; a flock of swans waddling away from the water towards the taxi. One by one, they spread their wings and rise into the air. “Look,” the taxi driver says. But as the birds fly over the road something seems to jerk them down. She knows it’s the ponderous weight of their own bodies. She remembers reading about it somewhere. “It’s a sign!” the taxi driver says. “No,” she says. “Sometimes swans do this. I saw it in an article somewhere. Sometimes they fall from the sky and no one knows why.” One of the birds slams into the windshield, shattering the glass.

36

Jef fr ey G ibb s

And then the screens go white, and it’s just their eyes.

Po e tr y

37

LISA LÓPEZ SMITH TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH BY THE POET

From the Ayotzinapa Investigation Report criminal operate within the borders of the State of Guerrero. In addition, it should be noted that within the preliminary investigation number consider the Social Representation of the Federation, filling the exdasghadl;akj;d;jdl;fd;l;dfklklal;kkdl;dfl;d;lf’’ds’f’ldpl[ disappearance of the social leaders of Iguala de la Independencia, Guerrero and particularly that is based on a over the kidnapping of MARIA DE LOS ANGELES PINEDA VILLA it was announced were members of the PGR / SEIDO / UEIDMS / 871/2014, se encuentra en calidad de indiciada C. MARIA DE LOS ANGELES PINEDA VILLA for the crime of kidna committed against students in the Municipality of Ayotzinapa in the State of Guerrero; being one of the people who also investigated in the is a relationship of events, among the preliminary inquiries under blicinistry, attached to the Unit specialized in Investigation of Crieived the declaration of the witness with identity key “X” who he said he knew ;ljk;akdgMorelos opinion on the subject of Criminology in which it was concluded that derived from the intervention in the Cocula landfill, based on the observation of the place, a - initiate the preliminary investigation AP / PGR / SEIDO / 439/2014 dated June 12, 4 by the lawyer Ignacio Quinainst Whoever Is Responsible for the commission of the crime of Organized Crime, the receipt of the the preliminary investigation number HID / SC / 01/0758aggrieved Nicolás Mend Homicide, toda vez que de la misma se desprende la participación al parecer deng, by virtue of the agreement of October 17, 2014 issue, by which criminal action was tona, Rafael Bandera

Román and Angel Román Ramírez, who were reported as missing on the thirtieth of May 30 of two thousand) events occurredkilometer 170 of thHighway e by otherg Raf without license plates, re Gregorio Dante Cervantes had managed to escape from their captors, and that Bertoldo At he left because they were going to kill him, like they killed dklArturo Hernández Cardona, Rafael Balderas and Ángel Román RamíreLomas del Zapatero kidnappArturo Hernández Cardona, José Luís Abar risking the same fate ...(sic), that" El May", was the head of assassins who was also known as “El Choky or,” also referring to " Gil el gallero "(pages 40 to 43, Volume XXV). With date the nineteenth of May of two thousand fourteen, the document virtud de encontrase relacionada con la diversa HID / Sal de Justicia del Estado de practiced by its similar common consisting of the Delgado the Municipal Palace, in which the City Council and the State Government were to participate, in the office of the Municipal President, that he sign them, , May tollbooth, followed them y, six people with firearms situation Jimmy Casdo run away, managing to escape since they did not follow him, that later they took them to a place of thorn bushes where had been kidnapped, hearing that to not kill these people they had to work for them since they called themselves members of "Guerreros Unidos" and that they were under the orders of the President Municipal of Iguala, José Luís Abarca Velázquez, later was no longer blindfolded, and Felipe Flores Velázquez, who kidd it was the dsicipalPreside who first dgd him a shot at the height of and then told him to hit him to kill them now dkdkkd “because it’s about to rain” , adding finallsdgdsgskljldslkjlsdfjl;sjagl;ajkgljlkdkdldklkdkdkdkdkkdkdkddkdkkdkdkkdkdkdkkdkdkdk

38

39

P o e tr y

UMA MENON

spoken language my uncle tells me that he can speak & asks me

with his hands

to translate his words into malayalam

i listen carefully: the rain weeps outside & the terrace lies open

unafraid both

with their mouths

of men who speak

& men who speak with

their roughened hands

in the shadows

a billowed body dances with his hands the wall where fingers trace wind air

here is a secret

against

& currents deflect

he says with his blundering

mouth & rolls his fist across the table flicker like lights before i see

my eyes

what he has shown me

Fic t io n

Mouse FLORIAN WACKER TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY RACHEL MCNICHOLL I only knew Mouse for a year, maybe a bit longer, and now here I am in the little graveyard on the edge of the city park, having a quick smoke before it kicks off. I’m sweating in this suit. It’s borrowed – I don’t normally go to funerals or weddings. It’s far too hot to be in a graveyard, actually. On the way here I passed the outdoor pool; the kids were shrieking; the air smelled of sun cream and chlorine, and I thought, this just doesn’t seem right. But now I’m thinking it’s not such a bad thing; who says the weather always has to be wet and windy in graveyards – isn’t it much nicer with sun and birds and sweat? I’m standing behind a tree; I don’t want the others to see me smoking, to see that I’m nervous, that I haven’t a clue what I’m going to say, even though I stuffed a piece of paper in my pocket with his name, date of birth, and things like that on it. But it would be a bit silly for me to be telling them that kind of thing, because they all know it anyway. They’re Mouse’s family, after all. I see a few people gathering in front of the church. That must be them. I squash the butt under my heel, smooth down my jacket, and head over. To be honest, I didn’t really know Michael that well. I’m not even sure when we met… a year or so ago maybe. Anyway, I got to know Mouse – I’m not going to call him Michael any more, just Mouse, because that’s what we all called him, because that was his name, no one actually called him Michael, ever – so, I got to know Mouse through the amateur radio club. I hadn’t been there long either, but

40

41 when Mouse joined I knew I’d stick with it. He was a good radio operator; he always took the amateur radio code, the “ham spirit,” very seriously. He often said that radio operators were pioneers because we’d always had an internet of sorts: we’d been communicating with Moscow and Havana and Beijing long before email took off. I still didn’t know Mouse well, though. At first, we only saw each other at the radio club; later, we also met at the Gute Quelle bar, but mostly it was at the radio club. Mouse was already quite an expert; he used to write articles for the ham radio magazine, Funkamateur; he was good at that. Now here I am, sweltering in the sun. Mouse’s family decided to have him cremated and put into one of those cremation walls. It’s like a whole wall unit with a pigeonhole for each urn. We’re standing in front of it. There’s a candle, though you can barely see the flame. My mouth is all dried up; I try to speak slowly and clearly, but at times I just can’t continue; then I stare at my piece of paper – or rather, I stare through the paper at the gravel – and I ask myself how all this could have happened and why it had to be Mouse, of all people. The first time Mouse invited me to his house was a few weeks after we’d met. I was about to push off on my bike when he planted himself right in front of me and said, “You’re coming to my place on Saturday. I’m cooking. There’ll be a few friends too – and a surprise.” So I nodded. On Saturday, then, I put on a shirt and a decent pair of jeans, and I took the tram because I didn’t want to arrive all in a sweat. On the way, I stopped off at Kaufland to pick up a bottle of wine. I figured that’s what you’re meant to do when you’re invited somewhere for the first time: bring a little gift. Even though I knew Mouse already, I felt pretty nervous as I rang the bell at the front door and waited for him to buzz me up; like it was a date, which was ridiculous of course, but that’s what it felt like. Mouse was very nice; he took the wine and introduced me to his friends. Maybe I should have twigged something at that stage, but I didn’t think of

Mouse

it until later, in the tram on the way home at midnight. That’s when it dawned on me: it wasn’t inflammation that gave one of Mouse’s friends those red lips. Mouse had made mushroom risotto. He showed me his room, where he kept his radio station, and we talked shop for a bit, but that was the end of the radio talk for the evening. For dessert we had strawberries and cream. Mouse laughed and drank a lot. He was constantly getting up from the table to fetch something or clear something away. At one point he said, “Now for a surprise,” then disappeared for half an hour. I went to the bathroom during this time, and I could hear Mouse’s voice coming from the bedroom. He was talking to someone called Petra; I figured he must be on the phone. Then a woman walked into the living room. I hadn’t heard the bell or the front door. The woman approached me, smiled, and held out her hand. I was shaking Mouse’s hand and Petra’s hand at the same time. “Hi, I’m Petra,” she said. “Nice to meet you at last.” The minister says a few more words and a prayer, but I’ve stopped listening. I screw up my eyes; I feel a headache coming on. There are five of us, including the priest. None of Mouse’s friends are here, the ones I met that evening and a few times since in the Gute Quelle, nor is there anyone from the radio club. I wonder why they aren’t here, but then I decide death is not a simple matter, and everyone deals with it differently. It’s over now anyway. The minister nods and shakes everyone’s hand; then he leaves. I stay behind for a bit, sit on a bench and light a cigarette. Smoking is forbidden in graveyards but right now I couldn’t give a shit. I lean forward, staring at my runners. These Adidas sneakers are the only black shoes I had. Someone sits down beside me. It’s the younger woman who was at the funeral. “Hi,” she says. “I’m Mouse’s sister, Sabine.” We shake hands – her fingers are cold, mine are sweaty. “That was nice, what you said.” “I hardly knew Mouse, you know,” I say. She smiles and looks away. “Sometimes the people who know you best are people you’ve

42

43 never exchanged more than a few words with,” she says, and I reckon she’s probably right. She asks if I’d like to get a cold drink. The park café is nearby, so we go there, sit under an umbrella, and order lemonade. Sabine seems younger than Mouse, but her face is like her brother’s, a narrow, pensive face, a little on the pale side right now. “It came as a shock to us all,” she says and sips her drink. I say I can well understand that. “Mum just stared at him,” says Sabine. “She didn’t say a word to him, ever again. I asked him if that’s what he really wanted, if he was really sure, and Mouse said: “It’s fucking awful to spend your whole life feeling like you’re stuck in the wrong skin. My whole life is the wrong way round.” Sabine looks over at the grassy expanse of the park; I stir my lemonade with the straw. “I still didn’t get it,” says Sabine. Mouse was my friend, I suppose. Maybe not my very best friend, maybe not the kind you’d go to hell and back with, but he was a friend, I’m sure of that. I didn’t really understand the Mouse and Petra business either, but I didn’t slag him or have much to say about it either way, and I think he liked that, the fact that I treated him the same as everyone else. If we met in the Gute Quelle, he was Mouse the radio guy. We’d flick through the Funkamateur and drink our beer. Sometimes I went to his place as well. Then it was usually Petra who opened the door and gave me a quick hug. She was a bit shyer than Mouse, but I liked her because she was always laughing; she laughed at practically everything I said. We often sat on the balcony, smoking, and Petra explained how you put on mascara and kohl, and she showed me her lingerie and said, “Soon my boobs will fit into that,” and we tried on her bras, stuffing them with oranges. Mouse stopped coming to the radio club. He didn’t really like the people there in the the time they really only wanted to bullshit and drink beer. I still go, but only in memory of Mouse, because the room and the smells and the bullshit always remind me a bit of him, and because I’m kind of

F l or ian Wa ck er

end; I think he thought they weren’t serious enough about radio; half

Mouse

afraid I’ll forget him otherwise. Everyone was pretty upset, of course, but the grieving didn’t last too long and soon everything was business as usual. For me things have changed, though – not outwardly, because I keep doing what I was doing anyway, but in how I think, how I go about things. I’ve never been religious, not in the slightest, but now I sometimes sit in the kitchen or in the Gute Quelle and mutter under my breath, “Please let it have been quick. Please don’t let Mouse have felt anything.” Sabine says, “I’m glad we got to meet.” I just nod in return. Now she doesn’t look much like Mouse after all; she seems taller all of a sudden, a bit better-looking too. She pays for our drinks and says she has to go, she has a few things to do, the apartment has to be cleared, formalities have to be dealt with. I offer to help if I can, say she can always let me know, and write my phone number on the corner of a serviette. “Sure, thanks,” says Sabine, offering me her hand. Then she leaves. I keep watching her until she disappears among the people at the station entrance, and for a moment it’s as if it’s Mouse who’s disappearing, as if it’s Mouse waiting patiently for the right moment to step onto the escalator. The rest of the day is a write-off, so I decide to go back to where it happened. It was at the back of a big sports shop. Petra was on her own, on her way back from a party, a little bit drunk. But she was so happy after her first party that she didn’t even register the guys who had been following her for some time. One of them kicked her in the back, and Petra fell to the ground. Her wig slid off. The guys kicked her and spat on her; one of them pulled her skirt off and raped her with a beer bottle. Then they all pissed on her and cleared off. Petra died two days later in the intensive care unit, from multiple blows to her head. It was all reported in the papers, including the fact that the guys were arrested quickly and are currently in custody.

44

45 Someone has left flowers by the wall, and a candle. The stain is still there on the ground; it hasn’t rained since. For a minute I feel sick, then I’m okay again. It’s still very warm, so I take off my jacket and sling it over my shoulder. For a split second I feel as if Mouse is standing right beside me, remarking on the stain on the ground, then laughing or giggling. “Mouse,” I say. “Jesus, Mouse.” I give myself a fright, because I really was talking to Mouse. Better get out of here, I think. There’s very little action on the streets, which seems like a fitting response. I’m going to head straight for bed, with a cool lemonade, and flick through Funkamateur. If I’m not too tired, I’ll read another of Mouse’s old articles; then I’ll feel like he’s kind of talking to me. Right now, as I root for my keys outside the front door, it hits me that it’s not just Mouse I’ll miss, but Petra too, that two people went into that cremation wall at the same time today, even if the

F l or ian Wa ck er

minister only spoke of one.

Po e t ry

LINDSAY COSTELLO

Peaches Between them a type of drowning. A distance measured in carpeting Or The furry halo around a peach, or That grey film of moving, seeing from a light place To a dark place. Squinting. That distance. I waited in the ash-glow staring At a lizard chasing itself, or nothing, As screams rattled the windows. My father once convinced me that Money lived in the ceiling. Quarters mostly, nested in plaster, Warm children. I stood on a chair and reached for them.

47

M a rc C o he n, " T h e I dea of P erman en ce, " 2 0 1 8

48

u n

A D IC E

ro

N

st

C

E

M

B

clarity behind each strike? One way or another, I reach out. Protecting myself from harm, or

tuck away the sun. Look for watches. Filled with heat, I ask why tongues dance in battle. Is there

sprinkles dust in our melanin. Satisfactory. I get darker. Under the eye of lust and saltwater, I

callaloo. Sneezed before dinner time. Make sure we say “bless you.” The secret of light

soil. Pick-a-pepper dashed with rice and peas, man, we say “Hallelujah.” Momma’s making

borrowed time.

H

ke

N

A man on the corner tucks a watch into his stocking. Reminds me of labour back home on island

S A

R

D

Po e t ry

49

F ic t io n

Citizen! CHRISTIAN BROOKLAND

You are late, speeding in a residential area, and to mark the last time you will collect your daughter from school, you feel miserable. You can’t seem to take your foot off the pedal, or your mind off work, and you briefly envision the worst possible outcome: twisted metal, flashing lights, sirens. When you finally come skidding to a stop next to her, she fixes you with her canny gaze. Barely seven and already much smarter than you ever were, than you’ll ever be. With a leap into the pre-heated passenger seat, your daughter paraphrases lines she must have picked up whilst scrolling through the news (she’s going through that impressionable phase), such as: Do unmanned libraries have a viable future? Should work be a baby-free zone? Why was this lady forced on to a plane? • •

See how your Maurice Lacroix wristwatch – an impulse buy on the strength of your relocation bonus – comes sliding off your arm? With your other hand you adjust its crown, turning it until VIII becomes IX. Your burgundy passport gets clamped down and punched in that mechanical, irreversible style that only border officials possess, then

Citiz en !

gets slipped back via the mouse hole in the Plexiglas divide (to make physical contact with the officials impossible) before you are waved through and the next person in line steps up. After retrieving your passport and smiling at nobody in particular, you walk through a gap in the row of booths. You manage to resist the urge to turn around one last time. • •

Your gym has a crèche in the shape of a diamond, big enough to accommodate maybe ten children, with a glass front like a shop window where you pause to look in. You look in every time you wander down a corridor connecting the weights room and the open-plan cardio landscape, and you imagine your children sitting on the floor, listening open-mouthed to a flurry of languages. The whole complex is submerged underground, and you try to visualise the challenges the builders must have had. The huge empty pit they had to fill. Your day tends to look like this: twelve Olympic pool lengths before work, then stow away your goggles and swimming cap in locker, then work, then return to cross the Channel on the rowing machine, gripping the oar and staring at the display. Then you spend the evening thinking of your children. • •

Where you came from, a colleague will one day be asked to recall the time when some of you were handpicked – there one day and gone the next – and they might say: …oh, without a doubt the boldest bunch of investors I can remember, which didn’t necessarily do them any favours; sure, they were ambitious, with a certain thirst for taking on anyone and anything, good and bad… a fearless

50

51 shine in their eyes. Can you even blame them? Do you? They were the kind of people the company knew wouldn’t entertain second thoughts. So, off they went. What they say about you amounts to much of the same: a single, brightly lit window at the top of an ostentatious glass wall cut out of the dark, flowing sky. • •

The day you gave Boris Johnson a tour of your school, he seemed happy to be led through the various fields, down the paths and into the old buildings. It was a long time ago and much has happened since, but the two details that have remained with you are: 1. Boris saying over and over again: give ’em hell, give ’em hell, give ’em hell, give ’em hell… 2. Boris complimenting your school’s Danish cinnamon swirls whilst stealing peeks at the curves of dinner ladies. • •

Your hotel room affords views across the old town; your office is sparsely furnished, and beyond its glass facade a 360-degree view keeps you company throughout the day. You focus your phone’s Carl Zeiss lens on the bell tower of a nearby church, from where you set out to shoot a wide panorama made up of many individual photowith the result, you send the composition to your other half without further comment. • •

C hr is tia n B r ook la nd

graphs. You swivel a few centimetres between each frame. Pleased

Citiz en !

At your old college, a professor will one day be asked whether you showed any early signs of megalomania, and they might say: …gosh, I suppose there was this splinter group that was obsessed with the idea – with all its implications – of endless possibilities; always looking to surpass loopholes and obstacles even where there clearly were none to begin with. If you’re convinced by what you’re doing, if you think it’s radical enough, nothing but your own conviction will make any sense to you. • •

You live in a room in a Sofitel with a king-sized bed and a TV with BBC News and thirteen channels in a language you can’t speak. You while away the early hours watching endless news tickers through bloodshot eyes. Today, an official in a raincoat is answering questions on the deck of a cargo ship, dissecting import and export for the layman whilst being buffeted left and right by malicious winds, spray all over the shaky screen. Just before the connection cuts out the official screams and promises something about mussels continuing to arrive on time, for the restaurants and their white wine sauces… stop. Did she just say on a wave of mutilation? • •

You maintain a brief, hedonistic affair with a cellist called Saskia or Simon who likes to drink pink champagne at a deli-island in the department store’s vast food court: a windowless, underground space with cold and warm aisles humming side by side. One Saturday afternoon, when the stool beside you remains unoccupied, you realise that orchestras travel to concert halls around the world. You also realise that by now your affair needn’t be termed “an affair” anymore.

52

53 • •

Your other half never replied to the panorama crammed with towers old and new, but did detect the faint reflection of your paisley-patterned suspenders – a gift given to you on a long weekend in the country. Memories of being confined to a yellow bed in a yellow B&B, building houses out of cards and balancing jugs of cider on your chests. • •

Unisex saunas. You think: Why is the rest of the West so fucking puritanical? You take three white towels with you. One for under your feet, one to sit on, and one to drape over your head and neck, a technique you’ve adopted by closely observing the other frequenters of Wolkenkratzer Wellness: the routinised guests can often languish until their vision begins to swirl and the sands of time render them inane lumps of flesh. The vocabulary of business transcends the chains that tend to lie heavily around two different languages attempting to correlate. Within fourteen minutes you’ve secured a lucrative investment with your towel-draped neighbour – a guy in his sixties who you’ve been attempting to network with for months, watching the way he slips off his Ermenegildo Zegna flip-flops and takes the stock market section of the day’s broadsheet into the heat with him every Friday evening. Draped, and with the strange, ember glow of the sauna igniting his shoulders and brown belly, in profile he looks like Death

• •

C hr is tia n B r ook la nd

reading the news, but you keep this to yourself.

Citiz en !

The gym has a great crèche, you tell your other half, who hangs up. • •

You are a flaneur of interiors, of exotic textures, rich furnishings, and high-end jewellery. Your speciality happens to be grand department stores, the kind whose endless adjoining spaces are like mournful sighs from a glorious past, a past the likes of which your grandchildren might never experience. Still, you’re positive that one day it will all come back around again. You have found a personal favourite on the edge of your triangle of commute (hotel–office–gym), a complex whose floors are more sparsely populated the higher one ascends, reaching its most luxurious at the top. The silent escalators manoeuvre you up the atrium. There are no windows, for the walls are lined with shelves of dark veneer, floor to ceiling, displaying long silks from Italy and handmade cravats from Croatia. There’s a sunken space at the very back of the room: a treasure trove of cufflinks nestled within soft, velveteen cushions. You wake up under a pile of Portuguese cashmere, soft sleeves of every colour flowing around your rising body. Some assistants have emerged from a hidden door lined flush within the soft, buttoned wall, and are watching you from a safe distance like they’re observing a wobbly fluid spreading in a Petri dish. You overhear how one of them, whilst following your movements, is uncomfortably reminded of Gregor Samsa. You catch your dishevelled appearance multiplying tenfold, trapped between opposite full-height mirrors. You check yourself to see if you are who you think you are... • •

54

55 A photo comes through, full of smiles and missing teeth. It’s of your son and daughter holding up their new navy blue passports emblazoned with crowned lion and unicorn. Looking at the lion, you are swept back to your childhood; it’s filled to the brim with sticky tins of golden syrup. You wonder if they’re still labelled with that unique line reserved for the most special of goods: By Appointment to Her Majesty. • •

Your other half is driving, and you imagine your voice coming out of the handsfree, how it fills the Audi’s leather landscape whilst the kids are singing car songs. You try the following with your daughter: Easter is a beautiful time of year to come visit. Unlimited chocolate: how does that sound? Me Me Me! I know this one! Go on! The government is pinning its hopes on exports ranging from Cheddar to Stilton to single malts! And Cadbury Creme Eggs!

You sit at the bar of a giant gingerbread house replica that smells of sawdust and tangerines. You snack forlornly on Parmesan shavings. The floor is covered with last night’s peanut shells, and people’s winter boots make crunching sounds as they walk between the long

C hr is tia n B r ook la nd

• •

Citiz en !

benches, balancing steaming mugs of Glühwein. You have fonder memories of last year’s batch, but then again you remind yourself how every Glühwein has a capricious way of luring you into supposed notions about community and festivity before violently pushing you away once more. A failed attempt to strike up a conversation with a local makes you acutely aware of your foreignness. You swipe past the headlines to a picture of your son captioned “My First Guitar.” He is strumming with a look of concentration that is almost discernible through his fringe. You make out a turtlenecked blur in the background of the picture and send a fireball of Glühwein down your throat. Swiping back to the headlines, you skip a few items, then there’s Boris Johnson again, smiling and waving at the camera as he bids farewell to the nation. You remember that time you met him, and the way he said just what you thought nobody would ever say… you think what now – he admits he’s always seen himself in education, and will begin by teaching Kipling to the natives in Burma. The shot pans to some helicopter-angled jungle footage. You swipe back to the picture of your son. Without looking up you reach for some more Parmesan shavings, and your hand accidentally collides with the hand of the local sitting next to you. “Breaking News” starts flashing up on your phone – you select the recommended video which begins with a familiar scene: a crowded high street with people going about their business, standing on corners, generally idling about whilst waiting for something to happen. Anything. You seem to recognise a market stall where somebody is paying for a bunch of flowers wrapped in a paper cone; this must be big red blur that comes swerving into the frame. A red double decker bus takes the corner at breakneck speed and as the screeching starts to build, you’re quite sure: it’s aiming for the people.

56

Ch r is tia n B r ook lan d

where you once— then the sound of a wailing engine followed by a

57

Ros ai re A ppel, "Weather," 2018

Po e t ry

TRACE HOWARD DEPASS

new american constitution (terms & conditions) the sunset’s heat nudges an avalanche to bear-hug a deer until it converts, convulses, culverts to, from its blood, several streams it would gladly drink from. ingredient: mandible of deer will never screw-in, thru its own jaw, enough English to concur: the deer fear in its damp squeal might incite, may excite, let’s say invite in the snow. the snow, mr. hayes, too may not own teeth but something caught in its taking nature something white, male, something that stampeded here before, taught me nations’ soil reminiscences of men’s incisors, molars, forefathers. in regards to redlining, i disremember this brand of poverty, acquiescence, its certain passivity knows to trail us, from black, red, translucent. in nature, doors are always open or there is no door; a cave rejects bartering its being with men but was its cliff Marxist? whimsy blushed, sloped down the brine of its deer’s dark jawline, bleached stuffs under it – dark, with too many legs to be men – to burnt sienna. & who would know

58

59 how many nieces we lost to poverty & snow? i, hovered me, choked me to me. i courted him once. &, a god, near us, from his coma, just woke his ass up. in this avalanche, i am its snow. in this avalanche, i am the deer

but who isn’t?

the deer unsuspecting that its cold-blooded killer won’t be, it turns out, human. snow unsuspecting its white sheets would wave not as surrender flag but, here, now: to whiteness conceding copies of, in fact, itself. some poems, perhaps

here, perhaps

not exactly here, as one and zero as a quark, i’m not, by the end, killing myself. i simply ain’t expect embracing what revolves to be this gruesome. Only a god can see his blood, see its snow, be unwilling to unsee, wake up from a coma, and see with deer eyes, you, and smile, as though Nothing with laws to kill it had killed it. in epistles wherein i’m no god, my lens faults to a click of misclick, a “Yes, I agree” with me thus colonizing my damned me. delusions of RAM, like grandeur, wherein a “he” placed his dimmed blueprint totalitarian, his framework’s shadow –

new ameri can consti tuti on ( terms & co n ditio n s )