Stories of Service

Military memories of Ryman residents

Military memories of Ryman residents

Military memories of Ryman residents

Military memories of Ryman residents

To commemorate Anzac Day we thought it was appropriate to share the amazing stories of some of our Ryman residents who have served their country.

We thank them for their service, the contribution they made to the freedom we enjoy today and for sharing with us their personal experiences.

We hope you enjoy their stories.

This booklet is not intended as a historical document, but simply to share memories and experiences of some of our Ryman Village residents.

Heather Haylock, says her World War II nurse aid service years were simply about her trying to help her country and the injured or suffering soldiers in need.

She was initially with the New Zealand Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), helping or aiding hospital nurses, and that work folded into the New Zealand Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

“I joined the army to help with the war,” she says of her work at Addington, Burnham and firstly in Nelson.

Heather Blair was born in Carterton, but at a young age her family moved to Nelson. Her schooling was cut short at Standard 6, and as the eldest she had to attend to her mother Agnes’ health needs.

When her mum improved, Heather went on to work for a time with Hannahs shoes. From the outbreak of WWII, she was very keen to help out.

Voluntary aids were trained from 1940 onwards with their help very useful to nurses, matrons and sisters of New Zealand hospitals. By February 1944 there were 268 voluntary aids on service overseas while there were 50 on duty at military camp hospitals and 119 on duty at air force station hospitals in New Zealand.

She served from August 31, 1942 through to April 18, 1946

Heather remembers hospitals could be hard work. For example, she would each day wash down the faded brown linoleum floors of the wards. “I think the patterns had worn off and we had to polish them every day.”

But the key part of her work was helping those in need. An early VAD memory is of feeding an ex-prisoner of war who was in a bad way and transferred into Burnham Military Camp. “He’d been deprived of food, so I just had to spoon it in,” Heather says.

To make things easier for the injured she would turn down the bedspreads for the men.

Her work in Nelson included the job of sewing a button back on a soldier’s shirt. That soldier just happened to be her future husband Roy. Son John says he thinks his dad had spotted his mum before the button sewing incident.

The couple got engaged but agreed not to marry at that point because of an uncertain future. Roy, who served for more than four years including in Egypt and at the battle of Monte Cassino, Italy was discharged in 1946

Heather and Roy married in May 1946 and moved back to Canterbury and the farm at Onuku, near Akaroa. Heather kept in touch with her friends from the army days but is now the only one remaining.

Heather was heavily involved in her Banks Peninsula community and only gave up driving, aged 94.

She lived on Banks Peninsula, for more than 70 years, eventually moving to Anthony Wilding village in 2017

In 1965 David flew into Singapore at a time of real conflict to be part of a Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) response to attacks on the island from Indonesia.

Indonesia’s left-leaning President Sukarno launched “Konfrontasi” in 1963. This undeclared war included military incursions into areas including Singapore and East Malaysia.

Sukarno, like many Indonesians, believed the creation of a Malaysian federation was unwarranted. New countries like Singapore were emerging as a period of British colonialism in the Far East came to an end.

David, who had already served in the Naval Volunteer Reserve as part of his compulsory military training, was commissioned and flew into the conflict zone for a period of nine months, during 1965-66.

“I saw an opportunity to go to sea in the Far East because they were short of officers. I was a radio operator, and I was commissioned, and I was a sub lieutenant.”

David points out the confrontation was real. Singapore experienced a series of bombing incidents in which people were killed as a result of devices planted by Indonesian saboteurs.

In August 1965, the Malaysian Parliament voted to expel Singapore from Malaysia, leaving Singapore as a newly independent country.

“We were there (because of) the Indonesians. They were causing disruption throughout Singapore and Southeast Asia,” David says.

“We joined forces with K D Malaya (naval base) ... we weren’t there on holiday.”

Part of his navigation officer role was on board a mine sweeper HMNZS Hickleton, that started operations in the Far East in April 1965. This and other minesweepers, including some from the Royal Navy, patrolled at night on set patterns. These operations were the RNZN's last large-scale operation with the Royal Navy.

David says the ships would tend to leave port at 4pm and be back into Singapore by 8am, as part of an effort to stop Indonesians getting into British territory.

The Indonesians tended to be on motorised-sampans, and gunfire was often exchanged.

The Hickleton, together with her sister ship HMS Santon, carried out hundreds of patrols, with dozens of incidents involving intruding Indonesians, and with some taken as prisoners.

“We challenged them and opened fire on them if they didn’t respond.”

Even then Singapore was a big city, he says, and offered rest and recreation for periods of time. “We used to hop in the car and drive down to Singapore... many nights.”

David, who had been given a leave of absence from his workplace, flew home and was soon back with Victoria Insurance Co. in Dunedin as an insurance assessor.

His naval reserve work continued for many years.

Born in 1946 Smokey (Rodney) Dawson had an early start in military service, joining the Royal New Zealand Air Force as a Boy Entrant in 1963.

He was attracted to the air force partly given his interest as a youngster in engineering, but there were a couple of false starts before he hit his straps in the ‘aerial’ armed service.

Smokey’s family farm was near the now holidaymaker’s paradise of Snells Beach. He was schooled in Warkworth, but home also provided an education. “Dad gave me an engine when I was about 10 that I used to strip and put back together again,” he remembers.

His Mum had ruled out his interest in the navy. Then one day when he’d come home from school she’d cut an advert for the air force out of the paper. “So, we filled that in and sent it away... I had to go for an interview in the Warkworth library after milking, and I passed that, so I joined.”

Within the Boy Entrant intake he soon earned the nickname Smokey (perhaps a reflection of Aussie country star Smokey Dawson). He left entrants school and went to complete a basic training course at Hobsonville Airbase, Auckland, and from there his work as a trainee and eventual instructor took him into air force workshop spaces throughout New Zealand and other military bases around the world.

He moved through to Woodbourne Air Force Base, Blenheim to do the aircraft mechanics trade course, and during the early part of his career saw him tinkering or doing real engineering work with aircraft such as North American T-6 Harvards and De Havilland DH100 Vampires. The RNZAF operated Harvards from 1941 (including within the theatre of war), and Vampires were used in 1955 by the RNZAF in Malaya as part of its first combat strike since World War II.

International travel beckoned from 1973, and three years later he journeyed to England in 1976 having been chosen as part of a RNZAF group to undergo three months of training at RAF base Brize Norton on Andover maintenance.

The course was intense and he returned to Auckland as an instructor on maintenance of Hawker Siddeley Andovers, one of the air force passenger transport workhorses from 1976 through to the mid-90s.

He also travelled on to North America, and widened his career achievements with 22 years working for Air New Zealand.

Smokey’s first contact with the Air Force Museum of New Zealand, where he now volunteers, began when he was still in the air force in the mid-1980s. “At Whenuapai I was the lead on rebuilding the (World War II) USAF Catalina Flying Boat for the Wigram-based museum. I enjoyed it.”

When Graham Fisher was deployed to Vietnam in 1967 his mother had a terrible sense of history repeating itself.

Graham vividly recalls his mother’s reaction when the family learnt his uncle would serve in WWII.

“She said ‘I bet you, when Graham’s old enough there will be another war’,” he said.

Graham enlisted in the Australian Army in 1964 when he was 18, with the rank of Private (Craftsman). After basic military training at Kapooka, NSW, he was posted to the Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Training Centre in Victoria to train as a Fitter and Turner to inspect and repair everything from small arms to tanks.

He was deployed to Vietnam in June 1967.

“Prior to being posted I had to pass a three-month training course at the Jungle Warfare Centre in Canungra, Queensland,” he said.

“We were jumping out of moving trucks, firing blanks into the hills, shooting rifles, swimming with our packs on; all of the stuff you could come into contact with in war.”

Graham was posted to Vũng Tàu, a relativity calm part of the country, but his role involved travel to more dangerous areas.

“I went to the demilitarized zone located on the South and North Vietnam border, and to Saigon.

“I fixed weapons on army ships in the Mekong Delta and you would have to hide when you were on the deck and

hope no one came out of the bush. It was pretty daunting.”

But, overall, Vietnam was a rich learning experience which shaped his military career.

“It felt like more of an adventure when I got home. But I loved the experience, I’d do it again tomorrow if I was able to.”

Back home, Graham served as a section supervisor in Bandiana and Puckapunyal. There, he led military and civilian personnel inspecting and repairing everything from tanks to medical equipment.

In 1975 Graham was posted to Papua New Guinea where he instructed local soldiers on the repair of vehicles, gauges, and medical and dental instruments.

When he returned to Australia in 1976 he had postings at Bandiana, Broadmeadows and lastly at the Melbourne Mechanical Engineering Agency where he travelled to army units across Australia investigating small arm defects and evaluating weapons prior to entry into service.

Upon discharge in 1984 Graham was a Warrant Officer Class 1.

His time in the military continues to shape his life.

“It doesn’t matter where I go in Australia, I always seem to bump into someone I was in the army with.

“And those army mates, you class them more as family because of what you’ve been through together.”

Gisborne-born James (Jim) Scott had his sights set on following in the medical footsteps of his father and grandfather by becoming a dentist before any idea of joining the military occurred to him.

Born on 1st October 1937, Jim went to Gisborne High School before heading to Dunedin and the Otago University Dental School.

But as the reality of being confined to a practice in a small room began to dawn on him, he followed a friend’s advice and applied to join the Navy and see a bit of the world.

Jim was commissioned as a Surgeon Lieutenant (D) in the Royal New Zealand Navy, and went on to enjoy a very rewarding 12 years. His commissions included HMNZS Tamaki, Royalist, Philomel, Otago and Waikato and took him to countries such as Singapore, Hawaii and Japan.

A significant highlight was being in Belfast in 1968 at the launch of the new frigate HMNZS Waikato, by Princess Alexandra.

By 1969, Jim was promoted to Surgeon Lieutenant Commander (D) and later was offered a two-year posting to Singapore – but only if he transferred to the Army first.

This was part of the Government’s decision to unify common services such as dental, medical, education and so on, and as dental was the smallest, they were unified first.

If Jim accepted, it would mean big changes, not least of them wearing a green uniform.

“I was very reluctant to make the change to Army because each service has its own culture and a different mindset.”

An ‘interesting’ period of Jim’s career was an operational tour of South Vietnam with a Mobile Dental Unit in 1972, soon after the Tet offensive.

“We treated all comers – NZ, US, Korean, Australian and local Vietnamese which probably included a few Viet Cong.

“I was embedded for several weeks with a US Special Forces (Green Beret) group, who were out actively patrolling the Cam Rahn Bay area.

“It bemused me that returning after risking life and limb on these operations, they would come to me, reporting that it was time for their routine fluoride application.”

During his last years in the Army, he had the honour to be appointed as an Honorary Aide de Camp to the Governor General, Sir Denis Blundell.

During this time, he assisted during a visit by Queen Elizabeth, selecting and introducing the various chosen people to meet her at a Government House garden party.

As a Major, it became apparent that if he wanted further promotion he’d be sitting behind a desk at Wellington Headquarters, so he decided to retire from the Defence Force after 17 years and go into private practice.

He is now a dedicated attendee of Anzac Day services in the village.

When she signed up for Red Cross training in 1941, legal secretary Joan Daniel thought the furthest she would be going would be Rotorua.

But just months later, the 22-year-old former Auckland Girls' Grammar student was setting sail for Suez on the hospital ship Maunganui as part of the Voluntary Aid Detachment.

Joan was initially based in Cairo working at 1 NZ General Hospital at Helwan, near Maadi Camp.

The bulk of her work was dealing with sick patients with complaints ranging from the standard to the more serious, such as dysentery.

Joan worked hard on her shifts and enjoyed exploring the many exciting new sights with new friends during her downtime.

“The invitations were pouring in from everywhere!” she says.

When the Battle of Alamein got under way, with the Germans pushing down towards Alexandria, Joan was sent to the coast of what was then Palestine where 40 of them lived in a big shed right on the beach.

“We were a happy hospital, they were a lovely crowd,” she says.

When the flow was reversed and the Allies started pushing the Germans back again Joan was sent back to the canal zone, living five to a tent with a Nissen hut used as a mess.

Duties included taking temperatures, doing washes, making the beds – even with a very ill patient still in them – and preparing the sisters’ afternoon tea.

One joyous occasion was during leave when Muriel, her best friend from Auckland who had trained and travelled with her, got married with Joan as bridesmaid.

There was tragedy too however. Three fellow nurses were killed when a vehicle swiped the side of the truck they were travelling in. Joan was the wreath bearer at the funeral.

On New Year’s Eve 1943, Joan was on her way to Caserta, Italy where she soon saw first-hand the true cost of war, with injured soldiers from the Battle of Cassino arriving daily.

“That was really hard work, the wounded came in all the time.

“The Māori Battalion were very good patients and were good fun even if they were really sick and wounded, always with a smile, but with some it was quite sad and used to upset me sometimes.”

The men who’d been shell shocked were particularly upsetting to see.

When Joan had reached her three years’ service, she applied to head back to New Zealand.

She returned to her job to await the return of her fiancé Maurice, who had been a POW in Greece for most of the war. They married in 1945

Maurice wasted no time in buying a one-man law practice in Onehunga which still thrives today.

Born on 11 March 1941 in Christchurch, Ron Longley joined the Royal New Zealand Navy as an Artificer Apprentice straight after leaving Papanui High School.

Nearly three decades later, he retired as Fleet Engineer Officer, responsible for all marine, weapons and electronic operational engineering matters for the whole fleet which included 12 ships. But there were plenty of peaks and troughs along the way.

His first New Zealand ship posting was to HMNZS Royalist.

“They put me on there and forgot about me! I was posted on ship as a leading hand, promoted through Petty Officer (PO), then Chief PO before I passed my exams for Warrant Officer – no one else got close to doing that in one posting.”

As a Dido class cruiser, the ship was originally designed for a crew of 450. But following modifications the crew was swelled to 550.

“It was cramped!” says Ron, who nonetheless looks back on those years with fondness.

As a ‘boiler room tiff’, Ron experienced a couple of near misses, both involving extreme throat-searing heat in the boiler rooms and passing out!

The Royalist took Ron to Pearl Harbour twice, a North America tour, three Far East tours plus patrols in Borneo during the Indonesian Confrontation in 1963, ‘64 and ‘65.

He was posted to Singapore for six months in 1967 as a member of the base support party for the Borneo minesweepers.

Ron was then the Squadron Engineer for NZ coastal patrol craft and was then posted to HMNZS Blackpool for a year.

In 1968 Ron was commissioned to officer rank with a stint in the UK at the Royal Navy Engineering College in Plymouth and more training courses in Portsmouth.

Ron also spent two years seconded to the Republic of Singapore Navy, responsible to their Head of Engineering for advice on all technical matters, and was promoted to Lieutenant Commander.

Ron’s engineering skills were clearly in demand and saw him posted to HMNZS Waikato for four years, which included a 21-month extended refit and modernisation, which he says was’ the longest and most comprehensive refit undertaken by our Dockyard’.

Later, Ron was promoted to Commander and sent to the UK for nearly 18 months.

For this role, he was the senior NZ representative responsible for the commercial refit of HMNZS Southland in Southampton, which was the first commercial warship refit in the UK. Ron was awarded an OBE for this achievement.

On his return to New Zealand, he was appointed the Fleet Engineer Officer role, responsible for all operational engineering matters concerning the Fleet, which included 12 ships and then retired in September 1985.

He is proud of his navy career and everything that the ‘senior service’ represents and says he wouldn’t change a single thing about it.

Ross Johnson’s five years in the New Zealand Air Force (NZAF) were action-packed, with Ross posted to an NZ fighter squadron based in Singapore at just 19-years-old.

As the middle child of five, Ross grew up on farms around Wellsford and Kaipara and was strongly encouraged to follow his dreams of joining the air force by farming neighbours and teachers from Wellsford School and Auckland Grammar School, many of whom had served in World War II just a few years before.

In 1955 aged 17.5, he spent a year at Taieri and Wigram, training to be an Air Force pilot, following which he moved to Ohakea to train as a fighter pilot.

“I was struck by an immediate sense of organisation and purpose. In pilot training, you passed well in academics and flying or took the train home!”

In Singapore, Ross worked with the British and Commonwealth Armies by bombing terrorist targets in the jungle of Malaya.

Flying in formation with other planes and being able to manoeuvre his aircraft upside down if necessary was certainly thrilling work but the sobering purpose of it was not lost to Ross and his fellow pilots.

“We were using real, live armaments and we treated it very seriously indeed.

“One of the things we probably all felt aware of was, just a few years before (in WWII), young guys of our age were going out and getting killed and captured.”

Ross treasures a 1958 photograph of him standing next to his plane meeting the New Zealand Prime Minister Walter Nash, who had come to Singapore to see the Kiwi troops.

After five years’ of service, Ross decided to make a switch, leaving the air force to fly for Air New Zealand and Singapore Airlines but maintaining his connection by being a reserve member for 20 years.

“I decided that the airlines looked very attractive, and were expanding rapidly, and getting modern equipment. I thought perhaps there would be more of a future there than in the military.

“Overall my service was very positive for my future technical and personal development.”

This chapter of his career lasted 35 years, with 25 of them spent as an instructor on large jets and working on projects to introduce new aircraft and simulators.

Ross feels strongly about marking not only Anzac Day but also Armistice Day and Battle of Britain Day.

“Not only to remind us of our fallen forbears but to show new generations that history may repeat unless we are careful.”

Albert Edward Thomson, nicknamed Tom, grew up fascinated with aircraft.

Born on 29 November 1935 in Christchurch, he dreamed of becoming a pilot in the RNZAF.

But he was met with a huge stumbling block when Air Force medics told 15-year-old Tom that his eyesight wasn’t up to standard.

“So, I signed up for the apprentice scheme for training as that looked like the nearest I would get to it.”

He spent three years at the RAF School of Technical Training in Halton, Buckinghamshire and when cadetship came along he was sent to Uxbridge in England where medics then told him there was nothing wrong with his eyes.

Tom went on to train as a pilot at the Royal Air Force College, Cranwell and graduated top of his intake with the Sword of Honour – an achievement his younger brother Russell went on to emulate.

In 1963, as an experienced transport aircraft captain, Tom was seconded to the US Navy squadron to operate C-130 Hercules equipped with skis to and within Antarctica. In March 1964, while expanding his professional experience as a flying instructor, his brother was killed while flying a Canberra bomber over the South China Sea.

After being posted back to 40 Squardron, training crews on the new aircraft destined for Vietnam, Singapore and Antarctic, Tom received a promotion to Squadron Leader.

In 1971, with wife Barbara and a young daughter now in tow, he was appointed

Commanding Officer 42 Squadron at Ohakea, a prestigious job as the unit incorporated the VIP flight, which carried members of the Government and official visitors including the King of Tonga and the Crown Prince of Japan.

Later, as Commanding Officer of 40 Squadron, he received a panicky call to evacuate Embassy people from Saigon.

"The late-night deployment to Singapore via a refuel at Alice Springs and two flights into Vietnam was the longest I have ever stayed awake and flown in my flying career!"

On leaving 40 Squadron, Tom was awarded the Air Force Cross for his leadership of the unit and was then posted as Military Attaché to Thailand, Burma and Laos.

Tom was promoted to Group Captain in 1980 and returned to NZ to Wellington with a number of special projects to oversee.

He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1982 and took over as CO of RNZAF base Auckland, which included Whenuapai and Hobsonville.

Overseas postings continued, this time with a year in Canada at the National Defence College. On his return, Tom was promoted to Air Commodore and took up the post of Air Officer Commanding Support Group with responsibility for all ground and aircrew training.

Another honour followed in 1988, when Tom was appointed a CBE and returned to Wellington for a promotion to Air Vice-Marshal before retiring in the early ‘90s.

Even though Bernie Lewis was still at Nelson College and too young to join up, he took a great interest in the air force during World War II. With two brothers as pilots, he was fascinated with flying, having taken his first flight in 1934.

By the time he could apply to join the RNZAF he had his private pilot’s licence, but the only position offered to him was as a navigator. It was that or nothing, he was told.

“So, I took the next boat to England at my own expense and applied for the RAF where there was big demand for air crew.”

Bernie joined the RAF in 1950 and served as a jet fighter pilot on Vampires and Sabres before becoming an instructor.

He started training at Cranwell in January 1951. Later at RAF Feltwell, he moved on to the cumbersome Percival Prentices and Harvards – the Tiger Moths were gone by then. Bernie was awarded “Wing” and a trophy for best pilot in February 1952.

At RAF Merryfield in Somerset, he moved straight on to jet conversion on the Vampire 1

Posted to Germany, Bernie was allocated to a squadron at RAF Oldenburg, near Bremen, which had updated Vampire 5s, and they were re-equipped with the American F-86 Sabre.

“A wonderful machine and very reliable; it performed magnificently.”

“It was there I managed to exceed the speed of sound a number of times. I’d go up to 42,000 feet … go belting along and roll over on your back and dive down vertically at full power, and for a glorious four-six seconds you could exceed the speed of sound.”

From there, Bernie went to Central Flying School, learning to become a flying instructor and then to instructing at Cambridge University Air Squadron at Marshall Airfield.

He was there for two and half years before he was accepted to go to the Empire Test Pilots’ School in Farnborough on special duties.

“There were 12 different types of aircraft, and we were expected to be able to fly them all. At the end of the first term, I volunteered to test helicopters even though I’d never flown them before.”

A year later he was testing in the tropics, before heading to Canada for winter testing.

“Three years after that I was asked by Rolls Royce to join them as an engine test pilot.

I flew a Vulcan bomber with a Concorde engine bolted under it, so the Concorde engine was well tested before the first official flight!”

Bernie also flew with the German, Austrian, and Irani air forces when they required assistance with their Rolls Royce engines.

After a long and succesful career his last flight was in 2008.

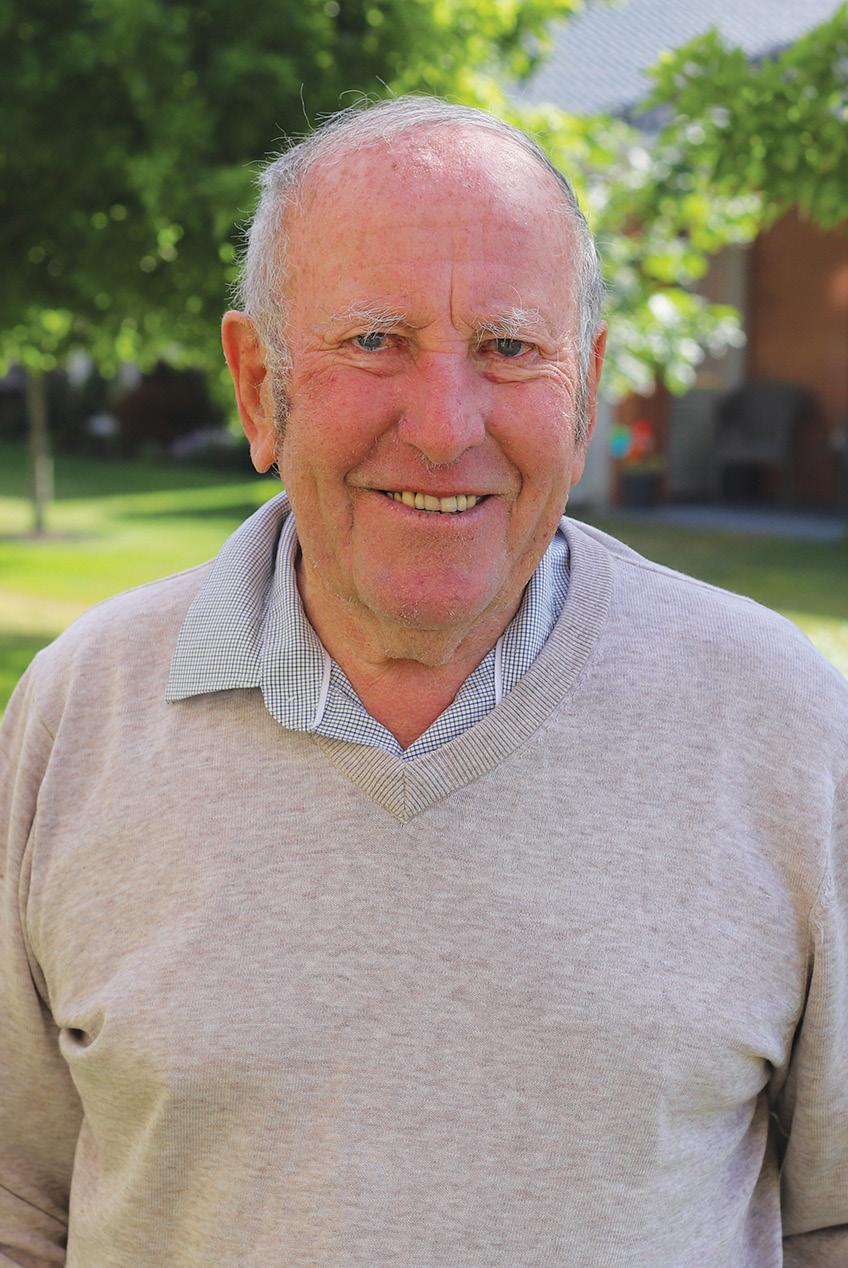

On leaving Nelson College, young Bill Morgan joined the public works as a surveyor. The staff there were mostly returned servicemen and they told some great stories. “My mother was not keen on me joining the army, but I didn’t want to be in public works.”

Bill joined the army in 1949, married his sweetheart, Ngaire in 1950 and over the years the army took him to lots of places, including Burnham, Linton, Dannevirke and Waiouru. Bill recalls shifting 14 times!

During the Malayan Emergency he was posted to B Company as quartermaster. Ngaire and the kids would go too. They were there for two years but Bill spent two or three weeks at a time with the Company at Tanjung Rambutan rubber plantation on the outskirts of Ipoh – a friendly tin mining town. Bill’s recollection of jungle warfare was of the enemy who were silent, quick and cunning.

“I enjoyed my time in Malaysia before moving back to the regimental depot at Burnham as quartermaster.”

During his stellar career, Bill held various appointments as an instructor in the Royal NZ Infantry Regiment and also that of the Regimental Sergeant Major of the 1st Battalion Royal NZ Infantry Regiment while stationed in Malaya.

In 1967 he was appointed to a quartermaster commission and was appointed as quartermaster to Burnham Camp.

After a brief period as Investigating QM for the Southern Army Region, Bill assumed the appointment of Commander of the

Nelson, Marlborough and West Coast Army area, the appointment he had until his retirement in 1979.

Bill recalls one posting to Dannevirke and wondered what on earth he had done wrong. But the army had plans for Bill and wanted him to spend some time with civilians building good public relations and community respect for the army.

Living now in his hometown of Nelson it’s easy to see he was the right person for the job with his hearty greetings and friendly quips to fellow residents as they pass by his seat in the café.

“But looking back, my last posting to Nelson was special and a great thrill as I was very proud to represent the army in my hometown.”

“Anzac Day is remembering,” he says. One loss that has never left him is of a young dog handler who was shot when his dog caught the scent of a band of terrorists, and it dragged him ahead of his patrol.

“My father went to WWI and WWII and received an MBE for his service.”

Following his second term in Malaya, Bill was also awarded the MBE for military service.

“Anzac Day to me is for remembrance. It’s the little things I remember.

War is hopeless. But what’s the answer? It seems so futile.”

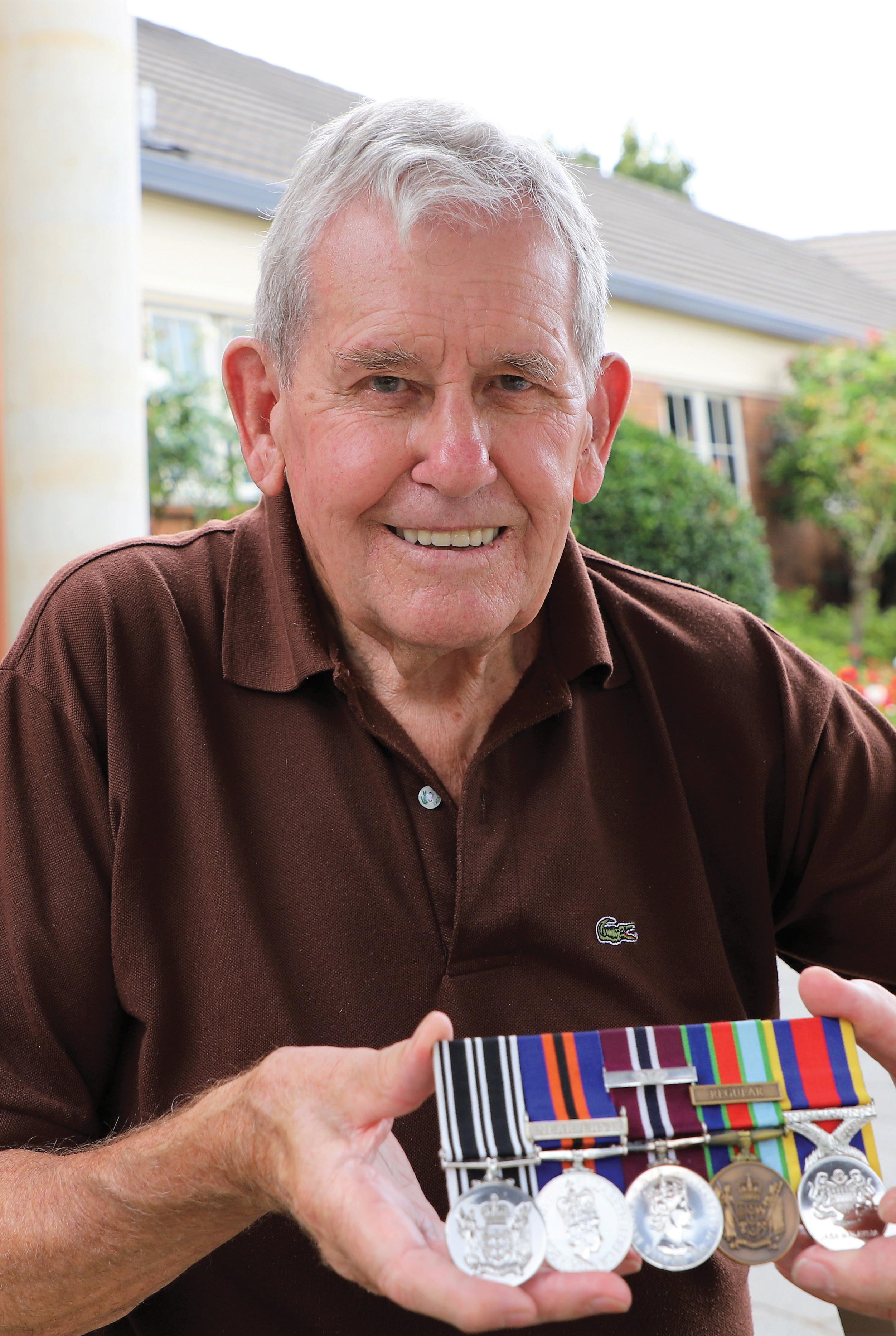

Norm Scoles personally received a Distinguished Service Medal from Queen Elizabeth II for his heroic efforts to rescue a fallen comrade from a skirmish on the Korean mainland.

Queen Elizabeth presented him with the medal at a special ceremony at the Civic Theatre in Christchurch. The Queen and Prince Phillip were on a royal tour and arrived at the Civic for the ceremony on January 20, 1954.

Norm’s award related to his actions and bravery on the west coast of Korea in September 1951, when he was still aged 21 and one of those serving with the frigate HMNZS Rotoiti. He says the objective of the landing was to cause the enemy a bit of trouble. But that aim soon rebounded on them when his mate Robert Marchioni was shot.

Norman carried the body of Able Seaman Marchioni over a cliff top and along a beach, before being forced to find a hiding place for the body. Norman, a Leading Seaman, and the landing party came under heavy enemy machine-gun fire and were forced to move quickly during the incursion on Go-Rin-Chi-Ki Point.

Marchioni was shot and killed as part of the Korean War, and since then there have been negotiations to repatriate the body. Whether or not his body remains where it was hidden is not known.

One press clipping from the time reported: “Scoles according to a Press Association message from Tokyo, knelt beside a mortally wounded comrade and applied a field dressing during heavy fire.” Scoles adds that he threw back a standard-issue

grenade, followed by a spray of bullets before instructing the troops to return to the boats.

Norm carried Robert on his shoulders around a rocky point to where the boats were waiting but left the body when he was exhausted.

In the recommendation for decoration, it says the grenade silenced guns and facilitated the withdrawal of the assaulting party he was part of.

Norm was born in Cromwell and grew up with four brothers and a sister in Arrowtown saying the Depression years were very tough. Food was so scarce they basically had to eat what they could catch, including rabbits, or grow.

His father had helped him get to as far as Dunedin before getting him on a rail car/then ferry in order to sign up for the navy in Auckland.

He trained in 1946 on the HMNZS Tamaki, then travelled throughout the South Pacific including Fiji, Tonga and on to Darwin and further above Australia. His first ship was the cruiser HMNZS Bellona. He remembers games of rugby against the Fijians.

Norm’s grandson Simon Bird wrote an account of his grandfather’s life, noting that after leaving the navy he worked as a watersider, then for 30 years as a foreman stevedore.

James ‘Curly’ Easton was born on the 12th of December 1916 in Kirkintilloch, just outside Glasgow, Scotland.

His family left Scotland for Winnipeg in Canada before settling in Australia’s Hunter Valley in New South Wales when James was 12.

When war broke out, he would take photos of the men wearing their new uniforms.

He then got called up to do his compulsory three months with the Militia – the then name of the Australian Army Reserve –and after that he put himself forward to fight overseas, becoming a Signalman in 8th Division Signals of the Australian Army at the age of 23.

He was soon sent on a boat to Singapore. The conditions on the island were basic with open drains running through the streets. James was posted onto front gate duty and after a relatively uneventful start to the war, he found himself being bombed by the Japanese.

The allies had no tanks and no planes so fighting off the Japanese became a challenge. They held them off for two to three months until they were captured and marched off to the troops’ base in Changi, where they were set some gruesome tasks.

In 1942 James joined 3,500 Aussies and 3,500 Brits designated as F party who were sent in cattle trucks to Ban Pong, Thailand, a journey which took four days.

The men learned that they had to build a railway going up to Kanchanaburi in Burma. They would march by night, set up camp and work 16-hour days, fuelled only by a cup of rice with three beans in it.

“The slightest thing you’d get bashed,” says James.

For the 3–400km length of railway he reckons there would have been 100,000 people on the route, all labouring by hand, sometimes standing waist deep in water.

“It was actually good to get back to Changi, after 14 or 15 months up on the railway it was like coming home!

And we put on a bit of weight, and we weren’t getting bashed.

“We went back the same way we came in, in the cattle trucks.”

By war’s end, James was down to 7.5 stone – his normal weight was 12 stone 4lb.

He says it was a long time before he could sleep in a bed again.

While James puts his survival of the war down to ‘a lot of luck’, his approach to life has always revolved around having a wicked sense of humour.

However, when it comes to paying tribute to his fallen comrades James takes his duties very seriously.

He has travelled to Singapore and Thailand six times to pay his respects at the POW cemeteries and only stopped his annual trips back to Sydney to march on Anzac Day at the age of 94.

Bruce was born 30th December 1931 and raised in New Plymouth. He was conscripted at 18, and this was his introduction to a long and distinguished career in the New Zealand Army.

After his three months training, he decided to leave his job as a newspaper reporter and joined the army at 20.

During that time, he was involved in three campaigns:

The Malayan Emergency – a communist uprising which he describes as the “British Vietnam” 1948 to 1960.

After World War II, the British, who had quietly supported and trained the Chinese communists to fight the Japanese, refused to let them become leaders. The communists retrieved their weapons hidden in the jungle, formed a guerrilla army and shot some British rubber plantation managers, which created a rebellion.

Britain had a lot of losses but gradually forced the communists out of the towns. The British had a lot of power. They were not only the army, they were the government.

At times the New Zealanders would be in the jungle for two or three months. The Kiwis were expert in the jungle and were desperately quiet, often using sign language. This unnerved the communists.

Posted to Borneo in the 1960s – when the British were withdrawing from Borneo, Bruce fought against the Indonesians who didn’t like the idea that Borneo should be joined (with Singapore) to Malaya, to form the new state of Malaysia. Bruce was in New Zealand Special Air Service (NZSAS) then.

He was a young married man when he went to Borneo and his wife was due to have a baby. He was in Borneo when the baby was born in New Zealand. He was nearly killed in Borneo, and he realised how hard that could have been for her.

Bruce and his family subsequently went to Singapore in the early 1970s for a two-year posting and this time his family was with him.

During this time, he was sent to Vietnam. He was 40 then, so he was in Australian Headquarters in Nui Dat, Phuc Toi Province east of Saigon.

“We were aware a lot of people did not want us there; but then a lot of people did. We were also aware there was good reason for us to be there. We were also conscious that our government didn’t really want us there but were forced to send us there!”

As a regular soldier you don’t get to choose your wars. When the soldiers got back, a lot of New Zealanders didn’t like them for having been there. “They should have been booing the government, not us!”

Bruce started as a private and went through every rank to finally become a major. He was awarded an MBE (Member of the British Empire) after 30 years’ service.

The war years for Catherine Brown were a far cry from her remote upbringing in the Shetland Islands but nothing seemed to faze the young nurse, dubbed ‘The Mighty Atom’ by her colleagues due to her short stature and strong work ethic.

Born on 31st March 1917, Catherine started her nursing training at Lincoln County Hospital in Lincolnshire before moving to Manchester to train as a midwife, which is when war broke out.

She volunteered to join the QAs (Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service) and left by convoy from Glasgow.

“I can remember sailing down the Clyde and the terrible noise of hammering in the port as it was wartime and they were building as many ships as possible, because they were getting torpedoed.”

The nurses were diverted to a site not far from Cairo to set up tent hospitals in the desert.

Until a desalination facility could be established, they were rationed to just a pint of water a day for washing themselves, their stockings and veils.

Catherine was a hospital sister in the theatre hospital, nursing around 600 men. Injuries were typically shrapnel wounds, with many needing operations on their eyes or amputations.

The nurses were doing things that the doctors would normally do because there weren’t enough doctors, and Catherine completed an eye operation.

“It was a very tough time and we worked really hard. I have tried to blot out these memories.”

Catherine says doing the job required at the time was always the priority. “You just had to get on with it.”

There were some lighter moments, when Catherine would do the tourist thing with a group of friends or a boyfriend.

She tells of ‘dancing in the streets of Damascus’ and riding a camel near the pyramids, or visiting the famous Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo.

From Egypt, Catherine was sent to Malta where she enjoyed the relative luxury of living and working in buildings rather than tents.

She was in Malta when it was razed to the ground and people were forced to live in caves.

After four and a half years, she went back to England and worked in an army hospital in Oxford until the end of the war.

With her great experience and obvious intelligence, friends suggested she train as a doctor at the Royal Free Hospital in London, but she never did.

At a family wedding she met up again with fellow islander Peter Brown, marrying him in Edinburgh in 1947 and then working as a nurse in a factory.

Two daughters followed, first Susan then seven years later Julia and the family emigrated to Australia before moving to New Zealand.

Catherine eventually worked as matron in a girls’ hostel and retired to Nelson in 1981.

The course was set for Peter’s 11-year career in the Royal New Zealand Navy after his cousin went on the Coronation Cruise in 1953.

“I decided ‘that’s me, I’m out of here!’” says Peter, who being born in October 1938, was only 15 years and four months when he signed up.

The eldest of five growing up in the tiny settlement of Sanson in the Manawatu and schooling at Palmerston North High School, Peter relished the chance to explore the world.

His first major posting was to Malaysia and Singapore on HMZS Black Prince in 1955 during the Malaya Emergency, but greater tension was to follow.

After being sent to the UK on HMNZS Bellona to bring back the HMNZS Royalist from Plymouth, Peter left England on 8 July 1956 travelling to Malta to join up with the Mediterranean fleet.

“That’s when we got caught up with Operation Musketeer, known as the Suez crisis.”

Peter was in Naples, Italy when the captain received word they had to depart immediately, and the sirens were sounded to call the crew on shore back in.

“We were oblivious to what was happening because you had no access to the news back then.”

They soon realised they were in the middle of a serious situation however as the world’s superpowers tussled over rights of access to the important link between the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean, and a very tense 10 days ensued.

“Even in the downtime we were on edge, and it would be action stations at 4am because when the light’s starting to get up it’s a good time for anyone to attack.”

The ship was finally released to return home in November 1956, travelling along the western side of Africa as the canal was still blocked, arriving back on 20 December, 14 months after they’d left.

His subsequent years included a return trip to Singapore in 1961 where he had a taste of jungle warfare on an exchange with 2 Battalion.

“We were training in the jungle then out in the bush, which was exhausting but luckily I did physical training every day and I’d run on the decks when we were alongside.”

Much of his remaining time in the navy involved being part of the admin team at the Tamaki training depot and the naval communications station HMNZS Irirangi at Waiouru until his term expired in October 1964.

Then, love came calling, and Peter left in order to marry Pamela.

“I always said I’d marry a farmer’s girl – and we’re still together!”

Peter gives back to the community as a life member of the Katikati RSA and is proud to play an active part in the Hilda Ross Anzac Day commemorations where he reflects on former colleagues.

George had a harder start in life than most, being a foundling baby in Christchurch, born in March 1932. His first few years were spent in an orphanage in Ferry Road before he was fostered out to the Roberts family.

He remembers moving up to Auckland in primer four and going to Albany Primary and Northcote Intermediate.

Like many children of that era, George left school at 14 and went to work at Stotts Butchers.

After the war, compulsory military training (CMT) was reintroduced and after turning 18, George was eligible for the first intake in 1950.

While the training was just a matter of weeks, the impact it had on his life was far-reaching.

He initially returned to the butchers but later did another six weeks training and joined the territorial army where he remained an active member for many years.

It was while he was with the 9th Coast Regiment of the Coast Artillery that he met his wife Hazel.

He later worked as a firefighter and was based out of various Auckland stations including Parnell, Auckland, Takapuna, and East Coast Bays.

When CMT was stopped in 1972 George was one of those keen to see it reintroduced because of the skills it gave him in life.

He believed there were great benefits including confidence and discipline that could be instilled in young men who may have had a similar rough start in life to him, with the ultimate hope that would reduce the rising numbers in youth crime.

George and Hazel married in 1954 later having two children, Gaylene and Gavin.

Hazel started driving school buses which eventually led to the couple buying into a bus business which later took them north to Whangarei.

At one point they had a fleet of 35 of Whangarei’s Blue Buses with George managing the business and Hazel still driving.

In 1996 George was awarded a Queen’s Service Medal for public services.

He wears that medal proudly alongside those he received for his CMT, his firefighting and his territorial army service and is always actively involved in village commemorations for Anzac Day.

While serving in Vietnam, Lieutenant Gordon James Keelty was sweltering in jungle patrols, and taking helicopter trips across enemy lines. He is still thankful he and his battalion unit survived.

Gordon rose to the rank of Lieutenant as part of the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment, having trained at Burnham, south of Christchurch. He served in Vietnam in 1969, having flown to Malaysia in 1967.

He motored down to an operations base at Nui Dat, to the east of Saigon, and also close to Long Tan, which had been the location of a famous battle in 1966 involving Australian troops.

He and other troops were there to make forays into Viet Cong territory setting up in camp in their hoochie tents. Firefights ensued.

“In Vietnam, for example, you’d be out on a patrol that would last 28 days. You didn’t shower in that time of course. You had to be particularly careful operating in the bush. You had to be careful of your hygiene...

“Then you had two sets of clothes which were just denim and light denim, so you’d wear one set during the day, and you’d be sweating in the heat of Malaysia, and you had another set in your pack.

“In the night you’d get into your dry clothes to sleep in and then get up in the morning and get back in the wet clothes.”

After he left the combat zone, two good friends he served with were killed by enemy fire.

Gordon says rendezvous times, for example for water drop offs, were dangerous. “Of course, helicopters coming in was a sure sign to the enemy of where you were... You'd get off out of that area as quick as you could.”

Anzac battalion members stationed in Nui Dat lived in tough conditions. New Zealand had two companies as part of the forces, he says. “They were large tents we lived in, sandbags round the outside... That was in the middle of an old rubber type plantation, that was quite different.”

He has images in his mind of his arrival into Vietnam. “We flew into Saigon from Singapore, and I was in a Bristol freighter, which was an old bucket of bolts.

“But they were an old aircraft, that was a bit of a source of amazement to the Americans, that they saw these planes and thought they can’t possibly be still flying because they were that old.”

It was overseas in September 1968, at Terendak Camp, he says he met his lovely wife Marjorie. She’d come from England to teach in the British army secondary school.

Gordon stayed in the forces until the early 1980s, retiring as a Major, and had various other periods of service including being stationed in Singapore from 1976 to 1978.

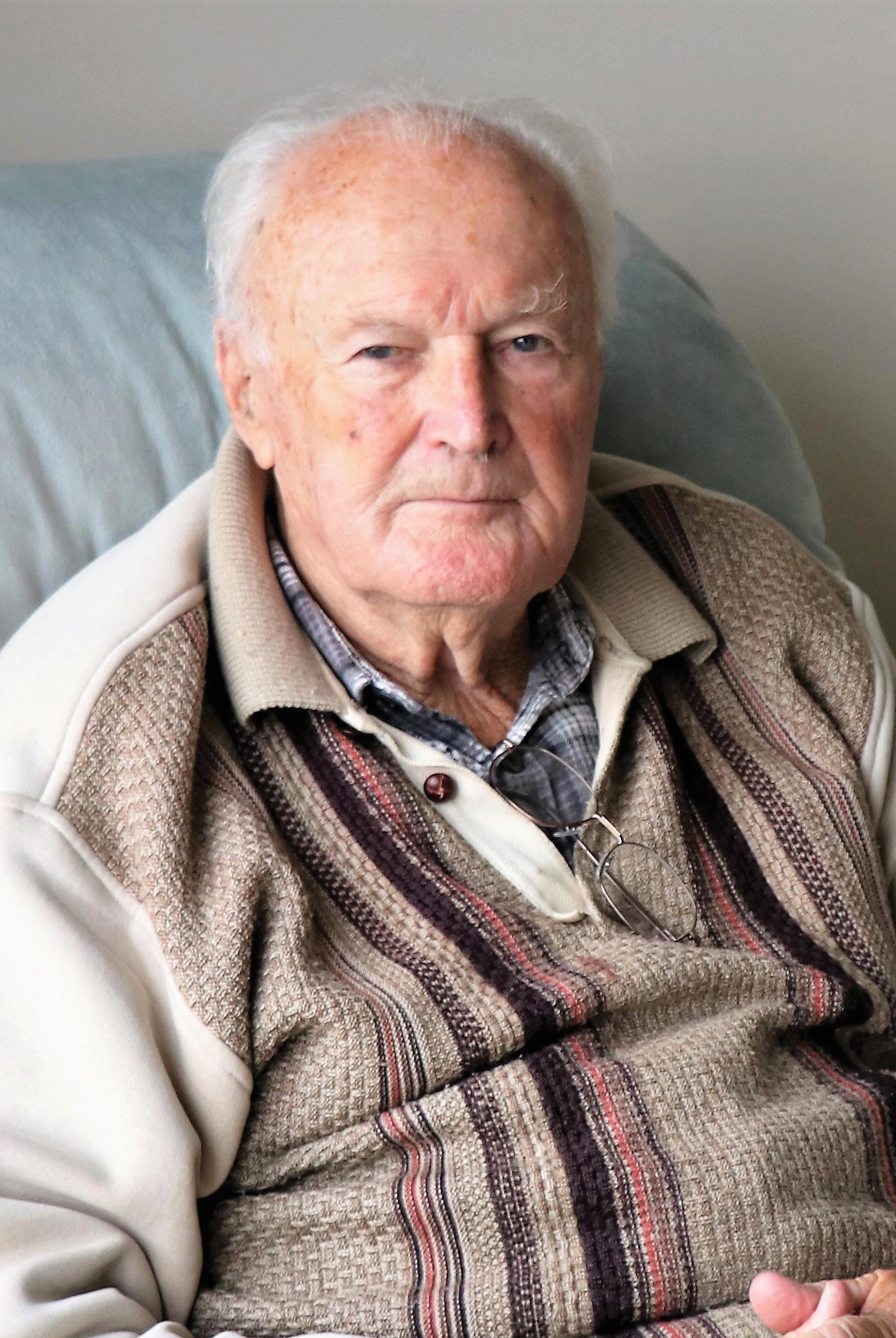

Jack was born in the small Central Otago town of Naseby in 1925 and grew up in nearby Ranfurly.

Living in an inland part of the South Island and having never left Otago, Jack had hardly ever seen a ship before and certainly had never been in a boat of any sort! At 18 he volunteered for the navy.

His training began at Devonport Naval Base, then on to nearby Motuihe Island, Lyttelton, and Auckland.

While finishing training in Auckland the HMS Gambia arrived.

“It was only about 8500 tonnes, but it seemed enormous to me. I had joined the navy and I wanted to go to sea,” said Jack.

Fortunately for Jack, a telegraphist had taken ill, and Jack joined the ship which headed to join the British Pacific Fleet forming in Sydney. It was his first time on a ship. “I thought this was marvellous,” he recalls.

“Sailing into Sydney Harbour I couldn’t believe the sight.”

They headed to the Admiralty Islands where there was a huge American naval base on Manus Island and then joined the American fleet, south of Japan just before they attacked Okinawa.

The 82-day battle began on April 1st and continued until June 22nd, 1945. During that time, they never left the ship and supplies were delivered about every two weeks.

They were the fleet guides escorting their aircraft carriers. Their role was to suppress Japanese air activity. They were bombing the Japanese airfields that kamikaze pilots were using.

“Eventually the Americans took over Okinawa and we all moved up.

“On the 6th August we detached from the main fleet to bombard some airstrips on Formosa (Taiwan).

“That day they dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. We thought the war would be over, but it wasn’t.

“On the 15th August the Japanese surrendered. We were still just off the coast. I was on the bridge when I heard all this gunfire – but the war was over!

I went outside, and a kamikaze was coming straight at us from the stern, being chased by an American fighter who shot it."

The Japanese plane hit the water about 50 meters in front of us and blew up.

“I have often wondered if this one guy even knew the war was over, or was he determined to give his life to the Emperor?

“About a week later we sailed into Sagami Wan Bay near Tokyo Bay."

After the signing the Gambia was detached and sent to the inland sea south of Tokyo. There were Japanese prisoner of war (POW) camps there.

“We went to help to get POWs onto hospital ships and send telegrams back, giving the names of the blokes who were rescued.”

“We never learn, and you never forget it.”

Together Murray and Ann Evans spent a combined 28 years plus service with the Royal New Zealand Air Force and NZ Army.

Murray joined the RNZAF in January 1958, as a 16-year-old ‘Boy Entrant’, while wife Ann joined the Air Force in 1968. Eventually, their service brought them together while they were both at the RNZAF Station Te Rapa.

Murray says joining straight out of high school meant he really didn't know what hit him. After his 18 months of initial recruit training, he was posted for his first 12 months of service at Wigram, Christchurch.

Then he was transferred up to No 1 Stores Depot, Te Rapa in Hamilton, which held all the spare parts for the air force aircraft. “We were commonly known as grocers; our trade was equipment and supply,” he says.

Ann started her service in Wigram in Christchurch, having lived in Papakura in Auckland.

“A friend talked me into joining the air force, so I went in and joined and went down to Wigram in Christchurch for my recruit training, and then was transferred to ASDA (Aeronautical Supply Depot Auckland) in Hobsonville,” Ann says.

“They then transferred me down to Porirua in Wellington as the air force was operating a new computer mainframe system, which was bigger than our house. As a data processor, I operated the NCR33 accounting machine.”

In 1970, Murray was transferred to RNZAF Air Movements at Wellington Airport for four years. He was in charge of all military aircraft flying in and out of Wellington, which included RNZAF, Royal Australian Air Force, Royal Air Force or visiting Air Forces from around the world, including all VIP flights for military, New Zealand dignitaries, and overseas royalty

“The first two weeks I was there, one of our Bristol Freighter aircraft landed on its regular freight run,” Murray remembers.

“The freighter missed the turn off to the hangar, and was cleared to ‘backtrack’. Unfortunately, his main landing gear found a soft spot where recently new runway lights had been installed. This resulted in the airport being closed for a short while as the aircraft was ‘cleared’.”

In the early 70s Ann was transferred to Woodbourne, Blenheim, to manage the Machine Room for the NCR33 Accounting Machines. By this time, she’d been promoted to Sergeant and was also in charge of the air-women's barracks as well as the machine room.

To visit Murray the base aircraft used to fly from Blenheim over to Wellington frequently. If there was a space Ann would hop on to visit Murray in Wellington for the weekend.

“We were married in ‘74 and had two children, both of which now live in Australia,”

“I left the Air Force in 1971 and came over to Wellington and worked there until Murray finished his term at Air Movements. We were married in ‘74 and had two children, both of whom now live in Australia,” Ann says.

Murray remembers that in 1972 while at Air Movements Wellington, the air force was asked to help with a shipment of pedigree bulls that had arrived from France which had to go into quarantine on Somes Island in Wellington Harbour. The 3 Squadron Iroquois helicopters lifted about 50 bulls off the ship that they were on and put them on the island. This was called ‘Operation Bull Ship’.

Murray says in the mid 70s he was transferred to No 1 MAM’S (Mobile Air Movements); an operational logistics role as loadmaster support for the aircraft operating within NZ and overseas. These included Bristol Freighters, C130 Hercules, Douglas DC3s and Hawker Siddeley Andover aircraft and travel beckoned.

“We went to Australia, Kathmandu, Burma (now Mynamar), the UK, most of the Pacific Islands, Papua New Guinea, Hawaii, the Azores, Antarctica, Singapore, Bangladesh, India,” Murray says.

“Our team flew to assist (42 Squadron) whenever when they were away overseas on operational exercises. The main one being 75 Squadron Skyhawks to Singapore and Malaysia.

“The C130’s would fly with them to Singapore, and Malaysia with all the squadron support equipment, then about 6-8 weeks later we'd recover them back to NZ.”

Murray made two trips to Kathmandu in support of Sir Edmund Hillary and the school and hospital trust he set up there.

“There were also relief support flights following cyclone and earthquake events around the Pacific islands, which also included Cyclone Tracey in Darwin 1974,” he says.

“Our team played a big part with Operation Deep Freeze support for the United States Antarctic Research Program (USARP) and the New Zealand Antarctic Research Program (NZARP) in both Antarctica and Christchurch.”

Murray says he completed 22 years of RNZAF service finishing in 1979. “Six months later, I enlisted back into the NZ Army... and because I had just come off operational movements logistics support, they were interested in my experience,” he says.

I was transferred to Christchurch, which again saw me involved with Antarctic Support and various other roles.”

Following a 25-year service career, Murray took on a second career of 27 years in the oil and gas industry. He finally retired in 2010.

Photo courtesy of Murray and Ann Evans

Photo courtesy of Murray and Ann Evans

Ted Grace joined the army as a cadet in 1955. His chosen Corps was Armour. In 1957 he volunteered for a tour with 1 New Zealand regiment, an infantry battalion established to join 28 Commonwealth Brigade in operations against the Malaya Communist Party.

In Malaya Ted was posted to an infantry platoon, the main task of which was jungle patrolling.

“Patrols were difficult. The enemy at that time were at home in the jungle and we had to be very disciplined in our operations,” says Ted.

Patrols lasted from about 10 days to several weeks. Long patrols were resupplied by airdrop.

During a deep jungle patrol of six weeks Ted’s platoon came across a tiny village of Orang Asli, the indigenous people of the area. These folk have a history going back thousands of years. At times the platoon was able to provide security for them when they went hunting – with blowpipes and poisoned darts!

After 13 months in Malaya Ted returned to New Zealand, re-joined his Corps and was posted to various units around the country. He met and married Avon in 1965 and their son was born in 1969.

In late 1970 Ted was posted to 1 New Zealand Army Training Team in Vietnam. He and eleven other senior non-commissioned officers formed the training element of the Team.

In Vietnam the team underwent orientation training with the US Army. This covered US and enemy weapons, organisations and tactics and a “crash course” in the Vietnamese language.

After this the 12 New Zealanders were, in pairs, attached to 4-man US Army units who lived in Vietnamese hamlets and trained and operated with local troops.

“This attachment was particularly stressful. One simply did not know who the enemy was until the shooting started. Adding to the stress was witnessing the dreadful effect enemy attacks had on women and children,” says Ted.

Soon after arriving in Vietnam Ted had received a telegram to say Avon was expecting a “blessed event” which was Post Office telegram code for “I am pregnant.”

Their daughter was born while Ted was on tour, which was tough for Avon particularly as Ted was able to make only two phone calls in the entire 13 months he was away in Vietnam. No cell phones, PC’s or Zoom. Snail mail only!

When Ted returned to New Zealand, anti-war sentiment was prevalent in the country, and Vietnam men and women veterans were not welcomed home as previous war veterans had been. “That left a bitter, long-lasting effect on those who made the sacrifice.”

And Ted says, “There are no doubt many stories of valour amongst those wives, husbands and children left behind who also made the sacrifice, and survived.”

Peter grew up in a remote part of New Zealand called Cape Turnagain, Herbertville on the East Coast of the North Island.

He was born on the 4th April 1925 and celebrated his 21st birthday on his way to Japan in 1946.

“I signed up just before the end of the war. I was excited after the army training,” he said, “and I was old enough to join up for the occupation force in Japan.”

He sailed to Japan on the troopship, SS Empire Pride and was there as part of J-Force for about 18 months. “I was a Jeep driver for our commanding officer, so I got to drive all over different parts of Japan.”

There he witnessed the remains of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the atomic bombing and recalled it as, “just flat”.

Part of their job was peacekeeping but also to check for hidden stashes of munitions. Many Japanese people did not want to surrender and there was always the chance someone might retaliate.

It was such a different culture for someone who had never left New Zealand, but Peter picked up some of the language and can still count to 10 in Japanese!

“We made good friendships.”

On return to New Zealand, Peter attended a carpentry course offered by the army and completed an apprenticeship to become a builder. “I chose Masterton,” he said. He is a firm believer in the benefits and discipline of military training for young men and women today.

A keen musician, Peter bought a tenor saxophone for £25 while he was in Japan and he still plays it to this day. He belongs to a band called ‘Top Hat’ and he sometimes entertains the village residents.

Peter commemorates Anzac Day. He had two older brothers who went to World War II and he said it brings back a lot of memories.

Anzac Day has always been an easy day for Howard (Clem) Robinson to remember, not least because it is his birthday. Clem was born on 25th April 1938.

Clem’s father, also named Clem Robinson, fought in the trenches of France during the First World War, and while the Robinson family avoided fighting in the Second World War, Clem was called for national service when he was 18.

“I passed the medical, so there was no getting out of it,” Clem said.

“I can’t say that military life appealed to me all that much as an 18-year-old, it was not really my cup of tea, but I must admit, it prepared me for a lot of things later in life.”

Clem completed his national service training at Campbell Barracks in Swanbourne, in Perth, Western Australia, during the summer break between his undergraduate and postgraduate Biochemistry studies at the University of Western Australia.

“After that basic training I joined the Western Australia University Regiment of the Citizen’s Military Forces,” Clem said.

“I was in it for the next three years, which was good fun, we went on annual camps and I’ve got lots of happy memories of those.

“We were fortunate that we did several weeks of basic training at Kingston Barracks on Rottnest Island [those Barracks are now a holiday resort].

We spent a good few weeks there training jungle warfare in what were not jungle conditions.”

But there were also challenging aspects of the training, including using equipment already well-used in two world wars.

“In one exercise we had to run and stab our bayonets into a big bag full of straw and I thought ‘can I really imagine doing this to another human being?’

“That was not a happy moment.

“I thought this was pretty horrifying.”

In 1960 Clem was awarded a Hackett scholarship from the University of Western Australia which enabled him to undertake further study at the University of Oxford.

“I went off to England and that cut my military training short by a couple of months,” he said.

“But I was very lucky and privileged to also meet my wife Ida there (Oxford).

“Being there was certainly a world changing experience for me.”

His time in the national service and Citizen’s Military Forces was formative.

“Whether it be military, or some other form of national service, I think the training is probably beneficial for many young people, Clem said.

“It was certainly good for me.

“I look back on it now with some fondness.”

It’s been 57 years since since John Flynn resident Robert Creek, then 22-years-old, served in Vietnam as a member of 3 Troop 1 Field Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers (RAE).

When Robert flew to Vietnam on November 10, 1967, he had only been married to his wife, Kay, for weeks.

While flying over East Timor, he signed off a letter to Kay; ‘Miss you a lot’.

He would see Kay sooner than anticipated, but he would be a changed man.

Robert spent 3 ½ months in Vietnam, but it was the events of a few hours between February 17th-18th, 1968, that irreparably changed him.

The ‘Tet Offensive’ had been mounted, and 3 Troop was on overnight standing patrol of Fire Support Base Andersen on the north-easterly outskirts of Saigon.

“I had never been so heavily loaded with arms in my life,” Robert says

“I carried a hand grenade in each top breast pocket, seven magazines of twenty rounds of SLR bullets were clipped to my web belt, a continuous metal belt of machine gun rounds hung over my shoulder down to my thigh, a Claymore mine complete with detonators, wire leads, and a rifle made up my armament.”

But when fierce grenade and mortar attack was launched at 3 Troop’s position, Robert and his mates were unable to defend themselves.

“We weren’t able to fire a shot in reply, the circumstances didn’t permit it,” he said.

When dawn broke, four of the 10 men in the patrol had been killed.

“To this day the sight of my four deceased friends, just lying there, squashed one on top of the other in a dishevelled heap on two stretchers is as clear as it was then, and often brings tears to my eyes,” Robert says.

Robert was treated for shrapnel wounds to his left arm and right leg in Vietnam, before returning to Melbourne on March 14, 1978.

His physical wounds slowly healed, and he and Kay raised two daughters.

But in 2000, Robert had a nervous breakdown at work.

He was subsequently diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and has seen the same psychiatrist for the past 24 years.

While PTSD will always live with Robert, the unwavering support of his family has eased the severity.

In 2011, Robert fulfilled a promise made in 1968.

“I visited the graves of my deceased mates and said a silent prayer for them,” he says.

On Vietnam Veterans Day, 2013, Robert laid a wreath at The Long Tan Cross in Vietnam.

“A huge weight of anxiety and depression has been lifted from my shoulders since this day,” he says.

Jenny Hodges’ air force career – and her life - came close to ending just six weeks in.

Returning home to Whakatane after graduating from the short recruitment course in Woodbourne meant sailing aboard the doomed Wahine ferry, which sank in Wellington Harbour on 10 April 1968.

Jenny and her friend Carol were on an upper deck and were separated from the other air force girls.

“It was about seven hours from the Wahine hitting the Barrett Reef until the abandon ship call, so there was a lot of milling around muster stations.

“We ended up in rubber rafts and went over to Eastbourne.

“We walked along the shore, and some policemen and army guys met us and we were taken to the RSA at Eastbourne.”

It took her by surprise when three local Māori wardens turned up asking for her.

“My mum was a Māori warden in Edgecumbe and she got hold of the Māori wardens in Wellington. All of a sudden these three ladies arrived and said ‘are you alright? Good, we’ll tell your mum!’”

Jenny says despite only having six weeks’ of training, it proved to be ‘really helpful’ when assisting the ferry stewards in getting people over the side.

“There were a lot of older people on the boat who needed help and our training really stood us in good stead. We learnt to work together and help out when needed.”

Jenny puts her survival down to ‘luck and intuition’ and says she never suffered any after-effects.

“Arriving back at Woodbourne the reaction was ‘good to see you!’. I met up with six of the girls at the 50th reunion which was a great weekend.”

It was Jenny’s love of planes that made her join up but it was romantic love that led to her leaving when her new husband Kerry was posted to Singapore.

“I got called up to my boss. The posting had come through and it had changed from a single man to a married man and for me to go with him I would have to come out of the air force. Back then there had never been any serving airwomen on overseas postings.

“I said that’s not a problem. My son Nathan was born over there a year later so it was the start of something new anyway,” she says.

The new skills she learned as a radio tech assistant, the huge amount of sports she played and the strong friendships were the highlights of Jenny’s service, with a group of four couples still regularly catching up.

Now, Jenny is enjoying the air force connections at Keith Park Village in Hobsonville where she moved last year to be near her grandchildren.

Tongan-born and raised until the age of 12, John Santos was the only one of his 12 siblings to join the military, following instead his father Manoel Santos’s example by joining a NZ force.

But after seeing a pamphlet brought by a career advisor to St Paul’s Catholic School in Ponsonby which said ‘Join the Navy and see the world’ John opted to pursue his lifelong affinity with the sea rather than join the NZ Army like Manoel.

John was amongst the last intake on Motuihe Island for training in May 1963. The first shock on arrival was seeing his Elvis Presley-style haircut ‘shaved off to half an inch all round!’

He was told later that he was the first Tongan to be recruited in the NZ Navy, but he never felt there was anything special about that.

“There was a Samoan and Niuean matelot who joined before me. I was just another sailor trying to fit in,” he says.

In fact he was included with the Māori sailors, even wearing piupiu and performing in Māori concert parties.

His first draft was onto HMNZS Royalist, taking the Governor General Bernard Ferguson on an island cruise which included returning to his homeland of Tonga after seven years.

Despite a leave ban, an appeal for leave was granted when his bosses realized he was Tongan. An emotional 12 hours ashore followed, reuniting with cousins, aunties and uncles and even his beloved horse Tough Guy.

John certainly saw the world, with a highlight being sent by Hercules to England to pick up HMNZS Blackpool and bring it back via the Suez Canal.

Despite considerable experience of rough seas, nothing could prepare him for the recovery mission of MV Maranui whilst serving on HMNZS Lachlan.

The cargo ship’s load of wheat had shifted during a severe storm in June 1968 causing it to sink with nine of the 15 crewmen lost.

“We went back to Auckland to get fuel and supplies and when we returned to look for more bodies a couple of the new young sailors who had joined us never came back.”

John is incredibly proud of his eight years serving in the Navy and is an active member of the Navy Club.

“I loved the camaraderie, and the friends I made are still some of my closest friends today.

“I learnt new skills and ways of coping with the many challenges that I faced – which often meant sorting it out yourself!”

This followed into John’s subsequent career in freight first with NAC Freight and then Air New Zealand where he worked as a Loader and also as a Freight Liaison Officer on the DC8 freighter transporting livestock.

Anzac Day is a big day in John’s calendar and this year he will travel to Tonga with his wife Kate to commemorate it with his youngest brother.

Gisborne-born John Schollum and his two brothers were strongly encouraged by their father to enter the military after completing their schooling at Tolaga Bay and Mercury Bay district high schools.

John’s fascination with planes prompted him to pick the New Zealand Air Force and the ‘young, shy 16-year-old’ was soon assigned to a group of 20 fellow teenagers in a dormitory, or flight, at Boy School at Woodbourne who quickly became friends for life.

John faced another obstacle that his new friends decided to help him overcome – a stutter.

“This has been a lifelong challenge and to be a radio operator it was even more of a challenge.

“My chances of continuing in this role were looking very slim as I stuttered and stammered through the training classes, so the boys in my flight decided to thump me on the arm every time I stuttered.

“Some weeks I could hardly lift my arms as they were black and blue, however I gradually started to stutter less and less, and my confidence increased.”

After eight years as a telegraphist/ communications operator, John was successfully remustered to be an airborne communicator (AEop), spending several years on the Orion before moving to the Bristol Freighter.

“The Bristol was an old, slow lumbering aircraft still operating with a WW2 flight configuration of Pilot, Navigator and Signaller – while some referred to it as 50,000 rivets flying in a loose formation, I loved it!

“We went to all sorts of out of the way places throughout the Pacific and South East Asia. To fly to Singapore was a five-day experience.”

Five days after marrying his wife Wendy, John was posted to Singapore for ‘a two-year honeymoon’ and what became the highlight of his flying career.

Coming three months after the Vietnam War ended, his operations instead included Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Japan and South Korea.

A later role back in New Zealand was Ops Officer at Whenuapai Base Operations which involved liaising between squadrons, bases, air traffic control and the Met offices to arrange flights through local and international air spaces.

This proved invaluable experience in his next career move as Logistics Controller working in the joint air operations/crew control unit with Air New Zealand.

“The skills I learnt in the air force as well as gaining the confidence to get on and do stuff enabled me to go on and work at Air New Zealand and later in an area school in Northland assisting senior students to seek employment.”

John always attends Anzac Day services and in 2015 was extremely proud to march alongside his two brothers, one of whom was a Captain in the NZ Army and the other a Colonel in the Australian Army, leading the NZ contingent in the Brisbane Anzac parade.

While many associate the military with war and fighting, for Don Bennington, a 25-year career in the Royal New Zealand Air Force was an overwhelmingly life-affirming experience.

“I felt that we New Zealanders were not the aggressors and in fact most of my time in the service our time was spent preserving life, in search and rescue missions, assisting with hurricane relief in the Islands, and, during my time on the HMNZS Canterbury, to be available to rescue citizens off the beach in Fiji during Colonel Rabuka’s coup.”

Settling on the air force in 1965 as the ideal way to learn a trade Don started out at Wigram followed by Hobsonville for basic engineering training with an eye on becoming an aircraft technician. He worked on Vampire Jets, DC3s, Harvards, Devons, Briston Freighters, Orions, Iroquois and Wasps all around the South Pacific and Asia.

While a lot of his work involved search and rescue and emergency relief missions, his most hair-raising experience was in New Zealand, with a mayday landing after the Iroquois helicopter he was in suddenly stalled while flying over the Auckland Harbour Bridge!

“As we were coming down, we thought it would be best to land at Hobsonville, and we made it to the end of the airfield. As we hit the ground the ambulance and fire engine were on the scene, it was pretty dramatic!”

One highlight during his 2 and a 1/2 year posting in Singapore was being part of the crew flying over the South China Sea and being asked to search for the very latest Russian submarine passing underneath.

“Standing there in the flight deck and seeing the submarine passing under the nose just 200 feet below was a tremendous feeling, realising that had this not been peace time, this was what we were all about, searching and destroying submarines.”

He finished his air force days with two years serving on HMNZS Canterbury from 1985-87 and then as Warrant Officer at #1 Technical Training School before retiring in 1989.

Since retirement he has been an active member in the Warrant Officer and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers’ Mess, Hobsonville Old Boys’ Committee and a member of the 3 Squadron and 5 Squadron Associations.

Don is proud to have attended Anzac Day services every year since retiring from the RNZAF.

“For me it is very important. I remember my great uncles, Alex Bennington who was killed in Gallipoli and his brother Spencer Bennington who flew Sopwith Camels in Europe but luckily returned after the war, and also my father and his brother who served in the Islands in WWII and who both returned.

“It is also a time to remember my fellow airmen and women who have since passed.”

Frank was born in 1939 in Waipawa, Central Hawke's Bay and grew up in small town Ōtāne where his father had the general store, before moving to Napier when he was 12 years old.

It had always been Frank’s dream to be a pilot, but his father wasn’t keen, so Frank followed his wishes and joined the bank for 18 months.

But the dream didn’t fade and finally Frank got to join the RNZAF aged 18, training at Wigram for his pilot wings, then Ohakea for the engine conversion course and finally at Whenuapai on Bristol Freighters, graduating in 1959.

“I was involved in the Indonesia-Malaysian Confrontation outbreak on Borneo.” This was the same year New Zealand became involved in the Vietnam war.

“The Indonesians were inserting people in behind the borders and they, [the British] were worried they were trying to take over Borneo.”

This was what Frank had been trained for and he was happy to go overseas.

It was 1965 and he got engaged on a Friday.

“On the Monday the boss said to me, ‘I have a posting to Singapore in two weeks.’ I told him I had just got engaged and he asked me if I could get married in a fortnight! I got married and then left for Singapore for two years.

“I was based in Kuching. I would do two weeks there, then four weeks back in Singapore.

“It was peaceful doing sorties first thing in the morning flying Bristol Freighters with supplies to support the army on the ground. The Bristol Freighter can carry five tons. We used to be finished by 11am. It wasn’t a hardship.”

One aircraft was hit by machine gun fire after it accidentally crossed the border, but no crew were wounded.

“The confrontation was diplomatically resolved, and Indonesia backed down.”

Frank also flew to Korat in Thailand and was involved in the Vietnam war flying in supplies. “We were not posted there. We were there to support the Americans.

“In 1967 I returned to Wigram as an instructor for four years, then went to Ohakea Air Base flying DC3s on the VIP squadron.”

He travelled to many places including Nepal and Antarctica and in 1979 helped in the recovery after the Erebus disaster.

After 22 years Frank left the air force and joined Air NZ as a simulator instructor for 19 years, but the desire to fly was still strong.

Germany offered that opportunity and Frank trained on the Dornier 228

He spent 12 months in Papua New Guinea training pilots, then returned to Germany for three years doing simulator training on the newer Dornier 328

Frank’s extensive flying career has left him with many memories.

His eyes light up as he says, “I always wanted to fly. It was my boyhood dream that came true.”

Pam Lewis was born and bred in Gisborne and is very proud of it.

“I loved growing up in Gisborne.”

Pam chose not to continue with her secondary education as she was keen to earn money so she could buy her own clothes.

She started working at the Gisborne Herald. She stayed there for five years, until the war started and then she moved to Wellington for war work.

“We volunteered because we knew we were going to be called up anyway.”

Pam went to work for the Canadian owned Ford Munitions Factory in Lower Hutt, where there was a severe shortage of female labour to help fuel the war effort.

It was one of many workplaces now employing women in jobs traditionally held by men, to free them up to serve in the armed forces.

Buses collected them to take them to work from the purpose-built women’s hostel. “They were very good to us there. It was a huge factory and we worked much longer hours than I was used to.”

“One of my jobs was to put the fuses on to 25-pound shells,” explains Pam.

“Our work was regularly checked and if we did 10,000 and one was wrong, we had to do them all over again.