How colleges, businesses and people just like you are reducing waste page 19

MAY 2023 / ISSUE 168 / GRIDPHILLY.COM TOWARD A SUSTAINABLE PHILADELPHIA

■ The massive Atlantic sturgeon urgently needs EPA regulation p. 6 ■ Volunteer steward keeps Morris Park beautiful p. 8 ■ Saving birds from fatal window collisions p. 14

Your one-stop-shop for organic produce, local meat and dairy, grocery staples, specialty ingredients, supplements, and more! Visit one of our seven locations in the Greater Philadelphia area. kimbertonwholefoods.com COLLEGEVILLE | DOUGLASSVILLE | DOWNINGTOWN KIMBERTON | MALVERN | OTTSVILLE | WYOMISSING

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 1

EXPLORE Home to over 6,000 trees and 700 tree species, we invite you to visit our vibrant 265-acre arboretum year-round! laurelhillphl.com Bala Cynwyd | Philadelphia 610.668.9900

The Arboretum At Laurel Hill

publisher

Alex Mulcahy

managing editor

Bernard Brown

associate editor & distribution

Timothy Mulcahy

tim@gridphilly.com

copy editor

Sophia D. Merow

art director

Michael Wohlberg

writers

Bernard Brown

Elizabeth DeOrnellas

Nic Esposito

Constance Garcia-Barrio

Dawn Kane

Sophia D. Merow

Bryan Satalino

Ben Seal

photographers

Chris Baker Evens

Rachael Warriner

illustrators

Bryan Satalino

Helen Gym for Mayor

The venue for the Climate Mayorlal Forum presented by Green Philly couldn’t have been more fitting. The auditorium of the Academy of Natural Sciences, home to decades of research about dwindling biodiversity and exhibits of extinct animals, was sweltering. The heat on this early April evening served as yet another reminder of how the seasons have become unmoored as we continue to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, with precious little sign of slowing down. None of us — not least the next leader of a city of 1.6 million — can afford to ignore the imperative of climate change any longer.

So, where were the candidates? Only two of the serious contenders showed up: Helen Gym and Rebecca Rhynhart. We’re left to assume that addressing climate change is not a priority for the others.

Even prior to this event, Rhynhart and Gym had distanced themselves from the pack. Readers can look to our Mayoral Voters Guide for their thorough and well-considered answers to Grid’s questions about flooding in Eastwick, carbon-free transportation and sustainable development, among other topics.

Philadelphia faces a host of environmental challenges that demand action from City Hall, first among them the current and looming impacts of climate change. These include increased flooding and extreme heat, problems that promise to have a disproportionate impact on communities of color and neighborhoods whose residents can least afford to cope with them.

There are two viable candidates to consider, and while Grid firmly believes the City should adopt a ranked-choice voting option, there is a clear choice in this race. Helen Gym should be the next mayor of Philadelphia.

First, a few words about Rebecca Rhynhart, our second choice. As the City’s controller, she issued critiques of the police and the Rebuild program to name just two,

zeroing in on inefficiencies and injustices — with the data to back up her assessments. She has proven herself to be an ethical and methodical public servant who genuinely wants government to be transparent, and she promises more data-driven solutions to the deep-seated problems facing the city.

Helen Gym is our choice because of the philosophical underpinnings of her candidacy. When she forms her political positions, everything begins with the needs of the people. Gym’s commitment to public health, racial equity, climate justice — all of which lie on the pathway to community safety — is apparent in her stance on issue after issue.

Because of her consistent approach and sense of urgency, Gym is easily the most inspiring mayoral candidate.

Of course, inspiration alone is not enough. Her advocacy for public schools, an issue close to her heart, has yielded big wins, including shifting oversight of the School District of Philadelphia back to the City after years of state control. She drove City Council to create a landmark eviction diversion program that keeps the city’s most vulnerable renters in their homes.

Gym is undaunted by an initial lack of resources as she tackles big problems. As she said in the Grid #165 cover story about the successful drive to get lead out of public school drinking water, “when we are clear about our mission, we can go out and leverage resources to make it happen.”

Philadelphia faces big problems that are centuries in the making—poverty, racism and pollution, to name a few. Helen Gym understands the gravity and scope of these problems, and she has a bold and cohesive vision to propel us into the future. On May 16, vote for Helen Gym.

published by Red Flag Media 1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

alex mulcahy , Editor-in-Chief ILLUSTRATED PORTRAIT

2 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023

EDITOR’S NOTES by alex mulcahy

BY JAMES BOYLE

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 3 Parka Fridays? Not the best way for your business to save. PECO has energy answers. Saving money is easier than you think with advice that leads to comfort and energy savings all year long. Learn more ways to save at peco.com/waystosave. © PECO Energy Company, 2023. All rights reserved.

Sweet Smell of Success

Retiree forges a second career by following her nose

Like many retirees, Vicki Moody wanted to spend what she calls her “seasoned years” doing something that fused her professional experience with making a product which she’d be excited about devoting her precious autumn years. After Moody’s career with Drexel University as a budget coordinator, starting a business made sense. But when she thought about something that piqued her passions, it came down to one of our human senses — smell.

Moody had always felt strongly impacted by scents in her life and wanted to bring that passion of hers to others, going as far as announcing her plans even before she announced her retirement.

“I used to tell my coworkers,” Moody recounts, “that when I leave here I’m gonna make perfume or candles.”

Even though she had only a hobbyist’s interest in scented products, Moody used the skills in analytics she acquired as a budget

coordinator to research and develop a process for making scintillating scents. With confidence in her product and business plan, Moody launched By Vicki in 2017 as a product line of face creams, lip balms, beard balms and, most importantly, candles.

Candles By Vicki has an expansive variety of scents including red currant and ocean rose, which Moody boasts as her signature scent. When asked why, she explains that everything in her business is about a rose, something she gained from a longtime love of tending to the roses in her front yard.

As Moody was beginning her research, she was shocked by how many chemicals went into producing scents. But using her research skills and dedication to natural products, she has ensured that Candles By Vicki contain no carcinogens, mutagens, reproductive toxins, organ toxins or acute toxins.

With an integrity-fueled vision and great products, Moody started selling candles through her website. But at some point she

decided she needed to get into a store. She had heard about Weavers Way’s vendor diversity program from other product makers and decided to send a product basket to the program’s coordinator, Candy Bermea-Hasan.

As Bermea-Hasan later told Moody, when she opened the basket at her desk, the scent was enough to prompt other Weavers Way employees walking by to ask, “Where did those candles come from?”

That was enough positive feedback for Bermea-Hasan to call Moody and invite her to start selling at Weavers Way. And it was an added bonus that the candles used natural materials like soy wax, which fit right in with the Weavers Way clientele’s desire for natural products. And for Moody, it’s not just profits that come from the greater exposure of having her products in Weavers Way. She has also credited the experience with teaching her even more than what she could research on her own, from improving her product packaging to developing a better production rhythm so she can ensure that her supply keeps up with the demand.

Most “seasoned” citizens may consider their after-retirement enterprise as a way to make money while slowing down a bit, but not Moody. The success of Candles By Vicki has led to expansions in her other product lines, such as lip balm and beard balm. Moody talks about the future with the energetic optimism of someone half her 70 years.

“I’m going to keep it going until the wheels fall off.” ◆

4 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023

sponsored content

By Vicki candles provide rich aromas without the toxins.

The Weavers Way Vendor Diversity Initiative provides assistance, support and shelf space for makers and artisans who are people of color.

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 5 PLAN YOUR TRIP AT ISEPTAPHILLY.COM

Dinos of the Delaware

As

Atlantic sturgeon numbers dwindle, revised oxygen standards from the EPA could help by bernard

Everyone is invited to a baby shower taking place from June 22 to 23 at Independence Mall in Philadelphia. There’s no need to bring gifts. Just be ready to advocate for Atlantic sturgeon, which will be hatching right about then a mile to the east, in the Delaware River. The shower will be held by the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, Waterspirit, and Saddler’s Woods Conservation Association to raise awareness of the perils faced by the endangered Atlantic sturgeon and what we can do to keep the mighty fish from going extinct.

For a fish that can grow to 14 feet long and weigh 800 pounds, baby sturgeon don’t look

brown

like much when they hatch. You could mistake them for little tadpoles. They hang out in the estuary (where fresh water flowing from inland mixes with salt water from the ocean) for a few years, and when they head out to sea they look a lot more like their parents, with a long snout and rows of bony plates down their backs. “Looks more like the top of an alligator” than a fish, says Ian Park, an environmental scientist who studies sturgeon for the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Sturgeon fossils date back 70 million years (the dinosaurs went extinct about 65 million years ago), and their looks haven’t changed much.

6 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 water

Clockwise from bottom left: Wee sturgeon, growing up in the Delaware River, temporarily detained for research. (The capture and photography of the Atlantic Sturgeon was conducted pursuant to NMFS ESA Permit No. 24020.); Atlantic sturgeon can grow to 14 feet long and weigh 800 pounds; Sturgeon spawning in the Delaware are often killed when boats run into them.

And for millions of those years, the Delaware’s estuary has likely had sturgeon swimming in it. (The estuary is also home to short-nosed sturgeon, which are much smaller than Atlantic sturgeon, are more numerous, and generally stay out of the ocean.) The Atlantic sturgeon adults spend most of their time sucking fish, worms and other critters out of the mud on the ocean floor. They can live as long as a human. In the spring they head back into river estuaries from Canada to northern Florida to breed. They tend to come back to spawn in the rivers where they hatched, meaning that each river’s population is distinct from the others.

Hundreds of thousands of adult sturgeon once spawned in the Delaware River and had been sustainably fished up to the mid-1800s, including by indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Their population crashed in the late 1800s and early 1900s, however, as a caviar boom led commercial fishers to net and kill virtually all the breeding females. (The next time you see caviar, keep in mind that a large animal that would otherwise live for decades was killed so that someone could conspicuously consume an expensive appetizer.) Humanity hasn’t been doing the sturgeon any favors since then. Water pollution rendered the tidal Delaware nearly uninhabitable for fish for much of the 1900s. The shipping channel has been deepened to allow huge container ships to make it upriver, and that deeper channel brings more salty water into the estuary, shrinking the freshwater habitat sturgeon use to spawn. Ships of all sizes collide with sturgeon, killing them.

It is hard to catch and count adult sturgeon in a busy river, so Delaware scientists catch young sturgeon every year to get a sense of breeding success. “In a good year we catch more than 200. In a bad year we catch less than 10,” Park says. Researchers have used genetic samples from these and

other sturgeon caught in the river to infer how many parents produced the young ones. They estimate that no more than 250 adults remain

In November 2022 the Riverkeeper, the Clean Air Council, Environment New Jersey and PennFuture petitioned the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to set stricter standards for dissolved oxygen in the Delaware to help improve conditions for the young sturgeon, which live in the estuary until they are big enough to head out to sea. The organizations also launched a Dinos in the Delaware campaign to raise public awareness of the sturgeon’s plight.

Pollution from wastewater treatment plants and other sources can indirectly lead to lower oxygen levels. Nutrients in the wastewater essentially fertilize algae, which uses up oxygen when it eventually decays. The coalition of environmental organizations argued that the endangered fish need higher oxygen levels than what they find in the river today.

The EPA agreed. In December it issued a determination that revised oxygen standards are necessary. The groups are now waiting for the EPA to determine what the higher standard will be.

Sturgeon don’t just swim. They also have a habit of leaping out of the water, impressive for a fish weighing hundreds of pounds. Once a routine spring sight on the Delaware, the few sturgeon remaining still propel themselves out of the water. “You’re just running along in the boat and you see a six-foot fish jump out of the water,” Park says. “It’s pretty cool to see them. You know they’re there, hopefully spawning.”

The campaign to save the Delaware’s Atlantic sturgeons continues. At the baby shower, organizers will encourage people “to sign in support of strong action,” says Maya van Rossum, the Delaware Riverkeeper. The goal is to make sure that when the EPA sets the new standards, “they are the robust standards that are needed, that they don’t kowtow to industry and go soft.” The demands go beyond oxygen, van Rossum says. She pointed out the new port and export facility infrastructure. These “require dredging and will bring big ships in to strike and kill sturgeon,” van Rossum says. “The government keeps approving, approving and approving. The sturgeon are given little thought.” ◆

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 7 CLOCKWISE FROM BOTTOM LEFT: DELAWARE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL; MAURO ORLANDO VIA FLICKR; GARRETT TEMPLES

The government keeps approving, approving and approving. The sturgeon are given little thought.”

— maya van rossum, the Delaware Riverkeeper

A Healing Nature

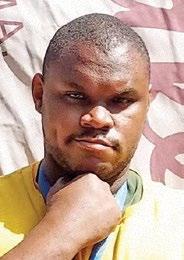

Volunteer steward Nicole Chandler continues to lead the charge to care for Morris Park by constance garcia-barrio

Nicole chandler has tended Overbrook’s Morris Park for so long that, when she talks, one imagines the scent of clean earth.

“The City had written the park out of its 2005 budget,” says Chandler, 53, who lives across the street from the 64-acre site. “They were … going to let it naturalize, which means let everything grow wild.”

Problems soon surfaced.

“There was an overgrowth of invasive plants,” Chandler says. “Trash was dumped. Dogs got ear mites because of the tall grass.”

Chandler took matters in hand by forming the Royal Gardens Association, a group

devoted to maintaining the park. She recruited neighbors to clean the park and got landscaping companies to mow the grass by letting them display signs advertising their services. Students from Penn State, Drexel, Penn and Villanova, eager to take part in service projects, helped too.

“I would always see Nicole in the park with other neighbors, clearing out trash and debris,” says Tamani Trower, a nurse who lives a few doors down from Chandler. “I was out there helping to plant trees and flowers, as my work schedule allowed. Nicole has a way of getting people involved. I also wanted to fight the stereotype that Black communities

don’t care about their surroundings.”

Chandler’s activism has roots in her childhood.

“We lived in Southwest Philadelphia,” she says. “Our father would have us practice karate with him in the park and walk everywhere. He’d have us close a [neighbor’s] gate if it was open,” says Chandler, who has a sister, Toya, and a brother, George Jr. “If there was trash, he’d have us pick it up. We didn’t just sweep in front of our house. We had to sweep the whole block.”

Morris Park’s green space swayed Chandler in choosing her present home.

“I love the park,” says Chandler, who was a SEPTA bus driver when she moved to Overbrook 26 years ago. Now she works in SEPTA’s Quality Control Department, ensuring that buses are in good repair and ready for service. “I would get off work, then spend two

8 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 PHOTOGRAPHY BY RACHAEL WARRINER

city healing

The park Nicole Chandler has stewarded for years serves as the classroom for her healing workshops.

or three hours tending the park.”

Chandler’s efforts earned her a 2021 profile on NBC10’s “Philly Proud” as well as the 2013 Keep America Beautiful Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson Award, the organization’s highest honor for volunteers.

“Nicole has empowered … [Philadelphians] to take pride in their community and clean and beautify Morris Park, part of the Fairmount Park System,” the award committee wrote. “Nicole continues to secure … in-kind donations and to forge partnerships with local businesses and global corporations to ensure [that] the work continues.”

While the park’s beauty delights Chandler, she also found that digging in dirt could help her release pain.

“My father was abusive,” she said. “I didn’t have a childhood. I got pregnant at 13 and had my son at 14. I struggled, but I kept my son and finished school. I’ve gone to therapy, and I also find that connecting with nature heals me. Nature doesn’t exist just for our pleasure, but also for the cleansing of our mental and emotional health. We must embrace that blessing.”

Research supports Chandler’s view.

“The term biophilia refers to the idea that we’re drawn to and benefit from nature,” says Anjan Chatterjee, MD, professor of

neurology, psychology and architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and director of the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics. “Nature is thought to have two effects on humans. First, our attention is opened up because we’re not so overwhelmed as we often are in urban or built environments,” Chatterjee says. “The second is that nature can be calming and help regulate our emotions. Our research suggests a slight modification to those ideas. We find that people are most drawn to nature with a slight … human imprint. For example, for most people gardens and parks are more restorative than … a dense jungle.”

Chandler built on that idea during the pandemic. She and volunteers had already created a serenity garden with flowers, benches and a Little Free Library. She started holding healing workshops there, emphasizing tuning in to nature’s organic guidance.

“Our Removing the Vines workshop focuses on the similarities between the effects of leaving vines wrapped around a tree and leaving a problem or trauma unresolved,” Chandler says. “The vine-covered tree can’t get nutrients it needs, and neither can we [with unresolved trauma].” During such workshops, Chandler encourages participants to journal about the trauma and to rip vines from trees to symbolize removing negative emotions from their lives.

“Everything that happens in our lives happens in nature, too,” Chandler stresses. “Say someone learns that a loved one has an incurable illness but struggles with accepting the situation. I might take that person to a diseased tree and explain that no matter what you do for that tree — give it water, light, nutrients — it’s going to die. Seeing the process in nature may help the person accept the situation. Nature gives us a different way to embrace events.”

Chandler’s workshops include about a dozen women of different ages and ethnicities. She begins by providing lunch.

“I don’t want people distracted by hunger,”

she says, “and having a meal together helps everyone get acquainted. It creates safety.”

After lunch, participants move to the serenity garden, taking with them chimes, drums and singing bowls for sound healing later. Chandler asks everyone to choose one concern to focus on.

“You can’t tackle everything at once,” she says.

Next, participants write in a journal Chandler has given them as a gift.

“I tell them, ‘No one is going to know what you write.’ That way, they’ll be able to express the truth of their feelings. You’re writing to release your feelings. Next comes observing something in nature or doing physical work, such as yanking vines off trees. Finally, participants sit and absorb healing sounds from the musical instruments. The three-hour sessions end with Chandler encouraging women to tap parts of their body with their fingertips, another energy-balancing technique.

“I took [the workshop] because I knew there would be a lot of women there,” says Fawziyya Heart, a musician. “That made it easier to be vulnerable. You hear people’s stories and realize that you’re not the only one struggling with something.”

Cynthia White, a SEPTA bus driver, felt drawn to Chandler’s eco-healing.

“I’ve known Nicole for five years,” White says. “When I learned that she favored natural remedies, it attracted me. I was dealing with [a] family [issue]. I was abandoned as a child. The meditation time in the park gave me a tool to go on.”

Besides the workshops, Chandler developed a serenity trail with signage to help people struggling during the pandemic. For example, one sign asks, “How does it feel when you enforce your boundaries?”

The pandemic led Chandler to new developments, but it hindered her work in Morris Park.

“We lost volunteers,” she says. “We lost partnerships of nonprofits. I’m rebuilding from the ground up. I need more volunteers.” ◆

Chandler will lead a workshop, “Pruning Your Life into a Healthy Shape,” Saturday, May 20, 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. The cost is on a sliding scale of $5 to $500. To learn more about the workshop or to volunteer, call (215) 768-9419 or email keeproyalgardensbeautiful@gmail com

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 9

Nature doesn’t exist just for our pleasure, but also for the cleansing of our mental and emotional health. We must embrace that blessing.” —nicole chandler

10 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 Private space, studio and office rentals are available at NextFab Rent your own dedicated space within NextFab’s shared makerspace workshop. Email sales@nextfab.com for more info. + Ideal for makers, manufacturers and small businesses + Makerspace membership included + Gain access to NextFab’s full suite of machines, tools, classes and shops (electronics, metalworking, CNC machining, 3D printing, woodworking, textiles, and jewelry) + Month-to-month rentals + Discounts available for for annual commitement

Crafted with incredible ingredients like our carbonnegative Biochar, Compost, Coco Coir, and Rice Hulls, our soils are earth-friendly to the core. From starting seeds to revitalizing houseplants to planting a raised bed, we have the perfect organic soil for you. This spring, let’s GROW LIKE A BOSS together!

Based

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 11 Our Mission is to assist people living with disabilities to learn, in a supportive environment, the necessary skills for meaningful employment and a fulfilling life. cosmicskills.org KIMBERTON.ORG 610.933.3635 EDUCATION THAT MATTERS The time-honored Waldorf framework paired with our thriving forest program preserves the most important elements of childhood and allows imagination and confidence to bloom. Discover the warm and magical setting of our two-year kindergarten program: GROW LIKE A BOSS™ with OrganicMechanicSoil.com Regenerative Organic Peat-Free

in Chester County, PA!

PUT A FISH ON IT

Angler artist shares love of wildlife through retro glassware

story by bernard brown

story by bernard brown

The biggest muskie that Eric Hinkley has landed in the Schuylkill was almost four feet long. Muskie (short for muskellunge) are possibly the most challenging (and awesome) game fish to catch in North America. The long and muscular ambush predators sit and wait for food to swim by, but their discriminating eye makes it hard to get them to bite on a lure.

“Even in my best seasons I’ve only caught five or six per year,” Hinkley says. An artist and avid angler, Hinkley estimates that he spends 30 hours casting for every muskie he reels in. Sometimes the fish will swim after a lure but decline to bite. “Muskies follow the lure a lot, and sometimes I consider that a success.”

Hinkley, who hails from Clarks Summit in Northeastern PA’s Lackawanna County,

grew up fishing and hunting. Even in the city he has found inspiration in the local fauna, as in his popular Wildlife of Philadelphia series of shirts, posters and tote bags. The designs feature a selection of Philly wildlife including opossum, raccoon and pigeon, as well as smaller household critters like a house centipede and long-legged cellar spider, arrayed in the style of mid–20th century educational posters.

“My original intent was to recreate some of those game commission posters, the poster you’d see on the wall in biology class,” he says. Hinkley sees the same species and their tracks on his hikes through Fairmount Park and the Wissahickon.

In the past year he has noticed more and more beaver sign (evidence of their activity such as chewed stumps). While Hinkley was fishing in the Schuylkill just above the Fair-

mount Dam, one of the industrious rodents followed his muskie lure as if to figure out whether it was a fellow beaver. “He came close enough to check it out and then turned right around and went back,” Hinkley says. Hinkley moved to Philadelphia in 2015, but he found himself spending more time in the Philly outdoors once he quit drinking five years ago, riding his bike from his Bella Vista neighborhood to the banks of the Schuylkill or the Wissahickon to hike and fish. Even if it takes him 30 hours to catch one of his beloved muskies, he considers the bike ride and the time spent along the water worth it. “It beats spending 30 hours in a bar, like I used to.”

Recently Hinkley has turned his focus to glassware adorned with wildlife such as white-tailed deer, eastern milk snakes and smallmouth bass, evoking “collect-themall” sets that fast food restaurants and gas stations used to issue. “The glasses are something I saw in vintage stores. There’s something satisfying about the tactile feel of the print on those glasses.” In an era in which every restaurant, bar and nonprofit organization sells T-shirts and tote bags that customers view as practically disposable, Hinkley hopes the glasses will have a longer lifespan. ◆

12 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

Artist Eric Hinkley casts into the Schuylkill River for the fish that inspire his work.

GET IT IN WRITING

South Philadelphia residents push for a legal agreement to govern Hilco’s refinery redevelopment

story by elizabeth d e ornellas

As the former Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery transforms into a 1,300-acre warehousing and life sciences hub termed the Bellwether District, South Philadelphia residents are pushing the developer to create a legal agreement to address their needs.

The past two years have seen little direct dialogue beyond virtual community meetings, but Hilco Redevelopment Partners announced on November 15 that formal negotiations will begin in January. Mia Fioravanti, vice president of corporate affairs for the Bellwether District, said the first order of business will be to elect a third-party facilitator and the goal is to sign a community benefits agreement (CBA) by early 2024.

“Now’s our chance to maybe get something back as they’re re-envisioning the site,” said Jessica Frye, president of the Girard Estate Neighbors Association. The association is one of nearly 20 neighborhood groups that established the United South /Southwest Coalition and worked to survey residents regarding their concerns and hopes.

Frye’s Girard Estate neighbors want green space added to the former refinery site and a plan for transportation links between the site and the neighborhood. They’d also like money to upgrade their library and make it more accessible for elderly residents.

Russell Zerbo of the Clean Air Council, which has offered advice to coalition members, explained that such a large and diverse group of residents must balance competing

economic and environmental priorities.

“One of the things that they’ve asked, or that they could ask Hilco for, is, you know, we want greening projects in our community. We want you to build a park. We want you to plant trees and do all these other things, and then those things … would be environmentally positive, but they could cause gentrification,” Zerbo says.

Frye said that concerns regarding gentrification were not prominent among her own neighborhood’s survey results but that the coalition’s overall survey results did contain frequent references to the issue.

Rabbi Julie Greenberg, climate justice director for the POWER interfaith advocacy group, has been supporting residents’ organizing efforts. Greenberg explained that a CBA could address gentrification concerns through investment projects that make it easier for residents to stay in their homes. For example, she said the agreement could include funds for weatherizing homes to lower energy bills.

While the United South/Southwest Coalition has been formally invited to participate in CBA negotiations, former coalition member Philly Thrive has chosen to take its advocacy in a different direction. On October 27, the group led a sit-in calling for the decommissioning of the oil tank farm located across the river from the former refinery site. Seven activists were arrested after hopping the fence into a restricted area.

Alexa Ross, a Philly Thrive organizer who was among those arrested, said, “It’s been way too long that Hilco has not made any progress that we want to see on really repairing the harm of 154 years of oil refining.”

Protesters demand oil facility be decommissioned.

A massive fire shut down the refinery in 2019.

Ross explained that advocating for an effective CBA remains a priority for Philly Thrive. She’d like to see two percent of the project’s $1.8 billion development budget — that would equal $36 million — go toward the agreement.

Zerbo confirmed that number would be in line with the standard set by other community benefits agreements.

Frye noted that Ross and her fellow activists played a crucial role in organizing the coalition and getting it ready to work on a CBA. Frye said, “We wouldn’t be where we are today without Philly Thrive.” ◆

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 13 PHOTO COURTESY OF LIZ DEORNELLAS

Now’s our chance to maybe get something back as they’re re-envisioning the site.”

jessica frye, Girard Estate Neighbors Association

A CLEAR DANGER

Early successes (and failures) stand out in the effort to reduce numbers of birds killed by windows

story by bernard brown

Without life to animate it, to hold it in a characteristic pose or to propel it through the air, a dead bird on the sidewalk can look like a rag or clump of dead leaves. But when I got a little closer to the mystery clump next to the Ciocca Subaru dealership in Gray’s Ferry, across from Stinger Park, it was clear that I was looking at a woodpecker. The mostly black and white bird sported a long, straight beak and bold, scarlet plumage on its throat and the top of its head. I rolled it over and revealed a pale yellow underside. I recognized it as a yellow-bellied sapsucker, so named because

it drills holes in tree bark and then drinks the sap that wells up. It was still warm. The bird died when it smacked into one of the windows above, which reflect the trees across the street in the park. Glass windows haven’t been around long enough for birds to evolve a recognition that what looks like a tree is sometimes an illusion. I found another sapsucker a few yards away at the edge of the street. The two joined the approximately 600 million birds per year that die in the United States by colliding with windows. (On the long list of ways humans kill birds, window collision ranks second only to house cats, which kill about 2.4 billion.)

The good news is that we know enough to keep birds like these from running into windows. The question is only whether building owners and architects are willing to implement the practices that will keep these birds alive.

Every spring billions of birds in the Northern Hemisphere fly north from their wintering grounds, which can be as far away as South America. Some will stay in our area, while many more will continue north to the vast forests of Canada and New England. In the fall they reverse their trip.

Virtually all of them spend most of their lives in places without many people, buildings or windows. Songbirds generally fly by night, when they navigate in part by the light of the stars and the moon. The glow of cities can draw them in like moths to a

14 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 PHOTOS COURTESY OF BIRD SAFE PHILLY

This common yellowthroat warbler did not survive its stop in Philadelphia after colliding with a window at the National Constitution Center. Opposite: Bird Safe Philly volunteer Stephanie Egger drops off window collision victims at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

porch light, making them more likely to end up in urban or suburban areas when day breaks, where they face window glass, house cats and other unfamiliar hazards. Particularly bright buildings can utterly confuse them, causing them to fly in circles until they fall to the ground, exhausted.

On October 2, 2020 low cloud cover and a busy night for songbird migration combined to create a massacre in Center City. Stephen Maciejewski, who volunteers collecting data on bird-window collisions, found hundreds of dead birds on his route through the urban canyons. As many as 1,500 birds may have died in total. The event caught the attention of mainstream news media, and it sparked a collaboration among conservation organizations and building owners and managers to try to reduce the carnage. The

group, Bird Safe Philly, settled on a simple first request: that building managers turn down their lights on nights during the heart of migration season. In the migration seasons since, volunteer monitors have walked routes through Center City and Old City collecting dead birds and relaying injured birds to wildlife rehabilitation clinics.

Spring 2023 marks the third year of Bird Safe Philly, and the Academy of Natural Sciences has released numbers that tentatively show at least one potential victory, a 70% decrease in dead birds collected at one monitored building, the atrium of the BNY Mellon Center. Annual bird collision numbers can vary, so it will take more years of monitoring to confirm the results, but this is a hopeful sign that turning the lights down helps. “Everyone wants to pat ourselves on the back, but with science you have to do it for a few years,” Maciejewski says.

Of course the lights at night are only one variable in the lethal equation for migrating birds. “Lights out is good when you have skyscrapers with a lot of lights,” Maciejewski says. “If you turn the lights off, then birds might still crash, but you won’t have a mass kill.”

Through the glass facade of the Comcast Technology Center, humans and birds can see ficus trees inside the lobby. “They’ve turned the lights down dramatically,” Maciejewski says. “It looked like a beacon, and many birds crashed into it, and now that’s dropped off.” Grid reached out to Comcast to see if the company had plans to reduce collisions further by making the glass visible to birds. The company’s response noted the lighting changes but did not mention any plans to make the glass more visible.

Large windows are particularly lethal when they reflect greenery, as is commonly the case near parks. In the fall of 2022 a

friend of Maciejewski alerted him to dead birds on the sidewalk along the Ciocca Subaru dealership across from Stinger Park. He followed up and found five in one visit, including a golden-crowned kinglet and a white-throated sparrow.

“You can tell at the Constitution Center where the bird hit based on where you find it. The second floor overhangs the first floor, so the ones that hit the first are underneath. The second floor, they sort of bounce off,” says Stephanie Egger, a biologist who has volunteered for two years as a collision monitor around Independence National Historical Park and as a driver for injured birds. She also coordinates other volunteers who monitor around the park. During migrations she walks her route five times in a morning shift lasting from 5:30 to 8:00.

Amid all the birds she has collected, some stand out. “I think it was the first season I was monitoring, we had a scarlet tanager at the Constitution Center,” Egger says. “It was so bright and beautiful, and I thought, ‘What a waste.’ These birds are doing what they need to do: migrating, resting, having a stopover. They try to leave, and they end up dying for some reason that’s so preventable.”

Bird Safe Philly volunteers found that the Sister Cities Café, a low glass building in Sister Cities Park near Logan Circle, killed as many birds as some skyscrapers. Architect Jamie Unkefer, partner at DIGSAU, worked on designing the building in the early 2010s. “We had this idea of a very transparent landscape-integrated building, and the glass was a way to give an illusion of being in the park,” Unkefer says. “We didn’t appreciate at the time that birds were flying around down there like that.”

Even smaller glass features that reflect or sit in front of greenery, like bus shelters and glass railings, such as at the Philadelphia

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 15

I think it was the first season I was monitoring, we had a scarlet tanager at the Constitution Center. It was so bright and beautiful, and I thought, ‘What a waste.’”

— stephanie egger, Bird Safe Philly volunteer

Museum of Art’s sculpture garden, can also pose a hazard.

Luckily windows can be made much safer for birds by making them visible. Research by ornithologists, much of it done by Daniel Klem at Muhlenberg University, has demonstrated that birds will mostly avoid flying through a tight pattern leaving spaces no more than two inches vertically and four horizontally. The pattern can be stuck onto the outside of the glass, or it can be built in with opaque coatings baked onto the glass (fritted) or patterns etched into it.

Unkefer attributes his current understanding of bird-window collisions to his firm’s work on the Discovery Center at the East Park Reservoir, managed by Audubon Mid-Atlantic and Outward Bound. The building, which opened in 2018, is a showcase of bird-friendly windows. “Working with experts like Keith Russell [a local Audubon ornithologist] introduced it as a more expansive topic. It’s been a slow evolution that really came to its full realization through the Discovery Center.”

Egger helped apply window films at Briar Bush Nature Center’s bird observatory building, which had large windows facing bird feeders. Egger has also started working with her daughter’s elementary school, Springside Chestnut Hill, to add a pattern to windows at the school that face the greenery of the Wissahickon.

According to Chloe Cerwinka, landscape planner at the University of Pennsylvania, the Bird-Friendly Penn initiative has guided the university to design new buildings with bird-friendly glass and to retrofit others. Joe Durrance, who has monitored bird-window

collisions on campus since 2013, found concentrations of dead birds below both a glass walkway at the veterinary school and windows of the medical school’s Johnson Pavilion. Patterned window films applied in 2015 and 2016 cut bird deaths dramatically. At the veterinary school’s walkway, 11 dead birds were found in the spring before the retrofitting. Only one was found in the fall following the work.

In Franklin Square the new PATCO station entrance will feature bird-safe glass. “PATCO explored the possibility of bird collisions during the project’s design phase,”

16 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023

I feel like a war correspondent. I can’t stop the war, but I can document the casualties and hopefully enlist more people to stop it.”

— stephen maciejewski, Bird Safe Philly volunteer

Volunteers Stephanie Egger and Ben Laws save some lives by making windows visible to birds at the Briar Bush Nature Center’s bird observatory in Abington, Montgomery County. PHOTO COURTESY OF BIRD SAFE PHILLY

says PATCO spokesperson Mike Williams. “As a result, a fritted pattern on the glass was incorporated into building specifications.”

According to Center City District spokesperson JoAnn Loviglio, “Center City District will be partnering with Bird Safe Philly on a ‘feather friendly design’ for the Sister Cities Park Café.”

Eric Narodovich, general manager at Ciocca Subaru, says the dealership is “actively working on trying to find a solution. We’re probably more at the information stage, trying to figure out what’s causing it, what are solutions.”

The National Constitution Center and the Philadelphia Museum of Art did not reply to Grid’s requests for comment about their windows and glass railings.

Although buildings that kill large numbers of birds draw media attention, most birds killed by windows die in residential neighborhoods. One house’s windows might only kill a couple birds per year, but there are a lot of house windows in North America. Egger ended up adding a pattern to the windows of her home in Manayunk. “I feed birds, and my partner said a downy woodpecker bounced off the window. I said, ‘What?’ and did my own house.”

Bird Safe Philly is still in its early stages, and Maciejewski sees preventing birdwindow collisions as a campaign that will take decades to be successful. “I think of what we accomplished with lead paint or cigarette smoking,” he says. He says he hopes more people sign up as volunteers. “I feel like a war correspondent. I can’t stop the war, but I can document the casualties and hopefully enlist more people to stop it.”

New York City Council passed legislation to require bird-friendly glass citywide, but until Philadelphia passes something similar, Unkefer sees a role for architects in keeping birds from flying into windows by raising the issue with clients. “We do it with life safety issues all the time. We say, ‘People are going to fall off this ledge. We need a railing.’ We could say, ‘Birds are going to fly into this and die. We should do something to mitigate it.’” ◆

bird safe philly is looking for more volunteers to monitor buildings for birds that have flown into windows and to drive injured birds to wildlife rehabilitation clinics. Email birdsafephilly@gmail.com to get involved.

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 17

PA

Interference with pedalcycles. No turn by a driver of a motor vehicle shall interfere with a pedalcycle proceeding straight while operating in accordance with Chapter 35 (relating to special vehicles and pedestrians).

Motor Vehicle Code § 3331(e)

MEDICAL BILLS BIKE DAMAGE LOST WAGES FOR YOUR INJURIES

18 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 ... NeedsYou! Support local journalism by subscribing or donating Pay what you can on PayPal or in our store

Sitting by the front door at my house are a couple bags of old toys. The next time one of us plans to be near the Goodwill, we’ll drop them off. A few weeks ago I bought our oldest (11) a new/used bike from Neighborhood Bike Works and dropped off two outgrown ones that had been taking up space on our wall. She is growing like curly dock, and she just filled a trash bag with what she’s outgrown. It’s still sitting in the hallway upstairs, waiting to be reviewed by my wife, who handles the stream of hand-me-downs that flows into our house from kids of friends and relatives and right back out in a couple years. Although we

BUY: REUSE:

think of spring as the time to clean and declutter, the process of getting new stuff and unloading the old never seems to end.

Everything we produce comes with an environmental impact we can measure in greenhouse gases, chemical spills, trees cut down and ore mined from the Earth. I am sure that somewhere in my house we’ve got clear plastic produced by the Bristol plant whose spill sparked a tap water panic in Philadelphia at the end of March. The same goes for goods carried by the ships that strike whales and Atlantic sturgeon. Anything we reuse is something we don’t have to produce.

In this special section we dive into the

stuff we get rid of and what it can be used for. We explore the lifecycle of a tee shirt. A hauler talks about what she does with the piles of stuff she drags out of customers’ basements. Colleges do their best to manage the heaps of belongings that college students leave behind in the spring, and groups take advantage of social media to connect people getting rid of furniture and other items with people who need them.

We hope you find inspiration and make the most of your own decluttering. Industry might run on planned obsolescence, endless production and runaway consumer spending, but we don’t have to play along. –>

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 19

MAN’S TREASURE

Gift economies keep goods in communities and out of the landfill

story by sophia d. merow

My boomer dad doesn’t do social media. So when he wanted to unload a decades-old desk ill-suited to his new condo, he went old school: He posted a flier on the bulletin board at MOM’s Organic Market in Bryn Mawr. “Free to a good home: pine desk in good condition.” He included the desk’s dimensions, a photo and his contact information. Crickets.

Eventually my dad’s eagerness to move the inventory overrode his distaste for all things cyber, and he took me up on my previously spurned offer to post the desk online.

Philadelphians itching to shed excess stuff have no shortage of options, even if they lack the time or hauling power to schlep to Goodwill, The Salvation Army or Philly AIDS Thrift. Too many options, for some tastes.

“I love exchanging goods without any

money involved,” wrote Mount Airy resident Nelson Chu Pavlosky on decentralized social media platform Mastodon in January. But there are so many “competing websites/apps/communities” in the region, he lamented, that “if you want to see all of the free stuff that’s available, you need to check them all, regularly. If you want to maximize the number of people who see the stuff you’re giving away, I guess you have to post on all of them.”

20 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 PHOTO COURTESY OF SOPHIA

D. MEROW

BUY NOTHING

With this preamble, Pavlosky polled his audience on the relative merits of four facilitators of moneyless exchange, but that’s just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. Hyperlocal social networking service Nextdoor has a “for sale & free” section. There’s a “free” subcategory within the “for sale” category on classified advertisement website Craigslist. At Freecycle.org one can join “10,568,815 members across the globe” in a “grassroots and entirely nonprofit movement of people who are giving (and getting) stuff for free in their own towns and thus keeping good stuff out of landfills.”

And then there are the Facebook-based groups. Those with “Buy Nothing” in their names are neighborhood affiliates of the Buy Nothing Project (BNP), a global conglomeration of community-based groups founded in 2013 with the aim of growing local gift economies. Groups that have broken away from Buy Nothing in reaction to perceived power plays by BNP’s founders bear names like “Community Gifting” and “Free Your Stuff.” Special-interest groups also abound: Frugal Fishtown Kids, for instance, is “a place for local Fishtown-area families to buy/sell/share new or gently used baby, kid and maternity items.”

Motivations for participating in the gift economy vary almost as widely as ways to do so.

For Adam Eyring, co-moderator of NW Philly Freecycle, the impetus was a desire to combat the too-much-trash problem. “I get frustrated with the amount of waste

going out,” he says. “So I joined Freecycle because I believed in the goal of it, which is to minimize landfill waste, to get people to exchange goods.”

Frugal Fishtown Kids admin Clare Dych cites the need to efficiently free up space often at a premium in Philadelphia residences. “We all live in rowhomes,” she explains, “and we’re all eager to get these, I call them LPOs — large plastic objects — out of our houses as quickly as possible once our kids don’t need them anymore.”

Decluttering and waste reduction feel even better, of course, when others in the community benefit. When Eyring’s cathode-ray tube television no longer met his entertainment needs — “it couldn’t handle some of the dig-

What brings tears to Dych’s eyes, though, is seeing groups like Frugal Fishtown Kids or Fishtown Mamas, a Facebook group she previously administered, spring into action in times of critical need. If someone unexpectedly gets custody of a grandchild, say, they might require diapers, a bassinet, a baby monitor — immediately and out of the blue. “It is really, really incredible,” Dych says, “to witness that when somebody is in a crisis that they can post within the community and say, ‘I’m really struggling a bit. Can you help?’ and everybody just rushes in.”

Gift economy regulars like Dych often credit their platform(s) of choice with forging a not-insubstantial fraction of their social connections. At a gathering of moms at

ital stuff” — a few years ago, he posted it on Freecycle, where someone claimed it for a homebound couple with health issues. “They didn’t need anything fancy. They didn’t need cable,” Eyring remembers. “And they were happy. So I was happy that they got something that works for them.”

For Dych, reminiscing about community gifting elicits warm fuzzies, happy tears, pride in her neighborhood’s solidarity. Her family gave the Barbie Dreamhouse they’d outgrown to a neighbor, who sent a video of her son “absolutely in heaven” setting up and playing with the new-to-him toy. “It’s just such a lovely feeling to get a video back of a kid being like over the moon,” Dych says.

Dych’s house last fall, a relative newcomer to the neighborhood asked Dych how she knew everyone. “Repeated small interactions over time for the most part,” she replied. “Every little interaction and touch kind of builds over time,” she explains, “and you really get to know people.”

“There’s so many people in my neighborhood that I know through Buy Nothing,” echoes South Philly textile artist Julie Woodard, “through swapping something with them.”

Another variant of internet-aided rehoming of unwanted possessions — stooping — presents fewer opportunities for forming friendships, but it does reduce landfill

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 21 REUSE EVERYTHING

The author helped her father find a new home for his storied desk through the online gifting community.

If you’ve ever plucked something out of someone’s trash and made off with it, you yourself have stooped.

influx and afford the thrill of the thrifting chase, the serendipitous find. Stooping need not involve social media or even the internet — if you’ve ever plucked something out of someone’s trash and made off with it, you yourself have stooped — but the Instagram account StoopingPHL increases the likelihood of castoffs getting into new hands before the trashman cometh. Philadelphians who “spot something free on the streets” direct-message a photo and location to StoopingPHL, and manager Tanya Mayeux tips off the account’s almost 7,000 followers: There’s a coat rack at Salter and South 2nd streets; a “small computer desk, tan leather couch, and fully functional 1970s organ” at 1705 Manton Street; a “stunning couch!” on Brown between 16th and 17th.

An avid stooper long before she took over management of StoopingPHL last summer, Mayeux says that much of the decor and furniture complimented by visitors in her Graduate Hospital apartment she snagged from a neighbor’s discard pile. She often refinishes or otherwise spruces up items she adopts and is cognizant of the potential sometimes disguised beneath a patina of wear, of her fellow stoopers’ ability to discern a future even for the seemingly played out. Seldom does Mayeux deem a submission to StoopingPHL unworthy of posting. “You never know what people are looking for,” she says. “So I try to keep an open mind about that.”

The old saw “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure” inevitably arises in accounts of Buy Nothing and its ilk, and for good reason. Perhaps it’s only stoopers who snatch diamonds in the rough from beneath trash collectors’ very noses, but all of the groups and tools under the gift economy umbrella accomplish the repurposing of items that would otherwise have been classed as rubbish.

One need not peruse community gifting listings for long before coming across offers of foodstuffs sampled but disliked, personal care products not to the purchaser’s taste: a bottle of keratin leave-in conditioner “about 90% full,” an open bag of strawberry-flavored electrolyte drink mix with “15 packets remaining.” “If you buy something in bulk for your kid,” jokes Dych, “the odds of them deciding they don’t like it the next day skyrocket. My kid hates these pouches and I have like 20 of them. What do I do with them?”

Community gifting to the rescue.

Once textile artist Woodard’s talent for

creative reuse — she transforms used and deadstock fabric into nature-inspired art — became known across the giveaway groups in and around her Point Breeze neighborhood, bags of scraps started appearing on her doorstep.

“I was getting people who had damaged textiles that weren’t in good enough condition to donate,” Woodard recalls. “People have ripped jeans, hole-filled sweaters, or they ask, ‘My dog partially chewed this pillowcase. Can you use it?’”

Even as she repurposes material most would regard as beyond salvage, Woodard has gifted neighbors some pretty big-ticket items: a spare Vitamix, for instance, and a brand new Instant Pot. When listing some-

thing sure-to-be popular on more than one group, Woodard will usually include a “cross-posted” notification so claimants don’t assume that just because they were first to express interest they’ll score the loot. How donors choose recipients on these platforms is up to them. “Some people say ‘first to respond,’ ‘first who is able to pick up,’” observes Woodard. “Others really want to hear a story of what you would use this for.”

“I am put off by the bluntness of people who sound greedy when they just say, ‘I’ll take this!’ or ‘When can I pick this up?’ instead of using some gratitude,” says Betsy Teutsch, a moderator of the Facebook-based Community Gifting West Mt. Airy. “We do try to model mutual appreciation.”

22 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023

BUY NOTHING

Mayeux says that much of the decor and furniture complimented by visitors in her Graduate Hospital apartment she snagged from a neighbor’s discard pile.

Ungrateful beneficiaries aren’t the only gift-economy frustration, of course. There’s the aforementioned drama between the Buy Nothing parent organization and individual groups resentful of attempts at top-down control. There’s the occasional scam whereby bad actors try to con a Freecycler out of money — by requesting an up-front delivery fee, say — or use a platform to harvest email addresses. Then there’s perhaps the most common scourge: the no-shows. “People tend to flake on pickups,” says Marlena Masitto, owner of Philly Neat Freaks

As a professional organizer, Masitto has mixed feelings about community gifting groups. She shudders to think of should-be-jettisoned possessions piling up — or being “pulled back into circulation” — if listings fail to spark joy in neighbors. “If you’ve had something posted, say, for a week and it hasn’t been picked up,” Masitto advises, “swing the items past your local donation spot and move along.”

For those keen to keep things local or hoping to exchange some in-person pleasantries

with their goods, swaps are a viable alternative. Northern Liberties’ Ray’s Reusables hosts clothing swaps, as does Narberth’s SHIFT. The third annual Plus Size Clothing Swap of Greater Philadelphia will take place at Philly Fatcon in October. On the last Saturday of every month, “anything that can be carried” — from outdoor gear, appliances and plants to pet supplies, non-perishable food and books — can be dropped off at the Really Really Free Market — “promoting a gift economy through mutual aid” — in West Philly’s Malcolm X Park.

That Philadelphia is a walkable “city of neighborhoods” makes it particularly well suited to the recirculation of goods within communities, says StoopingPHL’s Mayeux. “I’ve definitely hauled home a bench or side table,” she laughs, adding that, as a New Yorker, if she saw something desirable on the curb, it would often be impracticable to get it home via a long, public-transit-dependent commute.

“I can walk things to most people’s houses if they opt for something I’ve offered,”

says Teutsch, “or pick up on foot. It makes it even greener!”

The gift economy, then, has much to recommend it: it reduces waste, builds community, helps neighbors in need, saves participants money, curtails consumer capitalism

It can even encourage exercise.

“Get out there and get your steps in,” urges Mayeux, “and get some free stuff.”

My dad has neither started stooping nor joined Freecycle — “great if you do not want to deal with Facebook,” notes Eyring — but he does concede that my newfangled way of publicizing the availability of his desk produced a more-than-satisfactory outcome. My Craigslist post — 10 miles separate my dad and me, so neighborhood-specific groups were out — caught the eye of an up-andcoming novelist. When she arrived at my dad’s condo to collect the desk, they discovered a shared fondness for dogs and familiarity with Ithaca, New York. She gave my dad a copy of her first book. He likes to think that her second — due out in August — was written at what was once his desk. ◆

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 23 REUSE EVERYTHING PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

Tanya Mayeux has furnished her home with treasures left on Philly stoops.

THE THINGS THEY LEAVE BEHIND

Universities and neighbors contend with mountains of belongings discarded by departing students

story by ben seal

For residents of West Philadelphia, spring is a season for the senses. As trees and flowers break into full bloom, some of the city’s greenest neighborhoods reach their most beautiful state. The air feels fresh, the sun seems brighter than ever, and the community is rejuvenated.

But there’s an unwelcome companion that also emerges at the beginning of May, an annual tradition that stifles some of that spring spirit: the mountains of trash piling up on the sidewalks as college students head home for the summer.

“Year after year, the students just leave their stuff on the curb and go,” Vicki Mc-

Garvey, a member of the board of directors for the Spruce Hill Community Association, says.

With the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University and Saint Joseph’s University campuses all located in the same general vicinity, thousands of students will pack up their belongings this May, leaving

24 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 PHOTO COURTESY OF PENN SUSTAINABILITY

BUY NOTHING

Students moving out at the University of Pennsylvania drop off belongings that they can’t take with them.

behind a mess of household trash, food waste, furniture and clothing. Much of it remains useful and could be given a second life rather than heading to a landfill, but it requires a concerted effort from the universities and buy-in from the student body to make it happen.

“It’s frustrating to see that students don’t see the value in making sure something gets a good home or gets reused,” McGarvey says. “It feels a little contrary to the students being all about sustainability and caring about the environment when they just dump their crap and go. It’s disheartening.”

The same problem is present in North Philadelphia, where Temple University’s move-out has for years left neighbors navigating heaps of trash — some bagged, some not — often left out for days before it’s picked up by the City’s sanitation workers. As universities juggle the dual responsibility of ensuring both on- and off-campus students move out sustainably and respectfully, those renting apartments in the surrounding neighborhoods pose the biggest challenge.

Chris Carey, senior associate dean of students at Temple, says the university does its best to provide education and resources for students, many of whom are moving out of rentals for the first time. That includes offering free mattress disposal bags and encouraging students to donate items to Uhuru Furniture, GreenDrop and the Cherry Pantry, which works to fight hunger in the Temple community.

The school also employs off-campus dumpsters and for the first time this year will enable students to schedule trash pickup for larger items, following a particularly contentious process last year that left neighbors frustrated.

“We will be encouraging students to start early and create a plan with roommates so that they do not leave the community with headaches after moving,” Carey says.

At Penn, which collected about 130,000 pounds of donated goods during its 2019 move-out — the last before the pandemic significantly altered plans — the Office of Social Equity and Community is working to improve the relationship between students and neighbors. The office opened in 2020, and this year its director, Scott Filkin, collaborated with McGarvey on a community survey that received about 150 responses, helping Penn to better understand its neighbors’ most pressing concerns.

“One thing that is really important to people in the neighborhood is that the resources stay in the neighborhood,” McGarvey says. “People feel really strongly like if we have to deal with this, we don’t want this stuff just sent away for other people to benefit from.”

West Philly has a history of resourceful practices, including “Freecycling,” curb alerts and Buy Nothing groups, McGarvey says, so when spring rolls around, neighbors know they can expect to see everything from lamps and televisions to unworn clothing out on the curb. But the haphazard, unstructured approach to their disposal prevents many items from being rescued, and putting the onus on the community only perpetuates the ways that universities impose on their neighbors.

“It would be such a benefit to the student experience if they learned what it meant to

For its part, the Streets Department partners with universities to collect excess trash and divert as much as possible away from waste streams, spokesperson Keisha McCartySkelton says. Temple and Drexel have developed waste-reduction programs, “and we are looking forward to seeing the impact these will have in conjunction with our own efforts,” she says.

Minimizing waste — and ensuring it doesn’t end up spread over city streets — is a challenge that universities are still working to overcome. Keeping useful items from heading toward a landfill is a “heavy lift,” Filkin says.

Penn previously used its ice rink as a central gathering place for the redistribution of used goods, but in the wake of the pandemic, Penn and other universities are working to re-establish healthy move-out traditions. At St. Joe’s, for example, relationships with

be a good neighbor — to live as neighbors rather than have one body committed and one body transient,” Filkin says.

On campus, Penn offers containers for students to donate useful items that are shared with Goodwill centers in Philadelphia and New Jersey. The university even brings in a tractor trailer for students in its high-rises to donate large items. Some donations are also passed on to financially constrained students each fall as a starter pack for their college experience, Barbara Lea-Kruger, a Penn spokesperson, says.

Winter clothes are among the most common goods left behind by international students traveling home to warmer destinations. In the past, refrigerators and microwaves comprised a significant portion of the moveout madness, but Penn began installing them in many rooms on campus, cutting back on the chaos in spring. Last year, the university collected about 36,000 pounds of donated items, a decline largely caused by removing those appliances from the equation.

Philabundance, Books Through Bars and Goodwill

were all disrupted by the pandemic. The university now partners primarily with HawkHUB, a campus resource center, to steer nonperishable food and basic care items to anyone in its community experiencing need, according to Max Shirey, assistant director of residence life. St. Joe’s is aiming to rebuild those relationships going forward to make the most of the move-out process.

Across the city this May, universities will take the next crack at what Penn sustainability director Nina Morris calls an “iterative process” — teaching students about their role, learning from neighbors about their needs and working to ensure everyone can enjoy everything spring has to offer, without the side effects.

“We really can’t do this alone,” Morris says. “Students, Penn and other higher education institutions, neighbors, property managers and the City all have a responsibility and an opportunity to make this a better experience for everyone.”

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 25 REUSE EVERYTHING

◆

It’s frustrating to see that students don’t see the value in making sure something gets a good home or gets reused.”

— vicki m c garvey, Spruce Hill Community Association board member

DEEP IMPACT

A company with decades of reuse experience aims at zero waste

Long after its contents have been unpacked and used, the humble cardboard box can keep on working. Finding a second life for a box is relatively simple in the home, where it can help organize storage in a basement or closet, serve as a play hideout for kids and even morph into an end table. Boxes can also find new uses on a commercial scale. “Everyone sees a box every day of their lives,” says Mary Linn Leonards,

chief financial officer of American Box & Recycling, which helps connect businesses that need boxes with those facing mountains of cardboard. “Off-brand retailers can reuse the boxes to pack material that goes to stores; they’re not customer facing,” Leonards explains.

American Box & Recycling began in 1956 when the founder, Stuart Parmet, in his work with Tastykake, encountered one customer swamped with too many cardboard boxes

and then another saying he needed them. Parmet devised a matchmaking operation, and now, three generations later, the company has diverted more than 1 million tons of cardboard from landfills.

Reusing boxes doesn’t just save cardboard. According to a peer-reviewed study on the lifecycle of corrugated cardboard boxes published in Resources, reusing a cardboard box once instead of recycling right away cuts its lifecycle emissions by a third.

26 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023

story by dawn kane • photography by chris baker evens

BUY NOTHING

Mary Linn Leonards, CFO of American Box & Recycling.

Over the years American Box & Recycling has saved 4 million trees, 100 million gallons of water and 50 million pounds of carbon emissions, according to the company website. “We were a landfill diversion company,” Leonards says. “But that’s just the beginning — to go from landfill free to zero waste.”

A new division, IMPACT Recycling Partners, offers sustainability auditing for total resource use and efficiency (TRUE) through a program, Green Business Certification, Inc.

(GBCI), initiated by the U.S. Green Building Council. According to Steven Dege, a TRUE advisor and director of business development and sustainability programs at IMPACT, the process demands companies continuously evaluate their waste stream and look for solutions through composting or reusing materials to put them into a circular system.

Achieving true zero waste, defined as diverting 90% of waste from landfills and incineration, is a two-level process that takes

12 to 18 months and is overseen by a GBCI auditor. Pre-certification in the first six months sets companies up for full certification six months later. “The waste data must be collected every month of every year to monitor it,” Dege says. If the data shows an increase in waste, Dege must analyze why.

American Box & Recycling operates from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh and beyond, through Ohio, Wisconsin and North Carolina. IMPACT is just getting started with one client in Philadelphia and two based outside of the city.

Dege begins the trainings before handing the instruction over to the clients’ supervisors. “We develop the necessary training tools and let them take over,” he says. “It empowers them; they’re good at it. Employees are buying into it.”

“The number one problem we have is wrong habits,” Dege says. This is as true at the workplace as it is at home. “If everyone just washed out containers for recycling and set up a small composter for food waste, it would go a long way.”

Through fostering good habits and analyzing what gets thrown away, it is possible to get to zero waste. “We should be able to handle all of the waste,” Dege says. For clients “we’re transparent about letting them know what kind of products the materials go into,” he says. “There’s always a solution. Sometimes there’s a cost behind it. You have to be willing to pay that cost.”

Going zero waste can save money. Insurance is one area of saving, Leonards says. “Their insurance decreases because there’s less risk. In this process, everything can be traced throughout its lifetime, but if it goes into a landfill, there’s no traceability. So one doesn’t know what will happen to that material, which means there’s increased risk.”

Leonards, who got her start in industry by driving a 53-foot truck to pick up hazardous waste, says she’s passionate about the work. “Zero waste is what we do. We look at an entire company from the front door to the back door. We’re picking apart the process from start to finish so that nothing goes out the back door to the landfill.” ◆

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 27 REUSE EVERYTHING

Thanks to American Box & Recycling, the humble cardboard box can find a new home and new contents.

There’s always a solution. Sometimes there’s a cost behind it. You have to be willing to pay that cost.”

— steven dege, Director of Sustainabiltiy Programs, IMPACT

TUFTING TOWARD UTOPIA

Rug crafting company’s commitment to sustainability inspires foray into making recycled shipping supplies

Tim Eads pulls out his box cutter, slices a panel from a flattened cardboard box and then feeds it through a tabletop perforator. What goes in as waste comes out as packing material. What began as a way to source more-sustainable packing material for Tuft the World, the rug tufting company Eads owns with his partner, Tiernan Alexander, is now a new enterprise, Shred the World, geared toward the repurposing of cardboard boxes.

The cardboard perforator, which Eads discovered on TikTok during a bout of insomnia, was a middle-of-the night purchase. It was one of those “TikTok made me buy it things,” Alexander says. The couple has nicknamed their cardboard perforator the “Machine that Eats Cardboard,” and it has turned out to be a good fit for their business. Eads and Alexander were always on the lookout for more sustainable ways to do things, so they’re happy to ship their own products in eco-friendly packaging and created Shred the World to share the service with others.

Originally from Texas, Alexander and Eads relocated to Philadelphia from Detroit in 2009. They were attracted to the DIY art scene in Philly. “Philadelphia has this scruffy spirit,” Alexander says. In the beginning they did creative work, and Eads taught at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture.

Then Eads discovered a handheld rug-tufting machine online. Historically,

tufting had been an industrial process. How-to instructions didn’t exist. Eads knew the small machine would make the craft more accessible. He ordered machines, wrote an instruction manual, and in 2018 Tuft The World (TTW) was born.

Over the years Eads has built an educational program. He posts tutorial videos and teaches classes and workshops. He describes tufted rug-making as a fast craft. “With tufting you can make a piece of art in a few hours,” he says. When the pandemic confined people to their homes, tufting rugs filled a niche. “Now he’s the tufting guy on YouTube,” Alexander says.

As their business grew, Alexander became more involved in planning and logistics. By 2020 she took on the role of chief financial officer and head of human resources. “My role has essentially been helping develop what kind of business we want to be,” Alexander says.

Today a walk through the couple’s WestPhilly warehouse showcases an array of colorful rugs on walls, lamps and furniture. The sustainable materials on shelves range from the brightly colored eco-friendly yarns — some made from banana fiber — to the biodegradable packaging for the glue, to the backyard compostable coffee provided for staff. Thoughtful, sustainable design fills every nook. “It’s a tiny utopia, and it’s fuzzy,” Alexander says.

The drive toward sustainability within the company has led to a push to make their processes systematic. With the help of Jennifer McTague, who joined the team in 2022 as the human resources director and member of the sustainability committee, they have incorporated United Nations Sustainable Development Goals into their business model, and they are working to become certified as a B Corporation.

“We’re doing all of these good things, so

28 GRIDPHILLY.COM MAY 2023 BUY NOTHING

story by dawn kane • photography by chris baker evens

It’s not just somebody’s passion project; it’s woven into the fabric of the way the company operates.”

jennifer m c tague, Tuft the World human resources manager

let’s formalize it,” McTague says. “It’s more than just the environment. It’s all of it — like having a living wage. It’s a way to show our customers that we’re practicing what we preach. It’s not just somebody’s passion project; it’s woven into the fabric of the way the company operates.”

On the ground this plays out in many forms. Eads pays more for tufting machines to get them in biodegradable packaging. They also pay carbon offsets for shipping. Eads and Alexander pay themselves $25 an hour — the same as they pay employees. Their staff of 18 works a four-day week and receives benefits. “We’re not getting as rich

as we could be,” says Alexander. “All we ever wanted was a job we could deal with. We don’t need to get rich.”

Another part of the equation, Eads and Alexander say, is connecting others. Last year they joined Philadelphia’s Sustainable Business Network, where they network for ideas. And customers around the world can tag them on social media to get reposted and receive gift certificates.

Trish Andersen of Dalton, Georgia, is a fellow tufting artist. She has her own studio and connected with Eads prior to the pandemic. She describes the work as a kind of meditation. “What’s better than this kind of

soft thing during a really hard time? I credit them [TTW staff] with the growth of the community.”

While many connections have flourished online, Andersen says the tufting community hadn’t previously come together in person. To remedy that, Eads organized TuftCon, a tufting convention in Philadelphia in March. “Part of the circular economy is that sense of community,” Alexander says.

“The Shred the World work began ramping up a couple of months ago,” Eads says. “We’re starting to work with local companies. For example, partners who want to trade — they pay a small amount to take the shredded cardboard.”

The company website promotes shredded cardboard as “the ultimate eco-friendly packaging option” and a viable replacement for plastic packing bubbles, air bubbles and packing peanuts. “We figured that if we wanted to help save the planet in this small way, that other businesses would, too; they just need to know that we exist,” Alexander says. ◆

MAY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 29 REUSE EVERYTHING

Tim Eads and Tiernan Alexander have made an art of sustainability.

CLEANING UP

story by nic esposito • photography by chris baker evens

As a black woman, Taneesha Maxwell may be an outlier in the waste hauling business that has historically been dominated by men. But as owner of T Maxwell Junk Removal and Cleanouts (@tmaxmmovesjunk on Instagram), she is bringing a new face to the cleanout game, serving residents and property managers throughout Philadelphia and Delaware County, removing everything from furniture and appliances to trash and construction debris. Grid sat down with Maxwell to hear her thoughts on this evolving industry and to better understand a day in the life of a junk remover.