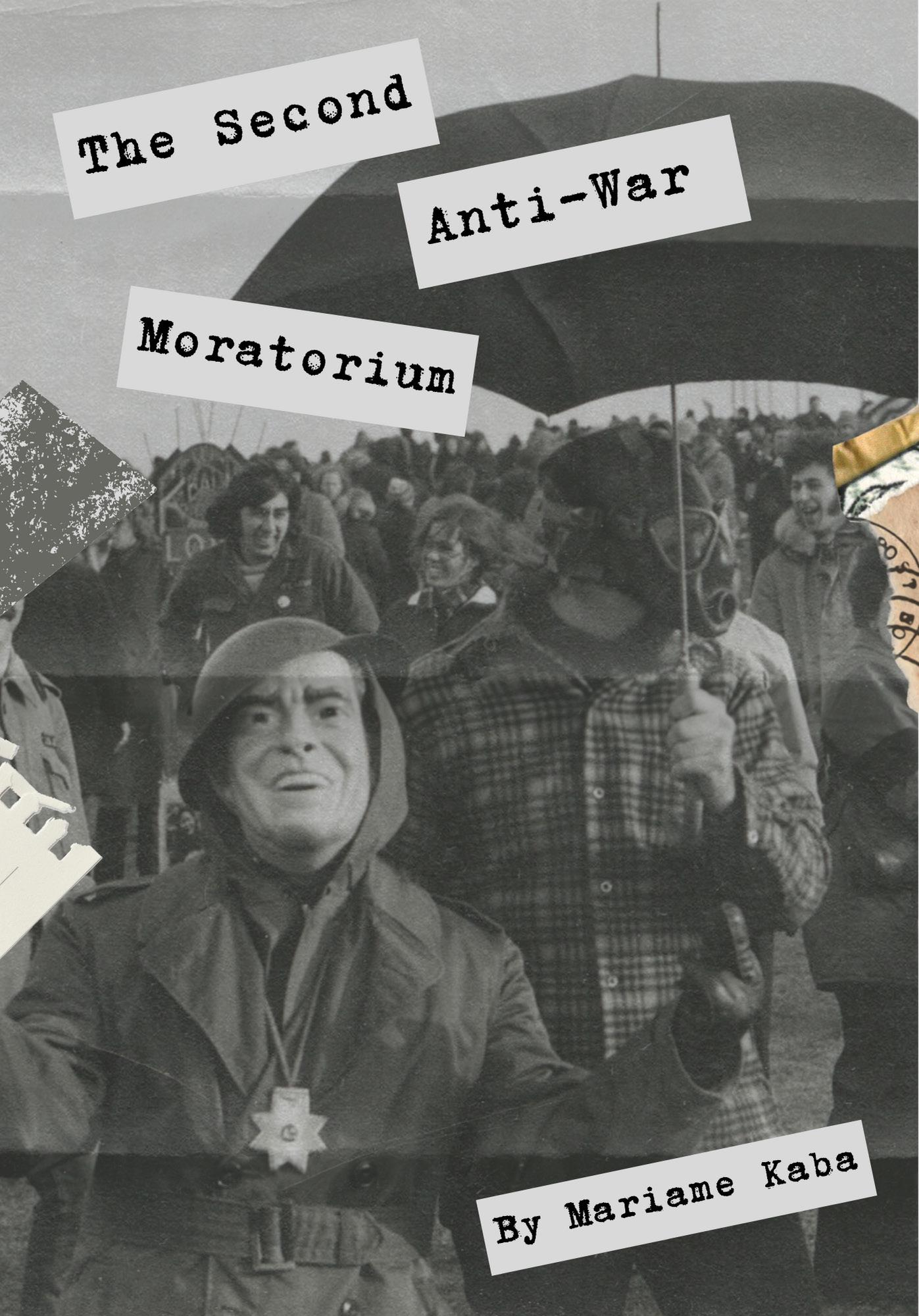

The Second Anti-War Moratorium

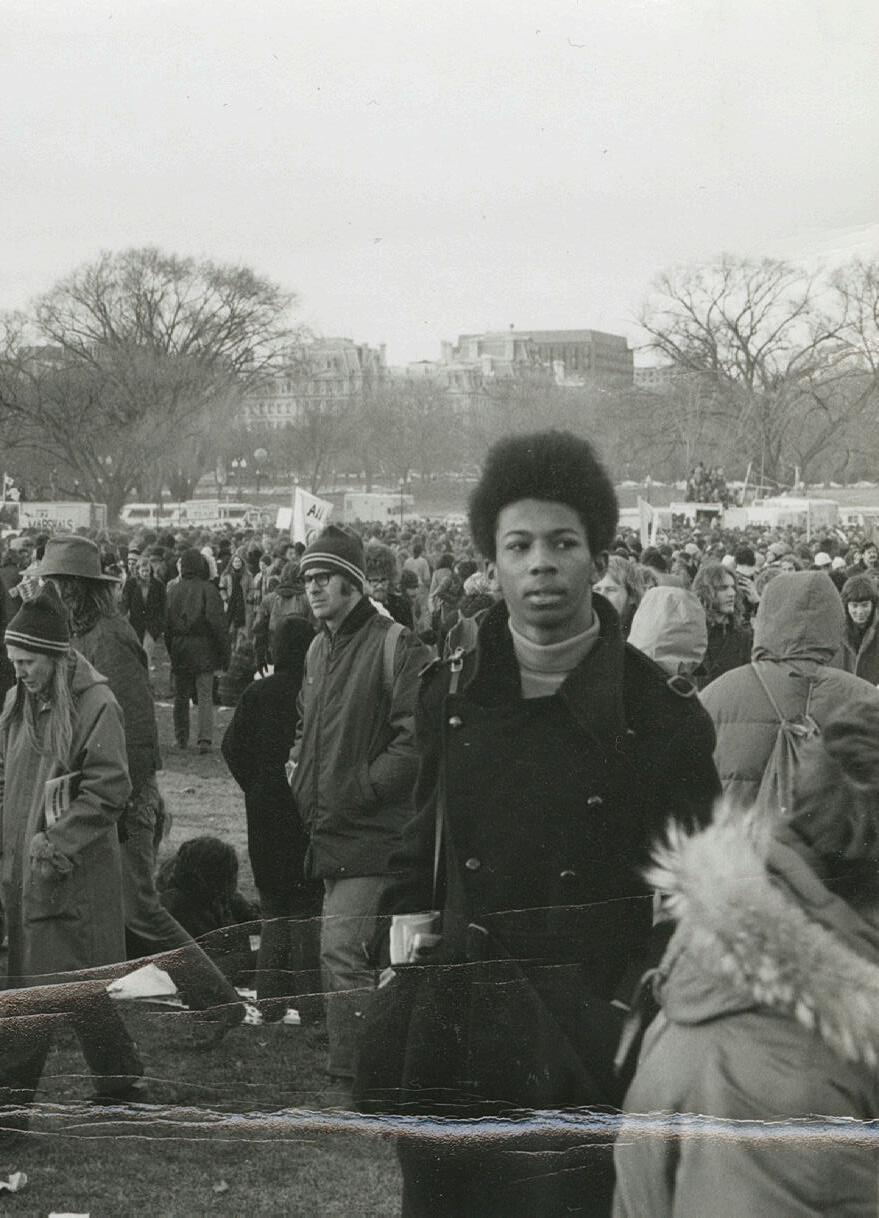

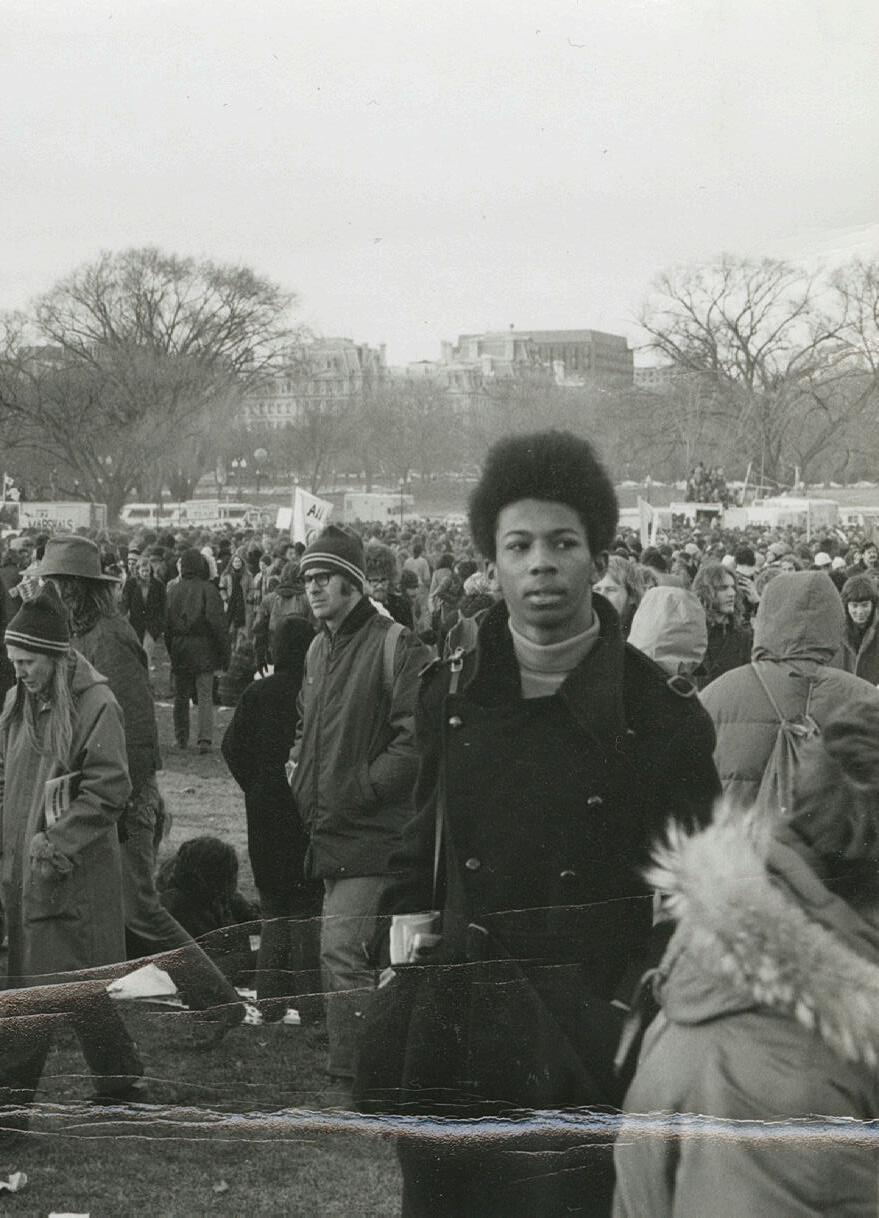

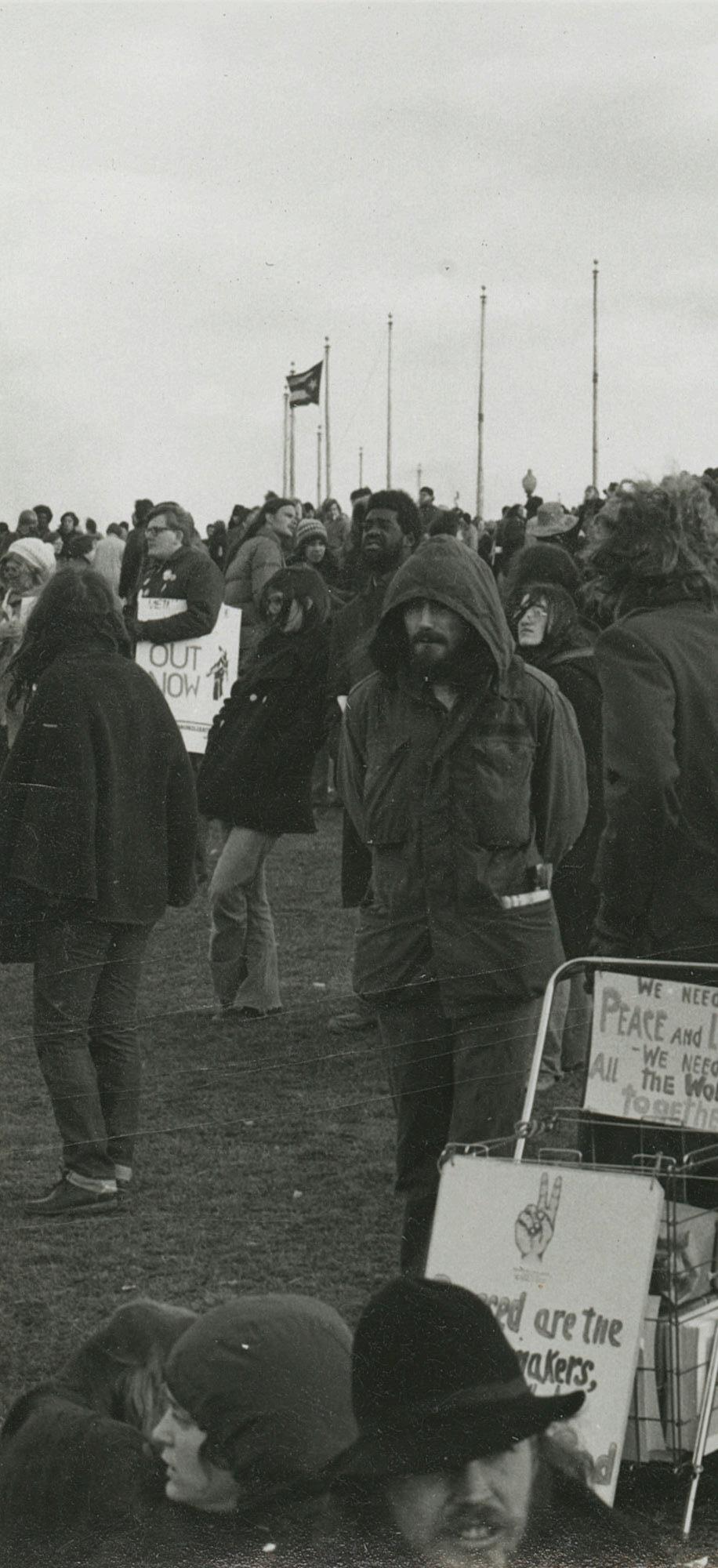

On November 15, 1969, 500,000 people marched on Washington in what was billed as the Second Moratorium Against the War in Vietnam. Smaller marches were also held in cities across the country. The mostly peaceful demonstration was believed to be the largest anti-war protest in United States history.1

The massive protest was supposed to be one part of an escalating series of actions that would force President Richard Nixon to end the increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam. However, despite its enormous size and galvanizing impact, the Second Moratorium did not immediately lead to further demonstrations. This was, in part, because of successful counter-mobilization by the Nixon administration and conservative pro-war forces. The Moratorium is, therefore, both an impressive example of

1. The Learning Network, “November 15, 1969: Anti-Vietnam War Demonstration Held,” The Learning Network (New York Times blog), November 15, 2011, https://archive.nytimes.com/learning. blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/15/nov15-1969-anti-vietnam-war-demonstration-held/.

successful organization and also a difficult chapter in an ongoing movement that would continue to resist the war till the US withdrawal from Vietnam four years later.

Early Protests Against the War

Public enthusiasm for the Vietnam War was fairly high when the U.S. sent its first wave of troops in August 1965. At that time, 61 percent of the American public said that the U.S. was right to enter the war.2 It didn’t take long for public opinion to change, though, and by mid-1966 that number had dipped below 50 percent3 .

One prominent early example, the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, or the Mobe, organized major rallies on April 15, 1967 where, in New York City, around 400,000 people protested, while simultaneously

2. Original source: George H. Gallup, The Gallup Poll of Public Opinion

1935-1971, accessed through Digital History, “Public Opinion and the Vietnam War,” Retrieved December 21, 2022.

https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/ active_learning/explorations/vietnam/vietnam_pubopinion.cfm

3. Ibid

6 THE SECOND ANTI WAR MORATORIUM

in San Francisco 75,000 turned out. Another rally in Washington in October 1967 drew 150,000 people.

The Mobe also participated in anti-war protests during the Chicago Democratic National Convention in 1968, in which Mayor Daley’s police force attempted to suppress dissent forcefully, leading to three days of riots and chaos. Mobe leader and principled advocate of non-violence, David Dellinger, was arrested, and the Mobe largely disintegrated.

Moratorium, Not Strike

The war, though, was only becoming more unpopular, with public support falling below 40

percent by the time Richard Nixon assumed office in 19694. Antiwar activists saw an opportunity to draw on this increased public opposition to the conflict to organize larger demonstrations. Sam Brown, David Hawk, and David Mixner, who had worked together on the 1968 presidential campaign of Eugene McCarthy, along with Jerome Grossman (the chairman of the Massachusetts Peace Action Council) began to make plans for a series of national protests in summer of

4. Gallup Poll via Digital History.

8 THE SECOND ANTI WAR MORATORIUM

19695. Together, they created the Vietnam Moratorium Committee (VMC) and called their planned action the Moratorium Against the War in Vietnam.

The word “Moratorium” was chosen carefully as an alternative to the perception of the more militant, “Strike.” Brown, especially, was very aware of how images of violence at the Democratic Convention had damaged the peace movement, and he and his colleagues hoped to put a more moderate face on this march6. Brown wanted to get away from the image of long-haired hippies and campus protest and “anything which irritates the nerve endings of middle-class values.7”

5. See University of Wisconsin Libraries, Vietnam Moratorium Committee Records 1969-1970, http://digital. library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/wiarchives. uw-whs-mss00202

6. Richard Ellison, Elizabeth Deane, and Sam Brown. Interview with Sam Brown, 1982. WGBH Educational Foundation, August 11, 1982. Web. 23 Feb 2023. <http://openvault.wgbh. org/catalog/V_A55BE9295E024182AD926622157A9791>.

7. Simon Hall, Peace and Freedom: The Civil Rights and Antiwar Movements in the 1960s, 2011, P. 160

9 KABA

Instead, Brown wanted to appeal to what he and the VMC saw as a centrist majority which included, “Senators, Congressmen, governors, mayors, businessmen.8” The movement deliberately distanced itself from Black radical movements which had been closely linked to earlier peace organizations, because Brown believed “unrelated issues” would dilute the push to end the war 9

A Broad Coalition

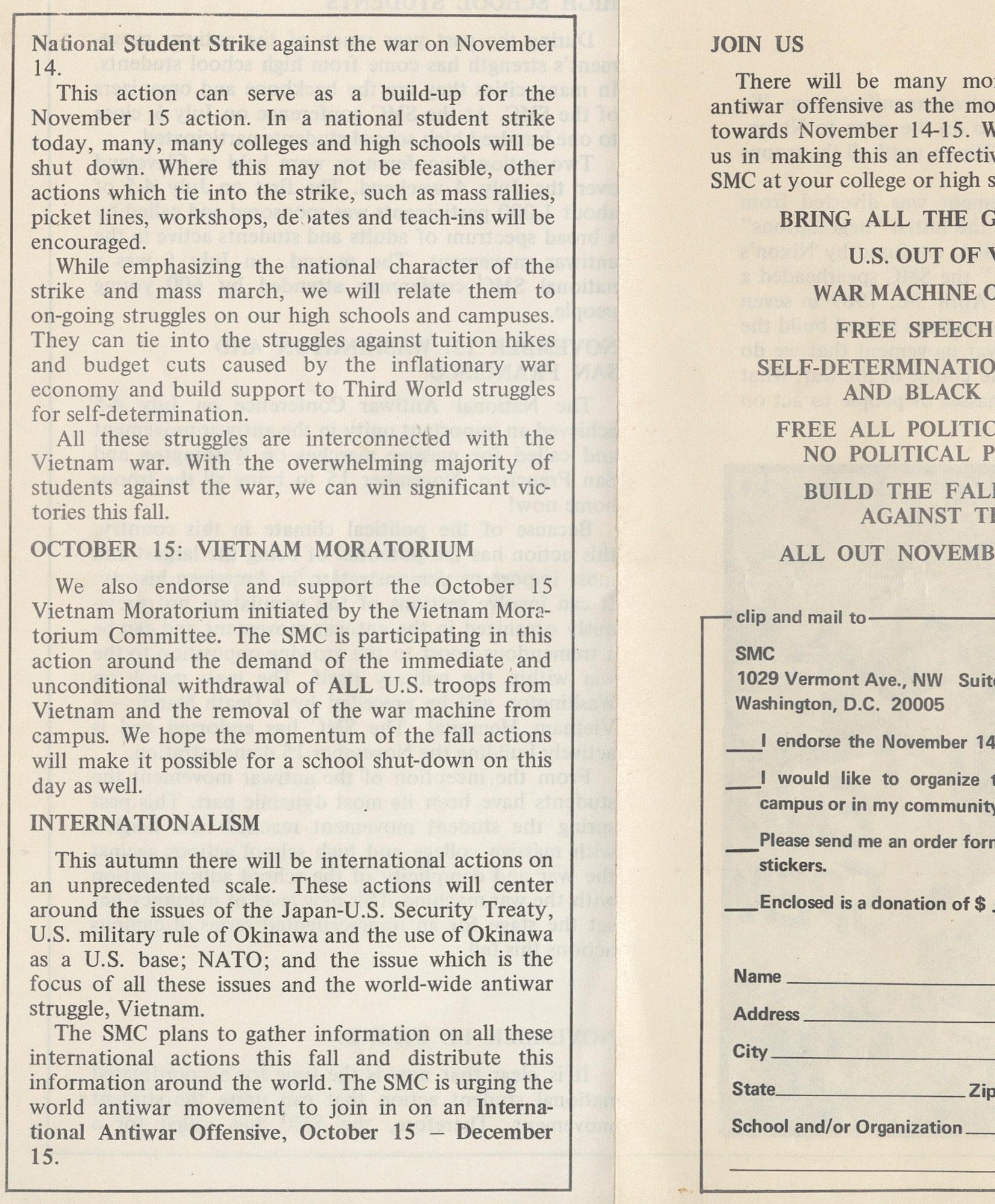

The plan of the VMC was to stage an escalating national action which was supposed to increase one day for each month that the war continued. The organizers hoped that these centralized protests would inspire other grass-roots demonstrations around the country. They scheduled the first “moratorium” for October 15, 1969.

The more moderate branding and the single issue focus paid dividends10. The VMC was

10. Hall, 160

.

8. Interview with Sam Brown, 1982

9. Ibid

10 THE SECOND ANTI WAR MORATORIUM

endorsed by The New Republic, John Kenneth Galbraith, the United Auto Workers, the Teamsters, and more than twenty Senators, including Charles Goodell, Eugene McCarthy, and George McGovern.

Despite intentionally distancing themselves from Civil Rights issues, the VMC was still championed by many Black leaders. Noted Civil Rights activist, Fannie Lou Hamer, said support for the VMC was “essential.” Moderate Black organizations, like the National Urban League and NAACP, which had kept their distance from earlier peace protests, embraced the movement11. They were motivated in part by the VMC’s moderate image, in part by young members in their own organizations, and in part by the growing unpopularity of the war. At that point, 45,000 US troops

had died12. African-Americans were disproportionately likely to be drafted and had casualty rates as high as twice that of whites. Nonetheless, most of the leadership and most of the participants in the Moratorium were white13.

The Moratorium of October 15

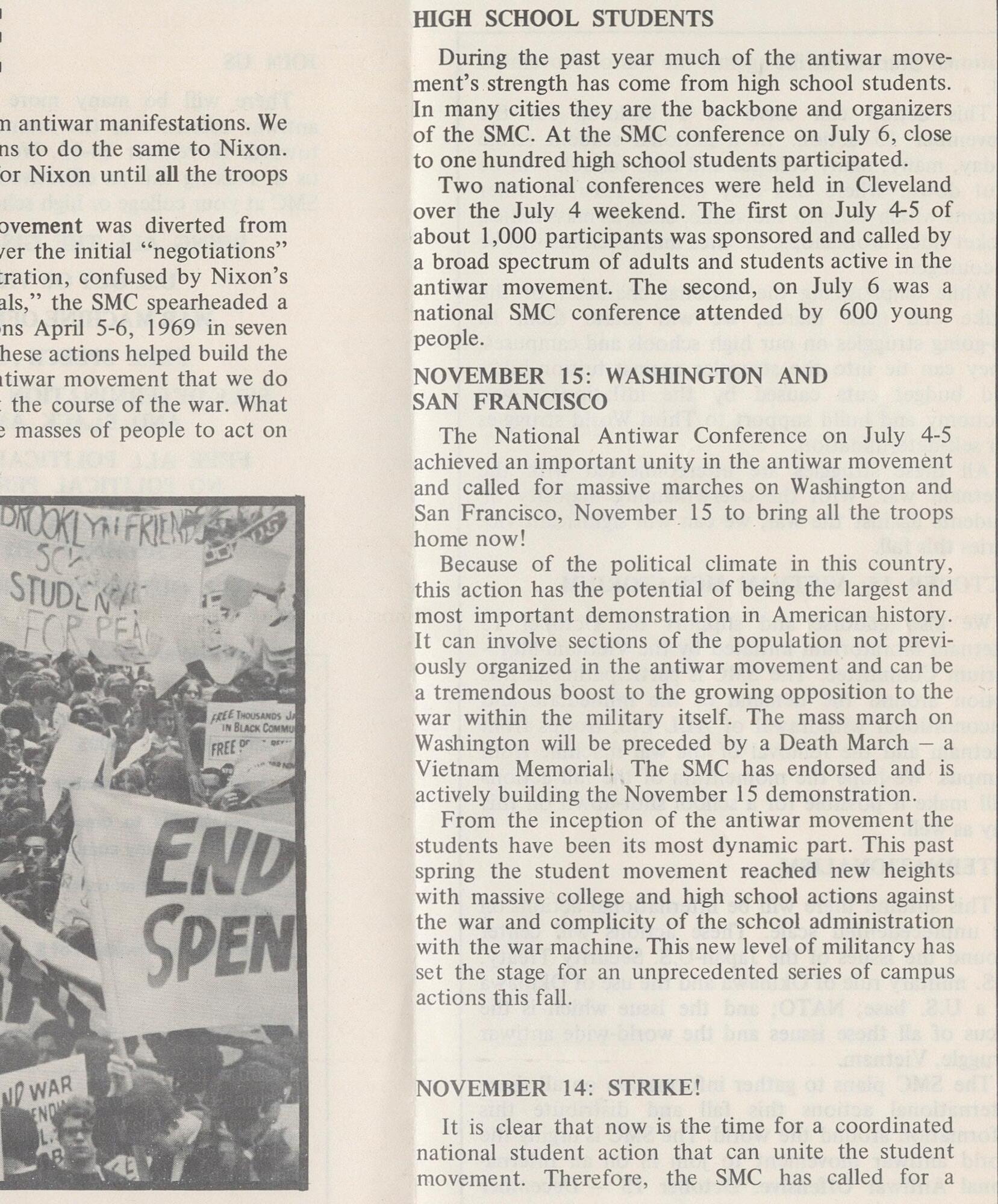

The protest on October 15, 1969 was massive, widespread, and to many observers, stunning. Some two million people took part across two hundred cities14. That included around 250,000 each in New York City and Washington.

But there were demonstrations everywhere. In North Newton,

12. BBC News, “Moratorium Day: The Day That Millions of Americans Marched,” October 15, 2019, https:// www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-49893239.

11. Inghram, Glen. “NAACP support of the Vietnam War: 1963-1969.”

The Western Journal of Black Studies, vol. 30, no. 1, spring 2006, pp. 54+. Gale Academic OneFile, link. gale.com/apps/doc/A182035987/ AONE?u=anon~292aee9b&sid=googleScholar&xid=5379a1cb. Accessed 23 Feb. 2023.

13. Amistad Digital Resource, “Section 13: Black Opposition to Vietnam,” https://www.amistadresource. org/civil_rights_era/black_opposition_to_vietnam.html.

14. Derek Seidman, “Fifty Years Ago Today, US Soldiers Joined the Vietnam Moratorium Protests in Mass Numbers,” Jacobin, October 15, 2019, https://jacobin.com/2019/10/ vietnam-war-moratorium-protest-gi-movement.

11 KABA

Kansas, a bell was rung every four seconds, once for each American soldier who had died in the conflict15. There was a funeral procession in downtown Milwaukee. Hastings College, a Presbyterian school in Nebraska with 850 students, closed classes for the day. In college cities like Madison, Ann Arbor, and New Haven, more than a quarter of the population came out to protest. In more than a thousand high schools, students walked out of classes. Solidarity demonstrations even spread globally, where 1000 people in London demonstrated in front of the U.S. embassy.

Support for the action was so broad that it attracted support from unlikely places: the Connecticut state chairman of Citizens for Nixon-Agnew participated in protests and so did twenty-thousand businessman on Wall Street, who marched to Trinity Church in protest. In the Capitol, twentythree Congressmen held the House floor for four hours, the longest sustained discussion of Vietnam in Congress to that point.

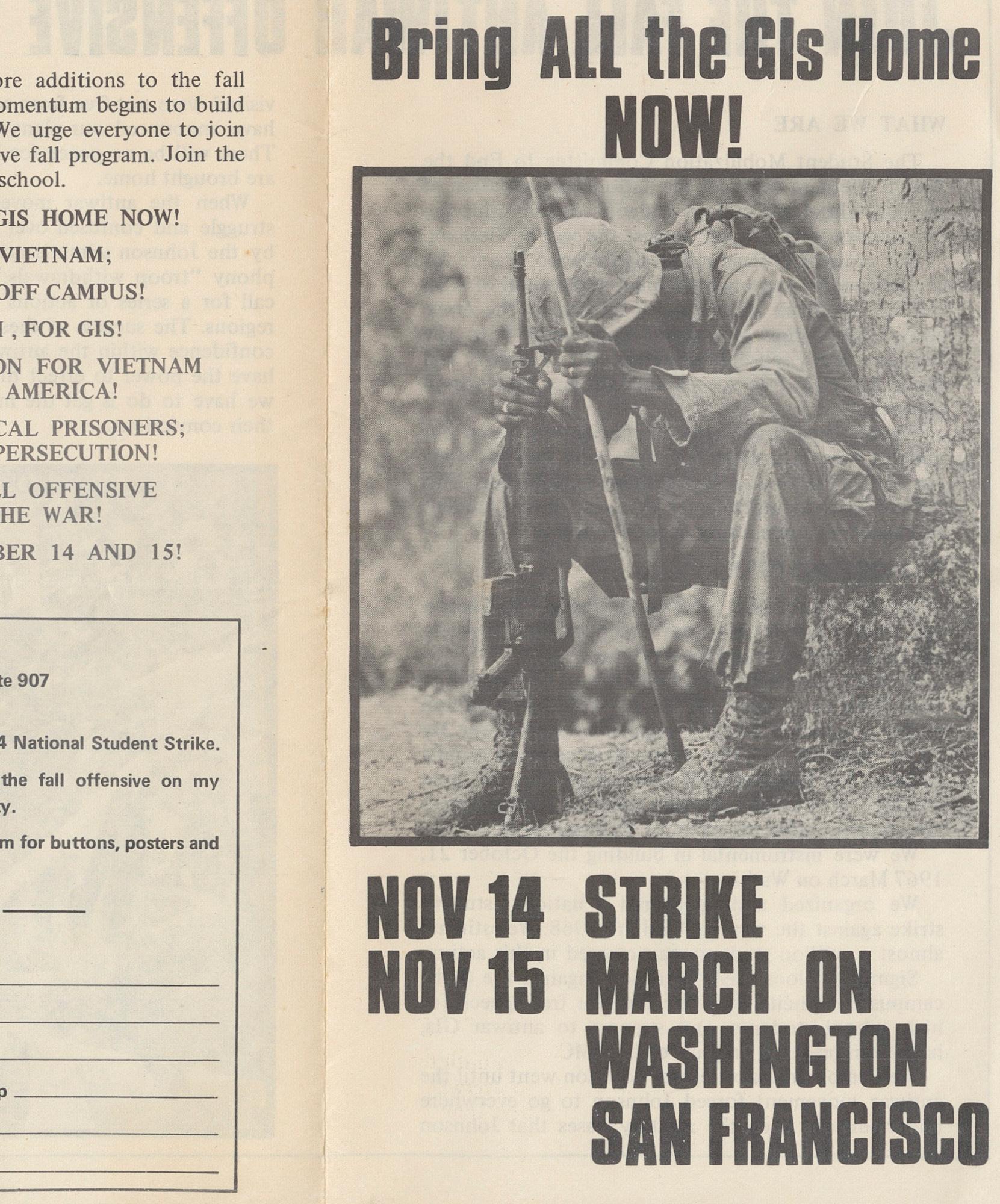

The VMC also reached out to soldiers and encouraged them to join by connecting them with antiwar GI papers and offering legal help to GIs who protested16. Many soldiers did take actions. About seventy-five soldiers at Fort Carson protested at Colorado Springs; some 150 soldiers signed a petition at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. Even some soldiers in Vietnam wore black armbands. One soldier interviewed at the time

15. Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, 2008, p. 424.

15. Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, 2008, p. 424.

16 THE SECOND ANTI WAR MORATORIUM

16. Derek Seidman, “Fifty Years Ago Today”

in Vietnam said of the Moratorium, “I think the protesters may be the only ones who really give a damn about what’s happening.17”

Commenters at the time were struck by the Moratorium’s power and wide appeal18. Life said the October Moratorium was, “a display without historic parallel, the largest expression of public dissent ever seen in this country.19” Fred Halstead, the

17. Ibid

18. Ibid

19. Ibid

1968 presidential candidate of the Socialist Workers’ Party, was also impressed: “The antiwar movement for the first time reached the level of a full-fledged mass movement,” he wrote20.

Nixon and the Silent Majority

Before the October protest, President Richard Nixon publicly insisted that “under no circumstances” would he be “affected whatever” by anything the protestors did.21”

Afterwards and in private, however, the protest did have an effect. Nixon was worried by the scale of the demonstration and by its favorable press coverage22. He was especially concerned because the demonstration included not just young people and radicals, but many moderates, middle-class, and middle-aged people, including politicians and other leaders.

The protest also had effects on policy. Nixon had issued a secret

20. Ibid

21. Melvin Small,, Antiwarriors: The Vietnam War and the Battle for America’s Hearts and Minds, 2002, p. 109.

22. Melvin Small, Antiwarriors, pp. 110-112.

17 KABA

ultimatum to Hanoi promising a major escalation of the war if they did not accede to American terms by November 1. There’s some evidence that the planned escalation might have even included plans for a nuclear attack23. The October Moratorium led Nixon to believe any escalation would be politically damaging, and he let the deadline pass without escalation.

After the success of the October Moratorium and the groundswell of support from so many places, President Nixon became determined to undermine the Moratorium and counter any momentum that had been gained. His Vice-President, Spiro Agnew, made public attacks on the peace movement which he said embodied a spirit of “national masochism.24” He linked protestors to “hard-core dissidents and professional anarchists” and called them “vultures” and “ideological

23. William Burr and Jeffrey Kimball, Nixon White House Considered

Nuclear Options Against North Vietnam, Declassified Documents Reveal,” National Security Archive Electronic

Briefing Book No. 195, July 31, 2006, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/ NSAEBB195/index.htm.

24. Rick Perlsetin, Nixonland, 431.

eunuchs.25”

25. Ibid

The president himself made one of his most famous and important speeches following the Moratorium to show that he “was not going to be pushed

THE SECOND ANTI WAR MOVEMENT

around by demonstrators and rabble in the streets.26” On television on November 3, he outlined a plan to slowly draw down U.S. forces, shifting the burden of fighting to Vietnamese

troops27. He also claimed that his policy had the support of a “great silent majority” of

27. A&E Television Network,”President Nixon calls on the ‘silent majority,’” November 16, 2009, https:// www.history.com/this-day-in-history/nixon-calls-on-the-silent-majority

26. Melvin Small, Antiwarriors, p.112.

26. Melvin Small, Antiwarriors, p.112.

Americans who agreed with his policy but were not given to protests or loud public statements.

A Gallup Poll following the speech found that 77 percent of Americans approved of Nixon’s policy—probably because many believed he was promising to end the war in the near term. He received 130,000 letters and telegrams of support, and 300 congressmen and 40 senators signed onto resolutions supporting his approach. As the administration’s confidence rose, Agnew became even more combative. He attacked the press directly on November 13, the same day when the second Moratorium got under way. He accused the press of being an out of touch elite and said that their coverage of negative news—like the Vietnam protests—was a “flagrant abuse of freedom of speech.28” News anchor Walter Cronkite responded that Agnew’s speech was “an implied threat to freedom of the press.29”

The threat worked. Television stations relied on government licenses and the direct attack from the White House, backed by what appeared to be rising public approval, frightened the networks. They did not turn out to film the second Moratorium that weekend.30

The Second Moratorium

The spectacle the networks missed was impressive. After October’s demonstration, the VMC had entered into closer coordination with the more radical New Mobe, a successor to the Mobe. The New Mobe hoped to reach more people with its message by participating in the Moratorium. The VMC hoped that it could capture some of the Mobe’s energy, and also encourage radicals not to engage in violent protest.

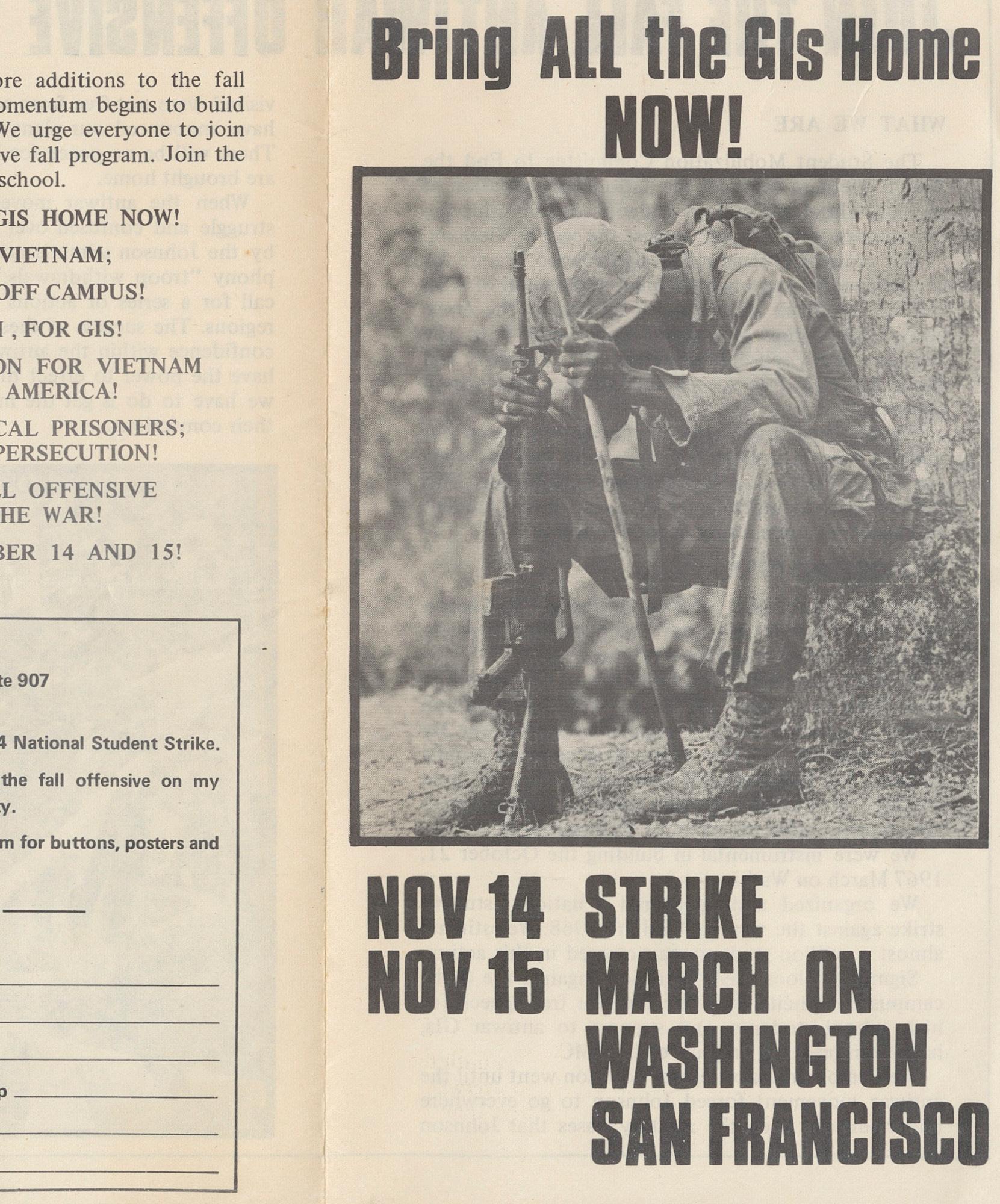

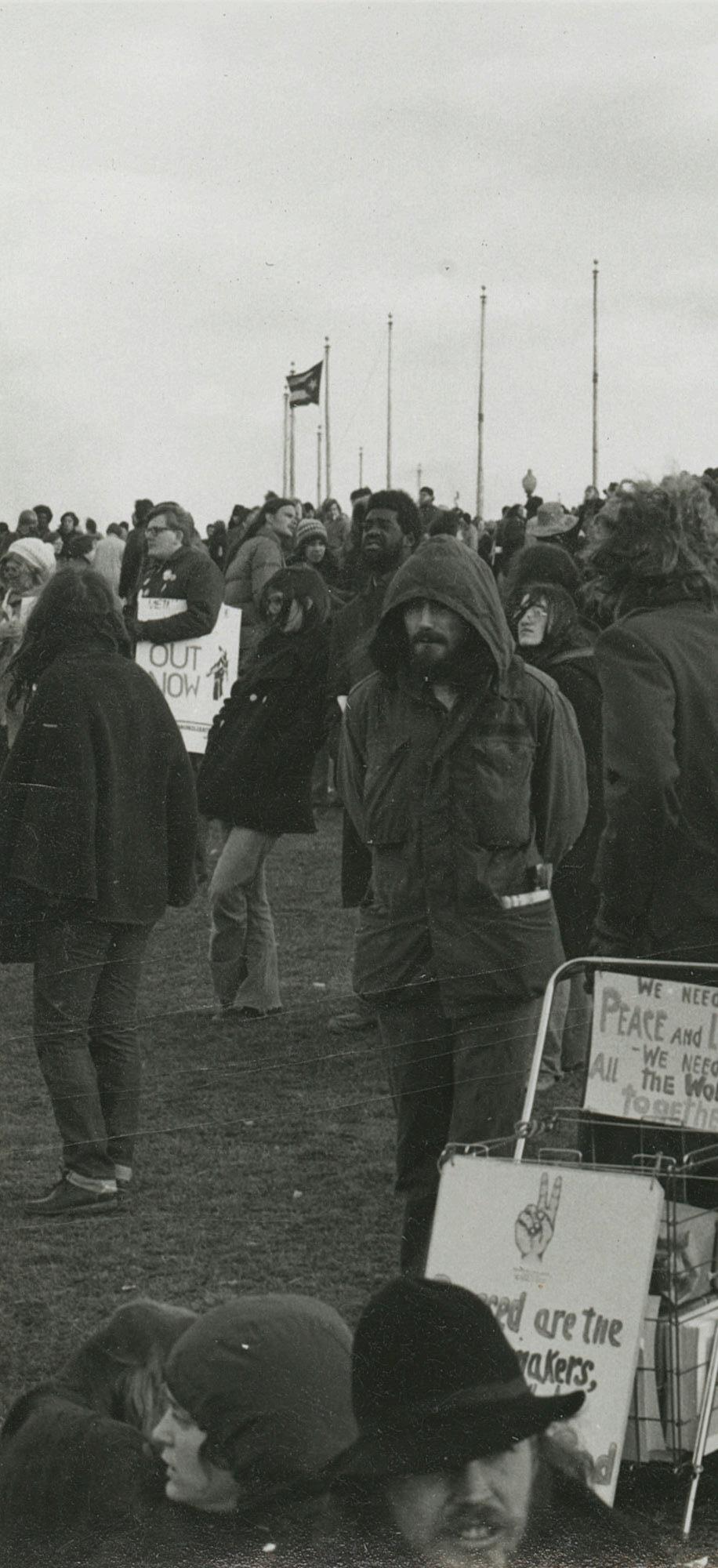

The events of the second Moratorium started on the 13th with a March Against Death organized by the New Mobe.31

30. Rick Perlstein, Nixonland

28. Library of Congress,”Hope for America: Performers, Politics, and Pop Culture,” https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/hope-for-america/political-speech. html

29. Ibid

31. “March Against Death,” National Museum of American History, Behring Center, the Smithsonian, https:// americanhistory.si.edu/collections/ search/object/nmah_1916680.

21 KABA

An incredible 45,000 people walked from the Potomac River in single file on a trek that lasted 36 hours. When they reached the White House, each person read the name of an American soldier killed or a Vietnamese village destroyed in the war, and then placed the placards in coffins. At the conclusion of the ceremony, the coffins were walked to the Washington Monument. The recitation lasted from 4:30 PM on the 14th through the night to 8:30 the next morning.

The Moratorium rally proper began at about 10 AM, as protestors marched via Pennsylvania Avenue to the Washington Monument. The crowd eventually built to around 500,000 people—again, the largest protest in United States

history. Speakers included Senator George McGovern, Senator Charles Goodell, and comedian and activist Dick Gregory. An all-star concert lasted throughout the day, and performers included four different casts from the musical “Hair,” Leonard Bernstein, John Denver and Arlo Guthrie. Pete Seeger led a ten-minute singalong to John Lennon’s newly released “Give Peace a Chance,” interspersing the performance by asking, “Are you listening, Nixon?32” (He was; he stayed up until 11PM to

32. Boot Leg, “Pete Seeger leads 500,000 people to sing “Give Peace a Chance,” on Moratorium Day, November 15, 1969.” YouTube, accessed December 21, 2022. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=dnXSElkl2jE

watch the protests on the news.)33

The rally was again mostly peaceful, despite a confrontation with police. Old Mobe turned New Mobe leader, David Dellinger, led a march to the Justice Department which included more militant activists, some carrying pictures of Communist leaders34. They threw stones at the Justice Department and broke windows35. The police responded by firing tear gas. Congressman Edwin W. Edwards of Louisiana said police should have used live ammunition, instead.

Backlash

Edwards’ response was extreme but the Justice Department clash was widely and negatively covered in the press and on the television networks, the latter of which were already cowed by the administration. Coverage focused on the small outbreaks of violence rather than on the huge size of and support for the march. “Although the demonstrations of November 13-15 were among the most impressive of the war, Nixon won this round with the antiwar movement,” historian Melvin Small concluded36.

33. A.J. Langguth, Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975, 2000.

34. Melvin Small, Antiwarriors.

35. Ibid

Pro-war rallies in Pittsburgh, Birmingham and Chicago in

36. Ibid

mid-November before and after the moratorium rally drew substantial crowds, and helped feed the narrative of a weakening anti-war movement. The VMC abandoned its plans for monthly rallies and staged no further demonstration in December.

The New Mobe, for its part, was split between factions arguing for a single-issue focus and those who wanted to more forcefully advocate for Black nationalism and decolonization.

Demonstrations in April 1970 across the country, by the VMC and the New Mobe, were small and received little press coverage. The VMC closed down

soon afterwards. The New Mobe’s internal divisions prevented it from doing much substantial organizing either.

Legacy

The Moratoriums’ most immediate influence was not on the U.S. but overseas. Inspired by the U.S. protests in October and November, anti-war groups in Australia launched a similar movement. The Australian Moratorium was, like its U.S. predecessor, focused on presenting a moderate face in order to garner mainstream support for ending Australia’s involvement in the conflict.

24 THE SECOND ANTI WAR MORATORIUM

The first Australian Moratorium took place on May 8, 1970 and drew a total of 200,000 people across the country; there were demonstrations in most major cities, including Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth, and Hobart. This was the largest demonstration in Australia’s history to that time.

A second Moratorium was held on September 18, 1970 and a third on June 30, 1971. Fewer people turned out, however, and during the second Moratorium, Melbourne police attacked protestors. In Sydney, too, there were clashes with police and 173 people were arrested.

Australia withdrew from the war in 1972, though it’s difficult to trace this as a direct result of the Moratoriums. The first Australian Moratorium did, however, likely cause the government to reduce the number of draft resistors it sent to jail. It was also a spur to the Australian women’s movements, as many of those leaders had first participated in the anti-war protest, gaining experience in organizing.

In the United States, the antiwar movement continued even though the Moratoriums did not. Shortly after the VMC disbanded,

Nixon’s announcement of an invasion of Cambodia on April 30 sparked nationwide campus protests involving hundreds of thousands of students. In response to these nonviolent protests, National Guardsman famously opened fire at Kent State, killing four people and wounding nine.

The Moratoriums demonstrated both the strength of antiwar sentiment and the difficulty of translating that sentiment into policy change in the face of an intransigent and ruthless establishment. Still, the Moratoriums did have real effects. They prevented Nixon from escalating the war in November 1969 and they were the impetus for changing military draft policy in Australia. They also contributed to an antiwar movement that did, eventually, after much suffering, lead to US withdrawal from the conflict in Vietnam.

25 KABA

References

Amistad Digital Resource, “Black Opposition to Vietnam,” Retrieved December 21, 2022.

https://www.amistadresource.org/civil_rights_era/black_opposition_to_ vietnam.html

Boot Leg, “Pete Seeger leads 500,000 people to sing “Give Peace a Chance,” on Moratorium Day, November 15, 1969.” YouTube, accessed December 21, 2022.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dnXSElkl2jE

Digital History, “Public Opinion and the Vietnam War,” Retrieved December 21, 2022.

https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/vietnam/ vietnam_pubopinion.cfm

Simon Hall, Peace and Freedom: The Civil Rights and Antiwar Movements in the 1960s, 2011.

History.com, “President Nixon calls on the ‘silent majority,’ November 16, 2009.

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/nixon-calls-on-the-silent-majority

Glenn Inghram, “NAACP support of the Vietnam War: 1963-1969,” Gale Academic Onefile, Spring 2006.

https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA182035987&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=01974327&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7E292aee9b

A.J. Langguth, Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975, 2000.

National Museum of Australia, “Vietnam Moratoriums,” Retrieved December 21, 2022.

https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/vietnam-moratoriums

New York Times, “Nov.15, 1969 Anti-Vietnam War Demonstration Held,” November 15, 2011.

26 THE SECOND ANTI WAR MORATORIUM

https://archive.nytimes.com/learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/15/ nov-15-1969-anti-vietnam-war-demonstration-held/

Genya O’Gara, “The Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam,” NC State University Libraries, June 23, 2011.

https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/news/special-collections/the-moratorium-toend-the-war-in-vietnam

Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, 2008.

Derek Seidman, “Fifty Years Ago Today, US Soldiers Joined the Vietnam Moratorium Protests in Mass Numbers,” Jacobin, October 15, 2019.

https://jacobin.com/2019/10/vietnam-war-moratorium-protest-gi-movement

Erin Skarda, “Moratorium Against the Vietnam War, Nov. 15, 1969,” Time, June 28, 2011.

https://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2080036_2080037_2080024,00.html

Melvin Small, Antiwarriors: The Vietnam War and The Battle for America’s Hearts and Minds, 2022.

Jon Wiener, “Nixon and the 1969 Vietnam Moratorium,” The Nation, January 12, 2010.

https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/nixon-and-1969-vietnam-moratorium/

Zinn Education Project, “Nov. 15, 1969: Second Anti-War Moratorium,” Retrieved December 21, 2022.

https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/second-antiwar-moratorium/

27 KABA

Thanks to Noah Berlatsky and Eric Ritskes for helping to make this zine a reality.

archival activations 2023

15. Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, 2008, p. 424.

15. Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, 2008, p. 424.

26. Melvin Small, Antiwarriors, p.112.

26. Melvin Small, Antiwarriors, p.112.