The Collapse of Housing Bubble in China

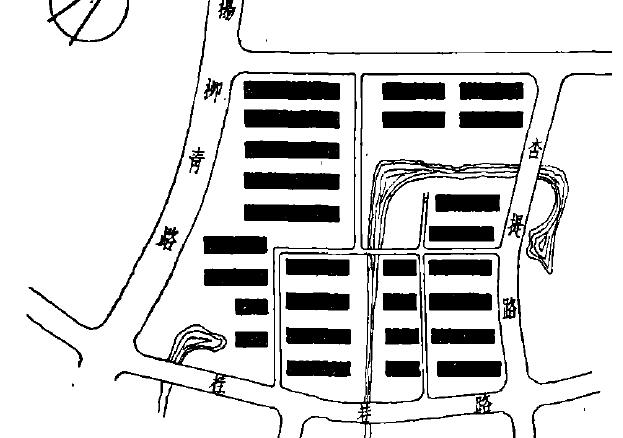

New Power as New Forms of Living

Hanwen Xu

Architectural Association School of Architecture

Projective Cities Programme 2021-2023

1

ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE GRADUATE SCHOOL

DECLARATION:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.“

SIGNATURE:

DATE: 24.04.2023

2

The Collapse of Housing Bubble in China New Power as New Forms of Living

Dissertation Submited in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design

Hanwen Xu

Architectural Association School of Architecture

Projective Cities Programme 2021-2023

3

4

Completing this thesis would not have been possible without the guidance, support, and challenging discussions of my supervisors and tutors at AA Projective Cities. I am deeply grateful to Dr. Plation Issaias, Dr. Hamed Khosravi, and Dr. Doreen Bernath for their selfless help and invaluable feedback throughout my research journey.

I would also like to express my gratitude to all my colleagues and friends in AA Projective Cities and in London, who have provided me with memorable experiences and insightful ideas.

Thanks to AA for supporting me with a bursary.

Lastly, I would like to give a special thanks to my parents. Their unwavering support and understanding have been a driving force for me to keep moving forward.

Hanwen Xu

April 2023

5

6

ABSTRACT

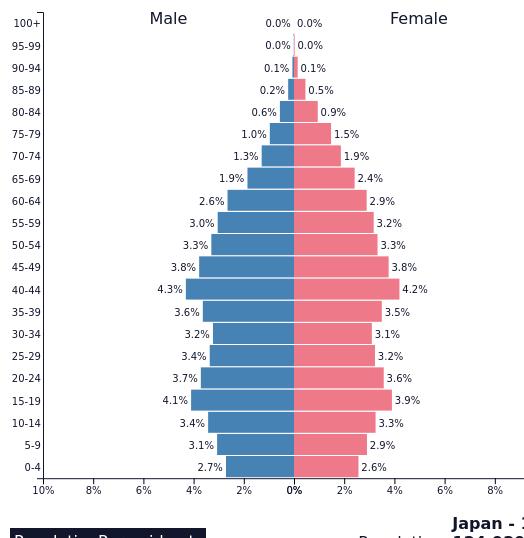

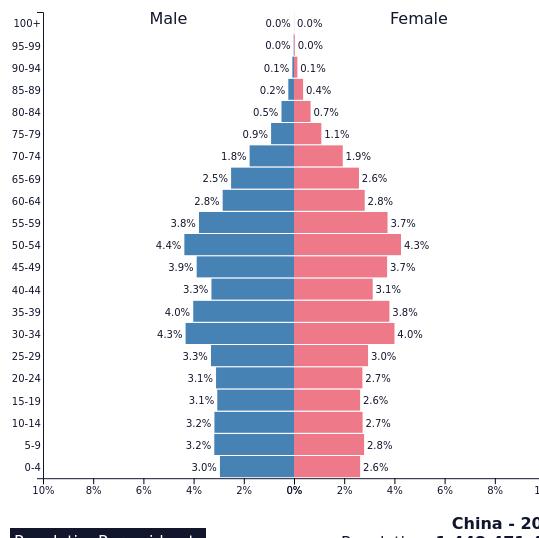

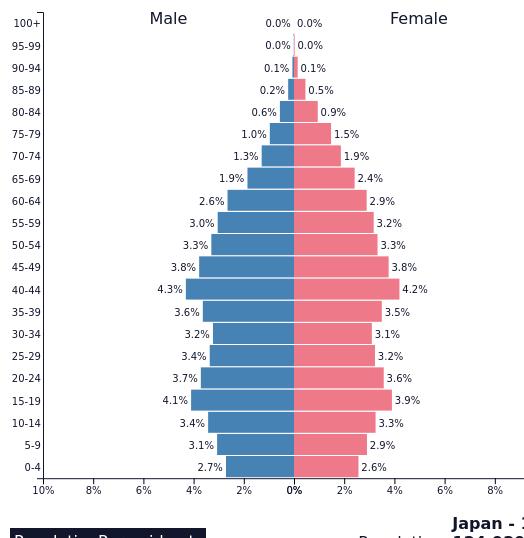

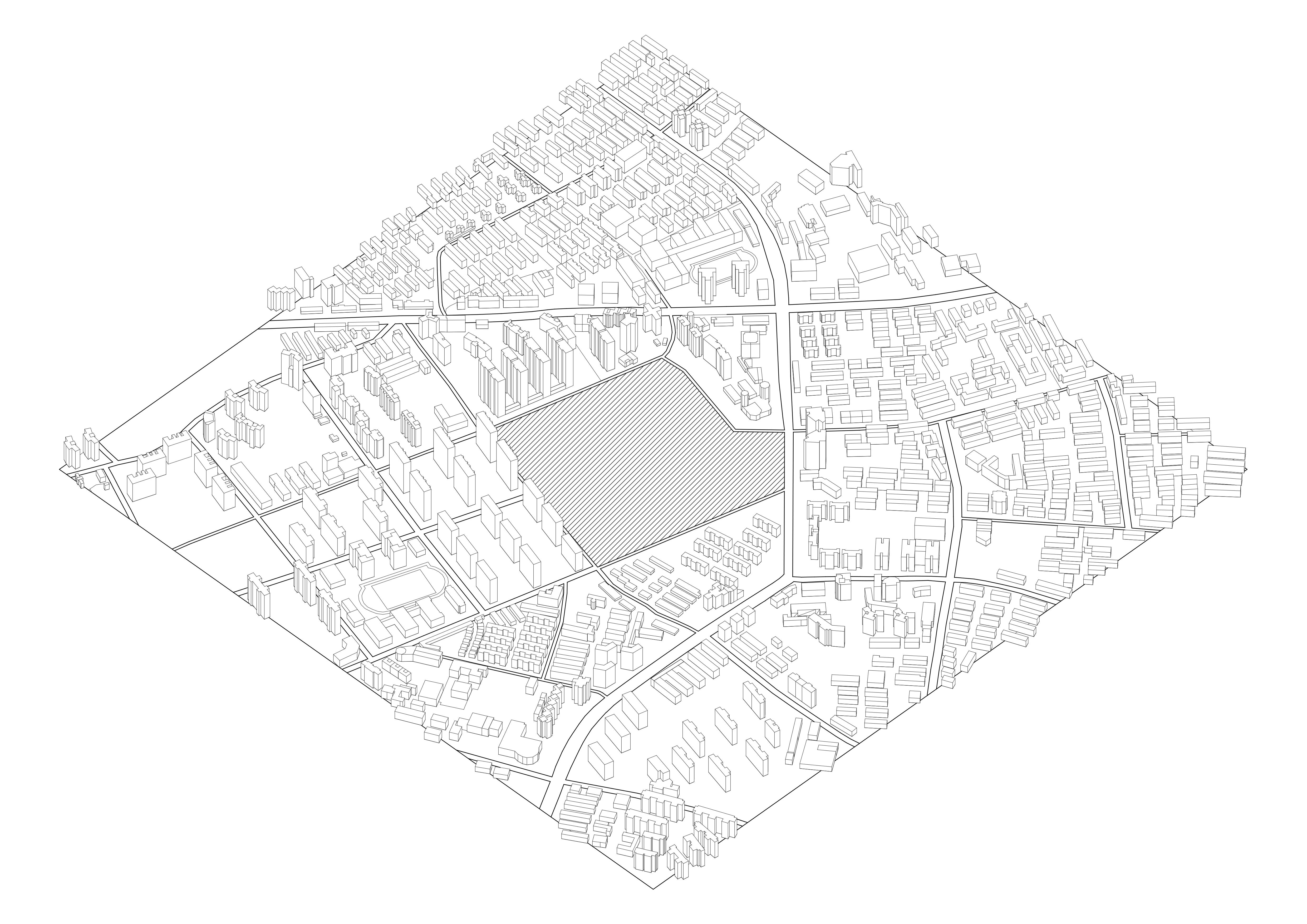

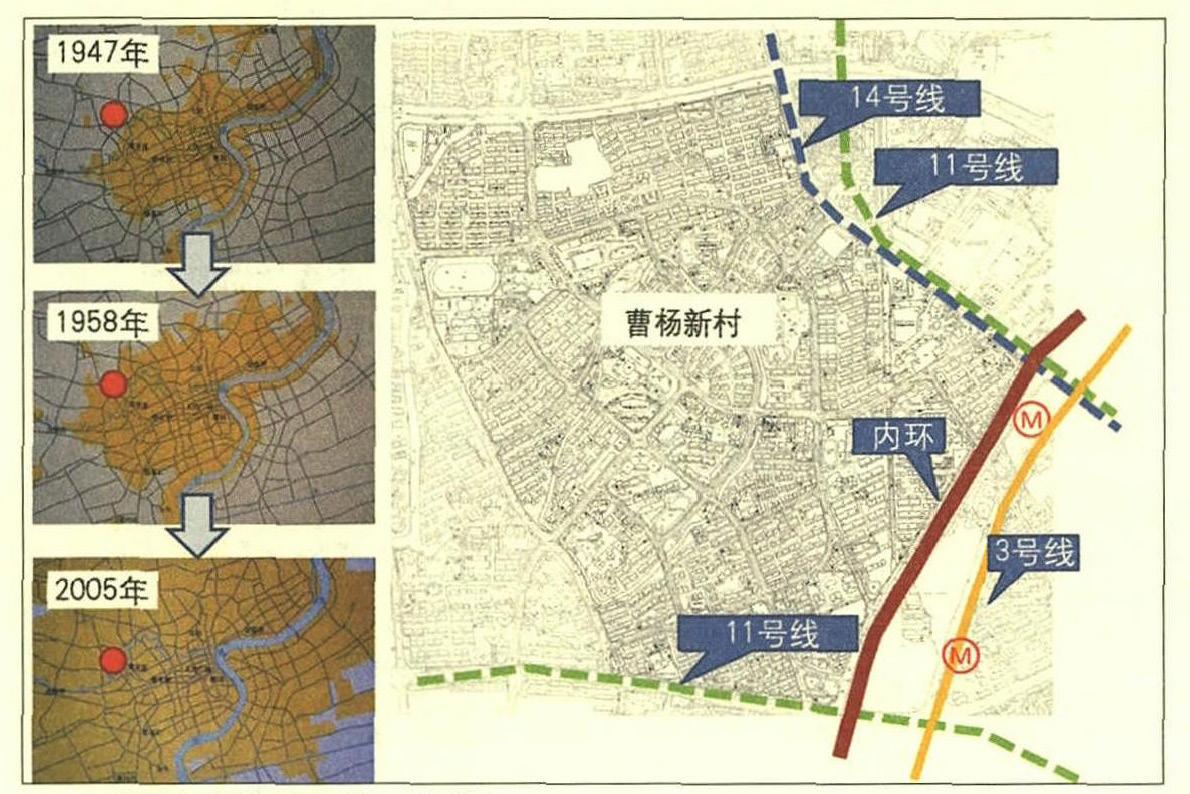

The Collapse of the Housing Bubble in China delves into contemporary issues facing China. The starting point is that a plethora of data points to the inevitable collapse of China’s real estate bubble in the 2020s. The collapse of financial capitalism’s logic in this industry goes beyond its surface-level implications and should be regarded as more than just an independent economic or industry crisis. Similar to Japan during the 1990s bubble economy, the collapse of the real estate market will not only lead to changes in housing typologies but also bring about changes in social structures, living forms, and even the urban context. Simultaneously, the housing market’s collapse represents a symbolic transformation of the four-decade-old system dominated by the big government in China, which prioritized “economic priorities” and rapid urbanization as the ultimate goals.

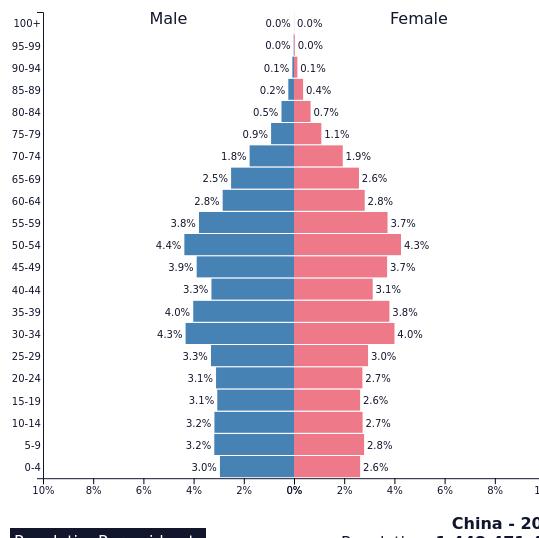

The thesis’ primary objective is to explore the new forms of living in China’s ‘post-real estate era’, which China had entered after real estate developers lost their absolute share in China’s housing industry. These new forms of living will be profoundly influenced by changes in power relations between the government, developers, and citizens resulting from the fall in land and housing prices and the rise of real estate tax. The burgeoning middle class in China, which has emerged in the hundreds of millions in the last two decades, will be a crucial subject of inquiry in this thesis. How they will exert influence in the housing system, fight for their agency, cooperate with the government/developers, and ultimately establish a new housing system will be explored.

Furthermore, the central argument’s ambition is to project such a change in living forms as a reflection of the state, providing the author with an opportunity to re-evaluate China’s past, present, and future. The thesis’s purpose is not to criticize capitalism, authoritarianism, or any other “-ism” in China using Western templates. On the contrary, this projection serves as an entry point to explore how different forces have played a role in the complex context during the past 70 years of the People’s Republic of China, which has undergone significant changes, ultimately shaping the prospect of China’s modernization.

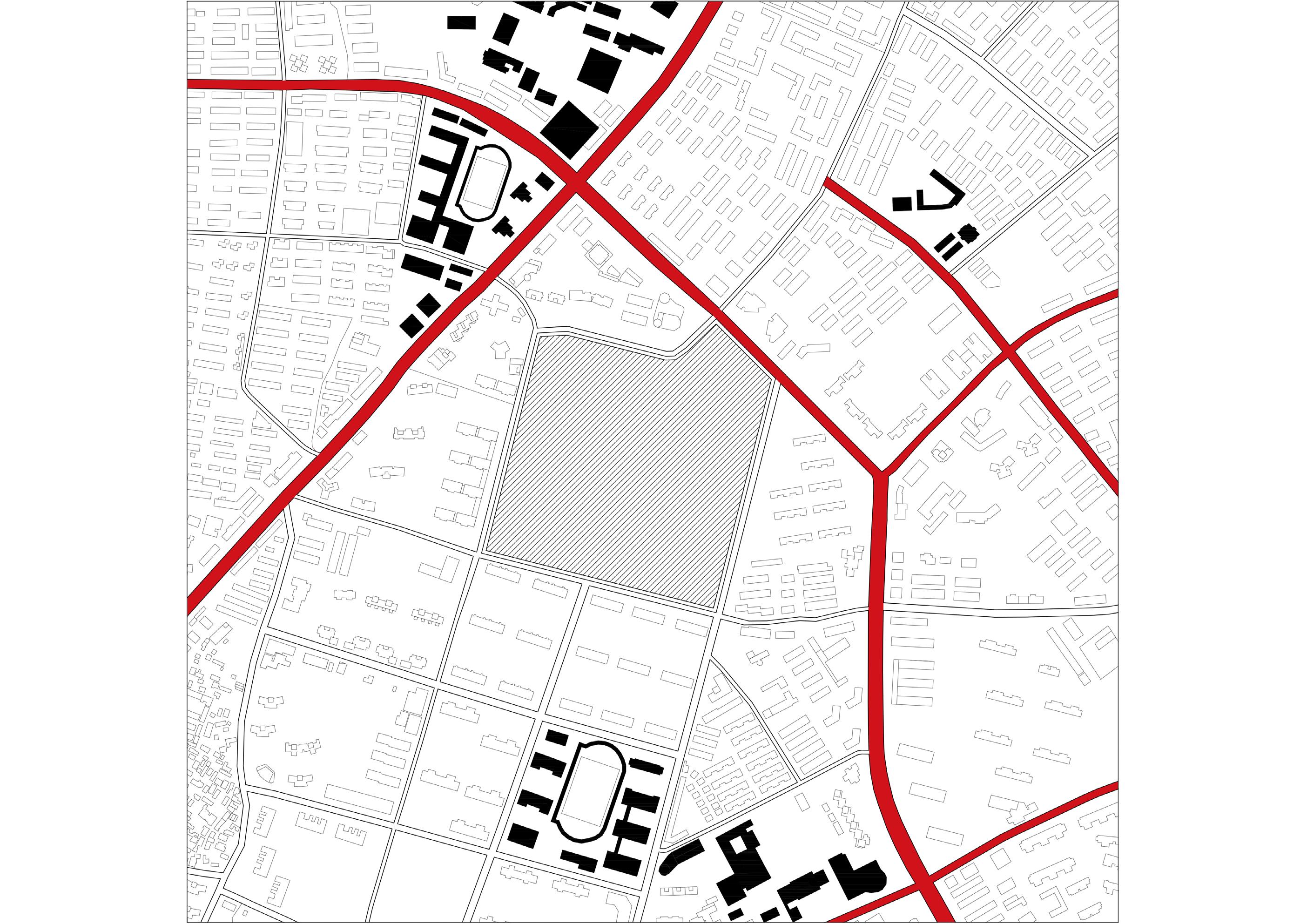

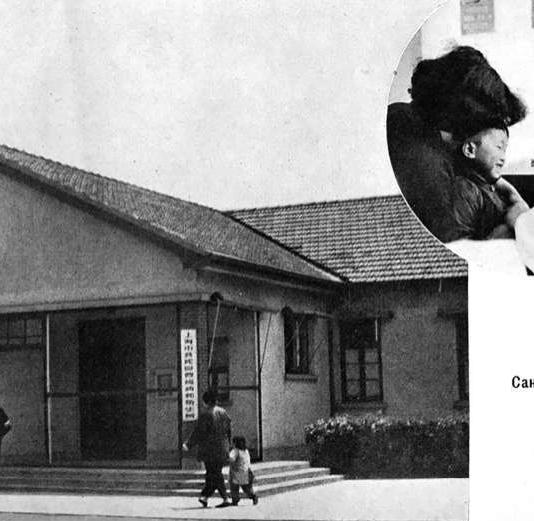

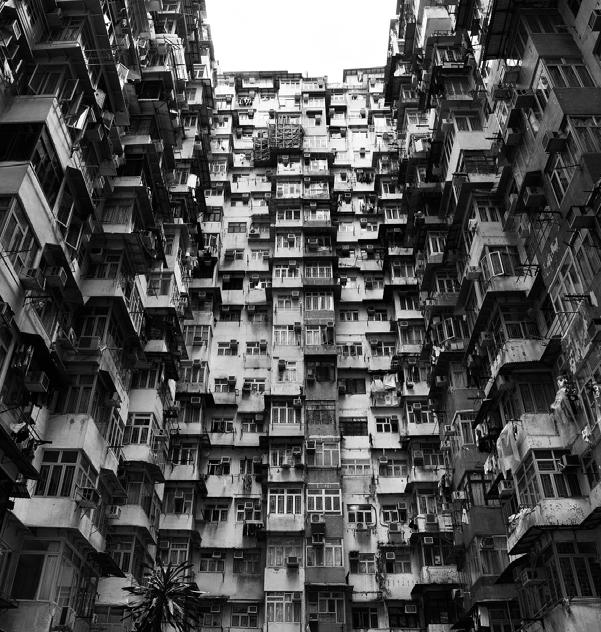

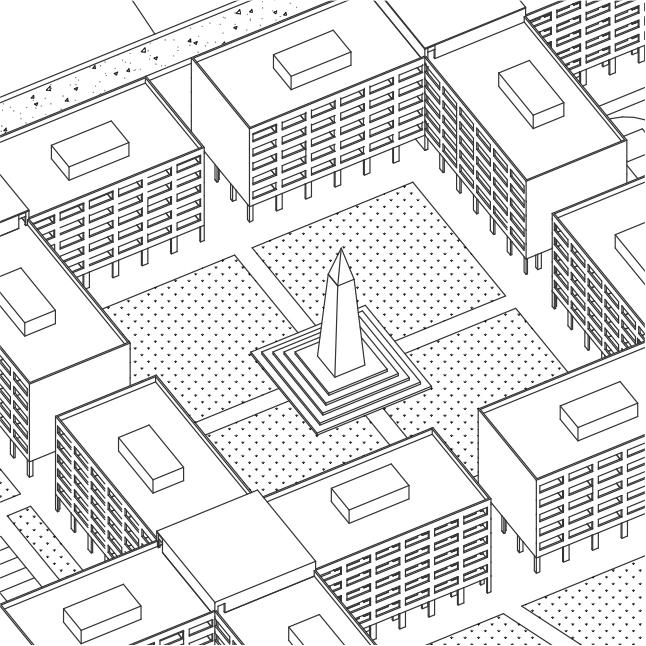

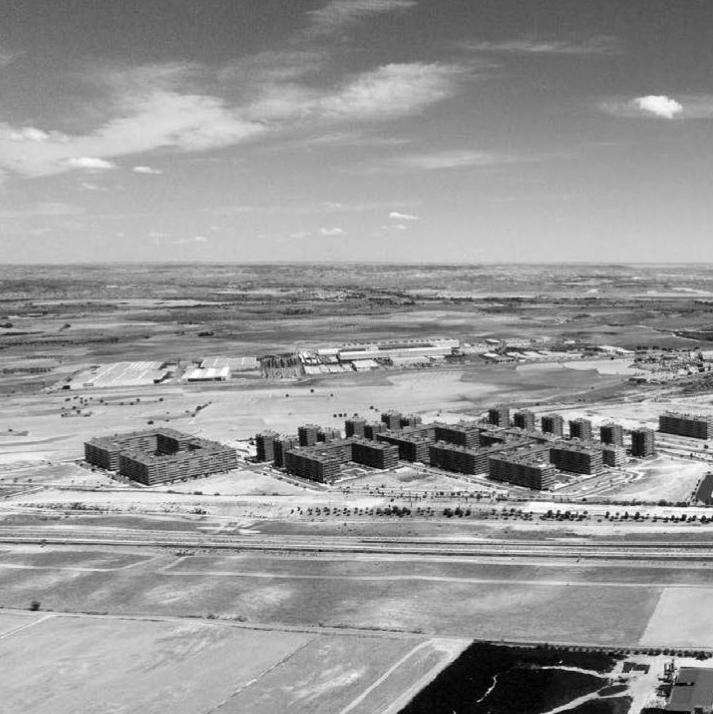

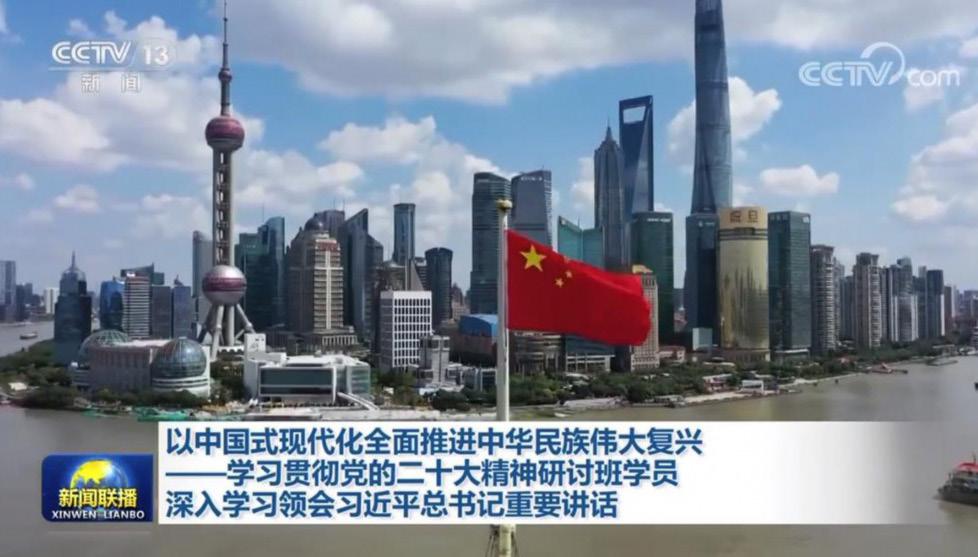

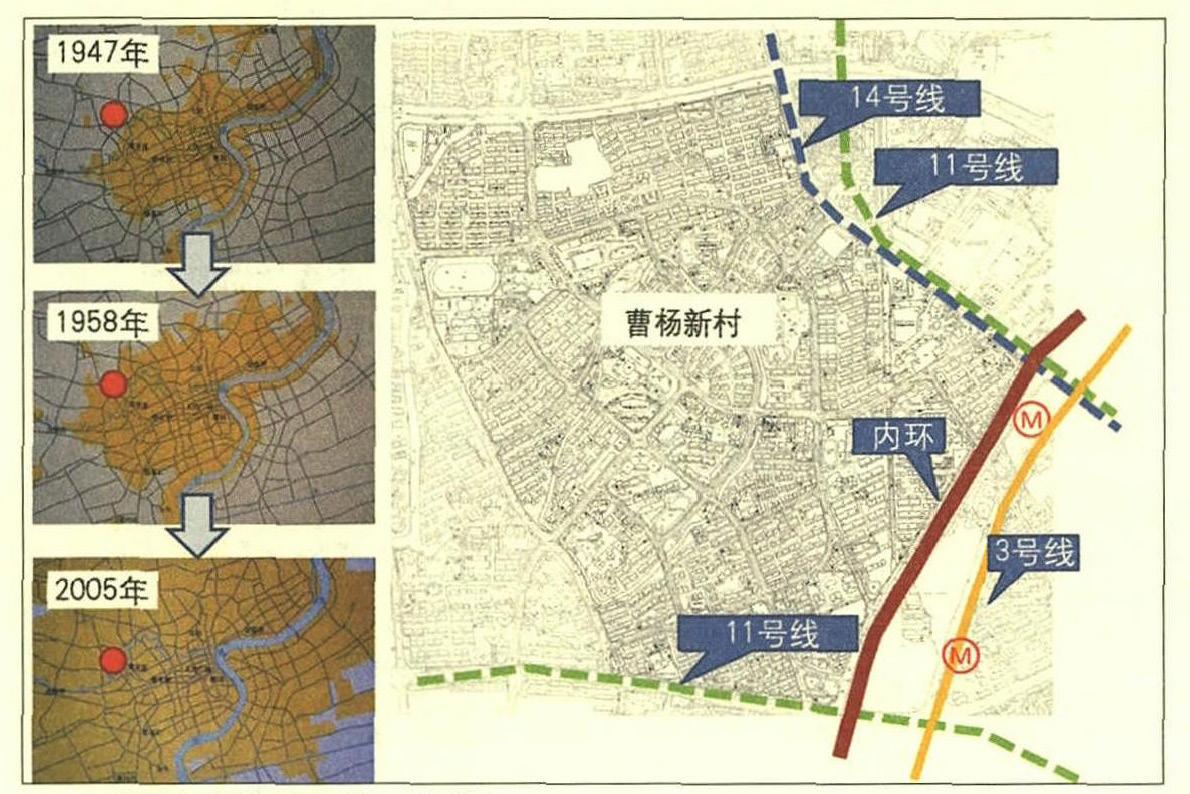

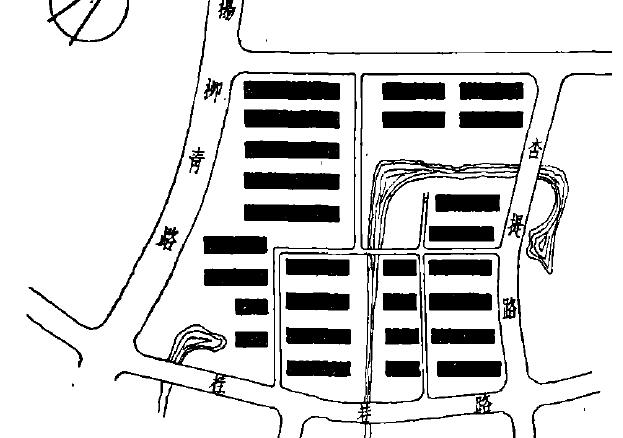

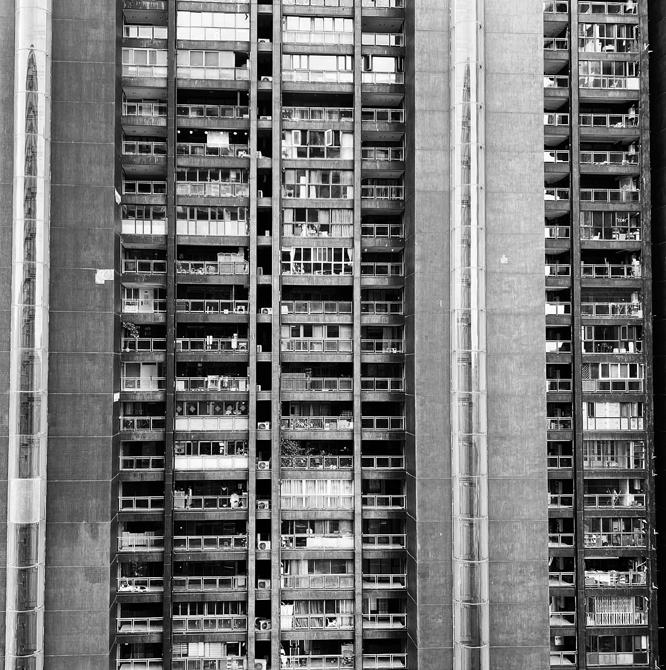

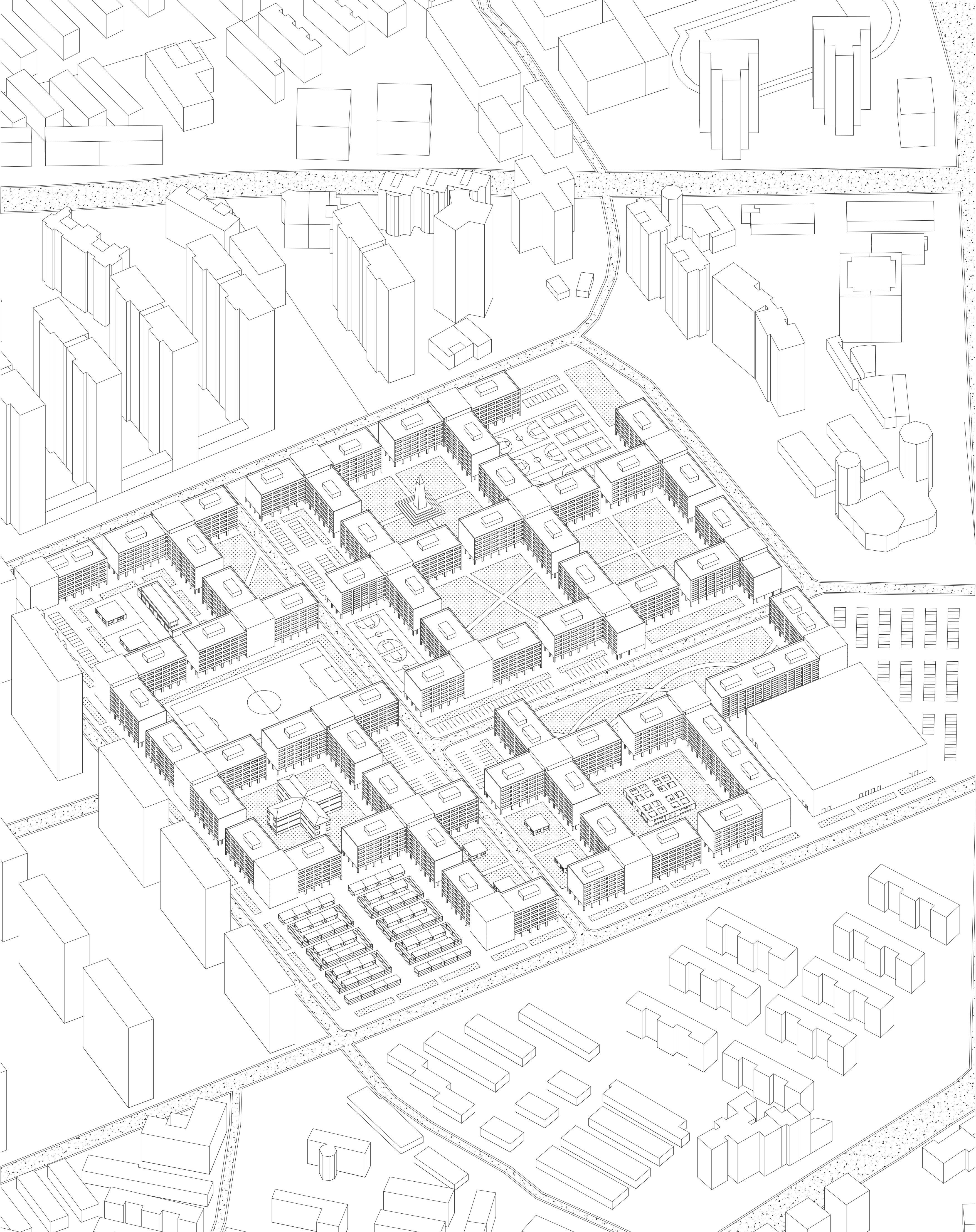

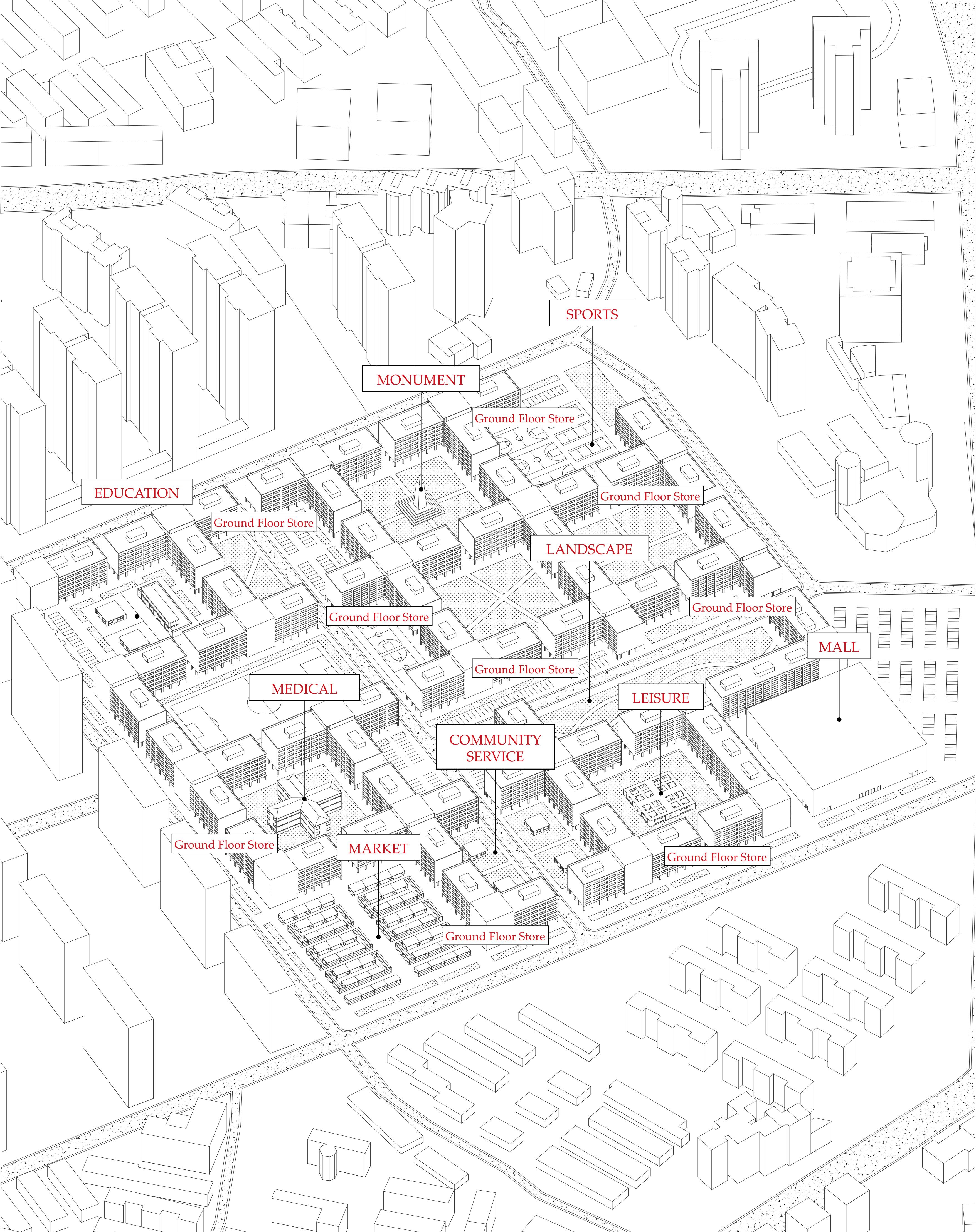

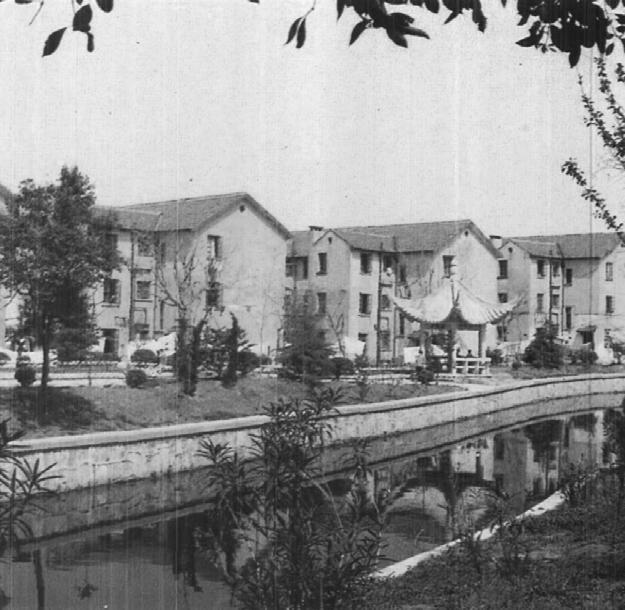

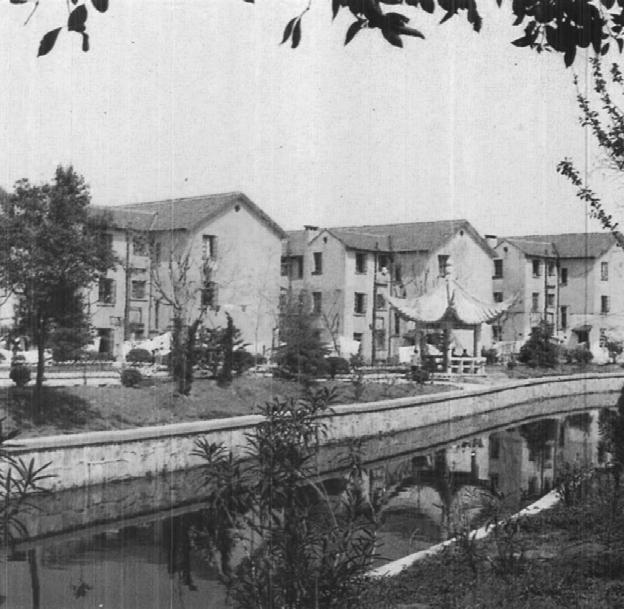

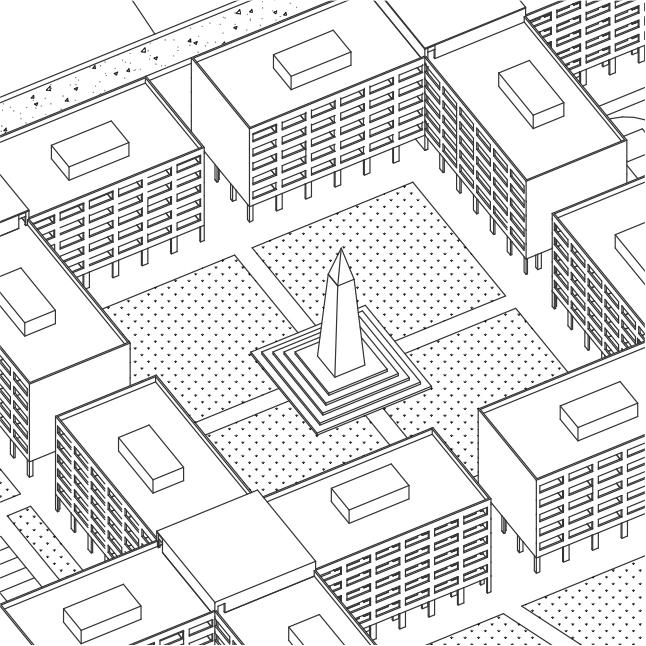

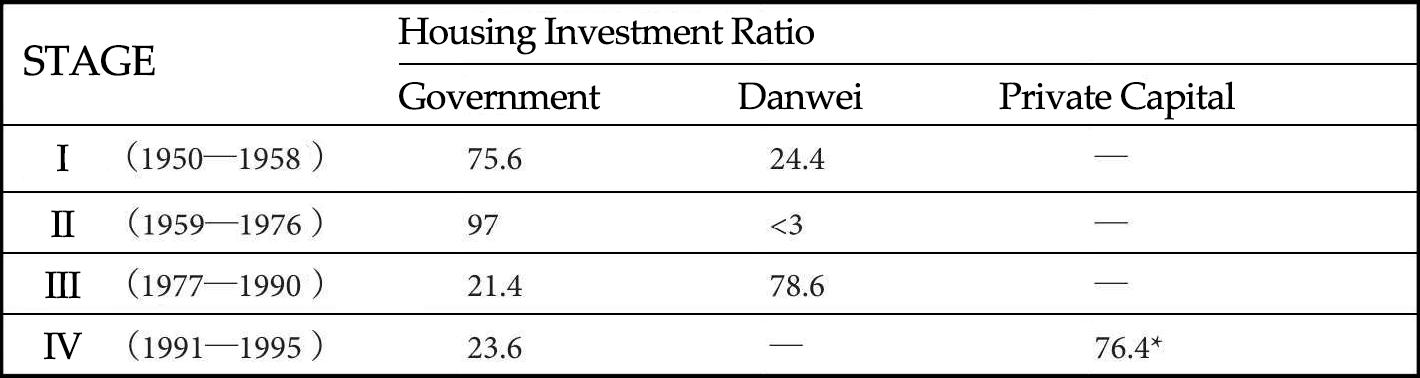

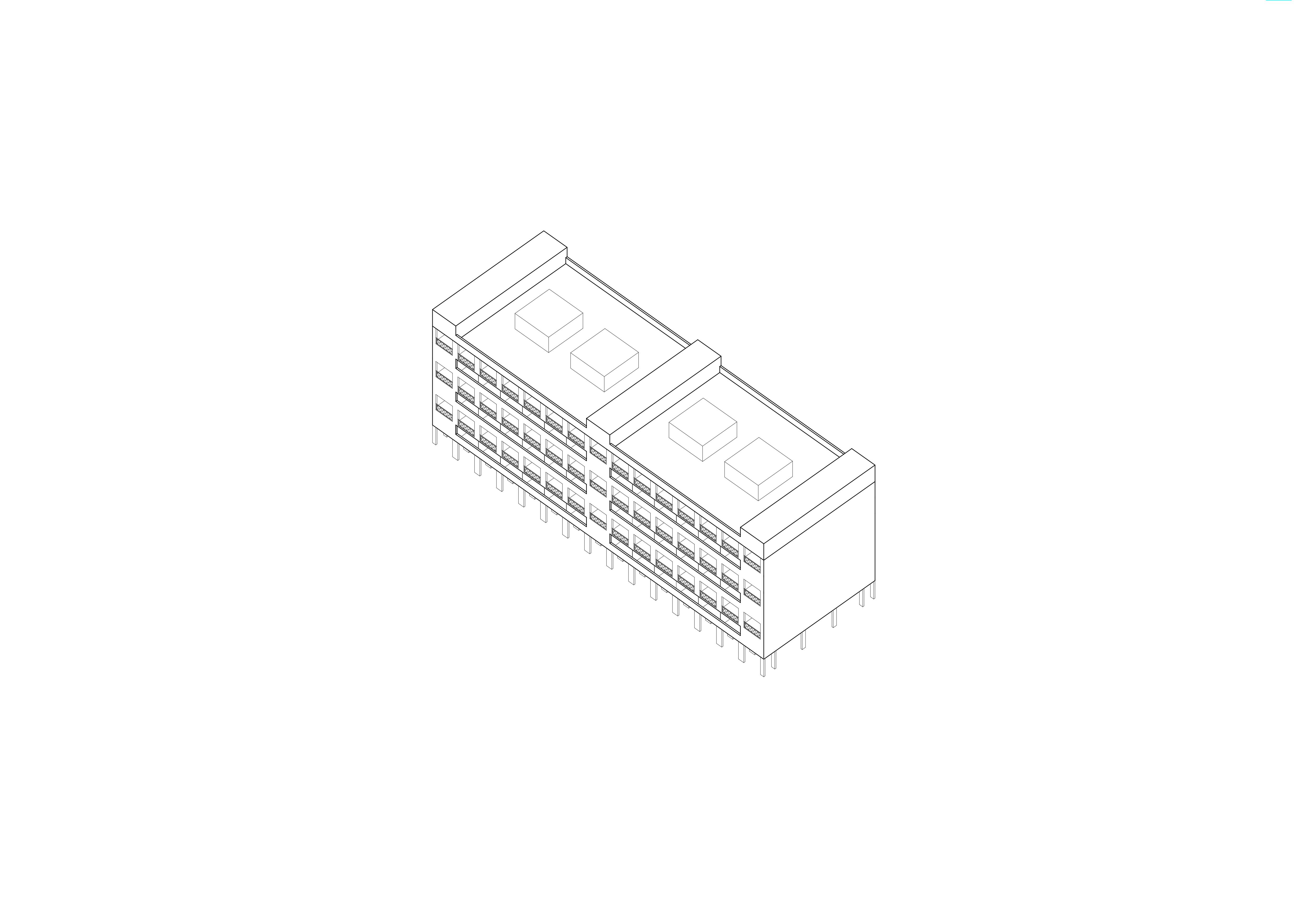

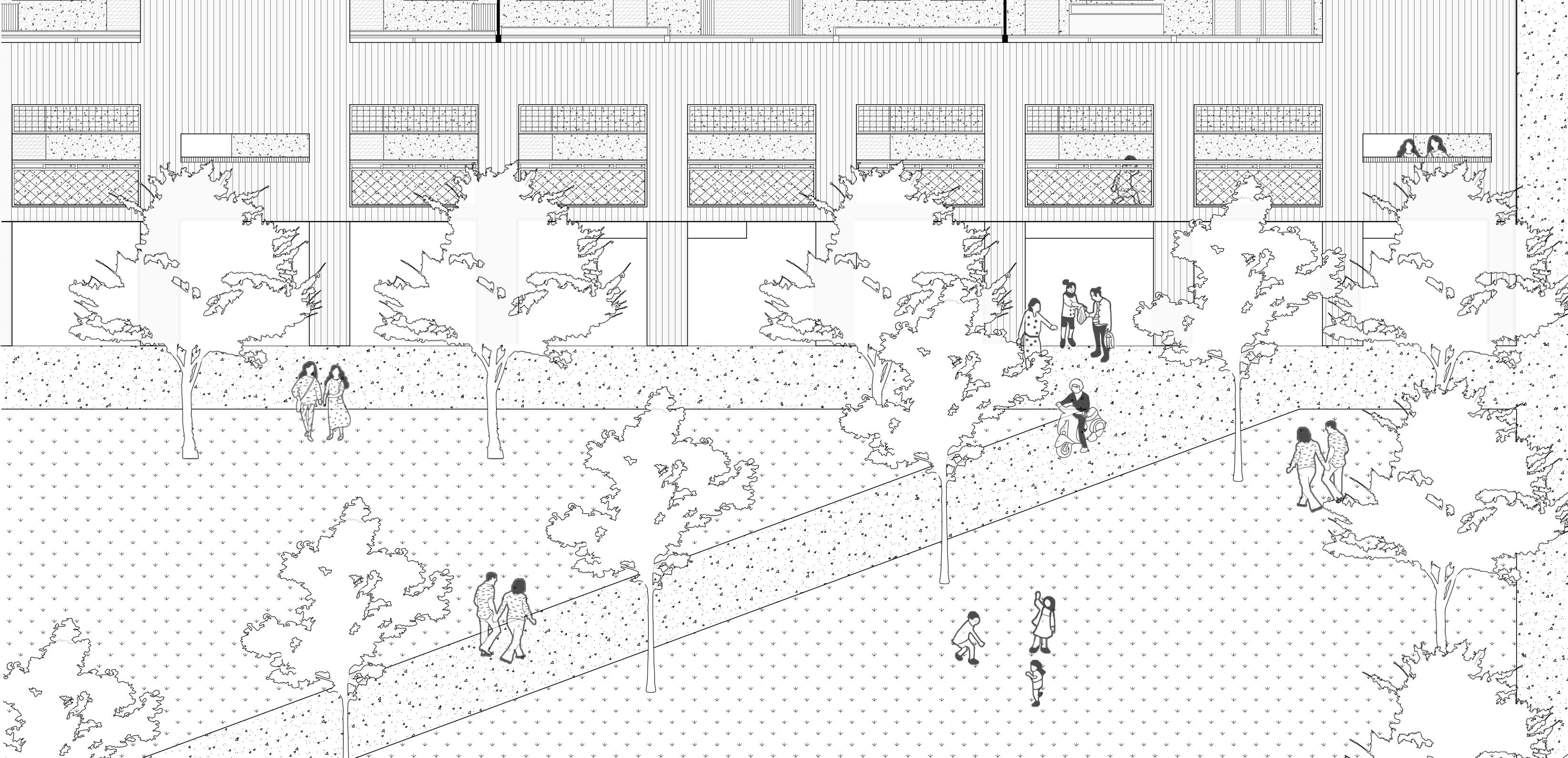

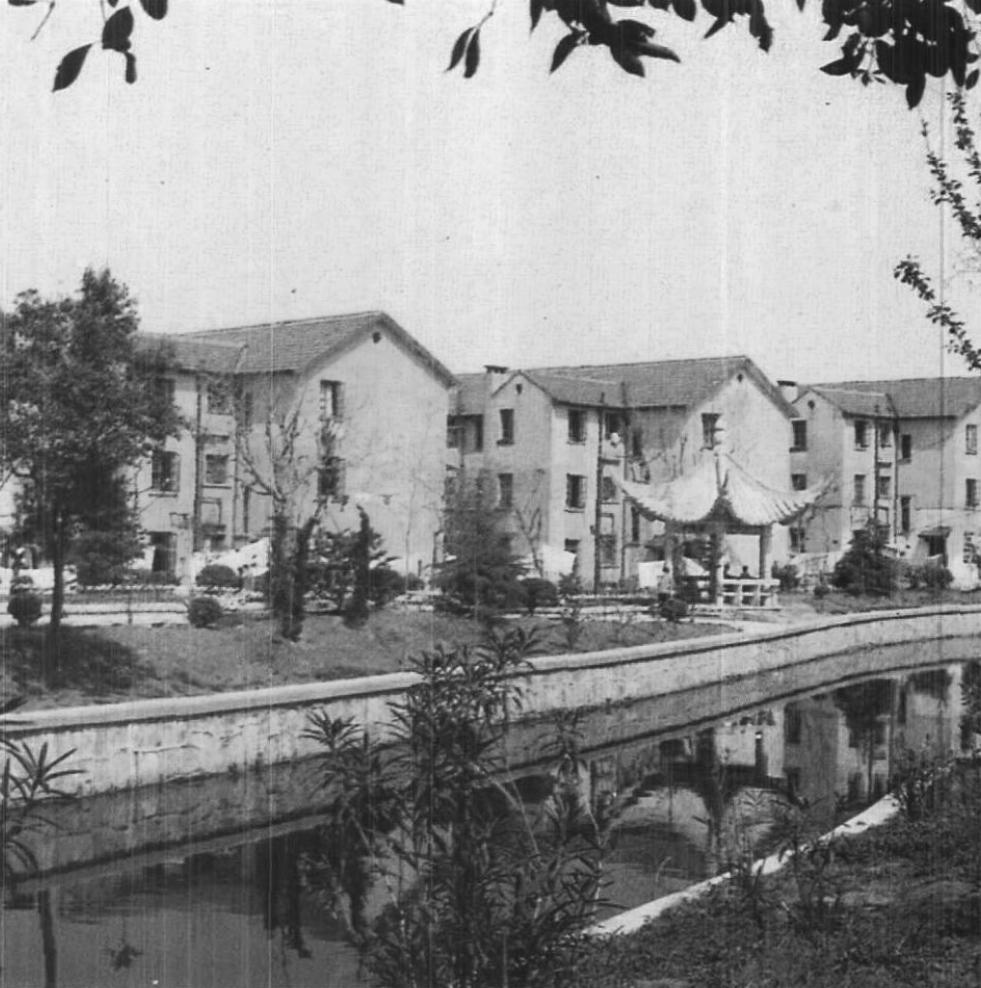

FIG.0.1

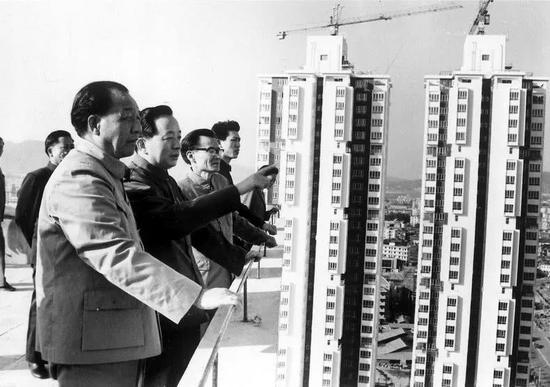

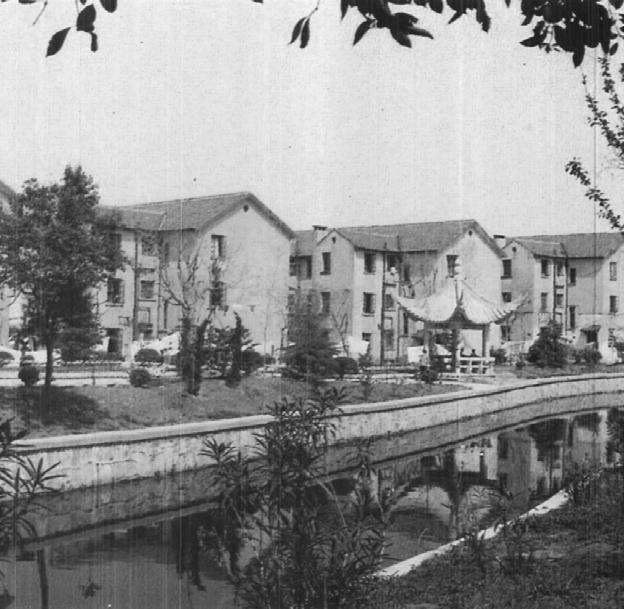

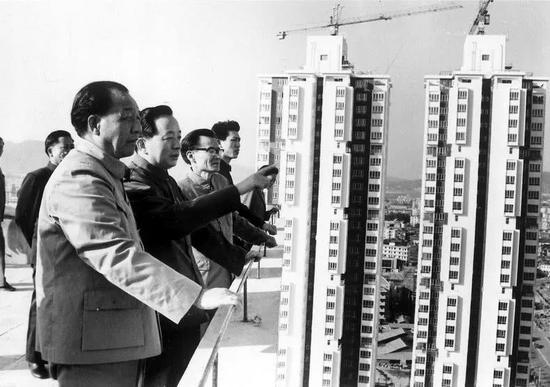

In the past seventy years, the living form of urban residents in China has undergone drastic changes along with the social changes.

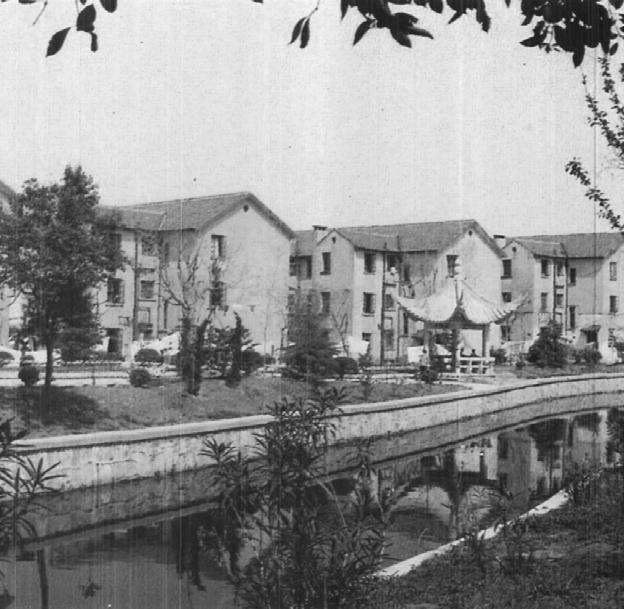

1. Left Top

The public housing in 1950s’ Shanghai. In planned economy China, urban residents lived in Danwei almost for free.

2. Left Middle

Henglong Housing, China’s first batch of commercial housing in Guangzhou. In 1993, a living unit sold for 170,000 yuan.

3. Left Bottom

In 2020s, the price of an apartment in Guangzhou is more than 3,000,000 yuan.

7

8

9 CONTENT CHAPTER 3. The Logic of (Financial) Capitalism CHAPTER 4. The Logic of Ownership CHAPTER 2. The Logic of Power Relation CHAPTER 1. From Welfare to Property: The Rise of Real Estate in Modern China INTRODUCTION RESEARCH STRUCTURE ABSTRACT BIBLIOGRAPHY CONCLUSIONS IMAGE SOURCES 7 10 14 17 35 59 105 140 146 150

1. The data comes from National Bureau of Statistics of China.

2. “People in the cities” (Chinese: 城里 人), In China’s dual urban-rural household registration system, “people in the cites” are considered to have better access to social welfare and public amenities, making them the envy of rural residents.

3. “the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” (Chinese: 中华民族的伟大 复兴) is a governing concept proposed by the Communist Party of China at the 15th National Congress in 1997, which prioritizes economic development. This concept was later developed by Chinese leaders such as Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping.

4. Real estate is a significant source of revenue for local governments in China. In 2017, China’s revenue from land sales reached 5.2 trillion yuan, accounting for 24.0% of local governments’ overall financial resources. Eleven real estate-related tax revenues reached 2.5 trillion yuan, accounting for 11.4% of local comprehensive financial resources. In total, the real estate industry contributed 35.4% of local fiscal revenues.

5. Yingfang Chen, City Chinese Logic (Chinese Edition: 城市中国的逻辑), (Shanghai: Shanghai SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2012).

INTRODUCTION

Capital, Power and Urbanisation

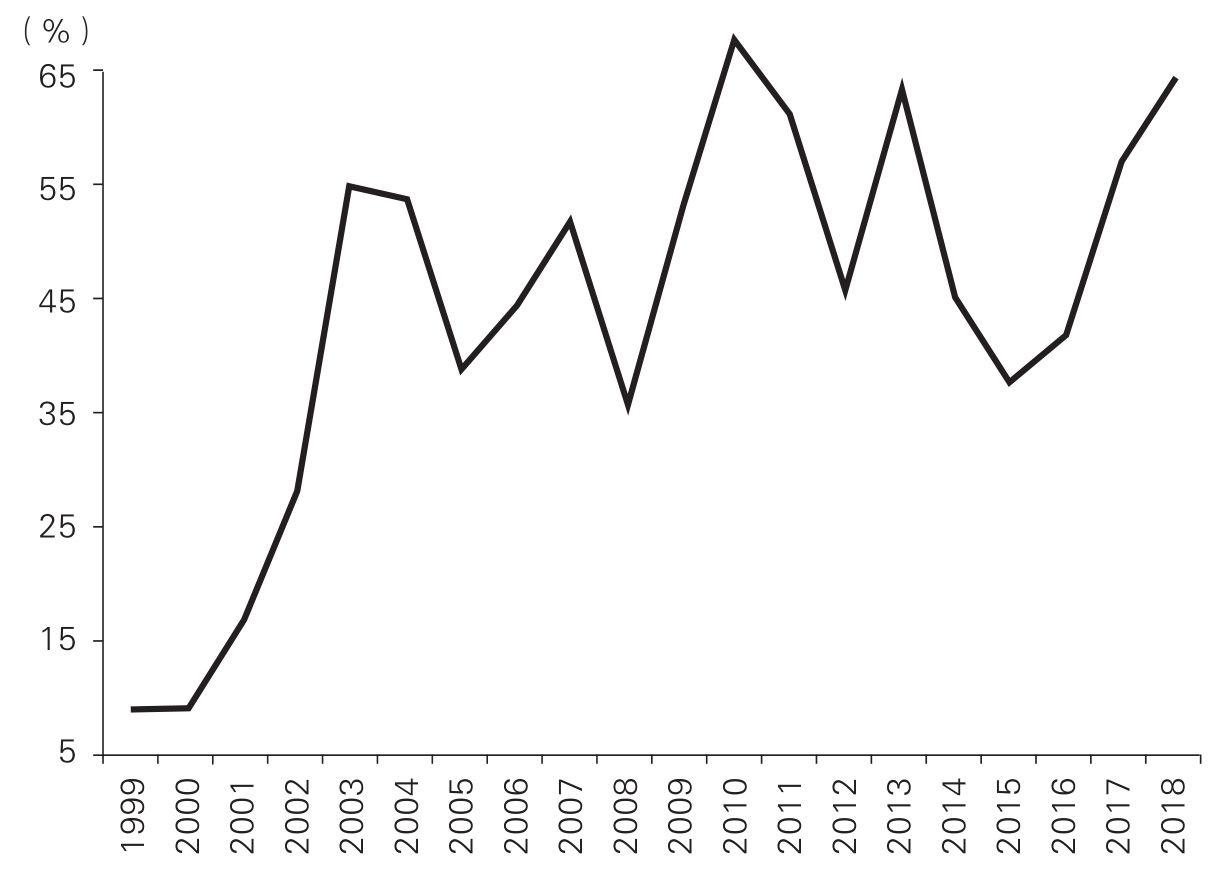

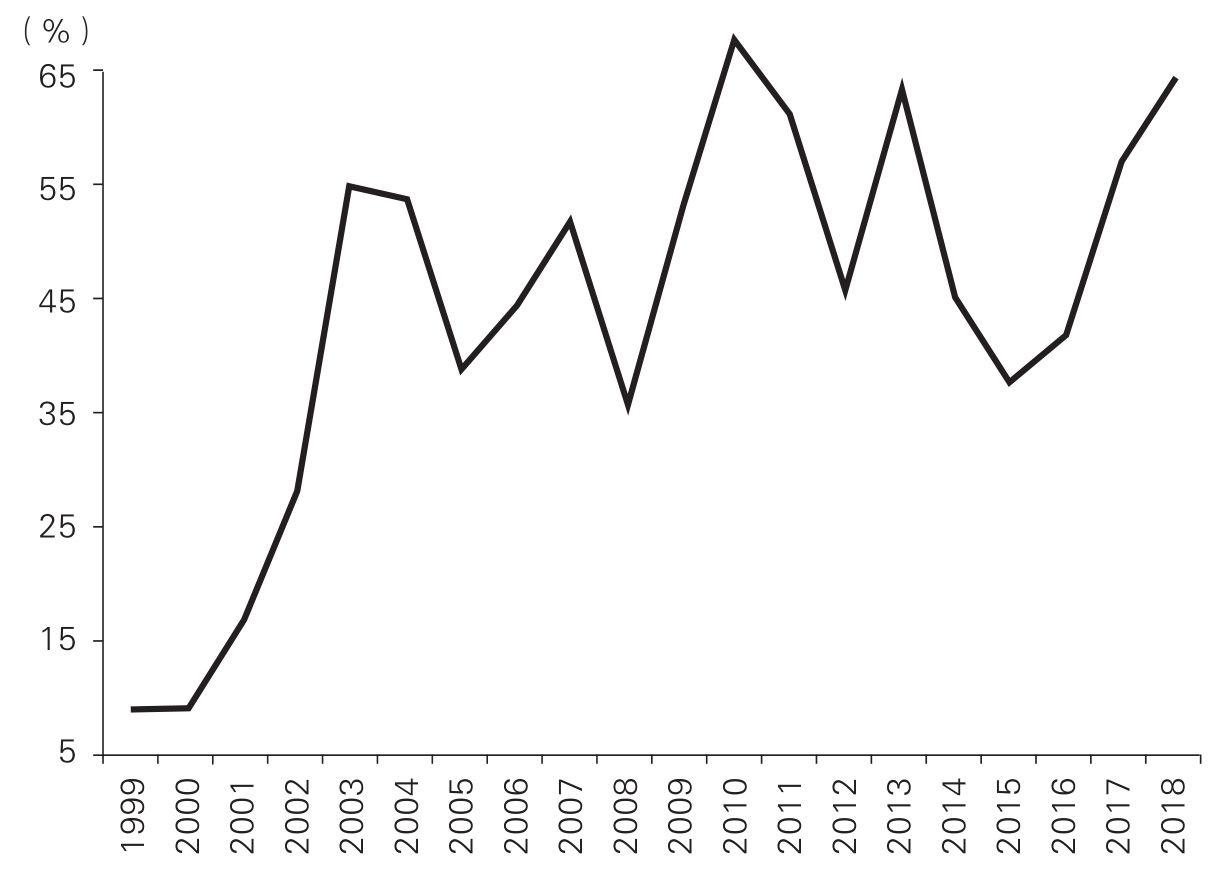

Following the reform and opening up of the 1980s, China’s urban development movement has been widely regarded as an economic development model dominated by the government’s power and developers’ capital, with the aim of maximizing land and space benefits as quickly as possible. In this model, China’s urbanization rate grew rapidly from under 20% in 1978 to over 60% in 2019 (FIG.0.2), as a large number of Chinese shed their rural identities and became “people in the cities 2”. This process has undoubtedly been a miraculous feat that has stunned the world. Amidst this backdrop of success and pride, the national ideology’s “economy-first” strategy of the last forty years has conferred unchallenged ethical and moral validity upon “urbanization” and “urban development” as instruments for realizing “the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation 3”.

After the tax-sharing reform in 1994, local governments in China were faced with financial difficulties and had to resort to land finance as solution 4, which led to a surge in land and housing prices. Local government’s dependence on land finance created a strong alliance between the government and real estate developers, which has been wildly criticized as unjust and non-transparent (FIG.0.3.1) 5. As a result, corruption in urban development have become frequent. Citizens, including landowners and residents, have been excluded from participating in the urbanization process and have suffered losses in the interests.

10

FIG.0.2 The Urbanisation of China, 1949-2019 1

GOVERNMENT

CITIZEN DEVELOPER provide legitimacy sourcesof finance

FIG.0.3.1

GOVERNMENT

CITIZEN DEVELOPER

FIG.0.3.2

11

Power relation in the housing system between government, developer, and citizen in the era of real estate.

The collapse of real estate will lead to transformation in power relations in the housing system.

6. All the above data comes from Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and CEIC Data.

7. Matthew Soules, Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century, (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2021).

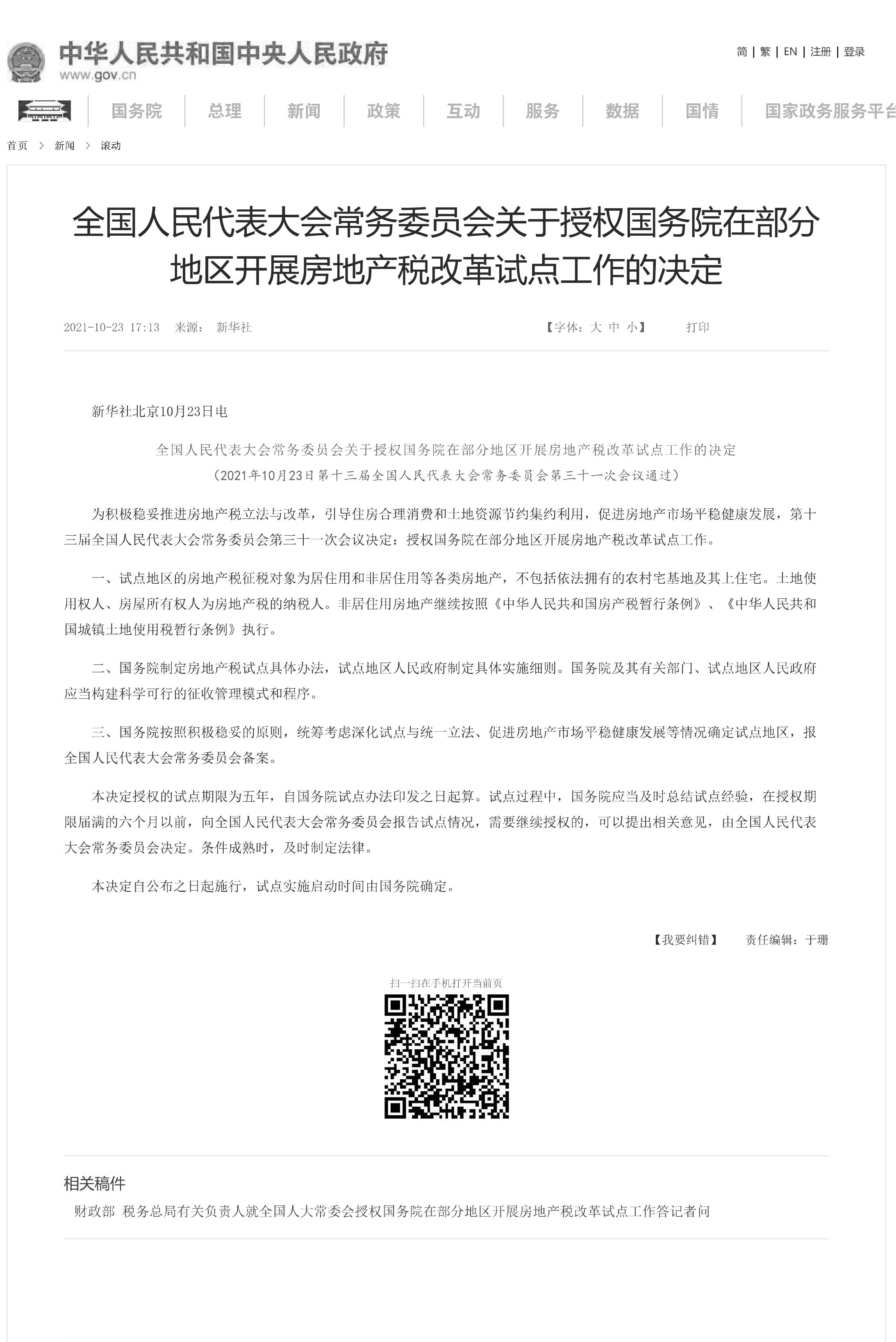

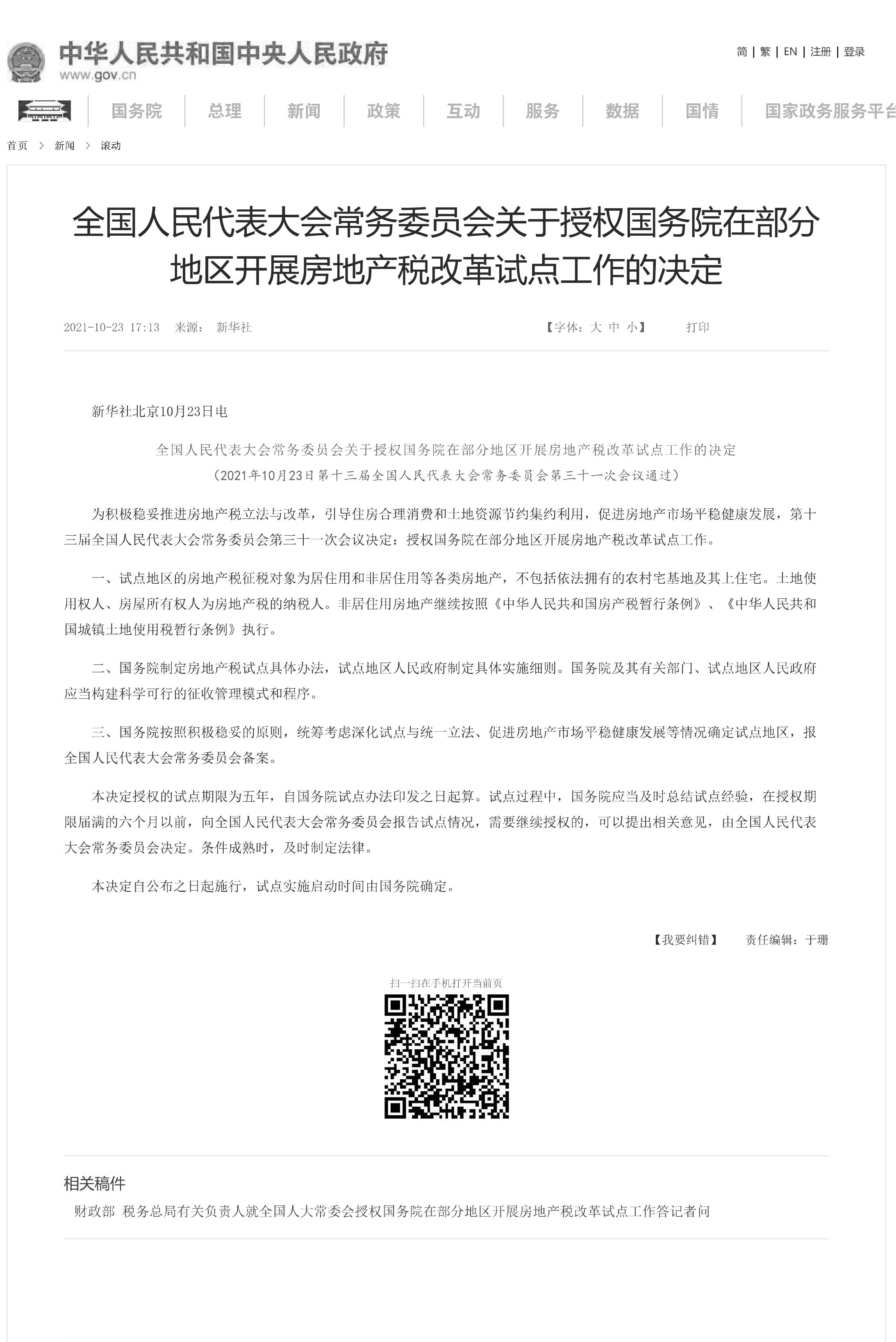

8. The State Council of The People’s Republic of China, Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on authorizing The State Council to carry out pilot real estate tax reform in some regions (Chinese: 全国人 民代表大会常务委员会关于授权国务院在部 分地区开展房地产税改革试点工作的决定), Available at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-10/23/content_5644480.htm.

The Collapse of the Real Estate Market and Real Estate Tax

After experiencing rapid economic growth for almost forty years, China’s economic growth is now gradually slowing down. However, with the depletion of land resource potential over the past 40 years, the Chinese government’s land finance policy has become unsustainable in the 2020s. The excess housing supply and exorbitantly high house prices have pushed the real estate industry to the brink of collapse. In the first quarter of 2022, the transaction area of new commercial housing in the top 100 cities in China dropped by 40% year on year. Since 2021, more than 400 real estate developers in China have gone bankrupt due to capital chain breaks. Among them are big names like Evergrande Group and Sunac China Holdings Limited, which have assets worth more than one trillion yuan and are now on the verge of total collapse. In the 2020s, the housing price in Shenzhen is 25 times higher than the average household disposable income 6, forcing many families to use all the money from six wallets (the wallets of the partner and their parents) to purchase a shelter. In the logic of financial capitalism, real estate is seen as an object of investment rather than a necessity for human habitation 7. To address this issue, Chairman Xi Jinping stressed in his address to the Nineteenth Party Congress in 2017 that “Houses are built to be inhabited, not for speculation.” This manifesto also reflects the end of China’s land development strategy during its rapid economic growth. After over two decades of the golden age, the logic of (state) financial capitalism has finally ended in China’s housing system.

Therefore, in 2021, the Chinese government initiated a pilot real estate tax reform program to fill the financial gap for land sales 8 (FIG.0.4). This reform is considered the Chinese government’s core policy to ensure the stability of local government finances. Although the nationwide roll out of real estate tax reform is still pending, it is reasonable to assume that the resources of government finance will shift from private capital (real estate developers) to property owners (citizens). As a result of this new source of tax revenue, the alliance between the government and real estate developers will gradually weaken, and a new power relation will form among the government, citizens, and real estate developers, creating diverse opportunities for new forms of living (FIG.0.3.2).

12

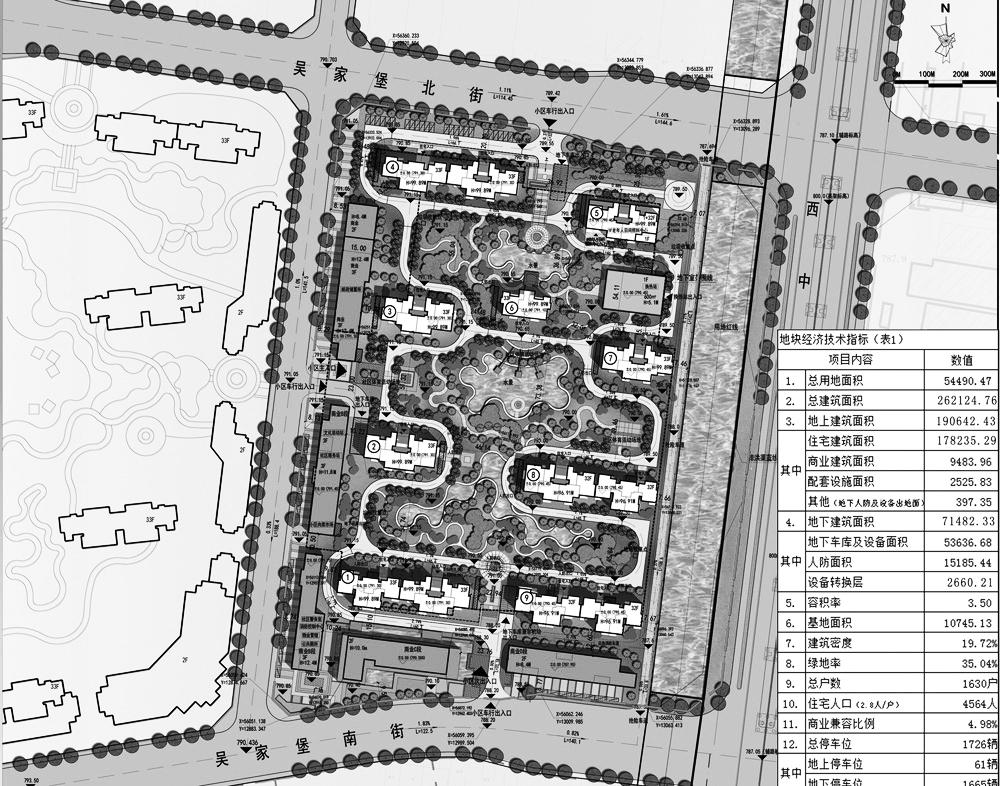

In 2021, Chinese government started real estate tax reform as core policy for the future. Real estate tax will become an important source of finance for China’s local governments in the future.

13

FIG.0.4

The Crisis of Real Estate as the Crisis of the State

Abstract and introduction

Chapter 1

From Welfare to Property: The Rise of Real Estate in Modern China

Looking at the transformation of China’s housing system since 1949, it can be gain insight into how China’s real estate industry developed from its birth to its peak, and then to its collapse in the 2020s.

Chapter 2

The Logic of Power Relation

The analysis of power among different interest groups within the housing system is the core methodology of this thesis. Through the analysis of this core element, we will guide the development of two different pathways of urban imagination in Chapters 3 and 4.

Different Pathway

The Continuation of Old Logic

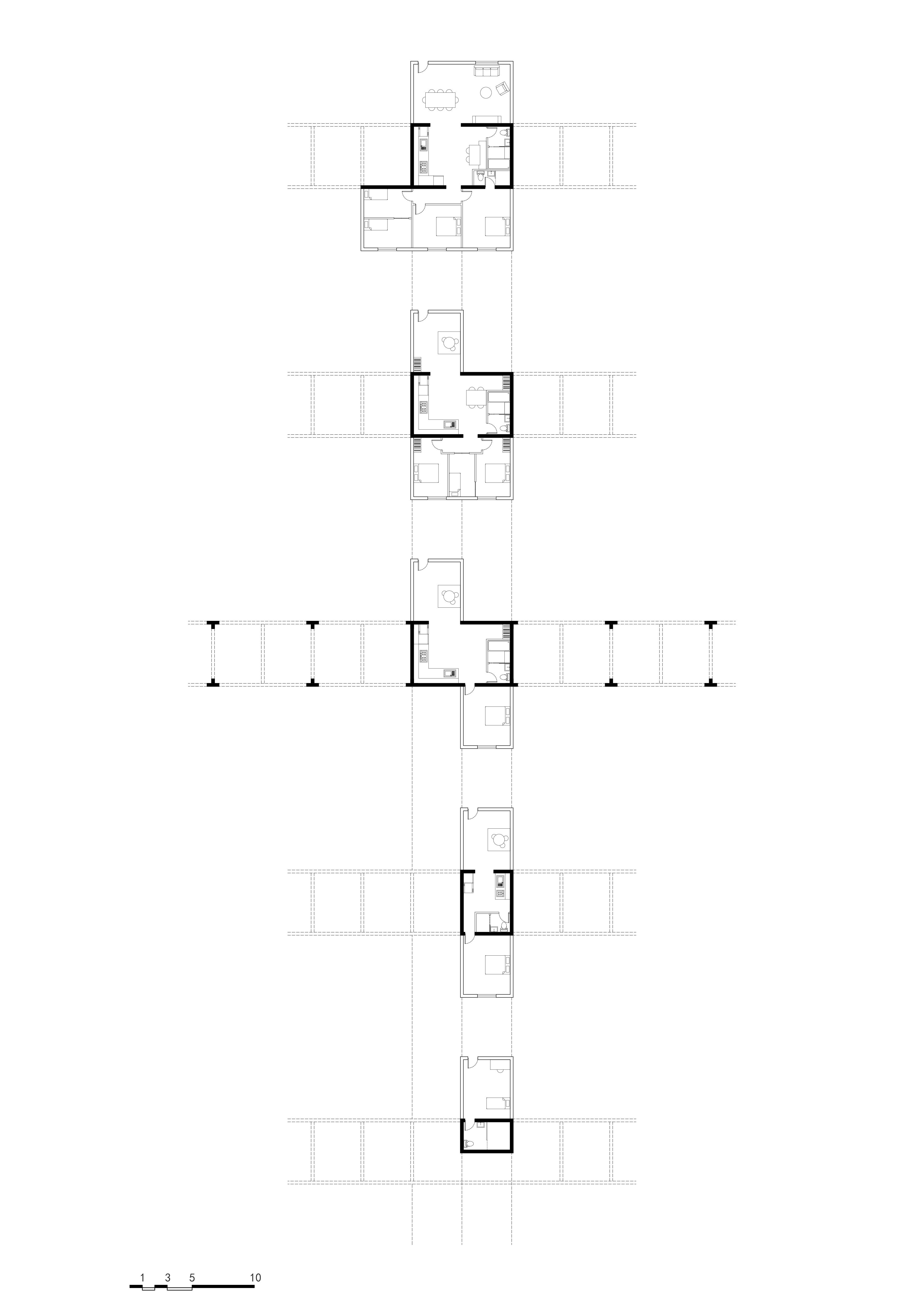

Chapter 3

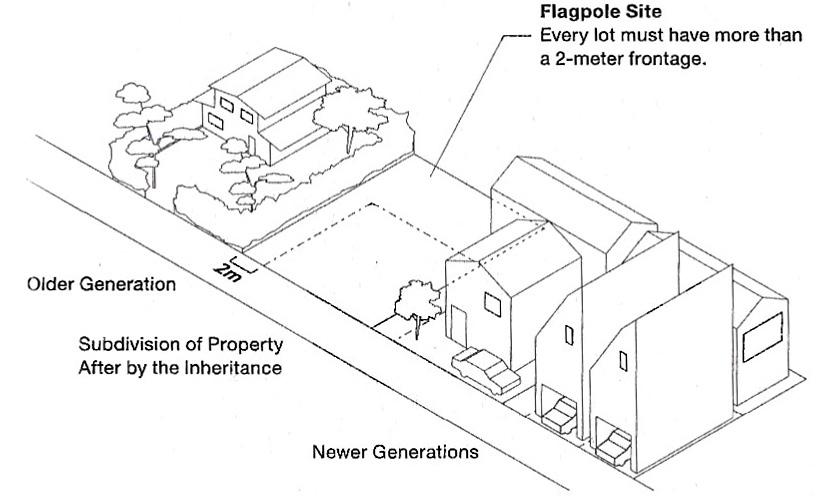

The Logic of (Financial) Capitalism

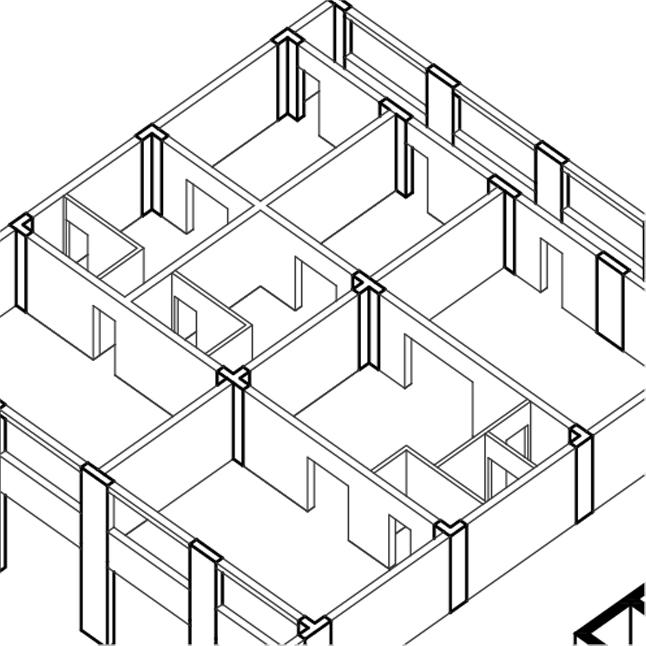

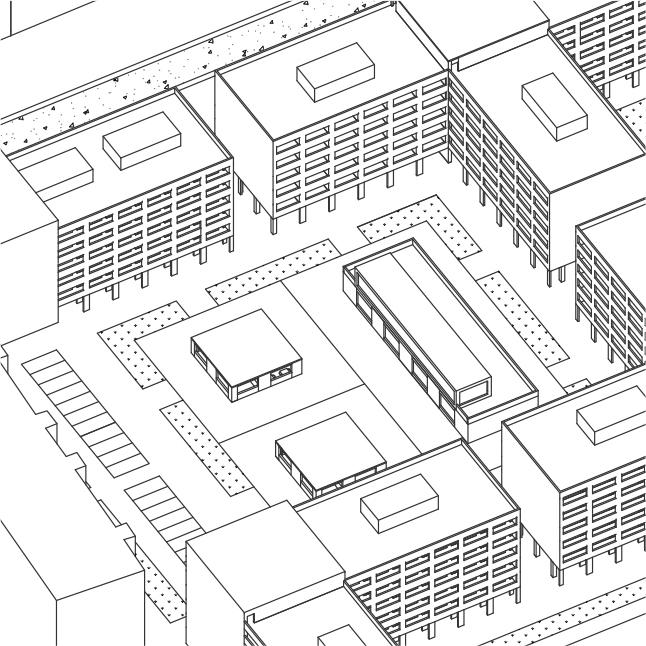

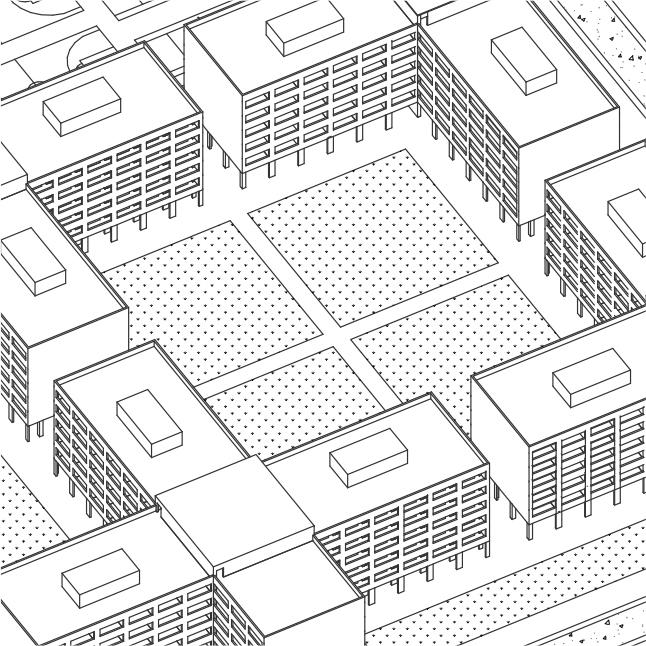

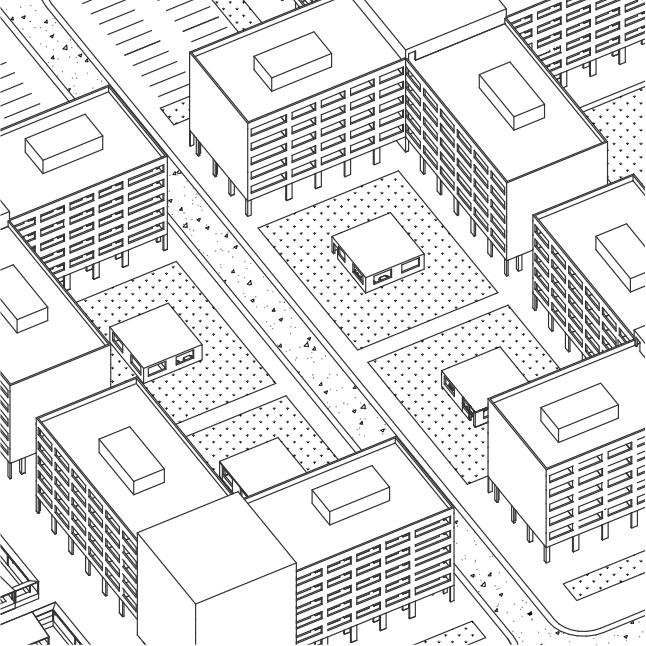

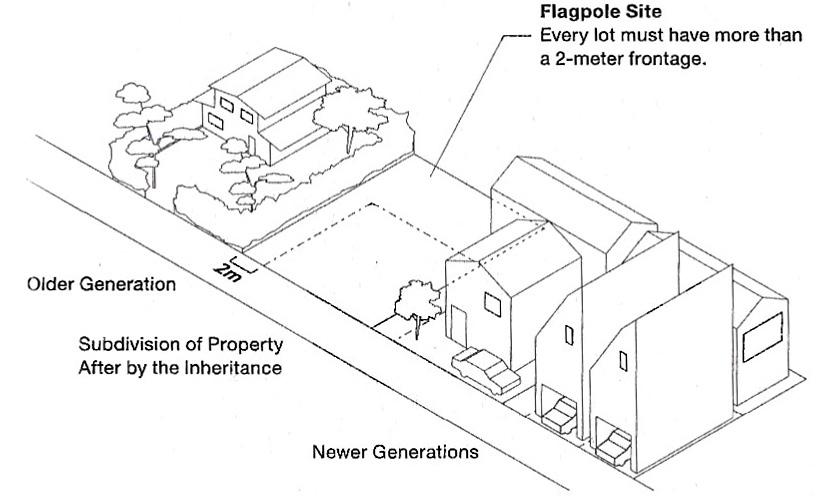

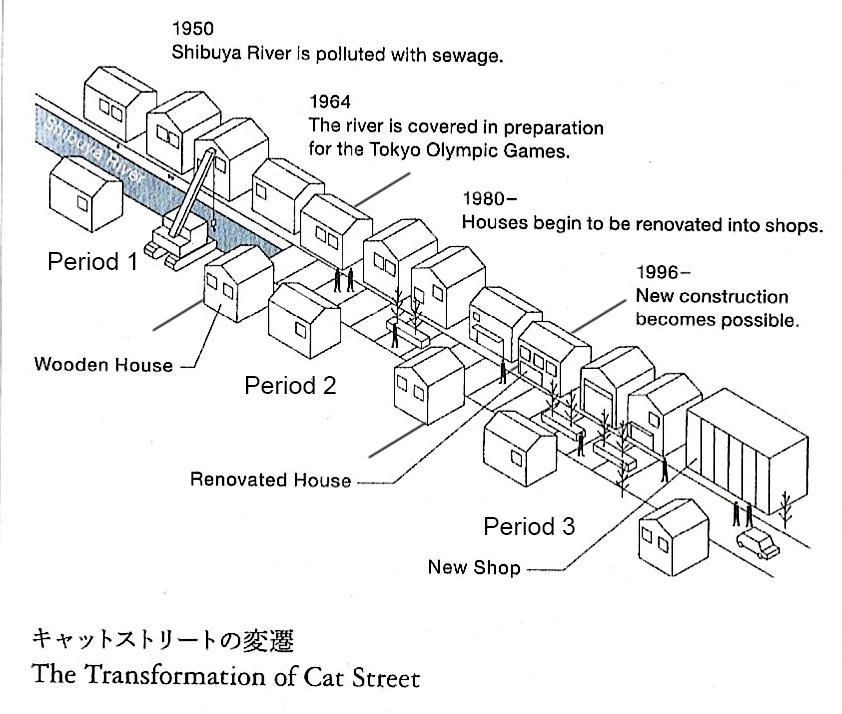

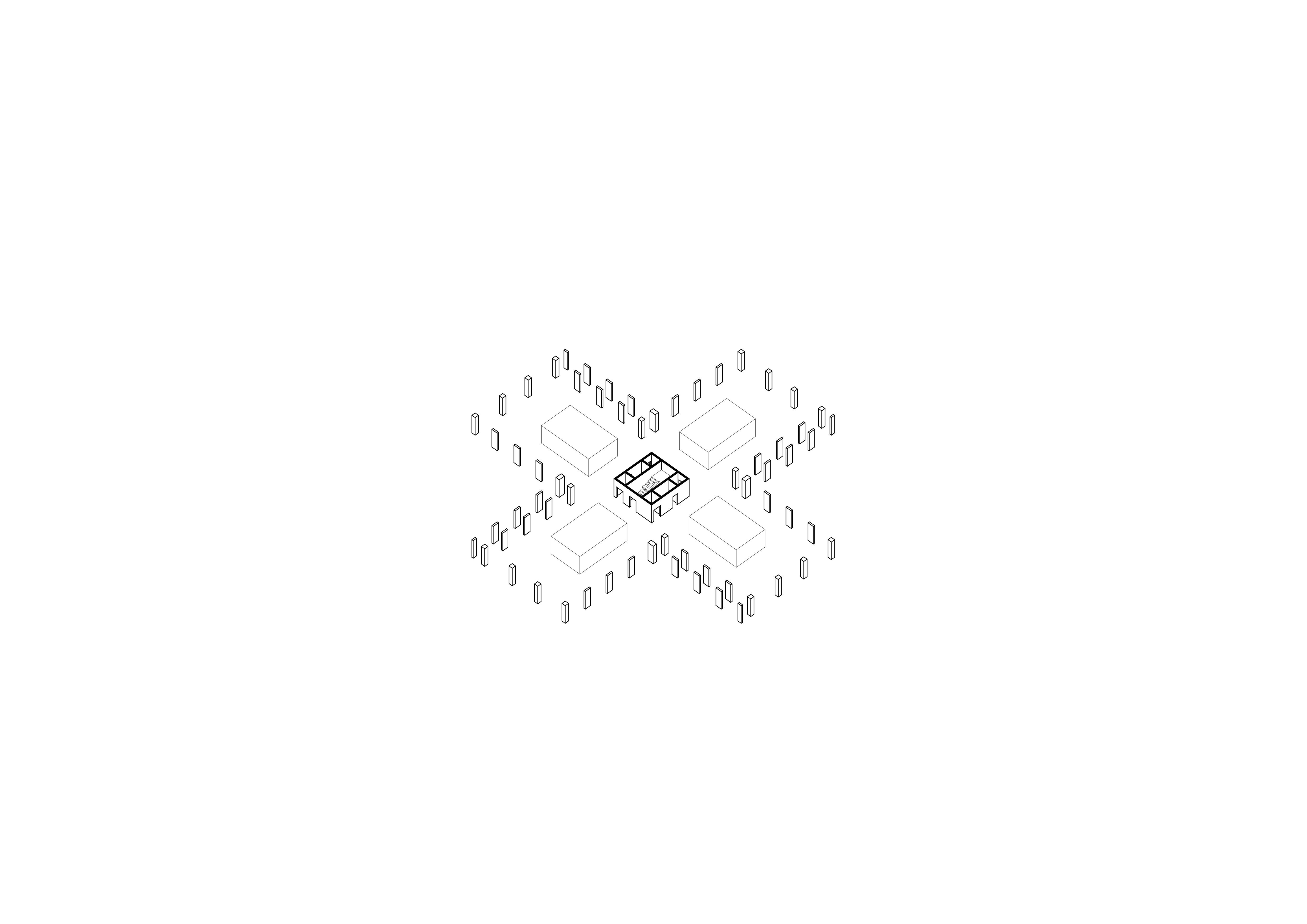

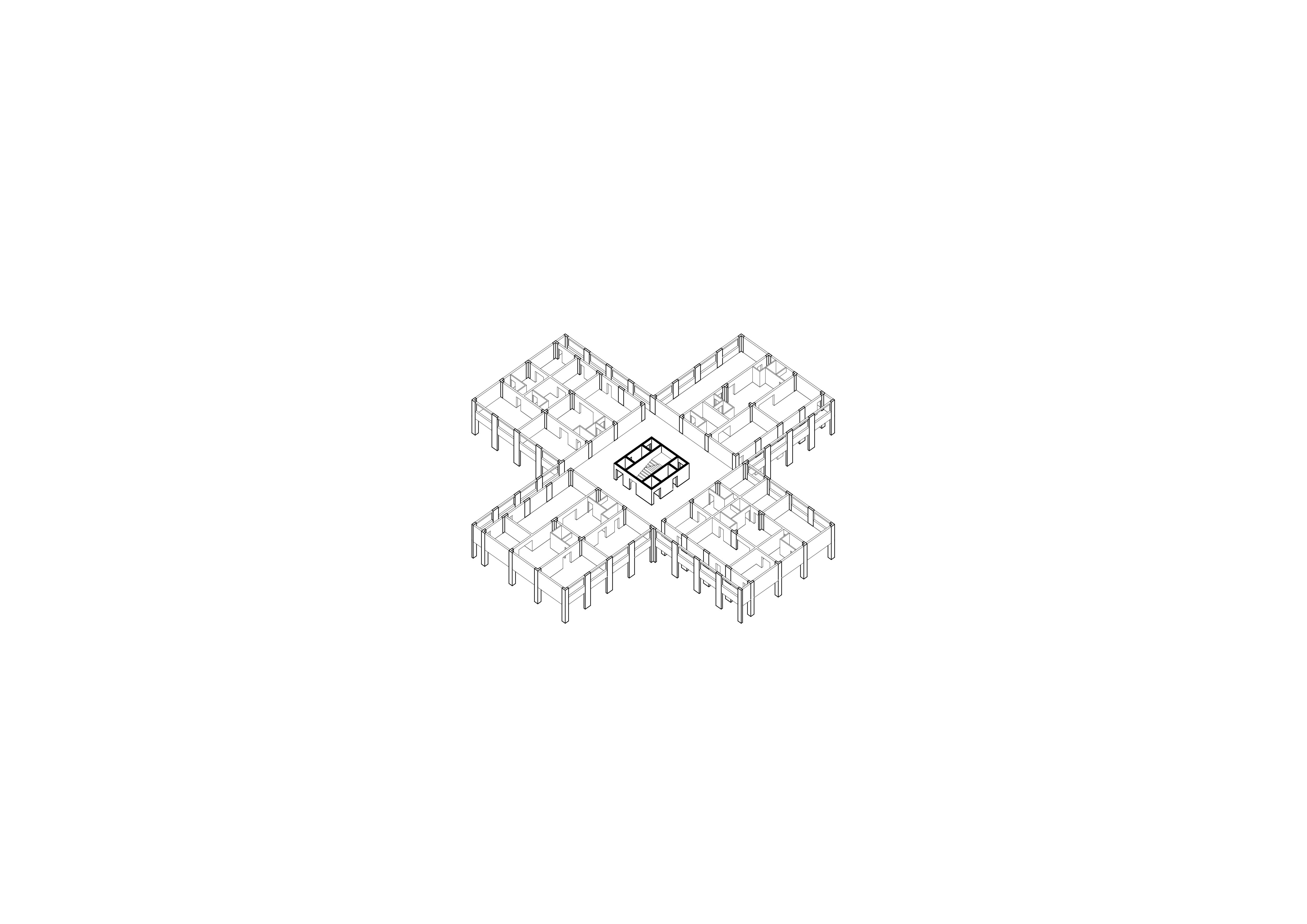

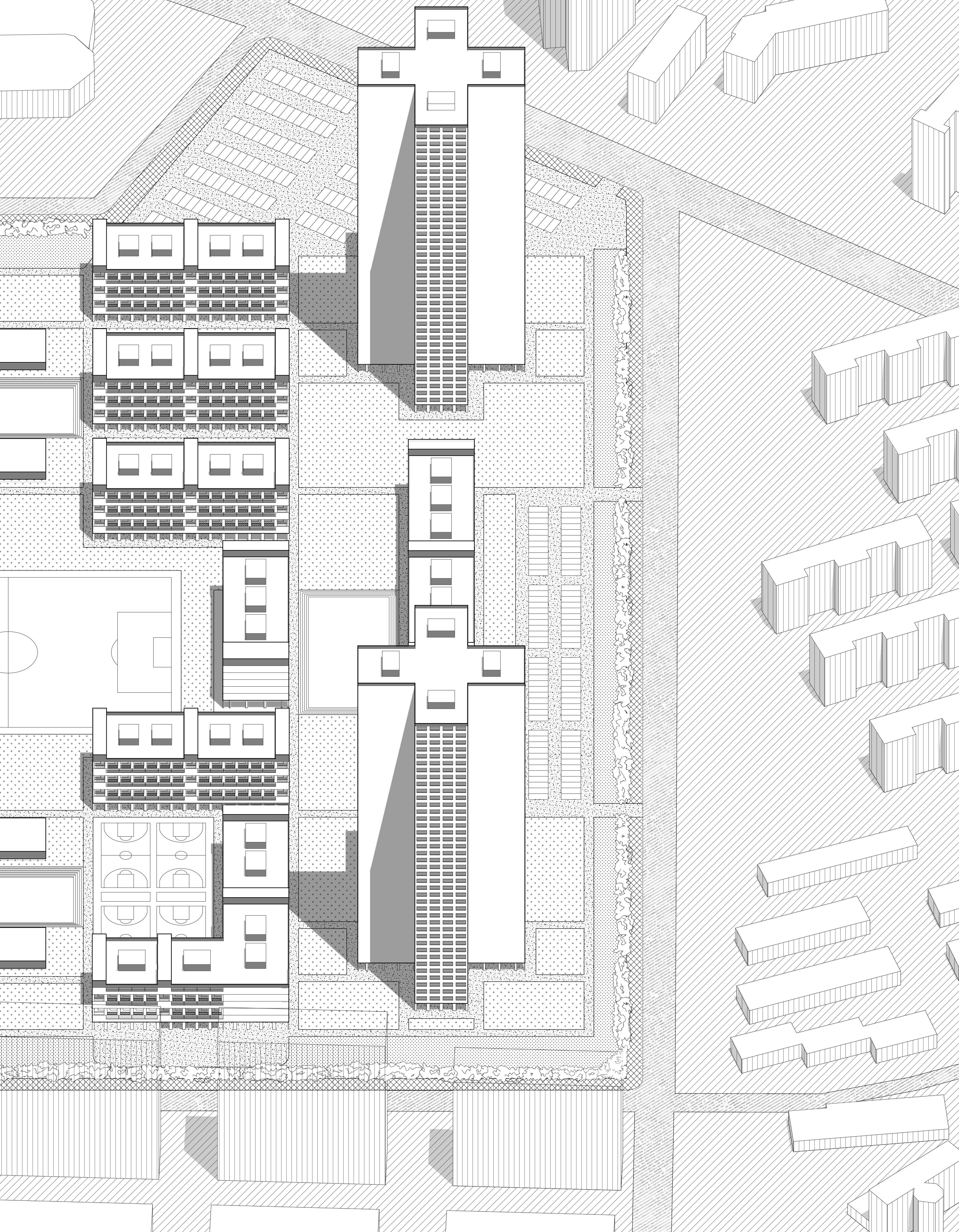

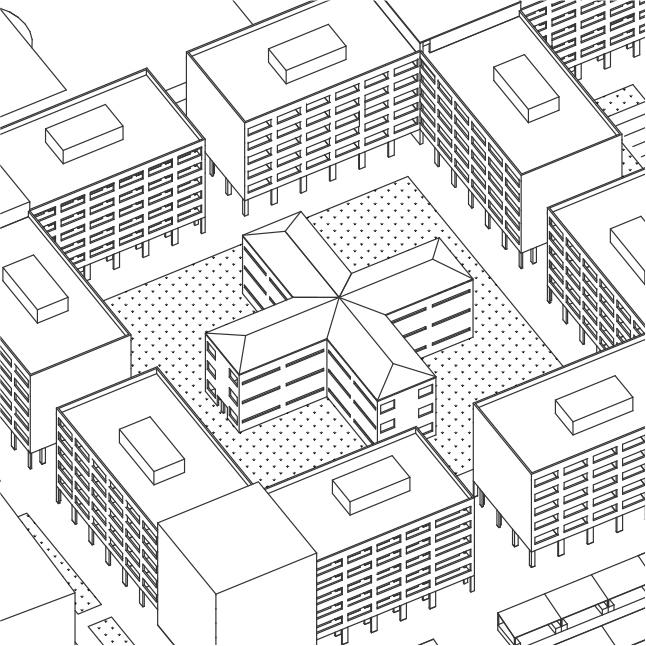

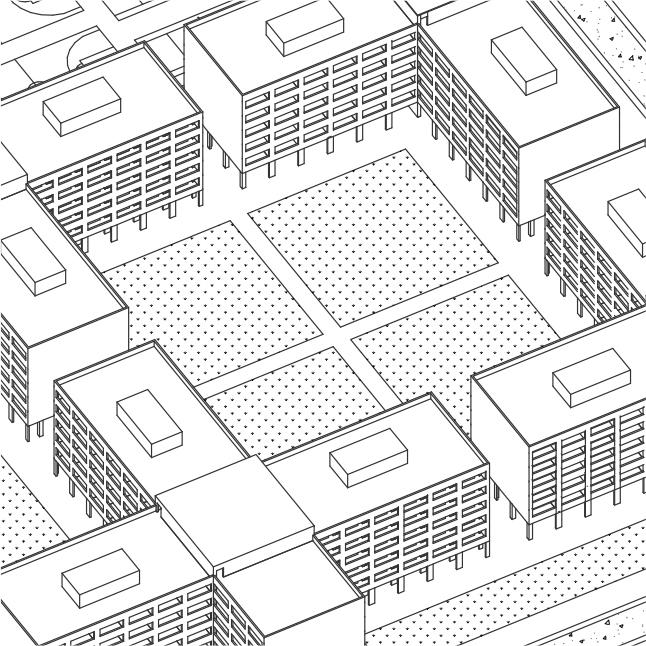

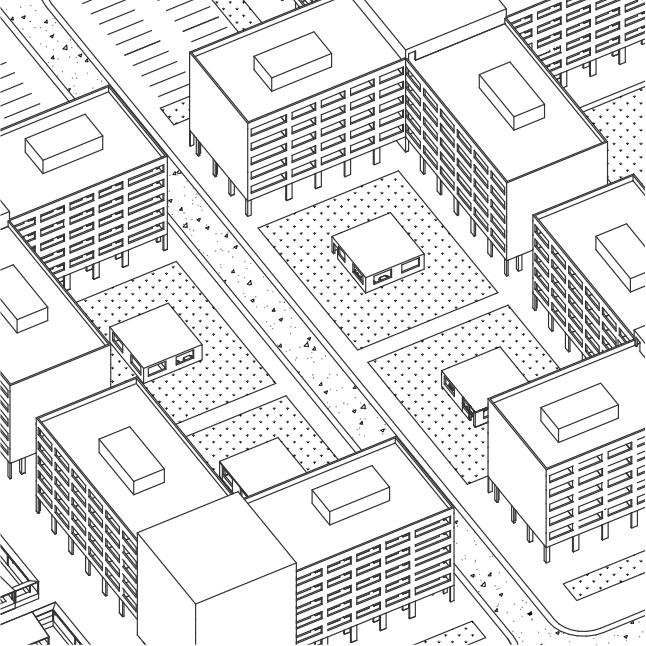

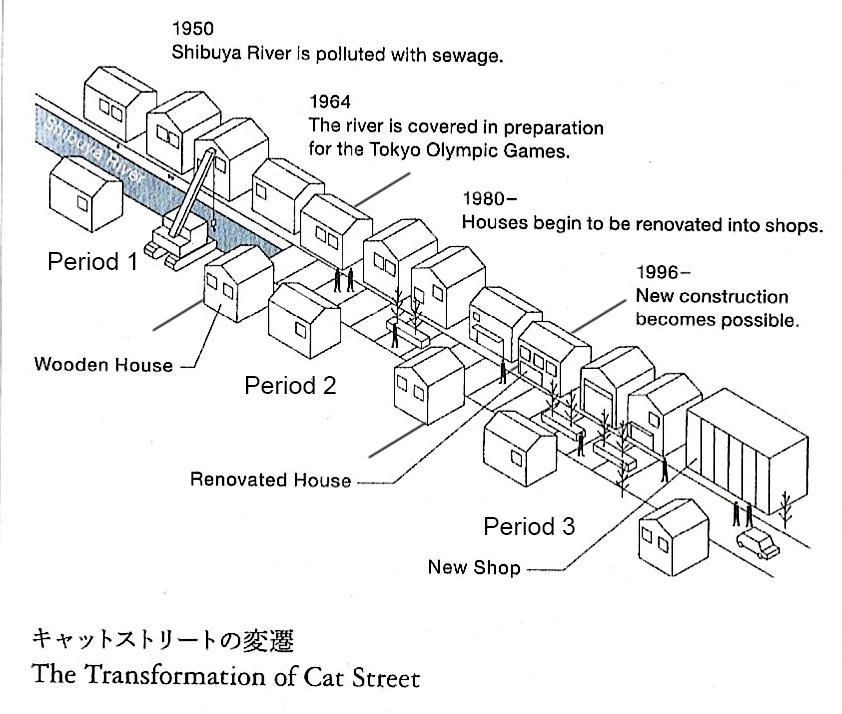

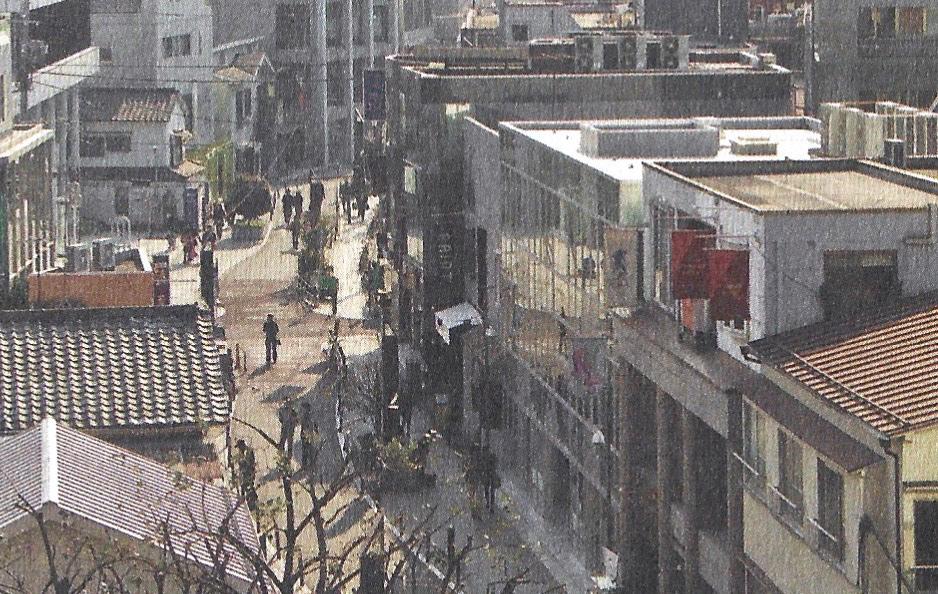

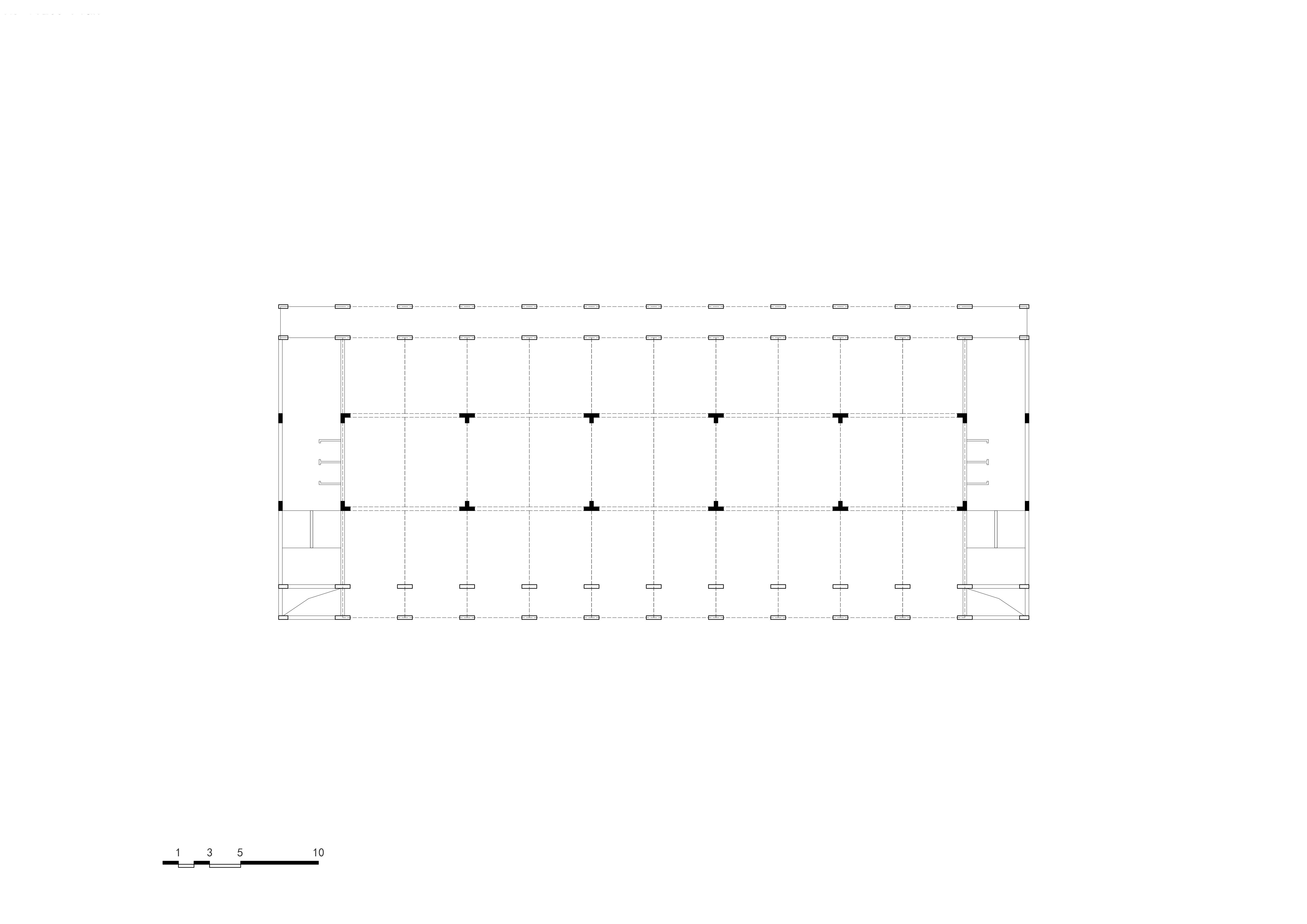

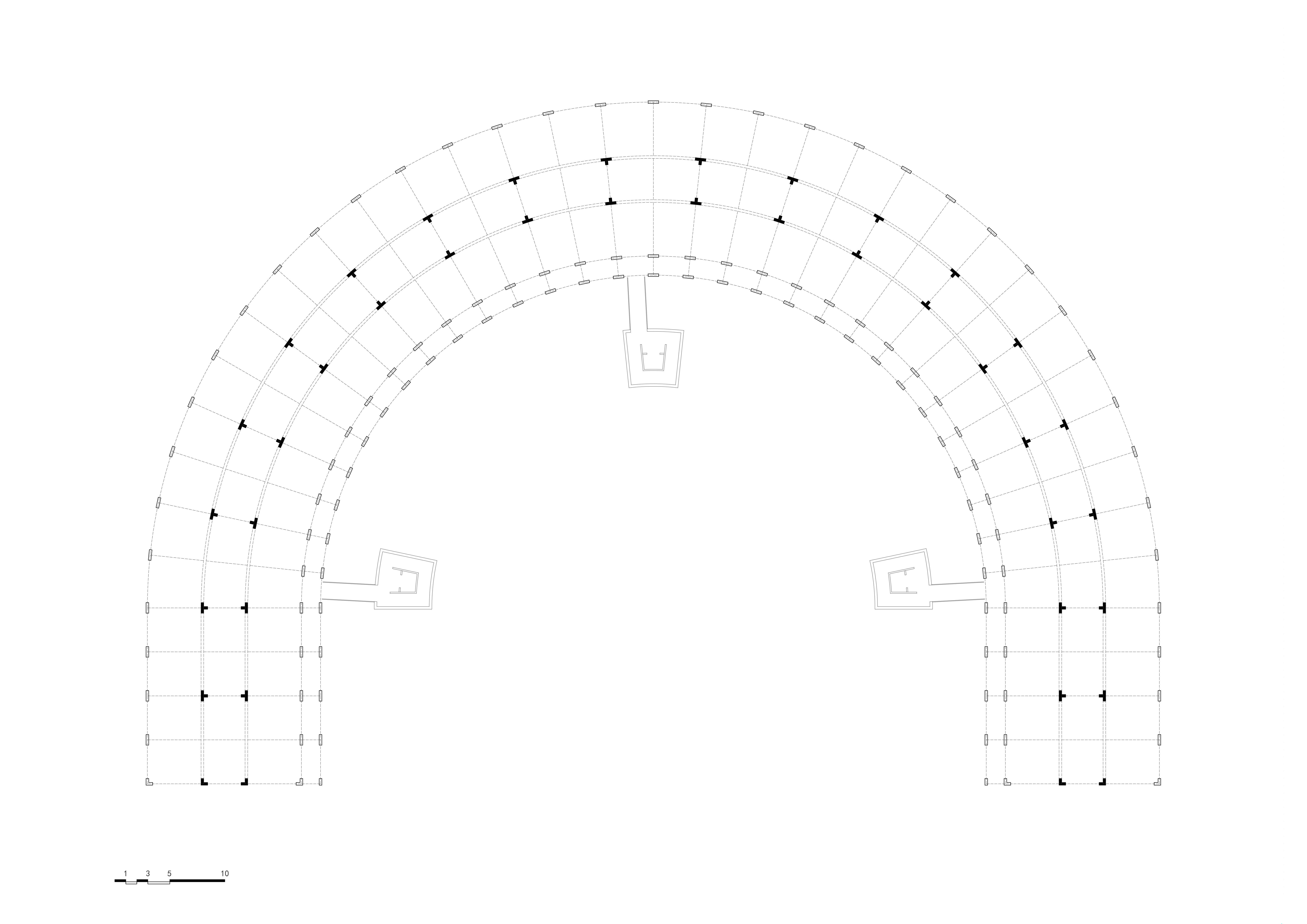

Based on the case of land fragmentation in urban Japan in the 1990s, how could for-profit developers cooperate with residents with new typologies?

The Transcendence of Old Logic

Chapter 4

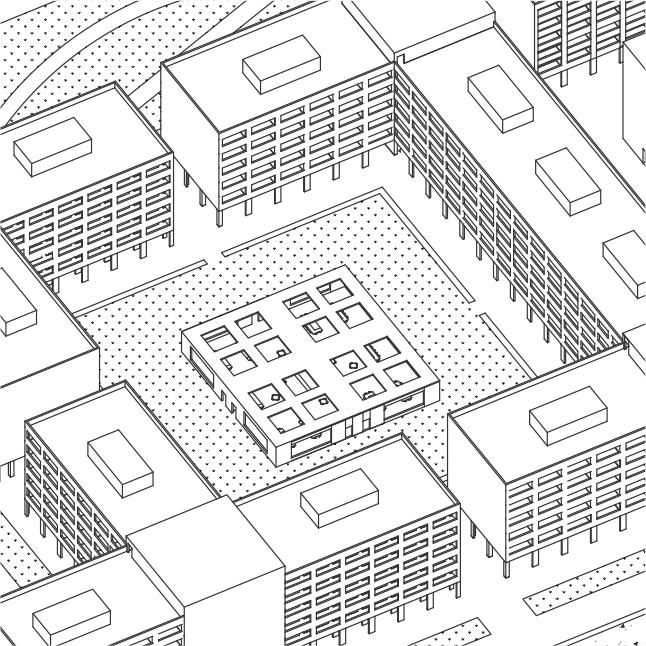

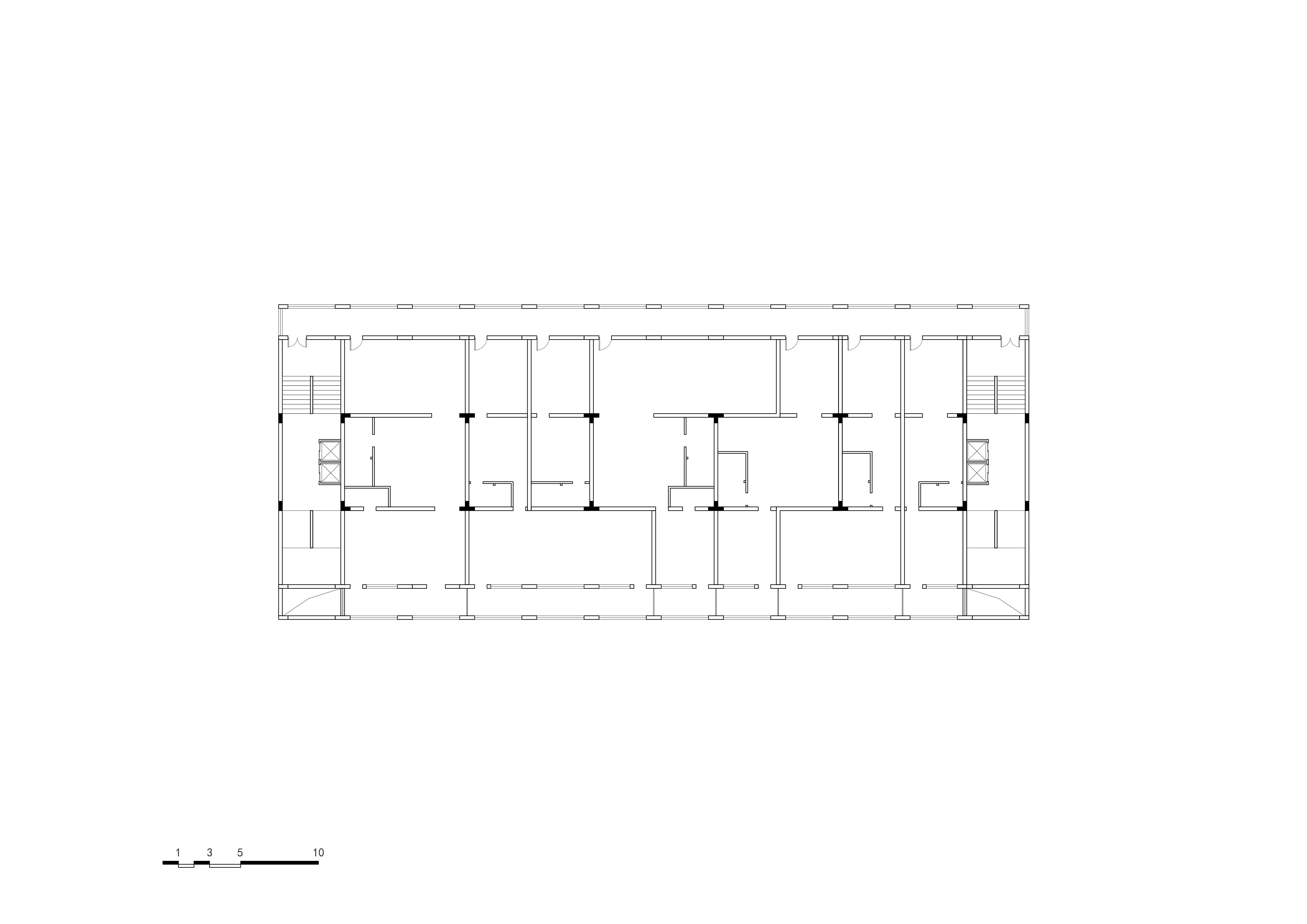

The Logic of Ownership

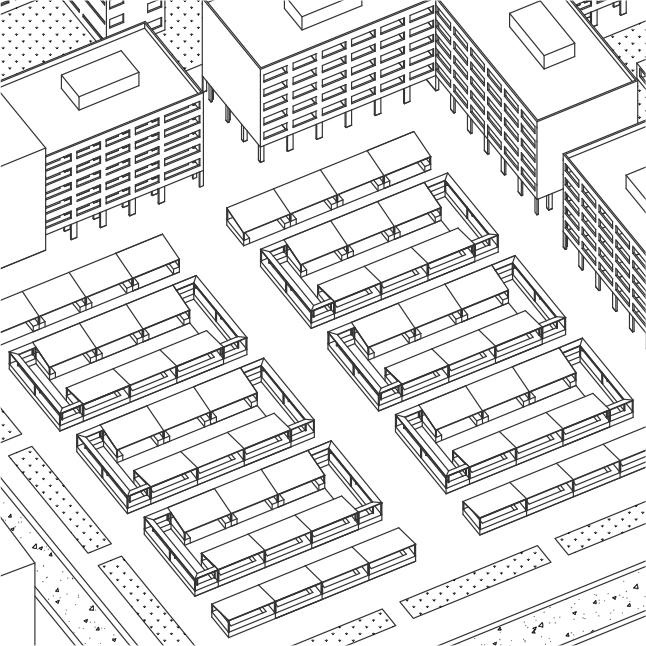

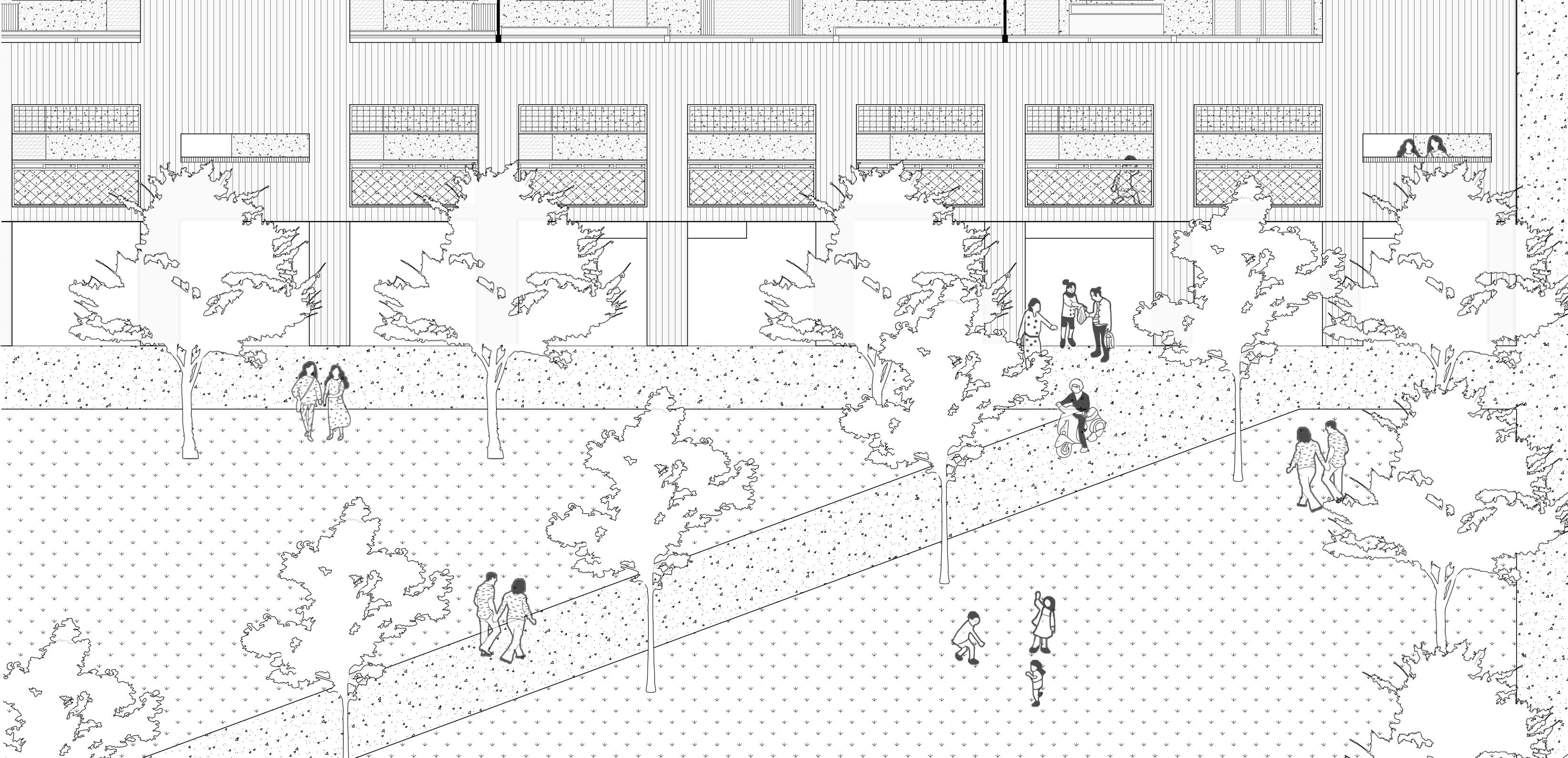

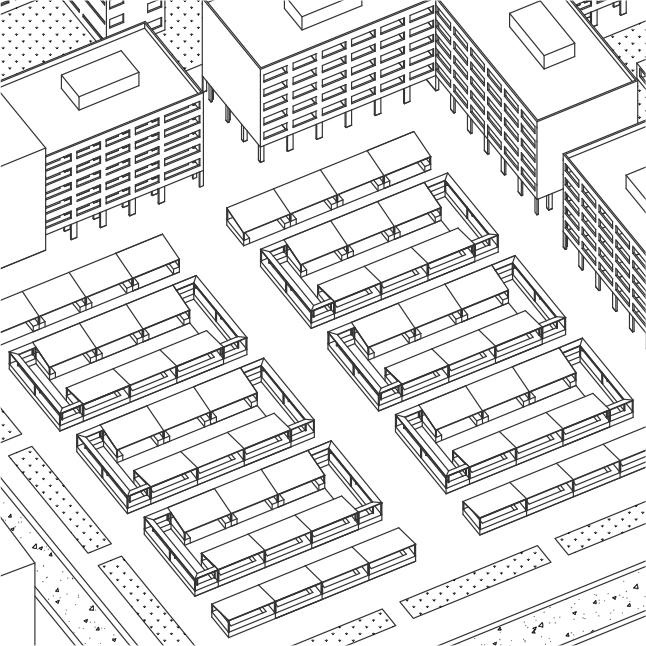

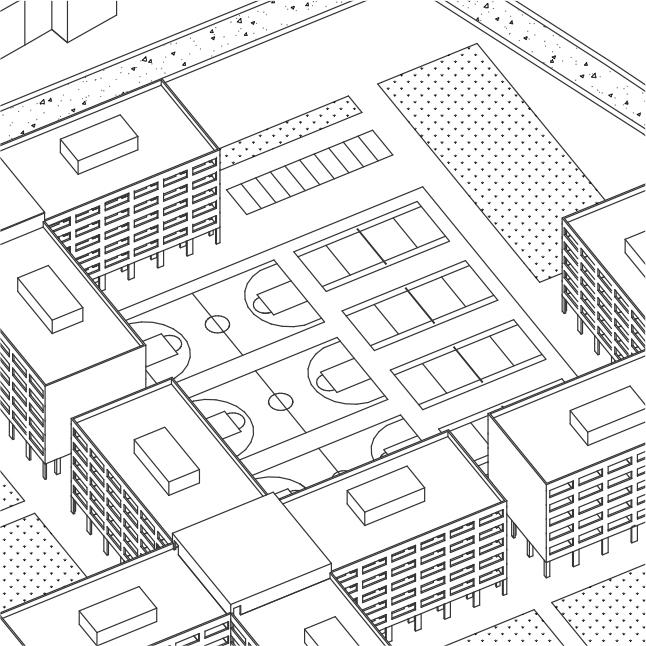

Based on the case of planned economy China housing system, how could the forms of living influenced by the definition of ownership?

14

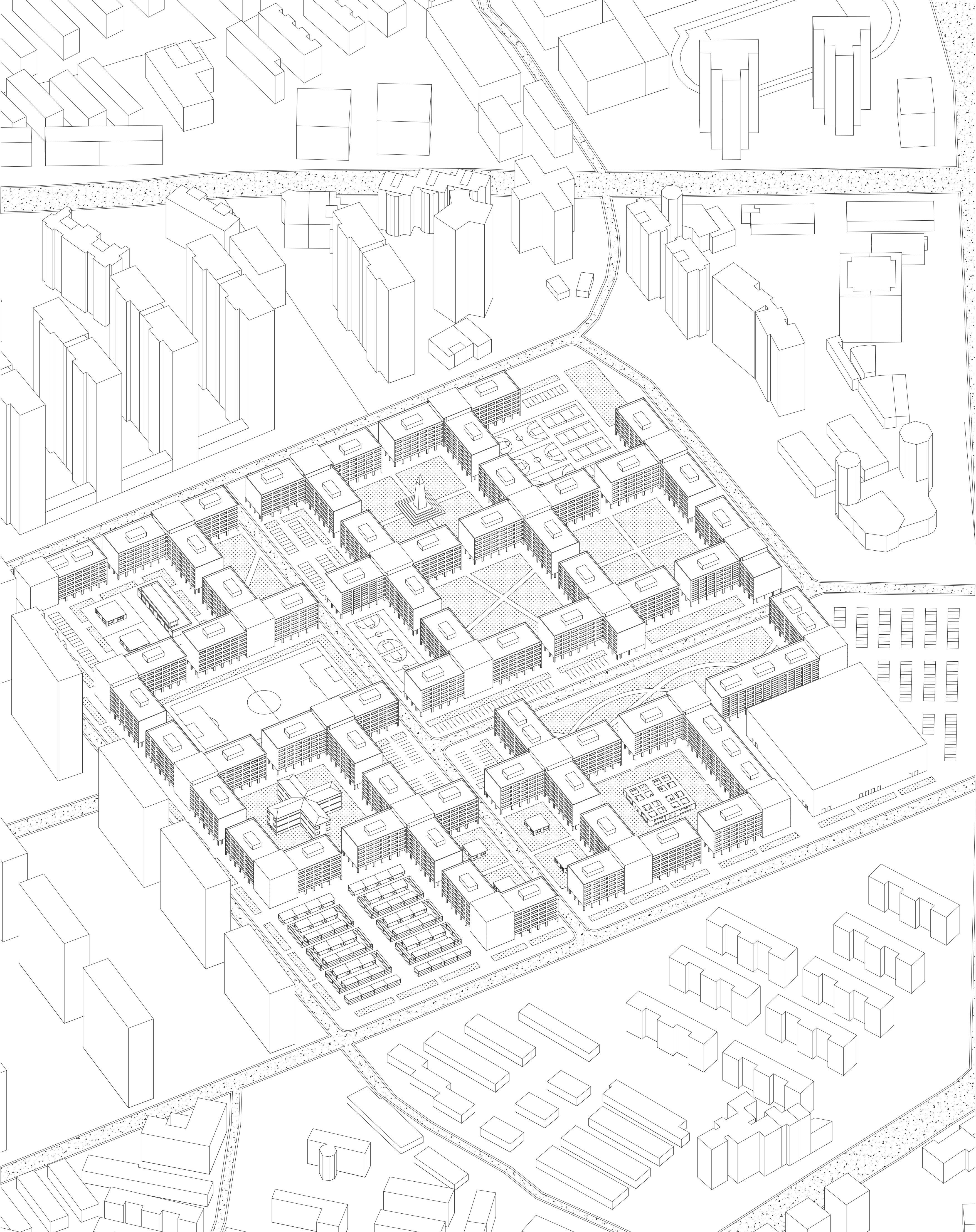

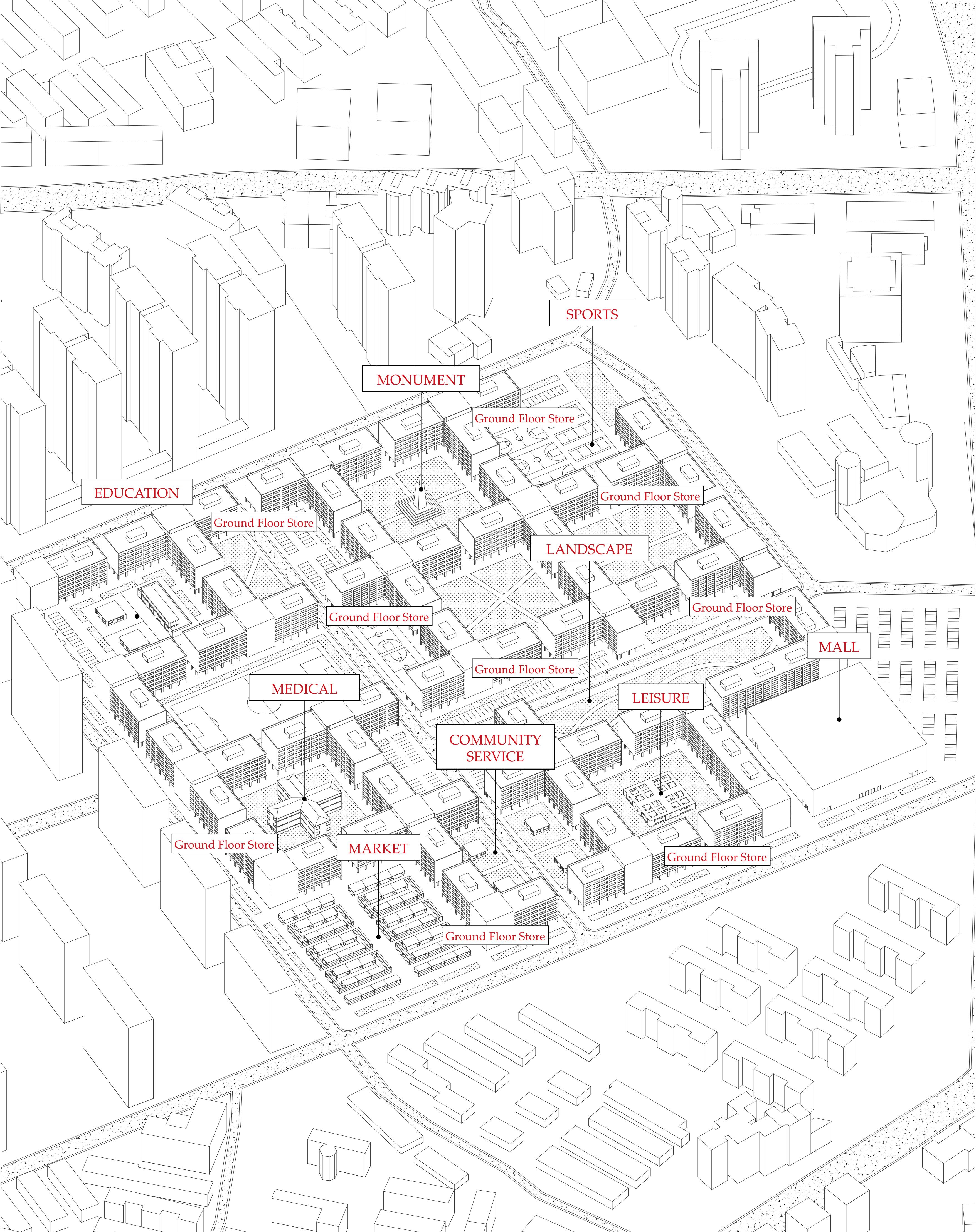

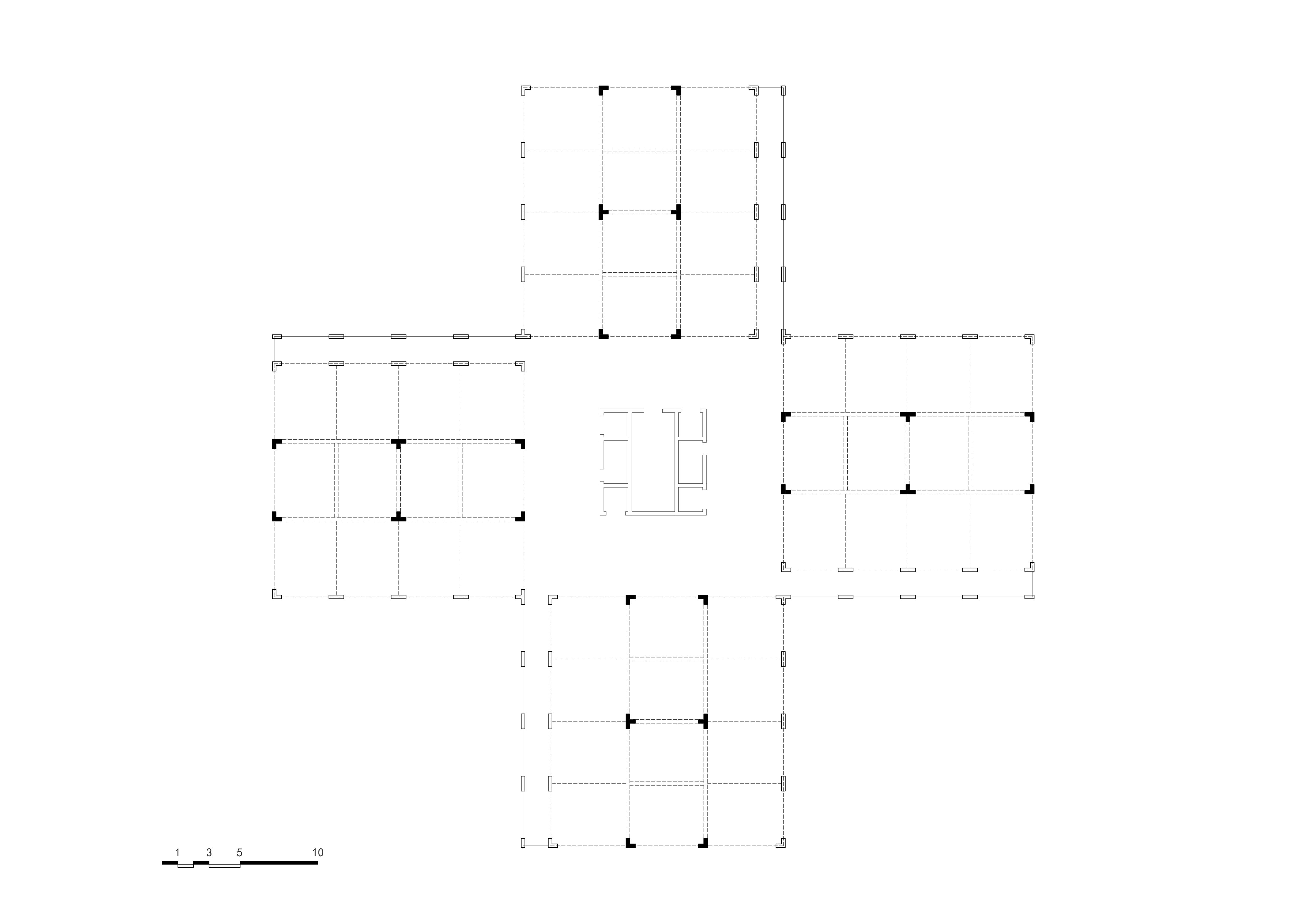

FIG.0.5 The Structure of the Thesis

RESEARCH STRUCTURE

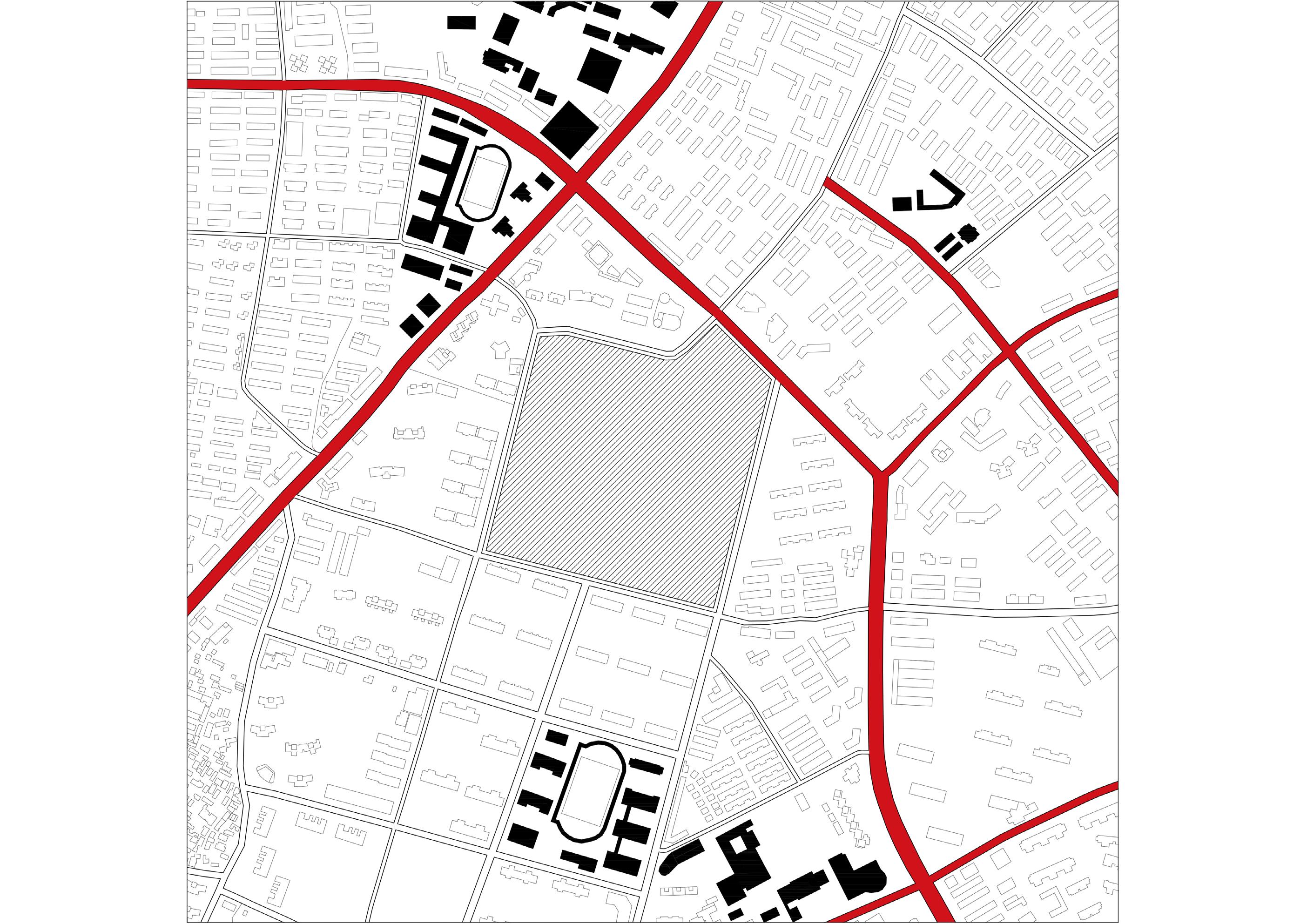

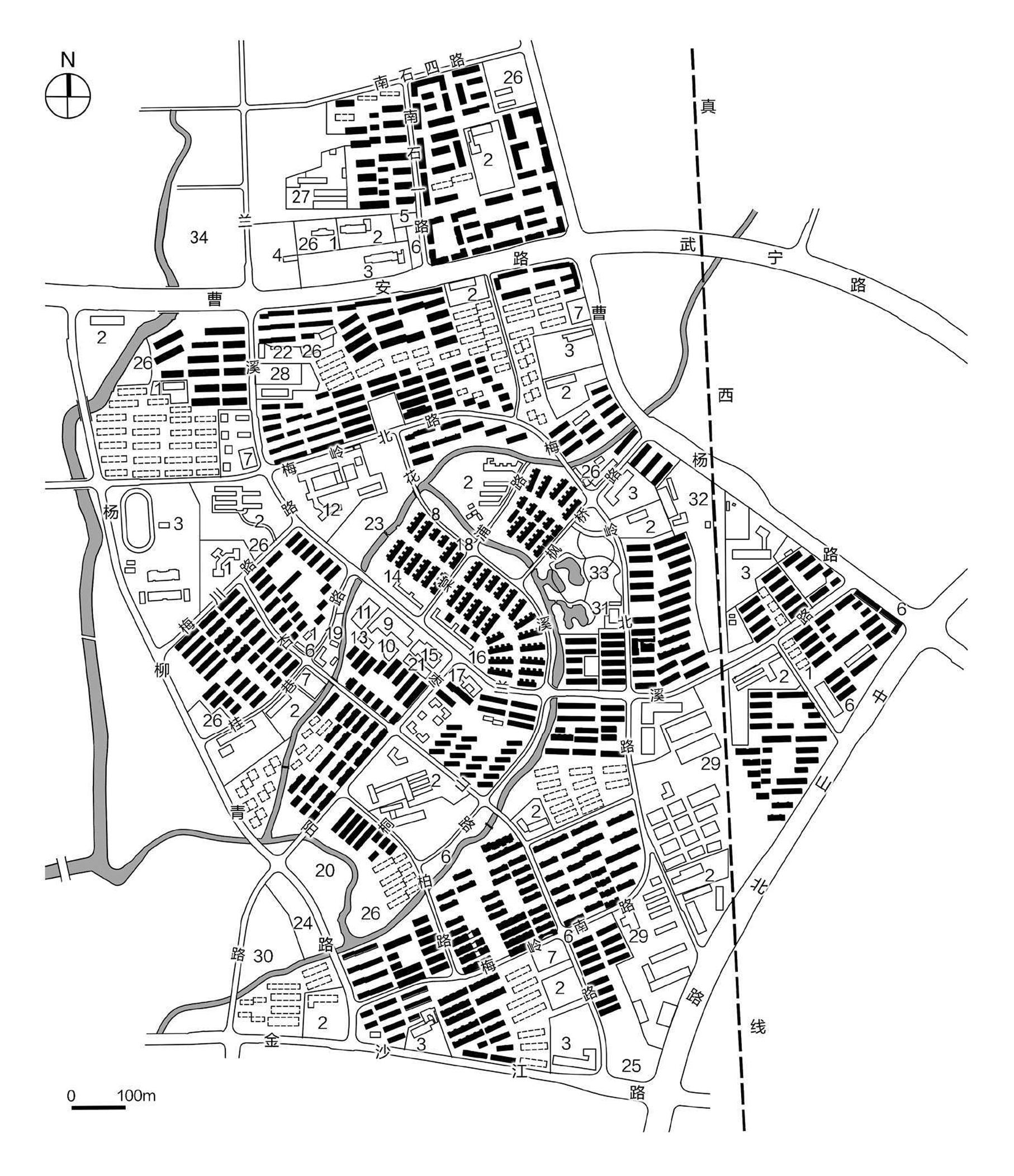

The main structure of this thesis is divided into four chapter (FIG.0.5). The First Chapter will trace China’s housing system since 1949. Two key time points will be emphasised, on the crucial transformations that occurred in 1949 and 1978, thus establishing a understanding of the contextual and background of this thesis.

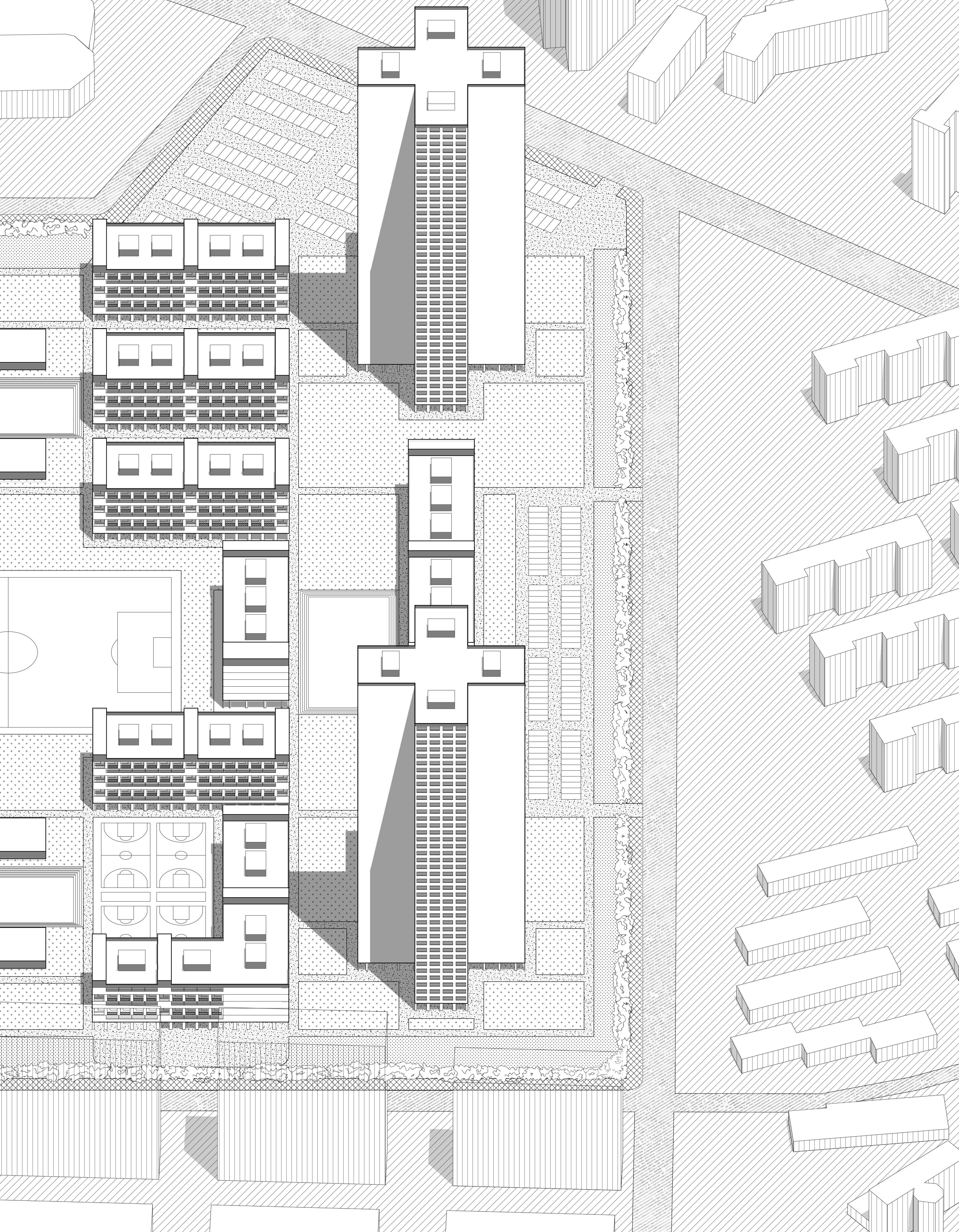

Chapter Two will continue the discussion in the Introduction, analysing the power relations among the government (public power), developers (capital), and urban residents (citizens) in China’s housing system, which is the core element of this research. With the decline of the real estate market and the emergence of China’s new city middle class, numbering in the hundreds of millions, how should they use their power to achieve a new balance with developer/government in the housing system? Moreover, what new forms of living will this lead to?

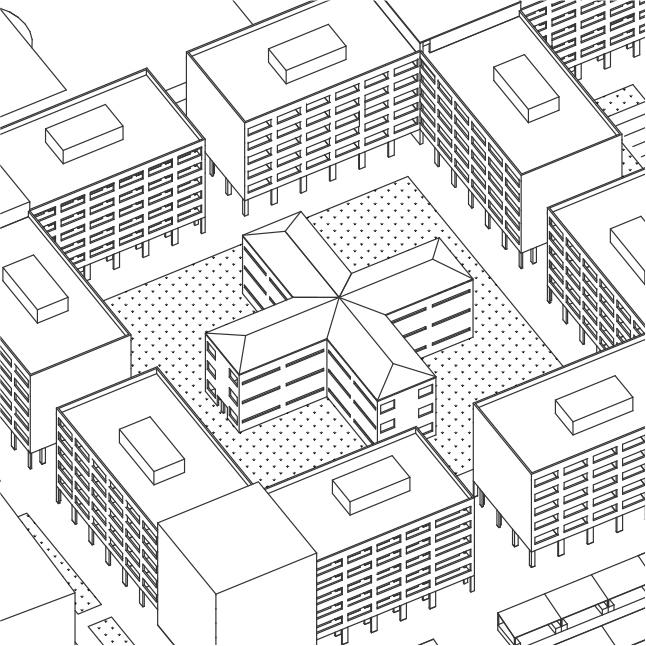

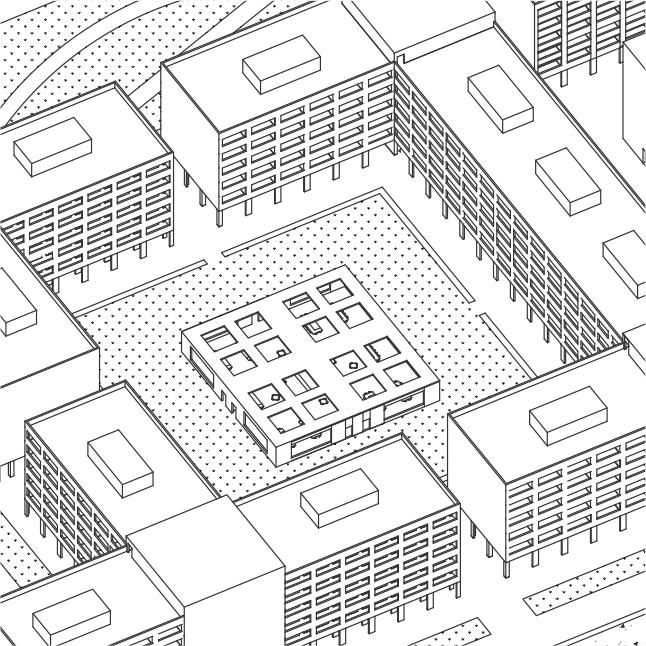

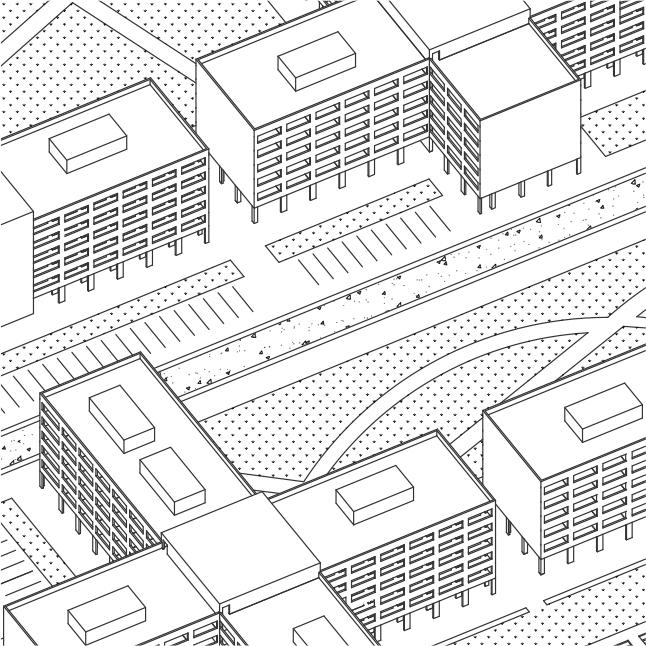

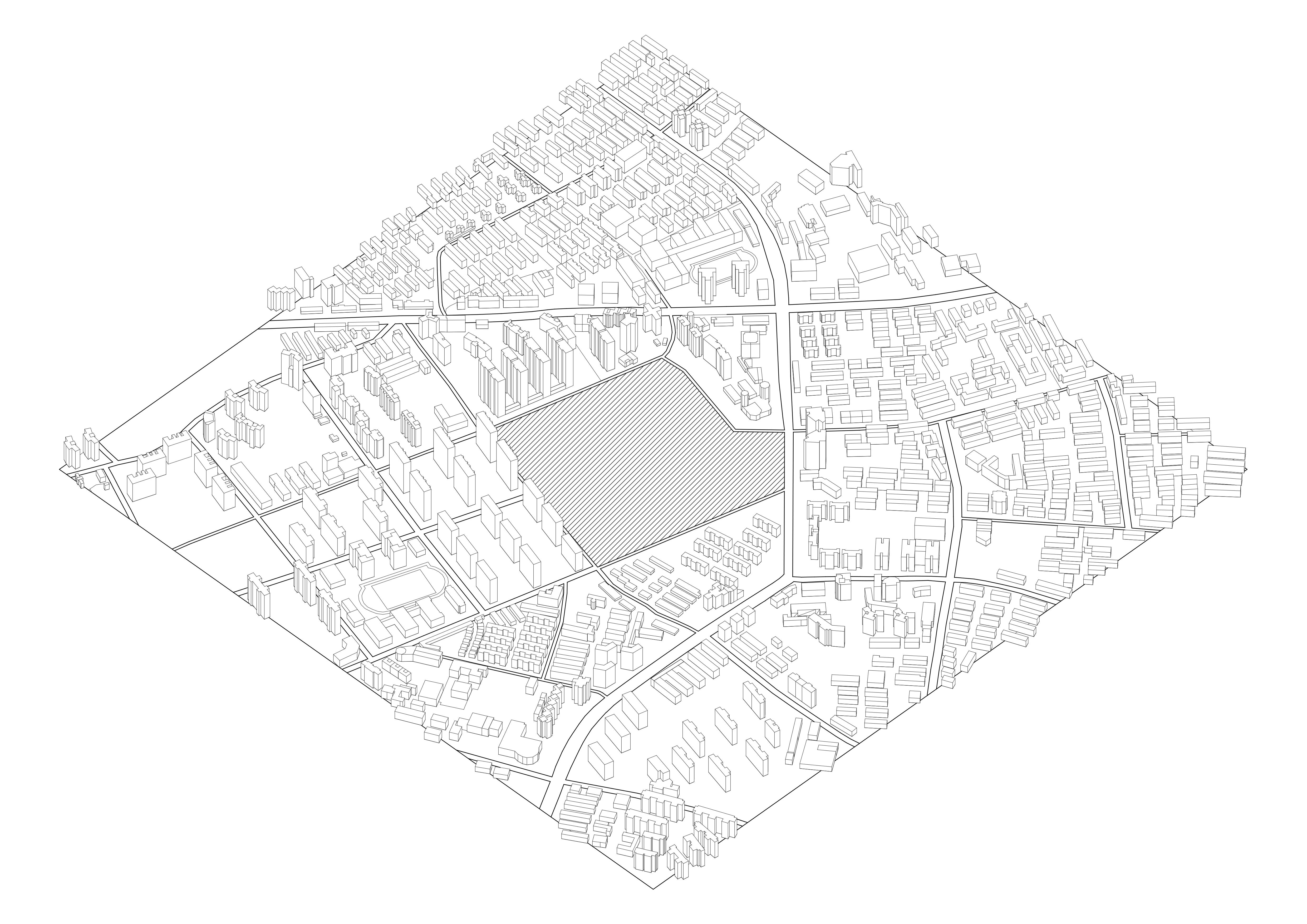

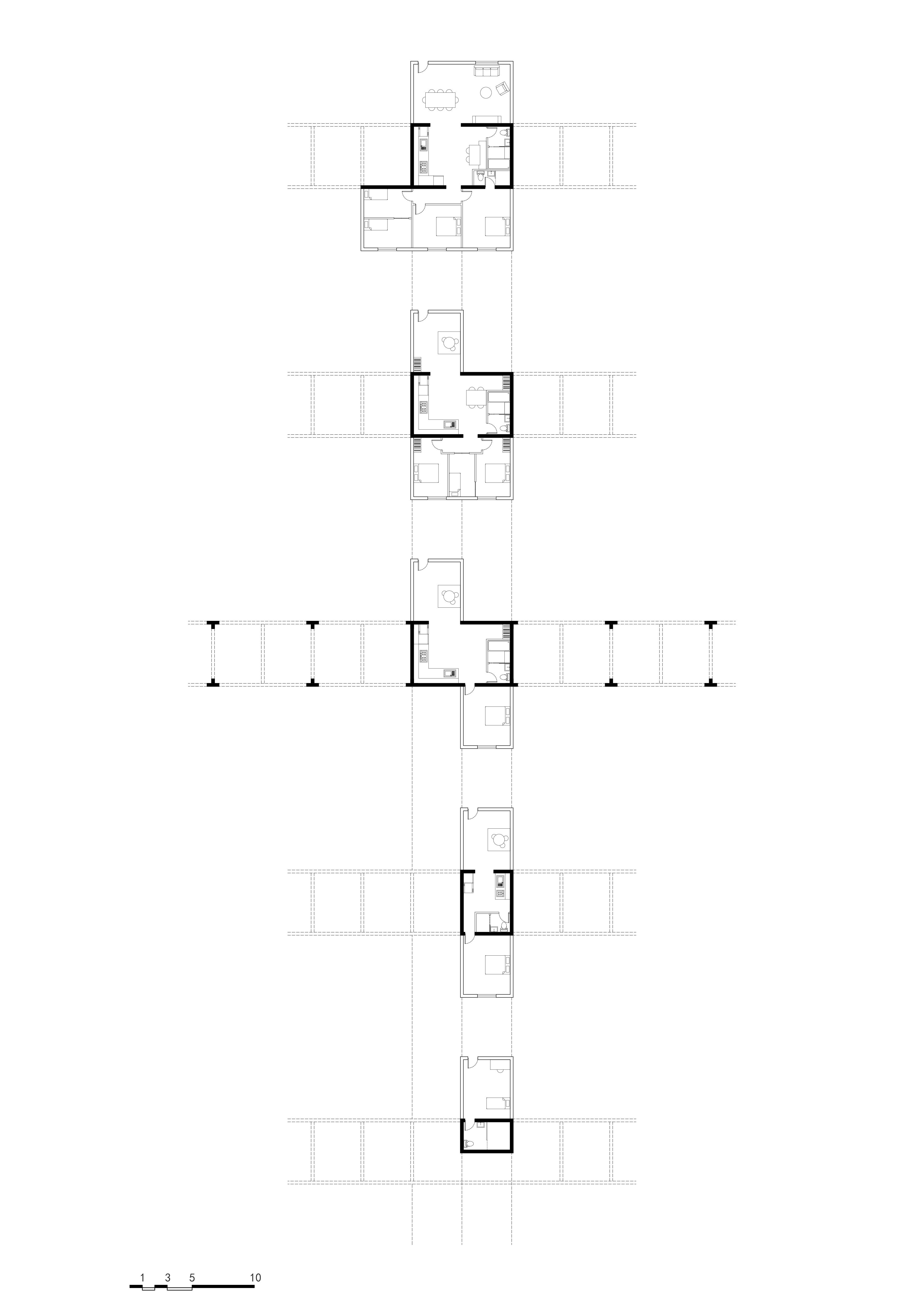

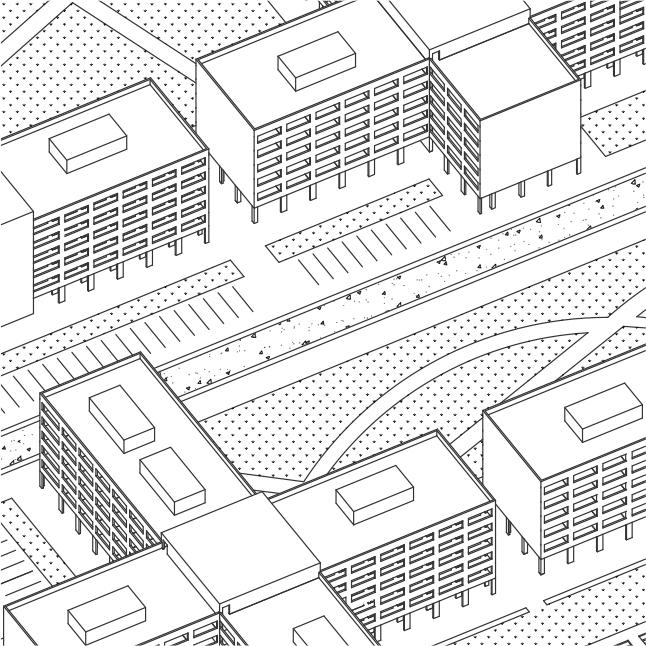

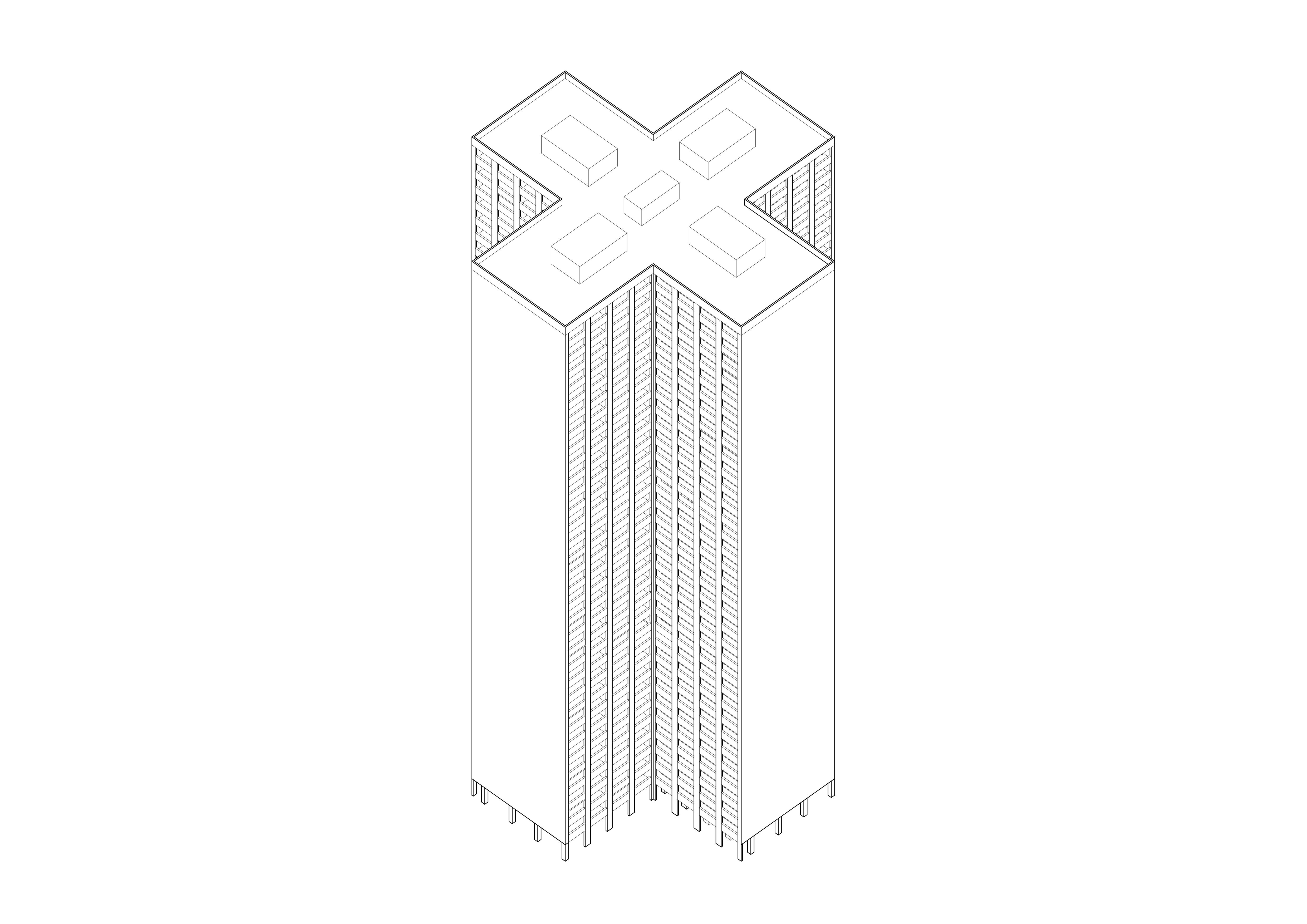

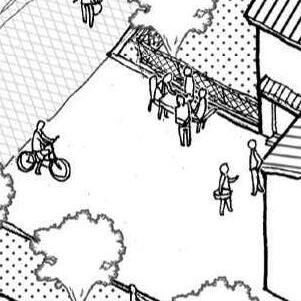

Chapter Three represents an empirical pathway for new living forms, examining how the old real estate logic could continue in the new housing system. Based on the Japanese case of land fragmentation and inter-generational spatial division in the 1990s’ real estate crisis, chapter three will show how residents in China’s high-rise, high-density urban fabric could cooperate with for-profit developers based on economic rationality as house prices drop and real estate taxes increase, and what kind of living form this will lead to.

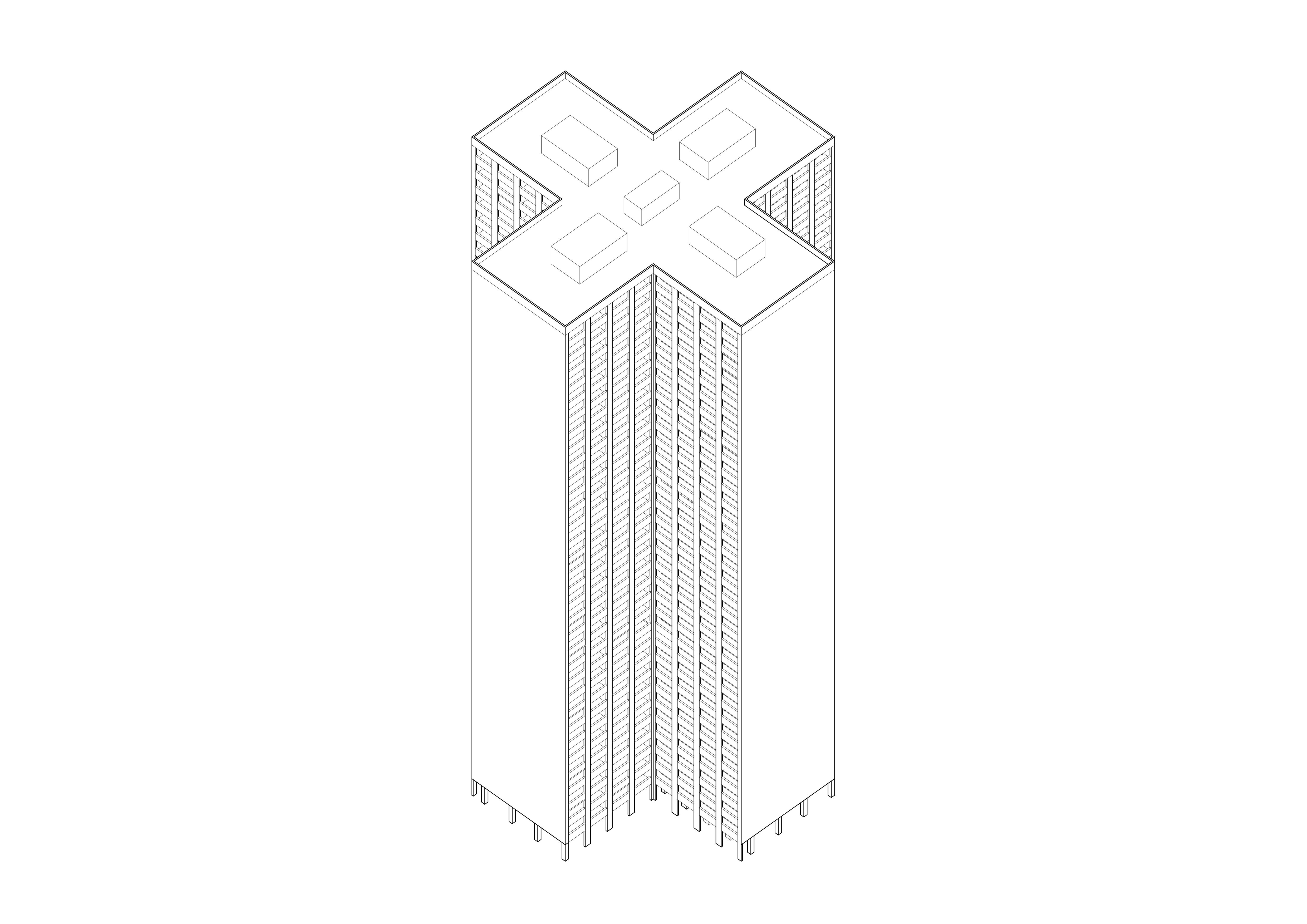

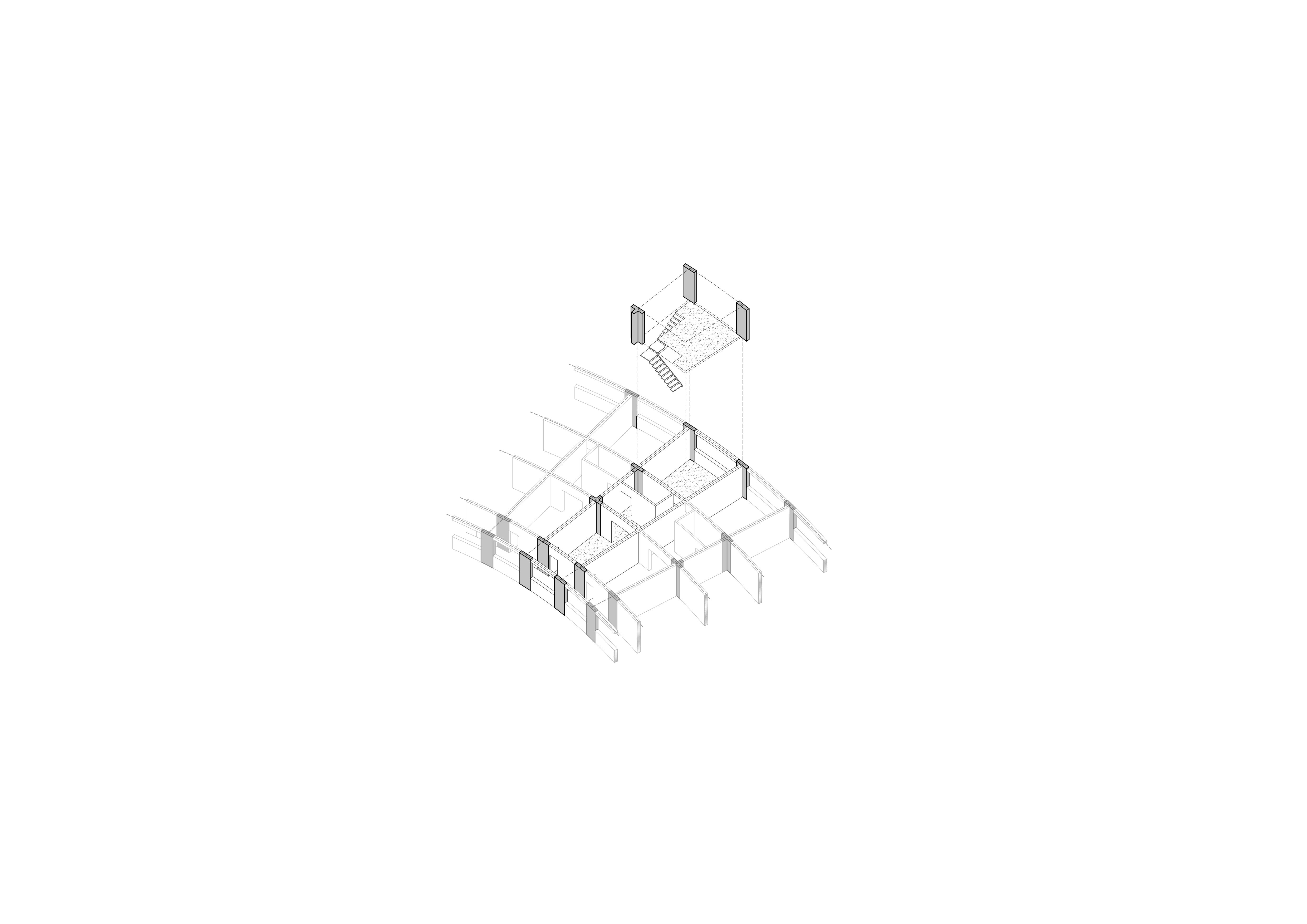

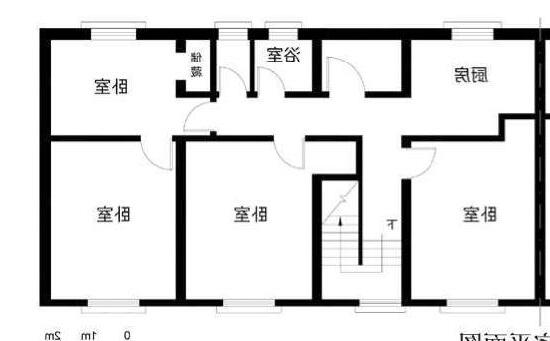

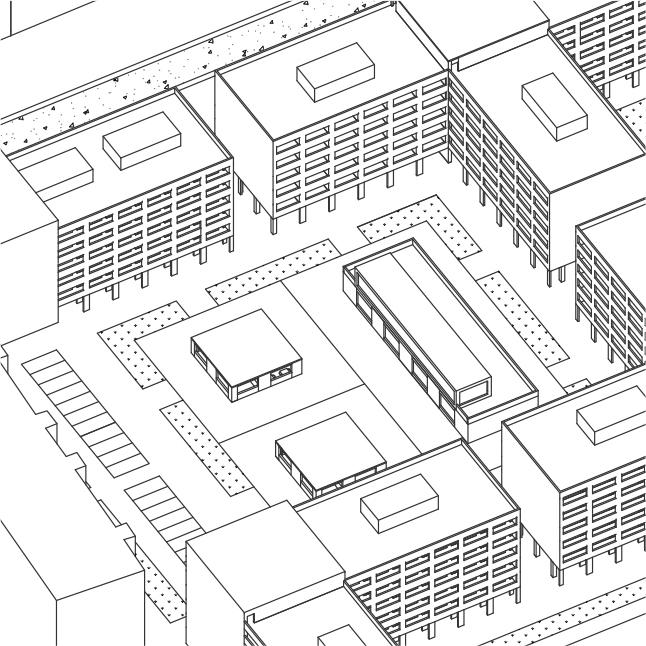

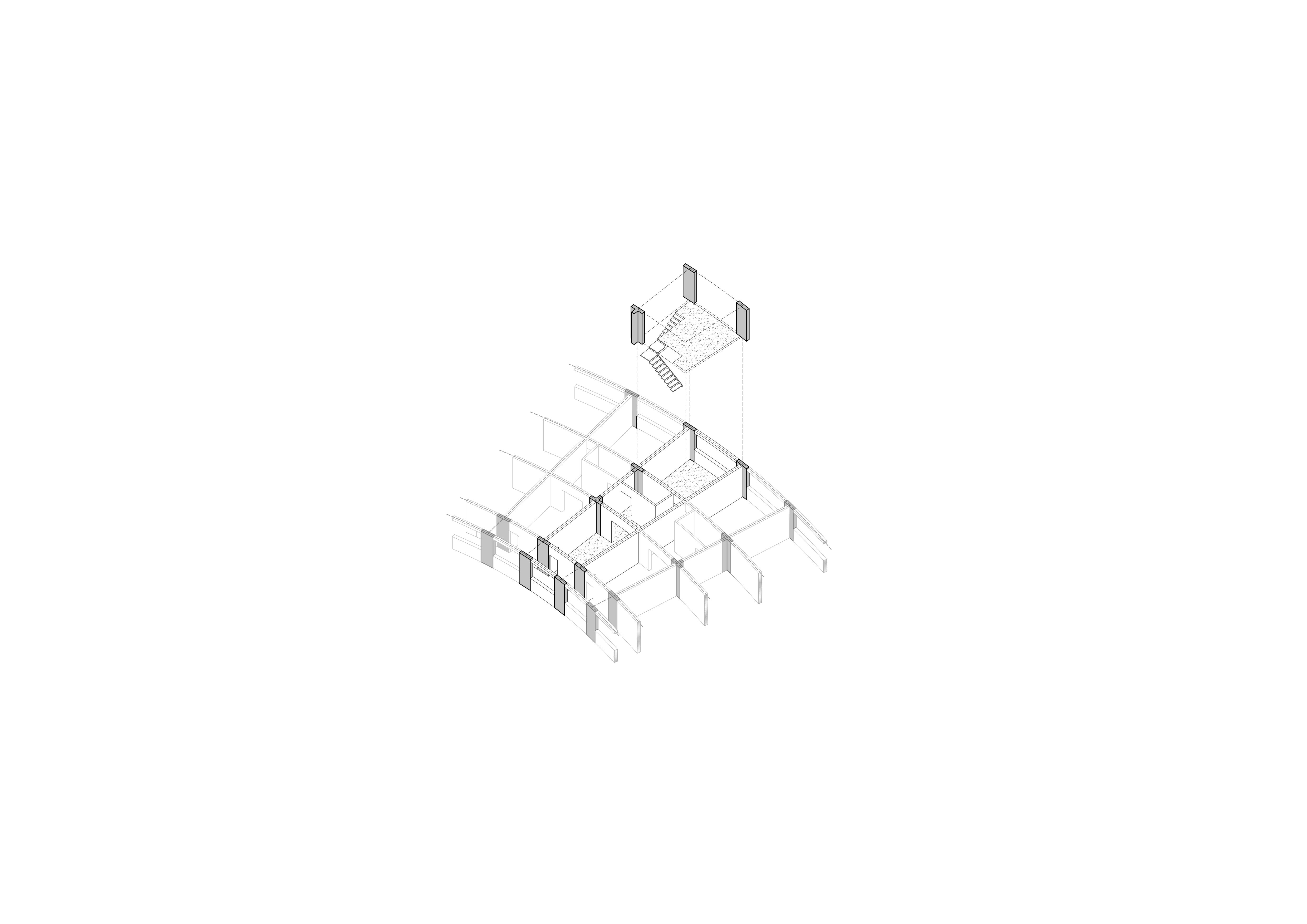

Chapter Four presents an entirely different urban imagination from chapter three, attempting to go beyond the original framework based on real estate. This chapter argues that the collapse of China’s real estate market has proven the inevitable failure of financial capitalism logic in the housing system. Therefore, ownership, as the essential element of using housing as an investment object, will be re-discussed in this chapter. Comparing public housing in China’s planned economy era and today’s commercial housing based on different scales such as living units, community and urban relations, chapter four will observe the different living forms resulting from the different ownership situations. Ultimately, by reconstructing the meaning of ownership, this chapter will provide a new living form based on this point.

Disciplinary Question

How will urban living forms in China change after the real estate market’s collapse, and what is the role played by the architectural discipline in the specific case of China, especially with the changes in the power structure?

Urban Question

How did such a process reshape the generic urban context and xiaoqu (residential compound) developmental template in future China? How did such a process influence the relationship between living and different programs in China’s urban area?

Typological Question

How the transformation of the current residential housing types can influence Chinese citizens’ living forms (family structure, space utilization, program organization...)

Economic Question

How does economic rationality (of government, developer and residents) shape the living forms in contemporary China? How do the living forms change due to the change of different groups’ economic status?

15

CHAPTER 1.

From Welfare to Property: The Rise of Real Estate in Modern China

Previous Page

The text on the board: “Time is money and efficiency is life!” This is a famous propaganda slogan during China’s 1980s, which also marks the market-oriented reform in China.

17

1. Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977, (New York: Random House USA Inc., 1980).

FROM WELFARE TO PROPERTY THE RISE OF REAL ESTATE IN MODERN CHINA

Chapter one provides a retrospective of China’s housing system before delving into the main discussion of the thesis. This chapter will briefly introduce the transformation of China’s housing system from the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 to the reform and opening-up era of the 1980s (from planned economy to market economy), and then to today. After that, chapter one will examine how China’s local governments have become dependent on land finance and formed alliances with real estate developers after the 1994 tax-sharing reform, which is also the key reason that China’s real estate industry has entered its heyday and now on the brink of collapse after rapid development for four decades.

This retrospective shows that the transformation of China’s housing system is closely linked to its modernization process after 1949. As Michel Foucault suggested, “Anchorage in space is an economico-political form which needs to be studied in detail” 1 . Housing, as the basic unit of human habitation, especially in urban societies, provides a practical perspective for understanding the complex relationships between different groups in society. What does real estate (housing development) mean in the Chinese context in the pre-reform and reform era? Also, the understanding of the term housing may be strongly different between those who plan and approve (central/regional/municipal governments), those who build (danwei, then private developer), and those who inhabit (governments, workers, users).

Seeing Like a State

The transformation of China’s housing system at two pivotal points1949 and 1978 - was, in a sense, a reflection of the country’s ideological and social logic. Therefore, a retrospective of China’s housing system will help us establish a contextualized thinking framework and prepare for the whole thesis. In particular, chapter one’s review is based on a state-government perspective. Especially given the absolute status of the Chinese Communist Party’s one-party dictatorship since 1949, and most of China’s social transformation has been considered a top-down process lead by the government and the party. What do ownership,

18

tenancy, and usership mean from the perspective of regulation and governing, which could be very different from the perspective of users and inhabitants? According to such a top-down perspective, a more indepth understanding of certain pragmatic, ideological differences and paradigm shifts could be explained.

The slogan on the banner reads “Struggle for the realization of the basic tasks of the First Five Year Plan”.

In the poster, it could be clearly seen that the worker takes the lead of everyone, and in the distance is a huge new factory. All these indicated that the Chinese government attached great importance to industrialization at that time

19

FIG.1.1

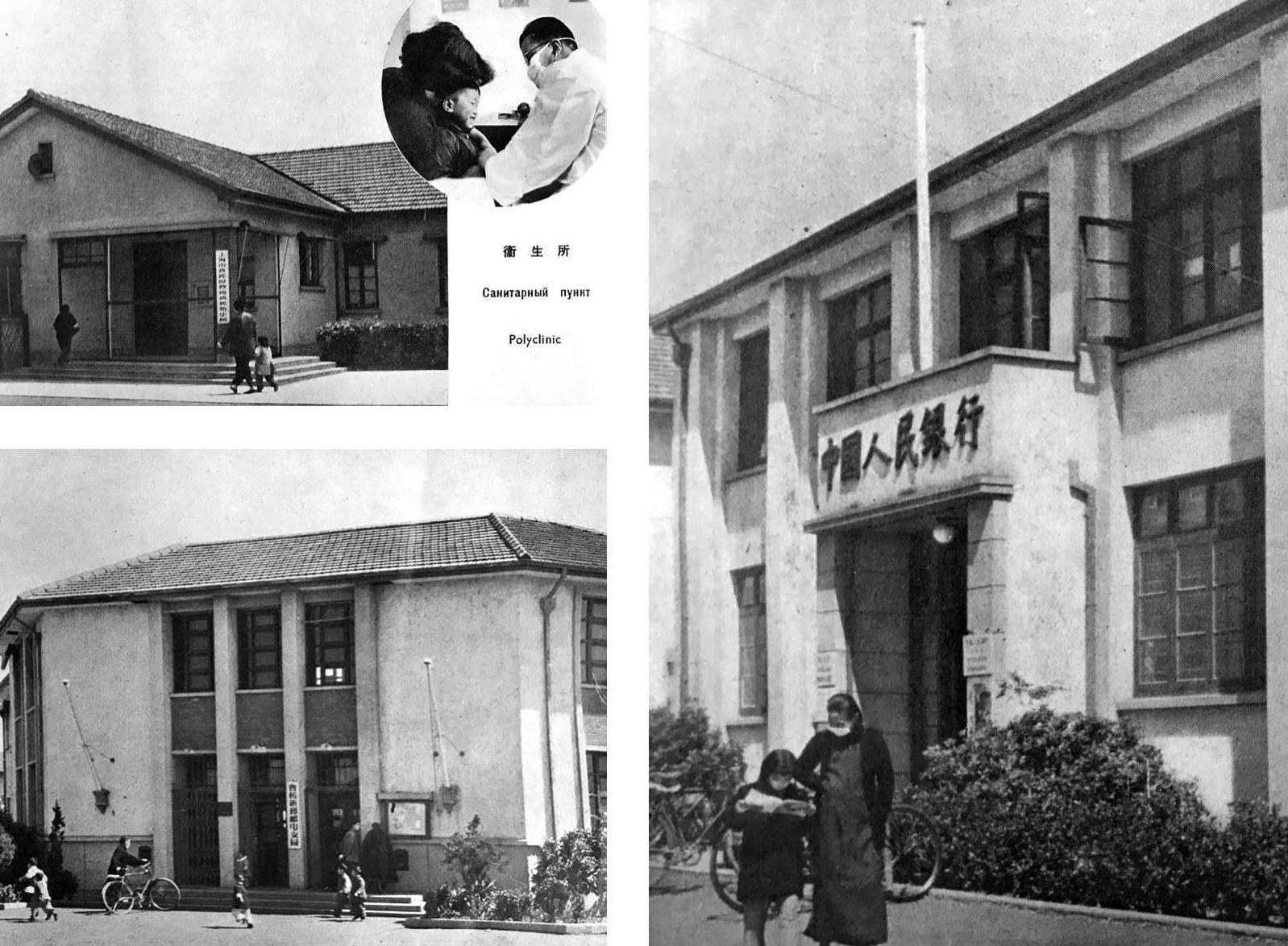

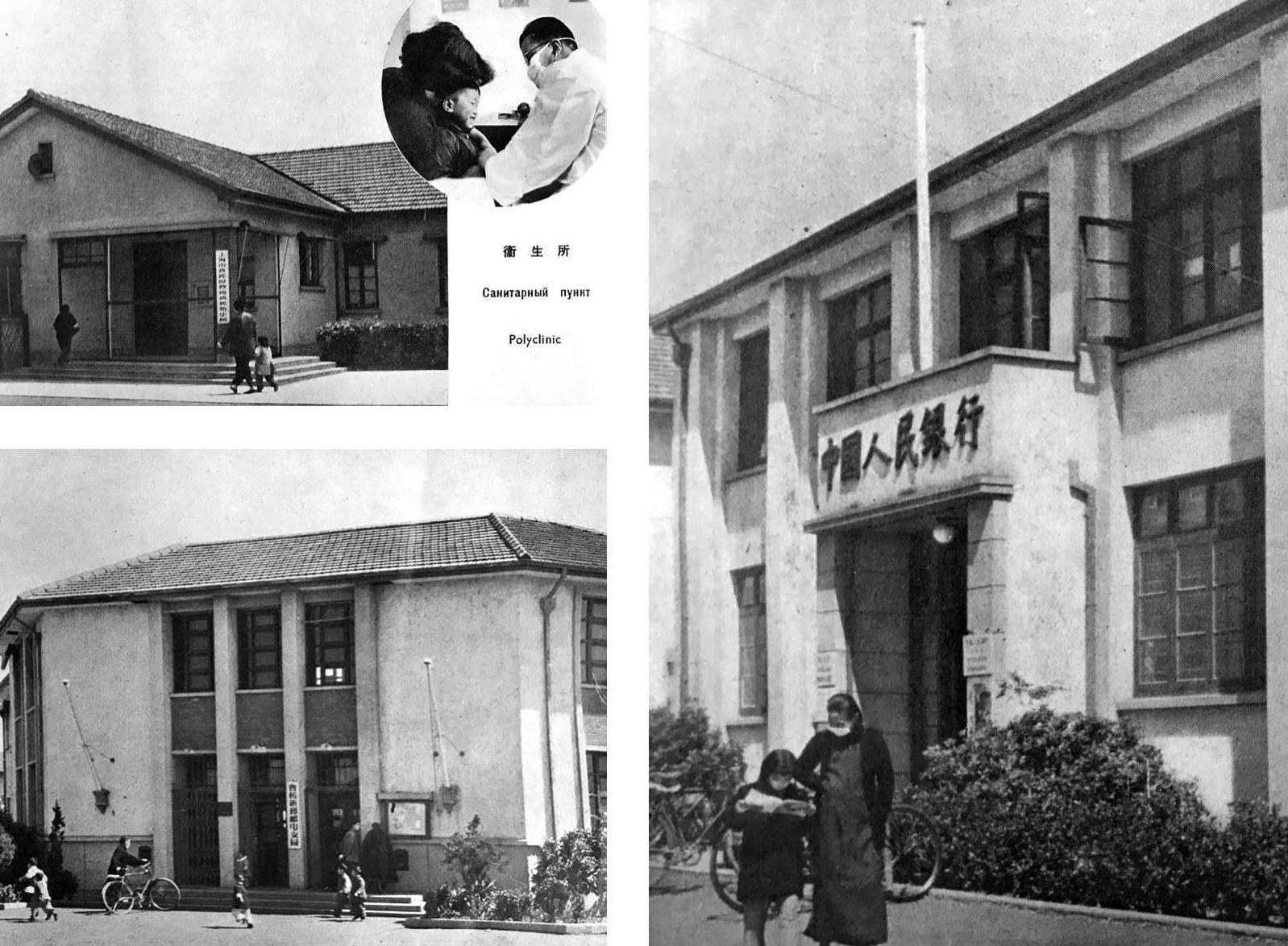

1949 - 1978, HOUSING AS WELFARE

Public Housing: the Danwei Framework

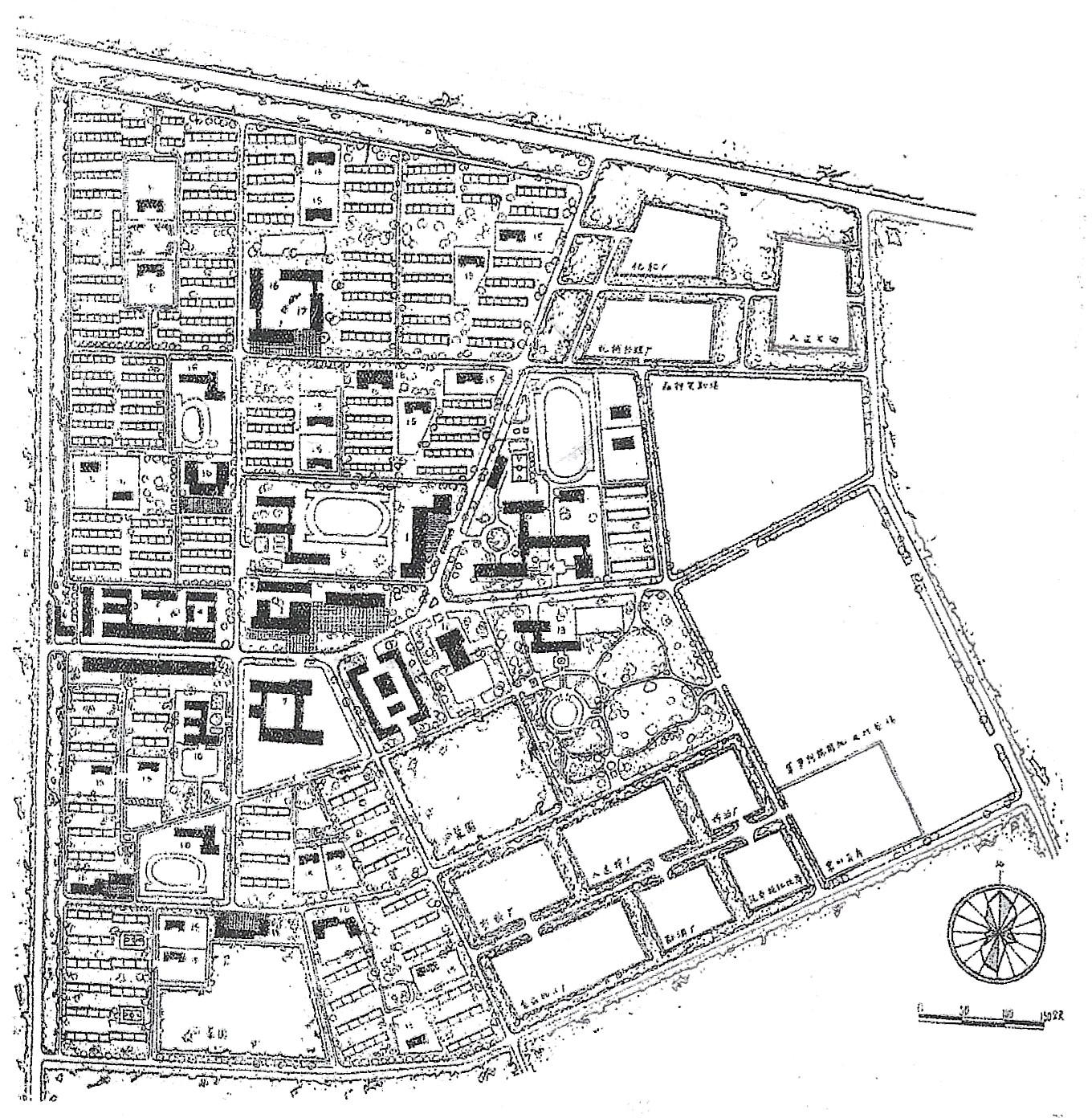

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, urban land was nationalized due to the basic ideology of the communist party. In such a process, the city government strengthened its control and management of all buildings and land. Under the influence of the Soviet Union, “New China followed the socialist urban theory of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to carry out socialist transformation of traditional old cities, transforming ‘deformed consumer cities into productive cities’ and building ‘people’s cities’” 2. At the same time, the development goal of industrialization (FIG.1.1) led to a significant increase of workers, which further resulted in a housing shortage in urban areas. Therefore, the government gradually relied on the framework of danwei 3, the basic organizational structure of the planned economic city, to build public housing for residents, in addition to the nationalization of existing private properties. Public housing established within this framework became urban residents’ main form of living in this period 4 .

2. Yingfang Chen, City Chinese Logic (Chinese Edition: 城市中国的逻辑), (Shanghai: Shanghai SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2012).

3. In planned economic China, “Danwei” (Chinese: 单位) referred to a system of work units or organizations that were responsible for the allocation of resources to urban residents. A Danwei units typically included factories, government offices, schools, hospitals, and other institutions, and were responsible for providing a wide range of services and benefits to their employees. These services included housing, healthcare, education, and social welfare programs, as well as opportunities for career advancement and promotion within the Danwei.

4. In 1978, 94.6% of the urban labor force worked in the danwei. The vast majority live in public housing provided by danwei. Data Source: National Bureau of Statistics and Social Statistics, Statistical Material on Chinese Society, (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 1994).

5. Xueguang Zhou, Stratification Dynamics under State Socialism: The Case of Urban China, 1949-1993, Social Forces, March 1996. 74(3):759-796.

According to the housing welfare system gradually established by the Chinese government in the 1950s, most of the public housing for urban residents was allocated by the state and danwei where residents worked in. In this housing system, the state and danwei were responsible for housing investment and construction, and the allocation of housing adopted the principle of welfare distribution (danwei housing division is generally based on the employee’s contribution to the danwei, technical level, length of service and family population...) and a symbolic low rent strategy. This strategy has resulted in relatively equal living conditions for the vast majority of China’s urban residents base on the strong government control, and in fact, institutionalized the socialist principles of fairness (FIG.1.3) which aimed to improve the social and economic status of the working class 5 .

The Welfare Dilemma: Stagnation of Housebuilding

Under the guidance of communist ideology, the government had complete control over urban housing development during the planned

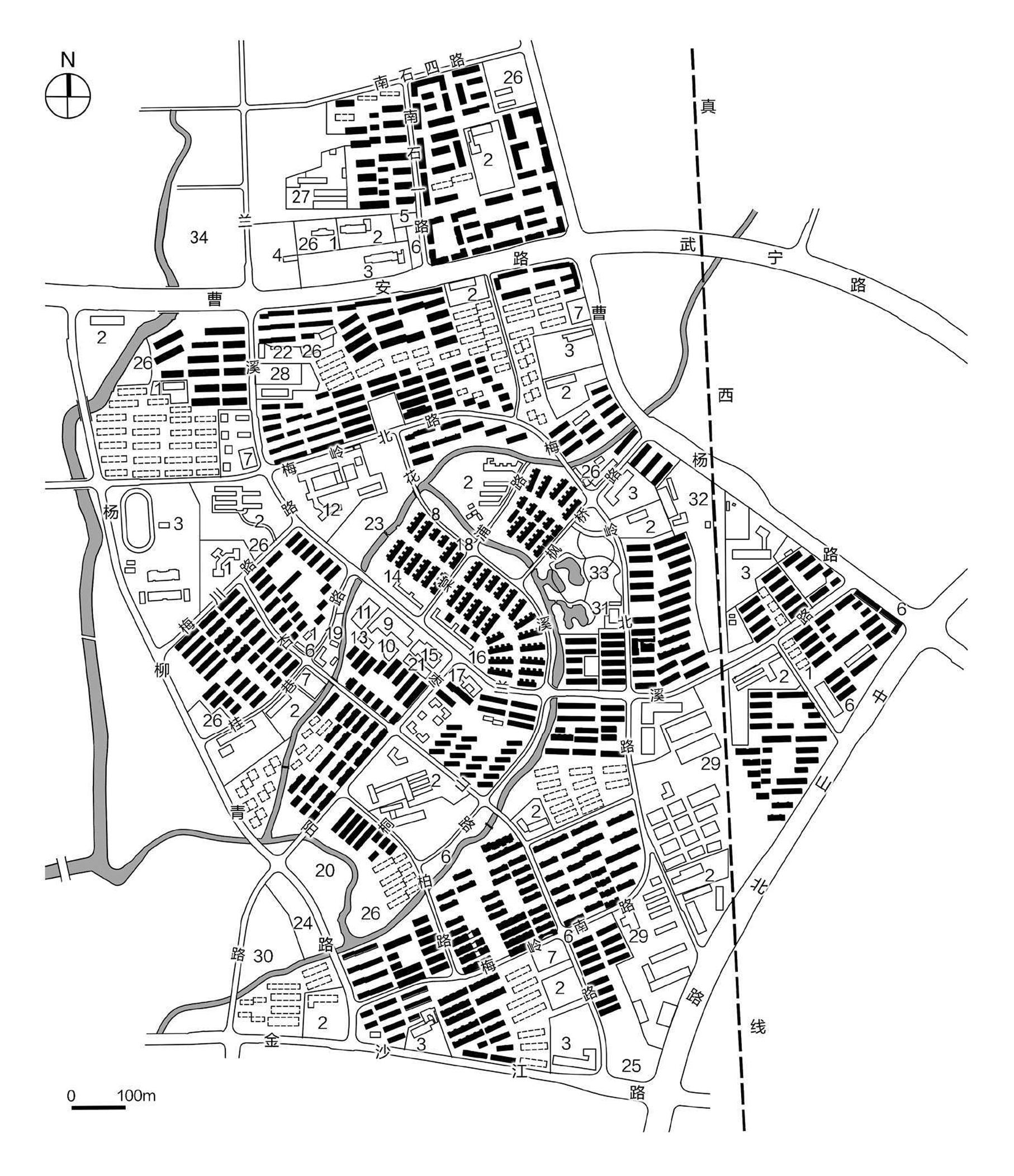

20

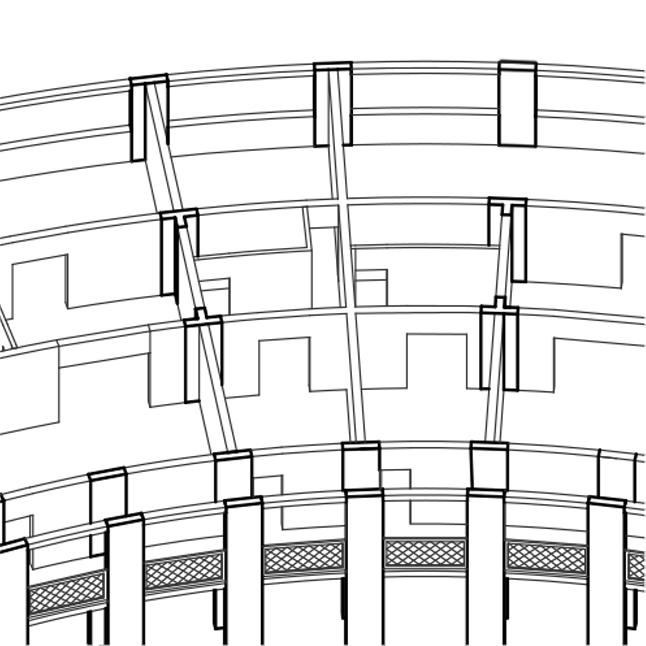

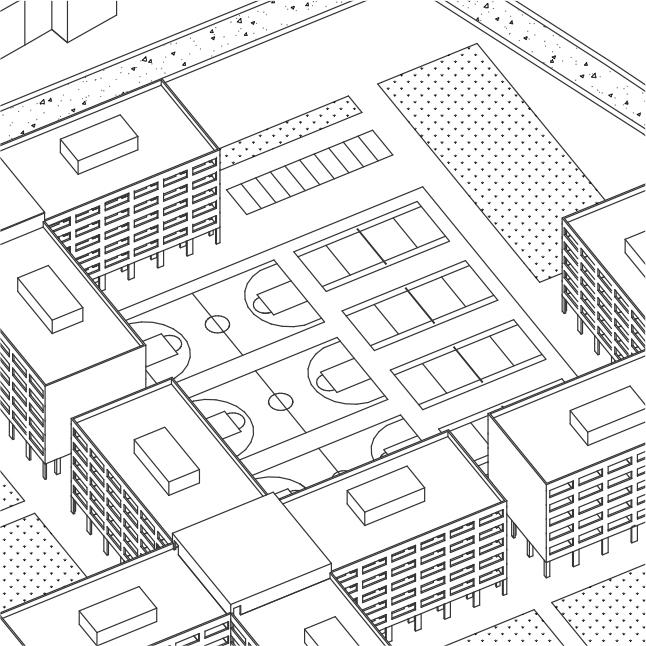

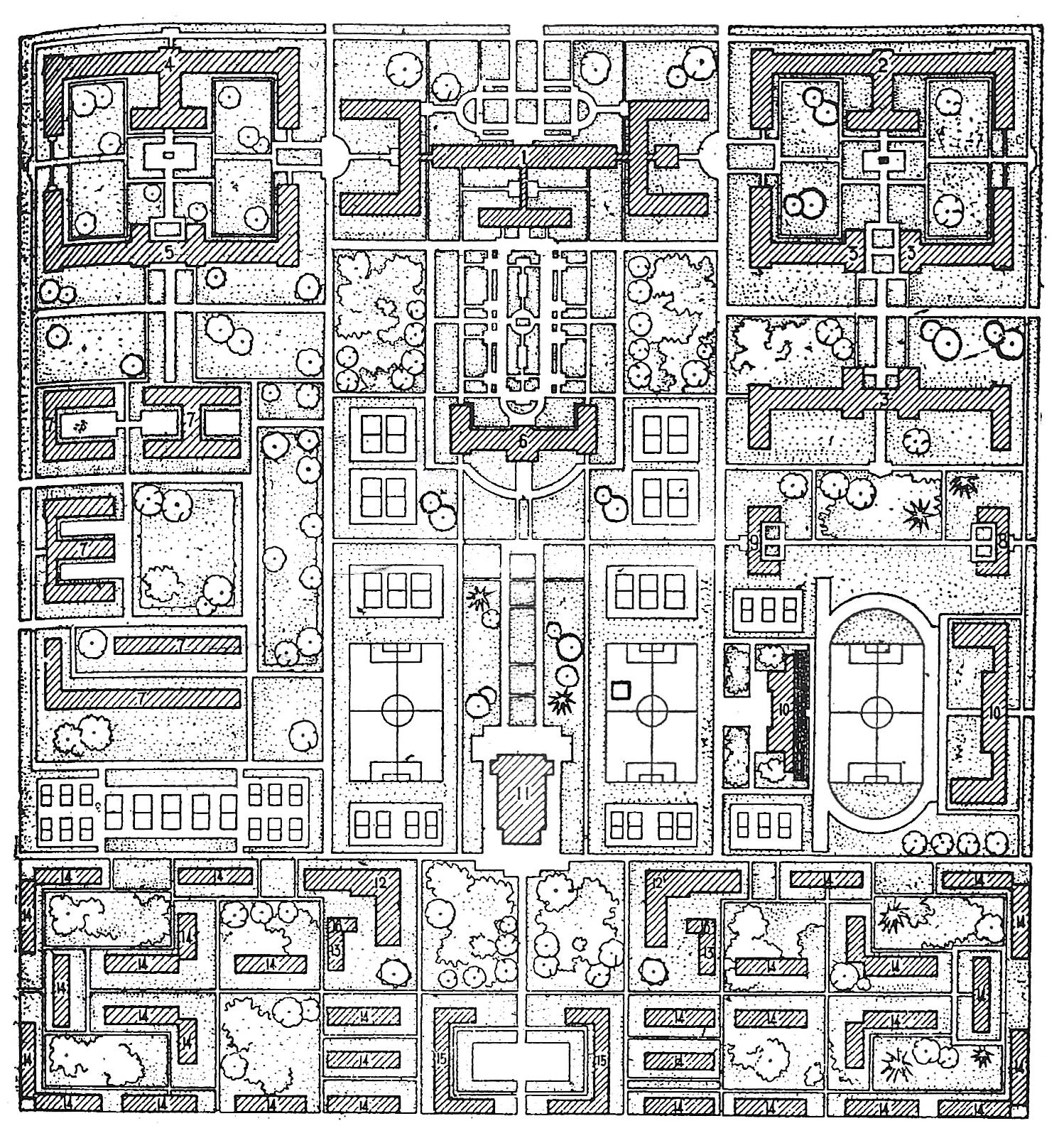

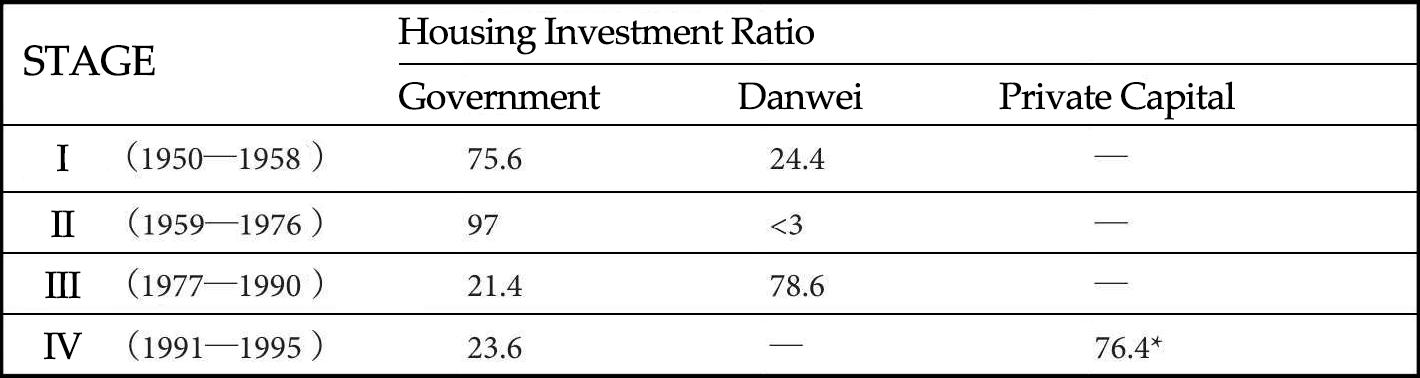

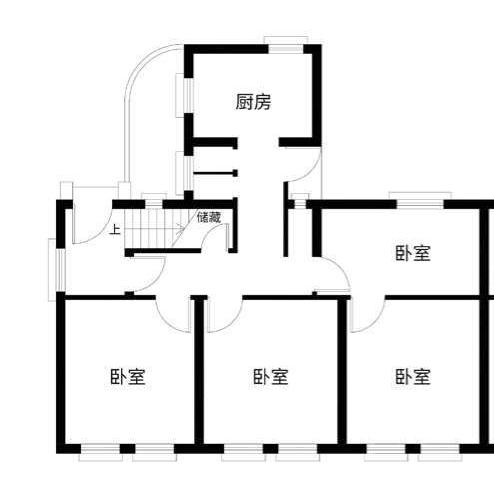

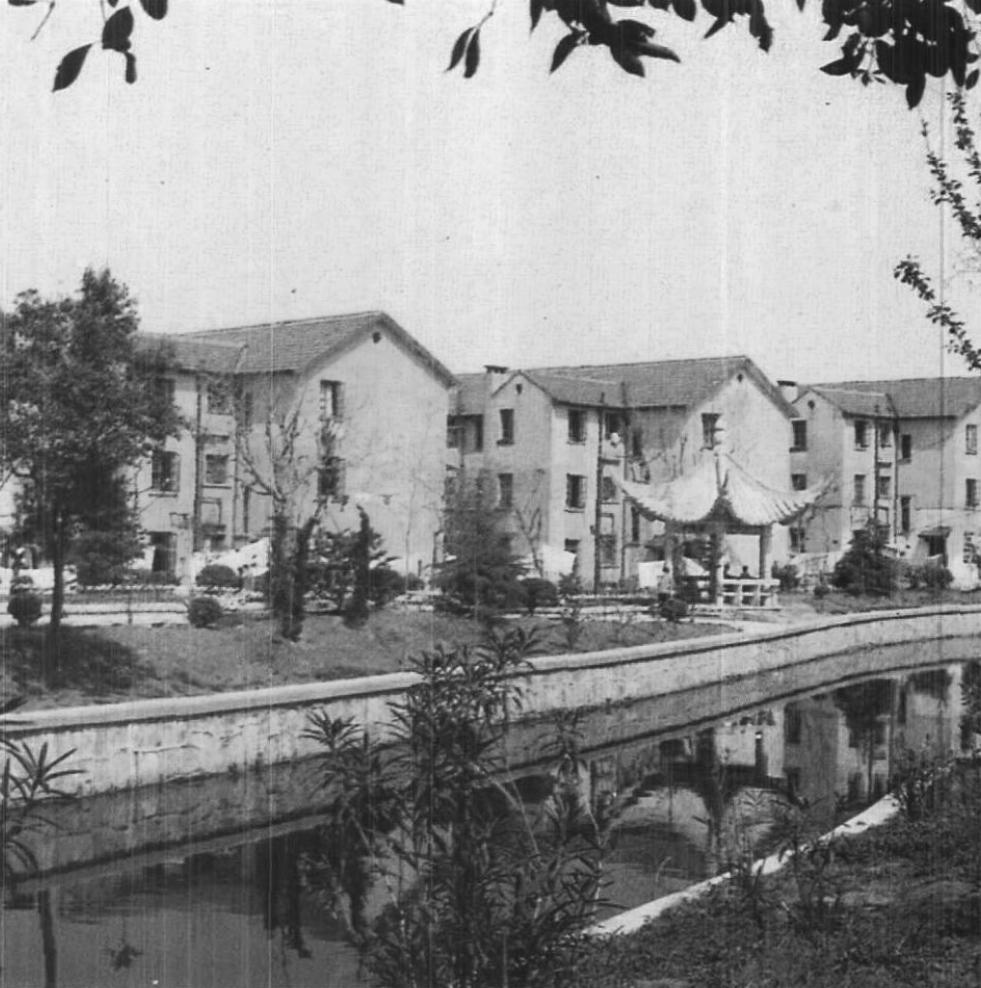

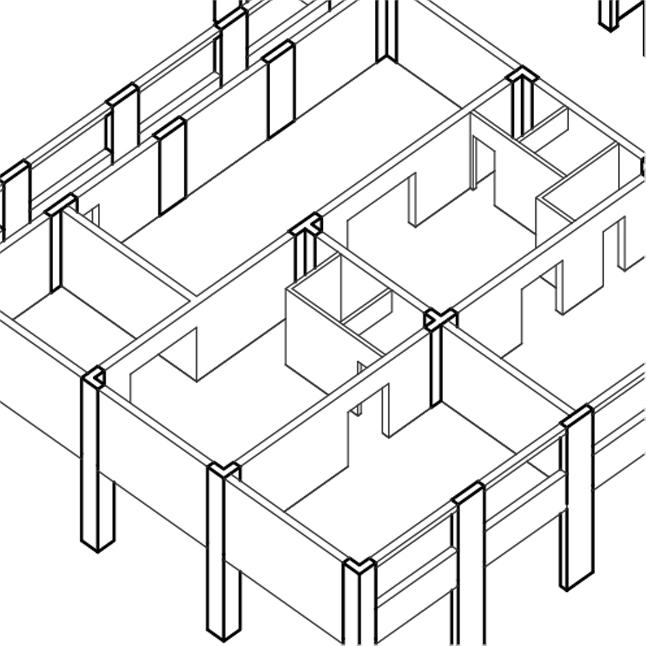

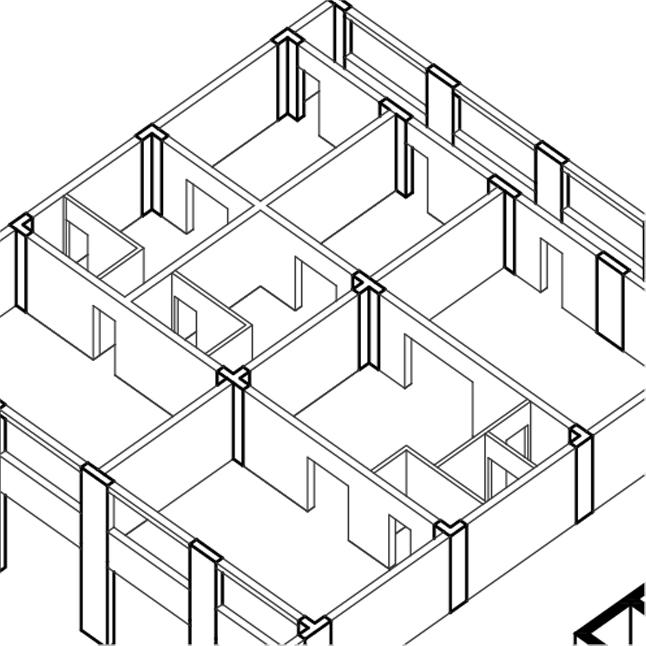

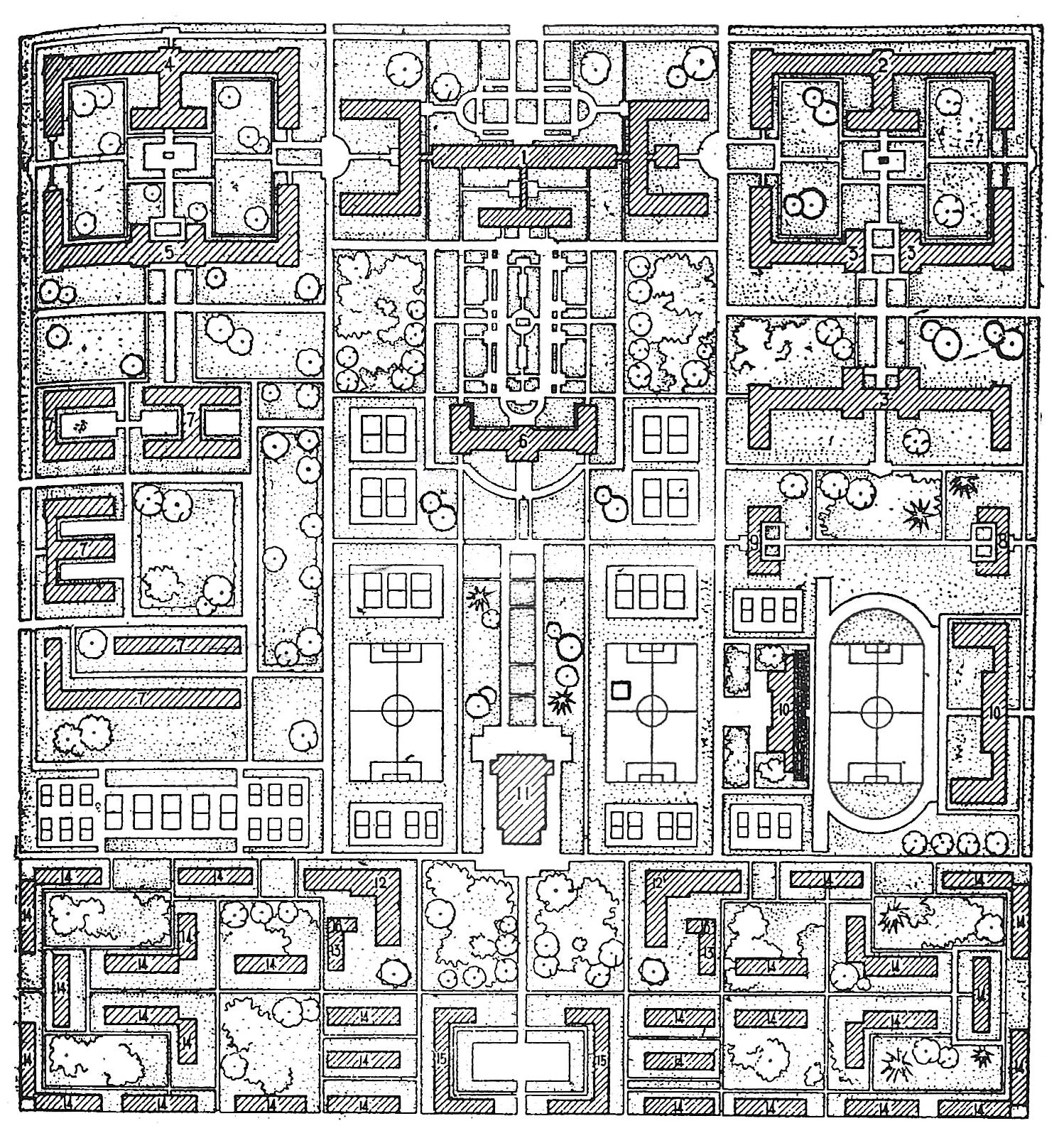

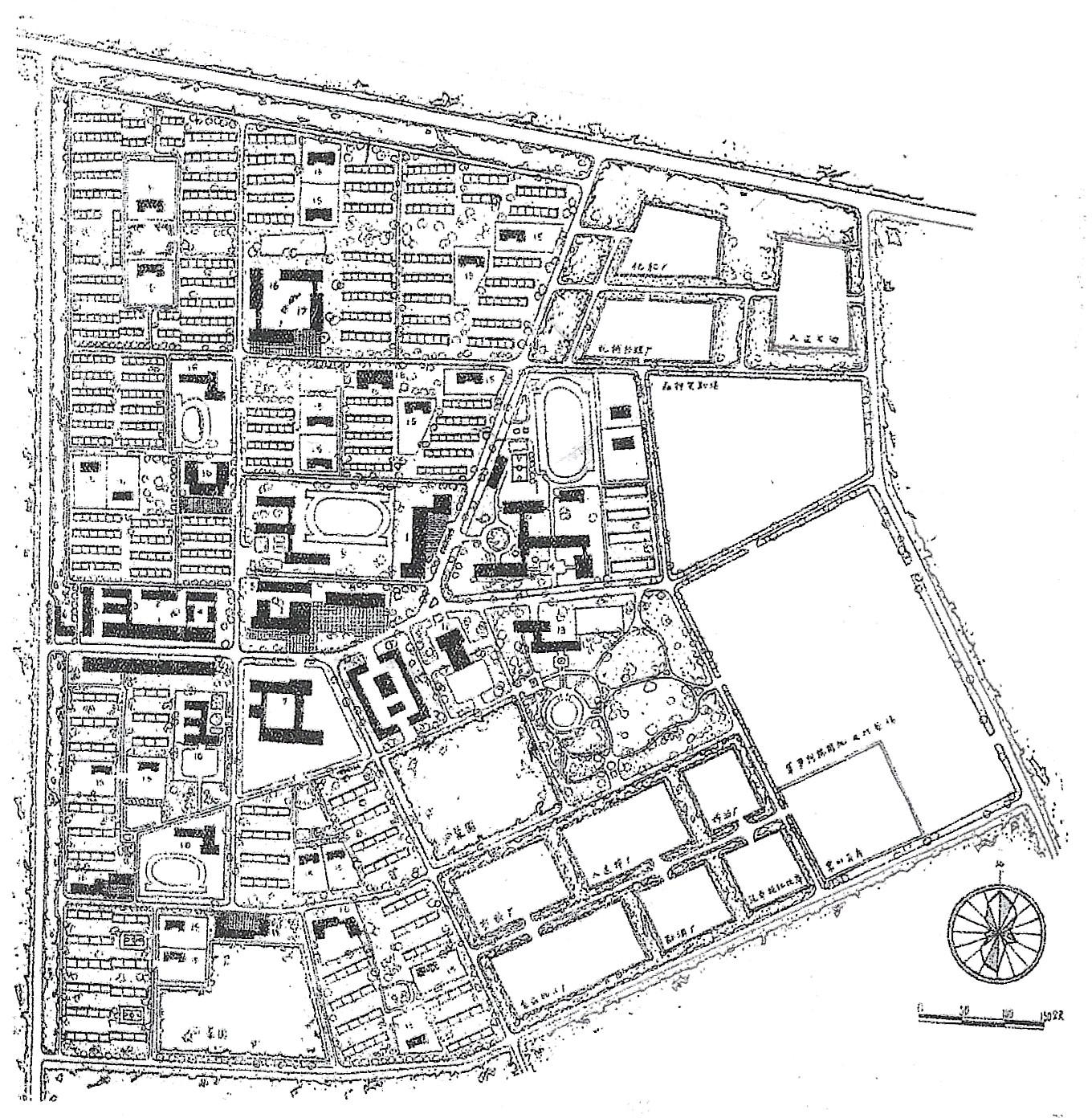

FIG.1.2

Plan for Xi’an University of Communications (a university Danwei), 1960s.

21

FIG.1.3 Crowds waiting for a lottery to decide on housing distribution in a danwei, 1970s.

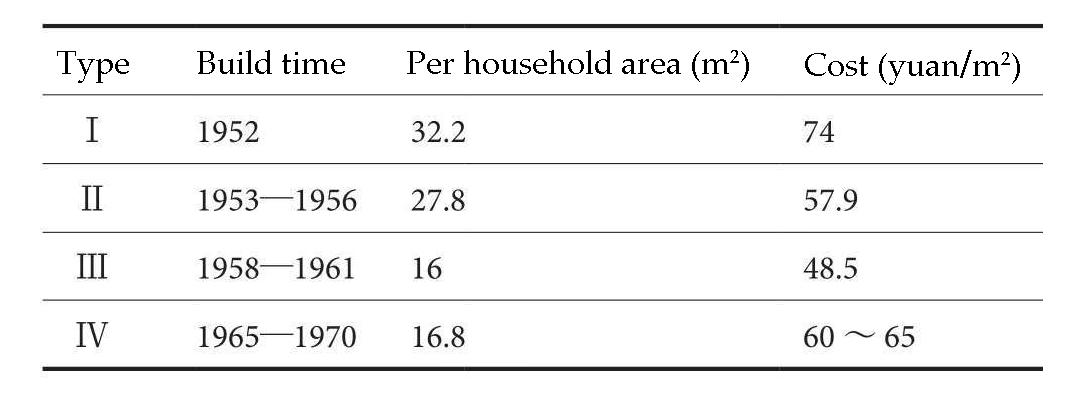

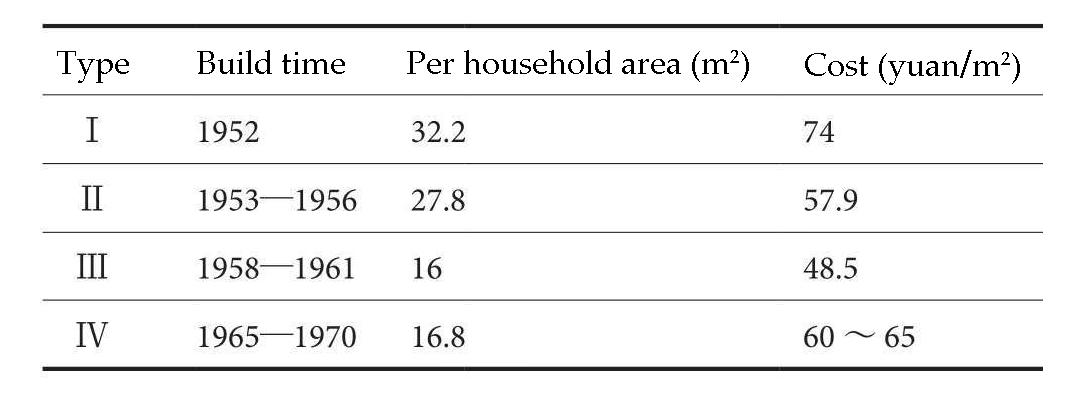

FIG.1.4 The construction standard of Shanghai’s public housing (1952-1970).

6. “Six Unifications“ means “unified planning, unified investment, unified urban design, unified construction, unified distribution, unified management” (Chinese: 统一规划;统一投资;统一设计; 统一建设;统一分配;统一管理).

7. David Bray, Social Space and Governance in Urban China: The Danwei System from Origins to Reform, (Stanford University Press, 2005).

economy China. Besides the urban land, building materials and skilled labor were also monopolized by the state. Since housing construction is not profitable base on the welfare distribution system, the cost of materials and labor force would be calculated by the government based on the cost of housing construction (the cost of each square meter), and then allocated to construction danwei in the total urban construction plan (FIG.1.4). Furthermore, in the early stages of housing development planning, the Six Unifications 6 principle had to be followed. Under such a logic, housing developers did not aim for profit but were considered a technical department for implementing the national development plan.

During this period, danwei became almost the only way for urban residents to obtain housing. Therefore, housing during this era only served as social welfare, with almost no investment attribute.

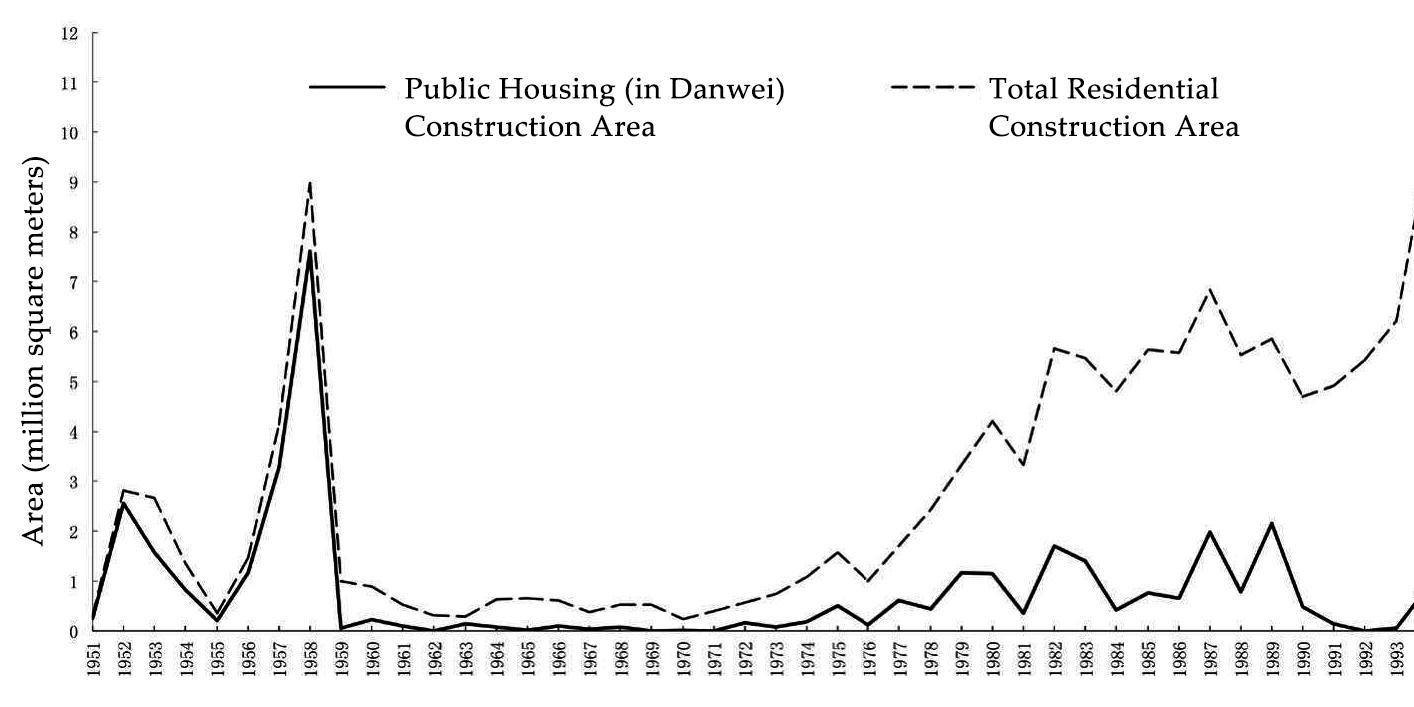

However, behind the beautiful vision of housing as a socialist principle of fairness and the welfare during the planned economy China, there was a serious shortage of housing construction and living space for urban residents during the whole period. Taking Shanghai’s housing construction as example (FIG.1.5), during the planned economy period (1949-1978), housing construction was mainly dominated by government-led public housing. However, except two periods of concentrated construction campaigns initiated by the central government in 1952-1953 and 1956-1958, housing development remained stagnant for a long time. In 1949, the average housing area for urban residents in Shanghai was 4.5 square meters, but by 1978, this number had dropped to 3.6 square meters. It is shocking that the long-term economic development movement even led to a regression in living space 7 of the urban area due to inadequate housing construction.

Such a long-standing housing shortage in planned economic China can be understood from three perspectives. First, in planned economic China, the constitution prohibited land expropriation, rental, and sale. Therefore, it is impossible for urban residents to obtain housing in the housing market, while danwei becomes almost the only way to get living space in the city. Secondly, based on the allocation of public housing, government and danwei invested money, land, and labor to supply and maintain non-profit housing for all urban residents. The state

22

relied entirely on its own funds to maintain this system, which not only made it difficult to guarantee the quantity and quality of housing but also resulted in unsustainable finances. Especially Chinese government kept facing the continued stagnation of economic development under the planned economy system from 1949 to the 1980s. Thirdly, the urban population grew rapidly in the early years of reform and opening up (the late 1970s) era. At the same time, the priority of developing industry and infrastructure for reform and opening up resulted in long-term financial shortages for the housing system, which further led to the inability of the government to provide public housing through the old welfare model.

Due to fiscal unsustainability, the welfare-oriented housing policy was gradually abandoned after the reform and opening up. Through the reform of the housing system since the 1980s, Chinese government collaborated with profit-oriented developers and private capital, and has achieved unprecedented advancement in the development of Chinese housing and urbanization speed.

23 Planned Economy Era Market Economy Era

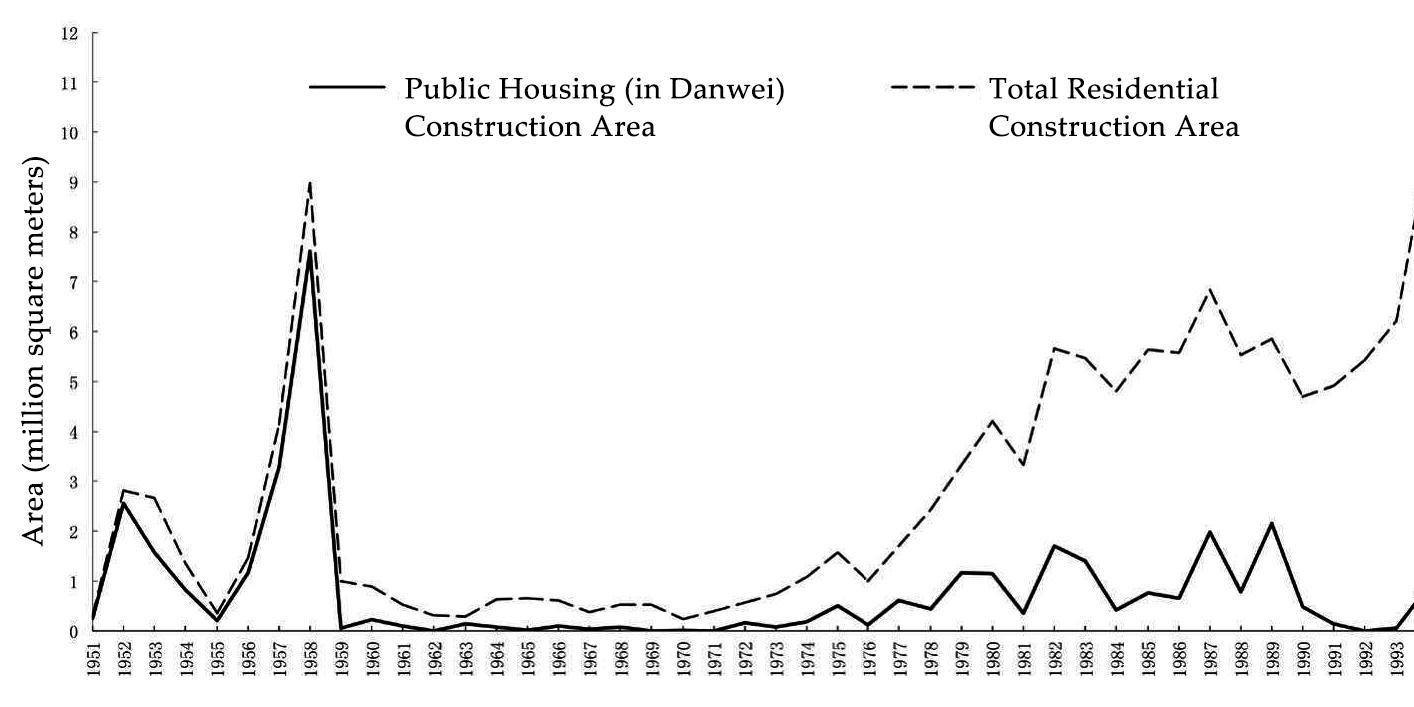

FIG.1.5

Construction of public housing (in danwei) and residential buildings in Shanghai over the years (1951-1995).

FIG.1.6

Since the reform and opening up in 1980s, Shenzhen has grown by an average of 200,000 to 300,000 residents a year. Today, Shenzhen’s urban district has a population of more than 5 million.

The different urban context of Shenzhen could be seen due to its super rapid urbanization in different periods.

8. The Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside movement (Chinese: 知识青年上山下乡运动)was a social and political campaign launched in China from 1968 to 1976.

The campaign aimed to send urban youth, especially high school and college students, to rural areas to work and learn from peasants and soldiers. In economic terms, the aim of the movement is to alleviate the problem of cities failing to provide enough jobs for youth.

9. Such a neoliberal tactic in the housing system could also be seen in mant other countries at the same time.

For example, in the 1980s, the UK implemented a series of Neo-liberalism policies, including the privatization of public housing (Right to Buy). These policies aimed to reduce government spending, relieve the government burden, and promote economic growth through increased market efficiency.

1978 - NOW, HOUSING AS PROPERTY

In this section, 1978, the beginning year of reform and opening up in China, was presented as an essential milestone of the housing system reform. However, it is necessary to figure out that, as a system directly related to hundreds of millions of residents’ crucial human basic needs, the housing system’s institutional change could not be completed in very short time. In fact, the market-oriented reform of China’s housing system should be seen as a gradual and ongoing process, adjusted according to the needs of society and the state. Therefore, the year 1978 should be regarded as the beginning of the Chinese state and government’s reform in spirit and ideology, which involved all aspects and gradually affected and changed China’s housing system. Over 40 years of continuous change, the housing system has gradually taken on its current form. This section attempted to provide a brief overview, demonstrating how China’s housing has evolved from a state-provided social welfare during the planned economy period to private property and investment objects in the market economy period, and what is the realistic logic behind such a process.

Housing System Reform and Neoliberal Magic

In the late 1970s, following the end of the Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside movement 8, a large number of educated youth returned from rural areas to cities. The shortage of urban living space led to a surge in demand for housing. However, long-term financial shortages made the city government cannot provide new public housing for urban residents. In addition, adopting the reform and opening up required the government to allocate limited funds to infrastructure development. The government had to rely on private capital for urban housing construction in such a context.

Nevertheless, during the planned economy era, the Chinese government (the only supplier) had long provided almost free housing to urban residents. Under such a system, China’s housing prices had long been maintained at extremely low levels (or no market for housing transactions), even lower than the cost of housing construction. As a result, private capital lacked the motive to enter the housing indus-

26

try for investment and construction purposes. To address this fundamental problem, the Chinese government adopted a neoliberal tactic to encourage private capital to invest in housing construction 9. Until the 1980s, the vast majority of housing in Chinese cities was non-profit public housing built by the government and danwei at a loss. In this situation, even if private capital invested in new housing construction, it was difficult to sell them due to the extremely low average housing prices. The strategy adopted by the Chinese government was to sell the ownership of non-profit public housing to individuals, allowing non-profit housing to flow into the for-profit housing market, which will gradually drive up market housing prices to above cost. With the rise in housing prices, private capital was encouraged to invest in housing construction, leading to an increase in for-profit housing. As a result, whether old or new housing, more and more housing was held by individuals rather than the state, non-profit housing was converted into for-profit housing that could be freely bought and sold. The market share of for-profit housing gradually expanded, driving up housing prices. When market prices became generally higher than cost, private for-profit builders took over the supply of housing.

Through this reform, the state transformed from the only housing supplier to a regulator outside the market, and rid itself of the financial unsustainability of housing construction, while also raising funds for urban development by selling land. By mobilizing the power of the market, urban housing supply became more sufficient and efficient (FIG.1.5 and FIG 1.9). After 1978, private capital poured into China’s housing system, significantly increasing the speed of urban housing construction. Such a market-oriented reform greatly improving China’s urbanization process, and enabling China to establish modern cities in a short period of time.

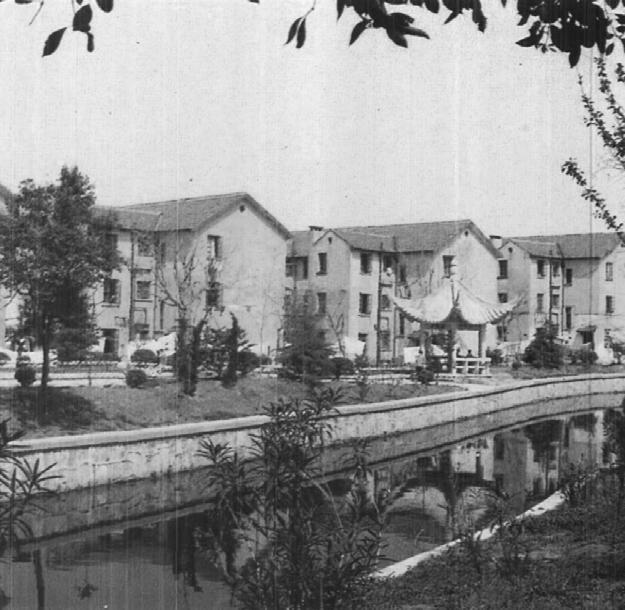

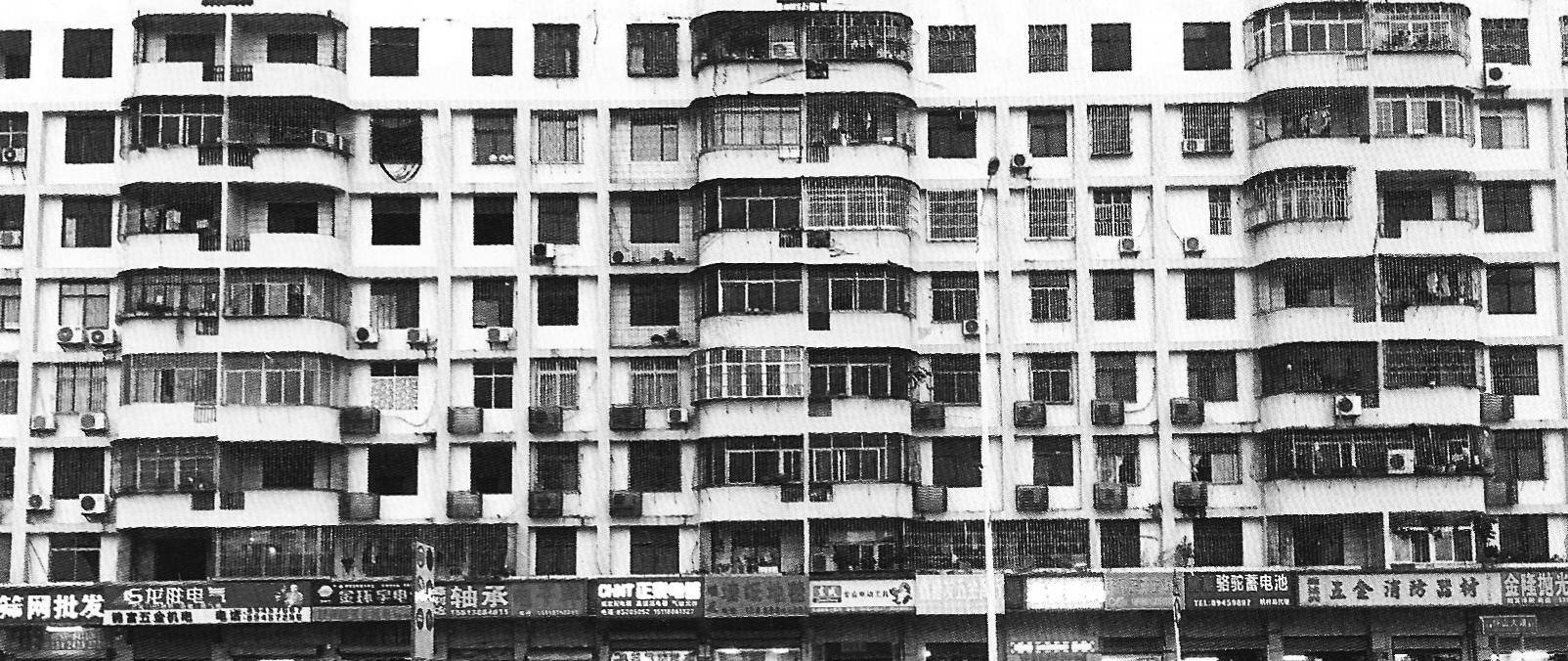

The

housing

in the 1970s in Shanghai. In the 1980s and 1990s, a lot of this public housing was privatised, mostly sold to its occupants (the employees of danwei) at low prices.

As can be seen from the data, take Shanghai for example, private capital investment in housing construction increased rapidly after 1977.

27

FIG.1.9

Proportion of Investment by different groups in urban housing construction in Shanghai (1950-1995).

FIG.1.8

Shenzhen’s first batch of commercial housing built by private developer, 1983.

FIG.1.7

public

built

TAX - SHARING REFORM IN 1994 AND THE BORN OF LAND FINANCE

In this chapter, the thesis has expounded on how China’s urban housing system has utilised the power of private capital to address the urban housing shortage after the 1980s. This neoliberal housing privatisation policy can be seen as a projection of the country’s overall policies and ideological transformations during the reform and opening-up era. However, overall, housing privatisation remains a technical strategy within the housing system, aimed solely at addressing the urban housing shortage.

Nevertheless, this still cannot explain how China’s real estate industry has been able to continuously expand into the abnormal state it is in today over the past four decades. Why has land finance become a crucial source of finance for China’s (local) governments, leading to an interest alliance between the government and private developers? Moreover, what ultimately led to the collapse of China’s housing market today? To answer these questions, linking them with the change in China’s financial system is necessary because all government actions are inextricably linked to finance and taxation. Without a solid financial foundation, administration and maintenance of government are all castles in the air 10 .

Tax-Sharing Reform and Local Financial Shortage

China’s financial system has undergone a complex reform process, particularly during the reform and opening up. Although this thesis does not intend to trace the complete reform process of China’s financial system since 1949, it is still necessary to highlight the far-reaching impact of the 1994 Tax-Sharing Reform 11 on China’s central/local governments and housing system. In a sense, the current dependence of China’s local governments on land finance and the collapse of China’s real estate market can be traced back to this financial system reform.

10. Xiaohuan Lan, Involved in the Matter: China’s Government and Economic Development (Chinese: 置身事内:中国 政府与经济发展), (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2021).

11. “the 1994 Tax-Sharing Reform” (Chinese: 1994年分税制改革).

In short, the Tax-Sharing Reform initiated by the Chinese central government in 1994 was a financial policy which aimed to centralise taxes to the central government. After the reform, the central government regained much financial power from local governments, strengthening

28

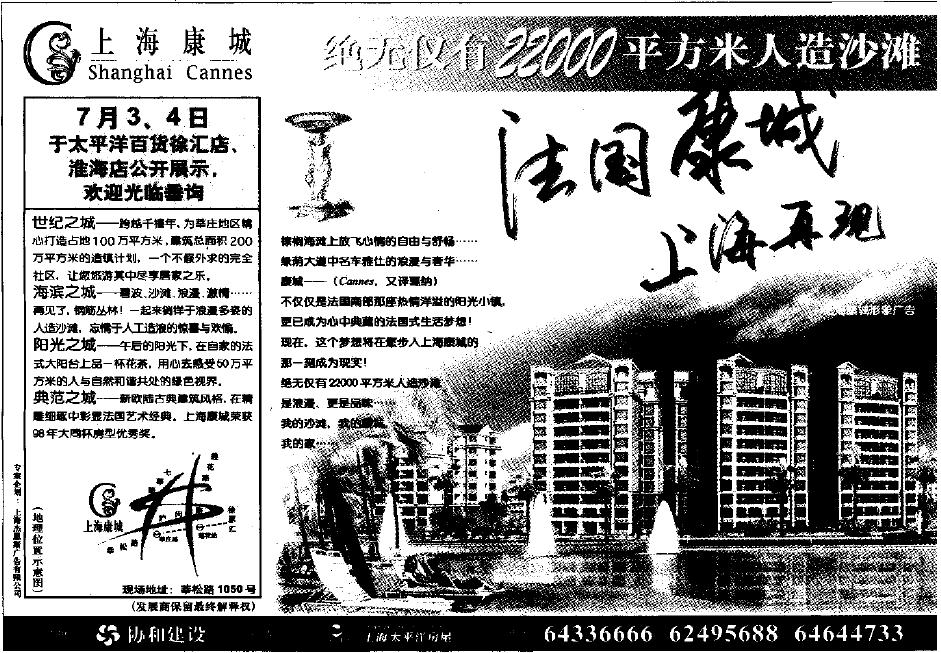

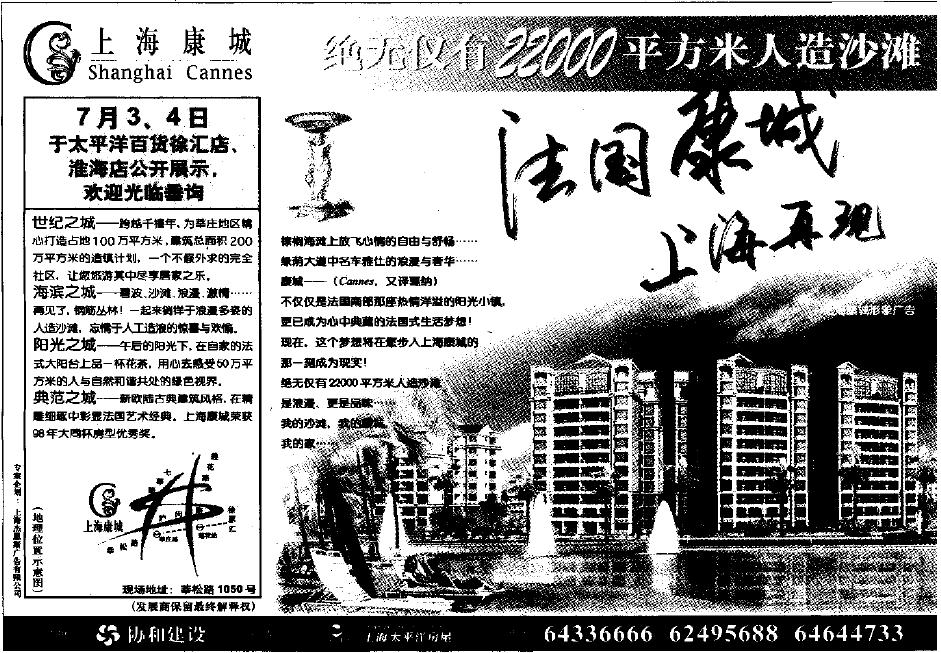

FIG.1.10

Real estate advertising in Shanghai in 1999. The text in the middle: “Recreating Cannes life in Shanghai.” The advertisement describes how to achieve “French style living” in this community.

its financial revenue and macroeconomic control ability (FIG.1.11)

12 . However, on the other hand, the reform did not change the task of local governments since the reform and opening-up period, which was to take economic development as the central task 13. In practice, the responsibilities of local governments should match their financial capacity. Especially after the reform and opening up, Chinese local governments have undertaken the heavy responsibility of economic development. The reduce of available financial resources, forcing local governments to seek new sources of finance.

The Seed of Land Finance

During the Tax-Sharing Reform in 1994, the decision-making power and revenue from the transfer of state-owned land were left to local governments, as this revenue was minimal then. Two significant events in 1998 led to the true value of urban land being revealed and gradually becoming the primary source of local government revenue.

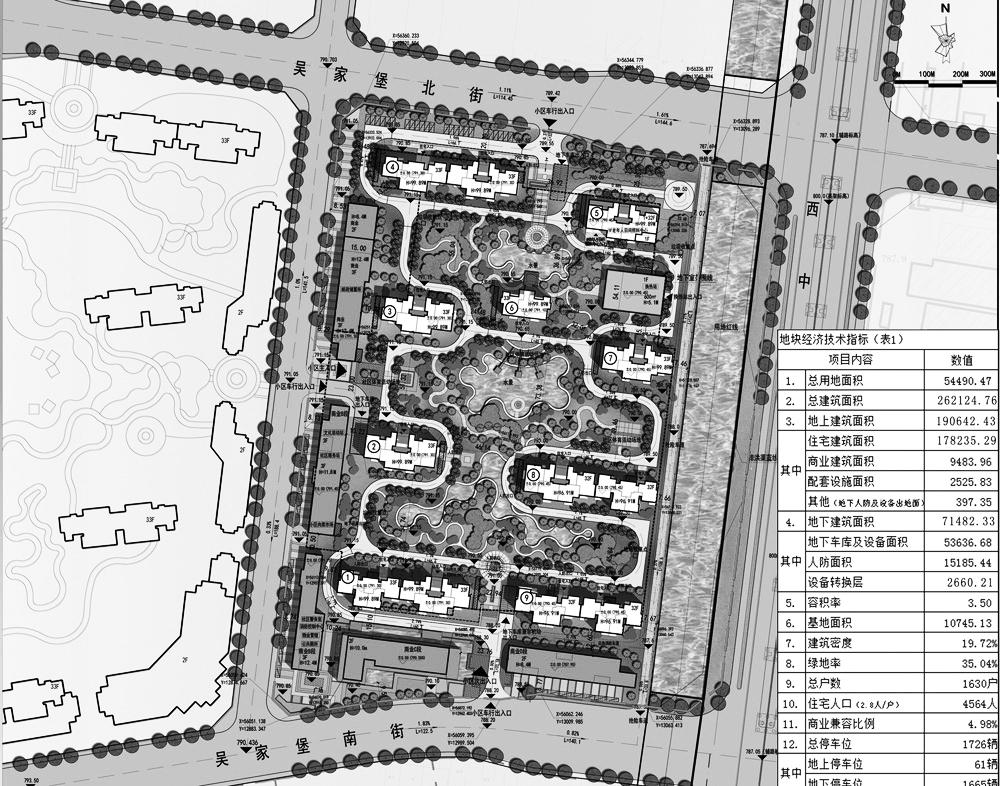

First, the completely stop of housing allocation by danwei system end the welfare housing system, forcing city residents to access housing only through the housing market. From 1997 to 2002, the annual average growth rate of newly started urban residential construction areas in China was 26%, which increased nearly four times in five years. Commercial residential buildings and xiaoqu (residential compound) gradually became the primary living forms in Chinese cities. Second, the Land Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China 14 came into effect, establishing the monopoly power of urban governments over land development (while it is difficult to use rural land as construction land in law, the land of urban area becomes even more valuable) 15. Since then, urban land prices have risen year after year, becoming the main source of local government revenue. Housing in China was finally officially defined as an investment object/property rather than social welfare.

12. Feizhou Zhou and Mingzhi Tan, the Relationship of Central and Local Government in Contemporary China (Chinese: 当代中国的中央地方关系), (China Social Sciences Press, 2014).

13. “Take economic development as the central task” is guideline of Chinese government during the period of reform and opening up (Chinese: 以经济建设为 中心).

14. Chinese: 中华人民共和国土地管理法.

15. Xiaohuan Lan, Involved in the Matter: China’s Government and Economic Development (Chinese: 置身事内:中国 政府与经济发展), (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2021).

29

the 1994 Tax-Sharing Reform

FIG.1.11.1 and FIG.1.11.2

The financial capacity of the Chinese central government has been greatly enhanced since the reform of the tax-sharing system in 1994. On the contrary, China’s local government’s fiscal revenue has fallen sharply.

30

Central government budget revenue as a share of total revenue

the 1994 Tax-Sharing Reform

Local government budget revenue as a share of total revenue

Proportion of local budget expenditure to total expenditure

31

The state provides and maintains housing for most citizens at a loss over the long term as a typical symbol of "socialism China".

The government sells housing to individuals to raise the market price of housing. When market prices generally increase, for-profit real estate developers took over the housing supply.

For-profit developers have almost become the only housing provider in China. At the same time, housing prices have reached the highest point in Chinese history.

HOUSING AS WELFARE

HOUSING AS PROPERTY

HOUSING AS WELFARE

HOUSING AS PROPERTY

HOUSING AS WELFARE

HOUSING AS PROPERTY

32

1949-1980s Housing as Welfare

1980s The Reform of Housing System

1980s - 2020s Housing as Property (Investment Object)

the 1994 Tax-Sharing Reform

FIG.1.12 Time line of housing system change in China

2020s The Collapse of Real Estate in China

CONCLUSION

To conclude, the first chapter provides a comprehensive historical background, stating how housing has evolved from being a social welfare in China’s planned economy era (1949-1978) to an investment object in China’s market economy era (1978-now).

During the planned economy era, the state completely controlled China’s housing system in accordance with the fair distribution principle of the Communist Party and socialist country and it was integrated with the city’s texture based on the basic urban unit in that time. However, with the advancement of reform and opening up in the 1980s, the state urgently needed the power of private capital to provide more housing for the increasing urban population. Through the public housing privatization policy, housing prices in Chinese cities have continued to soar, and an increasing number of profit-driven real estate developers have begun constructing urban housing, ultimately taking over the responsibility of urban housing supply from the government.

After the Chinese housing system reform, the value of urban land has also been continuously exploited. Especially after the tax-sharing reform in 1994, Chinese local governments urgently needed new sources of finance to fill the shortfall. In such a context, land gradually became the money printing machine of Chinese local governments, and land finance became the most important strategy to maintain the stable fiscal revenue.

In the next chapter, the thesis will elaborate on land finance and the operating mechanism of the interest alliance between the government and real estate developers. How has this opaque and unfair alliance maintained in China for over forty years after the reform and opening up? Why has this alliance moved towards the edge of collapse in the 2020s?

33

CHAPTER 2.

The Logic of Power Relation

Previous Page

The underground is under construction in downtown Shanghai, China. In China’s rapid modernization, infrastructure construction in, urbanization and land finance are inextricably linked with each other.

35

AND THE LOGIC OF POWER RELATION BEHINDE IT

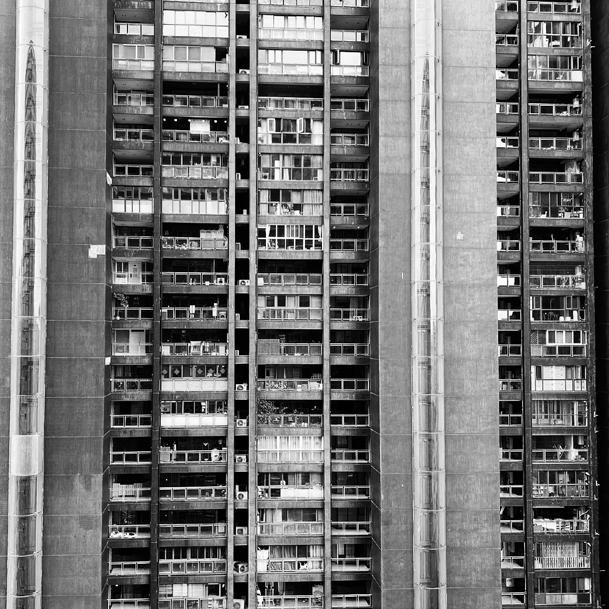

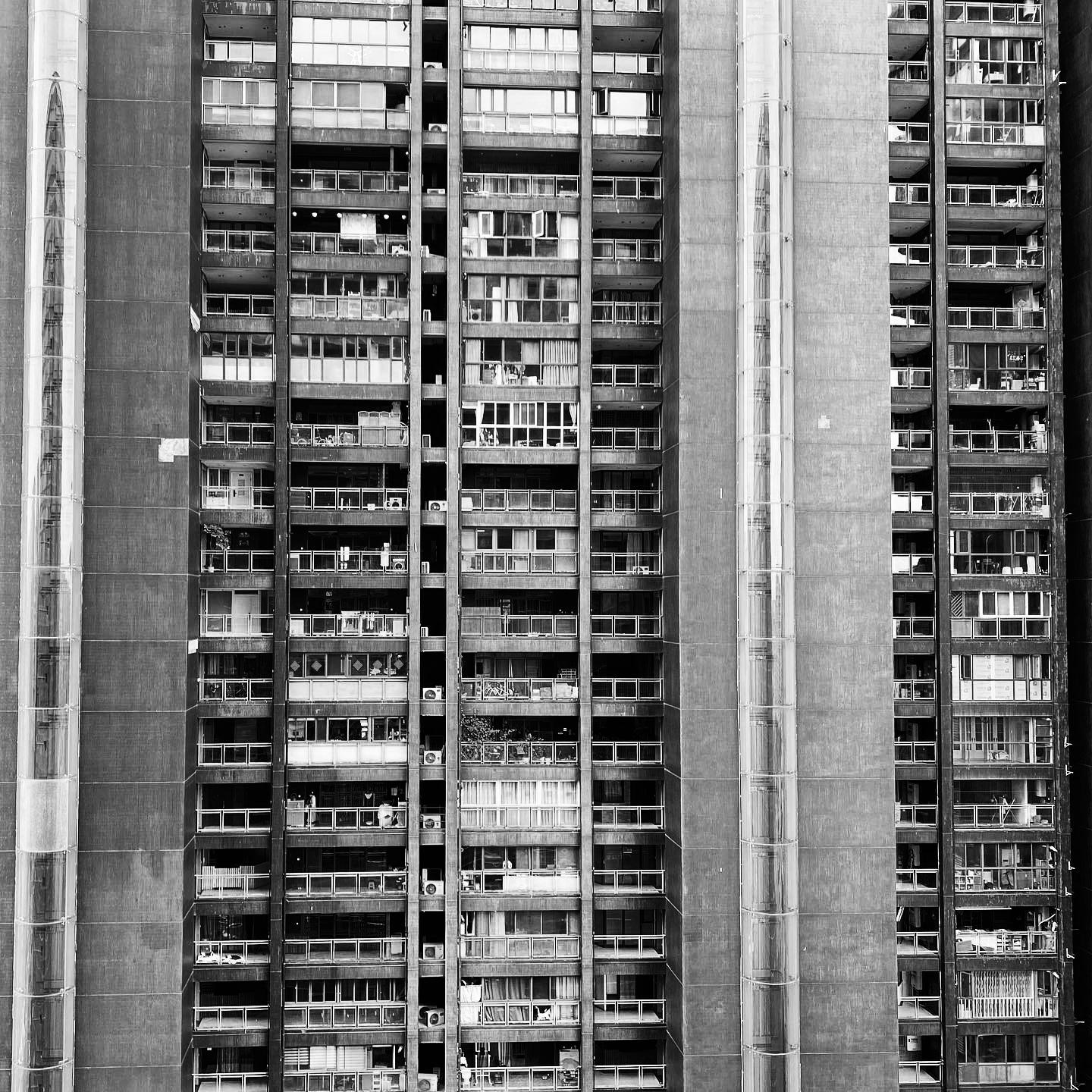

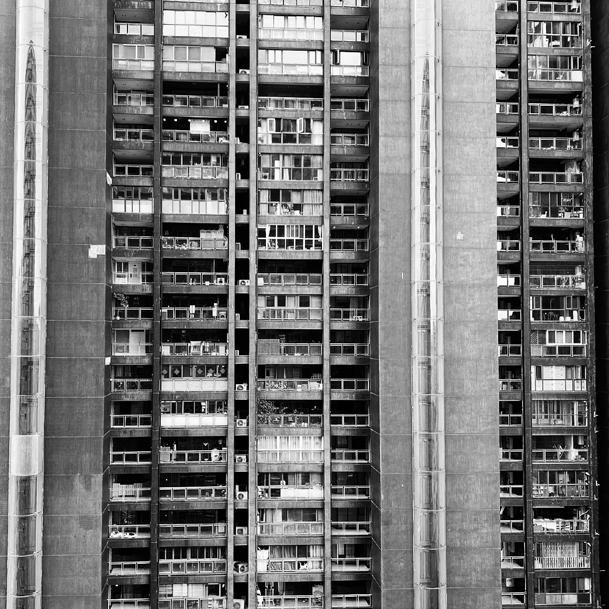

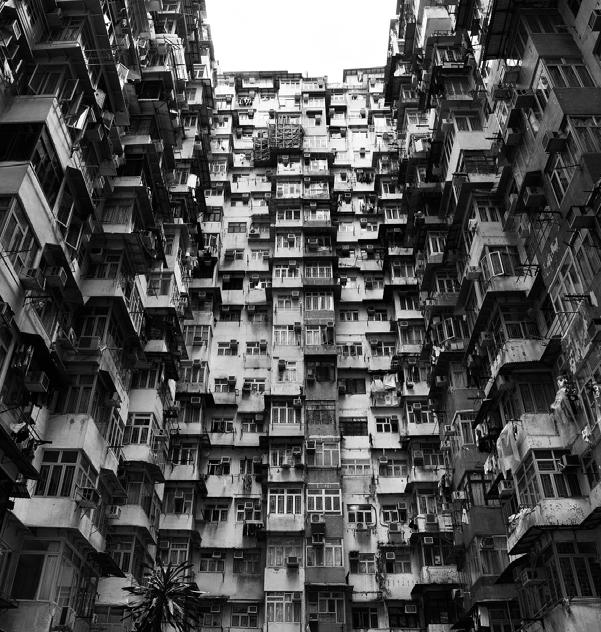

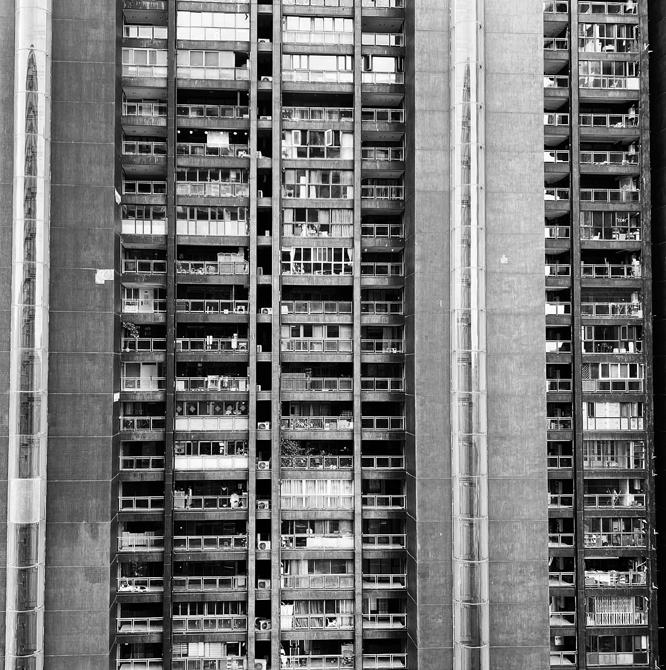

During the planned economy era, most urban housing in China was owned by the state. Especially during the Great Cultural Revolution period from 1966 to 1976, the state further centralised urban housing distribution, and private housing was almost all confiscated or nationalised. At this stage, housing was regarded as social welfare provided by the state and danwei to reflect the superiority of the socialist system and to provide socialist and collectivist education to urban residents. However, with the demand for reform and opening up in the 1980s, the housing system underwent market-oriented reforms. Through Privatizing public housing and encouraging private investment, for-profit developers quickly took over the task of providing housing for Chinese urban residents from the government. Today, more than 90% of the housing in Chinese cities is provided by these developers.

1. Xiaoqu (Chinese: 小区), also called residential compound, is a Chinese word that refers to the most common type of residential community or neighborhood in contemporary China. The typical features of xiaoqu may include: enclosed form, shared green space and high-rise, high-density buildings (apartments).

2. Matthew Soules, Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century, (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2021).

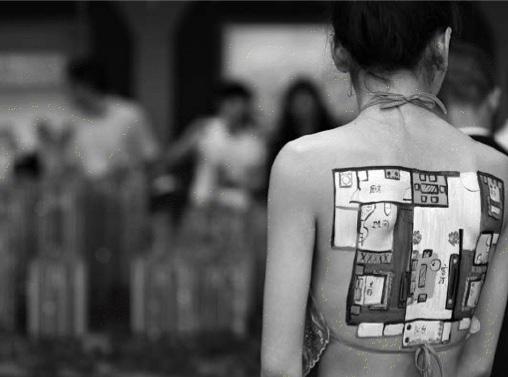

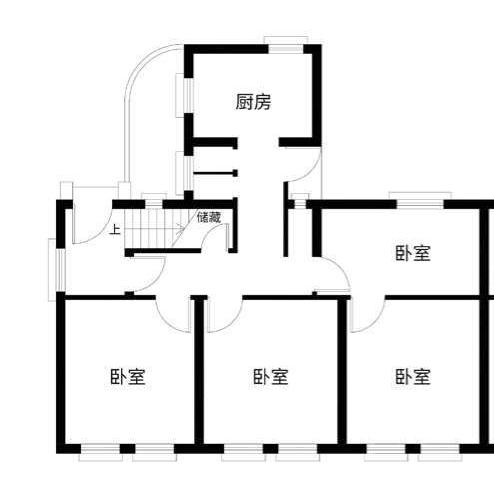

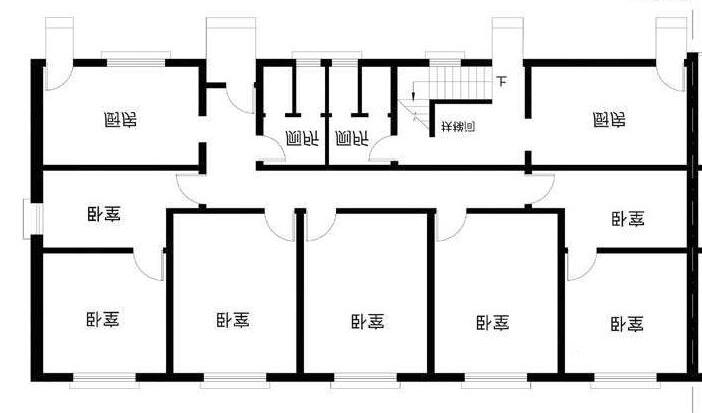

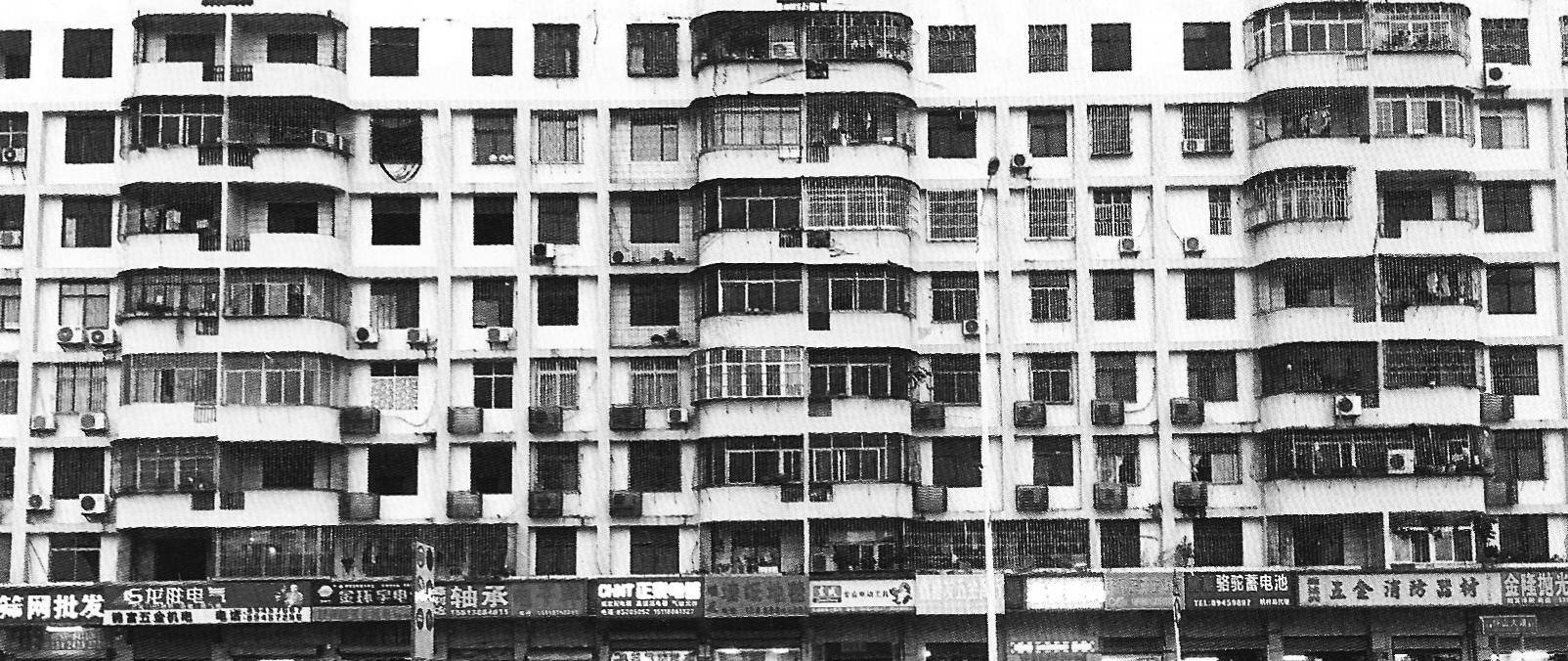

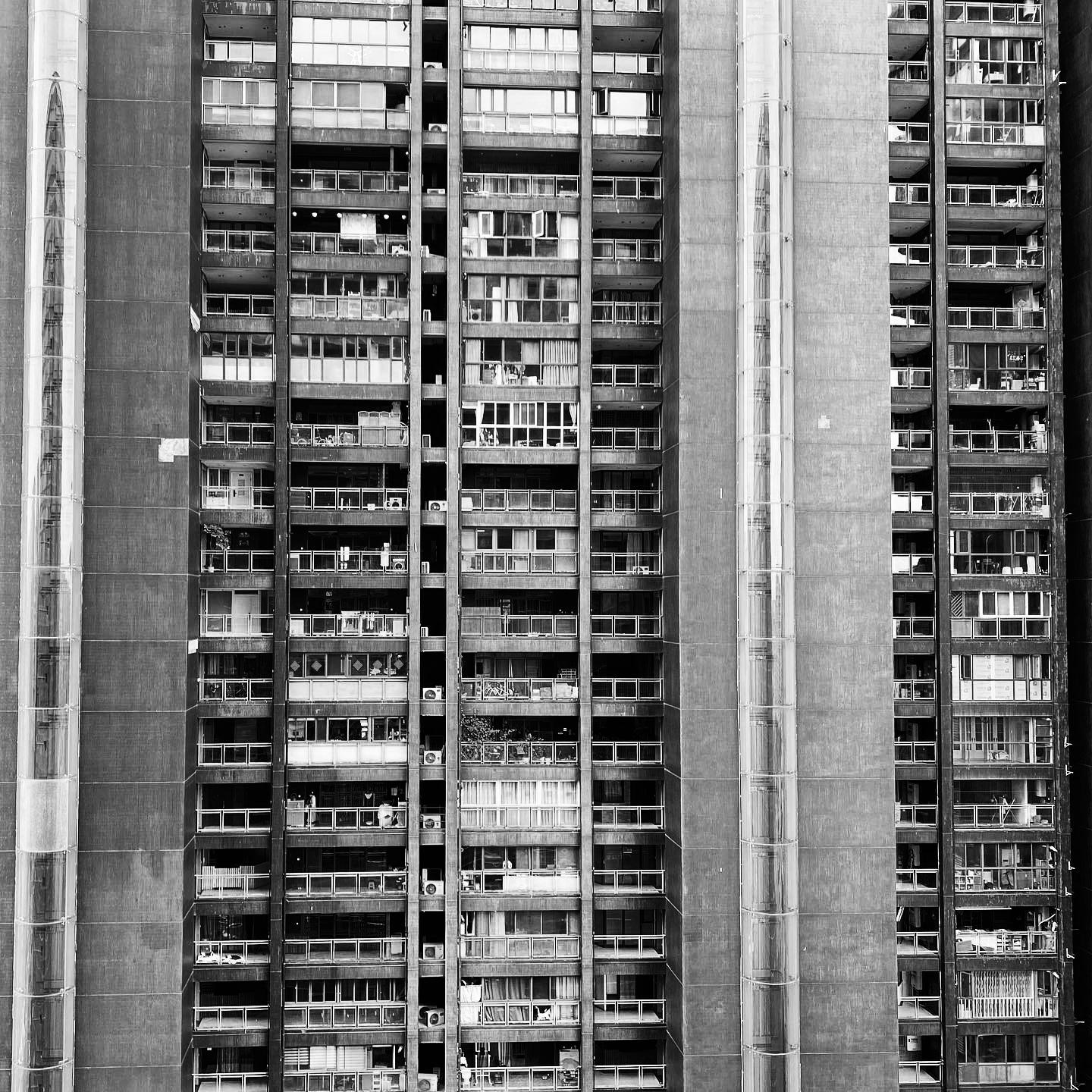

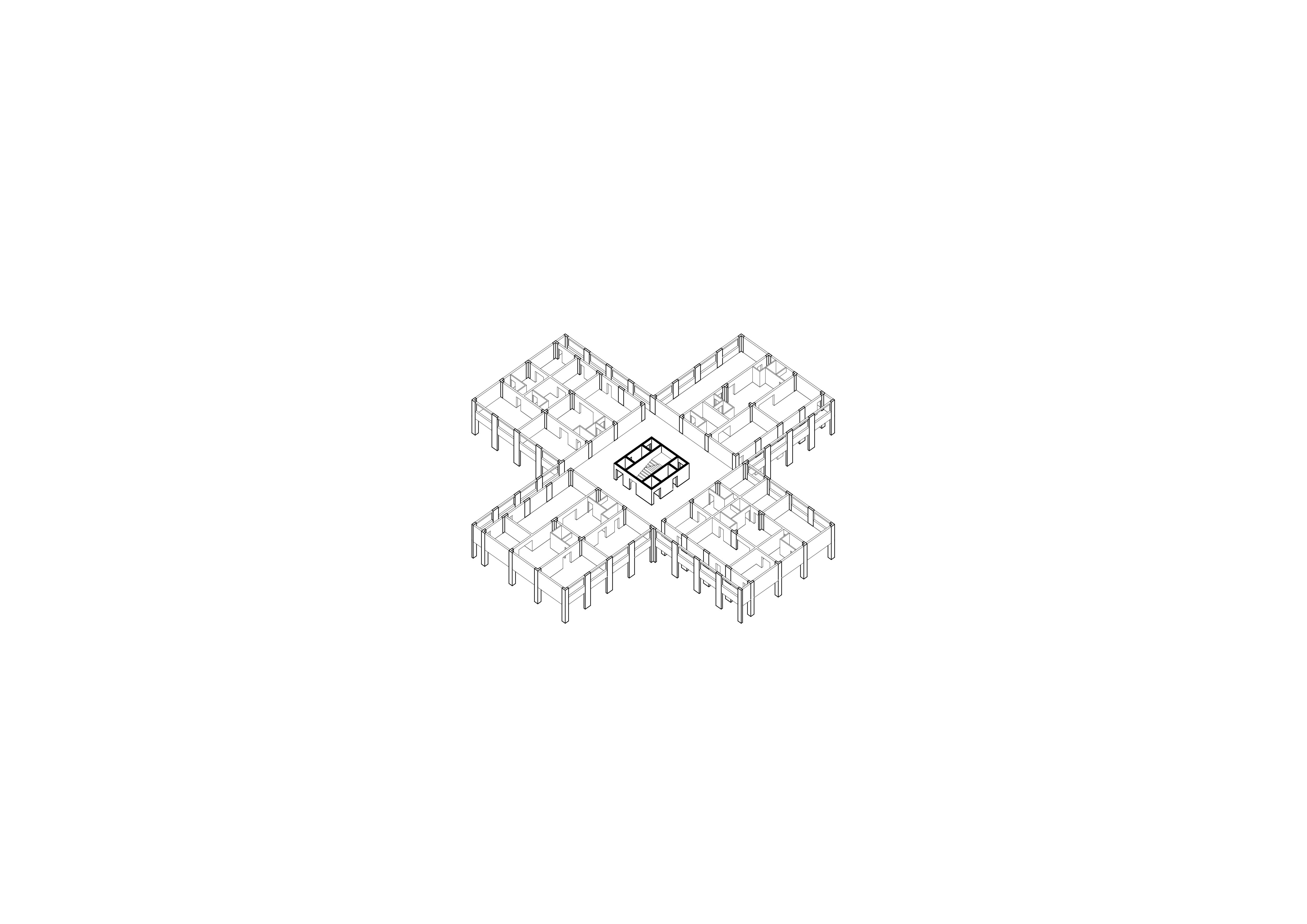

With the establishment of the dominant position of real estate developers, Chinese people’s living form has also changed. Most urban residents have moved out of public housing built during the planned economy era and moved into xiaoqu 1 with their own private space and no shared spaces. In fact, the typology of xiaoqu itself is the reflection of the logic of maximising development profits of developers and owners. All spaces in this enclosed living form have clear ownership, and every square meter of space is clearly priced. Shared kitchens/bathrooms and toilets in the design of old public housing have been removed, and replaced by infrastructure exclusive to each living unit (FIG.2.2). As there is no direct profit, open space in the community have also been minimised to the greatest extent (FIG.2.3), which become non-functional spaces and serve only as landscapes. Therefore, the texture of China’s urban housing areas today is the best manifestation of financial capitalism, whoes primary goal is to maximise and efficiently obtain the economic value of every inch of land 2 .

Structure of the Chapter

This chapter will address three questions. Firstly, the thesis will continue the discussion of the last chapter, explain the significance of land finance to local governments in China after the tax-sharing reform in

36

( FINANCE ) CAPITALIST URBANIZATION

FIG.2.3

The open space in xiaoqu, Shanghai, which is basically non-functional.

FIG.2.1

A typical housing cluster built by real estate developer, Guizhou. Such highrise, high-density apartment has already become the main living forms in city China today.

1994. The importance of land finance is also a prerequisite for the government-developer interest alliance in China’s current housing system. This section will also answer a crucial question, why is there a strong incentive for the Chinese government to maintain this system and such an urban development mode until it is on the verge of collapse?

Secondly, a more realistic question will be asked. In modern society, governments hold vast power and resources, but their actions are constrained by institutional, legal, and social oversight to ensure their behaviour aligns with ethical and just standards 3. In the context of China, even though the Chinese Communist Party government is widely perceived as a one-party authoritarian “big government,” its actions are still subject to the moral rationality of public power and the socialist ideology of the state. Unjust policies (policies with no legitimacy) could bring moral pressure on the government and even trigger political crises. This section will explain how the Chinese government attempts to demonstrate moral rationality (legitimacy) in dominating this unfair economic development pattern with the real estate developer, especially in the context that China is a socialist country and the Chinese Communist Party is seen as always “representing the interests of the vast majority of the people” 4. The legitimacy shaped by the government makes

3. Pual Hirst, Space and Power: Politics, War and Architecture, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005).

4. This sentence comes from the report delivered by Chinese President Xi Jinping at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2017. (Original sentence in Chinese: 中国共产党 始终代表最广大人民根本利益,与人民休戚与 共、生死相依,没有任何自己特殊的利益,从 来不代表任何利益集团、任何权势团体、任何 特权阶层的利益。)

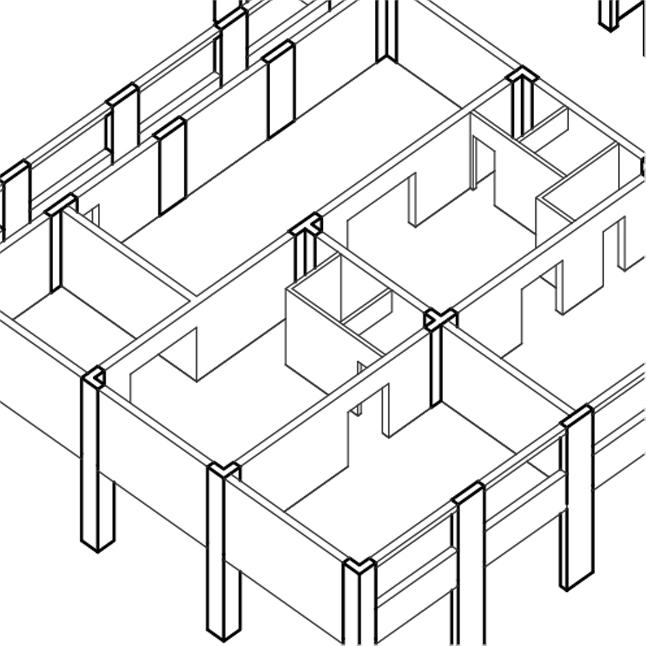

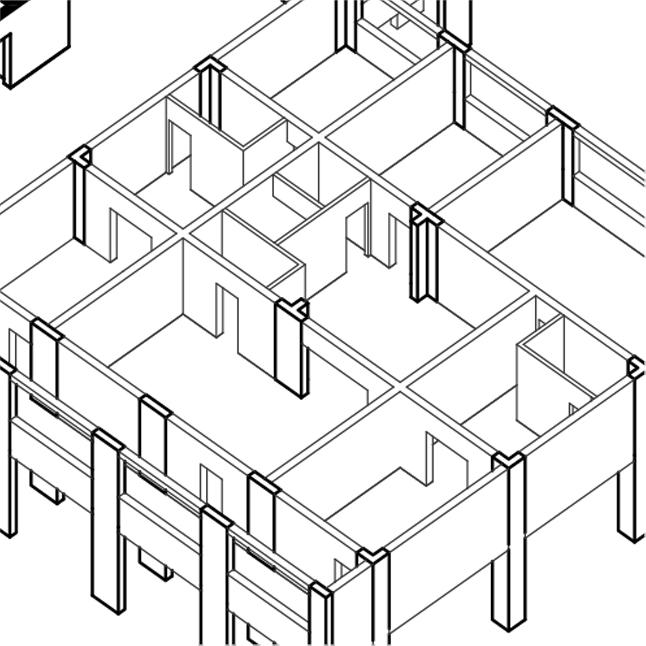

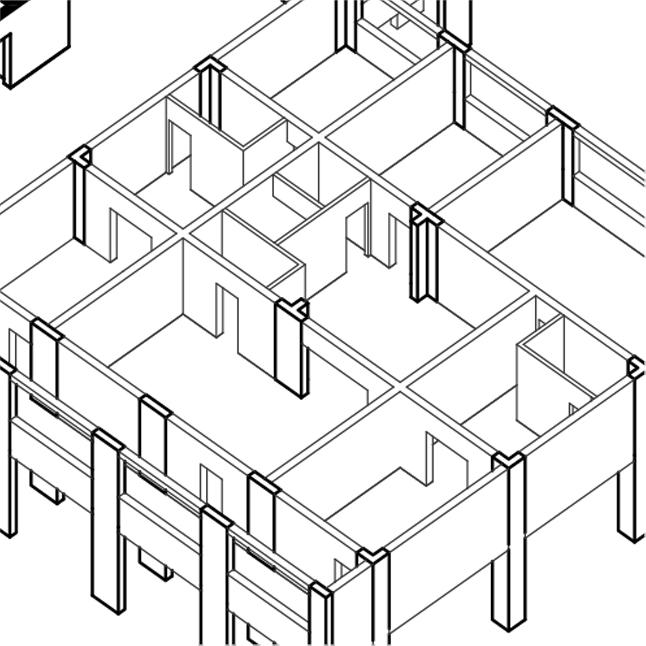

FIG.2.2

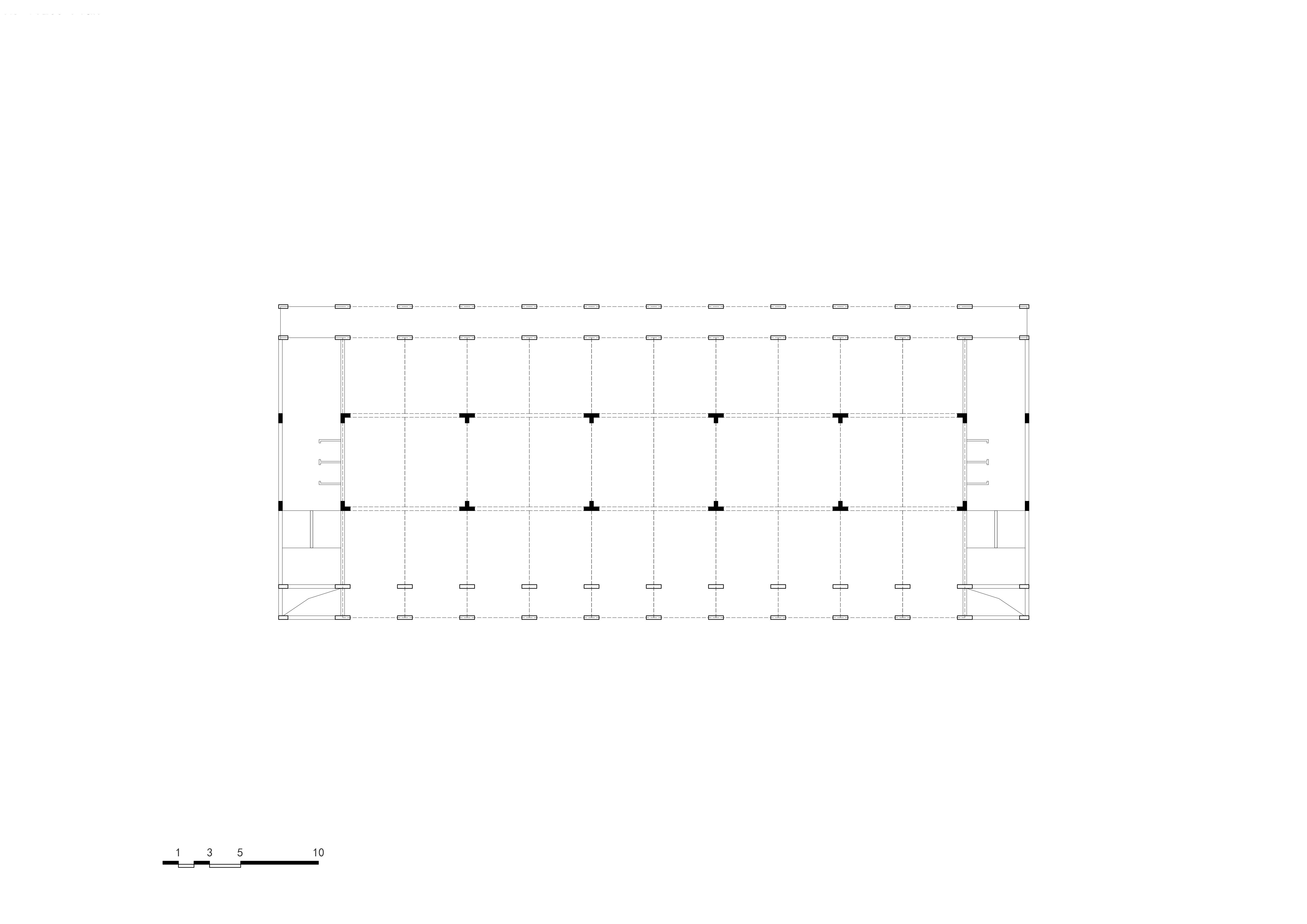

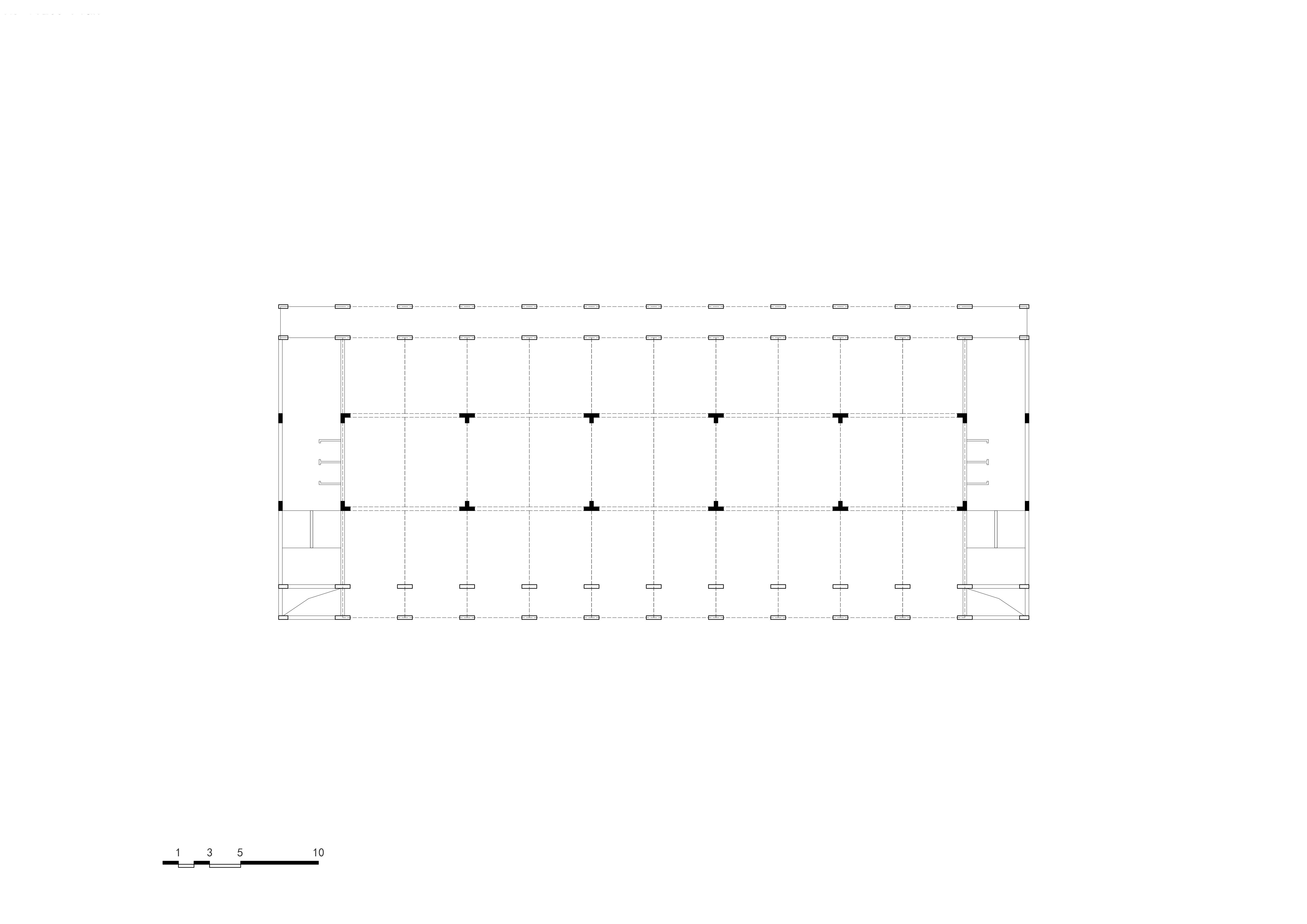

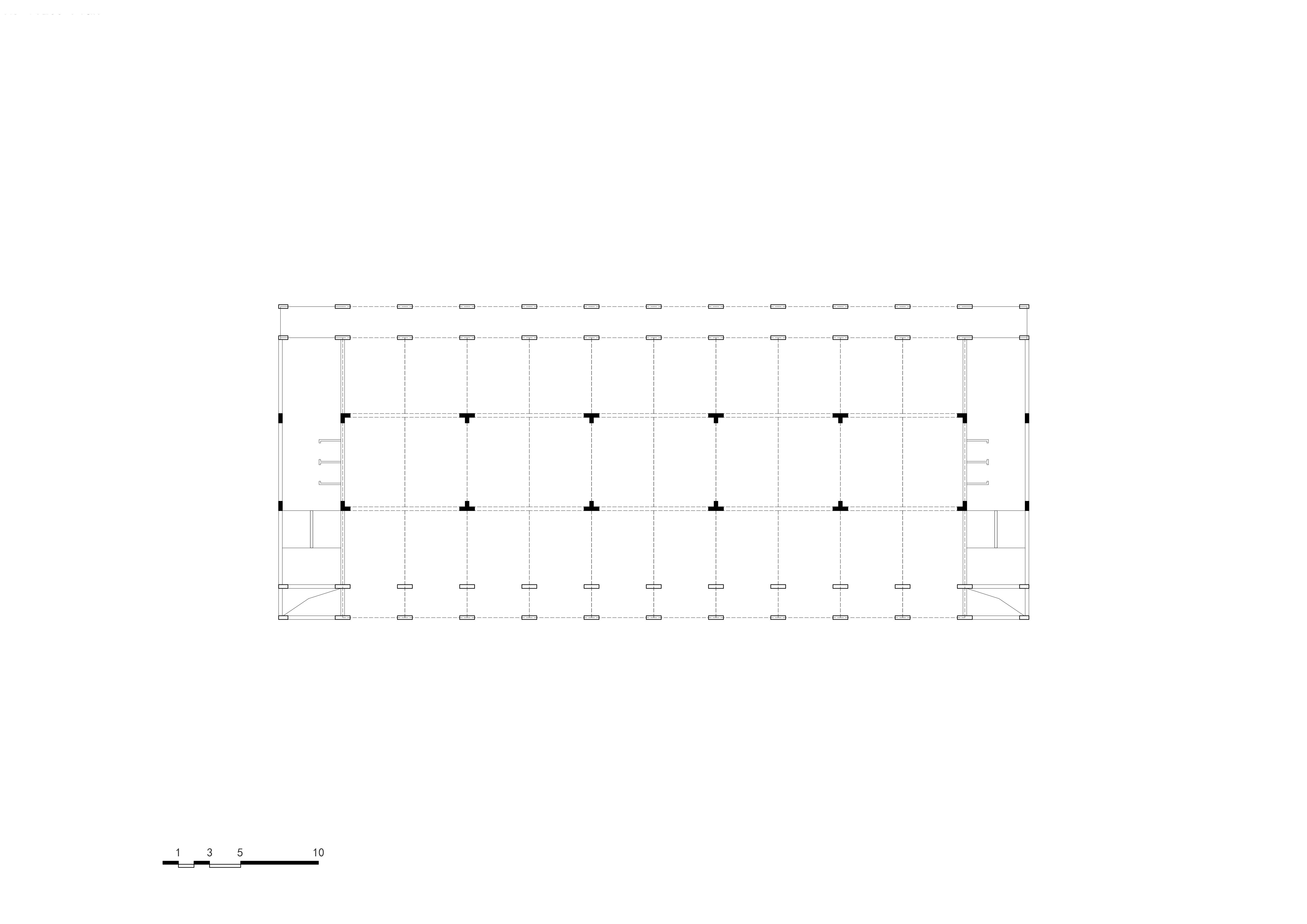

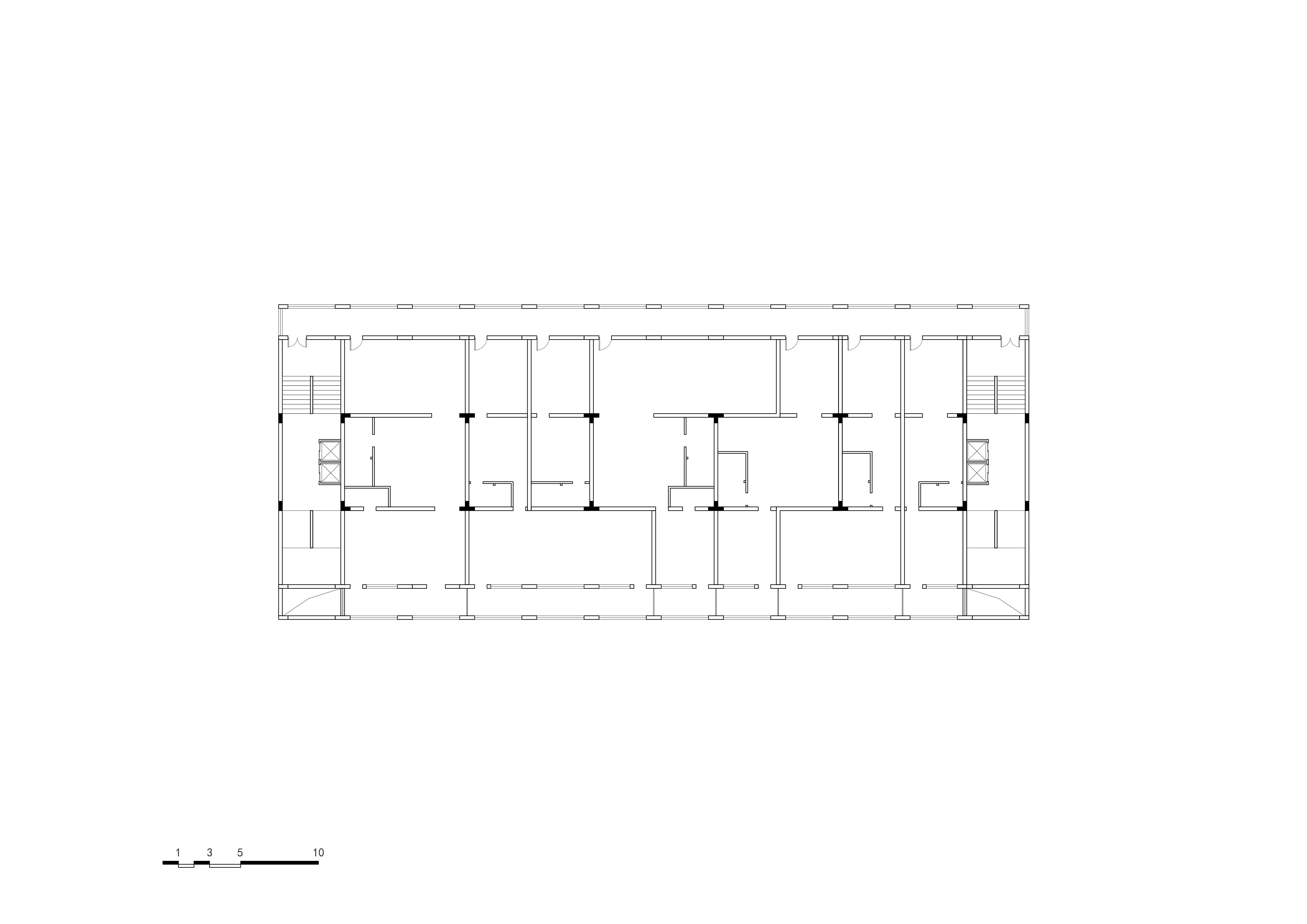

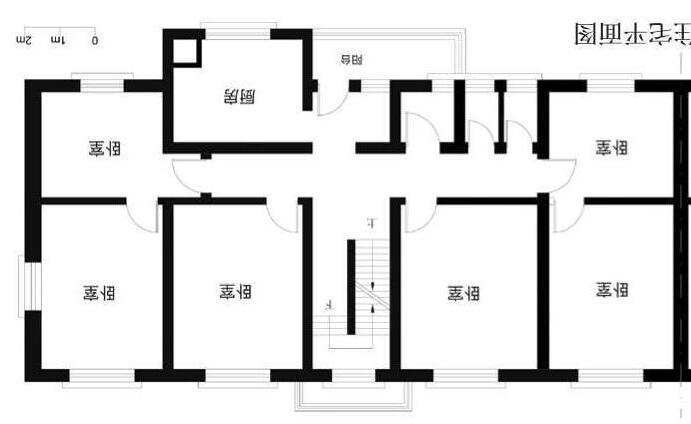

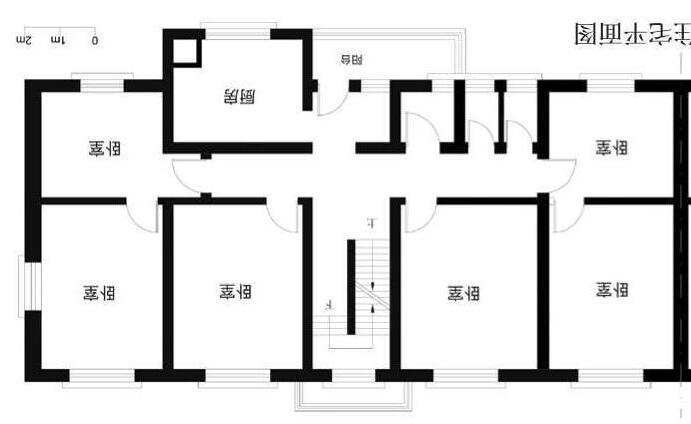

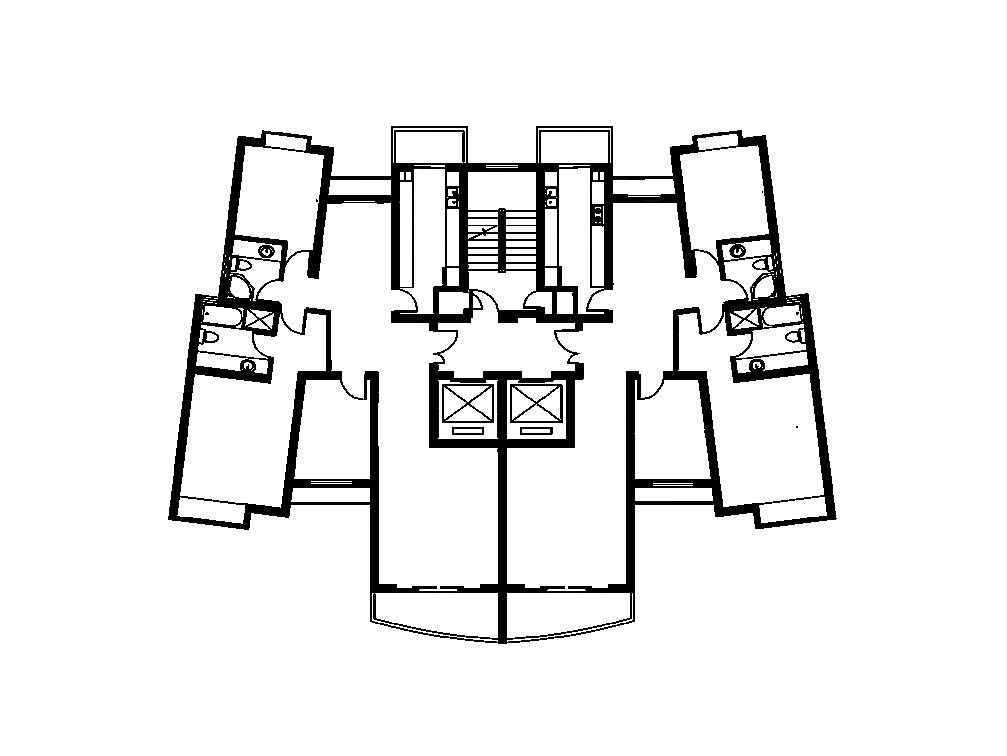

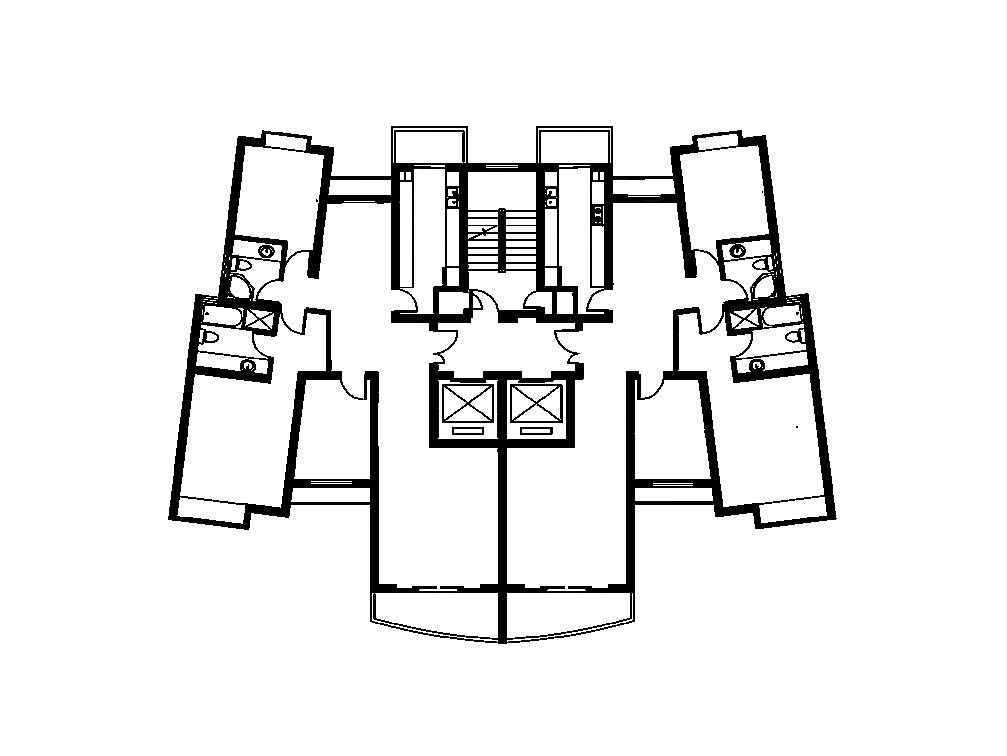

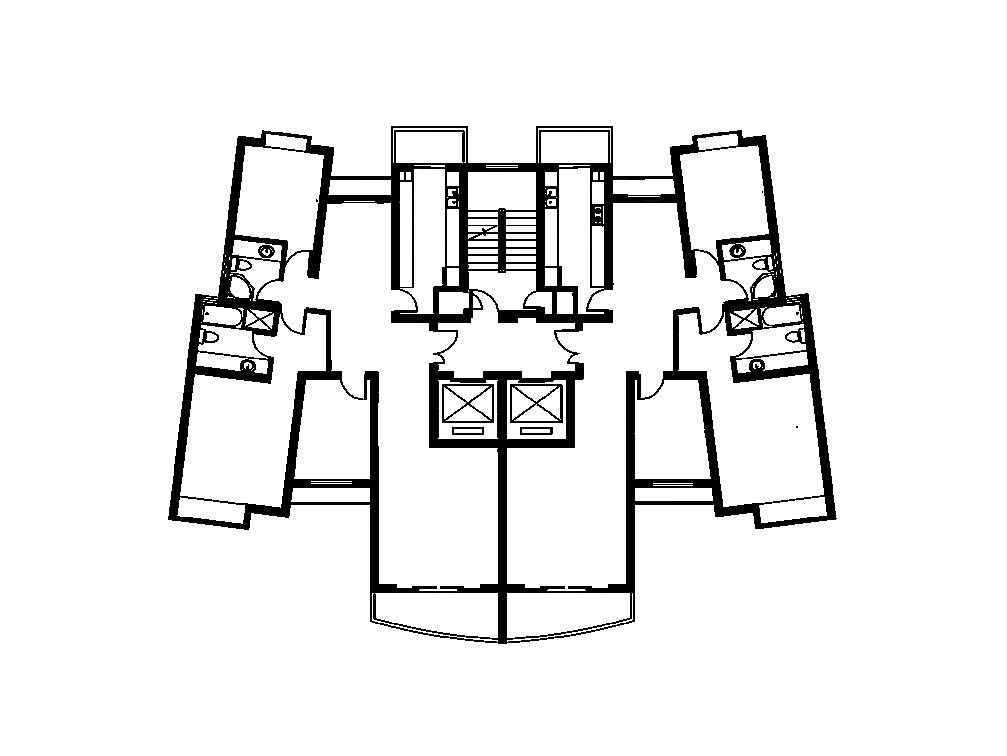

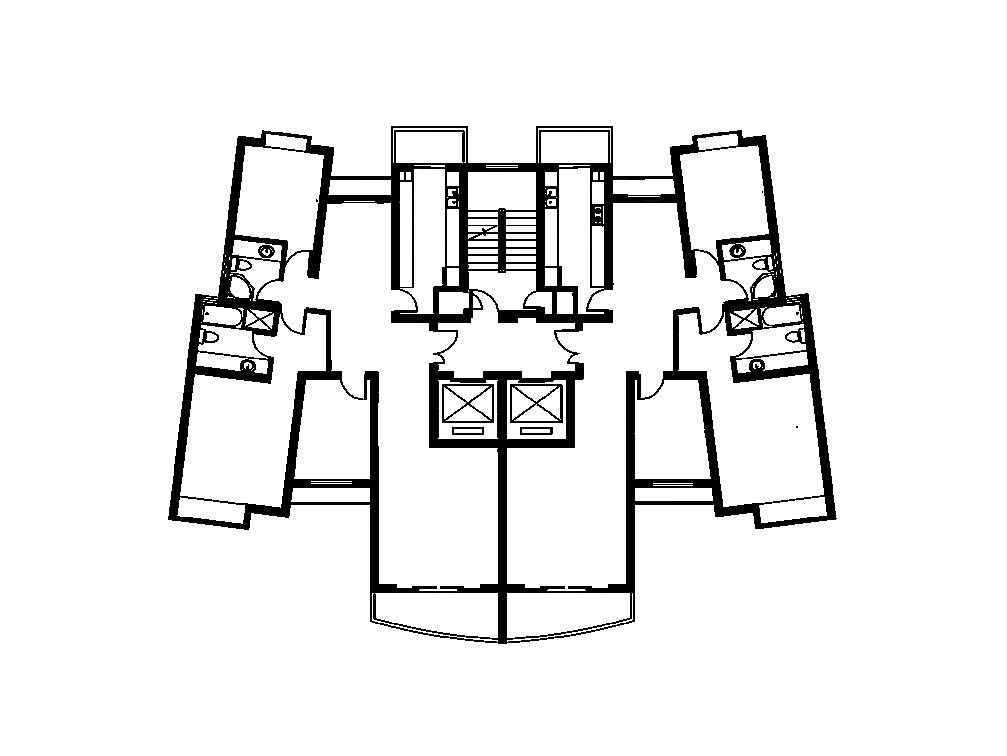

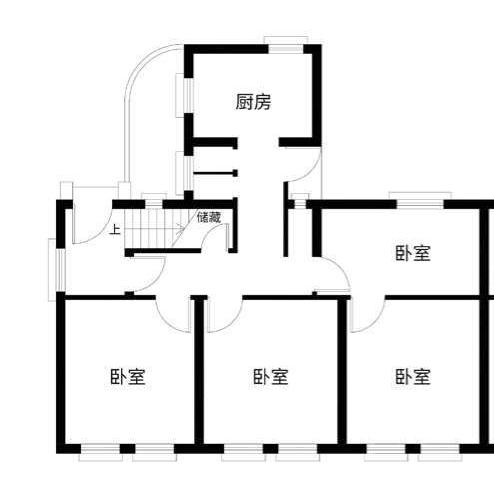

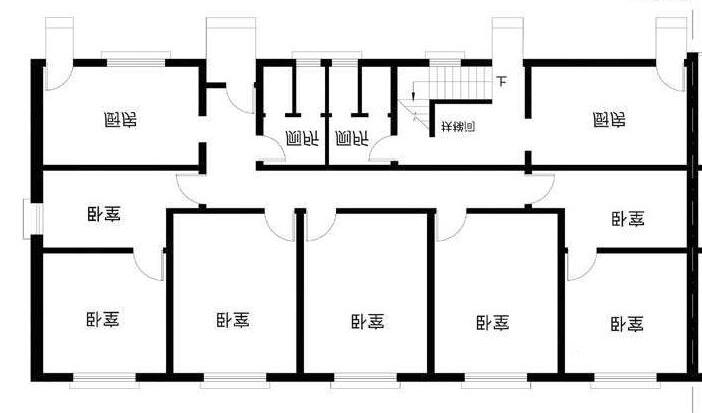

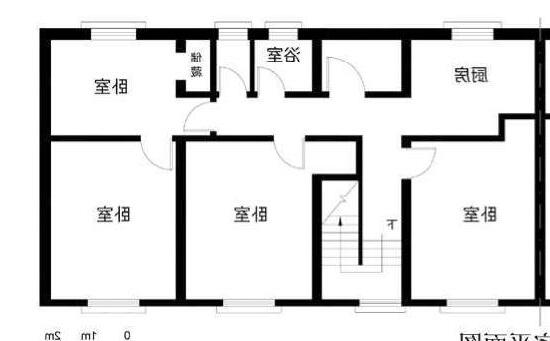

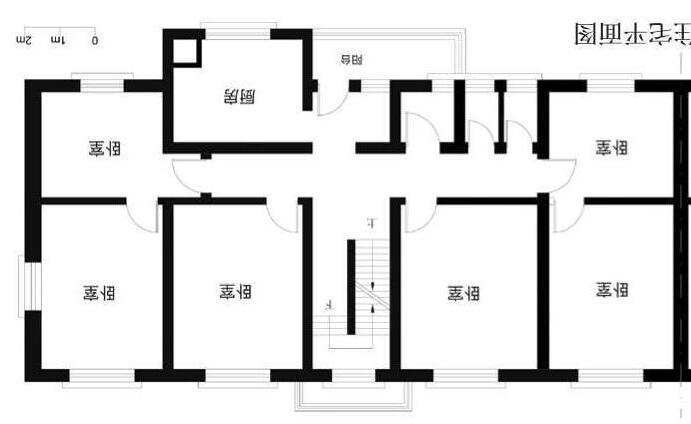

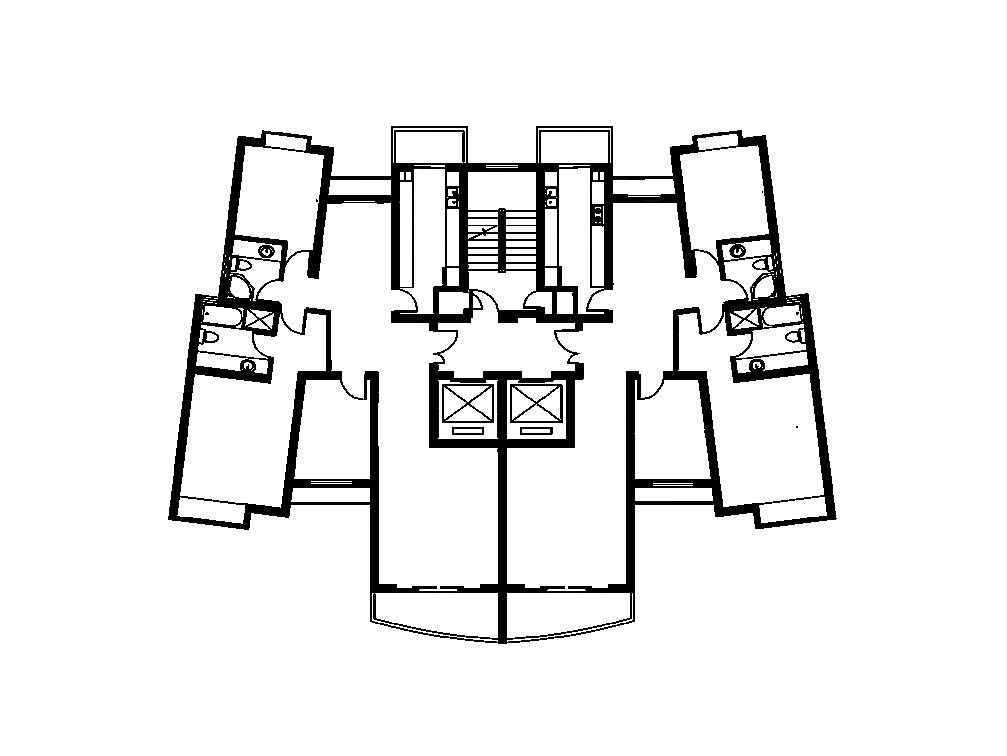

Some typical floorplan of the xiaoqu housing typology. It could be clearly seen that, except the space for circulation, all the space in them usually shows clear ownership.

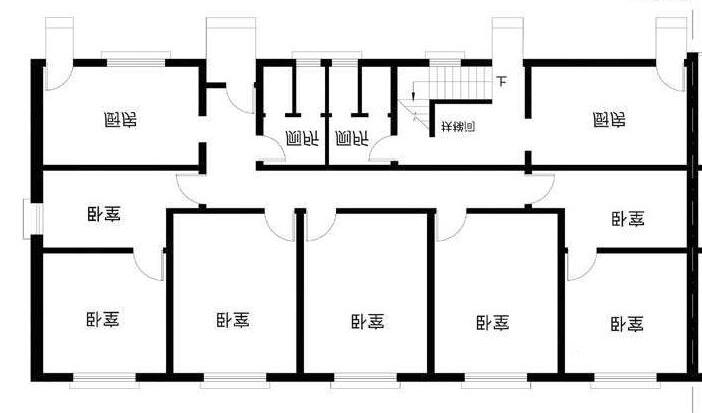

37 Circulation A3 1:200 A3 1:200 A3 1:200 Two Units Three Units Four Units Circulation Circulation Program Program Program XIAOQU (residential compound) Circulation Living units

this (real-estate led) development pattern relatively stable in Chinese society through the concession of various classes, even if the distribution of benefits is uneven.

Thirdly, the thesis will explore why this urban development model, based on financial capitalism and profit-driven logic, will inevitably move from its peak to collapse as it develops. Why is the crisis of the real estate collapse unavoidable in China or in other capitalist countries (FIG.2.4)? Futhermore, with the failure of the current housing system, the emerging middle class in Chinese cities, who have rapidly accumulated wealth during the urbanisation trend of the past decades, will play what role as the main body of real estate tax collection in the new housing system? What kind of living form will this lead to?

All these questions answered will bring the thesis to chapter three and four, which provide two pathways of new living forms imagination, especially with different ways of cooperation and compromise between the changing power balance between the government, the real estate developer and the citizen.

38

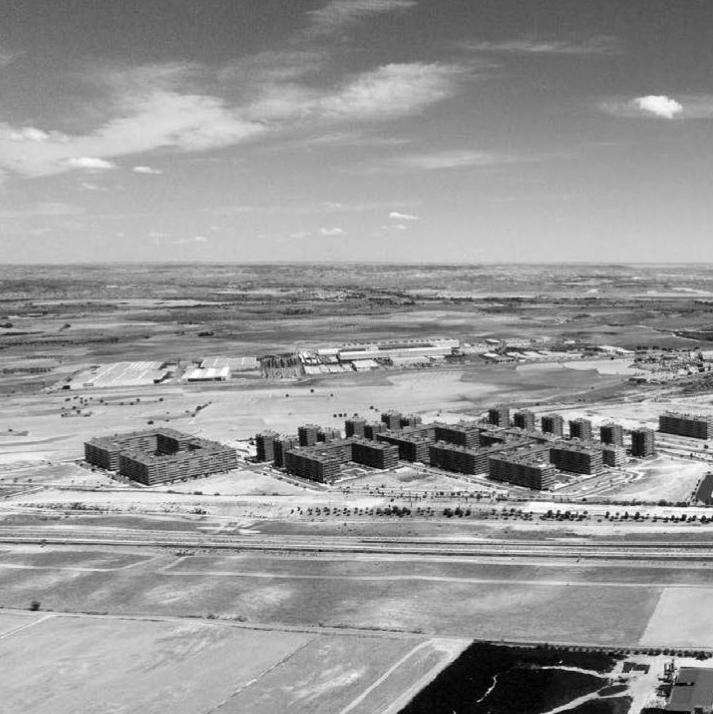

FIG.2.4

In the past few decades, the failure of profit-driven urban development models has been widely observed around the world. Despite the differences in political and cultural contexts, the failure of financial capitalism logic in the housing system seems to be no different in countries.

1. The two-thirds-incomplete Residencial Francisco Hernando, 2014, in Seseña, Toledo, Castile-La Mancha, Spain.

3. Complete but unoccupied homes (a ghost estate), 2013, in Drumshanbo, County Leitrim, Ireland.

2. Housing subdivision partially incomplete since the 2007– 8 financial crisis, 2015, metropolitan Phoenix, Arizona, USA.

4. Residential development that has been abandoned due to funding lack, 2012, Kangbashi District, Ordos, Inner Mongolia, China.

39

1 3 4 2

LAND FINANCE AND THE ALLIANCE

FIG.2.5

The satirical cartoon aims to the Chinese government’s land finance policies, portraying a surreal scene where government and real estate developers transform land into a money printing machine, conjuring up boundless wealth from the urban residents.

FIG.2.6

5. The numbers in this paragraph are from the “China Tax Yearbook” (Chinese: 中国税务年鉴) of previous years.

The field of finance and taxation is inherently complex and professional, and the focus of this section is not on finance and taxation itself, but rather on understanding Chinese government’s behavior (in the housing system) from the perspective of finance and taxation. Within the scope of this thesis, the question is why the Chinese government needs to establish a stable alliance with developers to maintain the policy of land finance. In this process, the behavior of the government and developers has gradually shaped the current housing system in China.

Land Finance and the “Endless Wealth”

The widely criticized “land finance” (FIG.2.5) of local governments in China includes not only enormous revenues from land use right transfers (land selling) (FIG.2.6), but also various tax revenues related to land use and development. These taxes are divided into two categories. One is directly related to land and mainly includes value-added land tax, urban land use tax, farmland occupation tax, and deed tax, with 100% of the revenue belonging to local governments. In 2018, the total revenue from these taxes was 1.5081 trillion yuan, accounting for 15% of local government revenue. The other category of taxes is related to real estate development and construction enterprises, mainly including value-added and corporate income taxes. In 2018, the portion of these two taxes belonging to local governments accounted for 9% of the revenue in the local public budget. If these taxes, together with land selling revenue, are considered the total revenue of “land finance,” the revenue in 2018 was equivalent to 89% of the revenue in the local public budget, which is a shocking number 5 .

With such data support, it could be said that “land sales” are the most critical source of financial revenue for local governments in China today. “Land finance” is an indispensable financing method to maintain the massive amount of funds invested by the government in infrastructure construction and urbanization every year since the reform and opening up. By land selling, primitive capital based on land credit can be accumulated, promoting rapid industrialization and urbanization. China’s unique state-owned urban land system has created con-

40

The proportion of revenue from the transfer of state-owned land in local public budget revenue.

ditions for the government to monopolize the land market 6, turning this hidden wealth into a huge capital for launching urbanization. It’s also important to note that, equating “land sales” with “land finance” is one-sided. Local governments not only generate revenue through “land sales,” but also benefit from a range of economic activities attracted by land development, including tax revenue from emerging businesses, the growth of related industries in development activities (such as building materials and construction), and a large number of new employment opportunities (FIG.2.7). However, the magic of land finance also makes the local government’s finances highly dependent on land values, real estate, and housing prices. Housing prices are connected to land prices, land prices are connected to finance, and finance is connected to infrastructure investment. Therefore, a complex relationship of “one prosperity begets all, one decline begets all” has been formed among economic growth, local finance, banks, and real estate 7

The Opaque Alliance and the Silence of the Civic Class

Therefore, it is easy to understand that, land finance not only plays an irreplaceable role in the financial revenue of China local government, but also becomes the magic wand to leverage Chian’s urbanization and economic development. Such a strong connection between all these factors makes the local governments in China must find ways to maintain this development model. On the one hand, keep-rising housing prices have brought substantial profits to real estate developers. On the other hand, continuous land development has provided sufficient financial sources for local governments and has become the engine of regional economic growth.

With such an opaque alliance between local governments (public power) and real estate developers (capital), the citizen class has become the the weak party in the process of urbanisation. In fact, in such a process, a series of severe corruption problems have occurred due to the alliance between the government official and real estate developer, which has seriously affected the credibility of the Chinese government. These corrupt practices include government officials using their authority to

6. During the planned economy era from 1949 to 1978, the Chinese government’s long-standing nationalization strategy accumulated a significant amount of urban land resources. In addition, according to Article 13 of the Chinese Constitution, the state may, in accordance with the law, requisition or expropriate private property of citizens (in the context of this thesis, referring to houses and urban land resources) for public purposes and provide compensation (Original sentence in Chinese: 中国 宪法第十三条: 公民的合法的私有财产不受 侵犯。国家依照法律规定保护公民的私有财产 权和继承权。国家为了公共利益的需要,可以 依照法律规定对公民的私有财产实行征收或者 征用并给予补偿。), which makes it is legal for the government to obtain urban land from the local residents.

7. Xiaohuan Lan, Involved in the Matter: China’s Government and Economic Development (Chinese: 置身事内:中国 政府与经济发展), (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2021).

41

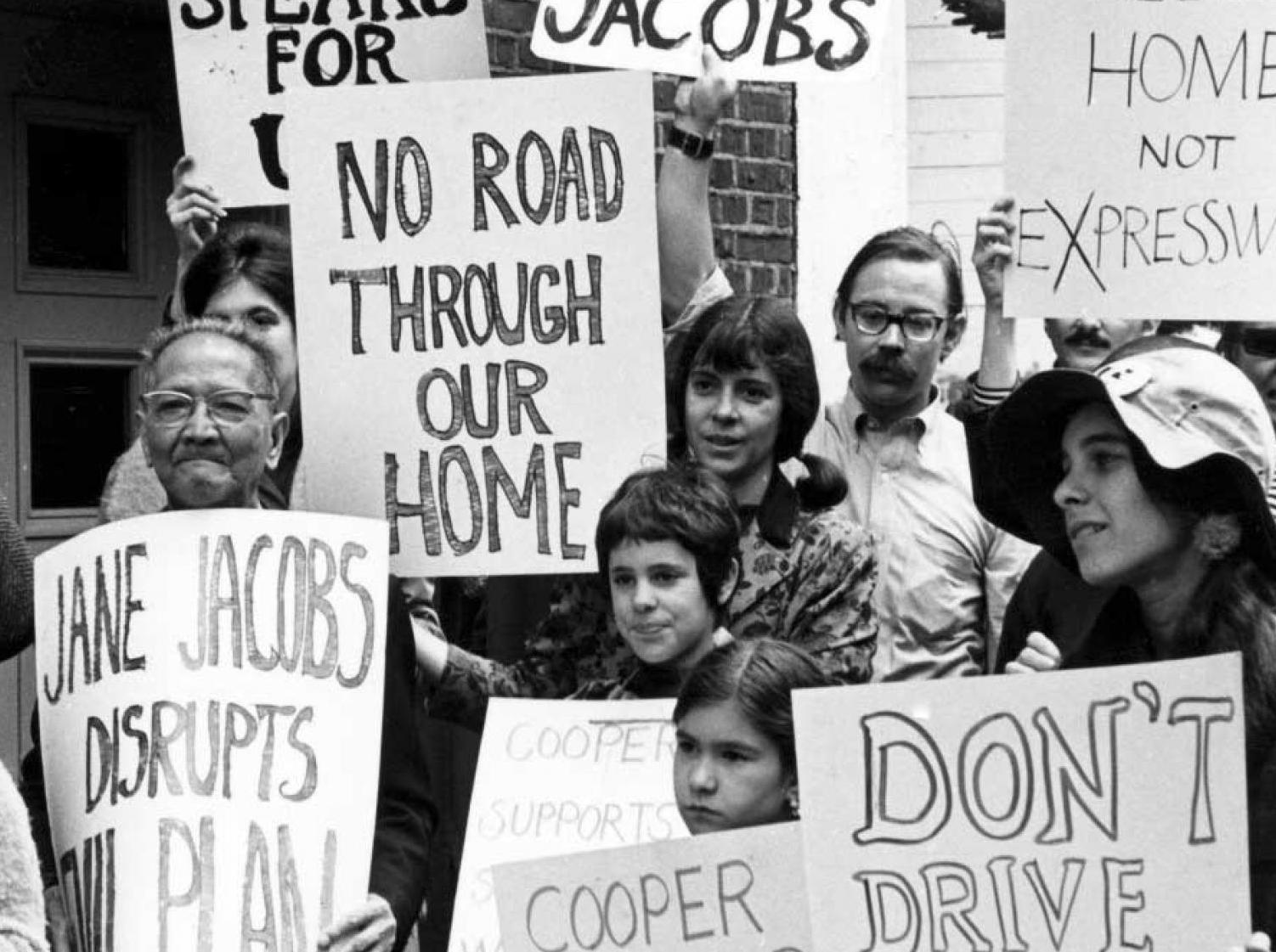

8. The relevant papers can be found in: Yingfang Chen, City Chinese Logic (Chinese Edition: 城市中国的逻辑); David Harvey, Social Justice, Postmodernism and the City; Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, et al.

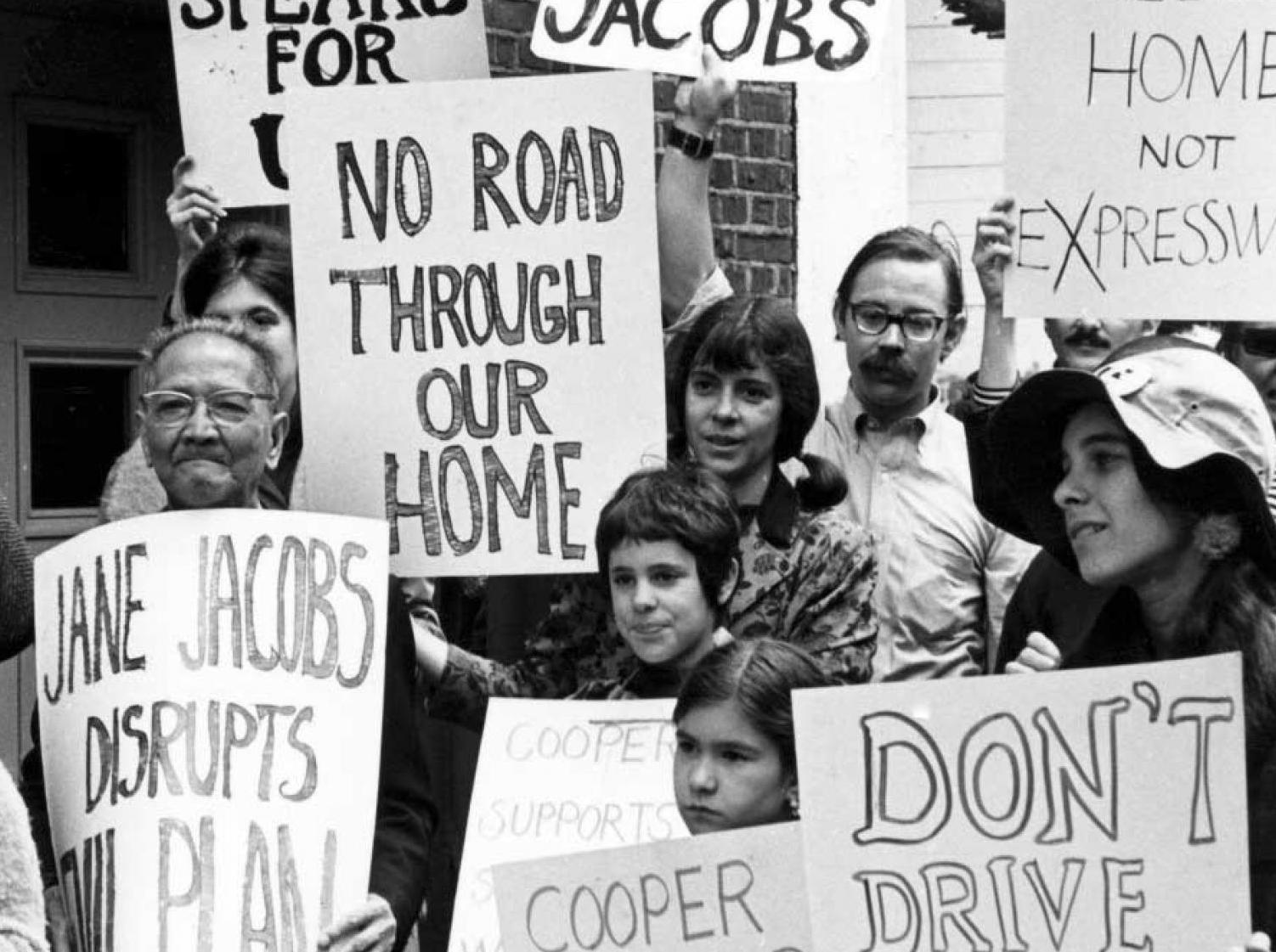

The criticism of this modernist and spatial profit-oriented urban development model has been an important topic of discussion since the rise of the post-urban era theory in the 1970s. Corruption in this development model and its destruction of the urban context have made it the target of widespread doubt and criticism in the western country.

intervene in bank loans and provide financing convenience for private developers; government officials assisting (or tacitly approving) private developers in carrying out forced demolitions to ensure the smooth implementation of development plans (FIG.2.8); and government officials’ relatives using their advantages to obtain land resources for development, and so on. Some corruption cases in urban development that have been investigated in recent years have involved hundreds of millions yuan. However, it needs to be pointed out that, such a corruption between the government and developers caused by this space-benefit-led development model has been a common problem worldwide, which is not not unique to China. There already have been thoughtful discussions on this in a series of theories 8 .

Rather than discuss the details of corruption, the thesis will point to a more core question in the next section. The land finance policy has brought so many problems about corruption and social equity, and aroused widespread controversy in Chinese society, which not only come from the citizens but also within the government and the party. Why does the Chinese government still show great enthusiasm for maintaining such a system till toady? As a representative of public credibility, how does the Chinese government solve the political pressure from citizens, farmers and within the government based on the requirement of social justice and moral rationality?

42

43

FIG.2.7

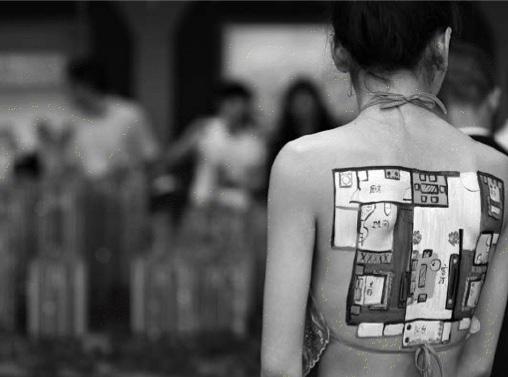

A residential floorplan painted on the back of a model as part of a marketing strategy, at 55th Housing Fair, Nantong, China. The real estate boom has spawned all sorts of crazy activity in related industries.

FIG.2.8

City outskirts’s farmers sit on the ruins of their homes after the forced demolition by the real estate developer.

URBAN

DEVELOPMENT

AND THE LEGITIMACY OF GOVERNMENT

FIG.2.9

After the 1970s, there were protests in the United States and around the world against this spatial profit-oriented model of urban development.

9. China’s cities are widely believed to have a surplus of housing due to irrational development. In 2023, China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development officially says now there are “30 million buildings in urban areas across China.”

10. According to a study conducted by the Beike Research Institute in 2022, the vacancy rate of urban residential housing in 28 large and medium-sized cities across China is generally higher than 12%. Generally speaking, the vacancy rate exceeding 10% indicates an oversupply of housing. Nevertheless, the development pace of urban housing in China has been continuously increasing until 2022.

11. Max Weber (1864-1920) was a German sociologist, historian, philosopher, economist, and political scientist. He is one of the founding figures of modern social science and made significant contributions to sociology, history, economics, cultural studies, and religious studies. Weber’s typology of authority and his critique of bureaucracy have been important contributions to the field of sociology. They have provided a framework for analyzing the distribution of power and authority in organizations, facilitated comparative analysis of different types of organizations, and stimulated critical examination of the role of bureaucracy in modern society.

The theroy of Three models of Organizational Authoritarianism used in this section mainly come for his book Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, (University of California Press, 1978).

After the 1980s, urban development movement led by private real estate developers provided a significant amount of housing for Chinese cities. However, even though the urban housing shortage has already been resolved in China 9, it can still be observed that this urban development model keeps running, and its pace is accelerating 10. In this context, the meaning of this profit-driven development strategy has transcended its original purpose of solving the problem within the housing system technically, but has become a projection of the state’s policy and economic development model. While at the same time, in the post-urban era, Western and East Asian developed countries, considered the learning objects for China’s modernization, have started widely questioning and criticizing this modernist-style urban development model that prioritizes economic interests. The new urban theory proposed by Henri Lefebvre, David Harvey, Edward Soja and other urban planners has profoundly revealed the unfair nature of this development model and the damage it inflicts on urban residents’ lives (FIG.2.9).

Therefore, this section tries to answer why the Chinese government has insisted on this high-speed economic development model with serious potential problems. Under such a development model, how could the tendency to pursue the government’s self-interests for economic efficiency and the ability to sacrifice other relevant interest groups (citizens and farmers) be reconciled with government’s represented public power (the government’s moral rationality and justice pressure)?

Max Weber’s Three Models of Organizational Authoritarianism

This section will reference three authoritarian organizational models of German sociologist Max Weber as the main theoretical foundation to analyze the current situation in China 11. In his book Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, Max Weber divided human society into three authoritarian organizational models. These three types of organizational authoritarianism represent the source and legitimacy of different types of government power. All three types are not mutually exclusive and can coexist with each other. Furthermore, each type has its required condition for existence. By using this theoretical frame-

44

work, this section aims to elucidate why the Chinese government persists in pursuing a high-speed economic development model by continuing the space-profit-oriented urban development model. Solutions can only be provided when the essence through appearances has been observed.

In Max Weber’s three models of organizational authoritarianism, the first type of organizational authoritarianism model is Traditional Authoritarian Organization. Such authoritarian organizations are based on tradition and custom, with their authority and legitimacy stemming from history and tradition. A leader or family usually controls them, and their domination is often seen as legitimate and justified because of their strict hierarchical system and unquestionable authority. Feudal dynasties in Europe and ancient China could be seen as examples of this organizational model (FIG.2.10). The second type is Legal-rational Authoritarian Organization. This type of authoritarian organization stems from a widely recognized ideology, such as religious belief, nationalism, or patriotism. Legal-rational authoritarian organizations maintain authority and status by grasping and utilizing these beliefs and ideologies. Most modern governments are based on this organizational form to obtain legitimacy (FIG.2.11).

The third type is called Charismatic Authoritarian Organization, also the main organizational models will be discussed in this thesis. Charismatic authoritarian organizations are based on the charisma of a leader or a group of leaders, with authority and legitimacy stemming from their exceptional personal qualities or abilities. The charisma of these leaders can inspire followers and make them willing to obey. However, it can also be unstable and dependent on the leader’s or leaders’ continued charisma. A typical example is Napoleon Bonaparte, who led the French from one victory to another victory with his charismatic military capabilities and eventually became the emperor of France (FIG.2.12). However, when he failed at the Battle of Waterloo, his myth shattered, and his reign ended.

45

46

FIG.2.10

“Coronation of Emperor Franz Joseph and Empress Elisabeth of Austria as King and Queen of Hungary, on June 8th, 1867, in Buda, Capital of Hungary.”

Emperors and kings have relied on the legitimacy conferred by history and tradition to justify their rule.

FIG.2.11

President Trump sworn in as the 45th president of the United States on a Bible, 2017.

U.S. president’s legitimacy comes from the free election process stipulated in the US Constitution.

47

FIG.2.12

“Napoleon Crossing the Alps.”

Napoleon I, Emperor of France, gained legitimacy for his rule through his genius abilities of war and charismatic leadership.

12. Chinese: “占人类总数四分之一的中国人 从此站立起来了!”

13. Li Zhang and Aihwa Ong, ed,. Privatizing China: socialism from after, (Ithaca : Cornell University Press, 2008).

“Charisma” and Economic Development in China

“It’s the economy, stupid!” ——1992 Presidential Campaign, Bill Clinton

The thesis argues that after the market-oriented economic reform in the 1980s, the charismatic authoritarian organization model became the dominated organization way of China’s government. In more detial, the “charisma“of the Chinese Communist governing is the rapid economic development after the 1980s under the authoritarian rule of the Communist Party system.

As the first national government to unify China in the long-lasting civil strife from the late 19th century, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has built its most crucial legitimacy on the independence, prosperity, and strength of the Chinese nation. This can be likened to the enthusiastic slogan Mao Zedong proclaimed upon the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949: “Now, the Chinese people have stood up! 12”. However, during the first three decades after the regime’s founding, the economic development campaign, which was conducted on a national scale under the planned economy system, failed to fulfil the ruling party’s political commitment of “building a prosperous and strong country and benefiting the people.” Even worse, the prolonged economic stagnation severely undermined the credibility of the communist party government of China. Therefore, the political crises that occurred in the ruling parties of Eastern European socialist countries and China during the 1970s and 1980s were more likely the result of the long-term economic decline of national states under the planned economy system than a strong demand for democratization 13. Consequently, after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, China’s reform and opening up policies, led by the new generation of CPC leader Deng Xiaoping, have consistently prioritized economic development. This can be viewed as a response to such a political crisis. The CPC government must demonstrate that in the post-war and ideologically divided 20th century, the Party can still lead China to achieve victory economically.

Therefore, the thesis believes that in today’s China, the legitimacy of the dominant authoritarian organizational model government depends on

48

its ability to “perform miracles.” In the context of China, this “miracle” refers to the rapid economic growth sustained since the adoption of market-oriented economic reforms. Under the leadership of the Communist Party of China, rapid economic growth has enhanced China’s international status, not only rapidly improving the living standards of its citizens but also “realizing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” 14. Due to the significant progress of the economy, China has become the world’s second-largest economy in jusr forty years, wielding significant global influence. This is the most successful manifestation of the Communist Party’s governance and its centralized and authoritarian regime.

At the same time, a strong connection has been built between China’s modernization, economic development and Communist Party’s governance. Under propaganda, economic development is considered the success of both the nation and the Communist Party (FIG.2.13). On the other hand, economic failure will also be seen as party’s failure. Therefore, as long as sustained and rapid economic growth is maintained, no matter the issues in the housing system (for example, the rising housing prices and the opaque interest alliances between the government and real estate developers), as well as structural problems in China’s society, can be considered the secondary issue 15 (and can be solve later).

However, due to the natural of economics, China’s economic growth now is slowing down like every successful economy. In housing system, real-estate-led developing strategy is also in the risk of collapsing. The financial chain of housing prices, land prices, and economic development is now facing challenges. Therefore, it becomes even more important to think about the new forms of living in the post reform and opening up China. The transformation of living forms will also become the projection for the country about new governance and political form in the post real estate era.

14. “The great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (Chinese: 中华民族的伟 大复兴) is a slogan put forward in the report of the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2002. In 2012, after assuming the position of General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, Xi Jinping proposed the slogan of the “Chinese Dream” on this basis.

15. In regards to this paragraph, reader can also refer to the China Communist Party’s concept of primary and secondary contradictions (Chinese: 主要矛盾和 次要矛盾). Since 1981, Deng Xiaoping’s explanation of China’s government’s “primary contradiction and secondary contradiction” during the reform and opening up era suggests that, inadequate economic development is the “primary contradiction” in today’s Chinese society and the most important governing goal of the Communist Party government in the new era.

49

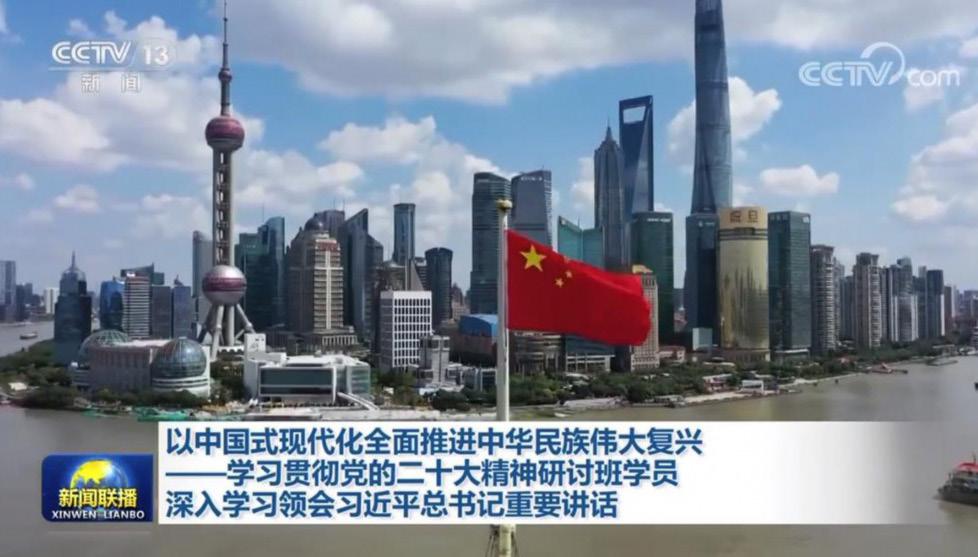

The relationship between China’s modernization, economic development and Communist Party governance has been strongly linked with each other.

50

FIG.2.13

Top left: “Unswervingly uphold the leadership of the Communist Party for one hundred years”. The elder in the image is Deng Xiaoping, the leader of the Communist Party in the 1980s, looking at the modern skyscrapers that rise up from the ground after the reform and opening up.

FIG.2.14

Text: “Promoting the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation with Chinese style modernity - Learning and implementing the spirit of the 20st National Congress of the Communist Party - Learning from Xi Jinping’s important speech”.

Urban development, China’s Modernization, Communist Party and top leader are closely linked in propaganda.

51

16. Tendentious housing shortages does not refer to a widespread housing shortage caused by inadequate housing construction, but to the housing shortage of specific groups, especially the low class in the urban area.

THE LOGIC OF FINANCIAL CAPITALISM AND IT’S FAILURE

A housing system solely based on a for-profit developer is unsustainable. Capitalism’s profit-driven nature will lead to an imbalance in the housing supply, ultimately leading to a crisis in the housing system. After China’s urban housing providers gradually changed from government and danwei to for-profit developers in the 1980s, more than 90% of urban housing is provided by real estate developers today. Such rapid urbanization and the flourishing of the real estate industry in China over the past four decades has resulted in severe problems of tendentious housing shortages 16, which further leads to a widening wealth gap and social differentiation.

This section will explain why it is impossible to establish a stable and sustainable housing system when for-profit housing developers become the only housing providers. Such a failure is not the failure of execution and governance, but the failure of the finalcial capitalism’s nature. Furthermore, this will also explain why China’s land finance strategy and national modernization model, which focuses on real estate development, cannot be sustained after four decades of rapid development.

Tendentious Housing Shortage

Housing, along with clothing, food, and transportation, is one of the four most basic human needs. Whether it is the wealthiest billionaire in the world, or an unemployed person with no income or savings, they both need a space as shelter for the body. The only difference is that people from different social classes choose housing that they can afford based on their income and wealth, which is also the basic logic of the market economy in modern society.

However, real estate developers who prioritize profits as their ultimate goal will inevitably lead to a tendency towards developing housing with more profit. This logic means that profit-driven developers always tend to develop housing projects (for investment) that cater to the middle-high-income class with higher profit rather than developing affordable housing with social care attributes for low-income earners.

52

High incomes have become more profitable and less risky by renting/selling their investment housing to low-middle incomes. Therefor, high incomes are more likely to buy housing for investment.

For-profit developers have become more profitable and less risky by providing investment housing for high incomes.

The number of middle-low incomes who cannot buy their own homes has increased

Too many people cannot afford their house. The real estate crash.

For-profit developers are more likely to provide (investment) housing for high incomes.

The housing market becomes more prosperous while housing prices becomes higher

53

FIG.2.15 The endless chain of Tendentious Housing Shortage

This imbalance in housing provision ultimately leads to a vicious cycle of tendentious housing shortages.

The logic chain of this vicious cycle is as follows (FIG.2.15): 1. High-income class who possess capital tend to invest by purchasing housing.

2. With this type of investment increase, for-profit real estate developers tend to supply investment properties for these high-income to gain more profit. 3. As investment properties increase, housing prices continue to rise. 4. Consequently, the number of middle-low incomes who cannot afford their housing expands, forcing them to rent or purchase housing from high-income individuals with investment properties. 5. The risk of purchasing housing for investment purposes by high incomes becomes smaller and smaller, and they can transfer the rising investment cost to middle-low income who rent or buy their houses. At the same time, the desire and purchasing power of high-income for housing investment becomes stronger and stronger. 6. As a result, for-profit real estate developers have become more and more willing to build housing for high-income investors...... The danger of such a logic is that, as the chain continues, more and more people cannot afford their housing, and the wealth gap between the classes will continue to widen 17. In the end, this will cause serious social problems (FIG.2.16).

Although China’s governments have tried to encourage real estate developers to build affordable housing for low-middle incomes by providing preferential tax rates, loan rates and financial subsidies for for-profit housing builders. However, the actual results have been limited. The essence of this phenomenon lies in the underlying logic of for-profit housing developers (find more profit) mismatching the logic to develop low-income affordable housing (provide social care), which like putting a sword in a mismatched scabbard. Especially considering that in China today, since the government stopped acting as a housing provider, the existing housing system cannot find a suitable affordable housing provider for low-middle incomes (while real estate developers are almost the only urban housing providers).

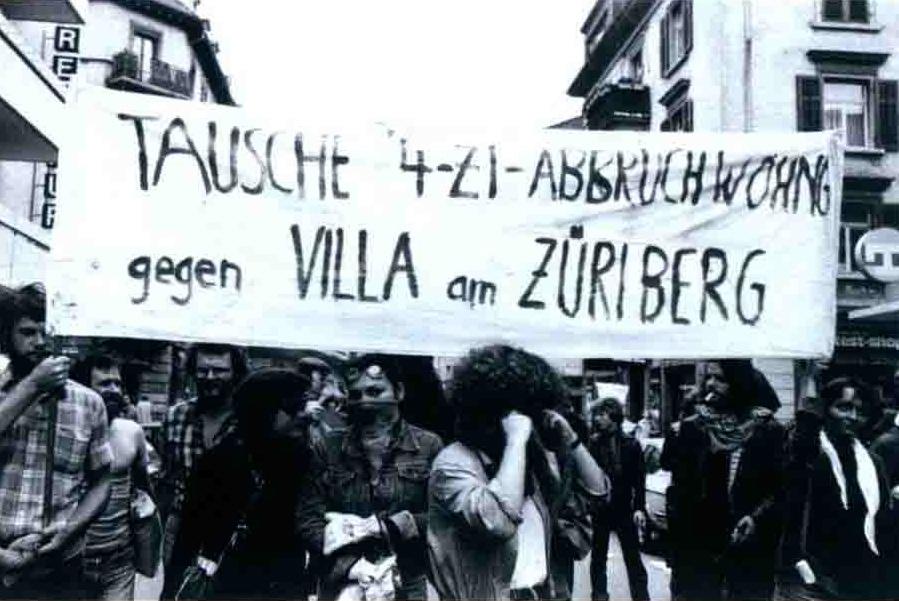

17. Rujun Jia and Yin Li, More Than Living: One Hundred Years of Experience in Non-profit Housing Construction in Zurich, (Chongqing: Chongqing University Press, 2015).

Once the number of people who cannot afford their housing exceeds a threshold, such a housing system that cannot provide living units to

54

FIG.2.16

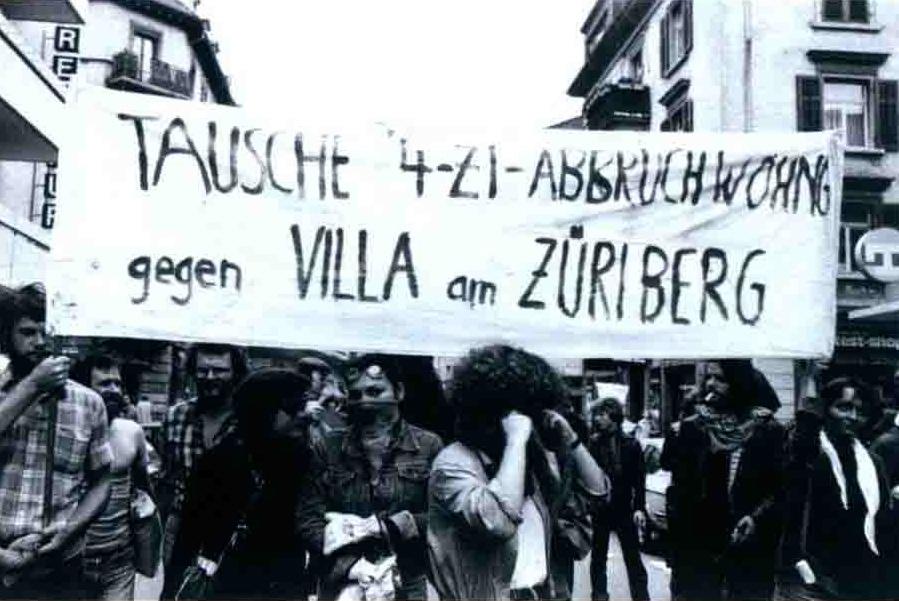

“Swap 4-room demolition apartment against Villa at Zurichberg!” Banner during protest against lack of housing in Zurich, 1980.

most residents will face a crisis of collapse. The collapse of the housing system will further lead to a chain reaction of decline in “real estate, banking, local finance, and economic growth” on the chain of land finance.

In China today, most people must use 60 to 70 years’ income to purchase housing. It must be realized that China’s housing system is already on the brink of collapse in this vicious cycle (FIG.2.17). The logic of (financial) capitalism once again verifies its unsustainability. Like all previous countries’ real estate collapse, its failure is no different in the system of China.

55

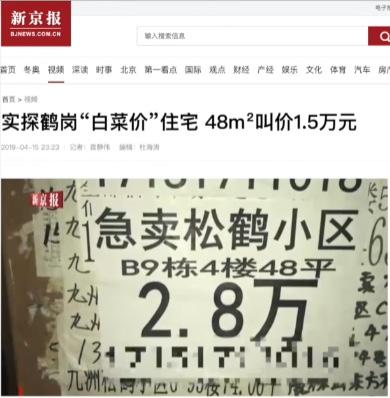

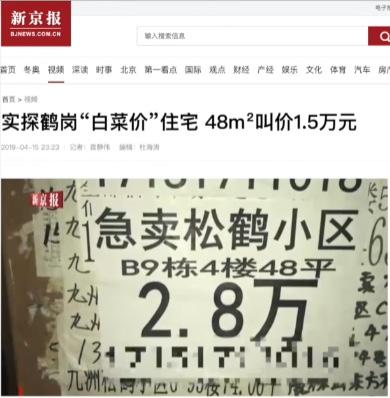

FIG.2.17

“Hegang (a city in Heilongjiang Province) cheap apartments 48 m2. Asking for only 15,000 yuan.” Until today, the bubble of housing prices in many small Chinese cities has already collapsed. Local government finances are already in trouble.

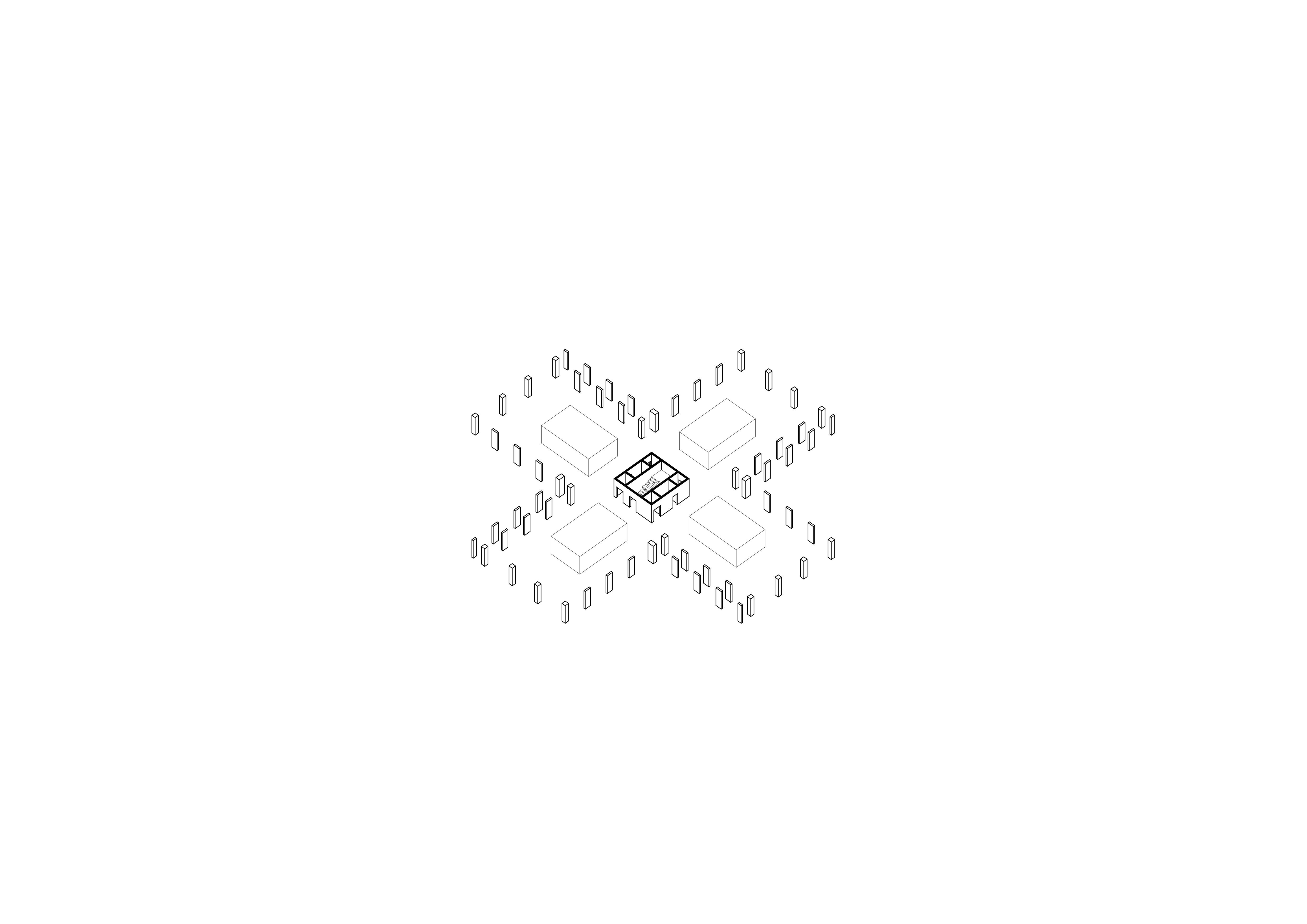

Pathway 1. (chapter 3)

Based on the case of land fragmentation in urban Japan, how could for-profit developers cooperate with residents with new typologies?

Pathway 2. (chapter 4)

Based on the case of planned economy China housing system, how could the forms of living influenced by the definition of ownership?

56 Government Citizen Developer Sources of Finance Provide Legitimacy Two

Continuous

Continuous Payment Government Citizen Developer

Pathway

Service

Government Citizen Developer Policy Provide Sourcesof Finance

Two different pathways of the thesis

FIG.2.18

TOWARDS HOUSING SYSTEM REFORM

NEW POWER AND NEW FORMS OF LIVING

Once the land finance model of the real estate era reaches its end, the government-developer alliance will no longer be able to maintain. For practical reasons, the Chinese government is attempting to use real estate tax to supplement land selling to compensate for the local fiscal deficit. Due to the coming of the real estate tax, the new middle class in Chinese cities, who have accumulated wealth rapidly during the urbanization wave of the past decades, will become the group that lose benefit from this important reform. This group of people often has received better education, has decent jobs and higher incomes, and often owns two or more properties (housing) in urban areas, making them the primary taxpayers of the real estate tax in the future.

“In reality, throughout history, the majority of ordinary people have been virtually powerless to affect the course of political events and have therefore rarely attempted to do so in an organized fashion. Such efforts, when undertaken, are usually fraught with danger and almost always doomed to failure” 18. In fact, most ordinary people pay more attention to how to deconstruct the “disadvantages of the system” through “everyday forms of resistance” in the framework of the system and minimize the impact on themselves 19. However, in some sense, the everyday resistance process also forces the rulers to compromise and adjust the system. Especially for China’s emerging middle class, they have corresponding wealth, as well as organizational and action capabilities brought by knowledge. The power of China’s neo-middle class and the government’s dependence on real estate taxes mean that their demands will no longer be ignored as they were in the era of real estate.