The Magazine of the Nordic Museum

The Magazine of the Nordic Museum

Grand Opening May 5 Special Edition

This special exhibition surveys the best of contemporary

Two dresses, 150 years apart, tell us the story of what’s changed—and what’s stayed the same

Icelandic First Lady Eliza Reid talks literature, life in Iceland, and how the Sagas have helped create a country of strong women

An enhanced evening program of music, art, and culture in the Nordic Museum’s state-of-the-art new facility

Introducing Mikko Joensuu, Finland’s next big thing

Celebrate Nordic art, music, and ideas in May 2018 with this citywide slate of events

This October, step into the magical, mystical world of the early

An interview with Timothy J. Boyce, editor of humanitarian Odd Nansen’s recently republished diary

Equality, diversity, and above all, personal liberty

The curious case of fishing and Nordic literary studies in the Pacific Northwest

A “Viking” boat with a unique history

Nothing says Nordic culture like a cup of coffee

Join us for our inaugural season!

The Magazine of the Nordic Museum

EDITORIAL BOARD AND MAGAZINE STAFF

Eric Nelson Chief Executive Officer

Jan Woldseth Colbrese Deputy Director of External Affairs

Danielle Hill Executive Assistant

Fred Poyner IV Collections Manager

Jonathan Sajda Program Manager

Michael King Adult Education Coordinator

Katie Prince Editor / Marketing Coordinator

Ani Rucki Design and Layout / Graphic Designer

Adam L. Allan-Spencer | Ana Cristina Alvarez | Dena Eichen | Olivia Noble Gunn | Marika Hedin

Jenny Iverson | Michael King | Geir Kløver | Kirstine Bendix Knudsen | Gabriel Moseley

Klaus Ottmann | Caroline Parry | Fred Poyner IV | Katie Prince | Jonathan Sajda | Kaia Wahmanholm

BOARD OF TRUSTEES Trustees

Hans Aarhus | Electa Johnson Anderson | Lars Anderson | Per Bakken | Steven J. Barker (Treasurer)

Brandon Benson | Anne-Lise Berger | Ray Brandstrom | Earl Ecklund | Arlene Sundquist Empie

Ann-Charlotte Gavel Adams | Irma Goertzen (President) | Mike Hlastala | Tapio Holma | Ken Jacobsen

Sven Kalve | Jane Klausen | Kurt Manchester | Thomas W. Malone (Vice President) | Valinda Morse (Secretary)

Kurt Ness | Allan Osberg | Aaron Overland | Rick Peterson | Maria Staaf | Birger Steen | Heli Suokko

Nina Svino Svasand | Lisa Toftemark | Tor Tollessen | Margaret Wright (Immediate Past President) Consuls

Mark T. Schleck, Denmark | Matti Suokko, Finland | Kristiina Hiukka, Honorary Vice Consul, Finland

Jon Marvin Jonsson, Consul General, Iceland | Geir Jonsson, Honorary Vice Consul, Iceland

Kim Nesselquist, Norway | Lars Jonsson, Sweden Honorary Trustees

Senator Reuven Carlyle | Leif Eie | Synnøve Fielding | Senator Mary Margaret Haugen

King County Council Member Jeanne Kohl-Welles | Senator Marko Liias | Bertil Lundh | Mark T. Schleck

Mayor Ray Stephanson | Representative Gael Tarleton

MUSEUM

Executive

Eric Nelson Chief Executive Officer

Jan Woldseth Colbrese Deputy Director of External Affairs

Sandra Nestorovic Deputy Director of Operations

Danielle Hill Executive Assistant

Kirstine Bendix Knudson Special Project Coordinator Erik Pihl Community Engagement Curatorial

Fred Poyner IV Collections Manager

Jonathan Sajda Program Manager

Alison Church Children’s Education Coordinator

Stina Cowan Public Programs Coordinator

Robin Kaufman Exhibitions Coordinator

Michael King Adult Education Coordinator

Kathi Ploeger Music Library Archivist

Kaia Wahmanholm Registrar

Development

Jenny Iverson Development Manager

Darryl Brown Sponsorship Coordinator

Caroline Parry Development Associate

Marketing & Communications

Katie Prince Marketing Coordinator

Ani Rucki Graphic Designer Operations

Adam L. Allan-Spencer Operations Manager

Pamela Brooks Finance Manager

Donna Antonucci Caretaker

Rebecca Bolin Weekend Receptionist

Carolyn Carlstrom Bookkeeper

Michael Ide Volunteer & Staff Resource Coordinator

Mary Ann Namvedt Gift Shop Purchasing Manager

to the sixth edition of Nordic Kultur, the magazine of the Nordic Museum—and the first issue to come to you directly from our new, world-class facility on Market Street! As I write this, I’m watching the boats come in from the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks, reflecting on all the hard work and dedication it has taken to get us here.

To celebrate the new Nordic Museum’s Grand Opening, this issue includes a special centerfold map of the new building. In it, you’ll learn all about the Museum’s exciting new features—from major exhibition highlights to Freya, our new café. You’ll also find a schedule detailing what’s happening during Nordic Seattle, the month-long celebration of Nordic culture that surrounds our Grand Opening; a sincere, in-depth interview with Finnish singersongwriter Mikko Joensuu, who performs at the Grand Opening Concert on May 5; and a preview of our Nordic Nights series, which kicks off Thursday, May 10.

In addition, this issue features detailed looks into the Museum’s first two special exhibitions: Northern Exposure: Contemporary Nordic Arts Revealed and The Vikings Begin. At first glance, these exhibitions couldn’t be more different. The former is a survey of contemporary art from the Nordic region, including works from the mid-1960s up to this year; the latter is a thorough investigation of the emergence of Viking society, which features priceless artifacts found in boat graves from the centuries preceding the Viking Age. However, much like the new core exhibition Nordic Journeys, which examines 11,000 years of Nordic culture, these two exhibitions serve to illuminate the Museum’s central purpose—to share all facets of Nordic culture, from all periods of history, with the entire community.

This year marks the centennial of Icelandic sovereignty, and we’re delighted to bring you an interview with Eliza Reid, Iceland’s first lady, who speaks to the legacy of writing and literature in Icelandic culture, as well as the country’s trailblazing approach to modern gender equality. Reid will be attending the Museum’s Grand Opening ribbon cutting ceremony with her husband, President Guðni Jóhannesson. We also take a look at the surprisingly patriotic origin stories of two dresses in our permanent collection: a nineteenthcentury Icelandic folk costume and a contemporary coat-dress by notable Icelandic designer STEiNUNN.

Also included in this issue are stories delving into the life of Norwegian explorer and diplomat Fridtjof Nansen, who will be the subject of a panel exhibition opening with the Museum; the WWII experience of his son, humanitarian Odd Nansen, whose concentration-camp diary will be the keynote subject of the 23rd annual Raoul Wallenberg Dinner; and the evolution of social justice and humanitarian ideals in the Nordic region since the turn of the twentieth century.

It’s important to note, however, that in all our new-Museum excitement, we haven’t forgotten where we came from. We’re pleased to present in this issue a heartfelt personal essay which examines, questions, and finishes the half-written history of the author’s grandfather, a celebrated local fisherman. The essay reminds us of this fact, also integral to the Museum’s mission: Our history is the foundation of our future.

I’d like to invite you to browse these pages—and take a sneak peek inside the new Nordic Museum before you arrive in real life. Your support has made this vision a reality. We can’t wait to see you here.

Eric Nelson Executive Director/CEO

By Jonathan Sajda

The Nordic Museum’s inaugural visiting exhibition, Northern Exposure: Contemporary Nordic Arts Revealed, will offer a survey of contemporary art from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the autonomous regions of Åland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland. This special exhibition of drawing, painting, installation, film, sculpture, video, and photography will showcase the artists who are producing the finest examples of contemporary art from the Nordic region today.

Northern Exposure has been produced in cooperation with Dr. Klaus Ottmann, deputy director of curatorial and academic affairs for The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., who agreed to loan the Nordic Museum contemporary works from the Phillips’s forthcoming survey of modern and contemporary Nordic art, Nordic Impressions, set to debut in October 2018. His careful curation of Nordic artists offers an expertly crafted range of media and visions, from Olafur Eliasson’s 1997 geographic photo exploration, The Island Series, to Marthe Thorshaug’s powerful and haunting 2014 film, The Legend of Ygg.

Northern Exposure’s additional works have been carefully curated by Nordic Museum program manager Jonathan Sajda and exhibitions coordinator Robin Kaufman, with support from the five Nordic embassies, the Nordic Council of Ministers, and the artists themselves. Contributors include Finnish ceramics sculptor Kim Simonsson, whose solo show The Fantastical Worlds of Kim Simonsson debuts this spring at the American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis, and Norwegian provocateur Bjarne Melgaard, who with the support of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York will loan a color- and controversy-rich painting to the exhibit. Swedish sculptor Cajsa von Zeipel will offer a pair of large-scale adolescent figures, confronting themes of identity, ego, and gender.

2014

CAJSA VON ZEIPEL

Blind-man’s Bluff

Styrofoam, fiberglass, aqua resin, plaster, 95" x 45" x 31"

In support of Northern Exposure, the Nordic Museum is pleased to offer the following essay by Dr. Klaus Ottmann (see next page), who offers some thoughtful context to the evolution of modern and contemporary Nordic art.

1965

POUL GERNES

Untitled Enamel on Masonite

1966

ÖYVIND FAHLSTRÖM

Mao-Hope March

16mm film transferred to DVD

A blue light streams out of my clothes. Midwinter.

Ringing tambourines of ice. I close my eyes.

There is a silent world, there is a crack where the dead are smuggled over the border.

—Tomas Tranströmer

2006–2012, Ragnar Kjartansson, Scandinavian Pain, Neon

Northern Exposure: Contemporary Nordic Arts Revealed and its expanded version, Northern Impressions, which spans almost two hundred years and will be on view this fall at The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., bring together a wide array of artistic expressions—paintings, drawings, photographs, installations, films, videos, and sound works—that reflect the rich diversity and global character of Nordic art.

Both exhibitions have their origin in an initiative formed on the heels of the highly successful Nordic Cool festival held in 2013 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. The objective of the four-year collaboration between The Phillips Collection and the five Nordic embassies in Washington, D.C., has been to promote Nordic artistic talent and organize this first major survey of Nordic art in the United States, reflecting a diverse range of stylistic movements.

The Modern Breakthrough movement of 1870 liberated Nordic art from the constraints of convention and the tradition of the School of Paris and spawned an unprecedented era of artistic innovation and nationalism evident in the diverse work of such artists as Edvard Munch, Vilhelm Hammershøi, Helene Schjerfbeck, Christian and Oda Krohg, Ellen Thesleff, Hugo Simberg, Nils Dardel, Anna and Michael Ancher, Elin Danielson-Gambogi, Fanny Brate, Franciska Clausen, August Strindberg, and Akseli GallenKallela.

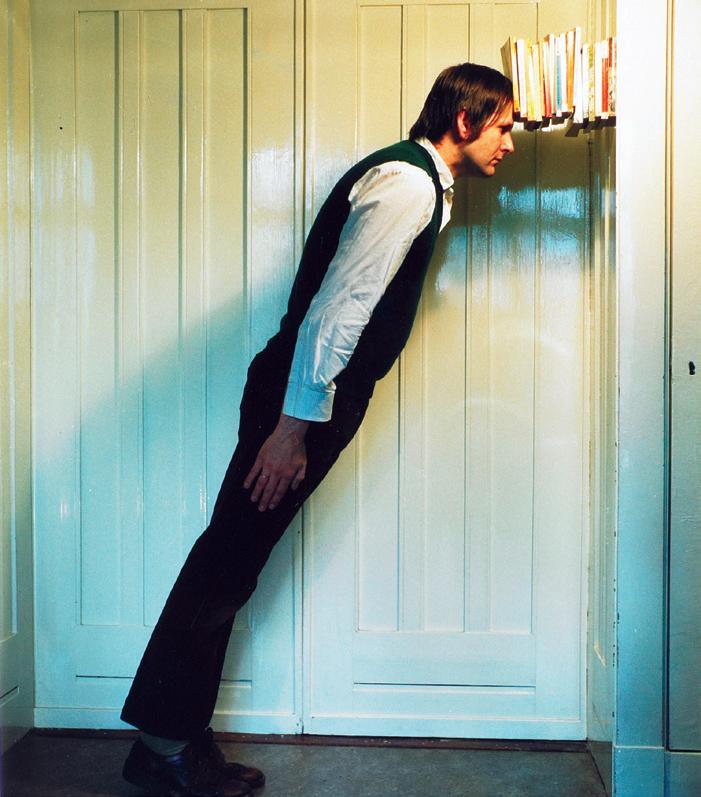

1974

SIGUR ÐUR GU ÐMUNDSSON

Extension

C-print, 20 1⁄8" x 17 3⁄8"

ARKE

Arctic Hysteria (Arktisk hyseri)

Video, 5:55 min.

2013–16

AASE SEIDLER GERNES

Untitled 2

Felt pen on paper, four drawings, 21cm x 29.7cm (each)

Dr. Klaus Ottmann

A second major breakthrough came in the 1960s and 1970s. This was sparked by work such as that of the German artist Dieter Roth, who, in 1955, moved from Switzerland to Copenhagen, where he began experimenting with Super 8 film. Roth lived in Iceland from 1957 to 1964; during that time he established a publishing company and created artists’ books and kinetic sculptures. In 1961, the Eksperimentirende Kunstskole (Experimental Art School, often referred to as the Ex School) was founded in Copenhagen by the artist Poul Gernes and the art historian Troels Andersen as an alternative to the 250-year-old Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Informed by Fluxus (which was introduced by Roth in Iceland and Joseph Beuys in Denmark), the Ex School led a new generation of artists—among them, Per Kirkeby, Poul Gernes, and Sigurður Guðmundsson —to pursue experimentation, performance, and conceptual art, work that would have a lasting impact on subsequent generations. Both the turn-of-the-century modernist accomplishments

and the experimental freedom gained in the 1960s and ’70s continue to inform much of today’s Nordic art.

The first exhibition of Nordic art in the United States was the Exhibition of Contemporary Scandinavian Art, which traveled under the auspices of the American-Scandinavian Society to New York, Buffalo, Toledo, Chicago, and Boston between 1912 and 1913. It was not until 1982, however, with Kirk Varnedoe’s groundbreaking Northern Light: Realism and Symbolism in Scandinavian Painting, 1880–1910 at the Brooklyn Museum, that Nordic art was no longer seen as an anomaly, as peripheral to the mainstream modernist movements that took place throughout the rest of Europe. Varnedoe’s Northern Light was the first exhibition to present Scandinavia’s unique mixtures of innovation and tradition, nationalism and openness, as an expansion of the idea of modernism and as a new paradigm for viewing the development of modernism in Europe.

The Guggenheim Museum in New York also presented an exhibition of Nordic art in 1982. Sleeping Beauty—Art Now, curated by Pontus Hultén, who had been the highly influential director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, featured the work of ten contemporary Nordic artists. In the exhibition catalogue, Hultén wrote: “For somebody looking at the Scandinavians from the outside, it is, however, probably easier to see how they are alike. For us, it is more interesting, to contemplate how we are different.”

After having traveled extensively in the Nordic countries in preparation for these two exhibitions, I also experienced diversity rather than homogeneity of artist expressions. Especially striking to me was the large percentage of woman artists represented throughout the ages in most museum collections—a significant departure from European and American collections, where the works of women artists are sparsely represented throughout the history and collections of nineteenth-century art. I was tempted to credit

SOFIA HULTÉN

Forking Paths I

Sculpture, 63cm x 44cm x 16cm

Crossing Paths

Wood and threads

the high participation of women in the arts to the relatively free status Nordic women occupied since the Viking Age (warrior maidens are recurring subjects in the drawings and paintings of Iceland’s most celebrated painter, Jóhannes Kjarval). However, it more likely can be traced back to legislative reforms and the opening of arts and crafts to women since the mid-nineteenth century in most Nordic countries.

With the seminal 1998 exhibition Nuit Blanché: Nordic Scenes, the 1990s, held at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Nordic art began to take its place on the world stage of contemporary art. Organized by Laurence Bossé and Hans-Ulrich Obrist as part of VISION du nord, a global event celebrating Nordic culture, Nuit Blanché presented the work of thirty young Nordic artists. Most of them have since gained international acclaim (notably Olafur Eliasson, Ragnar Kjartansson, Katrín Sigurðardóttir, Bjarne Melgaard, and Eija-Liisa Ahtila) and gone on to inspire a younger generation of Nordic artists,

many of whom are represented in both exhibitions (Tori Wrånes, Marthe Thorshaug, Nathalie Djurberg, Eggert Pétursson, Tal R, Sofia Hultén, IC-98, and Outi Pieski, among them).

Three contemporary Nordic works, two of them included in the exhibitions, in particular embody the enduring Nordic spirit. One, which will not be displayed in either exhibition, is a 36-foot-long pink neon sign that reads Scandinavian Pain by Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, one of today’s most celebrated performance and video artists. Originally conceived for the 2006 Momentum Biennial that took place in Moss, Norway, Scandinavian Pain was installed on the roof of an old barn on the edge of the town. Inside the barn, Kjartansson gave a week-long performance as the suffering Nordic artist of the Romantic and early Modernist periods. For an installation at the Moderna Museet Malmö for the Malmö Nordic Festival in 2013, the barn was recreated and hung with works by Edvard Munch. Kjartansson’s Scandinavian Pain perfectly captures and embodies

the unique blend of masculine vitality and elegiac romanticism that has become the dominant characteristic of much of Scandinavian art since the radical Norwegian avant-garde art movement known as The 14, which debuted at the 1914 Jubilee Exhibition in Kristiania, Norway.

1887, Oda Krohg, A Subscriber to the Afterposten, Oil on canvas, 46.5cm x 54.5cm

TORI WR ÅNES

Ældgammel Baby

Video projection, sound

The other is a video work by the important Danish-Greenlandic artist Pia Arke, Arctic Hysteria. The video shows the artist moving like an animal, naked, on hands and knees, across the enlargement of a black-and-white photograph of Nuugaarsuk, the region in Greenland where she grew up in the 1960s. During the six-minute silent video, Arke rips apart the entire photograph. The title of the work refers to Greenland’s colonialist past and to the phenomenon of pibloktoq, later known as “Arctic hysteria,” the strange, irrational behavior by Inughuit (Greenlandic Inuit) women first reported by the American explorer Robert E. Peary in 1892. It was compared to Freud and Breuer’s diagnosis of female hysteria and most commonly ascribed to the lack of sun and the long Arctic nights, but may also have been confused with shamanistic rituals of the Inughuit people.

The third is a video/sound projection by the young Norwegian artist Tori Wrånes, part of her imaginative series entitled Ældgammel Baby

Untitled Ceramics and nylon fiber, 90cm

(Ancient Baby), which features the artist wearing masks and costumes, grunting and singing. Her often deforming use of costumes, props, and sculptures creates timeless images that are both mesmerizing and disturbing.

Since the first American exhibition of Scandinavian art in 1912, Nordic art has become a major force in art both in Scandinavia and throughout the world. Nordic art no longer effaces itself, as the French art critic Victor Cherbuliez was supposed to have said after seeing Danish art at the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris, accusing it of presenting too sanitized a view of life and nature and thus being out of step with the works of the French Impressionists.[1] Even in today’s global world, however, Nordic art retains a certain mystique and focus on themes that have held a special place in Nordic culture for centuries: light and darkness, inwardness, the coalescence of humanity and the natural world. But these are now paired with more current subjects such as climate change, sustainability, and immigration.

As Nils Ohlsen, the director of old masters and modern art at the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design writes in his essay for the forthcoming catalogue of Nordic Impressions: From the Romantic period to the present day, an intense connection with nature has prevailed… This is due to the strong identification of the Nordic people with nature, a lively dialogue with the art of romanticism, and, last but not least, the perception of the north in the face of increasing globalization as a cultural region with unique values and traditions.

[1] “Le Danemark s’efface” (Denmark has effaced itself). In his published review, Cherbuliez doesn’t use that phrase but writes: “What distinguishes the painters of Denmark above all is that their brush is always clean, it is too clean, it is clean, and nature is never clean; to rid it of its dust, its scars, its warts, its holy maculae, is to attack its beauty”; Victor Cherbuliez, “La Peinture à l’exposition universelle,” Revue des Deux Mondes 28 (1878): 624. See also Lars Grambye, “Le Danemark s’efface,” in Nuit blanché. Scènes nordiques: les années 90, exh. cat. (Musée d’art modern de la Ville de Paris, 1998).

By Kaia Wahmanholm

Skautbúningur, Jon Guðmundsson, 1873

Nordic Museum no. 2016.103.001a–d

In the mid-1800s, European ideals were dominating women’s fashion in Iceland. This disappointed Icelandic painter and dedicated nationalist Sigurður Guðmundsson, who, in an attempt to reinvigorate national pride, proposed two new costumes in his 1857 treatise “On Women’s Clothing in Iceland.” Guðmundsson’s designs drew inspiration from traditional Icelandic dresses while introducing new elements to appeal to the more modern, European-influenced population. He felt it was important to bring Icelandic clothing back to the basics, prioritizing native materials such as wool and leather instead of more exclusive and increasingly popular fabrics like silk, which was used frequently in nineteenth-century European fashion.

The Skautbúningur costume, officially created by Guðmundsson in 1858, is a two-piece dress made with dark wool and embellished at the cuffs and lapel with metallic thread; an ornately carved belt buckle; and an intricate headdress. With an eye toward modernizing the traditional style, Guðmundsson maintained the original shape of the krókfaldur curved headdress, but added to it an ornamental gold crown to emphasize Icelandic wealth. The back of the veil includes a silk ribbon; this nod to the fashionable fabric constrains its use to a small portion of the costume, further illustrating Guðmundsson’s belief that a renaissance of Icelandic patriotism and values should surpass the Europhilia that was sweeping the remote island nation. However, by incorporating materials that were difficult to acquire in Iceland’s isolated location, he was able to create a ceremonial costume that unified the pageantry and luxury materials popular in mainland Europe with uniquely Icelandic themes—thus ensuring the dress would remain popular for years to come.

The Nordic Museum’s Skautbúningur (pictured) was brought to the United States by donor Rhonda Adkins’s great-great-grandmother Guðrún Guðmundsdóttir when she emigrated from Iceland in 1889. The dress was handmade by Jon Guðmundsson (no relation to Sigurður) in 1873, with silver thread embroidery added by a seamstress in Denmark. The wool, an integral part of the original Skautbúningur, was handspun in Iceland. Metallic floral tendrils are embroidered along the lapel of the jacket and cuffs of each sleeve, while green tendrils and red and blue flowers circle the bottom edge of the skirt. The white headdress and veil traditionally represent the white, snowy mountains of Iceland, while the floral embroidery represents the beauty of the land and the contrast between the desolate volcanoes and verdant pastures of Iceland’s topography.

Skautbúningur, Jon Guðmundsson. Photo courtesy Katie Prince.

Nordic Museum no. 2017.057.001a–f

With collections named Sand, Stream, and Black Snow, it is no surprise that artist Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who founded design house STEiNUNN in 2000, draws inspiration from the distinctive Icelandic landscape. The Long Coat in Lava Pattern, donated to the Nordic Museum’s permanent collection in spring 2017, is no exception; it perfectly demonstrates her ability to capture the tenor and texture of the landscape in her work.

Inspired by Iceland’s scenery and cultural history, Steinunn aims to revive those traditional customs that have fallen by the wayside in favor of mass production and increased consumerism. Much like the nineteenth-century Icelandic nationalists, Steinunn believes in using traditional fabrics and local fabricators to make her handmade pieces. The felting and knitting used to create the coat, hat, and scarf that make up this outfit were all done by hand, using traditional methods—an important feature of all Steinunn’s designs. In her Lava Glass collection, Steinunn used felting patterns to create distinctive, wine-colored versions of Iceland’s volcanic topography. The supple wool is hand-knitted to produce hard, jagged edges, similar to the lava ceramics that are staples of Icelandic pottery.

Like her nineteenth-century counterpart, Steinunn uses traditional Icelandic fabrics and techniques, draws inspiration from the landscape, and maintains a markedly modern look in her finished pieces. The combination of inimitable handcrafted designs, monochrome dyes, and contrasting textures in her work allows each collection to introduce new, bold styles to contemporary fashion while simultaneously paying homage to the bygone era of handmade and careful crafting.

In her Lava Glass collection, Steinunn used felting patterns to create distinctive, wine-colored versions of Iceland’s volcanic topography.

Iceland’s first lady, Eliza Reid, talks literature, life in Iceland, and how the Sagas have helped create a country of strong women

WBy Adam L. Allan-Spencer and Katie Prince

hen Seattle was named a UNESCO City of Literature in 2017, it joined a select group— one that our sister-city Reykjavík had been a member of for several years already. To celebrate, the Nordic Museum partnered with Seattle Public Library and Elliott Bay Book Company to create a new Nordic Literary Series for its Nordic Seattle celebration— featuring such acclaimed authors as Hallgrímur Helgason, Sara Blædel, and Jussi Valtonen, among others.

seen here on a visit to Oman, is also a United Nations Special Ambassador for Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Since becoming Iceland’s First Lady a year ago, Eliza Reid has championed a number of projects revolving around literature, literary heritage, and gender equality. Here, she comments on Icelandic literature, the #MeToo movement, and the differences between Iceland and her native country, Canada. Reid has made a successful career as a writer and editor in Iceland; in 2014, she and a colleague founded the popular Iceland Writers Retreat. She and her husband will be making a special trip to Seattle this year to attend the Nordic Museum’s Grand Opening.

NORDIC KULTUR: Your work as First Lady has included a range of literature-related projects, including supporting Icelandic writers and literary heritage abroad. What role do you see literature playing in Icelandic culture? ELIZA REID: Iceland’s former president once said in a speech that in Reykjavík there are more statues of writers than there are of politicians. Literature is vital to Icelandic culture. We have a long and rich literary history that we value very much. It influences many of our modern creative endeavors today and of course we enjoy celebrating it: Reykjavík is the world’s first non-native English-speaking UNESCO City of Literature and there are many literary festivals and events that take place around the country. We also have several museums dedicated to the life and works of former authors.

What makes Iceland’s literary scene so appealing? What makes it challenging? I think North Americans notice especially the tremendous respect that Icelanders have for writers (and really all creative pursuits). I like to tell the story about a woman from New Jersey who attended the first Iceland Writers Retreat: She said that when she told people in the States that she was a writer, they would scoff and say something like “Oh, but what’s your real job?” or “How can you earn a living

doing that?” But when she was in a café in Reykjavík, she said the same thing to someone and that person was just really interested in everything the American was writing and all her upcoming projects. So being a writer here is really seen as an honorable profession.

The challenge probably is having your work read by a large audience, especially in English where relatively few works are read in translation. Still, there have never been as many Icelanders’ works in translation as there are today. And the government supports writers and other artists through grants that are very competitive. So, for example, you can be a poet who writes in Icelandic and still eke a living from that.

Seattle’s natural surroundings infuse the work our writers create. What infuses the writing of Icelanders?

Of course living on a fairly remote island in the North Atlantic, where we are still often at the mercy of nature, has an impact on writing. The Icelandic Sagas too still influence creativity. Author Hallgrímur Helgason once said that the Sagas are what “give us confidence as writers.”

Who are the contemporary writers we should be watching on this side of the Atlantic?

There are many great writers and it’s hard to single out just a few. Sjón and Jón Kalman Stefánsson have both been mentioned in the international press as possible Nobel Prize winners one day. Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, Gerður Kristný, Vilborg Davíðsdóttir, Hallgrímur Helgason (see sidebar at end of article) are all great writers. In the world of nonfiction, former Reykjavík mayor Jón Gnarr has published some humorous memoirs in English, and Andri Snær Magnason is the only writer to have won the Icelandic Literature Prize in all three categories.*

Icelandic is one of the world’s oldest languages, as well as one of its most

complex. People often talk about it as a “dying” language, especially in the digital age. What do you think might be the future of the Icelandic language?

I think we are all quite aware of the threats to the Icelandic language, but we also know that preserving our language is vital and that we must make language protection a priority. Icelanders are very technologically advanced, so I think in the future we will see a lot of development in the field of digital/ voice communication that can also be conducted in Icelandic. As an immigrant to Iceland, and in an era of increasing immigration, I also believe that we need to ensure that immigrants have the tools and support that they need to help them learn what is often considered a very difficult language. And of course we continue to write books, songs, plays, and poems in Icelandic and continue to consume that material. So I am optimistic about the future of the language.

The immigrant experience in any country can be quite a difficult one; preserving the cultural heritage of the countries from which we’ve come has been a major part of the Nordic Museum’s history. As an

* Fiction, nonfiction, and children’s books.

immigrant yourself, are there parts of your Canadian upbringing that you’re working to preserve for your children?

I speak to my children exclusively in English, so they are bilingual, which I think is a wonderful gift. We try to keep in good contact with my family in Canada so they also learn about Canadian traditions. I think Iceland and Canada have many similarities, so there aren’t too many major traditions that are uniquely Icelandic or Canadian— although we do open Christmas presents on the morning of the 25th, rather than the evening of the 24th! And of course the kids have tried their hands at hockey.

You’ve been living in Iceland—one of the most literary countries in the world—for far longer than you’ve had the role of First Lady, working as a writer, editor, and freelance consultant. How have you found Iceland as a place to launch a career in writing and editing, especially as a nonnative Icelander?

Iceland has been great to me professionally. If I were living in a primarily English-speaking country, I would have had to focus my writing and editing work in a particular niche, for example writing exclusively for the upscale hotel industry. But in Iceland I was simply “the English speaker,” so I was able to take on a wide range of projects. When I was launching my freelance business it may have taken a while longer to get off the ground because I did not have the same built-in network of contacts that people who grew up here have, but once I got a few clients and they could refer me elsewhere, I was never lacking for work.

You co-founded the Iceland Writers Retreat in 2014, to great success. Tell us more about this project.

I founded the Iceland Writers Retreat with my friend and colleague, Erica Jacobs Green, an American writer and editor who lived in Iceland for two years. The Iceland Writers Retreat is comprised of a series of small-group writing workshops led by well-known faculty from around the world (past instructors include Adam Gopnik, Barbara Kingsolver, Ruth Reichl, and Geraldine Brooks), combined with a series of cultural tours designed to introduce people to Iceland’s rich literary heritage. This includes a literary walking tour

of Reykjavík, a visit to the home of our Nobel Prize winner Halldór Laxness, a full-day tour in the Icelandic countryside led by an Icelandic author, and a pub night with music and readings by local writers. We are a friendly and informal group, and we welcome anyone to sign up and attend. Our participants come from around the world and run the gamut from full-time authors to people who have no publishing ambitions but who enjoying tinkering with writing.

all aspects of households while men were away fishing. We know here that gender equality is a human rights issue and that we cannot have a functioning society or economy without the active and equal participation of fifty percent of our population. Of course much remains to be done. In addition to the challenges finally exposed by the #MeToo movement, it remains to be seen how effective the new gender equality law will be, and women

“Icelanders have always been leaders in the field of gender equality, but that by no means indicates that we should be resting on our laurels. . . We must and can do better.”

As First Lady, you’ve been active in promoting gender equality throughout Iceland and the world. This year, the #MeToo movement has seen a particularly strong reaction in the Nordic countries. Have you noticed a change over the past year in how Icelanders approach this issue? Icelanders have always been leaders in the field of gender equality, but that by no means indicates that we should be resting on our laurels. As elsewhere in the world, the #MeToo movement has had a strong impact on Icelandic society, and exposed serious issues that we clearly still need to address. I think we see this sentiment expressed in many other countries, although I think here in Iceland I could say there seems to hopefully be broader support of the movement, from both women and men. We must and can do better; I hope this movement spurs that on.

What in Icelandic culture makes this progressive movement possible? What work remains to be done?

Women in Iceland have long stood up for their rights; we see many strong women in the Sagas, and of course in more recent history women were responsible for managing

remain, for example, less featured in media and public roles, in CEO and other senior positions with companies, and with respect to their salaries when returning to work after taking parental leave. We need to see more women in leadership roles in the private sector, in government and politics, and in the media. We need these examples for the women and men of the next generation.

Hallgrímur Helgason will be giving a Nordic Literary Series talk on his latest novel, Woman at 1,000 Degrees, at 6:30 p.m. on May 23.