HAPPINESS & KNOWLEDGE

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Plato & Co. is North London Collegiate’s philosophy magazine, taken over by Maariya, Zara and Madeline in Year 13.

We are thrilled to be taking on this publication and continue its legacy. Our goal is to share different philosophical arguments that are not covered in the school’s curriculum. Each edition will have a separate broad theme, where each writer will break down and discuss the different elements and aspect of the ir sub-topic.

This edition’s theme is happiness and knowledge, we hope that you all learn something new and enjoy this edition!

Many thanks to our writers:

» Saani

» Hannah

» Gabriella

» Mehar

» Saachi

» Rathishaa

» Girisha

» Dara

» Abigail

» Imaan

» Madeline

» Maariya

» Zara

» Indrani

» Katie

» Anya

» Avika

» Zara

» Amber

Contents Page:

PLATO & CO.

i. Is There Really a Path to True Human Happiness?

ii. Happiness Through What You Buy

iii. The Path to Happiness

iv. What is Happiness?

v. Hustle Culture and its Effect on Happiness?

vi. How Can our Pursuit of Happiness be Harmful?

vii. Marxism and Universal happiness – Can it ever be achieved?

viii. To What Extent does Augustine’s Teachings Prove that the Soul must be Liberated from the Body to Achieve Happiness?

ix. Looking at Happiness & Virtue Through a Stoic nod Epicurean lens

x. Aesthetic Emotion: the Paradox of Fiction

xi. Applications of Utilitarianism to Economics

xii. Is Bentham’s Utilitarianism the Best Approach to Happiness?

xiii. Summer 2022 Philosophy Challenge

IS THERE REALLY A PATH TO TRUE HUMAN HAPPINESS?

By Saani

By Saani

Happiness is not a chemical. It is not an object. It is not something you can touch, or smell, or hear, or eat – but you can feel it. It’s a sensation that can come across your body; an emotion that’s so strong it can overpower any worries or fears. It can make you feel as if you could touch the clouds. However, just because we see people smiling, this doesn’t necessarily mean they are happy. Anyone can say they are happy, but how can we know if they mean it? This leads me to the question: is there a path to true human happiness?

Many people say that in order to achieve happiness, you need to please yourself and avoid any sort of pain. This is commonly known as hedonistic happiness. For example, if someone gave you a chocolate bar, you would feel happy – but once that bar is finished, you would chuck away the wrapper and never think of it again. Hedonistic happiness is often short-sighted and temporary, and although it might satisfy a human’s desires, in my view, it is not the best path to true happiness. This is for the simple reason that it does not last – if an eternal smile is not placed on the human face, they are not truly happy.

On the other hand, the eudaemonic side takes a more long-run view of happiness. It argues that we should live for the greater good. We should display kindness, honesty, and courage. When people talk about their feelings, it is scientifically proven that they feel happier, because they are allowed to work their way out of negative emotions. As a famous quote states, ‘The best way to cheer yourself up is to cheer somebody else up’.

If everyone was to take the hedonistic approach, they would have to keep searching for a new pleasure or experience. Negative feelings would be ignored, and this could cause stress and sudden bursts of anger. On the other hand, eudaemonic happiness requires people to express their feelings, give to others and strive for something greater than their own needs. Even though sometimes treating yourself is ideal, helping others evokes another kind of happiness. Whether it’s donating to charity, inspiring others or even just kindly smiling to a person who looks upset, you could make someone’s day a whole lot better. That, I think, more than anything, is the real path to true joy.

Thus, it is possible to attain happiness in the long-term if you follow the right directions. It can be tough, and you may sometimes feel unappreciated but sharing gives you a deeper level of happiness. All you must think about is the fact that someone is having a better day because of you – and that thought will often be enough to make you happier. Remember: Do not smile for the sake of it. Smile because you want to make others smile.

HAPPINESS THROUGH WHAT YOU BUY

ByGabriella,Hannah & Eden

ByGabriella,Hannah & Eden

Have you ever gone home to your parents to ask for that top you saw a few of your friends wearing at school? Do you ever buy things for the sake of being ‘popular’? In this article, we will investigate why we buy things to make us happy, and whether these things truly do make us happy, looking specifically at the ideas of philosopher Simone de Beauvoir. Beauvoir personally was not interested in things that were really expensive – in fact she loved cheap shops. She thought that what we really want is to enjoy our lives, but we make the mistake of thinking that the objects we buy are key to our enjoyment.

In youth, many people seem to think that if they have a specific item, they will be happy. If a lot of your friends have something, it’s easy to fall into the trap of wanting it too. For instance, you may ask your parents to get you a certain necklace from a specific shop. You would probably tell them that it would make you really happy, and you may also try and come up with a way to make them feel bad for not giving it to you, and then eventually persuade them to buy it for you, even if you’ve never enjoyed wearing jewellery! In a few months, it may have gone out of trend, and you may have forgotten about it entirely. Therefore, the object you received did not make you happy in the long term.

We all frequently fall into the trap of thinking a temporary purchase will give us long term happiness. However, if you have an item which has special meaning, it makes sense that you should prioritise it over something else that is currently in trend that you only buy because other people have it. Beauvoir once said; ‘Remember to ask yourself if you really want it or whether you just think you do. Keep in mind that even if you do not get exactly what you want, it might not have been the thing that would make you happy at all. Most of the time, what matters much more is whether we feel like we have enough time and freedom to do the things we like.’

The late Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks also wrote about finding happiness in unexpected places in his book ‘Celebrating Life’. After writing about a wealthy man who was very philanthropic, he said, “Happiness is not what we own. It is what we share.” This quote reminds us that what we buy will not necessarily bring us long-term happiness. Therefore, it is essential to search for longterm satisfaction in the moments that we share with others in our lives.

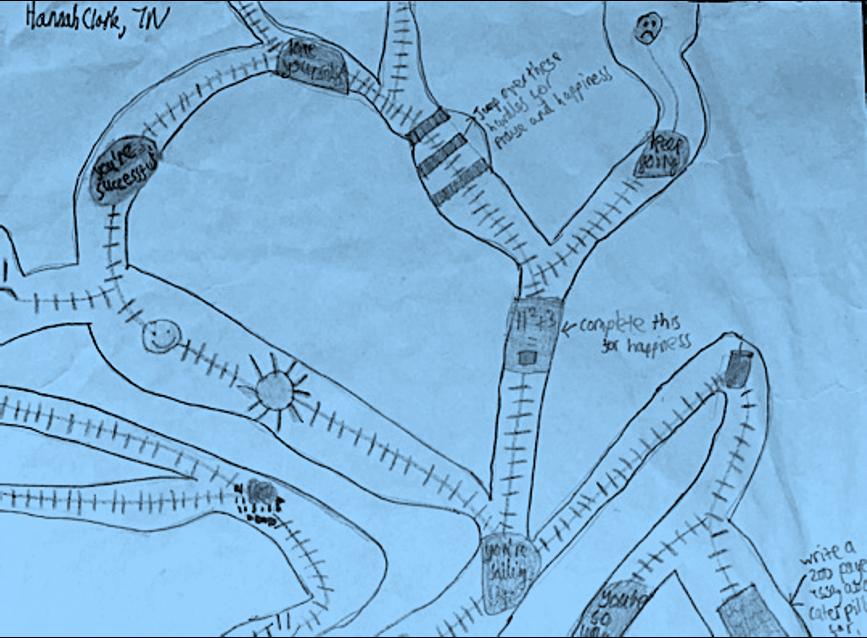

THE PATH TO HAPPINESS

ByMehar

ByMehar

Happiness can be a very complicated and confusing thing. One moment the most obscure thing may make us happy, but the next moment it doesn't, and the weirdest thing is that we have no idea why. Additionally, it differs hugely from person to person, and sometimes we can make up the oddest reasons to be unhappy or happy.

“The purpose of life” is one of the largest philosophical questions. I may be jumping to conclusions to make the statement that “the purpose of life is happiness”, however, I believe saying so takes away much of life’s complexities and hardships. As I mentioned earlier, causes of happiness differ for each individual. There are some who find happiness in bingeing Netflix shows all day and others who find it in a relationship or a career. This being said, a “path to happiness” isn’t as easy as it sounds – why would people go through the pain of studying to get into a good university, or a good job? Because the result brings them happiness. The idea is that the more you put in, the more happiness you get out of it. The more training an Olympic athlete puts in, the higher chance they have of receiving a gold medal.

So, is happiness that doesn’t require much of an input unworthy? For example, watching a Netflix show brings one happiness. But that contentment is short-lived and superficial. True, long-term happiness has to be earned: you have to train to be a good sportsman or practice to be a good musician, giving you skills which can then bring you happiness over time. The smaller bursts of happiness, like buying yourself a pair of jeans or a meal at a fancier restaurant, require smaller inputs and therefore last for a shorter time.

Kindness. Why are people kind? The first thing that comes to mind is to help others. Personally, after showing kindness to someone, I feel content and somewhat happy. This makes me wonder if, subconsciously, we are only kind in order to bring ourselves happiness. A fundamental concept in Jainism is Ahimsa, which means avoiding bringing harm to any living thing. Jain monks are shown to be calmer and more stressless than other people. Perhaps this is because they do not need to carry the weight of any guilt.

I believe that happiness should not be dependent on popularity and external factors. For instance, on social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram, people often find happiness in gaining likes and comments on their posts. Whilst there is nothing wrong or immoral with this, it may be risky to put your happiness in the hands of your social status. Popularity can be fleeting, and losing people’s admiration certainly hurts. Therefore, basing your happiness around external factors that are not in your own hands definitely comes with a price, whereas leaving your happiness in your own control may be a better option.

That is to say – all happiness comes with a price, whether that be hard work, sadness, or even money. As they say, nopainnogain .

Ultimately, despite the conclusion that all happiness comes with a cost, I do persist in believing that it should be our final goal or target. After all, isn’t it better to work towards something knowing it will result in bringing you pleasure, rather than blindly following what you and those around you perceive to be the right thing? Life will always be filled with struggles; however, it is up to you to decide where they take you.

WHAT IS HAPPINESS?

BySaachiAccording to the World Happiness Report 2020, Finland is the happiest country in the world for the third year in a row; Followed by Denmark, Sweden, Iceland, and Norway. When taking the global pandemic into account this may seem like an odd time to publish a report ranking countries based on their happiness. Across the globe, the Covid-19 outbreak has left many people fearful of losing their jobs, anxious about getting infected with the virus or putting their loved ones at risk, and lonely because of the lack of contact with their family and friends, induced by national and local lockdowns. However, according to the authors of the report, the best time to measure people’s happiness is during a crisis. This is because, the extent of people’s satisfaction for life and their confidence that they live in a place where people take care of each other, which is what the authors believe to be the essence of happiness, is revealed. They believe happiness is a consistent state of mind, as opposed to temporary pleasure. However, some philosophers say that happiness comes from satisfying desires, such as eating something that you crave, or even something as simple as finally managing to scratch that itch on your back. Below, I will discuss the different perceptions of what happiness is.

Many ancient Greek philosophers argue that we can only experience true happiness if we lead a good life. This does not just include doing things that we enjoy, but doing things that we genuinely believe are good, and following and practising the right morals. This way, they said, we will not have any doubts about ourselves and can therefore truly be content with our actions and the way we live our lives.

The Greek philosopher Epicurus believed that pleasure and pain can be used to measure good and bad. Things that we like and make us feel great are considered ‘good’ and things that we don’t like and hurt us are considered ‘bad.’ To achieve happiness, he thought we must try and look for what gives us pleasure and avoid anything that brings us suffering.

A group of Greek philosophers called the Stoics believed that happiness is down to leading a natural life filled with simplicity. They believed that it is wrong to try and strive for happiness through becoming rich, powerful, or famous and that we should instead try to seek happiness through minimalism. If we can find joy in the wonders of everyday life, then we will be able to enjoy a consistently happy state of mind.

Others find happiness in the most unlikely of things. What some people find frightening can be perceived by others as thrilling. Studies have shown that when you are doing something frightening or facing a scary situation, adrenaline is released in your brain initiating the ‘fight or flight’ response, causing a feeling of exhilaration and a surge in energy. This surge can make you feel very energetic and alive, which some people take pleasure in, and can even be healthy in small doses. So it could be that happiness is simply the result of chemicals in your brain.

In Danish culture (Denmark being one of the happiest countries in the world and being placed on the top spot in the World Happiness, Report 2016), there is a word that describes a mood of cosiness and a comfortable and cheerful atmosphere with feelings of contentment: ‘hygge'. Hygge is derived from a Norwegian word meaning ‘well-being’, ‘hygge’ is the feeling you get when sharing comfort food with your closest friends, cuddling up on a sofa with a loved one, when you see a sunlight lawn of grass that is that perfect shade of green, or even when you smell the warm earthy scent of freshly baked bread. They believe that lighting, food, and even how you decorate your house contributes to ‘hygge’, which is believed to be the magic of Danish life.

But how can you know what happiness truly is if you’ve never experienced anything different? Although we would all love to be happy all the time, this unfortunately is not always possible. Feeling emotions like pain, hurt and sadness is completely natural, and everyone experiences these emotions at some point in life. However, being unhappy may allow us to value happiness further If all we experienced was happiness at the start of our lives, we would be very under-equipped for the hurdle's life throws at us in our later life, having not suffered or learnt how to deal with any other emotions. Happiness is understood by different people in diverse ways – no perception is the same – based on our hobbies, personalities, background, and interests, but we cannot know what our idea of it is until we experience the opposite.

HUSTLE CULTURE AND ITS EFFECT ON HAPPINESS

ByRathishaaHustle culture is a lifestyle which has emerged due to the increasing influence of social media. It is a lifestyle in which your career becomes an overly integral part of your life and it is believed that the only way to achieve success is to work, thereby sacrificing sleep and happiness. Needless to say, there are many faults with this mentality. Social media doesn’t help fix this as it puts forth quotes like ‘hustle beats talent when talent doesn’t hustle’, ‘I’ve got a dream worth more than my sleep’, and ‘don’t stop when you’re tired, stop when you’re done’. Hustle culture has become so ingrained in our society that almost every individual is fully immersed in this mentality, hence making it hard to recognise a healthy and balanced work life. Furthermore, the rise of social media and influencers promoting their seemingly perfect lifestyles puts forth a platform for people to compare and criticise their own lifestyles. This can make people believe that other people live far more exciting lives, which ultimately affects our happiness. This constant need to compare ourselves to one another creates not only a competitive work environment but also extremely unhappy – and even depressing – lives. The pursuit of work (in fear of being replaced or losing their job) can cause in low levels of happiness and occupational burnout.

The stress ultimately leads people to exhaustion.

Hustle culture fosters constantly toxic lifestyles. For instance, if someone spends too much time relaxing, it fuels guilt because they aren’t spending time doing their work. As a result, it can create low self-esteem and again low levels of happiness for people. Conversely, if one spends an excessive amount of time on their work, this doesn’t always result in the greatest amount of happiness, as there is a constant urge to set expectations above their capability.

Hustle culture does not only arise in workplaces but can also occur in schools. The school environment can place pressure on students as they are expected to get good grades and achieve high, yet in the process of this it is hard to simply take a break when they know their education is important and their peers will be working towards the same goals. This thereby replicates the effect of hustle culture, causing students’ mental health to deteriorate.

Many philosophers, such as Plato and Bentham, would disagree with the hustle culture lifestyle because it doesn’t focus on the happiness of one’s wellbeing. They believed that happiness is the greatest aim of moral conduct, which means that hustle culture (and the stress it creates) should be avoided in order to achieve a happier life.

HOW CAN OUR PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS BE HARMFUL?

ByGirisha

ByGirisha

Pursuing happiness seems to be harmless, a positive goal which can cause no harm. It is safe to say that the pursuit of happiness is a common one, it is what drives people and inspires them, and many people make it one of their lives’ many goals: to achieve the greatest amount of happiness they can.

However, this pursuit of happiness is not as harmless as it seems. If we continue to yearn for it in this way, it could become very harmful.

First, we must understand what happiness is. Plato stated that it is “the enjoyment of what is good and beautiful” whereas Eleanor Roosevelt, former First Lady, said that “happiness is not a goal, it is a byproduct.” It can be split into two categories, hedonic and eudaimonic. The first meaning the greatest amount of pleasure brings the greatest amount of happiness, and the second being a broader idea of happiness being achieved through experiences and connections, these two build the basis of research on happiness.

Pursuing happiness can become a harmful obsession, the desire to feel happy at all times will set us up for failure. By highlighting the absence of happiness from our lives, we consequently make ourselves feel less happy, wondering why we aren’t happy, a repetitive and damaging cycle.

John Stuart Mill, someone who was taught and raised in accordance with utilitarianism at an early age, became severely depressed later in life. During this time, Mill realised that humans should aim for other goods, and happiness is a “felicitous by-product." This supports Roosevelt’s words, as well as the argument that pursuing happiness should not be our goal.

Focusing on ourselves and single-mindedly pursuing happiness could, ironically enough, cause us to be less happy. This is because we often isolate ourselves to achieve this happiness, which decreases our social support and thus decreasing our happiness. It is proven that social interactions and social support increases our overall level of happiness, so, by distancing ourselves from this, we create a negative impact on our happiness.

Robert Nozick, an American Philosopher created a thought experiment which was intended to prove that the view of happiness being the highest good was mistaken. He created a hypothetical machine that would allow anyone to experience anything they ever wanted and fulfil their dreams. It would all be a simulation, but Nozick asks if you would plug in. He believes that most people would choose not to lug in, as achieving those things in reality is much more rewarding that doing so through a simulation.

Nozick was right, as most people chose to not step into the machine. However, this proves that if people are willing to sacrifice endless and limitless pleasure for real pleasure, then happiness isn’t the highest good. This would also mean that the 81% of Americans who choose happiness over great achievements were wrong, as it was just proven that happiness is not the greatest good.

Overall, our pursuit for happiness leads us to believe that happiness is the greatest good, and that to live a fulfilling life, we must pursue happiness. However, happiness is achieved as a consequence or a byproduct, we do not know what makes us happy. We must learn how to achieve happiness through great accomplishments, social interactions, and experiences in our life, not just blindly pursue an intangible goal. Achieving happiness is possible, but the way that modern-day happiness is desired and described is harmful.

MARXISM AND UNIVERSAL HAPPINESS –CAN IT EVER BE ACHIEVED?

By Dara

By Dara

In 1848, radical German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published The Communist Manifesto, the most celebrated pamphlet in the history of the socialist movement. This book, along with other works by Marx and Engels, forms the basis of the body of thought known as Marxism. This originally consisted of three related ideas: a philosophical anthropology (i.e., the nature of man and human consciousness), a theory of history (i.e., historical materialism), and an economic and political program. Essentially, Marx predicted the emergence of a stateless and classless society without private property. This vaguely socialist society would be preceded by the spontaneous seizure of the state and means of production by the proletariat (aka the working class), who would rule in an interim dictatorship.

Unlike the capitalist society of its past, in Marx’s communist utopia, the workers are appreciated and work to benefit the common good. One way he outlines this is through the Labour Theory of Value, a major pillar of traditional Marxist economics. In his book, Capital (1867), Marx explained that the value of labour power – the worker’s capacity to produce goods and services – must depend on the number of labour hours it takes society to feed, clothe, and shelter a worker so that they have the ability to work. So, if five hours of labour are needed to feed, clothe, and protect a worker each day so that they are fit for work the following morning, and one labour hour equals one pound, the correct wage would be five pounds per day. This seems like a fair system, which could provide a starting point for potential universal happiness – workers would not be exploited by those in positions of power who pay unjust wages (in Marxists’ eyes, capitalists), and no one would have to worry about lack of monetary access to basic necessities. However, the Labour Theory of Value has since been disproved and critiqued by mainstream economists. Whilst Marxism argues that capitalists earn profits by exploiting workers, it is now believed that capitalists earn a majority of their profits by refraining from current consumption, taking risks, and organizing production. This means that it’s possible, albeit difficult, for individuals to increase their economic status by taking advantage of the economy where possible, without exploiting others. Thus, even if we implemented a society based on the Labour Theory of Value, it’s likely that an economic disparity between different social classes would still arise. Eventually, we would fall back into a system in which a ruling class enjoys privileges unavailable to the rest of society – although perhaps this would be a fairer society with a higher standard of living.

The concept of alienation, in which Marx wove together philosophy and economics to interpret the human condition, also plays a key role in his striving for social equality as well as his critique of capitalism. Marx believed that people are inherently free, creative beings who have the potential to transform the world. However, the modern, industrial world is beyond our full control. Marx used the free market (an unregulated system of economic exchange in which centralised economic intervention by government is minimal to none) as one example, condemning capitalism as a system that alienates the masses. His reasoning was as follows: although workers produce things for the market, these things are controlled by capitalist market forces who have full control over the means of production. Work, therefore, becomes degrading, monotonous, and suitable for machines rather than free, creative people. Hence,

people end up losing touch with human nature and making decisions based solely on cold profit-and-loss considerations. Marx concluded that capitalism blocks our capacity to create our own humane society and it should thus be abolished and replaced by communism. So, according to Marxist thought, universal happiness could potentially be achieved by implementing a communist system and consequently un-alienating the masses. Ideally, this society would be one where there is no government or private property, and the wealth is divided among citizens equally or according to individual need. However, in the numerous communist administrations that have cropped up throughout history, we have yet to see one actually foster social equality – rather, a majority see a poorer quality of life under authoritarian regimes. For example, Marxism was the basis of both Marxism-Leninism and Maoism, the revolutionary doctrines developed by Vladimir Lenin in Russia and Mao Zedong in China. Under communist governments, both China and the Soviet Union were plunged into dictatorships, where the freedom Marx sought to return to humanity was repressed. Regardless of whether Leninist and Maoist concepts represented a contribution to or a corruption of Marxism, it is evident that the implementation of Marxist societal constructs has often led to more harm than happiness.

To conclude, Marxism, in theory, could lead to a fairer, more equal society. Without class, exploitation of workers and autonomous control over production by certain groups or individuals, people would ultimately have less concerns and more time to pursue what makes us happy. However, in reality, a Marxist society leaves room for economic and societal injustice to arise, demonstrated through the oppressive regimes of both Maoist China and Stalinist Russia.

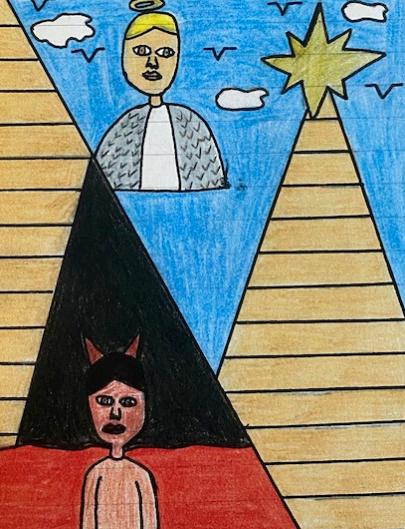

TO WHAT EXTENT DO AUGUSTINE’S TEACHINGS PROVE THAT THE SOUL MUST BE LIBERATED FROM THE BODY TO ACHIEVE HAPPINESS?

ByAbigail

ByAbigail

Augustine believes the soul’s mission is to achieve a sort of complete goodness and happiness, demonstrated by his first book ‘On the Happy Life.’ Augustine writes that ‘God alone is the sourceofallgoodnessandhappiness ’ and as God made human beings, He is the only one that can make them happy. Therefore, Augustine believes the way to achieve happiness is by entering into a meaningful union with God. This essay will explore if Augustine’s teachings prove that the soul needs to be liberated from the body in order to achieve this meaningful union, and therefore happiness.

On the surface it seems as if Augustine equally values both body and soul, stating that the body and soul have a ‘lovely partnership,’ and ‘strong binding force,’ thereby suggesting they are both needed to achieve happiness. Furthermore, a body may be needed to cultivate a meaningful relationship with God, as this might initially be done through following the Bible’s idea of morality. Therefore, a body is needed by the soul as a vessel to conduct even the most basic of behaviours advised in the Bible, such as praying. Consequently, the soul needs the body to achieve happiness, and therefore does not need to be liberated from it to achieve this union with God.

In addition, Augustine highlights the impossibility of hating our bodies, suggesting the soul does not need to be liberated from the body to achieve happiness. Augustine agrees with St Paul that ‘no one ever hates his own flesh,’ writing in his work ‘On the Usefulness of Fasting,’ that ‘even the most body-denying ascetic will demonstrate this by closing his eyes when threatened by a blow,’ highlighting humankind’s inability to truly hate their bodies. Augustine suggests we should ‘nourish and care for it (our bodies) just as Christ does for the Church.’ Therefore, Augustine highlights the value of our body, suggesting that the soul would not need to be liberated from the body to achieve happiness.

However, whilst Augustine does not desire for us to hate our bodies, he does emphasise the corruption of the body, and therefore his teachings more convincingly prove that the soul must be liberated from the body in order to achieve happiness. Augustine highlights the soul’s superiority over the body by saying the soul is responsible for ‘the appreciation of art, practice of virtue, pursuit of tranquillity and contemplation’ all of which are more profound, pure intentions than those of the body.

Augustine’s belief that the human soul is immortal, but the body is not, further demonstrates the soul’s superiority over the body. Genesis 3:19 states that after sinning, God told Adam ‘For dust you are and to dust you will return,’ proving Augustine’s belief that the body is only mortal due to man’s sin. Interestingly, both Plato (whose teachings Augustine was inspired by), and Descartes also subscribe to this belief that the soul is superior to the body. They broadly believe the body distracts the soul, and that the soul’s liberation from the body after death reflects this. Plato’s belief that the soul is more important than the body is also evident through his theory of Forms, which relies on the idea that the soul has knowledge of all the Forms

before entering the body. The shows it is not only Augustine who believes the body to be inferior to the soul, and therefore needs to be liberated from the body in order to achieve happiness.

Having established the body is often portrayed as inferior to the soul, Augustine demonstrates that the body challenges the soul with impure desires, and therefore the soul must be liberated from the body to achieve happiness. Augustine writes ‘the perishable body weighs down the soul, and its earthly habitation oppresses a mind teeming with thoughts,’ demonstrating the hindrance of the mortal body on the rationality and pure intentions of the immortal soul. In ‘City of God’ Augustine writes ‘it is not necessary to flee every kind of body in order to pursue happiness, but only the earth-bound, corruptible, mortal bodies,’ revealing that in order to fulfil the soul’s goal of a union with God, and therefore happiness, the earthly body must be escaped.

In conclusion, whilst the body may be seen as a communication of the soul’s pure desires, thereby helping the soul enter a meaningful relationship with God, Augustine more convincingly highlights the body’s hindrance to the soul, emphasising the body’s inferiority as its corrupt desires taint the purity of the soul. Therefore, in order to enter into a meaningful union with God, and subsequently achieve happiness, the soul must indeed be liberated from the body.

LOOKING AT HAPPINESS AND VIRTUE THROUGH A STOIC AND EPICUREAN LENS

ByImaanBackground of Stoicism & Epicureanism:

Stoicism was founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium in around 300 B.C.E and has flourished as a major philosophical school of thought: it moved to Rome during the period of the Empire, where it subsequently influenced numerous Emperors, the foundations of Christianity and many major philosophical figures. Epicureanism sought its foundations at a similar time period to Stoicism; it revolves around the teachings of Epicurus, who lived from 341-270 B.C.E. Both Stoicism and Epicureanism preach that happiness is the central goal of life, however, they differ vastly in their approaches to achieving such happiness.

Stoicism:

Like many Hellenistic schools, Stoicism centres much of its philosophy around Aristotelian ethics and the idea that Eudaimonia is the telos (end goal) of every human life. Stoics equate this Eudaimonia with the idea of pleasure; Zeno claimed that the highest pleasure was “a good flow of life” and “living in agreement [with nature]”. By answering the question “what is good for me?”, one can begin to see ethics from a Stoic perspective, as surely what must be genuinely good for a person ensures their happiness. Hence, a Stoic approach refutes a purely hedonistic lifestyle that may risk future pleasure and even money may be regarded as a hindrance due to its corrupting influences. In fact, Stoics refer to objects such as money, which are regarded as neither good nor bad as ‘indifferents’.

The only things that Stoics regard as truly good are virtues (in a truly Aristotelian fashion), the four Cardinal Virtues being prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. Stoics accept our natural propensities in their concept of oikeiosis, which would allow for a hierarchy of preferences, with human survival needs at the base. However, as one educates themselves and philosophizes, they can begin to perfect the rational capabilities, cultivating intellectual development. This will encourage the growth of moral virtue in comparison to temporary pleasures, allowing them to access the greatest good. Thus, the Stoic pathway to be happiness is revealed through becoming a virtuous agent, which them enables them to reach Eudaimonia.

Epicureanism:

Like the Stoics, Epicurus’ ethics originate from Aristotle’s idea of a happiness as the highest good, with Eudaimonia being the ultimate goal in life. Epicurus saw the pursuit of pleasure as the pathway to this goal and distinguishes between two different types of pleasure: ‘moving’ pleasures, which satisfy a desire (e.g., eating when hungry), and ‘static’ pleasures, which is the state of satiety after fulfilling a desire. He argues that the static pleasures, which are a state of no longer being in need or want, are the highest pleasures. Epicureans, like the Stoics, would regard virtues as a necessity to aid the pursuit of static pleasure, however, whilst Stoics believe virtues to be the only means of achieving the greatest good, for Epicureans, it is simply one of many.

Epicurus equates the ultimate pleasure (and Eudaimonia) with tranquillity (ataraxia), which can be achieved through katastematic pleasure (the removal of all pain, both mental and physical). To do so, one must fulfil their necessary desires, shedding excess desires related to luxury. Hence, many interpret Epicureanism as advocating for a more hedonistic lifestyle in order to satisfy any worldly desires.

Conclusion:

Therefore, whilst Stoics believe that there are many uncontrollable influences on every life, which they can learn to overcome through developing virtue (the greatest good in itself), Epicureans use virtue as

only one of the means to shed the desires that man is naturally plagued with. Instead, an Epicurean may also seek a hedonistic lifestyle to reach pure happiness and ataraxia.

AESTHETIC EMOTION: THE PARADOX OF FICTION

ByMadeleineThe paradox of fiction is best expressed as three premises:

(P1) In order to experience a rational emotional response to something, one must believe that it exists

(P2) People have rational emotional responses to fictional things

(P3) People do not believe that fictional things exist

These are evidently contradictory, which has led to much debate in the philosophy of art. In this article, I will consider various responses to the paradox.

RESPONSE ONE: IRRATIONALITY THEORY:

Our first response is to reject (P2). Colin Radford took this view with his Irrationality Theory, which states that, although it is irrational to have an emotional response to fiction, it is still possible.

There are various problems with Radford’s theory.

1. Rationality is normative. That means that we should behave rationally. Therefore, if something is irrational, we should stop doing it.

2. If all emotional responses to fiction are absolutely irrational, then they are all equally irrational. But I’m sure you can think of examples of emotional responses to fiction which seem more rational than others – such as being sad rather than happy over Ophelia’s death.

3. We see fiction as offering moral or spiritual guidance for our lives, and lots of this guidance is transferred through emotional reactions. How can this be the case if the emotion itself is irrational?

RESPONSE TWO: ILLUSION THEORY:

Our second response is Illusion Theory, which rejects (P3). It states that when we engage in fiction, we forget that it’s unreal and so do indeed believe that the events and characters exist. This is obviously false. Although we reference a “suspension of disbelief”, this is not literal.

However, a weaker version of the Illusion Theory could be more viable. Jonathan Frome distinguishes between global and local appraisals. Local appraisals are lower-level observations about what things are, such as “that chair is red” or “that painting is round”. Global appraisals are higher-level observations, such as determining whether something is real or a representation. Therefore, we can argue that emotional responses to fiction are prompted by mere local appraisals.

This even has psychological backing. When you perform an action, your motor command neurons fire in a specific way. There is a type of neuron called a “mirror neuron” which will mimic this firing when you watch someone else perform the same action. Irvin and Johnson theorise that emotional responses to fiction are thereby manufactured in the brain.

RESPONSE THREE: QUASI-EMOTION THEORY:

Our third response is Kendall Walton’s QuasiEmotion Theory, which again rejects (P2). It states that we don’t really have emotional responses to fiction – we merely participate in the fiction by pretending to have these reactions. Instead, we have quasi-emotions, which give us the same physical and psychological responses, and we merely pretend that these are part of an emotional response.

Walton outlines three differences between quasi-fear and real fear:

1. Quasi-fear is compatible with emotions that real fear isn’t. We can enjoy quasifear but not real fear.

2. They have different behavioural consequences. When you experience quasifear of the actions of a movie character, you don’t actually call 999.

3. Quasi-fear doesn’t depend on existence beliefs. This means that we don’t actually have to believe that the object of our fear exists.

There are many objections to this, so I will discuss only the most pressing.

First, this theory goes against the evidence of our own experience. Quasi-emotions feel identical to real emotions.

Second, our reactions are involuntary: we can’t help but feel these quasi-emotions. Therefore, Walton’s idea that we willingly participate in them appears flawed.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, the three differences paint a ludicrously simple view of emotions.

1. Quasi-emotions and real emotions are compatible with the same emotions. You can enjoy watching a scary film (quasi-fear) and you can also enjoy skydiving (real fear).

2. Although quasi-emotions and real emotions have different behavioural consequences, this is not necessarily due to the emotions in themselves. We could argue that our behaviour is more affected by our beliefs. For example, when you’re about to have an injection, you might feel scared, but you stay there because you know it’ll help you. Similarly, when you watch a horror film, you feel fear, but you don’t call 999 because you don’t think the events are actually occurring.

3. The only remaining difference is that quasi-fear doesn’t depend on existence beliefs. This isn’t enough – the very question here is whether we can experience emotions towards non-existing things!

APPLICATIONS OF UTILITARIANISM TO ECONOMICS

ByMaariya

ByMaariya

Utilitarianism is a well-known theory whereby an action has to promote the maximum amount of happiness for the maximum number of people. It focuses on the role of an individual in performing these actions. The theory originated with Jeremy Bentham, an English philosopher and economist.

The hedonic treadmill theory proposes that people’s happiness tends to return to a relatively stationary point after periods of heightened or fallen happiness. For example, when a person wins the lottery, they feel high levels of happiness due to both receiving the money and the novelty of the experience. As a person receives more money, their expectations and desires rise in tandem, such that they are no longer satisfied with their previous quality of life – they want to experience greater pleasure. This will increase motivation and work ethic, causing an increase in efficiency and thus creating more economic growth.

However, this contradicts the Easterlin Paradox, which states that at a certain point happiness increase doesn’t directly correspond with income growth. This is because there is a certain point at which one’s lifestyle is so high-quality that earning more money won’t have a large impact on their life and so won’t increase their happiness. We can reconcile the two by stating that the hedonic treadmill is true only to a certain financial extent.

The principle of utility states that economic acts are right if they cause happiness and wrong if they cause unhappiness. This idea is heavily linked to the idea of externalities. An externality occurs when the production or consumption of a good or service has either a positive or negative impact on a third party. For example, pollution is a negative production externality because overproduction of goods leads to pollution, which negatively affects society.

Externalities and utility principles are based on the same theory: that every individual action can be judged to have either a positive or negative impact. An externality occurs when face masks are produced. This is a positive production externality because the production benefits society not only by stimulating the economy but also by slowing the rate of Covid-19 transmission. The free market produces below the quantity of face masks which would optimise social benefit because they are primarily concerned with maximising profits. At point Z, producers only care about their own private benefits, but there is also an external benefit of producing face masks. If you take into account both external benefit and private benefit, the marginal private benefit will shift out to point R (marginal social benefit). Point R is the social optimum point, eliminating market failure as it reduces the problem of underconsumption by increasing production. Thus showing that the idea of externalities is based on the utility principle, analysing how the market either over- or underproduces to maximise benefit to society.

IS BENTHAM’S THE BEST APPROACH TO HAPPINESS?

ByZara

ByZara

Jeremy Bentham was the first utilitarian, creating this approach to move away from the common obedience to the Bible and fixed moral rules of the period. His ethical theory focuses on pain and pleasure as the Master of Human beings and the fact that our instinctive goal is to avoid pain and seek out pleasure. Therefore, it is the pursuit of happiness that motivates us, instead of God or human reason as others may suggest. Bentham developed a principle of utility: the extent to which an act produces “benefit, advantage, pleasure, good or happiness”, as well as preventing “mischief, pain, evil or unhappiness”.

Bentham presents his principle of utility as a democratic principle, and he views his utilitarianism as a process for weighing up alternatives to actions. Regarding this, he suggests a ‘Hedonic Calculus’, which uses certain criteria to calculate the balance of pleasure versus pain that an action brings. These criteria are Fecundity, Intensity, Propinquity, Purity, Duration, Extent and Certainty, and mean that his theory is one of ‘quantitative pleasure’ as it questions ‘how much’ pleasure is brought about by a decision. The Hedonic Calculus ties in with the principles that we associate with utilitarianism today: rules cannot benefit the minority and cause pain for the majority. These principles supposedly ensure that individual benefit is not prioritized over the pleasure of the majority.

Although this approach is favorable in Bentham’s perspective, this core idea of utilitarianism is often countered with the argument that his theory is not always effective as it does not address the issue of the rights of the minority which may be ignored to have the maximum pleasure for the majority. Thus, Bentham’s utilitarianism can be seen as ignoring the problems of injustices which utilitarianism produces.

Bentham’s Hedonic Calculus is very straight forward and easy to use, and it reiterates the convincing argument that morality is linked to the pursuit of pleasure. However, the Hedonic Calculus has been criticized by those who argue that accurately predicting the future is difficult and it may not always be appropriate to simplify pleasure in this way through this approach because pleasure is complex.

Those who disagree with some of Bentham’s ideas but agree with the general principles of utilitarianism may find that the ethical theory of John Stuart Mill is the best approach to happiness. Mill tackles the questions that often arise when discussing utilitarianism by adding certain rules surrounding happiness and deciding that pleasure cannot be oversimplified in the way that for example, Bentham does.

Similarly, to Bentham, Mill’s ethical theory argues that what makes an action good is the balance of happiness over unhappiness which it produces. However, unlike Bentham, Mill ensured to address the issue of justice by arguing that happiness could only be maximized if there were certain rules such as having higher and lower pleasures. Mill’s ethical theory based on utilitarianism focuses on qualitative pleasure and therefore distinguishes between higher pleasures such as music, art and poetry, and lower pleasures such as food and drink. To Mill, higher pleasures are always more valuable than lower pleasures. However, it is also important to note that with Mills theory, he is assuming that everyone will find higher pleasures to be more valuable or ‘happiness-producing’ than lower pleasures. In reality, this distinction can be subjective, and so making this universal claim may not be accurate.

Overall, having considered both the utilitarian theories of Bentham and Mill, I believe that Mill’s ethical theory is a better argument as it shows understanding that not all situations can be simplified into the box of traditional utilitarianism.

NLCS SUMMER PHILOSOPHY CHALLENGE 2022

It is 2050. You have been tasked with the creation of a new school curriculum thatwillprepareitsstudentstobecitizensofthefuturein2100.Whatdoesit looklike?Howwillitbedifferentfromtheschoolsoftoday?

Commended entry by Avika:

The rapid pace at which the world is evolving - especially in the field of science and technologymakes it next to impossible to predict the skills that may be of relevance for even the next decade, let alone all the way into 2100. For instance, there have been new branches such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) that were not even prevalent a decade ago, but given the ever-changing research, have now come to the forefront of current day technologies. To evaluate the skills and ethics required in the future, I would like to start with firstly exploring the new skills potentially required, then secondly, think about skills of today that may still be valuable even in future, and finally explore an ethics and principle’s view.

Firstly, in terms of new skills that may be needed in 2100, these are likely to stem from the key focus areas - space travel and climate change. Why will these topics come to the fore? Space travel will be a prominent part of 2100 as the effects of climate change will only have worsened on our planet, and our only solution will be to find a new inhabitable planet - for this we need advanced space travel. Alongside climate change, overpopulation will also lead to a lack of resources. The United Nations predicts that the world population will grow from 9.8 billion in 2050 to 11.2 billion in 2100. Also, given that the effects of climate change will be more visible by 2100, it will be useful for the curriculum to cover more about climate change. If we do manage to find a new planet, it is important that it is treated with respect and care and that some of the challenges we face with sustainability of Earth are avoided in our new home. Children should also learn about what went wrong on this planet. With new fresh minds, I would hope that we may be able to find a solution to preserve Earth alongside this new planet.

Secondly, although the above new focus areas are likely to come into existence, I feel some of the key skills of today will still be very much relevant. For example, we will always need to know how to communicate our ideas - making both written and oral communication and language skills an important part of the curriculum of 2100. Although the media we use to capture our ideas might change over time - for instance from paper to cloud, the core communication techniques will remain the same. Similarly, we will also still need maths, numerical ability as well as fundamentals of science, history, and geography - as it is important to be able to work out equations and formulae, to be able to use technology effectively, no matter how advanced humanity evolves.

Additionally, I see Religious studies and Philosophy still being a key part of the curriculum - one should always be aware of various beliefs of people around us as this helps us to be tolerant, understanding and accept and embrace our differences. I would also expect that Internet safety will still be taught in schools around the world. With new technology, our exposure to social media will increase and citizens in 2100 should not feel threatened by its omnipresence and should know what is safe to post on the internet and perhaps more importantly, what is not.

Finally, in terms of ethics and principles in 2100, despite all the new focus areas and changes that are likely to happen, the core values that people will still be expected to have will remain the same. Ethics are, at its heart, a system of moral principles that drive right from wrong. In spite of changes and

technical advancements around us over time, the guiding principles pointing our moral compass will remain the same.

In conclusion, whilst there are likely to be new focus areas (such as advanced space travel) that emerge in 2100 and cause the application of our knowledge and skills in a new field, the fundamental skills, principles and ethics that form the basis of today’s education will still be of relevance despite the advancement of technology and continued human evolution.

Commended entry by Indrani

Is there an Afterlife?

It doesn’t matter whether there is an Afterlife. What matters is that belief in an afterlife helps me live my life well now. As long as religion is useful, it doesn’t need to be true. Homo-sapiens are spiritual, social and moral beings by nature. So it is not really surprising that one of the things people get the most meaning from is taking part in something collective to achieve something together. We like being in a group as they bring people together and make us feel part of something bigger than ourselves. It gives a sense of belonging. And religion is one such group. Some people argue that we need religion to be moral. It sets a standard for good action and punishes the bad, which is fundamental in maintaining society's fabric. Human behaviour is a product of nature and nurture. It also plays a part in faith and belief in the supernatural. We are hard-wired in our brains to be good to each other. We are not angels, but we are not devils either.

But do we have to be religious to be moral, or is it possible to have morals and be happy without even believing in God? Morality is a lot older than religion. Irrespective of religion, culture, or where we come from, there is a universal code that all societies adhere to. Because these codes are fundamental to our existence (spiritual/physical morals and emotions). Societies, cultures and religions take these codes and wrap them in a supernatural, mystical clock with time myths and superstition growing around it. This entwining makes religion in general so powerful, but today we only learn about 5 different religions, which misses the whole truth. Experts estimate that there are over 30,000 versions of Christianity alone. Religion has the power to motivate people to lead a good life but also can support them emotionally through spirituality: at the same time, I am very much aware that many wars have been waged- many terrorist acts have been undertaken in the name of religion. Then others feel religion teaches negative actions. Discrimination and criminal injustice faced by the LGBTQIA+ community are prime examples. I believe that people who commit acts like this only look at nonrelevant aspects of religion and thereby completely sidestep the core principle of compassion. Pharaohs, on their death, present their claims to be innocent of all crimes against the divine and human order to be 42 gods. Then their heart is placed on a scale, counter-balanced by a feather. This represents an Egyptian Goddess named Maat- the goddess of truth and justice. If their heart was equal to a feather's weight, the Pharaoh would achieve immortality, but if not, it would be devoured by the goddess Amemet.

Buddhists believe that by following the Eightfold Path, they can gain enlightenment, ensuring a better future in the process. Good action would result in a better rebirth as a human or animal, or even ghosts or demi/gods. Being born as a human is a second opportunity, and humans should devote their life to escaping the cycle of life, death and rebirth, and attaining enlightenment.

One question every religion has tried to answer is what happens to us after death. Our body disintegrates and becomes one with nature, but what happens to our soul? In a Nachiketa story from Upanishad, Nachiketa asks Yama (The lord of death) if there is life after death. This is the same question that even we are still asking. Death and whatever happens to us afterwards impacts how we lead our life. The terracotta army of Emperor Qin Shi Huang and the legacy left behind by the pharaohs of Egypt are prime examples of that. Hindus, Buddhists and Muslims believe that our actions decide the kind of afterlife which awaits us. If we do good, we would either go to heaven or be

reborn as a human. Do heinous crimes, and you either go to hell or get reborn as an insect or a plant. Some might argue that religious people act as do-gooders with moral weightage because they seek the afterlife. But does it really matter in the whole scheme of things?

In my head, it is the same deal as whose pledge has more credibility- the one who refuses to eat meat because of religion or who abstains from eating meat purely because of their personal choice. For me, they both fall in the same category. As a society, they are both classified as vegetarians, and their efforts are also beneficial for the environment. Whether we believe in the afterlife or not, it is always important to live your life to the fullest, living every day as your last.

Commended entry by Katie R

If one is questioning their religion and its beliefs are about the afterlife, yet they are still doing good because they believe that religion ‘helps me live my life well now’. They know that there is a chance that the afterlife does not exist but she still chooses to do good deeds illustrating that she is not driven by religion to do good but by other means and are not truly faithful in their religion. This provides evidence for the fact that religion transcribes moral truths and with or without religion we would still be driven by the same moral ‘good’ deeds. We want to do virtuous deeds with no reward needed, showing that religion transcribes morality.

Although some commentators may argue that there is no truly selfless action regardless of an afterlife and we always do things for our own benefit – even if it is just to feel satisfaction in our good deeds. In order to determine if a deed is truly altruistic you must know what the intention was behind the action. A truly selfless act must be truly altruistic in order to be a categorical good deed, this means that an altruistic behavior is at a cost to oneself. However, this is not to say that you have to be making a bit sacrifice to do a genuinely good deed but as you can’t truly know the phycological motives behind an action, whereas in an action that you are sacrificing more for the other person objectively then this action is truly altruistic. For example: a stranger taking a bullet for another stranger – is truly altruistic as they have sacrificed their own life for another person and if they cannot have done it to feel like a good person as they will not live to feel the human feelings that they know are real.

In contradiction to the first point many commentators may agree with the statement as in a practical sense it helps to make the world a better place. Even if commentators such as Stephen Hawking are right in: ‘There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers. That is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark.’it doesn’t matter if people are believing in something not real they still make the world a better place, and if our idea of an afterlife with a Heaven and Hell is real then it just adds to the benefits. Doing morally good deeds does not do any harm to the world – only good! This argument links into Pascals Wager: which is that we should act as if God exists because the probability of hell, even if it is small, outweighs any immediate benefits of the lifestyle that you would lead if God doesn’t exist. Although, this is true, that there is some possibility that there is an afterlife and some people may argue that there is a lack of evidence on both sides of if there is an afterlife or if not – a 50/50 chance based of the premises that there either is an afterlife or there is not, a simple statement with fair odds on both sides. This is not a valid argument as it is talking about possibility, not probability – possibility is a chance that something may happen however the real probability of an afterlife is much less predictable than 50/50. It is possible that I will win the lottery – I either win it or I don’t, but this does not mean that my odds are 50/50, the same applies when talking about the probability of a heaven and a hell existing. When we use Pascals Wager as an argument, we may use it for anything – there could be an alien spaceship that will come to abduct us to a pain free world if we worship this alien or kill us if we do not. This is a possibility but is not very probable and if we applied Pascals wager to every event in our lives then we would live a worry filled life.

Firstly I believe that we should not only do good in order to get benefits in an afterlife that we do not know exists. We have no guarantee of the afterlife yet we still choose to do good things; ‘Feeling and thought are the only things which we directly know to be real’ - J.S Mill in Three Essays on Religion. When

somebody dies all we know is that they cease to exist in our view. So a logical person would argue that there is a very slim chance that the afterlife exists so we should honour what we already know and act in what we think is the best thing to do in the world that we see around us by abiding by laws and doing good deeds. By doing these good deeds we do help the world however, we don’t know the motives behind them and if they are truly altruistic. If we are only doing good deeds because we think that a divine power commanded us to in order to go to the afterlife then it is subjective whether these are good deeds or not. Whereas truly good deeds should have a good motive – we should react to bad things we see in the world and try to make the world a better place. It does matter whether there is an afterlife or not because the motives and meaning of our actions are as important as the action itself.

Commended entry by Anya

‘How do we know that our knowledge now is better or ‘more true’ than the knowledge of past societies?’

I will start by defining the concept of ‘knowledge’ in its entirety. Is knowledge an awareness of societal norms and stereotypes, a mental manual instructing us how to act in everyday life, for example etiquette and respect for elders? However, everyone is raised differently, their parents teaching them different moral values and principles based on their own experiences, thus everyone’s ‘manual’ differs slightly. Yet surely this ‘knowledge’ is more progressive and ‘more true’ than that of past civilisations as today’s society is the most humane and educated; we have the most advanced medicine and technology since history began. Or perhaps we should define ‘knowledge’ as an objective phenomenon. Concrete, scientific facts like the law of gravity and the anatomy of the human body. However, this begs many questions. How do we know these ‘facts’ are absolute, and will not be disproven in future generations? The answer is we simply do not. Regardless, these facts are ‘more true’ than that of the past due to technological and scientific advancements. Therefore, in this essay I will argue that we do know that our knowledge now is better than the knowledge of past societies.

I begin with my first definition of ‘knowledge’ - a social construct. Today’s modern society rests upon progressive values compared to our ancestors. For example, the acceptance of gay marriage and the emergence of feminism. Therefore our ‘knowledge’ today is more forward and therefore ‘better’ than that of the past. I will illustrate this through deduction.

1. In general, today the common population have more influence over public opinion due to social media. Meaning that anyone can voice an opinion, not just those in places of political authority and power.

2. Therefore, more are confident to speak up on social issues.

3. Thus, there are millions of opinions surrounding these issues. However, one could argue that the introduction of social media results in an overflow of contrasting opinions as everyone feels confident to speak up, rendering it hard to know what to believe. Yet this is irrelevant, as this new ‘knowledge’ however contrasting and overwhelming, still exists unlike in previous society. Therefore our ‘knowledge’ surrounding social issues such as gay marriage is ‘more true’ and ‘better’ simply because there is more of it, as opposed to one conservative viewpoint.

I continue with my second definition of ‘knowledge’ - an objective phenomenon. Today’s scientific ‘knowledge’ concerning the workings of the world is ‘more true’ than that of past societies due to empiricism. This is because:

1. Empiricism states that all knowledge comes from experience. Whether it be scientific experiments or space sightings of meteors.

2. Today in the 21st century, we have had the most time out of all civilisations.

3. Therefore today, we have had the most experience, as we know the experience that all past societies have gathered through historical documents, as well as our own discoveries.

Thus, we can deduce that our ‘knowledge’ today is the ‘most true’ as it has come from centuries of experience and thinking. Although a logical contradiction can be made against phase 1, in that all knowledge does not necessarily come from experience because of innatism and rationalism which state that we are born with some knowledge already, and some knowledge is acquired simply through intuition and deduction, respectively. This is however irrelevant because even if it were true, all humans would be born with the same ‘innate’ and ‘rational’ knowledge, therefore the only distinguishing factor is empirical knowledge, of which today’s people have the most. Therefore, our knowledge today surpasses that of all past societies.

But what if we are wrong? What if at some point in history, someone somewhere realised the nature of reality, and in fact, what we believe to be objective is merely illusionary?

Take the Buddha. After attaining enlightenment around 588 BC, he gained a higher wisdom and profound understanding of the universe that non-enlightened folk simply cannot comprehend. His ‘knowledge’ is thus ‘more true’ and ‘better’ than that of today’s world, disproving my arguments. However, due to how long ago this occurred, it is hard to prove the Buddha’s enlightenment and thus we cannot confirm it for sure.

To conclude, it is evident that we can know that our knowledge now is ‘better’ and ‘more true’ than that of past societies due to the more democratic and progressive nature of modern society which has catalysed citizens to voice their opinions, resulting in more perspectives on societal issues. Furthermore, we can deduce that the people of modern society have the most ‘true’ knowledge as we can learn from the mistakes and build on the experience of past societies. However, an exception is the Buddha who supposedly gained the highest form of knowledge after attainting enlightenment in 588 BC, far superior to that of 2022. Yet this cannot be proven due to lack of empirical evidence.

Commended entry by Zara H:

‘As long as religion is useful it doesn’t need to be true.’

Billions of people use religion as a guide for how to live a good life, while others argue that the philosophy of religion – such as the belief in God and the afterlife – is not true. Saying religion is not true means that God is not real, and the afterlife is not real. Religion being “useful” means that religious people gain something from religion that non-religious people do not have. It is therefore useful to consider whether, if religion helps people to be kind and live good lives, does it matter if it is true? Below we will discuss this issue and will come to the overall conclusion that religion does need to be true if it is useful.

One reason why it does not matter whether religion is true is because in daily life everyone uses things that are not true to help them become good people. For example, stories with morals, even though they are entirely made up, are regularly used to teach people life lessons – such as do not lie, and do not steal. Religion is very similar as religious texts contain stories with the same messages, only they are often linked back to God. Therefore, to say religion is useless unless it is true would be like saying “Never tell stories as they did not actually happen”. The addition of God to religious stories is often what makes people criticise religion, but if the concept of God helps people understand universal values and messages, why does God need to be real?

That said, I believe that religion does need to be true – and that truth is required in order for religion to be useful. For example, a humanist would say that belief in the afterlife stops this life being special, as if something is endless it loses its meaning. However, a religious person would say that God created the afterlife, and the afterlife helps them live a good first life. Both statements cannot be true, as the afterlife either exists or does not exist. Therefore, by believing in the afterlife one is believing in something that could be a hoax. Following a hoax for our entire lives to live a good life is like believing that Earth is the centre of the universe because it makes us feel important. Therefore, religion does need to be true to be useful because, if it is not true, it causes people to follow a hoax.

Secondly, we do not need religion to become good people: humanists and atheists have moral values and are able to live good lives without a belief in God. This means that if religion is not true, religious people are not gaining anything by being religious, as they can live the same good lives without religion. However, if religion is true, religious people gain something as they can go to Heaven. Therefore, religion does need to be true to be useful because non-religious people can live equally good lives as religious people; in contrast, religious people only gain something above nonreligious people if their belief in the afterlife is true.

Thirdly, to counter the above argument suggesting that religion is like moral stories, nobody follows moral stories and prays to them like people pray to God. The argument suggested that the addition of God to these moral stories in religion does not matter, but I believe this adds a whole other unknown dimension to life. Moral stories, for example “The Boy who Cried Wolf” have morals that are universally accepted and do not contain unknowns: in “The Boy who Cried Wolf”, this moral is “do not lie or nobody will believe you when something bad happens to you”. However religious stories have the moral “Believe in God”, which is entirely different from the universally accepted morals that non-religious stories have. This means morals from non-religious stories are more trustworthy than morals of religious stories – as religious stories often do not focus on what happened, they just focus on God. Therefore, religion does need to be true to be useful as there is no point focussing your life on relying on God to fix everything if God is not real.

Overall, I believe that it does matter whether religion is true: as the only part of religion that could help religious people live better lives than non-religious people is that part which could potentially be false. Only if religion is true, can it be truly useful.

Commended entry by Amber Y

‘It doesn’t matter whether there is an Afterlife. What matters is that belief in an afterlife helps me live well now. As long as religion is useful, it doesn’t need to be true. Discuss.’

Religion is a social-cultural system of certain practices, rules, beliefs, holy texts and places of worship. Billions of people across the globe follow a religion, with 85% of the whole population identifying with one. The truth of religion in general is a topic that people often have differing views on. Some believe that religion does not necessarily need to be true or real, as long as it is useful. I am fairly neutral on the subject, however I am slightly more in favour of the notion that religion being beneficial is more important than religion being true.

Some may feel that religion does need to be true for it to be worthwhile. It is foolish for someone to believe in something false throughout their entire lifetime, only to find that their whole religion is a lie. People follow their religion because they feel it is true, not because they wish to derive benefits from doing so. Religion should not be regarded as simply a tool; something ‘useful’ to live by in order to gain the most out of life. The statement suggests that some may choose to follow a religion just because its teachings will prove valuable, but religion is not something that we can bring ourselves to believe in if we feel it false, just because its teachings may benefit us. If a person had devoted their entire life to a single religion, then they would hope that they had not been living in ignorance and blindly putting their faith in something that was never true. From a personal, emotive perspective, people would absolutely wish that their religion was real. Additionally, part of the main reason why some choose to follow one religion over another is because they believe its teachings are real or more likely to be true than another. This therefore means that religion should really be true, so that the person can feel they are justified in the path they have chosen to take.

However, I to some extent agree that religion actually being true itself does not matter. What matters more is that we believe our religion is true. We will not ever discover that religion is false, so as long as we have lived a good life by following key religious principles, it doesn’t matter that we lived our life mistaken. Though we may have lived believing in something that doesn’t exist, or is not true, we have

not lost anything, which is a similar idea to Pascal’s Wager. Perhaps the main goal of following a religion is really for us to live a good, moral life where we reach contentment and are at peace with ourselves and the world around us, as we have been enlightened. Religion is something that can very positively impact people’s lives, developing their morality and ethics, bringing hope, fostering a community spirit, uplifting people through difficult times, bringing them a purpose, so it would not be right to say that just because religion is not definitively proven to be accurate, people should not believe in it. The main goal of following a religion is not to discover that it is completely true; we may never find sufficient, concrete evidence proving that religion is real anyway, meaning that it does not necessarily matter whether religious teachings are true or not. Additionally, it could be argued that life is supposed to be lived in the present, not in the future. The afterlife, possibly decades and decades away, is not as important as how we are living life currently. Also, something does not necessarily have to be undoubtedly true for us to believe in it. Theories, arguments and many concepts that people have faith in and credit as valid do not have concrete evidence to certainly prove their actuality.

In conclusion, after reviewing both sides of the argument, I believe that religion does not have to be true, as long as it is useful and beneficial to its followers. Although believing in something false throughout one’s lifetime is arguably pointless, religion should not be regarded as a ‘tool’, and its being true would help justify why followers had chosen to believe in it, the importance of religion being beneficial or useful does outweigh the importance of its being actual. By believing in religion that may not be true, we have still gained the most out of life by living well and morally and benefitted from various aspects of religion. Additionally, it could be argued that the main goal of following a religion is not to discover that it is completely true anyway, the present is more important than the future, and concrete evidence of truth is not always required for us to believe in something.

THANK YOU ALL FOR READING WE HOPE YOU ENJOYED!!