Annabelle Fowlkes, President

Susan Blount, Vice President

Carla McDonald, Vice President

John Flannery, Treasurer

Sarah Alger, Clerk

Nancy Abbey Patricia Anathan

Lucinda Ballard

Stacey Bewkes

Wylie Collins

Amanda Cross Cam Gammill Graham Goldsmith Ashley Gosnell Mody Robert Greenspon Wendy Hudson Carl Jelleme

Kathryn Ketelsen, Friends of the NHA Representative Valerie Paley Marla Sanford Denise Saul, Friends of the NHA Representative Sara Schwartz

Janet Sherlund, Trustee Emerita Carter Stewart Melinda Sullivan Michael Sweeney Jason Tilroe Alisa A. Wood

Ex Officio

Niles D. Parker, Gosnell Executive Director

HISTORIC NANTUCKET (ISSN 0439-2248) is published by the Nantucket Historical Association, 15 Broad Street, Nantucket, Massachusetts. Periodical postage paid at Nantucket, MA, and additional entry offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Historic Nantucket, P.O. Box 1016, Nantucket, MA 02554–1016; (508) 228–1894; fax: (508) 228–5618, info@nha.org. For information visit www.nha.org. ©2022 by the Nantucket Historical Association.

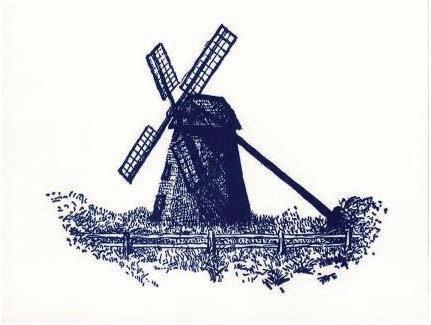

Bill Hoenk’s stunning image of the Old Mill on the cover of this issue of Historic Nantucket brings to mind a wonderful event that took place there earlier this fall. On a sparkling autumn day atop the Popsquatchet Hills, the NHA welcomed nearly 500 people from the community to play, learn about the Mill, grind corn, take part in Wampanoag crafts, and celebrate the 125th anniversary of the NHA’s acquisition of the historic structure. Likely built in 1746, the Mill was once one of five mills on the island. This one, a grist mill used for grinding corn, has stayed in continuous operation since it was built. In fact, it is believed to be the oldest American windmill in continuous operation and has been designated an American Society of Mechanical Engineers’ (ASME) Historic Landmark. As noted in Frances Karttunen’s article in this issue, the Mill was operated by a series of three Azorean men for most of the second half of the nineteenth century. When Francis Sylvia, the last of those three (and who had owned and operated the Mill for 30 years) passed away in 1896, the iconic structure was without an owner. Thanks to Caroline French, one of the NHA’s earliest supporters, the NHA had been encouraged to raise funds to acquire it— along with the Quaker Meeting House on Fair Street (purchased in 1894 as the NHA’s first home). When the Mill went up at auction in August of 1897, the NHA succeeded in purchasing it for $885. Since then, the NHA has performed a series of repairs and several major restoration projects in order to keep the Mill intact and operational. We are now beginning the research to determine the necessary repairs that we will have to make in the next few years to ensure that we continue to preserve the Old Mill and maintain its status as a beloved historic site on the island. Interestingly, just after the NHA had acquired the Mill, the organization began thinking about an addition to the Quaker Meeting House, which had quickly become filled with art and artifacts. With an idea that was ahead of its time, and which remains a rare, early example of this type of construction, the NHA built a poured-concrete struc ture at 7 Fair Street. Conceived as a fireproof vault to safeguard the important collections, the Fair Street Museum operated as such for nearly 100 years until the NHA renovated the building to become home to our Research Library in 2001. As with the Mill, we are currently working on a plan to perform important preservation work on that struc ture. Critical infrastructure upgrades, restored windows, and preservation of the rare poured concrete envelope will take place in 2023. The Nantucket Historical Association has grown considerably since acquiring the Old Mill, the Quaker Meeting House, and the Fair Street Museum. But as we look forward to future plans that will help us continue to carry out our mission in exciting new ways, it feels appropriate that we are first giving considerable attention to our foundation and preserving some of the most important historic buildings on the island.

Hazlegrove Photography Annabelle Fowlkes President, Board of Trustees Niles Parker Gosnell Executive Director

Niles Parker Gosnell Executive Director

Cary

Cary

We preserve and interpret the history of Nantucket through our programs, collections, and properties, in order to promote the island’s significance and foster an appreciation of it among all audiences.

Through this Society, the Board of Trustees recognizes the cumulative giving by individuals who assist with the NHA’s annual operating needs. 1894 Founders Society members contrib ute $3,000 and up toward the annual fund, membership, and fundraising events, as well as to exhibitions and collections, plus scholarship and educational programs. Their generous support is greatly appreciated and welcomed by the community.

$50,000 and above

Julie Jensen Bryan & Robert Bryan

Anne DeLaney & Chip Carver

Amanda B. Cross

Mark H. Gottwald

$25,000 to $49,999

Susan Blount & Richard Bard

Deborah & Bruce Duncan

Kelly Williams & Andrew Forsyth

William A. Furman

Barbara & Graham Goldsmith

Victoria McManus & John McDermott

Diane & Britt Newhouse

Ella W. Prichard

Laura & Bob Reynolds Helen & Chuck Schwab

Melinda & Paul Sullivan

$10,000 to $24,999

Nancy & Douglas Abbey

Elizabeth & Lee Ainslie

Gale H. Arnold

Patricia Nilles & Hunter Boll

Cornelius C. Bond

Maureen & Edward Bousa

Anne Marie & Doug Bratton

Christy & Bill Camp

Anita & Delos Cosgrove

Mary Jane & Glenn Creamer

John M. DeCiccio

Robert Ebert

Tracy & John Flannery

Annabelle & Gregory Fowlkes

Susanne & Zenas Hutcheson

Cecelia Joyce Johnson

Diane Pitt & Mitch Karlin

Diane & Art Kelly

Jean Doyen de Montaillou & Michael Kovner

Margaret Hallowell & Stephen Langer

Paula & Bruce Lilly

Sharon & Frank Lorenzo

Bonnie & Peter McCausland

Ashley & Jeffrey McDermott

Ashley Gosnell Mody & Darshan Mody

Mary & Al Novisssimo

Margaret & John Ruttenberg

Catherine Ebert & Karl Saberg

Denise & Andrew Saul Janet & Rick Sherlund

Georgia Snell

Kathleen & Robert Stansky

Harriet & Warren Stephens

Merrielou & Ned† Symes

Jason A. Tilroe

Louise E. Turner

Kim & Finn Wentworth

Paul E. Willer

Alisa & Alastair Wood

$5,000 to $9,999

Anonymous Patricia & Thomas Anathan

Mary-Randolph Ballinger

Peter A. Barresi

Deborah C. Belichick

Jody & Brian Berger

Donald A. Burns

Meredith & Gene Clapp

Beth A. Dempsey

Elizabeth Miller & James Dinan

Barbara & Robert Friedman

Suzanne & David Frisbie Karyn M. Frist

Julie & Cam Gammill

Robert I. Gease

Nan & Chuck† Geschke

Claire & Robert Greenspon

Gordon Gund

Amy & Brett Harsch

Barbara & Amos Hostetter Wendy Hubbell

Joy H. Ingham

Carl Jelleme

Cynthia & Evan Jones Jill & Stephen Karp

Carolyn B. Kelly

Anne & Todd Knutson

Coco & Arie Kopelman Helen & Will Little

Debra & Vincent Maffeo Holly & Mark Maisto Ronay & Richard Menschel

Franci Neely

Carter & Chris Norton

Liz & Jeff Peek

Gary McBournie & William Richards

Sharon & Frank Robinson Linda T. Saligman

Mary G. Farland & J. Donald Shockey

Kate Lubin & Glendon Sutton

Ann & Peter Taylor

Phoebe & Bobby Tudor

Liz & Geoff Verney

Susan W. Weatherley

Leslie Forbes & David Worth

Kirsten & Peter Zaffino

Carlyn & Jon Zehner

$3,000 to $4,999

Susan D. Akers

Lindsey & Merrick Axel Janet & Sam Bailey

Carol & Harold Baxter

Pam & Max Berry

Susan & Bill Boardman

Laura & Bill Buck

Olivia & Felix Charney

Jenny & Wylie Collins

Kim & Alan Hartman

Catherine & Richard Herbst

Wendy & Randy Hudson

Mary Ann & Paul Judy

Alison & Owen King

Helen Lynch

Alice & J. Thomas Macy

Mr. & Mrs. Peter deF. Millard

Laura & William Paulsen

Candace Platt

Ann & Chris Quick

Maria & George Roach Janet L. Robinson

Nancy & John Romankiewicz

Erin & Joe Saluti

Alison & Thomas Schneider Brooke & Michael Stanton Judith C. Tolsdorf

Joe Olson & Clay Twombly

This list represents donations from January–December 2021. † deceased

To learn more or become a member of the Society, call (508) 228-1894 ext. 122 or email giving@nha.org

Peter Whitney Nash was a loving Husband, Father, and Grandfather. He was born in Cambridge, MA, on April 7, 1933, to Francis P. and Marion Greenleaf Nash. Peter grew up at Groton School as the son of a longtime teacher and was educated at Brooks School in North Andover, MA, and Trinity College in Hartford, CT.

Peter served his many communities with grace and humor and was always engaged with organizations he loved. He served as the President of the Board of Trustees for Dedham Country Day School and the Nantucket Historical Association and was a Trustee Emeritus for Brooks School. He earned the Alumni Medal for Excellence and was on the Board of Fellows at Trinity College, and he also served on the Eaglebrook School Board of Trustees and Nantucket Cottage Hospital Board of Trustees.

His gift to those he met was his natural warmth and ability to connect. He was such a presence on the streets of his beloved Nantucket that he became the self-appointed "Mayor of Nantucket."

Peter is survived by his wife Sally; their four boys and daughters-in-law, Peter, II, and Sandy (Carlisle, MA), Tom and Lisa (Boca Raton, FL), Lew and Amanda (Rye, NY), Andy and Deneige (Dedham, MA); and eight wonderful grandchildren.

“ I got to know Peter best through the NHA, where we worked on renovation design and especially fundraising, the latter at which Peter was especially adept. The campaign for improvements was enormously successful, particularly because of his work. Peter preceded me as President of the NHA and set the tone for the continuation of the building campaign. Peter was best described as a true and gentle man who was genuinely liked and admired for these qualities throughout his life.”

— Geoff Verney, Former President of the NHA Board of Trustees

“ Peter Nash was such a warm and dedicated gentleman. He cared deeply about the NHA’s success and worked so hard during a crucial time to help build the new Whaling Museum. Raising the necessary funds and getting through all the politics sure wasn’t easy back then—he worked relentlessly with the team to help make it all come together. Peter was truly a good person; he will be missed by his many fans on Nantucket!”

— Arie Kopelman, Former President of the NHA Board of Trustees

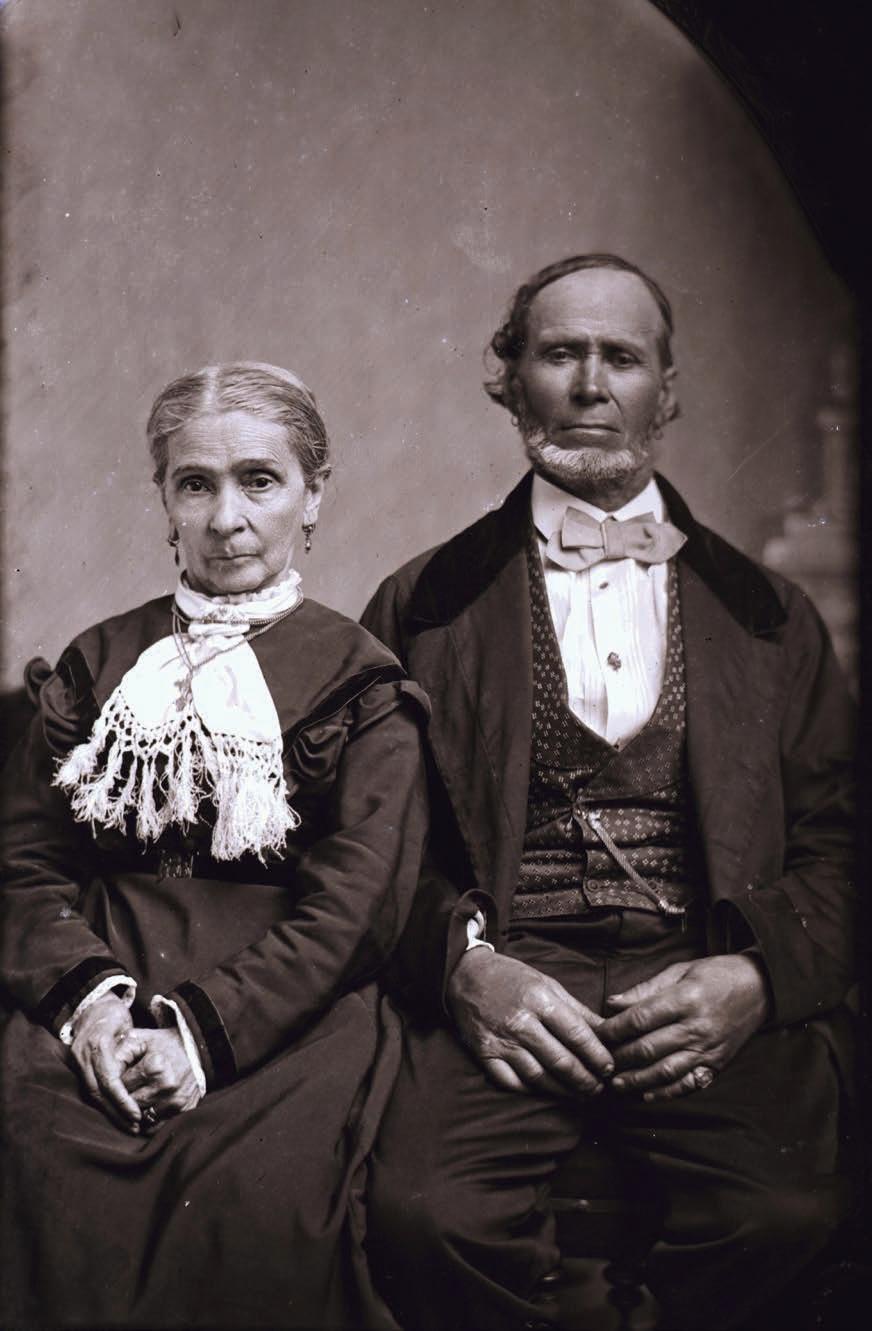

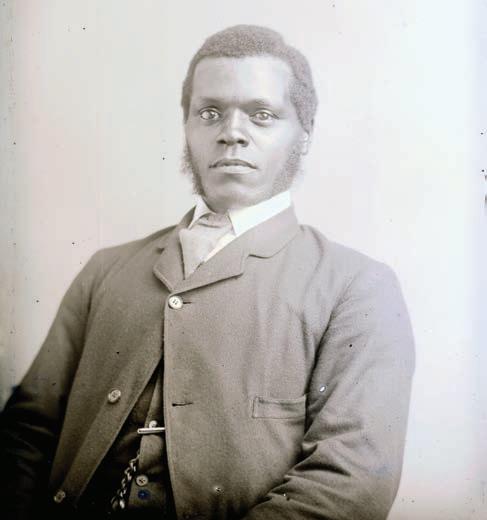

Beginning in 1854, Nantucket’s Old Mill was owned by a series of former mariners from the Azores. John Francis Sylvia, seen here with his wife Angelica in 1883, owned the mill from 1866 until his death in 1896. GPN55.

“In the early days of Atlantic whaling, vessels from Nantucket would sail east to the Azores, which were confusingly known as the Western Islands because of their location far out in the open ocean west of mainland Portugal.”

Today a vibrant Brazilian community makes its home on Nantucket, but the historic roots of Portuguese culture on the island—the source of our staples of Portuguese bread, linguiça, and kale— can be traced to two groups of Portuguese Atlantic islands: the Azores and the islands of the Cape Verde Archipelago.

These island groups, both regularly visited in the nine teenth century by Nantucket whaling vessels, are distant from each other geographically, with different popula tions and histories. Had any whaling captain confused them, he would never have returned home. Since the end of Nantucket’s whaling era, however, the two island groups have been chronically confused, conflated, and misidentified.

In 1899, The Inquirer and Mirror’s obituary of Captain John Murray—a whaleman from the Azorean island of Graciosa whose original surname was Mendonça—stat ed that he “was a native of the Cape de Verde Islands.” The following week the newspaper had to print a cor rection regretting “that an error on our part as to the place of his nativity should have caused his friends an noyance.”1

Annie Gebo—mother of six, grandmother of fourteen, great-grandmother of fifteen, and eventually a cente narian—was featured in The Inquirer and Mirror as she approached her ninety-sixth birthday and again three years later as she turned ninety-nine. In 1967, the news paper reported that “Mrs. Gebo was born in the Cape Verde Islands, Azores, on January 20, 1871, and came to

1 Inquirer and Mirror, Apr. 8, 1899, 1, and Apr. 15, 1899, 4. Such radical name changes were not uncommon. John V. Smith, a stalwart of the Azorean com munity on Nantucket, changed his name from João Vargas Correia when he relocated to the U.S. in the 1850s; Inquirer and Mirror, Sept. 21, 1899, 1.

Marianna A. (Lewis) Murray (b. 1865), also called Mary, photographed in 1891. Born on Nantucket, she was the daughter of George W. and Margaret Lewis, immigrants from Graciosa in the Azores. She married Philip Murray (original surname Soza, b. 1865), an Azorean immigrant also from Graciosa, in February 1889. They had six children together. He was a laborer at the time of their marriage but by the 1920s was proprietor of a livery stable on island. GPN3231.

this country in 1891, when she was 20. She took up her residence here in 1911, which means she has been liv ing here for fifty-six years.” Three years later, the error appeared uncorrected: “She was born in the Cape Verde Islands, Azores, and has lived in Nantucket since 1911.”2 Men from both island groups began to appear on Nan tucket around 1800, having made their way to the east coast of New England aboard whaleships. In the early days of Atlantic whaling, vessels from Nantucket would sail east to the Azores, which were confusingly known as the Western Islands because of their location far out in the open ocean west of mainland Portugal. There

2 Inquirer and Mirror, Feb. 2, 1967, 1, and Jan. 29, 1970, 6.

Mary Viera-Nichols and Joseph Roderick and their children Joseph Jr., Severino, James, and Alyce in the 1920s. Joseph Sr. and his brother John were born on Brava in Cape Verde. By 1918, Joseph was working as a mason on Nantucket. In 1947, he was one of the directors of the Cape Verdean American Citizenship Club of Nantucket. SC139.

they would take on fresh water, supplies, and sometimes additional crewmen before dropping down the coast of Africa to the Cape Verde islands, where they might take on more crewmen before heading back across the Atlantic to the Brazil whaling grounds and eventually northward via the Caribbean and the east coast of North America to the whaling ports of New England, Nantuck et included. When New England whaling expanded into the Pacific, the men from the Azores and the Cape Verde islands might spend years aboard ship before reaching the vessel’s homeport. Having finally set foot on land once again, rather than committing to returning home aboard another whaling vessel, some men stayed, mar ried, and established American families.

The early U.S. federal censuses did not record specific islands of origin when enumerating immigrants from these island group. Instead, an Azorean might be iden tified as “Portuguese” or from the Western Islands. Only in 1850 do the names of islands such as Fayal, Pico, Flores, and so forth appear in the census. For Cape Verdeans resident on Nantucket, the 1850 census sim ply states Cape Verde. To learn more, one must turn to other sources, such as vital records, court documents, and newspaper reports.3

The Portuguese roots of the Swazey family on Nan tucket go far back to mainland Portugal rather than to the Azores. In 1770, Anthony Swazey (probably Soares originally), a young man still in his late teens, married a woman named Jerusha on Martha’s Vineyard. After the birth of two children, the couple moved from Ed gartown to Nantucket. Ten more children were born to them on Nantucket, initiating a multigenerational Swazey family. Nonetheless, Anthony Swazey himself outlived any close family members who might care for

3 For example, Peter Antone’s grave stone in Nantucket’s Historic Coloured Ceme tery provides no dates but does state that he was “Born at St. Anthony, C.V.”

him in his last years, and he died at age 85 in Nantucket’s Quaise Farm Asylum.4

Michael Douglass (possibly da Luz or Degrasse), “a Cape di Verde Portuguese negro,” was born around 1766 and was on Nantucket by 1809. In 1811, he married the widow Mary Boston. Born in 1768, Mary was both first cousin and widowed sister-in-law of Black whaling cap tain and businessman Absalom Boston. The marriage of Mary and Michael came late in life, and they had no children together. Mary died in 1834, and Michael fol lowed her in death in 1836, having drowned in a pond at age 70.5

These two couples, the Swazeys and the Douglasses, epitomize the early documented Portuguese presence on Nantucket, single men who had found non-Portu guese wives—for Anthony Swazey a wife from Martha’s Vineyard and for Michael Douglass a member of a Black family in Nantucket’s New Guinea neighborhood. The white/non-white distinction in the records just quot ed reflects the history of the Azores and the Cape Verde islands. Both remote Atlantic Ocean island groups were uninhabited when discovered by Portuguese explorers

4 Vital Records of Nantucket to the Year 1850 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1925), 4:58, 273, 506, 559; Vital Records of Nantucket 5:258.

5 Vital Records of Nantucket 3:388; Vital Records of Nantucket 5:231.

in the mid 1400s. To the Azores, with their abundant fresh water and fertile volcanic soils, went settlers from the Iberian mainland and also from Flanders. To the arid Cape Verde islands, Portugal sent administrators, political prisoners, and conversos: Jews whose compelled conversion to Christianity was suspect. Few women were sent from Portugal. The intention was to establish plantations and to import enslaved labor from the Afri can mainland. The Portuguese men had children with African women, and, within a couple of generations, the Cape Verdean population was almost universally of mixed European and African heritage. As they spread out across the oceans, wherever Cape Verdeans have come to rest, they have been regarded as people of color.

In terms of both the federal censuses for Nantucket and Town of Nantucket records, Cape Verdeans have sometimes been classified as Black and at other times as white. When José da Silva, born on Brava in 1794, was naturalized before the Nantucket Court of Com mon Pleas in 1824, he was described as “a free white person,” at that time a necessary classification for be coming a citizen of the United States. The distinction has, nonetheless, held on Nantucket as elsewhere: Azoreans have enjoyed white privilege and acceptance, and Cape Verdeans, as people of color, have faced racial discrimination.

According to the 1850 federal census, twenty-seven Azores-born men were resident on Nantucket. All but five of these Azorean men had local wives, and some were approaching their twentieth wedding anniversa ries. Most of their families were large, with seven or eight children at home. As documented in the Eliza Starbuck Barney Genealogical Record, the Azoreans found wives from among the descendants of Nantuck et’s English settlers. The rule was Azorean men marry ing Nantucket women, but Henry and Theodate Star buck’s son James B. Starbuck, born in 1819, married Maria C. Silvia from the island of Fayal, home to the Azorean whaling port of Horta.

For Cape Verdeans, the potential for finding a wife on Nantucket was limited. The growing population of Nan tucket’s New Guinea neighborhood, home to most of its

non-white population, had reached 570 individuals in 1840, but of that number 423 were men and only 147 women. By 1850, as whaling from Nantucket declined, the population of New Guinea was falling, but men still outnumbered women by nearly three to one. One of the Cape Verdean whalemen who did manage to find a wife and establish a family was Joseph Lewis Sr. He married Julia Robinson, daughter of the Rev. John W. and Cecelia Robinson. Their son, Joseph Lewis Jr., went on one whaling voyage himself. Joseph Jr. and his unmarried sister Emma made their home together on the corner of West York Street and West York Lane, for merly the site of Nantucket’s AME Zion Church. From this convenient location Joseph Lewis Jr. served for a

“As they spread out across the oceans, wherever Cape Verdeans have come to rest, they have been regarded as people of color.”Joseph Lewis Jr., September 1883, GPN3852.

time later in life as one of the custodians of the Old Mill after it became a property of the Nantucket Historical Association.6

Before the establishment of St. Mary’s Cemetery in 1871, Azoreans went to their final rest in Nantucket’s old cemeteries, particularly in Newtown Cemetery, and Cape Verdeans were laid to rest in Nantucket’s Historic Coloured Cemetery.7

Some of the forces that drove men from the Azores and the Cape Verde islands onto whaleships were similar: volcanoes, pirates, and hunger. Earthquakes and erup tions rendered parts of the Azores unlivable from time to time, and the islands were plagued by raiders. Some times there was not enough to eat. Observance of the Feast of the Holy Ghost, a devotional practice associated

6 A letter from Captain B. W. Joy to the Inquirer and Mirror, Dec. 19, 1925, 1, me morializes Joseph Lewis Jr., whose death was announced in the same issue, as “a thorough sailor” and recalled being together aboard ship “in many a stormy night off Cape Horn.” An article about the Old Mill in the Inquirer and Mirror, June 11, 1949, 4, includes Joseph Lewis among the veteran whalemen who served as custodian of the mill.

7 There were exceptions. The graves of Cape Verdeans John and Lottie Deluz of Fogo are to be found in Newtown Cemetery.

with famine relief that dates to fourteenth-century Por tugal, survives at its strongest in the Azores. Although the islands are verdant and fertile, generations of pop ulation growth on sea-girt land led to excess population in need of an outlet. As Francis Chapin put it in Tides of Migration, “It is said that always being in sight of the ocean gives Azoreans a vital sense of the possibility of going somewhere.”8

Coastal towns on the Cape Verde islands also suffered at the hands of pirates, but it was severe drought, fam ine, and vulcanism that drove Cape Verdean men onto whaleships where they were willing to work for food. From the mid-1700s, when deep-water whaling began in earnest, to the late 1860s, when whaling from Nan tucket ended, five droughts and attendant famines struck the Cape Verde islands, resulting in massive death tolls. When the relief ship Emma, sent from Phil adelphia during the famine of the 1830s, made first landfall at the island of San Antonio, its crew came

8 Francis Chapin, Tides of Migration: A Study of Migration Decision-Making and Social Progress in São Miguel, Azores (New York: AMS Press, 1899), 70.

upon skeletal survivors on the shore too weak to raise a cheer for their salvation.9

On these dry islands, cultivation of sugar cane and cotton was unprofitable. There was nothing to export for the enrichment of Portugal and next to no means to sustain the imported population. Consequently, the administrators of the Cape Verde islands turned to the lucrative slave trade. The city of Ribeira Grande (now Cidade Velha) on the island of Santiago served as a way station between the west coast of Africa and the sugar plantations of Brazil. Most of the enslaved Africans who came to the island simply passed through, but West Af rican men with weaving skills were retained. This was because woven strips of indigo-dyed cotton known as panos served as currency for the purchase of yet more people on the African mainland. Already by the 1600s,

9 Nantucket Inquirer, Mar. 6, 1833, 3.

thousands of panos were required to meet demand, and the islands of Santiago and Fogo were centers of production.

Fogo and Brava are the two Cape Verdean islands that have contributed most to emigration from the Cape Verde islands. Fogo (meaning fire) is an active volcano but is populated nonetheless. During the whaling pe riod, it erupted five times, sending columns of smoke and fire high into the sky, serving as a beacon for whaleships. During eruptions, the residents would flee for their lives to the small companion island of Brava, where whaling vessels congregated in the anchorage of Fajã de Água. Men from Fogo as well as men from Brava joined the vessels there, and they were collec tively known as Bravas.

“Azorean families, having lost so much, packed up and set out to make new lives in places well-known through their whaling contacts.”

the south shore as a tourist attraction, and still there was plenty of housing stock available for newcomers.10

When whaling from Nantucket collapsed in the 1850s, the arrival of both Azorean and Cape Verdean men ceased as well. Whaling continued out of New Bedford for half a century more, however. Some individuals who had gone whaling during these latter years even tually moved from New Bedford to Nantucket, keeping the masculine whaling tradition alive, but new waves of immigration from both island groups were about to bring whole families to Nantucket.

The arrival of Azorean families came first, fueled by Portuguese political upheavals but also by two natural catastrophes. Wine production on the island of Pico had prospered, with its wines exported as far as the court of the Russian tsar. Then, the phylloxera aphid, which had destroyed French grapevines after crossing the Atlantic around 1850, also reached Pico, dealing a blow to that island’s economy. The island of São Miguel had grown prosperous exporting oranges to Britain; at about the same time that Pico’s vineyards were struck with phylloxera, a citrus blight arrived to wipe out São Miguel’s citrus crops. Azorean families, having lost so much, packed up and set out to make new lives in plac es well-known through their whaling contacts, destina tions including Nantucket and New Bedford.

By this time, Nantucket was in decline from the col lapse of its whaling-based economy, and the popula tion had dropped from over nine thousand in 1840 to just over four thousand by 1870. In 1895, barely three thousand people were residing on Nantucket. Some of the departing Nantucketers took their dwelling houses with them, ferrying them across to the mainland. Some vacant houses were demolished, and their brick and stone rubble used to construct a roadbed from town to

The Azoreans filled niches that departing Nantucketers considered too unprofitable to pursue. They set about farming, fishing, and establishing neighborhood gro cery stores. A series of Azorean men took over running the one surviving mill. What they lacked in capital, they made up for in optimism, and they were welcomed. When they constructed a building on Cherry Street to carry on their traditional social functions in their new home, naming it Alfonso Hall for the first king of Por tugal, the dedication celebration included speeches by the chairman of the Board of Selectmen, state repre sentative Arthur H. Gardner, and Rollin M. Allen, who had learned Portuguese as a child aboard his father’s ship. Captain John Murray arranged to have a crown brought from Portugal to be borne in annual proces sions on Orange Street between Alfonso Hall and the Church of St. Mary, Our Lady of the Isle, for the Feast of the Holy Ghost. Murray and his son became influential in the Nantucket business community to the point that when John Murray Sr. died in 1899, the businesses of Orange Street closed for the hour of his funeral.11

In 1895, at the same time they built Alfonso Hall, the Azoreans organized a local chapter of the Portuguese United Benevolent Association.12 Proceeds from the various activities held at Alfonso Hall, such as auctions held as part of the Holy Ghost observances, masquer ades, dances, and receptions, supported the work of the local chapter. The early summer Holy Ghost pro cessions and feasts continued from the mid 1890s to the mid 1930s, when participation thinned.

A second charitable organization came into being in 1909: Branch 18 of the Portuguese Fraternity.13 Sub sequently, both organizations appear repeatedly in

10 Inquirer and Mirror, Aug. 12, 1882, 2.

11 Inquirer and Mirror, Dec. 26, 1895, 1, Dec. 28, 1895, 1, Apr. 8, 1899, 1, and Apr. 15, 1899, 4.

12 The national Portuguese United Benevolent Association was founded in 1847. Nantucket sources sometimes refer to it as the “Portuguese United Benevolent Society” or just the Benevolent Society.

13 The Supreme Lodge of the Portuguese Fraternity of the United States of America was incorporated in New Bedford in 1899 for the purpose of providing death and disability benefits for its members.

cards of thanks and obituaries published in Nantucket newspapers. In 1915, a representative of Branch 5 of the Portuguese Fraternity came from New Bedford for the sixth anniversary of the founding of Branch 18, at a celebration held in Alfonso Hall.14

Nantucket Azorean activities began to subside in the 1930s. The Inquirer and Mirror reported that the 1934 Holy Ghost activities “were not on such an extensive scale as in some years.”15 Alfonso Hall was more and more rented out for dances, private parties, and even wrestling matches.16 By the beginning of the 1940s, the building was being referred to as Knights of Columbus Hall, and on May 14, 1949, The Inquirer and Mirror an nounced that to honor the late Father Joseph M. Griffin of St. Mary’s Church, “Knights of Columbus Hall, also known as Alfonso Hall . . . will be renamed and official ly dedicated as Joseph M. Griffin Hall.”17 Nantucketers continued to call the building Knights of Columbus Hall, and some even continued to refer to it as Alfonso Hall, for many years after.

The Cape Verdean immigrant family experience was different from the Azoreans’ experience. Nantucketers had tried many schemes to compensate for the loss of whaling, and, except for tourism, none had enjoyed success. At the beginning of the twentieth century, com mercial cranberry cultivation offered hope. The Bur gess Cranberry Company set out to radically alter the landscape in the area of Tashma’s Island, just north of

14 Inquirer and Mirror, July 31, 1915, 4.

15 Inquirer and Mirror, May 26, 1934, 4.

16 In 1923, “a number of Cape Verdeans who reside here” brought over the Ultramarine Cape Verdean Band from the mainland to play for a dance at Alfonso Hall; Inquirer and Mirror, Sept. 8, 1923, 4.

17 Inquirer and Mirror, May 14, 1949, 1, and May 21, 1949, 5. Father Joseph served St. Mary’s Church from 1913 until his death in 1947.

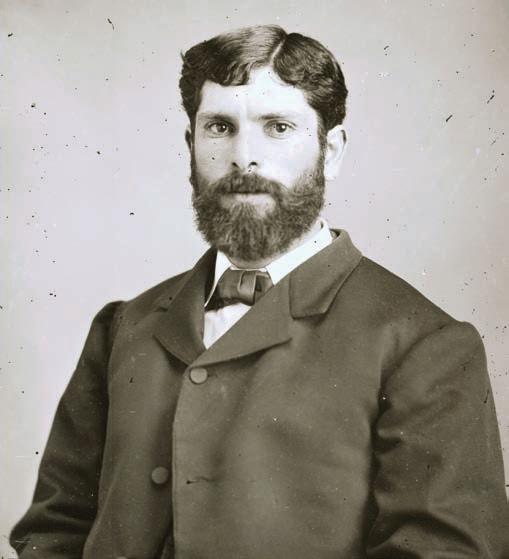

Alfonso Hall near Cherry and Williams streets, circa 1895. GPN4470.

Milestone Road before it enters Siasconset village. Land was flattened, ditches excavated, and a water course constructed to bring water from Gibbs’s Pond, all to cre ate what was then the world’s largest single cranberry bog. Labor for the leveling, planting, and harvesting of the bog was imported from the Cape Verde islands. At the time of the 1910 federal census, over one hun dred Cape Verdean men, women, and children—many of them just arrived—were living and working on the bog, which was briefly known as “Cranberry Centre.” Significantly, The Inquirer and Mirror acknowledged re peatedly that there was a community of immigrants liv ing at the bog. In 1909, for example, the paper reported on the wedding of Antone Correia and Marianna da Lomba, residents of “the Portuguese colony located on Tashma’s Island at Cranberry Centre.” Until the 1950s, weddings of couples of color were not permitted with in St. Mary’s Church; they were only performed in the rectory on Orange Street. In the case of Antone Cor reia and Marianna da Lomba, the couple chose not to have a Catholic wedding. Instead, the wedding party was driven into town in a carriage, where a recently arrived Baptist pastor performed the ceremony in his home, not in the Summer Street Baptist Church. The bride and groom were then driven around town to visit friends. They returned by carriage to Cranberry Centre to a reception and dance that lasted until dawn. All of this was described in The Inquirer and Mirror. 18

In 1916, American anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons and Fogo-born Gregorio Teixeira da Silva traveled from New Bedford to Nantucket to collect Cape Verdean folklore from the bog workers. They were turned away

18 Inquirer and Mirror, May 22, 1909, 4.

by the company foreman, but they were able to meet with Cape Verdeans in town the following day. Teixeira da Silva died three years later. When their collection of stories and riddles from Cape Verdeans in New Bedford, Providence, Cape Cod, and Nantucket was published in 1923, Parsons dedicated it to his memory, referring to him as her teacher. One story in the collection is about a contest between an elephant and a whale, but unfor tunately the location where Teixeira da Silva and Par sons heard it is not identified.19

The material Teixeira da Silva and Parsons collect ed was not told in standard Portuguese but in Cape Verdean Kriolu, a language that has developed in the Cape Verde islands with roots in both Portuguese and West African languages. Kriolu was the home language of the Cape Verdean immigrants and is not mutually in telligible with Portuguese. This has set Cape Verdeans apart from Azoreans, forcing them to use English as their common language.

19

Both Azoreans and Cape Verdeans settled into areas where there were inexpensive accommodations. Mov ing out of bog shanties and into town, Cape Verdean workers found some of their earliest housing on North Wharf and along Union and lower Orange streets, as well as in the Five Corners neighborhood, formerly known as New Guinea. Having established themselves years earlier, Azorean households were more dispersed in areas south of Main Street.

Cape Verdeans not only held themselves apart from Azoreans but also from the few African Americans on Nantucket, most of whom came to the island seasonal ly as domestics working for summer resident families. Cape Verdeans, from their point of view, were free-will immigrants; their ancestors had come to America on whaleships, not on slave ships. Nonetheless, as peo ple of color, Cape Verdeans experienced racial preju dice on island as well as off island. For Nantucket Cape Verdeans, one of the most salient examples of racism is that not until the 1950s were Cape Verdean couples permitted to be married in St. Mary’s Church. In 1947, in the wake of World War II, Nantucket Cape Verdeans founded the Cape Verdean American Citizen

ship Club, with both men and women as officers.20 Four decades went by before they formed a local chapter of the Sons and Daughters of the Arquipelago de Cabo Verde to celebrate the new status of their ancestors’ homeland. The islands had achieved independence from Portugal in 1975 and become a sovereign nation, celebrating July 5 as their Independence Day.21 In 1988, the Nantucket Sons and Daughters held a four-day fes tival at which the consulate general of the Republic of Cabo Verde presented the Nantucketers with a nation al flag, which was flown at Nantucket’s Town Building during the event. Activities took place at various sites, ending with Cape Verdean food, music, and dancing at Knights of Columbus Hall (Alfonso Hall). The festivals continued annually through 1994, moving to the Amer ican Legion Hall and then to the Veterans of Foreign Wars Hall in Tom Nevers, as each festival attracted more visitors from the mainland. By 1991, four to six hundred people were expected to attend, and the orga nizers hired a bus to transport visitors arriving by boat to the out-of-town location. Proceeds from the festivals were distributed in the form of scholarships to Nan tucket High School graduating seniors, whether Cape Verdean or not.

The Nantucket Historical Association has recognized the island’s Cape Verdean heritage in a series of exhi bitions and events. From October 2002 to February 2003, an exhibition called Jag! (for the traditional riceand-beans dish jagacida) was mounted in the Whitney Gallery at the Research Library. At the time, nearly one hundred Cape Verdean family photos were added to the NHA photographic collection, and Cape Verdean sto ry-telling events took place. The Nantucket premiere of Claire Andrade-Watkins’s film Some Kind of Funny Porto Rican? was attended by a standing-room-only audience in the Nantucket Whaling Museum on August 27, 2006. The Shoulders Upon Which We Stand, an exhibition about Nantucket Cape Verdean elders and their children and grandchildren, was mounted in the Whaling Museum

20 Inquirer and Mirror, Aug. 16 and 23, 1947.

21 Unlike the Republic of Cabo Verde, the Azores remain a part of the nation of Portugal, albeit an Autonomous Region since 1976.

Twelfth-generation Nantucketer Frances Karttunen was educated in the local public schools. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Radcliffe College and a Ph.D. from Indiana University and was University Research Scientist in the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas, at Austin. One of Dr. Karttunen’s grandparents was a native Nantucketer and the other an immigrant from Finland. The difficul ties they encountered were among the inspirations for her books Between Worlds and The Other Islanders: People Who Pulled Nantucket’s Oars. She is also the author of numerous other books and articles about Nantucket. In 2011, she was named a Nantucket Historical Association Research Fellow.

in 2021 and expanded in 2022 into the exhibition Cape Verde in Our Soul

Azoreans and Cape Verdeans share Portuguese family names, Roman Catholicism, Portuguese cuisine, a con nection with whaling, and a history of immigration to New England. They have been separated by home lan guages—Portuguese versus Cape Verde Kriolu—and by classification as white versus non-white. Yet, over de cades, both groups have made immense contributions to Nantucket’s economy and culture, contributions worth remembering and celebrating as part of the island’s rich history.

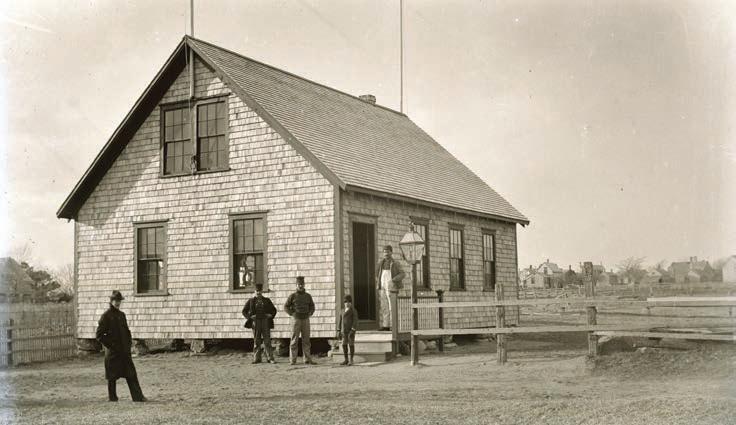

Joseph Myrick was a Nantucket sailor who fought in the American Revolution. His surprising wartime adventures included service in the American cause aboard two French privateers, a correspondence with Benjamin Franklin, and capture and imprisonment by British forces. In 1781, he secured his release from an English prison by switching sides and enlisting in the Royal Navy. At war’s end he deserted and returned to Nantucket. His remarkable story is told here in detail for the first time, providing a window on Nantucket’s complicated connections to warfare and world events.

Myrick was born on Nantucket in 1744. He and his twin brother Benjamin were the eleventh and twelfth of the fifteen children of Andrew Myrick (1705–1777) and Jedida Myrick (d. 1789). His father and his uncle Isaac were shipbuilders from Newburyport who moved to Nantucket when they mar ried the sisters Jedida and Deborah Pinkham. When young Joseph first went to sea and what adven tures filled his early life and voyages remain undiscovered. We pick up his story in 1779, aboard the French privateer cutter Black Prince.

Many Nantucket sailors took part in the Revolutionary War at sea. The Massachusetts State Navy brigantine Hazard, commanded by Captain John F. Williams, counted numerous Nantucketers in its crew between 1777 and 1779, including John Brock II, Henry Folger, David Gardner, Sylvanus Folger, and Benjamin Bun ker. John Paul Jones, the most famous commander in the small Continental Navy, recruited sailors from Nantucket to serve on the Bonhomme Richard, which gained everlasting fame for the capture of the more powerful Royal Navy fifth-rate man-of-war HMS Sera pis in September 1779. Midshipman Reuben Chase is the most famous of these, but there were more than a dozen others. Chase’s brother Joseph commanded the privateer brig Adventure, while Ebenezer Gardner and other islanders signed aboard the privateer sloop Saucy Hound at Nantucket in 1781. After some success, the Saucy Hound was captured by the British, and Gardner

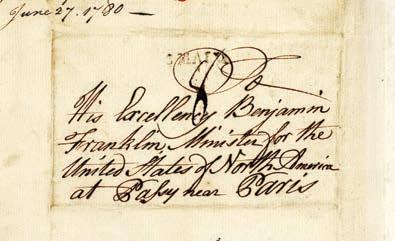

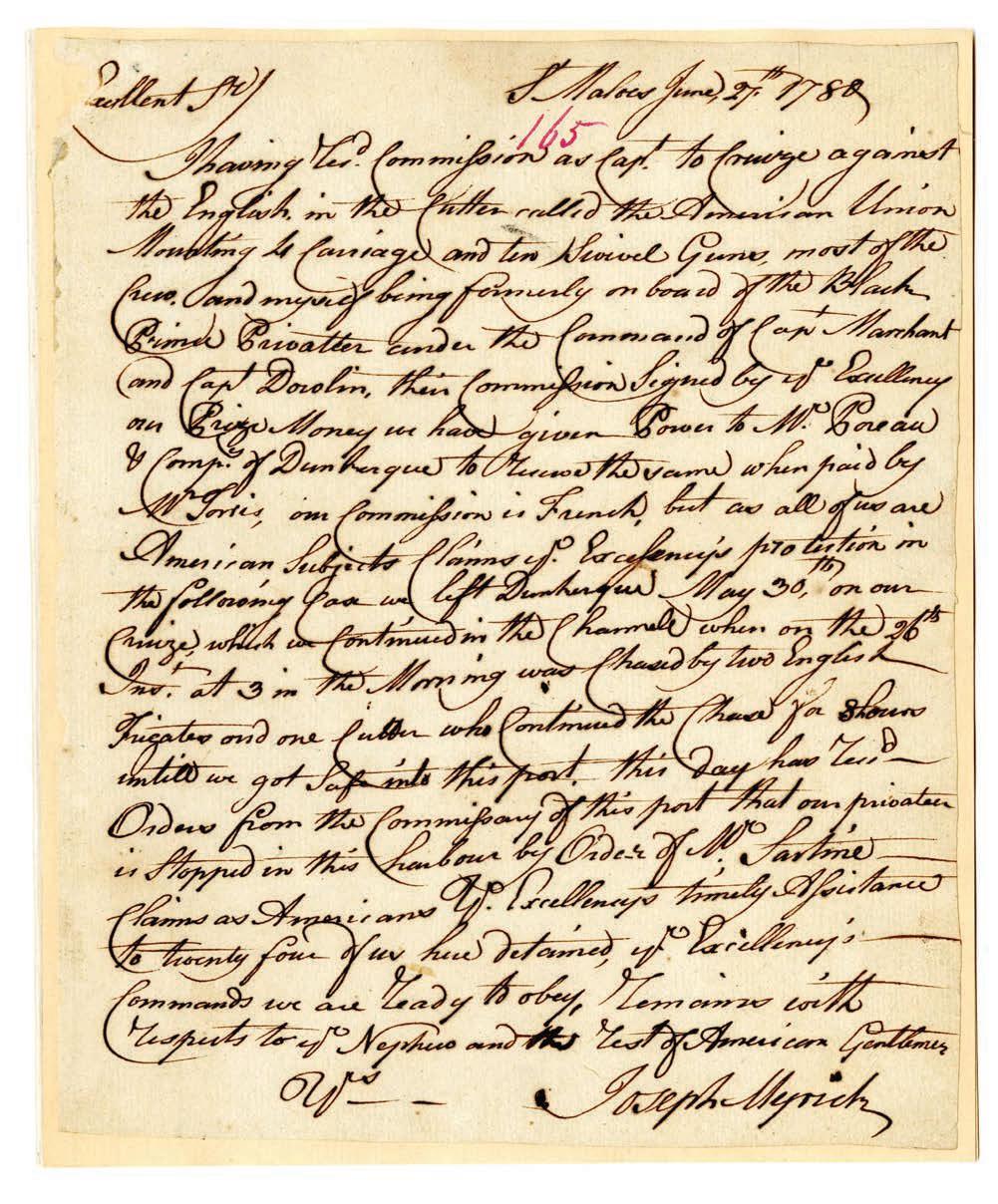

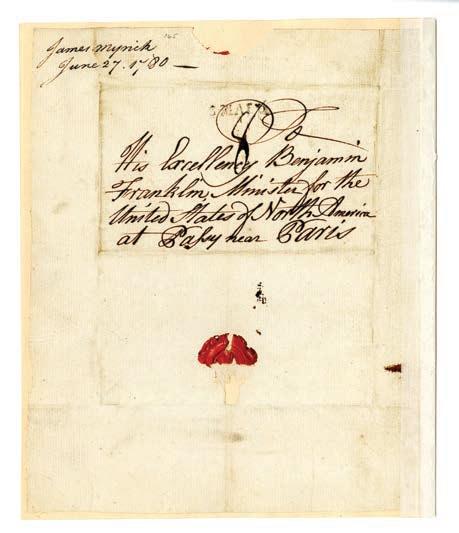

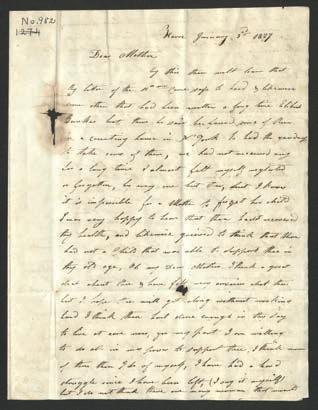

Reverse of the letter on the opposite page.

was pressed into the Royal Navy, serving first in the sloop-of-war HMS Rattlesnake, then later in HMS Marlborough during the Battle of the Saintes, Admiral George Rodney’s vic tory over French Admiral François-Joseph de Grasse in April 1782.1

The privateer contribution to the Revolu tionary War was considerable. When the war began, the American colonies had no navy. By 1777, the navy created by the Continental Congress had just 34 vessels and, by 1782, that number had dwindled to seven.2 Congress au thorized privateers—privately owned armed vessels licensed by the government to attack enemy shipping—to augment this deficien cy and, before war’s end, tens of thousands of men and thousands of privateer vessels had pursued an enemy which had the most powerful navy in the world. These American privateers sank or captured 2,283 enemy ves sels; the Continental Navy, by comparison, captured or destroyed 196 enemy vessels in total. Not only did privateers interrupt British merchant shipping, they assisted and protect ed the conveying of cargoes of material from European sources to supply the badly needed arms, gunpowder, and war materials which the Continental Army needed for victory. General George Washington, appointed commander of American forces by the Continental Congress in July 1775, arrived outside Boston to command a ragtag group of Massachusetts militia. His troops so lacked powder and shot that he could not risk returning enemy volleys for fear of having no munitions if the 6,500 British troops in Boston staged an attack. Hoping for some supplies from the sea, he promoted the enterprise of privateering in 1775. “Find ing we were not likely to do much in the Land way, I fitted out several Privateers or rather Armed Vessells, in behalf of the Continent, with which we have taken several prizes . . . .”3 Since privateers received a percentage of the spoils they captured, the call for citizen-sailors to raid British shipping tapped the same feelings of self-interest and comradeship that had led the colonies to seek independence in the first place.

Anton Hohenstein (b. 1823), Franklin’s Reception at the Court of France, 1778. Lithograph published in Philadelphia by John Smith, ca. 1869. Comtesse Diana Polignac places a laurel wreath on Franklin’s head in honor of the signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance between France and the United States, while Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI look on from their seats at right. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The American delegation in Paris was anxious to bring more American privateers to Euro pean waters. It called for more commissions from Congress to grant to privateers. Benjamin

1 “The Late Ebenezer Gardner,” Inquirer, May 13, 1859, 2; Emil Frederick Guba, “Revolutionary War Service Roll,” Historic Nantucket (July 1963), 5–17; Edouard Stackpole, Nantucket in the American Revolution (Nantucket: NHA, 1976), 50–51, 53.

2 Edgar Stanton Maclay, A History of American Privateers (New York: B. Appleton and Company, 1899), viii.

3 George Washington to Benedict Arnold, Dec. 5, 1775, quoted in Robert H. Patton, Patriot Pirates (New York: Vintage Books, 2009), xvi.

Franklin, the U.S. minister to France, was particularly interested in using privateers to cap ture British sailors as prisoners he could exchange for Americans in British prisons, whose plight greatly concerned him.4

“

About a month later, on June 26, British frigates and a cutter chased the vessel for eight hours.”

In February 1779, a bold Irish smuggler named Luke Ryan and his crew were captured and jailed in Dublin for smuggling. Ryan and his men escaped with their vessel and sailed to France, where he knew Americans were recruiting privateers. He appealed to Franklin in Paris but was rebuffed. He then found a down-and-out American captain by the name of Stephen Marchant, previously from Boston, who wrote to Franklin proposing that he could command a privateer, although it was really Luke Ryan’s vessel and crew. Franklin granted Marchant a Congressional commission, and the schooner was named Black Prince. Obvi ously Franklin wanted a genuine American connection even if the Irish crew all swore allegiance to America. With Luke Ryan’s knowledge of British waters, Black Prince proceed ed to wreak havoc on British shipping. When Luke Ryan became ill, the vessel was taken over by Patrick Dowlin, the first lieutenant under Ryan, with Marchant remaining as a figurehead. The secondary role played by Marchant was revealed to Franklin, but he was so pleased with Black Prince’s achievements that he did not care. He was disappointed that the officers of the Black Prince, more often than not, ransomed their prisoners to avoid the trouble of holding them, and the British authorities did not accept these ransom notes as worth a pris oner exchange.5

It is unclear when Joseph Myrick joined the crew of the Black Prince, but he was aboard when the cutter wrecked near Beck on the Pas-de-Calais coast in April 1780, the victim of a mistaken chase by a French frigate. Myrick and other members of the Black Prince’s crew made their way to Dunkirk. Apparently meeting with some kind of ill-treatment by John Torris, the Dunkirk merchant who was majority owner of Black Prince, Myrick and his fellows joined the cutter American Union. This small, 44-ton vessel, also referred to as L’Union Americaine in period records, was owned by the Dunkirk merchants Poreau, Mackenzie & Cie., and possessed a French letter of marque valid for one year from January 17, 1780. It was armed with four carriage-mounted cannon and ten swivel guns. Previous ly commanded by a man named D’Egigon, the vessel was placed under the command of Joseph Myrick on May 18, 1780. The American Union sailed from Dunkirk May 30, 1780. About a month later, on June 26, British frigates and a cutter chased the vessel for eight hours until Myrick sought safe harbor in the French port of St. Malo. Once there, however, Myrick discovered that all French merchant ships and privateers had been embargoed by order of Antoine de Sartine, the Secretary of State for the Navy under King Louis XVI, so that their crews could be transferred to the French fleet. In distress, Myrick immediately wrote to Benjamin Franklin in Paris, appealing for help. He reminded Franklin that he had sailed in the Black Prince, commissioned by Franklin himself. Although now sailing under

4 William Bell Clark, Ben Franklin’s Privateers: A Naval Epic of the American Revolution (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1956), 21.

5 Clark, Ben Franklin’s Privateers.

a French commission, he stated that his crew were all American subjects and claimed “yr. Excelency’s protection” and “timely Assistance.”6

Captain Myrick’s written plea was followed up by a personal visit to Franklin in Paris.7 On July 8, 1780, Franklin wrote a letter to Sartine to be delivered in person by Captain Myrick. It laid out the American Union’s situation and noted that the loss of his crew would “be ruinous for Captain Meyric [sic] who is an American and one of the owners of the vessel . . . . I beg your Excellency to be good enough (if the thing is feasible) to favour his humble request and permit him to continue His Cruise.” In justification, Franklin noted that “This captain has already taken five Prizes and as he and his Crew are familiar with sailing on the coast of England, I have no doubt that this Privateer is capable of doing much harm to the Coasting Trade of the common enemy. Captain Meynik [sic] has told me that among all his Crew he has only one Frenchman who has been established for several years in America where he has left a wife and Chil dren.” Sometime in July, after Myrick’s visit to Sartine, American Union was released and set out again privateering.8

On July 29, 1780, the frigate HMS Aurora captured American Union. Its commander, Captain Henry Collins, reported to the Admi ralty that the privateer’s crew of 22, although listed in the ship’s papers as Americans, were believed to be Irish except for three Frenchmen. Collins also incorrectly thought Captain Myrick was Irish. Captain Collins forwarded the testimony of a man taken prisoner from the sloop Betsey, one of Amer ican Union’s prizes. This hostage reported that he had been treated “with every civility his situation required.” Incidentally, Aurora also captured another Dunkirk privateer, May Flower, which ran aground south of Dublin when pursued by the frigate. Its crew escaped inland. The May Flower’s captain was Patrick Dowlin. Obviously, after the wreck of Black Prince, its captain, Patrick Dowlin, and Joseph Myrick outfitted separate vessels to continue privateering out of Dunkirk.9

Myrick was imprisoned with other captive American and French sailors at the Old Mill Prison in Plymouth, England. At various times, the Admiralty allowed American prisoners to gain release if they joined the Royal Navy. Myrick took this route, signing aboard the brand new HMS Anson, a 64-gun ship-of-the-line, on October 7, 1781. The Anson’s paybook

6 Joseph Myrick to Benjamin Franklin, June 27, 1780, in Barbara B. Oberg, ed., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 32:616–17. The original letter is in the collection of the American Philosophical Society.

7 Timothy Kelly to Benjamin Franklin, July 4, 1780, in Oberg, Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 33:26.

8 Benjamin Franklin to Antoine de Sartine, July 8, 1780, in Oberg, Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 33:44.

9 The National Archives of the UK [TNA], ADM 1/1613, Capt. Henry Collins to Sir Phillip Stephens, July 29, 1780.

Henri Rodolphe de Gueydon (1738–1807), Vue de l’intérieure de Mill-Prison de Plymouth et de ses environs en 1798. Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library, Brown Digital Repository no. 240699.

lists Myrick as a volunteer from Dunkirk, with no mention of his American status. It also gives his age as 25, although he was in fact 37. He received five pounds for signing on and was rated an able-bodied seaman. He evidently impressed Captain William Blair, master of the Anson, as Blair promoted Myrick to midshipman on November 1, 1781. On January 9, 1782, however, Myrick was discharged to the naval hospital at Haslar near Portsmouth. After discharge from hospital, Myrick joined HMS Stag, then transferred to HMS Egmont, Captain Edward Thornbrough, on June 28, 1782. Again, he was rated able-bodied seaman, but was again promoted to midshipman on July 28, 1782. Navy records list a final payment to Myrick as a member of Anson’s crew on February 7, 1783, and then that he deserted from Egmont at Portsmouth seven days later.10

HMS Stag, a 32-gun frigate, captured two French privateers in early June 1782 and another a couple of weeks later. If Myrick was aboard Stag during either of these engagements, he would have qualified for prize money. Aboard HMS Egmont, a 74-gun ship-of-the-line, Myrick undoubtedly took part in the Battle of Cape Spartel on October 20, 1782, an indecisive action where a Franco-Spanish fleet tried unsuccessfully to engage with the Brit ish Channel Fleet under Admiral Richard Howe, which had just successfully escorted a vital relief convoy into Gibraltar.

Keith M. Lindgren, M.D., practiced interventional cardiology and was medical director of an openheart surgery program in suburban Washington, D.C. He has been a Nantucket summer resident for fifty years and has a longstanding interest in island history. Dr. Lindgren lives on island in the New Mill Street house that may have been built for Joseph Myrick. Historian Steven Smith provided valuable research assistance for this article in the UK.

Although some Americans switched sides to es cape British prisons, a majority did not. Franklin himself commented on the remarkable loyalty of these patriotic prisoners and worked hard to get them exchanged. We do not know exactly why Myrick elected to join the Royal Navy in exchange for release, but it is clear that he was a professional seaman. He may have chosen this course rather than languish in prison under the threat of hang ing for treason. He also came from Nantucket, where ambivalence toward the war pre vailed. In any event, American ground forces defeated the British at Yorktown in October 1781, just after Myrick joined the Anson. By the end of January 1783, provisional peace treaties were in place among the war’s combatants, and hostilities ended, paving the way for Myrick to return home.

Myrick was back in Nantucket by mid 1783 because he and his wife Abigail welcomed an other child in April 1784. Myrick died of unknown causes in the Falkland Islands in 1791. The Falkland Islands, a whaling ground, was also a hunting location for seal pelts used in American trade with China. Joseph Myrick may have had an accidental death, which would be ironic after the dangers he had faced as a privateer. His life is a telling chapter of Nantucket history at a time in the American Revolution that left Nantucket with little else than hardship.

10 TNA, ADM 34/53 and ADM 34/70, pay lists for HMS Anson; ADM 34/293, crew list for HMS Egmont.

This summer has been active and exciting on the collections front at the NHA, with an unusual number of important items appearing at auction and being offered for donation. The NHA wishes to thank the many private donors who have given items, as well as the financial supporters who have provided funds to allow the association to acquire objects that appear for sale. The Friends of the NHA and individual members of the Friends have been particularly generous, along with the Tupancy-Harris Foundation and the H.L. Brown Jr. Family Founda tion. The NHA also especially wishes to thank Mary Longacre of Nantucket for her close attention to island-related listings on eBay; the pewter plate discussed below is just one of a number of items the NHA has been fortunate to ac quire thanks to her suggestions. On the following pages we explore the history of a few highlights from this busy year.

Gift

This painting depicts the Nantucket Golf Club, the first golf links on island, which was set up in 1897 by Sidney Chase, Harold Williams, and David Nevins near Washing Pond on the North Shore. The artist, William Wallace Scott of New York, was an island summer resident; he painted this scene when about 81 years of age. The golf club’s Saturday tournaments were strongly attended by both men and women, as reflected in the painting. The scene also shows the sheep employed to keep the grass trimmed and the club house, which featured a roof walk and expansive covered porches supported by rough-cut pine-tree trunks. A portion of the course was later owned and operated by Oswald Tupancy and today forms the Tupancy Links, a property of the Nantucket Conservation Foundation.

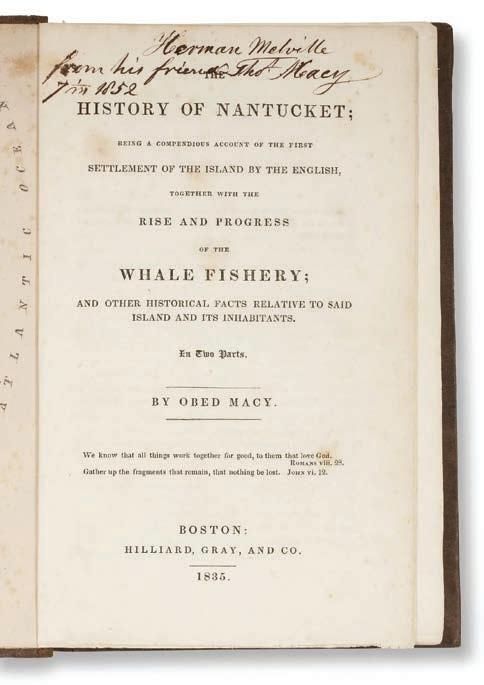

Herman Melville’s copy of Obed Macy’s History of Nantucket Gift of the Friends of the NHA, RL2022.32.

This book is believed to be the sole surviving souvenir from Her man Melville’s first and only trip to Nantucket. It is a first-edition of Obed Macy’s 1835 History of Nantucket, given by Obed’s son Thom as to Melville. The title-page inscription reads, “Herman Melville / from his friend Tho. A Macy 7 1852”. Characteristically, it uses the Quaker convention for writing the date, “7 ”, which was Macy’s quick way of writing “7 ” meaning “seventh mo[nth]” or July. Scattered pencil markings throughout the book are probably by Melville.

Herman Melville visited Nantucket just once, eight months after the U.S. publication of his novel Moby-Dick. He accompanied his father-in-law, Massachusetts Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw, who had court business on island. “I wish [Herman] to see some of the gents at New Bedford & Nantucket connected with whaling,” Shaw wrote beforehand.

Judge Shaw knew Thomas Macy from previous island visits. Signifi cantly, in 1851, Shaw had acquired a copy of Owen Chase’s Narra tive of the Essex disaster from Macy to give to Melville while Melville was writing Moby-Dick. The Essex story was essential inspiration for the novel, and Melville appears to have worked from various sec ond-hand accounts prior to obtaining Chase’s book. Naturally, Mel ville and Shaw called on Macy during their visit, and the gift of this book resulted.

NHApurchase,underwrittenbytheH.L.BrownJrFamily Foundation,RL2022.25.

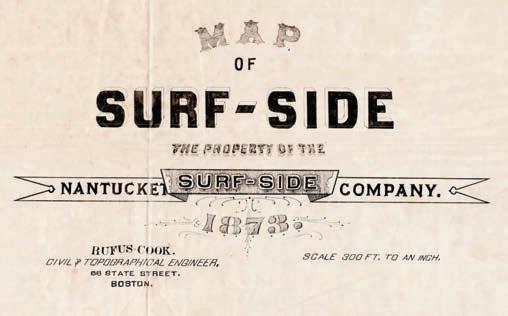

Thetitleblockshownatrightisfromtheoriginalink-on-linen drawingfortheSurf-sidesubdivision,aspeculativereal-estate developmentlaidoutin1873.ThedrawingispartofasetofimportantSurfside,’Sconset,andMadaketplatsacquiredbythe NHAthisyearthankstogenerousprivateunderwriting.Surfsidewasoneofanumberofunsuccessfulreal-estateschemes launchedinthe1870sthataimedtoprofitfromthesaleofcot tagelotstosummervisitors.AcartelofNantucket,Boston,and New York investors hired Rufus Cook of Boston to design Surf-side. Beautiful on paper, Cook’s plan was never realized on the ground. Containing 480 lots, it attracted no construction and was replaced in 1881 by a simpler grid plan that allowed for more than 12,000 tiny building lots and accommodated the right-of-way of the new Nantucket Railroad—itself a scheme by many of the same investors to encourage development on the South Shore.

Pewter plate of Priscilla and Caleb Bunker

NHA purchase, 2022.19.1.

Nantucket in the first quarter of the eighteenth century had a small English population, resulting in a great deal of intermarriage between the English families. This pewter plate demonstrates the interconnectedness of those families. Priscilla Bunker (1703–1795) was first married in 1721 to Joshua Coffin (1701–1722); he was her second cousin on her mother’s side. Joshua was lost at sea later that year along with his brother Elisha Coffin. Priscilla remarried in 1725, this time to Caleb Bunker, who was her first cousin on her father’s side as well as her second cousin on her mother’s side. Her first husband and her second husband were also first cousins of each other.

The initials “P B” stamped on the rim of the plate suggest that Priscil la owned the plate at the time of her first marriage. The initials “C B P” stamped on the opposite side of the rim probably commemorate her second union. The date 1671 is scratched into the bottom of the plate; it may indicate when was made or perhaps when it was purchased by one of Priscilla’s grandparents.

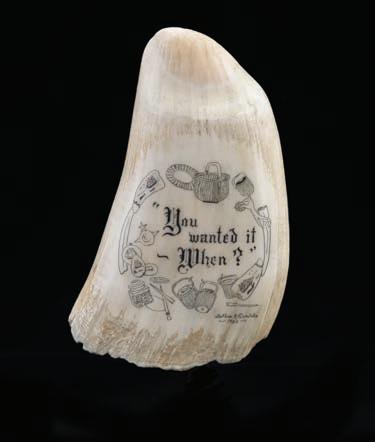

Scrimshaw tooth from Nancy Chase’s shop NHA purchase, 2022.33.1.

Nancy Chase (1931–2016) was well known on Nantucket for her skilled ivory carving and scrimshaw engraving. In the 1960s she worked for basket maker José Reyes making decorative elements for the lids of Friendship baskets before opening her own shop on Cobble Court. In 1980, her friend Dr. Lothar R. Candels (1925–2015) engraved this tooth as a gift for her. On one side is her portrait, and on the other is the exclamation “You wanted it—When?” surrounded by tiny images of lightship baskets and scrimshaw. The museum ac quired the tooth from Chase’s longtime assistant Tracy Murray.

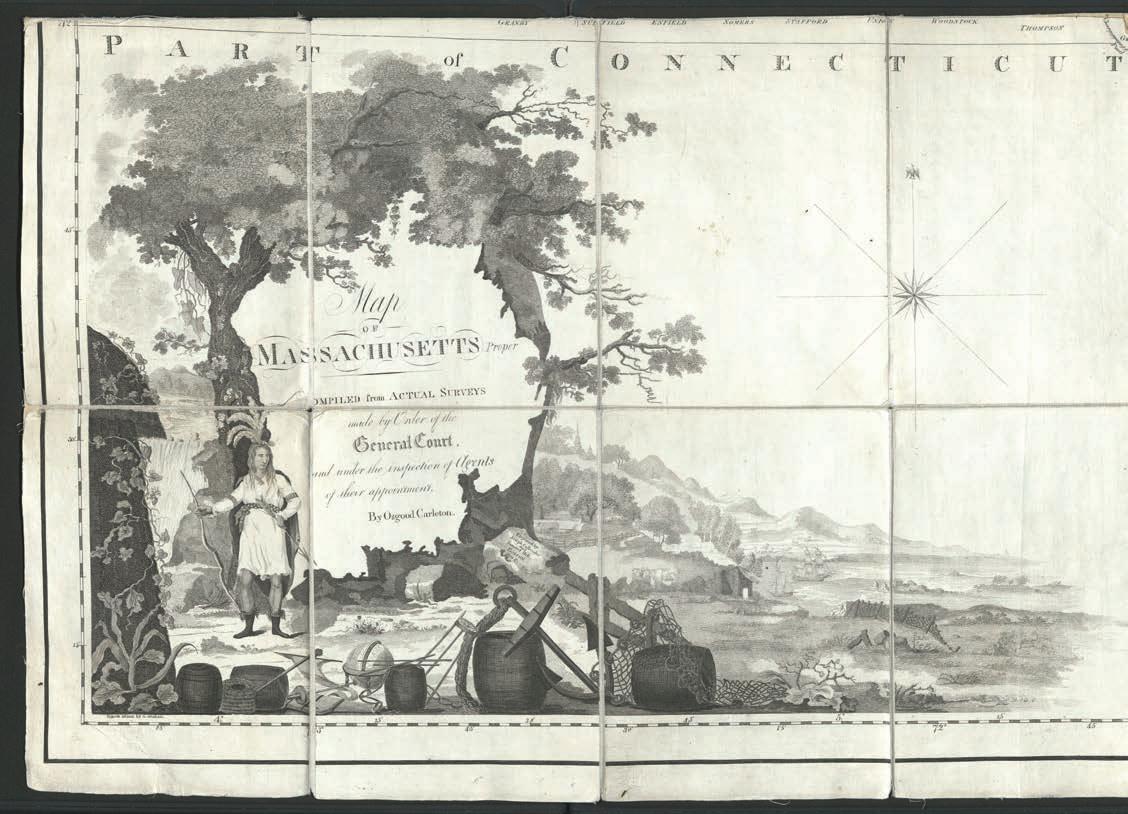

OsgoodCarleton,MapofMassachusettsProper,dated1801 NHApurchase,underwrittenbytheH.L.BrownJr.FamilyFoundationandtheFranciNeelyFoundation. RL2022.29. This is the first official map of Massachusetts, completed by Osgood Carleton, a Boston-based mapmaker and surveyor. Due to limitedstateandfederalfundingforsuchaproject,theMassachusettslegislaturerequiredeachtowntocompleteitsownsurvey, atitsownexpense,whichwasthenbecompiledtoformthefinalmap.Thecomplexprojectexperiencedanumberofsetbacks,and thefirsteditionofthemap,400copiesprintedin1798,wasrejectedbythestatelegislature.Thesecondedition,ofwhich500copies wereprintedin1801–1802,removesanumberoftopographicalelements,foracleanerlook,andfeaturestheelaboratecartouche depictedhere.

Take a decorative arts class inspired by Nantucket history! Get creative and enjoy a hands-on experience at one of the NHA’s historic properties.

Looking for a unique experience to do with your family and friends? Book a private workshop by emailing decoarts@nha.org

NHA Decorative Arts are generously supported by

As part of a new generation of full-time Nantucket lightship basket makers, Caitlin Parsons is young, energetic, and brimming with cre ative ideas to enhance the iconic Nantucket lightship basket genre, not losing sight of its antique origins dating back to the mid-1800s.

Caitlin is not new to the Nantucket lightship basket world. She was raised in the environment of the basket world since her dad, Tim Parsons, has spent decades as a prominent basket maker on island. Caitlin remembers playing with the shavings in his workshop as a child and making her first basket when she was eight.

Growing up on island, Caitlin felt restless and compelled to get away from Nantucket to see the world. Her mantra was to work at things that made other people’s worlds better, and she did that by spending time in Australia, New Zealand, and Africa working with various not-for-profit organizations.

Once back in Boston, Caitlin broke her ankle. While recovering, her father brought her materials for weaving, so she experimented with different weaving materials and wood, which then reignited and energized her interest.

She returned to Nantucket with her husband, who fell in love with the island. They decided to stay on Nantucket year-round, first getting a puppy and then having two children, now four and two. They built a home and reconnected with friends.

She has now committed to being a full-time Nantucket basket maker, wanting to create from scratch, making the entire basket from top to bottom, including parts like handles and bases. She also has learned how to make repairs: for baskets to endure, they need maintenance. In running her own basket-mak ing business, her goal is to have a balance of creativity and profitability.

For her, a handcrafted one-of-a-kind Nantucket lightship basket or bracelet is a great reminder that you can’t duplicate a basket and that one has to accept its flaws. In fact, the flaws are an intrinsic part of this art form, brimming with history and open to being modern and fresh in today’s world. It is exciting to see Caitlin Parsons, as part of the current generation, keeping alive this craft that resonates with Nantucket's history.

Charles Potter, a research associate from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, visited Nantucket this past Saturday to gather tissue samples from one of the NHA’s two whale skeletons. In addition to the sperm-whale skeleton at the Whaling Museum, the NHA holds the complete skeleton of a finback whale that died on Dionis Beach in 1967. It has been displayed at Nantucket High School since 2004.

When this whale was first collected, there was uncertainty wheth er it was a true finback or a more rare hybrid species. Potter’s sam pling will allow for DNA and molecular analysis to determine exactly what species the whale is, and perhaps tell us the environmental and health conditions that preceded its death.

Accompanied by NHA curator Michael Harrison and collections manager Meghan Luksic, Potter met with Nantucket Public Schools superintendent Beth Hallett and members of the high school science staff. He then took bone sam ples from two places on the skeleton. The NHA also made available some baleen for him to sample. The NHA and the high school will receive copies of the analyses and of any research papers that come out of this field work.

The NHA is pleased to be able to contribute to a better understanding of North Atlantic whale species thought Potter’s and his colleagues’ research.

Digitization of these collections was made possible thanks to the support of Connie and Tom Cigarran.

The team at the Research Library has recently digitized two collections of Nantucket family papers: the Joy family and the Gardner family.

The Joy Family Papers (MS7), while chiefly containing financial papers from Moses Joy and Moses Joy Jr., is best known for the scrapbook as sembled by Charlotte Austin Joy (1817–1892) following the death of her husband, and fellow abolitionist, David Joy (1801–1875). In addition to newspaper clippings about Joy’s life, the scrapbook contains letters of condolence from friends, including William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and Frederick Douglass.

The Gardner Family Papers (MS87) as seen on the left, contains corre spondence, deeds and other land records, poems, financial and legal pa pers, and other items. Notable materials include the papers of educator and activist Anna Gardner (1816–1901); the papers of Charlotte Coffin Gardner (1820–1882), Elizabeth Chase Gardner (1766–1840), and Susan Gardner Gardner (1789–1879), documenting voyages on the Sarah Parker and other ships taken with their whaling captain husbands, economic dif ficulties faced as widows, and other family matters; and those of Gideon Gardner (1759–1832), documenting difficulties encountered by islanders during the War of 1812.

Digitized materials are available to researchers online through the NHA’s collections catalog nantuckethistory.org.

This fall, the NHA maintenance team, and various island contractors have been busy with continued work at our Historic Properties and facilities as part of the $2 million investment project made possible through grant funding and the support of NHA donors.

Fall projects have included:

• A new roof by James Lydon, Sons & Daughters, and completed painting projects by Carlos A. Portillo at the Gosnold Collections Center.

• Replacement of soft or rotted shingles, gutter, and roof trim repair, as well as fabrication of corner boards to match the original woodwork by Joe Bedell of Native Restoration and exterior painting by Dean Miller at the Thomas Macy House

• Removal of overgrown moss and treatment for fungus prevention by Johnathan Miles at the Oldest House

• Two of the 2,000-pound millstones were relocated by Neil Paterson and his team to prevent walking hazards and stabilize the mill tail pole for the off-season at the Old Mill.

• Reworking and replacement of the cobblestone driveway by NHA Maintenance Assistant, Bill Mogensen at the Fire Hose Cart House.

Stay tuned for more project updates to come!

Laura comes to the NHA from San Francisco with over thirty years of development experience, including time at the White House Historical Association, Villanova University, University of Southern California, Stanford Medicine, UC Berkeley, and Boston University. She graduated from Clemson University with a Bachelor of Arts in English and a minor in Business Communications.

This December, we are partnering with the National Park Service (NPS) and the Rome-based International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property to host a symposium at the Whaling Museum to explore the latest climate change research and develop strategies for advancing climate conserva tion and protection. The symposium will include a com munity forum on December 8, from 9 am–5 pm, which will be open to the public and free of charge, as well as live-streamed on the NHA’s YouTube Channel.

To register to attend the public forum in person or watch via the live stream, visit NHA.org

The symposium is generously supported by The Osceola Foundation, Inc. (Walter Beinecke, Jr. family)

The ReMain Nantucket Fund managed by the Community Foundation for Nantucket

Michelle Kolb, Kolb Architects

NHA on the Road relaunched this October to continue deepening the NHA’s commitment to the Nantucket community, taking signature NHA programs “on the road” to different Nantucket elder services groups and residences, including the Salt Marsh Senior Center, the Homestead, Sherburne Commons, the Landmark House, and Our Island Home. This season, in addition to telling the Whaling Museum’s spirited story-telling, including Life Aboard a Whale Ship, attendees will en gage with artifacts from the collection for a hands-on experience to learn about topics like Wampanoag his tory and Souvenirs. NHA on the Road will also include Decorative Arts demonstrations to teach historic crafts. Through this program, the NHA looks forward to open ing up access to our history and connecting with this segment of the island community.

Generously funded by The Community Foundation of Nantucket

This past October, we hosted a program in celebration of the 125th anniversary since the NHA purchased the Old Mill in 1897. Nearly 500 islanders came out on a beautiful fall day to learn about one of Nantucket’s most iconic historic landmarks and the his tory of harvest season on the island. Attendees learned about the operation of the mill from NHA millers and were able to chat with curatorial staff at an artifact table with Old Mill-related objects from the NHA collection. There was a range of activity stations, including herb sachet making, beaded corn cob crafting, and hoop rolling. Further more, members of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe participated in the program, sharing several native traditions and crafts celebrating harvest, such as corn husk doll making, quahog shell wampum necklaces, and percussion music.