A JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY MARITIME STUDIES

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History

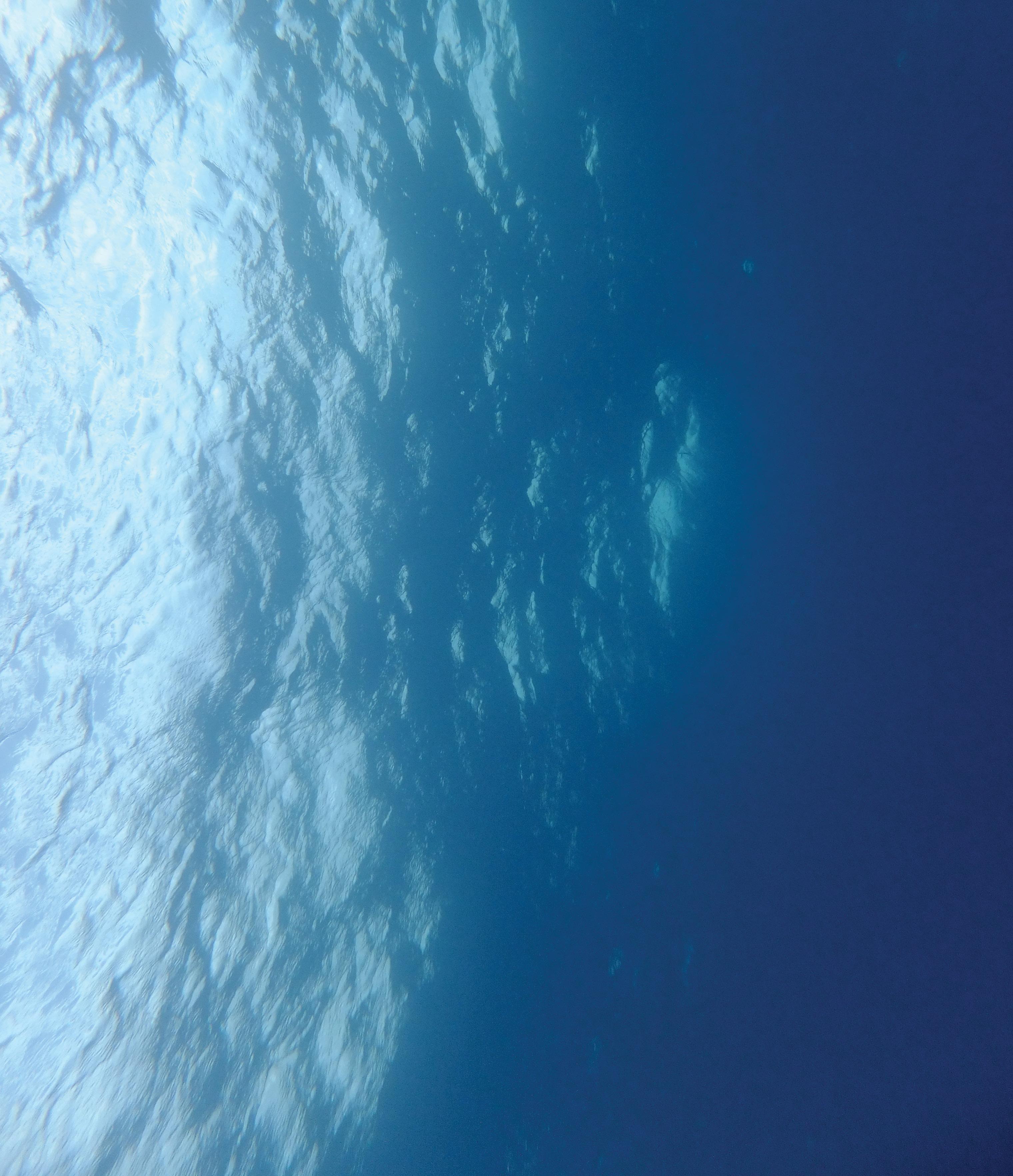

Front cover

Title: Keep reaching your dreams how high it may seem

Photographer: Vhernard Manalad Hernandez

Location: At sea near Las Palmas Spain

Photographer’s description: “In this photo our cargo hold has stain on the very top of the cargo hold frame, as an AB present that time I will be the one who is responsible for reaching and painting it to cover the stains for our cargo hold to soon pass the inspection, with a three fold ladder, light rolling and pitching as the vessel is underway, I set aside my fear and finish the work, just like my dream to become a master of the vessel in the future, I will still bring this courage and determination with me every time to reach my dreams how high it may seem.”

This issue’s covers feature photographs taken by seafarers for the ITF Seafarers’ Trust annual photography competition. The photographers’ descriptions have been lightly edited.

From the Editor in Chief

Christina Connett Brophy

PEER-REVIEWED

Liquid Motion: Reimaging Maritime History through an African Lens

Kevin Dawson

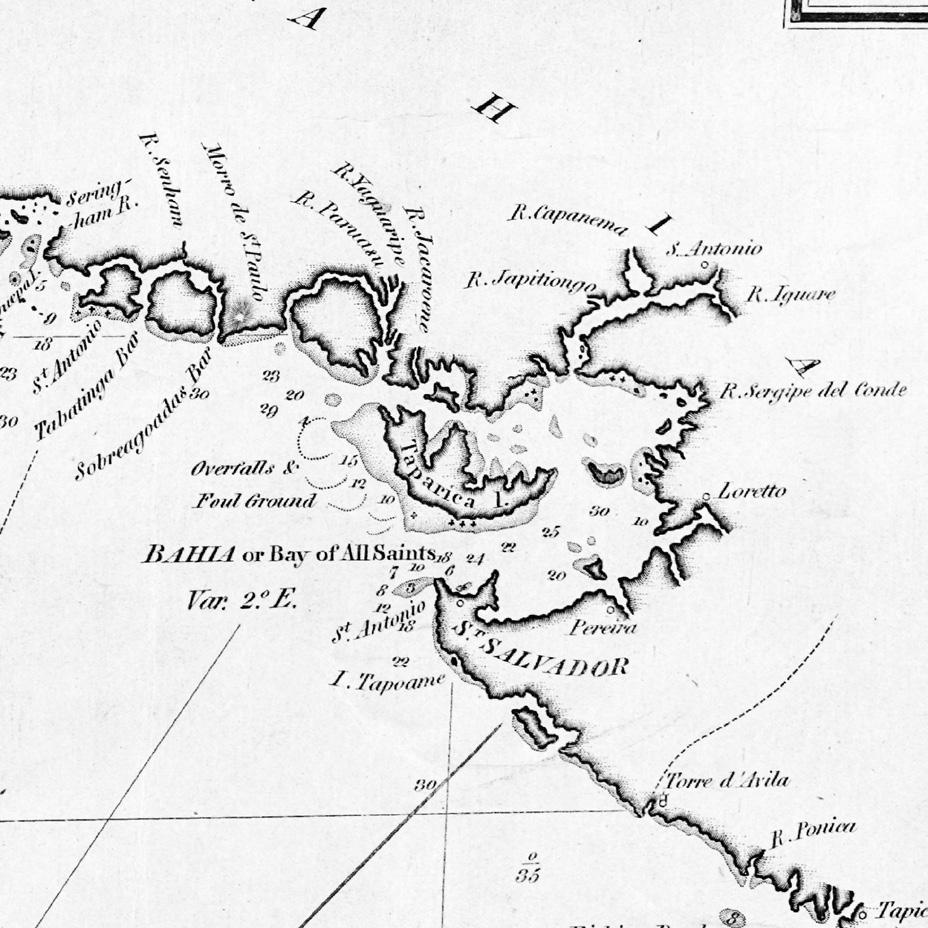

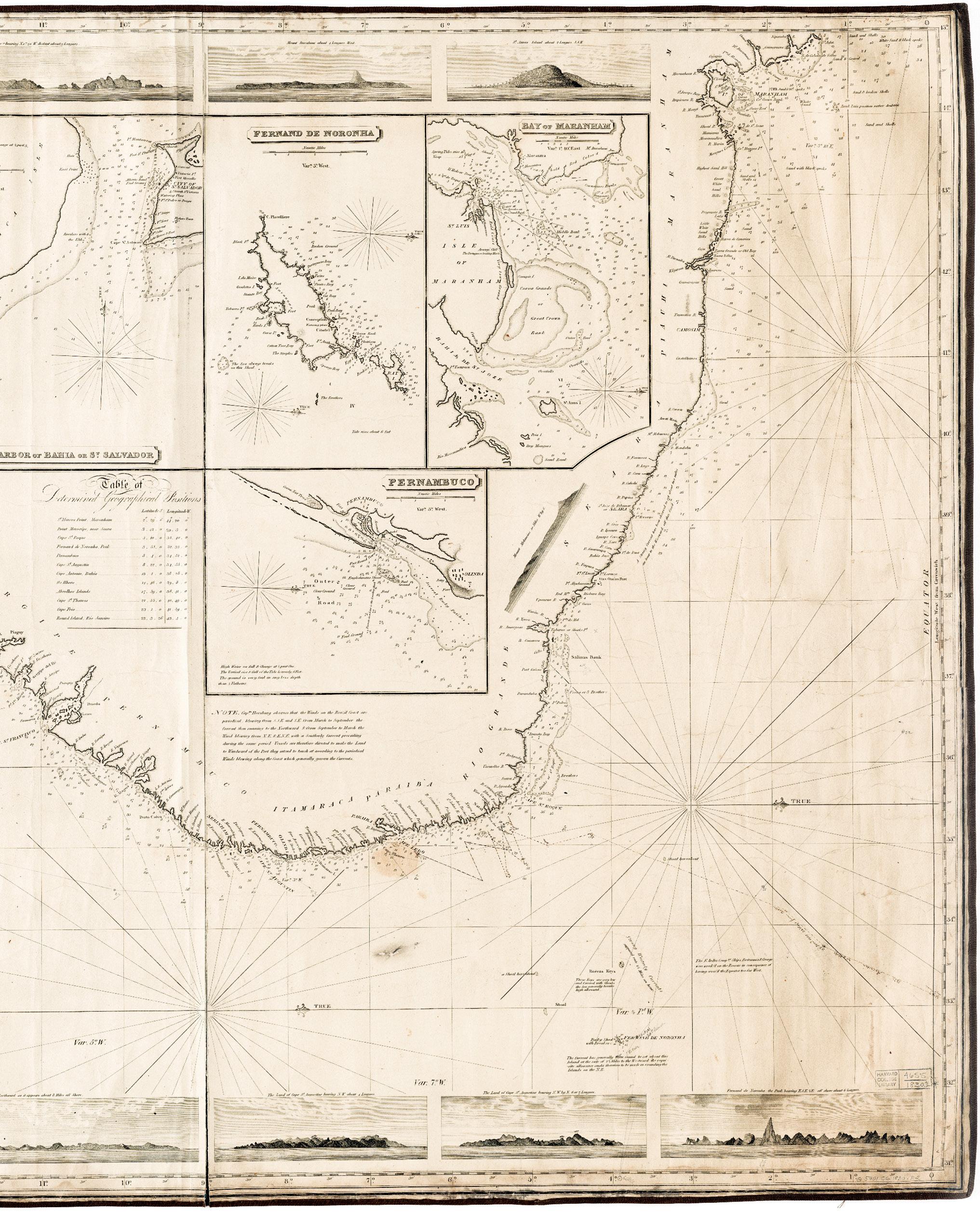

Our Lady of the Workboats: Solidarity and Spirituality on the Bay of All Saints

Alison Glassie

Dragon Ships to the Dawnland: Eugène

Alice C. M.

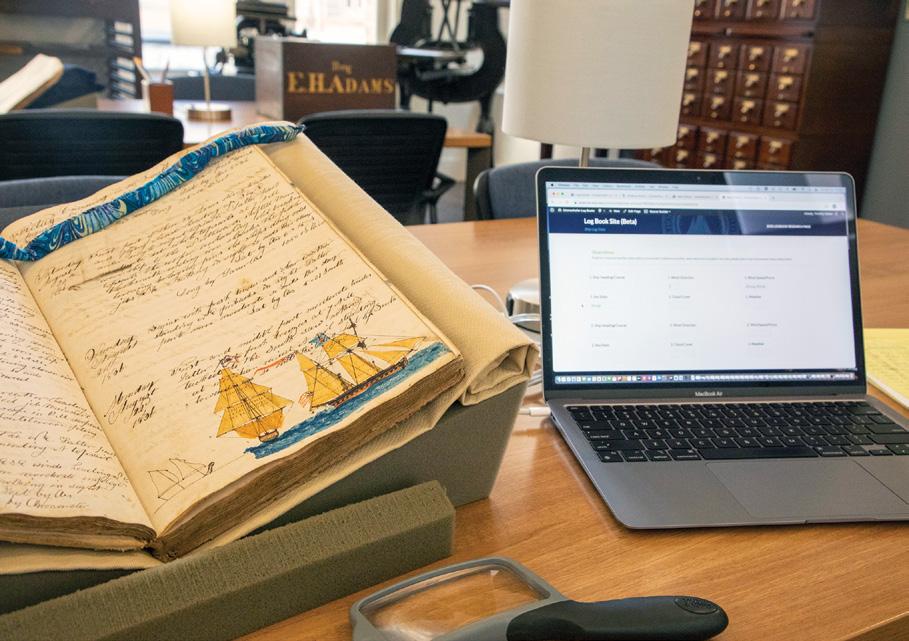

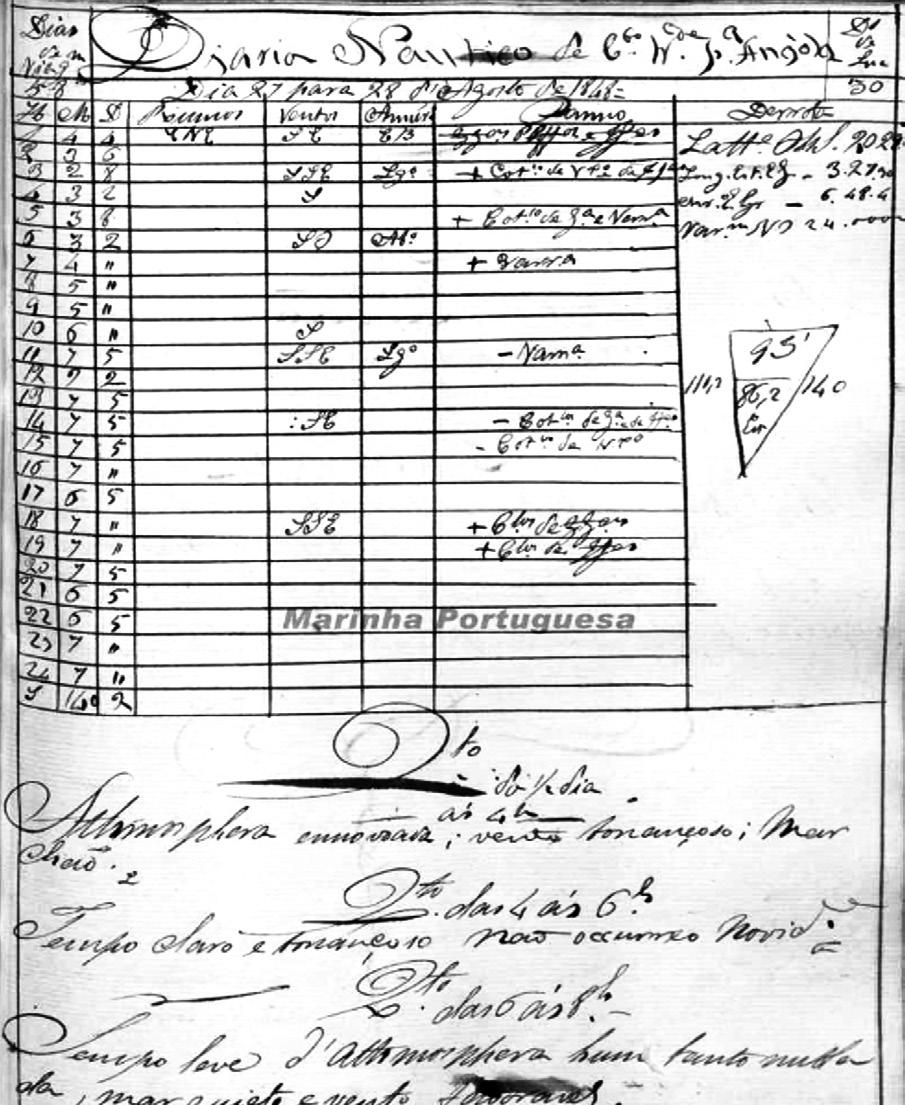

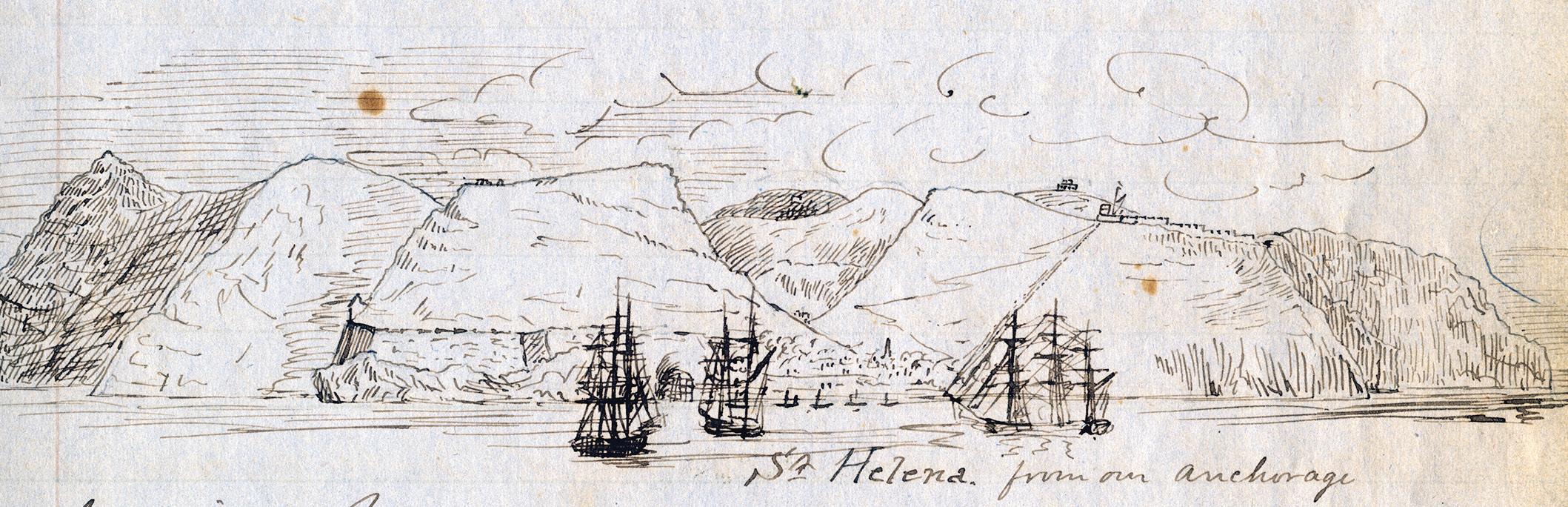

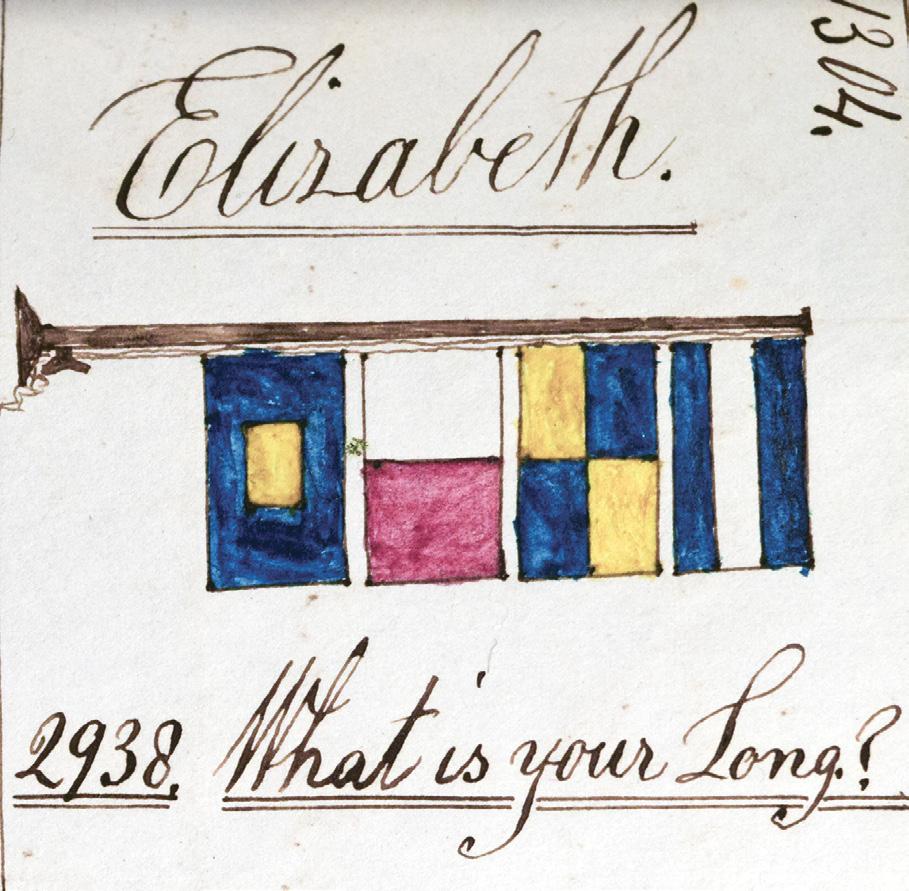

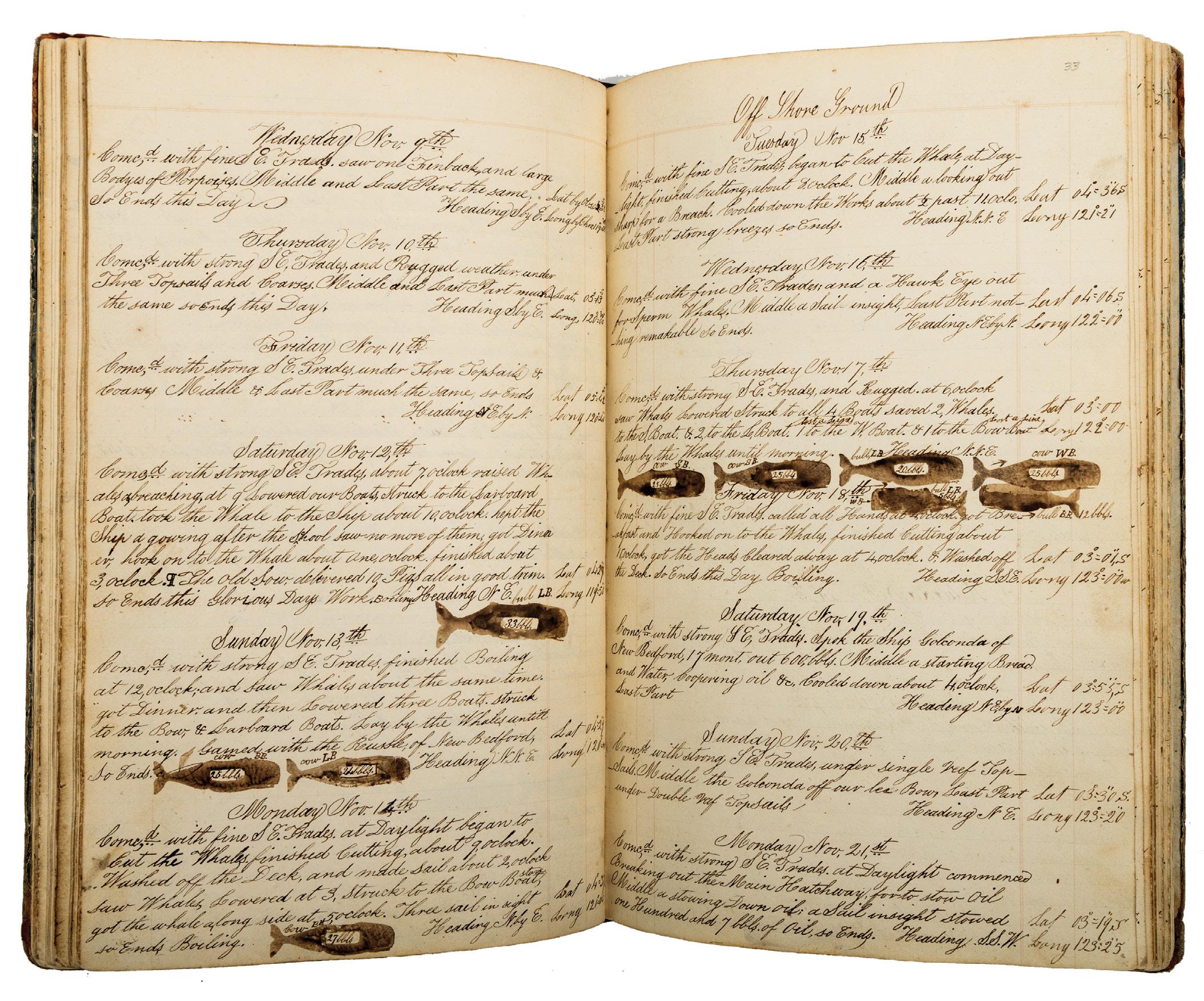

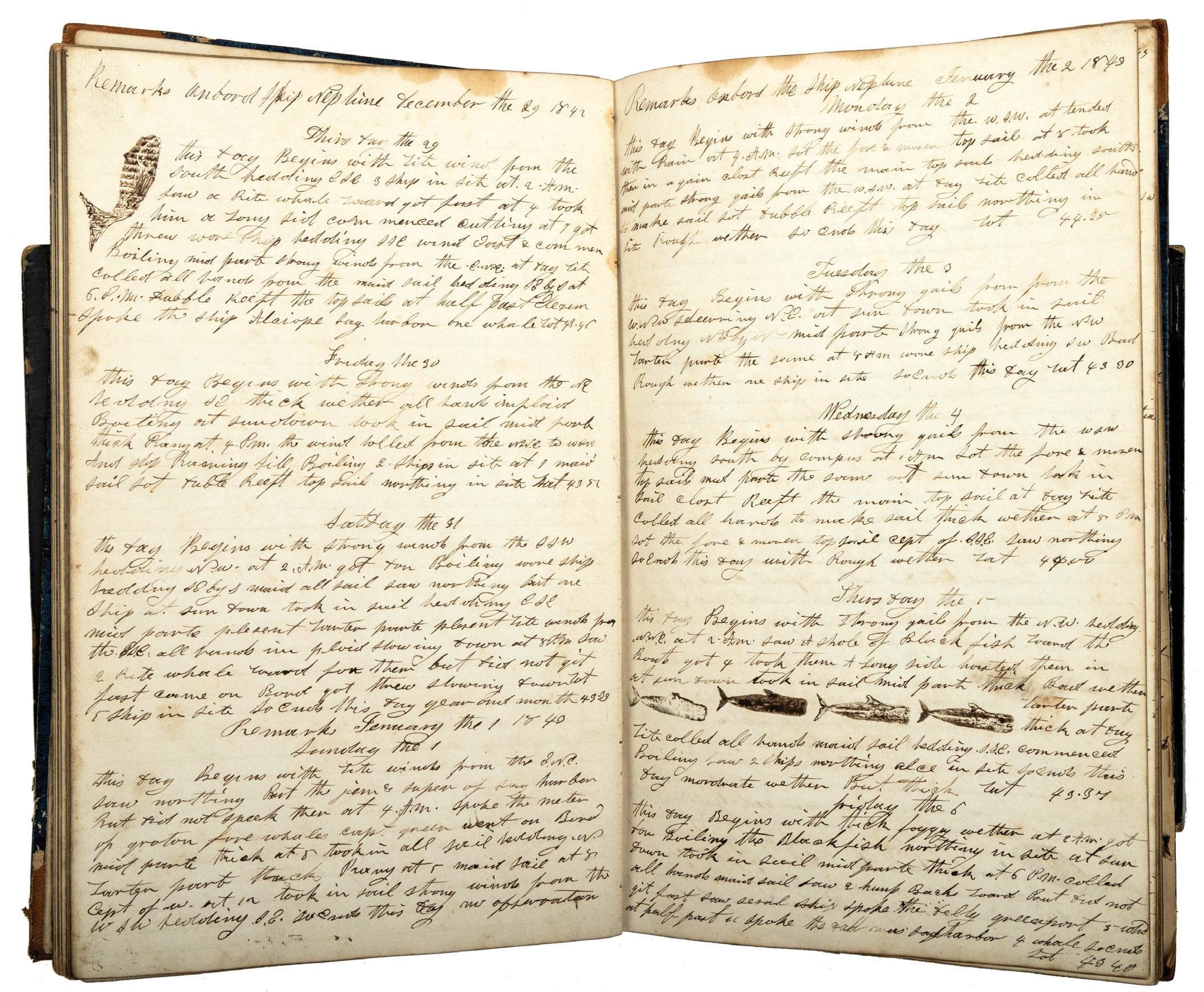

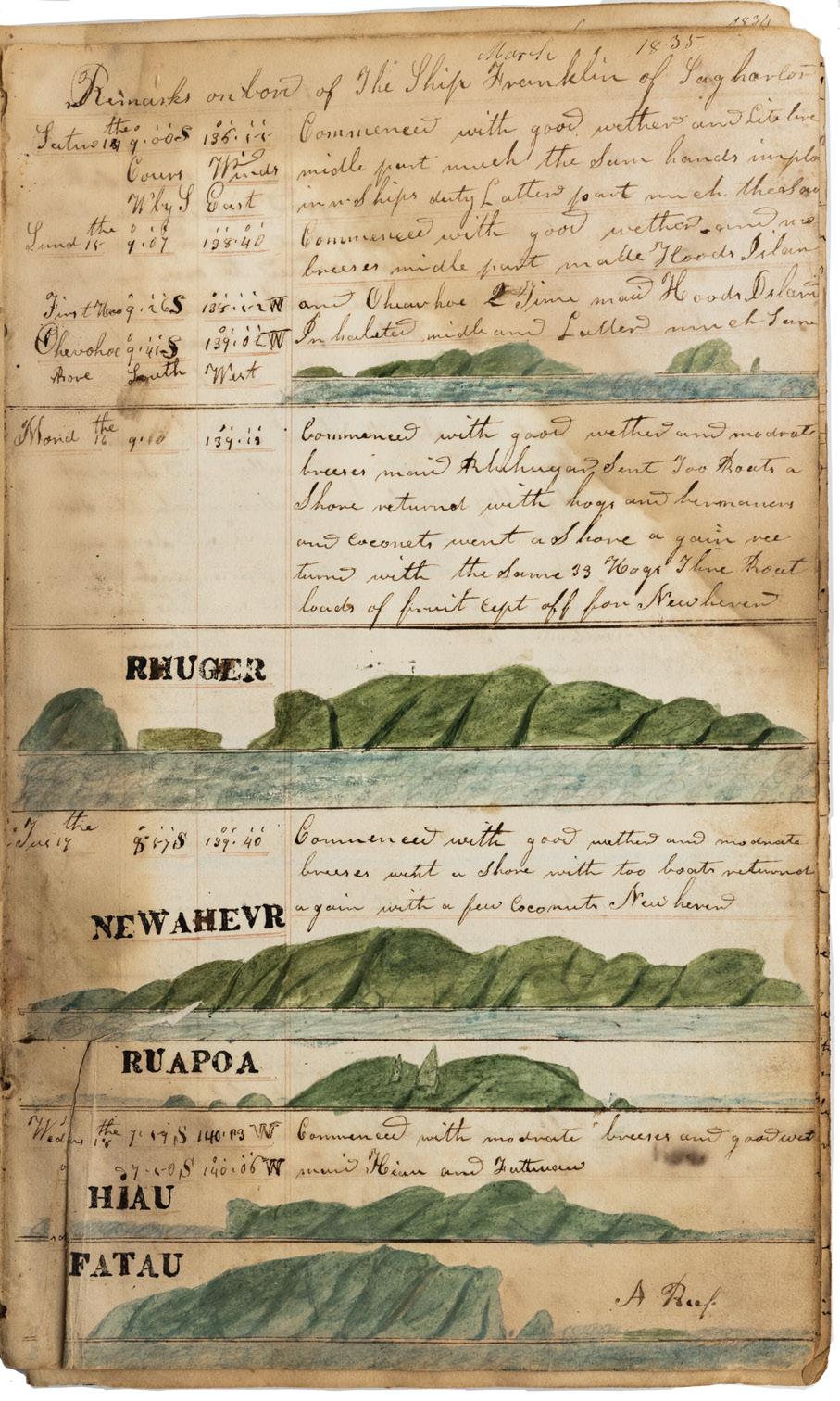

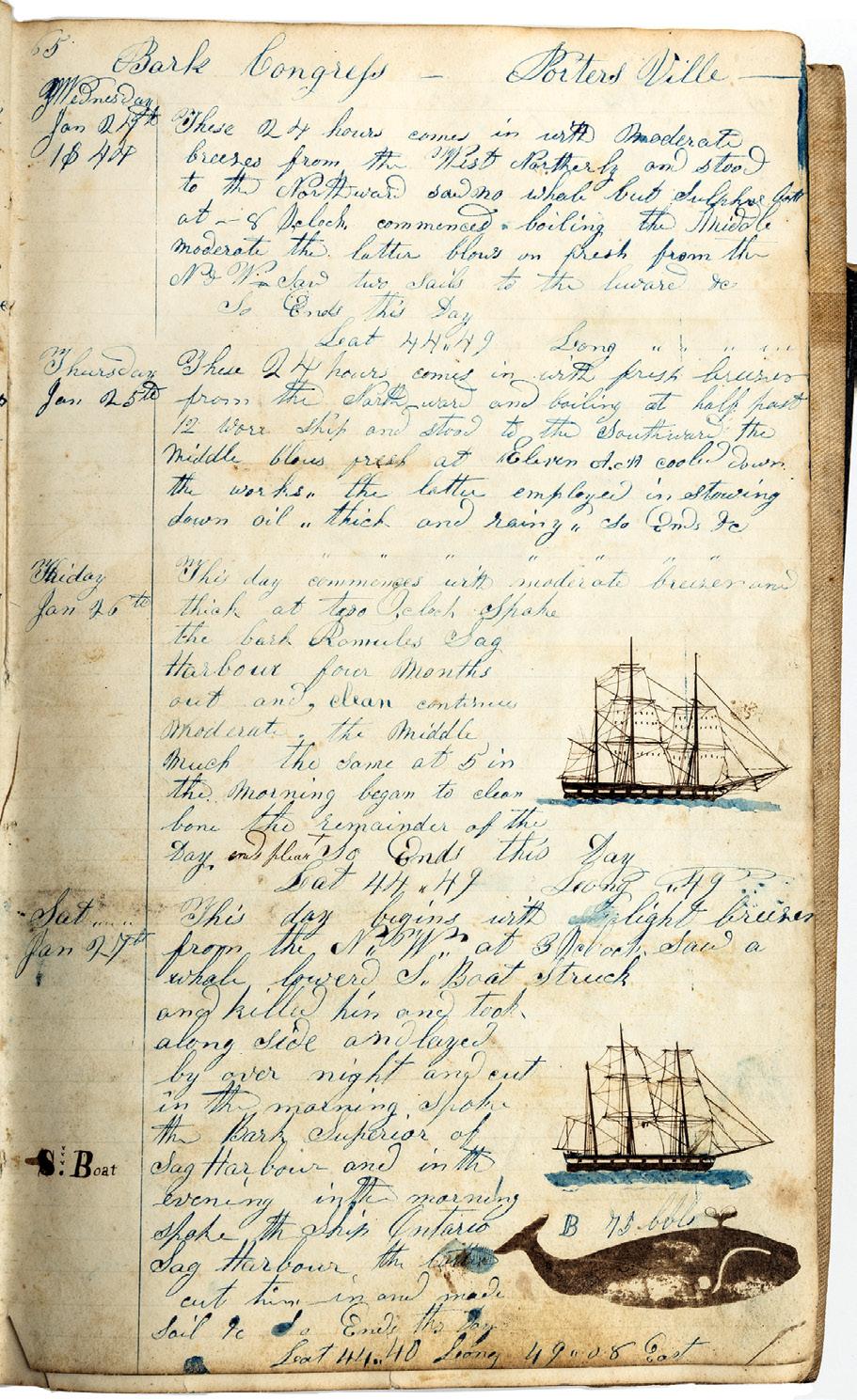

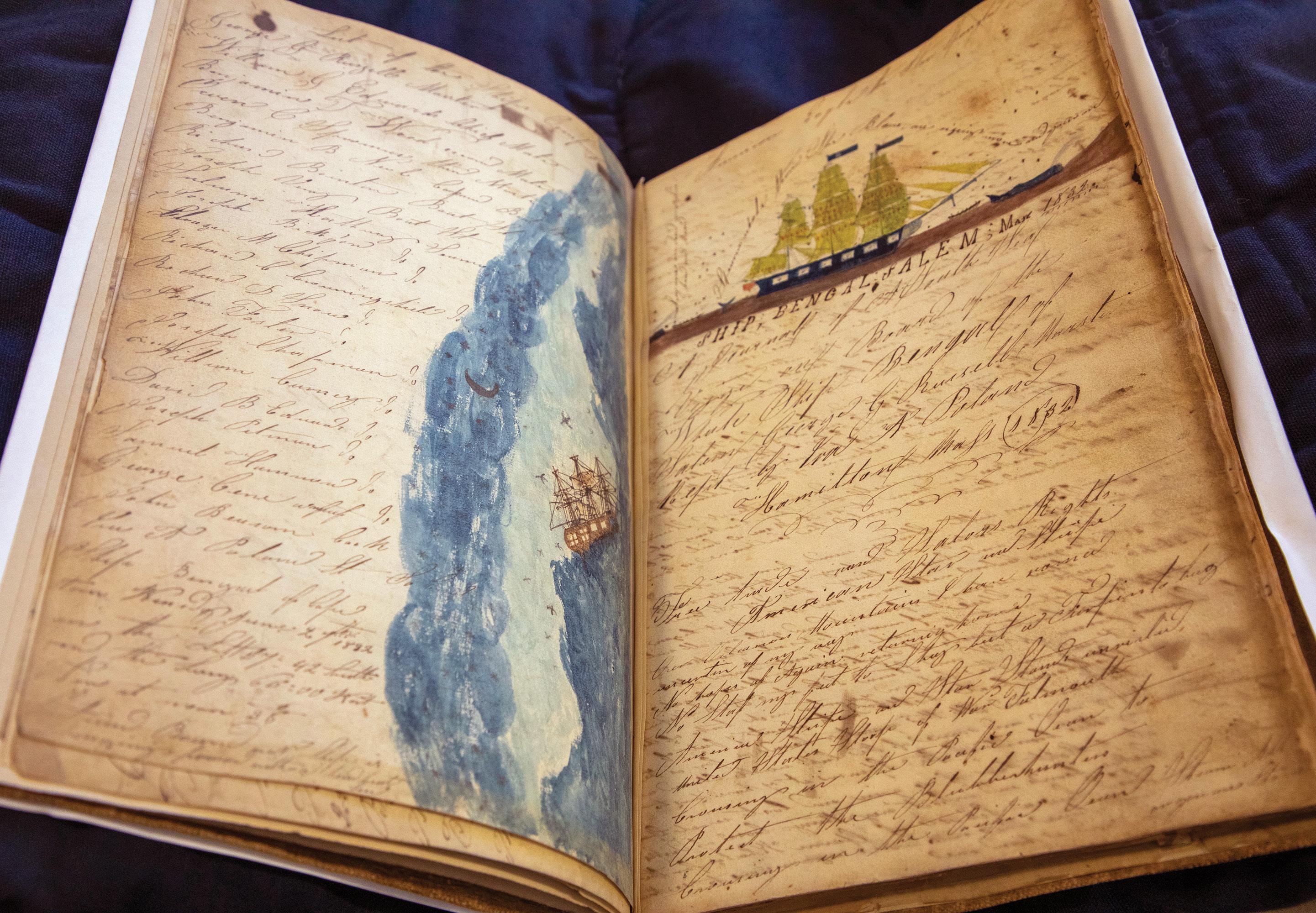

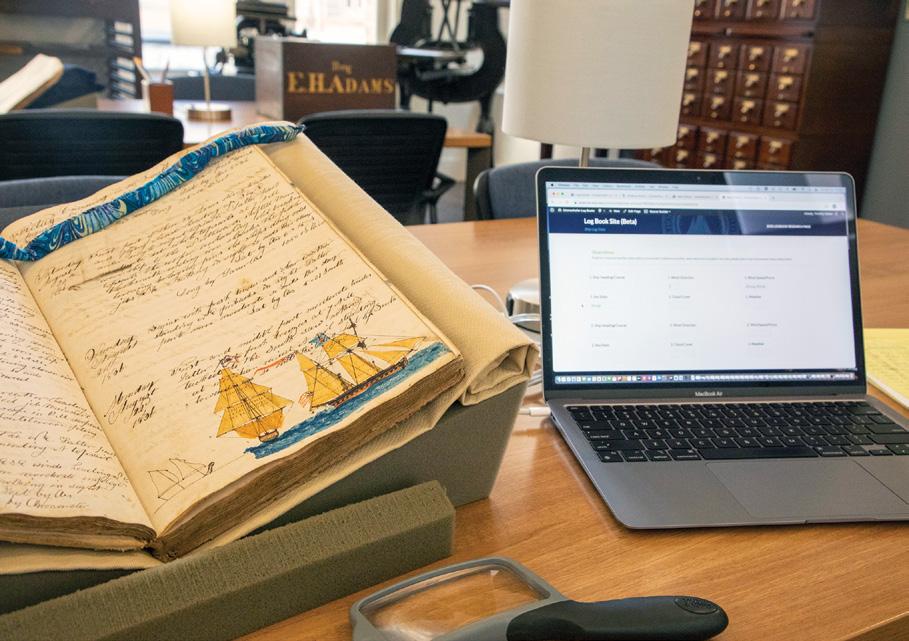

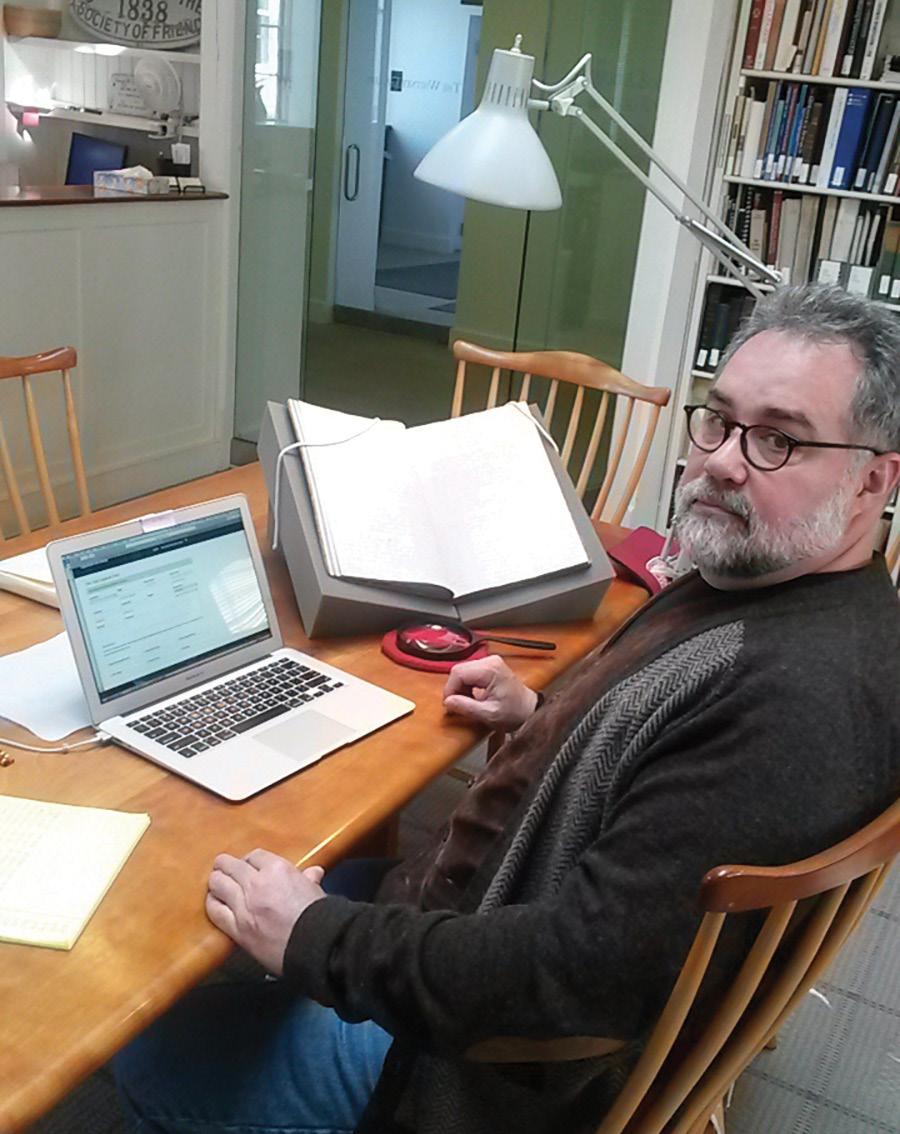

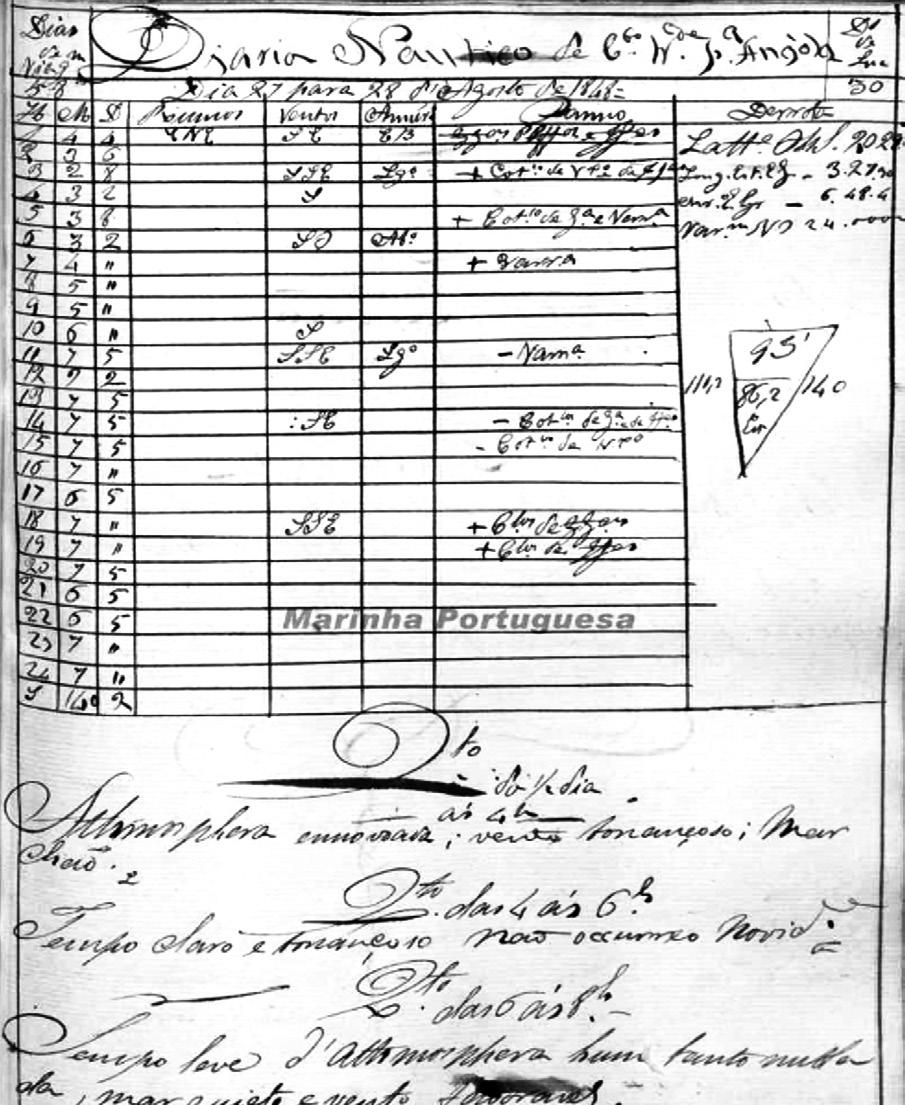

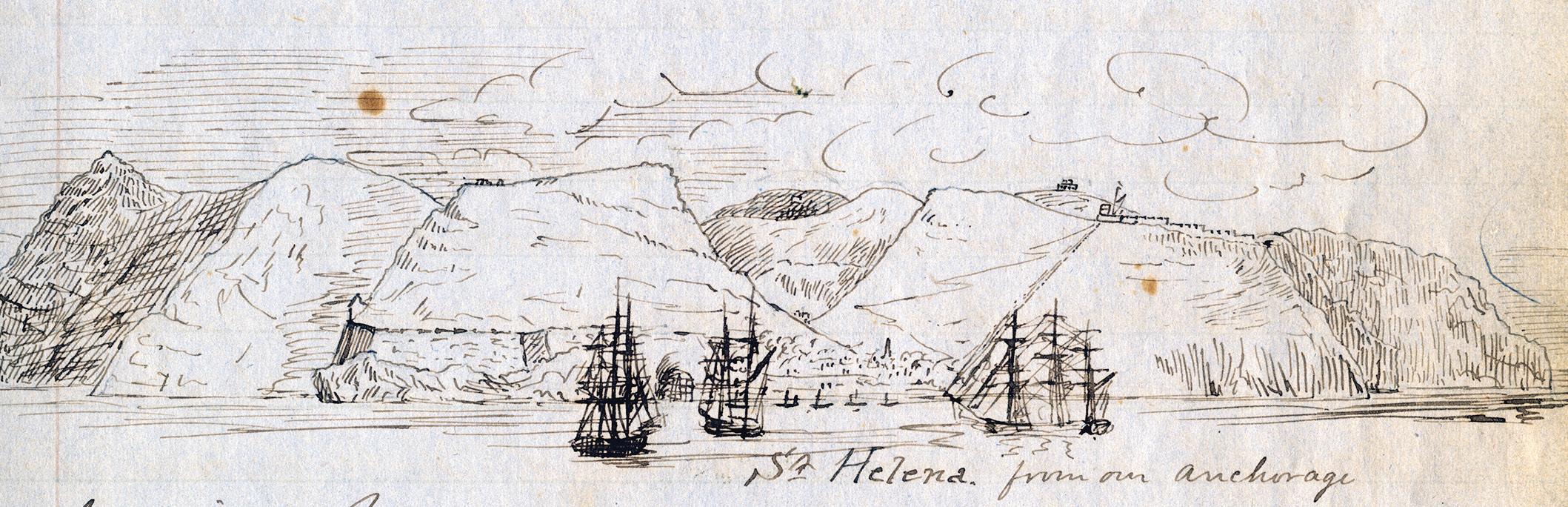

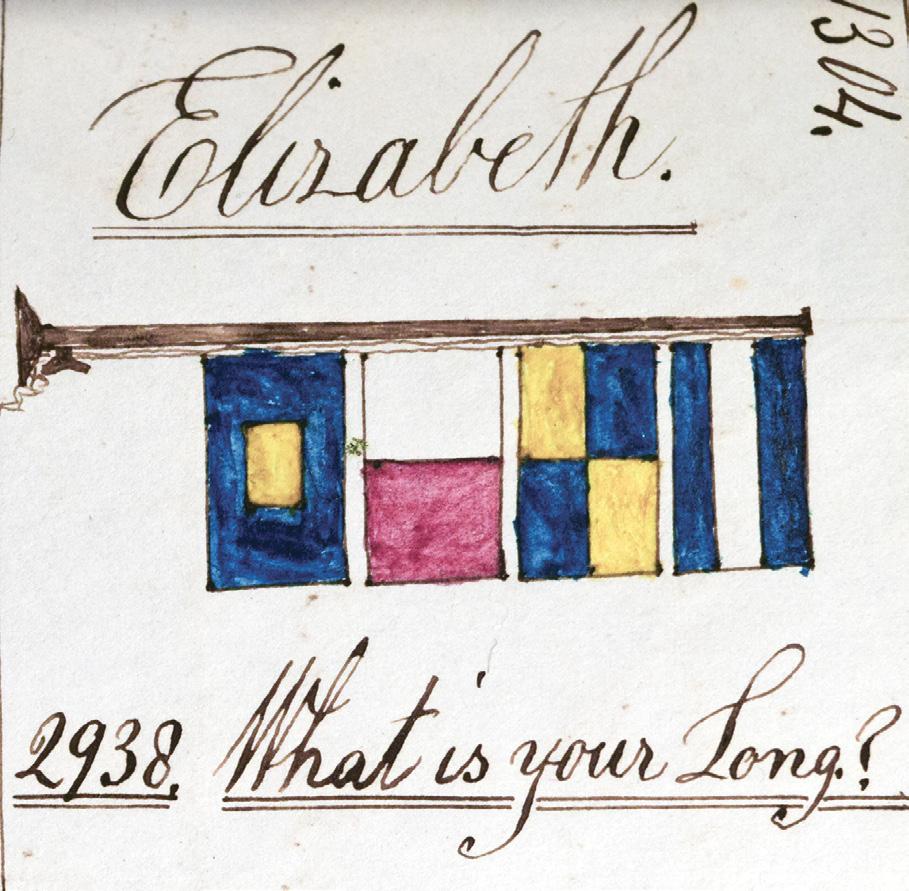

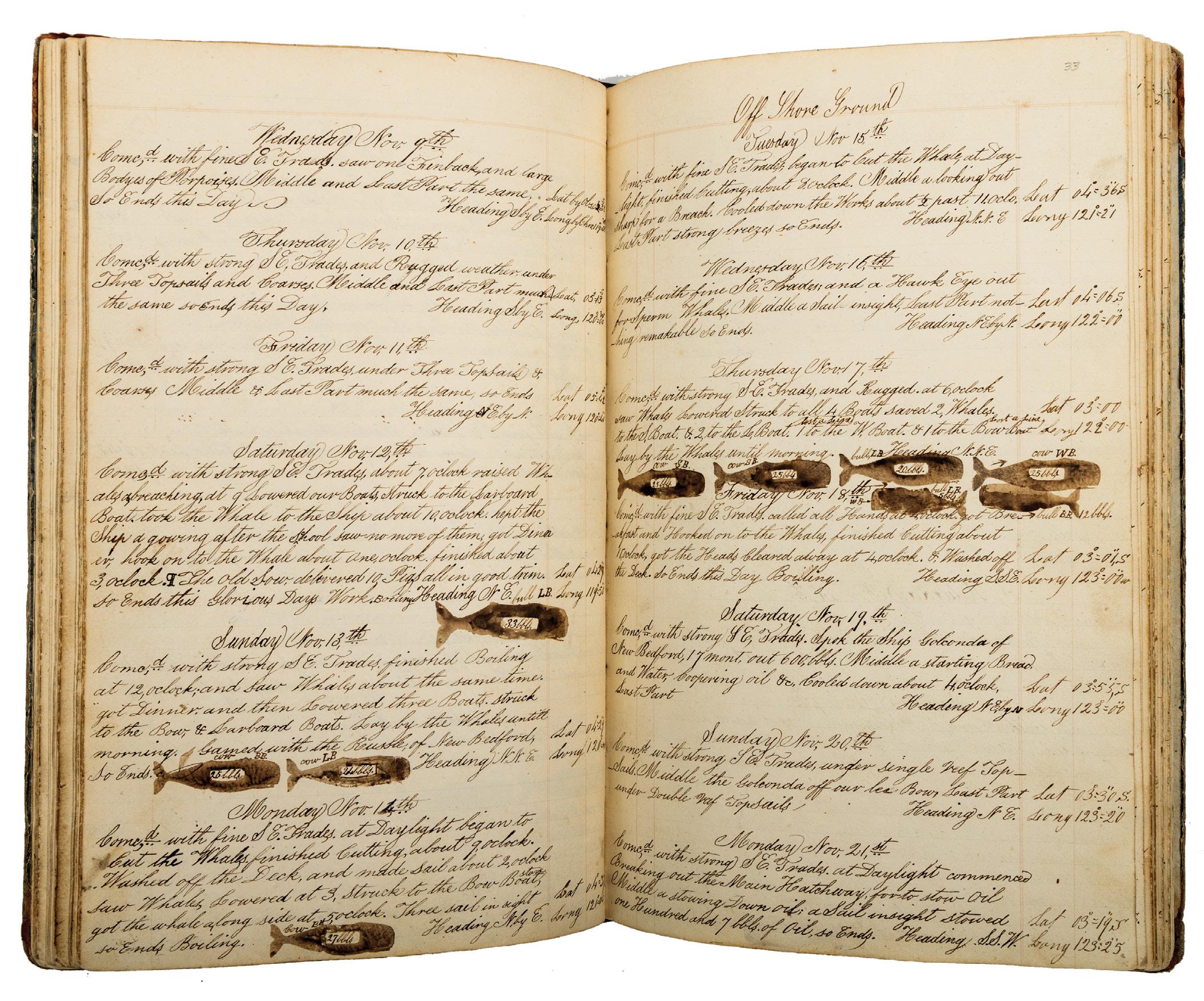

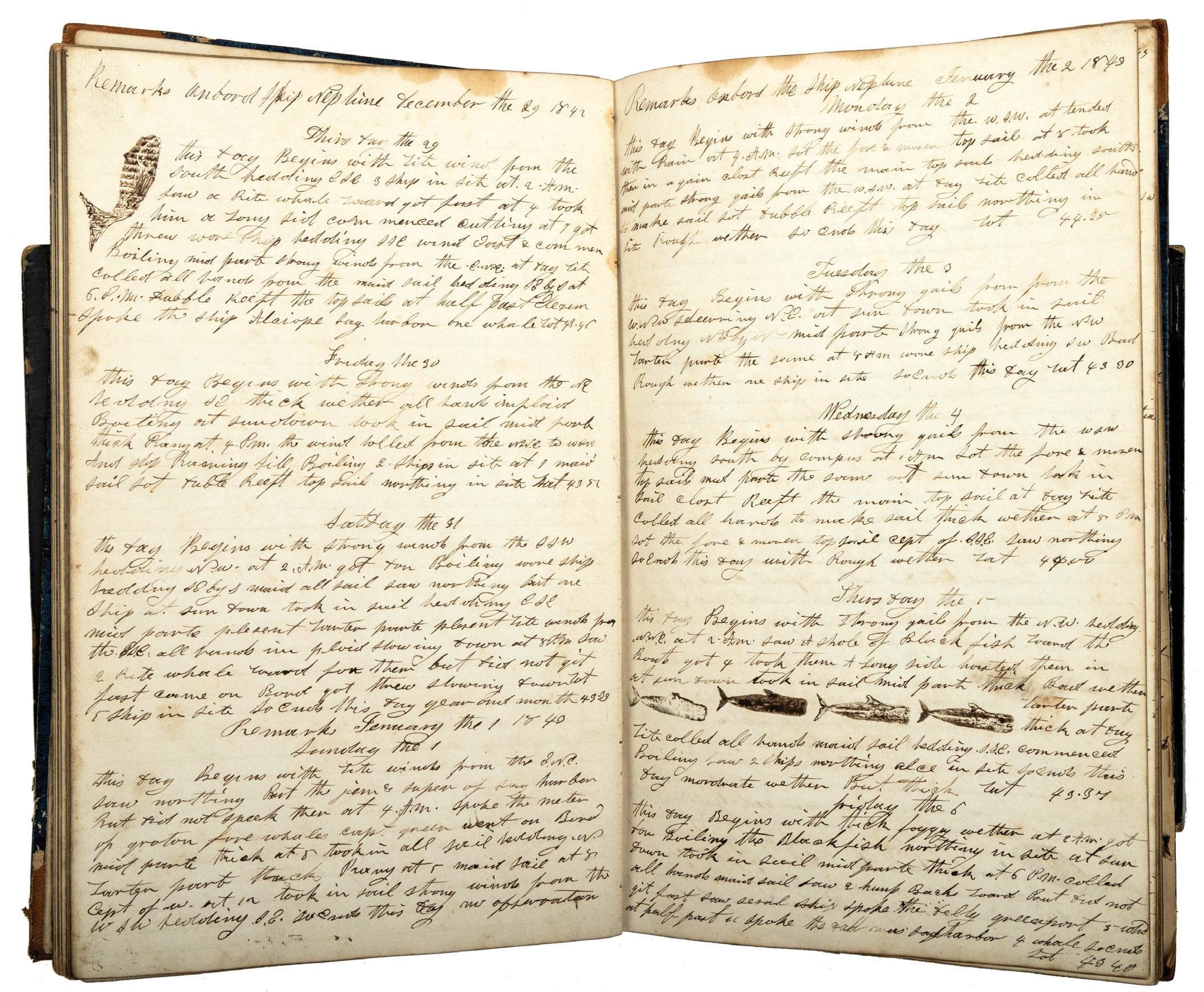

Extracting Global Maritime Weather Data from New England Whaling and Portuguese Navy Logbooks (1740–1960)

Timothy D. Walker and Caroline C. Ummenhofer

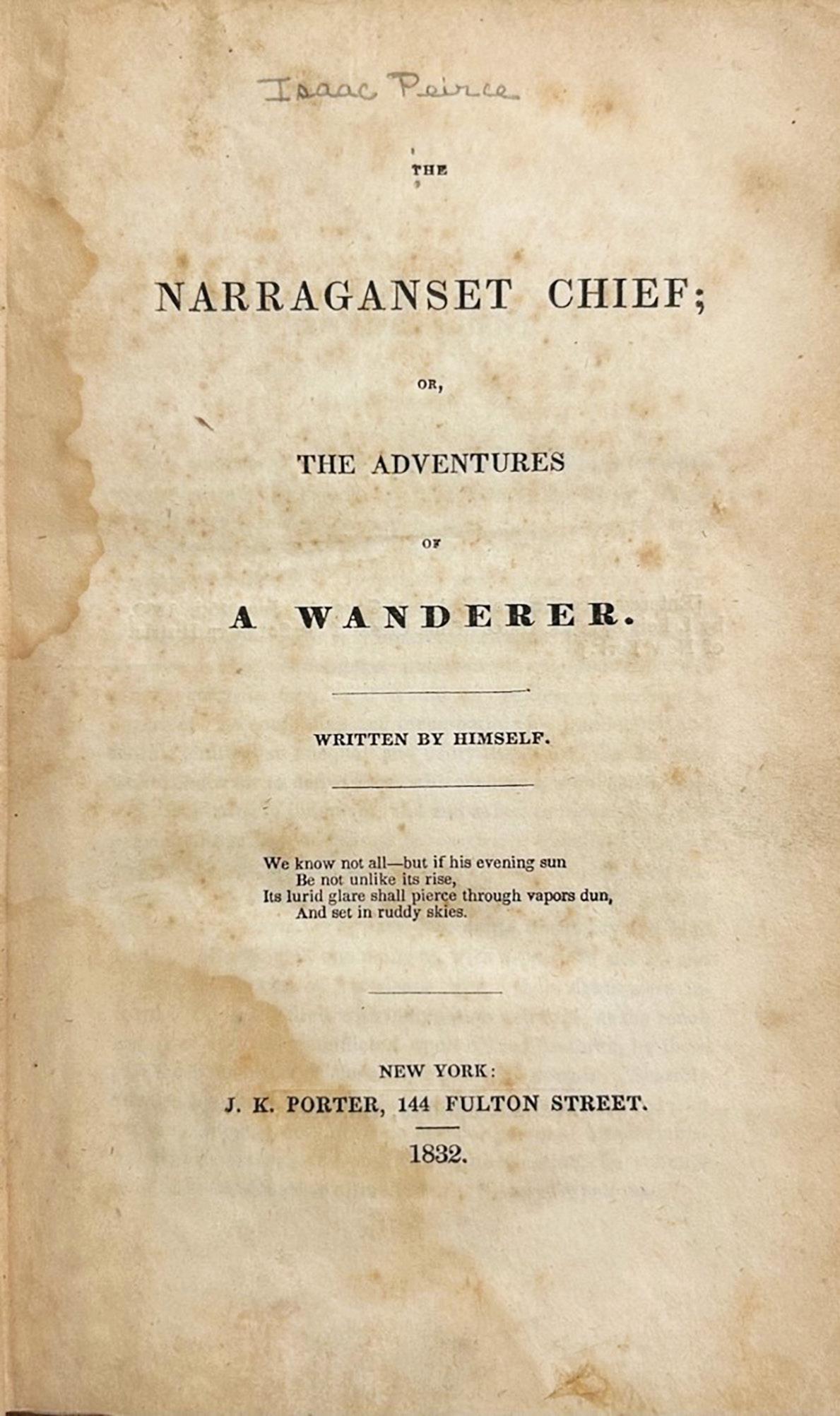

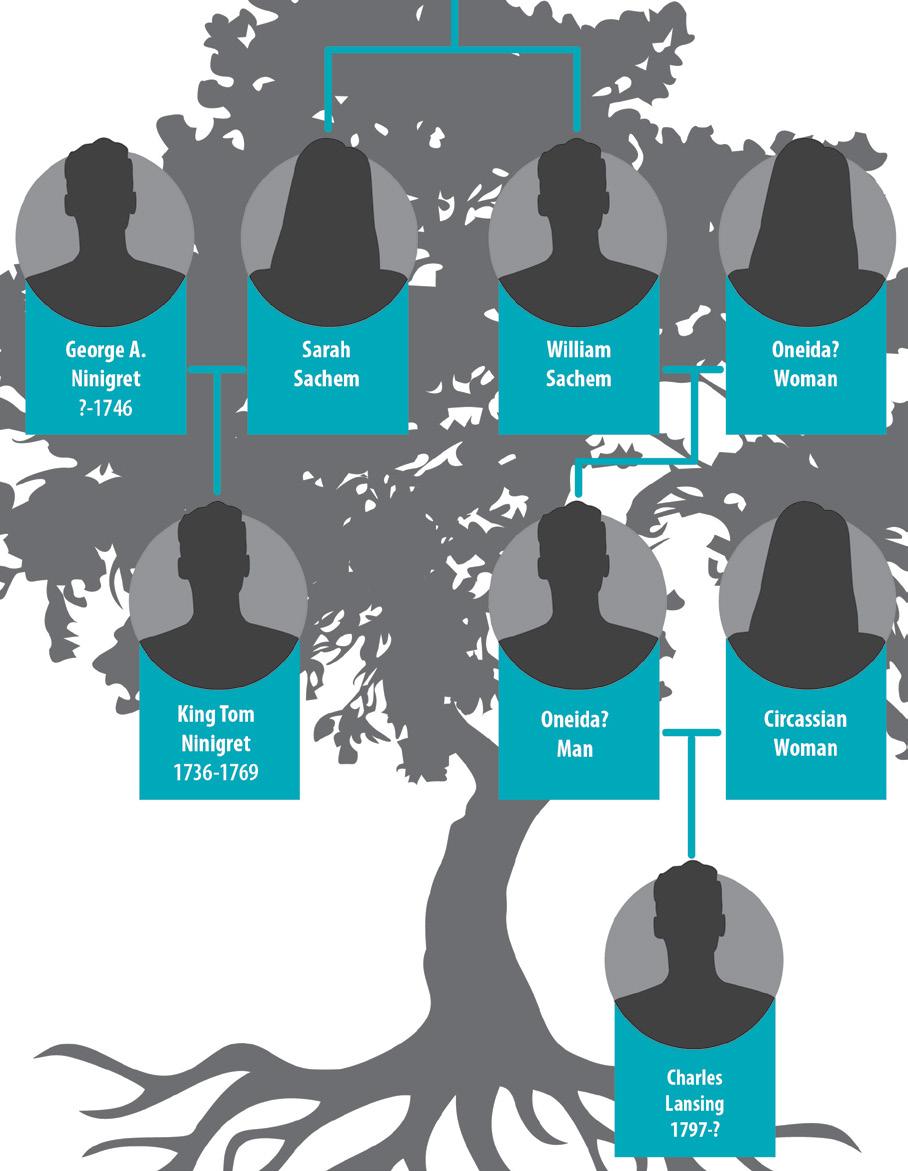

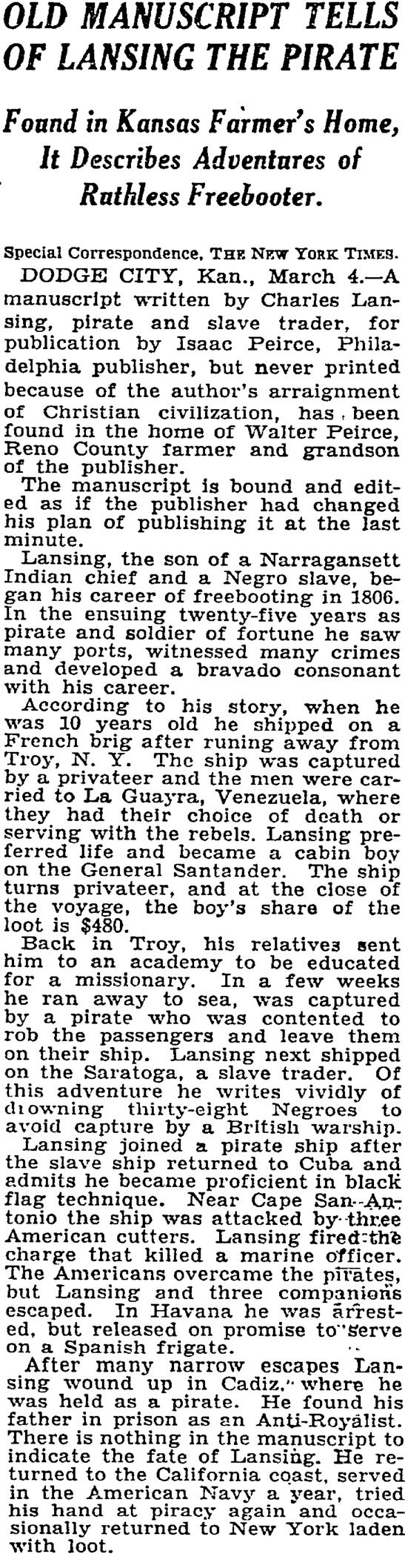

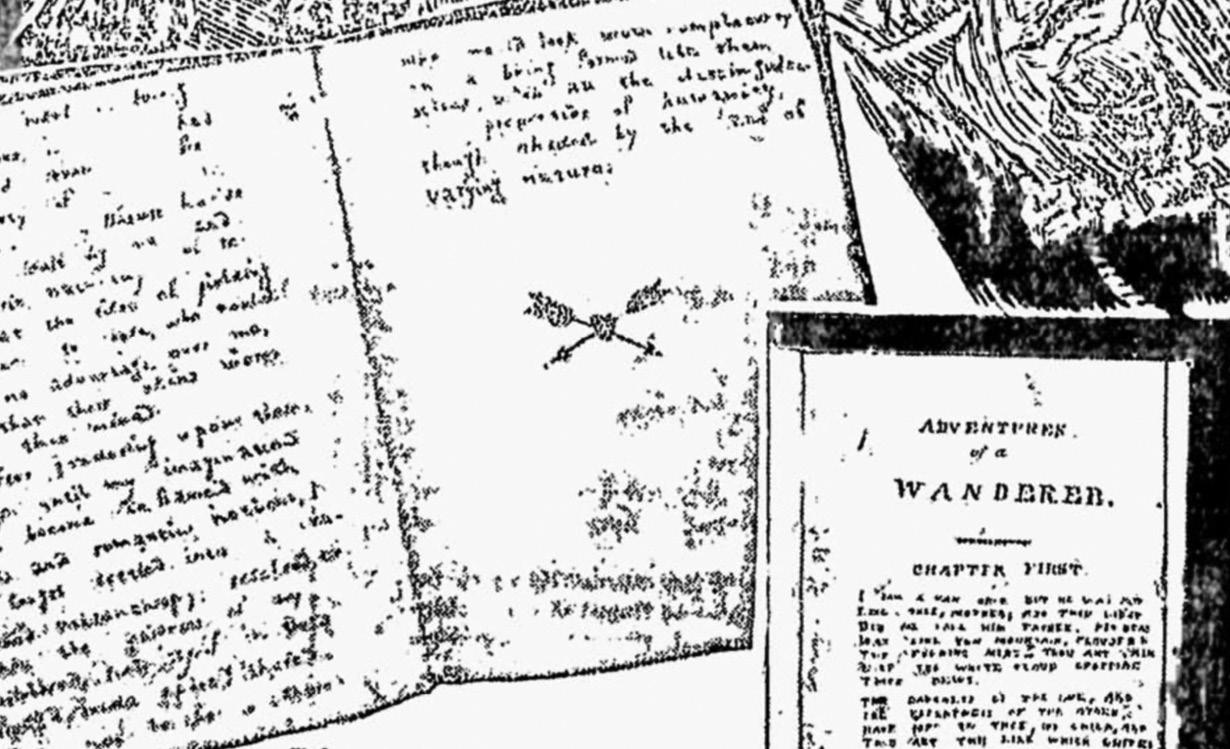

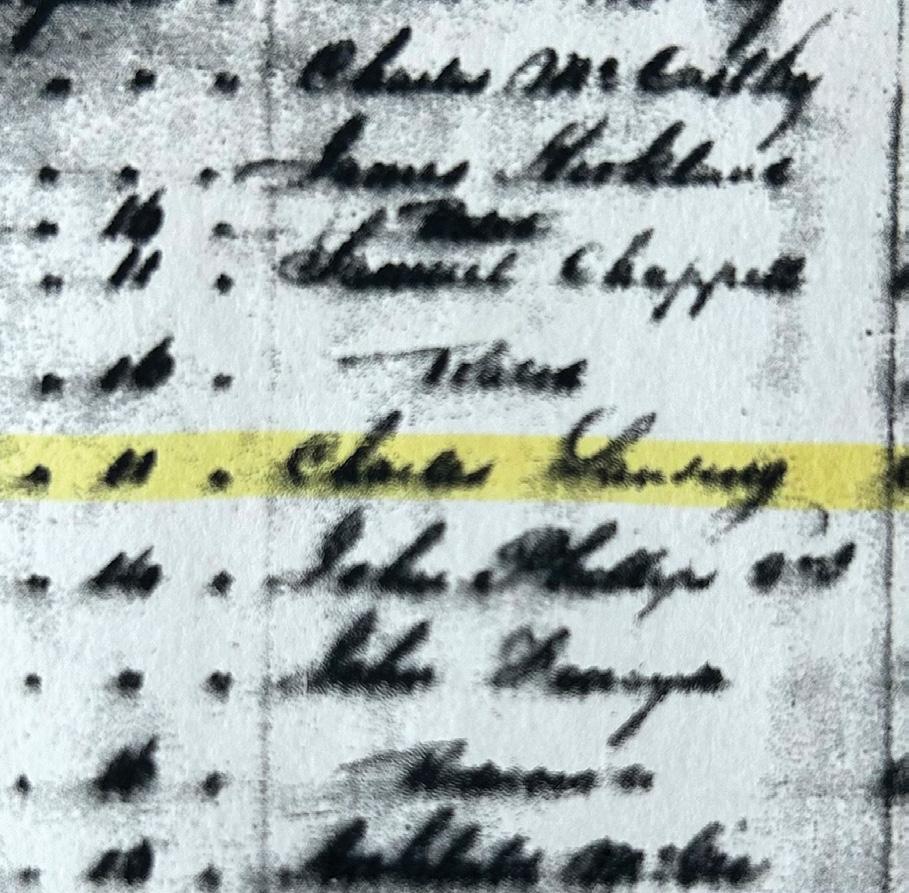

“The Narraganset Chief, or the Adventures of a Wanderer”: Recovering an Indigenous Autobiography

Jason R. Mancini and Silvermoon Mars LaRose

PERSPECTIVES

(Life) Cycles, (Ocean) Currents, and (Ancestors’)

Rhythms: Dawnland Maritime Histories through Indigenous and Black Voices

Akeia de Barros

FEATURES

Gold Trading and Crocodiles: Two Miniature African Canoes

Kevin Dawson

The Içar Project: Preserving the Ancient Art of Shipbuilders in Brazil

Marcelo Filgueiras Bastos

Unsung Heroes: The Invisible Workforce Powering Global Trade

Katie Higginbottom

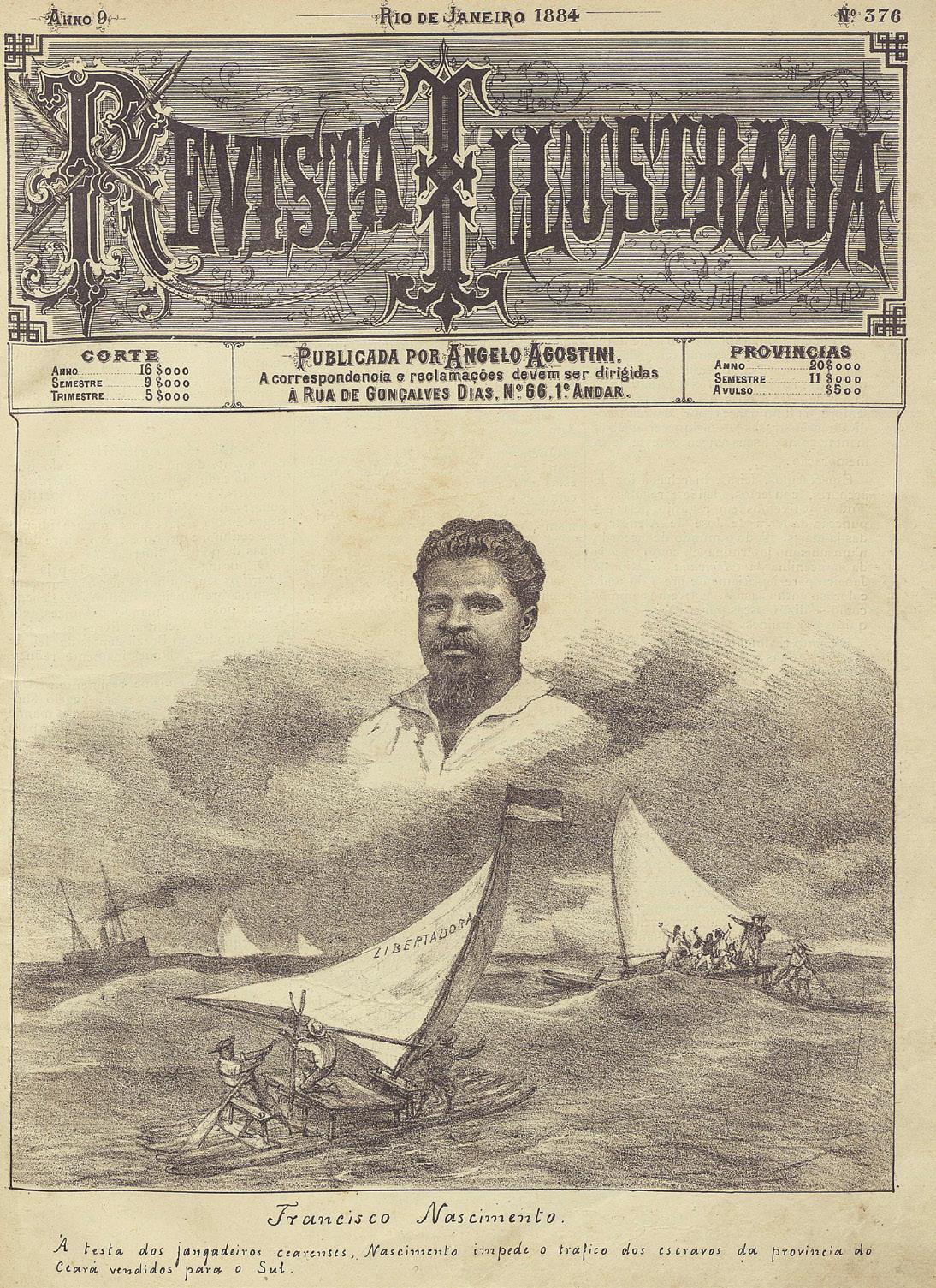

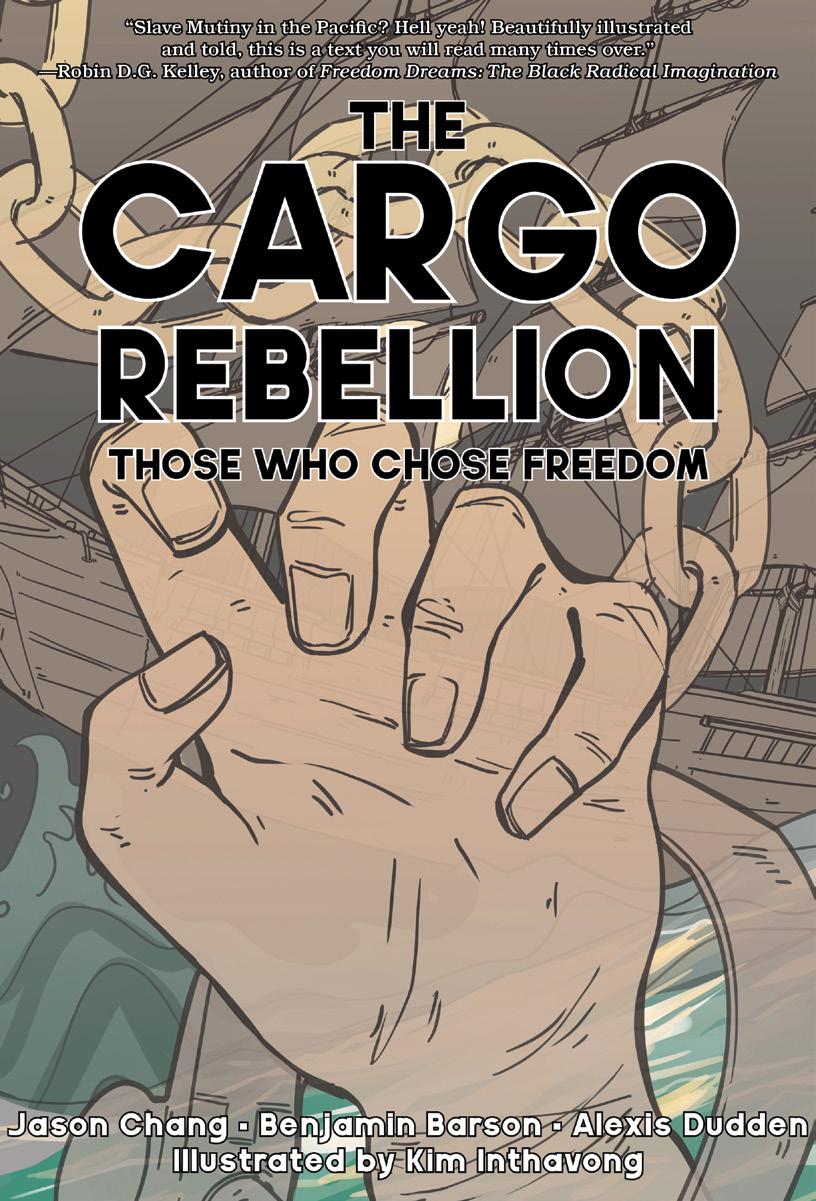

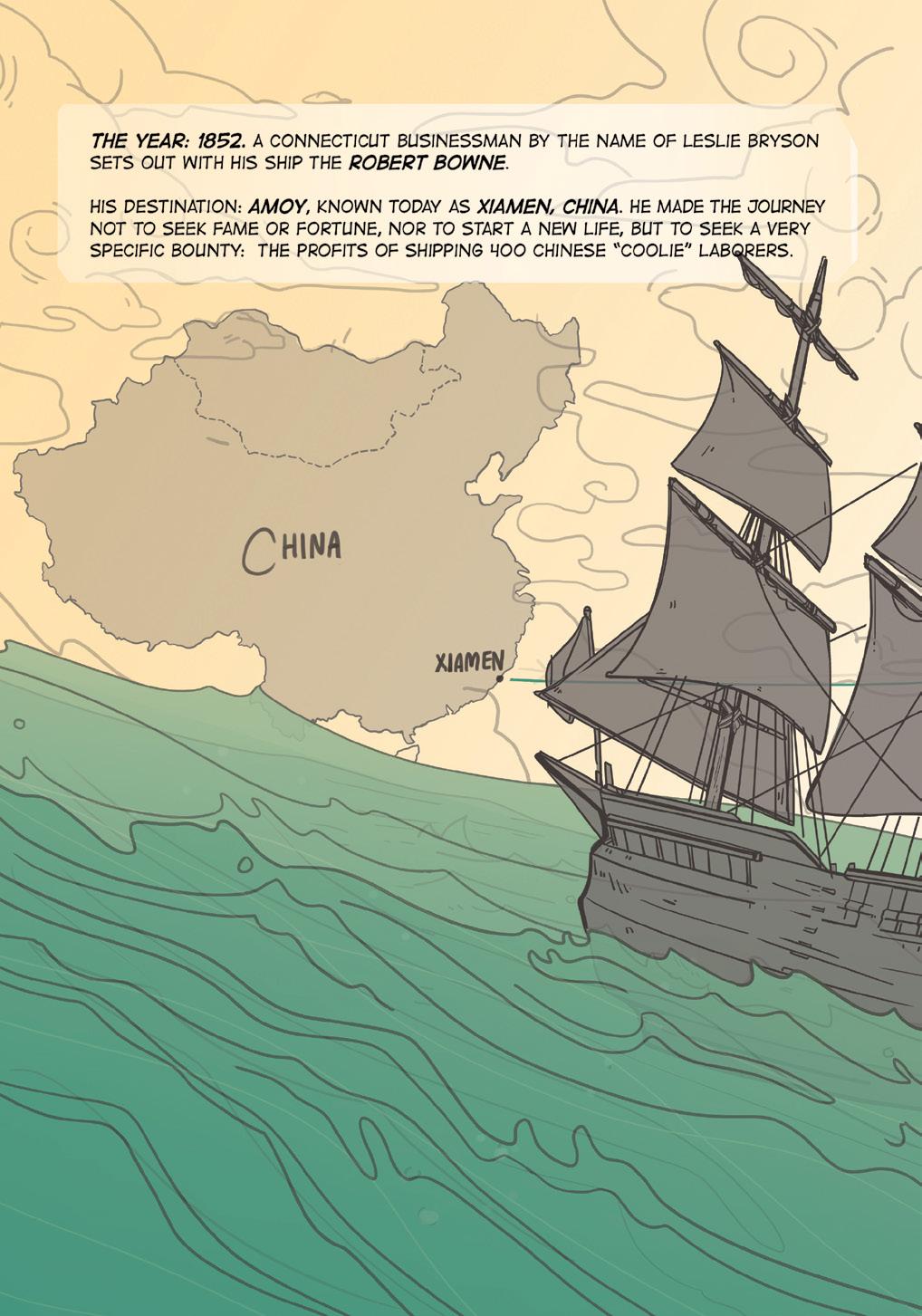

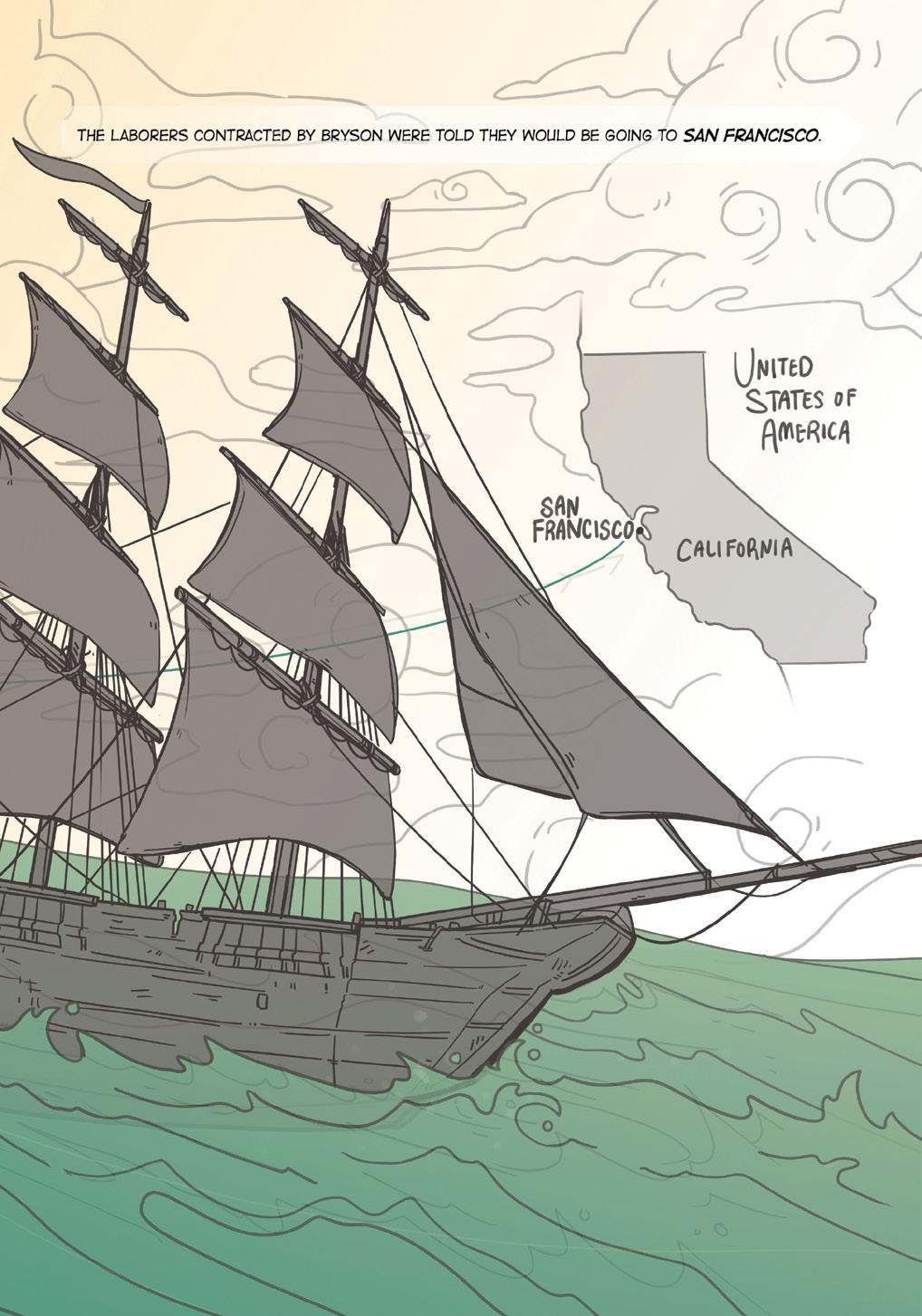

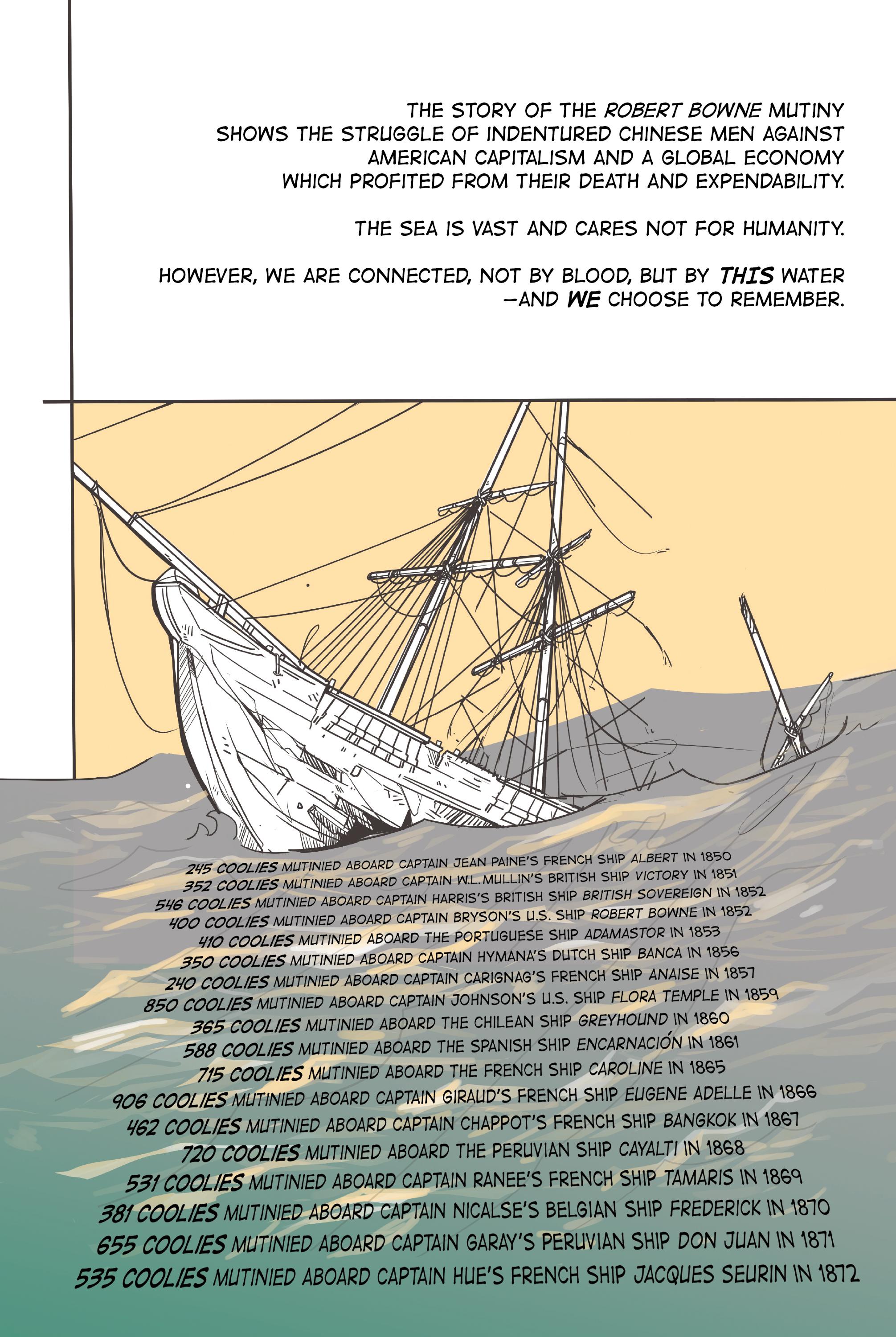

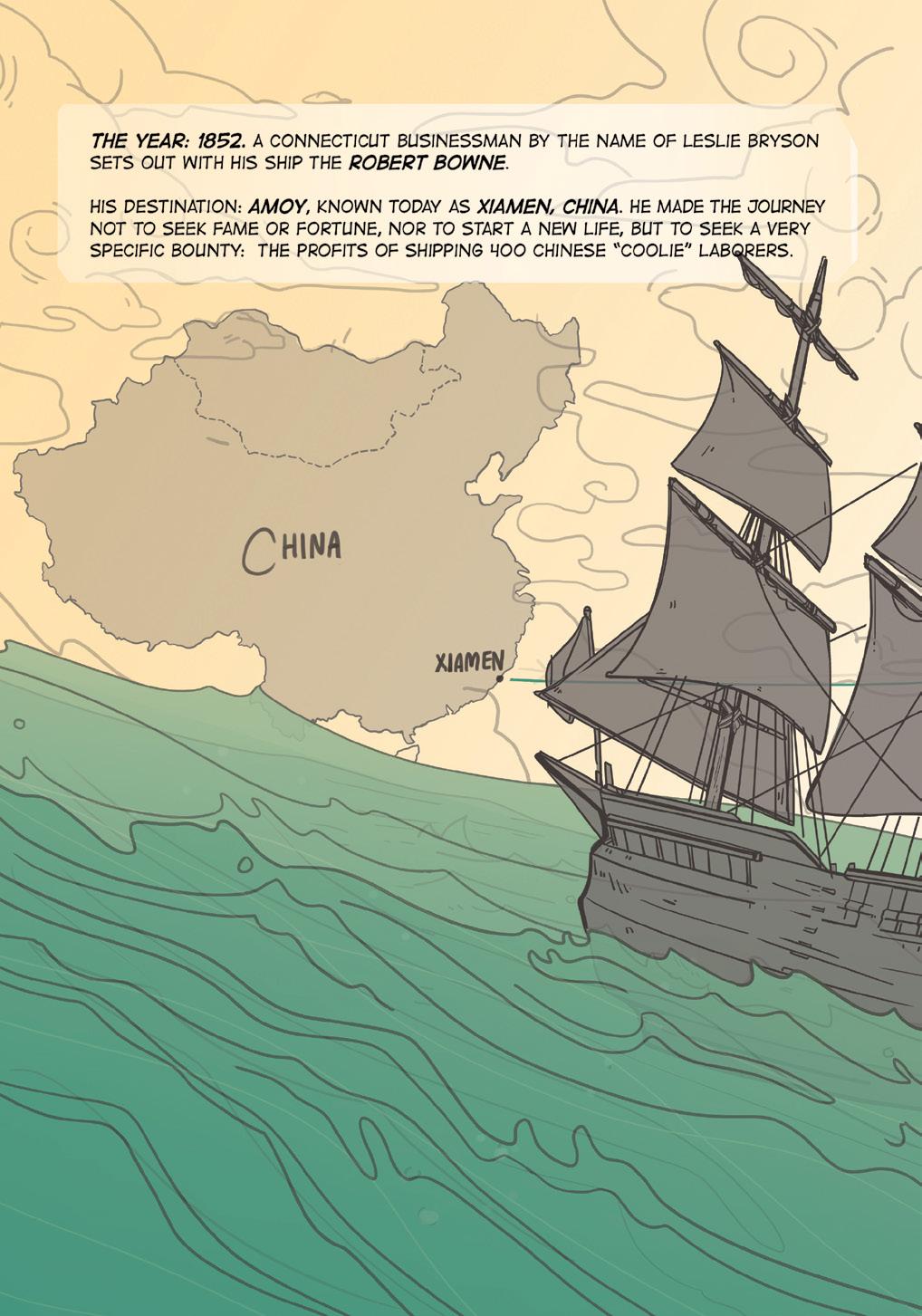

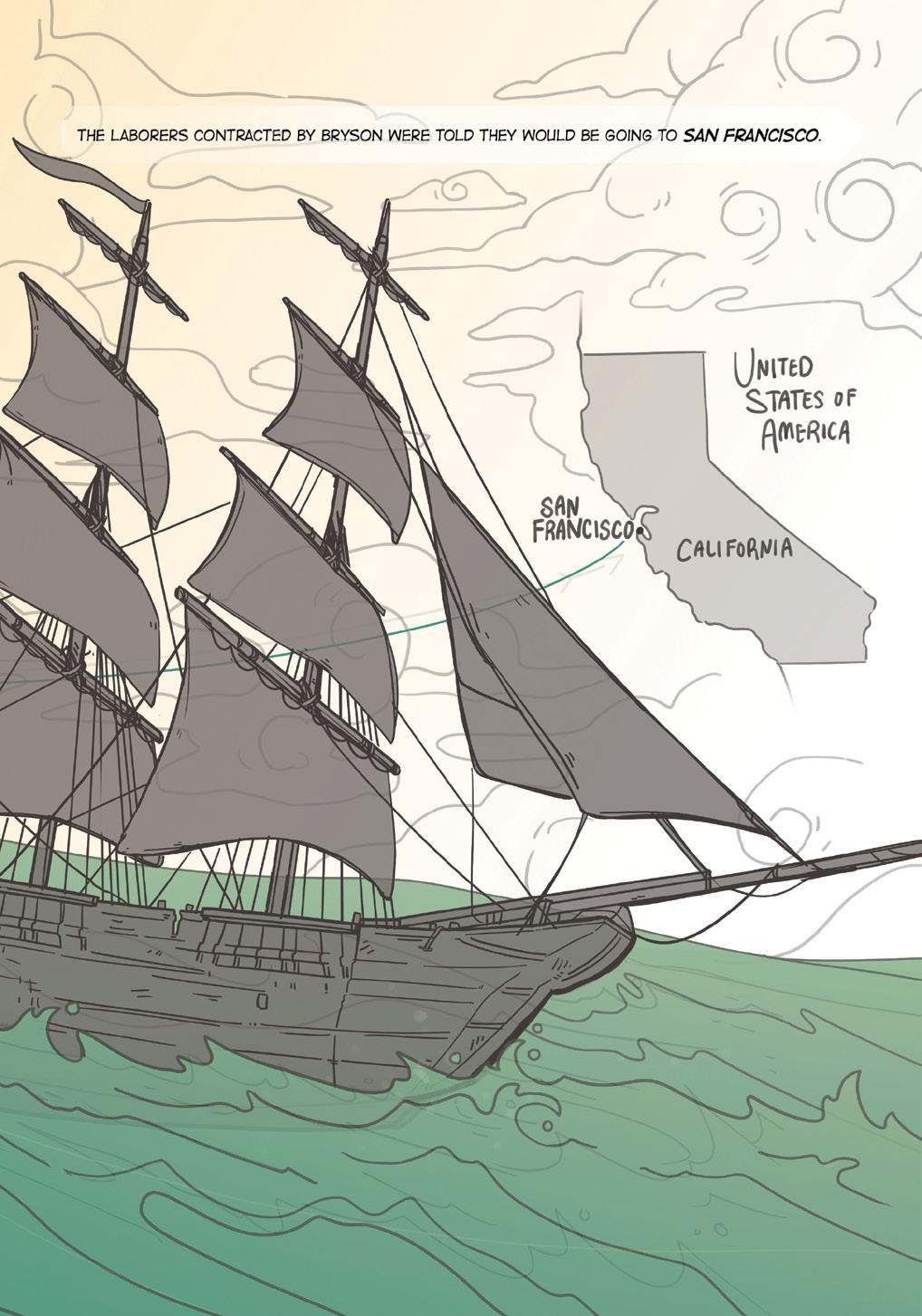

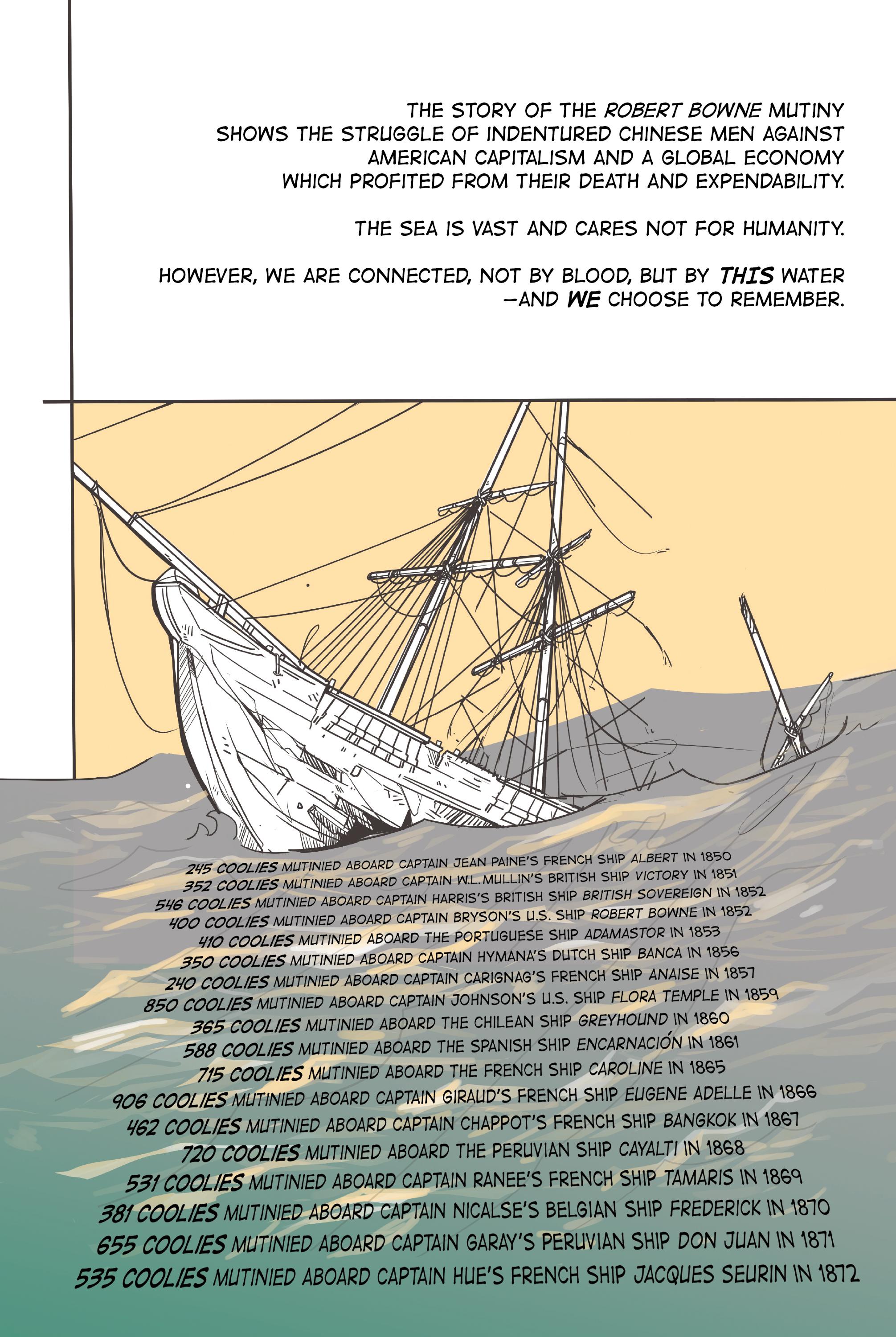

Selected Images from The Cargo Rebellion: Those Who Chose Freedom

IN EACH ISSUE

POETRY

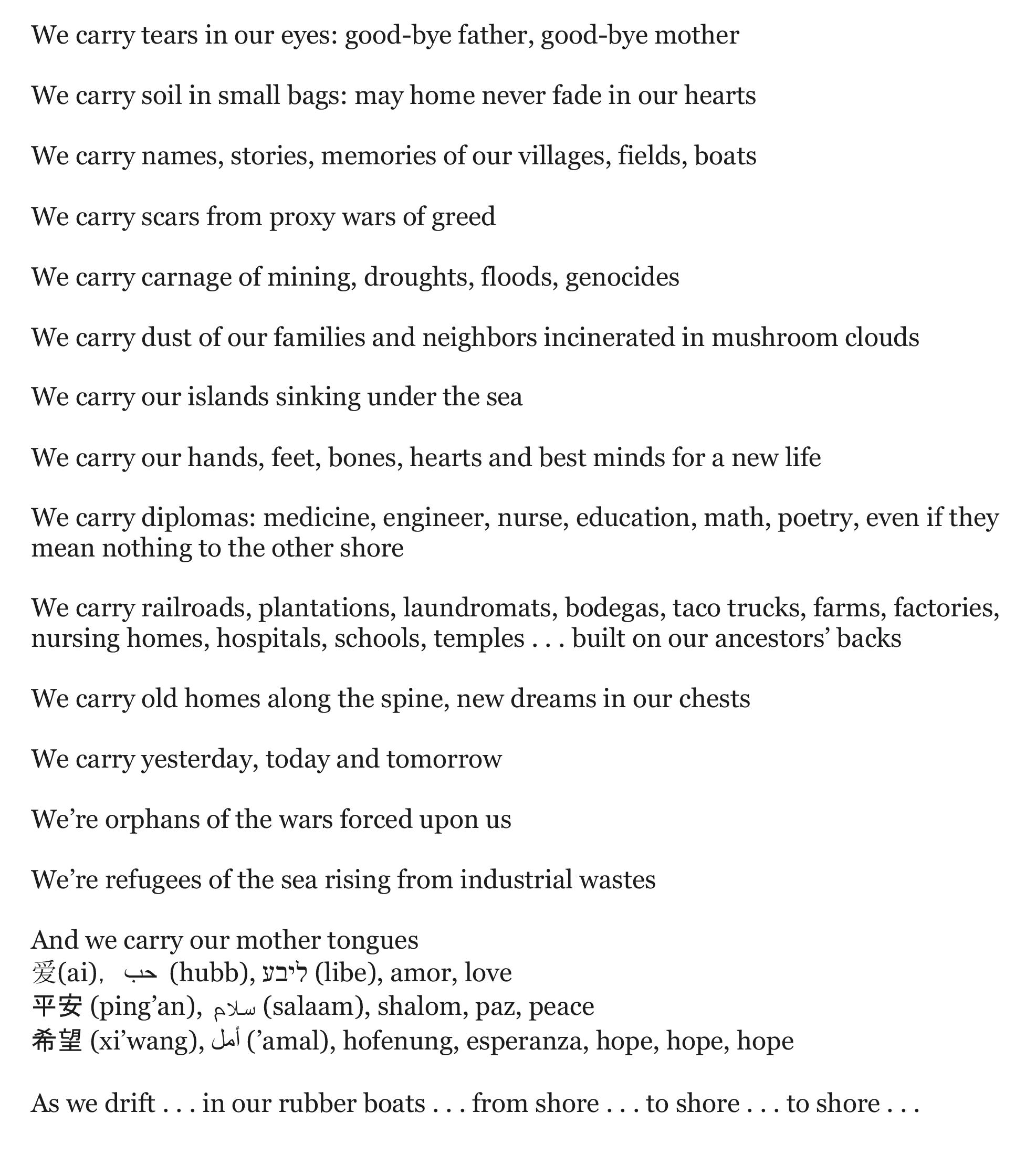

"Sea Church," Aimee Nezhukumatathil

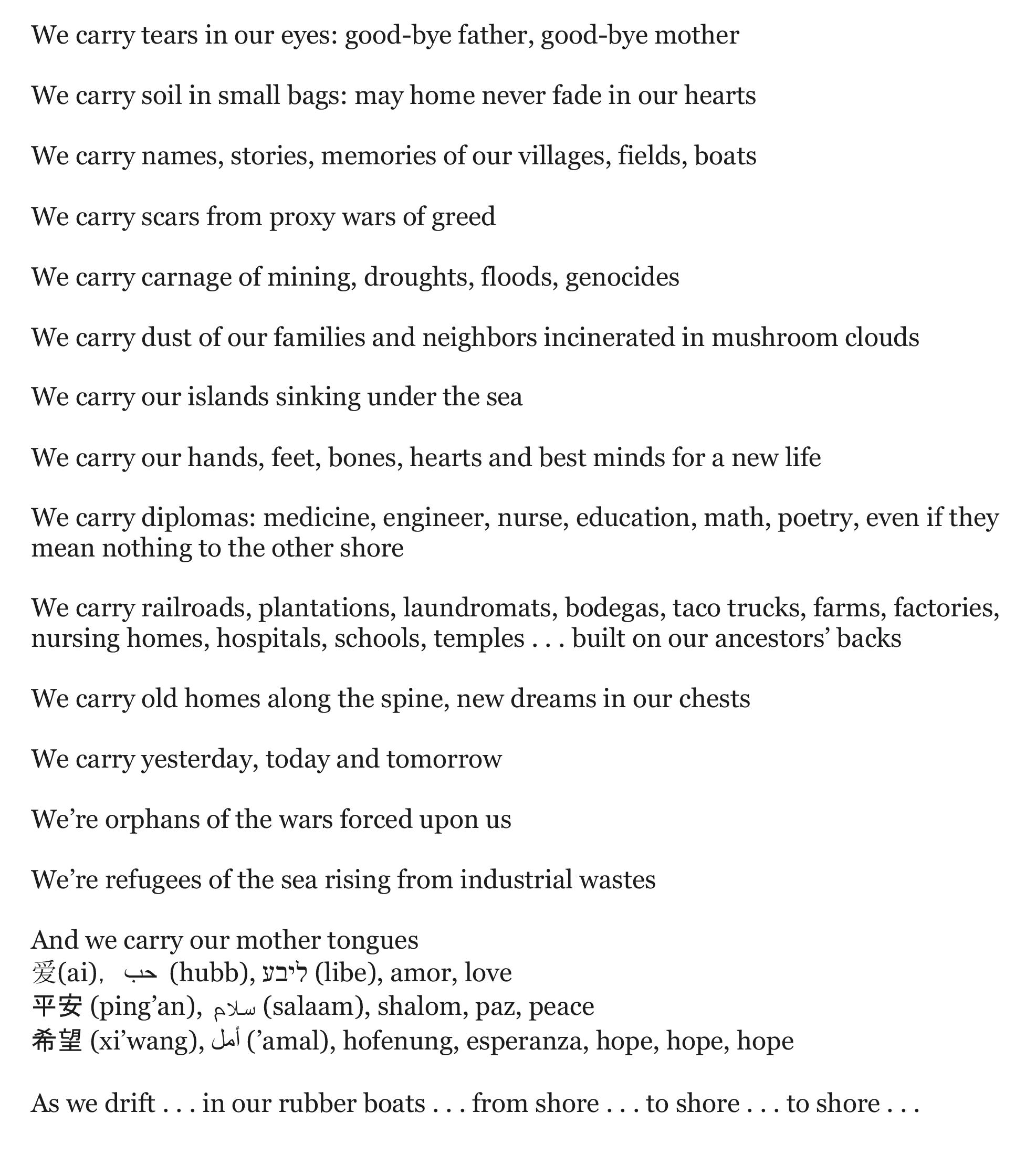

"Things We Carry on the Sea," Wang Ping

REVIEWS

The editors are grateful to John Zittel for his generous support of the launch of Mainsheet. We greatly appreciate his visionary investment in a groundbreaking new outlet for current multidisciplinary maritime scholarship from around the world. Thank you from all of us on the Mainsheet team for your essential contribution to this publication.

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History

SCHOLARSHIP

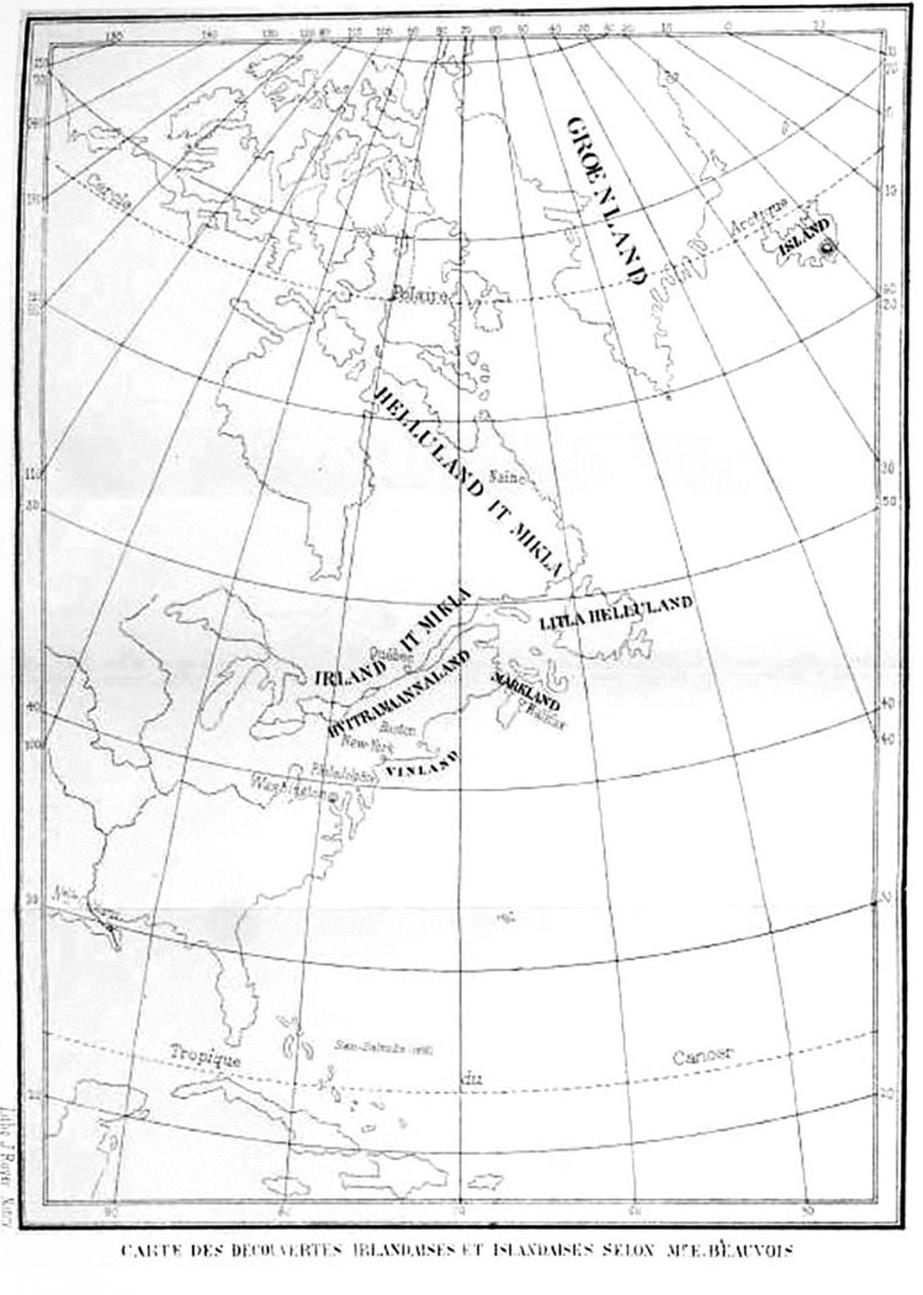

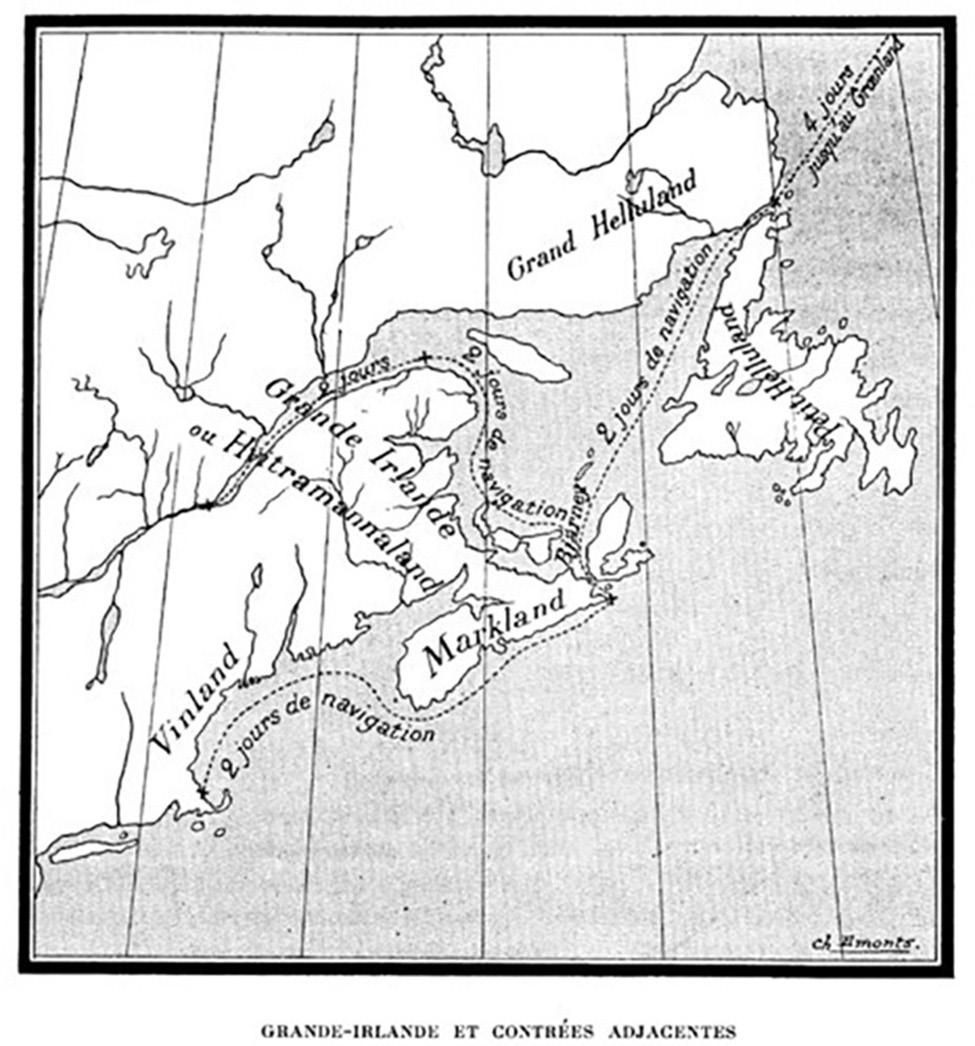

Beauvois

Expeditions

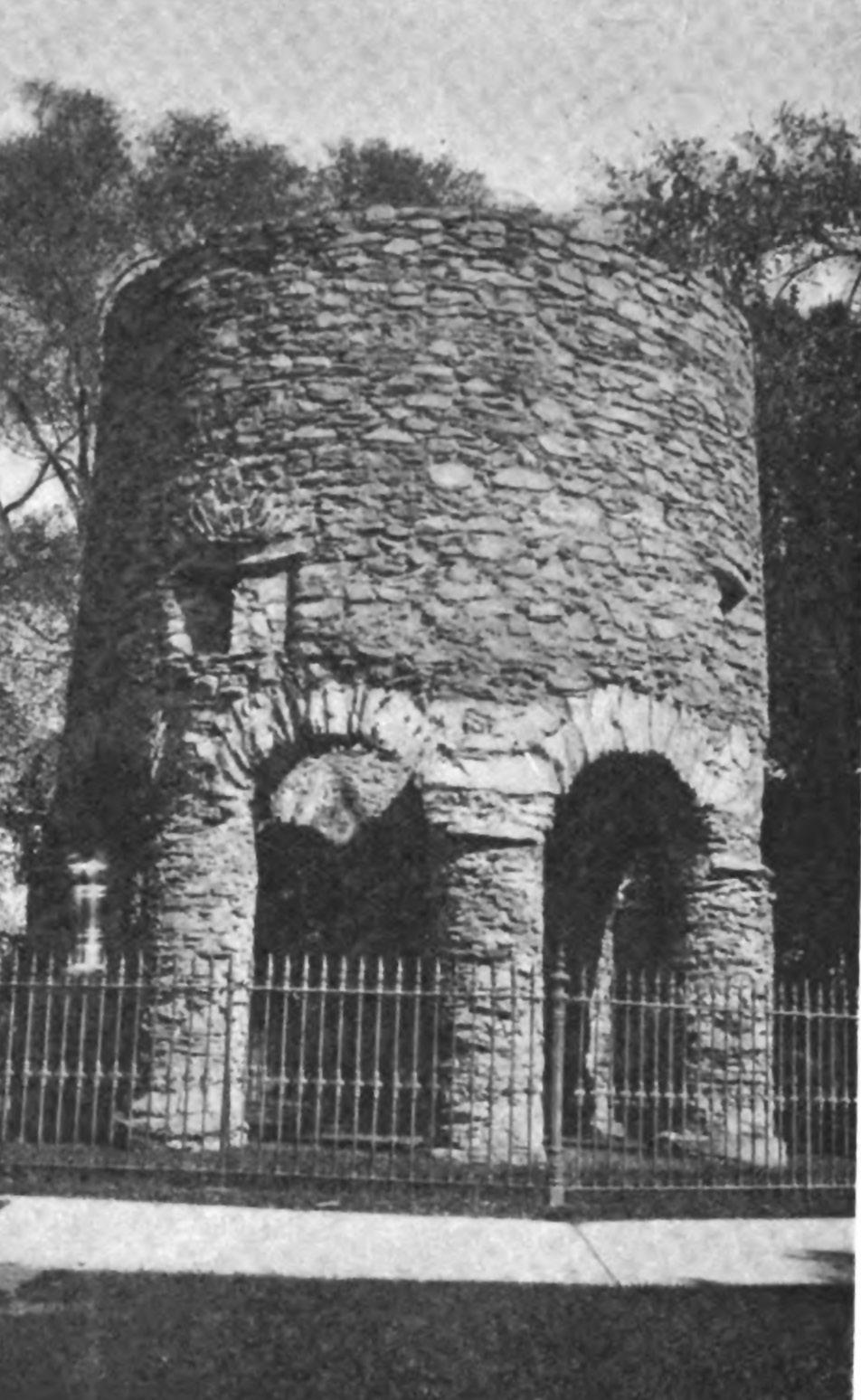

and the Vinland Viking

in the Nineteenth-Century Settler Imagination

Kwok

Gomes

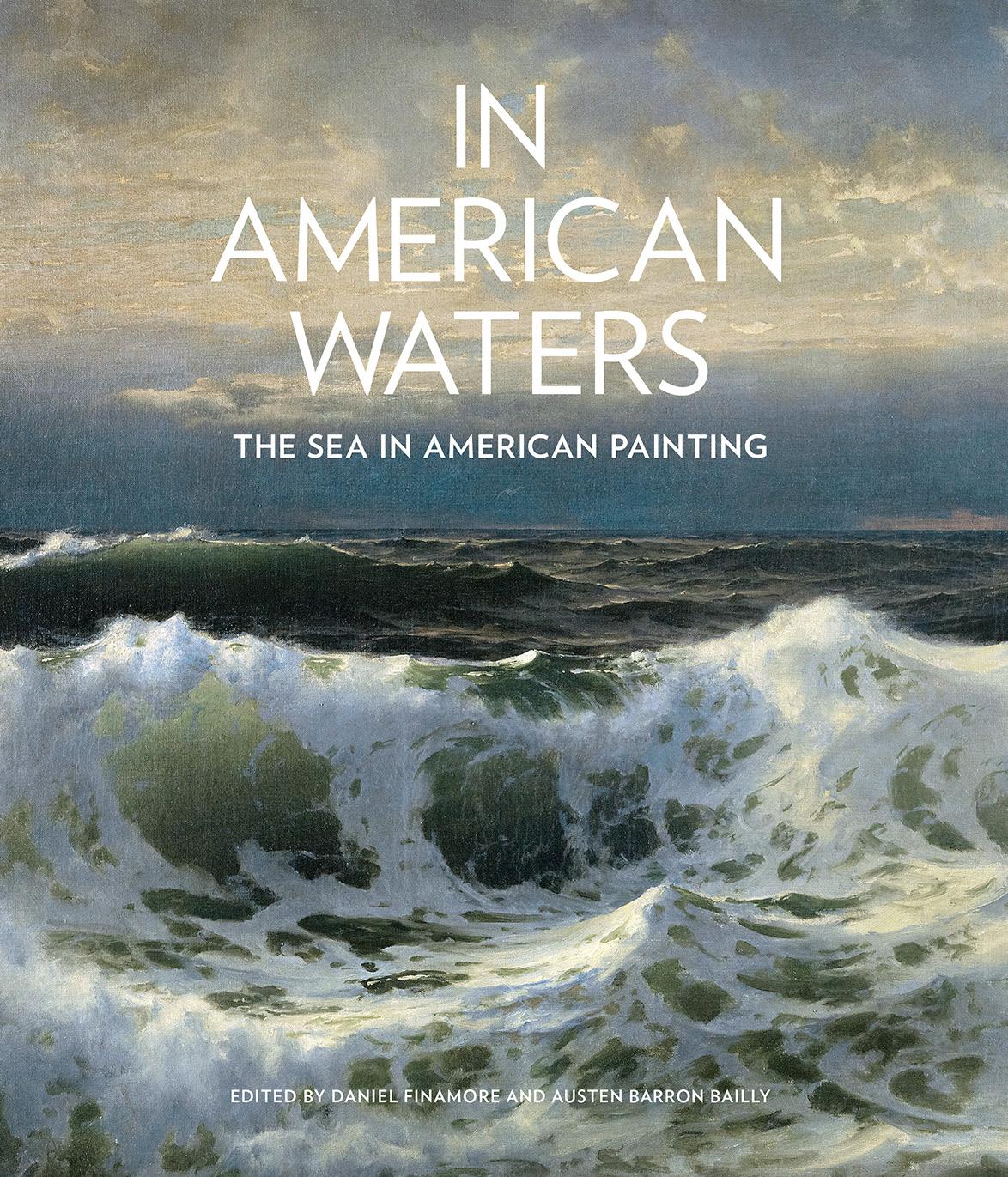

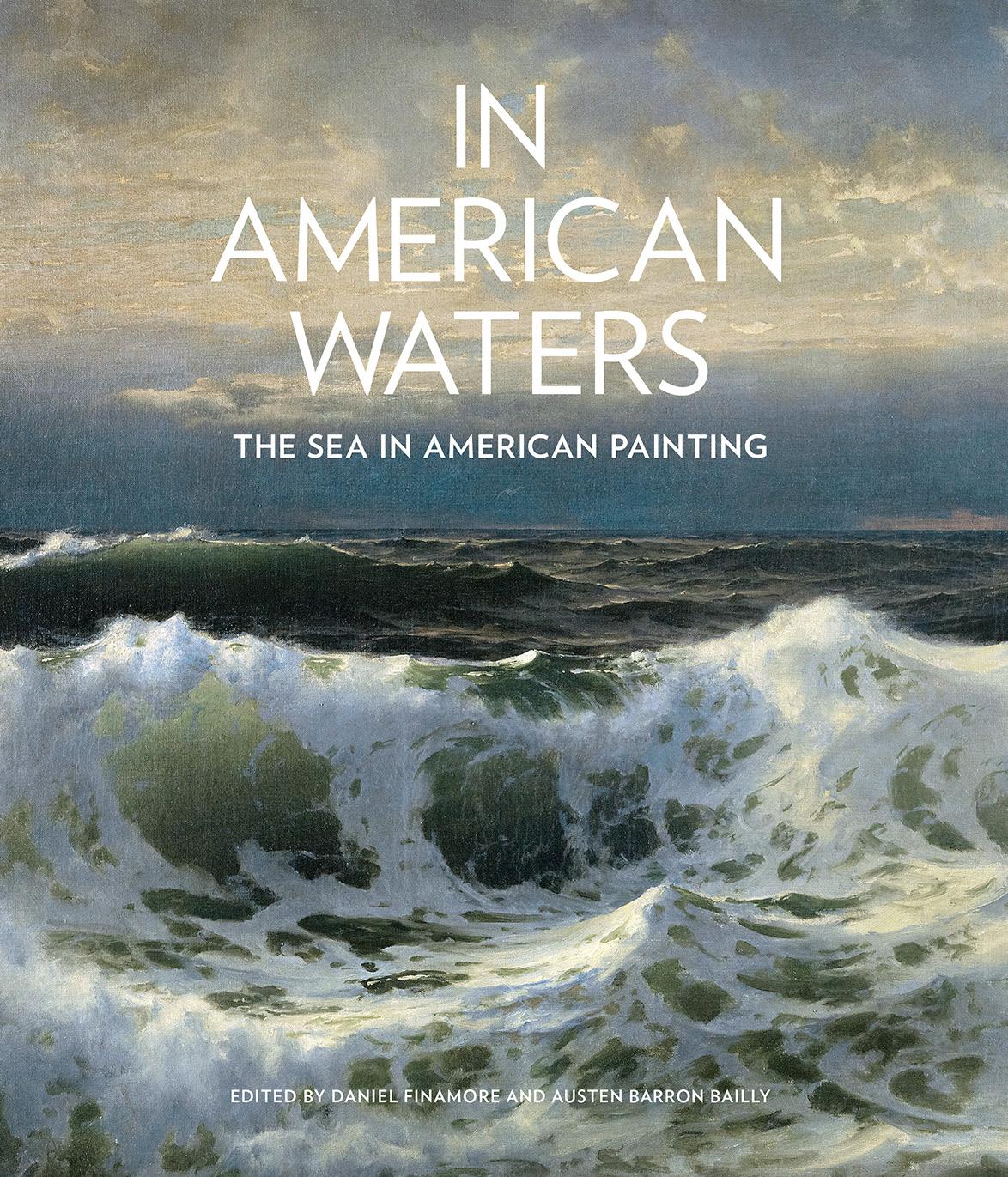

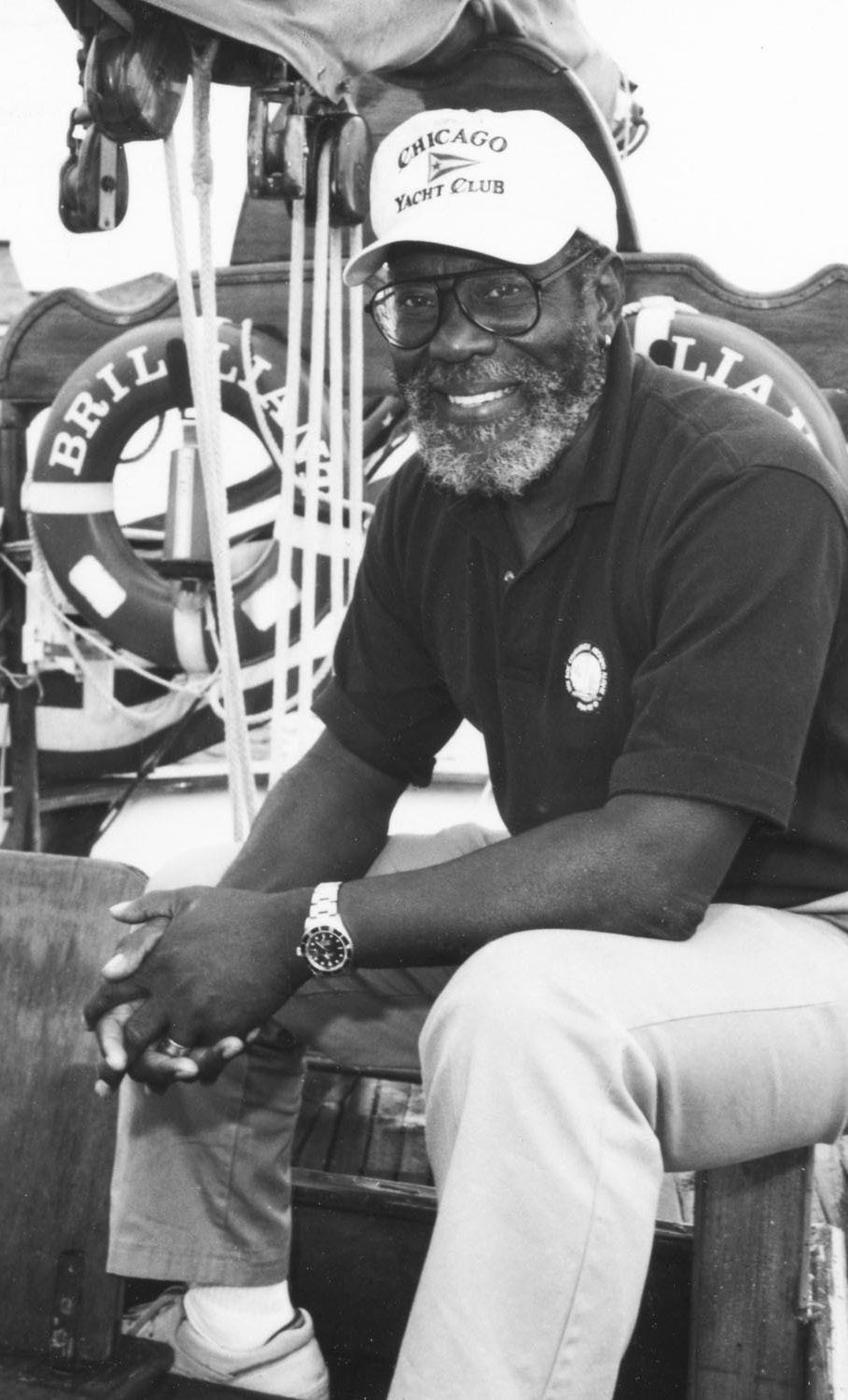

In American Waters: The Sea in American Painting. Edited by Daniel Finamore and Austen Barron Bailly Reviewed by Michael R. Harrison The Cargo Rebellion: Those Who Chose Freedom by Jason Chang Reviewed by Ramin Ganeshram Gullah Geechee, at the International African American Museum Reviewed by Akeia de Barros Gomes LISTINGS Upcoming Exhibits Academic Opportunities and Happenings FROM THE MUSEUM COLLECTION SPOTLIGHT Imagined Vikings: Alexander G. Law’s Viking Ship Model Jenny Carroll REMEMBRANCE Bill Pinkney – ZEST for life! – a Remembrance J. Revell Carr 4 16 42 66 108 124 6 38 62 84 154 83 101 150 152 156 164 166 102 162

Mystic Seaport Museum

75 Greenmanville Ave.

Mystic, CT 06355

United States

mainsheet@mysticseaport.org

Editor in Chief: Christina Connett Brophy, Mystic Seaport Museum

Managing Editor: Michelle I. Turner, Mystic Seaport Museum

Issue Editor: Akeia de Barros Gomes, Mystic Seaport Museum

Associate Editors:

Elysa Engelman, Mystic Seaport Museum

Paul O’Pecko, Mystic Seaport Museum

Mary Anne Stets, Mystic Seaport Museum

Claudia Triggs, Mystic Seaport Museum

Editorial Assistants:

Makenzie Metivier, Mystic Seaport Museum

Bridget DeLaney-Hall, Mystic Seaport Museum

Editorial Advisory Board:

Mary K. Bercaw Edwards, University of Connecticut

James Boyd, Brunel Institute/SS Great Britain Trust

Richard Burroughs, University of Rhode Island

James Carlton, Williams Mystic

Jason Chang, University of Connecticut

Richard W. Clary, Mystic Seaport Museum

Kevin Dawson, University of California, Merced

Christine DeLucia, Williams College

Michael P. Dyer, New Bedford Whaling Museum

Dan Finamore, Peabody Essex Museum

Michael R. Harrison, Nantucket Historical Association

Fred Hocker, Vasa Museum

Matthew McKenzie, University of Connecticut

Michael Moore, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Lincoln Paine, University of Maine School of Law

Christopher Pastore, University at Albany (SUNY)

Helen M. Rozwadowski, University of Connecticut

Joshua M. Smith, American Merchant Marine Museum

Lisa Utman Randall, Pocketknife Consulting

Jeroen van der Vliet, Het Scheepvaart Museum

Richard Vietor, Mystic Seaport Museum

Timothy Walker, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth

Publisher: Mystic Seaport Museum Inc.

Mainsheet is a biannual journal of multidisciplinary maritime studies. Information on subscriptions and back issues, as well as author submission information, is available at Mainsheet’s website, https://www.mainsheet.mysticseaport.org, or by scanning this QR code:

Copyright © 2024 Mystic Seaport Museum Inc.

Mainsheet (ISSN 2996-1602, E-ISSN 2996-1610) is published open access, which means that readers may access the works for free on the open web. Articles carry a Creative Commons (CC) license, allowing users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. Reproduction and transmission of journal articles must credit the author and original source and may also be restricted from commercial use in certain instances. Further information on CC licenses is at: https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/.

Some material published in Mainsheet (such as artwork, poetry, and photography) may require additional permissions from the publisher and/or rights holder. Please contact permissions@mysticseaport.org with inquiries.

2 MAINSHEET

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History

Dedicated to Paul J. O’Pecko

This inaugural issue of Mainsheet is dedicated to Paul J. O’Pecko, who recently retired as Vice President of Research Collections and Library Director of Mystic Seaport Museum, after a 39-year career at the Museum. A beloved colleague and a tireless advocate for the stewardship and building of our collections, Paul was also the leader behind our efforts to improve researcher access to collections. Decades before digitization and online sharing of collections became standard practice for museums and research libraries, Paul recognized the importance of that work and committed time, energy, and resources toward it. He also founded and edited Coriolis, a peer-reviewed journal that was an inspiration for Mainsheet, and he served on the internal team that created Mainsheet and edited this first issue. Paul’s commitment to multidisciplinary maritime research, along with his kindness and generosity in sharing knowledge and opening doors to scholars around the world, will guide us as we build Mainsheet and continue his work.

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 3

From the Editor in Chief

Mystic Seaport Museum is thrilled to launch our first issue of Mainsheet: A Journal of Multidisciplinary Maritime Studies, which fills a field gap in peer-reviewed scholarship that has been left by the dissolution of the marvelous Atlantic Neptune and other like-minded journals over the last twenty years. While several excellent journals still exist worldwide, what sets Mainsheet apart are its multidisciplinary perspectives; themed issues; its mission to attract, share, and inspire global diverse scholarship on issues past, present, and future; and its freshness of design and distribution. Mainsheet not only promotes scholarship but is visually arresting, and celebrates broader perspectives of maritime culture through poetry and the visual arts, photojournalism, and special features on the respective themes. The Editorial Board represents a national and international team of invited expert scholars from various fields and partner institutions, with guest editors for special issue themes.

While a beautifully produced print edition can be purchased individually or by subscription, Mainsheet is available online to provide open and equitable access to new and emerging scholarship in maritime studies. We have also chosen a model that does not require authors to pay for entry into academic journals, which can be a substantial burden for rising professionals. Continued support from our sponsors and subscribers will be critical for us to maintain this exceptional opportunity for maritime studies scholars and other contributors.

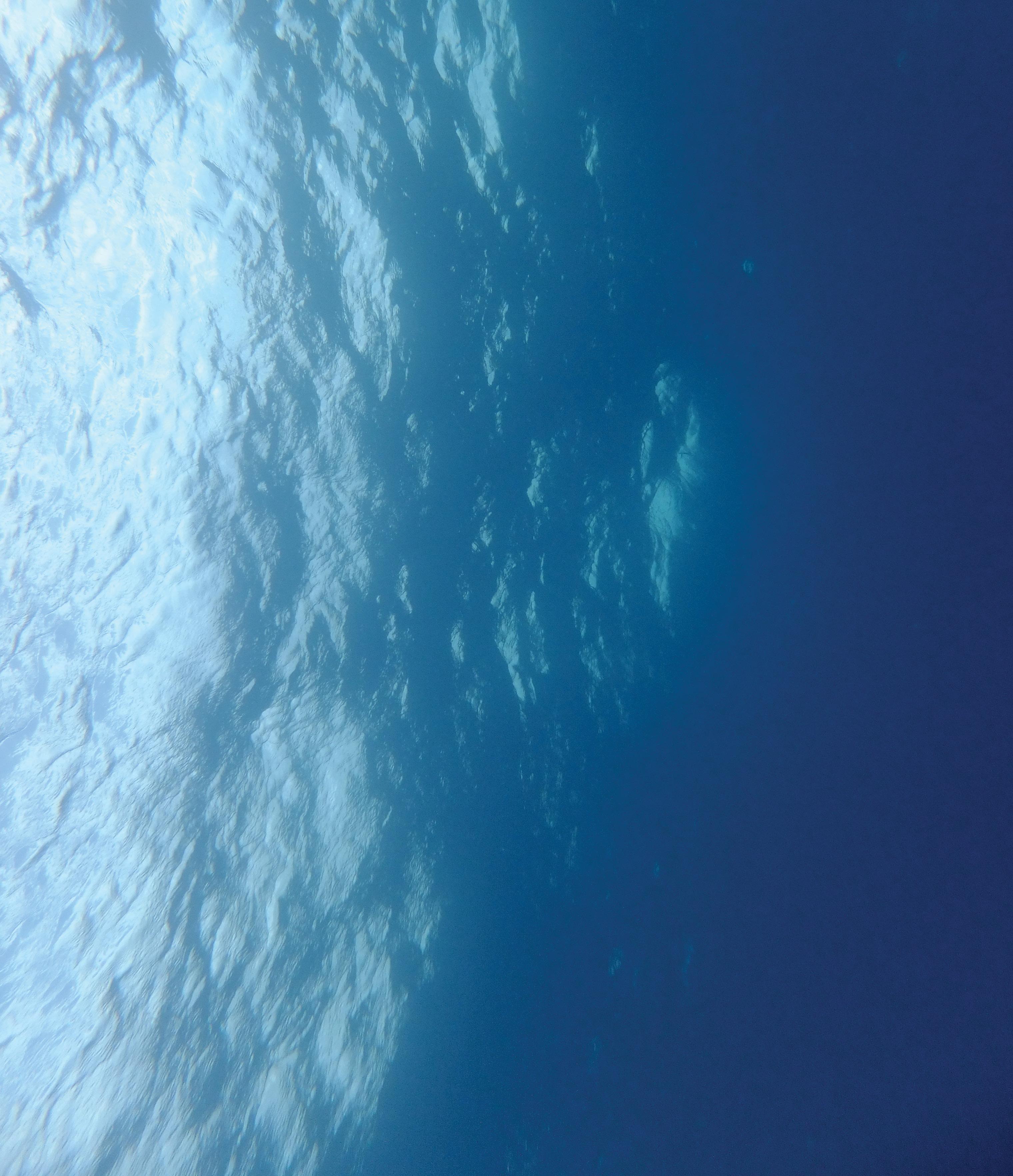

The ocean connects us all, and therefore the journal is globally focused and themes are chosen to inspire deeper multidisciplinary study of major topics influencing the field and society at large today. These topics will align with major projects at Mystic Seaport Museum and many of our partner institutions. For example, this inaugural issue features social maritime history and is launched in the year of our upcoming exhibition, Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea, which centers maritime histories in Indigenous, African, and African American worldviews and experiences. From Vikings to Narragansetts to Atlantic Africans and others, this issue of Mainsheet represents stories and voices that will broaden and expand our collective conversations around maritime societies beyond how we have historically engaged in these narratives.

The second issue of Mainsheet will explore maritime economy and technology, as leaders in government and innovators in industry look toward the exponential rise in the pursuit of a sustainable “blue” economy. As Mystic Seaport Museum engages in global conversations about new and efficient ship design, propulsion fuel technologies, sustainable aquaculture, energy sources, and undersea robotics as part of a new blue economy, we also remember our own iconic ship Charles W. Morgan, which represents the height of blue economy and technology when it was launched in 1841, purpose-built for the exploitation of whales. The issue will consider the trajectory of maritime economics and related technologies globally and across time.

4 MAINSHEET

There are many people to thank for their part in the creation of this journal. I would like to recognize, first and foremost, our generous supporter of this inaugural issue, Mr. John Zittel, who believed from the start that Mainsheet could play an essential role in elevating maritime scholarship. Championing the effort are Museum Trustees Richard Clary and Richard Vietor and the rest of the Editorial Board members, all of whom have volunteered many hours in their busy schedules to advise on the evolution of this publication. We are deeply grateful to them all for their time and expertise. I am thankful to Mystic Seaport Museum President, Peter Armstrong, for supporting the idea for this journal two years ago when I suggested, with my usual earnestness, that this was an important project for the field and for the institution. And to our Chairman, Mike Hudner, and the rest of the Mystic Seaport Museum Trustees, thank you for the enthusiasm and dedication that made this possible.

We are so fortunate to have an excellent internal Mainsheet staff team to oversee every detail of Mainsheet’s execution under the superb leadership of Managing Editor, Michelle Turner. Of course, to our expert contributors, reviewers, artists, and poets, thank you for producing such excellent and engaging content for our inaugural issue; you have set the bar very high for the next one. And to the global seafarers whose hard work at sea often goes unnoticed, thank you for allowing us to include your incredible photographs that tell your sea stories so eloquently, and to ITF Seafarers’ Trust for all that you do for mariners worldwide.

Lakuna Design has crafted a stunning and elegant journal; thank you, Misi and Dave Narcizo for your vision and expertise. Naming a new journal is almost as challenging as naming a new boat, and I have to thank renowned interior designer and dear friend Leslie Banker for coming up with the winner! Finally, to all of those at Mystic Seaport Museum who have come before us, your legacy is and will always be part of all we do; thank you for your stewardship and devotion to excellence.

Maritime studies are the key to our shared experience. It is impossible to consider our cultural, scientific, economic, social, or even physiological development without consideration of the sea above and below the surface. It is also impossible to understand where we are and where we are going without understanding where we have been. We hope to elevate and broaden deeper insight into how maritime studies, past, present, and future are an essential part of our global heritage. We welcome all of our readers to join us in celebrating and supporting this new and exciting chapter in maritime studies.

Christina Connett Brophy, PhD Editor in Chief Senior Vice President

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 5

6 MAINSHEET PERSPECTIVE

Figure 1. A village waterscape in West Africa that I travelled to by canoe. It is the village of Ganvie, Benin which was built on Lake Nokoué for protection from enslavers. Photo by the author.

(Life) Cycles, (Ocean) Currents, and (Ancestors’) Rhythms: Dawnland Maritime Histories through Indigenous and Black Voices

Akeia de Barros Gomes, Vice President, Maritime Studies, Mystic Seaport Museum, akeia.gomes@mysticseaport.org

What if the conventional maritime history of the Dawnland (New England) and the “founding” and development of Turtle Island (North America/the United States) had always been told through Dawnland Indigenous and African-descended voices? How would the story of the Dawnland be told? What parts of the story would be prioritized and how would the current narrative change? The upcoming Mystic Seaport Museum exhibition, Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea represents our work with Black and Indigenous communities to do just that—tell the maritime history of the Dawnland through Indigenous and Black voices as the authoritative history. Entwined opens to the public April 20, 2024.

What if the accepted, “legitimate,” central historical maritime narrative of the United States focused on the descendants of the African continent and the people of Dawnland Indigenous sovereign nations encountering one another during a cycle of disruption (dispossession and enslavement)—after millennia of our own maritime cultures, innovation, and development? What if the telling of Black and Indigenous American maritime histories always began before “America” and included our Indigenous and African ancestral contributions to American maritime industry and history?

Within our African and Indigenous worldviews, maritime history cannot be told without our cosmologies, spiritualities, our ancestors, cycles of time (rather than time lines), cycles of trauma and rebirth and acknowledgment of the sovereignty of the sea itself. These have largely been silent (or silenced) in the framing of the Americas’ maritime history. Typically, when traditional scholars engage in Indigenous and Black maritime histories, they “wedge” these histories into a Western, Eurocentric worldview that invalidates Black and Indigenous knowledges and perspectives. What if these perspectives and

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 7

(Life) Cycles, (Ocean) Currents, and (Ancestors’) Rhythms: Dawnland Maritime Histories through Indigenous and Black Voices © 2023 by Akeia de Barros Gomes is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

PERSPECTIVE

histories were validated even when they contradict what historians think they know?

I am a scholar who is the descendant of enslaved, “involuntary migrants” to the US who no doubt had deep maritime knowledge, traditions and experiences. I am also the descendant of voluntary migrants—Cape Verdean mariners who came to the Dawnland and established lives, and who themselves had to accommodate the US’s framing of “race.” I work with and within Dawnland Indigenous and African descendant communities to tell our Indigenous and Black maritime histories through our own voices and the voices of our ancestors to provide insight into the legacies, strength and resilience of the sovereign Indigenous nations and African-descended peoples of the Dawnland. My training as an anthropologist and archaeologist on the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Reservation, my spiritual training in Benin on the shores of West Africa (no doubt, the point of no return for many of my collateral ancestors), and my work among Rastafarians on the shores of the US Virgin Islands have given me the knowledge— both personally and professionally—that I must tell these histories in a way my ancestors would tell them, to acknowledge the perspectives of my ancestors and to honor them. As a scholar, with all I have been given, I must reclaim my place in the sea and its tributaries for myself and my ancestors.

I will share some knowledge about this maritime history that has been shared with me (knowledge that I have permission to share) from African, African American and Indigenous community members. Of course, the Indigenous stories are not mine. They are histories that have been told to me for the purpose of sharing and education. And I have been entrusted to relay these stories truthfully, respectfully, and sensitively, with humility and in friendship.

It feels odd to say as a scholar and an academic, but I don’t have many answers—I’m simply learning to ask better questions. I have been taught

to explore this history and ask these questions with a humble heart and the wisdom that not all of the story is meant for me to know or to tell. Nonetheless, I think asking new questions is vitally important in reframing the way we do maritime history—or even what we mean when we say “maritime history.” How would you define “maritime history”? Would you include rivers? Marshes? Wetlands? Landscapes? The divinity and sacredness of water? Ancestral stories? The sovereignty of the ocean? If we are looking at maritime history and maritime stories through Indigenous American, African and African American lenses, we have to see all of the above as inextricable from how we define “maritime.” I am relatively new to the discipline and definitely got the sense when I started that for most, true maritime history is about “white men on big boats”1…but my own history and training outside of the field have led me to approach maritime history differently.

What if scholars changed the way we framed the accepted maritime narrative of the Dawnland and the primary narrative was one of millennia-old Dawnland maritime peoples encountering the descendants of the African continent and sharing their very similar, millennia-old maritime traditions? What if they focused on the centuries of collaboration and conflict between these maritime communities that have had to accommodate and survive through this 500-year cycle of disruption? Changing the narrative in this way wouldn’t be so different from what we (as a larger society) already do—the story we tell is that the founding begins in 1620 with the arrival of the Pilgrims— even though there were already sovereign nations present on the landscape and waterscape. As often happens in colonized lands, Indigenous presence on land and waterscapes prior to 1620 is generally framed as happening before the actual story starts. So, the beginning of the story depends on whose story we’re choosing to center. If we removed European “discovery” and colonization as the cen-

8 MAINSHEET PERSPECTIVE

tral narrative in “American” maritime history, we can start to explore African-Indigenous encounters and connections in more meaningful ways and as a primary narrative—including themes like use of environment, different knowledges and sciences, cosmology, spirituality and maritime histories and experiences—really, a new, more holistic epistemology.

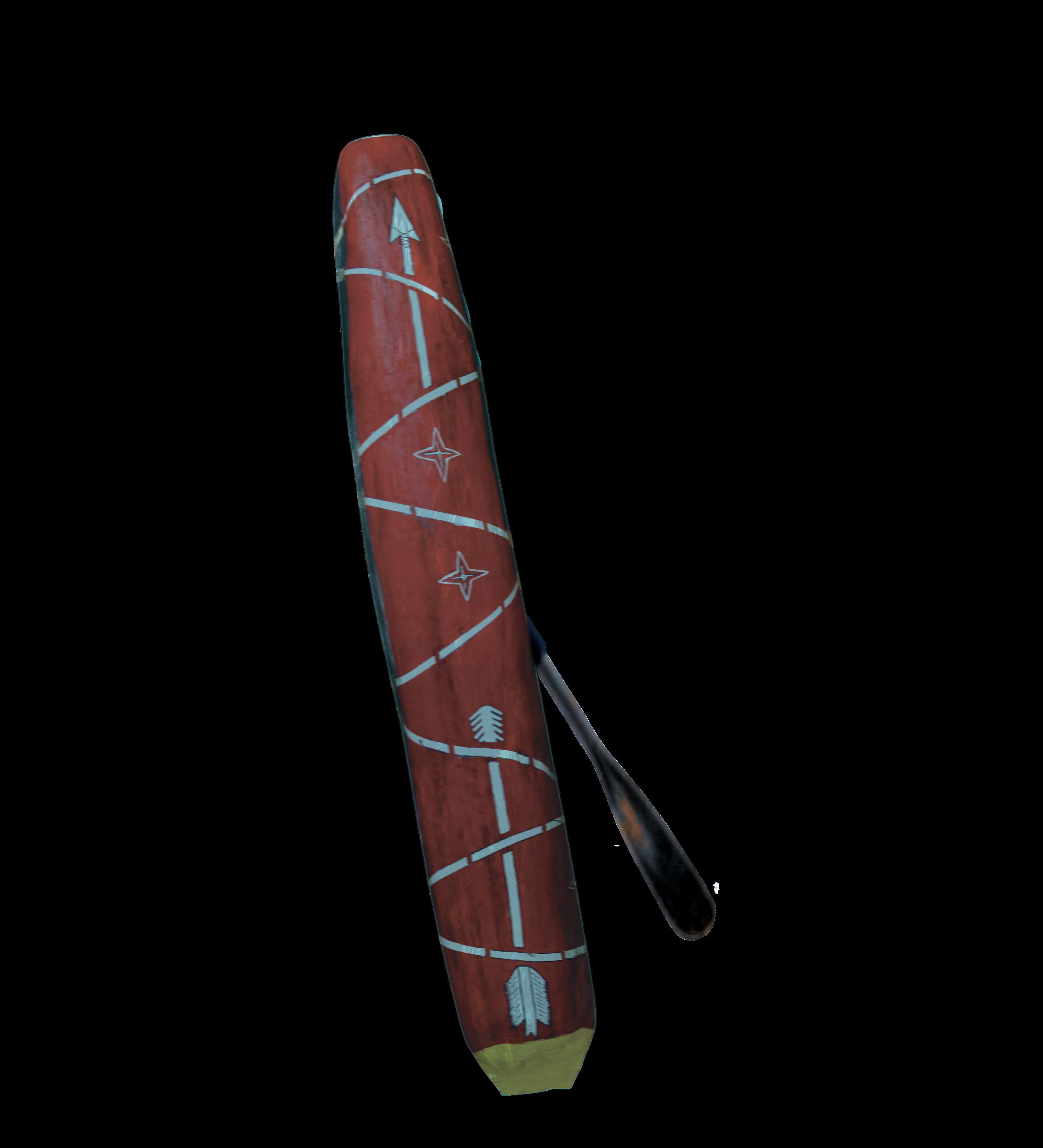

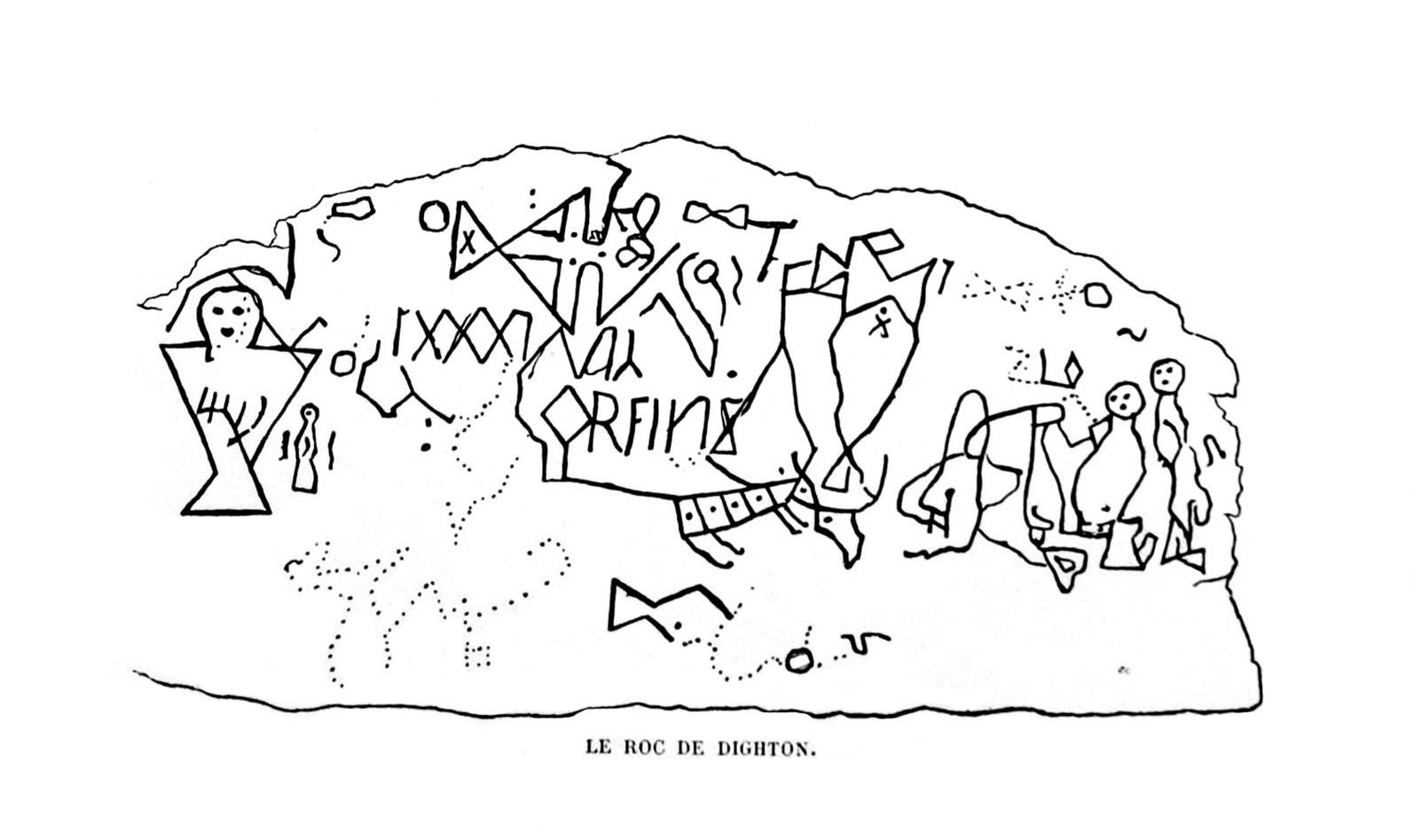

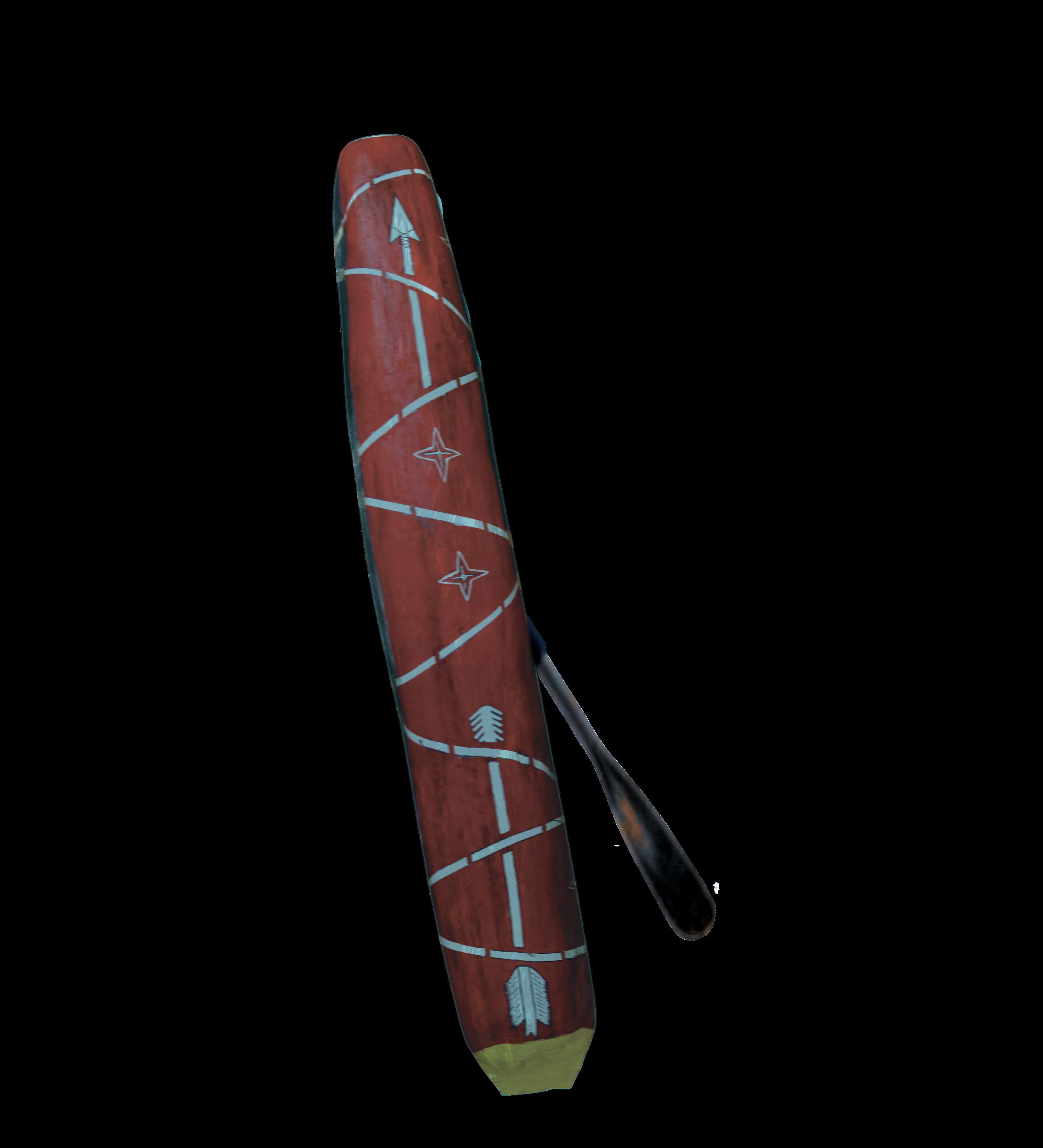

We might ask new questions about watercraft. Maritime communities in the Dawnland—for example, nations such as the Pequot, Narragansett, Nipmuc, Wampanoag and others built muhshoons/mishoons (dugout canoes). In the Dawnland and throughout sub-Saharan Africa, dugout canoes were used for fishing, maintaining community connections and for trade along the coasts and on rivers. Throughout Africa, they were also used for naval battles and long-distance travel (the river system on the continent spans from the west coast to the Sudan) and there was a distinction between those who used canoes to travel the open seas and those who navigated rivers in canoes. There are early Portuguese accounts of Senegalese fishermen who “fished up to three, four and five leagues to sea…and were expert and able swimmers and divers.”2 Some West African canoes were quite large and could carry up to 120 men, had cooking hearths, storage for sleeping mats and contained forecastles. They had the ability to carry heavy cargoes. Some were also recorded as having sails.3 Rivers connected inland communities with coastal people, and canoes were also used to navigate up and down the coast—from the Gold Coast to Angola (Figure 1). Throughout the continent, Africans utilized riverine and coastal routes for trade and warfare from Sudan to the Atlantic.

It is intriguing to think about how these existing Indigenous and African skill sets were incorporated into Euro-American boat building and navigation techniques…and we do know from the history of Southern plantations and from communities like the Wampanoag that they were. We also know that enslaved Africans were often employed

in boat construction all along the East Coast and throughout the Caribbean.

We can imagine Africans encountering the Indigenous peoples of the Dawnland and seeing that they often created watercraft using the same methods; that they used a similar selection process for the wood, and they constructed their watercraft in a very similar way—by burning them out. An early description of the construction of an African canoe by a European observer could very well have also been a description of the burning out of a muhshoon/mishoon:

They are made all in one piece, from a single tree trunk…They round off the trunk at each end, then dig it out with an iron tool4...[they] then burn straw in the hollow, in order to prevent the sun from splitting the boat or worms from entering.5

When the Trunk of the Tree is cut to the Length they design, they hollow it as much as they can with these crooked knives, and they burn it out by Degrees until it is reduced to the intended Cavity and Thickness, which they then Scrape and Plane with other small tools of their Invention, both within and without, leaving it sufficient Thickness, so as not to Split when loaded. The Bottom is made almost flat, and the sides somewhat rounded, so that it is always narrower, just at the Top, and bellies out a little lower, that it may carry more Sail. The Head and Stern are raised long, and somewhat hooked, very sharp at the End, that several men may lift them on Occasion, to lay it up ashore and turn it upside down, so that they make it as light as possible.6

On sea-going canoes, the sides are propped up by wooden posts because to [sic] prevent the wood from expanding. Riverine and lagoon watercraft are allowed to expand.7

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 9 PERSPECTIVE

Throughout the African continent, canoe-builders are considered almost religious leaders.8 Africans, early African-descended peoples in the Dawnland and Indigenous people in the Dawnland had the same personal and spiritual connection with their watercraft and conceived of the universe in similar, holistic ways. How did this contribute to free and enslaved Africans’ choices and desires to live in and marry into Indigenous communities? Was Indigenous spirituality and maritime perspective a means of maintaining their Africanness and their existing worldview? These were two maritime cultures that existed before “America,” and both were dealing with dispossession and enslavement at the hands of Europeans and later Euro-Americans. Conceiving of connections like these can help us rethink the many ways “free and enslaved Africans found respect, spirituality and safety in Native communities”9 and maintained their existing maritime traditions.

As mentioned, Black and Indigenous relationships with the sea and its tributaries predate “America.” There were knowledges of water, waterways, waterscapes and water divinities. On each side of the Atlantic, both Africans and Indigenous North Americans depended on deep knowledge of the sea and tributaries as fluctuating, cyclical ecozones, and they relied upon the sea and travel by water for sustenance, trade, and maintaining community and kinship. In many Dawnland creation narratives, people’s origins are in the marshes and the ocean is a divine and sovereign entity in and of itself.

In thinking about these maritime connections between sub-Saharan Africa and the Dawnland, it is also important to point out similarity with regard to worldview and feelings about the water that would have been a major point of connection between the two geographic locations (the African continent and the Dawnland)—and it is intriguing to think of how this may have played a role in BIPOC (Black and Indigenous People of Color)

identities, participation, experiences and perspectives when large numbers of Black and Indigenous men engaged in whaling and maritime trade.

Maritime scholars have not traditionally asked questions about the impact of traditional African-descended and Indigenous worldviews and how they informed maritime experiences for men of color. For example, among communities in Indigenous Nations of the Northeast, the (under) water world represented both spiritual power, history, and liminal status (being betwixt and between). Wampum, which comes from the quahog shell, has a special significance, in part, because of these associations. I came across beliefs about the sacredness of the ocean and the underwater world in a cemetery analysis I did many years ago as an archaeologist looking at who was buried with what in a mid-18th-century New England Indigenous burial ground. This was a cemetery that had to be removed and reburied/repatriated/rematriated because it was discovered on someone’s private property, and the work was done under the supervision of the tribe whose ancestors were in the cemetery. Upon analysis of the belongings interred in graves, it was clear that only a certain age group was buried with wampum. It was an age group that could be considered “liminal” with one foot grounded in this world and one in the spirit world. No one else in the cemetery was buried with wampum.

I highlight these meanings and uses of wampum as an aside, so that we can start to think about what non-Indigenous scholars and institutions (such as museums) must include in considering Indigenous maritime histories and narratives. These beliefs are also evident in stories of Maushop, the benevolent giant who creates waterscapes and landscapes and nourishes people with the bounty of the sea. There are many other Indigenous maritime histories that have been reduced to “myths” and have been invalidated by scholars and non-Indigenous people. These Indige-

10 MAINSHEET

PERSPECTIVE

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 11 PERSPECTIVE

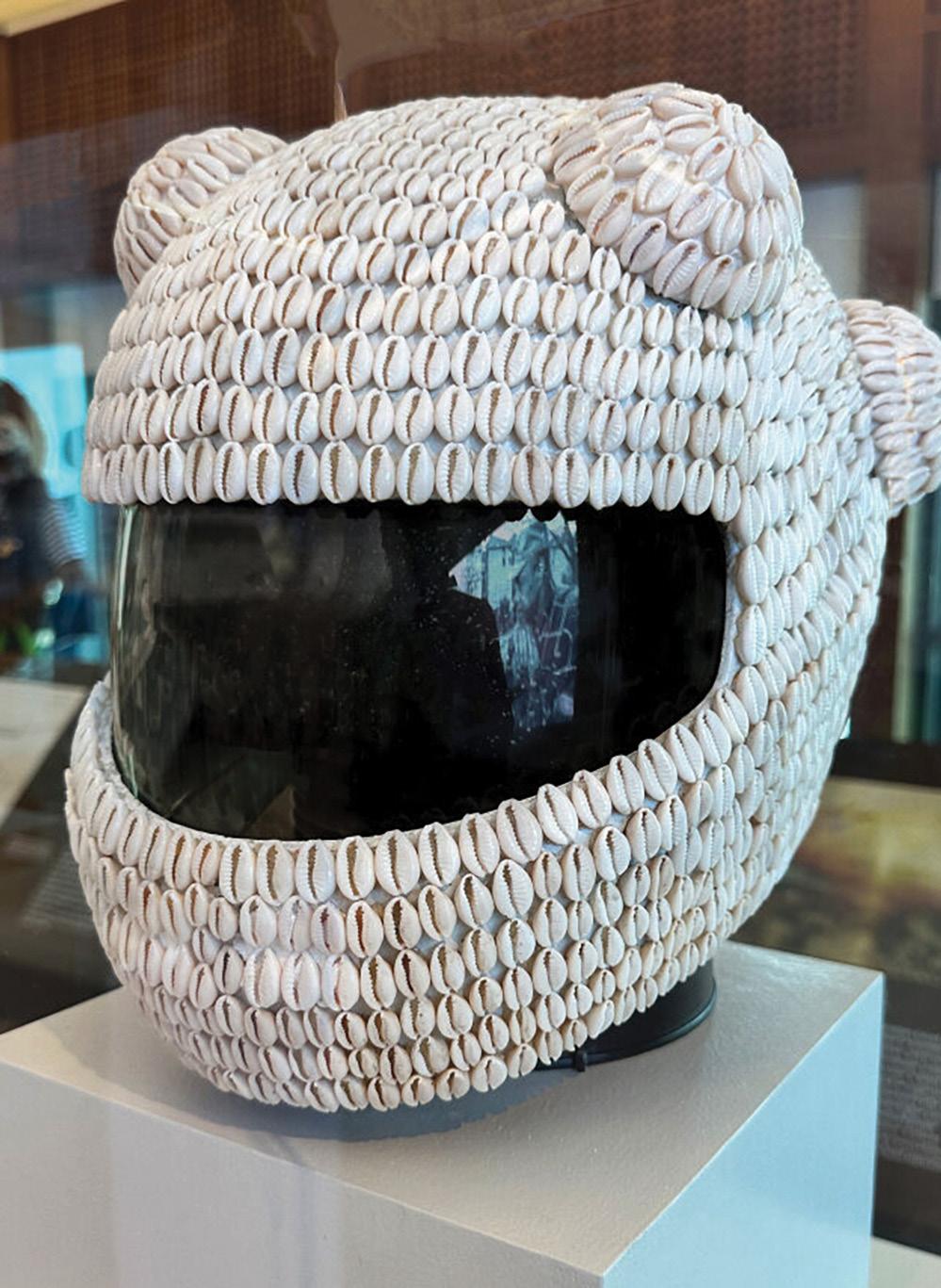

Figure 2. An African figurine representing Mami Wata, from the collection of Kevin Dawson. Photograph by Matteo Dawson

Figure 3. Cowrie shell transported from West Africa by an enslaved individual, discovered beneath an attic floorboard in Newport, Rhode Island. The shell was part of a bundle presumably created for prayer and to accompany its creator home when they crossed the waters. Courtesy of the Newport Historical Society

nous stories are present, valid, relevant and contain a wealth of traditional ecological knowledge—a holistic perspective that includes science, history, creation and the other disciplines that scholars tend to treat as distinct and separate. This knowledge has always sustained and continues to sustain the people of the Dawnland through the present. If this holistic and spiritual lens is how Indigenous people of the Dawnland conceive of materials from the water, envision the sea, and define water in general, it is an important component of telling a holistic maritime narrative if non-Indigenous scholars wish to do a new maritime history that is truly told through Indigenous voices.

The people who were enslaved and brought from the African continent to the Dawnland were sometimes coastal and often riverine maritime peoples. On both sides of the Atlantic, there were fishing communities and boat-building traditions. There were also surfing traditions on both coasts of the African continent. Fishing trips would often end in canoe surfing races. It amazed European observers that no one ever drowned10—because most Europeans could not swim, let alone surf. There were also deep-water diving traditions and other highly skilled maritime practices that were transported to the Americas along with the bodies of the enslaved, such as shark hunting11 and other skills detailed in studies such as Kevin Dawson's Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora (2018)

Both Africans and Indigenous North Americans conceptualized (and conceptualize) waterscapes as seamless intersections of land and water that create social, cultural, and spiritual understandings. Water is the source of human life and a life-force that sustains us, physically and spiritually. We know that these beliefs were transported from West, Central and Southern Africa when we hear Southern Black American folklore about “Simbi [also spelled Cymbee] spirits.” Simbi:

are water spirits that hail from western and central Africa. They live in unusual rocks, gullies, streams, springs, waterfalls, sinkholes, and pools, which areas they effectively “adopt” as territorial guardians. The Simbi are said to be able to influence the fertility and well-being of people living in their territory. At the same time, they can and will cause trouble if they are not treated with respect.12

Ras Michael Brown argues that these spirits allowed Africans who were strangers to the area and lacked ties with named ancestors to still have access to the agents of otherworldly powers and to feel attached to the land where they lived. These spirits were on the land and waterscapes “regardless of what inhabitants already occupied those lands and waters and what these indigenes called the spirits found there.”13 In the Dawnland, this may have again created a context within which, “free and enslaved Africans found respect, spirituality and safety in Native communities”14 through similar spiritual connections to land- and waterscapes.

Similar to Dawnland Indigenous knowledge about (under)water worlds and the spiritual significance of bodies of water, throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa and most notably the Kongo regions, the world under the waters is the land of the dead/spirits/ancestors. Stories of Mami Wata, the “mermaid” (the Mother of the fishes, the Mother of us all) encapsulate an African knowledge of the sea as divine, feminine space (Figure 2). The Mende describe death as “crossing the waters” and we see this sentiment repeated through the present day in the story of Ibo Landing, in which enslaved individuals walked off the slave ship in chains, turned around and walked into the water. Historians have interpreted Ibo Landing as a “mass suicide” but African descendants describe it as “flying home” or “crossing the waters.” And finally, although most enslaved African descendants in the

12 MAINSHEET PERSPECTIVE

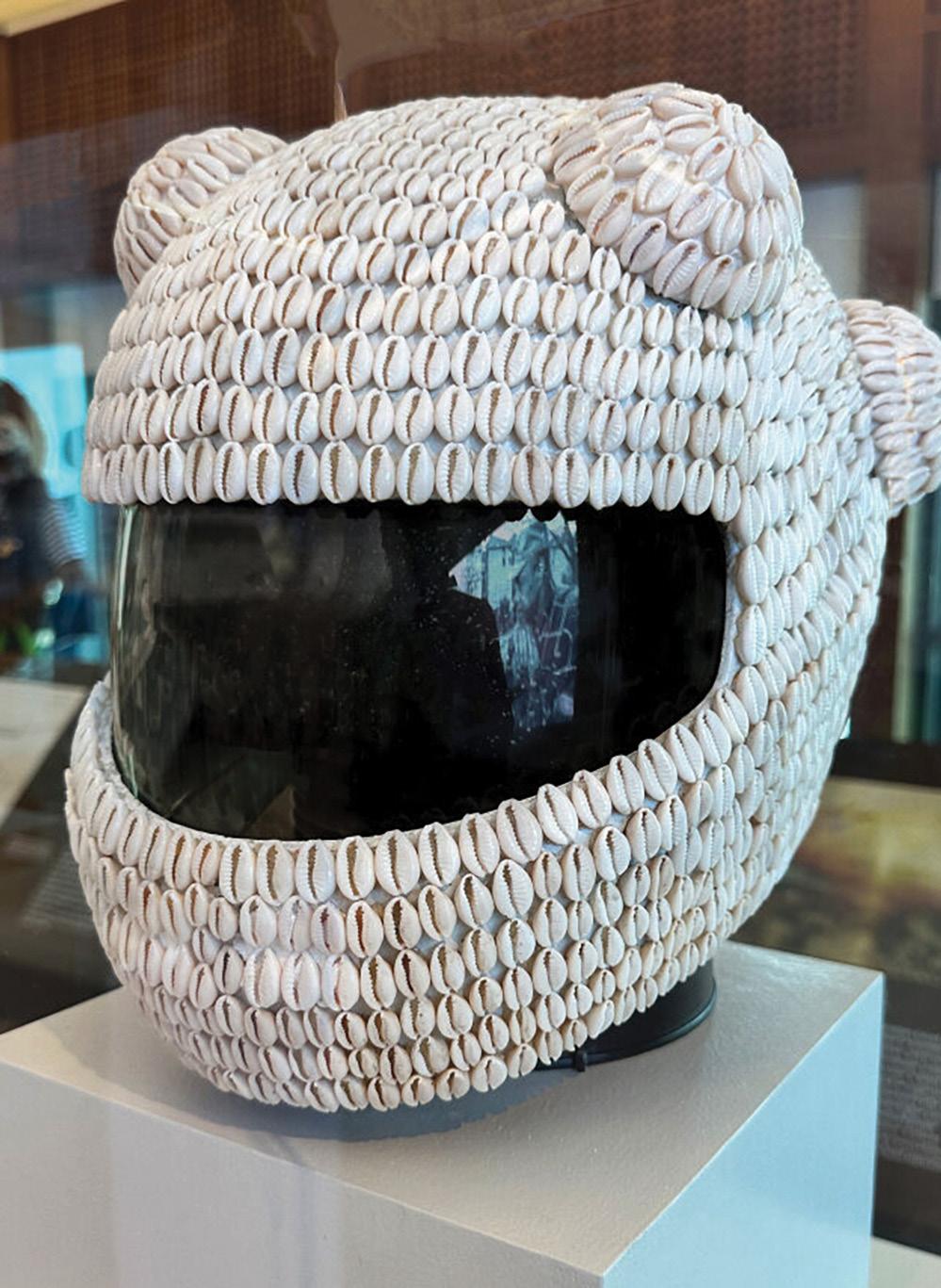

Dawnland were instructed in Christianity, there is evidence from Newport, Rhode Island and Deerfield, Massachusetts that the enslaved maintained their African spiritualities and practices (though hidden) with regard to water by gathering and maintaining nkisi bundles15 that contained shells, broken glass, nails, bones and other materials so that they would have these bundles to bring back home with them when they crossed the waters (Figure 3).

With regard to “conversion” to Christianity, it is important to consider how Africans and Indigenous peoples of the Dawnland were able to thread enforced concepts of Christianity into existing worldviews and maintain their spirituality (for the purposes of this conversation, specifi-

cally regarding beliefs about water). Maintaining African spirituality and community are not as apparent in New England as they are in the Southern United States or in the Caribbean (in practices like Vodoun or Santería), but we have rarely asked these questions beyond simply looking for “Africanisms” or “retentions.” For example, scholars and people of African descent who are far removed from African systems of meaning (because of time and disruption) can ask about meaning systems for enslaved Africans in the Dawnland when they were introduced to the Virgin Mary (the name Mary, which also literally means “the sea” and is whom seafarers pray to for safety at sea). Was Mary a common-sense representation of Mami Wata for African descendants in the Dawnland?

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 13

PERSPECTIVE

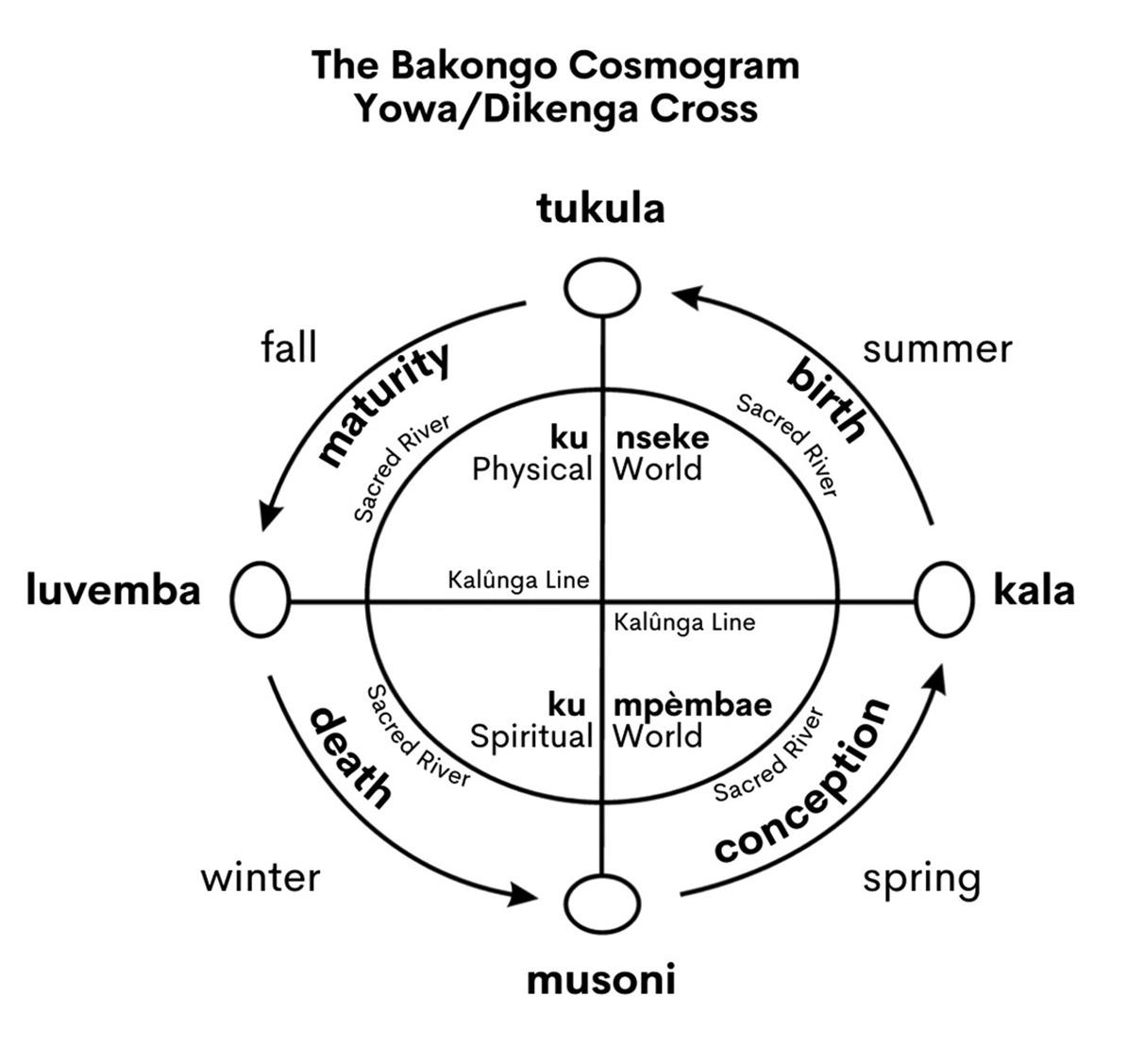

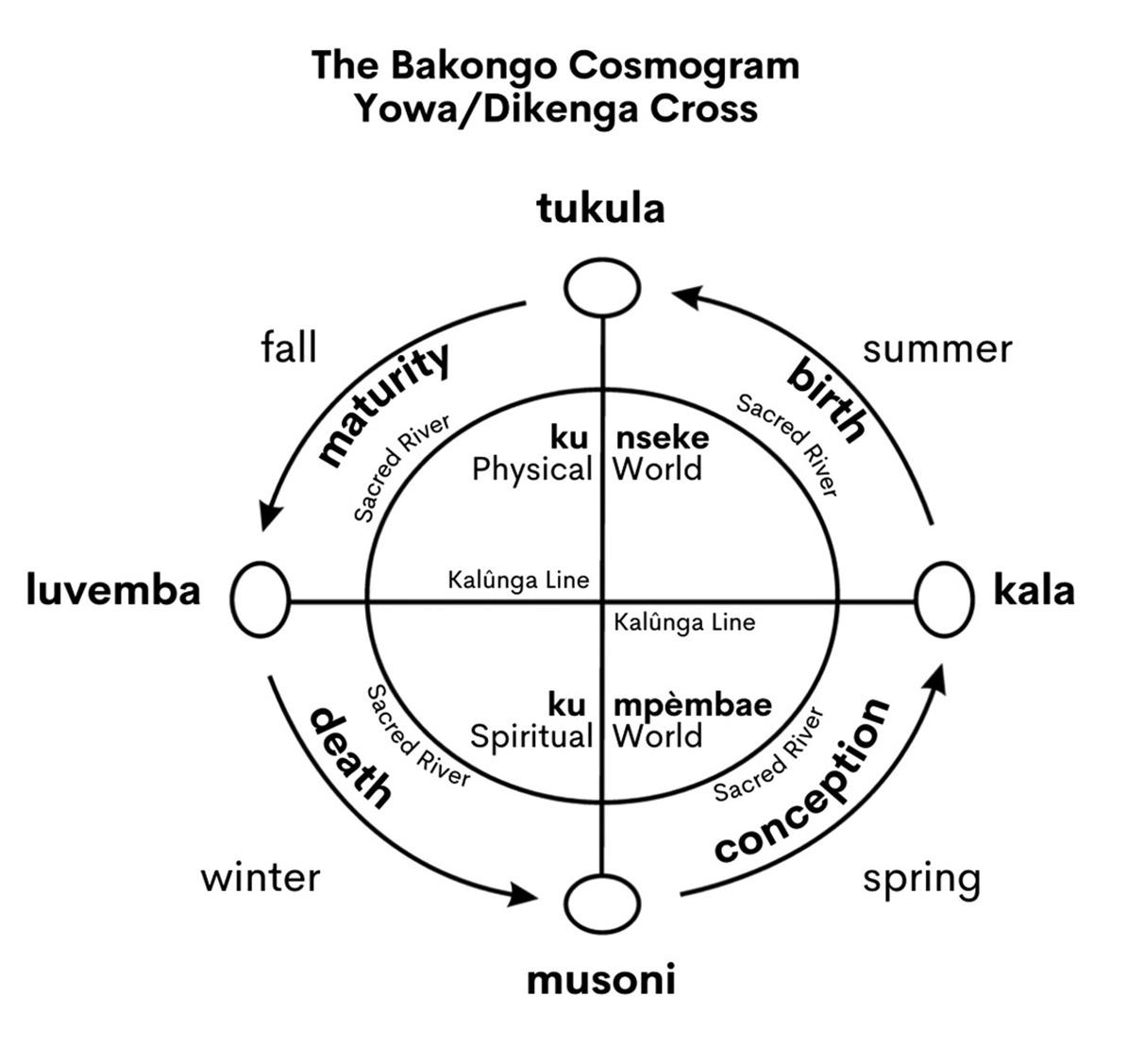

Figure 4. The Bakongo Cosmogram. Image by MiddleAfrica, CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kongo_Cosmogram_01.png

This representation of or exchange of imagery of Mary for Mami Wata is very visible in contemporary spiritual practice throughout the Caribbean and South America, where African belief and practice were kept out of sight through the use of Christian iconography like Mary to maintain spiritual and cultural practice.16

The Bakongo Cosmogram (a symbol of the interpretation of the universe in many traditional African religions) is a circle (representing eternal cycles of life, death and rebirth) surrounding a cross (Figure 4). The horizontal line on the cross is the kalunga, the watery threshold between the world of the “living” and the world of the ancestors and spirits. Would enslaved African-descended peoples in the Dawnland have seen and acknowledged the Christian cross and the story of resurrection in their own cosmogram and the (under)water world? Through hermeneutics and questioning how cultural and religious iconography would have been given meaning by enslaved peoples accommodating new, imposed worldviews, we all might come to understand how African-descended maritime peoples of the Dawnland sustained (and are currently reclaiming) their relationship to the seas.

For enslaved Africans then and both Indigenous and African-descended people now, the sea is fraught. There’s a duality—the same sea that was benevolent and sustained kin and community for millennia became the means by which people were enslaved, and lost communities and ancestral ties to the land; it was also the means by which colonizers came and brought disease and dispossession. And then that sea became one of the few avenues by which Black and Indigenous men could make a living and sustain their families, communities, and tribal nations.

There are many Indigenous, African, and African-descended individuals whose stories represent the complexities and contradictions of race and racism after the disruptions of colonialism and within our traditionally told maritime heri-

tage. We can see these contradictions in individual Indigenous and Black narratives of maritime life. For example, many men of color made their fortunes at sea. And, while the sea and river networks were the paths of enslavement, numbers of enslaved men and women alike also escaped their enslavement by sea—a much safer path to freedom than the terrestrial Underground Railroad.17 Again, utilizing hermeneutics, or the meanings people assign to things, we can explore whether this escape by water was seen by some through the lens of the spiritual power of water and the power of the ancestors beneath. And if we think about men like Venture Smith and Paul Cuffe, who made their fortunes at sea and in maritime-related trades, even though they lived steeped in racism and inequality and had to look at the enslavement of men and women who looked just like them. How did their African identities and knowledges shape and define Smith’s and Cuffe’s relationship with the water? Venture Smith was enslaved and taken from West Africa at the age of eight. By that time, he would have been well versed in the power of ancestors and the power of the sea. Paul Cuffe’s father was West African and his mother was Wampanoag. He undoubtedly grew up learning about the power of the sea, the power of ancestors and the sea as a sovereign entity. There are also numerous stories of Black women who maintained households and communities in port towns and stories of Indigenous women like Hannah Miller, a Pequot woman who acted as community leaders while the majority of men in their communities were out to sea.

We should all continue to explore the nature of the sea and waterways as a double-edged sword for Indigenous and Black peoples after colonial disruption—on the one hand, representing creation, divinity, ancestors, power, strength and agency, freedom and integration…and on the other hand a place of enslavement, trauma and death. Very appropriately, according to both Dawnland Indig-

14 MAINSHEET

PERSPECTIVE

enous and African wisdom, this framing is fitting—as water and the ocean itself are places of birth, death, and rebirth.

Maritime social histories can make a strong argument that the complex narratives of the modern world are rooted in maritime histories—but we cannot begin the telling of these histories at the point of colonial enterprise. We cannot begin to understand our world and our humanity (let alone the development of the modern world system) without understanding how waterways have shaped human interactions and human relationships from time immemorial. And non-BIPOC scholars cannot continue to force global maritime narratives into a Western frame. Doing so is a disservice to individuals and communities whose maritime histories we tell and is a greater disservice to the discipline.

As a “conclusion” and an aside, it is worth noting that when I asked a colleague, Bridget Hall, to review a draft of this article for flow and grammatical errors, etc., she responded that my use of “our” and “we” was very confusing. It wasn’t entirely clear to her when I meant “our” and “we” speaking as a person of African descent and embedded in African spirituality, and when I meant “our” and “we” speaking as a scholar of this maritime history. I hope that the issue has been clarified for the reader. But ultimately, the confusion is in part because I am not always clear on when I am acting as one or the other. I sometimes do not know when I should act as one or the other. Or perhaps the significance of this article is in pointing out the larger problem—that there is a distinction between one and the other.

Endnotes

1 At the end of the 2022 Frank C. Munson Institute of American Maritime History, one of the fellows stated to me that this was the first time they, as a maritime scholar, had thought about maritime history “beyond white men on big boats.”

2 Robert Smith, “The Canoe in West African History,” The Journal of African History 11, no. 4 (1970): 516.

3 Ibid., 518; Lynn B. Harris, “From African Canoe to Plantation Crew: Tracing Maritime Memory and Legacy,” Coriolis 4, no. 2 (2013): 35-52

4 In the Dawnland it would have been stone.

5 Kwamina B. Dickson, A Historical Geography of Ghana (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 297.

6 Thomas Astley, A New General Collection of Voyages and Travels: Consisting of the Most Esteemed Relations Which Have Been Hitherto Published in Any Language, Comprehending Everything Remarkable in Its Kind in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, vol. 3 (London: Printed for T. Astley, 1745), 650.

7 Smith, “The Canoe,” 520.

8 Harris, “From African Canoe," 43; Kevin Dawson, “Liquid Motion: Reimaging Maritime History through an African Lens," in this issue, 16–37.

9 Jonathan James Perry, Aquinnah Wampanoag, personal communication, January 6, 2022.

10 Harris, “From African Canoe,” 38.

11 John Lawson, A New Voyage to South Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1967), 140.

12 Natalie Adams, “The ‘Cymbee’ Water Spirits of St. John’s Berkeley,” African Diaspora Archaeology Network Newsletter, June 2007, 10.

13 Ras Michael Brown, African Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Low Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 91.

14 Jonathan James Perry, Aquinnah Wampanoag, personal communication, January 6, 2022.

15 One bundle was discovered under an attic floorboard of a colonial home in Newport, Rhode Island. And there is a description of Jinny Cole, a woman enslaved by Deerfield’s Minister, Jonathan Ashley, collecting and maintaining items for a bundle and then passing the tradition down to her own son.

16 See Alison Glassie, “Our Lady of the Workboats: Solidarity and Spirituality on the Bay of All Saints," in this issue, 42–59.

17 See, for example, Timothy D. Walker, ed., Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2021).

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 15

PERSPECTIVE

16 MAINSHEET PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

Figure 1. African brass figurine of Mami Wata. Unlike many other representations of her, she is shown here in her human form. She is sitting on another half woman, half fish. From the author’s personal collection, photograph by Matteo Dawson

Liquid Motion: Reimaging Maritime History through an African Lens

Corresponding Author: Kevin Dawson, Department of History & Critical Race and Ethnic Studies, University of California, Merced, kdawson4@ucmerced.edu

Abstract

“Liquid Motion” examines how African women and men perceived, understood, and interacted with oceans and rivers through swimming, underwater diving, surfing, canoe-making, and canoeing. Africans inspire us to rethink assumptions about maritime history, by considering maritime traditions absent in the Western lexicon, like harnessing wave energy to transport goods through the surf or swimming into the depths to salvage goods from shipwrecks or harvest pearl oysters. Enslaved Africans carried these traditions to the Americas, where they used them to benefit their exploited lives and enslavers exploited them to generate wealth.

Keywords

African diaspora, aquatics, dugout canoe, surf-port, surf-canoe, swimming

Submitted May 25, 2023 | Accepted July 13, 2023

Liquid Motion: Reimaging Maritime History Through an African Lens © 2023 by Kevin Dawson is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 17

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

Introduction

Atlantic Africans have cultivated maritime traditions on rivers and seas since the Neolithic age. Extending from Senegal in the north to Angola in the south, Atlantic Africa is embraced by the Niger River in the northwest, the Congo plunges through its southern heart, while numerous other rivers plunge through its expanse. Most Africans live near navigable waterways. Atlantic Africans did not just live along freshwater and saltwater, they were water-facing people who actively engaged with water to create “human shores.”1 Atlantic Africans seamlessly merged land and water into waterscapes, creating places of meaning and belonging as they crafted aquatic traditions in coastal plains, rainforests, savannahs, and Sahel to understand their diverse hydrographies—marine geography and how tides, currents, and winds inform navigation. Aquatics set African humanity in liquid motion through intimate, daily immersionary engagements with water while swimming, underwater diving, surfing, canoe-making, canoeing, and fishing. Many people were fishing-farmers who fished one season, farmed another, and used dugout canoes to transport goods to market, interlacing spiritual and secular beliefs, economies, social structures, political institutions—their very way of life—around relationships with water.

Most of the enslaved people forcibly transported to the new world2 were from Atlantic Africa. Enslaved Africans recreated and reimagined relationships with waterscapes to maintain cultural ties with home communities, while forging new communities of belonging that provided their exploited

lives with a sense of meaning, purpose, and belonging. Many employed aquatics in attempts to realign their stars, stealing their bodies and dugouts in attempts to regain ancestral waters. While there were ethnically specific traditions, many practices transcended ethnic differences, enabling us to consider the shared ways in which African-descended people were not just on the water, but in the water and of the water.

Africans unsettle assumptions about maritime history and Western maritime supremacy, inspiring us to rethink traditional approaches that center men, ships, and seaports. During an age when most white people were not proficient swimmers, African-descended women and men swam and dove into the depths for work and recreation. Unlike white women, African women were not precluded from aquatic activities, enabling many to pursue lucrative occupations.

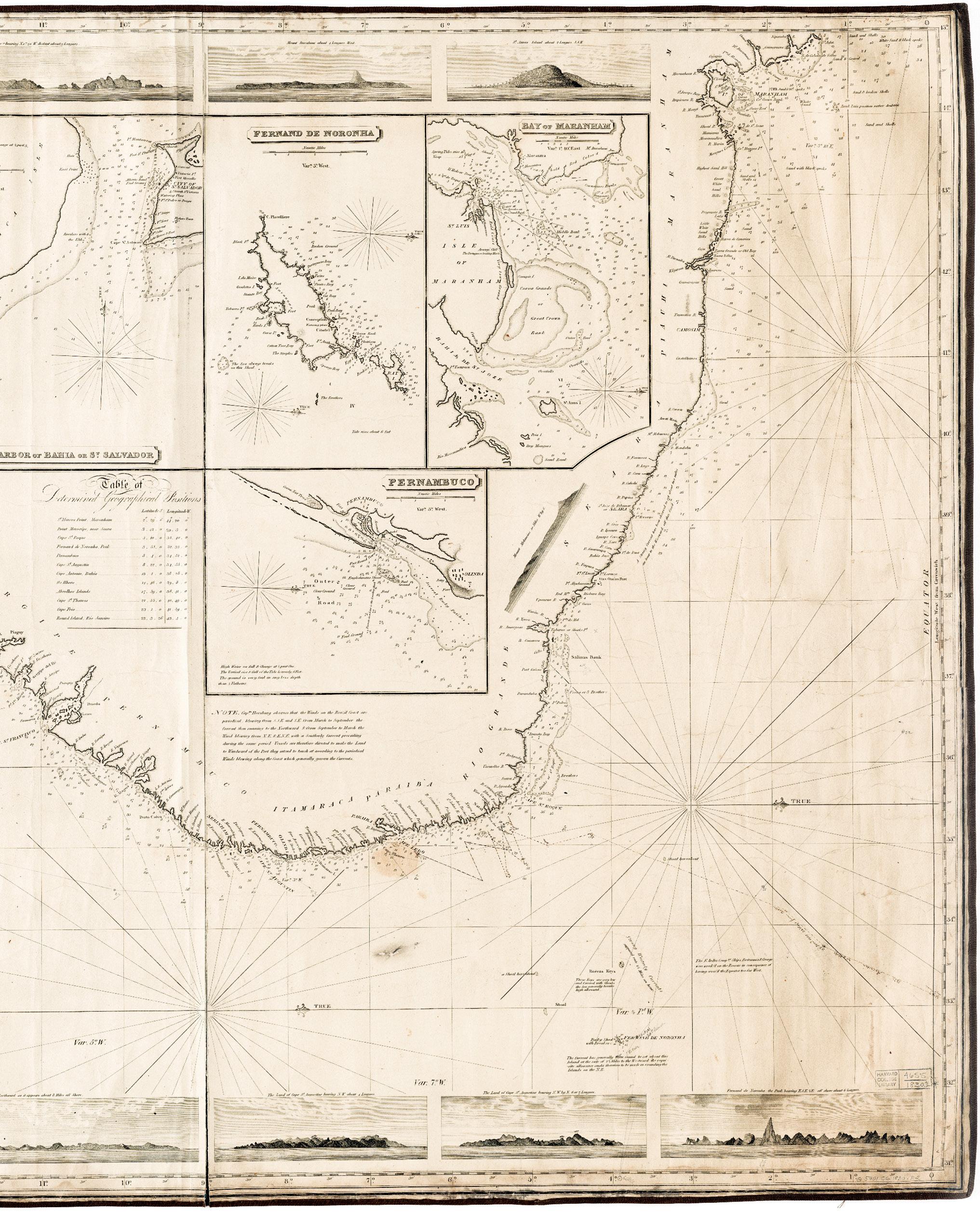

Atlantic Africans require us to reconsider seaports and how they were accessed. While Africa is four times larger than Europe, its coastline is shorter (18,950 miles or 30,500 km long, compared to Europe’s 24,000 miles or 38,000 km) because it has few natural harbors, inlets, bays, or gulfs.3 Surf breaks upon most of its shores. Thus, mariners had to cross surf-zones—that space where waves break—to go from shore to sea, developing surf-canoes and surf-ports as environmental solutions. Dugouts were ubiquitous throughout the world, with Amerindians, Oceanians, Indigenous Australians, and Europeans developing designs to meet environmental challenges and particular uses. Africans charted unique designs for equally

18 MAINSHEET

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

unique uses. Responding to environmental challenges, Africans designed surf-canoes, which were, and remain, singular in their ability to slide over and slice through waves when launching into the sea and surf waves ashore while loaded with several tons of cargo. They simultaneously imagined surf-ports. Surf-ports are ports that lack harbors— providing all the same shipping, storage, and distribution functions as a seaport but requiring people to pass through surf-zones to reach offshore fisheries, shipping lanes, and, with the eventual arrival of Europeans, ships.

Surf-canoes and surf-ports were central, though typically overlooked, components of the Atlantic trade system. Exports like gold, ivory, palm oil, timber (mahogany, ebony, teak), malaguette pepper, and violently enslaved African bodies, were important commodities. The Atlantic slave trade was the most lucrative sector of this commercial complex, while enslaved labor drove colonization and plantation slavery. Most goods exported out of and into Africa from the fifteenth century through the 1950s, when seaports were constructed, were lightered between ship and shore in surf-canoes.4 Slave-trading records suggest that probably eight to nine million of the twelve million people funneled into the Atlantic slave trade were taken from surf-ports to slave ships in surf-canoes, punctuating their central functions in overseas commerce, colonization, and the development of new world slavery.5

Unfortunately, assumptions pivoting around notions of race, civilization, and modernity have discouraged sustained scholarly analyses of African maritime traditions. Erik Gilbert, a maritime historian of East Africa and the Indian Ocean, explained that many scholars bind themselves to the “tacit belief in the triumph of modernity over tradition,” assuming Western vessels were superior to those of non-Western people.6 Such assumptions prompted generations of twentieth-century scholars to ignore sub-Saharan African maritime traditions, relegat-

ing them as primitive and unworthy of scholarly deliberation. Discussions of African maritime history were dismissive, as epitomized by an influential anthropologist in 1966, who, after examining one French document, concluded that Africans only engaged in “subsistence fishing.”7 Similarly, early twentieth-century misconceptions that Africans were uncivilized and offered nothing of value or merit to the rest of the world long discouraged the study of African-descended peoples, especially their accomplishments. In 1918, a leading American historian, who continues to inform the field, claimed the Atlantic slave trade and slavery rescued captives from Africans’ savagery by civilizing and Christianizing them, averring that Southern “plantations were the best school yet invented for the mass training of . . . backward people.”8 While such assertions plunged African maritime history into an intellectual abyss, it is ready for exploration.9

Canoes and Wet Bodies: Experiencing African Waterscapes

Built by Africans for at least 8,000 years, dugout canoes epitomize the conjoining of aquatic and terrestrial spaces.10 They were more than material objects. They were living entities that embodied and expressed generational wisdom; charted community expertise; and were engrained with cultural, spiritual, and social meaning. Canoes were companions, collaborators, and members of communities of belonging, transporting canoeists safely across liquid expanses, returning them home with fish and incomes.11 Canoe-making was a widely held skill. Non-professionals made smaller dugouts, while professionals crafted war and merchant canoes that could be over 120 feet long and carry over 100 people. Professional canoe-making was widely regarded as a sacred vocation, as reflected in the Senegambia proverb: “The blood of kings and the tears of the canoe-maker are sacred things which must not touch the ground.”12 A canoe’s worth was not solely measured by construction

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 19

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

costs, but by its ability to safeguard mariners and embody community valuations.13

Dugouts were versatile vessels, with their shallow draft (the distance a boat descends beneath the waterline) enabling them to navigate waters one foot deep while carrying several times their own weight. Unlike Western framed boats, dugouts will not sink, even when filled with water. Design nuances enabled them to better negotiate particular waterways while performing specific functions, like fishing, shell-fishing, transporting cargo, and waging war. There were probably several thousand types of dugouts, with each ethnic group assigning discrete names to the various dugouts they crafted.

Canoes were, and still largely are, hallowed objects. Most were carved from sacred silk-cottonwood trees, as they are widely distributed throughout tropical Africa and their timber is resistant to rot and bug infestation. Other trees were used in regions where cottonwoods did not grow. Over one hundred feet tall, cottonwoods had a soul and they connected heavens, earth, and water. Their spreading branches and buttress roots embraced the sky and earth; thus dugouts made from cottonwoods coupled the here-and-now to the spirit world. The souls of generations waiting to be born resided in their trunks, as Chinua Achebe expressed in his fictional representation of Ibo life in Nigeria: “the spirit of good children waiting to be born lived in a big ancient and sacred silk-cotton tree located in the village square. So women who desire children go to sit under its shadow so as to be blessed with children.”14 Members of many ethnic groups performed spiritual ceremonies beneath their spreading branches. For instance, cottonwoods and canoes figured prominently in initiation ceremonies that transitioned children into adulthood at the Bullom/Sherbro village of Thoma in Sierra Leone. During rites of passage, the spirit of the sacred grove gave birth to new adults. Cottonwood leaves were used to produce a gelat-

inous substance simulating afterbirth, which was rubbed upon initiates. As the forest birthed inductees, community members “beat on the ‘belly’ of the forest spirit (beat on buttress roots of the cotton tree or an up-turned canoe), announcing its labour has begun.”15

Canoes had a gender that determined how they rode, while the souls of the trees that dugouts were carved from continued to reside in their hull.16

Canoemen formed bonds with dugouts, performing welcoming ceremonies that included placing offerings on the bow of newly purchased canoes and calling them “bride” to symbolize symbiotic relationships. Well-treated canoes guided fisherwomen and -men to shoals of fish and merchants on safe passages. Charms were placed inside the hull, while elaborate figureheads and spiritual motifs, carved in high and low relief, articulated canoes’ relationships with water and the spirits residing therein.17

Water was a sacred space populated by deities and spirits whose voices were heard in the sound of moving water. People from Senegal to South Africa and as far inland as Mali believed in deities who were half woman, half fish, with Mami Wata being the most celebrated of these finned divinities. Shape-shifting between a woman and half woman, half fish, Mami Wata embodied dangers and desires while slipping between discrete elements and circumstances: water and earth; the real and surreal (Figure 1). She safeguarded followers from drowning, rewarded them with success, and healed people of physical and spiritual maladies.18 Canoes communicated with the water and aquatic deities, with dugouts and spirits guiding mariners to schools of fish and safe passages.

Many believed the realm of the dead lay at the bottom of or across the ocean or a large river, lake, or lagoon. For Africans, life was cyclical, and water channeled one’s soul across the Kalunga, a permeable divide between the living and dead, to the supernatural world, where it was reunited

20 MAINSHEET

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

with ancestors waiting to be reborn.19 Members of several ethnic groups buried the dead with a miniature canoe to facilitate transmigratory voyages to home-waters, a tradition carried to the Americas. While enslaved in South Carolina during the early nineteenth century, Charles Ball helped an African-born father and American-born mother bury their young son. The father made “a miniature canoe, about a foot long, and a little paddle, (with which he said it would cross the ocean to his own country).”20

Africans’ bodies, like canoes, were living entities that possessed a soul and were enshrouded in spiritual and cultural meaning. People used aquatic fluencies to transform their bodies into watercraft, sculpting them just as canoe-makers carved dugouts, allowing people to enjoy and take pride in their wet bodies while connecting with deities in sacred waters. Bodies were gifts from the creator, muscularly accentuated through aquatics, while ritual scarification, applied during a rite of passage, consecrated and ornamented them to visibly express clan, lineage, and ethnic membership. Bodies were to be proudly displayed; thus semi-nudity and nudity in certain settings, including aquatics, was not stigmatized. Indeed, Shaka, ruler of the Zulu Kingdom, told an English merchant, “the first forefathers of the Europeans had bestowed on us many gifts . . . yet had kept from us the greatest of all gifts, such as a good black skin, for this does not necessitate the wearing of clothes.”21

Swimming was valued as a life-saving skill and a means of personal cleanliness, with many incorporating it into work and recreation.22 Parents began inculcating aquatics into children’s lives between the ages of ten months and three years, transforming waterways into safe play spaces.23 After teaching children the fundamentals, parents promoted expertise through play. Boyrereau Brinch, who was raised along the Niger River in what is now Mali, explained that the Bobo, a Mende people, held swimming in high regard,

saying his “father and mother delighted in my vivacity and agility.”24 Recognizing the dangers of gliding through this potentially deadly element, parents created charms to guard against drowning and marine creatures, with Brinch’s father giving him protective “ornaments,” while encouraging them to use buddy systems as they explored their liquid worlds.25

Africans’ bodies enabled many to descend over one hundred feet deep to harvest seabeds and riverbeds. Coastal and interior women and men gathered oysters for their meat, while shells were burned to produce lime for construction. Carpenter Rock, Sierra Leone was “celebrated for its excellent rock oysters, which are brought up in quantities by divers.”26 Scottish explorer Mungo Park documented interior Senegambian people’s aquatic proclivities during two overland treks (1795-1797 and 1805). For instance, near the Bambara capital, Segou, located over five hundred miles (800 km) inland, Park observed a fisherman dive underwater to set fish traps. His lung capacity permitted him to remain submerged “for such a length of time, that I thought he had actually drowned himself.”27 Peoples of the Upper Congo River were equally expert, with one explorer noting “[r]iverine people can remain under the water for a long time while attending their fish-nets, and this habit is gained from those infantile experiences.” Another observed ivory merchants hide tusks underwater to prevent theft, penning: “It was curious to see a native dive into the river and fetch up a big tusk from his watery cellar for sale,” requiring considerable ability since tusks could weigh over one hundred pounds.28 Asante living around Lake Bosumtwi in Ghana, located about one hundred miles inland, incorporated swimming into fishing as the “anthropomorphic lake god,” Twi, prohibited canoes on the lake. Hence, people used paddleboards, called padua, or mpadua (plural), and dove underwater to catch fish with different types of nets and to set and collect fish traps.29

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 21

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

the eye’s lens shape, sharpening underwater vision up to twice the normal range.33 European travelers observed these physiological changes. During the 1590s Dutch merchant-adventurer Pieter de Marees recorded that Gold Coast peoples

are very fast swimmers and can keep themselves underwater for a long time. They can dive amazingly far, no less deep, and can see underwater. Because they are so good at swimming and diving, they are specially kept for that purpose in many Countries and employed in this capacity where there is a need for them, such as the Island of St. Margaret in the West Indies.34

Divers played a central role in some states’ economic development by obtaining forms of currency and export commodities. On Luanda Island, which was part of the Kongo Kingdom, women harvested nzimbu (cowrie) shells for circulation as Africa’s most common non-specie currency. Sixteenth-century “women dive under water, a depth of two yards and more, and filling their baskets with sand, they sift out certain small shellfish, called Lumanche.” 31 Elsewhere, people dove into rivers to collect gold nuggets, with gold being Africa’s primary medium for exchange by which other things were valued, as well as a major export.32

Diving with only the air in their lungs, Africans perfected what is now known as free diving. Free divers spent years honing their minds and bodies to submarine challenges, a process beginning during youth. Limited medical research suggests that the physiology of free divers adapted to prolonged submersion, water pressure, and oxygen deprivation. Free divers develop large lung capacities and their bloodstream possesses elevated levels of oxygen and reduced levels of carbon dioxide. Oxygen deprivation decreases heart, breathing, and metabolism rates, making divers more proficient. Prolonged, recurring submersion changes

Coastal and riverine states used aquatics to thwart European aggression. Africans experience the same symptoms from colds, flus, and many other diseases as Europeans while typically experiencing less severe symptoms from malaria than Europeans, including a lower mortality rate. Africans also produced iron since roughly 2,000 B.C. and possessed iron weapons and capable navies, enabling them to largely dictate the terms of commerce into the nineteenth century. States could defend home-waters, while some navies projected power against rival states and European trade facilities. Naval battles between African states fought on rivers, lagoons, and lakes could include hundreds of war canoes that could be upwards of 180 feet long, and tens of thousands of naval warriors and marines.35 African forces could defeat and capture European ships. In 1456, the Portuguese endured an early example of African naval strength. Responding to a prior Portuguese raid, Africans, who were probably Diola (or Jalo), dispatched 150 warriors in seventeen canoes to attack two Portuguese ships on the Gambia River. Firing arrows as they darted about, the warriors inflicted casualties, while Portuguese musket and cannon fire proved ineffective. The battle ended when interpreters aboard the Portuguese ships convinced

22 MAINSHEET

Figure 2. This is one of several images of mpadua in Robert Rattray’s study of the Asante. These men used mpadua, which were eight to ten feet long and about sixteen inches wide, to traverse Lake Busumtwe and for fishing. While women swam, fished, and employed mpadua, Rattray did not detail or photograph their aquatic traditions.30

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

the Africans that they sought peaceful trade. Similarly, in 1787, Africans on the Gambia, who were probably Diola, captured three British ships, and “killed most of their crews” after English slave traders kidnapped community members. Africans continued to defeat ships, including steamships, into the early twentieth century.36

African rulers employed male and female salvage divers to transform sunken and grounded ships into hinter-seas of production where they harvested the debris of Western commercial capitalism. Europeans wanted Africans to adopt Western salvage traditions dictating that ship owners retained possession of stricken vessels while permitting salvagers to collect compensation for recovering goods. Instead, rulers claimed Europeans’ inability to maintain control of their vessels caused them to forfeit the right to own shipwrecks, granting them the right to appropriate wrecks, their cargos, and crewmembers, who were ransomed. Rulers dispatched divers to salvage shipwrecks, often recovering goods they had sold to Western merchants. In 1615 a Portuguese official bemoaned that the Bijago in what is now Guinea-Bissua averred “what arrives on the beaches belongs to the first who seizes it.”

If a vessel “wrecked on any of their islands, they consider it fair gain; and . . . retain the unfortunate individuals whom they may have taken with it in captivity, until ransomed by friends.”37

The earliest written account of surfing was penned on the Gold Coast, now Ghana, during the 1640s.38 Surfing was independently developed throughout Atlantic Africa, though members of some ethnic groups, like the Fante and Ahanta (both part of the larger Akan language/culture group) and Kru from Liberia, as well as West Central Africans, transplanted it along the coast. Sixteenth-century captives from Ghana and West Central Africa (Congo-Angola) introduced surfing to the island of São Tomé, off equatorial Africa. Surfing was only developed by societies with deep aquatic connections who can gauge understand-

ings of fluid environments. Africans used surfing to understand how to navigate surf-zones in surf-canoes. While seventeenth-century accounts are confusing, later ones are unequivocal, suggesting many learned to surf when about five years old. For instance, in 1823, an Englishman documented Fante children “residing” around Cape Coast surfing, saying they

paddle outside of the surf, . . . they place their . . . [boards] on the tops of high waves, which, in their progress to the shore, carry them along with great velocity . . . while their more dexterous companions reach the shore amidst the plaudits of the spectators, who are assembled on the beach to witness their dexterity.”

Here, we see the connection between surfing and surf-canoeing as the children’s surfboards were crafted from “broken canoes."39

Coastscapes—the area bounded by the surf and seashore’s inland reaches—were important playgrounds and places of learning. Youth played with the sea, learning its movements and patterns through experiential play that entailed interacting with surf, currents, and tides; seeing and feeling the ocean’s rhythms. Youth learned the physics of breakers and wavelengths (the distance between two waves), by seeing and feeling how the ocean pushed and pulled their bodies. They learned that to catch waves one needed to match their speed, something Westerners did not comprehend until the 1880s. While at Elmina, Ghana, during the early eighteenth century, a French slave trader watched “several hundred . . . [Fante] boys and girls sporting together before the beach, and in many places among the rolling and breaking waves, learning to swim" and surf, concluding that Africans’ dexterities “proceed from their being brought up, both men and women from their infancy, to swim like fishes; and that, with the constant exercise renders them so dexterous.”40

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 23

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

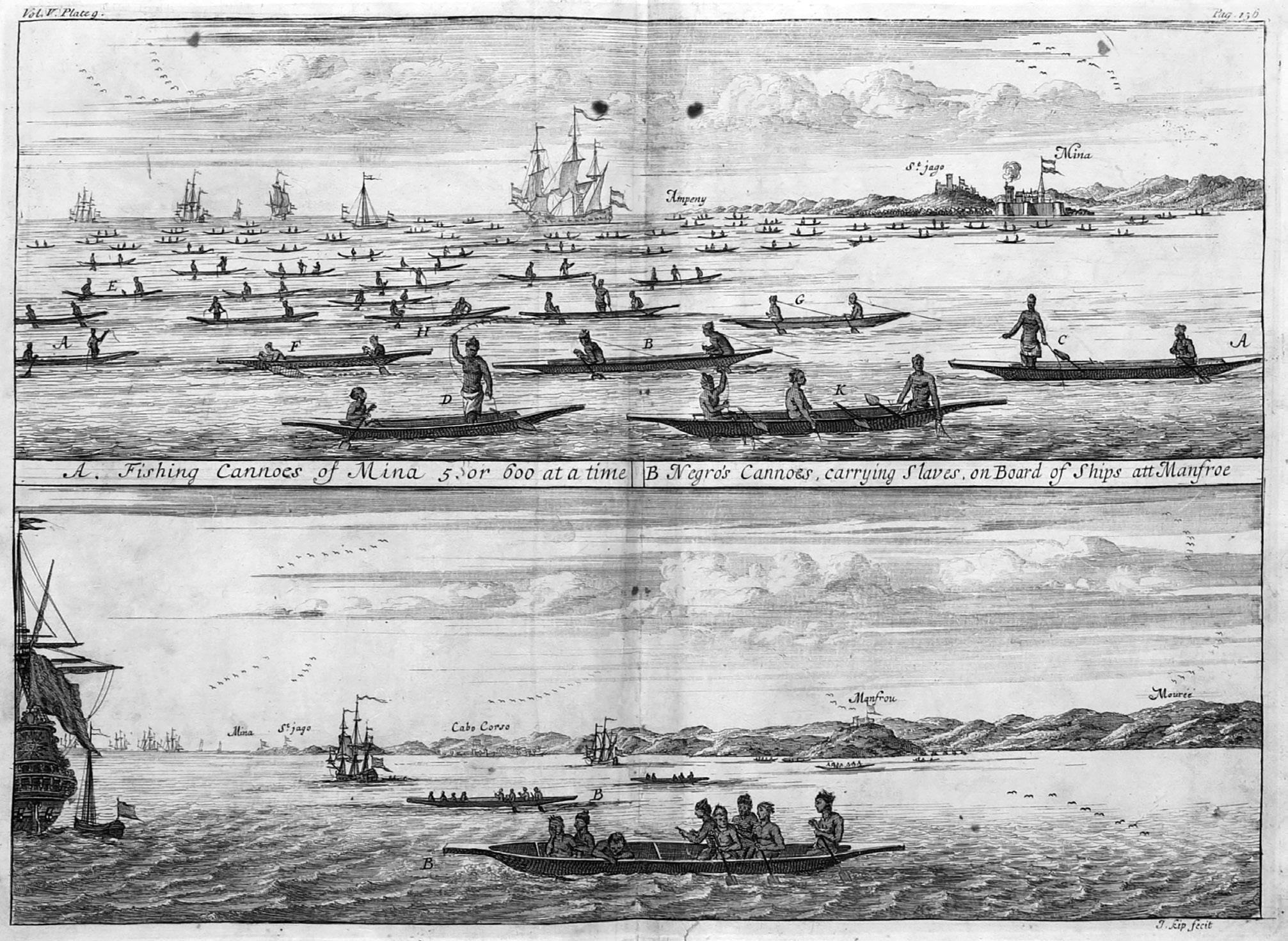

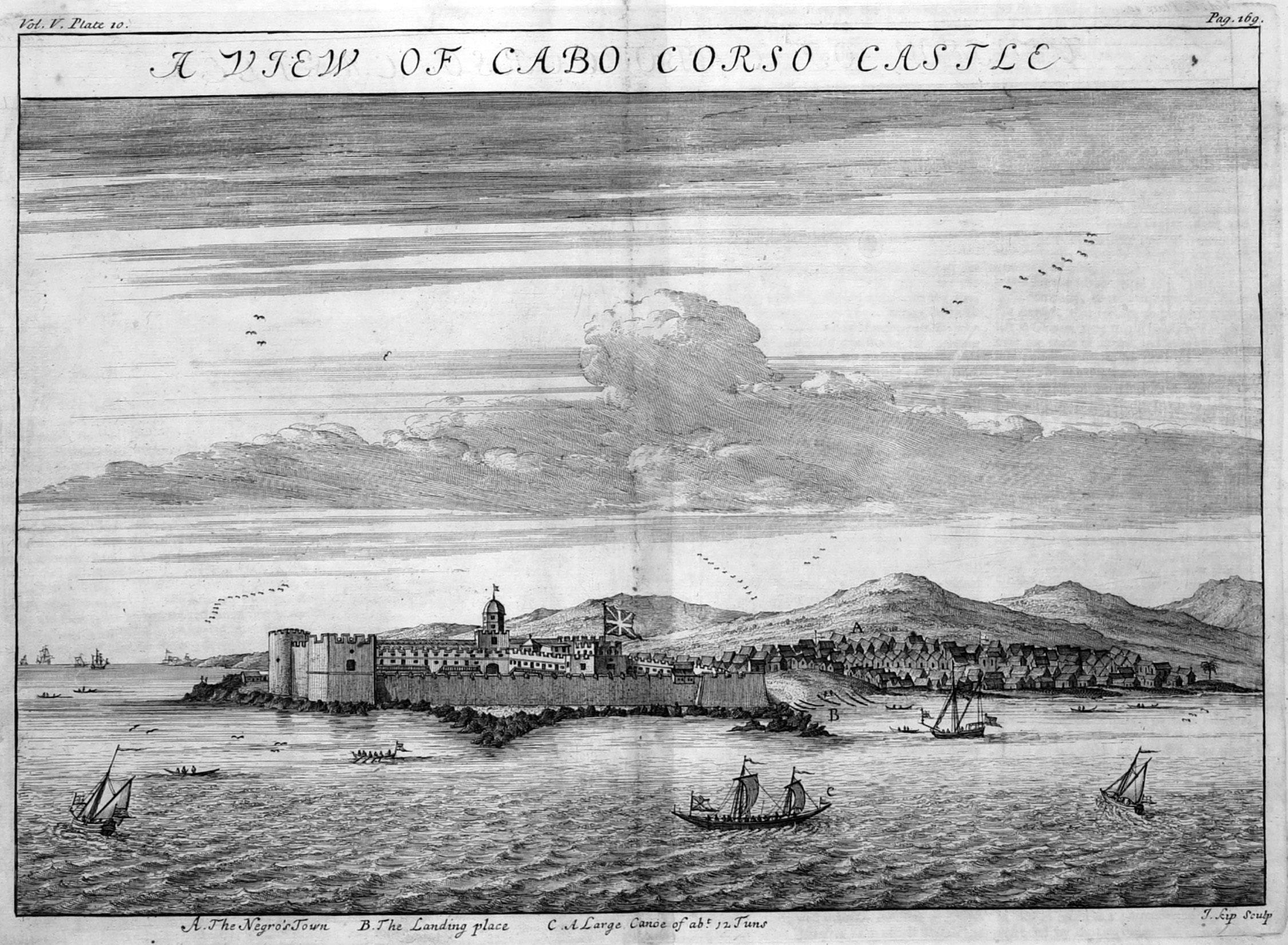

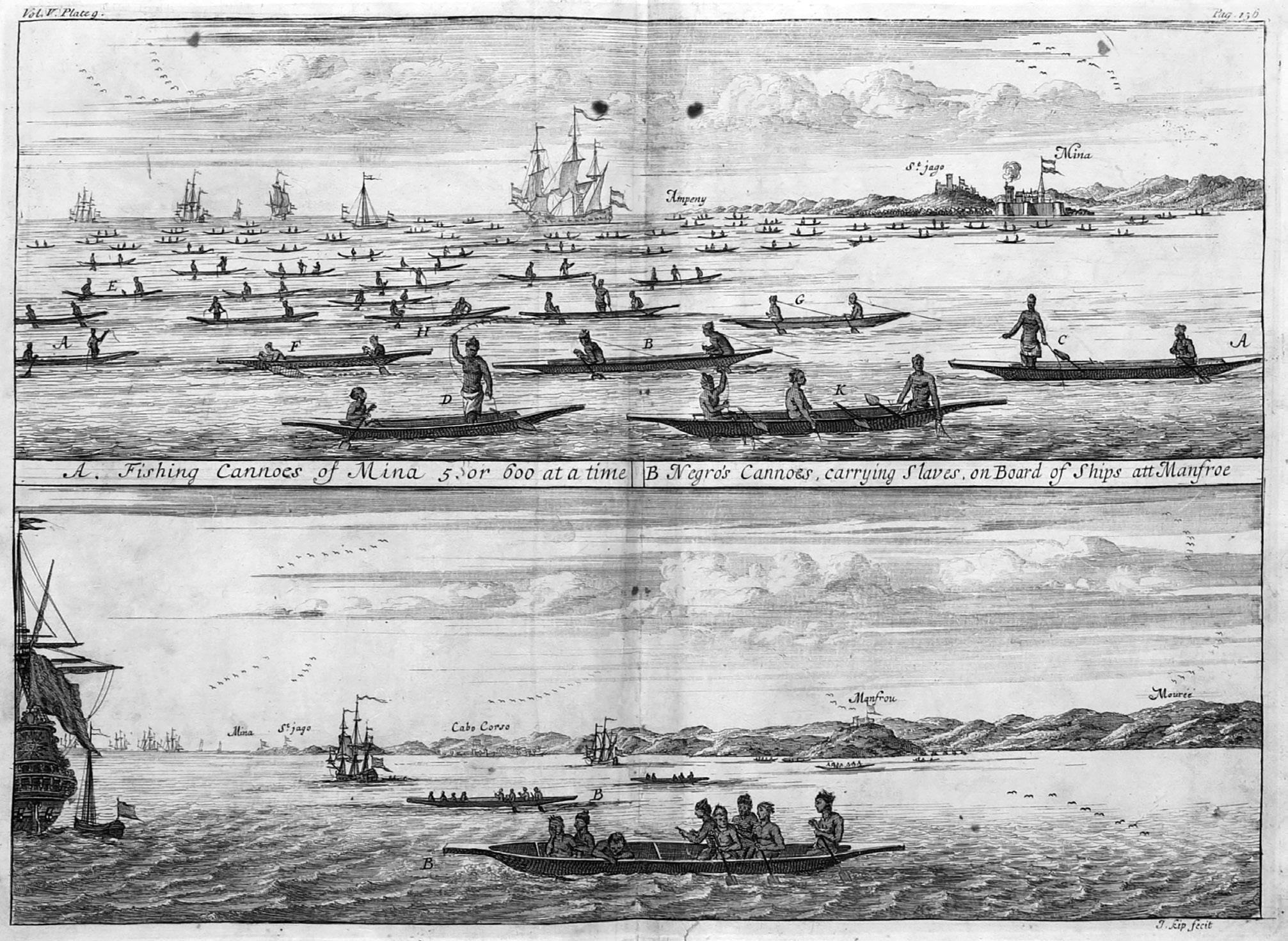

miles or 11 km west of Cape Coast), with the Dutch slave-trading castle of St. Jago.

enslaved Africans to a slave ship. In the back-

are the Fante

of Elmina (St. Jago Castle), Cape Coast, Mount Monfro, or Amanful (Fort Frederiksborg, later Fort Royal), and

“human shores”

Surfing opened seas of possibilities, with Atlantic Africans being the only known people to harness wave energy as part of their daily labor practices. Many Atlantic Africans had to pass through the surf to access coastal fisheries and shipping lanes, using waves to slingshot surf-canoes laden with fish or tons of cargo ashore. Surf-canoes were modified dugouts up to thirty feet long and eight feet wide. They were fast and responsive, capable of catching and surfing waves up to eight feet high. Sources suggest youth used surfing to develop the sophisticated understandings necessary to crew surf-canoes. When about fifteen years old, men and, to a lesser extent, women began applying youthful surfing experiences as they took up surf-canoe paddles, with women harvesting littoral waters while men fished up to twenty miles (32 km) offshore.42

24 MAINSHEET

Figure 3. This image illustrates some aquatic activities related to the Fante surf-ports. The top image shows Fante fishermen, who sometimes comprised fleets of up to 800 canoes catching fish sold in local markets, shipped into the interior, and sold to English officials at Cape Coast Castle to feed English officials and soldiers. There are also captives in the dungeons. In the background is the Fante surf-port of Elmina (about seven

The bottom image depicts surf canoemen transporting

ground

surf-ports

Moree (Fort Nassau), illustrating the concentration of surf-ports that created

that oriented people seaward.41

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

Surf-canoes were innovative vessels crafted by expert canoe-makers with probably hundreds of variations distinct enough to warrant their own name. Canoeists and canoe-makers used rivers, lagoons, and mangrove swamps as calm-water nurseries where they developed maritime architecture, technology, and techniques, before testing them in churning surf-zones. Developed long before the arrival of Europeans, surf-canoes continually evolved as fishermen and merchants from diverse ethnic groups exchanged design elements, making them strong enough to withstand being slammed against sandbars, while remaining lightweight and maneuverable. Surf-canoes were cut in half lengthwise and keels inserted. Keels remained flush with the surf-canoe’s underside to retain a shallow-draft. Cross-thwarts reinforced hulls while providing brackets for securing cargo while knees, which are curved rib-like braces, radiated from the keel and up the interior sides, providing additional support. Wave-breakers, which are triangular beams, were attached to the bow to deflect the force of oncoming waves. Additionally, planks, called weatherboards, were added to gunwales (the top edge of a vessel’s sides) to elevate their sides, while bows and sterns were further elevated to keep water from splashing into hulls.43

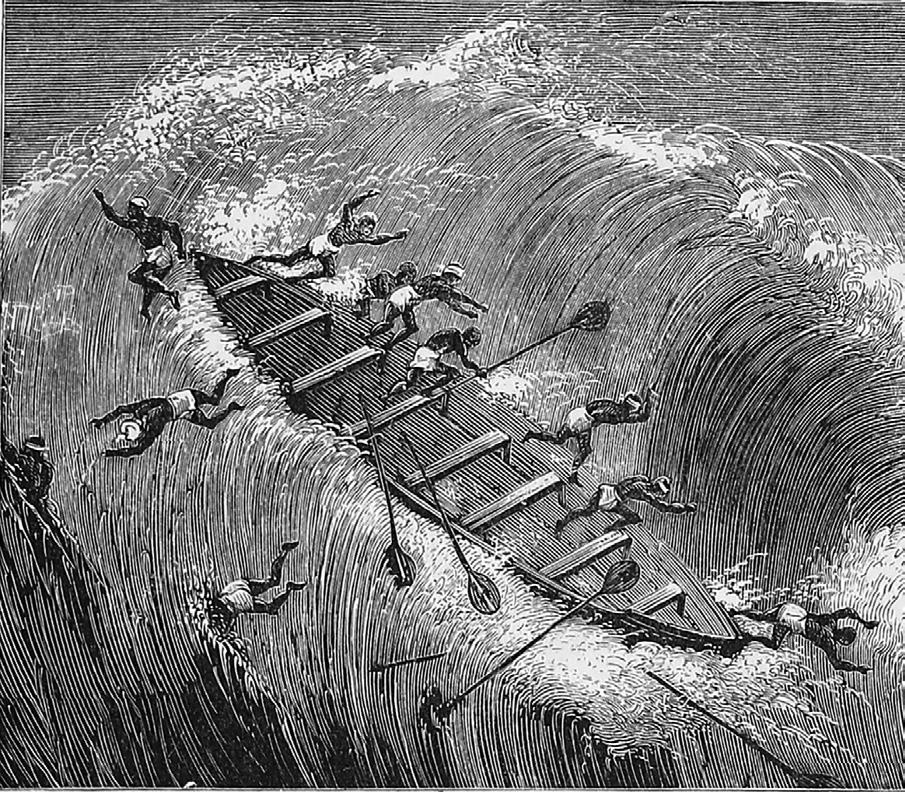

Surf-zones remained the realm of surf-canoes. Western mariners explained that rowboats were too slow to catch waves and regularly capsized in the surf; causing them to conceptualize Africans’ spaces of pleasure and profit as a “surf-bound coast,” and barriers of fear where white people drowned or were eaten by sharks. Thus, Westerners were compelled to hire surf-canoemen for over four hundred years. Royal Africa Company records extensively documented England’s reliance on surf-canoes to float its inhuman trade in human bodies, as did an American naval officer commissioned to suppress the slave trade during the 1850s, writing: “Uncle Sam’s boats are not built

for beaching, we have to trust ourselves again to a big dug-out . . . to bear us through the surf; for which we pay an English shilling, or an American quarter, each.” Into the mid-twentieth century, the British and American navies repeatedly advised ship captains against entering surf-zones but to instead hire surf-canoemen. For example, in 1893, the British Hydrographic Office described the skill of Batanga surf-canoemen of southern Cameroon, noting,“nothing can exceed the skill with which these people launch through a heavy surf which would prove fatal to ordinary ship’s boats.”44

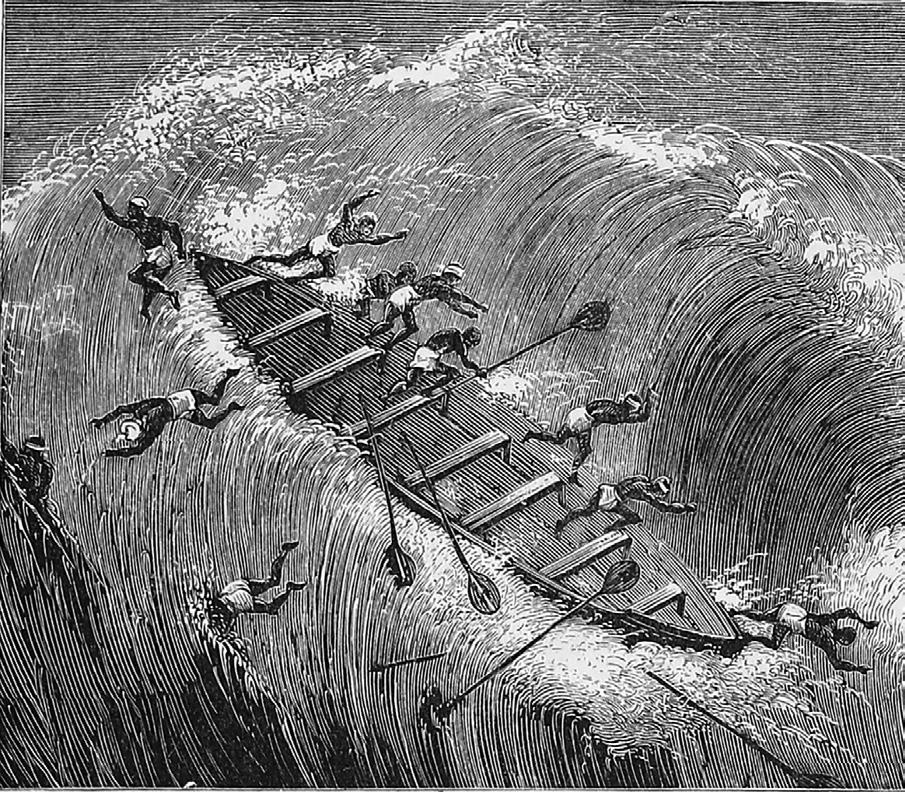

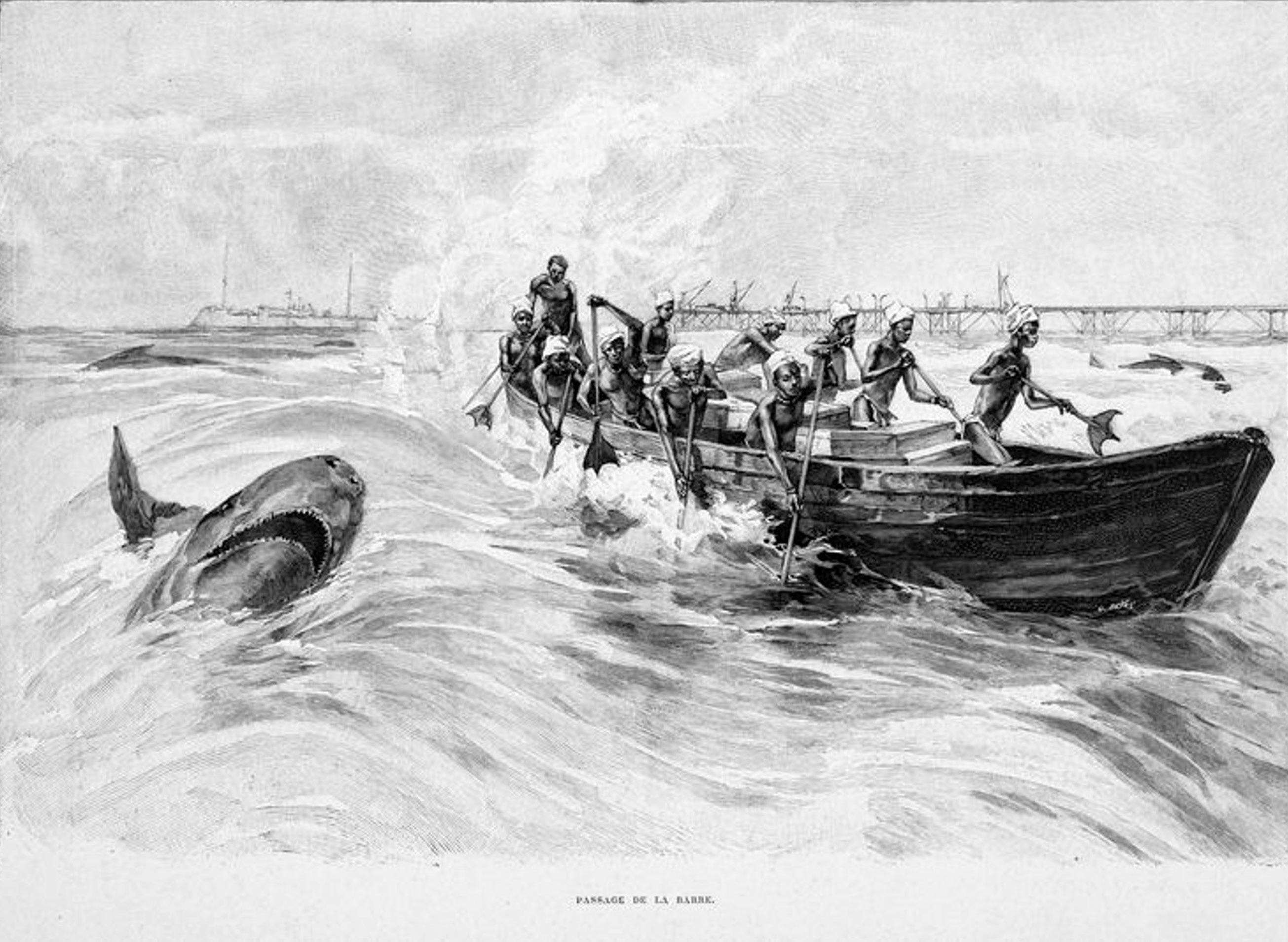

Figure 4. In 1774, William Smith of the Royal Africa Company described England’s reliance on “dexterous Canoe-men” to “carry the Passengers and Goods ashore,” through breakers, “which to me seem’d large enough to founder our Ship.” Conveying European fears, Smith expressed it was “barely possible, that a [white] Man may, if [a canoe] overset here, save his Life by swimming, but it is not very probable, for there are such numbers of Sharks here.” 45

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 25

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

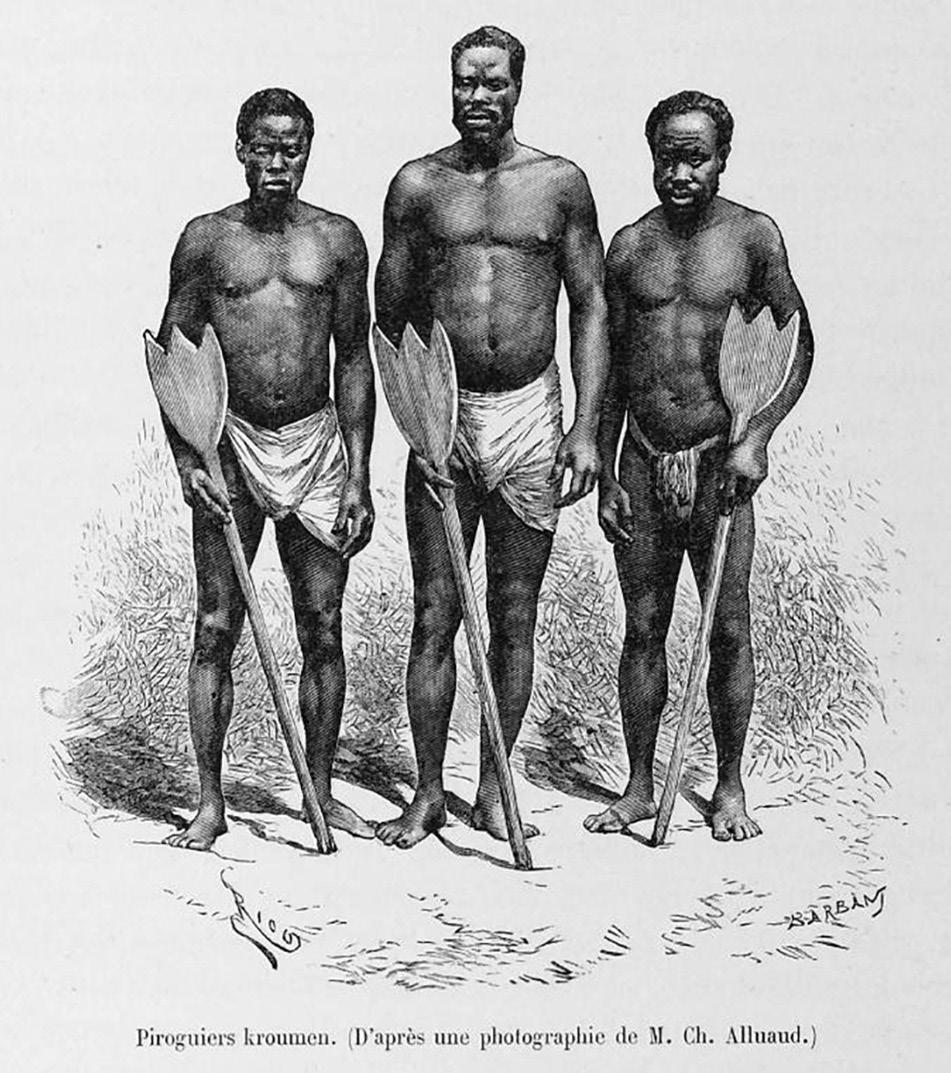

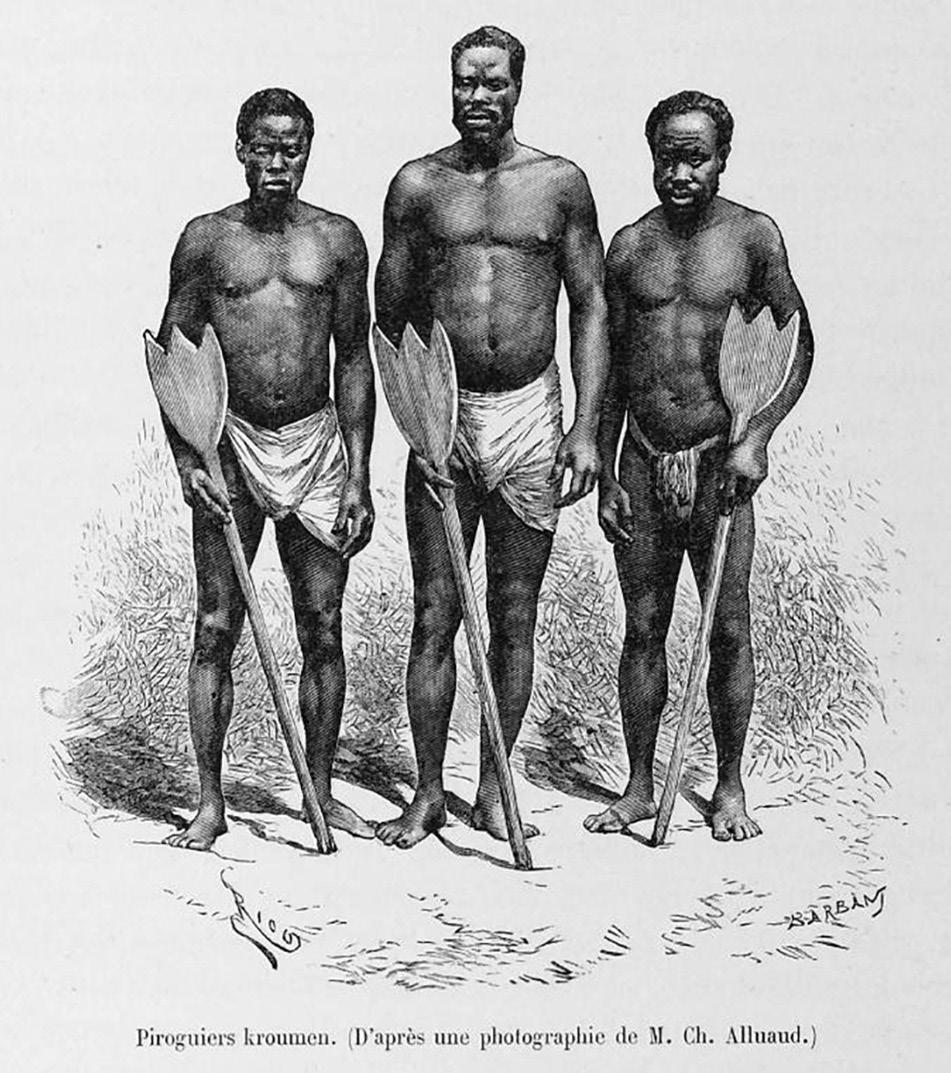

Surf-canoemen’s paddles further illustrate their ability to derive environmental solutions. They were designed to provide rapid acceleration necessary to catch waves while minimizing resistance when the blade accidentally struck chop during the forward stroke. The Fante developed an array of paddles, including the distinctive three-pronged, trident-shaped paddle. While there are numerous variations to this paddle, its three slightly spread fingers increase the blade’s surface area, as little water passes between the fingers when paddled rapidly.47 Most paddles seemingly had long narrow blades that widened dramatically near the handle. For instance, the bottom twenty-eight inches (71 cm) or so of Kru paddle blades was roughly six inches (15 cm) wide, broadening to about eighteen inches near the handle. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the Fante paddle became widely disseminated, with many Kru adopting it.48

26 MAINSHEET

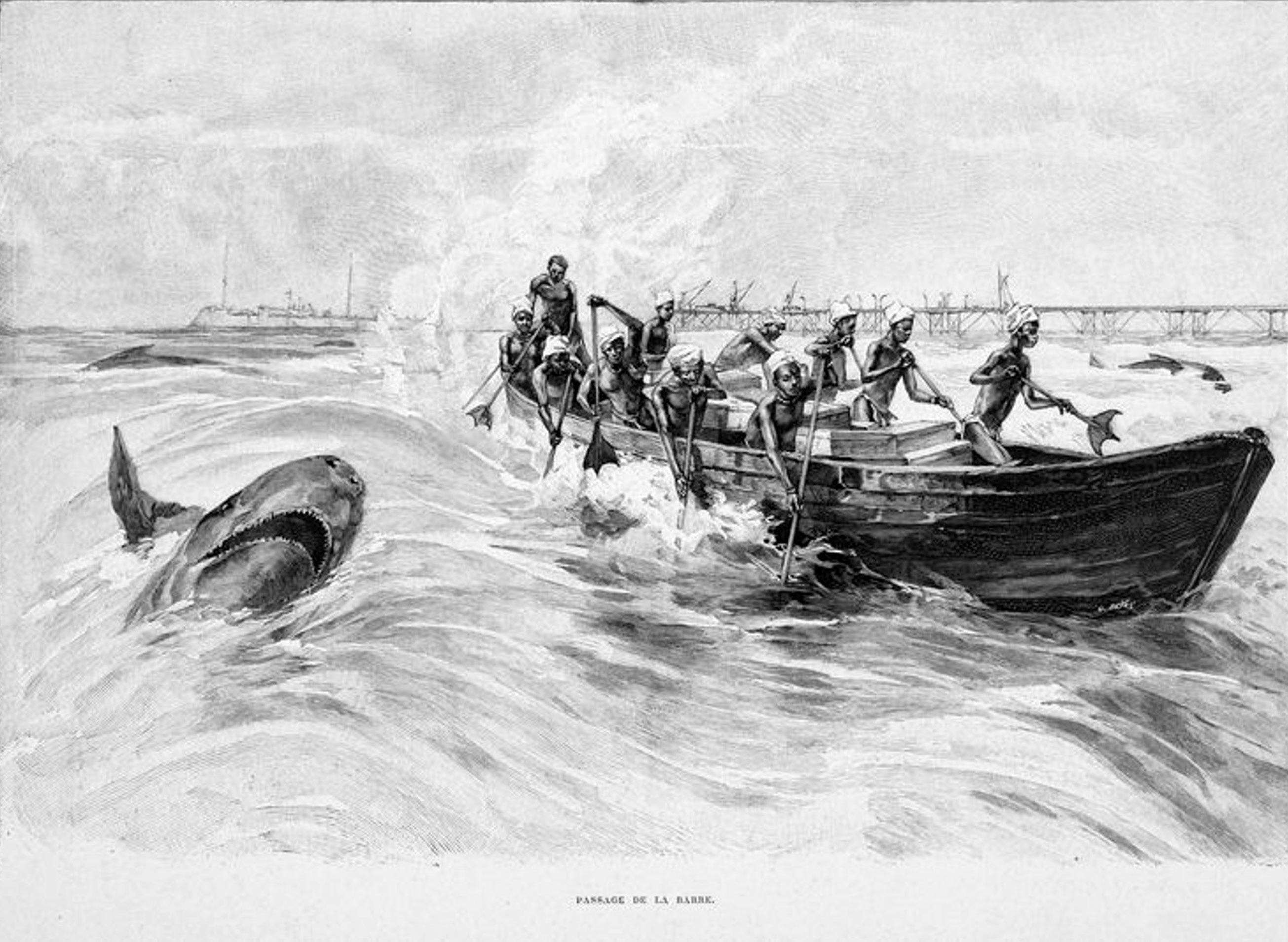

Figure 5. This stylized image of Fante surf-canoemen landing in what is now Benin illustrates trident paddles, while capturing white people’s fear of being devoured by sharks if they fell overboard from surf canoes. Note the trident-shaped paddles discussed below.46

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

Surf-Ports

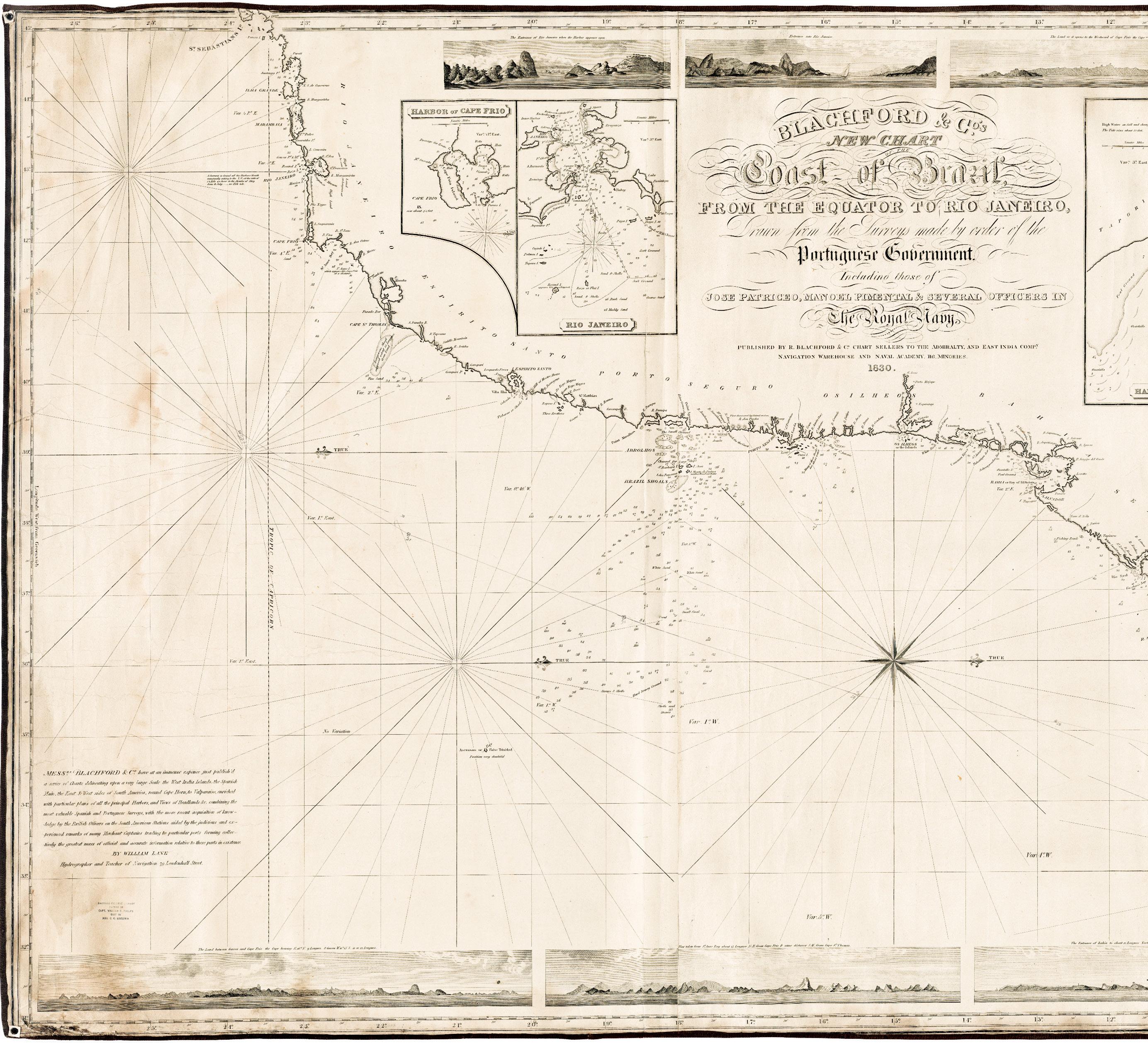

African sailing traditions predate European arrival, and surf-canoes could, as de Marees reported, “sail very well with” the wind, to “develop a great speed” and could sail against, but not close to, the wind. The morning air over tropical seas and large rivers warms faster than over land, causing it to rise and cooler overland air to blow seaward, creating offshore breezes that fishermen rode to fisheries and merchants to shipping lanes. 50 Merchants harnessed prevailing and seasonal winds and currents, sailing and paddling across coastal seas and up rivers. Senegambians seasonally traversed hundreds of miles of coastline while Fante canoemen voyaged “to all parts of the Gulf of Ethiopia [Guinea], and beyond that to Angola.” Riding the Guinea Current southward they traveled along the coast, during return voyages, they cut across the Gulf of Guinea as they rode the Benguela Current.51

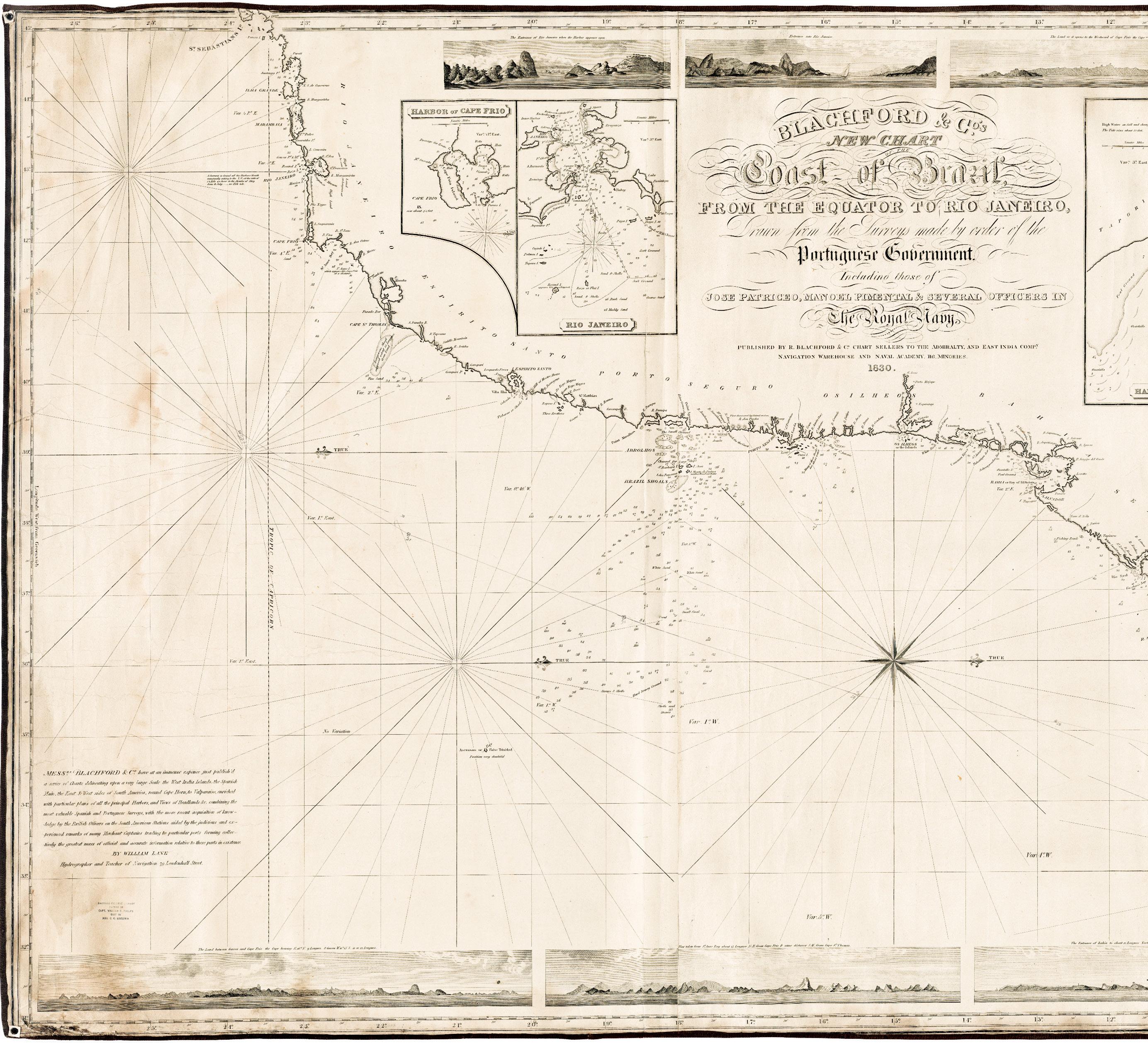

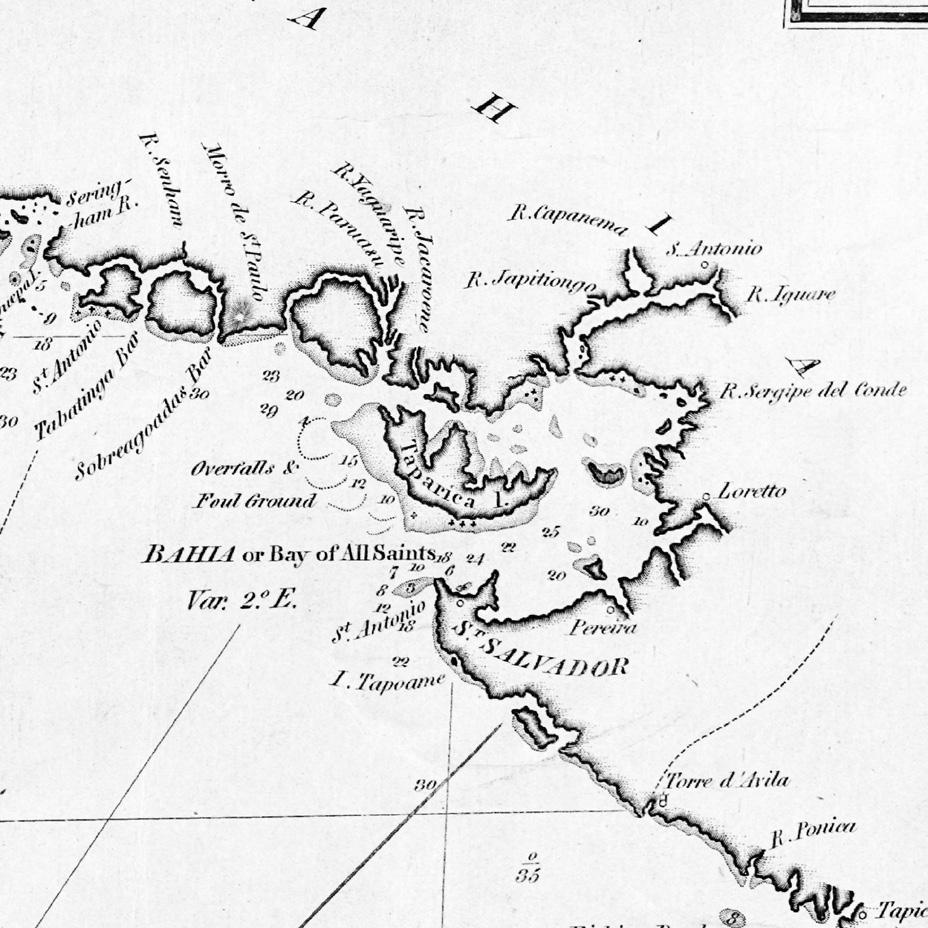

The absence of natural harbors inspired the creation of surf-ports, which provided the same shipping and distribution functions as seaports, but, since they lacked sheltered waters, required canoeists to pass through surf-zones when traveling between land and sea. There were hundreds of surf-ports, as most coastal towns were home to seaward-facing communities whose residents owned at least a few surf-canoes. Indeed, many surf-ports were a few miles, or even a few hundred feet, from each other. Beached canoes were meeting places and marketplaces where people of diverse ethnicities met to exchange news, information, and maritime techniques. Seafood processing, marketing, and distribution were primarily performed by women, most of whom were related to fishermen. On beaches, women organized goods for sale, discussed market prices, and created coastal and overland trade networks extending hundreds of miles. For instance, during the 1590s, de Marees noted hammerhead sharks were “dried and taken to the Interior, and constitute a great Fish-present.”52 Market women collaborated with and functioned independently of men, reinvesting earnings in surf-canoes and fishing gear, thus women could own twenty-five to sixty percent of the surf-canoes at any given surf-port, and employ numerous fishermen, making relationships between women and men reciprocal.53 With the arrival of Europeans, surf-ports quickly became central nodes in overseas trade. While never rivalling Amsterdam, Marseille, Lisbon, or Bristol in size, the number of surf-ports enabled African states to construct economies of scale. The Fante, for instance, controlled roughly 150 miles (240 km) of coastline, with eight larger and some thirty smaller surf-ports that were home to probably 4,000 surf-canoes during the seventeenth century.54 In 1482, Kwamin Ansa, the Fante ruler of Anomansah, which became Elmina, permitted the Portuguese to build St. Jago Castle, linking this surf-port to the Port of Lisbon. Over

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 27

Figure 6. This 1880s image provides an example of variation of the Fante trident-shaped surf-canoe paddle and how Kru mariners, who were highly skilled in their own right, adopted this paddle design.49

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

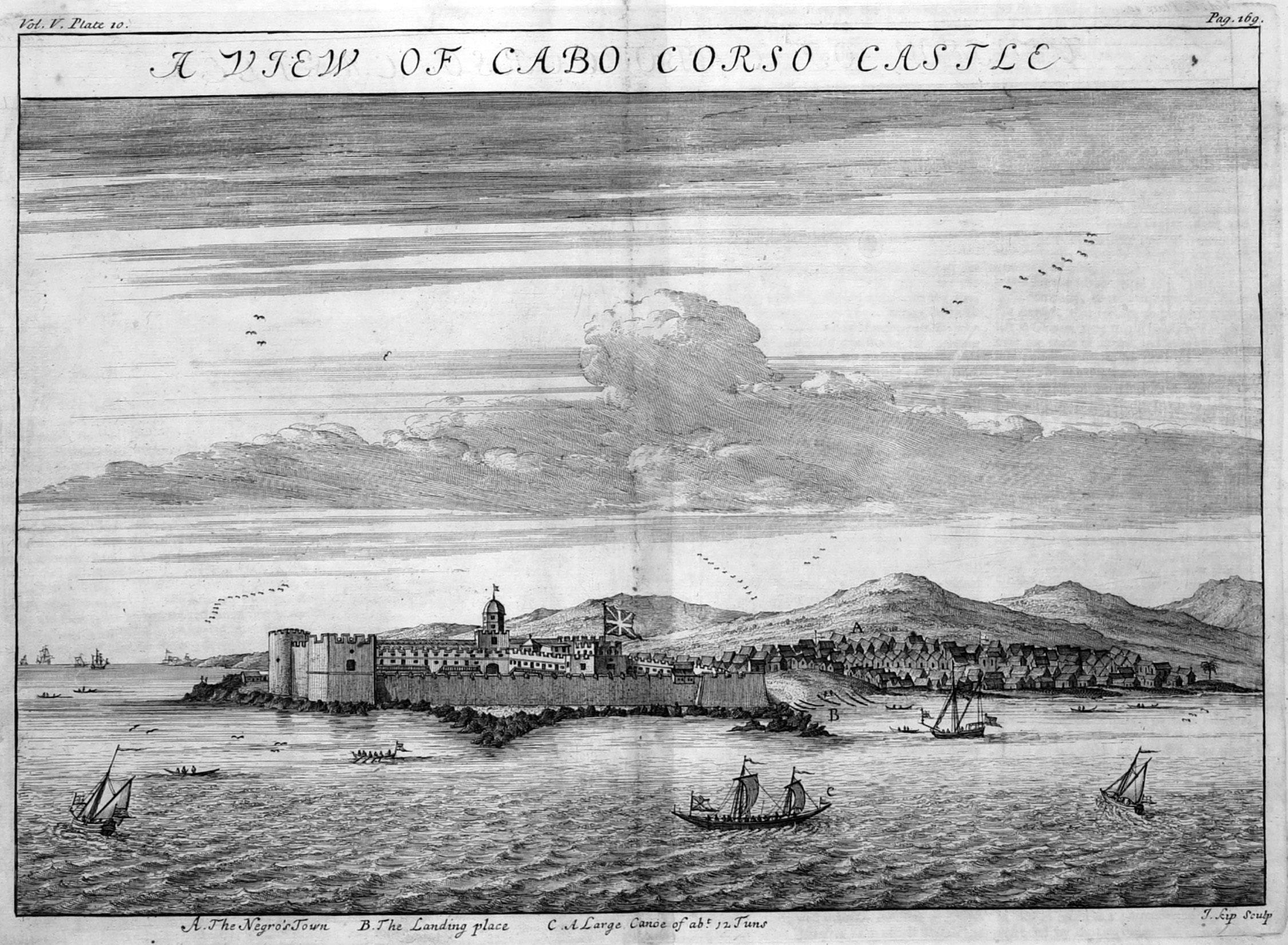

the centuries, many rulers allowed the Portuguese, Dutch, English, French, Danes, Swedes, and Germans to construct what came to be known as slave forts and castles, where they imprisoned Africa’s humanity before shipping them through the surf to slave ships. Some, like Fante leaders at Anomabu, did not permit Europeans to construct forts, preferring, instead, to trade with all comers. Regardless, the Gold Coast’s roughly 300-mile (480 km) shoreline quickly became home to some 60 slave-trading forts which exported roughly two million captives from 1501 to 1867, and over 100 surf-ports without these facilities.55

28 MAINSHEET

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

Figure 7. The Fante allowed the English to build Cape Coast Castle, which was a major slave-trading facility, at their surf-port to attract overseas trade. To the right of the castle is the beach where surf-canoes launched and landed. In the foreground are several surf-canoes, including one rigged with double masts and sails.56

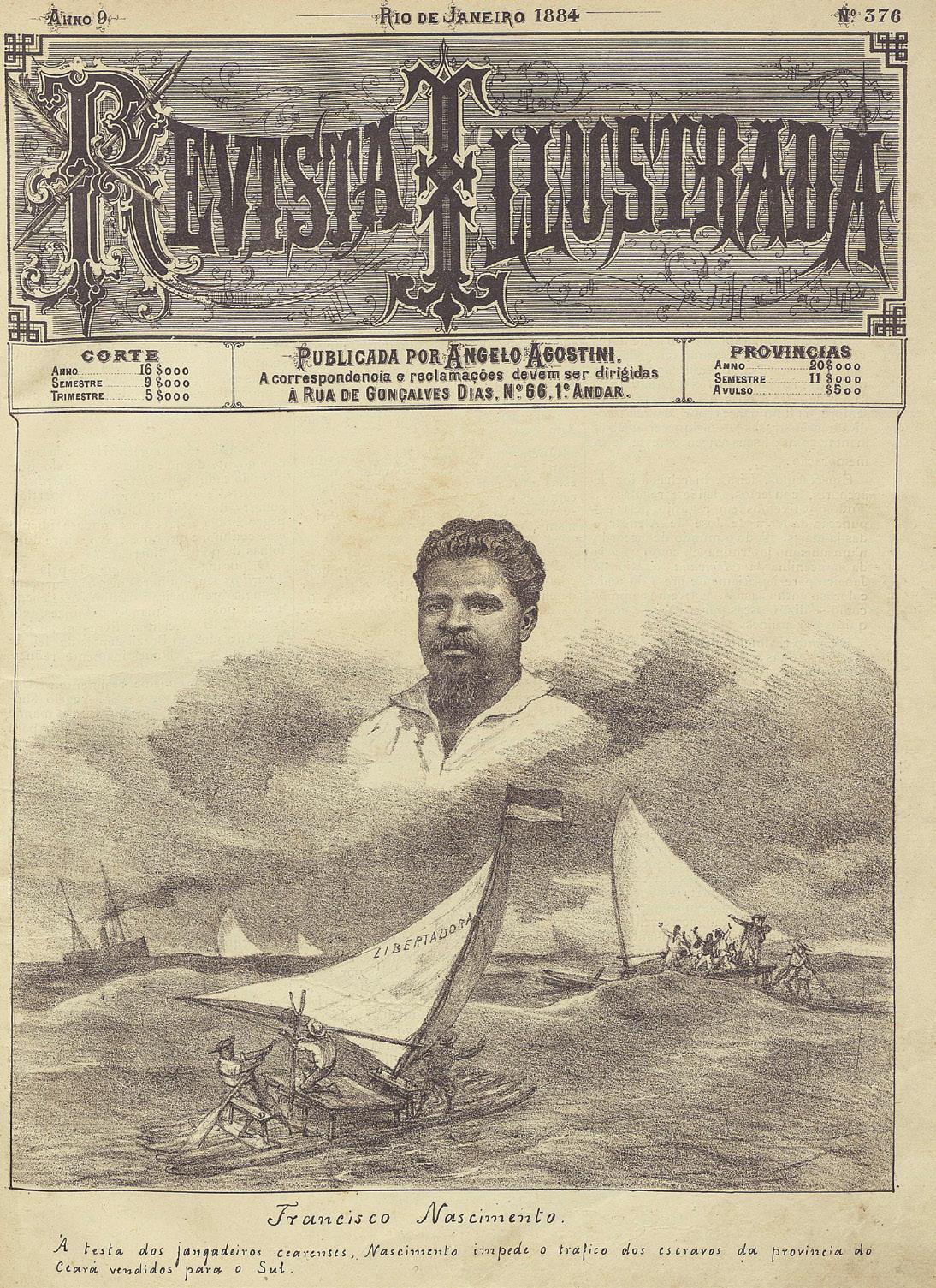

Maritime Maroons

Even as slave ships’ wake disrupted relationships with waterscapes, Africans remained in liquid motion, recreating and reimagining aquatic traditions in the Americas as a method of cultural resistance and a means for forging communities of belonging, as illustrated by maritime maroons who liberated themselves by escaping across water. Their experiences are but one example of how the enslaved explored and charted waterscapes, transforming the waters of bondage into places of meaning and value.57 As maritime maroons slipped their terrestrial moorings, they used islands to chart routes to new lives in communities of belonging in this life and the next.

For Africans, belonging, not freedom, was the antithesis of slavery. Traditionally, African slavery was, in many ways, a temporary punishment for transgressions, compelling offenders to work off debts to individuals and communities or a way of integrating conquered people into conquering societies (with the Atlantic slave trade changing how Africans treated the enslaved). This differed from racial slavery in the Americas, where enslavers owned one’s body and everything they produced, both through their labor and natural reproduction, while forced sales destroyed communities of belonging—including nuclear families—by selling people away from loved ones. Africans in the Americas responded to enslavement by continually seeking to regain their humanity, often through cultural recreation that linked them to communities of belonging in Africa, the Americas, and the spirit realm.58

ISSUE 1 // Maritime Social History 29

PEER-REVIEWED SCHOLARSHIP

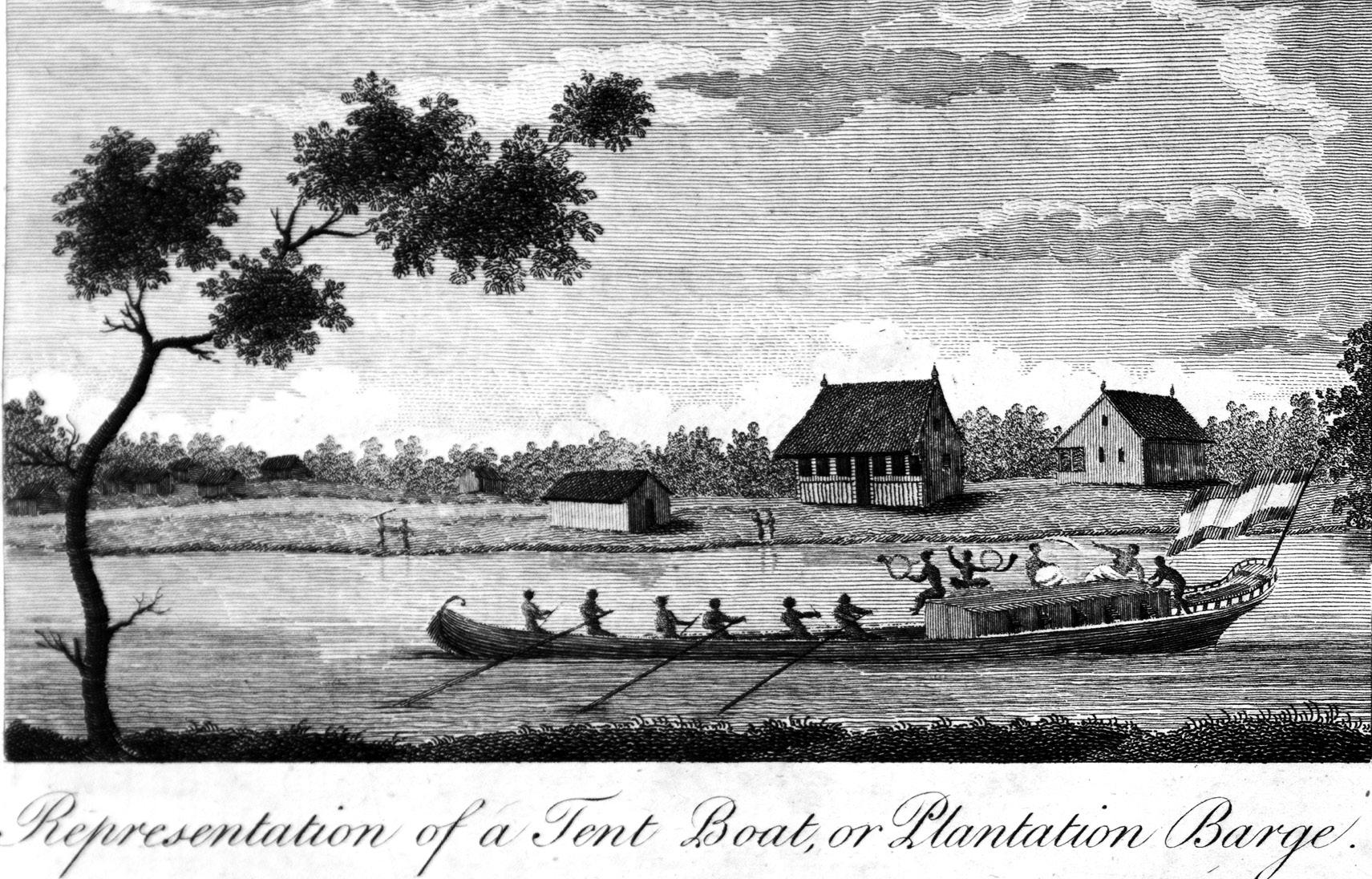

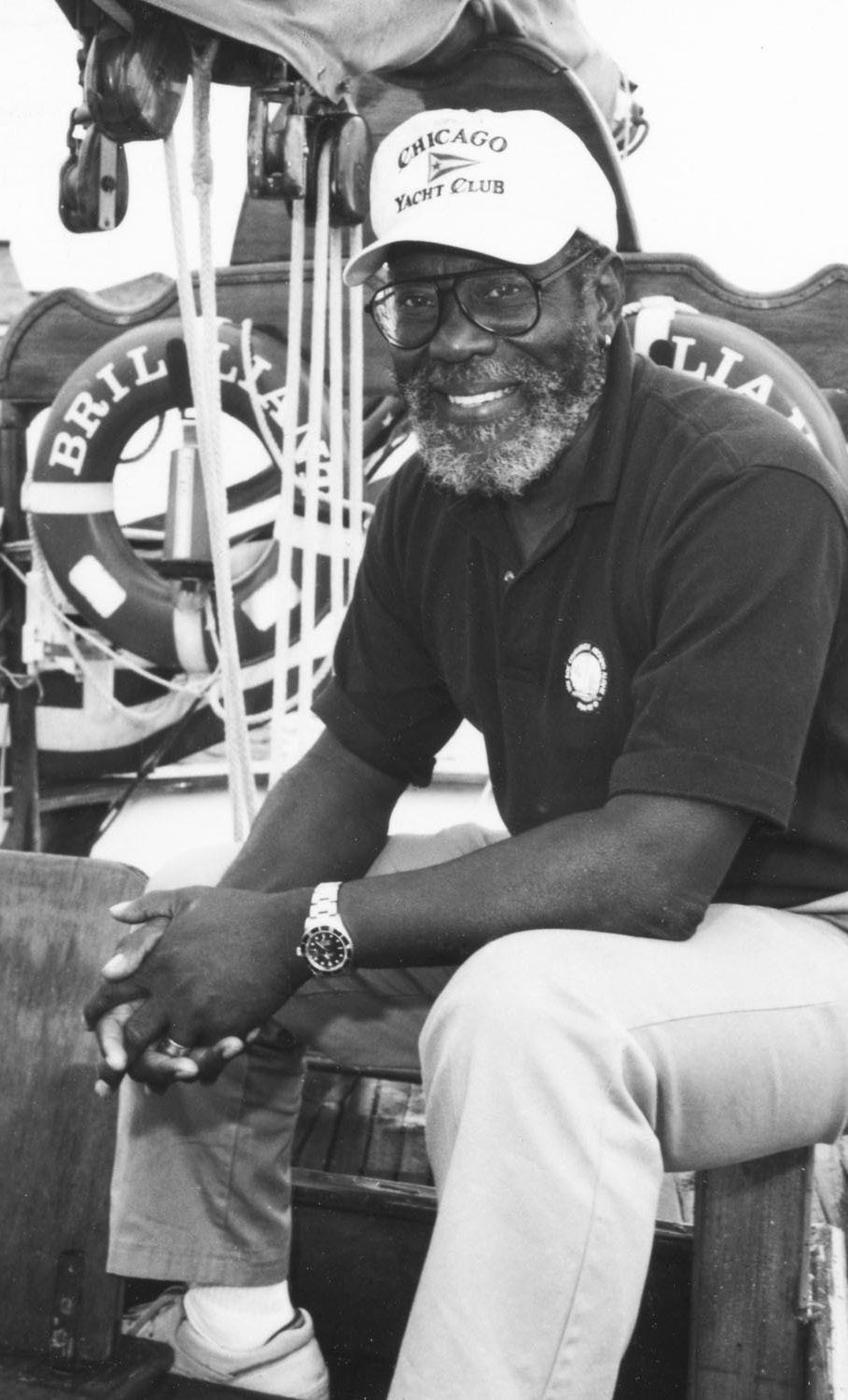

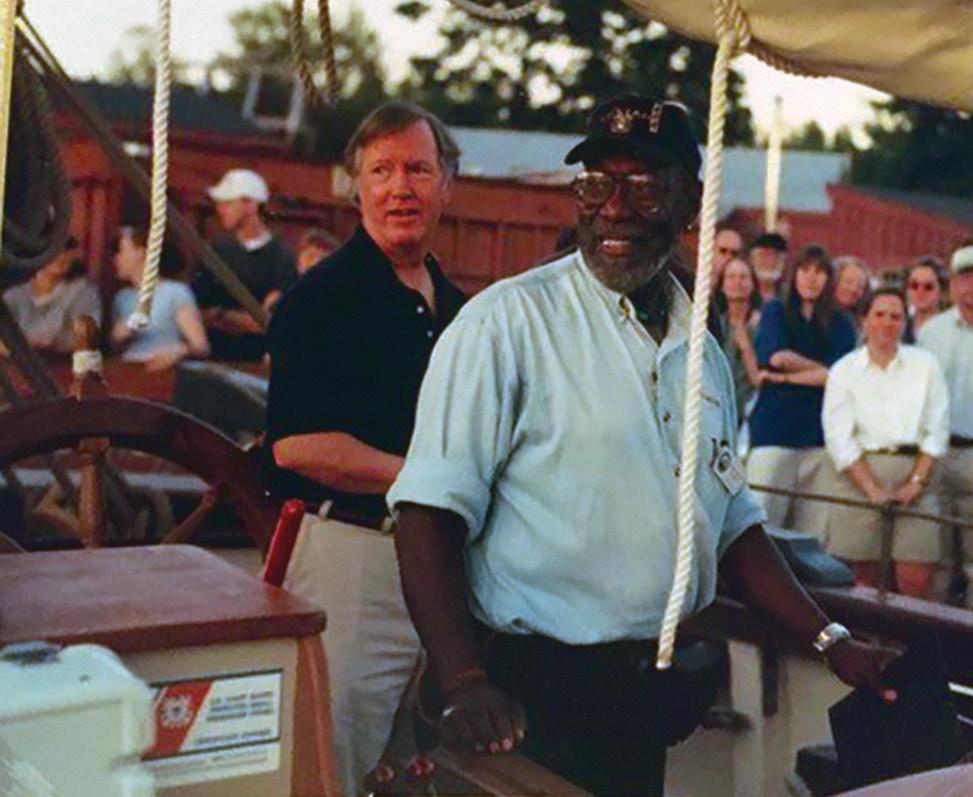

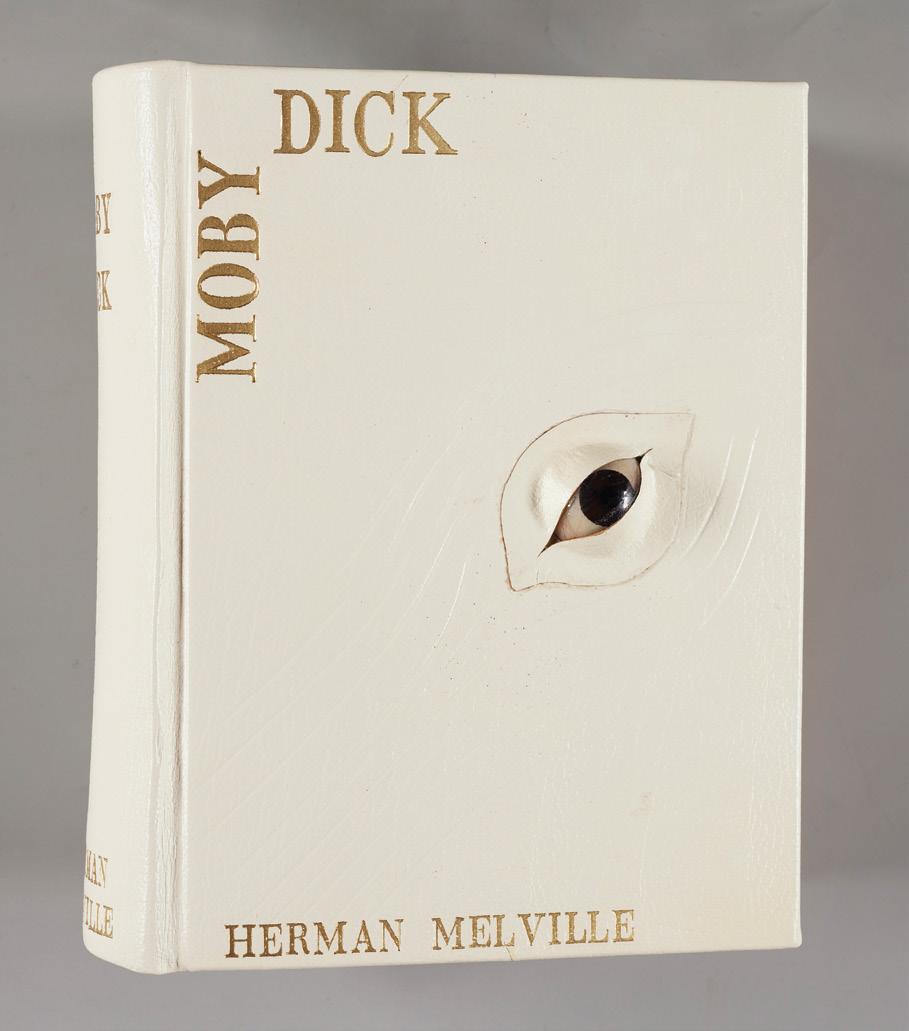

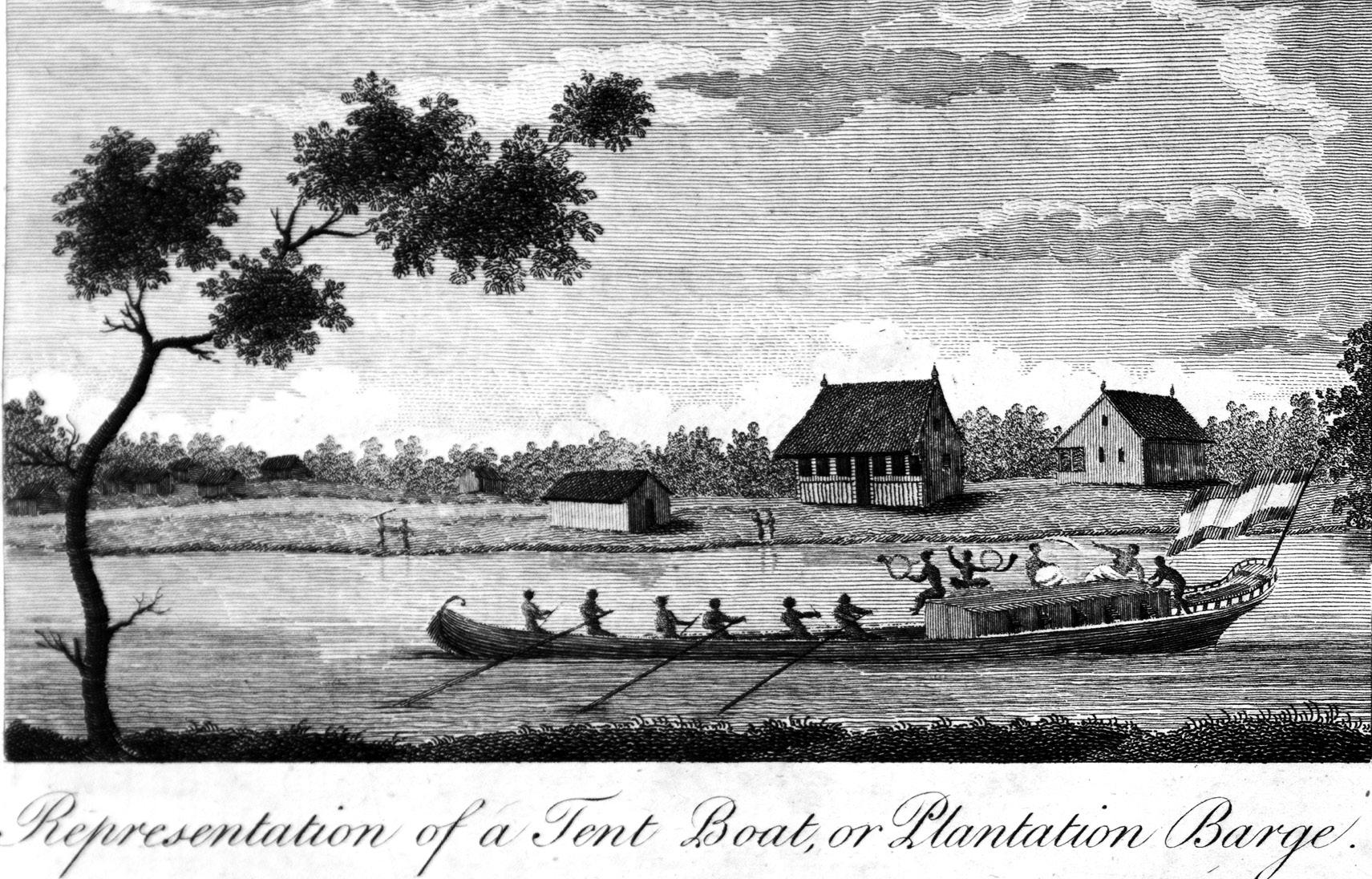

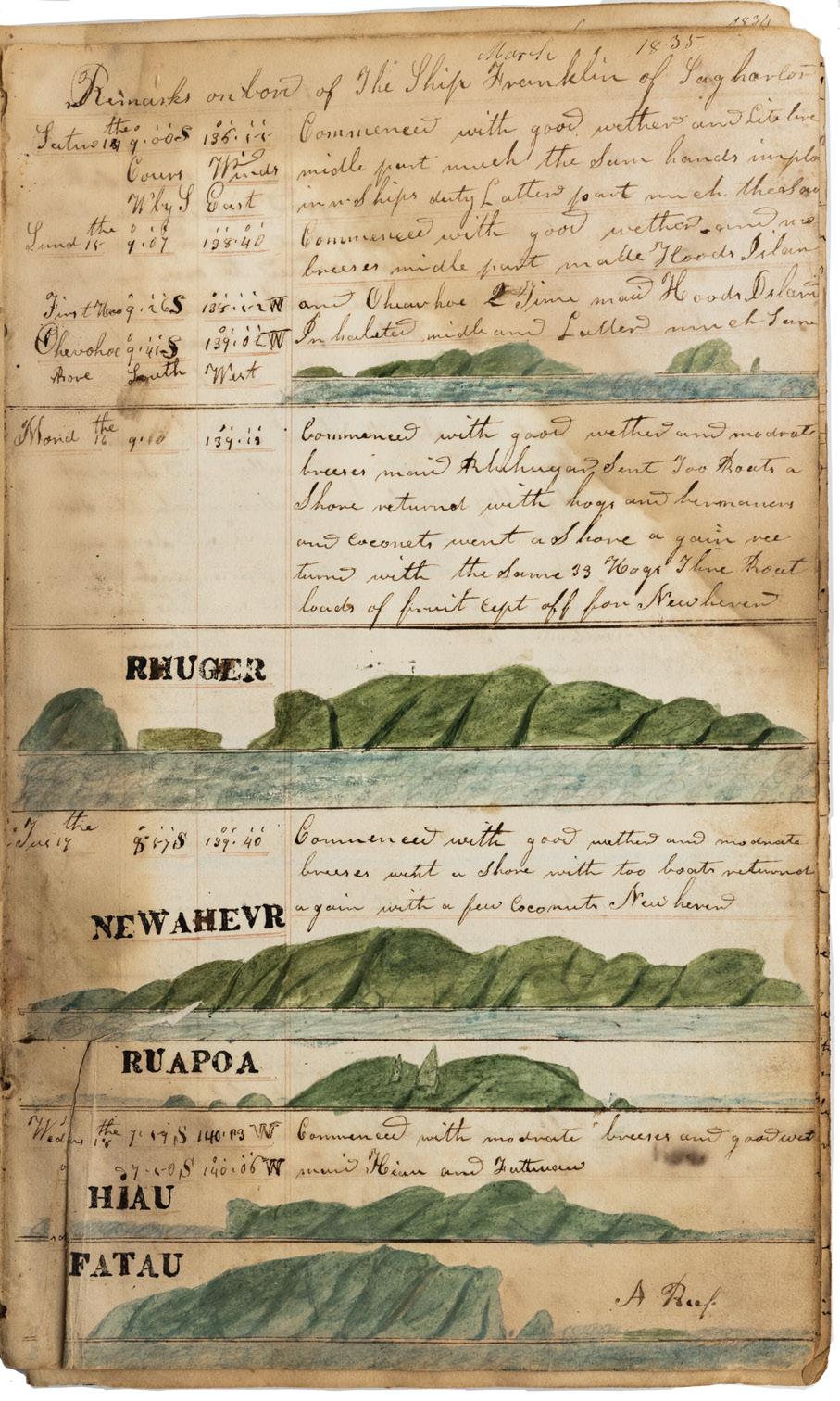

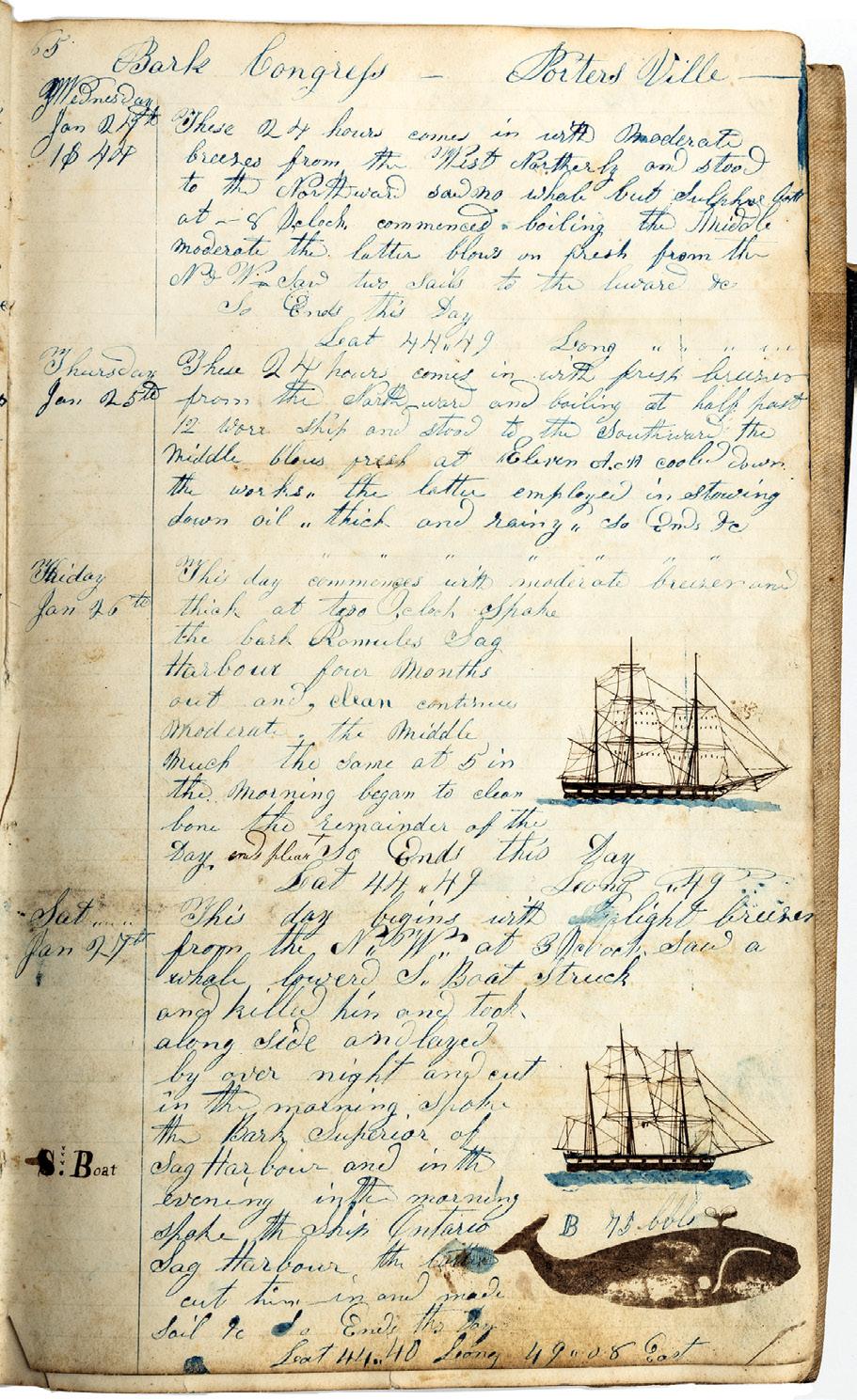

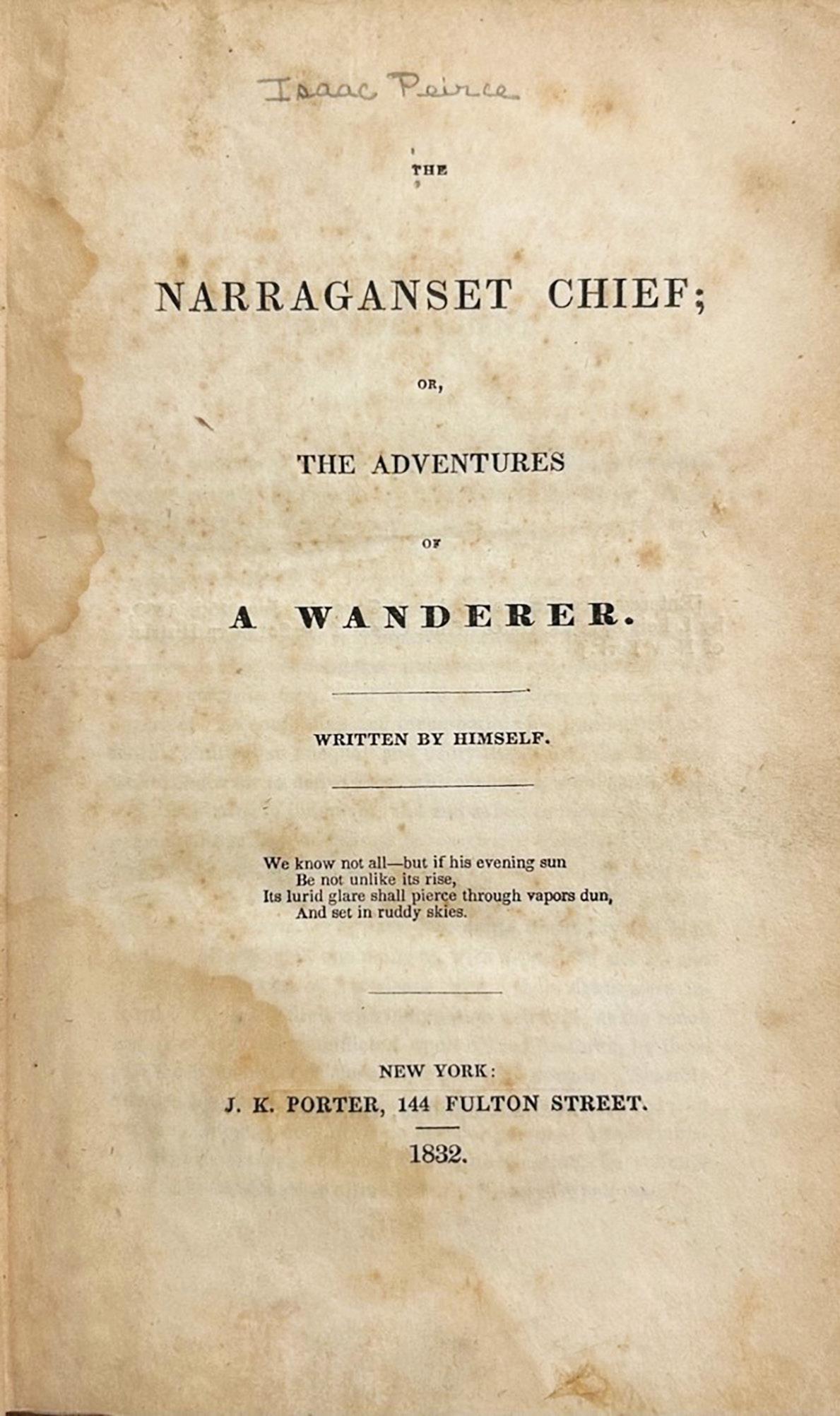

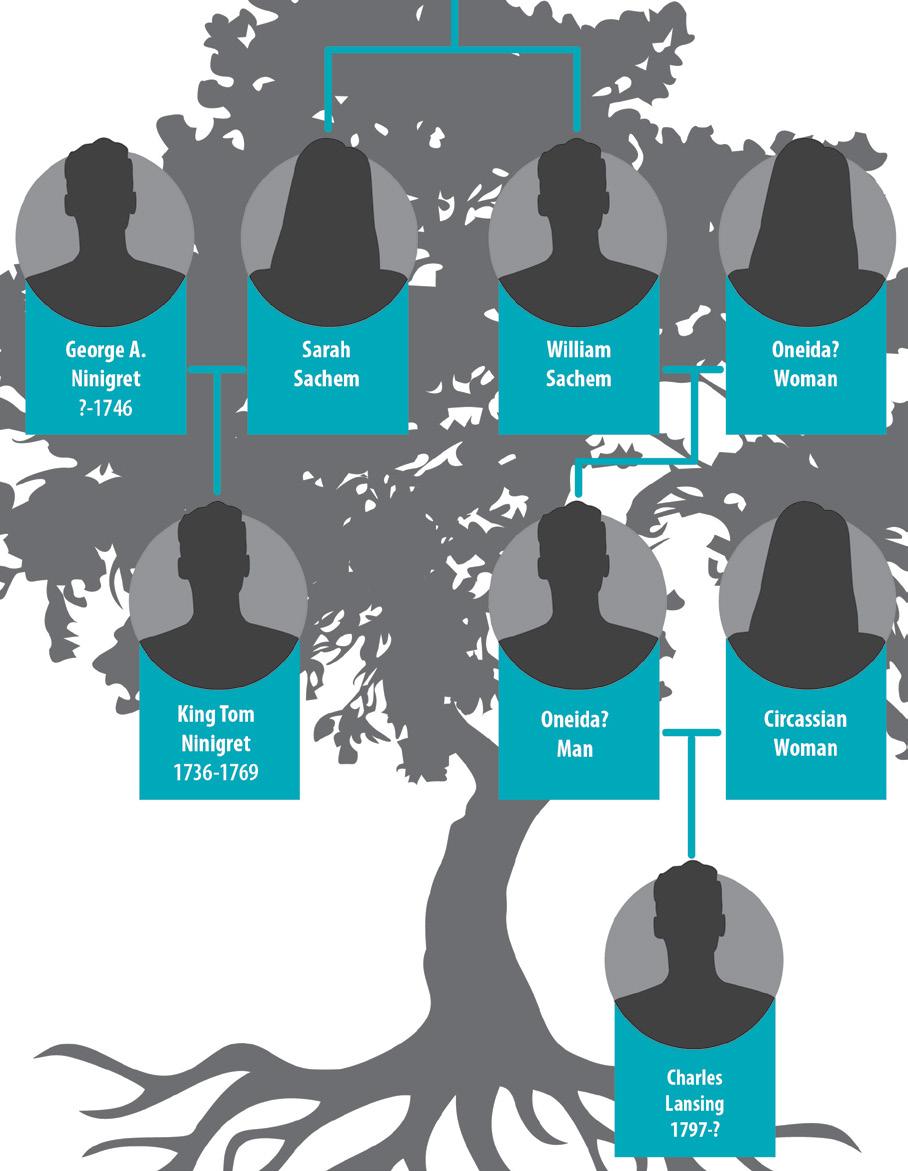

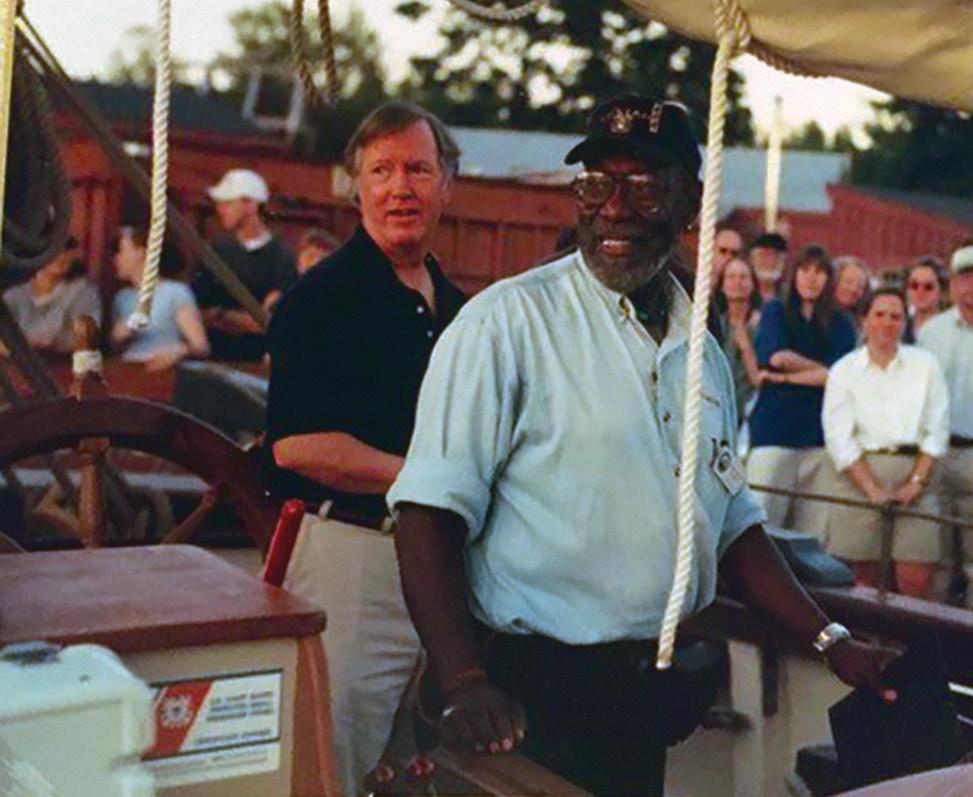

Figure 8. Enslavers forced enslaved canoemen to build and crew canoes and modified canoes used for pleasure cruises. This image shows how waterside slaveholding provided waterscapes where captives recreated and reimaged African aquatic traditions.59