ARTE E DEVOÇÃO NA COLEÇÃO CASAGRANDE BAROQJJE ORATOR/ES -ART ANO DEVOTION IN THE CASAGRANDE COLLECTION

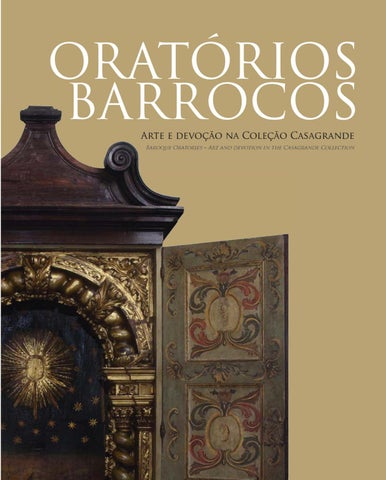

Oratórios Barrocos Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagrande

Baroque Oratories – Art and devotion in the Casagrande Collection

GOVERNO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO GOVERNMENT OF THE STATE OF SÃO PAULO Geraldo Alckmin Governador do Estado State Governor Andrea Matarazzo Secretário de Estado da Cultura State Secretary of Culture Claudinéli Moreira Ramos Coordenadora da Unidade de Preservação do Patrimônio Museológico (UPPM) Preservation Unit Coordinator for Museum Patrimony (UPPM) José Roberto Marcellino dos Santos Presidente do Conselho de Administração – SAMAS President of the Board – SAMAS Mari Marino Diretora Executiva do Museu de Arte Sacra de São Paulo Executive Director of the Museum of Sacred Art of São Paulo Museu de Arte Sacra de São Paulo Museum of Sacred Art of São Paulo Av. Tiradentes, 676, Luz, São Paulo, SP. Estação Tiradentes do Metrô. Fone: 11 5627-5393. www.museuartesacra.org.br Logotipo Arte Integrada

Opção 1

Coordenação editorial do catálogo Catalog Editorial Coordination Laura Carneiro, MTb19.0150

Arte

Integrada

Arte Integrada Serviços de Comunicação Ltda. Curadoria, pesquisa e textos Arte Curatorship, Research and Text Prof.Dr. Percival Tirapeli www.tirapeli.pro.br

Integrada

Restauradores da Coleção Casagrande Casagrande Collection Restorers Domingo Perez Gonzalez Maria Del Carmen Perez Fernandez antiguidades.carmen@gmail.com Fotografia Photography Jose Luiz da Conceição www.fotoimprensa.com.br Versão para o inglês English Version Tracy Williams Criação Visual e Diagramação Visual Creation and Design Gerson Tung Legendas Captions Rosângela Aparecida da Conceição Equipe de Montagem da Exposição Danielle M. S. Pereira, Mazé Spiteri, Rafael Schunk e Rose Santos(MAS)

Oratórios Barrocos Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagrande Baroque Oratories – Art and devotion in the Casagrande Collection

Coleção

Casagrande

Exposição

Or atórios Barrocos Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagr ande

De 23 de agosto a 23 de outubro de 2011 Exhibit

Baroque Or atories

Art and devotion in the Casagr ande Collection

August 23 to October 23, 2011

Ficha catalográfica preparada pelo Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação do Instituto de Artes da UNESP (Fabiana Colares CRB 8/7779) O63 Oratórios barrocos – Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagrande / textos Percival Tirapeli; fotos José Luiz da Conceição; legendas Rosângela Aparecida da Conceição. - São Paulo: MAS-SP, 2011. 124 p.; il. Curadoria: Percival Tirapeli Tradução inglês: Tracy Williams Ed. Bilíngüe: português/inglês ISBN 978-85-64719-01-9 1. Barroco brasileiro - Exposições. 2. Arte sacra - Brasil - Exposições. 3. Mobiliário barroco Exposições. 4.Coleções de arte – Exposições. I. Tirapeli, Percival. II. Williams, Tracy. CDD 720.981

Sumário Summary

Arte e devoção: beleza e fé paulistas ...................................... Art and devotion : Beauty and the Paulista Faith

07

A nobreza da fé presente ............................................................. The Nobleness of Faith

09

Andrea Matar azzo

José R. Marcellino dos Santos

Or atórios Barrocos Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagr ande ......................... Baroque Oratories – Art and devotion in the Casagrande Collection

11

Percival Tir apeli

Dr. Ary Casagr ande: coleção com paixão e encantamento ............................ Dr. Ary Casagrande: A Collection Built with Passion and Charm

13

Or andi Momesso

Caminhos da formação da coleção Paths Leading to the Building of the Collection

..................................

15

Ary Casagr ande Filho

Or atórios ..................................................................................... 33 Oratories Imaginária ..................................................................................... 82 The Imaginary ......................................................................

104

Bibliogr afia .................................................................................. Bibliography

122

textos em Inglês Texts in English

Arte e devoção: beleza e fé paulistas

A

exposição da Coleção Casagrande contém, em grande quantidade, peças paulistas de arte sacra, que geram e comunicam belezas e informações preciosas, não somente sobre a história de São Paulo, mas também do contexto cultural em que foram criadas. O empenho do colecionador é o de tornar acessível as obras por ele conservadas, aos diversos públicos, com a finalidade de suscitar interesses, sobretudo, pelas raízes culturais de São Paulo. Daí, a notabilidade do conteúdo desta coleção que reúne oratórios e imagens de santos paulistinhas, que são as primeiras manifestações artísticas da Arte Sacra Paulista. A coleção Oratórios Barrocos – Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagrande, que será a terceira exposição temporária do Museu de Arte Sacra de São Paulo em 2011, mostra a importância da arte sacra, por meio do acervo de grande conteúdo artístico, histórico e cultural. Andrea Matarazzo Secretário de Estado da Cultura

7

8

A nobreza da fé presente

O

Museu de Arte Sacra de São Paulo, com grande satisfação, realiza a exposição Oratórios barrocos – Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagrande, a fim de que esta se abra em diálogo com os públicos que a visitarão, despertando o esplendor da arte, e através dele o da fé inculturada. O grande mérito do acervo nesta terceira Exposição Temporária de 2011 é o de conter História, Cultura e Fé entrelaçadas, mostrando uma coleção de grande relevância nacional com dezenas de oratórios e imagens raras do séc. XVI, paulistas do séc. XVII e outras, provenientes de várias regiões do Brasil do séc. XVIII, todas de excelente qualidade estética e de beleza interior. Destacam-se os oratórios paulistas e os oratórios de viagem, sendo que esses últimos já podiam ser registrados nos fins do século XVI com o desbravamento bandeirante na Terra de Santa Cruz. Por outro lado, cada peça traz em seu bojo a memória histórica do seu momento e a mais alta expressão das raízes espirituais do povo brasileiro. A nobreza da fé, através desses Oratórios, foi alimentada nos lugares mais distantes do Brasil, e constitui não somente um patrimônio artístico cultural, mas também veículo de comunicação e de evangelização. A partir destes oratórios é que, em terras sertanejas, surgiram os rezadores, dos quais inúmeras tradições culturais e religiosas fluíram e permanecem até hoje no coração de nossa cultura. Assim sendo, a coleção Casagrande constitui para nós uma grande riqueza secular, através da qual nos remetemos aos nossos ancestrais para recuperarmos a memória histórica, cultural e, sobretudo, religiosa em nosso tempo presente, tão estigmatizado pela indiferença com relação ao transcendente. José Roberto Marcellino dos Santos, Presidente do Conselho de Administração do MAS-SP

9

10

Or atórios Barrocos – Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagr ande

A

e xposição Oratórios Barrocos – Arte e devoção na Coleção Casagrande reúne cerca de sessenta oratórios e igual número de imagens. Os oratórios barrocos do período colonial, oriundos de diversas coleções são provenientes de solares e fazendas, portanto sempre de particulares, do estados de Pernambuco, Bahia, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo. Dispostos no Museu de Arte Sacra de São Paulo, seguem o quanto possível cronologia e tipologia iniciando por um oratório ermida pernambucano – de estilo nacional português – e atingindo o ponto alto da exposição com um similar mineiro – no estilo rococó. Os oratórios de salão paulistas, com talhas ibéricas, são os mais antigos e severos. Os fluminenses são do período de D. José I e Dona Maria I, requintados e caprichosos. Dos oratórios de alcova e lapinhas, vários deles estão com os santos originais. Todos os oratórios, incluindo os de viagem e conventuais, guardam o ar devocional de seus usos durante séculos, expressos no desgaste do tempo e em transformações da materialidade, elevando-os ao status de arte. As imagens foram selecionadas entre tantas, privilegiando para esta exposição raridades maneiristas da arte barrista paulista do primeiro escultor brasileiro, Agostinho de Jesus. Esta linha completa-se com fragmentos e imagens, da escola dos seguidores daquele frei beneditino carioca seiscentista. As invocações de Maria nas configurações da Imaculada ou Piedade foram as privilegiadas. Mestres paulistas setecentistas e as paulistinhas, já do nosso século imperial são mostrados com suas iconografias do devocional popular. É um privilégio para os olhos percorrer a história do devocional brasileiro expresso na arte dos oratórios da coleção de Cristiane e Ary Casagrande Filho. É um alívio para a alma que tão rico acervo formado e conservado sob intuição aguda destes jovens colecionadores, rigorosos na escolha, nos surpreenda com a temática destes objetos devocionais. É louvável que tenham reunido e agora tragam a público estes oratórios de todas as tipologias, alinhados à qualidade de coleções museais mais conhecidas como a do Museu do Oratório em Ouro Preto (MG) da coleção de Angela Gutierrez, especializado no assunto e pioneiro no assunto, ou do rico acervo do Museu de Arte Sacra da Bahia, em Salvador (BA), com exemplares dos melhores oratórios ermidas ricos em pinturas. E ombreando-se ainda à coleção do Acervo dos Palácios do Governo de São Paulo e do Museu de Arte Sacra de São Paulo, este último com quem esta coleção particular ímpar tão bem dialoga nesta exposição Percival Tirapeli Curador

11

12

Dr. Ary Casagr ande: coleção com paixão e encantamento

O

colecionismo no Brasil, notadamente desde o último quartel do século XX até nossos dias, tem, percebo eu, tomado vulto singular em número de colecionadores. Por diversas e diferentes razões, nota-se um interesse enorme pelas artes, em especial a contemporânea, mas o colecionar no termo vernacular tem mudado sensivelmente, pois vejo hoje em grande parte a aquisição de obras, como mera especulação, esperando valorização imediata para em seguida colocá-las à disposição no mercado como simples objeto de consumo. Mas dentre tantos compradores de arte, nos dias de hoje, felizmente encontramos ainda sensibilidades que se encaixam dentro do termo colecionador de arte, aquele que pesquisa, estuda, namora a obra pretendida para só em seguida adquiri-la. Desta maneira vai formando, arquitetando sua catedral que, sabemos, nunca será terminada, pois o gosto, o desejo pelo colecionismo é sempre a obra inda não adquirida. É nesse campo dos eleitos que se insere a coleção do meu caro amigo Dr. Ary Casagrande. Quando entrei em contato pela primeira vez com sua paixão fiquei surpreso e encantado, tanto pela qualidade como pela quantidade de obras sob sua guarda. A acuidade e o carinho com que o amigo descreve cada peça de sua coleção deixam claro seu amor pelas artes. Temos agora o privilégio de apreciar nesse recorte de sua coleção, oratórios dos séculos XVII, XVIII e XIX, preciosidades da Arte Sacra. Desta maneira convido a todos apreciadores e amantes da boa arte a se deleitarem com a riqueza desta exposição com que em boa hora o Museu de Arte Sacra de São Paulo nos contempla. Orandi Momesso Colecionador

13

14

Caminhos da formação da coleção Já se vão mais de vinte anos de colecionismo. Ainda me socorre a memória o dia em que vim a adquirir a primeira peça sacra. Tratava-se de uma Nossa Senhora da Conceição de aproximadamente um palmo de altura, peça mineira, do final do século XIX, despretensiosa à luz de uma visão mais técnica, porém que teve decisiva influência no que viria a acontecer. Comprei-a de um “catador”, linguagem usual deferida àqueles que costumam recolher as peças sacras em cruzeiros, figuras estas que ao longo dos tempos foram desaparecendo paulatinamente. Hoje, este catador, meu querido amigo apelidado de Zito, já não se encontra mais entre nós. Entretanto, deve de alguma forma estar surpreso com a evolução verificada nestas duas décadas. Dedicar-se à formação de uma coleção, em qualquer seara que se ingresse, é algo complexo, de que só tomamos plena consciência depois das amarras estarem suficientemente sólidas a ponto de não mais poder recuar. Particularmente quando se concentra o foco no terreno da arte sacra, a magia deste universo - responsável pelo monopólio quase que pleno do movimento artístico brasileiro nos primeiros séculos de sua colonização - é fator revigorante e confirmador do caminho a ser trilhado, cujo trajeto é recheado de agruras e desafios que serão seguramente recompensados. Evidente que, à medida que a coleção toma corpo expressivo, surge paralelamente a necessidade de compartilhamento das obras com público mais abrangente. Neste contexto, a idéia de exposição de coleções particulares me parece ser o instrumento mais adequado. Não se pode olvidar que o povo sempre foi e será o destinatário final de qualquer produção artística.

Creio que todos os colecionadores deveriam trilhar este caminho, pois, na realidade, acabam por executar importante papel na conservação do acervo artístico religioso, bem como trazem, fruto do contato diuturno com as obras, contribuições sistemáticas relevantes para que o conhecimento se amplie e seja difundido a contento. Outro ponto a se considerar diz respeito á escolha das peças que irão compor o universo a ser exposto. Neste diapasão, em sintonia plena com o curador Percival Tirapeli, entendeu-se por bem centrar o foco nos oratórios aliados à imaginária paulista e mineira dos séculos XVII e XVIII, permitindo adotar linguagem histórico - evolutiva dos conceitos manipulados. As diversas semânticas conceituais destes pequenos templos, em suas diferentes vertentes, classificados como oratórios de viagem, esmoleiros, oratórios de alcova, oratórios de salão, até se alcançar a expressividade máxima com as ermidas, nos remetem ao culto devocional doméstico que extravasou as fronteiras dos conventos e das igrejas. Num país com dimensões inigualáveis e distâncias impercorríveis, estes objetos tornaram-se cúmplices da esperança, devoção e crença de todo um povo por centenas de anos. No que tange à imaginária, dois aspectos relevantes merecem ser frisados. O primeiro deles diz respeito à plasticidade imprimida às peças pelos hábeis santeiros que esculpiam as obras. Porém, não é só. Em perfeita simbiose, o segundo aspecto resulta na observação de que estas mesmas peças viriam a se tornar instrumento de veneração dos fiéis que buscavam conforto e respostas às suas aflições. O compartilhamento da beleza singular de tais obras com o público é, portanto, maneira de transcender todo o significado histórico, artístico, religioso e devocional que cada peça traz em sua gênese. Finalizando, agradeço a todos aqueles que de alguma forma contribuem pela conservação, estudo e valorização da arte brasileira, estando convicto de que assim o fazendo se resgata a dignidade e respeito pela nossa história. Ary Casagrande Filho

15

A forma retilínea externa deste oratório com portas almofadadas planas fechadas com ferrolhos, contrasta com as linhas sinuosas interiores. A compartimentação das portas em três segmentos,é conservadora em ambas as faces. Dentro, servem de moldura para pinturas monocromáticas em azul com cercaduras rococós para símbolos da Paixão. À direita a escada, a coluna e os dados, e à esquerda estão os cravos, as lanças e o monte Calvário. O oratório é surpreendente. Reproduz a parte superior de um retábulo a partir do embasamento com o sacrário (falso), o corpo com dois nichos, camarim e entablamento arrematado por urnas. O coroamento é um arco pleno e uma tarja completa na parte superior. A planta baixa da miniatura retabular é côncava, e o falso sacrário convexo. A pintura ornamental de cercadura monocroma em azul é encimada por uma cabeça de anjo com uma concha, e rosas e um brasão do sagrado coração são dourados e avermelhados. A pintura (de cunho popular) do camarim, com o Crucificado, é uma guirlanda de cabecinhas de anjinhos entre nuvens. Está emoldurada por um quartelão encimado por capitel compósito. As duas figuras, Maria e João Evangelista, se ajustam nas peanhas dispostas em tábuas côncavas policromadas com pinturas a imitar um nicho com volutas e lambrequins. O douramento é refinado, com punções nas partes douradas.

Oratório ermida Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada e douramento. Diamantina/ MG, séc. XVIII, 192 x 110 x 47 cm. Finíssima talha interior com predominância para as cores verde e dourado. Pintura central interna contendo dezoito anjos. Portas contendo os atributos da crucificação. Imagens: Calvário, Portugal, séc. XVIII, ornado com prata e ouro, composto por Cristo, Nossa Senhora e São João Evangelista. Small church oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome and gild, 18th century, 192x110x47 cm. Polychromatic and gilded wood carving. Inner central painting: eighteen little angel heads. Paintings on doors: objects of the crucifixion with rococo trimmings. Images: the Calvary, Portugal, 18th century, decorated with gold and silver, Crucifix, Our Lady and St. John the Evangelist.

16

17

“Ao cair da noite, todos os comensais se reunirão para entoar ladainhas, segundo o costume da terra, e nessas moradias solitárias ou ‘ fazendas’ costuma haver uma sala onde existe uma grande caixa ou armário, contendo algumas imagens de santos; os moradores se ajoelham diante dessas imagens para fazer orações” (Tamboril, BA, 1817 Príncipe Maximiliano de Wied-Neuwied, Viagem ao Brasil, p. 385).

A

Oratório – da palavra à função devocional

palavra oratório tem vários significados. São sentidos amplos, como o devocional doméstico, evocativo de oração, ou um gênero musical e até mesmo um estilo arquitetônico que designa local de reclusão. O verbo em latim para orar que dá origem à palavra oratório, significa “ falar, dizer, pronunciar uma fórmula ritual, uma prece, um discurso”, e inclui termos como oração e oráculo. Todas se interligam no ato da busca da verdade interior. Orar tem o significado de implorar com humildade e insistentemente de maneira particular e devota. Também pode ser um discurso formal que, proferido publicamente, busca a persuasão. O conceito de oração está impregnado em nosso cotidiano, incluindo nossa comunicação verbal por meio da qual nos mostramos ao mundo desde o balbuciar. A comunicação com os homens pode ser eloqüente e solene por meio das regras da oratória. Utilizadas pelo clero, atinge a oratória o elevado nível de retórica nos sermões do padre Antônio Vieira. Oratórios são considerados também arte literária, como a obra prima de Cecília Meireles, o Oratório de Santa Maria Madalena Egipcíaca. Musicalmente, o gênero foi criado por são Felipe Neri e difundido pelo compositor alemão George Frideric Händel com o Oratório Messias, em estilo barroco, cuja parte do Aleluia é a mais conhecida. Os oratórios como elementos arquitetônicos – laicos e religiosos - são espaços devocionais fixos ou móveis, tanto domésticos como conventuais. Juridicamente, cubículos onde se confinam condenados para orarem antes da execução. Quase todas as religiões determinam um espaço nos lares dos fiéis para se venerar divindades ou antepassados. A eles são oferecidos alimentos, flores, incenso e objetos que remetem a rituais ancestrais de queima das oferendas. O oratório fica no lar, podendo ser trasladado para outros lugares, pois é indissociável da proteção que confere. Pro

18

teção espiritual, dos antigos lares romanos e dos espíritos protetores das cidades, casas e ruas. Evocam ainda o domo, a morada dos deuses. O sentido devocional indica a prática piedosa, regular e privada.

Breve história do oratório

Cada religião tem seu histórico próprio para os oratórios. A arte paleocristã, desenvolveu-se nas catacumbas romanas, sobre túmulos onde estavam os restos mortais dos primeiros mártires, onde se punha um candeeiro e se assinalava o local com um símbolo cristão pintado. No período bizantino (séc 5 ao 15) fiéis levavam no peito o símbolo para a proteção. Objetos religiosos já faziam parte do comércio de pequenas pinturas ou imitações de iconostásio portáteis. Na Idade Média, os trípticos retabulares encomendados para as catedrais tinham seus doadores retratados na parte interna em posição genuflexa de orantes, ladeando a cena na parte central. Se fechados, pinturas monocromáticas acinzentadas evocavam anjos guardando as portas que, abertas, revelavam a visão evocada. A parte superior dos trípticos é ricamente ornada com pequenas esculturas intercaladas nos emaranhados arcos ogivais dourados. Objetos devocionais portáteis eram carregados pelos cruzados até Jerusalém para livrá-los da morte. No Renascimento e em especial no norte europeu, os trípticos apenas pintados ganharam notoriedade com Jan Van Eyck, Albrecht Dürer e, no período barroco, com Peter Paul Rubens e Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn. Depois do Concílio de Trento (1563), com a Contra Reforma, os altares em madeira dourada com colunas e imagens no trono e nichos laterais substituíram aqueles onde predominavam as pinturas. Esta forma de retábulo, que lembra o arco triunfal do qual se origina, disseminou-se na península ibérica e em suas colônias.

Oratório – da palavra à função devocional

A palavra oratório tem vários significados. São sentidos amplos, como o devocional doméstico, evocativo de oração, ou um gênero musical e até mesmo um estilo arquitetônico que designa local de reclusão. O verbo em latim para orar que dá origem à palavra oratório, significa “ falar, dizer, pronunciar uma fórmula ritual, uma prece, um discurso”, e inclui termos como oração e oráculo. Todas se interligam no ato da busca da verdade interior. Orar tem o significado de implorar com humildade e insistentemente de maneira particular e devota. Também pode ser um discurso formal que, proferido publicamente, busca a persuasão. O conceito de oração está impregnado em nosso cotidiano, incluindo nossa comunicação verbal por meio da qual nos mostramos ao mundo desde o balbuciar. A comunicação com os homens pode ser eloqüente e solene por meio das regras da oratória. Utilizadas pelo clero, atinge a oratória o elevado nível de retórica nos sermões do padre Antônio Vieira. Oratórios são considerados também arte literária, como a obra prima de Cecília Meireles, o Oratório de Santa Maria Madalena Egipcíaca. Musicalmente, o gênero foi criado por são Felipe Neri e difundido pelo compositor alemão George Frideric Händel com o Oratório Messias, em estilo barroco, cuja parte do Aleluia é a mais conhecida. Os oratórios como elementos arquitetônicos – laicos e religiosos - são espaços devocionais fixos ou móveis, tanto domésticos como conventuais. Juridicamente, cubículos onde se confinam condenados para orarem antes da execução. Quase todas as religiões determinam um espaço nos lares dos fiéis para se venerar divindades ou antepassados. A eles são oferecidos alimentos, flores, incenso e objetos que remetem a rituais ancestrais de queima das oferendas. O oratório fica no lar, podendo ser trasladado para outros lugares, pois é indissociável da proteção que confere. Proteção espiritual, dos antigos lares romanos e dos espíritos protetores das cidades, casas e ruas. Evocam ainda o domo, a morada dos deuses. O sentido devocional indica a prática piedosa, regular e privada.

Breve história do oratório

Cada religião tem seu histórico próprio para os oratórios. A arte paleocristã, desenvolveu-se nas catacumbas romanas, sobre túmulos onde estavam os restos mortais dos primeiros mártires, onde se punha um candeeiro e se assinalava o local com um símbolo cristão pintado. No período bizantino (séc 5 ao 15) fiéis levavam no peito para a proteção. Objetos religiosos já faziam parte do comércio de pequenas pinturas ou imitações de iconostásio portáteis. Na Idade Média, os trípticos retabulares encomendados para as catedrais tinham seus doadores retratados na parte interna em posição genuflexa de orantes, ladeando a cena na parte central. Se fechados, pinturas monocromáticas acinzentadas evocavam anjos guardando as portas que, abertas, revelavam a visão evocada. A parte superior dos trípticos é ricamente ornada com pequenas esculturas intercaladas nos emaranhados arcos ogivais dourados. Objetos devocionais portáteis eram carregados pelos cruzados até Jerusalém para livrá-los da morte. No Renascimento e em especial no norte europeu, os trípticos apenas pintados ganharam notoriedade com Jan Van Eyck, Albrecht Dürer e, no período barroco, com Peter Paul Rubens e Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn. Depois do Concílio de Trento (1563), com a Contra Reforma, os altares em madeira dourada com colunas e imagens no trono e nichos laterais substituíram aqueles onde predominavam as pinturas. Esta forma de retábulo, que lembra o arco triunfal do qual se origina, disseminou-se na península ibérica e em suas colônias.

19

Gestos e imagens: formas de comunicação

A comunicação com entes divinos na ancestralidade se dava pelos gestos e fala, expressos nas obras de arte de todos os povos. Hieróglifos no Egito sobre o suporte papiro possibilitaram uma nova linguagem cifrada que, evoluída pelos povos do Oriente Médio, possibilitou posteriormente aos hebreus a escrita sagrada em pergaminhos. A escultura grega dos kourai, jovens suplicantes com braços estendidos em preces ou agradecimento aos deuses, perdurou por séculos. Os romanos cultuavam seus ancestrais em pequenos altares na intimidade dos lares. Na clandestinidade, os primeiros cristãos assinalavam seus locais de reunião com símbolos como o peixe; mais tarde adaptaram figuras pagãs, como o pastor, ao imagético cristão. No império bizantino e nos primeiros concílios, as imagens cristãs foram oficializadas para o culto. A Idade Média adotou o tamanho e espaço simbólicos das figuras em fundos dourados. A perspectiva ótica condensando o espaço real foi restabelecida por Giotto, trazendo as figuras santificadas para o espaço terreno. O predomínio da imagem foi confirmado pela Igreja em todo Renascimento quando ela foi abalada pela tradução da bíblia para o alemão por Martinho Lutero em 1523. Enquanto a palavra bíblica era discutida entre os anglo-saxões, no mundo católico ela era explicada nas homilias, a explicação da Bíblica nas missas. Com a invenção da imprensa, a Bíblia impressa foi divulgada em língua vernacular pelos reformistas protestantes, que as vendiam de porta em porta. Os contra reformistas, por sua vez , intensificaram o uso das imagens impressas e multiplicadas que logo tomaram conta da América recém descoberta.

As Escrituras e as imagens sagradas

A necessidade matérica do contato espiritual deu-se de maneira diferente no mundo anglo-saxão – com a Bíblia traduzida – e do objetual pelas imagens, relíquias dos mártires pelos católicos romanos. A necessidade da comunicação com o sagrado seja por gestos ou por símbolos - uma forma ancestral - trouxe os santos devocionais, um intérprete entre as angústias do mundo e a busca da vida eterna. As cenas pintadas da vida dos santos eram compreendidas apenas na visualidade e eram educativas na busca da espiritualidade. Assim, tanto as esculturas como as pinturas (a visualidade) substituíam dentro do lar a indisponibilidade da leitura (a literatura sagrada em latim) reservada aos poucos letrados - em especial na colônia portuguesa. As imagens foram utilizadas para neutralizar as ações dos reformistas luteranos e dos anglicanos, mais empenhados na palavra bíblica, traduzida para as línguas vernaculares. A arte ibérica abraçou as formas barrocas no século 17 e os artífices logo se utilizaram da linguagem da arte sacra católica para a feitura dos oratórios, alimentando a prática devocional doméstica. Os oratórios tomaram formas de pequenos altares barrocos, evocando ainda os trípticos medievais com as pinturas, mas elevados a status de objetos intermediários na comunicação com o divino – tal como a palavra bíblica.

Oratório de salão Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. Séc. XVIII, 160x74x40 cm. Duplo frontão e portas almofadadas. Imagem: Crucifixo, madeira, MG, séc. XVIII, 72 cm. Ambos ex-coleção Maurício Meirelles. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome and gild. 18th century, 160x74x40 cm. Double pediment and door panels. Image: Crucifix, wood, MG, 18th century, 72 cm. Both belonging to former Maurício Meirelles collection.

Aqui a atribuição ao entalhador português Francisco Vieira Servas fundamenta-se primeiro na dimensão exata de todas as partes da peça com equilíbrio desde os pés enrolados e esgarçados, até a rocalha do arremate enlaçada da curva dupla em constante movimento até a flor que se eleva abrindo-se no espaço. Nesta flor, ou ornamento fitomórfico, está uma característica da obra de Servas que é o uso das curvas e contracurvas que ao se encontrarem criam novas pequenas ondulações. Neste caso, como no coroamento do retábulo lateral da igreja do Carmo de Sabará, nascem pétalas protegendo o peristilo de uma flor (Ramos, 2002, p.138). Pela dimensão da peça não caberia arbaleta – elemento curvo do coroamento – complexa, como acontece nos grandes retábulos. A complexidade se dá entre os elementos ornamentais externos e internos, como o arco trilobado com aduela floral rimando com as curvas externas.

20

21

A prática luso-brasileira

D. João III delegou aos jesuítas – integrantes da Companhia de Jesus criada em 1540 para combater os reformistas luteranos - a catequese dos indígenas e a prática religiosa junto aos colonizadores, desde a fundação da capital colonial, Salvador, em 1549. Beneditinos, franciscanos e carmelitas foram permitidos de aqui se instalarem durante o período da união das coroas espanhola e portuguesa (1580 - 1640). As vilas foram fundadas no litoral, iniciando por São Vicente (1532) e logo os religiosos fundaram São Paulo (1554) como a primeira vila do sertão. Sertão era praticamente tudo que não era litoral; pouco foi assistido pelos religiosos, assim permanecendo até a descoberta das minas auríferas nos imensos territórios de paulistas que abrangiam Minas Gerais, Goiás, Mato Grosso e parte do sul do país. A prática de se levar imagens em oratórios foi disseminada pelos bandeirantes tanto paulistas como baianos e pelos escassos padres que por vezes os acompanhavam em suas expedições na assistência espiritual. Nas vilas fundadas ao longo daqueles caminhos ficavam as imagens transportadas nos oratórios, que por vezes até serviam para celebrar cultos religiosos. Estabelecidas as fazendas, logo foram incorporados à arquitetura nas grossas paredes de taipa de pilão. Nas terras onde o ouro e as pedras preciosas floresceram, intensificou-se o uso do oratório doméstico. Os religiosos de ordens primeira que viviam nos conventos foram proibidos de se estabelecerem naquelas minas e a prática religiosa ficou em parte para os leigos das ordens terceiras, que contratavam o clero secular para os cultos. Já as religiosas femininas criaram oratórios conventuais em suas clausuras, quase sempre confeccionados em pequenas caixas ornadas com estampas de santos. A secularização de práticas religiosas, distante do rigor das regras das casas professas – conventos principais, em Portugal - era incentivada pela demanda dos fiéis enriquecidos, ávidos da materialização de suas espiritualidades. São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Mato Grosso e Goiás foram beneficiados por esta lacuna de assistência rigorosa dos ritos religiosos, e assim os oratórios domésticos preencheram esse vácuo na alma dos geograficamente isolados. Pernambuco, Bahia e todo o nordeste levaram esta prática para as casas de fazenda, enquanto Salvador e Rio de Janeiro atendiam uma clientela urbana, e no Vale do Paraíba os barões do café dominavam.

22

Da funcionalidade à estética

A disposição do oratório dentro de uma casa determina tanto sua forma, que lembra um armário, ornado ou não, como suas funções de uso como altar ou apenas para oração. Em ambos os casos, o conceito de encerramento, por meio de portas e portinholas, é o mais comum, sem depender do tamanho e do local. A privacidade, tanto dos santos como do suplicante, está garantida. A disposição e o acréscimo das imagens nos oratórios evidenciam a religiosidade, com a função de substituir o local sagrado público pelo privado do lar, devido à impossibilidade da prática religiosa social. Existem outros obstáculos, como a distância das fazendas até as cidades, a inexistência de igreja, questões de enfermidades ou condição social. A privatização de um conceito religioso leva a desdobramentos de outras funções, como a substituição da figura do clérigo pela do homem comum que se transforma no dono do oratório, e, portanto o rezador do terço e benzedor. Nestes casos, o status do oratório e de seu protetor se amplia para outras funções, como a de esmoler para a construção de uma capela, como ocorreu com a imagem de N. Sra. Aparecida - de oratório à capela e depois basílica nacional. As formas estéticas dos oratórios são determinadas pelas suas funções, e é o período artístico que determina o estilo ao artista ou artesão, tanto da marcenaria como da pintura, e os santeiros escultores. As posses do mecenas ou de quem faz a encomenda contribuem para a matéria, e para o contrato do artista que vai determinar a plasticidade. Os priores daquelas ordens terceiras eram os responsáveis pelos contratos dos mestres de obras e arquitetos para suas igrejas, e de artesãos para as esculturas e altares. Aqueles profissionais marceneiros, escultores, santeiros e pintores conceberam e realizaram os oratórios segundo as linhas estilísticas das obras dos altares das igrejas. O resgate de contratos de trabalho ainda hoje leva à descoberta da autoria de alguns oratórios, e a comparação entre os estilemas, as características compositivas e pictóricas daqueles artífices, completa a lista mínima de possibilidades para a atribuição. A materialidade – tipos de madeiras empregadas, pigmentos das policromias - ajuda na difícil tarefa de identificação dos autores dos oratórios e santos, visto que não eram assinados - segundo o costume da época. Quais santos estavam em cada oratório pode ser revelado pelas pinturas alusivas às cenas, pela ornamentação floral ou a disposição de peanhas, e até por marcas do tempo sobre as pinturas.

“Perguntei à mulher do meu hospedeiro se ela não se aborrecia por viver em solidão tão profunda.” ‘Não tenho eu’, respondeu-me, ‘minha família, os cuidados do meu trabalho e esta companhia?’ , ajuntou, mostrando-me pequeno oratório que encerrava a imagem da Virgem. (Arredores de Goiás, GO, 1818 Auguste de Saint-Hilaire, Viagem ao Espírito Santo e Rio Doce, p. 88)

Tipologia dos Oratórios

O

Denominações

ato devocional íntimo conquistou com o objeto oratório as prerrogativas artísticas das formas oficiais da fé. Os reluzentes retábulos barrocos das igrejas se compactaram em diversas formas, adaptadas para as residências. Os maiores, como os oratórios ermidas, comparáveis a pequenas capelas, eram incrustados nas paredes largas das casas de fazendas ou dispostos sobre pesados móveis. Tinham funções de celebrações coletivas semelhantes às das capelas. Esteticamente, concorriam com os altares das igrejas. Se menores, são denominados oratórios de salão, dispostos na parte social da residência ou corredor intermediário à parte íntima da casa – e, se nela colocados, são chamados de oratórios de alcova. Aqueles transportáveis são os de viagem e os menores, para bolso, oratórios de algibeira. Esteticamente, podem conter formas cultas, seguindo as diretrizes estilísticas das escolas do tempo. No Brasil, as linhas barrocas seguem as normas retabulares quanto às colunas internas, imitando os altares. Os estilos barroco nacional português, o joanino e as linhas suaves rococós foram utilizados por mais de duzentos anos. As colorações mais escuras do barroco ficaram esmaecidas com a vinda do rococó. Santos, anjos e flores completam o simbolismo ligado às imagens dispostas nos nichos. Os de cunho popular seguem as mesmas tendências estéticas, mas de maneira mais distante. O armário que encerra os santos pode ter soluções inusitadas diante das dificul-

dades encontradas pelo artesão. Portas modulares, gavetas para esmolas e arremates fantasiosos fazem parte das mesmas formas cultas que indicam funções similares. As pinturas singelas, tanto de flores como de figuras, garantem uma espacialidade sui generis , confirmada pela busca de perspectiva e tamanhos simbólicos. A estes elementos se unem aqueles de diversas etnias africanas afeitas aos sincretismos, ao uso de símbolos ancestrais de seus cultos e a objetos das religiões de suas origens.

Configurações

A configuração exterior de um oratório é a de um armário, lembrança de um local sagrado, a igreja, contendo o interior de um altar. As formas mais singelas remetem inclusive às torres e cruz no arremate. As portas lisas, almofadadas com losangos ou retângulos, ajudam na identificação regional. Pés em formas de peanhas os tornam mais elegantes e leves sobre as cômodas. O arremate, que corresponderia ao coroamento retabular, indica o período estilístico e mesmo a autoria. Portas articuladas lembram os antigos trípticos ou polípticos medievais. Os oratórios maiores acompanham a gramática retabular, com base do altar e falso sacrário como embasamento. O altar cumpre a função de sacristia para guardar as alfaias litúrgicas, o que pode ser feito também em espaços laterais substituindo o arcaz; o falso sacrário é apenas estético, pois não se permite guardar as hóstias consagradas a não ser nas igrejas.

23

O corpo do oratório ermida em geral se abre em grande tribuna e, se a altura permitir, há um trono ou peanhas para dispor as esculturas. Em geral colunas ladeiam os limites dos caixotões de madeira, ou então apenas talhas rendilhadas delimitam a entrada do camarim. O coroamento e as colunas definem a tipologia, sendo as mais freqüentes no estilo nacional português para os mais antigos, estilo joanino para os da primeira metade do século 18 e rococós que adentram o século 19 - quando são substituídos pelos neoclássicos. Pinturas e apliques de papéis com flores completam a ornamentação. O oratório arca cumpre a mesma função da celebração de missas. Nas almofadas internas das portas há cenas pintadas, cercadas pelas molduras formadas pela disposição das madeiras. Em jacarandá, indica a região, em geral nordeste; em cedro, Minas Gerais ou outra região do sudeste como o Rio de Janeiro. Os oratórios de salão se destacam pela configuração mais elaborada. Vistos também de perfil, ganham novas formas com portas articuláveis que se abrem como folhas das sagradas escrituras, revelando seus tesouros iconográficos. Os arremates podem ser pesados, como janelas ou portas com vergas curvas quando se remeterem às formas arquitetônicas das igrejas. Se o referencial for algum altar, são mais livres e fantasiosos, como permitem os coroamentos retabulares e pés que lembram peanhas elaboradas. Ganham espacialidade nas laterais, bem como aberturas. Se envidraçados, lembram os altares reservados para os relicários, prática difundida em especial pelos jesuítas. Os oratórios de alcova são menores e, dispostos sobre cômodas, ganham formas variadas que lembram os de salão. Em geral tem as portinholas com pinturas na parte interna, e a distribuição das imagens possibilita os acréscimos dos santos. Se abertos, tem francas aberturas mostrando os santos. Se pequenos, comprimem-se as esculturas, como os pequeninos santos paulistinhas, feitos em barro sobre base cônica ocada, disputando um pedaço do céu na intimidade do lar. Os oratórios chamados de lapinhas comportam uma quantidade maior de pequenas figuras. A iconografia de passagens bíblicas como o nascimento e a Paixão de Cristo, exige um acúmulo de figuras referentes a este tipo de oratório. A sequência cronológica dos fatos ganha narrativas desenvolvidas em níveis ou espaços verticalizados, como o presépio e o calvário. Se pertencentes ao hagiológio, os milagres são evidenciados pela sua importância, como as passagens franciscanas ou carmelitas. Os santos, ali pro-

24

tegidos pelo vidro que ajuda na integridade da obra, são facilmente identificáveis como mineiros, pela utilização da pedra talco ou calcita da região do rio Piranga e do quadrilátero ferrífero . Os oratórios conventuais tem forma de pequenas caixas. Em geral são assemblagens envidraçadas e ricamente ornadas, e sua materialidade costuma ser determinada pela riqueza de quem o fez ou encomendou. São utilizadas reproduções de santos ou pequenas imagens, papéis laminados dourados e perfurados, compondo a arquitetura ornamental que substitui as madeiras e o ouro. O aspecto cumulativo mostra o afetamento devocional perdido em preciosidades e singelezas. Instrumentos para se confeccionar flores, fios de pedrarias e bordados podem ser vistos ainda hoje nos espaços culturais em que foram transformados muitos conventos em terras ibéricas. Os oratórios de conchas formam um tesouro à parte, no qual reina o menino Jesus, ricamente paramentado com vestes e túnicas inconsúteis geradas no labor das minúcias e paciência artesanal. No Rio de Janeiro ainda colonial, Francisco Xavier dos Santos, depois apelidado das Conchas, criou oratórios com conchas que disseminou por Santa Catariana. No Recôncavo Baiano existe precioso acervo no convento de Santo Amaro da Purificação

Tipologia – a poética do oratório

Sem a paternidade das mãos que os criaram, sem a majestade retabular das igrejas, os oratórios devocionais se situam no limbo das classificações, entre o erudito e o popular. Pela função, desde para ser carregado na algibeira em forma de bala, só se consola, pois é companhia para o sertanejo; de alcova, para a donzela presa em suas esperanças de liberdades do casamento; de salão, para ser visto e lustrados seus dourados para impressionar visitas; de ermida, substituto do templo distante das casas grandes, de fazendas dos barões do café; se de viagem, nos lombos das mulas não apreciam a paisagem, abrem-se na escuridão da noite para rezas tristes, terços cadenciados e esperançosos para o novo destino; de tradições medievais como esmoleiros levados no peito de penitentes ou escravos de ganho a arrecadar para festejos; se presos em casas, com gavetas ou fundos falsos ocultando as patacas que serão revertidas em prendas e melhorias de igrejas; no silencio das virgens apartadas nos conventos, com suas mãos frias e colos de cor de cera, os oratórios tomam formas enclausuradas. Os Meninos são asfixiados in vitro,

aquecidos por roupas e fios tecidos por parcas viúvas orantes com vozes finas e celestes. A forma do oratório revela a intimidade devocional, com portinholas que ocultam e revelam segredos da alma. Se colocados nos salões, ficam no aguardo de uma visita distante; se abertos, revelam a riqueza material acumulada. Se ermidas, os oratórios são solenes, com as certezas de cerimônias batismais e presenças eclesiásticas. Sóis a iluminar as casas de fazendas nas distâncias dos sertões, complexos e robustos, à semelhança de seus senhores donatários, coronéis e brasonados da corte. Raros são os que se revelam ao primeiro olhar curioso: são humildes externamente. Olhai os oratórios soturnos por fora, abri-os com seu coração em preces e de lá exalará o perfume das rosas do campo e a certeza do lume a guiar a alma. Assim, lembranças de um tempo perdido entre imagens e arquétipos da religiosidade fazem-nos comungar com a ancestralidade.

Mudanças estilísticas

Oratórios são testemunhas mudas, dóceis, transportáveis por todos os períodos históricos das nossas regiões brasileiras. Quando a Linha de Tordesilhas (1494) nos encurralava contra as terras de Espanha, eles eram singelos, leves, verdadeira simbologia da espiritualidade corporificada naquele pequeno objeto portátil. Pesados como nas linhas barrocas pernambucanas transtornadas pela presença holandesa nos engenhos e capelas destruídas pelos reformistas. Sofisticados com sobriedade joanina e afeitos a rezas solenes dos senhores da capital colonial. Enigmáticos quando o negrume da noite se confundia com soluços dos homens escravos expatriados para as terras baianas. Leves, revestidos de ouro e resplendores, saídos das minas de ouro. Formas esgarçadas, prontos para subirem para ao plano espiritual, eternidade artística materializada nas mãos que antes rodavam as batéias. Elegantes e complexos como os ritos da corte. Enobrecidos por códigos formais estéticos advindos de Roma, Paris e Lisboa, os oratórios da então capital imperial desafiavam os rumores da maçonaria e seguiam pelas fazendas dos barões do café. No longínquo sertão de Anhanguera, acostumaram-se com o destino bravo das mortes. Em formas de pequenos caixões, apenas cruzes apontavam para a esperança de novas vidas.

25

A configuração do oratório de salão com gaveta na base é dura e tradicional. Linhas retas e perfis salientes austeros cercam toda a forma em armário. O arremate é singelo, com uma flor esculpida de maneira quase plana semelhante a outras duas que amainam os cantos rígidos superiores. As almofadas salientes tanto das portas como da gaveta animam a frontalidade excessiva. Os sinais das cavilhas que sustentam as almofadas apontam técnicas antigas. Ao ser aberto, duas pinturas em forma de cortinas criam uma profundidade estranha devido à desproporção de pequenos nichos acoplados às portas. Ainda nas folhas da porta. Abre-se uma cortina carmim. Uma cercadura vazada e contínua na borda do arco pleno e laterais até a altura das folhas das portinholas, deixa mostrar a generosidade de forma que qualifica o corpo de um retábulo. O trono é pentagonal de três degraus, ladeado por duas volutas que sustentam as colunas torsas marmorizadas em tonalidades do mármore rosso de Verona e lápis lázuli. Sobem as tonalidades pelas torções alternadas, rimando com flores policromas do fundo do camarim. Um estranho capital sustenta o entablamento encimado por pequenas pilastras coroadas com folhas. O dossel com lambrequim e borlas completa a gramática ornamental retabular. O forro da peça imita as abóbadas de canhão de uma capela mor.

Oratório de salão Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. Séc. XVIII, 155x73x44 cm. Imagem: N. Sra. da Conceição, madeira policromada, indo-portuguesa, séc. XVII, 40 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome and gild. 18th century, 155x73x44 cm. Image: Our Lady of Conception, Indo-Portuguese, polychrome wood, 17th century, 40 cm.

26

Estética Os arremates

O

s arremates dos oratórios evidenciam de imediato a configuração, o planejamento e o conceito da peça a partir da forma de armário, imitação de fachada de igreja, usual para os de salão e ermida aqui analisados. Os antigos paulistas, do período maneirista, dos séculos 17 e início do 18, ostentam formas rígidas, praticamente armários com portas almofadadas que se abrem. Os arremates são singelos, lembrando os frontões das igrejas jesuíticas com triângulos frontões levemente curvilíneos com duas volutas de entalhe plano. Os arremates são aplicados. Os barrocos, do final do século 17 e início do 18, com a gramática do estilo nacional português, com arremates independentes da estrutura, são curvilíneos, simétricos com as duas volutas e o triangulo com curvas e contracurvas. Exemplo é o oratório ermida pernambucano em jacarandá. Aqueles da metade do século 18 trazem os arremates incorporados às suas estruturas, lembrando as portas ou janelas com vergas curvas - que nos oratórios ganham mais frisos que na arquitetura. Outros sugerem portadas com arremates escultóricos, vindos das estruturas que suportam as portas almofadadas ou mesmo de vidro. Simétricos, ainda com ares de religiosidade severa, se apresentam sem policromia enfatizando os ornamentos e materialidade a explicitar a feitura da peça, em especial os relevos esculpidos. Aqueles de planta baixa em perspectiva ou mesmo poligonais, tem arremates em curvas que acompanham as laterais. Quando abertos, as curvas dos arcos das portas se multiplicam, tornando-os mais graciosos. Os oratórios de linhas estilísticas rococós, aqui os fluminenses, tem arremates em linhas curvas e contracurvas oriundas da estrutura do móvel. A assimetria ornamental pode nascer desde a base, passar pelas estruturas que delimitam as aberturas e se ampliar no arremate mais sensível. As portas de vidro ajudam na concepção da peça/vitrine, liberta da concepção de armário imitando a fachada da igreja ou janela e transformando-se em objeto para ser apreciado como obra de arte. Os arremates são fantasiosos, com caprichosas talhas vazadas em madeira de lei.

Já os oratórios lapinha seguem outra estrutura. São menores, em geral nascidos de uma só peça de madeira da qual nascem os pés, e as mesmas linhas curvas seguem os parâmetros estilísticos tanto para a abertura do camarim como para o arremate fantasioso do coroamento da peça. A sequencia de curvas forma arcos em geral trilobados na abertura do camarim e na base, onde se coloca a peanha. A divisória ali é mais reta e ornada com curvas, que rimam mais com os pés próximos.

Os interiores

Dependendo da tipologia - se ermida ou de salão - são mais profundos ou rasos. O de ermida chega a ser um verdadeiro altar, com a mesa embutida ou não no armário. Imita um retábulo na parte interna com um arco triunfal, como se separasse a nave da capela mor – e no caso de uso doméstico, pode separar a sala ou corredor da parte devocional doméstica. Se menor, imita um altar com a todas as partes como sacrário, colunas, camarim com nichos e peanhas, mesmo nas portas. Os oratórios de salão são mais rasos e, dependendo dos objetos devocionais, tem apenas base para o crucifixo e peanhas para as figuras, que completam a cena da Paixão. As figuras nas portas trazem também figuras e no fundo, aumentando a profundidade com cenas de Jerusalém. Cortinas pintadas ajudam neste intuito e flores complementam a iconografia em geral rosas para os santos ou a Virgem Maria. Os oratórios lapinha tem níveis diferentes que acompanham a cronologia das cenas como o presépio na parte inferior e outras cenas, em geral a Paixão no nível superior. Os oratórios conventuais imitam altares, melhor seria vê-los como caixas dentro das quais há uma sucessão de planos com as reproduções das gravuras formando os altares. Os de conchas são para serem vistos de frente como todos os outros, porém sua disposição sobre os móveis permite por vezes serem admirados pelos lados. A

27

cúpula de vidro, que lembra o oratório bala, facilita a visão por todos os lados.

As pinturas

A ornamentação pictórica pode ser figurativa ou com florais, ou apenas com a policromia resultante das diversas combinações, como a do marmorizado. As peças agraciadas pela pátina do tempo, marcas do uso e desgaste, ostentam um sabor de antiguidade que se espera das peças não restauradas. Cores vivas, como vermelhos e azuis, ficam esmaecidas como no caso dos oratórios paulistas do século 17. A policromia resultante de aplicação de fundos, marmorizados e efeitos de trompe l’oeil de molduras, vasos, flores com sombras, é característica das peças desta coleção. As figuras dos santos, dos apóstolos e da Virgem com ou sem as guirlandas de cabecinhas de anjinhos, surpreendem pela qualidade que vai do erudito ao sabor popular. A superioridade da pintura sobre o entalhe ou mesmo construção do oratório revela requinte na escolha das peças e busca de excelência para a coleção. O oratório com as duas figuras avolumadas de Maria e São João Evangelista, somadas à pintura da Jerusalém no momento da morte de Cristo, é um ponto alto das peças expostas. Os anjinhos aparecem aos buquês, mais ao gosto popular, e por vezes apresentam tez amorenada. A simbologia das flores está presente na maioria dos fundos ornamentais que completam a iconografia dos santos apresentados nas cenas. Nem sempre se pode concluir quais seriam os santos, porém as rosas indicam a presença

de Maria, os cravos o sofrimento de Cristo, as papoulas a dormência da morte, os lírios, a simbologia da pureza e os girassóis a atitude devocional. A apresentação das flores vai se compondo nos espaços livremente, em guirlandas ou em vasos de formas barrocas, retorcidas ou esgarçadas à maneira rococó.

Os santos

Por serem os oratórios domésticos, de devocional particular, os santos escolhidos para ali serem abrigados seguem apenas a vontade do devoto. Os indícios de que santos lá estavam são mais claros quando se trata de cenas da Paixão com marcas do crucifixo nascidas com o passar do tempo. As duas peanhas laterais indicam a presença de Maria e João Evangelista. O mesmo ocorre com as pinturas que trazem a mesma cena, com pinturas de Jerusalém para o presépio com o céu estrelado e com a estrela do Oriente. Os símbolos da Paixão – açoite, cravos, escada – também evidenciam a presença do crucificado ou da Piedade. Flores de maracujá simbolizam a Paixão e as rosas, Maria e outros santos. Portanto os resquícios, as manchas das antigas pinturas são caminhos a se seguir nesta trilha onde a vontade do devoto nem sempre segue a racionalidade iconográfica religiosa. Assim, os oratórios fechados são mais seguros para conservarem a imagens originais, mas nos de viagem, fica mais difícil saber quais eram elas, a não ser que se tenha o nome do devoto e de seu orago. Os colecionadores que adquirem os oratórios em geral adaptam neles imagens do mesmo período, seja por tamanho ou mesmo por intuição. São eles os novos admiradores, que se sucedem a tantos devotos que ali colocaram seus santos.

Oratório de salão Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada. MG, séc. XVIII, 105x61x27 cm. Nicho central ornamentado por baldaquim. Imagens: Sta. Cecília, MG, séc. XVIII, 24 cm, e Sto. Antonio, MG, séc. XVIII, 12 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome. MG, 18th century, 105x61x27 cm. Central niche decorated with a canopy. Images: St. Cecilia, MG, 18th century, 24 cm, and St. Anthony, MG, 18th century, 12 cm.

O oratório encanta pela policromia que aos poucos vai revelando as formas completas de um retábulo, resolvidas plasticamente de forma popular. Externamente destaca-se pelo coroamento curvilíneo acentuado pela cor avermelhada. Internamente as duas folhas das portinholas recebem dois jarrões com flores simbolicamente marianas que se espalham pelos intercoluneos e fundo do camarim. A imitação retabular , desde o embasamento com falso sacrário, colunas retas com pinturas de colunas torsas, entalhamento reto e dossel curvilíneo no coroamento, mostra o esforço do artesão em criar uma peça culta. Este pensamento se explicita na planta baixa que oscila entre o retilíneo dos socos das colunas e a convexidade da forma do falso sacrário transformado em nicho.

28

29

Do devocional doméstico ao objeto de arte do colecionador

D

estinado a todos os destinos, afeito a todas as angústias os oratórios prescindem de autoria. As mãos que ensamblam as madeiras, quem diz que não podem dourar? Quem prova não poderem tocar as superfícies lisas com os pincéis? Ao menos as rosinhas. Se seguidas as regras das confrarias, o trabalho é coletivo. Marcenaria, douramento, pintura e imaginária à parte. Concluso, seu destino é certo e logo incerto. Muda de lugar, seus santos saem de moda ao não atenderem os pedidos do suplicante. Perdem-se na genealogia.

ras européias garantem um lustro aristocrático expresso nos entalhes, nas pulsões a emoldurar peôneas, cravos e papoulas, símbolos lidos naqueles tempos, tão distantes dos nossos ananases, maracujás e margaridas do campo. Vidros e cristais bisotados garantem a impenetrabilidade de rezas simplórias no aguardo das súplicas, no francês condizente das matronas letradas. A garantia de terem sido testemunhas de rezas de baronesas, amantes do imperador, aumenta seu valor pecuniário e sua raridade é alardeada.

Ficam à espera de um novo fiel. São levados como mercadorias. Vendidos. Repletos de súplicas, ficam impávidos diante de novas falas estéticas. As madeiras ressequidas, escurecidas e carcomidas das imagens conferem-lhes a pátina do tempo. Observados, sentem-se retraídos, dispostos sobre mesas e fragmentos de altares. Disputam importância com pinturas e tapeçarias nas paredes. Seguem os oratórios aos olhos de especialistas em arte, antiquários, decoradores, colecionadores, quais objetos de desejo de posse de um tempo perdido de mistérios quando a religião regia a sociedade, e a vida privada originava-se da religiosidade portuguesa. Na disputa pela origem, se oratório indo-português ornamentado com marfins e madrepérolas incrustadas, no abismo do vazio entre os oceanos Indico e Atlântico, valorizava-se pelos riscos de suas viagens por rotas nunca dantes navegadas. As madei-

A antiguidade é garantia de admiração. As formas levemente embrutecidas os levam às regiões recônditas; sua sobrevivência nas selvas, incêndios de brigas entre senhores, escravos e indígenas, dignificam a historicidade e seu reaparecimento na civilização. As marcas das desventuras são glorificadas na hora da troca. As pinturas chamuscadas pelas chamas devocionais das velas fazem fundo para os craquelês dos rostos dos santos, que se metamorfoseiam em castigos de almas penadas e condenações de antigos donos avaros.

30

O requinte de formas estéticas precisa ser revisado sempre pelo colecionador, ampliando assim as qualidades que podem elevar a obra ao patamar de exclusividade, objeto único, distantes das oficinas populares. A raridade formal é valorizada pela introdução de eventual autoria. Se

confirmada, iniciam-se as comparações de estilemas, as características formais de cada autor. Cada forma então deve ser comparada à de obras maiores, altares conhecidos, douramento melhor brunido, panejamentos mais sombreados e formas mais requintadas, afetadas pelo estilo barroco ou rococó. Já o oratório popular tem sua valorização estética/cultural pela sua origem, no desenvolvimento da arte culta até sua apropriação pelas camadas populares. Este distanciamento dos paradigmas europeus cria ecos na busca da brasilidade. Formas mais retas, cores terrosas, imagens em barro, caracterizam um cenário propício para a rusticidade necessária da arte popular. O artesão é fruto de pesquisa de poucos estudiosos, o despertar de um regionalismo logo cantado por ter preenchido no tempo e espaço uma necessidade expressiva. Hoje deslocados de seus ambientes de penumbras, perdidas as sombras alongadas e movediças das paredes caiadas de solidões brancas e cinzas, os oratórios se exibem sob uma aura artística. Saídos de madeiras nobres, feitos por hábeis mãos de artesãos da confraria dos carpinteiros, uma procissão de josés encaminhou-os oratórios de suas oficinas coloniais até as casas das vilas, solares das cidades e casas grandes de fazendas. Mudados de endereços, os oratórios saíram das casas de ermas paragens para

as salas requintadas urbanas, convivendo com a modernidade das pinturas figurativas de ecos barrocos ou com aquelas abstratas e concretas. Esta valorização do barroco devocional tem origem no Movimento Modernista, quando da viagem de Mário de Andrade, Oswald de Andrade e Tarsila do Amaral em 1924 por Minas Gerais - que levou a artista a declarar-se apaixonad a pelas pinturas caipiras que antes fora proibida de usar em suas obras. A busca de uma nacionalidade e de figuras artísticas que confirmassem uma arte brasileira levou os modernistas à arte barroca do período colonial, como gênese de brasilidade. Nos anos 60, com a confirmação da modernidade e a ameaça da abstração internacional, os objetos barrocos entraram na decoração mesclada moderno/antigo daquele período de desenvolvimento dos anos JK. O colecionismo de objetos sacros ganhou força diante da destituição de elementos ornamentais das igrejas, que, anos mais tarde se modernizaram pela segunda vez , seguindo normas do Concílio Vaticano II. O Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo foram os principais receptáculos destas peças particulares, deslocadas do Nordeste para o Sudeste, garantindo assim suas sobrevivências nesta intensa mobilidade dos objetos barrocos devocionais.

31

32

Oratórios

século XVII – das casas grandes às bandeirantistas “Há também um oratório reservado ao culto doméstico, o mais das vezes colocado na varanda, no outro ângulo da casa” (João Maurício Rugendas, 1825/30, Viagem pitoresca através do Brasil, p. 113)

O

s oratórios do século XVII do Pernambuco e São Paulo, pertencentes à coleção, são severos na configuração externa com arremates imitando frontões de igrejas. Internamente, o arco pleno é o mais visível segundo normas do estilo barroco nacional português. O exemplar pernambucano é de talha culta, com excelentes pinturas. Os paulistas seguem uma tradição de talha plana e vazada

hispânica, com rosas singelas e policromia acentuada para os vermelhos. A pintura é de sabor popular com o frescor de traços incultos para as flores e motivos votivos e a policromia, quando há, é desgastada, comprovando a antiguidade das peças. Há em três delas pequenos balaustres imitando os espaços delimitados das igrejas, ou ainda a mesa da comunhão. O oratório com esmoler destaca-se pelo requinte da talha.

33

Oratório ermida Madeira (jacarandá) recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada e pinturas, PE, séc. XVII, 232x114x59 cm. Pertenceu à coleção Maurício Meirelles. Small church oratory. Carved and engraved wood (jacarandá), gild and paintings, PE, 17th century, 232x114x59 cm. Former Maurício Meirelles collection.

Destaca-se na coleção Casagrande o majestoso oratório ermida pernambucano, feito em jacarandá. Externamente, apresenta forma rígida de armário, pés pesados, suavizados por frisos na soleira da porta, e acima coroamento com duas volutas austeras e triangulo frontão com tímidas curvas e contracurvas. O interior é surpreendente: abre-se um verdadeiro retábulo com arco triunfal com colunas torsas, entablamento duplo, coroamento em arco pleno, aduelas e relevos de folhas de acanto. O requinte escultórico em madeira mostra a forma culta de trabalhar dos mestres nordestinos. A obra, impecável, completa-se com importante pintura. Nas almofadas das portas, são elas volutas emoldurando medalhões ovóides com o sol e a lua. Dentro do camarim há um resplendor do Crucificado, circundado por céu estrelado. Abaixo, das mais surpreendentes e bem conservadas pinturas em oratórios: a Jerusalém celeste, guarnecida de muralhas, repleta de torres e palácios cintilantes, protegida por uma abóbada azulada e estrelas faiscantes.

34

35

Oratório de salão Madeira recortada e entalhada, sem policromia. SP, séc. XVII, 138x73x37 cm. Adquirido por Francisco Roberto no ano de 1962 da Fazenda Velha de Lavras, Suzano/SP. Imagem: S.Bento, madeira, séc. XVII, 67 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood, no polychrome. SP, 17th century, 138x73x37 cm. Acquired by Francisco Roberto in the year of 1962 from the Velha de Lavras Farm, Suzano/SP. Image: St. Benedict, wood, 17th century, 67 cm.

O severo oratório de salão em forma rígida de armário, em madeira escura lavrada, remete às austeras condições de vida material, isolamento geográfico e adequação ao ambiente inóspito da vida dos bandeirantes carentes de amparos espirituais nos sertões. Nas portas abertas do oratório raso, a ornamentação tímida surge nas delgadas colunas torsas até a altura do diminuto capitel e perde-se no arco pleno com o friso torso quase plano. Uma balaustrada delimita os espaços sagrados, onde habitam os santos do mundo das atribulações dos devotos. O arremate imprime um pouco de leveza à austeridade da peça. As curvas e contracurvas, embora de entalhe plano, cumprem a função de embelezamento, e o recorte caprichoso dos coruchéus alivia as partes lisas que domina todo oratório.

36

O oratório de salão, paulista, aberto por um grande arco, mostra-se franco e simples em suas duas partes. A rigidez do retângulo frontal é aliviada não só pelo arco pleno, mas também pela ornamentação minuciosa floral, policrômica, de toda a cercadura - desde as colunas planas até o arco, além das rosas maiores nos ângulos superiores. Estas rosas repetem-se no arremate singelo, quase inocente, balbuciando arremedos de volutas que encimam a cruz sobre o globo. A sensibilidade do colecionador em eleger o Cristo de Ecce Homo de mãos atadas, reflete um feliz encontro entre a simplicidade do oratório, proveniente de Iguape, no litoral paulista, com a imagem em barro cozido de Santana de Parnaíba. O nicho do oratório tem um parapeito a conjugar com a cena, na qual Cristo é apresentado com o manto, porém já condenado. O uso da cor avermelhada lembra a proximidade das terras paulistas com aquelas do reino da Espanha. Oratório de salão Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada. Iguape/SP, séc. XVII, 95x45,5x25 cm. Pertenceu à coleção de Francisco Roberto. Imagem: Cristo da Cana Verde, barro cozido, Santana do Parnaíba,SP, séc. XVII, 40 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome. Iguape/SP, 17th century, 95x45.5x25 cm. Former Francisco Roberto collection. Image: Christ of the Patience, baked clay, Santana do Parnaíba, SP, 17th century, 40 cm.

37

A singeleza deste oratório paulista evidencia-se no exterior pelas formas populares que se esforçam para imitar aquelas cultas, em especial nas molduras que correm toda a estrutura. O arremate, que pode ser posterior, confirma a dificuldade do artesão em expressar-se em formas escultóricas serrilhadas. Ao abrir as portinholas, um sopro de fé advém das chamas das velas e castiçais desproporcionais. As linhas imitando molduras vazadas, ao gosto hispânico popular das terras missioneiras, limítrofes com aquelas paulistas, tomam maior corpo, ampliando o discurso pictórico ornamental nas tábuas do fundo. Estas linhas fortes aprisionam formas simbólicas com uma cruz grega, devido à forma quadrada do oratório. Lampejos dourados saem de pequenos losangos e quadrados com folhas de ouro aplicadas.

Oratório de salão Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. Itaquaquecetuba,SP, séc. XVII, 80x47x28,5 cm. Imagem: Cristo da Pedra Fria, barro branco cozido, 39 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome and gild. Itaquaquecetuba, SP, 17th century, 80x47x28.5 cm. Image: Christ of the Patience, baked, white clay, 39 cm.

38

Oratório de salão Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada. SP, séc. XVIII, 74x53x24 cm. Imagens: Crucifixo, N.Sra. da Soledade e N. Sra. dos Prazeres, marfim, séc. XVII. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome. SP, 18th century, 74x53x24 cm. Images: Crucifix, Our Lady of Soledade and Virgin and Child, ivory, 17th century.

Oratório de salão Madeira recortada e entalhada, com resquícios de policromia e douramento.SP, primeira metade do séc. XVIII, 99x75x32 cm. Imagens: figuras do calvário: crucifixo, Maria, S.João e Madalena, pedra sabão, MG, séc. XVIII. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood with vestiges of polychrome and gild. SP, first half of the 18th century, 99x75x32 cm. Images: Calvary figures: crucifix, Mary, St. John and Mary Madeleine, soapstone, MG, 18th century.

39

Oratório de viagem e de esmoler Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. Santana de Parnaíba, SP, séc. XVII, 35x25x12 cm. Imagem: N.Sra.com o Menino Travel and almsgiving oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome and gild. Santana de Parnaíba, SP, 17th century, 35x25x12 cm. Image: Our Lady with the Child.

40

Oratório de salão Madeira recortada. Pintura: no forro, a Santíssima Trindade; nas portas, jarros e flores. Recolhido em Santa Isabel,SP, séc. XIX, 84x51x25 cm. Imagem: Cristo crucificado, séc. XIX, SP, 54 cm. Drawing room oratory. Woodcarving. Paintings: ceiling, the Holy Trinity; doors, vases and flowers. Recovered in Santa Isabel, SP, 19th century, 84x51x25 cm. Image: Christ on the Cross, 19th century, SP, 54 cm.

Oratório de alcova de convento. Papel machê. SP, séc. XIX, forma circular com 15 cm de diâmetro e 7,5 cm de profundidade. Imagem: S. João Batista Menino. Convent alcove oratory. Papier mache. SP, 19th century, circular shape with a 15 cm-diameter and a 7.5 cm depth. Image: St. John the Baptist as a child.

Oratório de alcova de convento. Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. SP, final do séc. XVIII, 25x13x6,5 cm. Imagem: Sta. Teresa. Convent alcove oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome and gild. SP, late 18th century, 25x13x6.5 cm. Image: St. Teresa.

41

42

Oratórios

DAS CAPITAIS COLONIAIS “....havíamos de ter um oratório bonito, alto, de jacarandá, com imagem de N. Senhora da Conceição.” (Machado de Assis, Dom Casmurro, p. 69)

O

s oratórios das cidades litorâneas, em especial Salvador e Rio de Janeiro, capitais da Colônia e Império, oferecem sofisticações e soluções devidos ao constante contato com a metrópole. Os dois baianos são em jacarandá e o de viagem tem trabalho em marchetaria. As pinturas são presença marcante, em especial a das Dores e o São João Evangelista no oratório com pintura de Jerusalém.

Os oratórios fluminenses da Coleção Casagrande são em jacarandá e oferecem recortes fantasiosos nos arremates, que os distinguem dos mineiros. O estilo rococó D. José I é decorrente, com linhas suaves e entalhes preciosos, sem policromia. Três deles trazem três portas, possibilitando várias vistas e buscando para si o status de peças individualizadas.

43

44

As pinturas se sobressaem na ornamentação deste oratório de formas curvas requintadas, expressas no arco trilobado com moldura vazada, guardando a cena da Crucificação. A perspectiva de tamanho simbólico mostra os sofrimentos de Maria e do discípulo amado, que em nítida desproporção antecedem a pintura da cidade e do crucifixo. O artista segue a iconografia exata da colocação da Dolorosa do lado esquerdo, João Evangelista do direito e ao fundo a Jerusalém no momento da tempestade que Cristo exclama Eli! Eli! lama sabctani? (Meu Deus! Meu Deus! Porque me abandonaste?). A cidade mostra-se difusa, entre nuvens, e os raios atingem o véu do templo. Anjos morenos de lábios carnudos são testemunhas perplexas do momento da salvação. O entusiasmo do artista ao pintar as duas figuras nas portas coloca-as de maneira desproporcional tanto em relação ao Crucificado como à pintura de Jerusalém. Embora de traços barrocos, remetem à perspectiva simbólica medieval, aqui ampliando o sofrimento dos mortais ao depararem com o sacrifício divino. A riqueza do crucifixo, com resplendores de prata, ressurge entre os rolos de nuvens. A distância entre as duas figuras pictóricas laterais e a cena do fundo pode justificar o tamanho menor do Cristo.

Oratório de salãO Madeira (jacarandá) recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. BA, séc. XVIII, 147x115x41 cm. Portas com pinturas: N.Sra. e S. João Evangelista, cabeças de anjos ao fundo. Imagem: Cristo crucificado, BA, séc. XVIII, 1,25 cm, ornamentado com prataria vermeil. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood (Jacaranda), polychrome and gild. BA, 18th century, 147x115x41 cm. Paintings on doors: Our Lady and St. John the Evangelist, angel heads in the background. Image: Christ on the Cross, BA, 18th century, 1,25 cm, decorated with vermeil silver.

45

Oratório de salão Madeira (jacarandá) recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. Transição do estilo D. José I para Dª Maria I. BA, final do séc. XVIII, 150x78x41 cm. Portas com pinturas: S. Francisco e S. Mateus. Imagem: S. João Batista Menino, BA, séc. XVIII, 71 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood (Jacaranda), polychrome and gild. Transition from D. José I to Dona Maria I style. BA, late 18th century, 150x78x41 cm. Paintings on doors: St. Francis and St. Mathew. Image: St. John the Baptist as a child, BA 18th century, 71 cm.

46

Oratório de viagem Madeira recortada e entalhada, com incrustações em marchetaria. BA, séc. XVIII, 29x21x13 cm. Imagem: N.Sra. da Glória ou Assunção. Travel Oratory. Carved and engraved wood with inlaid marqueterie. BA, 18th century, 29x21x13 cm. Image: Our Lady of Glory or Ascension.

O trabalho marchetado nas portinholas, com os símbolos da paixão de Cristo, distingue esta peça de outros motivos pictóricos da coleção. A composição das lanças e a escada – maiores e centrais – soluciona os objetos menores do suplício: três cravos, martelo e tenaz. Ao fundo, a cruz e o sudário confirmam a presença de um Crucificado. Vista pela parte posterior, a pequena peça surpreende pela abertura, quase em segredo, e a visão da cena se faz inversamente, apresentado em primeiro plano a cruz com o sudário e, através da cercadura, vêem-se outros símbolos da Paixão. A peça em madeira confirma a habilidade do artesão, expressa nos frisos retos e curvos, nos encaixes, conferindo ao oratório um aspecto robusto e sólido, condizente com a iconografia. O apuro na feitura continua nas dobradiças em forma de caneta, chave e ganchos para se passar correia para o transporte, confeccionados em prata.

47

Esta peça se mostra dividida em duas partes distintas: o corpo envidraçado e o coroamento ricamente ornado. Abre-se em perspectiva, mostrando as aberturas laterais, destacando a central entre molduras lisas. Ao se aproximar, o devoto percebe pequenas flores emanadas da caprichosa goiva do artesão que vagarosamente se estiram na moldura e em um crescendo saliente acima preparam para uma surpresa visual. O coroamento comporta-se como uma chama que cresce em formas flamejantes. Revela-se aos poucos: a sinuosidade da peça central crepita em curvas e contracurvas ampliadas sob o eco dos frisos ondulantes. Os arremates laterais confirmam a configuração fantasiosa, a tomar toda a parte superior da peça. Há intervalos e vazados para abrigar os suspiros de admiração. Vista de relance, tem um ar oriental tanto na configuração de uma sombra de teatro à moda chinesa, como pelo brilho e coloração das flores com estampa a lembrar chinesices. Na penumbra, a materialidade da madeira escura faz a peça agitar-se em uníssono, desde os pés que a elevam e o colorido róseo realçado por linhas douradas demarcadas com punções, até a última curva que busca mais espaço nas alturas.

Oratório de salão. Madeira (jacarandá) recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. Estilo D. José I. RJ, séc. XVIII, 184x96x38 cm. Interior com pintura de flores. Imagem: S.Francisco das Chagas, madeira, Europa, séc. XVIII, 96 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood (jacaranda), polychrome gild. D. José I style. RJ, 18th century, 184x96x38 cm. Interior with floral paintings. Image: St. Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, wood, Europe, 18th century, 96 cm.

48

A sobriedade do corpo do oratório em madeira escura, de linhas retas, tem duas compensações visuais para sua leveza. A primeira é a base em linhas que se abrem possibilitando a visão das aberturas laterais. A segunda é o grande arco em complexas curvas e contracurvas, encimadas por formas que pulsam entre a ampliação e a retração da verticalidade da peça.

Oratório de salão Madeira (jacarandá) recortada e entalhada, sem policromia. RJ, segunda metade séc. XVIII, 164x100x51 cm. Estilo D. José I. Portas laterais. Imagem: Crucifixo, marfim, Goa, prataria, séc. XVII, 97,5 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood (jacaranda), no polychrome. RJ, second half of the 18th century, 164x100x51 cm. D. José I style. Lateral doors. Image: Crucifix, ivory, Goa, silver, 17th century, 97,5 cm.

49

50

O oratório é envidraçado em três faces, sendo a frontal encimada por grande curva emitindo frisos curvilíneos a ecoarem por todo o arremate. Refinado entalhe sobe desde a base pelas estruturas que suportam a parte superior e lá terminam em formas de quatro volutas. Acima do entablamento saliente, quatro coruchéus flamejantes ampliam a vertica-

lidade da peça. Das curvas ondulantes e ecos da estrutura curvilínea da porta com batente liso, nascem rocalhas fantasiosas que sustentam a forma conchóide do coroamento. As rocalhas pictóricas rimam com as formas esgarçadas do arremate e as flores se abrem, frescas tonalidades róseas no auge do viço.

Oratório de salão. Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada e dourada. RJ, séc. XVIII, 130x86x37 cm. Imagem: Cristo crucificado, MG, séc. XVIII, 45 cm. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome and gild. RJ, 18th century, 130x86x37 cm. Image: Christ on the Cross, MG, 18th century, 45 cm.

Oratório de capela Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada. RJ, séc. XVIII, 188x125x42 cm Imagem: N.Sra. da Soledade, Portugal, séc. XVIII, 103 cm. Chapel oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome. RJ, 18th century, 188x125x42 cm. Image: Our Lady of Soledade, Portugal, 18th century, 103 cm.

Oratório de salão Madeira (jacarandá) recortada e entalhada, com incrustações em marchetaria, policromada e dourada. RJ, segunda metade do séc. XVIII, 192x93x29 cm Portas com pinturas: S.Francisco e S.José. Imagens mineiras: Cristo, 67 cm, Sto. Antonio, 32 cm e Sta. Rita, 35 cm, séc. XVIII. Drawing room oratory. Carved and engraved wood (Jacaranda), polychrome with inlaid marqueterie, gild. RJ, second half of the 18th century, 192x93x29 cm. Paintings on doors: St .Francis and St. Joseph. Images from Minas Gerais: Christ, 67 cm, St. Anthony, 32 cm and St. Rita, 35 cm, 18th century.

51

52

Devoção dourada objetos barrocos particulares

“De regresso de curto passeio (...) encontrei a família toda rezando (...). Ficaram de par em par abertas as portas do Oratório e exposto o Crucifixo até o justo momento de servir-se a ceia no mesmo cômodo: o dono da casa aproximou-se então com grande seriedade e, após ter feito profunda reverência à imagem, cerrou-lhe as portas.” (Arredores de São João del Rei, MG. John Luccock, Notas sobre o Rio de Janeiro e partes meridionais do Brasil, p. 295)

U

ma conjunção de fatores incrementou a intensa produção nas terras das minas: a riqueza do ouro, levando uma plêiade de artistas para as cidades que durante todo século XVIII produziu das mais expressivas obras do barroco e rococó; a demanda para abastecer casas de fazendas afastadas dos centros urbanos; o modismo dos

oratórios nos solares dos abastados; a falta ou escassez de religiosos e a consequente maior liberdade do clero secular; e por fim o incentivo das ordens terceiras nas encomendas artísticas. Tudo isso contribuiu para o desenvolvimento de uma escola de artesãos no fabrico dos oratórios ermida e de salão.

53

Oratório ermida Madeira recortada e entalhada, policromada, pinturas em trompe l’oeil, segunda metade do séc. XVIII, 246x130x34 cm. Adquirido da coleção de Mauricio Meirelles - MG. Imagens: Cruz, madeira policromada, séc. XVIII, 145 cm, com Cristo de marfim, indo-português, séc. XVIII. Small church oratory. Carved and engraved wood, polychrome, paintings in trompe l’oeil, second half of the 18th century, 246x130x34 cm. Acquired from the Mauricio Meirelles collection - MG. Images: Cross, polychrome wood, 18th century, 145 cm, with Indo-Portuguese ivory Christ, 18th century.