Program notes by Elaine Schmidt

FRANZ LISZT

Born 22 October 1811; Doborján, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire (now Raiding, Austria)

Died 31 July 1886; Bayreuth, Germany

Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major for Piano and Orchestra, S. 124

Composed: 1830 – 1849; revised prior to publication in 1857

First performance: 17 February 1855; Weimar, Germany

Last MSO performance: 22 September 2013; Andreas Delfs, conductor; Jeremy Denk, piano

Instrumentation: 2 flutes; piccolo; 2 oboes; 2 clarinets; 2 bassoons; 2 horns; 2 trumpets; 3 trombones; timpani; percussion (cymbals, triangle); strings

Approximate duration: 19 minutes

Romantic-era Hungarian piano virtuoso, composer, and conductor Franz Liszt could improvise impossibly complex, wildly technical piano music at the drop of hat. But when he had to commit his ideas to paper, he would waffle over details, work, and then re-work sections again and again, and generally tinker with the music, sometimes for years, before calling it finished and ready to publish. He began his Piano Concerto No. 1 in the early 1830s, tweaking and rewriting it for 25 years before calling it finished. He performed as the soloist in the world premiere of the piece in 1855, and then worked on it for more than a year before deciding it was ready for publication.

Liszt wrote his second piano concerto, a one-movement piece, at about the same time as the first. It was premiered in 1857, with Liszt conducting the performance. He worked on that concerto for another four years before deciding it was finished.

Musicologists joke about how amazing it would be to find an unknown piece of music by a great composer in the attic of a castle, where it had been languishing for many years. That’s what happened with Liszt’s third piano concerto, although pieces of it were found in three different European libraries instead of a castle attic. Like Liszt’s second concerto, it is written as a single movement. Like his Concerto No. 1, the one on this program, it is written in E-flat major.

In the years of working on his Concerto No. 1, Liszt started out writing it as a standard threemovement concerto. But a single musical theme runs throughout the piece, which led him to fuse the three movements together into a single movement. But by the time Liszt finally published the piece, it was divided into four movements. Today, most performances honor a long tradition of following Liszt’s intentions for a single movement (as well as his final version of the piece) by presenting it in four movements, but with just the briefest of pauses between the movements.

MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 45

FRANZ LISZT

Totentanz for Piano and Orchestra, S. 126

Composed: 1847 – 1849; revised in 1853 and 1859

First performance: 15 April 1865; The Hague, Netherlands

Last MSO performance: 25 February 1991; Harvey Felder, conductor; Jeffrey Siegel, piano

Instrumentation: 2 flutes; piccolo; 2 oboes; 2 clarinets; 2 bassoons; 2 horns; 2 trumpets; 3 trombones; tuba; timpani; percussion (cymbals, tam-tam, triangle); strings

Approximate duration: 15 minutes

Franz Liszt performed with such virtuosity and personal charisma that he developed a frantically ardent following — particularly among women. They would mob him at stage doors, tearing at his clothing, hoping to take home a scrap of fabric that he had worn. If this reminds you of the reaction fans had to the likes of Elvis Presley, you’re correct. Musicologists often refer to Liszt as the “first rock star,” even though rock music wouldn’t hit the airwaves for more than a century after his experiences with fans.

Like Mozart, some 50 years before him, Franz Liszt toured Europe as a child, with his father as his chaperone and tour manager. Also, like Mozart, he lost a parent while touring. Mozart lost his mother in Paris, far from his Salzburg home. Liszt also lost his father while on the road. The 15-year-old pianist was suffering from nervous exhaustion and was recuperating on the French Coast of the English Channel when his father contracted typhoid and died.

Liszt’s father, an avid amateur musician, had been his son’s principal musical influence up until his death. After that time, virtuoso violinist Niccolò Paganini became Liszt’s musical mentor. Losing him left the young Liszt obsessed with death — images of death in artworks in particular — and wrote several pieces inspired by death or by artworks depicting death.

Totentanz (“Dance of Death”), which is highly dramatic and virtuosic, is often referred to informally as Liszt’s third piano concerto for its intense piano part. It opens with the ominous “Dies irae” plainchant, which you will also hear on this program in the fifth movement of Berlioz’s 1830 Symphonie fantastique. Liszt began his Totentanz in the late 1830s, completing in 1849 and revising it in 1853 and 1857.

Some historians think Liszt based the piece on one or another artistic depiction of death, but Liszt did not leave any clear indication of that. Curiously, ten days after the premiere of Totentanz, Liszt began the process of becoming a Catholic priest. He only got as far as taking minor orders, but was known for the rest of his life as Abbé Liszt.

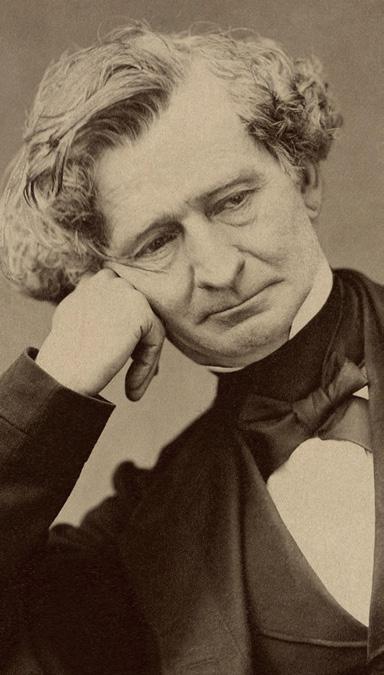

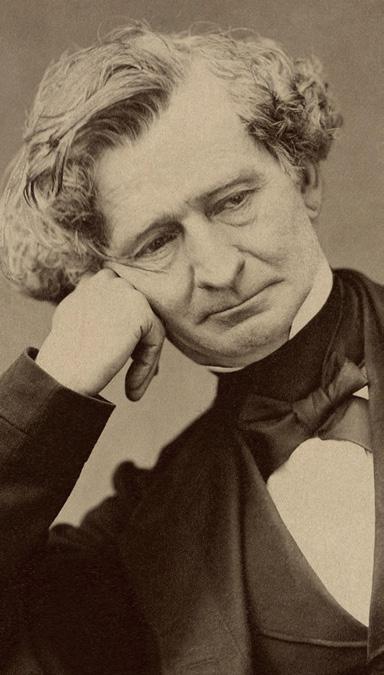

HECTOR BERLIOZ

Born 11 December 1803; La Côte-Saint-André, France

Died 8 March 1869; Paris, France

Symphonie fantastique, Opus 14

Composed: 1830

First performance: 5 December 1830; Paris, France

Last MSO performance: 4 March 2018; Joshua Weilerstein, conductor

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubles on piccolo); 3 oboes (2nd doubles on English horn, 3rd off-stage); 2 clarinets (2nd doubles on E-flat clarinet); 4 bassoons; 4 horns; 2 trumpets; 2 cornets; 3 trombones; 2 tubas; 2 timpani; percussion (bass drum, cymbals, off-stage chimes, tam-tam); strings

Approximate duration: 49 minutes

46 MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

French composer Hector Berlioz created his own musical language, largely because he had little training in music. He took some lessons on flute and banjo as a youth and learned to play a few chords on the piano. Expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a doctor, he began medical training, but quit to take up music. He studied for a time at the Conservatoire de Paris, but took very little away from those studies. For many years, the music world debated whether his compositional style was based on creative genius or was simply a mess.

Symphonie fantastique, Berlioz’s first symphony, was popularized in the 20th century through Disney’s animated film Fantasia. With it, he wanted to create “something new.” He succeeded, creating an early example of “program music,” a piece based on a non-musical idea or story. Composer Franz Liszt, who would later coin the phrase “tone poem” for symphonic program music, heard the piece’s premiere and struck up a friendship with Berlioz afterward. The two remained friends for many years. Liszt wrote a piano transcription of the Symphonie fantastique about three years after its premiere so that people who didn’t have an opportunity to hear an orchestra play the piece could still get to know it.

The story on which Berlioz based Symphonie fantastique was highly autobiographical, telling of his obsessive love-at-first-sight for an actress named Harriett Smithson. He wrote a couple of program notes for the piece, each describing his inspiration and intentions for each section of it. Berlioz eventually married Smithson. But without having a language in common, the two could barely communicate and did not stay married long.

If you listen closely to the end of the final movement, you will hear the “Dies irae” plainchant, which you heard in Liszt’s Totentanz earlier on the program.

Movement I: Rêveries – Passions (Daydreams and Passions)

An artist sees a young woman and falls in love with her, which plants a haunting musical image in his mind.

Movement II: Un bal (A Ball)

Finding himself at a festive ball and then in a scene of great natural tranquility, he is haunted by images of Harriet.

Movement III: Scène aux champs (In the Country)

The artist is in a field, where he hears two sheepherders conversing. He keeps thinking of his beloved, but suffers disturbing premonitions.

Movement IV: Marche au supplice (March to the Scaffold)

Thinking his love is lost to him, the artist poisons himself with opium. Having taken too small a dose, he simply sleeps, but is tortured by vivid dreams of his own execution.

Movement V: Songe d’une nuit du sabbat (Dream of the Witches’ Sabbath)

The artist imagines his own funeral — a nightmarish scene full of witches, sorcerers, and other hideous figures. His beloved appears but is swept up into the orgy of horrible creatures. The dance of the witches mingles with the “Dies irae.”

MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 47

2023.24 SEASON

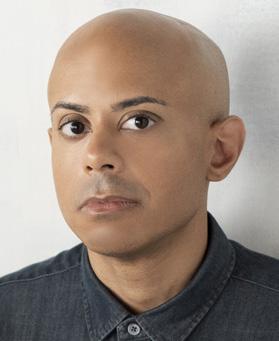

KEN-DAVID MASUR

Music Director

Polly and Bill Van Dyke

Music Director Chair

EDO DE WAART

Music Director Laureate

RYAN TANI

Assistant Conductor

CHERYL FRAZES HILL

Chorus Director

Margaret Hawkins Chorus Director Chair

TIMOTHY J. BENSON

Assistant Chorus Director

FIRST VIOLINS

Jinwoo Lee, Concertmaster, Charles and Marie Caestecker Concertmaster Chair

Ilana Setapen, First Associate Concertmaster

Jeanyi Kim, Associate Concertmaster

Alexander Ayers

Yuka Kadota

Elliot Lee**

Ji-Yeon Lee

Dylana Leung

Kyung Ah Oh

Lijia Phang

Yuanhui Fiona Zheng

SECOND VIOLINS

Jennifer Startt, Principal, Andrea and Woodrow Leung Second Violin Chair

Timothy Klabunde, Assistant Principal

John Bian, Assistant Principal (3rd chair)

Glenn Asch

Lisa Johnson Fuller

Paul Hauer

Hyewon Kim

Alejandra Switala**

Mary Terranova

VIOLAS

Robert Levine, Principal, Richard O. and Judith A. Wagner Family Principal Viola Chair

Georgi Dimitrov, Assistant Principal (2nd chair), Friends of Janet F. Ruggeri Viola Chair

Samantha Rodriguez, Assistant Principal (3rd chair)

Alejandro Duque, Acting Assistant Principal (3rd chair)

Elizabeth Breslin

Nathan Hackett

Erin H. Pipal

Helen Reich

CELLOS

Susan Babini, Principal, Dorothea C. Mayer Cello Chair

Nicholas Mariscal, Assistant Principal*

Shinae Ra, Acting Assistant Principal (2nd chair)

Scott Tisdel, Associate Principal Emeritus

Madeleine Kabat

Peter Szczepanek

Peter J. Thomas

Adrien Zitoun

BASSES

Jon McCullough-Benner, Principal, Donald B. Abert Bass Chair*

Andrew Raciti, Acting Principal

Nash Tomey, Acting Assistant Principal (2nd chair)

Brittany Conrad

Teddy Gabrieledes**

Peter Hatch*

Paris Myers

HARP

Julia Coronelli, Principal, Walter Schroeder Harp Chair

FLUTES

Sonora Slocum, Principal, Margaret and Roy Butter Flute Chair

Heather Zinninger, Assistant Principal

Jennifer Bouton Schaub

PICCOLO

Jennifer Bouton Schaub

OBOES

Katherine Young Steele, Principal, Milwaukee Symphony League Oboe Chair

Kevin Pearl, Assistant Principal

Margaret Butler

ENGLISH HORN

Margaret Butler, Philip and Beatrice Blank English Horn Chair in memoriam to John Martin

CLARINETS

Todd Levy, Principal, Franklyn Esenberg Clarinet Chair

Benjamin Adler, Assistant Principal, Donald and Ruth P. Taylor Assistant Principal Clarinet Chair*

Taylor Eiffert*

Madison Freed**

E-FLAT CLARINET

Benjamin Adler*

BASS CLARINET

Taylor Eiffert*

Madison Freed**

BASSOONS

Catherine Van Handel, Principal, Muriel C. and John D. Silbar Family Bassoon Chair

Rudi Heinrich, Assistant Principal

Beth W. Giacobassi

CONTRABASSOON

Beth W. Giacobassi

HORNS

Matthew Annin, Principal, Krause Family French Horn Chair

Krystof Pipal, Associate Principal

Dietrich Hemann, Andy Nunemaker French Horn Chair

Darcy Hamlin

Kelsey Williams**

TRUMPETS

Matthew Ernst, Principal, Walter L. Robb Family Trumpet Chair

David Cohen, Associate Principal, Martin J. Krebs Associate Principal Trumpet Chair

TROMBONES

Megumi Kanda, Principal, Marjorie Tiefenthaler Trombone Chair

Kirk Ferguson, Assistant Principal

BASS TROMBONE

John Thevenet, Richard M. Kimball Bass Trombone Chair

TUBA

Robyn Black, Principal, John and Judith Simonitsch Tuba Chair

TIMPANI

Dean Borghesani, Principal

Chris Riggs, Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Robert Klieger, Principal

Chris Riggs

PIANO

Melitta S. Pick Endowed Piano Chair

PERSONNEL MANAGER

Françoise Moquin, Director of Orchestra Personnel

LIBRARIANS

Paul Beck, Principal Librarian, Anonymous Donor, Principal Librarian Chair

Matthew Geise, Assistant Librarian & Media Archivist

PRODUCTION

Tristan Wallace, Production Manager/ Live Audio

* Leave of Absence 2023.24 Season

** Acting member of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra 2023.24 Season

48 MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA