Meteorites on Display

James Tobin

Well, first I guess I should report that the meteorite that was being classified in the last issue of the magazine and suspected of being a Howardite is a Polymict Diogenite Breccia. It ended up with less than 10% eucrite material. I am not at all unhappy about the results. I have never had a diogenite breccia classified for me so I think it is very cool.

This month it was hard to figure out what to write about. When that happens I put music on the computer and play it in the background. It seems to help with my rare writer's block. As I am starting this article Gioachino Rossini's William Tell Overture Finale is roaring out of the speakers. No word from the muse yet. Next on my playlist is three different versions of Johann Pachelbel's Canon in different keys. One of my favorite versions is done by a string quartet. Using of course baroque instruments. All of this has nothing to do with meteorites but listening to music does tend to inspire me when I am blue or don't feel like writing on a particular day. I am surrounded in my office by space rocks and one might think that they would be inspiring enough, but sometimes I need a bit of music in addition. Even Baroque music sometimes works. As the music played I found myself looking around the office and decided to just feature a few meteorites from the shelves and desktop. They are nothing too special other than they are from outer space, the rarest material on Earth, like nothing terrestrial, and are billions of years old. But nothing too special. The first meteorite is a 1449-gram "ordinary chondrite" that is partially fusion crusted and has some nice thumbprinting. I chose to leave it alone and not grind a window into its surface. That is a bit unusual for me as I like to see the insides of my meteorites. As the painted catalog number indicates this was acquired in Tucson in 2017. The chondrules visible on the light-colored broken surfaces would suggest it is a pretty nice meteorite.

Meteorite Times Magazine

The Baroque music was just not doing it so it was off to the 50s and 60s starting with Little Richard's Long Tall Sally and I began to feel a little more creative.

I put ordinary chondrite in quote marks above since as an amateur I dislike the term. I understand that it is a title used in the scientific community to describe the large group of stone meteorites that have chondrules and are not extra special. Not special such as the carbonaceous chondrites or enstatite chondrites. Still, as a lifelong avid collector, none of my meteorites seem really that "ordinary" to me.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

This meteorite is just left out on the top of my desk. It will rest stably in several different ways but I mostly have it broken surface down and best thumb printed end up.

The next meteorite is another from my desk that has been there for a couple of decades. (Chuck Berry-Johnny B. Goode playing in the background) It was pretty special when I got it back around 1998 just as the rush of meteorites from Northwest Africa was beginning. I never ground a window on this one either. And again from what I can see on the outside, it is a low petrologic type meteorite maybe a type 4 chondrite. In a different reality, I would get a big batch of these meteorites classified. But the system is rather overloaded all the time without me sending my collection of unclassified NWAs into laboratories. I never painted a number on this one. So I had to weigh it for the article. This worn fusion-crusted stone is 622.2 grams. If this stone had come into the business instead of into my personal collection it would surely have been a cutter. It would have made beautiful slices that would now be spread around the world. But it is still as originally bought and I don't know what I paid but it was not very much maybe 5 or 10 cents per gram, oh how things have changed. (Ritchie Valens-Come on Let's Go)

Meteorite Times Magazine

Oldies stopped working for me and so it was on to another type of music I like. (Put a lid on ItSquirrel Nuts Zippers) Oh, how I wish there was a soundtrack along with this article.

Meteorite Times Magazine

The next meteorite to feature is one from on top of a display case. It too has been around for about twenty years. My office is usually a messy wreck of an area and gets dusty up here in the mountains. We are noted for our winds and they carry fine dust that gets everywhere. I am less than vigilant about brushing and vacuuming the rocks. It is a very creative environment but messy and even though there is no one to tell me to clean up my space it seemed appropriate to listen and watch the Official Music Video of Twisted Sister-We're Not Gonna Take It. I love the beginning when the kid's dad is yelling at him about his messy room and is blown through the wall by the music.

Back in the day, I made caliper holders for many of the meteorites. This is one of those. I bent the steel rod and brazed huts on each of the ends of the curved rod. Then I brazed on a stem that I threaded on one end to hold the caliper in a base. With a pair of threaded brass rod sections inserted into the nuts, I could tighten the caliper against the stone. It made a nice display to go on a wooden base and under a glass dome. This meteorite is number 30 in my unclassified database. Weighing in at 680 grams it has a pleasing almost spherical shape, good remnant fusion crust, and nice thumbprinting. It is a meteorite that has been on Earth a bit

Meteorite Times Magazine

longer than the others shown so far. It has a crack on one side and a piece missing that has been popped out likely by frost heaving. Frost heaving is a process that breaks rocks down over a long time. A crack will form and water will get in the crack. When the temperature drops to below freezing the water expands when it turns to ice and having nowhere to go the ice will spread the crack. Eventually, the crack will open up to where a chunk of the rock will fall off. This stone looks to have lost a small piece to either that process or simply having had the piece broken off. Perhaps it broke on landing as so often happens. But now after so much time on Earth, it is hard to tell. However, the stone is missing a larger portion of what I would call the bottom where I numbered it. Still, I liked the stone years ago even as incomplete as it was, and bought it. I liked that I could see the thickness of the fusion crust along the big broken area. But again there is nothing really special about it other than after decades I have come to love it.

Meteorite Times Magazine

As most of the readers of this article know I have worked on a few meteorites in my lifetime. Actually, it's probably thousands now. Many just got windows ground and polished on them. Other meteorites got a broken end cut off and were then ground and polished. And many meteorites were cut into slices which now reside in collections and museums worldwide. The last meteorite for this article was a big surprise for me. It just almost knocked me to the floor when I finished an inspection cut and saw what I had gotten. That cut produced a type specimen that went off for classification literally in minutes. It turned out to be a beautiful L6 impact melt. It weighed 1500 grams give or take when I got it and was the strangest colored meteorite I had ever bought. It was far too orange and had a slate-gray interior. Was not sure it was a meteorite but bought it anyway. NWA 7347 also sits on my desk under a glass dome and I remember fondly cutting it and running into the house. I showed it to my wife before writing a quick email to Alan Rubin at UCLA with an attached image of the cut surface. He responded in minutes and asked how soon I could send him a piece. That was a fun day. As I wrap this article up I have made my way to another of the rock groups I like. These songs have been playing in the background. ELO-Hold On Tight To Your Dreams and Calling America

Meteorite Times Magazine

(Arlo Guthrie-Highway in The Wind and Mapleview 20% Rag)

Meteorite Times Magazine

NWA 5245 R3

John Kashuba

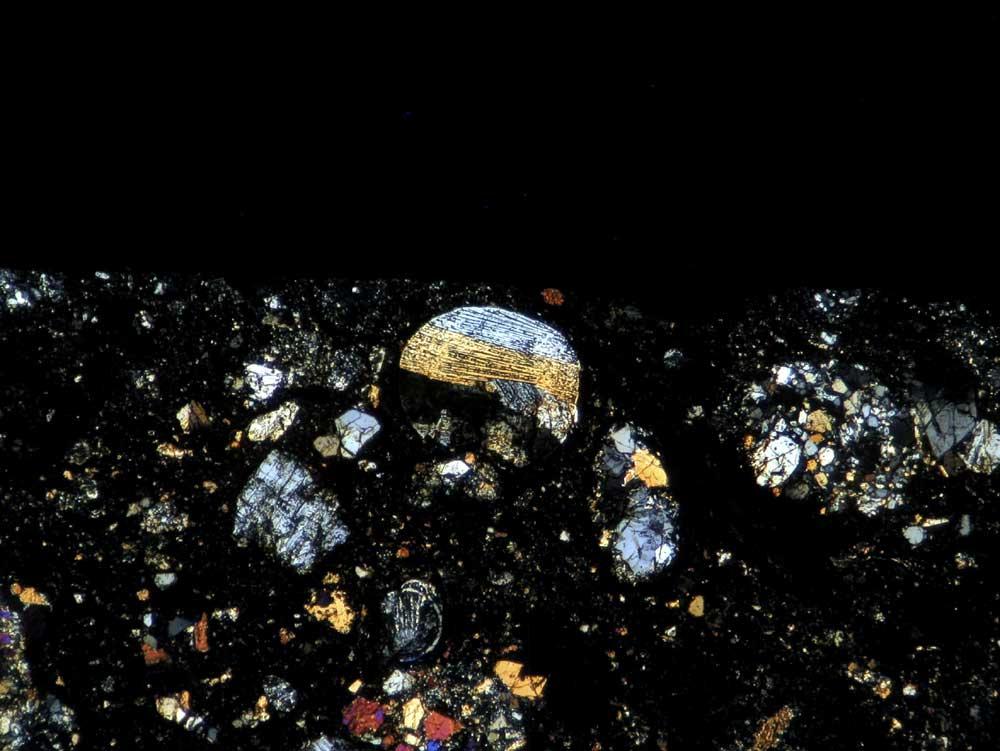

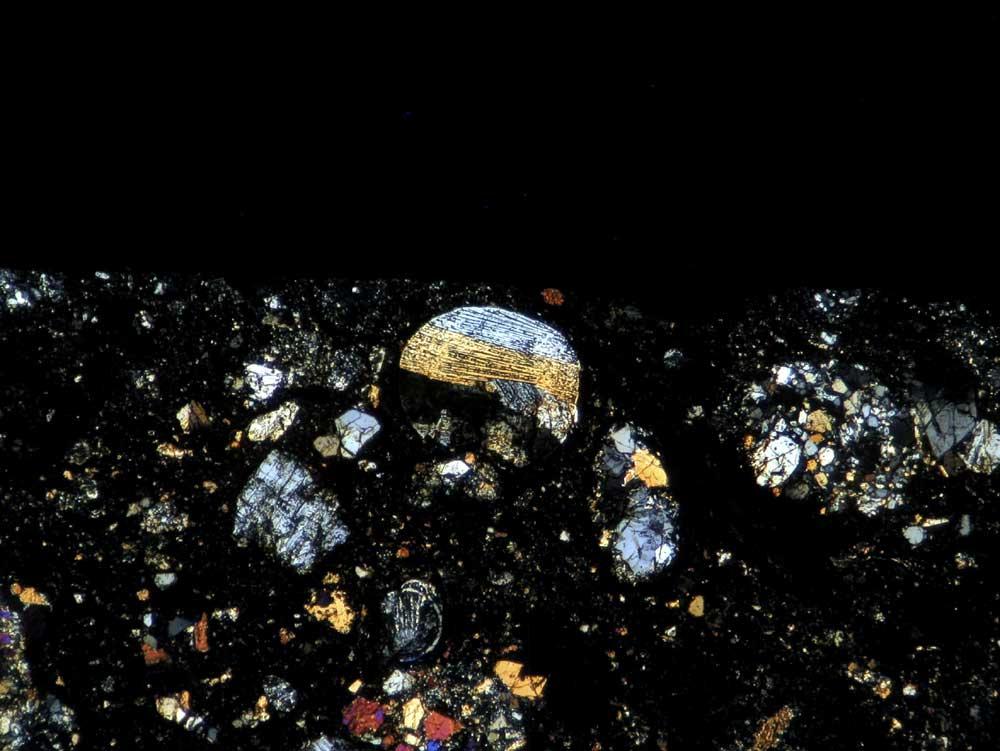

Here are some objects we found in the Rumuruti chondrite, NWA 5245 R3. All are in thin section and viewed in cross-polarized light.

We like the appearance of barred olivine; it is both ordered and varied. This 2mm diameter barred olivine chondrule with an igneous rim is much larger than usual for an R chondrite.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Also large. Less orderly. Field of view is 3mm wide.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

FOV=3mm.

Curiously, only part of this chondrule is barred. FOV=3mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

No rim. At 0.5mm it is about the average apparent diameter of R chondrite chondrules.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

Yellow BO chondrule formed and gained mass through several accretion and melting cycles.

Meteorite Times Magazine

The small red BO chondrule, too, went through several cycles. FOV=3mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

FOV=3mm.

Rumuruti chondrites are from the surface, the regolith, of the R parent body. This asteroidal soil has been tilled by impacts for eons. It is not surprising that we find these rounded fragments. FOV=3mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

FOV=3mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

FOV=3mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

BO chondrule 0.3mm long.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

BO chondrule 0.15mm in diameter, at the lower end of the size range in R chondrites.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

An irregular chondrule containing two large "dusty" relict olivine grains. FOV=3mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

The "dust" is fine particles of iron metal derived from the olivine by a reduction process. FOV=0.5mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Chondrule with a "dusty" relict olivine grain. FOV=3mm.

Meteorite Times Magazine

FOV=0.3mm.

Nihon Inseki or Japanese Meteorites - Co-authored with Jesse Piper

Dedication to Dr. Carleton Moore

I dedicate this article to my good friend, Dr. Carleton Moore. For those of you who were fortunate enough to know Carleton, I need not write anything more about him. For the others, Carleton was a pioneer in meteorite research and assisted with training the NASA Apollo astronauts on what type of samples to collect while on the moon, as well as, being one of the first scientists to study lunar samples brought back from the Apollo missions. He was Emeritus Regents Professor in the School of Molecular Sciences and the School of Earth and Space

Meteorite Times Magazine

Mitch Noda

Carleton and Mitch inside the ASU meteorite vault.

Exploration at Arizona State University. He was the founding Director of the ASU Center for Meteorite Studies, which houses the world’s largest university based meteorite collection. His accomplishments are too many to list here. Carleton was friends with Nininger, LaPaz, Monnig, Fales, and countless others. Dr. Laurence Garvey discovered a new mineral in the Norton County meteorite, and named it in honor of his close friend as Carletonmooreite. More importantly, Carleton was selfless and generous with his time enjoying and attending numerous outreach programs until the end and answering questions and being a friend to all who reached out to him and enriching all the lives he touched. Many years ago, when I started collecting meteorites, I reached out to Carleton with my novice questions. He patiently answered my questions, and that was the start of our long friendship. It was apropos, and I was honored to have written my first article for Meteorite Times about my friend with his blessing and assistance. It can be found here in the January 2021 Meteorite Times article Dr. Carleton Moore | Meteorite Times Magazine (meteorite-times.com) Carleton was the biggest supporter of my articles. He wrote me the following messages on various articles: “As you might expect the first thing I did was read your contribution to meteorite times . Thanks for your wonderful contribution. Smile” “Very glad to see your article. As usual a super job with lots of good information !! Cheers” “Just reread your article. Again thanks for your efforts. What’s next?” “This is super interesting! I wonder how good Howard’s analysis was? Also maybe only meteorite type named after a person (not important in your essay) didn’t go through with a fine toothed comb but think benedictine misspelled once??? Your research is really nice. Yes, of course I knew Ursula Marvin. She did a great job of assuming the meteorite historian’s position. Think she was at Harvard because her husband Tom had been a student there and they wandered back after his/ their field geology days were over. I’ll read again and again thanks and best wishes” There were other messages of praise and encouragement. Many times when I spoke with Carleton, the subject of meteorites never came up. With the passing of Carleton, the meteorite community’s loss is immeasurable, and Heaven’s gain is infinite. I am grateful for my friendship with Carleton, and I will miss him immensely.

Being of Japanese ancestry, I collect Japanese meteorites or in Japanese – Nihon Inseki. Since the Japanese revere meteorites and many are kept by institutions or shrines, they are very difficult, if not impossible, and expensive to obtain. I have been fortunate to have obtained a few of them in my collection. I asked my friend, Jesse Piper, who has an extraordinary collection, to assist me as co-author of this article. Without Jesse’s help, this article would not be as rich, detailed and enjoyable as it is now. There are others who come to mind when I think of collectors who have collected and appreciated Japanese meteorites – Jesse Piper, Mike Bandli, Dirk Ross Tanuki, Corey Kuo, Steve Schoner, Justin Boros, Martin Horejsi, Jay Piatek, Mendy Ouzillou, Russ Finney, John Shea, and Allan Lang (R.A. Langheinrich) to name a few.

Few natural objects have been worshipped by humans, more than meteorites. The Krasnojarsk meteorite weighing 1,500 pounds was regarded by the Tartars (native people of Siberia) as a holy thing fallen from heaven. The Emperor Maximilian brought the Ensisheim meteorite to a neighboring castle, and a council of state was held to consider the message from heaven the stone had brought them. In Casas Grandes, Mexico, a meteoric iron was found in a middle of a tomb. They probably worshipped the meteoric iron and hoped the meteorite would accompany the person and transition them smoothly into the afterlife. The myth about the Elbogen meteorite was that if it were thrown into the castle fountain, it would come back to its former place. In Australia, at the Henbury crater, the Aboriginal people warn: Don’t drink the rainwater that pools there, or a fire devil will fill you with iron. In Central Australia, meteors are believed to contain an evil magic which is harnessed in ceremonies to inflict harm or death upon someone

Meteorite Times Magazine

that breaks a taboo, like infidelity. There are many other examples of meteorite folklore, but I wanted to give a brief history, so that when comparing Japanese myths, there is some history to compare it to and not compare it to the current knowledge of meteorites from people around the world today. Folktales were used to explain the unexplainable due to lack of experience, knowledge and technology.

Japanese folklore, myths and legends regarding “fallen stars” is a complex mixture of animism, Buddhism, Shinto-ism, Confucianism and folklore. Japanese historic literature often mentions astronomical phenomena, such as, meteors and comets. Legends are found in various prefectures in Japan. In the Yamaguchi Prefecture, it is called Kudamatsu which means pine where stars have fallen. In Okayama Prefecture, it is called Bisei-cho which means beautiful star. In Osaka, it is called Hoshida which means village of the star. A prefecture is a district. Think of it like a state in the United States, a province in Canada or a region in European countries. Examples of Japanese folklore below were used to explain things centuries ago before modern science and technology.

Nogata (19 May 861 A.D.)

When I say, impossible to obtain, Nogata (Japan) comes to mind. Many people incorrectly assume that Ensisheim which fell on 7 November 1492 was the first meteorite fall recorded and preserved. Nogata, a 472 gram, stony L6, fell on 19 May 861 A.D. over six centuries before Ensisheim, and Nogata was the first meteorite fall that was recorded and preserved. It was witnessed by villagers who recovered the meteorite. The priests never doubted the fact that it fell from the sky, and preserved it in a Shinto shrine in Suga, Jinja, Fukuoka Prefecture (Kyushu, Japan). The stone was kept in a wooden box inscribed with the date of 19 May 861 A.D. The wood box and style of inscription correspond to the 9th century. The box was also carbon dated, and the fall date is in the range results. Old literature also confirmed the date of the fall.

The historic Nogata meteorite has been preserved for over a millennium by the priests of the shrine, and I am grateful and comforted to know they will preserve it for eternity. They appreciate and comprehend it is on loan to them by future generations. It is publicly seen every five years at the grand shrine festival, when it is carried in a decorated ornate cart, at its rightful place, at the head of the parade. There are several shrines dedicated to various different Japanese meteorites that were recovered, which evidence the wide spread acceptance in Japan that rocks fall from the sky. Whether it is because the Japanese people are trusting, forward thinking or ahead of their time, from no later than 861 A.D., they accepted the fact that stones fall from the sky. It would take the Siena (1794), Wold Cottage (1795), L’Aigle falls (1803), and Ernst Chladni’s 1794 book to start to convince the western world that stones fall from the sky. It is true that the falls of Siena, Wold Cottage and L’Aigle were scientifically studied at the time of their falls, but there could not be any meaningful scientific study on Nogata in 861 A.D. (or even for many centuries after its fall). The microscope was not invented until about the 16th century and not widely used until the 18th century. In the Journal of Geochemical Society, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1965 vol. 29, Dr. V.F. Buchwald acknowledges the limitation of early microscopes when he states, “It should also be borne in mind that during most of the 19th century it was quite common to etch the polished specimen by heat-tinting; with the microscope of those days it was not possible to see any influence on the structure, so the method was found quite adequate.” Modern chemistry did not begin until the

Meteorite Times Magazine

end of the 16th century (metals were not even considered an element in the 16th century, and the earliest attempt to classify the elements was not until 1789), and many chemists believe that chemistry became a proper science in the 18th century; therefore, it would be unfair to claim that because Nogata was not scientifically studied until later, that it should not be credited as the first recorded fall in which people accepted the fact that rocks do fall from the sky. More importantly, the people of Japan did not doubt that the stone had fallen from the sky, so it was not necessary to try and prove it. In addition, those near Nogata, who were alive at the time of the fall, their children, grandchildren, and even their great-grandchildren were long gone when any meaningful scientific research could be done on it. Modern meteorite classification was not worked out until the 1860s by Gustav Rose and Nevil Story-Maskelyne, over half a century after the first scientific research on Siena, Wold Cottage and L’Aigle. Nogata was studied in 1922 by K. Yamada, a principal of the Chikuho Mining School, who recognized it as a meteorite. In 1979, Nogata was studied by Masako Shima and Sadao Murayama, National Science Museum

Tokyo, Japan, Akihiko Okada and Hideo Yabuki, The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Hirosawa, Saitama, Japan, Nobuo Takaoka, Department of Earth Sciences, Yamagata University, Yamagata, Japan and again confirmed to be a meteorite.

Nogata should be credited, as not only the first recorded fall, but the first preserved one that started people believing that stones do fall from the sky. It earns its rightful place among the short list of the most historic meteorite falls.

Ogi (8 July 1741)

On 8 June 1741, after sounds like thunder, four H6 stones weighing 14 Kg fell in the city of Ogi of the Saga Prefecture on the Japanese island of Kyushu, Japan, where it was witnessed and collected and put in a temple in Ogi. A Japanese myth explains the fall of stones from the sky. The two largest stones were preserved in a temple in Ogi, where they became part of an annual offering to Shokujo at a festival on the 7th day of the 7th month over the centuries. The festival celebrates the rendezvous of the goddess Shokuja and her companion or spouse, who are identified with the constellations Lyra and Aquila and separated by the river of heaven, the Milky Way. No bridge spans the river, but on the festival night a huge jay spreads his wings across it and permits the two constellations to meet. Stones, once used to steady the loom of Lyra, the weaver, fell from the skies of the Milky Way to earth. In 1882, the two largest specimens were studied by Divers and Shimizu. In the 1960’s, Mason (1963) and separately Van Schmus and Wood (1967) studied Ogi, and classified it as an H6 chondrite. The fours stones weighted approximately 5.6, 4.6, 2 and 2 kg. Unfortunately, the two smallest specimens of approximately 2 kg each were lost. Tragically, the largest stone of 5.6 kg, which had been the property of the Nabeshima family, was destroyed by American incendiary bombs in World War II. The Catalogue of Meteorites by Monica Grady does list the Nabeshima family being in possession of a 69.3 gram piece which is now the largest specimen outside the British Museum. The remaining 4.6 kg stone was purchased by the British Museum in 1884. M.H. Nevil StoryMaskelyne, Curator of Minerals at the British Museum, goal was to make the meteorite collection at the British Museum the finest in the world, so he employed a strategy of asking museum trustees to prod government officials to get involved in obtaining meteorites. This was the case in the acquisition of Ogi.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

An 11.6 gram slice of Ogi obtained from my friend Corey Kuo. It now resides in the Mitch Noda collection.

Yonozu (13 July 1837)

A 30.44 kg meteorite fell at about 4:00 pm on 13 July 1837 in into a rice paddy in Yonozu-mura, Nishikambara-gun, Niigata Prefecture, Honshu, Japan. The H4 meteorite was observed by witnesses in the lowest portion of its trajectory as a black object flying in from the southwest accompanied by a noise like thunder. The meteorite penetrated about ten feet into the wet muddy ground of the rice paddy. The main mass has been preserved at the Japanese National Museum in Tokyo. There is a memorial at the place where Yonozu fell. A 63.5 gram specimen was sent for study to the University of New Mexico from the Japanese National Museum in Tokyo. The only previous study of the meteorite was a chemical analysis done by M. Kodera of the Imperial Geological Survey of Japan, and a general microscopic study by Y. Otsuki leading to a classification of the meteorite as a crystalline chondrite. The University of New Mexico analysis shows the Yonozu exhibits the chondritic structures to a high and varied degree and numerous irregular fragments of the metallic phase are visible in a completely random arrangement. A thin section analysis shows the non-metalic portion of this meteorite is composed primarily of olivine and hypersthene. On the basis of various studies, the Yonozu meteorite was classified as a hypersthene-olivine chondrite following the Leonard classification. The Meteoritical Bulletin Database lists Yonozu as an H4/5. In accordance with the meteoriteplanet hypothesis for the origin of meteorites, Yonozu would have its origin in the exterior mantle of a planet. The planet would be constituted much like Earth with a nickel-iron core and an exterior mantle of silicate minerals. The amount of nickel-iron would decrease from the interior of the planet to the exterior. Therefore, meteorites with a small percentage of nickel-iron scattered throughout a silicate phase are believed to have come from relatively near the surface

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Jesse Piper. A 2.01 gram piece of Ogi residing in the Jesse Piper collection.

of the planet. You can see a marker of Yonozu where it fell at https://goo.gl/maps/mv916MzT25Nx3Mdx6

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Jesse Piper. A 1.58 gram fragment of Yonozu from the Jesse Piper collection.

Kesen (12 June 1850)

On 13 June 1850, the Kesen meteorite fell in a swamp in the city of Rikuzentakata, Kesen District in the Iwate Prefecture, island of Honshu, Japan. The H4 meteorite initially weighed 135 kg (298 lbs), however, some local residents cut off pieces for charms or souvenirs resulting in its current weight of 106 kg (234 lbs). Henry Ward (Ward’s Natural Science) was informed by a friend who was traveling in the main island of Japan, that he thought he saw a stone meteorite in a temple in Iwate. After much effort, Ward was able to obtain a specimen about six ounces in weight. The sample was accompanied by a letter in Japanese which was translated to English. It mentioned the date of the fall, and that there was a loud sound like thunder at the village of Kesen which accompanied the fall. The letter claimed the meteorite entered the ground five feet

Meteorite Times Magazine

A 13.49 gram slice of Yonozu from the Mitch Noda collection.

and remained hot for two days. Besides the main mass there were ten or more pieces of it. O.C. Farrington noted that Kesen was preserved in a temple for many years and worshipped as an idol. I think it may have been seen as a sacred item and not worshiped like an idol. An analogy would be a crucifix or an altar which were seen as sacred items and not worshiped as idols. Kesen was moved to Tokyo and held at the Imperial Household Museum. It is currently housed at the National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo. Records of the fall are recorded in documents of the Yoshida family. In 1976, a monument of the “Heavenly Meteorite Falling Site” was built at the location of the fall. Sadly, the Great East Japan earthquake damaged the Yoshida records and replica of the meteorite. Here is the marker at the Chogoji Temple dedicated to Kesen

https://goo.gl/maps/JLh5TVREZzVc2mFH8

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy Jesse Piper. A 2.79 gram slice of Kesen with crust from the Jesse Piper collection.

Meteorite Times Magazine

An ASU vial containing chips of Kesen obtained from my friend Matt Morgan. The vial with Kesen samples now resides in the Mitch Noda collection. I wonder if ASU had done some experiments on the chips.

An

Meteorite Times Magazine

11.74 fragment of Kesen with University of New Mexico number and corresponding label. Previously held in the collections of my friends, Jay Piatek and Mike Bandli and now resides in the Mitch Noda collection.

Fukutomi (19 March 1882)

On 19 March 1882, three stones (1.7 kg, 2.5 kg and 16.4 kg) of the Fukutomi meteorite fell in Fukutomi-mura, Kishima-gun, Saga-ken, island of Kyushu, Japan. Later, one of the stones was missing. The Fukutomi meteorite was the first Japanese meteorite to enter in a Japanese museum. The research on Fukutomi shows it is a L5 olivine-hypersthene chondrite. The most conspicuous feature (peculiar structure) of the Fukutomi meteorite is the occurrence of lithic fragments. The occurrence of tridymite creates a lithic fragment in this meteorite. In stony meteorites, tridymite is often found in pyroxene-plagioclase achondrites, but it is rare in ordinary chondrites. The two stones are housed at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo. Michael J. Frost of the British Museum wrote a paper in Meteoritics in December 1967, “The Term “Meteorite” which said their modern usage of “meteorite” may have started around 1820, but not generally accepted until much later. He says, that “a fallen meteor” was used more frequently. Interesting that he does not mention “aerolite.” Frost referred to “recent”

Meteorite Times Magazine

A 5.9 gram specimen of Kesen with Nininger American Meteorite Laboratory label and corresponding number on the piece. This AML Kesen has crust. It is part of the Mitch Noda collection.

papers using the term: “The Fukutomi meteorite consists of two stones . . . .” (Miyashiru et al 1966). The other paper, (Keil et al 1964) “This . . . meteorite fell . . . as a shower . . . .” did not mention a meteorite by name. Interesting that a paper about the Fukutomi meteorite was one of the first uses of the modern term “meteorite.”

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy Jesse Piper. A 0.53 specimen of Fukutomi which resides in the Jesse Piper collection.

Meteorite Times Magazine

A 11.52 gram slice of Fukutomi which is from the Mitch Noda collection.

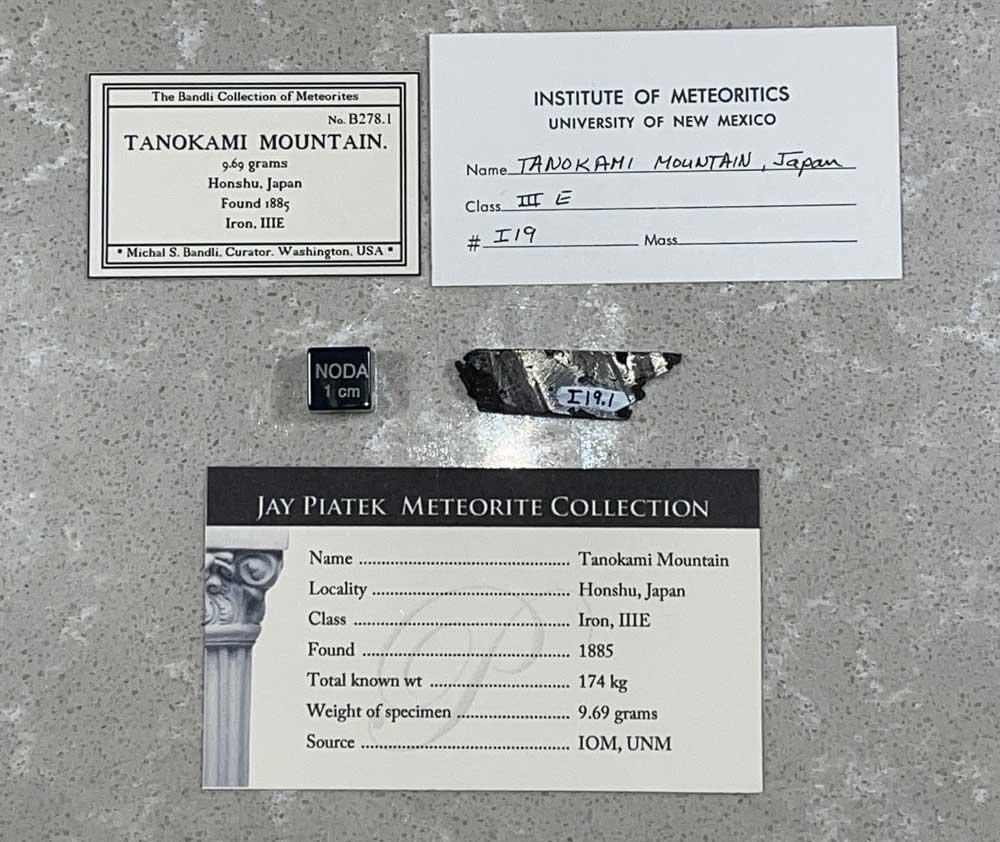

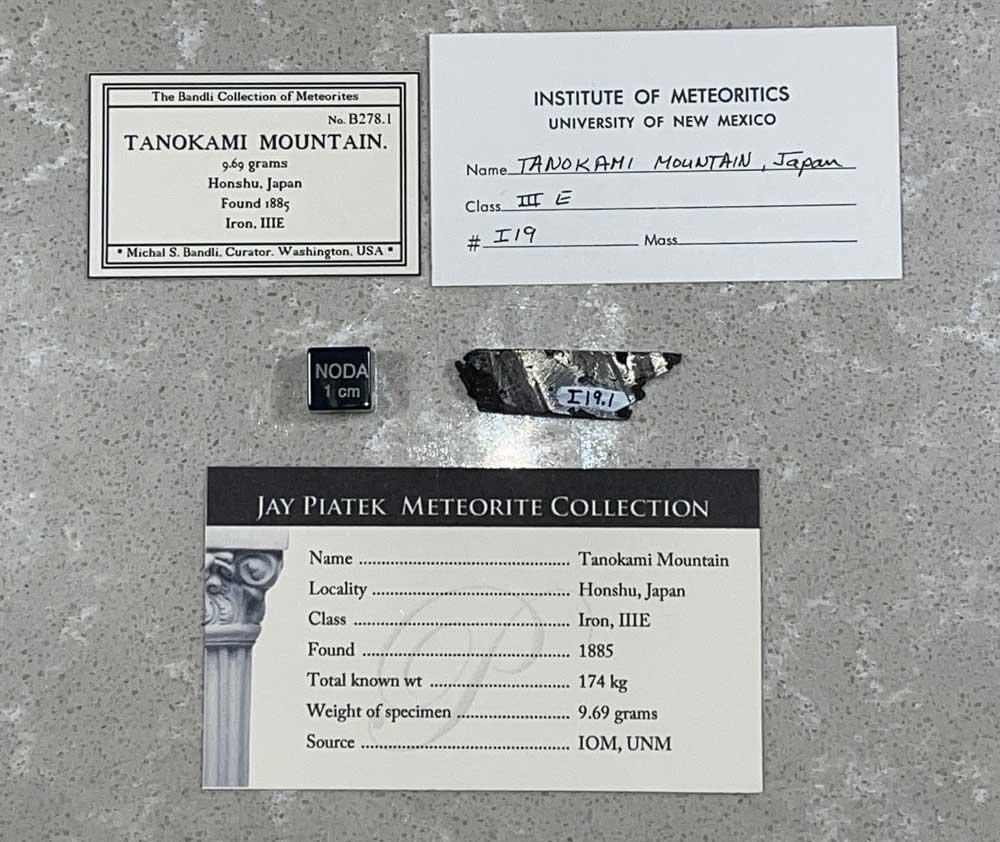

Tanokami Yama (Tanokami Mountain) (1885)

Tanokami means god of the rice fields, and the god is believed to observe and bring a good harvest. Yama means mountain. There are two stories of who found the meteorite. The first was a mass of 170.75 kg was found in 1885 by a farmer on the slopes of the mountain Tanokami in Kurimuto, Shiga on the island of Honshu, Japan. The other version is that Mr. Takizo, a mineral broker, who was hunting for quartz and topaz in the valley of mount Tagami. Thanks to the efforts of Mr. Kosokichi and others, it was confirmed to be a meteorite. Tanokami Mountain, the largest meteorite in Japan, was purchased in 1899 by the Imperial Museum in Tokyo. Very little has been cut and distributed from this iron. The Smithsonian Museum holds 65 grams of Tanokami Mountain. The small specimens in the Smithsonian Institution were examined and

Meteorite Times Magazine

A 7.2 gram piece of Fukutomi with a University of New Mexico label. This was obtained from Bruno Fetcay and Carine Bidaut of France. It is part of the Mitch Noda collection.

indicates that Tanokami is a somewhat unusual coarse octahedrite, with its anomalous kamacite morphology and a significant amount of carbide roses. Tanokami Mountain is classified as a IIIE iron – one of fifteen.

A 9.69 gram specimen of the ultra-rare Tanokami Mountain with University of New Mexico label and corresponding number. This piece of Tanokami Mountain graced the collections of Mike Bandli and Jay Piatek before finding its home in the Mitch Noda Collection. According to Grady’s Catalogue of Meteorites, The National History Museum in Tokyo holds the main mass of approximately 175kg, the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History has 65 grams, the Smithsonian has 90 grams and the University of New Mexico holds a 174 gram slice.

Meteorite Times Magazine

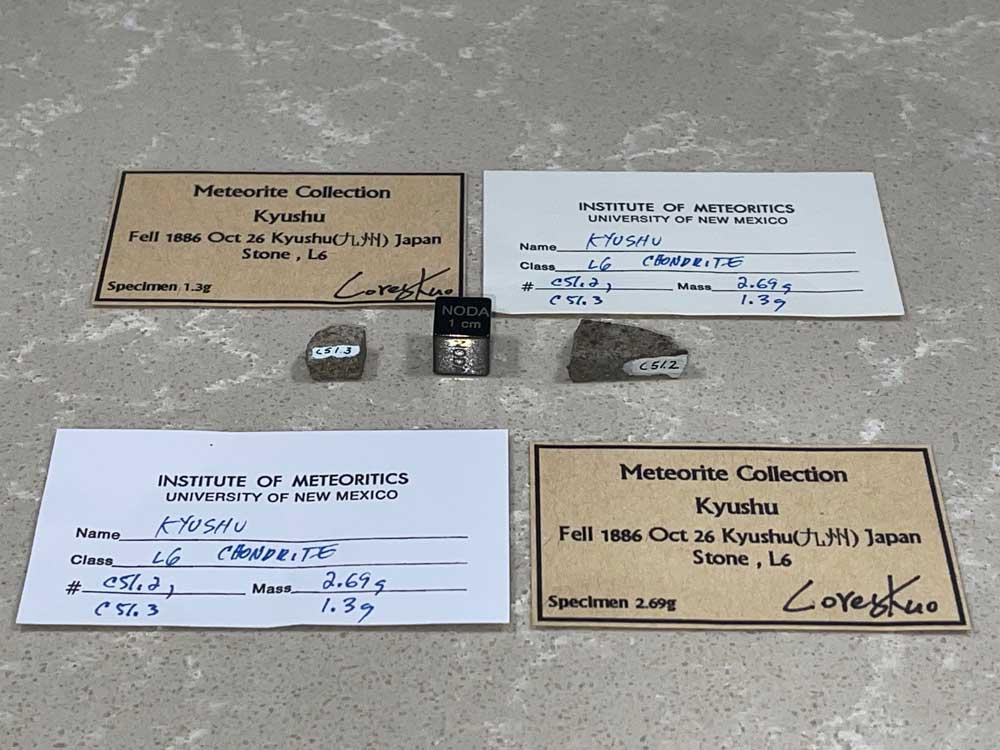

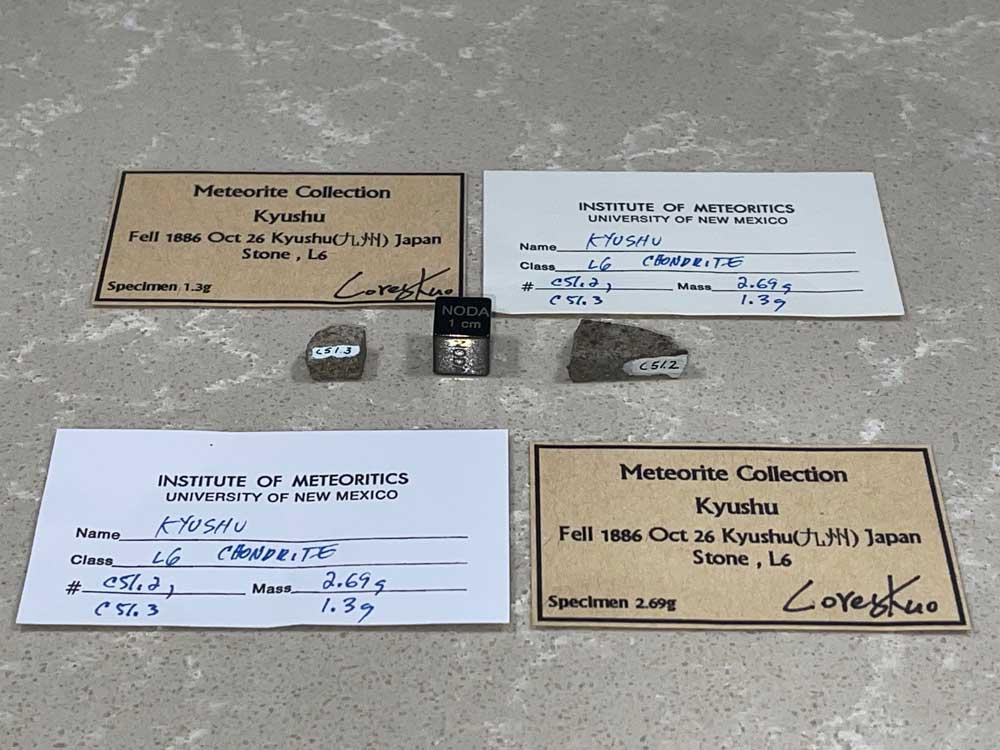

Satsuma (Kyushu) (26 October 1886)

In Japan, the name for the Kyushu meteorite is Satsuma. On 26 October 1886, after a detonation, Kyushu fell in the Satsuma and Osumi provinces on Kyushu island, Japan. The largest stone was 29 kg with numerous other stones recovered. Allan Lang (R.A. Langheinrich) traded some Peekskill for a 3.7 kg of Kyushu with the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. His specimen was larger than any the Japanese held. Al was honored to take it back home to Japan, and it was placed in a museum in the city of Kyushu. In Meteorite Times, Al said, “There’s nothing I enjoy more than to “institutionalize” my specimens, where they can be safe from the fiends who like to cut them up, in order to maximize profit.” The main mass is held by the Natural History Museum in London. The Catalogue of Meteorites, by Monica Grady lists the second largest specimen at 3.6 kg at the Science Museum in Tokyo (as of 2000) with the AMNH holding the third largest piece at 2kg. The marker for Satsuma (Kyushu) is at https://goo.gl/maps/tWy5nhEuMZe97AK69

Meteorite Times Magazine

The other side of the 9.69 gram specimen of Tanokami Mountain.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Sibling Satsuma (Kyushu) specimens from the University of New Mexico with corresponding labels and numbers. These siblings found a home in the Mitch Noda collection.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy Jesse Piper. A desirable crusted 2.77 gram specimen of Satsuma (Kyushu) from the Jesse Piper collection.

A 8.08 gram slice of crusted Satsuma (Kyushu) with University of New Mexico number and corresponding label. It has Mike Bandli and Jay Piatek pedigree. Now part of the Mitch Noda collection.

The Shirahagi iron is a fine octahedrite of group IVA iron and is the second largest meteoric iron ever found in Japan. The iron is folded or curled like an ocean wave or the letter “C.” Dr. Sadao Murayama of the National Science Museum in Tokyo thought the Shirahagi iron was probably distorted during its flight thru the atmosphere although Dr. Vagn Buckwald thought it was due to a cosmic shock event. It is a peculiar and interesting meteorite with an extremely distorted

Meteorite Times Magazine

A closer look at the 8.08 gram slice of Satsuma (Kyushu).

Shirahagi (1890)

Widmanstatten pattern, evidence of a violent cosmic collision.

There are two versions of where and who found the Shirahagi meteorite. One version is that it was found in April 1890 in the stream of the Kamiichi-gawa river in Shirahai-mura, Toyama prefecture, Japan, by a mine worker, Sadajiro Nakamura, and preserved by Issei Kobayashi, a mining engineer, who employed Nakamura. Initially, they did not know what they had, and in 1895, it was discovered to be a meteorite by Kwaijiro Kondo of the Geological Survey of Japan.

The other version of the story is that in 1890, a farmer was digging for potatoes and came across the unusual iron specimen. Curious as to what it was, the farmer presented it to a few appraisers. Not even the Osaka mint knew what it was. It spent the next several years being used as a weight in the pickling process of vegetables. In 1895, geologists from the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce determined that it was a meteorite.

The two versions of the story then merge. The 22.7 kg (50 pounds) Shirahagi meteorite was purchased in March 1895, by Enomoto Takeaki, a Samurai, who would go on to play a key role in the creation of Japan’s first modern navy and serve as Minister of various departments. Takeaki stayed in Russia as a special envoy, where he was fascinated by the Russian “meteor sword” – James Sowerby’s sword made from the meteorite Cape of Good Hope for the Czar Alexander I.

Since Takeaki was a Samurai, he must have been inspired by the “meteor sword.” According to the Samurai code or “Bushido” literally “way of the warrior,” a Samurai’s main sword represented his soul. “Bushido” was an ethical system, rather than a religion. The principles of Bushido emphasized honor, courage, skill in the martial arts, and loyalty to a warrior’s master (“Daimyo”) above all else. The Samurai usually carried two swords. The “Katana” or long sword (blade length about 100 cm or 40 inches) was mainly used in battle. The second companion sword was either a “Wakisazhi” or short sword (2/3 – 1/2 the length of the “Katana”) which was the Samurai’s back up sword used for close quarter combat, or a “Tanto” (blade about 8 inches or 21 cm) which was more like a long dagger.

The “Katana” was a two handed sword while the “Wakisazhi” and “Tanto” were one handed swords. The scared swords were handed down from one generation to the next.

Takeaki enlisted the services of master swordsmith, Okayoshi Kunimune, and commissioned the creation of five blades collectively known as “Ryuseito” literally “Comet swords.” Two “Katana” or long swords and three “Tanto” or short swords, were forged from the Shirahagi Meteorite. About four kilograms (8.8 pounds) of Shirahagi iron meteorite was used to create the five blades. The swords were difficult to work with due to higher nickel content, less carbon, more impurities, such as, schreibersite which required higher temperatures during forging, and the blades were comparatively resistant to hardening during quenching. It took three years to create the swords, and they were finally finished in 1898. The blades were made with 70% Shirahagi meteoric iron and 30% “Tamahagane” or iron sand-rich metal used for regular “Katanas.” The blades have a beautiful, and unusual dark swirling similar to a combination of tiger stripes and leopard spots “Hamon” or tempering pattern to them due to the meteoric content. The inner hilt of the swords had been engraved with solid gold inlay reading “Seitetsu,” or “Star Iron.” The remaining main mass (18.2 kg or 40.12 lbs.) was presented to the National Science Museium in Tokyo. The higher quality “Katana” was donated by Enomoto to the crown prince of Japan, who later became Emperor Taisho, who was the 125th Emperor and reigned

Meteorite Times Magazine

from 1912 to 1926. The remaining four swords were handed down to Takeaki’s heirs. The other Katana or long Samurai sword is owned by Tokyo University of Agriculture which grew out of an institution Enomoto founded. As for the three “Tanto,” one is housed at the Toyama Science Museum in Toyama city, another was donated by Enomoto’s great-grandson and is in the Ryugu Shrine as a “shrine treasure” in Otaru, on the island of Hokkaido, and the last space sword’s whereabouts are unknown.

Shirahagi is a historic meteorite with a royal connection and wonderful story. The swords created from the Shirahagi meteorite can also be called “Tentetsutou” or “Sword of Heaven.” Jesse and I would like to think that we obtained our specimens due to “Kami unmei” or “Devine destiny.”

Meteorite Times Magazine

An 11.7 gram piece of Shirahagi with University of New Mexico label and number. It is Mitch’s favorite Japanese meteorite in his collection.

Okano (7 April 1904)

On 7 April 1904, at 6:30 am, the 4.74 kg Okano meteorite fell in the village of Okano, in the neighborhood of the town Sasayama, in the province of Hyogo, island of Honshu, Japan. A noise resembling a distant cannon was heard. The fall was witnessed by a teacher and a farmer. Mr. Katsuzo Hata witnessed the fall and landing behind the temple near an Oak tree and recovered the meteorite. The iron was in a small forest with a long point upwards, imbedded about 80cm (31.5 inches). The meteorite was given to Professor Tadashi Hiki of Kyoto Imperial University. The 4.74 kg mass was acquired by the Metallurgical Institute of Kyoto, Japan. Okano is a normal hexahedrite, a single ferrite crystal larger than 10 cm. It is classified as a IIAB iron. A replica is on display at the local elementary school. On March 6, 2021, a celebration took place to preserve and share the history of the Okano meteorite, and a monument and information sign were erected at the fall site

https://goo.gl/maps/NdLhwStjtpcFdR5X9

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Jesse Piper. A beautiful 4.26 slice of Shirahagi with ASU number on it. It resides in Jesse Piper’s collection.

Meteorite Times Magazine

A 10.6 gram block of Okano with Corey Kuo label. This piece is from the Mitch Noda collection.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Jesse Piper and Takeshi Inoue, Akashi Planetarium Director. The Okano meteorite marker in Japan.

Kobe (26 September 1999)

In the evening of 26 September 1999, a large number of people witnessed the Kobe meteor which struck a roof of a house in Tsukushigaoka, Kita-ku, north of the city of Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, island of Honshu, Japan. The meteorite penetrated the tile roof and bedroom ceiling. Ryoichi Hirata, the homeowner, noticed about 20 pieces of the fragmented 136 gram meteorite on his daughter’s bed upstairs. The largest pieces were 64.9, 32.9 and 13.6 grams. My friend, Dirk Ross, was teaching English in Japan at the time, and a student told him about the Kobe fall. Dirk contacted the owner, Mr. Hirata, who was annoyed at all the people contacting him. After the passing of time and people ceasing to contact Mr. Hirata, Dirk, with his persistence, was able to meet with Mr. Hirata. Mr. Hirata decided to keep the meteorite fragments, and loaned some of them to museums and researchers. Dirk asked how they cleaned up the mess, and Mr. Hirata told him that they vacuumed the mess after collecting the fragments. Dirk purchased the vacuum cleaner bag. Luckily for Dirk, the bag was new, so he did not have to go through a lot of other materials to find small pieces of Kobe. Mr. Hirata’s daughter, who was in junior high, informed her father, that she wanted to sell her specimen. Dirk purchased, from Mr. Hirata, the small fragment which was 1-3 grams. The family of four used the money to go on a trip to Hawaii.

Kobe is a CK4 (Karoonda-like) carbonaceous chondrite. It is the first fall of a carbonaceous chondrite in Japan. Kobe is only one of two observed CK falls. In order to shed light on the ambiguous history and nature of CK chondrites, the Kobe Meteorite Consortium was organized

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Jesse Piper. A 5.2 gram Okano specimen residing in the Jesse Piper collection.

by sixteen leading laboratories in Japan and the United States. Two large fragments of Kobe were on loan from Mr. Hirata and used in the study. The noble gas study confirmed the meteorite as a CK carbonaceous chondrite.

Capsules containing a rare crusted 0.068 gram and 0.014 specimens originating from Dirk Ross in Tokyo, then Jesse Piper and now in my collection.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

A closer view of the rare crusted piece of Kobe.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Jesse Piper. A very nice 0.392 gram crusted specimen of Kobe with plaster evidencing its piercing the ceiling of the house in Japan. It now resides in the Jesse Piper collection.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Justin Boros. A 0.142 gram specimen of Kobe with a chondrule rarely seen in the Kobe meteorite. Formally from the Jesse Piper collection, and now part of the Justin Boros collection.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Jesse Piper and Takeshi Inoue, Akashi Planetarium Director. A photo of meteorite displays at the Askashi Planetarium in Japan. The display with the microscope is of a Kobe specimen donated to the Askashi Planetarium by Jesse Piper.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Photo courtesy of Jesse Piper and Takeshi Inoue, Akashi Planetarium Director. A close up photo of the Kobe display at the Askashi Planetarium in Japan.

Carleton at the ASU University Club.

References:

Phone call, emails and messages with Jesse Piper

Carleton B. Moore Obituary - The Arizona Republic (azcentral.com)

For a good list (not a complete list) of Japanese meteorites as of September 2012 by Nagatoshi Nogami, please go to Microsoft PowerPoint - NOGAMI-Meteorite in Japan.ppt [Compatibility Mode] (imo.net) (hit Ctrl and click while curser is on the link).

Cosmic Debris Meteorites in History – John G. Burke

American Journal of Science, Vol. 249, November 1951, “The Yonozu, Japan Stony Meteorite, Carl W. Beck and R.G. Stevenson, Jr.

Handbook of Iron Meteorites – Vagn F. Buchwald

Meteorite Times Magazine – Martin Horejsi – Ogi Japan: Meteorite Worship Then and Now –March 1, 2021

Meteorite Times Magazine

Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (metmuseum.org)

“Description, Chemical Composition and Noble Gases of the Chondrite Notata” Masako Shima and Sadao Murayama, National Science Museum Tokyo, Japan, Akihiko Okada and Hideo Yabuki, The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Hirosawa, Saitama, Japan, Nobuo Takaoka, Department of Earth Sciences, Yamagata University, Yamagata, Japan 1983Metic..18...87S Page 87 (harvard.edu)

Wikipedia – Nogata meteorite

https://www.facebook.com/Historyofmeteorites/posts/the-stone-of-nogata-japan-861-on-thenight-of-19-may-861-a-brilliant-flash-and-d/14679073386

History of Microscopes

Development of the periodic table (rsc.org)

Wikeipedia – Meteorite Classification

Oliver C. Farrington, 1900 "The Worship and Folk-Lore of Meteorites” Journal of American Folklore

Bull. Natn. Sci. Mus., Tokyo, Ser. 4, December 22, 1981 – “The Petrography and Chemical Composition of the Ogi Meteorite, from Ogi-machi, Ogi-gun, Saga-ken, Japan” by Hideo Yabuki, Masako Shima and Sadao Murayama.

Fallen star legends and traditional religion of Japan: an aspect of star lore - NASA/ADS (harvard.edu)

Yonozu meteorite, Niigata City, Niigata Prefecture, Japan (mindat.org)

Catalogue of Meteorites 5th Edition – Monica M. Grady

Preliminary note of a new meteorite from Japan | American Journal of Science (ajsonline.org)

Kesen meteorite - Wikipedia

Bull. Natn. Sci. Mus., Ser. E (Phys. Sci. & Engineering), 2 Dec. 22, 1979 – The Chemical Composition, Petrography and Mineralogy of the Japanese Chondrite Fukutomi by Masako Shima, Dept. of Physical Sciences, National Science Museum, Tokyo, Akihiko Okada, The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Wako, Saitama, and Sadao Murayama, Dept. of Physical Sciences, National Science Museum, Tokyo.

1967Metic...3..253F Page 253 (harvard.edu) The Term “Meteorite” by Michael J. Frost, British Museum (Natural History), London

Kyushu meteorite, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan (mindat.org)

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine Articles - Meteorites & Tektites, Meteorite Dealers, Links & Classifieds (meteorite-times.com)

Fallen star legends and traditional religion of Japan: an aspect of star lore - NASA/ADS (harvard.edu)

The Early Years of Meteor Observations in the USA - American Meteor Society (amsmeteors.org)

Our Astronomical Column | Nature

Memoirs of the College of Science and Engineering, Kyoto Imperial University, Vol. v., No.i, September 1912, Messrs. Masumi Chikashige and Tadasu Hiki

Kobe Meteorite (biglobe.ne.jp)

Kobe meteorite, Kita-ku, Kobe City, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan (mindat.org)

Meteoritical Bulletin: Entry for Kobe (usra.edu)

2001AMR....14...61M Page 62 (harvard.edu)

Meteorite Times Magazine

A Flurry Of New Falls: A Focused Review Of Muskogee, With An Aside For The Falls Of Texas, France, And Italy, And Perspectives On Mental Aspects Of Hunting

Michael Kelly

This has been an absolutely wild time for fresh falls, all around the world. I had a whole article written just for the Muskogee fall, and just before sending it off to Paul, there is an additional find and new main mass for Muskogee that happens to be a hammerstone! As if that was not enough, three falls in three consecutive days, the third of which was another US fall. So instead of grinding thin sections I am making the most of this article with all the extra asides added in. As far as the Texas fall goes, this will be a primer, and a full article will follow in the next edition, as of the time of this writing, the strewnfield is still developing and the hunt is still very much on.

On the three in a row set of falls. All of which look to be ordinary chondrites.

The excitement started on 13 February when asteroid 2023 CX1 was identified with a few hours of notice that it was on an earth impacting trajectory. The approximately 1 meter diameter meteoroid entered the earth’s atmosphere over the English Channel in a well observed bolide. It was fun to be able to watch remotely from my house in Pennsylvania via live stream. This is the 7th tracked meteoroid creating a bolide. Immediately after entry the frenzy of activity to calculate a strewnfield solution began. As of the writing 11 stones have been found some on the surface, with one, having punched a small divot in the ground and buried itself. This meteorite will potentially be named Normandy based on location. This is only the third meteorite recovered with a predicted impact, the first two being Almahatta Sitta, and Motopi Pan.

The excitement continued the next day with reports of a bolide event over Italy. A strewnfield was calculated off three videos with a terminus north of Matera, upon media reporting and informing the local populace on the 15th, a hammerstone was found broken into many fragments by Gianfranco and Pino Lossignore at the house of their parents. The reported recovered weight is 70g in the form of fragments created upon impact with the balcony tile which was damaged. The hunt is still ongoing in the area for additional pieces.

The final fall of the trifecta occurred in Southern Texas on the 15th. NASA put out data that the meteoroid was somewhere around 450Kg. Three days later on the 18th the first piece was recovered, so far this fall has yielded the highest total mass and the largest size pieces, as the saying goes, everything is BIGGER in Texas. It will be interesting to see what this fall is named, the NASA report mentions McAllen, but there is potential it gets named Rio Grande, or Rio Grande City.

For those interested there has never been three falls in three consecutive days, since we started recording the falls of meteorites. So this is a first. For those keeping track, there have been nine occurrences of two meteorites falling on consecutive days and 13 occurrences of two meteorites falling on the same day (potentially only 12, I am told the Indonesian set of Glanggang and Selakopi are actually one fall, thanks Elang)

Meteorite Times Magazine

Muskogee is my fourth United States witnessed fall installation in the article series. I was hoping for four in a calendar year, but 2022 just wasn’t that year. That got me thinking, what is the max in a calendar year, and what are the max for a 12 month period? 1933 holds the record at five in a calendar year (Athens, Cherokee Springs, Malaga, Pasamonte and Sioux County) with close runners up of 1998 (Elbert, Indian Butte, Monohans 1998, and Portales Valley) and 1938 (Aztec, Benld, Bloomington, and Chicora). There are a few ’ 12 month periods’ of high levels of fall that give a truer indicator of intensity vs sorting by year in the Meteoritical Bulletin. Having had five recoveries in this last 12 months is not unheard of, but for certain is not overly common, which makes this a great time to be a meteorite hunter. I am quite hopeful that between now and the 27ths of April (the first anniversary of Cranfield Mississippi, I will be writing to you with a record tying six in a 12 month period. For those inquiring minds Archie which fell 10 August 1932 squeaked in just in time to be six falls in a 12 month period with the closeout fall of 1933 Sioux County which landed 8 August 1933 (by two days!), making that 12 month period the most intense. Currently with its 5 falls this ongoing period is tied with those 12 month windows that had five falls. In the period are 2009-2010 with Ash Creek, Cartersville, Whetstone Mountains, Lorton, and Mifflin; and 1997-1998 by tagging on Worden which fell 1 September 1997 to the four 1988 falls already listed above. Hopefully I didn’t miss any, this was all researched on site, while writing about this fall on location, a first for me.

So now onto some of the local details. Oklahoma will soon have its 43rd classified meteorite. Of those 43 this will be only the 7th fall for the state. To date of the writing, only 6 stones have been recovered with a total mass of 1420.84g to be exact. The stones have great black primary crust, along with secondary and tertiary crust. So far of the 5 stones the two smallest are individuals with the 126 gram being nicely oriented with rollover lipping. The three larger fragments show a nice grey matrix, with beautiful brecciation and decent amounts of shock veining on the broken surfaces.

The bolide was very well documented. Event log 374-2023 on the American Meteorite Society’s website has 128 sightings and a phenomenal 49 videos of the event. The bolide was long, audible and displayed plenty of fragmentation at 3:38 AM local time on the 20th of January. The event showed up on lightning tracking, and also produced sonic data. From just the first few early videos posted to social media, several meteorite hunting veterans were saying it would be a productive hunt. Radar reinforced that with rocks being picked up on 4-5 separate radars, the hunt was on. The interesting nature of the hunt is that the data set, along with the opinions of many seasoned hunting veterans, points to what should be a decent multi kilo recovery. The grounds on site are very conducive to hunting, consisting of nicely manicured fields of low cut grass, and thinly wooded areas with low amounts of undergrowth. Even the roads are relatively free of stray rocks and are mostly concrete instead of asphalt, so provide high contrast. All that being said, the “small end” of the strewn field never materialized, and despite a strewn field searched by many veteran hunters, putting in a lot of hard searching, the stone count remains five with easily over 1000 person-hours of hunting. That being said, there is still hope for future finds with some spots in the “500g” radar hits needing exploration.

Muskogee continued the “Pre-Tucson fall” tradition, the running jokes is that just before the world’s largest show each year in Tucson Arizona we get a new fall. Vinales and Zhob made their presence known just before Tucson and were fun new pieces to both see and buy at the show in prior years. Four of the five stones found in Muskogee were present at the show for people to see and buy pieces of with quick turnaround cutting of material (70.6g, 260.3g and 262.7g stones were with Aerolite and the 309.6g main mass was in Mark Lyon’s room.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Before I get into the mental aspects of hunting and the question and answer session with several familiar veteran hunters. I wanted so share with you an interview I conducted over the phone with one of the two local Muskogee residents who made a find, Brad Ward, who had a 388 gram piece impact his barn roof.

Brad did you hear or witness the meteor bolide? No I was asleep and though my wife was awake she didn’t see or hear it.

When did you find out about the meteorite? It was on the local news, they discussed it and how its path went right over the area.

Can you provide some details on finding the piece? After the news I noticed some damage to the roof of the barn, that was on the 23rd of January, I joked to my wife that the damage could have been from the meteorites, and didn’t think much more of it. On the 18th of February I got out the ladder and climbed up to see what I needed to repair the hole. That’s when I saw the meteorite stuck in the roof of the barn.

Can you describe what you saw? The meteorite had hit at the spot where two sheets of the metal roof overlapped. It had torn the upper sheet and had dented the lower sheet and the piece was just stuck there. I didn’t touch it I got my phone to take a picture of it and told my wife that I was pretty sure we had a piece of the meteorite. The stone was broken and I found a second smaller fragment at the very edge of the roof, just above the gutter. I was pretty impressed the smaller piece has just stayed there, where it was located I figured it would have fallen off.

What did you feel when you found the stone? Just pure amazement. I’m still kind of shocked.

Anything else about the find you want to share with folks? This is pretty interesting, I don’t know if you are familiar with the last meteorite that fell in Oklahoma, Lost City which fell in 1970. But a relative on my wife’s side actually found a piece of that. His name was Philip Halpain he was her Great Uncle.

I would like to thank Brad for contributing to this article, it’s certainly interesting to find out details that would otherwise go unknown about these falls if not documented. Brads recounting of the interplay with the Lost City fall got me wondering what type of comparative documentation was done back then. In researching the fall in the NASA Astrophysics Data System I ran across this:

“A second small fragment (272 g) was found on January 17 by Philip Halpain while he was walking through his pasture. Fragment 2 is a highly flattened piece of roughly rectangular shape. The fusion crust is complete. The meteorite landed with its flat surface down and its heavy end in the forward direction. It was buried in the sod to its own depth. We propose the name ‘Lost City Meteorite-Halpain Fragment’ for this specimen in acknowledgement of Mr. Halpain’s discovery and his thoughtful generosity that permitted an early analysis of the fragment for short-lived isotopes.”-LOST CITY METEORITE-ITS RECOVERY AND A COMPARISON WITH OTHER FIREBALLS-R.E. MCCROSKY ET AL

Meteorite Times Magazine

This hunt for me was more complicated than the others I have been on: it was further away, to the point of pushing my driving endurance limit, it had a lesser factor of terrain influencing the find probability, and it was my first hunt where stones turned up but I went home empty handed. At the same time, I still thoroughly enjoyed the experience and so thought it would be an interesting topic to explore some mental aspects of hunting, both the highs and the lows. To kind of keep it all in order I stuck with addressing a hunt in phases as was done in my previous articles.

THE DECISION PHASE

The mental aspect of deciding if and when to hunt can be an emotional roller coaster. I certainly want to be at every hunt, and I would love to be there first. But like most everyone else, prior commitments, obligations and funding dictate when we will make it to the field and how long we can stay, if we can make it at all. Being stuck not able to hunt is depressing, and that feeling grows as information on first find comes out, along with any subsequent finds in the case of not being able to make it out. On the other hand, for those who can make it but are holding back with reservations either be it cost, or probability of a personal find, the release of find information can be incredibly exciting, and often times is the tipping point for committing to going. I have found myself in both scenarios and find it amusing the varying emotions someone else’s find can induce. For me with a limited amount of times I will be able to call off work, and coordinate

Meteorite Times Magazine

family scheduling, the process of choosing which bolides to chase is a particularly difficult one.

THE PREPARATION PHASE

Once I decide to go, I find myself in this weird mental space I like to call it my “waffle phase”. In my heart I know 100% I want to go, but my head keeps bringing up “what ifs” that make me question if I should. Am I killing the chance at a future hunt with better potential by committing to this one? Am I shirking too many other responsibilities to make this happen? Is the travel time worth the limited amount of time I will have to hunt? All these questions seep in and test my resolve to go on a logical level; on an emotional level I find the time spent preparing to go is full of anxiousness to have an adventure, along with a healthy does of nervousness about getting skunked.

GETTING THERE

Once it is time to embark on the trip, the mental aspect of getting to, and from, the field begins. By car or by air, most falls simply aren’t’t close by the majority of the time. The time commitment and discomforts of traveling can be enough to test your resolve to make future trips, and certainly is something I think about hard in the deciding and preparation phases. The many, many hours of travel is time I use to get my head in the game and plan out how I will execute my hunt. At the same time meteorites 24/7 can be draining so being prepared with a mental distractions to get your head cleared is also something to consider. With 48 hours on the road, I burned through a few audio books to take the edge off the monotonous task of “getting under the radar”. Mastering your excitement can be an interesting problem to overcome. I remember on my first several hunts facing 16 to 19 hour drives, finding myself being too excited to sleep the night before, basically guaranteeing I would have an absolutely horrible time traveling.

Compounding the travel issues, sometime life doesn’t’t allow you to be onsite for one continuous period, I know several hunters who have traveled to and from the strewn field multiple times to execute their hunt, having to stay convinced it is still worth heading back out to either get that first piece or risking committing more time and effort to get more.

IN THE FIELD

Time spent actively hunting can be full of highs and lows. Obviously making a find is the ultimate emotional high and the goal on every hunt of every hunter. But the reality of the field is that for most hunters spanning many hunts, you likely will go home empty handed. Being mentally comfortable with that going into the field is beneficial to not being too let down when it occurs, which it does quite often. The dedication to hunting and keeping at it over the long haul, despite often coming up short is one of the things I look up to most about the hunters who I run across who have been at it a lot longer than I have. Watching folks on open ended hunts or extending their hunts is also another interesting aspect I have witnessed. With no fixed end or a

Meteorite Times Magazine

somewhat flexible end date it is interesting to see how long without a find, or between finds, a person is willing to keep at hunting. Attitudes towards hunting length when the flexibility exists varies and is interesting to think about. I have hunted with folks whose commitment to a fall ranges from, “I am going to set a few days limit and if I haven’t succeeded in three days I am leaving,” to long haulers, where the longer they are on site, the more adamant they are on remaining till they succeed. This latter scenario can lead to overcommitting to a specific event, and in the long run can result in burn out. If hunting loses it fun, it is not worth doing. Since most hunters are not out for just one trip, it is worthwhile to take the long view of hunting, and keep that in mind vs a singular hunt.

The emotional flip-flop of feeling when finding an exquisite looking meteorwrong is the common bond of hunters. Especially on visual based hunts, from a little ways off you see that piece of something that is showing all the right characteristics. Maybe it’s modest sized, maybe it is substantial, but the black color is right, the shape is smooth, the texture has that bit of satin finish that fusion crust should have, it’s screaming meteorite. Then you get closer to examine it, heart racing, adrenaline pumping just to find out it is a charred knob of wood. There are some really convincing meteorwrongs out there! Some come home as reminders of just how tricked you can get.

Sometimes as you approach the piece with so much potential you don’t have to flip flop to disappointment, because it is exactly what you were after. At times like this it is easy to get overly excited and rightfully so. Having talked to others and done it myself, its super easy to rush over and pick up the piece. One thing that’s important in find documentation is recording the details of the find, and that means stifling the instinct to grab up your new found meteorite. Take the time to photograph it, get GPS coordinates, and memorize or better yet, record the time, conditions, orientation and other relevant facts.

Whether hunting solo or hunting as a team, two ends of a social spectrum, or blending the styles, it is important to figure out what makes you most happy as far as hunting style. It may vary day to day, or hour to hour on what you want as far as level of solitude, and ability to execute your plan on hunting. Maybe you have an area you just absolutely want to hit that others are not interested in looking in. Or maybe you have a permission that’s just too big to conquer alone and it makes sense to partner up to get it properly walked. Coming up with hunting strategies and staying in a good frame of mind is important.

HEDGING YOUR BETS

Regardless of whether you make a find or not, meteorite hunting is supposed to be fun. A strewn field is great place to meet folks you might not otherwise get to see too often. Hanging out after a long exhausting day of hunting to talk is a sure win and to me one of the most enjoyable parts of any hunt. Having activities planned out to break the meteorite focus is also something good to consider. Being overly focused can be mentally draining, figuring out other things to enjoy in the local area or on your route to and from the strewn field is a great way to have a successful trip: there are other ways to measure success then just coming home with the world’s newest meteorite. Shortly after departing on this trip, I began to think about what I could do to hedge my bets. After a short map recon, I knew I would commit a few extra hours to drive further south to add in a day of fossil hunting. Though not a Muskogee meteorite, the

Meteorite Times Magazine

echinoderm mortality plate I came home with was the icing on the cake of a great trip.

Finder: Pat Branch

Number of finds and weight(s): Two 127.5 and 262.7

What is your favorite thing about this find? I managed to find two and talked the local guy into him looking over his property and letting me know if he found anything. Any specific mental preparations you go through in the planning and prep phase of hunting? Trying to find the best properties and getting permission for at least one before I get into town.

How would you categorize your hunting strategy as far as determining how long you hunt each event? How much ground is searched, which ground has been searched, and what responsibilities I have in other places of my life.

Any advice on getting skunked? I spent many years hunting low probability falls before I found my first meteorite, so I expect to get skunked.

Anything in general I missed you want folks to know about be it a mental tip or otherwise? My big obstacle is cold weather. I do not enjoy hunting in the cold and it plays into my desire to even go to a fall.

Finder: Roberto Vargas

Number of finds and weight(s): One 309.6g

What is your favorite thing about this find? Before I found my piece, I was getting kind of discouraged. I had hunted the day before with Steve Arnold and his buddy Lance, and we hadn’t found anything. They had gotten a head start on me, so his first day hunting with me was actually his second day hunting the fall. He and Lance left after my first full day of hunting.

At that point we didn’t know if we were looking in the right spots, or if any had even made it to ground. So, when I came upon the 309.6g, it just confirmed that we were in the right spot and there were definitely stones on the ground (and that I wasn’t getting skunked). Rob Wesel and Mike Bandli were right next to me and I kind of just whispered, “guys, I think I found one”. It was more just a shock than anything else.

Thinking that I was first to find a witnessed fall was pretty cool. I later learned that someone else had found a piece before me, but it hadn’t been reported yet. It was fun while it lasted. However, in Junction City, I recovered a stone 61.5 hours after it fell, and I was really trying to beat that number. I successfully did that with this fall, finding my first stone after 56 hours. So, that was also cool.

Any specific mental preparations you go through in the planning and prep phase of hunting? Nope, I just get up and go. I’m mostly packed at all times. I got to Oklahoma from Connecticut

Meteorite Times Magazine

on the same day that it fell.

How would you categorize your hunting strategy as far as determining how long you hunt each event?

If nothing gets found in the first two or three days, I go home and wait to see if anyone finds anything. If people start finding, I fly back. If people are finding and I am there, I am staying because even if I don’t find any myself, I’ve found that it’s easier to negotiate with finders in person than over the phone or the internet. Also, because I’m not going to find any stones from my couch.

Any advice on getting skunked? Don’t get discouraged from getting skunked. Before Muskogee, I had hunted Lake Mead with Mark Lyon and Ashley Humphries, we got skunked. I had also gone up twice to hunt that fireball over Grimsby. Once, with Mike Kelly and once with Stephen Amara. We got skunked, but each of those trips was a BLAST! Memories I’ll keep for a long time and loads of fun. At the end of the day, it’s a numbers game. I got skunked three times after Junction City, but I lucked out in Muskogee.

Anything in general I missed you want folks to know about be it a mental tip or otherwise? Nah, you’re doing great!

Finder: Loren Miller

Number of finds and weight(s): One 70.6

What is your favorite thing about this find? The land owners were really awesome, three of the land owner’s kids came out and hunted with me and that was a great experience. Being able to help them know what to look for and seeing their excitement was fantastic.

Any specific mental preparations you go through in the planning and prep phase of hunting? Looking for cold finds is a big part of the hunting I do. The look of cold finds is much different than that of fresh falls, so I have to actually retrain my eyes a bit from what I am used to looking for.

How would you categorize your hunting strategy as far as determining how long you hunt each event? Usually I try to have two days of travel and have at least three days of hunting. Having found one early on, it drives me a bit to stay longer, but often times life’s other requirements call me back.

Any advice on getting skunked? Get used to it. I got a friend Mike Miller who told me “you don’t go on a meteorite find you go on a meteorite hunt so get used to getting skunked.”

Anything in general I missed you want folks to know about be it a mental tip or otherwise? One thing is definitely make sure to get proper permissions when going on property, can’t stress it enough. Getting onsite early is also important if you want to get the best access. This is twofold, being early there are a greater amount of properties that haven’t been looked at, and the chances of land owners allowing searching prior to being inundated with requests is higher.

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

1 IN SITU

WITH EXCITED YOUNG LOCAL RESIDENTS JENLEE, KENSLIE AND KOLBY

STONE

HUNTING

A SUREAL EARLY MORNING IN THE FIELD

Meteorite Times Magazine

Meteorite Times Magazine

LOREN WITH HUNTING FRIENDS SONNY (LEFT) AND TERRY (RIGHT) CELEBRATING THE FIND

Meteorite Times Magazine

STONE 2 IN SITU

Meteorite Times Magazine CRUST AND INTERIOR OF STONE 2

Meteorite Times Magazine

ROBERTO, MIKE BANDLI AND ROB WESEL ON THE HUNT

Martin Horejsi

By Kenneth J. Zoll

Martin Horejsi

By Kenneth J. Zoll

Photo by © 2010 James Tobin

Photo by © 2010 James Tobin