Programme

Written by Howard Brenton

Written by Howard Brenton

Directed by Philip Crawford

Anne Boleyn

King James I

Robert Cecil

Master Parrot

George Villiers

Lady Rochford

Lady Celia

Lady Jane Seymour

King Henry VIII

Thomas Cromwell

Cardinal Wolsey/Guard

Simpkin

Sloop

Country Man/Guard

Country Women/Courtiers

William Tyndale

Dean Lancelot Andrewes/Courtier

Dr John Reynolds/Courtier

Henry Barrow/Courtier

Lucy McCluskey

Kealan McAllister

Matthew Heywood

Dakota Ginesi

Caelan Stow

Nathalie Parent

Tabitha Smyth

Holly Moore

Tiarnán McCarron

Aaron Ferguson

Michael Clements

Eoin Rafferty

Jack Marshall

Ewan McCartney

Liza Kachura

Abigail Parker

Esmé White

Jack McGowan

Thomas McCullough

Caleb Shannon

Conor Joyce

Choosing a play for the annual Drama Studio production can be challenging: it’s got to have a relatively large cast and the text must offer our student actors the opportunity to put into practice what they’ve learned in the preceding 14 week course. This is my eleventh production for Drama Studio and the fourth play of Howard Brenton’s I have chosen. His work seems to match our needs perfectly and, while it is complex, the more you dig, the more you find hidden within it.

When I chose Anne Boleyn for this year’s production, I knew little more about the woman than that she was one of Henry VIII’s wives and that she met with a dismal end. However, there was no shortage of research

Director

Set Designer

Composer/Sound Designer

Lighting Designer

Costume Designer

Movement/Intimacy Adviser

Acting Tutors

Specialist props

History adviser

Graphic Designer

Philip Crawford

Stuart Marshall

Chris Warner

James McFetridge

Niamh Mockford

Maeve McGreevy

Kieran Lagan

Kathy Moore

Rachel Johnston

Ross Ewart

Adam Steele

Production Manager

Stage Manager

Deputy Stage Manager

Assistant Stage Manager

Scenic Construction

Scenic Carpenters

Scenic Apprentice

Sound Technician

Lighting Technician

Costume Design Assistant

Costume Assistant

Costume Maker

Technical Manager

Head of Production

Creative Learning Administrator

With Thanks

material: in fact, there is an almost overwhelming range of books, films and television programmes: seemingly endless hours of Channel 4’s The Tudors, Wolf Hall and The Boleyns: A Scandalous Family, together with an invaluable output from historians Lucy Worsley and David Starkey to name but a few. Add to that a plethora of fascinating podcasts on BBC Sounds on Thomas Cromwell and the King James Bible and the list could go on!

In rehearsals, we debated alternative titles for the play. Yes, it is about Anne Boleyn, but also about the outcome of many of the changes she helped initiate and those who came after her and their attempts to sort it all out. As we explored our text, Owen

Siobhán Barbour

Louise Graham

David Willis

Codie Morrison

Lyric Scenic Workshop

Aidan Payne

Finn Steadman

Jack McGarrigle

Declan Paxton

Corentin West

Liam Hinchcliffe

Ally McConnell

Mairead McCormack

Sarah Carey

Arthur Oliver-Brown

Adrian Mullan

Caragh O’Donnell Delaney

Dr. Anne Bailie

RockaFellas Barber Shop

McCafferty’s Agreement was playing on the main stage next door. It was most interesting to compare the challenges of negotiating the Good Friday Agreement with those faced by James I at the Hampton Court Conference in 1604 (featured in Brenton’s play) and of course, to trace the roots of differences between Protestants and Catholics back to the Reformation.

For those who, like me, were initially relatively ignorant of the subject, I hope the production serves to spark your interest in a most intriguing period of history.

Philip Crawford Director

Lucy McCluskey

Kealan McAllister

Matthew Heywood

Holly Moore

Liza Kachura

Tiarnán McCarron

Dakota Ginesi

Abigail Parker

Aaron Ferguson

Caelan Stow

Esme White

Michael Clements

Nathalie Parent Tabitha Smyth

Eoin Rafferty

Jack McGowan

Jack Marshall Ewan McCartney

Thomas McCullough

Caleb Shannon Conor Joyce

Lucy McCluskey

Kealan McAllister

Matthew Heywood

Holly Moore

Liza Kachura

Tiarnán McCarron

Dakota Ginesi

Abigail Parker

Aaron Ferguson

Caelan Stow

Esme White

Michael Clements

Nathalie Parent Tabitha Smyth

Eoin Rafferty

Jack McGowan

Jack Marshall Ewan McCartney

Thomas McCullough

Caleb Shannon Conor Joyce

My father, a Methodist minister, once had a blazing row with a butcher –a fiery lay preacher always with a battered King James Bible tucked under his arm. He argued that the miracles of Jesus really happened. Dad believed that many Bible stories were not literally true but “symbolic”. The butcher would have none of this. Everything in the Bible was true: the Word of God, end of argument. A realisation began to dawn on my father, and he said something like “but it is only a translation, from Hebrew and Greek”. The butcher exploded. Translation? No! He believed Jesus and the disciples actually spoke the words of the King James Bible. The language of biblical Palestine was Jacobean English.

This is not a dry point of theology. It is the idea that was used to challenge the power of the Roman Catholic church, the detonator of the 16th-century political and religious explosion we have come to call the Reformation. Countries, families and even individual consciences were torn apart but to most it brought uncertainty and fear to everyday life: can I still pray to the Virgin Mary, are those soldiers in the village Papist or Protestant? The aftershocks are still with us in the uneasy peace in Northern Ireland and the sporadic violence at Celtic v Rangers football matches.

The great reform leaders – the Frenchman John Calvin living in Geneva, Martin Luther in Germany, the Englishman William Tyndale who spent many years in hiding in the Netherlands – may have disagreed theologically on many things but on the word of God they were united: the Bible, not the Catholic church, is the sole source of authority for all Christians.

Henry wanted a male heir to secure his family’s dynasty. Henry’s wife, Catherine of Aragon had borne a daughter but they had no sons who survived infancy. In the second when Anne Boleyn caught the attention of Henry VIII during a court masque – she had thrown an orange at him – a chaos of religious controversy began.

What if one of Catherine of Aragon’s sons had survived – would England have stayed Catholic? What if Anne had a surviving son – she then would have been unassailable, the Church of England would have been thoroughly Protestant and never have split into the factions that beset the reign of James I.

Henry was given to taking a lot of advice and procrastinating; then suddenly something would provoke him and he would decide on a course of action from which he never deviated. He was only the second generation of a family that were little more than bandits who had taken over the country by force – there had to be a male heir.

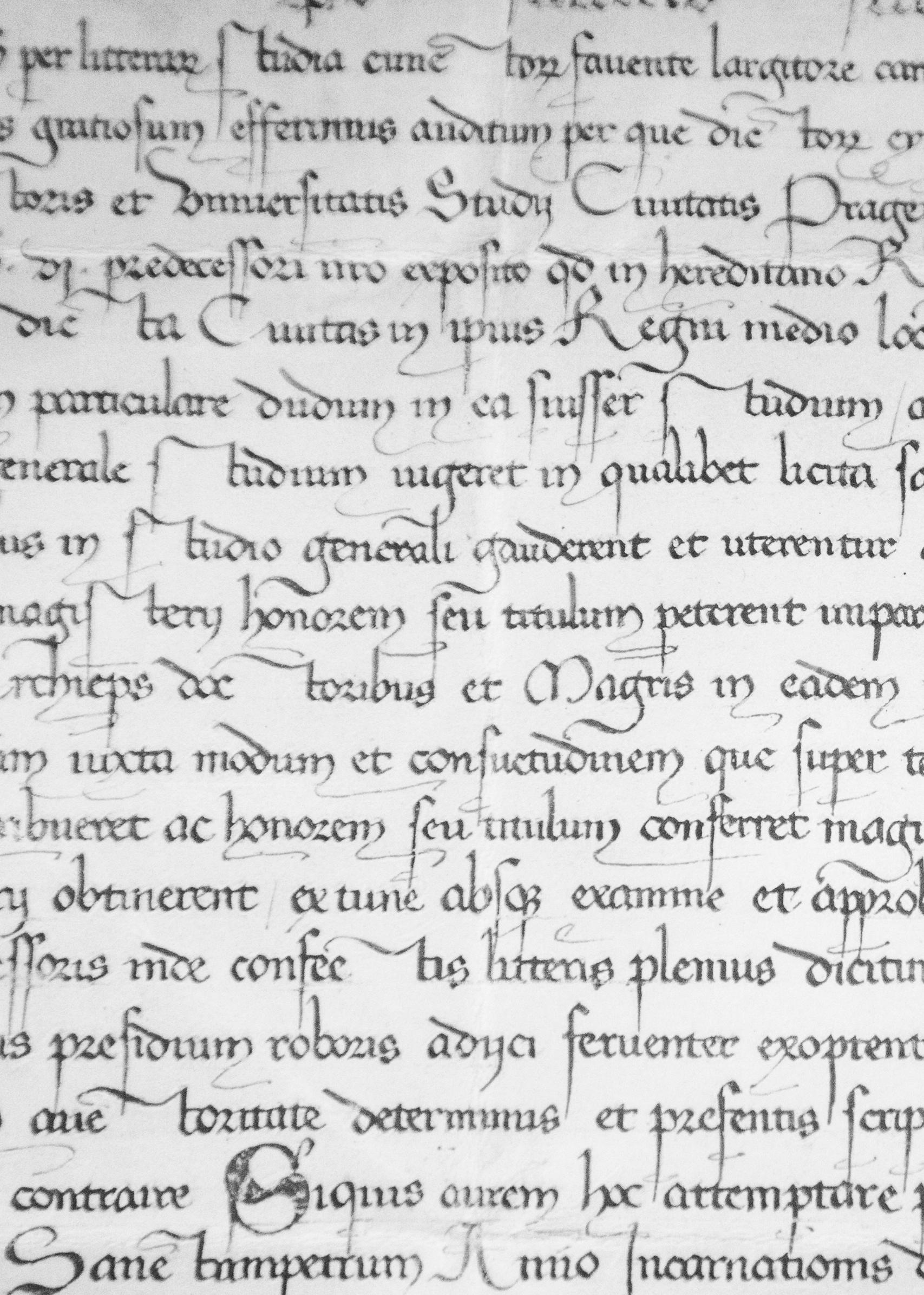

The title page of the King James version reads “newly translated out of the original tongues, and with former translations diligently compared and revised, by His Majesty’s special command”. For the faithful it was – and for many still is – the Word of God made ink on paper. So, the butcher was expressing a fundamental Protestant belief: the word of God must be absolute, certain, unquestionable.

In England at the Court of Henry VIII a Protestant underground, led by Thomas Cromwell, gave the King the grounds for breaking with Rome.

The Catholic church forbade his divorce. There is, however, a verse in the Old Testament Book of Leviticus (20:21): “If a man shall take his brother’s wife, it is an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness: they shall be childless.”

Henry argued that this verse meant that, in the eye of God, he should never have married Catherine because she was first married to his elder brother, Arthur. Catherine countered that she and Arthur had never consummated their marriage.

Cardinal Wolsey, Henry’s chancellor, did his best with Leviticus but Pope Clement forbade the divorce. However the King had made up his mind – and

there must be a divorce. Wolsey fell, Cromwell became Chancellor and the Protestants’ moment had come in England. The word of scripture, not the command of the Catholic church, would rule the King.

Church or the Pope. Wolsey, trying to stem the Protestant tide, confiscated the book from one of Anne’s ladiesin-waiting. Anne went at once to the King and Wolsey was forced to return it. She gave it to Henry who famously commented: “This book is for me and for all kings to read.”

And I had another crazy idea: what if when James ascends the English throne in 1603 he is looking through Queen Elizabeth’s effects and, hidden in an old chest, he finds her mother’s copies of Tyndale’s books and becomes obsessed with her?

began in Henry’s time exploded into the English Civil Wars. What James feared came to pass: monarchy’s divine power was broken forever.

When I was asked to write a play about the King James Bible, I couldn’t see how to do it. But I had long wanted to write about the Tudors. I then remembered reading that Anne Boleyn owned a copy of Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament. She also had got hold of a copy of his incendiary The Obedience of a Christian Man, published in 1528. This was a key text of the Reformation; it attacked the Catholic church and argued that kings, like all of us, are responsible directly to God who speaks to us through scripture, not through the

After Henry, Catholic and Protestant martyrs burnt. Elizabeth tried to damp down controversy but failed. James was faced with a dangerous schism between “high church” –whose adherents longed for the old Catholic glories and hierarchies – and “low church”, where worshippers wanted no bishops at their head, just Christ and his word. James saw where this could lead: a challenge to the authority of the throne itself, the Divine Right to rule. He called a conference at Hampton Court to settle the controversy. The idea for a new translation came from a moderate Puritan scholar from Oxford, John Reynolds. Immediately James saw the opportunity: a new Bible could unite the Protestant factions in agreement.

He set up many committees of translators from all sides. The King James Bible was a brilliant, inventive political manoeuvre. The text was largely based on Tyndale’s translation subtly amended to enhance the authority of the state and downgrade personal faith (Tyndale’s “congregation” became “church”, “elder” became “priest” and “love” became “charity”.) Now controversy could end. The Word of God was clear for all to read. James’s settlement failed. The Protestant revolution that

There is a deadly fault-line in the Protestant dependence on the Word. My father and the butcher were standing on it: it is interpretation. Tyndale’s book gave Henry the intellectual authority to break with Rome. But in a virulent pamphlet, The Practice of Prelates, Tyndale attacked Henry’s desire for a divorce quoting the Book of Deuteronomy (25:2): “If brethren dwell together, and one of them die, and have no child, the wife of the dead shall not marry without unto a stranger but her brother’s husband shall go unto her.” But which is true, Leviticus or Deuteronomy? Is God contradicting himself?

This is the tyranny of the word of God. It is meant to free you. But interpret it wrongly – that is against the interpretation of the men with swords or guns – and it can kill.

Howard Brenton WriterAnne Boleyn was born around 1501. In 1513 her father, Sir Thomas Boleyn, a diplomat keen to advance further at Henry VIII’s court, obtained employment for her as a maid of honour at the court of Margaret of Austria in Burgundy (modern day Belgium). Later she transferred to the French Court where she made a deep impression with her wit, intelligence and social graces. After eight years away she returned to England and in February 1522 her father succeeded in having her placed in the household of Katherine of Aragon, Henry VIII’s wife. Around the same time, Anne’s sister, Mary, was a mistress of the King.

In 1523 Anne accepted a marriage proposal from Henry Percy, the son of the Earl of Northumberland. This was subsequently undone by Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII’s Chief Minister, who may have been aware of the King’s burgeoning interest in Anne. Anne withdrew temporarily from Court but Wolsey’s action provoked Anne’s anger towards him that remained until the Cardinal’s death in 1530. When Anne returned to Court in 1525 the King resumed his courtship of her. Anne, pressured by her ambitious family to encourage his interest, dutifully did so for nearly seven years but steadfastly refused to become his mistress.

Henry’s pursuit of Anne coincided with his desire to end his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. Katherine had previously been married to Henry’s brother, Arthur. Although she had given Henry a daughter, Mary, Katherine’s failure to produce a male heir led Henry to appoint Wolsey to obtain an annulment of marriage from the Pope, an issue which became known as “The King’s Great Matter.” Henry’s argument was that God was punishing him for marrying his dead brother’s wife; however at the Legatine Court in 1529 the Pope’s representative, Cardinal Campeggio, delayed a decision. This failure ultimately led to Wolsey’s fall from office.

The failure to secure papal support for an annulment convinced Henry that Church reform, especially abolishing the Pope’s authority in England was necessary. These ideas had been advanced by William Tyndale, a Protestant who had fled to Europe to escape persecution from Henry’s ministers such as Wolsey and Sir Thomas More. Anne Boleyn, a strong believer in Tyndale and Protestant beliefs, owned a secret copy of his translation of the Bible and use her influence over Henry and Thomas Cromwell, Wolsey’s replacement, to advance previously heretical ideas. The Act of Supremacy establishing

Henry as Head of the Church in England was strongly endorsed by Anne and the Boleyn family.

At the commencement of Henry’s Reformation his relationship with Anne flourished. Towards the end of 1532 Anne finally succumbed to the King’s entreaties. In 1533 the couple were secretly married and in May 1533 the marriage was declared legal by the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. In June 1533 Anne was crowned Queen and on 7 September 1533 she gave birth to the Princess Elizabeth.

But by 1536 Henry’s infatuation with Anne had passed. Her feisty temperament often annoyed him and his flaunting of his new mistress, Jane Seymour, exacerbated tensions further. Henry’s priority for securing a male heir weighed heavily on him and a series of miscarriages by Anne convinced him he needed to remarry. Following the death of Katherine of Aragon in January 1536, Henry believed he could secure a resolution of several pressing problems.

As Anglo-French relations were deteriorating, Henry was keen to forge an alliance with Katherine’s nephew, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Cromwell was astute in realising that the removal of Anne, and also the political influence of her family – who had striven to promote relations with France -would satisfy the King’s matrimonial concerns, secure England’s vital interests in Europe and ensure his own self preservation. He embarked upon a ruthless course of action, informing the King that Anne had committed adultery with several members of the Court and incest with her own brother, George. In early May 1536 Anne was arrested, taken to the Tower of London and subsequently put on trial. Testimony from Lady Rochford – George Boleyn’s wife – and others, largely obtained under duress, helped to ensure Anne and most of her alleged lovers were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death.

On 19 May 1536 Anne Boleyn was beheaded on Tower Green by a French swordsman. The same day Henry’s betrothal to Jane Seymour was announced to the King’s Privy Council.

Ross Ewart History Adviser

Anne Boleyn

Catherine of Aragon

Jane

Ross Ewart History Adviser

Anne Boleyn

Catherine of Aragon

Jane

As a costume designer-maker, my love for the work stemmed from a background in amateur dramatics and sewing, and developed while at university. I was studying fashion and textiles, specialising in costume and embroidery, when I decided to carry out a placement year with the Lyric Theatre costume department, and the National Trust, for their historical costume conservation. It feels strange to think back to that time, nervously trying to learn how a costume department works and how a theatre is run, keeping my head down and working hard, to this, my first lead design role in the Lyric Theatre. It’s wonderful to be designing in the theatre that started my career in

costume, and to be working on a show that encompasses my understanding and ideas of costume and historical clothing. I especially loved researching Anne Boleyn’s execution dress as there are no paintings, only accounts from history that allow for interpretation. I wanted to have Anne wear a version of this dress in the show as a foreboding sign of her inevitable death, and with historical accounts of a grey damask dress with a crimson petticoat, I decided to take creative license.

As well as creativity, a significant part of designing this show was problem solving, for example, figuring out how costumes for the Jacobean characters, Barrow, Reynolds, and Andrewes, could

work for them as ensemble Tudor characters, without full changes. The solution was to have them in black costumes with interchangeable ruffs and lace collars depicting the era, which proved simple but effective. I enjoy creating solutions through creative thinking and have found it’s necessary in all aspects of costume.

This play has been incredible to work on. It is entertaining, wonderfully educational, and it has shown me how I work as a designer.

Descendants of Anne Boleyn, who was beheaded by Henry VIII in 1536, have been keeping her memory alive by sending a bunch of red roses to the Tower of London on the anniversary of her death for more than 150 years. Mystery has always surrounded the arrival of the flowers – historians, Tower staff and thousands of visitors have been intrigued by the tradition.

In 2000, after 3 years of painstaking research, a former director-general of the Tower, has traced the origin of the flowers back to Kent, where Anne’s descendants live. He identified the family – now called Bullen rather than Boleyn – who reluctantly admitted that the flowers came from them.

General Tyler eventually won the trust of the intensely private Bullens, and a group of family members accepted his invitation to visit the Tower to see where their ancestor was imprisoned, where she died and the place she was buried.

Washington Post, May 2000

Niamh Mockford Costume DesignerJames Stuart was born in Edinburgh on 19 June 1566, the only son of Mary Queen of Scots. Scotland had been profoundly affected by the religious fervour and turmoil that had swept Europe from the beginning of the 16th Century. By 1560 Presbyterianism, a branch of Protestantism derived from the beliefs of John Calvin, had become the established orthodoxy. The leaders of this Scottish ‘Kirk’ grew politically more powerful and in July 1566 Mary, a Roman Catholic, was forced to abdicate or face trial and execution having been accused of involvement in her husband’s murder and adultery. Her young son, crowned King James VI the following year, was to grow up under the influence of those who had sealed his mother’s fate.

James was a keen scholar and came to articulate strongly a belief in the Divine Right of Kings: as King, he was God’s anointed and his subjects should not challenge his ecclesiastical authority or primacy in secular affairs. In respect of church management he believed in a hierarchical system in which bishops were appointed by the King to enforce his will rather than the Presbyterian belief in elected’ elders and the parity of ministers within their congregation. However, James was by instinct averse to confrontation where compromise might be attainable and succeeded in maintaining a delicate balance of power in his kingdom amongst these conflicting beliefs.

In 1603 James VI acceded to the English throne on the death of Elizabeth I, uniting both kingdoms as James I of England and Scotland. He admired the Anglican Church (Church of England) – the ‘middle way’ –which Elizabeth had established to stabilise the country after the religious upheavals under her predecessors. He appreciated the urbane, serene world of Anglican bishops in which (Protestant)

theological soundness was combined with a proper deference for royal authority. Yet, having received the Millenary Petition presented to him on his journey to London in 1603, he was also aware of English Protestants, often termed Puritans, who viewed the Anglican Church as too Catholic in its services and structure, and who looked to James I to reform it.

James I decided that the Hampton Court Conference should be convened in January 1604 with representatives from both sides of the Church. Key figures included Richard Bancroft, Bishop of London and Lancelot Andrews, the Royal Chaplain, both of whom could be relied on to defend the status quo and, representing the Puritans, John Reynolds, a leading Oxford theologian but a moderate reformer. In three meetings over five days the King played a major role in the Conference, enjoying the cut and thrust of religious debate and expressing his ideas often in crude language! He appeared to act as an honest broker in the deliberations of the Conference, berating and poking fun at both the supporters of the status quo and the would be reformers but in reality, given the composition of the Conference and James’s own convictions, it was unlikely that any radical reform of the Church would be effected. When Reynolds in an unguarded moment mentioned the word ‘presbytery’ with all its connotations to the ecclesiastical governance of the Scottish Kirk, James angrily declared how a Scottish presbytery “as well agreeth with a monarchy as God and the Devil.” In a final flourish he added, “No Bishop, no King.”

Despite the apparent rancour there was to be a positive outcome from the Conference. Perhaps in an attempt to mollify the King, Reynolds suggested that there should be a uniform bible that would be acceptable to both wings of the Church. The Anglican establishment preferred

to read the ‘Bishops’ Bible’ whilst Puritans often read the Geneva Bible or William Tyndale’s Bible. James disliked the Geneva Bible because it contained annotations critical of the monarchy; on the other hand he disliked how parts of the Bishops’ Bible had been sloppily translated from older texts. The solution was that a new translation of the Bible was to be commissioned. However, only a translation acceptable to the King would be permitted; the word ‘congregation’ should be used instead of ‘presbytery,’ bishop should be used in place of ‘elder. Over the next seven years six committees and fiftyfour translators were to study and translate material considered ‘safe’ from previous bibles. In 1611 their work was finally completed with the appearance of the King James Bible or Authorised Version. Regarded by many people subsequently as a literary masterpiece, this Bible drew from many sources including Tyndale’s Bible once regarded as heretical in Henry VIII’s England.

The outcome of the Hampton Court Conference in largely preserving the status quo was ultimately more pleasing to King James and the Anglican establishment than to the Puritans. While some minor reforms to Church services were promised little subsequently changed. In the short term some Puritans may have been placated by the new Authorized Version of the Bible but others such as the Pilgrim Fathers, disenchanted by the lack of effective reform, decided to seek a new life for themselves outside England in North America. Nearly forty years after the Conference ended the religious divisions that James failed to resolve were to manifest themselves bloodily in the Civil War.

Ross Ewart History Adviser