Agora

THE LIBERAL ARTS AT LUTHER COLLEGE

Martin Klammer, editor

Bonnie Tunnicliff Johnson, production editor

Agora, an interdisciplinary journal grounded in the humanities, is a project of the Luther College Paideia Program. The Luther College Paideia Program encompasses many activities and resources for students, faculty members, and the broader community. It includes an annual lecture series, library acquisitions, student writing services, a faculty development program that includes sabbatical grants and summer workshops, and Agora: The Liberal Arts at Luther College. All these activities receive financial support from the Paideia Endowment, originally established through National Endowment for the Humanities grants matched by friends of Luther College. The Paideia owl logo was designed by Professor of Art John Whelan.

The primary Agora contributors are Luther College faculty; writing is also solicited from other college community members and, occasionally, from outside writers. Agora was established in 1988 by Paideia Director Wilfred F. Bunge, Professor of Religion and Classics, who edited the journal from 1988-1998. Other editors include: Mark Z. Muggli, Professor of English, 1998-2004; Peter A. Scholl, Professor of English, 2004-2014; and Martin Klammer, Professor of English, editor since 2014. Agora is distributed to on-campus faculty and administrators as well as to off-campus friends of the college. Anyone wishing to be included on the print copy list or donate to Agora should contact us at (563) 387-1153 or email agora@luther.edu.

To see the current issue and archival issues online, go to www.luther.edu/paideia/agora

SPRING 2023 THE LIBERAL ARTS AT LUTHER COLLEGE VOLUME 35 NUMBER 2 LUTHER COLLEGE

Seeking Wisdom in Community

PAIDEIA

Mychal

When Islamophilia Becomes Islamophobia: The Case of Hamline University (February 19, 2023)

Robert Shedinger

He Loved Them to the End (April 5, 2023)

Martin Klammer

Ramadan Reflections (April 19, 2023)

Jaraad Afroze Ahmed (’25)

Other People Are Not Me (May 10, 2023)

Anna M. Peterson

Cover: Vase (1971)

Josiah Tlou

Josiah Tlou was born in 1935 in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) and came to Luther College after an eight-year career as a school teacher and principal in Zimbabwe, graduating with a history degree in 1968. After earning his MA degree in history from Illinois State University in 1969, he returned to Luther as a faculty member for three years, helping to establish what was then known as the Black Studies Department. Tlou earned his Doctorate of Education degree from the University of Illinois and joined the faculty at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Blacksburg, VA, rising to the rank of full professor in 2002 before retiring in 2005. He received an honorary doctorate (humane letters) from Luther College in 2003 for his contributions to education in Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Malawi.

As an artist, Josiah Tlou took several classes in pottery at Luther, and during the summer of 1967 he studied with Marguerite Wildenhain at her Pond Farm workshops in Guerneville, CA. He later studied ceramics at South Bear School with Dean Schwarz. The vase featured on the cover was donated to the Pond Farm Collection by Edward (1939-2017) and Elizabeth Kaschins, emeriti faculty members. Josiah Tlou and his family are long-time friends of the college and of Decorah. For another Tlou family connection, see page 31 of this issue.

Essays Prairie Sinkhole Bluestem Sky: An Evening of Poetry and Readings Hayley Jackson, David Faldet, and Athena Kildegaard 3 Last Station Jenbach John Strauss 9 Sabbaticals Oboe in Community: Supporting the Next Generation of Oboists Heather Armstrong 13 Geophysical Remote Sensing at a Pre-Contact Enclosure Site in Northeast Iowa Colin Betts............................................................................................................ 17

Adventures

Stories Lise Kildegaard ..................................................................................................... 20

Institutional

Charlotte A. Kunkel .............................................................................................. 23

Talks

Celebration of Community and Heritage (December

Wintlett Browne 26 Bold Faith (February

Ashley Benson ....................................................................................................... 28

Further

in the Collaborative Arts: Louis Jensen’s Square

Thinking Through

Equity: Finding a GEM

Chapel

Kwanzaa:

9, 2022)

3, 2023)

Why Luther? (February 8, 2023)

Shed (’23) ................................................................................................. 30

32

34

35

................................................................................................. 38

Contents

Introduction

by MARTIN KLAMMER, Professor of English, Editor of Agora

When many Luther faculty go on sabbatical, they don’t seem to leave their students! This is the case with the student-centered sabbatical reports in this issue.

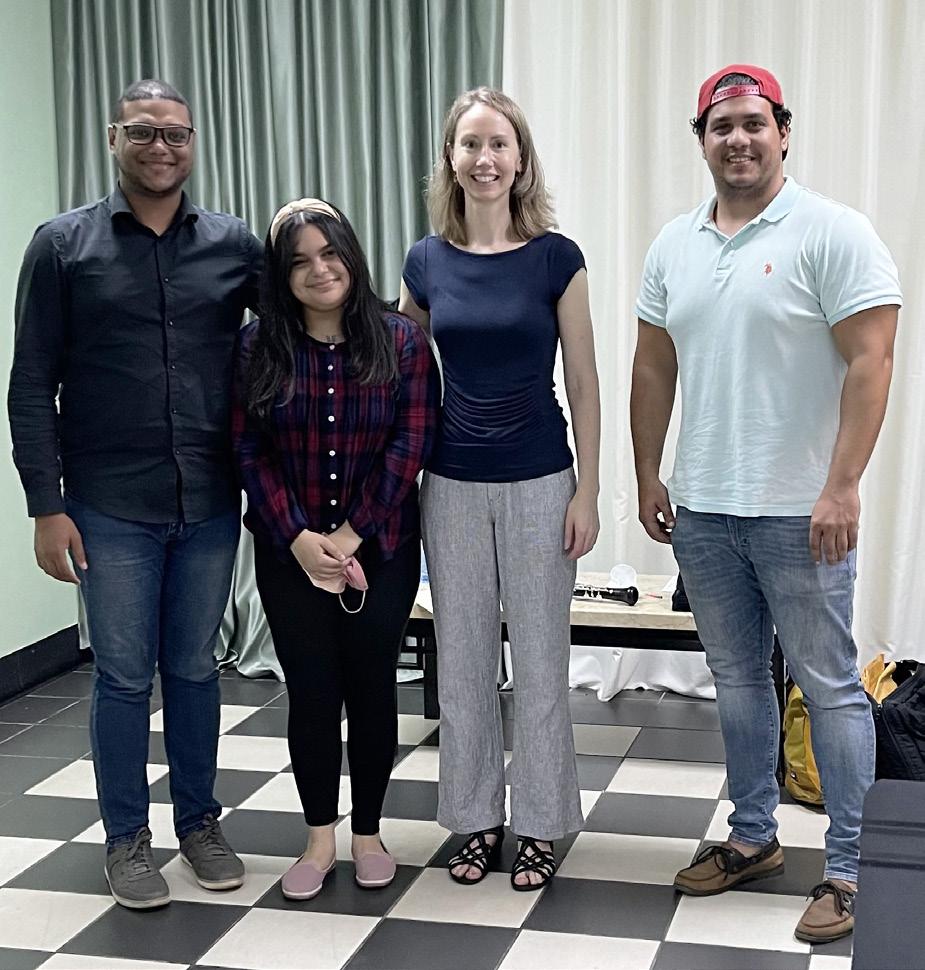

Heather Armstrong writes of her time working with young musicians in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Minnesota, “exploring organizations whose mission is to help make the oboe more accessible to students who want to learn to play it.” Learning to play the oboe can be a challenge, Heather writes, because of the instrument’s high cost and the lack of knowledgeable oboe instructors, especially in less populated areas. In all three locations, Heather worked with oboe students through various education programs. She taught individuals and groups, presented oboe workshops, and helped with reed-making. In addition, she performed with Luther alumni Maria Morel-Pierrot (’97) and Ingrid Scott (’12) at the national conservatory of the Dominican Republic in Santo Domingo, and in an oboe/horn quartet at the Oboe Fest in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Heather hopes now to create a sense of community among oboe students at Dorian summer programs like that which she saw and experienced in her sabbatical travels.

Lise Kildegaard continued her work sharing the Square Stories of Danish author Louis Jensen, though her sabbatical plan of visiting with Jensen in Denmark took a sudden turn when he died of a heart attack at age 77. Saddened, Lise decided that “other collaborations could continue.” She made new plans to share Jensen’s stories in collaborations with the Museum of Danish America in Elk Horn, Iowa, and in Seattle at the University of Washington and the National Nordic Museum. Lise writes that a “particularly enjoyable and productive collaboration” was her student-faculty

research collaboration with Jurgen Dovre, an English major and gifted cartoonist. While Lise refined her translations of Jensen’s stories, Jurgen created illustrations to go along with some of the stories, three of which are included in Lise’s essay. Lise notes that Jurgen’s drawings “display a gentle yet lively humor that makes them a good match for Jensen’s stories.”

Colin Betts collaborated with Anna Luber (’19) and Linh Luong (’20) in 2018 on geophysical archaeological research that explored northeast Iowa’s “pre-contact enclosure sites.” A primary goal of Colin’s fall 2021 sabbatical was analysis of the data that Anna and Linh helped collect. And while Char Kunkel did not work directly with students, it’s clear that the Global Ecological Mapping (GEM) of equity she developed on sabbatical will be an important new part of her teaching in sociology and Identity Studies.

Perhaps the best way to describe the value of faculty-student collaborations is with the Danish word formidler which, Lise tells us in her essay, means “a person who knows something of value or has access to something of value, and works to share it with others.” The

sabbatical essays in this issue are excellent examples of how Luther faculty are formidlerne, sharing their passions and knowledge with students, and receiving from students in turn their creativity, insight, and love of learning.

2 Agora/Spring 2023

Martin Klammer reads a condensed version of the great American novel with granddaughter Lana Maxfield, age 3.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

Prairie Sinkhole Bluestem Sky: An Evening of Poetry and Readings

by HAYLEY JACKSON, College Archivist; DAVID FALDET, Professor Emeritus of English; and ATHENA KILDEGAARD, Honors Coordinator, University of Minnesota, Morris

Editor’s note: This series of three writings reprises an evening of readings on February 10 about the prairies and natural world of the upper Midwest. The event was co-hosted by the Luther College English Department and the Center for Ethics and Public Engagement (CEPE).

Choice, Not Chance: Preserving Prairies and Archives

by Hayley Jackson

When Lise Kildegaard asked me to speak this evening, I had no idea what I would talk about. The prairie and the archives are two very different things, and I have far more experience with one than the other.

Initially, I thought I would talk about the history of Washington Prairie, a local prairie of great significance in the Norwegian immigrant community. When I couldn’t find the history behind why the prairie was named for Washington, I scrapped that and thought I might instead compare my journey to living in the Oneota Valley to the journeys of Elisabeth Koren and Linka Preus. I was going to make fun of myself. Growing up in the Chicagoland sprawl, my exposure and connection with prairies came from Laura Ingalls Wilder, the Oregon Trail computer game, and that one field trip to the prairie areas of Fermi Lab. Little City Girl on the Prairie. Several of Preus and Koren’s complaints about the cold and getting lost in the dark rang true to my early years here in Decorah. But that didn’t feel right either. Finally, at about nine o’clock this morning, it dawned on me what I really wanted to talk about. Surprise surprise, it’s a topic I always want to talk about.

I want to talk to you about preservation, something that truly unites prairies and archives.

In the popular media, we love stories of dramatic historical discovery. Someone opens a box in grandma’s attic and finds a set of diaries. A metal detectorist in England goes out for a walk and finds a cache of Roman coins. Someone cleaning out a basement finds boxes of glass negatives. We love these stories. How amazing, we say, that these have lasted so long. How fortunate we are to have found them. Look how well it has been preserved. Isn’t it unbelievable they’ve survived this long?

These events do happen, and they are incredible. In 2014, right here in Decorah, Kate Rattenborg Scott’s family found a trove of letters written by Elisabeth Koren to her father in Norway. I am grateful that Kate and her family donated those to the Archives. That same year, a student cataloging the papers of Professor Orlando W. Qual-

ley located some ancient papyri pieces Qualley had purchased in Karanis, Egypt. These events are exciting! It makes us feel a little bit like Indiana Jones.

I want to stress, however, that much of the material we use to study the past was not preserved accidentally. It was done on purpose, first by the family or organization who set the material aside, then by the archivist, museum curator or librarian who placed the material in their collection. The collections are cataloged, organized in boxes, and stored in spaces designed to maintain their existence as long as possible. These are all deliberate choices made because we value the past. We think these records have something to tell us about the people who wrote them, and the time and place they were written in. We think that there is something left to be learned from these records. We think there is value in knowing where we come from.

Spring 2023/Agora 3

Moderator Lise Kildegaard with Athena Kildegaard, Hayley Jackson, and David Faldet, following an evening of readings about the prairie

PHOTO COURTESY OF LUTHER SNOW

If we were to leave this all to chance, we would not have nearly the resources we have in the archives. Natural disasters, poor storage conditions, and a lack of care all contribute to the destruction of historical records. Every archivist and museum worker I know lives in fear of that 3 a.m. phone call that the pipes over the storage area burst, or of that well-meant donation of material so covered in mold we cannot save it. And to be fair, we can’t preserve everything. (That’s a talk for another time.) But if we leave the preservation of our past to chance, our historical record would be much less rich.

I want to read you a passage from Caroline Fraser’s 2017 book Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder

It is always a problem, in writing about poor people. The powerful, the rich and influential, tend to have a healthy sense of their selfimportance. They keep things: letters, portraits, and key documents, such as the farm record of Thomas Jefferson, which preserved the number and identity of his slaves. No matter how far they may travel, people of high status and position are likely to be rooted by their very wealth, protecting fragile ephemera in a manse or great home. They have a Mount Vernon, a Monticello, a Montpellier.

But the Ingallses were not people of power or wealth. Generation after generation, they traveled light, leaving things behind. Looking for their ancestry is like looking through a glass darkly, images flickering in their obscurity. As far as we can tell, from the moment they arrived on this continent they were poor, restless, struggling, constantly moving from one place to another

in an attempt to find greater security from hunger and want. And as they moved, the traces of their existence were scattered and lost. Sometimes their lives vanish from view, as if in a puff of smoke.

So as we look back across the ages, trying to find what made Laura’s parents who they were, imagine that we’re on a prairie in the storm. The wind is whipping past and everything is obscured. But there are the occasional bright, blinding moments that illuminate a face here or there. Sometimes we hear a voice, a song snatched out of the air.1

When I first read this book a few years ago, I was, as the kids say, shook. My archival training had taught me that the written records we have from ages gone by tend to be from the upper classes, often because those we have deemed to be significant hail from those classes. Thomas Jefferson liked to pretend to be a simple farmer but he was an aristocratic, wealthy man. But this passage touched me deeply because the stark contrast of care. Washington, Jefferson, Madison, cared about their legacies, their lands, what would be left behind. They had places to store their vast collections of papers, books, trinkets. When they died, these were

4 Agora/Spring 2023

Main II with prairie grasses

Anderson Prairie

PHOTO COURTESY OF KIRK LARSEN

PHOTO COURTESY OF LUTHER COLLEGE ARCHIVES

This cabin, near Washington Prairie, housed newly arrived Elisabeth and U.V. Koren as well as their hosts, the Egge family, during the winter of 1843-54. This 1955 photo

it at Luther College. In 1976 it

seen as valuable enough to preserve. The same cannot be said for the possessions of those they enslaved, if, in fact, the enslaved owned anything at all.

We see this in our own collections here at Luther. The diaries and letters of Elisabeth Koren and Linka Preus are such valuable resources for us to learn about life on the Wisconsin and Iowa prairies. Elisabeth in particular loved nature and plants—there is a letter to her father where she tells him all about the prairie wildflowers. She writes in her diary about her husband, Vilhelm, bringing her new flowers he has found while out and about. But these women were not your average pioneer women. They were well-educated and came from families of status in Norway. They married men who would become significant figures in the Norwegian Synod and the history of Lutheranism in America. They were not Caroline Ingalls.

To be sure, Linka and Elisabeth gave up their lives at home, leaving everything they knew behind to come with their husbands to this strange new country, where rumor had it that the birds didn’t sing and the flowers had no fragrance. Elisabeth later wrote to her father that rumors of American flowers having no fragrance was slanderous. While

they had help around their homes, they worked hard, making sausage from animal guts, scrubbing floors, ironing clothes, tending animals. They surely did not think their life story and legacies were as important as Jefferson or Washington did. And yet, they clearly thought their stories were worth writing down. I don’t get the sense that Erik and Helene Egge, the couple who shared their cabin with the Korens, felt their journeys from Norway were worth writing down. We know some of their story not from any writing they left behind, but from newspapers, government records, and later interviews with descendants. I’m not sure they would have had the time to write with all the labor it took to maintain their farm. We have no insight into the Egges beyond what Elisabeth writes, but I would be unsurprised if in the event the Egges had to leave and only had space for foodstuffs or letters from home, they chose the foodstuffs. The Egge-Koren cabin was not preserved because the Egges lived there, but because the Korens lived there. The history of the poor, and of other marginalized groups, is so often found by reading between the lines.

All of this is to say that most preservation is not “natural.” It is a choice. A deliberate choice. Archivists today are

working to be more inclusive in what we collect so we can preserve a wider range of stories that reflects more of our society because we recognize this choice.

So what does this have to do with the prairie? That preservation, or perhaps conservation, is choice applies to our natural landscapes just as much as our historical record. Anderson Prairie, that beautiful patch of tallgrass prairie here on campus, is a deliberate choice we have made as an institution. We believe it is worth preserving, that it has value, that we can continue to learn from it. Perhaps it is, as Athena writes in “Prairie Daughters 2036” only of “museum quality.” But it is there. We maintain it and run routine controlled burns. Prairie fires have always been part of the cycle of maintaining grasslands. This is something the indigenous peoples and later the settlers on these prairies knew. The prairie required deliberate choices to maintain it. This beautiful land we live on is here because of active choices we have made to preserve it. We do not, we cannot leave it to chance.

So as you listen to our readings tonight, think about preservation. Think about how the documents came to be that Athena was able to draw from for her poetry. Think about how David was able to experience the land similarly to his ancestors here in Winneshiek County. Think about how it is choice, not chance, that shapes so much of the world around us. Thank you.

NOTES

1. Fraser, Caroline. Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017, p. 28-29.

Spring 2023/Agora 5

shows

was moved to the Vesterheim Museum’s campus.

IMAGE COURTESY LUTHER COLLEGE ARCHIVES

Excerpts from Oneota Flow: The Upper Iowa River and Its People1

From “The Two Names of the River: Geological Beginnings”

by David Faldet

The waters that feed Upper Iowa springs often enter the ground through a rock feature called a sinkhole. A sinkhole is created when water nibbles out a widening funnel as it descends into the rock below the surface. These funnel vents collapse under the weight of the rock and soil above them, creating pockmarks: the most visible intake pores of the underground circulatory system of the river basin. The Upper Iowa may be fed by as many as six thousand of these. My childhood along the river taught me that sinkholes were repositories. Into the sinkhole on my family’s acreage, I dumped branches, leaves, lawn rakings, and grain sacks full of clinkers and ash. Over the biggest depression on our land, a previous landowner had parked an outmoded horsedrawn hayloading machine. It towered, rusting, over my sinkhole visits like the skeleton of some prehistoric reptile. Having made deposits, I expected returns; some of the best cure-all bottles, animal skulls, and antique curiosities I found in my childhood ramblings came from sinkhole depressions. Because of the predictable effect on groundwater quality of dead pigs, chemical containers, and junked refrigerators, it is now illegal to use sinkholes as dumps: a diminishment of life for young explorers but an enhancement for everyone else.

From

“Unknown World: 1634 to 1832”

In talking about repairs to stalactites on our hike through the subterranean waters of Coldwater Creek, Mike Lace uses a word that gives me pause. “Some of the speleothems we repaired a few years ago,” he says, “are already healing over quite nicely.” The cave is chiefly stone, water, and air. “Healing” suggests how much it is alive, a living system into which people have only recently pushed themselves. As we splash into the upstream edge of Pothole Country, Lace points out a perfectly circular depression, ten inches deep. At its center rests

a round black stone: a dark nucleus. “Boulders like this get rounded as they dig their way down into these potholes,” he explains. Looking down at the cabbage-sized rock nesting in its pool of water feels like looking over an unexpected precipice. The geologic life of the cave unfurls before me. This round rock in its round hole started as a squared-off block of limestone in a tight, square bed. Years of water, moving the rock, has dug out this new cave space. The pothole is like a single cell in a plant that has

spread its limbs sixteen miles, the flow of water essential to its continued life.

To gauge the climate of the world above over the last ten thousand years researchers have used the growth rings of stalactites in Coldwater. Groundwater seeps through the Galena limestone above the cave, absorbing calcium from the rock, leaving behind a microscopic film of calcium as it drips from the stalactites, new growth to cover the old, or to heal a break. The rate of growth and the mix of carbon and oxygen in

6 Agora/Spring 2023

OF JORDAN KJOME-DECORAH,

Rounded boulder in pothole at Coldwater Cave “MORTAR

AND PESTLE” PHOTO COURTESY

IOWA

the calcium carbonate of the stalactites changes, depending on whether the climate is damp and marked by forest growth, or whether it is drier, hotter, and marked by prairie.2 While the life above ground grows and decomposes, passing from chill winter into blazing summer, the cave lives and grows in steady darkness and temperature. The cave began growing when ground sloths pounded the turf above. It grows with the steady interplay of water and rock, even as I slosh through it. It will still be growing with quiet slowness in the dark when our impatient species passes into extinction. Exploring the cave is arduous, but I realize as my friends and I slosh tiredly to the ladder, the cave is insulated from much of the world above: a sanctuary as well as a frontier.

NOTES

1. Used with permission of the University of Iowa Press.

2. Denniston, Rhawn F., Luis A. Gonzalez, Yemane Asmerom, Richard G. Baker, Mark K. Reagan, and E. Arthur Bettis III, “Evidence for Increased Cool Season Moisture During Middle Holocene,” Geology, 27, no. 9 (1999): 815-818.

Spring 2023/Agora 7

OF

KJOME

Stalactite formation, Coldwater Cave “ROCK RIVER FORMATION”

COURTESY

JORDAN

To Unmake the Prairie

by ATHENA KILDEGAARD

by ATHENA KILDEGAARD

Begin with a long arrival, with stomach-hunger, prosperity-hunger. Or begin with despair.

Take down the sky, anything unfamiliar, the land, light a match. Take the land because your hunger sanctions taking.

Hitch whatever animal you have, yourself, if necessary, to your one plow.

Imagine the wheat you carried as seed in burlap grown tall as your first child

and do not rest until you cannot see just how straight and regular are the rows.

Years hence you won’t remember whether there were flowers, whether small mammals ran ahead

or meadowlarks or swallows, whether the chorus chided or blessed, who you saw walking toward the horizon, your daughter, your husband, or who you saw walking the field as if they’d been there before. You’ll forget this, too.

You won’t remember the bluestem bowing their precious and gullible heads.

8 Agora/Spring 2023

LUTHER COLLEGE: BY ARMANDO JENKINS-VAZQUEZ (’21)

Anderson Prairie in the fall of 2022

Last Station Jenbach

by JOHN STRAUSS, Professor of Music

Editor’s Note: The following is the final chapter of John Strauss’s book, published in German and English by Verlag Berger, Vienna (2022): Dr. Wilhelm Strauss, Kinderarzt: Eine Odyssee des 20. Jahrhunderts (Dr. Wilhelm Strauss, Pediatrician: A Twentieth Century Odyssey).1

On the fifteenth of December 2005, Uncle Franz was laid to rest in the Morgenstötter family plot of the parish church (Pfarrkirche) in Jenbach, Tyrol (Austria). Born in Wiener Neustadt in 1922, he had survived the harsh economic realities of the First Republic, the Revolution of 1934, the “Anschluss” (as Hitler euphemistically called the annexation of Austria in 1938) and the subsequent break up of his family, the Second World War, and the slow post-war recovery. He was the last surviving grandson of the dried fruit and coffee merchant Salomon (Samy) Strauss (1845–1933) of Prague and his second wife Berta Jeiteles (1857–1907), and the last Tyrolean grandson of Peregrin Morgenstötter (1860–1930) and his wife Maria Müllauer (1862–1924). The Morgenstötter family–farmers,

tanners, craftsmen, and innkeepers–were originally from the Zillertal, and the Müllauers were among the earliest inhabitants of the medieval town of Jenbach. Franz, who had assumed his mother’s maiden name to evade the Nazis during the war, was the last surviving member of the Morgenstötter/Müllauer clan to live in Tyrol.

Franz Strauss (1922-2005) was the second of three sons born to the pediatrician Wilhelm (Willi) Strauss (1885–1970) and Therese Morgenstötter (1892–1978). The oldest son was my father Felix (Fritz) (1918–1990), and the youngest was my namesake Johann (Hans) (1930–1941), who died in Budapest during the war of a childhood ailment or, as my father would have it, of a broken heart. Ironically, it was Franz, impaired both physically and mentally by polio and encephalitis at an early age, who lived the longest life.

I first met Uncle Franz in spring 1965, when I was sixteen years old. At that time, Franz was the gatekeeper (Türhüter) at the monastery in Schwaz, one town up-river from Jenbach. The Inn River had flooded with disastrous results that spring, and roads were nearly impassable, not that there were many cars on the road. Even in Vienna, only a wealthy Austrian could hope to own an automobile. Jenbach in the middle 1960s was a small, drab and dirty town, strongly redolent of coal and wood-burning stoves. Time seemed to have stood still in Tyrol, and its denizens looked as though they had recently stepped out of a nineteenth-century Biedermeier Era painting.

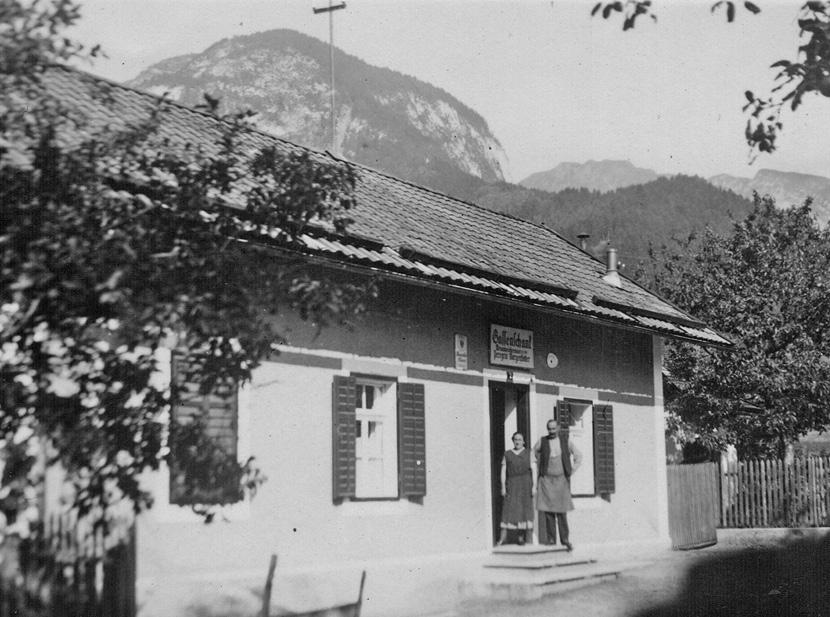

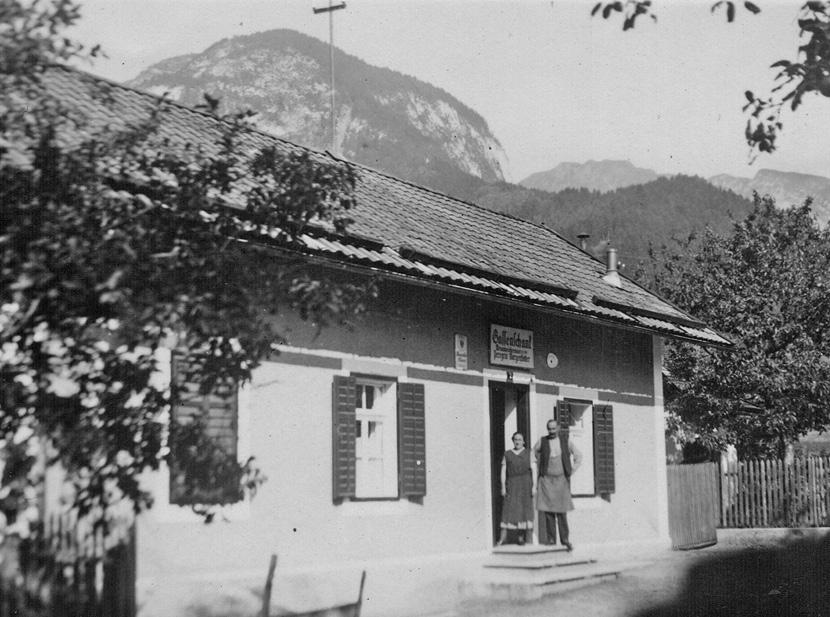

Franz was to meet us for a family reunion at the inn (Gasthaus) of Alois (Loisl) Morgenstötter (1914–1992) in Jenbach. Loisl was the only son of the younger Peregrin (1886–1940) and Leopoldine Esterhammer (1899–1942),

and therefore a first cousin of Franz and my father. It had been Loisl and his common-law wife Maria Harb (Mitzi) who had sheltered Franz during the war. The polite fiction was that Franz had helped out at the inn, although it was almost certainly remittances from his parents, then in Baghdad, which paid for Franz’s room and board.

Despite his infirmities, Franz was a handsome man: well-proportioned and broad-shouldered, with thick dark hair and regular features. There was something vulnerable and slightly haunted in his eyes, especially when he tried to speak: he both mumbled and stuttered terribly. He walked with a lurching gait and gave the constant impression that he was about to stumble. It was clear to me that spring when we met, that Mitzi accepted his presence on sufferance, and that Franz was uncomfortable.

There was another noteworthy family member present in the inn that day: Josef (Sepp) Morgenstötter, my grandmother’s only remaining brother, a barrel-chested, powerful looking gentleman of about eighty years. Sepp had held a high post in the Vienna police during the “Anschluss,” and

Spring 2023/Agora 9

John Strauss

Franz Strauss in his early 30s

IMAGES COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

had been instrumental in helping my father escape to France and eventually to the United States. Sepp sat with two companions in the corner of the common room, drinking beer and playing cards. The only conversation, as far as I could tell, consisted of the occasional “Well” (“Na ja;” the “ja” becomes a deep “jo” in Tyrol), delivered in tones that alternately expressed discovery, resignation, and absent-minded acceptance of the human condition. Sepp paid scant attention to the Americans–my parents, my sister Elizabeth and me–or for that matter to anyone else in the room save the other two card players.

Loisl’s inn consisted of an entryway, a long, low-ceilinged and dark eating room with wooden tables and an Austrian tiled heating oven, a primitive kitchen, and a small guest garden in the back. There were cubbyholes where regular guests kept their napkins and beer glasses. The only amenity in the unheated toilet off the entryway was a nail with strips of newspaper, and the inn fare consisted of little more than beer, sausage with mustard and horseradish, and black bread. Loisl and Mitzi lived simply in rooms above the inn which, except for electricity, had probably not much changed in appearance or function since the time of Mozart. They were generous hosts to their exotic American relatives, showering us with small gifts. Much later, after his death, I was astonished to learn that Loisl had been the owner of eight million dollars’ worth of real estate, and that he had died intestate.

Forty years after my first visit to Jenbach, when the Abbot of the Schwaz Monastery asked me to describe my uncle in preparation for the funeral eulogy, there was shockingly little I could tell him. Franz’s life had been severely circumscribed since early childhood. He had had a nursemaid and tutors, been given what we now call physical therapy, had learned to read, do elementary math and write with a shaky hand, had participated in family outings to the country: in short, he had been loved and cared for by his parents. The “Anschluss” must have been an unmitigated calamity for a highly dependent and sensitive sixteen-year-old: disability prevented his own departure from Austria, while his parents escaped to Baghdad, his older brother to America, and his younger to Budapest. Franz’s education came to an abrupt halt, and he was forced into a tenuous and probably unhappy living situation with no relief in sight. As an old man Franz kept his pre-Anchluss photo album by his bedside and spoke almost exclusively about his childhood and his parents. He never mentioned the war years or the monastery.

My grandparents were finally able to leave Baghdad and immigrate to America with the sponsorship of my parents in 1948. They revisited a greatly changed Austria for the first time since the war in 1959, and were able to place Franz in the Schwaz Monastery, where he worked for the next thirty years until his obligatory retirement. Upon Willi’s death in 1970, my grandmother moved permanently to an apartment near the monastery, in order to look after my uncle. He undoubtedly appreciated the attention, although he sometimes complained bitterly about having to eat bananas and keep to a strenuous exercise regime. My grandmother, by then a devout Christian Scientist in her late seventies, had a will of iron and was determined to make Franz physically fit.

Therese died in 1978, after establishing a trust fund for Franz, which first my father and then I administered. The so-called Strauss Trust Number One supplemented Franz’s meager state pension and permitted him to retire to the St. Josef nursing home (Altersheim), in Schwaz, a humane and well-run, managed care facility administered by the redoubtable Mother Superior (Schwester Oberin) Hilda, and supported by the Catholic church. Franz became “an institution,” as Sister Hilda was later to describe him, outliving all of the other residents who had preceded and many who followed him. Shortly after his arrival, and in spite of being relatively fit, Franz made it clear that he was going to eat exactly what he wanted (certainly no bananas), and that moreover, he wasn’t going to walk or exercise anymore.

Between 1990 and 2005, I visited Franz at least once a year, sometimes alone and sometimes with my helpful and lovely second cousin Dr. Gerda Kienesberger. (Gerda is the daughter of my father’s favorite cousin Lydia, and the grand-daughter of my grandmother Therese’s brother Martin.) Franz was always happy to see me and seemingly never surprised, although I sometimes dropped in unannounced. He was, above all, a stoic and extremely trusting person, perhaps because he had been dependent all of his life. He enjoyed playing solitaire, watching sports on television, doing crossword puzzles and arranging his ever-expanding stuffed animal collection. His ability to recall football (soccer) scores and recite the schedule of the entire Austrian federal train network by heart was truly astonishing. He also followed exchange rates with keen interest, in part because the Strauss Trust was denominated in U. S. dollars.

Gerda’s father, the psychologist Dr. Alfred Kienesberger, had been of the opinion that Franz displayed the intellectual and emotional development of an extremely bright fourteen year-old. He was lazy about exercise and walking, writing letters and socializing with the other residents of the nursing home, and he had a kind of peasant slyness about getting the sisters to do his bidding. He had picked up a few words of English

10 Agora/Spring 2023

The inn (Gasthaus) of Loisl Morgenstötter, 1965

and liked to display them when I visited. He particularly liked the expression “KO” (knockout), which he always delivered with a satisfied belly laugh. As he aged, he looked more and more like a Morgenstötter, his Tyrolean dialect became ever more pronounced, and his speech became less distinct, so that even Gerda had trouble understanding him. I tried to time my visits to Franz so that I arrived in the morning when he was relatively fresh. Even then, a visit of an hour to an hour and a half was as much as either one of us could take.

A few days before his death, Franz suffered an infarction of the bowel which emergency surgery was unable to remedy. Franziska (Franzi) Kienesberger, the second wife of Alfred and stepmother of Gerda, ministered to Franz during his last days, just as she had ministered to Loisl thirteen years earlier. Franz accepted his impending death as he had accepted life, stoically and without surprise. It was a source of great joy to him, as he repeated to Franzi, that the Abbot himself had come to administer the Last Rites.

Franz, like my father, had been baptized and schooled in the rituals of the Austrian Catholic Church, an institution peculiarly filtered through the prisms of Hapsburg history and custom. Sometimes described disparagingly as “Baroque Catholicism,” Austrian Catholicism is uniquely colored by Baroque architecture and its decorative trimmings, Viennese Classical music, bourgeois laissez-faire sensibility, and dramatic, often theatrical ceremony. Only the shell remains of its Counter Reformation roots. Rome has, from time to time, tried to tame Austrian liturgical excesses, but to little avail. As a result, even to religious skeptics, Austrian Catholicism can be deeply affecting and impressive.

Franz’s father Willi, on the other hand, had been what Austrians call an “assimilated Jew” (assimilierter Jude): a fourth generation beneficiary of Joseph the Second’s Edict of Toleration (1781). He had married Therese Morgenstötter in the impressive Catholic church, Maria Treu, in Vienna’s Eighth District, the Josefstadt. Nonetheless he was also a scientist and medical doctor, and prob-

ably an atheist or at least a religious skeptic, far more in tune philosophically with the Red Vienna movement than with Catholicism.2 He certainly did not interfere with his wife Therese’s Catholic convictions: she was after all from “the Holy Land of Tyrol” (“das Heilige Land Tirol”), as the Austrians like to call it. Later in life, however, the onetime nurse, Red Cross volunteer and wife of a distinguished pediatrician became a determined Christian Scientist. My father, on the other hand, followed the time-honored practice of converting to his wife Isabelle Bonsall’s (1917–1981) Protestant faith. Franz alone remained an unswerving believer in the one, true, Catholic Church.

Franz’s final temporal appearance, as announced in a Parte (an Austrian death announcement) prominently displayed in the Jenbach town square, was to take place in the Jenbach parish church. The Parte reads:

“Release everything into God’s eternal hands, happiness, pain, beginning and end.” In silent grief we take

leave of our dear uncle Franz (June 25, 1922–December 10, 2005) who has departed from us after receiving Last Rites. We will celebrate a requiem on Thursday, the 15th of December at 2:00 p.m. in the Jenbach parish church. We will also accompany the dearly departed to his last resting place in the cemetery. We will remember him at an evening mass at 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday in the St. Josef nursing home in Schwaz.

For this Parte, as for so many things regarding Franz’s last days and his funeral, I must gratefully thank the energetic and hospitable Franzi Kienesberger. Without her guidance, I would never have been able to avoid the many cultural pitfalls attendant on a Tyrolean funeral. It was Franzi who made the many requisite appointments for me with the funeral parlor director, the florist, the Jenbach priest, the Mother Superior, and other care-givers at the nursing home and the inn staff. We attended the Wednesday memorial service together, ate dinner together at the Schwaz Monastery, where I had eaten in years past with many longdeparted family members, and planned the Thursday funeral. I was instructed minutely in local forms and customs, and told how much money to slip the pallbearers, the choir director, the general organizer, the two priests, the Abbot, and the altar boy at the end of the ceremony. Local custom also demanded

Spring 2023/Agora 11

Dr. Wilhelm “Willi” Strauss, age 63, in 1948

The funeral dinner of Franz Strauss, December 15, 2005

that I invite all of the celebrants and other church worthies to a celebratory dinner at a local inn after the burial.

Franz was given a magnificent and very Catholic send-off, a ceremony, however, not without its surprises and anomalies. The Jenbach priest, whom I had first met at the rectory on Wednesday, turned out to be a young East Indian. (Few Austrians are willing to enter the priesthood today.) He used a cordless microphone to chant litanies which were broadcast, to my great surprise, from speakers mounted on the roof of the church. Two cloaked Muslim women in the florist shop provided another reminder that globalization and change had come, even to “the Holy Land of Tyrol.”

The Jenbach parish church is a tall, narrow, elegantly proportioned medieval structure with simple wooden benches, an ornately decorated Baroque chancel, and postWorld War II stained glass windows. I sat in the first row of the nave with Gerda and Franzi Kienesberger. On the three steps leading to the chancel was a simple wooden coffin, draped with flowers and wreaths from the Strauss, Fralick, and Eva Wagner families. Behind me in insular groups sat the brothers of the Schwaz Monastery; the sisters from the St. Josef nursing home, every one of them over seventy years of age, singing and chanting in high cracked tuneless voices; and a sizeable group of anonymous habitual mourners from the town of Jenbach. Above and behind was an organ with a Baroque façade, and a choir which sang in perfect Viennese Classical harmony. To the rear and left of the chancel was a high-backed wooden bench occupied by several well-dressed gentlemen whose function was obscure to me. At the altar, the Abbot with the assistance of the East Indian priest, a novice, and an altar boy, performed a solemn requiem in which everyone was invited to participate, and which lasted a bit longer than an hour. The lavabo, the consecration of the host, the communion, the incense,

the liturgical clothing, the music, and the medieval setting all combined to produce a memorable ceremony, at once theatrical, solemn and timeless. Franz, whose life had been so simple and limited, was honored and eulogized as a worthy member of an uninterrupted stream of the family and the townsfolk of Jenbach.

Nonetheless, as affecting as the ceremony was, I could not help but reflect that, in this very church during the winter of 1917, the congregation had been exhorted to pray for the death of my grandfather Willi: “Better he should die on the Eastern Front,” said the priest according to an oft repeated story, “than a Catholic girl should marry a Jew.” That is how the good people of “the Holy Land of Tyrol” thought in those times. Not surprisingly, several Morgenstötter family members in company with their compatriots became ardent Nazis during the Second World War. Those times too, I reflected at Franz’s funeral, were part of the pageant of Jenbach and the parish church.

After the requiem, the pallbearers, followed by the priest and his retinue, the family, and the congregation, led a

serpentine funeral cortege through the churchyard, while the priest chanted into his cordless microphone and the altar boy swung and clanked his censer, filling the air with that most Catholic of all smells. The procession came abruptly to a halt at a small chapel where each person in turn was invited to shake the aspergil, sprinkling holy water on the coffin. Finally, my hand was solemnly shaken and condolences were offered by people I did not know and would surely never see again, while I dispersed gratuities and proffered invitations to dinner as instructed by Franzi.

Quite suddenly it was all over: the crowd melted away and I realized that the coffin had been removed. I wandered alone to the Morgenstötter gravesite, where my parents’ urns are also interred, and was surprised to see the pallbearers lowering the coffin into an excavation precisely where I knew Loisl to be buried. The Abbot later explained to me that after ten years nothing remains of a coffin or its contents: So long as ten years elapse between burials, a grave site can be used over and over again. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust….

NOTES

1. The back cover reads: “ This compelling biography traces the life and times of pediatrician Wilhem Strauss from his childhood in Prague and his late Hapsburg monarchy medical education in Vienna, to his practice of social medicine in Wiener Neustadt during the Julius Tandler era, beyond the 'Anschluss' and exile in Baghdad, to his unexpected conclusion in New York. Reproduced in the book are valuable documents in Strauss’ own words describing the state of pediatric medicine at the beginning of the First Austrian Republic.”

2. Red Vienna refers to the period between 1911 and 1934 when the Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Austria (SDAP) maintained political control over Vienna and, for a short time, Austria as a whole. The SDAP pursued a program of housing construction and implemented policies to improve public education, healthcare, and sanitation.

12 Agora/Spring 2023

The parish church in Jenbach

Oboe in Community: Supporting the Next Generation of Oboists

by HEATHER ARMSTRONG, Professor of Music

by HEATHER ARMSTRONG, Professor of Music

As a professional musician who has experienced the changing landscape of “classical (concert/ art) music” over the last few decades, I have also developed an awareness of how important it is for the classical music profession, and the musicians within it, to become more communityfocused, more outward looking, and more engaged beyond the concert hall, the music studio, and the practice room. Young musicians are the future of music making, and when professional musicians actively nurture and support the next generation of musicians, they help to create a vibrant musical future. For my sabbatical project in the spring of 2022, I focused on this kind of musical engagement as an oboist, meeting people and exploring organizations whose mission is to help make the oboe more accessible to students who want to learn to play it.

Learning how to play the oboe comes with some unique challenges and barriers compared with some other instruments: a higher cost for a beginning level instrument (about $1,000 for a new, beginner instrument), the short playing life and high cost of reeds ($15-$30 each), and the lack of knowledgeable oboe instructors in many areas, particularly less-populated areas. In addition, the oboe is often (inaccurately) considered harder to learn and to play, so many band directors shy away from teaching it in band programs, which is where most U.S. students are introduced to instrumental music. If more young people are going to become interested in playing the oboe and developing the skills to play it well and enjoy it, oboe professionals will need to help develop new generations of oboists, especially those for whom finding and affording adequate musical equipment and training is more difficult.

When I crafted my sabbatical proposal in 2019, I planned to travel to Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic to teach and perform, having no idea that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic would greatly extend the timeline of my project and test my persistence and flexibility. My sabbatical was approved and scheduled for the spring of 2021. However, as the pandemic continued into the summer and fall of 2020, I realized that planning international travel might still be very difficult when I hoped to travel. I was very excited by the opportunity to personally interact with musicians in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, and hoped I wouldn’t have to give up that part of my project, so I made the difficult decision to delay my sabbatical until the spring of 2022. While this delay did not ultimately mean completely revamping my sabbatical plans, it did present several significant challenges: maintaining connections with my overseas partners for several years (and hoping they would sustain interest in my project), along with facing considerable uncertainty, even into March 2022, about whether in-person musical events would be permitted in each location. It wasn’t until late March and early April, 2022, that I finally received confirmation that the events scheduled as part of my project were approved to take place. Lastminute planning and traveling during a pandemic were more time consuming and complicated than I expected, but all the preparatory work was well worth it once I arrived in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico to begin the true work of my project—interacting with young oboists and learning about different music programs.

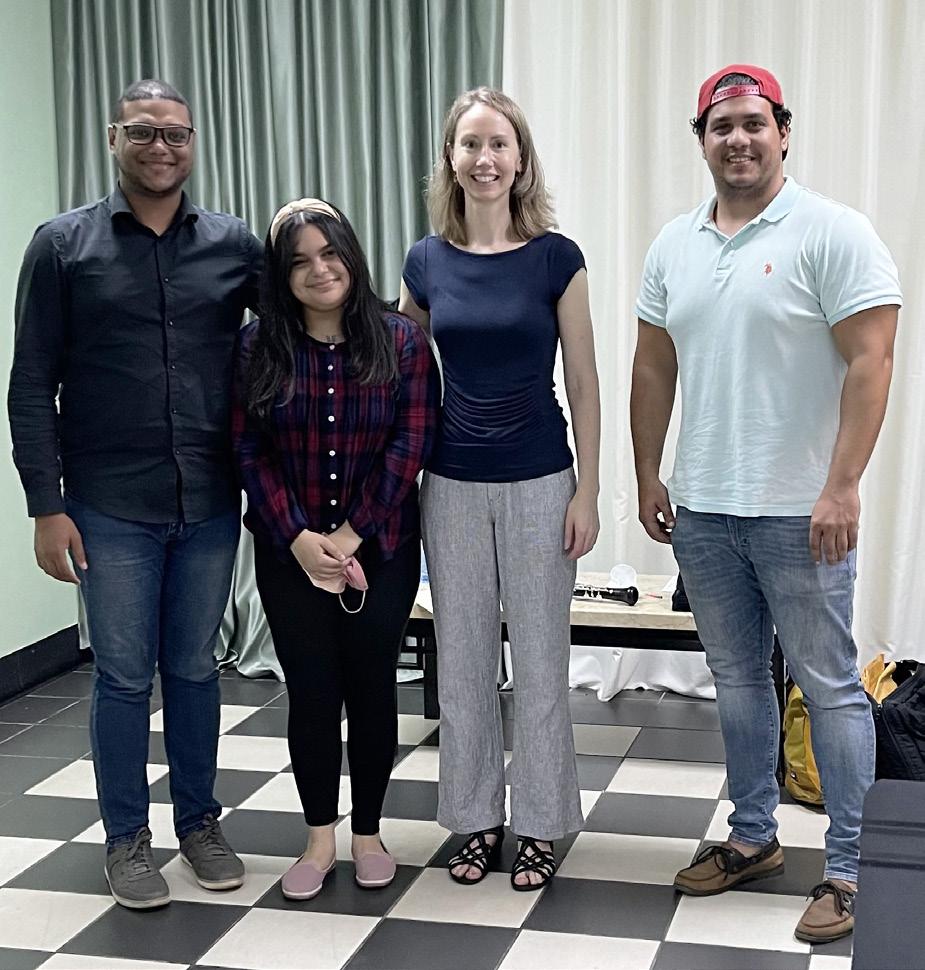

My initial connection to the Dominican Republic was through Ingrid Scott, a Dominican Luther College alumna

(‘12) who plays flute and also studied oboe with me during her time at Luther. Ingrid returned to the Dominican Republic after graduate school, and we have stayed in touch. I was intrigued and inspired by a program she created titled Flute Project, a several-day workshop in Santo Domingo that offers classes, performances, and other educational opportunities for Dominican flute players of all levels. While I had initially hoped to arrange a similar (but smaller) outreach workshop for oboe students during my visit, I discovered that I would need to let go of some of my goals for the trip because of scheduling challenges.

I visited Santo Domingo in May, 2022, and was able to meet and work with several oboe students studying at the Conservatorio Nacional de Música in Santo Domingo. They were eager and enthusiastic students! Before they played for me in a masterclass session, I asked each student how they started playing the oboe. Their stories were remarkably similar to those I hear from oboists in the U.S. One student,

Spring 2023/Agora 13

Heather Armstrong

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

still in high school, started her musical studies on the clarinet, but after an oboist visited her school to introduce students to the oboe (which at that time was an instrument she was not familiar with), she decided she wanted to play the oboe instead of the clarinet. She has been studying for about two years, and loves playing the oboe. The other two students were older—mid-twenties to early thirties. They too had played other instruments before the oboe (trumpet and percussion), but each of them had parents or mentors with musical backgrounds who encouraged them to switch to the oboe because it was less common and they might encounter more opportunities as oboists. These stories about how one begins playing the oboe are very common in the U.S. as well. Either someone discovers the oboe almost accidentally, or a more knowledgeable musical mentor guides stronger musicians to the instrument. After working with each student on solo repertoire they prepared, we spent a very enjoyable time exploring some oboe trio music I took along with me. Playing chamber music together as oboists was a new experience for these students, so I encouraged them to arrange another time to play together, a time when they could support, encourage, and motivate each other as “oboists in community,” a

theme that emerged during my sabbatical and has inspired some of my postsabbatical work.

Jacqueline Huguet, the director of the Conservatorio Nacional de Música, arranged my masterclass with the oboe students and helped to schedule my performance at the Conservatory. In preparation for my recital, Jacqueline connected me with María Morel-Pierret, a collaborative pianist who turned out to be another Dominican Luther music alumna (’97)! This additional Luther connection was an unexpected surprise, and María and I became fast friends during our rehearsals at the Conservatory. Even before I knew about María’s connection to Luther, I had already planned to perform a flute-oboe-piano trio with Ingrid on my program. It was especially meaningful to play the trio with Ingrid and María, two Luther alumni separated by about fifteen years. In addition, María and I performed several songs that I arranged

for oboe by Dominican composer Julio Alberto Hernández, which were recommended to me by Tony Guzmán, director of Luther’s jazz program and professor of music. The songs we performed are well-known and wellloved in the Dominican Republic, and María had played them many times. Through a family connection she is even related to the composer, and her enthusiasm and additional suggestions made them even more enjoyable. Many audience members approached me after our performance to express how much they appreciated and enjoyed hearing Dominican music on my program, and I am grateful to both Tony and María for introducing me to the music of Julio Hernández.

During my visit, Jacqueline and I had the opportunity to talk about how difficult it has been for her to find students to study oboe at the Conservatory and to play in the school’s orchestra. (The three students I met were the most oboists attending the Conservatory at one time in many years.) As in the U.S., many Dominican music programs, even in a large city like Santo Domingo, don’t have access to oboes or teachers qualified to teach young oboe students. Oboes are expensive and hard to find and repair on the island, reeds are complicated, and, since the oboe is fairly uncommon, many students don’t even know the oboe is an instrument until they encounter it by chance (like the high school student I met). Just as the three Dominican students came to play the oboe under circumstances similar to U.S. students, Jacqueline’s struggle to find oboe players for a youth orchestra, school of music/conservatory, or another educational music program is very common in many parts of the U.S. as well.

Frances Colón noticed these same difficulties in Puerto Rico when she moved back to the island after graduate school to play in the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra and teach at the Puerto Rico

14 Agora/Spring 2023

Heather Armstrong with oboe students at the Conservatorio Nacional de Música in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Heather Armstrong, María Morel-Pierret (‘97), and Ingrid Eileen Scott (‘12) after performing together at the Conservatorio Nacional de Música

Conservatory of Music. Inspired to help educate and support young oboe players, she started Oboe Mobile Foundation, a nonprofit organization that holds oboe events and workshops around the island and loans instruments from an established “bank” of donated oboes to students who don’t have access to one.

I traveled to San Juan in June 2022 to visit with Frances and participate in Oboe Mobile Foundation’s three-day educational program, Oboe Fest 2022, which was held in Caguas, about a 30-minute drive away. I taught alongside Frances and two other Puerto Rican oboists, interacting with around 13 young oboists as they participated in oboe playing, group activities, and reed making. Because of the pandemic, it was the first in-person Oboe Fest in Puerto Rico in two years, so most of the oboe students had not had opportunities to meet each other. While many of them were shy and a little reserved at first, they bonded considerably over their three days together, a tribute to Frances’s intentional focus on building an oboe “community” with the students during their time together.

Many of the students who attended Oboe Fest were using oboes provided by Oboe Mobile Foundation. Most students were 12-18 years old, but one older student from the Puerto Rico Conservatory participated as well. She had been at the Conservatory for a few years, and was using a professionallevel instrument, also provided to her

by Oboe Mobile Foundation. She explained that she grew up in a rural part of the island and had never had a quality instrument or an oboe teacher who could help her. By studying at the Conservatory, her goal was to become a music teacher and return to the place where she grew up (or a similar location), giving young oboe players better instruction as they learned to play. This cycle of investing in younger oboists, who then go on to teach and support the next generation of oboists, is at the heart of Frances’s mission for the Foundation.

I helped teach reed making during Oboe Fest, which was a brand-new skill for most of the students. The technical terms and detailed instructions about making reeds were well beyond my Spanish skills, so the Puerto Rican

teachers explained and described the various steps in Spanish, and I helped students with the hands-on activity of making reeds. Frances also invited me to present a musical/educational session for the students. I introduced them to the concept of musical variations by playing a set of variations for solo oboe based on the melody from Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star (students knew this as Estrellita, ¿dónde estás?, which we sang together in Spanish). They were perceptive listeners and engaged participants. I ended my presentation by playing a short set of variations on the Happy Birthday melody, but started with the most complex variation first and worked backwards to the simplest form of the song. I tried this “backwards” approach to challenge students to identify the tune in a more embellished form and to explore what they had just learned, and partly to surprise Frances, whose birthday was a few days after Oboe Fest!

Oboe Fest ended with a program for family and friends featuring all the oboe students playing a traditional Puerto Rican folk song together. In addition, Frances and the other two oboe instructors, Abraham and Christian, performed several trios, also based on traditional Puerto Rican songs. They generously included me in one of arrangements to form an oboe/English horn quartet. As in the Dominican Republic, I was excited to experience and learn about music deeply connected to Puerto Rican culture. At the end of the concert, Christian gave me the music for the oboe trio and quartet arrangements of

Spring 2023/Agora 15

Introducing students to musical variations at Oboe Mobile Foundation’s Oboe Fest 2022, in Caguas, Puerto Rico

Oboe Fest 2022 students and faculty, Caguas, Puerto Rico

Puerto Rican songs he had arranged, and the oboe studio at Luther explored this music together in September 2022.

By interacting with oboe students and teachers in other parts of the world, I observed that the barriers to playing and studying the oboe are remarkably similar across locations, although the magnitude of those barriers may differ: general lack of awareness about the instrument, lack of qualified teachers (especially outside urban areas), difficulty accessing an instrument in good playing condition (often for financial reasons), the challenge of finding reeds and addressing reed making, and the lack of persistence with the instrument when students feel isolated in their band programs and communities.

These are challenges noted by many players and teachers in the double reed community. Shortly after I returned from Puerto Rico, the most recent publication of The Double Reed (Vol. 45, No. 2) arrived in the mail. This edition of the international journal for double reed players and teachers included an article directly related to the focus of my sabbatical project: “The State of the Bassoon in Music Programs Across the U.S.” by Dr. Shannon Lowe, bassoon instructor at the University of Florida.1 Dr. Lowe surveyed K-12 music educators across the U.S. about how comfortable they are teaching the bassoon, about their access to bassoon reeds and bassoon instructors in the area, about their awareness of reed making and other equipment, and about the number of school-owned bassoons in their program and the working condition of those instruments. The results of her survey show there are “substantial underlying problems” related to bassoon instruction at middle schools and high schools across the U.S. While her study focused on bassoon, I believe a survey for oboe would show very similar results.

In July 2022 the International Double Reed Society annual conference hosted a workshop and conversation titled Broadening Access to Double Reeds. The description of the workshop begins: “Socioeconomic, racial, gender and locational barriers can restrict opportunities for double reed students, amateurs and

professionals. How can we reduce or remove these obstacles?” This question continues to inspire me as I look to the future.

In January 2023, with the help of Luther College graduate Willy Leafblad (’14) and his colleague Erik Stashek, I presented a workshop for oboe students and music educators at Lake City Public Schools (Minnesota). More than a dozen oboe students and teachers from the surrounding areas attended, including some younger students who were trying the oboe for the first time and some educators who were brushing up on their oboe knowledge and teaching skills. Through activities and exercises I created for everyone to play together, we spent time reviewing the fundamentals of breathing, reed preparation, embouchure formation, tone production and development, articulation, healthy holding habits, etc. For our culminating group activity, we played a three-part arrangement of the theme from the Harry Potter movies, a selection that provided opportunities for students to learn new fingerings and expand their range, and which I encouraged them to take home to inspire their continued growth. I hope to repeat workshops like this in other areas in the coming years.

I am also exploring how to create a more focused double reed experience as part of Luther’s Dorian Music Festivals and Summer Camps. Currently, my time with oboe students and their time together as oboists is fairly limited dur-

ing these programs. I see some students for lessons and hold introductory reed making classes during Dorian High School Music Camp, but I envision a program where oboe students play more music together and spend more time making reeds together, creating an oboe community as part of their Dorian experience. Many students I encounter through Dorian programs are the only oboe player at their school and live too far from larger population centers to easily find a qualified oboe teacher. I have seen the Dorian experience light a spark of enthusiasm in young oboe players by giving them a brief opportunity to meet other oboe players their age and to encounter oboe instruction that can transform their playing.

Bringing young musicians together is inspiring and formative for their musical development. Bringing young oboe players together can help provide confidence and camaraderie that are difficult to develop when so many school programs have only one oboe player and when oboe teachers are hard to find for many students. As I continue to synthesize my sabbatical experiences, I am excited to explore new and deeper ways to foster community for young oboe players and to help create a vibrant musical future where they can thrive.

NOTES

1. Lowe, Shannon. “The State of Bassoon in Music Programs.” The Double Reed, 45 no. 2: 67-79.

16 Agora/Spring 2023

Participants at the Oboe in Community workshop at Lincoln High School in Lake City, Minnesota

Geophysical Remote Sensing at a Pre-Contact Enclosure Site in Northeast Iowa

by COLIN BETTS, Professor of Anthropology

Northeast Iowa’s rich archaeological heritage is most evident in the various earthen constructions that are the material vestiges of the ritual and social cultural landscape created over millennia by the area’s original indigenous inhabitants. In addition to the more abundant mounds, enclosure sites represent a central, albeit less well known, component of the cultural landscape. These sites are defined by the construction of earthen embankments in circular, ovoid, and rectilinear forms which were often paired with an associated ditch. The best estimates are that they were most likely constructed during the last two millennia and with functions as variable as their external forms, likely serving symbolic

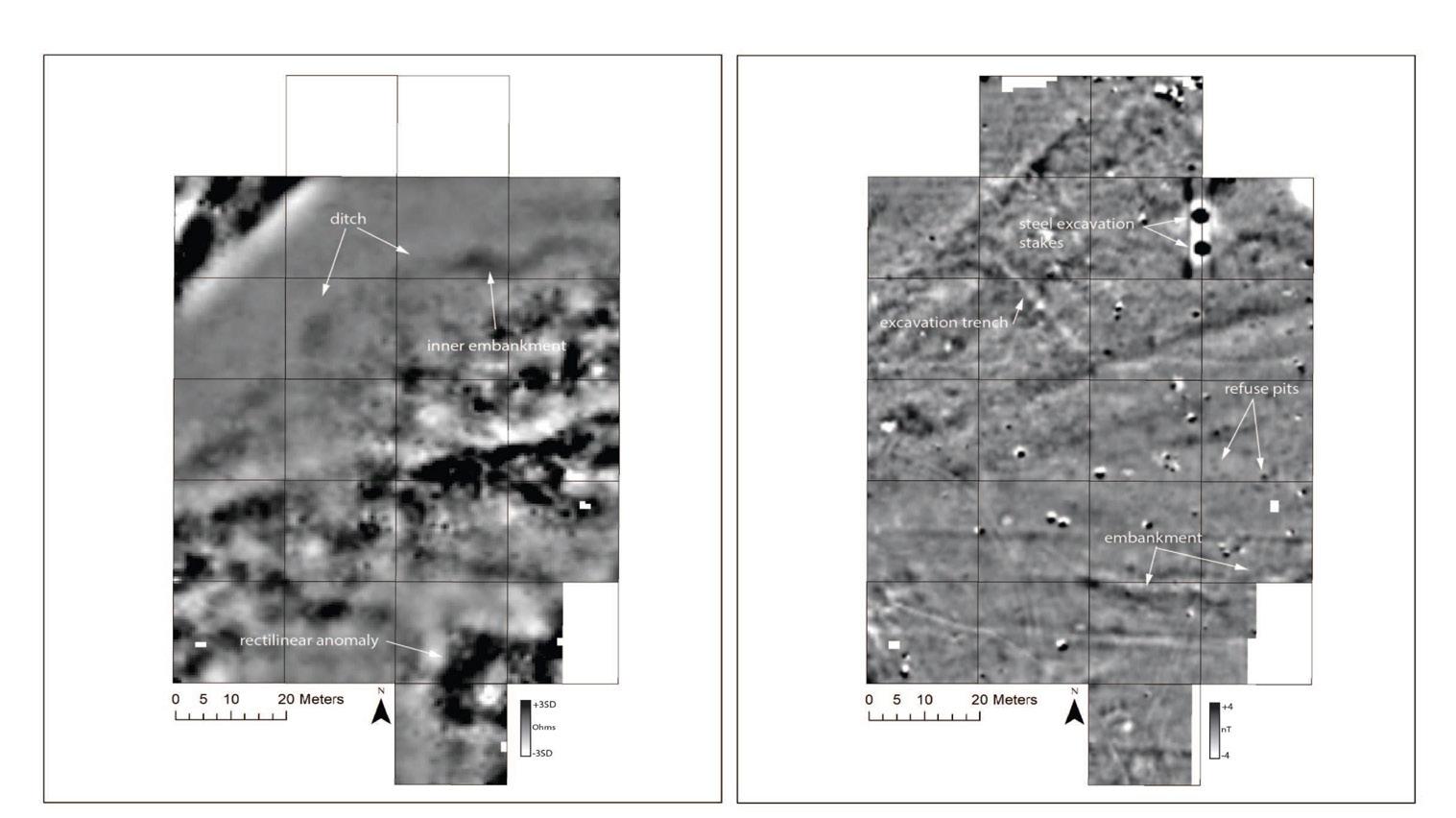

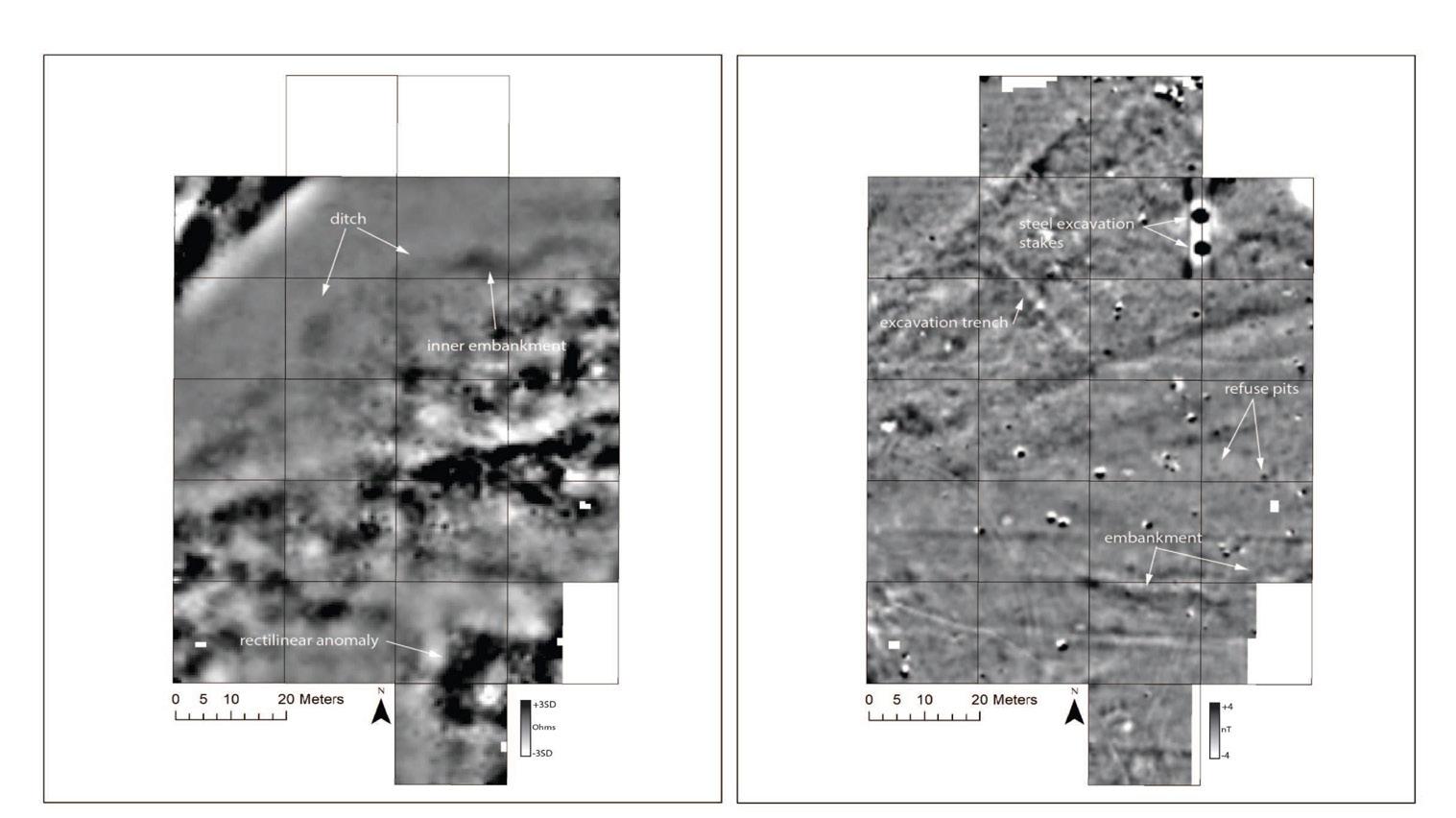

and defensive purposes. At the time of Euro-American contact, as many as a dozen of these sites once existed on the river terraces and bluffs of the lower Upper Iowa River valley in Allamakee County, a density matched nowhere else in the Upper Mississippi valley (Orr 1937; Wedel 1959; Whittaker and Green 2010). Sadly, due to the effects of agriculture only four have any remaining visible traces, and as a consequence our knowledge concerning their broader cultural roles is limited. However, geophysical archaeological research can play a role in bringing some of the more hidden vestiges of this landscape to light, while at the same time ensuring that these unique and fragile cultural resources remain intact.

One of the remaining enclosure sites, known as the Lane Enclosure, has been subject to several investigations over the past 150 years (Alexander 1882; McDowell 2011; McKusick 1973; Thomas 1894). When originally encountered in the late 1800s, the site contained a paired circular ditch and embankment approximately 80 m (262 feet) in diameter (Figure 1). Plowing has largely destroyed any visible trace of the enclosure, although some subtle traces of it remain. Excavations conducted at the site in the 1930s and 1960s revealed dense habitation debris, indicating substantial occupations of the site in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, with scattered indications of an earlier presence around C.E. 750. The habitations at the site were evident in both a large quantity of domestic refuse (archaeological jargon for garbage) including stone tools, broken pottery, and copious plant and animal remains. Much of this material was located within pits which had been used for waste disposal locations after their primary use-life for crop storage. Although previous investigations have provided some insights in to the form and possible use of the site, several significant questions remain. There are central inconsistencies in the reported

Spring 2023/Agora 17

Figure 1. P.W. Norris map of the Lane Enclosure (from Thomas 1894:100)

Colin Betts

IMAGES

OF THE

PHOTO COURTESY OF LUTHER COLLEGE

COURTESY

AUTHOR

form of the enclosure, although all agree on the roughly circular form. The earliest accounts report an overlapping entrance on one end. There is also the unresolved question of the function of the site. Research intended to determine if the site was primarily defensive in nature failed to conclusively identify the presence of a wooden palisade associated with the embankment. Similarly, efforts to resolve the specific relationship between the documented habitations at the site and the construction of the enclosure have also been inconclusive. One of the most vexing elements of the history of research at this site was that the specific locations of the earlier excavations could not be accurately determined, precluding the contextual information needed to make full use of the associated data. A geophysical survey of the site was conducted in 2018 with an eye towards resolving some of these questions to prove better insights into the Lane Enclosure site specifically, and the Upper Iowa valley enclosures more generally. The data collection and initial analysis were conducted during the summer of 2018 as part of a collaborative summer research experience with Anna Luber (‘19) and Linh Luong (‘20) (Figure 2). The analysis was one of the primary goals of my fall 2021 sabbatical, culminating with the publication of the results.

Geophysical methods are well suited for conducting large-scale investigations in a manner either not possible or desirable with traditional excavation techniques, allowing for the rapid investigation of large-scale archaeological features (Kvamme 2003). At a site such as Lane Enclosure these methods have the added advantage of being non-invasive, avoiding the need to conduct timeconsuming and destructive excavation. Geophysical methods detect variations in near-surface physical properties. The two methods used during our research, magnetic gradiometry and soil resistivity, are capable of detecting even the relatively subtle impact of human alterations to existing soil and sediment layers that are associated with the enclosure site—including the embankment, ditch, associated storage/refuse pits, as well as the traces of previous excavations (Gaffney and Gater 2010; Kvamme 2003; 2006; Somers 2006; Weymouth 1986). Soil resistivity largely measures minute changes in the ability of an electrical current to pass through the soil, largely reflecting the changes in the ability of the soil to hold moisture. Magnetic gradiometry can detect different concentrations of topsoil/subsoil, accumulations of organic midden deposits, burning, or the presence of ferrous metal. Ditches and old excavation trenches should be revealed as areas of lowered resistivity

and as negative magnetic anomalies. In contrast, the embankment and refuse pits would likely contrast with the surrounding soil as areas of higher resistivity and enhanced magnetism. The application of these two complementary methods provides the ability to detect a range of features likely to be associated with the enclosure.

As hoped, our research provided important insights into the structure of the site and its relationship to the associated occupations (Figure 3). Perhaps the most encouraging is that despite a century of cultivation and the impact of multiple excavations of the site, extant remnants of the enclosure are evident as a combination of both resistivity and magnetic anomalies. The ditch, in particular, is well preserved and appears to be present for most if not all of its original extent. There are also additional elements of the enclosure form which were previously undocumented, such as the apparent presence of a smaller interior embankment and an enigmatic rectangular area of high resistance in the vicinity of the possible overlapping entryway. The ability to conclusively locate the excavation trenches from earlier work at the site, coupled with the presence of magnetic geophysical anomalies likely to be previously undocumented refuse pit features, show that the domestic element of the occupations occurs throughout the enclosure interior, on the embankment itself, and extends into the exterior, calling into question the likelihood that it served a defensive role during the latest period of occupation. As a result, it may be better to view the primary function of this particular site as largely symbolic or ritual in nature. Our results also provide multiple avenues for future research both at this site and at other enclosure sites in the region. At Lane Enclosure the ability to accurately locate the ditch provides the prospect for targeted archaeological excavations to recover datable organic or sediment samples from the base in an effort to resolve the temporal and cultural origins of the site. Further, the identification of novel features at the site deserve further investigation with a combination of additional geophysical survey and excavation. The presence of readily definable elements of the enclo-

18 Agora/Spring 2023

OF THE AUTHOR

Figure 2. Linh Luong (left) and Anna Luber (right) gather resistivity data at the Lane Enclosure site.

IMAGES COURTESY

sure ditch, even in places where there are no longer any surface traces, provides hope that similar traces of other previously destroyed enclosures may also be detectable. And in the broadest sense, when combined with similar studies at other enclosure sites in northeast Iowa our work offers an important foundation for understanding the role they played in the construction of the indigenous ritual and social landscape of northeast Iowa.

REFERENCES CITED

Alexander, W. E. (1882) History of Winneshiek and Allamakee Counties, Iowa. Western, Sioux City, Iowa. Gaffney, Chris and John Gater (2010) Revealing the Buried Past: Geophysics for Archaeologists. The History Press, Gloucestershire.

Kvamme, Kenneth L. (2003) Geophysical Surveys as Landscape Archaeology. American Antiquity 68(3):435–457.

Kvamme, Kenneth L. (2006) Magnetometry: Nature’s Gift to Archaeology. In Remote Sensing in Archaeology: An Explicitly North American Perspective, edited by Jay K. Johnson, pp. 205–233. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

McDowell, Francis, Jr. (2011) The Sad Fate of the Lane Enclosure: Often Excavated, but Poorly Reported. Newsletter of the Iowa Archeological Society 61(3 & 4):8–9.

McKusick, Marshall B. (1973) The Grant Oneota Village. Office of the State Archeologist Report No. 4. University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Orr, Ellison J. (1937) Sundry Archaeological Papers and Memoranda, 1937, Iowa Archaeological Reports, Vol. 6, on file, Effigy Mounds National Monument, McGregor, Iowa.

Somers, Lewis (2006) Resistivity Survey. In Remote Sensing in Archaeology: An Explicitly North American Perspective, edited by Jay K. Johnson, pp. 109–130. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Thomas, Cyrus (1894) Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology. Twelfth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1890–1891, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Wedel, Mildred Mott (1959) Oneota Sites on the Upper Iowa River. Missouri Archaeologist 21:1–181.

Weymouth, John W. (1986) Geophysical Methods of Archaeological Site Surveying. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, Vol. 9, edited by Michael B. Schiffer, pp. 311–395. Academic Press, New York.

Whittaker, William E. and William Green (2010) Early and Middle Woodland Earthwork Enclosures in Iowa. North American Archaeologist 31:27–57.

Spring 2023/Agora 19

Figure 3. Resistivity (left) and magnetic (right) results from the geophysical survey of the Lane Enclosure site

Further Adventures in the Collaborative Arts: Louis Jensen’s Square Stories

by LISE KILDEGAARD, Professor of English

In March 2021, as I was working on finalizing my upcoming fall semester sabbatical plans, I got the sad news that Louis Jensen, the celebrated Danish author whose work I have been translating for several years, had suddenly died. His wife, the artist Elisabeth Wegger, told me he had been out for a bicycle ride through the woods with friends. They were heading toward a café, where they planned to share a cup of coffee and a piece of kransekage to celebrate the arrival of spring. When Jensen was struck by a massive heart attack, his friends surrounded him and tried to help, but he was gone before the ambulance arrived. He was 77 years old.

Jensen and I had exchanged email just a few weeks before. I was planning to travel on my sabbatical to Denmark in order to meet with him. I had several small translation puzzles I wanted to discuss with him. And I looked forward to being in his company. I was thinking we’d have the chance to share another evening like the one we once spent in his house just outside of Aarhus, singing old songs from the Danish folk school songbook. Or the one we spent walking through the streets of Copenhagen, talking about life and art and poetry, as the sun set and the lights in the harbor began to twinkle. I wasn’t done with him yet. And while Jensen at 77 had reached what my mother would have called an “opretstående alder” (upstanding or honorable age), it seems fair to say he wasn’t quite done yet, either. On his desk, his wife told me, he left behind a few manuscripts in progress—and a note that said he would be meeting with me in the fall.

Most of my translations of Jensen’s work have focused on the 1001 little microfictions he wrote between 1992 and 2016—the quirky and lyrical stories

he called Firkantede Historier, or Square Stories. While Jensen published over 90 books, ranging from picture books for little kids to poetry for adults, his Square Stories project represented his most sustained and most complex artistic achievement. Published in ten books of 100 very short stories, each story formatted in the shape of a square, and a final volume with 100 pictures and one last story, Jensen’s Square Stories are his own invented genre. In their variety and their number, they give full rein to his exuberant imagination.

In Denmark, the Square Stories have gained a wide audience of children and adult readers. Scholars and journalists who don’t typically analyze children’s literature have written commentaries and criticism, including the literary critics Rikke Finderup and Max Ibsen, who claimed in the journal Passage that the Square Stories were “one of the most radical projects in all Danish literature.” Jensen was proud of all his books—and ready to write many more—but he considered the Square Stories his major life’s work.

Jensen’s death shocked and grieved me. As I suddenly struggled to rethink my sabbatical, I had to let go of some of my elaborate plans and cherished hopes for how my time would play out. But I also had the opportunity to reflect on what could still be done. I began to consider more deeply what endures in the face of loss.

I believe Jensen’s Square Stories will endure for their literary merit and for the insight they offer into Jensen’s creative mind. I value these gifts that the Square Stories will keep on giving, even now that Jensen is gone. But perhaps even more, I value how these little art forms have brought me into collaboration with students, artists, teachers, and others.

What’s best about the Square Stories? Sharing them—and using them to create new art, new experiences, and new stories.

Before 2021, with the time and funding afforded me by previous sabbatical leaves, I shared the Square Stories in a number of ways. As a visiting speaker or an artist-in-residence, I brought them to classrooms in grade schools, middle schools, high schools, and colleges. I collaborated with teachers of drama, art, creative writing, and more. I gave talks and presentations at several scholarly conferences. And because of the generous time and funding I received in my two years as the Dennis M. Jones Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Humanities at Luther College, I was able to participate in several projects on campus that leveraged the Square Stories for artistic and educational enrichment. I collaborated with college ministers Mike Blair and Amy Larson, who brought the Square Stories into chapel series. Visiting artist David Esslemont worked with art students to print a gorgeous chapbook of illustrated stories. Printmaker and Art Professor David

20 Agora/Spring 2023

Lise Kildegaard

PHOTO COURTESY OF LUTHER COLLEGE

Kamm worked with students to create a gallery exhibition that paired stories with small works from the Luther College art collection. Theatre Professor Bob Larson devised a script using Square Stories for a marvelous Luther College production, with sets by Jeff Dintaman and costumes by Lisa Lantz. We brought Louis Jensen over from Denmark to see that production, and he told the students he felt as though he had walked right into a fairy tale. Now, as I prepared myself for my sabbatical, collaborations with Louis Jensen himself were brought to a halt, to my sorrow. But other collaborations could continue. I made new plans.