50 Years of IAOMS

The Development of the Specialty

Written by Paul J.W. Stoelinga & John Ll. WilliamsInternational Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Authors: Stoelinga, Paul J.W. and Williams, John Ll.

50 Years of IAOMS — The Development of the Specialty ISBN 978-0-615-59136-0 (hardcover)

© 2012 International Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons 17 W. 220 22nd Street, Suite 420 Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois 60181 United States of America www.iaoms.org

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Interior designed by Arc Group Ltd, Chicago

Printed in Canada by Friesens Corporation

Introduction

The authors were asked by the Executive Committee of the IAOMS to compose a book to commemorate the organization’s 50th anniversary. We were given a free hand to insert any information that we found relevant to the history of the IAOMS.

It soon became very clear that the emergence of the specialty was intimately related to the development of national, regional and international organizations of the profession. This is the reason why room has been made for a relatively large chapter on the development of the specialty that precedes the chapters on the history of IAOMS. It was clearly necessary in the context of the emergence of the International Association.

It was also obvious that the establishment of the international organization was preceded, in most instances by national organizations, although in some instances the International Association became the catalyst for establishing a national association. The role these national associations play and their particular history is well represented by the individual national accounts and was thought to be of interest for the international reader. The same is more or less true for the regional associations that are invaluable since they are the bodies that have significant impact on the daily practice of individual surgeons.

Both authors have witnessed the emergence and development of national and regional associations, as well as the International Association but, above all, the tremendous development of the specialty since the early 1960s. They have also been active clinicians, involved in education and training. That made them well equipped to reflect on it and to describe this development within the political environment in which both of them were active.

We seek forgiveness for any sins of omission but in a book of limited size, harsh decisions had to be made. We are very grateful to the various contributors who have made this venture possible, as well as to Kerry Spaedy and Susan Nowicki for their assistance in the production of this book.

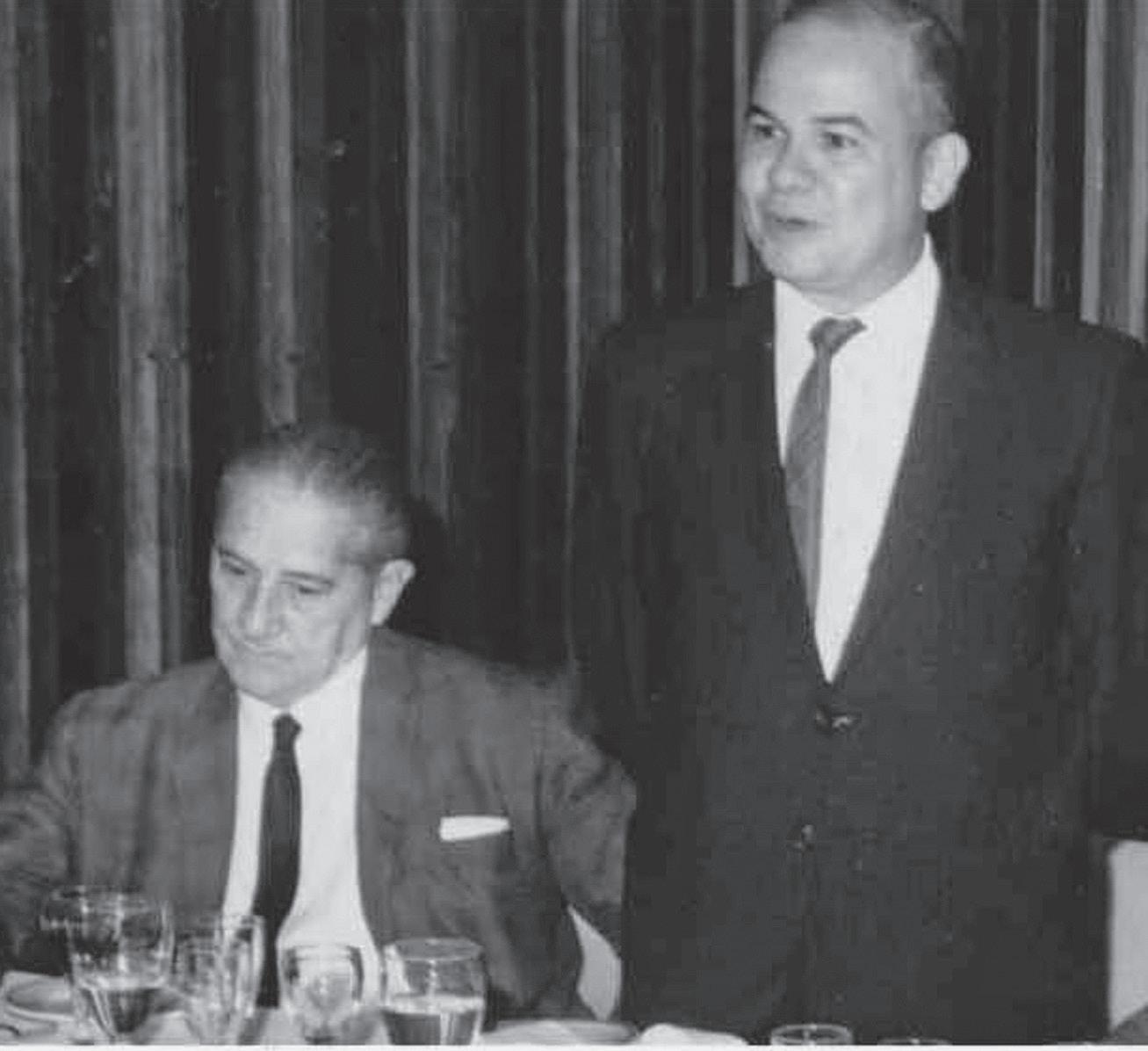

J.W. Stoelinga The book’s authors at work. Left to right: John Williams and Paul Stoelinga. Paul John Ll. WilliamsTable of Contents

Introduction 3

Paul J.W. Stoelinga and John Ll. Williams

Foreword 6 Larry W. Nissen, President, 2010–2011 and Kishore P. Nayak, President 2012–2013

Chapter 1 The Development of the Specialty 9

Introduction

The emergence of the journals The subspecialties

Dentoalveolar surgery Infectious diseases Trauma Clinical pathology

Oncology

Preprosthetic surgery Surgery of the temporomandibular joint Orthognathic surgery Cleft lip and palate and craniofacial surgery Epilogue References

Chapter 2 The International Association of Oral Surgeons (1962–1986) 61

The beginning (1962–1971) 1962: The 1st ICOS, London 1965: The 2nd ICOS, Copenhagen News Sheet begins 1968: The 3rd ICOS, New York 1971: The 4th ICOS, Amsterdam Consolidation and expansion (1971–1986)

1974: The 5th ICOS, Madrid 1977: The 6th ICOS, Sydney 1980: The 7th ICOS, Dublin 1983: The 8th ICOS, West Berlin 1986: The 9th ICOMS, Vancouver References

Chapter 3 The International Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (1986–1999) 75

A wind of change

The Tenerife and Bermuda conferences (1987–1988)

The governance of IAOMS 1989: The 10th ICOMS, Jerusalem 1992: The 11th ICOMS, Buenos Aires 1995: The 12th ICOMS, Budapest

1997: The 13th ICOMS, Kyoto 1999: The 14th ICOMS, Washington, D.C. Budget and membership fee Epilogue References

Chapter 4

The International Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (1999–2012) 87

Modern times

The headquarters

A new era of governance 2001: The 15th ICOMS, Durban

First IAOMS-sponsored educational course 2003: The 16th ICOMS, Athens 2005: The 17th ICOMS, Vienna

Futures Summit I 2007: The 18th ICOMS, Bangalore 2009: The 19th ICOMS, Shanghai 2011: The 20th ICOMS, Santiago Epilogue References

Chapter 5 The Foundation 105

Financial challenges

Structural changes Educational projects

African service Scholarships established

Strengthening the Journal Change in publisher

Albania Argentina Austria Azerbaijan, Republic of Bangladesh Belarus Belgium Bolivia Brazil Bulgaria Canada Chile Columbia Costa Rica Croatia Cuba Czech Republic Denmark Dominican Republic East Africa

Ecuador Egypt Estonia Finland France Georgia, Republic of Germany Ghana Greece Hong Kong Hungary India Indonesia Iran Ireland Israel Italy Japan Kazakhstan, Republic of Korea

Content expansion Epilogue

Latvia Lithuania Malaysia Mexico Moldova, Republic of Mongolia The Netherlands Nigeria Norway Pakistan Panama Paraguay

People’s Republic of China Peru The Philippines Poland Portugal Romania Serbia

Africa Asia Europe Latin America North America Oceania

The Affiliated National Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon Associations

Timeline for National OMS Association Affiliations with IAOMS

IAOMS Presidents

Honorary and Distinguished Fellows of the IAOMS

IAOMS Award Recipients

International Conferences and Executive Committee Members Report on Workshop on Training of the Oral Surgeon Throughout the World (1974) Report of Education Committee (1980)

International Guidelines for Specialty Training and Education in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (Durban, 2001)

Seychelles Singapore Slovakia Slovenia South Africa Spain Sri Lanka Sweden Switzerland Taipei — China Thailand Turkey Ukraine United Kingdom United States of America Uruguay Venezuela Epilogue

This chronicle of the 50 year history of the International Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons is dedicated to the founding fathers who recognized the need for an association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons and specialty organizations around the world, as well as those next leaders who continued to carry the torch, lighting the way for the specialty to flourish. These pioneers always understood the need to work together and that collectively, goals could be more easily achieved on a global basis.

It took the foresight of Fred Henny, of the American Association and Sir Terence Ward, of the British Association, who in 1962, while together at a meeting in London, began the construction on the foundation of a truly international organization. This international organization would prosper for years, but also see many challenges, some of which would threaten its very existence. The first such challenge was a lack of mutual understanding centering on the debate over whether medical qualification as well as dental qualification was required prior to surgical training. Unfortunately, it took most of the first 40 years sparring on this issue within the Association before a resolution was reached.

In 2001, it was finally decided through acceptance of the International Guidelines for Training and Education in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery that regional differences in training existed and were acceptable. This document stated that the actual surgical training in the oral and maxillofacial region was what qualified one to become an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, regardless of whether one had dental and/or medical qualification. Despite these early differences, the International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery was established and quickly became the well-respected flagship publication of the Association. The IAOMS Foundation was chartered to fund much needed educational programs and projects to enhance the specialty.

The history of the first 40 years provides a backdrop that underscores how maturation of an international organization made of diverse members sharing a common cause can be slow to develop but once achieved, great progress can result and move forward to great effect.

The past ten years have shown the Association has flourished in many areas. Numerous courses on the basics of the specialty have been provided in developing areas of the world that otherwise lack formalized training programs. This has expanded the knowledge base by bringing education to those who need it most.

Surgical interest groups (SIGs) were established and fellowship training programs developed to further expand the surgical expertise of the specialty. The Association’s membership has seen a dramatic increase, now approaching 5,500 and much of that is a result of the IAOMS website and the Association’s ever-expanding presence in social media. Information must be readily accessible, precise and timely; and the Association is focused on providing such information.

The International Conference on Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (ICOMS) is held every two years and the recently concluded 20th edition of the event was held in Santiago, Chile, and proved to be one the most successful attracting more than 2,100 participants. The ICOMS is undoubtedly the flagship event of the IAOMS and is growing from strength to strength with member countries vying and competing with each other to host the event with great emphasis on scientific and social content. The next three meetings of the ICOMS are scheduled to be held in Barcelona, Spain; Melbourne, Australia and Seoul, Korea, respectively.

Future endeavors of the IAOMS are likely to include development of an international accreditation process and a board certification process for programs and practitioners who may not otherwise have access to these opportunities. An internationally organized humanitarian aid and disaster relief effort is also being investigated. These and other programs of the Association are dependent upon the many volunteers who for 50 years have dedicated themselves to the mission of creating a better specialty worldwide. Many of them are mentioned in this work but unfortunately, in a brief document such as this, some dedicated individuals will go unnamed. Our thanks go to everyone who has participated in the activities of the IAOMS since 1962.

This publication would not have been possible without the timeless dedication of Paul Stoelinga and John Williams. Their endless hours of research, securing of photographs, reminding regional reporters of deadlines and mind-numbing editorial review are tasks that few of us can appreciate. Without their diligence and adherence to strict timetables, this work might never have been finished. The IAOMS owes them a huge debt of gratitude for their efforts.

The next 50 years will surely see great achievements by the IAOMS. We know future generations will rise to the challenge and continue to strive for excellence in the specialty of oral and maxillofacial surgery and this Association.

2010–2011 President, 2012–2013

Larry W. Nissen K ishore P. Nayak President,Chapter 1

The Development of the Specialty

Introduction

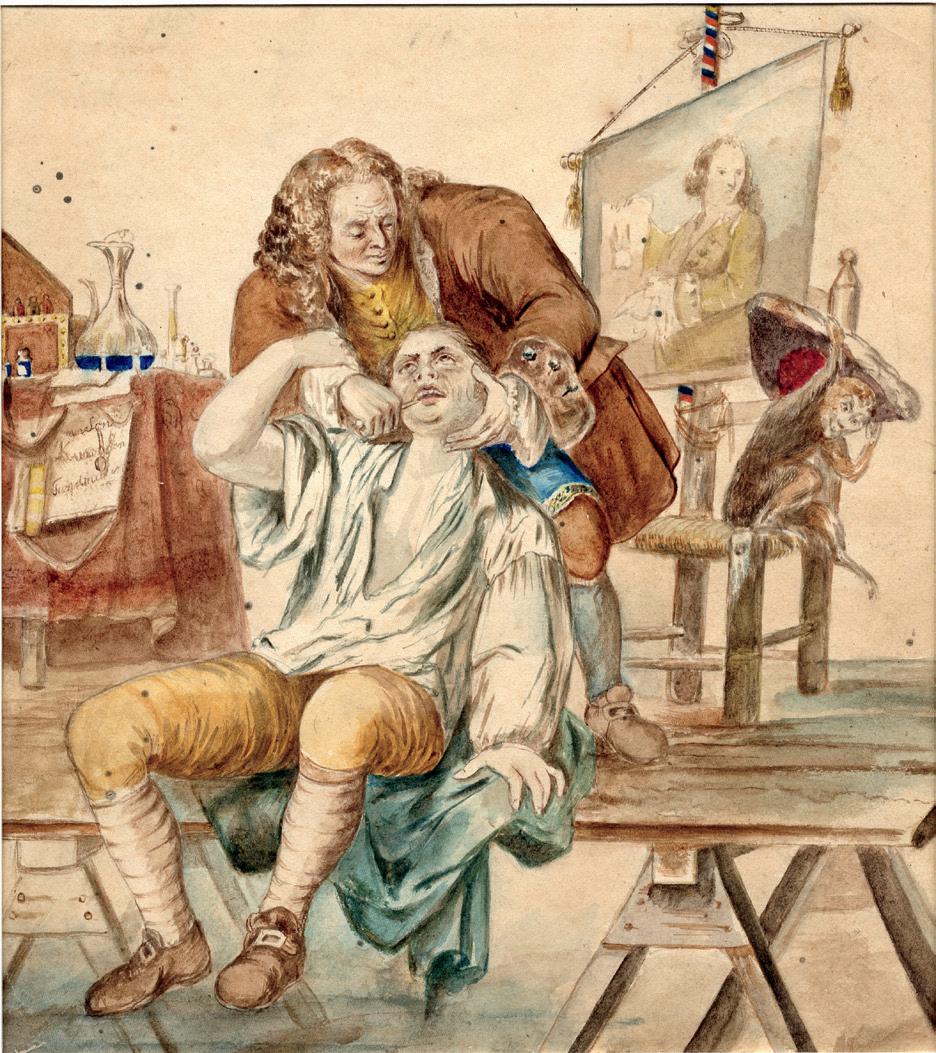

There is ample evidence that the Egyptians and later the Greeks dealt with fractures of the mandible and even dislocation of the jaw. Hippocrates (400 BC), in particular, is credited with describing a bandage to support the chin which would stabilize the mandible in cases of fracture. Several illustrations are proof of the fact that in many ancient civilizations in both Asia as well as Europe, teeth were “pulled.” Throughout the 16th to 18th century, artists in Europe made paintings of traveling barber-surgeons, or charlatans, pulling teeth in the open air (Ring, 1985). It is, however, safe to assume that these treatments were not widely available for the general public.

It is really hard to point towards the true beginning of the development of the specialty, because there are anecdotal reports of oral surgery in most countries of the world that go back to medieval times or even earlier. A detailed description of the development of the specialty in ancient times is presented by Hoffman-Axthelm (1995). With the Renaissance, however, a new era of medicine began which started with some important discoveries in anatomy, which, in large part, were carried out in Italy. Preceding the true development of our specialty, however, which really began in the second half of the 19th century, three surgeons paved the way for its emergence.

Artwork depicting a tooth puller. This painting was made during the 19th century in the Netherlands using a mirror picture from a copper etching made by F. Maggiotto. On loan from the Utrect University Museum, Medical-Dental collection, but in possession of the Dutch Dental Association. Reproduced with permission.

The Frenchman Ambroise Paré (1515–1590) is generally considered to be the father of modern surgery and the first to have published about oral surgery in a book called “A Treatise on Surgery.” As a military surgeon he became famous for the way he treated gunshot wounds. Contrary to the then current method of using hot oil, he dressed the wounds with “an unguent of egg whites, oil of roses and turpentine.” This practice was widely copied after his publication, probably much to the relief of the wounded soldiers. He also described the treatment of mandibular fractures for which he recommended manual reposition and wiring to the neighboring teeth, supported by a bandage around the chin, similar to the description by Hippocrates. His book also presents illustrations of instruments to elevate teeth from their sockets.

Another French surgeon, Pierre Fauchard (1678–1761), is considered to be the father of dentistry. He published the first comprehensive book on dentistry in 1728, “Le chirurgien dentiste, ou, traité des dentes” (The Surgeon-Dentist or Treatise on the Teeth). This book became the authoritative text for a century to come and was translated into German, which meant that it spread over most of the European continent. He settled in Paris and devoted his entire career to dentistry. He covered the whole field of dentistry, including oral surgery, for instance, extractions, re-implantation of avulsed teeth and homologous tooth transplantations.

The third person who was instrumental to dentistry and oral surgery alike was a Scotsman, John Hunter (1728–1793). Trained as a surgeon, he is seen as the founder of a scientific approach to the subject. He became interested in dentistry early in his career and wrote the classic, “Natural History of the Human Teeth” in 1771, in which he explained their structure, use, formation, growth and diseases. He introduced the nomenclature of teeth still used today and made observations about caries, periodontal disease

and inflammation around affected teeth. This book became a main reference for many practitioners in Europe as it was translated into German, Dutch, Italian and Latin.

Seminal discoveries

Advances in surgery have generally been by a process of gradual evolution but by the end of the 18th and throughout the 19th centuries, several seminal discoveries were made which had a profound influence on medicine as a whole. Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) recognized the role of bacteria as the cause of infection and Joseph Lister (1827–1912) developed the concept of antisepsis and applied these techniques to surgery through his carbolic spray.

The development of general anesthetic agents started with Horace Wells, who, in 1845, first carried out a painless dental extraction under nitrous oxide anesthesia at Massachusetts General Hospital. This work was followed by T.G. Morton (1846), using ether and, in Edinburgh, James Young Simpson, using chloroform, all of which changed treatments dramatically.

Carl Thiersch (1874) adapted the technique described by Louis Léopold Ollier (1872) and using the principles of Lister, introduced the split skin graft for reconstruction, which revolutionized this aspect of surgery. Additionally, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1895), a physicist, demonstrated the use of x-rays in the diagnosis and management of fracture care.

New interest in mouth surgery brings breakthrough

As previously mentioned, the real breakthrough came in the second half of the 19th century when general surgeons with a special interest in surgery of the mouth and related structures began to practice oral and facial surgery. This happened particularly in the U.S.A. and in the Germanspeaking areas of Europe but also in many other countries, as appears from the various reports of the affiliated national associations (see chapter 7)

This development came relatively late considering the development of surgery in general. This may be explained by the lack of knowledge about dentistry, which is of great importance when working in the orofacial area. It is, therefore, not surprising that the first pioneers are

to be found in the U.S.A. where dentistry had become an academic profession with the establishment in 1867 of Harvard Dental School, which was soon followed by several state universities. Before that time, however, there were already dental colleges where dentistry was taught, with Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, established in 1840, being the first.

James E. Garretson (1825–1895) is rightly considered by the American Association of Oral of Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) as the father of oral surgery. Garretson, a general surgeon with a formal dental degree, published in 1873 a book entitled: “A System of Oral Surgery: A Consideration of the Diseases and Surgery of the Mouth, Jaws and Associated Parts.” Almost 140 years later, one can only admire the vision this man must have had about the specialty considering the title of his book. He truly can be considered the father of oral and maxillofacial surgery worldwide, although colleagues in other parts of the globe had no knowledge of his work.

Probably the first surgeon who exclusively limited his practice to OMF surgery was Simon Hullihen (1810–1857). He also was a general surgeon who later received an honorary dental degree from Baltimore College of Dental Surgery. Despite his lack of formal dental training, he performed a wide spectrum of surgical procedures in the oral and maxillofacial area and is particularly known for the first mandibular, subapical, segmental set-back osteotomy, which was carried out in 1849.

There were several American colleagues at this time who held medical and dental degrees and who were specialized in oral surgery but a man who really stood out is Truman W. Brophy (1848–1929). In 1883, he established the Chicago Dental College and became a professor in oral surgery at that institution. He gained a tremendous reputation, particularly for his skills in cleft surgery. His major contribution to the specialty, however, was his 1916 book, “Oral Surgery: A

Treatise on Diseases, Injuries and Malformations of the Mouth and Associated Parts.”

It is also striking to note that in those days, Brophy, just like Garretson before him, had a wider vision of the specialty than just the mouth. One can only be deeply impressed by the quality of this two-volume book, which not only covered oral surgery in its widest sense, it also covered the treatment of fractures, tumors and congenital deformities. It is the color anatomy figures, in particular, of the mouth and related structures in color that impresses the reader today.

He was also instrumental in establishing the first U.S.A. association of oral surgery in 1921. Originally, the membership consisted of surgeons with both medical and dental degrees but two years later, membership was opened up to include those with a single degree, either medical or dental. Some well-known names that are either linked to surgical procedures or instruments, such as Cryer, Ivy, Risdon, Waldron and Lyons, joined this association. It is of interest to note that this association became the American Association of Plastic Surgery in 1941, after it had changed its name in 1933 to Oral and Plastic Surgery (Randall et al., 1996). From 1931 on, the membership of this association was only open to colleagues with a medical degree. Disciples of Brophy continued to advance the specialty and wrote another excellent comprehensive book, “Essentials of Oral Surgery” (Blair, Ivy & Brown), which first appeared in 1923, with updated reprints in 1936 and 1944.

Specialty grows in Germany

The early history of the specialty in Europe is largely defined by the activities of surgeons in the German-speaking countries, although there were also pioneers in other countries, such as France, England and elsewhere (see chapter 7). Similar to the specialty’s American beginnings, but somewhat later, it was general surgeons who began to develop an interest in the surgery of the mouth and face.

What were probably the first books in the German language, which dealt with what is now called oral and maxillofacial surgery, stemmed from general surgeons and were published in 1907 by Perthes and in 1913 by Bruns, Garré and Küttner. The German involvement in the 1870–1871 Franco-Prussian War and World War I apparently initiated some original thinking on how to treat soldiers with facial wounds and fractures. The use of arch bars, fixed to bands around the molar teeth, provided anchorage for intermaxillary fixation. This was often supported by a bandage around the chin. The use of splints, made of vulcanite, both for dentate as well as edentulous patients, was already known to surgeons of this period.

It is particularly interesting to read what these surgeons did for those poor young men who were missing parts of their mandible due to gunshot wounds. Extraoral pin fixation and devices that gradually repositioned the stumps in the desired position were fabricated, using very ingenious techniques. It is also fascinating to read about the first attempts to graft defects of the jaws with autogenous bone from various donor sites, including the mandible, tibia and even metatarsal bones, in times when no antimicrobial treatment existed. These first attempts date back to the very beginning of the 20th century in the German-speaking area and were used especially to treat large defects as a result of war injuries during and after World War I (Bruhn et al. 1915, Misch & Rumpel, 1916, Klapp & Schröder, 1917).

Very much the same discussions took place in Germany as those held in the U.S.A. regarding the need for oral surgeons to possess a dental education. Texts on oral and maxillofacial surgery from this period were written by general surgeons with an interest in the field (Sontag & Rosenthal, 1930). It was Martin Wassmund (1892–1956), however, who was one of the strongest supporters of the double degree. As a dentist with a keen interest in oral surgery and very much an autodidactic, Wassmund later studied medicine and became the leading surgeon at Rudolf-Virchow Hospital in Berlin. It is only fair to say that he probably wrote the first comprehensive book on oral and maxillofacial surgery (1935, 1939) which contained surgical procedures that are still widely practiced today. His name, of course, is also linked to the subapical anterior maxillary set-back osteotomy.

Georg Axhausen (1877–1960) also deserves special recognition. He was a general surgeon, departmental chair and professor at the University of Berlin in oral and maxillofacial surgery (Zahn-, Mund- und Kieferheilkunde), whose 1940 book presents some very impressive and still valid thoughts on free autogenous bone grafts and soft tissue transplantations. It also includes the description of a vestibuloplasty in the symphyseal area of the mandible, using a free skin graft.

If we regard the Huntarian period of English surgery, the years preceding this, comprising the 17th and 18th centuries, were marked by repeated wars in Europe. Military

surgeons wrote individual vivid accounts of severe facial injuries, particularly those resulting from gunshot injuries. Treatment consisted of suturing skin to mucosa and later, making good the anatomical defects with prosthetic shields made from silver.

These meticulous descriptions are exemplified by those of Richard Wiseman, who, in the 17th century, was probably the most advanced thinker of the age. A naval surgeon, he wrote up some 600 cases which accurately described the signs and symptoms of bone fractures and the nature of jaw fractures from gunshot wounds and assaults. His writeups included shrewd observations of a middle third fracture in a child, including the posterior displacement. He went on to describe the digital reduction of this displacement and the problems associated with retaining it in a forward position. He was also the first person to emphasize the need for early removal of facial sutures to reduce the scar from the continuous suture itself.

During this period, any surgery was carried out by general surgeons, but in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there was an increased influence from dental surgery. These were individual contributions which each added significantly to the practice of the specialty although no single one was responsible for any major breakthrough. The consequence of this greater awareness of the dentition meant that the treatment of fractures of the jaws advanced side by side with improvements in prosthetic techniques and later, in orthodontic techniques, so that at last, someone attempted to effect a cure other than by simple ligation of adjacent teeth and the provision of a submental bandage.

The first dental splint was probably made in 1780. Over the next 100 years it underwent significant modification to improve its ability to stabilize the jaw fragments. For instance, Naysmith, a dentist, working with Robert Liston, describes the use of a metal cap splint to prevent displacement of the jaw following resection for a tumor. With the exception of this case, the majority of reports were of extensive gunshot wounds and the subsequent replacement of missing parts by ingenious devices constructed of silver.

Lessons then poured in from the American Civil War, which resulted in significant developments in the dental splint. The very nature of trench warfare and the increased power of munitions all tended to increase the severity of facial injuries in particular. The introduction of anti-gas gangrene serum, the copious irrigation of soft tissue wounds

with hypochlorite solution, and the introduction of the tube pedicle by Harold Gillies and at the same time, but independently, by Filatov in Russia, together with bone grafting, greatly facilitated the management of these injuries.

Against this background, the U.K recognized the need for special centers within which this type of reparative surgery could be carried out. The first such center was at Queen Mary’s, Sidcup, where Major Harold Gillies, Captain Kelsey Fry and Captain Fraser worked together, aided by many noteworthy surgeons of the time including Kilner (U.K.), Blair, Ivy, Kazanjian and Curtis (U.S.A.), Valadier (France) and Pickerell (New Zealand), among many others.

Between the wars, iliac crest bone became firmly established as the site of choice for the reconstruction of jaw defects. An improved form of eyelet wiring was described by Ivy (1920) and Gillies, Kilner and Stone (1927) described the temporal approach to the zygomatic arch.

The British government at that time established a special task force charged with ensuring that in the event of further hostilities, the injured service men and women would be assured of far better care than ever before. From the maxillofacial point of view, Harold Gillies (later, Sir Harold Gillies) was charged with the task. It established the concept of a team of surgeons, dedicated to the management of facial injuries, who would work together in frontline hospitals, evacuate the injured after primary stabilization to rear positions, often to the U.K., when it was the most practical thing to do. The surgeons involved in these teams would be general surgeons, some of whom were already trained in reconstruction, and would be known as plastic surgeons, together with ENT and dental surgeons. It must be remembered that, at that time, the treatment of jaw fractures was largely by the use of cast silver cap splints, for which dental expertise was essential.

The development in France was slightly different and can only be understood when realizing that dentistry was not considered an academic profession until quite recently. Instead, a medical specialty called “Stomatologie” existed. Stomatologists would carry out dentistry but some specialized in maxillofacial surgery. There were, however, other specialists, such as general and plastic surgeons and ear, nose and throat surgeons who could attain a “competence” in maxillofacial surgery.

A French surgeon who contributed a lot to our understanding of maxillary fracture patterns was

Rene Le Fort (1869–1951). His classic studies were carried out in 1901, when he was still a young doctor in the military (Pons et al., 1988). One of the most renowned surgeons of his time was Victor Veau (1869–1951), a general surgeon who published his seminal work on the treatment of cleft lip and palate in 1938. There were several other French pioneers who contributed to the development of the specialty in France. Guillaume Dupuytren (1777–1875), for instance, was probably the first surgeon who described the typical signs and symptoms of a jaw cyst including crepitation of the thin overlying bone shell. He also called these lesions cysts but had no idea about their origin.

An excellent account of the early French contributions is presented by Dechaume and Huard (1977). One cannot escape the impression, however, that much published in German or English never penetrated into the French literature but that is also probably true the other way around. There is a French book on oral surgery that reflects the state of the art in France in the 1930s (Chompret, Dechaume & Richard, 1935). It is limited to pure oral procedures and is less comprehensive than the German or American books of the same period.

One of the factors that defined this early period, apart from the daring character that all of these pioneers must have had, was the fact that they were almost certainly unaware of what was going on in other countries, let alone in the transatlantic world, the one exception being Truman Brophy, who quotes Perthes (1907) in his book. For this reason, some operations or techniques were invented several times in different countries without the inventors knowing of each other. The reason for this was the limited number of journals available and the inability of most professionals to read each other’s language. Most medical and dental journals were also rather parochial as they had limited distribution. The event which changed this completely was World War II. Not only did this war profoundly change the profession due to the new developments caused by the need to take care of large numbers of wounded soldiers but soon afterwards, the world opened and English became the main language for scientific publications.

The specialty has benefited enormously from general advances in medicine and surgery that were made during the war. Probably the most important one relates to the discovery of Penicillin by Fleming in 1941. This enabled surgeons to begin exposing jaw bones more safely and to carry out procedures, including open reductions of fractures and osteotomies, in a predictable manner. This was certainly not common practice before and, for instance, Brophy warns in his book that, “this procedure, which should be the last resort, etc.” He was referring here to open reduction of some mandibular fractures and to applying a wire osteosynthesis. Also, inflammatory diseases caused by the teeth were no longer as life threatening as before, while specific infections, such as actinomycosis, could be adequately tackled.

The emergence of the journals

Another factor that contributed to the rapid spread of knowledge worldwide was the establishment of journals solely devoted to oral surgery. The AAOS began their journal in 1943, which appeared quarterly in the early years. It was later published every two months and became a monthly journal only in 1965. Although this journal was meant especially for the American colleagues, there were many subscribers from overseas but few contributions from abroad. The other American journal that appeared first in 1958, also quarterly, was called Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology. This journal, from the beginning, had a somewhat broader vision in that it aimed to attract international contributions and even had international editors. This probably had to do with the fact that its first

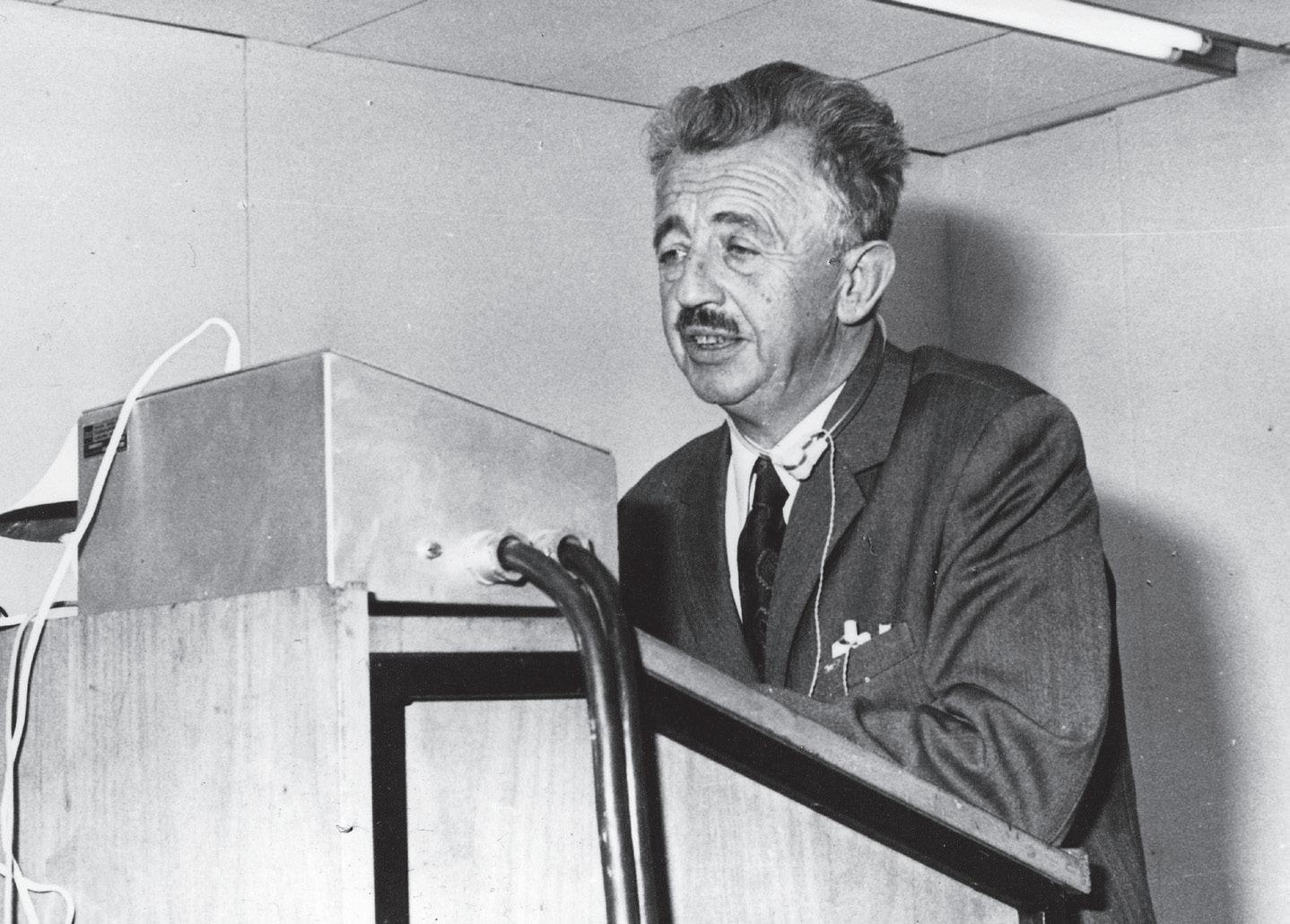

H. tH o maIn the first issue of the “Triple O,” Thoma writes a remarkable and extensive editorial, introducing the new journal: “The material will include advances in clinical procedures as well as information about new developments in the basic sciences. The latter are fundamental, since they furnish the foundation needed for the thorough understanding of disease processes and the application of correct treatment, be it medicinal or surgical in nature. Let us not forget that the true art of medicine and surgery is based on a thorough concept of the basic medical sciences, which include anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, bacteriology, pathology and pharmodynamics and that the clinician depends on investigation and research for progress. Yet, truly, the clinic is the proving ground for discoveries made in laboratories.”

He then goes on to mention the names of various pioneers, such as Pasteur, Semmelweis, Lister, Morton and several others in medicine and surgery who applied basic ideas to the development of an important discovery. This introduction led to the following narrative. “Today, we definitely accept organized investigations as the most promising method for success in the revelation of new scientific facts. We no longer wait for a genius to appear, for a lucky discovery to come along. The great wonder of organized progress is made by an army of patient investigators, by groups working together with leadership from within. Discoveries in modern times are made by cooperation and by the cumulative effort and therefore, it is necessary for investigators to study the accumulated scientific knowledge which has increased in an amazing manner, as highly trained specialists added fact upon fact by the sweat of their brow.”

Thoma then describes the passing of knowledge in ancient times as it was based by word of mouth and often went lost, contrary to the present time. “It was the advent of the printing press which facilitated the distribution of knowledge and today man is to a great degree educated by published material. Periodicals are published constantly to keep the reader informed of the most recent accomplishments of his contemporaries,” he wrote. He then continues to promise the reader to provide the best original articles, including all aspects of the profession and “Quarterly Reviews of the Literature.” He had appointed corresponding editors in many countries to report on the development outside the U.S.A.; “because the world is small and there should be complete cooperation, especially in the medical and dental professions, for the benefit of all.”

The reader, almost 60 years later, could not agree more with these wise and highly relevant words. Apart from his phenomenal accomplishments and broad knowledge of the pathology and surgery of his time, this man had a vision that has proved to be right until today.

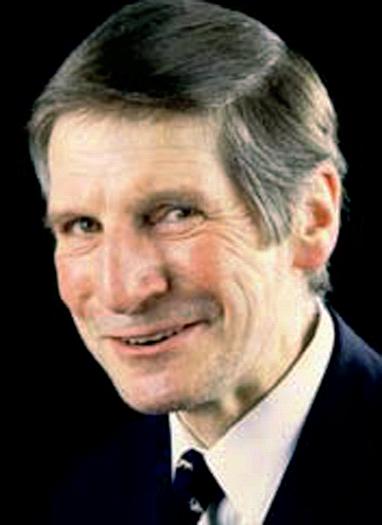

Paul J.W. Stoelinga

editor, Kurt H. Thoma, who was born in Switzerland, was brought up speaking both German and French. American OMF surgeons were hitherto sporadically publishing in either dental or surgical journals.

The German-speaking countries had their Fortschritte der Mund,-Kiefer,- und Gesichtschirurgie from 1954, which was not so much a real journal and was certainly not peer reviewed but rather was an accumulation of the papers presented at their annual meeting, edited by one of their leading professors. Nevertheless, it contained some very useful information and gave the reader a sense of where the specialty was heading.

The British established their journal in 1963, which only appeared twice a year and later, in 1980, three times a year. The IAOMS published its first journal in 1972, followed by the European association in 1976. Both journals started out by appearing six times a year.

It is of interest to note that French stomatologists had their journal from 1899, called La Revue de la Stomatologie. This journal, however, did not exclusively publish on oral and maxillofacial surgery but also on common dental issues. The same was true for the Acta Stomatologica Belgica, which first appeared in 1902.

In order to gain an impression of the scope and armamentarium of the OMF surgeon in those days, it is quite revealing to read the journals of these years. There were a lot of case reports and experienced based papers written by authors who were leaders in the specialty. This is well illustrated when comparing the 12 issues of the American Journal of 1963 and 1964 with the four issues of the British Journal from 1963–1965 (see table below)

The British Journal in those years appeared only twice a year, the American Journal six times a year. The contents

were quite comparable. Case reports, mainly pathology, made up about one third of the contents. Reviews and experience based articles filled about one third to one quarter, the remainder were technical notes and papers about anesthesia, the latter were only present in the American journal for obvious reasons. Of 225 published articles, altogether there were only 11 papers that could be classified as research and these were mainly clinical retrospective studies.

It is also of interest to note that in 1965, Fred Henny, the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Oral Surgery, wrote an editorial in a special issue of that journal which was completely devoted to research. He stressed the importance of research and, in fact, became very directive in indicating the areas that should be explored.

The subspecialties

Around 1960, it was possible to define nine specific areas of clinical practice. They will be discussed here in three time frames that are somewhat arbitrarily chosen, although some major trends mark the selected dates.

The period before 1960 is characterized by post-war recovery and the establishment of oral and maxillofacial surgery as a specialty in most western countries, as well as several others. In most countries, the development was still mainly orientated towards the national interests and based on historical customs, with very little awareness of what was happening in other countries. This changed in the period 1960–1990, largely as a result of the appearance of journals that were purely devoted to the specialty. They were read worldwide and caused a growing sense of international dependency on ideas brought forwards by various clinicians and researchers.

t h e e m e r g e n c e o f t h e j ou r n a l s

Type of Ar ticle

British Journal of Oral Surger y (19 63 –19 65) 4 issues

Journal of Oral Surger y (19 63) 6 issues

Journal of Oral Surger y (19 64) 6 issues

Opinion 8 4 14

Review 20 15 18

Research — 5 6

Anesthesia — 14 4

New Te chnique 9 9 3

Case Repor t 19 35 32

Total 66 82 77

This was also the time that elective surgery began to emerge, including orthognathic and preprosthetic surgery. These two subspecialties would flourish in this period and expand the scope of OMF surgeons enormously. The period 1990–2010 brought many new technologies into the specialty and also a growing awareness that the treatments chosen needed to be valid and preferably evidence based. For this, several mechanisms became available but not the least of which was the “Parameters of Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons,” as proposed by AAOMS and endorsed by the IAOMS and many affiliated, national associations.

In the following sections, the development of these specific areas will be described in the three periods mentioned. It was not the intention of the authors to describe a detailed or complete history of all aspects of the specialty but rather to present a bird’s eye view, with an emphasis on the reasons why and when we arrived at the present situation. When studying the literature of the past, the sheer number of articles on procedures that are no longer carried out and also the number of papers that are repetitive as they emphasize points previously made,

is striking. We inevitably had to be selective to illustrate the points made. In some sections, strong beliefs and even conclusions were postulated by various authors which later had to be reversed. Some of these conclusions were wrong and had to be changed dramatically. In that sense, the history is quite revealing and worth studying as it may happen again.

It is also acknowledged that the development is described from the perspective of “westerners,” with an emphasis on English literature and, to a lesser degree, on German and French literature. When reading the contributions of the affiliated associations from different parts of the world, it appears that important developments also took place in the non-English, non-German and non-French speaking world. However, it was not possible to get access to written documents from these countries, let alone that it would have been necessary to translate them.

Apart from many articles on specific items, it was most instructive to read the textbooks as they appeared over the years. They are listed in a separate column at the end of this chapter since many are quoted through all nine sections.

researc HFred Henny wrote an introduction in

of

Journal of

Surgery of June 1965, which was completely devoted

research and

of a research summit, which had taken place at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit in September of the previous year. This was an initiative of the American Board in conjunction with the leadership of AAOS at that time. He writes a lengthy introduction in which he stresses the importance of research as part of the training of residents. This column contains his main message and one cannot escape being impressed with the vision of this man who was the first president of this association. Everything he says would apply to the current situation and his warning is just as timely today as it was in 1965.

“Education and research are welded together in an unbreakable band and it is a basic truth that a high quality of training service in any of the health sciences cannot be developed or maintained without this combination,” he wrote. “Strength in a clinical science, such as oral surgery, is built like a Russian troika: three powerful forces all pulling equally together: clinical care, education and research. If one force gets out of balance, obviously the pace of progress must slacken and the overall result becomes less desirable.

“Although formal education provides the foundation for a capable specialty in the health sciences, it is research that keeps it moving forward at a vigorous pace. In the present day of rapidly expanding scientific technology, it is virtually impossible for a branch of health sciences to keep pace with others around it unless it is fed by a steady diet of imaginative, well-conceived and productive research. Oral surgery cannot be an exception to this principle and obviously it must conform or eventually be relegated to a minor professional position that could almost be considered a craft.”

He also outlines 11 areas where he foresees that research is very much needed so as to improve patient care. These include: growth and development, neoplasia, aging process, trauma, the painful temporomandibular joint, focal infection, neurological state, wound healing, anesthesia, vascular changes and speech. It would not be difficult to update this list so as to make it more applicable for the present time but how appropriate this message was in 1965 and how much did we benefit from research in all these areas.

Paul J.W. StoelingaDentoalveolar surgery

Before 1960

Dentoalveolar surgery had been carried out in many countries for about 150 years before the 1960s on a more or less regular basis. Exodontia, in particular, was most often performed, using various forceps and elevators. It was John Tomes, however, a surgeon who practiced dentistry, who in 1841 proposed a logical design for forceps that would fit the contour of the cervices of the various teeth. Since that time, extraction forceps exist until today with few variations, something which is particularly notable when comparing European forceps with those commonly used in the U.S.A.

It is not surprising that in the two countries where oral surgery began, i.e. the United States and the German speaking area that the first written instructions appear. There are even monographs, solidly devoted to exodontia, which were published at the beginning of the 20th century (Mayrhofer, 1922, Winter, 1926, Berger, 1929 and Sicher, 1937). The latter emigrated to the U.S.A. and became widely known for his contributions to oral anatomy.

It is of interest to note that the techniques described entail the complete removal of all teeth and their roots, without any attempt to split them. This is even illustrated when removing deeply impacted third molars in the mandible. The removal of bone was largely done by chisel, although Adolf Berger recommended the use of a dental bur as an alternative, apparently against the then prevailing opinion, as he remarked: “The use of the bur is not regarded favorably by those who scoff at the dental engine as a surgical instrument. It will be found, however, that this method is satisfactory from the surgical and from the patient’s standpoint. Furthermore, it often has several advantages over the chisel technique. The bone can be cut accurately, quickly and safely; the tissue destruction is minimal; and the trauma and postoperative pains are mild.”

Berger was ahead of his time and would not have found much opposition today. It is needless to mention that large amounts of bone had to be removed to expose impacted teeth and to be able to remove them in one piece. This practice was still advocated by Wassmund (1935), although he used burs to remove the bone around impacted teeth.

Just before, during or shortly after the war, several textbooks on oral surgery appeared, again, mostly written by American and German-speaking authors. From most of these books, several new editions appeared with updates

on techniques or new developments, sometimes changing the titles slightly. (Archer, 1952, Pichler & Trauner, 1940, Mead, 1933, Thoma, 1948, and Rheinwald 1958). Some of them had updated editions until the 1970s.

There is one French book written by Chopret, Dechaume and Richard (1935) that reflects the state of the art in France at that time. The chapters dealing with dentoalveolar surgery, however, hardly changed and most advocated the use of burs to remove the necessary bone and to split impacted teeth and remove them in pieces. This probably had to do with the development of drills that had evolved from simple engines, driven by foot pedals, to electrically powered machines. The burs also had evolved into various designs suitable for the removal of bone or to cut through the teeth in the desired fashion. The techniques described in these books have not changed much and probably served as a basis for many manuals published in many countries in different languages.

There is one exception that needs further explanation. It concerns the “lingual split” technique as was previously practiced widely in the U.K. According to Ward (1956), this technique was introduced by Kelsey Fry but never written up until the publication of Terence Ward. The rationale for this technique is beautifully described by Killey and Kay (1965): “When a chisel is preferred for 3rd molar surgery, use should be made of the fact that the buccal bone is relatively thick by comparison with the thin shelf of lingual plate and that when the latter is split off, the main bony support to the tooth is eliminated and with it the resistance to effective delivery. It also reduces the size of the residual socket and, therefore, the blood clot.” This author (PS) learned this technique in 1971 in East Grinstead and has used it ever since in selected cases, particularly distally tilted molars, very much to his satisfaction.

Apicectomies, with the intention of treating an apical cyst or granuloma and to save the tooth, also have a long history. According to Wassmund (1935), it was Partsch (1896) who introduced the principle of surgical endodontics, but Thoma (1948) refers to Farrar (1876). From the beginning, removal of approximately one-third of the root was recommended to include the apical inflammatory tissues along with the ”necrotic” cementum (Wassmund, 1935, Mead, 1940, Thoma, 1948, Archer, 1952), or even to resect to the deepest level of the bony defect so as to avoid any dead space behind the root (Rheinwald, 1958).

To illustrate the way of thinking of that time, it is revealing to quote Thoma in 1948 “…consists of the apex of the tooth because it harbors bacteria in the dentinal canals and the lacunae of the cementum which are not accessible to ordinary methods of sterilization. The apex of tooth undergoes necrosis, but, unlike bone, it is not sequestrated although resorptive processes are frequently present.” What did he see that we presently are not aware of?

All mentioned authors describe only an orthograde filling technique, apart from Pichler & Trauner (1940) and Rheinwald (1958), who also described retrograde fillings using amalgam. Most authors were also rather hesitant to embark on multi-rooted teeth such as molars and bicuspids. They warn of perforation of the sinus membrane with possible sinusitis as a result, or damage to the inferior alveolar nerve. Louis Grossman (1965) described the operation in a step-by-step version with simultaneous root canal filling. It is obvious at this stage that knowledge of the detailed anatomy of the dental root canals was lacking, while also the advances made in conventional endodontic treatment had not yet become apparent. The theories on which the treatment was based,

along with the subsequent recommendations, were all based on experience and assumptions rather than evidence, as we know it now.

A procedure that had certainly fascinated clinicians for a long time was tooth transplantation, be it autogenous or allogenic. It was already known, at this time, that allogenic transplantations did not result in long-lasting success. A very good description of autogenous tooth transplantation is found in the book of Georg Axhausen (1940), who describes the importance of maintaining the periodontal membrane and, thus, the need for atraumatic removal of the tooth used for re-implantation or transplantation. He had done animal experiments, without being specific about it, that showed replacement resorption occurring soon if the periodontal membrane is not preserved. He also showed some very good results in his book. This technique became very popular in the succeeding years.

There are, of course, other procedures that could be mentioned in this section but they will be dealt with in the specific sections, such as pathology and preprosthetic surgery. One exception has to be made; it concerns the handling of oro-antral perforations. In the second volume of Wassmund (1939), almost all methods used during this time to close an open antrum are beautifully presented with extreme detail, including excellent illustrations. There has been very little new published, in this respect, ever since. It also becomes very obvious when reading the American textbooks, that they had no knowledge about the things Wassmund had written about and vice versa and certainly not about this topic.

1960–1990

Exodontia had not developed further during this period, apart probably from some better drills to free retained roots or impacted teeth. All textbooks or monographs written in this period [Killey & Kay, (1980), Tetsch & Wagner, (1982), Laskin, (1985)], or adapted from earlier versions of published books and reprinted, show pretty much the same techniques. There was, however, more concern about the possible complications associated with removal of impacted mandibular third molars. This had largely to do with some follow-up studies that were done during this period. It became obvious that temporary or even permanent disturbance of sensitivity of the inferior alveolar and lingual nerve was a serious problem and occurred with a frequency of between 5–12 percent. The majority of cases, however, recovered spontaneously.

The issue of alveolitis was also addressed during this period, and with it came the discussion whether or not to use antimicrobial drugs as a prophylactic measure. The studies of Birn (1973), however, threw some light

on the etiology of alveolitis, pointing towards fibrinolysis as the causative factor rather than primary infection. In retrospect, it is surprising that there was no doubt about the recommendation of prophylactic removal of all impacted third molars, despite the absence of any evidence to support this notion, apart from personal anecdotal experience. The National Institute of Health in the U.S.A. even came out with a statement in 1979 saying:

• A ll third molars are pathological.

• T hey cause crowding over the years.

• R emoval at a young age causes fewer complications.

At present, this would be called level V evidence, the lowest level possible, based on a consensus of “experts.” At that stage no information was available on any longitudinal study supporting the statements they made.

The practice of apicectomies was still carried out according to the principles as laid out by the authors of the mentioned texts but some nuance was introduced, probably because of the progress endodontics had made over the years. Gerstein, writing the chapter on apicoectomies in Laskin’s book (1985), writes: “It is usually not necessary to remove the portion of the root that lies within the bony lesion, except for access to the area of pathosis.” Most current practitioners would agree with this statement in the light of the current knowledge of minimal exposure of accessory canals. There is also no hesitation anymore in treating posterior teeth.

The biggest progress in this period was made in the area of tooth transplantations and re-implantations. Research in this field had resulted in fairly predictable outcomes, particularly when teeth were transplanted with wide open apical foramina. One of the pioneers in this field was Shullman, who also wrote a chapter in Laskin’s book (1985) about tooth re-implantation and transplantation, for a large part based on his own research. He emphasized the advantages of transplanting teeth at a young age, when the apical foramen is still wide open, so as to facilitate survival of pulp vasculature. He preferred auto-transplanted teeth to implants, because erupting transplanted teeth stimulate growth of the alveolar process, contrary to implants. He also wrote: “Survival depends on maintained viability of the periodontal ligament and cementum on the surface of the donor tooth.”

This is pretty much in line with what Axhausen had said some 45 years previously. Considering the many articles in various journals on this topic, this technique was enormously popular. The ultimate book on tooth transplantation and re-implantation is written by Andreasen (1991), another pioneer in this area. It provides

the science behind the technique but also serves as a step-by-step atlas, demonstrating the procedures in detail. He also advocates transplantation of developing bicuspids into sockets of avulsed front teeth in growing children, as opposed to implants.

1990–2010

As stated before, dentoalveolar surgery did not change much during this period, apart from the improvement of instruments used and better imaging. Numerous manuals in various languages appeared but two classic books stand out, one from Sailer and Pajarola (1996) and the other from Andreasen, Kølsen, Petersen and Laskin (1997). In both texts, up-to-date information is provided about the currently used techniques, the preoperative preparation of patients and their aftercare.

In this period, the third molar issue came prominently into play, initiated by two thought-provoking articles (Mercier & Precious, 1992 and Shepherd, 1993). They questioned the routine prophylactic removal of asymptomatic third molars in the light of the morbidity associated with it and the cost effectiveness. This discussion prompted some research that in part is still going on but is notoriously difficult, because the necessary long-term, longitudinal studies are still not present. There are, however, some well-designed studies that, for the time being, are helpful in making up one’s mind.

Kugelberg et al. (1991–1993) from Norway did some excellent work on the healing capacity of the periodontium distal to the second molar and found that this was almost 100 percent when the patients were younger than 25 years. Beyond that age, the chances are that irreparable damage will occur, leading to loss of septal height distal to the remaining second molar, with subsequent problems. Ventä et al. (2004) found in a group of dental students that over a period of 18 years seemingly deeply impacted third molars in the mandible could still change their position and even erupt. Last, but not least, the assumption that third molars contribute to the crowding of the lower front teeth is seriously questioned by orthodontists as well as OMF surgeons, based on some rather convincing clinical research (Lindauer et al., 2007).

This would certainly be one reason less for contemplating prophylactic removal. The overriding argument, however, to question this policy is the fact that from several studies, it became apparent that only in some three percent is there serious pathology involved, including cysts and tumors, associated with impacted third molars (Eliason et al.,1989, Güven et al., 2000). It will probably take some time until this issue is settled, based on evidence rather than speculation or anecdotal information.

The AAOMS currently has a research project underway that should provide clinical and biological data to support effective third molar treatment (White, 2007). The Cochrane Group, however, has come out with a recommendation based on currently available information (Mettes et al., 2005): “Asymptomatic bony impactions and even third molars completely covered by soft tissues should not be removed, while only partially erupted wisdom teeth should be removed, preferably before the age of 25 years.”

There is no doubt, however, that there is another side of the coin. Removal of third molars at a later age, because of inflammatory disease or otherwise, particularly when elderly people are involved, leads to more morbidity. (Kunkel, et al., 2007). The longitudinal study that is currently underway, sponsored by the AAOMS, should establish whether hard data exist to support established practice.

Another issue in which much progress has been made concerns the avoidance and the repair of damaged branches of the trigeminal nerve after mandibular third molar surgery. Excellent studies have appeared on the anatomical variation of the lingual nerve position, which enables the prudent surgeon to avoid its damage (Pogrel et al., 1995). Three dimensional imaging allows for exact assessment of the relationship between the inferior alveolar nerve and the roots of a third molar to avoid traumatic injury of this nerve. It is thanks to Hillerup and coworkers (2007, 2008), that objective criteria have been established upon which to base the seriousness of the damage and a protocol for micro-surgical repair with subsequent follow-up.

The development of endodontics has narrowed the indications for surgical endodontic treatment (apicoectomies) considerably. Modern techniques to find and open obliterated canals, or to remove metal posts in previously treated canals, have eliminated the need for surgery. In addition, the current practice of conventional endodontic treatment has improved the outcome of the treatment in such a way that there is less need for surgical solutions. Yet, there are still indications for surgical endodontic treatment and the techniques as described above are still valid.

Infectious diseases

Before 1960

Infectious disease must have been very prominent in the old days as there was no emphasis on oral hygiene and both periodontal and pulpal infections must have abounded.

There are many illustrations made in the 17th and 18th centuries and even before that time, which show individuals suffering from a swollen cheek with a bandage around their heads. This probably was the main reason why general surgeons were called upon, since some of these conditions were life-threatening.

In the beginning of the 19th century, these surgeons had no idea what the cause was of the severe abscesses and indurations that they saw. This is well illustrated by the description of “an inflammation in the anterior part of the neck with an emphasis on the submandibular regions” by Friedrich von Ludwig in 1836. He describes that he favored a conservative approach, which in most cases would result in death. He also commented that in some cases, foul smelling, reddish-brown fluid escaped via the mouth. He had, however, no idea what the cause could be and suggested an “erysipelitic process probably related to a poor general condition or a weak nervous system.”

Contemporary surgeons such as Dupuytren in Paris, shared his approach (Hoffmann-Axthelm, 1995). It took some time before the link was made to the role of bacteria and the dentition.

A complete and accurate description of the often dramatic and rather quick development of a phlegmone of the floor of the mouth (Ludwig’s angina) is presented by Mickulicz and Kümmel in 1898. They recognized the delicate anatomical structure and the proximity to the throat as the main reason why the patients had difficulty swallowing and breathing. They also mentioned difficulty in inspecting the mouth because of trismus and the swollen tongue and realized that this condition had, of course, nothing to do with an inflammation of the throat. They also described the often fatal course of events, despite surgical intervention, such as incision and drainage and particularly emphasized that death might be a matter of days if the patient does not respond to the surgical treatment. Thoma, in 1948, added: “The clinical course might be mild but it may suddenly change and assume an alarming character. Deglutition is hindered, speech is difficult and saliva may run from the mouth since swallowing causes pain. There is a rapidly extending edema, which causes respiratory difficulties (angina). The larynx itself may be involved suddenly in the rapidly progressing edema and may become obstructed.” Today, one cannot think of a better description. It is only after the introduction of penicillin that the prognosis of this condition changed, as Thoma rightly noticed in 1948.

Textbooks in German and English from the first half of 20th century all mention the necessity of treating abscesses in and around the mouth by incision and drainage, recognizing that the cause of these inflammatory conditions in most instances were decayed teeth which, therefore, had to be extracted as well. The better knowledge of head and neck anatomy also led to the recognition of the stereotype appearance of deep space infections.

Osteomyelitis was another condition that gave rise to major concern in the days before antimicrobial agents were available. It was in particular, the acute form that worried the clinicians. One has to keep in mind that most of them had a general surgery background and were, therefore, inclined to compare the disease in the mandible with the often dramatic course of events in the long bones. Surgeons like Axhausen and Wassmund, but also others, were hesitant to go into the bone to remove sequestra, fearing uncontrollable spread of the inflammatory process.

A much feared complication was thrombophlebitis with hematologic spread to other bones, resulting in certain death. These considerations still played a role in the 1950s. For instance, Archer writes in the late 1950s and early 1960s that sequestrectomy should only be carried out “when the sequestra are freely movable.” There apparently was still this fear of manipulation in the infected bone with the idea in mind of metastatic spread despite “the use of massive doses of penicillin.”

Last but not least, specific infections were apparently a widespread problem. Tuberculosis, syphilis, gonorrhea and actinomycosis presented frequently in the orofacial area and also affected the jaw bones. The old German textbooks are full of case reports and describe drastic surgical approaches with often negative results. When reading, for instance, how clinicians struggled when treating patients with actinomycosis, one can only utter a sigh of relief that we live in a different era. Brophy (1918) quite flatly states “that spreading usually takes place in the soft part of the neck and even mediastinum and that there is no cure!” Wassmund (1935) mentions also that there is a high mortality rate associated with actinomycosis but recommends irradiation on top of rinsing with potassium-iodine. This therapy was followed by many German clinicians until the 1950s as they all quote Wassmund as the proponent of irradiation (Pichler & Trauner, 1948). Even in 1952, Hofer and Reichenbach still mention potassium-iodine rinsing in combination with irradiation, although they also mention the use of penicillin and aureomycin.

1960–1990

As mentioned previously, the introduction of antimicrobial agents changed the approach to infectious disease drastically

although the principles of incision and drainage remained valid and the old adage “ubi pus ubi evacue” the mainstay of proper management of an abscess. Textbooks written in this period all deal with odontogenic infections and emphasize the elimination of the cause by either extraction of the causative teeth or proper endodontic treatment (Thoma, Archer, Laskin, etc.).

Another factor that played an important role in the improved management of infectious disease was the introduction of better imaging as compared to the hitherto used plain radiographs. The orthopantomogram, CT scan, MRI and scintigraphy all contributed to the diagnostic capacity of the clinician. Most important were also the advances made in microbiology, in that better determination of the bacteria involved was possible. This had major consequences because the antimicrobial therapy could be directed specifically to the microorganisms involved. This was particularly important for deep space infections in which anaerobic bacteria are often involved.

Recommendations for the treatment of osteomyelitis and particularly the acute form included much more aggressive procedures than in the preceding period, including decortications and removal of sequestra along with proper antimicrobial treatment (Topazian, Goldberg 1981, Laskin, 1985). It is somewhat remarkable that there are relatively few papers written in this period on the subject of acute osteomyelitis.

In the early 1970s, the first reports appear on a special entity that was called chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis. It was Jacobsson et al. (1978) who emphasized the use of scintigraphy in the diagnosis of this therapy resistant lesion. Further diagnostic improvement was reported in 1984, also by Jacobsson, while the adjunct diffuse was added to the description of the condition. It is of interest to note that surgeons applied the techniques, as known from the suppurative form of osteomyelitis, including decortication and long term use of antimicrobials but with poor results (Montonen et al. 1990). There simply was no causative agent to be detected in most instances, which eventually changed the thoughts about this lesion and, consequently, the treatment.

The improved medication against tuberculosis, syphilis and other specific infections resulted in the fact that orofacial manifestations were hardly mentioned anymore in the world literature. That does not imply that these infections did not occur but probably not in the developed world as much as they used to. It is likely that in the developing world, this was still a problem, but there were simply no OMF surgeons in many of these countries who were prepared to write about these diseases. A condition which had not disappeared is actinomycosis. Early recognition and proper antimicrobial treatment had, however, changed the picture

completely. Cervico-facial actinomycosis used to be a killer in the old days, posing enormous dilemmas for the surgeons involved. The days of surgical exploration and rinsing with potassium-iodine and/or sulfanilamide were definitely gone.

An excellent book on the management of infections of the oral and maxillofacial regions was presented by Topazian and Goldberg (1981), who described the state of the art in the early 1980s.

1990–2010

The fundamentals of the management of infectious diseases had not changed in this period but some new conditions occurred as a result of immune suppression, be it acquired or drug induced and because of the side effects of biphosphonates. Clinicians are also more alert to bacterial resistance to the commonly used antimicrobials because of overuse of these drugs over the years. Plain penicillin, for instance, used to be the drug of choice for any odontogenic infection because streptococci always used to be sensitive to this drug. In many countries that is no longer the case.

Patients with AIDS or persons carrying the HIV virus became a giant problem for healthcare providers and certainly caused the OMFS profession to be alert to the typical oral manifestations. In addition to that, these individuals are very sensitive to infections, including specific infections such as tuberculosis.

The surprise of this period was undoubtedly the discovery that biphosphonates cause osteonecrosis of the jaw bones (Marx 2003). Since this publication, a large number of cases have been reported, cautioning the profession to be alert. Infection is only secondary to the primary problem but long-term antimicrobial treatment is certainly important in the treatment, along with surgical debridement of all necrotic bone and tension-free primary closure of the overlying mucosa (Williamson 2010). This is similar to the treatment of osteoradionecrosis.

The debate about chronic diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis went on and several new suggestions were made about its etiology and treatment. Van Merkesteyn et al. (1990) introduced the concept that the condition should be considered a tendo-periostitis because of overuse of the masseteric muscles. This idea was not unequivocally followed and probably rightly so, because promising results had been achieved by influencing the bone metabolism using calcitonin (Jones et al., 2005) and biphosphonates (Yamazaki et al., 2007 and Kuijpers et al., 2011). If these treatments appear to be successful in the long run, then this condition should no longer be considered an infectious disease.

As mentioned in the previous section, specific infections in the oro-facial area are rare but currently an interesting

phenomenon can be observed. Tuberculosis is emerging again since there is increasing global resistance to antituberculous drugs (Kakisi et al., 2010). It presents itself mostly in the soft tissues and lymph nodes, of course, but apparently also in the maxilla and mandible and even the TMJ.

In the last ten years, several case reports of tuberculous osteomyelitis affecting the mandible have been described, especially by authors from developing countries and often in the pediatric and radiological literature. It often concerns extrapulmonary presentations of the disease and frequently occurs in HIV patients (Bendick et al., 2002). In the developed world, it remains a rare phenomenon and, in particular, the bones are rarely affected (Chaudlary et al., 2004) but the migration of people means that even in the western world, every once in a while, a surprise finding occurs (Heibling et al., 2010). Actinomycosis, of course, is still around but is usually diagnosed at an early stage and, therefore, easily treated. It may also still involve the jaw bones (Finley and Beeson, 2010).

Despite the improved dental care in many parts of the world, odontogenic infections are still relatively frequently encountered. The present generation of clinicians, however, has the tools to deal adequately with them. Yet, danger lies around the corner and a certain degree of alertness is warranted, because the course of events may still run out of control.

The most dramatic example is the evolution of a seemingly simple odontogenic infection into a fulminant necrotizing fasciitis. Although the first reports of this often fatal condition were described in the ENT literature in the late 1970s, because of pharyngeal infections, it soon appeared that odontogenic infections could also cause this dramatic spread, which is mostly based on a mixed infection.

It is particularly during the last two decades that numerous case reports have appeared in OMFS literature. The most frightening observation is that, recently, cases have been reported caused by staphylococcus resistant to methicillin (Zhang et al. 2010). Apart from this unusual but potentially fatal condition, resistance against the currently known antimicrobials is increasing and will, therefore, play a more prominent role in the future.

The massive number of AIDS and HIV infected patients in the developing world who are not adequately treated to control the underlying condition, still pose an enormous problem. Although better drugs are on the market, they are often not available for patients in the developing world (Bendick et al. 2002). Hence, it might be expected that unusual infections that were thought to be eliminated will appear again and even present in the developed world because of the migration of people.

Trauma

Before 1960

Although trauma has been with us since the dawn of time, it is only relatively recently that we have been able to approach it scientifically. For this reason, the reports of treatment do not necessarily follow any logical pattern, really amounting to a series of case reports contained within the literature from the earliest pre-Christian times to Egypt in 2000 B.C. when a dislocation of the mandible is described as well as a fractured mandible. Hippocrates, described reduction and fixation of mandibular fractures with strips of calico glued to the skin immediately adjacent to the fracture and laced together over the scalp. The ancient physicians of Alexandria and Rome also mention the ligation of teeth using fine gold wire or Carthugian leather strips glued to the skin. The principles laid down by Hippocrates really extended through the literature as far as the turn of the first millennium.

It was probably Salicetti in 1474, in Bologna, who first described the simple expedient of ligating the teeth of the lower jaw to the corresponding teeth of the upper jaw to effect immobilization of a fracture. Previously, it had been recognized that within three weeks, union of jaw fractures was complete.

The 16th and 17th centuries saw the introduction of gunpowder and the first reports of gunshot wounds. It was Ambroise Paré to whom we must attribute the first significant change in the management of facial wounds through copious irrigation of wounds and the application of balms rather than cauteries. His particular care to facial injuries and his application of what he described as “a dry suture” facilitated secondary healing of facial wounds, particularly compound injuries.

The next milestone was with Richard Wiseman, a surgeon in the latter part of the 17th century who described the management of maxillofacial injuries. As well as describing the signs and symptoms of a fracture, he also described many individual cases, including a child with a comminuted fracture of the cribiform plate of the Ethmoid. He also described the disturbance in occlusion and related protrusion or recession of the lower jaw and the destruction of soft tissues in association with these injuries (Rowe, 1971). These astute clinical observations were added to those studies of anatomy and physiology at the Italian schools of Bologna and Padua as the eighteenth century arrived. Together they laid the foundation for serious advances in the systematic management of jaw injuries.

Chopart and Desault (1780) were the first to describe a different type of approach by introducing the concept of a dental splint which consisted of a shallow trough of iron, inverted over the occlusal surface of the lower teeth, which

they protected with cork on lead plates. A bar projected from the front in the incisor region, being bent at right angles and fastened by thumbscrews to a submandibular plate of sheet iron. Movement of the fragments was thus prevented by compression between the occlusal surface of the teeth and the lower border of the mandible.