Herbal History of Bartram’s Garden

Blast from the Past: 7 Native Herbs

Stachys in the Garden

The Rose: Queen of Delight & Use

The Remarkable Chenopods

Herbal History of Bartram’s Garden

Blast from the Past: 7 Native Herbs

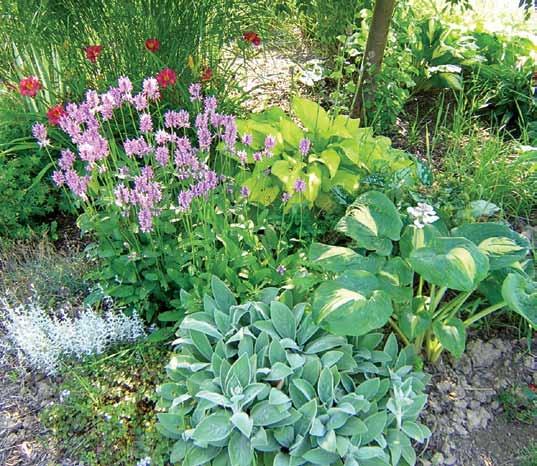

Stachys in the Garden

The Rose: Queen of Delight & Use

The Remarkable Chenopods

How could such sweet and wholesome hours Be reckoned but with herbs and flowers?

— Andrew Marvell

Linda Lain, President

Debbie Boutelier, Vice President

Sue Edmundson, Secretary

Linda Lange, Treasurer/ Finance & Operations

Open Position, Central District Membership Delegate

Linda Wells, Great Lakes District Membership Delegate

Cindy Meier, Mid-Atlantic District Membership Delegate

Claudia Van Nes, Northeast District Membership Delegate

Mary Doebbeling, South Central District Membership Delegate

Rae McKimm, Southeast District Membership Delegate

Karen Mahshi, West District Membership Delegate

Carol Czechowski, Education Chair

Elizabeth Kennel, Botany & Horticulture Chair

Diane Poston, Membership Chair

Karen O’Brien, Development Chair

Lois Sutton, Ph.D., Nominating & Awards Chair

Jim Adams, Honorary President

Katrinka Morgan, Executive Director

Laurie Alexander, Membership

Karen Frandanisa, Accountant

Helen Tramte, Librarian/Horticulturist

Janeen Wright, Educator/Horticulturist

THE HERBARIST

Editor: Janeen Wright, Meister Media Worldwide

Designer: Bill Rigo, Meister Media Worldwide

Printer: Duke Printing, Mailing & Marketing

THE HERBARIST COMMITTEE

Lois Sutton, PhD (Chair) Anne Abbott, Caroline Amidon, Joyce Brobst, Stefan Lura, Sara Moore

The opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of The Society.

Manuscripts, advertisements, comments and letters to the editor may be sent to:

The Herbarist

Connecticut artist, Ellen Hoverkamp has been using her flatbed scanner as a camera to photograph arranged garden cuttings since 1997. Several of her images were featured in Natural Companions, The Garden Lover’s Guide To Plant Combinations, published in 2012 by STC of Abrams Books, in collaboration with author/photographer Ken Druse. Please visit Ellen’s website, www.myneighborsgarden.com to view work from the recent book and her portfolio.

John Bartram was born in Philadelphia in 1699 and purchased this property in 1728. He had little formal education, but his acquired knowledge of Latin, as well as his ability to document and describe 200 species of American plants, inspired Benjamin Franklin and the famed Swedish botanist, Carl Linnaeus, to agree that he was the greatest

Revolution. The relationship between these two friends laid a foundation that connected American history, botany and herbs (2).

In 1743, John Bartram and Benjamin Franklin established the American Philosophical Society, the first scientific association in America. Bartram

numerous herb articles for Benjamin Franklin’s almanacs and newspaper. William Darlington notes in his book, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphrey Marshall, that Bartram had “. . . a very early inclination to the study of physic and surgery . . and in many instances he gave great relief to his poor neighbours” (1). It is possible that this

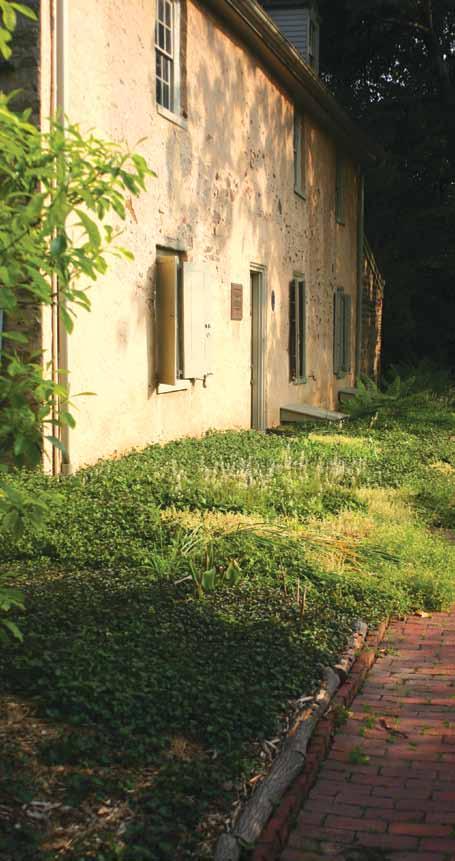

Bartram’s Garden cradles the oldest botanical garden in America on its 45 acres near the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The botanical garden was once the home of America’s first botanist, John Bartram. The grounds feature a premier collection of North American plant species. Herbs are integrated throughout the garden in naturalistic habits rather than in formal settings. The garden’s curator, Joel Fry, reminded me that the notion of a separate herb garden did not occur until the late nineteenth century. Today, the eighteenthcentury farm buildings, built from local rocks that John Bartram split himself, house a gift shop and museum. Gardens, meadows, wetlands and a meandering trail along the river surround these structures.

American artist Howard Pyle’s illustration of John Bartram was printed in Harper’sNew MonthlyMagazinein February 1880.

natural botanist in the world. Bartram traveled extensively in America to gather plants and seeds and record their statistics (1).

John Bartram

John Bartram and Benjamin Franklin were confidants, as seen by their frequent and warm communications with salutations such as, “my good and dear friend.” They exchanged plants, seeds and botanical information throughout their lives and believed that agriculture was the cornerstone of the American economy. When living in Europe, Franklin assisted Bartram with his seed import-export business, which helped make Bartram seed boxes increasingly popular in Europe. These carefully constructed shipping containers kept the seeds in good condition while they were in transport to customers. They were purchased and shipped even during the American

connected with many intellectuals of the day through this organization.

In 1765 King George appointed Bartram as the Royal Botanist of North America; this was a distinctive honor for an American colonist to receive. In 1769 he was further acclaimed with a membership to the Royal Academy of Science in Stockholm (3).

Bartram had a passionate interest in medicinal herbs as plants and medicaments. He collected all the native and European varieties available. Bartram also compiled a treatise on twenty new North American medicinal plants and noted which were available in American gardens for Thomas Short’s Medicina Britannica in 1751. He wrote

interest in the welfare of others was a driving factor for the study of botany and medicinal herbs. This would be in line with his Quaker belief in doing good for others.

Bartram’s essay, “True Indian physick or ipecacuanha,” touted the American ipecac, Gillenia spp., as a treatment for “the bloody flux” (dysentery). This article is one of the earliest in American pharmacognosy and was published in the American Almanac and Ben Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac in 1741 (2). These almanacs, as well as herbals, were an important source of health information for the colonists, because medical practitioners were in short supply. Bartram was a gentle but assertive Quaker who believed all people were equal. He freed his family slaves and gave them a salary like other laborers. Bartram’s kindness solidified strong loyalties and

friendships. His workers were also more willing to share their herbal remedies.

recorded by John Bartram 1751*

Ilexvomitoriawas used as a diuretic.

Lobeliasiphiliticawas used to treat venereal disease.

Erigeronphiladelphicuswas used for snake bites.

Bartram related well to the Iroquois Indians during an extensive botanical expedition to Lake Ontario, even though he needed an interpreter to communicate. He was able to learn how the Iroquois used plants medicinally, and he brought back several specimens and seeds to propagate.

American colonies. These ventures ignited the younger Bartram’s fascination in flora and fauna, and they were enhanced by his talent in art and taxonomy.

Whether due to nature or nuture, the father and son were dissimilar. John had experienced many hardships, including the loss of his wife and the challenges of building a home and life in a new land, so he was a realist. William looked at the world through rose-colored glasses.

His beautiful and accurate sketches were commissioned by his father’s network of botanical associates as splendid enhancements to their own works, which covered all aspects of nature in America.

recorded by John Bartram 1751*

Araliaracemosawas used to treat flesh wounds.

Veronicaspicatawas used to induce vomiting.

Triosteospermumperfoliatum (currently Triosteum perfoliatum) was used to treat fever and ague.

In 1772, Dr. John Fothergill, one of these associates, financed a five-year venture that solidified William’s reputation as an artist, explorer, writer

In 1783, William published the new nation’s first catalog of American plants. He became so well known for his nature drawings, detailed cataloging and communication skills that President Jefferson asked him to join Lewis and Clark on their famous expedition, but he declined the assignment due to ill health. William was a talented writer and expressed his father’s lifelong interest

By 1807 the Bartram plant catalog listed 1,123 herbaceous plants (i.e., herbs used for medicine and seasoning).

Bartram put a lot of effort and detail into his research. For example, the Iroquois used Lobelia siphilitica to treat venereal disease. Bartram recorded in his research, “After making a decoction of it, the patient is to drink about two gills (four ounces) of it every morning, fasting, the same before dinner and bedtime. Add or diminish as you find it agrees with the patient’s constitution. The third day begin bathing, and continue it twice a day until the sores are well cleansed and partly healed, then use the lotion but once a day until quite well: observing all the time to use slender diet (vegetable food and small drink)” (2).

William Bartram

From a young age, John Bartram’s son, William, traveled with his father exploring the natural wonders of the Groundcovers

John

In spite of their differences, John supported William at the Philadelphia Academy and in several failed business ventures, always recognizing his son’s talent and wanderlust. In 1766, the 26-year-old William was invited to accompany his father on a 400-mile journey to help record, draw and explore parts of the American South. This trip was a career-maker for William.

Herb Blend for Gout

direct quote from MedicinaBritannica1751 by John Bartram*

“But in the Gout Sim. Pauli gives a much better Poultise from Sennertus, viz. of Corn-fry Roots three Ounces, of Althæa Roots two Ounces, Tops of Southern-wood a Handful, of St. John’s-wort. two Handfuls, of Camomile Flowers three Handfuls, of Elder Flowers four Handfuls, of Fenugreek Seed two Ounces, of Linseed four Ounces prepare and boil all in Elder-water, to a Consistence; then add Ointment of Marshmallows to make a Poultise, and a very good one.”

and botanist. Fothergill requested “seeds and specimens of plants that were useful, beautiful, singular or fragrant” (4). William sent 200 dried specimens and 59 drawings, along with details of the geography and inhabitants of Florida and Georgia. Fothergill submitted the botanical specimens to Daniel Solander, a student of Linnaeus, for classification (4). He confirmed that they were new genera and species. William’s work continued to be recognized by many and imitated by some. Much of the information on Iris versicolor and Iris verna as well as yaw-weed or cock-up-hat, found in Benjamin Smith Barton’s Collections is virtually identical to information in Bartram’s Observations (4). The good news is that over time, students in this field have confirmed and credited his work to William Bartram.

in medicinal plants through his pen. William spent 40 years of his life exploring all aspects of natural America, and his most famous book, entitled Travels, is a treatise on these excursions. Like his father, he was adored by Indian tribes, who named him Flower Gatherer. John and William are also credited with saving the Franklin-tree (Franklinia alatamaha) from extinction. In 1765, they found a grove of these trees next to Georgia’s Alatamaha River. They named the species in honor of Benjamin Franklin and propagated it from collected seeds. All F. alatamaha growing today are descended from those trees, which were never located again. The early dissemination of Franklinia seedlings fell to promoters like Benjamin Franklin, and this was an appropriate way to honor him.

After his father’s death, William continued his fieldwork while his brother, John Bartram Jr., maintained the family farm and business. They were an extended family cooperative with the same passion that drove their father—to discover, preserve, and share native seeds and plants with friends and through their mail-order business. John Bartram Jr., had two sons who were famous Philadelphia apothecaries interested in prescribing plant medicines; these two apples did not fall far from the family tree. William never married. He lived with his brother and eventually his niece when she inherited and continued to run the family business.

were well acquainted with Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, John Adams Sr., James Madison and other politicians of the day. Many of them were friends, farmers and customers.

When they and other politicians met in 1787 for the Constitutional Convention, Bartram’s garden was chosen as a retreat from a summer of heated debate on states’ rights and other issues. In her book, Founding Gardeners, author Andrea Wulf notes, “It can only be speculation that a three-hour walk on a cool summer morning among the United States of America’s most glorious trees and shrubs influenced these men. But what we do know is that the three men who changed sides and made the Great Compromise possible that day had all been there and marveled at what they saw” (3).

The house overlooks gardens that have herbs integrated throughout in naturalistic habits rather than in formal settings.

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams distributed Bartram’s seed boxes and catalogs when they visited England and France. They found the citizens of those countries enthralled with growing the native American plants that had been delivered to them in these boxes for four decades. This was an indication that agricultural goods were an excellent American export. Every time someone told Franklin about a new edible plant, he was thrilled by the possibility of its economic potential for American farmers (2). While living in Europe, Benjamin Franklin sent rice and tallow trees from China and seeds of useful plants from India and Turkey to the Bartrams and others. Farm products were seen by many colonists, including the American Founding Fathers, as the way to achieve independence from England and realize domestic liberty. Many were gentlemen farmers who did not envision America as an industrial country and believed they could live without many imported products (3). William and his brother John

Although Bartram’s garden is not primarily an herb garden, several generations of this family of farmers, botanists, nature explorers and entrepreneurs have spread the knowledge, utilization, and appreciation of herbs throughout Europe and the New World.

Their passion for all aspects of botany and their connection to influential people made their sphere of influence one that helped to shape the course of

Chamaeliriumluteum-anthelmintic (anti-worm)

Irisverna-cathartic (purge for bowels)

Podophyllumpeltatum-anthelmintic (anti-worm)

Sassafrasofficinalis(currently Sassafrasalbidum) to purify the blood.

Eupatoriumperfoliatum-emetic (induces vomiting)

In 1783, William published the new nation’s first catalog of American plants, and by 1807 the Bartram plant catalog listed 1,123 herbaceous plants (i.e., herbs used for medicine and seasoning). That meant herbs were nearly 70 percent of the inventory and proof of their importance.

The catalog is a testimony to the important role that the Bartram family played in the dissemination of native American herbs throughout the world.

The significance of the Bartram’s discoveries is demonstrated by their being listed even today in the United States Pharmacopeia. (4).

References

1. Darlington, William. 1967. Memorials of John Bartram and Humphrey Marshall (Facsimile of the 1849 edition). New York: Harper Publishing.

2. Hobbs, Christopher. “Pharmacy in History.” Accessed August 1, 2011. http://www.healthy.net/scr/article.aspx?ID=861.

3. Wulf, Andrea. 2011. Founding Gardeners New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

American colonial history. Many of the founding fathers advocated and practiced their belief that “Agriculture and the independent small-scale farmer were the building blocks of the new nation. Ploughing, planting and vegetable gardening were more than profitable and enjoyable occupations; they were political acts bringing freedom and independence” ( 3). The industrial revolution eventually changed this agrarian emphasis.

This garden site is worthy of our consideration, admiration and emulation.

4. Ray, Laura E. 2009. Podophyllum Peltatum and Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians: William Bartram’s Preservation of Native American Pharmacology.” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 82(1):23-36.

Bibliography

Berkeley, Edmund and Dorothy Smith Berkeley. The Life and Travels of John Bartram: From Lake Ontario to the River St. John. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1990.

Some Letters of Franklin’s Correspondents. Cornell University Library. Accessed August 1, 2011. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu3192403270.

Fagin, Nathan Bryllion. William Bartram, Interpreter of the American Landscape. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1933.

Hathi Trust Digital Library. “Medicina Britannica.” Accessed August 1, 2011. http:// hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.3204.

Wulf, Andrea. The Brother Gardeners: Botany, Empire, and the Birth of an Obsession. London, England: William Heinemann, 2008.

Edna McCallion is an herb columnist, lecturer, author and avid herb gardener from Tehachapi, CA. She teaches and writes about the cultivation, culinary uses, medicinal properties, ornamental applications, folklore and the history of herbs. She is a member at large of The Herb Society of America, and her Articles “Herbal Beverages Make a Social Splash” and “Italy, an Herb Lover’s Paradise” have been featured in The Herbarist.

McCallion’s herbal expertise and country herb garden have been featured in the Bakersfield Californian, the Bakersfield Magazine and the Tehachapi News. She is an award-winning cook and her book, Pesto, the Royal Ingredient is in its third printing and will be available as an eBook.

Edna’s forty-year passion for herbs is “on growing”! Contact her through her website at www.herbbasket.net.

*NOT recommended remedies but of historical interest ONLY! Even small amounts of Podophyllumpeltatum can be lethal if ingested.

by Susan Wittig Albert

by Susan Wittig Albert

According to Greek mythology, violets helped the god Zeus out of a bind. He fell in love with a priestess named Io. When Zeus’ long-suffering wife, Hera, found out about this illicit affair, she was understandably miffed. To keep Io out of his wife’s way, Zeus turned her into a white heifer. When she complained that she had nothing to eat, he created a field of violets for her — and while he was at it, he probably sent a bunch of violets to Hera, as an apology. The flowers must have soothed the jealous goddess, because the Greeks began using them medicinally to calm anger and induce sleep.

Zeus wasn’t the only philanderer who sent violets to his spouse. Napoleon Bonaparte’s wife, Josephine, loved the flowers. She wore them on her wedding day, and Napoleon (who wasn’t the most faithful husband on record) sent her a bouquet of purple violets every year on their anniversary. Napoleon adopted the plant as his political emblem, and when he was banished to Elba, he promised to “return with the violets.” While he was in exile, his followers persisted in wearing the flower as an emblem of their own loyalty, even when a law was passed against it. After Waterloo, Napoleon reportedly visited Josephine’s grave, picked a few violets he found growing there, and kept them in a locket he wore until his own death.

In the Middle Ages, herbalist Hildegard von Bingen used violet juice as the basis for a cancer salve. In the sixteenth century, violets were widely used to treat insomnia, epilepsy, pleurisy and rheumatism. A couple of hundred years later, Nicholas Culpeper wrote that the plant was ruled by the planet Venus. This made it a natural as a treatment for throat ailments, since Venus also ruled the throat.

In fact, violet leaves and stems do contain a soothing mucilage, as well as salicylic acid, the precursor of aspirin. They’re also rich in vitamins A and C, and for people who didn’t have access to fresh veggies in the winter, an early spring salad of violet leaves was a very good idea. The flowers themselves taste sweet, and they’re often made into syrup or even marmalade. You may have seen them in popular cookbooks, candied or crystalized and used to decorate pastries or cakes.

Sweets to the sweet, then—and even to the not-so-sweet. I’ll bet Hera was charmed by the bunch of violets she got from Zeus.

According to Greek legend, the peony began as a beautiful nymph named Paeonia. Apollo rather liked this innocent young girl, who was a bit of a flirt. One day, the two of them were carrying on in their usual bantering way when Aphrodite happened along. The goddess was not amused. She stamped her foot and called Paeonia a brazen hussy, a harlot and a strumpet. Apollo thought Aphrodite was overreacting, but he didn’t think it was a good idea to tell her so. Paeonia, who hadn’t meant any harm, was so distressed and shamed by Aphrodite’s unjust accusations that she blushed bright red. She was still blushing when Aphrodite changed her into a flower—the plant we know today as the peony.

The Chinese tell a similar story. It seems that there was a solemn young scholar who admired peonies and grew an entire garden of them, all pure white. He was watering them one day when a pretty young woman appeared and offered her services as a gardener. The scholar was swept away by her innocent smile and delightful laugh. He hired her on the spot, even though she didn’t have a resume. Under her tender care, the white peonies flourished, growing larger and more beautiful than before, while the young scholar—always so sober — learned to laugh and enjoy his garden in a new and delightful way.

One day, the scholar learned that his teacher, a famous monk, planned to drop in that afternoon for a cup of tea. Afraid of his mentor’s disapproval, the scholar hid the girl in a closet while the two men drank tea and discussed academic affairs. As soon as the stern-faced old monk had gone, the scholar ran to fetch the girl. But the locked closet was empty. She had vanished into thin air. He searched everywhere without success, until he came at last to the garden. There, he saw that all his white peonies were blushing red with the indignation and shame that the girl must have felt. He knew that her soul had fled into the flowers.

The Victorians, who were in some ways more censorious than the old Chinese monk, associated the peony with the shame of an illicit relationship. According to the elaborate language of flowers that was developed in the early nineteenth century, the red peony’s blush represented the fiery cheeks of a guilty and dishonorable nymph. Perhaps for this reason, red peonies fell out of favor with proper Victorian matrons, who preferred to grow pure white ones.

This story has no moral, only a happy ending. However the peony began, it is still one of our most beautiful plants. And that’s what counts, when you’re a gardener.

My father hated mullein. When I was growing up in the 1950s in Illinois, he used to pay me a dime an hour to cut this weed out of the fence rows. As I hacked with my hoe, I whiled away the hours by imagining that I might use the plant as a flaming torch to light my path through dangerous forests, or as an enchanted sword to ward off the goblins. Or that I might sew a magical shirt out of the plant’s flannel-like leaves.

Over the centuries, mullein has been used in all three of these ways—as a torch, a magical sword or rod, and as a piece of flannel cloth.

One of its old Latin names, Candelaria, goes back to the Roman occupation of Central Europe, when the soldiers stripped the leaves and branches from the tall plants and dipped them in tallow to be burned as torches.

In England, where mullein was called the candlewick plant, its stringy fibers were twisted and used as wicks for lamps and candles.

Another story has it that poor women were the chief users of mullein as a source for lamp wicks, hence, another name, hag’s taper. And during the last century, miners in the American West burned the stalks as torches in their mines. They called it the miner’s candle.

Here’s a mystery for you.

So what about that magic sword? One of mullein’s most interesting legendary uses is found in the works of Homer, where Odysseus holds off the sorceress Circe with a stalk of mullein, thereby avoiding the fate of his men, whom she had changed into swine. And still other folk names for mullein suggest the same idea. Jupiter’s staff, for instance, and Aaron’s rod—perhaps the magical rod that enabled Moses to part the Red Sea? And one story has it that the plant was the staff of St. Fiacre, the patron saint of gardeners.

As far as that magical shirt goes, that was just my own private fancy. But the leaves of mullein were once called old man’s flannel and used as a poultice to treat bronchial illness—sometimes with mustard smeared on them to increase their effectiveness. (Who remembers the mustard plaster?) And the large, fuzzy leaves were just the right size to put into shoes to stimulate circulation and keep the feet warm.

The mullein in my Texas garden makes me think of those hot summer days on that Illinois farm, and my torch, my enchanted sword and my magical shirt. What does it make you think of?

St. John’s wort had been around for centuries before the Christian era, but you wouldn’t know that by its name. For one thing, St. John the Baptist didn’t live until the time of Christ. For another, the word “wort”—an AngloSaxon word that means simply “plant”—didn’t come along until about the eleventh century. Before the plant was called St. John’s wort, it was known as Hypericum. This word was made up of two Greek words, hyper, meaning “over” and icon, or “image.” The plant was called hyper-icon or Hypericum, because it was hung over the statues of the gods to ward off any evil spirits that might want to possess the images. When the leaves were steeped in oil, the oil turned blood red. This red oil was used both medicinally and in purification rituals.

The idea that Hypericum could protect against an invasion of evil spirits was a persistent one. During the Dark Ages in Europe, it was used to drive out the devil from those who were thought to be possessed. It was also an important part of the rituals of the summer solstice, or Midsummer’s Eve, when bonfires marked the beginning of the sun’s descent toward winter darkness. Hypericum’s sunshine-yellow flowers were

gathered with special rites. The plant was then burned in the Midsummer bonfires or hung over doors and around the neck to guard against the menacing powers of evil.

When the Catholic Church moved into Europe, the priests wanted to control the pagan fire festivals, which sometimes grew into drunken parties. They sanctified the winter solstice by connecting it with the birth of Christ. To consecrate the summer solstice, they made it the birthday of John the Baptist. The Midsummer’s Eve bonfires became the “fires of St. John” and Hypericum became — of course — St. John’s wort. The plant was said to symbolize the sun that dispels the darkness and the Baptist who proclaimed the coming of the Light, the Son of God.

But the idea that St. John’s wort had the power to exorcise evil spirits was not entirely a pagan superstition. What might once have been called “possession” and treated with a tea made of Hypericum leaves might today be called clinical depression, and treated with St. John’s wort.

Think about this, when Midsummer’s Eve rolls around.

The next time you go to visit Beatrix Potter’s Hill Top Farm in the village of Sawrey in England’s Lake District, look up at the ledge under the second story window on the addition that she added to the house in 1906. You’ll see a thriving colony of houseleeks growing on the roof overhang. For most people, these plants are a mystery. Why are they growing there? But it’s no mystery for herbalists, who know all about the secret of the houseleeks.

Houseleeks (my mother always called this plant hen-and-chicks) are native to central and southern Europe and the islands of the Mediterranean. Houseleeks were considered sacred to Jupiter in Roman mythology and Thor in Teutonic. In both mythologies, it is said the gods’ pointed beards could be seen in the pointed leaves of this succulent. And since both gods were known to play around with thunderbolts, houseleeks were planted on the roof to protect the structure against lightning and fire.

In the Middle Ages, Emperor Charlemagne of France (who knew a thing or two about thunderbolts) commanded that every roof in his realm ought to wear some houseleeks. It was thought that this would not only protect them from storms, but also guard against misfortune and evil sorcery and ensure the prosperity of the inhabitants. And if you had a grudge against your neighbor, you went out after dark and stole the houseleeks off his roof.

The first written text of the medicinal use of houseleeks comes from Dioscorides in the first century. He recommended that the leaves be crushed and mixed with wine to get rid of intestinal parasites. The bruised leaves were used to treat burns and scalds. Split leaves were placed over corns, calluses, warts, ringworms and insect stings. The juice of houseleeks was used to treat shingles, eye irritations and earaches.

So now you can go home and plant a houseleek on your roof. When the neighbors ask why, just give them a mysterious look, suggesting you know something they don’t.

Pretty soon, every house on the block will be wearing a houseleek.

The opium poppy has been around for a very long time. Three millennia before the time of Christ, it was cultivated in Mesopotamia, where the Sumerians and the Assyrians knew it as the “joy plant.” Its effectiveness as a narcotic, a painkiller and a euphoriant was well known, and the dried, milky juice of the unripe seedpods was prescribed as a potent medicine by early Greek and Egyptian physicians. By the time the Romans withdrew from England, the opium poppy was known in Europe and had migrated eastward to India and China.

Opium came into its own in Europe in 1527, when a German doctor named Paracelsus mixed it with citrus juice and called it laudanum. Throughout Europe, his black pills became an increasingly popular painkiller and euphoriant. By the end of the century, Britain’s trading ships were returning from India loaded with opium for the medicine cabinets of the land. By the time morphine was first refined from opium (1803), the British East India Company completely controlled the poppy fields of India and the opium production around Calcutta.

IBut opium doesn’t just deaden pain, it is addictive—and that’s what led to war. British traders introduced opium to China in the late 1700s, and opium addiction rapidly became epidemic. The Chinese government tried desperately to keep the drug from entering the country, but the British East India Company defied its restrictions. Finally, in 1839, the Chinese government made a big drug bust, seizing some two-and-ahalf million pounds of opium. To enforce their right to sell opium to the masses, the British Home Office dispatched 16 warships. In brief but bloody battles, the Brits seized the cities of Canton, Shanghai and Nanking—and then it was all over. The victorious British got Hong Kong. In 1856, still attempting to stem the opium tide, the Chinese government renewed the war—and lost once again. This time, they were required to pay for their defeat by legalizing opium imports. It wasn’t until 1910 that the British yielded to pressure from the international community and finally agreed to end their opium trade. And it wasn’t until the year 2000 that Hong Kong was handed back to China.

The opium poppy has given us a powerful and effective medicine. Properly used, it relieved human suffering through thousands of years. But it is also an addictive drug with deadly consequences for its users, and society is still at war with those who illegally traffic in it.

t all started in the English spring of 1768, in the county of Shropshire, when Dr. William Withering rode out to make a house call on Miss Helena Cooke. Her illness confined the young lady to her home and required the good doctor to visit frequently. The two young people fell in love. He proposed marriage and she accepted.

Because of Miss Cooke’s confining illness, the engagement was a lengthy one. She filled the idle hours by painting watercolors of plants and flowers. As a medical student, Dr. Withering had found botany exceedingly dull and disagreeable, but his fiancée’s fascination with plants quite naturally charmed him. Since his medical practice took him on long horseback rides throughout the Shropshire countryside, he often brought back interesting specimens for her to paint. By the time they were married in 1774, Dr. Withering was as passionate about plants as was his new wife.

One subject of the doctor’s passion was the poisonous foxglove, known by its Latin binomial as Digitalis purpurea The year after his marriage, the doctor acquired a secret herbal recipe from an old Shropshire woman. The recipe, which contained foxglove and other herbs, was used to treat dropsy; the disease we now know as congestive heart failure. Dr. Withering began to experiment with this powerful herb, administering it in different forms and dosages and carefully observing its effect on his patients. He learned that the plant increased the strength and efficiency of the heart muscle without requiring more oxygen.

He also learned that the best effects were obtained from the leaves of a two-year-old plant, gathered just before it bloomed.

By 1780, the success of his clinical trials encouraged Dr. Withering to recommend foxglove to his fellow practitioners. Five years later, he published his now-classic study, Account of the Foxglove, and many physicians began to administer the herb. Unfortunately, some of them did not follow Dr. Withering’s careful practices.

Over the decades, after the publication of his book, a great many people died from the improper use of this powerful plant. But eventually, its administration was standardized, and Digitalis—as it is now called—became a safer medicine.

If you use Digitalis, you can thank Dr. Withering for making it possible, and you can thank his romance with Mrs. Withering for inspiring his interest in plants.

But while you’re enjoying the foxglove in your garden, do remember that it can be fatal. Grow it for its beauty, admire it for its life-saving potency, and give it all the respect it deserves.

eing stung by a nettle is no picnic. First it bites, then it burns—for a long while. Some nettles can cause death, and all can sting even when they’re dry. For example, when a plant museum was being moved out of London during World War II, a long-dead 150-year-old nettle stung one of the workers. That’s persistence for you.

Some etymologists say that nettle takes its common name from the Anglo-Saxon word noedl, or needle. Or it might come from the word net, which is derived from a verb meaning ‘to spin’ or ‘to sew.’ Before hemp and flax were introduced into northern Europe, nettle was the chief fiber plant. A fine-spun thread might be used to weave bed-linens, a coarse-spun yarn for sacking or sailcloth. Even after flax was available, nettle was preferred for fishing nets— stronger than flax, not as rough as hemp. Eventually, though, flax won out as a fiber plant because it could be grown and harvested more economically—and without biting.

Of course, you can always bite back. In England, the young plants were cooked and eaten like spinach. In Scotland, they were used in vegetable soup and cooked with leeks and broccoli to make nettle pudding. Nettle beer was also a favorite. One recipe calls for a bucket of nettles, a couple of handfuls of dandelions and goosegrass, and some ginger.

Nettle is rich in vitamins and minerals, so herbalists recommend it as a spring tonic and blood purifier. The powdered leaves were used to stop bleeding. And even the infamous sting had a medicinal use. Flogging with nettles was an old remedy for chronic arthritis. Some herbalists believe the nettles serve as a counterirritant— easing one pain by causing another—while others think that the histamines and formic acid in the stings operate as a pain reliever.

If you get stung and you don’t have arthritis, folk medicine offers a pain reliever. Remember the old saying: Nettle in, dock out? Rub those stings with some dock leaves. Where will you find them? Look around. That’s probably a dock, growing right beside the nettle. Nature likes to arrange things that way.

In 1985, Susan left her career as a university English professor and administrator and began working fulltime as a novelist. Her books include the best-selling China Bayles mysteries, the Cottage Tales of Beatrix Potter, and the

The Notable Native may be a new program from The Herb Society of America, but The Society has always had an abiding interest in the use and delight (and conservation) of native herbs. In 1965 several members of The Society wrote an article for The Herbarist in which they highlighted native plants. Members of The Herb Society of America’s native herb conservation committee continue to study and promote the use of plants which have always been around us, which have historically been useful to us, and which have provided balanced ecosystems for man and animal alike.

— Elizabeth Kennel, Botany and Horticulture Chairhe following seven brief articles deal with herbs native to our country from the East Coast to the Pacific. Each is written by a member of the bibliography committee whose unit is in the locality where the plant grows wild. As an herb each of these has an interesting history, often of use by the Native Americans who taught the colonists what to do with it. These seven herbs are only a sampling of the interesting lore of our native plants.

[Note: When reading these short articles, remember their historical context and the advances in botany and medicine, herbal and traditional, since their original publication. The article has not been changed from when it was originally published in 1965, only the taxonomy and references have been updated. — Editor]

Astiff-branched shrub which grows chiefly near the coast; narrow upright leaves crowded at the ends of gray twigs; dense clusters of small nutlets, their green surfaces thickly coated with grayish-white granular wax; “berries” and resinous leaves balsamic aromatic when bruised.

These are the ‘candleberries’ used by the early colonists in making bayberry candles—the ‘wood-galle’ of the Pilgrims. In his History of Virginia (1) Robert Beverley described “the myrtle bearing a berry, of which they make a brittle wax of curious green color . . and candles of pleasant aroma.” Peter Kalm (2) wrote of the “candle-berry tree” and use of its wax for candles, soap and sealing wax. Both noted that surgeons used the wax in salves or plasters.

In Cape Cod, Thoreau, writing of the bayberry and boiling berries for wax, added, “If you get any pitch on your hands in the pine woods you have only to rub some of the berries between your hands to start it off.” Our grandmothers often enclosed bayberries in little bags to wax their flatirons.

The water, left after skimming off wax from boiled berries, was sometimes used as a home remedy for intestinal disorders, a

gargle for sore throat, a mouthwash to heal sore gums, or to dye woolens a dull, fastcolored blue. The bark, and especially the root, are an astringent and stimulant; an old Native American remedy for toothache. Powdered, it was much used for diarrhea, jaundice, scrofula and dysentery. As snuff it was used for catarrh or nasal congestion. It was applied externally for ulcers, bruises and cuts.

As a condiment, the dried leaves add a pleasing flavoring to soups, stews and gravies. Used as a substitute for bay-laurel, it has a distinctive savour of its own.

Branches of the silver-gray berries, often combined with red alderberries, are much used for Christmas decorations, and to many, the burning of fragrant bayberry candles is a cherished tradition.

“A bayberry candle burned to the socket brings luck to the house, and gold to the pocket. (3)”

American pennyroyal, one of the many mints common to our country, is similar to the English pennyroyal only in flavor and strong aroma, but owes its great use and flavor to it. Hedeoma comes from the Greek, hedys (sweet) and osme (scent). To some it is known as stinking balm for its effect on mosquitoes and is used at unscreened windows to discourage them.

The small branching plant is an annual whose penetrating aroma announces its whereabouts. It is common on dry slopes, roadside banks, woods and fields. Any walk through the woods or countryside is more comfortable if a bunch of pennyroyal is carried or the plant crushed and rubbed on legs and arms.

This herb has been continuously used by our people. It was one of the most cherished herbs of Colonial days, a “hanging herb,” always found in quantities in attics for medicinal use. Even today it is in demand, the distillation of its oil being carried on in some eastern states, and both pharmacy and folk remedy recognize its medicinal value. The Pennsylvania Dutch use it an as aid to indigestion, “brings warmth to the

old, relief of stomach to the young.” In early days it was used for flatulence, colds and pneumonia. The Native Americans used it for obstructed menses, thereby came the name squaw mint. It is a stimulative and carminative. From an old Western Pennsylvania family record the following uses are listed: in food, “½ cup of pennyroyal added to 50 lbs. ground meat for liver pudding” to discourage vermin, “put a bunch of pennyroyal in a hen’s nest when hatching” for the spiritual, “use sprigs of pennyroyal in the Advent wreath.” It was used from the earliest times in our country to the present day and it might almost be said of it, like its cousin dittany, “everybody cured everything with it.”

Sassafras has a long history as beverage, remedy and condiment. It is a scraggly tree with distinctive mittenshaped leaves, three lobed and oval, which turn orange in fall. Its Asiatic relatives are sources of spice and camphor. An aromatic oil pervades the whole tree which gives forth a fragrance from the leaves, twigs, roots and bark.

Explorers brought back reports of this tree which the Native Americans said cured so “many evilles.” In 1577 Dr. Monardes (1) described sassafras as a remedy for “fevers,” “griefes of the breast and head” and that it “comforteth the liver and Stomacke,” and was good for “them that bee lame.” Sea captains for years brought back quantities of the root to Europe.

Later as sassafras failed to cure all these ailments, it became less in demand in Europe. The colonists continued to value it, to thin the blood, prevent colds, check fevers and for rheumatism. The Iroquois taught them to use the powdered leaves in poultices for wounds, and the Mohawks to extract the pith and soak it in water for sore eyes.

The colonists used sassafras sticks in hen roosts to repel lice, on bedsteads to keep away bedbugs, (and the wood for) long

lasting dug-out canoes, ox-yokes, barrels and fence posts. An extract from the bark dyed wool orange.

Sassafras tea, called “Saloop”, was sold on London street corners. Commercially it is used in the coarser perfumes, for scenting the cheapest grades of soap, and to flavor root beer, sarsaparilla and candies.

In Louisiana, learned from the Choctaws, young leaves, dried and powdered, make filé, to thicken and flavor stews and soups. Young leaves are delicious in salads.

You can enjoy sassafras tea. A teaspoonful of root bark, cut in small pieces, is steeped for a minute or two in boiling water. It is delicious with milk and sugar or good maple syrup.

ur fields, pastures, and roadsides are lovely each June and July with the abundantly blooming prairie rose— Rosa setigera. It is one of a number of “wild roses” which grow all across our nation. It is so typically American that the French botanist André Michaux, to whom it is credited botanically, at first named it “Rosier d’Amerique.” It is either a very prickly shrub or a mildly climbing plant. The ovate leaflets are usually three in number, rarely five; the almost scentless five-petaled flowers are borne in corymbs, rose color when they open but fading almost to white. The hips are round and red and of medium size. It is the only native American rose with a tendency to climb. Because of its vigor, its beautiful foliage and abundant flowers, its climbing proclivities, its adaptability, and most important, its lateness of bloom, R. setigera was used as a parent to produce climbers suited to American climates. Samuel Feast of Baltimore (1) used R. setigera to produce several fine first-generation hybrids. For two of these he received the first medals awarded in America for new roses, namely his “Queen of the Prairies,” (Rosa setigera × probably a form of R. gallica), and “Baltimore Belle” (R. setigera × probably a Noisette). These were

Linnaeus named the group of lobelias for Matthias Lobel, a Flemish botanist. Because of its small, pale blue flower borne at short intervals in spike-like racemes, this species is perhaps the least attractive, no others having so inflated a seed vessel. This annual herb grows in the Blue Ridge Mountains where so many crude drugs are collected. All parts are medicinal, but according to Eberle, the roots and inflated capsules are most powerful. It is one of the most valued remedial agents of the American flora.

The activity of lobelia is dependent on a liquid alkaloid first isolated by Proctor in 1838(1) and named lobeline. Pereira (2) found the peculiar acid which he named lobelic. A powerful, nauseating emetic, a poison in large doses, it is prescribed

produced in 1843. In writing of R. setigera, Robert Buist (2) said in 1844, “Its constitution is such that it will bear without injury the icy breezes of the St. Lawrence, of the melting vapours of the Mississippi.”

in spasmodic asthma, whooping cough and bronchitis. Cigarettes or the burning leaves are inhaled for the same purpose. Its odor and taste resemble tobacco.

Dr. Millspaugh (3) says its principal use is upon the pneumograstric nerve and is a cure of pertussis, spasmodic asthma, croup and gastralgia. Its secondary importance is in causing general muscular relaxation, curing strangulated hernia, titanic spasms, convulsions, hysteria, and mayhap, hydrophobia. Its third is upon mucous surfaces and secretory glands, increasing their secretions.

The scientific evidence of the dangers of cigarette smoking has been mounting as a major cause of lung cancer and a contributing cause of other deadly diseases. Teenagers, too, are becoming smokers. It is hoped that tobacco users may realize the jeopardy in which they are involved and be educated to the virtue of Lobelia inflata

Bernadine G. Neil, Member at Large

Yucca, a genus of the family Asparagaceae, is found growing from the Southern Atlantic coast to the Southern Pacific, but is most abundant in the Southwest, where it thrives under conditions of drought, wind and sudden temperature changes.

These bold-looking plants have stiff, sword-like leaves and pale cup-shaped flowers borne in erect panicles. Blooming at night, their great plumes grow in the moonlight and lure the moth, Pronuba yuccasella, for pollination. This then is a perfect example of symbiosis; an insect and a plant absolutely dependent upon each other. Members of this group are commonly known as soapweed, Spanish dagger, Our Lord’s candle, Spanish bayonet, wild date, amole, datil, palmilla and under many other names.

Beginning in April, the stalks of fragrant white blossoms of Yucca baccata rise more than six feet above the crown of thick leaves. Y. elata, the palmilla of New Mexico, Texas and Arizona, is the tallest and most spectacular of the narrow leaf yuccas. In West Texas, the huge Y. faxoniana stages a thrilling Easter show in Big Bend National Park. Most grotesque of all is the Joshua tree, Yucca brevifolia, of the Mohave Desert.

Grindelia, a coarse, sticky herbaceous plant with gummy exudations grows on dry hillsides of inland California. There are several species in the Southwest with similar uses. Grindelia camporum grows to two feet with alternate leathery serrate leaves and solitary heads of yellow ray and disk flowers. The upper third of the plant is harvested in July and dried. It is named for a European botanist.

Long before the Spaniards came to California the Native Americans knew the “virtues” of the gum plant. They boiled the root and drank the tea for liver troubles. Other internal uses were from decoctions of the gummy buds, flowers and leaves as a blood purifier and to relieve colds, nasal congestion, throat and lung troubles. For toothache the decoction was held in the mouth for a time but not swallowed. The crushed plant was used externally for running sores, burns, blisters, poison oak or ivy infections. Hot baths with the plant immersed were used for paralysis. Dried sprigs sprinkled with hot water and wrapped in cloth were held on the aching parts for “cold in the bones.” Many of these uses were adopted by the Spanish settlers.

It was not until late in the nineteenth century that Grindelia was recognized by medical science. It is now listed in Merck and the U.S. Dispensatory. From this native plant grindelol, robustic acid and tannin are extracted. It has practically the same uses as our Native Americans knew so long ago. Current uses listed are stimulative, expectorant, sedative and anti-spasmodic.

Apothecaries’ jars are still found labeled GRINDELIA. And recently, in an orange grove being changed to a suburb in Mexico, an old man was seen harvesting the wild Grindelia for his ills.

References

Bayberry

A Navajo legend describes how yuccas were created. The Slayer of Alien Gods, upon killing the Tracking Bear Monster, told him that since he has been evil all of his life, upon death he must furnish sweet food to eat, foal for cleansing, and thread for clothing. The Slayer then threw a piece of the Bear’s head to the west where it became Y. baccata, whose fruit is edible. Another piece he threw to the south and it grew into maguey, Agave americana which is used for fiber. A third piece remained, for all yucca species are used for cleansing.

Since the first monograph on yucca by Engelmann in 1873(1), the genus has interested botanists and now especially fascinates Herb Society members studying native plants.

1. Library of Southern Literature. 1705. “The History and Present State of Virginia, In Four Parts.” London, printed for R. Parker. Accessed 31 July 2012. http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/beverley.

2. Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University. 1937. “Peter Kalm’s Travels in North America, I-II.” Benson, Adolph, ed., New York. Accessed 31 July 2012. http://www.evolutionsmuseet.uuse.

3. “Traditional Colonial Poem.” Accessed 13 August 2012. http://eHow. www.ehow.com/about_5057238_bayberry.

Yuccas of the Southwest

1. Biodiversity Heritage Library. http://biodiversitylibrary.org/.

Sassafras

1. Ancient Lights. 1577. Monardes, Nicolás, Joyful News out of the New Found World, trans. John Frampton. Accessed 13 August 2012. http:// ancientlights.org/gosnold.html.

Prairie Rose

1. Help Me Find. Accessed 13 Aug 2012. http://www.helpmefind.com/ rose

2. Help Me Find. Accessed 13 Aug 2012. http://www.helpmefind.com/ gardening.

Indian Tobacco

1. Botanical. Accessed 13 Aug 2012. http://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/l/lobeli38.html 2.

2. Rosenlake. Accessed 13 Aug 2012. http://www.rosenalke.net/er/ Grieves_Lobelia.html.

3. Wikipedia. Accessed 13 Aug 2012. http://wikipedia.org/wiki/ Charles/Frederick_Millspaugh.

Bibliography

Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). http://www.arsgrin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/queries.pl?language=en

Bown, Deni. The Herb Society of America New Encyclopedia of Herbs and Their Uses New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2001.

Duke, James. http://www.greenpharmacy.com or www.ars-grin.gov/ duke.

Engelmann, George. “Notes on the Genus Yucca, (Trans.)” St. Louis Acad Sci. Vol III (1873): 17-54. Accessed July 31, 2012.

National Academy of Science. http://www.nasonline.org/publications/ biographical-memoirs.

Sumner, Judith. American Household Botany: A History of Useful Plants, 1620–1900. Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2004.

Full page: Chenopodium

Insert top: Chenopodium quinoa in flower Christian Guthier-Wikimedia Commons

Insert Middle: Colored quinoa M. Herman-Wikimedia Commons

Insert Bottom: Chenopodium quinoa greens Christian Guthier-Wikimedia Commons

Opposite page: Chenopodium sp. Robin Siktberg

While researching the introduction of herbs and culinary plants to Texas, I repeatedly encountered references to the goosefoot family, Chenopodiaceae. There were chenopods for foods, for medicines, for dyes and body-coloring. Clearly an intriguing family about which I knew little.

Chenopodiaceae is a broad family of familiar vegetables and long-used weedy plants. The family name reflects the resemblance of the leaf shape to a goose footprint (Greek: chēn, goose; podion, diminutive of pod-, foot). Several common vegetables of European, Eurasian or African origin are chenopods: beets, orach, Swiss chard and spinach. American chenopods include such plants as greasewood, quinoa and saltbush. A look at the chenopods found in the National Herb Garden, in Washington, D.C., speaks to the variable uses of the plants:

Dye garden: Chenopodium album (lamb’s quarters), bright yellow and green dyes

Colonial garden: Atriplex hortensis (garden orach), medicinal Culinary garden: Chenopodium ambrosioides (epazote, American wormseed), flavoring for beans and stews

The Chenopodium genus contains many of the plants I encountered in my Texas research. Hortus III notes there are approximately 250 species occurring worldwide. Plants are usually mealy or glandular and often odiferous. The plant height varies from one foot to nearly ten feet. Leaves are alternate, ranging in length from three to five inches.

The perfect flowers are small and inconspicuous, born in spikes or panicles. The fruits are small as well, enclosed in a dryish, persistent calyx. For those species of economic value the density of flower panicles and leaf size are influenced by selection as well as by location. The pollen tends to be windborne with little need for insect pollination. The fruits are thin-skinned, and the seeds germinate quickly upon contact with moisture. This allows the “weedy” members of the family to spread quickly while falsely contributing to the impression that some cultivated species (e.g., Chenopodium quinoa) had limited viability. Early seed collectors did not realize that due to less than ideal storage, the seeds gathered in South America had germinated during the ocean journey back to Spain (1).

The most familiar, and most documented, “grain” plant is quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). Since Chenopodium is not a grass, its seed is not a true grain, although it is used in much the same way. The term “pseudocereal” or “pseudograin” is often used for these kinds of plants. Hugh Wilson, a botanist at Texas A&M University, entitled his 1983 Herbarist article “Quinoa Significant Past–Questionable Future.” Quinoa’s future use as a health food seems assured with red, black and tan quinoa available both packaged and in bulk and quinoa flour is available in standard grocery stores. Quinoa fruit offers up to 22% protein, iron, calcium, and vitamins B and E; the leaves add vitamin A (1).

plants may be Mexican domesticated forms. Smith (1984) concurs and notes that fruits dated to 2,000 years ago found at an Alabaman site provide either evidence of Mexican plant introduction or “independent domestication.”

A close “cousin” occurring as a wild plant is C. berlandieri ), pitseed goosefoot. Remarkable Plants of Texas describes the Pre-Columbian domestication of pitseed goosefoot. The Aztecs bred the plant to have denser, more compact flower heads with simultaneous fruit set and maturity. He cites a may have been included with amaranth in the pre-Columbian Aztec annual tribute of seed grains (2). Despite the highly nutritious qualities of the plant, the Spanish in Mexico appear to have discouraged its use in the same way they suppressed quinoa’s use, due to its use in pagan religious ceremonies and/or their unfamiliarity

There is archaeological evidence that C. berlandieri was an important grain for prehistoric Native Americans living in the Southwest and Southeast.

Wilson (1981) identified seeds found in Ozark Bluff Dweller excavations as C. berlandieri , a “product of Mexican agriculture.” He also suggested that other specimens previously thought to be from wild

Of interest in addressing this question are the recent studies exploring the genetic relationship of C. berlandieri to C. quinoa. Wilson describes the ease of cross-fertilization between the species. A sampling of wild C. berlandieri growing around fields of cultivated C. quinoa showed 30% to be crop/weed hybrids (3). In another study of Chenopodium spp. relationships, molecular data grouped C. berlandieri with C. album while eight cultivars and two wild varieties of quinoa formed an independent group. Additionally the authors noted that there was a low level of infraspecific variation within C. quinoa (4).

In the wild, C. berlandieri now survives mainly in the highlands of central Mexico. Turner lists three cultivars:

‘Huauzontle’—similar to broccoli

‘Quelite’—similar to spinach

‘Chia’—a grain crop with large fruits.

A recent study identified C. berlandieri among the principal non-cultivated greens eaten by the Mahazua living in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in Mexico (5).

The Navajo and Akimel O’odham (Arizona) boiled the young tender plants. The Tohono O’odham (Arizona) and tribes of southern Appalachia used a variety of Chenopodium species in this way. Turner notes, “At least until recently, residents of all nineteen pueblos of New Mexico boiled or fried goosefoot greens” (2).

Chenopodium album, lamb’s quarters or pigweed, is one of the weedy, culinary and medicinal plants in the genus.

Lamb’s quarters has a worldwide distribution. An annual with an average height of three feet (but with a potential of reaching ten feet), the plant has triangular leaves up to four inches in length. Flower spikes are dense with small light green flowers, each ultimately producing one black seed. The undersides of the leaves often have a silvery appearance leading to another common name, white goosefoot. Lamb’s quarters is not used in the landscape because of its aggressively weedy nature and, as Garrett notes, it “gets pretty ugly as it matures” (6).

The leaves contain iron, protein, and vitamins A, B-2 and C. Authors frequently describe lamb’s quarter’s nutritional value: “More plentiful in calcium, vitamins A and C than spinach”(7) and advising “Eat Your Weedies!”(8). Several ethnobotanical references note that Native Americans ate lamb’s quarters to remain healthy and to treat aching limbs and joints. The high vitamin C content certainly could have provided antiscorbutic actions, including management of scurvy’s accompanying joint and muscle aches. The stems and leaves may be boiled like spinach and topped with vinegar or pepper sauce, stir-fried in butter or eaten raw in salads. Turner notes that the seeds (fruits) match corn for calories but are higher in protein and fat.

In Europe lamb’s quarters has been used since Roman times. Virtually all North American Indian groups have a history of using lamb’s quarters leaves and stems – fresh when available, and dried or even frozen for future use. The flour from the dried ground fruits is likened to buckwheat (2). Mixed with cornmeal and formed into balls, one might steam them or cook them in a broth or vegetable stew. Pioneers, with their wheat-based culinary histories, added the seeds to breads, pancakes, muffins and cookies.

Additional minor uses of C. album demonstrate its routine use in early people’s daily lives. The Pawnee Indians used lamb’s quarters to paint bows and arrows (9). For the Ramah Navaho a piece of stem made into a snake figurine acted as a charm or treatment for snake bites (9).

Dysphania chilensis (syn. Chenopodium ambrosioides) is another chenopod with a culinary and medicinal history. Common names include Mexican tea and American wormseed, but in Texas it’s epazote. The plant is a strongsmelling, upright annual or short-lived perennial with spear-shaped, toothed leaves growing to five inches long. D. chilensis grows to six feet high with a horizontal spread of nearly three feet. Black seeds follow the summer bloom of tiny, light green flowers. It self-seeds readily and as Garrett notes, “Once established, it will come back from seed forever except in thick mulch”(10). While native to tropical America, it is now widely naturalized into subtropical areas.

A traditional use of epazote is in the bean pot ( frijoles or dried beans) as it is rumored to reduce flatulence. In Mexican and Guatemalan cooking, the leaves may be added to stews, and occasionally the seeds are pounded and used as a dry rub on meat.

D. chilensis has a stronger medicinal history. Oil of Chenopodium, extracted from the leaves and seeds, contains a broadspectrum vermifuge (terpene ascaridol) toxic to Ascaris spp. (pig and human round worms). Folk medicine accounts commonly note wormseed’s use as a vermifuge in veterinary practice as well as for humans. One source even notes: “To expel worms with more success plan to give the above during a full moon, as the tenants are more active at this time”(11). On Southern plantations, it might have been an annual event to treat both slave’s and plantation owner’s families for roundworms and tapeworms (12). Further medicinal uses are as an antispasmodic (hence, for relief from menstrual cramps), a small daily dose to overcome hysteria and all other things from aphasia to tinnitus and tonsillitis.

Lesser Known

Jerusalem oak goosefoot ( another aromatic plant of the genus.

The Thompson Indians of British Columbia created a variety of uses: stems and leaves wound into necklaces, stems used in basket weaving, leaves stuffed into pillows and small bags which were then tied to their clothes as a scent (13). The Cherokee drank a cold infusion for colds or to treat worms and moistened a cloth for external application to relieve a headache. A warm infusion from the root treated fevers (13).

We can appreciate the widespread nature of and the clever use of local resources by looking at Northern native groups. The fruits of blite goosefoot or strawberry spinach (C. capitatum) supplied rouge for lips and cheeks, a temporary tattoo for clan symbols, coloration for animal skin clothing, and children’s paints (native groups from Wisconsin to British Columbia to Alaska). Even a mash of the plant tops provided writing ink (14).

Chenopodium album is a host plant for a number of butterflies and moths, including the virgin tiger moth (Grammia virgo ). Butterfliesandmoths.org

where they are not native. It is this ease that has created a problem for controlled agriculture. D. is included in the pan-European inventory of alien species with concerns related to potential harmful impact on agriculture, waterways and forestry: “Notorious invasive alien weeds are of major economic significance, e.g. Mexican is close behind in its classification as a weed. Adding to this concern is its herbicidal resistance (18).

C. album is a major weed for Indian many parts of India it is pulled Folia Geobotanica studied the on the growth of sugar beets and shaded out sugar beets resulting in decreased growth, but the wheat grew more quickly than the lamb’s quarters and was not affected (20).

C. leptophyllum, narrow-leaved lamb’s quarters, carries the most romantic of histories. Matilda Coxe Stevenson tells her readers that “The Zuñi declare that the seeds of this plant, with those of another plant (Artemisia carruthii), also called K/ a’tsanna (k / a, k / a’we seeds; tsan’na, small), were among their principal foods when they first reached this world.” (15).

Lest we think that the goose-footprint looms large only for humans, we need to be aware that other populations in nature have come to use the chenopods. C. album is a host plant for a number of butterflies and moths, e.g., Western pygmyblue (Brephidium exilis), the common sootywing (Pholisora catullus), and virgin tiger moth (Grammia virgo) (16). Further, the seeds and greens feed birds and grazing wildlife.

From the plant’s point of view, the genus has been very successful. They frequently, and with ease, naturalize in areas

In their respective books, Bown (21) and Garrett (10) both note antifungal and/or insecticidal properties of D. chilensis. Epazote tea is used externally for athlete’s foot and as a spray for minor insect pests in the garden. Studies in the Journal of Chemical Ecology and Plant and Soil have demonstrated the fungitoxicity of C. ambrosioides against Aspergillus spp, Fusarium spp. and Rhizoctonia solani (22, 23). In particular the last is known to contribute to damping off of some seedlings.

Chenopodium spp., particularly C. album and C. quinoa, are being explored as potential plants to extract heavy metals such as iron, zinc, copper and nickel from contaminated soils (24). Following their research, Bhargava et al. suggests that this phytoextraction occurs even when the soils show a low heavy metal concentration. They recommend continued study of other species and suggest this as a goal in plant breeding efforts.

Referring back to Dr. Wilson’s 1983 article in The Herbarist, many Chenopodium species, not just C. quinoa, have had a significant past; they appear to be facing a significant future as well.

CAUTION Chenopodium album and Dysphania chilensis are both listed on the FDA Poisonous Plants data base (www.accessdata.fda.gov/ scripts/Plantox) as having potential harm to humans, pets and livestock. Potentially toxic substances include oxalates and saponins. Descriptions of their culinary uses are for educational purposes only and carry no recommendation for their utilization.

References

1. McCamant John F. 1992. “Quinoa’s Roundabout Journey to World Use.” In Chilies to Chocolate, Food the Americas Gave to the World edited by Nelson Foster and Linda S. Cordell, 149-161. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press.

2. Turner, Matt Warnock. 2009. Remarkable Plants of Texas Uncommon Accounts of our Common Natives. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press: Austin.

3. SpringerLink. 1993. “Abstract of Wilson, H. and Manhart, H., Crop/Weed Gene Flow; C. quinoa Willd. and C. berlandieri Moq.” Theoretical and Applied Genetics 86: 642. Accessed January 11, 2011. http://www. springerlink.com.

4. SpringerLink. 1999. “Abstract of Ruas, Paulo M. et al., Genetic Relationships Among 19 Accessions of Six Species of Chenopodium L., by Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA fragments (RAPD).” Euphytica 105:25. Accessed January 11, 2011. http://www.springerlink.com.

5. SpringerLink. 2007. “Abstract of Farfan, Berenice et al., Mazahua Ethnobotany and Subsistence in the Monarch Butterfly Reserve, Mexico.” Economic Botany 61:173. Accessed January 6, 2011. http:// www.springerlink.com.

6. Garrett, Howard. 2001. Herbs for Texas. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

7. Cusumano, Camille. 1989. The New Foods New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

8. Caduto, Michael J. and Bruchac, Joseph. 1996. Native American Gardening Stories, Projects and Recipes for Families. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

9. University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany Database. “Chenopodium album.” Accessed January 6, 2011. www.http://herb.umd. umich.edu.

10. Garrett. op. cit., 90-91.

11. SpringerLink. 2007. “Abstract of Lans, C. et al., Nonexperimental Validation of Ethnoveterinary Plants and Indigenous Knowledge and Use for Backyard Pigs and Chickens in Trinidad and Tobago.” Tropical Animal Health and Production 39: 375. Accessed January 21, 2011. http://www.springerlink.com.

12. Sumner, Judith. 2004. American Household Botany a History of Useful plants 1620–1900. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

13. University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany Database. “Chenopodium botrys L.” Accessed January 6, 2011. www.http://herb.umd. umich.edu.

14. University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany Database. “Chenopodium capitatum L. Ambrosi.” Accessed January 6, 2011. www.

http://herb.umd.umich.edu.

15. Stevenson, Matilda Coxe. 1993. The Zuñi Indians and Their Uses of Plants (1915 report). New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

16. Illinois Wildflowers. Accessed January 11, 2011. www.illinoiswildflowers.info/weeds/ plants/lamb_quarters.htm

17. SpringerLink. “Abstract of Philip E. Hulme et al., Invading Nature.” Springer Series in Invasion Ecology, volume 3: Handbook of Alien Species in Europe Accessed January 21, 2011. http://www.springerlink.com.

18. Weed Science Society of America. “International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds.” Accessed January 21, 2011. www.wssa.net.

19. SpringerLink. 1977. “Abstract of H. N. Shahi., Studies on the Chemical Composition of Chenopodium album L.” Plant and Soil 46: 271. Accessed January 22, 2011. http://www.springerlink.com.

20. SpringerLink. 1990. “Abstract of Tomaš Frantik et al., Interactions of Two Species of the Genus Chenopodium with Two Production Plants–Sugar beet and Spring Wheat.” Folia Geobotanica 25: 137. Accessed January 16, 2011. http://www. springerlink.com.

21. Bown, Deni. 2001. The Herb Society of America New Encyclopedia of Herbs and Their Uses. London, U.K and New York: Dorling Kindersley

Limited.

22. SpringerLink. 2008. “Abstract of Carolina M. Jardim et al., Composition and Antifungal Activity of the Essential Oil of the Brazilian Chenopodium ambrosioides L.” Journal of Chemical Ecology 34:1213. Accessed January 22, 2011. http://www.springerlink.com.

23. SpringerLink. 1983. “Abstract of N.K. Bubey et al., Fungitoxicity of Some Higher Plants Against Rhizoctonia solani.” Plant and Soil. Accessed January 22, 2011. http://www. springerlink.com.

24. SpringerLink. 2008. “Abstract of Atul Bhargava et al., Chenopodium: A Prospective Plant for Phytoextraction.” Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 30: 111. Accessed January 21, 2011. http://www.springerlink.com.

Bibliography

Smith, Bruce D. “Chenopodium as a Prehistoric Domesticate in Eastern North America: Evidence from Russell Cave, Alabama.” Science (1984) 226: 165-167.

The Staff of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium. Hortus Third. New York: Macmillan, 1976.

United States Department of Agriculture Plant Database. http:// plants.usda.gov

Wilson, Hugh. “Domesticated Chenopodium of the Ozark Bluff Dwellers.” Economic Botany (1981) 35:233-239.

By Henry Flowers

By Henry Flowers

In May of 2012, The Herb Society of America held its Educational Conference and Annual Meeting of Members in Austin, Texas. Among the herbs celebrated at the meeting was the rose. This conference, the wonderful HSA Essential Guide to the Rose, and many studies and presentations by HSA members throughout the year have taught us that the rose is an herbal plant of much merit. Beyond a doubt, it is a plant that is extremely useful and which brings immense delight to all of our senses. While

its time as herb of the year is ending, the rose, a timeless treasure, will continue to sail gracefully onward with her head held high and her trailing scent warming our hearts.

The rose is believed to have originated in Asia, most likely in China, more than 35 million years ago (8). It spread throughout the Northern Hemisphere and was quickly adopted as a favorite by most cultures. The rose has been an important part of Chinese gardens and culture since as early as 2700 BCE (3). In more modern times, western civilizations utilized the wealth of native Chinese roses to breed

remontancy (repeat blooming), new colors and new scents into the rose, which led to the explosion of new varieties from the early nineteenth century to the present day (7).

At the time of her death in 1814, the Empress Josephine of France had about 250 rose varieties planted in her garden, representing most of the roses in cultivation at that time (5). Today there are many thousands of varieties available in commerce, while many others have sadly been lost from cultivation (7).

In India the rose has long been highly popular. It was here that the rosary, a string of beads used to help with memory and concentration while reciting devotions, was first created using rose buds or hips and later beads made of kneaded and molded rose petals (6). These strung beads, now more commonly glass, wood or plastic, are still used by many in the Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim faiths. Lakshmi, an important Hindu goddess associated with good fortune, love and beauty, is believed to have been born of a rose comprised of 108 large and 1008 small rose petals. In India, just as in most of the rest of the world, the rose plays an important symbolic role in weddings. Flowers are used lavishly in the ceremonies, and the bridal bed is often strewn with rose petals and rose garlands (6). The rose is believed to bring joy and love in addition to fertility.

her works. She was credited with first referring to the rose as the “Queen of Flowers” in 600 BCE, but it is now known that this appellation is from Leucippe and Clitophon by Achilles Tatius of Alexandria (late second century CE) and translated by Elizabeth Barrett Browning in her “Song of the Rose” (5). Here are the first four lines:

“If Zeus chose us a King of the flowers in his mirth, He would call to the rose and would royally crown it, For the rose, ho, the rose! is the grace of the earth, Is the light of the plants that are growing upon it.”

Thus, it is no wonder that in ancient Greece the goddess of love and fertility, Aphrodite, is associated closely with the rose, which has long been known as the “blossom of Aphrodite.” Legend says that it was her blood, dripping from a rose prickle during her flight to the wounded and dying Adonis, that changed the original white rose to red. On a famous Greek island, the rose became so popular that it was named Rhodes in her honor. The Greek poetess Sappho, of the island of Lesbos, referred lovingly to the rose in many of

In Egypt the rose has been found in depictions on the walls of royal tombs dating back as far as the fifteenth century BCE (1). The Egyptians associated the rose with Isis, goddess of fertility and motherhood. It was not until the time of the Ptolemaic pharaohs (who were of Greek descent) that Egypt, especially around Alexandria, became an important rose-growing area. The last pharaoh, Cleopatra VII, loaded her royal barge with rose petals in order to seduce the Roman general Mark Antony. Her plot was to gain his love and support, but even their combined efforts were not enough to keep the might and wrath of the Romans at bay.

The Romans were infatuated with the rose. It is said that they created the first greenhouses, with roofs of selenite and piped in heat, in order to force roses into bloom out of season (roses at that time were still only spring bloomers). They would create garlands of rose blossoms to decorate for festivities, especially triumphs, and would crown victors with wreaths of roses, much as the Greeks traditionally did with parsley or bay laurel. In honor of the conquering of the known regions of Northern Africa, the Roman VIII Legion was given permission to have roses emblazoned on its shields.

With time, the use of roses in Rome became more and more elaborate. Rose petals filled cushions and nets that were hung

from the ceiling for parties. When the nets were released, the petals dropped onto the heads of guests below. Occasionally, there were reports of guests being smothered to death (5, 9). Roses displaced crops, and by the time of Emperor Domitian in 81 CE, the smell of roses in Rome was said to be overpowering. In addition to being used for decoration, the rose was used to flavor wines and a wide variety of dishes, especially entrees—additions that would make our modern culinary use of the flower seem quite weak in comparison. When fresh rose petals were not available near Rome, they were imported from Egypt or as far away as Persia, possibly in a dried form. Such decadence had an impact on the Roman economy, as a result, the poet and writer Martial (credited with creating the modern epigram) wrote, “Send us wheat, O Egyptians, we shall send you roses in return” (9).

As the Roman Empire slipped into decay, the Christian church began to grow. Since the rose was associated with the pagan goddesses Aphrodite and Isis, it is not surprising that the early church attempted to stamp out its use in ceremonies. Eventually, the peoples' love of the rose won out, and the church put it back into the spotlight by associating it with the Virgin Mary. Today that association is still strong; many paintings depict her with roses and statues of her are adorned with rose-filled garlands and bouquets.

martyred in Rome on February 14, 271 BCE by Claudius II. He was canonized in 337 BCE with his saint day as February 14th. Much later, the English author Geoffrey Chaucer would equate this day with the mating rituals of birds and human lovers in his "Parliament of Fowls" (5):

For this was on seynt Valentynes day, Whan every foul cometh ther to chese his make [choose his mate].

The introduction of the language of flowers into Europe from Ottoman Turkey in the eighteenth century would further associate the rose with this day. More roses are sold by florists on St. Valentine ’s Day than on any other.