A story defined by growth and change.

Contents 6 1920–1929 A Zoo Is Born 4 Introduction 16 1930–1949 Growing Pains 24 1950–1969 Building Boom 34 1970–1999 Caring and Conservation 46 2000–2022 Your Houston Zoo 63 Looking Forward 65 Acknowledgements and Attributions 64 Award-Winning Zoo

4

Cityscape of Houston looking south on Main St. at Capitol Ave., 1920

INTRODUCTION

In 1900, Houston was still a small town–Galveston and San Antonio were far bigger cities and Houston’s roads were more of a muddy concept than a paved reality–but large fortunes were already being made. The early wealth was rooted in the rich agricultural resources of southeast Texas. Cotton and lumber were king and built the fortunes of cotton merchants Monroe D. Anderson and William Clayton, lumber baron Jesse Jones, businessman William Marsh Rice, and real estate speculator George Henry Hermann. These men and others funneled portions of their fortunes into developing Houston’s civic infrastructure and their influence is still felt today.

On January 10, 1901, everything changed when the Spindletop well near Beaumont exploded and sticky, black drops of oil rained in a new era. Less than a century later, Houston would become the fourth largest and most diverse city in America, a global energy powerhouse and an incubator of international leaders.

George Hermann made his fortune when the early Humble Oil Company struck oil on his property. He donated the land that became today’s Hermann Park, home to the Houston Zoo.

5

(left) George Henry Hermann

1920–1929

A ZOO IS BORN: It All Started with a Bison Named Earl

It all began with a bison named Earl. In 1922, the city of Houston built a fence around a tract of land in Hermann Park to house Earl and an eclectic collection of animals. This small fenced area grew, and grew some more over the nearly one hundred years, and is now the fifty-five acre Houston Zoo we know today.

7

7

A ZOO IS BORN:

It All Started with a Bison Named Earl

1906

March 10: Sam Houston Park's collection of animals sold to Little Rock without community notice because of a poor economy. There is public outcry.

1906

Houston Mayor Horace Rice turns down an offer from a private collector in Michigan.

8

1908

March 1: Announcement of new nine-acre zoo and park at Beauchamp Springs “Temperance Park.”(Now Woodland Park, Heights).

EARLY 1900s

The city's first zoo on record started in Sam Houston Park in 1901. The park was a popular weekend spot with the zoo, gardens, and a natural history museum. The zoo didn’t last long and in 1906 it moved to Little Rock much to the dismay of Houstonians. To fill the gap, several small zoos opened in the early 1900s. In 1906, fire chief Thomas O’Leary started a zoo at the central fire station. The collection included goldfish, a panther, and three alligators. Other zoos included a nine-acre zoo in Highland Park (now Woodland Park, Heights) and a zoo at Louisiana and Rusk. These zoos eventually closed and in 1920 plans for the zoo in Hermann Park began to take shape.

1920s Houston rapidly expanded. Still tied to agriculture, the local economy fluctuated with harvests and drought, but oil speculation attracted adventurous newcomers and Houston’s population grew from 44,000 to nearly 385,000 between 1900 and 1930, a mind-boggling 760% increase. Money flowed; Houston began to flourish.

“All great cities are remembered chiefly by their parks,” wrote Houstonian essayist Oliver Allstorm in 1921 in a letter to the Houston Chronicle, “It is so the world over, people take pride in their parks and boast about them. … It is civic pride that makes a city great.” Houston hired George Kessler, landscape architect, engineer, and star designer of the City Beautiful Movement to design Hermann Park. Kessler passed in 1923, just after creating this draft sketch. The project was then picked up and led by Hare & Hare out of St. Louis.

(left) George Kessler (pre-Hare & Hare) pen-and-ink drawing of Hermann Park concept.

1918

Small zoo in Cypress run by Bill Sporn, where a local team’s mascot bobcat is sent for “training.”

9

“People take pride in their parks and boast about them. …” — Oliver Allstorm

IT HAPPENS TODAY!

First of many animals to call the city’s zoo home, Earl the American bison became a Houstonian on March 29, 1921, arriving via rail. He was part of a government herd in Cache, Oklahoma, established by the Bronx Zoo with just a few individual animals after the original population of 30–60 million American bison was reduced to just over 1,000 by mass slaughter, land encroachment, and sport hunting. Clarence Brock, superintendent of the Parks Department, penned Earl temporarily in the new Hermann Park.

In early 1922, newly elected mayor Oscar Holcombe made the Zoo a priority and on April 30, 1922, the Houston Post announced that the Zoo was finally a reality.

1921

First bison on display at Hermann Park in hopes that other animals would be added to have a “complete zoo.”

1921

Editorial calls for a zoological garden and park system.

1922

April 30: Houston Mayor Oscar Holcombe declares that the Zoo “is started today.”

1922

May 1: Announcement of a formal fundraising campaign to acquire animals.

10

(above) Earl the bison

1922

Hans the Elephant

Nellie, Houston’s thirty-two-year-old first elephant, arrived at her new home October 5, 1924. Head zookeeper, Hans Nagel, knew she needed another elephant and Houston citizens began funding “Nellie’s Dowry” to provide her with a companion.

Nagel journeyed to New York in early 1925 and arrived March 31 with the new elephant, a nine-year-old male named Jello who was renamed “Hans” after the popular zookeeper. Though much younger than Nellie, Hans’s arrival made headlines. A public wedding—veil and all—was performed by Nagel in Houston’s Luna Park, a massive amusement park just southeast of Houston Heights.

Nellie passed away in 1941 and young Hans remained alone for many years. He also continued to grow; the Zoo had trouble housing him because of his size. He had a reputation for lashing out at keepers and was confined much of the time until Lucille Sweeney spent a semester working at the Zoo to train him. They were a perfect match: Hans found peace and companionship and Sweeney found her calling, eventually becoming head elephant keeper for the Zoo. Hans passed away on April 27, 1979.

1924

September: The Houston Post-Dispatch initiates a campaign to purchase the city’s first elephant.

11

May 1: Announcement of birds coming and a cage being built. 1923 April 1: Two lions arrive; Russian bear arrives later in the month.

1924 September 1: Purchase of additional land for Hermann Park and zoo growth.

BUILDING A ZOO

Oscar Holcombe was a passionate supporter of the Houston Zoo, which was established during his first term as city mayor. Elected several more times, Holcombe served as mayor from 1921 to 1929, 1933 to 1937, 1939 to 1941, and 1956 to 1958. All major improvements to the Zoo before 1960 were made during his administrations.

Mayor Holcombe called on all civic clubs and organizations to help find animals for the new Zoo. The Houston Elks Club donated a breeding pair of elk in 1923, and it didn’t take long for Earl’s corner of Hermann Park to become crowded. By the end of 1922, the Zoo had thirty animals; in 1926 there were more than eight hundred.

Children Built the Zoo

“Houston’s zoo wants an elephant. An elephant costs about $2,500. Park Superintendent Clarence Brock thinks the school children might donate their pennies to buy one. The average gift would need to be about 9c if every school child helped.” —Galveston Daily News, November 26, 1922

Houston’s Zoo was a gift to the city’s children, and they gave their all to help it grow. Many of the animals, most notably elephant Nellie, arrived in Houston thanks to thousands of children emptying their savings into donation buckets. They and other civic leaders brought the young male elephant Hans from New York.

The local newspapers also held contests for children to name animals with winners getting the opportunity to not only name the new babies, but to also appear in the papers holding them. Sometimes called “The Lion Namer’s Club,” the contests were extremely popular, and letters poured in from children around the state suggesting names.

1925

March 31: Bull elephant named Hans arrives at the Zoo to join Nellie.

1925

July 1: Lions and tigers at Zoo have outdoor run under construction.

1925

Lion Namer's Club was started for children in an effort to name two cubs born at the Zoo.

12

Portrait of Oscar Holcombe

A male and female elk

Clarence Brock

Ambitious and politically savvy, Clarence Brock was the first Houston Superintendent of Parks, holding the position for thirty years from 1913 to 1943, through eleven mayoral administrations.

During his tenure, he expanded the number of parks from three to more than sixty, founded what is now the Houston Museum of Natural Science, and established the Houston Zoo.

Brock was an avid Zoo supporter, organizing and participating in expeditions to fill the collections of both the natural history museum and the Zoo. He was often accompanied by head zookeeper Hans Nagel, who was also an expert collector.

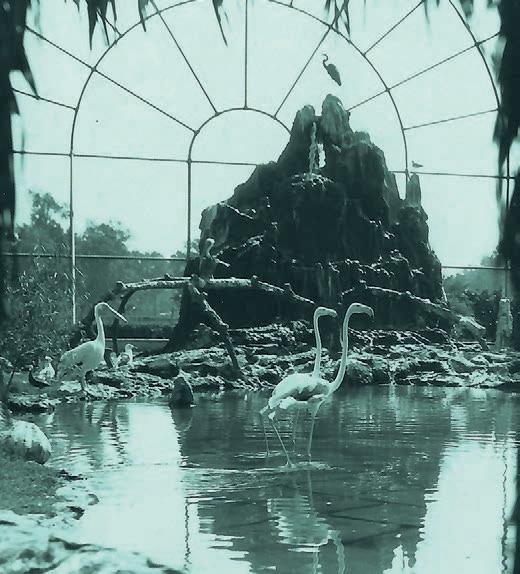

Brock designed the flying cage for the Zoo’s bird collection. It was one of the largest in the world. He hired noted Mexican sculptor Dionicio Rodriguez to create the faux bois concrete tree sculptures that still stand in the Zoo today (look for them in the flamingo exhibit).

1926

April 25: Houston Post-Dispatch article appeared: “Move to enlarge Hermann Park Zoo Launched Here” by the newly organized Houston Zoological society.

1926

June 1: Bird flying cage opened and the cost is $8,000—one of the largest in the United States.

13

(top left) Portrait of Clarence Brock

(top right) Bird flying cage (bottom)

A Zoo postcard from the 1920s. One of the Rodriguez sculptures is on the right

Galápagos Tortoises Thrive at the Houston Zoo

In early May 1928, 109 Galápagos tortoises arrived at the Bronx Zoo in New York as part of a global effort to save them from extinction. The tortoises were and still are severely threatened and on the edge of extinction. Tortoises were harvested by mariners and pirates as a meat source, and hunted by wild dogs, rats, and pigs introduced by those same mariners visiting the islands. The rescued tortoises were small and meant to be raised until big enough to survive predation.

Unfortunately, the tortoises didn’t tolerate New York’s cold weather, so fifteen were brought to Houston where they thrived. Houston’s climate was ideal except for the cold months, which is when Hans Nagel and the other zookeepers kept them in the primate house. When they first arrived, many of the tortoises weighed only twelve to fifteen pounds. By 1930, the largest was 166 pounds. Twenty years later, in 1954, each tortoise weighed between 365 and 400 pounds.

August 3: Zebu born at the Zoo. 1928

April 1: Sea lion pool is dedicated with water from the Pacific Ocean.

1928

July: Galápagos tortoises arrive in Houston. Fifteen young tortoises thrive in Houston’s climate.

1927

1927

14

Museum at the Zoo

Today’s Houston Museum of Natural Science was established in 1909 by the Houston Museum and Scientific Society and was housed in the city’s early auditorium, then moved to the Central Library downtown (now known as the Julie Ideson Building) for seven years. In 1929, the museum was moved to the Houston Zoo, where the two institutions shared collections. It remained at the Zoo until moving into its current building in 1969.

1929

1929

15

The Museum of Natural Science collection moved to the Houston Zoo.

June 1: First jaguars born at the Zoo.

1929

August 1: Baby leopards born.

Dan Smith, staff artist, examining the Museum of Natural Science collection at the Houston Zoo, 1956.

1930–1949

GROWING PAINS: Impact of the Great Depression

The Great Depression hit the United States hard, and the Houston Zoo was no exception. The Zoo narrowly avoids closure and made plans for modernization after World War II.

17

17

ECONOMIC DOWNTURN

By 1929, Houston’s population growth made the city the largest in the state. People came to Houston fleeing issues such as drought, the boll weevil, and efforts to reduce cotton acreage, which cost many families their farms. By 1930, Houston—with its surging infrastructure—offered an opportunity for a new life with work available for nearly everyone. Between 1920 and 1930, Houston’s population grew 111% from 139,000 to 292,000. Between 1930 and 1940, it continued to swell another 30% to 380,000 and beyond.

With such a meteoric rise, Houston did not immediately feel the crash of the New York Stock Exchange on October 29, 1929. Riding high on success, Houston’s leaders considered 1929 a good year; the large cotton crop sold for record prices and ship channel construction and shipping growth kept employment levels high. But like the rest of the country, Houston was eventually forced to adjust when the new financial reality of the Great Depression finally sank in and money became tight.

Houston leaders slashed the city budget, then slashed again. City staff saw their hours reduced; people were laid off. Institutions like the Houston Zoo, which were built on expectations of continued growth, were soon forced to survive with pennies rather than dollars. And, like much of the city’s infrastructure, the Zoo began to suffer, with buildings originally intended to be temporary instead becoming permanent and falling into disrepair.

GROWING PAINS:

Impacts of the Great Depression

1929

New financial reality of the Great Depression and money becomes tight—budget cuts.

1930

Hermann Park Zoo is the “most patronized, most educational” institution in the city.

18

Aerial of downtown Houston looking north, 1930

1932

Hay barn burns down in fire.

THE DEPRESSION HITS THE ZOO

Though money was tight, the city kept the animals well-fed while still being economical: hoofstock were fed hay reaped from empty park land and stored in a barn in Hermann Park. The barn and 1,700 bales of hay burned in 1932, but the loss was made up by harvesting hay on Rice Institute land (today’s Rice University.)

The Zoo’s first Big Cat House was intended to be a temporary wood-framed building until a more substantial one could be built. But times got tough and the facilities got less attention. One night in late January 1934, Hermann, the 600-pound African lion, fell through the rotted bottom of his cage floor. Surprised and scared, he jumped back and curled into his nesting box. The keepers surrounded the cages and kept watch all night until the floor could be patched. There was no money to properly fix the issue. Anxious to keep the animals and the public safe, Hans Nagel quickly worked every connection he had to get materials to repair the floor.

1934

Floor of lion enclosure rots out; lion falls through it. City starts planning for a new lion and primate house.

19

Hoofstock in yard

Hebridean sheep, a Scottish species of domestic sheep

Early Zoo Leaders

The Houston Zoo was a city-owned property, but only in its formative years did the city provide any budget for acquiring animals. Beyond the 1920s, leaders only provided money for the maintenance of the Zoo and wages for the keepers. Animals were either donated, secured through breeding, or traded with other zoos.

Parks Superintendent Clarence Brock was passionate about the creation of the Zoo but relied on professional keepers to maintain it so he could focus on his other duties.

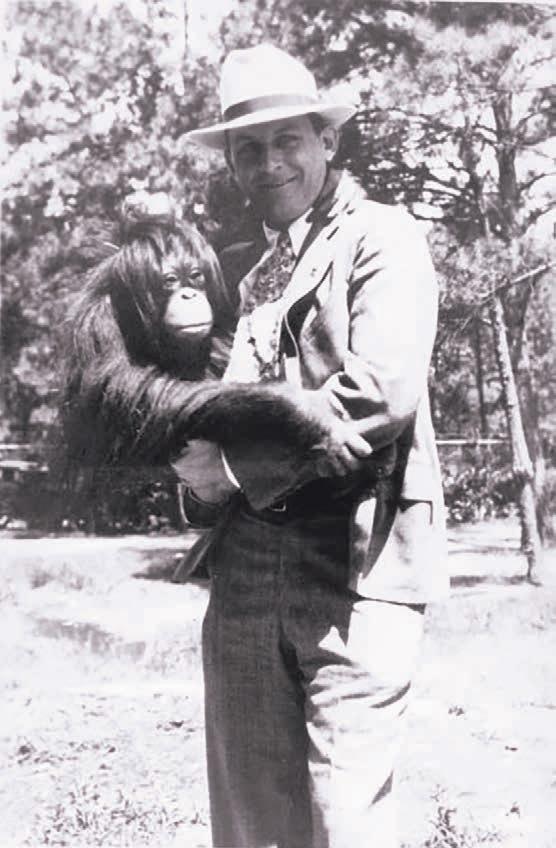

Hans Nagel was Houston’s first head zookeeper. A German immigrant, Hans ran away from home at an early age and joined the world-renowned wild animal exporter Hagenbeck and Company in German East Africa. At nineteen, he immigrated to America by jumping ship and swimming across the Hudson while transporting hippos to New York. Later, he moved to Texas and became president of the Washington County Rabbit Raiser’s Association, which is likely how, in 1918, he first met Clarence Brock, who was secretary of the South Texas Rabbit Breeder’s Association. Nagel was talented with animals and was particularly known for his skill with lions. He and his wife Frieda moved to Houston, where he took over management of the Zoo in 1922.

Nagel loved the media and the media loved him. The arena pictured here was custom built for Nagel to do large cat demonstrations, which were extremely popular with large crowds coming to watch.

1937

A new lion house opens after the city was awarded a grant in 1936.

1938

City Council strongly considers closing the zoo altogether, selling the animals and saving the operating expenses.

Hans Nagel, Houston's first head zookeeper

Custom built arena for Nagel for large cat demonstrations

During his nineteen years with the Zoo, Nagel was stomped, bitten (by the venomous and nonvenomous), nearly strangled, kicked, and hit dozens of times, many of which landed him in the hospital, but he never went to the doctor or surgeon without first calling his contacts at the local newspapers, who fed Houston’s hunger for stories of Nagel’s daring exploits.

Hans Nagel was shot and killed November 17, 1941, by a police o icer patrolling the Hermann Park properties. Nagel was also a commissioned police o icer and charged with patrolling the park, but the

1941

Nellie, the Zoo’s first elephant, passes away.

city was in the process of transitioning authority. The two men argued about jurisdiction and in the heat of passion and anger, Nagel was shot six times. A large funeral was held before he was buried at Forest Lawn Cemetery.

Nagel’s trusted number two, Tom Baylor, always had Nagel’s back when his various adventures landed him in the hospital. After Nagel’s death, Baylor assumed the role of head keeper and held it for twenty-two years until retiring on January 22, 1963. He was a quiet and more private man than his predecessor, but equally passionate about the animals and their welfare.

1941

November 17: Hans Nagel is shot and killed by a police o icer patrolling Hermann Park.

Tom Baylor was at the helm through what were undeniably the hardest years of the institution’s existence. The Zoo was a political football during Baylor’s tenure. He repeatedly dealt with promises of investment that took many years to materialize. His staff decreased but the demands increased, and he suffered repeated threats to the funds. Despite these many di iculties, Baylor remained quiet publicly and maintained his focus on the animals.

1941

Tom Baylor assumes the role of head keeper.

21

(from right) W.H. Irwin, Hans Nagel, Tom Baylor, and unidentified Zoo staff

Tom Baylor, holding cubs

1943

April 29: Houston Chronicle reports that despite WWII rationing, Zoo animals are still eating heartily.

FINANCIAL STRUGGLES AND POLITICAL HURDLES

Except for a short stint between 1932 and 1933 when the city charged admission in an attempt to provide money for infrastructure, the Zoo remained free to all Houston citizens. The Zoo needed financial support for upkeep, and many letters to the editors of Houston's newspapers called attention to deteriorating conditions, but Houston still loved its Zoo. Described in the papers as “the most patronized and most educational institution in the city,” daily attendance was 8,000 to 12,000, near 20,000 during holidays.

In 1936, the city applied for a Works Progress Administration (WPA) grant and opened a new lion house in 1937. Individual groups adopted the Zoo, such as the Herbert Dunlavy Post of Foreign War Veterans, who named the Zoo facilities as their major local civic project in 1936. But the small efforts were not enough; the city council narrowly decided against closing the Zoo altogether in 1938.

Financially, Houston began to rebound in the ‘40s. Wartime production along the ship channel kicked off Houston’s financial recovery and the refilling of the city’s coffers. In 1944, the Houston city council was presented with the latest budget and it seemed municipal government was finally ready to invest in the Zoo.

Change was not immediate, however; there were many opinions about how city funds should be spent and the Zoo remained in disrepair. In 1947, Oscar Holcombe, longtime friend of the Zoo, was reelected mayor and he and councilmember J.S. Griffith became champions of the Zoo. Griffith made a motion in city council to “revamp, rehabilitate, and expand” the long-neglected Zoo.

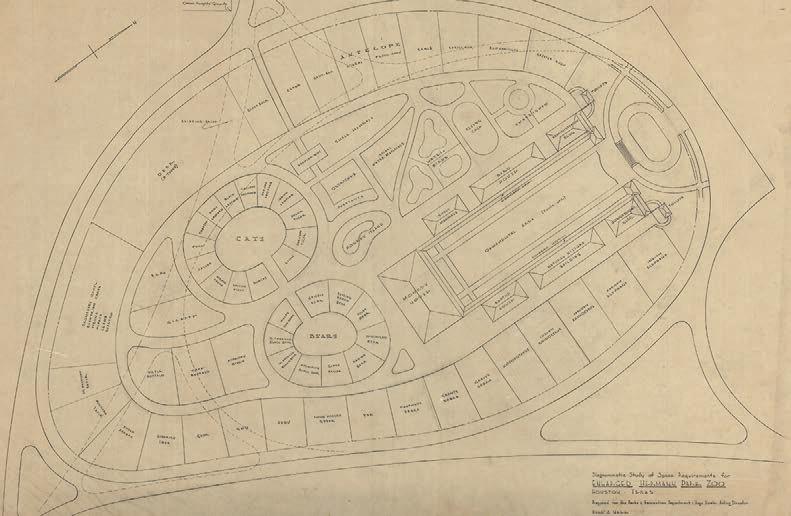

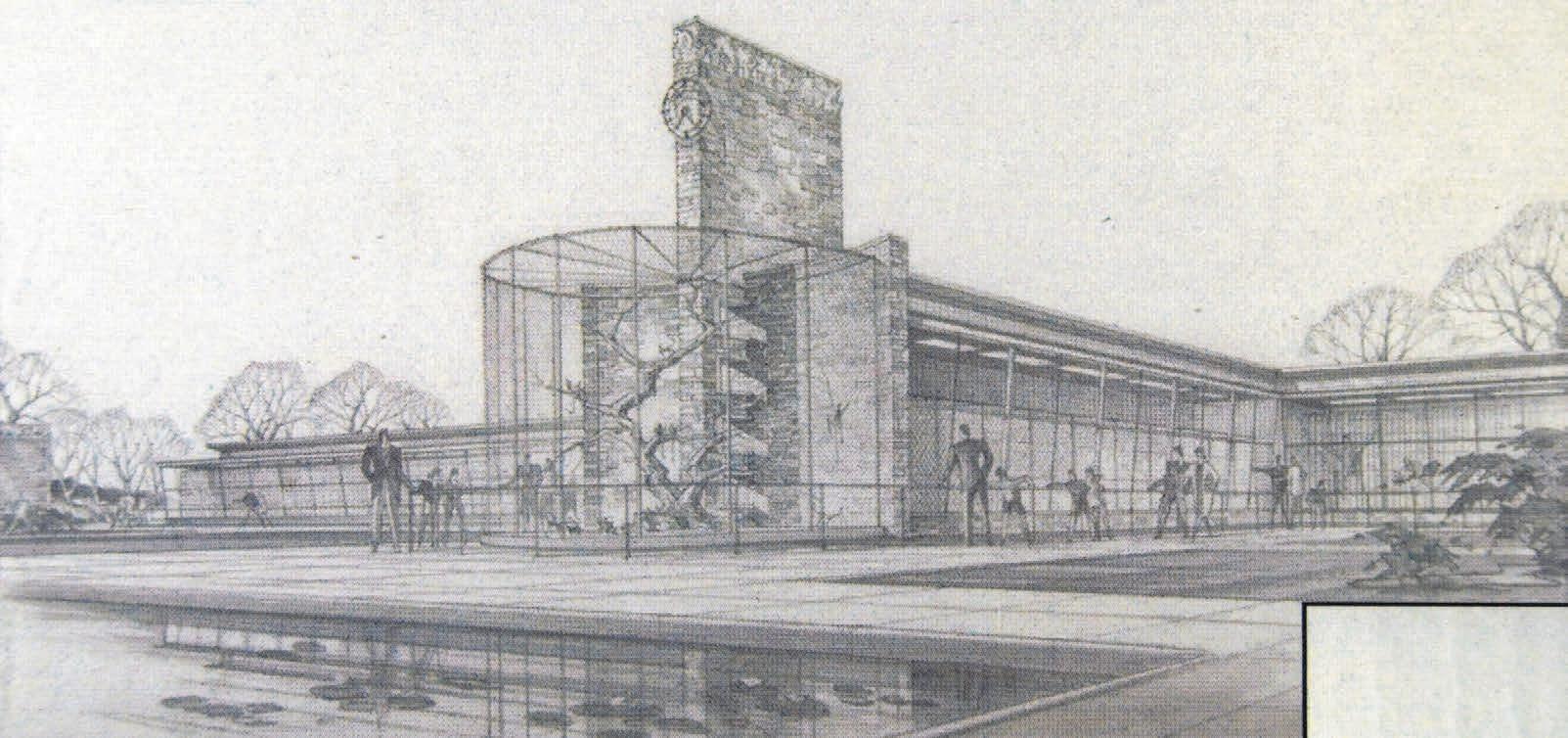

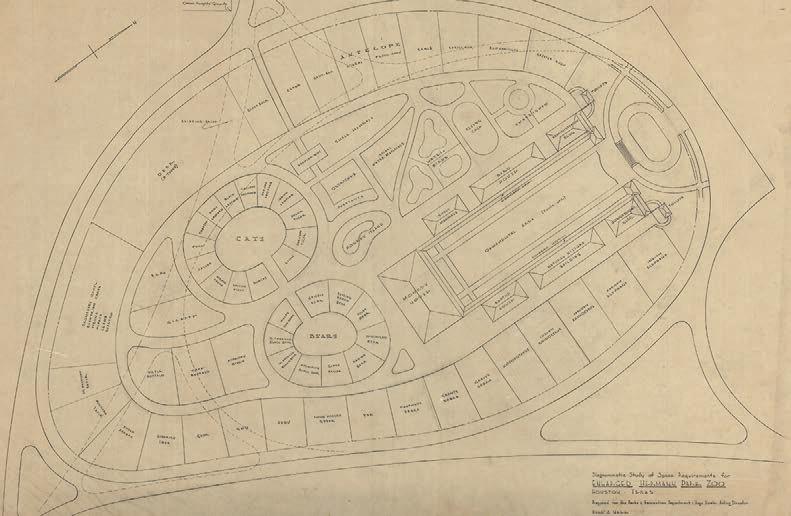

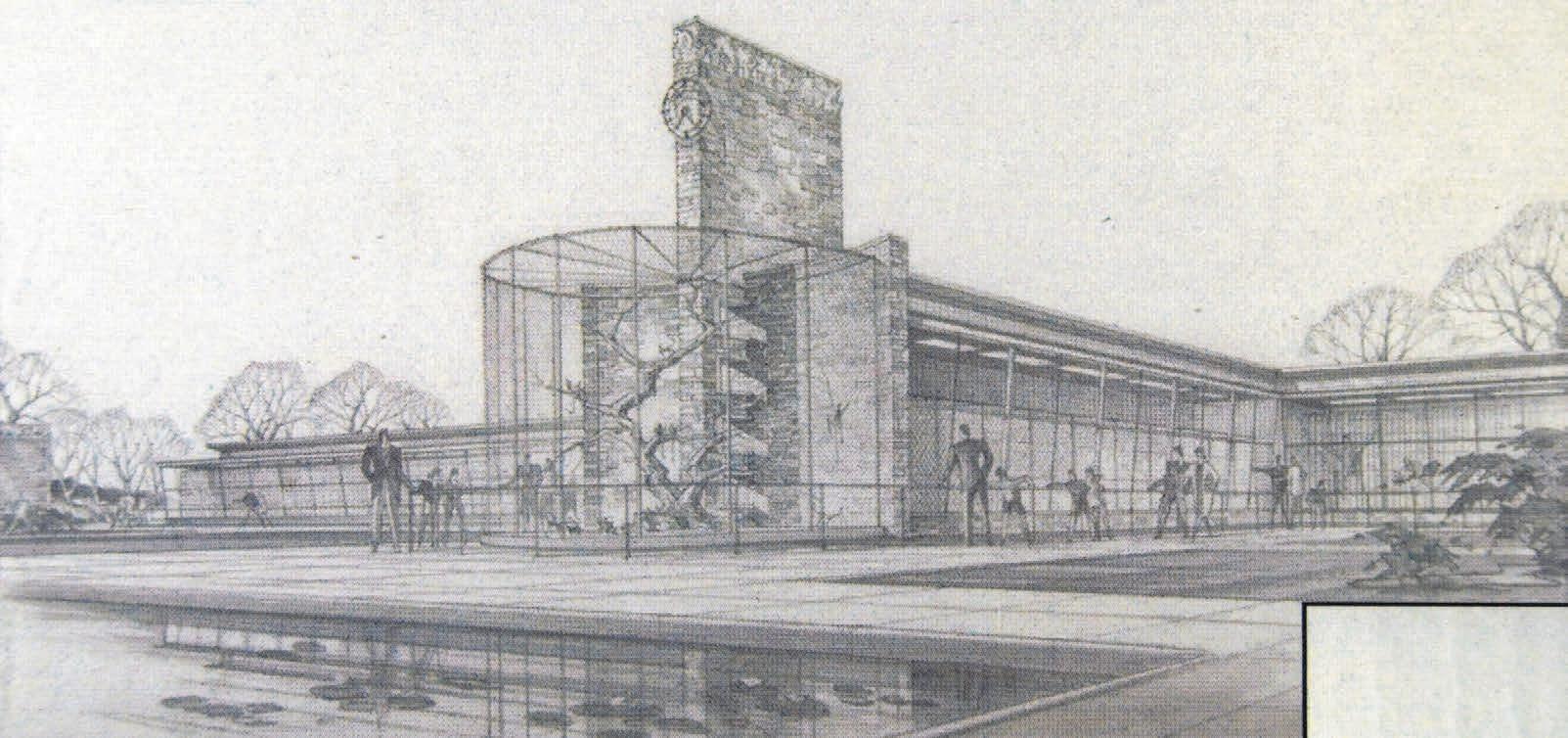

Some consideration was given to moving the Zoo with three alternate sites named, including Memorial Park. Hermann Park remained first choice, but the new plans required expanding the inadequate thirty-acre footprint and moving roads within the park to create more space. The architectural firm Hare & Hare was once again hired to propose designs using Hermann Park as the foundation. The new designs were animal-focused and called for barless enclosures. Instead of cages, animals such as the bears and big cats would live on islands surrounded by moats.

1943

Rebuilding of Zoo plans are underway after the war.

1944

The city announces $500,000 modernization project for the Zoo.

22

A Houston Zoo postcard sent by a guest in 1936

Hare & Hare sketch of Zoo renovation, 1947

University of Houston Gets a Mascot

In 1947, while the city debated the expansion and improvement of the Houston Zoo, the University of Houston Alpha Phi Omega fraternity donated a cougar to the university as a mascot. The new cougar would have a permanent home at the Houston Zoo. The Zoo committed to teaching students to take care of the animal while it was on universitysponsored excursions. She was dubbed “Shasta” by a student; all following UH mascots have also been named Shasta.

The most recent Shasta to live at the Houston Zoo arrived after a hunter illegally shot and killed his mother in Washington State. Shasta VI was rescued and transported to the Houston Zoo on December 11, 2011. During his long life at the Zoo, he acted as an ambassador for his counterparts in the wild while representing the spirit of the University of Houston.

Shasta VI passed away on August 4, 2022, after being treated for a progressive spinal disease. Female cougar Haley will continue to represent the University of Houston until the Zoo brings in another orphan cougar cub, which will be named Shasta VII.

Prioritizing Zoo Improvements

Houston’s municipal budget began to expand, but, because of politics, the Zoo failed at first to see any benefit. An updated primate house was needed; however, politicians couldn’t agree on a budget.

By 1949, the Zoo was at a tipping point. City council member J.S. Gri ith made the Zoo his personal mission and in 1949, he used local newspapers to publicly shame his fellow councilmembers for not supporting the Zoo. Mayor Oscar Holcombe got tired of the

infighting and forced councilmembers in April 1950 to join him at the Zoo for an onsite inspection.

They were shocked by the state of disrepair and head keeper, Tom Baylor, told them how he and other keepers were forced to maintain the facilities with the scant budget. Though the Zoo was the most popular tourist destination in the city, the council’s shoestring budget had forced it to become subpar. The council members were strongly affected and emerged from the tour nearly unanimous about taking immediate action to prioritize improvements.

1947

October 9: Houston Chronicle

Live cougar mascot for UH to be housed at the Zoo and a contest was held to name the cougar “Shasta”.

1948

The council votes to keep the Zoo in Hermann Park.

1949

Ground is broken on July 21 to build the new $296,000 primate house.

23

Shasta VI

This aerial image shows the Zoo in 1944

Shasta I

1950–1969

BUILDING BOOM: Construction Takes Center Stage

Expansion and revitalization of the Zoo takes the spotlight in the ‘50s and ‘60s with a renewed interest in building new and more modern facilities for the animals.

25

25

BUILDING BOOM:

Construction Takes Center Stage

EMERGING FROM WAR

World War II dramatically changed Houston; where agriculture once reigned supreme, transportation, petrochemical engineering, and manufacturing, along with hydrocarbon production and refining, dominated the economy.

Once the war ended, federal investment left behind a robust synthetic rubber production infrastructure in Texas. More investment and innovation followed. Petroleum speculation, production, and processing attracted adventurers from all over the country and world, and the infusion of people, entrepreneurship, investment, and scientific training resulted in the region’s flourishing as a center of innovation and leadership, a position Houston still holds today. The ‘30s and ‘40s were hard decades for the city; with the human need so great, the needs of the Zoo often fell to the bottom of the list of priorities and it was under constant threat of being closed.

Mayor Oscar Holcombe continued to be the Zoo’s greatest political friend. Holcombe understood the Zoo’s value to the city and during each term he used his political clout to help it not just survive, but thrive; Holcombe’s leadership is an essential reason the Zoo exists today.

In the 1950s, money finally began to flow into the city’s coffers and reinvestment began. On February 2, 1950, Mayor Holcombe announced the city’s commitment of $700,000 to reconceptualize and rebuild the entire Zoo property and its structures. On the list: a new Zoo entrance, sea lion pool, reflection pool and colonnade, and new concession areas. It also included adding a moated, open area for animals at the cap of the primate house, movement of perimeter roads to facilitate adding another thirteen acres to the Zoo grounds, new storm sewers to drain the frequently flooding property, and a new parking area. The annual operating budget expanded to nearly $1 million.

1950

Mayor Holcombe announced $700,000 in improvements to the Zoo.

26

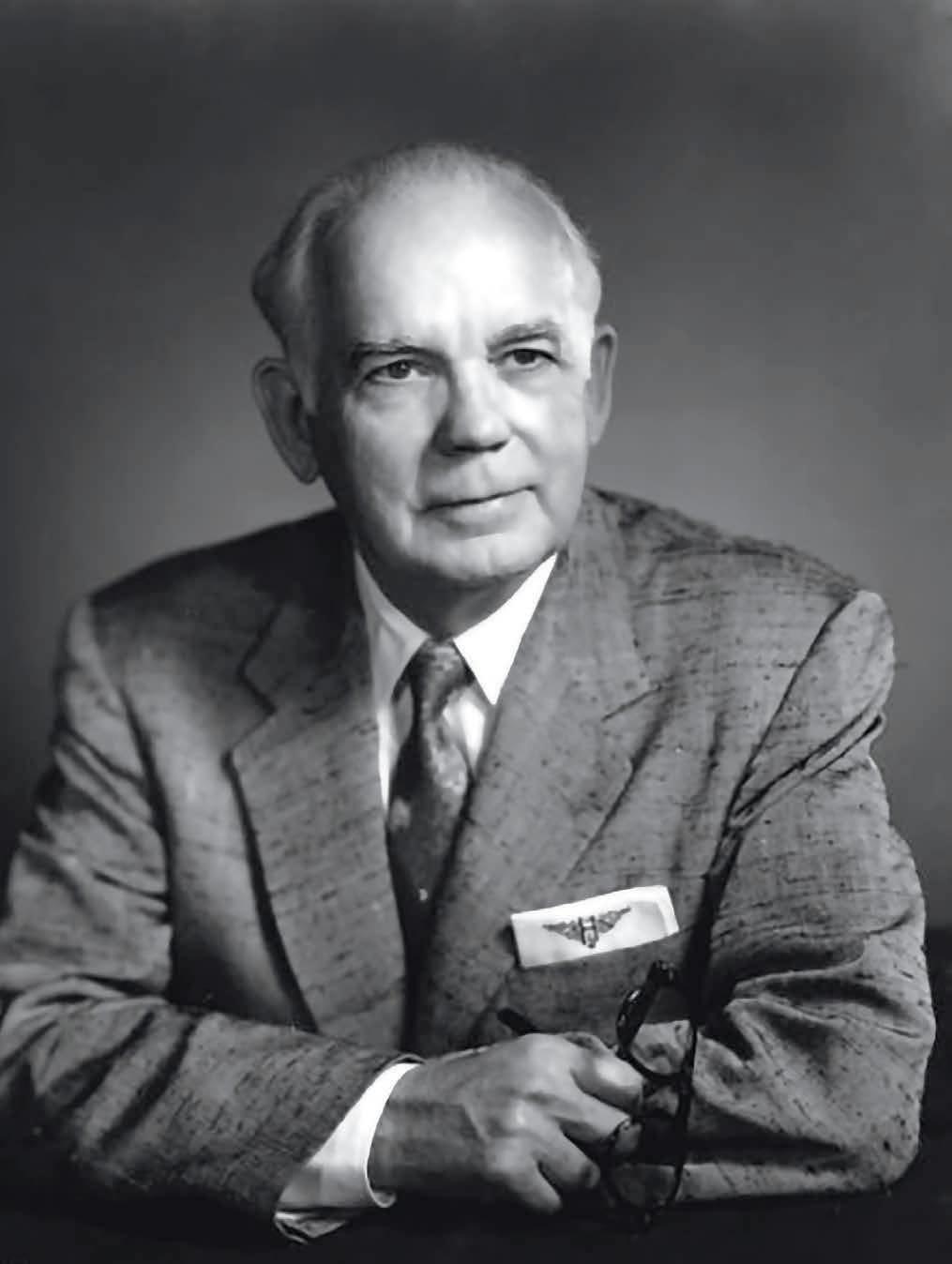

Oscar Holcombe, mayor of Houston, 1921–1956

MODERN ARCHITECTURE

In the mid-‘50s acreage was added to the Zoo and many examples of modern architecture were built. Construction on the Primate House started in late 1949 and it opened in 1950. It served as the central focal point in the Zoo, occupying the area of the original sea lion pool built in 1927–28. The Primate House was heated in the winter and allowed the animals refuge from Houston's summer heat.

Two wings of cages stretched from a central point capped with a moated island mounted with a stylized concrete tree where primates could hang out in the open without bars.

The Primate House roof and the Zoo’s new modern entrance included artistic bas reliefs depicting different primate species. These concrete features were preserved when the structures were later replaced and can be found throughout the Zoo today.

(top) Zoo in the mid-‘50s. The circle in the center is the shade structure at the entrance of today’s Cypress Circle Café. To its right, the reflection pool and colonnade.

(bottom) Proposed primate house sketch

1950

1950

Zoo

27

October 15: The new primate house opens.

is celebrated during a Texas Society of Architects show at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston.

1951

New sea lion pool opens in August.

A modern sea lion pool was next. The new pool opened in August 1950 and was a project of Mayor Holcombe’s, who personally added it to the list of improvements approved by the city council. Sea lions were brought from California to live in the new aquatic quarters.

In Hare & Hare’s 1922 plan of Hermann Park and the Zoo, the 232-foot-long Reflection Pool was originally designed to consist of three contiguous pools that would mirror the long pool (now known as the Mary Gibbs and Jesse H. Jones Reflection Pool) at Hermann Park’s entrance. The Reflection Pool is still a major focal point of the Zoo and the site of many special events.

The Zoo’s new concession building, now rebuilt as Cypress Circle Café, opened in April 1952. The café was built around the two century-old cypress trees that still grow there today; the original plan called for the trees to be cut down and a new fountain put in place, but Houston Parks and Recreation Director Hugo Koehn insisted the trees be kept.

During the Zoo’s leaner years, Hans the elephant lived in a small barn that he quickly outgrew, but there were no other alternatives. The Zoo’s keepers, Houston’s citizens, and animal advocacy groups pushed the city hard in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s to provide him with a new home. Finally, in September 1952, the new barn and yard was complete; Hans had ample space to roam, a large new barn, and space for future companions. By the early ‘50s, Hans the elephant was the largest in any American zoo.

1952

The new concession building, Cypress Circle Café, opens in April.

1952

The new elephant barn and yard are completed in September.

28

(top left) Sea lion exhibit, 1950; (top middle) Reflection Pool

(top right) Cypress Circle Café, 1952; (bottom) Hans, the elephant

JOHN WERLER BECOMES THE FIRST GENERAL CURATOR

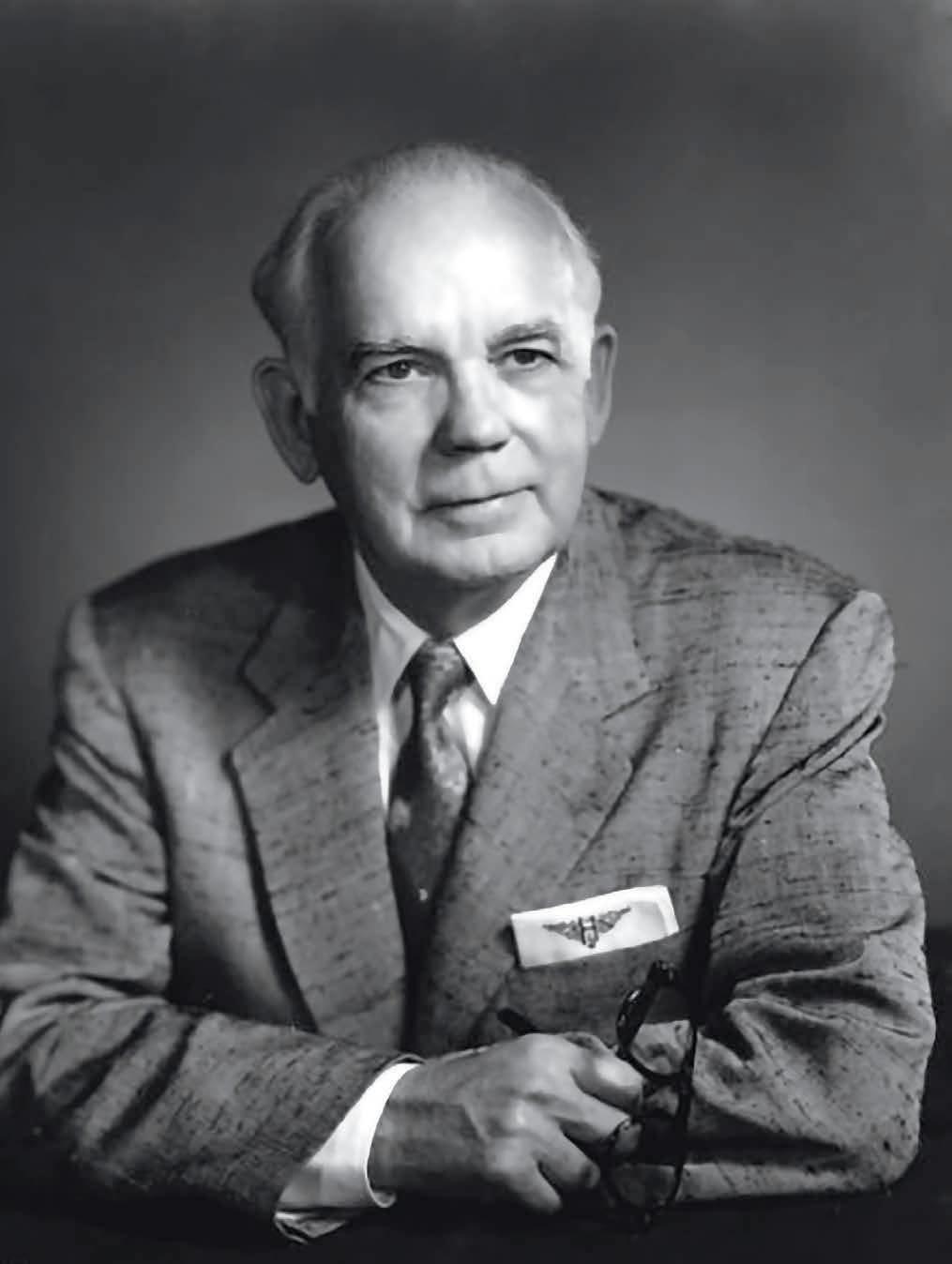

The city of Houston hired John Werler in 1956 to become the first general curator of the Zoo and the eventual manager when Tom Baylor retired in 1963.

Born in Germany in 1922, Werler and his family migrated to New Jersey and lived on the outskirts of New York City. Fascinated with reptiles, Werler joined the Staten Island Zoo’s Reptile Study Society against his father’s wishes at sixteen years old and by eighteen was hired as a keeper. Werler became the reptile curator at San Antonio Zoo at Brackenridge Park in 1946, and later the assistant director, before coming to the Houston Zoo in 1956.

Vampire Bat Exhibit in Houston

While in San Antonio, John Werler established the world’s first zoo collection of vampire bats and in 1957, he organized a bat collection trip to Veracruz, Mexico. He used animals gathered during that trip to establish the world’s second exhibit of vampire bats in Houston. The collection became the world’s first breeding colony and by 1989, the Houston Zoo’s collection of vampire bats was the largest in the world.

Attendance at the Zoo doubled between 1951 and 1961, to almost 1.4 million people a year. Though Hermann Park traffic congestion became difficult, people kept coming. Public transit in Houston was almost nonexistent and visitors to the Zoo, as well as the golf course and other park amenities, arrived by car and walked long distances to get to the front gate.

1961

29

John Werler, first general curator of the Zoo

1956

John Werler becomes the first general curator of the Zoo.

1957

George Luquette was the Zoo’s first veterinarian.

Reptile House opens in February.

1961 Vampire bats debut at the Zoo.

REPTILE HOUSE OPENS

The Reptile House opened in February 1961 with housing for approximately 250 animals, one hundred glass-fronted cases for public viewing, additional cases behind the scenes for housing, and a special demonstration pit. The iconic brass cobra statue was installed a month later.

JOHN WERLER

That year, the Zoo was the only facility in the United States to have a Russian cobra, a snorkel viper from Formosa, and a pair of Mexican tree frogs. Within the first three years, Werler added nearly one hundred reptiles to the collection, including a Gaboon viper, Malayan pit vipers, tiger rattlesnakes, an African spitting cobra, tentacled snakes, a mangrove snake, Russell’s vipers, Japanese rat snakes, dusky pygmy rattlers, and many more.

The Zoo’s TV fame began in the ‘50s during Tom Baylor’s term as Zoo Manager. He retired in 1963 at the age of sixty-nine and, as predicted, John Werler took over the position. Werler was a natural communicator. He made hundreds of appearances throughout his twenty-nine years as Zoo Manager and often shared the stage, insisting on the Zoo’s curators and keepers being co-presenters. Both he and his wife are remembered by the people who worked with him as being kind, supportive, and generous.

1961

“Magic Lion” water fountain is installed— a big cartoon character made out of masonry.

1961

In 1961, the Zoo was the only facility in the United States to have a Russian cobra, a snorkel viper, and a pair of Mexican tree frogs.

1962

Small mammal house opens.

30

(left) Willie Gonzalez, keeper and live cobra “Marie”

(right) One of John Werler's many onscreen appearances

Children’s Zoo

Werler began pushing for a new Children’s Zoo within weeks of becoming the manager. The project became a major part of the new incarnation of the Zoo, and Houston really wanted a Children’s Zoo. While politicians debated whether to approve the plans, Houstonians found ways to encourage the effort, including twenty-two students in Mrs. Garnett Phillips’s fourth-grade class at Helms Elementary who wanted the Zoo to acquire a cow in the Children’s Zoo. Each student wrote a letter to the Zoo. “We have never seen a cow,” student Wes Sutherland wrote in his letter, “we have lived in the city all our lives and have never touched one in our whole lives.” The Bayou City Cat Club also created a special championship show to benefit the Children’s Zoo and repeated the event for several years in a row.

In response to the excitement and demand, Werler created a temporary petting zoo just inside the front gate, supervised by trained volunteer Girl Scouts, until the final version was completed. The Houston-based Rockwell Fund gave the city $150,000 in unrestricted funds for the Children’s Zoo. The money was used to build the world’s first clear, underwater “Aqua Tunnel” which ran under a ten-foot-deep pool with two sections: a freshwater environment featuring catfish, alligator gar, needlefish, and turtles and a twenty-foot run through the seal lagoon, which had two-month-old harbor seals.

A new nursery was the largest building in the Children’s Zoo. It had a big window that allowed visitors to see baby animals being raised by staff. Myra Mehrtens was the supervisor of both the Children’s Zoo and the new nursery. Two baby gorillas donated by the Zoo Society Ladies Guild, with proceeds from their Go-Go-Gorilla party, were the first occupants.

The Children’s Zoo had thirteen major displays and the area included four animal contact areas designed to simulate the cultural environments of four regions: North America, Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Each area featured animals and a stylized dwelling from the designated region.

1963

1964

Capybara birth at the Houston Zoo is the second captive breeding of the species in the country.

31

John Werler becomes Zoo Manager.

Children's Zoo “Aqua Tunnel”

Children's Petting Zoo, 1968

Children’s Zoo Supervisor Myra Mehrtens holding a baby gorilla, 1970

“We’re trying to indoctrinate these kids to wild animals and help the conservation effort in the long run. If they never have exposure to [wild animals], then they really don’t care.” — John Werler

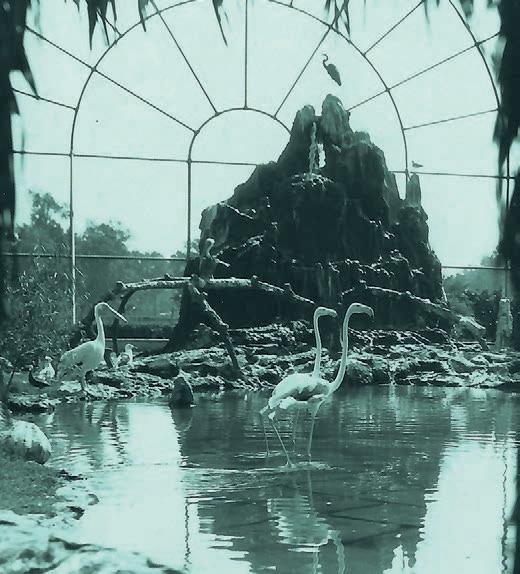

TROPICAL BIRDHOUSE OPENS

In 1956, during Oscar Holcombe’s last term as mayor, Parks and Recreation director Gus Haycock proposed a bird house to replace the flying cage designed and built in the ‘20s. However, nothing happened with the plan until December 1964 when the Maurice & Wilkins architecture firm was hired to design the structure and ground was broken in 1965.

The Houston Post created a fundraising campaign to help the Zoo acquire birds and the new Tropical Bird House opened in August of 1966. It was filled with lush plants and featured a raised walkway that went through a stylized stone temple in the center. The Tropical Bird House delighted guests for nearly fifty-five years! The structure was removed in 2020 and is now the location of Flamingo Terrace Beer and Sculpture Garden.

The excitement of the Tropical Bird House opening, along with the extreme popularity of the petting zoo and the building anticipation of the soon-to-be-opened Children’s Zoo had an incredible impact on attendance; the Zoo became the most popular tourist destination in the region. In 1967, annual attendance for Sundays only was just over 900,000 people and by the end of 1968, that number doubled with over 1.7 million people attending the Zoo just on Sundays. Houstonians loved their Zoo.

1964

Maurice & Wilkins architect firm is hired to draw up specific plans for the bird house structure.

ZooMobile

In 1967, the Junior League of Houston adopted the Zoo as a cause, buying the first ZooMobile, cameras, and other materials for $17,000. The ZooMobile would be used to visit schools and fairs as a mobile exhibit space. The vehicle was owned by the Zoo but run by volunteers, with the visits being free for students.

1966

The new Tropical Bird House opens in August.

Zoo docent, Sam Gardner volunteers with the ZooMobile, 1971

1967

Junior League and the beginning of the Zoo’s ZooMobile Program.

32

Houston Post (published as THE HOUSTON POST) November 8, 1965 page November 8, 1965 Houston Post (published as THE HOUSTON POST) Houston, Texas Page CITATION (AGLC STYLE) (AGLC HoustonPost(online), Nov 1965 ‹https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.rice.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A10EEA3FE61C5B8B0%40EANX-NB17347A7A83E92725%402439073-17332404DDD78ED1%403-17332404DDD78ED1%40› © This entire service and/or content portions thereof are copyrighted by NewsBank and/or its content providers.

John Werler visits the Tropical Birdhouse during construction

For The Birds Fund Form

Houston Zoological Society

Houston’s zoo began as an entirely municipal effort with all parts of the Zoo owned by the city. But, only in the first years of the Zoo was there financial support for acquiring animals. City leaders hoped that private citizens would fill the gap, but the unexpected regional financial downturns all but removed that possibility. Zoo leadership found other ways to stay in business. Manager Tom Baylor became adept at finding new animals for the Zoo through trades with other institutions. The Zoo also became skilled at breeding animals. But, to do more than survive, the Zoo needed real, committed help from the community.

In 1963 Werler began holding meetings with Houston business leaders. Werler’s effort became the seed of the Houston Zoological Society, which incorporated four years later in 1967 with its first president, Bert Wheeler. During its thirty-five years, the society raised millions of dollars to acquire additional animals, improve the Zoo’s facilities and operations, develop and train future scientists and leaders in zoo management, and educate Zoo visitors about animals and human impact on nature.

Zoological Society membership drive. Designed to be forty days and nights of fundraising for the Zoo, the initiative encompassed a wide variety of events that included dance benefits, a comedy showcase modeled after Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, the first annual Animal Garden Party, and the first-ever Zoo Ball. The “Go-Go-Gorilla Ball” was a wildly successful event that raised funds for a pair of young gorillas.

Breeding Leader

During the ‘60s, the Houston Zoo became well known internationally for its breeding programs. It was the first breeder of many rare and di icultto-breed species. Among notable births were the Malayan pit viper, Kodiak bears, and brown pelicans.

Later, in the ‘70s, Houston built upon this expertise to become the first to breed the South American cockof-the-rock, the St. Vincent Amazon, the red bird of paradise from New Guinea, Bolivian grey titi monkeys, and many more. By the end of the twentieth century, the Houston Zoo was regarded as one of the best breeding zoos in the world.

Soon after its founding several women formed a Ladies Guild as the fundraising arm of the Zoological Society, to be later known as Zoo Friends of Houston. Their first initiative was the Needs of Our Animal Home (NOAH) fundraising campaign and Houston

1967

The Houston Zoological Society is formed.

The society’s commitment helped create the Zoo we know today: an internationally recognized institution working around the world to save animals in the wild; the ideal incubation ground for leadership in both industry and philanthropy; and a strong, connected, multi-generation community committed to charitably supporting Houston’s cultural and scientific institutions.

1968

Children’s Zoo Opens and includes the Lillian Rockwell Aqua Tunnel, built with a $150,000 donation by Norman Rockwell (Rockwell Foundation).

1968

Zoo

33

Mammal Curator Richard Quick, feeding a Kodiak bear cub

acquires first St. Vincent Amazon.

Members of the Girl Scouts of the San Jacinto Council collected stamps to help the “NOAH Needs Help” project. Kathy Anishi, right, and Melinda Mullis present 745 books to Bland McReynolds, president of the Houston Zoological Society.

1970–1999

CARING AND CONSERVATION:

A National Shift Toward Collaboration

Zoos across the country begin coordinating animal breeding programs in earnest and with accreditation by the American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums (now Association of Zoos and Aquariums), Houston Zoo becomes an industry leader. Efforts to support wildlife conservation pop up around the world.

35

35

SHIFTING THE MISSION

On July 20, 1969, the Apollo 11 lunar module landed on the moon and billions around the world heard American astronaut Neil Armstrong announce “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” The arc of human history dramatically changed with Houston at the epicenter.

By 1970, 1.2 million called Houston home. Financial and political investments in institutions of higher learning, the establishment of the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center, advancements in chemical and mechanical engineering, and petroleum exploration and production paid off and Houston became a global center for innovation.

The Houston Zoo and its support organizations served as the ideal gathering place for many to create a community, grow as philanthropic leaders, and build strong bonds between families that would last generations. Zoos reflect the worldview of those who create them. When established, Houston’s zoo was to be an expression of the early twentieth century “City Beautiful” movement which inspired moral and civic virtue through grand parks and heroic architecture. The Zoo’s role was to provide recreation. The design prioritized animals while also attempting to instill respect for science by highlighting order and taxonomic classification.

By the 1970s, Western society was forced to realize the natural world’s fragility and began to recognize that animals in zoos are not entertainment; they are ambassadors to the human world and they—like us—need their mental, emotional, and physical needs met to remain healthy and thrive. As a result, public awareness of animal welfare increased, and civic and political leaders responded. In the 1970s, the lives of animals in America and around the world began to change for the better.

36

CARING AND CONSERVATION: A National Shift Toward Collaboration 1970 Volunteer Program: the first class of 125 volunteers whose sole responsibility was guest education.

John McLain, reptile keeper, holds rare Angolan pythons. The Zoo's successful breeding program earned it an Edward H. Bean award from the AZA. (1982)

EDUCATION

Between 1970 and 1976, under the guidance of Director John Werler, education became increasingly emphasized and a group of 125 volunteers was organized to interact with guests and provide information about animals and exhibits. In 1972, fifty thousand children experienced animals through the ZooMobile program. Over the years, an estimated five thousand volunteers have donated more than one million hours to the Zoo.

1971

Zoo Friends produces an annual fund-raising benefit such as the Animal Garden Party and the “Go-Go-Gorilla Ball.”

1972

Alban-Heiser Award

In 1970, Joseph Matthew (J.M.) Heiser Jr., together with his niece Barbara Heiser Alban, created and funded the Alban-Heiser award to honor “a Texas citizen who has made significant contributions to the appreciation and preservation of the earth’s heritage of living creatures, their environments, ecology, and/or their relation to human welfare.” Today the Alban-Heiser Award is given annually to a Texas teen who has shown promise of becoming a great leader in saving wildlife.

The Houston Zoo becomes the first institution to successfully hatch a St. Vincent Amazon.

37

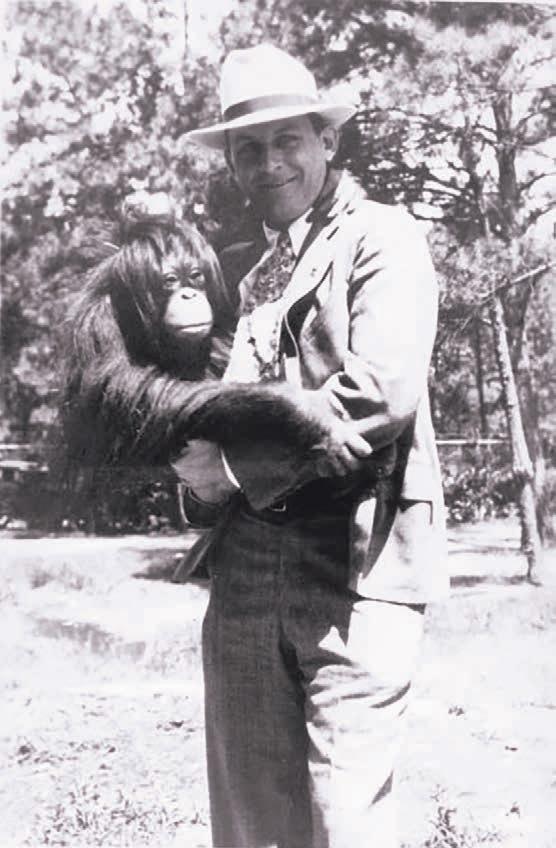

Joseph Heiser Jr. holding an orangutan

THE PROFESSIONALIZATION OF ZOO KEEPING

The fields of zoo management and zoo keeping became further professionalized and better organized through the newly independent American Association of Zoo Parks and Aquariums (AAZPA, today the AZA). Once an affiliate organization of the larger American Institute of Park Executives, the AAZPA became one of many groups that pressured the federal government to enact laws protecting animals in captivity. The new federal (Laboratory) Animal Welfare Act became law in 1966, but in 1970, the AAZPA assisted in rewriting the law to expand protection to animals in zoos or in other exhibition settings such as circuses, carnivals, and roadside attractions.

The AAZPA followed the law’s passage with the formation of an accreditation process of all member organizations to drive the creation of best practices in animal care and operations. The Houston Zoo was accredited in 1974. Today, accreditation evaluation every five years is required to maintain AZA institutional membership.

In December 1973, the federal Endangered Species Act went into effect. Designed to protect species from extinction, the law aimed to recover species populations to the point where they could thrive, and protection was no longer needed.

(top left) A baby hippopotamus and its mother, 1977

(bottom left) A Zoo staff member bottle feeds Rudi the orangutan, 1978

(right) Keeper Barbara Coffey with a green winged macaw, 1975

1973

Gorilla House opens in October.

1974

The

38

Houston Zoo is accredited by the American Association of Zoo Parks and Aquariums.

Docent Council

For five years, beginning in 1964, Merrick Phelps volunteered her time at the Zoo providing personal tours and teaching youngsters about what animals ate, how they lived, their indigenous habitats, and effects of human encroachment. She developed her practice with the curators and keepers and attracted and trained many others to serve as educational docents.

In March of 1968, representatives of Zoo volunteer groups met to create a formal docent organization. Other volunteers served the Zoo, but only members of the Docent Council received specialized natural history and interpretation technique training. They engaged with hundreds of thousands of people providing personal tours, sometimes accompanied by an ambassador animal.

The docents traveled with the original ZooMobile, a large, customized mobile version of the Zoo that traveled to area hospitals, libraries, and other locations bringing animals to people who could not access the Zoo. There were many generations of ZooMobiles, all staffed by members of the Docent Guild. The Guild disbanded in 2003 after the Zoo privatized, however, more than three hundred volunteers continue to work with the Zoo annually today.

1976

39

1975

50,000 children experience animals through the ZooMobile program.

Houston Zoo ZooMobile visiting children in the Hermann Hospital Pediatric Unit

1975

Zoologist Greg Mengden develops a program to determine bird gender.

A special exhibit and breeding facility for St. Vincent Amazon is built thanks to donations by Zoo Friends.

Merrick Phelps in front of the giraffe habitat

Zoo Friends

In 1969, the Ladies Guild of the Houston Zoological Society became an independent nonprofit organization and renamed themselves Zoo Friends. The group was a powerful source of leadership for the Zoo.

Zoo Friends donated a number of animals and greatly improved the Zoo’s physical plant during its three decades of service, including pairs of snow leopards, rhinos, and Siberian tigers. They helped fund the Kipp Aquarium and provided money for the large cat facility built in the ‘80s. For many members, the organization was the center of their social lives and they dedicated themselves to the Zoo.

QUALITY OF LIFE

A new $100,000 Gorilla House opened in October 1973. Designed by Robert Maurice, the Gorilla House featured the latest in climate control and a television set to entertain the gorillas. It had plexiglass skylights that let in ultraviolet light, and an environment that included tropical foliage.

During this time period much changed in the way zoo exhibits were designed. John Werler embraced and advocated professionalization of zoo management at the Houston Zoo. He was a well-regarded leader within the AAZPA and believed that the highest standards of animal well-being demanded an enriched environment and the means to protect the animals from disease and infection. In the early 1970s, a fully indoor environment was deemed the best method to keep the gorillas safe and happy. Today’s design practice is centered on quality of life for the animals and is focused on immersion in a more naturalistic landscape.

1977

Zoo plans for staff participation in a federal grant study of the endangered Houston toad with a scheduled kickoff in 1978.

1978

One-year-old orangutan, Rudi Valentino, arrives at the Zoo.

40

Houston Zoo Gorilla House, 1973

Members of Zoo Friends with Asian elephant

ANIMAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

New animal buildings were not enough. Animals also need quality veterinary care facilities and the city did not provide full-time veterinary care for the Zoo until 1976. Instead, a city veterinarian split time between the Zoo and other animal programs. There was no dedicated space for a veterinarian to perform surgery on animals aside from a small room in the back of the nursery in the Children’s Zoo. The expanding zoo population made the situation untenable.

The new veterinary hospital was named after Dr. Denton Cooley, native Houstonian, world famous Texas Medical Center heart surgeon, and advocate for the Zoo. He and his Denton A. Cooley Foundation donated $250,000 specifically for the hospital. It opened in 1985, after taking a year to complete. Dr. Cooley, shown here with Marcella Perry, chairwoman of the Houston Zoological Society board, attended the “M*A*S*H-themed” opening. Dr. Joe Flanagan, the Zoo’s current senior veterinarian, smiles in the background in a surgical cap.

In 1972, the Houston Zoological Society and the city’s veterinarian, Fred Soifer, worked with area teens who organized a youth march to fund a temporary medical facility for the Zoo. Teen organizers went door to door and raised more than $12,000, which funded two temporary buildings that served as a hospital until a permanent one was built in 1985.

Even the largest animals were treated in the Denton A. Cooley hospital, which featured the Patti Shafer specialized zoological-surgical suite, and the latest in diagnostic technologies, funded by the Fondren Foundation. Today, the Zoo trains interning veterinarians and medical personnel around the world.

1978

$800,000 is donated to help pay for the Kipp Aquarium and Entrance Building.

1979

AZA Awards: Edward H. Bean Award for propagation of the bird-of-paradise.

1979

Reptile Curator Hugh Quinn and Greg Mengden received a federal grant to breed the Houston toad in capitivty.

41

(left) Baby colobus monkey

(right) M*A*S*H Bash opening of the new Denton Cooley Animal Hospital

The St. Vincent Amazon Breeding Program

The Zoo acquired the first St. Vincent Amazon in captivity in 1968 when Houston physician and avid birder, James R. Oates, vacationed to Saint Vincent Island, a small Caribbean Island in the Lesser Antilles, and discovered the parrot in the lobby of his hotel. The bird, named Vincent, was owned by hotel employee John Warfield. Understanding the parrot’s rarity, Dr. James talked Warfield into donating the parrot to the Houston Zoo.

St. Vincent Amazon are rare, only existing on their namesake island. Human encroachment, poaching, hurricanes, and volcanic eruptions had reduced their numbers. The last count before Vincent’s donation estimated only five individual Saint Vincent parrots living in the wild. Finding such a bird in a hotel lobby was a stroke of luck. Breeding was essential to preserve the species, but di icult because there is no visible difference between a male from a female.

Two more St. Vincent Amazon were found at other zoos in 1970: one at the Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo and the other at the Bronx Zoo. Given Houston’s success as a breeding facility, it was agreed to attempt to mate the birds here, hoping that at least one of the animals was a different sex from the others. Chicago’s bird was

1980 Houston Zoological Society raised $2.5 million (more than their goal) for construction of new cat facility and animal hospital.

the first to try. Soon after meeting, the new bird, named Awk, began feeding Vincent, which was good news, since males tend to feed females.

The Zoo Friends funded the creation of a special breeding cage, and everyone watched and hoped for romance to bloom.

In April 1972, Vincent and Awk became proud parents of Kirby, the first St. Vincent Amazon born in captivity. Houston Zoo’s aviculturist Holly Nichols was credited with the hatch.

“Ecology is no longer a fad or luxury,” Nichols said, “We must work for endangered species because it is for the good of all of us.”

HOUSTON HOSTS ZOO LEADERS

October 6–11, 1973, John Werler and the Houston Zoo hosted the second annual national meeting of the independent AAZPA. Attendees included more than six hundred zoo leaders from around the country, including Werler’s friend Marlin Perkins, director emeritus of the St. Louis Zoo, and star of the Wild Kingdom TV show.

The conference included several technical papers on breeding as well as small population management of animals. Attendees discussed the stress of managing and improving zoos with dwindling funds and the need to create and maintain self-sustaining populations in a more scientifically rigorous way. The National Academy of Sciences published the proceedings of the meeting in 1975.

In September 1975, Werler became president of the AAZPA during the Calgary meeting. He served from 1975 to 1976 and was also inducted to the International Union of Directors of Zoos.

1980

AZA Awards: Edward H. Bean Award recognition of the successful breeding of the scarlet cock-of-the-rock.

1980

Thai the elephant arrives at Houston Zoo in June.

42

Family of Saint Vincent Amazon Kirby, left in the photo, was born April 25, 1972.

John Werler, 1978

1981

Methai the elephant arrives at the Zoo in May.

GROUNDBREAKING SCIENCE

Waiting to see if love blooms between birds is a frustrating way to determine sex, especially when trying to save a species. A better method was needed. Enter Greg Mengden, a twenty-six-year-old zoologist at the Houston Zoo, who in 1975 discovered a way to identify male and female parrots and raptor species through microscopic analysis and staining of chromosomes found in feathers. Male chromosomes turn one color, females another; sex is revealed, and the guesswork is removed.

Mengden developed his technique in a special laboratory built by the Houston Zoological Society using birds in Houston’s collection. He collaborated with M.D. Anderson biologist A. Dean Stock who conducted similar research on human chromosomes. Mengden’s discovery simplified the quest to preserve endangered species and he was soon asked by the US Department of the Interior to go to Puerto Rico and determine the sex of ten captive endangered Puerto Rican parrots. He then was asked to sex the whooping crane hatchlings at the Patuxent, Maryland, research station.

Thai and Methai

African and Asian elephants were declared endangered in the ‘70s and the only way for zoos to have more elephants was to breed them. A young Asian bull named Thai arrived in April 1980 to help start Houston’s breeding program. In 1981, Methai arrived at the Zoo.

1981

The Kipp Aquarium and the Administration Building (North Admin) are completed.

1982

AZA Awards: Bean Award recognition of the successful breeding of the Angolan python.

1985

43

Greg Mengden working in a special laboratory built by the Houston Zoological Society.

Denton A. Cooley Veterinary Hospital opens.

KIPP AQUARIUM

During the early to mid-twentieth century, Houston civil engineer and landscape designer Herbert A. Kipp designed many of Houston’s most wealthy and well-known neighborhoods, including River Oaks and the Texas Medical Center. When he died at age eighty-five in 1968, he bequeathed $500,000 to the city of Houston, specifically requesting that the money be spent building an aquarium in Hermann Park. That money, along with $285,000 raised by the Houston Zoological Society, $2.1 million in Houston Parks bond funding, and additional donations from the Zoo Friends of Houston, funded the Herbert A. and Elizabeth N. Kipp Memorial Aquarium, which opened in 1981.

Nelson Herwig was the Zoo’s first aquarium curator. The initial aquarium had room for 2,500 fish in tanks ranging from twenty-five to five thousand gallons. In 1986, the Kipp Aquarium was the first outside of the Bronx Zoo to display venomous yellow-bellied sea snakes.

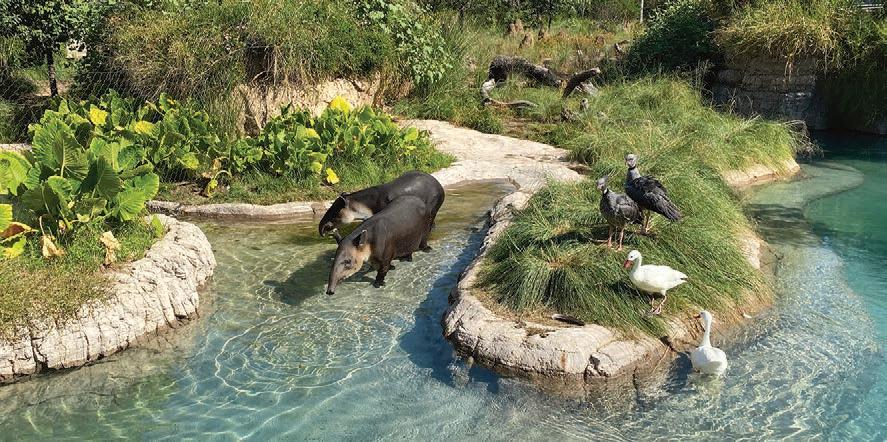

After nearly forty years of welcoming visitors, the aquarium closed in 2020 to make room for Galápagos Islands, opening in 2023.

Houston Toads, the Beginning

Though named after the city, the last Houston toad was seen in Houston in 1975. Only a few small populations were found in surrounding areas. The species was listed as endangered in 1970 and was the first protected toad species when the Endangered Species Act passed in 1973. A Houston toad recovery team was created in 1978 with the Houston Zoo as a key partner, and in 1979, Houston Zoo reptile curators Hugh Quinn and Greg Mengden received a federal grant to breed the Houston toad in captivity to begin repopulating the species.

A recovery plan was published in 1984 and the Houston Zoo continued with the project and established the first Houston toad program with the goal of breeding healthy toads and releasing them into their historic areas. The Zoo continued participating until the late ‘80s, then rejoined the effort in 2006 when the toad was again in severe decline. Today, the Houston Zoo’s Houston Toad Recovery Program works toward recovering wild populations by releasing mass quantities of eggs in the wild. Over 5.5 million eggs were released by 2021.

1987

Mr.

1988

The Brown Education Center opens.

1989

The Houston Zoo initiates a public admission fee and introduces a “new zoo” to the city. Nearly $1 million in improvements are unveiled.

44

Herbert A. and Elizabeth N. Kipp Memorial Aquarium, 1981 Giant Pacific octopus

Hugh Quinn looking over Houston toad tadpoles

Pickles, a critically endangered radiated tortoise, arrives at the Zoo.

A zookeeper places Attwater's prairie chicken eggs back into the incubator after they have been candled and weighed.

WORTHAM WORLD OF PRIMATES

In October 1991, the Zoo announced the demolition of the Primate House to be replaced by a two-acre open-air, immersive, naturalistic primate area. Funding came from corporations, individuals, and foundations, including the Kresge Foundation, which provided a $200,000 challenge grant requiring $750,000 in additional private funding by June 1992. The Houston Zoological Society launched the “The Great Ape Escape” campaign to help raise remaining funds.

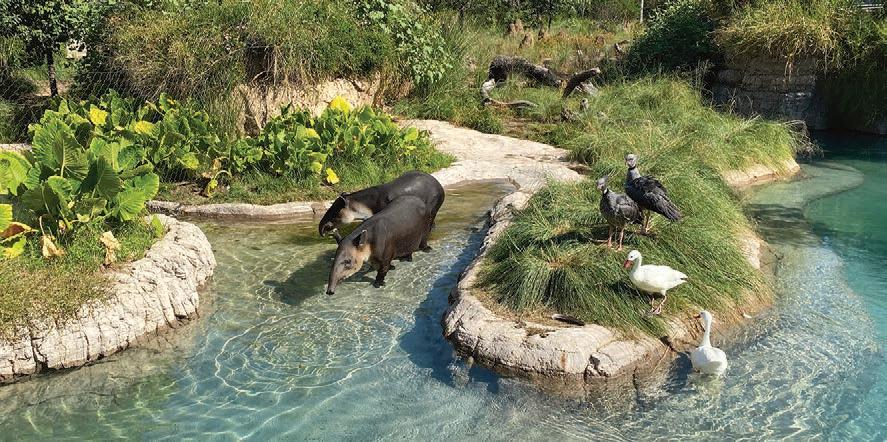

With a lead gift from the Wortham Foundation, the $7.5 million Wortham World of Primates opened in 1993. It was the first of the Zoo’s modern, immersive habitats.

ATTWATER’S PRAIRIE CHICKENS

A federal census in 1994 estimated only forty-two individual Attwater’s prairie chickens remained in the wild. In 1900, the birds were estimated to number a million on the Gulf coastal prairies of Louisiana and Texas. Human encroachment was to blame.

In 1972, the Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge was established near Eagle Lake, Texas. Later, private land on the Goliad Prairie near Victoria, Texas, was offered to create another protected space for the birds.

The Attwater’s Prairie Chicken Restoration Program began in 1990 to support habitat improvements on private land and a captive breeding program at Texas A&M University. In 1994, the program was expanded and included captive breeding at Fossil Rim Wildlife Center and at the Houston Zoo.

The Zoo’s work with the species continues, releasing captive-bred birds into the refuge areas. The species continues to slowly grow, now numbering more than 180 birds.

John Werler's Legacy

John Werler spent thirty-eight years of his career at the Houston Zoo, beginning in 1956 as the Zoo’s general curator then becoming director in 1964. He was a dynamic leader who was creative and warmhearted. During his tenure, he led the Zoo to become an international leader in zookeeping best practices, breeding, and research.

An internationally renowned herpetologist who built a well-respected reptile and amphibian collection at the Houston Zoo, Werler loved interacting with visitors and enjoyed educating young keepers. In 1978, Werler authored Poisonous Snakes of Texas, still the definitive guide to venomous snakes of Texas, and co-authored Texas Snakes: A Field Guide with James Dixon.

Werler retired in 1992 and passed away in 2004 of cancer, leaving behind a large, loving following and an impressive body of work. Several animals were named in his honor, including Rhombifera werleri (Tabasco watersnake), and Pseudoeurycea werleri (Werler’s false brook salamander). Werler even named a new species of lizard after his wife Ingrid (Diploglossus ingridae). At the Zoo, the green space between the current Reptile and Amphibian House and Carruth Natural Encounters is named Werler Lawn in his honor.

1993

Don Olson becomes zoo manager following the retirement of John Werler.

1993

The $7.5 million Wortham World of Primates opens.

1994

The Houston Zoo begins breeding and releasing Attwater's prairie chicken in partnership with the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

45

Wortham World of Primates

2000–2022

YOUR HOUSTON ZOO:

Becoming a Leader in the Global Movement to Save Wildlife

The Zoo became a private, nonprofit organization with a fifty-year lease and operating agreement with the city of Houston. This public/private partnership has allowed the Zoo to undertake the most ambitious scope of improvements in its history.

47

47

LEADING WILDLIFE CONSERVATION

Twenty-first century Houston is a fully evolved metropolis. It left the small, scrappy city behind, emerging as a sprawling, international powerhouse with global influence. Houston’s growth and success comes at a price; the early economic base of lumber, cotton, and rail, and today’s energy-based fortunes, are all tied to the harvest of natural resources.

Zoo and aquarium professionals recognized the threats to the environment as early as the 1970s and responded globally by taking on the responsibility to do more to preserve, recover, and protect species around the globe. However, the Zoo’s budget and aspirations, like other municipally run zoos, were tied to the city’s fortunes and politics; Houston Zoo’s ambitions had to remain limited. To realize its potential as a leader in wildlife conservation, the modern Houston Zoo needed to evolve. It was time to privatize.

48

YOUR HOUSTON ZOO: Becoming a Leader in the Global Movement to Save Wildlife

2000 McGovern Children’s Zoo opens.

McGovern Children's Zoo, 2000

MCGOVERN CHILDREN’S ZOO

With a lead gift from the John P. McGovern Foundation, the Zoo opened the new McGovern Children’s Zoo in 2000. The $6 million expansion has been a favorite of generations of Houston’s children as they get nose-to-nose with mongooses, North American river otters, bats, and interact with goats in the popular goat yard.

THE HOUSTON ZOO BECOMES PRIVATE

Don Olson, previously director of Houston Parks and Recreation, took over leadership of the Zoo after John Werler’s retirement in 1992. In 2000, the Houston Parks and Recreation Department underwent an independent audit, which revealed stagnation in Zoo attendance; the Houston Zoo ranked fifty-five out of seventy-eight zoos nationally. The auditors recommended increasing admission fees to the Zoo and other facilities to bolster the Parks Department’s finances. The Zoo’s physical plant was deteriorating, and increased funding was needed for repairs.

Before Disney, Barongi served as mammal curator at the Miami Metro Zoo and was later mammal curator of the San Diego Zoo. When initially approached for the zoo director role by Mayor Brown, Barongi had one stipulation: privatize the Zoo.

Huge financial needs loomed. Barongi pointed out that zoos run by private nonprofit organizations were healthier financially. Mayor Brown responded by creating a task force chaired by Bill Barnett, former lead partner of law firm Baker Botts. Barongi served as the vice chair. On June 26, 2002, Houston’s city council voted 13–1 to approve forming the Zoo Development Corporation, a local government entity that would contract with and oversee the private nonprofit created to run the Zoo with a fifty-year lease. The agreement stipulated the city provide funding to the privately run Zoo’s budget as well as all utilities. The newly privatized Zoo would be responsible for the budget, operations, and management. A member of the task force generously covered all legal fees involved with moving the Zoo away from city operation, and McKinsey & Company donated change management expertise to help coordinate the process.

Houston Mayor Lee P. Brown wanted better for the institution.

With Don Olson’s retirement, Brown hired well-known and highly respected zoo curatorial and management professional Rick Barongi as director in 2000. Barongi served as a lead animal professional engaged in the planning, design, and initial operation of Disney’s Animal Kingdom theme park in Florida.

Houston Zoo Inc. (HZI) was launched in late July 2002. The new, independent nonprofit organization’s board of directors, chaired by Bill Barnett, hired Philip Cannon, an equity investment professional, as the Zoo’s first president and CEO. Rick Barongi became executive vice president-zoo director and secretary of the board.

49

2000

Rick Barongi hired as Director. 2002

Wildlife Carousel opens.

2002 City council votes to privatize the Zoo.

A NEW AGE OF CONSERVATION

Rick Barongi understood that conservation of animals in the wild was the core mission of modern zoos. Zoo animals are ambassadors, representing their wild counterparts; every exhibit element must connect visitors to animals in the wild. Zoos must also work to preserve the genetics of endangered species through thoughtful breeding programs and contribute to conservation efforts.

Houston Zoo’s reorganized conservation effort launched in February 2001, with a donation of $10,000 to support the first international tapir symposium in Costa Rica. The Zoo’s commitment to the preservation of wild animals and wild places was bolstered by creating a full-time director of conservation position in 2004. Bill Konstant was the first to hold the position, facilitating the Zoo’s active participation in efforts to combat threats to biodiversity around the globe.

Under the new approach, the Zoo’s animal and plant collections have become windows for visitors into the diverse and threatened natural world. New programs are connected with the ambassador species within the collection, the expertise of the Zoo’s staff, and the Zoo’s other conservation partners.

(top)

(bottom)

2004

Wildlife Conservation Program formally developed.

2005

The Zoo enters Space Act Agreement to raise Attwater’s prairie chickens at Johnson Space Center.

50

“You can’t run a zoo without conservation. [If you do,] you’re not doing your job.”

—Rick Barongi

Dr. Pati Medici and the Lowland Tapir Conservation Initiative (LTCI), which protects tapirs in Brazil.

Dr. Arnaud Desbiez with the Giant Armadillo Project

2005

Carruth Natural Encounters opens.

CARRUTH NATURAL ENCOUNTERS

Built in the ‘60s, the Small Mammal House had sat empty since 2001 and was prime for renovation. It became the first exhibit area for Rick Barongi to demonstrate his vision for the Zoo’s future. With support from the Carruth Foundation, the building was reimagined as Carruth Natural Encounters, an immersive experience of forest canopies, the river’s edge, estuaries, the sea, savannas, and deserts—inspiring visitors to feel affinity and care for wild habitats. When it opened in 2005, Natural Encounters housed over one thousand animals including African cave cockroaches, Asian small-clawed otters, tamarin monkeys, and naked mole rats. The exhibit won the AZA Significant Achievement Award for exhibits in 2007.

ATTWATER’S PRAIRIE CHICKEN AND NASA

A chance encounter in the early 2000s between Zoo CEO Philip Cannon and NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) Director Jefferson D. Howell Jr. resulted in a partnership between the two organizations to help save the Attwater’s prairie chicken. At a social event, Cannon happened to mention the Zoo sought a few acres of quiet, protected prairie to raise young birds.

NASA’s focus is the protection of our home planet and Howell and Cannon realized the overlap in interests. An agreement was reached in 2005 providing two acres of protected land for the prairie chicken program and another ten acres to raise plants needed to feed the Zoo’s animals.

2005

2009

A research collaboration is established with virologist Dr. Paul Ling at Baylor College of Medicine to develop an EEHV vaccine.

2009

Naturally Wild Swap Shop opens in the McGovern Children's Zoo.

51

Attwater’s prairie chicken chicks at the NASA facility.

Deborah Cannon hired as president and CEO.

DEBORAH CANNON

Philip Cannon retired from his position as president and CEO of Houston Zoo in February 2005 and recently retired president of Bank of America’s Houston Region, Deborah Cannon (no relation), stepped into the role. She was passionate about transforming the Zoo into a world-class institution. Deborah held the post for ten years and saw the Zoo through its earliest growing pains as it moved forward and became a private organization. The Zoo broke multiple financial records and attendance grew from 1.5 million to more than two million guests annually. In 2011, Deborah also started one of Houston's most beloved holiday traditions, TXU Energy presents Zoo Lights.

ELEPHANTS GET A NEW HOME

In 2001, the Zoo launched a multiphase elephant habitat expansion project. Several years and many elephant babies later, the first phase of the McNair Asian Elephant Habitat opened in 2008 with a new elephant barn, an expanded two-acre yard, and an 80,000-gallon tiered swimming pool. The project was funded in part by a generous gift from the Robert and Janice McNair Foundation.

Phase two of the habitat opened in 2017 with a new bull barn, another habitat expansion to 3.5 acres, an updated interpretive program, and a larger 160,000-gallon pool edged by a boardwalk and tiered visitor seating area.

The Zoo is committed to protecting wild elephants in Malaysian Borneo by providing mentorship, training, and support for conservation partners at Seratu Aatai whose mission is to ensure the survival of the Bornean elephant populations inside and outside the protected areas. Seratu Aatai’s current work is focusing on increasing the local community and private sector capacity to accept a peaceful cohabitation with the elephants.

2010

2011

52

Deborah Cannon

Dr. Nurzhafarina Othman, a Houston Zoo conservation partner since 2009 and founder of the Seratu Aatai organization

Elephant bull yard

African Forest opens.

TXU Energy presents Zoo Lights at the Houston Zoo debuts.

ELEPHANT ENDOTHELIOTROPIC HERPES VIRUS (EEHV)

Born in 2006, baby elephant Mac easily became a darling of visitors and staff. But, in November 2008, when Mac was just two years old, his legs suddenly became stiff, he was lethargic, and his head swelled. He was examined by the veterinary staff and extreme intervention measures were taken to address his symptoms, but by the end of the day Mac died from elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV).

2012

A partnership begins with the Giant Armadillo Project in Brazil.

EEHV is a variety of herpesvirus. Herpesviruses are common in all mammal species, including people. All elephants carry EEHV, both in zoos and in the wild, and younger elephants are more vulnerable to damaging symptoms because their bodies’ defenses are not yet fully developed.

Houston and the zoo world

mourned. Immediately after Mac’s death, Dr. Allen Herron, a comparative biologist at Baylor College of Medicine and friend of the Zoo’s senior veterinarian Dr. Joe Flanagan, worked with the Houston Zoo’s veterinary and elephant staff to form a team to study the disease. They recruited Dr. Paul Ling, an associate professor in molecular virology and microbiology who had spent twenty years studying human herpes viruses. Dr. Ling leads a team of scientists who work closely with the Zoo’s veterinary and animal care team to research the virus.

In 2011, at the close of the 7th Annual International EEHV Workshop held in Houston, the Dan L Duncan Foundation announced a grant of $550,000 to support the Baylor College of Medicine and Houston Zoo EEHV research collaboration.

The Duncan Foundation provided funding for the development of early warning testing, and the creation of a treatment protocol. The testing and treatment saved the lives of several young members of Houston’s herd and no other elephants have died at the Houston Zoo since Mac in 2008. The research collaboration shares its treatment protocols and findings with zoos and elephant conservation groups around the world.

The Bug House opens. 2014 First clouded leopards are born at the Zoo.

2014

53

Dr. Paul Ling

Shanti and Mac

HOUSTON TOADS TODAY

The 1984 plan for recovery of the Houston toad aimed to identify all remaining populations of the rare amphibian and to restore it to its original, native range. A census conducted in 2007 revealed the toad was still in a dire position and in 2008, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Texas Parks and Wildlife, and Texas State University partnered with the Houston Zoo’s existing program to increase the population. The Zoo stepped up its efforts toward establishing a captive assurance colony and a propagation, head start, and toadlet release program. Unfortunately, drought and wildfires devastated the toad’s refuge areas near Bastrop in 2011 and the program was set back. The Houston toad was again on the brink of extinction.

The collaborative developed a new strategy; rather than raise toadlets for release, the Houston Zoo would instead focus on maximizing the number of eggs produced and then place the egg strands in the range’s wild ponds. Other organizations and zoos joined the effort, including the Fort Worth and Dallas zoos, and later the San Marcos Aquatic Resources Center. Combined egg releases by the collaboration went from 150,000 to one million annually. Today, over 6.3 million eggs and tadpoles have been released into the wild.

The results are astounding: In 2021, a chorus of nearly 450 males were heard around the release sites and forty-two wild egg chains were identified. Even more exciting, juvenile toads have been found over two miles away from the original release sites.

First okapi is born at the Zoo.

2015

2015

54

Gorillas of the African Forest opens. 2015 Lee Ehmke is hired as president and CEO. 2014

CONSERVATION GALA

What began as a 2005 luncheon chaired by Zoo supporters Annie Graham and Cathy Brock to raise funds to save cheetahs in the wild became the foundation of the Houston Zoo’s annual Conservation Gala. Between 2009 and 2019, the gala raised millions of dollars for the support of the Zoo and its conservation efforts around the globe and featured world-recognized conservationists and ecological leaders as speakers, such as Dr. Jane Goodall and National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore.

AFRICAN FOREST

Once privatization was complete, Rick Barongi’s short list of immediate goals included creating the African Forest, an experience of Equatorial Africa where habitats would mimic native range and connect visitors and animals. The African Forest would also, for the first time in decades, bring chimpanzees back to the Zoo.

When shown the proposed chimp habitat in the Zoo’s new African Forest, Dr. Jane Goodall said, “If I were a chimp I would want to live here.” The habitat includes an air-conditioned viewing area for guests and a fabricated termite mound from which the chimps retrieve treats using a stick as a tool, just as they do in the wild. There are grasslands and the animals have access to large, fabricated trees with ropes and hammocks for climbing and resting.