HORIZONTES REVISTA DE ARQUITECTURA Arquitecture Magazine No. 6

El lado social y humano de la condición de Patrimonio de la Humanidad | Proyecto experimental con BTC en Trinidad, Cuba | Construcción con tierra y tecnologías sociales | El ruedo tradicional en Campeche y su impacto ambiental | Paisaje cultural cafetalero de Santiago de Cuba | El proyecto de restauración de la arquitectura | Letrinas virreinales en el Santo Desierto de Cuajimalpa | El edificio del Centro Impulsor de la Construcción y la Habitación

ISSN 2007-2759

índice 1

3

11

17

13

31

39 50

56

Editorial ENSEÑANZA / TEACHING El lado social y humano de la condición de Patrimonio de la Humanidad Karla Nunes Penna José Hernando Torres Flechas TRANSFERENCIA TÉCNICA / TRANSFER OF TECHNIQUES Proyecto experimental con BTC en Trinidad, Cuba Nancy Benitez Vázquez Duznel Zerquera Amador Construcción con tierra y tecnologías sociales Rodolfo Rotondaro Fernando Cacopardo COMUNIDADES / COMMUNITIES El ruedo tradicional en Campeche y su impacto ambiental Amarella Eastmond Aurelio Sánchez Paisaje cultural cafetalero de Santiago de Cuba Yaumara López Segrera INTERVENCIÓN / INTERVENTION El proyecto de restauración de la arquitectura Olimpia Niglio Letrinas virreinales en el Santo Desierto de Cuajimalpa Tarsicio Pastrana Salcedo SUSTENTABILIDAD / SUSTAINABILITY El edificio del Centro Impulsor de la Construcción y la Habitación Víctor Manuel López López

EDITORIAL

E

stimados lectores a nombre de los integrantes del Consejo Directivo, del Comité Científico Internacional y colaboradores de Horizontes Revista de Arquitectura, reciban nuestro agradecimiento con la presente edición, Indexada. Desde su inicio en el año 2009, Horizontes, ha sentido la necesidad de contar con una edición independiente, analítica y reflexiva, no solo de arquitectura sino también de otras especialidades, en la convocatoria del presente número, nos propusimos abordar temas, no solo del interés actual, sino también de trascendencia como: patrimonio cultural, diseño industrial, arquitectura de paisaje, urbanismo y arte, desde múltiples disciplinas, pensando siempre en la orientación dirigida a un amplio público académico y profesional, donde se involucraran arquitectos, urbanistas, diseñadores, artistas, historiadores, críticos y teóricos del arte, de la arquitectura y de las ciencias humanas. En las últimas décadas la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO), incluyó en su concepción del patrimonio cultural, “tangible e intangible”, aspectos tan variados como los paisajes, la arquitectura vernácula, las artesanías, los rituales y las lenguas indígenas, lo que nos permite presentar una gama con bastante diversidad de temas en la presente edición. Y bajo esta perspectiva Horizontes ve en el patrimonio, en el siglo XXI un proceso histórico, una construcción social y un proceso formado por un conjunto de objetos de carácter estéticos y estáticos. Con esta sexta edición, no solo ampliamos nuestro horizonte sino también, pretendemos contribuir en la preservación y cuidado del Patrimonio Cultural, que nos permita valorar lo tangible, intangible y natural de cada cultura, ciudad, país y comunidad, considerado al patrimonio como el conjunto de bienes, objetos culturales heredados del pasado, herencia pública y colectiva triplicidad en su naturaleza: histórica- producto del tiempo- antropológica- reformulación de la elaboración de la cultura adaptada-, y sociológica- resumen y producto de los intereses sociales- fenómeno de la contemporaneidad. Las secciones: Enseñanza, Transferencia Técnica, Comunidades, Intervención y Sustentabilidad, muestran no solo la experiencia y capacidad de cada uno de los autores de los temas que se manejan en cada artículo, sino también su interés y preocupación por la preservación y salvaguarda del patrimonio cultural. Asimismo un reconocimiento especial a los integrantes del Comité Científico por su valiosa colaboración en la presente edición, quienes pertenecen a prestigiadas y reconocidas universidades e instituciones en el mundo, que de manera profesional, ética e imparcial realizaron el arbitraje de cada uno de los artículos, para hacer posible una edición de contenido científico y especializado, digna de promoción a nivel internacional. Pastor Alfonso Sánchez Cruz Director de Horizontes de Arquitectura

D I R ECTO R I O FUNDADORES DE NHAC M.A. Verónica González García Arq. M.A. Pastor Alfonso Sánchez Cruz COORDINADOR EDITORIAL M. en Arq. Marco Antonio Aguirre Pliego CONSEJO EDITORIAL Dr. Alfonso Ramírez Ponce/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Dr. Daniel Gómez Escoto/Universidad Veracruzana, Campus Córdoba Arq. Ibo Bonilla Oconitrillo/Universidad Latina de Costa Rica Mtro. Prometeo Alejandro Sánchez Islas/Fundación Amigos de la H emeroteca Pública “N estor Sánchez H ernández” de Oaxaca, México Arq. Miguel Angel Castro Monterde/Federación de Colegios de Arquitectos de la República Mexicana, A.C. Arq. Ramón Aguirre Morales/Red Iberoamericana Proterra Mtro. Robert Fredericks/Facultad de Idiomas–Universidad Autónoma “Benito Juárez” de Oaxaca COMITÉ CIENTÍFICO INTERNACIONAL que dictaminaron los articulos de esta edición

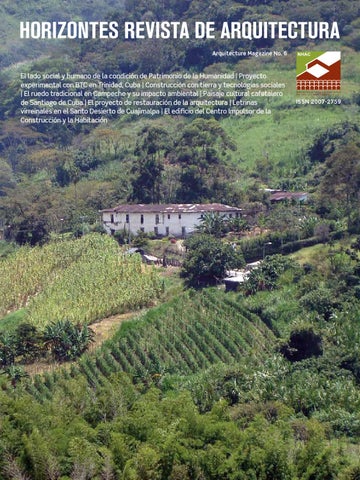

Dra. Natalia Jorquera Silva/Universidad de Chile (Chile) Dr. Fernando Vegas/Universidad Politécnica de Valencia (España) Dra. Giovanna Liberotti/Universidad de L’Aquila (Italia) Dra. Yuko Kita/Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Becaria del programa de Becas Posdoctorales de la UNAM (México) Dr. Luis Silvio Ríos Cabrera/Universidad de Asunción (Paraguay) Dra. Eugenia María Azevedo Salomao/Universidad Michoacana de San N icolás de H idalgo (México) Dr. Luis Fernando Guerrero Baca/Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (México) M. en Arq. Francisco Uviña Contreras/The Univsersity of New Mexico (U.S.A.) Dra. Manuela Mattone/Politécnico di Torino (Italia) Traducción al Inglés: Robert A. Fredericks S. Diseño editorial: Color Digital. En portada: Ibagué, Colombia. Foto: Olimpia Niglio. Horizontes es una revista de arquitectura enfocada a la investigación de la arquitectura regional con características de sustentabilidad. Las opiniones expresadas por los autores no necesariamente reflejan la postura del editor de la publicación. Queda estrictamente prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de los contenidos e imágenes de la publicación sin previa autorización del Instituto Nacional del Derecho de Autor. Horizontes Revista de Arquitectura, Año 6, No. 6, abril 2013–abril 2014, es una publicación anual editada por Nuevos Horizontes para la Arquitectura de las Comunidades, A.C. Editor responsable: Arq. M.A. Pastor Alfonso Sánchez Cruz Número de Certificado de Reserva 04–2013–041212442500–102. Registro ISSN 2007–2759, ambos otorgados por el Instituto Nacional del Derecho de Autor. Número de Certificado de Licitud de Título y Contenido: 15944. Domicilio de la publicación y distribuido por Nuevos Horizontes para la Arquitectura de las Comunidades A.C. Manuel Doblado Número 1010 A, Centro C.P. 68000 Oaxaca de Juárez, teléfono (951) 5011418. Imprenta: Carteles Editores, Colón No. 605–3, Centro C.P. 68000 Oaxaca de Juárez, teléfono (951) 67029. Se terminó de imprimir el 30 abril de 2014 con un tiraje de 1,000 ejemplares. Indexada por: Latindex

|3

ENSEÑANZA/TEACHING

KARLA NUNES PENNA y JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS

The social,

human side of World Heritage status KARLA NUNES PENNA Is an architect, urban planner and cultural manager, lecturer at the Centre for Advanced Studies in Integrated Conservation (CECI, Brazil), and PhD researcher at Curtin University (Australia). She has worked in Brazil and in other in developing countries, planning, coordinating, and implementing projects and public policies for cultural heritage preservation at UNESCO World Heritage sites. JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS Is an architect, lecturer at the Universidad Colégio Mayor de Cundinamarca (Colombia), and PhD researcher at University of Salamanca (Spain). He has expertise in strategic planning, organisation, management and project controlling, and programs at the local, regional, national, and international levels, focused on sustainable development and local communities’ engagement programs. Head of the program Vigías del Patrimonio Cultural Colombiano, by the Fundación Contexto Cultural. KARLA NUNES PENNA Arquitecta, urbanista y directora cultural, conferencista en el Centro para los Estudios Avanzados en la Conservación Integral (CECI, Brasil) y Doctora Investigadora en la Universidad de Curtin (Australia). Ha trabajado en Brasil y en otros países en desarrollo en la planeación, coordinación e implementación de proyectos y de políticas públicas para la preservación del patrimonio cultural en los sitios de Patrimonio para la Humanidad del UNESCO. JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS Arquitecto, Docente Investigador en la Universidad Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca (Colombia) y Doctorando de la Universidad de Salamanca (España). Con experiencia en planeación estratégica, organización, gerencia y control de proyectos culturales, incluyendo proyectos a nivel local, regional, nacional e internacional, enfocados en el desarrollo sustentable, patrimonio y programas para fomentar la participación activa de las comunidades. Coordinador del programa: Vigías del Patrimonio Cultural Colombiano, auspiciado por la Fundación Contexto Cultural. FECHA DE RECEPCIÓN: 29 de octubre de 2013 FECHA DE ACEPTACIÓN: 18 de febrero de 2014

ABSTRACT

RESUMEN

The following essay emerged as a reflection of the authors based on their professional and academic experience working with the development and implementation of preservation programs in several historical centers in Latin America. The purpose of this article is to contextualize the process of listing a historical urban center as a World Heritage site through the United Nations for Education, Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO) and the fundamental role of local communities in achieving the proper preservation of these environments.

El siguiente ensayo se presenta como una reflexión de los autores teniendo en cuenta sus experiencias profesionales y académicas en trabajar con el desarrollo y implementación de programas de conservación en varios centros históricos de América Latina. El propósito de este artículo es contextualizar el proceso de inclusión de un centro urbano histórico como Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la UNESCO y el papel fundamental de las comunidades locales para alcanzar con éxito la preservación de su ambiente construido.

key words: world heritage, local communities, social participation, cultural appropriation.

palabras- clave: património mundial, comunidades locales, participación social, apropiación cultural.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCCIÓN

Everything starts with a governmental decision. Governments undertake great political efforts, investing significant economic resources on technical instruments such as inventories, maps, charts, surveys, archaeological and environmental analyses, and all types of reports, to pursue the desired World Heritage (WH) status from UNESCO. With the acquisition of this status, what was only local suddenly becomes globally relevant, thus making a WH site an international attraction. At first glance, the new status might be considered an opportunity to gather a large amount of resources for the development of programs and projects, not only for the conservation and preservation of the

Todo comienza con una decisión gubernamental. Los gobiernos emprenden grandes esfuerzos políticos e invierten recursos económicos significativos en los instrumentos técnicos tales como los inventarios, mapas, diagramas, levantamientos topográficos, los análisis arqueológicos y ambientales, y en toda clase de reportes, para ir en pos del deseado estado de Patrimonio de la Humanidad (PH) de UNESCO. Con la adquisición de dicho estado, lo que fue algo solamente local de repente se convierte en algo globalmente relevante, así transformando un sitio PH en un atractivo internacional. A primera vista, este nuevo estado puede brindar una oportunidad para conseguir una gran cantidad de recursos para HORIZONTES

4|

The social, human side of World Heritage status

El lado humano y social de la condición de Patrimonio de la Humanidad el desarrollo de programas y proyectos, no sólo para la conservación y preservación de la estructura urbana, sino también para la formulación de iniciativas culturales, sociales, económicas y políticas. Sin embargo, esta presunción está equivocada, ya que, de hecho, ningun recurso económico se invierte directamente en los sitios PH. En vez de eso, el estado abre las puertas hacia la recaudación internacional de fondos y estimula el interés de entidades particulares, públicas, locales y nacionales para apoyar los proyectos locales. Además de las expectativas políticas y económicas, ¿Cuál es el verdadero impacto del estado PH en las vidas de los habitantes de ese territorio? ¿Participan ellos, o son tan sólo

observadores del nuevo contexto? ¿Entienden su papel en el proceso? Este artículo pretende examinar los asuntos involucrados en los intentos de vincular a las comunidades locales al proceso de la preservación de los sitios Patrimonio de la Humanidad y cómo el sentido de pertenencia, posesión y aprecio por parte de dichos ciudadanos afecta el éxito del manejo de los sitios.

Al comenzar esta reflexión, tenemos que clarificar el detalle de que utilizamos ciertos términos de la preservación reiterativamente al elaborar el mapa de preguntas y problemas que nos inspiraron a escribir este artículo.

Al considerar el proceso de la inclusión de un sitio en la lista de UNESCO, podemos observar sus efectos en tres niveles: (1) al nivel del territorio en torno a los edificios incluidos en la denominación y los conceptos de patrimonio tangible e intangible (y quienes los determinan); (2) al nivel de la comunidad local, incluyendo la apropiación de su patrimonio; y, por fin, (3) al nivel definido por la construcción de la memoria, la esencia de las comunidades, y de la expresión colectiva del sentir, ser y hacer. Ese último punto permite la re-creación de los pasos y las experiencias que serán proyectadas hacia los nuevos horizontes para dichas comunidades. El problema es muy similar para cada unos de estos tres escenarios. En

urban structure, but also for cultural, social, economic, and political initiatives. However, this assumption is incorrect, since, in fact, no economic resources are directly invested in WH sites. Instead, the status opens doors for international fundraising and arouses the interest of private, public, local, and national entities in supporting local projects. Political and economic expectations aside, what is the real impact of a WH status on site inhabitants’ lives? Are they participating, or they are only spectators of the new context? Do they understand their role in the process? This article aims to examine the issues involved in engaging local communities in the preservation process of World Heritage sites and how the sense of ownership, belonging, and appreciation by these citizens affects the success of the sites’ management.

cepts of preservation reiteratively in constituting the map of questions and problems that inspired this writing. In considering the process of a site’s inclusion on the UNESCO list, we can observe effects at three levels: (1) at the territory level, regarding the buildings encompassed by the nomination and including concepts of what tangible and intangible heritage are (and who determines them); (2) at the local community level, including these communities’ heritage appropriations; and, finally, (3) at a level defined by the construction of memory, the essence of communities, and the collective expression of feeling, being and doing. This last one allows the re-creation of steps and experiences to be projected to the new horizons of these communities. The problem is very similar for each of the three scenarios. Regarding the territory, when a site nomination is granted, it is because there was a political decision to change the local strategic plans, allowing local governments to

identify which expressions are worthy of global recognition. The governments must undertake a long process, involving researching, mapping, planning, marketing, and weaving an intricate network of actions and movements to obtain WH status (UNESCO, 2013). The question here is whether the decision is made based on detailed studies of the site load capacity, risk analyses, and urban studies, considering factors such as vehicular traffic conditions, pedestrian access, access for people with disabilities, and other issues that will arise with the increased tourist flow and economic pressure that accompanies the status. These context-related issues impact on heritage management and an integrated approach needs to be taken into consideration when establishing management plans (UNESCO et al, 2013). It is necessary for identifying and addressing issues regarding strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that can affect these sites. Let us address communities. The objective of pursuing a World Heritage

EFFECTS OF LISTING: AN OVERVIEW

In beginning this reflection, we must clarify that we do mention some con-

LOS EFECTOS DEL REGISTRO: UN PANORAMA

HORIZONTES | KARLA NUNES PENNA y JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS

El lado humano y social de la condición de Patrimonio de la Humanidad

|5

cuanto al territorio, cuando se otorga la denominación de un sitio, es porque existió una decisión política para cambiar los planes estratégicos locales, permitiendo así que los gobiernos locales identifiquen cuáles expresiones merecen un reconocimiento global. Los gobiernos tienen que emprender un proceso largo que involucra la investigación, la cartografía, la planificación y la mercadotecnia para tejer una red intricada de acciones y movimientos para obtener el estado de PH (UNESCO, 2013). La pregunta aquí es si se toma la decisión basada en estudios detallados de la capacidad de carga, los análisis de riesgos y los estudios urbanos, tomando en cuenta factores como las condiciones del tráfico vehicular, el acceso peatonal, acceso para la gente con discapacidades y otros asuntos que aparecerán ante el aumento de el flujo turístico y por la presión económica que acompañan al estado designado. Estos asuntos vinculados al contexto tienen su impacto en el manejo del patrimonio, y hay que considerar una

estrategia integrada cuando se elaboran los planes de manejo (UNESCO et al, 2013). Eso es necesario para identificar y ponerse a trabajar en los asuntos relacionados a los puntos fuertes y débiles, las oportunidades y las amenazas que pueden afectar a estos sitios. Vamos a dirigirnos al asunto de las comunidades. El objetivo de buscar el estado de Patrimonio de la Humanidad es alentar la conservación de un lugar por medio del empoderamiento de las comunidades locales para mejorar sus prácticas de manejo (Convenio UNESCO, 1972). Sin embargo, Rössler declaró (2012) que la mayoría de las nominaciones para el Patrimonio de la Humanidad hace diez o veinte años, fueron elaborados y presentados por instituciones centrales y ministerios, y se inscribieron en la Lista del Patrimonio de la Humanidad sin cualquier consulta con las comunidades locales y las partes interesadas. Así, es pertinente preguntar cuántos sitios PH gozan una verdadera y fuerte conectividad con sus comunidades locales. Por consiguiente, podemos pre-

guntar si ellas están preparadas para confrontar un nombramiento UNESCO con toda la presión nacional e internacional que conlleva. Estamos conscientes que, sin la adecuada preparación en términos de conocimientos, sensibilización, consciencia, aprecio y apropiación, las comunidades locales no están en condiciones de reconocer la importancia del ambiente histórico que habitan. Por eso, no están preparadas a defenderlo, y están expuestas al riesgo de ver que su precioso patrimonio se desvanezca con el tiempo. Al analizar los documentos oficiales en los sitios de patrimonio de la humanidad en América Latina, podemos observar que a menudo no tienen planes de manejo a largo plazo que establezcan acciones programadas y que incluyan el fortalecimiento de la participación, apropiación, la sensibilización y las actividades tendientes a elevar las consciencias locales. Otra pregunta pertinente es si los planes actuales para la preservación de los sitios PH han sido instrumentos eficaces para fortalecer a las comunidades y asegurar su bienestar, o si han sido

status is to encourage conservation of an area by empowering local communities to improve management practices (UNESCO Convention, 1972). However, Rössler stated (2012) that most World Heritage nominations ten or twenty years ago were prepared and processed by central institutions and ministries and inscribed on the World Heritage List without any consultation with local communities and stakeholders.Thus, it is pertinent to ask how many WH sites have a true, strong connectivity to their local communities. Consequently, we can ask whether they are prepared to face a UNESCO nomination with all the national and international pressure that comes with the status. We are aware that, without the correct preparation in terms of knowledge, sensitization, awareness, appreciation, and appropriation, local communities are unable to recognize the importance of the historical environment they live in. Consequently, they are not prepared to defend it, being exposed to the risk of seeing their precious heritage vanish over time. In

analyzing official documents at world heritage cites in Latin America, we can observe that sites usually have no longterm management plans that establish programmed action plans including the reinforcement of local appropriation, sensitization, and awareness-raising activities. Another pertinent question is whether the current plans for the preservation of WH sites have been effective tools to strengthen communities and guarantee their wellbeing, or whether they have been configured as tools to strengthen governments and the economy. What we can often observe in our historical centers is that, after the WH status, territories no longer serve as cultural spaces where people live and participate; where the essence of the place no longer has a true sense; where living and enjoying the streets, the parks, and the shops are substituted with the coming and going of tourists, as a stage for projects targeting international projection. The place is no longer a cultural environment for enjoyment; instead, it is a commercially feasible enterprise.

Then, a very complex and long-known process takes place: gentrification. The cost-benefit ratio makes governments and private initiatives the best recipients of the buildings, as only they have the resources to maintain them and make the adjustments required by the contemporary world. Because of the economic pressure, the people who originally lived in the space must be displaced from their own cultural scenario. Regarding memory, understood here as the process of recognizing a site’s value, we cannot think of building any history within a single dimension. Historic centers were built by and for specific groups of people, thus requiring these people to give sense to them. People need the possibility of rescue in order to be proud of, to reproduce, and to transmit their own history. Concerning community and memory, we must be aware that these people are the only ones who are capable of understanding their history. What should be done if they are no longer able to live in their sites?

KARLA NUNES PENNA y JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS | HORIZONTES

6|

The social, human side of World Heritage status

configurados como herramientas para reforzar a los gobiernos y las economías. Lo que podemos observar a menudo en nuestros centros históricos es que, después de conseguir su estado de PH, los territorios ya no pueden ser considerados como espacios culturales donde la gente vive y participa; donde la esencia del lugar ya no tiene un sentido verdadero; donde vivir y disfrutar las calles, los parques y las tiendas es re-emplazado por el vaivén de los turistas; convertidos ya en “escenarios” para proyectos enfocados hacia la proyección internacional. El lugar deja de ser un ambiente cultural para el disfrute; en vez de eso, se convierte en una empresa comercialmente rentable. Entonces se da inicio a un reconocido y complejo proceso: la gentrificación. La relación de costo-beneficio hace que los gobiernos y las iniciativas privadas sean los mejores destinatarios de los edificios, puesto que tan sólo ellos tienen los recursos para mantenerlos y hacer los ajustes requeridos por el mundo contemporáneo. Debido a la presión económica, la gente que originalmente vivió en

el espacio tiene que ser desplazada de su propio escenario cultural y vivencial. En cuanto a la memoria, algo que se entiende aquí como el proceso de reconocer el valor de un sitio, no podemos concebir la construcción de cualquier historia dentro de una sola dimensión. Los centros históricos fueron construidos por y para ciertos grupos de personas, con su propio contexto y así, se necesitan aquellas personas para brindarles algún sentido. La gente necesita la posibilidad de un rescate para poder sentirse orgullosa de, y así reproducir y transmitir su propia historia. En lo que se refiere a la comunidad y la memoria, tenemos que ser conscientes que estas personas son las únicas capaces de comprender su historia. ¿Qué se debe hacer si ya no es posible que puedan habitar en sus propios territorios?

NEW WORLD HERITAGE STATUS: HOW THE PROCESS SHOULD BE DONE

this first question, heritage is what is valuable to the local community, defined through an open process of social participation, considering what all related areas—academia, government, practitioners, industry—think is relevant. The definition of what needs to be preserved and how it is going to happen is a constructive, collective, and joint effort. Second, who determines what heritage is? Heritage will be meaningful only if it is a joint output resulting from a dialogue among all involved actors—social, private, public, cultural, and political—and considering their administrative and economic contexts. Focusing on the communities’ role, if local people do not participate collaboratively, the process no longer meets the first main condition of being a recognized socio-cultural expression, and the risk of its disappearing increases.

Let us approach this theme under the WH’s question approach: what, who, how, when, where, why, for what, and for whom. For each question, we will have a different answer, finding common points and differences among them. First, what is heritage? According to the World Heritage Convention (UNESCO, 1972), heritage consists of three main categories: (1) monuments, (2) groups of buildings (ensembles), and (3) sites, which include historic buildings, historic areas and towns, archaeological sites and the contents therein, and historic and cultural landscapes. That is the official concept. However, at the local level, how does the process of determining what heritage is happen? To become a cultural heritage, an asset must be considered valuable within the community and then by the city, the state, the nation, and finally UNESCO. This means that there are several criteria to be considered and a long path to be taken before achieving UNESCO’s WH status. Concerning

EL NUEVO ESTADO DE PATRIMONIO DE LA HUMANIDAD: LA MANERA EN LA CUAL SE DEBE LLEVAR A CABO EL PROCESO

Permítanos abordar este tema bajo la clásica estrategia de las preguntas in-

How does a cultural asset become a World Heritage site for its people? The most positive way is to harmonize and reconcile the interests of all actors in-

HORIZONTES | KARLA NUNES PENNA y JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS

dagatorias: qué, quién, cómo, cuándo, dónde, por qué y para quién. Para cada pregunta, tendremos una respuesta diferente, encontrando algunos puntos en común y diferencias entre ellas. Primero, ¿Qué es patrimonio en este contexto? De acuerdo a la Convención del Patrimonio Mundial (UNESCO, 1972), el patrimonio consiste en tres categorías principales: (1) monumentos, (2) conjuntos de edificios y (3) sitios, lo que incluye edificios históricos, lugares y pueblos históricos, los sitios arqueológicos y todo el contenido adentro de ellos, y los paisajes históricos y culturales. Este es el concepto oficial. Sin embargo, al nivel local, ¿Cómo se lleva a cabo el proceso de determinar lo que es patrimonio? Para convertirse en patrimonio cultural, un elemento debe ser considerado “valioso” dentro de la propia comunidad y entonces por la ciudad, el estado, la nación, y por fin, UNESCO. Eso significa que hay varios criterios a contemplar y una ruta muy larga a seguir hasta conseguir el estado de PH de UNESCO. Diríamos, en referencia terested in the status, including those in local communities. This process must take into consideration the fragilities and risks that the status can bring, while finding ways to incorporate cultural preservation, social inclusion, touristic promotion, political interests, and economic balance into the equation. In such a process, it is essential to establish mechanisms, such as forums for shared management, capable of linking, conciliating, and potentiating these different interests, experiences, and resources from the public, private, and social sectors. An example of this type of forum is the Historical Center Management Council of São Luís, Brazil, created in 2003 (Decree n. 25441, 2003), which seeks to build partnerships between the public and private sectors and civil society to establish and articulate strategies for regional and local development (see Chart 01). Such mechanisms improve the relationships among all interested stakeholders, encourage the involvement of local people, prepare social actors for decision-making processes,

El lado humano y social de la condición de Patrimonio de la Humanidad

a esta primera pregunta: El patrimonio es lo que es valioso a la comunidad local, definido por medio de un proceso abierto de participación social y contemplando lo que todas las áreas relacionadas—academia, gobierno, practicantes, industria—consideran relevante. La definición acerca de lo que hay que preservar y cómo se va a realizarlo es un esfuerzo constructivo, colectivo y colaborativo. Segundo, ¿Quién determina lo que es patrimonio? El patrimonio tendrá un significado tan sólo si es un resultado

producido por medio de un diálogo entre todos los actores—sociales, particulares, públicos, culturales y políticos—y tomando en cuenta sus contextos administrativos y económicos. Al concentrar nuestra atención en el papel de la comunidad, si la gente local no participa de manera colaborativa, el proceso ya no satisface la primera condición principal, la de ser reconocida como una expresión socio-cultural local, y así, aumenta el riesgo de su desaparición. ¿Cómo se convierte un elemento cultural en un sitio de Patrimonio de la

|7

Humanidad para su gente? La manera más positiva es la de armonizar y reconciliar los intereses de todos los actores interesados en el estado, incluyendo representantes de las comunidades locales. Este proceso tiene que considerar las fragilidades y los riesgos que el estado puede provocar, mientras se buscan maneras de incorporar la preservación cultural, la inclusión social, la promoción turística, los intereses políticos y el equilibrio económico en la ecuación. En tal proceso, es esencial establecer mecanismos de participación, tales como

1 and 2. Historical centre management council meetings – são luís, brazil. By: edgar rocha. The city of são luís created an institution that gathered all the historic center’s stakeholders to define shared objectives and strategies in order to face structural problems affecting the historic center, promote social development based on the potentialities of its cultural heritage, and strengthen integrated planning action towards preservation. Following negotiation within a shared management environment, the community could better discuss issues and initiatives pertinent to the area (penna et al, 2003). Reuniones del Consejo del Manejo del Centro Histórico de Sao Luís, Brasil Por: Edgar Rocha. La Ciudad de Sao Luís creó una institución que aglomeró todos los actores del Centro Histórico a definir los objetivos y estrategias compartidos para poder confrontar los problemas estructurales que afectan al Centro Histórico, promover el desarrollo social basado en las potencialidades de su patrimonio cultural y fortalecer la acción integral de la planeación para orientarla hacia la preservación. Después de la negociación dentro de un ambiente de manejo compartido, la comunidad pudo debatir mejor los asuntos e iniciativas pertinentes a la zona. (Penna et al, 2003). photos

and demonstrate the available resources. Through such a collective effort, it is possible to prepare the community for the WH situation. When are people ready to recognize an asset as a WH site? Inclusion on the list takes time and depends on a long sequence of events, which depends on the type of population living at the location. It means undertaking a serious and long process of sensitization and appropriation, including fostering strong education programs and awareness-raising activities to mobilize everyone living in the location. For example, the awareness program “Vigias del Património Cultural” implemented in Colombia illustrates an effective involvement of local communities and their heritage (see Chart

2). The focus of such programs is on building the sense that, since heritage was constructed by people in response to past social needs, its value must also be transmitted essentially by people. That transmission is an important part of conservation, safeguarding not only the cultural heritage but also, more importantly, the sustainable and social development of the community of a specific place (Flechas, 2013). Furthermore, regarding the places to be preserved, defining where heritage is, it is not about a geographic space, a historic center, or an ensemble. The definition includes a reference to representation, how a specifically built environment represents a specific community, and the people who live in, understand, and give sense to the place.

Why hold WH status? This is a complex question. For people who appreciate their heritage, the meaning of their cultural values is clear, so it is easier to determine why such a status is important to their lives. However, in interviewing local people around World Heritage sites, we can identify that, for them, such appreciation is not a sufficient justification for the extensive effort required to obtain the WH title. Then, the question is whether this perception is the same for those who have other types of interests in the WH status. Politicians and the economic sector consider heritage relevant, but the economic factor may lead the motivation. This is a risky situation. Considering heritage merely as a source of economic benefits and disregarding the fragility and capacity of these loca-

KARLA NUNES PENNA y JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS | HORIZONTES

8|

The social, human side of World Heritage status

foros, talleres, y demás actividades que se consoliden como espacios de diálogo, que permitan vincular, reconciliar y concertar estos diversos intereses, experiencias y recursos derivados de los sectores públicos, privados y sociales. Un ejemplo de este tipo de foro es el Consejo para el Manejo del Centro Histórico de São Luís, Brasil, creado en 2003 (Decreto N° 25441, 2003), el cual busca forjar asociaciones entre los sectores públicos y privados y la sociedad civil para establecer y articular estrategias para el desarrollo regional y local (vea Tabla 1). Tales mecanismos mejoran las relaciones entre todos los actores interesados, alientan la participación de la gente local, preparan a los actores sociales para los procesos de la toma de decisiones e identifican los recursos disponibles. Por medio de tal tipo de esfuerzo colectivo, es posible preparar a la comunidad para una situación de PH. ¿Cuándo está lista la gente para reconocer a un bien cultural como un sitio PH? La inclusión en la lista requiere tiempo tions transforms historical places into mere attractions for the attainment of resources and political benefits rather than cultural environments to be enjoyed. Simultaneously, we ask for whom heritage is being preserved? People understand heritage as a culturally valuable property but also start to understand how it can be economically valuable to foreigners. UNESCO should establish the development and implementation of strategies for strengthening local communities as a sine qua non condition for governments before granting the WH status, thus ensuring better long-term management plans that consider local people. This can lead to a more administratively, economically, and socially sustainable preservation process. The last question is, what is the purpose of being a WH site? In general, being a WH site involves political and economic decisions in converting places that offer attractive commercial products for tourism. This view has proven not to be the most effective

y depende de una larga secuencia de eventos, lo que depende del tipo de población que vive en el lugar. Implica emprender un proceso largo y serio de sensibilización y apropiación, algo que incluye el fomento de fuertes programas educativos y actividades de concientización para movilizar a toda la gente que vive en el lugar. Por ejemplo, el programa de concientización “Vigías del Patrimonio Cultural” que se implementó en Colombia ilustra una participación eficaz de las comunidades locales y su patrimonio (vea Tabla 2). El enfoque de este programa consiste en ayudarle a las comunidades a fortalecer su sentido de pertenencia y la apropiación social del patrimonio cultural, puesto que sus manifestaciones y expresiones culturales han sido construidas por sus ancestros en respuesta a las necesidades y contextos sociales y culturales del pasado, su valor también tiene que ser transmitido y construido esencialmente por sus habitantes. Aquella transmisión es una parte importante de la conservación, ya que salvaguarda no tan sólo el pa-

trimonio cultural en sí, sino también, y especialmente, el beneficio social de las comunidades en la consolidación de su memoria y el desarrollo sustentable del territorio. (Flechas, 2013). Además, en referencia a los lugares a ser preservados, podemos recalcar que definir el “dónde” de un patrimonio no se trata tan sólo de un espacio geográfico, un centro histórico o un conjunto. La definición incluye una referencia a la representación y cómo un ambiente construido específicamente representa una comunidad específica, y a las personas que lo habitan, lo comprenden y otorgan sentido al lugar. ¿Por qué conseguir el estado de PH? Esta es una cuestión compleja. Para la gente que aprecia su patrimonio, el significado de sus valores culturales es claro, y así, es más fácil determinar por qué tal estado es importante en sus vidas. Sin embargo, al entrevistar a la gente local alrededor de sitios Patrimonio de la Humanidad, podemos identificar que para ellos, tal aprecio no es una justificación para el esfuerzo

way to manage a WH status. In fact, we cannot prioritize either tourism or culture. The successful management of historical sites relies on a balance between tourist activities and cultural respect, where both areas support and collaborate with one another (Pedersen, 2002). Tourism by itself is dangerous and exposes the fragilities of the site. Tourism can bring benefits only if it provides the resources required by cultural initiatives, based on pre-established studies of all strategies undertaken by all institutions and considering all stakeholders related to the cultural environment in a joint process of construction aimed at achieving shared outcomes by all and for all, as heritage must be.

egies for the development of preservation policies focused on the demands of local people. In this sense, social engagement is essential. Every citizen must learn how to appreciate and value their heritage so that they become active agents in preserving and propagating it. The recognition between individuals and their culture is built on the individuals’ sense of ownership and consequent appropriation and respect, making citizens conscious of their role as protagonists in the three scenarios (territory, community, and memory). It is also important to keep all actors working together, aiming at common objectives, joining their efforts, combining forces, and thus consolidating a single and true identity. This will result in the strengthening of the administrative and political local structure while maintaining the essence and roots of the site. This is essential for the preservation process, considering that the preservation guidelines for each historic site need to be defined in accordance with what the

CONCLUSION

Being listed as a World Heritage site puts a historic site on the global stage, providing access to international technical and financial resources, tourism promotion, and stimuli for the local economy. However, attached to these benefits, the status requires new strat-

HORIZONTES | KARLA NUNES PENNA y JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS

El lado humano y social de la condición de Patrimonio de la Humanidad

extensivo que se requiere pare obtener el título de PH. Entonces, la cuestión es si esta percepción es la misma para aquellos que tienen otros tipos de intereses en el estado de PH. Los políticos y el sector económico consideran al patrimonio como relevante, pero el factor económico puede ser el incentivo principal de la motivación. Es una situación de riesgo. Al considerar al patrimonio solamente como una fuente de beneficios y al hacer caso omiso de la fragilidad y la capacidad de esos lugares, se transforman los lugares históricos en solo atractivos para conseguir recursos y beneficios políticos en vez de ambientes culturales para disfrutar. Simultáneamente, preguntamos ¿para quién está siendo preservado el patrimonio? Las comunidades entienden el patrimonio como una propiedad culturalmente valiosa, pero también comienzan a entender cómo puede ser económicamente valiosa para los extranjeros. UNESCO debe establecer el desarrollo y la implementación de estrategias para fortalecer a las comuni-

dades locales como una condición sine qua non para los gobiernos antes de conferir el estado de PH a un sitio para así asegurar mejores planes de manejo a largo plazo que incluyan a las comunidades locales. Esto puede producir un proceso de preservación más sustentable en términos administrativos, económicos y sociales. La última pregunta es: ¿Cuál es el propósito de ser un sitio PH? En general, ser un sitio PH involucra decisiones políticas y económicas en convertir lugares que ofrecen atractivos productos comerciales para el turismo. Esta perspectiva no ha resultado ser la manera más eficaz para manejar el estado de PH. De hecho, no podemos dar una “prioridad”, ni al turismo, ni a la cultura. El manejo exitoso de los sitios históricos depende de un equilibrio entre las actividades turísticas y el respeto cultural, donde ambos rubros se apoyan y colaboran entre sí (Pedersen, 2002). El turismo por sí sólo es peligroso y expone las fragilidades del sitio. El turismo puede traer beneficios tan sólo si provee los recursos requeridos

|9

por las iniciativas culturales, basado en estudios pre-establecidos de todas las estrategias emprendidas por todas las instituciones y considerando a todos los actores relacionados al ambiente cultural en un proceso conjunto de construcción dirigido al logro de resultados compartidos por todos y para todos, tal como un patrimonio tiene que ser. CONCLUSIÓN

Tener un registro como un sitio de Patrimonio de la Humanidad coloca al sitio histórico en un escenario global y provee acceso a los recursos técnicos y financieros internacionales, así como genera la promoción del turismo y estímulos para la economía local. Sin embargo, agregado a dichos beneficios, el estado requiere nuevas estrategias para el desarrollo de políticas de preservación enfocadas en las necesidades de las comunidades locales. En este sentido, un engranaje social es esencial. Cada ciudadano debe aprender cómo apreciar y valorar su patrimonio para que se convierta en un agente activo

3 and 4. Vigias del Património Cultural workshop – Villa de Leyva, Colombia. By: José Hernando Torres Flechas (2011). Taller de Vigias del Patrimonio Cultural – Villa de Laya Por: José Hernando Torres Flechas (2011). The Vigias del Património Cultural program is a strategy for encouraging citizen participation in the social appropriation of cultural heritage that focuses on promoting respect for cultural diversity. Under a voluntary scheme, Colombian communities are organized to recognize, value, protect, retrieve, disseminate, and identify initiatives for sustainability of the nation’s cultural heritage (Ministerio de Cultura, 2013). / El programa de las Vigias del Patrimonio Cultural es una estrategia para alentar a la participación ciudadana en la apropiación social del patrimonio cultural que enfatiza la promoción de un respeto para la diversidad cultural. Bajo una esquema voluntaria, las comunidades colombianas son organizadas para reconocer, valorar, proteger, rescatar, diseminar e identificar iniciativas para la sustentabilidad del patrimonio cultural de la nación (Ministerio de Cultura, 2013).

photos

local people perceive as worth preserving (Gilmour, 2006). On the one hand, it is necessary to have a commitment from UNESCO in seeking more effective instruments of social inclusion. On the other hand, communities need to be committed and improve both their capacity to understand and their participation in the preservation deci-

sion-making process. People cannot just wait for national and international institutions to decide what is best for them. They are the only ones who have a comprehensive understanding of life on the site and therefore can help in making decisions, since they know how the place has changed over the years and how it can be better adapted to today’s globalized world.

The communities that inhabit potential WH sites, especially when they are traditional societies, should be intimately involved in the safeguarding of sites’ memory, vitality, and continuity through history (ICOMOS, 2008).

KARLA NUNES PENNA y JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS | HORIZONTES

10 |

The social, human side of World Heritage status

para preservarlo y propagarlo. El reconocimiento entre los individuos y su cultura se erige sobre un sentido de “pertenencia” del individuo y por consiguiente de apropiación y respeto, el reto es hacer que los ciudadanos sean conscientes de su papel como protagonistas en los tres escenarios (territorio, comunidad y memoria). También es importante lograr que todos los actores sigan trabajando en conjunto, orientándose hacia objetivos comunes, juntando sus esfuerzos y así, consolidando una sola identidad verídica. Esto traerá como un resultado el fortalecimiento de la estructura administrativa y política local mientras mantiene la esencia y las raíces del sitio.

Este es algo esencial para el proceso de la preservación; al considerar que las pautas para la preservación de cada sitio tienen que ser definidas de acuerdo a lo que la gente local estime como digno de la preservación (Gilmour, 2006). Por un lado, es necesario contar con un compromiso por parte de UNESCO a buscar instrumentos más efectivos para fomentar la inclusión social. Por otro lado, las comunidades en sí tienen que ser más comprometidas y mejorar tanto su capacidad de comprender como su participación en el proceso de toma de decisiones referentes a la preservación. La gente no puede permitirse el lujo de esperar para que

las instituciones nacionales e internacionales decidan lo que más les “conviene”. Ellos son los únicos que tienen una comprensión global de la vida en el territorio, y por eso, pueden ayudar a tomar las decisiones, puesto que ellos saben cómo el lugar ha cambiado a lo largo de los años y cómo puede ser adaptado al mundo globalizado de hoy. Las comunidades que habitan los sitios potenciales de ser PH—en particular cuando son sociedades tradicionales—tienen que ser involucradas íntimamente en las acciones para salvaguardar la memoria, la vitalidad y la continuidad del sitio a lo largo de la historia (ICOMOS. 2008).

REFERENCES

Penna, K., Campelo, S. and Taylor, E. (2013). The

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultur-

Decree #25441. (2003). Dispõe sobre a instalação do

challenge of cultural heritage shared management in de-

al Organization – UNESCO, International Centre

Núcleo Gestor do Centro Histórico de São Luís e dá

veloping countries. 8th International Meeting Ciudad

for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of

outras providências. In 15 August 2003. DOM: Sao

Imagen y Memoria. 20-24 May 2013. Santiago de

Cultural Property - ICCROM, International Coun-

Luis, Brazil

Cuba, Cuba: Universidad de Oriente.

cil on Monuments and Sites – ICOMOS, and Inter-

De la Mora, L. (2002). Os desafios a superar para

Penna, K. and Taylor, E. (2013). Managing institutions

(2013). Managing cultural world heritage. UNESCO:

desenvolver programas de conservação urbana in-

or managing egos? The challenges of cultural heritage

Paris. Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/up-

tegrada. In Zancheti, S. (Ed.). Gestão do patrimônio

shared management. XII International AIMAC Con-

loads/activities/documents/activity-703-1.pdf

cultural integrado. Recife, Brazil: Ed. Universitária

gress. 26-29 June 2013. Bogota, Colombia: Universi-

da UFPE.

dad de los Andes.

Flechas, J. H. (2013). Vigías del Patrimonio Cultur-

Pedersen, A. (2002). Managing tourism at World Her-

ner and cultural manager, lecturer at the Centre

al Colombiano: Una experiencia de sensibilización,

itage Sites: A practical manual for World Heritage Site

for Advanced Studies in Integrated Conservation

aproximación y apropiación del patrimonio desde el

managers. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

(CECI, Brazil), and PhD researcher at Curtin

aula. 8th International Meeting Ciudad Imagen

Retrieved from: http://whc.unesco.org/en/series/1/

University (Australia). She has worked in Brazil

national Union for Conservation of Nature - IUCN

ENDNOTES 1 Karla Nunes Penna is an architect, urban plan-

and in other in developing countries, planning,

y Memoria. 20-24 May 2013. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba: Universidad de Oriente.

Rössler, M. (2012). Partners in site management - A

coordinating, and implementing projects and

shift in focus: Heritage and community involvement.

public policies for cultural heritage preservation at UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Gilmour, T. (2006). Sustaining heritage: Giving the

In Albert, M.-T., Richon, M., Viňals, M.J. and Wit-

past a future. Sydney, Australia: Sydney University

comb, A. (eds). Community Development through

2 José Hernando Torres Flechas is an architect,

Press.

World Heritage. Paris, UNESCO World Heritage Cen-

lecturer at the Universidad Colégio Mayor de

tre. (World Heritage Papers 31, pp. 27-31). Retrieved

Cundinamarca (Colombia), and PhD researcher

from http://whc.unesco.org/en/series/31/

at University of Salamanca (Spain). He has ex-

International Council on Monuments and Sites

pertise in strategic planning, organisation, man-

(ICOMOS). (2008). Quebec declaration of the spirit of the place. Retrieved from http://www.internation-

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

agement and project controlling, and programs

al.icomos.org/quebec 2008.

Organization (UNESCO). (1972). World Heritage

at the local, regional, national, and international

Convention. Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/

levels, focused on sustainable development and

archive/convention-en.pdf

local communities’ engagement programs. Head

Ministerio de Cultura. (2013) Programa Nacion-

of the program Vigías del Patrimonio Cultural Co-

al Vigias del Patrimonio Cultural. Retrieved from http://www.mincultura.gov.co/areas/patrimonio/

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

investigacion-y-documentacion/programa-nacio-

Organization – UNESCO. (2013), Operational guide-

nal-de-vigias-del-patrimonio-cultural/Paginas/de-

lines for the implementation of the world heritage con-

fault.aspx.

vention, Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/archive/ opguide13-en.pdf..

HORIZONTES | KARLA NUNES PENNA y JOSÉ HERNANDO TORRES FLECHAS

lombiano, by the Fundación Contexto Cultural.

| 11

TRANSFERENCIA TÉCNICA/TRANSFER OF TECHNIQUES

Nancy Benítez Vázquez y Duznel Zerquera Amador

Proyecto Experimental con BTC en Trinidad, Cuba

DUZNEL ZERQUERA AMADOR Licenciado en Construcción Civil, Master en conservación y restauración de edificios históricos, miembro del grupo iberoamericano PROTERRA. Aspirante a doctor, Facultad de Construcciones de la Universidad Central de las Villas. Profesor de la Escuela de Oficios de Restauración, Oficina del Conservador, Trinidad. Cuba. Email: duznel@restauro.co.cu NANCY BENÍTEZ VÁZQUEZ Arquitecto. Trabaja desde 1986 en la conservación del patrimonio de Trinidad y el Valle de los Ingenios,Cuba. Actualmente es especialista en la Oficina del Conservador deTrinidad. Miembro de la Catedra de Arquitectura Vernacula “ Gonzalo de Cardenas” y miembro del Comité Cubano de ICOMOS. Email: nbv@restauro.co.cu DUZNEL ZERQUERA AMADOR B.S. in Civil Construction, M.A. in Conservation and Restoration of Historic Buildings. Member of the Ibero-American group PROTERRA. Doctoral candidate in the College of Construction of the Central University of Las Villas. Professor in the School of Restoration Crafts, Office of the Conservationist, Trinidad, Cuba. Email: duznel@restauro.co.cu NANCY BENÍTEZ VÁZQUEZ Architect. Has worked since 1986 in the conservation of the patrimony of Trinidad and el Valle de los Ingenios, Cuba. She is currently a specialist in the Office of the Conservationist of Trinidad. Member of the “Gonzalo de Cardenas” Chair of Vernacual Architecture & member of the Cuban Committee of ICOMOS. Email: nbv@restauro.co.cu

FECHA DE RECEPCIÓN: 14 de Febrero de 2013 FECHA DE ACEPTACIÓN: 13 de marzo del 2013

RESUMEN

ABSTRACT

El presente artículo expone condiciones de la arquitectura de tierra en Trinidad, Cuba y detalla un proyecto utilizando Bloques de Tierra Comprimida (BTC) para edificar viviendas a partir de una serie de pruebas con dicha tecnología. El texto presenta los problemas encontrados en el proceso constructivo y las alternativas posibles para plantearlo como solución viable de viviendas sustentables en zonas rurales de la región.

This article describes the condition of earth-based architecture in Trinidad, Cuba and explains a project using Compressed Earth Blocks (CEB) to build homes after a series of tests with the technology. The text explains the problems that were encountered in the course of the building process and the alternatives that exist in order to propose it as a viable solution for sustainable dwellings in the rural zones of the region.

palabras clave: Embarrado, BTC, Arquitectura vernácula, Trinidad, Cuba

key words: Plaster, CEB, Vernacular architecture, Trinidad, Cuba

INTRODUCCIÓN

INTRODUCTION

En Cuba el surgimiento de las ciudades del periodo colonial, propició el uso de diversos materiales constructivos, entre ellos: la tierra, como el más universal y abundante. En Trinidad, como en el resto de los asentamientos, fueron usadas diferentes tecnologías a partir de la tierra: el tapial, el mampuesto y el embarrado. De ellas, la más frágil y pobre fue la técnica del embarrado, que por sus características y las agresiones del medio ambiente, expone un mayor deterioro dentro de las edificaciones realizadas con esa técnica constructiva. En el Centro Histórico de Trinidad, aun conviven edificaciones de tierra con otras de ladrillos y mampuestos, y en el Valle de los Ingenios –extenso territorio vinculado a la historia económica y social de Trinidad– encontramos igual solución constructiva, pero a diferencia de la ciudad, si fue el embarrado la técnica más utilizada en los asentamientos agroindustriales del azúcar.

In Cuba, the rise of cities during the colonial period led to the use of diverse building materials, and among them, earth as the most universal and abundant. In Trinidad, as in other settlements, different earth-based technologies were used: earthen walls, masonry, daub and wattle. Of them, the poorest and most fragile was daub and wattle, which, because of its characteristics and climate conditions, suffers greater risk of deterioration. In the Historic Center of Trinidad, earthen buildings can still be seen alongside those made with bricks and those made with concrete blocks, while in Valle de los Ingenio—an extensive territory linked to the social and economic history of Trindad—we can find the same building solution, but as opposed to the city, daub and wattle was the most common technique in the agroindustrial sugar settlements. An example of the foregoing is the community of San Pedro, foundHORIZONTES

12 |

Experimental proyect with CEB in Trinidad, Cuba ed at the end of the XIXth century in the coastal plain of the valley. An inhabited zone was created with earthen homes around a central square and was gradually extended along the radiating lanes to form a nucleus of 190 homes which together create an environment of undisputed value within local vernacular architecture. (Image 1) ANTECEDENTS OF THE CEB PROJECT

During the 1990’s, this small nucleus was still maintained as an important example of popular architecture in Valle, but a progressive deterioration could been seen in the urban center, above all because of the loss of the original earthen structures and the lack of a plan for the improvement both of the homes themselves and of services to the community. This led Muestra de lo anterior es el poblado de San Pedro, fundado a finales del siglo XIX en la llanura costera sur del propio Valle. Un caserío conformado por viviendas de tierra y tejas construidas alrededor de una plaza, que se extendió por callejuelas hasta formar un núcleo de unas 190 casas, integradas en un ambiente de indiscutible valor dentro de la arquitectura vernácula local. (Imagen 1) ANTECEDENTES DEL PROYECTO BTC

En los años 1990 aún se mantenía este núcleo poblacional como ejemplo importante de la arquitectura popular del Valle pero se notaba un progresivo deterioro de su núcleo urbano, sobre todo por la pérdida de las estructuras originales de tierra y la falta de un plan para el mejoramiento de las viviendas y los servicios de la comunidad. Esto provocó la desaparición de importantes ejemplos construidos con HORIZONTES

to the disappearance of important examples that were built with earth and the insertion of new homes that differed from the traditional model, the “modernity” of a few homes based on private efforts as well as a few ideas about improvements without adequate planning to make the best use of the resources available. In visits to San Pedro, we confirmed that there are still inhabitants erecting their homes with the tradi-

imagen

tional daub and wattle, a technique they learned from their ancestors and used as a solution to remake their homes with earth and “mountain poles”. Benítez, N. (1999) In order to demonstrate the feasibility of conserving their architecture to the community, the Office of the Conserver of Trinidad carried out the restoration of one daub and wattle home in 2000, a project that had satisfactory results, but which also showed

1. Poblado San Pedro. fuente: Autores.

tierra, la inserción de nuevas viviendas alejadas del modelo tradicional, la “modernidad” de algunas viviendas por iniciativa privada así como algunas ideas de mejoras sin una planificación adecuada de los recursos. En visitas a San Pedro comprobamos que existían pobladores levantando sus viviendas con el embarrado tradicional, técnica aprendida de sus antepasados y usada como solución para rehacer su vivienda con la tierra y los “palos del monte”. Benítez, N. (1999)

Para demostrar a la comunidad la factibilidad de conservar su arquitectura, la Oficina del Conservador de Trinidad realizó en el año 2000 la restauración de una vivienda de embarrado, proyecto con resultados satisfactorios pero que demostró la complejidad que requería la técnica del embarrado, razón que incentivó buscar otra solución que – además de resolver el deterioro de las estructuras de tierra – hiciera más viable y rápida la ejecución de las viviendas.

Proyecto experimental con BTC en Trinidad, Cuba

the complexity involved in the daub and wattle technique. Those difficulties prompted the search for another solution that—in addition to solving the deterioration of the earthen structures—would make the execution of the jobs faster and more viable. Starting with these facts and enjoying the cooperation provided by Italian professors Dr. GiacomoChiari and Roberto Mattone, we decided to initiate the Experimental Compressed Earth Block (CEB) Home Project using blocks that were made with the ALTECH Geo 50 manual press manufactured in France and designed by Mattone himself. This was seen as a solution to the necessities for homes that could be seen in the community, and it could be done by means of local materials, in this case, earth.

• Inserting a technology that would combine with the traditional architecture of the Valle de los Ingenios. • Maintain the use of earth as the main material. • Preserve the rural lifestyle and the customs of the inhabitants. • Achieve the participation of the population of the community by means of self-building efforts. Among the first actions of the project, there was the design of three models for homes according to the vernacular typology of the region, inserting both kitchens and bathrooms in the homes and thus improving living conditions, since the majority of them carry out these functions outdoors. (Image 2) MODELO 1

| 13

Image 2: The three prototype models. ANALYSIS, LABORATORY AND RESULTS

Studies were carried out in quarries near where the experimental home would be built, thus avoiding the transportation of large volumes of earth. Once the earth banks had been selected, preliminary tests were carried out: granulometry, the shrinkage of the clays and their plasticity. The granulometry tests carried out on samples from the first bank showed a sandy loam with 3% clay, a level that is considered low, so it was necessary to combine this soil with another in order to have a higher concentration of clay. In his way we were able to get to a 10% proportion of clay in our final product.

MODELO 2

MODELO 3

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE CEB PROJECT

Among the fundamental objectives, we had: A partir de este hecho y contando con la cooperación ofrecida por los profesores italianos, el Dr. Giacomo Chiari y el arquitecto Roberto Mattone decidimos iniciar el Proyecto experimental de viviendas con Bloques de Tierra Comprimida (BTC) fabricados con la prensa manual modelo ALTECH Geo 50, de fabricación francesa y diseñada por el propio Mattone, como solución a las necesidades de vivienda que presentaba la comunidad, a través del uso de materiales locales, en este caso la tierra. DESARROLLO DEL PROYECTO DE BTC

Entre los objetivos fundamentales tuvimos: • Insertar una tecnología acorde a la arquitectura tradicional del Valle de los Ingenios. • Mantener el uso de la tierra como material principal. • Preservar el modo de vida rural y las costumbres de los habitantes. • Lograr la participación popular de la comunidad a través del auto esfuerzo constructivo.

image

2. The three prototype models / Variantes de los modelos. fuente: Autores.

Entre las primeras acciones del proyecto estuvo el diseño de tres modelos de vivienda acorde a la tipología vernácula del territorio, con la inserción de cocinas y baños en el interior de las viviendas, mejorando así las condiciones de habitabilidad, pues la mayoría realizan estas funciones en el exterior. (Imagen 2). ANÁLISIS, LABORATORIO Y RESULTADOS

Se realizaron estudios de las canteras cercanas a donde se emplazaría la vivienda experimental, evitando la transportación de grandes volúmenes de tierra. Una vez seleccionada la cantera de tierra se realizaron los ensayos preliminares: granulometría, comportamiento de retracción de las arcillas y plasticidad.

Los ensayos granulométricos en la primera cantera mostraron un suelo arenoso limoso con un 3% de arcillas, considerado bajo, por lo que fue necesario combinar este suelo con otro, hasta lograr un mayor contenido de arcillas, de esta manera obtuvimos un nuevo suelo con un 10% de estas. Como estabilizador químico fue usado el “cieno”, producto originado en la producción del gas acetileno, obtenido de mezclar la piedra caliza (CaCo3) con carbón, sometido a 1400 º C en un horno eléctrico. Obteniendo el Carburo de Calcio (CaC2) que al añadirle agua desprende el acetileno (C2H2) quedando como residuo industrial a un 70% de sólidos disueltos el hidrato de calcio (Ca (OH)2). De color gris y olor característico del residuo de carbu-

NANCY BENÍTEZ VÁZQUEZ y DUZNEL ZERQUERA AMADOR | HORIZONTES

14 |

Experimental proyect with CEB in Trinidad, Cuba

ro, convirtiéndose en un contaminante ambiental, que es desechado. El cieno una vez mezclado con tierra pierde estas características. Una vez seleccionados los materiales se realizaron ensayos con diferentes proporciones para determinar la dosificación correcta en la fabricación de bloques, obteniéndose por el método de tanteo y ensayo la siguiente proporción: material tierra con un 20% de cieno. Para comprobar la calidad de los bloques se realizaron tres ensayos: capacidad a la compresión, absorción capilar y resistencia a la erosión producida por lluvia.

table

RESULTADOS DE LOS ENSAYOS A COMPRESIÓN (Tabla 1)

Las cargas solicitadas en la estructura calculada para un bloque en estado crítico son de 1.34kg/cm². Como se observa en la Tabla 1, los BTC ofrecieron un buen comportamiento a la compresión.

RESULTADOS DE ENSAYOS A LA EROSIÓN POR LLUVIA

Prueba de resistencia a la erosión del agua (Imagen 3). Se sometieron los bloques a los efectos del agua de una ducha a 1.4 bar (1 bar = 0,1 MPa = 100 kPa = 105 Pa) de presión por un período de dos horas y posteriormente, se calculó la pérdida

de volumen del BTC. El volumen total del bloque es igual a 3150 cm³, la pérdida obtenida fue de 0.305 cm³ de volumen. Se considera bueno hasta menos de 1cm³. Para la construcción de la vivienda experimental de BTC se confeccionó un grupo de Especificaciones Técnicas¹, Benítez, N y Zerquera, D. (2008), que abarcan las diferentes etapas del proceso constructivo desde el replanteo modular a partir de las dimensiones de los bloques hasta el tipo de mortero a emplear para el asentamiento y relleno de las juntas. La vivienda experimental fue realizada en el año 2002 y los resultados hoy, a 10 años de su construcción,

1. Results of compression test / Resultados de ensayos a compresión

Nº

Mass/ Masa (Kg )

Area/Área (cm² )

Load/ Carga ( Mpa)

Resistance Resistencia (kg/cm² )

1

6,250

38.50

25

6

Saturated Saturado

2

6,350

38.50

22,5

5,8

Saturated Saturado

3

6,250

38.50

70

18,2

Dry/Seco

4

6,200

38,50

100

25,9

Dry/Seco

5

6,150

38,50

55

14,3

Dry/Seco

6

6,200

38,50

52,5

13,6

Dry/Seco

7

6,025

38,50

50

12,9

Dry/Seco

As a chemical stabilizer, we used “silt,” a product from the production of acetylene gas and obtained from a mixture of limestone (CaCo3) charcoal and heated to 1400° C in an electric oven. Once calcium carbide (CaC2) is obtained, water is added to free the acetylene (C2H2), leaving an industrial waste of 70% of dissolved solids of calcium hydrate (Ca (OH)2). A gray color and with the characteristic odor of carbide residues, it becomes an environmental contaminant that is just dumped. Once the silt is mixed with earth, however, it loses those negative characteristics. Once the materials were selected, tests were carried out with different proportions in order to determine which mixture was the best for the production of the blocks. The one that scored the best in the tests wad 80% earth with 20% of silt. In order to confirm the quality of the blocks, three tests were carried

State Estado

imagen

3. Ensayo del chorro de agua. fuente: Autores.

out: compression capacity, capillary absorption and resistance to erosion caused by rain. RESULTS OF THE COMPRESSION TESTS (Table 1)

The calculated loads demanded of a block in a critical state in the structure are 1.34kg/cm2. As you can see in Table 1, CEB offer good compression behavior. RESULTS OF THE RAIN EROSION TEST

Test of the resistance to water erosion. (Image 3) Theblocks were subjected to the effects of a stream of water at 1.4 bars of pressure (1 bar = 0.1 Mpa = 100 kPa = 10/5 Pa) for a period of two hours, and afterwards the loss of volume suffered by the CEB was calculated. The total volume of a block is 3,150 cm3, and the loss obtained was 0.305 cm3. Anything less than 1 cm3 is considered good.

HORIZONTES | NANCY BENÍTEZ VÁZQUEZ y DUZNEL ZERQUERA AMADOR

For the construction of the experimental CEB house, a list of Technical Specifications was drawn up. Benítez, N. &Zerquera, D. (2008) The items range over the stages of the building process, from the proposed modular design to the dimensions of the blocks and even the type of mortar to use for the footings and the filling for the joints between blocks. The experimental home was built in the year 2002, and the results now, more than 10 years after its construction continue to demonstrate the feasibility of the project, with the following benefits: • It permits architecture with local materials as an alternative when facing the energy crisis and the scarcity of resources. • It recuperates the vernacular image of certain rural areas that have seen the disappearance of traditional

Proyecto experimental con BTC en Trinidad, Cuba

continúan demostrando la factibilidad económica del Proyecto, obteniéndose las siguientes ventajas: • Logra una arquitectura con materiales locales como alternativa ante la crisis energética y la escasez de recursos. • Recupera la imagen vernácula de ciertas áreas rurales que han visto desaparecer el empleo de materiales tradicionales ante la inserción de la “modernidad”. • Permite acciones de mantenimiento con costo mínimo y al alcance de los habitantes. • Garantiza buenas condiciones de habitabilidad con la inserción de baños y cocinas con los requerimientos actuales. • Propicia la recuperación de los ecosistemas en las canteras de áridos (extracción del material tierra). • De fácil realización para las comunidades, no necesita mano de obra calificada.

• •

• •

materials as they face the insertion of “modernity”. It permits minimal-cost maintenance activities that are possible for the inhabitants. It guarantees good living conditions with the inclusion of kitchens and bathrooms in the current requirements. It promotes the recovery of ecosystems in the areas for the extraction of earth. It is easily done in communities and does not need specialized work.

RISKS OF THE PROJECT IN OUR CONTEXT

As with any other style of architecture, that which is carried out with earth has its own risks, whether they be natural or human, ranging from fires, hurricanes and earthquakes to the simple abandonment of buildings. In addition to have a plan for the mitigation of risks, the systematic monitoring of the experimental home let us propose actions that could lead to improving the load capacity of this technology:

RIESGOS DEL PROYECTO EN NUESTRO CONTEXTO

Como otras arquitecturas, la de tierra está expuesta a diversos riesgos, ya sean de origen natural o humano, desde incendios, huracanes, sismos hasta el abandono de los edificios. Además de contar con un Plan de mitigación de riesgos, el monitoreo sistemático de la vivienda experimental nos permitió proponer acciones en aras de reforzar la capacidad de resistencia de esta tecnología: 1. Sujeción de marcos de puertas y ventanas, a una pieza de hormigón o de madera, evitando la fijación directa en el BTC. 2. Cuando los bloques quedan expuestos se recomienda aplicar un fijador que estabilice las arcillas, lo más económico resultó ser una solución de carbonato de calcio y agua en proporción de 1 litro de cal x 6 de agua, reposada durante 24 horas y aplicada por aspersión. 3. Para una mejor estabilización quí1. Attaching door and window frames to a piece of concrete or wood in order to avoid attaching them directly to the CEB 2. When the blocks are exposed, it is recommended to apply a fixative to stabilize the clays. The most economic solution turned out to be a solution of calcium carbonate and water mixed with one liter of lime to six of water, which then sits for 24 hours and is sprayed on. 3. In order to achieve the optimal chemical stabilization of the clays and silt and thus avoid the formation of lumps, it is necessary to have a homogenous, fluid past, drying it until it reaches the optimal humidity for compaction. In spite of the demonstrated perspective, in our context we have discovered a few inconveniences with the project, among which we can mention: • A rejection of the technique, which many consider backward and poor, including a lack of willingness on the part of the institu-

| 15

mica de las arcillas con el cieno y evitar la formación de grumos se requiere una pasta fluida y homogénea, secándola hasta que la masa alcance nuevamente la humedad óptima de compactación. A pesar de la perspectiva demostrada, en nuestro contexto hemos encontrado algunos inconvenientes al Proyecto, entre ellos: • Rechazo a esta tecnología, considerada como atrasada y pobre. Incluyendo falta de voluntad por parte de las instituciones encargadas de los planes de viviendas. • Desconocimiento en las aulas universitarias de la arquitectura de tierra, lo que provoca la incertidumbre de profesionales al enfrentar el análisis y los proyectos. • La fragilidad de la tierra nos obliga a utilizar estructuras de cubiertas ligeras que no siempre están al alcance de los pobladores. • Preferencia por materiales contemporáneos y tipologías alejadas de nuestra tions charged with the plans for the homes. • Ignorance in university classrooms regarding earth-based architecture, thus leading to uncertainty among professionals when it comes to analysis and projects. • The fragility of the earth makes us use structures with light coverings that are not always within the economic means of the inhabitants. • A preference for contemporary materials and typologies far removed from our traditional habitat, but that many consider to be of a higher esthetic level. NEW DIMENSION OF THE PROJECT

Our work is to demonstrate the feasibility of the earth in housing programs for rural zones where deterioration advances and new technologies continue to be far from the traditional system but without managing to cover all the necessities of the people, by means of the promotion and divulgation of the results as well as seeking financing

NANCY BENÍTEZ VÁZQUEZ y DUZNEL ZERQUERA AMADOR | HORIZONTES

16 |

Experimental proyect with CEB in Trinidad, Cuba

imagen

hábitat tradicional y que muchos consideran con un mayor nivel estético. NUEVA DIMENSIÓN DEL PROYECTO

Nuestra labor es demostrar la factibilidad de la tierra en los programas de viviendas para zonas rurales, donde el deterioro avanza y las nuevas tecnologías continúan alejadas del sistema tradicional sin llegar a cubrir todas las necesidades, a través de la promoción y divulgación de los resultados así como while trying to raise the awareness and sensitivity of all the main actors as to the plans of the project. CONCLUSIONS

• It is a viable, sustainable project using earth that is available to everyone. • It’s a proposal that integrates society, nature and culture. BIBLIOGRAFÍA Benítez Vázquez , N. (1999). San Pedro: exponente de la arquitectura popular de tierra. Ponencia presentada en el Segundo Curso Panamericano sobre Conservación y Manejo del Patrimonio Arquitectónico Histórico – Arqueológico de Tierra. Chan Chan , Perú. Benitez, N., Casal, F. , Chiari. G. , López , R., Mattone R. , Tellez, E. , Zerquera, D. (2002). Auto – construccion of rural housing using hand compressed earthen blocks stabilized with lime. Ponencia presentada en el 5° Simposio Internacional de Estructuras,

en la búsqueda de financiamiento y sensibilización de los actores fundamentales de los planes de viviendas rurales. (Imagen 4) CONCLUSIONES

Es un proyecto viable y sustentable, con la tierra al alcance de todos. Es un propósito que integra sociedad, naturaleza y cultura. Se logran aceptables condiciones de habitabilidad y así lo demuestran

4. Casa experimental de BTC. fuente: Autores.

las terminaciones realizadas en cocina y baño. La textura, color y ambiente de la tierra proporciona una sensación estética y ambiental no lograda con los materiales que hoy se están utilizando. La falta de motivación y el desconocimiento por el tema de la tierra condiciona el rechazo de una gran parte de los organismos responsables de implementar el Proyecto.

• Acceptable living conditions can be achieved, as has been demonstrated by incorporating kitchens and bathrooms. • The texture, color and esthetic atmosphere provided by earth-based structures cannot be matched by any of the other materials that are being used nowadays.

• It is only a lack of motivation and ignorance about the theme of earth-based architecture that lead to rejection by the majority of the organisms that are responsible for implementing the project.

Geotecnia y Materiales de Construcción. Santa Clara, Cuba.

Houben, H. y Guillaud, H. (1989). Traité de construction en terre. Grenoble, CRATerre– EAG. (ed.) Parenthèses Marseille