Les Visionnaires

In the Modernist Spirit

Image:

Françoise Gilot (French, 1921-2023)

#IX, from On the Stone: Poems and Lithographs (Sur La Pierre: Poemes et Lithographies), 1972

Lithograph

12.75 x 9.75 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections, Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library, Hofstra University © Françoise Gilot Archives

Long before Hofstra was founded, indeed before there was “Long Island,” the Indigenous peoples called this region Sewanhacky, Wamponomon, and Paumanake – sacred territory inhabited by the Carnarsie, Rockaway, Matinecock, Merricks, Massapequa, Nissequoge, Secatoag, Seatauket, Patchoag, Corchaug, Shinnecock, Manhasset, and Montauk. Each tribe had its own territory, whose boundaries were respected by the others, and all inhabitants were united in their shared desire for peace. The land that surrounds Hofstra is part of that history. We want to protect its legacy and honor the Indigenous peoples who have made untold contributions to our region.

© 2024 Hofstra University Museum of Art

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the Hofstra University Museum of Art.

Les Visionnaires In the Modernist Spirit

January 30-July 26, 2024 | Emily Lowe Gallery

Curated by:

Kristen Dorata

Assistant Director of Exhibitions and Collections

Hofstra University Museum of Art Alexandra Giordano

Director

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Guest Essayist and Contributing Historian: Catherine E. Clark

Associate Professor of History and French Studies

Faculty Director of the Programs in Digital Humanities Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Hofstra University Museum of Art’s programs are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature.

The mid-19th century was a time when new technologies, industries, and inventions launched society forward. Machines and materials such as steam and steel not only changed the landscape of Europe and the United States, but they also introduced the world to its future, one that their arrival would forever alter.

Suddenly, artists whose work was tethered to the French Academy realized that new modalities, mediums, and methodologies were a more appropriate way to respond to the rapidly changing world in which they lived. Political, economic, and cultural shifts inspired a new forward-thinking attitude in artists who, in turn, discovered radical innovations in aesthetic forms, techniques, and content. Paris was the epicenter. Artists were drawn to the city, where a drive for pushing boundaries and sharing their transformative vision thrived.

The avant-garde in France, a term inspired by a military term meaning the advanced guard or front line, was adopted by artists whose approach and ethos embraced exploring experimentation in art making. The advanced guard, in times of war, would forge into the unknown, gather information, and return to the troops with knowledge from their excursion. Artists of the 19th century, particularly in France, identified with this role. They ventured into a new terrain and rejected the notion that distinctions in art, such as drawing, painting, and sculpture, existed. Instead, they exercised an interdisciplinary approach that synthesized, for example, photography with typography, or poetry, music, and dance with drawing and painting. They blurred the lines that had previously existed.

These ideas were further explored in the dawn of a new century. Twentieth-century artists continued to deviate from the academic standards set forth by the French Salon. Instead, they were inspired by literature, poetry, dreams, psychology, science, stream-of-consciousness writing, theater, and new materials, such as cinema and photomontage. They strayed from conventional mediums such as oil paint and embraced the ideology of the global movement referred to as modernism. Representational styles no longer captured current trends and events, as they appeared nostalgic or naive. World War I and the political and societal circumstances of the early 20th century influenced artists’ creative endeavors and camaraderie. They plowed ahead, inventing ways to respond and record the excitement and trauma of their world.

Not only was their art unique, so too was their interconnectedness. Artists worked together, lived together, created together, and loved each other. Their interwoven relationships and collaboration were at the heart of their creativity. Their partnerships and collective approach captured the realities and hopes of modern society – a traditional explanation of the world no longer applied.

Several artists in the exhibition were forced to leave Europe before and during World War II. Their progressive ideas were perceived as degenerate and not aligned with the oppressive, totalitarian ideas that were taking hold in Europe. Ultimately, many found their way to New York, where they inspired and shaped the post-World War II American art world.

It is in their spirit that this exhibition was developed. While it began in the usual way, with one curator, it quickly morphed into a far-reaching collaboration. Initially, the exhibition was planned in conjunction with the Society for French Historical Studies Annual Conference hosted by Hofstra University. Sally Charnow, PhD, chair, and professor, Department of History, Hofstra University, and co-president of the Society for French Historical Studies, and Catherine E. Clark, PhD, associate professor of history and French studies and faculty director of the Programs in Digital Humanities, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, became valuable allies in early discussions. Their support continued throughout the planning and culminated with Dr. Clark’s catalog essay and insightful historical references. Kristen Dorata, the Museum’s collections manager at the time, became an innovative partner in choosing works from Hofstra University’s Special Collections and the Howard L. and Muriel Weingrow Collection of Avant-Garde Art and Literature. Her contributions and creativity were integral to the development of the exhibition. Mike O’Connor, archivist, and Debra Willett, senior library assistant from Hofstra University’s Special Collections, supported inquiries, patiently searching for original works of art listed in the annotated bibliography. The Museum offers a graduate curatorial assistantship each semester. Mary Conroy, however, redefined the role as she became essential in organizing and conducting research, proofreading, and being a catch-all for anything needed. Fortuitously, Leo Valenti, a student from Vassar College, found his way to the Museum as a summer volunteer. His research and writing of artist biographies for wall labels proved invaluable, as were his notetaking and subtle design suggestions. Lastly, NYC poet and prose writer Hannah Nussbaum generously donated her time to translate poems in the exhibition from French to English, and retired French teacher Mary Ann Ferri assisted in the translation of titles. Credit must also be given to the Museum staff, who participated in daily conversations that were instrumental in developing ideas.

Perhaps this will be a new model and vision for the Museum in planning future exhibitions. As the tide in our modern world changes, so must we. Who better to use as a reference and inspiration than the artists in this exhibition?

Alexandra (Sasha) Giordano Director Hofstra University Museum of ArtCatalog Essay

Following World War II, the Long Island population increased; in tandem, Hofstra University experienced significant growth in student enrollment, leading to new campus construction projects. It was during this period that Hofstra initiated the acquisition of an art collection.

To establish a comprehensive timeline and foundation for the exhibition, the Howard L. and Muriel Weingrow Collection of Avant-Garde Art and Literature was a valuable resource. Donated to Hofstra University’s Special Collections in 1972, the collection contains approximately 4,000 items of original works representing nearly all the major avant-garde movements of the 20th century, including surrealism, dada, cubism, and futurism. Nearly half of the works included in this exhibition are selected from the Weingrow Collection, to complete the spectrum of artistic output and the European approach during a time when visionary artists and literary luminaries like André Breton, Max Ernst, Man Ray, and Tristan Tzara wove their subconscious dreams into art and literature.

Les Visionnaires: In the Modernist Spirit also draws upon the Museum’s extensive permanent collection to complement the works from Special Collections. The works from the permanent collection trace the successive waves of artists, camaraderie, and their creative methodologies, such as collage, a strategy in art making associated with modernism and the spread of inexpensive printing technology.1 The work demonstrates a period of new expression and experimentation in the arts, from artists such as Berenice Abbott, Jean Arp, Alexander Calder, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dalí, and Lee Krasner.

The Weingrows were avid collectors of different mediums. In 1973, they had the opportunity to visit Paris and meet with Man Ray in his distinctive one-room dwelling. Howard L. Weingrow described this experience as a moment when “it was through Man Ray’s eyes that I started to see the excitement and the spirit that drove this movement.”2 Central to this exhibition, this meeting had an impact on Mr. Weingrow and instilled a profound appreciation for surrealism and the avant-garde. The Weingrows’ visit to Paris validated their dedication to Hofstra University and prompted the expansion and meticulous cataloging of the collection – thus enhancing accessibility for students, scholars, community members, and beyond.

This exhibition features artworks spanning over 60 years, ranging from Picasso’s early cubist etching Female Nude with a Guitar (Femme nue à la guitare) from Le Siége de Jérusalem: Grande tentation celeste de Saint Matorel (1913), to Lee Krasner’s screenprint and collage Free Space (Yellow) (1975). The works on view provide the opportunity to witness the artists’ embrace of various techniques and mediums, employing the laws of chance, creativity, and myriad styles.

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to Barbara Lekatsas, PhD, Hofstra professor of comparative literature, languages, and linguistics, for her invaluable annotated bibliography, The Howard L. and Muriel Weingrow Collection of Avant-Garde Art and Literature at Hofstra University, which served as a guiding light for the exhibition research. Her comprehensive work provided a roadmap and instilled the confidence needed to navigate such an extensive collection.

Kristen Dorata

Assistant Director of Exhibitions and Collections

Hofstra University Museum of Art

1 Shannon Taggart, Séance (Los Angeles, USA: Atelier Éditions, 2022), 27.

2 Barbara Lekatsas, The Howard L. and Muriel Weingrow Collection of Avant-Garde Art and Literature at Hofstra University (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1985), xiv.

Essay

“Cocteau in Conversation”

Catherine E. Clark Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyFrench artist Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) was a creative polymath, a poet of many media. The pen and ink of his words unfurled into line drawings, darted across the stage at the theater, and came to life on the big screen. He painted with oils, sculpted with bits of cardboard and candlewax, and wrote seemingly everywhere, on beer coasters, “invitations, record jackets, cigarette boxes, theater programs, book covers.”1 He choreographed dancers and played the drums in his own jazz band. He produced collaborative works and served as impresario for musicians, composers, and a Black American boxer. Even his most solitary endeavors became collaborative: He worked with lithographers, jewelers, ceramists, and publishers to bring his creations to life. Such interdisciplinarity can make it hard to understand Cocteau as a whole – few people could know enough to discuss his poetry and his paintings, his pirouettes and his plates in the same breath. Rather than impediments, such interdisciplinarity and collaboration are key to understanding him, for the medium in which Cocteau’s career most expressed itself was human sociability.

Cocteau courted and collected the great names of his day, including Marcel Proust, Pablo Picasso, and Coco Chanel. He introduced Picasso to Stravinsky, attempted to rescue composer Erik Satie from obscure poverty, and even tried to find Marcel Proust, 20 years his senior, a publisher. He befriended the photographer Man Ray and cast the American’s model and partner, Lee Miller, an important photographer in her own right, in his second film Le Sang d’un poète/Blood of a Poet (1930). He stayed close with Picasso across the decades by maintaining ties with the Spaniard’s wives and lovers. Cocteau championed the careers of generations of talented and not-so-talented young writers, actors, and painters. He often, as with the case of novelist Raymond Radiguet or Jean Marais, star of La Belle et la Bête/Beauty and the Beast (1946), fell in love with them in the process. That love was not always consummated or even reciprocated. He became addicted to opium in 1920 and remained dependent on the perfumed smoke that allowed him to leave his earthly pains behind. His lovers and followers often ended up addicted as well.

Cocteau was never politically active, although as a gay man with a drug habit, he was often at odds with the forces of order. During World War II, he suffered violently at the hands of France’s extreme-right writers and critics, including Alain Laubreaux and Lucien Rebatet, who were backed by the French government controlling “Free,” or Vichy, France. They denounced him for decadence and homosexuality, declared him “enjuivé” (tainted by Jewishness), and decried his prewar support for the left-wing Popular Front and International League Against Antisemitism. To stage his plays, Cocteau sought protection from the German Occupiers and in 1942 became close friends with Arno Breker, official state sculptor of the Nazi Third Reich. He also tried to use these connections to rescue friends and colleagues from German camps. He never joined the Resistance, which his friends who did considered a good thing: Cocteau’s lips were famously loose. Through all of this, he created some of the most highly regarded works of the 20th century. Cocteau, in short, was complicated.

1 Claude Arnaud, Jean Cocteau: A Life, trans. Lauren Elkin and Charlotte Mandell (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 169, 771.

While he sought friends, collaborators, and admirers with a frenzied energy, his work and very existence also drew intense criticism and hatred. Starting in the 1920s, Cocteau was the subject of a nearly two-decades-long campaign of insults and violence by André Breton and the surrealist group. Motivated by jealousy and vitriolic homophobia, they hounded Cocteau, disrupted his plays with catcalls and insults, physically attacked those who dared to read or cite his work, and repeatedly prank-called his mother with obscene couplets and the (fake) news that her son had committed suicide. Americans never fully knew about or understood this feud and rather almost universally fêted Cocteau and understood him as kin with the surrealists. And yet it still feels important to make the invisibility of those attacks discernible in the U.S. Showing Cocteau, Francis Picabia, and Breton side by side here dulls the force of the surrealists’ hatred, yet permits visitors to continue to understand these works in conversation – however brimming with hate that exchange might have been.

Featuring Cocteau in the catalog allows us to lay out the show’s important themes. First, Cocteau reminds us that the visual arts are implanted in social worlds. The material objects we are left with today are all that remain of the rich, lived contexts in which they were born. They were touched, passed around, and argued about. They were made for events or exhibitions, theater and the ballet, shows that were booed, applauded, and roundly discussed by critics. Second, Cocteau reminds us that these acts of creation were necessarily collaborative. Les Visionnaires saw and rendered the world differently than those who had come before them because they saw it together: sometimes in parallel, sometimes in conflict, but always in dialogue.

If modernist art took place, then the place it took was Paris. In Cocteau’s poster for a 1954 exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Visage de France/Face of France (1954), France becomes an elegant head, a Hermes for whom La Bretagne extends like a wing from its helmet. Paris is its single-lashed eye. The French capital in the years before WWII drew young creatives from around the world. The Spaniard Picasso, Catalan Joan Miró, Americans Alexander Calder and Berenice Abbott, English Leonora Carrington, and German Max Ernst, as well as Jewish artists from across Eastern Europe, including László Moholy-Nagy – they all made their way to Paris. They lived in cheap lodgings and talked endlessly in inexpensive cafés in the Left-Bank neighborhood of Montparnasse. Paris truly was the eye of the messenger god in those years, the connective hub of people and ideas.

Born on July 5, 1889, the day the Eiffel Tower was inaugurated, into a wealthy and artistically well-connected Right-Bank Parisian family, Cocteau was only a bridge away from the new avant-garde. But to cross that bridge required him to change social worlds, and the journey was by no means easy. He came of age in the great salons of the prewar period, where he learned the craft of witty conversation and entertaining impressions. He befriended everyone who “mattered,” including the remnants of French nobility, symbolist poets, and various literary heirs who acclaimed his symbolist poetry while he was still a teenager. And yet, by 1921, Cocteau was not just part of the new scene, he was its hub, the informal host of the Right-Bank cabaret Le Boeuf sur le Toit, named after his own 1920 ballet set to music by Darius Milhaud. Here its luminaries sat down at the keys, read poetry, and otherwise drank and danced the night away. It was often the first place that artists from other countries stopped, hoping to plug into the Paris cultural milieu via Cocteau.

The 1917 ballet Parade, which premiered during World War I, made this transformation possible. Like all of Cocteau’s work, it was collaborative but also fraught with tensions. He wrote the libretto (whose words ended up being scrapped) for the Ballets Russes, the popular, yet financially precarious itinerant troop led by Russian Sergei Diaghilev since 1909. He invited Erik Satie, a friend of his mother, Eugénie Lecomte, to compose the score, and insisted that it include parts for machines such as a typewriter and air raid siren. His new friend, competitor, and lust object Pablo Picasso designed the costumes, set, and curtain. Cocteau found a more malleable collaborator in dancer Léonide Massine, who worked alongside the artist on the choreography.

Parade’s subject was neither myth nor literature but the entertainment of the Parisian street, the music hall, and the circus. The plot is almost nonexistent. Acrobats tumble, a Chinese magician and an American schoolgirl cavort, and a horse built of two dancers, one bent and clutching the other’s waist, prances, while a French impresario and an American businessman cajole the crowd to enter a fairground theater. An imaginary public watches but mistakes the advertisement for the full show and disperses before it begins. It was self-reflexive, a ballet about modernism itself, a mise-en-scène of its incessant self-promotion.2

The ballet premiered to mostly hostile reviews, which charged it with frivolity and unFrenchness during wartime. Erik Satie’s vitriolic response to one critic resulted in a slander trial and the composer’s imprisonment. During the trial, Cocteau physically attacked the critic’s lawyer and was taken from the courtroom by the guards.3 But Parade quickly came to be understood as an artistic success. It was a total departure from the orientalist themes that the Ballets Russes had traded in.4 The poet Guillaume Apollinaire reportedly coined the term “surrealism” to describe it, three years before Breton’s movement took shape. Parade brought modern life to the heart of contemporary dance and helped fuel Picasso’s career – and Cocteau’s as well.

The ballet also presaged the register of themes that ran throughout the rest of Cocteau’s life and work. As his interests and identity morphed and shifted over the years – from opium addict to converted Thomist Catholic, to defender of the Popular Front, friend of Hitler’s sculptor, and finally darling of the Cannes film festival – Cocteau remained fascinated with creativity itself. In part, his opium smoking introduced him to the deformed space in the mixed-media drawings on display. Doorways recede into the distance, arms elongate, and perspective stretches and shifts. But the creative process and the obsession of love can render such transformations too. In Untitled (undated), the artist’s creations come alive, a cheeky bird looks back at him, while self-doubt takes the form of the artist’s stool, which seems to double as a toilet. Male morphs into female: The outstretched male hand becomes the head of a woman while two lovers levitate and come to share a face in Untitled (undated).

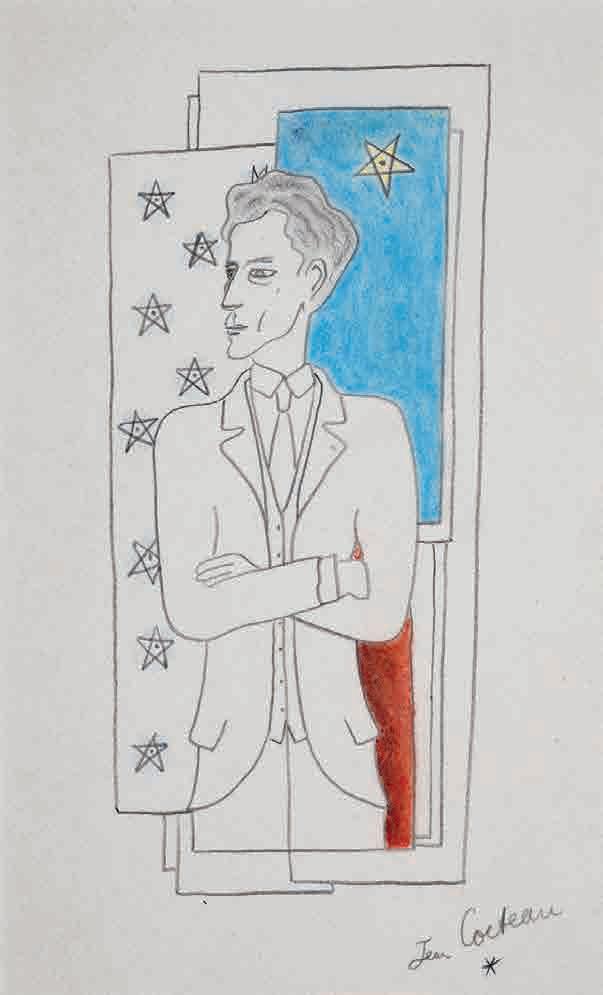

Cocteau was at his best in conversation, telling stories or mimicking postures and voices. And yet, so many of Cocteau’s contemporaries drew or painted him. His stand-up hair and long profile were distinctive, easy to freeze with but a few strokes of the pen. In Self Portrait (1957),

2 Arnaud, 167.

3 Arnaud, 201.

4 Kenneth E. Silver, “Jean Cocteau and the Image d’Epinal: An Essay on Realism and Naiveté,” in Jean Cocteau and the French Scene (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984), 101.

Cocteau has drawn himself, arms crossed, a red matador’s cape in his right hand, framed by a window open onto the sky that holds a single star. More stars adorn the window itself, where he appears as if flung by the gods, the hero of myth enshrined not in the cosmos but in the firmament of a Parisian apartment.

In Visage de France/Face of France (1954), Paris may be Hermes’ eye, but the other heart of modernism beats just below where the figure’s left shoulder should be: in the Riviera. Here in the little villages of the Côte d’Azur, artists such as Picasso, Françoise Gilot, Man Ray, and Cocteau decamped to dip in the sea, lie in the sun, and work. Theirs was the generation that popularized tanned skin and the Mediterranean summer holiday. Cocteau often went to the port of Toulon, whose opium bars and sailors he loved in equal measure, but spent many months and years, especially toward the end of his life, near Villefranche-sur-Mer, a village just east of Nice. We see his implantation in the region in Matarasso (1957), a poster he drew for his fall 1957 exhibition at the Matarasso gallery in Nice, where Picasso and Miró were also exhibited that same year. To go to the Riviera wasn’t to get away, per se; it was to frequent the Parisian world in a different context.

Because so many of the works in this show are from Cocteau’s last years, they are strongly rooted in the dreamy colors, sea, and sun of the South. In 1956-1957, he restored and decorated a Romanesque chapel dedicated to St. Peter, patron of fishermen, in Villefranche. The fisherwoman, with her distinctive flat hat, appears in profile in La Chapelle/The Chapel (1958), a poster for the chapel. The endless self-promotion of Parade returns, but this poster demonstrates an interest in the naïve and the popular, a canonization of the everyday people who lived and worked along the coast. During the same period, Cocteau met Marie Madeline Jolly and Philippe Madeline, ceramists with an atelier in the hills above Villefranche. Cocteau asked to apprentice himself and began to work with oxide crayons, thin layers of watery clay called engobes, and brilliant enamels.5 He decorated plates with faces, mythical figures, and even his own handprint.

Cocteau was taken with fairytales and myths, not to resurrect neoclassical tradition, but to understand them as metaphors for modern life, and often his own. Such was the case of La Belle et la Bête, his adaptation of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s 18th century account of a classic tale. His childlike choice of subject was perhaps out of step with the day’s intellectual vogue for more cerebral matters, but Cocteau wanted something more innocent. Cinema, with its trick shots and elaborate costumes and makeup, brought the eerie and erotic tale to life. Real human arms hold candelabra, disembodied hands pour wine, and statues blink and turn their heads. Belle’s tears turn to diamonds, and her mirror shows not her reflection but the subject of her reflections: her sick father back home. Jean Marais’ beast head and paws are particularly striking. The brilliantly lit action unfurls against the black background that Cocteau often deployed in the theater.

Biblical stories functioned as fairytales of sorts as well. Eve hands reclining Adam a half-eaten apple, brilliantly enameled in red and yellow, while the lustrous green serpent looks on in the ceramic Adam et Eve sur Bleu/Adam and Eve on Blue (1952). The minotaur stares back at us from another plate, its horns, eyes, and nostrils all reduced to intersecting geometric forms, a reference to Greek myth and perhaps the real-life animals of the bullfights Cocteau attended

5 Annie Guédras, Jean Cocteau, céramiques: catalogue raisonné (Paris: Teillet-Dermit, 1989).

with Picasso in the 1950s. There’s something satyresque to the face that graces the 1958 platter Visage Oval/Oval Face, while the faun with cat eyes on the goblet titled Printemps/ Spring (c. 1960) evokes the lost world of the Ballets Russes’ 1912 Après-midi d’un faun/Afternoon of a Faun. Rome forms another point of reference in the plate featuring a scene from the Satyricon, a work of fiction written in Latin during the first century AD. The characters are reduced to shadows, bedazzled perhaps by the Mediterranean sun. The woman with the candle on her head is stranger, closer to modern life, the arcs of her lips and brows formed as carefully as the dripping wax.

Spending time along the Riviera brought Cocteau closer to the Greeks, and so too did his love of the theater, embodied in the laurel-crowned hero’s bust on the poster advertising the complete edition of his plays from 1957. In graphic works, on the stage, and in the cinema, he returned repeatedly to two stories – those of Oedipus and Orpheus – in which he found particular personal significance. It is hard not to read the drawing titled Mother and Father (1950-57) along biographical and mythic lines. The artist’s father, Georges Cocteau, a banker and amateur painter, committed suicide when Jean was just 8 years old. Already close to his mother, he became unbreakably bonded to her. She supported him financially, and they lived together long into Cocteau’s adulthood. Here is the mother drawn with concise precision, her blue eyes clear and sharp, while the father hovers behind, a disembodied suit in glasses, which do not focus but rather obscure his vision. In Cocteau’s artistic universe, in which eyes appear everywhere, melt together, seem often to form the heart of the soul, the father has no eyes. It is Oedipus who is cursed to see, and the father who is blind.

The unseeing character shocks because so much of Cocteau’s work looks back at us. The hull of the sailboat in a promotional poster for the principality of Monaco becomes a toothy smile and its lines the flair of nostrils. Eyes bedeck its sails in the poster Monaco (1959). The eyes of doubles or twins fuse in the 1958 plate Double Masque aux Feuilles/Double Leaf Mask and the drawing Untitled (undated), in which lovers share not only an embrace but also a face. The ceramics all look back too although none so innocently as the satyr who dares you to cover him with a roast chicken or kilo of figs. Even the Beast in La Belle et la Bête can only be saved by a “loving look.” Fish with giant dilated pupils dart across the poster Matarasso (1957) for Cocteau’s exhibition at Matarasso’s gallery. Another specimen of the watchful creature of the sea is the fisherwoman’s eye in the poster for the Chapel Saint-Pierre, La Chapelle/The Chapel (1958). This is not a fish so much as an ichthys, the simple drawing that appeared throughout the first years of Christianity’s spread through the Mediterranean basin. Here is Cocteau the Catholic but also Cocteau the founder of clubs and communities playing with a badge of belonging, and perhaps the symbolist poet who finally returns.

In their mixed media forms, in their reference to other events and places, these works bear testimony to the social relations that made them. Here are traces of the work of ceramists, lithographers, publishers, actors, and camera operators – the list could go on and on – who worked alongside Jean Cocteau over the years. As he himself wrote about cinema, “beauty is made up of relationships.”6 And yet the work too looks around the gallery at that of his contemporaries, his friends and rivals, the members of his social world. Decades later, it is as if Cocteau, more than any of the others, still wants to know what is going on and how he stacks up. Does it, he seems to ask, belong here? I think we can agree that it does.

6 Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema, ed. André Bernard and Claude Gauteur, trans. Robin Buss (New York: Marion Boyars, 1992), 43.

Works of Art

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Adam and Eve on Blue (Adam et Eve sur Bleu), 1952

Ceramic

12.125 x 2.625 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.183

© ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Monaco, 1959

Original lithograph poster

25.5 x 19.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg, HU88.132

© ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Spring (Printemps), c. 1960

Ceramic

13.875 x 7.812 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.191

© ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Self Portrait, 1957

Colored pencil, pencil, paper

10.5 x 5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.194

© ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Mother and Father, 1950-1957

Ink, colored pencil, and graphite on paper

11.75 x 8.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.195

© ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

The Chapel (La Chapelle), 1958

Original lithograph poster

25.75 x 19.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg, HU88.134 © ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Matarasso, 1957

Original lithograph poster

25 x 19.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg, HU88.136

© ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Oval Face (Visage Oval), 1958

Ceramic

14.5 x 10.5 x 1.625 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.188

© ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Double Leaf Mask (Double Masque aux Feuilles), 1958

Ceramic

13.75 x 2.812 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.181

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Free City by the Sea (Ville Franche Sur Mer), 1959

Original lithograph poster

29.5 x 20.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg, HU88.148 © ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Woman in Candlelight (Femme a la Chandelle), c. 1960

Ceramic

14.75 x 5 x 6 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.193

© ARS / Comité Cocteau, Paris / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

SALVADOR DALÍ (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Untitled, from Memories of Surrealism portfolio, 1971 Etching and lithograph

20.75 x 16.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Benjamin Bickerman, HU93.12.3

© 2023 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society

MAX ERNST (German, 1891-1976)

The Conjugal Diamonds (Les Diamants conjugaux), from Natural History (Historie Naturelle), 1926 Collotype after frottage 16.875 x 10.125 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections, Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library, Hofstra University © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

S.W. HAYTER (English, 1901-1988)

Salt Wave, from the monograph Death of Hektor Engraving, etching bound in monograph

11.625 x 8.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mr. J. Tyler Griffin, HU80.41.2 © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

RENÉ MAGRITTE (Belgian, 1898-1967)

Rose and Pear. The Means of Existence (Rose et Poire. Les Moyens d’Existence), 1968 Color etching

6.28 x 4.312 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Mr. Louis Shorenstein, HU90.6

© 2023 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

JOAN MIRÓ (Spanish, 1893-1983)

Homage to Joan Prats (Homenatge a Joan Prats), 1975 Lithograph

22 x 29.75 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mimi Lipton, HU87.22

© Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, 2023

Exhibition Checklist

BERENICE ABBOTT

(American, 1898-1991)

Pendulum (Small Arc), 1958-1961

From the portfolio Retrospective, 1982

Gelatin silver print

22.25 x 4.75 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Lazarus Weiner

HU83.27

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE

(French, born Italy, 1880-1918)

The Cubist Painters.

Aesthetic Meditations, 1913

Illustrated book

9.960 x 7.480 in

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

JEAN ARP

(French, 1886-1996)

Elemente, 1965

Lithograph

19.3 x 13.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Dr. Milton M. Garder

HU70.96

JEAN ARP

(French, 1886-1996)

Relief Documenta III, 1964

Die-cut brass and aluminum

10 x 8 x .25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Dr. Frederick Mebel

HU89.31

ANDRÉ BRETON

(French, 1896-1966)

International Exhibition of Surrealism, 1940

Illustrated book

10.5 x 6.375 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

ANDRÉ BRETON

(French, 1896-1966)

Surrealist Manifesto; Soluble Fish (Manifeste Du Surrealisme; Poisson Soluble), 1924

Original edition

7.5 x 4.75 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

ANDRÉ BRETON

(French, 1896-1966)

ROGER CAILLOIS

(French, 1913-1978)

RENÉ CREVEL

(French, 1900-1935)

SALVADOR DALÍ

(Spanish, 1904-1989)

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO

(Italian, 1888-1978)

PAUL ÈLUARD

(French, 1895-1952)

MAX ERNST

(German, 1891-1976)

MAURICE HEINE

(French, 1884-1940)

GEORGES HUGNET

(French, 1906-1974)

JEAN-PIERRE LÉVY

(French, 1911-1996)

MAN RAY

(American, 1890-1976)

ALBERT SKIRA

(Swiss, 1904-1973)

TÉRIADE

(Greek, 1897-1983)

Minotaure n. 5, 1934

Periodical, cover by Giorgio de Chirico

12.5 x 9.75 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

ANDRÉ BRETON

(French, 1896-1966)

PIERRE NAVILLE

(French, 1904-1993)

BENJAMIN PERÉT

(French, 1899-1959)

The Surrealist Revolution (La Revolution Surréaliste), 1924

Periodical

11.375 x 7.75 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

ALEXANDER CALDER

(American, 1898-1976)

Octopus, from the portfolio

Our Unfinished Revolution, 1976

Offset color lithograph

29.875 x 22 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg

HU91.71

BLAISE CENDRARS

(Swiss, 1887-1961)

FERNAND LÉGER

(French, 1881-1955)

The End of the World (La Fin Du Monde), from the film script of The End of the World Filmed by the Angel of Notre Dame, 1919 Illustrated book

12.625 x 19.75 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MARC CHAGALL

(Belarusian, 1887-1985)

The Blue Sky, 1964 Poster

26.5 x 20.5 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Adam and Eve on Blue (Adam et Eve sur Bleu), 1952

Ceramic

12.125 x 2.625 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein

HU88.183

JEAN COCTEAU (French, 1889-1963)

Beauty and the Beast (La Belle et la Bête), 1946

Black and white film, 93 min, 1.33:1

Courtesy of Janus Films/The Criterion Collection

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Double Leaf Mask (Double Masque aux Feuilles), 1958

Ceramic

13.75 x 2.812 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein

HU88.181

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Face of France (Visage de France), 1954

Original lithograph poster 25 x 17.75 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg

HU88.137

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Face (Visage), c. 1960

Ceramic

11.125 x 6 x 6.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein

HU88.189

Exhibition Checklist (continued)

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Free City by the Sea (Ville Franche Sur Mer), 1959

Original lithograph poster

29.5 x 20.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg HU88.148

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Grasset Theatre Sold Out (Grasset Theatre Complet), undated

Original lithograph poster

20.25 x 13.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg

HU88.135

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Matarasso, 1957

Original lithograph poster

25 x 19.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg

HU88.136

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Monaco, 1959

Original lithograph poster

25.5 x 19.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg HU88.132

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Mother and Father, 1950-1957

Ink, colored pencil, and graphite on paper

11.75 x 8.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.195

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Oval Face (Visage Oval), 1958 Ceramic

14.5 x 10.5 x 1.625 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.188

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Ram with Yellow Horns (Belier aux Cornes Jaunes), c. 1960

Ceramic

9.75 x 4.375 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.190

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Self Portrait, 1957

Colored pencil, pencil, paper

10.5 x 5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.194

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Spring (Printemps), c. 1960

Ceramic

13.875 x 7.812 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.191

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Totem, 1957

Ceramic

12.125 x 1.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.185

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

The Chapel (La Chapelle), 1958

Original lithograph poster

25.75 x 19.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg, HU88.134

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

The Couple with the Dog (Le Couple Au Chien), from Le Satiricon, c. 1960

Ceramic

14.25 x 2.625 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.175

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Untitled, undated Black ink, watercolor, paper

11.75 x 8.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.196

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Untitled, undated Black ink, watercolor, colored crayon, paper 9.5 x 8 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.197

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Untitled, undated Black ink, watercolor, colored crayon, paper 11 x 8 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.198

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Untitled, undated Watercolor, black ink, paper

9.25 x 7.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.199

JEAN COCTEAU

(French, 1889-1963)

Woman in Candlelight (Femme a la Chandelle), c. 1960 Ceramic

14.75 x 5 x 6 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Louis Shorenstein, HU88.193

SALVADOR DALÍ

(Spanish, 1904-1989)

Floral Suite, undated Lithograph

21 x 30 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Leon Harris, HU78.63.7

SALVADOR DALÍ

(Spanish, 1904-1989)

Surrealistic Flower Girl, from Memories of Surrealism portfolio, 1971

Etching and lithograph

20.75 x 16.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Benjamin Bickerman, HU93.12.1

SALVADOR DALÍ

(Spanish, 1904-1989)

Untitled, from Memories of Surrealism portfolio, 1971

Etching and lithograph

20.75 x 16.25 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Benjamin Bickerman, HU93.12.3

ADRIEN DAX

(French, 1913-1979)

Untitled, from Alert Box: Lustful Letters (Boîte Alerte: Missives Lascives), 1959

Original lithograph

6.375 x 4.875 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

Exhibition Checklist (continued)

ROBERT DELAUNAY

(French, 1885-1941)

JOSEPH DELTEIL

(French, 1894-1978)

Hello! Paris! (Allo! Paris!), 1926

Illustrated book with 20 lithographs

11.18 x 9.44 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

SONIA DELAUNAY

(French, born Ukraine, 1885-1979)

Untitled, 1964

Etching

19.5 x 13.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Dr. Milton M. Gardner, HU70.97

MARCEL DUCHAMP

(French, 1887-1968)

ANDRÉ BRETON

(French, 1896-1966)

The First Papers of Surrealism, 1942 Paperbound exhibition catalog with front and back cover design by Marcel Duchamp

10.5 x 7.25 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MARCEL DUCHAMP

(French, 1887-1968)

Untitled, from The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box), 1934 Collotype reproduction

7.5 x 12 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MARCEL DUCHAMP

(French, 1887-1968)

Untitled, from The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box), 1934 Collotype reproduction

9.5 x 12 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MARCEL DUCHAMP

(French, 1887-1968)

Untitled, from The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box), 1934 Collotype reproduction

9.125 x 7.5625 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MARCEL DUCHAMP (French, 1887-1968)

ANDRÉ BRETON

(French, 1896-1966)

Alert Box: Lustful Letters (Boîte Alerte: Missives Lascives), 1959 Cardboard box, catalog, telegram on paper, four lithographs on paper, etching on paper, 10 envelopes, and other materials

25-29 x 18 x 7in. (object)

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAX ERNST

(German, 1891-1976)

The Conjugal Diamonds

(Les Diamants conjugaux), from Natural History (Historie Naturelle), 1926 Collotype after frottage

16.875 x 10.125 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAX ERNST (German, 1891-1976)

The Fugitive (L’Évadé), from Natural History (Histoire Naturelle), 1926

Collotype after frottage

10.25 x 17 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAX ERNST

(German, 1891-1976)

LEONORA CARRINGTON

(Mexican, born England, 1917-2011)

The Oval Lady (La Dame Ovale), 1939

Illustrated book with eight offset lithographs after collages

7.5 x 5.5 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAX ERNST

(German, 1891-1976)

JOAN MIRÓ (Spanish, 1893-1983)

YVES TANGUY

(French, 1900-1955)

TRISTAN TZARA

(French, born Romania, 1896-1963)

The Anti-Head (L’Antitête), 1949

Three-volume illustrated book with 46 etchings (23 with aquatint, 23 with pochoir, eight with drypoint, and eight with watercolor and ink additions)

5.51 x 4.52 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAX ERNST

(German, 1891-1976)

MARCEL ZERBIB

(French, 1924-1980)

Sept Microbes, 1953

Illustrated book, etchings in color

7.28 x 5.11 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

FRANÇOISE GILOT

(French, 1921-2023)

Bluebirds in Flight, c. 1970 Lithograph

25 x 19 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Philip Berman HU87.11

FRANÇOISE GILOT

(French, 1921-2023)

#VI, from On the Stone: Poems and Lithographs (Sur La Pierre: Poemes et Lithographies), 1972

Original poem and lithograph

11.75 x 19.625 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

FRANÇOISE GILOT (French, 1921-2023)

#IX, from On the Stone: Poems and Lithographs (Sur La Pierre: Poemes et Lithographies), 1972 Lithograph

12.75 x 9.75 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

FRANÇOISE GILOT

(French, 1921-2023)

#XI, from On the Stone: Poems and Lithographs (Sur La Pierre: Poemes et Lithographies), 1972 Lithograph

12.75 x 9.75 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

S.W. HAYTER

(English, 1901-1988)

Death of Hektor, from the monograph

Death of Hektor

Engraving, etching bound in monograph

11.5 x 8.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mr. J. Tyler Griffin, HU80.41.7

S.W. HAYTER

(English, 1901-1988)

Salt Wave, from the monograph

Death of Hektor

Engraving, etching bound in monograph

11.625 x 8.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mr. J. Tyler Griffin, HU80.41.2

Exhibition Checklist (continued)

LEE KRASNER

(American, 1908-1984)

Free Space (Yellow), 1975

Screenprint and collage on Arches paper, deluxe edition

19.5 x 26 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art Gift of Carole and Alex Rosenberg HU88.13

RENÉ MAGRITTE

(Belgian, 1898-1967)

The Art of Living (L’Art de Vivre), 1968

Color etching

5.59 x 4.34 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mr. Louis Shorenstein, HU90.5

RENÉ MAGRITTE

(Belgian, 1898-1967)

The Green Eye or The Object (L’Oeil Vert [or] L’Object), 1968

Color etching and aquatint

7 x 5.812 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mr. Louis Shorenstein, HU90.7

RENÉ MAGRITTE

(Belgian, 1898-1967)

The Prester Maria (The Hesitation Waltz) (Le Prêtre Maria (La Valse Hésitation), 1968

Color etching

3.75 x 5.5 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mr. Louis Shorenstein, HU90.8

RENÉ MAGRITTE

(Belgian, 1898-1967)

Rose and Pear. The Means of Existence (Rose et Poire. Les Moyens d’Existence), 1968

Color etching

6.28 x 4.312 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mr. Louis Shorenstein, HU90.6

JOAN MIRÓ

(Spanish, 1893-1983)

Homage to Joan Prats (Homenatge a Joan Prats), 1975

Lithograph

22 x 29.75 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Mimi Lipton, HU87.22

JOAN MIRÓ

(Spanish, 1893-1983)

Untitled, from Alert Box: Lustful Letters (Boîte Alerte: Missives Lascives), 1959

Original lithograph

9.75 x 6.625 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

LASZLO MOHOLY-NAGY

(American, born Hungary, 1895-1946)

Painting, Photography, Film (Malerei, Photographie, Film), 1925

Illustrated book

19.17 x 7.12 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

HENRY MOORE

(English, 1898-1986)

Thirteen Standing Figures, 1958

Lithograph

12 x 9.875 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Joseph Tucker HU79.8

FRANCIS PICABIA

(French, 1879-1953)

Thoughts without Language (Pensées Sans Langage), 1919

Illustrated book

7.36 x 4.72 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

PABLO PICASSO

(Spanish, 1881-1973)

MAX JACOB

(French, 1876-1944)

Female Nude with a Guitar (Femme nue à la guitare), from Le Siége de Jérusalem: Grande tentation celeste de Saint Matorel, 1913

Illustrated book with three original prints by Picasso

8.77 x 6.14 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAN RAY

(American, 1890-1976)

ANDRÉ BRETON

(French, 1896-1966)

Photography is Not Art

(La Photographie N’est Pas L’Art), 1937

Photomechanical prints

9.875 x 6.375 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAN RAY

(American, 1890-1976)

PAUL ÈLUARD

(French, 1895-1952)

Free Hands (Les Mains Libres), 1937

Illustrated book

11.18 x 8.85 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAN RAY

(American, 1890-1976)

Photographs by Man Ray: 1920 Paris 1934, 1934

Illustrated book

12.5 x 10.25 in.

Courtesy of Greg Dorata

MAN RAY

(American, 1890-1976)

Untitled, undated Color lithograph

22.8125 x 17.437 in.

Hofstra University Museum of Art

Gift of Reese Palley, HU96.2

KURT SCHWITTERS

(German, 1887-1948)

The Flower Anna: The New Anna Flower (Die Blume Anna: Die neue Anna Blume), 1922

Illustrated book with 34 dada poems

8.93 x 6.02 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

MAX WALTER SVANBERG

(Swedish, 1912-1994)

Untitled, from Alert Box: Lustful Letters (Boîte Alerte: Missives Lascives), 1959

Original lithograph

7 x 5.4375 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

DOROTHEA TANNING

(American, 1910-2012)

Orphans, from Dorothea Tanning: Bilder, Gouaches, Zeichnungen, 1957-1963, 1963 Etching, soft-ground etching, and open bite

7.875 x 6.3125 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

TOYEN (MARIE ERMINOVÁ)

(French, born Czech Republic, 1902-1980)

Untitled, from Alert Box: Lustful Letters (Boîte Alerte: Missives Lascives), 1959

Original lithograph

6.375 x 4.875 in.

Courtesy of Special Collections

Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library

Hofstra University

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY

SUSAN POSER President

CHARLES G. RIORDAN

Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs

COMILA SHAHANI-DENNING Senior Vice Provost for Academic Affairs

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART

ALEXANDRA GIORDANO Director

RIS AGUILÓ-CUADRA Museum Educator

TAMARA ALFANO Museum Educator

KRISTEN DORATA

Assistant Director of Exhibitions and Collections

JACKIE GEIS

Senior Assistant to Director

STEPHANIE MCGEE Museum Educator

SARA SCHAEFER Museum Educator

AMY G. SOLOMON Director of Education

UNDERGRADUATE ASSISTANTS

Sarah Braun, Makayla Egolf, Syd Hartstein, Angelina Olivo, Bella Palaia, Josie Racette, Aurisha Rahman, Paxton Splittorff, Caitlin Treacy

GRADUATE ASSISTANT

Brian Malloy

GRADUATE CURATORIAL ASSISTANTSHIP

Mary Conroy (former), Olivia Baeza (present)

GUEST ESSAYIST and CONTRIBUTING HISTORIAN

Catherine E. Clark

Associate Professor of History and French Studies

Faculty Director of the Programs in Digital Humanities

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

MUSEUM VOLUNTEER

Leo Valenti