11 FAL L / W I NT E R

NIGO® FUTURA A$AP FERG GIORGIO MORODER MARK GONZALES TA K A S H I M U R A K A M I KITH

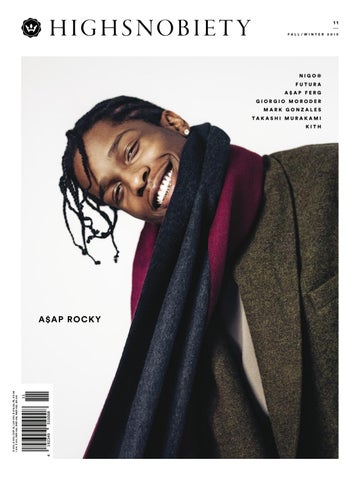

A$A P R O C K Y

2 01 5

NIKE.COM/SPORTSWEAR

DANNY CARE

introducing the element wolfeboro jacket collection fall 2015 product : belton jacket photos by element advocate : brian gaberman @elementbrand

#elementwolfeboro

© 2015 adidas AG

ENERGY ELEVATED

handcrafted with polartecÂŽ performance fabrics

reigningchamp.com

www.carhartt-wip.com Photography by Joshua Gordon, artwork by Tim Head

P R E F A

C E Welcome to Issue 11 of Highsnobiety Magazine. The publication you are now holding represents the second piece in a two-part print celebration of Highsnobiety’s 10-year anniversary. In part 1, Issue 10, we showcased the youth and young creators who are making an impact on our culture in 2015. Part 2, this issue, is an examination of longevity and the increasingly difficult feat of achieving it in a world that has become increasingly focused on the “now.” Over the past 10 years we’ve seen countless brands come and go, numerous designers rise and fall, and trends seemingly change with the weather, yet through it all there are certain players who have endured. Some of them blossomed in the post-blog era, but many of the individuals we’ve chosen to present were already household names in a time before the web and have stayed true to their vision through the years, continuing to thrive and capture our attention. With a whopping eight cover stories (for a total of 10 covers this year) we’re highlighting a range of key creators from across various disciplines and cultures. The iconic works of artists Futura and Takashi Murakami have been mainstays of our web content throughout the last decade and count our first two covers. Prolific Japanese designer NIGO®, whose work is referenced in countless stories on Highsnobiety.com, fronts our third. The look and sound of Harlem-based hip-hop collective A$AP Mob have been among the most influential in recent years, and their two most prominent members, A$AP Rocky and A$AP Ferg, each star individually on another two covers. Perhaps more low-key than the above, but living legends and important creators nonetheless, Academy Award-winning producer Giorgio Moroder and skater-cum-artist Mark “The Gonz” Gonzales make up covers six and seven.

12

Finally, we created a limited KITH exclusive cover that coincides with our Highsnobiety 10th anniversary PUMA collaboration and ties to an article exploring how the creator – represented by KITH’s Ronnie Fieg and the curator, personified by Highsnobiety founder David Fischer – fuel one another, and how this process has evolved since our inception a decade ago. In addition to all the cover features, this issue explores numerous other stories of continuance, including the journey of OG Stussy Tribe member Alex Turnbull, the 30th anniversary of Jim Philips’s iconic Santa Cruz Screaming Hand, and the history of tailoring through the lens of Patrick Grant’s E. Tautz label. Others, such as fashion designer Nigel Cabourn (who founded his eponymous label 45 years ago!) and Editor Andrew Richardson (of his self-created magazine Richardson) talk about their enduring output. We also produced a series of photo editorials to support this issue’s theme. Fashion-wise we focused on the Fall/Winter 2015 collections from important legacy brands like Lanvin and Stone Island, as well as those of persistent young labels such as Our Legacy, OFF-WHITE and newcomer adidas YEEZY Season 1. Furthermore, photographer trashhand explored abandoned America, showcasing the beautiful decay of forgotten architecture. And there’s much more. Our global team of editors, photographers, stylists, and contributors have put together a fantastic new issue that we hope succinctly captures the theme of longevity and will itself serve as both a reference and as a collectible publication for years to come. Thank you for being a part of our journey. To another 10 years. Enjoy. Pete Williams

Contents

Covers

LOOK

INTERVIEWS

16 Editor’s Choice

38 Carhartt WIP

32 From the Hoods to the Woods

70 Alex Turnbull

46 The Road Not Taken 58 Going Home 66 Crafted Comfort 98 Noli Me Tangere 112 We Were Not Here First

76 Liam Hodges 84 Nic Galway 90 NIGO® 106 Mark Gonzales

144 The Mystery Which Binds Me Still

158 Craig Ford

248 America, Abandoned

Photography 13thWitness

Photography Graham Hiemstra

Photography Allen Park

Photography Thomas Welch

126 KITH & Highsnobiety 152 Nigel Cabourn

222 Horizontal Volumes

Photography Robert Wunsch

120 Futura

136 Karrueche

214 Rowley Way

Photography Robert Wunsch

166 Takashi Murakami 172 Andrew Richardson 178 Giorgio Moroder 190 Jim Phillips 198 A$AP Rocky / A$AP Ferg

READ 184 How to Make It in London 228 Established (est.) 238 Travel 246 Sir Stirling Moss 254 Louise Nevelson

TA ST E 36 Double U Frenk 44 Kit and Ace 50 JackThreads 54 Converse Chuck Taylor All Star II 56 Nike's Tech Fleece

Photography Kento Mori

14

OUTDOOR ORIGINAL DANNER.COM/STUMPTOWN

We honor our past with the new Danner ® Mountain Pass, a careful balance of t radition, craftsmanship and modern comfort. Handcrafted in Portland, Ore.

EDITORS’ CHOICE

R A F S I M O N S H A N D P R I N T E D N A R R OW COAT

16

#H EINEK EN1 0 0

OPEN YOUR CITY

PHOTOGRAPHED BY trashhand

Please visit: EnjoyHeinekenResponsibly.com Brewed in Holland. Imported by Heineken USA Inc., New York, NY. ©2014 HEINEKEN® Lager Beer, HEINEKEN PREMIUM LIGHT® Lager Beer.

CO M M E D E S G A RÇO N S S W E AT E R

18

see the film on nixon.com

C R A I G G R E E N Q U I LT W R A P V E S T

20

H E R S C H E L S U P P LY C O. S T U D I O C O L L E C T I O N S U T TO N D U F F L E

22

R A I S E D B Y W O LV E S F E R G -YA N G H AT

24

R E P L A C E

W W W . H I C K I E S . C O M W W W . H I C K I E S . C O M

T H E

L A C E

T R I WA C H A M PAG N E S KA L A A N D M I D N I G H T H VA L E N WATC H E S

26

WWW.TRIWA.COM

TIMBERLAND BLACK FOREST COLLECTION BRITON HILL BOOT

28

FA L L / W I N T E R 2 0 1 5

ONEPIECE.COM

@ONEPIECE

#COMFORTBRINGSCONFIDENCE

H I G H S N O B I E T Y × A N I CO R N S E R I E S 000 WATC H

30

ELEMENT WOLFBORO COLLECTION FALL / WINTER 201 5

FROM THE HOODS TO THE WOODS PHOTOGRAPHY

ALEX DE MORA STYLING

AT I P WA N A N U R U KS GROOMING

LY D I A WA R H U R S T USING MAC COSMETICS & BUMBLE AND BUMBLE CASTING

S A R A H B U N T E R @ B U N T E R C A S T I N GÂ P H OTO G R A P H Y AS S I S TA N T

THEO COTTLE MODEL

JOS WHITEMAN @ AMCK MODELS

32

33

34

35

DOUBLE U FRENK THE BEAUTY OF THE OCCULT

WORDS BROCK CARDINER

36

Born in February 2013 in the ancient city of Modena, Italian jewelry brand Double U Frenk began as a creative outlet for a group of friends. Bringing their very first design, a skull necklace, to local clubs, the group’s influential circle indoctrinated others on the scene and soon enough their occult creations could be found in some of the region’s best shops. Fast forward to today and Double U Frenk is carried in 80 dealers throughout Italy with an online shop that ships to every corner of the world.

DOUBLE U FRENK

While most brands would take that early success and set up a flagship, Double U Frenk, doing things their own way, has outfitted a caravan in their distinct design language to drive across the country and stop by some of the best festivals, reflecting their early club-going days. Best of all, the travels that served as inspiration when they were starting out are now on the road beneath them and the adventures ahead. What they’ll come up with next, we’ll have to wait and see.

DOUB L E COLLEC TI ONS

U

F R E NK

15/ 16

|

|

Ita l i an

Stre et

d ou b l e u f re n k. n et

J ewe l r y |

38

CARHARTT WIP

25 YEARS OF CARHARTT WIP A CONTINUOUS WORK IN PROGRESS

WORDS BROCK CARDINER INTERVIEW DAV I D F I SC H E R PHOTOGRAPHY OLLIE ADEGBOYE & R YA N H U R S H

How do you continue to stay relevant after 100 years? Besides that, how do you bring your heritage and history to an entirely new audience after a century of existence? Those are the questions Edwin Faeh had to answer when he launched Carhartt Work in Progress (WIP) in Germany 25 years ago as part of a licensing deal, exactly 100 years after the birth of Detroit’s most famed clothing brand, Carhartt. At a time when streetwear was dominated by California surf culture through imprints like Stussy, Quiksilver and Ocean Pacific, the decision to launch a brand based on workwear seems odd in the context of the ’90s yet genius in retrospect. After all, who could foresee pop culture’s near fetishization of working-class fashion in the coming years? Sure, Ralph Lauren did it decades before but that was for a different generation, one that romanticized the countryside, and still held figures like James Dean and Marlon Brando as the pinnacle of cool. Cool in the ’90s was something entirely different. Cool in the ’90s was grunge and hip-hop; slap bracelets and light-up sneakers; Calvin Klein and Michael Jordan. The particulars hardly matter though as there are two things that define cool across generations: attitude and authenticity. The same values that defined cool in the rebellious characters of the ’50s and the summer-lovers of the ’60s defined cool in the existential disaffection of Kurt Cobain and in the social critique of Tupac Shakur. The attitude and authenticity were there, as they were when Faeh brought Carhartt to Europe. Although Carhartt already had a cult following and a reputation for rugged, authentic workwear outside of the U.S. when Faeh launched the brand’s European branch, Carhartt goods were nearly impossible to acquire beyond the States’ borders. His former business partners even thought the brand “was unsellable,” leaving Faeh to his own devices. In the early days of Carhartt WIP in fact, they “would only buy from America, from their catalog.”

Fortunately, with an expertise in fashion dating back to the ’70s, it was only a matter of time before Faeh was able to turn the ship around and bring Carhartt’s essence to a discerning European audience. “I went to business school and then I practiced in a textile company, but no one was wearing denim in the ’70s besides people like the Hells Angels. You wore corduroy and that was it.” Fast forward 20 years and denim has supplanted every fabric to become the great sartorial equalizer across the world. Rich or poor, young or old, everyone owns or has owned a pair of jeans. Armed with a deep and thorough understanding of denim and the distribution world at large, Faeh was wellequipped to start bringing Carhartt’s legacy to the Old World. “Carhartt was a foundation. It was jackets and pants. I was especially interested in the pants. I thought denim would be out one day but 25 years later and we’re still waiting, we’re still waiting for blue to be out.” Young, creative, inquisitive minds in particular were intrigued by the denim hip-hop artists wore, pairing “XXXL” jeans with buckwheat Timbs for a look that was straight off the streets of New York. “Hip-hop was the beginning, then came graffiti, skateboarding and DJing,” and the stockists reflected this. “We were never in a jeans store, never in a department store. It was very strict. We only sold in skateboard shops, streetwear/ hip-hop – these kinds of stores.” A sort of antimarketing form of marketing. As Faeh tells it, “There was no marketing meeting at all. We had no idea about marketing.” It’s plain to see from the start that Carhartt WIP’s fanbase was different from its counterpart in the U.S. While Carhartt was supplying farmers in the south with reinforced jackets and hip-hop artists in the north with oversized jeans, Carhartt WIP was supplying European skaters, graffiti artists and BMXers with refined versions of this multipurpose gear.

CARHARTT WIP

39

Despite their devotion to Carhartt’s renowned quality and their love of the musicians they idolized, Faeh knew he had to clean up the brand’s key silhouettes for his European consumers. “They had work pants with loops, We wanted it without loops.” Step by step they gained more control of the brand. “We used poly-cotton – the Americans never used poly-cottons. We wanted to do chinos in poly-cotton and we had to get the license to make them. Basically, we had to get the ‘OK’ on every piece. We had to get licensed for every product. We did well but all of the products were American products.” Things really turned around though when Faeh said they “wanted to make grays instead of browns, because no one buys browns in Europe.” To do this, Faeh and co. had to order a certain amount of product, known as a minimum. Through what was essentially a custom order, Carhartt WIP had created an exclusive colorway for their European audience. The next influential moment in the brand’s move for independence came when Faeh placed an order for Siberian parkas. The workers responsible for crafting these pieces at Carhartt’s Kentucky factory were on strike and Faeh was told by the head of Carhartt at the time, Robert, that they couldn’t produce enough for them and that they’d have to produce them themselves. In the end that’s exactly what they did, showing their parent company they could stand on their own two feet. Today, the relationship is symbiotic and even though they still have to send each and every collection to Detroit for approval, Carhartt fully understands what their Work in Progress siblings are doing. Look no further than the brand’s shorts offerings for proof. Carhartt didn’t even make shorts until Carhartt WIP scouted ahead and made sure the coast was clear. That’s not to say Faeh’s operation was completely void of hurdles by the aughts. On the contrary. Although Carhartt WIP had completely supported their fanbase from the start, the times were changing and streetwear as a fully-fledged lifestyle was on the rise. No longer limited to skaters, artists and musicians, anyone even remotely associated with

40

CARHARTT WIP

urban culture wanted a piece of the pie. Heritage, functionality and durability – three of Carhartt’s defining characteristics – started trending and simple pieces reworked for the continent’s fashion climate like the single-knee and double-knee pants, as well as the Detroit jacket, proved a hit. Eager to take this shift in lifestyle to new heights, Faeh started thinking about how he could take the brand’s 100+ year history and adapt it to the times. Carhartt eventually gave them permission to fashion jackets out of leather after refusing for some time, merging the brand’s time-tested design with sleek materials fit for the streets of London, Paris, Berlin and Milan. By 2006 Carhartt WIP was undoubtedly a formidable part of Europe’s fashion landscape. As the ultimate cosign, Japanese brand A Bathing Ape, under the leadership of streetwear impresario NIGO®, reached out to Carhartt after being impressed by their offerings in the UK to inquire about a collaboration. Even Faeh was taken aback by the request due to what he sees as Japan’s fondness for originality, while his business revolved around a license. The two quickly came to an agreement, however, and a collaborative zip-up hoodie was on the way. Carhartt WIP’s traditionally earthy color palette was swapped in favor of BAPE’s Ape Head camo – three versions of it in total – and the lining was stuffed full of down. The bridge between Japan’s historically insular fashion scene and Europe’s was finally built, with additional support laid down by brands like uniform experiment and SOPHNET. In 2008, Carhartt WIP set up their first collaboration with iconic footwear brand Vans. Together the two revamped the California marque’s Half-Cab silhouette, this time opting for a workwear-inspired makeover. Countless collaborations have followed since, most recently with fashion institutes like Paris’s A.P.C., Milan’s RETROSUPERFUTURE and Amsterdam’s Patta. In every single case, the brand has taken a unique approach that honors both entities’ DNAs to the fullest. Whether it’s through materials or colorways, each project holds its own as an extension of both brands’ roots.

CARHARTT WIP

41

Entering their 25th year, it’s only appropriate the brand celebrate with a 25-piece anniversary collection. Included are some of the most iconic workwear styles from the Carhartt archives, alongside a selection of classic pieces from Carhartt WIP. Many have been redesigned and reinterpreted, modifying the original fabrics, colors and trims for 2015. All 25 products come complete with silvercolored hardware and labels (the traditional color used for 25th anniversaries), together with a heartshaped button as an homage to the original Carhartt logo created in the late 19th century. Expect the celebratory goods to arrive in all Carhartt WIP stores and selected retailers around the world on September 25. With a proven track record of success, which now includes 75 flagship shops alongside 2,500 stockists, Faeh stays motivated simply by not driving himself crazy. Talking with him you get the sense that even though he’s older and wiser than he was when he entered this business 40 years ago, those same basic principles are still at play. He likes the people he works with. He appreciates simplicity; the same kind of simplicity he was surrounded by during his childhood in the countryside. He likes

42

CARHARTT WIP

to work as a team and he never lets his pride or his ego get in the way of what’s best for the brand. Listening to him recall his earliest fashion memories come off as childish, innocent even, like when he talks about seeing a pair of bleached denim for the very first time at a Parisian flea market. “You know who invented bleached jeans? Hippies. But they didn’t use stone like we do today. There was only chlorine bleach. They didn’t have stone-bleaching in the ’70s. They just put bleaching chlorine and jeans in the water.” It’s that wondrous, almost naive approach that has made Carhartt WIP what it is today – a brand unafraid to take something that has absolutely no faults to begin with and make it even better. As for what the next 25 years holds, Faeh says they’ll probably keep focusing on their simple Brown Duck offerings. Nothing too fancy; nothing too fashion. It’s been a remarkable quarter-century for the brand but as Faeh himself puts it, “We have history but we have to play our cards right.” In other words, it’s a work in progress. — carhartt-wip.com

You know who invented bleached jeans? Hippies. But they didn’t use stone like we do today. There was only chlorine bleach. They didn’t have stone-bleaching in the ’70s. They just put bleaching chlorine and jeans in the water.

CARHARTT WIP

43

GET UP AND GO WITH KIT AND ACE’S TECHNICAL CASHMERE™ WORDS BROCK CARDINER

PHOTOGRAPHY ALAN CHAN

The latest brand to emerge from the creative environs of the West Coast is Kit and Ace. Founded in technical apparel hotbed Vancouver just less than one year ago, Kit and Ace has quickly emerged as one of the industry’s leading innovators due in no small part to their machine washable Technical Cashmere™. Designed explicitly to keep up with the pace of life maintained by the creative class, the material is redefining the term “luxury” as we know it. While in the past the “L” word has conjured up images of opulence, grandeur and delicacy, Kit and Ace’s Technical Cashmere™ signals a shift in the trajectory of clothing with its get-up-and-go construction that focuses on fit, form and function combined with refined style.

44

KIT AND ACE

Each piece featuring the brand’s unique cashmere interlace is equally at home in a converted loft that doubles as a workspace as it is weaving through the city on a bike. In a word, those leading the way are no longer constrained by the limits of traditional fabrics, nor are they forced to change outfits three times in one day. Starting the day with a French press at home? Technical Cashmere™. Cycling to the office in a rush? Technical Cashmere™. Meeting with clients across town? Technical Cashmere™. Dinner with friends in a former brick factory? Technical Cashmere™. Best of all is the part that comes after a busy but satisfying day like that. Throwing the outfit in the wash and doing it all over again the next day like it was nothing. Because it wasn’t.

K I T A N D A C E . C O M

N O

M A T T E R

H O W

Y O U

F R O M

A

D R E S S

G E T

T O F O R

B , Y O U R

T R A J E C T O R Y.

T H I S

I S

M A C H I N E

T E C H N I C A L

W A S H A B L E

C A S H M E R E â„¢

G-STAR RAW FALL / WINTER 201 5

THE ROAD NOT TAKEN

PHOTOGRAPHY

A M A R DAV E D STYLING

AT I P WA N A N U R U KS HAIR

ERNESTO MONTENOVO @ PHAMOUSARTISTS USING BUMBLE AND BUMBLE MAKE UP

M A R T I N A L AT TA N Z I @ O N E R E P R E S E N T S USING KIEHLS P H OTO G R A P H Y AS S I S TA N T

LIAM YOUNG MODEL

JACK BUCHANAN @ SELECT MODELS

46

47

48

49

50

JACK T H R E A DS

THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT A CULT BRAND FOR THE MASSES

You may not know Tony Kretten by name, but there’s a strong chance you have seen, and perhaps even own, his work. In his 13 years at Gap, Kretten headed up the iconic (RED) campaign and revitalized Gap’s 1969 denim line. Now hired as Creative Director of Commerce for new fashion line JackThreads, Kretten is setting out to build a new namesake vertical brand within the walls of a Silicon Alley startup. Launching in Fall 2015, the JackThreads label will take a former flash sale site and evolve it into a fashion resource for guys who appreciate fit and feel as much as good value. On a mission to bring good style to every man that’s interested, the new JT aims to update the timeless American look using the kind of unique customer insights only a tech company can truly master. As Tony himself tells it, they want to be nothing less than your go-to style destination.

WORDS E M I LY S I N G E R PHOTOGRAPHY MAX SCHWARTZ

JACK T H R E A DS

51

You’ve spent the past 13 years designing menswear at Gap. JackThreads is obviously a very different company and an entirely new brand. What has been the biggest change for you? When I was on the outside looking in, I always felt that tech companies were the future of e-commerce, because they’re part of that connectivity-based consumer culture. I looked at the marketplace and asked myself, “Okay, who’s really appealing to guys in a way that a) has great potential, but b) speaks a language that I understand?” There are other players out there who didn’t get it right because they speak to a very specific type of consumer, whereas I think JackThreads speaks to everybody, which I love. There’s also the tech side of [JackThreads] and how quickly we can respond to shifting demands in the market. We have the ability to engage in a dialogue with the customer every single day, and the customer is telling us, either via his click-throughs or what he’s buying, what he wants. That means we can give him more of those things. This level of real-time reaction makes the company grow in a far smarter capacity than traditional retail, because tech is in our DNA. Where brick and mortar takes six-to-nine months to react to customers, we can do so overnight. Speaking very broadly, what’s been the biggest change between when you first started designing and now? Beyond being a naive kid from Cincinnati who wanted to be Geoffrey Beene? I think the big difference between me then and me now is the fantasy portion of design. Along my career path I could have gone into the high-end sector, but the intellectual challenge of making ubiquitous clothing that’s both modern and relevant is, for me, more challenging than the high-fashion side of things. There’s still an art to what we make, but I’m more interested in the craft and commerce portion of fashion, as opposed to the outright craziness of runway shows. Menswear and men’s style has really picked up in the last two to three years. Do you think that an awareness of style has become an accepted thing? I think it’s certainly heading that way. I think there are mainstream guys who look at iconic sports stars and celebrities for style cues, they look at GQ, and now they’re going to look at the curation and editorial portion of JackThreads for advice on how to look good. But yes, I think it’s a part of men’s culture now to talk about style and not be embarrassed about it. With this new awareness, how is the classic American look changing? There are still some iconic heritage pieces in the regular guy’s wardrobe; it’s just that the details, the fit, the fabric – the things that actually make style modern and relevant – are more important than ever.

52

JACK T H R E A DS

About 80% of a guy’s wardrobe is made up of products that you can list off the top of your head, and the remaining 20% is trendbased style. I think that 80% needs to be modernized, retouched and thought about. Instead of just doing a T-shirt, we want to ask “what’s the cut of the T-shirt, what’s the fabric, what are the internal details?” Basics don’t have to be simple. So what can we expect from the new line? Confident style. The products that we’re creating in the new line are going to be those favorite pieces a guy will feel happy turning to time and time again. We want people to think “JackThreads makes the most awesome T-shirt for $18, so why would I shop anywhere else?” Since there’s so much competition with online retail, especially in the realm of basic menswear, how will JackThreads differentiate itself? It’s through our voice and our ability to curate confidently that we’ll stand apart. There are three sides to our business. There’s the value portion, in which you’re getting a really great product at a really great price, but it’s not outright cheap – there’s a big difference between being cheap and offering great style for a great price. Then there’s the fact we’re building an editorial component into the JackThreads experience, so we can actually educate our shoppers and have a daily conversation on style. Finally, there’s the speed and IQ of the tech involved. It’s taking the science of smart shopping and blending it with the skill of great products and the art of great style. Finally, is there anything you think is missing, or simply not being done right, in men’s fashion that you want to change? That’s a big question. My main problem is that shopping is either based on cost, or it’s based on some sort of elitist position. A lot of men want more than bargain basics, but don’t feel comfortable engaging with the fashion scene at large, so they feel excluded and un-catered for as a result. We want to create somewhere for these guys; we want to create a community where they feel at home, and feel confident expressing their taste and sense of style without having to know a secret handshake.

JACK T H R E A DS

53

54

C O N V E R S E C H U C K TAY L O R A L L S TA R I I

CONVERSE CHUCK TAYLOR ALL STAR II THE BEGINNING OF A NEW ERA WORDS BROCK CARDINER PHOTOGRAPHY DA M I E N VA N D E R V L I ST FASHION EDITOR AT I P WA N A N U R U KS

10 years after being acquired by Nike, Converse has unveiled the successor to the longest-running sneaker of all time. Appropriately named the Chuck Taylor All Star II, the sneaker draws heavily on the groundwork laid down by the 1917 Chuck and invigorates it with today’s best innovations. While the sneaker comes loaded with new features and improvements, the first thing wearers will notice is the cushiony Lunarlon insole. No more stiff footbed. The Swoosh has got your back. Ready for more, the Chuck has been streamlined, getting rid of contrast stitching in favor of tonality. The iconic patch is seamlessly embroidered, while the license plate branding has been upgraded for 2015’s HD requirements. On par with the Lunarlon sole is the foam-padded collar and gusseted tongue, eliminating the annoyance of a sliding tongue. Completing the premium package is a perforated micro-suede liner so your dogs won’t be sweating during extended periods of wear. In a word, the Chuck Taylor All Star II continues the legacy of the first and ushers in the second generation. Long live the Chuck. — Find out more at Converse.com.

C O N V E R S E C H U C K TAY L O R A L L S TA R I I

55

NIKE’S TECH FLEECE RETURNS FOR FALL 2015 STAY WARM

WORDS BROCK CARDINER

DANNY CARE

56

TOM WOOD

The Swoosh takes one of their most innovative clothing offerings and revamps it for the Fall 2015 season. Hitting the scene a few years ago, Nike’s seasonal Tech Pack collection returns including all-time favorite Tech Fleece pants and a new printed Tech Fleece full-zip hoodie (pictured) for men. The last is done up in camouflage while the latter comes in midnight black. Both pieces are specifically engineered to stand up to unfavorable weather and to keep urban athletes moving in all conditions. Modeled by rugby stars Danny Care and Tom Wood, the new Tech Fleece styles are constructed for professionals and made for the everyday. Details of the camo hoodie include a scuba hood with extended bill, an extra-long chest zip pocket and a longer hem for added protection from the elements. The pants, meanwhile, are made with a thermal construction to provide lightweight warmth. In addition to hoodies, a vest, crew necks and pants, upgraded garbs for women arrive in the form of a cape. A new heathering pattern energizes the Tech Fleece and an interior bungee at the waist allows for a customizable fit. The silhouette of the centerpiece is carefully redone with a slightly oversized hood and extended drop tail for added coverage. Just in time for the clouds, rain and colder nights, you can pick up the Tech Pack Fall 2015 collection now online at Nike. — nike.com/sportswear

NIKE’S TECH FLEECE

57

GOING HOME

PHOTOGRAPHY A M Y GWAT K I N FASHION EDITOR VINCENT LEVY GROOMING M A K I TA N A K A , Y U M I N A K A DA- D I N G L E U S I N G AV E DA P H OTO G R A P H Y AS S I S TA N T S M A R I A M A I N E R & D I A N A PAT I E N T MODELS ELLA KING @ PREMIER HAMISH STEED @ SELECT K E I R O N @ T O M O R R O W I S A N O T H E R DAY R I C H @ T O M O R R O W I S A N O T H E R DAY T E D @T O M O R R O W I S A N O T H E R DAY KEVIN ROWSELL @ FM

58

T-S H I R T

V I N TAG E R E E B O K

COAT

FILA

TROUSERS

MARTINE ROSE

59

60

JACKET

LE COQ SPORTIF

SHOES

V I N TAG E A D I DA S

S W E AT E R

M AT T H E W M I L L E R

KEY CHAIN

M AT T H E W M I L L E R

TROUSERS

M AT T H E W M I L L E R

ROKIT

POLO SHIRT

C O A T

CRAIG GREEN

TROUSERS

ROLL-NECK

TOPMAN DESIGN

SHOES

H AT

ELLESSE

DC SHOES

N I K E

61

HOODIE SHIRT

COTTWEILER

TROUSERS

62

MARQUES ALMEIDA ROKIT

SHOES BAG

V I N TAG E A D I DA S LIAM HODGES

63

TRACKSUIT SHOES

64

CHRISTOPHER SHANNON SAUCONY

JACKET TOP

Q U I KS I LV E R

ELLESSE

TROUSERS

LIAM HODGES

65

ONEPIECE FALL / WINTER 201 5

CRAFTED COMFORT

PHOTOGRAPHY SARA SANI STYLING MARIANNE KRAUSS MAKE UP R EG I N A K H A N I P OVA MODELS INDES & LUCAS

66

67

C

M

Y

CM

MY

CY

CMY

K

68

ALEX TURNBULL ALL THE WAY LIVE TRIBE

WORDS

DK WOON PHOTOGRAPHY

OLLIE ADEGBOYE

70

We live in a dilettante’s age – one where it’s increasingly common for people to dabble very publicly in a whole multitude of interests, occupations and “creative exploits.” The tale of the model/actress/ DJ is, by now, a yarn spun too often to be of any real interest (much like said individual’s record collection) and the sad fact is that to be a polymath in 2015 is to risk being lumped in with a whole raft of people who don’t take what they do very seriously. Alex ‘Baby’ Turnbull is very much the antithesis of this – a true polymath (and that’s not a term to be thrown around lightly). His “career” path has seen him play the role of skateboarder, punk posterchild, DJ, martial artist and, most recently, filmmaker. Yet, while somehow wearing all these hats simultaneously, he manages to pay due diligence to each of the cultures that exists behind them. Still regarded as a credible underground presence, his name isn’t known to masses of people, yet in each of his fields he has successfully engaged a willing audience. As he himself would phrase it, he is “proper,” oftentimes foregoing commercial gain in favor of genuine artistic integrity. I meet Turnbull on a crisp February morning at his studio in East London. A striking space he shares with his brother Johnny, the space is dotted with sculptures and paintings by his father, the British modernist William Turnbull, lending it a soothing ambiance. The studio feels like a quiet haven in an area that, at weekends, you might find littered with discarded drinks bottles, takeaway wrappers and laughing gas canisters. On weekdays it’s a bustle of media types rushing from one important meeting to the next. Alex is noticeably tall, with a physique honed by years of Jeet Kune Do. His passion for the martial art has been instrumental in defining his take on the world, especially the phrase “absorb what is useful, reject what is useless.” This mantra strikes me as increasingly difficult to live by, given the fast-moving, disposable culture of the city he’s surrounded by.

ALEX TURNBULL

ALEX TURNBULL

71

72

FASHION

SKATEBOARDING

Readers of Highsnobiety will perhaps be most familiar with Alex for his involvement with Stüssy. Perhaps you’ve seen him modelling their clothes, or maybe you’re even old enough to remember him DJing at Stüssy parties way back in the day. Either way, Stüssy is a name that will forever be associated with Alex, and likewise, I don’t think he’ll ever be able to extricate himself from the “Alex Baby” moniker embroidered on his OG Tribe jacket. His introduction to the brand came in 1986, through friends he’d met a decade before while skateboarding at London’s notorious Southbank. That said, the intro itself happened over the Atlantic Ocean, on a visit to New York. It was there that Alex reconnected with old friend Jules Gayton at Madam Rosa’s (the hot Downtown club at the time). Though they hadn’t seen each other in around 10

Of course Alex’s fascination and involvement with street culture came long before his affiliation with any one brand. As I mentioned before, Alex had been introduced to Stüssy through friends he’d met skateboarding, and it was this that was his first foray into the life he is so known for today. Picking up a skateboard around ’75/’76 (at just 14 years old), Turnbull was amongst the first wave of British skateboarders to embrace the pastime. It was an exciting period: urethane wheels had only just landed and across the Pond it was the era of Dogtown and the Z-Boys. People like Jay Adams and Tony Alva were the first introduction for a young Alex into the world of fashion. In his words, “They were punk rock before there was punk rock” and their combination of physical prowess, attitude and style was both lethal and completely new. The world of Dogtown and the Z-Boys, with its backyard pools

years, their paths had run remarkably parallel, both now working as semi-successful DJs. At the time Gayton was living with Jeremy Henderson, an American skateboarder who’d also spent time living in London. One day, Henderson beckoned Alex down to a midtown warehouse. When he reached the location he was met with two rails of clothing, and Paul Mittleman. What was on these two rails was enough to blow Alex away: “I remember getting a T-shirt, the first T-shirt with a sorta skull and surf crossbones thing, some beach pants, and a kinda sailor crewneck long-sleeve thing. I remember just thinking ‘wow… this is what we’ve all been waiting for!’ Because we were all wearing adidas tracksuits, Goose and bootleg Gucci!” It’s easy to see why Alex connected so easily with Stüssy. To Alex, Stüssy represented a brand that didn’t concern itself with “empire building.” Instead it was very much about the Tribe: a global set of people affiliated with a shared set of values, who weren’t snobbish in their exclusivity, but were nonetheless select in who they welcomed. To receive one of the infamous Tribe jackets back then was a big deal. “I remember that day so clearly,” he recounts with excitement. “It was like ‘I’ve got a jacket with my name on it – nobody else has this jacket and I’m the only person that has this jacket.’” Fast forward to 2015 and Alex is sporting a Louis Vuitton jacket he’d been given by Kim Jones (Louis Vuitton designer, who has also designed for GoodEnough whilst also working at Gimme5). The jacket itself is an incredible bomber referencing the designs of Christopher Nemeth, which he was given after DJing at a show alongside Grammywinning mega-producer Nellee Hooper. Whilst there, he remarked to Kim that it was the first thing that had felt like a Tribe jacket since that original piece. While I struggle to resist getting misty eyed, few brands can elicit such a powerful response these days. It’s clear Alex feels it too – a certain lack of ease with brands of the modern age. He’s by no means an overly reverential old man, and knows it would be all-too-easy to slip into lazy armchair criticism. Yet still, there’s a certain discomfort with how things work today – the endlessly peddled cycle of recycled culture. As he puts it, “You see someone wearing a Clash T-shirt and they don’t know what the Clash are.”

and surf breaks, was – as Alex is keen to remind me – incredibly exotic in comparison to London in the ’70s. This was a period when the nearest you could get to Vans were a pair of Dunlop Green Flash, and even they were prohibitively expensive (“mum certainly wasn’t going to spend £5.99 on shoes!”). Back then, it was a more innocent age – a time where information was scant, and the only insight into what was going on in California were issues of skateboard magazines passed around from person-to-person down at Southbank. British skateboarding was a different animal, one where the protagonists barely even knew what surfing was. A few years on, and it was through Jeremy Henderson that Alex went on to meet Mark Gonzales and Jason Lee: two of street skateboarding’s pioneers and still two of the best skate styles that have ever graced this planet. It was Alex and his brother who first showed Mark Gonzales to a gap under the Westway now referred to as “The Gonz Gap” (not to be confused with the one in San Francisco), and it was his brother who taped the footage of Gonz ollie-ing it in era-defining, Spike Jonze-directed skate flick Video Days. Skateboarding helped expose Alex to, in his words, “People from all different cultures. Color, race, creed. Kids from Stockwell, kids from Camden, kids from Kensington and Chelsea. Everyone hung out and it didn’t really matter where you were from.” Instead, their scene was a meritocracy. “What mattered was whether you could skate! In a way it’s like breaking or graffiti. It’s a performance-based thing. It’s like hip-hop was. Not what it is now. I guess MCing still is – to an extent. Either you can do it or you can’t. Goldie said it best when he said ‘I can tell if you can paint or not. I can tell if you can dance or not. I can tell if you can DJ or not.’ In the end, anybody that knows, knows! If you get up on the decks, there’s no way you can pretend – there’s no halfway.”

ALEX TURNBULL

73

It’s about underground culture and style, but style is the thread that runs through... It’s important that someone inside tells the story, rather than some producer from some TV channel who doesn’t really know. This story has to be told from the inside.

MUSIC

FILM

After punk fizzled out in the late ’80s, Alex joined 23 Skidoo – a band that were incredibly ahead of their time. Punk served as a liberator, but Skidoo borrowed from a far wider spectrum of influences: everything from Fela Kuti to reggae to William Burroughs and Cabaret Voltaire. The name 23 Skidoo was a reference to an Aleister Crowley poem, although Alex is keen to point out they weren’t into the occult. “People tend to think that we’re some sort of mystical witchcraft. It was nothing to do with that. What [23 Skidoo] meant to us was to evolve and to move on.” It might seem a bit of a jump to go from 23 Skidoo to hip-hop and DJing, but for Alex it was quite a natural progression. He recalls going to one of Afrika Bambaataa’s first shows in Britain, all by himself because “no one else knew who he was!” Here he saw the “cutting up of funky drum breaks on beat” which immediately appealed to him, given his background as a drummer and love of the writer William Burroughs (a man famous for his ‘cut-up’ aleatory technique). Inspired by this, he took to DJing – starting out with little more than a makeshift DJ setup consisting of one belt-drive deck and another turntable hot-wired into an amp. Finding tunes was the next step, and for that Alex credits UK radio mainstay Tim Westwood, who turned him onto a lot of early hip-hop through his show on LWR. “For all the jokes he gets, [Tim] was one of the earliest DJs on radio,” he extols. This was around 1983, and two years on Alex started playing his first gigs. Hip-hop – by virtue of being underground – had a raw authenticity which Alex thrived off. After Skidoo’s Icarus moment, it seemed only natural to Alex that he and his brother form a record label. The label was dubbed ‘Ronin,’ chosen for its renegade connotations, and the inspiration was to form a place filled with assassins for hire, operating entirely outside the system. With artists like Roots Manuva and Estelle on the books, Ronin remained underground through-and-through. When artists they were involved with were being offered five-album deals by major labels, they came to Ronin and were signed for one. It was very difficult to maintain, and Alex cites the “artist-driven” nature of the label as part of its eventual failure. Ultimately, Ronin was trying to sell British hip-hop to a public that wasn’t quite ready for it, and eventually Alex became disenchanted, refusing to kowtow to the commercial end of the spectrum.

Moving on to the present day, and it’s filmmaking that is Alex’s most recent preoccupation. It’s that for which he’s best known in 2015, and he sees it as a means to combine his many passions in a way that allows him to remain artistically pure. In a way, filmmaking acts

74

ALEX TURNBULL

as a conduit between Alex’s past, present and future; his most recent project focuses on the phenomenon of British street style: “It’s about underground culture and style, but style is the thread that runs through,” he explains. “It’s important that someone inside tells the story, rather than some producer from some TV channel who doesn’t really know. This story has to be told from the inside.” And it’s this inside track that Alex has unprecedented access to. He’s already interviewed a whole host of incredible names – Boy George, Paul Simonon, Don Letts, Goldie, James Lavelle – but for him the real point is to give credit where credit is due. “Yeah, I’ve got some people that are higher profile, but it’s as much about the other people. The Judy Blames, the Mark Lebons – the people who have been very, very influential, but aren’t as well known.” So what does Alex envision himself getting up to beyond all that? Given his propensity to switch disciplines, you’d be foolish to rule him out from doing something completely different with his time. Then again, there’s a sense that, with filmmaking, he’s finally found something that suits his natural inclinations. Here he has a vehicle for expression that can be turned towards any one of his interests, no matter how varied they might be. “One day,” he says, “I’d like to make the first great British kung fu film.” Until then, we’ll just have to wait and hope.

ALEX TURNBULL

75

76

LIAM HODGES

LIAM HODGES EVERYDAY ESCAPISM

WORDS VINCENT LEVY PHOTOGRAPHY TA K A N O R I O KU WA K I STYLING NAZ & KUSI (TZARKUSI) HAIR TA K AO H AYA S H I

MODELS DARIUS @ SELECT MEL @ SELECT MACKENZIE JAMES @ MODELS1 O S I N AT I KO @ M O D E L S 1 — FOOTWEAR PALL ADIUM

MAKE UP ALEXANDRA PILCH

Several months ago a small makeshift dwelling made up of discarded scaffolding, army green canvas and graffiti-stenciled pagan symbols appeared in the basement of London’s Dover Street Market. Beneath the streets of Mayfair, this dystopian scene – distinctly British in its campsite and car trunk sale eccentricity – could have been torn from the page of a Terry Gilliam movie script or a 2000 AD comic. In reality, it was the creation of Liam Hodges – one of the city’s brightest young menswear talents. An art installation cum sales rack created to mark the arrival of his designs at the prestigious concept store. Simultaneously familiar and strangely filmic, it seemed to perfectly capture the essence of his brand. An impressive feat of clarity, considering he only graduated from the Royal College of Art’s Menswear Master’s Degree in 2013. Hodge’s first collection was presented at London Collections Men for Spring/Summer 2014, through the prestigious Fashion East program. The six-outfit presentation immediately outlined a unique ability to play with narrative-driven concepts, in an easy-tounderstand and street-relevant way. Titled “Morris Nomads,” elements of Morris (a form of English folk dress) maintained approachability within a mash-up of more familiar hip-hop, punk and military design codes. This scrambling of reference points, which has now become his signature, seemed to speak of an internet-armed generation’s propensity for what Hodges calls “cultural overeating.” But the clothes themselves maintained an authentic depth through their hardwearing and highly detailed

finishes. The look was made all the more real and relatable through the pre-drinks style staging of the presentation, which saw models slumped on a single sofa with a seemingly endless supply of beers. Fall/Winter 2014 offered an even more immersive invitation to join the party. Facilitated by Red Bull Catwalk Studios, Druid Road featured a soundpiece collaboration with psychedelic rock band Puffer. Set amongst symbolically piled masses of stage equipment, the setup was part gig and part spiritual ceremony. While Hodges has since shown three collections through the more conventional runway format of Topman and Fashion East’s MAN show, his work has maintained the same balance between escapism and reality. In person, Hodges explains each collection’s concoction of unexpected ideas in the most matter-of-fact ways and essentially his clothes do the same. Whether exploring druid roadies, a cult-like band of boy scouts, or an imaginary set of market-stall traders, each concept is illustrated within the confines of bold and bloke-ish shapes. Subduing his theatrical thinking with a clear concern for the practical needs of his customer, the designer has created a standout look that’s uncomplicated but never uninteresting. Clothes that are loud when they want to be but never dandified or pompous as a result. As if mimicking the pose of models at his very first presentation, Hodges took an hour out from working at his East London studio to crash on a couch and explain the development of this aesthetic.

LIAM HODGES

77

Setting up your label must have been a daunting experience. Are you fully into the rhythm of things now? Well the first season was done from my bedroom (laughs). That’s crazy. I heard that there were only three weeks between your graduate collection and your first collection at Fashion East? Something like that. On the MA (at the RCA) there are two “friends and family” shows, and one press show, and between each of them I was running upstairs and ordering fabrics. Luckily, I’d finished my collection early and I wanted to carry over part of the story. I always have more than I need. What gives you the drive to create so much? Deadlines? The responsibility of interns? (Laughs) I always have a slight crash after going to Paris for sales but right now it’s easy. The lead up to the collection is the fun bit. When did you set your sights on fashion? I hadn’t even entertained the idea of it until my Foundation Degree. I always thought I’d do graphics or sculpture. It was the one thing that sort of let me do a mixture of the two. Do you think of your work as art then? Definitely not. It can be that for some designers but for me it’s probably someplace between art and product. It’s difficult to describe really. Ultimately I make clothes I want to see my friends in. I think it’s hard for most designers to explain what they’re making or why they’re making it. If they could explain with words, they might not be making it in the first place. Exactly. I communicate my ideas by making things. I remember having a meeting with my tutors (at the RCA) and telling them I wanted to focus on Morris dancing. They looked at me like I was mad because I’d turned up to every tutorial before that with pictures of street art and different militias. In the end I made a video to explain. I created these weird Morris dancer outfits for my mates, got them pissed and high, and filmed the whole thing, and

78

LIAM HODGES

then they got it. I might be bringing together some random things, but they won’t feel random when I’ve finished, because they’ll always be shown within my world. Have you always been like that in some way? Were you into a lot of different things growing up? I definitely dipped in and out of stuff. I grew up in suburban Kent so I suppose everything got filtered down and blurred a little bit. It was a bit of this, a bit of that. I had the Nike TN hat and trainers so I wouldn’t get beaten up in the park on the weekend. But I also used to go to Korn concerts. I’d listen to garage but I was also buying Offspring albums. Scene-wise, everything seemed to get a little blurry around that time anyway. If you look at nu-metal, for example, that had certain elements of hip-hop mixed in. Yeah and I mix references in that way now. It can be quite all over the place. Each show will be different but you should always have a rough idea of what I’m about, because it’ll always be my slant on things. I suppose the thing that connects everything is the idea of subculture and that slightly outsider point of view. Video is an unusual medium for a fashion designer to use but it’s played a part in pretty much all of your collections. Are you interested in filmmaking in a wider sense? Definitely. When I was studying I’d always use film and also do life-size paintings of the outfits. There isn’t always time to do these things now, but I try to do one or the other. For me there’s always a narrative. It’s always about what will fit within my world and each season it’s just a different set of characters within that world. Would you ever want to do costume for film? Not “costume” in such a dramatic sense but I’d love to design the clothing aesthetic for a film. Like what Gaultier did for The Fifth Element, for example. You’ve got this place and this moment in time, and you have to create something that fits. That’s how my mind already works with each collection.

LIAM HODGES

79

80

LIAM HODGES

How did film play a part in Fall/Winter 2015? Well we’ve just moved to a new studio in Walthamstow, which has Europe’s biggest street market. We based the collection all around that. Primary research has become pretty important to me recently, so the obvious thing to do was take a video camera and start talking to some of the stall owners. We then edited the footage and used it as a backdrop to the show. At the same time we found loads of cool graphics from cardboard boxes and newspapers, for manipulating and feeding into the designs. “Fake Booze” was actually a headline in the Walthamstow Guardian. Someone had been selling counterfeit alcohol. There’s a big slogan on one of the Fall/Winter 2015 T-shirts that says “Totally Safe Classics.” Is that a bit of a tongue-in-cheek commentary on menswear in general? I think there’s always an element of comedy to what I do. When we talk about the clothes that we make and look to, they’re things that have a classic position in most men’s wardrobes and then we take it from there. We were also imagining if I had a market stall, what it’d be like, what it’d sell. What snappy name we’d give it. But actually a heater blew up in our studio, and we were joking around about health and safety. And “safe” has another meaning. Exactly. There’s an element of humor in your show notes, too. They’re not written in a typical way. My friend Daniel Cullen writes them all. Without wanting to offend anyone, a lot of other show notes seem to basically tell journalists how to write their reviews. I don’t think that’s cool. Daniel writes for television and that’s great because it becomes another way to tell the collection’s story.

There’s a line that’s repeated in each of yours, which says you’re not creating clothes for “any man driving a Volvo.” What would the Liam Hodges man drive then? An old Hummer would look pretty good with the big bold shapes of your clothes. (Laughs) Well, it’d be one of my dream cars of the moment. There’s this guy you’ll see sometimes on Kingsland Road who has an old Belgian army truck with a massive sound system and he’s always playing Slayer at full volume. That’s how it’d be. Or a ’90s Merc or maybe a Bimmer. It’d be something old with a lot of attitude. You mentioned reviews. Do you think designers are only as good as their last collection? I think when you’re just beginning you are, but ultimately it should be about the whole body of work. I read an interview a few years ago with Alber Elbaz of Lanvin, where he summed things up pretty well. He said something like a musician can have one or two great albums, an artist can do one great painting. They’re both seen as successes, but he has to do this many collections this many times a year, and if one of them is no good, then apparently he’s useless. That’s tough! I suppose you’re at the point where you really have to push, do the legwork, and then hope to plateau for a little bit? Yes, but you don’t want to become same-y either. Look at someone like Walter Van Beirendonck who’s really gone through a couple of different guises in his career. Personally, I like his “Wild And Lethal Trash” stuff the best, like when the models couldn’t see and would fall off the end of the catwalk. Or the shows turned into giant parties. But that doesn’t mean I like him any less now because he’s changed direction a bit. It’s important to keep moving on and changing.

LIAM HODGES

81

I wonder whether Walter’s really a product of Antwerp; where there isn’t such a rulebook. There seems to be a specific kind of pressure in London. The pace of things? The pace and the fact that if you’re too “out there” these days, people can fail to see a commercial viability. Some amazing London names have disappeared because of it. I’m lucky because there’s a natural commerciality in the way I dress and what I put into my clothes. Even though there’s the madder stuff in the collections, there’s always something fairly simple, and hopefully that’ll help it survive. London is really important to me. Given the opportunity I’m an inherently lazy person. If you look at my school reports, “bone idle” was written on pretty much all of them. But there’s a pressure here that means I can’t be lazy and that’s great. When you’re surrounded by a load of other creatives all going hell for leather it sort of spurs you on. You said you make clothes you want to see your friends in. Does that mean each collection needs their seal of approval? Not always, but I definitely always talk to them about my ideas down at the pub, including the ones who aren’t really into fashion because they’ll question things. I suppose that can be rare in the industry. There’s a lot of yes men around, who’ll say something’s good because everyone else says it is. Exactly. Talking to them makes me question myself and that’s healthy. Beyond your circle of friends, do you get more of a thrill seeing your clothes on real people or on the runway? I love the process building up to the show, but when I see someone choosing the clothes and enjoying them, that’s really special. We street cast a boy for last season’s campaign and let him pick a T-shirt when we’d finished shooting. On the way back to the studio I could see these two guys skating down the road and I was like “oh, that’s him,” he’s already wearing it. That kind of instant approval feels pretty great.

82

LIAM HODGES

You mostly use non-professional models in your shows. What is it that you’re looking for? What does the Liam Hodges man look like? There’s nothing too specific I’m looking for. It’s more about their mindset and who they actually are. A lot of them are guys I know and their personalities play a major role. I did a sample sale in Hackney a few months ago and this guy came along who’s in his late 60s. We’ve become friends and he’s really supportive of the brand. For me, it’s important that the label doesn’t have those boundaries. I don’t want there to be that bracketing, so we try and reflect that a bit with the casting. What does the Liam Hodges man aspire to? Well there’s the archaic view of what’s aspirational, which is the model-looking dude with the gold watch and “nice” suit, which is all fine and good. But the value and luxury in my clothes comes from other things; however many hours have gone into it, what stories are attached to it. For me what’s aspirational is doing what you really enjoy doing and just enjoying your life beyond anything. It’s not about this huge capitalist thing. It’s not about having the gym-fit body, a Rolex on your wrist, and a leather bag under your arm. It’s a bit more “I forgot to shave – oh well.” What about your aspirations for the brand? Well sales-wise, the first catwalk season just blew my mind and now we’re in places like Dover Street Market. It became very real at that point. The little space inside my head, my world I call it, well I just want to keep that going. I just want to keep developing and communicating that. Not just with my established customers but new customers, too. And also the friends and people I work and party with. I just want to keep collaborating and building things bit by bit. It’s about sustaining things ultimately? Yes, I want it to have a decent lifespan. I want to keep coming up with stories and I want to keep seeing people wear what I make.

LIAM HODGES

83

84

N I C G A LWAY

THE CREATIVE COMPLEX ADIDAS’S NIC GALWAY TALKS CREATIVITY, LONGEVITY AND SPORT

WORDS STEPHANIE SMITH-STRICKLAND PHOTOGRAPHY THOMAS WELCH

adidas was founded in 1924 and officially registered on August 18, 1949. From the company’s fledgling days, when brothers Christoph and Adolf “Adi” Dassler worked (somewhat peacefully) together,

projects, including the Yamamoto collaboration (and the Y-3 Qasa silhouette), the wildly popular Tubular shoe, and the equally sought out ZX 8000 Boost. As a “special products” designer, Galway says he

to their tempestuous split in 1947, innovation and creative problem solving have been synonymous with the adidas ethos. In the beginning, when the duo had no access to consistent electricity at their home base of Herzogenaurach, Germany, they solved the problem with a stationary bicycle, which they took turns pedaling to create the necessary power to run their factory equipment. In 1936, Adi, the younger of the two, ventured onto one of the world’s first motorways to drive from Bavaria to the Summer Olympics in Berlin. There, while Germany was still in the thrall of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi dictatorship, he went against the propriety of the times and managed to talk African-American track and field athlete Jesse Owens into attaching a novel new creation to his running shoes: spikes. Dassler promised Owens it would give him increased traction while competing on the track’s sandy turf. Owens went on to win four gold medals, and in the process, single-handedly dispelled Hitler’s rhetoric of Aryan supremacy. He also became the first African-American male athlete to be sponsored by a brand. Today adidas Originals Creative Director Nic Galway sums up Adi Dassler’s future-facing attitude most succinctly: “People sometimes say to me, ‘How could you do that to such and such shoe’ or ‘shouldn’t you leave it as it was?’ But that was never the spirit of the founder of the company. Nearly everything that is in our archive is somehow a progression of what came before it. I want to build on that progression.” Galway, who took over the role of Vice President of Global Design in September, says much of his long-term strategy will focus on evolving existing ideas in a way that stays true to adidas’ sportfocused DNA. Prior to his appointment, Galway had already been working on Originals’ special

was given full creative control to conceptualize and execute projects as he saw fit. “I wanted to bring that freedom to my team and re-energize everyone by getting them sketching and making things,” he shares. His long-term goal, however, involves bigger picture thinking. Galway wants to instill a mentality of imagination and discovery into every part of the design process; it is something he believes will ultimately work to build internal confidence around creating a “challenging leading product.” Perhaps part of Galway’s outlook on the creative process comes from his background. He was originally an automotive and product designer who spent years working in consultancy before his tenure with adidas. “I worked on many, many different products,” he explains, “You were never really an expert in one thing, so you were always exploring and trying to understand, so I’ve taken that with me.” Galway also acknowledges that coming from a background outside of the footwear industry often works in his favor because he does not feel limited to finding inspiration solely within the trade. In fact, he rarely gets his ideas from anything relating to shoe design. He rather gets ideas from life’s simple pleasures: perusing hardware stores, traveling and observing the inner-workings of everyday objects. “It’s still really important to understand what’s going on in the industry,” he states, his lightly accented tenor projecting despite the softness of the timbre. “I use the media to find out what the status quo is in the industry, but you should never really use it for inspiration. If you’re researching what’s already there by the time you’ve made it, it will be too late. My whole point for adidas and adidas Originals is to be pioneering. You can’t pioneer by seeing what’s already on the table.”

N I C G A LWAY

85

What Galway believes you can do, and what has been working tremendously well for adidas in recent years, is reappropriate the past. For Galway and his team in particular, this means constantly picking over the archives. “I think the most important thing is my view of what the archive is,” he explains, “I’ve never viewed the archive as a museum or a closed chapter. To me it’s much more of a living document. People love sneakers, and we have such a wealth of information about them — more than most companies. My job is to go in there, pick up the stories, understand why they [past designers] did what they did, and then bring that to life in a new way, or a way that celebrates it. The Tubular, for instance, was truly an idealist’s shoe at the time it was dreamed up. In Galway’s hands, however, it proved to be perfectly suited for today’s times. “The original brief was amazing. It was made at such a time when there were a lot of new possibilities coming into the world of manufacturing, but it was just one step too soon. The idea was right but it just wasn’t really achievable. I loved the intention so that was the start of it for me.” From there Galway recognized that he needed to simplify the original idea, which, though clever, was more complex than necessary. Ironically, it was his automotive background that helped him complete the project. “Basically the idea of the original Tubular was to suspend the foot over a tire. What they [the original designers] found is that suspending it over a tire would require making a very hard plastic plate, which somehow defeated the object of the soft thing underneath because it created a layer between the two. When I looked at the Tubular what I felt was interesting was the idea of suspending the foot; it’s a simple thing to understand. I then looked at the complexities that had to be built in which took the idea away from the original brief, and I stripped those out. In motorcycles and offroad vehicles they use airless tires, so that was an obvious, easy transferrable solution. So you just remove the complexity and keep the integrity of the idea.” Galway has brought a similar way of thinking to adidas’s many successful collaborations. And though he believes a successful collaboration must be a true partnership, he also understands the importance or preserving the authenticity of the adidas brand. “I want to find a balance between

86

N I C G A LWAY

reissuing and reappropriating archival ideas,” says Galway. “I want to do both [reappropriate and reissue], but I want to do both true,” he explains. “In reissuing something I want to understand what it is that people love about it and why it was made in the way it was, and then I want to build it with truth. So it’s a reissue, it’s for the sneakerhead who really loves the genuine classic. I think there’s always a place for that and that’s something I like. When it comes to doing something new I think you have to see and say ‘I haven’t seen that before, but I get where it’s coming from,’ but it’s genuinely new. What I don’t like is in the middle.” State-of-the-art advancements like Primeknit and BOOST technologies are a result of this desire to avoid the mediocrity of “the middle.” While the former is often thought to be an answer to Nike’s Flyknit technology, in a 2014 article published on Fast Company’s digital platform, adidas former Global Creative Director of Performance, James Carnes, claimed the company had been working on the technology for almost 12 years prior to its release. He went on to say that in 2008, when they realized “the potential of knitting,” a team began to focus more on developing what would become Primeknit. Today, the second-skin fit and one-panel construction of Primeknit can be found in more than just adidas’ sport-focused categories, which, in Galway’s estimation, is a true testament to the versatility of the adidas brand. Versatility similarly comes into play where choosing a collaborator is concerned. In the past, adidas has worked with fashion icons like Yohji Yamamoto, who though committed to his own instantly recognizable personal aesthetic, wanted to speak to audiences interested in more sport-led categories. Conversely, when adidas collaborated with Rick Owens and Raf Simons, the designers’ ability to create a narrative that elevated sneakers – a hallmark of sport – into something that resonated with fashion-obsessed consumers proved to be a successful departure from the brand’s primary audience. However, the best testament to adidas’s understanding of universally appealing design is the recent, runaway success of the Stan Smith tennis shoe. Although it was embraced across the board, the voracious obsession of the fashion crowd was undoubtedly the most unexpected outcome of all. Galway credits the success to smart marketing and adidas’s respect of its own history.

I think the most important thing is my view of what the archive is... I’ve never viewed the archive as a museum or a closed chapter. To me it’s much more of a living document... My job is to go in there, pick up the stories, understand why they [past designers] did what they did, and then bring that to life in a new way, or a way that celebrates it.

N I C G A LWAY

87

88

N I C G A LWAY

“I think taking the Stan Smith out of the market and giving it space to breathe before bringing it back was a risk, but it was smart. We were hoping people would embrace it, which was our intention even though there’s never a guarantee. My feeling is that something like the Stan Smith should always be special, and that’s the reason we took it out for a while. We wanted to make sure it always remains secure. We didn’t have to give the Stan Smith back, but it got to a point where people really wanted it. You saw it on the feet of editors or fashion designers after their show and it became coveted.” Circling back to his philosophy regarding collaborations, Galway states, “We don’t endorse, and I’m not interested in endorsements. I like collaborating. To me collaboration is two partners who have something to prove to each other, and want to really make a difference. And provided we pick a partner who has a love for what we do and has ambition and wants to make a difference, I think it’s always the right fit. That’s one of the unique things about adidas — we do take chances. We’re very much a people’s company.” When Galway’s attitude about partnerships is understood, suddenly projects like Yeezy Season One make all the sense in the world. After all, who better to work with than a notoriously ambitious musician who is determined to prove that he can design as well as he can produce and write songs? Galway was also interested in the polarizing nature of Kanye West, stating, “When I think of Kanye I think there are some people who can exist within culture and be very popular within culture, and then there are those who can change culture. I believe Kanye can change culture… His energy and his vision and his wish to show a different potential are very powerful things.” Many will remember that before the official announcement that West and adidas would be collaborating, Galway and West were spotted spending time together. One particular picture of the pair walking through a mall in China sparked a flurry of speculation that something big was coming. What is more interesting about the scenario, especially now, is the knowledge that getting to know each other on a personal level is an absolute requirement for Galway to move forward with a partnership. “The first part of that year was just getting to know each other,” he explains. “We discussed a lot

of things, we made mockups — none of which we actually ended up with, but it was still really valuable time. We just really got to know each other on a collaborative level. From there we figured out what we wanted things to be together. “ The result is a collection Galway describes as “balanced and nuanced.” Although the assortment is not heavily branded, there are subtle cues that point to the adidas ethos. “You don’t have to write something on it for people to know what it is,” Galway states. “I think you just need to have cues within it. For instance you’ll see the hidden three stripes on the back strap or the boost on the inside of the shoe. That is adidas, not writing adidas on the side of something. It’s that mix of innovation and new territory; that’s adidas enough. After a moment of pause he adds, “You do need to have a balance though. If you look at the overall offer for the year there’s a good amount of the branded and the less branded.” After another moment of pause he finishes, “Still, it’s more important to me that it’s all leading to the product.” As for the future of adidas, Galway is confident that respecting the brand’s history and positioning will always lead to longevity and success. “What is important and true with adidas is that it started in sports. I sit more on the fashion side now, and I’ve worked on some really amazing collaborations, but I started in sports. In my early years I was head of sports and performance, and what I always really admired in adidas is that sports comes first, and it always should. So whilst I love everything we’re doing I always believe that football or soccer or running, these have to be important to a brand like us. If you let that go then you’re not true to where you started. So when we do projects like Y-3 or Originals everything still comes from sport. If I even think back to my previous job with the Qasa, this shoe was hugely popular in high fashion and streetwear. I think it was that popular because it was a sneaker and it was from sport, as opposed to something a fashion brand would do. That is why sport should always be our strategy, and from there we can take it as far as we want. We can take it all the way to Kanye or Rick or Raf, but as long as it still remains true to who we are then I’ll always believe we got it right.”

N I C G A LWAY

89

NIGO®’S NEW LEASE OF LIFE

WORDS DAV I D H E L LQV I ST PHOTOGRAPHY KENTO MORI

90

NIGO®

THE BATHING APE FOUNDER DISCUSSES HIS NEW CREATIVE ADVENTURES, MIXING THE MAINSTREAM APPEAL OF UNIQLO WITH THE AMERICANA VINTAGE DESIGNS OF HUMAN MADE. How do you progress and develop when leaving behind one of most influential brands in streetwear history? That was the question facing NIGO® when he sold A Bathing Ape to Hong Kong retail consortium I.T in 2011, and then stepped down as its creative director two years later. For two decades, NIGO® and his famous camouflage – eventually found on just about every garment and accessory streetwear has ever known – was at the forefront of contemporary urban culture. In 1993, when NIGO® and Jun Takahashi set up their Harajuku store, NOWHERE, and launched their brands BAPE and UNDERCOVER, the term “streetwear” hardly existed in the popular lexicon – at least not in the way we use it now. NIGO® and BAPE helped shape that definition.

NIGO®

91

NIGO®’s love of American and British culture, alongside his fascination with gadgets, first meant the Japanese underground scene embraced BAPE – especially the characteristic camouflage logo designed by SK8THING (now founder of Cav Empt). As the BAPE logo spread across the world – helped, in part, by popular leftfield musicians such as Cornelius and UNKLE’s James Lavelle – European and American consumers of counterculture began to warm to the brand’s notoriously difficult-to-find merchandise. By the end of the ’90s, BAPE had earned cult status in London and New York, as well as in Tokyo. Yet, by the late ’00s BAPE’s fortunes had started to turn, and the brand was no longer the exclusive property it had once been. Having not only revolutionized the uniform of an entire youth generation, but also rewritten the rules on what it’s acceptable to name a brand, NIGO®’s time in the BAPE driving seat had come to an end. But where should he go from there? Characteristically, he chose a two-fold path. Today, among several other side projects that include a boutique Tokyo store and collaborative fashion endeavor with WTAPS founder Tetsu Nishiyama, NIGO® also runs his own independent brand, Human Made, and works as creative director of Uniqlo’s UT T-shirt division. Considering the size and statement of intent between these two brands, they couldn’t be further apart. But, to NIGO® that makes complete sense. “For two decades I’ve worked with my own brand and I had my own company. I feel like I’ve completed that and come to some sort of closure in that respect. When I was looking for my next step, that’s when the approach came from Uniqlo to head up UT,” the man himself explains over coffee in Paris. “I thought it was a great chance, as it also offered an interesting learning experience for me. Officially, it’s been just over one year now, but I actually started working with Uniqlo about a year before that. The last 20 years was all about me and my life on Earth, but now, in this capacity, it’s like looking at Earth. It’s not just my perspective that counts, and that’s very exciting.”

92

NIGO®

NIGO®

93

94

NIGO®

If we look back 20 years to the late ’80s, early ’90s, the people who wore tees everyday would have been the Japanese, the Americans, and maybe the British. But today, the sweat-culture has been adopted by the Maisons of Paris, so I think that means it’s finally been accepted on all levels of fashion!

It’s no coincidence that it’s UT, and not the general apparel line of Uniqlo, that NIGO® is hard at work on. T-shirts have always been a big part of his work, and his own personal wardrobe. Looking back, the T-shirt was the fundamental streetwear basic; it was a blank canvas for designers and artists to express themselves through text, images and graphics. Its casual aesthetic and simple design made it a street staple and, for NIGO®, T-shirts and sweatshirts are the ultimate menswear garments. “If we look back 20 years to the late ’80s, early ’90s, the people who wore tees everyday would have been the Japanese, the Americans, and maybe the British. But today, the sweat-culture has been adopted by the Maisons of Paris, so I think that means it’s finally been accepted on all levels of fashion!” But NIGO® won’t dictate how your T-shirt should look, though he’s got a very clear point of view when it comes to his own perfect tee: “For me, what makes it ideal is the fact that a tee is something you wear and wash over and over, and as you go through that process it becomes, in a way, deformed. But deformed in the respect that it takes on the form and shape of your body. And that to me is the perfect T-shirt!” With his two creative outlets, NIGO® caters for very different audiences. This fact has obviously not escaped him and, even though he won’t say it out loud, that was probably why he accepted Uniqlo’s offer. He needed to find a balance. In the