CONNECTIONS

ALONG THE GRAND RIVER

A JOURNEY THROUGH WEST MICHIGAN HISTORY

Grand Valley State University

Kutsche Office of Local History

Grand Valley State University

Kutsche Office of Local History

WEST MICHIGAN HISTORY

12,000 Years of Life on the Grand River Jan Brashler

Traffic on the Grand Wally and Jane Ewing

C leaning Water for the City of Grand Rapids Kayne Ferrier

Dynamiting the Grand Grand Rapids City Archives & Records Center

North Park Tourist Camp on the Grand

Rails on the River Paul Trap Changing

Lake

Transportation

Saranac’s Early Industries

Boston Saranac Historical Society

Ionia’s Bounty

Ionia County Historical Society

Kruger, Kelland, and the Grand Portland Area Historical Society

Connections Along the Grand River offers a glimpse into the histories of the communities and towns along the Grand River—how they came into being—and the role of the river in their survival and revitalization. The project locates the Grand River and its tributaries as a significant driver of the region’s growth. Connections Along the Grand River also considers the environmental realities shaping the health of the Grand River and how this impacts communities’ relationships with local waterways. Presenting snapshots of community histories, this project encourages readers to further explore the role of diversity in shaping the growth of these communities to ensure stories of the vibrant, intersectional lives of the region are remembered and told. We look forward to continuing to listen to and share the multitude of voices and stories in our communi ties. Featuring more than 20 organizations and lo cal historians, the Connections Along the Grand River project creates a dynamic portrait of how a single body of water impacted generations of Michiganders in similar and contrasting ways.

This project included conversations at Grand Val ley State University’s L. William Seidman Center and Mary Idema Pew Library in March 2019 and October 2019, respectively. These conversations explored the river’s role in shaping the region with particular attention to the rise and growth of communities along the river from the interior to Lake Michigan. We also discussed the effects of environmental challenges and changes to the region on the Grand River and the communities it touched. Conversation attendees examined how the communities along the river survived and thrived as they evolved from the 19th-21st centuries. In October 2019, an exhibition featuring the historical and contemporary impact of the Grand River on communities from Grand Haven, MI to Portland, MI was on display in the Mary Idema Pew Library.

Connections Along the Grand River is funded in part by a Michigan Humanities Third Coast Conversations: Dialogues about Water in Michigan grant. Thank you to the the Vander Veen Center for the Book Fund of Grand Rapids Public Library Foundation and Grand Rapids Historical Society for supporting magazine publication. A special thanks to the Kutsche Office of Local History staff, Justin Allen, Vinicius Lima, and

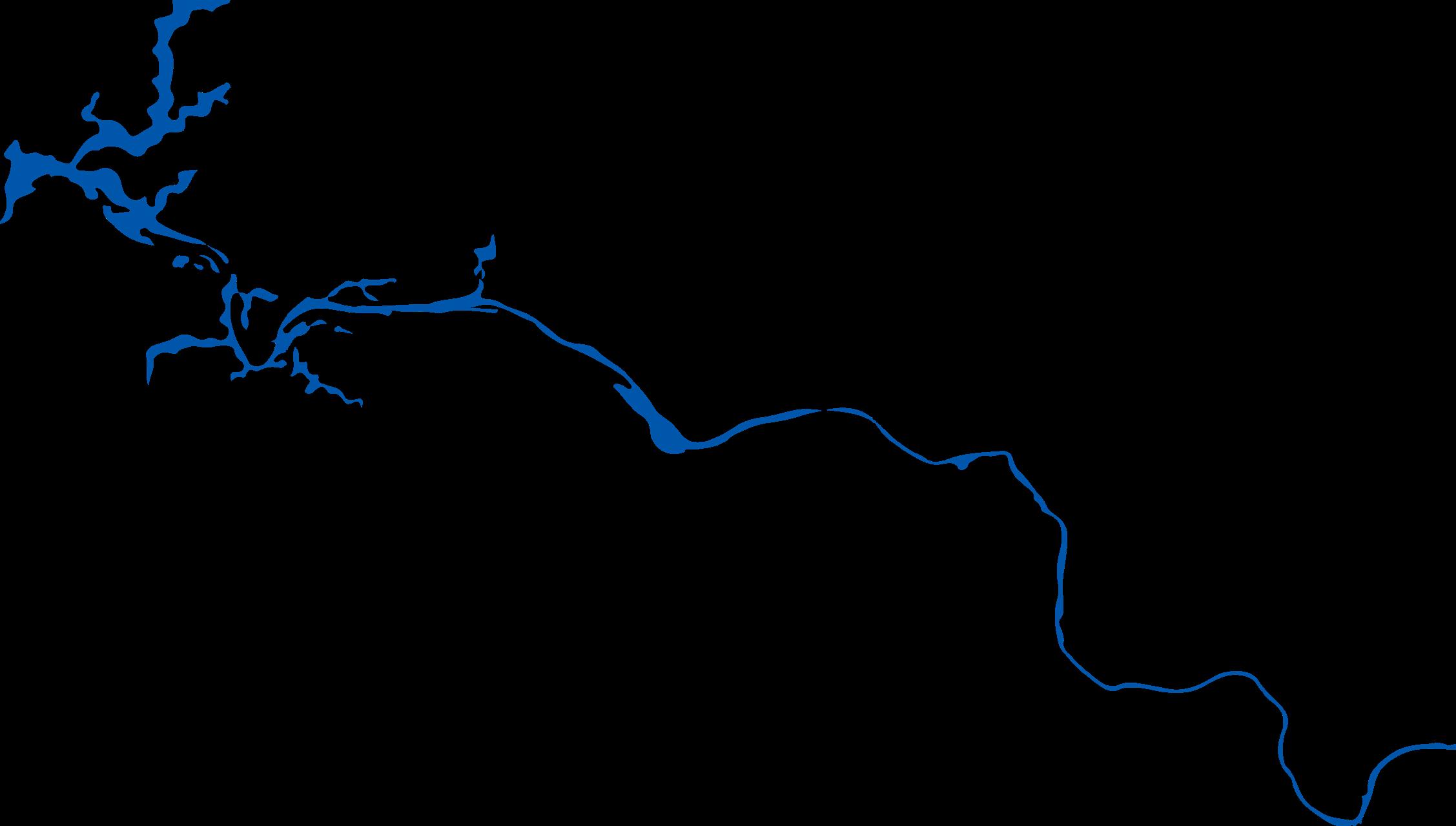

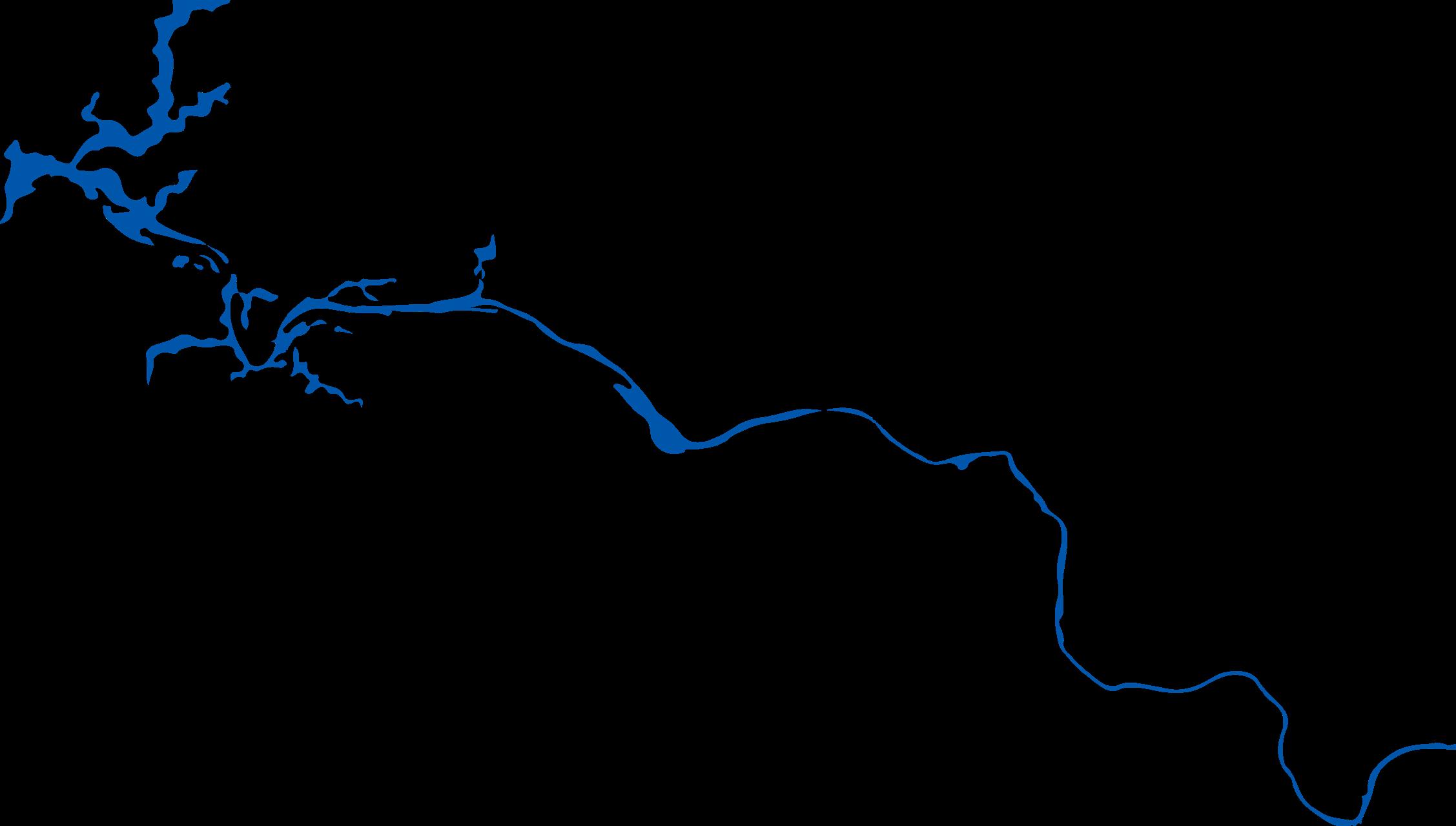

The state’s longest river, the more than 250-mile waterway flows through Jackson, Lansing, Grand Rapids, Grand Haven, and the communities in between before reaching Lake Michigan. In its focus on West Michigan, Connections Along the Grand River illustrates the ways the Grand River indelibly shapes the communities of the region. The histories captured in this magazine provide a portrait into the lives of those who live along this magnificent waterway.

LOWELL

ADA

PLAINFIELD

CHARTER TOWNSHIP

CASCADE

TOWNSHIP

LOWELL

ADA

PLAINFIELD

CHARTER TOWNSHIP

CASCADE

TOWNSHIP

JACKSON

SARANAC

JACKSON

SARANAC

For 12,000 years before the coming of Europeans, the first settlers of the Grand River traveled from the Michigan lakeshore throughout the Grand River basin. Archaeology provides a voice to understand the rich and diverse experiences of people whose contributions to our shared past are otherwise muted. Material evidence of the first peoples of the Grand River is sparse and consists of a few dozen locations where distinctive fluted projectile points have been recovered. Archaeologists refer to this time period between 12,000 years ago and about 10,000 years ago as the Paleo-Indian period. Occupants of the area during this time period did not live in settled villages, but followed game, such as caribou, in a late Ice Age landscape that would have posed enormous challenges and required great ingenuity.

For 7,000 years, people hunted and gathered plants around 700 BC, archaeological research shows that indigenous people began identifying with specific places by building earthen monuments. Most of these were sacred burial locations but one monument near the juncture of the Thornapple and Grand Rivers is a unique earthen enclosure. Near Grand Rapids, the Mounds are anoutstanding example of Hopewellian mound building and long distance exchange. They provide archaeological evidence that conforms with the Anishinaabek earth diver creationstory.

Archaeology also gives voice to experiences of indigenous communities at time of contact in the 17th century and during the following 200 years of struggle where the historic record, largely written by Europeans, fails to provide a rich indigenous perspective. Archaeology, combined with oral history and careful research, enriches our understanding of the indigenous experience and has led to creative partnerships between anthropologists, archaeologists, and indigenous communities.

When European Americans first arrived in the Grand River Valley, they found people living in 19 scattered villages. The Anishinaabe, who became known to European Americans as Ottawa and Potawatomi, established numerous villages in southwest Michigan, including at least 13 horticultural villages along the Grand River. In the early 19th century, Ottawa people participated in the fur trade and settlers and Native people interacted.

Many of the original Grand River Anishinaabek were eventually dispersed throughout Michigan and the Midwest due to treaties and other laws which provided the basis for removal through land patents and allotments. Today, Anishinaabe people are found throughout West Michigan and have a vibrant culture and heritage that continues to enrich the region and community. Ron Yob, Tribal Chairman of the Grand River Band of Ottawa Indians, leads efforts to continue rich spiritual traditions, along with others who work to preserve sacred sites. The Anishinaabe actively collaborate with many organizations in efforts restoring natural habitats to the river including wild rice and sturgeon and are active in efforts to preserve traditional and sacred sites.

Jan Brashler

Stabilizing 19th century Native American cemetery on the river (Courtesy of GVSU Department of Anthropology Laboratory)

Stabilizing 19th century Native American cemetery on the river (Courtesy of GVSU Department of Anthropology Laboratory)

The Ottawa and Potawatomi peoples of West Michigan used the Grand River as a highway. The 263-mile river, its tributaries, and occasional portages, provided an effi cient way to cross the Lower Peninsula and deliver furs to trading posts along the river. They were adept at building and maneuvering canoes for long distances. In the early years of white settlement, the Grand was the most convenient and fastest way to travel between Grand Rapids and Grand Haven. The 84-foot Mason

steamer to run on a regular schedule between the two settlements. The boat sounded a bugle rather than a whistle to signal its arrival and departure. Local res ident William Kanouse piloted its maiden trip down the Grand on July 4, 1837. The the 1840s onward, carrying passengers, mail, and freight along the Grand. Boats of this type often were referred to as packets.

By 1850, traffic on the river increased to such an extent that the screw-propelled Humming Bird steamboats operating between the Rapids and the Haven. The 130-foot Independence Day 1851, offering rides on Spring Lake for a 25¢ contribution to the Grand Haven Library Fund. Steamboats like the sternwheeler eration into the early 20th century, despite the arrival of railroads in 1858.

The Grand River also allowed lumber companies to float timber from forest to mill. Soon after Grand Haven’s founding in 1834, William Butts and William Hathaway built the area’s first sawmill. Their millmarked the beginning of a tumultuous and lucrative era in the history of West Michigan. The long and broad Grand

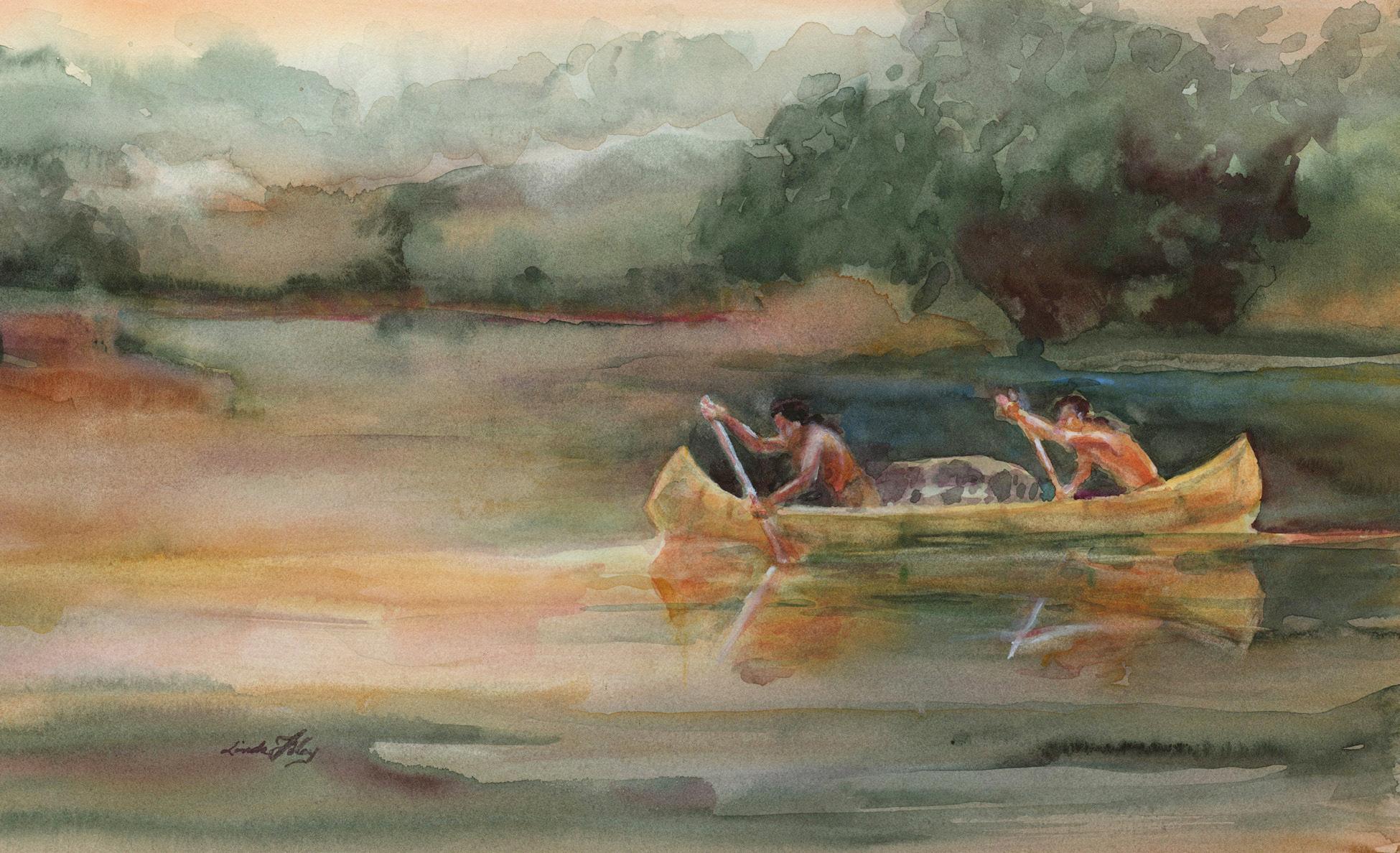

This watercolor by Linda Foley shows how Ottawa and Potawatomi used the Grand River as a highway for traveling long distances (Courtesy of Wally Ewing)

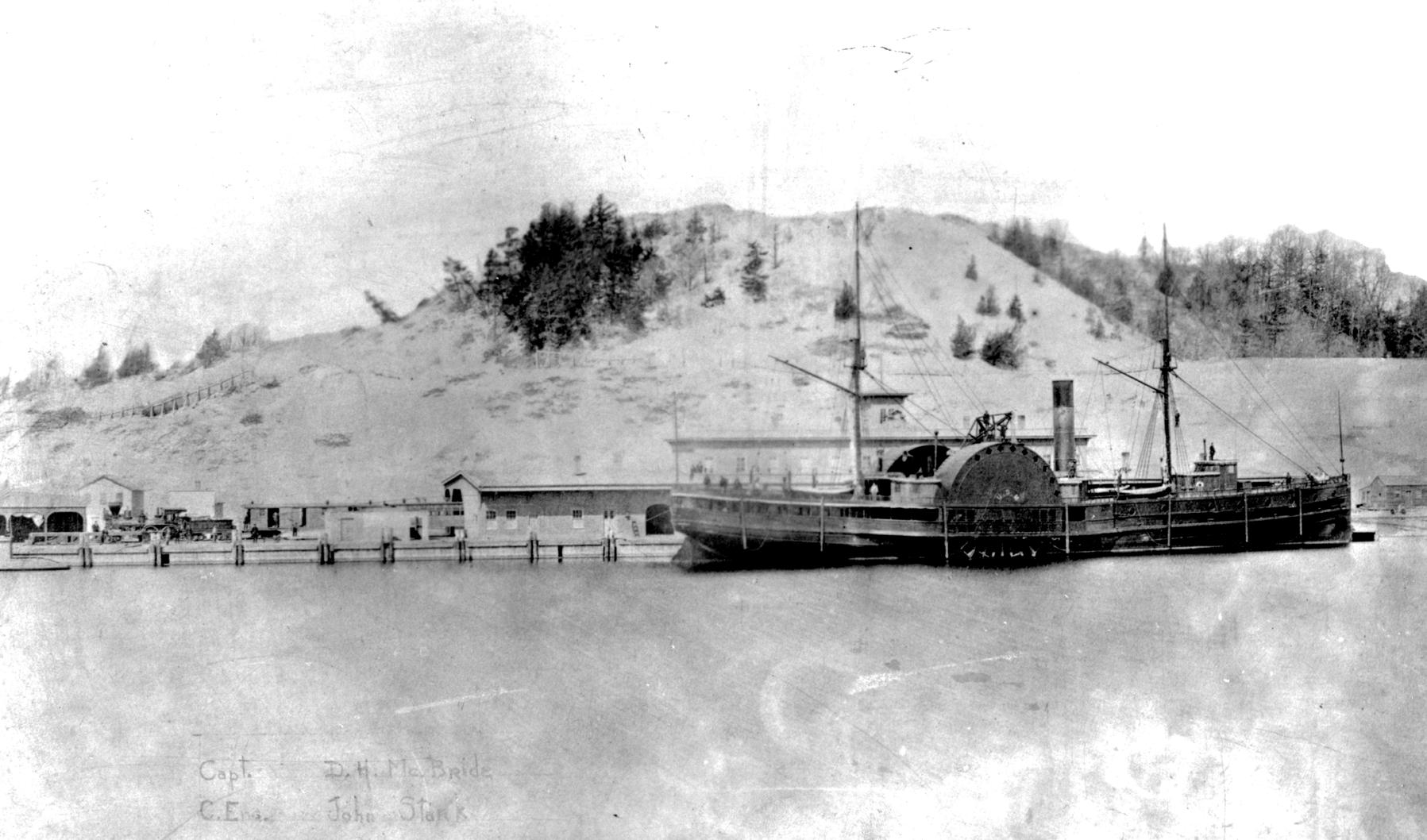

The rear-wheeler Grand ready to receive passengers (Courtesy of Wally Ewing)

This watercolor by Linda Foley shows how Ottawa and Potawatomi used the Grand River as a highway for traveling long distances (Courtesy of Wally Ewing)

The rear-wheeler Grand ready to receive passengers (Courtesy of Wally Ewing)

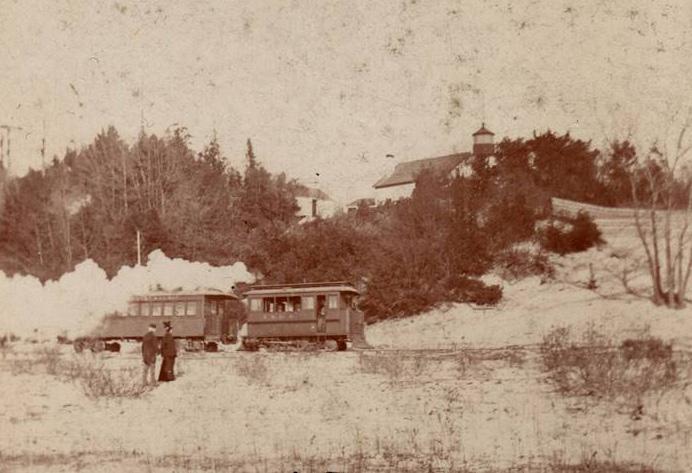

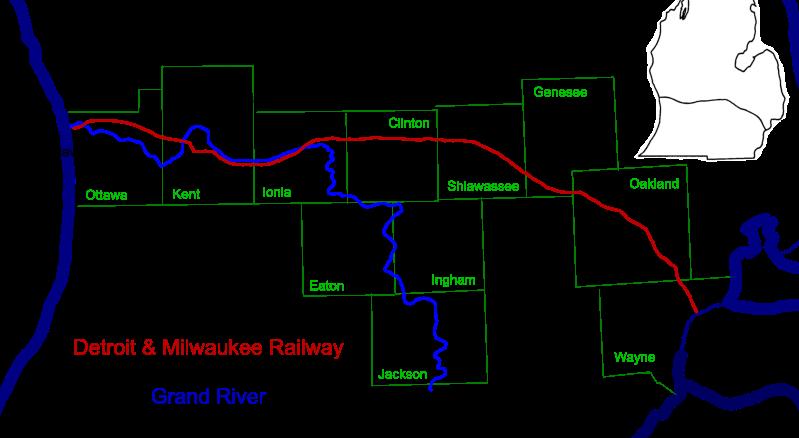

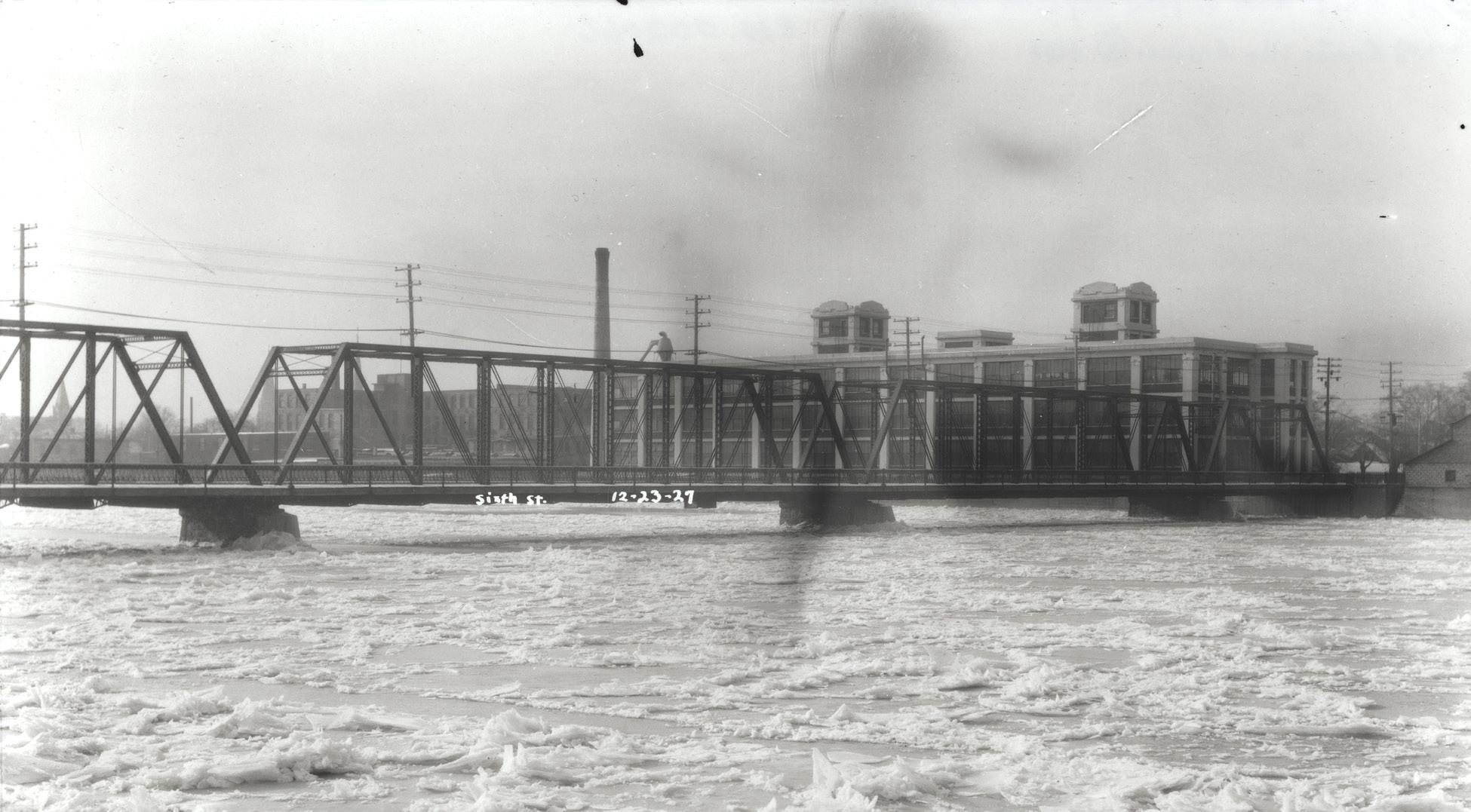

The mouth of the Grand River became an important transportation hub, as railroads carried goods and people across the state while steamships connected Grand Haven with other Lake Michigan cities. In 1855, the Detroit & Milwaukee Railway was organized to build a rail line from Detroit westward to Ottawa County. When the line reached Muir, tracks roughly continued along the Grand River, crossing the Grand over bridges at Ionia and Grand Rapids. Financial difficulties caused in part by the Panic of 1857 slowed construction until money came from the Great Western Railway of Canada, which saw the railroad as a bridge line to carry wheat east.

The Detroit County in 1858. Tracks were laid on the north side to avoid the cost of another bridge across the Grand. Two paddlewheel steamers, the Milwaukee across Lake Michigan. A depot, hotel, and docks were built on the north bank. This was inconvenient for the people of Grand Haven, so citizens offered to pay the railroad to build a new bridge to be shared with the

Michigan Lake Shore Railroad (later part of the Pere Marquette Railway). The Detroit & Milwaukee Railway built an extensive terminal in Grand Haven including a depot, engine house, warehouses, ice house, and grain elevators.The mouth of the Grand River became a busy place, as many daily trains and ships owned by the railroad and private companies arrived and departed. In 1905, ferries began carrying rail cars across the lake toMilwaukee.

There was another rail service along the Grand River, one unique to Grand Haven. As the logging industry declined, Grand Haven hoped to rebuild as a resort town. The beaches at the mouth of the Grand River drew resorters, but getting to the beach was difficult. The town was built behind dunes and there were no good roads to the lakeshore. Enterprising developers proposed to build the Grand Haven Street Railway, a two and one-half mile line following the Grand River from downtown to Lake Michigan. It used small steam engines made to look like a carriage or street car to avoid scaring horses. It was built cheap and everything was secondhand: rails from a logging railroad, cars from a Grand Rapids line, and two used engines from Kansas City. It provided safe, reliable service from its downtown station to a beach pavilion below Highland

An interurban electric line, the Grand Rapids, Grand Haven & Muskegon Railway bought the little dummy line in 1903 and replaced the steam engine and cars with trolley streetcars. They were popular as thousands of people came from Grand Rapids to the beach to swim, use the giant waterslide, and enjoy the dances andentertainment.

But rail service at the mouth of the river was doomed. The first to go was the interurban and the line to the beach. As automobiles became popular and roads improved, rail traffic declined. The electric railroad shut down in 1928. A road was built to the beach and Grand Haven State Park opened. Following a series of financial failures, the Detroit & Milwaukee Railway was reorganized as the Detroit, Grand Haven & Milwaukee Railway, and later owned by the Grand Trunk Railway and thus by the Canadian government. In 1933, the car ferry service moved to Muskegon and all Grand Trunk service ended in 1976. The rails along the river are gone but the old coal tower stands as a reminder of a bustling past.

The Life Saving Service was established in 1871 to address the growing need for a professional rescue group to assist mariners who were in trouble. Grand Haven was chosen for a post, which opened on May 1, 1877. The increasingly busy harbor at the mouth of the Grand River made it an ideal location for the Service’s base. A two-story building equipped with a two-stall rescue boat house was built on the north bank of the mouth of the Grand River. From here, the rescuers would be able to launch their boats into the calmer river before venturing out into the chop of Lake Mich igan. They trained to operate these boats in the most extreme of conditions as to be ready for anydisaster.

The U.S. government converted the Life Saving Service to the U.S. Coast Guard on August 4, 1915. The men’s equipment, uniforms, and command structure were brought up to military standards at that time. The sta tion in Grand Haven became the district headquarters with command over nine other stations in the region. Coast Guard Cutters such as the Raritan while calling Grand Haven their homeport.

The commanders of the Grand Haven station decided in 1924 that they would like to hold a picnic in honor of the Coast Guard’s birthday. The first event was only attended by officers, enlisted men, and their families. In 1934, Grand Haven’s community leaders offered to help sponsor the now annual event, assisting with the organization and production of the picnic. The next year these community members were invited to join in the festivities. “Coasties” from all over the Great Lakes region attended the 1937 picnic in order to compete in rescue games that had become part of the celebration. Civilian spectators gathered along the south bank of the river to watch and cheer their local service men. The picnic in 1937 became a three day celebration complete with land and water parades, dances, games, and races with over 100,000 people in attendance. Today, the Coast Guard Festival has become a week-and-a-half long celebration drawing more than 350,000 people to honor those who have served. On November 13, 1998 Grand Haven, Michigan was officially named Coast Guard City, USA by a presidential decree. One small picnic by a group of heroic men stationed at the mouth of the Grand River helped shape the identity of this

The Grand River Greenway Initiative has been a primary focus of the Ottawa County Parks & Recre ation Commission. A greenway is a linear, open-space corridor that creates connections between people, nature, cultural features, and historic sites. Nearly 3,000 acres of land and 14 parks and open spaces along the Grand River Greenway have been preserved by Ottawa County Parks. Investment in the greenway and the Idema Explorers Trail not only protects some of the highest-quality land remaining along the river, but also connects many of these properties.

The communities on the river between Grand Rapids and Grand Haven are among the most rapidly developing in West Michigan. The Grand Valley State University Allendale campus has been an important factor in the region’s growth and future. Student access to the river and recreational opportunities was once limited, but the development of the popular Grand Ravines park

on the campus’ south side, and a segment of the Idema Explorers Trail that connects the campus to the park,

The true benefit of the greenway investment is its key linkages and the Idema Explorers Trail’s open access for all to enjoy. The completed system will connect 9,000 acres of public land to Grand Rapids, Grandville, Jenison, two Grand Valley State University campuses, and to the lakeshore in Grand Haven. The public can explore this 36-mile pathway and the many spectacular

Ottawa County Parks and Recreation

The Grand River acted as a highway in Allendale in the days before paved and even dirt roads. French fur trader Pierre Constant established a fur trading post in the area where Trader’s Creek flows into the Grand River, to buy furs from Native Americans. In 1836, speculators platted out a city in this same area and named it Charleston. None of the lots in this city were ever sold and it proved to be a paper city only. The area eventually became part of Allendale. In 1843, Richard and Rebecca Roberts purchased the first tenanted land in Allendale Township: 160 acres located near Constant’s trading post.

In the winter of 1848-1849, pioneers of Allendale Township held meetings to petition becoming an organized township. These men chose the name Malta, presenting it to Senator Henry Pennoyer who presented it to the state legislature. Pennoyer changed the name to Allandale (later spelled Allendale) to honor Agnes B. Allen, the first person on the tax roll in the area. Agnes Allen was the widow of Captain Hannibal Allen; he was the son of Ethan Allen, the leader of Vermont’s Green Mountain Boys and the hero of the taking of Fort Ticonderoga during the Revolutionary War. Following her husband’s death, Agnes moved to Eastmanville to live with her sister, Mrs. Benjamin Hopkins. Agnes purchased 100 acres near what later became the County Farm. This area, north of the Grand River, was part of the six square mile area proposed to be Allendale Township. Agnes Allen is buried in the Eastmanville Cemetery, and according to an article in the Coopersville Observer, she had the body of her husband reinterred at Eastmanville Cemetery.

In 1913-1914, Senator William Alden Smith proposed to dredge the Grand River from the Fulton Street Bridge in Grand Rapids to Lake Michigan. This was to enable big lake steamers to dock on river ports inside the city limits of Grand Rapids and also to protect the city fromflooding.

In the 1850s, the Grand River presented an obstacle to get from Eastmanville to Allendale, since there was no bridge. To address this dilemma, chain link ferries across the Grand sprang up not only in Eastmanville, but also in Lamont, Jenison, and other river villages. A chain ran from one side of the river to the other. The ferry had a wheel on the side and the sprockets on the outside of the wheel fitted into the links of the chain, hence a chain link ferry. Although the ferry was owned and operated by a private enterprise, in an emergency, a farmer with his horses and wagon could get on the ferry, grab the crank, and crank the ferry across the Grand. Perhaps the chain still rests on the bottom of the Grand River at Eastmanville today.

The first bridge across the Grand River in Eastmanville opened for traffic in June 1917. It replaced the chain link ferry. The day the bridge was dedicated, the residents of Eastmanville thronged to the north side of the bridge and eagerly looked south toward Allendale. The 512-foot wooden swing bridge with its swing span

of 35 feet was opened or swung frequently in its early years. Its last opening occurred about 1939, after which the bridge’s turntable rusted shut due to lack of use. Depending on water level heights, the riverboats and other riparian traffic could go right under the bridge.

riverboats that cruised the Grand River from 1905 to 1908, stopping frequently in Eastmanville. These wooden ships were identical in size, 134 feet long and 28 feet

the Grand River between Grand Rapids and Grand Haven for both people and goods. Unfortunately, these riverboats could not compete with faster rail service and were soon out of business. The Grand burned in 1921 in Louisiana, and the Rapids was crushed by ice in the Ohio River in 1917.

Two notable women who also helped build up Eastmanville during this time were Aphia Perry Eastman and Evelyn Leonard Avery. The daughter of Abijah Perry and Eleanor Doty Perry, Aphia was born on February 7, 1824 in the town of Porter, New York. Aphia was a Mayflower descendant of Edward Doten Doty. She married George Eastman in Polkton Township, Michigan on April 25, 1850. George, the first-born

child of Dr. Timothy Eastman, owned and operated a steam sawmill just west of 68th Avenue on the Grand River. Thelumber baron built a grand home along the Grand River along the eastern portion of Eastmanville for Aphia and their five children. Aphia died in Grand Rapids on December 20, 1895 and is buried in Fulton Street Cemetery beside her husband.

Born on February 28, 1883, in Grand Rapids to the Leonard Refrigerator family, Evelyn married Noyes Latham Avery on June 5, 1907. Noyes was president of Michigan Title and Trust in Grand Rapids. Evelyn and Noyes acquired the former George and Aphia Eastman mansion on the Grand River plus a square mile to the east and north in 1922. Beautiful green barns and out buildings were built. Over a decade, Evelyn transformed the swamp just west of the home into an informal English rock garden, which was lighted and filled with beautiful statuary and turned her into a sought-after expert on rock gardens throughout the Midwest.The whole estate was named “Green Vale,” and it was their summer residence from April to October until about 1940. Evelyn died on August 4, 1972 in Grand Rapids. She is buried beside her husband, Noyes, in the Avery family plot in Fulton StreetCemetery.

Rochelle Rollenhagen Reagan acquired the Eastman/ Avery property in 2012, fulfilling a childhood dream. A farmer’s daughter born to Rose Buwaj Rollenhagen and Ellis Rollenhagen, Rochelle longed to live in this property on monthly trips from the Rollenhagen farm to Grand Rapids when she was a youngster. Named “Rollenhagen House,” the property makes visitors feel like they are going backward in time from the rugged days of logging on the Grand to the colorful, Gatsby-ish

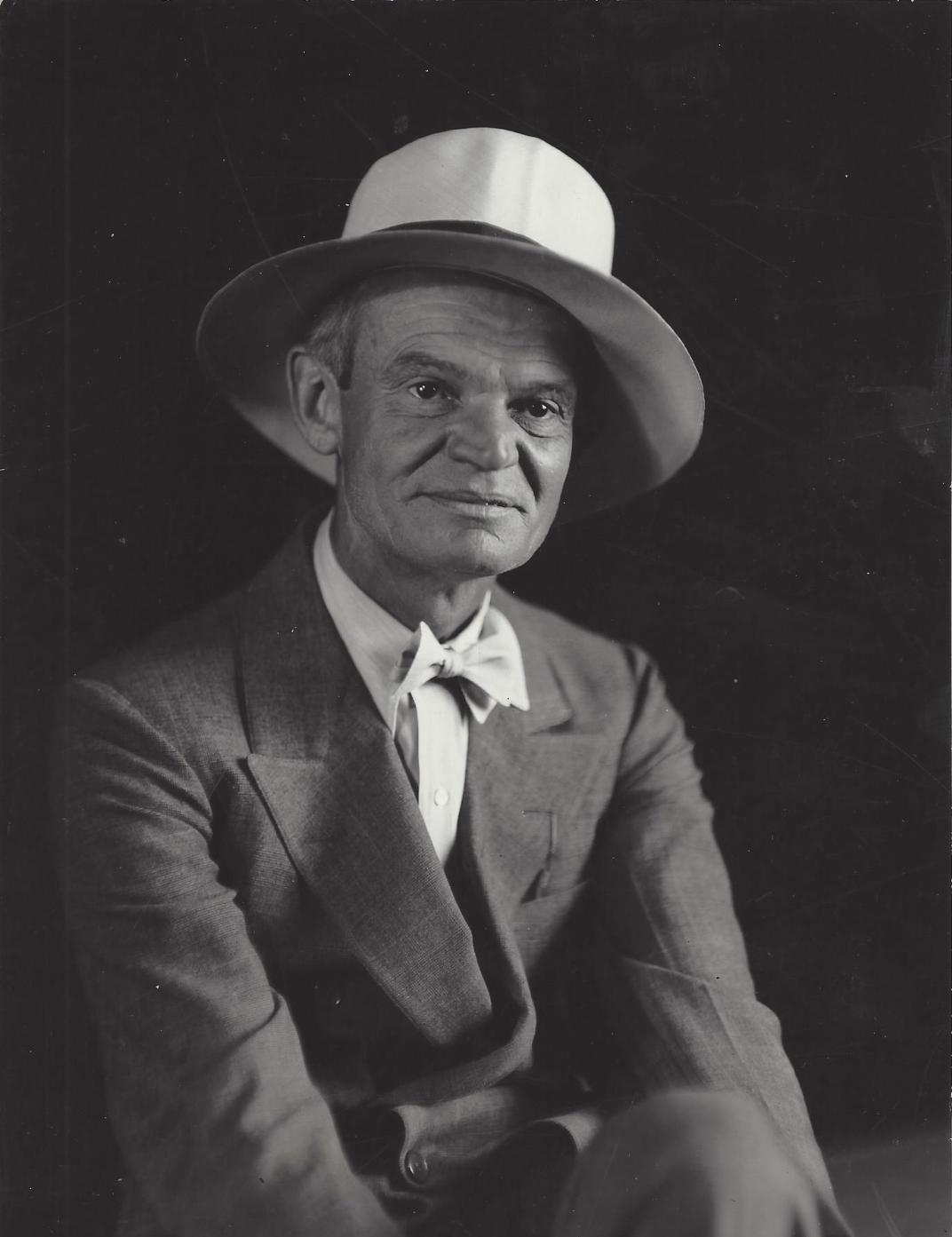

Evelyn Leonard Avery (Courtesy of Rochelle Rollenhagen Reagan)

When you approach Lamont from the east, the beauty of the Grand River is enhanced by the tranquil peacefulness of the boulevard, guarded by the giant pine and spruce trees, which have faithfully stood watch for many years.

Past churches in Lamont tell the history of the community’s stability and growth. The social and religious meetings in the village were first held on the banks of the Grand River. Families came from miles around in boats, scows, and canoes. The children especially looked forward to the get-togethers. The rigors of winter weather, however, demanded a more sheltered place to worship, and the Methodist Church in the village met that need. This first church was built by an English settler and located just west of Elmwood Cemetery on Leonard Street. Years later, it was destroyed by fire during a Sunday morning worship. A new “red brick church” was built that eventually became the community center after it was sold to a local woman. It was finally torn down after it was badly damaged in a tornado.

The Congregational Church, built in 1851, overlooked the Grand River and served as a news center during the Civil War. Each time an important dispatch arrived, the bell was rung to alert the community of important news. The church was torn down sometime before 1927. In its day, the Congregational Church’s parsonage served as a marrying parlor, a gathering place for news, and even a tea room.

Presently standing is the Christian Reformed Church. Its sanctuary was constructed in 1883-84, although the congregation was organized in 1879. In the previous 20 years, several Dutch-speaking families had moved into the Lamont area, settling on both sides of the Grand River. Property for the church was purchased when the number of families living on the north side increased to 12. In those years, the center aisle divided the women and children (who sat on the east side) from the men and older boys (who sat on the west side). Remodeling and expansions took place in 1945, 1975, and 1980.

As the community grew in the 20th century, so did the town’s business and recreational opportunities. Metron was voted one of the best nursing homes in Michigan by . Formerly the site of the old button factory, Metron of Lamont is located on the banks of the Grand River and has been in operation since 1911. Community members can also receive and

Lamont Community Park is inviting, with a playground, pavilion, walking paths, picnic, volleyball, and softball areas. This land was the previous location of the Lamont Public School and the location of an old four-room schoolhouse. The school was boarded up in 2006. The Coopersville Board of Education approved the sale for $10 to the Lamont Civic Association to restore the three acres of land into a community park.

Betty Kingma

Jenison Landing shared the same location at the end of River Avenue as the Jenison Ferry. The Jenison family moved to Michigan from New York in 1836 and purchased 1,600 acres of land and two sawmills in 1838. Following the death of patriarch Lemuel Jenison, sons Hiram, Lucius, and Luman took over the lumbering business. The two sawmills were located along Rush Creek. The Jenison grist mill replaced the smaller sawmill in 1864. That grist mill was torn down in 1964. The Jenison Ferry started in 1908, connecting Tallmadge Township with Georgetown. The ferry allowed for shopping and attending church services in both Grandville and Jenison. Permission from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had to be obtained to remove some of the river channel pilings for the ferry crossing.

Boynton Landing and Grove, located on the Boynton farm, was a busy place in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It was a gathering place for the community, church groups, and even the Grand Rapids Board of Trade. The Old Settlers Picnics were held there until 1934. Today, The Grand Lady

Haire’s Landing was established by John Haire, who arrived in 1851. His cabin grew into a small settlement with sawmill, boarding house, and school. He later built a home so large he once called it a “hotel with no bills.” John raised eight children and seven nieces and nephews. When the trees were cleared by the mid1850s, he was one of the first to pull up the stumps and begin farming. The stumps were often turned into fences surrounding the fields. Haire served as Township Supervisor and Treasurer as well as two terms as a State Representative in the 1850-60s.

Later he became judge advocate for the regiment. After the war, he became the prosecuting attorney for Ottawa County. Today, Ottawa County’s Grand River Park is part of Lowing’s Ohio Docks.

Luke Lowing, Stephen’s son, established a farm and landing at the end of Bend Drive in the 1880s. Luke pastured his cows in the ravines and lowlands next to the Grand River while he farmed the flat fields up and away from the river. He removed trees from his front yard to have a beautiful view of the riverboats. Many early homes faced the river instead of a road because it offered an easier way to travel. Riverboats would stop when flagged by local farmers with produce or passengers. The property is now close to the Ravines County Park, helping preserve the area’s beauty

Stephen Lowing bought 80 acres of land along the river in 1836. His lumber business was very successful and included a sawmill with a mill pond close to the Grand River. He called his landing Ohio Docks. One building had so many additions to accommodate the lumberjacks that it was called the Beehive. During the Civil War, Lowing trained and led Georgetown Township area men who became part of Michigan’s 3rd Regiment.

Blendon Lumber Company. John Ball purchased 2,500 acres for the company and A.C. Litchfield built and operated the sawmill. It was one of the largest on the Grand River. A settlement to support the sawmill rivaled the size of Jenisonville in the 1860s, and was located on a high bluff overlooking the Grand River.

possibly the first steam powered, logging railroad in Michigan. There was also a small brick factory and shipyard where at least four schooners were built. Grand Valley State University owns the site today and

Township with Georgetown. The ferry allowed for shopping and attending church services in both Grandville and Jenison. ”

Grandville,

The city of Grandville was founded in 1832, on an 80-acre plot north of Chicago Drive. The early white settlers hoped this location would serve as the Grand River’s main city. However, many original plots were abandoned until the 1870s Plaster Boom.

By 1841, the first gypsum mill in the Grand Rapids area began operation, following the discovery of gypsum by Native Americans at the mouth of Plaster Creek in the 1830s. The Union Mills Plaster Company and Durr Mill would come to prosper in Grandville. The Durr Mill, lo cated where the Grandville Senior Center sits today, be came the property of Lafayette Taylor and Loren Day in 1875, before they sold it to Mr. Durr in 1886. Originally a flour mill, an addition was constructed to allow for the milling of plaster. It would burn three times before being sold in 1902 to the U.S. Gypsum Company.

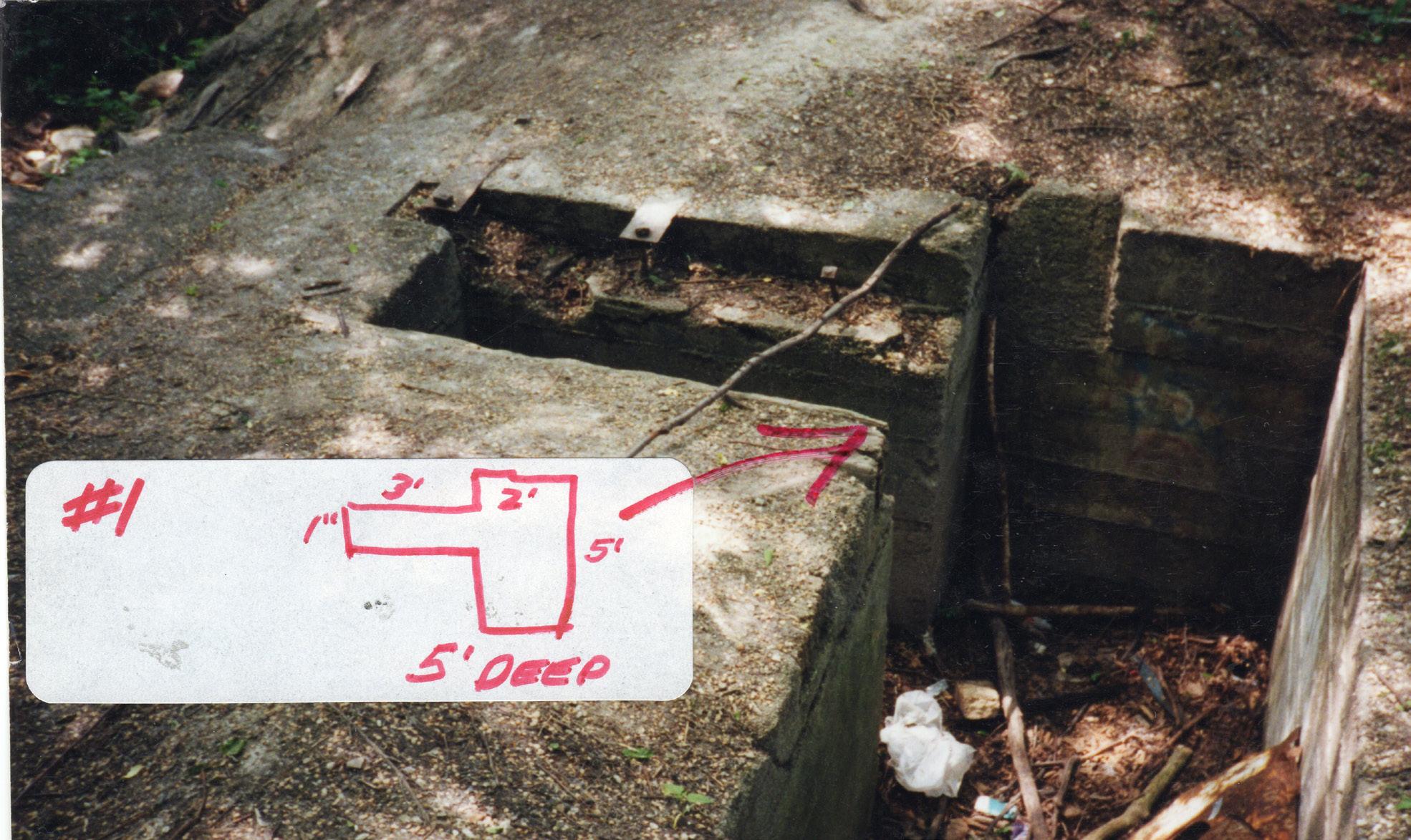

The White Plaster Mill began operation in 1842 at the site of the modern Big Spring Lake. Gypsum was exposed five to eight feet below the surface through dynamite blasting and was then hauled to the “Red Mill” (named for its color) located where Grandville Middle School stands today. The mill crushed and ground 120 tons of gypsum daily, which was shipped to neighboring states, or, in the latter half of the century, loaded onto trains to travel south. The Union Mutual Life Insurance Company gained possession of the two mills due to foreclosure in the 1870s.

Employment in the mines and mills drew large num bers of workers to the area, particularly immigrants. Though the pay was generally good in comparison to other labor, the work was dangerous. Several mining accidents in Grandville reveal the nature of that danger, perhaps none more than the striking of an underground spring at the White Plaster Mill, which flooded the quarry in the 1880s. Though the men escaped, the mill and equipment were forever lost. Despite the dangers,

gypsum mining affected Grandville’s economy and left a permanent mark on the landscape when the quarry of the White Plaster Mill rapidly flooded, leaving oxen and heavy mining equipment at the bottom of what is now Big Spring Lake.

After the White Plaster Mill flooded, lumbering, farming, and the oil industry dominated. The location of the city in the river’s floodplain would continuously pose problems, with 1838 and 1883 earning the reputation in the area as the years of the “great floods.” With the arrival of the 1904 floodwaters, new records were set. Having experienced heavy snow in the winter of I903-1904, the river was unable to contain a week’s worth of rain in March. Drain Commissioner Frank Bouma’s records demonstrate the severity, noting that 54,000 cubic feet per second of water flowed down the river. On March 28, the river crested at a record 19.5 feet. People traveled by boat down State Street (now Chicago Drive) from Wilson Avenue, where 18 to 24 inches of water stood. The waters stopped transportation in the area as well. Interurban cars halted at Central Avenue. The railroad bridge over Buck Creek faced such tremendous floodwaters that a train was placed on the bridge

As the waters rose, residents loaded up salvageable items and moved to higher ground. Businesses like the original Osgood’s Tavern experienced their own set of challenges. The flood waters reached as far inland as Prairie Street. For over a week, residents remained stranded without food or water. Roads and rails were impassible. To travel west from Grandville, boats were used to ferry people from the village limits past Buck Creek to Jenison and the business district for groceries, while saloons and hotels remained closed. The flood led to the eventual relocation of facilities and shopping

The Grand River watershed was originally covered with forests and wetlands, which slow down runoff and filter out pollution. European settlement drastically changed that landscape. In the 19th century, water-powered, river-dependent industries relied heavily on the Grand River for their operations. Discharges of chemical wastes and sewage were common, contaminating the water for the city and downstream neighbors.

In Grand Rapids, the upper rapids were submerged by construction of the Sixth Street Dam to make it easier to transport logs during Michigan’s timber boom. Boulders and bedrock making up the lower rapids were removed to build the foundations of many of the city’s buildings and to provide backfill for the flood walls. Logs significantly damaged major river beds and stream channels as they floated downstream. The result was a scoured and silty river channel, corralled by floodwalls and blocked by dams, that was much less hospitable to aquatic life. In the 1920s, the installation of “beau-

tification” dams in Grand Rapids became necessary to maintain sufficient water levels to cover up the foul-smelling river bottom. Water quality remained poor until environmental protections were put into place in the 1960s and 1970s to curb industrial pollution. Over the past 30 years, the city has continued to improve water quality by separating its storm and

In addition to physical changes in the riverbed and degradation of water quality, the overharvest of key Grand River species such as lake sturgeon, freshwater mussels, and clams significantly impacted biological communities. Once abundant in the Grand River, lake sturgeon populations today are estimated to be at just 1% of historic numbers and are listed as a state threatened species. Of the 27 species of freshwater mussels in the Grand Rapids area of the Grand River, two are federally endangered and nine are state threatened as a result. While water quality has improved significantly, the long-term impact of many of these practices is still felt in the river today.

The Great Lakes region and the Grand River have been home to lake sturgeon for thousands of years. Native Americans relied on the fish for subsistence. Lake sturgeon play a role in the structure of some Native communities, in their creation and migration stories, and in ceremonies, art, and songs. A Sturgeon Song was gifted to the Grand Rapids Public Museum for the opening of the Grand Fish Grand River exhibit in 2016. Dan Bissel and Elizabeth Caldwell sang the song on the instruments that Bissel created and also donated to the exhibit. The song is called Nme’ Ogema Kegon (Sturgeon king of fishes).

“Nme’ taw bikaabii, taw biskaabii, taw biskaabii... Nme’ Ogema kegon “ (Sturgeon he will come back, he will come back, he will come back...Sturgeon king offishes.)

When European American settlers began arriving in the Grand River Valley, they noted the importance

1850s when his grandfather arrived as one of the first paidhis bill.”

Today, on all but a select few waters in Michigan, fishing for lake sturgeon is catch-and-immediate release using hook and line gear. On the Grand River, anglers rarely catch sturgeon. In the spring when fish migrate up toward the fish dam to spawn there are often reports of sturgeon sightings. With this in mind, the Grand Rapids Public Museum is working to document spawning and use of the Grand River by lake sturgeon.

Grand Rapids Public Museum

The early years of Grand Rapids saw the establishment of a trading post on the east side of the Grand, near where Pearl Street is today. As the city grew, the population saw a need to traverse the river by something other than canoe or ferry. The first span to be built across the river, a toll bridge, was at what is present-day Bridge Street. And since its initial wooden covered bridge, Pearl Street has seen a steel bridge and cement bridge cross the Grand River.

The city’s growth can be attributed to growing industries in the area, including the world’s first hydroelectric power plant, which also was the first to supply commercial electric lighting service in Michigan. William T. Powers, an enterprising manufacturer, purchased the necessary river frontage in 1865 and 1866. In the two following years, he constructed the West Side Water Power Canal, completing it in September 1868. Powers became interested in electricity after he learned of an 1877 electric lighting system exhibit at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. Frederick W. Powers, grandson of William T., recalled that his grandfather attempted to make an incandescent lamp before Thomas Edison’s in 1879. The elder Powers could not solve the vacuum problem, and his lamps burned out withinminutes.

William T. Powers organized the Grand Rapids Electric Light & Power Company on March 22, 1880, in association with William H. Powers (son), Amasa B.Watson, James Blair, Henry Spring, John L. Shaw, Thomas M. Peck, and Sluman S. Bailey. The company acquired a sixteen-light Brush dynamo which was installed in the Wolverine Chair & Furniture Company factory. The machine was belt-driven from the factory’s line shaft, powered by a water turbine. On Saturday evening, July 24, 1880, sixteen electric lights glowed in Campau Place. The first businesses illuminated were Sweet’s Hotel, Powers’ Opera House, E. S. Pierce’s Clothing, Spring & Company Dry Goods, Mill & Lacey Drugs, A. Preusser’s Jewelry, and Star Clothing. The brilliant electric lights proved such a draw for merchants that demand outgrew the capacity, and the machine was moved to Powers’ sawmill at the downstream end of the canal, and output was increased by the installation of a new forty-lightgenerator.

Growth of the business by the city street lighting contract in March 1881 justified even more extensive operations. Powers transferred water rights fromthe West Side Water Power Company to Grand Rapids Electric Light & Power, which included 16 first run-ofstone, amounting to two hundred and forty horsepower. On May 27, 1881, a contract was awarded to John H. Hoskin for the construction of a permanent powerhouse which was completed November 1, 1881.

The expansion of Grand Rapids, and West Michigan more generally, gave rise to the need for additional types of transportation. This includes the development of an interurban system with trains that took people from Grand Rapids to the lakeshore from the middle of town and across its own bridge to destinations west. Additional bridges arose as a result of a desire to move quickly from place to place and the addition of expressways to the city. Bridges located on the stretch of the river where the rapids once were are Leonard Street, Sixth Street, I-196 Expressway, Bridge Street, interurban (now pedestrian), Pearl Street, the Blue Bridge (formerly for rail traffic, now pedestrian), Fulton

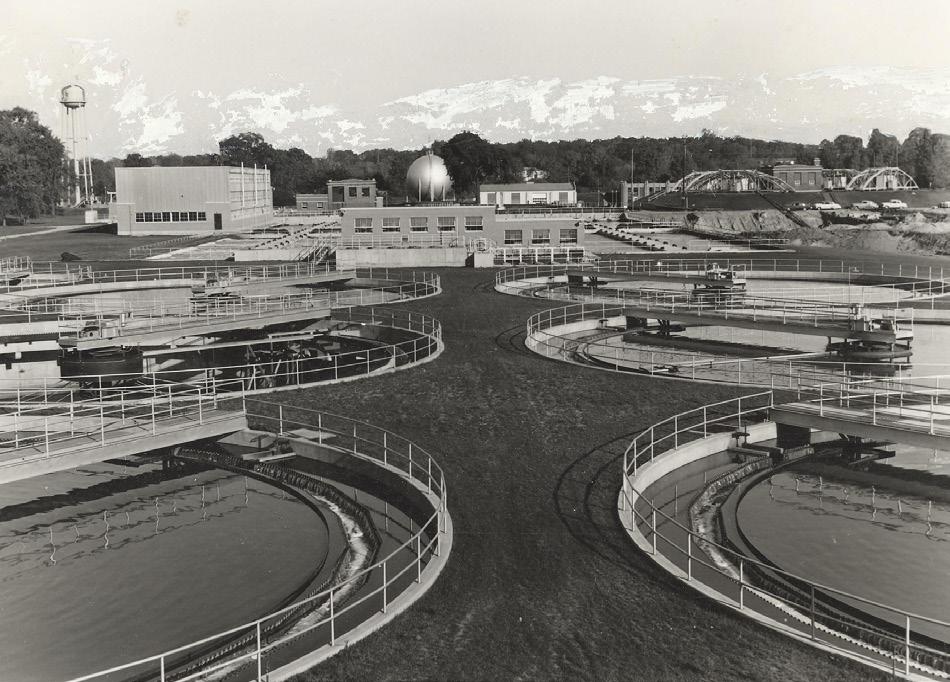

Established in 1930 and located at 1300 Market Ave. SW, the first Grand Rapids treatment plant was the result of lawsuits, fundraising, political wrangling, and careful planning. A combined sewer system delivered waste to the plant where solids were separated out and turned into fertilizer called RapidGro, that was sold to farmers.

While secondary treatment was included in the original design of the plant, it was delayed for years due to lack of funds. The plant underwent improvements in 1954. Secondary treatment was finally added along with two digesters that produced enough gas to be stored for use later. A new administration building and modern laboratory were also included during theimprovements.

Like Grand Rapids, many cities designed sewer systems to capture both sewage and stormwater using the same pipes. During heavy rainfall, this consolidated system was easily overwhelmed, causing sewage to overflow into the river. In 1969, Grand Rapids was dumping 12.6 billion gallons of untreated water in theriver.

In 1976, most of the aging equipment at the plant was updated or replaced. Huge Archimedes Screw Pumps were added to pump effluent water uphill during times when the Grand River level was high. The growth of industry, especially metal plating finishers, warranted creation of the Industrial Pretreatment Program to keep more than just household waste out of the GrandRiver.

Today, Grand Rapids has a separated sewer system so that stormwater is the only thing released directly into the Grand River. After nearly three decades of work, the city has ceased dumping untreated water into the Grand River.

Kayne Ferrier

Kayne Ferrier

In 1936, Grand Rapids was threatened by the possibility of a flood. Ice had formed on the Grand River, rising above the water. Ice had been known to reach heights of 20 to 30 feet, plus snowfall was a major concern that year. The supervisor of the Public Works Administration, George H. Waring, wrote to the Director of Public Services that, “there is more snow on the ground today in the Grand River valley than ever at one time before.”

A sudden thaw and a buildup of ice would produce a devastating flood, which happened in 1904. The flood of 1904 was one of the worst in the history of Grand Rapids. William T. Powers, of the West Side Water Power Association, went before the city council to ask that something be done about the great buildup of ice that was threatening to spill into the canals, stating that if something was not done soon, the results, “may be very disastrous to the city as well as to ourselves.” The

city engineer thought that Powers was unnecessarily alarmed. Further up the river, a backup of ice caused dams to burst and water rushed down the Grand River to the city. The resulting flood submerged much of the west side. In the aftermath of the flood the city began to put measures in order to prevent another

More than 30 years later, there was a thaw in early March of 1936. The melting of the snow caused the Grand River to rise. This time, however, the city was prepared. The city had constructed flood walls and enforced riprap stone embankments. The Engineering Department used dynamite to break up the ice that threatened to back up the water. The ice was cleared and the flood wasaverted.

Grand Rapids City Archives & Records Center

The City of Grand Rapids built a municipal tourist camp in 1931 for use by the traveling public. It was located on eight acres at North Park, fronting the Grand River on the north end of Riverside Park. The site was previously occupied by the North Park Pavilion, and the Boat and Canoe Club. The camp was built using Scrip Labor, a local program created by City Manager (later Mayor) George Welsh, that was similar to the national Works Progress Administration.

The municipal camp was maintained and supervised by the City Department of Parks. They furnished maps and information for visitors. The property was fenced, well-lighted, and policed at all hours. A large number of camping spaces were reserved for tourists who brought their own camp tents and gear. Originally, the camp offered six furnished cabins, complete with kitchens, and one duplex cabin that could accommodate six to eight people. Every cabin faced the river, and all windows and doors were screened. Additional cabins were added over the next few years, totaling 16. A dormitory con tained four single rooms and six individual kitchens. The kitchens could be rented for 10¢ per half-hour.

Travelers paid a small fee for the accommodations. At a rate of 50¢ per car, camping privileges entitled the guest to the use of showers, laundry, and club rooms. Single rooms in the dormitory rented for 75¢ a day. Depending on occupancy, the cabin fees ranged from $1.50 a day to $4.00 a day.

Unfortunately, the State Health Department condemned the camp in 1946 because of inadequate sanitary facilities and possible springtime flood conditions. During this time of the post-World War II housing shortage, the cabins were sold on the strict promise that they would be used for housing.

The camp was built using Scrip Labor, a local program created by City Manager (later Mayor) George Welsh, that was similar to the national Works Progress

The Grand River running through Grand Rapids is a focal point in the community, with five parks on the river giving both locals and visitors different kinds of river experiences. Riverside Park is the largest park within the city limits with 180 acres, located in the northern section of the city.

The park was opened in 1929 after the swampy areas were dredged. Additional work was completed using Scrip Labor, a local program created by City Manager (later Mayor) George Welsh similar to the national Works Progress Administration. Riverside Park offers a wide variety of both active and passive recreational amenities, including bike and walking paths along the river, lagoons for fishing, boat launching ramps, ball diamonds, disc golf courses, and spots for bird watching and nature study.

nial celebration. Ah-Nab-Awen, meaning “resting place,” was named in 1979 by the Three Fires Council (comprised of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi peoples). The park exhibits several pieces of art and interpretive markers, and hosts many community-wide festivals, including the July 4th

Fish Ladder Park is located on the west side of the river at the Sixth Street dam. The Fish Ladder is a functional piece of art, designed by Joseph Kinnebrew, to allow migrating fish swimming upstream a means of circumventing the dam . The site also allows visitors to watch the fish jump up the “ladder” during seasonal migration in the spring and

Ah-Nab-Awen Park is located between Pearl and Michigan Streets, in front of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum. The six-acre park was constructed during the 1970s as a part of downtown urban renewal and the 1976 Bicenten-

Sixth Street Bridge Park and Canal Park are two smaller parks that are part of the collection of pathways forming a continuous loop on both sides of the river. Sixth Street Park was an early part of the city’s effort to reclaim the waterfront that started in the 1970s with property purchases and exchanges. Canal Park takes its name from the East Side Power Canal that once extended north from downtown and provided power to the many factories along the river. Both of these parks offer picnic and boat launching facilities, as well as bike paths and lookouts along the river.

Pond built by Scrip Labor, circa 1930 (Courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Library, Archives 67-2-2) Grand Rapids Historical CommissionGrand Rapids’ downtown Grand River waterfront had long served as the city’s principle industrial area. Starting in the 1920s, city planners envisioned reworking the space for public use but the Great Depression and World War II halted those plans. The 1950s brought the decline of waterfront manufacturing and the movement of business and retail to new suburban areas. The construction of US-131 and I-196 along with the closure of the West Side Power Canal resulted in the demolition of dozens of buildings during the early 1960s.

The new highways intersected on the West Side waterfront, and the junction effectively isolated the area from the rest of the street network. To the north of I-196, the cleared land became the West Side Industrial Park with new facilities replacing older

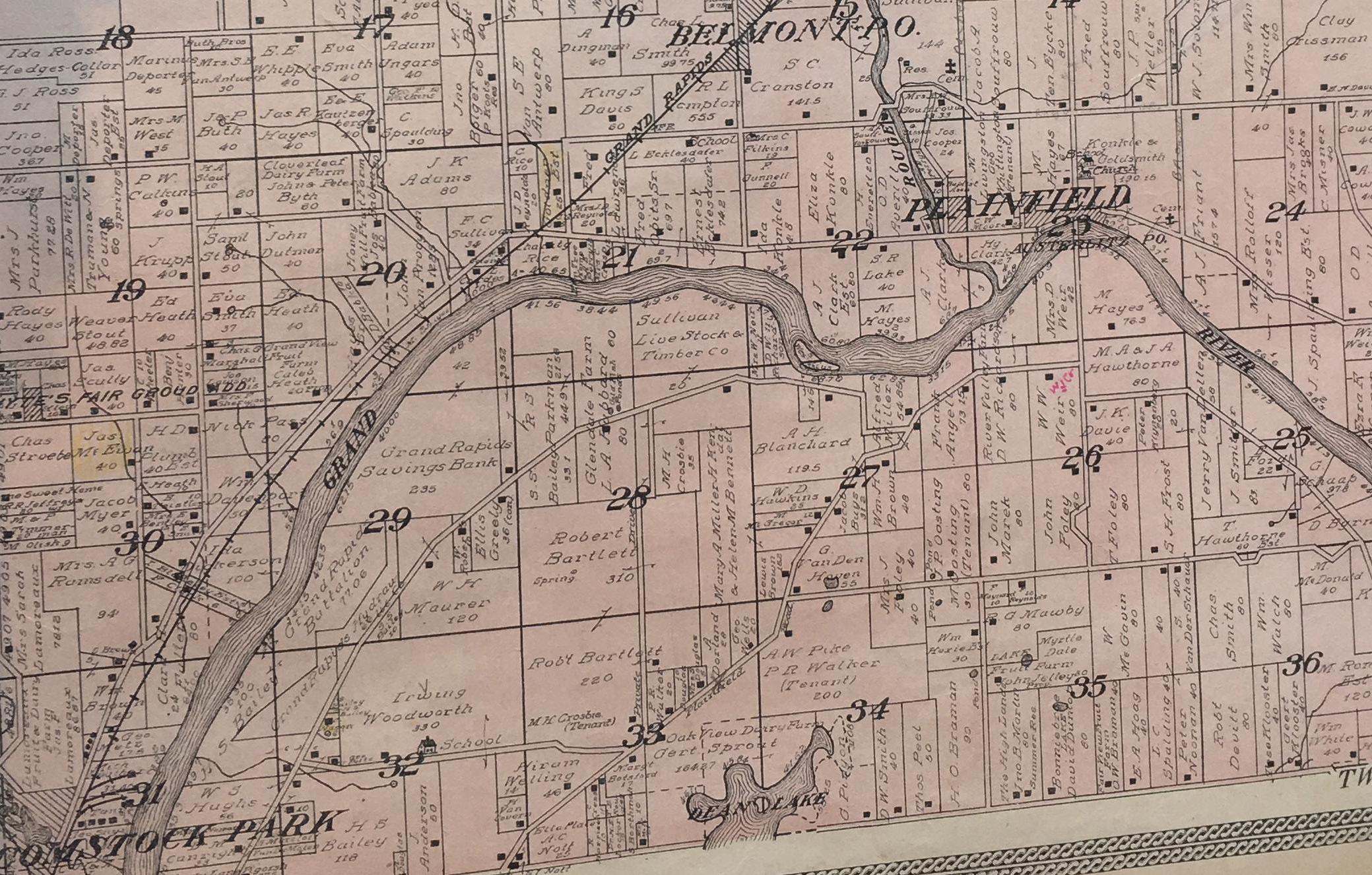

At first glance, the 1830s location of the Village of Plainfield was a spectacular one. The upstream view to the southeast as well as the downstream view to the southwest were both beautiful and comforting when gazing at the village from the high bluff on the north bank of the Grand River, which overlooked the village. The view was comforting because you could see an enemy coming and protect yourself from these heights. But, protection from any human enemy would not save the village from another enemy: nature.

In the 1830s, Plainfield was the first settlement of any size upstream from the rapids of the Grand River. Any goods which it desired to ship downstream to Grand Haven had to be unloaded above or below the rapids and reloaded on boats or rafts to reach its destination. This rapids was two miles long: not a simple obstacle to go around.

As long as the destination was only Grand Rapids, Plainfield businessmen could make a profit from their loads of shingles or other forest products. Shipment beyond the rapids removed the profit.

Nature would show the Grand River as another detriment to Plainfield Village: flooding. A map of Plainfield Charter Township reveals that the Grand River enters it at its southeast corner in section 36. From there it flows northwest to the center of section 31. The turning bend in section 23 is the northernmost point of the Grand River’s flow in the state of Michigan. Along this bend, both sides of the river would flood, which made another crisis residents had to endure.

The extreme elevation swings of the village’s topography, plus the river itself, meant that the railroads of later years would take another route through the township

would become a ghost town and just another road

A family enjoys fishing in the Thornapple River many years ago (Courtesy of Cascade Historical Society)

The Thornapple River is an easy-going stream which meanders through woodlands in four counties in Southwest Michigan: Barry, Eaton, Ionia, and Kent. It is 88 miles long and is a tributary of Michigan’s longest river, the Grand. It was carved out by the advance and retreat of glaciers some 7,000 years ago.

Before European settlement, the Thornapple drainage basin had mixed hardwood and conifer forests and barrens. It was home to the Ottawa and Potawatomi peoples who named it Tomba-Signe, meaning “river with the forked stream.”

River in 1821. The post served as a site for trading with Native Americans. By 1837, fur trade declined and Robinson facilitated a treaty between local tribes and the federal government that opened the area to

In 1862, there were a number of businesses including a flour mill, sawmill, and basket factory. Development

The picturesque river slowly flows through farm land and features small rapids. There are several charming spots along the way for canoers and kayakers to relax and picnic. Rafting, kayaking, sailing, water skiing, and swimming are favorite pastimes of those enjoying the river. Fishermen enjoy catching smallmouth bass, perch, and trout. Along the way, one can spot osprey, bald eagles, herons, and ducks.

Rix Robinson was the first permanent white settler in Kent County. He established a fur trading post, in conjunction with John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Trading Company, at the mouth of the Thornapple Cascade Historical Society

Lucius Lyon (Courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Library, Archives 54-30-50)

Lucius Lyon (Courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Library, Archives 54-30-50)

The place where the Grand and Thornapple Rivers meet has been prime real estate for a very long time. Native groups came to hunt, gather, fish, trap, farm, and trade. A fur trading post was established as part of a network extending through the Grand River Valley, along the Lake Michigan shoreline, and north to Mackinac Island. As European settlement grew, farmers sought the land of the lush, fertile river valley. Today’s real estate market continues to reflect the area’s desirability.

to an infant heir. Legal tie-ups and complications to clear title halted progress in Ada. The village sat idle during pivotal years of westward expansion in the United States.

Ada’s subsequent development was tied to its bridg es, given the village’s river location. It is said that the earliest bridge (1848-1853) was the first bridge along the length of the Grand River. The covered bridge that replaced it (1857- 1917) was built for $5,725 ($165,000 in 2019) and had a 20-year charter to be used as a toll bridge. The later iron bridge (1917-1959) had two lanes for traffic and cost $30,000 ($590,000 in 2019). But, it was construction of the concrete and steel bridge (1957-2011) that made quite a stir.

In 1833, Ada’s largest early landowner acquired property with an eye toward its value for development. Lucius Lyon, a government surveyor and sometime-speculator, bought prime real estate with backing from Arthur Bronson, a wealthy New York investor. As a result of a national financial crisis in 1837, Lyon defaulted on his debts and lost many Michigan properties to Bronson. A few years later, Bronson died and his estate was left

M-21/Fulton Street used to make a hairpin turn in crossing the Grand River at Ada. As motor vehicles replaced horses and both speed and volume of traffic increased, the route turned dangerous. In 1957, the Michigan Department of Transportation relocated the mouth of the Thornapple River 500 feet east to straighten the path for a new bridge. An archeological dig conducted during the relocation revealed two previ ously unknown burial groups and an adjacent camp site that predated white settlement, revealing the history of the Ottawa people in the area. The dig highlighted the Grand River’s early role as a highway for trade and exploration. Time and traffic over the Grand River bridge continues on. Today’s crossing is a 500-foot-long,

a network extending through the Grand River Valley, along the Lake Michigan shoreline, and north to Mackinac Island.

Ada Drive in the heart of the village (Courtesy of Ada Historical Society)

Ada Drive in the heart of the village (Courtesy of Ada Historical Society)

The fur trade was an important contributor to the early 19th century Michigan economy. The confluence of the Flat and Grand Rivers combined with the large Odawa village and abundance of furs in the area helped to make Lowell an important trading site. A network of trappers, traders, voyageurs, and clerks moved furs from the Grand River and Great Lakes to Europe. Traders worked independently and later contracted with John Jacob Astor’s American FurCompany.

The first major fur trader in Lowell was Joseph LaFramboise. LaFramboise and his wife, Magdelaine, operated a chain of about 20 posts including one in Lowell. Upon Joseph’s death, Magdelaine took over their fur trade operation herself. She became a very successful fur trader in her own right. In 1821, she retired to Mackinac Island where her influence continued until her death in 1846.

Daniel de Marsac came to Lowell in 1828 on a trip to visit his sister Sophie and her fur trader husband, Louis Campau. Marsac learned that the Flat River was a very rich furring river. White ermine pelts, desired by Europeans, were especially abundant. He returned with trade goods and lived in the home of Chief Wabwindego at the Flat and Grand Rivers. In 1831, he built a permanent post on the south bank of theGrand.

Marsac later placed his post in the care of John S. Hooker, who moved to Lowell at 16. Hooker grew up among the Odawa and became a clerk and interpreter in Lowell’s first store. He operated Marsac’s post until it closed in 1857, when the Odawa left for the Oceana County reservation.

was run by power furnished from a dam and conducted by a mill race. It was constructed of logs floated down the river with the help of local Odawa. The mill became known as the Forest Mill and transferred through several owners before the Wisner Bros. Mill sold it to King Milling Company in 1896. Francis King, Frank T. King, Charles McCarty, and Reuben Quick owned King Milling Company. Six years previously, King Milling Company purchased the Superior Mill in 1890. Built in 1867, that mill was located on the west side of the FlatRiver.

Owning the Forest Mill and Superior Mill gave King Milling two flour mills, one on each side of the river. McCarty’s and King’s shares were sold to the Doyle family in 1911 and 1940. In 1943, the Superior Mill suffered a devastating fire but was rebuilt. Only 10 days after completing the new mill in 1945, William Doyle died. He left the mill to his wife and two sons: King, age 23 and Mike, age 15. King Doyle, who was serving in World War II, came home to operate the mill. King Milling remains family owned and is the longest running

Rix Robinson came to West Michigan as an agent of the American Fur Company. He took over Madame LaFramboise’s enterprise upon her retirement in 1821. Robinson established his post in nearby Ada where his wife’s family lived. Several of his family members moved to the Lowell area and built a fur trade warehouse on the north bank of the Grand River.

A later but equally essential piece of Lowell’s economy were its flour mills. The first mill was built by Cyprian S. Hooker in 1847 on the east side of the Flat River. It

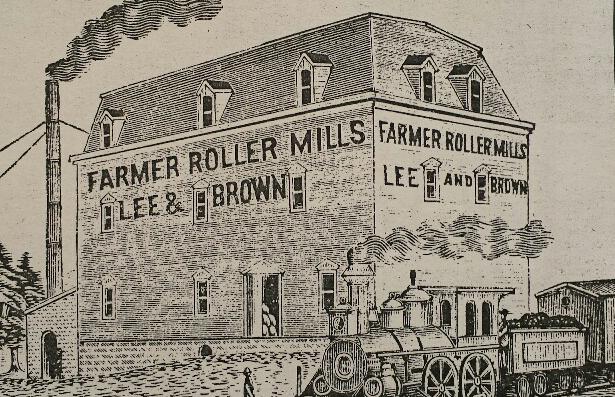

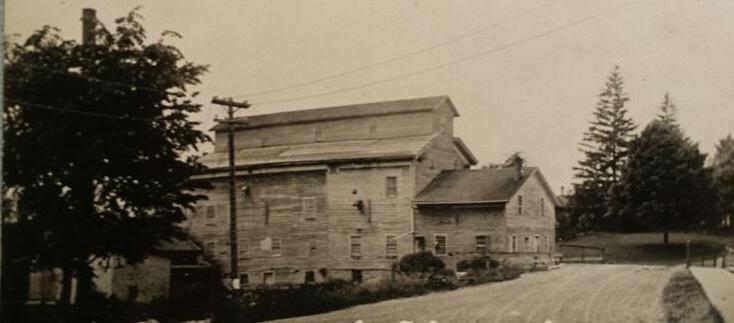

The land on which Saranac now lies was purchased in 1836 by Judge Jefferson Morrison of Grand Rapids. Soon after his purchase, he sold some of the land to Dwight & Hutchinson of Detroit. This land included a mill site on Lake Creek, which flows from Morrison Lake and empties into the Grand River at the site of the future village of Saranac. Dwight & Hutchinson donated some land to Cyprian S. Hooker of Oakland County provided he would build a sawmill on the Lake Creek mill site. In 1841, the mill was in operation.

Other mills also operated in the community and were powered by Lake Creek’s surrounding mill pond and flats. Elijah Pratt built Boston Roller Mills and operated it for about 25 years prior to its purchase by Daniel Huhn, who used the mill for flour making and grinding feed. In 1903, Pratt obtained a franchise to operate an electric lighting plant and built an addition to the mill to house the dynamo. Waterville Mill, located south of Saranac, was built on Lake Creek in 1838 and ground buckwheat flour and grist for farmers. The first owner was J.J. Hoag, while Charles Stutz was the last to run the mill. The building still stands and is located at MacArthur Road and Morrison Lake Road.

As the mills formed part of the Saranac business community, so did the American button industry, formed in the late 1800s. By 1912, button factories

operated in Lamont and Lowell (1932-1946). They turned freshwater mussels (or clams) into buttons. Native Americans had gathered clams for food, while shells were used for pottery, tools, utensils, and jewelry. The Saranac area was an ideallocation for clams, with no nearby dams to change their environment.

Flat bottomed boats, outfitted with four pronged iron hooks attached to lines on a bar, would drag the river bottom. Open clam shells would close on the hooks and be brought to the surface. Clam shells would be steamed, emptied, and cleaned. The clam meat would be eaten or sold for pig feed. Some say the pork would taste “fishy.” Sometimes a pearl would be found in the shell—more income!

Roving buyers bought wagon loads or train boxcars of sorted shells to sell to the button factories. Broken shells remained in piles. In the 1930s, a man was paid 5¢ for each five-gallon pail of shells. The button factories had special equipment to punch circular shell plugs, which were sent to other factories for finishing. Some women earned money sewing the finished buttons on cards for retail. By the 1950s, most buttons were made of plastic and the button factories closed. The Grand River clams had been over harvested. Today, the clams

The Grand River served as a major Anishinaabe route for dug-out and birch-bark canoes and also was important for the white settlers as they moved supplies and commercial freight. Along the north bank of the Grand River in Ionia there was a gathering place long before the town was there. To the Anishnaabe, this was the site of a seasonal village where they fished, hunted, and grew vegetables. When the white settlers arrived, this farming tradition continued and pioneer harvest festivals and tent revivals were held on the river bank. Families could enjoy a leisurely picnic and watch the boats go by.

In the 1860s, a “driving park” was established west of the river bend. This was a circuit of paths to drive carts and buggies along the river’s edge. Races, both organized and spontaneous, were staged here, too. In 1874, the Ionia County Agricultural Society purchased the parkland and adjoining property, establishing the County Fairgrounds. This became the site of the annual Ionia District Fair, and other celebrations such as May Day, Independence Day, outdoor concerts, and Chau tauqua programs. In 1915, the District Fair organization suffered hard times and needed a fresh start. Local businessmen came to the rescue under the leadership of Mayor Fred W. Green. They proposed that the Fair eliminate the gate fee and bring in more family enter tainment. Thus the Ionia Free Fair began.

From the 1920s onward, buildings were built, renovated, updated, and expanded to accommodate what would become “The World’s Largest Free Fair” and “Michigan’s Greatest Outdoor Event.” Today, there’s a campground, picnic areas, playgrounds, and a scenic footbridge. Between those festive occasions, folks still “gather by the river” at Ionia’s Riverside Park to fish, paddle, or just stroll along enjoying the tranquility.

As the community grew, the floodplain that benefits the community’s agriculture also means the river’s banks overflow annually. Sometimes the record floods reached as far as Main Street, and locals are used to the Ionia County Fairgrounds being under water every spring. In the early years, the settlers north and south of the river were cut off from each other, sometimes for weeks at a time. Brave ferry operators risked their lives to traverse the rushing flood waters, delivering supplies and passengers between the banks. As improved roads connected communities across the state, the fords and ferries were replaced by bridges, and rails and highways crossed the river. The railroad bridges have become part of the trail network, and the canoes on the river are joined by kayaks, rubber rafts, and motor boats. Folks fishing from the banks or floating along leisurely appreciate the Grand River for its natural aspects. A breathtaking sunset over the water or bald eagle soaring above the river is just as inspiring as it was 200

In 1790, when British fur trader Hugh Heward traveled the Grand River, little was known about the river. Heward kept a journal of the journey, which can be found in the Askin Papers published by the Detroit Library Commission. He began his explorations near Detroit and eventually found his way into the Grand River from the Portage River. He and seven engagés then made their way to present-day Grand Haven.

Topologist Jim Woodruff used the journal and topo graphical maps 200 years later. In 1990, his friend Verlen Kruger, a world-renowned canoeist, replicated the jour ney to verify Woodruff’s calculations. Nine years later, Woodruff concluded that on April 24th, Heward’s party traveled the 45 miles between Dimondale and Port land in one day. He challenged Kruger to repeat the feat. Kruger accepted (and met) the challenge. Kruger’s motivation was to spark interest in the 2000 Grand River Expedition. Kruger, Woodruff, and others were concerned about the river’s condition and wanted to generate more interest in cleaning up the pollution. Canoeing enthusiasts, environmentalists, and students traveled the river, taking water samples and document ing habitat. Their findings were compared with the 1990 exhibition findings to see what water quality and habitat improvements occurred in 10 years.

Kruger had traveled the rivers of the world, but he loved the Grand. He lived on the Grand in DeWitt, but he had a special fondness for the Grand at Portland. After his death, the Portland canoeing community com missioned sculptor Derek Rainey to create a bronze statue of Kruger to be placed in Thompson Park, the landing site of Challenge canoers. Kruger and Woodruff are both deceased but the Challenge and Expedition continue. The challenge takes place every year and the Expedition every 10 years.

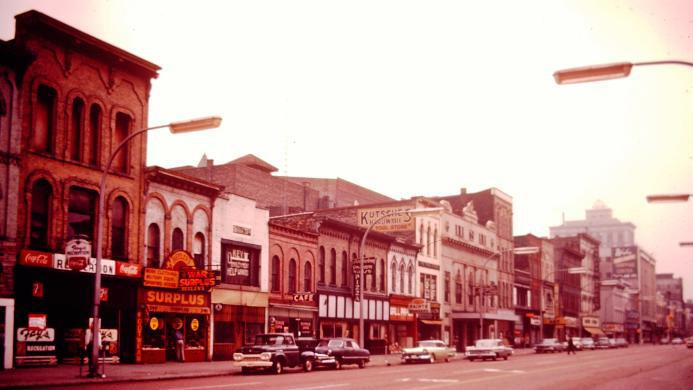

millions of American families. In his October 4, 1950, Saturday Evening Post Life,” he recounts, “Why should we want toys, when there was the Grand River to fish in and to explore: when there was the swimming hole at Butternut Island.” Kelland’s boyhood memories and his recollection of time spent playing with his friends on the islands and riverbank caves of the Grand and Looking Glass Rivers provided the backdrop for many of his stories.

Kelland painted a picture in words, for all America to read and enjoy, of the lasting influence that a boyhood spent in Portland and on the Grand River had on his life and writing. Additionally, in his first Mark Tidd book, the hero and his friends agreed to form a secret society and “to have the meeting place in a little cave up across from the island where the swimmin’ hole was.” Kelland produced over 60 novels and 400 short stories in his 60 years of writing. He died February 18, 1964, at the

valley, as all villages should be, with a clean, rapidly-running river passing parallels the river, one row of stores standing with their hind legs in the water, as it were.

Portland and the Grand River also inspired artists and writers. Famous American author Clarence Budington Kelland was born in Portland on July 11,1881. He lived there until he was ten years old. His short stories, which appeared regularly in serial form in the Saturday Evening Post for over 30 years, were read weekly by

– Kelland’s thinly-veiled description of Portland in Heart,1923.

Main Street parallels the Grand River (Courtesy of Portland Area Historical Society)

Main Street parallels the Grand River (Courtesy of Portland Area Historical Society)

The Ada Historical Society preserves, shares, and celebrates the unique history of the Ada, MI community. AHS offers programming, events, and opportunities to connect with the community as well as operates the Averill Historical Museum featuring exhibits about Ada’shistory.

http://www.adahistoricalsociety.org / 7144 Headley Street, Ada

The Allendale Historical Society promotes the understanding and appreciation of the historical and cultural heritage of Allendale Township and the surrounding area. Members Patricia Gemmen and Betsy Groendyk contributed to this section. They also serve as curators of the Knowlton House Museum in Allendale. https://allendalehistoricalsociety.weebly.com / 11083 68th Ave., Allendale

The Boston Saranac Historical Society preserving their area history so future generations will take interest and pride in their culture and roots. The society has preserved a 1907 Grand Trunk Railroad depot and caboose to use as a museum of local history. https://www.facebook.com/SaranacDepot/

Jan Brashler

of anthropology at Grand Valley State University’s Anthropology Department. Her professional background is in higher education, historic preservation, and archaeology, with particular interest in the people and cultures of the pre-contact Americas and their descendants. She received her doctorate in anthropology from Michigan State University.

The Cascade Historical Society ensuring that present and future generations will not only know the significance of traditions of the area but also will learn from the past and recognize the need to preserve the historical heritage that has been bestowed upon them. Their holdings include photos, newspaper clippings, journals, diaries, and other memorabilia. https://www.cascadetwp.com/Community/HistoricalSociety-(1).aspx

Matthew Daley is an associate professor of history at Grand Valley State University. His research and teaching focuses on the modern history of Michigan and the Great Lakes region, and he also has a background in historic preservation, exhibit curation, and digital design. He received his doctorate in history from Bowling Green State University.

Wally and Jane Ewing are interested in every aspect of history. They enjoy seeking ways to stretch the boundaries of their research and knocking the dust off what they find. While Wally writes books and articles focused on history, Jane calligraphically scribes artist books about what’s historically important to her.

Kayne Ferrier wrote about the history of water treatment in Grand Rapids while employed at the

She was hired to document the 90 years of sewage treatment in the City of Grand Rapids. The city began

Grand Rapids City Archives and RecordsCenter houses, preserves, and makes accessible the municipal records of the City of Grand Rapids. Their collection dates back to 1838 with the Village of Grand Rapids Board of Trustees proceedings and includes property records, departmental records, maps, and an extensive

Departments/City-Archives-and-Records-Center / mission is to collect, preserve, publish, and disseminate the history of Grand Rapids. Established in 1962, the 13-member commission has published several books and videos established in 1894, is dedicated to exploring the history of West Michigan, to discover its romance and tragedy, its heroes and scoundrels, its leaders and ordinary citizens. GRHS collects and preserves our heritage through lectures, books and education projects.

http://www.grhistory.org / 616-988-5497

The Grand Rapids Public Museum is home to more than 250,000 unique artifacts that tell the history of Kent County, MI and beyond. GRPM houses the only planetarium in the region and is responsible for protecting The Mounds, a national historic landmark. www.GRPM.org / 272 Pearl St NW, Grand Rapids

The Grandville Historical Commission was formed by the city in 1969. In addition to maintaining photo and record archives, it is responsible for the Grandville Museum and the Historic #10 1887 School House. The Museum is located in the lower level of the City Hall, and the #10 School is located in beautiful Heritage Park. https://www.cityofgrandville.com/community1/museum 616-531-3030

The Jenison Historical Association organization working to collect, preserve, and display information and artifacts about Jenison and Georgetown Township. JHA operates the Jenison Museum which offers two open houses a month and a local history room at the Georgetown Township Library. www.JenisonHistory.org / 616-457-4398

Betty Kingma

and director of several historical home tours. Betty is an active member of the Lamont Civic Association, which works to preserve the beauty of the boulevard, the Community Park, and history of the village.

The Lowell Area Historical Museum delight and inspire our community and its visitors through the preservation and presentation of Lowell area history. The Museum uses exhibits, public and educational programming, and historical collections to present the history of Lowell. http://lowellmuseum.org/ / 325 W. Main Street, Lowell

The Lower Grand River Organization of Watersheds (LGROW)

organization that seeks to celebrate our shared water legacy in the Grand River region.

The Plainfield Charter Township Historical Preservation Advisory Committee oversees the operation of the Hyser House Historical Museum and opportunities to preserve the heritage of Plainfield Charter Township in physical landmarks and written and photographic documentation.

6440 West River Drive NE, Belmont / 616-363-9399

The Portland Area Historical Society was organized in 1970 for the purpose of preserving Portland’s historical heritage and for preserving its current history for future generations. Authors Mike Judd and Margaret Sheffer are members of the society. mi.pahs@gmail.com

www.lgrow.org

The Ottawa County Parks & RecreationCommission enhances quality of life for residents and visitors by preserving parks and open spaces and providing outdoor and natural resource-based recreation and education experiences. As of today, the Ottawa County park system is made up of 40 properties, over 7,000 acres, and 150+ miles of trail.

https://www.miottawa.org/parks/

Rochelle Reagan resides in Eastmanville, MI in a century-old, riverfront estate, which she is restoring for all to enjoy. Rollenhagen House and Buwaj Gardens sits on the north bank of the Grand River. Rochelle grew up on an 88-acre working family farm northwest of Coopersville. After earning degrees from Western Michigan University and the University of Michigan, Rochelle spent the bulk of her career as a systems engineer working with mainframe computers on behalf

creates connections

Ferrysburg. Their educational programs, outreach, and museum exhibits interpret the area’s past and present.

has been studying and sharing Michigan’s railroad history for four decades, as a history teacher and in many local history groups including the Grand Haven Dusties. He is a member of the Lexington Group in Transportation History and a board member of the was founded in 1917 with the mission to market the whole of West Michigan as a destination, from the southwestern state line to the Straits of Mackinac and into the Upper Peninsula. WMTA is a nonprofit, privately-funded membership association promoting West Michigan’s tourism industry.

https://www.wmta.org / 616-245-2217

The Kutsche Office of Local History at Grand Valley State University believes local history is vital to promote growth, intercultural understanding, community engagement, and learning. We are a leader in the West Michigan local history community and serve as a resource to support local history organizations’ efforts to preserve the histories of diverse communities in the region. The Kutsche Office was established with a generous gift to the University from Grand Rapids resident and retired anthropology professor, Dr. Paul Kutsche. He dreamed of creating a hands-on history program and Grand Valley State University’s Brooks College of Interdisciplinary Studies with its emphasis on both academics and service offered the perfect location where students from a wide variety of disciplines could creatively blend knowledge with experience.

The Kutsche Office of Local History supports local history and cultural heritage institutions, organizations, and practitioners in West Michigan through expertise, networking, and collaborative projects. Examples of this include our National Endowment for the Humanities Common Heritage grant funded projects, Community: Oceana County life in the twin lakeshore communities of Saugatuck and Douglas, Michigan. Previous Kutsche Office projects also include the collection of oral histories of Asian Americans and Latinos in Holland, MI and urban Native Americans in West Michigan, as well as working with African American and Latino communities in Grand Rapids. These projects in addition to our annual programming—the local history roundtable and fall luncheon— reflect the Kutsche Office’s commitment to giving voice to diverse communities and working with underrepresented communities to tell their own stories.

We value deep community connections with a respect for storytelling to tell the histories of communities throughout West Michigan. These values involve bringing together faculty, staff, students, local historians, and community members to facilitate conversations and develop programs that leverage the lessons learned from the region’s past. Connections Along the Grand River reflects the Kutsche Office’s contribution to the larger mission of the Brooks College of Interdisciplinary Studies and Grand Valley State University to connect the university community and community-at-large through high impact practices and intentional and innovative programming.

Credits

Special Thanks to Michigan Humanities Third Coast Conversations:

Dialogues about Water in Michigan

Vander Veen Center for the Book Fund of the Grand Rapids Public Library Foundation

Grand Rapids Historical Society

Editors

Kimberly McKee