DON’T WORRY, DARLING, ABOUT DON’T WORRY DARLING Maanasi Chintamani

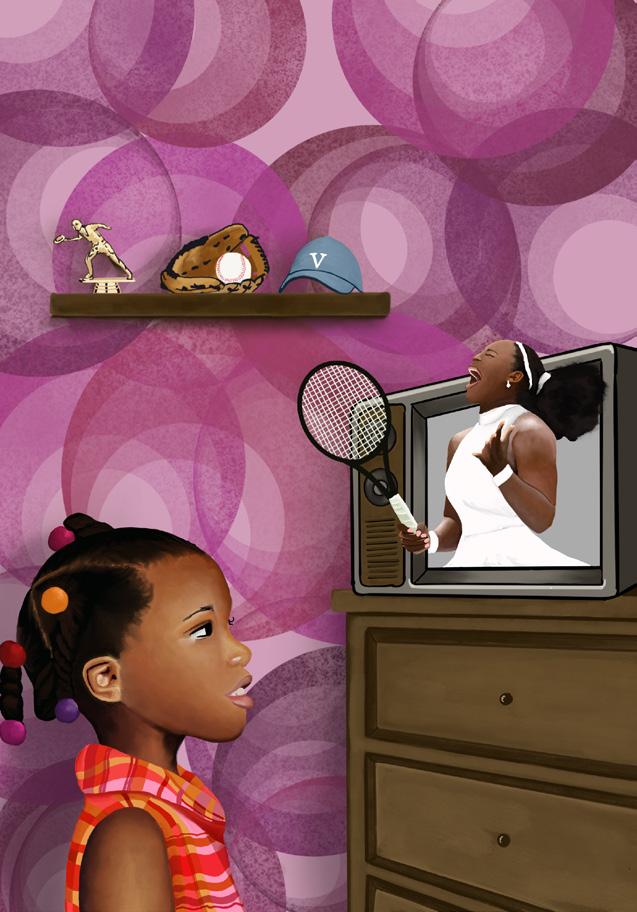

MORE THAN LEGEND: A TRIBUTE TO SERENA WILLIAMS

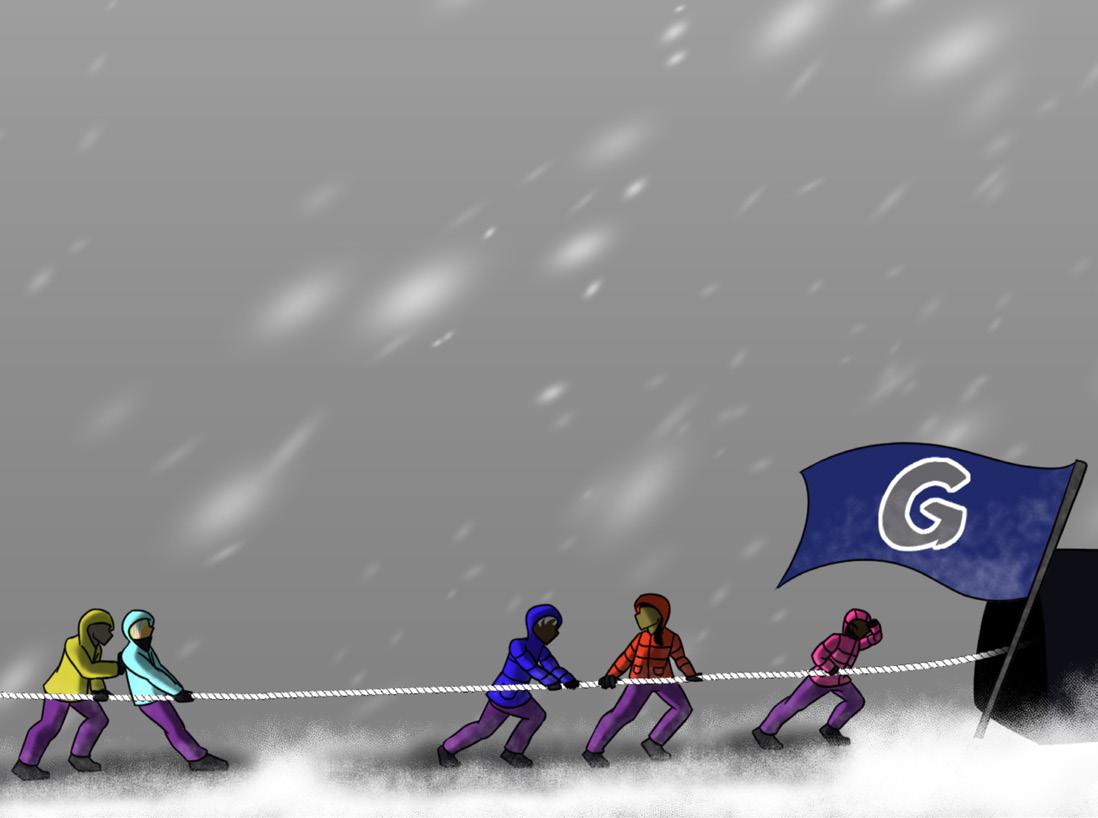

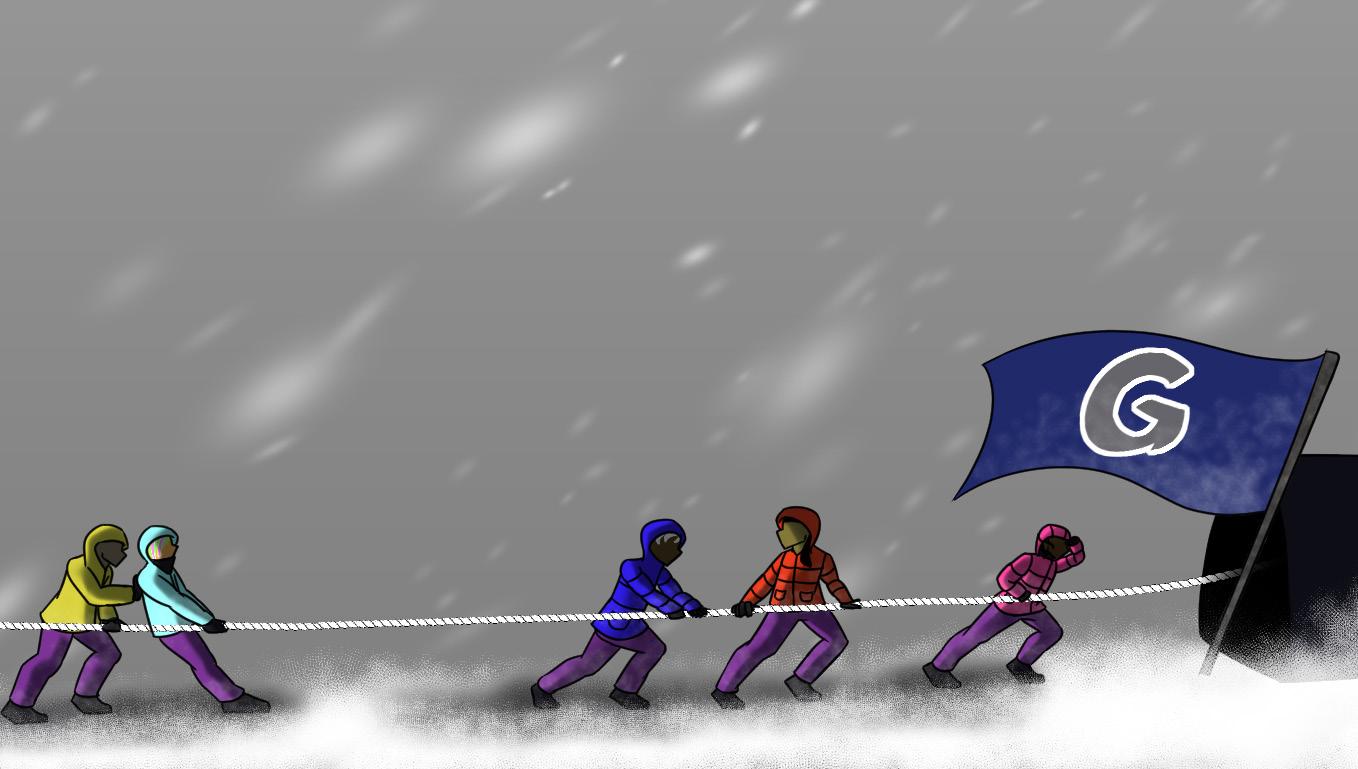

BEYOND INCLUSIVITY: WHY GEORGETOWN MUST BETTER SUPPORT ITS AFFINITY SPACES Yen

By Jo Stephens and

SEPTEMBER 23, 2022

By Amanda

By

Daniel Greilsheimer

Don’t worry, darling, about Don’t Worry Darling MAANASI CHINTAMANI sports

More than legend: A tribute to Serena Williams STEPHENS AND features

All pup and plenty of play makes Jack the Bulldog Georgetown’s best boy

Editor-In-Chief Max Zhang

Managing Editor Annabella Hoge

internal resources

Executive Editor for Resources, Diversity, and Inclusion Andrea Ho

Editor for Sexual Violence Coverage Paul James

Service Chair Devyn Alexander

Social Chair Sarah Watson news

Executive Editor Jupiter Huang Features Editor Margaret Hartigan

News Editor Nora Scully

Assistant News Editors Anthony Bonavita, Joanna Li, Franziska Wild opinion

Executive Editor Sarah Craig

Voices Editor Kulsum Gulamhusein

Assistant Voices Editors Ella Bruno, Lou Jacquin, Aminah Malik

Editorial Board Chair Annette Hasnas

MARGARET HARTIGAN voices

Searching for a smile: Reconsidering trauma narratives in media

AMINAH MALIK news

"To be a truly welcoming campus that encourages the growth of all of its students, we need to maintain affinity spaces designed by the people they are intended to support." us editor@georgetownvoice.com Leavey 424 Box 571066 Georgetown University 3700 O St. NW Washington, DC 20057

After nearly two years of dislodgement, GSP is proudly returning home

JOANNA LI sports Field frustrations: Club sports teams deprioritized

SARAH WATSON sports Aaron Judge’s home run chase restores the mythology of records

NICHOLAS RICCIO leisure

Bad Bunny’s “World’s Hottest Tour” is the perfect summer send-off

ISABEL SHEPHERD

Editorial Board William Hammond, Annabella Hoge, Paul James, Allison O'Donnell, Sarah Watson, Alec Weiker, Max Zhang, Jupiter Huang leisure

Executive Editor Lucy Cook

Leisure Editor Chetan Dokku

Assistant Editors Pierson Cohen, Maya Kominsky, Isabel Shepherd

Halftime Editor Adora Adeyemi

Assistant Halftime Editors Ajani Jones, Francesca Theofilou, Hailey Wharram sports

Executive Editor Carlos Rueda

Sports Editor Tim Tan

Assistant Editors Andrew Arnold, Thomas Fischbeck, Nicholas Riccio

Halftime Editor Lucie Peyrebrune

Assistant Halftime Editors Jo Stephens design

Executive Editor Connor Martin

Spread Editors Dane Tedder, Graham Krewinghaus

Cover Editor Sabrina Shaffer

Assistant Design Editors Alex Giorno, Cecilia Cassidy, Deborah Han, Ryan Samway copy

Copy Chief Maanasi Chintamani

Assistant Copy Editors Devyn Alexander, Donovan Barnes, Jenn Guo multimedia

Podcast Editor Jillian Seitz

Assistant Podcast Editor Alexes Merritt

Photo Editor Jina Zhao online

Website Editor Tyler Salensky

Assistant Website Editor Drew Lent

Social Media Editor Allison DeRose business

General Manager Megan O’Malley

Assistant Manager of Accounts & Sales Akshadha Lagisetti

Assistant Manager of Alumni & Outreach Gokul Sivakumar

support

Contributing Editors Sophie Tafazzoli

Staff Contributors Nathan Barber, Nicholas Budler, Romita Chattaraj, Leon Chung, Elin Choe, Erin Ducharme, Christine Ji, Julia Kelly, Lily Kissinger, Ashley Kulberg, David McDaniels, Amelia Myre, Anna Sofia Neil, Owen Posnett, Omar Rahim, Brett Rauch, Caroline Samoluk, Michelle Serban, Amelia Shotwell, Isabelle Stratta, Amelia Wanamaker

The opinions expressed in The Georgetown Voice do not necessarily represent the views of the administration, faculty, or students of Georgetown University, unless specifically stated. Columns, advertisements, cartoons, and opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the views of the Editorial Board or the General Board of The Georgetown Voice. The university subscribes to the principle of responsible freedom of expression of its student editors. All materials copyright The Georgetown Voice, unless otherwise indicated.

2 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE

PG. 8 Contents contact

September 23, 2022 Volume 55 | Issue 3 4 leisure

5 halftime

JO

DANIEL GREILSHEIMER 6

10

11

12

14 halftime

15

design by elin choe

on the cover “Representation matters” SABRINA SHAFFER 8 voices Beyond inclusivity: Why Georgetown must better support its affinity spaces AMANDA YEN

An eclectic collection of jokes, puns, doodles, playlists, and news clips from the collective mind of the Voice staff.

→ FRANCESCA'S QUIZ

Which pop culture protagonist are you?

Pick things from 2013-2015 and we’ll tell you which of this week’s pop culture protagonists you are with 107 percent accuracy.

1. Pick an accessory

a. A flower crown

b. A black My Chemical Romance rubber bracelet

c. A black choker

d. A “fries before guys” Forever 21 tee

2. Pick a song

a. "Whip/Nae Nae"

b. "All About that Bass"

c. A Hamilton Parody d. "Fight Song"

3. Pick a boyband

a. Big Time Rush b. The Wanted c. 5 Seconds of Summer d. One Direction

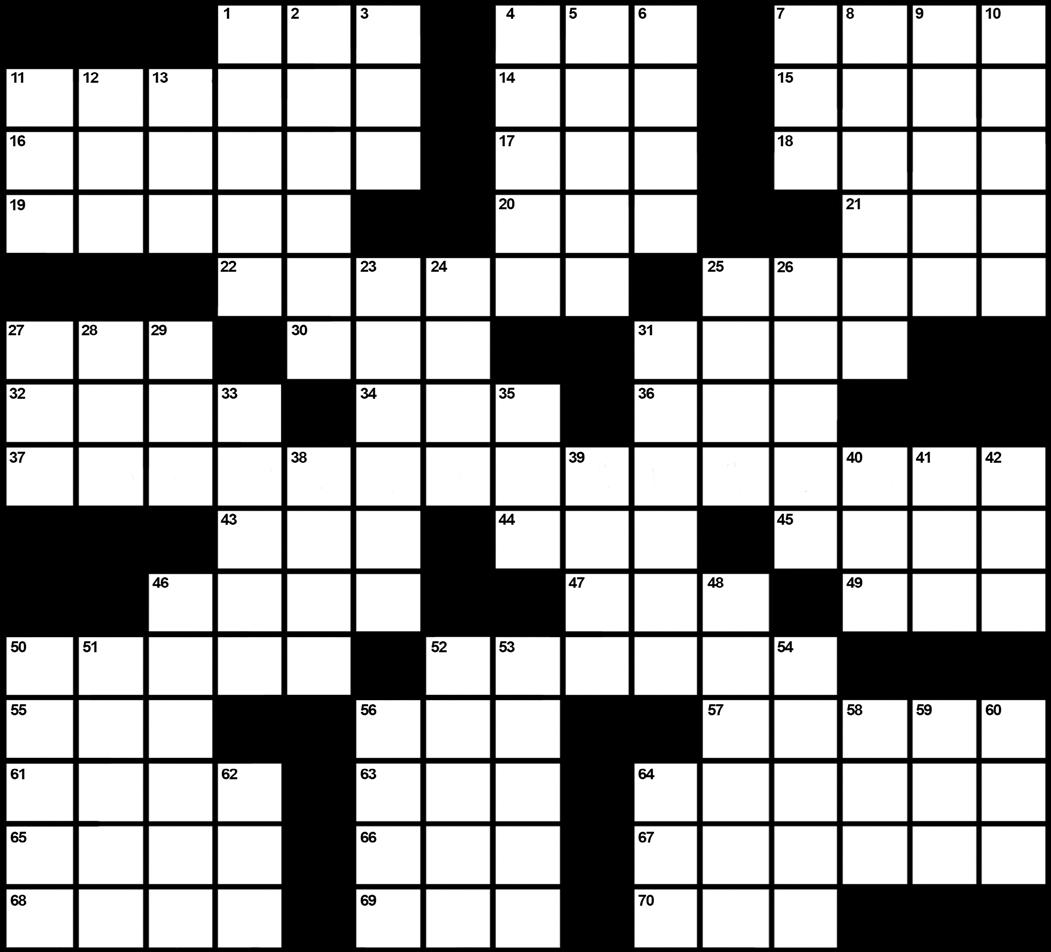

"fish are friends not food" by allison derose, quiz by francesca theofilou; crossword by graham krewinghaus

4. Pick a design. a. Thick Stripes b. Mustaches c. Galaxy Print d. Chevron

5. Pick a ship. a. Jelena (Justin Bieber and Selena Gomez) b. Chocolate milk c. Miso soup d. Straight whiskey

Check your results at the bottom of this page!

43. Wonder Woman actress Gadot Muhammad or Mahershala Wife of Abraham Sweet potatoes Granola grain A bull's least favorite color Native New Zealander Fictional swine of a timid disposition and affinity for acorns Noah's craft What several social media platforms now allow you to do to a comment Premiere class of gasses Clairvoyant Unsuccessful candidate: also-___ Sleep breathing problem, to a Brit Part of YOLO ___Medical Fictional tiger who bounces and refers to himself in third person plural Houston in “Houston, we have a problem” In favor of Dash lengths appropriate when describing a range

DOWN: Follow, as chaos Prolonged attacks from all sides According to Complete and total River through Lyon Require Gorilla is a great one Cosmetic cream that may contain 32-across

Okaygirlbossqueen!Slayiconlegend!Noteveryonehasthecouragetowearasemi-ironic“friesbeforeguys”tee,goodonyou!Youareaninspirationtousall.

parodyaboutthe2016election,itwassooriginalandprofound,especiallyknowingthatyouhadtomemorizetheentirething,sinceyoucan’tread.MostlyD’s:OliviaWilde.

ofgirlwhotiesuphermessybun,wearsglassesaroundhersparklingbrownorbs,andlistenstoMCR.MostlyC’s:LeaMichele.Goldstarsallaround!IlovedyourHamilton

that“thereisnoQueenofEngland!”ButIseeyou!Youareproper,elegant,andpoised,butyoualsolovetojamout.Thedichotomyofman!MostlyB’s:TrishaPaytas.You aresoooquirkyandnotlikeothergirlsatALL!Honestly,lifewithyouiscrazyyyandthat’sawesome.Showoffthatmustachephonecasesoeveryoneknowsyou’rethekind

MostlyA’s:QueenElizabeth.It’shardtofeelvalidandvisiblewhensome—likethevillainofthegeneration-defining2010animatedclassicMegamind—havestated

9. Climb, as a peak or a horse Glimmer Tie the knot Radio personality Glass Snare Sings like viral Walmart boy Outstanding, as charges Brim Cat's calls "That's the spot!"

28. Seasonal virus for which GU has a free vaccine clinic on Tuesday ¹/₃ to ¹/₄ the weight of a baby whale Of the air, as gymnastics or photography Painter Degas Black sheep’s exclamation, infamously Mr. Robot actor Malek Plumbing problem Rower’s need Raw rock "Dear old" guy Country types, derisively Garden variety bowling, in most of the US ____-Dixon Line Large venue The ivories, in a weird phrase tickling Fun kind of Picker-upper-thingies Instructor, for Quagmire or Bruce, Spike, Mr. Potato Head piece Shaggy Scandinavian rug Gobbled

3SEPTEMBER 23, 2022 Page 3

publicly

44.

45.

46.

47.

49.

50.

52.

55.

56.

57.

61.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

10.

11.

12.

13.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

29.

31.

33.

35.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

46.

48.

50.

51.

52.

involving

53.

tube 54.

56.

short 58.

wetland 59.

or Harper 60.

62.

64.

up ACROSS: 1. Sixth sense 4. Vessel for ashes or carnations 7. Charitable donations 11. With 14- and 15-Across, fictional bear who loves "hunny" and Christopher Robin 16. Tip for test-takers? 17. It's easily stubbed 18. Decorative sewing case 19. Problem-solve, in programming 20. Conclude 21. Resting place 22. Fictional donkey with a detachable tail and glum attitude 25. Celebration in "Fortnite" 27. Toward the stern 30. What to do to seeds 31. Arabian Sea gulf 32. Soothing succulent 34. Interior Secretary Haaland 36. Swelled head 37. Residence of four of this puzzle's answers in a children's series → ALLISON'S DOODLE → GRAHAM'S CROSSWORD "fish are friends not food"

DON ,T WORRY, DARLING, about DON ,T worry darling

BY MAANASI CHINTAMANI

From Top Gun: Maverick to Elvis, films this year have achieved both box office success and cultural relevance, generating buzz from highbrow critics and Twitter memes alike. This feat has become more difficult than ever—with streaming and increasingly personalized algorithms fragmenting entertainment consumption along micro-demographic lines, media is rarely so universally seen and discussed. However, in 2022’s post-pandemic landscape, that trend appears to be reversing, and one film has particularly stood out for its dominance of the zeitgeist: Don’t Worry Darling

Leading up to the film’s release, fans, critics, and reporters flooded timelines and tabloid covers with endless questions and salacious headlines: Did director Olivia Wilde leave ex-fiancé Jason Sudeikis for actor Harry Styles? Did Styles really just spit on castmate Chris Pine? Do Wilde and lead actress Florence Pugh hate each other? And, most importantly, should we be worried, darling?

Allow me to reassure you: Beyond the gossip and noise, there’s no cause for concern. While Don’t Worry Darling is far from the thought-provoking

justice to none of them, largely due to the erratic pace of the film’s storytelling—the plot’s rising tension escalates in a stepwise fashion, leading to significant lulls before each all-too-rapid heightening in conflict, culminating in a rushed, unsatisfying conclusion that leaves viewers with unresolved questions.

While the cast, and particularly Pugh, delivers consistent, persuasive performances, the script flattens some supporting characters, especially Styles’ Jack, stripping depth from roles with real potential. Styles excels when performing pure emotion but falters when faced with nuance, leaving some scenes feeling either like exaggerated SNL sketches or low-effort table reads. Nevertheless, Pugh’s superb acting, along with the film’s compelling premise and well-executed production, more than compensate for these occasional shortcomings.

In a now-viral moment during the film’s premiere at the Venice Film Festival, Styles observed insightfully that his “favorite thing about the movie is, like, it feels like a movie.” While the quote, out of context, sounds incredibly stupid, it actually captures Don’t Worry Darling’s greatest strength: the immersive viewing experience it creates. The film excels at world-building, convincingly crafting a too-good-to-be-true, always-sunny utopia filled with impeccably groomed men and equally chic housewives blissfully flitting between the pool, the mall, and the kitchen.

John Powell’s soundtrack perfectly complements the film’s tone—saccharine 1950s tunes juxtaposed against increasingly ominous imagery emphasize the discrepancy between Alice’s peaceful quotidian life and the sinister hidden reality. As the plot progresses, the film’s decadent visuals guide viewers along Alice’s journey; at first, the characters’ wellappointed homes and stylish outfits signal luxury and relaxation, while the neighborhood’s manicured lawns and meticulously organized layout feel spacious and inviting. Yet by the end, as Alice’s world increasingly closes in on her, those same elements instead appear stifling and artificial.

Styles’ movie-that-feels-like-a-movie spiel rings particularly true during the film’s most ambitious moments, including a climactic car chase and an opulent 1920s-themed soiree. As Styles put it, Don’t Worry Darling has all the makings of a “go-to-thetheater film,” but ongoing negative press coverage and reviews may dampen Wilde and Warner Bros.’ box office expectations.

Innocuous jokes and serious scandals alike have plagued the film since the outset. The drama started with paparazzi pictures of Wilde and Styles looking coupley, on and off set. Observant (and nosy) fans questioned the timeline of their relationship

life reeks of double standards, as male directors experiencing off-screen turbulence regularly enjoy the privilege of separating their professional and personal lives. Nevertheless, the love triangle narrative came to a head in May when Wilde was served custody papers onstage at CinemaCon while pitching Don’t Worry Darling to movie theater owners, a public spectacle that solidified the intertwining of the film and Wilde’s private life.

Furthermore, in recent months, much has been made of Pugh’s apparent reluctance to promote Don’t Worry Darling on social media, as well as her refusal to participate in any premiere events aside from walking the red carpet at Venice.

The most concrete insight into the purported tension emerged when Wilde discussed the departure of Shia LaBeouf, the actor originally cast to play Jack. Wilde claimed she fired LaBeouf because Pugh was uncomfortable working with him, but LaBeouf immediately refuted this narrative, releasing receipts ostensibly showing he quit of his own volition against Wilde’s wishes. Regardless of the logistics of his departure, LaBeouf was out, and Styles was hired instead.

Months after his exit, LaBeouf was sued by his ex, musician FKA Twigs, for alleged physical, mental, and emotional abuse, raising further questions about his conduct in general. If LaBeouf’s behavior and Wilde’s handling of the matter were indeed factors in Pugh’s strained relationship with the film, the stakes are significantly higher than mere tabloid gossip. While some aspects of the drama (like the now-debunked spitting debacle at Venice) are genuinely funny, the nonstop chatter and memes, particularly about the LaBeouf situation, epitomize social media’s tendency to trivialize serious topics.

Some say all press is good press, but when headline-grabbing rumors are accompanied by unfavorable reviews, even the most inquisitive audiences can be deterred. Despite its shortcomings, the film is ultimately enjoyable, although it remains to be seen whether that will be enough for Don’t Worry Darling to channel its notoriety and star power into tangible sales. If not, at least it gave us a few entertaining weeks on the Internet. G

design by muna aden; layout by max zhang

LEISURE

More than legend: A tribute to Serena Williams JO STEPHENS

When Serena Williams stepped onto Arthur Ashe for the final tournament of her career, cheers from a sold-out crowd rumbled across the U.S. Open stadium as her daughter Olympia looked down from the stands. Olympia had white beads braided into her hair—a callback to her mom’s first U.S. Open, over two decades ago.

Those white beads have become a symbol of sea change and the women who wore them international icons. From the moment Serena and her older sister Venus entered the world of tennis, it was abundantly clear they were something extraordinary—in 1997, Serena became the lowestranked player (No. 304) to upset two top-10 opponents in one tournament, and Venus became the first unseeded player to reach the U.S. Open women’s final since 1958. The record-setting would only keep coming. With Serena’s career at its close, there is nothing she deserves more than celebration for both her accomplishments and what she means to people—and that recognition can only start back in Compton, California when three-year-old Serena first picked up a racket.

Serena and Venus’ father, Richard Williams, was the lead architect behind their meteoric rise. Spending hours with his daughters on Compton’s public courts, Richard used his own coaching philosophy, incorporating drills developed from watching hours of tennis while simultaneously preserving their education and a relatively normal childhood.

In 1991, the Williams’ family relocated to Palm Beach, Florida where Serena and Venus attended the Rick Macci Tennis Academy until their professional debuts. Venus began her career in 1994, paving the way for Serena to follow in 1995.

Serena has spoken extensively about the impact Venus had on her development. Throughout their childhood, Venus molded Serena’s character and playing style as her chief competitor; she instilled an underdog, “little sister” sentiment in Serena. She set a wonderful for Serena, fighting for equal pay at Wimbledon and illustrating how to confront racist resentment from fans at matches. The bond between the Williams sisters extended on and off the court, and success struck for both. In her final on-court interview, Serena battled tears: “And I wouldn’t be Serena, if there wasn’t Venus. So thank you, Venus! She’s the only reason that Serena Williams ever existed.”

In 1999, Serena broke through at the U.S. Open with a stunning two-week performance, which produced her first Grand Slam singles title. Over her 27 years of dominance, Serena won an Open Era record of 23 Grand Slams, the last of which

came at the 2017 Australian Open while eight weeks pregnant. Her list of accolades also includes 14 Grand Slam doubles titles (all of which partnered with Venus; together, they were undefeated in major finals), two mixed doubles Grand Slam championships, and four Olympic gold medals. Serena holds the career Grand Slam (one of only nine women to have won all four majors in her career) and has completed the “Serena Slam” twice (winning all four of the Grand Slams consecutively over two calendar years).

On a technical basis, Serena has revolutionized women’s tennis. Her fierce serve was one of history’s most dominant, beautiful shots and has inspired today’s female tennis players to develop 120-plus mile-per-hour serves. With Venus, she turned

composition of the sport, opening pathways into tennis for young Black girls—the Naomi Osakas, Sloane Stephenses, and Coco Gauffs of today. They proved not only that Black women could be represented in tennis, but also fought fiercely for their public respect and pay equity.

Gauff, the 18-year-old phenom who’s quite possibly the future of American tennis, wrote in an Instagram post, “Serena, THANK YOU. It is because of you that I believe in this dream.” Earlier in the tournament, Gauff said, “Growing up, I never thought that I was different because the No. 1 player in the world was somebody who looked like me.”

Serena’s impact goes beyond just Black women; she has inspired countless athletes to begin their careers and has earned respect from players across the sporting world through her competitive play and outspokenness.

“What you have done for the sport of tennis, what you've done for women, and what you've done for the category of sport, period, is unprecedented,” basketball superstar LeBron James said of Serena. “Win, lose, or draw, it didn't matter, we all knew that you were the greatest.”

The commitment to women and people of color is evidenced by Serena’s plans for her “evolution,” a term she prefers to “retirement.” Her brand, Serena Ventures, founded in 2014, has invested in more than 60 startups created by members of those communities with the goal of business empowerment. Other financial endeavors include S by Serena, a sustainable fashion brand, and minority ownership stakes in the NFL’s Miami Dolphins and the NWSL’s Los Angeles-based Angel City FC. She also has a lifetime sponsorship from Nike and deals with Gatorade, among other brands. In addition, Serena will no-doubt continue to have a strong presence in popular culture; she recently made several appearances at New York Fashion Week and will be releasing a children's book in late September. Simply put, Serena has shown no signs of slowing down.

Her tennis career, though, has come to an end. There was Serena, hair laden with tiny, twinkling diamonds, taking her final post-game twirl and beginning the process of “evolving away” from the game of tennis. From the first game of her career to its eventual end, she was a fighter; she saved an incredible five match points before eventually falling in a bruising, three-hour final match against Australian Ajla Tomljanović. Really, it was this tenacious match— this moment—that encapsulated all Serena has brought to the game, and all that she is.

Serena’s game was gritty, and it was graceful. Her play was powerful, and persistent, and, most of all, unapologetic. Whether it was 1995 or 2022, Serena gave this sport her all, and because of that commitment and sacrifice, she has firmly cemented herself as nothing short of an icon. Her career may have ended, but her legend will persist. She is Serena Williams, the girl from Compton who picked up a racket at three and, at 40, put it down as the greatest of all time.

Max Zhang contributed to the writing of this article. G

5UPDATE PUB DATE SPORTS SEPTEMBER 23, 2022

BY

AND DANIEL GREILSHEIMER design by dane tedder HALFTIME SPORTS

All pup and plenty of play makes Jack the Bulldog Georgetown’s best boy

BY MARGARET HARTIGAN

You saw him at the Welcome Back, Jack BBQ. You’ve seen him on your walks to White-Gravenor, or through the window of the yellow house on the corner of 36th and N St. (if you have the misfortune of living in LXR). You may have even seen him at a basketball game or two. Jack the Bulldog, Georgetown’s canine-inresidence, is well known on campus.

“He’s like your furriest first welcome to Georgetown,” Justin Iorio (SFS ’20), a former member of Jack Crew, our mascot’s highly prestigious entourage of caretakers, said.

We all know Jack. But do we really know Jack?

From puppyhood to retirement, the life of Jack the Bulldog is far more eventful than that of most dogs. For Jack, greeting students, posing for photos, and performing tricks on and off campus are a part of daily life. But how he became the busy bulldog we know today is a century-long saga that continues to this day.

Though ‘Hoya Saxa,’ (Latin and Greek for “what rocks?”) has been Georgetown’s rallying call since the end of the 19th century, the university has never adopted a rock mascot, instead opting for a long line of dogs.

The canine tradition began when soldiers returning from World War I brought a terrier named Stubby back to campus from the French trenches, the dog having garnered some awards for battlefield heroism. After his passing, Stubby was succeeded by another terrier, who was followed by a Great Dane.

The first bulldog mascot did not arrive at Georgetown until 1962, where he was supposed to go by ‘Hoya’ instead of his original name,

refused to respond to ‘Hoya,’ instead only accepting the nickname ‘Jack.’ Since then, Jack’s identically named successors have continued to represent Georgetown.

“Bulldogs are stubborn and persistent and hardworking—values that I think were seen as very similar to Georgetown students,” Iorio said.

In the late ’70s, Georgetown seemed to transition away from the live dog tradition and made history as one of the first schools to incorporate a ‘human mascot’—a person dressed in a bulldog costume—into sporting events and celebrations. But Jack the Human couldn’t replicate the sense of community that rallies around Jack the Bulldog.

In 1999, after a number of years without an actual bulldog, student activists called for the return of a live bulldog mascot and the university resumed the tradition.

“[Jack is] a real-life part of the community, which I think is a really special thing,” Iorio said. “The dog is happy to see you, whether you’re a student, or whether you’re alumni or you’re visiting.”

Most Jacks spend five or six years as the official mascot, with puppy training before the job and a lengthy retirement. Students today interact with the eighth iteration of Jack the Bulldog.

“I really like the bulldog as a mascot. I think that they’re well-tempered and good dogs to have,” said Maya Hambrick (COL ’22). “I think that’s probably why a lot of schools have bulldogs, because they’re great, and they’re so cute and good with people.”

Jack is no longer a nickname for Royal Jacket, as each successive mascot has his own official name. The current Jack is ‘IROC Casagrande John F. Carroll.’

The Jack Crew gives each bulldog a nickname, too. “[The current one] is Puppy Jack or P.J. Then there was Old Jack, which is the one previous, and then J.J.,” Amelia Smith (COL ’22), another former member of Jack Crew, said. “It’s very unofficial.”

In collaboration with Jack’s official university caretaker, Cory Peterson, members of the Jack Crew share the responsibility of taking Jack on his three daily walks—at 10 a.m., 1 p.m., and 4 p.m.—and making sure that Jack is always safe and comfortable on such excursions.

Jack Crew members often act as university

representatives, tour guides, and semiprofessional dog handlers, helping to keep up his training when on Jack duty.

“When you’re in charge, you handle Jack, you greet people, you answer questions. Anything that comes up—whether it’s greeting an unfamiliar dog or a small child runs up and grabs on to Jack’s face—that is your responsibility,” Smith said.

Smith, Hambrick, and Iorio all went through an intensive application process to join the Jack Crew. The process typically consists of a written application, a video submission, a dog walk, and an in-person interview round with Peterson, as well as some active crew members. Although countless students apply for the exclusive club, there are usually only six crew members at a time so that they can better bond with Jack and form a close community with one another.

The crew helps maintain Jack’s training by posing him for photos and videos, keeping him calm, and leading him through tricks at events and games. According to former members of the crew, being a member is a big commitment.

“It really is a labor of love being on the crew. It’s hard work at times. Sometimes there are days where you do have two, three walks a day, maybe also an event. Your whole day sometimes is encompassed by Jack,” Smith added.

Each Jack has a unique personality and skill set. Old Jack—who served from 2013 until 2020—was famous for riding a skateboard at basketball games. Puppy Jack, the current mascot, more often rides a small remote control though he trains on the skateboard as well (he can now get two paws on the board).

“He’s slowly getting the hang of it. Certain dogs just really take to skateboarding. You get him on the skateboard,

illustrations by olivia li & grace nuri; photos courtesy of janice hochstetler

illustrations by olivia li & grace nuri; photos courtesy of janice hochstetler

FEATURES

and then they figure out how to shift their body weight,” Smith said. “And it’s like, ‘Whoa! That’s just so cool!’”

Other Jacks have popped balloons and chewed up cardboard boxes with images of other teams’ logos on them at events.

Training a new Jack in a range of skills is a challenging, lifelong process. Janice Hochstetler, a professional dog handler and parent to Georgetown alumni, occasionally travels from California to campus to help with Jack’s training and was primarily responsible for breeding and training the three most recent Jacks from infancy. That training begins in Hochstetler’s California home until the dogs are ready for the demands of the Hilltop. The current Jack arrived on campus when he was six months old, shadowing the previous mascot until ready to take over all duties.

“You want to start socialization and training super early on to instill a positive association with all the things that he’s going to come across in life,” Smith, who has experience in dog training and showing, said.

The most recent Jack was born to a Canadian breeder, as Hochstetler was not breeding bulldog puppies at the time when Georgetown needed a new Jack. While she speaks fondly of her love for dogs, Hochstetler described the process of raising bulldog puppies as “a lot of work.”

“You’re up every two hours from birth until they’re about four weeks old, helping [the mother] nurse those puppies 24/7. That’s how you know their personality because you spend as much time with them as humanly possible,” she said.

Some students have critiqued the university’s choice to buy a purebred bulldog from a breeder rather than rescue a dog in a shelter. But Smith pointed out that the requirements and demands placed on Jack from a young age would be unfair to a rescue dog. Jack is constantly interacting with humans, often in ways that are stressful for most dogs, and that could be exceptionally harmful to a rescue, Hochstetler added.

“People do things to Jack they wouldn’t do to any other dog. I mean if you saw a dog in the street, you would never walk up and touch it without asking the owner. People do that to Jack all the time,” Hochstetler said.

Hochstetler recommends that students approach Jack from the front and pet or scratch him under his chin and take on a non-dominant position so as not to intimidate him. Fans of Jack should also know that he loves back scratches.

A salient ethical concern over the breeding of bulldogs centers on dog health. Due to

their biological makeup and inbreeding, bulldogs are prone to respiratory issues, and 90 percent of bulldog puppies are delivered via a cesarean section due to their large heads.

Several of the University of Georgia’s bulldog mascots have died prematurely due to various health complications.

Georgetown’s bulldogs have also faced health issues. Both Jack Jr. and Old Jack were delivered by C-section. And Jack Sr., who was active before Jack Jr. between 2003 and 2013, tore his ACL jumping off a couch in 2012.

During his active years as mascot, Old Jack had part of his tail amputated for health reasons.

“He had to have his tail removed nobody noticed,” Hochstetler said. The same gene that can cause spina bifida in humans, according to Hochstetler, makes bulldogs flatfaced and short-backed.

“One of the side effects is they have a screwtail [like a pig] sometimes,” she explained. “If it is out, it’s fine. But some of them start kind of growing in, like screwing in, and then it’s painful for the dog, and they just removed the little last end of it under anesthesia.”

After spending the last several years retired from his official mascot position, Old Jack died of cancer this past spring while in the guardianship of his caretaker, McKenzie Stough.

The current Jack has so far not seemed to suffer the medical problems of Old Jack and Jack Sr. “We got a great puppy. This breeder is great. It’s really about who you get your puppy from,” Smith said. “He is super fit. Watch him run across the court next time you’re at a game, and just see how fast he moves.”

Jack Jr., who preceded Old Jack, remains alive and well and now lives with a family in Virginia. He held the position for only about 15 months, less time than other Jacks, having retired following an incident involving a minor injury to a child.

“He didn’t bite anybody. He jumped up and got excited, and his tooth made contact, but it wasn't a bite,” Hochstetler said.

While Jack Crew members say each Jack has been a good dog in his own way, Puppy Jack seems much better suited to the job than some previous mascots.

“This Jack is super outgoing. He’s really social and personable, and likes the student interaction and the previous Jack, not so much,” Smith said. “This Jack is a lot more fit for the job.”

Puppy Jack, like Old Jack before him, lives in a townhouse off campus; previous Jacks lived in the dorms and could be overwhelmed by the near-constant student traffic. Both on and off campus, Jack Crew students interact with Jack regularly and enjoy his company. For

paw print cookies.”

Though Jack is essential to campus culture, other Georgetown dogs have gained notoriety too. Crouton is a three-legged dog who resides with Professor Elizabeth Grimm, a faculty member in residence with her family on the first floor of McCarthy Hall. He is often the recipient of adoration during his daily walks, on social media, and even among certain student clubs.

“He doesn’t play favorites among groups, although GUGS has a bit of a built-in advantage when it comes to Crouton’s attention,” Grimm wrote. While Jack and Crouton have been neighbors for years, they “haven’t had much close interaction.”

But while Crouton is undoubtedly wellloved on campus, members of Jack’s crew think there’s something special about the bulldog as Georgetown’s primary canine representative. For current students, faculty, staff, and alumni, there seems to be near-universal adoration for Jack.

“It’s a real way for people to still connect

SEPTEMBER 23, 2022layout by graham krewinghaus

BY AMANDA YEN

We called NSO “The Blizzard.” It was the weekend the white kids appeared on campus, the event that suddenly shunted us to the margins. From then on, we—the 20 new students in Young Leaders in Education About Diversity (YLEAD), Georgetown’s pre-orientation program for new students passionate about “diversity and social justice”—would feel our marginalized identities in everything we did. We’d feel them in every room we walked into, every person we talked to, every small aggression directed our way. The Blizzard was the moment Georgetown stopped letting us exist so much as people and more so as the labels ascribed to us: Black, white, Asian American, Indigenous, Latiné. Queer and nonbinary at a Catholic university. Disabled on a highly inaccessible campus.

I didn’t go to most of my New Student Orientation (NSO) programming. It wasn’t for lack of enthusiasm—I’d been dreaming of the brick and cobblestone of Georgetown all summer long. My absence at NSO had more to do with what I learned the week prior in YLEAD. My transition to Georgetown was guided by the program’s peer leaders—eight former YLEAD participants—who framed the end of the program and the beginning of NSO as The Blizzard. In doing so, they primed the other YLEADers and me for an adversarial relationship with the rest of our freshman class before we’d even met them. They wanted to prepare us for what they understood as the reality of Georgetown: the chasm that separated us from everyone else.

Some of what they said about The Blizzard was true. After YLEAD, I felt as though I had

been dropped into a completely different Georgetown. I felt passed over by white peers who, although well-meaning, didn’t think they’d have anything in common with me because of what I looked like. A friend of mine said it was like being looked through instead of looked at, as though we didn’t exist with the same substance as the white kids on this campus. I heard horror stories from other dorms—slurs tossed at students of color, casual racism coming from peers and professors, institutional ambivalence to our trauma.

As a result, I felt unmoored as the YLEAD space naturally faded over the semester, and it became painfully clear that Georgetown was a predominantly white institution (PWI). There was no longer a designated, easily accessible space to unpack the racial dynamics I was experiencing at Georgetown, causing me to bottle up my confused emotions or vent to people who weren’t ready for these conversations. All of this made me understand how important the YLEAD space was for me, and how necessary it would be for future students of color. During my sophomore year, I came back to the program as a peer leader, and as a junior I was co-coordinator. YLEAD consistently gave me the language to understand myself and how I fit into the world. It gave me a community of some of the best and brightest people I know. But as a co-coordinator, I was faced with questions about the program that I had never grappled with before.

To start: Who is YLEAD for? The answer seemed obvious: It’s for diverse people. But what does it really mean to be diverse? According to Center for Multicultural Equity and Access (CMEA) leadership, YLEAD was designed by

a white man over 20 years ago as a space for all the “diverse” people—those who didn’t fit the wealthy, white, Christian, cis, and hetero boxes—to amass. While the origin of YLEAD demonstrated a desire to include marginalized students in pre-orientation programming, the success of the space depends on more than inclusion. We need to radically and intentionally reimagine what successful affinity spaces should look like, and the conditions must be set by the people they’re made for.

One of the problems of redesigning a space like YLEAD is that the program relies on staff member roles with low retention rates. Low retention isn’t specific to the program, but is a larger issue that has manifested across studentfacing centers at Georgetown. One of the reasons there wasn’t a YLEAD for the class of 2026 is that the YLEAD staff supervisor in the CMEA left for a job with better compensation and work/life balance. The CMEA is home to multiple-degreeholding professionals who are underpaid for the kind of work they do, leading to a high turnover rate. This is particularly concerning considering the largely peerless work that the CMEA does on campus for Black, Indigenous, and students of color, which includes advising multiple affinity organizations, creating community spaces, and providing resources. These opportunities are essential, and could be strengthened with a greater investment in staff wellness and support.

The problem of high turnover and staff labor gaps persists in other student-facing centers on campus. Staff turnover in the Center for Student Engagement (CSE), for example, pushed CSE Associate Director Vanice Antrum into advising the Leadership & Beyond pre-

graphic by elin choe; layout by dane tedder

8 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE

orientation program in August, even though this was not her direct responsibility. The CSE role of Director of Orientation, Transition, and Family Engagement—which oversees programming such as NSO, Georgetown Weeks of Welcome, and Parent and Family Weekend—has remained vacant since the last director’s departure a week before NSO. Patrick Ledesma, the new Director of the CSE, advised NSO this year because of that absence, covering the labor gap at the last minute. Student affairs staff genuinely care about supporting students, so they step in to meet labor needs, but Georgetown capitalizes on that spirit of goodwill under the banner of “Hoyas for others.” If Georgetown’s upper administration truly valued its staff members, they would better compensate them not only with higher wages but also with better opportunities for wellness.

Faced with these gaps, students often end up filling labor needs, and they don’t always get the appropriate training to do so. In spaces like YLEAD, student leaders can bring their own unresolved traumas about Georgetown into the pre-orientation space, and may unintentionally project them onto new students. Trauma is an inevitable part of existing as a marginalized student at a predominantly white and wealthy institution, but somewhere along the course of its 22-year run, YLEAD became a reproductive site of student trauma, leading to new students believing they did not belong at Georgetown.

I was ashamed to learn later in 2021, when I was coordinator, that many YLEADers were doubting whether they had made the right choice of college. Just as I had in my freshman year, they feared that this institution would not care about our community, and that they would be ostracized from circles of student life because of identities they could not change. Against our best intentions, YLEAD left its first years feeling that they would never be full participants in campus life.

Now, in my senior year, I understand that this narrative of exclusion is far from the truth. Yes, there were ups and downs in the time I’ve had here, moments of catastrophe and trauma that I wish had never happened, but there have also been moments of joy and triumph, moments when I knew this was where I belonged. They happened in unexpected places—in a Harbin double late at night, in the sticky living room of a Burleith townhouse, at the waterfront at sunset on the first day of summer. It took time, but I feel like a part of the Georgetown community in a way YLEAD initially led me to believe that I never would.

But inclusion alone is not enough to help marginalized students feel at home on campus. It isn’t enough to include us in competitive clubs and societies, or to feature us as speakers at commencement and convocation. Marginalized Hoyas—specifically those who identify as Black, Indigenous, and/or people of color—need our own affinity spaces supported and maintained by the university from semester to semester and from year to year.

In spite of the problems with YLEAD’s implementation, it does allow students of color to safely debrief their experiences on campus away from their white peers. Affinity spaces like YLEAD are crucial at PWIs because there are aspects of BIPOC student experiences that can only be shared comfortably with those who carry the same marginality. In navigating power relationships often skewed against us, we need these affinity spaces to make sense of what happens to us, to be affirmed in the ways that these relationships affect us, and to collectively

be briefed on the historical contexts of the roles they step into, so that they will understand the historical needs of students and how best to support them in the present.

The post-pandemic transition bred at least one new effectively designed affinity space: the Cookout. This overnight retreat for Black students was conceived last spring by four Black student leaders: Veronica Williams (COL ’23), Annaelle Lafontant (SFS ’23), Saleema Ibrahim (SFS ’23), and Kwabena SekyereBoateng (COL ’23), three of whom are former YLEADers. They designed the Cookout around Black joy and community building, physically removed from the Hilltop at the Calcagnini Contemplative Center. The Cookout’s success is owed to the values of its four co-coordinators, who used their experiences as ESCAPE leaders, pre-orientation organizers, and Black student organization board members to create a space of uplift and radical hope rather than trauma rehashing. Its success is likewise inseparable from its partnership with Campus Ministry and the funding provided by it. That such a space is not only possible but actual, and that it has been achieved with Campus Ministry’s support, reveals which parts of campus Georgetown’s administration values and which it has relegated to the periphery.

organize both healing and resistance. YLEAD is not the only affinity space on campus; others include the Black House and La Casa Latina, both also operated by the CMEA. In the 20192020 school year, there was an Asian American Home on Magis Row, which sought to provide an affinity space for Asian and Asian Americanidentifying students. That designation on Magis Row, however, was temporary, and there hasn’t been an AA Home since.

Many of the traditions that were strong within BIPOC student circles on campus were disrupted by the pandemic. The loss of student tradition, coupled with the staff turnover intensified by the pandemic, has led to a compounded loss of momentum and navigational knowledge of the institution when it comes to BIPOC student organizing. In order to resist this institutional inertia, we need detailed and accessible documentation of students’ organizing strategy—how they navigated administrative dynamics, built solidarity with staff and faculty, engaged other stakeholders, and so on. New staff members should likewise

Even so, the Cookout is not institutionalized in the same way that other retreats are. It has no official staff program coordinator employed full-time by Campus Ministry, meaning that once the current student coordinators graduate in May, there’s no guarantee that the Cookout will continue. Students have organized countless times for more support of marginalized students, but our efforts can only go so far without the support of the administration and the staff who supervise programs for marginalized students. Affinity spaces like the Cookout and YLEAD are meant to welcome students who represent some of the most vulnerable populations at Georgetown, but without an intentional commitment to the well-being and development of these students and the spaces meant for them, Georgetown is complicit in their marginalization.

We need a complex inclusivity that goes beyond having students of color merely represented in the clubs and organizations around Georgetown. To be a truly welcoming campus that encourages the growth of all of its students, we need to maintain affinity spaces designed by the people they are intended to support. That means the upper administration at Georgetown must fund and systematize these programs so that institutional memory isn’t lost in the transition between student leaders and the staff members who advise them. Only once we’ve established long-standing institutional support for BIPOC student organizations can we imagine a Georgetown that is truly a community in diversity. G need to radically and intentionally reimagine what successful affinity spaces should look like, and the conditions must be set by the people they’re made for.

9SEPTEMBER 23, 2022

We

Searching for a smile: Reconsidering trauma narratives in media

BY AMINAH MALIK

BY AMINAH MALIK

For you, a thousand times over.

This iconic sentence from Khaled Hosseini's The Kite Runner is well known by readers of contemporary fiction. The novel, a New York Times bestseller, has become a modern classic, garnering enough traction to secure a Broadway debut of its stage adaptation this past July. Though deserving of its fame, the novel’s content and popularity fit into a complex trope regarding narratives about Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC).

Throughout literature, film, and television, it seems that the majority of popular stories centering characters of color in the U.S. primarily focus on sadness. Oftentimes, these stories focus on some combination of generational trauma, war, poverty, abuse, or an identity struggle that leaves the story with a dark cloud hanging over it. Think Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko, Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West, or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus all novels where suffering is central to the plot.

Of course, these authors and their works are critically acclaimed for a reason: Their writing prowess has enabled them to touch hearts and minds of millions of readers around the globe. They have also contributed to the diversification of media—we are experiencing a period of unprecedented representation. Additionally, there is no denying that the inclusion of hardships completes stories: It adds depth and richness to any plot, and character development often runs parallel to experiencing friction. Sharing stories that discuss the difficulties unique to communities of color also raises awareness about the realities of BIPOC experiences in a media space that is still incredibly white. Thus, these stories should and must be told, but an issue arises when they are the only ones given attention.

The reality is, publishers and film companies generally won’t give a project the green flag unless they believe the proposed story is profitable. But what is considered “profitable” is based on the tried and true: What kinds of products have achieved critical success in the past? When it comes to stories centering BIPOC, this tried and true is a trauma narrative. Celebrated authors of color—your Toni Morrisons, Amy Tans, and Jhumpa Lahiris—wrote extraordinary books that oftentimes focused on trauma and are now modern classics. Their success, while merited, has established a legacy of trauma narratives

that publishing and production companies are perpetuating for the sake of profitability. Now, when audiences try to even think of a story about people of color that is simultaneously about joy, many find themselves at a deadend.

For stories about people of color, trauma has become entwined with profitability. The continued dominance of trauma as the prevailing narrative has set a dangerous precedent for what sells and what doesn’t. For example, Lee’s Pachinko follows a Korean family from their roots in Korea to their new home in Japan. Documenting experiences of different descendants of the same family, the novel examines generational trauma, as the parents, children, and grandchildren grapple with immigration, discrimination, and poverty. While this novel does not specifically focus on an American experience, its popularity among American audiences is a testament to the notion that sadness is required to become a bestseller for a story centering BIPOC. Strife, pain, and misfortune guide the most popular kind of storytelling, squeezing more lighthearted works out of the spotlight, while white-centric media still sees a plethora of sunny rom-coms, sci-fi adventures, and fantasy wonderlands. This further begs the question: Why is this formula successful in the first place? In an increasingly diverse nation, why are so many of the stories about people of color still so deeply sad?

Dominant representation of traumacentered narratives paints a misguided image that happiness is rare—or even unattainable— for people of color. The result is a onedimensional representation of life experiences, suggesting that BIPOC can only be characterized by trauma or negative experiences. While reading stories about racialized harm can be healing, doing so should be an active choice. It

But with the prominence of trauma narratives, it is difficult for people of color to access media that is both representative and joyful. Fiction and story-telling can often be used as a means for escape, a break from the unpleasant aspects of life, but the ubiquity of trauma narratives makes this difficult for people of color, who find their few choices of representative media center around the harsh realities they already know so well.

But stories need not conform to the trauma narrative mold to gain popularity, as already proven by multiple other narratives centering BIPOC. Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians is one example of a feel-good story that saw both literary and box-office success. ABC’s Abbott Elementary, Hulu’s Ramy , and Netflix’s Never Have I Ever are a few recent examples of more light-hearted BIPOC stories that still achieved critical success and popularity. Although these stories incorporate the harsh realities that come with racial marginalization, they are not solely grounded in trauma, but maintain a comedic and fun tone, allowing BIPOC to see themselves represented while still having a laugh. These works, however, remain outliers among stories surrounding people of color. BIPOC stories with lighter tones are still emerging in the literary and film worlds and frequently find themselves overshadowed by their heavier counterparts.

While breakthrough BIPOC narratives may have involved the main characters living through catastrophe and coping with historical abuses, the foundation for increased representation in media has already been established. Now there is an opportunity to diversify the types of stories used to achieve this representation. Communities of color deserve to see themselves represented in stories of success, love, and happiness.

While it remains important to bring attention to real injustices these communities face, people of color are entitled to representation in the fullest measure. They deserve to be imagined thriving and to have media industries value their happy selves just as much as their sad halves. Better representation means new opportunities for dreaming, for imagining a happier world where their existences are not boiled down to the negatives. It is essential to move beyond the profitable mold of trauma narratives and create enough stories for people of color to see themselves love, laugh, and smile—a thousand times over. G

illustration by natalia porras; layout by graham krewinghaus

THE GEORGETOWN VOICE VOICES

10

After nearly two years of dislodgement, GSP is proudly returning home

BY JOANNA LI

The Georgetown Scholars Program (GSP) is finally returning to a renovated, permanent space in Healy Hall next year, according to a recent university announcement. The flagship program for first-generation and low-income (FGLI) students was moved out of its long-time space in Healy Hall last January and has resided in a temporary Leavey Center office since November 2021.

A more detailed plan from Aug. 26 revealed that construction for the new GSP space will begin on the ground floor of Healy Hall this spring, and will conclude by Fall 2023. In addition to housing the GSP office, the renovated Healy space will include a new Catholic Student Life Center, a Catholic ministry community space, an office for health and wellness programming, and an all-access student lounge.

While Healy would be the first home for most of these new planned ground-floor offices, GSP had operated out of Healy for over a decade before its relocation in 2021. The proposed return to Healy, therefore, is a homecoming.

“The GSP office’s location in Healy not only serves as a central, easily accessible space for support and community to some of the most disadvantaged students on campus, but allowing this space to be located in the heart of campus also signifies that the university recognizes and supports us,” Otice Carder (COL ’23), a GSP scholar, wrote to the Voice

That recognition and support have not always manifested in an adequate physical space—the current temporary office is separated into three different rooms. The new floor plan will triple the office’s original size, and will house workstations, a lounge, and a meeting area for GSP scholars, providing valuable opportunity for community building. In addition, it will provide phone booths, a kitchen, storage space, a bathroom, and private offices for GSP staff— basic amenities the program has long advocated for.

“I have heard from alums and current seniors about how the GSP lounge used to always be filled with movement from both staff and students who would stop by to say hi, grab something to eat, study or just hang out in community—quite the contrast from our current lounge

situation that can’t fit much more than 6 people,” Sabrina Perez (COL ’24), marketing coordinator of the GSP Student Board, wrote to the Voice

GSP started as a university scholarship that supported around 50 students in 2004 and became a full-fledged program in 2009 following advocacy by Amy Hang (COL ’09), who believed that FGLI college students required more than mere financial resources to navigate Georgetown. This transformation made it clear to students and administrators that GSP needed a physical space to adequately support its students.

Throughout the years, GSP stayed persistent in its core mission of building a more equitable Georgetown experience for FGLI students. The program currently serves over 650 students by providing advising and mentorship opportunities, allocating necessity funding, hosting event bondings, and organizing advocacy—resources their more privileged peers often enter Georgetown already having. These resources can be lifechanging: The graduation rate of GSP scholars is 94 percent, compared to a 26 percent national average for first-generation students.

“I love being a part of the GSP community because it is a supportive group of people that I am able to relate to,” Munasip Ertakus (NHS ’25) said. “It really is an instant connection when you meet another GSPer because there are not many of us and we can understand one another. It definitely makes me feel safe and

appreciated having GSP as a program on our little campus.”

In January 2021, the university announced a proposal to move GSP out of Healy, planning to co-locate GSP with the Women’s Center, LGBTQ+ Resource Center, and Center for Multicultural Equity and Access in the basement of New South, a freshman dorm on the edge of campus. The university had attempted a similar consolidation and relocation in 2014, but stopped after receiving significant student pushback.

In contrast to the 2014 procedure that solicited student feedback, the university did not preemptively announce the 2021 GSP relocation plans to most scholars. The pandemic further inhibited a collective in-person response; by the time most students returned to campus in Fall 2021, the former Healy office was empty.

Nevertheless, when students found out about this change, they organized in opposition. Nearly 400 students and 40 student organizations signed a GUSA petition advocating for preserving the GSP office in Healy. “Healy is a Georgetown landmark, and therefore a symbol that FGLI students not only belong at Georgetown but that they are central to the university’s mission,” the petition read.

Alumni also rallied resistance to the relocation. Emily Kaye (COL ’18), a former president of the GSP Student Board, helped garner more than 1,200 signatures for a change.org petition opposing the relocation.

In response, the administration amended its plan, and announced last fall that GSP would return to Healy—instead of moving to New South—once renovations are complete. Between January and November of 2021, however, GSP was officeless. In November 2021, GSP began operating out of its current transitional space in Leavey 433.

“Staff members and student workers alike have tried to make the best out of the change, making the current lounge as cozy as possible with couches, snacks, tea and coffee, but the inaccessible, hard-to find location and the small size of the space does not have the same capacity as our old space,” Perez wrote.

“I’ve seen GSP come to life in various university spaces over the years,” Missy Foy, the executive director of GSP, wrote. “There is no substitute for the opportunity that students are given when they are able to congregate physically together. I think that’s what our office space does best: create casual opportunities for first gen students to meet other students and navigate college together.”

“Our new large space in the center of campus will represent how we deserve to be heard and take up space in a traditional academic setting that has oftentimes forgotten to include us,” Perez added. G

11SEPTEMBER 23, 2022 NEWS design by lou jacquin

When Georgetown Athletics told the men’s rugby team they couldn’t use Cooper Field just two hours before their scheduled practice time, the team played anyway—on Healy Lawn, cleats and all.

The issue wasn’t just the lost practice time. On Aug. 30, Georgetown Athletics and the Center for Student Engagement (CSE) informed club sports teams that field space for games could only be confirmed on a weekly basis, preventing teams from communicating their game schedules. Now, Georgetown wasn’t even offering club sports a guaranteed place to practice.

“I get it, varsity soccer is varsity soccer. Our issue was that we were not told until two hours before,” Mark Kearney (SFS ’23), captain of the men’s rugby team, said. According to Kearney, club coaches make major time commitments to visit campus, and athletes structure their weekly schedule around practices. So, club rugby staged an informal protest with an unsanctioned Healy Lawn practice. “We were just students throwing around a ball, a little bit of a ‘sticking it to the man’ situation,” Kearney said.

Club sports teams feel neglected by Georgetown’s new field scheduling policies. While varsity teams understandably take precedence in field use, the new policy threatens clubs’ seasons if they are forced to forfeit games.

“They basically told us, ‘club sports does not have a priority to any of the spaces on campus.’ We have less priority to field space than anyone else,” Claire Smith (SFS ’23), captain of the women’s frisbee B team, explained. In addition to only scheduling club games a week in advance, club practices can be canceled at any time to accommodate changes in varsity schedules.

Club sports did not play on campus in the fall of 2021 due to COVID-19, making this fall the first season in two years the university needed to schedule varsity and club games simultaneously. Club sports teams are under the jurisdiction of the Advisory Board for Club Sports (ABCS) and the CSE, but the use of Cooper Field is coordinated by the

athletics department.

Club sports teams are now in a battle with all three bodies to secure onceguaranteed spaces.

“By NCAA rules, visiting teams for varsity sports have to be given a practice time, so Georgetown wanted to wait for these teams to confirm when they get to D.C.,” Liam Jodrey (COL ’24), captain of the men’s club soccer B team, explained. “As a knock-on effect, they did not schedule the club sports games.”

Georgetown Athletics’ failure to schedule games causes serious implications for club teams’ seasons. Men’s club soccer games must be scheduled and played by a certain date, or the team risks probation or suspension from their league. If games are canceled, they are difficult to make up as other teams’ schedules are already set.

“[CSE and Athletics] were just not sympathetic to that at all,” Jodrey said. “I would have felt horrible had I been the one on watch when we got put on probation.”

Men’s club soccer isn’t the only team at risk of losing league standing due to field use issues. Kearney explained that the men’s rugby team’s inability to communicate a schedule with their league could derail the season if they forfeit games.

“It would impact the likelihood of playoffs or going to nationals,” Kearney explained. “We are an ambitious team hoping to go far. If we were to lose a league game because we weren’t able to get Cooper, it would be a devastating way for the season to end.”

Given the high stakes of forfeited games, club sports leaders have jumped into action, submitting concerns over the new policies. Club leaders in rugby, soccer, and frisbee sent emails to ABCS and the CSE, and Jodrey contacted alumni who also communicated their frustration with Georgetown’s Athletics director.

“There has been a big uproar from club sports, in my opinion, rightfully so,” Kearney said, explaining that Athletics has now blocked out Cooper Field from 6 p.m. to midnight on weekends for club games. “They only did that after people complained a lot. I think we got the message across,” Jodrey said.

Set-aside field times resolve some of the challenges faced by club sports

teams, but not all. Kearney explained that rugby league rules require games to be played during the hours of 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., which go outside Georgetown’s allotted hours for club sports’ field use. “We are grappling with the university and our league setting requirements for us. Because they don’t jive together, we are running into quite a few problems,” he said.

Both the club men’s soccer and rugby teams have tried to find new solutions by playing on fields off campus. Last weekend, rugby moved their game from Cooper to an off-campus field to accommodate their league’s 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. time range for games. Kearney explained that the costs of reserving fields and transportation create financial strain on the club.

“We have to pay for that field and Georgetown has given us no indication they will be providing us any financial support in that regard,” he said. If they spend their budget on field reservations, Kearney explained, men’s club rugby will struggle to hire EMTs and purchase safety equipment. It will also impede the team’s ability to travel for away games.

Men’s club soccer has run into similar difficulties. According to Jodrey, the club considered seeking other field space in D.C., but found all the fields had been booked since the beginning of August. The team is unsure if it has the budget to reserve off-campus fields.

“The university also refused to comment on whether we would have to fund the costs to reserve all these fields from our budget, which we probably wouldn’t have the money for,” Jodrey said.

Beyond games, club teams have struggled to solidify spaces and times for practice. Practice times are impacted by Cooper field’s stadium lights being turned off, or by varsity sports moving their practices due to weather. With club sports practice spaces potentially occupied with mere hours notice, club leaders must scramble to acquire backup fields. According to students in the Aug. 30 meeting, ABCS and the CSE instructed club sports not to interfere with varsity practices. If any varsity players showed up during club practice times, club teams would be expected to accommodate them.

For ultimate frisbee, regular practices are essential to keeping the sport open and

12 THE GEORGETOWN VOICE SPORTS graphic by jina zhao; layout by alex giorno

accessible. Jacob Livesay (COL ’23), captain of the men’s frisbee A team, explained that at peak activity levels, the men and women’s teams have about 200 participants in total. Ultimate frisbee is a no-cut team, meaning all are welcome to play, and tryouts are only held for those wishing to secure a spot on the A teams.

“I can’t emphasize enough how important practice is to our team. Our entire model relies on converting athletes from other sports, which means we constantly have to be teaching the sport of ultimate frisbee for the success of our players,” Livesay said.

Smith explained that changes in practice times and spaces are confusing for new players. “This is the time of year we are trying to recruit more people and be welcoming, so we need a sense of normalcy,” Smith said.

Even when granted field space, frisbee teams flag safety concerns. In the past, both men’s and women’s practices have shared Cooper, each taking half the field. With up to 200 participants in the club, however, Livesay explains Cooper is just too small for both teams to practice without collisions or frisbees crossing to the other half.

Men’s club rugby reached out to ABCS in advance of the season, requesting that the men’s and women’s practices be separated. Though requests were initially well received, according to Livesay, men’s club frisbee was then paired with women’s softball.

“Instead of dodging people in the women’s program, we are now dodging softballs,” Livesay said.

Only practicing on half of Cooper— smaller than a normal frisbee field—also creates inaccessibility issues. While the club prioritizes teaching new players, athletes with ultimate frisbee experience from high school on larger fields are likely to be more competitive in tryouts for the A teams.

“The way we have been given field space means we never get to practice on a full field until an official competition,” Livesay explained. “This means that people who were exposed to ultimate frisbee in high school are the ones who are going to get roster spots and the most minutes in game time,” he said.

Ultimate frisbee is already a sport with predominantly white athletes, as the sport is offered mostly in white and affluent communities and high schools. Ultimate’s homogeneity and history of racism are long-standing barriers towards greater inclusion in frisbee. Livesay stressed the need to promote accessibility in a club designed to be open for all students. “We do our best to make sure that people who haven’t played before, especially players of color or players from different backgrounds, have an opportunity to learn the game,” he said.

Club leaders explained they do not blame any specific party, as they are aware the CSE is understaffed. They also understand the difficulties that come with coordination between the CSE, ABCS, and the athletics

department. The Director of Facilities, Events & Operations position, who schedules field use, has not been consistently staffed since the summer of 2021, leading to additional challenges.

“As an urban campus with limited oncampus space and facilities, 30 Division I Varsity Sports, and more than 30 club teams and numerous intramural recreational sports, we recognize the limitations and work hard to maximize access for all students as best we can,” a university spokesperson wrote.

Kearney acknowledged the university’s challenges. “ABCS and CSE have quite a tricky job in that they are obviously representing a lot of teams to Athletics to use the facilities and don’t want to ruffle any feathers,” he said. “I have a lot of sympathy for what they do. It’s just frustrating to go through the extra steps of communication.”

Frisbee has been granted permission to use Kehoe Field as a backup practice space, but requests must be processed through the

CSE. According to Livesay, club sports leaders asked the CSE to be cc’d on emails regarding their field requests, but were denied, as these emails filter through multiple departments. According to Livesay, club sports leaders just want more transparency and communication.

“We still really don’t have updates on things as we try to get them scheduled. We submit requests, but then they just sit in the void for a while,” Livesay said. “We try very hard to give them as much grace as we can, but it is very frustrating when it impacts our sport,” he said.

Livesay explained that while students handling finances have Blueprint Training, club sports leaders were not prepared for the season’s unexpected stressors. Team captains should be focusing on maximizing practices and building competitive teams, not scrambling for field space. “Other schools’ team captains aren’t having to deal with this logistical stuff, and can spend time on actual things that are going to win them games,” he said.

Moving forward, Livesay hopes to see more university support for club sports, including securing more practice spaces. Shaw and Kehoe, for instance, often go unused for most of the day. Additional ABCS funding for offcampus fields could also be an easy solution to scheduling conflicts. Club sports leaders have also asked the CSE to coordinate use of Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School’s nearby field.

Kearney hopes that club sports teams are granted more respect as strong athletic programs playing in competitive leagues. “When we go out there and play, we represent Georgetown,” he said. “It’s a bad look for us when we can’t play on our own field because our university won’t let us.”

Until policy changes are negotiated, however, club sports teams cannot help but feel deprioritized and frustrated. “As a student leader, speaking for club sports, they have made it hell for us,” Livesay said. “Club sports are awesome. It’s a great experience for all involved, but the university makes it such a pain in the ass. When it’s not in the classroom, the university doesn’t seem to care about cura personalis that much.”

Editor’s note: Livesay once contributed to the Voice . G

Kearney hopes that club sports teams are granted more respect as strong athletic programs playing in competitive leagues. "When We go out there and play, We represent georgetoWn,” he said. "It’s a bad looK for us When We can’t play on our oWn field because our university Won’t let us!"

13SEPTEMBER 23, 2022

Aaron Judge's home run

There is a unique mythology surrounding records in baseball, a canon of stories behind the numbers that demonstrate the Herculean exploits of individual players. And no record has greater mythology—and controversy—than the single-season home run record.

Babe Ruth, the first home run king, set the single-season record four times. In 1919, he hit a record 29 home runs, then demolished that total over his next three record-breaking seasons: 54 in 1920, 59 in 1922, and then, in 1927, he reached 60. That waterline stood for over three decades, until Roger Maris dared to challenge the Babe. Maris’ 1961 attempt caused so much stress that his hair started falling out in clumps, and as he approached the record, he received so many death threats that an NYPD detective was assigned to watch over him. Maris broke the Babe’s record in the final game of the season, finishing with 61 home runs.

Then there was the 1998 home run chase, a feel-good story that revitalized baseball after the strike-shortened season of 1994. Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa both broke Maris’ record, with McGwire resetting the record books with 70. Finally, in 2001, Barry Bonds set the current single-season record of 73. Roger Maris’ major league record was dead, his feats of power hitting buried under the stars of the next generation. Just one problem: All three men used performanceenhancing drugs (PEDs) to surpass Maris and each other.

For many baseball fans, it’s difficult to square the reality of the record books with the reality of cheating. Bonds’ 73-home-run season might hold the top spot, but some still hold on to 61 as the true single-season home run record—and it still stands as the American League record. Fans, for the most part, want to see records broken—but by someone whom they deem “worthy” of the mythology.

Different translations of the Bible put Goliath’s height at nearly 10 feet tall, while others, perhaps

more reasonably, put him at 6-foot-9. If the latter measurement is accurate, Aaron Judge, the star outfielder for the New York Yankees, would nearly be as tall as Goliath. Fitting, because Judge seems like a myth himself, clocking in at 6-foot-7 and 280 pounds with superhuman muscle definition. And he condenses that size and strength into his wooden sledgehammer, rocketing balls into the stratosphere.

As of Sept 21, Judge has hit 60 home runs in 148 games and captured the attention of the baseball world. He has 14 games to hit two home runs to break the record. This is September baseball— muscles aching from swings, minds aching from play nearly every day—this is the grind. To hit a home run, it takes the right pitch, the right pitcher, a good read, and the perfect swing to put a ball in the seats—to give the fans a souvenir, a tangible symbol to represent the chase as the season races to a close.

Judge’s home run chase is the litmus test for purity in baseball. That purity, protecting the sanctity of the sport, is something that the MLB has struggled with in the last 30 years—and it’s resulted in a change in the national psyche.

Many sports fans, especially baseball fans, are cynical about the accomplishments of great players. There is no such thing as “the benefit of the doubt” for athletes anymore. No player can claim ignorance because too many icons have been embroiled in cheating scandals, emptying the reserves of empathy among fans. Fernando Tatís Jr., one of baseball’s brightest young stars, was suspended for PEDs in early August. He proclaimed his innocence, that it was a misunderstanding. The sports world mocked him, turning his excuse about needing treatment for ringworm into memes. He broke the trust of the fans, and now he’ll suffer ridicule for the rest of his career. He’s not old enough to book a rental car, but he’s already made a mistake that will cost him the Hall of Fame.

2013 featured what could’ve been the greatest Hall of Fame class of all time, but it ended in a voting process where nobody was selected. The names of the players shunned read out like a list of the FBI’s Most Wanted: Bonds. Sosa. Clemens. Palmeiro. McGwire. The Hall of Fame voters spoke for the country: You broke our hearts, and we want revenge. You cheat us, we cheat you. That’s what happens when a player eats the forbidden fruit; he’ll never be allowed into Eden.

The damage has destroyed the suspension of disbelief for fans. They can no longer cherish the spectacle that comes from the exploits of stars. Deep down, if a player recovers from an injury ahead of schedule, or if a player rewrites the record books, there’s always those lingering thoughts in the subconscious: God, I hope he didn’t cheat to get there.

When I watch Aaron Judge at the plate, I still marvel at his presence. His wide stance, front foot slightly behind his back foot—nearly parallel, but just off. His towering frame makes him an imposing presence, and when he holds the bat at a 30-degree angle above his head, chin buried in his left shoulder, he seems even bigger—close to that mythical 10 feet tall, ready to chop down at anything he can reach. Then he swings with seemingly no effort, like it’s a completely natural activity to wield a piece of 35-ounce wood, like it’s second nature, no more difficult than tying a pair of shoes. And the ball explodes off his bat, whistling beyond the fence, until the scream of the ball is drowned out by the sound of cheers.

I sometimes wonder if my amazement makes me naïve. But I realize that Judge represents a breath of fresh air for fans everywhere. He’s a legitimate player with a real shot at breaking a long-standing AL record in home runs—and for many people, the true home run record. As we come down the stretch of the season, keep your eyes glued to him, because hopefully number 62—a clean, genuine 62—will whiz over the fence. G

photos courtesy of patrick tomasso and keith allison, cc-sa graphic by nicholas riccio; layout by graham krewinghaus

THE GEORGETOWN VOICE HALFTIME SPORTS 14

2.0;

As the late August sun set on Nationals Park, the overhead lights dimmed and the transcendent synths of Bad Bunny’s “Moscow Mule” shook the sold-out stadium. Greeted by 41,000 screaming fans, he emerged in an orange tie-dyed t-shirt and his signature sunglasses. Bad Bunny transported concert-goers to the beaches of Puerto Rico and gave D.C. a much-needed opportunity to let loose and say goodbye to summer.