Issue 3 • Fall 2010 gamesauce.org

e c u a S e m Ga l a i t n e d i Conf

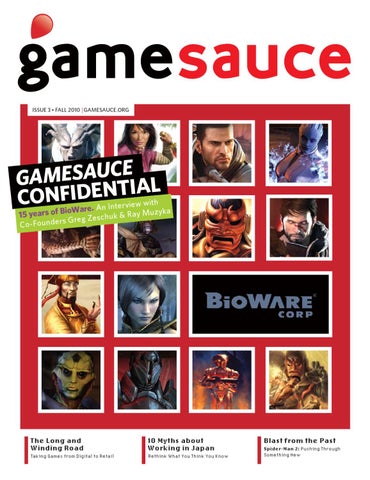

terview with In n A . e r a W io yka 15 years of B k & Ray Muz u h c s e Z g re G Co-Founders

The Long and Winding Road

10 Myths about Working in Japan

Taking Games from Digital to Retail

Rethink What You Think You Know

Blast from the Past Spider-Man 2: Pushing Through Something New

A note from the editor

O

nce more unto the breach gentle reader! Another issue of Gamesauce graces your eyes! So the Gamesauce Conference! A rousing day of sessions from such diverse developers as Bungie, Infinity Ward, EA, Runic, Robot Entertainment and more! (Name dropper! And can we possibly get some more exclamation marks in here? Ah, a question mark. Better.) The Conference also featured sessions from luminaries such as John Romero, Brenda Braithwaite and Laralyn McWilliams (the subject of our 10 questions article in this very issue!). Next year’s conference, in sunny Seattle, is already on the drawing board and we want to hear from YOU, dear reader. Ideas for what you’d like to see sessions cover, actual proposals for sessions, let us know what you want to see. Drop a line to cathy@gamesauce.org and she’ll let you know what the next stages are. We need to know what you want to hear about since the major thrust of the Gamesauce conference is By Developers For Developers. It’s not about students, or press, it’s about people who are in the trenches actually doing things, sharing that with the rest of us. So sit back, relax and enjoy another issue of Gamesauce Magazine. Spend an extra 10 minutes on the porcelain throne absorbing one of our many articles, and then pass on the experience to your co-workers. The article I mean, not the extra 10 minutes on the WC—that would be gross. Enjoy! Jake Simpson, Editor in Chief, editor@gamesauce.org

gamesauce.org

Gamesauce.org is all about putting the people of our industry out front. We leave the business talk, sales numbers and analytics to others. We want to be the voice of the coder, the developer, the marketer, the all-nighterpulling crunch-guy. We want to help others get to know you—what drives you, what makes you successful at your job, what (besides caffeine) keeps you going hour after hour, year after year. Most of all, we want to tell your story. We want to hear your anecdotes and wisdom, your lessons learned and secret tricks, and we want to share those tales with other. What’s your story? Share it through Gamesauce.org. Submit your ideas to vlad@gamesauce.org.

issue 2 • spring 2010

Issue 3 | Fall 2010

COVER STORY

36 Gamesauce Confidential An Interview with Greg Zeschuk and Ray Muzyka, Co-founders of BioWare

COLUMNS

2 4 7

Let ter from the editor Postcards from a Studio Team 17 Blast from the Past Spider-Man 2: Pushing Through Something New by Jamie Fristrom 15 10 Questions A Conversation with Laralyn McWilliams 20 Industrial Depression Bonus Schemes 72 The Aha Moment with Will Kerslake

FEATURES

24 10 Myths About Working in Japan Rethink What You Think You Know by James Kay 32 Let ting Go On Designing Games with Dynamic, Non-linear Game-play by Harvey Smith & Raphael Colantonio 48 The Long and Winding Road Taking Games from Digital to Retail by Dawn McKenzie & Kate Freeman 52 The Life of a Booth Babe Reflections by One Who Knows by Yvonna Lynn 58 Why Are Sound Guys So Grumpy? Don’t Get Me Started… by David Chan 66 Extrasensory, Extravagant, Exhausting The Pomp and Pageantry of E3 by Jon Jones

MISSION STATEMENT Gamesauce is for those who have already discovered the great secret about making games: it’s fun, it’s cool and you get paid to do it. In publishing this magazine, we make the following promises: • G amesauce will be fun and cool—just like making games. • We will give you a 30,000-foot view of the gaming industry so you can see where it’s going as clearly as you can see where it’s been. • We will give you the good, the bad, and the ugly of the game industry, leaving you free to form and express your own opinions. • We will not merely be interesting; we will be provocative. We will not shy away from asking the awkward question or printing the controversial answer. • We will not spend our pages giving away source code for particle systems, but we will give you the history of them. Or we would if that wasn’t quite so boring. • We will never take ourselves too seriously. Seriously.

gamesauce • Fall 2010 1

Letter from the Publisher

W

ow. Can you believe the year is almost over? It seems like only yesterday we were tearing the shrink-wrap off the latest Call of Duty. But when I think about how fast our industry has changed over the last 30 years, I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that one of those 30 years has vanished more quickly than a burrowing zergling. Ah, the passing years. When I was a clueless young coder, my boss always used to hammer on us about passion. “Always be passionate about what you do, that is the most important,” he would say. His point was that even if you’re coding up the UI or you’ve been appointed the Art Director of Rocks and Dirt, your efforts will be reflected in the final product. And regardless of whether you create Flash games for kids or console games for the frothing fringe, whatever you’re doing is worth doing well. (I think

Publisher Jessica Tams Editor in Chief Jake Simpson Editor, Gamesauce Magazine Peter Watkins Copy Editors Tennille Forsberg, Catherine Quinton

Contributors David Chan, Raphael Colantonio, Kate Freeman, Jamie Fristrom, Jon Jones, James Kay, Will Kerslake, Yvonna Lynn, Dawn McKenzie, Harvey Smith Editor, Gamesauce.org Vlad Micu Special thanks to the Hub Bay Area

Creative Director Gaurav Mathur Art Director/Designer Shirin Ardakani Contributing Illustrator Crystal Silva Comic Artist Shaun Bryant Comic Writer Ed Kuehnel

2 gamesauce • Fall 2010

Contact Us Address Changes or Removal: Tennille Forsberg, tennille@gamesauce.org Magazine Article Submissions: Jake Simpson, editor@gamesauce.org Gamesauce.org Submissions Vlad Micu, vlad@gamesauce.org Publisher: Jessica Tams, jessica@gamesauce.org

my Dad is the one who used to say that, but then again, don’t all dads say that?) My point is not to get all paternal on you (which would be no small feat considering I just had a baby), but rather to get you to pause and think about what you want to do. So let me ask you: What are you working on? What do you want to work on? Wanna relocate to Japan, maybe? Quit your job and start your own studio? Finally get a piece of one of the big franchises? If any of that sounds even mildly interesting, then read on. There’s something in this edition of Gamesauce for you. And lots of other really good stuff as well. As for me, my goals are simple: I want to become a booth babe. And the good news—especially for you members of the frothing fringe—is there’s an article about that in here as well.

Jessica Tams, publisher, jessica@gamesauce.org

Trademarks © 2010 Mastermind Studios LLC. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or part of this magazine is strictly prohibited. Gamesauce and the Gamesauce logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Mastermind Studios LLC. All other product and company names mentioned herein may be trademarks of their respective owners. Disclosures Mastermind Studios LLC’s (“Mastermind”) Gamesauce (“Magazine”) is for informational purposes only. The Magazine contains current opinions which may change at any time; furthermore, Mastermind does not warrant or guarantee statements made by authors of articles in the Magazine. While the information included in the Magazine is derived from reliable sources, the reader is responsible for verification of information enclosed in this Magazine and Mastermind does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy or completeness of the information.

Usage Companies inside the entertainment industry may use information in this Magazine for internal purposes and with partners and potential partners. Members of the press may quote the Magazine. Subscriptions Gamesauce is available to professional game developers and members of the press. Professional game developers may visit http://www.gamesauce.org/ to sign up for a free subscription. Gamesauce is postal mailed to over 19,000 game industry professionals and 2,500 members of the press.

Kate Freeman & Dawn McKenzie

Kate and Dawn oversee the sales and marketing teams at MumboJumbo, LLC. Kate has three amazing boys and some of the best retail relationships in the industry. Dawn loves frozen yogurt, the creative process and market statistics. Kate can be reached at freeman@mumbojumbo.com; likewise, you can drop Dawn a line at dmckenzie@mumbojumbo.com.

Dave Chan

Dave has always had an interest in computers and audio. While in the systems department at BioWare, he was offered a chance to make placeholder sounds for MDK2. They liked the sounds so much, they asked him to do the whole game. The rest, as they say, is history. Since 1999 he’s worked on over 20 titles. He has been an active member in the Game Audio Network Guild since its launch and is a co-chair of the GANG Voice Acting Coalition. He has spoken at the GDC and is on an AIAS panel selecting licensed music for the Interactive Achievement Awards. Currently he works in serious games at 3DI in Canada.

Jon Jones

Jon has spoken at Casual Connect Seattle and Europe, the Montreal International Games Summit, the Savannah College of Art and Design’s Game Developer’s Exchange conference among others. He’s been making games professionally for nine years and involved in the video game art community for fourteen. He recently managed outsourced art teams for MMO projects at 2K Games and NCsoft. He has run his own outsourcing consultancy, but not long ago joined Vigil Games as Outsourcing Art Director. Jon is recognized by many as an expert on the subject of outsourcing art, and can be contacted through his website at TheJonJones.com.

Jamie Fristrom

During his 19-year career in the industry Jamie has worked on games such as Magic Candle, Die By The Sword, Tony Hawk, and SpiderMan. He’s written for Gamasutra, Game Developer Magazine, and his own blog, gamedevblog.com. Currently, he’s a partner, technical director, and designer at Torpex Games, creators of the game Schizoid—“The Most Co-Op Game Ever”. He’s on the committee for the IGDA Leadership Forum. Jamie can be reached at jdfristrom@gmail.com and his Xbox LIVE tag is “Jamie Fristrom”.

Raphael Colantonio & Harvey Smith

Game designers Raphael and Harvey have been making games professionally since 1993. Colantonio is the founder, CEO and Creative Director at Arkane, based in Lyon, France, with a second office in Austin. He is currently teamed up with Harvey Smith, co-directing an unannounced project. Smith has worked as lead designer at Ion Storm and studio creative director at Midway Games. He won the Game Design Challenge at GDC 2006 with his concept “Peace Bomb”. Both have spoken at numerous game conferences and are passionate about immersive, highly interactive games with simulation elements.

Contributors

James Kay

James has worked as a game artist for over a decade in both the UK and Japan. He cofounded Tokyo-based independent video game development company Score Studios LLC, score-studios.jp. For several years he was the inside voice reporting on Japanese game development under the pseudonym “JC Barnett” on the popular blog “Japanmanship” and has written for various video game magazines and websites. James can be contacted at james.kay@score-studios.jp.

Yvonna Lynn

Yvonna began modeling in France on a 3-month contract which somehow lasted 6 years. Combining a passion for video games with a career in modeling and acting, Yvonna built the Charisma+2 agency for talent who share her enthusiasm for gaming. Direct and agency gaming credits include: Bioshock 2, Starcraft 2, Rage, Borderlands, QuakeLive, Nickelodeon Fit, New Carnival, Nocturne, Dragonball Z, Doom 4.

Will Kerslake

Will is a Creative Director at Radar Group in San Jose, CA. He got his start programming training simulations for the local fire department and joined the professional gaming industry in 1998 as an artist at Atari Games. Since then he helped found Lightspeed Games and has held design positions at Maxis and EA. He has worked on everything from racing games, to action RPGs to openworld licensed properties. He can be found on Twitter and is jumping back into the blogging space at ndlabs.net. gamesauce • Fall 2010 3

Postcards from a Studio

Team 17 Name: Team 17 Location: West Yorkshire, England Year Founded: 1990 URL: www.team17.com Softography: Worms™, Alien Breed, Superfrog

T

eam 17—based in Osset, West Yorkshire in the UK—has been around a long time. A long, long time in video game developer terms: 20 years in fact, or 160 years in developer years according to the eight-game-years-equals-one-human-year scale we just invented. The teams came originally from a publishing group called 17-bit software, and once they got into making games themselves, Team 17 was born. Not that they’ve left their publishing legacy behind—with the advent of digital direct-tocustomer sales over the Internet, Team 17 is back in the publishing biz, starting to pick up and distribute games from other small indie outfits. As Creative Director Martyn Brown puts it: “We’ve been able to move back into self-publishing and liberate ourselves to work that way.” This is my first visit to Team 17’s offices, but Team 17 is a it is not my first encounter with Martyn Brown. Martyn is a blunt Yorkshireman: plainspoken, full original of humor, with a twinkle in his eye that indicates IP, licensed IP, and he’s not afraid to have a little fun at your expense (and that he expects you to return the favor). His recently, for cohorts, producers Mark Kilburn and John Denother indie studios. “Our nis, have that same twinkle, making it clear that these guys are merciless to each other—that any are all weakness is seized and exploited for full humor over the place, so it’s hard to potential. Before long, in fact, John launches into a story about being caught inadvertently without his define what we do because trousers at the office and never living it down. we’re doing Having been around so long, Martyn reminisces about being in business before the Internet was what it is today. “You’re talking about a time where the Internet was still six years away. There was no email when we started. Everything was phone calls, letters, disks through the post and modems. It’s easy for us to forget that’s how we started. You couldn’t even imagine running a business these days like that.” Team 17 has made a lot of games over the past 20 years. “We’ve probably done about 50 titles in those 20 years,” Martyn explains, “but most people they just think of one. Worms is about 30 to 40 percent of what we actually develop right now; that’s far and away the biggest hit, you know. We’ve probably sold 28 to 30 million in 15 years. It’s a lot of titles really.” It is a lot of titles—from Amiga games all the way up to Xbox 360, PS3, and Facebook games, with everything in between. They use their own technology for the most part, only using an external engine when absolutely necessary (as they did for the recent Alien Breed remake for Xbox LIVE Arcade). Team 17 fans will remember titles like Alien Breed, Phoenix, Assassin and licensed IP’s like Lemmings and Army Men. Martyn makes the point that Team 17 is a blend of many things: original IP, licensed IP, and recently, mentoring for other indie studios. “Our opportunities are all over the place, so it’s hard to define what we do because we’re doing so many different things. For example we did Lemmings on PSP two or three years ago, then we also did a PS3 version, so if it’s something we feel an affinity for.”

blend of many things: mentoring

opportunities

so many different things.”

4 gamesauce • Fall 2010

These are the people who make Team 17 games. Note the one female who is reading a book. See? There should be more women in game development.

Martyn is a blunt Yorkshireman: plainspoken, full of humor, with a twinkle in his eye that indicates he’s not afraid to have a little fun at your expense (and that he expects you to return the favor). gamesauce • Fall 2010 5

Which appears to be the root of what Team 17 is about—there’s a studio culture there and they make games that fit into the studio culture rather than trying to make the studio culture fit around a specific game genre or IP. It’s something they can afford to do, inasmuch as they are 100 percent self-financed. “We’ve never used any outside investments,” says Martyn. “Everything is self-funded. Any f**k-ups are our f**k-ups.” The makeup of the teams at Team 17 is interesting from an age standpoint. “We’ve probably got a higher average age than a lot of people,” says Martyn. “Quite a proportion of our guys have been 10 to 15 years just with Team 17. I would say early 30s is the average. I’m 43 now which makes me feel like a bit of a dinosaur in the industry. We have a very, very low staff turnover. I mean people working in the games industry should not take for granted how f**king great this industry is. Yes it’s difficult and all the rest of it but, my God, if you’re going to be in it, you might as well enjoy it. We’re always good fun. We’re always good for a laugh. We’re not ego-driven. It’s always about just having a good time and enjoying life.” That philosophy is apparent in Team 17’s expansive catalog of games that seems to span every platform and every genre. “I saw an opportunity with digital distribution of being able to produce great games at great prices, giving back to the community. The stuff we’re doing on Facebook for example—with the people playing that game we have direct access to them and the feedback is

fantastic. We’ve got so many plans with different platforms and different games it’s hard to come up with a single statement of intent, really.” After some reflection, Martyn continues: “If there’s a word that’s really key to our approach, it’s real. We’re real, genuine, open and transparent. And it’s those kinds of sentiments we like to be associated with.” Even though they’re based in Yorkshire, Team 17 doesn’t have any trouble attracting talent. “Not at all,” says Martyn. “We’re besieged. There aren’t that many studios around these days— certainly not that have been around 20 years. We’ve proven we know how to stay in business. And it’s surely a cheap place to live and a great place to raise kids.” Team 17 has been around for 20 years, bending with the twists and turns of the industry, re-inventing themselves when appropriate—and they show every indication of being around for another 20 years. It’s not hard to wonder what they’ll be making 15 years down the road— Worms Mental Control, perhaps, for PlayStation 5. 6 gamesauce • Fall 2010

Blast from the Past

Spider-Man 2 Pushing Through Something New by Jamie Fristrom

had a lot of trouble reproducing our previous success. Since Spider-Man 2, we’ve had many more ideas for game mechanics, only one of which actually made it to ship (the color-coded two-ship game-play of Schizoid on Xbox LIVE Arcade). Most of the others have been canceled, shelved, or are placed on hold, looking for funding or a perfect storm of greenlights at a big publisher. And yet we’ve been following those same steps we followed with Spider-Man 2—prototype, play-test, prototype again. Why did it work so well then but not now? Let me go back and unearth some of the history of how the Spider-Man 2 web-swinging idea came to be.

A

lot of people assumed that the video game for Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 2 film was just another movie tie-in game, necessarily mediocre because of a tight schedule and a strict licensing agreement. But it ended up being legendary as one of the few movie tie-in games that were actually good, getting scores above 80 on metacritic.com and gamerankings.com. Even game critic curmudgeon Yahtzee Crowshaw—known to hate everything—gave it props. Part of the reason for its positive reviews was its innovative core game mechanic: web-swinging that actually felt like webswinging. Previous Spider-Man games did not do web-swinging justice. In Neversoft’s Spider-Man game for the PlayStation, web-swinging was essentially old-school platforming—you could jump far, but it was still essentially a jump, albeit with a cosmetic web painted on. And with Treyarch’s SpiderMan 1, the web-swinging was essentially running in mid-air, again with webs hanging from the sky that were purely cosmetic. But Spider-Man 2 was different. The webs no longer attached to the sky, they attached to buildings in the environment. And then “physics” took care of the rest: A pendulum simulation evoked the gut-wrenching feeling of falling from a great height only to be caught by a stretchy web. And yes, it was harder to control—less accessible—than its predecessors; even after two years of tweak-

ing and iterating on tutorials there was a steep learning curve. But most gamers rose to the challenge, losing themselves in the feeling of swinging about New York City. Bottom line: Spider-Man 2 had new, interesting, fun game-play—which was a rare thing, even in 2002. The console game industry might not yet have been as risk-averse then as it is now, but it was still plenty risk-averse! Even then, players could typically only look forward to yet another level of polish and graphical refinement on a succession of first-person shooters. I’ve written and talked about the development of this mechanic for Spider-Man 2 multiple times. (Some of you must be getting pretty sick of hearing about it.) My hope was that by talking about our development process, not only would I get to brag, but people adopting the process would be empowered to also create new sorts of interesting gameplay. Sadly, not only is there a dearth of new game-play out there among retail, disc-based games, but those of us at Torpex Games have

Theory 1: You Probably Have to Invest Your Own Time and Money During Spider-Man 1’s development I lay awake nights thinking: “Wouldn’t it be cool if….” I wasn’t satisfied with the swingingis-flying game mechanic we had then. I had this crazy idea that we could simulate it “for real.” I developed the idea in my head, and knew I had to tell the higher-ups at Treyarch—but I also knew that they wouldn’t buy it. And I was right—“Spidey Vsim,” they called it, after Treyarch’s first game, Die by the Sword, in which we used a physical system we called “Vsim” to simulate sword fighting. Die by the Sword was a modest success, profitable, but only just. We came away from that game with the conclusion that people do not, in fact, want something new. “They want Coke and Pepsi” was the way Peter Akemann put it. The fighting gamesauce • Fall 2010 7

in our next game, Draconus, was much more traditional: button-mashing with canned animations. (To mediocre sales and reviews, I should add.) We felt burned by physics and tough-to-control game mechanics, and weren’t likely to try that again. Spider-Man 2 may have had a particularly rough row to hoe there, but this is typical of any new idea, isn’t it? When anyone hears an idea that isn’t theirs, their first impulse is always to shoot it down. Which is why, if you have an idea you believe in, you have to make it happen yourself. So about a third of the way into development, I decided to do something about it. After the workday was over, and I had logged my hours meeting the “lead programmer” job description (tracking the team’s tasks,

assigning bugs, and programming the things that slipped through the cracks) I would stay late and work on a separate branch of the code, prototyping this crazy idea. I didn’t have kids back then—I could do that sort of thing. These days when I prototype I do it during regular work hours (but usually for no pay.)

Theory 2: Good Ideas Take Time to Incubate I got it to the point where I thought it was pretty cool: To me, it really felt like being Spider-Man. Sure, you stuck to walls a lot. A whole lot. And you couldn’t really control

where you were going. But I liked it. And I couldn’t wait to get it into the game. We had already started making levels for the system we had in place, and I needed to get it in front of people and see what they thought. And most of the team thought it was pretty cool, pretty interesting—“It’s like the real Spider-Man,” Tomo Moriwaki said. But as you can guess, since that mechanic never showed up in SpiderMan 1, as we went up the management chain cooler heads prevailed. We had already started making levels—we’d have to throw that work out and start over. And although it was somewhat promising—it might be fun enough and accessible enough someday—it wasn’t worth betting the farm on. And hey, the cooler heads were probably right. We shelved the mechanic and went back to work and shipped a safer game, challenging in itself because it was our first game on the new consoles and one of the first games in history to ship on all the consoles simultaneously. So what’s the lesson here for Torpex Games? Well, I can’t go into details because of nondisclosure agreements and such, but we have several prototypes and many more ideas that have yet to gain traction. At this point it’s hard to tell which of those ideas are merely on the back-burner and which have been irrevocably canceled. It took about three-and-a-half years for the original webswinging idea to finally appear on the retail shelves, after all. So maybe that’s the trouble with Torpex’s prototypes: They’re still embryos in the “on hold” phase. Stay tuned.

Theory 3: Threaten to “Quit” Jake Simpson once said on his blog Jakeworld: “If you can’t get fired over an idea, it’s not worth having.” When Spider-Man 2 rolled around, and they asked me if I wanted to be technical 8 gamesauce • Fall 2010

Original design maps for Spider-Man 2, along with plan views of the actual layout of the city. One day developers will be able to make these from Google Earth!

gamesauce • Fall 2010 9

director again, I was already tired of the gig. I’m not sure what I thought I could do instead, but I said, “I’ll do it, but only if we get to try the physical swinging again.” It wasn’t threatening to quit per se. Rather, it was threatening to quit the job description, and I don’t think Pete Akemann and Dogan Koslu, the executives at Treyarch, took it as a threat. But making that bold proclamation did enable me to show them how much I believed in the idea. What does “Threaten to Quit” mean for an independent studio? It’s easy for an independent studio like ours to put our own IP on the back burner and instead make ports and licensed titles—in fact, we’re glad to do it, because the alternative usually means going out of business. But at some point we have to ask if that’s really what we got into business for—and be willing to burn bridges and take that big risk to make those new ideas happen.

Theory 4: Avoid the Stench of Failure

Prototyping is everything—rapid testing of ideas in ‘bad art’ environment means that no one imagines this work is finished or representative of the final game.

10 gamesauce • Fall 2010

It was right around this time that Game Developer published an article by Mark Cerny on what he called “Method” development. It was this article that really launched the idea of the value of prototyping in our industry— but another thing the article mentioned was The Stench of Failure: the notion that it is damn hard to tell an unfinished idea from a bad one, and when people mistake an unfinished idea for a bad idea, the smell spreads until that idea is doomed. Cerny’s conclusion: Keep upper management the hell away from your ideas until they’re ready. I’ve seen multiple promising prototypes, loved by many, killed because they were unveiled to a large audience before they were ready, so I think Cerny’s definitely on to something here. (Sometimes it’s not just upper management you have to keep away from your ideas, by the way. Sometimes it’s the rest of your team as well!) The problem: How do you keep upper management away from your ideas? Well, we showed Pete and Dogan Cerny’s article and they bought into it and its arguments. It also helped that upper management was busy fighting fires on other, more urgent projects, so they didn’t pay close attention to what we

were doing. They gave us a deadline to make a prototype that would prove the concept and agreed they’d keep eyes off for the duration. The deadline, in hindsight, was very generous: three months. These days, I can’t imagine spending that much time on an idea that might fail! What does this mean for a studio looking for a publisher? I can guarantee you that no publisher will let us work on a prototype while they keep their eyes closed. But one thing a studio might be able to do is convince the publisher-side producer to wait as long as possible before demoing your game to others at the publishing company.

Theory 5: Keep Avoiding the Stench of Failure Although Pete and Dogan were willing to let us “go dark” for a while, they did have second thoughts. Once Pete saw the game running in one of our empty offices late at night, and went in to try it out, and couldn’t figure out the controls. He was tempted to cancel the project right there, but Tomo and Greg John somehow talked him out of it. And then there was the day Dogan brought me and Greg into his office to air his misgivings about the whole thing: how Treyarch had been burned multiple times trying physics-based game-play. The actual conversation is lost, but it went something like this: Me: But you guys said we could try this if I took the job! Dogan: I hope it’s more important to you to make a fun game than to try out your pet idea. Me: We’ve got to do something cool if we want this game to be as successful as the first—we can’t just rest on our laurels. Dogan (shrugging): Do something else cool. Me: Like…what? In the end, he agreed to let us have the time to finish our prototype. And with the amount of time we had, we were able to do quite an impressive demo. My original proof-of-concept prototype had no animation, just a cruciform SpiderMan lurching through the skies. With animation and iteration and some other cool

More in-game images—note the story boarding of cinematic events, and even game play events.

sorts of Spider-Man-like locomotion such as wall-running, we had a demo that really impressed people. We showed it to Pete and Dogan and our Activision-side producer; they showed it to their boss; and it went up the chain until Ron Dornink was in the office smiling at our work.

Theory 6: Worry About Accessibility Later Here’s the thing: We had a game that was fun…once you were past the learning curve. Tomo demo-ed the game very well. But it was profoundly inaccessible. In the hands of a noob, Spider-Man would bang into walls and generally look like a spaz. I’m surprised our Activision-side producer took so swimmingly to it. He was the highest management type to actually play the thing.

And this was a relief—we were afraid that if upper management actually tried to play it, they’d hate it. Now if I were on the publishing side, I never would have greenlit the idea without trying it myself. I might have insisted on seeing it in a focus group. And as a result I probably would have ended up killing my own idea—which would have been too bad, because we did manage to make it accessible enough before we shipped. (Although it was never as accessible as the previous Spider-Man games, for which I do not apologize.) Although I’m really lying here—we were absolutely always worried about accessibility, to the extent that we were building various sorts of tutorials (that never shipped) in the hopes of gradually introducing the player to the system, time that was in large part wasted. My point is that, in this case, at this moment, the executives weren’t concerned gamesauce • Fall 2010 11

An example texture page for an in game character. Peter Parker has never looked so flat!

with accessibility. Otherwise the idea might have been shot down. Who knows how many great game ideas get killed because they’re hard to play at first?

got Bruce Campbell to encourage the player to keep trying if he gives up on the whole swinging thing and starts running through the city: “I know it’s your game and all, but I really think you’d have more fun if you tried the swinging.”)

On the Other Hand…. Theory 7: Don’t Use Focus Tests To Evaluate Prototypes Think of this as the “Worry About Accessibility Later” corollary. I’ve seen prototypes killed by focus tests too. It’s another failure stench. Your first testers probably won’t be able to figure out how to play your new game mechanic. As a result, they probably won’t have fun, which means they probably won’t like your prototype—even though they might learn to really enjoy it if you spent the time and money later to make it accessible, be it with changes to the mechanic or tutorials. Eventually, you absolutely need Kleenex testers to help you figure out why your game is confusing or frustrating so that you can fix those problems. But when deciding whether a prototype is good or not, you should be considering whether it’s fun once you’ve learned how to play it, and have the confidence that you’ll be able to make it accessible to the public later. (For example, we 12 gamesauce • Fall 2010

It occurs to me that all of these theories have something in common. They’re risky. You’re spending time and money working on something that might never pay off, or you’re trying to get the executives and business-heads to leave you alone and give you space while you spend their money, or you want to make a game that maybe nobody will buy because they can’t figure out how to play it. All of those things make businessmen nervous. And, well, now I am a businessman, a coowner of Torpex Games, and so the designer in me and the businessman in me are often at odds. When I’m wearing my businessman hat, I like to talk about “new product science” and “the funnel” by which ideas are filtered down to actual products: You start with n ideas, go to n/3 proofs of concept, go to n/9 prototypes. Then you take even fewer of those to full production, but you cancel some along the way, and maybe even ship a few things, sometimes canceling the marketing budget because, really, at this point, you’re only shipping them to partially recoup losses.

Even the designer in me sometimes accepts that the opportunity to make a bunch of prototypes increases the likelihood that some of them will get through, right? As a designer, if I want the right to make prototypes, don’t I have to accept the fact that most of them will be canceled? Even so, accepting and expecting that most prototypes will get canceled is part of the reason I haven’t been fighting as hard to get our ideas past that “canceled” stage. If I had this attitude back when we were making Spider-Man 2, would I still have said, “Let’s keep trying the weird thing, even though that first proof of concept sucked?” Hmmm. Maybe the important thing with SpiderMan 2 was that we created enough space and time to actually give the idea an honest shake. Which is to say (I suppose) that if you’re trying to push an idea through, you shouldn’t put on your businessman hat. If you’re being the inventor, let someone else be the businessman.

Work’s not all fun and games? It is here.

Boston - Los Angeles - New York

gsn.com/careers

gamesauce • Fall 2010 13

1 14 gamesauce • Fall 2010

10 Questions

A Conversation with Laralyn McWilliams Laralyn McWilliams is Creative Director of Free Realms at Sony, was Game Director at Edge of Reality for Fear & Respect and Over the Hedge, and Lead Designer for Full Spectrum Warrior at Pandemic. She also happens to be an all-around good egg. As if you didn’t know…. – ed.

1

1. Why did you decide to build Free Realms? What was the rationale behind this project? We had a lot of different reasons behind the decision to make Free Realms. One of the main reasons is that everyone at Sony Online Entertainment loves MMOs—they’re our business but also our biggest hobby! We wanted to share that with our families and friends, but fantasy settings, traditional MMO play styles, and the usual grind don’t

Free Realms

have much appeal to non-gamers and kids. We really believe people can have fun and build emotionally fulfilling and meaningful relationships through cooperative and competitive play, so we wanted to find a way to make that experience more appealing for casual players—and safe for kids.

We also saw an opportunity to go beyond the expectations of how an MMO “had to work” and look at the online game space in a new way. MMOs are complex from a development perspective, but they’re usually complex from a player’s perspective too, with lots of rules, stats, POIs, NPCs, quests, and items—and then on top of that, all of those things interact and affect each other. It’s why sites like Zam exist: There’s more minutia in a traditional MMO than a player can figure out without help. For Free Realms, I vowed that players wouldn’t have to use a calculator to figure out what pair of pants to wear! Free Realms was a big investment for SOE. We spent over four years working on it, and we had over 130 people on the team at its peak. I’m really proud of the game and how well it’s doing: We hit 12 million registered players in July, and the game continues to grow. We’re still pushing forward into new spaces and audiences with our upcoming games, including some that haven’t been announced yet, because we still want to find ways to bring the fun and community of online games to new audiences.

2

games. Loving the games themselves isn’t enough because it’s a really exhausting, stressful and sometimes frustrating line of work. I’ve enjoyed working on and I’m proud of every game I’ve made. Nevertheless, I’ve never had the chance to make the kind of game I really love as a player. It’s a funny dichotomy because I’m at the head of the crowd, shouting about how game development needs to diversify and how we really need to start making games that appeal to “normal” people as opposed to games that appeal to game developers. I really believe that’s true, but I also recognize and respect core gamers as a valid (and fun) target audience because I am a core gamer. At some point in my career I really want the chance to make a great, story-based, action game with RPG elements. I’ve had the chance to make that game twice, and in both cases the game was cancelled (by the same publisher, now defunct). One was Fear & Respect, and one was a Vietnam-era game at Pandemic with a great military license. Someday I hope to get that chance again.

3

2. In a perfect world, what game would you love to have made and why? I believe in designing the right game for the audience—whoever that is—and I find the process fascinating and fulfilling by itself. I don’t think you’ll last long as a game developer if you don’t love the process of making

3. What was Fear & Respect—and what happened? Like every developer, I’ve had a few games cancelled over the years. Fear & Respect was gamesauce • Fall 2010 15

more action (or at least interaction) in my games. I also question whether realism is always good in games. I blogged about that topic before playing Heavy Rain, but it really proved the point, in my opinion. I don’t play games to simulate shaving, or opening a fridge, or sitting on a teeter-totter. It’s why movies don’t spend five minutes with the hero sitting on the toilet with a magazine. On my PC, I’m playing Starcraft II and I just finished Singularity. I’ve been working on an old-school 2D RPG as a personal project, so I’m also having a little RPG renaissance on my laptop with Wizardry V-VII, Lands of Lore, Anvil of Dawn, Divine Divinity, Might & Magic IV, and Stonekeep.

Free Realms

4

the roughest cancellation I’ve been through, though, because it would have been something really special if we’d had the chance to finish it. I was with Edge of Reality in Austin—one of the great, independent thirdparty developers still out there, working hard and making games. We were working with Midway as the publisher, in a partnership with John Singleton and Snoop Dogg. Fear & Respect was a story-driven shooter, set in Los Angeles. The first part of the game took place in the late 1990s. It gave players a tutorial while also showing how gang-related decisions made by the main character, Goldie (played by Snoop Dogg) landed him in prison. The rest of the game took place in the present day, when Goldie gets out of prison and restarts his life. He discovers his little brother is making some of the same choices he did, and he has to encourage him or intervene. Everything you did in the game affected your reputation in the game world, where you could earn Fear or you could earn Respect. Fear came from backing your gang, and Respect came from backing your neighborhood. It was really important to me that the game and world be honest—we didn’t make any judgments about whether Fear or Respect was the right path. It was up to you to make decisions, see what happened, and decide how you feel about it. It was a lot like a present day Deus Ex in terms of the choices you could make. We had some really fun levels, and a great cover system that focused on assessing risk rather than taking damage. 16 gamesauce • Fall 2010

We also had fantastic art and great characters, and I was just finishing the game script with John Singleton. I still regret that we had to set it aside. 4. What are you playing now? I tend to play games almost everywhere, and I play just about anything, so my list of what I’m playing always sounds schizophrenic. Right now, I’m playing Red Dead Redemption on my Xbox, although to be honest I think

Free Realms

the game really bogs down in Mexico so I’m not sure I’ll finish it. It was a great game until Mexico though—it really reminds me of Oblivion in a wild west setting. I’m also replaying Gears of War 1 and 2 with a friend to get ready for Gears 3. I’ve got Heavy Rain in progress on the PlayStation 3, and it’s an interesting attempt to create deeper storytelling—but it’s having trouble holding my interest because I prefer

5

5. How can our industry do a better job of welcoming and encouraging women? The game industry is driven by the market. Sure, to some extent it’s a chicken and egg problem—if you don’t make any games that appeal to women, no women will buy your games, and then there’s no proof that women are a viable market. That’s not the whole answer, though. I think most non-gamers just aren’t interested in the games we’re making right now, at least on traditional (non-Wii) consoles and on the PC. The industry is evolving though—you can see it in the reaction to Facebook games and to many of the announcements at this year’s E3. Hardcore gamers sometimes feel threatened or marginalized when there are announcements about family or nontraditional products, but they’ll get over it once they realize we’ll still be making just as many (if not more) traditional games. Eventually the industry will be as mature as television and film, so that it will not merely be OK but will be considered interesting and refreshing for the same developer to make a family game, then turn around and make a hardcore fantasy RPG, then start on a modern-day shooter after that. When we get to that point, the industry will be more welcoming for women simply because we’ll be making more products that have mainstream appeal.

6

6. Tell us about Full Spectrum Wargoals, especially in terms of giving an honest rior. What was the brief and how well look at a soldier’s daily life. I’ll never forget do you think you guys hit that? one of our press events, where we hosted Full Spectrum Warrior was originally a US press the first day and European press military training tool, developed to help the next. The US press kept asking me how Army squad leaders make better decisions I felt about making such a pro-war game. in the field. As a training tool, it was almost finished when I joined the team in 2003. The team was led by Wil Stahl, who had worked on Battlezone and Battlezone II. He’d made a really brilliant leap in the control scheme and behind that training simulation was a secret: It was the first real RTS for a console. It was also amazingly complex, intended to reinforce four years of Army training with brutal realism. One wrong choice and a soldier on your squad was dead in less than a second: Game Over. As you would expect, it had no real levels or game spaces, no progression, no difficulty system, no story or characters, and the control system, while brilliant, was super complex. kept asking me I was brought aboard as lead about making such a designer to take that hardcore military training tool and make . asked it into a commercial game. I how we thought a game that was didn’t want to make something would be received in so that would just appeal to the people already playing Rainbow America. At that point, 6 and Ghost Recon—I wanted to make something an armchair general could enjoy, something for the guys who only played Madden and Halo. I also wanted to take a The European press asked how we thought a documentary approach and show what it’s game that was so anti-war would be received like in the field for actual soldiers. My father in America. At that point, I knew it had was career Army and it was really important worked—people were playing FSW and to me to give an unflinching look at what the deciding for themselves how they felt about average soldier deals with every day. war, weapons, and what soldiers experience I always say game design is the ability to in the field. understand your box and then work inside it—and FSW was a really, really small box. 7. What’s your favorite thing you’ve Giving a sense of progression was really designed or worked on over the years? challenging in a setting in which we had to It’s a tough choice for me, because I really stay absolutely realistic. The soldiers on your love Free Realms. It was a lot of fun to make, squads are dismounted light infantry—they and I’m really proud that we pushed the aren’t the guys who sneak into the dictator’s envelope in terms of what you can do in an house to defuse the nuke, they’re the guys online virtual world. I’m also really happy who patrol a bridge for two weeks. Their that we were able to make something that weaponry is very specific, and they don’t appeals to non-gamers, because broadendrive tanks or man rocket launchers. We ing our audience as an industry is really worked really hard to find ways to keep each important to me (and, I think, to the future level dynamic and entertaining. of games). Although I think FSW shipped a little I’d have to say my favorite things I’ve too difficult and complex, I think we hit our designed, though, are the systems in FSW

because I’m a systems nerd at heart. Wil Stahl and I worked hard together to come up with new ways to handle cover, enemy fire, and control schemes to balance complexity and playability. Of all those systems, I’m most proud of something people don’t notice because it works: the soldier personality/VO system. My goal was to create something brand new—soldiers with genuine personality who would respond in real-time and dynamically to events around them. It was a crazy complex system, with something like 10,000 lines of diaFull Spectrum Warrior

The US press how pro-war I felt game The European press anti-war

I knew it had worked.

7

logue that all worked in a non-linear fashion in response to literally thousands of events. Even cut-scenes were dynamic because you could go into the cut-scene with up to two soldiers unconscious and being carried by squad members—so other characters had to pick up their lines in a way that still made sense but reflected their personalities. It was a powerful moment for me when the audio files came into the build, a soldier on my squad got shot, and the other soldiers reacted, calling him by name, the young recruit freaking out while the sergeant shouted a command to regain control. My goal was to create something that felt so natural and so much like a movie that you wouldn’t notice it, and I think we got there.

8

8. Which is easier to make: A story game in which you are given a predetermined path to follow, or a sandbox game in which you are given tools and told to go have fun? And which is better? I wouldn’t say either story-driven or sandbox games are better from a play perspective— it’s all about personal preferences and play style. I think they’re equally difficult to make in their pure forms, but in different gamesauce • Fall 2010 17

Studios open and close, games are started and cancelled, and the cycle continues. There are only so many places you can live to make games, and I feel like I’ve hit almost all of them in the past 15 years! I’ve liked different aspects of everywhere I’ve lived, but my spouse and I love San Diego. It has all the pros of LA without all of the crowds and congestion, and most of the pros of San Francisco with cheaper housing and less traffic. I liked the really great game development community in Austin, but I missed the ocean.

10

ways. Story-driven games are challenging because you have to find ways to keep the experience fresh and interesting over hours of play, and you also have to tell a compelling story while giving the player meaningful choices and opportunities to feel like he has shaped the story in significant ways. Sandbox games are challenging in terms of creating systems that are robust and fun enough to hang hours and hours of play on them—the systems have to be fun in themselves, so adding play spaces and toys (like weapons) on top of that just becomes gravy. I think there is a middle ground, however, and I believe it’s an answer Warren Spector and other developers came up with years ago. Create a great story, then let the player steer and direct his experience through that story via a series of natural choices that come out of his personal play style. When you look at Ultima Underworld, System Shock, Deus Ex and Thief, you can see the marriage between a strong story with linear progression and a sandbox that lets you decide where and how to solve problems and move through the space. It’s really brilliant when it’s working well—in Deus Ex, for example, I discovered that friends completed levels in different ways I didn’t even know existed, because the way I’d played felt so natural to me that I assumed it was the only path or choice. I love some of the games trying for that same mix today, like Oblivion, Fallout 3, and Red Dead Redemption, but (so far) they haven’t managed that great combination you see in 18 gamesauce • Fall 2010

10. What’s next for Laralyn McWilliams? I’m really interested in finding ways to bring games to a new audience, and ways to bring new experiences to core gamers. My current Free Realms project at SOE is an unannounced online game for Facebook, bringing the real-time games like Deus Ex. The newer games still communities and personal connections from feel like you play sandbox for a while, then MMOs into the social space. We also have have an opportunity to step out of the sanda strong sense of story and a mature theme box for a minute to play some story. It feels that will feel really fresh. It’s a new frontier like stepping onto a ride at a theme park, on Facebook, where everyone is still figuring out what will work, and it’s an exciting place to be. I believe Facebook gamers are true gamers—I think was to create something that they’re the same people who and so much like a bought adventure games like Myst and who still buy “cait, movie that sual” games from PopCap and I think we got there. and Big Fish. The majority of the game industry just wasn’t making many games that appealed to them. In my personal time, and not like a continuous experience. The I’m working on an old school RPG. It’s games that got it right years ago also tended partly because I really miss those games, to be too complex (by today’s standards), so and partly because I really miss working on I think they get overlooked in terms of how art and scripting—so it sounded fun to have they blended story and sandbox. I hope we’ll a side project. More than that, though, it’s get back around to that style of game-play because I think we game developers threw soon, because I think it’s where games really out the baby with the bathwater when we shine as a unique entertainment medium. went real-time, action 3D with pretty much every game on the PC. Games go where 9. You’ve moved around a lot: San Dithe market is, and the mainstream market is ego, LA, San Francisco, Austin, Seattle. definitely in present day, realistic, real-time Any preferences? 3D action games. I love those games and I was an Army kid, so I moved all the time, I play a lot of them—but I don’t think I’m but it still sounds crazy when you list them the only one who misses some of the slower all out like that. And you missed Chicago, paced, more thoughtful 2D CRPGs. I’m Michigan, and North Carolina (where I posting development updates on my blog at made my first game)! Being a game develhttp://www.eluminarts.com. Drop in, check oper often feels like being a migrant worker. it out, and tell me what you think!

My goal felt so natural you wouldn’t notice

9

gamesauce • Fall 2010 19

Industrial Depression

Bonus Schemes W

e’ve all seen the amazing, royalty-driven excesses that some developers have been prone to—the cutting-edge electronic toys, the fast cars, the expensive bikes, the million-dollar homes in the Hollywood Hills, and (lest we forget) the twoweek vacations on the International Space Station. After reading stories in the mid-‘90s about John Carmack and John Romero racing each other to work in identical Ferraris, it was easy to conclude that making video games was finally a real job that any young gamer could aspire to—with an honest-toGod pot of gold at the end of it. Sadly, these stories of financial windfalls have turned out to be aberrations. Indeed, it’s the fact that they are so few and far between that makes them so newsworthy. These days publishers want to own the IP rights (because that’s where the long-term monetary value really is). Owning both IP and getting a great royalty rate from a publisher is getting rarer all the time—especially if you’re a startup without 100 percent self-financing. Add to that the fact that 85 percent of games do not, in fact, make their development costs back, and you realize why distributing royalties (or bonuses)—when they do happen—can become such a political nightmare, particularly when the sums are small. That may sound contradictory, but experience shows that financial envy is strongest when the amounts are low because who-gets-what suddenly becomes that much more important. Once your own personal bonus goes beyond $100K, it becomes less about what other people got because what you got was 20 gamesauce • Fall 2010

sufficient for you to feel ok about yourself, your position and your contribution. However, if you got $10K and the guy over there got $25K, well, a difference of $15K suddenly assumes that much more importance:

are so uncommon, it’s probably smart to understand what kinds of royalty schemes are out there, how they work, and how they might affect you.

Because “bonus” opportunities are so uncommon, it’s probably smart to understand what kinds of royalty schemes are out there, how they work, and how they might affect you.

$15k can keep you from buying that car you want, or from totally paying off your credit cards. When the values are of a magnitude larger than that, then you’ve already satisfied your immediate wants. At that point bonuses start becoming a means of keeping score. But let’s return to the point that this is less likely than more likely. Most games do not make their development and marketing costs back. Unlike movies, games have only one avenue of revenue, and even that’s diluted by the buyback policies at companies like GameStop and GameFly. Given this point of view, worrying about what you might earn versus what you are earning is somewhat premature. Because “bonus” opportunities

Bonuses, Royalties, and Profit-sharing A bonus is, at root, just that: a lump sum given at a company’s discretion to say, “Thanks for working here and contributing.” It might be for something specific (shipping a game, for instance) or for doing something above and beyond the call of duty (moving to another location for six months to help finish something up). Or you may receive a bonus just because the company wants to reward everyone. Yearly bonuses are most often a predetermined value (a percentage of your actual salary, perhaps) tied to a performance review. For instance, your company’s policy might be to give bonuses of up to 30 percent of your annual salary, depending on the degree to which you have met your various performance

targets. At some places your bonus may depend on a combination of factors: overall company performance, your studio-specific performance, your individual contribution, whether you shipped that year or not, and so on. Bonuses may be mandated by employment contract or left to the discretion of company executives. In general though, they are a onetime lump sum that doesn’t fluctuate with how well the product did in the market place. Especially if your bonus is calculated as a percentage of your salary, you may have the world’s bestselling game but your bonus remains the same regardless. EA, for example, is fond of this approach. In contrast, royalties are the sharing of income from a specific project— much like profit-sharing, which is the sharing of all of the income a company generates across various projects. If you share only profits generated by games you were directly involved in, that’s royalties; but if you share the profits from every game your studio makes, regardless of whether or not you worked on it, that’s profit-sharing. Royalties can often be applied across different SKUs as well. Say you build the Xbox version of a given game but someone else makes a DS version—you might well be eligible to share in royalties for that game simply because they used an IP you created. Royalties and profit-sharing typically are not a function of your salary but rather of the company’s income. The actual value a studio passes on to its developers varies widely depending on a variety of factors— fixed and variable marketing costs, R&D earmarks, and working capital allowances

can all eat into what might otherwise look like “profits.” Publishers who front money for development and marketing tend to take their cut first, with the developer not getting a royalty until the publisher’s money is recouped. This means that if the ad spend was high and the game took a while to make, it’s entirely possible to sell a million units and still not see any money at the developer end.

Getting Personal The real question is: Assuming there are profits to share, how does your company determine how much you get? That’s the bit that matters to each individual, and it’s often the part that generates the most heat and resentment.

Generally, the amount given to each contributor tends to be left to a lead’s discretion. Most studios have the leads all sit down with the project lead/exec producer/guy-in-charge and map out percentages for each person based on the lead’s personal experience through the development process. It’s usually pretty informal and depends on personal knowledge of what you contributed to the project. The final scoring for each individual is usually tempered with duration-on-project: If you’ve only been on that project for the last six months, you’re

likely to receive relatively less than someone might receive for filling a similar role over the course of a year or two. Now this can be viewed as a popularity contest—who is liked by the leads and who is

Assuming there are profits to share, how does your company determine how much you get? That’s the bit that matters to each individual, and it’s often the part that generates the most heat and resentment.

not has a huge impact on this scoring methodology—and sometimes it’s true. On the other hand, human discretion in the scoring process can also take into account edge cases that a purely mathematical approach cannot. A set formula can’t really take into account the junior engineer who stepped up and created a system that has been universally applauded for making the game two times better. It also can’t be appropriately sensitive to the fact that a designer soldiered on even though his wife left him in the middle of the project. There are other methods of allocating individual profit shares based on statistical methods that assign values to seniority at the studio, seniority on the project, check-in count (seriously!), values from a pre-negogamesauce • Fall 2010 21

tiated contract and so on. Lots of companies prefer these hard-coded equations since, while they may be unfair in certain circumstances, they are uniformly unfair to everyone. Seniority is often used as a multiplier for percentage calculations, however it has the

Inspired by The Wisdom of Crowds, Linden Lab (creators of Second Life) used to have an allocation method that left the bonus pool in the hands of the employees. Say, for instance, that the pool provided the equivalent of $2,000 per person. Each employee would then receive $1,000 to keep and $1,000 to

While hard-coded equations may be unfair in certain circumstances, they are uniformly unfair to everyone.

downside of allowing employees who have been around for a while to coast more because their guaranteed percentage is higher than the average anyway. For such people, there may be less incentive to really kick ass because they are going to get a decent bonus anyway. On the other hand, seniority is often viewed by management as a way of rewarding loyalty.

22 gamesauce • Fall 2010

distribute to anyone else in the company. The money could be split in any way the person saw fit—distributed to an individual, a group of individuals, or a team, or to anyone associated with a specific task. The idea behind such an approach is that any given individual probably knows what about 20 percent of the rest of the studio does in any detail, but for everyone, that 20 percent is a different 20 percent—so that in the end, those most deserving will be appropriately recognized and rewarded. The downside to this tack is that people who do repetitive work—work which never changes, like MMO maintenance for example—may go under-appreciated and compensated because their work lacks the flash and sex appeal of

more highflying projects, even though what they do may be equally valuable to the company. The ultimate point may be this: There is no universal, everyonewill-always-be-happy bonus-awarding scheme. Whatever you choose, someone at some point is going to have a problem with it.

Keeping Things “Fair” Whatever method of remuneration is employed, there is some debate regarding whether or not the company should make the details of the profit-sharing public. Some argue that if the details are made public the company will be forced to be fairer in how it shares the wealth (although what constitutes “fairer” is open to interpretation). Others argue that making this kind of information public fosters unrest—that unless everyone is receiving large bonuses, there will always be individuals who feel that they deserve more than someone else. Speaking of “fairness”: What happens when people who were crucial to a game leave before the money comes in? Do they not deserve to share in the post-ship rewards? They did the work right? At most studios, the answer to that question is a resounding no. Studios use the bonus system as a retention tool, requiring employees to stick around for at least six months after ship in order to participate. Companies that share profits even with those who have gone elsewhere are definitely in the minority; it’s just too easy to use profit-sharing restrictions to entice developers to stay with the company and become invested in the next game before they get their bonuses from the last one.

However, at the end of the day, the lure of large house-purchasing bonuses is hard for a game developer to ignore. And it’s right that this potential be out there. Developers work hard. They put in long hours and they take risks. It’s only right that they share in the final rewards from their hard work

There is no universal, everyone-will-always-behappy bonus-awarding scheme. Whatever you choose, someone at some point is going to have a problem with it.

because it provides impetus to do that hard work in the first place. At the same time, wise developers consider any sort of profit-sharing gravy. Even though it’s very easy to feel that you deserve a bonus of some kind, the fact remains that you are paid for your day to day work. A bonus isn’t an entitlement, after all; it’s a reward for building something successful. Which is, perhaps, the ultimate lesson here: Do good work, and the rewards will come.

gamesauce • Fall 2010 23

10 Myths about Working in Japan Rethink What You Think You Know by James Kay

F

ew countries receive such gushing praise and adoration as Japan when it comes to video games—from the West at least. It’s not uncommon for Western developers and game aficionados to look longingly Eastward and imagine the possibilities of moving and settling in the Land of the Rising Sun, and maybe even making a career out of developing the kinds of games that many of a particular generation grew up with. The good news: It’s no pipedream. It’s entirely possible! That said, developing games in Japan might not be all you imagined, and though I would hate to dissuade anyone from coming over, I would highly suggest becoming as well informed as possible before making such a lifechanging decision. Permit me to summarize some of the common misconceptions I have identified through my blog, “Japanmanship.”

24 gamesauce • Fall 2010

illustrations by Jim Moore gamesauce • Fall 2010 25

Myth #1 The Japanese Game Industry is a Closed Shop

Though Japan has been slow to hire expatriates, even in recent years we’ve seen a surge of foreign developers working at Japanese companies.

This is a line I’ve come across often on forums. Usually the reply to a young hopeful who has expressed his desire to work in Japan goes something like this: “Well, I went to Japan straight after college, and after two weeks I applied for a position as CEO at Sony and they turned me down. It’s such a closed shop! Forget it!” I think you’ll find if you have little experience, no marketable skills and high expectations, every country’s game industry will appear to be a closed shop. Though Japan has been slow to hire expatriates, even in recent years we’ve seen a surge of foreign developers working at Japanese companies. In the apparent belief that adding “foreign” to their studios will enable them to compete globally, Japanese developers have opened their doors wide to foreigners with the right experience. Those who wish to move to Japan could make good use of this misconception to land themselves a decent job. Whereas it would have been slightly more difficult to find work in Japan even just a few years ago, these days your nationality might actually be seen as a

competitive advantage—assuming you are otherwise qualified to fill an open position.

Myth #2 To Work in Japan You Must Be Fluent in Japanese Though it is undeniable that you’ll have a lot more job opportunities and choices if you are fluent in Japanese, it is by no means a requirement anymore. A few studios have entire sections made up of foreign talent, and some even offer Japanese lessons to their foreign staff and English lessons to their local staff (though time and budgetary constraints make these fairly rare overall). Depending on your job description, it is not entirely unthinkable that you’ll do well enough with conversational Japanese alone. That said, you will be working with Japanese colleagues and you will be living in Japan, so do yourself a favor and start learning the language as soon as possible! I know of a few foreigners in Tokyo who have lived here a long time without ever cracking open a textbook, and though they manage at work, buying groceries can still be a monumental task. The better you can communicate— both inside and outside of the office—the better off (and happier) you will be.

Myth #3 The Japanese Have an Exemplary Work Ethic This is one of the most persistent myths floating about, due in no small measure to great PR by the Japanese themselves. From the outside it certainly seems to be the case that the Japanese work long hours, deep into the night—sleeping under their desks, giving up their weekends and family life all for the glory of game development. It isn’t the full story though. One tenacious tradition that blights any Japanese company is the unspoken, unwritten rule that employees should not be seen leaving the office before the boss does. Knowing this, and realizing that working flat out for 14 hours a day is a sure path to karoushi (death by overwork), your average Japanese employee has adapted a few survival techniques. They come in as late as possible, they stretch six hours of work into 12, and they take copious breaks and the occasional nap. And who can blame them? If you know from the start you’ll be at the office until midnight, why hurry and work yourself to death?

26 gamesauce • Fall 2010

From personal and anecdotal evidence I’d confidently state that your average Japanese employee working the “Japanese way” is no more productive than a dedicated employee working nine to five. In fact, as projects drag on (as they are wont to do), the long hours, lost weekends and lack of sunlight seem to make the listless, groggy Japanese employee less productive over time. It is fun to note that such working practices, especially when they go unremunerated, are illegal, even in Japan. If a game company has strict working hours, it’s probably because some tired or bitter employee reported them to the Labor Standards Office, who themselves annually spot-check and fine hundreds of companies all over Japan. Nevertheless, working long hours is still a fairly common practice and a surefire way to be seen as a good employee. Just don’t confuse it with work ethic.

Myth #4 Japanese Salaries Are Very Low Japanese salaries are lower than those in the West, that is damn sure as mustard. I’ve often been shocked—horrified even—to learn what junior Japanese members of a team earn. One of the great things about being considered an “outside person” (or gaijin, as some Japanese would say) is that you are not expected to follow all the rules and societal obligations that Japanese people pretty much are forced to. Even though there is no escaping the long working hours, it is almost expected that foreigners will negotiate for a decent salary during an interview. If you take a job at a level of pay you are unhappy with, it’s pretty much your own fault, as it is everywhere. Even in Japan the only real way to get a pay raise is to switch jobs. That said, there is no way you’ll earn as much in Japan as you would in, say, the U.S. Luckily, reports about the high cost of living in Japan are somewhat exaggerated. If you can adapt to smaller housing and a different lifestyle—one that excludes champagne and oysters for breakfast every day—you can live a pretty comfortable life in Japan on a Japanese salary. With a more favorable tax system than you may be used to, you’ll also find yourself taking home a bigger chunk of your wages than you would in other countries. With the recent vogue for hiring foreign talent, Japanese companies have found their salaries creeping up somewhat too. With

the right talents, the right experience, at the right time, at the right company you could earn a decent wage—but it won’t make you rich.

Myth #5 At Least They Give Bonuses in Japan There is a thing that is laughably referred to as a “bonus system” in Japan. One sometimes reads reports on bonuses given to employees of certain companies in Japan, but as with many things this isn’t the full story. The “bonus system” (note my sarcastic use of quote marks) works if you have a full-time contract at most companies. It basically means the company will withhold a certain amount of money from your yearly salary and pay that back to you in June and December. Consequently, when you are interviewing you’ll probably want to inquire about the bonus system and ask to be excluded from it. Otherwise, rather than have your yearly salary divided into 12 monthly chunks, it is more likely to be paid out in 14 installments—that is, assuming the company survives and is in the pink when it is time to receive your semi-annual “bonus.” I understand why employers do this: The bonus system is something of a pair of leaden handcuffs that prevents employees from quitting before June or December.

If you can adapt to smaller housing and a different lifestyle—one that excludes champagne and oysters for breakfast every day—you can live a pretty comfortable life in Japan on a Japanese salary.

gamesauce • Fall 2010 27

When you are interviewing you’ll probably want to inquire about the bonus system and ask to be excluded from it.

28 gamesauce • Fall 2010

Why employees so readily agree to this is the real mystery. The “bonus” is taxed as salary, which it really is anyway, and though it’s the annual salary you’ve negotiated there is no guarantee you’ll actually get it. Performance reviews may bite into the total and the company might lay you off or go down in May or November. Not only that, but the system also prevents you from switching jobs until July or January, when you will be compelled to join the thronging masses looking for new jobs.

familiar relationship with your leads (possibly even your boss) and I’d be very surprised if you end up having to bow to anyone— ever—aside from visiting clients. There are a few limitations, of course, and as usual the Japanese employees suffer a little more under the pressures of hierarchy than foreign employees have to, but your working day will very probably not resemble any of the overblown and somewhat comical scenes you may have seen in films or television shows.

Myth #6 The Hierarchy is Obtuse and Strict

Myth #7 At Least I’ll Have Job Security

Stories of tight suits, deep bows and shouted morning greetings often lead Westerners to look askance at “silly” Japanese corporations. Such customs do exist, but the game industry is a lot more relaxed than most in Japan. Sure, there may be a few older companies in which such traditions still linger, some that even make you wear company windbreakers, but generally it’s pretty relaxed. You won’t need to wear a suit, you can have a pretty

Compared to the West, where the laying off of masses of employees seems to have become a bi-annual tradition, Japanese companies generally will seem more stable. The government prefers badly run companies to survive and continue to pay into the welfare system rather than let them go bankrupt, and often smaller, ailing companies will seek solace in numbers and combine into larger umbrella corporations.

Even so, “job for life” is a thing of the distant past—but all in all, it’s pretty difficult to get yourself fired, or to find yourself kicked out on the street. But don’t make the mistake of thinking you’re perfectly safe, of course. Companies do close down, and people do get laid off or asked to take voluntary separation or redundancy. With a dodgy economy and the general malaise that the Japanese game industry is suffering, I predict we’ll see more studio closures and layoffs in the coming years. But if you’ve experienced the Western postChristmas-release reduction waves Japan may seem a wee bit more secure for your average employee.

Myth #8 You Get to Work on Cool Franchises Sure, you might—if you’re lucky. Perhaps your dream will come true and you’ll get hired by that company that has been making that franchise that you love so much. But what few people seem to realize is that there is so much more to the Japanese industry than what filters through to the West. So many games get made here that are either too low-budget or too culturally Japanese to be worth localizing and releasing in the West. Even highly-informed Western geeks who can read Japanese might still only be seeing the tip of the iceberg. And as probability dictates, you may also be working on one of these. Not that there is any shame in working on a furry dating sim or Japanese talento karaoke game, as opposed to, say, Final Fantasy 25. Just be aware that if your goal is to work on specific franchises because of some perceived cachet you are not only severely limiting your options but also in danger of being rather disappointed. Employees get moved around teams, your company may be taking onboard an outsourced project—anything can happen. So don’t be too prejudiced when it comes to your future résumé. You might not have the choice.

Myth #9 Life in Japan is Super Awesome Special Don’t get too excited now, tiger. Japan is a country, like any other, and has many good points to appreciate and its fair share of negatives to annoy you. The question is: Do the positives outweigh the negatives? Only you can answer that, and only in the long run.

You’ll find your first couple of years in Japan to be a magnificent adventure, full of surprises, technology, discovery and fun. Hell, you’ll probably even start blogging about things like ramen lunches and that small temple you found tucked away in between some high-rises. You’ll love the food, the people, the opposite sex, the nightlife, the shops, the service—everything that seems so much better than home. Then you’ll invariably enter a bleak period of hatred and frustration. You can’t order pizza without wasabi and mayonnaise on it; the trains are too crowded, the summers hot and humid, the people rude and xenophobic, the red tape cumbersome and obtuse. You might even consider giving up and just moving back home, you hate it so much here. You’ll probably blog about how annoying Japan and the Japanese are. However, if you have the gumption to work yourself through this phase, you’ll find it’s all relative and that Japan is no more special than any other country and that life here is just what you make of it. It’s not for everyone, of course, but if you find the good outweighs the bad, it’s a perfectly fine place to settle and build up a new life. But you’ll need to live here for a few years before you truly know.