COMPOSITION CLASSROOM of a

Dhrithi Vishwa

Dhrithi Vishwa

Dhrithi Vishwa

Dhrithi Vishwa

Dhrithi Vishwa

Dhrithi Vishwa

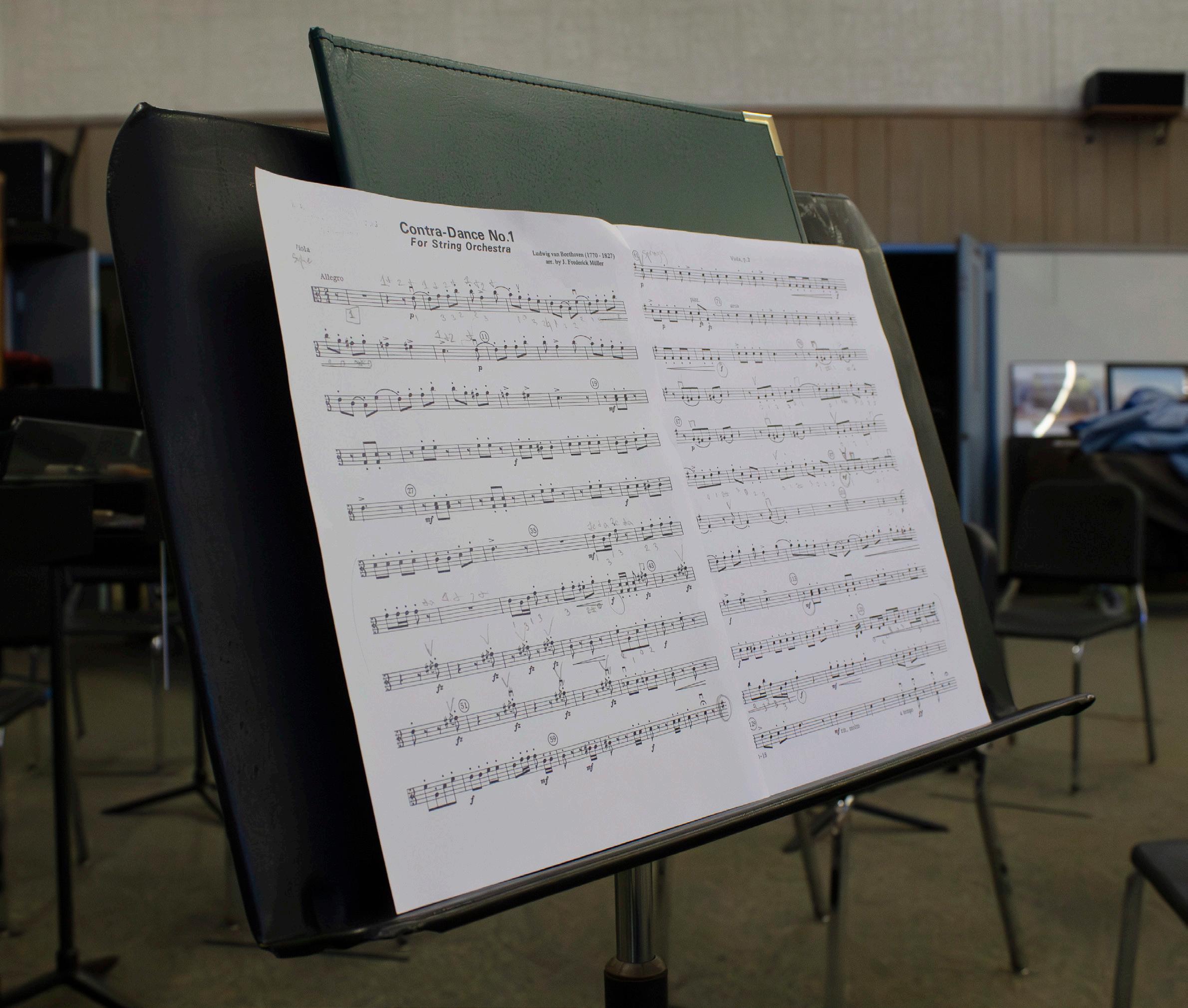

Jo looking at her score while teaching.

For my wonderful orchestra teacher, Jo Nilsson. Thank you for all that you’ve taught me.

Jo working at her desk.

Jo working at her desk.

Thank you to Freestyle Academy for providing the tools and resources I needed to make this project possible. I would especially like to thank Mr. Greco and Ms. Parkinson for lending me their support, guidance, and expertise in this project’s writing and design components, respectively. Last but not least, I’d like to express my appreciation to my peers in my Design class for inspiring and encouraging me every single day.

The Documentary project initially seemed like something far out of my comfort zone. The thought of interviewing a subject, writing about them, and ultimately designing a book that does them justice was intimidating. But as challenging as it seemed, its creative elements were compelling, and I found myself excited to profile someone while exploring publication design.

This project helped me develop several skills that I will carry with me into the future. For example, I studied how to create visually interesting and meaningful designs in the context and style of a documentary book. I worked in Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and InDesign to achieve the results I wanted. I learned how to conduct an interview in a professional manner, which required question prep, recording, and transcription.

When I was looking for a documentary subject, I knew I wanted to profile a person who leaves a positive impact on the lives of others. My search for a subject ultimately took me to Jo Nilsson, my orchestra teacher. Her cheerful and welcoming demeanor and effort to be a positive educator drive the relationships she forms with each of her students and work to create a positive influence on their lives. Her personality and her perspectives as a music educator made her the perfect subject for this project.

The Documentary project is very dear to me. From working with Jo to designing this book, I enjoyed it thoroughly, despite the many challenges I faced in the process. We can learn many things from Jo about education, music, and empathy, and I will be forever grateful for having the privilege of knowing her. I hope this book will allow others to get to know her as well.

It was a chilly Monday morning, and Johanna “Jo” Nilsson was still in her office. Chatty high school students in Packard Hall busied themselves with their usual routine of setting up the room for orchestra rehearsal. Discussions ranged from favorite video game characters to upcoming exam topics; in Packard, students could express themselves freely. At 8:40 AM, with a gentle smile on her face and a cup of coffee in her hand, Jo finally emerged from her office. Jo’s students did not hesitate to include her in their conversations, cracking jokes and making small exchanges with her even after class officially began. Though the weather outside was cold, the atmosphere in the room felt warm.

Jo’s interest in music was sparked when she was just a toddler, and since then she has been involved with music for over 20 years. As a high schooler, she was heavily involved in Mountain View High School’s music program (where she now teaches orchestra) and always dedicated time to music practice. However, music wasn’t her only passion. Growing up, Jo found herself in mentoring roles in several of the groups she was in; the skill of teaching came to her naturally.

Today, she is not only perceived by her students as an exceptional educator but also as an ap-

proachable one. While many public school educators take traditional approaches to teaching, Jo extends her methods beyond the music sheets. In the cutthroat landscape of Silicon Valley’s public school system, she puts her students’ well-being first by fostering a positive classroom culture, supporting them through personal challenges, and fostering an inclusive community in the context of music education.

“You have to balance time for folks to just chit chat, while also having an efficient rehearsal.”

Jo Nilsson

While academic pressures intensify in American high schools, student mental health suffers a toll. A recent Pew Research Center survey revealed that 61% of teens feel a lot of pressure to get good grades, while 70% recognize that anxiety and depression are major problems among their peers (Horowitz and Graf). In Mountain View High School, one of the top public high schools in Silicon Valley, the pressure to excel endures. Relentless grind culture, high parental expectations, and dwindling college acceptance rates drive students to take on crammed schedules in pursuit of achievement, often at the expense of rest and social activities. Amidst their tedious schooldays, Jo’s class serves as a refuge for tense students.

In most classes, students are occupied by stress-inducing assignments, lectures, and exams. When teachers give them time for discussion, it is often for purely academic purposes. In contrast, Jo believes that giving unstructured talking time to her students helps create a comfortable learning space. She expresses that the nature of orchestra is inherently “less conversational” than academic classes, so “you have to balance time for folks to just chit chat, while also having an efficient rehearsal” (Nilsson).

Jo’s teaching style was partly shaped by the music instructors she studied under as a student in Silicon Valley. What struck her most was their commitment to building genuine connections with their students and creating positive learning environments. Lara Fernando, one of Jo’s former students and president of Mountain View High School’s music council, attests that Jo takes the time to get to know each of her students and their passions. “She could tell you what I do outside of orchestra,” says Lara, “and she knows me well enough to understand what’s going on in my life” (Fernando).

While Jo appreciates some aspects of her past instructors’ teaching styles, she has mixed feelings about their approaches to assignments and assess-

ments. For example, despite their common appearance in her music classes growing up, she avoids assigning practice logs–sheets where students are required to record their weekly practice hours and have signed off by their parents. Jo acknowledges that practice logs can increase the level of personal accountability that students feel towards their music program. However, she also recognizes that they can be challenging for those who struggle with assignment submissions: “They would get a worse grade because they didn’t turn in their practice log, and I know they’re practicing because I see them practice” (Nilsson).

To Jo, forming positive connections with her students and encouraging them to bond with one another is crucial to creating a classroom where they feel secure enough to take risks. Failure to establish a safe space can lead students to withdraw and avoid participation because “they’re so afraid of making a mistake in front of others” (Nilsson). This is why Jo prefers to give feedback to individual students privately instead of pointing out errors in front of their classmates. When providing feedback in a group setting, she addresses it to either a section of the ensemble or the orchestra as a whole. This allows students to learn without feeling insecure and also makes risk-taking seem less scary (Nilsson). In the results-focused Silicon Valley, Jo has created an atmosphere where students feel at ease taking risks and making mistakes.

Previous pages: The violin part for an orchestral piece. One of Jo’s students practicing.

“Knowing she had something similar happen to her made me feel like it will be okay.”

Lara Fernando

As a high schooler, Jo was diagnosed with severe depression. In her junior year, she decided to drop out of all her academic classes, yet she continued to attend her music classes. It was her bond with music that gave her motivation to show up to school, and it was her peers and music teachers who kept her “anchored” in the community (Nilsson). Reflecting on this period, Jo shares that, if she didn’t have those musical communities, she “might have not come back to high school or decided to not pursue college” (Nilsson).

Jo’s openness about her experience enables her music students who are facing similar struggles at Mountain View High School to connect with her on a deeper level. When Lara experienced a setback in her career path due to a brain injury, she found inspiration in Jo’s resilience. “Knowing she had something similar happen to her made me feel like it will be okay,” says Lara, “Sometimes redirection can turn into something really positive” (Fernando).

Jo also recognizes that many teenagers “go through a tumultuous time emotionally and hormonally,” an experience similar to hers as a high schooler (Nilsson).

According to a 2021 report by the CDC, 42% of American high schoolers experienced persistent feelings of hopelessness or sadness. Furthermore, 22% seriously considered attempting suicide, and 10% attempted, indicating a concerning rise in mental health issues among teenagers over the past decade (CDC).

Lara also recalls another instance where Jo’s support helped her cope emotionally. As she was preparing for an upcoming concert, Lara received news that her middle school music director was hospitalized for cancer. Lara’s middle school music director had taken her under her wing and taught her how to conduct, so the news deeply affected her. Despite being unaware of Lara’s trouble, Jo allowed Lara the opportunity to conduct a piece for the concert. The day following the concert, Lara learned of her music director’s passing. To this day, Lara maintains gratitude for Jo’s support: “She was willing to try something new with me, and it was really helpful in healing from the loss of someone who had been a critical part of my life” (Fernando).

In Silicon Valley, poor mental health in teenagers can often be traced back to achievement culture: pressure to “stand out” for elite universities undermines students’ well-being, leading them to measure their self-worth by their achievements. However, as award-winning journalist and New York Times bestselling author Jennifer Breheny Wallace points out, “It’s not the prestige of a college that matters; it’s how students fit into their environment and feel valued in a meaningful way.” This sentiment is echoed by Jo, who believes that parental pressure for students to join top-level ensembles should be avoided. “Emphasizing prestige negatively impacts students’ experiences in the class,” says Jo, “and I think that if we can instead focus on why we love making music and participating in the community, then students are more likely to persist with the music program and enjoy it.” Breheny Wallace highlights that many of the students who struggle most feel like their value is “contingent on their performance,” so Jo underscoring the importance of valuing enjoyment over achievement offers a vital strategy educators can take to support their students amidst Silicon Valley’s demanding academic climate.

copy

“She can find music that’s a good balance between a suitable challenge for an experienced player, and something accessible for a beginner.”

Lara Fernando

Jo not only supports her students’ emotional well-being but also makes them feel included by considering where they each fit into the orchestra, accepting student input, and promoting collaboration. In selecting concert pieces, for instance, Jo thoughtfully considers the musicians’ skill levels and their enjoyment. Lara notes that “she can find music that’s a good balance” between a suitable challenge for an experienced player, and something accessible for a beginner. This approach encourages new members to join the orchestra while also keeping older members engaged. Additionally, Jo makes sure to balance the melody of the music among different instrument parts. Often in orchestral music, violists may find their parts less significant. But Jo makes an effort to select pieces that highlight the viola section–a choice that violists like Lara have come to greatly appreciate.

Furthermore, Jo’s approach to musical selection is highly inclusive of student input. In one class, Jo played a professional recording of “Hungarian Dance No. 5” for the students–a piece they were preparing for a concert. After hearing a glissando–a technique where a string player will slide upward or downward between two notes–a student pointed out its usage by the performers in the recording. Jo then asked the student to demonstrate a glissando to the class and opened the floor to the other students for discussion on its inclusion in their performance. Rather than simply instructing the students to use the glissando, Jo actively engaged her students in a conversation surrounding the technique. She explains,

“I think those conversations increase a sense of ownership and enhance the collaboration that’s already happening” (Nilsson).

Jo further encourages student collaboration by scheduling sectionals as part of the class’s weekly activities. During sectionals, students who play the same instrument work together to improve on specific segments of the concert repertoire. While there may sometimes be a designated section leader, the environment of a sectional is typically more of a “collaborative give-and-take conversation” where students can freely exchange ideas on how to approach certain passages and the best techniques to use (Nilsson). This practice not only benefits the students’ musical skills but also strengthens their interpersonal bonds as they develop teamwork skills.

For Jo, collaboration in an orchestra serves as a metaphor for teamwork in life. “If the student next to you is playing completely wrong notes, while you’re playing all the right notes, it’s not going to average out to the middle,” Jo explains, “Our ear is going to pick up the wrong notes” (Nilsson). This orchestra principle applies to a broad spectrum of scenarios. From group projects to relationships, effective collaboration can’t happen before individuals take on self-responsibility. It’s only then that individuals can develop an awareness of how they fit into the whole.

As an orchestra teacher at Mountain View High School, Jo has grown to cherish the vibrant community of students and educators that make up the music program. In the relentless academic climate of Silicon Valley, she is dedicated to supporting her students, but just musically but also emotionally and socially. Jo’s goal is for her students in the music program to feel safe and included in the musical community, and she aspires for them to “leave the music program with a lasting love for music” (Nilsson).

Music guided Jo to where she is today. But it’s her love for her students that has brought them closer to the world of music.

“I get a kick out of hanging out with my students and making music with my students, and I love it when they just can’t stop practicing.”

Jo Nilsson A signed card for Jo from the IMPA. Previous page: A boquet of chocolates gifted to Jo after a concert.

Jo Nilsson A signed card for Jo from the IMPA. Previous page: A boquet of chocolates gifted to Jo after a concert.

Breheny Wallace, Jennifer. Interview by Samantha Laine Perfas. The Harvard Gazette, 11 Sept. 2023, news.harvard.edu /gazette/story/2023/09/how-achievement-pressure-is-crushing-kids-and-what-to-do-about-it/. Accessed 29 Apr. 2024.

Fernando, Lara. Personal Interview. 15 March 2024.

Horowitz, Juliana M., and Nikki Graf. “Most U.S. Teens See Anxiety and Depression as a Major Problem Among Their Their Peers.” Pew Research Center, 20 Feb. 2019, http://www.journal ism.org/2017/05/10/americansattitudes-about-the-news-media-deeply-divided-along-partisan-lines/. Accessed 4 Apr. 2024.

Nilsson, Johanna. Personal interview. 28 Feb. 2024.

“Progress At-a-Glance for Mental Health and Suicidality Variables.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021, www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/yrbs_data-summary-trends_report2023_508.pdf.

Dhrithi Vishwa is a junior at Mountain View High School and a Design student at Freestyle Academy. Outside of school, Dhrithi is often found designing spreads for Mountain View’s student-run social justice and culture magazine. A vice president of her Girl Scout troop, Dhrithi is also involved in community service and advocates for social change. She also plays the viola in her high school’s string orchestra. In her downtime, Dhrithi enjoys reading comics, making playlists, and napping. She lives in Mountain View with her parents and sister. Dhrithi is looking forward to growing as an artist, designer, and individual, and is excited to see what the future holds.