the best of culture, tr avel & art de vivre

S umm e r 2 0 0 9

$5.95 U.S. / $6.95 Canada / francemagazine.org

No.90

ARLES Goes Gehry

The Art of Christian BOLTANSKI

Artisanal BEER

Spo nsors France Magazine thanks the following donors for their generous support.

For additional information on our sponsorship program and benefits, contact: Marika Rosen, Director of Sponsorship, Tel. 202/944-6093 or e-mail SponsorFrance@gmail.com.

Summer 2009 features 28 Being Boltanski A contemporary artist’s struggle with fleeting time, lost memories, forgotten lives by Sara Romano

38 Arles Will this Provençal town be the next Bilbao—only better? by Amy Serafin

50 Blondes, Brunes & Rousses France’s new artisanal beers are turning heads by Renée Schettler

departments 5 The f: section Culture, Sons & Images, Beaux Livres, Bon Voyage, Nouveautés edited by Melissa Omerberg

18 Voyages A Village in the Médoc by Alexandre Kauffmann

22 Evénement Madeleine Vionnet by Rebecca Voight

58 Calendrier French Cultural Events in North America by Tracy Kendrick

64 Temps Modernes Almost Famous

© Pat r i c k G r i e s

by Michel Faure

• A detail of an evening gown from

Vionnet’s Summer 1931 collection, part of a retrospective at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Story page 22.

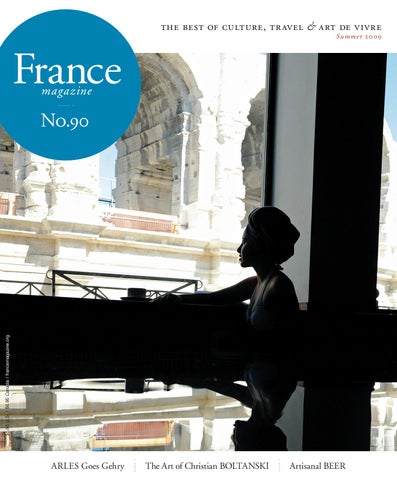

Dear Readers, This past week, i ran into an old acquaintance, a french journalist who had been posted to Washington, DC, 20 years ago. He was back in town on a Toquevillesque assignment to observe and sum up the United States for his readers. Having just read David Brooks’s insightful and amusing article on such undertakings (“Mirror on America,” in The New York Times Sunday Book Review), I was in awe of his courage. As Brooks wrote, “Jacques Barzun once observed that of all the books it is impossible to write, the most impossible is a book trying to capture the spirit of America.” I admire the French who take up that daunting challenge, just as I admire American efforts to capture France and Frenchness for Americans. The latter is a genre that runs from the ridiculous to the sublime and just keeps growing—our books editor has an entire shelf of such tomes to prove it. Curiously, the more I know about France, the less I understand how one can come up with the sort of generalizations and summary declarations that are typically the mainstay of such books. During my Arles’s sleek Aux Bains du •Calendal nearly 25 years editing this magazine, I have been spa, with views of the told more than once that I know France better than ancient Roman amphitheater. Story page 38; photo Hervé Hote/ many if not most French people. And it is always Agence Caméléon. tremendously gratifying when French residents of a city we have reported on tell me they learned something about their hometown by reading our magazine. Yet I don’t feel even remotely close to having mastered my subject. Truth be told, I don’t really want to understand the French, at least not completely. And I don’t want to know everything about their country. What would be the fun in that? I think the joy of putting out this magazine—and, we hope, of reading it—is that France can be like that most wonderful mate, the kind with whom you enjoy a tremendous comfort level yet who always remains something of a mystery, who keeps evolving and changing just enough to keep you interested. The kind you can spend a captivating lifetime getting to know. Sometimes, France manages to upend even our most basic assumptions. Everyone knows the French are all about wine, right? Yet it turns out that during the past couple of decades, while we were focused on the vineyards, craft brewers were springing up throughout France, bringing an entirely new attention to quality ingredients and technique. Right under our noses, they had been redefining “French beer” and winning over discerning palates, including some of the country’s leading chefs. Thanks to Renée Schettler’s article in this issue, now we know. Yet again, we were delighted to discover how little we know about France. K a r en Tay lor

Editor 2

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

France magazine Editor Karen Taylor

Senior Editor/Web Editor Melissa Omerberg

Associate Editor RACHEL BEAMER

Copy Editor lisa olson

Proofreader steve moyer

Art Director todd albertson

Production Manager Associate Art Director/Webmaster patrick nazer

Contributors MIchel faure, now

retired from L’Express, is pursuing a variety of journalistic ventures • Alexandre Kauffmann is a Paris-based author and journalist; his latest book is J’aimais déjà les étrangères • TRACY KENDRICK is a freelance journalist who often writes about French culture • Sara romano covers French cultural topics for a number of publications • RENéE SCHETTLER is a freelance writer with a special interest in food; she has worked as editor and writer at Martha Stewart Living, Real Simple and The Washington Post • AMY SERAFIN, formerly editor of WHERE Paris, is a Parisbased freelance journalist who has contributed to The New York Times, National Public Radio, Departures and other media • Rebecca Voight writes on style for Interview, The New York Times T Magazine, the International Herald Tribune and V. She was previously co-editor of Dutch magazine. EDITORIAL OFFICE

4101 Reservoir Road, NW, Washington, DC 20007-2182; Tel. 202/944-6069; mail @ francemagazine.org. Submission of articles or other materials is done at the risk of the sender; France Magazine cannot accept liability for loss or damage. POSTMASTER

Please send address changes to France Magazine, Circulation Department, PO Box 9032, Maple Shade, NJ 08052-9632. ISSN 0886-2478. Periodicals class postage held in Washington, DC, and at an additional mailing office.

France Magazine

Gift Subscriptions

France magazine Publisher EMMANUEL LENAIN

Director of Sponsorship Marika Rosen

Director of Advertising DREW SCHMIDT

Accountant Maria de Araujo

Intern BAPTISTE AUGIER

France Magazine is published by the French-American Cultural Foundation,

a nonprofit organization that supports cultural events as well as educational initiatives and exchanges between France and the United States. Tel. 202/944-6090/91/69 advertising

USA

style

wit

beauty

insight

... for only $19.97!

www.francemagazine.org

Drew Schmidt Tel. 202/944-6476 azschm @ gmail.com France

AVANTAGES MEDIA Caroline Ducamin / Didier Cujives 99 route d’Espagne - Bâtiment A 31100 TOULOUSE Tel. 05/61-55-01-01 - Fax 05/61-53-90-94 Info @ avantagesmedia.com subscriptions

Photo credits

Being Boltanski pp. 28-29: angelika platen ; pp. 30-33: courtesy christian boltanski and marian goodman gallery, paris /new york ; pp.

34-35: bernd uhlig ; pp. 36-37: courtesy kunstmuseum, vaduz, liechtenstein.

Arles pp. 38-39: courtesy of réattu museum, office du tourisme d’arles, hervé hote /agence caméléon ; pp.

40-41:

© jean delmarty/andia , © jacques guillard / scope, © d. bounias / office du tourisme d’arles ; pp.

42-43: 44-45: jean dieuzaide, office du tourisme d’arles, kahala; pp. 46-47: l’instantanée, michel denance, hubert marot; pp. 48-49: hervé hote /agence caméléon, courtesy of bistro à côté, © jacques guillard /scope. Blondes, Brunes, Rousses... pp. 50-51: ©jacques guillard /scope; pp. 52-53: ©musée carnavalet/roger-viollet, courtesy of agence vianova ankea ; pp. 54-55: courtesy of brasserie georges, lyon, © envison /corbis, © john wigmore /agstock images /corbis ; pp. 56-57: courtesy of dbdg /new york city; brasserie de bretagne ; © jean-luc barde, jacques guillard, roland huitel /scope. bernard touillon, courtesy of bistro à côté, © philippe matsas ; pp.

4

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

France Magazine is published four times a year. Yearly subscriptions are $23.80 ($28.79 for Canadian and other foreign orders, $24.78 for DC residents). To subscribe, go to www.francemagazine.org or contact Subscription Services, France Magazine, PO Box 9032, Maple Shade, NJ 08052-9632. Tel. 800/324-8049 (U.S. orders), Tel. 856/380-4118 (foreign orders), Fax 856/380-4101.

www.francemagazine.org

• The pâte-de-crystal

“Troya” by Spanish sculptor Carlos Mata is part of Daum’s new “Hippic” collection. See Nouveautés, page 16.

TransMedia Group

magazıne

f

Edited by melissa omerberg

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

5

Culture

Paris & the provinces

Helen Frankenthaler’s luminous “Spring Bank” •(1974) is part of the Centre Pompidou’s new look at women in art.

1970s and 1980s, Bernard Lamarche-Vadel wore many hats, curating exhibits, editing the review Artistes and establishing his own collection. Dans L’Oeil du Critique, at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, gathers more than 250 works—paintings, sculptures, installations and photographs—that he loved, wrote about or purchased. Among the 72 artists included in this eclectic show are Arman, Joseph Beuys, Sophie Calle, César, Helmut Newton, William Klein and Richard Serra. Through Sept. 6; mam.paris.fr.

exhibits paris

Kandinsky The completion of a catalogue raisonné as well as recent discoveries in Russia challenge the narrow view of Kandinsky as “merely” the inventor of pure abstraction. Kandinsky, a major retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, revisits the oeuvre of this lawyer-turned-painter who saw the artist as prophet and art as a spiritual endeavor. The exhibit includes Kandinsky’s work with the Blue Rider, watercolors and manuscripts from his “Russian” period, and the Bauhaus portfolio produced for his birthday in 1926. Through Aug. 10; cnac-gp.fr.

6

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

Changing Design The Espace Fondation EDF presents Paris, design en mutation, featuring 11 of the most original designers of the past few years including François Azambourg, Matali Crasset, Delo Lindo, Mathieu Lehanneur and JeanMarie Massaud. Through the use of new materials and manufacturing processes, their humor- and poetry-infused work goes beyond the merely aesthetic, taking into account the impact of environmental changes and energy consumption on our way of life. Through Aug. 30; http://fondation.edf.com. A Critical Eye A major art critic and theoretician during the

Henri Cartier-Bresson In 1975, Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) curated a traveling retrospective of his work dubbed “Forty Years of Photography”; he later donated all of the photographs to the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. To fête the master’s centennial (give or take a few months), the museum is presenting L’imaginaire d’après nature, a reconstitution of the earlier show featuring 70 large-scale photographs as well as a film about the man sometimes referred to as the “father of modern photojournalism.” (Through September 13; mam.paris.fr.) A companion show at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Henri Cartier-Bresson à vue d’œil, showcases its own collection of the master’s works. Through Aug. 30; mep-fr.org. Valadon - Utrillo Suzanne Valadon carved out a place for herself in the bohemian, male-dominated art world of late 19th-century Paris, posing for Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec and creating her own powerful work. She transmitted this passion

J a c q u e l i n e H y d e l / © 2 0 0 9 H e l e n F r a n k e n th a l e r

Watchmaker Watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747-1823) played a revolutionary role in the art and science of watchmaking; an ultra-talented inventor and technician known for his style and entrepreneurship, he created stunning timepieces that were prized by the crowned heads of Europe and the Continent’s political, military, scientific and financial elite. Breguet au Louvre: un apogée de l’horlogerie européene offers a timely tribute to this quasi-mythical figure and to the company that bears his name. Through Sept. 7; louvre.fr.

to her son, the noted Impressionist Maurice Utrillo, who went on to become one of the most important exponents of the Paris School. Suzanne Valadon – Maurice Utrillo: Au tournant

at the Pinacothèque de Paris, focuses on their creative dialogue before and after World War I. Through Sept. 15; pinacotheque.com. du siècle à Montmartre,

50 Candles The Musée de la Poupée is fêting the 50th birthday of a certain statuesque blonde: Rêve ta vie avec Barbie® ! looks back at five decades of the improbably proportioned doll that lots of people love and plenty of others love to hate. Nearly 500 Barbies are presented with their original outfits and accessories—a fun way to revisit the fashion trends of several generations. Through Sept. 20; museedelapoupeeparis.com.

© G e r a r d B l o t / R M N ; X av i e r R e b o u d

Bath Time The reopening of the Cluny frigidarium— the pool that ancient Romans cooled off in after taking a hot bath—has inspired a twovenue exhibit at the Musée de Cluny and the Musée National de la Renaissance at the Château d’Ecouen, 12 miles from Paris. Le bain et le miroir examines the history of hygiene and the development of cosmetology through a variety of objects—personal implements, combs, mirrors, perfume bottles, cosmetic jars and so on—as well as sculptures and paintings. The Musée de Cluny focuses on the period between the Roman era and the Middle Ages, while the Château d’Ecouen looks at the beauty secrets of the Renaissance, when paintings of half-naked ladies sitting at their table de toilette became the hottest thing in portraiture. Through Sept. 21; museemoyenage.fr and musee-renaissance.fr. Moi Tarzan The world’s most famous yodeling ape-man swings his way into the Quai Branly this summer with Tarzan! ou Rousseau chez les Waziri, an exhibit devoted to Edgar Rice Burroughs’s loincloth-wearing hero. Inspired by various legends and literary antecedents—Rousseau’s

• Breguet timepieces, now on view at the

Louvre, were must-have accessories for the 18th-century European elite. Top to bottom: Breguet No. 2585, with an engraved map; No. 611, sold to Joséphine Bonaparte in 1800; No. 1320, created for the Turkish market.

“noble savage” and Kipling’s jungle boy, to name just two—the character had an indelible impact on pop culture. The show, which features an original soundtrack composed for the occasion, includes comic strips, film stills, movie excerpts, parodies and African artifacts. Through Sept. 27; quaibranly.fr. Occupation Fashion Between 1940 and 1944, the women of Paris learned to adapt to chronic shortages, becoming experts in recycling and substitution. Their resourcefulness found its expression in the fashion accessories of the time—often made out of unconventional materials, such as car tires—with items often serving more than one use: A scarf bearing Pétain’s likeness functioned as Vichy propaganda while a bag with a false bottom might conceal Resistance pamphlets. In Accessoires et objets : témoignage de vie de femmes à Paris 1940-1944, the Mémorial du Maréchal Leclerc de Hauteclocque et de la Libération de Paris-Musée Jean Moulin displays 300 Occupation-era articles, with photos, fashion magazines, newsreels and sheet music providing context. Through Nov. 15; ml-leclerc-moulin. paris.fr. Madeleine Vionnet Considered a “designer’s designer” for her technical prowess and rigorous vision, Madeleine Vionnet is known for pioneering the bias cut, among other things. Inspired by ancient Greece, she also perfected the art of drapery, achieving an extraordinary purity of line. Madeleine Vionnet, Puriste de la Mode, a major retrospective at the Musée de la Mode et du Textile (see page 22), traces the career of this influential couturier whose rejection of the corset helped emancipate the female body. Through Jan. 24, 2010; lesartsdecoratif.fr. Cherchez Les Femmes The Centre Pompidou is devoting its entire fourth floor and part of the fifth to more than 200 female artists from the early 20th century to the present. Featuring some 500 works drawn from the museum’s permanent collection, elles @ centrepompidou highlights the role of women in the artistic avant garde. A wide variety of media will be represented: painting, sculpture, photography, design, architecture, video, film…. Through Feb. 2010; centrepompidou.fr.

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

7

Culture Aix-en-provence

Strasbourg

Estuaire, a three-part cultural event that debuted

Picasso Plus Provence is Picasso Central this summer: Aix’s Musée Granet hosts Cézanne-Picasso, featuring 70 works by the Spanish artist and 30 by the man he famously called his “only master.” The paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints on view explore Cézanne’s inf luence on Picasso and the themes and shapes that fascinated both artists, from fruit bowls and skulls to Harlequins and bathers. (Through Sept. 27; picasso-aix2009.fr.) Visitors can continue their pilgrimage at the nearby Château de Vauvenargues —open to the public temporarily, for the first time— where Picasso once lived and is buried. On the tour: the artist’s studio, several rooms and a bathroom where he painted a faun over the tub. By reservation only; through Sept. 25; aixenprovencetourism.com.

Color Codes Strasbourg offers a two-part look at color:

in 2007 and will conclude in 2011. The festival, which runs along the Loire River from Nantes to Saint-Nazaire, features site-specific sculptures and installations, with venues including the former LU cookie factory, town squares, the roof of a submarine base—even the waters of the Canal Saint-Felix, which serve as a screen for the projection of images. Sites may be visited by car, bicycle, public transportation and by a special river cruise. Through Aug. 16; estuaire.info.

Doisneau’s Artists There are no kissing couples in Doisneau, Portraits d’artistes; this exhibit at the Musée Angladon focuses on some of the photographer’s least known works. On view are 50 portraits—many commissioned by magazines such as Vogue or Le Point—of 40 important artists, including Utrillo, Picasso, Braque, Arp, Léger and Duchamp. Though shot in the studio, they manage to convey the same feeling of intimacy that comes across in Robert Doisneau’s most emblematic images. Through Nov. 11; angladon.com.

at the Musée Zoologique, explores the role of color in nature, and particularly in the animal world. Chromamix 2: des pigments aux pixels, at the Musée d’Art moderne et contemporaine, examines pigments and the color choices artists make. The show brings together a wide array of works, from archeological shards to contemporary videos. Through September 27; musees-strasbourg.org. Vic-sur-Seille

Japanese Influences Emile Gallé, one of the founders of the Art Nouveau movement, was a trained botanist whose passion for nature led him to appreciate Japanese culture and its sensitivity to natural forms. That fascination, nurtured by the rise of le japonisme in France, drove him to seek a new style of art that melded East and West. Emile Gallé: Nature et Symbolisme, Influences du Japon, at the Musée départemental Georges

de la Tour in the Lorraine region, explores this aspect of the artist’s œuvre through some 150 exquisite items, including ceramics, glassware and preparatory drawings. Through Aug. 30; vic-sur-seille.fr.

FESTIVALS Nantes to Saint-Nazaire

Estuaire 2009 This summer marks the second installment of

Manderen

Imperial Splendor Built in the early 1500s, the Château de Malbrouck—named for a famous occupant, the Duke of Marlborough—is located in the Lorraine region near France’s border with Germany and Luxembourg. The latest in a series of important exhibits hosted by the château, Splendeurs de l’Empire: Napoleon et la Cour Impériale examines every aspect of Napoleonic society, including Napoleon’s military victories, his influence on modern France, Empire Style and the imperial family’s support for the arts through nearly 300 works of art, historical artifacts and documents. Through Aug. 31; chateau-malbrouck.com. 8

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

flacons •byTwo Emile Gallé (c. 1900), on view in Vic-sur-Seille.

Avignon

Theater Fest The famous Festival d’Avignon has joined forces with theater festivals in Athens/Epidaurus, Barcelona and Istanbul to identify and showcase Mediterranean artists. All four festivals will be premiering French-Israeli director Amos Gitai’s Guerre des fils de la lumière contre les fils des ténèbres—based on Josephus Flavius’s War of the Jews—at outdoor locations this summer. Also on the menu in Avignon: new plays by artists from Lebanon, Egypt, Madagascar, Congo and Quebec. July 7 through 29; festival-avignon.com. Orange

Grand Operas Orange’s majestic Roman Theater turns into a Paris salon and a Sicilian village this summer during the venerable Chorégies opera festival. Patrizia Cioffi and Vittorio Grigolo star in “La Traviata,” while “Cavalleria Rusticana” is performed in a double bill with “Pagliacci” (look for Beatrice Uria-Monzon, Roberto Alagna and Inva Mula). Symphonic performances feature works by Berlioz, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff and Mussorgsky. July 11 through Aug. 3; choregies.asso.fr. La Roque d’Anthéron

Keyboard Magic Aldo Ciccolini, Hélène Grimauld, Katia and Marielle Lebèque, Boris Berezovsky and Anne Queffélec are just a few of the headliners at the 29th Festival International de Piano de la Roque d’Anthéron. Featuring solo performances and chamber music, this extraordinary festival takes music to such unconventional sites as a quarry, a château garden, an abbey and a lake. July 24 through August 22; festival-piano.com.

© H i d a Ta k aya m a M u s e u m o f A r t ( J a pa n )

Avignon

Chromamix 1: du camouflage à la seduction,

• Dervishes whirl their way through France during “La Saison de la Turquie.”

© F i n b a r r O ’ R e i l ly / R e u t e r s / C o r b i s

spotlight on... Saison de la Turquie Visitors to France this summer get a twofer—a trip to Turkey thrown in for free. The SAISON DE LA TURQUIE EN FRANCE kicks off in July, showcasing Turkish culture in such major cities as Paris, Lille, Marseille, Lyon, Strasbourg and Bordeaux, as well as smaller towns throughout the country. Events include exhibits of traditional and contemporary art, architecture and photography; theater and dance performances; film festivals and concerts; literary events; and lectures and panel discussions. Head over to Paris’s Trocadéro for an unforgettable opening performance on July 4, when Mercan Dede—a famous Sufi DJ inspired by both traditional music and electronic sounds—spins discs for a whole troupe of whirling dervishes. They’re followed by Fire of Anatolia, holder of the Guinness World Record for fastest dance (241 steps per minute!). For something a little more leisurely, stop by the Turkish café set up in the Tuileries gardens; you can dream of the Bosphorus while sipping a syrupy Turkish coffee and enjoying a bite of sweet lokum. Fall ushers in a slew of intriguing museum shows, including “Istanbul, un port pour deux continents” at the Grand Palais, “François 1er et Soliman” at the Château d’Ecouen, “VideoSeZon” at the Centre Pompidou and a trio of exhibits at the Louvre. The festival wraps up next spring in a burst of poetry, when Turkey steps into the spotlight at the Printemps des Poètes. All in all, the year promises to be a true Turkish delight. July 1, 2009, through March 31, 2010. For a complete program of the Saison de la Turquie en France, visit culturesfrance.com.

9

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

• Yolande Moreau

won a best actress César for her title role in Séraphine.

On Screen

new on dvd

SERAPHINE Visionary painter Séraphine de

LOUISE BOURGEOIS: THE SPIDER,

Senlis (1864–1942) lived a simple life in a small village outside of Paris before being discovered by influential German art critic Wilhelm Uhde, for whom she worked as a maid. Her complicated partnership with Uhde (who also discovered Henri Rousseau) helped establish her as a player in the naïve art movement, but that success didn’t come without a price. Yolande Moreau brings a remarkable sensitivity to the role of the religiously devout and mentally fragile painter, delivering a performance that has earned her a best actress César. Slated release: June. (Music Box Films) GIRL FROM MONACO Something’s fishy when bikinis, mopeds and carefree Mediterranean romance start popping up in an Anne Fontaine film. A director who specializes in psychological tension, she created the part of the complicated main character, a smug and uptight lawyer, with Fabrice Luchini in mind. Luchini’s comedic delivery and his chemistry with his straight-and-narrow bodyguard—as well as his fling with the local TV weather girl—might trick you into thinking Fontaine has switched genres. But the film’s disturbing conclusion hits hard and is all the more shocking, given the seemingly goofy and initially likeable characters. Slated release: July. (Magnolia Pictures) AGNES’S BEACHES Although some have called Les Plages d’Agnès Agnès Varda’s swan song, the tirelessly curious 81-year-old “grandmother of the New Wave” shows no signs of slowing down in this documentary. The film traces Varda’s life and overlapping oeuvre from Sète (where she filmed her first feature, La Pointe Courte) to Los Angeles (where she made documentaries in the early ’80s) to Paris, where an artificial beach stretches in front of her home/production company. Select screenings. (Film Forum)

Music Serge Gainsbourg Histoire de Melody Nelson

Some four decades after Melody Nelson was released in France (where it initially flopped), this inventive album from music icon and quintessential dirty bird Serge Gainsbourg has made its way across the Atlantic. Written as a gift for his paramour, Jane Birkin, and loosely inspired by their relationship, the concept album details a lecherous older man’s pursuit of a young virgin. (Light in the Attic)

Phoenix Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix

Since appearing on Saturday Night Live in April, the Versaillesbased indie rock foursome (friends since childhood) has been selling out venues on their U.S. tour in a matter of days. The band’s clean-cut front man, Englishspeaking (and singing) Thomas Mars, enthusiastically belts out the peppy danceable tracks on their fourth studio album. (Glassnote Records)

Additional film and music reviews as well as sound clips are available on francemagazine.org.

By RACHEL BEAMER

10

F r a n c e • summ e r 2 0 0 9

THE MISTRESS AND THE TANGERINE (2007) Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach

spent 14 years filming groundbreaking artist Louise Bourgeois, creating what may be the most comprehensive documentary of a visual artist’s life and work. Bourgeois opens up as uninhibitedly on camera as she does in her art work, offering not only insights into her pieces but opinions on the role of the artist. The film is the final work of awardwinning director Marion Cajori, who died from cancer in 2006, a year before its completion. (Zeitgeist Video) THE HAIRDRESSER’S HUSBAND (1994)

Director Patrice Leconte (Les Bronzés, Ridicule) stretched his versatility a notch further with this dreamlike tale of a young boy’s sexual obsession with the village’s curvaceous hairdresser. Jean Rochefort (a Leconte regular) plays the boy as a grown man with a new coiffeuse on his mind. DVD extras include an interview with the director and actress Anna Galiena. (Severin) A GRIN WITHOUT A CAT (1993) Le fond de l’air est rouge (a reference to Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat) is a two-part documentary from experimental and reclusive director Chris Marker. Marker flashes haunting and horrific video footage and photographs of world events from the ’60s and ’70s (the Vietnam War, May ’68 in Paris) in newsreel style. Narrators, including Simone Signoret and Jim Broadbent, provide voiceover. (Icarus Films) SCIENCE IS FICTION: 23 FILMS BY JEAN PAINLEVÉ (1902-89) Jean Painlevé’s

underwater shorts offer a comprehensive look at the six decades he spent uniting his passions for film and science. His cast of sea horses and jellyfish and their dance-like movements were appreciated by the public and scientific community alike. This compilation includes The Sounds of Science, for which alt-rockers Yo La Tengo created an innovative 2001 soundtrack. (Criterion Collection)

TS Production

Sons & Images

Beaux Livres THE CULTIVATED LIFE Artistic, Literary, and Decorating Dramas by Jean-Philippe Delhomme

A prolific illustrator and animator, Delhomme is sometimes described as Paris’s answer to the droll cartoonists who publish in the New Yorker. This first-ever English-language compilation of his work—a monograph featuring more than 100 illustrations—introduces his instantly recognizable style and signature dry wit to American readers, along with the favorite targets of his gently satirical pen: interior design mavens, art world snobs, literary poseurs…. In other words, the arbiters of Paris chic. Rizzoli, $30.

ERIC KAYSER’S NEW FRENCH RECIPES

by Eric Kayser with Yaïr Yosefi, photographs by Clay McLachlan

Master baker Kayser has some 30 boulangeries to his credit in eight countries ranging from France to Lebanon to Ukraine. With this latest collection of 50 sweet and savory recipes—all gorgeously styled—he makes his way into American kitchens. Inspired by his favorite nutritious ingredients— whole grains, seeds, dried fruit, nuts—he renews classic French dishes and creates some fresh new ones. Exotic fruit salad with quinoa, anyone? Flammarion, $34.95.

HIGHS AND LOWS

by Jean-Jacques Sempé

Sempé’s fifth album of cartoons and illustrations is being released for the first time in English this summer together with Panic Stations, his sixth; both were originally published in France in 1970. Beautifully illustrated in Sempé’s inimitable style, they wryly capture the absurdities of modern life and feature some of his stock characters—artists, psychoanalysts, old married couples—along with a few newcomers, such as gigantic computers and friendly aliens. Modern Library, $15.

PHOTOGRAPHING AMERICA Henri Cartier-Bresson / Walker Evans

edited by Agnès Sire

Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans had great esteem for one another’s work; they shared an insatiable intellectual curiosity, and the Frenchman once said that it was Evans’s work that inspired him to remain a photographer. This intriguing new book—edited by the director of the Fondation Cartier-Bresson in Paris—offers a fascinating opportunity to compare and contrast the work of the two photographic masters between 1929 and 1947. Thames & Hudson, $50.

A HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Musée d’Orsay Collection 1839-1925

edited by Françoise Heilbrun

The Musée d’Orsay was the first French art museum to amass a collection of 19th- and early 20th-century photography—one renowned for both its quality and size. This impressive volume, which showcases the collection’s most treasured works, traces the origins and evolution of photography from the first daguerreotypes to the Modernist works of Stieglitz and Steichen; thematic sections focus on portraiture, landscapes, still lifes, photo-reportage and so on. Flammarion, $75.

LONGCHAMP

by Marie-Claire Aucouturier, photographs by Philippe Garcia

Longchamp got its start creating leather goods for smokers before expanding its line in the 1950s; today it is probably best known for its Le Pliage line of foldable travel bags made of vinyl with leather trim (two billion of them have reportedly been sold since 1993). In commemoration of the company’s 60th birthday, this lavish coffee table book chronicles the history of a maison whose name has long been synonymous with quality and style. Abrams, $75.

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

11

Bon Voyage

Notes for the savvy traveler

HOTELS

• Hôtel Gabriel in the Marais bills itself as a “detox hotel”; its 40 rooms and suite boast a

très modern eco-zen aesthetic interpreted in a soothing palate of neutrals. Massage spaces feature green products; the lounge/bar serves up herbal teas. But it’s not all New Age-y: Rooms have flat screen TVs, iPods and Wi-Fi access. €180 to €280; hotel-gabriel-paris.com. Hôtel Gabriel offers •calming hues, organic products and high-tech amenities.

(a ) avignon anniversary

In 1309, amid civil strife in Italy, the newly elected Pope Clement V moved the seat of the Papacy to peaceful architectural savvy to Paris’s 17th arrondissement. The building’s undulating glass façade is highly distinctive yet fits in perfectly with the surrounding neighborhood. Rooms are sleek and contemporary with pops of color; the restaurant combines Malaysian and Indonesian cuisine with French savoir faire. €289 to €399 with special promotions online; renaissancearcdetriomphe.com. • Hidden Hôtel, a four-star, 23-room oasis near the Arc de Triomphe, is said to be one of Paris’s first all-organic hotels—the four-star establishment incorporates such natural materials as linen, slate, wood, marble and stone as well as hand made ceramics. From €240 with special promotions online; hiddenhotelparis.com. BIRTHDAY CELEBRATIONS

With a fresh (60-ton!) coat of paint, new offerings for visitors and a starring role in several summertime events, the Eiffel Tower celebrates its 120th birthday in style: • The first floor brasserie has been renovated and reopened as the 58 Tour Eiffel, with contemporary French menus from €45 at lunch and €65 at dinner. restaurants-toureiffel.com • A new discovery trail leads kids through the Eiffel Tower in the fluorescent yellow footsteps of “Gus,” their cartoon guide. Pick up a game book at Cineiffel, the theater located in the Ferrie Pavilion on the first floor. eiffel-tower.com • L’Epopée Tour Eiffel, an exhibit tracing the Iron Lady’s evolution from construction project to international icon, is on view on the first floor and along the stairs. Through December 31; eiffel-tower.com. • Gustave Eiffel: Le Magicien du fer is a free exhibition at the Hôtel de Ville about the brilliant engineer behind the tower and the structure’s role as a muse for artists, photographers and filmmakers. Through August 31; paris.fr. • This year’s Bastille Day fireworks pay tribute to Gustave Eiffel and his most famous creation; starting at sundown on the Champ de Mars.

12

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

Avignon, where it would flourish for almost a century, leaving a lasting architectural and cultural legacy. This year Avignon celebrates the 700th anniversary of that event with concerts, art exhibitions and festivals, including a 3-D sound-and-light show screened on the façade of the Palais des Papes. avignon-700ans.com

© b i e l s a ; © B r u c e B e n n e tt / g e tt y i m a g e s

• The Renaissance Paris Arc de Triomphe brings Christian de Portzamparc’s

Bon Voyage

Notes for the savvy traveler GREAT DEALS

• City Passes Pretty much all major French cities now have their own special city passes offering travelers everything from free guided tours, museum entries and monument visits to discounts on transportation, dining and shows. Ask for it at the tourist office of your destination. • Bike Tours Book an allinclusive, self-guided cycling vacation with company Rando Vélo from just €100 per day, Rando Vélo’s including accommodations, bike tours include bike rental, luggage transfer the Loire Valley. and most meals. Available in regions throughout France including Provence, Loire Valley, Normandy and Bordeaux. http://randovelo.fr • Rail Atmosphere Travel between French cities in the style that suits you best with “iDTGV.” There are three different specially themed train carriages: iDzen (the quiet trip: no cell phones or kids), iDzap (the fun trip: mobile bartenders, video game and DVD movie rentals), and iDNiGHT (the night trip: live DJs, bars and parties). Book up to four months in advance at rates starting from €15 one way. http://ventes.idtgv.com • Responsible Travel Rent a holiday home, stay in a B&B or book a nature adventure in the French countryside with Responsible Travel. Their “Special Offer Holidays” offer great discounts for last-minute getaways such as walking trips in the Mercantour National Park and lodging in a country retreat in the French Pyrenees. responsibletravel.com

•

14

Through January 2010, the Tahiti Tourism Board is sponsoring a contest to send six lucky couples or families on the vacation of their dreams. Contestants must send in a short video showing why they and a loved one need and deserve the trip. The prize includes air fare, accommodations for seven days and six nights, two meals daily, and land and

guides

• Paris: Made by Hand by Pia Jane Bijkerk. Known for her discerning eye, Australian stylist, blogger and sometime Paris resident Bijkerk divulges the addresses where she shops for her own clients. Organized by arrondissement, this charming guide features some 50 unique boutiques—milliners, stationers, umbrella makers and artisans of all kinds—where things are still made “the old way.” The Little Bookroom, $18.95. • The Flea Markets of France by Sandy Price; photographs by Emily Laxer. This attractive little book is a great resource for anyone who enjoys the thrill of the hunt. Laxer covers flea markets in every region of France (including Paris), rating them for their value, visual appeal and nearby amenities. She also explains what collectibles to look for at each venue and offers suggestions on neighborhood cafés, restaurants, bakeries and museums. The Little Bookroom, $18.95.

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

lagoon excursions. For contest rules, visit investinyourlove.com. L o i r e Va l l e y T r av e l ; T h e Ph e l p s G r o u p

(g)

NEXT STOP PAPEETE

Nouveautés

What’s in store

world views Working under the name Cahokia Creations, Lyonbased designer Elsa Somano creates lamps with a pointillistic flair: Made of industriallooking aluminum, they have perforated lampshades that add a touch of poetry when illuminated. Her latest: Etape 1, featuring a map of the world. From €150; http://elsa-somano. blogspot.com.

Pot Addiction Alain Gilles’s modular planters for Qui est Paul? are equally at home in settings ranging from rock gardens to living rooms. They vary in height from about one to four feet and come in a number of shapes and colors. €94 to €320; qui-est-paul.com.

Equestrian Arts A horse is a horse? Not necessarily. Daum’s new Hippic Collection comprises 13 noble steeds inspired by art and archeology; each unique piece is hand-crafted using pâte-de-crystal and the ancient technique of lost-wax casting, imparting a rich, subtle palette and delicate bubbles. From $1,300; daumusa.com.

16

F r a n c e • S U M M ER 2 0 0 9

QUI ES T PAUL ; e l s a s o m a n o ; T r a n s M e d i a G r o u p ; d r i a d e

Hot Seat You like this chair? Put a ring on it. Otherwise Driade’s sexy polypropylene ring chair by Philippe Starck and Eugeni Quitllet—a big hit at the Milan Furniture Fair—is sure to be snapped up by someone else. $506; driade.com.

ROCk STAR THRILL SEEkERS

u n -T i e d a r T i s T s ; l F o / l i G n e r o s e T; l o u i s v u i T T o n ; T H e p r o M o T i o n Fa c T o r y

A small publisher based in Silicon Valley, Un-Tied Artists has adopted some of Hollywood’s principles—writers work collectively on novels using colorful storyboards. One such tale is Trap, a mystery about an American Interpol agent in Paris. The company donates its proceeds to the Nobel Prizewinning Doctors Without Borders. $13.49; http:// siliconvalleynovel. com/Trap.aspx

With its simplified shape and bright colors, Claudio Colucci’s MiNi DaDa CHair for Ligne Roset has undeniable appeal. Put it in the nursery and let it rock your toddler’s world. $650 to $1,185 for a set of two; ligne-rosetusa.com.

LINENS AND THINgS With its first collection of aCCESSOriES, luxury linen maker D. Porthault moves from bed to beach. Its summery sacs and beach bags come in two patterns: “Corail Matisse,” evoking works by the French master, and “Fond des Mers,” inspired by the aquatic world. $125 to $495; dporthault.fr.

NEw HuES Louis Vuitton wowed fashionistas six years ago with its popular Monogram Multicolore line, a collaboration with Japanese artist Takashi Murakami. The pair blurs the lines between art and commerce once again with new, cheerfully colored Insolite pOCKETBOOKS. $710; louisvuitton.com

ADuLT PLEASuRES

If you ever envied the little kids who got to wear those cute petit Bateau togs, your time has come! The purveyor of classy cottons has vastly expanded its selection of clothing for les grandes personnes to include undies, T-shirts, sleepwear, dresses, accessories and more. And to make your selection in a child-free setting, visit the brand’s first boutique for adults, located on rue 29 juillet, in Paris’s 1st arrondissement. Fr a nce • SUMMer 2009

17

Voyages

S

a winemaker revives a charming bit of local history

by Alexandre Kauffmann

Stendhal wouldn’t believe his eyes. The writer who complained of Pauillac’s poorly paved roads in his 1838 Travels in the South of France would be amazed if he could come back today and visit Bages, a picturesque village just south of the town. Here, the Place Desquet has seamlessly aligned paving stones, a gleaming white stone fountain and small businesses with freshly painted 1930s-style storefronts. A stone’s throw away, just past a few houses, manicured vineyards slope down toward the Gironde estuary. But for a few TV antennas, you have the curious sensation of having gone back in time—at least until you notice “Wi-Fi” printed in neat letters on the façade of the café, right between “Cuisine de famille” and “Apéritifs de marque.” Along with its retro-French vibe, Bages also conjures up another century in another place: the Quattrocento, when the arts flourished under the great patrons of the Italian Renaissance. This tiny hamlet boasts artists’ studios, exhibition spaces, frescoes, a literary prize and a cooking school. It’s not uncommon to run into writers, artists, actors and Michelin-starred chefs as you browse in Bages’ Bazaar or grab a bite at Café Lavinal. Yet barely a decade ago, Bages resembled a ghost town. Most of its residences were in ruins, its narrow alleyways deserted. Despite its location in Pauillac, one of the world’s most prestigious wine appellations, it had fallen into neglect—a fate it shared with a number of other Médoc villages. The rural exodus that began in the mid-20th century was to blame. Over the years, owners of small vineyards, blue-collar workers and artisans 18

Fr a nce • summer 2009

had left the area; businesses and workshops had closed; old buildings not linked to winemaking had been forgotten. Even the unprecedented boom experienced by the grands crus in the 1980s, when winegrowers spent freely to restore their vineyards and châteaux, couldn’t reverse the tide. One man, though, would change Bages’s destiny. Owner of the famous Château Lynch-Bages, Jean-Michel Cazes didn’t even know that he also owned most of the village adjacent to his vineyards until architects suggested that he tear down the empty buildings to make way for new wine storage facilities. “I didn’t want to go down in history as being the guy who destroyed Bages,” he laughs. So instead, he decided to bring the place back to life, to revive a colorful and convivial aspect of Médoc life that had long existed in the shadows of the great Bordeaux châteaux. Considered a visionary among wine professionals, Cazes had already revamped Lynch-Bages’s 19th-century cellars back in 1989, refitting them for art exhibitions. With the collaboration of renowned galleries, he regularly mounts shows featuring some of the great names in contemporary art, such as Pierre Alechinsky, Titus Carmel, Ernest Pignon-Ernest…. When contemplating Bages’s future, he knew that he wanted culture—painting but also literature, cuisine and crafts—to be part of the mix. Bit by bit, plans were drawn up, buildings were restored, streets were repaired. In 2003, Bages inaugurated its first new business: Le Baba d’Andréa. Named after Cazes’s grandmother, this boulangerie celebrates tradition and authenticity; all its breads, for example, are made with only natural, slow fermenting yeast. Bakers turn out a tempting selection of pâtisseries—including local classics and, of course, babas au rhum— and the shop also carries artisanal jams and other gourmet goodies. For local residents such as retired teacher Hugette Mérian, Le Baba d’Andréa has been a blessing. “There used to be traveling sa lesmen in this area, but they have disappeared. Now you have to get in your car whenever you need groceries. So I was

C o u r t e s y o f Ly n c h - B a g e s

A Village in the Médoc

• Top: Little by little, the once desolate Bages has regained the convivial ambiance of a Médoc village. Above, left to right: Displays in Bages’ Bazaar; an accordionist in front of Café Lavinal; artisanal breads at Le Baba d’Andréa; baskets woven on site by resident artisans. Opposite: Jean-Michel Cazes, the man responsible for Bages’s renaissance.

Fr a nce • summer 2009

19

Voyages happy when a bakery the days when ships opened near my house. from all over the world It has given a bit of life docked in the Garonne, back to the village. It and passengers set sail needed it, because as for America and Africa old people passed away, from the port of Verdon, no one was moving in just north of Bages. to replace them.” Back then, ocean liners Ca fé L avina l a nd frequently glided past Bages’ Bazaar were the the family vineyards. next to open their doors. “In the evening, we’d sit With its red-leather on the terrace and watch b a nque t te s , mo s a ic the ships sail by, all lit tile f loors and brass up. The wind would fixtures, the Café is a carry music all the way delightful blast from to the house.” the past. Even the prices He is a lso deeply at this brasserie are oldattached to another bit fashioned—a €14 lunch of vanished local hismenu includes three tory: the Montagnols. courses and coffee. The T he se a g ricu lt u ra l equally quaint Bazaar workers came from the caters more to tourists Eastern Pyrenees in the than locals, with an • The stars came out in Bages for the advanced screening of the film Mes Stars et moi. late 19th century, spade a ssortment of wines Festivities included their induction into the Commanderie du Bon Temps du Médoc, in hand, to replant the et Barsac. Left to right: actor Kad Merad, producer Christophe Rossignon, from the Cazes Family Sauternes vines t hat had been winemaker Emmanuel Cruse, screen legend Catherine Deneuve and Jean-Michel Cazes. Estates, gifts (including ravaged by phylloxera. quintessentially French brands such as Of course, it’s one thing to restore a Cazes’s own family, originally from the Opinel and Laguiole knives, Jean Vier village, another to make it economically Ariège, descends directly from these laand Artiga Basque linens, Bernardaud viable. Cazes explains that part of Bages’s borers who were forced by poverty to leave porcelain), and books on food and wine. success is the synergy it enjoys with his their native region. “When I was a child,” Bages now also has its own playground family’s other ventures—the bakery, for he recalls, “I used to meet shepherds who and pétanque area; later this summer, a example, supplies their two restaurants, had come here from the Ariège—they still reeked of goats!” His grandfather, JeanCharles Cazes, became a boulanger in Pauillac and in the 1930s acquired Château Lynch-Bages. “It’s important to remember the history of the immigrants who shaped this region,” says Cazes. “Hardly any of the owners of grand cru vineyards were native to the Médoc.” Today, too, Bages is being repopulated largely by families of diverse backgrounds who h ave moved here f rom out side the region. A couple of basket makers butcher shop is slated to open, and an Le Chapon Fin in Bordeaux and the two- from eastern France weave their wicker épicerie is on the drawing board for 2010. star Cordeillan Bages, located just a few creations in a local atelier; Cordeillan Meanwhile, a dozen houses have been hundred yards away. Bordeaux Saveurs, the Bages chef Thierry Marx, who grew up renovated and rented, and ateliers welcome family enterprise that offers tours, cooking in Paris’s Belleville neighborhood, lives visiting artists and artisans. A full calendar classes and wine tastings, holds a number near Place Desquet; Cazes’s mother-inof events draws ever yone from loca l of its activities in the village, and bakers law, whose Portuguese family resided in children (Easter egg hunts) to intellectuals and chefs working in Bages often hail from Mozambique, has a home just north of the village. That’s the charm of the Médoc: It (the annual literary prize) to celebrities (film other Cazes establishments. screenings). There are traditional fêtes du There is no doubt that Cazes has put renews itself by adopting all those who village, seasonal outdoor markets—even Bages back on the map, but not even he can cross the Garonne. manga festivals, complete with cosplay. truly turn back time. He nostalgically recalls For more information, visit villagedebages.com.

Bages also conjures up another century in another place: the

20

Fr a nce • summer 2009

C o u r t e s y o f Ly n c h - B a g e s

Quattrocento, when the arts flourished under the great patrons of the Italian Renaissance.

Evénement

L

Madeleine Vionnet fashion’s force tranquille

by Rebecca Voight

© D R ; © L a u r e Al b i n - G u i ll o t / R o g e r - V i o ll e t

Luxe, calme et volupté—Baudelaire’s famous words perfectly capture the essence of designer Madeleine Vionnet. Her remarkable clothes convey a whispered elegance, which perhaps explains why she has always been something of an insider’s secret, a designer’s designer. The fact that the world’s first retrospective of the couturier is taking place only now, almost 35 years after Vionnet’s death at age 99, indicates how difficult it is to pin down the creative talent who laid the foundation for 20th-century fashion. How do you describe clothes that seem to have no beginning and no end, that fall over the body in a seamless swirl as they suggest every curve and respond to the slightest movement? Vionnet (1876-1975) is most commonly credited with having invented the bias cut, a construction technique using fabric on the diagonal (bias) rather than straight across, allowing the body to dictate the shape of the clothes. As it turns out, not even that most basic assumption is exactly right. Pamela Golbin, curator of “Madeleine Vionnet, Puriste de la Mode” at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (June 24, 2009, through January 31, 2010), explains: “Bias already existed in couture before Vionnet, but it was used only for small pieces such as cap sleeves. She was the first to apply bias to an entire dress, which meant there was no need for hooks and eyes, zippers or buttons. Total bias construction was her way of continuing the liberation of women that she had started earlier, when she did away with the corset.” Dramatically breaking with ornate, constricting 19th-century fashion, Vionnet’s designs were all about the body, movement, proportion, balance. She was so revolutionary

that the aftershocks of her work continue to ripple through the fashion industry. Azzedine Alaïa has always collected Vionnet, and John Galliano has taken her bias slip dress on a wild ride over the past decade at Christian Dior. Issey Miyake—who has fathered his own share of inventions, notably his A-POC seamless clothing—says his first contact with Vionnet’s work was as powerful as the moment he first saw “Nike of Samothrace” in the Louvre. “I again stood transfixed,” he recalls in his introduction to Betty Kirke’s 1991 book on the designer. “It was probably awe from the realization that her basic concept of the relationship between the body and cloth is the basis of all clothing. Vionnet’s clothes transcended her times.” Along with Paul Poiret (1879-1944) and Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel (1883-1971), Vionnet is responsible for launching the major trends, or vocabularies, that established contemporary fashion. Of the three, Vionnet was the only one to have dressmaking

• Above: Madeleine Vionnet in 1937. Left: Hundreds of photographs showing front, back and side views were taken to document copyrighted Vionnet creations. This gown is from the 1938 Winter collection.

expertise—Poiret did not know how to sew, and Chanel started her career as a hat maker. Their approaches to their craft were also very different: Poiret’s designs were flamboyant and exotic; he loved throwing costume balls and making the outfits for them. Chanel created simple and comfortable clothes for the modern woman, establishing a signature look. “But for Vionnet, technique and aesthetics were one,” says Golbin. “Technique determined her silhouettes. She was the purist— hence the title of this exhibition.” Fr a nce • summer 2009

23

investment bank Natixis to restore almost the entire Vionnet collection made the show possible. “They’ve been an amazing partner,” says Golbin. Thanks to them, we were able to restore not only the clothes but also photos. We could not have put together a show like this without that support.” The bank has long been involved in cultural philanthropy, having underwritten restoration projects at the Louvre, the Musée Rodin and other venues, but this was its first foray into fashion. “I think what convinced them was that this project involved an important collection, not just certain pieces,” says Golbin.

At Jacques Doucet, Vionnet’s radical innovation was to create

déshabillés to be worn outside the home— and to show them on models walking barefoot. easier. The museum has been sitting on a gold mine: In 1952, Madeleine Vionnet gave her extensive archives to the Union Française des Arts du Costume, whose holdings are on permanent loan to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. The collection includes not only 122 dresses but also 750 patterns, 75 volumes of photographs of models wearing copyrighted designs, accounting ledgers and books from her personal library. Of the 125 pieces in the show, only three had to be borrowed from other museums. The unprecedented decision by corporate 24

Fr a nce • summer 2009

Another coup was getting Andrée Putman to design the exhibition. She was the perfect person for the job: In the 1980s, the worldfamous designer did much to revive interest in Vionnet’s contemporaries, including JeanMichel Franck, Eileen Gray, Pierre Chareau and Robert Mallet-Stevens. She was such a proponent of their work that she even reissued some of their designs. Madeleine Vionnet started her career while still a child—a brilliant child with a grudge. By age 10, she had already obtained

her primary school certificate, and her teacher was angling to get her a scholarship. Her dream was to become a teacher herself. Vionnet’s father raised her on his own—her mother had left them when Madeleine was only three to open a vaudeville casino—and although he was ready to let his daughter continue her studies, an acquaintance convinced him otherwise. Saying Madeleine would be a financial burden to him for many years, the woman persuaded him to have Madeleine apprentice at her sewing shop in Aubervilliers. “Vionnet never forgave that woman,” says Golbin. “But the setback only increased her determination to make something of herself.” Years later, Vionnet would acknowledge that it had probably all been for the best—how else would she have discovered the great talent that was in her hands? Vionnet married at 18 and soon had a daughter of her own, although the child did not survive. Then in 1895, she decided to divorce, leave her job and cross the Channel to learn English—a daring plan to say the least. “Initially, she worked as a linen maid at a psychiatric hospital outside London,” explains Golbin. “Built by Thomas Holloway, a wealthy philanthropist, it was an amazing place, the most luxurious, modern building in England dedicated to treating the middle class.” The asylum’s large windows, plumbing and ventilation would later inspire Vionnet’s design for her own atelier in Paris. Soon, the young woman managed to get a position better suited to her talents, working for London dressmaker Kate Reily, who did a lot of business with the U.S. There, Vionnet got her first taste of dealing with an international clientele. When she returned to Paris in 1900, this experience positioned her to climb the fashion ranks, first as a première, a kind of technical assistant, for Marie Callot Gerber at Callot Soeurs, whose clients included Mrs. Astor, the Vanderbilts and Mme Eiffel. She credited that experience with a number of formative lessons, such as teaching her that the body must be at the center of every design and that nothing short of perfection would do. Within five years, Jacques Doucet had offered her a position as modéliste, or designer, asking her to rejuvenate his house. While Doucet himself adorned actresses Régine, Lantelme and Cécile Sorrel in sequins, feathers and embroidery, Vionnet wanted to introduce a more simplified look. Her first

F r a n ç o i s K o ll a r / Pa r i s , B i b l i o t h è q u e F o r n e y

Golbin had to work like a stylish private eye to prepare this retrospective, as no one had previously drawn up a definitive chronology of the designer’s life (her finished manuscript is some 30 pages long). Indeed, the only major reference work on the couturier to date is Betty Kirke’s masterful Madeleine Vionnet, which was two decades in the making. In addition to biographical material, it contains 38 patterns of Vionnet gowns that Kirke reconstructed from garments loaned to her by the designer and museums. But Kirke didn’t meet Vionnet until she was 98 years old and had to limit her technical questions, due to the designer’s “age and frequent forgetfulness.” To fill in the blanks, Golbin pored over tax records, death and marriage certificates, previously unpublished texts by Vionnet and the few interviews she gave. Time was short—there was little more than a year to prepare the show—and locating sources was difficult. “When I worked on the Balenciaga exhibit [in 2006], I was able to contact people who knew him, but with Vionnet, we were about 10 years too late.” She did manage to track down two women, aged 95 and 96, who had worked for Vionnet, and they helped sort out the facts. Locating the objects to display was infinitely

• Above: A 1939 cover of L’Officiel de la Mode featuring Léon Benigni’s drawing of a Vionnet design. Right: A 1935 evening gown illustrates Vionnet’s masterful touch with draping, a technique she admired in the clothing

© Pat r i c k G r i e s

of ancient Greece. Opposite page: A 1931 photograph showing a Vionnet employee carefully dressing a model.

collection—inspired by Isadora Duncan, who in 1906 had danced barefoot, braless and without a corset—included déshabillés. These loose-fitting dresses were typically worn at home, perhaps for afternoon tea, and offered a relaxed reprieve from the period’s bone-crunching corsetry. Vionnet’s radical innovation was to create déshabillés to be worn outside the home—and to show them on models walking barefoot. Her work attracted the attention of Doucet’s more fanciful clients, such as the

eccentric Marquise de Casati. Betty Kirke describes Casati’s look: “a black velvet Vionnet dress, a top hat made of tiger skins, a black patch over one eye, and live snakes wrapped around her arms.” The Doucet saleswomen, however, were not amused. Deeming Vionnet’s less decorative and unrestricted silhouettes heretical, they simply refused to show them to clients. Frustrated, Vionnet began toying with the idea of opening her own house and finally did so in 1912, setting up shop at 222 rue

de Rivoli. By then, however, Poiret had gotten all the credit for freeing women from the corset. His designs came out after her déshabillés, but because her styles were boycotted by the Doucet saleswomen, no one knew this. It was something she bitterly resented for many years. Within two years, WWI had broken out and Vionnet had to close her business. She reopened at the same location after the war, Fr a nce • summer 2009

25

• Above: Vionnet’s innovations included the halter top, the cowl neck and the handkerchief hem, which can be seen on this 1937 dress. Right: An evening dress from the Winter 1938 collection. Opposite page: Madeleine Vionnet working with

encouraged by the fact that women were now looking for simpler, more functional garments and excited by the possibilities presented by new textile technologies, which produced fabrics that lent themselves better to her bias-cut designs. By 1924, her business had grown to the point where she needed more space, and she moved to 50 avenue Montaigne—currently home to Ralph Lauren. There, by the mid’20s, she employed a team of 1,200, making Vionnet et Cie the largest couture house in Paris, larger even than Lucien Lelong and Chanel. But her contributions to the fashion 26

Fr a nce • summer 2009

industry went well beyond clothes. “She was extremely progressive, a feminist at the helm of this huge company,” says Golbin. “She was the first to introduce social responsibility in her industry, giving workers paid vacations and other benefits such as paid maternity leave and access to an in-house dentist and gynecologist. French legislation on these issues did not come about until 1936.”

She was also a pioneer when it came to protecting intellectual property, joining with other couturiers in lobbying efforts to obtain international copyright laws and engaging in numerous lawsuits to prevent copyists from selling knock-offs of couture designs. At one point, she even included her thumbprint on her label to indicate that the garment was an authentic Vionnet.

© Pat r i c k G r i e s

the articulated doll she used throughout her career to create new designs.

Thérèse Bonney

Meanwhile, her business flourished. She outfitted the best-dressed women in the world, the ones who could get away with total simplicity and who could afford the prices. That included royalty, actresses and the wives of the powerful, from Mrs. Edouard de Rothschild and Mrs. Robert Lazard to Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford, Katharine Hepburn, Princesse de FaucingyLucinge and Begum Aga Khan. “Her clientele was women who didn’t need all the frills you could find at other fashion houses,” says Golbin. “And she was unapologetically the most expensive in Paris.” Throughout her career, Vionnet designed not with pen and paper but with an articulated wooden doll that was about two feet tall and attached to the rotating seat of a piano stool. Turning it to see her work from every angle, she would drape and redrape muslin before cutting patterns that her assistants would then enlarge to full size. Then she would try her design on a mannequin or a client and correct the proportions until she found perfection. The Depression took a serious toll on French couture, and Vionnet et Cie was no exception. Even when times improved, her business never regained its former momentum. In 1939, another war meant she had to once again shutter her house. This time she would never reopen it. As Betty Kirke recounts, she was nearly 70 years old when the war ended, and the world was a different place. Knowing that she would never recapture the glory that was once Vionnet, she retired. The first floor of the exhibition is devoted to Vionnet’s designs from 1910 to 1920, with a focus on structure and decoration. “Vionnet always said, ‘For me a dress is mental.’ She first thought about the concept and then made the dress,” says Golbin. “She repeatedly worked with three shapes: the square, the rectangle and the circle.” One observer even called her the “Euclid of fashion.” Vionnet herself described her job in these terms: “Dressmaking should be organized like an industry, and the couturier should be a geometrician, for the human body makes geometrical figures to which the materials should correspond.” Her thinking was likely influenced by the Purism movement, launched in 1918 by Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant. They

rejected a decorative approach to art in favor of clarity and objectivity, preferring the architecture of geometry to pictorial qualities. “Vionnet was part of that,” says Golbin. “She knew those people, they were her friends.” With their sensuous draping, Vionnet’s clothes also recall classic Greek dress. “She was inspired by these primal clothes, the first cloth that enveloped the body, in which nothing has been cut,” says Golbin. In an interview with Betty Kirke, Vionnet remarked: “I like to look at old costumes and fashions of times gone by, because of what they say about their times. They tell me so much about their era and the people

Golbin thinks part of Vionnet’s great talent was her ability to balance creativity and practicality. “She never called herself an artist, but I think she considered her work artistic. The fact that she decided to give her archives to a museum proves she had that vision of herself.” But Vionnet was fluent commercially as well. She produced 500 to 600 models every year, which puts her on a par with a modern house. She understood that collections need to have something for all body types, and she offered every piece in five colors as well as black and white. Even her use of bias was practical because working on the diagonal gives fabric a stretch that makes fit much easier. And when the house closed during WWI, Vionnet allowed her team to stay on and work independently for her clients— her workers maintained their income, clients were happy and the atelier was ready to re-open as soon as the war was over. By the end of her research, Golbin felt almost as if she had known Madeleine Vionnet personally, and the show’s catalogue includes her imaginary interview with the designer, with “answers” culled from unpublished texts by Vionnet, who gave very few interviews throughout her career. When asked her definition of taste, Vionnet is succinct: “Taste is what allows us to differentiate between what is beautiful and what is merely

Vionnet repeatedly worked with three shapes: the square, the

rectangle and the circle. One observer even called her the “Euclid of fashion.” in it. My inspiration comes from Greek vases, from the beautifully clothed women depicted on them, or even the noble lines of the vase itself.” A second floor features creations from the 1930s, with dresses from every collection that came out during this period. Other displays focus on various aspects of her life and work; there are deconstructed dresses revealing her extraordinarily complex technique; objects showing her efforts to fight counterfeiting and, perhaps most riveting of all, her wooden doll.

spectacular—and also, what’s ugly. It’s usually handed down from mother to daughter, but certain people don’t need to be educated to have taste, it’s within them, and I think that’s my case.” For many in the fashion world, Vionnet had not only taste but genius, that rare gift for achieving timelessness. “Vionnet’s clothes speak of values that are considered very important today: authenticity, purity and truth,” says Golbin. “With her, there’s no frills, there’s no thrills. There’s no space between you and the garment, so there’s no place to hide.” Fr a nce • summer 2009

27

By Sara Romano

“What drives me as an artist is that I think everyone is unique, yet everyone disappears so quickly. [...] But I like something Napoleon said when he saw many of his dead soldiers on a battlefield: “Oh, no problem—one night of love in Paris and you can replace everybody.” — Christian Boltanski , Tate Magazine

Franc e • su m m e r 2 0 0 9

29

The seminal events that shaped Christian Boltanski’s

career occurred while he was still in his mother’s womb. The son of a Jewish father and Catholic mother, he was born in Paris on September 6, 1944—just weeks after the French capital’s liberation. His father had spent most of his wife’s pregnancy crouched beneath the floorboards in their apartment, concealed in a space so cramped that he could neither lie down nor stand. The family preserved the dark and dusty lair for years afterward, a physical reminder of its close brush with tragedy. The episode was seared into Boltanski’s consciousness. “I am an artist who began working in the second half of the 20th century,” he explains. “And World War II is one of the major question marks of that century. For the past five decades, I have been wrestling with that question mark.” Yet rather than dwell specifically on the Holocaust, Boltanski ponders the transience of all human existence. He chases lost moments, lapsed lives—his own, those of people he knows as well as those of strangers. While each of us is one of a kind, he muses, we are all cogs in a wheel that will continue turning long after we’re gone. “Every individual is unique yet at the same time so fragile that, after two or three generations, he or she disappears completely,” he says. “My work is a sort of exploration of uniqueness and disappearance.” Boltanski’s art addresses everyone, not just those with experience of Nazi atrocities. “The beauty of being an artist is that when you talk about your village, your village becomes universal,” he says. “And if you’re a good artist, when you talk about your childhood, people say, ‘That’s me.’” Few today would dispute that Boltanski is a “good

artist.” In the past decade alone, he has participated in exhibitions in the U.S. (New York, San Francisco, Austin, Boston), Germany, Italy, Mexico, Poland and Venezuela, not to mention his native France. Some two dozen museums have acquired his installations for their permanent collections, among them the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Tate in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. These installations aren’t pretty. Made out of clay, dirt, razors, rusted cookie tins, light bulbs, old photos or used clothes, they don’t dazzle the way a Botticelli or a Rembrandt might. Instead, they grab you by the gut, making you ponder your time on earth. The artist is a visual philosopher, constantly tugging at that cruel thread called time. 30

F r a n ce • s um mer 2 0 0 9

Entre-temps (2003) Throughout his career, Boltanski has created pieces that document his past. This video presents a string of photographs showing the artist’s face at different stages of his life, from early childhood to age 60. The installation reflects his signature preoccupation with the inevitable passage of time and the loss of childhood, “the first part of us that dies.”

He recounts his past, real or imagined, struggles with his memories and documents the lives of those who have come and gone. MoMA’s “The Storehouse” (1988), for example, consists of seven blurry black-and-white portraits of young women. Lit by seven lamps, they are set atop a stack of 192 “old” cookie tins with pieces of cloth inside them. Although none of the elements are authentic (the photos were taken from magazines and newspapers, the fabric is generic), the association of these elements evokes mourning, relics of lives lost, the Holocaust. “Strange it is, beyond a doubt, and first cousin to performance art,” the New York Times’s John Russell wrote when MoMA first exhibited it in 1989. “Mr. Boltanski is a true poet, even if he doesn’t happen to use words.” The enigmatic artist is currently the subject of a major retrospective at the Kunstmuseum in Liechtenstein. On view through September 6, 2009, “La Vie Possible” features works from the mid-1980s to the present, with most pieces dating from the past 15 years. Kunstmuseum director Friedemann Malsch, who curated the exhibition, wanted to focus on these pieces in order to show the German-speaking world a side of the artist that is less funereal and less related to World War II. “Since the 1960s, especially in Germany, we have constantly been saying, ‘We must not forget,’” he says, referring to the death of millions

6 septembres (2005) This interactive video, just five minutes long, consists of footage of events that all took place on September 6— the artist’s birthday. The images fly by 2,000 times faster than usual, offering a remarkable overview of the past 60 years and emphasizing the fleeting nature of existence. Viewers may select one of the events to examine and remember, giving them the illusion of stopping time while heightening their sense of its inexorable flow.

of Jews in Nazi concentration camps. “So Boltanski’s art has been perceived within that context. But his newer work emphasizes life itself. With this show, I want to make clear, or more apparent, that there is another side to his work that is much more vital, one that is oriented toward the real life we live every day, every one of us.” Among the pieces on view is “La Vie Impossible” (2001), on loan from the Centre Pompidou in Paris. It is a series of 20 large glass display cases containing random paraphernalia—an electric bill, a Japanese journalist’s business card, a picture of the artist at a restaurant with friends, a letter from a Culture Ministry adviser, blood-test results. They are all traces of the artist’s life, yet they could just as well be the contents of anyone’s desk drawer: yellowing mementos of yesterday. The exhibition’s introductory text points out that such works are not monuments to the past; rather they are meant “to activate memory, i.e., to promote a culture of memory that constantly underscores the living in the face of what has been lost.” Boltanski created several new works for the Lichtenstein show while at the same time preparing what will likely be his biggest installation ever: In January 2010, he will become the third artist—after Anselm Kiefer in 2007 and Richard Serra in 2008—to participate in Monumenta, a series that invites a single artist to create a work

specifically for the giant vaulted space of the Grand Palais. Built for the 1900 Exposition Universelle, its glass dome rises 150 feet above a 145,000-square-foot nave. One of Boltanski’s preliminary sketches shows rows of old items of clothing laid out flat in neat, cordoned-off rectangles, the entire space divided up as if it were an enormous vegetable garden. Although the artist will not yet comment on the work, the abandoned clothing immediately evokes the garments taken from people interned in Nazi death camps. Judging by the themes of his works, Boltanski would

seem to be a distressed, and distressing, character. Yet he is in fact something of a Parisian bon vivant. He enjoys food and wine, and is a cook—although by his own admission, not a good one. A pipe smoker, he dresses in dark denim and fashionably cut jackets, shaves his head and still has a boyish look about him. “I am a joyous person, a man who’s very much at peace with dying, at peace with life,” he says. “I know that you have to take advantage of every moment of happiness on this Earth.” Boltanski lives and works in the close Paris suburb of Malakoff; his partner, the equally renowned artist Annette Messager, lives and Franc e • su m m e r 2 0 0 9

31

Monument: Les enfants de Dijon (1986) Small tin frames hold photographs of children from a Dijon middle school; the snapshots have been re-photographed and enlarged, resulting in a loss of detail. Each image is softly illuminated by a small bare light bulb. Displayed in the Chapelle de la Salpêtrière, this installation—complete with a central altar—evoked a shrine, possibly commemorating a massacre of innocents. For Boltanski, the children, by becoming adults, have been murdered by time.

works elsewhere. Her art addresses the condition of women by exploring themes such as sexual abuse, physical appearance and motherhood through photography, drawing, embroidery and found objects. Although the two have collaborated in the past, he says they lead parallel careers and never attend one another’s openings. In spite of the family trauma caused by his father’s wartime experience, Boltanski says he never lacked affection from his eccentric parents while he was growing up and that overall, his was a happy childhood. In a book of conversations with Catherine Grenier, set to be published by Boston University Press in the U.S. in September (La vie possible de Christian Boltanski), he reveals that his mother was from a fine but penniless Corsican family and published novels under a pen name (he says he never read them). When she was a child, she lived for a time with a foster family and thereafter constantly feared separation from her loved ones. She contracted polio after the birth of her first son, and from then on needed her family’s help to get around. She kept her sons close to her at all times—even when the family vacationed, they never checked into a hotel though it was well within their means. Instead, they piled into the family car and slept in it for weeks, inseparable. Boltanski’s father, a Jew of Lithuanian decent, was a respected 32

F r a n ce • s um mer 2 0 0 9

doctor, quiet and devout. War had made him reluctant to be a practicing Jew and determined to blend in, so he had converted to Catholicism. Yet he was too intimidated to attend Mass; instead, he would drive the family to the Eglise Saint-Sulpice every Sunday and they would sit in the car quietly until the service was over. Young Boltanski was a sensitive and curious boy, and like many artists-to-be, he felt a world apart from other kids. “I was very strange, almost mentally ill, very closed, with no friends,” he remembers. “I tried hard to fit in but couldn’t.” His unconventional parents (his mother was also a card-carrying Communist) made it difficult for him to mix with the bourgeois students in his class. At age 12, Christian announced that he was dropping out of school. His family did not object. “I was lucky enough to have parents who understood me,” he says. “Had I been the son of a peasant from Corrèze, I would have been sent off to be an apprentice somewhere. That wouldn’t have worked—I would have ended up in a psychiatric ward.” The boy gleefully gave up classroom dictation and math for hours of idle play inside the family home. Those undisciplined years spent away from school proved to be decisive ones. At age 13, he made a little clay object that he showed to his brother Luc (now a prominent

Théâtre d’ombres (1986) The metal figurines featured in this “theater”—displayed at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme for a full year—were inspired by traditional shadow puppets. The mystical installation conjures up images from many ages and cultures: Plato’s cave; the Danse Macabre; the myth of the Golem; the Mexican Day of the Dead. Whether this spectral dance is joyous, eerie or downright sinister depends on the viewer.