Well done

#3 in Canada

Top 50 in the world

U

We can’t help but be proud of our world-class programs, faculty, research endeavours, grads and students. For all those who continue to pursue excellence in pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences at the U of A we say…take a bow.

Learn more. uab.ca/ranking

10

features

10 e Renaissance Pharmacist

Our scope of practice has changed. Mid-career pharmacists are rising to the challenge.

14 A Preceptor and a Student Reflect COVID-19 didn’t keep pharmacists home but it changed mentorship.

16 Pharmacist-led Clinic: A First in Alberta Patients in Lethbridge beneft from a new model of care.

17 Generations of Generosity

Today’s students enter an evolving profession with help from alumni.

5 34

departments

18 e Future of Pharmacy is Experience

Pharmacists who trained in other countries are learning the world's largest scope of practice.

22 Personal Best

Pharmacogenomics means personalized prescriptions.

4 Message from the Dean of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences

5 e Dose: Quantum pharmacy; Male menopause; Insulin resistance and obesity link; Prepping for the next bad bug — and more.

29 Compounding: White Coat ceremony; Recommended reading and viewing; Class notes; Rural health gets a boost; Alumni in the know — and more.

mortar&pestle

The Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at the U of A is at the forefront of pharmacy globally. We have served as Alberta’s sole pharmacy school since 1914. We hold consistent rankings among the top three institutions in Canada, top 50 globally, and top 15 for global research. Mortar & Pestle magazine is dedicated to highlighting the achievements of our community, distributing to alumni and friends of the campus.

Supervising Editors

Lisa Cook, Tarwinder Rai

Editor

Mif Purvis

Senior Associate Editors

Karen Sherlock, Lisa Szabo

Editorial Advisors

Trina Harrison, Christine Hughes, Debbie MacIntosh, Janelle Morin, Jennifer-Anne Pascoe

Contributing Writers

Colleen Biondi, Caitlin Crawshaw, Kalyna Hennig Epp, Adrianna MacPherson, Anna Schmidt

Copy Editing, Fact Checking, Proofreading

Joyce Byrne, Philip Mail, Matthew Stepanic

Art Director

Brent Morrison

Photography

Stephanie Jager, John Ulan

Illustration

Byron Eggenschwiler, Lily Padula

Circulation Associate

Madisen Gee

Contact Us

The editor, Mortar & Pestle alumni magazine, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences

University of Alberta 2-35 MSB, 8613-114 St., Edmonton, Alta., Canada T6G 2H1 phcomms@ualberta.ca

Advertising newtrail@ualberta.ca

The views and opinions expressed in this magazine do not necessarily refect those of the University of Alberta, the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, or its alumni community. All material is © The University of Alberta, except where indicated. If undeliverable in Canada, please return to: Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta, 2-35 Medical Sciences Building, Edmonton, Alta., Canada T6G 2H1.

The Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and the University of Alberta respectfully acknowledge that we are located on Treaty 6 territory.

Change Is Our Only Constant

The field of pharmacy is expanding at a rapid pace, and the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences is transforming right alongside it. As the only school of pharmacy in Alberta for more than 100 years, our scope of teaching and research is growing to meet the needs of the diverse communities across this province and beyond, and to match the pace of change in our industry. Today, we are focused on preparing our learners for the workforce of tomorrow so that they can become true partners in advancing the profession of pharmacy. Even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, our faculty has developed new programs that have already begun to flourish. anks to our dedicated sta from both academic and administrative areas — and our passionate preceptors — we have successfully introduced the entryto-practice Doctor of Pharmacy program (PharmD) and the Certificate to Canadian Pharmacy Practice (CCPP).

I’m very proud of the entry-topractice PharmD program, and of our very first cohort, which graduated this year. Designed to prepare graduates for the scope of pharmacist practice in Alberta, the

PharmD program o ers several pathways to practice, through in-person and online options, for new learners and for professionals returning to upgrade their skills. Meanwhile, in partnership with the Alberta College of Pharmacy, the CCPP supports the transition to practice for internationally trained pharmacists both here in Alberta and in other Canadian markets.

Along with these fantastic new programs, we are also bolstering our other degree programs with more opportunities for students to take part in team-based learning and gain valuable industry experience, while ensuring a strong focus on equity, diversity, inclusion and Indigeneity (EDII) in our teaching and research, which will translate to more culturally appropriate patient care.

We couldn’t do any of this without the robust alumni community that continues to support our faculty in so many ways — as mentors to the next generation of professionals and researchers, as donors to our programs, as leaders in the field. I’m filled with gratitude for the relationship we have with our alumni.

As I look ahead to the coming year, there is much to look forward to in our faculty. We will embrace the growth in opportunities for interdisciplinarity and collaboration within the College of Health Sciences at the University of Alberta and beyond. We will continue to share our research discoveries with the community and invest in preparing our learners for a bright future. And through it all, we hope to be able to gather in person as o en as we can, to connect with each other and with you as we celebrate our successes together.

Christine Hughes, ’94 BSc(Pharm) Dean, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences

Each One, Teach One

“My vision for the Black Pharmacy Students’ Association (BPSA) is to increase representation and engagement of Black pharmacists in the profession. With the BPSA, I’d like to ensure that Black pharmacy students engage in leadership-building activities, professional development and mentorship. I want to provide su cient resources to BPSA members so they’re cognizant of these opportunities and are using them for career growth. I see the BPSA making the biggest impact when it comes to increasing the number of future Black pharmacists. Initiatives centred around that goal include: Pharmacy School 101 webinars, a career series highlighting Black pharmacists and our mentorship program, which pairs a pharmacy student with an undergraduate student to mentor, as well as a practising pharmacist to be mentored by. ese initiatives will inspire Black students and show that there’s a space for them in the profession.” —

RAYMOND OTIENO, CO-FOUNDER AND PRESIDENT OF THE BLACK PHARMACY STUDENTS’ ASSOCIATION, AS TOLD TO TARWINDER RAI

New student association president is working to make sure the seeds the organization is planting today will come to fruition

MOLECULAR IMPACT

Partnership and Potential

New quantum technology hub brings together Alberta’s world-leading expertise

Whether we’re aware of it or not, quantum technology a ects the way we all live in the world. It allows us to measure even the smallest things with more precision, add layers of security to our communications and puzzle through complex problems normal computers aren’t able to solve. Pharmaceutical sciences is no exception.

To bolster this potential-packed area, the University of Alberta, University of Calgary and University of Lethbridge formed the Quantum City partnership, creating a hub to advance progress in quantum technology. e hub received $23 million in funding from the Government of Alberta in 2022.

“ e U of A houses world-leading expertise in quantum research and technology, including areas with immediate

commercial potential, such as quantum sensing,” says Elan MacDonald, vice-president of external relations. “ e Quantum City partnership accelerates research and its potential to revolutionize industries and create thousands of jobs.”

In the pharmaceutical industry, quantum computing could allow for complex multi-atom chemical calculations to be er predict which drugs would be most e ective against certain diseases. A recent McKinsey & Company report stated, “Given its focus on molecular formations, pharma as an industry is a natural candidate for quantum computing,” with its biggest impact in discovery phases.

e provincial funding builds on what’s already an area of strength in Alberta, says the U of A’s Lindsay LeBlanc, who sits on the board of Quantum Alberta, an organization that brings together academic and industry experts to help elevate quantum research and commercialization in Alberta.

— ADRIANNA MACPHERSONTIMELY CARE

Hypogonadism Is Real — and Treatable Guidelines to help pharmacists treat testosterone deficiency in aging men

A pair of University of Alberta pharmacy professors have published guidelines to help pharmacists support men experiencing a common but underdiagnosed problem that's called late-onset hypogonadism.

Also sometimes called “manopause,” this medical condition refers to men’s declining testosterone levels. Unlike women’s menopause, which usually occurs over a few years in the 50s, men’s sex hormones may start to drop as early as the late 20s, with symptoms such as fatigue, weight gain and low libido progressing gradually over decades.

“People think, ‘I’m just under stress,’” says lead author Cheryl Sadowski, professor in the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. “Low testosterone is not the first thing that comes to mind for patients or their physicians.” e new guidelines, developed by Sadowski and co-author Nathan Beahm, were published in the Canadian Pharmacists Journal to give pharmacists

the tools to screen patients, address risk factors, initiate lab testing and work with physicians to manage treatment.

Pharmacists can help men understand that their symptoms aren’t just a normal part of aging and that they may be treatable, says Beahm, a clinical assistant professor. e evidence indicates that 50 per cent of men will experience symptoms at some time during their lives, but more

study is needed to determine the exact prevalence.

Ultimately, the researchers say they hope taboos around talking about men’s sexual health will fall away. “In geriatrics, we talk about a lot of things that you could say are uncomfortable, but we try to take care of all aspects of health for the patient,” said Sadowski. “We have to start the discussion.” — GILLIAN RUTHERFORD

Connecting with Care

Pharmacy care is changing, and the way we meet with patients is, too

Virtual care in pharmacy practice is an important and empowering tool. It provides access to care for people who have di culty visiting their pharmacy in person — like seniors, people with mobility issues, patients staying home due to illness, or people who live in remote areas. COVID-19 hastened changes already underway. e Alberta College of Pharmacy’s (ACP) Standards of Practice for Virtual Care were implemented recently for all pharmacies in the province, replacing the previous guidelines from 2021.

“Virtual care can be a valuable tool that optimizes and complements inperson care,” says Je Whissell, Deputy Registrar, ACP. It’s opening the door to more in-depth and precise care than ever before. “New technologies are constantly emerging, and lead to changes in patients’ expectations of their health-care team,” Whissell says. “Wearable technology like smartwatches is becoming more common, which makes it easier for people to track

their health and share that data with their health-care providers.” But burgeoning tech doesn’t mean your next visit with a pharmacist will happen over FaceTime.

Whissell says that pharmacy teams have to consider the limitations of technology when providing virtual care. For example, in a virtual se ing it’s harder to pick up on a patient’s non-verbal cues and pharmacists aren’t able to undertake necessary physical exams. en there’s the ma er of ensuring secure platforms. Pharmacists are duty-bound to proceed virtually only when they have access to

a patient’s provincial electronic health record and can take reasonable steps to protect their privacy and confidentiality. Pharmacists have to make sure their tech connection is sound and may not record the encounter.

Patients can look forward to a balance between in-person and virtual care as the la er becomes more common. In the end, Whissell says, it’s about connecting. “Pharmacists’ ability to routinely engage with patients in-person is fundamental to the practice of pharmacy.”

— KALYNA HENNIG EPPONLINE

2022 Alumni Award Winner

Robert Foster, ’79 BSc, ’82 BSc(Pharm), ’85 PharmD, ’88 PhD is a scientist, businessman and inventor whose discovery o ers hope for millions of people su ering from a complex autoimmune condition. Voclosporin, commercially known as Lupkynis, is based on a drug molecule he discovered. One of few made-in-Canada drugs to receive FDA approval, it’s the first oral treatment for lupusrelated kidney diseases. Foster le academia to become an entrepreneur and his first business, Isotechnika Pharma, focused on anti-rejection drugs for transplant patients. Foster holds approximately 170 patents and now heads Hepion Pharmaceuticals, which is developing therapies for several liver conditions. Foster maintains strong ties with the U of A, where he remains an adjunct professor to pharmacy students. More at ualberta.ca/pharmacy.

NUMBERS

The number of donors to the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences during 2021/22

CONTAINMENT LEVEL 3 LAB

Suiting Up

Canada should be much be er prepared for the next bug with pandemic potential, thanks to new federal funding

The University of Alberta will soon have more capacity to study the world’s most dangerous pathogens — and develop the vaccines and treatments needed to combat them.

e U of A is set to receive nearly $11.5 million from the Canada Foundation for Innovation to expand its Containment Level 3 laboratories. e funding is among $127 million given to eight research facilities across the country to bolster Canada’s biomanufacturing and life sciences sector.

“To continue protecting the health and safety of Canadians, Canada’s post-secondary institutions and research hospitals require innovative research spaces and biocontainment facilities like the eight state-of-the-art facilities announced today,” says François-Philippe Champagne, federal minister of innovation, science and industry.

At the U of A, funds will be used to upgrade lab suites, updating them with new equipment such as incubators, biocontainment hoods and freezers to study some of the world’s deadliest pathogens. e expanded facilities will be used by cross-faculty research teams, focused on managing the impact of infection.

e U of A has a long history of infectious disease research. is new funding will allow researchers to remain at the forefront while supporting the needs of the Canadian pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors.

— GILLIAN RUTHERFORD

— GILLIAN RUTHERFORD

NEW USES

Enzymes, Energy and Explanations

Old antipsychotic drugs may o er a new option to treat Type 2 diabetes

A class of older antipsychotic drugs could o er a promising treatment option for people with Type 2 diabetes who aren’t able to take other available therapies, according to new research. “ ere is a growing need to find new therapies for Type 2 diabetes,” says John Ussher, professor in the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and lead author of a recent study published in the journal Diabetes

e drug metformin is one of the most common therapeutics for Type 2 diabetes, but about 15 per cent of patients aren’t able to take it, explains Ussher, a member of the Alberta Diabetes Institute and the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute. Another type of drug class (insulin secretagogues) commonly used to treat diabetes isn’t as e ective for later-stage patients.

In their study, Ussher and his team looked at succinyl CoA:3ketoacid CoA transferase (SCOT), an enzyme the body needs to make energy from ketones. ey used computer modelling to find drugs that could potentially interact with SCOT and landed on an older generation of antipsychotic drugs, a drug class called diphenylbutylpiperidines, or DPBP for short. “We’ve tested three drugs from the class, and they all interact with this enzyme,” says Ussher. “ ey all improve blood sugar control by preventing the muscle from burning ketones as a fuel source.” ough clinical trials are still needed, repurposing an older drug will allow the researchers to focus specifically on the e cacy and safety of the new intended use — o ering the potential to provide a new therapeutic more quickly and coste ectively. —

ADRIANNA MACPHERSONIN THE COMMUNITY

Are One of the Most Accessible Entry Points”

Pharmacists could help bridge a health-care gap by o ering more sexual health services

People seeking sexual and reproductive health services have one more place to turn. Pharmacists can reduce barriers to access, a new University of Alberta study shows.

U of A researchers surveyed pharmacists in community pharmacies across Alberta to determine which sexual and reproductive health services they were already providing, and where they wanted to expand their training.

e study found that most participants were confident in educating patients in many sexual and reproductive health topics, but that many wanted additional training in sexually transmi ed and blood-borne infections as well as health concerns specific to people in the queer and trans community.

With more training and a

co-ordinated e ort across the country, pharmacists could become a critical resource to increase access to sexual and reproductive health services. Currently, many people face barriers to these services, from limited clinic hours to lack of a primary care physician. “Pharmacies are one of the most accessible entry points for people to get into the system,” says Javiera Navarrete, a pharmacist and research co-ordinator. “COVID-19 has highlighted how important it is to use all the health-care resources we have.”

Navarrete co-authored the study alongside Christine Hughes, professor and interim dean in the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

e pair is collaborating with Nese Yuksel and Terri Schindel (Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences) and researchers in Japan and ailand to get a more comprehensive view of what pharmacists around the world are providing in terms of sexual and reproductive health services. One of the World Health Organization’s Sustainable Development Goals is to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health services by 2030, and research is a key step toward creating a more unified strategy.

e EPICORE Centre and the Alberta

SPOR Support Unit Consultation and Research Services supported the survey development and distribution, data management and statistical services. Navarrete received funding from the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID-Becas Chile) scholarship program.

— ADRIANNA MACPHERSONNUMBERS

The number of frst time donors in 2021/22

“Pharmacies

The scope of practice in pharmacy has changed. Many mid-career pharmacists are rising to the challenge

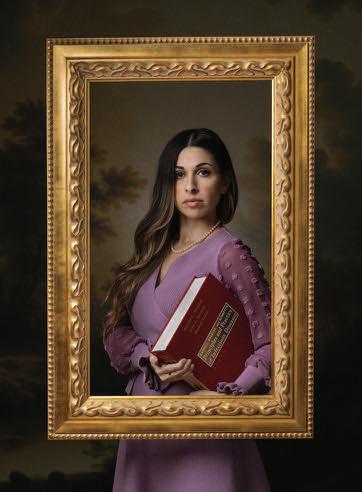

Renaissance PharmacistW The

ByNegar Golbaras told to Adrianna

MacPhersonPharmacy is in my blood. My mother graduated from the University of Saskatchewan with her bachelor of science in pharmacy (BSP, a moniker specific to U of S grads) in 1999, and I graduated with the same degree in 2013. My husband and my brother-in-law both hold BSPs, too. But that designation is a bit of a dying breed. Now, new graduates finish as PharmDs. And the U of A has a postgraduate program for practising pharmacists — including BSPs like me — to obtain their PharmD. Both programs reflect how the overall scope of practice for pharmacists has been expanding.

At this point in my career, I’ve worked in nearly every pharmacy role and se ing. I got my first taste of pharmacy in high school, when I was an assistant at a Superstore. I was promoted to intern, which meant I could apply what I learned to real-life se ings. Of course, the pharmacist was there to mentor me and ensure accuracy.

roughout my undergraduate years, I worked as a pharmacy student and had the opportunity to counsel patients, dispense drugs and do what I could to ease the burden on the pharmacist, who was the final set of eyes.

When I graduated, I was lucky enough to get a “floater” role, filling in at various pharmacies, which started my career. I developed my skills and learned how di erent pharmacies operated. It was a great experience, but I knew I wanted to be a hospital pharmacist. When I was o ered a job at the Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon, I jumped at the opportunity.

I was ecstatic to practise hospital pharmacy. Before that, I had felt

as though the disconnection between me and my nursing and physician colleagues wasn’t allowing me to provide patient care to its full potential. For community pharmacists, reaching nurses and physicians is challenging as they’re on a tight clinic schedule. In the hospital, I could have face-toface conversations with my nursing and physician colleagues. I think my community counterparts should have these same privileges and opportunities to liaise with the health-care team. ese privileges and opportunities exist to some extent in the Primary Care Network but not everywhere.

Even a er three years as a hospital pharmacist, building my skills and knowledge, I felt as though I wasn’t up to the level of the hospital pharmacists around me. So I decided to do a postgrad doctorate. I wanted to remain in a clinical role, so I pursued the PharmD for Practicing Pharmacists degree at the U of A, a professional doctorate. In the program, you must meet a minimum number of rotations on-site in specific disciplines, which was the game changer for me because I am a hands-on learner.

I applied my new knowledge as a hospital pharmacist in Calgary. e move to Alberta has been great professionally. Alberta is a world leader in pharmacy from both a logistical and therapeutic perspective. I was able to expand the scope of my practice.

In Alberta, pharmacists are, at baseline, able to adapt prescriptions, order lab work, apply for special coverage, get compensated for doing

medication reviews, renew prescriptions — the list goes on. But the real game changer is the APA designation (Additional Prescribing Authorization), which allows a pharmacist to write new prescriptions for patients, excluding controlled substances. In other provinces, pharmacists would have to send the patient to the emergency department or a walk-in clinic, only to see a physician who likely doesn’t know the patient as well as the pharmacist does. APA is a huge cost saver for our health-care system. Since we’re supposed to have universal health care in this country, it ba es me that this isn’t the standard across Canada. is doesn't seem very “universal” to me.

Pharmacists do so much in Alberta! at became clear during the pandemic. When patients couldn’t see doctors or even book phone consultations, we were diagnosing patients and using our APA to prescribe medications.

e narcotic restrictions were

li ed temporarily by the Alberta College of Pharmacy to help patients at a time of overflowing emergency departments. Supply chain issues meant drug shortages, and pharmacists were tasked with finding therapeutic alternatives at equipotent doses of di erent life-saving drugs. People needed vaccines and boosters. Pharmacists took all that on and received li le recognition. COVID-19 demonstrated how much responsibility pharmacists have in providing patient care.

A lot of people don’t know what a pharmacist does, beyond dispensing medication. In fact, dispensing is o en the responsibility of our amazing technicians and assistants, especially in the hospital se ing. ey keep the medications flowing. e scope of practice for pharmacists in Alberta has made us an even more important part of the healthcare system in the province, and I think our roles definitely need more exposure and advocacy. MP

I pursued the PharmD for Practicing Pharmacists degree at the U of A, a unique post-professional doctorate that allowed me to further educate myself and build my confidence.

A and a

PreceptorStudent Reflect

Pharmacists never stayed home during COVID-19 restrictions, but the pandemic did change mentorship

By Caitlin Crawshaw

By Caitlin Crawshaw

The first wave of COVID-19 brought life to a near standstill for many Canadians, but not for pharmacists who, as healthcare professionals, found themselves on the front lines of a public health emergency.

Ashley Davidson, ’10 BSc(Pharm), was one of them. When the pandemic hit, she faced new challenges as a practising pharmacist and owner of a Shoppers Drug Mart location in north Edmonton. She also continued to serve as a preceptor for the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, as she’s done for more than a decade.

“I really felt that the students were in an incredibly challenging position,” she says, “and that it was important for them to be able to progress in their studies without interruption.”

In fact, Davidson continued to mentor pharmacy students throughout the pandemic. One of these students was Damion Barnes, ’21 PharmD, who began working with Davidson in February 2021. “It was right at the peak of pandemic chaos,” she says with a laugh.

At the time, Barnes was in the last year of the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) for Practicing Pharmacists program at the U of A. He came to Canada from Jamaica specifically for this program, as a practising pharmacist with six years of experience. Before being matched with Davidson, his sixth and final practicum had been delayed because of the preceptor shortage.

We asked Davidson and Barnes to share their experiences as preceptor and student during the pandemic, which presented novel challenges not only in the practice of pharmacy but in its teaching and learning.

What was happening in your life when the pandemic hit?

BARNES: I was working part time, as well as doing my studies. At the time, I was already doing online learning, so the pandemic didn’t really impact my classes too much.

But my final practicum was about to begin and there were fewer sites than students, so I didn’t get matched. I reached out to the co-ordinator, and she told me that there were two options: a rotation involving a three-hour commute daily in February, or a second community rotation. I'd previously completed a community pharmacy rotation, but I chose to do another out of fear of travelling such a distance in winter. Fortunately, Ashley agreed to take me on.

DAVIDSON: I was trying to run my pharmacy in a safe manner and navigate issues with sta ng and supplies (especially toilet paper!), while raising three small children who were two, four and six years old at the time, so I was very busy. We’d planned to take on just three students, but a number of students had their placements cancelled due to the pandemic so we took on a fourth — Damion.

What were some of the challenges of being a preceptor/ student during COVID-19?

DAVIDSON: For me as a preceptor, it was very hard not to be able to spend as much one-on-one time with my students. Typically, I like to take time to have co ee or a meal with them and learn more about where they want to head in their learning and career paths. During the pandemic we were o en restricted with social distancing and masking requirements. When Damion was with us, I didn’t see his face during the entire rotation.

ere were practical challenges, too. ere would be days when one of my kids would be sick and daycare wouldn’t take them, or they couldn’t be at school — like when we were homeschooling, early on. ere were instances when I had to say, ‘Hey, Damion, here’s what you’re doing. I won’t be here.’ Luckily, he was such an amazing pharmacist, because he could just pick up and fill his day with things that were helping him learn, but also helping me.

BARNES: ere was a lot to navigate during my practicum. It was a year into the pandemic, but we were still concerned with staying safe and sanitizing properly. At the same time, I wanted to make the most out of my rotation and learn as much as I could.

e PharmD program encourages practicum students to be really self-driven, so you create goals and targets that you want to achieve. ere were some days when Ashley was beside me and I could ask, ‘What do you think about this? Do you think this is a good approach?’ and other days when I had to figure it out on my own. But it built my confidence in terms of my clinical skills and being able to navigate situations independently.

As a practicum student, you need to quickly build trust and connections with patients to understand their needs, which is a challenge. During the pandemic, social distancing and masking made it much harder.

What were some of the challenges facing community pharmacy during COVID-19?

DAVIDSON: Community pharmacies saw an increase in requests from patients. Some were scared to visit medical clinics or emergency rooms, while others simply didn't know where to turn. Pharmacists worked with patients to assess their needs, provide care, or refer them appropriately. We faced the same infection control, sta ng and supply shortages as elsewhere and made adjustments so that patient care was maintained.

BARNES: As Ashley stated, it was really di cult for persons to connect with their physicians, but we were accessible and open 12 hours a day. We did things like provide suggestions and recommendations, renew or extend prescriptions and, in some cases, prescribe medications.

Was the pandemic at all advantageous to teaching and learning?

DAVIDSON: From a teaching perspective, the pandemic provided a lot of opportunity to talk about expanded scope of practice and how we can have an impact on the health of patients. In the last couple of years, the learning opportunities for my practicum students have grown.

e pandemic has also taught us the importance of practising to the fullest extent of our pharmacy competencies and scope. I believe that this was something the students saw first-hand. When access to health care was challenged, we were able to provide a convenient, accessible and reliable point of care for patients.

BARNES: It allowed for more exposure to di erent circumstances and helped build my competence and confidence. As no two individuals are alike, there was no cookiecu er way of dealing with patients' disease conditions, so it challenged me to broaden my disease management skills. It also showed me how important pharmacists are in the health-care system and how much patients rely on us. MP

Pharmacist-led Clinic Alberta First a in

Patients in Lethbridge beneft from a new model of care

By Caitlin CrawshawAt a walk-in clinic in Lethbridge, the sta in white coats aren’t doctors. Rather, they're pharmacists, trained to provide many of the health services patients traditionally associate with doctors.

e Pharmacist Walk-in Clinic, on the second floor of Lethbridge’s Real Canadian Superstore, is operated by Loblaw Companies Ltd. In partnership with the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Loblaw is undertaking a new model of care. Since the summer, patients have been seeking care from the clinic’s pharmacists, as well as pharmacy students in training.

“Loblaw had approached us about their idea of opening this clinic as a way to improve access to primary care services,” explains the faculty’s interim dean, Christine Hughes. “It really aligns with our view of supporting the expansion of pharmacists’ roles and pharmacists using their full scope of practice.”

At a time when many Albertans don’t have family doctors — including 33,000 people in Lethbridge alone — the clinic represents a model of care with the potential to meet the health-care needs of patients and decrease emergency room visits.

“It’s not meant to replace physicians or emergency care,” she says. “But there are a number of services that pharmacists can provide that a lot of people don’t know about. And when there are physician shortages, it just adds to the capacity of the overall health system for pharmacists to use their full scope.”

Many of these services have been available to pharmacists since legislation changes in 2007, but Hughes says it’s taken some time for the profession to “create the space, time and competencies of pharmacists to o er them in their practice.” e clinic o ers an opportunity for students to experience the profession’s full scope of practice, as well as plenty of hands-on experience with patient care assessments.

A $500,000 gi from Loblaw will support the training of students at the clinic and on-site research into clinic operations. “We’re planning to take data collected within the first six months of full operation and look at things like the characteristics of people coming through the door, the conditions being managed, what referrals are being made, and those sorts of things,” says Scot Simpson, a Faculty of Pharmacy

and Pharmaceutical Sciences professor leading the assessment. “We’ll characterize what pharmacists are doing to answer the question, ‘What care do pharmacists provide in this se ing?’ and compare it with a template of what pharmacists could be providing.”

Ultimately, the research will identify where the clinic might enhance or expand the services o ered by its pharmacists. And this research could help inform pharmacy practices elsewhere in the province, too. Simpson, who holds a chair in patient health management, explains that a er determining gaps, the assessment will analyze the reasons why patients aren’t accessing certain services. “Is it because the patients don’t know what the pharmacists can provide or are there internal or policy issues preventing pharmacists from o ering services?”

e research might reveal other, more surprising reasons, too.

Alberta was the obvious choice for the research to take place, according to Je Leger, head of pharmacy at Loblaw Companies, and President of Shoppers Drug Mart. “Pharmacists in Alberta are uniquely positioned to relieve some of the burden on the province’s health-care system,” he said in a news release when the clinic opened, “and this innovative clinic will make access to care easier for residents in Lethbridge.”

Simpson agrees. He says that, at a time when the health-care system is overtaxed, it’s more important than ever for pharmacists to use their full scope of practice. He adds, “ is clinic is one way to try to o er those services more broadly.” MP

GenerationsGenerosity of

alumni Dwayne Samycia and Salwa Tarrabain-Samycia are supporting today’s pharmacy students as they prepare to enter an evolving profession

By Anna SchmidtIn the spring of 1952, Myros Samycia, ’51 BSc(Pharm), purchased a pharmacy in the heart of Edmonton’s McDougall neighbourhood, launching a legacy. Today the Samycia family has 11 pharmacists in three generations — including Myros’ son Dwayne Samycia, ’76 BSc, ’79 BSc(Pharm) and Dwayne’s wife, Salwa TarrabainSamycia, ’78 BSc(Pharm).

In 2014, they established the Dwayne Samycia and Salwa Tarrabain Pharmacy Fund, supporting projects and students in financial need. ey contribute to the Myros Samycia Family Award Fund. Created by Dwayne’s parents, it provides a scholarship to students based on academic standing and contributions to student life.

Emma Luger, a student in the second year of the Doctor of Pharmacy program, received the scholarship. We spoke with Dwayne, Salwa and Emma about the impacts of this generational generosity.

Why do you support U of A students?

SALWA: We were both fortunate to live at home during university. Many students came from afar to study at the University of Alberta and didn’t have the comforts, or supports, of home. We are so grateful for that.

DWAYNE: We want to give back to those in situations where a li le assistance goes a long way. We want to lighten students’ load.

What does the Samycia Family Award mean to you?

LUGER: It makes a huge di erence. e student financial burden, especially when

you move to a new city, is well known. Having a li le bit of that burden taken o of me — especially when my mind is on schoolwork and learning — allows me to focus and not worry about finances.

It also shows recognition. It’s a nice way to be rewarded for your dedication to the program — especially when it comes from alumni who have been where I am right now. ey’re proud of the profession and excited for the future generation. at’s motivating.

What drew you to pharmacy?

LUGER: I grew up in Redwater, Alta. Being in a small town, there was one local pharmacy. I was always interested in what was going on there. I remember my mom going in and asking questions when we couldn’t get in to see the doctor. ey always seemed helpful and knowledgeable. And I had an interest in biology and chemistry, so pharmacy was the perfect fit.

What value do pharmacists bring to the health-care system today?

SALWA: Pharmacy has changed a lot over the years. Pharmacists have vast

knowledge and they’re becoming more involved in patient health care. It’s that whole team approach. e pandemic has taxed the system in more ways than we thought possible. Pharmacists can help with that gap.

DWAYNE: With the increased clinical approach, education has changed significantly. My dad's education was a three-year degree that evolved into the four-year program and now the PharmD program. I have no trouble saying that the quality of education through the years has improved. ey’re stronger students with greater knowledge and confidence in their abilities. Pharmacy has come more to the forefront. We can use our backgrounds, experiences and knowledge to alleviate pressures and costs to the system. rough time, we’re showing our value. We support students so they get the education to meet the demands of changing health care. Today, there’s so many opportunities.

SALWA: Whatever path they choose is theirs, but if we can help make that decision just a tiny bit easier or walk along beside them — that’s all we want. ere are many avenues they could follow. e whole world is out there for them.

What’s next for you?

LUGER: I’m just excited to see where the career takes me. One of the reasons I went into pharmacy was because there’s so many options once you graduate. But I have experience in the community pharmacy se ing, and I really enjoy it. I like the relationships you build with patients. It would be ideal to have my own pharmacy one day and be able to spend the time with patients that I know they deserve. =MP

The Future of Pharmacy is Experience

seasoned pharmacists from other countries are learning skills and earning success in the world's broadest scope of practice

By Kalyna Hennig Epp

By Kalyna Hennig Epp

Illustrations by Lily PAdula

Illustrations by Lily PAdula

Aer working as a pharmacist in a hospital dispensary in Ghana for four years, MaryAnne Akpanya, ’22 CCPP, wanted to do more. She explored her potential in public health as a program pharmacist for Ghana's National Tuberculosis Control program and completed both a master’s and a PhD.

But it wasn’t until she made a couple of short trips to Canada — almost 20 years a er graduating from pharmacy school at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology — that she found her calling.

“I was so surprised at the scope of practice of pharmacists in Canada,” says Akpanya. “ ey worked so closely with patients, and I yearned to be part of it.”

So, in 2020, she packed her bags and arrived in Calgary. is time, to stay.

To practise in Canada, internationally educated pharmacists are required to pass a two-part qualifying exam through the Pharmacy Examining Board of Canada, which is called the PEBC Certification Process for International Pharmacy Graduates. To practise in Alberta, they need also to pass the ethics and jurisprudence exam through the Alberta College of Pharmacy. And they must register with the Alberta College of Pharmacy and then complete 1,000 hours of training in Alberta pharmacies.

Add the pressures of meeting English language requirements, adjusting to a new life, culture and climate, and the fact that Alberta pharmacists have the largest scope of practice in the world — and this licensing process can seem daunting.

So, when Akpanya was notified of an additional requirement to the licensure process — the University of Alberta’s Certificate to Canadian Pharmacy Practice (CCPP) — she felt discouraged.

“Initially, I saw it as another hurdle to overcome,” says Akpanya. “But once I started the program, I

began to understand it and appreciate its value. “ e things that I admired — that motivated me to want to practise pharmacy — were the things that Alberta pharmacists do. And I didn’t have their patient-care skills yet. e CCPP program gave that to me.”

e 10-month program, introduced in April 2021, is designed to further develop the knowledge and skills that internationally educated pharmacist graduates already have. It aims to prepare them to be competent and confident practitioners within Alberta’s healthcare system.

“We want to support their transition to the Canadian health-care context, culture and practice,” says Sherif Mahmoud, ’10 PhD, clinical associate professor and director of the CCPP program. “To help new pharmacists integrate really well, Day 1 — and to change them from excellent pharmacists into super-pharmacists.”

With the largest scope of pharmacy practice in the world, Alberta’s health-care landscape and pharmacists’ place in it is quite di erent. For both internationally educated pharmacists and pharmacists from other Canadian provinces, some of the duties of Alberta pharmacists, such as the ability to prescribe Schedule 1 drugs, adapt prescriptions, order and interpret lab tests, and administer injections, are totally new.

For others, like Akpanya, the patient-centred care model is the main learning curve. at is, it involves personally assessing patients, coming up with appropriate recommendations, creating long-term care plans and regularly working in collaboration with other health-care practitioners. Even handling health and medication insurance can be new to someone who practises outside of Canada. ere are a lot of moving parts. All of these areas, and more, are addressed by the CCPP program.

“Part of the program aims to help

We were treated like the professionals that we are and felt like we could openly share what we know, and what we didn’t know, without judgment.Mary-Anne Akpanya CCPP graduate

students understand how Canada’s health-care system functions, to know the roles of pharmacists within this context, to understand how to manage the interprofessional relationships and collaboration that happens within the system and generally guide cultural competency,” says Mahmoud.

“ en, in the skills lab, learners have the opportunity to practise and demonstrate patient-care skills in simulated interactions.”

For Akpanya, her undergraduate pharmacy education had focused on sciences, such as pharmaceutics and chemistry. Clinical and patient-care skills were not taught as they were outside the scope of what pharmacists did in Ghana at the time.

But she had practised as a pharmacy professional for almost 20 years, completed a master’s and PhD in public health and had a wealth of knowledge and experience that couldn’t be ignored.

“It is important to us that we acknowledge the learners as pharmacists,” says Mahmoud. “I myself am an internationally educated pharmacist, so I know it’s important to

understand and value all of the things they already know, in addition to what they need to learn.”

“ e environment didn’t feel like traditional schooling,” says Akpanya. “It was more like professional learning empowerment. It was conducive for us to have discussions and share our thoughts easily with our lecturers and colleagues. We were treated like the professionals that we are, and felt like we could openly share what we know, and what we didn’t know, without judgment.”

An important part of that professional empowerment was connecting learners with other Alberta pharmacists. In CCPP’s Community of Practice sessions,

pharmacists from a variety of practice se ings led collaborative sessions to talk to the learners about their areas of work. ese se ings include: community, hospital, rural, compounding, Indigenous communities, policy and governance.

“ e networking prepared me for the job market and my career ahead,” says Akpanya. “We learned about leadership, how to develop and navigate our careers and all the paths that were open to us.”

In July 2022, Akpanya graduated from the CCPP program and received recognition for excellence as the top learner in her cohort. She is currently completing her 1,000 hours of internship at Shoppers Drug Mart, and she intends to finish her exams with the Pharmacy Examining Board of Canada and register with the Alberta College of Pharmacy to become a practising pharmacist in Alberta before the end of this year.

“ e CCPP program was exactly what I needed to meet the expectations of practising here and to write my exams,” says Akpanya. “It’s going so well! So far, I’ve had no challenges integrating into the Canadian system. And I feel super excited that I am ready for this.” MP

It is important to us that we acknowledge the learners as pharmacists. It's important to understand and value all of the things they already know, in addition to what they need to learn.

Sherif Mahmoud clinical associate professor and director of CCPP program

PERSONAL BEST

The type and dose of drug a person is prescribed might not be optimal for their personal genetic makeup.

Pharmacogenomics means personalized prescriptions.

By Colleen Biondi

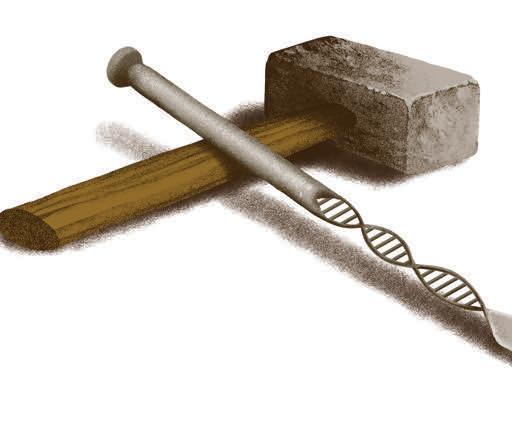

Illustrations by Byron Eggenschwiler

By Colleen Biondi

Illustrations by Byron Eggenschwiler

PERSONAL

Pharmacists provide a wide range of critical health-care services. But pharmacy, like most health care, is changing to accommodate the needs of the community and to adapt to the latest scientific research. Case in point: there’s an emerging field that personalizes drug dosing based on a patient’s DNA profile. It’s called pharmacogenomics and researchers at the U of A are leaders in this emerging field.

“Pharmacogenomics is the study of using patients’ genetic profiles to tailor dosing for optimizing results and reducing side-e ects,” explains Tony Kiang, researcher and associate professor (as of July 2023) in the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at the U of A.

Currently, medication is prescribed and dosages are determined based on what is recommended by empirical studies and what works for the average population. is framework is generic and has its limitations.

“People respond to drugs di erently,” Kiang says. “It doesn’t make sense that we’d all get the same dose or medication.”

Pharmacists and doctors already take into account some key factors when prescribing and dosing — weight and age, for example, and in some cases, sex.

But identifying genetic information — say, a gene that creates enzymes that a ect how your body metabolizes a drug — could be another helpful factor in determining e ective dosages and medications for patients. People with a genetic predisposition to metabolizing a drug slowly may need less of the medication

as it would remain in the system longer. People with a genetic predisposition to metabolizing a drug faster might need more of the drug. Also, a DNA profile can inform which medications might be more or less e ective for a particular individual. ere’s a lot of research underway that explores the potential of pharmacogenomic practices with drugs such as immunosuppressants and antidepressants.

THE PUZZLE OF VARIABLE SIDE-EFFECTS

Kiang and his student crew at the university lab are particularly concerned about the side-e ects stemming from immunosuppressant drugs used for kidney transplant patients and are conducting pharmacogenomic research to reduce toxicity and

PHARMACOGENOMICS IS NOT YET COMMON PRACTICE IN CANADA.

Tony Kiang Researcher in the Faculty ofenhance e cacy.

A recent study looked at an immunosuppressant drug called mycophenolic acid (MPA). is is a common anti-rejection drug that patients take a er transplant, but it can come with sidee ects such as stomach upset, dizziness and neutropenia (low white cell counts). Kiang theorized that kidney transplant patients who developed neutropenia would have higher MPA exposure than patients without neutropenia. Further, he hypothesized that metabolism and transporter genes might be responsible for this disposition. He tracked 21 patients — via blood work — at one month, three months and 12 months, measuring levels of MPA and neutropenia. He

found that an inverse relationship existed between normalized exposure of MPA and neutrophil counts (when MPA cleared normally, there was less toxicity). And he found some alterations in the minor allele frequencies of drug metabolism and transporter genes in this patient population that warrant further research.

ese results speak to the importance of monitoring the use of MPA in kidney transplant patients. Down the road, this kind of genetic reason for the way patients metabolize MPA could inform dose — and outcome — for patients.

Kiang and his research team also looked at bacteria in the gut that generate toxins and a ect metabolism. A healthy person is able to clear gut bacteria toxins, but kidney transplant patients may not be able to because of reduced kidney function. Here’s how it worked: Kiang’s team looked at engineered enzyme samples from both normal and dysfunctional genes and found three key discoveries. First, the enzyme responsible for the

creation of p-cresol sulfate (a toxin) was SULT1A1. Second, dysfunctional copies of the SULT1A1 enzyme led to reduced production of the toxin. ird, mefenamic acid was able to reduce the production of the toxin from the system. But so what? Well, these findings suggest that patients with kidney disease might be a ected by high toxin levels and might benefit from the monitoring of SULT1A1 activities. Perhaps genetic testing for this particular enzyme in the future could help predict which patients may have high or low toxin levels. Kiang’s lab also discovered a potential therapeutic agent that could reduce toxin levels. Kiang’s studies are funded by national foundation grants and TriCouncil grants.

With the majority of medications, genomics is not used for dosing.

Before you change a dosing strategy, you need to do extensive scientifc research to prove that the strategy works.

Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences

“But pharmacogenomics isn’t yet common practice in Canada,” explains Kiang. “With the majority of medications, genomics is not used for dosing. Before you change a dosing strategy, you need to do extensive scientific research to prove that the strategy works.” at means more work along the lines of what Kiang and his research team are doing: identifying genes responsible for metabolizing a medication and identifying variations in those genes and associated enzymes, which might influence metabolism; testing that theory to see if di erences in dosages result in be er outcomes; and then moving on to larger randomized, double-blind clinical trials. is process is conducted drug by drug, before Health Canada approves adjusting dosages.

“Health Canada has to screen the data and weigh benefits versus conventional dosages. It’s a long process,” Kiang says. “It will be a few more years before pharmacogenomics enters the mainstream.” But novel research happening in Kiang’s lab now may be mainstream in the future. Processes have to be in place to get there.

In tandem with identifying genes and enzymes that a ect

metabolism, broad and speedy access to genotyping is necessary. at’s where a patient’s DNA is retrieved and assessed for genetic information to tailor drug dosing. is process varies depending on the sample used, the technology used and the cost. Currently, people in Alberta who are interested in ge ing their DNA sequenced must pay.

“ ere will be costs associated with broad-scale genotyping — the technology, the training, the lab work — but these could lead to bigger savings to the health-care system if the paradigm works,” says Kiang. ere’ll be fewer negative sidee ects from medications with a tailored dosing and fewer trips to the hospital emergency department a er a bad reaction, Kiang predicts. e goal would be for genotyping to be publicly funded, accessible to all and an integral part of Canada’s universal health care. He’s not the only one who’s hopeful.

THE PROMISE OF AVOIDING TRIAL AND ERROR

Lisa Guirguis, ’97 BSc(Pharm), ’00 MSc, is also at the forefront of pharmacogenomics research. She’s a researcher and pharmacist as well as an associate professor in the faculty. Her focus is innovation and the uptake of new technologies in pharmacy practice. She is particularly interested in how pharmacogenomics can be used to address issues with

antidepressant medication.

“Depression is widely seen and managed in the community but — in some patients — it can be hard to treat. With pharmacogenomics, we have the tools to assess which drugs won’t work for you and which will likely work based on your genetic code,” she explains. “And patients have a right to know these tests are available.”

But there is a disconnect: most pharmacists, clinicians and patients don’t know this kind of testing is available. drives Guirguis. “I have a moral imperative to put these tools in the public domain.”

In fall 2021, she and her research team conducted a comprehensive literature review, focusing on pharmacogenomics and community pharmacy, to determine what data existed in the field and to assess if the research was evolving. Early studies were about awareness (there was li le); recent studies reported positive outcomes for patients with pharmacogenomic testing. “ e research is going in the right direction,” she says.

Guirguis’s team is now doing interviews with pharmacists in Alberta to generate quantitative and qualitative information about the use of pharmacogenomics in community pharmacy, with funding from the Margaret and Andrew Stephens Family Foundation. So far, pharmacists appear invested. report that they’re teaching themselves how to use and interpret the technology. And they say that success stories of patients who’ve realized improvement in their quality of life due to pharmacogenomics have been the biggest factor in requests for testing. “Finally, pharmacogenomics has helped patients find medication that

improves their mental health,” says Guirguis.

ese discussions also include looking at what shared decisionmaking tools pharmacists can use to hold clear and honest conversations with patients about pharmacogenomics. “We have the technology and we have the science,” she says. e next step is to plan a path to access, interpretation and clear communication with patients.

It won’t be an easy road; Guirguis estimates less than five per cent of Albertans using antidepressant medication are incorporating pharmacogenomics today. But she is in it for the long haul. “We need to develop solutions that are scalable in the community,” she says. “And we need to get this publicly funded. O en the people who need this most are least able to a ord it.”

RESEARCH AND APPLICATION

In addition to the work of researchers and educators like Kiang and Guirguis, other stakeholders are key to moving the technology and science into broad pharmaceutical practice. Pharmacy students will need to be receptive to theoretical information, practical training and a new approach to doing their jobs. Governments and other funders will need to provide money for stateof-the art research, equipment and genotyping. Clinicians will need to learn how to interpret ever-changing data and be prepared to create space to have those conversations with patients about the benefits of dosing di erently. Finally, patients will need to be on board with participating in clinical trials and — when we get to that point — providing their own DNA samples for tailored dosing at their local pharmacy.

New technology brings questions. How do we handle consent regarding DNA retrieval? What about minors or people who

are vulnerable? How will companies, government and clinicians use these samples respectfully and responsibly, respecting a patient’s privacy? And how will clinicians have honest, plain-language conversations with patients about the benefits and risks? For example, you could be “genetically neutral.” at is, neither one drug nor another is known to be more beneficial, which could be deflating, says Guirguis.

Pharmacogenomics is in its infancy. But down the road, it’s likely you will have the option of walking into your local pharmacy with a prescription that will have your genetic profile a ached. A er all, DNA only needs to be retrieved once and, in an ideal world, this could happen at your community lab, along with blood work and a urinalysis test. Your pharmacist could then give you a specific medication and dosage based specifically on your DNA profile. As promising as pharmacogenomics is, it will remain a single tool in the clinician’s toolbox. “Clinicians will still need to monitor the patients closely for side-e ects and e cacy. It is a great start, personalized genomic dosing, but it should complement current clinical practices,” says Kiang. “It’s just the beginning.”

But it is a bright beginning, he admits. “It’ll take a while before cars will fly in the sky, but it is possible. It’s important that we still support robust research and focus on quality of care for patients. at’s the reason why we are doing this.” MP

HERE. BOOST YOUR CAREER

If you’re already working in the feld of pharmacy, pursuing your master’s or doctorate degree is possible, while you continue to support your patients.

With real-world experience, you’ll be able to apply valuable context to your studies as you gain the expertise and specialization you need to open new doors in the everevolving world of healthcare.

Apply today for Fall 2023. uab.ca/pgs

Legacy of Care

“Your white coat symbolizes commitment, respect, empathy and integrity,” said Christine Hughes, interim dean of the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, at the Class of 2025 White Coat ceremony. Pharmacy students from the classes of 2024, 2025 and 2026 celebrated their entrance into the profession of pharmacy at the first in-person White Coat ceremonies since pandemic shutdowns. e three events saw new generations of pharmacists-in-training read the code of ethics and sign the pledge of professionalism in front of friends, family and pharmacists. “When you don your white coat, you embrace your responsibility to our health-care profession and make a promise to your patients. As pharmacists, you’ll be the first source of care and information for managing your patients’ overall health,” Hughes said. “And this is an oath to the patients — that you’re worthy of the trust they have in you.” — TA RWINDER RAI

Donning the white coat is a potent symbol of professional responsibility

Smarten Up Class Notes

What have you been reading or watching that you have applied to your career or life? Have you a ended any webinars or courses that have inspired you or given you new skills or certification? Have you worked with a mentor or mentored anyone? Submit your “Smarten Up” note to phcomms@ualberta.ca. We edit for clarity, length and style.

Compiled by Tarwinder Rai

HUMANITY IN HEALTH CARE: “Recently, I picked up a copy of Ducks in a Row: Health Care Reimagined by Sue Robins,” says Jeff Whissell , ’98 BSc(Pharm). “Sue is a health care activist and patient experience champion who openly shares the experiences she and her family had within the health-care system — the good, the bad and the ugly. I first met her at a conference years ago, and I have strived for the importance of bringing

humanity to health care ever since. It’s a concept that has influenced my career in significant ways. Humanity matters to people, especially when they’re at their worst, and it’s the little things we do as health-care professionals that can make a profound difference.”

TALKING TOOLS: “I’m always looking for opportunities to enhance my leadership skills,” writes Ethan Swanson , ’21 PharmD. “I would highly recommend reading Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes are High by Joseph Grenny. It will help you make the most out of your work and personal relationships through meaningful dialogue.”

RECOMMENDED READING: Five Little Indians by Michelle Good — Gezina Baehr, ’20 PharmD

TUNE IN TO EQUITY: PharmD student Justin Peters recommends tuning in to the American Academy of HIV Medicine’s webinar: “Am I a Risk Factor? Addressing Stigma, Social Determinants, and Interventions for the Transgender Community.”

We’d love to hear what you’re doing. Tell us about your new job, career pivot, latest award, or new baby. Celebrate a personal accomplishment, tell us about your volunteer activity or share a favourite campus memory. Submit your class notes to phcomms@ualberta.ca. We edit for clarity, length and style.

A GOLDEN JUBILEE: “I have been honoured to organize many reunions for our very close knit group over the last 49 years,” says Deb Holmes, ’72 BSc(Pharm). “But 2022 was extremely special. It marked 50 years since we le the U of A. We were a class of 68 grads, of which 12 are now deceased and six have unknown locations. So just imagine my surprise when 22 of my classmates registered for several events that I put together. It was so heartwarming to gather together and remember all the great times.”

THE TOP SPOT: Join us in congratulating Zachary Kronbauer, ’22 PharmD, who won the George A. Burbidge Memorial Award in recognition of the highest overall combined grade on the Pharmacist Qualifying Examination — Part I and II for 2022.

DOING IT ALL: Amanda Leong, ’17 BSc(Pharm), is working as an ICU pharmacist at Rockyview General Hospital and Foothills Medical Centre while completing her PhD in epidemiology — focusing on the intersection of pain and delirium — in QUOTED

“Our role as pharmacists is evolving, and the landscape of pharmacy practice is changing. We contribute to ground-breaking research and strengthen community health care. Our students are prepared to meet the demands of the workforce of tomorrow.”

– Christine Hughes, '94 BSc(Pharm), Interim Dean and Professor, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences

the Department of Critical Care with the Cumming School of Medicine. She’s also the chair of the education commi ee for CSHP Together. What’s next? Leong hopes to be a clinician scientist.

PERSON-CENTRED CARE: “I spent six weeks at the Palliative Care Unit at the Grey Nuns Hospital in Edmonton, and it was one of the most rewarding experiences I've had post-graduation,” says Alyssa Aco, ’17 BSc(Pharm). “Palliative care can have negative connotations because you’re caring for people who are dying, but I have never worked in a place with more colour, life and hope. e team was extremely collaborative, empathetic and kind. ey work to help palliative patients pass with dignity and provide emotional support for patients and families. I learned that caring for people who are dying requires immense empathy and deep understanding of the patient and their families, lived experiences, personalities, values and priorities. At this placement I learned what it truly means to provide person-centered care, and I’m a be er pharmacist for it.”

WELCOME TO THE WORLD:

Congratulations to Na y Mack, ’15 BSc(Pharm), who welcomed baby Oskar into the world — three weeks early — in August 2022. A er her parental leave, she’ll be back at work, managing the pharmacy at the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton.

SUPERPOWERED PHARMACY: “I am passionate about supporting learners, pharmacists and other health-care leaders as they tap into their mix of strengths and enact positive change in themselves and their communities,” says Maria Anwar, ’04 BSc(Pharm). “My superpower is that I’m an EXTRAextrovert! row me in a room full of strangers, and I will find a way to connect and get to know them all. is year, I transition into a new role with the Alberta Health Services Design Lab, where I’ll join a small team of design consultants who help solve complex problems, facilitate strategic discussions and educate using design-thinking

In Memoriam

The Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences notes with sadness the passing of the following graduates, based on information we have received in the last year.

Jolaine Allan

Irene Black

Teddy Brewerton

Olly Chorney

Patrick E. Connell

Robert Donahue

Brian Foster

Phil Horne

Lois Johnson

Christopher Lee

Wing Lew

John Lymer

Bob D. MacKenzie

Robert MacKlem

Jack T. Mah

Margaret M. Mah

Kathleen McClellan

D. Terrence McCool

Peter Melnychuk

Jane Musey

approaches inside and outside AHS.”

INNOVATION: Je May, ’85 BSc(Pharm), is a director on the board of HumanisRx Corp. HumanisRxʼs unique Canadian clinical analytics platform proactively identifies medication risks and supports pharmacists to achieve be er health outcomes.

PIECE OF CAKE: “For amusement, I took a short trip to Reno last summer and passed a wri en test to become a certified cake decorating judge,” says Denise Kervin (nee Wyrstiuk), ’88 BSc(Pharm), who recently reached her 25-year milestone with Alberta Health Services. “I’m looking forward to completing the practical training at a yet-to-be-determined time and place.”

NUMBERS

Irvin Rude

Joyce Sawchuk

Wasyl Skakun

Carl Sobolewski

Valerie Soderberg

H. Malcolm Sutherland

Lorna Teare

Grant Tu

Derek West

Joyce E. Zelmer

The number of undergraduate and graduate students benefting from donor-supported bursaries, awards and scholarships in 2021/22

Rural Health Care Gets a Boost

Community connections and a wide scope of practice in Alberta make an appealing mix for career opportunities

Health care can be difficult to access in rural communities. row in part-time clinic hours, an Alberta winter or a global pandemic, and those accessibility challenges only become more apparent.

But many services that once required an appointment with a family doctor can now be provided by an Alberta pharmacist — including some prescriptions, referrals, disease screenings, provision of health advice, precision medicine and vaccinations. And pharmacists, along with the students they train, are prepared to serve rural communities.

“Every year I work in a small town, I love it more and more,” said Alma Steyn '10 BSc(Pharm), owner of Gourlay’s Clinic Pharmacy Canmore. “ at connection you get with people — the patients and the other health-care professionals we work with — is unbelievable.”

In rural pharmacies like Gourlay’s across the province, University of Alberta pharmacy students are training in a complex work placement and discovering the benefits of practising in a smaller community.

“Some of the products that I’m compounding here, I've never seen anywhere else,” said Olivia Stephen, a fourth-year pharmacy student completing her final placement with Steyn at Gourlay’s Canmore. “For example, we have di erent compounds and medications that we make for emergency pain management for the ski hills.”

Return to Rural After Graduation

Over their four-year degree, U of A pharmacy students complete 1,600 hours of hands-on training in pharmacies and hospitals, with 10 to 20 per cent of those

hours spent in rural placements. Of those students who have found jobs on graduation, 30 per cent choose to return to work in rural areas.

“ e No. 1 thing for me is the seamless care and the ease of communication in rural se ings,” says Preston Eshenko, a recent graduate of the U of A pharmacy program. Eshenko completed three of his placements in rural communities during his degree, and on graduation started work as a full-time pharmacist at Gourlay’s Pharmacy in Ban , sister branch to Gourlay’s in Canmore. He also works a few shi s per month at Ban Mineral Springs Hospital.

“It benefits the patients because we know what went on during the di erent levels of care,” Eshenko says. “It's much easier to find information and communicate between areas of the system when you also work at the hospital and know all the nurses, emergency room sta and acute care team. It’s just a human connection.”

Steyn is one of more than 1,000

volunteer preceptors who give their time to train U of A pharmacy students. She said the training experience benefits her and her patients, as well as the student. Eshenko, who has signed up to be a preceptor and is waiting to take on his first student, agrees.

“I had very good preceptors throughout school, and I wanted to pass that on,” said Steyn. “And I'm looking forward to learning from my students and staying up-to-date on the most recent progressions in health care — because it’s always changing — and being able to change my practice for the be er because of their input.”

Filling a Gap in Care

“Pharmacists are filling a much bigger role than we ever have,” said Steyn. Pharmacies have been one of the only health-care providers that have stayed open to the public and accessible throughout the pandemic, and they are steadily taking on responsibilities that have traditionally been fulfilled at family practices, drop-in clinics or urgent care centres. Alberta pharmacists have the largest scope of practice in Canada, and are the largest single provider of the COVID-19 vaccine and flu shot in the province.

“If your patients know you, like they do in a small town, they’re more likely to trust,” said Stephen, who plans to work in a rural area once she graduates. “And that makes for be er patient care and be er health outcomes.

– KALYNA HENNIG EPPIt Takes a Village

Owning a pharmacy business is about building relationships

Before Jerry Saik, ’74 BSc(Pharm), finished school, he knew he wanted to get into business. He’d always been drawn to mathematics and any opportunity to use his analytical and clinical skills. So a er he graduated, he spent three years working as a pharmacist in Daysland, Alta., population 800, a couple of hours southeast of Edmonton. en he decided to put his entreprenurial skills to use and open an independent pharmacy business.

Forty-five years later, he knows pharmacy ownership seems daunting as ever. But he also knows what it takes.

You’ll make mistakes. Learn from them. Owning and running a pharmacy requires experience as a pharmacist, a whole lot of confidence, strong business acumen and resilience. You need expertise with business principles, financial planning and metrics, data analysis and cash flow. ese were all in Saik’s toolbelt when he first struck out on his own — but his first venture was not very successful.

Saik’s first choice was to create his own business from scratch. He was prepared for some lean years but facing the late 1970s and mid-’80s high interest rates and the deepening of Alberta’s worst recession, things didn’t go according to plan. “ e economy collapsed, and the expected

growth did not materialize,” says Saik. “But I would do it again, because it prepared me for success on my second try.”

Put people first.

Saik returned to Daysland with his family and, in 1991, bought Daysland Pharmacy. It was an established business with a cash flow and existing clientele. But Saik knew it would still require a lot of work. e mainstay of maintaining and growing his client base, he says, has been intentional relationship-building.

“Develop an environment where people want to come into your pharmacy because they feel comfortable, valued and able to interact,” says Saik. Professionalism and trust leads to relationships that increase loyalty, “which is exactly what you need to succeed.”

He applies a similar philosophy to marketing. “Focus marketing on the customers you already have, who are going to tell their community what a great pharmacy you have, leading to more loyalty.”

Empower your team.

Saik says that those who recognize and embrace change in the practice of pharmacy are going to be successful.

“Maximizing the clinical skills of your pharmacists leads to higher billings for clinical services and creates a positive feeling as a professional,” Saik says. “Without full scope, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians may not feel professionally satisfied. Empower your team to do their best work and create the most satisfying environment.” Most importantly, Saik says working within a full scope means patients experience be er health outcomes.

Become a part of your community. In small centres, everyone knows the pharmacist. Over the years Saik has cared for patients and their children, and their children’s children. “I cared for the people that I played hockey with, met at barbecues, a ended weddings and graduations with,” Saik says. “ ey are my dear friends and family.”

Saik says that you can also become entrenched in your community in an urban se ing. Get involved with your neighborhood and support local programs. Get involved with your city — join a small business association or mentor a pharmacy student and become a preceptor. Interact directly with your patients.

Beyond Daysland, he runs the Saik Family Foundation, which has supported the Golden Bears Alumni Football Scholarship program, Adopt-an-Athlete program and Bears Education and Tutoring program. And he endowed a gi for student athletes in the pharmacy program called e Jerry Saik and Family Athletics and Pharmacy Award. He is also one of the first partners of Edpharm Partnership, acting as long-time treasurer. Edpharm is a group of 36 independent pharmacies in Alberta that develops working and social relationships with pharmacy owners and family, pharmaceutical manufacturers, wholesalers, and other pharmacy-related companies.

“You need to build meaningful relationships with everyone associated with your profession,” Saik says.

– KALYNA HENNIG EPPNUMBERS 764

The number of undergraduate and graduate students benefting from donor-supported bursaries, awards and scholarships in 2021/22

Breaking Down Barriers

In his final rotation, Dylan Moulton, ’19 PharmD, didn’t expect to be launched into a unique clinical pharmacy practice in less than a year, or that it would transform Medi-Drugs Millcreek into a welcoming place for LGBTQ2S+ folks. Encouraged by his preceptor, Aileen Jang, ’83, BSc(Pharm), Moulton created a business plan to implement policy-based changes that would support a more inclusive space for all patients. By the end of his rotation, Jang was so enthusiastic about the prospect that she hired him to facilitate the program upon his graduation.

Today, Moulton is manager of Medi-Drugs Millcreek. He has also been hired by the University of British Columbia as a pharmacy practice consultant, to which he brings his skills,

knowledge and diversity training into the classroom for pharmacy students.

“Pharmacy sta should respect a patient’s identity, but also take it one step further and communicate in a way that shows appreciation and celebration of patients’ diversity,” says Moulton. One of his favourite professional tasks is injection training with trans and non-binary patients. He says administering a first hormone injection — a long-anticipated moment for some trans patients — is a gi .

“I get to practise in a community that is amazingly diverse," says Moulton. "Having such a broad scope of practice in Alberta makes it easier to improve access to care and break down health-care barriers for our patients.” –

KALYNA HENNIG EPPOur pharmacy students and our communities simply wouldn’t be the same without our preceptors. By opening your practices to aspiring pharmacists, you not only give them hands-on experience, you demonstrate the importance of empathy, communication and professionalism. It’s a legacy of excellence that will continue for generations.

Where ideas collide.

This world has been challenged like never before. We meet those challenges grounded by our roots — yet spurred forward by our profound responsibility to seek truth and solve problems. Because at the University of Alberta, we will never be satisfed with the “now.” We will always be seeking, always be innovating and, most of all, always be leading.

Leading with Purpose.

ualberta.ca