IN DEPTH EMERGENCE OF A NEW AGRICULTURAL PARADIGM

DESIGN FOR LIFE: URBAN PRACTICES FOR AN AGE-FRIENDLY CITY

DESIGN-DRIVEN DATA: HUMANCENTRIC CONSIDERATIONS

SINGAPORE’S URBAN FUTURE –LOOKING THROUGH THE LENS OF GOLDEN MILE COMPLEX

IN PERSON BUILDING BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES

COMMUNITY INTERVENTIONS & PARTICIPATORY APPROACH

MCI (P) 057/01/2023 | VOLUME 13 NUMBER 1 | 2022 SINGAPORE | WWW.DPA.COM.SG

ISSUE 13.1

THE DESIGNFUTURE ISSUE

FOREWORD

As practitioners and advocates of the built environment, we may have pondered questions like: How do we design more meaningfully for the future? What can we do to sustain our living environment in the face of daunting threats? What is the future of design as a profession?

Trials and tribulations continue to dominate the news as part of the world struggles to navigate out of the pandemic. Climate change, geo-politics, global supply disruption, public health and social fragmentation are changing the way we live and design.

Since Singapore lifted mass gathering restrictions in April this year, we have been able to recalibrate, re-strategise and renew our commitments in the face of these global challenges. With the aim to bring creative minds and expert partners together, we held a series of design dialogues on a range of issues that could redefine the future of cities.

These earlier design series and forums culminated in the DesignFUTURE conference on 2 nd December 2022, which aims to drive discourse and garner conviction in designing for sustainability, equity, wellness and resilience, champion the notion of healthier community, greater synergy and a brighter urban future.

For these carefully curated conversations, we invited advocates, educators and thought leaders from respective domains, to examine pressing issues related to biophilic and sustainable cities; social, physical and planetary wellbeing; and the role of community

participation and technology in designing a better future. Traversing across disciplines, we hope to cast a holistic view of the future through design, inspire alignment and build momentum for change to happen.

Coming together in person with our friends and partners in the Built Environment community and with fellow DPians across the globe, this reinforced the power of the collective to accelerate a positive transformation.

Presenting these dialogues in this special edition of Design in Print, we celebrate DPA’s thrusts of DesignFIRST and People + Partners, and highlight the concerted and coordinated effort in building a healthy and resilient future.

On behalf of DP Architects, I would like to thank our distinguished panellists for giving their voice and invaluable insights to the discussion on designing our future. The strategic subject matters they spoke passionately about are critical in deciphering our urban future puzzle.

I hope you will enjoy these thoughtful exchanges and be inspired to come together and make a difference for our future. Though the year is coming to an end, the opportunities for conversation and collaboration are endless.

Here’s wishing everyone a wonderful holiday season and an inspiring 2023!

SEAH CHEE HUANG CEO of DP Architects

EDITOR IN CHIEF Angelene Chan

02 – 05 IN

BRIEF

01 NS Hub

02 SAFRA @ Choa Chu Kang

03 Penn Colour Design Centre 04 Punggol Green

05 The INLET

06 China-Singapore Guangzhou Knowledge City –Knowledge Tower

07 The MRT Purple Line (South)

08 NEXity

06 – 07

INDUSTRY

01 Changi Airport T5: DPA Appointed the Retail and F&B Planning and Design Consultant

02 Moving Forward with Golden Mile Complex: DPA is the appointed architect

03 DP Architects is the Architectural Consultant for Lego Group’s 6th Factory

04 Digital Twin Explorer: DPA and VIZZIO Form

Partnership to Provide a World-first AI-powered Geospatial Platform for the Architecture Industry

05 DPA and SUTD sign MoU to Develop AI-enabled Envelop Designer

08 – 17 IN

DEPTH

01 Emergence of a New Agricultural Paradigm

02 Design for Life: Urban Practices for an Age-friendly City

03 Design-driven Data: Human-centric Considerations

04 Singapore’s Urban Future – Looking through the Lens of Golden Mile Complex

18 – 38

IN PERSON

01 Building Biophilic Communities

02 Community Interventions & Participatory Approach

DESIGN IN PRINT TEAM

| EDITORS Belle Chung, Ng San Son | CONTENT Sean Ng, Toh Bee Ping | GRAPHICS Kirsten Wong

PHOTOGRAPHERS Bai Jiwen, Pocholo Mauricio, Mazterz, Sean Ng, Schran Image, Juliana Tan, Jerome Teo, Marc Tey, Kirsten Wong

CONTENTS

UNDER

NS HUB SINGAPORE

The new NS (National Service) Hub is envisioned primarily as a one-stop service centre; centralising NS services including registration, medical services, recruitment and fitness test facilities. Comprising amenities such as an e-mart, a childcare centre, F&B outlets, and an outdoor community area with a running track, football field and fitness equipment that will be accessible to the wider public, it is also intended to serve as a symbolic touchpoint with the country’s institution of defence.

The architectural scheme of the new NS Hub, therefore, seeks to be a physical embodiment of Singapore’s unique NS commitment and culture while communicating the institution’s key values of transparency, accountability and accessibility. This meant careful and thoughtful curation of its spatial programming so that the spaces are inviting and encourage public engagement without compromising security. The NS Hub will also integrate landscape and green design features that are in line with the nation’s wider sustainability goals.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

SAFRA @ CHOA CHU KANG SINGAPORE

Envisioned as a one-stop weekend hangout for SAFRA members and their families, SAFRA Choa Chu Kang (CCK) is the 7th SAFRA clubhouse to be built and the first to be located within a park. Also sited in close proximity to a future integrated transport hub, SAFRA CCK acts as a condenser and activator; playing host to a thriving, multi-generational neighbourhood and fostering an active and robust community as symbolised in its feature of v-columns.

Nature and fitness form the core themes of this architectural scheme. Programmatically, the development’s spaces are sensitively choreographed to house SAFRA’s comprehensive suite of recreation and wellness facilities. This includes an elevated sheltered swimming pool, sky running track and sheltered futsal court; all of which are premier features not seen in any SAFRA clubhouse before. Acutely aware of its surroundings, the building harmonises with the park by utilising a cloister form to create a “Fitness Oasis” that offers views out to the parkland. Verdant boulevards, planters, green curtains, terraced and landscaped roofs blur the boundaries between park and clubhouse, creating a symphonic “green experience”.

For its integration of sustainable concerns with humanistic elements, the project has been awarded the Green Mark Platinum-SLE certification.

CONSTRUCTION

2 IN BRIEF | SHORT TAKES ON UPCOMING PROJECTS

COMPLETED

PENN COLOUR DESIGN CENTRE SINGAPORE

In the conceptualisation of the first Design Centre for Penn Colour in Asia, DP Design prioritised three things in its scheme: comfort, collaboration and solitude. This led to the thoughtful curation of varied spaces that catered for both group and individual work settings, and in which Penn Colour presents as a designer’s partner in his/her creative journey and process.

To facilitate this, it was crucial that a welcoming and comfortable environment is created. Lush elements of horticulture imbue the space with warmth. Complementarily set in contrast to raw concrete and plywood surfaces and finishings, the overall design scheme lends a tangible sense of honesty, openness and functionality to the space. At the same time, the choice of materiality allowed for a reduction in use of chemical treatments and false ceilings, which contributes to a healthier indoor environs and minimises material waste. The space actively practices the principles of daylight harvesting, with greenery strategically placed to strengthen wellness and workspace-friendliness. There was also no tear down of the existing site, which reduces embodied carbon emissions. All of these align with Penn Colour’s vision for the Design Centre as a crucial touchpoint with the creative industry it services and its commitment towards ethical business practices.

COMPLETED

PUNGGOL GREEN SINGAPORE

Punggol Green, located in the ‘Heart of Punggol’ under the LRT viaduct, is DP Green’s take on turning dis-amenities into amenities and reclaiming places for the people. The landscape architecture scheme effectively transforms the un-utilised space into a 500m social and wellness linear park. Programmatically, the park not only integrates walking and cycling arterials that stitch existing and upcoming developments (including the recently completed One Punggol) together but also incorporates play and recreational facilities; all of which are set within a lush verdant-scape that carefully considers the existing PUB drainage and LTA rail structure. Seeking to increase the biodiversity of the locale, the proposed landscape architecture mimics the ecological habitats of the proximal coastline with a mix of native and exotic species well-suited to the urban environment and low-light conditions.

The result is more than a park. Through ideas generated from public engagement and guided by the SG Green Plan, Punggol Green serves as a key social spine, transport node and recreational nook in which a rich sense of community is fostered, public welfare is promoted and biodiversity is supported.

3 IN BRIEF | SHORT TAKES ON UPCOMING PROJECTS

THE INLET

SHANGHAI, CHINA

The INLET, which forms the first phase of the larger mixed-use development – Chong Bang’s Life Hub @ Bund Central – consists largely of heritage Shikumen buildings conserved in-situ with contemporary insertions in both architectural and landscape design. Designed by DP Architects in collaboration with local conservation expert, Zhangming Architectural Design, the project has been wellreceived by locals and the architectural field alike.

Block 2 is among one of the contemporary retail insertions for The INLET. The three-storey retail building, along North Sichuan Road in Hongkou District, Shanghai, features an intentionally simple form which draws its inspiration from the peculiarities of its site and accentuates the rich heritage of its genius loci. Regenerating the continuous street elevation, the building’s main elevation adopts the rhythm of party walls from the adjacent shophouses with two-storey terracotta fin-walls lining the transparent main façade. At night, the solidity of these fin-walls is dissolved by warm glows of light, emitted through the groove lines. The resulting architecture of Block 2 is an urban portal that transcends time and space, inviting visitors to freely construct their unique spatial, social and retail experiences.

The INLET Block 2 is designed by DP Architects with DP Green and DP Lighting for the project’s landscape and lighting design.

CHINA-SINGAPORE GUANGZHOU KNOWLEDGE CITY – KNOWLEDGE TOWER

GUANGZHOU, CHINA

Located on the north bank of Jiulong Lake within China-Singapore Guangzhou Knowledge City, the 330m-tall Knowledge Tower project is a symbol of continued cooperative relationship between Singapore and Guangzhou City. The tower’s core structures have currently reached 100m with record-breaking speed since the start of construction in June 2021. It is the first of a series of super high-rise developments along the city’s Jiulong Lake CBD District, and will feature a ‘Lifespine’ which will run through the middle of the tripartite-form tower and consists of five thematic atria that act as active social spaces for future work communities. Topping the tower will be a five-star international hotel. The Knowledge Tower is slated for partial completion in 2025.

COMPLETED

UNDER CONSTRUCTION 4 IN BRIEF | SHORT TAKES ON UPCOMING PROJECTS

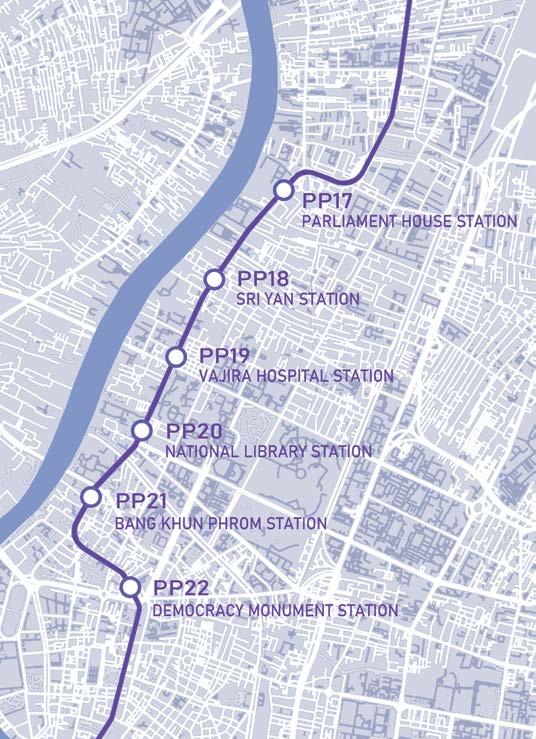

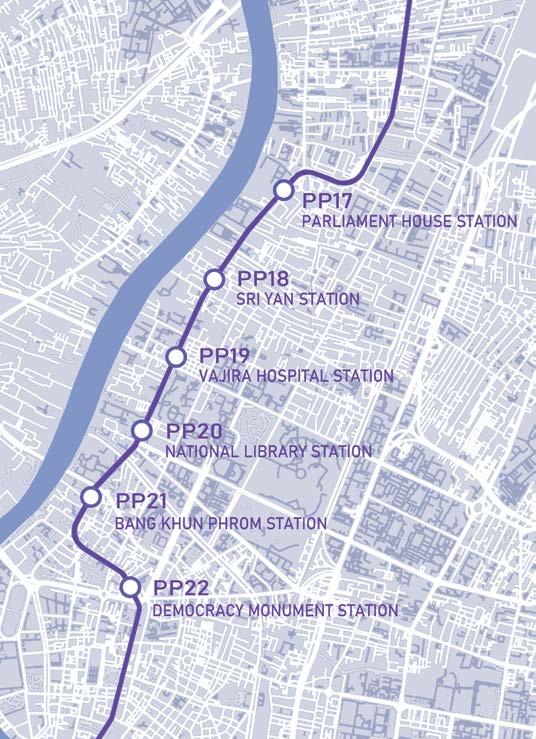

THE MRT PURPLE LINE (SOUTH) BANGKOK, THAILAND

The Tao Poon-Rat Burana section of the southern Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Purple Line project is currently underway in Thailand. It will consist of a 13.6km underground stretch with 10 stations and a 10km elevated stretch comprising seven stations. DP Architects is the appointed Architectural Consultancy for six of the 10 underground stations, starting from the Parliament House to Phan Fa intersection. The project, which involves interior design and landscape design of the stations, will be led by its team and office in Thailand. The Design & Build component of the project is a collaboration with AECOM Thailand under CH. Karnchang Plc.

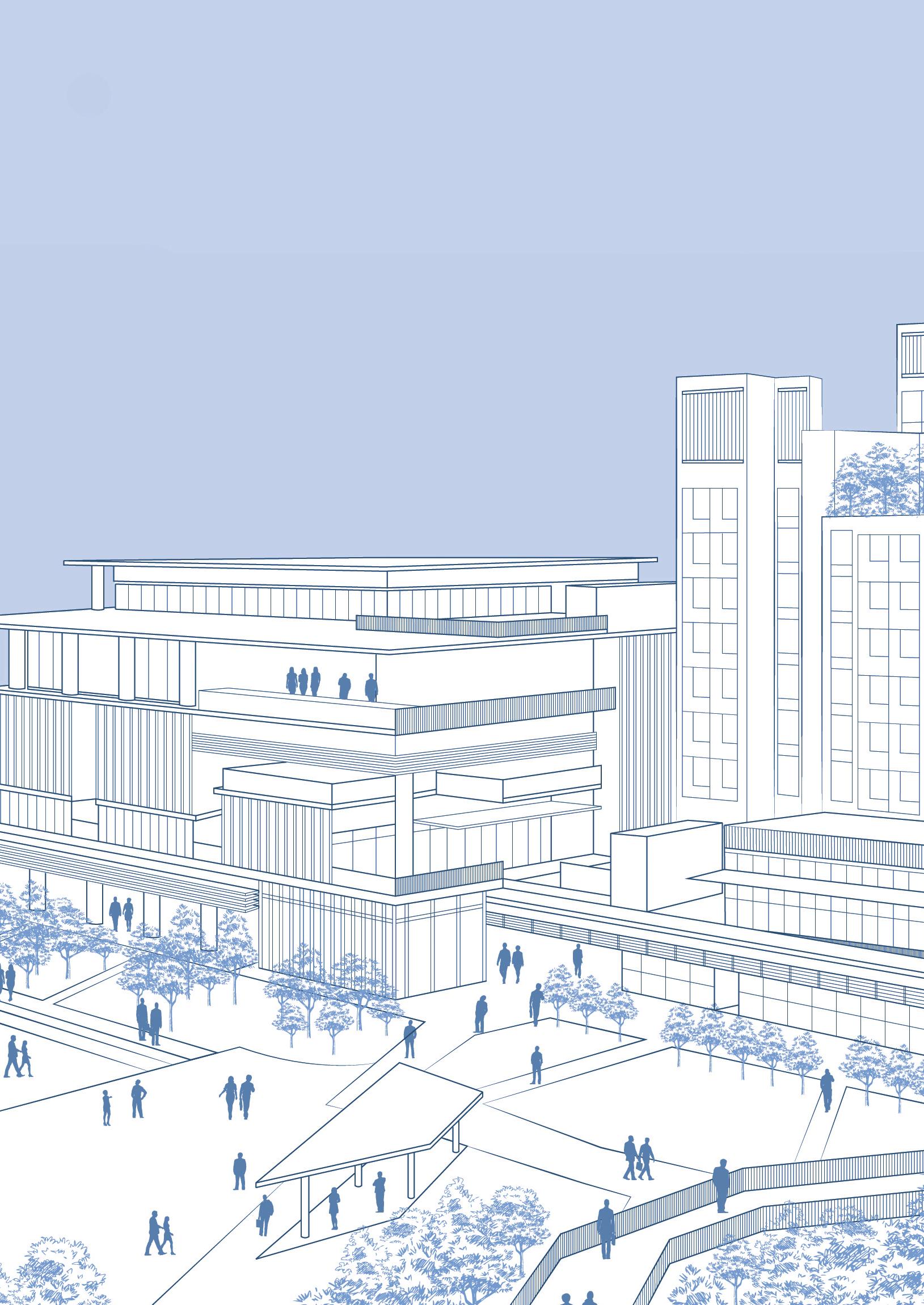

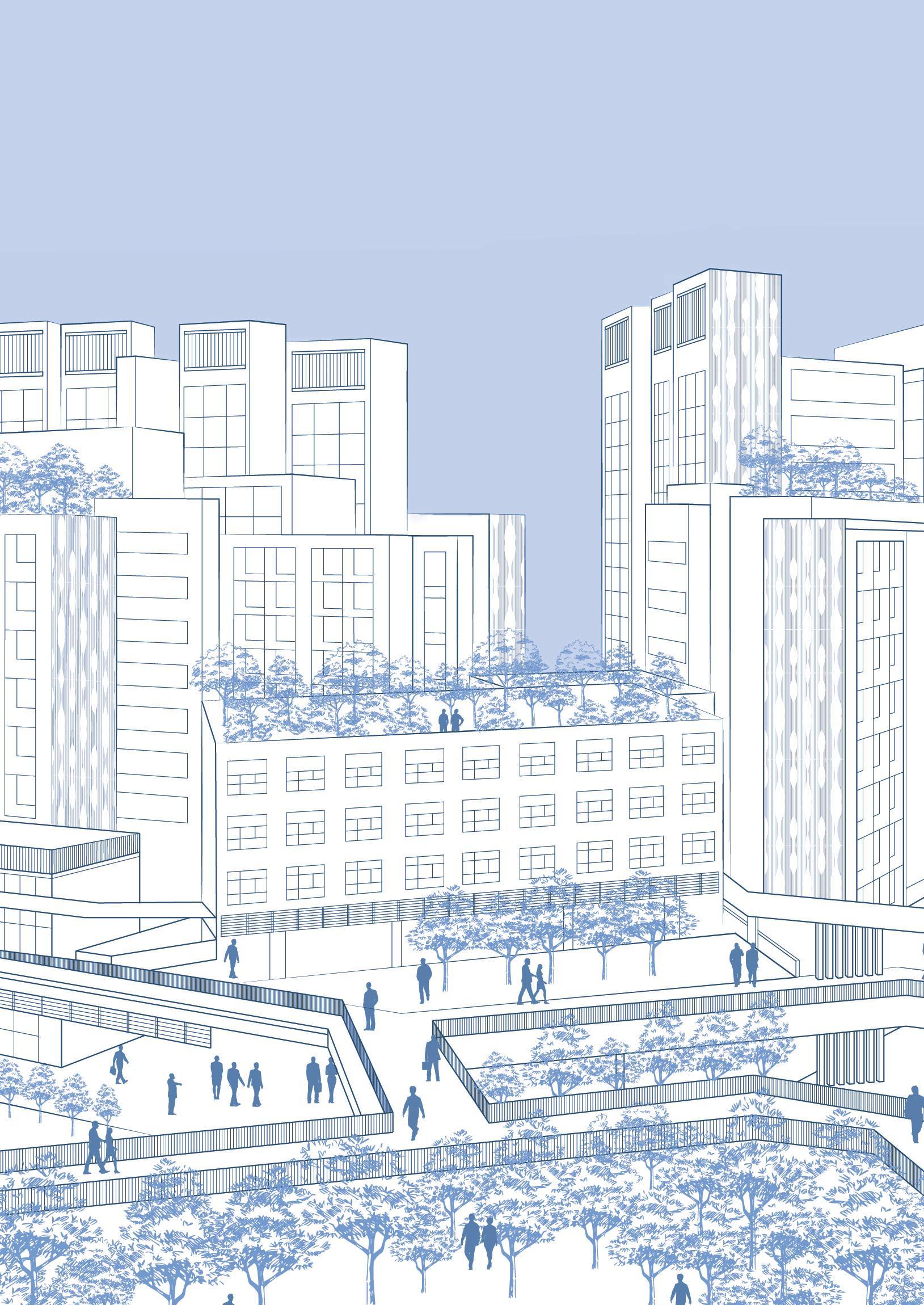

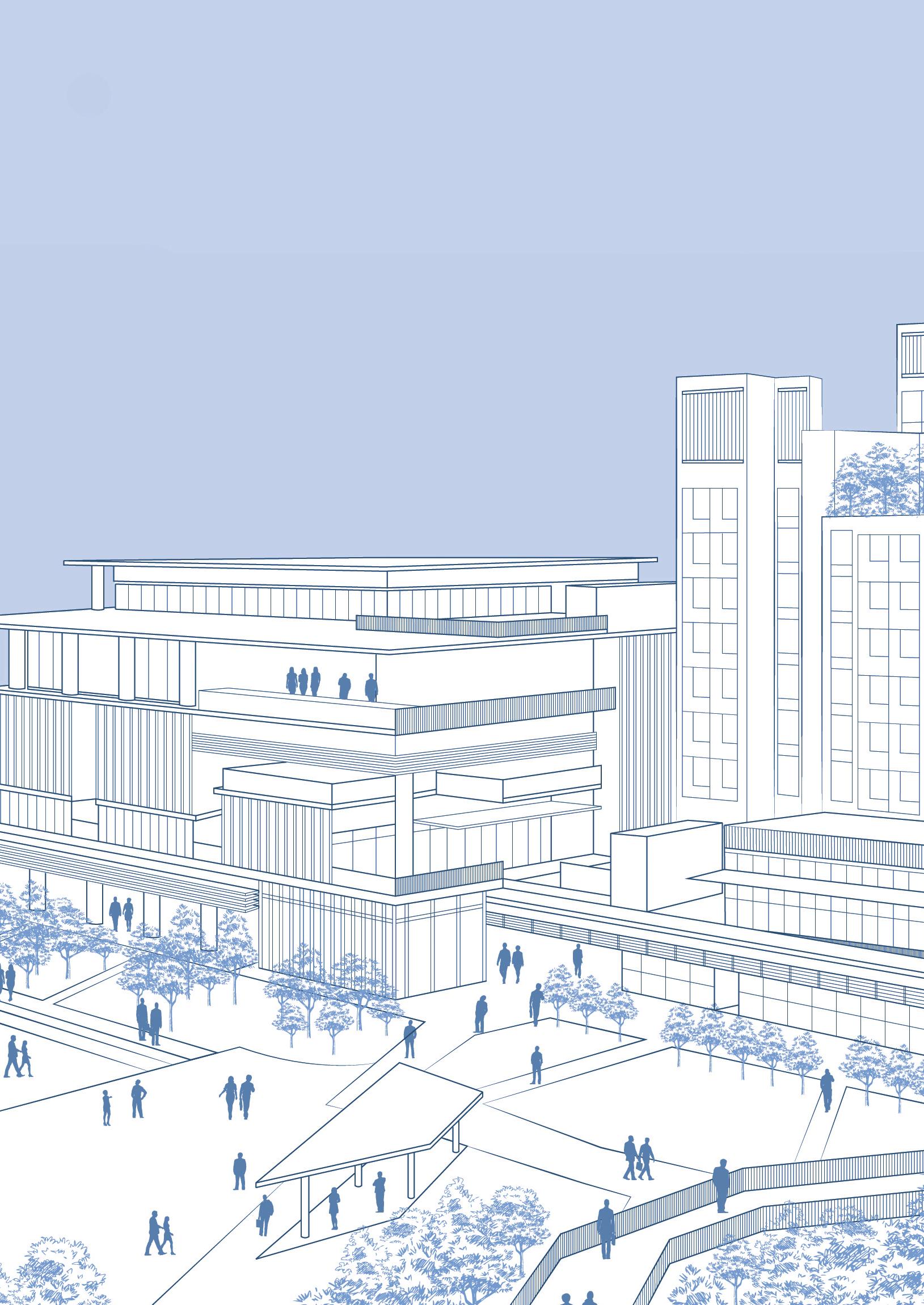

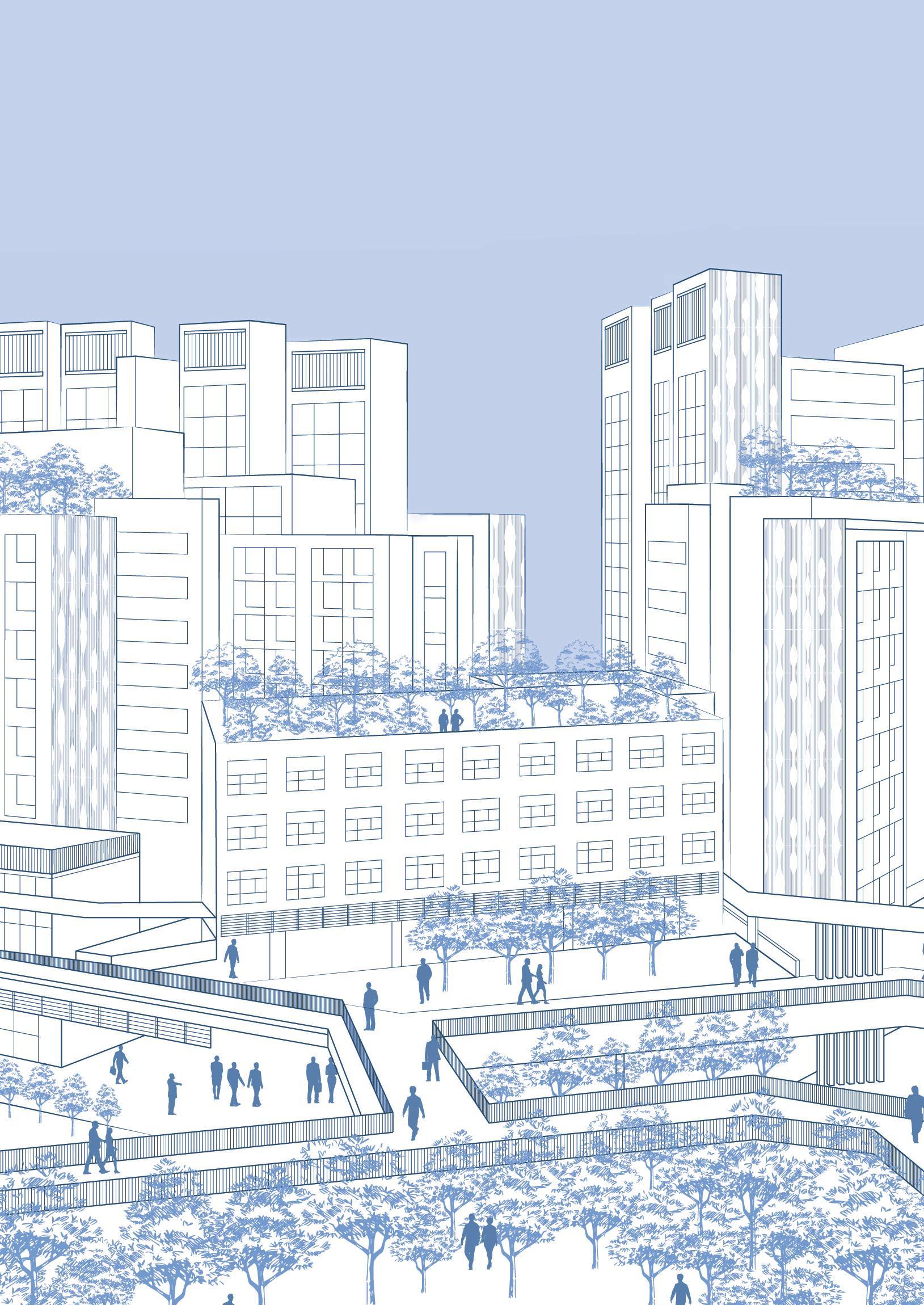

NEXITY HYDERABAD, INDIA

NEXity’s architectural scheme employs the twin strategy of green and wellbeing design to deliver an office environment that will celebrate a new type of work-play culture. Thus envisioned, the result is an office development characterised by rich landscaping that features well-crafted green spaces throughout, room for leisure at podium level and flexible formal office spaces above. The office spaces on the floors above are formally designated work environments elevated from the active podium. The textured quality of the formal office spaces is in contrast with the more playful appearance of the podium space.

An open central core anchoring the twin 22-storey office towers serves to integrate elements of nature (such as sculpture gardens and Bio-pond water features) into the development, while providing panoramic views of the city that enable maximum filtration of daylight into the office floors. Porous and pedestrian-friendly, this landscaped park offers multipurpose courtyards, retail and alfresco dining – all aimed at facilitating social interaction, sparking meaningful connection and nurturing a dynamic work culture.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

DESIGN CONCEPT 5 IN BRIEF | SHORT TAKES ON UPCOMING PROJECTS

CHANGI AIRPORT T5: DPA APPOINTED THE RETAIL AND F&B PLANNING AND DESIGN CONSULTANT

DP Architects (DPA) is resuming work on the Changi Airport Terminal 5 project post-pandemic. As the appointed retail and F&B planning and design consultant, its team of dedicated retail specialists will be focusing their research on changes in consumer habits and human movement patterns to create a differentiated and delightful experience for travellers. Construction of Changi Airport T5 will commence in approximately two years and is poised for completion in mid-2030.

MOVING FORWARD WITH GOLDEN MILE COMPLEX: DPA IS THE APPOINTED ARCHITECT

Golden Mile Complex is a residential and commercial development in Singapore’s central area completed by Design Partnership (succeeded by DP Architects) in 1973. It was gazetted by the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Singapore in October 2022, making it the “first modern, large-scale, strata-titled development to be conserved in Singapore” as announced by Minister for National Development Desmond Lee.

Following its en-bloc sale to a consortium comprising Far East Organisation, Perennial Holdings and Sino Land in May 2022, DP Architects has been appointed the Architects for the development. Conservation and redevelopment work for Golden Mile Complex involves the addition of a new residential tower beside it and the alienation of the adjoining state land. The total site area will be 13,462sqm and the maximum GFA will be 75,389sqm with plot ratio of 5.60.

DP ARCHITECTS IS THE ARCHITECTURAL CONSULTANT FOR LEGO GROUP’S 6TH FACTORY

DPA is delighted to be the Architectural Consultant for the Lego Group’s 6th factory globally. Led by its team in its Vietnam studio, the practice is working with Lego Group towards the shared goals of sustainability. The facility, spread over 44 hectares, is being designed to meet the globally recognised green building standards of LEED. Upon completion, it will be powered by solar panels and will be the group’s first carbon neutral-run facility.

The ground breaking ceremony was held on 3rd November in Binh Duong Province, Vietnam; attended by His Royal Highness Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark and His Excellency, Standing Deputy Prime Minister of Vietnam, Pham Binh Minh.

INDUSTRY | AWARDS & EVENTS

6

DIGITAL TWIN EXPLORER: DPA AND VIZZIO FORM PARTNERSHIP TO PROVIDE A WORLD-FIRST AI-POWERED GEOSPATIAL PLATFORM FOR THE ARCHITECTURE INDUSTRY

On 2nd December, DPA signed a strategic partnership with VIZZIO Technologies, a Singapore-based company that specialises in AI modelling and 3D visualisation. In this exciting cross-industry collaboration, the parties will further develop Digital Twin Explorer (DTE) into software products and services, as well as explore the commercialisation of the solutions for the Built Environment sector.

DTE, which is designed to address the pain points of architects, urban planners and designers, will provide not just a digital twin city platform. It also comprises application tools to help practitioners map, analyse, augment and experience their designs within a realistic digital twin of a city; which will change not only the way the industry designs but also the manner in which design is experienced.

The agreement was signed by Ar. Seah Chee Huang, CEO of DPA and Dr. Jon Lee, CEO of VIZZIO Technologies at DP’s 2022 DesignFUTURE Conference.

DPA AND SUTD SIGN MOU TO DEVELOP AIENABLED ENVELOP DESIGNER

Recognising the climate crisis and built environment needs of its time, DPA is pushing ahead to evolve its craft through the integration of smart technology and development of smart design tools. Key to this is its strategic partnership with the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), which was officialised between the two parties with the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on 2 nd December.

Both DPA and SUTD have always been in active dialogue with one another through industry engagement and knowledge exchange. Now, in a joint studio collaboration that brings practice and research together, the two parties will leverage each other’s strengths, know-how and academic research to develop tools, specifically an Envelop Designer, that will change the way DP designs. This involves exploring and harnessing the power of artificial intelligence in the Envelop Designer to enable architects to meaningfully derive data-driven designs that meet performance objectives and are geared towards carbon neutral outcomes.

The MoU with SUTD was signed by Ar. Seah Chee Huang, CEO of DPA and Prof. Stylianos Dristsas, Assoc. Head of the Architecture and Sustainability Pillar at SUTD. This strategic collaboration is forged in alignment with DPA’s broader Green-Well-Tech thrust, in which technology is used to advance DP’s design capabilities to deliver on its goals of a better, greener and more liveable future.

READ MORE WATCH DTE DEMO INDUSTRY | AWARDS & EVENTS

7

DESIGNFUTURE CONFERENCE 2022

GREEN-WELL-TECH: FUTURE DESIGN FOR PEOPLE & PLANET

DR EMI KIYOTA

DR EMI KIYOTA

8 IN DEPTH | DESIGNFUTURE CONFERENCE 2022

MR BJORN LOW DR BIGE TUNÇER

Emerging from three years of pandemic, one thing is clear: Change is necessary for a more sustainable, sociallyresilient, biodiverse and liveable future. In the fourth edition of its DesignFUTURE Conference, DP Architects convened with thought leaders to discuss the socio-economic and ecological problems compounding the climate and humanitarian needs of today, and how the Built Environment industry can contribute to alleviate these issues.

Each a renowned expert in their respective domains of sustainability, wellbeing design and technology, the conference saw unique insights and engaging discussions from its keynote speakers Dr Emi Kiyota, an environmental gerontologist with over 20 years of experience in designing and implementing person-centred care in long-term care facilities and hospitals globally, founder of Ibasho and Director (Program) of the Health District @ Queenstown; Mr Bjorn Low, co-founder of Edible Garden City, an urban farming social enterprise; Dr Bige Tunçer, an Associate Professor at the Architecture & Sustainable Design Pillar of Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) where she founded Informed Design Lab, which focuses on

research on big-data-informed urban design and planning; and, Ar. Seah Chee Huang, CEO of DP Architects. They were joined by Dr Hossein Rezai, Global Design Director at Ramboll and Founding Director of Web Structures, who moderated the panel discussion.

DesignFUTURE Conference 2022 was held on 2nd December at SUTD. From the intersections and synergies between sustainability and wellbeing to the role of innovation and technology as well as the necessity of a multidisciplinary urban response in shaping a better, greener, healthier and more resilient future, we bring you the imminent issues and challenges facing our people and planet today.

LISTEN TO THE FULL PANEL DISCUSSION ON OUR PODCAST.

APPLE SPOTIFY

LISTEN TO THE FULL PANEL DISCUSSION ON OUR PODCAST.

APPLE SPOTIFY

9

AR. SEAH CHEE HUANG

IN DEPTH | DESIGNFUTURE CONFERENCE 2022

DR HOSSEIN REZAI

EMERGENCE OF A NEW AGRICULTURAL PARADIGM

MR BJORN LOW ON THE GROWTH AND NECESSITY OF URBAN AGRICULTURE WITHIN THE GARDEN CITY.

Geo-political tensions and disease outbreaks, compounded by global economic uncertainties, have produced broad supply chain disruptions affecting wide swathes of the economy. These overarching issues have resulted in inimical consequences for both global and Singapore’s domestic food security. Availability bias would lead us to think that food crises are a modern phenomenon brought about by a confluence of volatile contingent factors.

However, as Bjorn Low, Founder and Managing Director of Edible Garden City explains, food crises have been a perennial concern across the annals of human history. Charting the history of food systems across recent human history, Bjorn identified the current age we live in as one of “Neo-Productionism”, where farms in industrialised countries are increasingly consolidated to create multinational corporations that exert enormous influence over global food systems. The hallmark of this age is a “corporatised and globalised food system that absorbs all small

holding farmers and producers into a highly specialised global supply chain, weakening land rights for the most vulnerable goods producers in the world”.

Questioning the efficacy of this highly optimised and industrialised global food system, Bjorn portends that both past and ongoing food crises showcase the extant vulnerabilities in today’s international food system. Evidencing the extractive approach taken by modern industrialised farming, Bjorn uses Cameron Highlands as a case study of how rampant unchecked manipulation of landscapes and ecosystems have caused habitat loss, soil erosion and environmental pollution.

Recognising that “the current industrial agricultural model and its biotechnological derivatives” are incapable of handling future agricultural challenges that require increased levels of food production with the same land base, incorporating greater sustainability demands while proving resilience against various

10 GREEN | EMERGENCE OF A NEW AGRICULTURAL PARADIGM

international and domestic disruptions, Bjorn lays out how urban agriculture farms are one such solution to buttress against future disruptions due to three factors: the “Ecosophy” approach embodied in their development, their intrinsically small-scale and decentralised nature, and the level of socio-community engagement they engender.

The “Ecosophy” approach practised by urban farms encourages the mimicry and supporting of nature, rather than the conventional extractive approach undertaken by large-scale industrialised farms that manipulate land without concern for broader impacts on biodiversity and the surrounding environment. “Ecosophy” is also a highly functional and practical undertaking, ensuring the long-term fertility of the harboured plants and trees through recycling the organic material on-site, preserving biodiversity within cultivated areas. Intercropping and the conscious creation

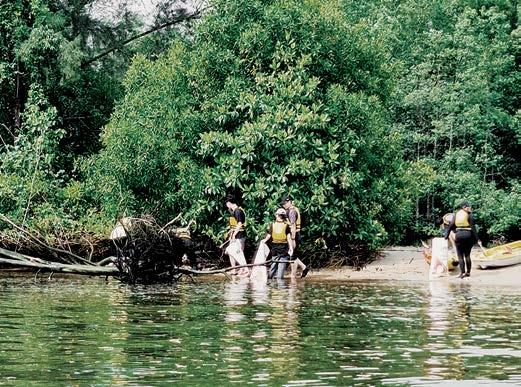

experience leading Edible Garden City as an example, with the community-centric nature of urban farms leading to greater interaction with marginalised or underappreciated societal groups such as migrant workers, the Orang Pulau and Orang Laut communities, as well as elderly folk. These groups have either autochthonous knowledge of the land and its rich biodiversity, or possess a wealth of experience in understanding the culinary heritage and use cases for a large variety of plants, contributing to greater appreciation of lesser-known produce and broadening both production outcomes and palates of consumers.

Another benefit of urban farms in promoting interactions across multiple diverse social groups is the empowerment it provides to marginalised members of society, creating social value and a fair, equitable environment for all stakeholders. Aside from the aforementioned groups in the paragraph above, Edible Garden City

URBAN FARMS ACTIVELY ENCOURAGE COMMUNITY, WEAVING A SPIRIT OF CAMARADERIE INTO THEIR MODELS THAT EMPOWER INDIVIDUALS WHILE GALVANISING COMMUNITY OUTREACH.

of a Food Forest, where plants are brought together in a symbiotic manner that maximises their complementarity, preserve and enhance the biodiversity within cultivated areas while ensuring production of a broader variety of food than the mono-crop approach of our modern-day systems.

Food systems founded upon centralised, large-scale production methods enable economies of scale and create a profitable business case. However, as Bjorn shares, they require immense input to sustain long-term viability while the ability to increase output in these models are highly vulnerable to major disruptions, affecting many centralised production systems. Urban farms, operating on a smaller local scale, are decentralised entities where disruptions in any inputs will only partially affect the output of each producer, and overall output will be affected less significantly than in a centralised production model.

Contrasted against standard commercial farms that are often closed for visitation, being highly private sites that exclude the community, Bjorn highlighted how urban farms like Edible Garden City promise the opposite experience because they actively encourage community participation, weaving a spirit of camaraderie into their models that empower individuals while galvanising community outreach. Urban farms in Singapore are active organisers of community and volunteer programmes that elicit citizen participation, simultaneously maturing civil society and nurturing one’s identification with larger society.

Small-scale urban farms often uphold the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s message of diversified planting, growing a wide variety of different crops and produce that are not commonly eaten today. Their ability to plant a panoply of produce also stems from the unique knowledge base inculcated into and available at every urban farm. Bjorn highlighted his own

also provides social employment opportunities to a diverse group of individuals, engendering a sense of dignity and autonomy.

Acknowledging the placemaking capabilities of urban farms in activating spaces and fostering common space for residents, Bjorn’s analysis of the benefits of urban farms was also balanced by a cautioning against the greenwashing that can occur in these projects, coupled with complications of aesthetic politics that is challenging in Singapore’s landscape context.

As Singapore pushes towards the 2030 SG Green Plan target of having locally produced food comprise 30% of domestic food intake, urban farms will gain increasing relevance, and how the local urban environment can smoothen integration and harness the utility of urban agriculture elements will play a decisive role in creating Singapore’s future sustainability developments.

11 GREEN | EMERGENCE OF A NEW AGRICULTURAL PARADIGM

EXAMPLE OF ECOSOPHY IN SINGAPORE

Design for Life: Urban Practices for an age-friendly city

DR EMI KIYOTA ON IBASHO, COMMUNITY-BASED CARE BUILT ON A MODEL FOR EMPOWERMENT.

The speed of aging is accelerating. In just two decades, the percentage of population aged 65 and above have doubled from 7% to 14% in countries like Singapore, China and Thailand. At the same time, demographic data also reveals a lesser-known fact: while the growing silver tsunami is oft reported in developed countries such as Japan and Singapore, 85% of the world’s elderly population actually live in developing cities. The social and structural implications, compounded by limitations in public policies and funding, include increasing inequity and lack of appropriate urban infrastructure.

Yet, does the solution lie in commissioning more healthcare facilities for institutionalised care of elderly persons? Is personcentred care enough? What more can be done to alleviate these issues? In her presentation, Dr Emi Kiyota opens with a simple but all-important perspective shift: design for life. Examined in the context of urban practices for an age-friendly city, she put forth not just the power of design to uplift lives but also the designers’ responsibility to deliver socially conscious and sustainable works.

Endearingly, she brought the audience through her personal exploration to experience and understand the different paradigms of available eldercare facilities and designs, which she informally

broke down into three broad categories:

1) Institutional, a medical-based model that is designed on the principles of efficiency and aims to provide collective care; 2) Person-Centred, a socio-medical based model that is designed to offer a home-like environment where care is individualised and incorporates socialisation; and 3) Ibasho, a community-based care built on an inclusive/empowerment model conceptualised by Dr Kiyota herself. Beginning with a nursing home in Fargo, North Dakota in the US, she pointedly highlights the limitations and flaws of healthcare design that she experienced during her three-week stay. From the long hallways to the nurse stations, the nursing home was conceptualised in the format of a hospital with well-intended designs that lopsidedly catered for its healthcare workers and their operations more than it did for its long term, stay-in patients and their needs.

So, what then, of the patients’ needs? Can we design more empathetically for the elderly who suffer from dementia? More pertinently, where is ‘home’ in a nursing home? In challenging these norms, person-centred healthcare models came about as a response and sought to humanise institutionalised care and facilities. Gojikara Village, an atypical nursing home in Japan pushes the boundaries; going against the grain that form

12 WELL | DESIGN FOR LIFE: URBAN PRACTICES FOR AN AGE-FRIENDLY CITY

necessarily follows function. Here, spaces are designed to resemble home and configured to facilitate interaction. The result is an assisted living facility where the organic use of the common/ shared spaces has allowed it to grow beyond its intended purpose and imbued the environment with a sense of homeliness.

The experience of assisted living in both medical and personcentred model highlighted three important things for Dr Kiyota. Regardless of geo-location and nationality, elderly persons fear 1) social isolation, 2) loss of dignity and respect, and 3) loss of a positive social role; which is exacerbated by the narrative that one loses agency and autonomy along with age and the decline in one’s health, and therefore, requires care by the younger generation.

Responding to this, Dr Kiyota conceptualised a differentiated approach, anchored in community-based care and built on an inclusive and empowerment model. Termed Ibasho, which means ‘a place where one can be at home with oneself’ in Japanese, the design principle puts forth that a sense of security and belonging – whether emotional, psychological or physical – is necessarily fostered through participation. their life skills and experiences, continue to give back to society through volunteerism. Among the activities they engage in and manage are the operation of a small vegetable farm, organising and running community programmes such as a monthly Farmer’s Market, an Ibasho Restaurant, tri-weekly night classes called ‘The Study Room’ and a shopping service. Its simple but carefully thought-out open floor plan effectively facilitates a multitude of group activities and creates opportunities for multi-generational interaction.

Such an inclusive model, according to Dr Kiyota, can also benefit the wider community. Ibasho’s view of aging aims to break away from the old assumption that an aging society is a burdensome one, and instead moves to empower our aged as valuable assets. Their life experiences and wisdom are not only precious knowledge for the younger generation but will also strengthen the resiliency of their communities. She further pointed out that the continued assimilation of elderly persons and perspective shift are important because aging affects everybody and no one is spared from ageism.

The Ibasho concept thus advocates for a participatory design process in which agency is given to the elderly to cocreate community hubs where they can find opportunities to contribute to community members of all ages. This is built on eight principles: Elder Wisdom, Normalcy, De-marginalisation, Community Ownership, Multi-generational, Culturally Appropriate, Resilience and Embracing Imperfection.

Translated into architecture and design, the application of Ibasho is crucially the creation of ‘Place Experience’ as exemplified by the Honeywell Ibasho House project which opened in June 2013. Located in the residential district of Massaki-cho in Ofunato City in Iwate, Japan, it began as a place for elders to demonstrate their leadership and contribute to the community following the devastation wrought by the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011. Here, the elderly convene and by leveraging

The Honeywell Ibasho House is designed as a community space. Its design model and concept not only challenge the current elder care system but also demonstrate that the narrative that an aging society is necessarily a detrimental one can be changed. How a space is designed, therefore, has strong implications. Wrapping up her presentation, Dr Kiyota aptly summed it up, “When we try to specifically design a space for older people, it can create dependency. When we try to design special services for elders, it might [exacerbate] ageism. With specially designed services and built environment, it might create stigma and age-specific design might create segregation. And excessive convenience and technologies might create social isolation.”

“I think we have a task for ourselves to create an environment that is more integrated rather than isolated and segregated,” she added. And in challenging the architecture and design industry to relook at its approach and effect positive change, she concluded with a radical call, “How can each of us be a part of co-designing a shared future for elders across the globe in which aging is not something to fear but an opportunity to appreciate the potential within us for meaningful growth throughout our lives? We have a big task to come up with a better living environment for older people because [aging] does affect every one of us.”

Dr Emi Kiyota is currently based in Singapore and looking into incorporating Ibasho into the Health District @ Queenstown. The pilot programme aims to design a age-friendly community by creating integrated solutions to enhance the health and well-being of residents across their life stages.

WE HAVE A BIG TASK TO [CO-DESIGN AND] COME UP WITH A BETTER LIVING ENVIRONMENT FOR OLDER PEOPLE BECAUSE [AGING] DOES AFFECT EVERY ONE OF US.

13 WELL | DESIGN FOR LIFE: URBAN PRACTICES FOR AN AGE-FRIENDLY CITY

HONEYWELL IBASHO HOUSE IN JAPAN COURTESY OF DR YASUHIRO TANAKA

design-driven data: human-centric considerations

DR BIGE TUNÇER ON DATA, DIGITALISATION AND DESIGN: FUTURE-ORIENTED DESIGN IN THE INFORMATION AGE.

AMALGAMATING QUALITATIVE, QUANTITATIVE, BIG AND SMALL DATA INTO A COHESIVE ANALYSIS PACKAGE WILL ENABLE DESIGNERS AND PLANNERS TO ADJUST DYNAMICALLY ACROSS DIFFERENT SCALES, WHILE FRAMING AND SOLVING PROBLEMS IN A CONSECUTIVE AND SIMULTANEOUS FASHION.

The growth of climate change awareness and the urgency of sustainability demands, coupled with the acceleration of digitalisation and big data implementations across various economic sectors, have affected significant long-term changes

across all industries, including the Built Environment sector. The confluence of these phenomena has generated profound yet exciting shifts in urban planning and architectural design, bringing the dual concerns of people- and planet-centricity to the forefront of conversations.

Are considerations made within the people- and planet-centricity dyad necessarily a zero-sum game, where the needs of one are completely sacrificed over the needs of the other? Dr Bige Tunçer, Associate Professor at the Architecture and Sustainable Design Pillar of Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and founder of the school’s Informed Design Lab which focuses on big-data informed urban design and planning, proposes that there is no inherent conflict between people and planet, and peaceful co-existence is possible, so long as it is not impinged by considerations for excessive profit, which would result in “unsustainable physical growth and huge energy consumption.”

14 TECH | DESIGN-DRIVEN DATA: HUMAN-CENTRIC CONSIDERATIONS

Calling for a shift away from an endless consumption of material resources, Dr Tunçer explains how a non-exhaustive, coordinated, multi-disciplinary implementation of digitalisation, computational design, building science, urban science, complexity science can aid in affecting a change in the public mindset. If conceptualised thoughtfully and applied meaningfully, these disciplines could produce methods, tools, platforms and mechanisms that form foundational instruments for awareness creation, mitigation and solution strategies for the myriad of future complexities and uncertainties faced in our urban future. She spotlights the importance of technology that is created to benefit people and planet, rather than for profit. Harnessing research data gathered with emergent technology would enable us to dispel certain assumptions made during design/planning and replace them with grounded empirical evidence.

Identifying the various big-data elements present in urban research, such as sensor data from various types of urban infrastructure, real-time transport tracking data, opinion and event data from social networks, various open data sources provided by the government and other publicly available data sets, Dr Tunçer advocated for how such qualitative data can be harmonised to create a well-rounded and comprehensive urban studies analysis. In this research field, qualitative small-n data sets help in addressing issues of correlation and causality, buttressing the analytical dearth that quantitative data sets are unable to fully provide.

Amalgamating qualitative, quantitative, big and small data into a cohesive analysis package will enable designers and planners to adjust dynamically across different scales, while framing and solving problems in a consecutive and simultaneous fashion. The provision of ample multi-source, multi-scale and multi-time evidence for analytics enables better visualisation and greater support for designing and planning of the urban environment. However, as Dr Tunçer outlines, for researchers to make best use of this rich array of available data, the right questions have to be investigated and the appropriate problem sets have to be identified.

Founded in 2013, the Informed Design Lab which she leads, is a multi-disciplinary group of architects, software engineers, data scientists and social scientists that have been involved in various funded collaborations with significant public and private sector organisations such as URA, HDB, LTA, A*STAR, DP Architects and Singtel Dataspark. With research questions that focus on how data can be integrated into urban planning and design to be made fit-for-use, as well as how stakeholders (designers/planners) can interact with said data, her team employs Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a mechanism for analysis and research, intimating that AI possesses unparalleled ability to “answer specific questions, find hidden patterns, plan scenarios and predict outcomes”, all critical performance parameters that enhance research outcomes.

Dr Tunçer also showcased some of the projects her team has been involved in, all of which highlighted how pairing data and digitalisation methodology could enhance design schemes. One such study the lab conducted, in collaboration with Future Cities Laboratory, called “Pedestrian Comfort in High Pedestrian Activity Areas” sought to design comfortable and functional pedestrian walkways that could accommodate pedestrian movements and needs in high-traffic areas. The project employed field cameras, micro-simulations and machine learning to identify pedestrians in high-activity zones near Transit-Oriented Developments. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) were also utilised to simulate pedestrian flows and scenario planning, while virtual reality was employed to simulate building layouts and various crowd sizes to examine crowdedness. The outcome of the research produced a design guide and interactive dashboard that illustrated how good pedestrian walkways should be designed.

In the modern Information Age we live in, the importance of applying data-driven design ideas in a conscious judicious manner garners growing attention. Forging a complementary rather than antagonistic relationship with AI will enable Built Environment decision-makers to become better equipped in understanding and designing for the needs of involved stakeholders.

AN

ASSESSMENT

OF DESIGN FEATURES TO MINIMISE IMPACT OF CROWDING CONDUCTED AS PART OF THE ‘PEDESTRIAN COMFORT IN HIGH PEDESTRIAN ACTIVITY AREAS’ STUDY.

15 TECH | DESIGN-DRIVEN DATA: HUMAN-CENTRIC CONSIDERATIONS

Singapore’s Urban Future –Looking through the Lens of Golden mile complex

SEAH CHEE HUANG EXAMINES THE OPPORTUNITIES AND POTENTIALITIES OF SINGAPORE’S URBAN FUTURE.

The gazetting of strata-titled GMC elevated the potential of conservation-led intervention as a winning strategy for urban regeneration – a move that opened up an exciting new avenue for purposeful reconfiguration of our precious land resources, but refreshed socio-economic and environment synergies. With increased plot ratio, and extension of site boundaries to encourage conservation, it will show the way forward for adaptive re-use of existing building stock to attract investment and deliver long-term and urban transformation. Conservation, Seah said, bodes well for our pursuit of a Green Economy.

The Golden Mile Complex is a watershed in Singapore’s urban renewal journey. Turning 50 next year, the modernist icon bears the hallmark of innovation – not only in form but also in ideas –that we see in Singapore’s modern architecture of the late 60s and early 70s like People’s Park Complex and Pearl Bank Apartments. Today, we see less of such visionary and innovative architecture. What was it about that zeitgeist that favoured experimentation?

DP Architects CEO Seah Chee Huang pondered this question and more about designing Singapore’s urban future.

In his presentation, Seah expounded on the revolutionary ideas and urban strategies that Golden Mile Complex (GMC) proffered five decades ago and their relevance to our evolving landscape today and tomorrow.

Using the post-independence landmark as scrying glass to postulate our urban future, Seah outlined five potential propositions: Regenerative in Approach, Integrative Urban Systems, Whole-of-Society Participation, Strategic Experimentation and City as Second Nature.

REGENERATIVE IN APPROACH

Citing the highly anticipated redevelopment of GMC – the plot itself was the first brownfield government sales site when the original building was proposed – as an example of the progression of land redevelopment towards land and infrastructural regeneration, Seah hailed the building’s conservation as a step towards deepening the concept of urban circularity in our planning approach.

The conservation of GMC also presents a compelling case for accounting and reducing embodied carbon that is unprecedented in Singapore’s urban conversation. Introducing carbon as an essential vocabulary in future planning and developmental economics will reshape the way we think about architecture and the urban landscape, supporting the transition towards a circular economy.

INTEGRATIVE URBAN SYSTEMS

A pioneer in the pursuit of a multi-dimensional planned city, GMC’s sectional organisation and mixed-use programming drove the thinking behind future urban planning in Singapore then, which seems to be the default today, especially with the emergence of the integrated hub typology in these recent years. Pioneered by Our Tampines Hub (OTH), the typology considers not only spatial composition multi-dimensionally, but also looks at programmatic synergy and pushes thinking of spatial adjacency and interdependency for greater productivity and operational efficiency.

LINE SKETCH OF THE CROSS SECTION OF GMC.

16 GREEN-WELL-TECH | SINGAPORE’S URBAN FUTURE – LOOKING THROUGH THE LENS OF GOLDEN MILE COMPLEX

Multi-dimensional planning offers opportunities for next-level connectivity, allowing urban systems to sync on multi-dimensions: whether at grade, elevated or underground. Plantation Village –the first eco-town in Tengah, Singapore planned with pedestrian experience and walkability as its prime consideration – is an example of 3-D thinking in city planning which will further the realisation of the 10-minute micro-community and micro-economy as we think about cities of the future. Through city planning, the notion of whole-systems thinking and the harmonisation of systems can be advanced to become a powerful reality.

WHOLE-OF-SOCIETY PARTICIPATION

The conservation of GMC illustrated the power of engaging governance and engaged citizenry to achieve desired outcomes. The ground-up dialogues and urban advocacy it inspired is not commonly seen in Singapore society. With the conservation of GMC, the stage has been set for a more consultative and collaborative process to be adopted for future redevelopments.

A domain where such engaged citizenry has been integrated is arguably the array of integrated community hub projects. The post-occupancy studies of Our Tampines Hub – a project on which Seah spent nearly a year reaching out to Tampines residents on the ground – makes a strong case for successful urban solutions through a whole-of-government approach and participatory process. The design of OTH helped to promote stronger collaboration and generate synergy among the various agencies through the integration of programmes, and achieved 30% increase in efficiency of soft services1. The uniquely high monthly visitorship of 1.5 million is a testament to the success of the participatory design process in placemaking and placekeeping, engendering greater inclusivity and ownership.

STRATEGIC EXPERIMENTATION

Referring to GMC’s innovative structural design, depicted by its slender pillars and dramatic shear walls, Seah recalled a recent conversation with structural engineers who said it would be near impossible nor feasible to achieve such slenderness ratio today. 50 years later, the spirit of experimentation appears to have diminished.

Seah also noted the young age of the GMC architectural leads, averaging 30, who designed what would become an iconic project. Apart from WOHA winning the design competition for Bras Basah and Stadium MRT stations and Arc Studio

for The Pinnacle@Duxton – both over 20 years ago – there seems to be fewer examples of young architects and young firms having such breakthrough opportunities in recent years. While some have questioned if Singapore’s highly regulated practice leaves room for experimentation, Seah highlights the capacity of urban policies, beyond shaping built environment, to contribute to the nurturing of local talents and allow aspects of city to be sandboxes and testbeds for developing innovative urban solutions.

He is hopeful in that regard and cited the recent commission of the Singapore Institute Architects and the Singapore Institute of Planners to propose two concept masterplans for the Paya Lebar Airbase for novel ideas of future live, work and play – where the architects and experts were engaged not by firm but by individuals, not by portfolio but by the merit of their ideas. Giving greater voice to alternative views enhances the potential for positive change and new possibilities in our urban future and in the future of our urban practice.

CITY AS SECOND NATURE

Finally, Seah shared a press article from 1971 which likened GMC’s unique terracing form with unobstructed views to a modern Babylonic hanging gardens. Indeed, the stepped profile would have allowed for an urban form blanketed with green, surrounded by blue water. Expounding on this vision, he speculated the potential to evolve our city not just as a City in Nature as envisioned in the SG Green Plan 2030 but as Second Nature. Seah proposed for the relationship between the urban and natural systems to be a reciprocal and restorative one.

Drawing on the larger network and ecosystem behind Bukit Canberra – a community hub project that DP Architects is working on with Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl – the project connects district-level ecological and landscape networks to the site where the terrain, greenery, heritage including the new building become connective tissues for life.

To realise the aspiration for a city that is designed to generate and sustain people and planetary health, Seah holds that the industry must think beyond human activities and spatial economics to calibrate our built environment to become restorative and potentially regenerative; beginning with inserting urbanism that responds to and evolves with the natural systems so as to support nature to mend and heal injured ecologies.

Notwithstanding Singapore’s modest size and deficiency in natural endowment, the city-state has defied the odds to become one of the world’s most liveable and vibrant cities. GMC is part of the result of bold vision and tall dreams, grounded by precise, long-term planning, strong governance and robust principles. Seah concluded that we must continue to dream big, as its predecessors have done, so that the city can continue to be a powerful vehicle for translating the collective aspirations for a better, healthier and happier future in form and substance.

1

Seah, C. H., Teo, S. E. K. (2020). Learning from Our Tampines Hub: Co-Generative Hubs for Urban Regeneration. Built Environment: The Power of Plans. 76-98. https://www.alexandrinepress.co.uk/built-environment

THE GAZETTING OF STRATA-TITLED GMC ELEVATED THE POTENTIAL OF CONSERVATION-LED INTERVENTION AS A WINNING STRATEGY FOR URBAN REGENERATION – A MOVE THAT OPENED UP AN EXCITING NEW AVENUE FOR PURPOSEFUL RECONFIGURATION OF OUR PRECIOUS LAND RESOURCES, AND REFRESHED SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENT SYNERGIES.

17 GREEN-WELL-TECH | SINGAPORE’S URBAN FUTURE – LOOKING THROUGH THE LENS OF GOLDEN MILE COMPLEX

DESIGN SERIES 2022

A DP ARCHITECTS’ INITIATIVE TO DEEPEN THE DISCOURSE ON THE NOTION OF SOLIDARITY, SYNERGY, SOCIAL WELLBEING AND SUSTAINABILITY IN COMMUNITY ARCHITECTURE.

CHONG KENG HUA TAN BENG KIANG LARRY YEUNG 18 IN PERSON | DESIGN SERIES 2022

Held in early 2022 at our headquarters in Singapore, the Design Series was organised as a knowledge-sharing platform for DPians to learn from experts on architecture and urban matters. This inaugural series featured two deeply engaging panel discussions, which we hope you will enjoy in this special In Person coverage of the event.

In the first, Building Biophilic Communities which took place on 26 th May, DPA invited Dr Srilalitha Gopalakrishnan, President of the Singapore Institute of Landscape Architects (SILA), Mr Jelle Hendrik Therry, Design Director at Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl and Ms Yvonne Tan, director at DP Green. Co-moderated by Ar. Seah Chee Huang, CEO of DP Architects and Ar. Ng San Son, director at DP Architects, the panellists delved into the topic of biophilic design and the making of community architecture and infrastructure that generate community wellness and consciousness while inspiring regenerative solutions and circular mindset shift.

The second, Community Interventions & Participatory Approach took place on 30 th June. DPA invited Dr Chong Keng Hua, Associate Professor of Architecture & Sustainable Design at the Singapore

University of Technology and Design (SUTD), Dr Tan Beng Kiang, Associate Professor of the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and Mr Larry Yeung, Executive Director of Participate in Design. Moderated by Ar. Seah, they delved into the impact of neighbourhood-level and self-organised initiatives in the larger ecosystem of community support. The panellists also discussed the participatory approach to designing community architecture to advance policy agendas, promote equitable access and generate positive social experiences for the wider community.

Organised inkeeping with DPA’s culture of learning, Design Series not only hopes to encourage meaningful discourse but also to champion equity, sustainability, wellness and resilience through purposeful design.

SRILALITHA GOPALAKRISHNAN

YVONNE TAN

JELLE HENDRIK THERRY

SRILALITHA GOPALAKRISHNAN

YVONNE TAN

JELLE HENDRIK THERRY

SKETCH OF PLANTATION VILLAGE 19 IN PERSON | DESIGN SERIES 2022

Building Biophilic Communities

THREE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS SHARE THEIR VIEWS ON NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS, DATA IN DESIGN AND URBAN PLACEMAKING.

Srilalitha Gopalakrishnan is a landscape architect with over 15 years of professional experience. As President of SILA, she represents the landscape architecture profession in Singapore and the region. Her research interest is in the performance of integrated landscape design in highdensity urban environments for resilient and sustainable urban design solutions. She currently works as a Postdoctoral researcher and Project Coordinator for Dense and Green Cities: Emerging Models of Integrated Urban Developments project at Future Cities Lab Global.

Yvonne Tan is a landscape architect with a keen interest in placemaking, biophilia, creating wellness and therapeutic landscapes and species rich habitats. With over 25 years in designing and delivering local and international projects, Yvonne works with developers and clients to exponentially value-add, to create visions and future-positioning for projects. She is chairperson of the Urban Greenery Technical Committee for the Singapore Green Building Council and 1st Vice President of the Singapore Institute of Landscape Architects.

Jelle specialises in the multidisciplinary integration of art, urban hydrology, environmental engineering and landscape architecture within an urban context. He is drawn to projects where architecture and landscape respond, respect and reinforce each other. He has a deep love for the details of design, and believes that careful attention to details and manipulation of a space’s natural characteristic have the power to transform everyday lives. He has developed and delivered high profile projects that contribute significantly to the public realm.

JELLE HENDRIK THERRY DESIGN DIRECTOR, RAMBOLL STUDIO DREISEITL

SRILALITHA GOPALAKRISHNAN PRESIDENT, SINGAPORE INSTITUTE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS

YVONNE TAN DIRECTOR, DP GREEN

JELLE HENDRIK THERRY DESIGN DIRECTOR, RAMBOLL STUDIO DREISEITL

SRILALITHA GOPALAKRISHNAN PRESIDENT, SINGAPORE INSTITUTE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS

YVONNE TAN DIRECTOR, DP GREEN

20 IN PERSON | BUILDING BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES

HOW CAN BIOPHILIC DESIGN BE INTEGRATED MORE MEANINGFULLY IN OUR URBAN ENVIRONMENT?

SRILALITHA GOPALAKRISHNAN (SG): The practice of biophilia should not be something that we look at from the outside; it should be part of daily life. When people feel that they can make a difference then the efforts they make would be more genuine, more honest. When we see that the trees around us are drying out or greenery is not growing well, the common mentality is: NParks will take care of it; it’s not my responsibility. This mentality needs to change. We value trees when they give us shade; but when the trees are not doing well, isn’t it also our responsibility to do something? This is the mindset we need to build into the community.

Empowering becomes extremely important – helping the people who use the space take up the social responsibility of managing and maintaining the space. The idea of placekeeping is very important. It may require a change in policy. NParks and the Housing & Development Board (HDB) put great effort into the Community in Bloom programme to provide resources to citizens for community gardening. However, the success of that is dependent on the grants or subsidies provided. The moment that stops, the interest also stops. It is not a sustainable model. Incentives can be given to initiate actions, however there needs to be mutual give-and-take. If we do not build that into the whole process, the thinking that ‘it’s not my responsibility’ will persist. So, empowering needs to be done at a wider level in terms of

government set-ups and community set-ups. It is doable. It has been done in Europe, in the Americas. Of course, we have to contextualise the process because Singapore has its own advantages and disadvantages, strengths and weaknesses, but it’s possible. We just need to make effort in that direction.

JELLE HENDRIK THERRY (JHT): The context of Singapore is one that is amazing from a biophilia point of view. The regulatory environment helps us to embrace the green within our built environment by incentivising the provision of communal green spaces. The beauty of biophilic design is that it does not have to cost more than regular green. We just have to be smart about the resources at hand and how to design with them.

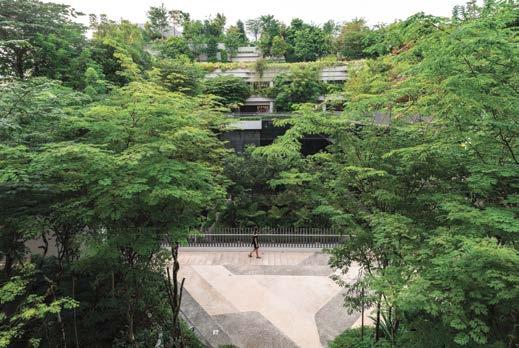

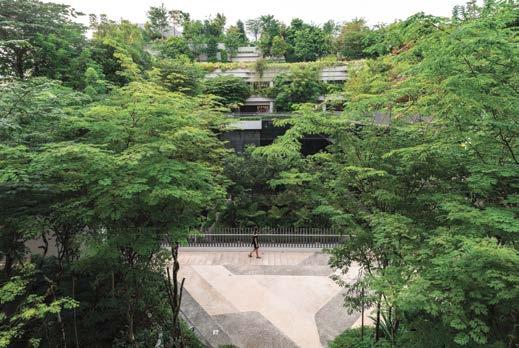

Biophilia is about giving nature (fauna and flora) a meaningful contribution to our everyday life, and for nature to communicate with and to us; that’s the first thing. Bukit Canberra is an upcoming project that will TOP soon. When the Sembawang community walks through Bukit Canberra, they will embrace the richness of nature within the environment. The hawker centre will have draping plants and amazing trees and ground covers, creating a place for animals like birds and butterflies to call home, providing food source; and this is a part of a larger ecosystem. Visitors will feel immersed in nature. I am confident that people who visit Bukit Canberra might feel less stressed and more relaxed. Because that’s what nature does to us. For people entering the polyclinic integrated within the development, they will be in touch with the green as they will see nature everywhere they look. From

21 IN PERSON | BUILDING BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES

the moment they walk into the clinic, they will feel connected to the innate healing quality of nature. Bringing nature to our doorstep is what we have to do, to create possibilities for us, to create awareness of the importance of nature within the built environment.

What we as architects and landscape architects have to do is to embrace the possibilities that are alive in a site and highlight them. People are attracted to and tend to stay longer in a healthier, greener, more natural environment and will return to it. And when people feel more engaged within their surroundings, it becomes a place where the community connects, more social interactions take place, and thus we live a more fulfilling and healthier life.

YVONNE TAN (YT): For us as designers, we need a huge change in mindset. We have to start looking at biophilia and sustainability right at the start – at day one or day zero, rather than trying to figure out whether it’s biophilic after we are finished with the design. Same for clients. They need to start with a biophilic mindset rather than coming to us when the building is right at the building setback and asking us to make it a biophilic building.

We need to consider every material that goes into developments. Even the soil, we need to consider: is it enhanced, is it recycled? How can we reduce the waste in our developments? It’s not just about looking at the things that we visually see but also what goes in the skeleton of the buildings, what is in the materials, whether it is green concrete, whether it is drainage cells that are more sustainable, and what is the re-use as well as what is the endof-life. It requires a total change in mindset to build a green and circular economy.

MORE CLIENTS ARE ASKING FOR BIOPHILIC DESIGN AND MORE CONNECTIVITY TO THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT. AT THE SAME TIME, THEY EXPECT A CERTAIN LEVEL OF INDOORLIKE COMFORT OUTSIDE. YOU MUST HAVE FACED THIS SITUATION BEFORE.

JHT: This is what you called thermal comfort, isn’t it? How comfortable do I feel out there and how does the landscape help me to be outside? How can we as designers stretch the time that

people can be outside? Our parks come alive at 4am until about 10am. After that time, it is simply too hot to be outside. The parks come alive again at about 5pm until about 1am in the morning. So, the question landscape architects have to ask ourselves is, what can we do to enable the community to spend longer time outside. I think one of the answers is to really think about thermal comfort – where shade, wind, sunlight, humidity are the environmental factors that we can influence as they impact the way we deal with outdoor temperature.

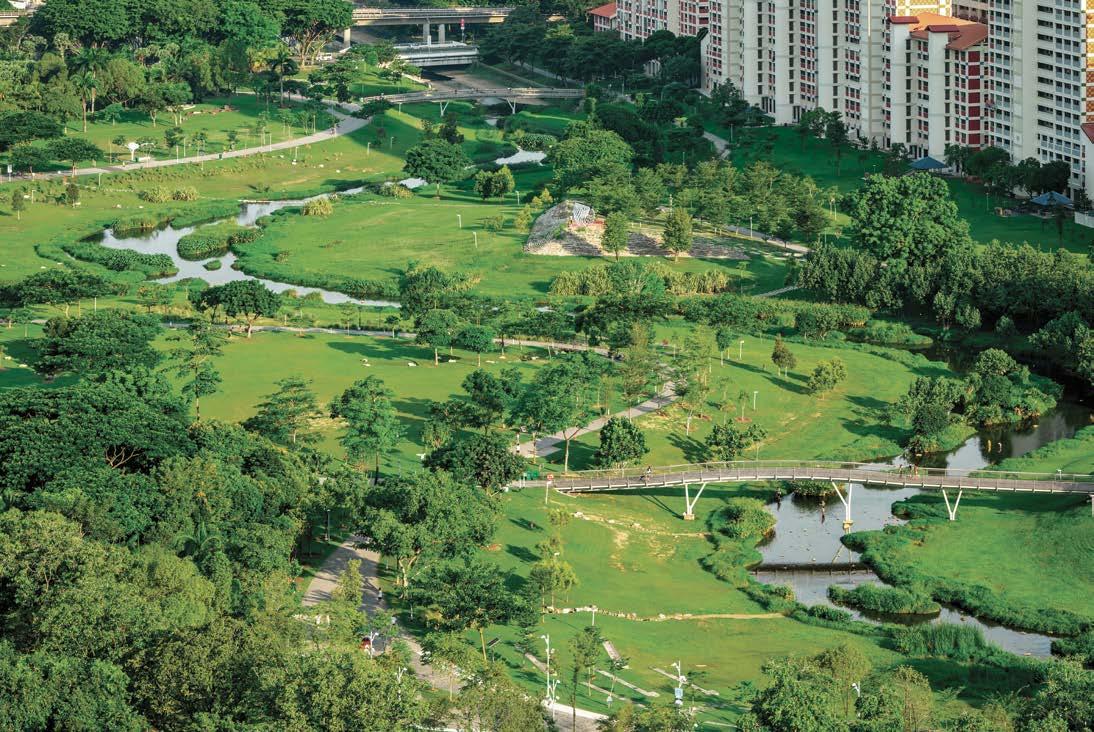

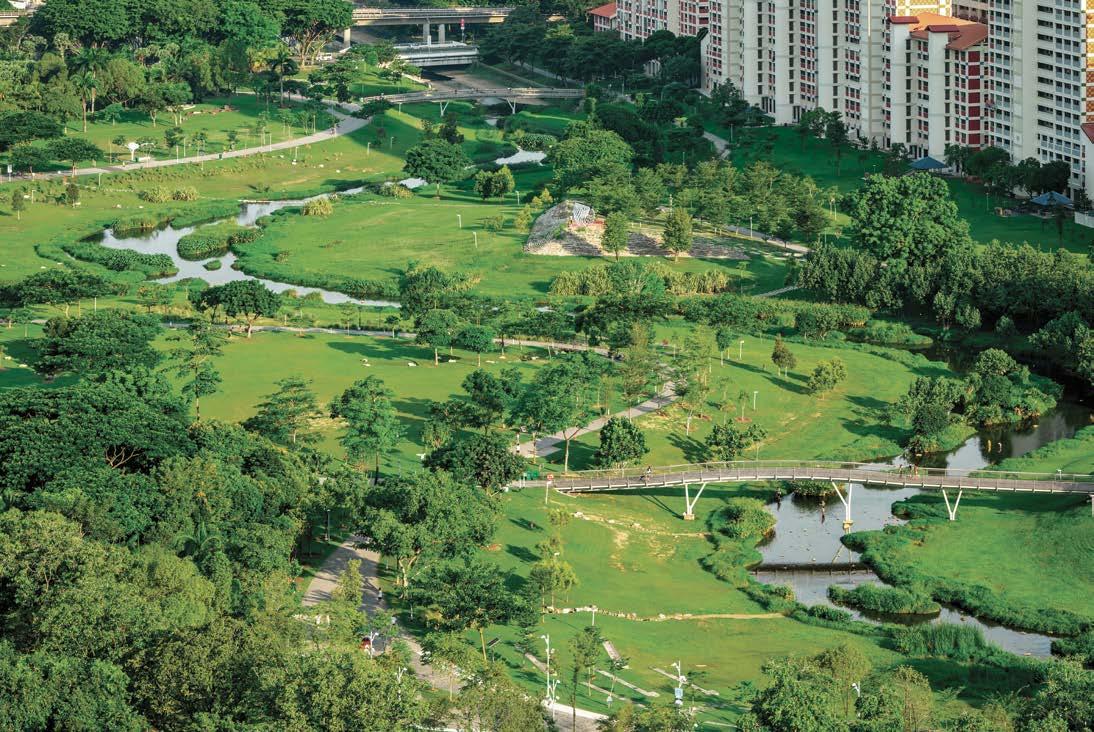

YT: It is also a matter of perception. Thirty-eight degrees in the city is very, very hot. Thirty-eight degrees on the beach does not feel so hot. At Bishan Park, you may not feel so hot when you are next to the water or under the shade of trees even though the temperature could be high.

During the Covid circuit-breaker period, when there was less maintenance and Singapore became wilder, there was more acceptance by the public. In response to surveys by NParks and NUS, the public were more accepting of the wildness. Of course, it was not as wild as hiking in the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, but there was an acknowledgement of the comfort that flora and fauna bring. That awareness will help to foster a greater sense of ownership towards nature and towards our estate or community.

THE PRACTICE OF BIOPHILIA SHOULD NOT BE SOMETHING THAT WE LOOK AT FROM THE OUTSIDE; IT SHOULD BE PART OF DAILY LIFE. WHEN PEOPLE FEEL THAT THEY CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE THEN THE EFFORTS THEY MAKE WOULD BE MORE GENUINE, MORE HONEST.

– SRILALITHA GOPALAKRISHNAN ON HOW BIOPHILIC DESIGN CAN BE INTEGRATED MORE MEANINGFULLY IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT.

22 IN PERSON | BUILDING BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES

BUKIT CANBERRA SINGAPORE

SG: When I was working on Parkroyal on Pickering where the access to the rooms is along a natural corridor, the first question from the client was: The rain in Singapore doesn’t fall straight, it falls at an angle; when it rains, people walking along the corridor will get wet. Should we put a shading device? This contradicted the idea of an open garden, of walking along a space where one can feel the natural elements. We asked the client, why not allow the rain to come in and let guests feel the mist falling on them? Eventually, we planted long curtain creepers. When the breeze comes, the creepers move and create a sense of rustling breeze. When it rains, there will be a little splash but that’s the whole beauty of this hotel. It took a bit of time, but the client was convinced in the end. The space would not look the same with louvres and sunshades. Sometimes it’s also a matter of being a little more assertive, of convincing clients to be a little bit more adventurous. When you’re in a resort and it rains, you use an umbrella. You don’t complain about not having a covered walkway. That’s part of being in a resort in nature. So, I think it’s a matter of persisting.

COST OF MAINTENANCE IS A BIG PUSH FACTOR. IS IT POSSIBLE TO DESIGN SELF-SUSTAINING LANDSCAPES THAT TAKE

CARE OF THEMSELVES?

YT: The types of clients we work with sit on extreme ends of the spectrum – one who hugs trees and says no concrete drains within the site, and the other doesn’t care at all for trees. To clients who tell me that they do not want leaves to fall, I ask them, does your hair fall? Plants and trees are living things like us, and we need to accept that maintenance is necessary. But there are ways to mitigate this. For instance, instead of smaller planters, have larger planting spaces so that the foliage falls within the planting area to reduce the maintenance. The selection of vegetation is very important. A way to reduce maintenance is to choose plant species that at their maturity grow only to a manageable height

and do not require frequent trimming. Another way is to avoid monoculture and choose the right base materials in the soil. If the soil is healthy and you have different plant species, you are mimicking the natural ecosystem and the plants will become more self-sustaining.

FOR US, AS DESIGNERS, WE NEED A HUGE CHANGE IN MINDSET. WE HAVE TO START LOOKING AT BIOPHILIA AND SUSTAINABILITY RIGHT AT THE START – AT DAY ONE OR DAY ZERO, RATHER THAN TRYING TO FIGURE OUT WHETHER IT’S BIOPHILIC AFTER WE ARE FINISHED WITH THE DESIGN. SAME FOR CLIENTS. THEY NEED TO START WITH A BIOPHILIC MINDSET RATHER THAN COMING TO US WHEN THE BUILDING IS RIGHT AT THE BUILDING SETBACK AND ASKING US TO MAKE IT A BIOPHILIC BUILDING.

23 IN PERSON | BUILDING BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES

– YVONNE TAN ON MEANINGFUL INTEGRATION OF BIOPHILIC DESIGN IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT.

DP Green has started a research project with permaculture experts. Permaculture farming is a closed-loop system where waste from the fauna becomes fertilizer for the flora. It is very sustainable but tends to look like a hippie garden. The idea is to combine landscape architecture and permaculture to make it more attractive and convincing to clients developing commercial projects.

JHT: We build buildings to last for a minimum of 25 years to 30 years, why don’t we think of trees the same way? Trees need time to grow too. We know that buildings will need some renovation; gardens do as well. As Yvonne said, we need to think about which trees to plant where. We also have to dare to say that some of our planting will change. For example, Bishan Park was planted with a certain planting palette when it opened in 2012. We found out through a survey of NUS that by 2018, the planting palette had dramatically changed. Certain plants did not like to live where we planted them and disappeared, and other plants were not even on the planting list and came through nature’s way via seeds brought in by birds, water or humans; and that’s okay. Let nature take over. Let it grow towards what nature believes is his/her succession vegetation, belonging within the space and working with the available elements like drought, water, wind, sun. We have to communicate this to the client and let them understand that the image they have today might not be the same tomorrow. If they want to retain that same image, high-end maintenance is necessary. So, it’s about managing expectations – educate the clients to help them make informed decisions. If they allow for transformation of the natural planting palette, then we should

design for this too, think about low-maintenance and natureinspired planting palettes.

SG: I think maintainability is something that can be addressed. It doesn’t need to be a big issue with high costs. What in your perception is maintenance? If clients are willing to accept a more wild and natural approach, then maintenance will not be such a big pocket item. By choosing the types of plants and allowing them to grow naturally, less maintenance will be required. I don’t think it’s an issue of whether I should plant or not plant, it’s about setting the expectation level when it comes to maintenance. That may help clients to look at the whole idea of biophilic integration in a different way.

WHAT IS THE NEXT AGENDA THAT WE SHOULD NOT BE AFRAID TO PUSH?

JHT: I think we should not be afraid of data. For example, data tells us that Kampung Admiralty has 25% more biodiversity in one hectare than a comparable sized plot and adjacent park space. Just knowing that, we have a better understanding of the impact not only from a biodiversity point of view but also how that relates to the building, to lowering ambient temperature on the roof and nearby environment, the way the building will be used by the community, the re-use of rainwater or potentially even the reduced use of air-conditioning. With data, we can achieve more accurate modelling to design buildings that are one step ahead. We are almost there, but we’re not fully harnessing the power of data yet. We must push it further and allow design to be driven by data if we

BISHAN PARK | SINGAPORE

BISHAN PARK | SINGAPORE

24 IN PERSON | BUILDING BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES

PHOTO CREDIT: RAMBOLL STUDIO DREISEITL

I THINK WE SHOULD NOT BE AFRAID OF DATA. WITH DATA, WE CAN ACHIEVE MORE ACCURATE MODELLING TO DESIGN BUILDINGS THAT ARE ONE STEP AHEAD. WE ARE ALMOST THERE, BUT WE’RE NOT FULLY HARNESSING THE POWER OF DATA YET. WE MUST PUSH IT FURTHER AND ALLOW DESIGN TO BE DRIVEN BY DATA IF WE WANT TO PUT SUSTAINABILITY AT THE HEART OF DESIGN.

– JELLE HENDRIK THERRY ON THE NEXT FRONTIER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND BIOPHILIC DESIGN.

want to put sustainability at the heart of design. Designers should not be afraid of data. As designers, we will always be here to pursue the emotive elements of designs, to combine that with data and science to create better environments for you and I to be in.

SG: Jelle has touched upon the most important aspect in regard to what’s next, where we should push, what we should not be afraid of. It’s the idea of informed design. Informed design doesn’t take away creativity. We need to change this mindset that if it’s performative or computer driven, there is no room for creativity. On the contrary, it empowers us. It gives us more ammunition to push our designs to clients. If a client wants to reduce 10 trees, I can explain how much carbon emissions will increase and how much thermal comfort will be compromised with 10 trees less.

But we do need to be conscious of how we use data. Carl Steinitz (Professor Emeritus GSD Harvard) said that data cannot be a solution but data can be a means to a lot of solutions. In most of our research we look at performance. With technology and the availability of sensors and real-time data, we can see how every space we design performs post-occupancy. This helps us to build a predictive methodology. That means before a project is built, we can see how well that design will perform spatially, socially, environmentally and ecologically. So, data empowers us to inform the client in a very convincing way what they will get if we design a certain way. We can give a 70-80% assurance of how the performance would be. It’s essentially proof of concept. I think this is where we need to really push ourselves. We have to leverage on that.

SINGAPORE HAS A SOPHISTICATED STORMWATER MANAGEMENT SYSTEM AND A LOT OF BIG CANALS THAT TAKE UP A LOT OF SPACE. SINGAPORE IS ALSO PRONE TO FLOODING. IS IT POSSIBLE TO TRANSFORM THESE SPACES INTO MULTIPLE BISHAN PARKS TO VARIOUS DEGREES ACROSS THE WHOLE ISLAND IN DIFFERENT SIZES?

JHT: Singapore has 724 square kilometres of island; within that, we have to find space. My statement is that the cake is only as big as it is and you can only divide it up to a certain point; after that it is meaningless to even have a piece of the cake. To translate this back to land-use planning and the need for more space for water – within the available space, there’s only one solution from my point of view, we have to start thinking about a layered approach within a system, more than just individual programme. ABC Waters programme by PUB is really emphasising that every drop of water counts. We need to harvest, clean, store and re-use our storm water; to do that, we need space. In the case of Bishan Park, the transformation of a concrete canal into the river park we all know, we had to think across boundaries set by the different government agencies to find more space for each of them. And the result is this unique environment. Creating more Bishan Park-like projects is just one solution. A systems-thinking approach is where we need to look at too, where water quality and water quantity are taken care of via natural features like swales, rain gardens, bio-retention basins, detention ponds, and how they create a network of naturebased solutions harvesting, cleaning, storing and re-using the rainwater. That’s the agenda that all of us need to look at. It’s not about protecting spaces anymore; it’s about sharing spaces and creating this network. Above all, we need to think in big and small

KAMPUNG ADMIRALTY 61 | SINGAPORE

25 IN PERSON | BUILDING BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES

PHOTO CREDIT: RAMBOLL STUDIO DREISEITL

steps, as we citizens can also contribute – by removing a tile in our garden, harvesting water and reusing it to irrigate our garden, green roofs to reduce run-off speed of water, all with the aim to make rainwater visible.

YT: We do not have to replicate the Bishan Park system everywhere because we do not always have that kind of space. There are other solutions, for example in Hougang and towards Serangoon River, where we softened traditional concrete canals using the ABC Waters design principles, or by creating event spaces that are cantilevered over the canals to meet the needs of the community. For example, the entire stretch of community public space at Paya Lebar Quarter was actually built over PUB drain reserve. But it is also important to consider how to placemake and placekeep these spaces.

SG: What Bishan Park showed us is that there are ways to look at using blue and green spaces in the urban context to create a more sustainable and resilient solution. But we must remember that every inch of space is precious in Singapore. Even if you’re

designing very urban plazas, you could still design them in a way that allowed them to flood, to be dynamic.

I worked on a condominium project in Kovan called The Tembusu, where we asked the private developer to allow us to design a dynamic landscape. That means creating water features that will flood when it rains, to slow down the water. We do not need a Bishan Park to do this. We need to start looking at every small space we design as part of a bigger system. It doesn’t mean that every space has to have everything in it, but it can have something that can then lead to the next.

Most of us are trying to prevent floods, but in Netherlands there was a Room for the Rivers project where they did the opposite. Instead of fighting the water, their solution is to let nature do what it does, to allow lands to flood and absorb the water. It is about looking at the same issue from a different perspective. Bishan Park is one of many possible solutions. In Singapore we have many opportunities to come up with innovative solutions for very specific urban challenges with unique conditions. The

26 IN PERSON | BUILDING BIOPHILIC COMMUNITIES

idea of Bishan Park is water sustainable design at ground level, whereas Kampung Admiralty takes a vertical approach. We can apply the same principles in different contexts. We should not limit ourselves to one solution, even if it was an excellent one like Bishan Park. It’s about pushing ourselves to see how many solutions we can find.

HOW DOES BIOPHILIC THINKING HELP TO SHAPE BEHAVIOURAL CHANGE. WHAT ELSE CAN WE DO TO FOSTER GREEN THINKING AND GREEN ACTION?

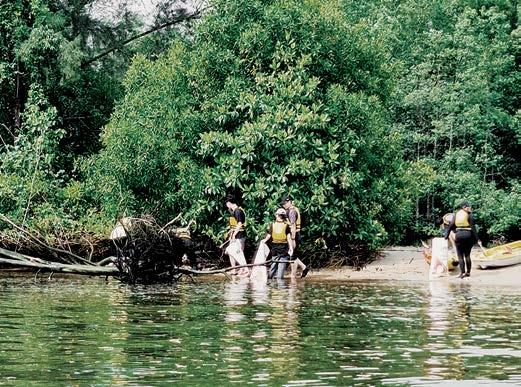

YT: Join Kayak and Klean to clean up coastal rubbish. Join the One Million Tree movement and plant a tree. Plant something on your balcony or kitchen counter.

An interesting thing happened during Covid: a lot of people suddenly found their green thumbs. Gardening became a newfound national hobby and people who weren’t interested in gardening before became experts. Instead of traffic jams on the roads, parks were jam-packed with people. It is very encouraging, but it is a slow journey because Singaporeans are generally not the kind who would find a lawn and sit on it.

JHT: Speaking of lockdown, when people walked through their park space, they saw more butterflies and small animals simply because there was no maintenance. When the circuit breaker was over, NParks sent in their people to clip all the grass away. The empowerment Sri mentioned earlier, is about the people who spoke up and asked, “NParks, why are we doing this?” There are other examples, like the retention pond at Kampung Admiralty at the end of the protective landscape – there was a bug living in it and the fishes were dying. The community came together to save the fishes, fed them medicines and cleaned up the pond. So, I do believe that there is a very strong possibility for us to be empowered and for us to become a biophilic community.

SG: This idea of behavioural change doesn’t need to be a big change. It doesn’t need to be a bold step or a statement. I think it’s more about small, everyday things. We have to understand that when we talk about living in nature, we need to accept all aspects. You cannot want the butterflies but not the caterpillars or the bees. During Covid times, maybe you see some birds and you think biodiversity is better when in fact they have always been there;

it’s just that you’ve never been at home to see it. So, it’s the small things happening around us that will trigger change; when we start learning about it and appreciating it. Now, when a dragonfly comes and sits on your balcony, you know it’s going to rain. These are small things that go a long way.