COLLABORATING TO CONQUER CANCER WINTER 2022 WOMEN IN CANCER BLAZING NEW TRAILS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO CANCER CENTER 10: PEDIATRIC BRAIN TUMOR RESEARCH 12: SPOTLIGHTING PATIENT NAVIGATION 14: COUPLE BATTLES COLON CANCER 18: GET TO KNOW PAUL MARONI, MD 20: LIFESAVING CLINICAL TRIAL

Leading clinical trial of new drug to treat metastatic colorectal cancer

University of Colorado Cancer Center member Robert Lentz, MD, is leading a new phase 2 clinical trial for patients with metastatic colon cancer for whom standard therapy is no longer effective. Lentz is mentored by Wells Messersmith, MD, associate director of clinical services at the CU Cancer Center.

The trial is for a new medication called evorpacept (ALX148), used in combination with cetuximab and pembrolizumab, commonly used immunotherapy drugs in cancer treatment. Evorpacept specifically blocks a protein called CD47, which is found on the surface of most cells in the body. CD47 is known as the “don’t eat me” signal, as its primary function is to signal immune cells called macrophages not to eat them. Diseased or aged cells have lost enough CD47 that macrophages see them as OK to consume. Researchers have found

CU Cancer Center welcomes new leaders

that CD47 is overexpressed in tumor cells, however, as the tumor looks to protect itself against the immune system. When CD47 is blocked by evorpacept, cetuximab and pembrolizumab are able to prime the immune system to go in and destroy the cancer cell.

Patients in the study are being enrolled across five sites, including the CU Cancer Center’s clinical partner, UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital. They receive treatment once a week, and it takes at least nine weeks to see a response—ideally tumor shrinkage or tumor stability. Messersmith and Lentz hope to have the study fully enrolled in early 2023, with early data on safety and efficacy to follow by the end of 2023. The trial also includes a two-year overall survival follow-up to determine the longer-term effectiveness of the medication.

The University of Colorado Cancer Center has named seven individuals to key leadership positions in the past several months.

Richard Duke, PhD: Deputy Associate Director of Commercialization, serving as a liaison to center-level oversight, strategic planning, and process improvement for CU Cancer Center commercialization efforts, working closely with CU Innovations and the Anschutz Medical Campus SPARK/REACH program.

Jan Lowery, PhD, MPH: Assistant Director for Dissemination and Implementation, taking a leadership role in the development, conduct, and dissemination of implementation-focused projects in cancer prevention, early detection, and survivorship. Responsibilities include leading community outreach, education, and engagement events.

Jessica McDermott, MD: Deputy Associate Director for Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Research, working to identify new opportunities, strategies, and partnerships in which the center should invest in to ensure that participation in clinical trials at the CU Cancer Center reflects or exceeds the state cancer demographics.

Sharon Pine, PhD: Director of the Thoracic Oncology Research Initiative (TORI), which was created in 2015 with the goal of advancing lung cancer research at the University of Colorado, building on a long history of collaborations spanning basic, translational, and clinical research.

Get

Hatim Sabaawy, MD, PhD: Associate Director of Translational Research, responsible for fostering translational research activities across the academic and clinical partner institutions of the CU Cancer Center, including Children’s Hospital Colorado and UCHealth.

Natalie Serkova, MSc, PhD: Interim Associate Director of Shared Resources, a new role that oversees a set of resources that offer researchers at the cancer center and throughout the CU Anschutz Medical Campus access to technologies and expertise that are too expensive or technically challenging to develop in individual labs.

Marie Wood, MD: Co-Director of Hereditary Cancers, increasing access to and awareness of genetic counseling and genetic testing, supporting ongoing clinical and lab work, and facilitating research. Wood is also medical director for the Cancer Clinical Trials Office.

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG 2 N WS

more

Center

on our

CU Cancer

news

blog: news.cuanschutz.edu/cancer-center

RICHARD DUKE, PHD

HATIM SABAAWY, MD, PHD

JESSICA MCDERMOTT, MD

SHARON PINE, PHD

JAN LOWERY, PHD, MPH

MARIE WOOD, MD

NATALIE SERKOVA, MSC, PHD

Researchers from Anschutz, Boulder campuses receive funds for collaboration

American Cancer Society awards nearly $2 million to CU Cancer Center researchers

Three University of Colorado Cancer Center scientists have received a combined total of close to $2 million in grant funding from the American Cancer Society to support research addressing a broad spectrum of cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

The AB Nexus Research Collaboration Grant Program, which funds collaborations and innovations between researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz and CU Boulder campuses, has awarded funding to two projects led by members of the CU Cancer Center. These cancer-specific grants also include co-funding from the CU Cancer Center.

Daniel LaBarbera, PhD, director of the Center for Drug Discovery in the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, is partnering with Karolin Luger, PhD, a professor of biochemistry at CU Boulder, on a study that proposes to execute a new drug discovery and therapeutic strategy involving PARP inhibitors, a type of cancer drug that prevents cancer cells from repairing, allowing them to die. The CU Cancer Center members’ research will target a specific protein complex with PARP that is implicated in cancer, with the aim of developing a therapeutic strategy that requires lower dosages and shows fewer adverse side effects.

And Jill Slansky, PhD, co-leader of the CU Cancer Center Tumor Host Interactions program, is partnering with CU Cancer Center member Xiaoyun Ding, PhD, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at CU Boulder, on a project that will use mechanical biomarkers of cells to identify specific T cells that effectively bind to tumor antigens. An antigen is any substance that causes the immune system to produce antibodies against it. Slansky and Ding hypothesize that mechanical biomarkers of T cells can be identified for adoptive cell therapy that will show which T cells are antigen-specific and have the optimal binding properties for the tumor, resulting in enhanced antitumor immunity.

• Amanda Winters, MD, PhD, is leading a study seeking to improve clinicians’ ability to determine pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients’ risk of relapse early in treatment. Winters will work to develop tests that can measure genetic measurable residual disease in these patients, with a goal of earlier intervention for patients at high risk of relapse.

• Swati Patel, MD, MS, is conducting research to study the yield of expanding genetic evaluation to people with advanced polyps, which are the immediate precursor to colorectal cancer. A further research goal is to design a mobile and digital health intervention that empowers patients to orchestrate their prevention care.

• Srinivas Ramachandran, PhD, is working to predict and track response to immunotherapy treatments by developing a more sensitive and less expensive method for generating gene expression signatures for cells that shed cell-free DNA (cfDNA). Normally, cfDNA is generated during normal blood cell turnover, a process that dilutes DNA from a tumor when one is present. By generating gene expression signatures for cells that shed cfDNA, Ramachandran’s goal is to better identify patients who will benefit from immunotherapy and, once it’s started, identify earlier whether the treatment is working.

Leading research on new treatment for large B-cell lymphoma

A multi-site, international study led by University of Colorado Cancer Center researcher Manali Kamdar, MD, has found that liso-cel, a CAR T cell immunotherapy drug developed to treat adult patients with large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL), is an effective second-line treatment for the disease.

In response to this research, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved liso-cel for use as a second-line treatment for patients with LBCL who either didn’t respond to frontline chemotherapy or who responded but relapsed within 12 months. Liso-cel had previously been used as a third-line treatment for the disease.

C3: WINTER 2022 3

AMANDA WINTERS, MD, PHD

MANALI KAMDAR, MD

SRINIVAS RAMACHANDRAN, PHD

SWATI PATEL, MD, MS

Women Leading the Way

Half of CU Cancer Center leadership roles are held by women, bringing vital representation and perspective to research and cancer treatment.

By Rachel Sauer

By Rachel Sauer

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG 4

Two important numbers to keep in mind are that 50.5% of the U.S. population is female, and that cancer will account for more than 606,000 deaths in the United States this year, making it the second-leading cause of death.

At first, these numbers may seem unrelated. Some might point out that even when these numbers are linked, cancer mortality is higher among men than women.

But as women increasingly pursue careers in cancer treatment and research, they bring not only vital insight and perspective that help to drive innovation, but ongoing attention to longstanding gender disparities in the field. These disparities have long existed not just in the clinic and the laboratory, but in cancer leadership roles as well.

For example, recent research from the European Society for Medical Oncology found that in 2019, 36.8% of invited speakers at international and national oncology congresses were female. Further, 35.8% of board members in international and national oncology societies were female, and just a handful of NCIdesignated cancer centers nationwide are led by women.

Even though half the population is female, half of cancer leadership worldwide isn’t, which is why “it’s so critical that women are represented in cancer leadership,” says Cathy Bradley, PhD, MPA, deputy director of the University of Colorado Cancer Center and associate dean for research in the Colorado School of Public Health. “Women in cancer leadership roles bring vital perspective to the clinic and to research.”

The CU Cancer Center is unique among many cancer centers nationwide because women represent half of its leadership in administration and research.

“For so many years, the academic world has been largely homogenous, largely male, largely white, and we were not getting diverse perspectives because we weren’t seeing a diversity of backgrounds represented,” says Heide Ford, PhD, associate director of basic research at the CU Cancer Center and chair of pharmacology in the CU School of Medicine. “There’s data now that show if you get more people in a room from different backgrounds, your organization will see more innovation, more advancement, have better retention. That means people of color, members of the LGBTQ community, the spectrum of cultural backgrounds and economic backgrounds, and women. Women need to be in the room.”

Inspired by women in science

There are many different avenues to approach the conversation about women in cancer leadership, and a few persistent “devil’s advocate” arguments. One of the most prevalent is that science is science—ideally genderless, apolitical, and driven only by evidence and data. However, ideal and reality often diverge.

“I’m a fan of pure, merit-based science, but I also have to be realistic, and women are still underrepresented in science,” says Patricia Ernst, PhD, co-leader of the CU Cancer Center’s Molecular and Cellular Oncology Program and a professor of hematology, oncology, and bone marrow transplantation in the CU School of Medicine. “I had this experience once of organizing a conference, and the male organizer before me said, ‘Oh, it’s so hard to find good female speakers.’ Funny, I didn’t have a problem at all.”

Like several of her colleagues in leadership, Ernst didn’t consciously chart her career toward her current position. “I’m really more of a scientist, and where I want to be is at the bench doing research,” she says.

C3: WINTER 2022 5

“But I’ve come to appreciate that leadership is a seat at the table. It gives you a certain voice, and it lets you open doors that you otherwise might not be able to.”

Ernst’s fellow co-director, Tin Tin Su, PhD, a professor of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology at CU Boulder, pursued cancer research because of her passion for the process of scientific inquiry and testing hypotheses. Leadership “came about partly as a way to pay back the support I received over the years to get where I am,” she explains.

“Also, I grew up in Burma, and we barely had shoes to wear, so women in cancer leadership was not something I would have ever thought about. But I read about women scientists and women pioneers, and they were really inspiring. That’s one of the reasons it’s important women are in leadership roles.”

Stacy Fischer, MD, co-leader of the CU Cancer Center’s Cancer Prevention & Control Program and an associate professor of internal medicine in the CU School of Medicine, adds that “when you dismiss half the population, you’re simply not going to thrive. Women bring leadership styles that are an important part of team science.”

Increasing representation

Many women in cancer leadership are quick to note that overall, women have made important and significant strides in representation in research and in the clinic. More than half of medical students are now women, and in 2015, 46.5% of physicians in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries—representing 37 democracies with marketbased economies—were women, up from 39.1% in 2000.

“I think we’ve been doing a much better job of getting girls interested in STEM and supporting them in pursuing those interests,” says Jennifer Richer, PhD, co-leader of the CU Cancer Center’s Tumor Host Interactions Program and a professor of pathology in the CU School of Medicine. “We’re much better at being role models and providing them with role models. We know we’re losing great minds if girls are uncomfortable because they don’t see role models that look like themselves.”

However, one of the biggest challenges associated with retaining women in science and medicine is supporting them in finding and maintaining work-life balance. Research shows that of oncologists surveyed, more than 64% of women reported that the biggest challenge to career progression was work and family balance.

“I remember my mother-in-law telling me that she wanted to go to medical school like her father, but he told her, ‘If you go to medical school, you can never get married or have a family, and your commitment will be to your career,’” Fischer says. “So she made the decision not to go to medical school and was a stay-at-home mom. Even though, for me, it feels like I’m swimming upstream some days, I know the current is less forceful than it was for previous generations. At least I was never faced with a ridiculous dichotomous decision like that.”

Women still have to make some very heavy decisions, though. Richer says she hears “a lot of the younger female graduate students and medical

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG 6

students, the younger trainees, worry about whether they can juggle having a family. Even in this day and age, a lot of the daily tasks of managing the kids’ schedules, of going home when they’re sick, a lot of the work of caregiving for parents or friends does still fall to women.”

In fact, while the majority of medical students are now women, that percentage steadily decreases moving up the hierarchy in academic medicine—just 18% of department chairs and deans at academic medical institutions in the United States are women, the Association of American Medical Colleges reports. However, at the CU School of Medicine, close to half of department chairs are women.

Facing longstanding stereotypes

While women continue to narrow the gap in representation in many STEM fields, data show that they still are an overall minority in these fields. Ford says she has observed a more even gender balance among graduate students in biological sciences, “but as you move up the ranks, women start dropping out,” she explains. “Getting into post-docs, you have fewer women, and by the time you get to junior faculty and then full faculty, it’s really skewed toward men.”

She adds that she has mentored a number of female graduate students “who would come to me and say, ‘I don’t know how you do it.’ I was an assistant professor when I had kids, and I had my two sons late, but I remember a female faculty member who told me, ‘You shouldn’t do this now; it’s a terrible time for your career.’ But I was in my late 30s. I couldn’t wait.”

Many women still contend with the perception that they’re not as dedicated to their careers or as able to do the work, even as cultural expectations persist that women will perform the majority of domestic labor.

“We saw this with COVID, where women took on the responsibility of childcare, and now the data are showing that women’s careers declined—what some economists refer to as the ‘she-cession,’” Bradley

explains. “In economics, a lot of research has studied what happens to women’s and men’s careers after maternity and paternity leave. Women take maternity leave and take care of the baby, whereas men take paternity leave and write a paper. I was the primary wage earner in my family, yet every time the kids had something come up, the school called me. They never called Dad.”

Women in many fields, not just science and medicine, also encounter conscious or unconscious gender biases that manifest in small or large ways. Many women across the spectrum of leadership can relate to the situation of being in a meeting, sharing an idea, and having it be ignored or brushed aside, but then hearing a male colleague say essentially the same thing and it’s given credence.

Further, women in leadership often must still contend with persistent cultural stereotypes that paint assertiveness in women as aggression and ambition as calculation, “even though there’s no real data to support these stereotypes,” Bradley says. “As a woman in leadership, there’s still a part of me that worries, when I disagree with a man in power, whether I’m being threatening or too aggressive.”

Continuing to make strides

However, though barriers and stereotypes persist, many women in CU Cancer Center leadership positions point out that great strides have been made and continue to be made.

“There’s more of a recognition that these gender biases exist and an awareness that even as we’re seeing more women in cancer leadership roles, there are very few women who are cancer center directors in the whole country,” Bradley says. “When I visit other cancer centers and walk down the hall where there are portraits of previous directors, it’s usually a long line of white men. But we’re recognizing that we can and must get some different faces up there.”

Among the first steps is recognizing that “solving any problem requires a lot of different ways of thinking,” Su says. “I think that alone is justification for not overlooking the 50% of the population who are women. If we’re missing those brains, those ways of thinking in solving problems, then we’re missing solutions. Having a diverse leadership team is essential, and it matters to

C3: WINTER 2022 7

“For so many years, the academic world has been largely homogenous, largely male, largely white, and we were not getting diverse perspectives because we weren’t seeing a diversity of backgrounds represented.”

have representation, because that’s how the population looks, and that how we solve problems.”

Evelinn Borrayo, PhD, associate director of community outreach and engagement at the CU Cancer Center and associate director of research for the Latino Research and Policy Center, adds that a growing emphasis on inclusivity and equity is increasingly bringing diverse perspectives to research, cancer care, and cancer leadership. “Representation is so important because people who for a long time haven’t had a voice in these areas are seeing people who bring the unique perspectives of their communities to cancer leadership. I do this work because I’m passionate about it, and it’s important that people from diverse backgrounds can see that.”

Because science is, in some ways, still stereotyped as the realm of men, Ford says, mentorship is vital—more experienced female leaders, researchers, and clinicians supporting and advocating for the female students, researchers, and faculty members working to advance through the ranks of science.

“I had a really good female faculty mentor when I was starting out who put me up for a talk at a meeting that I thought was over my head,” Ernst recalls. “I thought I was going to be embarrassed because maybe I didn’t have enough data to talk about, but she encouraged me to do it, and now I can trace eight different ways that speaking at that event snowballed and got me other opportunities.”

Seeing women in leadership roles

Women aiming to build fulfilling careers in science and medicine, which could include cancer leadership roles, also benefit from more honest conversations about the issues women in these fields can face.

“As women, I think we tend to always feel guilty about something,” Richer says. “When my kids were tiny and I started going back to scientific meetings again, people would ask me,

‘Didn’t you just have a baby? Don’t you miss your baby so much?’ And I was like, ‘But they’re home with their dad.’ It’s important that we recognize and talk about these unfair expectations and the ways they might prevent us from pursuing a well-rounded professional life.”

There are national and international professional organizations that bring together women in cancer leadership and aim to develop women as leaders, as well as female-driven research and fundraising efforts like the American Cancer Society’s ResearcHERS, with which Richer is involved.

“That’s one of the things that I really love about the CU Cancer Center, is it’s a really nice place to be, and as an institution it has prioritized supporting women in their various roles and as they develop in leadership,” Ford says. “We’ve started asking things like, ‘OK, this researcher has a baby and is still breastfeeding; can we find ways to support her in taking her child to the professional meeting or finding childcare during the day?’ We’re more aware of all the different ways we can support women in finding balance, because many of us have also needed that support.”

Bradley notes that she advises post-doctoral researchers who are considering faculty positions to look at the leadership of the institutions they are considering. “I tell them, ‘If you don’t see many women, don’t go there.’ I’m proud that the CU Cancer Center is an institution where students and younger researchers and faculty see women in these roles and know that this is something they can achieve.”

Ford adds that not only is the CU Cancer Center committed to supporting and mentoring women in reaching leadership roles, “but the women in these roles now are committed to continuing to make this a place where women in science and medicine can thrive. They’re committed to not just being examples, but to doing the work of supporting and encouraging women in cancer.”

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG 8

“We’re more aware of all the different ways we can support women in finding balance, because many of us have also needed that support.”

CU Cancer Center Female Leadership

C3: WINTER 2022 9 DEC DING CANCER

Sharon Pine, MD Director, Thoracic Oncology Research Initiative (TORI)

Jennifer Richer, PhD Co-Leader of Tumor Host Interactions Program

Jessica McDermott, MD Deputy Associate Director for Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Research

Stacy Fischer, MD Co-Leader of Cancer Prevention & Control Program

Stephanie Farmer, MHA Associate Director of Administration and Finance

Patricia Ernst, PhD Co-Leader of Molecular and Cellular Oncology Program

Natalie Serkova, PhD Interim Associate Director of Shared Resources

Jill Slansky, PhD Co-Leader of Tumor Host Interactions Program

Tin Tin Su, PhD Co-Leader of Molecular and Cellular Oncology Program

Lia Gore, MD Co-Leader of Developmental Therapeutics Program

Heide Ford, PhD Associate Director of Basic Research

Jan Lowery, PhD Assistant Director for Dissemination and Implementation

Breelyn Wilky, MD Deputy Associate Director for Clinical Research

Marie Wood, MD Medical Director of Cancer Clinical Trials Office

Evelinn Borrayo, PhD Associate Director of Community Outreach and Engagement

Linda Cook, PhD Associate Director of Population Sciences

Cathy Bradley, PhD Deputy Director

Focused on Pediatric Brain Tumors

BY RACHEL SAUER

RAJEEV VIBHAKAR, MD, PHD

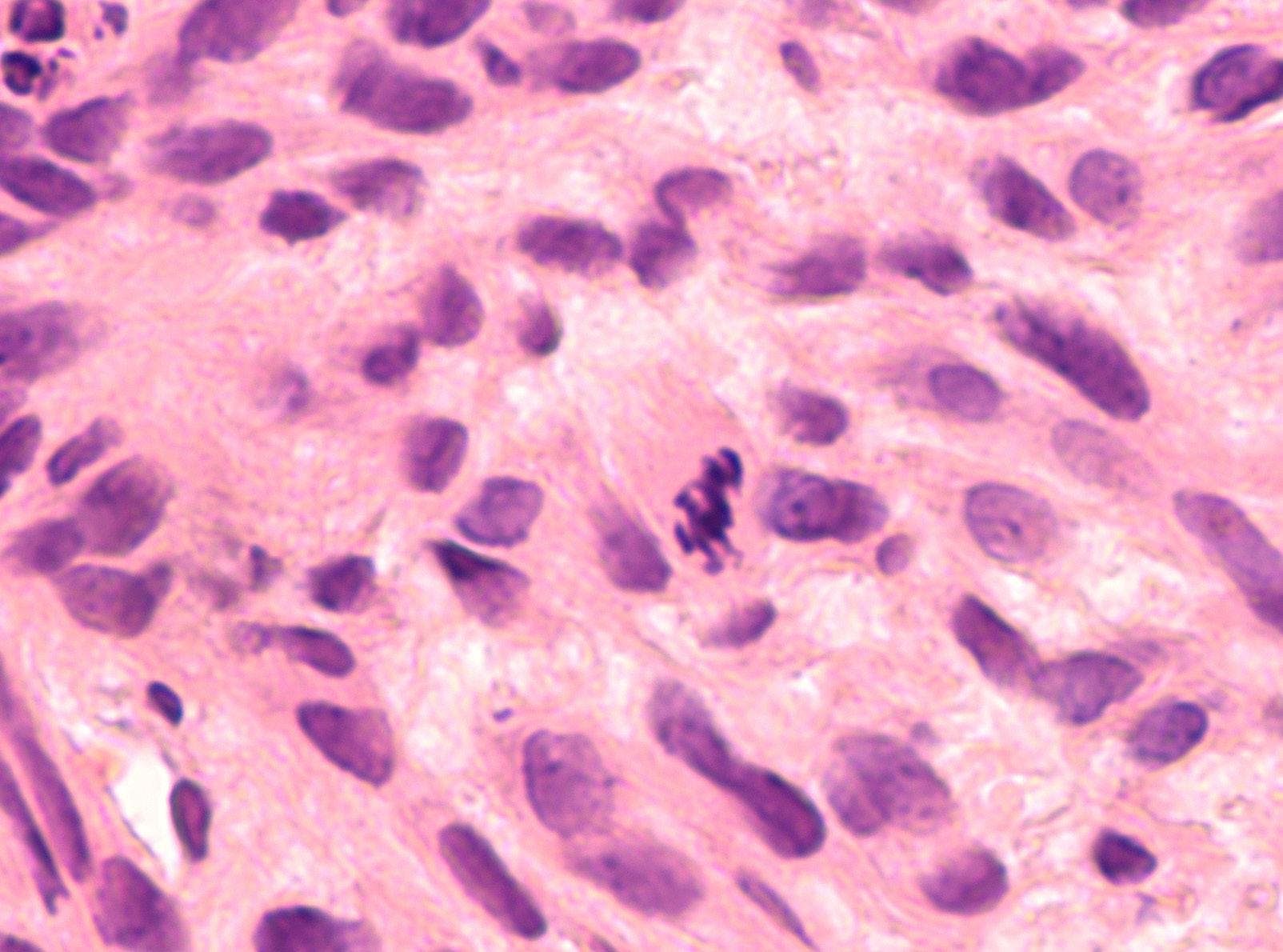

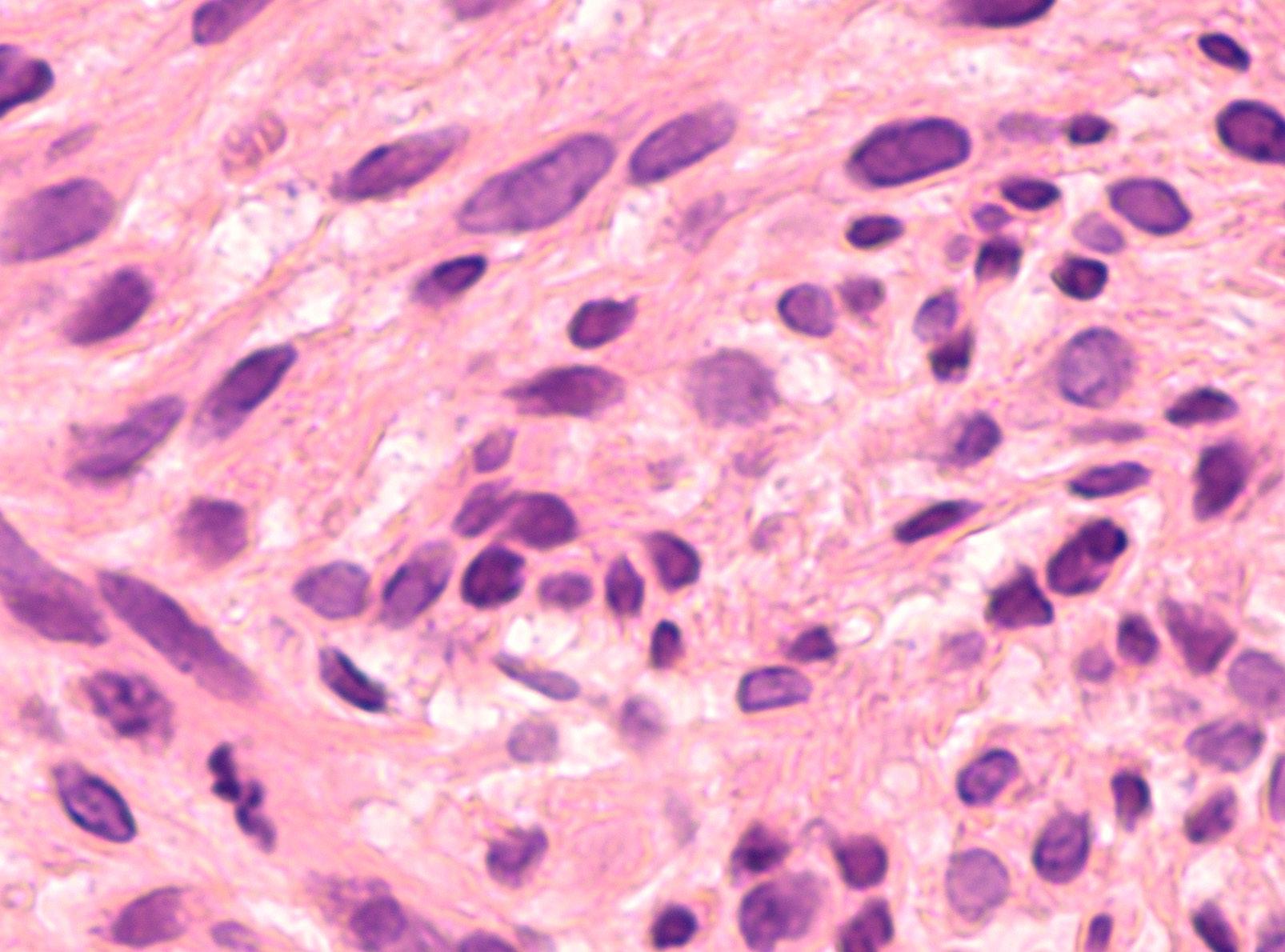

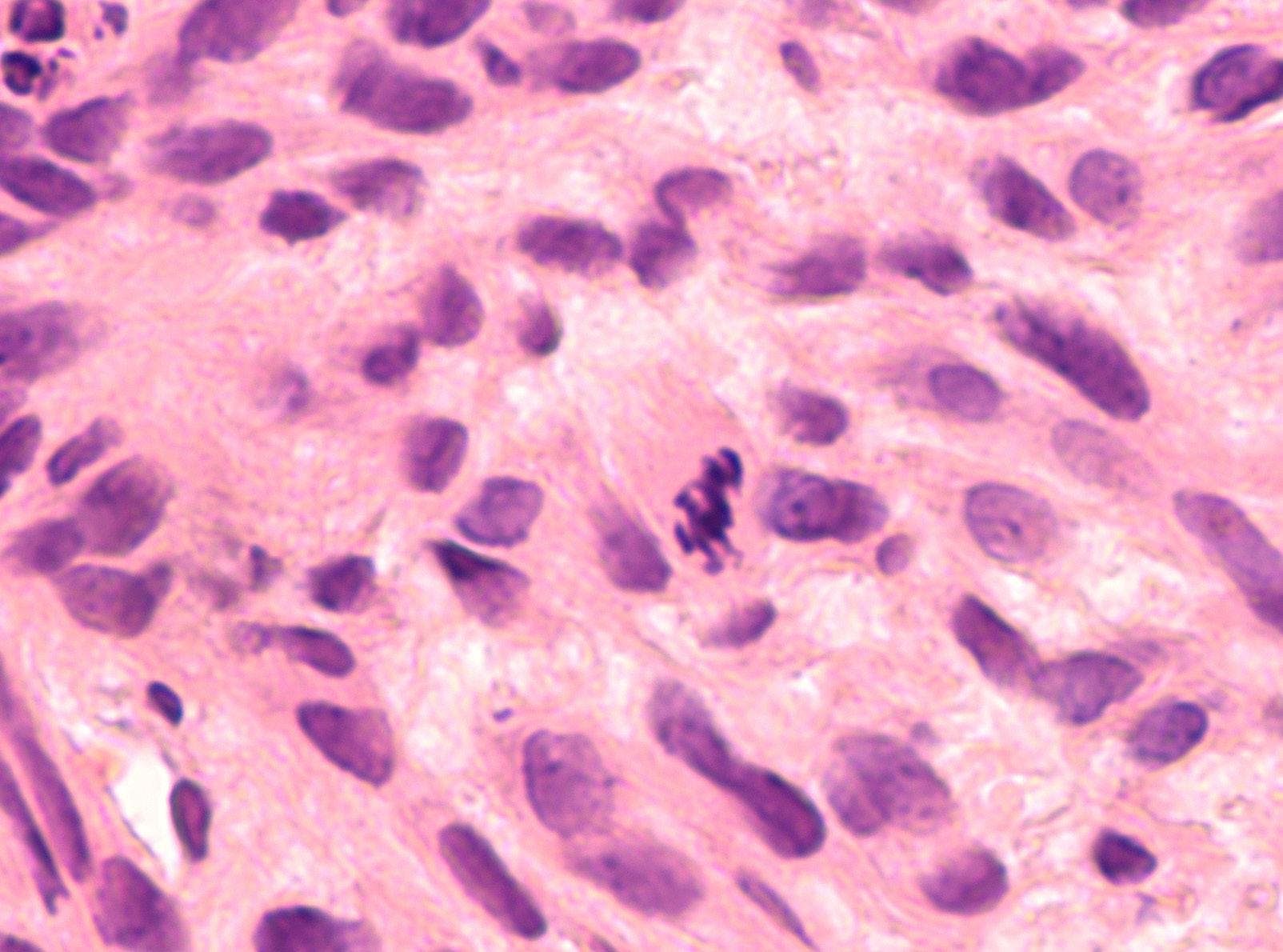

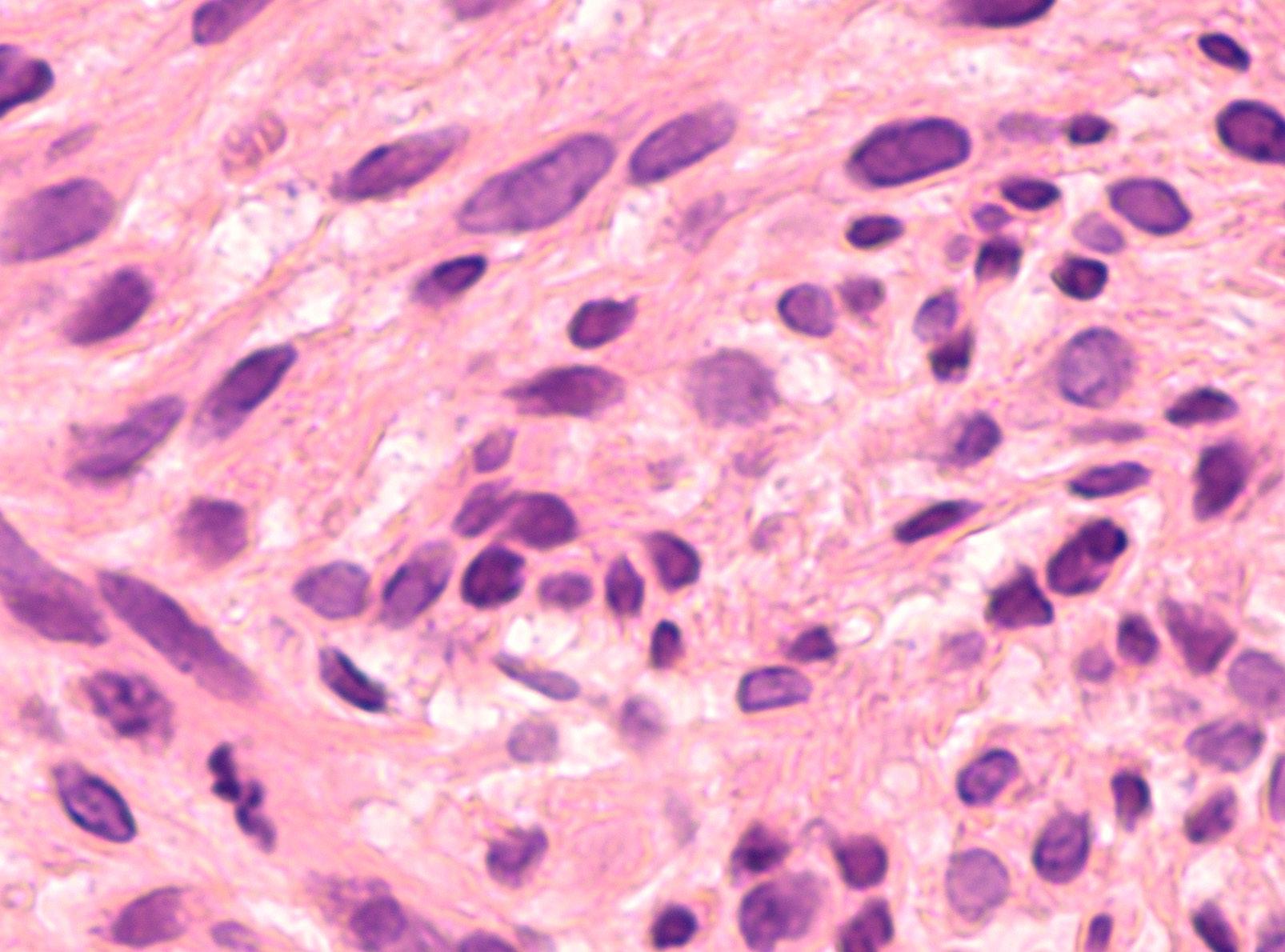

Initially, the big picture looks severe: Pediatric brain tumors are now the number-one cause of death for children diagnosed with cancer. Though leukemia is four times more common in pediatric patients than brain tumors, about 90% of children diagnosed with leukemia will experience a cure “because we’ve done such a good job of researching leukemia, and treatments have come so far that cure rates have improved significantly,” says Rajeev Vibhakar, MD, PhD, MPH, a professor of pediatric hematology and oncology in the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “We need to see that same level of support and advancement in finding cures for pediatric brain tumors.”

Vibhakar, who leads the Morgan Adams Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program in the CU Cancer Center, says that while the data present a very serious picture of pediatric brain tumors’ place among all childhood cancers, research and innovations happening at the CU Cancer Center offer a lot of reasons for hope.

We asked Vibhakar to highlight some of the innovative work being done to conquer pediatric brain tumors.

It seems that a lot of people would be surprised to learn pediatric brain tumors are the leading cause of death for children diagnosed with cancer.

The fact is, more kids die from brain tumors than any other type of pediatric tumor because we don’t have great treatments. If we compare it with leukemia, leukemia is four times more common than pediatric brain tumors, but we’re curing 90% or more of those kids because researchers and clinicians have done such outstanding work for decades and because the public and our research institutions have supported it. Now we’re really catching up in understanding how brain tumors work and developing treatments that can benefit patients.

What innovations in pediatric brain tumor research are happening in the CU Cancer Center?

We have one of the largest groups of pediatric brain tumor researchers in the country; it’s one of the hidden secrets on campus. Currently, on the research side, there are seven principal investigators who run research labs focused on pediatric brain tumors. We work as a cohesive group sharing ideas, resources, and expertise to drive research from basic genetic mechanisms to testing new drug therapy. Our work has been supported by the Morgan Adams Foundation for over two decades, which has allowed us to pursue many high-risk, high-reward studies.

Rajeev Vibhakar, MD, PhD, leads one of the nation's largest research groups targeting the leading cause of death among pediatric cancer patients.

We’ve created a patient tumor bank with more than 1,400 patient tumor samples. We’ve done lots of genomics on these samples, published a lot of papers, and we’ve also been doing a lot of single-cell sequencing. We’re making all that data publicly available through an online portal, and we’re working on a second portal for all the genomic data, so these will be available to anyone in the world.

What’s happening in clinical research for pediatric brain tumors?

A lot of the work we’ve done in the lab over the past seven years or so has translated into clinical trials. Currently, we have three open trials that came directly out of work done in our laboratories, and two additional trials in various stages of the federal approval process that we hope to open in the next few months. We’re one of 17 institutions around the U.S. that are part of a pediatric brain tumor consortium funded by the NIH for phase 1 trials.

A significant amount of cancer research involves immunotherapies; is that also true in pediatric brain tumor research?

On immunotherapies, we have several big projects. One of them, research being led by Nick Foreman, MD, is looking at two subsets of tumors: those that don’t relapse and those that relapse very quickly. Among the ones that relapse very quickly, the macrophage infiltration is very different, so this research is working to understand what those mechanisms are and what suppresses response to therapy.

We also have Sujatha Venkataraman, PhD, who’s looking at the immune mechanisms targeting diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). It’s the one tumor in pediatrics for which there is no therapy currently, so every patient with DIPG will

die within 12 months, and we’ve made no improvement over the last four decades. We discovered, when Dr. Venkataraman was working with me as a research associate, a protein on DIPGs that could be targeted with CAR T cells. Dr. Venkataraman is working to develop those CAR T cells toward DIPG and has done some beautiful work. We have models where we can deliver CAR T cells directly to the brain through a pump system or direct infusion.

Nathan Dahl, MD, who trained with us, is also doing really great work in understanding how DIPG resists radiation and understanding what makes cells more sensitive to radiation.

How does the CU Cancer Center’s multidisciplinary approach to treatment affect pediatric brain tumor patients?

If you have a brain tumor, it’s likely you’re going to have issues with coordination, with speech, swallowing, vision, your hormonal function. Your pituitary gets impacted, your thyroid, your cortisol levels. We have patients who develop obesity because their hormonal control has completely gone wacky. All of these things are part and parcel of what we treat, and there are great teams throughout campus who we partner with to give the best care to our patients.

I am particularly proud of how we have developed a team across multiple specialties including pediatric neurooncology, neurosurgery, radiation oncology, radiology, social work, ophthalmology, rehabilitation medicine, and endocrinology to treat our patients in a comprehensive manner. The research we do in the lab is also based strongly on teamwork and collaboration. As clichéd as it may sound, we have truly developed a culture of working together at all levels to ensure that the present and future for kids with brain tumors is better than in the past.

Emphasizing the Importance of Patient Navigation

By Greg Glasgow

By Greg Glasgow

A cancer diagnosis can be difficult to work through in the best of circumstances, but factor in barriers related to language, insurance status, educational achievement, geographic location, income level, and more, and the cancer journey—everything from prevention and screening to diagnosis and treatment—can become nearly impossible to traverse.

Enter the patient navigator—a specially trained health worker who offers individualized assistance to patients, families, and caregivers negatively affected by health disparities to facilitate timely access to quality health and psychosocial care.

Patient navigation is one of the few interventions that has proven to be effective in increasing access to and completion of cancer screenings and treatment in populations adversely affected by health care disparities, including racial and ethnic minority populations, immigrant and refugee populations, low-income populations, and underserved rural populations.

Thought leadership on navigation

In June, members and leaders from the University of Colorado Cancer Center and Colorado School of Public Health (ColoradoSPH) were primary contributors to a supplement in the American Cancer Society’s Cancer journal that outlined the impact of patient navigation and the critical role it plays in improving outcomes for cancer patients. The collection of 13 articles was published by the National Navigation Roundtable (NNRT), an organization chaired by Andrea Dwyer, director of the Colorado Cancer Screening Program (CCSP) at the CU Cancer Center and senior professional research assistant in ColoradoSPH.

“Navigators can be within systems where treatment, prevention, early detection, and even survivorship care is deployed,” Dwyer says. “The articles speak to that continuum, but one of the things that's central to all of the articles is, what do we know about how navigation is being implemented? How are the navigators being funded? What patient population are they serving?”

Dwyer is the lead author on the articles “Collective Pursuit for Equity in Cancer Care: The National Navigation Roundtable,” which describes the role of the NNRT and details recent advancements in patient navigation, and “What Makes for Successful Patient Navigation Implementation in Cancer Prevention and Screening Programs Using an Evaluation and Sustainability Framework,” which explains the role of patient navigators in the CCSP and the success the program has had in increasing endoscopic screening in medically underserved populations.

“The best evidence that navigation works is in prevention and early detection,” Dwyer says. “Data is still emerging on the impact of navigation in the treatment realm and throughout the rest of the continuum.”

The effects of COVID-19

CU Cancer Center member Patricia Valverde, PhD, MPH, clinical assistant professor of community and behavioral health and interim director of the Latino Policy and Research Center for ColoradoSPH, was the lead author on the article “Flexibility, Adaptation, and Roles of Patient Navigators in Oncology During COVID-19,” which goes into detail on the results of a national survey the NNRT conducted to study the impact of COVID-19 on cancer care and patient navigation during the first six months of the pandemic.

“Within our workforce, we were hearing stories of navigators losing jobs, being furloughed, or not really being used during the very early days of the pandemic,” Valverde says. “We thought that was crazy, because navigators should be on the front lines. Their skills and knowledge should be used.”

To find out more, the NNRT created a survey that received more than 200 responses from navigators whose duties had changed during the first half of 2020. Many moved away from cancer-related services and received new training on COVID-19 and

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG

CU Cancer Center members and leaders were key contributors to an American Cancer Society supplement on patient navigation.

12

telehealth. Still working within medically underserved communities, the navigators addressed myths related to mask use, COVID-19 spread, disbelief, risk, clinical changes, transmission prevention, finances, and politics.

“They all had new duties related to the pandemic, which is excellent,” Valverde says. “That's what we wanted. We wanted to see that navigators, because of their skill set, could be flexible and adaptable and move into talking to community members and patients about any kind of situation.”

A grant for infrastructure and coordination

The patient navigation program within the CU Cancer Center and its clinical care partner, UCHealth, got a boost in June with a $300,000, three-year grant from the American Cancer Society. Focused on infrastructure, the funds will help to standardize the role of the patient navigator across multiple care sites, as well as to develop trainings and improve reporting.

“We have a number of patient navigators in oncology throughout the UCHealth system, but each program has grown up organically, and there’s not a synchronized workflow across the system,” says Stacy Fischer, MD, co-leader of the Cancer Prevention and Control Program at the CU Cancer Center. “The opportunity this grant affords us is to look at what the navigators are doing in each location and build synchronicity to increase our impact—not just for our health care system, but for patients.”

That includes creating synchronized job descriptions and metrics that can be used to track the effectiveness of patient navigators, including identifying barriers to treatment and tracking how those barriers are addressed. All are beginning steps to ensuring navigators are able to continue helping those from medically underserved populations access the care and services they need.

“The next step in realizing the value of patient navigation is being able to sustain navigation, to pay patient navigators fair and equitable wages, consistent implementation of navigation, and allowing the entire care and medical team to work at the top of their licensure. The efforts at the University of Colorado Cancer Center and Colorado School of Public Health are strong contributors to ensure navigation is a reality for cancer patients most in need,” Dwyer says.

C3: WINTER 2022 13

Battling Stage IV Colon Cancer — Together

Kacie Peters and Erik Stanley are working with multidisciplinary CU Cancer Center care teams to treat the cancer they’re both fighting.

By Rachel Sauer

Kacie Peters and Erik Stanley got together despite an early-morning walk home that felt like it would never end.

It’s a funny story, actually: They met at a New Year’s Eve party in Chicago in 2012. Kacie had flown in from Philadelphia to visit a friend and didn’t know anyone else at the party, and then her friend decided their apartment was too full, so Kacie would need to find somewhere else to stay.

Erik offered to sleep on his couch so Kacie could have the bed in his studio

apartment, and they walked, took a bus, took a train, and walked some more for almost four miles, with Erik sheepishly promising, “Just a little bit farther” every so often. When she woke up the next morning, Kacie noticed a book about serial killers on Erik’s nightstand.

What could have been a big “uh-oh…” moment instead developed into a long-distance relationship and then a wedding a year and a half later. In their 10 years together, Kacie and Erik have had adventures in far-flung places, have

moved halfway across the country, and for the past five years have found daily delight in raising their son, Nate.

They’ve been through some things, but always together, generally laughing, grateful for the steadiness in a hand to hold. And now, together, they’re each battling stage IV colon cancer.

Kacie is 36—34 when she was diagnosed on New Year’s Eve in 2019—and Erik is 41, and despite the growing number of young people being diagnosed with late-stage colorectal

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG 14

cancer, the odds of this happening with both members of a couple are “one in a hundred million,” says Chris Lieu, MD, associate director for clinical research at the University of Colorado Cancer Center and Kacie’s oncologist. “It’s almost incalculable.”

Despite the improbable odds, “this is what’s happening, so we’re dealing with it and living our life with our son,” Erik says.

“I try to find the silver linings with things and try not to focus on the bad stuff,” Kacie adds. “Of course there’s stuff we talk about to each other in private, plans we have to make, but we’d rather be an example that you can get through things together and still have a really good life, the life you want to live.”

Paying attention to the symptoms

For Kacie, it started with pain in her upper abdomen. She had a busy job she loved and frequently traveled for work, so she figured it was stress. For months she was in and out of doctors’ offices, in and out of urgent care, always leaving with incorrect diagnoses and medications that offered only temporary relief.

The pain grew worse and became persistent enough that she was hospitalized for an urgent colonoscopy on the last day of 2019. She had barely regained consciousness after the procedure when she received the news that not only did she have cancer, but the medical team wanted her to consent to surgery that night.

“I was alone when I got this news—Erik was at the children’s museum with Nate—but I don’t think it was a total surprise because I’d had a month and a half of throwing up blood,” Kacie says. “But I still had to call Erik and say, ‘Guess what, I have cancer; I’m going into emergency surgery right now.’”

“Definitely the worst call I’ve ever received,” Erik says.

Kacie was initially diagnosed with stage III colon cancer and spent much of 2020 having surgery and chemotherapy treatment, working with a multidisciplinary team from the CU Cancer Center.

“She’s definitely benefitted from multidisciplinary management,” says Lieu, associate professor of medical oncology at the CU School of Medicine. “She’s had surgery with Dr. Steven Ahrendt, chemotherapy with me. The whole team has worked in conjunction to make sure we’re doing everything possible for her.”

Kacie had a brief period of remission, but the cancer returned in August 2021 and this time it was stage IV.

A second colon cancer diagnosis

Through 2020 and 2021, Erik did everything he could to support Kacie through chemotherapy treatments and surgery and to make sure life was as normal as possible for Nate.

“This is hard to talk about, because I don’t want to imply it was a burden,” Erik says. “She’s the person I love and I wanted to do everything I could for her, and she made it easy. But I don’t think we talk enough about the pressures that come with a cancer diagnosis.”

At the beginning of 2022, Erik began experiencing symptoms that by now were painfully familiar: exhaustion, constipation, abdominal pain. He knew he couldn’t write it off as just stress, and on February 22 he received results from a CT scan that were an awful near-repeat of Kacie’s three years before.

“It was a shock,” Erik recalls, and Kacie adds, “We’re thinking, ‘How could this be happening with both of us?’”

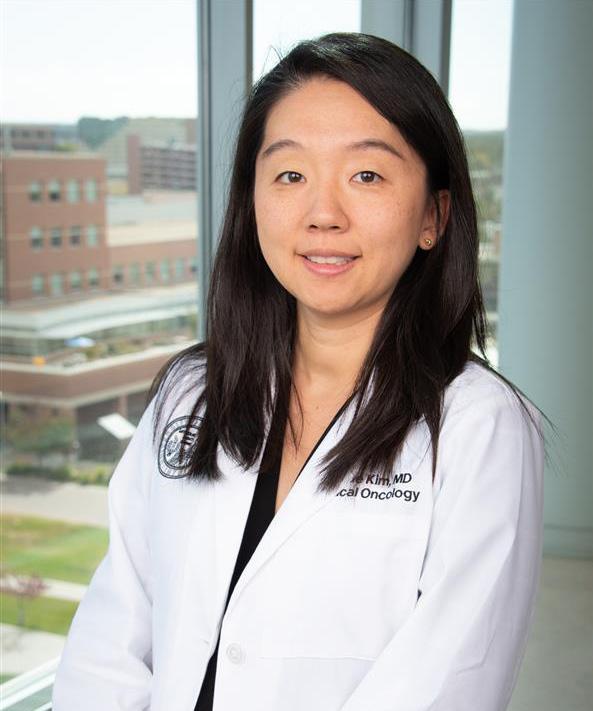

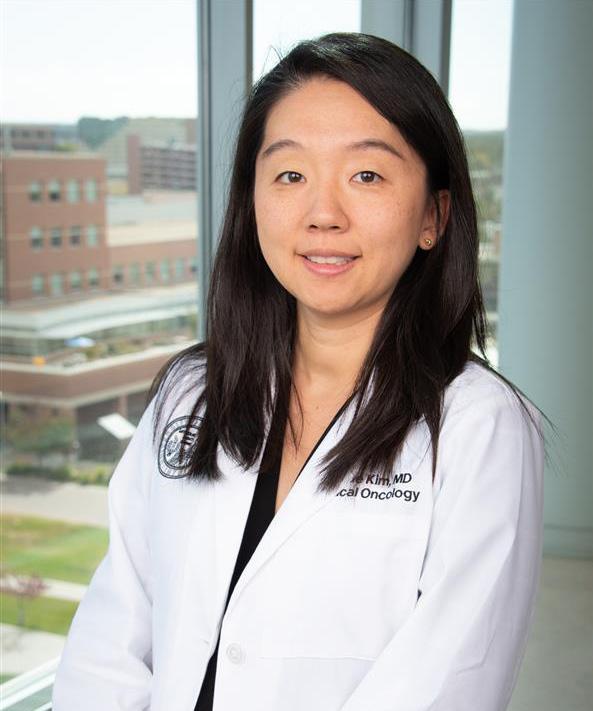

“When I first met Erik, he’d had a CT scan that showed sigmoid colon cancer that unfortunately was involving his kidney, the abdominal wall lining, and his liver,” says CU Cancer Center member Sunnie Kim, MD, Erik’s oncologist. “The sigmoid lesion was so big that we as his care team debated whether to start chemo right then and there.”

His multidisciplinary care team suggested he first have a nephrostomy—a procedure in which an opening is made between the kidney and the skin of the back to let urine drain from the kidney—and a diverting colostomy.

C3: WINTER 2022 15

SUNNIE KIM, MD

CHRIS LIEU, MD

“I try to find the silver linings with things and try not to focus on the bad stuff.”

“After that, I felt very nervous about sending him home, so we ended up just starting chemo in the hospital,” says Kim, assistant professor of medical oncology at the CU School of Medicine. “We were concerned that the mass was causing issues with his kidneys, and we didn’t know the pace of its spread, so it was important to be very aggressive and get the ball rolling.”

Since then, Erik has had eight cycles of chemotherapy. A CT scan in April showed that his liver metastasis has shrunk, as has the primary sigmoid mass.

Lieu and Kim have worked in close collaboration, and after consulting with Kacie and Erik following Erik’s diagnosis, they decided it would be beneficial to have them be treated by different oncologists.

“We did leave it open to Kacie and Erik,” Kim says, “but that’s one of the benefits of a multidisciplinary approach. We’re in constant communication as a team and with Kacie and Erik.”

Benefitting from multidisciplinary care

Because of that communication between Kim, Lieu, and other members of the care team, Kacie and Erik are able to receive their chemotherapy treatments in the same week, easing the logistical challenges of childcare and recovery. Both Kacie and Erik have gone on disability while they receive treatment, “and we’re so lucky that was an option for us,” Kacie says. However, having cancer can be costly, and unexpected expenses are almost guaranteed. In spring 2022, a friend established a GoFundMe for the family that so far has raised more than $122,000, which they’ll use to help with any unexpected medical expenses as their treatment continues.

The financial cushion has been a significant stress relief, Kacie says, though their ultimate goal is to see their cancers shrink enough that they can go back to work and pass the rest of the GoFundMe donations along to others dealing with cancer.

The most common question the couple receives, Kacie says, is how? Were there environmental factors that caused this? Some rare twist of genetics?

“Unfortunately, the answer is we just don’t know,” Lieu says. “There’s research happening here at CU and all over the world trying to figure out the confluence of factors that can lead to this, because it’s not just one thing. With Kacie and

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG 16

Erik, my hypothesis is that it’s probably a combination of things—genetic factors, environmental exposures that just slightly increase the chance of developing colorectal cancer in people as young as they are.”

Both Kacie and Erik, as well as Lieu and Kim, emphasize the importance of not ignoring out-of-the-ordinary symptoms “and I would even say getting a second opinion if you’re still concerned,” Kim says. “Patients know their bodies, and it’s important that we don’t automatically think it can’t be colorectal cancer because they’re too young. We’re seeing more and more that there isn’t a ‘too young.’”

Realizing that time is a gift

For now, and for each day, Kacie and Erik are focusing on their time together as a family. “It’s really important to us not to look at it as ‘buying time,’ but as appreciating time,” Kacie says. “Nate’s 5, and he needs to have as much of a normal life as we can give him.”

“I know it sounds so cliché, but you realize that time is a gift,” Erik says. “And we don’t want to waste it,” Kacie adds. “Not a minute of it.”

C3: WINTER 2022 17

“I know it sounds so cliché, but you realize that time is a gift.”

A Cut Above

Paul Maroni, MD, pursued urologic surgery for its potential

to help patients.

By Greg Glasgow

PAUL MARONI, MD

It was all his grandma’s doing, says CU Cancer Center member Paul Maroni, MD.

When Maroni and his brother were young, their grandmother used to joke with them, telling them Paul would grow up to be a doctor and his brother, Peter, would grow up to be a lawyer.

“I think it was just the respect that those professions commanded that our family wanted us to consider those,” Maroni says. “I was pretty open-minded when I went to college. I did the premedical curriculum as my primary area of study, but I was open to the idea that something else may pique my interest, and I’d want to do that.”

But his grandmother’s words stuck in his head, and once Maroni went to medical school at the University of Illinois, his fate was sealed.

“Once I got into the anatomy lab and started picking apart human organs, that’s when I fell in love with surgery and realized the miracle of the human body,” he says. “The way the chemistry and the anatomy and everything interacts is so spectacular, and the fact that we could actually get in there and do an operation and put somebody back together, and they heal up from that, and they do well? That was pretty amazing to me.”

Finding a home in Colorado

After receiving his MD from the University of Illinois, Maroni came to the University of Colorado School of Medicine in 2000 for his residency. Aside from a yearlong fellowship in urologic oncology at the University of Indiana early in his career, he’s been in Colorado ever since. Now an associate professor of surgery in the

Division of Urology, he also is co-clinical director of urologic oncology for the CU Cancer Center, treating patients with prostate cancer, testicular cancer, bladder cancer, and kidney cancer.

“This has been a great place to work,” Maroni says. “I love being out here; people are friendly. My brother lives in Fort Collins, and the rest of my immediate family have all moved to Colorado now as well.”

A problem-solver by nature, Maroni was drawn to cancer care because it combined his love of surgery with strategic thinking that is different for each patient he treats.

“There is a thoughtful component to this,” he says. “It’s like, ‘OK, surgery is an option here, but it’s not the only option. What can we do to supplement this with good radiation treatments or good chemotherapies?’ In prostate cancer specifically, there’s a more nuanced discussion about what treatment means, how it impacts sexual function, how it impacts urinary function. It’s a more challenging cancer to treat, but it can be very satisfying when people do well.”

Patient focus

Maroni also appreciates the long-term relationships he is able to develop with patients over time, and the shared decision-making that goes into a successful treatment with which a patient is comfortable. And since most men with prostate cancer will die from another cause, he says, an important part of his role is educating his patients about other health issues.

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG 18

MD CLINICAL CARE

“They might be concerned about a prostate cancer that I know is not going to be a big problem for them in the next 10 to 20 years, but I observe that they’re struggling with other issues—maybe they’re overweight, or their cholesterol is high, or we might spend some time talking about sleep and the importance of exercise,” he says. “When I get the opportunity, I try to spend some time talking with them about more global aspects of their health.”

Confronting burnout

Other aspects of Maroni’s job are conducting research and leading clinical trials—including a recent trial

testing the effects of grape seed extract on the spread of prostate cancer—and being an advocate for physicians in the area of burnout. He speaks on the issue annually at the American Urological Association convention.

“We put a big focus on patient safety, and I think that sustaining your workforce is patient safety,” he says. “If you don’t have the right personnel in place, that’s a patient safety issue. In their desire to improve patient safety, our leadership will sometimes create a new regulation or a requirement that has the unintended consequence of contributing to physician burnout. I think there needs to be more awareness around the implications of some of these things we’re asking providers to do.”

When those burnout risks are managed successfully, however, Maroni can’t think of a more rewarding job than being a cancer surgeon—especially at the CU Cancer Center, where patients have more options than they might at other facilities.

“One of the nice things about being at the University of Colorado is that we can take our patients through their cancer journey with advanced diagnostics and technology, clinical trials, special kinds of imaging, and new treatments,” he says. “We’re pretty fortunate to be able to offer that to patients here.”

C3: WINTER 2022 19

Beating a Deadly Sarcoma

How a CU Cancer Center clinical trial saved Ward McNeilly’s life.

By Greg Glasgow

Ward McNeilly thought he was a goner.

It was summer 2021, and the sarcoma that had started in the Denver resident’s left thigh seemed to be under control, subdued by radiation and chemotherapy following a surgery in 2018 to remove the initial tumor and another surgery in 2019 to remove cancerous tumors in his groin. McNeilly was doing so well, in fact, that his doctors at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital authorized a “chemo vacation” to give his body a break from some of the side effects of the treatment.

That’s when things got worse. “When you do a chemo vacation, the physicians monitor it with periodic CT scans to see your progress,” says McNeilly, 71. “If the tumors grow again, then typically you go back on chemo; if they shrink, then they’re trending in the right direction and you could maybe continue with the chemo vacation.

“In my case, I had a three-month follow-up CT scan, and the cancer had metastasized to my upper body, my lungs, a number of

places in my bone, and my stomach lining, and I had a couple of tumors on my scalp,” he continues. “Then they identified a brain tumor also, and I thought, ‘Oh man, I’m dying. This is it. I’m gone.’”

Approved for a clinical trial

After the cancer had metastasized, McNeilly’s care team expanded to include CU Cancer Center member Breelyn Wilky, MD, who knew she had to act fast.

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG 20

BREELYN WILKY, MD

“He had developed disease all over his body, very symptomatic, miserable, and all of a sudden his quality of life was horrible and we were worried he was going to die,” says Wilky, associate professor of medical oncology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “It was this horrible situation where our hands were tied, and he was getting worse by the day. We wanted to get him on a

clinical trial, but we kept running into logistical hurdles. But finally we got him started on treatment.”

Within days of McNeilly’s first treatment on Wilky’s clinical trial, his tumors began to shrink.

“I thought I was dead,” he says, “and then it was like, this miracle.”

C3: WINTER 2022 21 SUPPORTER F CUS

It all started with a lump McNeilly’s cancer journey started in January 2018, at his annual physical. McNeilly mentioned a lump he had noticed on his left thigh, and his primary care doctor sent him for an ultrasound with a vascular specialist. Concerned the lump could be a sarcoma, the specialist referred McNeilly for an MRI, where the diagnosis was confirmed. “That immediately sent us scampering: ‘Oh my God, what is this, and where can I get treatment?’” McNeilly remembers. “We did whirlwind research, and my wife really got into it and identified places we could go.”

They found the perfect fit at the CU Cancer Center—not only would it allow them to stay local to Denver, but McNeilly was reassured by the center’s multidisciplinary clinic model, where multiple specialists meet to review a patient’s case and devise a joint recommendation for care and treatment. The McNeillys felt fortunate they had the resources—along

with other grateful patients—to establish the Cheryl Bennett and McNeilly Family Endowed Chair for Wilky.

Endowed chairs are vital to the future of academic medicine and are the highest academic award the University can bestow on a faculty member. Endowed chairs are established with a minimum gift of $2 million; additional gifts to a specific endowment would enable the chairholder to increase the amount of research, for example by hiring a PhD to assist them, or purchasing new equipment or technology.

“Sarcoma, unfortunately, is a fairly rare type of cancer, and they haven’t had a lot of the research that some of the other major cancers have had,” McNeilly says. “But there’s a small group of researchers throughout the world, including Dr. Wilky, who worked together closely

22

COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG

"Sarcoma, unfortunately, is a fairly rare type of cancer, and they haven't had a lot of the research that some of the other major cancers have had."

to leverage their capabilities. She knows what’s going on throughout the world, and she’s a great networker. It’s fantastic, what they’ve been able to do.”

Sarcomas explained

Sarcomas are rare cancers that account for only about 1% of all adult cancers and about 15% of cancers in children. They can

form in various locations in the body, including the bones and the soft tissue (also called connective tissue) that connects, supports, and surrounds other body structures. This includes muscle, fat, blood vessels, nerves, tendons, and the lining of the joints. Most sarcomas occur in the arms, legs, or trunk of the body, but they can occur anywhere from head to toe. There are more than 150 different types of bone and soft tissue sarcomas.

“Most people with sarcoma will have a growing soft tissue mass, most commonly on an arm or leg or the flank,” Wilky says. “If you have a mass that’s bigger than a golf ball or is starting to grow or is causing you pain, you really need to get that looked at. There are simple tests like an ultrasound or an MRI that can tell the difference between the more common things, like a cyst or a hematoma, and a tumor. That early recognition is so important because if you catch it early, you can just remove it. But if they get bigger than that, that’s where you start to run the risk of having it spread and become more complicated.”

C3: WINTER 2022 23 Get more CU Cancer Center news on our blog: news.cuanschutz.edu/cancer-center

WINTER

2022

www.coloradocancercenter.org

C3: Collaborating to Conquer Cancer

Published twice a year by University of Colorado Cancer Center for friends, members, and the community. (No research money has been used for this publication).

Contact the communications team: Jessica Cordova | Jessica.2.Cordova@cuanschutz.edu Greg Glasgow | Gregory.Glasgow@cuanschutz.edu

Design: Jack Dunker | Design & Print Services University of Colorado

The CU Cancer Center partners with:

UNIVERSITIES

Colorado State University University of Colorado Boulder University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

INSTITUTIONS

UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital

UCHealth Cherry Creek

UCHealth Highlands Ranch Children’s Hospital Colorado Denver Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Visit us on the web: coloradocancercenter.org

To support the fight against cancer with a philanthropic gift visit giving.cu.edu/cancercenter

The CU Cancer Center is dedicated to equal opportunity and access in all aspects of employment and patient care.

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO

ANSCHUTZ MEDICAL CAMPUS

13001 EAST 17TH PLACE, MSF434 AURORA, CO 80045-0511

RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED

THE MESSAGE

Non-profit organization U.S. POSTAGE PAID Denver, CO Permit No. 831

FROM THE DIRECTOR RICHARD SCHULICK, MD, MBA

DIRECTOR, UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO CANCER CENTER

ARAGÓN/GONZALEZ-GUÍSTÍ

ENDOWED CHAIR OF SURGERY, UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Celebrating our female leaders

At the University of Colorado Cancer Center, our diversity doesn’t just set us apart; it makes us stronger. We are proud that our membership includes doctors and researchers from countries around the world—and equally proud that females make up half of our leadership team. That distinguishes us from other cancer centers around the country, where leaders tend to be predominantly male.

As Heide Ford, PhD, associate director of basic research at the CU Cancer Center, says in this issue’s cover story, “For so many years, the academic world has been largely homogenous, largely male, largely white, and we were not getting diverse perspectives because we weren’t seeing a diversity of backgrounds represented. There’s data now that show if you get more people in a room from different backgrounds, your organization will see more innovation, more advancement, have better retention. That means people of color, members of the LGBTQ community, the spectrum of cultural backgrounds and economic backgrounds, and women. Women need to be in the room.”

Those female voices have only served to elevate the departments and divisions in which they serve—at the CU Cancer Center, women are in leadership roles in areas ranging from scientific research and clinical trials to population health

and cancer prevention and control. The amount of high-dollar research grants, professional awards, and other accolades bestowed on our female leaders over the years is simply staggering.

When the National Cancer Institute (NCI) renewed our designation as an NCI Comprehensive Cancer Center in spring 2022, it paid special attention to our efforts in the prevention and awareness of cancer, led by Deputy Director Cathy Bradley, PhD, and the work of Evelinn Borrayo, PhD, associate director for community outreach and engagement, to provide equal access to cancer prevention and treatment to people in underserved communities in Colorado.

We know that to succeed and innovate going forward, the CU Cancer Center has to become even more diverse and welcome voices from still more communities not yet fully represented in our membership.

Our female leaders will provide leadership in those areas and many more as we strive to truly represent the communities we serve.

24 COLORADOCANCERCENTER.ORG

A Cancer Center Designated by the National Cancer Institute

Comprehensive Cancer Center

By Rachel Sauer

By Rachel Sauer

By Greg Glasgow

By Greg Glasgow