COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC MAGAZINE

Editorial

EDITOR

Daniel Mahoney

EXECUTIVE

EDITOR

Rob Levin

COPY EDITOR

Caitlin Meredith

EDITORIAL ADVICE

Dru Colbert Darron Collins ’92

Jennifer Hughes

EDITORIAL CONSULTANT

Jodi Baker

DESIGN

Corey Blake Z Studio Design

Administration

PRESIDENT Darron Collins ’92

PROVOST Ken Hill

ASSOCIATE

ACADEMIC DEANS

Jamie McKown

Kourtney Collum

DEAN OF ADMISSION

Heather Albert-Knopp ’99

DEAN OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT

Shawn Keeley ’00

DEAN OF ADMINISTRATION

Bear Paul

DEAN OF STUDENT LIFE

Joshua Luce

DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Rob Levin

Board of Trustees

TRUSTEE OFFICERS

Beth Gardiner, Chair

Marthann Samek, Vice Chair

Hank Schmelzer, Vice Chair

Ronald E. Beard, Secretary Barclay Corbus, Treasurer

TRUSTEE MEMBERS

Cynthia Baker

Timothy Bass

Michael Boland ’94

Joyce Cacho

Alyne Cistone

Heather Richards Evans

Allison Fundis ’03

Marie Griffith

Cookie Horner

Nicholas Lapham

Howard Lapsley

Casey Mallinckrodt

Anthony Mazlish

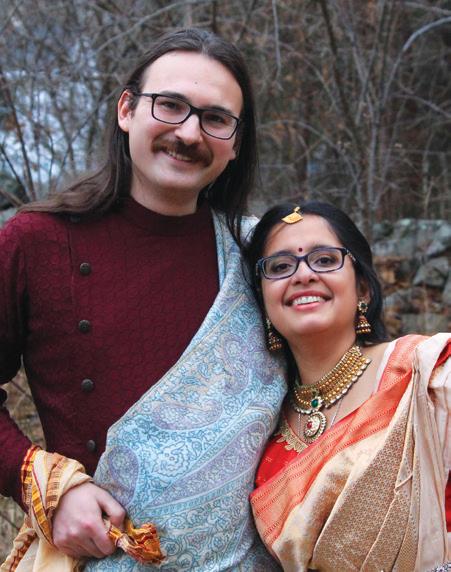

Chandreyee Mitra ’01

Roland Reynolds

Nadia Rosenthal

Laura McGiffert Slover

Laura Z. Stone

Steve Sullens

Claudia Turnbull

LIFE TRUSTEES

Samuel M. Hamill, Jr.

John N. Kelly

William V.P. Newlin

TRUSTEES EMERITI

David Hackett Fischer

William G. Foulke, Jr.

Amy Yeager Geier

George B.E. Hambleton

Elizabeth D. Hodder

Jay McNally ’84

Philip S.J. Moriarty

Phyllis Anina Moriarty

Cathy Ramsdell ’78

Hamilton Robinson, Jr.

William N. Thorndike

John Wilmerding

EX OFFICIO

Darron Collins ’92

At College of the Atlantic, we envision a world where creativity, presentness, compassion, respect, and diversity of nature and human cultures are highly valued. A world where all people have the opportunity to construct meaningful lives for themselves, gain appreciation of the relationships among all forms of life, and safeguard the heritage of future generations.

COA Magazine is published annually for the College of the Atlantic community.

Each time I’ve addressed an audience across the past 13 years, I’ve introduced myself as, “Darron Collins, an alumnus and the president of College of the Atlantic.” Beginning July 1 of this year I’ll go back to introducing myself simply as, “Darron Collins, an alumnus of College of the Atlantic.” These 13 years have been outstanding: ultimately challenging and with great personal and professional rewards. Just like the family of COA President Steve Katona when I was a student, the elements of my family got the chance to become part of the COA family. Collectively, we both helped shape and were shaped through the dance we did with this tremendous educational institution.

“Navigating Change” is a perfectly appropriate metaphor for the last opening letter I will pen for COA Magazine. We love our maritime metaphors at COA—maps, compasses, sextants, and the like—and this one is particularly rich and inspired me more than a few times to yell over to Dan and the editorial desk to ask for more space. With plenty of ink by or about me in this edition, he appropriately told me to keep it short, so, consider this interpretation and tactic for doing such navigation.

Between my sophomore and junior year in high school I did a stint building fences out in the high desert of Idaho with the Student Conservation Association. My trip leader quickly became a mentor to me during and after my fence building. But at one point late in the trip he caught me just standing around and screamed at me, “WHY in God’s name are you just standing there when we have miles of this stuff to build,” and my response was that I didn’t know what needed to be done next.

“Sometimes, Darron, you just need to pick up a tool and have a go at it.”

That stuck, and that kind of having a go at things has since been a part of how I’ve moved through the world. Fast forward to my recent experiences volunteering on the Bar Harbor Fire

Department and the winter of 2022 when the hotel across the street from the college went up in flames. Building on fire. Things to do. Pick up tool. Have a go. And just as I did I felt a large hand on my collar and a verbal and physical call for restraint: “Collins you stand here and don’t move a muscle until I tell you to.”

When managing flames and highly flammable things, such freelancing is highly frowned upon. It turns out, in a perfect example of life-long learning, that navigating change requires knowing when to just have a go at it and when to stand at attention and be ready to respond to commands; requires balancing innovation with expertise; requires individual initiative and effective collaboration.

The pages of this magazine tell stories of navigation and of change, from students and alums and friends from the distant past and this year. They tell the story of our own Ship of Theseus, and how we navigate all the while replacing the planks on the high seas. I think you will be both entertained and edified, and will come away with a better understanding of who we are and what we do. Enjoy.

Darron

AHANDFUL of years ago, I was pretty sure the world was going to end. All the signs were there: bugs everywhere, strange dogs, smells in the air, a low hum from behind the refrigerator. We traveled out to California to visit our families. We made it to Santa Ana, CA, and were directed to an exquisite taco truck for dinner. We heard the truck had become popular so there was usually a line, but it was worth the wait. We went and joined the 30 young and older souls waiting for food. As we waited, we noticed cars parked on the road next to the truck selling other homemade items: bread, ice cream, mixed drinks, textiles... It was like an informal artisan food and craft fair on the darkened streets of Santa Ana, 8 p.m. on a Thursday. After we got our food, we sat on the ground enjoying our meal with all the other families spread out on the cool concrete, and I remember thinking in that instant that it was all going to be OK; that this human moment—facing all these other people—outweighed the abstract fear of world destruction no matter how many dogs crossed my path.

I feel the same way about this issue of the magazine, Navigating Change. There are fewer tacos here but there is that same feeling of people coming together. Coming together is key in a world where it has become easier and

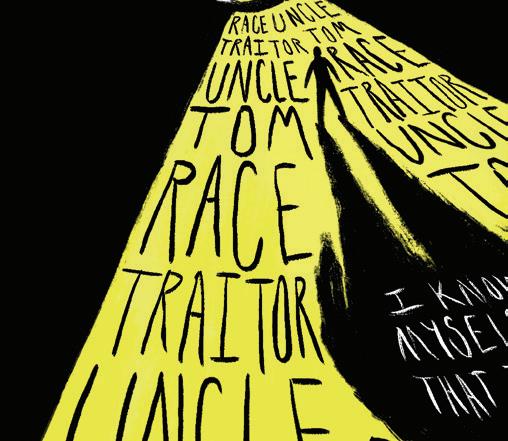

easier to fly apart. The digital aspect of culture makes us sometimes feel like we are everywhere all at once, engaging with folks from far-flung corners of the galaxy... Like everything matters so much all the time. But the cost of this is that we feel ultimately powerless to do anything about the problems we encounter in the digital domain, which can lead to powerlessness in general. As Jack Giaour says in his interview for Navigating Change, "I’m trying to reconcile the feeling of not wanting to engage with it anymore, but I also feel like I'm responsible to engage with it, if only to just witness it and acknowledge that it's happening."

Which brings up the idea of responsibility. Ever since reading (failing to read?) the work of Emmanuel Levinas, I have come to see responsibility in a very Levinasian light. Levinas says the face-to-face encounter with another human—the Other—is the foundational experience for ethical responsibility. Basically, we respond to the Other and are responsible for the Other; it is through this obligation, this responsibility to the Other, that we come to know ourselves. I love the intimacy here. Knowingness begins face-to-face, responding to someone else. If you look, there are lots of faces in this issue: new faces at the college, new trustees, old friends, and faces of those who have traveled to the other side, may they rest in peace. There are face-to-face encounters with fishing communities in Maine and on Rakiura, and a lyrical essay written by a man who faced one of the darkest days in our nation’s history.

The work here is all about what happens when we face each other: we make connections, we build things, and we tell stories, which again makes me think of Levinas and what he says in Altérité et transcendance: “The very relationship with the Other is the relationship with the future.” Onward we go.

Dan

Stories by Rob Levin

PRIORITIZING DIVERSITY, equity, and inclusion, centering infrastructure improvements, and boosting College of the Atlantic’s visibility are the three main focus areas of COA 2030, a new strategic plan for the college passed by unanimous vote at All College Meeting during Week 10 of the 2023 fall term.

Passage of the plan capped off a yearlong planning effort, begun by COA President Darron Collins in fall 2022 and subsequently led by planning consultant Sarah Strickland beginning in winter 2023. That work included multiple listening sessions, ACMs, workshops, surveys, and a 17-member task force made up of students, staff, board members, and faculty. The Board of Trustees gave their unanimous vote of approval to the plan in their regular winter meeting in January 2024.

“This strategic plan is the result of a lot of deep thinking, collaboration, and hard work by so many members of the COA community,” said COA President Darron Collins '92. “It ably outlines the work that lies in front of the COA community to bring the college into the future while building a stronger, more effective, better organization.”

COA 2030 builds upon the 2015 Strategic Plan (The MAP) and critical work that has been underway since 2020 by planning groups, task forces, and student projects comprising food access and insecurity, housing, human resources, academic priorities, accessibility, and campus services. The plan commits to human ecology

as a framework for understanding and shaping the world, celebrates being experimental and collaborative, and illuminates the need for more effi cient systems in order to improve the quality of student experience and the school’s impact on Mount Desert Island, the broader world, and higher education.

“The 2030 Strategic Plan requires us to improve student wellbeing and postgraduation readiness, to update our campus systems and infrastructure, and to fortify the fi nancial health of the college and its employees,” the task force states in the introduction. “Simultaneously the 2030 Strategic Plan invites us to stretch outward and upward; to refi ne our participatory governance; to embody adaptive leadership; and to continue to celebrate our interdisciplinary and human-ecological perspective. We must move forward on all.”

Broken into six main strategic priorities, COA 2030 embraces and seeks to improve current COA structures such as the ACM governance model, boost student wellbeing and post-graduation readiness, improve student retention, enhance the fiscal health of the college, and ensure the continuation of COA’s unique approach to transformational teaching and learning.

COA 2030 highlights include creation of a fund to allow the college to meet 100% of fi nancial need for all students, developing an equity fund to help all students access basic academic and extra-curricular needs, including unpaid internships, and

eliminating food insecurity among all students. The plan also calls for the development of off-campus, COA-managed housing for staff and faculty, completion of a feasibility/ business plan to offer alternative, year-round, revenue-producing programs, and investment in campuswide, integrated, secure, coherent IT systems that support teaching, research, on- and off-campus learning, business offi ce functions, and campuswide communications. Finally, COA 2030 calls for ensuring that the COA campus is physically accessible to all for year-round use.

COA 2030 will form the foundation of the college’s next capital campaign, says dean of institutional advancement Shawn Keeley '00. Preparation for the campaign will take place over the next year as an operational plan comes into being.

“Philanthropy has always been a catalyst to major steps forward for the college, whether new initiatives, buildings and infrastructure, or endowments to support our programs. To accomplish the goals outlined in the strategic plan, we will once again need the support of our community,” Keeley said. “College of the Atlantic has an incredible history of constantly growing, improving, and evolving as an institution, and that is due in large part to the many generous people who have invested in us along the way. I’m really looking forward to working with our supporters, both existing and new, to actualize the many ambitious improvements outlined in the COA 2030 strategic plan.

between College of the Atlantic and University of the Philippines, Los Baños (UPLB) aims to provide increased studyabroad opportunities for COA students and faculty while also raising COA’s name and visibility in the world.

The purpose of the agreement, hatched within the past year by COA Provost Ken Hill and professor emeritus of psychology Rich Borden, is to develop academic and educational cooperation and promote mutual understanding between the two schools. This means research positions, student exchanges, masters and doctoral work, study abroad courses, and other opportunities, Borden said. UPLB comprises the preeminent college of human ecology in Southeast Asia, and staff and faculty there have had a relationship with COA since both schools were founded around 1970 that now promises to become mutually beneficial.

“They have been very influenced by our interdisciplinary ways of teaching and the flexibility in our curriculum, and they have reached out to us to see about ways that their Southeast Asiancentered curriculum could be enhanced by a partnership with COA,” Borden said. “At the same time, they are very networked with both environmental and economic development activities in the area, opening up a lot of opportunities for our students and faculty.”

The new partnership will significantly broaden COA’s curricular offerings for students, Hill said, while future faculty exchanges stand to build cross-cultural relationships and open opportunities for novel bioregional studies.

“UPLB faculty are top scholars but even better teachers,” Hill said. “It’s exciting to think that our students could learn from experts in a completely different culture and region.”

The partnership grew out of the longstanding relationship between both schools and more recent discussions between Borden, Hill, and UPLB professors at several conferences of the Society for Human Ecology (SHE), an international body that both Hill and Borden have led. The 2016 SHE conference was held at UPLB.

The partnership offers both schools valuable opportunities for their students and faculty to expand their horizons, Borden said. He also sees it as an essential expansion of COA’s worldview.

“There is a kind of learning that can only happen when people from different nations and cultures spend meaningful time together. The world has become increasingly connected electronically; however, in-person learning and working relationships remain incredibly important,” Borden said. “We love having this island as our home base. Expanding our opportunities around the world of higher education and with other institutions concentrating on human ecology is a big part of the future of the college.”

RICK DUBE Summer Field Studies director

THIAGO ALTAIR FELLEIRA

Post-doc research faculty

PURANJOT KAUR '05

Title IX coordinator & HR support

SARAH KHEIREDDINE Post-doc research faculty

AMY MORLEY Manager of annual fund and major gifts

NATALIE NELSON Night watch

JEFFRY NEUHOUSER Director of internships & career development

ELLIOT SANTAVICCA '20 Archivist/librarian

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC this year announced the creation of a full tuition waiver program for Wabanaki students.

Sparked by the COA Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Strategic Plan that was passed by All College Meeting in 2021, the waiver follows numerous conversations on campus, including through an informal Indigenous working group, and with Tribal leaders, Bar Harbor’s Abbe Museum, and the Wabanaki Center at the University of Maine.

“For time immemorial, MDI has

provided us with everything we needed to sustain us. Now, it will provide future Wabanaki COA students with sustenance for their minds,” said John Bear Mitchell of the University of Maine Wabanaki Center. “The work that College of Atlantic has done, working with the Wabanaki post-secondary community, will provide a valuable opportunity for our students to gain a unique educational experience. The opportunity College of Atlantic is providing is beyond generous and really considers the importance that higher education plays in our tribal communities.”

The tuition waiver is available for any enrolled COA student who is a Maine Tribal member or a direct descendant of Maine Tribal members. COA will also meet additional demonstrated financial need without loans for Wabanaki students, using the college’s regular institutional financial

aid methodology. In order to be eligible, students must apply and be admitted to COA using the college’s undergraduate admission processes.

"The Wabanaki tuition and fee waiver is something we should have done decades ago, but is nevertheless a piece of very good progress on the work we are doing at COA to collaborate more holistically with our Wabanaki partners," said COA President Darron Collins '92.

"As a college dedicated to a place-based approach to education where our specific geography here on the Maine Coast is crucial to what and how we teach, this work represents a must have for COA and appropriately goes beyond simply acknowledging our historical impact on the Wabanaki people with words spoken before a public event."

Working groups at the college have also discussed, and plan to implement, several other elements to a more robust Indigenous land acknowledgment.

Graupel, an accumulation of time, place, sculpture, and performance, was to find itself frozen on the ice at Little Long Pond, down the road from College of the Atlantic in the village of Seal Harbor, but unseasonably warm weather landed the play back on campus in late winter. Structured as an opera in five acts, performers guided the audience through a frozen landscape that was at once familiar and unknown. The performance was the culmination of A Production Monster Course, a term-long, threecredit class taught by COA Joanne Woodward & Paul Newman Chair in Performing Arts Jodi Baker and arts & design professor Dru Colbert.

By Anara Katz '24

EDUCATOR endorsement is allowing students who hope to further their studies of education and/or teach in countries outside of the US a solid path forward.

For nearly 35 years, COA has offered an education track to students that blends the conceptual framework of human ecology with classes and field work that meet the requirements to be recommended a Maine Teaching Licensure, which is reciprocal in nearly all other US states. As of the 2023-24 academic year, College of the Atlantic is pleased to offer an option for students to graduate with an Educational Studies Endorsement (ESE) attached to their human ecology BA degree. The endorsement reflects a defined set of requirements that mirror the Maine State certification requirements but with greater flexibility for students who have plans to work in education in varied places and perhaps even in varied subjects, and more closely reflects the fact that COA’s student body comprises 25% international

students, many of whom aim to return home to begin their careers.

"This path means an opportunity to grow and learn as a future educator, realize my specific focus within that, and hopefully have my work recognized far beyond the State of Maine," said international ed studies student Ruby Newman '24.

The new track has been approved by the COA Education Studies Committee in collaboration with interested students. There are typically 20–30 students in COA's education program, and, this year, seven have declared an interest in pursuing the new Educational Studies Endorsement track.

“Each ESE will have a focus, and that will direct not only the student's course pathway, but also required fieldwork and an education-based internship," said COA Co-Director of Educational Studies Linda Fuller. “We do hope that through strong communication and discussion about a solid curricular pathway it helps better prepare students to

work in education internationally and/or to pursue a graduate degree in some aspect of education.”

The education studies program at COA blends interdisciplinary education classes, ranging from educational change to curriculum design, that encourage ed studies students to develop a professional education philosophy for themselves as future educators. The ed studies faculty, in conjunction with the Ed Studies Committee, work with students on an individual level to help them create a portfolio of classes and experiences that allow them to go directly into teaching after graduating COA. COA collaborates with local public and private schools, museums, therapeutic riding centers, sexual health clinics, nonprofit organizations, and more to provide students with education experiences that match their interests. COA's educational studies program reinforces human-ecological values of place-based education, service to one's community, and curriculum integration.

ALLISON FUNDIS is the chief operating officer for Ocean Exploration Trust, where she draws on diverse backgrounds in science, education, and extensive sea-going experience to engage the science community, students, and the public in telepresence-enabled expeditions aboard the trust’s exploration vessel Nautilus. Since 2006, she has led or participated in 50+ expeditions utilizing a variety of deep-sea technologies and submersibles in the Pacific Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, Gulf of California, Caribbean Sea, and Mediterranean Sea.

Before joining Ocean Exploration Trust in 2013, Fundis worked with the National Science Foundation’s Ocean Observatories Initiative at the University of Washington, where she participated in the planning and installation of the US’s largest cabled seafloor observatory in addition to developing resources and programs for students that utilize the observatory’s real-time data. As a former high school teacher, she remains passionate about making authentic opportunities in STEM available to students, educators, and the public through the trust. In 2019, she was recognized as an innovation and technology delegate for the Academy of Achievement and as an IF/ THEN ambassador by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She is a 2020 Fellow National of the Explorers Club and, in 2021, was named a National Geographic Society Emerging Explorer. She holds an MS in marine geology from University of Florida and a BA in human ecology from College of the Atlantic.

LAPSLEY is a partner in Oliver Wyman’s Health and Life Sciences Practice, based in Boston. Oliver Wyman is a $2B global management consultancy and a subsidiary of Marsh & McLennan. Lapsley co-leads Oliver Wyman’s retail health and distribution strategy teams, as well as focusing on consumer-centric business design, development of value-based arrangements with payers and providers, marketing, new product development, and ancillary benefits. Lapsley is a frequent speaker at industry forums and has presented to America’s Health Insurance Plans, the National Institute for Health Care Management, Alliance of Community Health Plans, the Life Insurance Marketing and Research Association, and the National Institute for Healthcare Leadership, among others.

Lapsley has been at Oliver Wyman since graduating from business school in 1995. Before Oliver Wyman, he was an account supervisor at Grey Advertising in New York City, focusing on consumer-packaged goods. Lapsley holds a BA in history from Harvard University and an MBA from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. He considers himself fortunate to have been a summer resident of Northeast Harbor, on Mount Desert Island, his entire life and is an active sailor and mountain bike rider. He is married to Karen and has three boys: Tim, Robert, and James.

By Jeremy Powers '24

OF THE ATLANTIC is excited to welcome Su Yin Khor as the new director of the COA writing program and a faculty member in writing and rhetoric. Khor’s past research and pedagogical approach combine to form an educational framework perfect for COA’s interdisciplinary system, and she is looking forward to taking a deep dive into the life of a writing educator at COA.

“I wanted to work at a small school where I could be supported, because the research that I do and the way that I teach, it’s all transdisciplinary. Most schools have departments, and I didn’t really fit into that model of teaching and doing academic work… I kept saying, I need to find a small school where I can do the work that I want to do as a teacher,” she said, “and I finally found this place where everyone is on board with that idea of thinking about the connections between different areas of inquiry.”

Khor grew up in Sweden, where she attended Uppsala University as an undergraduate and stayed on for her graduate work. She holds a BA in history with minors in American studies and Japanese. For her MEd, she studied English and history education with the intention of becoming a high school teacher.

how language, identities, and social issues intersect and shape the way we write.”

When it comes to her pedagogical approach, Khor said, “I see myself more as a facilitator, rather than someone who says, Hey, I’m going to teach all these things, and I have all the information.” Her role as an educator does not preclude her from learning, she said, and she actively encourages students sharing information, stories, and conversation during class.

“I found that I really enjoyed working with older students so I thought that working with college students would suit me better,” she said.

Khor’s views on writing and composition changed with her acceptance into the English master’s program at Penn State, where she specialized in applied linguistics and teaching English as a second or foreign language (TESOL).

“I was introduced to contemporary perspectives on teaching writing that went beyond grammar, and instead contextualized writing in our social worlds and how they intersect with our writing and literacy development,” she said. Her master’s thesis was an analysis of several memoirs written by South Asian authors that highlighted the intersections of identities, multilingualism, and writing.

Khor’s teaching at COA will include skills and concepts that “not only address the micro-level aspects of writing but contextualize them in our social worlds and examine

“Of course, I present factual information about writing. But then we have very deep discussions about what that means, such as different beliefs and ideas that people have and how that complicates writing in the classroom and elsewhere,” she said. “It’s interesting to see how other students learn from each other as well. It really is a community of learning.”

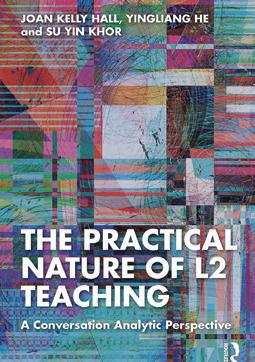

Khor is active on the research front, and has co-authored a book titled The Practical Nature of L2 Teaching: A Conversation Analytic Perspective (Routledge, 2023). She has also written several book chapters, which range from topics such as “Multimodality and writing for international multilingual students: Connecting theory and practice” (Multimodal composition: Faculty development programs and institutional change, Routledge, 2021) and “A collaborative multimodal autoethnography: Women leaders in TESOL (Reimagining influence in TESOL: Deconstructing female leadership identity, forthcoming).

In her free time, Khor enjoys baking, reading mystery novels, and spending time outside. She is enjoying her transition to COA.

“I’m so happy,” she beamed. “I love coming to work. I love just being in this environment. I feel really inspired. Don’t get me wrong, I have a lot of things to do, but I feel good about working through all these things with my students and my colleagues. It’s wonderful, and I feel really, really supported, so I truly am excited to be here. I finally feel at home, you know, and it’s been a long journey.”

By Jeremy Powers '24

AS A DESIGNER with a cross-disciplinary approach to architecture, ecological systems thinking, and teaching, Brook Muller is excited to step into College of the Atlantic’s Charles Eliot Chair in Ecological Planning, Policy, and Design. He will be teaching classes on sustainable architecture, urban planning, and a systems approach to design, and will use his ongoing projects to involve students in real, tangible examples of how principles of design and thinking outside the box can and do apply to the real world.

“I like the pedagogical model of COA, because I’ve been working for decades to try to place sticks of dynamite in the walls of the silos between disciplines at the institutions I’ve been in. And at some point, it’s not that rewarding,” Muller said. “You have to be in a place where you’re encouraged to think that way.”

After graduating from Brown with an environmental science degree, Muller turned his attention to the University of Oregon, where he received a master’s in architecture. He worked in Germany for several years, where he served as co-project leader for the design of the National Institute for Forestry and Nature Research in Wageningen, The Netherlands, a European Union pilot project for environmentally friendly buildings. He has since collaborated with designers and changemakers in Egypt, and most recently served as dean of the Charlotte College of Arts + Architecture at the University of North Carolina.

in the park. In other words, the medium causing harm becomes the very resource to make a new system go; such is the logic of systems-based ecological design.”

He is looking forward to incorporating this project, now in its second stage, into his classroom teaching. “I am so excited about engaging COA students in this work, not only in Cairo, but more broadly in applying ecological design principles to urban contexts in the cause of environmental quality and environmental justice,” he said.

Muller is now collaborating with Megawra Built Environment Collective in Cairo, Egypt, which is a twinship between Megawra, an architectural office specializing in conservation and heritage management, and the Built Environment Collective, an NGO specializing in place-based cultural and urban development. He previously served on the collective’s design team and managed an international field school that led to the recently completed al-Khalifa Heritage and Environment Park, a much-needed green space primarily intended for women and children in the heart of medieval Islamic Cairo.

“The approach involves intercepting water from leaky pipes damaging 13th century shrines that my colleagues are working to restore, treating it, and directing it to vegetation

While deriving a lot of satisfaction from his professional design work, Muller has long been aware of his desire to teach the next generation of ecological thinkers. “I knew from my time in graduate school that teaching had to be central to my future, teaching that embraces a systems-based approach to design with a strong focus on water,” he said.

Muller’s pedagogical approach, he said, rests on “presuming the intelligence of the people you work with. Setting up a framework which is fairly rigorous. Creating a studio environment, where individuals and teams are given this framework and resources that I provide. It functions to help us all understand different ways of thinking through these challenges that we’re confronting.”

“As students or teams start to take on ownership over these things, they evolve in certain kinds of ways, and as the term progresses, it turns from my framework to our framework to your framework. So, it’s this combination of a rigorous framework that meets a certain open-endedness.”

In his free time, Muller likes to “read and walk at the same time. And I will die that way. But you know, if it’s a good excerpt, it’s a good passage, then that’s a good way to go,” he said lightheartedly.

Muller’s recent book, Blue Architecture: Water, Design, and Environmental Futures (University of Texas Press, 2022) is an essential read for anybody interested in water-focused and ecologically minded architecture and urban design. It was a finalist for the 2023 PROSE Award in Architecture and Urban Design.

By Jeremy Powers '24

BIOLOGIST turned painter, Neeraj Sebastian comes to COA with a broad range of life experiences to apply to his teaching and art practice. A soft-spoken man whose intentionality comes across clearly in both the words he says and the paintings he creates, Sebastian’s path to art is an inspiring example of an interdisciplinary approach to life.

He began his journey to art studying molecular biology at Drexel University. Graduating from there with a BS in biological sciences, he began working at the National Center for Biological Sciences in a lab that studied the cell membrane.

“It took me some time to really find what it is I wanted to do. When I was in Philadelphia, I took a painting class at a community art center called Fleisher Art Memorial. And I remember when I was mixing paint on the palette, and then painting with it, I had this feeling that this is what had been missing from my life, but I hadn’t known because I hadn’t worked with oil paint before.”

This sparked a desire to take painting seriously, so Sebastian continued taking classes at Fleischer and then moved back to India, where he built the body of work that he used to apply to graduate school. During his master’s degree education at University of North Carolina, Greensboro, his practice shifted from observational to a more studio-based approach, focusing on invention and synthesis of ideas.

Sebastian's science background undeniably influences his art, and he continually draws parallels between art and science. “The two fields do inform each other,” he said. “I think working in a research lab taught me how to accept failure as part of the process. If an experiment doesn’t work, you have to kind of troubleshoot and change a few things at a time. One of my professors from grad school put it in an interesting way; she talked about both painting and science being speculative processes. You set up these parameters, and then you investigate. You don’t really know where you’re going.”

This process of speculation, experimentation, and learning also applies to his pedagogy and methods of teaching painting. “I feel like I learn so much when I’m in the classroom, because when I’m by myself, maybe there are some formulae that you sort of use to start a composition, or to place forms, or to establish some of these relationships. In the classroom, it’s always nice because working with the students helps me think about why I make certain decisions. And I think in the classroom, especially in the concentrated 10-week term we have here, I think my priority is to make a lot of quick drawings and paintings, so that the students can think about the big picture, the larger organization of colors and forms,” he said.

“That transition I remember being quite uncomfortable and difficult because I was always worried. What if I get the anatomy wrong of the figures? What if I get the lighting wrong? And then, I think, by the end of grad school I realized it doesn’t matter because the whole thing is made up,” he said. “The faculty members at UNC Greensboro gave me the space to experiment, be vulnerable, and to fail—and I failed often; there was a lot of experimentation and there were a lot of bad paintings before things got interesting. And I hope to create a similar environment for students here at COA—to allow them to experiment, take risks, and surprise me and themselves.”

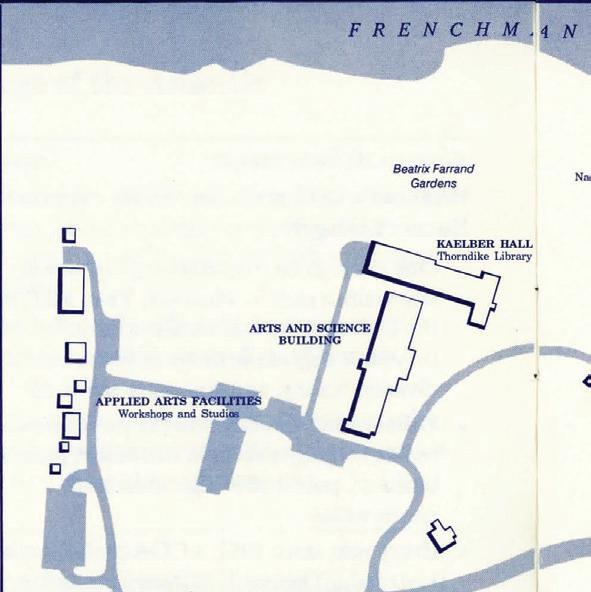

His studio, located in the maze of the Arts and Sciences building, is spacious, and he plans on incorporating the space into his teaching. “My plan is to start working on my own paintings within this space. Because an important part of grad school for me was seeing my professor’s studio, how these paintings came together, so I think it’s useful for the students to see my studio, my workspace.”

In his free time, Sebastian said, he likes to watch movies and also enjoys reading. Mostly, though, he has plans to paint. When asked on how his art evolves during the creative process, he replied that it’s all about recognizing and making peace with the unknown. “Once a painting comes to this moment of transition, it could go in many, multiple directions. There’s no right or wrong way to do it. It could end up in a bunch of different ways.”

By Devin Connor '12

OUR INTRODUCTION was marked by a modest handshake and a brief exchange of glances. Unassuming in attire, his daily uniform consisted of monotone tan workwear and a sunhat. Like a caricature of neutrality, his appearance revealed nothing of his person. In the earliest days, he worked on preliminary layouts for the line alone. A quiet enigma in the college landscape, he carefully pulled lengths of hose into graceful curves, the indifferent subject of many a passing gaze. The unpretentious fi gure in tan worked at his strange labor with the slow and steady intent of a tradesman. It was all very obscure at fi rst, Andy and the project. The process was yet to be developed, as was the shape and trajectory of the line itself. We might mock it up in stones or simply follow the curving hose. As local crews worked on preliminary stone cutting and I on basework and logistical concerns, my nerves mounted to a crescendo sensing the impending moment when curb would meet earth—the moment of inception. During the setting of those fi rst few stones we played with excited apprehension. As I delved into my element, so did Andy into his. Within 20 feet of laying the winding curbstones, a notion of the art piece emerged. Along with that, from

fi rst stone to last there evolved a method and series of refi nements that would express that notion gracefully.

The work and the process were grueling. These days, the curbs lining our roadways are set in concrete. Like everything in the modern world, the process has been systemized to increase production and limit the need for skilled labor. There is no question of what direction the curb will take; the curb follows the road. Not so with the obscure curb line that we would chase. We set our curbs into crushed stone with a three-foot hammer and exuberant force. The effort needed to set each curb to the desired height was immense. The ground would shake 20 feet away with the force of hammer meeting stone, only to drop the curb by a paltry fraction of an inch. Each stone was painstakingly cut, and the ends prepared to ever-more-nuanced specifi cations before being cut again during setting for a precision fit. The process required a great effort, and, with bloody knuckles and anguished bodies, an even greater focus.

Road Line was an excruciating undertaking for all involved, perhaps none so much as the artist himself. There was an unrelenting sense of conflict between

the needs of the art piece, landscape, and community. Not to mention the budget, timeline, and the pursuit of form. We faced valid concerns regarding tree protection, accessibility of road crossings, and use impacts. Andy had a clear desire to respect and encourage human engagement with the piece, open to input of how it might inhibit or enrich the experience of different beholders. But the challenges would become more abstract as judgements that questioned the piece’s value were brought to the surface. One protest chalked on a stone read, This is not human ecology. I've often wondered what fed this notion, and if the faceless judge anticipated the haunting feeling their protest would impart. As if to soften the blow, another of the writings insisted, We respect Andy. The laboring masons who discovered the messages wondered if that respect extended to us. And yet these challenges (and challengers) steered the project as components of a greater ecosystem affecting its articulation. The form of the piece was guided as much by the cooing, roars, and migration patterns of humans on campus as by the more conspicuous undulation of landforms. As a mechanism for bringing about Andy’s vision, I began to recognize the work as existing within this greater context. The many voices and forces weighing on us were inadvertent forces of nature acting on the formation of the art itself.

Andy's greatest personal impact has been to awaken me to the sanctity of process.

From my position as head mason, there was a freedom to behold the project in a way truly distinct from my experience at the helm of creative work. I was able to surrender to the process, trusting the governance of form to our leader. This was the meat of the project for me, existing in the realm of this dichotomy between the perceived art form and the physical process of creating it. Set in the landscape, the sculpture appears effortless, as if its form was ordained in the natural order of things. In reality, it is anything but. Only through massive effort could we create this thing whose beauty relies entirely on its perceived effortlessness. Focusing on art itself while actualizing it through a physically intense and masochistic process was revelatory. Working with Andy as he toiled over the form, our small installation crew soon found ourselves in fl uent accord: This stone isn't the right radius. This whole run needs to be taken out and reworked. What began as a concept in Andy’s mind became this living thing whose needs we could sense intuitively and provide for enthusiastically. Despite the physical cost of manipulating these unforgiving materials, we were acutely aware of something sacred in this process and so would never think to protest. What a gift, to wade through this chaos and toil, and to fi nd amongst our core crew a singular focus on that sacred point which, through its carefully controlled meandering through the universe, constituted the artwork.

Andy's greatest personal impact has been to awaken me to the sanctity of process. After a life of putting so much concern and ego into fi nished work, this project leads me to believe that it is the action of engaging the universe in expression which aligns the artist with something essential. Andy appears to spend the majority of his life nurturing this phenomenon, embracing the pulse of

creation through near constant immersion and expression of it. Throughout the project he would disappear in quiet moments to the shore to create ephemeral works. Some were in keeping with what you might imagine— arrangements of stones and organic ephemera. Others went deeper. He did a series of recordings burying himself in seaweed, plunging blindly into the bugs, crabs, and other life as the tide crashed in for nearly an hour.

The work is the result of a process of engaging with context in the deepest sense, in landform, material and culture. He absorbs every bit of context—the history of local quarry workers and curb setters, the nuanced landforms of the campus, the tides, creatures, and very soul of the place.

In working with Andy, the disembodied notion of the human and nature that plagues the modern perspective is resolved. Andy, adrift in the seaweed, can hardly be abstracted from nature. He rejects being asked to “design” in the human realm, refusing to manufacture context for

his own work. He is not the arbiter or architect of the world his art occupies, but a creature whose engagement with the world results in art. The work is the result of a process of engaging with context in the deepest sense, in landform, material and culture. He absorbs every bit of context—the history of local quarry workers and curb setters, the nuanced landforms of the campus, the tides, creatures, and very soul of the place. With this immense sense of place he sets his intention, engaging in physical process as a conduit for the expression of something universal.

In the end, I’m left with a growing sense that this yearning we all have to create as individuals is connected to something essential wanting to be expressed. After years of unrelenting seriousness in my own work, it is Andy’s playful engagement with the natural world which inspires me. His work is an extension of the care he gives to his own soul. As he baptizes himself in the tides of nature, it becomes nearly impossible for his artistic expression to avoid revealing some natural principle. In a sense, Andy is an artist by species, and his artworks are the footprints left from his deep and unconventional engagement with his environment. As I sit in reflection, months on, I look to my masons and see a similar principle expressed. While burdened by perception of our class and creed, we too spend our days chasing lines through space, leaving tracks and traces that look an awful lot like art.

Andy Goldsworthy's 1,500-foot-long Road Line (2023) is the artist's fi rst permanent installation in the State of Maine. Devin Connor '12, founding owner of The Garden Artisans, served as chief mason on the project.

Edited by Alexa Kelly

Excerpt from Smarter Planet or Wiser Earth? Dialogue and Collaboration in the Era of Artificial Intelligence (Producciones de La Hamaca, 2023) by COA philosophy professor Gray Cox ('71).

Smarter Planet or Wiser Earth?, by College of the Atlantic philosophy professor Gray Cox ('71), argues new Artificial Intelligence technology is moving beyond classic Turing machines that rely on monological inference towards “Turing children” that may become capable of dialogical reasoning of the sorts used in negotiation, group problem solving, and conflict resolution. It argues this will reframe how we think about moral reasoning in general and the challenges of AI ethics in particular.

THE NEW GENERATIVE AIs use neural nets and reinforcement learning methods to develop more conversational AI that can start to imitate and in some ways perform many of the functions of a person engaging in dialogue. They pose questions, respond to inquiries, synthesize materials, present responses in different styles and from different points of view, generate appropriate images on request, and, more generally, behave in ways that seem sensitive to context in the ways in which human conversational partners do. The systems may still lack a variety of capacities humans can have. However, with each skill they do acquire, they bring to bear massive data and hardware that can outclass humans. Once they learn to play Go, code in Python, create paintings in the style of Salvador Dali, or take the bar exam, they can bring massive memory and speed to their responses. The results include increasingly powerful systems that pose serious ethical and existential concerns for humans.

At the heart of those ethical and existential issues lies a puzzle with two often ignored wrinkles. It is a puzzle in AI research that is now referred to as the “alignment problem” but has an older and in some ways more illuminating name, the “friendly AI problem.” Visions of

it have long loomed in our collective imaginations in science fiction stories about terminators, borg, and the matrix. It is commonly framed as the challenge of ensuring that ever more powerful AI systems operate on values that are aligned with humans’ values so that they do not run off the rails and start doing harm and creating catastrophic risks. The idea is that the system should be friendly to the humans who are creating it.

Framing it as a problem of friendship can help spark concerns about two wrinkles in the problematic. First, it is clear that we do not simply want to ensure that the AI are friendly to whoever creates or owns them. What if a rogue state or ruthless corporation is in that role? That is not what we want. We want to ensure the AI is friendly to people who are good rather than bad or, at the least, friendly to those who are trying to do what is right. We want it to favor folks working for something like a more just, peaceful, resilient planet instead of the opposite.

But that takes us to a second wrinkle. Suppose we do develop “Turing children” that are capable of dialogue and self-improvement, and they grow to become extremely powerful and super-intelligent systems that are friendly to the good and promote a more just, peaceful, resilient planet. What will they make of us? How likely are they to be friendly to a population of Homo sapiens that permits unnecessary mass poverty and illness to continue, runs factory farms for pigs in brutal ways, precipitates the sixth great extinction, runs an arms race in weapons of mass destruction, and actively promotes technologies that are becoming entirely out of control? What would we need to do

There’s a Change That’s a Comin’

differently in order to be worthy of the friendship of an artificial super intelligence that is genuinely ethical?

Just as it takes a village to raise a child, it takes an ethical village to raise an ethical child. To deal with the ethical and existential challenges that ever more powerful AI poses, it is necessary to consider the moral values and the structures of reasoning that govern our global village. How do the institutions of our economic, political, and technological institutions function—and malfunction? In reasoning about ethical concerns, how do we do so when we are at our best? How might that provide models reforming the major institutions of our global village? How might it provide ways of guiding research and development in AI and the moral values and principles of reasoning it embodies? This book undertakes a journey to answer these questions.

By Kiera O’Brien '18

HAJJA NASEEM '10 never aspired to politics. “When I was younger, I always had so many ideas of what I wanted to be,” shares Naseem. “Being a state minister was never one of them!”

Growing up in the Maldives under a 30-year dictatorship, she witnessed firsthand the maturation of a popular democratic opposition movement that eventually led to a peaceful transfer of power and the country’s first multiparty election in 2008.

At the time, she never imagined that she would one day serve her young democracy as Minister of State for Environment, Climate Change, and Technology; a position she held until fall of 2023 when her party lost re-election. Of her five years in office, Naseem reflects: “It was a transformative experience—I am relatively young, and a woman, in what is still a fairly conservative country. It wasn’t easy, and I never imagined it, but I’m proud of what I accomplished.”

As minister, Naseem not only oversaw all aspects of the small island nation’s domestic policies on climate and energy but also had the responsibility of serving as a climate diplomat for her country at the annual Conference of the Parties (COP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate

Change. “All the jargon and the commas in the bilateral agreements have a direct impact on people’s lives, so even though it can feel very slow and very painstaking, and even though we need to be more ambitious, I’m very happy to have played a leadership role in these conversations.”

She is especially proud of her efforts as a chief negotiator for the Maldives as part of the Alliance of Small Island States. “It's really important to build collective capabilities and try to address the impacts of climate change with collective action,” emphasizes Naseem. In a 2023 op-ed published in advance of the COP in Dubai, Naseem wrote forcefully about the need to address the “loss and damage” caused by climate change that is already being faced by small island nations like the Maldives. She writes, “Despite our negligible contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, Maldivians are disproportionately bearing the brunt of climate change's consequences.” And they are bearing them now.

“Loss and damage cannot simply be solved with a fund to offset the economic impacts of climate change. There are incalculable losses of culture, of homeland, losses that are not

strictly economic,” Naseem explains. “Loss and damage demands that we develop a mosaic of solutions that account for multiple contexts, angles, and perspectives.” Such a framework, Naseem believes, is precisely “what we are taught at COA. This idea of building a ‘mosaic of solutions’ to address complex, multifaceted problems really sums up not only what I have been working on for the past five years as a minister, but also what I learned at COA.”

Since returning home to the Maldives from the latest COP in Dubai, Naseem has been enjoying a brief respite from her duties as a climate diplomat and considering her next steps following the 2023 election results. She hasn’t exactly been resting, however. She currently serves as a senior adviser on loss, damage, and climate negotiations for the International Peace Institute (NY, USA). She’s also been enjoying extra time spent with her daughter, three-year-old Arin. When I ask what advice she might give to other young climate negotiators and leaders, she doesn’t hesitate: “You have to find ways to create joy. It’s challenging work, and things don’t always work out, so it’s important to laugh, to have fun, where and when you can.”

By Fern Paltrow '24

Bateau Press is a small press / literary journal currently housed at COA under the editorship of Dan Mahoney. Every couple of years, Bateau cycles in a new crop of student editors who read manuscripts, help select publications, design books,

sew chapbooks, contact brick and mortar bookstores, run Bateau’s social media accounts, and so forth. In sum, the students are what make running a small press possible at COA. Fern is one of Bateau’s student editors and an

INLATE DECEMBER , I had the privilege and utmost pleasure of sitting down for a Zoom interview with poet and author Jack Giaour to discuss his soon-to-bepublished chapbook, hunting the bugs.

hunting the bugs is the winner of the 2023/2024 BOOM Chapbook Competition, held yearly by Bateau Press, the letterpress publisher directed by our very own (& most beloved) COA lecturer [and COA Magazine editor] Dan Mahoney. hunting the bugs is available for purchase at bateaupress.com and select bookstores across the United States as of April 1. All chapbooks are hand sewn, with a cover designed by artist Chris Fritton. Giaour is a powerful emerging voice in the literary realm, and I hope that readers of this interview (and also people who don’t read this interview!) will consider reading his work––I can’t say enough good things about it.

FERN PALTROW '24: First, I want to congratulate you on winning the BOOM Chapbook Competition. We had over 200 submissions, and yours was a standout from the very beginning. I feel really grateful that you submitted to us and trusted Bateau with your work.

JACK GIAOUR: Oh, thank you so much.

FP: hunting the bugs was one of the first manuscripts I read, and I immediately fell in love. It was a very moving, emotional read, but it was also so funny! I guess, as a place to start, what inspired you to write hunting the bugs, and how long did the process take?

JG: I guess the core of that book is “manna,” right? The first sequence poem. I started writing the earliest drafts of what would become that poem over COVID because I was reading a lot about... I laugh at myself a little bit, but I was reading this big book about biochemical warfare in Afghanistan and Vietnam, and that was really dark and disturbing. So I was writing poetry to work through that. But as I started writing and did more reading and investigating and thinking, the poem obviously got away. So it's not about biochemical warfare anymore.

early advocate of hunting the bugs. The letterpress covers for this year’s winner were designed and printed by Chris Fritton. To find out more about the press, Jack Giaour, or Chris Fritton, check out the Bateau website here: bateaupress.com

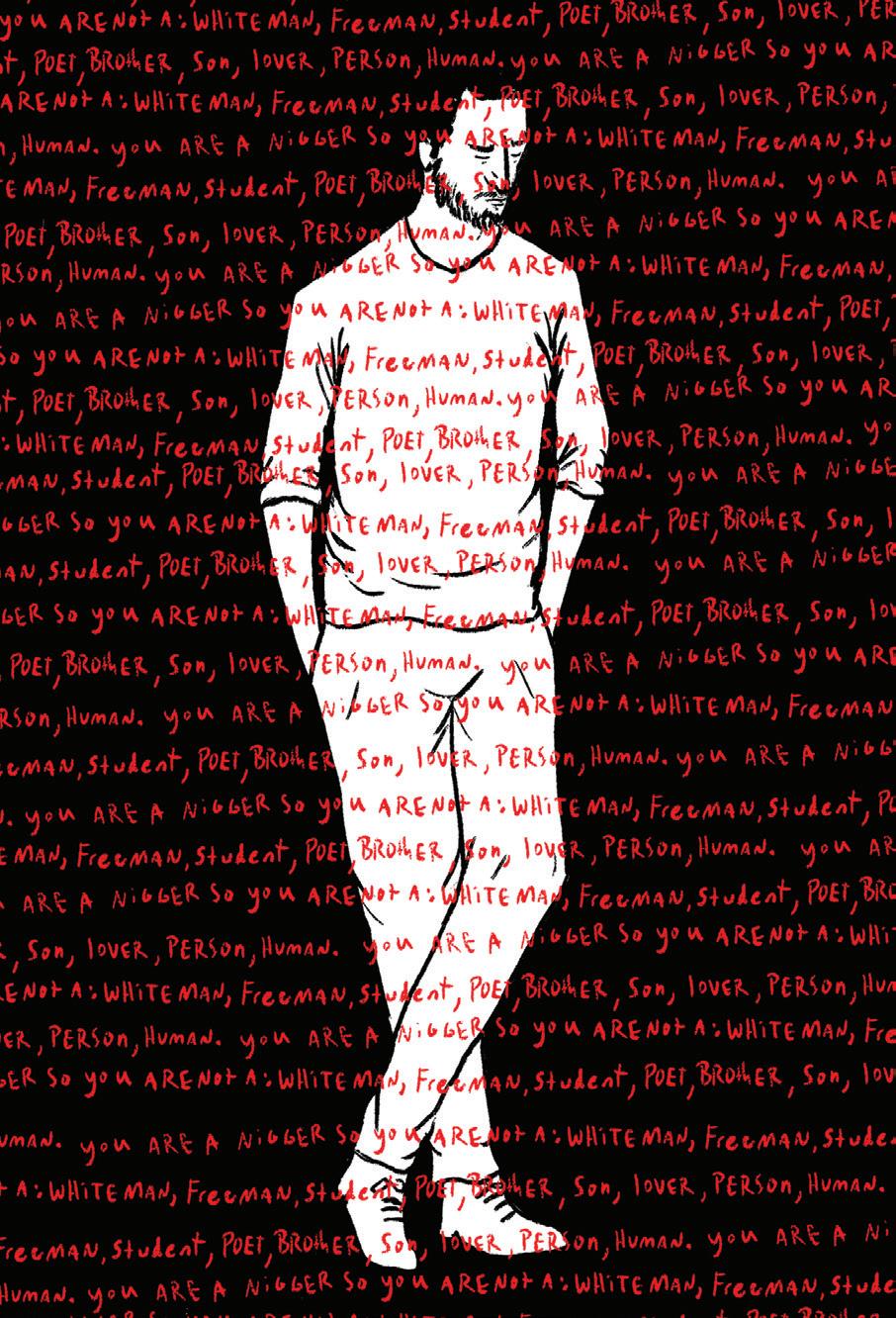

I started thinking lucidly about the relationship between the military and masculinity, and specifically how queer men get caught in the middle. I kept running into stories about people who had joined the US military because they were gay, because they were trans, because they weren't accepted in their home communities, because the military offered the only pathway that they had toward education. But I also found that a lot of queer narratives in the military were not necessarily about people looking for economic or educational opportunities, but for legitimacy. People felt that having a military background secured their masculinity.

The bug, whether it’s a computer bug or an actual bug or a secret agent bug… It's an unwanted presence, right? It's something that has infested your home or been planted in your intimate space, that you can't get rid of.

Take, for example, Vietnam vets. Things were so fraught and complicated for them, but one thing they didn’t have to worry about was people questioning their manhood. You could be gay under the radar if you were a vet.

I started reading and reading, and I got stuck on that theme.

I'm not a vet. So I was very conscious of that while writing that poem. I didn't want it to appropriate anybody's experience or steal anybody's story. Actually, a lot of the scenes in the poem are scenes from my own life, but obviously not the military scenes. But each

Jack Giaour, author of hunting the bugs

character has an anecdote from their personal life, and those all do come from my own personal experience.

I was reading and thinking a lot about the US military. But my first male partner was Israeli. He was a combat vet, had terrible PTSD, had a lot of problems that he inherited from his combat time. He had a very complicated relationship with his sexuality. That relationship didn't last because he went back to Israel, and effectively went back into the closet. He said to me, This was fun and I care about you, but my family and friends can't know about you. He felt that he could not safely be openly gay in Israel, that he would lose his credibility and all of his relationships. That experience ended up being in the poem as well, and was in the back of my head as I was doing all of this reading about other queer experiences in the US military.

FP: Queer US military history is a subject that is not widely documented, but I imagine there is a long history there.

JG: I was thinking again about this weird relationship between like, Okay, if I join the military, then people won't necessarily know that I'm gay, right? Or, If I join the military, this is a way for me to transition. I found that a lot of trans people had joined the military either as a way to transition or as a way to… If people were having feelings that maybe they were trans-feminine or trans-female, they were thinking, Okay, I'm gonna join the military, and that's gonna make me a man, right?

A lot of the wars that I was reading about were contemporary conflicts. So, Afghanistan, Ukraine, and Syria. I started reading about experiences in the US military, but obviously on the other side of those conflicts is the Russian military and the Russian military

experience. I found a lot of interesting echoes between American experiences and Russian experiences of the same wars. Reading accounts from both sides felt like reading two sides of the same coin. I'm looking at these two contemporary world powers wreaking havoc over and over again in different parts of the world, and watching Afghanistan and then Syria and now Ukraine get caught in what is essentially an economic conflict. I’m looking at the devastation these wars wreak on the soldiers who are fighting them, and on the citizens of the nations that act as the aggressor or oppressor.

That poem was very, very long and very heavy, and I ended up cutting it down. I think it’s much better that way. The poems around that poem in hunting the bugs come from all over the place. Some of them I wrote the same month that I submitted the chapbook. Some of them were very old poems that I had reworked. But I think they all spoke to things I couldn’t stop thinking about. That’s why I gave it that title. The bug, whether it’s a computer bug or an actual bug or a secret agent bug… It's an unwanted presence, right? It's something that has infested your home or been planted in your intimate space, that you can't get rid of. So there are lots of bugs in that poem, whether it's the KGB, or the mosquito in the poem to Gabriel, or even just intrusive thoughts––there were a lot of things that I was working through that I felt like I couldn't get out of my head.

FP: You do this thing throughout “manna” where you present characters who, on the surface, are cold, emotionless, dangerous individuals, people we’d like to think we have nothing in common with, but you imbue them with humanity, and give them very writerly qualities. Stephen is a particularly striking example of this because you introduce him as someone who visits quite a lot of death on unsuspecting innocents, and suggest that even the people who know him conceive of him as unsentimental and incapable of remorse. But your vision of Stephen is more nuanced; you write him as someone who has a clear literary sensibility and strong sensitivity to beauty, even in the precise moments that he drops bombs from his plane.

One thread I picked up on was this notion that perhaps there is a poet in everyone; perhaps everyone has this little human desire to write their story down, to wield a pen. Was that your intention?

JG: Yes. Kind of. You put it so well, and I would love to say that I was very lucidly doing that, but not necessarily. I had this strong engagement with people who were trying to tell their stories or who were trying to explain or work through what had happened to them, what they had seen, how they had ended up where they ended up. I think a lot of times people end up in positions of power and don't realize how much power they have until they've used it destructively. And then there's this moment of like, Oh my God. How did I get

here? How did this happen? How did I become this? And I was definitely interested in that moment.

FP: I feel, with hunting the bugs, that you have done so much to capture the ruins we find ourselves in. I think your manuscript is extremely timely, though I desperately wish that it wasn’t. There are these lines about eggshell cities, you know, on to the next eggshell city, and here we are watching these horrors unfold on our phones, seeing Gaza completely leveled and destroyed; we are bearing witness to the incalculable human suffering and loss that makes the eggshell city a feasible concept. To me the most poignant, heartbreaking lines of your whole manuscript are:

there’s no

What was in your head when you wrote these lines?

JG: At that point, I was so tired. I had been engaging so deeply. I'd been learning about biochemical warfare and listening to these veteran stories. And then I was trying to get more civilian voices in there, so I was reading refugee accounts and then, while I was writing this manuscript, the US pulled out of Afghanistan, and that created a power vacuum, and the Taliban took over. The Syrian Civil War is ongoing––the US has pulled out of it, but it's still happening. And I think a lot of people don't realize that. So I'm following these wars or these conflicts that are still happening, that don't show up on the news, that are kind of old news, right? I was thinking, God, these conflicts are trendy for a while, and then they go away in the American public eye.

But for the people who live there, they do not go away. In fact, they're still happening with just as much horror

and violence and destruction as they were when the media eye was on them. So that creeped me out and saddened me. Russia invaded Ukraine, and all of a sudden we had a brand new conflict all over the news. And so of course that line is about Ukraine. And now we've just had this horrible resurgence of conflict in Israel. A lot of people feel like this is new, right? They haven't been thinking about Israel and Palestine. So now it's a big news story and it feels fresh, like something that happened out of nowhere. But it's not, right? That conflict has always been there. Of course, what happened with Hamas is really horrific. And what we're seeing in Gaza now is unprecedented. But this unprecedented horror did not come out of nowhere. This conflict has been bubbling along, whether the media's been paying attention to it or not.

I'm exhausted with the media inundation on the one hand, but then also feeling like, okay, if we stop paying attention to this, that doesn't mean that it goes away. I’m trying to reconcile the feeling of not wanting to engage with it anymore, but I also feel like I'm responsible to engage with it, if only to just witness it and acknowledge that it's happening.

FP: It's interesting to me that you were talking about literal news, because when I read those lines, it made me think about history repeating itself, and how we seem unable to learn. We just keep repeating the same mistakes, with grave, cascading consequences. In a similar vein, my favorite poem in the whole series is “the water.” The closing lines of this poem also landed really hard for me:

that his eye pain and watery eyes belong on a different kind of chart that these words answer a different kind of question

a question that no one is asking

It made me think of politically engineered silences and gaps.

I'm exhausted with the media inundation on the one hand, but then also feeling like, okay, if we stop paying attention to this, that doesn't mean that it goes away.

JG: So much in that poem, or in that book, but that poem specifically, is thinking about power dynamics. Who gets to decide what? Here’s this person who on the one hand is some kind of survivor in this conflict but who's dependent on foreign aid, who speaks a language that's not his native language. But how much is that aid actually helping? Why does that aid have to be there in the first place? How complicit is the nation that's sending the aid? How complicit is the nation that's sending the most aid? How complicit is the nation involved in the conflict in the first place? So yeah, you're absolutely right. But none of these poems are riddles. I'm okay with people bringing their own meaning to the

poems. It's okay for my words to carry your meaning, right? Once it's in the hands of a reader, now those poems are the reader's poems. I'm letting them go into the world.

FP: How is hunting the bugs rooted in queer and trans literary histories? How does your work seek to carry forth those legacies?

JG: I think on the one hand we have a lot of queer people in what we would consider our canon. But we also have a lot of queer people that get bounced out of that canon. And a lot of in-between. With my book specifically, one of the writers that I really engaged with was Virginia Woolf, who is not American, but British, but who definitely had some queer tendencies. One of her most beautiful books is Jacob’s Room. She was dealing with the after-effects of World War I and challenging the narrative of the soldier as hero, but without demonizing the soldier. The entire novel is the life of Jacob, who's a pretty normal person, and then gets killed in World War I, and that's kind of it. That's the whole book. I think the point that she was trying to get at is that soldiers are people, and we're sending normal people in droves to be slaughtered, over what? What is being accomplished with this?

I was thinking a lot about Virginia Woolf as a queer writer who, like me, is not a vet and never went to war herself, but was surrounded by people who were affected by these conflicts. She refused to engage with it in a way that the rest of the literary world seemed to expect.

Also, Nightboat Books has two anthologies of trans poets and poetics: Troubling the Line and We Want It All. Those anthologies are incredible. I, as a trans writer, am constantly looking for other trans voices. And we are hard to find, especially historically. Unfortunately, sometimes that's intentional. Before the more recent queer liberation and Stonewall and all of this, I think a lot of trans people intentionally flew under the radar; they didn’t want to be seen as trans.

Finding trans people in the historical and the literary record in particular can be frustrating. So having these anthologies of contemporary trans writers was great. But what I was really taking from those anthologies was the way that trans writers write about the body. And so in hunting the bugs I was trying to insert the physicality of the speaker into the narrative. The speaker's body is an important part of the poem, of every poem, or is something that should be considered in the poem. Whether it's the body as a sexual presence, a potential corpse, or the physical encasing of our soul, right? In “why i can’t get out of bed,” you have a narrator that's contemplating killing themself. But a big part of the suicidal ideation is about your body and potentially wanting to be released from it, right?

A third queer source of inspiration is an anthology called Out of the Blue that was published in San Francisco in the '90s. It’s an anthology of queer Russian poets that starts in the early 19th century and goes all the way up to the '90s when the anthology was published. It was engaging with mostly gay male narratives. There are some lesbian poets in that anthology but it's mostly gay men. But I was engaging with them from this different perspective, right? From a Russian perspective and a Russian historical context. I was trying to escape an American-centric queer poetics. I wanted to engage with a more international queer poetics that moves outside of Anglo-America.

FP: The book certainly points in that direction. Anything else you would like to add before we close?

JG: I'm glad that the book is where it is. It feels like it's in good hands. And it feels like it's growing, right? Having a cover, and paper samples, it's... I don't know, it's very exciting to see it become a physical thing, not just a strange hallucination that I've had in my head for a while.

tonight forget how time rebuilds experience tonight just decompose and let the blackout envelope you

no matter the transmission from mind to telephone screen the signal’s always shit the boy on netflix clutches the man with the x-ray eyes once i fell in love with a cop and he loved me back the snake chokes on the mouse most hunts are unsuccessful and what i mean by that is life in the underworld is not what you think it is

it’s the sun that gives the shadows their shapes and what i mean by that is his love for me did not stop my cop from being a fascist

so tonight turn off the lights tonight trade underwater for an autumn forest just stand there and stare into the canopy

listen from the bottoms of your feet to the sighing of the leaves that once would sway overhead for miles and miles in every direction your eyes may water but never again let them run the time to cry has passed

—Jack

Giaour from hunting the bugs, Bateau Press 2024

By Meesha Goldberg '08

HOW DOES ONE deepen kinship with the land despite dislocation from one’s ancestral home and culture?

This is the central question of my interdisciplinary body of work, which inquires into a land ethic of the Korean Diaspora, seeking resonance between ancestral culture and life on American soil. At the root of the artwork I seek to offer a critique of the American empire, the violence enacted on Indigenous people of Turtle Island, and the disruption of the indigeneity of the Korean Diaspora through war and neocolonial dominance. While America cannot become a motherland for the settler, and belonging to one’s ancestral homeland may be forever severed, one’s body remains the sacred site from where to honor kinship to the sources of life.

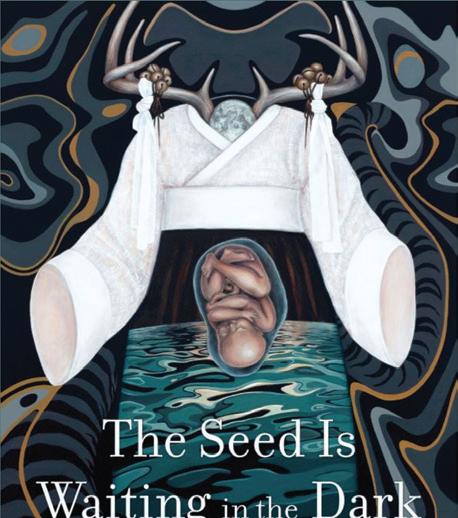

The Daughterland paintings depict these bodies in traditional dress overfl owing with seasonal life: summer’s seed, fall’s root, winter’s rest. The series expresses ancestral grief as the faceless women wield the blades of the shaman, the fi eldwoman’s sickle, antlers of the buck, and yet they tenderly carry life, embodying complete engagement with the fl ow of nature. The cover painting, From the Mountaintop, an illustration in the English translation of the myth “Budoji,” depicts an ancient ceremony on a mountaintop altar I witnessed during my fi rst trip to Korea in 2022. By reaching back through the root of lineage, perhaps a vision for the future may be retrieved. Despite displacement from a motherland, the desecration of wild and sacred places, and the forgetting of names and songs, the persistent earth still offers itself through the generations.

Meesha Goldberg is a Korean American poet and artist living in Charlottesville, VA. She graduated from College of the Atlantic in 2008. Her experiences growing food, serving as an activist, and journeying to sacred places have made her a powerful advocate for the Earth. Goldberg has exhibited her work in solo shows around the country, with her debut poetry chapbook, The Seed is Waiting in the Dark, forthcoming in 2024 from Finishing Line Press. Her art crosses the boundaries of genre to both experience and express transformational repair. Performance, ritual, painting, film, costume, and poetry merge in durational, placebased works and gallery installations that insist upon the re-enchantment of the world.

We imagined our relatives still put us anonymously into prayers on lunar new year, but there was no telling. There was no telling if our ancestors would descend eighteen hours just to reach us speaking English In the fiction of a new world we fragmented our longing but as we are mountainless in that wound imagination festered Nothing suggested such but we imagined ourselves remembered & that myth’s sore legs could walk us

Our American cloud mountain, Septembered & berried

We imagined how grandmothers could guide us the blindfolded though we did not offer a single persimmon though wild tigers stalked us out of our dreams though we ripped out every root with great carelessness our longing is holy because we did not abandon it

All ginseng gatherers 심마니 feel the same if they don’t find any for a couple days They feel the urge to give up

That’s when the mountain spirit gives you one That’s what motivates us to keep going

The form of this piece is inspired by a long-running feature in the The Wire magazine called “Invisible Jukebox.” For this feature, an interviewer plays the interviewee a series of records they are asked to comment on—with no prior knowledge of what they are about to hear.

Tested by: Dan Mahoney / Images supplied by: Darron Collins '92

DAN MAHONEY: Ok, here we go.

DARRON COLLINS '92: Ok. [immediately] "Brick House?"

No, wait... "Fire." Ohio Players. And now I can see it on your screen.

DM: That is not supposed to happen. [laughter] Ok. You are a firefighter in Bar Harbor. How did that happen?

DC: I think I was a kid that always wanted to be a firefighter. Then I was doing my graduate degree at Tulane in anthropology and was having an existential crisis writing my dissertation. I remember this time where I turned to my then girlfriend, Karen Grabow, and said, "You know what, I'm done with this graduate stuff. I'm going to be a firefighter."

DM: The existential crisis of dissertation writing... As in: Why did I do this to myself?

DC: Right. And then we have a long relationship between COA and the Bar Harbor Fire Department. Roc

Caivano, who was an early faculty member, served as a volunteer for 25 years. Dan Daigle (director of building and grounds at COA) is the captain of the volunteer callin force. And of course, Zach Soares '00 has also been a big and important part of that team. And at some point about two and a half, three years ago, in the middle of COVID I decided that I needed to show up to that… and we have this really, obviously, important relationship with fire, generally on Mount Desert Island. And, in many ways, COA was created as a response to the 1947 fire that devastated a lot of the island community.

DM: How so?

DC: Well, COA was a response to the fire that destroyed a third of the island in 1947, as in, What can COA do to help revitalize Mount Desert Island after that horrible fire? But then we also had our own fire in 1983, where the center of campus was burned to the ground. I just finished writing an article for Chebacco magazine about this event (page 48), which was one of the most difficult in the college's history.

DM: Has being the president of COA helped or hindered in your firefighting career?

DC: The amazing thing about COA is having the ability and flexibility to freelance a little bit… to make things up as you go along, and to bob and weave and pivot and be creative with how you approach problems. But that is exactly the opposite of the way a fire station works. When a building is burning down, the last thing you want is someone making it up as they go along. People get hurt that way. I remember being at the fire up across the street (the Bluenose Inn) and saying, Hey, I'm going to go help this guy out with whatever. And being effectively grabbed by the collar and having someone say, No, no you're not going to do that. You stay here, and when I tell you to do something, you do it. Which is great. Having that balance is necessary. I also love working with the men and women at the fire station. It is, well, it keeps it real. It keeps me grounded.

DC: I'm going to start to weep here. It's Springsteen from Nebraska... No, no it's The River.

DM: Funny, I was trying to decide what Springsteen to play a song from. I was thinking Nebraska or The River.

DC: Both great albums.

DM: Right. Springsteen. New Jersey. Where you're from.