15 minute read

Football Sunrise | Emily Pulsifer, Faculty

When it was over, Sheila May refused to admit the fuss she’d made about me going. After the camera crews showed up with their bright lights and questions, she made it sound like she sent me out that night, like she wrote up instructions on how to be a hero and passed them to me like a grocery list. But that wasn’t how it was. Not one bit. After dinner that night, she followed me to my truck. “No bathroom needs a babysitter,” she said, wagging a pink latex fingernail under my nose. “You spend your weekdays hotfooting after those boys. You’d think they could find their way to the crapper without you on the weekends. Have some self-respect, Tiny.” I tried to look down at my work boots but Sheila May stepped close and rubbed her stomach below my belt. “I could get us a pecan pie and some Cool Whip down at Ingles,” she said. “We could watch us a movie, head upstairs?” She blinked her loaded lashes and did some more rubbing. There was a time when this would have had me hustling to the bedroom but not anymore. “I gotta go,” I said. “It’s the state championship.” “You think I don’t know that? There’s nothing in the paper except Lions Football and that Hastings kid. I’m sick to death of it.” “He’s special, that one,” I said. “I’ve never seen any like him.” Sheila May removed her stomach from my mid-section. She was wearing her favorite Jeff Gordon t-shirt and when she crossed her arms over her DD-cups, her forearms cut off his head. “You say that about all of them.” “Sure, there’s always a few real good ones every year, but I tell you, Jon Hastings’s different.” She rolled her eyes. “Don’t start.” “He’s the best player I’ve ever seen. I’d bet good money on him going all the way.” “Is that you’re doing now, placing bets? Doesn’t surprise me. Here I am, trying to keep house on the nothing you make and you go and piss it away on high school football. This isn’t what I signed up for when I married you, Tiny Smalls. If my momma were here, bless her soul, she’d have something to say about this.” Whenever Sheila May summoned her momma, that was my cue to get moving. “See you around eleven,” I said and lifted my right leg to the truck’s bench seat. I had to grip my hand under my thigh to get it up there; after my own years of football, my right hip didn’t do all it should. “Shower before you get in my bed,” Sheila May yelled as I pulled onto Chester Street. “I can’t stand that football smell.” I opened the truck’s back window and let the cool breeze clear the cab. It felt good to be moving

38

Advertisement

away from Sheila May’s disappointment. That woman could argue with her shadow and find fault with the Virgin Mary. She could have come – I used to invite her – but she didn’t like spending three hours on cold metal bleachers for a game she’d never taken the time to learn (she still called the referees “umpires” and asked how many innings in each game). I’d given up asking years before. Passing through town, I saw Coach Pharr’s wife loading her Explorer. She smiled at me and leaned down to direct her twin girls to wave. They flapped both arms and danced on the sidewalk, blonde curls jigging over matching Montford Lions sweatshirts. Mandy Blevins, Contess DiAngelo and her squeeze of the week, Andy Stills, were leaving Dairy Queen with sodas in their hands. They shouted, “Yo, Tiny!” as I drove by. I was pretty sure I’d see them at the game, along with every other student from Montford High. This was the first time we’d made it to the state championship and everyone (except Sheila May, it seemed) was riding high. Jon Hastings lived with his mom and younger sister in Serenity Woods, Montford’s only apartment complex, and I often gave him a lift to home games so his momma could take her time. When I pulled in and honked, I saw a banner hanging from the porch next to the Hastings’ place. “Lions ROAR!” it said, with Jon’s face glaring from one end. “That kid looks scary,” I said, jerking my head toward the banner as Jon hopped in beside me. “I wouldn’t mess with him.” Jon threw his head back and laughed, a full, nervous bellow that spawned a chuckle in me, too. “You could take him,” Jon said. “He’s no more than 260, 265.” “I might have thirty pounds on him, but that wouldn’t do me no good. He’s pure ‘muscle, skill and speed’. I’m a load of lard with arthritis and lazy mixed in.” Jon laughed again and brushed a hand over his new crew cut. I was quoting a line from his scouting profile in Mainframe Sports and I was sure he knew it. “You ready?” I asked. We were still a mile

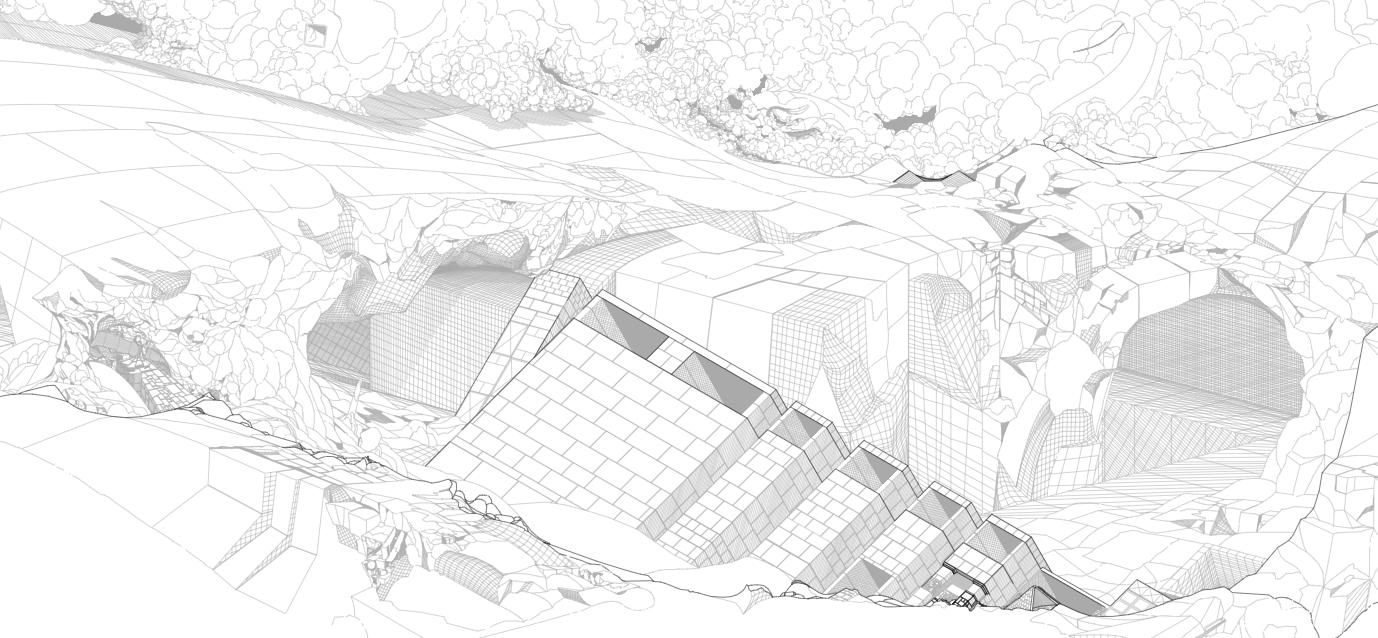

nature’s engine, digital photography michael posse ’21

39

from school but green balloons swayed over every mailbox, hydrant and lamppost along the route. Another banner flapped over the school’s main entrance, too, only this one read, “Welcome to the Lions’ Den!” Underneath it, somebody had taped a messy handmade sign: “Hastings: 39.” Jon had sacked 39 boys so far that year, just three shy of the state record. “I’m always ready,” Jon said, his voice suddenly steely, all the anxiety boxed up and put away like wool sweaters in May. This, I knew, was the voice he’d use ninety minutes later to get his teammates riled up.

Trent Pace and Marley Elmes, co-captains with Jon, met us in the parking lot. “You want to help us on the line tonight, Tiny?” Trent asked as Jon grabbed his backpack and thanked me for the ride. “Oh, I’d love to,” I said, “but I wouldn’t want to get in Jon’s way.” My hip wouldn’t let me move fast so I got to watch the boys walk toward the field house. They marched in cinque, Jon at the center, much the way they moved as a unit on the field. They were all good players – Trent at quarterback, Marley running for both offense and defense, and Jon on the line – but there was something different about Jon. You could see it in the bulge of his calves, the rise of his shoulders, the loose tension in his arms. In the few minutes he stood on the sidelines during each game, his eyes never left the play and his voice was as steady as a drumbeat. When he was on the field, he moved as if he’d seen the whole thing before: finding the only hole for a sack, spreading those long arms wide to block two players at once, leaping like an overgrown grasshopper to deflect a field goal. He read the game like nobody I’d ever seen in my years at Montford High or the two I spent at Western Carolina. And he did it like it was just part of the job. No showboating. No smack talk. At the door to the fieldhouse, the boys paused. Trent and Marley headed inside but Jon turned and jogged back to my truck. “If you can break away, you think you might come down to the field for the second half?” he asked. “The team’s hoping you will.” I wasn’t sure what to say. During games, I kept close to the snackbar and the restrooms above the bleachers. Somebody had to deal with the hot cocoa machine when it fizzed out and the dimwits flushing paper down the johns, and for three decades that somebody had been me. These days, Principal Thomas liked me up there looking out for hecklers and breaking up tussles, too. But don’t get me wrong, I kept track of what was happening on the field. Oh, yes, I kept my ears open, and when I could, I stepped into the shadows by the storage closet to watch a play from start to finish. Watching those boys in uniforms as shiny

40

and green as holly leaves, their white helmets striped and splattered with mud, I’d catch myself holding my breath. Only a dull ache under the nameplate on my grey uniform told me to snap-to and breathe again. And when I did breathe, I felt my heart and head fill with that football smell Sheila May fussed about: the smell of ripped grass, sweat, old leather and big dreams. Did I want to be down on the sidelines with Jon and the team? Heck, I couldn’t imagine anything more fine. My face must have shown my surprise and uncertainty because Jon rescued me from it before I had a chance to patch two words together. “Come down if you can,” he said. “It would mean a lot.” He punched my shoulder hard, like he did every time he saw me wheeling my cart through the cafeteria or swabbing floors in the locker room, and then he was gone.

Principal Thomas kept me busy right up until kickoff -- parking cars, delivering water coolers, breaking up a fight behind the visitors’ bleachers -- and I was grateful for it because Jon’s invitation had set my mind awhirl. I could be on the field for the second half, maybe see Jon break that record. As I fixed a running toilet in the ladies’ room in the first quarter, I thought about it, and when I rumbled down to the lower lot to retrieve traffic cones midway through the second, I thought about it some more. We were up 21-10 at halftime when the band marched across the field and fans mobbed the snackbar and restrooms. I patrolled, watching for trouble. I returned a toddler to his mother and shoved a backpack from an aisle where it might trip someone. The hot chocolate machine cut out after too many cups – the November night was chilling down – so I stepped behind the snackbar’s counter and fiddled with its innards until it took to

dirt road, digital photography jack britts ’22ghosts

41

producing again. Back in the stands, Andy Stills, one of the kids I’d seen leaving the Dairy Queen, passed by and asked if I’d seen Jon’s numbers for the first half. “He’s gonna bust it, Tiny,” he said. “He had two in the first quarter.” Contess DiAngelo was right there with him, one of those fancy camera phones in her hand. She flashed a picture at Andy before turning the screen my way. “That’s you, isn’t it?” she said. “My momma said it’s your record Jon’s gonna break.” I squinted at the picture. “Where’d you find that?” I asked. “Montford High yearbook, 1983. You look so different! Mom showed it to me and I was like, ‘That’s not Tiny!’” She was right. There I was in my own # 3 green jersey, fifty pounds lighter and a whole lot better looking. And she was right about the rest of it, too: Jon was about to toss me from the record books. “Pretty cool,” Andy said as he looked me up and down. He seemed to take me for something different now that he knew what I could do three decades before. The loudspeaker had been playing music with lots of screaming and yelling after the band finished up, but it cut out for Principal Thomas’s voice. “Tiny Smalls, please report to the Lions’ bench. Tiny Smalls to the Lions’ bench.” From the top of the stands, the crowd looked like a waterfall dropping to the field’s perfect grid. The players – miniature green and blue figures from that high – spilled from the locker room as insects ducked and dove under the stadium’s lights. I felt that pain in my chest again and took a deep, deliberate breath. No sense in fainting before making it to the field. I hitched up my pants where they sag at the small of my back and tipped my chin up. Above my head, the stars were lost in the wash of light, like they were drowning in a football sunrise. Easing down the stairs, kids and friends shouted “Tiny!” as I passed. I smiled, waved and shoved that same dang backpack out of my way. I was glad Sheila May wasn’t there to commentate. She’d want to know why, if I could break away to pal around with the boys on the field, how come I couldn’t sit with her in the stands from time to time? She’s make fun of my limp, too; the way I had to grip the handrail and roll my bad hip to find the next step. But she’d save the worst for what she took to be my intentions. “You’re just following the spotlight, Tiny Smalls, like you always did. Hoping for glory you don’t deserve.” “I’m happy for him,” I would have said to her if she’d been there to listen. “Let Jon break my record and go on to do what I never done. Let him go to college on that scholarship like mine, but let him put more

42

stock in it. Let him study more than he drinks and take care of his body better than I did with this tub of lard I call mine. Let him find a girl who really loves him, loves him for who he is and not the glimmer of what he should have become. And let him go all the way. All the way.” On the grass, I tried to stay out of the way but Jon found me before he hustled onto the field. His helmet was all mussed up and crooked but I could see his brown eyes flash behind its facemask. Few people were tall enough to look me in the eye. “Thanks for coming down,” he said. “No sweat. Go break that record,” I said. “Your record.” I lifted my Lions ballcap and scratched the thin hair above my left ear. “How long you known it’s mine?” I asked. “Since we met,” he said. “I’ve been gunning for you this whole time.” I laughed. “More power to you, son.” He smacked my shoulder hard and I pounded his chest pad harder and then he threw his head back and yowled like an animal on the hunt. “Go get it,” I shouted as Jon and the other Lions filed out to the line of scrimmage. The whistle blew and the game resumed with a draw play for a Lion first down. A few minutes later, Trent made a smart playaction pass to Marley on the five and the Lions had their fourth touchdown and a 17-point lead. I was hanging back near the bench, keeping clear of the boys as they celebrated on the sidelines. Jon came in to swallow a spray of water and then he was back on the field with defense. I closed my eyes and imagined the way his heart must be drumming, the fiery tingle behind his ears and down his back. When he dropped to his stance, I could almost feel the wet grass under his knuckles and hear the huffing and cursing from the big fellow marking him. I knew he could hear our cheers, too, the bellows and whistles from the fans, but he’d be too focused to think about them. He’d have one thought as he waited for the whistle’s release: shut them down. I suppose it was that kind of thinking that kept me from understanding a heartbeat too late. I opened my eyes to the same lights and the same game and the same shiny cheerleaders I’d watched a moment before. I peered past the giddy players, the chain crew and the referees to the same field. The air still

the center point, digital photography brandon brown ’25

43

rippled with excitement and anticipation. Nothing had changed. But then it did. A boy brushed past me, a short boy with long, dust-colored hair and a backpack slung over his shoulders. I recognized the backpack from the stands as I registered the incongruity of the boy’s bare head and low-slung black jeans among the boys in uniform. He had no business on the field but he was moving toward it. As the play ended and the teams pushed up from the ground, the boy in the backpack slipped between Marley and Coach Pharr and stepped into the glare of the open field. They say I started yelling about then but all I remember is fire in my belly and that goddamn weakness in my right hip. I moved as fast as I could, willing my fat, beaten body to run. But I was no match for that silent, angry boy with his grandpa’s service-issue Colt tucked under his arm and nothing but everything to lose. I was five clumsy steps from him when he extended his rail-thin arm and fired into the circle of green jerseys on the forty yard line. “Thwock!” And then another. “Thwock!” I was on him then, all my weight slamming down on his tiny, splintery frame. I heard a snap, then a whimper like a kitten’s. But I didn’t care. From where I lay, I could see feet moving every which way. Cleats, boots, shined loafers. After a minute, hands nudged my back and I heard Principal Thomas’s voice. “Come on up, Tiny. It’s done.” I rolled to my side and felt the boy flop away. Not far off, I could see another boy lying on his side. “Who is that?” I asked, my voice sharp and high. Principal Thomas gripped my arm and tried to turn me away from the ring of paramedics and police officers but I shook him off. “Who is that?” I wailed. Sheila May, when she tells the story, doesn’t tell the reporters what I did then. She likes to describe my fierce dash into the fray. “That crazy boy would’ve killed the whole team if Tiny hadn’t shown up,” she says in her church clothes on our porch with the bright lights on her. No, she has no use for the truth. She doesn’t tell them how I shoved my way to the forty yard line where the boy lay. How, when I saw Jon’s face, I blubbered like a baby and bulled my way to drop by his side. She doesn’t tell how I ran my hand over and over his sweaty forehead, my tears and snot spotting his jersey, or how I watched them wheel him from the field and I cursed God and Christ and the invisible stars above.