PETER MALONEY THE MIRROR: Angles of resistance

Curated by Mark Bayly

This project examines Peter Maloney’s practice from the perspective of the artist’s gay male / queer sexuality in a single major exhibition and associated public program, for the first time in his 40-year career. Since our meeting in 1995, I’ve enjoyed the opportunity of being introduced to and becoming familiar with much of Maloney’s body of work. Being both his partner, and curator of this exhibition, I’m in the unique position of having free access to the artist’s studio. This situation provides me with intimate knowledge of Maloney’s vast archive – plus the ability to witness changes in the artist’s processes as they occur, and to contextualise these within the chronology of his evolving practice. While the numerous qualitative differences Maloney elects to make in the production of his works might appear promiscuous, these choices are discerning and arise from decades of committed studio experience.

Maloney has a decades-long engagement with language, text and meaning, and has continued to refrain these themes in his practice through a variety of expressive techniques. By incorporating multiple examples of Maloney’s modes of expression, the exhibition introduces them as vernaculars of the artist’s visual lexicon – displaying completed works, plus numerous informal sketches and studies sourced directly from his studio, at times directly from the floor, installed ‘salon’ style. The result is a revealing account of Maloney’s working method – appearing at times as an accretion of imagery – reflecting the ephemeral material that a visitor might experience on his studio walls.

Over the past half century, Maloney has produced a polymorphous body of work across multiple media, including, collage, painting, photography, performance, sound, and video. As a painter, his early commitment to gestural abstraction has given way to a practice of genre-defying bafflement. I suggest this, because in examining Maloney’s series of works over the past twenty years, I propose that they can best be mentally assembled and appreciated – as a puzzle – in the form of a funfair hall of mirrors.

This exhibition offers an opportunity for visitors to enter the maze representing Maloney’s practice – and then begin to appreciate the works on display as mirrored distortions of the artist’s own reflection and his expressive thinking. In Maloney’s practice, nothing is quite as it initially appears, and meaning can only be inferred – not taken literally. By not having developed a readily identifiable appearance, or ‘brand’ associated with his body of work and its visual expression, Maloney has perhaps risked being misunderstood, or his conceptual intentions misrepresented. Rather than electing for the optics of easy comprehension, he prefers to be visible through the eclectic character of his work and its very distortion. In doing so, he insists on being identified as different – hybrid – non-prescriptive – queer.

Maloney’s work has certainly incorporated images representing the queer male gaze – at times using conventional Western

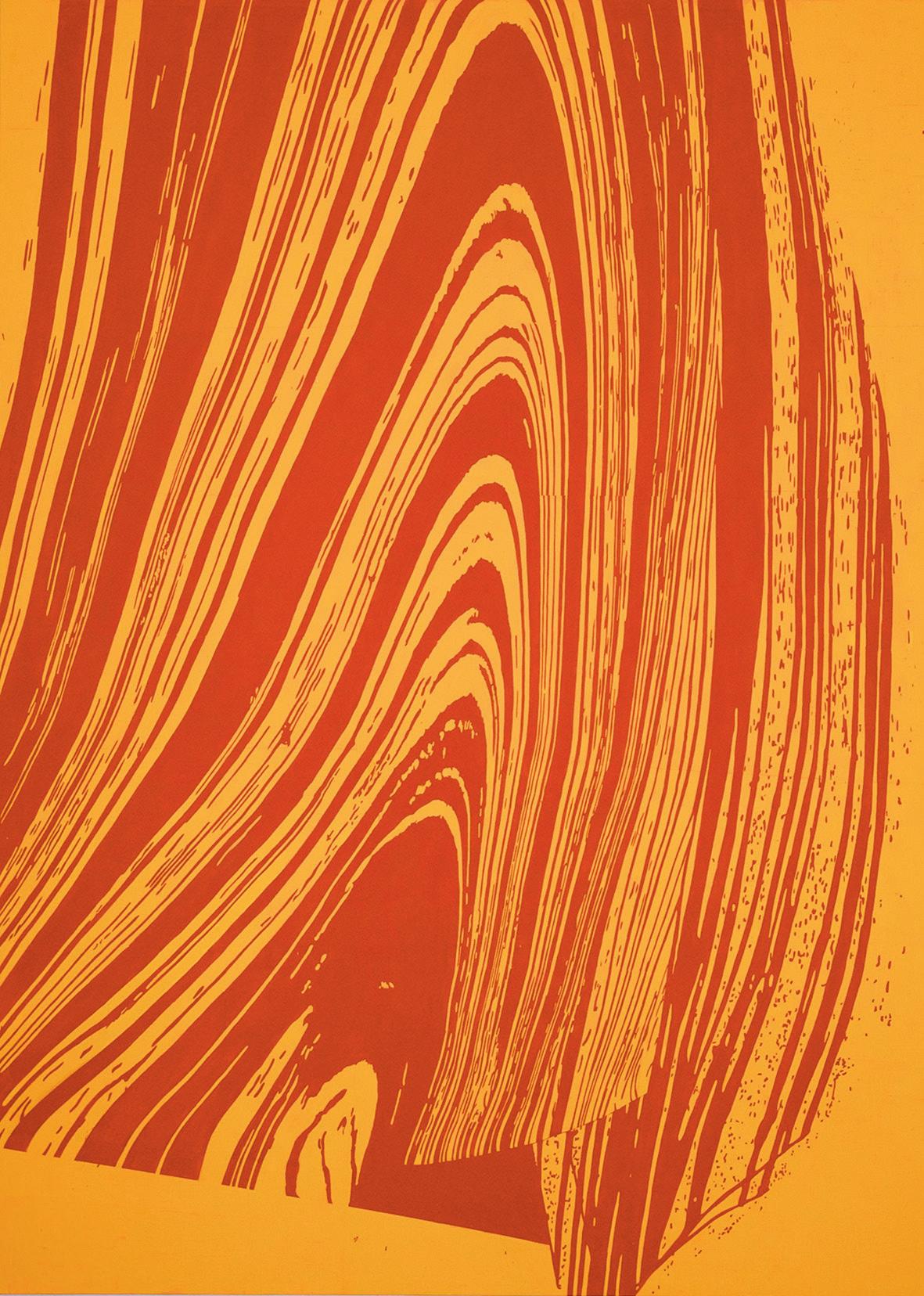

The Honey, 2010

Acrylic on canvas, 226 x 162.5cm

Image PETER MALONEY

Photo courtesy of Utopia Art Sydney

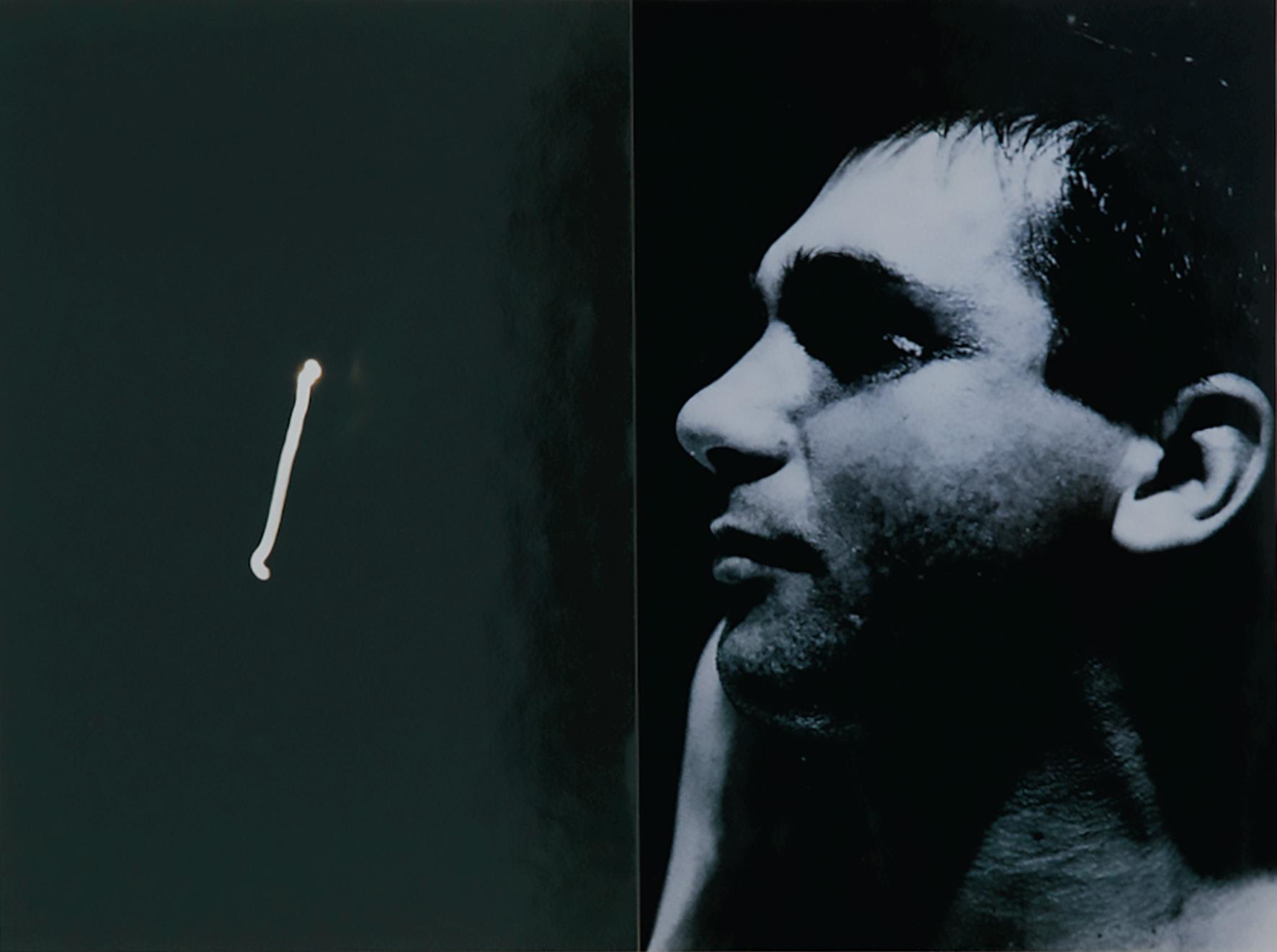

Image PETER MALONEY

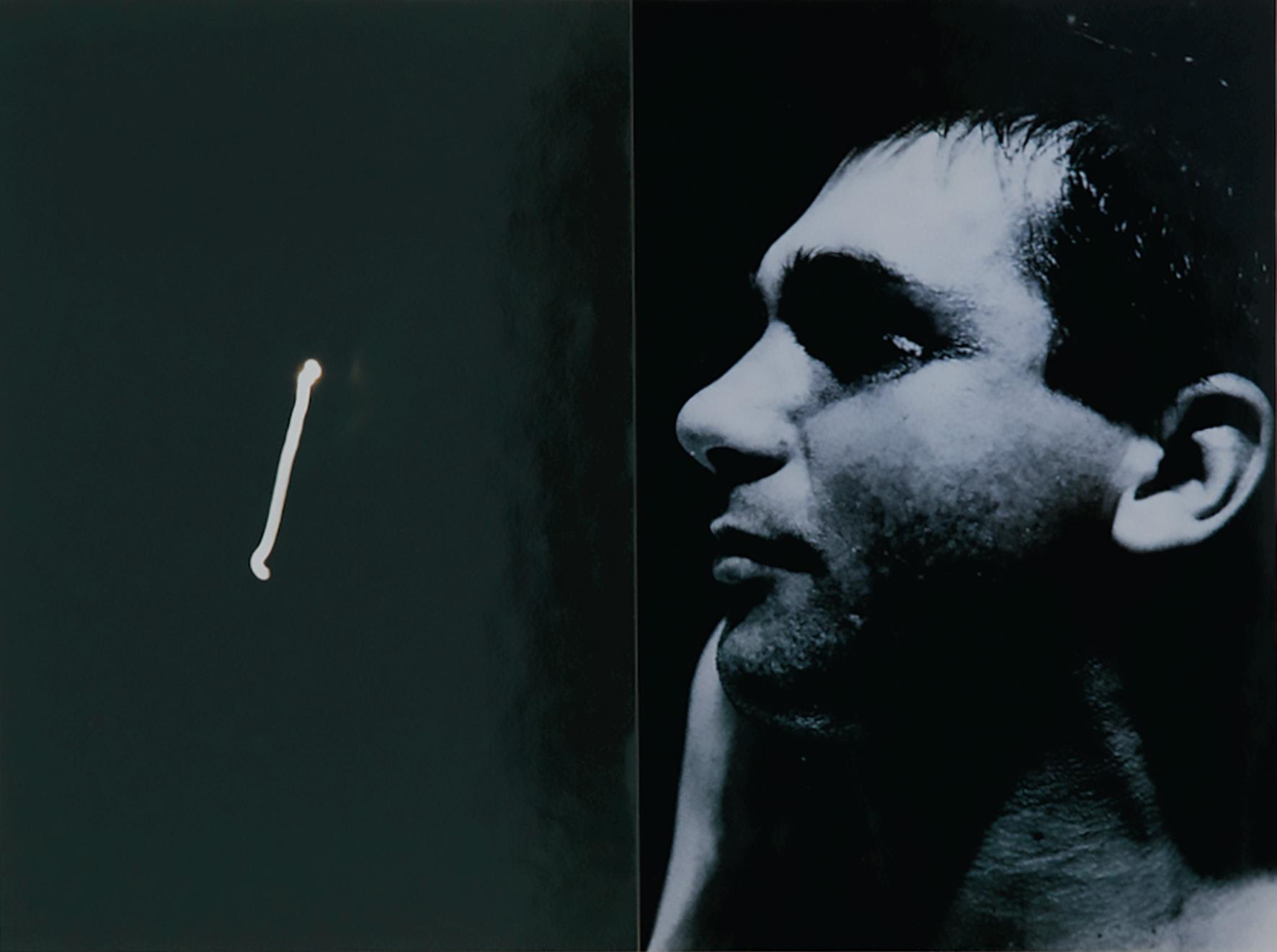

Untitled (lies that life is black and white), 2018

Photomontage, 30 x 40cm

Photo courtesy of Utopia Art Sydney

Image PETER MALONEY

Untitled (lies that life is black and white), 2018

Photomontage, 30 x 40cm

Photo courtesy of Utopia Art Sydney

art historical approaches, including the nude, and the portrait – of friends, lovers, and favoured models. At other times, he resists this inclination towards intimate depiction, and alters the angle of his gaze when re-photographing images from gay male ‘skin’ magazines. The nuances of time and place become significant when examining this aspect of his practice, because he intentionally chose to appropriate images from American publications from the 1980s and ‘90s – a period when a high proportion of men who had sex with men1 were falling to the ravages of AIDS.

Born in 1953, Maloney is of the generation for whom the coded practices, and secretive behaviour required of individuals (men in particular) who engaged in homosexual acts remained the norm, in order to ‘pass’ as straight – or apparently heterosexual. By the 1970s – a time when both he and I had become sexually active – strong social pressures, including the ever-present threat of criminality – remained in place for young queer people to enact, or perform2, hetero-normative behaviour. In behaving this way, individuals hoped to be accommodated within broader community expectations. Consequently, sex, and the search for it, was often carried out in furtive ways. For young men who were his contemporaries, this behaviour was so secretive and distorted, that it became understandably aligned with inversion3 – itself a distortion of reflection – and an anachronistic psychological term for homosexual inclination.

After leaving high school, Maloney studied at Canberra School of Art, prior to moving to Melbourne, where he undertook graduate studies at Victorian College of the Arts. There he was taught by two highly influential figures of Australian contemporary art – the late Bea Maddock4, and Gareth Sansom5. He eagerly absorbed Sansom’s iconoclastic approach to image production, which included sexually charged photographic collage, and pop-infused, hallucinogenic pictorial devices. From Maddock, he learned to approach his work with rigour, and to use his camera as a tool with which to capture images, including some that were apparently random, and others that were overtly sexual.

During this period, Maloney was introduced to the work of another artist whose practice proved influential for him. Georgiana Houghton6 was a 19th century British artist and self-described medium, whose visionary, abstract ‘spirit drawings’ were then on open view in the rooms of the Victorian Spiritualist Union, Melbourne7. This experience, and the links evinced between the material world and a ‘spirit realm’ espoused by Houghton, made a lasting impact on the development of the young Peter Maloney’s thoughts about pictorial composition, methodology, and process.

1 I use the term intentionally because many men didn’t, and still don’t, identify as ‘gay’, or acknowledge their proclivities as homosexual, despite the reality of their sexual activity.

2 Erving Hoffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Doubleday, Garden City, New York, 1956. Hoffman was a sociologist, whose break-through book became the basis of what is understood as ‘dramaturgical analysis’.

3 Havelock Ellis, Studies in the psychology of sex, Vol.1, Sexual Inversion, University Press, Watford, London, United Kingdom, 1897.

4 Bea Maddock (1934–2016)

5 Gareth Sansom b.1939

6 Georgiana Houghton (1814–1884)

7 The Victorian Association of Progressive Spiritualists was founded by William Terry in 1870, at which time it was one of the first Spiritualist churches in the world. When Peter Maloney visited the organisation a century later, it was known as The Victorian Spiritualist Union, with premises in A’Beckett Street, inner Melbourne.

Consensual sex between men remained a criminal act in New South Wales until 1984 – just four decades ago – by which time the festive solidarity of Sydney’s gay community was becoming increasingly fractured by the daunting spectre of AIDS. Maloney had friends and acquaintances who were falling desperately ill and being admitted to hospital8. A community-led public relations campaign sought to highlight safe-sex practices, while also attempting to minimise the high degrees of intolerance being spread by negative media reports. At the time, the ugly term, ‘gay plague’ was in wide-spread use – often emanating from the tabloid press – inflaming fear of homosexuality itself as the root cause of the disease. This distressing and misleading admonition reinforced the prevailing stigma already in existence, against people who identified as gay or trans.

In 1989, Pete Maloney’s partner of ten years, Michael,9 died of AIDS-related illness. Pete not only lost the man he loved, but this tragedy occurred at a time of almost unparalleled fear, ignorance and community paranoia concerning queer male identity – not only in Australia – but internationally. In recalling this tumultuous period, he recounted that he attended at least one funeral a week – week in, week out – month after month – until the funerals themselves began to peter out, before finally disappearing. These men – friends and their lovers – all gone. Maloney’s current situation reflects the existential paradox of what it means to remain alive – to have survived – following the trauma of this time. In retrospect, it seems that the deep emotional wounds he experienced then remained open, undiagnosed, and untreated.

Unsurprisingly, Maloney remains absorbed by the devastating circumstances of the decade between the mid 1980s and ‘90s. However, while his recollection of these events, and the emotions arising from them remain key to understanding what has continued to fascinate him10, they are reflections – not obsessions. Unlike Georgiana Houghton, who considered herself to be both an artist and a medium, perhaps Maloney can more plausibly be understood as a ‘sensitive’ – a person who senses – or in some way is in irregular contact with what some people identify as, the ‘other side’.

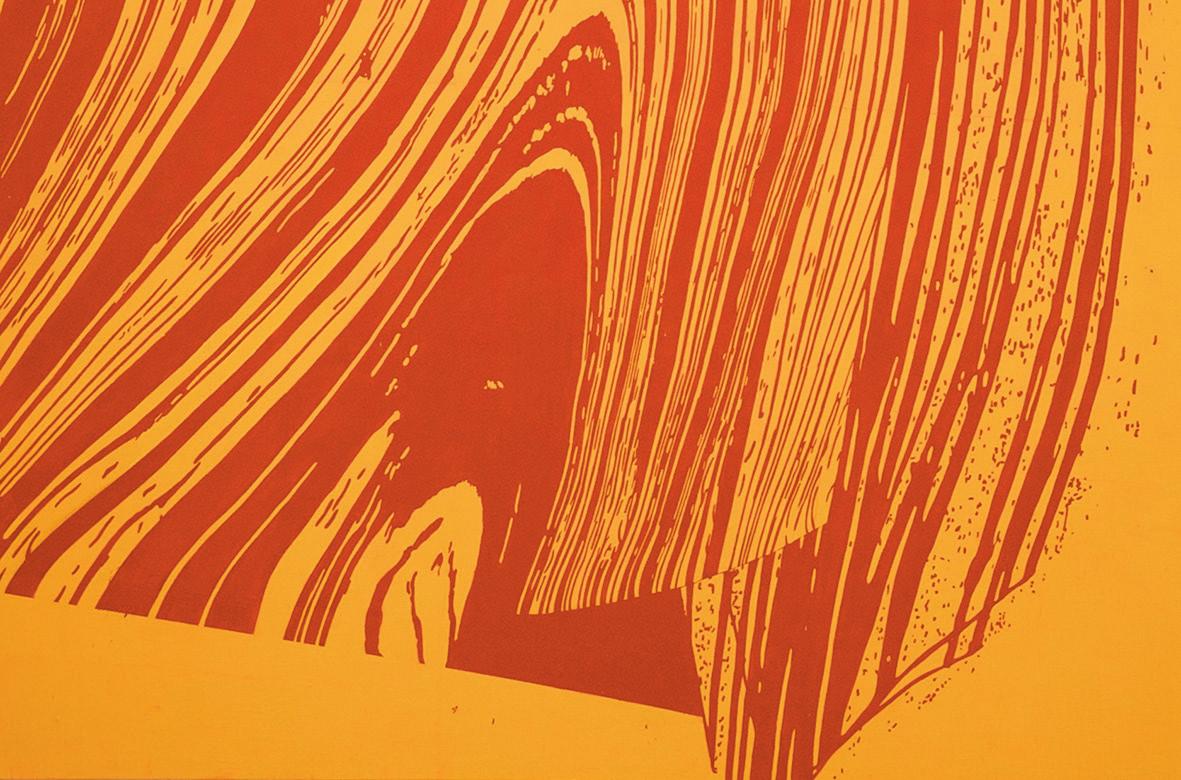

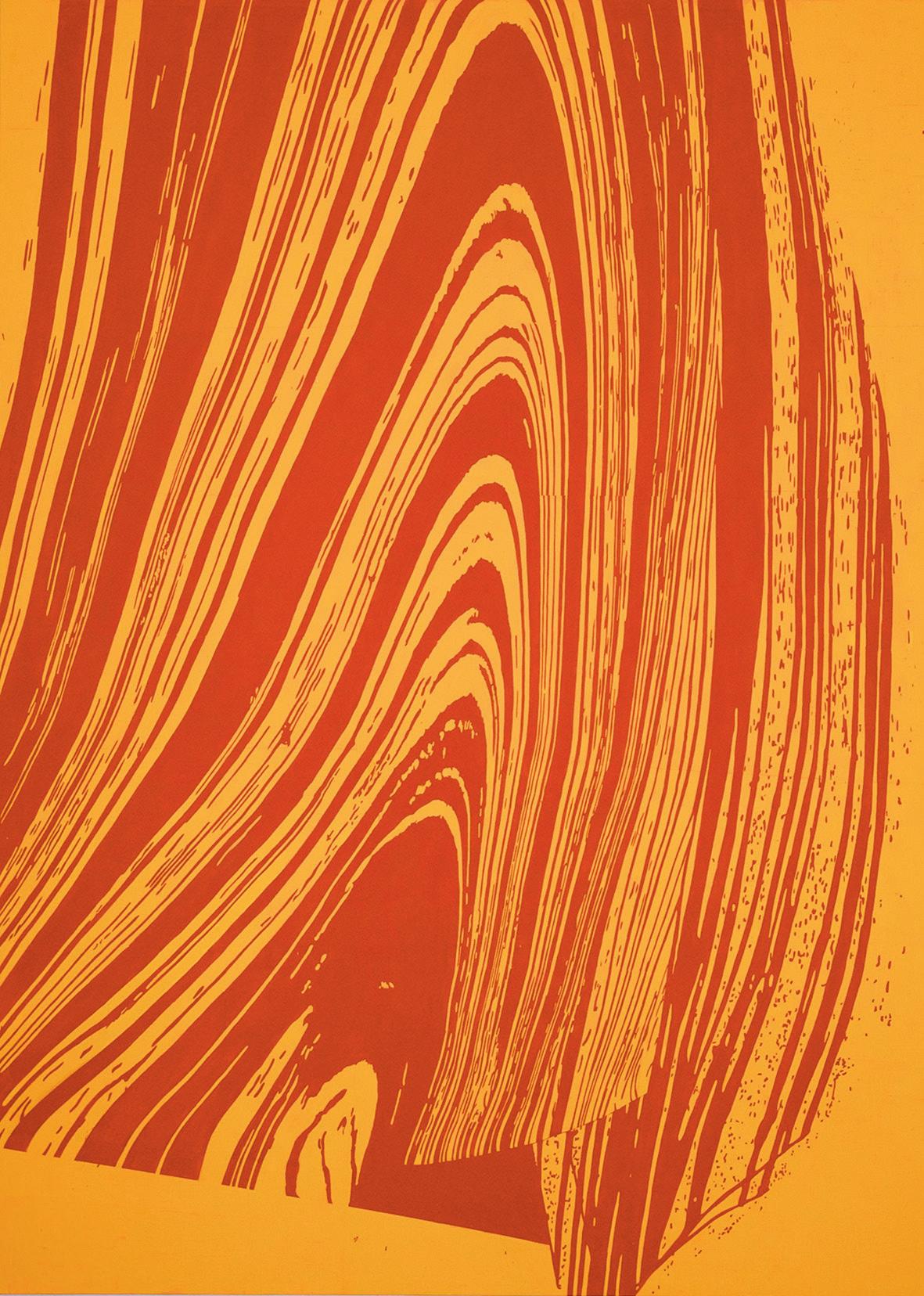

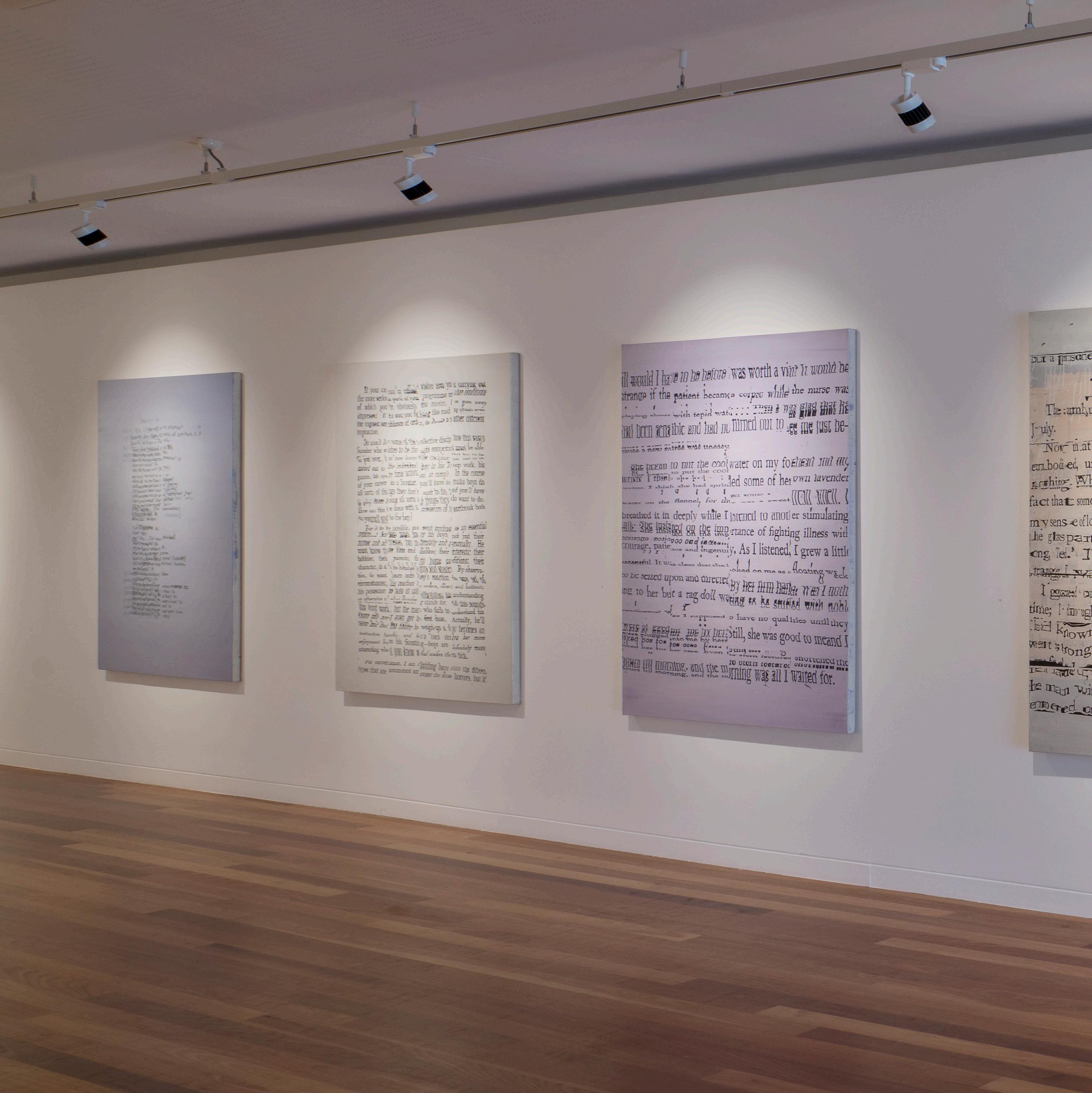

Around the time I met Pete in 1995, he was beginning to interrogate his existing gestural practice, which he now believed may have outlived its generative use in the formation of his personal conceptual language. Without any sense of how his future might take shape, he ceased exhibiting with his then representative gallery in Sydney – to take time out to consider and re-evaluate his working methods. Perhaps it was merely a random effect of the turn of the century, however by the year 2000, Maloney had largely abandoned gestural painting in favour of producing abstract compositions that were dependent upon complex and time-consuming techniques. The resulting paintings, consisting of hypnotic, linear abstract imagery, originated from drawings that were then enlarged, piece by piece, on a photocopier, and re-assembled to become templates for precise and methodical tracing via carbon paper onto prepared canvas. This methodology initiated by Maloney paradoxically had links to the skills and patience required of craft practitioners, but also to the more prosaic conventions of mechanical reproduction.

8 Ward 7 South, St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst, Sydney, was the first dedicated HIV/AIDS unit in Australia and became the healthcare epicentre for patients suffering from related illness, because a large proportion of the affected communities resided in the inner suburbs surrounding the hospital.

9 Michael Kendall (1955–1989)

10 I use the word in its archaic form, as in, ‘spellbound’, or ‘to cast a spell’ over someone.

The resulting works can be understood as reflections, or in my view – queer distortions – of the egotistic machismo historically associated with mid-century gestural abstraction. Maloney’s works now provided a visual effect that appeared to mirror ‘action painting’, while resulting from a high degree of scrupulous preparation. These works can perhaps be most effectively appreciated as rendered images of experience with liminal space – or as reflections on lost time11 – intimate messages to oblivion – to those who died too young – to those who left behind grieving lovers and bewildered families –and possibly to those whose memories float around in other dimensions.

Due to the ways in which he now disregarded – not so much the principles of gestural abstraction, but its history of patriarchal narrative and exaggerated masculinity, and by employing new processes associated with his own persona – Maloney began describing his paintings as examples of ‘sissy abstraction’12. While this sounds ironically camp and whimsical, there was nothing lightweight about the way he approached his work in the studio – characterised by intricate technique, and long hours of laborious application. It’s essential to note that the artist’s continuing use of paint as a medium remains important for him and should be instructive for others. I suggest this because his somatic imagery is closely linked with a personal history of wrestling with the considerable demands placed on his body, when faltering health and associated fatigue increasingly compromise his ability to undertake studio practice.

Only months after Pete and I originally met in 1995, I relocated from Sydney to Brisbane for professional reasons, and Pete joined me there a couple of months later. In the following year, he was awarded a studio at the Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, where he continued photographing – both the city, and the men who inhabit it – inviting guys he met in bars back to his studio. On his return to Brisbane, he began to produce prints from colour film before assembling them in intriguing ways. Many were constructed in diptych and triptych formats, and subsequently often inscribed with painted text – ranging from the declarative, to the poetic, to the random and disassociated. The resulting juxtapositions are illuminating – at times tender and poignant in appearance, while others are sexually explicit. However, while some might find Maloney’s imagery provocative, this isn’t the artist’s intention. In considering this body of photo-based work and its formal devices, the imagery expresses his belief that there is little of substance dividing the imagined binaries of emotional response and sexual gratification.

While Maloney didn’t initially gain traction for these works in Australia, this imagery was more eagerly adopted by international audiences, as works were exhibited at il Ponti Contemporanea, Rome, 1999, and in an exhibition titled Ecstasy, at Wessel and O’Connor13, New York City, 2002. Two decades later, at the instigation of curator, Shaune Lakin14, a number of these

11 In reference to, Marcel Proust, In search of lost time (À la recherche du temps perdu), Grasset, Paris, 1913–1927.

12 Interview between Matthias Herrmann and Peter Maloney, They Shoot Homos Don’t They?, pp 14-15, n.d.

13 Wessel and O’Connor changed location numerous times, but one of the gallery’s early manifestations was in SoHo NYC. At this time the gallery was known for showing queer identity art.

14 Dr Shaune Lakin, Senior Curator of Photography, National Gallery of Australia.

works were assembled in book form under the title, ‘Fugitive Text’15. Maloney’s photographic depictions of the male nude are the most obvious expressions of the queer male gaze featuring in his practice. Some of the most defining of these images are of favoured models – identified only by their first names – David, Gene, Greg, Jasper, Miek, and of course, Michael – all of whom were intimate friends, and occasionally lovers of the artist, and whose serial depiction reflects back to the time when Pete had been the same age as these young men and criminality was the potential outcome of acting out his sexual desires. These images form a cryptic, diaristic narrative throughout his practice and this exhibition.

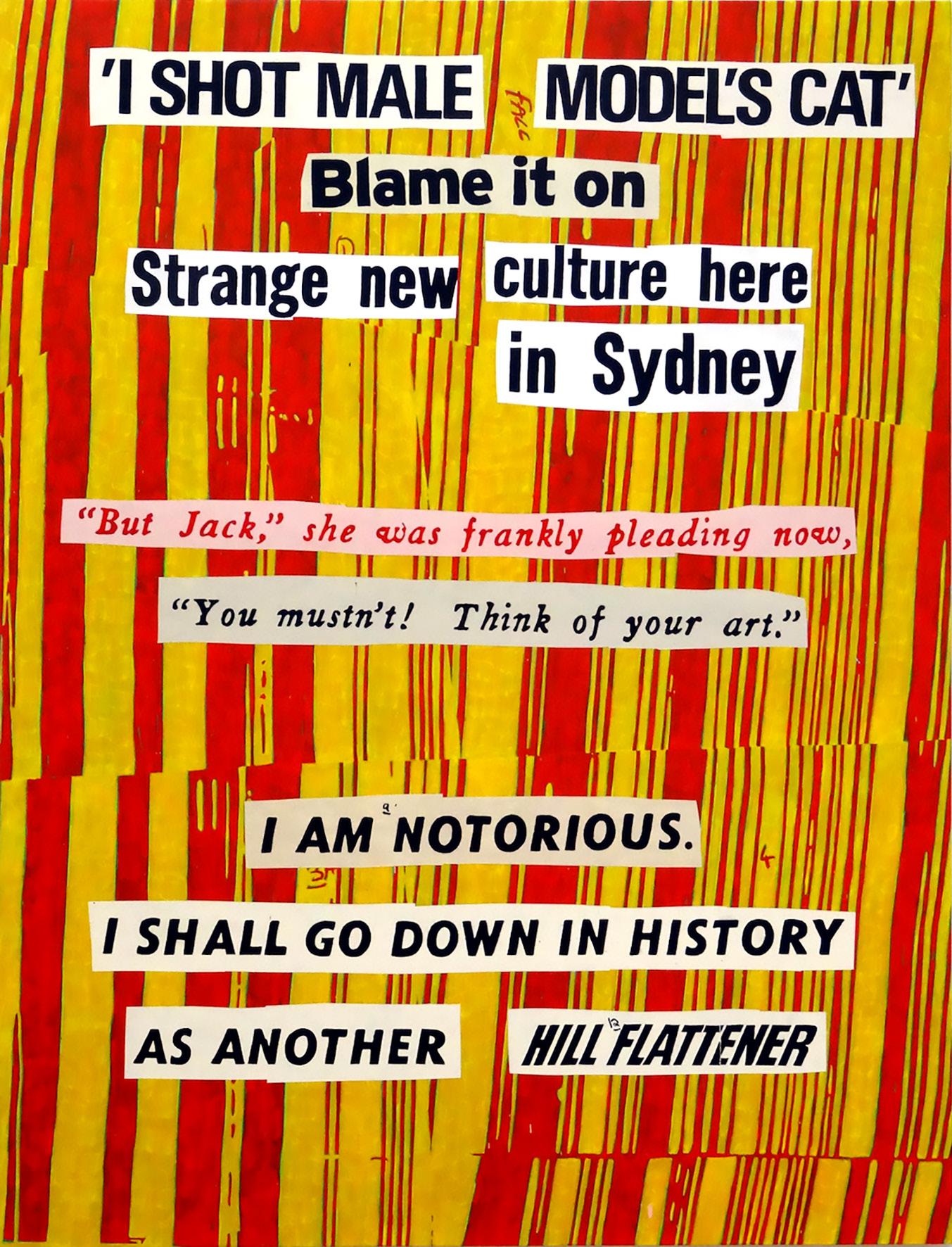

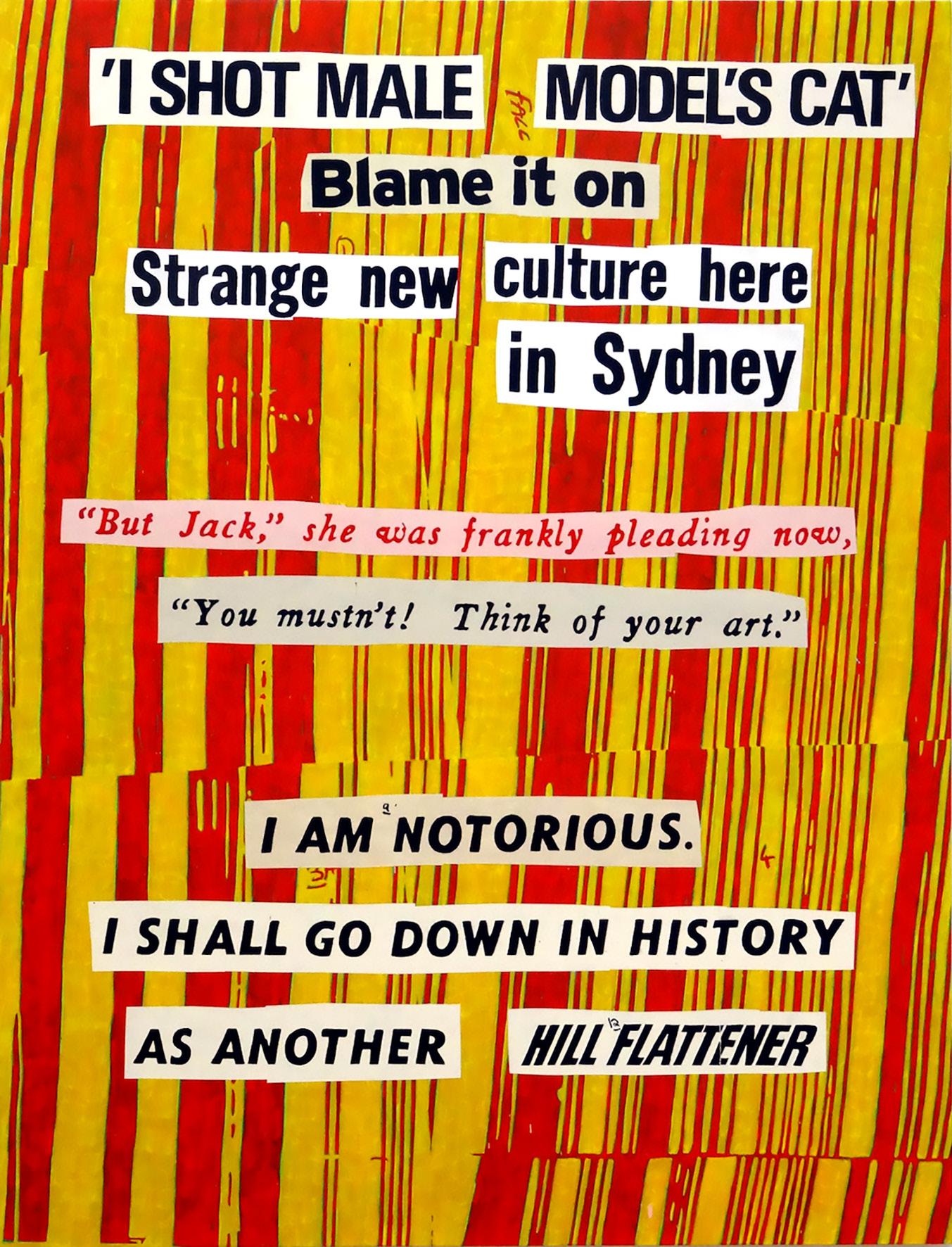

A number of these images have been reproduced in international journals devoted to alternative, or underground modes of queer male culture, such as, Butt; Kink, and They Shoot Homos Don’t They? in which contemporary photography is a core component. Of these, perhaps Butt16 is the most well-known, and its tabloid layout on pink newsprint ironically reflects the material form of certain English-language newspapers, which had an active history of homophobia. Often, the same media companies were involved in publishing the tabloid press during the 1980s as remain central to media issues today. Maloney maintains an ironic stance on pulp media and the disinformation it circulates, by producing small, meticulously painted canvases depicting his own lurid, fictitious headlines. These works operate as an overt site of resistance within the artist’s practice – as he consciously employs these pieces in totality, to interrogate contemporary issues through the introduction of absurdist text.

The artist had an existing interest in ironic wordplay – one of the aspects of his personality that drew us together – including confrontation with political decisions with which he disagreed; public governance which lacked transparency; a disregard for sexual taboos; and a low regard for upstanding social morality. While Maloney’s practice often appears intimate to the point of being private – make no mistake – his is a practice of activism. The collected works are a site of resistance that not only interrogate conventional thinking but speak truth to power.

Over the course of his 40-year career, Peter Maloney has continually elected to favour difference in his practice – in the form of artifice, distortion, hybridity, and indeed, queer identity – in resistance to any inclination towards homogeneity and appealing aesthetics. Consequently, the works he produces possess an enigmatic quality – equally robust and poetic and often obscure in meaning. Individual works can appear highly graphic – bursting with kinetic energy, while others simmer quietly in their depiction of human frailty – inferring loss, elegy, and lamentation.

15 Fugitive Text, M.33, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2022.

16 Butt magazine was founded in The Netherlands, 2001, by Gert Jonkers and Jop van Bonnekom.

Image PETER MALONEY

Red Hot Hill Flattener, 2014

Acrylic on canvas, 226 x 162.5cm

Photo courtesy of Utopia Art Sydney

The works displayed in ‘PETER MALONEY, THE MIRROR: Angles of resistance’, capture a sense of Maloney’s dialogue with the paradoxical, yet related ideas that are central to his practice: Self-perception – and its distorted reflection in the hall of mirrors of his own invention; the faceted surface of a mirrored disco ball – and the ghost of a gay subculture and related nightlife now existing only in memory; the human body and its physiology – both muscled and emaciated – displaying visceral strengths and weaknesses.

Maloney’s practice is one of shapeshifting and the changes apparent in his working method reflect the code-switching guises required of queer people to ‘fit in’ with social conventions. I believe the artist’s entire practice can perhaps be understood as performative – appearing at times ‘in drag’ – with varying changes in appearance altering context and meaning as his work adapts to its evolving environment. The works that have been gathered for this exhibition have been selected to assist with a meaningful understanding of Maloney’s practice viewed through a queer male lens. When viewing these works and the ways in which they relate to each other, each of us can reflect upon our individual experiences with related forms of transition – from friendship to sexual adventurism, from contentment to distress. From personal experience the artist understands joy, elation, loss and grief, and his familiarity with these extremes of emotional response reflects our own journeys through liminal space, the unconscious, and the unknown.

Mark Bayly

2023

Peter Maloney has held over 30 solo exhibitions throughout his 40-year career. His work is represented in numerous public collections, including National Gallery of Australia; Art Gallery of New South Wales; Art Gallery of South Australia; Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; and Australian National University.

Peter Maloney’s practice is represented by Utopia Art Sydney.

Peter Maloney and Mark Bayly have been partners since 1995.

Mark Bayly is an independent curator, with a 30-year career of producing exhibitions in prominent art museums, galleries, and heritage buildings.

Curator’s acknowledgements

At Peter Maloney’s request, this essay is dedicated to his good friends and kindred spirits, the late Pat and Richard Larter – with whom he shared a mutual and enthusiastic regard for the merits of sex, art, and rock ‘n roll.

(Pat Larter 1936–1996)

(Richard Larter 1929– 2014)

My sincere thanks to Janice Falsone, Director, Canberra Contemporary Art Space, and the CCAS Board for their strong commitment to the initial exhibition proposal. I also thank Alexander Boynes and Dan Toua for their support in helping to bring the project to realisation.

My grateful thanks to Benjamin Shingles, Assistant Curator, Drill Hall Gallery, Australian National University. Without Ben’s enthusiasm for the project from its inception, and his practical support and assistance throughout production, this exhibition wouldn’t have been feasible.

Thanks of course to Christopher Hodges and the team at Utopia Art Sydney, for the generous assistance provided to me in the production of the exhibition.

The exhibition has been a substantial undertaking and wouldn’t have been possible without considerable professional assistance from friends and colleagues within the Canberra arts community. My thanks go to the following dedicated individuals and the teams who work with them:

Tony Oates, Drill Hall Gallery, Australian National University, for his empathy and consistent support;

Rebecca Richards, Assistant Director, Exhibitions and Collections, Canberra Museum and Gallery, for the loan of display furniture;

Michael Cammack and Henry Han respectively, for framing;

Kim Morris, Art & Archival conservation;

Brenton McGeachie and David Paterson, for photographic documentation of Peter’s work;

Shaune Lakin, Tony Oates, Dioni Salas and Ruth Waller for their contributions to the exhibition public program.

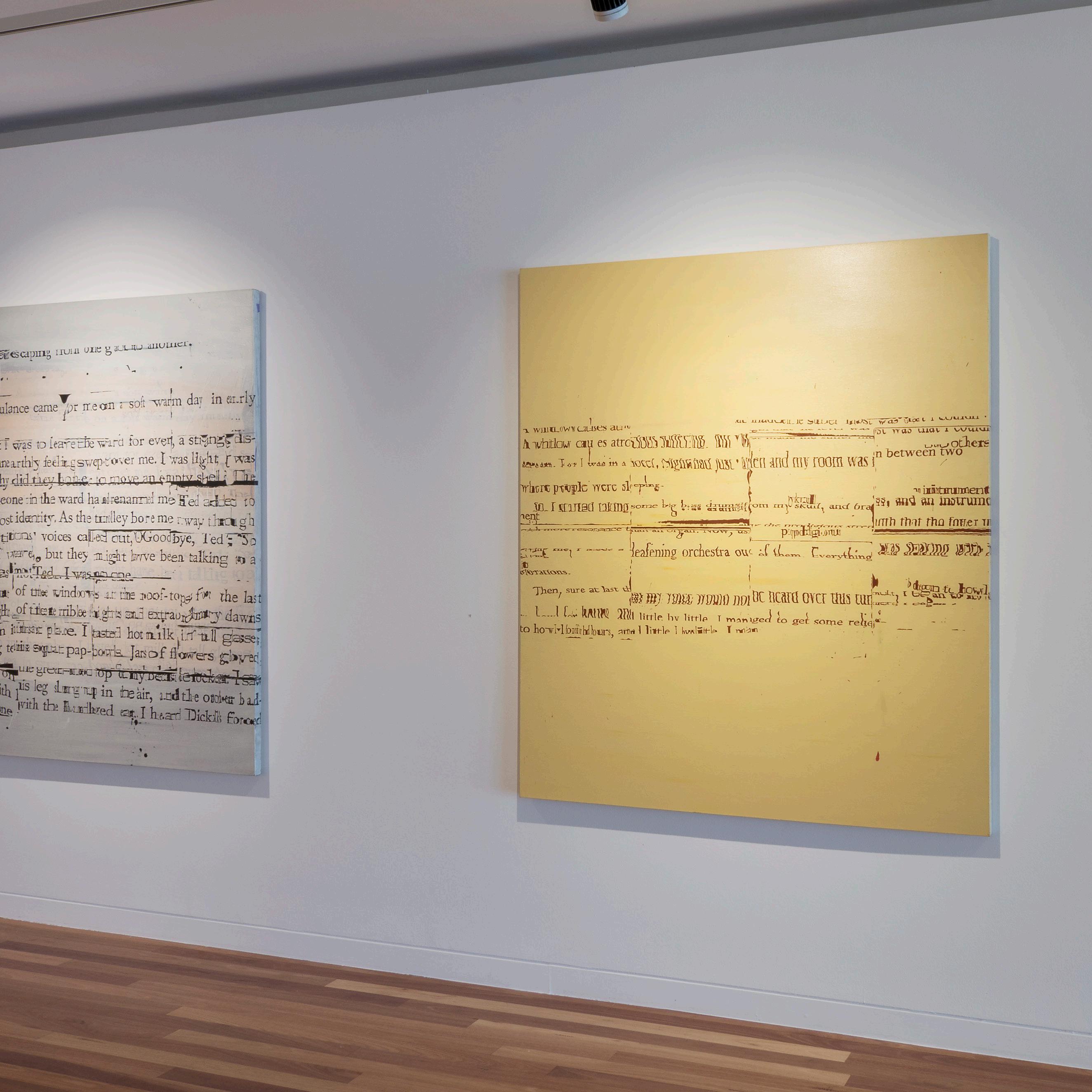

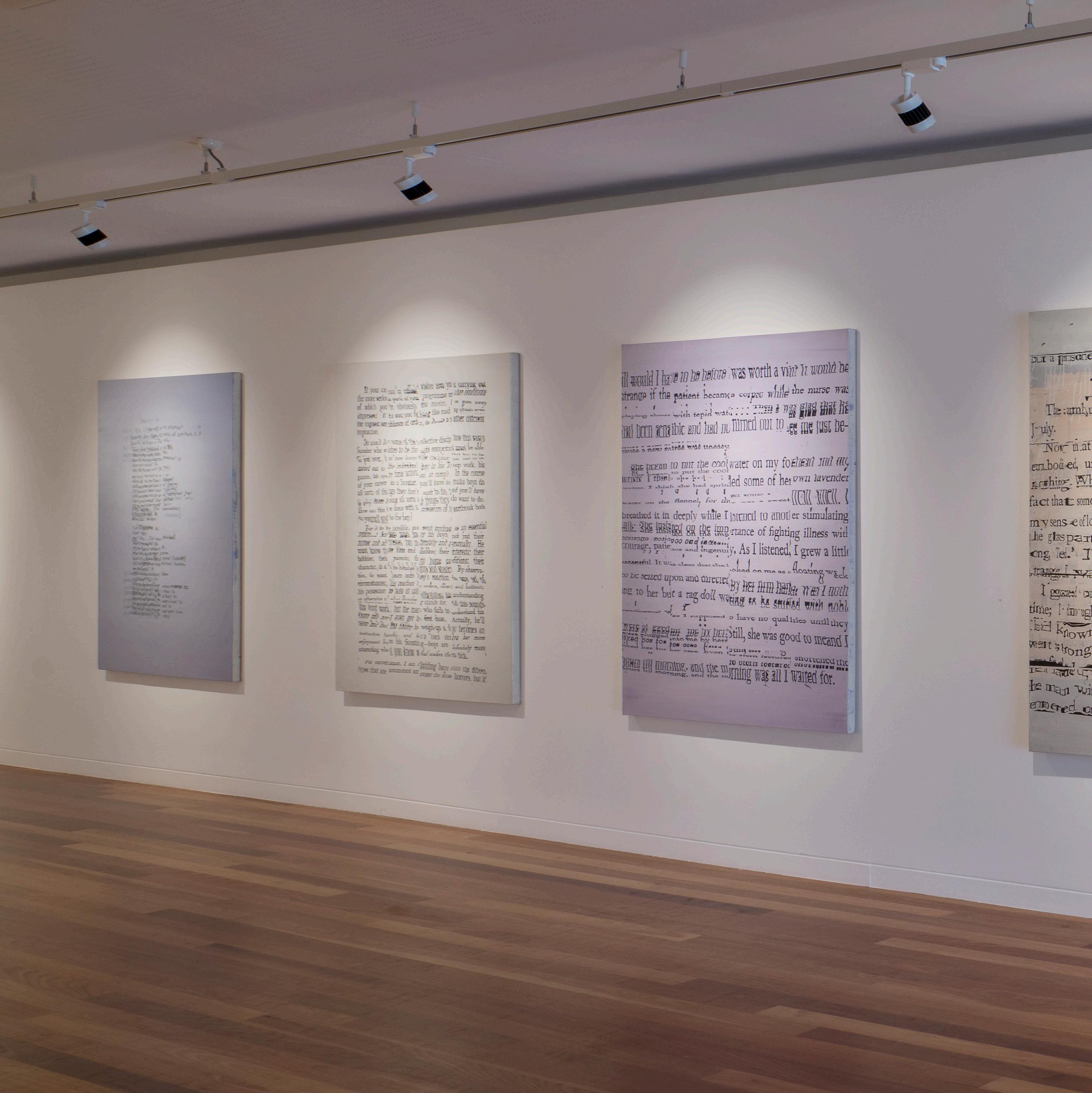

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

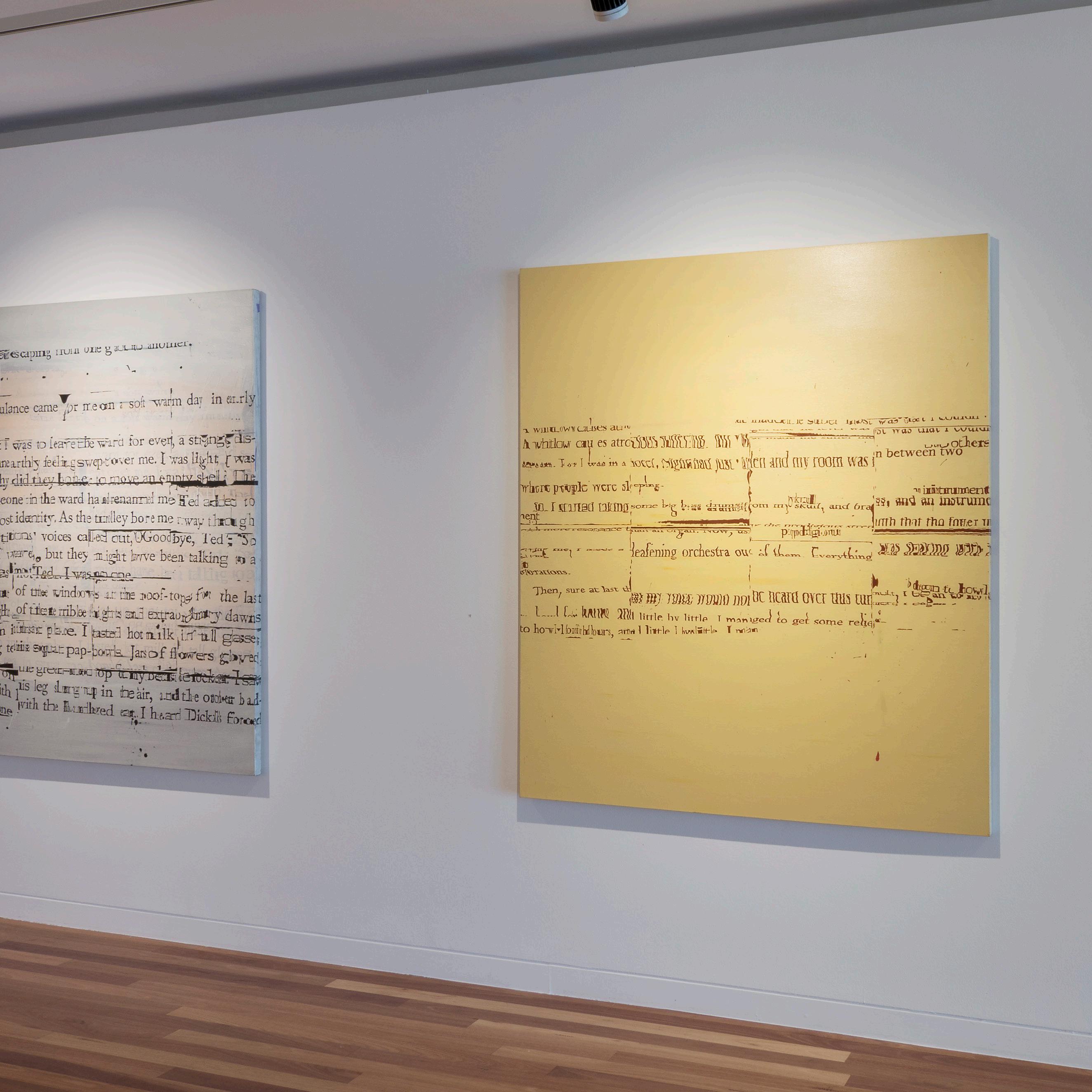

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Image PETER MALONEY

Untitled (lies that life is black and white), 2018

Photomontage, 30 x 40cm

Photo courtesy of Utopia Art Sydney

Image PETER MALONEY

Untitled (lies that life is black and white), 2018

Photomontage, 30 x 40cm

Photo courtesy of Utopia Art Sydney

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

PETER MALONEY

The Mirror: Angles of resistance exhibition installation, 2023

Photo by Brenton McGeachie