Cover by Sol Heo OCT 5 VOL 32 — ISSUE 3 In This Issue Family As Self Portrait Daniel Hu 4 Grief In Practice gabrielle yuan 3 Write About It Ayoola Fadahunsi 2 Nothing Much is Happening Sarah Kim 6 postThe Road Back Home Samiha Kazi 5 Sartorial Season Sean Toomey 7 It's a BeautiFALL Day Lily Coffman 8

And the winner of poetry interpretation is… I sat on the edge of my seat, waiting for the results that would a rm or dismantle my budding 8th-grade ego. "...Ayoola Fadahunsi."

When my name was announced, I hurried to the stage, immense glee consuming me. Although the powerful, award-winning poem I had presented about writing through one’s pain and grief was merely a performance, unbeknownst to me, it would soon become my reality.

Poetry interpretation, a category in speech and debate, is a competitive speaking style where the speaker utilizes a published poem to tell a story through emotive hand gestures, intense tonal inflections, and the like. The National Speech and Debate Association describes the

Letter from the Editor

Dear Readers,

As a lover of warm days and naps on MG, it feels only right that I dedicate my first editor’s note to this beautiful, sunny week. This week has felt like a never-ending justification for skipping classes, a celebration of the last time the sun will grace us with her presence before winter descends. It is the act of labeling the day as the last that makes it all the more precious, that makes the warmth feel so fleetingly perfect. The Last Warm Day. But it seems that every year, without fail, the sun manages to come out for one more day after that last day, and I have an excuse to skip one more class, spend one more hour outside, let one more day pass before my paper is written. Despite my dread of the cold, it is precisely the promise of winter that makes the last sunny days so spe -

Write About It

When Performance Meets Reality

By Ayoola Fadahunsi illustrated by Junyue MA

interpretation of literature as “bringing words to life.”

From the age of 12, I have devoted countless hours to public speaking, finding other’s tales and sharing them in expressive ways. Through speech, I have restructured narratives from various speakers into a collective story. But an impersonal story was all that it was to me at the age of 12.

When preparing for my speech competition, I stumbled upon spoken-word poetry after unsuccessfully reading through poems from books. Spoken words such as “Table Games,” “If I Was a Love Poet,” “Ode to the Women on Long Island,” and “Hide Your Shea Butter” filled my computer screen and transported me into di erent worlds. From the comfort of my bed, I became

cial—the inevitable cold reminding me to drink in every last drop of sunlight.

As campus clings to summer, grappling with change as the sunshine begins to fade, our writers, too, contend with seasons of grief and transition. This week in Feature, our writer considers how her aunt’s love and journey with cancer has informed how she writes and expresses emotions. Our Narrative writers also reflect on family—one on processing the grief of losing her grandfather, and the other on attempting to reconcile his father’s and grandfather’s descriptions of one another. In A&C, one writer speaks to living in her new apartment and the nostalgia she feels for campus life, while the other illustrates a collection of moments with friends, finding intimacy in the most mundane of moments. Our Lifestyle writer echoes my reflections on

a heartbroken partner, a woman from Long Island, Shakespeare’s summer’s day, and an undercover detective. I was enamored by the power of words. Poets like Sarah Kay and Rudy Francisco knew how to wield words like swords and shields, piercing the veil of my childlike ignorance and exposing me to new realities.

The poem that stuck with me, though, was “Cancer and Poetry Don’t Mix” by Mickayla Jade Noel. The vulnerability of Noel’s poem and her ability to reflect the humor and light of her grandmother awed me. In the poem, her grandmother’s cancer diagnosis is “announced politely over a cup of sweet tea,” and I could not understand why Noel included this in her poem. Cancer is aggressive and deadly, polite did not seem to fit, but I performed it

the transition of weather, giving advice on how to dress according to the French countryside aesthetic. As the cherry on top, our crossword invites cool temperatures with some fall-inspired clues.

I hope you enjoy this week’s articles. Read them on the Main Green, the ledge of Manning Chapel, or in a hammock on Ruth J. Simmons. As I write this, the sun has just begun to shift on the Quiet Green, and I can feel The Last Warm DayTM beginning to depart. In spite of it all, I’m looking forward to shorter days and crisp mornings—the perfect weather to curl up by the fire with a cup of tea and a copy of post-.

Walking

on sunshine,

Tabitha Lynn Lifestyle Managing Editor

FEATURE

2 post –

“

nevertheless, oblivious to the nuances of life.

I learned of my aunt’s breast cancer diagnosis in my dimly lit dining room, surrounded by amala ati ewedu filled plates. Although it was some time later, my mind returned to Noel and that sweet cup of tea. The mundane scene is preserved in my mind and associated forever with the somber voice of my mother: “Your aunty has stage 4 breast cancer.”

Noel’s euphemistic description of the news of cancer finally made sense to me. When cancer waltzed into my life, there was no break in life’s eight-count rhythm. Sunny Ade’s Yoruba melodies bounced along the walls, drifting into our unwilling ears, lively laughter permeated from the neighbor's backyard, and the inconsistent whooshing of car engines ticked along with time. Life kept going, even as my family was stunned into silence, the only sound we recognized being the amala dropping from our hands. Questions of concern followed the silence, but my mother assured us that all would be well—“They caught it early.”

My aunt came to live with us in 2020. She had been battling breast cancer for five years, and it was the first time I had seen her in person since her diagnosis.

My aunt lived in New York City, while my family lived in Virginia—but distance did not cause our limited interactions. I was 13 when I learned of her diagnosis, and I was initially afraid to speak with her as I did not know what to say. She’d spend hours on the phone with my mother, and I would pretend that I was not in the room, shaking my head vigorously when my mom o ered the phone. Eventually, I gathered the courage to speak to her, though we never spoke of cancer. Instead, she would remind me of our grocery shopping shenanigans, the fake stories we crafted of my neighbors’ lives, and the bus stop conversations that shaped my childhood.

Despite consistent communication, however, my family was never able to see my aunt in New York. She was a private person, and while she expressed her joy openly, she often hid her struggles. On a trip to New York, my mother tried and failed to get her recent address. She called the day after we got home and apologized for missing us during our visit. It was evident that she wanted privacy.

Fear, accompanied by shame, plagued me as I anticipated her arrival in 2020. I had always kept her diagnosis in the back of my mind, but now, it was face-toface. I was ashamed of my unwillingness to face her cancer head-on. I had compartmentalized it into a small box in my mind, and as a result, I had minimized the gravity of her lived experience. Facing her would force me into reality, and it petrified me.

When I finally saw her, I was met with a warm smile that calmed my nerves and assured me that fear would not be welcome in our shared space. For the few months my aunt lived with us, she and I created a story all on our own. Movie nights, selfies, endless tales of our past adventures, and reminders of my beauty encapsulated our time

together. My aunt’s smile never wavered, even as her pain grew and medicine failed to su ce. Her childlike spirit was essential to her being, seeking joy in all things.

My aunt’s name, Florence, meant blossoming and prosperous, and it could not have been more fitting; her radiant smile lit up every room she walked into. Her mere presence was a comfort to those around her; she loved deeply and hard, even at the end.

In her last days—days we did not know would be her last—she told me she had a serious message for me. She sat me down and told me to write about her. “I know you like to write. You should write a story, or a book, or an essay about me. Write, Ayoola.”

I was instantly drawn back to my 12-year-old self, performing Noel’s poem. “I couldn’t write about this” became my own reality. “Cancer and poetry do not mix.” “How do you tell a person you love them enough to make peace with them leaving?” “I have tried to write many poems about cancer but they have all ended in tragedy at the bottom of a recycling bin.”

Words that were mere recitations now had meaning and substance; this was bringing life to literature. Or perhaps the life was in the literature itself.

Marc Kelly Smith founded the modern slam poetry movement in the 1980s as a means of infusing passion back into written work. He aimed to make poetry more accessible to the general public, and his ideas have transformed into a mainstream form of expression. Smith reconfigured poetry performances and invited the audience to become active participants. At weekly poetry events, five random audience members would be chosen to rate the slam poetry on a scale of 1 to 10. And although there are designated judges in current competitions, audience input through snaps and hums persists. Smith’s goal was to bring the life present in written work into a tangible, performative form. In understanding the history of slam poetry, I began to understand that life is in the words themselves, and not an interpretation.

When performing poetry interpretation in middle school, I was merely going through the motions. In Smith’s slam poetry, people were sharing their real experiences, and the emotive hand gestures and intense tonal inflections— life—simply came as a result of their words.

Any writing about my aunt would be life. The honor of preserving her legacy was bestowed upon me, and I felt unfit for the task.

I still do not know how to write her story, but I’d imagine starting with the song she wrote for me the day I was born. A song that reflects her love more than anything else—she was the delight.

Ayo baby delightful baby, Delightful, delightful, Delightful baby."

Grief in Practice

On finding ourselves through loss

by gabrielle yuan

Illustrated by Emily Saxl

While spiders have always paralyzed me, my greatest fear appeared when I least expected it, looming over me during moments of great happiness and great pain.

In the month of June, my mother and I explored Asia, passing first through Japan, then Taiwan, China, and ending with Singapore. One of my favorite moments was witnessing Mt. Fuji in its full greatness, happily recording the breathtaking view on my GoPro. I will also never recover from the divine and diverse cuisine I devoured in each country. From the most a ordable and fresh sashimi to savory dishes of roasted eggplant and minced pork, my Asian stomach will never grow accustomed to salad again.

This trip was also planned around seeing my grandfather, whom I had not visited since 2019. The video calls on WeChat and exchanges of scattered messages over the years couldn’t measure the connection I felt with him. This visit will be the greatest surprise he’s received yet, I thought to myself, imagining our reunion as I boarded the plane.

With the lack of turbulence, the airplane began to lull me to sleep. There was a comforting paleness in the air, the noise soothing me after days filled with bounds of excitement. Just as I was drifting into a deeper slumber, my mother gripped my arm. To this day, I can remember the intensity with which she grabbed me, parts of my arm turning white from her clawed fingertips.

I turn to find her eyes already brimming with tears, and see the message on her phone: “老爷不行了.”

“The old man is gone.”

I thought that when this day came, the nightmare I had conceived in my mind, that I would have no thoughts at all. Instead, among the thoughts swimming in a sea of panic, with my mom collapsed against me, I knew we would never recover.

“I don’t know if there’s any good time to say this, but I’m allergic to milk.”

FEATURE

“I’ve been to Albany, NY and London, England, and Albany is better.”

1. Maffa ;)

2. MAMA

3. Sleepy

4. Sloppy

5. Trader!

6. Carberry (of psychoceramic fame)

7. Cuppa

8. -Jo Siwa

9. Alwyn (someone pls check on him)

O ctober 5, 2023 3

10. Jesus’s step-dad

“

Joe's

Through processing my grandfather’s death, I never imagined the progression of thoughts that occurred:

“Will there be dinner tonight?”

“Are my mother and I going to eat?”

“How long will my mother be leaning against me, gripping my arm?”

“How are we going to fit all the luggage in one taxi?”

Am I selfish? A horrible person to have feelings other than immediate sadness about my grandfather? Was I not as close to my grandfather as I thought? Did I not make enough of an e ort to talk to him? Am I broken to not immediately mourn his death?

These thoughts consumed me completely day after day as I stood, paralyzed, next to my crying mother, watching the funeral progress. I was afraid that I was unable to mourn for the death of someone I loved. The emotions that continuously washed over me were not ones of complete grief or despair, like those of my distraught mother. Instead, I thought of continuing to follow my standard routine, completing the tasks on my todo list. Attempting to find normality at the cost of everything else exhausted me.

Two months later, my mother walked into my room with a worried expression on her face.

“You had a good day today, right?” she asked me slowly, as if testing the air of the tense room.

I nodded hesitantly, unsure of what would follow.

“I’m not sure if I should tell you this today or tomorrow then. P’s mother passed away in her sleep last night.”

I laughed. I was genuinely amused and confused with how ridiculous this idea was. P was one of my best friends, and I knew her mother well. She would rise at sunrise to run before working at her law firm. The woman I had greatly admired for her endless happiness had passed away at age fifty?

There are those specific, powerful feelings that seem to hit me at the most unexpected of times—similar to the sudden crippling thoughts that come to me mid-shower, that force me to sit down, and turn the scalding hot water shivering cold. Tears stream down from my face. And now, I feel the full impact of the death of my grandfather.

As I embrace P, I feel the weight of the sorrow I have for my mother the day my grandfather died, and all the hugs I won’t be able to give to my grandfather.

As I give the care package I put together to P, filled with her favorite candies and a white orchid, I think of the peanut candy my grandfather would, without fail, share with me, and the white bouquet of flowers I placed by his bedside for the last time.

As I watch P’s family members and friends embrace her fully, I think of how I cared for my mother, heating up her favorite leftover pork buns and slowly walking with her through local Shenyang. I watched as her eyes softened at the sight of the tattered swing set and convenience store she frequented during school, and as I watched her select her red bean popsicle from the icy fridge, a piece of me broke. I realize just how much older and younger my mother has grown over this time.

I now notice the constant hand against her back, or the slight lift of her heels when she spots a gentle sunset. I see now that times of unwarranted crisis are when we grow up the most. I now understand that each person deals with grief di erently, from my mother to my friend to myself. My mother is reminded so early of her own loss and has to find space in her brokenness to be sympathetic of others. I mourn for my friend and the fleeting time she has to navigate the loss of her dearest person before leaving for college and making the right impressions on new strangers.

Times when life seems unbearable, constantly full of mundane tasks, can also yield to moments spent with loved ones. Watching P surrounded by triumphing love after her mother’s death is a reminder that through grief, there is hope. As my mother and I continue to navigate the unpredictable future, I know for certain that our feelings of loss are temporary in our healing.

Family as Self Portrait

my father his father

by daniel Hu

Illustrated by emilie guan Insta: @emilieguan42

I. KNOWN FACTS ABOUT MY FATHER

He grew up in a village around Wuxi. He has a brother whom I have never met. He says that he cannot handle spicy food anymore after an incident in his youth when he passed out while eating spicy huo guo in Sichuan. He is afflicted with gout. He loves gardening for the simple joy of clipping stalks of jiu cai . He strains soybeans over a colander every morning to make soy milk for my mother. He is fascinated by feng shui and the movement of invisible energy across space.

In his undergraduate years in China, he trusted a friend of his to give him a haircut. The results were so abominable that my father decided to buzz off the rest of his hair and start fresh. When he next came home, my Nai Nai did not recognize him, thinking he was a soldier coming knocking at her door. She knew he was her son only by the timbre of his voice.

He arrived in America after my mother had already been living here for seven months. He arrived in late November, just a day after a blizzard had deposited a blanket of snow on top of New York. My parents lived in Flushing, in a neighborhood that had lost power in that recent snowstorm. My father spent his first week in America in a cramped, cold, and lightless apartment.

In every house we have lived in since, my father has set our wifi password to the address of their first house in America. I have heard more about New York than my father’s hometown. He seems to remember the freezing terror of those early years in New York more than any other period of his life.

II. STORY AS A RIVER

Our family stories seldom hold up to scrutiny. We never tell a story the same way twice because families never fall in straight lines. I have heard three versions of how my parents met. My cousin’s nickname is Ding Ding and there are four different etymologies, four different explanations of how this name came to be. Nai Nai could speak to the wind, and she could tell from the creak in

her bones when a thunderstorm was coming.

My father once told me a story about Ye Ye, how he once wrestled with a rampaging pig until the pig was so exhausted it could no longer walk. Ye Ye, with his powerful voice and his wide palms, forced the pig’s head into the mud and shouted so loud the water receded from the riverbank. As nature recovered from the force of Ye Ye’s voice, he whispered into the pig’s ear: hui jia . Go home. My father does not remember telling me this story.

My father talks about childhood in China like I talk about dreams. When he speaks, words evaporate into the air, leaving only the suggestion of their contexts and the texture of language. Our conversations about China usually take place after he has had a few beers. He will fix his glasses and lean forward onto the dinner table. He will look at me solemnly and trust that this family knowledge will carve itself a canyon in my mind.

Folkloric detritus accumulates onto our family like snow.

III. HIM IN HIS YOUTH

It is impossible to reconcile my father with the man I see in my parents’ wedding photos. This unknown man stands with his arm around my mother, who will always be recognizable as my mother, who is smiling with her whole face, just the same way that I now also smile. He stands, an obelisk, his slim-fitted black suit cutting a volcanic figure against an otherwise pastel photo. My father is stone: solemn and sharp. The camera has captured him at his most deadly angle.

IV. WINTER OVERSEAS

My father used to travel often for work when I was younger. He was only ever gone for a week or two at a time, but time passed differently back then. As I felt it, he was missing for months at a time.

Ye Ye took care of me in his absence. Ye Ye, who, in his old age, is nothing like the stories that my father used to tell me. Ye Ye, who is now quite small in comparison to the towering oak tree

NARRATIVE 4 post –

figure in my father’s stories. Ye Ye, who taught my father how to clip stalks of jiu cai and how to stirfry leftovers into rice. Ye Ye, whose fingers are gnarled and brown from too many years under the sun. Ye Ye, whose fury my father describes as legendary, but who I have never seen get angry. Living here outside of China has changed him, my father explains. He is softer now.

V. MY FATHER AS SELF PORTRAIT

And here is where we once were, my father says. He uses the word jia , which in Mandarin means home. He is pointing at a shallow depression in a plot of dirt. We are walking through my father’s hometown in Jiangsu. The hole used to be deeper, my father tells me, when Ye Ye used to live here. That was before he married Nai Nai and moved in with her family, after which this plot of dirt became where they kept the pigs and also where Ye Ye and Nai Nai sent my father and his brother to sleep if they weren’t doing well enough in school.

As a schoolboy, my father walked to school with a bowl and a pair of chopsticks in his bag. Back then, school cafeterias offered food only, not utensils. He would walk this way the whole day, with his bowl and his chopsticks clanging together in his bag.

This is the only way I might imagine my father as a child, walking on dirt paths, a porcelain chime-tone with every step.

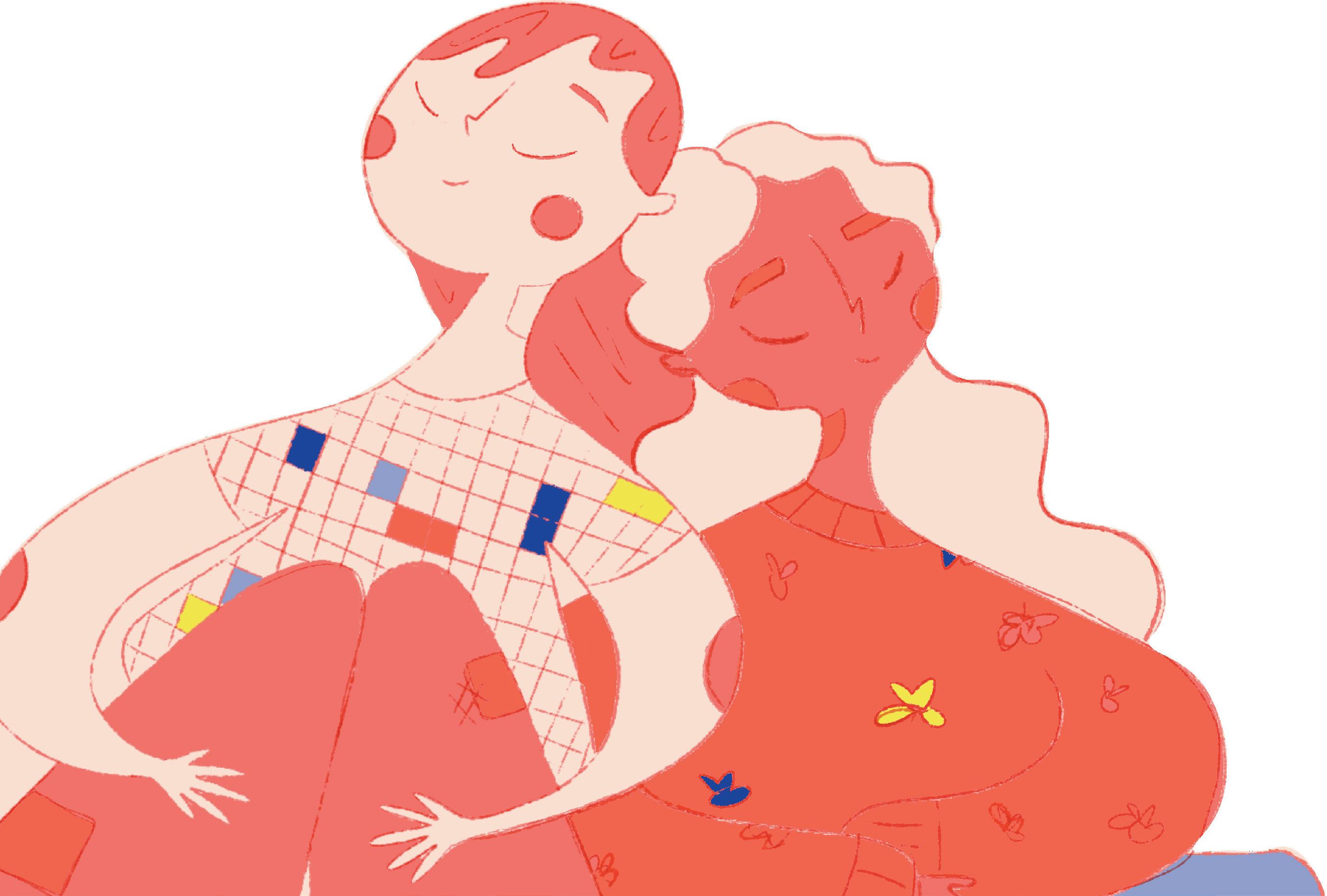

The Road Back Home

by samiha kazi

Illustrated by Ella Buchanan

I fumble with my keys as I try to juggle my umbrella, lanyard, and packages without dropping everything. I finally get a grasp on my green-nail-polish-spattered key, and sigh with relief as I slide it into the keyhole. I turn it to the right. The door doesn’t budge. I try again; the door remains shut. I start messing around with the top lock, rotating my keys in every direction. Shivering in the rain, my socks getting damper each minute, I’m about to give up on any possibility of making it back to my apartment when I try the bottom lock once more, and the door finally swings open. With “Homesick” blasting through my AirPods, I stand in the rain for just a few more seconds, taking in the scene.

I am an avid fall enthusiast; I love everything about the season. I love transitioning my closet from tank tops to chunky sweaters and trading in the green blades of grass for a collage of leaves. I am satiated by the overwhelming scent of cinnamon that washes over me when I enter Trader Joe’s, and I am thrilled when cafes unveil their coveted drinks for the season. But on top of everything pumpkin- and apple cider-related, I am always most excited for the start of school. Call it nerdy, call it lame, but I will never deny how delighted I get when that first day of classes rolls around. The prospect of picking out a first-day-of-school outfit, packing my new school supplies, and sending my parents that “FDOC” photo makes those last days of summer bearable.

This September, I got ready for my last first day of school. I woke up hours before my alarm, lying in a shallow pool of my own sweat. It was pushing 90 degrees outside and my non-air-conditioned, o -campus bedroom was at least another 10 degrees hotter. My pool of sweat grew as I lay, contemplating the fact that it would be my last first day at Brown.

For once, that first-day-of-school spark was nowhere to be found.

Was I supposed to be excited? The growing pit in my stomach said otherwise. Should I have felt nostalgic? Riddled with this heavy feeling that I could not push aside, I turned to the JBL speaker on my nightstand and dialed it down to the lowest volume level. Without having to scroll through my playlist library, my fingers took me straight to my most recently played playlist: “Exit 30A.”

For my whole life, Exit 30A was the road back home. As a young child fighting to keep my heavy eyelids from closing in the back of the car, I could breathe easily whenever I saw that familiar sign loom ahead through the window. As a confused teenager (and adult, unfortunately) who could never tell whether I was driving north or south on the interstate, I could relax my grip on the steering wheel once that same sign came into view through my right window. Like a tattered treasure map, Exit 30A had always marked my most valuable possession for the past 21 years: home.

It’s funny to think that I am currently living in an apartment with four other people whom I met less than two and a half years ago, and that these are also the people I’d trust with nearly anything. I think about how much Providence means to me, and how it is permanently etched into my identity no matter where I go next—in a way, it is home as well.

Still, I find myself feeling wistful about the close of this chapter. Where did my mornings of defending my love for Ratty house co ee as my friends labeled it “battery acid” go? What happened to setting my alarm up at ungodly hours in the morning so that I could secure my own table on the second floor of Faunce? The disconnect from campus has felt stronger than I expected it to, and the detachment seems to grow with each passing day. I’ve unintentionally started counting the number of people I recognize and wave to when I find myself on campus; the number has dwindled more than I’d like to admit.

“Exit 30A” transports me back to wherever I feel most comfortable. With the tap of my finger, the playlist anchors me and reminds me that no matter how disconnected I may feel from a place or others in a single moment, they’re still there. Noah Kahan never lets me forget how proud I am to be from New England. Clairo reiterates my relief every time the Red Line comes to a halt at my station. Novo Amor reminds me to give my friends in Providence a hug and to give my friends scattered across the world a call.

Being away from campus serves as a reminder that I am slowly outgrowing this space that I’ve learned to call home. We settled into our little houses in various

neighborhoods, with fewer and fewer reasons to bounce around campus buildings; I’ve started seeing the same faces as we rotate through di erent living rooms to pass our nights together.

There is nothing wrong with a little disconnect—in fact, it’s truly just a little growth. I think I speak for most of us when I say I am happy to not be the same frantic firstyear, trying to claim each corner of campus as my own. Adopting this perspective may be a lot easier said than done, but I think that the little spontaneous moments of appreciation for this place make it just a little bit easier to do so. Even just lying here in my bed, my heart soars when I look at my framed Narragansett Lager and Del’s Lemonade prints on the wall.

It might be quite di cult for me to let pieces of Brown and Providence go when I think about the future, but I need to remind myself that I am in fact still here. I still have nearly two whole semesters left with the people and campus that have sculpted me over the past few years.

I can still hold onto these pieces. I can still sit for hours in the ERC lobby, watching every person who walks in and out of the front doors. I can still take a trip to the Main Green with the intention of studying, despite never unzipping my backpack.

I can listen to the song that I reserved for study sessions on the fourth floor of the Rock throughout the summer semester. I can listen to the song that my roommate and I played every morning of sophomore year to wake each other up. I can listen to the song that my friends and I deliriously kept on loop while quarantining. And I know exactly where I can find all these songs: “Exit 30A.”

When I came back home after my first year at Brown, all the interstate exit numbers had changed. Nobody thought to notify me of this renovation. I found out in the back of my minivan, when the exit signs grew more and more unfamiliar as we supposedly got closer to home. Finally, my dad hit his right blinker and took an exit under a new number; underneath the new sign was a much smaller sign, labeled “OLD EXIT: 30A.”

I know the future holds many more new exit numbers for me. Everywhere I've ever called home will stay tucked away, but just within memory's reach when I need to feel the comfort of belonging.

I don’t know if I will ever forgive I-95 for redoing the exit numbers. But just because the highway was able to erase components of its identity does not mean that I will ever do the same—and I will keep adding them all to “Exit 30A.”

NARRATIVE O ctober 5, 2023 5

how a simple playlist fills you with ease

To do:

1. Get flu shot

The winter season is beginning, and Maddie has verbally announced she will likely get her flu shot soon. I tell her that I will join. We can go tonight; she’ll pick me up. We arrive at the pharmacy and I have forgotten to have my insurance information on hand; Maddie stands while I sit in a chair trying to remember passwords and resetting them only to be met with last year’s outdated information. She waits, and I finally click through enough things on my phone to land on a file with my insurance info. Once again, she waits as I now fill out the forms she’s finished long ago.

We roll up our sleeves and then roll them back down within seconds. Our friendship is confirmed in the matching teal Band-Aids that brand us, and we linger in the aisles, tagging ourselves as toothbrushes and pointing out which vitamins we used to eat as children. Maddie gets a Diet Coke for the road, and as she drives us back to Providence, we deem this our new activity to regularly do together. Add it to the list: farm visit; long drive to some location; volunteer hour; tea time; flu shot.

2. Work on AMST1600C paper

The first paper of the term is due tomorrow. It is already midnight. The assignment is confusing, MaiThanh and I need to do other work urgently, and we wish we didn’t have to write this. I write one sentence, then delete two. The data I need is Cambodia’s 2007 TIP Report, located in a 500-page file, and the first page is barely even loading. I wait. As I do, I turn to Mom’s all-purpose remedy for any cough and throat problem (and hopefully to stress and this lack of motivation too): tea with lemon and honey. I bring two mugs to the living room and hand one to MaiThanh who is under a blanket on the couch with her computer. We sip our teas as we continue to work, the only sound in between the moments of typing being sni es and coughs. Tired, sick, and cold–school has really begun, it seems.

There is banana bread in the oven that fills the house with warm notes. I put it in half an hour ago when I realized this would be a long night: why not make it a bit sweeter? Tommy calls on the phone and asks what we are doing. We groan. “Working,” we say. He really should be working too; there’s a discussion post due by the morning. But there’s banana

by sarah kim

Illustrated by Lulu Cavicchi

bread coming out of the oven soon, so come, do it here with us.

Five minutes later, Tommy meekly pushes open the door, pajamas on, holding his laptop in his arms.

It is nothing spectacular: we are three students up late on a school night. But now the banana bread is out. We gather on the floor, sitting around the living room co ee table where the loaf and a knife take center stage. No computers or books or tissues are in sight; instead, moments of friendship are revealed in a series of exchanges: of the first slice, of hazelnut spread, of honey, of napkins.

Mai-Thanh and I finish our papers and Tommy writes his discussion post, our tasks for the day done. Ask me, and I will tell you that on Tuesday night, we sat on the floor and shared banana bread.

3. Lunch in the park

You suggest sandwiches. Let’s pick them up and go to the park to eat—it’s a late summer day in New York and people-watching in Washington Square Park entertains us for hours. We find a bench right on the perimeter of the fountain, the perfect spot for pointing out cute corgis frolicking in the summer sun or imagining backstories for the characters who filter in and out of our periphery.

What do we talk about? I can’t remember, but I’ve just checked and two hours have passed. We decide we should wander around for a bit. I learn how you like your co ee, and you begin to learn the subway lines (though you call it the metro). We grow lazy under the summer sun, and as it sets, we walk back home learning the slip of each other’s hand.

4. Brown Market Shares Volunteer hour

If you walk past the potatoes, rhubarb, nectarines, and bread, you’ll see a table in the back left, next to the swinging doors of the kitchen: cheese, eggs, and Maddie. This is our station, the only two-person one (or so we’ve determined it to be. It actually can very feasibly be done by a single person, but it is eggs and dairy and sometimes even meat. So, like we said in our joint application, the station is a two-person job and we’re perfect for it). Maddie arrives early to secure our spots, and when I arrive, I

walk straight to the back, give her a hug, fetch dozens of eggs to restock our table, and pour us each a tea.

The next hour is mostly uninterrupted, spent unpacking and investigating life sitting side-by-side at a folding table. Occasionally, we’ll need to pause to tell people that Maddie will check you o and I’ll be back with your milk! We say about 10 words during that hour outside the two of us, and it is always 10 too many.

Thursdays 3-4 p.m. is simple, easy, sometimes boring, always lovely.

5. Tomorrow: Bank, pick up desk, UPS—all with Thanh

I can’t wait.

***

I find myself thinking about the moments I’ve talked about above and wonder why I hold onto them so tightly. When you pointed out the four boys sideby-side, eating half watermelons with spoons, why did my heart almost burst? Was it the delight of the scene itself, or was it the feeling that you, charmingly and unexpectedly, knew the joys of my own heart?

I believe I am good at being alone. My sister and I dedicated ourselves early to instruments, and practicing was always a solitary activity. The greater the number of hours in the room, door closed, focused and practicing, the better the violinist I would be and the better cellist she would too. I learned that play dates were never to be spontaneous, that Saturdays meant music school day, and if time could be spared (it never could), it should be spent practicing.

Eventually, Holly would go to college, Mom would return to work, and Dad to school. I loved music, so I kept playing the violin—which meant I should keep practicing, and which meant I should be home, alone, honing my skill. After school, I’d go to my bedroom and open my case to practice. Then, until Mom and Dad returned from work late, I’d make food, and dance, and practice, and nap, and push myself around the room on a swivel chair. I got good at being alone. I got used to it. Because of this, I believed that when I was with others, it had to be eventful. Loud, exciting, robustly planned with activities—this is how friendships grew and thrived.

But if that is true, why does my heart wince whenever I realize I won’t be repeatedly opening and closing a cooler of cheese with Maddie forever? I want her to promise me she won’t ever get a flu shot without me, and I want Tommy to always be barging into my home when the banana bread will be out in five.

Something keeps pulling me back to these moments when nothing much happens. Even as I write this, I am in my living room surrounded by four friends whose friendships were all formed individually and separately. The house is still; everyone is silently doing their own work. I can hear the kettle’s growing boil in the kitchen. There is music playing from the speaker, but the hum of the dishwasher fades it into the background. And this is what I find myself missing already. Perhaps it is that intimacy flourishes in the gentlest of spaces, in the most ordinary of moments, when a single heartbeat can expand and deepen, as if to extend a hand and ask to dance.

ARTS & CULTURE

Nothing Much is Happening and still, the heart is full

Sartorial Season: That French Countryside Look a fall aesthetic for you

by sean toomey

Illustrated by Joyce Gao

by sean toomey

Illustrated by Joyce Gao

There is no showcase for one’s carefully crafted aesthetic quite like the fall season. Fall is when the nice little leaves fall off the nice little trees and we all get to wear our nice little outfits before giving in to the sludge of winter. With that in mind, I’m dedicating these next few articles to you, dear reader, to give some pointers for dressing this fall.

The basis of this look is both linked to cosmopolitan France and the rich tapestries of the French countryside (less gloomy than the English Moors—try pretending you’re in a Cézanne). If French city-fashion is a Parisian intellectual—drooping cigarette, roped shoulder double breasted suits, sadness—then the French Countryside look is if that Parisian intellectual had a penchant for clothes that weigh more than a small child. Combine the classic items of French style but add a heritage twist to it. Put yourself in the scenery of it all; the ochre of the fields—rose red, deep river blue. This is the look for riding an old bicycle while carrying an even older book in your jacket pocket. Old clothes, old things, warm tones, and warm coffee. This is the look for writing poetry while eating an unhealthy number of cheeses and pastries.

On the clothing front, use natural colors to create unified and textured looks. Instead of a crewneck, throw on a jewel tone sweater vest or a cable-knit turtleneck. Instead of a navy blazer, throw on a wide herringbone suit and

your favorite pair of boots. The clothes should be functional, warm, and have giant pockets to carry all your things. I, for one, don’t even carry a bag to class anymore—I picked up an Italian habit of just shoving my books (and sandwiches and groceries and receipts) into my blazer and coat pockets. You would also be remiss to forget the classic chore coat, the most famous garb to come from the French countryside. These are great for more casual looks and layer well over sweaters and even crew-neck shirts (go for a breton shirt for the full French experience). For outerwear when the weather really turns, go for loose fitting, unstructured coats with raglan sleeves. A doublebreasted coat in this style with a belt is a great look—my preferred look in Italy. And, while partly off-theme, I can never not recommend a doublebreasted camel hair polo coat which goes with everything (and even a tuxedo if you have enough panache).

For pants I would go wide, wide, wide. It’s not only trendy (although this should never be the deciding factor in your purchases), but also very comfy and flattering. Go for highwaisted numbers in corduroy, moleskin, hardy work fabrics, and light wash denim for a more citifed air. Gray flannel trousers are also to be considered as they go with literally everything and—most importantly—are very soft. Rakishly patterned tweed pants can also fill a fun role (big sweater, big pattern, big heart) but can be difficult

to match. As a general tip, make sure the patterns are of different scales.

Shoes should be thick and hardy to match the overall landscape we’re aiming for. Think double soled shoes, work boots, rain and riding boots, plain toe derbies, and longwing brogues. A great shoe to bridge the gap in the formality spectrum of this aesthetic is the Norwegian split toe derby, which is sleek enough for casual suits but also chunky enough for casual wear. Loafers can work here but avoid anything a little too modern, so no black tassel loafers or Oxfords. A good workaround for those of you who worship black shoes is black derbies that are sleek enough to almost appear as a boot. I have no actual name for these so I’m calling them “fancy lad shoes.”

Closing with accessories, you can’t go wrong with fun scarves in brighter colors, tweed caps (be careful or you’ll look like you run an independent brewery and use Bluetooth headsets), and ties in wool and cashmere.

I hope with this guide you can get a good start to your fall aesthetic instead of scrounging last minute for the sweater, joggers, and gray and white sneaker fit that everybody and their mother is wearing. Some final tips for the road: start drinking espresso, get concerningly into red wine, watch the complete filmography of Robert Bresson without subtitles, and actually do something about that situationship. Now go out there and bring Provence to Providence.

ARTS & CULTURE O ctober 5, 2023 7

It's a BeautiFALL Day (to solve a crossword)

post- mini crossword 14

by Lilly Coffman

1 2 3 4

5

6 7 8

Across

1 5 6 7 8

Not fake

Yard barrier that might keep animals out of your pumpkin patch

Order option, like getting pumpkin spice syrup in your latte

Autumnal vegtable family

TV channel for watching the fall football season

“I wish I had all of their memoirs. But since I don’t, I cut out space in my personal history for these unknown ones and fill it with imaginary women: women who loved. Who stayed. Who left. Who saved themselves, so I could be here, writing them down.”

—Siena Capone, “How I Read Your Mother” 10.08.21

“Because language is the only thing that has never felt like a waste of time. So you will leap into the ocean—or you will let yourself fall—over and over again, and in the end you will write about it all. You will warp your words, like Pygmalion does his clay, until you convince yourself that your creation is as good as the real thing.”

—Emily Tom, “From Here, You Can See Everything” 10.07.22

Down

1 2 3 4 5

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Kimberly Liu

FEATURE

Managing Editor

Klara David -

son-Schmich

Section Editors

Addie Marin

Lilliana Greyf

ARTS & CULTURE

Managing Editor

Joe Maffa

Section Editors

Elijah Puente

Rachel Metzger

NARRATIVE

Managing Editor

Katheryne Gonzalez

Try-agains

Arrive somewhere, but not intentionally

This squash is a type of 7 Across

Offer, as a hand

Greek yogurt brand sometimes found in the Blue Room or Jo's

Section Editors Emily Tom

Anaya Mukerji

LIFESTYLE Managing Editor

Tabitha Lynn

Section Editors Jack Cobey

Daniella Coyle

HEAD ILLUSTRATORS

Emily Saxl

Ella Buchanan

COPY CHIEF

Eleanor Peters

Copy Editors

Indigo Mudhbary

Emilie Guan

Christine Tsu

SOCIAL MEDIA

HEAD EDITORS

Kelsey Cooper

Tabitha Grandolfo

Kaitlyn Lucas

LAYOUT CHIEF

Gray Martens

Layout Designers

Amber Zhao

Alexa Gay

STAFF WRITERS

Dorrit Corwin

Lily Seltz

Alexandra Herrera

Liza Kolbasov

Marin Warshay

Gabrielle Yuan

Elena Jiang

Aalia Jagwani

AJ Wu

Nélari Figueroa Torres

Daniel Hu

Mack Ford

Olivia Cohen

Ellie Jurmann

Sean Toomey

Sarah Frank

Emily Tom

Ingrid Ren

Evan Gardner

Lauren Cho

Laura Tomayo

Sylvia Atwood

Audrey Wijono

Jeanine Kim

Ellyse Givens

Sydney Pearson

Samira Lakhiani

Cat Gao

LIFESTLYE 8 post –

involved? Email: mingyue_liu@brown.edu!

Want to be

by sean toomey

Illustrated by Joyce Gao

by sean toomey

Illustrated by Joyce Gao