Italian o Calvin o It aliano Calvin o

FOR & MAGAZINE URBANISM LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

ATLANTIS POLIS

From the Board

This issue is printed in the aftermath of the earthquakes in the broader region of Syria and Turkey as well as the recent tragic train crash in Greece. In light of these, we would like to express our deepest condolences and support to all those affected directly or indirectly. We hope that the next issue will be delving in the underlying criticalities of such catastrophes.

We could not be as visible as we are without the great effort of a lot of active students. With their help and the support of our partners and sponsors, we can organise excursions, lectures, workshops, drinks and events. The Polis board wants to thank all the people involved for their great efforts and positive input.

Polis Board

CHAIRPERSON Jens Berkien

SECRETARY Sani ka Charatkar

ATLANTIS Myr to Karampela-Makrygianni

Sani ka Charatkar

PR Lar issa Muller

EVENTS Ann Eapen

EDUCATION Ann a Kalligeri Skentzou

Join Us

We are always looking for enthusiastic people to join. Interested in one of the Polis committees? Do not hesitate to contact us at our Polis office (01.west.350) or by e-mail: contact@polistudelft.nl

Subscribe

Not yet a member of Polis? For only €17.50 a year as a student of TU Delft, €30 for individual membership, or €80 for professional organizations you can join our network! You will receive our Atlantis Magazine four times a year, a monthly newsletter, possibility to publish and access to all events organized by Polis.

E-mail contact@polistudelft.nl to find out more.

Editorial

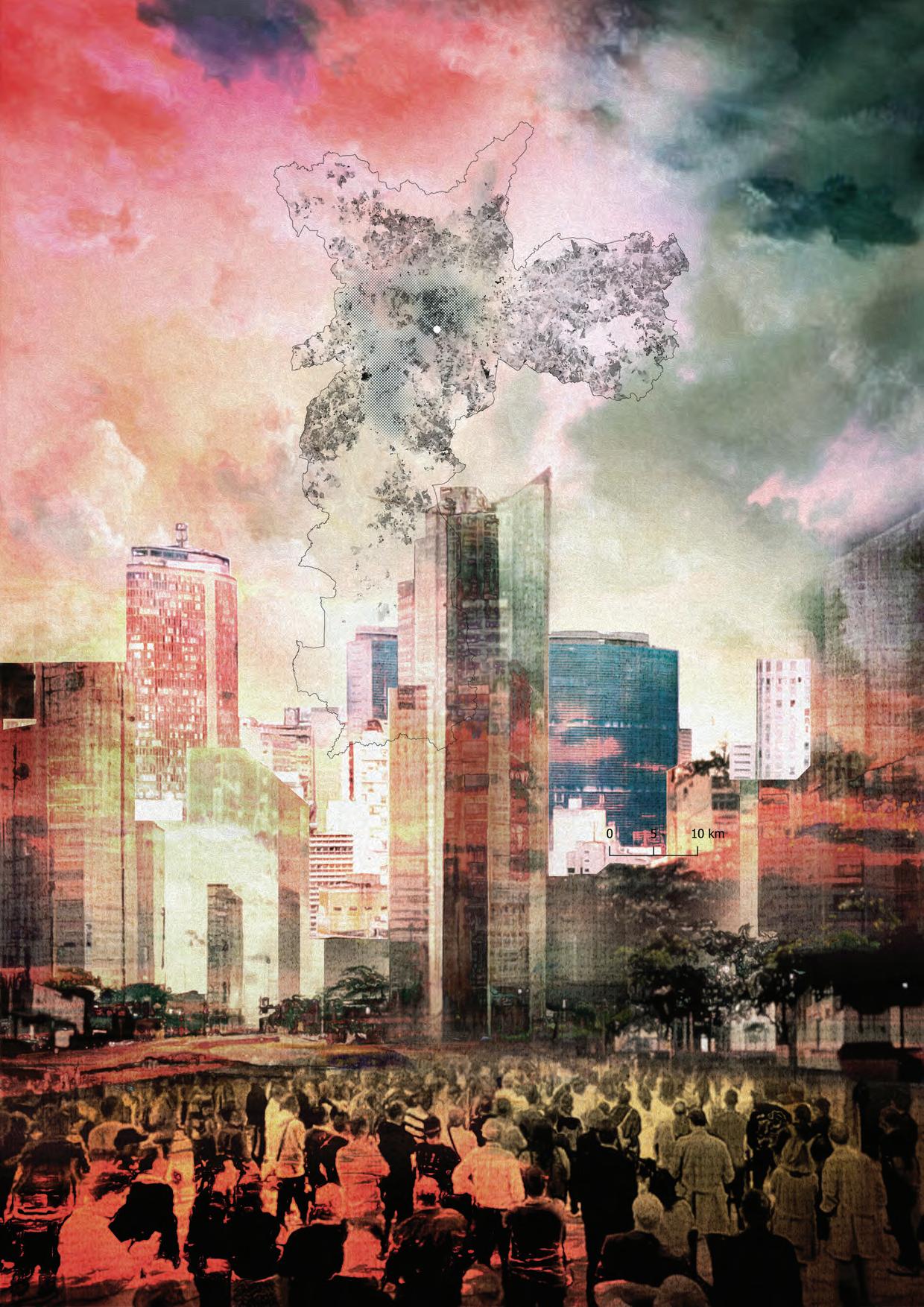

“It is not answers or solutions that architecture requires, but incisive questions and problems that demand of it inventive knowledges and practices.”- Elizabeth Grosz (2003) This issue of Atlantis attempts to define a reflection and experimentation space around the issue of (In)Visibility. What does it mean to be (Un)Seen? What does the very act of rendering the invisible visible entails? And how does the visualization of things, processes and structures that are viewless, hidden, undervalued, or underrepresented transform the researcher or the designer? How does it transform the object of its observation and representation? Deriving from these questions, Volume 41(a) seeks to trace underlying structures that shape the 21st century urbanization patterns reproducing conditions of social segregation, to decode hidden socio-cultural processes that have participated in the formation, maintenance or instrumentalization of complex urbanized landscapes, to reveal unfamiliar or unseen territories created by human activity in the era of the Anthropocene and to reflect upon the spatial transformations performed by the very act or the tools of visualization.

The following narration begins with an investigation on the way urban freeway construction projects - working together with simultaneous ‘urban renewal’ schemes - have been used as government-led segregation tools in American Cities after the 1950s. In a similar tone, the postwar VINEX policies introduced in the Dutch Residential Neighborhoods are critically examined as initiators of residential and socioeconomic segregation and as facilitators of gentrification projects. Touristic gentrification as a new form of colonization and capitalization is discussed also in the context of Hawaii where language, land and culture have been systematically commodified to serve the image of the ideal holiday destination. In a different form but still under the notion of capitalization, the next article tracks current cross-border capital investments in the European context dictating the emergence of supranational territorial formations. Closing the chapter, the work of the Vertical Geopolitics Lab around the exposure, challenge and reconstitution of spatial patterns, practices and visual material related to imperialcolonial expansion is presented and discussed attempting a counterhegemonic approach to the power-space relation.

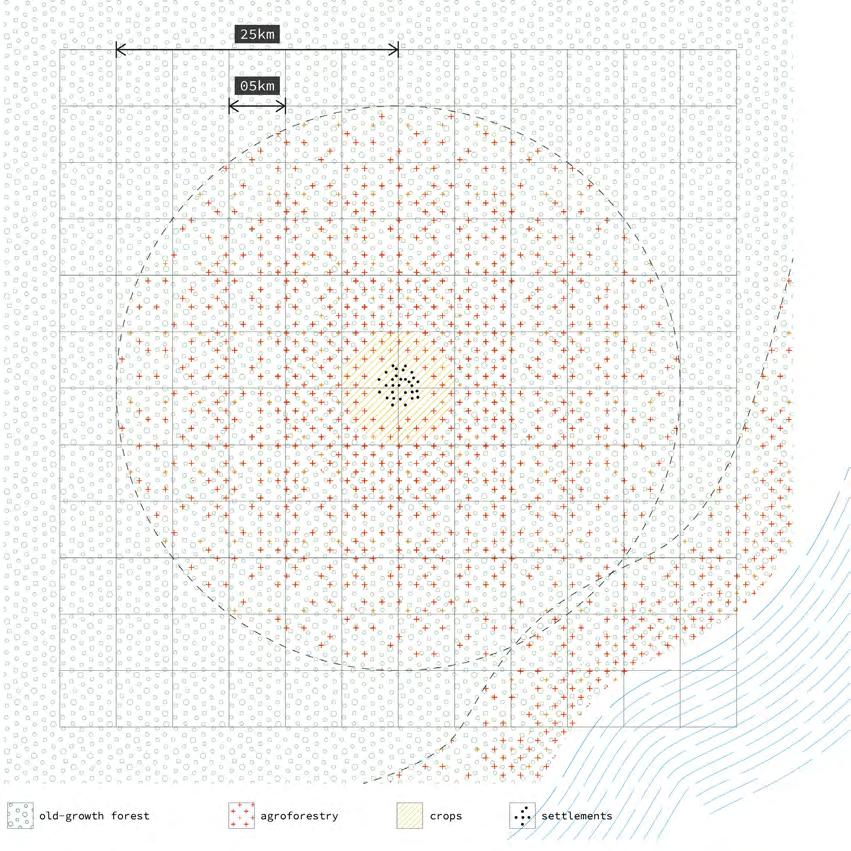

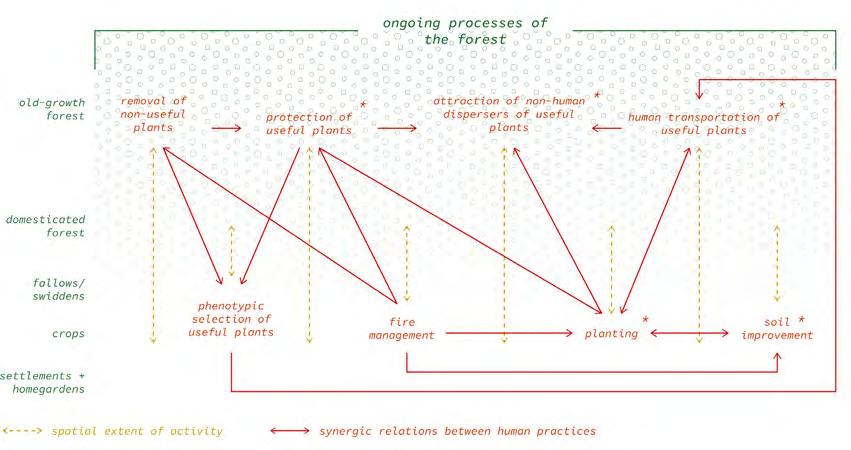

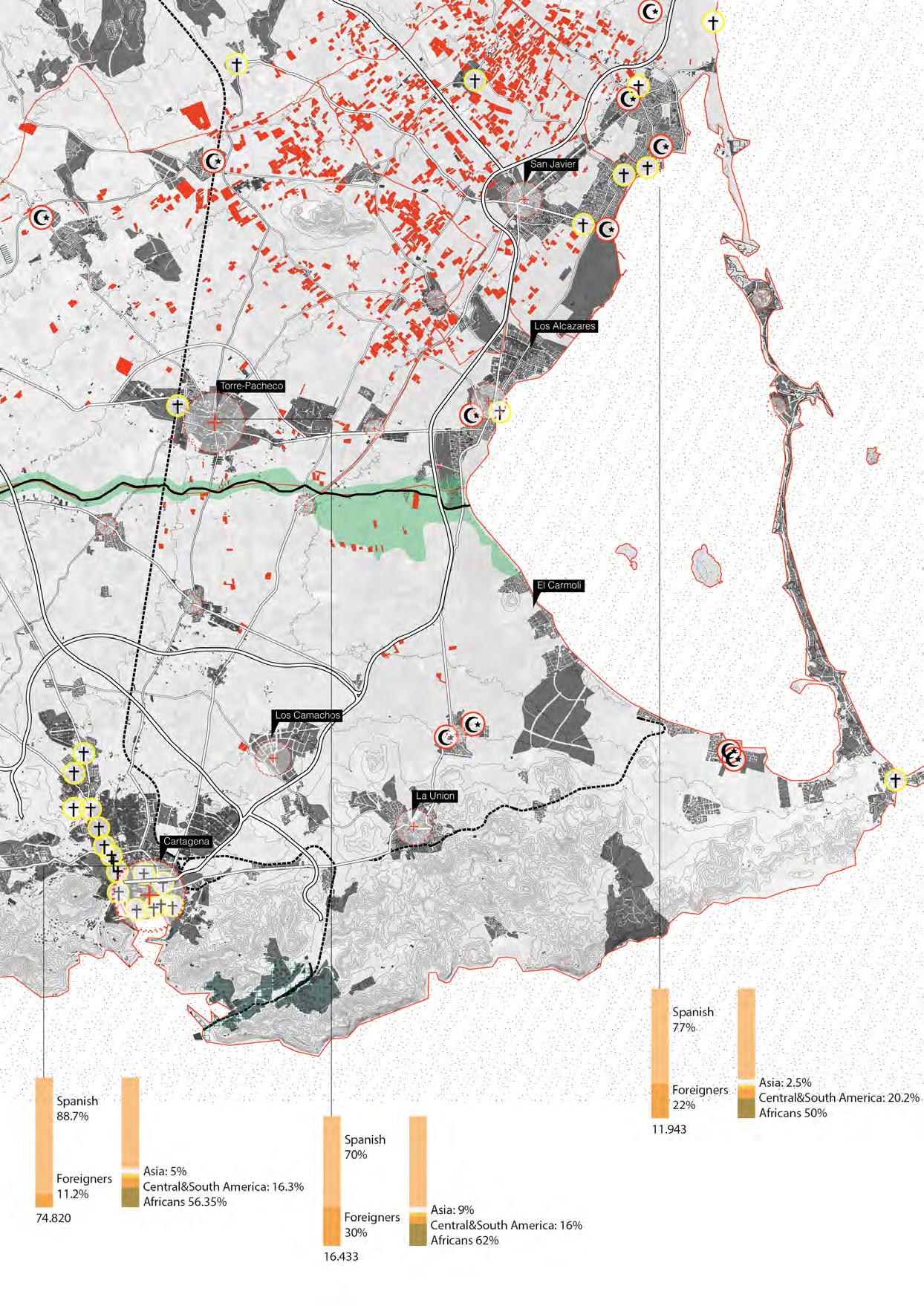

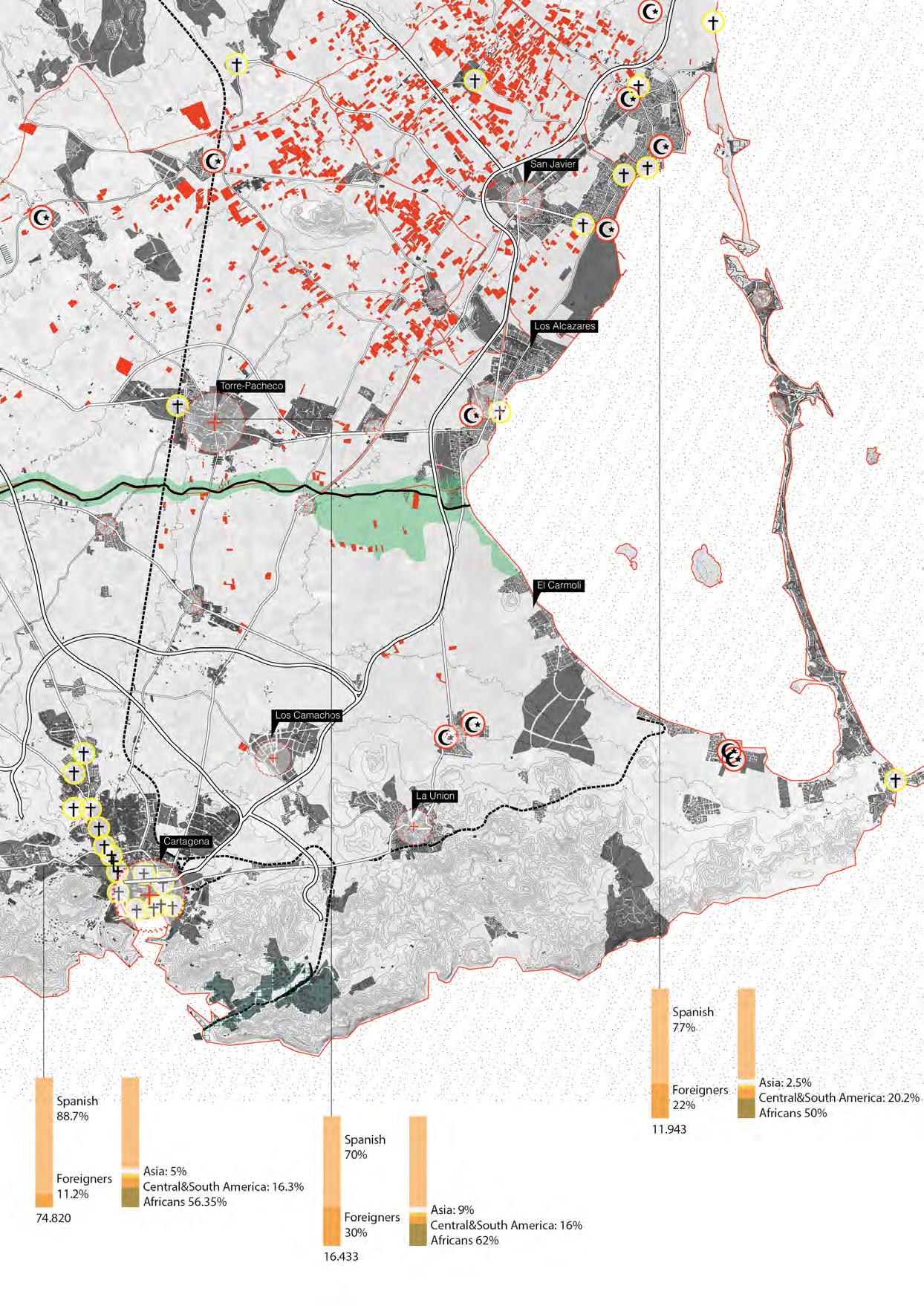

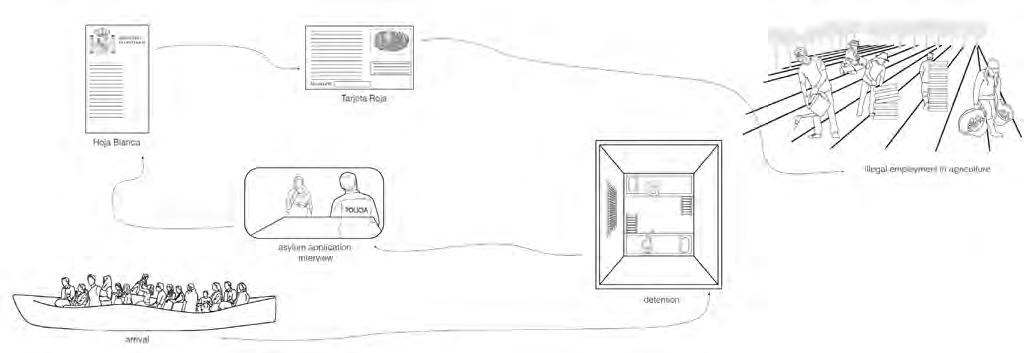

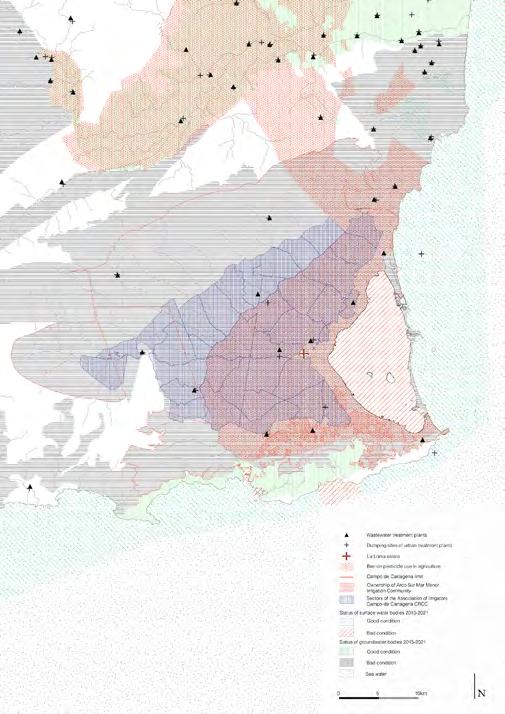

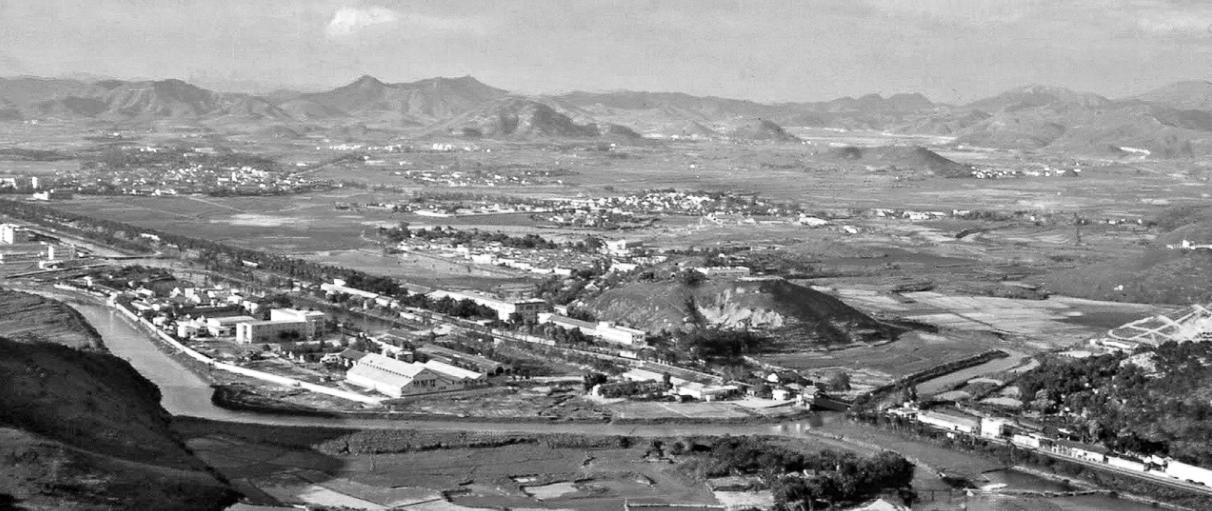

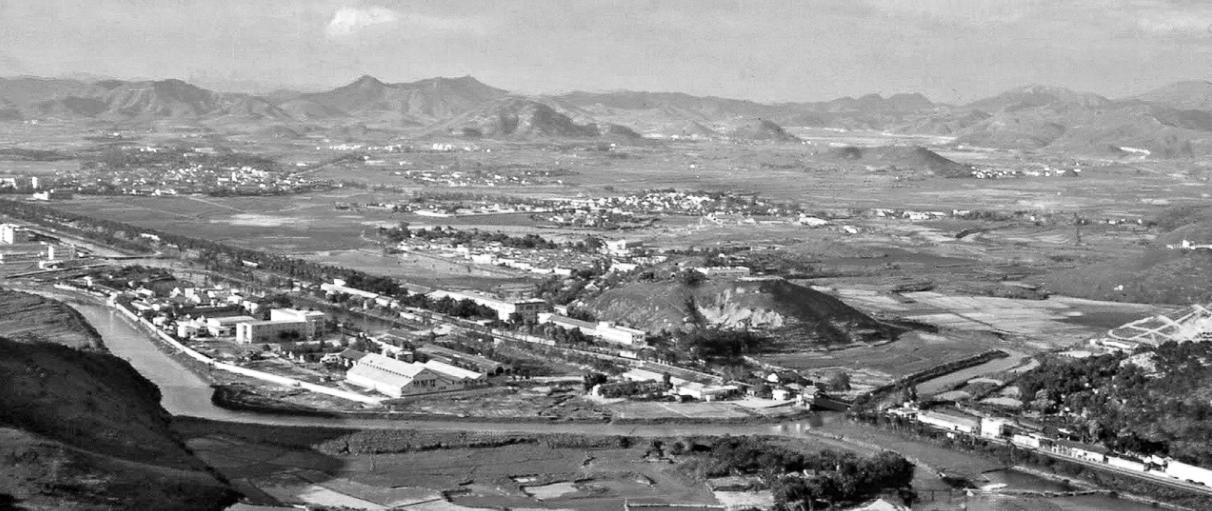

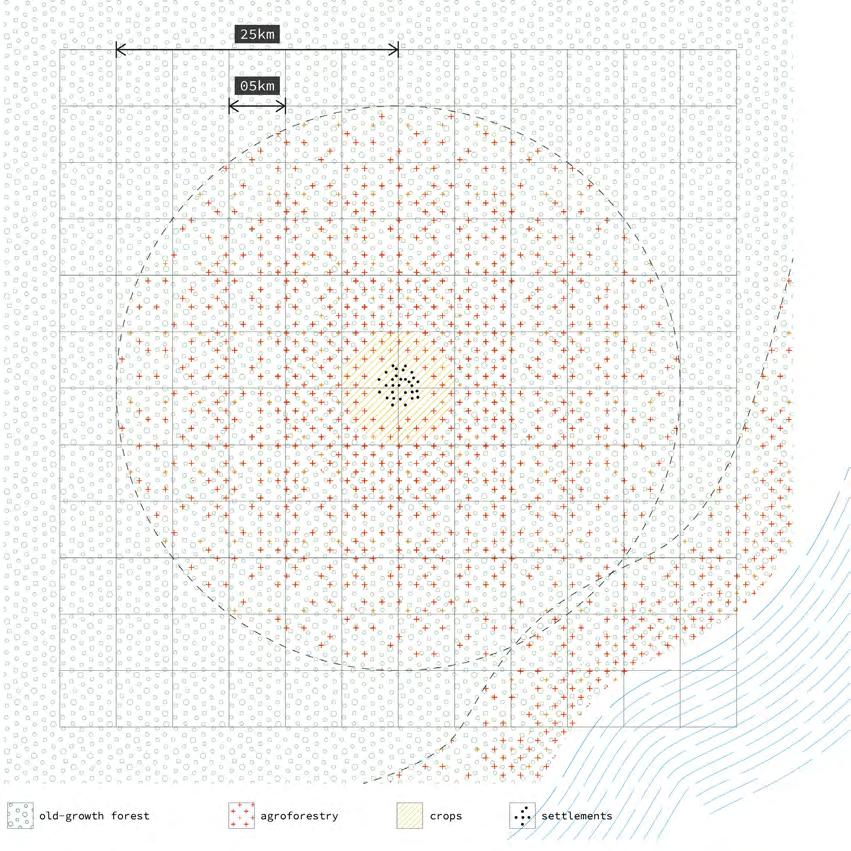

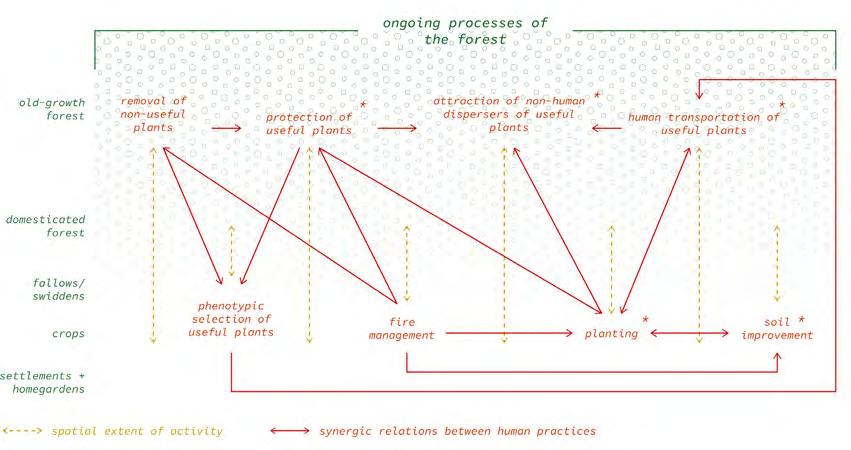

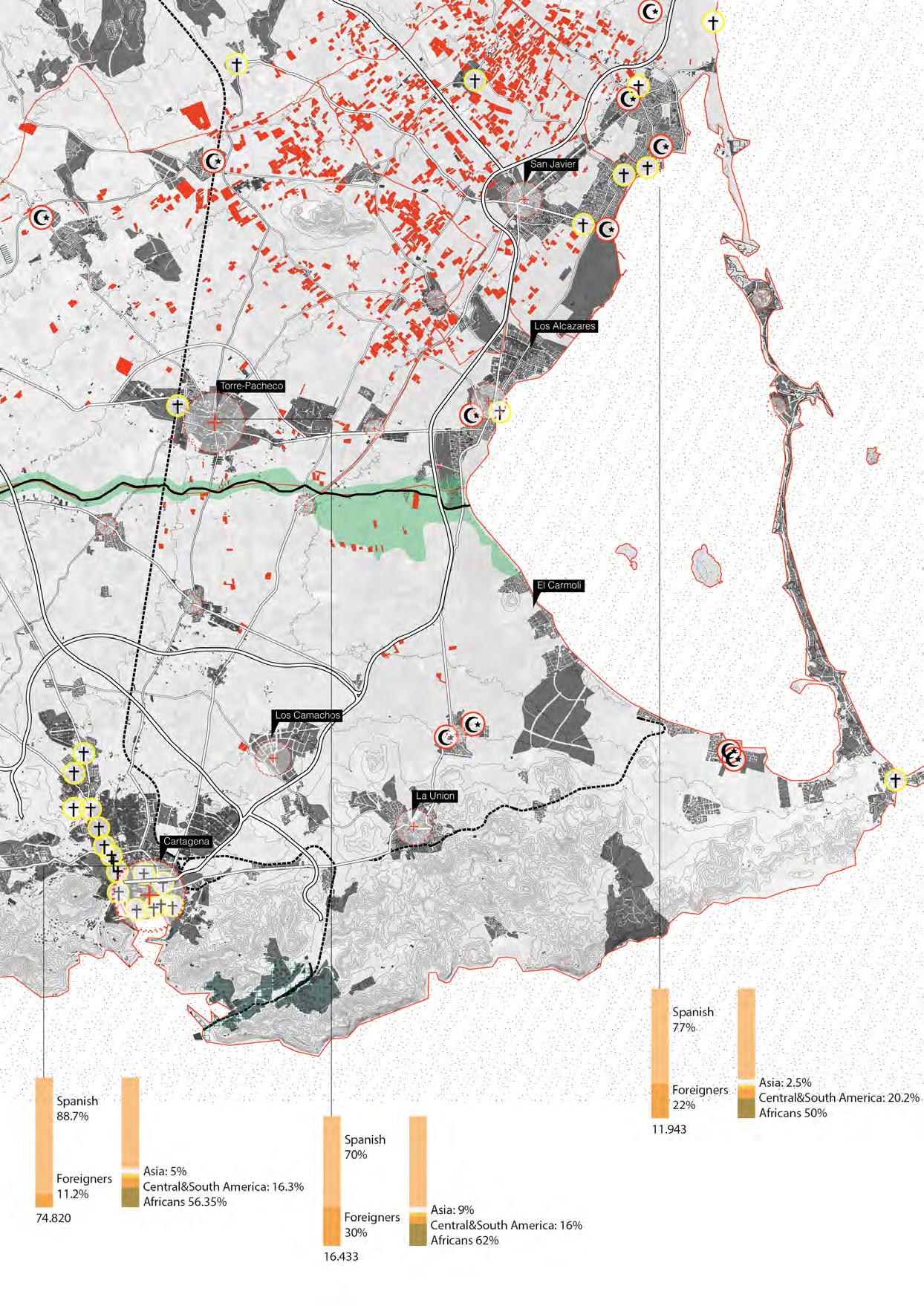

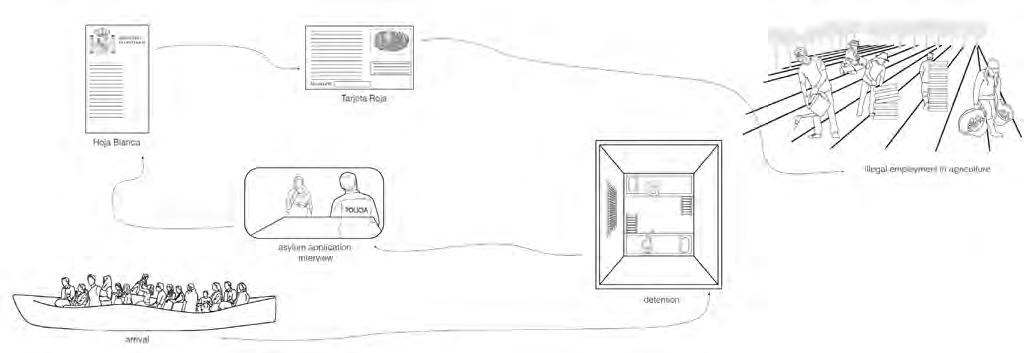

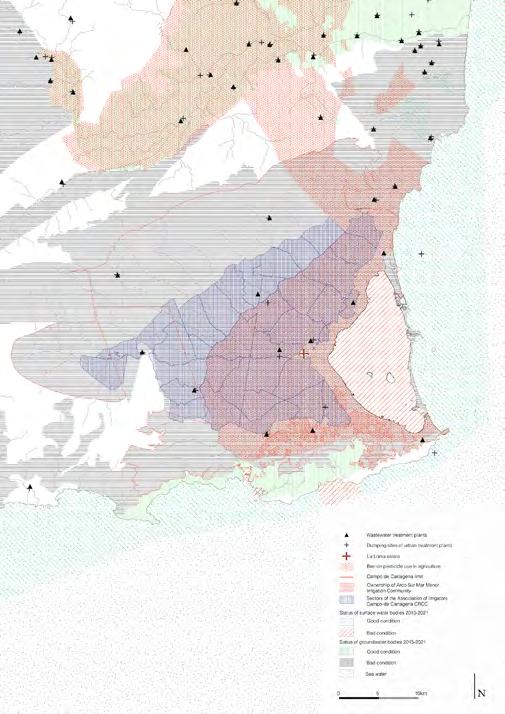

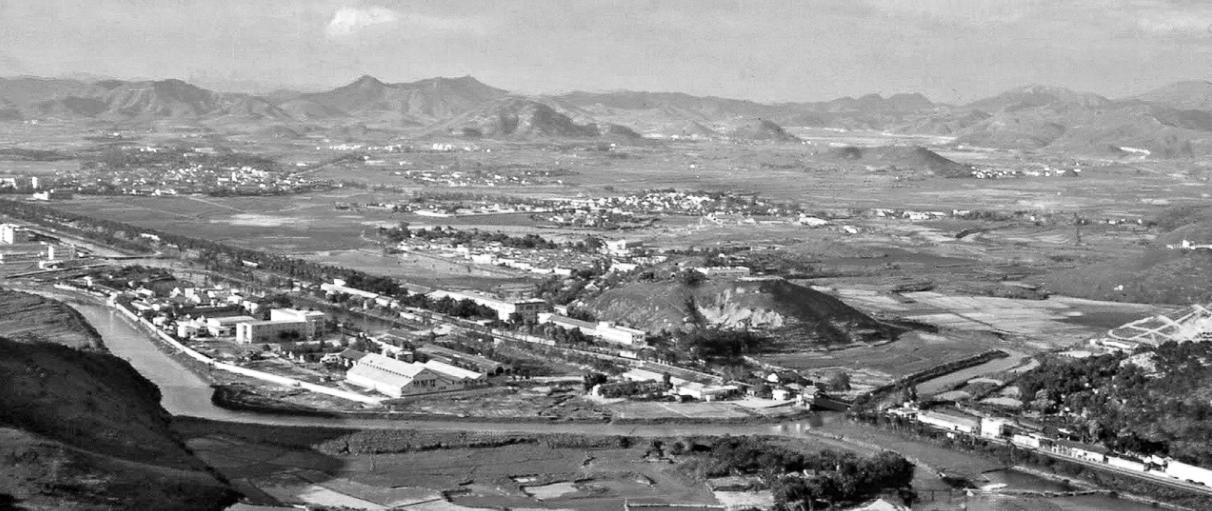

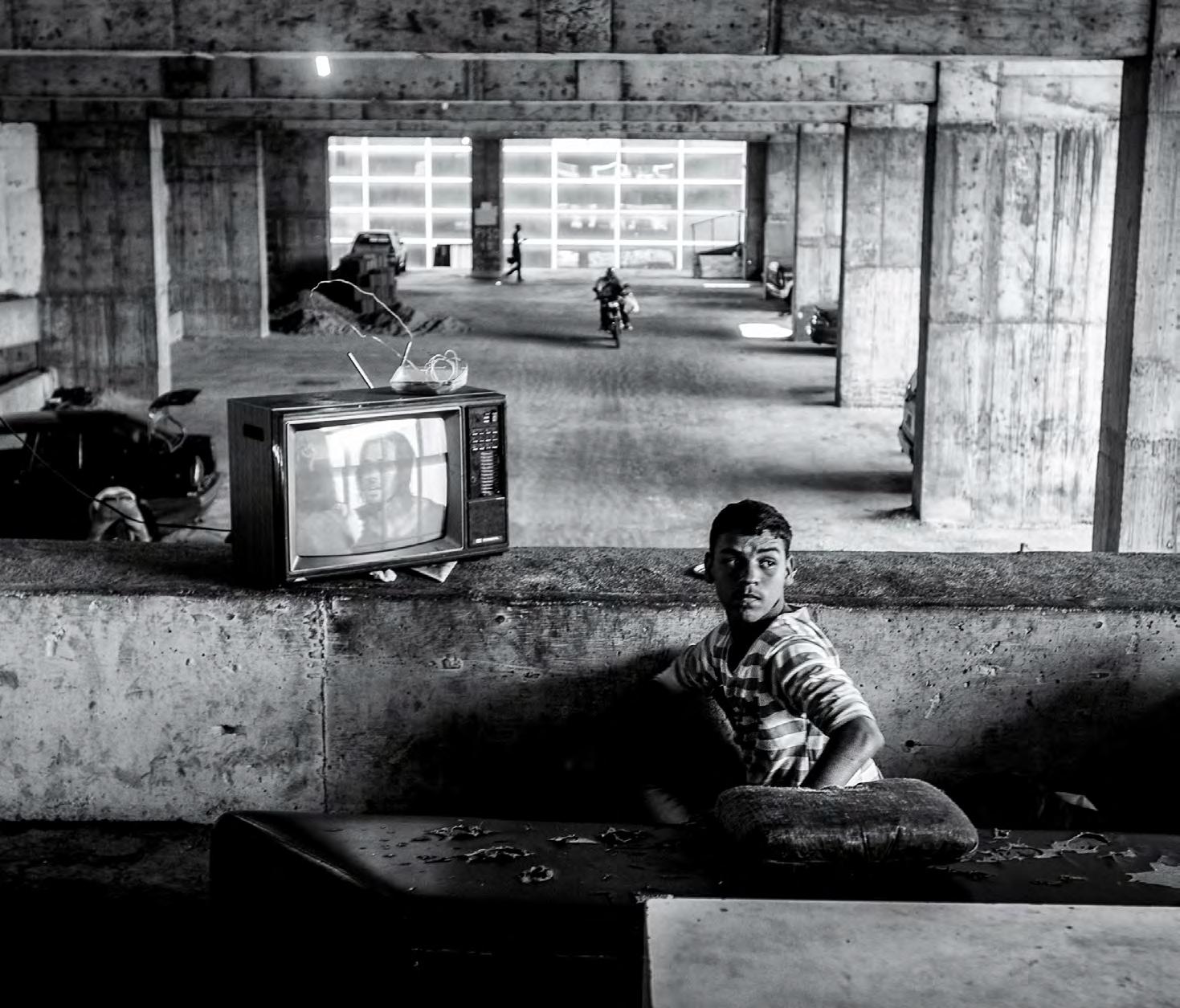

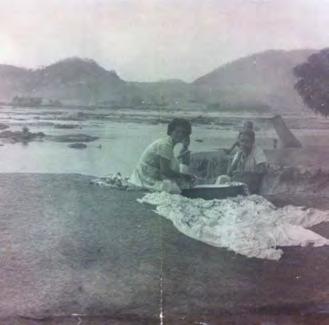

This relation is then investigated further in the next chapter taking the form of unknown or hidden processes that shape the urbanized landscape. In this direction, the Amazonian Forest’s pristineness is questioned under the examination of the hidden human-made cultivation layer; present already from the pre-colonial era. And this type of cultivation may entail a story of care, but that’s certainly not the case in the mechanization and instrumentalization of Campo de Cartagena in Spain caused by a complex interplay of interconnected

processes and circulations. Among them, the temporal migration is also researched in the Chinese context using the case study of Shenzhen’s floating populations to document the impact of their living and working patterns in the fragile deltaic environment. Finally, the concluding article offers an overview of all the circular social, material and spatial practices that remain invisible in the conventional linear understanding of the built environment’s construction reflecting upon our current delimitations of knowledge.

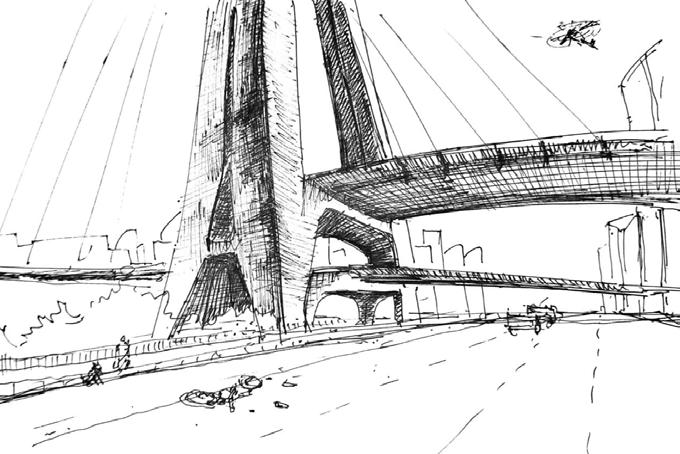

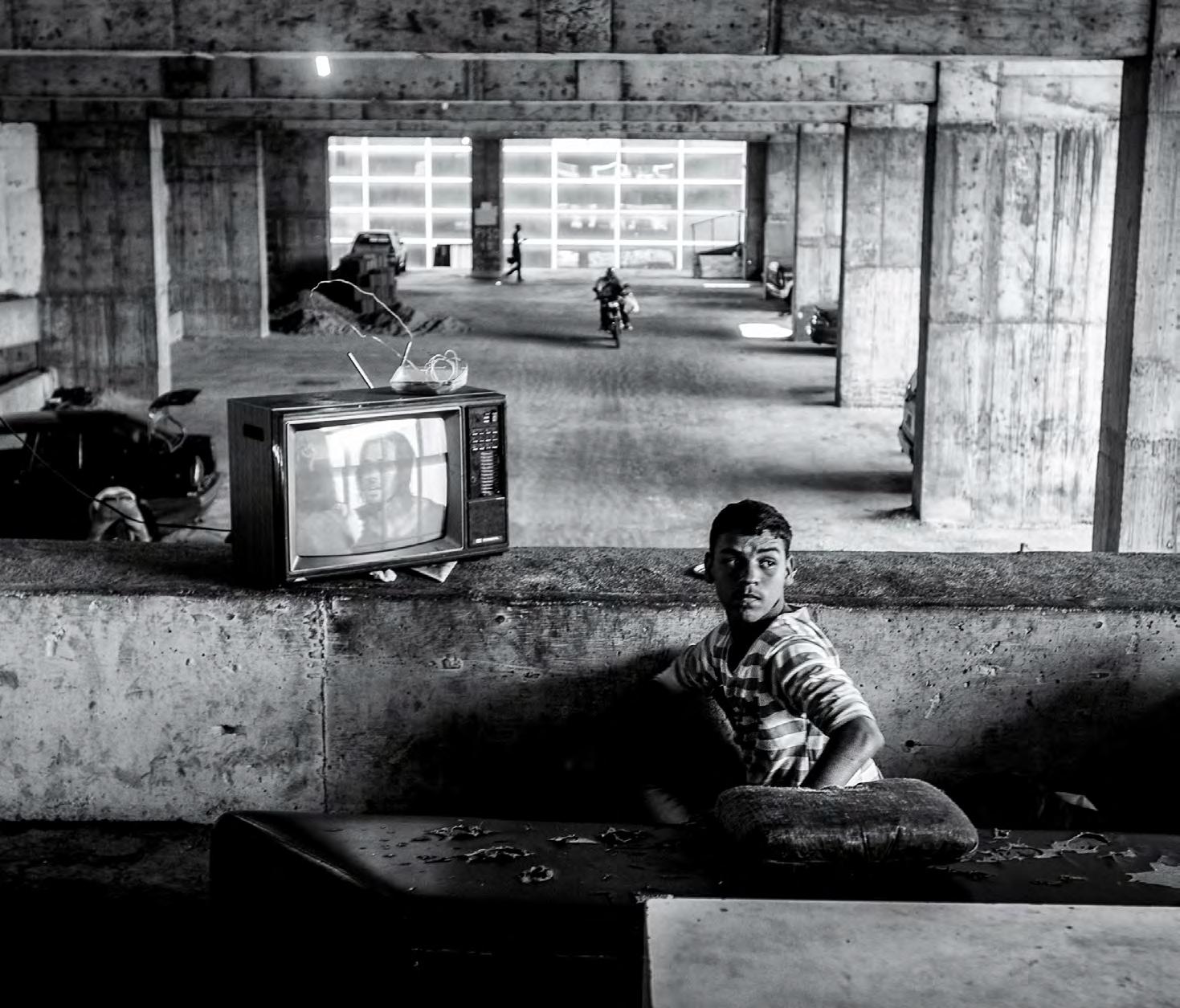

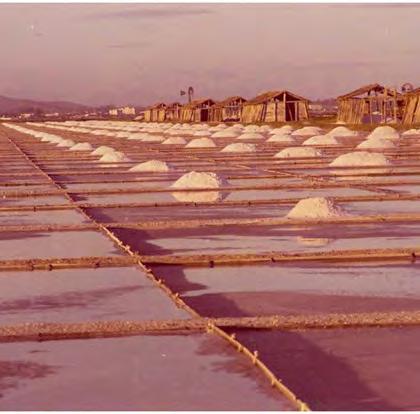

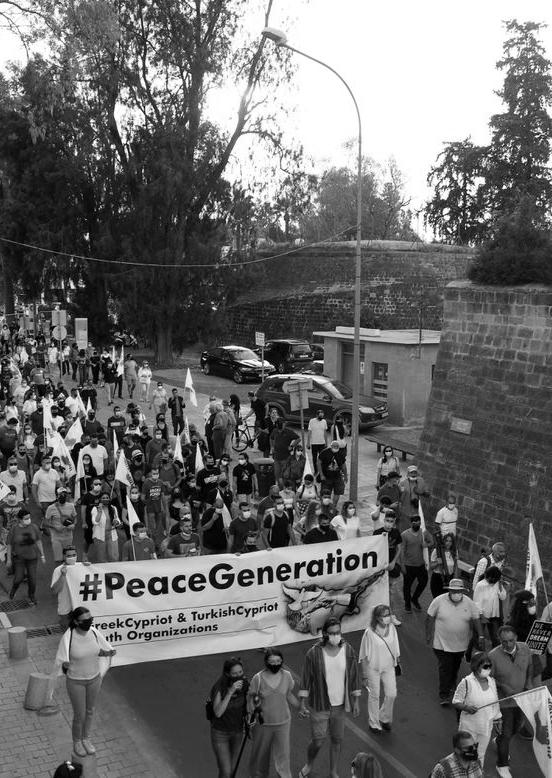

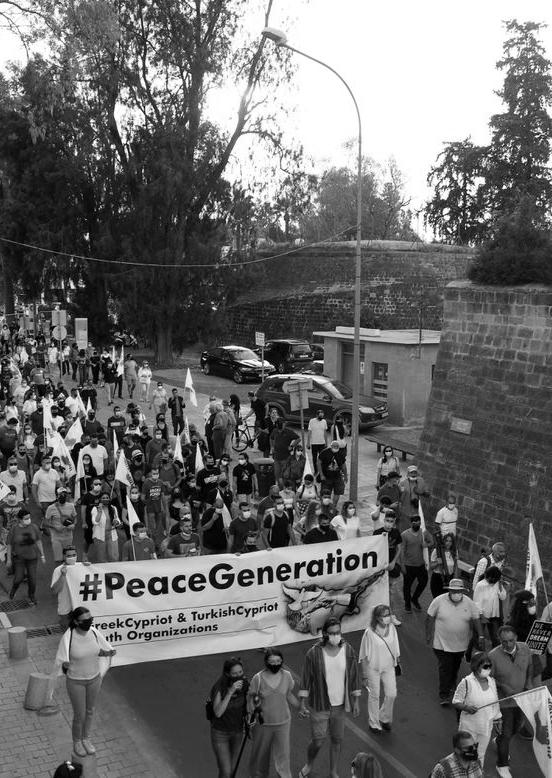

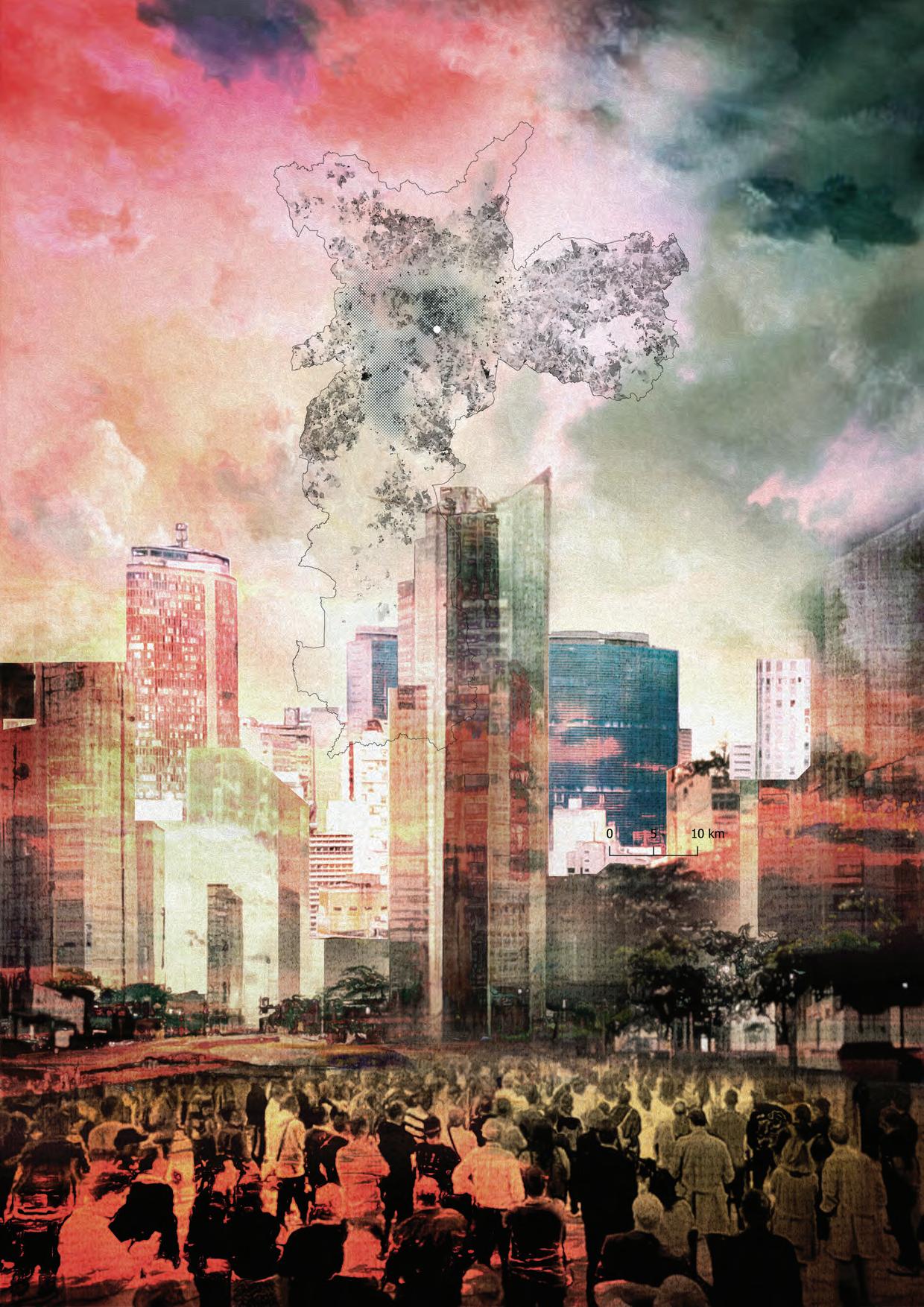

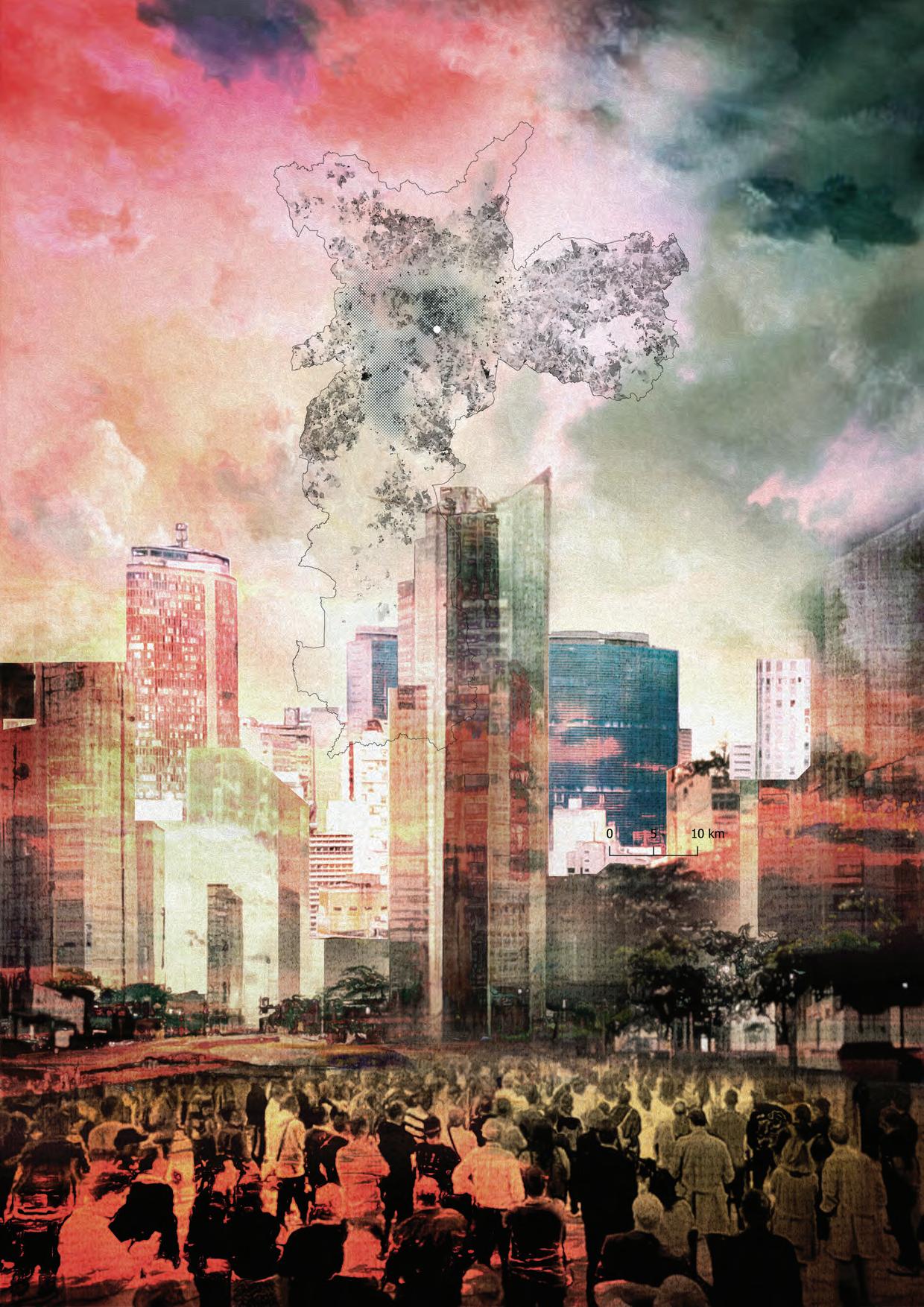

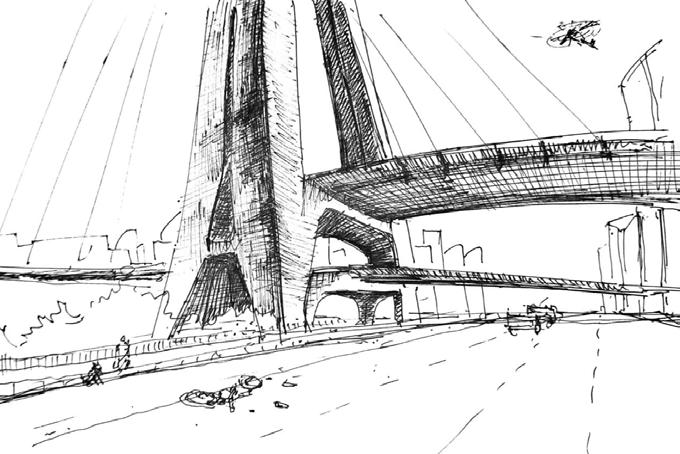

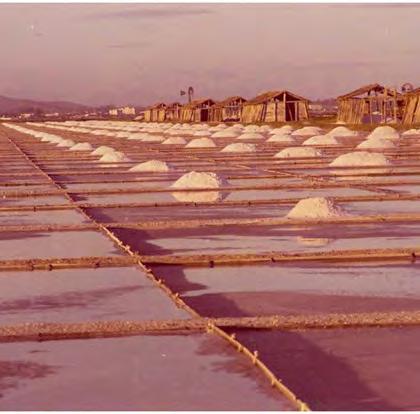

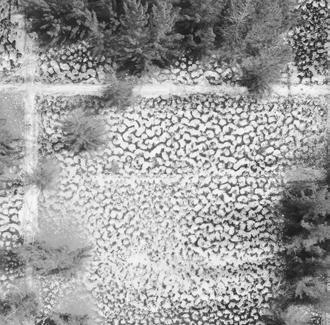

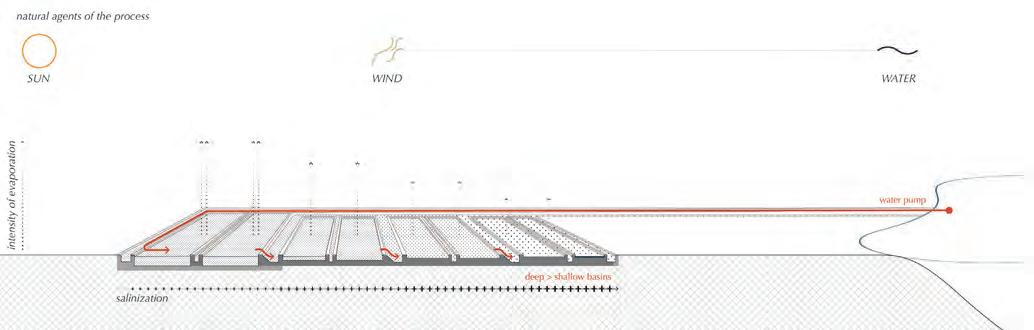

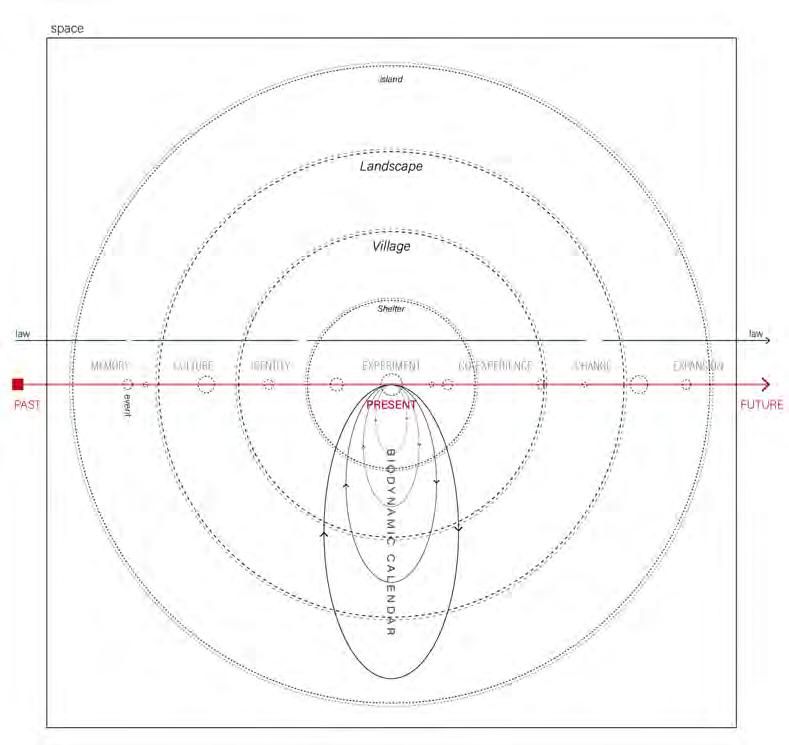

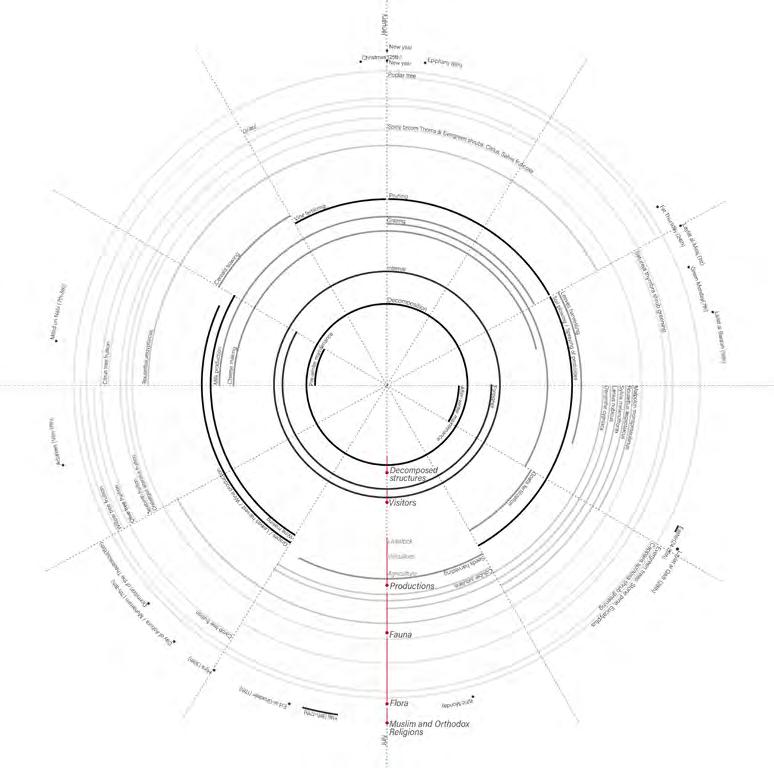

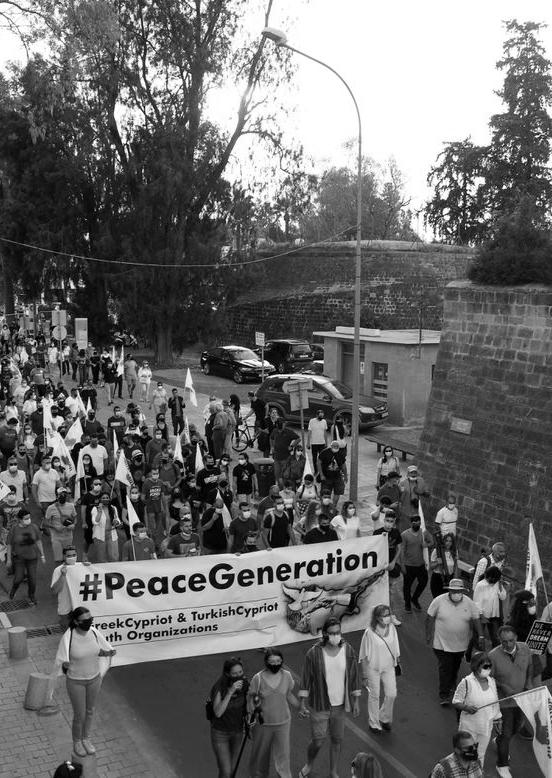

The issue continues with an exploration of different Unfamiliar or Unknown territories starting with the drosscape salt extraction industry of Arraial do Cobo in Brazil where the very act of abandonment is not understood only functionally but first and foremost symbolically. Similarly, the post-conflict landscape of Pitargou in Cyprus is studied as a material embodiment of the identity crisis caused by the island division establishing a strong connection between its human and non-human entities. In a different context, but with the same preoccupation for the projection of the cultural in the natural, the next article brings to light Subsurface Habitation in its current and potential forms reflecting upon human preoccupation with the exploration and the colonization of the underground. The form of exploration inspires the last part of this chapter that follows the narrative of a fictional literature figure to re-discover the future city of São Paulo questioning the distinction between the visible and the invisible.

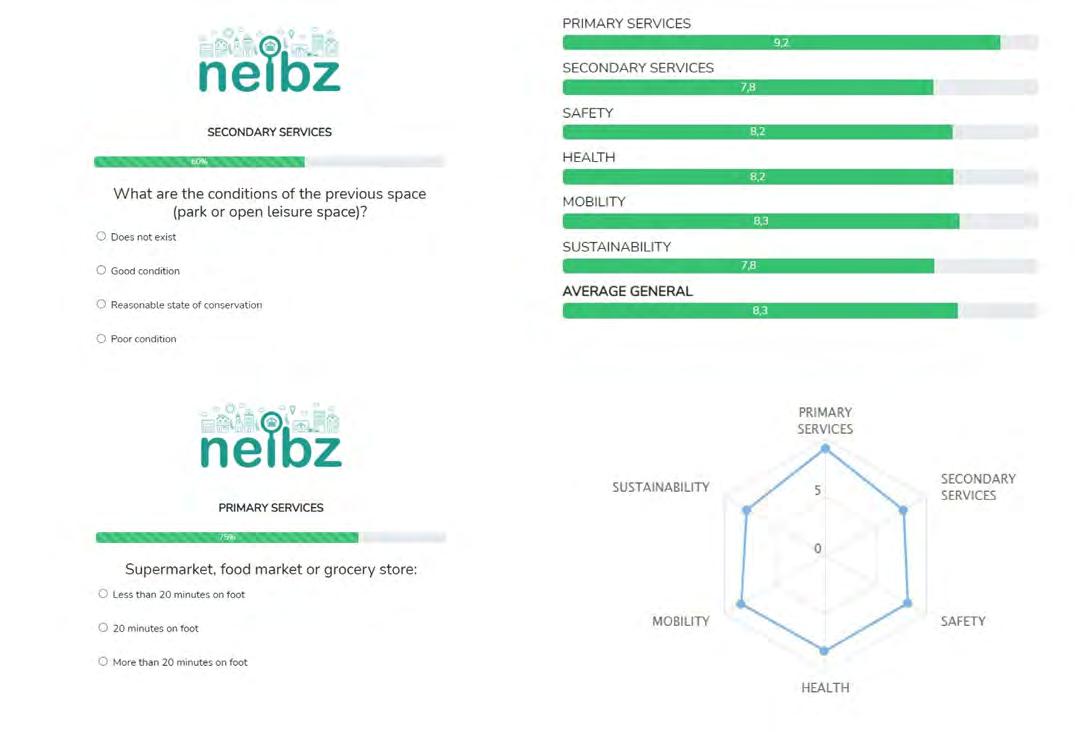

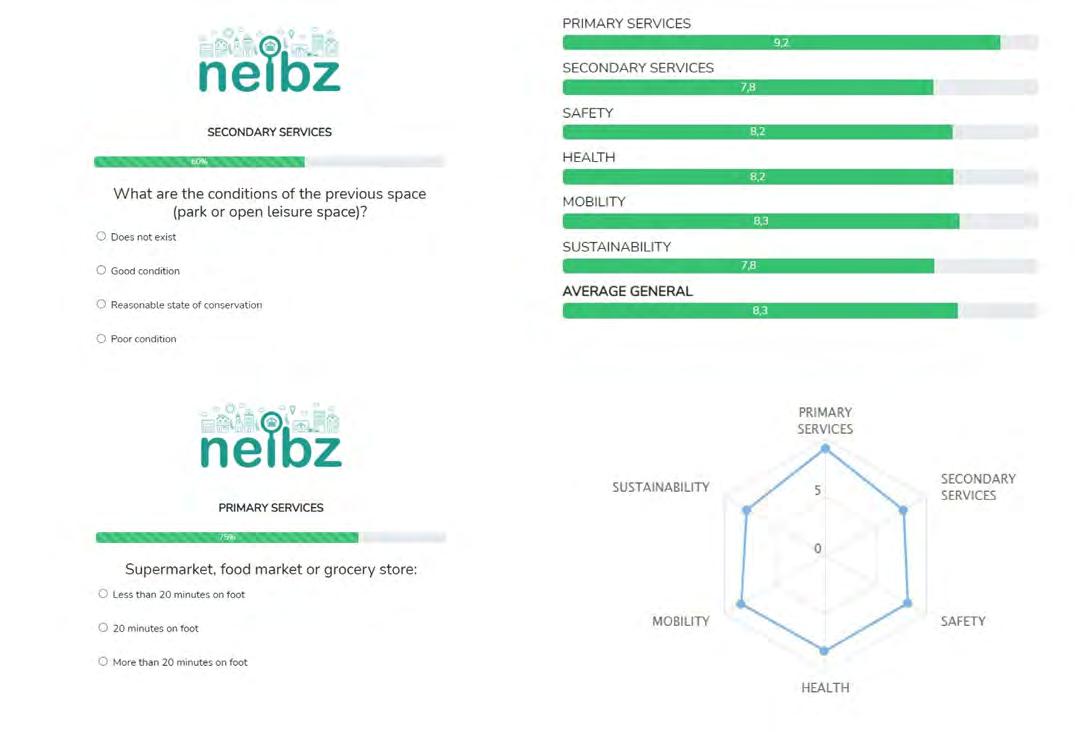

This article marks the transition from the effort to visualize the invisible to the reflection on the process and the act. In this sense, the use of digital survey tools for the documentation of favelas is tested through the development of Neibz software for the case of Vila Missionaria in São Paulo suggesting new methodologies for urban research in viewless or inaccessible conditions. And while the process of portrayal is definitely marked by good intentions, the final piece is meant to remind that every act of revelation entails a simultaneous act of translation-transmutation that tends to result in a complete alteration. Nested in the field of conceptual ambiguity inspired by the recent quantum physics developments, this argumentation was rendered of critical importance in a global context that seems to often instrumentalize the subjects that are rendered visible.

As you read through, we urge you to keep this concern in mind while engaging further with the notion of (In)Visibility as conceptualized by the contributors of the current issue. We hope that the following pages managed to assemble the explorations and inquiries of both its authors and readers and to offer them a common ground which is meant to evolve in the upcoming issues.

-Myrto Karampela-Makrygianni and Sanika Charatkar

+ + + + + + + + +

Part 1: Underlying structures in post-war urbanization

08 Segregation by Design by Adam Paul Susaneck

14 Total Segregation by Jens Berkien

22 The Price of Paradise by Larissa Muller

26 Invisible Currencies shaping European Urbanism today by Ishka Mejia

32 Recognising Facts on the Ground- in conversation with Lukas Pauers, Vertical Geopolitical Lab

Part 2: Hidden processes, in the formation, maintenance or instrumentalization of urbanized landscapes

38 Amazon Forest: Pristine Nature or Domesticated Garden by Victoria Imasaki Affonso

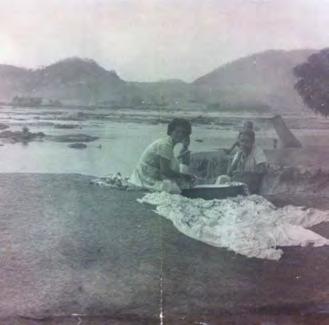

44 Agroecologies of the Stateless by Katerina Inglezaki

50 Shenzhen’s Floating Population by Zuzanna Sliwinska

54 Flipping the Iceberg by Tamara Eggers

Part 3: Unseen or Unfamiliar Landscapes

62 The Omitted Inbetweens by Julia Daher

68 Reintroducing an Erased, Shared Identity by Panagiota Patrisia Tziourrou

74 The Subsurface as a Collective Geography by Akhilesh Shishodia

78 The Two Cities in Sao Paulo by Fabio Alberto Alzate Martinez

Part 4: Transformations in Spatial Relationships

86 Accessing Invisible views through digital durvey in Favela Communities by Maria Luisa Tarozzo Kawasaki

90 Architecture and Queer Super-positioning by Michael Kowalsky

Contents

Contributors

Adam Paul Susaneck is a Master in Architecture whose work focuses on addressing historic inequity and ongoing climate issues through urban planning, architecture, and transportation infrastructure. In his professional work at AECOM, he has been involved in the retrofitting and upgrading of New York City Subway, commuter rail, and Amtrak stations for ADA accessibility.

Jens Berkien is an Urbanism Student at the Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft. Alongside his inclination towards the urban consequences of climate change on the Dutch Water management system, he is also passioned about addressing the social inequalities that have risen from the Dutch spatial planning practice.

Larissa Müller a designer from California, USA,is now working on her education in urbanism at TU Delft. Her passions lie in addressing social inequalities in urban environments manifesting as expressions of urban segregation. Previous to TU Delft, she received her Bachelors of Architecture at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, in California.

Ishka Mejia is a Filipina architect from Manila pursuing the Urbanism track, while also resisting the madness that comes with the adventures and challenges of a field that encompasses all aspects of life and time itself.

Lukas Pauer is a licensed architect, urbanist, educator, and the Founding Director of the Vertical Geopolitics Lab, an investigative practice and thinktank dedicated to exposing intangible systems and hidden agendas within the built environment.

Panagiota Patrisia Tziourrou is an Urbanism Masters graduate from TU Delft. She holds a bachelors and masters degree in architecture from the University of Cyprus. She has also practiced as an architect in the past in Cyprus and Spain.

Katerina Inglezaki is an architect and urbanist working at the intersection of landscape ecology and urban design. Her research investigates agroecology as a holistic and integrated approach that aims at applying both ecological and social concepts to the design and management of sustainable food systems and problematizes on the upscaling of Nature-Based Solutions.

Zuzanna Sliwinska is of Polish origin, however her current educational and professional background is based in London and Hong Kong. Strongly influenced by time spent at Chinese University of Hong Kong as well as voluntary work in the Chinese countryside, her interests and efforts focuson urban development on the Asian continent and China in particular.

Tamara Egger is an Architect and Urbanist from Austria who worked for several years in co-productive urban transformation processes in Latin America and the Caribbean. Currently, she is a Ph.D. researcher at TU Delft’s Faculty of Architecture, where she focuses on diverse human agencies in transitioning toward a Circular Built Environment.

Julia Daher is a brazilian-portuguese architect with a Diploma in Architecture & Urban Planning from FAU-UFRJ Brazil. She has been conducting research in collaboration with PROURB regarding the interaction of urban and landscape dynamics in the shaping of socio-cultural practices.

Akhilesh Shisodia is an urban planner/ Urbanist working towards experimental Urban and Territorial strategies at TU Delft. Currently his research is centered around the augmentation of urban spaces, especially underground real estate, ubiquitous technologies, and digital cities.

Fábio Alberto Alzate Martinez graduated from FAAP in 2019 (São Paulo, Brazil) as an architect and urban planner. He is the recipient of several awards and design competitions, such as Urban21, Schindler Global Award 2017, Best Undergraduate Thesis ArchDaily 2020, and recently being granted the excellence scholarship Justus and Louise van Effen by TU Delft.

Maria Luisa Tarozzo Kawasaki is an Urbanism and Geomatics graduate student from TU Delft. She is the founder of Neibz and the winner of the Future Cities Challenge by UN-Habitat and Fondation Botnar in 2020. Her main passion is to make urban geodata visible and accessible.

Michael Kowalsky is an architect based in New York City. Working largely within the realms of urbanism and public infrastructure, his research is focused on the ways that social systems enter, define, constitute, and resist the built environment. His work is heavily impacted by his queer identity and desire to draw connection between the disparate communities he engages with.

Victoria Imasaki Affonso Victoria is a MSc 4 student in the Landscape Architecture track at TU Delft. She previously worked as an architect in São Paulo, Brazil - her homeland.

Victoria Imasaki Affonso Victoria is a MSc 4 student in the Landscape Architecture track at TU Delft. She previously worked as an architect in São Paulo, Brazil - her homeland.

Segregation By Design

During the mid- to late-20th century, using the policies of “urban renewal and slum clearance,” combined with the construction of the Interstate Highway System, the United States federal government mounted an unprecedented intervention into the built form of the American city. The goal of this intervention was explicit: racial segregation via the construction of an automobile-based suburbia; and the remaking of downtowns to cater to that suburbia. The scale of this project was astounding—across every region of the country, nearly every single city in the United States was and continues to be affected.

Introduction

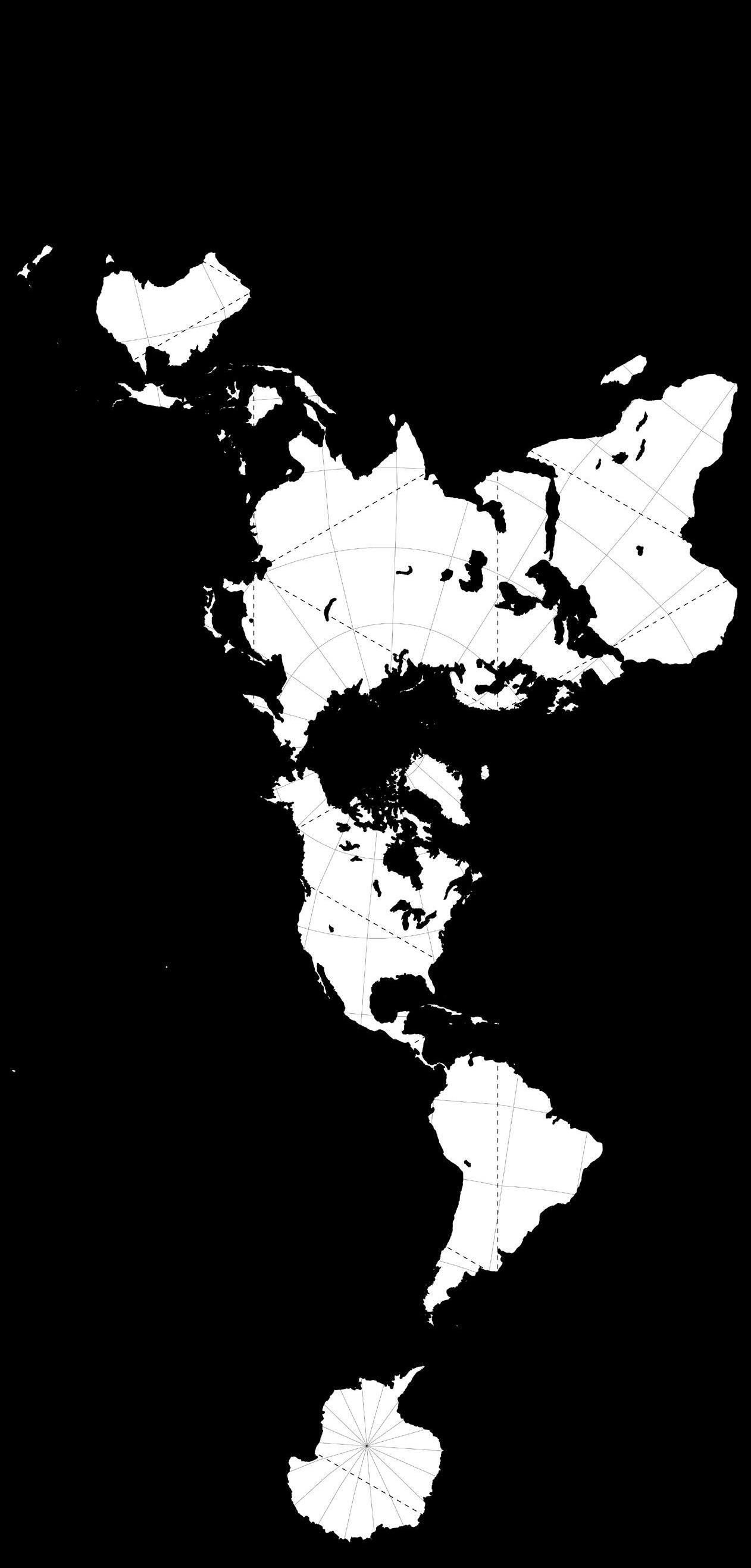

Since the creation of the Interstate, urban freeway construction has been an integral tool in the systematic, government-led segregation of American cities. Used not only as a direct means to destroy the communities in their paths, freeways have also been used to cement racial segregation and ensure its endurance. Beginning in the 1950s, working synergistically with the legacy of redlining, freeway planning became the ultimate enforcement mechanism: literal walls of concrete and smog that separated black communities from white. Working in tandem with simultaneous “urban renewal” schemes, the freeways took the red lines off the map and built them in the physical world.

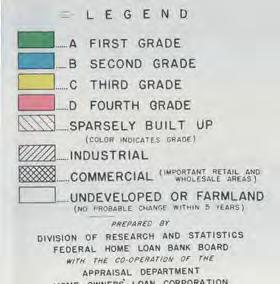

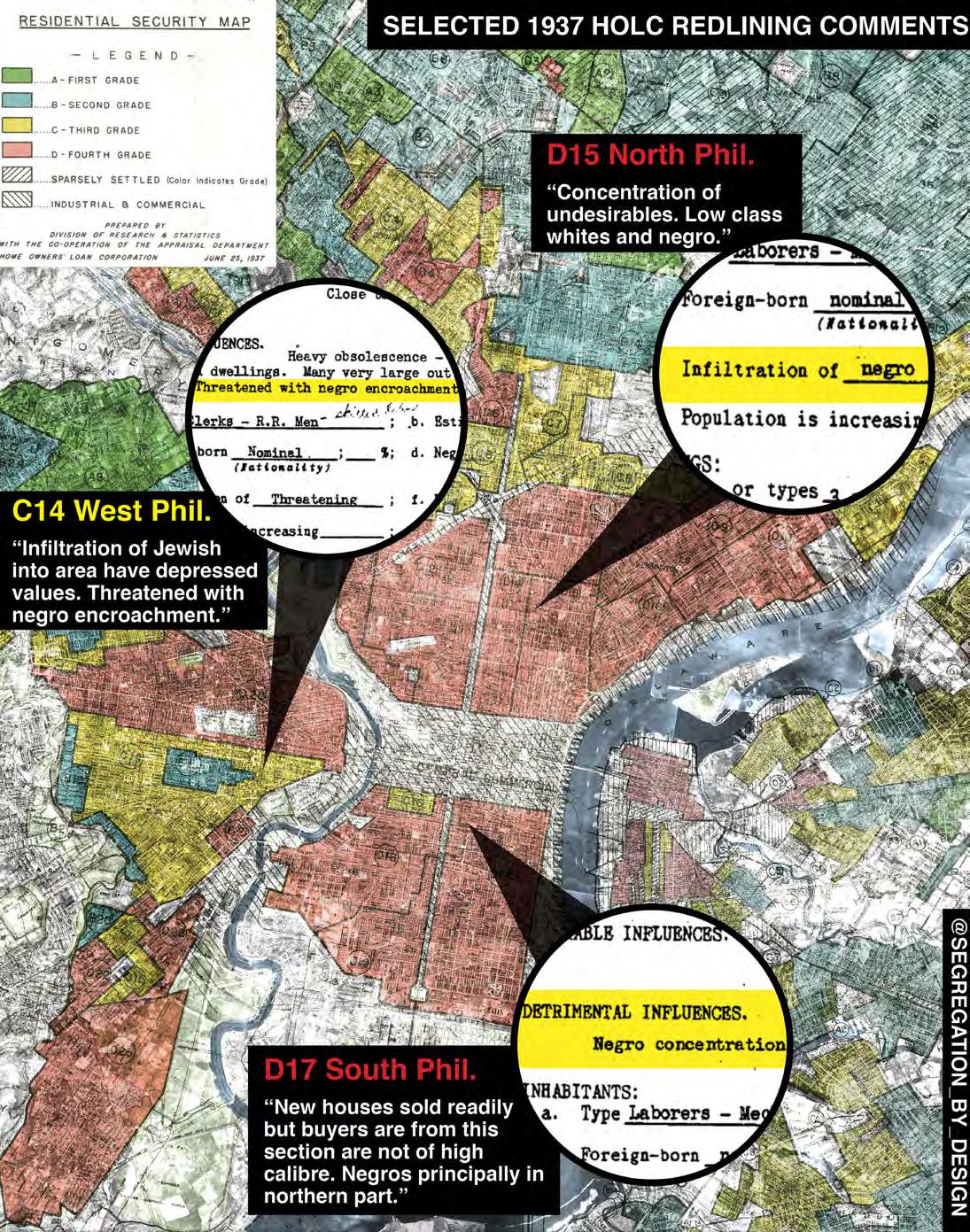

Red Lines And “White Flight”

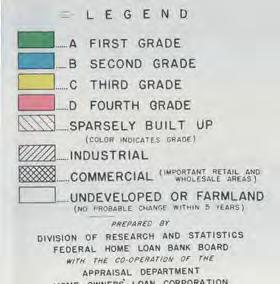

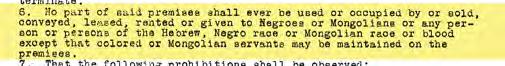

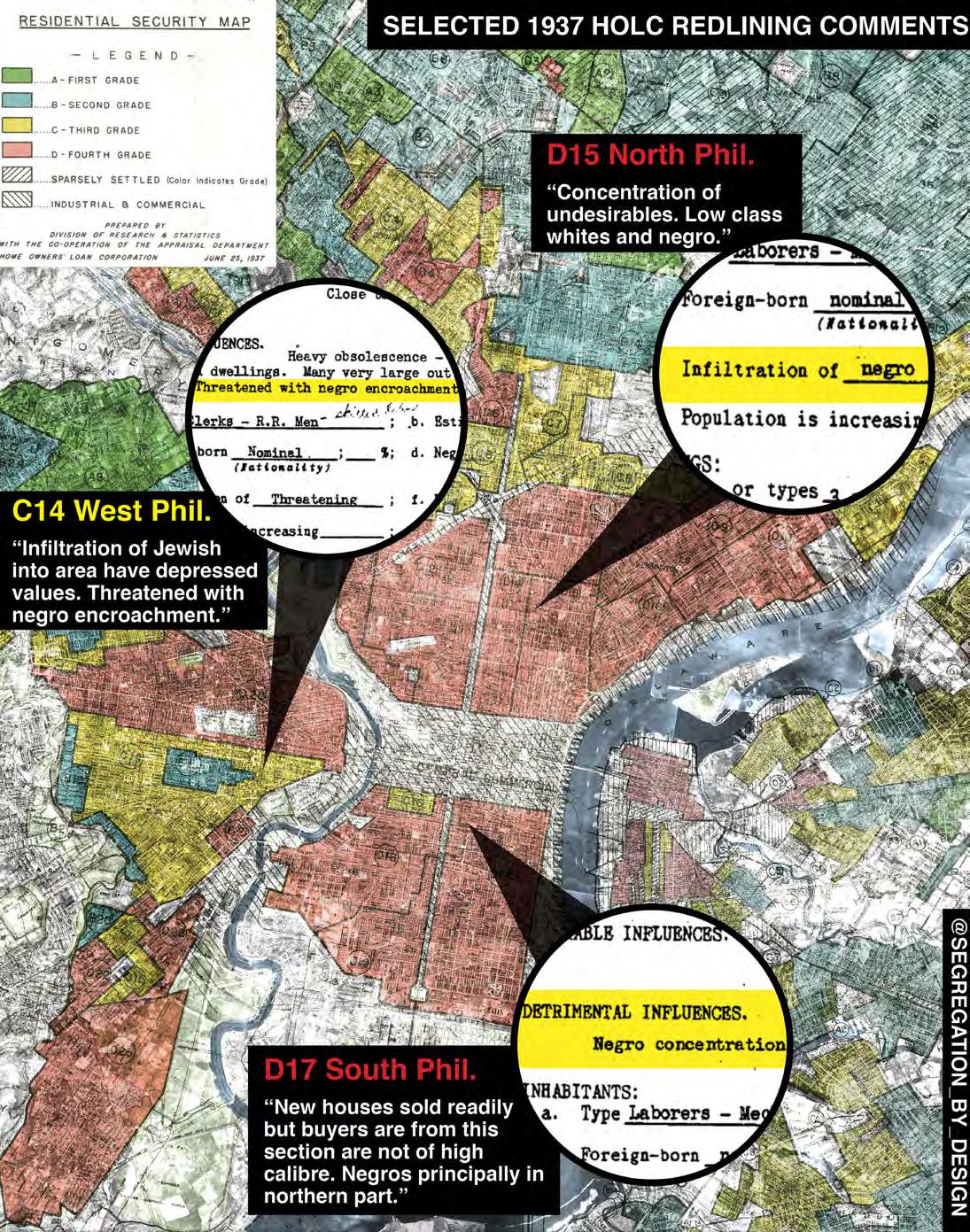

The project of federally-incentivized residential segregation commenced in earnest in the 1930s with the practice of “redlining” during the New Deal. Redlining was a policy in which the federal government went city-by-city, neighborhood-byneighborhood, grading each block for investment worthiness—based on race. The agency created to administer the program, the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), drew thick red lines on the map around neighborhoods with what the agency’s appraisers determined to be an “infiltration of undesirable racial elements.” Such neighborhoods were officially deemed “hazardous for investment.”

8 01

ADAM PAUL SUSANECK

UNDERLYING STRUCTURES IN POSTWAR URBANIZATION

9 Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41

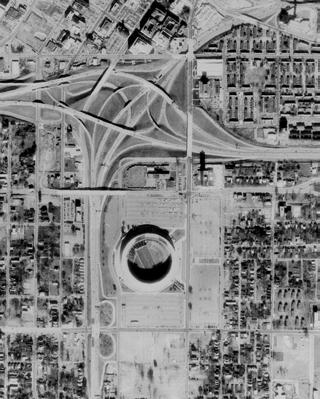

Fig. 1: Redlining Map of Chicago Image Source: Segregation by Design and HistoricAerials.com

The effect of redlining was the crater property values and enervate tax-bases, reducing municipal services, and creating a feedback loop of physical decay. The comments in redlining maps below reveal the FHA’s intentions.Typically, the neighborhoods with the highest percentage of people of color (and thus redlined) were in the most central parts of cities, clustered around Downtown jobs and transit. As physical decay set in, whites began to “flee” redlined neighborhoods to the newly constructed suburbs. “Blockbusting,” a real estate practice which preyed on white homeowners’ fears that their neighborhood was “transitioning,” encouraged whites to panic-sell their properties below market-rate, exacerbating the trend.

White flight further accelerated after World War II. Spurred on by the lobbying efforts of automobile manufacturers and real estate speculators who realized the profits to be made in suburbanization, any and all housing assistance Congress provided to the millions of returning soldiers was suburban in nature. Thus, in 1945 the GI Bill provided low-interest mortgages—but only in the newly built suburbs.

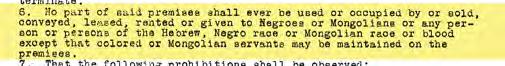

While Black soldiers were technically eligible for the GI Bill, the deeds for these new suburban houses typically contained “restrictive covenants,” officially permitting sale to “members of

the caucasion race only.” Therefore in practice, people of color (and Black people in particular) were forced to remain in the intentionally crumbling inner-cities. In no small part because of this, white families have been able to build generational wealth and equity in the suburbs—while the government has intentionally withheld that opportunity for all those considered “non-white.”

The War Against The Center

In an attempt to combat the physical decay in inner-cities caused by the effects of redlining and white flight, the federal government began the next era of its segregationist project with the 1949 Federal Housing Act and the 1956 National Interstate and Defense Highways Act. The aim of these two

10

Fig 3: Examples of restrictive covenants in Minneapolis Image source: Mapping Prejudice Project

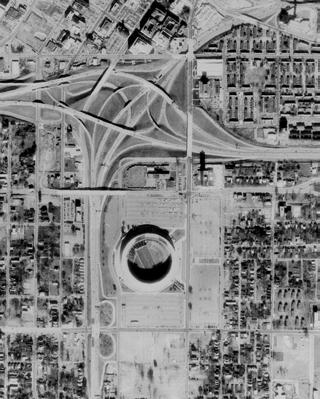

Image 1: Atlanta 1955.

Summerhill, a primarily-black neighborhood adjacent to Downtown Atlanta, was redlined in the 1930s.

Image 2: Atlanta 1960

In an effort to attract whites back to Downtown, the city used federal funds to construct a new stadium adjacent to the city’s new central interchange.

Image 3: Atlanta 1978

The construction of such suburban focused entertainment centers was typical in cities across the country.

Fig 2: (Image 1, 2, 3)

Underlying structures in postwar urbanization

Image source: Segregation by Design and HistoricAerials.com

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 11

Fig 4: Redlining Map of Philadelphia

Image Source: Segregation by Design and HistoricAerials.com

bills was to attract white suburbanites back to downtowns, if not necessarily to live there, then to at least spend money. To that end, these two bills provided America’s cities with a carte blanche to physically remake their downtowns and transportation systems to better serve suburban automobile commuters.

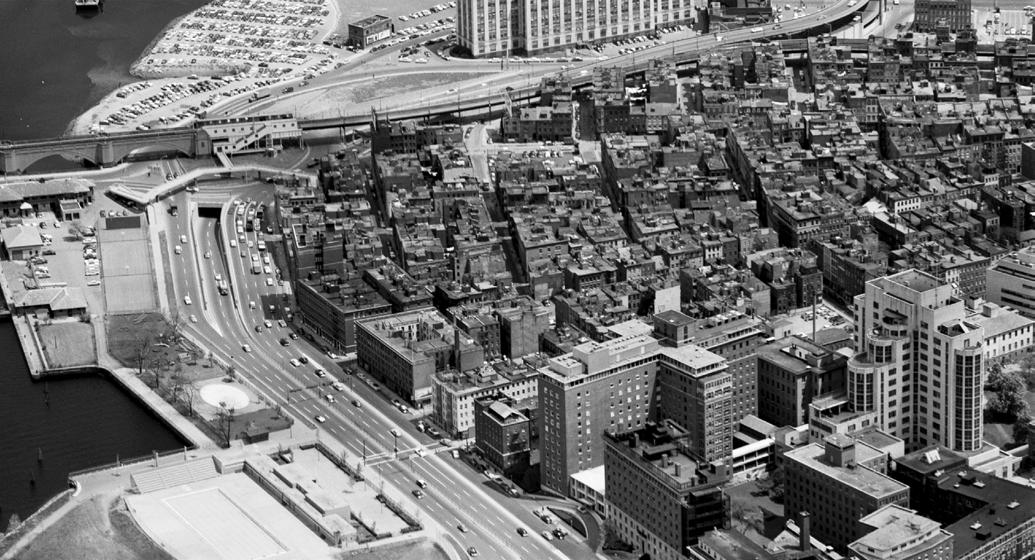

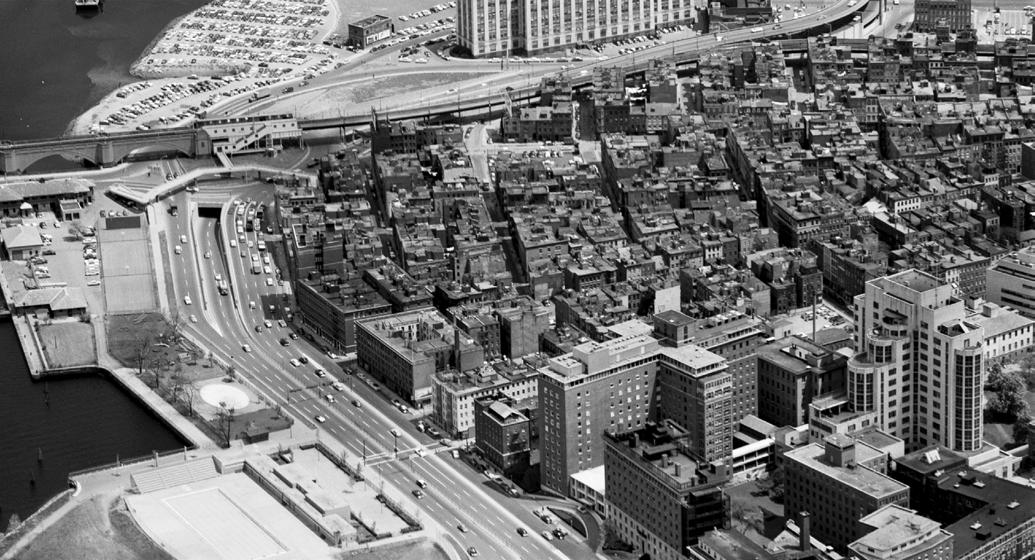

With the ‘49 Housing Act providing cities a 2/3rds federal match for “slum clearance and urban renewal” schemes and the ‘56 Interstate Highways Act providing a 90% federal match, taken together these two bills represent the largest single investment in infrastructure ever undertaken by the American government. Municipal governments used these novel and generous funding sources to remake their cities on a scale previously only seen in natural disasters or war.

Planners at the time were inspired by the maximalist practices of Baron Haussman in Paris in the late 1800s, the “Modernist” schemes of designers like Le Corbusier, and the contemporary projects of Robert Moses in New York. With these ideas in their heads, planning departments razed whole neighborhoods under the auspices of “slum clearance and urban renewal.” After years of neglect due to redlining, inner-city neighborhoods were easy targets for such schemes, especially attractive due to their prime locations. While communities often resisted, in cities around the country most were unable to withstand the city’s federally-funded assault.

Seizing properties through eminent domain, cities erased neighborhoods and replaced them with amenities focused on suburban commuters, such as massive sports complexes, entertainment centers, single-use office complexes, outsized institutional expansions, and parking—lots of parking. Existing urban amenities such as parks, public spaces, and extensive public transit systems were paved over as the city was remade for those driving from the suburbs.

Freeways were built in tandem with these “renewal” projects, designed to provide easy access from the suburbs, while physically dividing and destroying the close-in, primarily Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in between. When not barreling directly through communities of color, freeways often followed the borders between redlined and non-redlined areas, acting as physical walls of smog and concrete between different races.

Through freeway construction and urban renewal, it is estimated that the government displaced over one million of its own citizens, the vast majority of whom were people of color, while providing virtually no financial assistance to the internal refugees it had created. It obliterated entire communities, destroyed livelihoods, and robbed people of color of hard-earned equity in their cities. The generational

Seizing properties through eminent domain, cities erased neighborhoods and replaced them with amenities focused on suburban commuters, such as massive sports complexes, entertainment centers, singleuse office complexes, outsized institutional expansions, and parking—lots of parking.

effect of this has been to create a cycle of poverty, a feedback loop which prevents those in poverty from obtaining any equity in American society.

Breaking The Cycle

The people whose houses and business were destroyed, whose communities were wiped away, whose social networks were decimated: these people were assaulted and robbed by the government. They deserve direct reparation both financially and in terms of the built environment. This means first recognizing the freeway network as a physical tool of white suprematism, radically rethinking it, and wholesale dismantling of much of it.

Unfortunately the trend is in the opposite direction. Cities across the country continue to pursue highway widening projects in communities of color. After all, that is where the freeways were built. From Los Angeles to Houston—even Portland, Oregon— many cities are doubling down on the mistakes of the past. Putting aside issues of encouraging sustainable transportation, as well as the absurdity of using the same old toolkit to relieve traffic, despite ample evidence at this point that induced demand will simply wipe out and speed increase; all of these projects will result in the demolition of hundreds of homes and businesses in primarily Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, continuing the cycle.

While the recently-passed infrastructure bill includes $1B designed to redress these issues in the form of the DOT’s “Reconnecting Communities Program,” the continuation of projects such as these across the country is a worrying sign. Unless the United States begins to meaningfully address its automobile-based segregation, this will be yet another example of the United States’ institutional prejudice and failure to adapt to a rapidly changing world.

12

“ “

Underlying structures in postwar urbanization

Caro, Robert. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Knopf, 1974.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Ghetto and Public Policy.” The Atlantic, 2013. Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It. NYU Press, 2016.

Harvey, David. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. Verso, 2013.

Jackson, Kenneth. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press, 1985.

Lewis, Tom. Divided Highways: Building the Interstate Highways, Transforming

American Life. Cornell University Press, 2013.

Madden, David and Marcuse, Peter. In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis. Verso, 2016

McGhee, Heather. The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together. Random House, 2021.

Norton, Peter. Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. MIT Press, 2008.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liverright, 2017.

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 13

Fig 5: “urban renewal” projects in Boston West End 1995-1959 (top to bottom) Image source: Segregation by Design and the West End Museum

Total Segregation

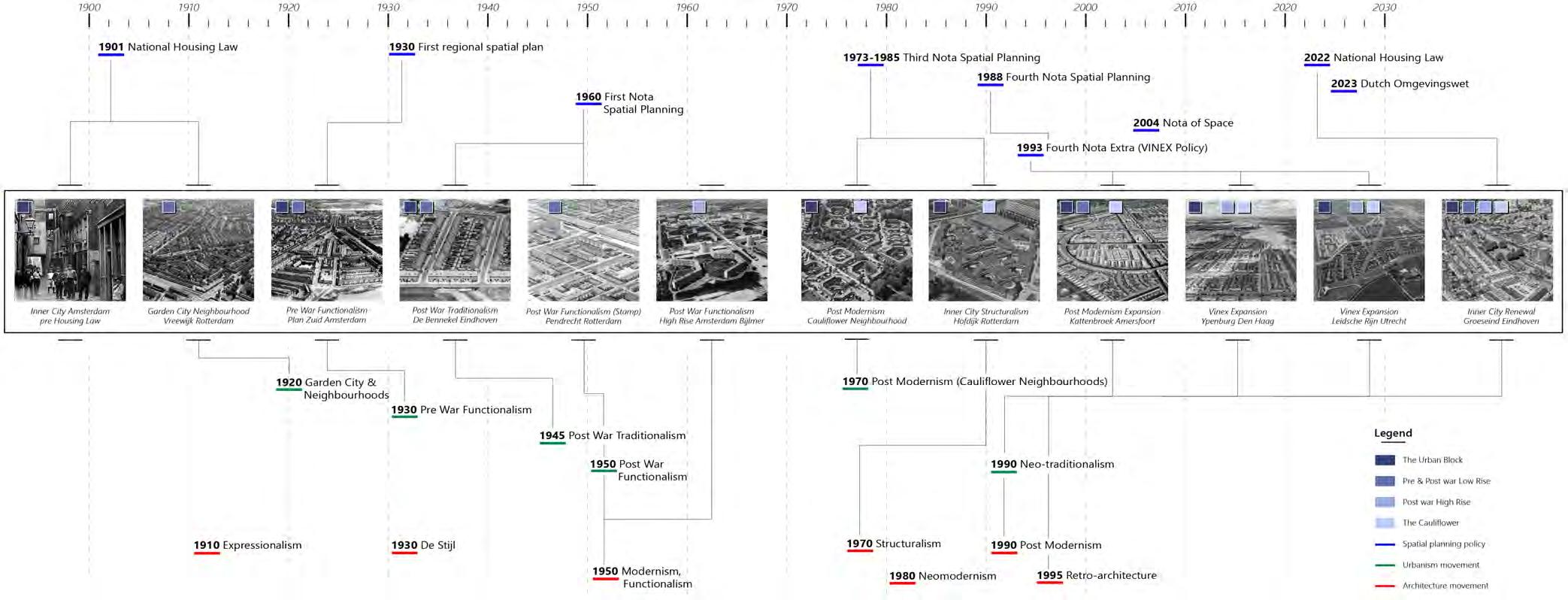

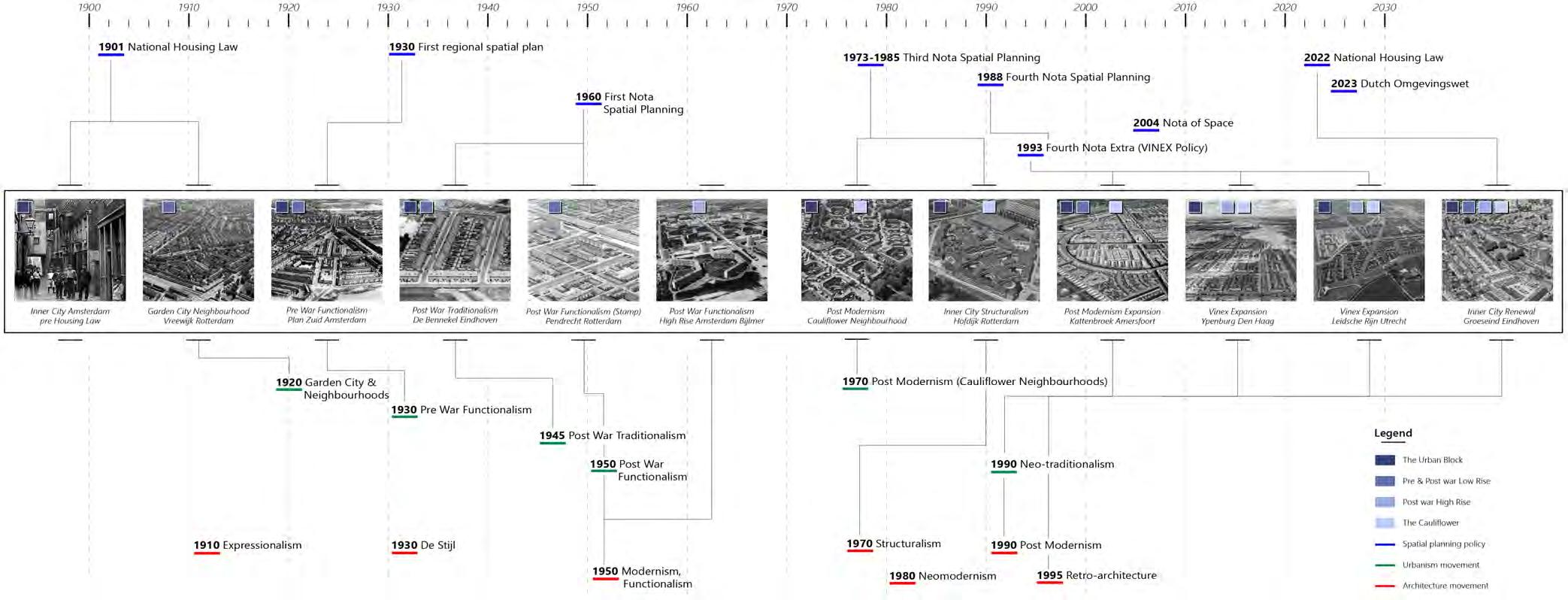

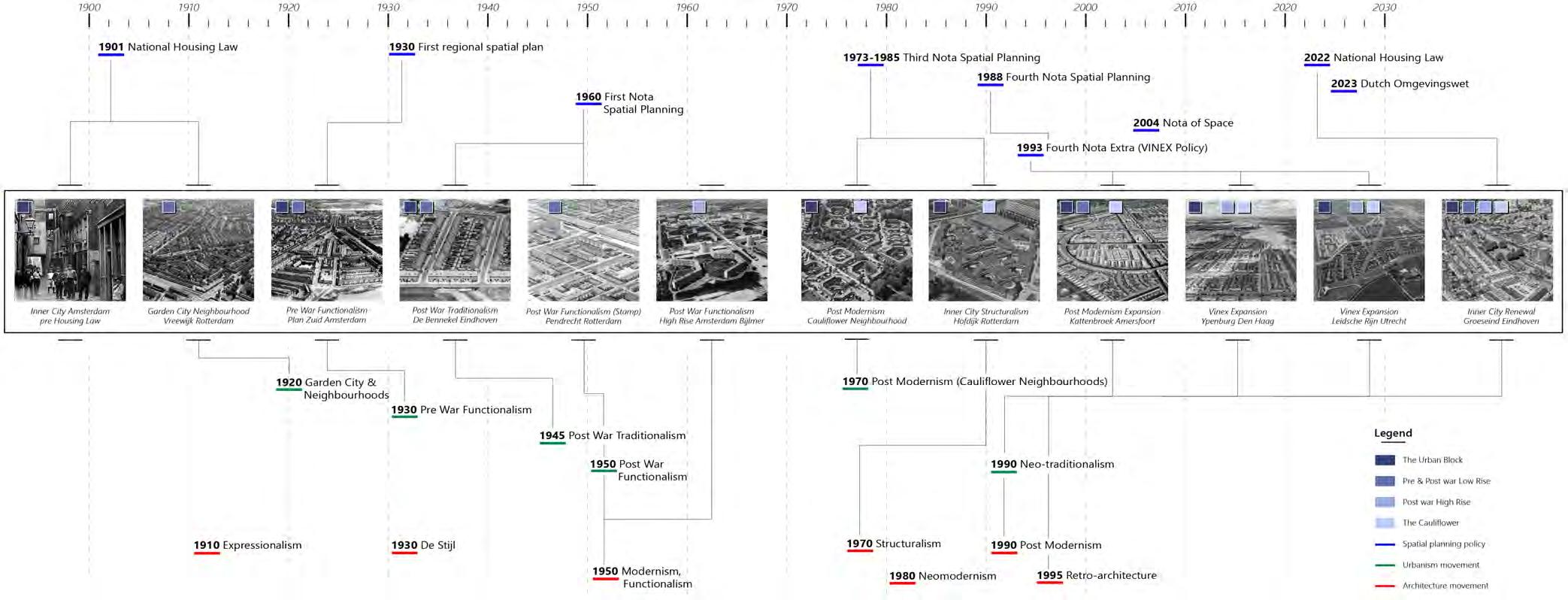

The Dutch urban landscape forms a pattern of historical neighbourhood ideologies, public space and urban fabric. Without clear connections and interrelations between these patterned neighbourhoods, the danger arises for fragmentation of the urban system leading to increasing sensitivities of socio-spatial segregation within Dutch society. Only until the end of the last major urban expansion program of the VINEX in 2015, little had been done to restore urban livability and vitality. Now the Dutch are standing in front of the same crossroad again, where housing shortages have started new nationwide housing policies. Maybe we can use this opportunity for densifying through integration rather than through expansion.

JENS BERKIEN

Introduction

Various contradictory spatial planning policies from the 1950s until the last major national policy of the VINEX in 1993, created a spatial pattern of different neighbourhood ideologies concerning, public and private space, infrastructural hierarchies, architectural identities and built densities. Whereas the cauliflower neighbourhoods of the late 80s had facilitated a so-called maze of public space, allocating the focal point to the private realm, the highrise estates of the 70s created private islands in a sea of unconditional public space, leading to dangerous situations at quiet times of the day. Although people might admire the strict planning and control of public space when they walk through Dutch cities, the underlying ideas and structures form a complete ‘structured’ mess.

As the urban fabric is key in facilitating a potential framework for a socially just urban system, allocating place for all residents of society, the Dutch spatial planning experiment lab fostered an increasing

sensitivity to socio-spatial segregation within the society. Not only did this make socio-spatial segregation issues appear, but large influences from the private sector also had a major impact on sociospatial segregation within Dutch society. .

The VINEX neighbourhood stands as an example of the last major nationwide spatial planning policy, still manifesting in the form of new large expansion neighbourhoods along the edges of cities. With the end of the VINEX, we have seen an increase in residential and socio-economic segregation in Dutch cities due to the expansion of our patterned urban landscape using the same ideologies within a different coat.

Now the Dutch are standing in front of the same crossroad again. Current housing shortages have resulted in the formation of new nationwide housing policies, but how do we focus on Densification now, through integration or again through expansion?

14 01 UNDERLYING STRUCTURES IN POSTWAR URBANIZATION

The Effects of VINEX policy on residential and socioeconomic segregation in the Dutch housing market dividing the connectivity between neighbourhoods.

15 Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41

ATLANTIS | (In)Visible | Volume:41 | Feb: 2023 15

Fig 1: The Dutch Urban Pattern Landscape Image Source: Author

Vinex As The ‘Last’ Urban Expansion Policy

In 1993, a new policy - the VINEX policy - was introduced in the Netherlands to tackle the growing pressures on the housing market and the escalating suburbanisation of highincome households to rural areas. The introduction of the VINEX transformed the Dutch housing system to a marketoriented sector; one that was supposed to retain high and middle-income residents in large cities through new expansion neighbourhoods along their edges. Favourable financial benefits for investors, high demand for owneroccupied dwellings, the sense of homophily in social networks, high-quality facilities and amenities and the high number of family houses triggered a residential movement from cities towards the new VINEX neighbourhoods instead of the rural countryside. This marked the beginning of increasing residential segregation rates in adjoining VINEX and other, primarily, post-war expansion neighbourhoods.

Urban Expansion Counter-movement

A counter-movement to the Vinex urban expansion related to urban restructuring was implemented in 1997 to decrease the increasing residential segregation. The main idea of urban restructuring was the creation of mixed neighbourhoods in ‘deprived’ areas where large concentrations of low-income residents lived (Priemus, 1998). The Dutch government saw these low-income concentrations as a problem in the integration process. Interventions in the housing stock of urban restructuring areas were planned to mainly retain more middle and higher-income residents (Boschman et al., 2012). Although these neighbourhoods succeeded in retaining more higher-income residents, most residents decided to move to the new VINEX neighbourhoods (Boschman et al., 2012; Jilisen, 2013). Because the VINEX neighbourhoods consisted of more single-family dwellings, these neighbourhoods were primarily attractive for high to middle-income family households who

16 Underlying structures in postwar urbanization

could afford an upgrade in their housing situations. The idea of homophily (McPherson, Smith-Lovin & Cook, 2001) – in the housing sector of the VINEX neighbourhoods gave searching families the opportunity to live with residents who are similar to themselves, therefore extending this moving trend even more. The urban restructuring neighbourhoods were planned to house residents with different values, attitudes, ethnicities and social classes balancing out the income distribution of households in neighbourhoods. Although cities like Rotterdam, The Hague and Amsterdam had successful urban restructuring campaigns in the 2010s, VINEX neighbourhoods still remained a better alternative for high to middle-income families. So, a possible cause for the rise in mostly residential segregation in the Netherlands can be found in the policiesmainly the VINEX - the state introduced in the housing sector.

Future of the Vinex neighbourhood

VINEX neighbourhoods brought more expensive dwellings, public transport and a ban on further housing development locations in rural areas but the focus is now moving towards the cities to resolve the future challenges of the Dutch urban areas. The VINEX neighbourhoods will endure as pleasant neighbourhoods on the outskirts of cities. Only time will tell what kind of future the VINEX neighbourhoods will see in the ever-changing societies. The era of large-scale urban developments in rural areas has ended. The VINEX neighbourhoods are probably the last urban greenfield developments the Netherlands will see in a very long time, although the current housing crisis calls for the development of even more expansion neighbourhoods and plans than before. The Netherlands has to make the decision of expanding its city borders or integrating its neighbourhoods.

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 17

Fig 2: Timeline of spatial planning policies from 1901 to the new national housing policies of 2022 with connecting urban and architectural ideologies Image source : Author ,based on Lörzing, et al. 2006.

Growth of residential and socio-economic segregation

The current politico-institutional context of society has created a mentality of growth first, society second (Brenner, N., 2013). In the welfare state of the Netherlands (which is also changing) this can be seen as two sides of the housing market that have been overrepresented in the past decades. The niche of owner-occupied dwellings was incentivised by the national government to attract families to the cities (van der Wouden, 2020) of which the VINEX policy was one of them. On the other hand the social housing sector had always been directed to promote equal housing opportunities for lowincome residents (Kleinhans, 2004).

The division in the Dutch housing market correlates with the division of the increasing gap between high and lower-income residents, with almost a completely disappearing middle class. This increasing division can also be seen spatially where neighbourhoods over time have been segregated by their prominent homogeneous housing stock. Urban renewal processes can diversify the housing stock but socio-spatial segregation is accelerated since urban renewal is mainly understood as a way for local businesses to further act upon the financial benefits (Brenner, 2013) instead of a potential binding of socio-economically or culturally diverse residents.

Nevertheless, research over the years concluded that humans tend to live close to other people with similar trades on a cultural, social or economical level, due to the lower percentage of perceived discrimination and a higher sense of safety, while it related segregation studies to the formulation of reference groups of society. If , then, a changing look at the formulation of the reference groups in these studies indicates a need of diversification, maybe the idea around segregation also needs to be re-examined.

Urban renewal processes of municipalities often address these neighbourhoods and try to improve their living qualities. As the paradigm shifted from the industrial age to the post-industrial age - with the rise of mass media and telecommunication - it changed how people identify themselves within representative reference groups, making the prexisting segregation studies inadequate in formulating the overall identity of these groups. (Sassen,1998; Holloway, Rice & Valentine,2003; Slevine, 2000; Schnell et al,2015). However, since municipalities and policymakers still see segregation as a dangerous situation for the development of a city, the understanding of its positive and negative effects becomes more intertwined, placing the focus of segregation studies on the local sociological issues between and within neighbourhoods of the city. Thereby emphasising on the need to understand Netherlands as a patterned urban landscape.

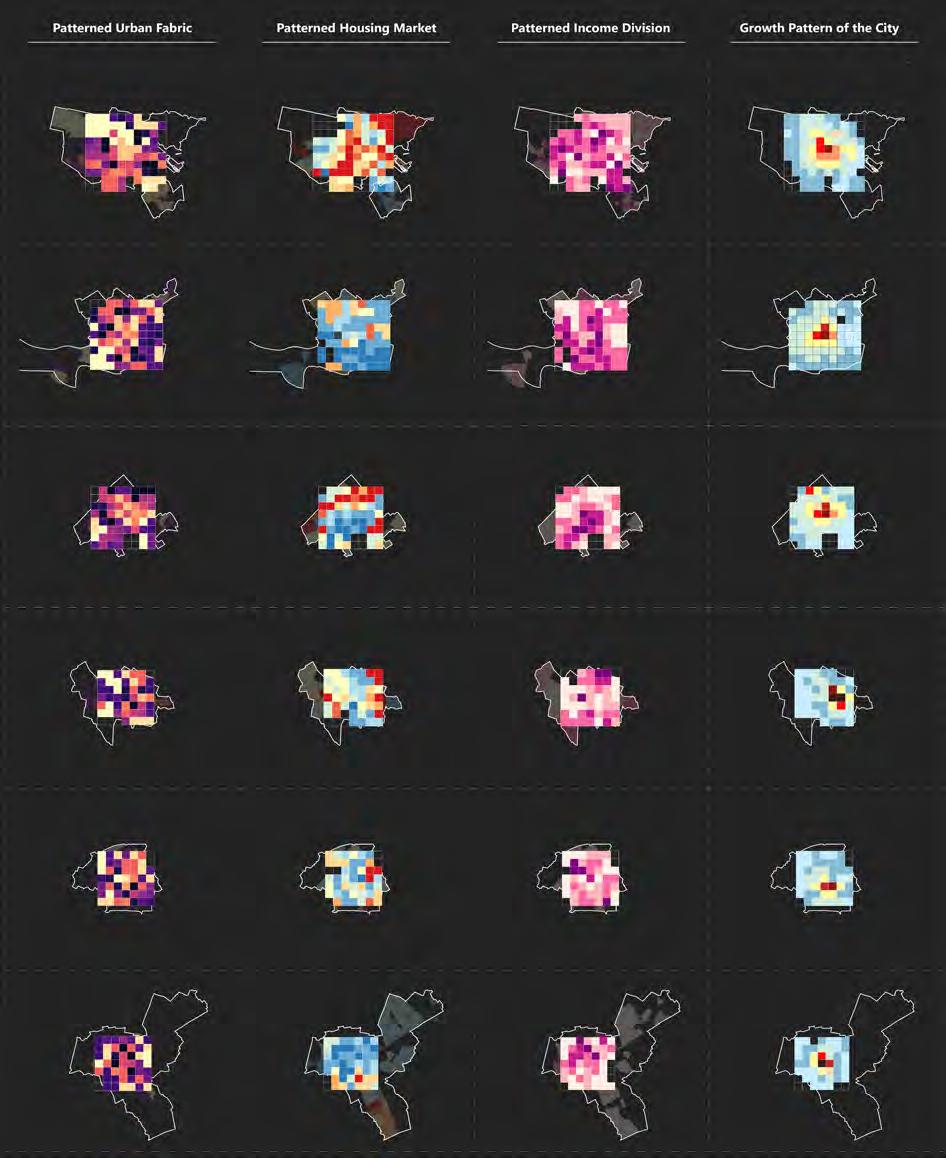

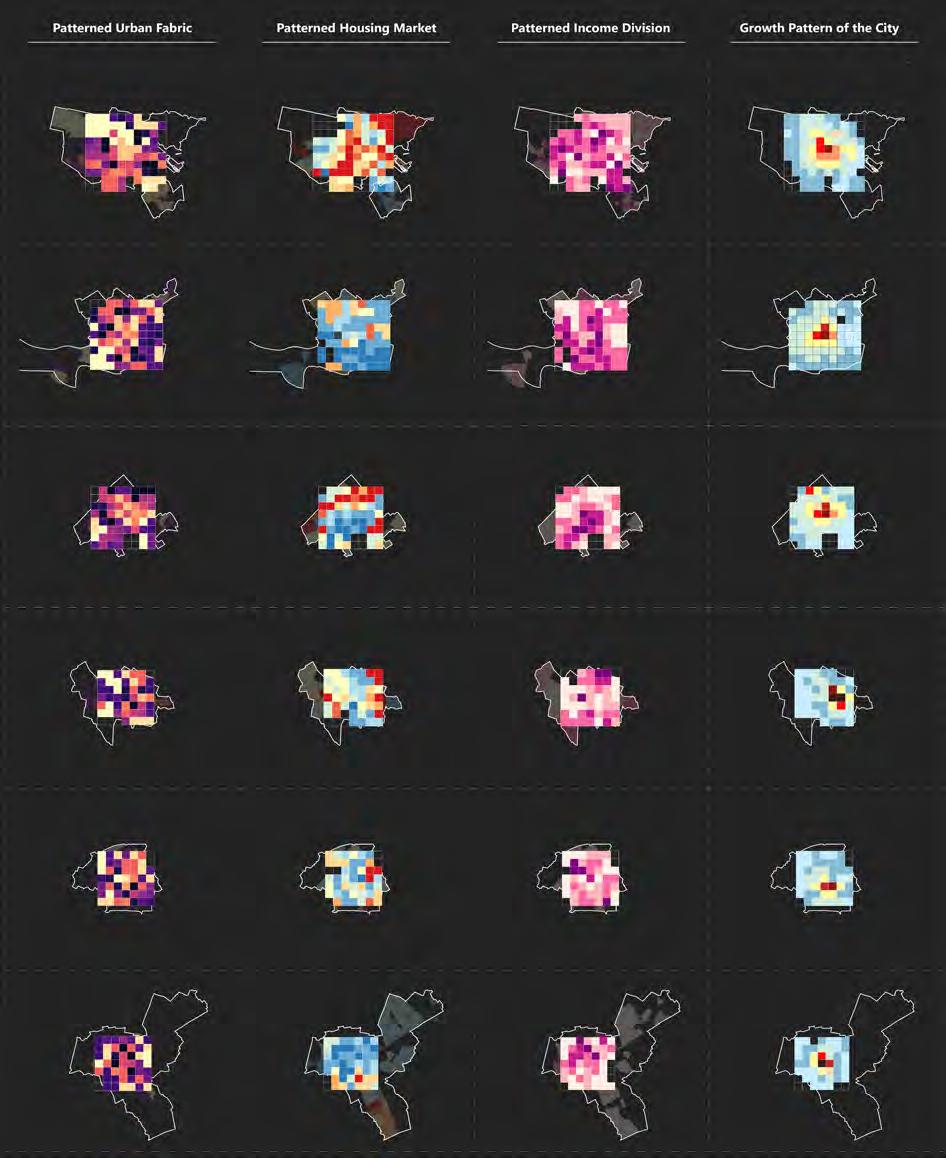

The Netherlands as a testing ground of spatial planning typologies

The Dutch city seems to be a rational unit of intertwining pieces, planned to perfection. But only after the effects of WWII, a new managerial revolution ignited. An extensive post-war reconstruction program required a new managerial system to build housing fast and efficiently (Wagenaar, 2011). New ideologies of constructing neighbourhoods, like the garden city, the neighbourhood unit, and the VINEX, created an abundance of neighbourhoods with different public spaces, functions, housing typologies, and infrastructure. The result led to an experimenting ground of various adjoining neighbourhood ideologies. Consequently, the urban fabric started to look like a pattern of neighbourhood units without clear connections between them; only related with the city centre. Hence the urban fabric of the Dutch city tends to be separated and divided. In fact, the six largest municipalities of the Netherlands - as shown within a grid of 1x1 km - are divided according to the growth pattern of the city, low-income residents, neighbourhood typologies and housing value. Although these patterns are based on a conceptual framing of these 6 big municipalities, relations between low-income residents and certain neighbourhood typologies (pre- and postwar garden city neighbourhoods), housing value and the period of construction are shown. It becomes clear that even though the redevelopment of pre-and post-war neighbourhoods in the 1980s and 2000s changed the outlook of the city, making better connections between neighbourhoods was not part of it. As Dutch spatial planning has been relying on different ideologies all considering influences of the neighbourhood units, the main focus of redevelopment was to change its housing stock. Therefore the concept of the neighbourhood unit and its spatial distribution persisted without affecting the segmentation pattern of the city. Research by Read, on the integration of the Dutch urban fabric, showed that the spatial form of neighborhoods only resulted in integration patterns within, and not between adjoining neighbourhoods (Read, 1998). The segmentation of spatial form in the city can be an indicator of potential socio-spatial segregation developments (Hillier, & Vaughn, 2007), therefore establishing a correlation between the patterned look of the urban fabric and sociospatial segregation.

Public space integration

To cope with the fast-growing individualism of different identities scattered across neighbourhoods, urban renewal processes often fail to improve social integration for the people who need it the most. To further enlarge the scope of urban renewal processes between multiple neighbourhoods, it needs to focus on connecting the ‘segregated’ neighbourhoods, instead of improving single neighbourhoods with the idea of

18 Underlying structures in postwar urbanization

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 19

Fig 3: Patterned urban landscape of the 6 biggest municipalities in the Netherlands (top to bottom: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Utrecht, Eindhoven & Groningen) according to its Neighbourhood typologies, Housing values, Income divisions and Growth patterns.

19 ATLANTIS | (In)Visible | Volume:41 | Feb: 2023

Image source: Author,; based on data from PDOK, 2019, 2021; Rutte, R. & Abrahamse, J. E., 2014

‘improving the living quality’. To follow the words of Julienne Hanson that urban transformation can be encapsulated in just two words: ‘street’ and ‘estate’ (Hanson, 2000., p 99), more attention should be given to the street and public use instead of improving the ‘estate’. Therefore urban renewal processes should try to find possible locations for establishing better connections between neighbourhood units, and connect not only their borders but also residents of different social groups. The essence of publicly accessible space on the borders of neighbourhoods can be a key solution in further urban renewal processes.

According to Legeby (2013), access to public space is dependent on the location of amenities, the distribution of space and the experience of space. Therefore less attention should be given to urban renewal processes diversifying the housing stock, and more towards the accessibility and the typology of public space between ideologically different neighbourhoods. The ideal integration would be along neighbourhood borders because these are the locations where space syntax research of the Dutch city has shown to be the least integrated part of the urban fabric . Therefore future urban renewal processes should focus on making better connections between the neighbourhoods and connecting people from different social groups with an active and accessible public space.

Conclusion

The introduction of the new ‘Omgevingswet’ in Dutch spatial planning and the current stress on the housing market will again put an emphasis on nationwide controlled planning policies. Although it seems that the current minister of Housing: Hugo de Jonge, wants to build fast and efficiently, scholars and experts are divided on how to solve this ‘big’ crisis. Are we going to expand our city borders in the already stressed greenfields of the rural countryside or are we going to densify by urban renewal projects in the heart of the city? While the latter seems favourable, the changing globalizing world demands a widening scope of urban renewal processes (Brenner, 2013). To cope with a fast-growing amount of different identities scattered across various neighbourhoods, urban renewal processes often fail to improve the living quality of the people who need it most, leading to further issues of segregation. Despite the addition of superior dwellings to the housing market, they fail to integrate adjoining neighbourhoods and their different ideologies, resulting in increasing figures of socio-economic and residential segregation. Urban renewal processes seek ways of overlapping architectural ideology, infrastructural layouts with the public and private realms. Only then the Dutch can look for densification by integrating its patterned urban landscape like puzzle pieces.

Boschman, S., Bolt, G., Van Kempen, R., & Van Dam, F. (2012). Mixed neighbourhoods: Effects of urban restructuring and new housing development. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 104(2), 233–242. Brenner, N. (2013). Open city or the right to the city? The International Review of Landscape Architecture and Urban Design. Hanson, J. (2000). Urban transformations: A history of design ideas. Urban Design International, 5(2), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave. udi.9000011

Hillier, B., & Vaughan, L. (2007). The city as one thing. Progress in Planning 67, pp 205-230. Retrieved from http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/3272/ Legacy, A. (2013). Patterns of co-presence: Spatial configuration and social segregation. In TRITA – ARK Akademisk avhandling 2013:1.

Lörzing, H., Klemm, W., van Leeuwen, M., Soekimin, S. (2006) VINEX! Een morfologische verkenning. NAi Uitgevers, Rotterdam & Ruimtelijk Planbureau, The Hague.

Read, S. (1998). Space syntax and the Dutch city. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 26(2), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1068/b4425

Schnell, I., Diab, A. A. B., & Benenson, I. (2015). A global index for measuring socio-spatial segregation versus integration. Applied Geography, 58, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.01.008

Wagenaar, C. (2011). Town Planning in the Netherlands since 1800. Responses to Enlightenment Ideas and Geopolitical Realities. 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

20 Underlying structures in postwar urbanization

19thCentury&21stCentury Renewal

Image Source:

Image

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 21

Cauliflower GreenSpace BuiltArea BlueSpace PrivateSpace PostModernism Functionalism,Structuralism Functionalism,Traditionalism

UrbanBlock (Pre&Postwar)LowRise (Postwar)HighRise

Fig 4: Conceptual drawings of the neighbourhood unit in the four main neighbourhood typology ideologies of the urban block, the post-war high and low rise and the so-called ‘cauliflower neighbourhoods’

Author, based on BRIGHT & Tauw, 2019

Fig 5: The Dutch housing market in a 10x10 km grid as a patterned urban landscape towards integrating puzzle pieces

WOZ Value Dutch Housing Market 0 - 150.000 150.000 - 180.000 180.000 - 210.000 210.000 - 240.000 240.000 - 270.000 270.000 - 300.000 300.000 - 330.000 330.000 + 21 ATLANTIS | (In)Visible | Volume:41 | Feb: 2023

Source: Author, data from PDOK, 2019

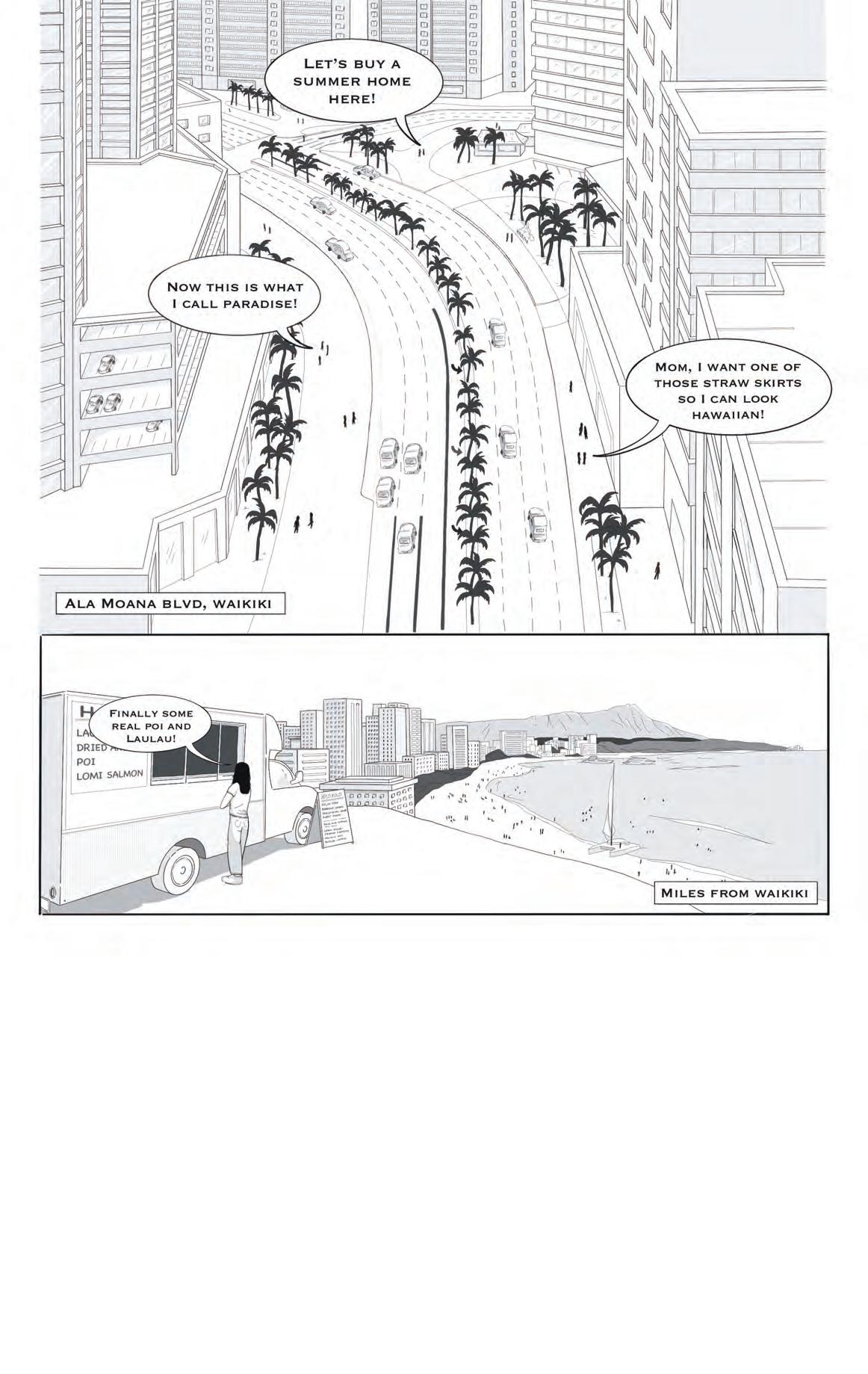

PARADISE PARADISE THE PRICE OF

“Spectacular sand beaches, outdoor adventure, and a Mai Tais under a palm tree - paradise awaits”.

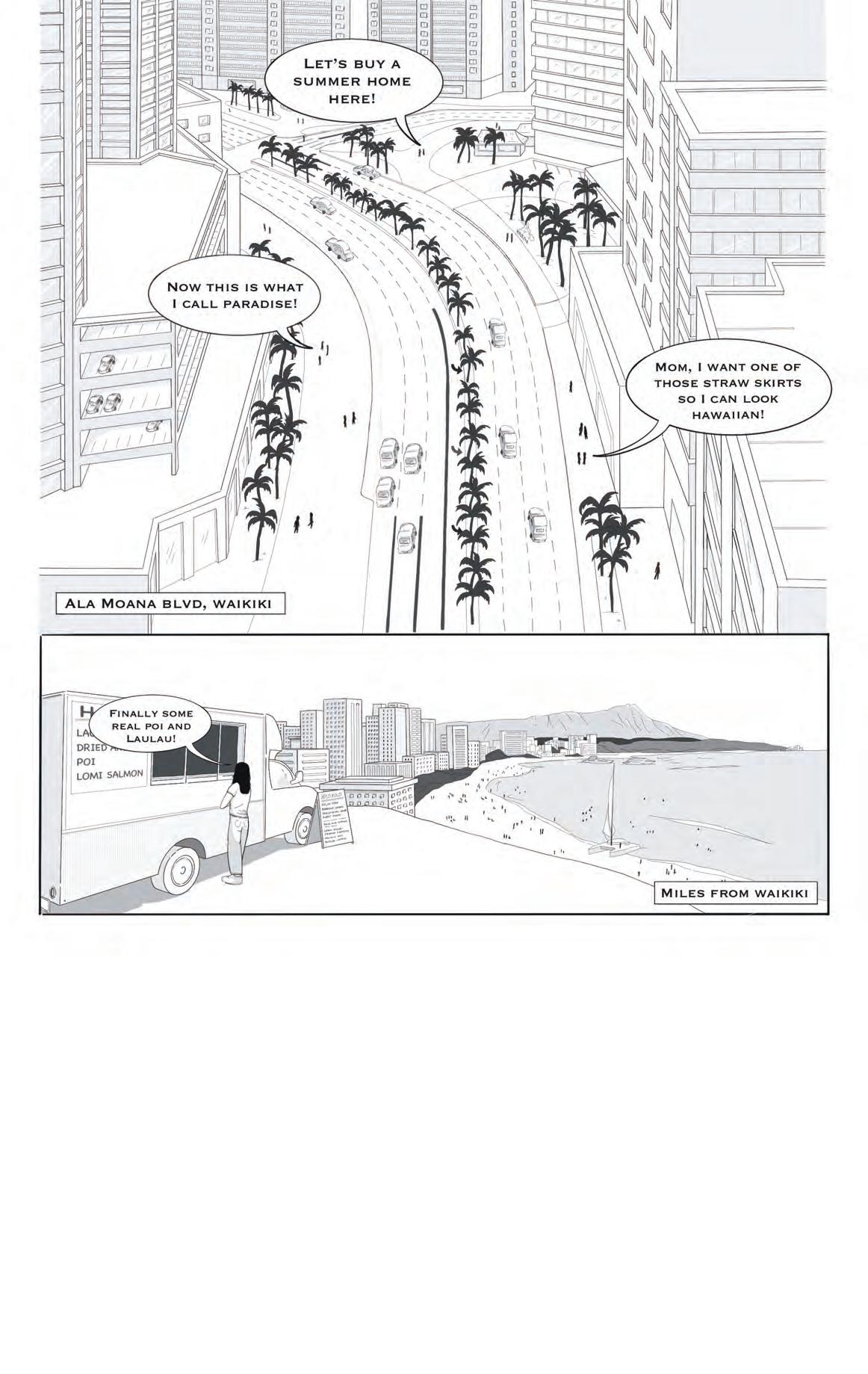

This is the scene marketing for Hawai’i, to feed the tourism industry. However, as ever increasing numbers of people visit the islands to experience the superficial level of Hawaiian culture, native Hawaiians and locals are being forced out of their homeland due to skyrocketing real estate prices, rampant luxury development, lack of workforce housing and a high cost of living while their sacred lands suffer. The price of paradise is too high for its residents.

01

LARISSA MULLER

UNDERLYING STRUCTURES IN POSTWAR URBANIZATION

Spectacular sand beaches, outdoor adventure, and a Mai Tai in hand under a palm tree - Paradise Awaits...

This is the scene marketing for Hawai’i, to feed the tourism industry. However, as ever increasing numbers of people visit the islands to experience the superficial level of Hawaiian culture, native Hawaiians and locals are being forced out of their homeland due to skyrocketing real estate prices, rampant luxury development, lack of workforce housing and a high cost of living while their sacred lands suffer. The price of paradise is too high for its residents.

Introduction

Stories of struggling Hawaiians in their homeland become increasingly common as the visible effects of a colonized island and the prioritization of the tourism industry by the state government continues to maintain patterns of inequality and exploitation. The destruction of the land and the exploitation of the culture in favor of business ventures turned the island into a paradise for tourists and multinational corporations at the expense of the local population.

The Commodification of the Hawaiian Language

Since the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and the start of the colonization of the islands in the 1890s, the United States has continued to exploit the culture of the native Hawaiians for monetary value. It started with the ban of the Hawaiian language in education as well as the discouragement of speaking the language at home as a way for American colonizers to further suppress locals and enforce western-style schooling. Although the language was re-instituted a century later in the mid 1980s (Goo, 2019) with numerous attempts to resist the colonialist suppression, the Hawaiian language is still critically endangered according to UNESCO. There isn’t a more representative example than the commodification of the word ‘Aloha’, often used for commercial purposes that is far removed from the literal and cultural context. For the global world today, ‘Aloha’ simply translates to hello or goodbye. This understanding developed as merchandise corporations, pubs, and travel agencies advertise this phrase to aid their monetary gains and ultimately diffuse its true significance. ‘Aloha’ goes beyond these simple meanings and has multiple translations, the literal meaning is ‘breath of life’ and ‘spirit of positivity and love’. It is an example of how the local language was and is used to give the impression of a reflection of real local culture, when instead it’s just a reflection on a superficial level and neither aims nor achieves to truly represent the local traditions.

The Exploitation of Hawaiian Lands

In the 1970s, Hawai’i continued to urbanize and attract tourists from America and around the world. Soon, the idea of the land as a respected entity and a source of food ingrained in Hawaiian culture, the land in the Hawaiian language called ‘Āina’ which means to feed, was replaced with the use of land as real estate. Since then, expensive hotels and resorts began to transform the scenic landscape of the islands and overshadow the previous sense of deification of the land. As the tourism industry quickly became the dominant economic force in Hawai’i, rapid developments, sold with the promise of providing locals with a better financial standing, resulted in a pattern of exploitation and a decimation of a respecting relationship with the land.

The Hefty Price Tag of Living

At the same time as the construction of new developments, eviction notices of locals surged, coinciding with the influx of tourists and migrants. Nowadays, the lack of affordable housing and the increase in living costs are the main drivers of the increasing homeless population of locals. When we observe the average cost of rent in 2019 compared to 2022, Hawaiians pay about an additional 13% more, with an average monthly rent tab of $2,500 (Napier, 2022), while prices are still increasing. Short-term vacation rental industries, such as Airbnb, continue to add pressure to an already constrained housing market with skyrocketing prices by reducing long-term housing options for Hawaiians (DeLuca, 2018) and increasing short-term options for tourists. This development cements a problematic situation for locals that Hawaiian land and culture stands available to everyone who can afford a hefty price tag.

Promise of Jobs that Fail to Deliver

As locals are being forced out of their homeland, Hawaiian land and the natural resources are exploited for resorts, military reservations, and multimillion-dollar private homes. In this sense, in the urban planning landscape, the economic benefits outweigh local interests when it comes to the consideration of land development. Large developments on the islands, such as the Thirty Meter Telescope Observatory as well as the Coco Palms Hotel, were built or are proposed to be built on sacred ground that holds significant value to the native Hawaiians. Consolidation arguments were made from these corporations, claiming that these projects, although seizing sacred land, would provide economic benefits to the Hawaiian economy. However, the bulk of the profits from these projects go to non-Hawaiian owners with the “promise of jobs that fail to deliver” (Mzezewa, 2020). This shows a pattern under which local Hawaiians often don’t receive the benefits and are left employed in lower-paying service jobs.

24

“ “

Underlying structures in postwar urbanization

Cultural Prostitution

As land is exploited, local culture becomes commodified. Hawaiian culture often degrades to beautiful women dancing the hula. This strips the dance from its historical and cultural value to an ornamental performance solely attributed for entertainment and thus profit. Lū’aus, where the hula dance is often performed, still remains a connection to Hawaiian culture. However, a majority of Lū’aus put on by resorts or hotels are watered down and Americanized, and show a business interpretation of a cultural performance. These industries commonly portray events like Lū’aus as genuine encounters with Native Hawaiian culture when in fact, the coconut shell bras and teriyaki chicken, are far from local Hawaiian culture. This overall creates a manufactured scene, leaving tourists with a distorted view of Hawaiian culture and a romanticized view of the islands. All these trends and developments lead to an ambivalent image of Hawai’i.

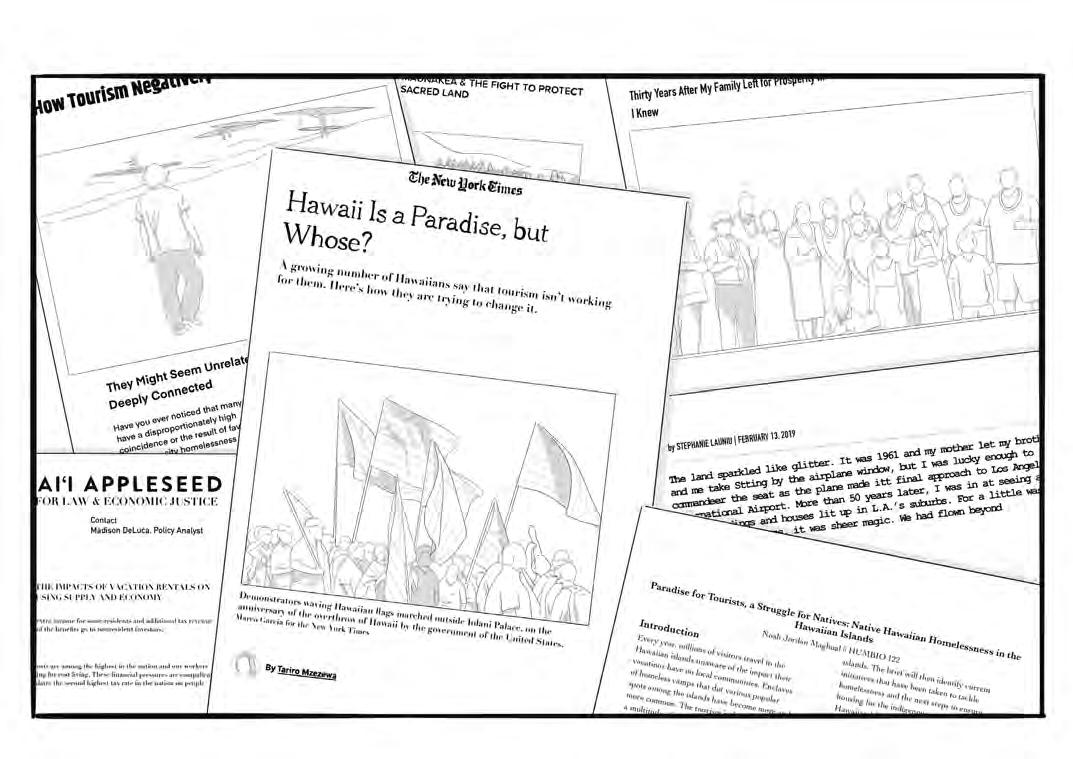

Conclusion

Around the globe, the identity of Hawai’i has been transformed into an image of hula dancers and mai tais, caused by historical exploitation and cultural prostitution. Many people, even the in neighboring states, are unware of the impact of these global neocolonial behaviors on locals. These patterns of over-tourism, unbound in culture and history of the context, further roots the Hawaiian culture in their colonized past in a postcolonialism world. However, over the past couple of years, together with the rethinking economic structures tied to the tourism industry and the start of the pandemic in 2019, the stance on the dangers of over-tourism in the state has become more widely accepted. Hawaiian locals and news articles have recently begun advocating for tourists to become aware of the effects of neocolonial tourism leading to gentrification, the displacement of locals, whitewashing of the culture, and their ill effects on sacred lands. The question then remains, how do we reconfigure the role of tourism in a context altered by past and current practices of colonialism, exploitation, and cultural prostitution?

‘A Native Hawaiian Returns Home | Essay’ (2019) Zócalo Public Square, 13 February.

Arista, N. (2018) Aloha Not For Sale: Cultural In-appropriation, Ka Wai Ola. Available at: https://kawaiola.news/cover/aloha-not-for-sale-cultural-inappropriation/.

Erin (2021) Native Hawaiians Are Disproportionately Affected by Poverty and Homelessness, Invisible People. Available at: https://invisiblepeople.tv/nativehawaiians-are-disproportionately-affected-by-poverty-and-homelessness/.

Goo, S.K. (2019) ‘The Hawaiian Language Nearly Died. A Radio Show Sparked Its Revival’, NPR, 22 June.

How Tourism Negatively Impacts Homelessness - Invisible People (2022).

Jedra, C. (2020) Survey Counts Over 4,400 Homeless People On Oahu Before

COVID-19, Honolulu Civil Beat. Mzezewa, T. (2020) ‘Hawaii Is a Paradise, but Whose?’, The New York Times, 4 February.

Report documents the impacts of vacation rentals on Hawaii’s housing supply and economy (no date) Hawaiʻi Appleseed. Available at: https://hiappleseed. org/press-releases/vacation-rental-impact-hawaii-housing-economy.

Riker, M.S. (2022a) Good Luck Finding A Place To Rent If You Own A PetEspecially On Maui, Honolulu Civil Beat.

Riker, M.S. (2022b) Report: Maui Needs A Plan If It Actually Wants To End Homelessness, Honolulu Civil Beat.

The Hawaiian Homelessness Crisis (no date). Available at: https:// thehomemoreproject.org/blog/the-hawaiian-homelessness-crisis?format=amp. Tourism and The prostitution Of Hawaiian Culture (no date).

25

Fig 3: The history in newspapers and articles Image Source: Author

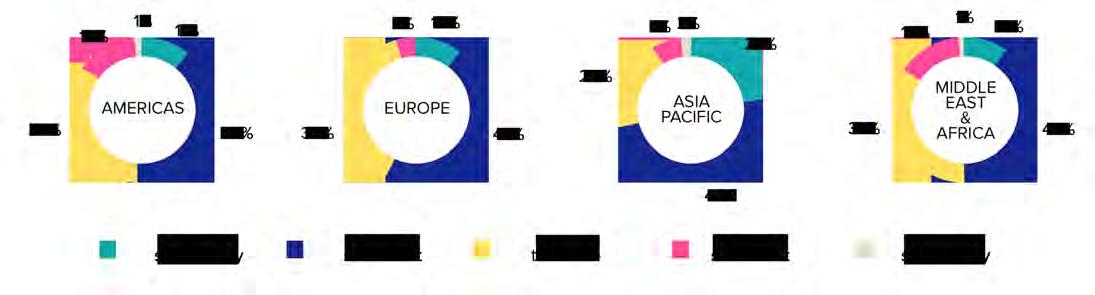

The Invisible Currencies Shaping European Urbanism Today

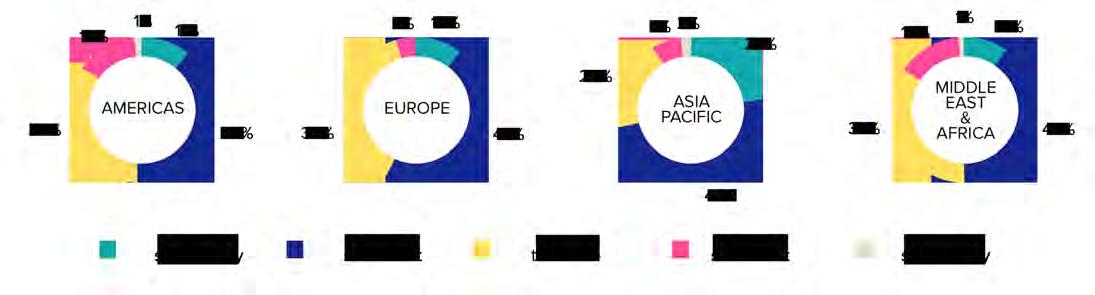

An invisible current of cross-border capital is flowing into Europe today, shaping how its cities are growing and the way its citizens are living. As these foreign capital investments are projected to increase, particularly from the Asia-Pacific region, it is crucial for urbanists to be able to discern and embrace the vital influence of global geopolitical and socioeconomic factors in both their thinking and practice. With three case contexts; Greece, Poland, and Spain, a compact illustration of the esoteric and ulterior force of foreign investment and acquisitions in properties and public assets reveals some of their socio-spatial impacts. From Real Estate, Infrastructure, Energy, to Logistics companies what else have some cross-border investors not bought in Europe? Perhaps its soul.

According to the Urban Land Institute, crossborder Asian and Pacific capital investment into the real estate and property market in Europe is projected to increase by a total of 71% in 2022 onwards.

Although main investments from the eastern part of the world coming from China began increasing since 2008, the influence of investments from other Asian markets are expected to continue pouring in. China as an investor has already acquired a chunk of London’s real estate, Albania’s Tirana International Airport, Swedish car manufacturer Volvo, Swiss energy’s Addax Petroleum Corporation, as well as a minority stake at Rotterdam’s Euromax Seaport

Terminal. Additionally, it is also looking into investing in more infrastructure and energy industries stretching from France to Eastern Europe. South Korean, Middle Eastern, as well as Southeast Asian capital is following suit by making its way to acquiring stakes in and ownership of European developments and assets either privately or in partnership with EU governments.

In a hyper globalized world as today, this is perhaps business as usual (which is a phrase we have already been using to describe a bad accustomed practice or way of living), yet the seeming socio-political balance in terms of key investments between the east and the west is now coming to an upturn.

26 01

ISHKA MEJIA

UNDERLYING STRUCTURES IN POSTWAR URBANIZATION

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 27

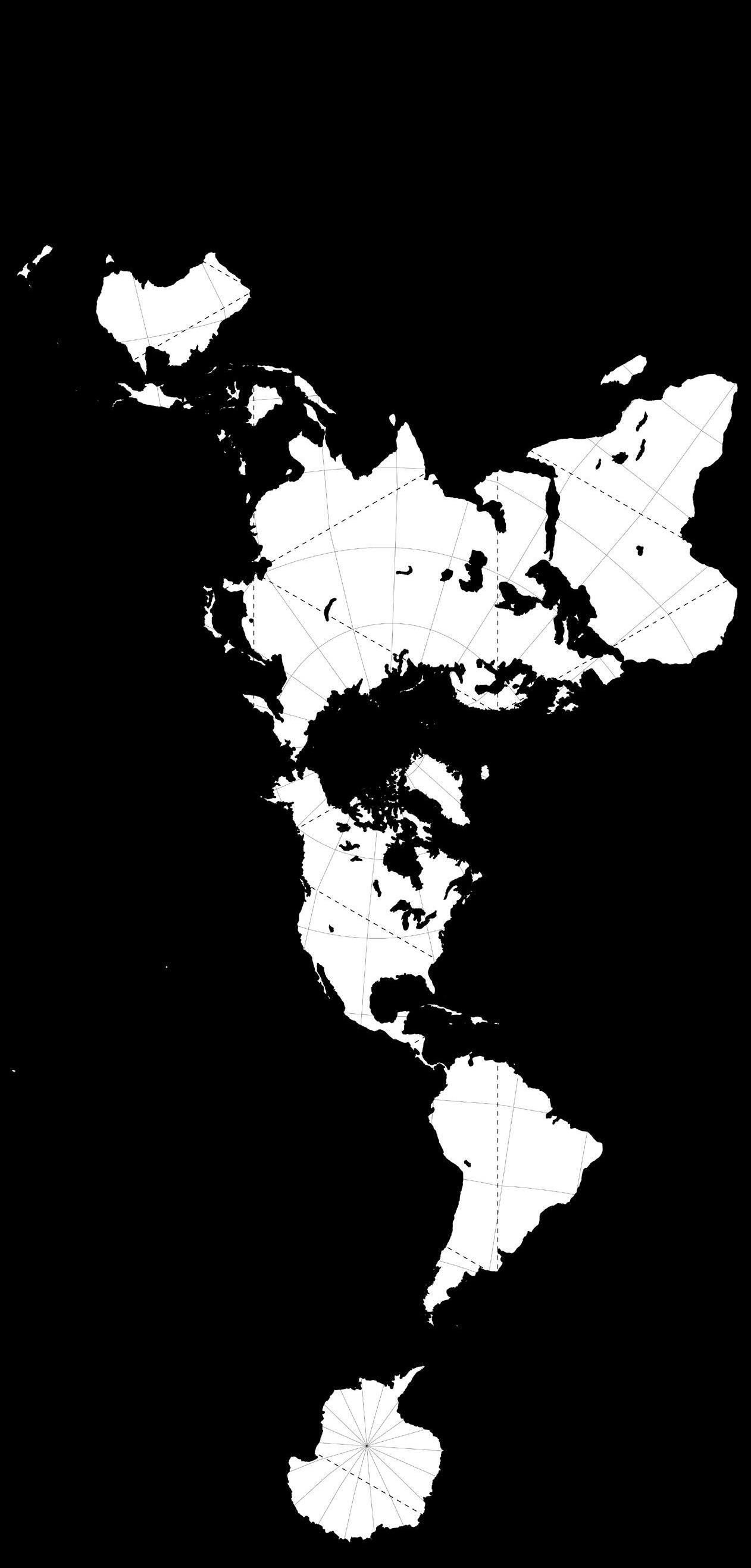

Fig 1: Territorial Deposits

Image Source: Author’

An invisible, yet multifarious current of capital is flowing from Asia to the European Union, unwittingly changing and redefining the very cities and systems where European properties and industries are located. Ones whose wheels are now being steered by a more dynamic and diverse set of players and stakeholders that may not necessarily care for the immediate environments of their assets or have a wider agenda for strategic sociopolitical interests. A simple investigation of how this unseen force is manifesting in communities and space in some European countries such as Spain, Greece, and Poland can allow urbanists to view and think about global socioeconomic power translated into the places we are designing and for whom more critically, yet also more openly.

Greece

The Port of Piraeus is the leading seaport of Greece, but it is majorly owned by the China-owned company COSCO Shipping with a 67% stake which takes salient control of operations. With a total investment of €1.2 billion since 2016, the facility has already expanded its capacity five times. COSCO initially pursued the investment in Piraeus as the country was under a state of colossal debt and possible bankruptcy when the government decided to privatize state-owned assets such as the port. Since then, an agreed 3.5% of yearly revenue from the port’s yields has been contributing to the local economies of the 5 municipalities in the Greater Piraeus area, also having created more than 10,000 jobs. The mayor of Piraeus, Yannis Moralis, declared that they receive € 3 million annually and that as the port’s yields are directly proportional to the boost in municipalities’ benefits, its progression shall be a win-win situation. Yet now it is unfolding that unemployment and financial matters are not the only concerns of locals.

A leader of a dockworkers union has expressed that, “China

created jobs, but not good jobs.” As safety training is foregone in some port procedures, it has been reported that operations which receive little compensation for high-risk jobs have caused a series of fatal incidents in the port. Additionally, a new plan for an entertainment and leisure hub worth €294 million in Piraeus in the works has been delayed. The foreign port owner ascribes this to the Greek government’s slow bureaucratic processes and local resistance, yet the latter’s defense is that environmental studies conducted and contracted by COSCO needed for construction to continue are lacking and substandard. Although with COSCO’s huge stake, it will still most likely go through. Most of the construction materials for the port expansion and new developments are imported from China, displaying disregard for local industries. Despite labor issues and interrogations on how the port’s revenues are being used by the beneficiary municipalities, the port is presently considered the 3rd largest and busiest cargo port in the Mediterranean, and the 5th top port in Europe. Yet the position of this port has a greater significance in the global urban fabric as it is a key link within the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of China, poised to be a regional distribution center that would connect Asia, Africa, and Europe.

Spain

Residency by real estate investment such as the ‘Golden Visa’ program shrouds foreign capital investment in Spain. This migration scheme permits residential or commercial property investments of a minimum threshold of €500.000 from any individual or company outside the country to acquire and hold residency for as long as the property is maintained. Due to this mandate, several cities in Spain and more particularly in its capital city, Madrid, have spurred many financial investments, incentivicing real estate development companies to direct their efforts towards a more diversified market. This not only

28

Fig 2: Expected cross-border capital into Europe in coming three to five years

Underlying

in

Source: Urban Land Institute (2021)

structures

postwar urbanization

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 29

Fig 4: Salamanca under the Peso Image Source: Author

Fig 3: The Piraeus Port under the Yuan Image Source: Author

includes the US,Britain, and other EU investors, but now also clients from China, The Middle East, Southeast Asia, and other emerging industrialized economic countries in the Asia Pacific. Since its establishment in 2013, the scheme itself has accumulated an amount of €911 million, of which the share sold to Chinese buyers for residential property is 30.5% as of 2016.

The Philippines, whose ties with Spain go back for centuries due to its colonial past, has many investors into this program as only 2 years of residency are required to hold citizenship, encouraging high-net-worth Filipinos and their families to purchase properties for investment or even decide to reside in Spain altogether. As these private investors come from a certain socio-economic class, they search for more expensive or forthcoming areas with the Salamanca district in Madrid as one of the main preferences. This has also defined how the district is growing and which kind of commercial properties are emerging in the area, generating more diverse yet upscaled neighborhoods whose calles are now frequently dotted with Asian cuisine and other foreign retail brands unbeknownst to Spanish locals literally setting up shop. This is causing both a shift in the local design, construction, and hospitality industries with a greater demand for different visions in residential and commercial property development in several districts in Madrid to serve this new market. Aside from the construction of newly built homes, the refurbishment and renovation of dilapidated or foreclosed properties are now in full swing as capital flows from these foreign private investors and have had significant impacts in the localities where these spatial assets are located. Despite criticisms of the scheme from locals, it is reported that this residency by investment program has substantially cushioned the blows of Spain’s debts and stimulated its lagging economy.

Poland

In Central Europe, Poland’s diplomatic ties with South Korea that begun in 1989 are seemingly more transparent with the East Asian nation’s plans to develop transportation and energy infrastructure in the EU territory. By 2021, South Korean investments –ranging from kimchi to electric vehicle battery factories – in Poland are valued at €5.1 billion. Recently, a private nuclear reactor plant to bolster Poland’s key nuclear energy program is set to be constructed as proposed and agreed upon by state-owned Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP), Polish energy group ZE PAK, and a Polish power company in the city of Konin. This position suggests a boost in the Polish economy and its role in the energy transition that, apparent in these engagements, it cannot pursue alone and is receiving support from an ‘outsider’. Notwithstanding, the transport

hub called Central Transportation Port (CPK), converging air, rail, and road transit located at a 45-km proximity from Warsaw is planned for development beginning next year. This collaborative effort between the Polish and South Korean governments is to be dubbed “the Far East’s gateway to the European Union.” Historically, this is the biggest infrastructure project in Poland, and is the EU’s largest infrastructure project at the moment. This megaproject is composed of building a greenfield airport tabula rasa whose design was bid for and won by Foster + Partners and direct rail connections to Warsaw and other cities. The latter is set as new high-speed railway lines measuring up to 2,000 km to reach other Polish cities in less than 2.5 hours, integrated in the CPK development. As the project’s entirety is expected to be finished by 2034, how much further Polish cities, as well as other EU states shall be shaped by these investments and their corresponding developments that will translate to new living and working environments for locals and even migrants shall soon emerge.

The contexts illustrated are just a few examples of how Europe’s regions are being shaped by such external forces as foreign financial capital that is usually too abstruse for most urbanists to relate to but must. It is of no question that they are stirring the processes that have historically also defined them – migration, industry, and infrastructure – by virtue of their effects on local employment, mobility, and quality of the built environment that directly affect people and how they live, and by extension, their futures. These ulterior yet strong currents of cross-border capital flows from Asia to Europe, the very historical representatives of East and West, are of interest in urbanism today as key drivers of change in new socio-spatial relations and connections that encompass the myriad scales of the urban fabric – from the neighborhood as seen in Spain, yet also that of global trade and regional infrastructure as in Greece and Poland. Furthermore, this also dispels a portion of the antagonistic views on foreign migration and capital as detrimental to the European economy, when in fact it could also be saving it. Nevertheless, there are many and more political and ethical aspects to this as well; like how the ‘Golden Visa’ scheme itself implies the privileged rights to reside in the EU if only one had a certain net-worth or how these partnerships and deals are conducted as they differ from one EU state to another. And if one has not already noticed, this article has spilled over more numbers in Euros than the people and spaces affected and perhaps the local situations whence these investments are coming from. How much better then can we think about, represent, and expose the deeper and more complex relationships between cross-border financial investment and space, which are, in essence, the two main instigators of development and urbanization today? These ‘invisible’ currents through the medium of financial capital only reveal their power in time, in built space, and in this case, perhaps the future of the European spirit.

30

Underlying structures in postwar urbanization

Alderman, L. (2012, October 12). Under Chinese, a Greek Port Thrives. The New York Times.

Aranda, J. (2018, November 28). Spain consolidates as a European paradise of the “golden visa.” El Pais.

Barczynska, E., & Kang, B. (2022). Korean Wave in Poland: Success and Challenge., 34, 5–38. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002820834

Brattberg, E., le Corre, P., Stronski, P., & de Waal, T. (2021). China’s Influence in Southeastern Central, and Eastern Europe Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries CHINA’S IMPACT ON STRATEGIC REGIONS.

Constandras, N. (2019, May 23). Who Is Playing Politics With the Port of Piraeus? The New York Times.

Engin, Y. (2019, November). Investor trends: Koreans continue march into Europe. IPE Real Assets Magazine.

Genius Properties. (2016, February 15). Spain’s Golden Visa Scheme Accumulates €911 Million. Https://Geniusproperties.Com/En/News/SpainsGolden-Visa-Scheme-Accumulates-911-Million/.

Harper, J. (2021, October 23). Why Poland is South Korea’s gateway to the EU. Emerging Europe.

Henley & Partners. (2022, May 30). How Filipinos can become Spanish Citizens.

The Philippine Daily Inquirer.

Kidera, M. (2021, December 10). “Sold to China”: Greece’s Piraeus port town cools on Belt and Road. Https://Asia.Nikkei.Com/Spotlight/Belt-and-Road/Sold-

to-China-Greece-s-Piraeus-Port-Town-Cools-on-Belt-and-Road.

Murcia Today. (2022, July 11). Spanish Golden Visa is One of the top European investors’ choices in 2022. Https://Murciatoday.Com/Spanish-Golden-Visa-IsOne-of-the-Top-Investor-Choices-in-Europe-in-2022_1800026-a.Html.

Polish Investment and Trade Agency (PAIH). (2021, September 23). PAIH organized a Polish-Korean Business Forum. Https://Www.Paih.Gov. Pl/20220923/Paih_organized_a_polish_korean_business_forum#.

Popescu, R. (2022, February 22). House Hunting in Spain: A Restored TwoBedroom in Central Barcelona. The New York Times.

Savills Research. (2019). South Korean Investment into Europe.

Spocchia, G. (2022, November 11). Foster + Partners lands design of major new Polish airport. The Architect’s Journal. SVI. (2022, July 18). Spain’s Golden Visa Among Top Investor Choices in Europe for This Year. Https://Www.Schengenvisainfo.Com/News/Spains-Golden-Visaamong-Top-Investor-Choices-in-Europe-for-This-Year/.

Tartar, A., Rojanasakul, M., & Diamond, J. (2018, April 23). How China Is Buying Its Way Into Europe. Bloomberg.

Tilles, D. (2021, November 8). Poland to become European kimchi hub with new South Korean factory. Https://Notesfrompoland.Com/2022/11/08/Poland-toBecome-European-Kimchi-Hub-with-New-South-Korean-Factory/. ULI. (2022). Emerging Trends in Real Estate: Road to recovery.

Varvitsioti, E. (2021, October 21). Piraeus port deal intensifies Greece’s unease over China links. The Financial Times.

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 31

Fig 5: The CPK Airport under the Won Image Source: Author’s Own

UNDERLYING STRUCTURES IN POSTWAR URBANIZATION

Recognising Facts on the Ground

in conversation with Lukas Pauer at Vertical Geopolitics Lab (VGL)

Lukas Pauer is a licensed architect, urbanist, educator, and the Founding Director of the Vertical Geopolitics Lab, an investigative practice and think-tank dedicated to exposing intangible systems and hidden agendas within the built environment. At the University of Toronto, Lukas is the Assistant Professor of Architecture, Inaugural 2022-2024 Emerging Architect Fellow. At the Architectural Association in London, Lukas has pursued a PhD AD on political imaginaries in architectural and urban design history with a focus on how imperial-colonial expansion has been performed architecturally throughout history. He holds an MAUD from Harvard University and an MSc Arch from ETH Zürich. Among numerous international recognitions, Lukas has been selected as Ambassadorial Scholar by the Rotary Foundation, as Global Shaper by the World Economic Forum, and as Emerging Leader by the European Forum Alpbach — leadership programs committed to change-making impact within local communities.

We would like to begin our conversation by understanding your work’s position in relation to the theme of our issue; (in) visibility.

I realize that conceptually speaking it has been a running theme in the work of my practice, the Vertical Geopolitics Lab (VGL), and its teaching branch, which is currently affiliated with the UofT Daniels. A lot of my work has saught in some form or another to render the seemingly invisible visible. It seeks to expose hidden agendas and power dynamics that are manifested in the built environment. Power is all around us. Built objects of the everyday can be instrumentalized to convey subversive messages of power. Still, most people think that power dynamics are shaped by and conducted through written policy documents and cartographic drawings. Few people recognize the workings of power as visibly inscribed and manifested in the built environment itself. People often perceive the workings of power as less visible or effectively invisible in the built environment. Given my original training as architect and urbanist, I am really concerned with the

workings of power that people often perceive as immaterial and aspatial. My integrated practice, teaching, and research seeks to recenter the study of how power over people and land is projected as a practice-based matter of space and power.

Can you tell us a bit more about what you mean by the seemingly invisible, immaterial, and aspatial that you talk about?

Within architecture, far too little attention has been paid to how built objects are not merely their material make-up in form, nor their functional capabilities. Built objects are also markers that can convey messages to those affected by them in disputed domains, in places where power is being exercised. Objects can give the impression that their function is an apparently non-violent or innocuous one. Still, any object can be instrumentalized, implicitly, to convey more subversive messages of power. Although the people behind the design of built objects may not have had this in mind when conceiving them, objects can be instrumentalized to make meaning in other ways.

32 01 JAN’23

Your research findings emphasize on the existence of a ‘gray zone’, could you elaborate on these vocabularies of imperial-colonial powers, that you developed in the process and how you went about with doing so?

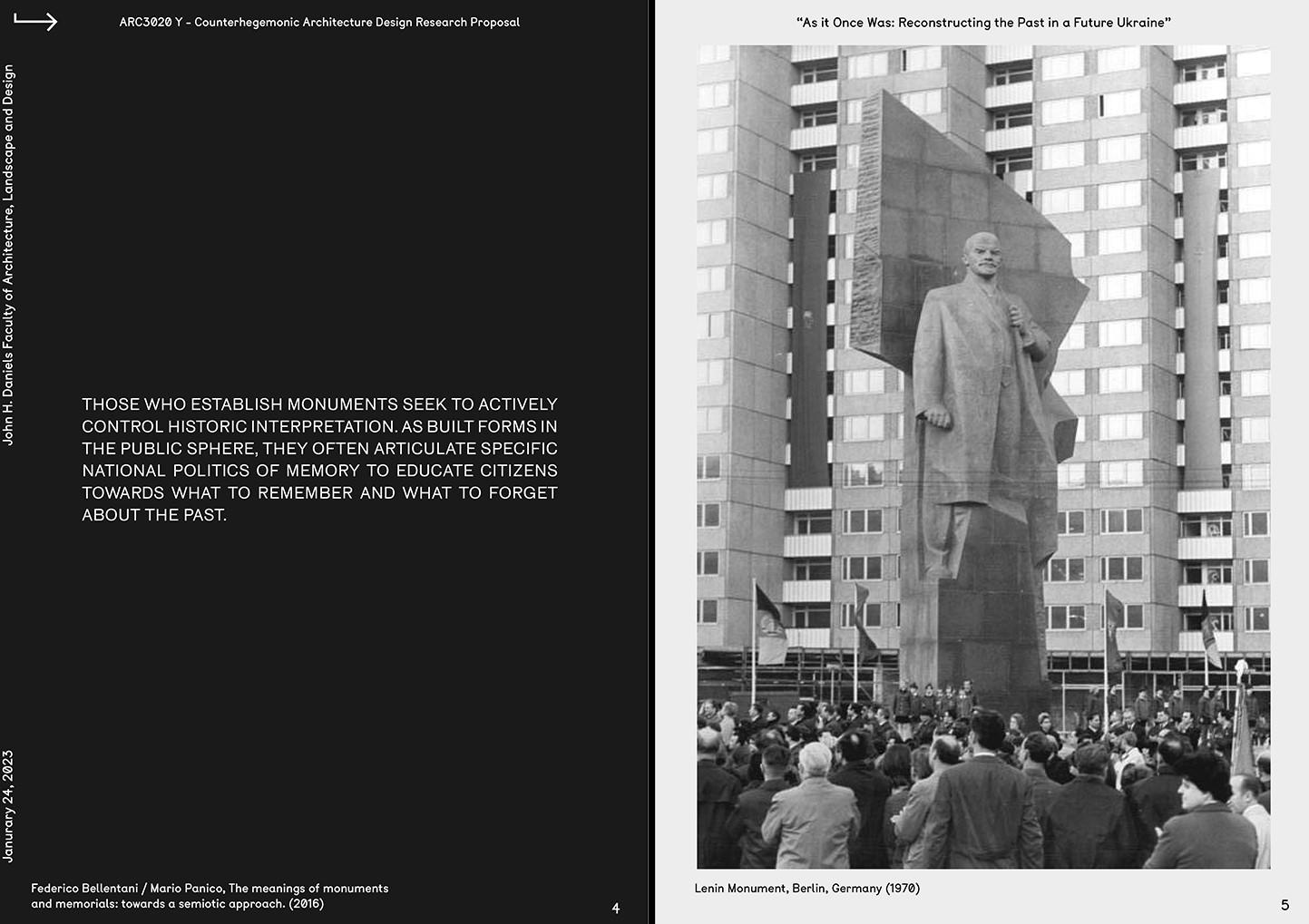

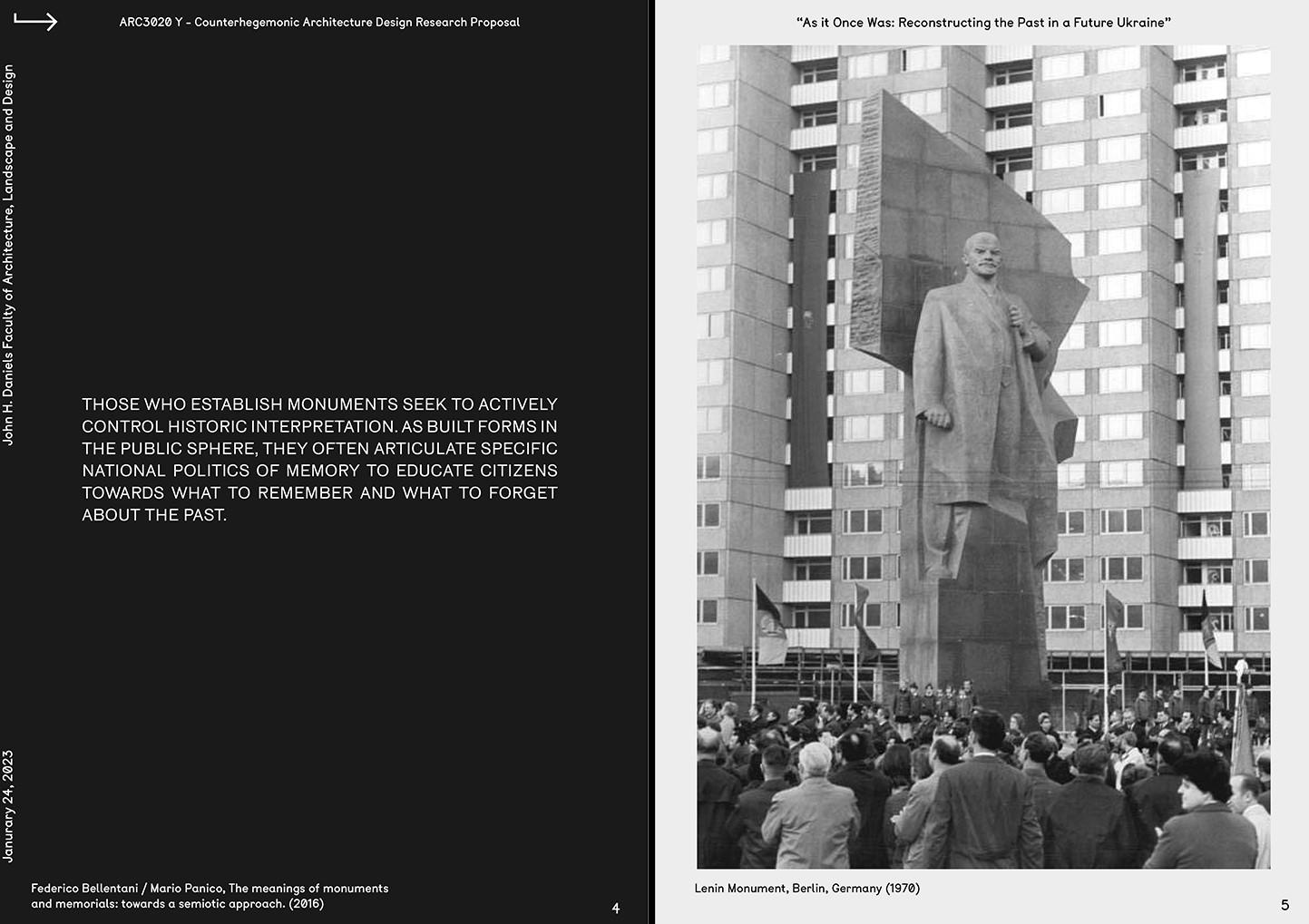

Given the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, I would like to share another timely case part of Russian power projection in Eastern Europe, which I have recently written about in the latest issue of the RMIT DSC AUD Kerb Journal. In recent years, the Russian government has politicised a near-cult of victory as central to Russian national pride and identity. Emblematic for this near-cult, various scenographic techniques of visual spectacle and historical reenactment of a Russian club called the ‘Night Wolves Motorcycle Club’ (‘Motoklub Nochniye Volki’) have been instrumentalised for the manipulation of public perception, memory, and mass emotion. Among its controversial activities, the Night Wolves motorcycle club coordinates various annual motorcade rides to architectural relics of Russian history. Since 2015, timed with the anniversary of the Soviet military victory over the Nazi German Empire, the Night Wolves have embarked on a particular motorcade ride called ‘Roads of Victory: To Berlin!’ (‘Dorogi Pobedy: Na Berlin!’), which may seem minor or banal in appearance but has posed a threat to international relations in the eyes of various European and Western polities. Along this route, members of the Night Wolves planned to stop by and lay plant wreaths at various sites dedicated to the history of the Russian people; Russian Orthodox Christian

sanctuaries, Soviet war memorials, cemeteries, museums, and ethno-linguistic monuments of Panslavic significance. Rides organised by the Night Wolves have intentionally been led through disputed and self-declared separatist regions in Russia’s sphere of interest including Nagorno-Karabakh, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Donbass, Crimea, Pridnestrovian Moldavia, and Bosnian Serbia. Many of these can effectively be referred to as ‘semi-colonies’ of Russia and its allies. The ambition to project power, spatially, through the motorcycle club’s activities becomes most clear in the words of its leader, Alexander ‘Khirurg’ Zaldastanov, when he affirmed: ‘Wherever we are, wherever the Night Wolves are, that should be considered Russia’. As such, several years before it would become a reality, the Night Wolves motorcycle club symbolically legitimized the Russian occupation of Ukrainian territory in the Crimean and Donbass regions.

Can you share an example of how your work is able to address this circumstance?

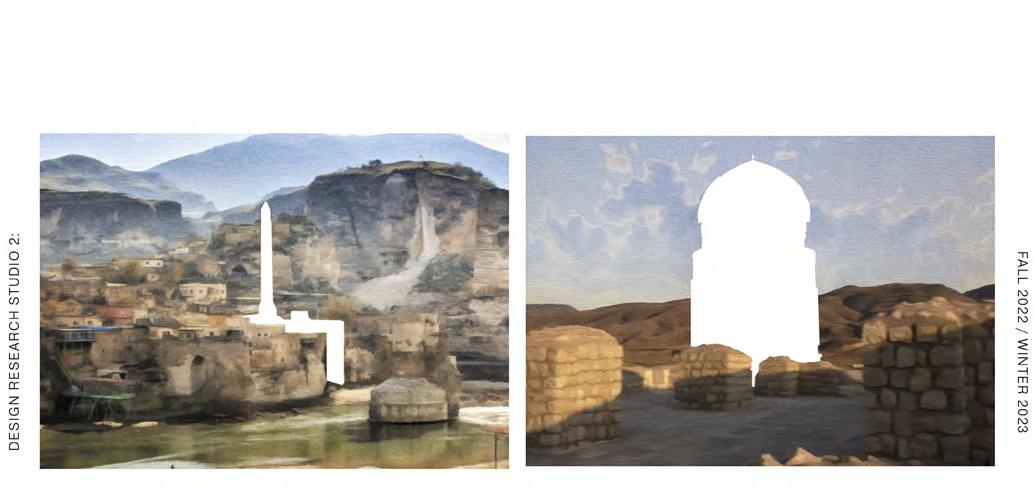

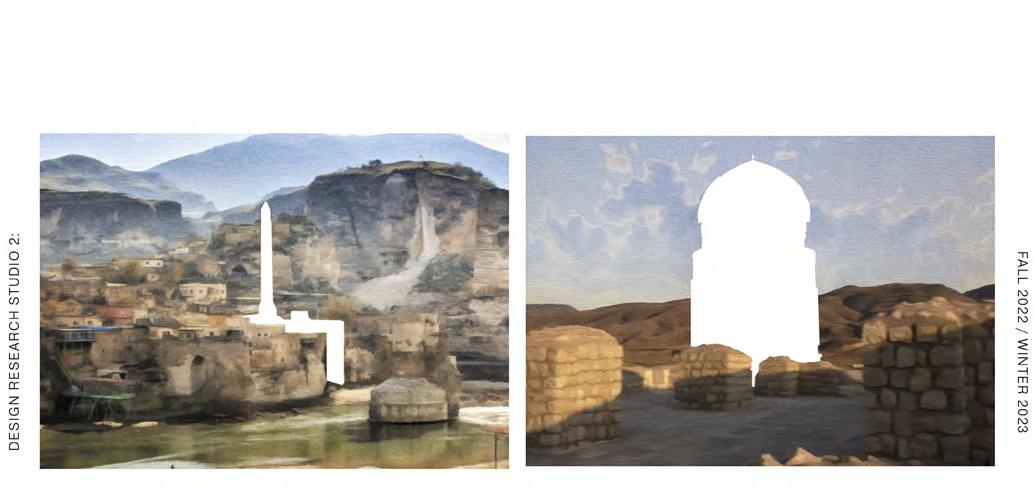

For example, as part of my appointment here at the UofT Daniels, I am teaching three courses. One of them is more analytical in the history/theory of the built environment. The other two form a year-long course sequence that is more projective in the design of the built environment. Both of them directly address the invisible, immaterial, and aspatial but at different scales, in different contexts. In our undergraduate architectural studies program, I teach a near 300-student

Atlantis Magazine |Invisible | volume 41 33

Fig 1: Excerpt from the Counterhegemonic Architecture Studio at John H. Daniels faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design headed by Lukas Pauer. Work by Bryson Woods.

core lecture course in which the understanding of public space as ‘public’ only to those who are politically represented and organized is central to it. In our graduate architecture program, I supervise a group of final year students in a year-long thesis research studio course sequence supporting investigations on space and power in an effort to expose, challenge, and reconstitute the pervasive and ongoing reality of imperialcolonial expansion. Both of these teaching engagements are dealing with vulnerable people being effectively rendered invisible. Both of them address how the instruments for doing so are often not visible to people.

In your work on the built environment, how do you identify and describe vulnerability along the spectrum of power dynamics, given that it is a highly relational condition?

Historically, politically organized communities have imaginarily seen and divided their world through a self-other or us-them binary. In the social sciences this is often referred to as the hegemonic gaze. Most of my work is directly concerned with how this gaze has affected the construction of the built environment around us. In a more mundane urban design context, in the case of provincial or municipal authorities projecting their power over vulnerable people and land, we can see how identity, demographic factors such as age, gender/ sex, race/ethnicity, and body ability, as well as socio-cultural factors such as belief/religion, nationality, education, and income class have been mobilized to produce ‘Otherness’. In a much larger international relations context, the hegemonic gaze has given expansionist polities the power to redefine and therefore to control the ‘Other’ and the ‘Them’, as well as, by extension, the ‘Self’ and the ‘Us’, through socially constructed labels such as the supposedly inferior ‘Barbaric’, ‘Oriental’, and ‘Exotic’, the ‘Second’ or ‘Non-Aligned Third World’, the ‘Underdeveloped’ or ‘Developing World’, the ‘Non-Integrating Gap’, and the ‘Global South’.

This practice of othering or alienating has allowed European and Western polities to represent the ‘Other’ as inferior, backward, irrational, and wild, as opposed to itself, which is seen as supposedly ‘exceptional’, superior, progressive, rational, and civil(ized). By suppressing people from expressing and representing themselves, individually, expansionist polities have conflated and reduced non-European and nonWestern people, collectively, into supposedly homogeneous entities. So with this framework in mind, as one of the first things I give my students on their way as they may start engaging with more sensitive materials and communities from an outside perspective, I remind them that marginalized and underrepresented people are not a monolith. In other words, for example, there is not ‘the one’ LGBTQ+ or ‘the one’ Indigenous community, just like there is not ‘the one’ US American or ‘the one’ Canadian community. Politically organized communities and so-called ‘nations’ are socially constructed groupings

of people or individuals. Such umbrella terms refer to many diverse cultural groups under the same name. There will be plenty of disagreements between communities. Furthermore, there will likely be a variety of perspectives even between individuals in the same community.

You talk about the social construct of the nation, which brings us to the ongoing discourse on the demise of the nation-state. What is your position in this discourse?