GALERIE MAGDELEINE

Spring 2024

Paris

Lucie Bouclet & Paul MenouxGalerie Magdeleine was founded by Lucie Bouclet and Paul Menoux, two enthusiasts who studied at the École du Louvre from undergraduate to master's level. Its aim is to offer a fresh perspective on paintings and drawings from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Drawing on our academic backgrounds and our shared love of in-depth research, the works we present are given special attention before being shown to the public. Our artistic sensibility, nourished by a deep admiration for the spirit of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, guides each of our choices. As young dealers, we wish to offer our customers an immersive experience in this captivating artistic universe. We are committed to the careful study of each attribution and to telling the story of each painting.

Through our exhibitions and carefully selected collection, we invite art lovers to explore the many facets of this pivotal period in the history of art.

The Musée Léon-Dierx of La Réunion has acquired from the Galerie Magdeleine the Virginie au bain, exhibited at the Salon of 1844 by Henri-Frédéric Schopin (1804-1880). This work echoes another by the artist, exhibited at the same Salon: Manon Lescaut et d'Esgrieux dans le désert, presented on page 55 of this catalogue.

WORKS OF ART

Antoine Monnoyer, Anemones bouquet. Circa 1720

Charles-Louis Clérisseau, Decorative project. Antique house for the Tsarkoe-Selo gardens for Catherine The Great. December 1773 ..........................................................................................5

Gérard van Spaendonck, Bouquet of flowers and fruits. 1779...................................................9

Henri-Nicolas Van Gorp, The young mother. 1791

Émilie Bounieu, Helen, busy embroidering, sees Laodicea arrive. 1800.

JENNY DESORAS Portrait of Marie-Charlotte Georgette Nizon de Saint-Georges. 1807-1809………..23

Augustin THIERRIAT, Study of Poppies. 1809 .........................................................................26

Julie DUVIDAL de MONTFERRIER, The death of Cleopatra. Circa 1818......................................28

Attributed to Anthelme TRIMOLET, The Spinner. Circa 1820-1825

Angélique MONGEZ, Study of the group for the Seven Chiefs in front of Thebes Circa 1825.

Jan Adam Kruseman, The fortune teller. 1825 37

Attributed to Ary Scheffer, Flood scene. Circa 1820-1825. .....................................................41

Christian Albrecht JENSEn Portrait of a young girl. Circa 1823-1825..................................45

Jean-Baptiste-Louis Maes-Canini, Young roman praying Second half of the 19th century .....47

Jean-François Eliaerts, Bouquet of flowers. Circa 1830........................................................53

Henri Frédéric Schopin, Manon Lescaut and D'Esgrieux in the desert. 1844.

Augusta LEBARON-DESVES, Saint Marane and Saint Cyr. 1843-1844 58

Anemonesbouquet.

Circa 1720

Oil on canvas, Régence frame.

H: 41 ; W: 31 cm.

A group of nine anemones are assembled in a bouquet in a free composition that combines naturalism with an artistic interpretation of nature. The stem of one of the anemones escapes from the bouquet, forming a sinuous curve that defies the laws of gravity, and contrasts with the almost scientific representation of the anatomy of the flowers and their foliage.

Antoine Monnoyer was trained by his father, Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer (1636-1699). His apprenticeship took place in England when his father was summoned by Sir Ralph Montagu, Charles II's ambassador extraordinarytoFrancesince1666,todecorate the Burlington Hotel1. By assisting him in the creation of this sumptuous décor, Antoine Monnoyer learned to work with his master's decorative formulas. From this period onwards, the Anemone coronaria was given pride of place in his floral compositions.

Antoine Monnoyer then spent time in Rome and was admitted to the Académie in 1704, after working at the Trianon. He worked on the decoration of the chapel at Versailles and painted two large formats for the Château de Meudon in the 1710s.

It was abroad that the young Monnoyer distinguished himself and spread the family style, first returning to England until 1729, then staying in Rome before travelling to Denmark and Sweden around 1733. He was a much sought-after travelling artist at the great European courts, whose seductive depictions of fruit and flowers were a great success throughout the eighteenth century.

Influenced by his father's paintings, he nevertheless succeeded in developing his own style, which was much more decorative in scope. This painting of pale blue anemones, a colour that does not exist in nature, is an illustration of this. Antoine Monnoyer reinterprets natural specimens using a somewhat fanciful palette of colours, enabling him to harmonise his composition and play on the effects of chromatic contrasts that are pleasing to the eye.

1 Claudia Salvi, « Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer et Antoine Monnoyer. Problèmes d'attributions (…). Identification de son morceau de réception à l'Académie de Peinture et Sculpture », La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France, Réunion des musées nationaux, Noisiel, 2002, no2, p. 55-63.

Charles-Louis Clérisseau (Paris, 1721 - Auteuil, 1820)

Decorativeproject.

Antiquehouse,Tsarkoe-SelogardensforCatherineTheGreat. December 1773.

Watercolour, pen and brown ink, brown and grey wash on paper On the back: stamp of the Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky.

H: 33; W: 32 cm.

Framed byfriezesof foliageandmedallionsrepresenting ancientscenes, animatedruinsaredepicted in the centre of this study sheet. The plinth of the wall on which the decoration was to be placed is shown, completed by a few mouldings, giving an idea of the monumental scale planned for this project.

A pupil of Blondel and Boffrand at the Royal Academy of Architecture, Charles-Louis Clérisseau won the Grand Prix in 1746 and stayed in Rome as a student of the Académie de France in Rome 1749 to 1754. There he painted architectural compositions influenced by the master of the genre, Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765). He became a friend with Piranesi, whose taste for ruins and passion for ancient Rome he shared. Although the rules of the Académie de France in Rome authorised him to stay for two or three years to perfect his artistic education, he extended his pension before leaving the Académie abruptly in 1754. He stayed in Rome, made trips to Venice and Paestum, before returning to France in 1768.

On hisreturntoParis, hewasaccepted into the Académie royale on 2 September 1769, presenting two gouaches: Baths and Architectural Ruins. His career took a decisive turn when he was chosen by the administration of the Bâtiments du Roi to execute a commission for Catherine The Great. Clérisseau was recommended by Falconet, a close friend of the empress.

On 2 September 1773, Catherine The Great, inspired by Michel François Dandré Bardon's book Collection of ancient costumes (Paris, 1772)1 , wrote to Falconet: « I would like to have a drawing of an antique house, with an antique interior layout. [...] I want it all; I beg you to help me fulfil this fantasy, which I will no doubt pay for 2 » In this letter, she asked Falconet to write to Charmes Cochin, secretary of the

Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, asking him to provide her with the name of an architect who could create a house in the antique style in the gardens of Tsarskoe-Selo. Cochin proposed Clérisseau in November.

On 6 December, the Empress wrote:

« I have found the letter from Cochin that you sent me. I agree with him and with you that he could not have chosen a better person for the antique house than he did; Mr Clérisseau seems to have all the qualities required to carry out to perfection the project for the antique house that I have in mind.3».

Driven by his characteristic taste for the colossal, and echoing his Roman studies of ancient monuments, Clérisseau took no account of the programme transmitted by Falconet in the twenty-four drawings he sent to the Empress. He transformed the little caprice commissioned into a gigantic palace on the scale of the Baths of Caracalla.

In a letter to the Prince of Galitzine from the end of December, Falconet reported on the poor reception of Clérisseau's drawings:

« It has been shown that M. Clérisseau is as impertinent as he pretends to be deaf. You have seen, my prince, everything I wrote in Paris about the ancient house and you know that the request from His Majesty I contained nothing other than a small pavilion in a garden. You have read the cursed project, which would have involved building an immense palace three times the size of the Empress'. It has put H.M.I. in a very bad mood, and rightly

1 Thomas J. McCormick, Charles Louis Clérisseau and the genesis of neo-classicism, 1990.

2 Louis Réau, Correspondance de Falconet avec Catherine II, 1767-1778, Paris, E. Champion, 1921, p. 217.

3 Idem, p. 229.

so. [...] Her Imperial Highness no longer wants anything, absolutely anything, from this shop 4 »

Apart from this work, several other drawings in the Hermitage bear witness to Clérisseau's work on Catherine The Great's antique house. One of them, depicting a niche decorated with a statue, is particularly close to our drawing in its multiple panels with candelabra and arabesque motifs, as well as its medallions with antique scenes. A complete view of a section of wall also reproduces the same structure on the central panels.

30.3 cm. Saint Petersburg, Hermitage Museum (Inv. OP-2606).*

4 Idem, p. 231.

Charles Louis Clérisseau, Architectural fantaisie, 1782, gouache, pen and brown wash, underlined with Indian ink on paper, 47.1 x 60.5 cm. Saint Petersburg, Hermitage Museum (Inv. OP-16919).

It should also be noted that the view of ruins depicted in our drawing remains a leitmotif in the artist's work. Two drawings bear witness to Clérisseau's work on this motif: a small pen-and-ink drawing that appears to be a preparatory study for the large central painting in our set design. A large gouache on which, however, some modifications can be seen is also kept by the Hermitage Museum.

Despite the rejection of his project, Clérisseau put his experiments to good use in a later design for a Parisian private individual. Using the same aesthetic, between 1779 and 1782 he created the interior decor for the salon of the Hôtel Grimod de la Reynière.

The stamp on the back of the sheet seems to indicate that the drawing passed through Russia. Indeed, despite her disappointment with the artist, Catherine The

Jan Chrystian Kamsetzer, View of the Grand Salon of the Hôtel Grimod de La Reynière in Paris, watercolour on paper, Warsaw University Library.

Great decided to buy his collection of drawings in 1783.

Today, it is not easy to identify the twenty-four drawings from the project for Catherine the Great and to know whether they were all present in the collection sold to the Empress in 1783, since the latter comprises a collection of more than a thousand drawings, with various projects for several museums5 All the drawings in the Hermitage were stamped by Paul I, which is not the case for this drawing. It therefore never entered the collections of Catherine The Great. It would have been sold or given away before the collection was bought

Detail. Back of the drawing.

5 Chevtchenko, Valerii. Charles-Louis Clérisseau : 1721-1820 : dessins du Musée de l’Ermitage, Saint-Pétersbourg : [exposition, Paris, Musée du Louvre, salle de la Chapelle, 21 septembre - 18 décembre 1995 ; Saint-Petersbourg, Musée de l’Ermitage, 1996. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1995, p. 73.

Gérard van Spaendonck (Tilbourg, 1746 - Paris, 1822)

Bouquetofflowersandfruit. 1779.

Watercolour and gouache on paper.

Signed and dated lower right: Van Spaendonck / 1779

H: 15.5 ; W: 13 cm.

Provenance :

Anonymous sale (Me Bussillet), 28 January 1936, no. 76.

This work depicts a bouquet of numerous species of flowers in a gadrooned marble vase resting on a shelf on which fruit is arranged, and the edge of which is signed with the artist's name. The miniaturised work has a spontaneous, lively touch that brings to life the idealised nature of the 18th century.

Gérard van Spaendonck was one of the first artists to introduce Dutch floral painting to France. Born in the Netherlands into a family that was more likely to have given him a career in administration, he nevertheless studied at the Antwerp Academy of Painting with Jacob III Herreyns from 1764. Five years later, in 1769-1770, he went to Paris and managed to get into the Ecole Supérieure de Dessin run by Jean-JacquesBachelier, a painter at the French court. In 1773-1774, Gerard van Spaendonck madehisdebutat theManufacture royale de Sèvres as a supplier of models to porcelain painters.

He exhibited for the first time at the Salon of 1777 and was admitted to the Royal Academy ofPainting andSculpturein1781.He was then appointed professor of floral painting at the Jardin des Plantes, following in the footsteps of Madeleine Basseporte. In 1786, he became painter to Marie-Antoinette's cabinet.

Closely associated with the government, he contributed around fifty watercolours for the King's Vellums and supplied drawings for the Royal Manufactory at Sèvres.

Some species of flowers were highlighted by van Spaendonck, in particular Rosa Centifolia or the « Hundred Leaf Rose », also known as the « Dutch Rose »1 . Today, the gouache appears as a visual signature of the painter, appearing in the vast majority of his compositions, and often in the centre, as is the case with our gouache.

As miniaturist to Louis XVI, Spaendonck adapted his favourite subject, flowers, to miniature painting, as in this gouache and watercolour, a technique that the artist favoured throughout his career. The execution isquickerand moreenergeticthan in his oils. It is underpinned by his perfect knowledge of the species represented and his experience of painting on vellum.

His miniatures of bouquets enjoyed great success throughout his career. He used them in elaborate medallions and miniature frames, and some were mounted on precious boxes. The bouquets were lar ge, filling the space and carefully arranged to give harmony and balance to the colours.

1 Florine Albert. Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint de Gérard Van Spaendonck (1746-1822). Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2020, p. 21.

TheYoungMother.

1791.

Watercolour gouache on paper.

Signed and dated on the tree trunk on the ground: 1791 Van Gorp. H: 31; W: 22 cm.

This charming watercolour is set in a lush garden where two young women are seated While one holds the parasol that shelters them, the other squeezes her breast from which milk is flowing. A statue of love completes the scene, seemingly shooting its arrow at the young mother.

Henri-Nicolas Van Gorp was admitted to the Académie Royale de peinture et de sculpture in 1773, where he was Étienne Jeaurat's protégé. He was a boarder at the Académie for twelve years, during which time he became a pupil or fellow pupil of LouisLéopold Boilly (1761-1845). These artists were part of the same movement, as was JeanBaptiste Mallet (1759-1835), to whom many of Van Gorp's watercolours have been attributed.

But his paintings, with their moralizing and sentimental overtones, set in a contemporary context, stand out from the works of his fellow artists. Some of his paintings, notably The Return of a Hussar to his Family, Salon of 1798, and The Lesson in Charity, 1806 (Saint-Omer, Musée de l'Hôtel Sandelin), were very famous and were reproduced in engravings.

Van Gorp exhibited at the Salon regularly from 1796 to 18191. It was only during the first period, until the beginning of the 19th century, that he exhibited genre scenes. Thereafter, heseemed to devotehimself exclusively to portraiture.

Henri-Nicolas Van Gorp's tender genre scenes, like this watercolour, can be compared with one of his works reproduced in engraving, called Le déjeuner de Fanfan, which takes up the same theme of maternity, with a sentimental inflection.

1 Database « Salons et expositions de groupes 1673-1914 », salons.musee-orsay.fr, musée d’Orsay project and the l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Ministry of Culture and communication, consulted on the 03/12/2023.

Marie-Cunégonde HUIN (Strasbourg, 1767 – Metz, 1840)

Hébé.

Salon des artistes vivants, Paris, n°215, 1798.

Miniature on ivory.

H: 10.5; W: 9 cm.

Set in a rich gilded wooden frame, this miniature depicts the goddess of youth looking straight at the viewer, her three-quarter bust and her hand holding the cupbearer of the gods stopped in her tracks.

Marie-Cunégonde Huin was a miniature painter who grew up in an environment conducive to the development of her artistic talents: her father, Charles-Alexis Huin, was a painter, and her mother was close to Jacques-Louis David, with whom she kept up a correspondence that was rediscovered in the 1900s1 Marie-Cunégonde Huin was a pupil of the master and exhibited at the Salon from 1796 to 1801.

This miniature on ivory of a Hebe was exhibited at the Salon of 1798. It is the only known work by the artist depicting a mythological subject. Since miniature painting is considered to be a very feminine art form, Marie-CunégondeHuinisherefollowinginthe footstepsof thewomen painterswho tried their hand at historical subjects, by choosing a figure suited to a medium that was more often reserved for portraits. The sensitive line, the expression of thefigure and the precision of the work are worthy of a pupil of David.

1 Roger Peyre, « Quelques lettres inédites de Louis David et de Madame David », La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité, n.11-12, 17 et 24 mars 1900, pp. 97-98.

Émilie Bounieu (Paris, 1767 - Paris, 1831)

Helen,busyembroidering,seesLaodiceaarrive 1800.

Oil on canvas.

H: 131 ; W: 88 cm.

Exhibitions:

- Salon des Artistes Vivants, Paris, 1800, n° 50: "Hélène, occupée à broder, voit arriver Laodice.".

Reviews:

- Journal des débats et des décrets, 28 October 1800, p.2.

- Mercure de France, n° 9, 22 November 1800, p.44.

As the only daughter of MichelHonoré Bounieu, a history painter and member of the Académie Royale, Émilie Bounieu grew up in a family particularly favourable to the education of young girls in the field of Arts and Letters. Nicole Vestier, a close relative and also the daughter of an Academician, was brought up in the same way.

The education that the two girls received was not an isolated initiative on the part of their family, we found a wider echo among a certain category of the French artistic elite. In 1785, two eminent members of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture took a public stand in favour of art education for young girls.

In 1785, Antoine Renou declared that

“you don't need, it seems to me, to be more robust to hold a paintbrush than a needle1” and JeanJacquesBachelier, in hisplan to open adrawing school for girls, presented a long argument in favour of aspiring female artists:

“Why leave in ignorance, which is harmful to society, the sex that is equal to us in courage and intelligence, and that outstrips us in consistency of work? Nothing could be simpler or easier than the means to bring about this happy revolution: it is simply a question of enlightening the sex that we have kept away from the sciences and the arts2 ”

Immersed from childhood in this liberal environment in favour of women's

1 Journal de Paris, n° 190, 9 juillet 1785, p. 187-189.

artistic practice, and after studying the rudiments of drawing with her father, Émilie Bounieu turned to miniature painting, an art reputed to be more feminine. In this specialisation, she was probably taught by the famous François Dumont, who had married Nicole Vestier in 1789.

At the same time, the young girl stood out for her eloquence, having taken lessons from the poet Pierre-Nicolas André-Murville since her youth. André-Murville dedicated a series of stanzas to her, published in 17923 , in which he praised her talents as a painter, singer and poet.

On 14 July 1791, the young Émilie Bounieu took the stand at the National Assembly4 In her father's stead, she offered to donate an allegorical painting to the nation, which she described at length and forcefully. Her speech, which was crowned with “lively applause”, allows us to grasp the reality of her qualities as an orator, but also the vivacity of her revolutionary convictions.

Totally committed to the new revolutionary ideas, the Bounieu family was particularly close to the Conventionnel Charles Duval5 , also a member of the Conseil des CinqCents. This close relationship with the revolutionary authorities provided MichelHonoré Bounieu with professional opportunities, and from 1792 to 1794 he was appointed director of the Bibliothèque's

2 Ulrich Leben, L’Ecole royale gratuite de dessin de Paris (1767-1815), Saint-Rémy-en-l’Eau, Monelle Hayot éd., 2004.

3 Almanach des Muses ou Choix des Poésies fugitives de 1791, Paris, Delalain aîné et fils, 1792, p. 47-48

4 Archives parlementaires de 1787 à 1860, Première série, Tome 28, Paris, Paul Dupont, 1787, pp. 278-280.

5 Charles Vatel, Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins, Tome III, Paris, Henri Plon, p. 545.

Cabinet des Estampes. During this period, several collections of books on plants and flowers were registered in his name6 These were actually intended for his daughter's studies. In fact, Émilie Bounieu devoted herself with talent to naturalist painting on vellum during her father's tenure at the Library, and some of these works are now kept by the Natural History Museum in Paris.

Around the same period, Émilie Bounieu took part in the Salon for the first time in 1793, exhibiting her Self-portrait while painting a miniature. With this painting, Bounieu was part of a wider phenomenon: the exponential increase in the number of women's self-portraits exhibited publicly7 These selfportraits are true facts of society, and they all carry the same message. They speak to the reality that more and morewomen are painting professionally. Women painters want to exist publicly as artists and represent themselves with brushes in hand, creating and disseminating a new iconography of women painters, worthy and proud of their vocation. For the first time, women painters were massively visible as artists. What's more, they claimed to be equal to men, rejecting the label of second-class artists.

After several years' absence, Émilie Bounieu reappeared at the Salon of 1798, exhibiting “two miniature paintings”. Like her,

many women artists exhibited at this event. However, as soon as the Salon closed, voices raised against the development and multiplicity of female talent. In the Journal de Paris, Charles-Paul Landon published two open letters in quick succession8 where he totally reproved the new implication of women in the official artistical instances

An answer from a female artist, hidden under the pseudonym of Anna Cleophile, was published in the columns of the same newspaper9 We are particularly tempted to recognise the pen of Émilie Bounieu. A scholar by education, she uses a pseudonym here which, under the guise of a real patronymic, turns out to be a play on words in Latin: “Anna Cleophile” literally meaning “She who loves glory”. Bounieu mastered Latin, having read the original version of Virgil's Bucolics, as evidenced by the subtitle of his Galatea in the libretto of the 1810 Salon: “Malo me Galatea / Eglog de Virg” .

Moreover, it appears that Anna Cléophile's text published by the Journal de Paris fits in perfectly with Émilie Bounieu's point of view on the place of women in the Beaux-Arts. Even though her father was a history painter, Émilie Bounieu deliberately turned early on to miniature and naturalist painting, arts that were considered appropriate

6 Le Bibliophile français, Tome VI, Paris, Alcan-Lévy, p. 181.

7 Marie-Jo Bonnet, « Femmes peintres à leur travail : l’autoportrait comme manifeste politique (XVIIIe-XIXe siècles) » in Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine, n° 49-3, 2002, p. 144.

8 Charles-Paul. Landon, Aux Auteurs du Journal dans « Journal de Paris », 25 pluviôse an VII (13 février 1799), pp. 636-639. ; C.-P. Landon, Suite de l’article : Sur les femmes Artistes in « Journal de Paris », 11 germinal an VII (31 mars 1799), p. 884.

9 Réponse d’une Femme artiste aux deux Articles du citoyen Landon, peintre, insérés dans le Journal de Paris, les 25 Pluviôse et 11 Germinal an 7 in « Journal de Paris », 8 floréal an VII (27 avril 1799), p. 959.

This specialisation was undoubtedly prompted by the advice of her father, MichelHonoré Bounieu. As an Academician, he trained his daughter in accordance with the recommendations of the Royal Academy, which neveradmittedafemale history painter10 because it would imply to admit the study of the live model and, therefore, naked bodies Anna Cléophile concedes that “painting flowers is, in every respect, suitable for a delicate sex”, and puts forward an anatomy course for women as a substitute for the study of live models. The latter is implicitly judged by the author to be incompatible with women's artistic practice.

Anna Cléophile's comments in several respects echo the experience of the young Bounieu, both in her study of naturalist painting when her father was head of the Bibliothèque and in her work as a miniature portraitist: “she who best imitates a flower often envies the happy talent of being able to trace a beloved being, or the different species of living bodies that animate the globe”

Finally, Anna Cléophile makes no secret of her demands for women's advancement, such as access to knowledge: “ a precious means of instruction that they should not have assumed existed only for men”. Thanks to Dr Sue's picturesque anatomy lessons, which the

author highlights, women are overcoming the “difficulties that hitherto seemed insurmountable” , thereby “pushing back the boundaries” that hitherto condemned them to the practice of minor genres. These words are once again echoed in the person of Émilie Bounieu. In addition to a quality education, it would seem that Michel-Honoré Bounieu very early on passed on to his daughter, and more generally to his pupils, the idea that their value in painting was equal to that of men. During the revolutionary period, women thus felt sure of their worth and abilities in the arts, on an equal footing with men. When, in 1796, Élisabeth Quévanne-Chézy, a pupil of Michel-Honoré Bounieu, saw her application for the post of drawing teacher at the École Centrale de Chartresrejected in favourof anunknownmale painter, she had no hesitation in describing herself as a victim and feeling wronged “because of her sex”11 She immediately drew up a petition which she submitted to the legislature, eventually winning the case.

In any case, Anna Cleophile's text had a definite audience and forced Landon to write a third letter12 explicitly intended for the young artist. With no response from Anna Cléophile, the debate seemed to be over when theSalon opened on 18 August 1799. However, a new article, this time anonymous and particularly vehement, published the day before the exhibition closed, once again

10 The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture counted three women miniaturists among its members: AnneRenée Strésor (received in 1676), Catherine Perrot (received in 1682) and Marie-Thérèse Reboul (received in 1757). Perrot and Reboul specialised in naturalist miniatures. Finally, Perrot also wrote a treatise on miniature painting, Les leçons royales, ou La manière de peindre en mignature les fleurs et les oyseaux.

11 Séverine Sofio, Artiste femme. La parenthèse enchantée XVIIIe-XIXe siècle. Paris, CNRS Éditions, p. 193-194.

12 Charles-Paul. Landon, Réponse à un Article d’une Femme Artiste, inséré dans la Flle du 8 floréal dans « Journal de Paris », 20 floréal an VII (9 mai 1799), p. 1011.

18 for a woman according to morality and tradition.

attacked women artists, and in particular aspiring history painters:

“Peste! Thirty women meeting at Legacque's, at a restorer's, to celebrate the author of Marcus-Sextus; that's what we call knowing each other in painting.

[...] But you see what dignity this dinner spreads over the arts! David, Vien, Regnault, Vincent, and twenty other distinguished painters, celebrated Guérin; how childish! Nice consistency for the young man! But Guérin in the midst of thirty women painters, at table who, it is said, did not speak; that is august: that is what can be called seriousness in the arts. Guérin's painting and thirty serious women! That's something you don't see twice in a century. [...] What a beautiful thing painting is for a woman. Be a father, a husband, a child; if your daughter, your wife, your mother are painters, they will need no other virtue. Father, will you be unfortunate? They will paint a Roman Charity. Husband, will you be suspicious? You will be wrong; don't they know how to paint a Lucretia?

Child who cries after your mother's breast, keep quiet; she paints a she-wolf suckling Romulus. Guerin, you think you are famous because your masters have crowned you? Wait until women artists have given you immorality. Nihil sub soli without women artists. Oh, what a happy republic it will be when there are so many women artists! How these mothers of families will make excellent citizens-!13”

This last text seems to have been an essential driving force behind Émilie Bounieu's decision to produce her first history painting, a material response to the anonymous author of the Journal des Arts and clear proof of women's abilities in the genre.

It was a real challenge for the young artist, who had been painting miniatures until then. Another major constraint is that Émilie Bounieu only has eight months to complete her work. Artists are required to submit their finished workstoan admissionsjuryby 29 June 180014 On 1 August 1800, she obtained15 an extension of almost a month, until 26 August 1800, to complete his work and submit it to the jury. This delay is further proof of the sudden and unexpected nature of Émilie Bounieu's decision to confront a historical subject

At the Salon of 1800, she exhibited under no. 50 a Hélène, busy embroidering, when she saw Laodicé arriving, a technical and intellectual tour de force, particularly accomplished in its execution and complex in its subtle references.

The format, like the attitude of the figure and the colour of the costume, is an unequivocal tribute to Nanine Vallain's Liberté (fig.1), which adorned the meeting room of the Jacobin club until 1794. Painted by a woman, this painting was undoubtedly much admired

13 Journal des arts, des sciences et de littérature, n° 18, 30 vendémiaire an VIII (22 octobre 1799), p. 11-13.

14 « Attendu le jugement à prononcer par le Jury, les ouvrages qui devront lui être soumis ne seront plus reçus passé le 10 Messidor, terme de rigueur ». Henri Lapauze, Procès-verbaux […]de la Société populaire et républicaine des arts (3 nivôse an II - 28 floréal an III), Paris, Imprimerie Nationale – Bulloz, 1903, p. 493.

15 « Les citoyens Vafflard , Pallier, […] et Mlle Emilie Bounieu demandent un délai pour terminer leurs ouvrages . La Commission leur accorde jusqu'au 8 fructidor après lequel terme les ouvrages seront de nouveau examinés. ». Idem, p. 507.

by Émilie Bounieu. The Bounieu family was intimately acquainted with Charles Duval, who was secretary and then president of the Jacobins Club from 26 March to 6 April 1794. It is therefore hardly surprising that Vallain's Liberté, as a symbol of the young Bounieu's revolutionary and feminist convictions, served as a model for her Hélène.

1. Nanine Vallain, La Liberté, oil on canvas, 124x95 cm, Musée de la Révolution française, Vizille, deposit of the musée du Louvre (Inv. 8258).

Bounieu did not stop there, borrowing certain elements from Pierre-Narcisse Guérin's Marcus Sextus (fig. 2), a masterpiece unanimously praised at the previous Salon. Wasn't it also the author of Marcus Sextus, admired by “thirty women painters” at a dinner party in 1799, who was at the heart of the virulent criticism in the Journal des Arts at the very origin of Bounieu's initiative in history painting?

The subject chosen by Bounieu can thus be interpreted as a variation on Guérin, this time from the point of view of the female experience. Alone in a foreign land, passive and watching her family kill each other, isn't Hélène representative of the fate of emigrant women during the revolutionary period?

Bounieu uses a number of interesting effects to support her connection with Guérin with the same dramatic force: light, a petrified face, scenery, objects and colours. And she cites Guérin by depicting, notably on Hélène's himation, the flowing, wet drapery so characteristic of Guérin's painting.

did not have good visibility for his drawing; this was due to the hanging of the painting, which was probably very high up and poorly lit. Monsaldy only managed to sketch the broad lines of the composition after several erasures.

Finally, her self-portrait probably merges with Hélène's face. The Journal des Débats et des Décrets (Journal of Debates and Decrees) said that “there is not enough of that ideal beauty in the head that suits the subject” and the Mercure de France, in a tone of irony, wrote that Mademoiselle Bounieu “has certainly taken for her model a very pretty Frenchwoman, very busy with the pleasure of being painted”. These reviews show that her Hélène did not go unnoticed: among the dozens of works exhibited at the Salon, it struck a chord with two of the most important newspapers of the time.

She thus repeated an idea already put into practice in Marie-Geneviève Bouliar's Aspasie, a female masterpiece unanimously praised at its exhibition at the Salon in 1795 and presented to the public again in 1796 in view of its immense success.

Following her participation in the Salon of 1800, Émilie Bounieu systematically presented a history painting at each exhibition until 1810: A Bacchante in 1801; Psyche emerging from the underworld and coming to open Proserpine's make-up box in 1802; Venus wounded by Diomedes in 1804; Pygmalion in love with his statue in 1806; Psyche drawing water from a fountain after putting the Dragon to sleep in 1808; Galatea in 1810.

None of these six paintings is signed. Norhaveanyappearedinpublicsalesunderthe artist's name since the beginning of the 19th century, with the sole exception of an engraving (fig. 3), representing the painting Truth in wine, exhibited at the Salon of 1808 and described as follows in the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (The journal of the political and literary debates), 1808:

“It was a rather difficult idea to render this joyful adage, in vino veritas. Here, Mademoiselle Bounieu has imagined (N°67), a beautiful woman, naked, holding in her hand a mirror bursting with rays of light, crouching in a glass of wine”

This engraving offers a glimpse of the original iconography used by Bounieu, as well as the female type, close to Hélène

Jeanne LevachÉ known as JENNY DESORAS (Saint-Symphorien-de-Lay, 1776 – Coutarnoux, 1858)

PortraitofMarie-CharlotteGeorgetteNizondeSaint-Georges. 1807-1809.

Oil on canvas.

H. 27 ; W. 21 cm.

As the inscription on the stretcher shows, this precious portrait of a fresh-faced lady represents Madame Marie-Charlotte Georgette Nizon de Saint-Georges. She is dressed in a white dress whose play of transparency is finely rendered by light layers of glaze. Her coral jewellery, in particular her imposing cross-shaped necklace and comb, date the painting fairly precisely to the years 1807-1809. The detail of the satin ribbon wrapped around the lady's hat and fingers is treated like a miniature, with great precision.

It has been possible to retrace the life of this mysterious artist, of whom nothing was known apart from the name by which she signed her paintings and appeared regularly at the Salon from 1804 to 1835. In fact, only her first entry in 1804 was under the name "Jenny Levaché-Desoras", after which she presented herself as "Jenny Desoras" or "Jenny Berger", named after her husband. Thanks to the discovery of ajudgementhanded down in 1827, we have been able to establish with certainty that Jenny Levaché, Jenny Desoras and Jenny Berger were the same person1

Jeanne Levaché was a hatter's daughter2, she grew up with her younger sister in Lay, not far from Lyon in France, until her teens. Nothing predisposed her to painting, and she was orphaned at the same time. Her father disappeared suddenly in 17913 , and her mother died in 1794.

Thanks to her godfather's network of contacts, Marshal Joseph George4 , Jenny Levaché appears to have been entrusted to the care of a family of local notables, the Lords of Soras5 They certainly showed a marked aptitude for drawing, and probably invited her

to continue her apprenticeship and hope for an artistic career.

The young artist took her first lessons from a certain "Sermaize". It is probable that this first teacher was Simon Jean Malard de Sermaize, a lawyer from the neighbouring Sâone-et-Loire region and a dilettante artist.

When she came of age in 1800, Jenny Levaché moved to Paris and joined JeanBaptiste Regnault's famous women's studio. After a few years perfecting her art, she took part in her first Salon in 1804. In the booklet6 , she became known under the patronymic of Désoras-Levaché, an assumed name that seemed to be a tribute and a mark of gratitude to her youthful protectors. She subsequently exhibited under this name alone, adding her husband's from 1813, and then mentioning "widow Berger" after her husband's death in 1826.

The artist enjoyed a certain success with her humorous subjects on the theme of love and marriage, reproduced in engravings: "Lovers of the graceful genre will hasten to obtain two charming engravings, entitled Deux jours de Mariage and Deux ans de Mariage, after the pretty

1 Gazette des tribunaux, journal de jurisprudence et des débats judiciaires, n°409, 27 janvier 1827, p. 317. L’article stipule que « Mlle Levacher Desoras est auteure de plusieurs tableaux (…) en 1813, Mlle Desoras a épousé M. Berger. »

2 Archives départementales de la Loire, État civil, Lay, Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures - 1773-1780, Acte de baptême de Jeannette Levacher.

3 D'après un acte de notoriété du juge de paix du canton de Saint-Symphorien de Lay du 20 août 1811 cité dans l'acte de mariage du 10 septembre 1811 de sa fille Sophie, Barthelemy Levaché est alors absent de Lay depuis environ 20 ans et on est sans nouvelle de lui depuis. Archives départementales de l'Allier, État civil, 2 Mi EC 142 7, LE DONJON, Mariages et décès, 1801-1822, an X-1822, Acte de mariage d'Hubert Morgat - Sophie Levaché du 10 septembre 181.

4 Archives départementales de la Loire, État civil, Lay, Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures - 1773-1780, Acte de baptême de Jeannette Levacher.

5 Barthélémy Veyre de Soras étant capitaine de cavalerie et ancien gendarme de la Garde du Roi.

6 Explication des ouvrages de peinture et dessins, sculpture, architecture et gravure des artistes vivans... imprimerie des Sciences et des Arts, Paris, cat. 308.

paintings by Mme Berger, born Jenny Desoras, exhibited at the Salon of 18197 ».

Jenny Desoras, half-length portrait of Catherine Josephine Duchesnois, Bibliothèque PaulMarmottan, oil on canvas, Ville de BoulogneBillancourt, Académie des Beaux-Arts.

We also know that she worked on many portraits. Some of them are well known, and their execution is very similar to ours. In fact, she treated the faces with wide hemmed eyelids, strongly drawn features, a very fresh complexion, and a broadly brushed landscape in the background, in contrast to the precision of the fabrics represented. The portrait of Madame Duschenois was certainly painted during the same period. It shows the same

inclination of the face and the friendly gaze turned towards the viewer.

A medical article published in 18068 reporting a long illness that affected her between 1806 and 1810, bears witness to her work. The doctor who treated her describes her as follows: "Her cheerful character, her lively imagination; she carried the love of her art to excess, and often sacrificed to it, through prolonged study, or in the enthusiasm of composition, the hours of raps, sleep and exercise” and specifies that "the patient had a dominant passion for painting; she continued to sit 6 to 8 hours a day in front of her models, her brushes in her hand". It is rare and touching to have access to such an account of an artist's life.

Jenny Desoras, Hunter and his dog, oil on canvas, 58x45 cm, 1823. Osenat, 3 July 2016, lot no 437.

7 Le Corsaire : journal des spectacles, de la littérature, des arts, des mœurs et des modes, n°22, 1er août 1823, p. 4.

8 Journal général de médecine, de chirurgie, de pharmacie, etc. ou recueil périodique de la Société de Médecine de Paris, Société de Santé de Paris, 1811, pp. 3-14.

Augustin THIERRIAT (Lyon, 1789 - 1870)

StudyofPoppies.

Competition for the Fleur class at the Lyon School of Drawing, 1809.

Charcoal drawing and white chalk on grey paper.

H: 53; W: 40.5 cm.

This large drawing depicts poppy flowers in a lively composition that runs diagonally across the sheet. The two poppy flowers in full bloom are symmetrical, while the foliage and buds escape from this arrangement in a movement that brings the composition to life. The precision of the textures, the veins in the leaves, the very fine grooves on the petals and the slight reflection of the stems all bear witness to the artist's technical mastery.

Augustin Thierriat was born in Lyon on 11 March 1789 and died there on 14 April 1870. Orphaned during the Terror, he was placed with a friend of his uncle, the painter Alexis Grognard, in 17961 . He was a pupil at the Ecole de Dessin de Lyon in 1806, then attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts from 1807 to 1813, where his teachers were Revoil, Grognard and Berjon. He opened a drawing class for silk designers in 1812 and became a teacher of the Fleur class at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, where he taught until 1854. He exhibited regularly at the Paris and Lyon salons, where he won medals in 1817 and 1822. He became curator of Lyon's Museums and Palace of Art in 1830, a position he held until his death in 1870.

Specialising first and foremost in the depiction of flowers, which gave him a taste for precision in representation, the artist was also renowned for his landscapes and genre scenes. He was also a seasoned collector whose cabinet was dispersed at auction in 1872.

This drawing is the first referenced work by Augustin Thierrat, a key flower painter of the Lyon school. In 1807, the young Thierrat enrolled at the École Impériale des Beaux-Arts in Lyon and joined the "Flower Class" taught by an eminent professor, Jacques Barraband. As soon as the school opened, competitions for students were organised at the end of the school year for each of the classes (painting, sculpture, architecture and flower

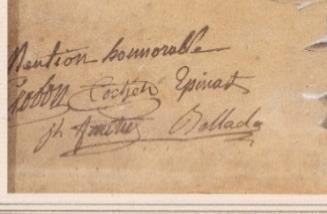

painting), leading to official prize-giving ceremonies. Our drawing is Augustin Thierrat's entry for the 1809 "Flower Class" competition. At the prize-giving ceremony on July 31, 18092 , Thierrat receives an honourable mention3 Several annotations, visible on our drawing, bear witness to this verdict.

On the bottom right corner, the inscription “BonypourMrBarraband” refersto Thierrat's teachers at the drawing school: Jacques Barraband and Jean-François Bony. In 1809, Bony was appointed substitute teacher for the Fleur class, replacing Barraband, whose healthdeteriorated until hisdeath on 1October 1809. Thus Jean-François Bony, in place of the school's historical teacher, validated Thierriat's work in preparation for the competition.

On the bottom left corner, the "honourable mention"received by theartist iswritten above the signatures of the members of the jury. We can see the names of three painters from Lyon, Jean-Michel Grobon, Claude Cochet and Fleury Épinat, and an embroidery dealer, Jacques Bellacla. The last signature could not be identified.

1 « Thierriat (Augustin) », in Adolphe Vachet, Nos Lyonnais d'hier : 1831-1910, Lyon, p. 355

2 Bulletin de Lyon, 2 septembre 1809, p. 2.

3 Marie-Claude Chaudonneret, "L’enseignement artistique à Lyon.Au service de la Fabrique ?" in Le temps de la peinture, Lyon 1800-1914, Fage éditions, Lyon, pp.29-35.

Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, Fleurs de Lyon 1807-1917, catalogue exposition au Palais Saint-Pierre, Musée des Beaux-Arts Lyon Juin-Septembre 1982, Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Art, 1982, p. 329.

Julie DUVIDAL de MONTFERRIER (Paris, 1797 – 1865)

ThedeathofCleopatra.

Circa 1818.

Oil on canvas.

H: 100 ; W: 80 cm.

This sober, close-up composition depicts the Egyptian queen a few minutes before her death, bitten by an asp. Cleopatra is already turning her gaze towards the afterlife; with one hand she delicately grasps the clasp of her garment to reveal her breast, while the deadly snake coils around the other. The drape of heavy red fabric contrasts with the immaculate flesh and the precious treatment of the jewels that soberly adorn the queen's shoulder and head.

This is one of the earliest known paintings by Julie Duvidal de Montferrier, who wasapupil ofFrançoisGérard at thetime,having received a particularly careful education from Madame Campan at the Légion d'Honneur education centre, where the study of fine art was high on the curriculum. The painting probably dates from the year before it was first exhibited at the Salon in 1819. There, she exhibited a portrait of her sister that bore witness to her distinctive personal style, which she would continue to develop over the years.

This painting was done when the young artist, still learning and more confident in her talents, at around 20 or 21, chose to try her hand at a historical subject. Gérard's influence is perceptible in the expression of the face and the complex, flowing drapery. This same expression

was repeated by the artist at the Salon of 1819 with L'Enfant malade/Clotilde asking for her son's recovery: the weeping mother raises her eyes to heaven and shows the same highly detailed touches of ornamentation standing out against drapery treated in broad brushstrokes.

L'Enfant malade, or Clotilde asking for her son’s recovery, 1819. Bourg-en-Bresse, Musée du Monastère Royal de Brou.

But Julie Duvidal de Montferrier very soon expressed herindividuality in relation to her master through very velvety fades. David, in his correspondence with Gros, speaks of "whipped cream" in her manner and "flattering talents"1

Details such as Cleopatra's brooch or diadem, treated with great precision and a sharper line, add points of light and contrast to the composition which, through its tones and the background treated in a subtle monochrome, give

1 Wildenstein Daniel et Guy, Documents complémentaires au catalogue de l’œuvre de Louis David, Paris, 1937, n°1945, p. 227.

the scene its dramatic effect. She liked to depict broadly sketched backgrounds with little detail, in order to highlight the main figure.

This portrait bears many similarities to Cleopatra, in terms of the treatment of the background and, surprisingly, the same red drapery used years later.

Julie Duvidal de Montferrier, later known as Julie Hugo after her marriage in 1827 to Abdel Hugo, Victor Hugo's brother, had a brilliant career as a painter. She won a medal at the 1824 Salon, spent a year in Rome and was a pupil of François Gérard, Marie-Eléonore Godefroid and JacquesLouis David. Her paintings can now be seen in a number of museums, including the Musée de Compiègne,theMuséedesBeaux-ArtsinOrléans and Caen, the Musée de l'Armée, the Musée du Louvre, the Château de Versailles and, of course, Victor Hugo's house.

Attributed to Anthelme TRIMOLET (Lyon, 1798 – 1866)

Spinnerinaninterior.

Circa 1820-1825.

Oil on canvas.

H. 65 ; L. 54 cm.

Seated in front of a window, a woman spins the wool wrapped around the distaff she is holding in her left hand, while with her right hand she turns the wheel of her spinning wheel. The room in which the scene is set is bathed in soft light, highlighting such minute details as the reflections on the wood of the spinning wheel, the basket of spun wool on a footrest, the leather of the shoes delicately placed on the carpet, the small jewellery box on the mantelpiece and the firebrand glowing discreetly behind the cloth resting on the chair. A knotted fabric nonchalantly holds back the hair of the spinner, who is wearing a shirt whose play of transparency on the embroidery, rendered by a very slight impasto of the lines around the edges of the fabric, contrasts with the heavy red petticoat covering her legs.

This painting is undoubtedly by Anthelme Trimolet, a painter from Lyon renowned for the meticulousness of his work, inspired by the Dutch masters and updated by his work on 19th-century genre scenes.

Anthelme Claude Honoré Trimolet was born in Lyon. His father, an embroidery designer, had turned to metal painting following the French Revolution. He entered the Lyon School of Fine Arts when it was founded, at the age of ten. He won awards in several classes. In 1810, he distinguished himself in the Principles class. In 1812 he won the silver medal in the Bosse class, in 1813 for Figure from lifeand, finally, the coveted Laurier d'Or in 1815, exempting him from military service1 His teacher was the painter PierreHenri Révoil (1776-1842), who also taught Claude Bonnefond (1796-1860), MichelPhilibert Genod (1795-1862), Augustin Alexandre Thierriat (1789-1870) and JeanMarie Jacomin (1789-1858), the leaders of a movement that was first described as the "Lyon School" at the Salon of 1819.

At the same Salon, Trimolet won a gold medal for his mechanic's workshop, commissioned by Professor Ennemond Eynard. The artist's skilful eye for detail, developed as a result of his discovery of the Dutch masters during his first trip to Paris, was noticed by the Duc de Berry, who commissioned a painting from him, which was not completed until after his assassination in 1823. He also met the Marquis Victor de Costa, a close friend of the

King of Sardinia, through whom he obtained a commission for the Prince de Carrignan. This was the artist's first large-scale historical scene, the deputies of the Council of Basel presenting the tiara to Amédée VII, which he presented to the Prince in Turin in 1831.

Anthelme Trimolet. Interior of a mechanic's workshop, oil on canvas, 1819 (Inv. A33). Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon.

Suffering from what he describes as « languor »2 , Anthelme Trimolet does not seem to have sought to develop his official career despite his early successes. However, the number of portraits he produced testifies to his reputation among Lyon's aristocrats, as Aimé

1 Élisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, Étienne Grafe, Portraitistes lyonnais (1800-1924) (cat. exp., Lyon, musée des Beaux-Arts, juinseptembre 1986), Lyon, musée des Beaux-Arts, 1986

2 Archives municipales de Lyon. Cote 65II/129. Autobiographie et liste de ses œuvres peintes, écrite et donnée par lui-même à Aimé Vingtrinier.

Vingtrinier points out in his portrait of the artist:

“He shunned glamour and noise, but the city's wealthy families sought the favour of posing for him. These canvases, carefully preserved in private galleries, have not been subjected to the judgment of the public or the criticism of newspapers; they will not enhance the name of the artist until the brush has fallen from his hand and art has contemplated with horror the loss it has suffered3” .

His wedding to one of his pupils, Edma Saunier (Lyon, 1802 - Saint-Martin-sousMontaigu, 1878) in 1824 endowed him with a large fortune, as his wife was the daughter of a wealthy landowner. Through their archives and collections, the couple left a touching testimony to an engaging couple,curiousabout everything and prolific in their artistic creations through sketchbooks and diaries. From 1825 onwards, the Trimolet couple amassed more than 2,000 works, with a strong taste for the Haute Epoque and the Middle Ages. This veritable museum of books, paintings, furniture and sculptures was bequeathed to the Musée de Dijon following the death of Edma Trimolet in 1878.

Thanks to this bequest, the couple's entire collection of drawings came to the museum, but only a few paintings by Edma and Anthelme Trimolet are now in the museum's collection. A study of the Trimolet collection does, however, shed light on the development of the artist's career and allows us to link La Fileuse to the period following Trimolet's first success, Intérieur d'un atelier de mécanicien (Interior of a Mechanic's Workshop), painted in

1819. We have noted that, among the dated drawings, domestic and intimate genre scenes are concentrated in the period 1820-1830. After 1830, we know only of portraits and a few scenes inspired by Dante's Inferno.

The style of the painting we are presenting is similar to a painting kept by the Musée de Dijon, Portrait de son père et de sa mère jouant aux cartes, which is also unsigned. The latter still seems to bear some of the stiffness of his youth, as well as a less detailed finish than the Fileuse, but it has all the characteristic features that would make the artist famous: abundant detail, materials rendered by light impastos, velvety brushwork, highly drawn and detailed hands, and so on.

All these elements are found, more fully developed, in Intérieur d'un atelier de mécanicien (Interior of a Mechanic's Workshop). The lighting is provided by a side window, which forms a lighter halo around the heads of theprotagonists, the draperies have the same velvety heaviness and the details are adorned with sparkling points of light in the Dutch manner.

3 Aimé Vingtrinier, La paresse d’un peintre lyonnais, Lyon, 1866, pp. 10-11.

Anthelme Trimolet, Portrait of his father and mother playing cards, oil on canvas, 19th century, Inv. CA T 120. Bequest from Anthelme and Edma Trimolet, 1878 © Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon/ François Jay.

Another drawing from the Trimolet collection at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, depicting a Woman Reading, uses the same type of composition, with a heavy drape running back between the protagonist's legs. The somewhat restrained attitude is also typical of the artist

At the same time as the arrival of the Romantics was calling into question the

pictorial techniques that were the artist's speciality, he indicated in his correspondence the contradictions in taste that he had to face:

Anthelme Trimolet. Woman reading, black pencil on paper, Inv. CA T 203. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon.

« This controversy quickly spread, especially in the provinces, a disfavour for art and artists. It was no longer fashionable to admire painting, but on the contrary, to criticise it. What had been praised in us then became our greatest flaw. - It's microscopic, my dear; so go wide! Put on thick colours and leave the needlework to the nuns. - Your paintings look like porcelain, so make them crisp and easy! - Look at Bonington, look at Delacroix, etc...; - and the odd thing was, these same people would come to me to have their portraits done, recommending that I paint them finely, and not spare the details that, they said, I did so well! - It was enough to demoralise the best mind! »4

4

Angélique MONGEZ (Conflans-l’Archevêque, 1775 – Paris, 1855)

StudyoftheleftgroupfortheSevenChiefsinfrontofThebes Circa 1825.

Black stone and brown ink on paper.

H: 25.3; W: 19.2 cm.

This preparatory drawing shows a few variations from the final painting on display at the Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Angers, showing the artist's creative process and the thought that went into each detail.

A pupil of Jacques-Louis David and married to one of his closest friends, Angélique Mongez turned to monumental and complex history painting from the outset. When she first exhibited at the Salon in 1802, Mongez challenged the male privilege of monumental history painting by presenting a large-format painting, Astyanax torn from his mother. Adopting the style of her master Jacques-Louis David, she also tackled the most "masculine" themes in history painting. From 1802 until the end of her public career in 1827, she systematically presented a very large-scale mythological history painting at every exhibition.

Her works quickly acquired the reputation of "illustrating a man's brush". Admiring the success of his former pupil, Jacques-Louis David saw in her a worthy heir to his art, and he did not hesitate to promote her to illustrious collectors, including the Russian prince Nicolaj Youssoupov.

The Seven Chiefs in front of Thebes (fig. 1), presented at the Salon of 1827, was the final masterpiece of an extraordinary career and the artist's most ambitious work. The martial subject was used as a pretext for depicting two male nudes, one from the front and the other from the back.

As a woman, Mongez nevertheless maintained a certain modesty in her work, but preserved the nudity of her representations entirely. On the occasion of the Salon of 1814, the Journal de Paris highlighted the care that the artist took to "round off, embellish, and offer to our gaze in their entirety, certain forms that the valiant Perseus surely did not show to the enemy". Her Mars and Venus of the same year, and even more so The Seven Chiefs in front of Thebes, the last masterpiece of which we offer here a preparatory drawing, bear witness to this strong attraction to the male arch. She awas inspired by the back of Romulus in David's Sabines in 1799.

Jan Adam Kruseman (Haarlem, 1804 - 1862)

Thefortuneteller.

1825.

Oil on canvas.

Signed and dated upper left. H. 74 ; L. 80 cm.

Provenance:

Exhibition of Living Masters (Tentoonstelling van Levende Meesters), Haarlem, 1825, no. 240.

Albertus Bernardus Roothan, 1825.

Ryfsnyder collection; his sale, Amsterdam, 28 October 1872, number 124.

On a sober background, an elderly woman is reading in the palm of the hand of a younger woman turned three-quarters. Both figures are dressed in contemporary clothing typical of the 1825s. The fortune-teller's gaze is raised towards her client's face, while the latter lowers her eyes to read the lines in her hand, directing the viewer's eye towards a triangle with the old woman's pointing hand in the centre. The tight framing amplifies the feeling of being absorbed in their conversation

This painting is mentioned in the catalogue raisonné of Jan Adam Kruseman's work, its location unknown1. It was exhibited in Haarlem in 1825 underthenumber240 "Een Brabandsche Waarzegster"/"A Brabant fortune-teller"2 .

Born inHaarlem in 1804 toabourgeois family of German origin, Kruseman left his home town for Amsterdam in 1819, where he joined the studio of his cousin, Cornelis Kruseman, seven years his senior. He continued his apprenticeship until 1821, when his cousin left for Italy. He then continued as a self-taught artist, while taking his first portrait commissions after winning a prize with Felix Meritis.

In 1822, buoyed by his initial success, he went to Brussels to complete his apprenticeship with the two most influential artists of his time, François-Joseph Navez (1787-1869) and Jacques-Louis David (17481825). Under the guidance of the latter, he produced numerous study sketches and history paintings. Navez, for his part, exerted a classicistinfluenceonhiswork.Whenhebegan studying under Navez, the latter had just returned from Italy, where he had discovered the paintings of Ingres and the Nazarenes, in his quest to reconcile the tensions between realism and idealism.

Kruseman lived in Paris during 1824 and his work really began to emerge from the public eye in 1825 when he returned to

Amsterdam. On 11 May 1826 he married Alida de Vries (1799-1862), with whom he had five sons, two daughters and an adopted son, Alida's sister.

The end of the 1820s marked the rise of the artist; he became a member of the Dutch Society of Fine Arts and Sciences in 1828, and was then appointed director of the Royal Academy of Art in Amsterdam.

In 1832, he opened his own studio and from 1834 to 1836, he made several study trips to Germany, England and Scotland.

In 1844, King Wilhelm II appointed him a member of the Royal Netherlands Institute. He was also made a Knight of the Order of the Lion in the same year. He was an accomplished artist who was particularly appreciated, as demonstrated by the commentary accompanying the works he exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Vivants in Amsterdam in 18413 : "J.A. Kruseman, in Amsterdam, has again supplied some of these portraits, which are proof of the great merits of this artist (...); it is therefore not without reason that this artist is the darling of the public".

The artist maintained close links with members of the royal family, who commissioned portraits from him and bought his works when he exhibited. His most famous work was the portrait of King Wilhelm II.

He played a central role on the artistic scene of his time, was present in all the artistic

1 Renting Anne-Dirk et al. Jan Adam Kruseman, 1804-1862. Nijmegen: G.J. Thieme, in samenwerking met Stichting Paleis Het Loo Nationaal Museum, 2002, cat. 55.

2 Levende Meesters, Haarlem, 1825, catalogue n. 240.

3 Levende Meesters, 1841.

societies and received dozens of distinctions throughout his career. As he himself admits, all thistakesup so much of histime that heregrets not being able to spend more time with his family.

After 50 years of rather happy family life, one tragedy followed another in the Kruseman family and the painter finally succumbed to an illness on 17 March 1862. He was so much appreciated and integrated into Dutch society that no fewer than 394 letters of mourning were sent to his family4

The Fortune Teller represents a very interesting and little-known milestone in Kruseman's career, as known paintings from this artistic period are rare. Indeed, the influence of Navez can beseen inthetight framing andthesubject, but Kruseman was already expressing a style that would provesuccessful on hisreturn to the Netherlands, using contemporary costumes and seeking agentlenessof expression that was less marked by the heroic expression sought by David and Navez.

After his return to Amsterdam in 1825, Kruseman keptintouchwith Navez,buthewas also still under the influence of David, who was making his mark in the southern Netherlands. He sought expression in his portraits and we can compare the self-portraits of Navez (1826), David and Kruseman (1827) for their strong expression: Navez represents himself with a heroic expression while Kruseman seeks to highlight a friendly look.

Jan Adam Kruseman, self-portrait, oil on canvas,1827,Rijksmuseum(Inv.BR2885)

4 Renting Anne-Dirk et al. Jan Adam Kruseman, op. cit.

A touching detail in this painting bears witness to this: the young woman's lowered eyes shine through her long lashes and a slight pout appears on her face.

Attributed to Ary Scheffer (Dordrecht, 1795 – Argenteuil, 1858)

Floodscene.

Circa 1820-1825.

Watercolour and gouache on paper.

H. 61.5 ; L. 81 cm.

Perched on the roof of a house around which the composition is organised, the inhabitants of a village are rescued by other inhabitants in a boat. In the centre, a man leans on a stone to lead a woman to the boat and an old man steps forward to help her. A distraught woman reaches for the sky, another lies on top of some personal belongings that may have been saved, while in the background other worried figures look in different directions. The drama of the scene is underpinned by the expressions on the faces, the muddy waves in the foreground and background that enclose the scene, the stormy sky and the drifting furniture in the foreground. The pictorial treatment, which combines broad watercolour brushstrokes and gouache details, renders the cottony aspect of a light obscured by the storm.

This work can be associated with the second artistic period of Ary Scheffer (1795-1858), who, after exhibiting a few works with a neoclassical inflection, sought his way through dramatic romanticism.

Ary Scheffer was born in Dordrecht on 10 February 1795. His father, Johann-Bernhard Scheffer(1764-1809), hismother, CorneliaScheffer (1769-1839) and his brother Henri Scheffer (17981862) were artists. He learned to draw with them from an early age and then at the Amsterdam Academy of Painting between 1806 and 1809. He exhibited at the Amsterdam exhibition of living masters in 1808 and moved to Paris in 1811. A presumed pupil of Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (17581823), hethen entered thestudio ofPierreNarcisse Guérin1 (1774-1833) and exhibited at the Salon from 1812. In Guérin's studio, he met Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and, like his fellow artists, took the path of Romanticism.

From 1815 onwards, he exhibited canvases inspired by national history and mythology, which enabled him to express strong feelings of grief, mixed with heroism. He evolved over the next five years, painting more sentimental works in parallel, depicting scenes of everyday drama. A turning point came in 1827 with Les femmes souliotes, when the colours became more crystalline, the figures more lanky, and the compositions closer together with fewer figures. It is for this last period that the artist is most famous, particularly for his works inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's masterpiece Faust (18491832).

The central figure thrusts his foot forward forcefully in an unusual posture reproduced in our gouache.

However, the twelve years or so between 1815 and 1827 were a veritable laboratory for the young artist's fertile creativity. These early years of the Restoration in France saw the advent of a new genre of painting, prized by the burgeoning bourgeoisie. These were scenes from the lives of the common people, tinged with maudlin sentimentality.

1 Ary Scheffer, sa vie et son œuvre, Leonardus Joseph Ignatius Ewals, ed. Nijmegen, 1987.

During the 1820s, Ary Scheffer made a speciality of these paintings, which brought him great fame.2 The composition, the brushstrokes, certain attitudes and several faces of the protagonists can be found in other compositions by the artist, notably The Tempest (fig.1) and The Fire (fig.2). The subject is also closely related to his Flood scene, exhibited at the Salon of 1827, where the action takes place after the drama, unlike our gouache.

In the latter, Scheffer depicts the rescue in extremis of disaster victims from the roof of their house by a boat. Ary Scheffer immortalised the profound suffering of the common people with great accuracy. He subtly depicts the various emotions involved in the flood and the rescue, ranging from fear and gratitude to sadness and pleading.

Scheffer's style is also recognisable in the spotlight on the central characters, while other afflicted people remain in the shadows. We find this particularly in The Souliote Women (fig. 3) and TheTempest (fig.1). Theuseofthebrushwith

broad strokes, the free touch for the representation of certain details such as the straw on the roof of the dwelling are also the artist's speciality in his watercolour work, surely under the influence of Delacroix's manner. The pyramidal composition with a fairly low horizon line, a weeping figure in profile and clasped hands was also a formula used by Scheffer to depict other dramatic scenes. The figure of the man in the centre, and of the old man in The Flood, were reused in an engraved scene, The village set on fire by the Cossacks (figs. 4&5), by Hippolyte Garnier and now lost. As for the woman wearing a bonnet, a very similar figure was also reproduced in engraving after another lost work by Scheffer (fig. 6).

2 Antoine Etex, Ary Scheffer : étude sur sa vie et ses ouvrages, Lévy fils, Paris, 1859, p.12

4: Hippolyte Garnier, after Ary Scheffer, The Devastated village, lithograph, Ecole nationale supérieure de Beaux-Arts de Paris.

Christian Albrecht JENSEN (Bredsted, 1791 – København, 1870)

Portraitofayounggirl.

Circa 1823-1825.

Oil on canvas.

H. 29 ; W. 19.

Set against a dark background, the young woman is portrayed with a dreamy expression and distant gaze. The artist skilfully played with the complementary contrast of the green dress and the red shawl, which complemented the very fine coral earrings.

Known for his many highly sought-after portraits of the Danish elite in the early 19th century, Christian Albrecht Jensen can be described as the "Boilly of the North" in the golden age of Danish painting.

Jensen shared with his French colleague the smallness of his formats, limiting the time needed to pose the model and then execute the painting. The low cost of these small portraits, coupled with a fashion effect resulting from a growing clientele, contributed to the fame of the young Jensen.

After an apprenticeship lasting several years in Italy, Jensen was unknown to the general public when he returned to Copenhagen at the end of 1822. However, his rapid and sure specialisation as a prolific portrait painter ensured him almost instant success. He painted over 400 portraits during his career, representing most of the leading figures of the time, including the writer Hans Christian Andersen, the painter Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, the physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss and the theologian Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig.

Although an early portrait, it bears eloquent witness to Jensen's personal style from the outset. The young woman is depicted with a skilful economy of means. Using a cold palette, a straightforward brushstroke and a certain humility in the choice of attitude, Jensen focuses on the humanity of his model, praising simplicity and eliminating all superfluous elements.

YoungRomanwomanpraying,withasleepingchild,surroundedby amonkandagirl.

Second quarter of the 19th century.

Oil on canvas.

H: 50 ; W: 41 cm.

In a church, a woman in Italian costume is holding an infant in her arms. She seems to be looking up at the altar while a monk and a young girl are praying behind her. The perspective of the painting is opened up by the rich décor of the church in the background, despite the tight framing of the figures. The shining oil lamp in the foreground completes the setting, while the delicate expression of the young Roman woman and the soft brushstrokes lend the painting a gentle, melancholy atmosphere.

Unlike François-Joseph Navez (1788 - 1869), who went to Rome but stayed for only four years, a handful of contemporary Belgian painters chose to settle there permanently. These include Martin Verstappen (1773 - 1852) from Antwerp and JeanBaptiste-Louis Maes from Ghent. While the former found his niche in landscape painting, the latter established himself in the mid-1820s as one of the most sought-after painters in Rome in the popular genre of the Italian scene.

A pupil at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, Jean-Baptiste-Louis Maes showed a precocious talent for painting landscapes1 He won prizesin the art school competitionshetook part in, in Mechelen in 1810, Ghent in 1817, Brussels in 1818, Antwerp and Amsterdam in 1819. Elected a member of the Royal Society of Fine Arts of Ghent in 1820, he was granted an annual pension by his native city for two years in order to continue his training abroad. From Paris, where he stayed with the landscape painter François Vervloet (1795 - 1872), he competed successfully for the Prix de Rome at the Antwerp Academy in 1821. With a subsidy from the Dutch government, he quickly set off for the Eternal City with Vervloet. Leaving Paris in mid-August 1821, the two artists arrived at their destination on 16 September.

When he entered Rome, Jean-Baptiste-Louis

Maes was an established artist who had already distinguished himself in various genres: history, allegory and portraiture. New commissions came in from his home town, including a large altarpiece: The

1 Sur J.B.L. Maes-Canini, on se reportera en priorité à L. De Bast,

Holy Family with Saint Anne and Saint Joachim for the church of Saint-Michel (in situ).

These signs of interest in his painting enthused the painter, who still aspired to be a history painter: "I have just learned with great satisfaction that the church of St. Michel [in Ghent] has just commissioned me to paint a picture for the chapel of St. Anne"2 , On 30 June 1824, he wrote to Liévin De Bast, the secretary of the Royal Society of Fine Arts in Ghent, "I am now happy to find the opportunity to devote myself entirely to the historical genre, and I will try to fulfil it with honour to the general expectation of the public and my fellow citizens: here I am happy and content, always finding myself in the midst of masterpieces".3

Fig. 2 J.-B.-L. Maes-Canini, The Good Samaritan, Rome 1825, oil on canvas, 251 w 200 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. SK-A1078.

2 Annales du Salon de Gand et de l’école moderne des Pays-Bas, Gand, chez P.F. De Goesin-Verhaeghe, 1823, p. 135-136 ; D. Coekelber- ghs, Les peintres belges à Rome de 1700 à 1830, Bruxelles-Rome, Institut historique belge de Rome, III, 1976, p. 404-406, et à A. Jacobs & P. Loze, in cat. expo. 1770-1830. Autour du Néoclassicisme en Belgique, Ixelles, Musée Communal, 1985/86, p. 243-245 &433.

Il s’agit de La Sainte Famille avec sainte Anne et saint Joachim, 1827, huile sur toile, 285 x 215 cm, Gand, église Saint-Michel.

3 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. RP-D-2017-888.

Along with a small group of Belgian-Dutch compatriots, the aforementioned Vervloet and Verstappen, Hendrik Voogd (1768 - 1839), Cornelis Kruseman (1797 - 1857), Philippe Van Bree (17861871), and the sculptor Mathieu Kessels (1784 - 1836), Maes made excursions into the Roman countryside, visiting the Alban Hills, Castel Gondolfo, Genzano, Nemi, Palestrina, Zargalo, Fracati and Grottaferrata, places renowned for the beauty of their village women and their colourful, shimmering costumes. He also frequented more cosmopolitan circles. In July 1823, for example, he found himself at the convent of Santa Scolastica in Subiaco, in the company of Vervloet, the mysterious Russian Abasettel, the Frenchmen Louis Étienne Watelet (1780 - 1866), Raymond Quinsac Monvoisin (1790 - 1870) and François Antoine Léon Fleury (1804- 1858). Finally,herubbed shoulderswith Germanic artists.

Stimulated by his colleagues and by the special atmosphere of the Eternal City, he turned increasingly to the genre that was then in fashion: the Italian scene. In a letter to Lièvin de Bast dated 30 June 1824, he wrote: "I have the honour of announcing to you that I have just sent three paintings at the beginning of this month, representing a St Sebastian, an old woman in prayer, and the third the Pifferari in front of a Madonna: at the beginning of next month I will send another, the subject of which is a young and beautiful Vignerola with an old man, a group of natural size".ThesepaintingswereincludedintheGhentSalon of 1824.

In 1827, in Rome, he married Anna Maria, daughter of the engraver Bartolomeo Canini. From then on, he would add his wife's name to his own. They had a son in 1828, Giacomo, a painter like himself. Maes-Canini also remained a useful intermediary for Belgian-Dutch artists arriving and staying in Rome.

Withtheexceptionofafewreligiouspaintings, such as The Good Samaritan of 1825 (fig. 2), which he sent to Belgium, Maes-Canini from then on devoted himself solely to Italian scenes, becoming one of the specialists in Rome in this genre. He was so successful that, in 1834, he ran a workshop in which he employed severalyoungartists,includinghisson,inordertofulfil his many commissions. Gifted with an unquestionable mastery of drawing and the technique of modelling through skilful lighting effects, he delighted in pandering to the tastes of the Eternal City's cosmopolitan clientele with somewhat saucy depictions ofthepicturesqueRomanpeople.Someofhisworksare reminiscent, in a gentle way, of the paintings by Léopold Robert (La-Chaux-de-Fonds 1794 - Venice 1835) (fig. 7), with whom he was undoubtedly acquainted, as Denis Coekelberghs suggests. He paintedpilgrims,hermits,shepherds,contadini,pifferari and, finally, seductive young Roman women.

Fig. 3 J.-B.-L. Maes-Canini, Portrait of a Young Italian Girl, Rome 1828, 47 x 37 cm, Ghent, Bijlokemuseum, inv. A65.02.029

They were his favourite theme. Under his brushes, they usually appear in three-quarter view, sometimes in bust form (fig. 3). He sometimes depicted them undressed (fig.6), most often in their traditional colourful costumes. They are grooming themselves, preparing for the annual carnival on the Corso (figs. 5 & 8), filling a lamp with oil (fig. 4) and so on. Sometimes they appear alone, sometimes accompanied by an older maid, which brings out the freshness and delicacy of their youth. Through the

tight framing of the compositions around the figures and the intensity of the chiaroscuro, some of MaesCanini's paintings offer a suave variant of the Roman neo-Caravaggio of the second quarter of the 19th century (fig. 8).

TheyoungRomanwomanpraying.

Some of his paintings weresuccessful. Such is the case of The Young Roman Woman Praying. The work analysed here is one of several variants of the same painting, depicting a young Roman woman in Frascati costume, praying in a church before a pious image. Theimage isnot depicted in the paintings, but is subtly suggested, notably by the copper lamp hanging infront of thealtars, asisthecasewith many examples in Rome.

The artist took two approaches to the subject. The first shows the young woman alone, her hands clasped and her elbows resting on an altar beside a bouquet of flowers (figs. 9, 12 & 13). One example bears the date 1845.

The second variant of the subject is known to us from several paintings. This time, the young Roman woman is holding a sleeping child in swaddling clothes (figs. 10 & 11). One of them also bears the date 1845.