By Giacomo Puccini

By Giacomo Puccini

A GUIDE TO THE STUDENT DRESS REHEARSAL

By Giacomo Puccini

By Giacomo Puccini

Cesare Angelotti, an escaped political prisoner, dashes into the Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle to hide in the Attavanti family chapel. At the sound of the Angelus (a bell that signals a time for late-morning prayer in the Roman Catholic church), the Sacristan enters to pray. He is interrupted by Mario Cavaradossi, a painter who has been commissioned to paint a portrait of Mary Magdalene in the chapel. The portrait bears a strong resemblance to the Marchesa Attavanti, who frequently comes to the chapel to pray for her brother. The Sacristan leaves and Angelotti emerges from his hiding spot to embrace his friend, Cavaradossi. Angelotti explains that he has just escaped from the Castel Sant’Angelo, where he was imprisoned by orders of Baron Scarpia. They are interrupted by

Floria Tosca – (soprano)

A famous Roman singer who is in love with Mario Cavaradossi.

Mario Cavaradossi – (tenor)

A painter with revolutionary sentiments.

the voice of Floria Tosca, Cavaradossi’s lover. Angelotti returns to his hiding spot. Tosca is furious because she heard voices and is convinced that Cavaradossi is cheating on her! Cavaradossi convinces Tosca that he was alone and promises to see her after her opera performance that evening. Tosca leaves and Angelotti comes out of his hiding place. When a cannon is fired, Angelotti and Cavaradossi realize that the police are looking for Angelotti. Cavaradossi suggests that Angelotti hide in the well on his property and the two quickly flee to Cavaradossi’s villa. Baron Scarpia enters the church in pursuit of Angelotti and deduces that Cavaradossi is helping the escaped prisoner. Scarpia finds a fan embroidered with the crest of the Marchesa Attavanti. Tosca returns and Scarpia uses the fan as evidence to convince Tosca of Cavaradossi’s unfaithfulness. Tosca tearfully vows revenge and exits the chapel. As the act closes, Scarpia sings of the great pleasure he will have when he destroys Cavaradossi and has Tosca for himself.

Baron Scarpia – (baritone)

The power hungry chief of police who is in love with Tosca.He is trying to capture Cesare Angelotti.

Cesare Angelotti - (bass)

An escaped prisoner who shares Cavaradossi’s revolutionary sentiments.

Spoletta – (tenor)

One of the policemen who works for Scarpia.

Act II – Scarpia’s apartment in the Palazzo Farnese

Scarpia eats dinner and waits for the spy Spoletta to report back on whether or not Tosca has led them to Cavaradossi or Angelotti. Scarpia muses to himself how he will use Tosca for his own political gain and then toss her aside. Spoletta enters with Cavaradossi, who has been brought in for questioning. Scarpia begins his interrogation of Cavaradossi, while Tosca is heard singing in the next

, continued from page 1

room. Once Tosca enters, Scarpia will not stop torturing Cavaradossi until Tosca tells him where Angelotti is hidden. Unable to bear the suffering of Cavaradossi, Tosca breaks down and reveals Angelotti’s hiding place. News arrives that the Battle of Marengo has been won by Napoleon (a defeat to Scarpia’s side), to which Cavaradossi cries, “Vittoria!” Scarpia places Cavaradossi under arrest and sends him to prison to be shot at dawn. Tosca pleads with Scarpia for Cavaradossi’s life. Scarpia agrees to stage a fake execution if Tosca will surrender to him. Scarpia signs the reprieve but secretly has no intention of freeing Cavaradossi. As Scarpia writes Tosca and Cavaradossi a note of free passage out of the state, Tosca realizes that she cannot bear the thought of giving herself to Scarpia. She sees a knife on the dinner table,

Puccini’s Tosca is full of moments of high drama, high action, and high notes. Some of these action- packed moments (like the execution of Cavaradossi at the end of Act III) rely on the precise coordination of actors and crew. There are many stories from productions of Tosca where things didn’t exactly go as planned.

At the Macerata summer festival in 1995, an overzealous props assistant added too much powder when he loaded the blanks into the guns. The blanks pierced Cavaradossi’s (Fabio Armiliato) boot as well as his leg. When Tosca (Raina Kabaivanska) ran over to him, she fainted at the sight of the blood. After an hour in surgery, Armiliato was on his way to recovery. Five days later, when entering for the beginning of Act II, Armiliato’s crutch slipped, causing a double fracture of the other leg!

and just as Scarpia is about to embrace her, she stabs him to death through the heart. Before she leaves, she places candles on the floor around his corpse and a crucifix on his chest.

Cavaradossi is led to the roof of the Castel Sant’Angelo to await execution. He bribes a guard to allow him to write a letter to Tosca. He is overcome with grief as he writes his farewell. Tosca soon arrives and tells him of the arrangement with Scarpia and the fake execution. She coaches Cavaradossi on how to fall realistically (so the guards will not know the execution is staged) and tells him that she has killed Scarpia. After the execution, Tosca approaches Cavaradossi, complimenting him on his performance, but soon discovers that he is actually dead! Scarpia betrayed her. As she hears the guards approaching to arrest her for murder, she leaps off of the parapet of the Castel Sant’Angelo to her death.

Maria Callas’ portrayal of Tosca at Covent Garden in 1962 almost burned down the house!

Duringthesecondact,shewalkedtooclosetothe candles burning on Scarpia’s desk and ignited her hair! Scarpia (Tito Gobbi) jumped on Tosca,embracedher,andextinguishedtheflameswith his gloved hand. Tosca rejected Scarpia with disgust but not after whispering a quick “Thankyou”toTito.

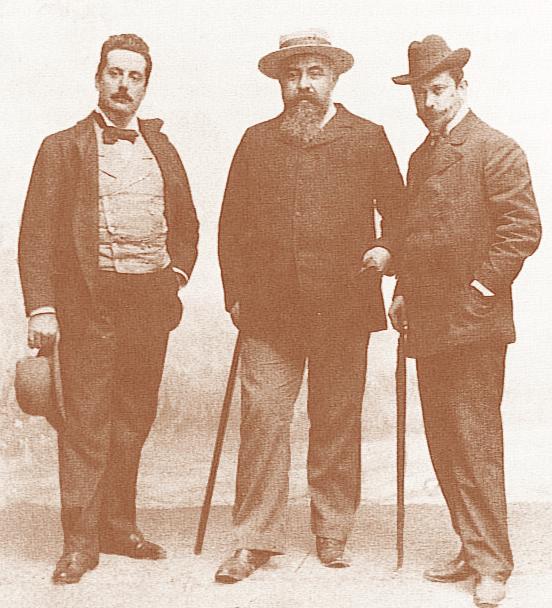

The winning team of Puccini, Illica, and Giacosa produced such memorable operas as La Bohème, Madama Butterfly, and Tosca. Illica planned the scenario and drafted the dialogue and then Giacosa put the dialogue into polished verse. Puccini wrote the music.

Giacomo Puccini, composer

Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Seconda Maria Puccini (December 22, 1858 – November 29, 1924) was born into a poor, but musically talented family in the town of Lucca, Italy. Puccini descended from a long line of musicians, conductors, and composers. Puccini attended his first opera, Aida (by Giuseppe Verdi), in 1876 at the age of 18. This experience ignited his desire to become a composer. He entered the Milan Conservatory of Music on a scholarship arranged by the Queen of Italy. Puccini’s career as an opera composer was secured in 1893 with the premiere of his third opera, Manon Lescaut From then on, he was recognized as one of the greatest composers in Italy. The more substantial his success, the grander his personality and tastes became. He built a reputation as an excellent hunter, a collector of cars, and a great romantic figure. “I am always in love!” he once declared. Puccini also had a fascination with the technological advances of the day, and was involved in one of the first car crashes in Italy. Like many of his heroes and heroines, Puccini had his own torrid love affair. His affair with Elvira Gemignani attracted much attention from the public. The two eloped, but were not officially married until the death of her husband. Elvira and Giacomo were an odd pair and were eventually the center of scandal when Elvira accused a young maid of having an affair with Puccini. The maid committed suicide and Elvira was jailed for five months for her false accusation. Giacomo and Elvira separated, and then reconciled, but after considerable damage was done to their relationship. Puccini died of throat cancer just before finishing Turandot, the opera he considered his crowning achievement.

Luigi Illica, librettist

Luigi Illica (May 9, 1857 – December 16, 1919) was born in Castell’Arquato, Italy. At a young age, he ran away, joined the navy, and fought against the Turks before settling in Milan. His career as a librettist began in 1889

with the melodramatic opera Il vassallo di Szigeth, written for Italian composer Antonio Smareglia. His association with Puccini began three years later when he completed the libretto for Manon Lescaut, Puccini’s first commercial success. For Puccini’s next three operas (La Bohème, Tosca, and Madama Butterfly), Illica wrote the dialogue, while Giuseppe Giacosa transposed it into verse. Illica is credited with writing 35 libretti and was one of the earliest librettists to devise his own plots, rather than basing his opera stories on existing works.

Giuseppe Giacosa, librettist

Giuseppe Giacosa (October 21, 1847 – September 1, 1906) was born in Colleretto Parella, Italy. He received a law degree from Turin University and joined his father’s legal practice until the success of his one-act verse comedy, Una partita a scacchi (1873). He initially focused on stylized period drama, though he did write a number of prose plays, one of which was written especially for Sarah Bernhardt (see Creating Tosca on page 6). Often regarded as one of Italy’s leading playwrights at the turn of the twentieth century, Giacosa’s association with Puccini began in 1894 at the insistence of the publisher, Giulio Ricordi. Although Giacosa frequently protested against Puccini’s ideas, he often acted as the intermediary between Illica and Puccini, and would usually give in to Puccini’s wishes.

People often think that the stories in opera are fantasy or make believe. In fact, many elements of opera are derived from actual people, places, and events. Scholars have spent years trying to discover the sources, which inspired the opera (and novel and play) Tosca. Puccini’s Tosca was adapted from a book by Victorien Sardou, entitled La Tosca, published in 1887. Can you sort fact from fiction in Tosca?

Castel Sant’Angelo Prison (Castle of the Holy Angel)

Castel Sant’Angelo Prison (Castle of the Holy Angel) in which Cavaradossi is imprisoned – The Roman Emperor Hadrian originally built this structure between 135 and 139 A.D. as a tomb for himself and future emperors. During the fifth century, it was converted into a fortress. In the Middles Ages and Renaissance, it was connected to the Vatican by a secret passage. The castle was used as a fortress and prison until 1870, and in 1901, was converted into a museum.

Floria Tosca – Scholars have suggested several people after whom Tosca might have been modeled, including Italian soprano Angelica Catalani. In 1856, prior to the publication of Victorien Sardou’s book, La Tosca, a French book entitled Vies et aventures des cantatrices célébres, was published which documented the life of Angelica Catalani. The parallels between the lives of Catalani and Tosca are quite extraordinary. Another opera singer, Francesca Costa, born a century earlier, is usually credited with supplying Sardou with the inspiration for the name of his heroine (Sardou simply rearranged a few letters in her last name to create his character of Tosca). Both Catalani and Costa stood out as very successful and popular opera singers.

Cesare Angelotti – Liborio Angelucci (1746-1811) was a Roman Republican in the eighteenth century, and was likely the inspiration for the character of Cesare Angelotti. In 1794, he was arrested and imprisoned in the Castel Sant’Angelo for working against the Roman government. Angelucci was part of a circle of intellectuals who were interested in new democratic ideals.

Palazzo Farnese (Farnese Palace) where Scarpia resides - designed by Giuliano de Sangallo, this is considered to be the most impressive Roman palace of the sixteenth century. It was built for Cardinal Allesandro Farnese, who later became Pope Paul III. The façade is three stories tall and thirteen bays (or windows) wide. The palace was purchased by the king of Naples. Puccini’s Tosca takes place during this time and Scarpia’s apartment would have been on the top floor. Since 1874, the Palazzo Farnese has been home to the French Embassy.

Baron Scarpia – Baron Sciarpa (notice the spelling change) was a recently appointed Bourbon police officer at the time that the book, La Tosca, was written. After being dismissed from his post as chief of the palace guard, he became a powerful mercenary soldier. He raised his own mercenary army and pillaged the country in the region of Salerno, in the name of the true king, Ferdinand IV. When Ferdinand IV was restored to the throne, he rewarded Sciarpa with the title of “Baron,” along with a large estate and an annual income.

In a production in Hamburg, Plácido Domingo broke the cartilage in his nose duringtheActII“Vittoria!Vittoria!”scene. A doctor examined him during intermission and determined that it would not affectthequalityofhisvoice.Plácido finished the performance with a standing ovation.

Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle (Church of Saint Andrew of the Valley)–The church was built in 1591, and contrary to the story of Tosca, there is no painting of Mary Magdalene inside. Instead, enormous frescos by artists Mattia Preti and Domenichino depict episodes from the life of St. Andrew. There is also a statue of St. John the Baptist by Pietro Bernini.

Battle of Marengo – The Battle of Marengo, whose mention interrupts the second act, was fought on June 14, 1800, and brought to a close the last of the French Revolutionary Wars. Napoleon Bonaparte gathered an army at Dijon and marched into Italy, determined to regain the territory lost to the Austrians. However, a surprise attack by the Austrians at Marengo caught Napolean with his forces scattered. A French defeat seemed imminent until the arrival of a French division led by General Desaic de Vaygoux. The French were then able to counterattack the Austrians and win the battle.

When the star of the Athens Opera Company’s production of Tosca fell ill on open- ing night, Maria Callas, the understudy, was given her first big break. Just before the curtain rose, how- ever, Callas overheard a stagehand exclaim, “That elephant can never be Tosca!” Outraged, the young soprano leapt upon the man, tore off his shirt and bloodied his nose. Just as her bruised eye was beginning to swell from the fight, she made her entrance on stage and dazzled the audience with her spectacular performance.

Mario Cavaradossi – The character of Mario Cavaradossi was probably based on the Roman artist Giuseppe Ceracchi (1751-1801). Ceracchi worked in France during the eighteenth century and would have been in the same intellectual circle as Liborio Angelucci. Ceracchi once sculpted a bust of Angelucci’s wife, which is now housed at the Museum of Rome. He eventually fled to the United States, where he became acquainted with Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson, Adams, and Lafayette. He created busts of Washington (now in The New York Public Library and the Metropolitan Museum) and Jefferson (in Monticello), and an alabaster profile of Madison (at the State Department, Washington). At one point, Ceracchi tried to assassinate Napoleon!

In order to compose the music of the morning bells of Act III, Puccini required a list of all of the churches surrounding Castel Sant’Angelo and their bells, including their respective pitches. Puccini wanted to replicate the pitches exactly, to ensure historical accuracy.

During a production at the San Francisco Opera, a last minute casting change placed a group of extras onstage as the firing squad at the end of Act III. With no rehearsal time, they were instructed to enter, shoot, and then exit with the principles. Once on stage, there was some confusion as to whom they were supposed to shoot. Since the woman (Tosca) was singing, they decided to shoot her. Much to their surprise, it was the man (Cavaradossi) who fell to the floor. Seeing Tosca jump from the rampart into the Tiber River, and realizing there were no more principle actors on the stage, the soldiers followed Tosca’s lead. They leapt off the rampart, causing a mass suicide!

The role of Tosca is one of the most famous in all opera. Several stars can be credited with helping to originate the role and set the standard for what you will see at the dress rehearsal.

The first person ever to play the role of Tosca on stage was the famous nineteenth century actress, Sarah Bernhardt. “The Divine Miss Sarah” was considered one of the first real stars of the stage. Victorien Sardou (1831-1908) wrote the stage play, La Tosca, especially for her. Puccini saw her performances in Milan in 1890 and in Florence in 1895. Though Puccini only spoke a few words of French, he fell instantly in love. Bernhardt’s portrayal of Tosca not only inspired Puccini’s opera, but set the standard for future productions.

During the nineteenth century, one of the most popular forms of entertainment was the melodrama. In its popular usage, a melodrama is generally defined as a stage play—usually with a romantic and sensationalized plot—with music added to heighten emotion and intensify situations. Often a melodrama includes special effects such as fire, explosions, or earthquakes; and the dialogue is spoken over musical accompaniment. Today, we think of melodrama as being a highly emotional, overly dramatic rendition of an event. When something is described as “melodramatic,” it has a negative connotation. The exaggerated acting and simplified characters (hero, heroine, and villain) of melodrama contrast sharply to the highly developed characters and intricate plots of opera. Or do they? Is there really such a great difference between melodrama and opera?

Musicologist Joseph Kerman once described Puccini’s Tosca as that “shabby little shocker.” Critics have often dismissed Puccini’s work as melodramatic and sentimental. This, however, doesn’t necessarily mean it is bad. If you contrast opera to melodrama, both involve the use of music to heighten emotion and situations, though music, of course, plays a far more significant role in opera. The words in opera are sung, rather than spoken as in melodrama, but does that make it any less dramatic? Most melodramas portray a simplified morality tale of good against evil. The anguish that the hero or heroine must go through at the hands of the villain is usually central to the plot.

Is Tosca a melodrama? The heroine of the opera, Tosca herself, is agonized at the hands of the evil Scarpia. The villain and the hero are clearly defined. However, Puccini was very interested in incorporating real life drama and emotion in his composing. Are the elaborate plots, costumes, and characters that typify opera really just covering up for a simple melodrama? Is Tosca just the heroine who will do anything to save the man whom she loves?

While it is clear that opera and melodrama have many similar characteristics, it is important to compare and contrast their differences.

In 1900 Hariclea Darcleé sang the world premiere of the operatic version of Tosca. It was a few years later when, during a revival of the production, another singer made an indelible impression on the role of Tosca. While on her way to the sofa from which she was supposed to sing “Vissi, d’arte,” Maria Jeritza slipped and fell. Not wanting to break character, she began singing her aria from that position on the floor. Puccini, enthralled with her dramatic performance, changed the blocking of the scene. Even in today’s productions, after struggling with Scarpia, Tosca falls to the ground and addresses her aria to heaven, rather than to Scarpia. Maria Jeritza’s simple accident actually changed the characterization of Tosca. The “new” staging reinforces the character’s Christian beliefs, and adds poignancy to the end of the

act when she places the candles around Scarpia’s corpse.

Current performance standards were set 40 years ago when the role was sung by Maria Callas at Royal Opera House Covent Garden in 1962. Wanting to perfect the character, Callas practiced picking up the knife to stab Scarpia sixteen different ways and analyzed each time how this gesture affected the character of Tosca. This attention to dramatic detail has set the gold standard not only for the interpretation of Tosca, but also for all operatic roles.

Opera companies will continue to produce Tosca in new and innovative ways. What will not change is the lasting effect that these three women will continue to have on the character of Tosca.

You will see a full dress rehearsal of one of the most popular operas of all time—Puccini’s Tosca—in the Kennedy Center Opera House. Performed by some of the world’s most acclaimed opera stars, Washington National Opera’s featured artists will offer you a rare insider’s look into the final moments of preparation before an opera opens to the public.

The characters will be in full costume and makeup, the opera will be fully staged, and a full orchestra will accompany the singers. Because it is so close to opening night, the dress rehearsal is often a complete run through, but there is a chance that the director or conductor may ask to repeat a scene or two. The dress rehearsal is the last opportunity the singers will have on stage to work with the orchestra before opening night; they need to take advantage of this valuable time to work. Since vocal demands are so great on opera singers, some singers may choose to mark (not sing in full voice) during the dress rehearsal in order to preserve their voices and avoid unnecessary strain. The rehearsal will be sung in Italian with English supertitles projected above the stage.

The estimated running time for this rehearsal of Tosca is two hours and 31 minutes with two intermissions.

In the early 1960’s, during a production in NewYork,Toscawasassuredthathersuicide jumpofftherampartwouldbeprotectedbya mattressandatrampoline.Attheendofthe opera,Toscaleaptofftherampartanddid land on the trampoline – only to bounce back up again in full view of the audience!

The following list will help you enjoy the experience of a night at the opera:

• Dress in what is comfortable whether it is jeans or a suit. “Fun casual” is usually what people wear—unless it is opening night, which is typically dressier. A night at the opera can be an opportunity to get dressed in formal attire.

•Arrive on time. Latecomers will be seated only at suitable breaks—often not until intermission.

• Please respect other patrons’ enjoyment by turning off cell phones, pagers, watch alarms, and other electronic devices.

continued on the back page

•At the very beginning of the opera, the concertmaster of the orchestra (the violinist who sits closest to the conductor) will ask the oboe player to play the note “A.”

Listen carefully. You will hear that all the other musicians in the orchestra will tune their instruments to match the oboe’s “A.”

• After all the instruments are tuned, the conductor will arrive. Be sure to applaud!

•Feel free to applaud (or shout BRAVO!) at the end of an aria or chorus piece to signify your enjoyment. The end of a piece can be identified by a pause in the music. Singers love an appreciative audience!

• Go ahead and laugh when something is funny!

•Taking photos or making audio or video recordings during a performance is not allowed.

• Do not chew gum, eat, drink, or talk during the perform-

EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY PROGRAMS OF WASHINGTON NATIONAL OPERA ARE MADE POSSIBLE BY THE GENEROUS SUPPORT OF THESE FUNDERS:

as of March 7, 2005

$50,000 and above

Mr. and Mrs. John Pohanka

National Endowment for the Arts

$25,000 and above

Bank of America Foundation

Chevy Chase Bank

Fannie Mae Foundation

Prince Charitable Trust

$10,000 and above

Anonymous Foundation

Dominion

Jacob and Charlotte Lehrman Foundation

The Washington Post Company

Dr. and Mrs. Hans P. Black

$5,000 and above

International Humanities

TJX Foundation

Washington National Opera Women's Committee

$2,500 and above

Mr. Walter Arnheim

The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation

Target Stores

The K.P. and Phoebe Tsolainos Foundation

Clarke-Winchcole Foundation

$1,000 and above

Paul and Annetta Himmelfarb Foundation

Horwitz Family Fund

continued from page 7

ance. If you must visit the restroom during the performance, please exit quickly and quietly. When you return, an usher will let you know when it is appropriate for you to return to your seat. Let the action on stage surround you. As an audience member, you are a very important part of the process that is taking place. Without you, there is no show!

•Read the English supertitles projected above the stage. Usually operas are performed in their original language. Opera composers find inspiration in the natural rhythm and inflection of words in particular languages. Use the supertitles to gain better understanding of the story.

• Listen for subtleties in the music. The tempo, volume, and complexity of the music and singing depict the feelings or actions of the characters. Also, notice repeated words or phrases; they are usually significant.

Have fun and enjoy the show!

Founded in 1956,Washington National Opera is recognized today as one of the leading opera companies in the United States. Under the leadership of General Director Plácido Domingo,Washington National Opera continues to build on its rich history by offering productions of consistently high artistic standards and balancing popular grand opera with new or less frequently performed works.

www.dc-opera.org

Please contact Education and Community Programs at Washington National Opera with any questions and/or requests for additional information at 202.448.3465 or education@dc-opera.org.

Text:

Meghan Dunn,Intern, Washington National Opera

Education and Community Programs

Contributors:

Gianna Wichelow,Creative Manager, Education and Outreach Department,Canadian Opera

Graphic Design:

LB Design NEED