BAA A A L O VE FALL 2022 WORLDING RICKER EST. 1953

BAA A A L O VE

From social autonomy and the agency of scale to mutual aid and the climate crisis, the following issue of the Ricker Report takes a glimpse into worlds that could have been and those that are still yet to be. Interrogating histories of colonization, material extraction, and consumerism, the work of our featured artists, architects, and designers construct narratives that pull back the curtains to the construction of these worlds and the communities that helped build them. These narratives show that the world we inhabit is and will always be constructed of many worlds and can only be built with even more people.

In our current context, we present the building of these narratives as acts of worlding. Inspired by post-colonial thinkers and our relationship with non-human inhabitants, worlding provides us with a platform to recognize and celebrate worlds that have historically been rejected, forgotten, and unrepresented. We see our newest installment of the Ricker Report as an opportunity to recenter our future around worlds and communities that have been considered as the “other” for far too long.

In the future, the Ricker Report will continue to stand as a platform for worlding and collective action. We believe that we can only build a more just and sustainable world when we are able to stand hand-inhand and learn from one another. The worlds to come will require a collective act of worlding.

Other worlds are possible.

The Ricker Report Team

Editor-in-Chief

Shravan Arun

Art Director

Denise Carmona

Graphic Designers

Daniel Bogdal

Emilie Cooper

Giorgio D'Attoma

Runyan Guo

Pushpanjli Mehra

Lead Editors

Gabriela Abril

Alejandro Toro-Acosta

Editors

Rhea Dulipsingh

Eneyda Salcedo

Chrisvin Tel Nova Rathnakumar

Daniel Tsai

Faculty Advisor

Joseph Altshuler

Architecture for Social Transformation Scale Down to Take Up Space

Comunal Reza Nik

Of Artifacts and Time

Liz Gálvez

The Last Impervious Surface in Portage County Ohio

Galen Pardee

Antifascist Architectural Annotations

Andrew Santa Lucia

Critiquing and Legitimizing Reality through False Identities and Highly Rendered Utopias/Dystopias

William Hohe

6 26 50 72 86 108

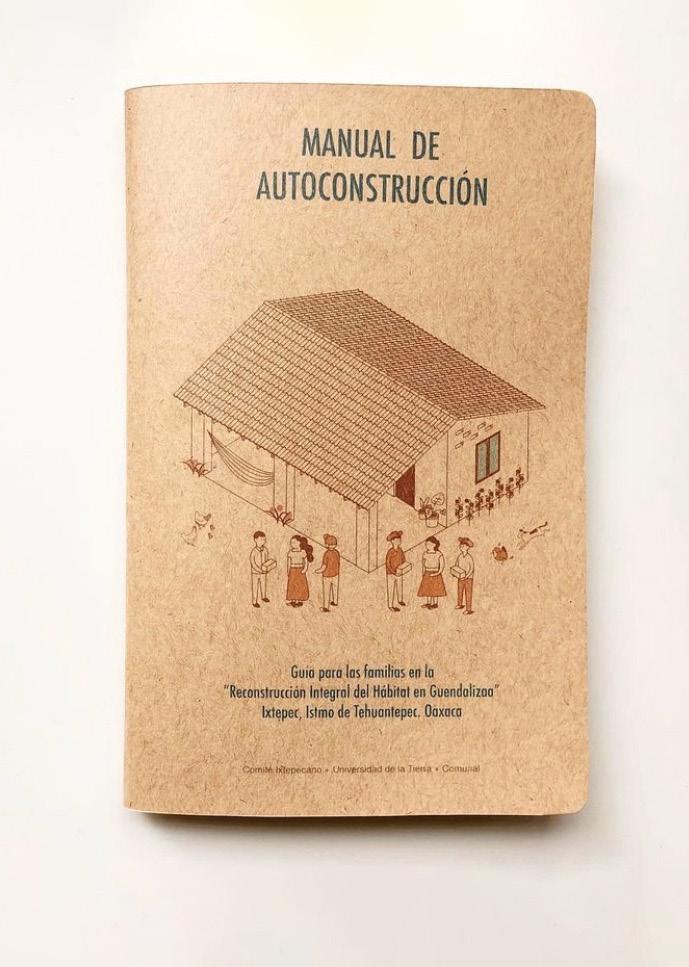

COMUNAL Comunal is an interdisciplinary group made up of women who collaborate integrally with organized groups, collectives, and inhabitants in the design, management, defense, and self-production of their habitat. They collaborate under the complex vision of the “Social Production and Management of Habitat”, an ethical-political position that starts from recognizing habitat as a collaborative social process and participation as a collective right. Therefore, they do not conceive architecture as a work of individual authority or as a static, artistic, and immovable object, but as a participatory, evolving, and in constant transformation process that recognizes people as subjects of action and not as objects of intervention.

Comunal's collaborative practice has led them to reflect critically on what they call the “architecture of patriarchy”, the hegemonic professional work that operates from the racist, capitalist, and colonialist vision of modernity, to accommodate for a transformative idea: everyone has the creative, political, epistemic, and organizational agency to design and produce their habitat collaboratively.

ARCHITECTURE FOR SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION COMUNAL

The practice of traditional architecture is based on the complex understanding of inhabiting, the collective production and transmission of knowledge, the construction of the habitat through communitary processes of mutual aid that strengthen the social fabric, as well as cultural and territorial identity. It is a practice of community self-production where the inhabitants, without intermediaries, are the ones who manage the multiple processes involved in the production and transformation of the habitat and themselves. In other words, the creative activity of praxis (understood by Sánchez Vázquez as praxis for social transformation and revolution) is a process not only of self-production of the habitat but also of self- production of the collective consciousness through the dialectical and recursive relationship between reflection-action or theory-praxis. Here lies the importance of critical reflection and the philosophy of praxis: recognizing ourselves as historical beings with the ability to collectively transform and produce our social reality.

Otherwise, the past centuries of architecture have gone from being a diverse common good at the service of people (for the production of habitat and collective consciousness) to a hegemonic practice whose purpose is the accumulation of capital and domination, leading to alienation, the transformation of socio-ecological relations and the fetishization of architecture: where architecture is understood as an object (commodity) and not as a process and network of social relationships. This type of practice, despite continuing to require the organized participation of various actors, attributes its production to an individual author: an entity that, without having the multiple knowledge necessary to carry out a job from start to finish, can be recognized as the mastermind behind the architectural object, hiding social relations of exploitation, dispossession, racism, coloniality, and violence.

WORLDING 8

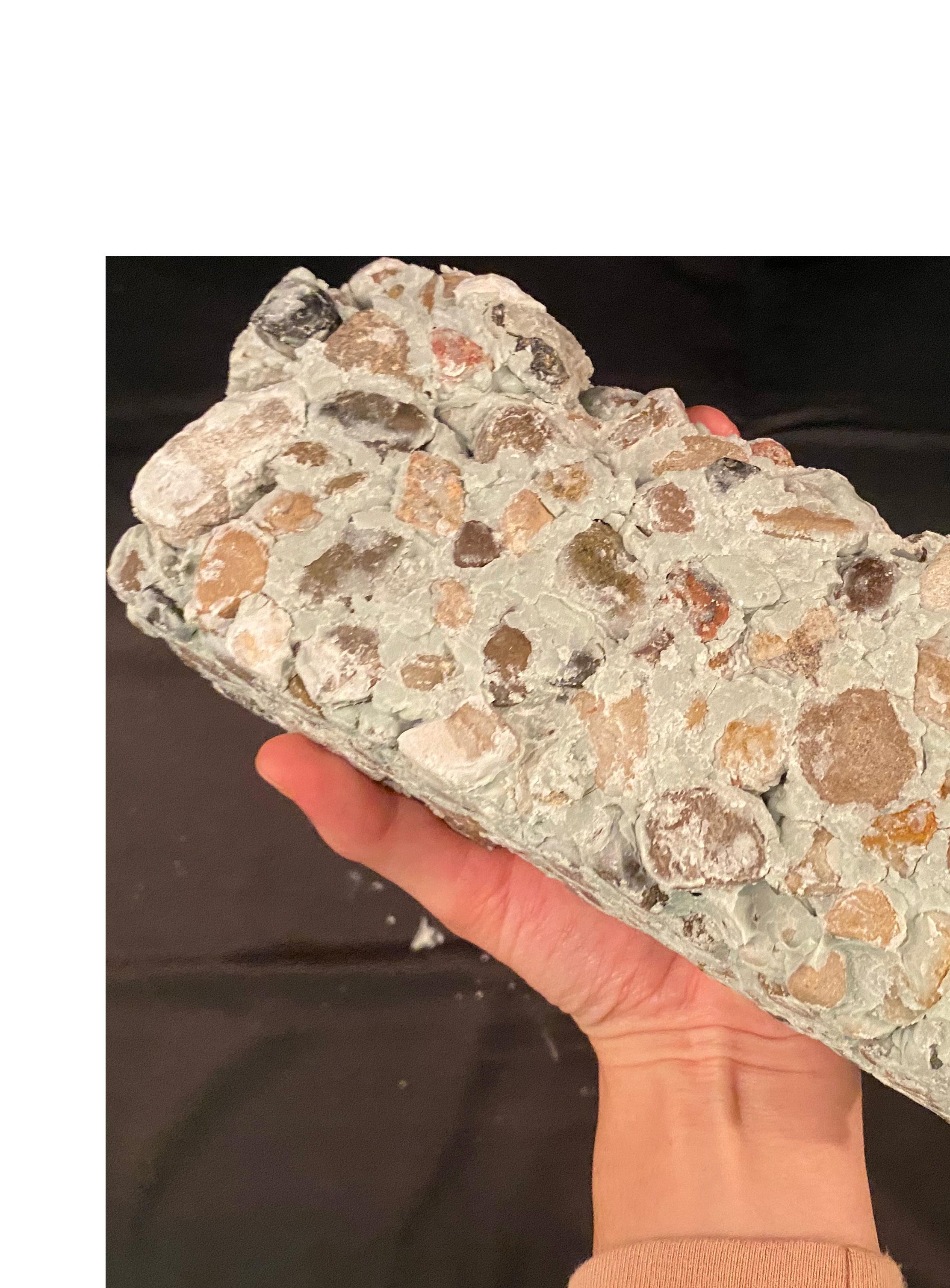

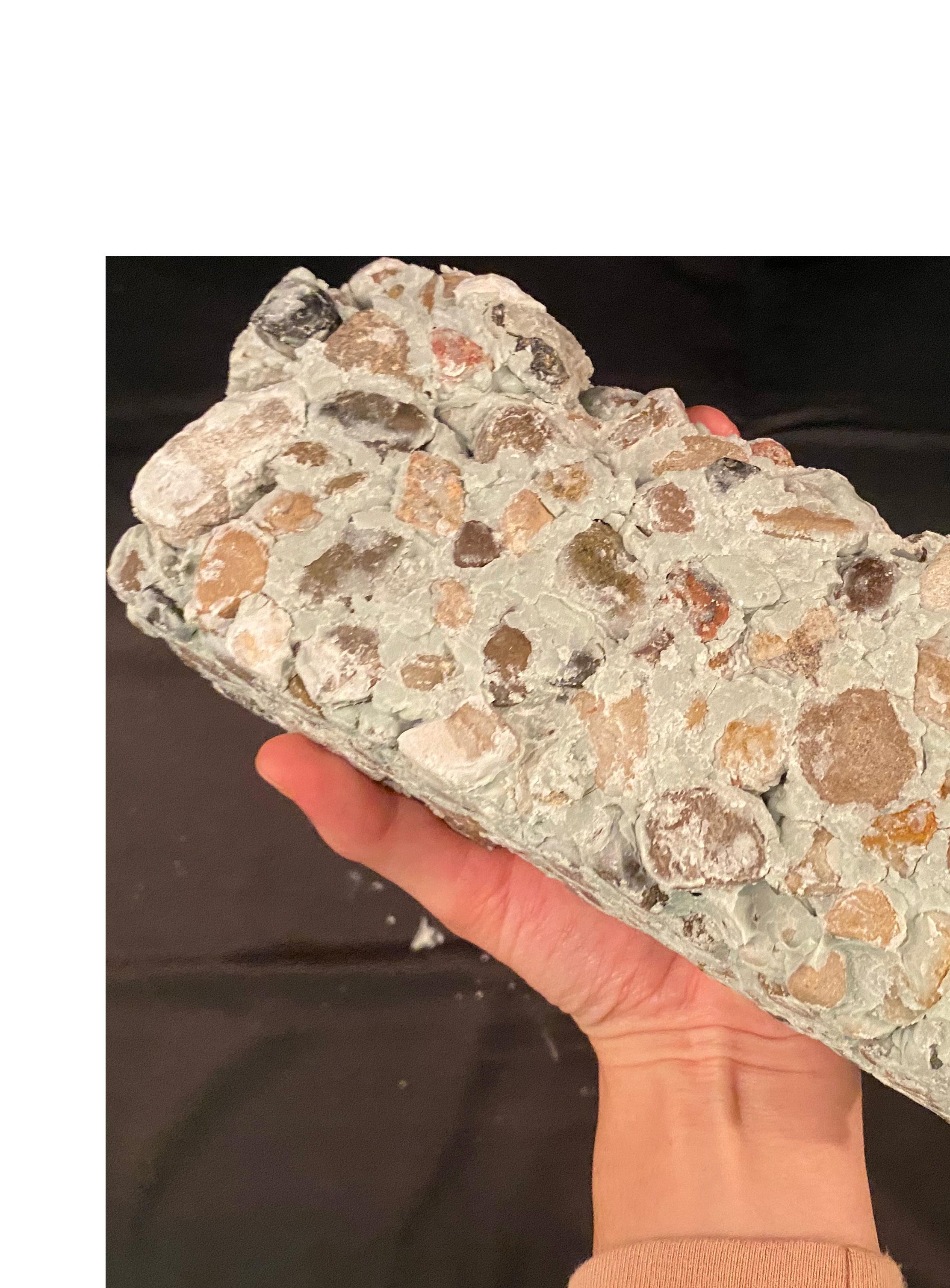

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Violence, defined by Sánchez Vázquez as the denial of the creative capacity of the human being, is related to the hegemonic vision of a social order that fragments the collective and places the market (and the accumulation of capital) as its main axis (Herrera et al., 2020), leaving aside the collective subject. There are different types of violence, however, they do not operate in isolation. On the contrary, the forms of violence that we present here (which we have identified from our learning by doing through integral accompaniment) are part of an interdependent and articulated economic-political system that generates great social inequalities. Therefore, we consider it urgent to rethink together the ways in which we exercise our praxis: what actions reproduce violence from architectural practice in the multiple dimensions that conform inhabiting? What hegemonic thoughts and conceptions of architecture reproduce acts of domination, dispossession and exploitation?

Epistemic violence:

Marginalize or make invisible the knowledge of people in the management, design, and production of their habitat, validating only the knowledge generated in hegemonic academic spaces and "professional" spheres, reproducing racism and the coloniality of knowledge (Anibal Quijano).

Appropriating multidimensional collective knowledge (construction techniques, medicinal, productive, textile, ritual, etc.), exercising extractivism, and epistemic dispossession.

Considering traditional ways of living and vernacular architecture as backward, deny traditional constructive knowledge as appropriate, and appropriable community sciences to the socioecological context.

Enviromental violence:

Denying the right of the inhabitants to participate and decide the future of their territory.

Exploiting and putting at risk the natural assets that sustain the life of communities, for example, through real estate development that embodies accumulation by dispossession (David Harvey), expelling people from their territories (and cities), and breaking the socioecological relationships established in them.

Making invisible the production of nature and the uneven development (Neil Smith) generated by the extraction of construction materials.

COMUNAL 11---

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Economic violence:

Imposing megaprojects and architectural projects that promote a capitalist and developmentalist economic model that displaces people from their territories (and cities) and puts their economy at risk.

Introducing construction technologies for the accumulation of capital at an accelerated rate (such as 3D printers used to produce houses in Mexico) and not the democratization of science and redistribution of power, undermining traditional trades, local production chains, and solidarity economies.

Using architecture as a means of accumulation through touristification (of rural and urban areas), causing an increase in the cost of living and the eviction of the inhabitants.

Institutional violence:

Implementing institutional programs and public policies that promote unworthy forms of living (such as minimum housing) that only benefit the economic, political, and quantitative interests of power groups: politicians, developers, architects, among others.

Applying decontextualized, racist, and technocratic construction rules and regulations that homogenize the habitat and erase people's technical-constructive and territorial knowledge.

Generating population censuses that characterize non-hegemonic ways of life as precarious. For example, in Mexico a dwelling that uses traditional constructive systems and local materials (bamboo, palm, wood, reed, bajareque, etc.) is considered precarious. This leads to replacing constructive cultures with prototype and authorial housing models.

Based on the above reality, it is necessary to understand participation as a collective right that recognizes people of any social class (and not only the dominant social classes) as subjects of action and not as objects of intervention, with the capacity to decide the future of their habitat through intercultural processes that necessarily imply political solidarity and class consciousness (bell hooks). Autonomous participation, and not forced, simulated, and instrumentalized participation for political and economic purposes, is a necessary tool for social transformation and spatial justice. From this ethical-political position, architecture must no longer be conceived as a work of authorship or as a static and unmodifiable object; but as a living, open, and evolving social process that operates at the individual and community level with the ability to transform our collective consciousness, the way we produce our habitat and our social reality.

WORLDING 14

---

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

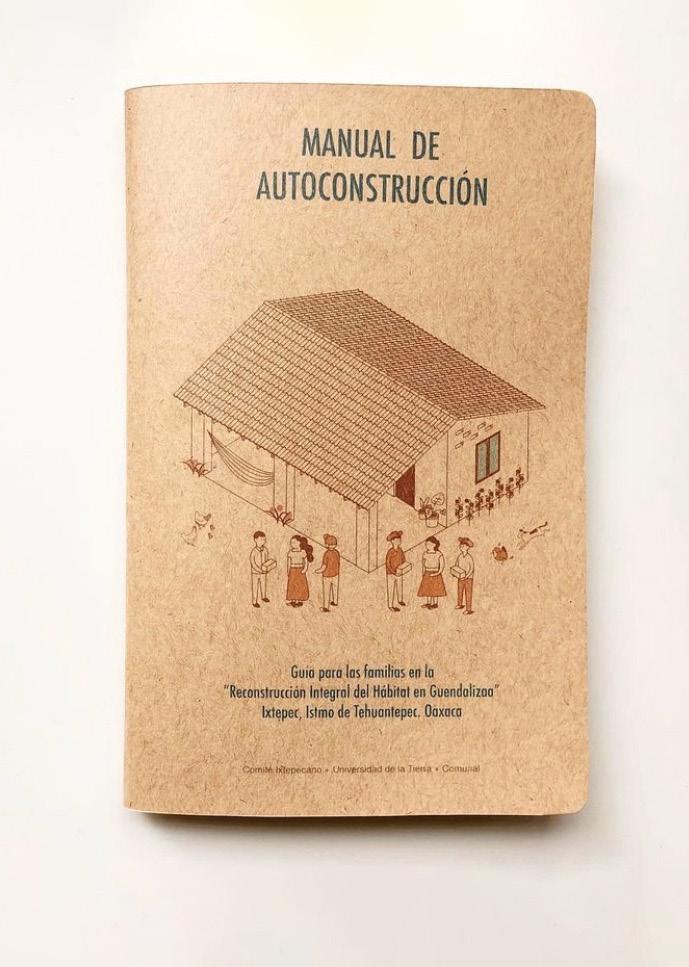

The Social Production and Management of Habitat [SP&MH], a concept [theory] coined by Enrique Ortiz in the 1960s and an architectural practice [praxis] that has been developed for more than 50 years in Mexico and Latin America, conceives the habitat as a dialectical relationship: as a product and producer of socio-ecological relations that implies the active, informed, and organized participation of the inhabitants in its management and development, under the control of self-producers and other social agents, where use value (social needs) is prioritized over exchange value (merchandise).

Although it is true that self-production and self-construction have multiple challenges for the inhabitants (technical, economic, political, organizational, administrative, etc.), these challenges cannot be reduced to the design of the architectural object, as it would be leaving aside the systemic and complex vision of inhabiting. In this sense, participation focuses on the recognition of the social subject through an integral accompaniment during the diagnosis of strengths, challenges and needs, the construction of collective strategies, the search for the efficiency of the economic and material resources of the inhabitants, and the strengthening of the community organization. Speaking exclusively from a technical perspective, the solution is not to replace the self-producer but to recognize that the only way to address the challenges related to the production of the habitat, without replicating structures of oppression and violence, is through participation and recognition of otherness with a respectful accompaniment that promotes the horizontal exchange of knowledge. Also, an integral accompaniment (technical & social) must be understood as a diverse epistemic practice in order to address the complexity of the habitat. That is to say, it is not an exclusive task of professionals, much less a process that should be carried out only from technical and architectural knowledge.

For the above, we would first have to unlearn and disarticulate the academic discourse that we have been introduced to since our formation: design as a sublime act that can only be performed by a few endowed with cultural capital for that purpose. It is necessary to eliminate the romantic vision around participation as an "inclusive" practice granted by professionals or institutions to the inhabitants and recognize it as a collective right that strengthens the autonomy and self-management of urban and rural communities. A political and ethical stance that rejects assimilation and finds its values in the diversity of thought and the collective construction of knowledge and, finally, an anti-colonial, anti-patriarchal, and antiracist vision that defense the free self-determination of each community.

It is essential the importance of training architects capable of working from decolonial positions that reject the hegemonic, patriarchal, and neoliberal discourses of technocratic education. This type of academic training requires a critical pedagogy that allows us to exercise the philosophy of

COMUNAL 17

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

praxis, in the words of Paulo Freire: "critical teaching practice, implicit in thinking correctly, encloses the dynamic and dialectical movement between doing and thinking about doing." Critical pedagogy for freedom also invites us to reflect on the impossibility of having a neutral and depoliticized practice, since it is precisely our reality as historical beings that leads us to take an ethical-political position, whether or not we are aware of it. In this regard, Sánchez Vázquez argues that depoliticization creates a consciousness vacuum (useful for the dominant classes and power groups) that is filled by the dominant hegemonic ideology, which leads us to a repetitive practice and distances us from the philosophy of praxis. In this sense, if we want to move away from an alienated and violent practice, the only alternative for hope and transformative praxis is to politicize design through critical thinking.

“Participation is not a matter of good faith, assistance or good will. It is not the sharing of ignorance and altruistic voluntarism, nor is it a simple methodological question of instrumental reason. From the vision and stance of SP&MH, participation is understood as an ideological, political and democratic posture.”

The processes of integral accompaniment, based on the theoretical-practical vision of Social Production and Management of Habitat, are focused on raising social awareness through political training and popular education, as well as strengthening the community fabric and autonomy, the organizational capacities of groups or collectives, legal and administrative accompaniment, the recovery of local construction systems and knowledge, the maintenance of productive chains and economies specific to each community (rural or urban), and the close relationship of the inhabitants with their territory. This implies recognizing that collective creativity is not found only in the design of the project but rather permeates each of the complex and recursive moments of participation. In other words, creativity is also manifested in the design of participatory tools, decolonial collective research, pedagogical processes of mutual learning, shared hopes, and social bonds. Always hand-in-hand with an integral accompaniment that has a clear ethical-political position and promotes collective rights to exercise a creative praxis that enables social transformation.

We must work for the construction of a world where many worlds can be.

WORLDING 20

Gustavo Romero. "Participación en el diseño urbano y arquitectónico en la PSH”.

Self-Build Manual Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Onnis Luque

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Onnis Luque

23

We must work for the construction of a world where many worlds can be.

— Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Onnis Luque

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Onnis Luque

BAA A A

REZA NIK

Reza Nik is a Toronto-based licensed architect, artist, and educator and the founding director of SHEEEP, an experimental studio working at the intersection of community, culture, and architecture with an interest in smallscale human-focused public projects. Reza comes from a background of Art History, and he is also an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto’s Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design. His research is focused on a deeper dialogue between the socio-political nuances of the urban context and playful experimentation. Disrupting the traditional architectural processes and institutions is at the forefront of his pedagogy and practice.

SCALE

DOWN

TAKE

UP

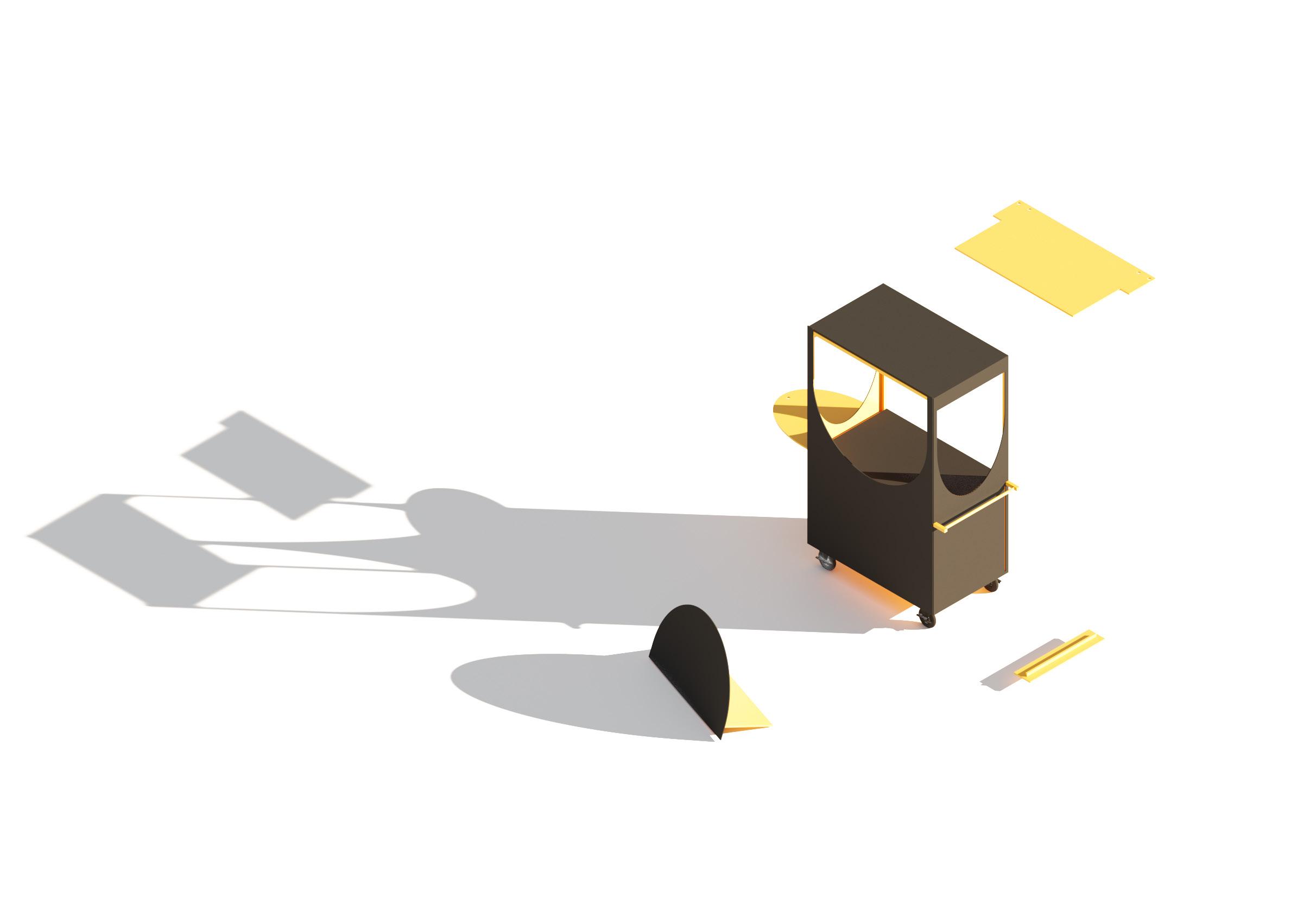

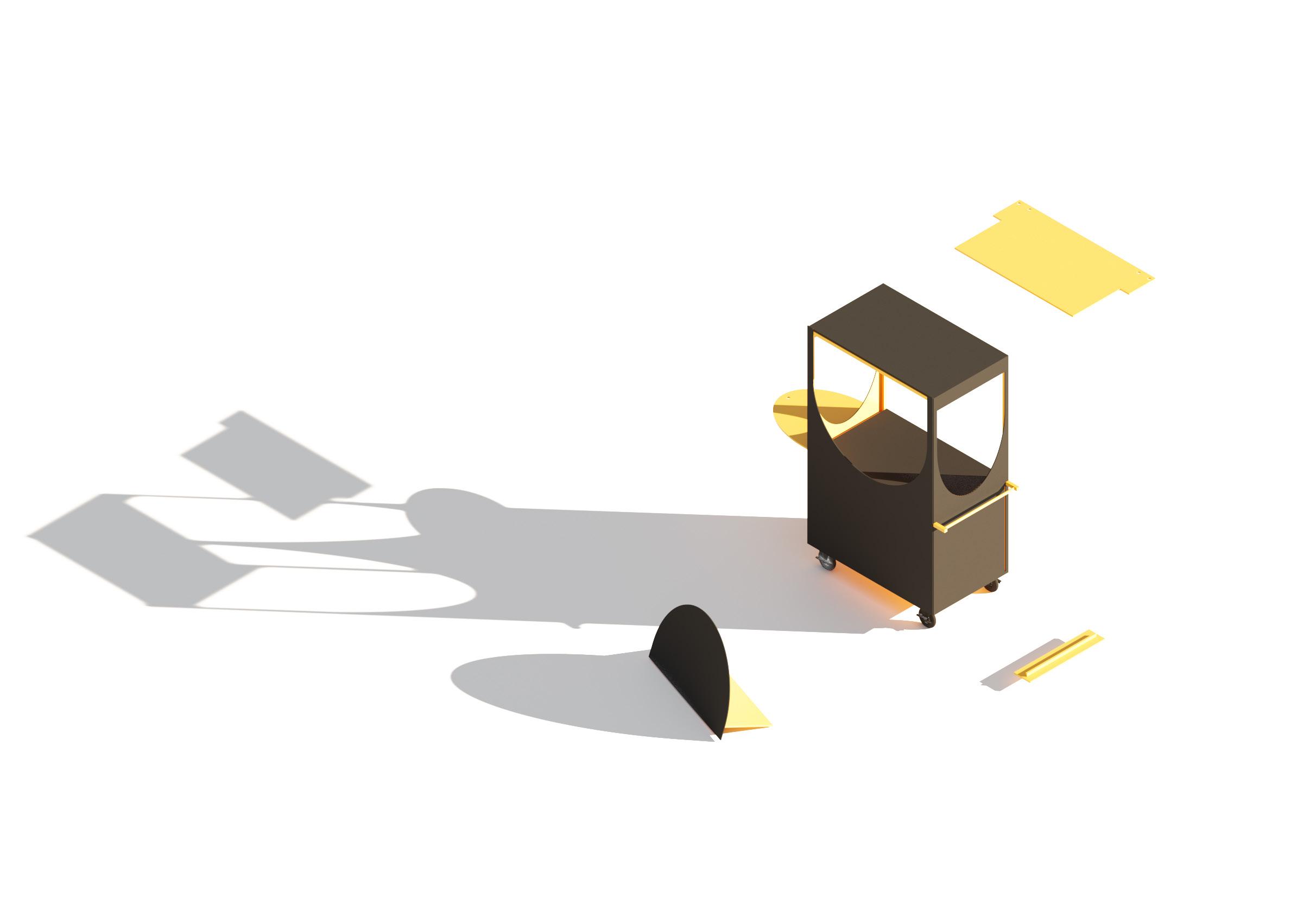

M-1

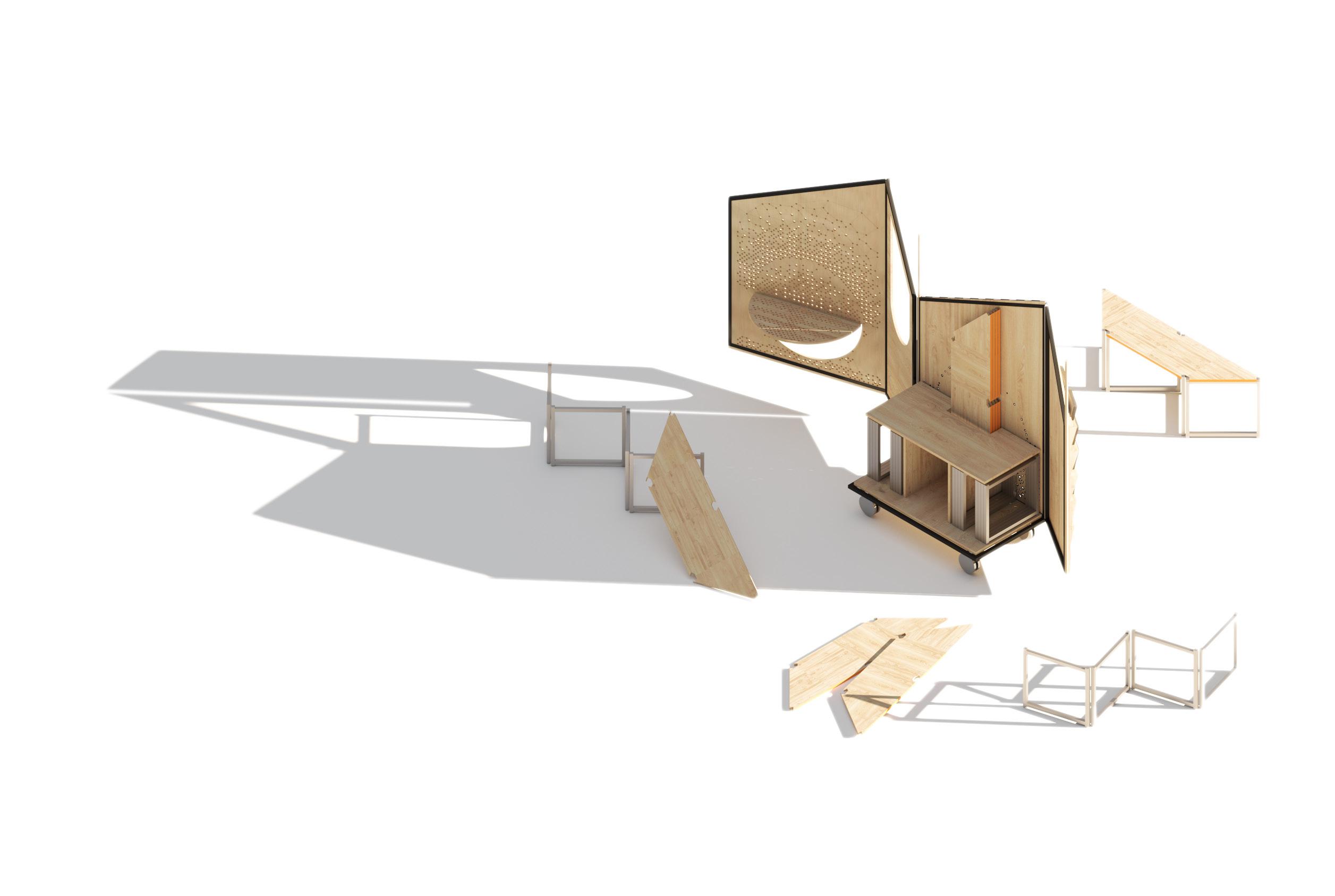

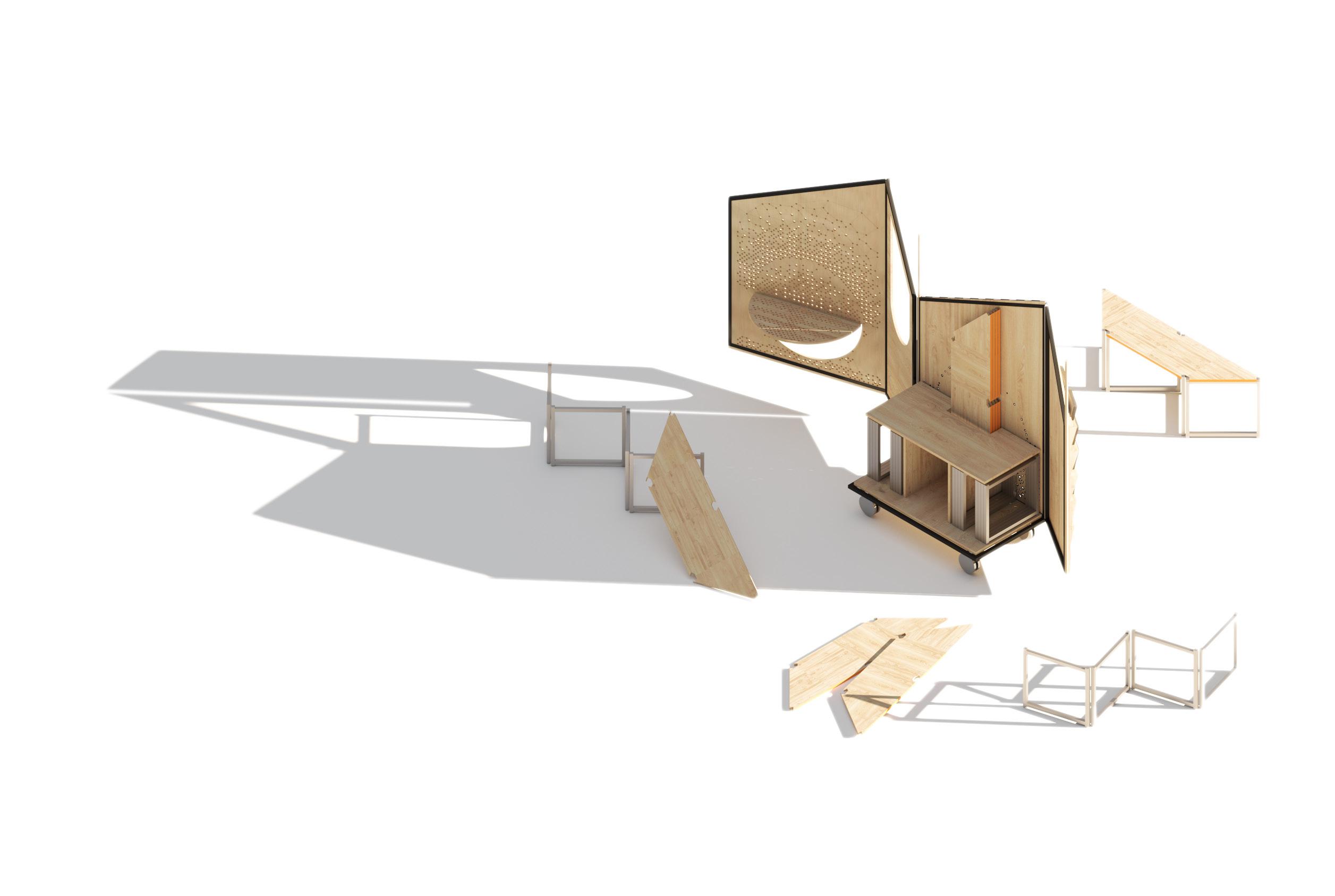

MOBILIZER 1.0 2019

This project was completed in a two-week intensive Design-Build course at the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at University of Toronto. The idea was to design and build a mobile structure for this important community organization that could function as an armature to take up (public) space, while acting as a storage unit in their tiny office. A fast-paced design and building exercise to produce a flexible structure for the community, with the community.

For: Parkdale Neighborhood Land Trust

Faciliators: Reza Nik, Andrew Winchur, and Angela Cho

Student Team: Aizah Bakhtiyar, Eunice Cheuny, Felipe Coral, Alejandra Cortez Paz, Dennis Fichman, Karen Gebara, Jane Guberman, Hannah Hui, Mehreen Khan, Bella Osterman, Sam Shahsavani, Bhavika Sharma, Sibora Sokolaj, and Zainab Wakil.

R ez A NI k 37

MOBILIZER 2.0 2020

Designed and built for an artistic intervention by Dana Prieto for the Beyond Extraction Counter-Conference and the People Before Profit rally held in response to PDAC (Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada) in 2020. As described by Prieto, ”Food Beyond Extraction is a food cart that mobilizes foods, written materials and conversations related to the impacts of and resistances to Canadian mining extraction in Global South territories. Our cuisine highlights foods and ingredients from regions whose land, food, and cultural rights are being threatened by Canadian mining projects in the three countries sponsoring PDAC this year.”

For: Dana Prieto & Food Beyond Extraction Collective

Collaborators: Aemilius Milo Ramirez, Meech Boakye, People Beyond Profit

Team: Reza Nik, Sam Shahsavani, and Ghazal Elmizadeh

WORLDING 38

M-2

M-3

MOBILIZER 3.0

2021

A project for a community kitchen in need of a set of mobile garden beds to support their 100+ free lunches per day that they provide to Toronto’s unhoused population. This project was about resourcefulness, and a collaborative design and building process with the client’s needs in mind.

For: Unity Kitchen TO Collaborators: Lily Jeon, Julia Nakanishi, Siobhán Allman, Mona Dai, and TAL-TO (The-ArchitectureLobby-Toronto)

R ez A NI k 41

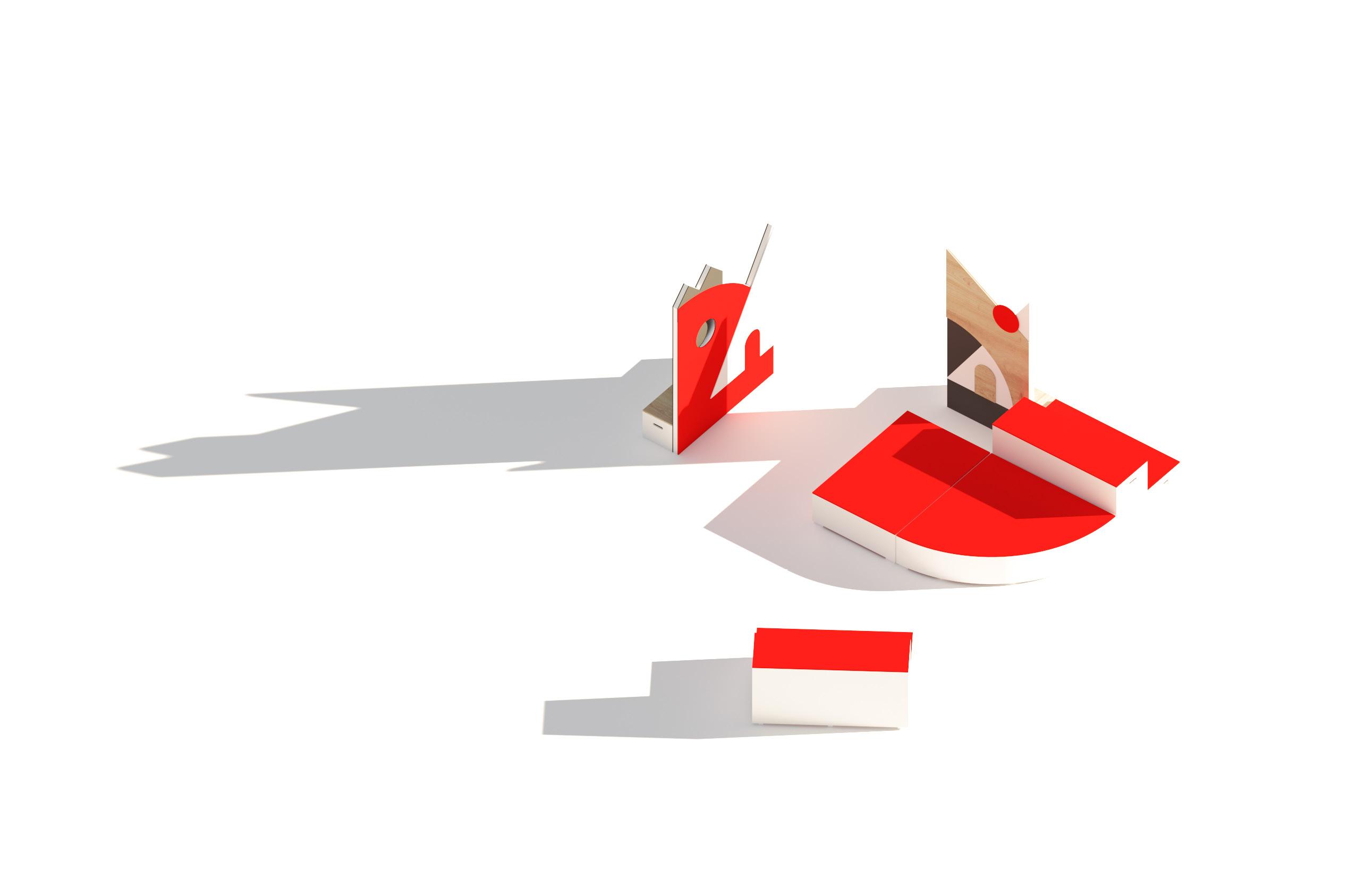

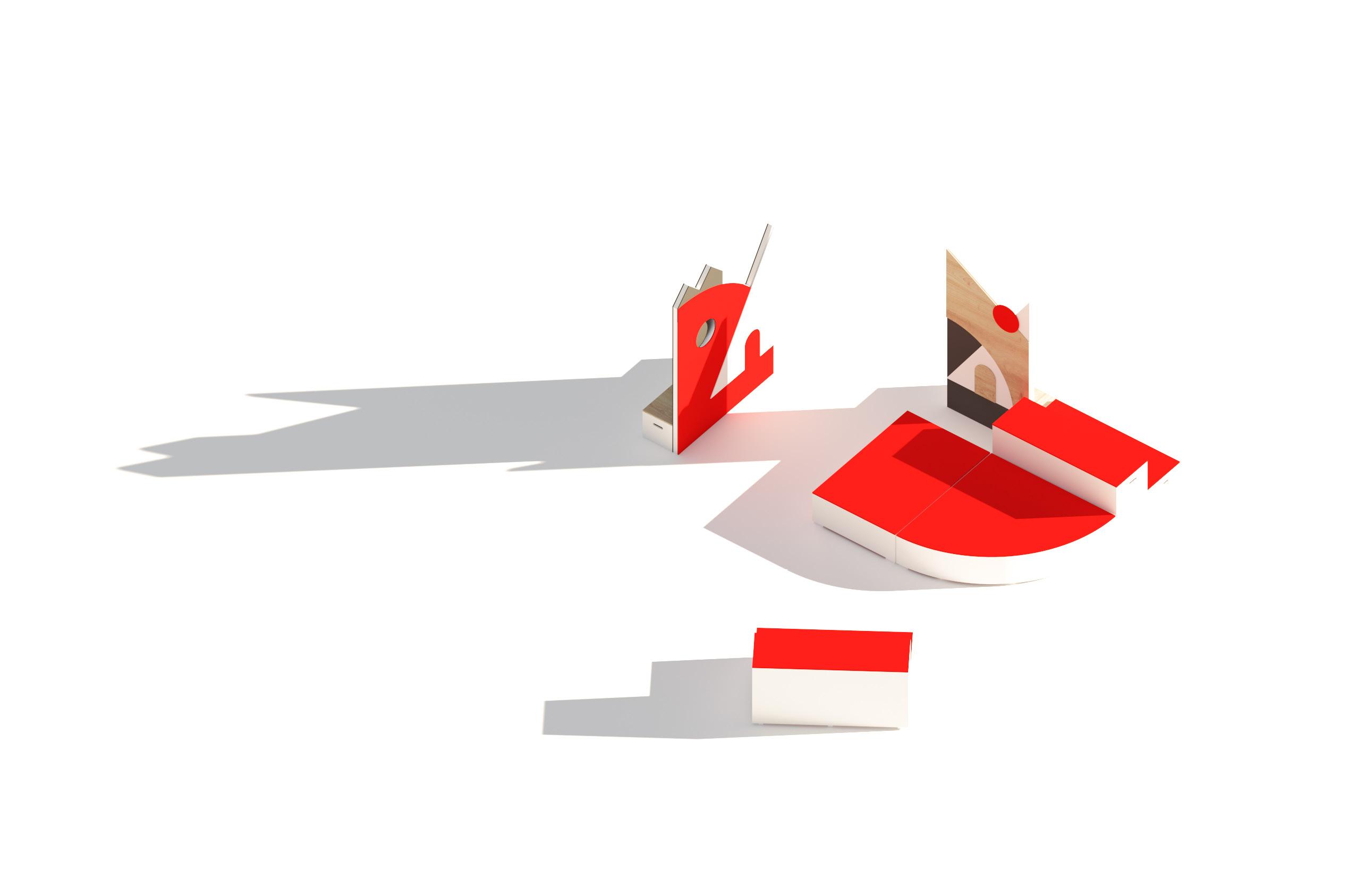

MOBILIZER 4.0 2021

A project for Homes First - a provider of affordable and stable housing who operate several transitional housing complexes. They needed a modular platform for various programming needs indoors and outdoors. The process was highly collaborative and involved designing, building, and painting with the community.

For: Homes First, North York Arts

Collaborators: Makeshift Collective (Aileen Ling, Derek Simmers, Nam Hoang, Dylan Johnston, Nassim Sani), Lily Jeong, Heather Breeze, and Muse Arts

WORLDING 42

M-4

M-5

MOBILIZER 5.0 2022

The Mobilizer 5.0 is a prop to facilitate conversations within a community—in this context, at the Malton Greenway in Mississauga—a suburb west of Toronto. As a multi-faceted performance piece, it occupied the site while engaging with the local community in discussing climate change and the importance of neighbourhood green spaces.

For: City of Mississauga, Temporary Public Art Team: Reza Nik and Connor Stevens

Mentees: Jada Wallace and Zaynab

R ez A NI k 45

Furniture Series 1.0 2022

This mobile & modular furniture series was designed for the antichamber of the locally loved queer theatre Buddies in Bad Times. Our scope included the conceptualizing, design and coordination of a variety of loose furniture pieces that could function for a variety of programmatic needs while being small enough to be stored away within the tiny room. The resulting design included two floor to ceiling half concealed storage niches that the furniture would tuck into when not in use. We also designed a modular two-piece bar on hydraulic wheels that could be moved around and set up for the different types of events.

For: Buddies in Bad Times Theatre

Team: Connor Stevens, Reza Nik, Yoon Chai

Builder: GoodSh.t Studio

WORLDING 46

F-1

Scale down to Take Up Space

SHEEEP % REZA NIK

Resist the urge to go BIG

We’re in need of small-scale thinkers & tinkerers, with visions of a better tomorrow. Resisting the urge to go big is powerful, It is counter to the norm, No more monumental utopias, dystopias or cities of tomorrow built from scratch, even if they are assembled by the best minds.

The Architect is not the savior. Architecture won’t save us.

We’ve got lots around us to build from, And lots of voices to learn from & build with, voices silenced for too long, working hard on the ground, with grass roots, growing movements.

Scaling down enables a sense of agency.

A - G - E - N - C - Y

Small is a seed, offer nourishment, and these small gestures can grow and take up space.

Wherever needed. go small.

R ez A NI k 49

LIZ GÁLVEZ

Liz Gálvez is a registered architect, directs Office e.g., and teaches at the Yale School of Architecture. She received an M.Arch. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a concentration in history, theory, and criticism of architecture and a bachelor’s degree in architectural and philosophical studies from Arizona State University. Her work focuses on the interface between architecture, theory, and environmentalism through an examination of building technologies.

Previously, Gálvez taught at the Rice School of Architecture and at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College, where she was the 2018–19 William Muschenheim Fellow. She has practiced at architecture firms in the United States and in Mexico, including Will Bruder Architects, NADAAA, and Rojkind Arquitectos. Her writing has been published in Footprint, Pidgin, PLAT, Thresholds, and POOL. Her work has been exhibited at MIT, the Hohensalzburg Fortress in Austria, the University of Michigan, the Space p11 Gallery in Chicago, and the Farish Gallery at Rice University. She received the 2021 Rice Design Alliance Houston Design Research Grant and the 2016 Seebacher Prize for the Fine Arts. In 2021, she was awarded the Architectural League Prize.

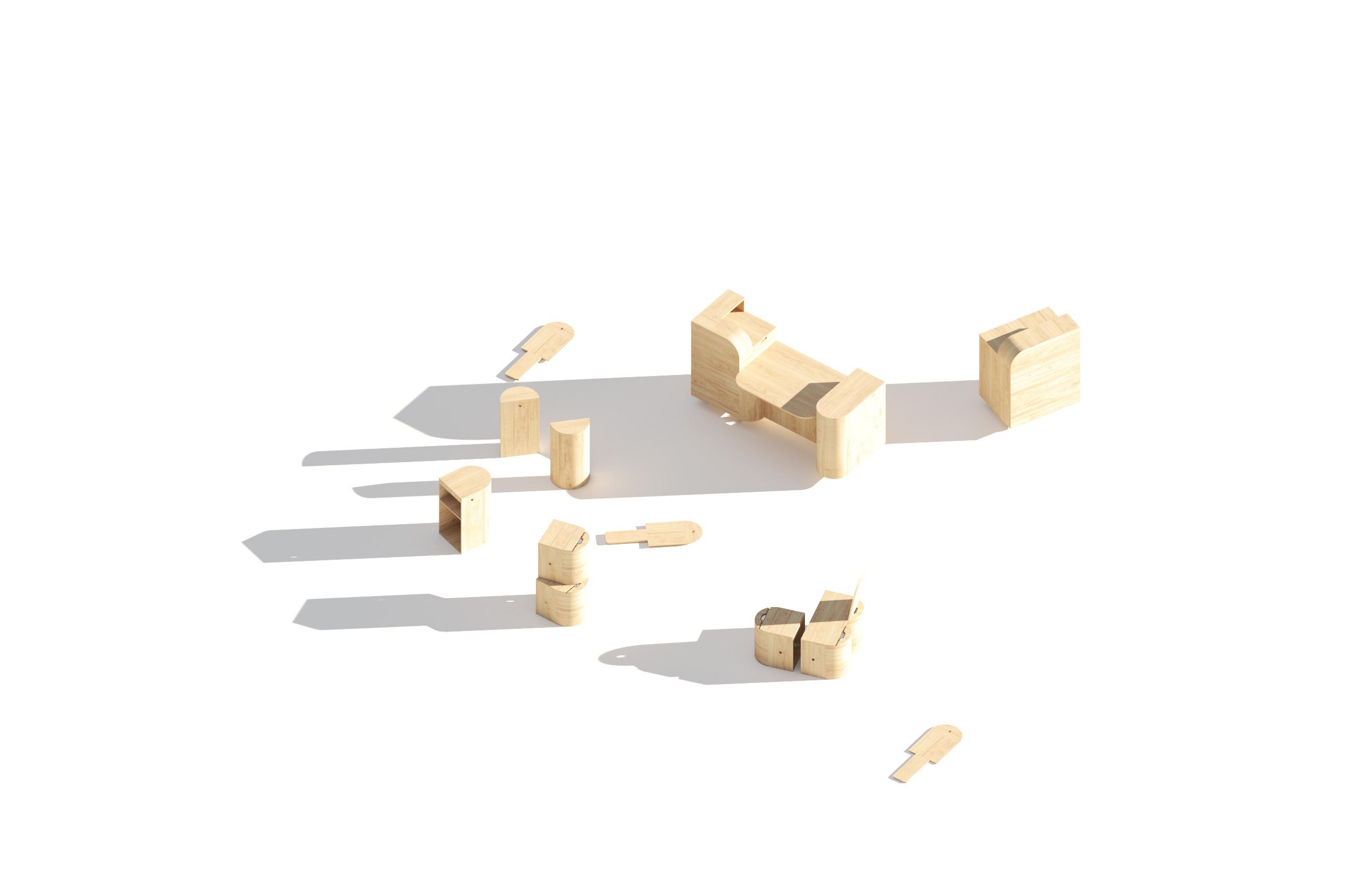

OF ARTIFACTS AND TIME

LIZ GÁLVEZ

“It seems that architects build in an isolated, self-contained, ahistorical way. They never seem to allow for any kind of relationships outside of their grand plan.”

- Robert Smithson, 1973, Entropy Made Visible.

In the Spring of 2022, I taught a first-year design studio at Rice University based in Houston, Texas. To familiarize the students with the most ubiquitous system of residential and small-scale construction, we presented the students with a hands-on exercise in wood framing systems. Curiously, and as many of our students come from an international background, the most pressing questions about this construction system were about durability. Will these materials last? How long will they last? There was a complete aversion to the thought that our precious artifacts would not stand the so-called test of time. Everyone wanted to build in concrete. The Pantheon was cited. It was, after all, an artifact whose unreinforced concrete dome continues to stand nearly 2000 years after its construction. And yet, it isn’t. It isn’t the bare concrete material that lasts this amount of time.

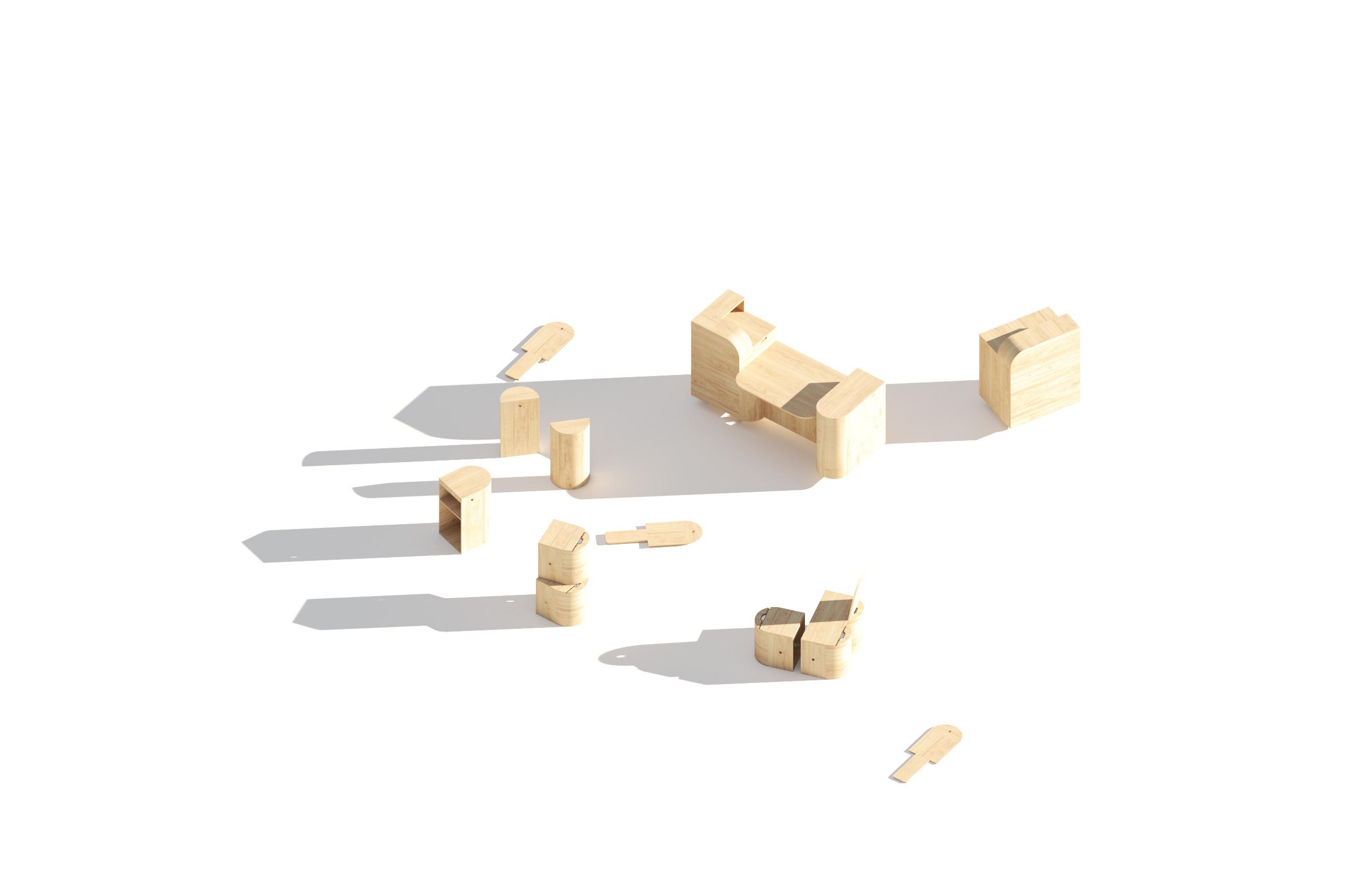

The following project images are from Office e.g.'s "An (Im)material Space", "From Wood to Tree", and "Of Envelopes & Air". All images are courteous of Liz Gálvez and Office e.g.

WORLDING 52

Rather, this concrete matter is in a constant state of entanglement — living and changing — with those societies who have sought to preserve, evolve, and maintain it.

L I z Gá L vez 55

Architectural objects are in a constant engagement with their time-based material and immaterial systems—atoms slowly (solids) or quickly (fluids) bouncing, and sweeping within or throughout enclosures. Extractive forms of energy and material production catalyze ever-more climatic changes, which manifest at multiple, tangible scales through the production of architecture. An architecture which experiences a rupture in thinking between the art of material tectonics and the mechanics, climatisation, and making of buildings. That is – material and immaterial matters of concern have little reciprocity between one and the other.

WORLDING 56

L I z Gá L vez 57

WORLDING 58

L I z Gá L vez 59

Where do materials come from? How will this environment perform? How will it be fueled? And importantly, how will humans, and other living and non-living beings, interact or be affected by such a subject?

WORLDING 62

L I z Gá L vez 63

WORLDING 64

L I z Gá L vez 65

WORLDING 68

The design methodology “(im)material matters” seeks to re-engage the relationship between artifacts and time to include the processes of making, inhabiting and operating temporary states of matter.

L I z Gá L vez 69

Insulation, resistance value, vapor barrier: Contemporary rhetoric around the building envelope tends to present its role primarily as one of separation. The narrative of the tight building, realized in the service of energy efficiency, perpetuates our understanding of the envelope as a modern agent: the membrane materializes a separation of culture from “nature,” or that which lies outside the human realm.

WORLDING 70

Yet there exists another, often overlooked, narrative. Through the medium of air, Of Envelopes and Air explores the transgressive relationship between our atmosphere and the building envelope.

L I z Gá L vez 71

GALEN PARDEE

Galen Pardee directs the design and research studio Drawing Agency. He received his BA from Brandeis University and an MArch from Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP). Galen has taught at Columbia University GSAPP, Barnard University, the University of Tennessee, and The Ohio State University, where he was the LeFevre Emerging Practitioner Fellow. Drawing Agency explores dimensions of architectural advocacy, material economy, adaptive reuse, and expanded practice through writing, exhibitions, and design commissions in California, Colorado, and New York. Research projects have been funded by The Ohio State University, Columbia University GSAPP, and the Graham Foundation, and published in the Avery Review, Faktur Journal, Urban Omnibus, and Thresholds, among others. Drawing Agency’s work has been included in solo exhibitions, group shows, and symposia in the United States and abroad including the Chicago Architectural Biennial and Venice Architecture Biennale.

THE LAST IMPERVIOUS SURFACE IN PORTAGE COUNTY OHIO

GALEN PARDEE

On December 8th, 2008, the States and Territories of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Montreal, and Quebec, signed into law the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact [The Great Lakes Compact], prohibiting water removal outside the Lakes’ drainage basins and creating a sealed eco-political zone within the United States and Canada. On April 25th, 2018, Wisconsin approved Foxconn’s request to withdraw 7 million gallons of Lake Michigan water per day for a private LCD panel factory outside Racine: Foxconn claimed its factory’s water consumption a “public use” to skirt full Compact review. This feat of semantics exposed the Compact’s lack of actionable public water definitions and created a leak in the Compact’s closed loop.

Finally, on February 26th, 2019, the citizens of Toledo, Ohio approved the Lake Erie Bill of Rights, granting the city legal guardianship of the Lake and its’ watershed. Unchecked agricultural runoff in 2014 had rendered Lake Erie’s water undrinkable for half a million people for days at a time: algal blooms would return regardless in July 2019.

These three events inspired the foundation of the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition, an experimental public architecture office entrusted with protecting the spirit of the Great Lakes Compact, researching and designing the Watershed’s public realm, and advocating for the Compact’s human, non-human, and material subjects. The Expedition’s mission has prompted a fundamental re-thinking of architecture’s role in the Great Lakes Megalopolis—engaging legal and physical terrains with equal dexterity, expanding architectural practice with non-human client structures, and transforming architects into agents for public materials in a world of increasing scarcity.

74

Portage County Spillway Site Courtesy of Galen Pardee

75

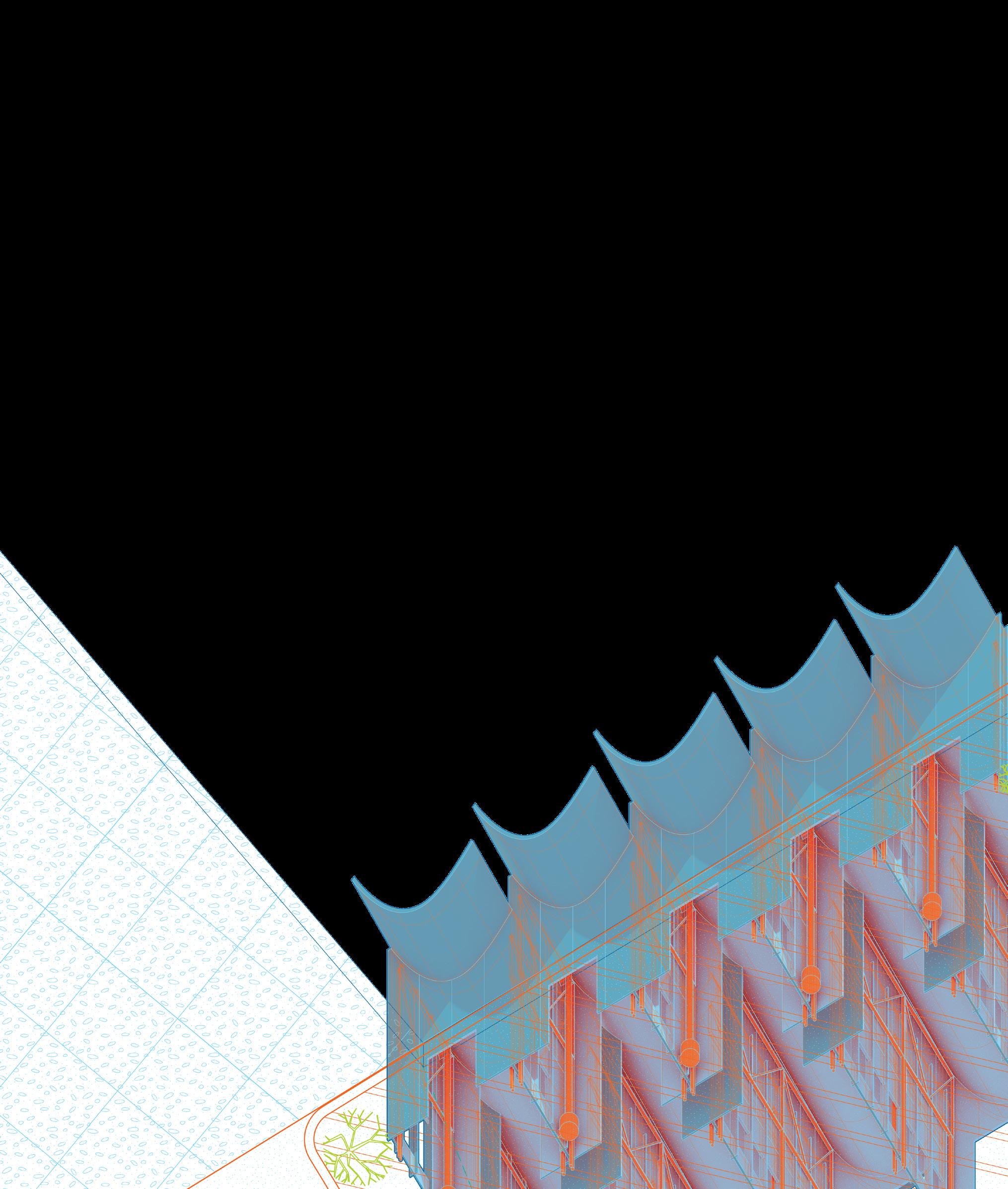

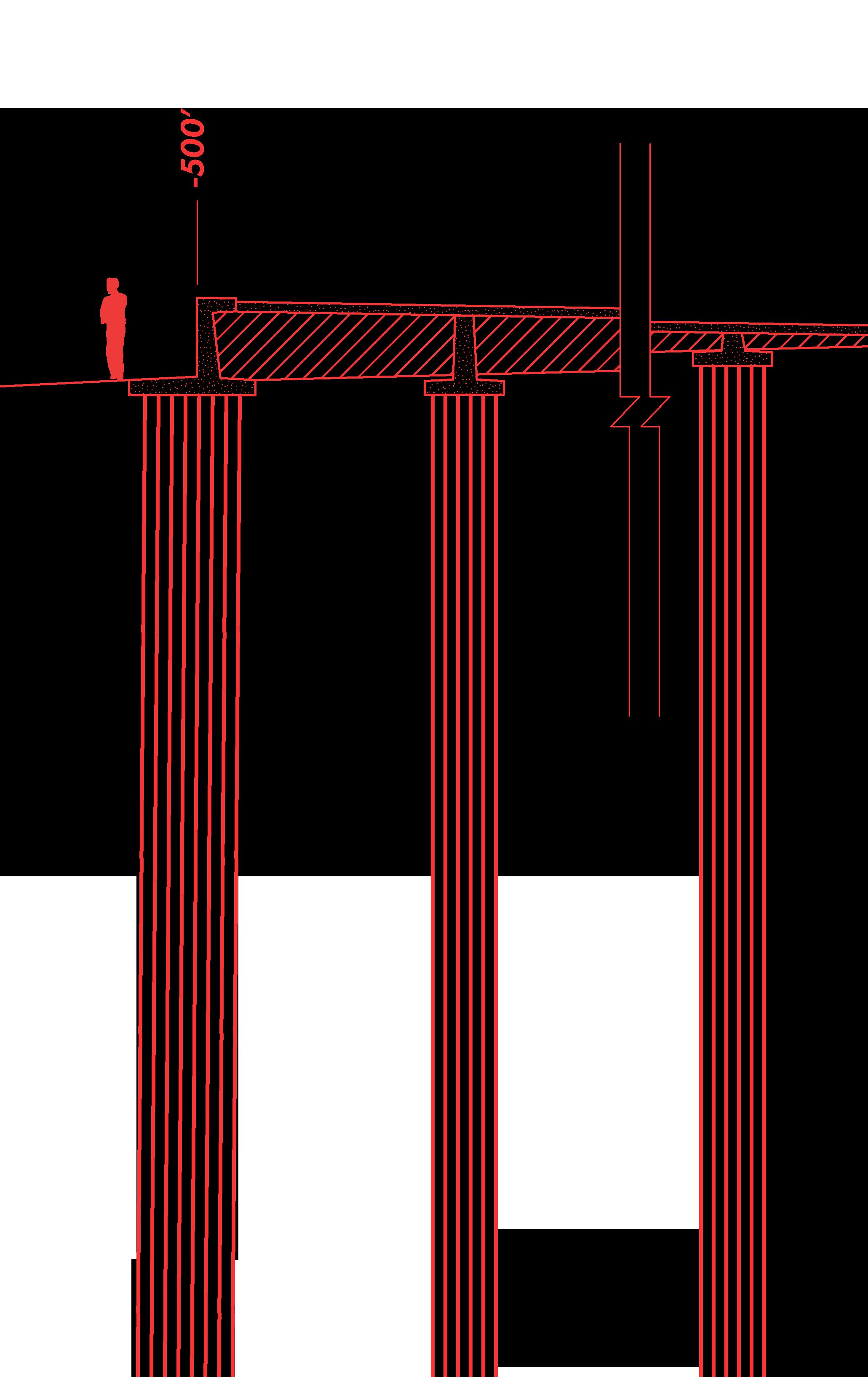

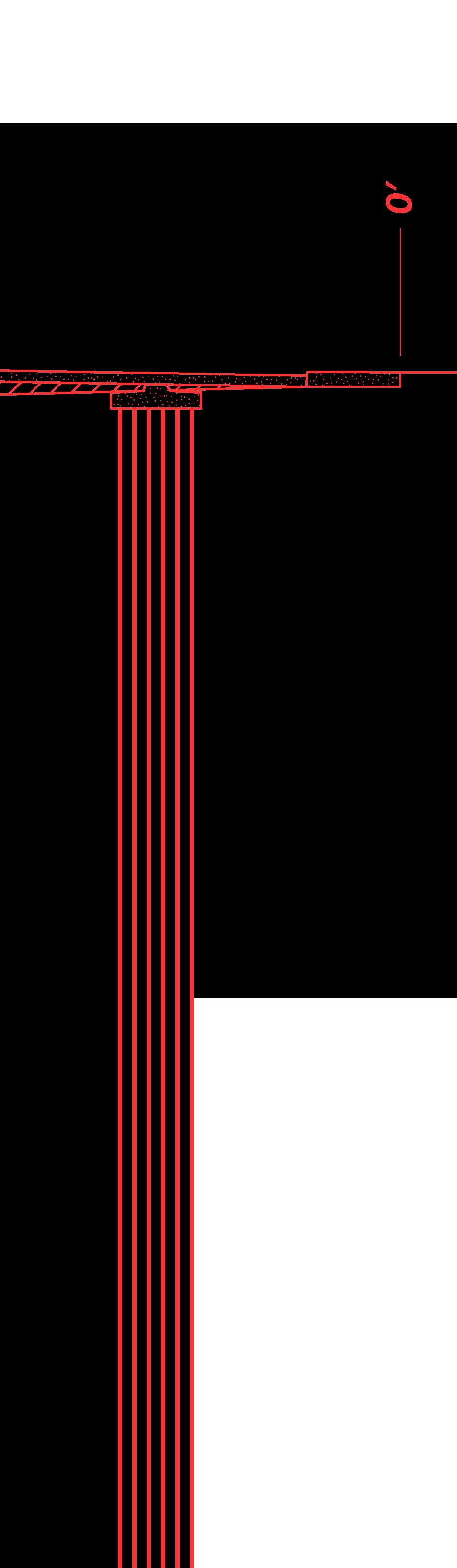

Great Lakes Watershed and Spillway Hazard Zone Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Great Lakes Watershed and Spillway Hazard Zone Courtesy of Galen Pardee

WORLDING 78

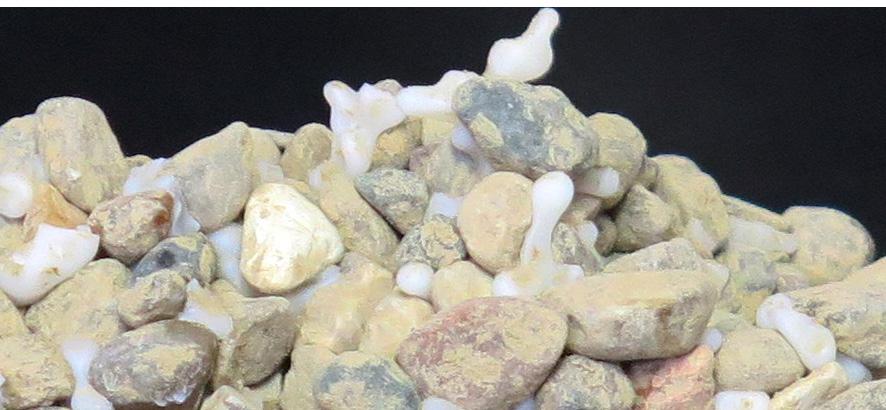

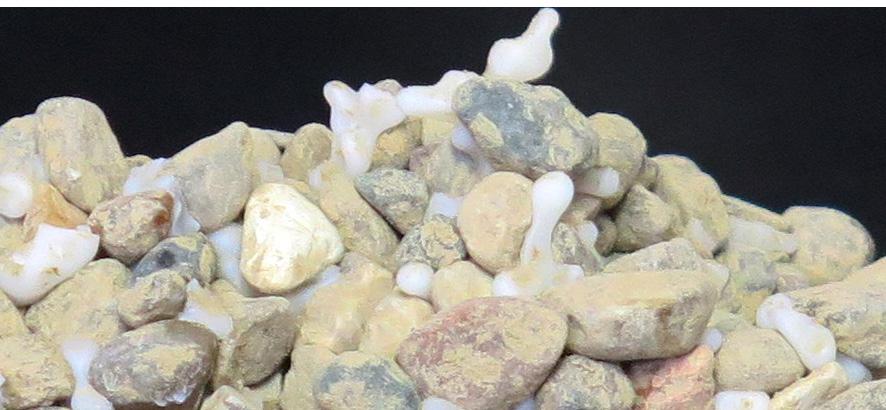

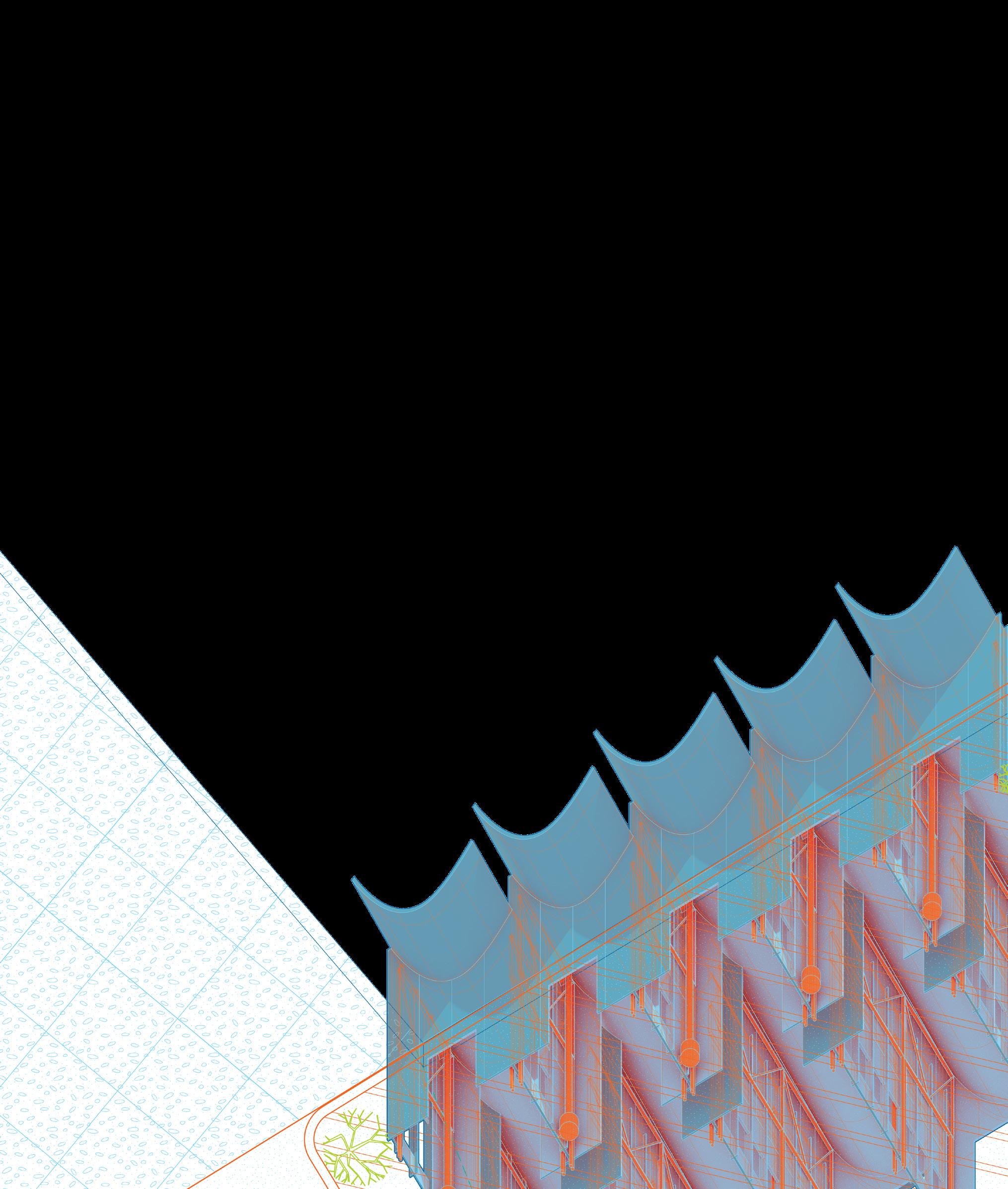

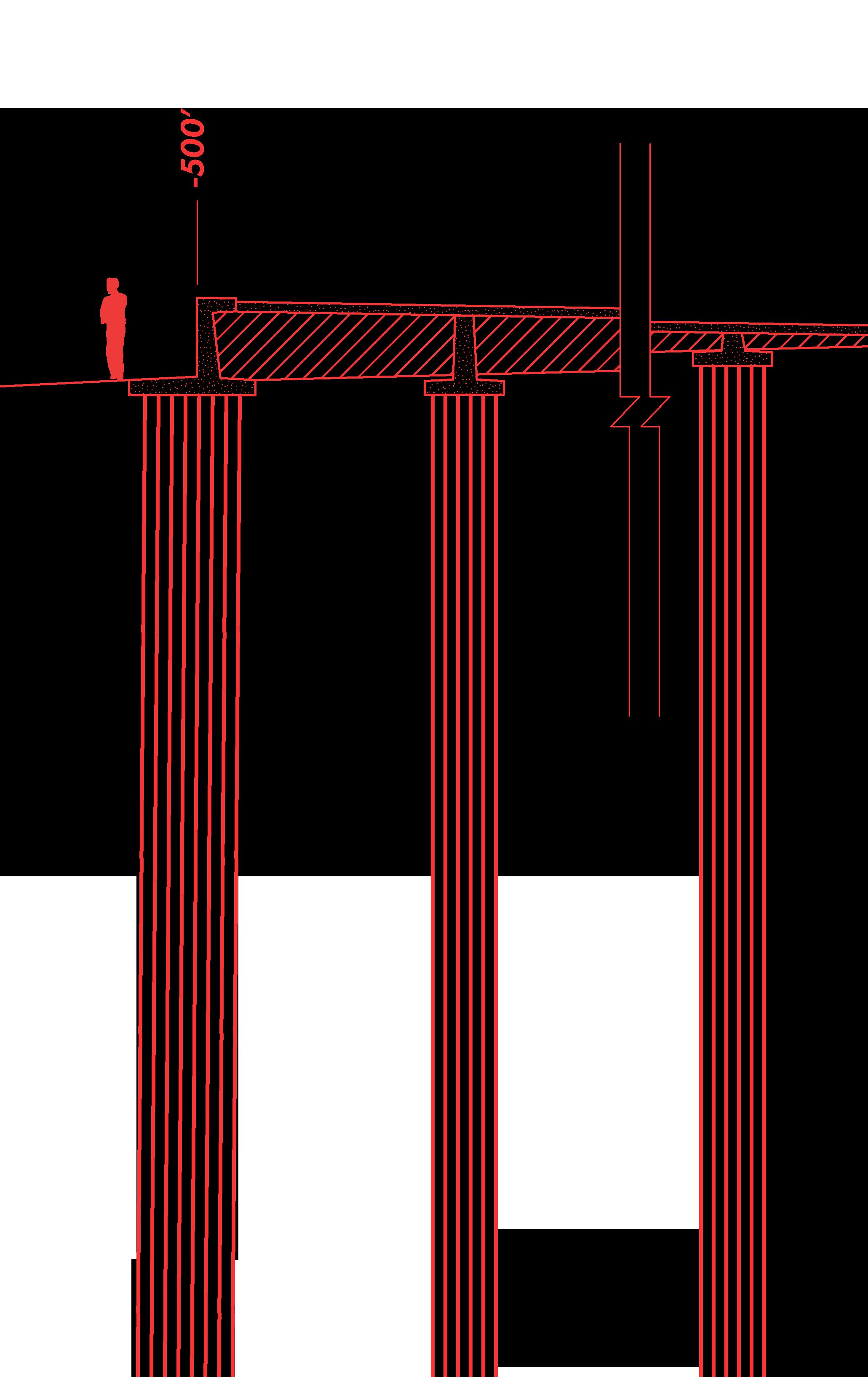

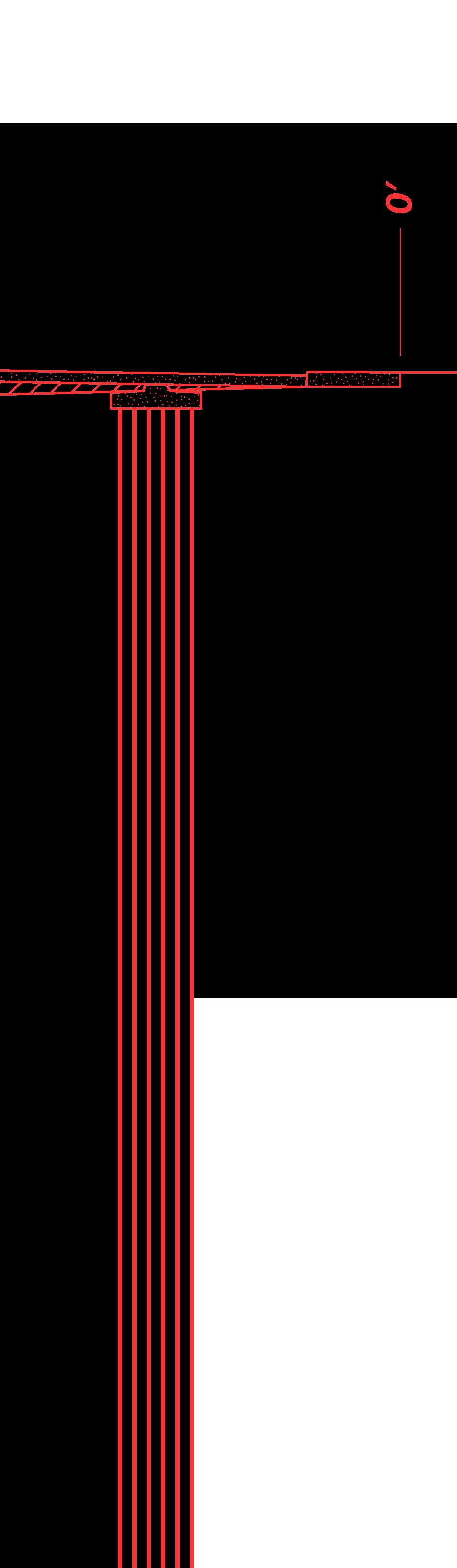

The Last Impervious Surface in Portage County Ohio examines the disjuncture between material boundaries and political boundaries; using the Portage County Spillway—a 30-mile long, 500-foot wide, 5-foot tall asphalt megastructure spanning Portage County as a lens. A topographical intervention, the Spillway is able to redirect enough rainfall towards Akron to support 100,000 people per year.

The Portage County Spillway was rehabilitated by the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition to create a continuous public space for the entire county. With integrated supergraphics to enable satellite monitoring of water flows, the Expedition spearheaded a ban on the construction of further impervious surfaces county-wide to ensure equitable access to fresh water on both sides of the boundary. In addition to the permeable streets on the Lake Erie side of the Spillway, a full series of hazard maps were developed to educate residents on the new risks to existing structures while highlighting the public amenities developed on the Spillway’s surface.

The transformation of the Portage County Spillway was an early success for the Great Lakes Architectural Expedition, acting to mitigate unequal water conservation practices, and establishing an obligation to serve the interests of the public realm defined by the Lake Erie Watershed and straddling counties and cities. The Spillway also exposes an ugly truth to the Great Lakes Compact: although ostensibly developed for ecological reasons, many suspected the true motive was to entice thirsty manufacturing firms to return to the Great Lakes. In acting to increase their share of the Watershed, Portage County ’s decisions could be replicated elsewhere along the Great Lakes’ watershed boundary; a cautionary tale about mixing ecological and financial regulations.

G AL e N P ARD ee 79

Spillway Detail Plan Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Spillway Section and Axonometric Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Spillway Section and Axonometric Courtesy of Galen Pardee

WORLDING 82

Spillway Model 1:500 Courtesy of Galen Pardee

G AL e N P ARD ee 83

Great Lakes Exhibition Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Great Lakes Exhibition Courtesy of Galen Pardee

ANDREW SANTA LUCIA

Andrew Santa Lucia is a Cuban American designer, educator, and critic based in Portland, Oregon. He is Assistant Professor of Practice at Portland State University’s School of Architecture, where he teaches design studio, history/ theory/criticism seminars, and is graduate thesis coordinator. He has lectured and exhibited internationally, including Art Basel, the Chicago Architecture Biennial, as well as the Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2021. Andrew’s writing can be found in a broad range of media including ACSA, Architect’s Newspaper, Artlurker, Bad at Sports, Dichotomy, EVOLO, MAS Context, and Luxury Home Quarterly. He runs Office Andorus, which designs architecture for activists, institutions, and private clients with the goal of influencing public perceptions through the architectural discipline. His work is a hybrid of bold colors, graphics, and shapes used to translate and amplify contemporary issues of social justice through aesthetics. His current research is investigating the effects of color on public health initiatives associated with harm reduction, drug treatment programs, and drug reform activism.

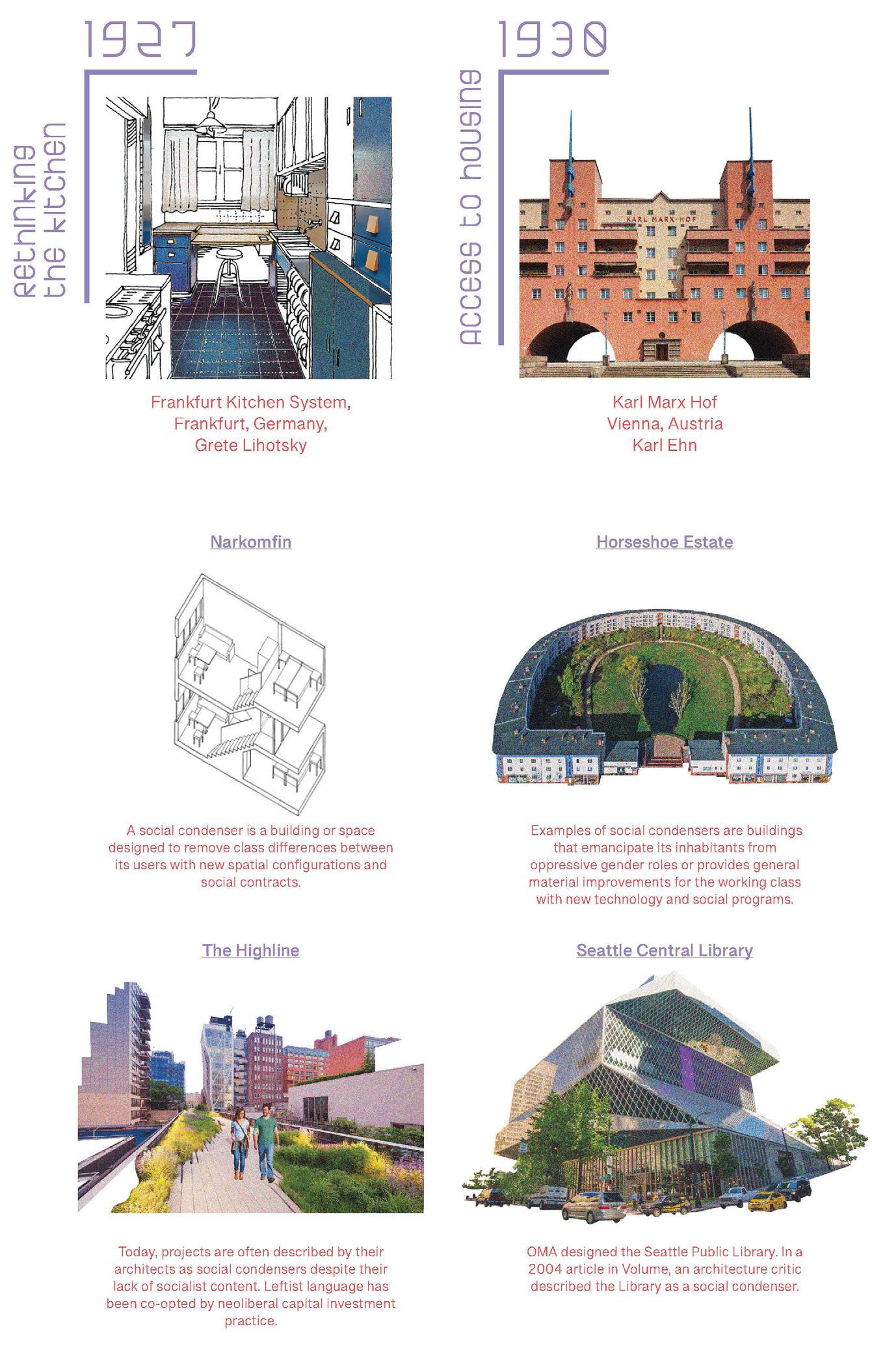

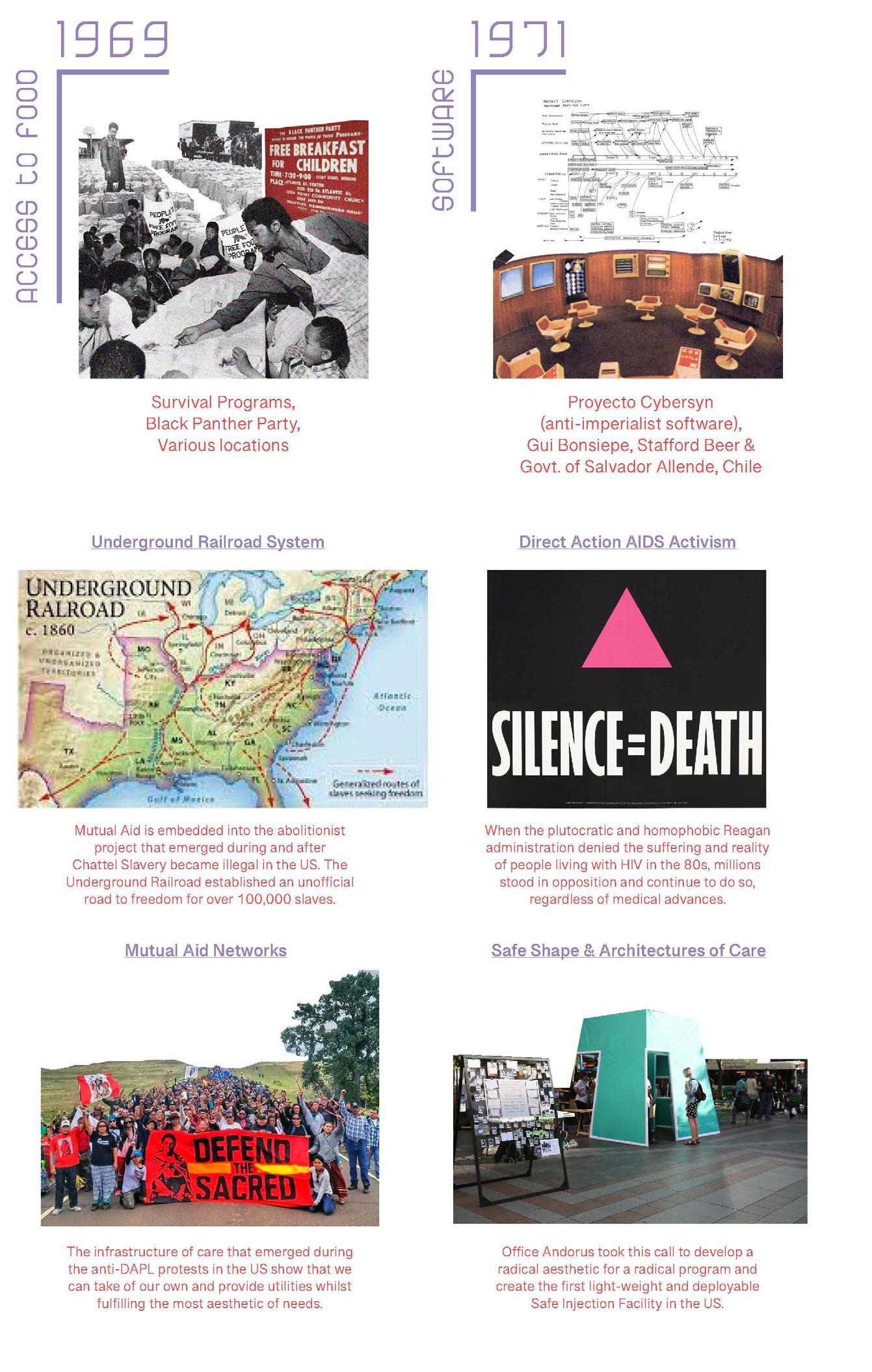

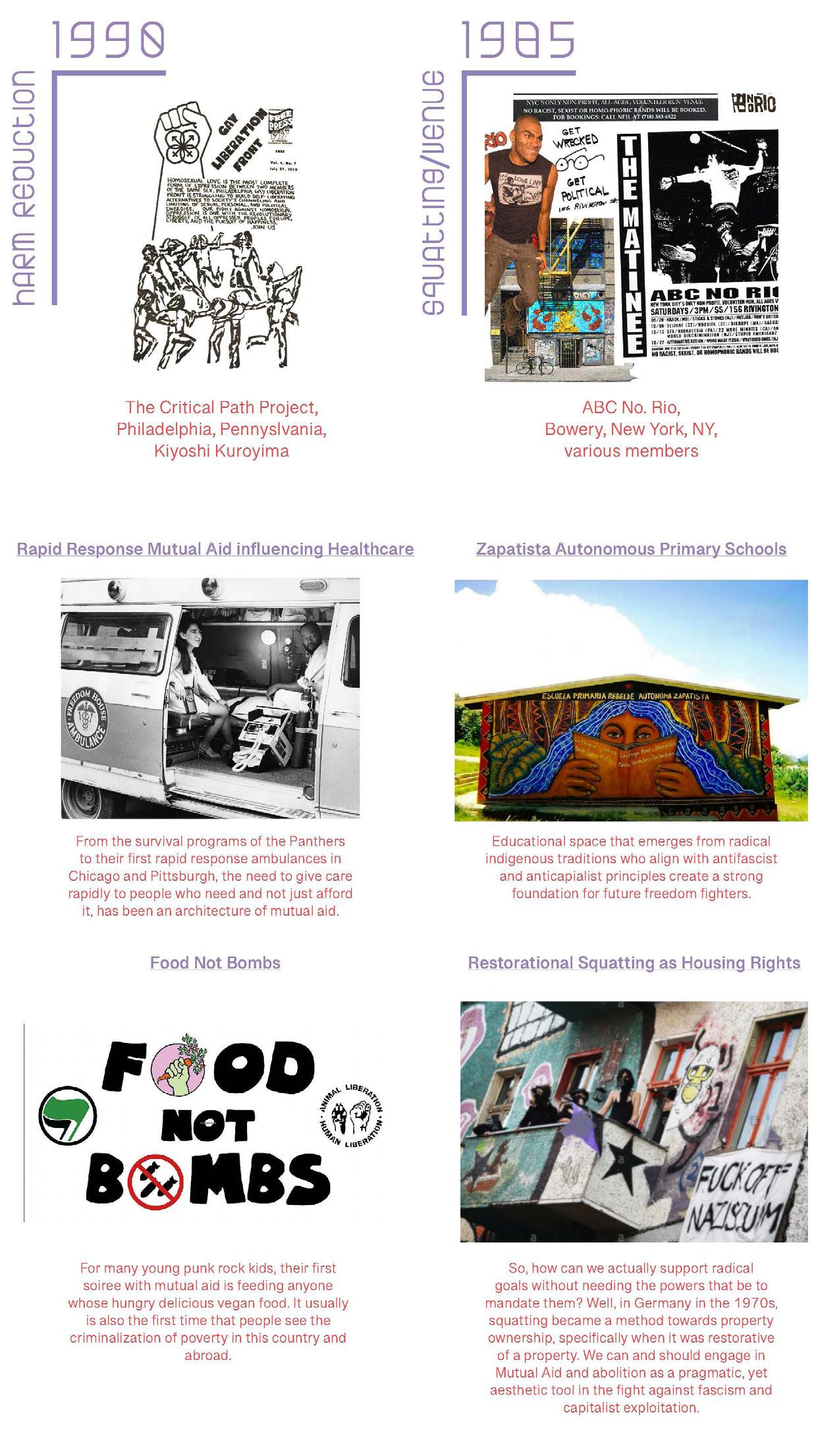

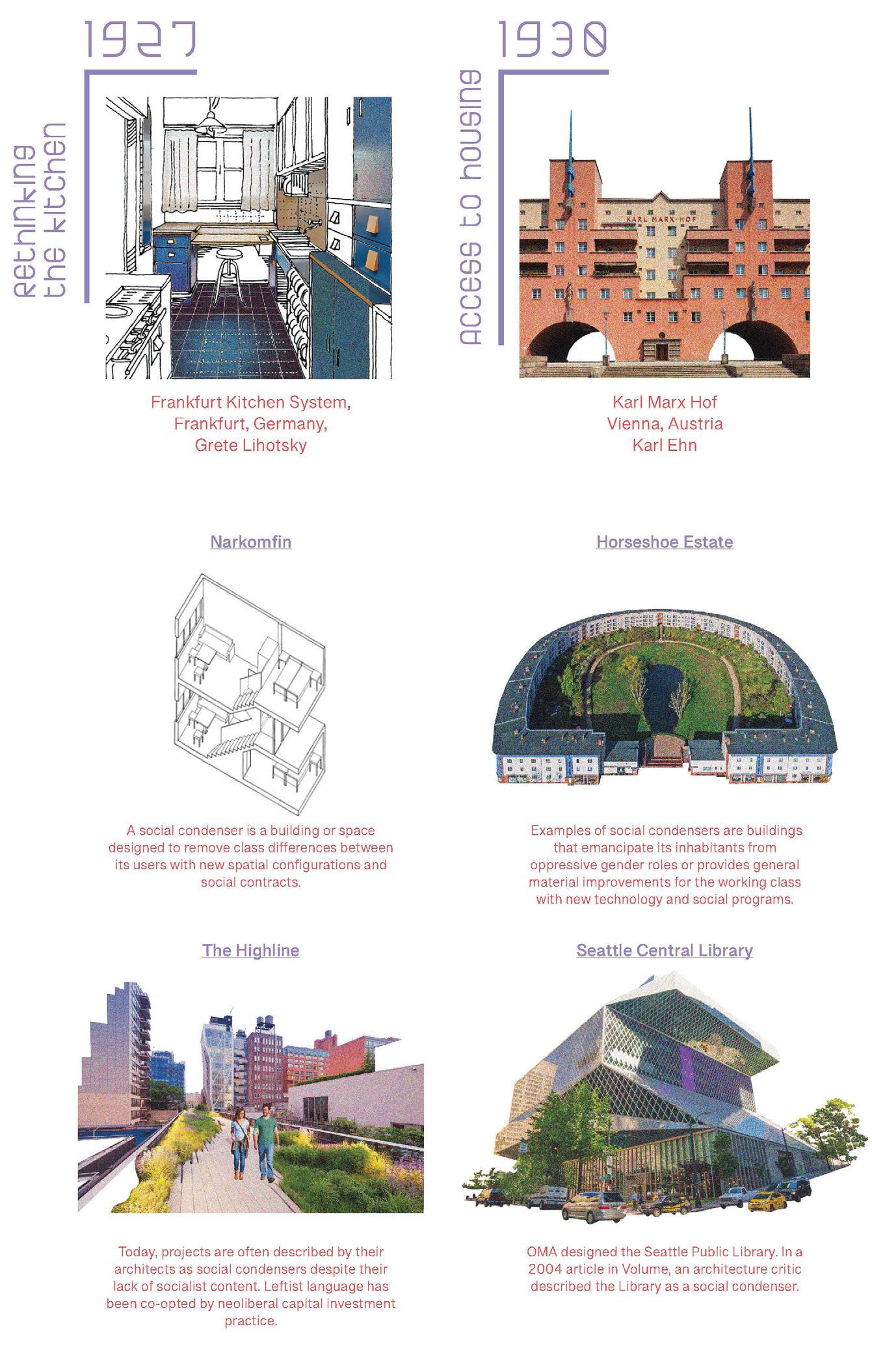

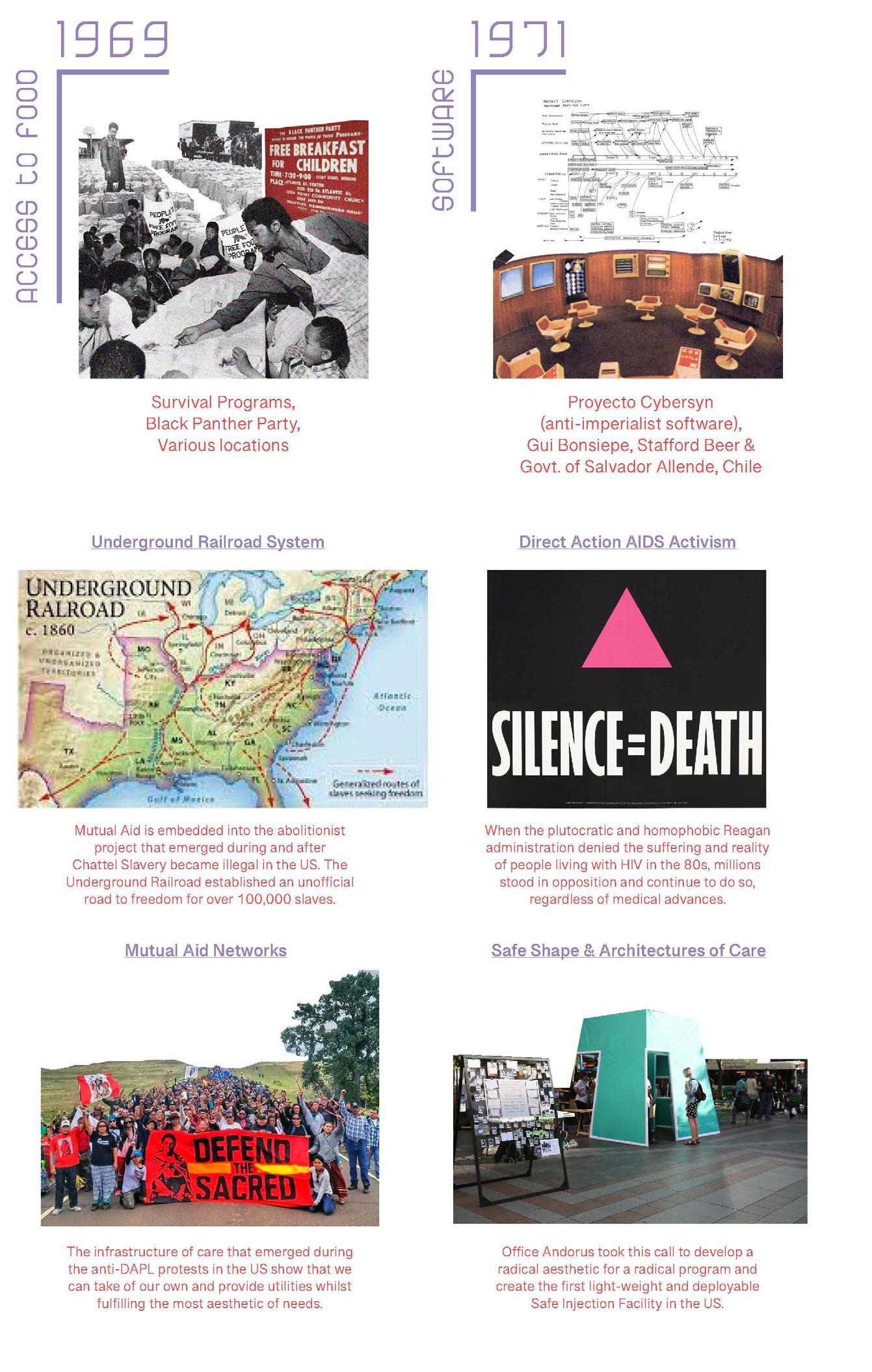

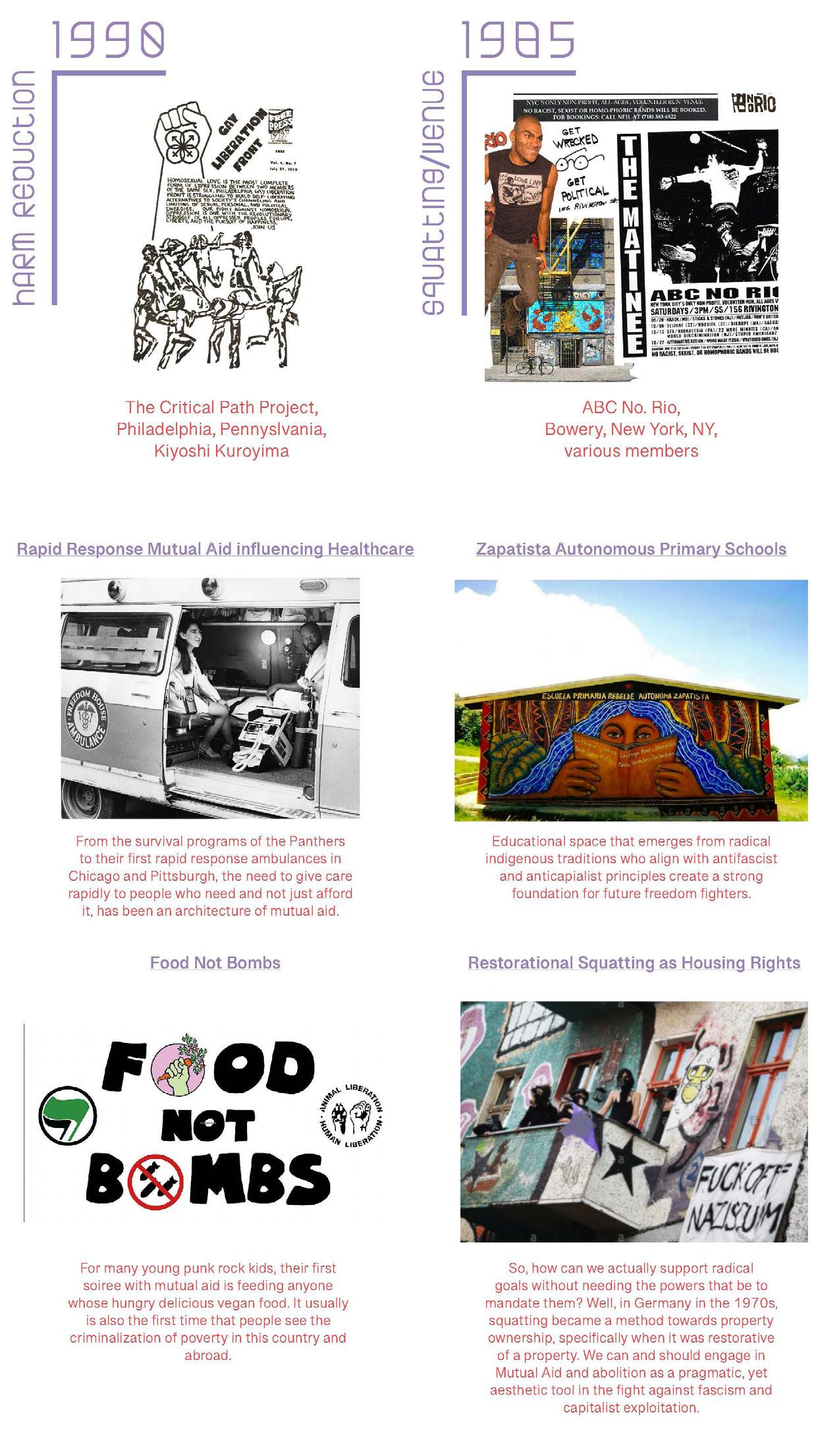

ANTIFASCIST ARCHITECTURAL ANNOTATIONS ANDREW SANTA LUCIA

Why is it that the practice and teaching of architecture’s collective imagination, or more aptly put, canonical proselytization, is so comfortable covering projects not only of capital, but of plunder, settlement and mass murder?

I can see how if you’re reading this right now you may be thinking that I am being dramatic or inflammatory. I hope you take what I say at face value, not in the sense of the mask being the face but more in the sense of facing your fear. What is imperative in this worlding exercise is that you and I can collectively come to a conclusion, of course whilst I guide you towards some points of my lived experience being an architect and educator in this particular epoch of humankind.

To answer that first rhetorical question, it is because architecture has always been the second line of offense in the process of colonialism and imperialism—first comes murder and stealing of land, then comes buildings that further destroy the worlds that were there before. In many ways, architecture in its current state can be seen as anti-worlding because it contributes to carbon emissions eventually leading to mass extinction and the end of the world as we knew it. To build off the recent words of Douglas Spencer, the architectural imagination in the US seems more like a never-ending nightmare than a dream. Congruently, teaching architecture has always been about teaching the version of itself most valuable to the ruling class, which is to say that in our contemporary moment of an ebb-and-flow political & ethical awakening around the world; architects are reckoning with these realities and asking the question, can architecture be decoupled from capitalism (from anti-worlding)?

88

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 89

WORLDING 90

In short, there have been hundreds of thousands of examples of anticapitalist and, perhaps more importantly, antifascist architectures throughout the last 120 years. There is no shortage of buildings, networks and worlds conceived outside of the logic of capital, and extraction.

Why, at least in the United States, do we not focus on these projects as examples of alternatives to capitalist architectural endeavors?

This second question is much less difficult to answer because once you work through the plausible reasons, it becomes clear that it's because many bosses and educators do not want to. Why they don’t want to is maybe more difficult to surmise, mainly because there are lots of excuses out there: ‘I didn’t get taught these,’ or ‘there isn’t as much material on this, as I have on something Philip Johnson curated or MOMA funded,’ or even ‘that would be great but we need to teach a canon.’

Why are we more knowledgeable about the Jeffersonian grid replete with the chattel slavery needed to produce its proto manifest-destiny-colonialism than say Narkomfin, the Soviet era housing proposals which abolished the kitchen as a private and invisible space for a woman’s free labor, instead opting to make this labor visible, collective and accessible shifting society away from a misogynistic architectural enterprise? Again, it's simple. The Jeffersonian grid needs no justification—we hold these truths to be self-evident—while Narkomfin abolishes something and in doing so strips power away from a typology, a ruling class and a system (patriarchy). It’s a lose-lose for people in power.

However, even in that description I have missed the core of my own argument, on purpose. Stripping away the radical socialist origins of Narkomfin’s conceptualization allows for a depoliticized architectural narrative to emerge. Who wouldn’t be against giving more rights, visibility, and credit to people? But more importantly, removing socialism or anarchism from the equation of architecture allows for fascist architecture to be freely presented, enjoying the same depoliticization as radical social projects, but this time without the baggage of mass murdering and business first political enterprises.

There is no reason we need to be teaching with Terragni, Speer, Johnson and hell even Schumacher, outside of maybe what not to do. Many will critique this approach as problematic because we need to know history to not repeat it. My critique of this is, then why are you repeating this fascist history over and over again?

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 91

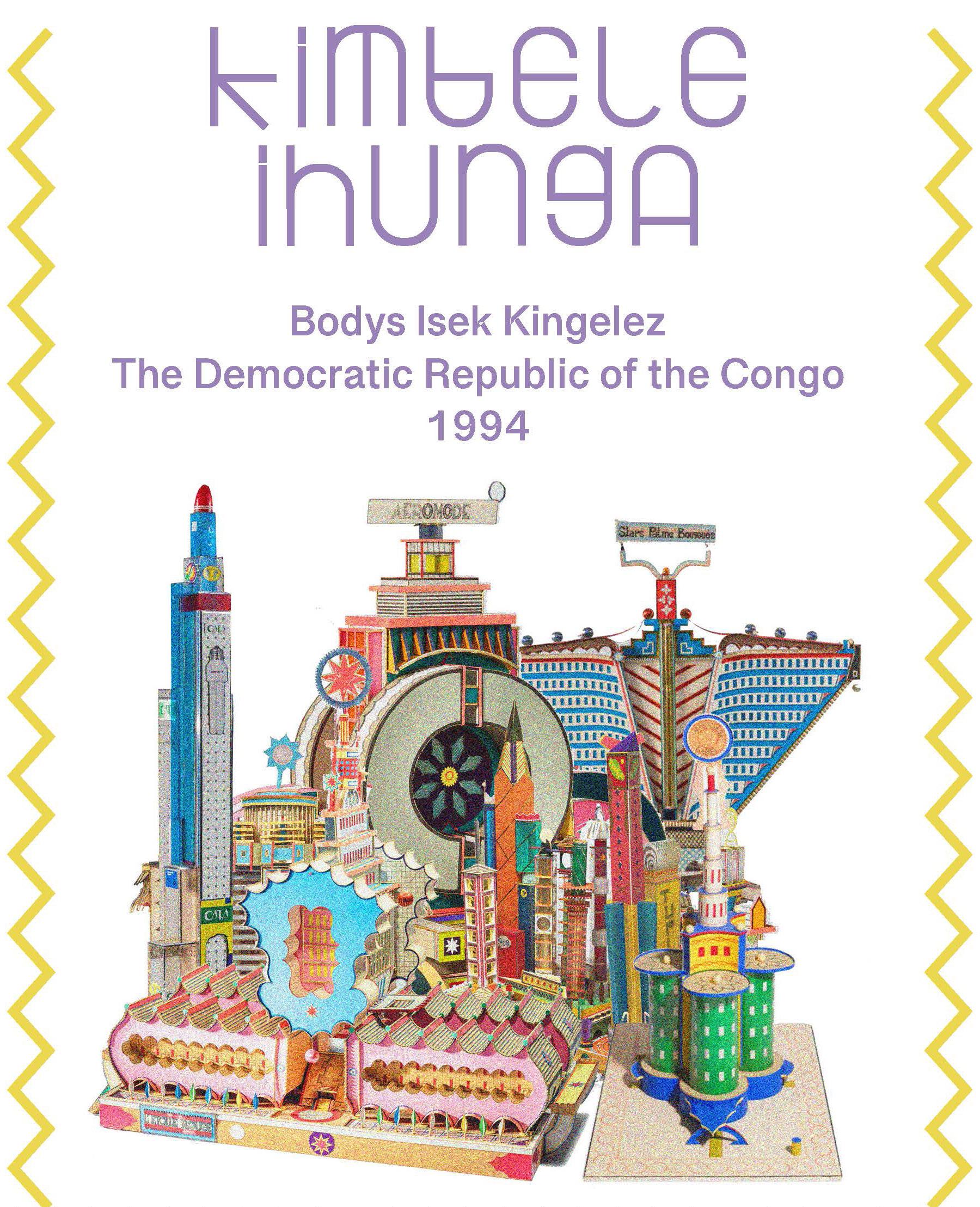

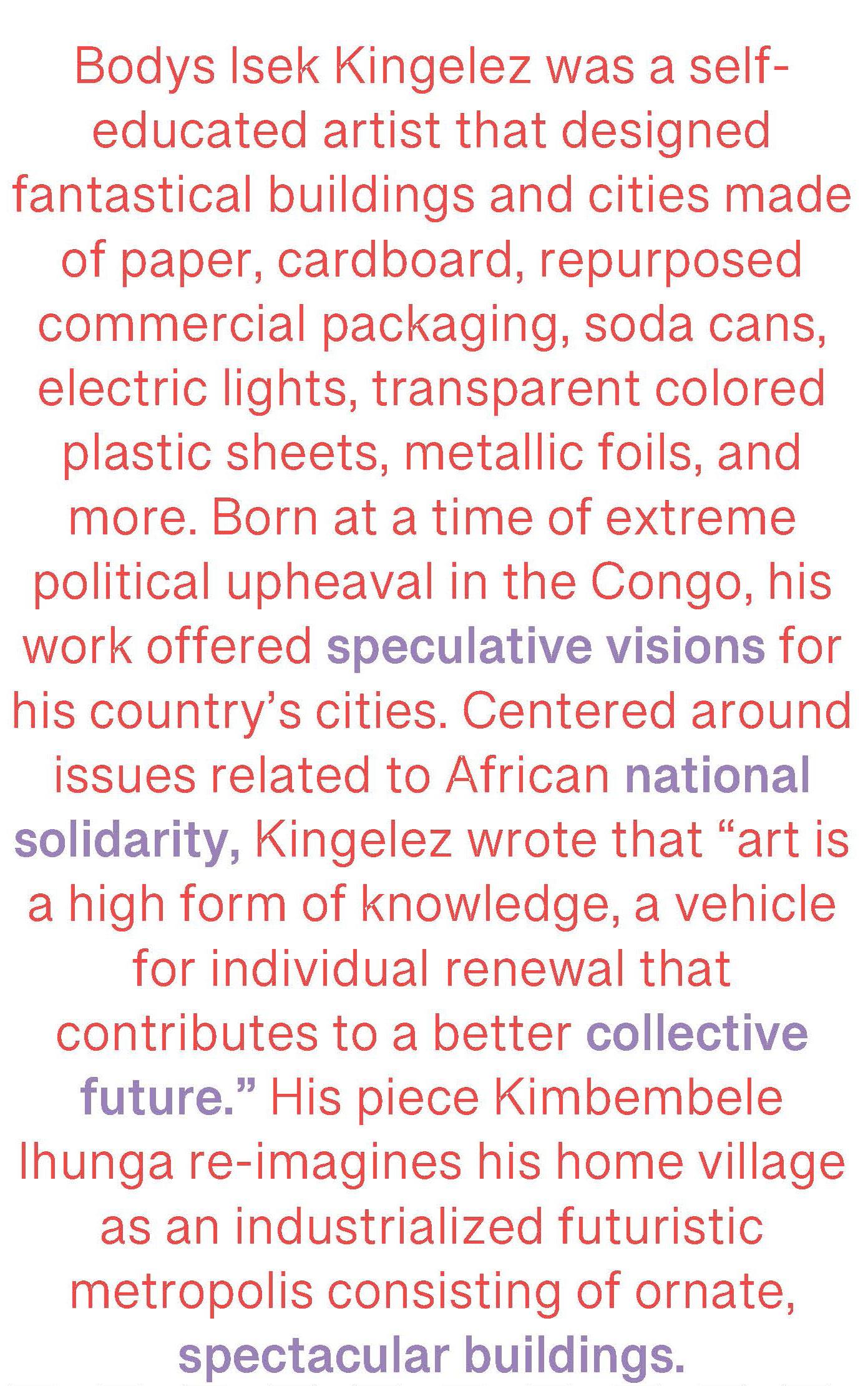

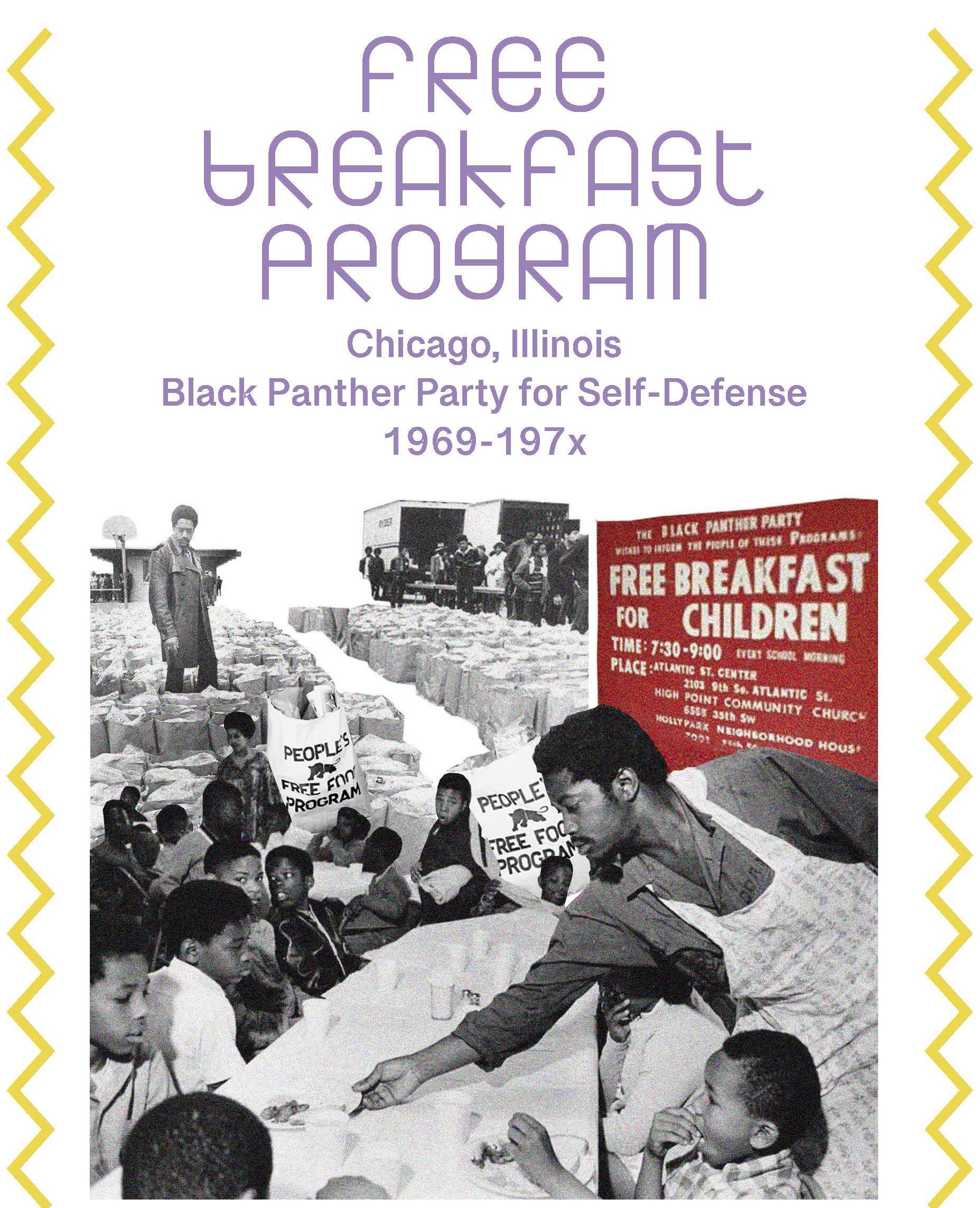

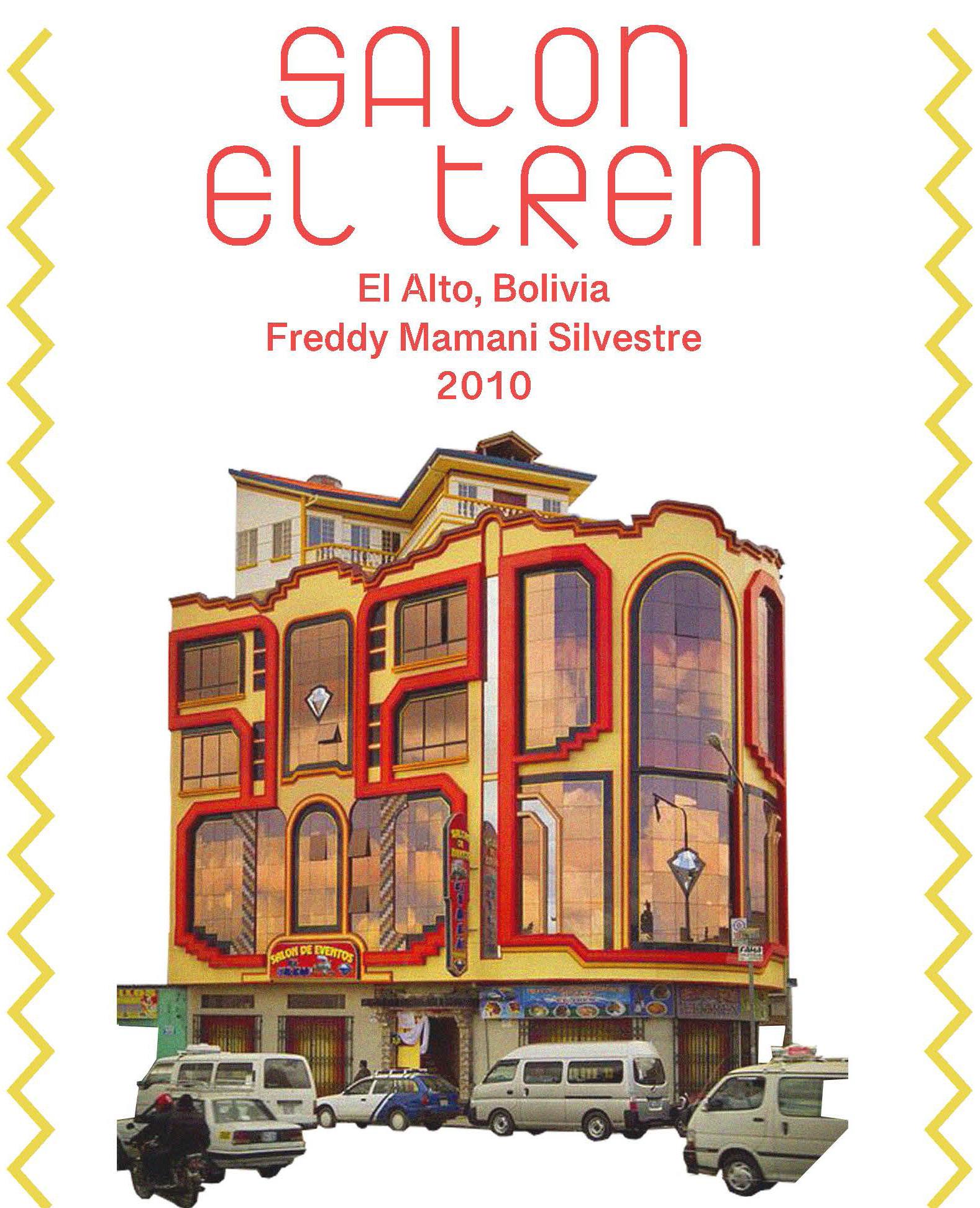

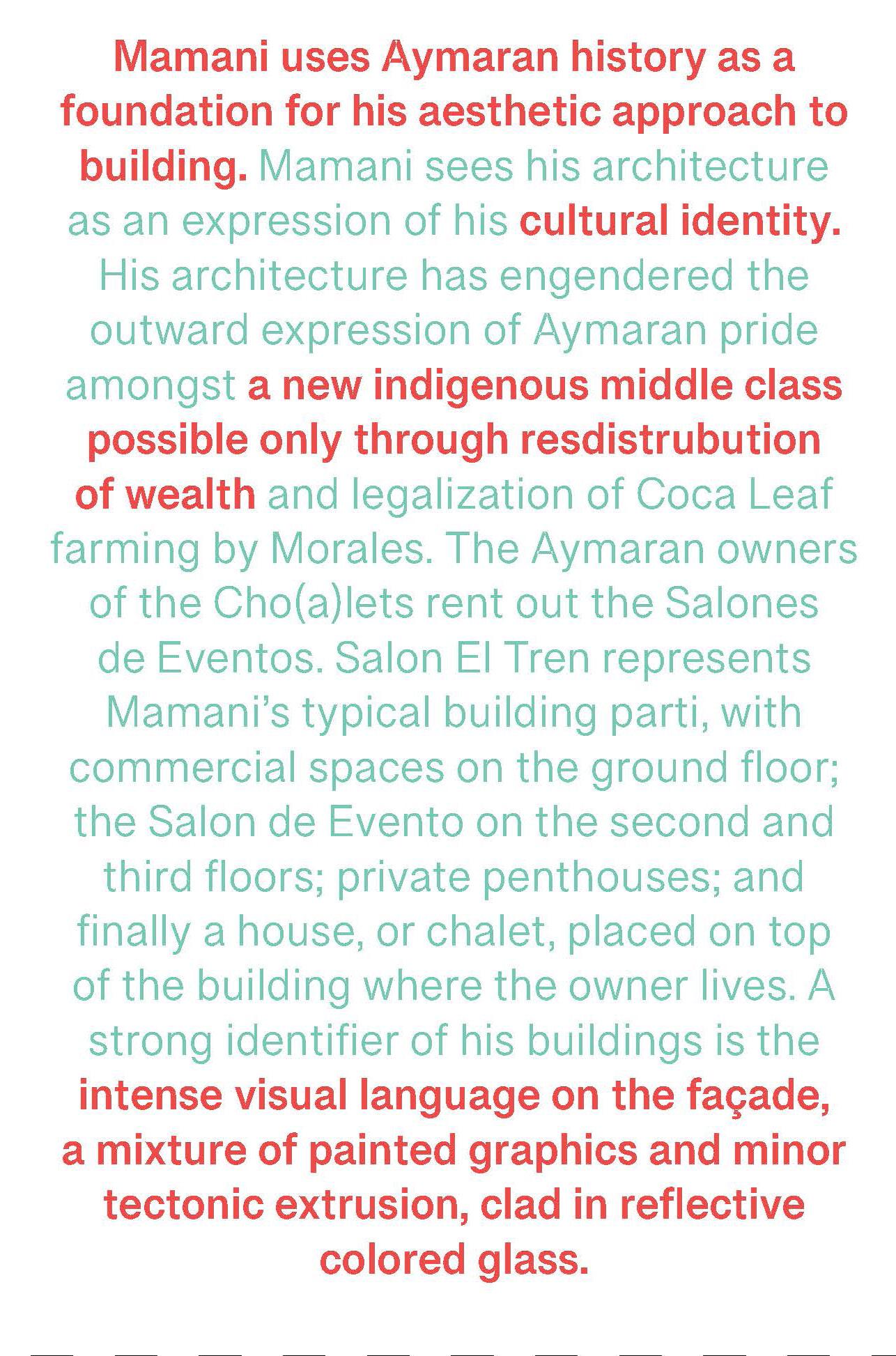

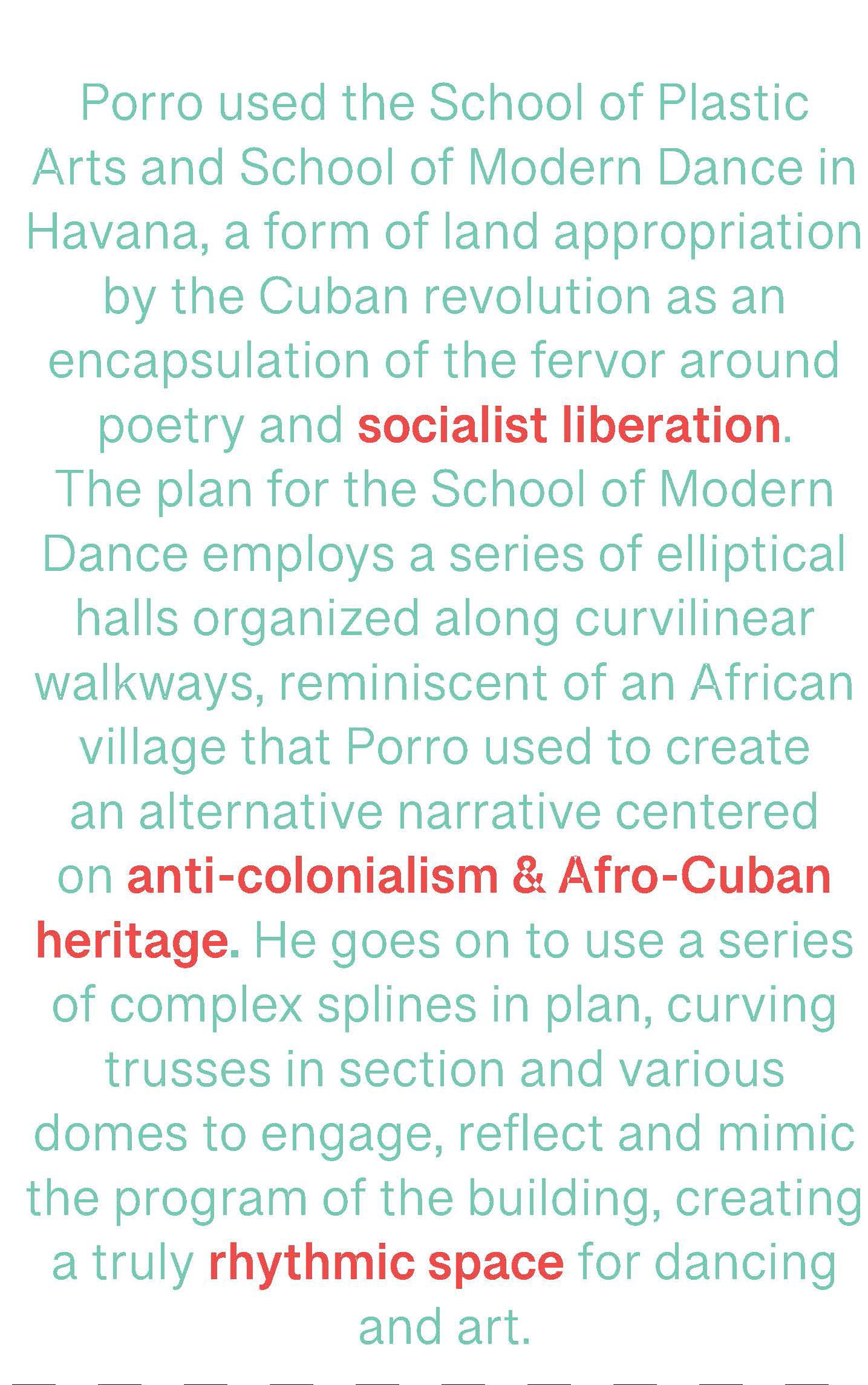

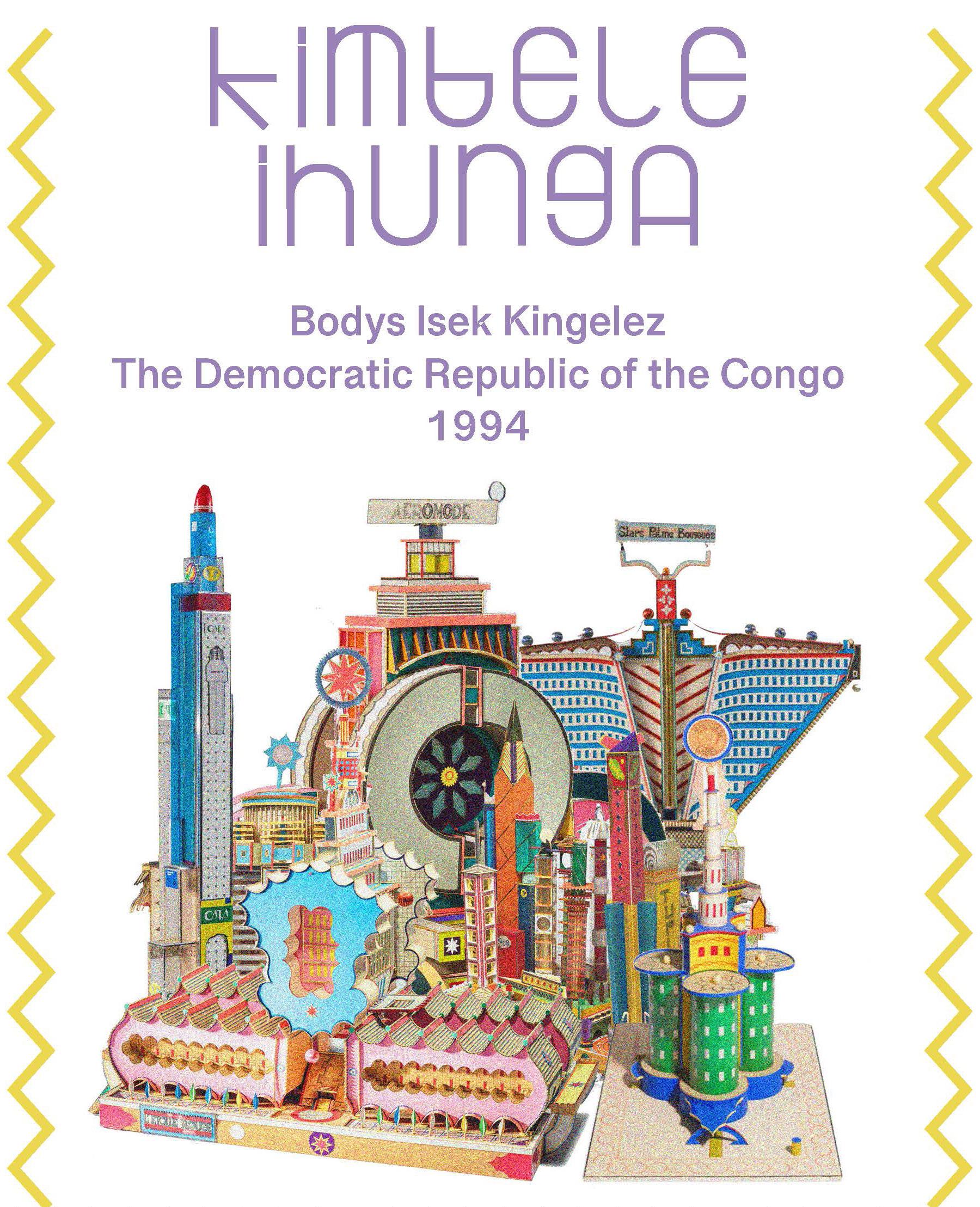

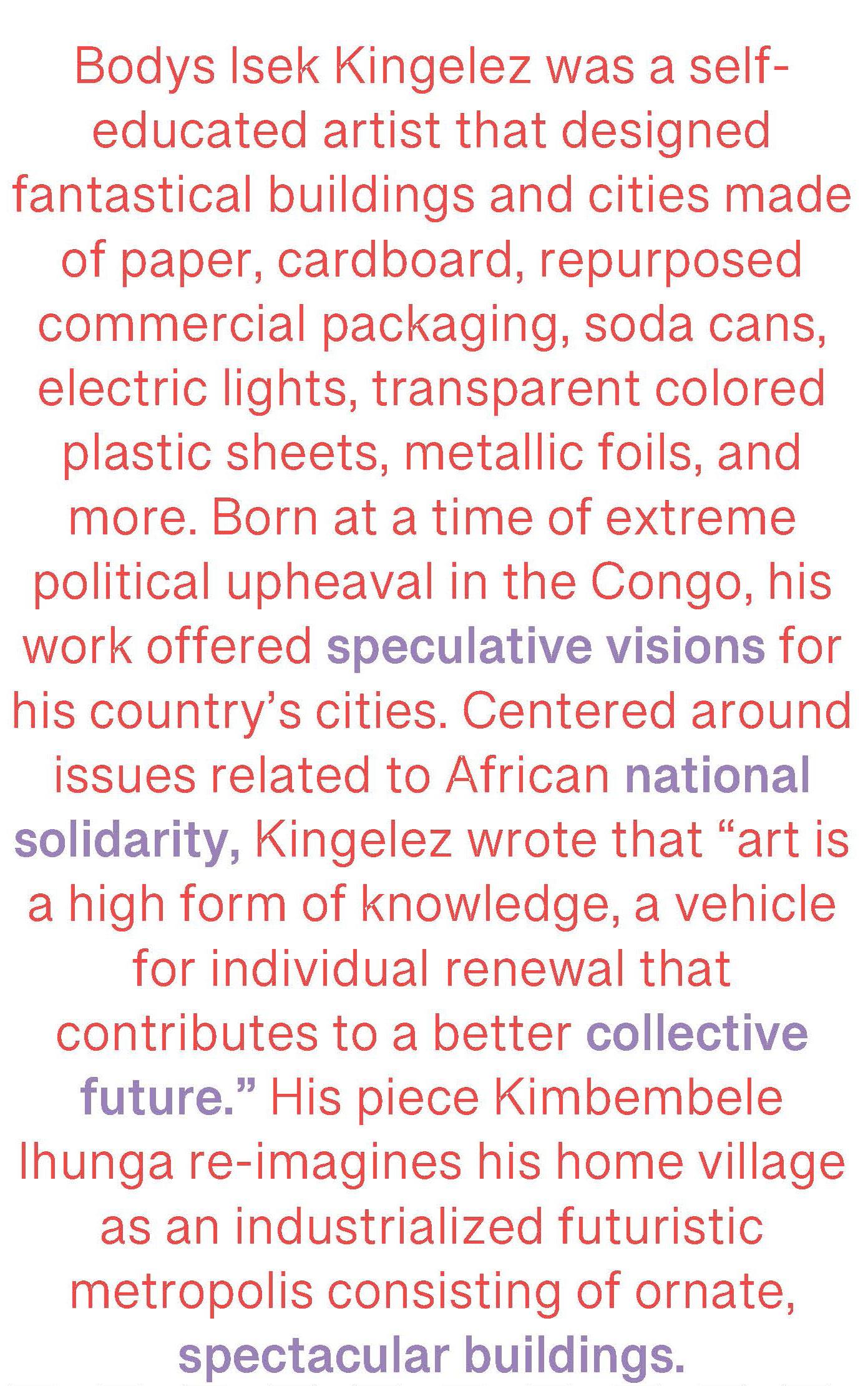

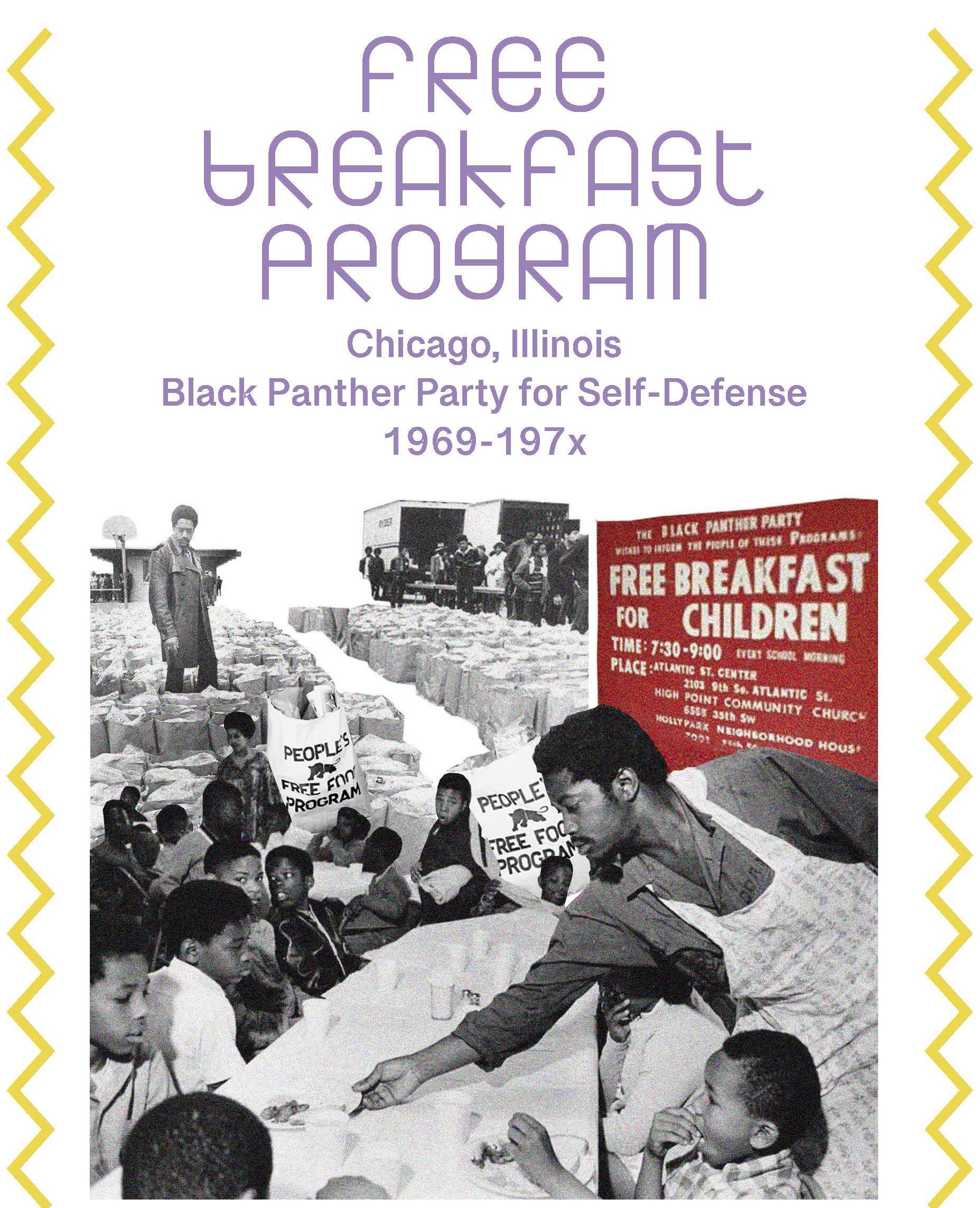

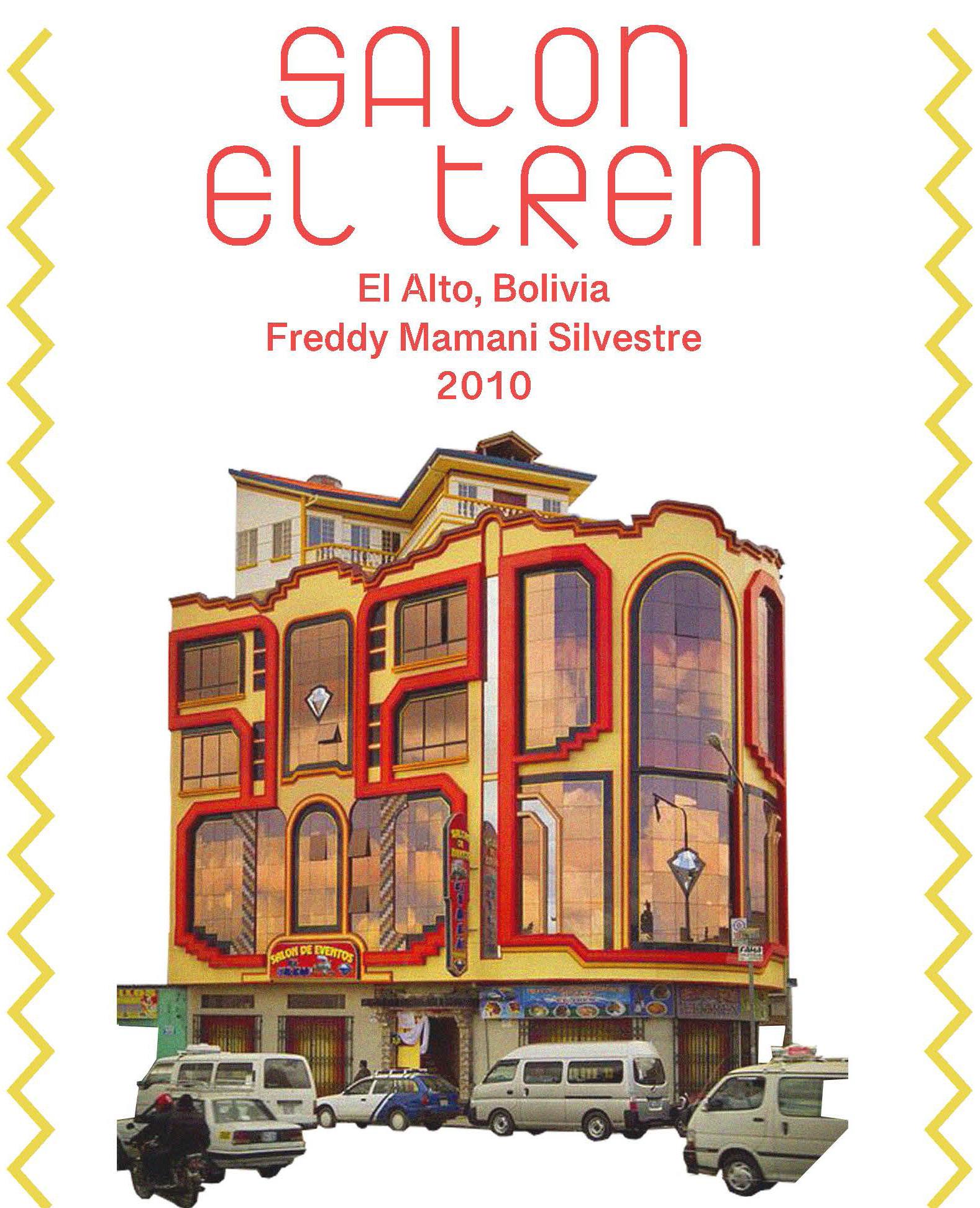

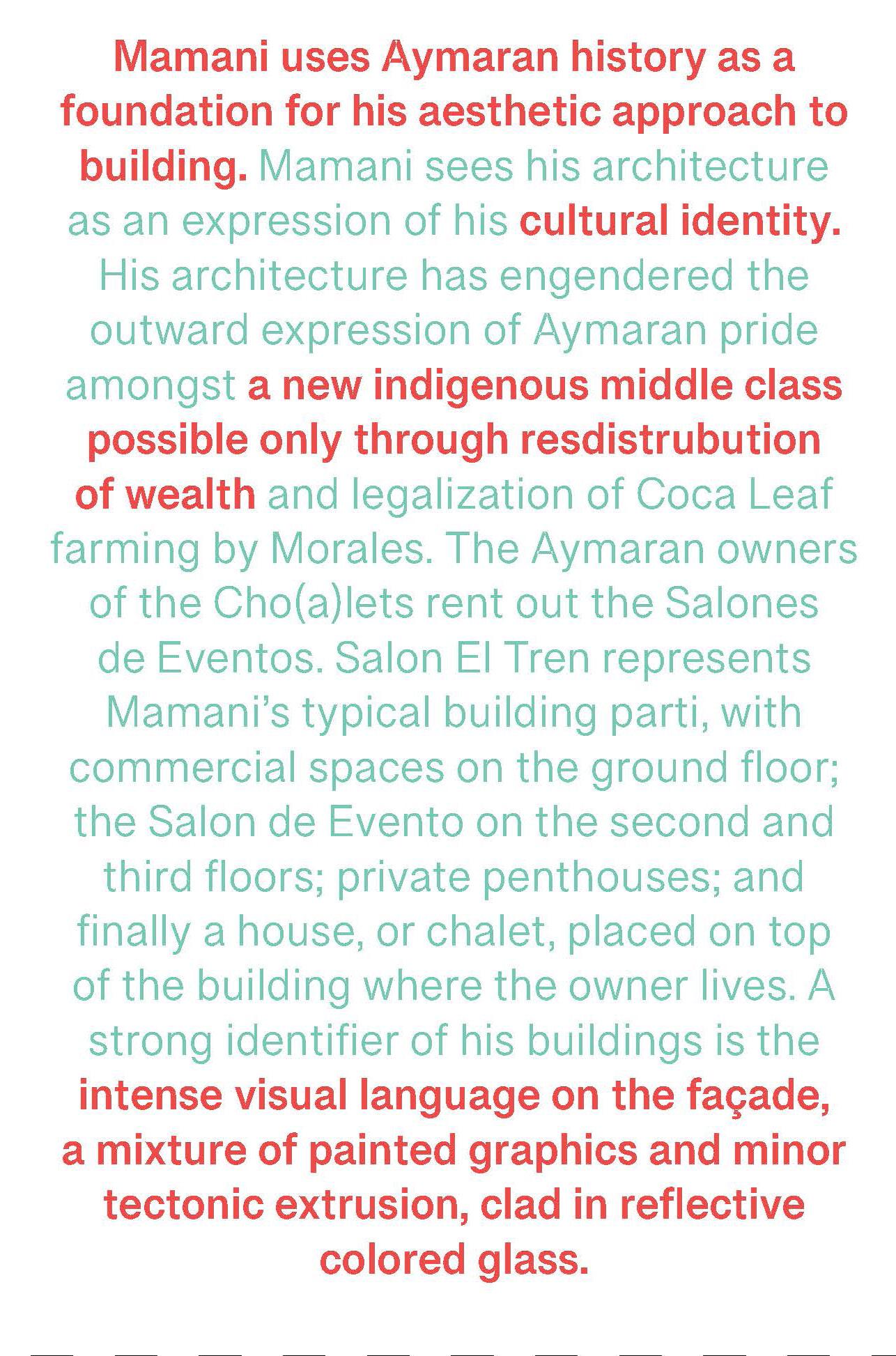

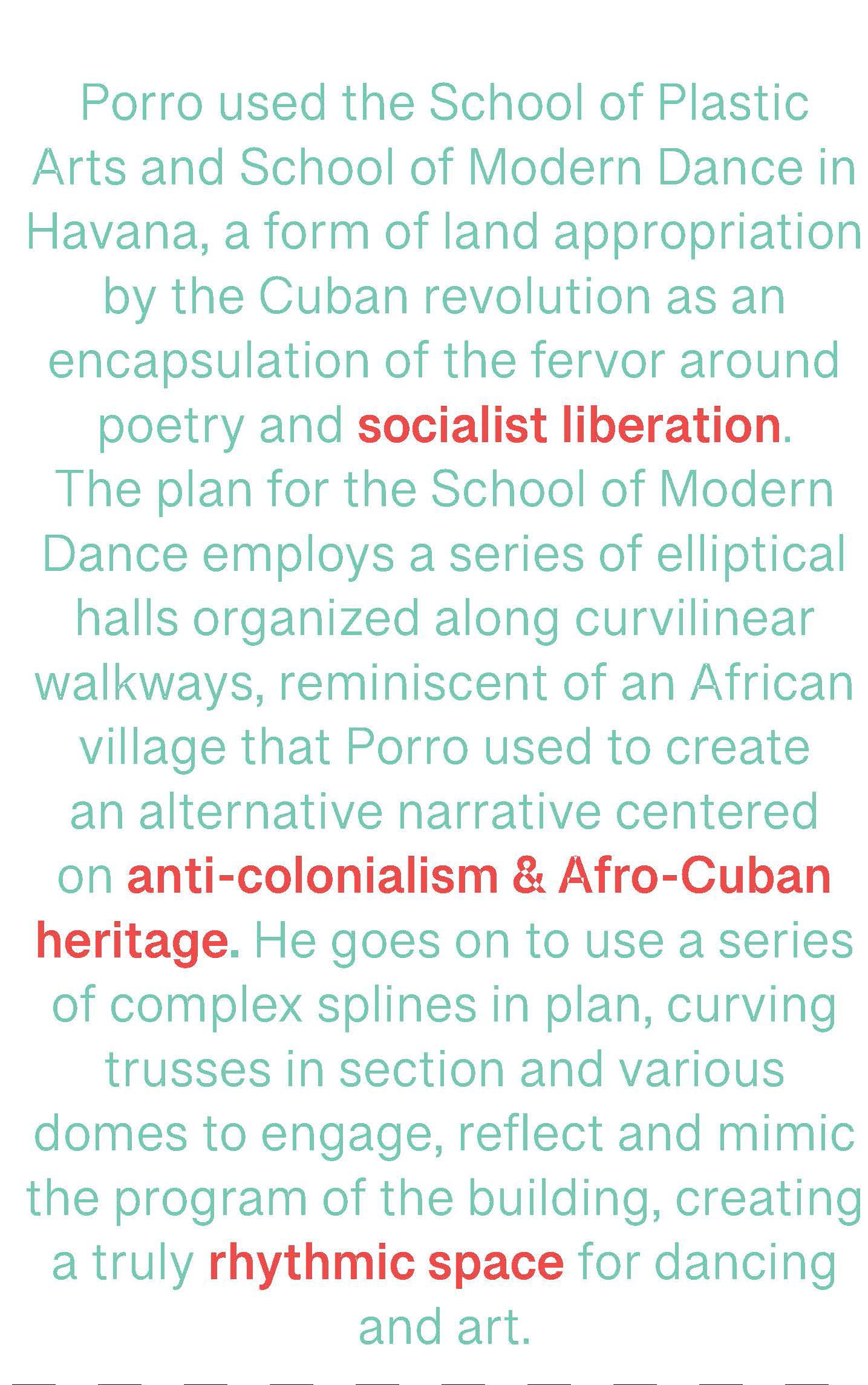

A Genealogy of Antifascist Architecture is necessary if we are to find ourselves within the liberatory projects of the last 120 years spanning Eastern Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, the Global South, and Asia. These projects such as: Centro Gabriela Mistral in Santiago and/or the Agostinho Neto Mausoleum in Angola and/or the Black Panther Party Free Breakfast program and/or Schools of Modern Dance & Plastic Arts in Havana and/ or Monument to Patrice Lumumba in Africa and/or Spomenik’s in Eastern Europe and/or the National Memorial to Peace and Justice in Birmingham, AL, all use a social, political & ethical foundation to the architectural forms presented. There is no way to decouple the victory of these projects from the systems that created them because to do so would perhaps even remove them from the discipline of architecture. That is to say, if we are to rescue architectural practice and discourse from the neoliberal capitalist extractive machine then the inclusion of these and the exclusion of fascist projects can and will augment architecture’s affective footprint in this world.

Finally, finding ourselves within antifascism is about killing any inkling of fascism within us and that includes the indoctrination we’ve had as architects towards certain projects and people. There is an almost flippant nature to architectural theories today dealing with issues of copying & influence, repetition & genealogy, specifically because of the depoliticization of precedent by historicist postmodernists. If everything is pop, then everything is commodifiable and follows the logic of capitalism. Capital wins, we lose. So, if we were to find ourselves within subcultures and communities actively pushing against the logic of capital (not just trying to reform it) then perhaps a new form and function for architecture outside of it is possible. In a simple sense, architects must be activists as citizens first before ever dreaming of knowing how to push against a disciplinary juggernaut with thousands of years of power manifestation at its core.

All projects images and text are included in Office Andorus’s ALANAR (An Altar to Antifascist Architecture) designed for the Bellevue Art Museum Biennial 2021, curated and researched by Daniel Roche and Andrew Santa Lucia. These images are found on prayer candles adorning the Altar. ‘ANTIFASCIST’ typeface designed by Briar Levit.

WORLDING 92

¡Hasta la Victoria, Siempre!

— Comandante Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara de la Serna

93

WORLDING 94

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 95

WORLDING 96

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 97

WORLDING 98

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 99

WORLDING 100

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 101

WORLDING 102

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 103

WORLDING 104

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 105

WORLDING 106

A NDR e W S AN t A L UCIA 107

WILLIAM HOHE

William Hohe is a multimedia artist, photographer, and creative entrepreneur from Wheaton, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. His work meets at the intersection of photographic processes, printmaking techniques, and sculptural installation. William’s work conceptually relates to queer theory, sexuality semiotics, pop culture, and, amongst other things, psychedelic imagery. He is currently a junior at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign studying Photography and Advertising with minors in Art History and Business.

You can find William and his art at williamslenses.com and on all social media @williamslenses.

CRITIQUING AND LEGITIMIZING REALITY THROUGH FALSE IDENTITIES AND HIGHLY RENDERED UTOPIAS/DYSTOPIAS

WILLIAM HOHE

As a creative and an artist, my lens and medium of choice is one that at first glance is highly technical, rooted in science, and a recorder of reality; that is camera and photography. In essence, the camera is supposed to render the world in a copy through analog or digital means and postproduction is usually adapted to fit the colors and perception of the human eye; what is seen ought to be what is truth.

In my work, I enjoy turning that principle on its head in full rejection. That’s where “worlding” comes in. In my photographic work, I often times contain a duality of personal expression and cathartic emotional processing amidst a wider critique on society and the current events for which I am enraged, inspired, saddened, or passionate about.

I find that I am able to get across the point I am trying to make to myself and to my audiences best when I create a world, an imagined state, or false identity in my images. This means highly elaborate colors, sets, backdrops, and environments that typically use elements of material goods and items from my own life that I have obsessions and symbolistic meanings for but are rendered and transformed in such a way that they become otherworldly. I find that I am able to relate and feel a sense of satisfaction more when the image is so wrong that it becomes right. This can be achieved through turning a model into a tinfoil alien or painting my face blue. The opportunities and experiences are endless.

In Hell with High Water, 2022

Photographed by William Hohe

110

At its best, art and specifically photography works to create an illusion, suspend the disbelief of the viewer to captivate them in such a way that moves whatever you are trying to get across, whether it be nothing, something so specific, or broad, that it sticks with the human viewing or experiencing it for much longer than they bargained for. In much of art history, this was done through creating an ideal, a realistic depiction, or façade of reality. In my art, I want to create something so illusioned, so idealized, and so far removed from our current reality that it becomes substantiated in the mind as if it was of this world. By “worlding” away from what we can experience in this realm, I hope I can impact, through outlandish and often overwhelming means, a rendering of a world that could be, of a situation that might be, and of circumstances that help us question and critique our current dilemmas. Through fantasy, psychedelic journeys, and worlds not yet legitimized, maybe this reality can be much more thrilling, imaginative, and tolerable in the process.

WILLIAM h O he 113

Madonna of the Cinema, 2021

Photographed by William Hohe

Prom Song (Gone Wrong) is from a highly stylized shoot that featured models sporting their moms’ prom dresses. It’s a questionable scene that looks more like a film still than a photograph, begging the viewer to ask what happened before…and after.

Prom Song (Gone Wrong), 2021

Photographed by William Hohe

WORLDING 114

Prepare for Impact was a spontaneous shot that I took while with Alexa and Rece, two of my friends. We were stopped at the train tracks, and everything looked perfect; I forced Alexa out of the car and we got the shot using the car’s headlights. In this way, a world was created out of thin air, circumstance, and what was available.

Prepare for Impact, 2021

Photographed by William Hohe

WILLIAM h O he 117

WORLDING 118

Right: Organic Reincarnation, 2022

Photographed by William Hohe

Left:

All Fake Flowers as Seeds of Her Depression, 2022

Photographed by William Hohe

In All Fake Flowers as Seeds of Her Depression, Alex let me into her home and showed me her fake flower collection, one she bought every time she was sad or depressed. I wanted to celebrate this coping mechanism in her own space, taking bits of her being through material goods and creating this environment that was both familiar, foreign, and surreal.

Davion is a model that I met whilst at the St. Patrick’s Day parade this year. In this shoot, I felt he radiated a certain organic, environmental, earthly spirit that I felt was evident in this work. His love for all things relating to the environment and the calming, soothing presence he exuded went hand in hand with the concept of this shoot.

WILLIAM h O he 119

Photographic Manipulation is Prison of the Mind, Spirit, Body contemplates the possessive nature of an art career and the fulfillment versus draining nature of constantly living, breathing, and thinking about art. As a selfportrait, this work solidifies and legitimizes the feeling of being in the darkroom until the early hours of the morning and the passion that goes behind the work you create and contemplation of if all of it is really worth it in the end.

WORLDING 120

WILLIAM h O he 121

Photographic Manipulation is Prison of the Mind, Spirit, Body

Photographed by William Hohe

WORLDING 122

Oh Beautiful, 2021

Photographed by William Hohe

My friend Emily, modeling here, looks fearfully as American flags pop out of her ears. Much of my work during 2020-2021 was fueled by rage and critique against America amidst the 2020 election, and this series was no different, questioning all I knew about pride, bias, stereotypes, capitalism, and business.

WILLIAM h O he 123

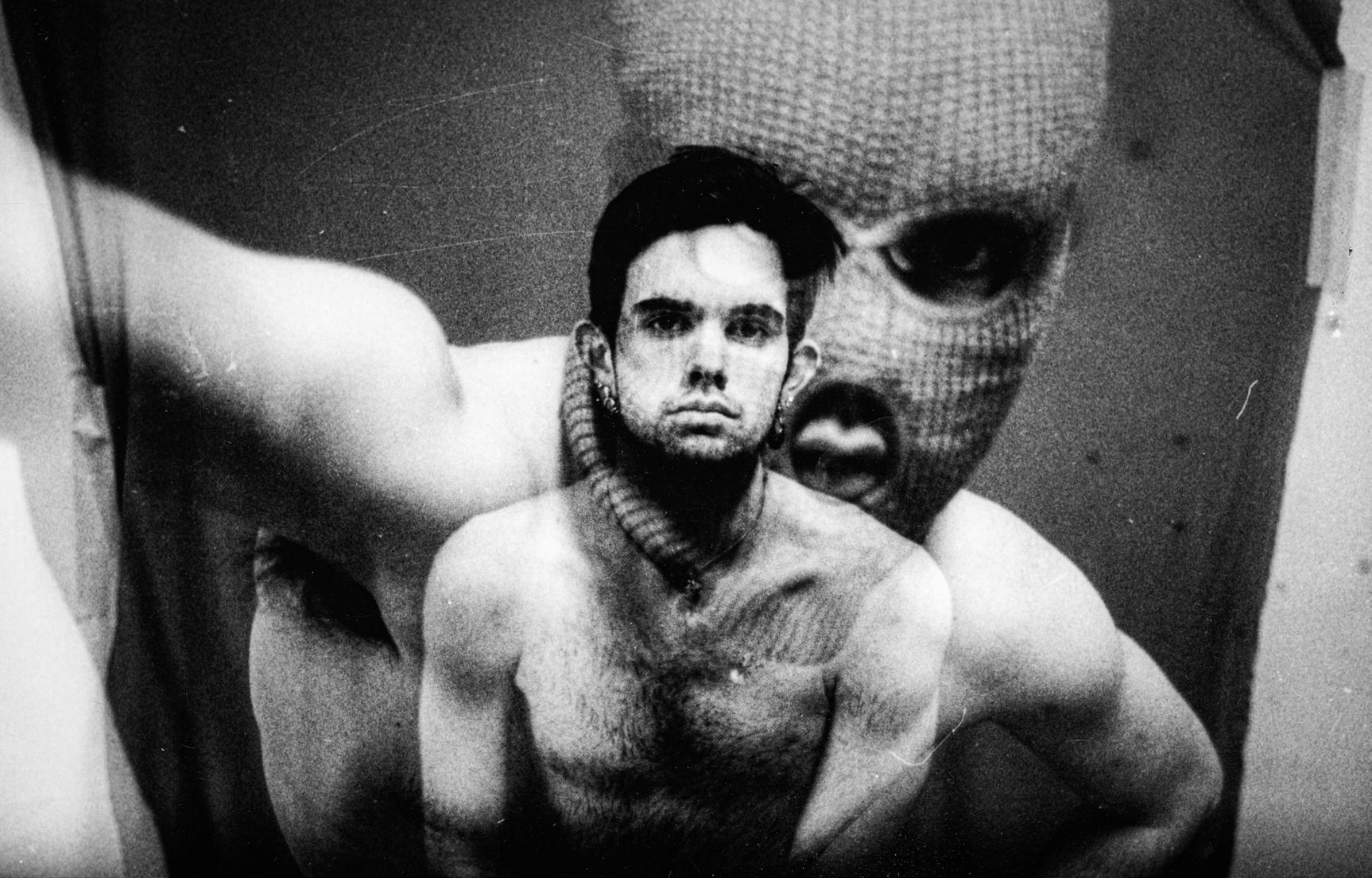

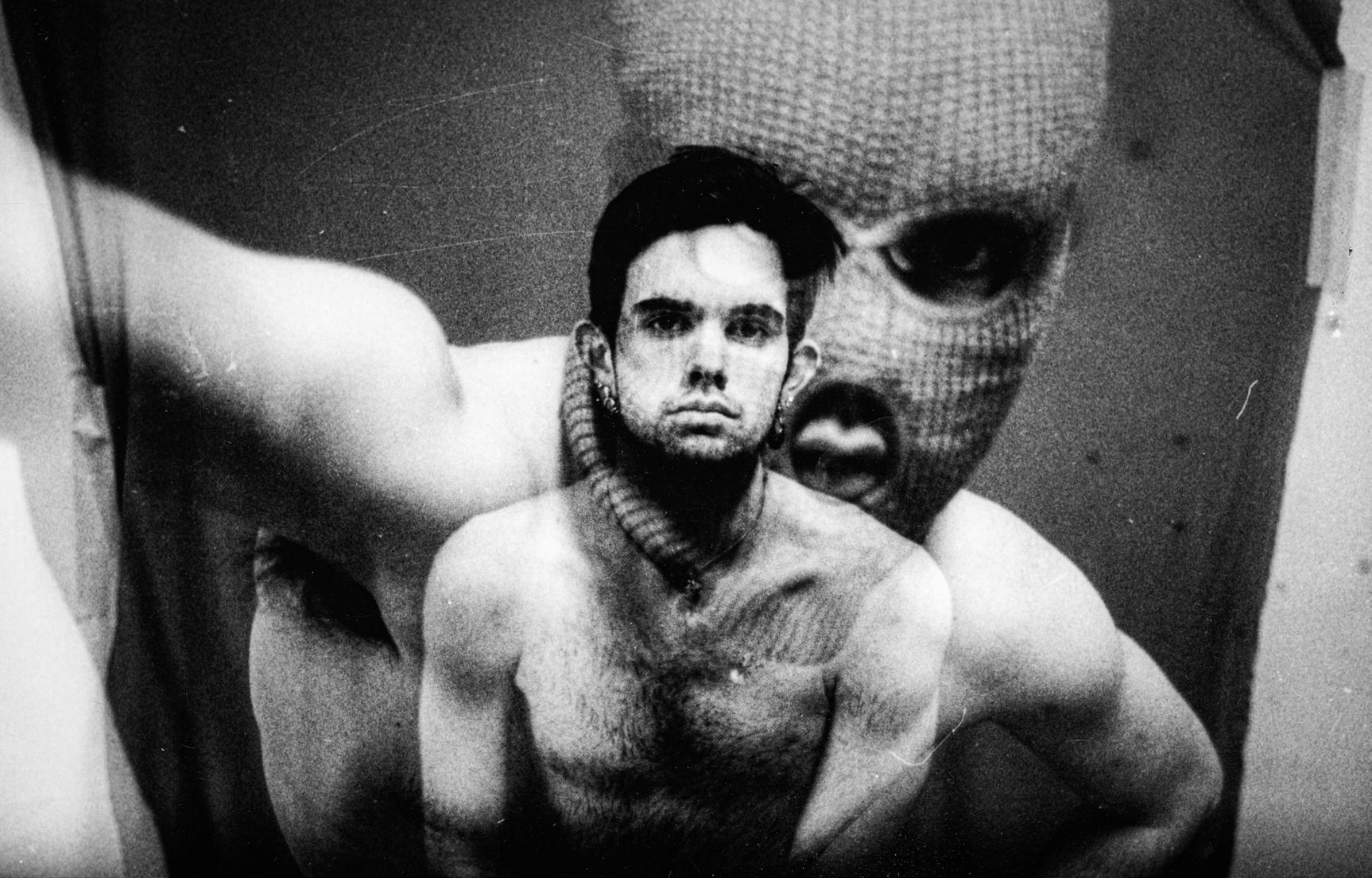

If You Could See Me Now is a 35mm film enlargement that double exposes two separate self-portraits. Alter egos and dual personalities is a practice and performance that I have been investigating and how it relates to my perception of self, vanity, and sanity. I enjoy ski masks quite a bit as a fashion statement as well as the way in which they hide the face but reveal the most distinguishing features. This piece is one that is to enlighten but also disturb, creating this world between the self, asking which of either the “fake” or “true” person is more authentic than the other.

WORLDING 124

If You Could See Me Now, 2022

WILLIAM h O he 125

Photographed by William Hohe

Fall 2022: Worlding Comunal

Reza Nik

Liz Gálvez

Galen Pardee

Andrew Santa Lucia

William Hohe

OTHER WORLDS ARE POSSIBLE.

RICKER REPORT

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Comunal

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Onnis Luque

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Onnis Luque

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Onnis Luque

Social Reconstruction of Habitat Courtesy of Onnis Luque

Great Lakes Watershed and Spillway Hazard Zone Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Great Lakes Watershed and Spillway Hazard Zone Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Spillway Section and Axonometric Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Spillway Section and Axonometric Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Great Lakes Exhibition Courtesy of Galen Pardee

Great Lakes Exhibition Courtesy of Galen Pardee