HUGLI HERITAGE MANAGEMENT STRATEGY

Contributors

Prof. Soumyen Bandyopadhyay

Dr. Suranjana Bhadra

Claudia Briguglio

Purba Chatterjee

Ben Conwell

Dr. Urmila Jha-Thakur

Reshma Khatoon

Dr. Ramanuj Konar

Livia Lucilla Luciani

Dr. Ian Magedera

Debanjan Mitra

Dr. Antara Mukherjee

Edited by ArCHIAM Centre

Sketches by Trina Bandyopadhyay

Photographic contributors: Trina Bandyopadhyay, Pinaki De, Srinjoy Hazra, Ramanuj Konar, Debanjan Mitra, Neline Mondal, Saibal Mondal, Patit

Paban

Halder, Subrata Roy Chowdhury

Publication date: July 2020

ISBN: 978-1-910911-17-4

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

Scope and Focus - Ian Magedera

Statement of Intent - Ian Magedera

THE HUGLI RIVER CORRIDOR

Introduction

Tangible heritage along the Hugli Purba Chatterjee

European influence on the intangible heritage along the Hugli Purba

Chatterjee

Delivering environmental sustainability in cultural heritage tourism along the Hugli corridor - Urmila Jha-Thakur

Gondolpara - Ramanuj Konar

Jagadhatri Puja: the power of myth and might through intangible heritage - Purba Chatterjee

CASE STUDIES

Introduction

Case Study I. The Gowers Committee (1950) and the saving of the English country house - Ben Conwell

Case Study II. Serampore and all that: creating spaces for intangible cultural heritage beyond Danish-Bengal initiativesSuranjana Bhadra

Case Study III. Critiquing the Restoration Methodologies of Barrackpore Park - Debanjan Mitra

Case Study IV. Half-done Heritage Revitalization of Hooghly riverfront towns: A ray of Hope in Konnagar - Antara Mukherjee

CHANDERNAGORE

Introduction

History of Chandernagore: A Brief Overview - Purba Chatterjee

The Ghats of Chandernagore - Reshma Khatoon

Population and migration - Purba Chatterjee

HERITAGE MENAGEMENT STRATEGY

Introduction

Heritage policies: international and national developments

Hugli Heritage Audit: a case for an integrated river heritage corridor

- Ian Magedera

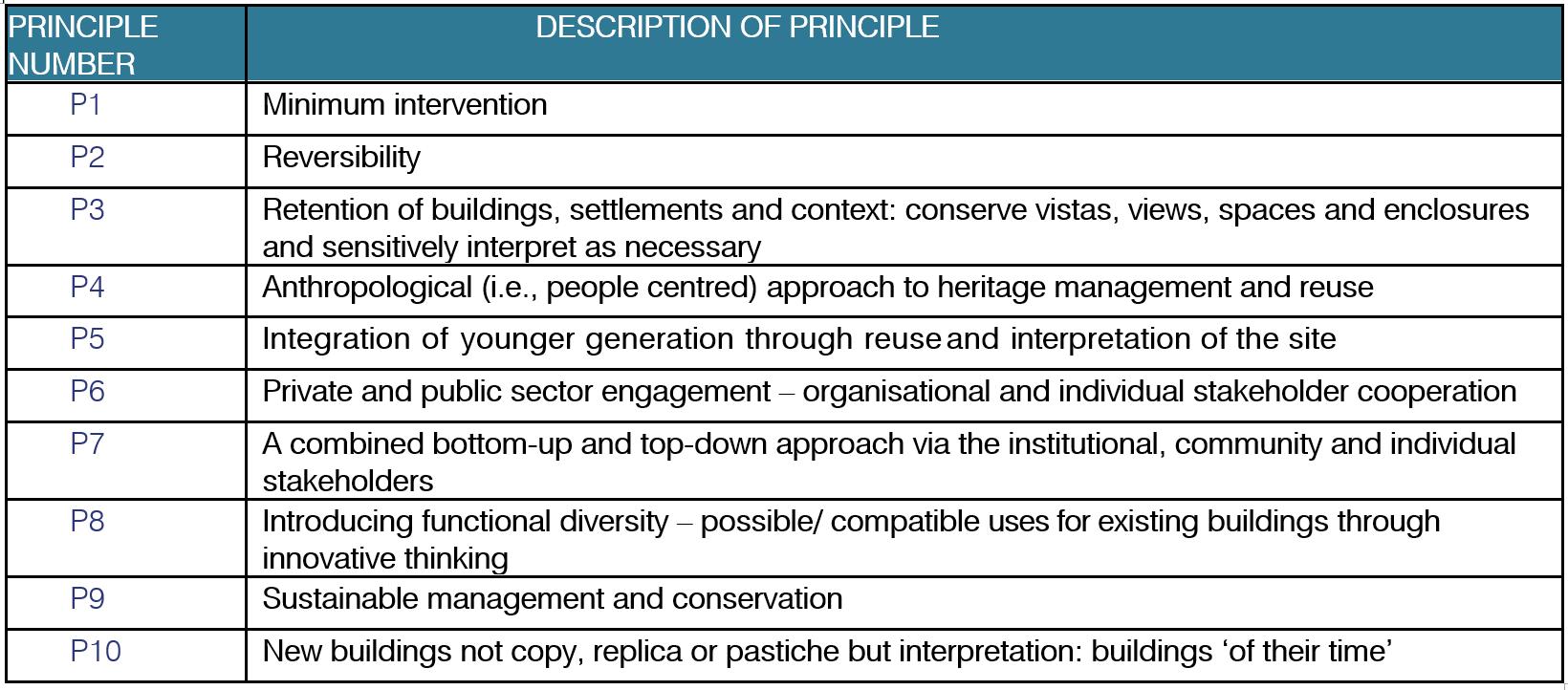

Principles and approaches to heritage management and development - Soumyen Bandyopadhyay

SUMMARY

Heritage in a box? Assessment of initiatives undertaken through the Hugli River of Cultures project

Key recommendations - Ian Magedera Soumyen Bandyopadhyay

APPENDICES

Bibliography

Drawn documentation

Photographic documenation selection from Chandannagar

HUGLI HERITAGE MANAGEMENT STRATEGY

1.1 SCOPE AND FOCUS

With over 91,276,115 inhabitants as recorded in the 2011 census, West Bengal is the fourth most populous state in India. While cities and districts in other states such as Ahmedabad, Jaipur, Bhubaneswar, Cuttack, Chanderi, Leh, Champaner, Surat and others have seen the publication of heritage management plans, this document is the first since West Bengal’s foundation on 26 January 1950. This document is called the ‘Hugli Heritage Management Strategy’ (HHMS) because it focuses on the five riverine settlements from Bandel to Barrackpore. While recognizing the distinctiveness of each settlement (not least in administrative terms), the naming convention ‘Hugli’ considers them as one unit for heritage purposes. Indeed, this unitary treatment as a networked and unified cultural landscape is one of the HHMS’s key recommendations for the future. Naming conventions for this part of the river are highly variable and range from the symbolic and spiritual denotation of ‘Ganga’ to the material infrastructure focused term ‘NW-1’, National Waterway One. The justification for considering this riparian area as distinct springs from the globally unique concentration of the traces of five European nations: Portugal, the Netherlands, France, Denmark and the United Kingdom along this 35km stretch of water and the river banks. In the words of the UK historian of heritage Philip Davies, ‘the Hugli is a river does not only belong to India, but to the world’. Furthermore, as in the Hugli River of Cultures Project, the international UK and Indian government funded university research initiative out of which the HHMS grew, it emphasizes the river as a conduit of culture for local inhabitants. In short, the Hugli River allow more local inhabitants to gain a common vision that helps them regain their heritage.

The focus in this HHMS on the Hugli corridor either side of the river is the reason why we write ‘Hugli’ and not ‘Hooghly’. Towns such as Pandua, Arambagh and Tarkeshwar, to name just three, are outside the remit of this riverside HHMS, but they are the backbone of the region’s future heritage

and leisure potential that this HHMS recognizes as vital for the sustainable development of the region as a whole. It should not be forgotten that the population of Hooghly as an administrative and electoral district is 5.52m and, therefore in future state heritage planning beyond this HHMS it will be necessary to consider how to include inland areas as a population counterweight to the megacity of Kolkata (population 16.04m in 2011). This is only one of five or six districts that border Kolkata. The term ‘hinterland’ is deliberately avoided in this HHMS with reference to the inland settlements of Hooghly away from the river because it is a reductive term which reimposes a separation between a ‘Hugli’ centre and a ‘Hooghly hinterland’ that is rejected here. It is separations of this sort that have so often been imposed on the river corridor from Bandel to Barrackpore, the subject of this HHMS. Those separations and the naming of the region as a so-called ‘dormitory’, ‘peripheral’, ‘threshold’ or ‘suburban’ zone, in the shadow of Kolkata has hindered sustainable development in the Hugli Corridor from Bandel to Barrackpore.

First, this present ‘Scope and Focus’ section of the HHMS will situate its object: heritage and quality of life in Bandel, Chunchura, Chandannagar, Srirampur and Barrackpur in both space and time. Second, it places the heritage management strategy itself in a continuum spanning preproject research to the pathways in which it plans to effect change in the Hugli Corridor. Third, by critically comparing itself to previous heritage management strategies in India and in Northern Ireland (taking cultural differences into account), it will set out the innovative new methodology for achieving effectiveness in the future. This will be done by the HHMS including feedback from stakeholder groups on its proposals, a summary of the future initiatives of other cognate projects in the region and, most importantly, a flexible, forward-projecting implementation action plan with funding built in. In this way the first heritage management strategy in West Bengal aspires to be world-leading within its class. It is a report as a key output point in a continuum of research-based new knowledge, set in the context of wider community action and engagement.

1.1.2 Hugli in space and time

Writing about the Mediterranean and Mediterranean World, the French historian Fernand Braudel coined the term ‘geographical time’ to describe

the slow, but cumulatively momentous changes that happen over many centuries. Whereas the Mediterranean is a comparative stable body of water with tidal amplitude of a few centimetres due to the comparatively narrow outlet/inlet with the Atlantic Ocean, the ostensibly slower form of ‘geographical time’ moves comparatively rapidly in the Hugli Corridor. This is confirmed by the fact that during the seventeenth century the silting up of the channel of the Saraswati River at Saptagram about four kilometres from Bandel and the increased flow in the Hugli shaped the distribution of human settlement. This was at the horizon of the period of shared Indian and European history in the region from the mid-sixteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. In the short, medium and long-term future, climate change in this area, where the mean height above sea level is around nine metres, also suggests that settlement patterns and thus built and cultural heritage will be determined by water levels.

During the course of its two-year lifespan, the Hugli River of Cultures Project worked at six historical levels. First, its initial premise was that the region had been undergoing rapid urban change since India’s economic liberalization in the 1990s. That said, West Bengal lagged behind national growth and this and the Hugli Corridor’s peripheral location meant that the pace of change from 1990s to the early 2000s was 10-20% slower than in the metropolitan peripheries around Mumbai and Delhi. Locally however, the evidence of the demolition of residential and commercial heritage properties documented in Petit Paban Halder’s photographic biography of Chandernagore (2004) and his accompanying photographic archive meant that the degradation of built heritage gathered pace, after 2004 forcing the Hugli Corridor to become an ever higher density dormitory settlement for Kolkata.

Second, the project had a major focus on repeated seasonal patterns in the region though its docudrama Samayita (the Healer) that foregrounded the annual galvanising of the community spirit in Chandernagore and its environs during the Jagadhatri Puja each November. In this way, continuity and change in folk traditions that go back around two hundred and fifty years are explored.

Third, the project’s batik banners focus on visual depictions of the five settlements of Bandel, Chinsurah, Chandannagar, Srirampur and Barrackpur from the period from 1396, the construction of the Serampore Roth, to the coming of the Eastern Bengal Railway to the Hugli Corridor

in 1854. This is a focus on hybridity vehiculated by the slower forms of river and road rather than the faster and larger scales that were ushered in by the railways. The suburban railway and how it allows people to be in Kolkata and in Hugli in one day still dominates the pace of live in the region. Even in 2020 the railway covers the same distance approximately three times faster than by road.

Fourth, fifth and sixth, Andrew Davies’s work focused on the struggle for Indian independence from the 1900s to 1947, Ian Magedera’s work on the horizon of living memory of the French in Chandernagore around 1950 and Helle Jorgenson’s on the contemporary understanding of heritage in Hugli. This major contemporary focus was further anchored by the project delivering event-based community stakeholder events and broader public outreach through two Hugli Heritage Days, a HeritageFest a photographic exhibition. To quote the works of the HRCP’s May 2018 Statement of Ethics and Intent, the Project’s events ‘aim to awaken in Hugli [Corridor] citizens, a sense that the river binds them as a conduit of cultures. This Project is future-focused, aware of the past, but not stuck in it’. Moreover, a successor organisation the form of a ‘Hugli River Corridor’ Chapter of the Indian National Trust for Arts and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) furthers these aims from January 2020. This Hugli Heritage Management Strategy uses the six historical perspectives to interrogate buildings, zones, borders and how they contribute to water- and landscapes that interact with their histories while also being the reflection of a particular time of day, asking the question that is the title of Kevin Lynch’s 1978-book What Time is This Place?

1.1.3 HHMS, a point in a continuum of heritage research in the Hugli Corridor

As stated above, this Hugli Heritage Management Strategy situates itself in a continuum of work for heritage done by private citizens of both Indian and European born in the region going back into the period of shared history under limited French sovereignty in the region before 1950 and stretching back into the documents, maps, paintings and archives and records that were created during the period of the Portuguese, Dutch, Danish and British presence (a selection of these documents are listed in the bibliography).

Moving into the contemporary period of researchers who are currently

active, there is the research and writing on history produced by academics such as Biswanath Bandyopadhyay and Subhendu Majumdar outwith the project (see bibliography) and also to the pre-project historical research of local inhabitants, such as Akshay Addya, who are now affiliated to the project and to its successor organization the Hooghly Regional Chapter of the Indian National Trust for Arts and Cultural Heritage. Though the Hugli River of Cultures Project was the first academic project to focus on this region as a whole, irrespective of the project and of the HHMS, the work of these researchers will go on as it is independent, though informed by the Hugli River of Cultures Project. The same applies to the photographic archives of Ramanuj Konar on Jagadhatri Puja and Patit Paban Halder on Chandannagar and its environs that predate the project. These photographers were given a new impetus to photograph for the project and have the AR App juxtapose examples of their work from the early 2000s with that from 2018-2020. Also feeding into the HHMS is the start-of-project Heritage Audit of the most successful heritage projects in West Bengal in the last ten years (not including Kolkata).

1.1.4 Heritage, ‘Otijiyo’ or ‘quality of life’? Is heritage translatable into Bangla?

‘Reverberations, Voices from the Riverfront’, the 2019 film about the impact of the Hugli River of Cultures Project, illustrates the issue clearly: Bengali speaking interlocutors more frequently use the English word ‘heritage’, rather than the word Otijiyo, a synonym. That latter word, though accurate, is precisely that, a translation. That is to say that heritage is an internationalized discourse which came to India via English and international organisations such as UNESCO. ‘Otijiyo’ [BANGLA SCRIPT] does not feature in the public discourse about heritage and in the titles of heritage organisations in West Bengal such as the West Bengal Heritage Commission which is not known by a Bengali title. In etymological terms Otijiyo and ‘Otijiyo’ / Aitihya come from a scholarly didactic and personalized traditions of epistemology relating to traditional teaching vehiculated by individuals and schools via texts and oral legends. The semantic field is therefore quite different from material and intangible cultural heritage. Naturally, the English-language word ‘heritage’ will be continued to be used in West Bengal because of the international dimensions to the origins of the particular types of heritage found here, but in terms of its relevance to wider public good it

is useful to link it in to urban quality of life. As Helle Jorgensen, HRCP CoInvestigator has pointed out and as recorded in the project’s Statement on Ethics and Intent, Urban quality of life is a common general concern at the interface between citizens and the state. ‘Urban quality of life’ should not supplant heritage in the names of outward public-facing initiatives and publications and in terms of research contributions, but there should be flexibility by practitioners and volunteers to choose terms such as ‘history’ and ‘sustainable development’ which better speak the aims and objectives in actions that flow from this Hugli Heritage Management Strategy.

1 PEARL, p. 27

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XhLhnshfyX8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tD-HsIQXlM8 (Hindi)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCRloQLOYNA (English)

3 2005

4 La Méditerranée et le Monde méditerranéen à l’époque de Philippe II (Paris: Colin, 1949), p. 14. He would look at similar material from three perspectives: ‘Thus we have arrived at a decomposition of history into three stacked levels. Or, one could say, the distinction in historical time between a geographical time, a social time and an individual time/ ‘Ainsi sommes-nous arrivés à une décomposition de l’histoire en plans étagés. Ou, si l’on veut, à la distinction, dans le temps de l’histoire, d’un temps géographique, d’un temps social, d’un temps individuel.’

5 So in Braudel’s terms, ‘geographical time’ in Hugli moved so quickly that it impacted on Braudel’s next level up ‘social time’ (his third and final level was ‘individual time’ – the time span of a single human life).

6 WB vs National average.

1.2 STATEMENT OF INTENT

1.2.1

The fundamental intention of this development plan is to achieve the sustainable preservation and continued habitation of the settlements within the Hugli River Corridor (HRC) region.

1.2.2

While of course recognizing the crucial contribution of expertise, political representatives and the economies of scale that can be achieved though state and union participation in heritage safeguarding and promotion activities, HRCP members favour an approach which consults and collaborates with local inhabitants as widely as possible, even if this increases the duration of projects. We advocate heritage ‘with’ local people and not heritage ‘for’ them. Such an approach is also aligned with international best practices.

old people and those passing through the region, such as tourists and migrants), it should also be spatially flexible. Naturally, laws, byelaws and protected heritage precincts and their buffer zones have demarcated jurisdictions, but the sentiment that people as belonging to a place such as the Hugli corridor or Hooghly should extend as far as people want it to and should definitely allow for overlap with the spheres of influence of other regional identities. Heritage has no linear borders and is incompatible with strict territoriality. In Hooghly and in West Bengal in particular, it must be generous with overlapping zones and not frontiers.

1.2.5

Heritage needs to generate money and wealth for local inhabitants, heritage practice needs money to function, but there should always be a gifted component in heritage to resist its commodification. These gifts may be a token gift to paying heritage walk participants, but most likely it will be the precious gift of time by heritage volunteers.

1.2.3

Under sustainability we understand not only the ecological and cultural aspects which form the principal appeal of the site/s and must therefore be protected, but also the financial concern of investing in the HRC’s future. Capital for the maintenance and investment in the settlements and sites will necessarily require external (i.e., union, state and international) input to begin with, but the final goal is to reach a level of self-sufficiency where proceeds from locally generated revenue sustain the required heritage management expenditures of the HRC communities, managed through a locally-based collective or cooperative approach. These bodies, comprised by local stakeholders and community members, would be set up to safeguard HRC’s heritage value and ensure that the heritage and developmental needs of HRC inhabitants are met.

1.2.6

The need for heritage management in the Hugli Corridor is not a given in West Bengal, because the region has been administratively fragmented and suffered from its proximity to the built and intangible cultural heritage riches of Calcutta, the capital of British India until 1911. In making the case for safeguarding and adaptively reusing heritage structures in an architecturally and culturally sensitive manner, heritage management in the Hugli Corridor needs to be historically informed, open to global cultural difference and to multiple languages. There are unlikely to be funds for dedicated bricks and mortar institutions in the region in the medium term, so heritage activists and budding heritage practitioners will need to be fleet-of-foot and project-based, forming and disbanding as project income comes and goes. It is for this reason that the engagement of local inhabitants, as detailed in points one to three above, is so important.

1.2.4

In the same way that heritage practice should be as socially inclusive as possible (actively including all minority groups, as well as children,

1.2.7

The ultimate intention of this Heritage Management Strategy is to provide

a road map for the relevant authorities to work together at state and union level to protect heritage from rapid urbanisation and to promote its enjoyment by local inhabitants, and Indian regional and international tourists in a sustainable manner. This is the result of realizing that the Hugli Corridor is either a region in heritage transition or perhaps one in heritage decline, in this way, the broad thrust and methodological key points of sustainable heritage for development will be elaborated, including those which relate to the pressing environmental threat in a region that lies at a mean of nine metres above sea level. The strategy sets out the general direction of travel and the wider intellectual context that is relevant for other peri-urban areas in India and around the world; however, future iterations of a future Hugli Management Plan at five years intervals to 2050 and beyond may include anything from floating buildings of the Dutch architect Koen Olthuis’s Waterstudio, to managed decline and selective abandonment.

1.2.8

HRCP proposes that traditional values such as social and economic selfsufficiency be the guiding principles that lead the future development within HRC, providing a model for sustainable development and ecological responsibility for West Bengal and India.

1.2.9

All measures here proposed are in accordance with international conventions and ICOMOS guidelines and it is expected that all future interventions will continue to uphold these values.

THE HUGLI RIVER CORRIDOR 2

2.1 INTRODUCTION

This chapter provides an overview of the heritage significances within the Hugli River Corridor (HRC) region, as well as an assessment of the environmental challenges faced by the heritage landscapes and assets and the tourism industry. The heritage significance is both tangible and intangible with a strong emphasis on the interaction that took place between the European traders and colonial powers and the local communities. The impact of European architectural ideas on the organisation of dwellings and the decorative elements that adorned these, was significant. Domestic spatial order took on a composite form with the juxtaposition of traditional organisation of space around a courtyard and an Europeanised formal arrangement orientated towards the display of wealth or status. Portuguese and other European influences have also permeated the intangible heritage of the region, especially in the preparation of sweet dishes distinctive of this region, which have later received international acclaim. Traditional textile crafts received impetus through the European presence and the opportunities of expanded production and trade it offered. The environmental challenge faced by the HRC, it is argued, should be addressed by combining a bottom-up, stakeholder orientated approach with the extant, more conventional government and institutional initiatives. This potentially provides significant opportunities for sustainable development and growth.

2.2 TANGIBLE HERITAGE ALONG THE HUGLI

In a word, Bengale abounds with every necessary of life; and it is this abundance that has induced so many Portuguese, Half-castes and other Christians to seek an asylum in this fertile kingdom

François Bernier (1660)

2.2.1 Introduction

This section is a short gazetteer of key heritage sites within the Hugli River Corridor (HRC). This gazetteer is not meant to be comprehensive; rather the aim is to establish the broad heritage significance of the HRC, in this case, focusing on its tangible heritage (intangible heritage is discussed in the following section, 2.3). The following description covers, from North to South, the towns of Bandel-Hooghly, Chinsurah and Serampore along the western bank of the river. The case study focus town of this report –Chandernagore – is not discussed here but dealt with in more detail in the subsequent chapter (Chapter 3). The discussion mainly covers buildings erected by the European trading establishments during the height of their activity in the so-called ‘Little Europe’ region (the Hugli River Corridor). However, several buildings and structures erected by the local population were also influenced by Europeans architectural and decorative traditions, having observed at least a sample in close proximity. A few examples of such buildings have been cited here too.

2.2.2 Bandel and Hooghly

2.2.2.1 Basilica of the Holy Rosary or Bandel Church:

The oldest Christian edifice of worship in Bengal. This Portuguese Church was built in 1599. The arrival of the Portuguese in Hooghly coincided with the fall of Saptagram port due to the progressive silting of the once mighty river Saraswati and the Hugli river becoming navigable because of the increased flow of water in it. The Portuguese set up the Hugli port and carried on a flourishing trade through it. Probably they left Saptagram and came to Hooghly in 1580. Hooghly became the most prosperous and most densely populated town among all the ports under the control of the Portuguese in Bengal. In 1588, British traveller and merchant Ralph Fich described Hooghly as the main centre of Portuguese control. But, along with trade, the Portuguese had another chief goal – to spread Christianity. As early as 1498, a merchant of Vasco Da Gama’s ship at Calicut is supposed to have said, “We have come here in search of Christians and spices.”

Very often, the Portuguese used to import missionaries from Goa for the purpose of spreading Christianity. In 1599, two such Augustinian monks came down to the newly built Convent (dedicated to St. Nicholas of Tolentino) and the Church (dedicated to Our Lady of Rosary). This Church

is now commonly known as ‘Bandel Church’. It is thought that the name ‘Bandel’ may have originated from the Bengali word ‘Bandar’ meaning ‘port’. The more than four centuries old Church has been witness to many historical events. There are no ends to legends surrounding the Church –the most remarkable among them being about the statue of Mother Mary and a mast of a ship kept in the churchyard. The mast was seen beside the cemetery until it was damaged by the Aila storm in 2009. Now it is protected inside a glass enclosure. But, people across all religions remain devoted to Mother Mary. Every year in December, people throng to the Bandel Church in hordes, during the Christmas week, to light a candle in front of Mother Mary, who is said to perform miracles in curing people suffering from incurable diseases. Hindus, Muslims, Christians, people of all religions, caste and creed, pay homage to Mother Mary all the year round. She may have originally been a Christian symbol set up by colonial rulers, but now she is a symbol of secularism in a modern free India.

Architecture: Mainly Portuguese style, with fusion of other European elements, not surprising since Portuguese culture is marked by the advent of settlers from various other European countries and also the Arabs. The Bandel Church is small in comparison to other churches. There is a large courtyard, resembling a cave, with a fountain at the centre, where people light candles or toss coins into the fountain, praying for wish fulfilment. The Doric style church comprises of three alters, a shrine to Mary, an organ, beautiful chandeliers, stained glass windows, beautiful paintings on the life of Jesus (remarkable is The Last Supper), a cemetery and a grand clock tower – all reminiscent of the colonial style of architecture.

2.2.2.2 Hooghly Imambara:

It is a Shi’a Muslim congregation hall in Hooghly, built on the estate donated by Haji Md. Mohsin in 1861. Though the architecture is predominantly Persian, there remains the stamp of colonial architecture on it. The Persian influence consists of the huge Zaridalan or prayer hall, whose walls are covered with lines from the Hadish, the maxims of Prophet Mohammad, the seven starred throne of the Imam, Islamic calligraphy on the other walls of the Imambara, different sitting arrangement for the ladies, the rectangular tank in the huge courtyard with beautiful fountains, for washing hands before prayers, the long corridors with numerous rooms housing the classes of the madrasah. But, the colonial influence is also clearly visible in the huge

courtyard in the middle, the black and white chequered marble floors, the lanterns and chandeliers of Belgian glass, the sun dial in the backyard and the grand clock tower which houses a clock in the middle of twin towers erected upon the gateway, with the clock having been manufactured by Black and Hurray Co., Big Ben, London, at the cost of Rs 11,721 in 1852.

2.2.3

Chinsurah

The Clock Tower at Ghorir More: This is the iconic landmark of Chinsurah, instantly recognisable by one and all. It is a Gothic Tower of cast iron, constructed by the British in memory of Edward VII in 1914. This clock tower standing at the intersection of four roads still has the clock in working condition.

engraved near the entrance. It started functioning from about 1896-7, when the headquarters of the Hooghly District was transferred to Chinsurah.

2.2.3.3 Hooghly Mohsin College:

It was established in 1836, with wealth donated by Muhammad Mohsin for charitable purposes before his death in 1812. It was initially called the New Hooghly College. It became associated with Calcutta University since the later’s inception in 1857 and later started functioning as an affiliated college under Burdwan University from 1960. Notable alumni of this college include Bankim Ch Chatterjee, Dwijendralal Roy, Kanailal Dutta, Muzaffar Ahmed, Brahmabandhab Upadhyay, Upendranath Brahmachari. The college building incorporates the octagonal shaped

2.2.3.1 The Dutch cemetery:

This cemetery has not been used for nearly two centuries. It was used during the 18th and 19th centuries and has 45 graves of persons who died between 1743 and 1846. It was built by the Dutch Director, Louis Taillefert in the 1760s, in order to replace an older one close to Fort Gustavus. Many prominent people of the times are buried here. The southern part of the cemetery, measuring about 200 x 100 metres contains 22 Dutch tombs which are of three kinds – pyramids, rectangular sepulchres and plain graves. Though it is no longer in use, it continues to be an active place of interest for researchers and tourists. The cemetery is now protected and maintained by the ASI.

2.2.3.4

Armenian Church:

The construction of the earliest church in Chinsurah was started by an Armenian merchant-diplomat called Margar Avag Sheenentz of Julfa, as early as 1695 and was completed in 1697, after his death, by the members of his family. The church is dedicated to St. John the Baptist. It is the second oldest Christian church in Bengal, after the Bandel Church, and the oldest Armenian Church in India. It has a clock tower, so typical of colonial architecture, erected in 1822 by Mrs. Sophia Bagram of Kolkata, in memory of her husband Simon Phanoos Bagram. The clock has long since vanished.

2.2.3.2 Chinsurah Court:

Just south of the clock tower is the Chinsurah Court, a building said to have the longest corridors in India, a veritable Dickensian ‘Bleak House’, so typical of the 19th Century. It was built in 1829, with materials from the demolished Dutch fort of Gustavus. It was originally used as barracks for British soldiers who arrived at Chinsurah long after the British acquisition in 1825. Hence the endless corridors and never-ending stairways, which seem to lead nowhere. Typical 18th Century details on the woodwork (doors and shutters) and iron locks are still visible. The name of the building is

Each year, the Armenian Christmas is celebrated on 6th January in the Armenian Church at Kolkata. On the next Sunday after this, the entire Armenian community of Calcutta, along with the students of the Armenian College, make an annual pilgrimmage to the church. They carry with them the golden hand of St. John the Baptist, a relic with a piece of bone from the right hand of the saint, who is said to have baptised Christ himself in the waters of the Jordan river. The relic is kept at the Armenian Church of Holy Nazareth in Kolkata and is only taken out during the annual pilgrimmage to Chinsurah. The Armenian Church at Chinsurah remains otherwise closed throughout the year, for, there are no Armenians left in the town anymore. The churchyard contains a cemetery of no more than 100 graves, 28 of them being within the church itself, of notable people who lived and died in Chinsurah.

2.2.3.5 Boro Seal Bari:

The majestic mansion was built in 1763 by Nilambar Seal, a rich and influential merchant of Chinsurah. It is a grand example of the fusion of Indo-Dutch architecture. The house has been planned around multiple courtyards, a typical colonial feature. Imposing Ionic columns support the verandahs. The arches of the thakurdalan are supported by thin fluted columns with Corinthian capitals. The projecting semi-circular balconies are embellished with decorative metal grilles. Some of the intricately carved timber panelled doors still survive.

2.2.3.6 The tomb of Susanne Anna Maria Yeates:

Susanne Anna Maria Yeates (nee Verkerk), died in 1809. She was the widow of Dutch upper – merchant Pieter Brueys and had later remarried Englishman Thomas Yeates. The structure is an 8 metre high domed tomb built of brick with lime plaster in the neo-classical style and set on a high plinth. The square columns rise on the plinth, both truncated at the corners to make them virtually octagonal with Palladian elements like semi-circular archways, short classical columns and pediments, statuette niches, and circular window-like openings on four main and four smaller walls. A lantern was placed on the top of the tomb. The Verkerk family was one of the last families to stay on in Chinsurah.

royal monogram of Christian VII, the King of Denmark when the church was consecrated. Above the portico is a square bell tower which holds a clock. The church bells are no longer in use, but one of them bears the inscription ‘Frederiksvaerk 1804’, which proves it originates from a Danish iron factory. The church has a 25ft high spire.

Though the church has been actively used by the local congregation, it was so severely damaged that it was closed down in 2013, for restoration work. With initiative from the National Museum of Denmark in association with the West Bengal Heritage Commission, it underwent a massive restoration and was finally reopened on April 16th 2016. The conservation project was rewarded by the 2016 Unesco Asia Pacific Heritage Awards.

2.2.4

Serampore

2.2.4.1 St. Olav’s Church:

It remains as one of the most important relics from the times when Serampore was a Danish colony and was known as Frederiksnagore. The construction was initiated in 1800, by Ole Bie, head of the Danish trading post at Serampore and was continued after his death by his successor Captain Krefting. It was completed in 1806, curiously with the help of Englishmen John Chambers and Robert Armstrong, who were hired to look after the practicalities.

The architecture of the church is not characteristically Danish, but bears stamps of British influence, especially of St. Martin–in-the-Fields in London, the standard references for churches in contemporary England. The roof of the church is flat and the front is characterised by an open portico with double columns. The broken cornice on the front is decorated with the

2.2.4.2

Serampore College:

The college, established in 1818, is not only the oldest educational institution in India but one which is still functional. It was established by the famous Serampore Trio: William Carey, Joshua Marshman and William

Ward. The college has two separate entities : the Theological Faculty and the faculty of regular studies in Arts, Science and Commerce, just like any other regular college. The college is affiliated to the Senate of Serampore College (University) and the University of Calcutta. The Senate is associated with the administration of all the theological colleges affiliated with it. The council of Serampore College in fact holds a Danish Charter which could be used for conferring any degree from the college but is now currently used only for conferring the theological degrees. The other degrees are conferred by the University of Calcutta.

The college building is a stately structure, though curiously not listed as ‘heritage’ till now. The majestic main building contains a giant portico of the Ionic order. The ornamental main gate,the cast iron double staircase in the high ceilinged entrance hall were imported from Birmingham as gifts from Danish king Frederick VI. But, as with many other structures, this magnificent structure too is in dire need of massive restoration. Meanwhile it continues to impart education as envisioned by the Trio, to students of every ‘caste, colour or country ‘.

2.2.4.5 The Danish Government House:

It was the centre of the Danish administration from 1755, as well as the private residence of the governor. The Danish Government House is located in a 6.7acre compound. It is not ornate yet has an imposing façade. It is a yellow and white house with an extended porch and six Ionic columns. The Danish Government House continued to be the administrative headquarters even under the British. It was occupied till 1990, until a fire broke out. The campus today houses the Sub-Divisional Magistrate’s house, but is otherwise rundown. A restoration work is underway. The ‘Serampore Initiative’ acts as special consultants to the restoration of the Danish Government House. It is funded and led by the West Bengal Heritage Commission. It contributes with the historical knowledge of the 250 year old buildfing with conservation expertise. The government house from 1771 holds traces of Danish, British and Indian periods respectively, which make the preservation work extremely challenging.

2.2.4.3

The Mission Cemetery:

The cemetery of the Baptist Mission was previously located at the outskirts of Serampore, but now it is in a populated part of the town. The Mission Society paid an annual rent to the Danish government for the use of the land. The ground is now maintained by the Serampore College and houses the tombs of the famous serampore Trio : William Carey, Joshua Marshman and William Ward, which have recently been restored under the supervision of INTACH Kolkata.

2.2.4.6 The Danish Tavern:

2.2.4.4 The Danish Cemetery:

The Danish Cemetery in Serampore was reserved for Protestants, and adjoining it, separated by only by a low wall, was the burial ground of the Roman Catholics. A total of 33 burial places can be presently identified, though only a few gravestones with inscriptions have been preserved. The most notable commemorative epitaphs include the two governors of the Danish possessions in Bengal, Ole Bie and Jacob Krefting. The cemetery is maintained by the ASI.

A restored wonder has been the Danish Tavern of Serampore. The Hugli river flowing past gives it a special ambience of grandeur. The British innkeeper James Parr opened the Denmark Tavern and Hotel in 1786. It boasts of famous inmates like William Carey. The English, the French, the Danes, have all stayed at the tavern for government jobs, for business, as religious missionaries or simply for espionage. But, gradually with time it had decayed beyond recognition and has recently been restored and is back in business by the initiatives of the National Museum of Denmark, along with support from the West Bengal Heritage Commission. After two years of renovation that cost nearly Rs 5 crore, the building has been made ready to host visitors to the historical town of Serampore. It will now serve as a café and lodge for visitors. The 232 year old building has once again come alive with its white colonnaded façade, bright yellow walls and green doors and windows, all reminiscent of an era long gone by.

2.2.4.7 Serampore Court:

A major landmark of Serampore is the court compound. At first, it will look like a bustling bus teminus like any other, but a little probing will lead to

a semi-ruined arched gate. Inside stands the old court house, a building which used to be the major seat of Danish power in Bengal, though now dimmed of its former glorious appearance, bearing the stamp of colonial architecture in its colonnaded arches. The building overlooks a big ground, once probably gardens with pathways and parking spaces for horse carriages of the Danes.

Though the Danish administration in Serampore was limited by staff and finance, the governor had the responsibility to maintain law and order in the town. So, a court house and jail, or catcherie, was therefore a necessary measure for the Danish judicial system. The first jail in Serampore was built in 1800. It was a single building, containing two rooms only with a verandah and a surrounding brick wall. A new plot was bought in 1803 and the Danish engineer and Major, B.A. von Wickede, who subsequently also supervised the construction work at Serampore College and St. Olav’s Church,prepared a plan for a new jail or catcherie.The original plan by Major B.A. von Wickede provided for separate jails to Europeans, women and each of the native communities divided into Christians, Muslims, Bengalis as well as a scratch group referred to as the ‘turbulent or drunken’. A court house with a hall, two rooms and two verandahs was situated at the centre, whereas the guard’s rooms and offices were located on both sides of the main gate. Also, a large tank was situated within the compound to serve the religious demands of the faithful Hindu and Muslim inmates. In 1832, the prison was further extended with a new ward for women and a wall surrounding the adjoining courtyard. Yet another brick building, 9 feet by 60, in which convicts were kept at night, was added later, as it appears from a description from 1845 (Elberling 1845, p. 6). At the time of construction, the jail was considered a modern institution based on both humanistic ideals and experiences of the colonial administration in dealings with the local population. The Danish council of Serampore was definitely proud of its new catcherie which they described as being better and more beautiful than any other found in the surrounding European colonies. The jail still functions today as Serampore Subsidiary Correctional Home under the administration of the Sub-Divisional Officer.

The original courthouse has been demolished in favour of a new administrative building and a new partition wall has been added for security. But, the surrounding wall, the main gate, the tank is preserved and the original jails are still in use. Gone is the Royal Danish Coat of Arms, which originally adorned the pediment of the main gate, as it appears from older

drawings and photographs and only the date and year of construction, i.e. 1803, remains visible on the frieze above the keystone of the arched classical portal.

2.2.4.9 Jagannath Bari:

2.2.4.7

Serampore Rajbari:

The fortunes of the Goswami family of Serampore flourished along with that of the Danes in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They amassed huge fortune and bought landed properties in Calcutta and in the districts. Radhakanta Goswami first settled in Serampore. His grandson Raghuram Goswami, finding too much fragmentation of his original property of Goswamipara, left to build a house for his own family and thus the giant mansion today known as ‘Serampore Rajbari’ came up sometime between 1815 and 1820.

The house has two separate blocks – north and south. The two storied structure of the south is now used as a residence and also hired out for various social functions. The more magnificent section is on the north, with its cast iron gates, large driveway and Ionic columns. Though it was turned into ‘debottar’ property, it is still used for residential purposes. The most stiking feature inside is the ‘chandni’ or ‘naatmandir’, a covered courtyard like space measuring 120 by 30 feet. It was used for festive occasions, for staging plays and for feeding about 500 people at a time, during the Durga Pujas.

Raghuram’s grandson, Kishorilal, constructed another palatial residence on the banks of the Hugli river at the cost of Rs 1,50,000, to which he moved his branch of the family in 1910. The building exists in a better shape than the original Rajbari and is still in use. The property had a formidable wall, built right from the river bed, which afforded it an attractive river frontage and made it possible to lay out a big garden. It is now occupied by the Vivekananda Nidhi, which is a public charitable trust established in February 1980 by the late Swami Yuktananda, a monk of the Ramakrishna order. Since 1981, when the Prime Minister Indira Gandhi deliivered the keynote address in the first ever national seminar on ‘value orientation in human problem solving’, the organisation has been working in the field of value orientation, environmental education and ecological ethics.

The temple of Lord Jagannath is situated in Mahesh in Sermpore. Mahesh hosts one of the biggest and the second oldest Ratha Yatra festival in India, after Puri. The Ratha Yatra has been taking place since 1396. The 15th century poet Bipradas Piplai, who is known as one of the contributors of the ‘Manasamangal’ genre and for having written many of the stories of Chand Saudagar, first mentioned Mahesh, probably from around 1495. The area was probably under the rule of the Oriya kings and Jagannath may have found acceptance because of being the royal family’s favourite deity. It is not known what happened to the original temple, but, the present temple at Mahesh was built in 1755 with a cost around Rs 20,000, the finance being donated by Nayan Chand Mullick of Pathuriaghata, Calcutta. Once , when the ‘shebaits’ gave shelter to a Nawab of Bengal in a severe storm, the grateful Nawab gave them a piece of revenue free land in Mahesh. The present Ratha had been constructed out of solid iron by Martin Burn, through the financial patronage by a rich landlord of Kolkata,named Sri Krishna Chandra Bose.

2.3 EUROPEAN INFLUENCE ON THE INTANGIBLE HERITAGE ALONG THE HUGLI

2.3.1 Introduction

This section outlines some of the European influences on the intangible heritage and textile craft traditions in the Hugli River Corridor (HRC). Again, the discussion below is not meant to be exhaustive but illustrative of the significant interaction that took place between the European traders and colonial powers and the local population and their culture. The aim is to highlight the intangible heritage significance of HRC by focusing on the interactions mainly along the western bank of the river, including those that look place between local communities within a broad colonial framework.

2.3.2 Portuguese influence:

The Portuguese left behind a legacy of cultural influences in Bengal. They brought the New World crops of potato, tobacco, maize and chillies, along

with cashew nuts, papaya, pineapple, guava and the Alfonso mango to Bengal. The delicious Bandel cheese, both the smoked and unsmoked varieties, is a delicacy from the times of the Portuguese rule. What makes this cheese so special is the fact that almost all of the ‘chhana’ confections (made from splitting milk), such as sandesh or rosogolla in Bengal, owe their origins to the Portuguese and their Bandel cheese. The Krishnakali plant ( mirabalis jalapa ), is a Portuguese gift to Bengal. Many common Bengali words, which we use everyday, have their origin in the Portuguese language – chabi, balti, perek, alpin, toalia . The first printed book in Bengali prose, as well as the first Bengali grammar and dictionary, were printed in Lisbon in 1743. Father Sosa translated a religious tract in Bengali, in 1599, which is no longer extant.

Any history of the Bengal textiles would be incomplete without a reference to the Satgaon quilt, which the Portuguese exported to Europe in large numbers. It was a rare group of embroidered quilts manufactured in Bengal, probably at the initiative of the Portuguese. These exquisite quilts were pictorial in ornamentation and cross cultural in motif, of very large dimensions (often 2.6m x 3.4m) along with smaller pieces, presumably shawls or mantles. The embroidery was done on coarse cotton, jute fabric or on layers of thin cotton which were later wadded and backed. Sometimes backgrounds of silk backed with cotton are found, on muga, tussar or eri , which Bengal was famous for. Some of these characteristics can be found in the later kantha embroideries. Along with Hindu motifs, European themes of Graeco- Roman legends and Biblical stories were also used. The Satgaon quilt is a document of a period, of a culture, signifying the meeting of two vastly different worlds, rich in imagination and experience.

The Christmas week celebrations at the Bandel Church (see Section 2.2) has assumed a secular character. People from far and near flock to the church, for a short trip with their families. Most of them combine this with a visit to the nearby Hooghly Imambara (see Section 2.2). Lighting a large candle in front of Mother Mary or gazing at the inscriptions of the quranic verses on the walls, does not seem out of the ordinary at all. If not on the scale of Bandel, other churches along the Hugli carry on the tradition of celebrating the Christmas week in a similar manner with one and all –Chinsurah, Chandernagore or Serampore – the tradition is similar.

2.3.3 Chinsurah:

There prevails a mixed heritage of the Dutch, Armenian and the British, with the latter prevalent, since they were the last to leave. Chinsurah, which was once described as the most beautiful town along the Hugli, is now similar to any other bustling suburban town, where it is very difficult to distinguish the different phases of history it has been through, in the cultural life of its people.

The Kartick Puja of Chinsurah is a tradition which has been there for several centuries. It is mainly celebrated in the Bansberia region of Chinsurah Municipality. It is celebrated for five days, just like the Durga Pujas or the Jagadhatri Pujas of Chandernagore. The procession of the Kartick Puja had in fact influenced the tradition of the procession of immersion of the Jagadhatri Pujas of Chandernagore.

The bonedi bari Durga Pujas of Chinsurah have dominated its culturescape for more than three centuries. The Durga Puja of Sil Bari hails from the times of the Dutch rule and throughout history, this house has been the centre of many political and cultural activities. Another Durga Puja, nearly 280 years old, is that of the Auddy family. Speaking of religious matters, Shandeswar Shiva temple should also be mentioned. Daniel Overbeck, the last Dutch governor gifted two brass drums to the temple, which are still used during ceremonies. Muslim traditional practices are as predominant, in parts of Chinsurah, with several mosques dotting the town – Dharampur Jame Masjid, Tolafatak Masjid, Phulpukur Masjid etc. So, it comes to the fact that modern Chinsurah is predominantly Indian in essence, as any other place. It is curious that nothing Portuguese remains in Chinsurah, though it was founded by them.

The heritage of Chinsurah reverberates throughout India through the strands of Vande Mataram , which Bankim Chandra composed while sitting on the steps of Jora Ghat at Chinsurah.

2.3.4 Chandernagore:

The greatest intangible heritage of this erstwhile French colony consists of one of the greatest spectacles of the world – the Jagadhatri Pujas. The spectacular procession of immersion is second only to the carnival of Rio de Jeneiro. The involvement of the people of the whole town and its

administration, the job opportunities it generates, the cottage industries is sustains, all go to make it the largest exercise in community work.

Once again speaking of the Portuguese influence, Surya Modak learnt to make ‘chhana’ (curdled milk), from the Dutch cook at the Bandel Church and hence was born all sorts of sandesh and other sweets that Chandernagore is so famous for. His descendants carry on the tradition of making jolbhora , motichur, along with modern additions to their list. Come winter and the sweet shops of Chandernagore are stuffed with rows of sweets made of nolen gur or jaggery. Sandesh, rosogolla, jalbhara or chhana cakes, all contain the delectable taste of gur.

One direct colonial heritage could be said to be the practice of the French language in Chandernagore. It is still taught in schools and colleges and most families consider it an honour to learn the language, not for any professional gains, but just for the sake of it.

2.3.5

Serampore:

Leaving aside the Christmas celebrations at St. Olav’s Church, one heritage that comes to mind while speaking of Serampore, is the Ratha Yatra of Mahesh. It has been there from presumably 1396, and still continues to draw crowds in huge numbers. It can be considered second only to Puri in importance. The present four storied ratha of Lord Jagannath was built

by Martin Burn in 1885 and has a steel framework with wooden scaffolding and iron wheels.

Perhaps the most valuable gift that Serampore has gifted to the world is education coupled with social reform. The Serampore trio – William Carey, Joshua Marshman, William Ward, can be called the real architects of the Serampore renaissance. They established schools, including girls’ and the Serampore College (1818). They dedicated their lives to spreading education and also for social reforms, although they had initially come for spreading Christianity. For the poor, they established more than a hundred ‘monitorial schools’ in the region. Carey founded the Serampore Mission Press in 1800, where wooden Bengali types were installed. Besides publishing quite a few books in Bengali, the first issue of the second Bengali daily Samachar Darpan came out in 1818, edited by Carey. It also brought out A Friend of India , precursor to The Statesman . Their legacy is for all to see in a new world where knowledge reigns supreme. People may or may not know, but they were the first people to initiate changes which gradually opened doors of a conservative society for posterity. The Danes may have had marginal presence in trade in the Indian sub-continent, but their involvement in the religious and the educational life in Bengal was by no means insignificant.

2.4 DELIVERING ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY IN CULTURAL HERITAGE TOURISM ALONG THE HUGLI CORRIDOR.

2.4.1 Introduction

The Hugli River of Cultures Pilot Project, has predominantly used the lens of cultural heritage in upskilling heritage activists along the five former trading posts and garrison settlements located southwards downstream on the river Hugli, from the megacity of Kolkata. These hinterland towns, namely Bandel, Chinsurah, Chandannagar, Serampore and Barrackpore are endowed with a hybrid cultural heritage owing to its European colonial past and indigenous cultural practices. This makes the corridor particularly attractive for generating tourism, especially, considering the recently formulated Tourism Policy by the state of West Bengal (2016), which recognises ‘Bengal heritage’ as one of the six tourism circuits to be developed in the state. However, the evolution of this corridor historically

as well as contemporarily is largely owing to its location along the river Hugli, which is a distributary of the river ‘Ganges’ traditionally known as ‘Ganga’. Unfortunately though, based on a global study conducted by World Wide Fund (WWF), the Ganges has been identified as one of the top ten, most endangered rivers at risk in the world (2007) (Wong et al, 2007). This coupled with the environmental challenges of climate change, industrial pollution and accelerated pace of urbanisation in the region, poses severe environmental threats to the corridor and beyond.

Tourism based on cultural heritage assets will no doubt encourage economic sustainability of the region, while upskilling local people is bound to deliver social sustainability. However, in cases of cultural heritage tourism (CHT), environmental sustainability often is the weakest link (See Jha-Thakur et al, 2019). If the environmental parameters and their influence on heritage assets are not given due consideration then the sector is unlikely to deliver long lasting sustainable yields. Eventually, poorly planned tourism within the context of CHT would lead to the decline of the heritage assets themselves along with the monetary profits (Aas et al, 2005). Therefore, in delivering any meaningful sustainability to cultural heritage or tourism ambitions, incorporating environmental considerations is of paramount importance. Accordingly, this chapter explores sustainability, especially environmental sustainability within CHT in the Hugli corridor region and conducts a SWOT (Strength, Weakness, Opportunity and Threat) analysis.

SWOT analysis can play useful role in analysing business prospects, which in this case is within the context of developing cultural heritage tourism (see e.g. Vonk et al., 2007). However, they are not limited for business use and can be applied on a broader scale for assessment studies and policy analysis (See Jha-Thakur and Fischer, 2016; Paliwal 2006). SWOT analysis in this case will be particularly insightful as it allows to take into consideration internal factors which are Strength and Weaknesses, as well as external factors through Opportunities and Threats. A holistic consideration of internal and external factors can help in fine tuning planning for CHT in the Hugli corridor. In doing so, information is gathered through current policies related to tourism and environment in the State of West Bengal, desktop research, literature review, observation carried out by the research team and finally seven semi-structured interviews conducted amongst stakeholders in the region. Interviewees included locals, academics, tourism professionals, heritage activists and media personnel.

In delivering this, the rest of the chapter is organised in five sections. Following the introduction, the concept of CHT is further elaborated in relation to sustainability. The third section briefly outlines the dominant baseline environmental issues likely to impact CHT along the Hugli corridor.

A SWOT analysis in relation to CHT along the Hugli Corridor is presented under the four broad headings of Strength, Weakness, Opportunities and Threat in the fourth section and finally initial recommendations are provided and conclusions are drawn.

2.4.2 Sustainability in Cultural Heritage Tourism

Tourism is the largest and fastest growing industry in the world (Du et al., 2016; Khosravi and Jha-Thakur, 2018). The sector accounted for 10.4% of global gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017 (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2018). Although growth in tourism can lead to positive impact on economies, mass tourism can also lead to severe degradation of the environment (Michalena et al., 2008). Tourism policies, which are built upon sustainable development principles, can contribute to more inclusive growth through the provision of environmental considerations, employment and economic development opportunities and the promotion of social integration (OECD, 2017). Sustainable tourism attempts to minimize the environmental and cultural impacts and helps maximize the overall socioeconomic benefits for tourist destinations (Sofronov, 2017).

Heritage tourism is a variety of heritage sites, which represent their historical background (Smith, 2009) whilst Cultural tourism is related to cultural aspects that include customs and traditions of people, their heritage, history and way of life (José & Hernández, 2012). Cultural Heritage Tourism is an interface of both cultural and heritage tourism (Sangchumnong & Kozak, 2018). The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has combined the terminologies of “cultural tourism” and heritage tourism” into the single concept of “Cultural Heritage” in registering World Heritage Sites (Sangchumnong and Kozak, 2018, p.184) and identifies cultural heritage assets as both tangible (e.g., monuments, archaeological remains, artefacts, etc.) and intangible ones (e.g., traditions, social practices, rituals, etc.) (Dragouni, 2017).

Like any type of tourism activity, CHT may have negative impacts on destinations (Wall and Mathieson, 2006). The influx of tourists and

associated economic activities may endanger cultural heritage by affecting both the ancient built environment and the cultural practices associated with it. The New Urban Agenda (NUA) recognizes the need to consider cultural heritage as an important factor for urban sustainable development (Nocca, 2017), especially in urban and semi-urban centres of emerging economies. The speed of development in such contexts often does not give historic built environments the time to adjust to changes in lifestyle and dwelling patterns, thus resulting in being abandoned instead of adapted, or, conversely, tampered with (Quattrone, 2018). This imposes serious threats to cultural heritage and may negatively impact the environment and social fabric of these areas.

Ironically, even with the current global rise of the sustainability agenda, evidence shows that cultural heritage resources are still repeatedly damaged and destroyed. Based on the study conducted by Loulanski and Loulanski (2011), tourism over-development, uneven distribution of tourism costs and benefits in communities, undervaluation and exploitation of cultural heritage by tourism, loss of place character and identity, dominance of economic interests and short-term profits over sustainability, poor impact planning and lack of integrated management on all levels, are the main causes of unsustainability (also see e.g. Richards and Wilson, 2006).

2.4.3 Baseline Environmental Concerns along the Hugli Corridor

The environmental concerns discussed in this section will feature to some extent as threats in our SWOT analysis, nevertheless, due to the fundamental role they play in the region, it is important to appreciate their magnitude and hence develop a sound understanding of the issues. The list discussed below is not exhaustive, but certainly are the overarching concerns, which are likely to breed further sustainability problems if left unchecked.

economic activities such as agriculture, leather tanneries and religious tourism. In its upper reaches in the state of Uttarakhand, the river is also seen as valuable resource in generating hydro power electricity with the potential of 20,000MW against which only 16% is being currently generated. On the basis of this potential, the energy plan of the state of Uttarkhand is proposing to make it the future energy state of India by constructing 70 dams (See Joshi 2007, Rajvanshi et al, 2012). This is expected to impact the flow of the river especially during the lean season when the river will have to maintain a certain flow to enable it to play the socio-religious roles along the plains.

Along with the pressures of economic activity, the Ganges serves as a cultural diaspora for Indian traditions and cultural practices, which further puts the river under immense environmental pressures. For e.g. During the ‘Kumbh Mela’ which is the largest gathering of people on earth, millions of devotees take a dip in the Ganges. This leads to excessive pollution levels. In addition to this, during festivities the idols are also submerged in the river waters. Unfortunately, the Ganges is now one of the top ten threatened rivers of the world at risk (Wong et al, 2007). Hence, if cultural heritage is to be protected or promoted for tourism along the Hugli, the plan has to align itself intrinsically with the protection of the river. In doing so, the cumulative impacts along the Ganges need to be taken into consideration while ensuring that the Hugli stretch in West Bengal is doing everything to limit negative environmental impacts and work on enhancing the health of the sacred river in India.

b) Climate Change

a) Deteriorating Health of the Ganges

As mentioned earlier, the Hugli Corridor’s identity is inseparably linked with its association to the river Ganges. Flowing across the five states of Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal in India, the perennial river bank serves many major cities and is central in facilitating

According to the European commission funded project of “Global Climate Change Impact on Built Heritage and Cultural Landscapes” water, in the form of intense rain, flooding and storm or surges has been identified as the greatest threat to heritage (Sabbioni et al, 2008). This is also from the perspective of the material with which the heritage assets are made of and their likely impacts due to the influence of water. In case of the Hugli corridor, this influence of water is compounded owing to the dependence on the river and the close proximity to the sea. The Hugli corridor is located in the lower stretch of the river Ganges, which is in close proximity to the Bay of Bengal. Climate change leading to sea level rise has resulted in submergence and erosion of some islands in the Hugli estuary (Lohachahara, Suparibhanga

and Bedford) and is also leading to an increase in climate refugees in the region (Ghosh et al, 2014). Additionally, this has led to an increase in informal population and makeshift arrangements resulting to an increase in slums in the region. Furthermore, 80% of the annual flow of the Ganges occurs during the Monsoon seasons when widespread flooding can occur (Rajvanshi et al, 2012). Coupled with the impacts of climate change, the region has been witnessing an increase in rainfall and flooding. In addition to this, built up areas are on a rise without proper planning, at the cost of the natural marshy land, back swamps and agricultural land (Dasgupta et al, 2013), which is not allowing excess flood water to be absorbed naturally. During high tide and floods, it is common for flood water to find their ways to lanes and homes further causing drains to overflow. Health problems such as dengue fever are at a rise in such areas (See Sengupta, 2018).

Apart from a rise in excess water related problems, summers are becoming even hotter and due to climate change resulting in receding Gangotri glacier, which is the source of the river Ganges, water levels are going down in the lean season. Climate change has resulted in complex hydrodynamic conditions along the river Hugli and many of the sources of these problems are beyond the reach of the Hugli stretch itself (Ghosh et al, 2014). On the other hand, the impacts of climate change can be mainly predicted for broader regions, and therefore developing detailed strategies on the basis of identifying specific issues along the five towns in the Hugli corridor may not be possible. A holistic understanding of the climate change impacts considering the entire river system is therefore imperative.

c) Rapid urbanisation

India is rapidly transforming from a rural to an urban society and according to Hoelscher (2016, p.28), this is one of the ‘largest and most transformative demographics shifts the world has ever seen’. The urban agglomerations of India such as Bangalore, Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata have seen phenomenal growth and it is projected that India will consist of the largest urban agglomerations seen in the world with Kolkata urban agglomeration already ranking amongst the top ten urban agglomerations in the world (UN, 2011). A recent study on the Kolkata agglomeration by Sahana et al (2018), revealed the alarming rate at which agricultural land and rural landscapes are being transformed to built up areas without planning. The study further concluded that some cities which included Kolkata and Chandannagar

have grown at a higher rate during 1990-2000 than 2000-2015 and have no room left for further expansion. As many of these urbanisation is rather random and unplanned, their socio economic and environmental impacts are not yet fully understood. Population explosion in the region is another unwanted impacts of urbanisation with Kolkata agglomeration having one of the highest density of population in the world. Furthermore, the state of West Bengal has received a record number of tourists in the last few years (Chakraborti, 2019), which though promising in terms of Tourism, poses serious concerns towards the cumulative impact on the environment and the infrastructure of the state.

It should be noted that managing waste, pollution control and infrastructure are already stretched in the state and especially along the Hugli corridor, therefore the influx of additional tourists is only likely to exert even more pressure. Rapid urbanisation, coupled with the increasing impacts of climate change is creating a two edged sword, which bring along with it several types of other socio-economic and environmental complexities that will need to be taken into account if any form of sustainability was to be delivered.

d) Polluting Industries

The Hugli has been a major corridor for industrial growth from precolonial times. Many industries including jute textile, cotton mills as well

as engineering groups such as Braithwaite Company Limited, Hindusthan Motors Limited have been located here. However, Hugli corridor is more famous for its textile industry (Tusser weaving in Chandannagar, silk weaving in Shrirampur) compare to engineering, which is mainly concentrated in Haora (?). During the 1980s, hundreds of polluting industries along this corridor led to severe pollution in the river (Singh et al, 1986). In recent times though, this area has been experiencing a decline in its industries (See Sahana et al, 2018). Many have ceased to exist, however, some are in the state of decline and continue to be sick units with inadequate environmental protection measures. One of the major causes of pollution through these industries is due to the fact that environmental pollution measures through Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) was only made mandatory in 1994 in India (Jha-Thakur et al, 2009). Environmental compliance measures along the Hugli region is poor (See Paliwal and Srivastava, 2012). In addition to this, many of these industrial units are likely to fall below the requirement of an EIA and with lack of any cumulative assessment of these units, the pollution problem continues to be severe.

Environmental apathy as a legacy from the past has been further causing serious environmental threats to the Hugli river, which as we understand from the above paragraphs is deteriorating in health and is impacted by climate change and urban population expansion. Understanding these baseline context condition, which puts pressure not only on the environment but also on wider socio-economical factors are important in conducting a SWOT analysis for environmental sustainability for realising the potential of cultural heritage tourism in the area.

Additionally, exploratory in depth interviews were conducted amongst locals and experts to tease out the contextual factors of the region with respect to CHT and environmental sustainability.

a) Strengths

Within the state of West Bengal, the recently drafted tourism policy (2016) gives special emphasis on promoting ‘Heritage Bengal’ and further the policy emphasises on delivering sustainable development. It takes into account the impacts on the natural environment but also very importantly recognises the need to engage and empower the local community in delivering the tourism objectives. The policy has spelled out many positive initiatives that can strengthen the CHT potential in the Hugli corridor. For e.g. the tourism policy (2016) states that ‘primary Tourism Circuits’ will be developed and linkages with well-known hotspots will be strengthened. This is conducive for the location of this corridor, which is at the hinterland of the Kolkata megacity hotspot. Furthermore, its hybrid mixed European influence (Dutch, French, Danish, English and Portuguese) with the local practices makes it a unique experience, which is not to be found elsewhere. Especially the way all these influences can be spotted across the five towns in close proximity.

2.4.4 SWOT Analyses of Environmental Sustainability in CHT Planning along the Hugli Corridor

In conducting the analysis, related policy documents have been studied at the state level, which are namely the West Bengal Tourism Policy (2016), West Bengal State Action Plan on Climate change (2010). In addition to this, national policies have been referenced where ever felt appropriate. A site visit was conducted of the region (Bandel, Chinsurah, Chandannagar, Serampore and Barrackpore) in 2019 to further appreciate the challenges and strengths of CHT in the area. The site visit was a team effort from inputs of experts in the field of heritage, tourism, independent film makers, academics and researchers who all take an interest in the region.

The Tourism policy encourages ‘Home stays’ to add authenticity to the tourism experience. This is especially good news from the point of environmental sustainability. As we have pointed out due to rapid urbanisation, the population density of this corridor is very high. Building too many new hotels may further stretch the capacity of the regions. Additionally, during site visit, the richness of the heritage assets was obvious. Though facing deterioration, a lot is still out there, which has the potential to be staged to national as well as international, especially European tourists. The area presents innumerable heritage buildings with the potential to be converted to economically viable buildings thereby encouraging tourism, while sustaining local economy and protecting the heritage assets. However, one of the interviewee who is a local heritage enthusiast as well as independent film maker and travel designer commented that apart from certain seasons like during the local ‘Jagaddhatri Pujo’ and the winter months, the uptake of home stays may be limited in the corridor. He suggested that ‘these heritage buildings should be given economic purposes, such as being converted to Government offices to retain their original features while

breathing new life to them’. He further cited examples of such a practice in Darjiling, a popular hill station tourism destination, where several such government offices were residing in heritage buildings.

There is evidence to suggest that the experience of cultural heritage attractions can be heightened with the role of sensory experiences such as sight, taste, smell, hearing and touch (Rahman et al, 2016). The Hugli heritage corridor certainly has the potential in delivering sensory experiences. For example in terms of sight, the region offers the famous lighting during the ‘Jogoddhatri’ and ‘Durga Pujo’, displays huge idols as well as offer beautiful intricate designs found in its heritage buildings. Figure 1 and 2 illustrates the intricate designs, and Belgium chandeliers still being used in Imambara in Hooghly. The region also offers taste and smell through its renowned sweetmeat known as ‘Joynagarer Moya’, a speciality of Chandannagar.

b) Weaknesses

Though its location is its strength in relation to the close proximity of

Kolkata, during the field visit it was felt that not all five hinterland towns could be visited on the same day. Furthermore, the traffic and approach to the heritage sites were cumbersome and not well managed. This would make it very difficult to stage the heritage assets to the tourists. In addition to this, signage was an issue. For e.g. in the Imambara in Hooghly, which is well known for its ‘Vaulted clock’, only one signage written in Bengali (the local language) was displayed. Absence of signage was noted almost in all heritage sites where even if some were present, they didn’t do justice to what the site had to offer. It was further noted that some heritage sites such as the ‘Bandel Church’ had undergone recent transformation and refurbishments. Unfortunately, these were not sensitive to the heritage properties of the buildings. Terracotta temples too were refurbished with tiles and cements destroying the original heritage value of these assets. Therefore lack of heritage awareness and understanding, clearly stands out as one of the weaknesses in the region. This is also observed in other areas of India such as Srirangapatna (See Jha-Thakur et al, 2019).

Though the tourism policy encourages ‘Home stays’, discussions with stakeholders revealed that the owners of these heritage buildings usually have lack of funding. Attaining heritage status does not imply that they

receive any funding support. Furthermore, if tourists do come about, there are no opportunities for any economic incentives to be passed on to these custodians, who as a result are left with no choice but to sell their heritage properties to estate agents. These heritage assets are then pulled down and replaced with new buildings. One of the interviewee suggested that left with no option, even if these buildings are sold out to estate agents, the new buildings can be made keeping certain aspects of the old heritage building intact, while modernising the rest. These can act as ‘heritage marks’.

One of the academic who was interviewed also talked about the infiltration of people from outside who didn’t originally belong to the area. As a result, these new people are less sensitive about the heritage of the place than those who belong to this land. He further cited examples of natural environmental management strategies of the past such as leaving fish in the nallas which fed on mosquito lava, keeping a check on the disease that are caused by it. Based on interviews, field visits and literature review it was further realised that the heritage feeling of these places were lost as they were being bombarded with new construction and population increase due to rapid urbanisation. The interviewees also highlighted how the depleting health of the Ganges was affecting the nature and feel of these heritage places. One of them said he clearly remembers college students sitting and dipping their toes in the Ganges water, now the level of the river has gone down dramatically.

c) Threats