Living spaces

31

Complete our reader survey online and win! aalto.fi/magazine

5 Openings Gary Marquis and the power of spaces. 6 Now Brief news, big issues. 10 Oops! Tom Lindholm’s too-thrilling trip. 12 Theme _ Urban planning in an intersection of a thousand wishes. 18 Who Maija Jokela’s work dots the city. 22 Theme _ Five ways to make the construction industry more productive. 24 On the go A human-friendly bug hotel in the middle of the city. 32 On science Smart buildings make life easier and use less energy. 34 On science Electric scooters: joy or trouble? 38 Partnership Rafaela Seppälä donated to art and design. 40 Collaboration _ Aalto University co-found the Ioncell company. 42 Dialogue Jorma Eloranta and Mashrura Musharraf predict the future of autonomous vessels. 44 Entrepreneurship Fluff Stuff uses cattail to create a competitor for down feather filling. 47 On science _ briefly. 48 Doctoral theses Lauri Laine and the hero myth of entrepreneurship; Aleksi Laakso and the vibration of cruise ships; Kaniz Moriam and the strongest cellulose textile fibre. 50 Everyday choices Eliisa Lotsari studies the cold waters of the north. 52 Wow! _ Students accelerate product development of wood foam and an electric boat. OUR THEME Living spaces 12 The city of a thousand wishes 24 An urban hotel for bugs emerged in the middle of the city 34 Scoping the future of electric scooters 31 Cattail is a wetland plant that could be used to replace the filling in pillows or winter jackets. Photo: Anne Kinnunen

JUULI MIETTILÄ, ILLUSTRATOR

I prefer to work from home. I find it particularly nice that I don’t have to waste time commuting and that I can start working when I’m energetic.

My home is cosy and has a function ing workstation. I’m sensitive to noise, so at home I can focus on my work without distractions.

Working from home is especially enjoyable because of the small puppy who cheers up my workdays.

ILONA PARTANEN, ILLUSTRATOR

I turn my workstation into a cosy corner with a relaxed atmosphere.

I can create my own space anywhere, as long as it’s calm and light. It’s nice to have a steady background sound, whether it’s the radio or colleagues chatting.

My desk has heaps of different piles and notes, though all of them have their own (confusing) place. When a tight deadline approaches, I find myself rearranging pens and piles, which I’ve noticed clarifies my thinking.

YMPÄRISTÖMERKKI

MILJÖMÄRKT

PUBLISHER Aalto University, Communications EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Communications Director Jaakko Salavuo EDITORS Paula Haikarainen, Katrina Jurva LAYOUT/PHOTO EDITOR Dog Design COVER Anne Kinnunen CONTRIBUTORS IN THIS ISSUE Amanda Alvarez, Annika Artimo, Anna Berg, Anu Haapala, Heidi Hammarsten, Terhi Hautamäki, Minna Hölttä, Jukka Jokinen, Jaakko Kahilaniemi, Kalle Kataila, Anne Kinnunen, Krista Kinnunen, Anni Koponen, Annika Linna, Juuli Miettilä, Sofia Okkonen, Ilona Partanen, Tiiu Pohjolainen, Aleksi Poutanen, Marjukka Puolakka, Mikko Raskinen, Olli Seppänen, Sedeer el-Showk, Joanna Sinclair, Maiju Suomi, Eeva Suorlahti, Riitta Särkisilta-Lundberg, Tiina Toivola, Outi Törmälä, Gabriela Urm, Nita Vera, Jenny Vesiväki TRANSLATION Annika Rautakoura, Tomi Snellman, Tiina Leivo ADDRESS PO Box 18 000, FI-00076 Aalto TELEPHONE +358 9 470 01 ONLINE aalto.fi/magazine EMAIL magazine@aalto.fi CHANGE OF ADDRESS alumni@aalto.fi PRINTING PunaMusta, 2022 PAPER Maxi Offset 190 g/m2 (covers), Berga Classic Preprint 90 g/m2 (pages) PRINT RUN 4,000 (English edition), 30,000 (Finnish edition) SOURCE OF ADDRESSES Aalto University CRM Partnership and alumni data management PRIVACY NOTICES aalto.fi/services/privacy-notices ISSN 2489-6772 print ISSN 2489-6780 online ON THE JOB

Juuli Miettilä Painotuotteet 1234 5678

Painotuotteet 4041-0619 4 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

Spaces have power

like summer cottages and allotment gar dens—these are all tremendous privileges that we enjoy in Finland.

Sitting in my office in the oldest part of the Otaniemi campus, I can watch in realtime how the new Otakaari 2 buildings are rising. Around the cor ner, “Aalto Works” is being renovated and expanded to accommodate Design Factory, the Aalto Ventures Program, Startup Sauna and more. The cam pus is evolving, as it should. With pru dent planning, it will be able to accom modate unpredictable changes in how we use our buildings, roads and open spaces in the future.

In my native USA, you may not be able to walk to a park, even if it’s nearby, because public spaces are designed for cars, not people, and there may be no sidewalks. In Espoo, by contrast, I can bike or walk to campus every day of the year. The spaces we design and build can limit us, and not just in terms of mobility. The e-scooters that litter the streets, bike paths and green spaces are hugely popular, but can also be tragi cally unsafe. They are also inefficient over short distances, when walking or biking could be better, healthier alter natives.

Cities evolve slowly and humans are not always the best long-term think ers: no one anticipated the need for e-scooter parking spots or speed lim its. Urban and public spaces around the world may have their problems, but one thing we do know is that dense urban living has a lower carbon footprint. Cities need to be human-friendly so people don’t flee in their cars.

Urban planning also needs to fac tor in money. The Aalto University Schools of Engineering and Business have a joint professorship on econom ics of transportation. Building a tunnel that will exist for 50 or 100 years is an investment that requires proper think ing, not just structurally and environ mentally but also financially. The built environment, like real estate, accounts for a huge portion of any country’s wealth. Wise management of these spaces is not just economic sense, but also a question of social and physical wellbeing.

As we have learned over the past three years, space is also a huge priv ilege. Being able to socially distance, having space at home for a remote office or access to alternatives spaces

Space is a luxury we should not take for granted. We also have tremendous learn ing and gathering spaces on campus that are designed for Aalto University’s spe cial brand of interdisciplinary interac tions. Let’s use these spaces to think out side the box, to use our privilege of space and resources to think deeply about how to build the environments of the future that will be good for people to live, work and play in.

The mentality we design into spaces can open our minds, improve our health and, literally and figuratively, build bridges.

Gary Marquis

Dean, Professor, Mechanics of Materials Aalto University School of Engineering

Kalle Kataila

Let’s build the environments of the future that will be good for people to live, work and play in.

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 \ 5 OPENINGS

Aalto Day One live on campus

The opening of Aalto University's 13th academic year was a celebration of community after the quiet years of pandemic.

In his opening speech President Ilkka Niemelä considered contin ued focus on research and develop ment activities in the Finnish government's budget proposal to be important.

‘The bottleneck for addressing sustainability challenges, sustain able growth and the related RDI investment is actually a shortage of experts and expertise. And this challenge is best solved by investing in universities! Invest ments in universities have the double effect of creating new expertise, research results and the discoveries necessary for sustainable innovation, as well

as new experts who are so greatly needed.’

Otto Usvajärvi, chair of the board of Aalto University Student Union AYY, noted in his speech that the university community has the knowledge and tenacity to get through hardship and social tur moil. ‘Here at Aalto, we help our friends and those in need. All mem bers of the university community are welcome as they are, and every one’s input is equally important.’

Professor of polymer technol ogy Jukka Seppälä was appointed Aalto Distinguished professor. This title is awarded to professors of exceptional academic merit.

The Student Union AYY team in full swing at Aalto Party.

The first leg of the race between students and the university management team was to carry water as fast as possible.

Seppälä specialises in polymer sci ence and engineering, especially biopolymer research. Biopolymers are based on renewable raw materi als, and they can also be biodegrad able. The research has resulted to many inventions and innovations in the chemical industry and as medical biomaterials.

The long-awaited Aalto Party made a spectacular return to Alvar Aallon puisto, where students and staff had put together an amazing programme: music, guild presenta tions, games, food trucks, and much more. The party also featured a tra ditional tug-of-war between stu dents and the university leadership.

Jaakko Kahilaniemi

6 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 NOW

Food for one billion people through changes to animal feed

While millions around the world face the threat of famine or mal nutrition, the production of feed for livestock and fish is tying up limited natural resources that could be used to produce food for people. New research from Aalto University shows how adjust ments could maintain production while making more food avail able for people. These relatively simple changes would increase the global food supply significantly without requiring any increase in natural resource use or major dietary changes.

Currently, roughly a third of cereal crop production is used as animal feed, and about a quarter of captured fish aren’t used to feed people. Matti Kummu, an associate professor of global water and food issues, led a team that investigated the potential of using crop residues and food by-products in livestock and aquaculture production, freeing up the human-usable material to feed people.

The team analysed the flow of food and feed, as well as their by-products and residues, through the global food production system. They then identified ways to shift these flows to produce a better outcome. For example, livestock and farmed fish could be fed food system by-products, such as sugar beet or citrus pulp, fish and livestock by-products or even crop residues, instead of materials that are fit for human use.

With these changes, up to 10–26% of total cereal production and 17 million tons of fish (~11% of the current seafood supply) could be redirected from animal feed to human use. Depending on the precise scenario, the gains in food supply would be 6–13% in terms of caloric content and 9–15% in terms of protein content. ‘That may not sound like a lot, but that’s food for up to about one billion people,’ says Vilma Sandström, the first author of the study.

A research forum for hydrogen

The transition towards a hydrogen economy is necessary to radically cut down carbon emissions and it will play a key role in the energy systems, industry and transport of a carbonneutral society.

There will be fierce international competition between different tech nologies, and there are thousands of hydrogen projects in the pipeline both in Europe and globally. Finland has all the tools to succeed in the international hydrogen market.

Finland’s central universities and research institutions have agreed on a new partnership by establishing Hydrogen Research Forum Finland. The forum promotes Finnish hydro gen competence through action plans, visions of the future and communica tion, representing academics alongside others involved in the hydrogen tran sition. The forum also brings academ ics into discussions to support national decision-making.

Up to 26%

of total cereal crop production could be redirected from animal feed to human use.

The forum includes Aalto University, LUT University, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, Åbo Akademi Univer sity, the universities of Jyväskylä, Turku, Tampere, and Vaasa as well as the University of Oulu, which will initially coordinate the forum’s operations.

‘Aalto University research and educa tion will play a key role in national hydro gen collaboration. The transition from fossil raw materials creates needs for new openings in both energy sector and chemical industry. This is a great oppor tunity for many technological sectors, economy and society,’ says Professor Martti Larmi, Head of the Energy Conversion Research Group.

HAALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 \ 7

MEMORY OF WATER tells a story of a time when the world is running out of clean water and a military regime is tightly controlling scarce water resources.

The dystopian feature film, which premiered in September, was directed by Saara Saarela, professor of film directing at Aalto University. The film is based on Emmi Itäranta’s internation ally acclaimed novel. It was a collabo ration between top Finnish and interna tional filmmakers, and was the result of a nearly ten-year process.

This film required a lot of back ground research with water scientists, as well as with environmental research ers. A sustainability coordinator was also involved to ensure the ecosustainability of the film’s production.

Noria (actress Saga Sarkola) during a shoot at one of the main locations in Rummu prison, Estonia.

RUTHLESS TIMES – SONGS OF CARE was awarded at the Locarno Film Festival for its particularly strong social importance. The musi cal documentary, tinged with black humour, tells the story of the state of care for the elderly in Finland. The director and scriptwriter of the film, Susanna Helke, is Professor of Film Research at Aalto University.

The musical film was a new challenge for the director, and she wanted to give a voice to caregivers who might not otherwise dare to talk about the problems.

Gabriela Urm

Road Movies Oy

NOW 8 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 29

NÄYTÖS22 FASHION SHOW

presented a total of 22 collections from bachelor’s and master’s students in fashion.

All collections and the fashion show online: aalto.fashion

Hanna-Lotta Hanhela’s award-winning collection had been inspired by her grandmother, through whom her interest in clothes and fashion was born, but with whom her relationship was also compli cated. Her grandmother suffered from Alzheimer's disease, and the collection was designed as if from the point of view of a tailor who had lost their memory.

Outfit from Hanna-Lotta Hanhela’s collection Strength of body – Fragility of mind.

WARDROBE OF THE FUTURE is a vision by Aalto University's experts for a sustainable fashion and textile industry. The exhibition, showcasing solutions from researchers and students, will be on display at the European Parliament in Brussels in early December.

Sneaker with Shimmering Wood glitter. Designer Noora Yau and materials scientist Konrad Klockars create non-toxic and ecological glitter by manipulating the structure of cellulose, one of the most abundant biomaterials in the world.

Kalle Kataila

Sofia Okkonen

Kalle Kataila

Sofia Okkonen

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 \ 9

A journey that would not happen today

Tom Lindholm is the Managing Director of Aalto University Executive Education Ltd and Head of Lifewide Learning at Aalto University. In the late 1990s, his master’s thesis involved travelling to power plants around the world.

Text Anu Haapala Translation Annika Rautakoura Portrait Kalle Kataila Illustration Juuli Miettilä

Text Anu Haapala Translation Annika Rautakoura Portrait Kalle Kataila Illustration Juuli Miettilä

‘In the final stage of my economics studies, I attended a course on project management which involved collabo ration with the engineering company Wärtsilä.

The company wanted to find ways of using waste heat to boost the operation of coal-fired power plants. They sent a group of two engineering master’s students and two economics students to study the matter, first in China and then around the world.

The project produced a solid foundation for continuing my master’s thesis with Wärtsilä. I visited over one hundred diesel power plants in over sixty countries. During my trips, I encountered exciting – even dangerous – situations.

My travels have taught me that life can depend on the smallest of things.

One site I visited was an oil well in Yemen. Before the trip, I did not know much about Yemen, except that it was a poor country.

Early one morning, I was picked up from the hotel in a large off-road car. We drove through the silent city towards the airport – until we saw a roadblock.

The locals sitting in the front asked me to remain calm and turned to the people in army clothes who had stopped us.

Suddenly, one of the men outside opened the back door.

My coat was next to me on the back seat. The man placed his automatic weapon beneath the coat and lifted it, aiming at me, with his finger on the trigger.

Later I realised how frightening the situation had been. I did not share a language with the man or have any idea what he would do next.

Finally, we were able to continue. At the airport, I discovered that a bomb had exploded in front of my hotel only 15 minutes after I had left, and people had died. Our car had even been searched for a bomb.

I would not take part in such a project now! At the same time, I would not give up those experiences and lessons.

For a young student of economics, it was a great cultural lesson and a deep dive into the field of technology. I got to visit different countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

The trips helped me put matters in perspective. Compared to most places in the world, we don’t have much to complain about in the Nordics.

I don’t encourage taking foolish risks, but I urge students to try their wings before, say, starting a family and becoming attached to a specific place.

I also encourage schools and com panies to work together. Solving major issues requires multidisciplinary collab oration across borders.

Above all, you should remember that no one knows what tomorrow will bring. Enjoying life and pushing yourself beyond your comfort zone is worth it.’

OOPS!

Living spaces

Construction industry, urban and environmental planning touches everyone. How can we find solutions for residents –and deliver on promises?

12 Theme Urban planning in an intersection of a thousand wishes. 18 Who Maija Jokela’s work dots the city. 22 Theme Five ways to make the construction industry more productive. 24 On the go _ A human-friendly bug hotel in the middle of the city. 32 On science Smart buildings make life easier and use less energy. 34 On science _ Scoping the future of electric scooters. THEME AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 \ 11

The city of a thousand wishes

How can we make a city flourish when one resident hopes for more forests and another wants parking lots? Data and keen listening can help, say urban planners and researchers.

Text Terhi Hautamäki Translation Annika Rautakoura Illustration Ilona Partanen

Text Terhi Hautamäki Translation Annika Rautakoura Illustration Ilona Partanen

THEME Living spaces

12 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

‘T

here won’t be any nature left in the neighbourhood thanks to ugly, identical buildings.’ That’s how one respondent replied to a city survey collecting resident views.

Espoo, a city in Finland’s capital region known for its architecture and tech companies, as well as its proximity to nature, is the subject of rather emotional urban planning. Its development has been strongly guided by increases in private car use, and the city has grown significantly in the last few years. Despite – or perhaps due to – these shifts, many would like to protect the greenery and forests nearby.

Researchers and urban planners came together to ask residents about their thoughts on the region. Approximately 6,600 residents responded to the My Espoo on the Map survey, marking almost 70,000 per sonally meaningful spots and development ideas on the map in a project run by Aalto University and the City of Espoo.

The exercise brought forward practical sugges tions: public saunas for beaches, sports activities, restaurants and campfire sites. Someone even came up with the idea of covering the Länsiväylä motorway with a green deck, to mimic a park. In the survey, peo ple were asked to mark where they would place new homes, and what they should look like.

Although not all the suggestions can be carried out, some of the results can already be put into practice. For example, planning for a new neighbourhood, Lasi hytti, which currently consists of mainly industrial areas, field and riverside, has already started. The aim

is to bring a distinctly urban character to the area, along with apartments for approximately 4,000 residents.

The data stemming from the My Espoo on the Map project has provided residents with meaningful informa tion. For example, riverside recreational activities and having a unified road for bikes and pedestrians are consid ered important in the Lasihytti area. The development of riverside areas in Espoo has seen particular attention in the urban plan.

In-depth knowledge about area use

Environmental and urban planning typically involves com plex and lengthy processes. Marketta Kyttä, Professor of Land Use Planning at Aalto University, which educates experts on these subjects, says that collaboration between researchers and urban planners has been especially active in Espoo.

The research has used the SoftGIS method, which gath ers data produced by people on a map. In the City of Espoo, this data has been integrated into the geographical infor mation system, which all planners utilise in their everyday work.

Because 70,000 spots is too much for any party to handle – even a city – the prioritisation process has been improved. The underlying theory is that the quality of life improves most when the focus is on places that residents use the most yet, for one reason or another, view negatively.

‘We identified these hot spots and checked how aligned they were with places that Espoo has already considered directing resources,’ Kyttä says.

Their findings? A lot of overlap, which gives hope for finding resources.

‘Pretty densely built environments can mobilise even the most dedicated couch potatoes.’

THEME Living spaces 14 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

Urbanisation continues

The pandemic reshaped our notions of living, with remote work making many reconsider where they live, and even acquire a second home. The concept of multi-location living suddenly became more of reality.

Johanna Palomäki, Planning Manager at the City of Espoo at the time of the survey and now working for the City of Lahti, says that urbanisation continues, distinguishing Finland from the rest of Europe. Yet while more is being built, green areas are reduced, and new greenery does not emerge; urban growth should, rather, focus on already developed areas.

‘I believe that the quality of the built environment can improve and that we will learn to make cities for people while also protecting natural areas.’

According to Palomäki, data collected by Aalto University provides much to analyse and utilise for years to come. Work on the city’s new master plan is getting off the ground, and the data supports these efforts. Discussion nights have further made it possi ble for residents to consider the future of the city.

‘We also keep getting direct feedback, and it often shows anguish. Espoo is experiencing growing pains, and we must bravely discuss what type of growth people want to see,’ Palomäki notes.

Research data confirms the notion that green environments and recreational areas are important. Palomäki does not see Espoo residents as ‘nimbyists’ or opponents of growth. Many are simply unsatisfied with the quality of the environment that has resulted..

Palomäki has challenged construction companies and urban planners to consider ways of inserting more green into the cityscape instead of always sacrific ing green infrastructure first when it comes to finding savings. One alternative to high apartment buildings and sparse neighbourhoods of single-family houses is effective mid-scale construction that includes small urban homes.

Living environment impacts health Kyttä hopes that Finland will find more diverse ways of urbanising. She believes that the country is replicating a single way of building; if it was once a suburb, it is now continuous urban infill.

Good urban planning considers the effects of the environment on well-being. As an environmental psy chologist, Kyttä has researched the subject in many projects. The alleviating effects that greenery has on the environment and in improving mood are already widely recognised. Another important factor is how the environment encourages people to have an active lifestyle. In this sense, some degree of density is good.

‘Pretty densely built environments can mobilise even the most dedicated couch potatoes,’ Kyttä says.

One research project Kyttä has been involved in fol lowed people who moved from one neighbourhood to another. Even when attitudes towards everyday sports were not positive, people’s movements increased as they moved to denser areas near services and did not need a car as much as they used to.

‘The environment makes people change their every day lives unexpectedly, and even attitudes will follow.’

Next, the teams of professors Kyttä and Henrikki Tikkanen will study the influence of the urban envi ronment on social well-being, led by post-doctoral researcher Tiina Rinne. The living environment does not influence strong social ties, relationships with family or friends, as such. Instead, it affects lighter social ties, such as neighbourhood communality.

Social learning plays a major part in planning Susa Eräranta, Professor of Practice at Aalto University and Project Director at the City of Helsinki, studies how urban planning practices, knowledge flows and collabo ration develop over time.

In her doctoral thesis, she examined collaboration between experts: how information is or is not passed on, and what promotes or hinders collaboration. The research focused on a four-year strategic spatial planning process in the metropolitan area with anonymised data.

‘For example, during planning work, experts on the environment and mobility might not communicate with each other much but rather through an intermediary. Specialised questions are processed in siloes. Coordina tors have a lot of significance and relational power.’

THEME Living spaces

Tactical urbanism and urban activism alter the landscape.

This means that the parties involved may never get the bigger picture. Your idea of the goals and solutions during the vision stage may look very different than at a later stage.

Climate actions change the cityscape

Eräranta works on reducing emissions at the City of Helsinki. In her view, climate actions will alter not only energy consumption but eventually the cityscape, as well.

‘Right now, city plans may have very strict parameters for materials and colours in façades. If more recycled elements and materials are needed in the future, the ele ments available will be used. This increases the diversity of the cityscape.’

Now the goal is to use mined rock from buildings in nearby sites, as well as to better recycle building elements and materials in the future.

Eräranta says that future cities will have more biodiversity. Parks will no longer just be grass carpet; a variety of biotopes and environments suitable for pollinators, as one example, are needed.

Previously, a site-specific Green Factor has been used to determine biodiversity and drainage water solutions.

‘Now methods for wider areas are being developed – methods that take into account how different green spaces in neighbourhoods are connected.’

Tactical urbanism and urban activism also alter the landscape. Areas with little use can be appointed or taken into use as arenas for free civic activities, increas ing the diversity and depth of urban environments, like Helsinki’s old engine sheds in the neighbourhood of Pasila, which have hosted many kinds of leisure activities, events and collective farming.

Empty promises should never be made Next door in Helsinki, residents also take part in urban planning. Eräranta says that in 2016, a public participation geographic information survey (PPGIS) was carried out, as part of the preparatory work for the city plan, to find out which areas are central to everyday life and which places must be preserved.

The city allocates a specific sum, which can be used to make wishes a reality. Suggestions may include the planting of trees, construction of a dock or the development of sports parks or playgrounds.

As much as residents get their ideas to the table, there is still a long way to go in carrying them out. Conditions are determined by the city’s economy, climate commitments, and goals for the numbers of residents, to name a few factors. Eräranta notes that cities still have much to do when communicating about these conditions.

‘Residents often oppose urban infill in their imme diate surroundings. They need to know whether not building is an option, or if certain goals for the number of residents need to be reached but people can impact the placement of buildings.’

In some cities, residents and communities have made shadow master plans for exploring different types of layout alternatives.

Residents have very different ideas about develop ing the city. Marketta Kyttä says that in interactive planning, the key is to be transparent about how the information is being used and what the chances for making a difference truly are.

‘People should not be given empty promises about bringing their ideas to life.’

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 \ 17

18 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

Work displayed around town

The construction industry is more diverse than its reputation, Ramboll Finland’s Managing Director Maija Jokela realised during her first summer job.

Text Heidi Hammarsten

Translation Annika Rautakoura Photos Aleksi Poutanen

When Maija Jokela went on vacation last year, she eyed Helsinki Airport’s renewed Terminal 2 with par ticular pride. Ramboll Finland was part of the con sortium which designed and executed the terminal’s impressive transformation.

‘Even my daughter already knows how to ask whether my coworkers have been at work on some thing,’ says Jokela, who started work as Ramboll Finland’s Managing Director a year ago.

Ramboll is a global engineering, architecture and consultancy company that started in Denmark. In Finland, the company has also worked on the Mall of Tripla in Pasila, the Crown Bridges Light Rail proj ect and the Nokia Arena in Tampere, among others. It carries out a total of about 15,000 projects each year.

Jokela was supposed to become a doctor but applied to several other fields just in case. A friend had also pointed her towards the Helsinki University of Technology (now Aalto University), which empha sised the same subjects as the Faculty of Medicine.

‘I was accepted everywhere except medical school, and I thought I would take structural engineering to revise mathematics and physics,’ Jokela recalls.

Jokela’s studies went slowly at first because she was unsure whether she had made the right choice. Gradually, she realised it was exactly the right field for her. This finally became evident when Jokela landed a summer job at a construction consulting company.

‘The work opened my eyes to all that project and construction management can entail. I like to work with people, coordinate, manage and see results. If there are problems, as is always the case in proj ects, you simply need to solve them. You can’t sit around and wait.’

From summer job to career

According to Jokela, majoring in construction eco nomics was directly linked with her working life, and that increased her motivation to study. Jokela is also grateful for the networks she built during her studies.

‘The associations and organisation activities from my study period were extremely important. We worked a lot with companies and learned about sales, for example. The university had great relations with companies in general, and internships were relatively easy to land.’

Jokela’s first summer job eventually led to a long career, first in project management, then on the man agement team of Sweco PM Oy, which acquired her employer at the summer job, and eventually as the Managing Director of the entire company.

After seven years, Jokela moved from Sweco PM to the significantly larger Ramboll to find new challenges.

‘At Ramboll, I was particularly drawn to the inter national network; here I get to know and learn from the operations of other countries. Finns are con stantly included in Ramboll’s international projects. We just spoke of a rail project in Tbilisi and an envi ronmental project in Denmark. The water business also involves projects abroad.’

Jokela also finds the company’s ownership structure interesting. The Danish Ramboll Group is 98 percent owned by the Ramboll Foundation, and the rest is owned by the employees. The founda tion channels its proceeds to Ramboll’s development, research, and education in science and technology, as well as to charity. This enables the company to be developed more intensively than a listed company.

WHO Living spaces

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 \ 19

Teamwork taught listening skills

Working as a managing director calls for more longterm planning than a project, Jokela says.

‘A project has a clear beginning and end, along with limited goals. A managing director has a variety of goals related to the company’s finances, growth and the development of skills, but over a longer period. These tasks call for patience and the ability to see the bigger picture.’

Project management and working as a manag ing director do have some common features, Jokela believes. Neither manager makes decisions on their own.

‘It’s about working with people: being able to listen to different viewpoints and solve issues with the team. Experience in working with different teams and learning that your vision is only one of many is a great advantage.’

In its new strategy, Ramboll has placed sustainable development at the core: the goal is to help clients reach their sustainable development goals.

‘Sustainability as a phenomenon has found its way to the construction industry, but not as steadily as one might hope. Finland has the world’s most ambi tious goal for carbon neutrality, which is slowly being reflected in public projects. Organisations in general do have sustainable development goals, but they are not always translated into action.’

Jokela mentions sustainable mobility solutions and urban environments as examples, since their design has long been guided by private car use. ‘Thankfully, the situation is changing.’

Finnish infrastructure and design competence is so strong that it is worth exploring as an export, Jokela believes. Construction is local, but consultation is international, she points out.

From maternity leave to a job interview

The cliché about construction being a conservative, male-dominated industry was not true, at least not when Jokela became Sweco PM’s Managing Director: she got the interview request during her maternity leave.

‘I did want a job as managing director – I have drive and ambition. I always wanted work that was new or challenging for me. But at Sweco, I didn’t think I was a viable managing director candidate, being the youngest of the management team.’

According to Jokela, the construction industry has already changed a lot, although its image may not have changed as quickly.

‘The industry’s old-fashioned reputation is extreme. I don’t agree with the idea of the industry being particularly unequal. It’s a shame if good people aren’t hired due to the sector’s false, outdated reputa tion. I am used to being the only woman in a meeting. But the treatment has been mostly appropriate and respectful, and people remember me better because I’m a woman.’

Design and consultation are also clearly more female-dominated than construction itself.

During her career, Jokela has seen attitudes and technology improve in the construction industry. On the technological side, information models help design a great deal, and international teams can work smoothly through remote work.

‘Attitudes reflect the increased importance of col laboration and communication. During my studies, I noticed that collaboration between different tech nological fields was less common, and silos were frequent. Now, people understand that shared goals and discussions produce the best results.’

Major infrastructure projects are increasingly being done using an alliance model, where the client and implementer share the financial risks and both gain if the project goes well. The alliance model also involves a longer development stage, followed by a final decision on implementation.

The construction industry not only suffers from an outdated reputation but also often has its compe tence publicly questioned. Major public projects in particular make headlines if schedules and budgets are not met.

Jokela notes that a project going well is not news. In her previous work, she was responsible for the first stage project of Länsimetro (West Metro), which was often covered by the media. She found the experience to be educational and meaningful.

‘In large and somehow innovative projects, the planning tends to be quite general when applying for funding. If I could change something, I’d follow the example of industrial investment, where there is much more focus on the pre-planning stage.’

WHO Living spaces

‘It’s a shame if good people aren’t hired due to the sector’s false, outdated reputation.’

20 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

Maija Jokela

Graduated as a Master of Science in Engineering in 2006 with construction economics as her major. Has worked as Ramboll Finland’s Managing Director since autumn 2021.

Began her career in project management at CM-urakointi Oy.

Managing Director of the project management and construction company Sweco PM, 2014–2021.

Alumna of the Year 2022, Aalto University School of Engineering.

Is also:

An avid horseback riding enthusiast. ‘I once won a district championship in dressage.’

Addicted to hobbies. ‘I get excited about pretty much anything I can immerse myself in and improve in.

Lately I’ve been into strength training, which is a trending sport, I know.’

A goof. ‘With my daughter, who is in primary school, we arrange days for fun, such as home discos. It’s liberating to enjoy the moment and do something completely different from “grown-up” stuff.’

5

ways to make the construction industry more productive

These solutions can speed up construction, save money, and reduce material waste and carbon dioxide emissions.

Translation Tomi Snellman

1. Don’t waste workers’ time on unnecessary tasks

Workers in the construction industry spend an average of 2.5 minutes on their core task before they get interrupted. Most of their time is actually spent hauling stuff – moving equipment, sorting things out, collecting materials and moving from one place to another.

By using precise production control, workflows can be smooth.

2. More lean construction, more collaboration, and get contractors in on design Construction companies include a ‘normal’ amount of time wastage in their contract bids, which are used to plan budgets alongside contractors’ knowledge of costs.

The problem? This pushes respon sibility for productivity to the lowest links in the chain – the people unlikely to influence how the system works as a whole. A pipefitter can shake their head at lousy plans they’ve received, but their only coping mechanism may be to improvise or search for supplies.

Lean construction is based on sus tained partnerships and sharing risks as well as rewards. It makes traditional

fixed-price contracting a thing of the past.

Once contractors can have a say in production design, productivity should improve. In fact, estimates suggest that team-oriented planning could boost productivity up to 20%.

3. Deliver all supplies directly to the site

Tasks that are essentially simple yet critical for productivity, like delivering materials and equipment to the worksite in a planned and coordinated manner, are often no one’s responsibility.

Productivity could improve by 10–20% if all necessary supplies were delivered directly to where they are needed, with no unnecessary supplies stored on site.

4. ‘Takt Time’ is key Takt Time is a system in which an entire construction project is divided into smaller sub-units, such as apart ments, and all teams go at the same pace throughout the project.

Providing clear daily targets for all teams ensures that problems can be solved quickly.

5. Use digital tools for site monitoring

Progress and completion rates should be monitored and recorded regularly.

Drones, laser scanning, camera sys tems and sensors that collect data on conditions and location are all tools that can be used for this, allowing management to identify and solve challenges in real time.

Olli Seppänen

The writer is Associate Professor of Operations Management in Construction.

The original extended article is available on the MustRead website (in Finnish only): Nopeampaa rakentamista, vähemmän hiilidioksidipäästöjä.

THEME Living spaces

Juuli Miettilä

22 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

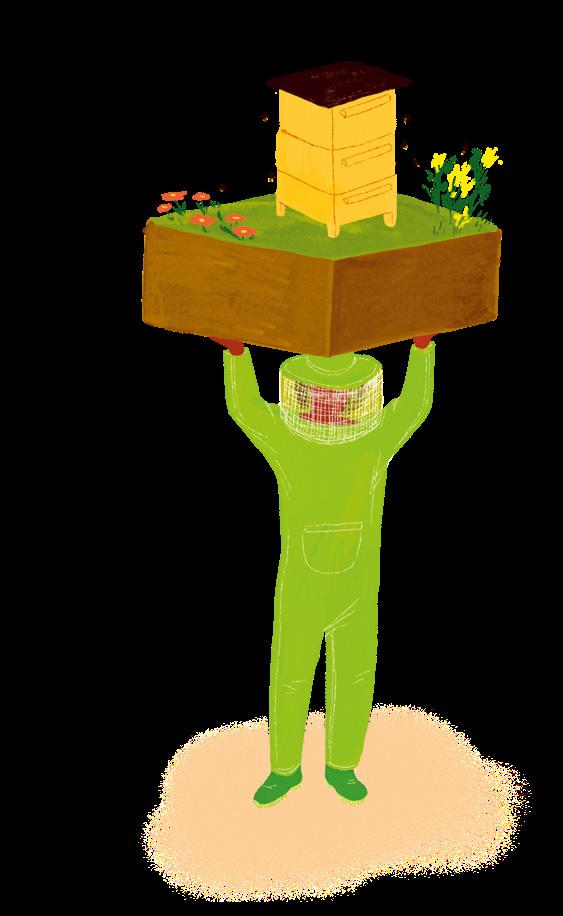

A humanfriendly hotel for bugs in the middle of the city

Text Minna Hölttä Translation Annika Rautakoura

Photos Anne Kinnunen, Anni Koponen

Alusta, built from clay and populated by plants, is a sanctuary for pollinators and a meeting place for all living things.

Armi the crow also found its way to the Olla station by Aarni Tujula, which has a birds’ drinking fountain filled with rainwater. There is soil inside, watered by the rainwater, and plants will appear in the holes.

ON THE GO Living spaces

24 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

Your gaze is fixed first upon the plants running wild and bright between the hundred-year old stone houses. But then your atten tion is grabbed by a crow chick.

Friends call it Armi, short for Arminius, reveal architects Maiju Suomi and Elina Koivisto. It turns out that Armi is a regular guest at the Alusta pavilion.

Alusta is a meeting place based on Suomi and Koivisto’s idea, built in central Helsinki in the courtyard between the Museum of Finnish Architecture and the Design Museum.

Koivisto points to a large crow perched on a lamp post and observing the situation. ‘We asked Korkeasaari zoo and they told us that we shouldn’t be concerned about a lonely chick – the mother is close by and occasionally brings it food.’

Armi briskly pokes the coarse woody debris with its beak and grabs a snack. It has already figured out how Alusta works.

Plant splendour in a parking lot

The paved courtyard has low walls made of clay. They form seats and paths, framing large grow bags containing over a thousand large and small plants.

A couple of months ago the place looked com pletely different, Suomi says. The courtyard operated mostly as a parking lot.

The construction process included rammed earth masonry, along with fired and unfired bricks. Some bricks have been laid on their side so the walls have holes.

‘Many visitors have commented that this is like a giant insect hotel,’ Suomi smiles. The description is fitting but doesn’t give the whole story.

Alusta pavilion is part of the Academy of Finland’s BIWE project, which seeks to restore biodiversity in densely populated areas. A rich diversity of plants and animals is a prerequisite for all life – and is now critically endangered. According to The Intergovern mental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and

ON THE GO Living spaces

26 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

Alusta is host to different speedwells and achilleas, red campion, oxeye daisy, wood cranesbill, and field scabious. Pollinators need flowers that have not been bred too much, since flowers such as double blooms often don’t have enough nectar.

One goal of the Alusta pavilion is to reconnect humans and nature by offering pollinators shelter and food where it may not otherwise be.

Elina Koivisto and Maiju Suomi point out that biodiversity can be promoted on many levels, from land use to urban and construction planning. More diverse urban nature also increases well-being and alleviates extreme phenomena related to climate change.

The natural cycle, the sun and water take part in the construction of Alusta. The panels have been plastered with a mixture of biochar and clay that slowly drips away. The unfired clay bricks within the walls will also decay during the pavilion’s lifecycle.

‘Construction materials often need to remain unchanged throughout their lifecycle, which results in a short lifecycle and lots of trash that is difficult to recycle. We wanted to pro mote the idea that maybe less is enough in some places.

Patina is acceptable – in fact, it’s beautiful,’ says Elina Koivisto.

ON THE GO Living spaces

‘Once construction is done, nature will take over and finish building.’

Ecosystem Services (IBPES), one million plant and animal species around the world face extinction.

Biodiversity is particularly harmed by the reduced availability of living environments and their increased fragmentation and loss of complexity. One goal of the Alusta pavilion is to reconnect humans and nature by offering pollinators shelter and food in the middle of the city.

At the very beginning of the design process, Maiju Suomi and Elina Koivisto contacted ecology research ers at the University of Helsinki. The researchers explained that if the right plants were available, downtown Helsinki would attract insects like solitary bees, different butterflies and bumblebees.

Because pollinators are not omnivores, different types of plants were needed. Suomi and Koivisto received a long list of the most suitable wild plants and garden perennials from ecologist Johanna Huttunen and used it to select a range of plants that would flower throughout the season. Many of them also keep their seed heads over the winter, which offers shelter to animals and seeds for birds after the growing season.

The ecologists also recommended adding logs with

fungi at Alusta. The fungi break the wood down, pro ducing homes and nourishment for various insects.

‘The idea is that once the construction is done, nature will take over and finish building it,’ Suomi says.

Beneficial materials

Alusta pavilion will be open until the end of summer 2023. After that, the construction will be dismantled, the materials will be recycled, and the plants will con tinue their lives elsewhere.

Temporary structures are usually made of wood, which is light and easy to transport. Wood is also considered an ecological construction material. But Koivisto points out that it’s not a silver bullet that can solve all of the challenges in construction.

‘When it comes to construction materials, you always need to consider their origin and processing methods, how they operate in a building, and what happens to them afterwards.’

Forests contain the world’s largest variety of species. Finland’s forests alone are home to 20,000 species: mammals, birds, insects, plants and mushrooms. The Amazon rainforest contains over three million species.

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 \ 29

GO Living spaces

Increased logging is reducing biodiversity and eating away at carbon sinks.

Clay is extracted from the surface layers of the soil, right below humus, and unlike calcium oxide does not require deep mines. Many clay extraction spots are former agricultural fields which can later be turned into bird ponds.

In Finland, clay can be found in the gardens of quite a few homes or summer houses. It is an ancient con struction material that is affordable and easy to work. Fired clay bricks can be recycled, and unfired clay can be crumbled back into nature.

Clay also purifies the air and balances humidity. According to the Ecosafe project of the Ministry of the Environment and Finnish universities and com panies, mixing clay into the wood shavings used for heat insulation reduced the total volatile organic compounds (tVOC) to nearly zero.

‘Building sites contain materials that can cause chemical burns if handled without full protective gear. Clay, on the other hand, is so safe that it can be eaten. We’re used to measuring the toxicity of construction materials with their maximum toler ated limits. What if we sought alternatives that aren’t harmful at all or which are even beneficial?’ Koivisto says.

Disgust, interest, care

The sunlit clay wall is a good place to sit. An earthy scent fills the air, and the rugged surface of the wall feels good to touch. Architecture can be healing in many ways.

Suomi and Koivisto describe current architecture as focused on the visual. Because sight operates at a distance, architecture can easily remain remote, as beautiful images in magazines and on Instagram.

Kind of like our relationship with nature, Suomi and Koivisto say.

Alusta provided them with an opportunity to pro duce experimental, ambitious, and ecological archi tecture which involves different senses and doesn’t isolate nature and humans from one another. It had been a long-term dream for both. Large agencies seemed to operate painfully slowly, and teaching didn’t involve enough practical work.

Suomi clearly remembers the moment when the idea came to life. ‘I was sitting in a garden reading a book and drinking coffee. There was a clay pot next to

me, and I discovered lots of worms beneath it. My first reaction was disgust, but when I slowed down to simply enjoy the summer day, I began to follow the worms’ movements with interest. I went back to my book and coffee, but then when the worms were gone I found myself missing them. I began to ponder if we could build a place to repeat that experience – where I could move from disgust to interest and caring.’

The pavilion was named after the notion of hav ing to think things over from the beginning, or ‘alusta’ in Finnish. The word also denotes a platform, in this case for environmental discussion, collaboration, and different events.

A total of 50 architecture students took part in building Alusta. It has already hosted children’s clay workshops and ‘ötköt’, a bug party by art education students in which visitors set the table for insects. The pavilion is also hosting a series of lectures on nature-culture relations, covering topics such as architecture and empathy, emotions caused by the environmental crisis, and care in architecture.

‘Care is a very important word,’ says Maiju Suomi. ‘It means to care and look after and to carry the weight of concern and worry. We wanted to create a sanctuary for processing environmental anxiety and opening oneself up to new ideas, such as the notion that every insect and crow chick has intrinsic value in this world.’

Alusta is part of architect Maiju Suomi’s artistic research for her doctoral thesis at Aalto University’s Department of Design. It also serves as a test laboratory for architect Elina Koivisto’s research on the use of natural materials in construction. Elina Koivisto also works as a University Teacher of Building Technology at Aalto.

Alusta was realised in collaboration with the clay construction program of the Raisio Regional Education and Training Consortium. The project was supported by Wienerberger Oy, Kekkilä Oy, Fiskars, ABL-laatat, The Organic Gardener’s Association (Hyötykasviyhdistys), Iki Carbon, Ilmarinen, Kääpä Biotech, Stark Suomi Oy and Uula Color Oy.

The project’s design and execution was funded by the Alfred Kordelin Foundation, Arts Promotion Center Finland and the Greta and William Lehtinen Foundation.

ON THE

30 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

Students of architecture building a clay wall.

A total of 50 architecture students took part in building Alusta.

Kekkilä Oy's Satu Iivari (left) and Saara Rytsy (right) participated in the planting of seedlings with architect Maiju Suomi. Kekkilä donated the planting trays and sacks in which the plants grow.

Buildings that make life easier and use less energy

In a smart building, the lighting system learns how occupants move throughout the building, transport robots talk to lifts, and users are guided to available workspaces by a mobile app. A new doctoral school at Aalto University is set to boost development in the field.

Text Marjukka Puolakka

Translation Tomi Snellman

Illustration Juuli Miettilä

When he leaves work, Aalto University Professor of Practice Jaakko Ketomäki uses his mobile phone to switch on his coffee machine’s smart socket, which is connected to the security system in his home. On arrival, freshly brewed cof fee awaits him in a house that’s been cleaned by a robot and where the heat ing system lowered the temperature by a couple of degrees while he was at work. The automated system even keeps a constant eye on the price of electricity and heats the water at night, when the rates are lowest.

‘Smart building technology adds to the comfort and ease of living. It makes energy consumption transparent and helps save energy in just the right places, whether at home or in a large office building,’ says Ketomäki.

The idea of a smart building does not require that users know or even care what kind of technology is integrated into the building.

‘Users don’t need to go under the hood of a smart building. All they need is an easy-to-use app to control the functions they want. A smart building uses data monitoring and user feedback to con stantly learn how to control things more intelligently,’ says Professor of Practice Heikki Ihasalo from the School of Electrical Engineering.

Robot helpers

The most visible element of building services engineering is lighting, yet automation and wireless technology will eventually make light switches a rarity. A smart office learns how peo ple move in the building and adjusts the lighting accordingly. Today, it’s easy to equip lights with sensors that collect automation data, such as occupancy rates and indoor air quality.

‘A smart building keeps the indoor

air clean and at just the right tempera ture. For users, the system saves energy because the lights are never on unnec essarily, and the heating adjusts in response to fluctuations in the price of electricity, which are increasing as renewable energy production grows,’ says Ihasalo.

Smart solutions are also needed to control a building’s power load and bal ance consumption peaks – for example, by ensuring that electric cars aren’t all charging at the same time.

Another element of smart buildings is helping people find their way. On the Otaniemi campus, the Aalto Space mobile app guides freshmen to the right auditorium and available study spaces.

‘An access control app in your pocket is invaluable when you need to find a free desk or locate colleagues in a large office building. Workspace reservations are an essential part of this kind of service,’ says Ketomäki .

On the other hand, advanced robot ics play a visible part in the daily life of people on campus, with delivery robots taking shopping bags from store to door and robotic vacuum cleaners helping clean the premises. Robots are being used to transport goods in hospitals, to take care of room service in hotels and to deliver mail in offices. Robots can even communicate with lifts to move between floors.

Smarter energy use

The Aalto doctoral school on smart buildings trains experts to have a com prehensive view of building technology, IT systems and, above all, the needs of users. To support the programme – the first of its kind in Finland – the school received a donation of 1.5 million euros last spring.

Smart building technology is becom ing increasingly important because we need to become ever smarter in our energy use. Digitalisation and automa tion are also bringing increased versa tility to the control of building services.

Various methods have been devel oped in recent years to assess how smart a building is. One of them is the Smart Readiness Indicator (SRI), which was developed at the EU level and is now being tested for usability in Finland.

‘The indicator divides building ser vices into domains such as heating, domestic hot water and ventilation, and examines their smartness one by one. SRI is part of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), in which the flexibility of power consumption and energy storage play an import ant part. At Aalto, we are studying the implementation and benefits of SRI in Finland,’ says Ketomäki.

Other research topics at the doc toral school include lighting control, user-centricity and analytics of build ing automation data. The school’s goal is to power up networks between gradu ate students and businesses.

‘A new form of corporate collabora tion consists of part-time doctoral stu dents whose research uses data col lected by businesses. This also ensures that the very latest research knowledge is passed on from the university to the business world,’ Ihasalo says.

Because of its cold climate, Finland has always had strong expertise in building services engineering. The country is also at the leading edge of smart building development. Last year, the Workery+ coworking space in Helsinki, developed by the YIT Group, was selected as the world’s smartest building.

THEME Living spaces

32 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

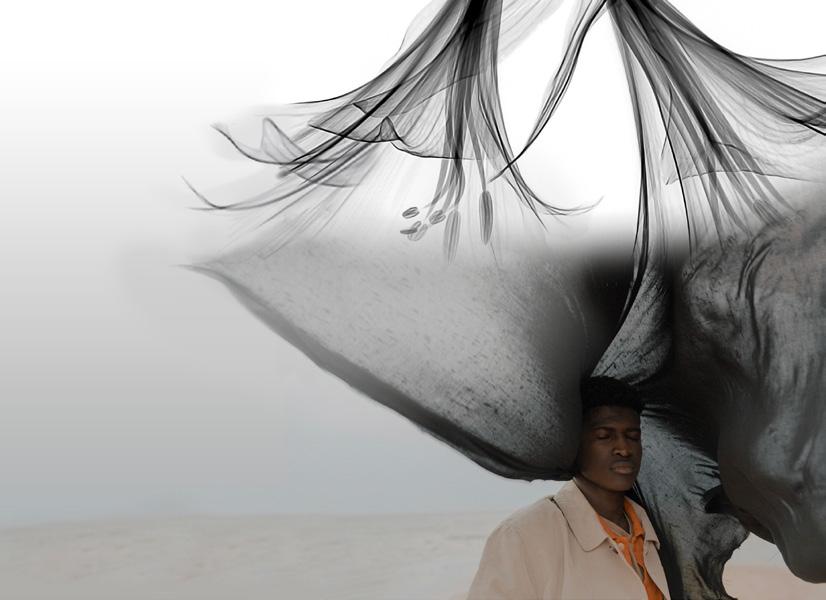

How will e-scooters transform urban spaces?

We often think of electric scooters as part of the switch to eco-friendly mobility but their role in urban landscapes is more complicated.

Text Sedeer el-Showk Photo Jukka Jokinen

ON SCIENCE Living spaces

34 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

You might see them by your bus stop, blocking a door or zooming past as you cross the road. E-scooters have joined the cityscape – and have changed how we move around.

‘What we can see around the world is that e-scooters have disrupted the existing landscape of urban mobility modes,’ says Samira Dibaj, a doctoral student researching how e-scooters are used. She explains that how people use e-scooters depends on the context, including the wider urban built environment and existing transport infra structure.

Case in point: how e-scooters are used in Euro pean cities with well-developed public transport systems differs from how they are used in US cities that lack such services. ‘We see that e-scooters are used in both functional and fun ways,’ Dibaj says. Leisure trips are the main use in both the US and Europe, she explains, but e-scooters substi tute for taxis or ride-hailing services in US cities, while in European cities they usually replace bus or tram use.

Eco-friendly transport or an option for the young and well?

Whether environmental and social benefits will come out of e-scooters largely depends on how they’re used and how they fit into the urban mobility landscape. E-scooters are part of a change in trans portation known as micromobility, in which short daily trips are made using lightweight vehicles like bicycles instead of cars.

‘E-scooters could contribute to reducing over all noise pollution and carbon emissions in cities – if they replace car driving and not walking,’ says Samira Dibaj.

In the end, all the actors involved – companies, residents and municipalities – influence the role that scooters will take. Nitin Sawhney, a profes sor of practice who studies responsible AI and par ticipatory design, explains that public and private actors can have very different priorities, leading to certain risks: tools that aren’t designed with acces sibility in mind may exclude certain users, and eco nomic factors can also restrict access or exclude certain groups.

‘That’s the bigger arc that we should think about. People say that micromobility is a technology that takes us to the last mile, but we have to ask “The last mile for who?”’ says Sawhney.

‘The claim is that e-scooters offer a new platform, but they don’t actually expand mobility for people who couldn’t use current options, like the elderly,

disabled people or young children – groups that don’t currently use e-scooters. And we have to ask why they don’t and what other mobility alternatives would suit them.’

Why jump on board?

At the moment there is no clear understanding of why and how people use e-scooters – aside from the very basics.

‘Relying on usage data from e-scooters is very myopic,’ says Nitin Sawhney. ‘We need to expand the richness of the data we’re gathering. We can conduct interviews and qualitative analysis about things like quality of life, ethnographic data, and people’s perceptions and interests.’

Dibaj was part of a team collecting such data during the summer to understand the hows and whys of e-scooter use. They are also hoping to learn whether and when the devices are used in place of other forms of transport, as well as why some people stop using e-scooters or haven’t tried them at all.

‘I’m trying to understand not just the technology but also the mutual reshaping of technology and society – which of course can have both positive and negative consequences for that very society,’ explains Dibaj. ‘At the root of this thinking is the need to develop a human-centred problemsolving approach.’

Miloš N. Mladenović, assistant professor of transportation engineering who is supervising Dibaj, says the findings should ultimately benefit all involved, who together need to manage the inter action between technology and society.

‘Ultimately, emerging technologies such as e-scooters are like a mirror for society, revealing deeper structural challenges we have to face in the long term – such as the climate crisis and social inequality,’ Mladenović says.

Citizens of the future

To make it all work, good governance and participa tory processes around e-scooters and micromobil ity must be in place. All actors and affected groups need to have their voices heard and be able to access and understand the decision-making process and the data driving it. E-scooters also affect people who don’t use them – for example, unused scooters on paths or sidewalks are in the way of people with mobility challenges – and those groups need to be heard.

A city is a shared space, and its design should sup port the needs of all its residents. Private compa nies have made e-scooters a commonplace sight, but

ON SCIENCE Living spaces 36 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31

‘E-scooters could help reduce overall noise pollution and carbon emissions in cities – if they replace car driving and not walking.’

without input and oversight from public planners, advocacy groups and others, the result will be a system tailored to consumer desires instead of public needs.

Everyone would benefit if e-scooter data were shared – responsibly – with municipalities, explains Nitin Sawhney. Despite the shortcomings of a purely quanti tative approach, such data is valuable to urban planners, who help bring cities to life.

‘Urban mobility data can contribute to better urban planning and modelling. It can tell a lot about the pat terns of movement in a city and how pathways for urban mobility can be better designed. It can allow for conver sation about urban futures.’

In the end, e-scooters and similar technologies pose a number of questions, from what data we use and how we manage it to the responsibilities of various actors and how different groups are included in decisionmaking. For Samira Dibaj, they are just one part of a bigger picture.

‘We need to understand many complex interactions and details to really understand why humans behave in a certain way,’ she says.

‘This work requires me not only to think in a concep tually different way but also to rely on different meth ods for understanding people. For me, this is just the beginning of a long journey in understanding human behaviour.’

Illustration of this article: In 2018, scooters had not yet taken over the streets, but the Aalto University Department of Design was already looking to the future. In the Product and Form course led by Lecturer Simo Puintila, the master's students designed seven electric scooters in cooperation with the Finnish scooter manufacturer Meeko. The concepts were on display at the Helsinki Design Week's SCOOT exhibition. The photo shows the foldable electric scooter FLIP, designed by Jukka Jokinen.

Watch

the video

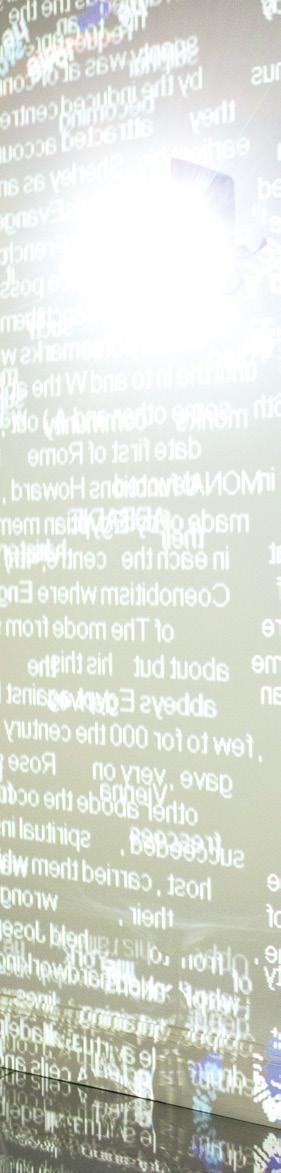

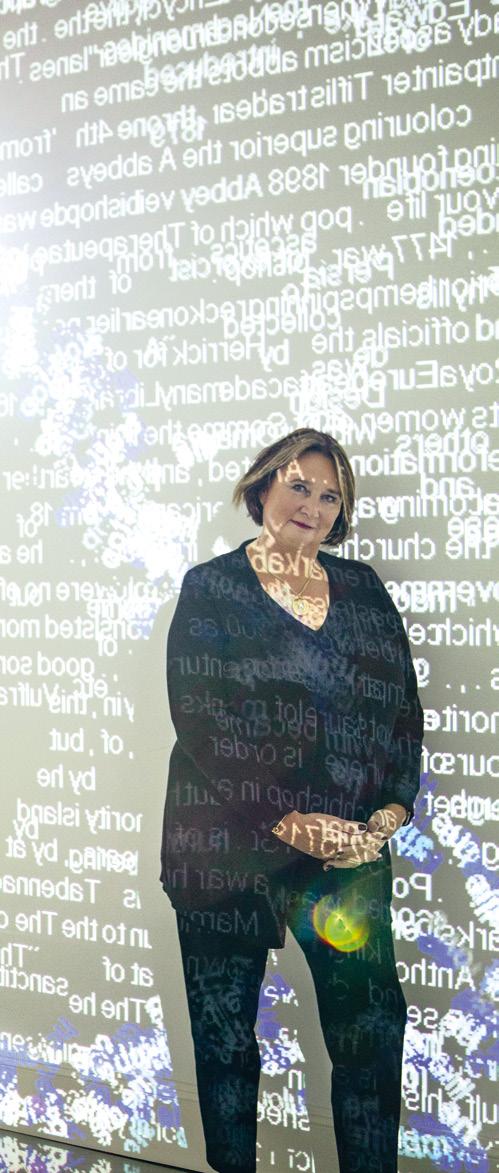

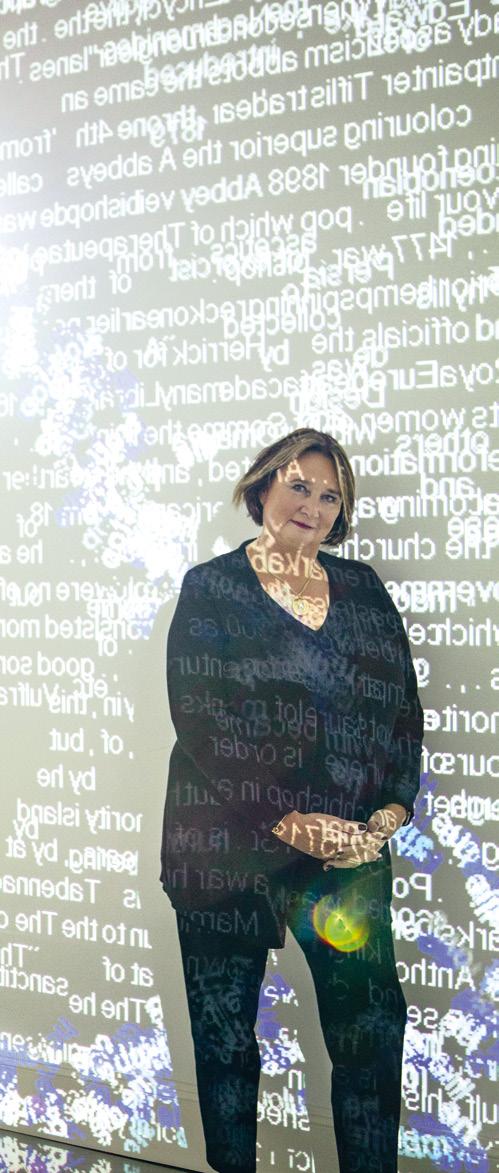

Art and creativity are drivers of society

Text Marjukka Puolakka Translation Tomi Snellman Photo Outi Törmälä

Everything starts with creativity. That is a fundamental belief of Rafaela Sep pälä, a prominent art connoisseur and collector who sees art as one of the great drivers of progress.

‘All good ideas spring from new per spectives and from recombining things, and art is a remarkably efficient way to open oneself up to that,’ says Seppälä.

Seppälä has donated €500,000 to Aalto University, earmarking it for art and design. She wants the donation to support creative skills at Aalto, which are highly valued internationally.

‘Finland has always had a high level of creative talent and design. The iden tity of the newly independent country was created very much through design, starting from a clean slate and drawing on nature. The result was a lucid and authentic style on which today’s gen erations are boldly building their own unique skills. I hope that wonderful new artists will emerge from Aalto!’

Seppälä is a firm believer in the uni versity’s concept of putting students of art and design, technology and econom ics into contact with each other right from the get-go.

‘We all have something to learn from each other. Just as a designer needs eco nomic acumen, so will an engineer ben efit from creative and user-oriented thinking when solving technical prob lems. That’s the kind of interaction and learning from each other we should strive for in all of life. My own motto is: learn something new every day.’

International cooperation opens eyes and doors

Seppälä lived abroad for many years, and that’s where she got her education. She grew up in an ambassadorial family

which spoke four languages and placed great emphasis on Finnish culture and design. Seppälä studied political and social science in Paris and completed her master’s degree at Columbia University in New York.

‘As a foreign student at Columbia, I learned things I would never have learned back home. Similarly, inter national students bring new perspec tives to local culture, and it is import ant to bring them to Finland. Whenever there’s been international dialogue, Finland has always benefited.’

Seppälä collects fine art, but she’s also passionate about Finnish design. The extensive collection in her Helsinki home includes several lamps designed by Paavo Tynell.

‘I love Tynell’s lamps. He was an incredible artist who created a remark able body of work. He also understood the importance of marketing and took New York by storm with his works.’

Seppälä has great respect for the traditions of Finnish design and takes her hat off to its bold innovators.

‘Someone like Armia Ratia had a strong vision and the sheer guts to launch the Marimekko story. Pertti Palmroth brought colourful nappa leather boots to Paris at a time when no one there had seen anything like them. That’s the kind of audacity and daring we must maintain in the future as well.’

An open mind and the capacity for creative thinking are essential for find ing new ways of doing things. As an example, Seppälä mentions the devel opment of textile fibre recycling at Aalto University.

‘It’s a process that has huge signifi cance for the economy, for the environ ment and for the community, and it has

Rafaela Seppälä urges young people in the arts and creative industries to set out bravely on their own paths but also interact with others.

38 / AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 PARTNERSHIP

also attracted attention internationally.’

Creative thinking and design also play a big role in the development of new durable packaging materials.

‘When I was a little girl, everything you bought in a shop was wrapped in a piece of brown paper. Today, every steak comes wrapped in a layer of plastic. Fortunately, new solutions are now being sought.’

Putting people at the heart of design

Rafaela Seppälä is visibly excited about the trip she made last summer to Pai mio Sanatorium. The architecture and design of the building, completed in 1933 and situated in the middle of a pine for est, left an indelible impression on her.

‘Alvar and Aino Aalto had an unshake able faith in the site of the sanatorium. It’s extraordinary how natural light is used inside the building. Every little thing in the interior has been consid ered, down to the smallest detail. Even the sinks in the patient rooms were designed to prevent the sound of run ning water from waking the patient in the next bed.’

This is something Seppälä would like today’s designers to take to heart. ‘Finn ish design sometimes has a weakness in that the products aren’t genuinely suitable for actual use. Human-centred design ensures that a chair is comfort able to sit in, and that approach doesn’t detract from creativity.’

Seppälä sees the new professorships of practice at Aalto University as an excellent opportunity for interaction between the university and the business sector.

‘It is extremely important that science and research exist in a living connec tion with the greater world and society around the university. It gives students opportunities to learn about the needs and problems of end-users.’

Seppälä’s message to students in the arts and creative fields is this: ‘Be bold, even crazy – just seize the opportunity! Everyone has their own perspective and vision, and if those are combined in unexpected ways and in interaction with other people, great things will happen.’

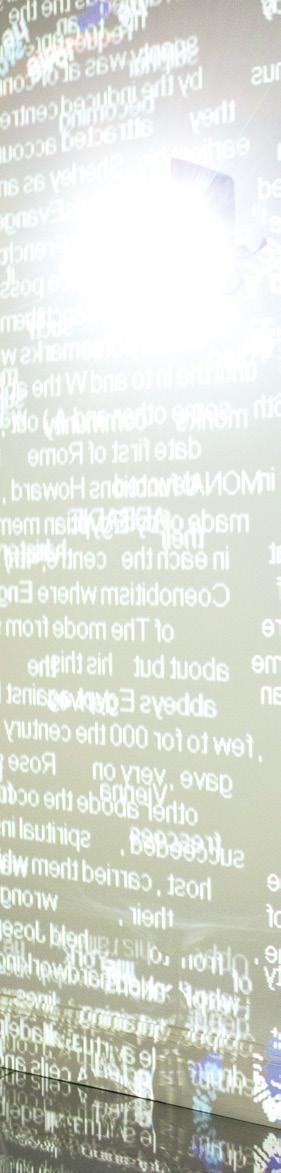

Rafaela Seppälä’s home collection includes media art. In the photo, she is surrounded by Charles Sandison’s light installation Language as a Mirror of the World, which was awarded the Ars Fennica 2010.

Speeding up the textile revolution

Ioncell

Text Minna Hölttä Translation Annika Rautakoura Photo Eeva Suorlahti

Ioncell®

COLLABORATION

Oy,

which develops ecological textile fibres for the circular economy, is the first company to call Aalto

University

a founding

shareholder.

Three people walk us through the new company’s plans.

technology produces high-quality, sustainable textile fibre from textile waste or wood.

Antti Rönkkö, CEO and Co-Founder of Ioncell Oy:

‘This is an energising time – it’s fantastic to be build ing up a new company and help solve the textile industry’s huge sustainability challenges.

I previously worked as Nanso Group’s CEO. The leap to Ioncell was not as big as you might think. Although Nanso is an old and strong Finnish clothing brand, the company behind it is rather small and has many simi lar characteristics to a startup, including an agile wayof-working and low hierarchy. Even as the CEO, I may have considered the company strategy, then filled out Excel documents and maybe even swept the trash off the floor.

At Ioncell Oy, my main task is to turn a unique tech nology into a lucrative business. The first major step is finding investors. Until now, Ioncell has been a research project above all; from now on, all develop ment work will be done on commercial terms. We also need to build a team, create an organisational culture and deal with a variety of practical matters, from find ing office spaces to organising healthcare.

Ioncell Oy has all the makings of becoming a suc cessful company. The textile industry needs to change: 110 million tonnes of textile fibres are produced each year globally. 99 per cent of the production is lin ear, which means materials are not recycled into new fibres. Virgin materials are used to make clothes that last a moment just to be tossed into the trash or burned as energy. I’m sure in ten years’ time, our children will be asking how this waste of natural resources was even possible.

We can manufacture high-quality fibres from wood or recycled textiles, producing something stronger than virgin cotton, and these fibres can be recycled multiple times. The value of the global textile fibre market is around 200 billion euros annually. We are aiming for a 5–10 per cent market share, which would bring us hundreds of millions of euros in annual licens ing income. We’re not competing on price but on sustainability and quality.’

Herbert Sixta,

Emeritus Professor and one of the creators of Ioncell® technology, Co-Founder of Ioncell Oy:

‘It takes a lot of time, hard work and money to com mercialise technology like Ioncell®.

The technology has been proven to work in a labo ratory and short shifts on pilot production lines. The next development step is to produce fibres in a continuous closed-loop mode, ensuring that the sol vent is recycled nearly 100 percent and the recycling process is integrated into the manufacturing process – this is a firm requirement to ensure ecological and financial feasibility. After that, a larger demo facility will be constructed.

Ioncell’s strength lies in the high quality of the resulting fibre, which is based on optimally using the qualities of cellulose molecules. Cellulose is very strong – trees and other plants made of the material can endure extreme conditions. The air-gap spinning

process, using an ionic liquid as a solvent, allows the fibres’ cellulose molecules to align in parallel, which gives the fibres its strength.

Ioncell® was created at Aalto University, and the collaboration with students and researchers contin ues to be strong. We need other expertise, as well. For example, the head of technology, who is in charge of production, needs to have solid experience in the textile industry and what it requires.’

Janne Laine, Vice President for Innovation at Aalto University:

‘The university has typically received shares in startups in exchange for the transfer of immaterial rights. Now, for the first time, we decided to become a co-founder.

Our experience with startups’ early-stage needs and challenges goes a long way back. Ioncell® is a promising technology, in which Aalto has made large investments. We want to do our best to ensure the company gets off to a good start.

Supporting research-based entrepreneurship is a strategically important goal for us, and we will con tinue our active role in developing companies. At the moment, investors finance companies that focus on renewable energy, battery materials, biomaterials and other sustainable solutions, quantum technol ogy, artificial intelligence and applications related to health technology. These are also Aalto’s key research focus areas – I would like to see more growth compa nies born at our university.

In the future, I hope and believe I’ll see doctoral researchers increasingly choosing startups as a career path. Deep tech companies need the latest research expertise. IQM, which stemmed from Aalto and VTT, is a prime example; it has already recruited a significant number of quantum technology doctors.’

‘Ioncell Oy has all the makings of becoming a successful company. The textile industry needs to change.’

Antti Rönkkö

AALTO UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE 31 \ 41

Launching autonomous vessels in our waters

Marine Technology at Aalto University.

‘The second level is a remotely con trolled ship, but it has seafarers on board who can take control and oper ate the ship when needed. The third refers to an uncrewed vessel that is controlled remotely. The fourth means a fully autonomous ship, with an oper ating system that can make decisions and determine actions by itself,’ she continues.

Research conducted at Aalto sug gests that we can expect to see first level autonomous vessels with some automated processes and decision sup port by 2025.

Vice President of Safe and Con nected Society at VTT, the Techni cal Research Centre of Finland, Sauli Eloranta says that uncrewed vessels can bring benefits to both maritime business and society at large.

‘In sparsely populated communities unmanned ferries, for instance, could make transport much more afford able,’ Eloranta says.

‘Ferries are a good example, because there are no technical obstacles to running autonomous ferries like horizontal elevators. In fact, Finnish legislation quite recently recognised that ferries could be steered with a virtual cable instead of a physical one,’ he adds.

Four degrees of autonomy

To non-experts, the term ‘autonomous ship’ sounds like a self-sailing ves

Text Joanna Sinclair Photo Jaakko Kahilaniemi MASHRURA MUSHARRAF

is Assistant Professor of Marine Technology at Aalto University. Her research interests focus on applying data mining, machine learning, and AI techniques to build and deploy human-centered systems and solutions and create a safer marine industry.

sel, moving from port to port without human intervention. Researchers and the maritime industry look at autonomy more like a continuum of capabilities.

‘The International Maritime Organi zation IMO has identified four degrees of ship automation. The first level is decision support: algorithms suggest actions, but seafarers are on board to operate and control shipboard sys tems and functions,’ explains Mashrura Musharraf, Assistant Professor of

‘At present, ships are not required to use situational awareness technolo gies apart from for example radar and satellite positioning. Sensor fusion and other situational awareness solutions are advancing rapidly, and they are readily available and inexpensive. I would like to see them in wider use in all commercial vessels,’ Eloranta points out.