Academic patenting and social welfare Professor Roberto Mazzoleni Department of Economics “What is available to everyone is of value to no one.” Really?

UNIVERSITY INVENTIONS YOU MAY HAVE HEARD ABOUT INVENTION

The idea that more or stronger patents are a good thing inspired US legislation that required universities to seek patent protection on the results of publicly funded research. Since public funding and universities are not generally driven by profit motives, the justification for this policy was that patents (as opposed to the publication of research results) were necessary in order to trigger follow-on investments by business aimed at developing commercial innovations based on scientific results. Really?

INVENTOR W. Chalmers

McGill University

1930

Production method for Penicillin

H. Florey and E. Chain

University of Oxford

1939

Electronic Computer

J. Mauchly and J.P. Eckert University of Pennsylvania

1946

Gatorade

R. Cade and D. Shires

University of Florida

1966

Recombinant DNA Technology

S. Cohen and H. Boyer

Stanford University and UCSF

1974

Production method for mAB

c. Milstein and G. Kohler

University of Cambridge

1975

In search of better policy

Evidence related to the process whereby academic inventions are transferred to industrial firms led me and several colleagues to argue that transfer of technology from academia to industry follows much more variegated patterns. While some academic inventions are developed by business firms that require the exclusivity terms associated with a patent license, many others are adopted and developed by industry without any concern for exclusivity or the existence of a patent.

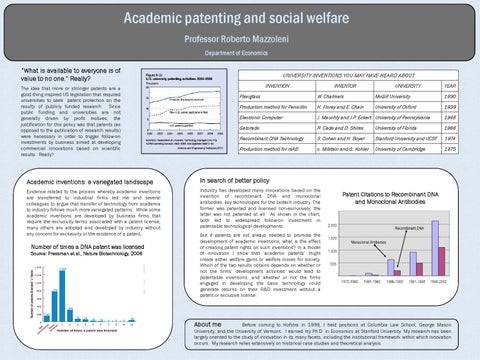

Industry has developed many innovations based on the invention of recombinant DNA and monoclonal antibodies, key technologies for the biotech industry. The former was patented and licensed non-exclusively; the latter was not patented at all. As shown in the chart, both led to widespread follow-on investment in patentable technological developments.

Source: Pressman et al., Nature Biotechnology, 2006

YEAR

Plexiglass

Academic inventions: a variegated landscape

Number of times a DNA patent was licensed

UNIVERSITY

Patent Citations to Recombinant DNA and Monoclonal Antibodies

But if patents are not always needed to promote the development of academic inventions, what is the effect of creating patent rights on such inventions? In a model of innovation I show that ‘academic patents’ might create either welfare gains or welfare losses for society. Which of the two results obtains depends on whether or not the firms’ development activities would lead to patentable inventions, and whether or not the firms engaged in developing the basic technology could generate returns on their R&D investment without a patent or exclusive license.

About me

Before coming to Hofstra in 1999, I held positions at Columbia Law School, George Mason University, and the University of Vermont. I earned my Ph.D. in Economics at Stanford University. My research has been largely oriented to the study of innovation in its many facets, including the institutional framework within which innovation occurs. My research relies extensively on historical case studies and theoretical analysis.