EIPh capillaries causes them to burst, with leakage of blood into the airways. In a small proportion of horses that bleed, the amount of blood is sufficient to appear at the nostrils. capillaries in the upper part of the lung, immediately in front of the diaphragm, tend to be most affected and this is generally the site affected by EIPh. The capillary stress failure theory was first put forward in the mid 1990s and it explains why EIPh occurs but it does not shed any light on why some horses bleed more than others or why bleeding tends to get worse over time. Professor Robinson and his colleagues have spent several years unravelling the much more complex events that are at play.

Venous remodelling

Robinson’s team has shown with detailed pathology studies that horses that bleed have scar tissue within the walls of the small veins in the lung. As the walls thicken, the veins become less stretchy, causing a backing up of pressure into the connected capillaries, making them prone to burst. Robinson suggests that venous remodelling is likely to begin when horses first enter training and is a response to the increases in pressure that happen every time a horse gallops. The degree of remodelling in any specific horse is dependent on the number of “high-pressure events,” i.e. gallops or races it has been exposed to during its lifetime coupled with an individual sensitivity. In other words, some horses’ veins are more prone to scar tissue formation than others.

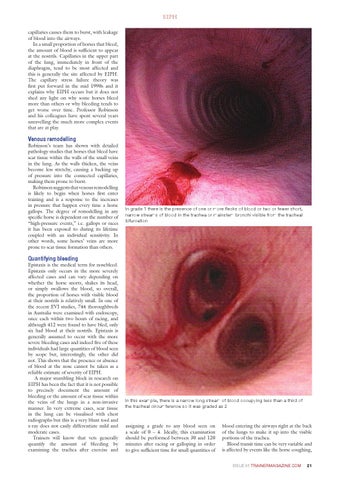

In grade 1 there is the presence of one or more flecks of blood or two or fewer short, narrow streams of blood in the trachea or mainstem bronchi visible from the tracheal bifurcation

Quantifying bleeding

Epistaxis is the medical term for nosebleed. Epistaxis only occurs in the more severely affected cases and can vary depending on whether the horse snorts, shakes its head, or simply swallows the blood, so overall, the proportion of horses with visible blood at their nostrils is relatively small. In one of the recent EVJ studies, 744 thoroughbreds in Australia were examined with endoscopy, once each within two hours of racing, and although 412 were found to have bled, only six had blood at their nostrils. Epistaxis is generally assumed to occur with the more severe bleeding cases and indeed five of these individuals had large quantities of blood seen by scope but, interestingly, the other did not. This shows that the presence or absence of blood at the nose cannot be taken as a reliable estimate of severity of EIPh. A major stumbling block in research on EIPh has been the fact that it is not possible to precisely document the amount of bleeding or the amount of scar tissue within the veins of the lungs in a non-invasive manner. In very extreme cases, scar tissue in the lung can be visualised with chest radiographs but this is a very blunt tool and x-ray does not easily differentiate mild and moderate cases. Trainers will know that vets generally quantify the amount of bleeding by examining the trachea after exercise and

In this example, there is a narrow long stream of blood occupying less than a third of the tracheal circumference so it was graded as 2

assigning a grade to any blood seen on a scale of 0 – 4. Ideally, this examination should be performed between 30 and 120 minutes after racing or galloping in order to give sufficient time for small quantities of

blood entering the airways right at the back of the lungs to make it up into the visible portions of the trachea. Blood transit time can be very variable and is affected by events like the horse coughing, ISSUE 51 TRAINERMAGAZINE.COM

EUROPEAN TRAINER ISSUE 51 EIPH .indd 21

21

25/09/2015 08:18