The Patrician

T he P atrician

“T

(Victoria

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

ACTING PRESIDENT Colin Williamson

SECRETARY Joey Martin

TREASURER Reg Smith

DIRECTORS Paul Rutten

Glen Rippon

Don Devenney Al Johnston

GENERAL MANAGER Mike Schlievert

NEWS Around the Club

FROM THE EDITOR:

Can you believe the year's almost over?

Autumn has brought with it shorter days, crisp evenings, and the smell of leaves and rain hanging thick in the air. Of course, that also means that before long the holidays will be here and we'll all have to remember to write 2026.

It's also a time for reflection and remembrance, and the VFC would like to honour the bravery and sacrifice of the men and women who gave everything for Canada.

This issue celebrates some of their stories through a few of our articles, including one on pathfinder George McGladrey, an article by Canadian comic legend Ken Steacy, and John Addison's Cold War adventures over Lincolnshire.

Until next time!

—Kelly Clark, Editor of the Patrician

EVENTS & HOLIDAYS

DEC 5 SATURDAY COFFEE & DONUTS

DEC 14 HANUKKAH

DEC 21 WINTER SOLSTICE

DEC 24 CHRISTMAS EVE

DEC 25 CHRISTMAS DAY

DEC 26 BOXING DAY / KWANZAA

DEC 31 NEW YEAR'S EVE

JAN 1 NEW YEAR'S DAY

Did we leave any events out?

Let us know at vfcpatrician@gmail.com!

HELP US BRING THE HOLIDAY CHEER

The holidays are coming and the Patrician needs YOUR HELP! Do you have any pictures, stories, or other materials about the holiday season? We want to make our next issue a festive extravaganza! Send anything you have to me: vfcpatrician@ gmail.com and you're sure to get on the Nice List this year!

BLAST FROM THE PAST

This issue of the Patrician features an article written by the legendary Canadian comic book artist and writer Ken Steacy about how his dad survived a particularly nasty bail out in 1957! If you're looking for a piece of Canadian heritage to read, we strongly encourage you check out his 2019 graphic novel War Bears, which was co-created by another Canadian legend, Margaret Atwood. It follows the early days of Canadian comic books in Toronto and the effect international competition and World War II had on the industry and its creators.

“Airspeed, altitude, and brains. Two are always needed to successfully complete the flight.”

–Basic Flight Training Manual

CHRISTMAS AT THE MUSEUM

The Canadian Museum of Flight in Langley, BC is hosting its annual Christmas Event in its Hanger #3 on Saturday, November 29th from 10 AM to 4 PM. There will be a visit from Santa Claus, crafts for the kids, a fun photo booth, and lots of holiday joy! Admission is by donation.

FIRST SOLOS

"Without disruption of air traffic, these fearless, forthright, indomitable and courageous individuals did venture into the wild blue yonder in flying machines.

Furthermore, these skillful individuals did safely land said flying machines at Victoria International Airport, incurring no significant damage to self or machine, thus completing first solo flights."

THIS ISSUE WE CELEBRATE THE FIRST SOLOS OF THESE PILOTS:

Alistair Smith

Jacob Di Battista

Helen Lu

Neil Libbenga

Yanhe (Jack) Yang

Oliver Barrett

Devin Antoniazzi

Benjamin Sharret

We want your first solo or achievement in the Patrician! Send your photos to vfcpatrician@gmail.com or tag us on Instagram.

Ethan van Tol has earned his PPL!

Julien Bahain is ready for the skies with his PPL!

MEMBER ACHIEVEMENTS

PPL WRITTEN TEST

Graysen Vistisen-Harwood

Julian McLachlan Alonso

Alexander Cabrnoch

Andrew Schmidt

Bruce Cousins

Victoria Wood

Nicholas Finnerty

Zoe Leduc-Wright

PPL FLIGHT TEST

Johnathan Watkins Garcia

Dayton Parsons

Gen Kiffiak

Jasper Baker-McCue

Luke Langlois

Cole Patterson

Stanley Mathew

CPL WRITTEN TEST

Daniel Wang

Bernie Tremblay

CPL FLIGHT TEST

Cameron Byers

Trevor Birrell

Juan Pablo Cobo

GROUP 1 INSTRUMENT RATING

Gavin Johansen

Sean Brenton

MULTI-ENGINE RATING

Takumi Satake

Cameron Byers

VFC MENTOR PROGRAM

Do you want other pilots to fly with, split flight cost, share knowledge, or get help getting to a new airport for the first time? Find potential mentors and their resumes posted on the Mentors bulletin board beside the Dispatch counter. Contact details are on each mentor's resume or you can email mentors@flyvfc. com for more information.

Interested in becoming a mentor?

There's always room for more experienced pilots! Send an email to mentors@flyvfc.com for more information on how to join up!

WELCOME NEW VFC MEMBERS

Hayden Klassen

Silas Benjamin

Heidi Applegate

Dylan Parker

Luther Mann

Jonathan Hickle

Eric Wilson

Owen Stacey

Matthew Wolniewicz

Arwyn Paice

Jiorde White

Stephanie Stewart

Magnus Chan

Benny McGuire

Nova Batten

Matthew Wood

Elizabeth Bingham

Navi Macknak

Cameron Hoyle

Martin Gibbs

Alain Hagenbach

Darryl Saunders

David Murray

Kartike Nayyar

Jordan Hammett

Jarrette Silverthorne

Nicholas Kannegieter

John Beardsley

Samuel Heaven

Escalus Burlock

Spencer Gordon

Thomas Kudor

Katryna Faddegon

Andrea Anscombe

Deborah Gogela

Braeden Hedderick

Shannon Quinn

Jonathan Rowbotham

Ernest Volnyansky

David McLeod

Rose Weekes

Alison Prince

Alexander Nowak

Man Lung Wong

John Faux

Alexander Richardson

Thomas Matchett

Adil Kayani

Emily Claus

Ayanna Dawkins

PARKING AVAILABLE!

Interested in prime paved parking spaces for your aircraft? Good News:there are spots available!

Secure, pull-in/pull-out, easy access.

Call Dispatch at 250-656-2833 to arrange a spot or to get on the waitlist for hangar spaces!

New

COMIC BOOK COURAGE AND REAL CANADIAN HEROISM

Real Canadian (and Comic Book) Hero George "Scrammy" McGladrey RCAF is now part of the Vancouver Island Military Museum

Visitors to the Vancouver Island Military Museum are now able to experience the new permanent display called Real Canadian Hero and Comic Book Hero George (Scrammy) McGladrey RCAF. This display tells the story of George McGladrey, a flying officer with the 405 Squadron's Halifax bombers during WWII. McGladrey's job was to a pathfinder who illuminates targets on bombing raids using flares. However, on one such mission things went haywire as a midair collision with an allied bomber caused their fuselage to ignite.

McGladrey survived the mission, but was killed in another bombing run three months later. However, the story of that night outlived him and was later turned into a comic book by True Comics Press in November 1943. It took nearly sixty years until a member of McGladrey's family—his

cousin Richard—even learned that the comic existed. Richard McGladrey was surprised to discover that the story was about his cousin, but also impressed by the incredible story it chronicled.

For more information about this exhibit, check out Jessica Durling's article in the Nanaimo Bulletin (where the information and the photos in this article are from).

Vancouver Island Military Museum present Brian McFadden shows off the next exhibit.

THE PROFESSIONAL

PILOT

by David Gagliardi

“‘Professionalism’ is commonly understood as an individual’s adherence to a set of standards, code of conduct or collection of qualities that characterize accepted practice within a particular area of activity.” -Universities UK et al. 2004

THE MENTAL TRANSITION FROM TRAINING FLIGHTS TO FLYING AFTER OBTAINING YOUR LICENSE

Professional pilots embody the attributes in the definition above. Being a professional pilot has nothing to do with what license you hold, it is ultimately about the attitude with which you approach flying. This article is the twelfth in a series that will examine aspects of piloting light aircraft to a professional standard.

My last 2 articles discussed ways newer pilots could gain skills and experience by completing added training. However, I now realised I missed a more fundamental challenge for new pilots who aspire to fly with professionalism.

That is making the mental transition from training flights to flying on their own after obtaining their license.

Your experience for most flights when you were learning to fly:

• Flight structure:

Training flights have a plan for the flight set by the instructor with the student told what maneuvers will be conducted and how they will be done.

• Pre-Flight Preparation: Weather, NOTAMs, fuel requirements and weight and balance will be covered but the reality is the weather is going to be good and is unlikely to change

because the practice areas are not far away, the airplane will have much more fuel than it needs and the weight and balance numbers will be the pretty much the same as all the other training flights.

• Navigation:

Since most training flights will be short and to very familiar practice area locations, navigation is not going to be very demanding

• ATC and Airport Procedures: Again, you will be very familiar with the home airport layout, departure and arrival routing and ATC communications.

Contrast this for a flight where you are for example, going to Tofino for the first time with three friends and now consider the above points in the context of this flight.

• Flight Structure:

What is your aim going to be, get to Tofino as quickly as possible or make it a scenic flight as well? Going up the West Coast trail or going via Cowichan and Nitinat lakes or Direct is up to you but will profoundly affect you flight planning from the beginning.

• Preflight Preparation:

With you, three passengers, and some beach gear, you will need to calculate the Gross Weight and Centre of Gravity for a load you may have never seen before and you will

almost certainly not be able to take full fuel. This means that you must give the club dispatch a heads up on what fuel you need ahead of time, so you are not given an airplane with too much fuel. Do you need a survival kit? Are you taking round trip fuel or refueling in Tofino? If you want to refuel is there a NOTAM for no fuel, a fairly frequent occurrence at Tofino? Are you comfortable with refueling

an airplane on your own? Notice we haven’t even talked about weather or routing yet. Is the weather suitable not only for our arrival but will also hold for our departure? There is no point in going if we are likely to get stuck there. Which route will often be driven by the weather. In this case the direct route may be wide open, but the coastal route is fogged in.

• Navigation:

Following the coast is pretty easy but what if you have an in-flight problem with the airplane? Where are you going to go? The same consideration needs to be applied to the more direct route. Should I go GPS direct or put some bends in the flight plan so that I stay over more hospitable terrain in case of an engine failure?

• ATC and Airport Procedures:

On the departure am I going to climb into terminal airspace right away or stay low but then fly through the CYA. Can I get flight following, and if so by whom? When I arrive at Tofino who am I going to be talking to and what are the airport call in points and circuit procedures. Where am I going to park?

Conceptually there is nothing new on this flight compared to that training flight to the Cowichan Valley and the decisions to be made are the same, the differences are that there will be many more choices to be made and the first choices made will influence other available choices affecting this flight.

Professional pilots consider all the factors affecting every flight even the routine ones. They know that you can get away with little or no planning for simple familiar flights but also know that sweating the details for even the simple flights builds the skills to ensure flight critical considerations aren’t missed for those flights where it matters.

O UT OVER LINCOLNSHIRE

By

OVER LINCOLNSHIRE

John Addison

Former VFC Instructor

The biting November sleet driving cross the Lincolnshire countryside soaked me to the skin in moments as I sprinted from the crew bus to the looming Vulcan bomber. The ground crew huddled beneath the massive delta wing were looking helplessly miserable.

Eastern England was the heartland of Britain’s formidable ‘V’ force, its squadrons of nuclear armed bombers based across the Lincolnshire farmlands ready to ‘scramble’ at a moment’s notice.

The period is the early 1960’s, at the height of the Cold War; Kennedy and Khrushchev had just stood toe to toe during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 and the military world was still extremely twitchy.

Following the 1957 Bermuda conference between Eisenhower and Macmillan, the RAF’s Bomber Command had forged a tight bond with the USAF’s Strategic Air Command and with the RAF’s V-Force in England being 3,000 miles closer to the Soviet Union than the US based B-52s, the importance of Bomber Command’s role was out of all proportion to its size. We were, so to speak, the tip of the nuclear spear.

With our squadron’s role being offensive, life consisted of training, training, and yet more training. Occasionally, perhaps just to boost morale, we had the chance to drop high explosive on a bombing range somewhere which, while thoroughly enjoyable, only served to remind us that we should probably stick to the nuclear role where pinpoint accuracy was rather less important. Our ‘active’ role, in addition to surveillance flights such as today’s and tossing practice bombs about the

countryside, included suffering through 24-hour bouts of QRA (Quick Reaction Alert). The idea here was to be able to take off within 15 minutes of a red button being pressed somewhere beneath London, but in fact, as no button was ever pressed that wasn’t cancelled before we could get airborne, QRA was an activity that perfected the game of bridge and defined boredom.

It was against this backdrop that we had planned our afternoon flight from Lincolnshire to the North, across Scotland, past Norway toward the frigid waters of the Barents Sea. Just to keep an eye on things, you understand. These long surveillance flights were extremely boring, and while today’s flight over those Northern waters was doubtless purposeful and seemingly dramatic, the high point of the flight would hopefully be, (apart from a tin of warmed soup and a ham sandwich) the light show put on by the Northern Lights should weather conditions permit; they can be truly spectacular.

Lincolnshire winter weather could be

foul… either South-westerly gales sweeping in off the Atlantic or Northeasterly Arctic gales from the Russian steppes. Today we had the South-westerly gales. The Meteorological Officer seemed to take a perverse delight when describing the foul weather, adding that we could also expect embedded thunderstorms up to 30,000. He did, however, promise improving conditions with frontal passage by our return in early evening.

Following our flight planning we spent half an hour in the Flight Operations canteen lining our arteries with a ‘full English breakfast’ (for lunch !) before leaving the Operations centre in our crew bus. The 15-minute drive through the rain to the waiting Vulcan gave me time to reflect on how seriously uncomfortable the beginning of this flight was going to be owing to the sets of tightly cinched webbing straps from my parachute and seat harness pressing the cold wet flying suit to my body. Today though, because of our planned altitude above 50,000’ we wore an air-vent suit under our flying suits next to the skin which extended from ankle to wrist to neck and was filled with thin flexible piping full of holes. We could connect this suit to an air supply on the ejection seat and control the temperature of the circulating air, so hopefully I would be warm and dry after an hour or so. The climb out after take-off was going to be a bitch too; banging through the turbulence caused by thunderstorms embedded in the cloud layers. We didn’t avoid weather, if it was on track, we went through it. The editor's example of a "Full English" from the aptly named "aglugofoil.com".

We spent the next hour discussing the aircraft’s technical state with the Crew Chief, strapping into the cockpit, and completing our preflight checks before Take-Off. There was one technical fault with an Engine Air switch which we could work around perfectly easily but which was to play a pivotal role before the day was done, although there was no way we could have known that.

Finally, with the windscreen wipers making an infernal racket but no impression

whatever on the slashing rain and sleet, we roared down Waddington’s southwesterly runway, rattling windowpanes for miles around, to be quickly engulfed by the overcast and so began our climb to altitude.

The Vulcan, with its big delta wing, is extremely rigid, and with no wing flex to absorb the bumps, we felt every single one of them. Not fun at all ! But on the positive side, the newer Vulcan B2 with its upgraded Olympus engines certainly did not lack power, and we shouldered our way up through the thunderstorms in true alpha fashion until after 4 minutes at 29,000’ we burst out of the clouds into the blazing late afternoon sunshine. Smooth, finally. Today, with an extra 10,000lbs of fuel in bomb-bay fuel tanks, we were at our highest take-off weight without a bomb load but still we expected to reach our initial cruising altitude of 41,000’ in less than 10 minutes. No civil traffic reached anything like our altitudes, so as usual, we had the sky to ourselves. As we were looking for serious altitude before reaching the Barents Sea north of Murmansk we set engine power to its most efficient, which was more or less flat out, and in order to maintain the best L/D ratio, hung

onto a specific IAS. The aircraft would climb gradually as fuel burn decreased our weight, and we expected to be in the mid 50’s before arriving on station. At these altitudes, we wore pressure jerkins over the top of everything else, giving us the appearance of Michelin men. Their job was to supply pressure to our abdominal areas in the event of depressurisation. We did not mind wearing these, as we could squirt a little air inside them which would remove the pressure from the ejection seat harness and with a little wiggling about, we were really quite comfortable. Don’t even think of going for a pee though. To this day, I have a bladder good for 10 hours.

We two pilots up front at least had a windscreen to see through, albeit the size of a letterbox, but the two navigators and the AEO (Air Electronics Officer) were below and behind us, facing backwards, with no windows, working in perpetual darkness. With the excitement of the departure now behind us and having stabilised in our cruise/climb mode with the autopilot engaged, we settled down to the routine that would occupy us for the next six hours or so. Nothing new here, we were old hands at this. Very little chatter, each preoccupied with their own duties and thoughts.

I was admiring the view of Scotland’s Western Isles when the AEO’s voice crackled through the intercom … ‘What have you done to number 4 engine? My alternator has dropped offline …!’ I glanced at the engine gauges and sure enough, #4 engine was decaying to idle rpm.

Bloody hell, what a nuisance. A single

engine failure in a Vulcan is easily managed, certainly not a handling issue, but I realised that unless we could recover the engine we were going to have to abandon today’s mission as we could not maintain the altitude for our planned surveillance flight on three engines. So, back to Waddington which meant descending back through all that foul weather. I started a descent down to around 30,000’, as three engines couldn’t maintain 41,000’ at our weight, all the time wondering why #4 had stopped. There was no obvious reason. We continued a few more cold relight procedures during the descent before giving up as no amount of trying could start it. We would try again when lower down in denser air.

So, what now? We were in UHF radio range of our Scottish airfields at Lossiemouth and Kinloss operated by Coastal Command, so I spoke with Lossie who told me that the weather was not so bad, just a wee bit windy. I asked what a wee bit windy meant and they replied laconically that they didn’t have an exact figure, as the wind had ripped the cups from the anemometer again! So, Scotland was out. Bomber Command would not even consider the idea of an operational Vulcan using a civil airfield, something to do with all of our fancy black boxes, I expect, so our own bomber command airfields with their 9,000’ southwesterly runways were our only options.

The AEO contacted Bomber Command HQ on HF radio to let them know what was going on. Their Lordships, with no concern whatever for crew or aircraft were seriously upset that we were not going to continue our surveillance. Typical ! the AEO next

spoke to Waddington to let them know we were returning owing to an engine failure, and we began to prepare for our approach. Waddington were not particularly concerned as these Olympus engines, with their relatively short lifespans, did fail from time to time and as I’ve said, the Vulcan with three engines is easily managed.

The two navigators, having absolutely no interest in engines, alternators, and the like, had come alive, and having given me a heading to steer towards Waddington were now chattering away, delighted at the prospect of a U-turn back to the bar at Waddington. However, their gleeful chatter was brought to an abrupt halt as #3 engine began to wind down immediately followed by #1.

Now we really did have a problem, as Jack Swigert was to famously tell Houston some years later. Often, at the end of a shorter sortie, we would practice single and double engine failures on the same side of the aircraft in the circuit before a final landing but three and four engine failures were not even simulator exercises and considered beyond remote.

OK, so I guess today was becoming beyond remote.

With this, we were all now keenly focussed; I had by now lowered the nose to increase speed to 300kts to attempt snap relights, but these didn’t work so began slowing to 200kts to reduce our descent rate and increase glide range. I turned to the heading the navigator had called out to me towards a point just Northeast of Waddington from where we would start our approach and left the Co-pilot and AEO

to see if they could sort out the engines. The copilot and AEO were the only ones talking, the navigators silent with nothing to do, and I was hand flying the aircraft as the autopilot couldn’t cope with the asymmetry. I sat trying to figure out the big picture, but despite the gravity of the problem, found myself momentarily distracted by the beauty of the setting sun to the West … the mind is a funny thing.

Anyway, the engines had just wound down, three of them; no bangs, no fire, no drama at all; they just stopped. Clearly there was nothing wrong with the engines themselves which left fuel, or rather lack of it, as the problem. However, after checking and double checking the rather complicated fuel system, we could find nothing amiss; there was no indication whatever of any malfunction anywhere; three engines had just shut down. The Vulcan had no provision for dumping fuel to reduce to a sensible landing weight and with one engine being insufficient to maintain level flight, we were in a controlled descent to somewhere, just not sure quite where yet. With our present rate of descent, we had 40 minutes to fly but should we lose the fourth engine, and there was no reason to think that we would not, then considerably less.

Each pair of engines was buried together in the wing root sharing a common air intake and double engine failures on the same side were not unheard of; usually following some sort of disturbed airflow, or bird strike. One engine blowing up would inevitably take out its neighbour. Crews were well practiced in this, and two engine performance was adequate even at gross

weights. However, we had to consider the very real possibility of losing the fourth. Should that occur, then we would be faced with abandoning the aircraft, and abandoning the Vulcan at low level had always proved fatal for the rear crew, with the pilots surviving only because of their ejection seats.

But today we had altitude, and although the Vulcan had suffered several accidents over the years, I was confident we could abandon the aircraft successfully if it were to come to that. We two pilots had ejection seats, but the rear crew had to go through a fairly complicated procedure before finally sliding from the aircraft’s entrance door in the belly when a static line would open their parachutes. Crews had discussed this sort of scenario often during training, as had we, and generally agreed that should the occasion arise, we would ideally like to have the aircraft at around 15,000’ to provide the maximum chance of success for rear crew exit.

Today we had time, another 15 minutes or so before arriving at 15,000’ with our present descent rate so we discussed what seemed to be our only two options. None of us could recall a single engine approach ever having been attempted in the Vulcan and I didn’t particularly relish trying to manage it in today’s rough weather with a 200’ ceiling at such a high landing weight. I had never attempted it, even in the simulator, and it seemed fraught with risk. The decision of whether to attempt a landing at Waddington or abandon the aircraft had to belong to the rear crew, as the two of us up front had ejection seats. The decision was quickly made, to jump,

and we headed toward the coast just south of Flamborough Head where we would orbit if necessary until reaching 15,000’ when the rear crew would slide out and we two pilots would eject. RAF Leconfield, with its Search and Rescue helicopters were conveniently located just 20 miles from our intended ejection point and having been told of our plight promised to have us all out of the North Sea within moments of our splashing down into it. The Meteorological officer had not yet kept his promise; and the weather over Eastern England was still foul with gusty winds, low ceilings, and turbulence. I wondered what the parachute ride through the stormy weather would be like.

The next 5 minutes, with nothing more to do, seemed to take an age; the crew was completely silent, the two navigators had reviewed the escape procedures, the AEO stopped trying to find an explanation for the engine failures and the co-pilot patiently continued cold relight drills.

Now, with a full-fledged emergency, Bomber Command quickly relinquished operational control to Waddington who, naturally, became keenly interested. The control tower staff included an experienced duty pilot whose job was to provide sage advice for just such an occasion. He was, however, as baffled as we, and after a couple of quick questions recommended we continue as planned, adding that he would liaise with the helicopter. I could only imagine the scene in the tower as each successive senior officer arrived repeatedly asking the poor controller and duty pilot the same questions. At least they had the good sense not to talk to us.

We were now passing 20,000’ in the descent and with only a few more minutes left before jumping out, I was beginning to feel somewhat apprehensive … had we forgotten anything? Overlooked something? The aircraft was still completely silent, all eyes glued to the nearest altimeter waiting for me to give the command to abandon the aircraft.

Then the co-pilot broke the silence, calmly informing us that he had succeeded in recovering #1 engine. I was ecstatic; with two engines running, the aircraft was readily flyable ! Needless to say, the rear crew held their breath as I manoeuvred the aircraft at various power settings and found engine performance to be normal. Chuffed with his success the co-pilot had continued with his relight drills on #3 and #4 and recovered

#3. #4 wouldn’t start, but at this stage we didn’t really care, three engines operating normally was practically routine. What a relief ! Having spent the best part of the last half hour in near silence, the crew started chattering like a troop of monkeys. Their job was done; it was just left to the two of us up front (as they emphatically reminded us) to do our pilot stuff and get them back onto the ground soonest.

We advised Leconfield that they would have to wait for another day before having the pleasure of winching a V-force crew out of the North Sea and we turned smartly back towards Waddington, just 15 minutes away with a completely irrational blind faith that those three engines would keep running.

Waddington tower had said goodbye to

us, wished us luck with our ejection and were waiting for a call from the helicopter telling them that they had picked us all up so were somewhat surprised when we called them giving our position and altitude simply requesting a PAR approach. Without even the slightest of pauses, the approach controller identified us on radar, assigned a heading and altitude before switching us to the talk-down frequency. I recognised the talk-down controller’s voice with his thick Scottish accent politely asking if we were able to complete a normal approach and told him we were, that we had 3 engines running and were looking forward to one of his very best talk-down approaches please. Mac congratulated us on our good fortune adding that a bottle of Scotch would be dispatched to our parking spot for our arrival then got on with his usual immaculate talk-down. The sense of relief was indescribable; we had been spared a dip in the North Sea but still had no idea what was going on with the engines. Mac was comparatively ancient, mid 40s at least, but his talk-downs were legendary throughout the Air Force; he could put me onto the runway, 1000’ down, straddling the centreline in any weather. I actually remember flying that approach quite well, completely detached from the flying; I suppose the pilot part of me was following Mac’s instructions, but my conscious mind was still churning with what might have been. Anyway, it all seemed to have worked as Mac seemed happy, and we had the aircraft safely on the ground in moments. I later learned that as soon as we had spoken with Waddington an hour or so earlier with our single engine failure, that the tower had

sent a car to fetch an off-duty Mac from the Officers Mess just in case.

He was that good.

It was dark and still somewhat stormy when we landed, and quite the relief as we sat with the Crew Chief and ground crew and began on the bottle of scotch. After 10 minutes or so, the crew chief received a phone call instructing us to proceed to the Operations centre for a de-briefing. On arrival, we were ushered into a conference room already occupied by the Station Commander and a few other senior officers where the climate seemed to be the same as outside – dark and stormy. There was still no apparent reason for the engine failures, so I was immediately judged to have mishandled the fuel system which, as I said earlier, was somewhat complicated. No matter how clearly we explained what had taken place, the station Commander was adamant that I had caused the failures by fuel system mismanagement. As he had not even congratulated us on our good fortune before tearing into me, I was left with the distinct impression that my RAF career was going to become a great deal shorter than I had planned. After half an hour of this bullying, a technical officer entered and began talking with the Station Commander. An airman also came in motioning me to leave to leave the room with him, which I did, and in the hall was met by the crew chief who told me they had found a large hole in a bomb-bay fuel tank. They did not yet know why the tank blew, but it would seem I was off the hook. I re-entered the conference room and sat down with the crew telling them the news. We expected some sort of apology, but nothing of the

sort; the Station Commander simply left the room, still in his foul temper.

(It was not until the following day that my boss contacted me to say they had found the cause. The fuel tanks were normally pressurised to around 2psi above ambient to provide a positive head of pressure. Each of the sixteen tanks had a built-in pressure relief valve which was simply a ball bearing held closed against spring pressure. When tank pressure built up above 2psi or so, it overcame the spring pressure and the valve opened. On this day, one valve jammed shut for reasons unknown and the tank continued to pressurise. As the tank emptied, it forced air into the fuel chassis at a much higher pressure than the supply pressure from the other tanks resulting in air going to the engines instead of fuel, causing the flameouts. The tank continued to pressurise for a few moments more before rupturing which instantly relieved all air pressure from the fuel chassis, allowing fuel from other tanks to then flow, which is why only three failed and why we eventually were able to restart two more. Remember that Engine Air switch we switched off before take-off? If it had been working normally, the tank would have pressurised at a different rate, and we might have lost all four with no chance of recovery.)

Interestingly, on reflection, and as a testament to the depth and discipline of the RAF training, the crew never showed a moment of doubt, uncertainty, or indecision during the flight. The eldest of us was the AEO at 31, I was 24.

GROUND SCHOOL SCHEDULE

PRIVATE PILOT LICENCE GROUND SCHOOL

PPL #25-11: NOVEMBER 16, 2025 TO FEBRUARY 01, 2026

Sundays (09:00 - 16:00)

Instructor: Neil Keating (Zoom attendance possible by arrangement)

PPL #26-01: FEBRUARY 08, 2026 TO MAY 03, 2026

Sundays (09:00 - 16:00)

Instructor: Neil Keating (Zoom attendance possible by arrangement)

COMMERCIAL PILOT LICENCE GROUND SCHOOL

CPL #25-15: NOV 22 5, 2025 TO MAY 31, 2026

Saturdays (09:00 - 16:00)

Instructor: Ken Kosik, Ben Holden, and Neil Keating

INT: INSTRUMENT TRAINING GROUND SCHOOL

TBA – Expected on Sundays beginning in NOV/DEC 2025 to FEB/MAR 2026. Instructor: Warwick Green

Individual scheduling requests are available for Private Pilot Licence, Commercial Pilot Licence, Mountain Awareness Training (MTA), Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (Drone) Courses (RPAS) by request.

Individual tutoring is also available for PPL and CPL upon request.

Confirm your attendance with Neil Keating on cell at 204-291-9667 and VFC Operations (Russell) at 250-656-2833.

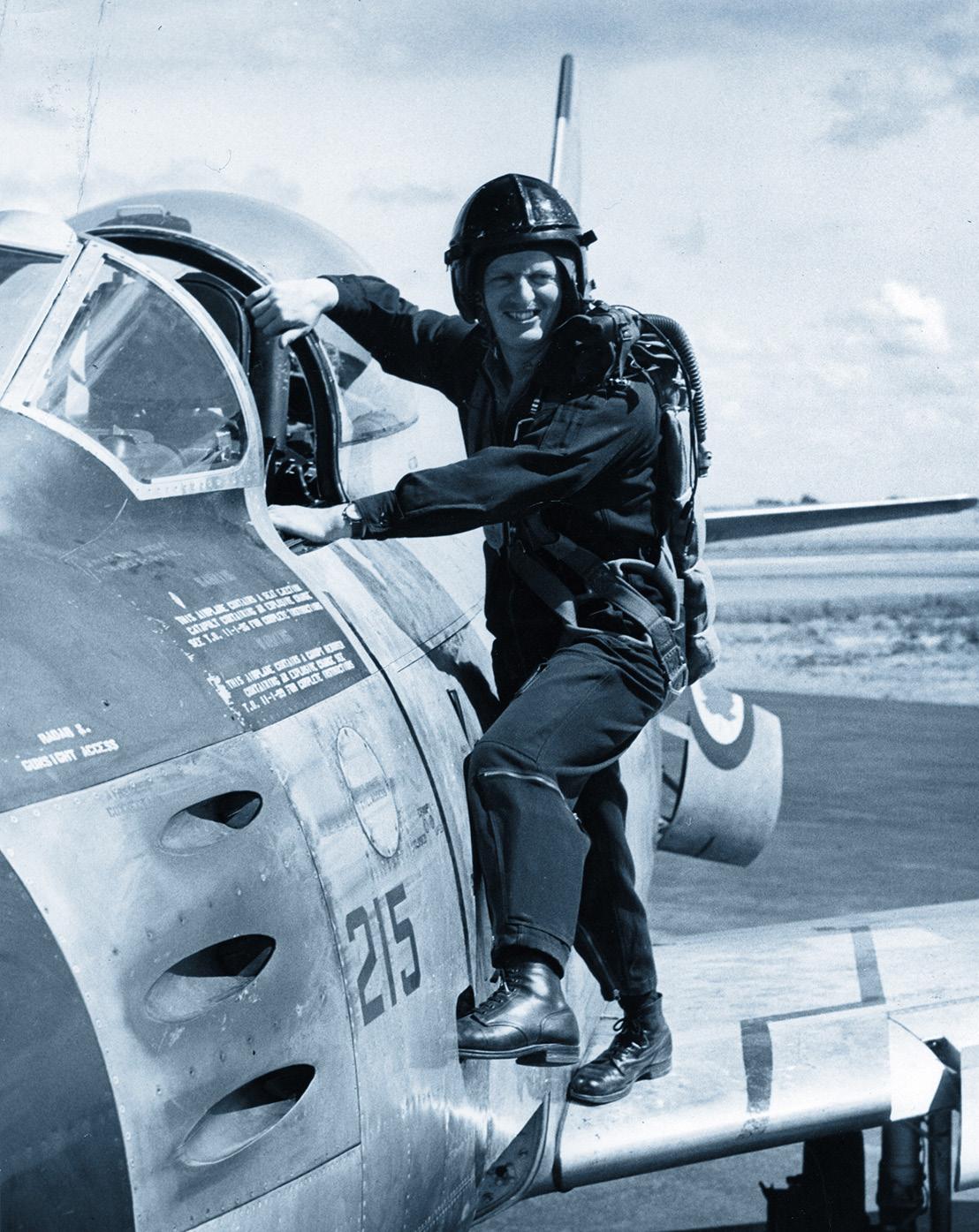

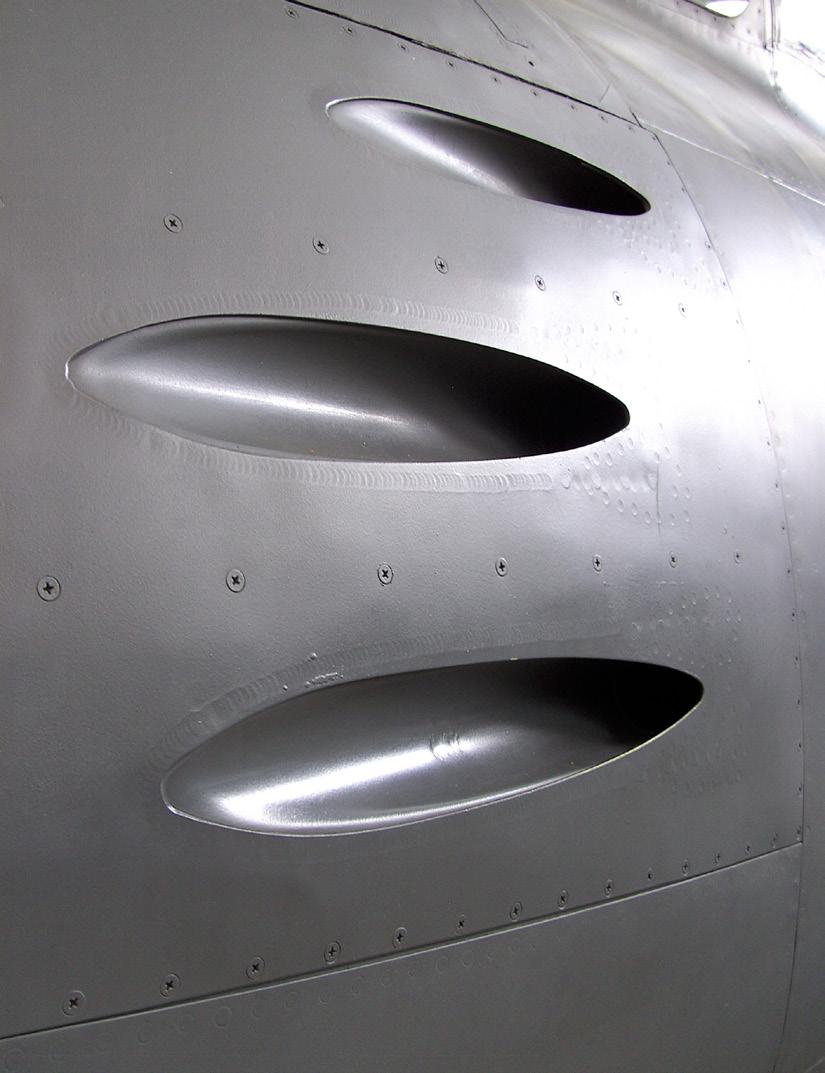

THE STORY OF HOW MY DAD SURVIVED BAILING OUT OF A SABRE IN 1957

by Ken Steacy Canadian Comics Legend

Back in the day, flying high-performance jet aircraft was the most dangerous occupation in the world, and sadly a number of pilots paid the ultimate price. One of my dad’s squadron-mates did just that near Chatham NB during the winter of 1957; crashing into a frozen lake.

The investigation noted three holes in the ice: one apiece for the plane, the seat, and the pilot. It was believed that

the pilot had been unable to extricate himself from the seat until just prior to impact.

Dad (by then a S/L) took a Sabre up shortly thereafter in an effort to understand the conditions under which that tragic event had occurred. The salient difference being that his plane had recently been retrofitted with the new, improved automatic ejection seat. After a few attempts, he found he was unable to recover from what I believe

was a flat spin. He mentioned punching off the drop tanks, but not before ducking his head down in case they collided with the cockpit— imagine his dismay when he peered over the sill to see them formatting just off the wingtips!

Ultimately, it was time to go; he recalls an enormous bang, but was knocked unconscious and the next thing he remembered was shaking his head and looking up at

Originally published in the Jan/Feb 2022 issue of the Patrician.

that beautiful big silk (or was it nylon?) canopy fully deployed over his head! Happily, the new automatic ejection seat had worked perfectly, and had freed him from the seat and pulled the d-ring, just as advertised.

Coming down fast into a stand of trees, dad tried to steer towards a clearing, but when he pulled the risers the leading edge of the ‘chute folded under, and not wanting to press his luck he thought it best to land where gravity and the wind decreed. All went well, but he was lost, and decided to hunker down and wait for rescue—which took a while.

Apparently, all of the squadron’s planes had been accounted for from their sorties that day, so imagine the controller’s surprise when a farm lady called to say that she’d just witnessed a crash! She was assured that she must be mistaken, but fortunately someone must’ve gone down to the flightline and counted, coming up one plane short. Somehow, they managed to track dad down, and four hours later a ground crew got him out as the terrain was too rough for a helicopter extraction.

By then, my stalwart mom was starting to worry, and as I recall it was actually Duke Warren who came to reassure her that dad was okay. But not wanting to unduly dismay her, his opening line was something like: “How do you like my new greatcoat, Peggy?” She cut straight to the chase,

ULTIMATELY, IT WAS TIME TO GO.

and replied: “That’s not why you’re here, Duke—what’s happened to Charles?” I’ve always maintained that it’s pilots' wives who really have the right stuff!

I can’t honestly say what the result of the investigation was, or what caused the crash. I do know that dad’s life was saved by his helmet (the impact with the back of the seat was so severe that it was cracked almost in two!) and the automatic ejection seat— thank you, Canadair!

It was five years later that Dad applied for membership in the famous Caterpillar Club, and duly received his card and pin. As he responded in a letter; “Thanx you very much for enrolling me in the Club. Should I ever again decide to bale out, I shan’t wait five years before applying for a bar to my caterpillar.”

Ken Steacy is a Canadian comics legend known for his work for NOW Comics and his collaborations with Harlan Ellison, Dean Motter, and Margaret Atwood. He was inducted into the Canadian Comic Creator Hall of Fame in 2009. He was also a member of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets 386 Comox Squadron.

Images courtesy of Ken Steacy and Wikimedia Commons

SOME OF THE PEOPLE WHO TAGGED US ON INSTAGRAM!

From top, left to right: @heathergibb: "Well it was definitely a birthday for the books."; @flyboy_dane: "Soaring over Mars."; @suborbitalben: "Fly with Dad day!"; @davemcrobb: "Sunset flight with Jess and Jeff."; @thewaramps: "At 21 years old, Ethan is reaching new heights. He recently earned his pilot's license!" @burtonader: "Pretty cool to see a Norseman in the wild! // Thanks for the share!

Tag us on Instagram & get featured! @victoriaflyingclub #flyvfc #victoriaflyingclub