Spring/Summer 2025

‘Our

Spring/Summer 2025

‘Our

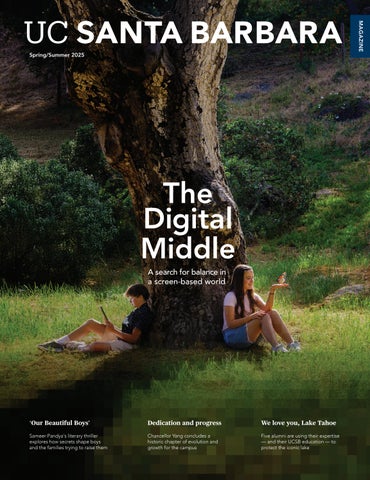

A search for balance in a screen-based world

Dedication and progress

Chancellor

We love you, Lake Tahoe

Five alumni are using their expertise — and their UCSB education — to protect the

Whether you're visiting for a weekend or working remotely at the beach, make UC Santa Barbara your summer home

Rates starting at $160 per night. Book Now.

The UC Santa Barbara Summer Inn offers affordable accommodations for seasonal guests visiting campus. The inn's private, residence-style rooms feature great views of the university. Guests can enjoy sun, sand and surf with friends and family at Goleta Beach, or the tide pools and bluffs along Isla Vista's shoreline.

alumni.ucsb.edu/vacation/summer-inn

In the desert heat, time stood still like the air. Nothing moved. There was no sound but the patter of white blossoms — freed by the season from a towering Mexican palm — dropping softly onto an umbrella.

Stately Tahquitz Peak, all granite and grandeur, stared down from 8,500 feet up. Expectation vanished in its shadow. No one was waiting on me. I had nowhere to be. What a gift.

So went my internal monologue one recent weekend in Palm Springs, where I’d gone to visit old friends, disconnect from my day-to-day and just generally detox from adulting. There was a lot of lounge time and scant screen time. And it was great.

In our always-on world, it’s nice to turn off for a few. Call it a reboot for the brain. It works for our devices, so why not us? Even a quick reset can do wonders. The key here is balance, and, with credit to Oscar Wilde, “everything in moderation, including moderation.”

Speaking of devices, and balance … Our cover story this issue explores the idea of finding middle ground between all-out brain rot and total abstinence from screens — especially as it pertains to kids, but for all of us, too. With so much of life now rooted in technology, how do we mitigate the downsides while embracing the upsides?

Elsewhere in this issue: a teacher-turnedscholar devoted to uplifting kids from vulnerable populations; an in-depth introduction to firstyear women’s basketball coach Renee Jimenez; reflections on the evolution of campus under outgoing Chancellor Henry T. Yang; and an alumni screenwriter whose first feature film is now in production — and starring one Mr. Brad Pitt.

And so much more.

Wishing you a good read, and an occasional reboot,

Shelly Leachman ’99 EXECUTIVE EDITOR

3 From the Editor ON CAMPUS

6

News & Notes

Top stories from around campus

Then & Now

Mad about the Bard

Summer Streams

Scholars and researchers in popular media

Athletics

Celebrating our coaches and teams

The Backstory

Education scholar

Hui-Ling Malone

Honors & Awards

Our distinguished, award-winning faculty

Research Highlights

UCSB scientists are advancing knowledge on every scale

Gaucho Giving

Give Day wrap-up

Letter From the

Executive Director

Bright Spot

Alumni work to Keep Tahoe Blue

Newsmakers & Milestones

Cori Close ’ 93

Gaucho Creators

Cameron Alexander ’10

Global Gauchos

LMBK Surf House

Noteworthy Alumni successes

64

Lifting each other up UCSB’s Girl Gains club

Spring/Summer 2025

Volume 4 No. 2

UC SANTA BARBARA MAGAZINE

Executive Editor Shelly Leachman ’99

Associate Editor Debra Herrick

Ph.D. ’11

Art Director/Designer Matt Perko

Contributing Writers

Lola Alvarez ’27

Samantha Bronson

Nora Drake

Sonia Fernandez ’03

Keith Hamm ’94

Alex Parraga

David Silverberg

Jillian Tempesta

Isabella Venegas ’27

John Zant ’68

Copy Editor

Julie Price

Contributing Photographers

Jeff Liang

Matt Perko

David Bazemore

Miranda Flores

Joshlyn Wright

Caren Nicdao

Ross Turteltaub

UC SANTA BARBARA EXTERNAL RELATIONS

Vice Chancellor

John Longbrake

Executive Director

Alumni Affairs

Samantha Putnam

Editorial Director

Shelly Leachman

Chief Marketing Officer

Alex Parraga

UC Santa Barbara Magazine is published biannually by the University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-1120.

Email: editor@magazine.ucsb.edu Website: magazine.ucsb.edu

The UCSB Dance Team brings the spirit all year long to the sidelines at basketball and soccer games. Now they’re bringing the Universal Dance Association College against top programs from across the nation for Division 1 Jazz, and sixth in

1

The UC Board of Regents approved the appointment of James B. Milliken as the 22nd president of UC’s world-renowned system of 10 campuses, six academic health centers and three nationally affiliated laboratories, succeeding Michael V. Drake. Chancellor of the University of Texas system since 2018, Milliken will begin his UC tenure Aug. 1.

4

The UCSB Women’s Center celebrated its 50th anniversary year, five decades to the day after it first opened its doors. Founded to represent and support women on campus, the center today takes a come-one, comeall approach to combating systemic oppression and sexism.

2

Professor David Valentine and his discovery of DDT barrels dumped on the ocean floor near Catalina Island are the subject of “Out of Plain Sight,” a new documentary from LA Times Studios that is currently screening — and winning awards — on the festival circuit.

3

Beating out over 200 schools, UCSB became the first UC campus to win the California University and College Ballot Bowl, a biannual competition meant to motivate college students to register, vote and showcase their civic engagement.

5 Janine Jones has been named UCSB’s new Anne and Michael Towbes Dean of the Graduate Division and Associate Vice Chancellor for Graduate Affairs. She will officially join the campus community on July 1, taking over from outgoing interim dean Leila J. Rupp.

6

UCSB earned its highest-ever finish in the prestigious and rigorous William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition, placing fifth among 477 universities. College of Creative Studies student Pico Gilman ’27 earned an individual ranking of sixth out of nearly 4,000 competitors.

8

To bolster its presence downtown and support the revitalization of Santa Barbara’s primary business corridor, UCSB has acquired property on State Street. With commercial space and a residential building, the mixed-use portfolio could be a new anchor in the business district, while enabling the university to offer workforce rental housing in a prime location.

7

Following approval by the UC Regents, the California Coastal Commission has approved UCSB’s development of the San Benito Student Housing project, the first phase of a two-part plan to create a combined 3,500 new student beds on the main campus.

Who doesn’t love the phrase “in a pickle”? Who hasn’t used it or, for that matter, actually been in said pickle themselves? But how many among us know who first coined it? It was the Bard himself, one William Shakespeare, a major contributor, by way of his works, to our everyday vocabulary. See also: wild-goose chase, bedazzled, swagger and good riddance!

More than 400 years after he was first published, Shakespeare remains the original cultural juggernaut.

Sigh no more

Pictured in the 1982 La Cumbre yearbook, these actors donned legit-looking Renaissance period regalia to play forlorn lovers from “Much Ado About Nothing,” the Bard’s statement play about, in part, the misfortune that can come from miscommunication.

Jump ahead four decades — and swap the elaborate costumes for plain linen ensembles — to see Naked Shakes, the UCSB theater program that stages strippeddown versions of Shakespeare plays, and a 2024 remake of “Much Ado” in their trademark simple style.

Sharing their expertise and talents well beyond campus, scholars and researchers from across the university often turn up on major networks and streaming platforms, both behind the camera and out front. Here are a few to check out:

Disney+ and Hulu

James McNamara

Creator/head writer and executive producer

The Magic of Menopause

MasterClass

Emily Jacobs

Featured expert

YouTube

Brian Haidet

Creator and host

YouTube

Wendy Eley Jackson

Producer

Mighty Monsterwheelies

Netflix

Maryam Kia-Keating

Consultant

NBC Rae

Host

Coaching UCSB women’s basketball is a dream job for

BY JOHN ZANT '68

THERE MAY NOT HAVE BEEN A BETTER TRIBUTE to Renee Jimenez’s first year as head coach of the UCSB women’s basketball team than the Big West Conference’s award for the “Best Hustle Player.” It went to Skylar Burke, a 5-foot-8inch Gaucho junior who fought fearlessly for possession of the basketball whether she had to outmuscle taller players for rebounds or dive headlong to secure loose balls on the hardwood.

Leading the league in floor burns was the hallmark of former coach Mark French’s teams when he began turning around the program in 1987. The players’ all-out hustle captivated fans before the Gauchos started piling up victories and claiming 12 Big West championships from 1992 to 2008.

Of the coaches who have succeeded French since he retired with 438 wins in 21 seasons, Jimenez is by far the most connected to UCSB’s heritage. She grew up in Ventura and attended basketball camps at the Thunderdome. She was a sharpshooting guard at Ventura High, playing against future UCSB standouts Nicole Greathouse and Lisa Willett. As a junior in 1999, she helped Ventura win the Santa Barbara Tournament of Champions.

A quarter century later, Jimenez has established a residence in the Thunderdome. Athletics Director Kelly Barsky hired her to take the Gaucho women’s reins following the retirement of veteran coach Bonnie Henrickson. Jimenez’s journey included a college playing career at San Francisco State and 15 years as a head coach at the Division II level. She led Cal State San Marcos to the 2024 NCAA D-II Final Four.

“This is near and dear, my dream job,” Jimenez says of leading the Division I Gauchos. “This is the one job going through my career that I’ve always had my eyes on — one, because it’s home, and two, because I know how much pride is here, how much the community loves UCSB women’s basketball.

“The biggest thing, talking to former fans, they want to see a new energy, a new excitement, a different pace of play,” she says. “We want to put a product on the floor that people want to come to watch. We should be filling this place like they did in 1999, 2000. This is a job I would not have taken if I didn’t think that was possible. I definitely think, (with) 20-win seasons, we’re going to have this place rocking.”

The 2024-25 season marked some progress toward that goal, as the Gauchos finished with a record of 18 wins and 13 losses. They went 12-8 in the Big West, tied for their best conference record in the past 10 years. Among the teams they defeated were Hawai’i, the regular-season champion, and UC San Diego, winner of the Big West Tournament.

“My biggest takeaway is how winnable the Big West is,” Jimenez said after the season. “We’re not far off. Our goal is to get a bid to the NCAA.”

The coach’s inaugural season ended in a 56-54 loss to Cal Poly San Luis Obispo at the conference tournament. Senior guard Alyssa Marin, named to the All-Big West Second Team, scored 23 points in her final game. She scored 1,234 points in her career, ranking No. 21 in Gaucho history.

Marin, who hails from Camarillo, got a boost in motivation from Jimenez’s arrival.

“The reason I came here was to be close to home,” Marin said after her last game at the Thunderdome, with six family members — her parents, two brothers and two grandparents — in attendance. “(Jimenez) was everything my senior year. She’s from Ventura, and she felt like home to me.”

UCSB claimed the nation’s best free-throw shooting percentage (80.8%) among NCAA Division I women’s teams, led by Marin’s 85.3%.

The Gauchos team graduated five seniors. Returning players include Burke; sophomore Zoe Borter, an All-Big West honorable mention; and All-Freshman selection Olivia Bradley.

“Kids like Skylar and Zoe, that’s what we’re about — a gritty, tough team,” Jimenez says. To find more players like them, Jimenez and her staff were busy meeting recruits in the spring.

“We’re knocking on doors, introducing ourselves,” she says.

Unlike the Mark French era, when it was no surprise to see UCSB defeat USC or UCLA in women’s hoops, the new landscape of college athletics — in which it’s allowable to pay athletes beyond their scholarships — will be dominated by schools that are enriched by football TV contracts. “That’s coming,” Jimenez says, “whether we like it or not.”

What the UCSB coach will try to do is convince players that there’s no place like her home.

went undefeated against conference opponents on the way to the 2025 Big West Championship — the team’s third title in five years — and a bid to the NCAA Tournament.

UCSB

in 2025 scored its first Big West Championship, winning six straight elimination games to get it done and sending the Gaucho squad to the NCAA Tournament for the first time since 2007.

Going 36-18 and making it to the Big West Championships, Gaucho Baseball marked its sixth consecutive full season with 35 or more wins, and saw seven of its student-athletes earn Big West honors.

& Field sent 10 student-athletes — the most since 2017 — to the 2025 NCAA West Regionals. Junior hurdles expert Maddie Conte, pictured, competed in both the 100-meter and 400-meter hurdles.

BY NORA DRAKE

A HIGH SCHOOL WALKOUT protesting the suspension of three Black students was a defining moment for Hui-Ling Malone, who developed a lifelong passion for scholarship and activism. She went on to advocate for justice and equality in her time as a secondary teacher in underserved communities, eventually becoming an expert in the topic as an assistant professor at UC Santa Barbara’s Gevirtz Graduate School of Education. In addition to collecting and analyzing data for her research and teaching, she uses her findings to foster positive change and amplify the voices of vulnerable populations.

In the following conversation, Malone talks about how her own experiences as a student leader and teacher of color led her to strive toward creating a more just and equitable educational experience for all.

Your research touches on issues that schools around the country are grappling with, like educational access for students from different backgrounds. How would you describe your academic interests?

Mainly, I’m looking at K-12 education with a focus on educational equity and educational justice. I am particularly focused on students of color and students who are coming from more vulnerable backgrounds, whether that’s because of race, language, ability, income or something else.

I look at different parts of education like how youth experience school socially, emotionally and academically, youth activism and youth advocacy. I also do youth participatory action research — exploring an issue that students are encountering, usually around educational disparities and disproportionality, and then working with them to research it in their context. Together, we gather the data and explore their experiences and use that to suggest policy change or do some kind of activism to help address these issues.

I also have a project around future teachers of color and their shared experiences, because I was one, and I understand the challenges and complexities.

Did you always want to be a teacher? What path led you there?

I didn’t know I was going to become a teacher! I thought I was going to be some kind of lawyer. Then I was recruited into Teach for America (an organization I now know is controversial, but I didn’t know that then).

I ended up in the Bronx. I remember feeling completely unprepared. Even though I was a student leader and had led groups like the Black Student Union, I was unequipped at the time. I was a social justice-oriented person, but I was still not able to fully address the challenges my students were experiencing.

Largely, we are taught that the education system is one size fits all, but that just wasn’t the case in my experience. As I moved through my career, I got to be involved in more

teacher social justice groups. It was affirming and eye opening and it helped me come into myself as a teacher.

How did you pivot from teacher to scholar-activist?

I linked up with a researcher named Django Paris, who does culturally sustaining education. He had heard about work I was doing in my classroom that was community oriented. I knew nothing about research or what people like him did. He gave me another perspective on the research side of what I was experiencing as a teacher and suggested I think about going into academia one day.

What does being a scholar-activist mean to you?

I am a scholar, someone who does research, using data, theory and other literature around my topics of interest. But since the topics are so close to people’s lived realities — students, teachers, their schools, their communities and family members —

Hui-Ling Sunshine Malone centers youth and community to build stronger school relationships and tackle urgent social issues — together.

being a scholar-activist means using that information to help promote change that positively impacts the lives of students and their families and teachers.

For example, I’m currently working on a project in Santa Barbara County with Black high school students who felt they weren’t being heard by school leadership. Because I have a title and an advanced degree, I can come in as a resource and collect and present data in a way that validates their experiences and also gets through to school leadership. I sent a synopsis of the project and its findings to the superintendent and the school board members, and then we all sat down together to talk about how we wanted to move forward. I find myself trying to use my power and privilege to push for change and do something good.

What is one thing that you wish more people understood about the challenges facing teachers today? Is there something that you think is not being talked about enough?

There are so many issues that teachers encounter that they aren’t prepared for, or can’t prepare for. When you’re a teacher and you really care, you want to be a good teacher in helping your students learn, but you can also become like their therapist and so many other things because they come to you if they feel safe with you. And, though that is a great privilege, it can really be emotionally and mentally draining. Teaching can be isolating because you have so much going on, and it’s hard to find collectives to support you. As a teacher of color particularly, it can

BY

be even more isolating, because 80% of teachers are white. Even though the percentage of students of color are increasing, among leadership and teacher education programs and teachers themselves, there’s still one demographic that is the norm. With that said, I encourage all teachers to think about what justice and equity mean in broader ways to really serve your students. That often involves doing some identity work. We all have areas we can’t see because of what our experiences are. The first steps are to unlearn and relearn, so that you can better serve all of your students.

HONORS & AWARDS

Thuc-Quyen Nguyen

Distinguished Professor Chemistry and Biochemistry

2025 Henry H. Storch Award in Energy Chemistry American Chemical Society

2025 Ambassador in Chemical Sciences French National Centre for Scientific Research

2025 Suffrage Science Award University of Oxford

2024 Fellow European Academy of Sciences

“I am extremely happy and honored to be recognized. It’s great to be recognized and awarded for your science, but at the same time, it comes with a responsibility. You’ve been given a voice. What will you use your voice for? I really love helping young people, student researchers and other women in science. I am a strong supporter of women in STEM, and I hope to continue all of these things.”

Irene Beyerlein

Mechanical Engineering

2025 Fellow American Academy of Arts & Sciences

Leda Cosmides Psychological & Brain Sciences 2025 Fellow American Association for the Advancement of Science

Rachel Segalman

Chemical Engineering

2025 Fellow American Association for the Advancement of Science

Adina Roskies Philosophy 2025 Fellow American Association for the Advancement of Science

Leah Stokes

Political Science

2025 Schneider Award for Outstanding Science Communication Climate One, The Commonwealth Club

Christopher Parker Political Science 2025 Fellow Carnegie Corporation

Joan Dudney

Bren School of Environmental Science & Management

2025 Early Career Fellow Ecological Society of America

Craig Hawker Materials

2025 Herman F. Mark Polymer Chemistry Award American Chemical Society

From the smallest quantum particles to global climate cycles, UC Santa Barbara scientists are advancing knowledge on every scale

A Microsoft team led by UCSB physicists, including Station Q Director Chetan Nayak, has unveiled a first-of-its-kind topological quantum processor: an 8-qubit chip that could speed progress toward fault-tolerant quantum computing. The chip demonstrates a topological superconductor, key to stabilizing quantum states.

UCSB researchers including mechanical engineer Elliot Hawkes, with colleagues at TU Dresden, have created a robotic material made of small, disk-shaped robots that assemble into different shapes. Inspired by biology, the robots can switch between stiff and fluid states, holding a form or flowing into a new one.

Lithium batteries advance

Materials scientist Jeff Sakamoto and collaborators at Argonne National Laboratory have advanced research into solid-state lithium batteries, seen as safer and more energy efficient than today’s versions. Their study explores solid electrolytes that let lithium ions flow while reducing fire risk.

Enzymes from scratch

Chemist Yang Yang and collaborators at UC San Francisco and the University of Pittsburgh have developed a new method for designing enzymes that paves the way toward more efficient, powerful and environmentally benign chemistry. The technique may enable an array of applications, from drug development to materials design.

An international team including earth scientist Lorraine Lisiecki has linked Earth’s ice ages to predictable orbital cycles. Using a million-year climate record, the team matched changes in ice sheets and deep-ocean temperatures with shifts in the planet’s orbit and tilt. The findings suggest the next ice age could begin in about 10,000 years.

Cellular biologist Meghan Morrissey is developing new cancer immunotherapies by targeting macrophages — immune cells that can destroy tumors but are often overlooked in treatment strategies. Her work aims to harness these cells to improve outcomes, especially for patients with solid tumors that resist current therapies.

Using advanced laser microscopy, neuroscientists Michael Goard and Nora Wolcott observed the powerful influence of hormone fluctuations on the shape and function of neurons in the mouse hippocampus, a brain region crucial for memory formation and spatial learning in mammals. The findings have strong implications for humans as well.

Architect-engineers in professor Marcos Novak’s lab have developed AI-driven software that is among tools being tested to combat the psychological toll of isolation for people living and working in extreme environments. Their system is now in use at St. Kliment Ohridski Base in Antarctica.

BY JILLIAN TEMPESTA

On April 10, the Gaucho community celebrated UCSB Give Day with all the energy and optimism that define our campus. The annual 36-hour fundraising event took place online at giveday.ucsb.edu and through email and social media. Throughout Give Day, community members participated in creative competitions to support their favorite areas. Donors made 3,712 gifts — a 5% increase over last year — and raised $6,661,690 for the programs and opportunities that make UC Santa Barbara a top public university.

“I’ve really gotten into UCSB Give Day as the importance and gamesmanship has taken hold,” says R. Marilyn Lee ’69, UC Santa Barbara Foundation trustee and past member of the Alumni Association Board of Directors. “There are key departments and programs that I always give to: my political science major, the American Presidency Project, Larry Adams Scholars, the Alumni Association, and areas that my UCSB friends support. Give Day is priceless. It helps UC Santa Barbara continue its world-class excellence.”

courses like World of Heroes. Gifts received on Give Day supported the department’s new Gallucci Summer Internship program.

“We chose to celebrate Ralph on Give Day because of the sheer number of students whose education he has contributed to; he's taught thousands during his 28 years at UC Santa Barbara,” says Rose MacLean, chair of the

“It is with sincere gratitude that we thank all of our Gaucho alumni, family and friends for supporting our mission to serve student-athletes and bring together the community on Give Day,” says Kelly Barsky, the Arnhold Director of Athletics. “Your support and connection is critical to providing an exceptional studentathlete experience, continuing the tradition of highly competitive programs and unifying an engaged and connected community. Give Day is such a wonderful celebration of community and so full of Gaucho spirit! Support received not just on Give Day but every day is noticed, impactful and truly appreciated.”

Through Give Day, UCSB raises support for campus, engages alumni and models philanthropy for current students. It’s an opportunity for areas to rally alumni, friends, parents, staff and faculty.

This year, the Department of Classics celebrated the retirement of Professor Ralph Gallucci, a beloved educator who introduced students to ancient Greece and Rome through general education

Department of Classics. “We wanted to honor his commitment to undergraduate education. Our vision is to establish a fund that is self-sustaining through donor support. We will provide scholarships for professional development opportunities so students can thrive in their careers.”

For many of UCSB’s 20 Division I sports, Give Day is the biggest fundraising event of the year. Connection is a core value of UCSB Athletics, and on Give Day, all sports fans can cheer for their teams.

From classics to athletics, donors’ interests were broad and varied. Nearly 200 funds received support. Some 35% of gifts were from alumni. More than 800 people made their first-ever gift to USCB on Give Day, a truly global tradition, with support from 44 states and 19 countries. On campus, the student philanthropy group UCSB First popped up with T-shirts and colorful stickers as they shared the power of giving back with current students.

“I look forward to Give Day every year,” says Corey Lewis ’27. “I’m so grateful to be part of this Gaucho community and inspired to give back when I’m an alum. To everyone who forwarded an email, liked a post or wore their Give Day T-shirt, thank you!”

‘Our Beautiful Boys’

Sameer Pandya’s literary thriller explores family secrets

Three decades of dedication — and progress

Chancellor Yang concludes a historic chapter

Bridge to a bright future

Undergraduates walk FUERTE’s wild path toward environmental careers

Finding balance in a screen-based world

EARLIER THIS YEAR , onstage in front of a large audience of middle and high school students and their parents and grandparents, scholar Robin Nabi asked by a show of hands how many had a smartphone. “Silly question, right?” she commented as raised hands filled the gymnasium at Laguna Blanca School in Santa Barbara. She quickly followed up with another question she knew the answer to: “How many of you have been told that phone is bad for you, unhealthy, harmful?” Same show of hands. Since the widespread arrival of smartphones to classrooms starting around 2012, conflicts between teachers and students have boiled over. These pocket computers and their social media apps are distracting and isolating and provide online playgrounds for bullies. At home, as well, parents have noticed that as screentime ramps up, their kids grow more withdrawn, anxious and depressed. Family tension can be compounded by the shame a parent may feel for failing to protect their child from real or perceived harms, even as parents themselves struggle with addictive doomscrolling and bingeing podcasts and TV shows.

During her recent TEDx Talk at Laguna Blanca, Nabi, a professor of communication at UC Santa Barbara, noted it’s gotten so bad and ubiquitous over the years that the 2024 Oxford Word of the Year was “brain rot,” defined as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging.”

But what if it’s not as bad as we think?

That’s a fair question, says Nabi, an expert on the impacts of media on emotional health, decisionmaking, coping and overall well-being.

In her TEDx talk, “Using Smartphones in Smart Ways,” Nabi invited her audience to take the proverbial deep breath and step back a moment to consider that American author Henry David Thoreau coined the term brain rot in 1854. Ever since, Nabi continued, brain rot has been linked to a long series of media forms — from comic book crime capers and the beguiling glow of television to video games, rap and heavy metal music and, of course, social media.

“Is there reason for concern?” Nabi asks. “Of course there is. But is there reason for panic? No.”

Is there reason for concern?

Of course there is. But is there reason for panic? No.

Professor Robin Nabi

Too much screen time — particularly related to social media use in kids, teens and young adults — is a major concern in modern society. Cellphones are ubiquitous. Social media is enticing. And the impulse-control and decision-making capacities in young brains are not yet fully developed.

“Social media is the modern moral panic,” says Kylie Woodman, a graduate student in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Communication and the Media Neuroscience Lab. “It’s everywhere. We see children, adolescents — even adults — glued to it. Yes, it can be a way to connect to others, but it also has an addictive aspect about it.”

However, she adds, it’s important to remember, “This is not the first time we’ve seen something like this.”

Reading fever: In the 1700s across England and Europe, the widespread popularity of reading novels was causing young people to hole up, shirk responsibility and act out immorally. Reading fever, as it was called, was also blamed for a spate of suicides among fans of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s “The Sorrows of Young Werther,” first published in 1774. As the epistolary novel’s popularity grew, a sub-affliction — dubbed Werther fever — presented mostly among young men, who dressed as the protagonist and, pistol in hand, killed themselves in the throes of unrequited love. The book was banned in Denmark and Italy; for other fictional offenders, a sin tax was floated as a general countermeasure.

Radio: In the 1930s, a new household technology took hold of young people. In the U.S., parents became exasperated with their kids’ obsession with listening to the radio and blamed it for interfering with other interests, including reading, sports, playing music and participating in family conversations. Responding to content deemed overstimulating or inappropriate — such as the glorification of criminals in fictionalized dramas — parent activism prompted the National Association of Broadcasters to establish guardrails for children’s programming.

Television: Starting in the 1950s, televisions became standard in American homes. Not all shows were considered family friendly, however, and in 1969, the U.S. Surgeon General launched a three-year study of TV violence. The report’s summaries were mixed; while TV violence was found to promote aggressive behavior in some kids, it also put forth other considerations, including personality type, parental influence and local levels of violence. “Television is only one of the many factors which in time may precede aggressive behavior,” the report stated. “It is exceedingly difficult to disentangle from other elements of an individual’s life history.”

Video games: Video game popularity has been on an upward trajectory since the late 1970s. Research dating back to the early 1980s suggested that video game addiction was problematic among students. In 2018, the World Health Organization recognized gaming disorder as a mental health condition that intrudes on an addicted gamer’s sleep, work, education and ability to foster and maintain relationships in real life, while also impacting memory, attention span and stress management.

Social media: Social media addiction hasn’t been officially recognized, Woodman says, “but it’s pretty clear — at least within the literature — that it seems to be transposable to the extent that all the criteria for gaming disorder also apply to a social media or smartphone addiction.”

“For teens and college students," she adds, "when you see those grades drop, that’s a big signal that their media use is actually becoming detrimental.”

Kylie Woodman researches media effects at the intersection of communication, psychology and neuroscience.

Fundamentally, a smartphone is a handy tool to or facilitate certain tasks, not unlike a simple stick. As a tool, for example, a stick can be used to reach ripe fruit among the high branches of an apple tree. The same stick, however, can also be used as a spear.

For parents, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that children are always poking each other’s eyes out online. Even small doses of social media can quickly reveal that these virtual gathering places are often more akin to a vicious battle in the Roman Colosseum than a cordial debate in the public square.

“But when you really look at kids’ motivations and gratifications, oftentimes being on their phones is linked to something positive,” Nabi says. They’re learning new languages, recipes and Minecraft strategy. They’re learning how to ollie and to play chess and guitar. They’re listening to music and connecting with other kids with similar interests. “Sometimes they’re using their phones for learning and social connection,” Nabi points out. “These are needs we all have as human beings.”

In no way does she downplay connections between social media use and anxiety, depression, low selfesteem and disordered eating, among other maladies. “But if we focus only on the harms, we can miss the benefits,” she says.

Recently, for example, preliminary studies by Nabi and her colleagues found no harm to well-being among adult users scrolling on their phones for five minutes; at the same time, other users who engaged with inspirational content experienced benefits similar to those who meditated for five minutes. “This could be an example of how we can start thinking about the ways we can use media to uplift, to support, to enhance, so that we can make choices that can benefit us physically, psychologically and socially.”

Just as mindless eating can be unhealthy, Nabi told the TEDx audience, “when we’re on our phones, we have to think about the content we’re consuming and how it makes us feel. You are in control of that tool in your hand.”

Like many families, Nabi and her husband started having conversations about smartphones and social media when their daughter was in sixth grade. They took a modified “Wait Until 8th” approach, a “no smartphone until eighth grade” parent pledge officially launched in 2017 by a Texas-based nonprofit.

“We slowly on-ramped with a phone that was less expensive and didn’t have the temptations that come with smart technologies connected to the internet,” Nabi remembers. “Our choices were based on who she is, as well as our priorities as her parents.”

The next step — a smartphone — arrived when their daughter finished eighth grade. She had proved she could take care of her phone, not lose it, and not be distracted by it during school work or family time. The whole process has been a family conversation. That’s not to say they’ve never had a cross word over screens and phones.

“When you’re talking about tablet time for a 4-year-old, they’re not in a space to negotiate, but in junior high and certainly in high school, they have opinions,” Nabi says. “They know what they like and don’t like and what they think is fair. Including them in those conversations is really important so that they have some agency and a voice. Not having an authoritarian style around the phone issue means you’ll likely get more buy-in from your kid.”

With some negotiations and agreements, they set some house rules: no phone in the bedroom or at the dinner table. She keeps it on mute at school and while she’s doing homework. After a long day at school, she takes some downtime to decompress by watching videos and catching up with friends. Every family has its own dynamic, Nabi adds, “and we realize how very lucky we are that our daughter is not especially attached to her phone.”

“Every so often,” Nabi says, “we check in with her” about what she’s watching and how she’s feeling about the phone and all the things that come with it. “She’s aware that it can be addictive and that there’s a lot of information and imagery that’s inappropriate.”

Kids remember stranger danger from kindergarten, she adds, and for the most part, they’ve been taught to take the same precautions online.

Nabi credits the schools for teaching digital literacy and online safety, and nonprofits such as Common Sense Media for publishing free, up-to-date, helpful resources for parents and educators.

“Many families struggle with issues around screens generally and phones specifically,” Nabi says. “It’s important that we recognize that adolescents have the same needs and temptations as adults when it comes to their phones, and we as parents serve as role models for them on how to integrate these devices into our lives.”

“The key is keeping the lines of communication open about what our kids are doing online,” she says, “and perhaps we can even find opportunities to share those experiences and have more points of connection with them rather than strife.”

BY

At UCSB, scholars like Nabi have long studied the complex relationships between media, technology and adolescent well-being. So when Jonathan Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation” burst onto the scene, framing smartphones and social media as the root cause of a mental health crisis among youth, it sparked immediate interest — and some debate — among experts in the field.

Since its debut in April 2024, “The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness” has skyrocketed to the top of bestseller lists and sold more than a million copies. A social psychologist and professor at New York University, Haidt has been touring extensively, giving talks to sellout crowds and sitting down with media giants, from “Good Morning America” to Oprah to Joe Rogan and Trevor Noah.

The book’s general theme is that we overprotect our kids in the real world as we underprotect them online. Too many of our kids have indoor, screen-based lives, Haidt says, often replete with bullying, fear of missing out, beauty shaming and disturbingly explicit content — and it has a negative impact on mental health and academic performance.

Haidt’s book and speaking tours have stirred a grassroots movement of parents and educators as more and more school districts — even entire states and countries — have banned phones from schools entirely, not just during class time.

His argument to get phones out of schools isn’t controversial. Most educators and parents can get behind that. However, there’s been some frustration among researchers about how Haidt makes his case that smartphones and social media are rewiring kids’ brains for the worse.

“The high-level reviews of the published literature suggest that there is a small but significant relationship between social media use and anxiety and depression among adolescents,” Nabi says. “That same research also has found a positive correlation between social media use and social well-being. In other words, the relationships are smaller and more nuanced than Haidt suggests, and sometimes may even be positive.”

Haidt and the movement his book has sparked promote four “achievable goals” they believe could create meaningful change: no smartphones before age 14; no social media before 16; phone-free schools; and more offline activities for kids. “We can fix this in three years,” Haidt says, “and it’s actually happening.”

“The research is messy about whether or not social media is truly bad or good for you,” says Woodman. “It’s not necessarily that a person gets on social media and starts becoming depressed. Some individuals already have a psychopathology of depression that’s leading them to develop a compulsive relationship with social media.”

For Nabi, the conversation Haidt has reignited is ultimately a meaningful one, even if the realities are more complex than his framing suggests. “As a researcher, it’s frustrating to see a scholar lean into a moral panic while dismissing evidence that doesn’t agree with their particular conclusion as it distracts attention away from addressing the larger factors influencing adolescent mental health,” Nabi says, “But to the extent that Haidt’s book has elevated the conversation around the challenges of phones in schools and protecting children from harmful online content, perhaps there is value there.”

Teachers have always battled fragmented attention spans and academic disinterest among students. The smartphone’s widespread classroom debut around 2012 has only made matters tougher. Over the years since, collaborations between parents, teacher groups and school board members have sparked policy efforts up the political food chain, from regionally elected leadership to state and federal educational and health agencies.

Locally: Santa Barbara County Education Office Superintendent Susan Salcido notes that policies regarding smartphone use are an overall priority but differ among districts. For example, in 2023, Santa Barbara Unified School District, which oversees roughly 12,000 students across 18 schools, enacted its “Off & Away” policy, requiring high school classroom “cell hotels,” out-of-reach dropoffs for devices.

Statewide: In an August 2024 letter to California public schools, Governor Gavin Newsom called on “every school district to restrict smartphone use in classrooms.” He followed up by signing the Phone-Free Schools Act (AB 3216), requiring that schools develop and adopt policies to limit or prohibit student use of phones at school.

Nationally: In December 2024, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Technology released “Planning Together: A Playbook for Student Personal Device Policies” to help guide policy on student use of personal devices. This April, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services indicated it was working with states on "bell-to-bell legislation" to restrict the use of smartphones at school.

They’re protecting each other. And themselves.

Sameer Pandya’s literary thriller “Our Beautiful Boys” is a slow-burning, intimate look at how secrets shape boys — and the families trying to raise them

By Debra Herrick / Photos by Jeff Liang

Early in Sameer Pandya’s new novel, four teenagers wander into a Southern California cave. It’s a moonlit scene, heavy with adolescent swagger, the precarious balance between friendship and rivalry hanging in the air. When only three emerge unscathed, readers are plunged into a literary thriller exploring secrets, privilege and the blurry ethics of identity.

In “Our Beautiful Boys” (Ballantine, 2025), Pandya, an associate professor of Asian American studies at UC Santa Barbara, frames his narrative around a central ambiguity inspired by E.M. Forster’s “A Passage to India,” where an incident in a cave leaves questions of truth unanswered. Pandya transplants that uncertainty to contemporary California, intertwining race, privilege and passing — both racial and social — into a story that ripples outward through families and friendships.

Vikram, one of the novel’s teenage protagonists, is caught between two worlds: the idealistic nonviolence of his Indian American family, symbolized by a prominently displayed photograph of Gandhi, and the aggressive physicality of American high school football. Pandya underscores the irony: Is there a sport more un-Gandhian than football?

“Vikram excels precisely because of his strength and aggression — traits seemingly at odds with his parents’ values,” Pandya, also the author of “Members Only” (HarperCollins, 2020), says in an interview. This internal contradiction runs throughout the novel, highlighting broader tensions around immigrant identity, masculinity and family expectations.

Yet Vikram isn’t alone in shaping his identity to navigate his suburban world. When an Indian restaurant owner dismisses his white friends as “these American boys,” Vikram thinks, “I’m

an American boy too,” but stays silent, strategically shifting identities based on context. Each of the teenage protagonists — Vikram, MJ and Diego — carefully crafts his sense of self, reflecting Pandya’s broader exploration of American identity, shaped as much by class and privilege as by race.

MJ’s wealth grants him a certain aloofness, crystallized by his refusal to wear shoes — a choice he considers carefree but his father points out as a subtle marker of privilege. Similarly, MJ’s home, filled with inherited furniture, quietly signals inherited social capital. Pandya peppers his novel with a litany of status symbols — watches, cars and insider trading, fine fish, upscale produce and leisure activities — shifting in value depending on perspective. “I’ve always been interested in money, class, privilege and how we use objects to leverage status,” he says. Diego, a gifted math student and football player, is raised by his mother, an academic whose carefully curated identity complicates notions of authenticity and clout. In her portrayal, Pandya subverts traditional narratives of racial passing and examines how identity shifts within families: “We often think about identity as individually performed,” Pandya notes, “but within domesticity — an entire family — how does it shift?”

Beneath these identity performances lies a darker undercurrent: hidden family truths. Parents, consumed by college applications and securing their children’s futures, inadvertently become catalysts for their children’s transition from boys to men. “Teenagers are far savvier about race than we sometimes give them credit for,” Pandya says. “They’ve lived through discussions on racial reality, the post-racial and the return of race. They’re extremely perceptive; they’re just figuring out how to navigate it.”

“So much that’s unspoken …”

At the same time, “Our Beautiful Boys” discreetly functions as a sports novel, using football to explore how teenage boys navigate intimacy beneath their bravado. “It’s how boys are intimate without being intimate,” Pandya says, describing sports as a language of friendship and a conduit for learning to express regret and disappointment.

“There’s so much that’s unspoken in this novel,” says Bakirathi Mani, the Penn Presidential Compact Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania. “The violence at the center of the story is one layer — but there’s also racial violence, class violence and the kinds of damage families do to one another quietly.”

The novel’s intrigue deepens through Pandya’s handling of multiple perspectives, a departure from his earlier first-person narratives. Shifting viewpoints augment readers’ empathy and complicate simple judgments. What happened in the cave? Who’s to blame? And what happens when no one talks, but everyone knows something?

In this silence, the parents become desperate. They’re used to managing, orchestrating, fixing. But here, their children refuse to explain, and it’s destabilizing. “The novel keeps asking, ‘Are the parents complicit?’” Mani says. “Because while they’re accusing the boys of keeping secrets, they’re all harboring secrets themselves.”

“I’ve always been interested in how class and race shape the stories we tell — and the ones we don’t”

— Sameer Pandya, author of “Our Beautiful Boys”

And those secrets aren’t abstract. They’re embedded in Cadillacs, status watches, grocery lists, even college essays. In one of the novel’s threads, Vikram writes a personal statement about a photograph of Gandhi that hangs in his living room. It’s a symbol of inheritance, of performance, of memory — and, it turns out, it's a photograph taken by Pandya’s own grandfather.

“The trick is using different characters to explore various issues,” Pandya says. By capturing multiple angles of the same incident, Pandya mirrors the cave’s echoes, where truth fractures unpredictably. Structured as a whodunit, the narrative compels readers to question not only what occurred but why. “There’s something about caves,“ he adds. “The echoes and darkness make truth and reality slippery.”

In “Our Beautiful Boys,” the stories we inherit are just as consequential as the ones we choose to tell. Pandya’s characters live inside a thicket of expectations: racial, familial, social. They lie to protect each other, but also to preserve a version of themselves they’re still trying to believe in.

Pandya isn’t offering clean answers. He’s asking the harder question: How do we raise boys to tell the truth in a world where everyone’s faking something?

Following this feature, we’re publishing an excerpt from “Our Beautiful Boys” — a short but charged kitchen scene between Vikram, his mother Gita and his father Gautam. It’s a deceptively simple conversation about football, extracurriculars and college applications, but it hums with the novel’s deepest contradictions.

“It felt like the right slice to share,” Pandya explains, “especially for a college alumni audience. There’s something so now about how early these kids — and their parents — start thinking about college. The anxiety lives in everyone.”

And once again, that quiet symbol of Gandhi appears. “It’s a family defined by nonviolence,” Pandya says. “And Vikram’s skill at football — this violent sport — sits in direct contradiction to that. That tension, that irony, is doing a lot of the novel’s heavy lifting.”

In the excerpt, there are no blowups or revelations. Just three people in a kitchen, circling around the future. And like the rest of the novel, the heat comes not from what’s said — but from what no one wants to say out loud.

Sameer Pandya

Chapter 2, adapted from pages 11-14

Vikram was showered and clean, wearing shorts and a T-shirt. He was big and strong and self-contained, like a semitruck idling at a stop sign. He walked over and gave his father a kiss on the cheek, now having to slightly lean down to do so.

“We have to win at least two of the remaining games to make the playoffs. I won’t get any playing time. There have been a bunch of injuries and so they need to have people on the sidelines just in case there are more.”

“The injuries should be the red flag,” Gautam said.

“I know. But there are plenty of guys ahead of me who want playing time. Honestly, I only want to do it because the college essay practically writes itself. ‘How I Went from the Gandhian Nonviolence of My Ancestors to the Violence of the Gridiron.’ ” He had a slight smile on his face as he said this, as if he knew how absurd it was and how he’d hit essayistic gold before he’d written a single word or played a single down. “I’m just a cliché if my only sport is golf. Golf and football together? And an Indian kid? Admissions counselors will gobble it up.”

“How did you become such a cynic?” Gautam asked, winking at his son.

“It’s not cynicism,” Gita said. “It’s practicality.”

Gautam looked over at his wife, annoyed that she’d interjected.

“And this is all coming from him,” Gita said. “I’m not thrilled about him being on that field either.”

Yes, Vikram getting into a good college was important to her. Perhaps more important than she cared to fully admit. Where he’d get in, and where he would end up going, would be a reflection of the success of her parenting, a preview of his and their collective futures. He’d scored high on his SATs without really studying; his GPA was well north of a 4.0; he’d tutored disadvantaged kids in math. He just needed a few more key, properly curated pieces for his applications. Gita had taken her daughter’s indifference to college personally.

“You had to pick the one sport that would make your great-grandfather turn in his ashen, watery grave?” Gautam asked. “You can’t just be the big body in basketball instead?”

“Dad, I didn’t pick it. It picked me.”

Gautam enjoyed his son’s ironic bravado.

“Easy there. They’re watching.”

Gautam motioned to an 8x10 framed black-and-white photo hanging on their living room wall of Mahatma Gandhi striding at the Salt March in 1930, surrounded by a few other marchers, including Vikram’s teenage great-grandfather. Gautam could not remember a time when the photo wasn’t a part of his life. Like his parents before him, Gautam had hung the photo on his family’s wall, in the same way other families might have a cross to remind them of their faith. The great man and his beatific smile, watching and reminding them to remain austere and humble, to keep things simple, and yes, most of all, to chill on the violence. Gandhi’s omniscient presence in the family had never been preachy or insistent, and yet for three generations a certain Gandhian ethos had seeped into the family marrow. Gautam’s father had never raised prices in his restaurant for the sake of increasing profits; Gautam felt the need to keep his work ambitions in check; and Vikram, when picked on in junior high, seemed to instinctively know that the way to deal with a bully was not to punch him in the nose.

But was there any sport more un-Gandhian than American football?

“I’ll be careful,” Vikram said to his parents. “I promise. They teach you ways to protect yourself when you tackle and when you get tackled. And I like how exhausted I felt after practice today.” He paused and then slightly lowered his voice, as if to make sure Gandhi didn’t hear. “I don’t know, I’ve never used my body in this way. You know? Plowing into other players. It was kind of fun hitting them. And getting hit was not nearly as bad as I thought it would be. You bounce right back up.”

Gautam looked at his son, then his wife, and then back to his son. Vikram had apparently already had his first practice. And they had clearly strategized about how to make this pitch. Standing there, still feeling the residual effects of a rough workday, he felt a little lonely. He walked over to the other side of the kitchen and signed the release form, which Gita had signed already.

“Don’t say I didn’t warn you,” Gautam said, taking half a sip of his warming beer before pouring it out in the sink. “Necks aren’t elastic.”

Neither Vikram nor Gita heard him.

After 30 years as UC Santa Barbara’s leader, Chancellor Henry Yang is preparing to step down and return to teaching and research. As he looks ahead, we are looking back at how the campus has evolved and grown over the course of his tenure.

Stepping in Henry T. Yang was named the fifth chancellor of UCSB in 1994. He joined the picturesque campus from Purdue University, where he was formerly the Neil A. Armstrong Distinguished Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and, for 10 years, the dean of engineering.

After Chancellor Yang arrived, UCSB in 1995 was elected a member of the Association of American Universities, a prestigious collective of leading researchintensive higher education institutions in the U.S. and Canada. The university

consistently ranked highly among its peers — for decades. In 2013, the Centre for Science and Technology Studies at Leiden University in the Netherlands ranked UCSB second in the world for scientific impact, out of the top

500 universities. A few years later, UCSB reached an all-time high ranking in U.S. News & World Report’s listing of the “Top 30 Public National Universities” for 2019, placing No. 5.

In 1998, physicist Walter Kohn, founding director of the campus’s Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He was the first UCSB faculty member to receive a Nobel, but he wouldn’t be the last. Five more faculty members won Nobel Prizes over the next 14 years:

2000: Alan Heeger, Nobel Prize in Chemistry

2000: Herbert Kroemer, Nobel Prize in Physics

2004: David Gross, Nobel Prize in Physics

2004: Finn Kydland, Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel

2014: Shuji Nakamura, Nobel Prize in Physics and energy-saving light sources

In line with its high rankings and academic excellence across disciplines, UCSB has expanded the breadth of its academic offerings over the past 30 years. Under Chancellor Yang’s leadership, the number of majors, degrees and credentials offered at UCSB has grown to over 200. In the 1994-1995 academic year, the university awarded approximately 4,000 degrees. That figure for 2024-2025 is nearly 7,000. All told, some 200,000 degrees have been awarded during Chancellor Yang’s tenure.

UCSB in 1994 attracted approximately 22,000 freshmen and transfer applications combined. By 2023, that number had reached nearly 129,000. First-generation college students account for many of those applications and subsequent enrollments. Taking a closer look, UCSB in fall 1994 enrolled 4,361 first-in-family students. By fall 2023, that number had grown to 7,662.

The average high school GPA of incoming freshmen for the 2024-2025 academic year reached an impressive 4.30. By comparison, the 1997-1998 incoming freshmen class had an average GPA of 3.58. UCSB attracts students from an array of backgrounds, which has led to notable recognition and programs. In 2015, UCSB was named a Hispanic-Serving Institute (HSI) by the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, becoming the first member of the Association of American Universities to receive this designation. HSIs are defined as colleges or universities in which Hispanic enrollment comprises at least 25% of the total undergraduate enrollment. UCSB is also an Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institution, indicating an enrollment of undergraduate students that is at least 10% Asian American or Native American Pacific Islander.

UCSB’s physical campus has undergone significant improvements over the last three decades. An increase in study spaces, classrooms, research facilities, living quarters and student activity spaces has helped to foster a collaborative and energizing environment. During the Chancellor's tenure, more than 6.1 million square feet of campus space were added or renovated.

Philanthropy has played a crucial role in these improvements. Henley Gate, Charles T. Munger Physics Residence, Henley Hall and Arnhold Tennis Center are among the capital projects that were funded via philanthropy. To that end, UCSB has experienced tremendous growth in fundraising over the past three decades, climbing from $10.5 million in fiscal year 1995 to $167.3 million in fiscal year 2024, and eclipsing $100 million raised in each of the past 10 years. Over that same time period, the university’s endowment has grown from $35.8 million to $647 million.

Partnering with surrounding communities is a longtime priority for UCSB. That starts in Isla Vista, home to thousands of Gauchos and other local students. Following the tragic 2014 Isla Vista shootings, Chancellor Yang and the campus community responded quickly and generously with widespread support and healing initiatives. Collaborative efforts to maintain safety and well-being in the vicinity continue to this day.

In that same spirit of community, the campus responded to broader Santa Barbara tragedies, including the 2017 Thomas Fire and subsequent mudslides, offering campus resources and a safe haven for those affected. During the COVID-19 pandemic, UCSB researchers contributed significant time and expertise throughout the region. The university also partners with communities beyond campus to help ensure strong local economies.

know?

On the following pages are excerpts from an immersive multimedia feature that weaves together photography, video and narrative storytelling to bring you inside UCSB’s FUERTE program. Follow a cohort of undergraduates as they venture into California’s Eastern Sierra, learning from world-class scientists and gaining the skills — and inspiration — they need to launch careers in environmental science.

See the full story now on our news website, The Current. news.ucsb.edu

Students in UCSB’s FUERTE program head to the Eastern Sierra to explore the natural world, gain hands-on research experience and prepare for careers in environmental science

Written by Sonia Fernandez

On a sunny, windy morning, 10 students peer over the edge of the Long Valley Caldera, the remnant of a supervolcano that erupted 760,000 years ago. From their vantage point, on the side of Mammoth Mountain in California’s Eastern Sierra, they take selfies with the 20-mile-long, 11-mile-wide crater — ephemeral humans against a landscape forged by magma and sculpted by glaciers.

Only a few steps away is one of the world’s premiere snow labs, the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, also known as CUES. From the partially buried bunker and surrounded by supplies and equipment, climate scientist Ned Bair talks about a life spent studying snow: the cold, the rigor, the danger.

Participants in the FUERTE (Field-based Undergraduate Engagement through Research, Teaching and Education) program get a firsthand taste of what it’s like to be field scientists while developing the fundamental skills necessary to get their future careers off to a good start. Funded by a National Science Foundation program to enhance STEM education for underserved communities, FUERTE students are taught and taken into the field by world-class UCSB scientists and mentored by a cadre of graduate students.

The adventure begins with a two-week intensive summer course that immerses students in ecosystems located in the rain shadow of the East Sierra Nevada, also known as the “granite curtain.”

UCSB manages two protected spaces in this region — Valentine Camp and the Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory — collectively known as the Valentine Eastern Sierra Reserves.

“While many types of science can be done in the lab, natural systems are so large and complex that the questions can’t typically be taken out of the field and studied in sterile petri dishes or test-tubes.”

— Hillary Young, FUERTE ecologist

While open to all undergraduates, FUERTE was created primarily to serve students from ethnic or gender minorities, low-income households, or those who are the first in their families to attend college — groups traditionally underrepresented in environmental science.

Students arrive bright, curious and eager to learn. They ask questions, set up field experiments, translate data, hike through backcountry terrain and take turns cooking for one another.

“We’re secluded from everyone. We’re off our phones.”

— Victor Rodriguez, biology major

The mountains, valleys, trees and stars of the Eastern Sierra have a way of making time feel infinite. Visitors walk in the footsteps of earlier inhabitants. The Milky Way that once guided Indigenous peoples continues to awe hikers, scientists and students alike.

As climate change intensifies drought and fire risk, the ecosystem — and the food webs it supports — face mounting challenges.

“We literally talk about community building. How do we want to behave as a field team? How do we express that we’re responsible for one another? We teach kindness and compassion, and very quickly they start to automatically support one another.”

— Gretchen Hofmann, FUERTE principal investigator and director

Being out with these students, talking about these same issues in a place that’s already changing, gives me a huge amount of inspiration because they’re not going to tolerate seeing the worst-case scenarios that we can see in our models come to fruition. They’re going to have the motivation to come through, to use the tools of science that we’re teaching them to make 2050 a better future.

— Douglas McCauley, FUERTE ecologist

I’M ALWAYS GRATEFUL for the chance to write in this magazine. It gives me a direct line to the incredible UC Santa Barbara alumni community, including many of you I haven’t yet met in person. A recurring theme across the many conversations I have with alumni is this: a desire to give back. The question I hear most often is simply, “How can I help?” It’s a question that resonates deeply with me. Like many of you, I often find myself thinking about where I can contribute, how I can be of service at home, in my friendships, in my work, and in the broader world.

My personal vision for our alumni community is simple: connection. From the student experience to the C-suite, Gauchos are connected. We’re showing up for each other, celebrating together, offering support and taking pride not just in our individual journeys but in the collective success of the entire UC Santa Barbara community.

So if you’ve ever asked yourself that same question — “How can I help?” — here’s a small challenge for you: Try one of the ideas below. Then send me a note. Let me know what it meant to you, how it felt or what it sparked. I’d love to hear from you.

In 1958, UC Santa Barbara became the third campus to join the UC system. Today, with more than 2 million UC alumni, our collective voice is powerful. By joining the UC Advocacy Network, you’ll receive quick, easy opportunities to speak up on behalf of public higher education. It takes only a click to support students and future alumni. www.universityofcalifornia.edu/get-involved/advocate

This year, we’ve hosted alumni events across California and in Seattle, New York, Washington, D.C., and Boston. Our volunteers have hosted many more. There’s power in coming together. Keep an eye out for events near you. Show up. Bring a friend. See what happens. www.alumni.ucsb.edu/events

There are many ways to lead: volunteering in your region, speaking on campus, being profiled in an alumni spotlight or serving on our Alumni Board of Directors, for example. If you’re proud of your journey, we want to hear about it. Let us know what you have to offer, and we’ll help find the right space for you to lead.

“How can I help?” is a powerful question. I believe the answer lies in showing up — imperfectly, genuinely and together. Let’s talk. I’d love to hear what being of service means to you.

With gratitude,

Samantha Putnam Executive Director UCSB Alumni Association Executive Director, Alumni Affairs

samantha.putnam@ucsb.edu

Meet five former Gauchos who are leveraging their expertise — and their UCSB education — to protect one of the nation’s most iconic alpine lakes

BY SHELLY LEACHMAN

PORTRAITS

JOSHLYN WRIGHT

“As

it lay there with the shadows of the mountains brilliantly photographed upon its still surface, I thought it must surely be the fairest picture the whole earth affords.”

—Mark Twain

IF YOU KNOW, YOU KNOW: There are few places more magical than Lake Tahoe. The first time you catch sight of this glorious blue beauty, you’ll also have to catch your breath. It’s that stunning.

As a Northern California native, I grew up visiting Tahoe on the regular — snow skiing many weekends over winter, frolicking on and around the lake for a week every summer. The latter tradition continues today with my own kids, who are now officially as smitten with Tahoe as me.

Whether it’s thick pine forests that get you, the gorgeously rugged terrain, the ever-crisp mountain air or the rejuvenating chill of the water (talk about a cold plunge!), the one feature of Lake Tahoe that all can agree is captivating almost beyond comprehension — its color.

The stickers are everywhere up there: Keep Tahoe Blue. It’s not just a catchy call to action to slap on the back of your car; it’s a movement, 68 years strong, to safeguard both the lake itself and the environmental health of the entire Tahoe Basin, so it can be enjoyed by all for generations to come.

The organization behind the slogan is the League to Save Lake Tahoe, a nonprofit that uses education, advocacy, engagement and, importantly, science and innovation, to identify problems and find solutions. Since 1957, when it was founded to stop a proposal to fill the Basin with a year-round population to match San Francisco’s and build a bridge over Emerald Bay — imagine?! — the League has been working to protect and restore the environmental health, sustainability and scenic beauty of the Lake Tahoe Basin.

These days they’ve got a handful of UCSB alumni helping them do exactly that, rolling up their sleeves and putting their minds together to confront all manner of evolving challenges, from wildfire and climate change to development, litter, invasive species and traffic.

Darcie Goodman Collins, Jesse Patterson, Kristiana Almeida, Matisse Geenty and Gavin Feiger — each with unique experience and expertise, but environmental champions all — are the slogan come to life: Keep Tahoe Blue.

Without further ado …

Chief Executive Officer

A native of Lake Tahoe, Darcie Goodman Collins grew up with all that beautiful blue right in her backyard. The water, like the jaw-dropping region itself, wasn’t just the stuff of pretty pictures — it was her way of life. And it would become her calling.

“I was certain at a young age I was going to do science, and I thought for sure I was going to do marine biology,” she says. “That was kind of my focus, really, since the time I was 6 years old.”

A high school internship with Keep Tahoe Blue — she was the organization’s first-ever intern — sowed the early seeds of what became her professional trajectory. Working closely with the executive director at the time, Goodman Collins saw firsthand a need that she, decades on, would come to fill: using science to inform policy.

“That veered my interest toward environmental policy and science, and it’s the reason I chose UCSB,” says Goodman Collins, who double-majored in aquatic biology and political science through the College of Creative Studies before earning her Ph.D. at the Bren School. In between degrees, she worked at UCSB’s Coal Oil Point Reserve, learning to fuse science and research with environmental management and community engagement.

That pursuit became her north star, ultimately leading her back to Lake Tahoe and to the League — this time as executive director. She had come home, and come full circle. Now helming the organization where she once interned, Goodman Collins is doing what first struck her as a teenager: applying science to the organization’s core aims of action, advocacy, education and community engagement.

Using a data-informed approach to combat trash — an issue that landed Tahoe in the national news after an especially messy Fourth of July — the group’s Tahoe Blue Beach initiative reduced litter at one popular beach by 97% and included the use of sand-sifting, beachcleaning robots. They also secured a national first-of-itskind municipal ban on the commercial sale of single-use plastic bottles. Most recently, they opened doors on an environment and education center to engage the public and nurture community stewardship around that lovely blue lake.

“What I love most is the interdisciplinary nature of the work,” says Goodman Collins. “Science, policy, community — all of it. And it’s incredibly rewarding to see the impact right here in the place I’ve always called home.”

Chief Strategy Officer

A love of nature has driven Jesse Patterson’s decisions for most of his life. Raised along California’s central and south coasts, surfing, boating, diving — “all things ocean,” he says — had his heart from an early age.

“So, it took about 20 seconds into a campus tour to go, ‘Yeah, this’ll work,’” Patterson recalls of his choice, in 1998, to attend UCSB. He stayed for 10 years. “What was really solidified at UCSB was my appreciation for the natural world, how amazing and beautiful it is. And honestly, how complex and fragile it is, and from a human perspective, how quickly we could destroy it.”

After earning bachelor’s degrees in aquatic biology and political science, Patterson worked several years for a coastal research and monitoring program within UCSB’s Marine Science Institute. His belief in the power of applied science to effect environmental change inspired him to pursue a graduate degree at the Bren School.

That belief — solidified at UCSB, validated in professional practice — has only grown over his years at the League to Save Lake Tahoe, one of the oldest (the organization was founded in 1957, 13 years before the first Earth Day) and, he says, most effective advocacy organizations in the nation for environmental work. This, in a place that sees some 17 million visits annually, where two states, five counties, two cities and 80 different groups have at least some jurisdictional authority.

“Being able to navigate not just the regulatory issues, the planning issues and the environmental issues but also the people issues is a big part of what’s made us successful,” Patterson says, “the ability … to bring people along to the solutions.”

That approach has been proved repeatedly in efforts like the Tahoe Blue Beach program, which incorporated “leave no trace” principles — alongside upgrades to visitor education, wayfinding and facilities — to impact beachgoer behavior, reduce environmental impacts and gather the kind of data that precipitated local bans on the most commonly found litter items in Tahoe, including plastic bags, Styrofoam and plastic bottles. Another example: a groundbreaking, scientific test to evaluate all available tools — proven and emerging — to contain and control the largest infestation of aquatic invasive weeds in Lake Tahoe.

Patterson and the League pilot innovative approaches, convene partners in collaborative projects, provide seed funding and engage the public to move from environmental threats to proven solutions. “All our work demonstrates, to my mind, that people can visit and live in a place like Tahoe without wrecking it,” Patterson says. “Anyone who comes to Tahoe, the first time they see it is like, ‘Whoa.’ It’s worth protecting. Nature is essential. We’ve only got one planet, as far as we know, so we better take care of it.”

Kristiana (Kocis '06) Almeida Chief Operating Officer

A degree in medieval studies may not exactly scream “solid route to environmental policy work,” but it sure worked that way for Kristiana Almeida , who credits the former discipline for imbuing her with the critical thinking skills that have made her so successful in the latter.

“Probably the biggest part of my job is problem solving,” she says, “and the medieval studies major, though zero environmental background is associated with it, really taught me to look at big problems from a multitude of angles to get to interdisciplinary solutions.”

Then there are the operational skills and fundraising expertise Almeida honed as a member of UC Santa Barbara‘s development team post-graduation and, later, the communications savvy she sharpened while working for National American Red Cross. All of her prior experiences paid dividends when she joined the League in 2022.

It also doesn’t hurt that she grew up just outside Lake Tahoe.

Almeida’s rich personal connection to the region — paired with the interdisciplinary ethos she gleaned in her time at UCSB — underpins her belief that a holistic approach is key to successful environmental advocacy and action.

“You can’t use just one tool to fix everything when it comes to protecting Lake Tahoe,” she says. “It

really is a breadth of tools we’ll need to protect Tahoe for generations to come. And we’re committed to continuing evolving that process because especially with climate change, what worked yesterday isn’t going to be what works tomorrow.”

To that end, Almeida and her Keep Tahoe Blue colleagues are looking ahead.

The League recently secured passage of the Lake Tahoe Restoration Reauthorization Act, ensuring that $300 million of unspent funds from 2016 legislation will keep federal support flowing for restoration, research and aquatic invasive species and wildfire prevention. They also supported a partner public agency’s acquisition of 31 acres of severely disturbed land along a river corridor, and are now helping guide the site’s restoration to native habitat that will reconnect nearly 800 acres of marsh and meadow.

To Almeida, it’s all part and parcel of a League-wide commitment to using an interdisciplinary lens to consider problems and craft solutions.

“What happens outside of Tahoe can deeply impact what happens in Tahoe,” she says. “So how do we educate people visiting the basin, and empower people living in the basin, to help create and be part of those solutions? As we’re looking at the interconnectivity of everything, this is an opportunity for us to help others, too.”

Arriving on campus with a violin under her arm and stars in her eyes, Matisse Geenty chose UCSB for the opportunity to continue her classical music studies in a multidisciplinary setting while pursuing a performance degree. Life had other plans.