12 minute read

À La Carte

Monet

Master of Light

by Catherine Bailey

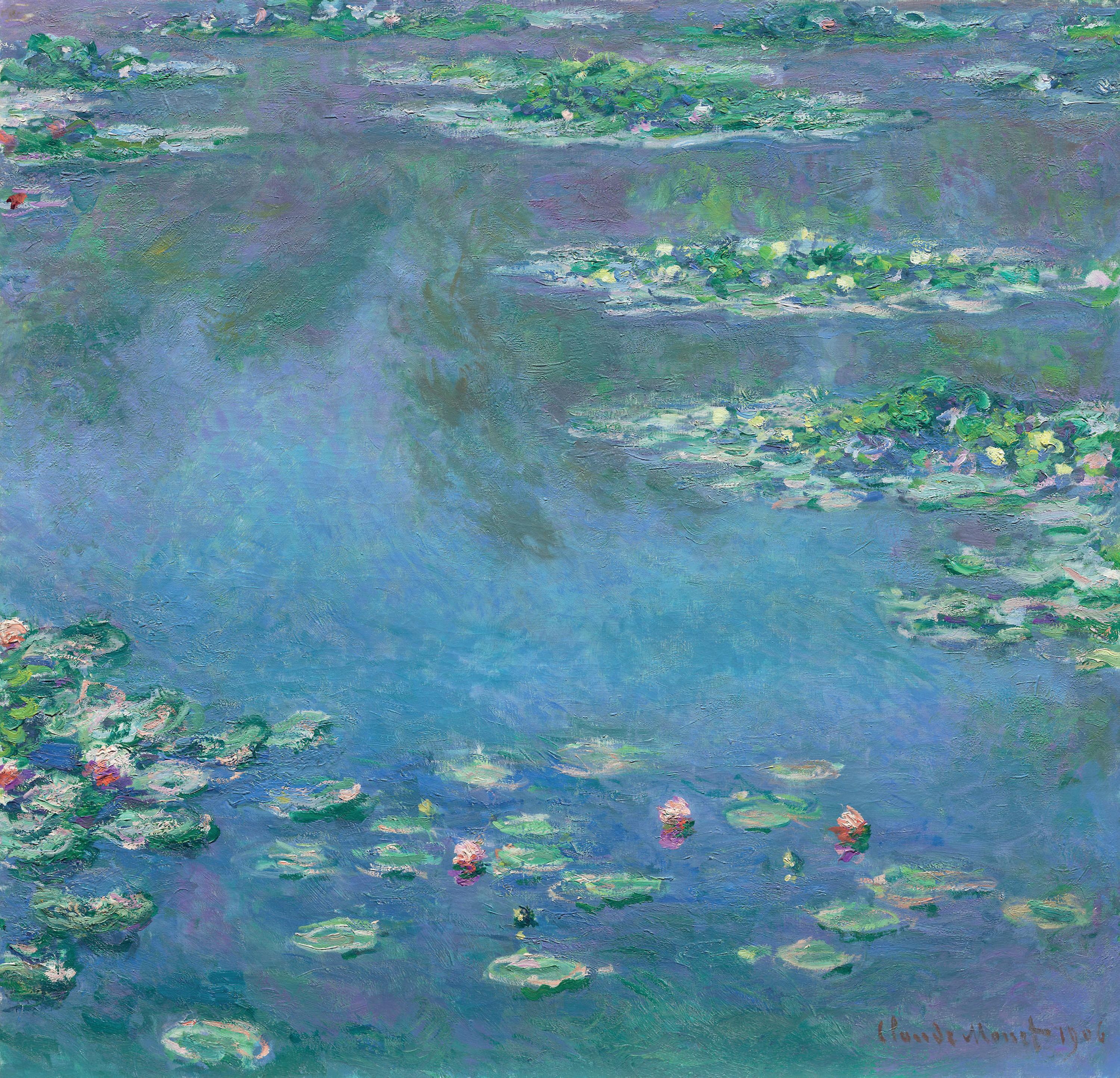

Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge (1899)

Known for his significant contribution to the Impressionist art movement, Claude Monet was born in Paris on 14 November 1840, but from the age of 5 he spent his childhood in Le Havre after his father took over the management of his family’s thriving ship-chandlering and grocery business. The time spent along the beaches, and the intimate knowledge he gained of the sea and the rapidly shifting Normandy weather, would shape his fresh vision of nature.

Monet developed his artistic passion over time and at the age of 15 sold caricatures that were carefully observed and well-drawn. In these early years he also completed pencil sketches of sailing ships, which were almost technical in their precise clarity. The burgeoning, and occasionally arrogant, student was befriended in 1857 by Eugène Boudin who persuaded him to give up his teenage caricature drawings and to become a landscape painter by the, then, uncommon practice of painting in the open air, installing in him a love of bright hues and the play of light on water - so evident in Monet's impressionist paintings. The two remained lifelong friends and Monet later paid tribute to Boudin's early influence. He first visited Paris around 1860, where he was impressed by the work of the Barbizonschool painters Charles Daubigny and Constant Troyon. To his family’s displeasure, he refused to enrol in the École des BeauxArts, instead he frequented the known haunts of artists and worked at the Académie Suisse, where he met Camille Pissarro. This informal training was interrupted by military service for a year in Algeria, where he was inspired by the African light and continued to experiment with different artistic forms. Forced to return to Paris in 1862 due to illness, Monet met the Swiss painter Charles Gleyre and also worked with Alfred Sisley, Auguste Renoir and Frédéric Basille who all become his close friends with the group often working outdoors on painting sojourns. Monet won acceptance to the Salon of 1865, an annual juried art show in Paris; the show chose two of his paintings, which were marine landscapes. The following year Monet was again selected

to participate in the Salon. This time, the show officials chose a landscape and the portrait "Camille The Woman in a Green Dress" (La femme en robe verte ) which featured his lover and future wife, Camille Doncieux. From a humble background, Camille was substantially younger than Monet, she became his muse sitting for numerous paintings during her lifetime. The couple experienced great hardship around the birth of their first son, Jean, in 1867. Monet was in dire financial straits as he developed his own style and no gallery would carry his work. His father was unwilling to help them because of his relationship with Camille and Monet became so despondent that, in 1868, he attempted suicide by trying to drown himself in the Seine River.

As the Franco-Prussian War broke out Monet married Camille and moved his family to London to escape conscription. He was impressed by the works of JMW Turner with his treatment of light which led to his own repeated painting of the Thames (an example below) and it was here he met the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel who would buy his works and help in making Monet’s impressionist paintings known. The Royal Academy, however, refused to exhibit his work. In the spring of 1871, Monet learned of his father’s death. Often in financial difficulties during this period, the inheritance from his father together with a few sales of his paintings allowed them to return to France via The Netherlands.

Monet eventually settled in Argenteuil, an industrial town west of Paris, and began to develop his own technique. During his time here, Monet visited with many of his artist friends, including Renoir, Pissarro and Edouard Manet - a small part of the future impressionist group movement. Banding together with several other artists, Monet helped form the Société Anonyme des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs, as an alternative to the Salon and exhibited their works together. The society's April 1874 exhibition proved to be revolutionary. One of Monet's most noted works in the show, "Impression, Sunrise" (1873), depicted Le Havre's harbour in a morning

The Houses of Parliament, Sunset (1904)

Water Lilies (1906)

fog. Critics used the title to name the distinct group of artists "Impressionists," saying that their work seemed more like sketches than finished paintings. While it was meant to be derogatory, the term seemed fitting. Monet sought to capture the essence of the natural world using strong colours with bold, short brush-strokes, turning away from the blends and evenness of classical art. Despite the criticism, the impressionists would produce six exhibitions until 1882.

Monet's personal life was marked by hardship around this time. Camille became ill during her second pregnancy and with the birth in 1878 of their second son, Michel, she continued to deteriorate. Before her passing, the Monets went to live with Ernest and Alice Hoschede and their six children. After Camille's death in 1879, he grew closer to Alice and the two eventually became romantically involved. Ernest spent much of his time in Paris, and he and Alice never divorced. Despite numerous trips around France to gather inspiration, Monet found his spiritual home when he rented a house in Giverny. The family worked and built up the gardens and Monet's fortunes began to change for the better as Durand-Ruel had increasing success in selling his paintings. After Ernest's death, Monet and Alice married in 1892 and he finally purchased the property in 1890.

Monet gained financial and critical success during the late 1880s and 1890s and he began the serial paintings for which he would become well-known. In Giverny, he loved to paint outdoors in the gardens that he helped create there. The water lilies found in the pond had a particular appeal for him, and he painted several series of them throughout the rest of his life; the Japanese-style bridge over the pond also became the subject of several work. As Monet's wealth grew, his garden evolved. He remained its architect building a greenhouse, a second studio and purchasing additional

land with a water meadow. White water lilies local to France were planted along with imported cultivars from South America and Egypt, resulting in a range of colours including yellow, blue and white lilies that turned pink with age. Over the years the size of his water garden grew by nearly 4000 square metres with easels installed all around to allow different perspectives to be captured.

Sometimes Monet travelled to find other sources of inspiration. In the early 1890s, he rented a room across from Rouen Cathedral and painted a series of works focused on the structure. Different paintings showed the building in morning light, midday, dull weather and more; this repetition was a result of Monet's lifelong fascination with the effects of light and in 1900 Monet returned to London where the Thames River captured his artistic attention.

His second wife Alice died in 1911 and his oldest son Jean who had married Alice's daughter Blanche died in 1914. Blanche became his carer and it was during this time that Monet began to develop the first signs of cataracts. During World War I, in which his younger son Michel served and his friend and admirer Clemenceau led the French nation, Monet painted a series of Weeping Willow trees as homage to the French fallen soldiers. In 1918, Monet would donate 12 of his water lily paintings to the nation of France to celebrate the Armistice. The paintings done while the cataracts affected his vision have a general reddish tone which is characteristic of cataract vision, he underwent two operations for them in 1923. It is possible that after surgery he was able to see certain ultraviolet wavelengths of light not normally visible by the lens of the eye which may have had an effect on the colours he perceived and he repainted some of his paintings with bluer water lilies than before.

Monet died of lung cancer on 5 December 1926 at the age of 86 and is buried in the Giverny church cemetery. Insisting that the occasion be simple only about fifty people attended the ceremony. At his funeral, Clemenceau removed the black cloth draped over the coffin, stating: "No black for Monet!" and replaced it with a flower-patterned cloth. His famous home and garden with its waterlily pond were bequeathed by his heirs to the French Academy of Fine Arts (part of the Institut de France) in 1966. Through the Fondation Claude Monet, the home and gardens were opened for visit in 1980.

Monet remains one of the world’s most famous artists. Copies of his works adorn many a wall and visitors from around the world flock every year to Parisian institutions like the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée Marmottan Monet to experience his artworks. In May 2019, his 1891 painting Meules became the most valuable Impressionist work of art sold at auction, achieving $110.7 million.

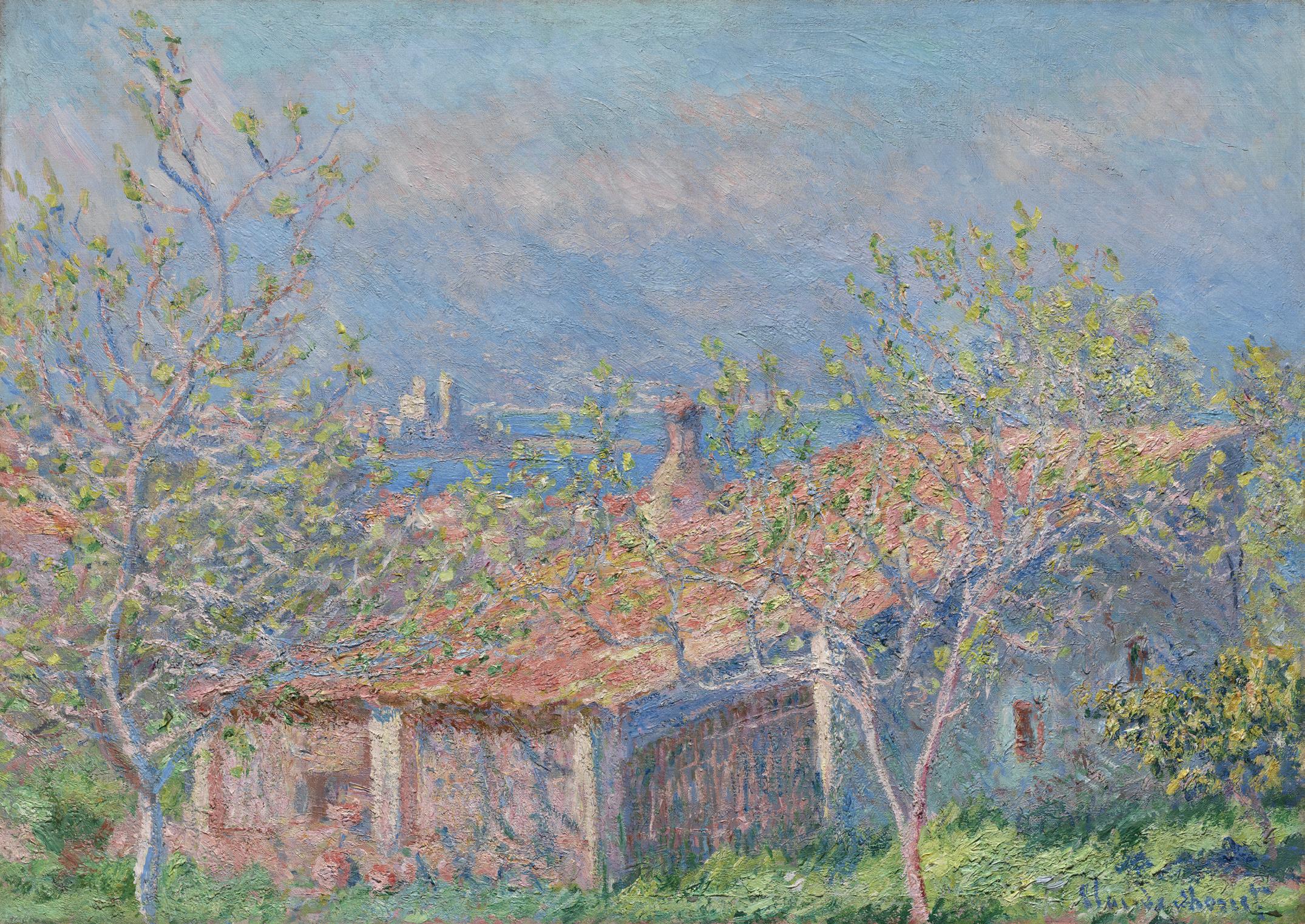

Gardener's House at Antibes (1916)

Taking Better Photographs ...

Images that contain water – be that droplets, frost, or full ice can change completely if you shoot them into the light. The drops and the crystals catch, refract and reflect the light.

Into The Light

by Steve Marshall

The key here is to move slowly around and about the subject to see what shots might work. This includes raising and lowering your camera position. A good friend recommended photographers should always carry a bin liner with them so no matter the state of the ground you could kneel down for a shot. Carrying a ladder so you can get up high may be impractical but beware of always shooting at eye level.

Sunrise and sunset can produce magnificent images – if you get the light right. That means timing is vital.

You may be lucky and be at the right place at the right time but be prepared to spend an hour or two as the sun rises or falls and the picture changes utterly. A tripod becomes really useful so you can set your camera up in the most likely position rather than having it weigh you down while you wait for the light.

Unencumbered, you can then walk around and consider other shots, moving the camera if opportunity arises.

Light is the photographer’s equivalent of the artist’s brush or the sculptor’s chisel. Shooting from a darker area into one that is more strongly lit can carry the viewer through your image. You may well find that this sort of shot needs some editing to bring out detail in the shadows and reduce the highlights.

As with brush and chisel it should be used with care and thought. Arriving at a location, pointing your camera and clicking the shutter may win you Photographer of the Year, but it is unlikely. First look at your subject and then move, continually asking the question, ‘How does the light work?’. Look at the shadows and the brightly lit areas.

As you move and look you might find a better shot or an entirely new perspective.

Most photographs are taken with the sun or artificial lights full on the subject. That may work but not always.

Full sun makes people squint and flattens the image by wiping out contrast. Side light creates shadows and depth. And light from behind your subject brings something that can be wonderful. The Japanese even have a separate word – komorebi – for sunlight that is filtered through the leaves of the trees.

Taking photographs into the light needs particular care. Even through a camera viewfinder looking directly at the sun can damage your eyes, so please be careful. When shooting into the light it is very important to decide on the balance of light coming from behind your subject and coming from the front.

No light at the front will create silhouettes which can be bold and dramatic. You will usually want your silhouette to be in sharp focus so use spot focus, as discussed last month, on one of the edges of the silhouette. If the light is low the longer shutter speed may mean you will need a tripod or something to keep the camera steady. If you use your flash and find it is too strong you can usually change the power in the camera settings. Alternatively you can use a diffuser or even drape a paper tissue in front of the on-camera flash.

If I am photographing people then I almost always use some flash to make sure there is a catch light in their eyes.

From cityscapes to small natural details, from formal portraits to close ups of insects, it is always worthwhile considering and possibly checking what happens if you turn the camera around and shoot into the light.

Have fun. If you fancy meeting some fellow photographers or have areas of photography you would like me to include in these pages please get in touch on

stevemarshall128@gmail.com

Portraits taken into the light can produce an aura in the subject’s hair – be that human, animal or insect.

If you do not want a silhouette you may need to increase the light from the front. The easiest ways to do this are to use a reflector or a flash.

You can buy high quality reflectors in varying colours such as white, silver and gold, which allow you to warm or cool the light. And you can also use a white card or a white sheet. Unless you have an assistant you will need to find a way of supporting this in the right position. Distance can be used to adjust how much light is added.