A plea for Third Spaces in the U.S.

July 2024 * Sofīa Belen

Our

fences

are getting taller We need longer tables

Grounding

This zine was inspired by my experiences visiting Catalan Ateneus during my time in Spain in the Summer of 2024. These grassroots community hubs, rich with a sense of purpose and collective identity, sparked a deep reflection on the state of community spaces in the United States. I am deeply worried about our lack of third spaces in the U.S. and what this implicates about our culture and health as individuals and communities.

Through this zine, I aim to explore the concept of third spaces, highlight their importance, and advocate for the revitalization and creation of such spaces within our own diverse communities in the U.S.

Hopefully, this collection of ideas and information will inspire you to explore your connection to community spaces, whatever that means for you.

Background

-> Third Spaces

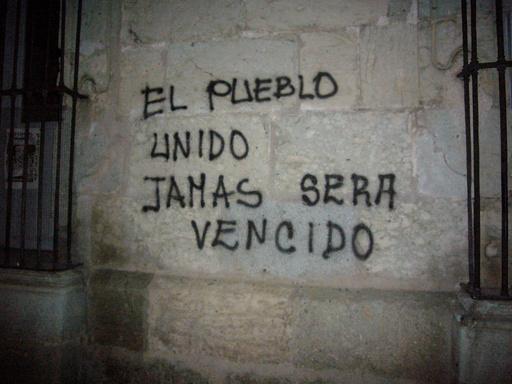

Sociologist Ray Oldenburg first coined the concept of Third Spaces in his 1989 book "The Great Good Place" in response to the growing concerns about the lack of informal public spaces in modern American society. He identified the need for more public spaces that differ from our homes and places of work: we need a third space. These third spaces are to be places for social interaction, community building, and fostering a sense of belonging. He was interested in designing physical spaces that promoted a sense of community. Third spaces are intentionally made for communion and the gathering of individuals outside of a professional or home space. Although Ray Oldenburg coined the term 'third spaces,' these spaces have existed since the inception of communities. People have been gathering to play games, learn new skills, organize, and converse around the world for centuries. Only recently have we seen a decline in these spaces and this culture of community in the U.S. Gathering in community is natural; it is our responsibility to understand why we are more disbanded than ever in the U.S. and how to revive third spaces.

-> The Commons

In urban discourse, the commons refer to property shared by individuals, which isn’t privately owned by any single person or entity but rather held in common. Due to these spaces being held in unison by community members,

collective responsibility is fostered as is collective ownership. These ideas of the commons are inextricably tied to grassroots conceptions of third spaces. Today, third spaces and the commons are under threat in a country that has become more focused on individual rights than collective ones.

-> The Lack of Third Spaces in the U.S.

The U.S. first began intentionally shifting away from the construction of public infrastructure after World War II. With the creation of suburbia and a push for private development over public development in the U.S. communities were weakened. The U.S. emphasized the value of cars and our cities’ infrastructures began appearing to favor automobiles over humans. Corporate schedules began being put at the forefront and instilled a home-to-work-and-backagain echo chamber that strengthened the capitalist system and deteriorated people power. The effectiveness of the market has always been the goal of our cities’ infrastructure, allowing for the productive life of working men. It is essential to shift out of this paradigm and reimagine public spaces in cities for young and old alike, for women and marginalized identities, and for new residents.

Our lack of public community spaces has had dire effects on Americans’ mental health, daily lives, and ideologies, and

most likely has ties to the growing prevalence of American isolation and loneliness. And as with all negative American social phenomena, minority groups are hit hardest due to historic systemic inequalities, discrimination, and structural barriers. Communities with limited access to resources are proven to be associated with poorer physical and mental health; Third spaces are that much more important for American minority groups due to the unique challenges they face. As Gary Anderson et al explain, the properties of third spaces are pathways toward healing for minority communities. “Especially in communities struggling with poverty and the trauma of both physical and symbolic violence both in the home and in the streets, learning in third space is also healing; it requires radical cariño and the centering of effect, which is often in short supply, especially in schools for poor and working-class students.” Secure futures, well-being, and the health of citizens have been put on the back burner and public-private partnerships have been given a greater value in our current government system. This capitalist model of cities allows for occupational, situational, and vital insecurities to coexist with resource inequalities, lack of access to essential services and goods, and deepening segregation. Rethinking our current economic, social, and governmental systems is essential to appropriately meet the needs of folks.

a third space

Third spaces are intersectional spaces in which individual and collective identities are continually negotiated.

Third spaces are not the result of top-down reform efforts, but emerge from or are embedded within political activism, community organizing, and/or social movements.

Third spaces seek to foster critical consciousness through conversation, co-learning, and resistance.

Third spaces seek to democratize society by democratizing social relations and institutions.

Third spaces move beyond critique and resistance to foster radical imagination that embodies new social imagination.

Third spaces are cognitive and embodied spaces that involve emotions, memory, artistic expression, ritual, social solidarity, and performativity.

Third spaces are also physical, geographical spaces that illuminate and expose spatial injustices.

Third spaces are always evolving and filled with imperfections, contradictions and tensions that are acknowledged and are the focus of ongoing collective reflection and dialogue.

Funding and Management

A recent investigation by The Project for Public Spaces documented the decline of public spaces in many American cities, their research highlighted the importance of these spaces for community health and how cities struggle to maintain or create them due to funding and policy challenges. With the conflicting interests local government deals with, public third spaces are often not seen as priorities in policy-making, especially in low-income neighborhoods. In fact, a study by Jessica Finlay et al. that investigated the number of third spaces since 2008 found that:

“The overall declining number of establishments since the Great Recession is striking, with categories such as food and beverage stores decreasing by 23 percent and religious organizations by 17 percent”

Local governments have issues with the sustained upkeep of third spaces and disparities across income make equitable resource distribution nearly impossible. In Baltimore, public spaces, such as parks and community centers, have been neglected, leading to deteriorating conditions and reduced public use. The reality is governments have become allegiant to corporations and global capital, even governments considered “progressive” have remained operating from extractivist ideologies, with serious impacts on land and human rights. Giving power back to people and dismantling the political power of oppressive corporations means fighting against the mechanisms that underpin publicprivate partnerships through grassroots initiatives.

Relying on local and/or federal government to fund and manage third spaces is unwise if we plan on creating horizontal spaces. As with non-profits in the U.S., government funding also often inhibits full agency in decision-making due to red tape that prevents radical changes. Having third spaces be self-sufficient in financing and management ensures complete autonomy. This means participants, citizens, and community members involved in the third space would be the ones directly funding it through fees and/or donations. These fees can be associated with markets, cafes, activities, or workshops linked to these third spaces. This form of funding opens the door to opportunities that stimulate local economies by attracting visitors and encouraging spending within the community. These spaces thus become hubs of economic activity, supporting small businesses and entrepreneurs. In addition, having third spaces be local community-run spaces that are funded by the very individuals that interact with the space encourages citizen participation, ultimately, participation is the vehicle through which that power asserts itself. This self-management returns power to the people; in a system where decisions about urban planning are often out of citizens’ hands, autonomous third spaces could be a path toward reimagining the relationship between cities and their people. Moreover, they provide opportunities for folks to distance themselves from solely relying on corporations for their income. This all being said though, it can be very difficult to solely rely on participant funding to maintain and create third spaces. Grants and private funds could be essential to kick-starting many third spaces when there still may be a small amount of member participation. The goal though is to ensure third spaces remain grassroots and

grounded in the needs of their community, not swayed by stakeholder interests. As for management, creating structure is vital to the success of these grassroots spaces. Seeing that these places are true citizen spaces, democracy, and a bottom-up approach must be employed. Third spaces are special in their ability to neutralize; oppressed and oppressor can come together, free, maybe only momentarily, of oppression. In the U.S., where vertical governance is pushed as being the only model for organization, these spaces are radical, poignant, and reimagine ties to leadership. The local is prioritized in bottom-up governance, this ensures that initiatives tackled by third spaces are tailored to address the unique circumstances of each community. Third spaces are direct products of the communities that revolve around them and an act of placemaking, or the process by which people transform the locations they inhabit into the places they live. For marginalized American communities, these public spaces can

In discourses of dissent, the Third Space has come to have two interpretations: That space where the oppressed plot their liberation: the whispering corners of the tavern or the bazaar

be empowering and inspire autonomy and leadership among community members. An important facet of liberation is minority representation and participation in government; Third spaces empower individuals to take an active role in shaping their communities.

This all being said, it is important to create management structures that:

Establish processes to identify needs and goals

Create transparent and democratic decision-making processes

Creates leadership groups and/or committees focused on specific areas

Implement membership programs to encourage community participation

Offer training and workshops to community members to build their skills in areas like leadership, event planning, fundraising, and conflict resolution.

Develop diverse fundraising strategies, including grants, donations, membership fees, and events.

Ensure the spacer is welcoming and accessible to all community members, regardless of background, age, or ability.

Regularly collect feedback from community members on programs, services, and governance; Strive for accountability.

Reimagining Daily Life

-> American Lifestyles: How third spaces can reimagine daily life and change ideology

Third spaces are multi-faceted in their use and purpose and challenge uni-lateral definitions of place. They are places to express culture, organize, learn, and build people power. Within colonial models of capitalism, division, and categorization are encouraged, and although these are cognitive processes that help humans make sense of the world, they can also hinder community building. Division within our social spaces has eroded community resilience, stifled innovation, and inhibited open communication. American lifestyles have been corrupted by the capitalist system. More and more, leisure costs money, culture costs money, and community costs money. American capitalism has commodified creativity, learning, and cooperation. Third spaces disrupt this pattern of American capitalism. In addition, these community spaces encourage play and togetherness that inspire a reduction in work-centered values. These spaces are unique in their ability to bring folks together across ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, and age; unity is prioritized over individualism. These spaces breed community identity and allow it to flourish; they promote a care ethic. They allow folks to understand their shared sense of purpose within a community where no one is left behind. Community challenges are tackled together within this community model. Third spaces challenge, strengthen, and mold our ideas of identity. They can be avenues to celebrate diversity and promote mutual

respect and understanding that break down prejudices and promote learning and understanding. As mentioned above the American system has allowed its citizens to become isolated and depressed. A 2018 survey by YouGov found that 30% of millennials (ages 23-38) often or always feel lonely, and 22% say they have no friends. The AARP Foundation reports that over 42.6 million adults over age 45 suffer from chronic loneliness. Individualism is imbued in our culture and our city’s infrastructures and can be seen in the focus on private over public property. Car dependency and sub-par public transit systems in most American towns further fuel this individualism. Third spaces combat social isolation and challenge individualism by offering venues for people to participate in the community. In addition, these community spaces highlight the importance of rest and fostering a balanced and humane approach to life. An approach that understands the value of human life over production and economic activity. The opportunities third spaces create for cooperation, rest, and creativity are essential to guide us out of oppressive capitalist norms. It offers pathways to envisioning and creating more equitable and fulfilling social structures. It encourages reevaluating what is truly valuable in society, promoting well-being and human connection over profit and consumption.

Ateneus

Ateneus are cultural and intellectual centers that originated in 19th-century Spain, many are scattered throughout Catalunya today. These third spaces are designed to promote culture, arts, science, and literature through various activities and resources, and many are grounded in radical conceptions of management, funding, and ideology.

Below are three different Catalan ateneus compiled to highlight where they excel and get a better idea of how grassroots initiatives manifest in reality.

-> Ateneu Popular de Salt

This Ateneu sits in Girona and is one of the rare Catalan ateneus that put into practice the idea that the citizens themselves are the ones who maintain the public facility. The Ateneu Popular de Salt sits in the heart of a neighborhood with a diverse ethnic population; being so this ateneu actively works with its community to develop projects. These projects rely on the participation and empowerment of their participants and are constantly promoting sustainability, social cohesion, feminism, and diversity through workshops, activism, and cultural events. This ateneu is sustained and funded through membership fees, donations from private entities, and government grants. This allows the Ateneu Popular de Salt the ability to take on large and comprehensive projects.

A group of women hold up the first books they’ve ever read completely in Catalan through a reading program at

Highlights:

It plays a crucial role in preserving and promoting the cultural heritage of Salt and the broader Girona region Serves as a platform for marginalized voices and provides resources for vulnerable populations. Strengthens community bonds and fosters a sense of solidarity by providing a space to gather. Promotes and employs bottom-up governance and community funding to maintain the space.

-> Ateneu La Base

The Ateneu La Base is a radical grassroots Ateneu found in Barcelona. It was established as part of a broader movement to reclaim urban spaces for community use, aiming to create a more inclusive and participatory social environment. This ateneu is openly anti-capitalist and against neoliberal politics. They employ a self-management economic infrastructure where spaces, tools, services, and resources are local and shared. This allows them autonomy from the market and the government. Cooperative work is also stressed in this ateneu and horizontal governance structures are employed. The ateneu holds bi-yearly general assemblies, where common resources and needs are taken stock of. In addition, decisions are made regarding large-scale operational issues and projects. Membership and a membership fee are required to participate in the governance process: this allows the ateneu to stay autonomous. Their projects include:

A traveling library and book club.

Self-managed access to food to obtain agro-ecological, local, and reliable products.

A trades workshop, to share knowledge; and offer home repair services.

A cafe space for organizing, eating, spending time with friends, or learning.

Highlights:

Complete transparency on governance and funding structures.

Projects that operate on principles of mutual aid and solidarity.

Providing a space for organizing, meeting, and mobilizing around various social and political causes.

Through its educational and participatory activities, it empowers residents to become active citizens and advocates for their rights.

-> Ateneu Popular Salvadora Catà

This ateneu is another openly political community space in Girona, named after the anarchist and feminist Salvadora Catà, this ateneu was established as a hub for grassroots cultural and political activities. The Ateneu Popular Salvadora Catà organizes a wide variety of cultural activities from concerts, theater performances, and art exhibitions, to literary events. In addition, holding a political stance is important to this ateneu and they regularly host discussions, workshops, and events focused on social issues like feminism, environmentalism, and workers' rights. The space is also simply a place to meet, get a drink, or do work as they have a bar and leisure space that help financially sustain the ateneu. Financially, this ateneu is independent of governmental or corporate influence and maintains itself through membership fees, donations, and activities. Although this gives the ateneu complete decision-making autonomy, it has also led to some difficulties in maintaining financial stability. In addition, to this challenge, the ateneu has faced poltical pressure from local authorities or opposing groups, for their radical care-oriented ideology.

Highlights:

Initiatives aimed at improving the local community, such as food distribution, support networks, and cooperative projects.

Financial freedom from government and corporate entities

Language courses and conversational groups, for new or old residents to learn the local language: Catalan. A feminist self-defense group that gives class and encourages empowerment and safety for femmes.

Barthold, Charles, et al. “An ecofeminist position in critical practice: Challenging Corporate Truth in the anthropocene.” Gender, Work & Organization, vol. 29, no. 6, 11 July 2022, pp. 1796–1814, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12878.

Bayas Fernández, Blanca, and Joana Bregolat i Campos. Ecofeminist Proposals for Reimagining the City Observatori Del Deute En La Globalització, 2021

Bossi, Lorena Fabrizia. GAC: Pensamientos, Prácticas, Acciones Tinta Limón Ediciones, 2009

Bruzzone, Victor. “The moral limits of Autonomous Democracy for Planning Theory: A Critique of Purcell.” Planning Theory, vol. 18, no. 1, 23 May 2018, pp. 82–99, https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095218776042.

Finlay, Jessica, et al. “Closure of ‘third places’? exploring potential consequences for collective health and Wellbeing.” Health & Place, vol. 60, Nov. 2019, p. 102225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102225.

Martí Comas, Julia, and Maite Mentxaka Tena. An Ecofeminist Toolkit to Fight against Corporate Power. Libros En Acción, 2023.

Rose, Carol M. “Thinking about the commons.” International Journal of the Commons, vol. 14, no. 1, 2020, pp. 557–566, https://doi.org/10.5334/ijc.987.

Routledge, Paul. “The third space as critical engagement.” Antipode, vol. 28, no. 4, Oct. 1996, pp. 399–419, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14678330.1996.tb00533.x.

Silva Junior, Igino, et al. “The Great Urban Games: Rationalization of play, leisure and capitalism.” XII Seminario Internacional de Investigación En Urbanismo, São Paulo-Lisboa, 2020, June 2020, https://doi.org/10.5821/siiu.10019.

Creating third spaces and empowering individuals and communities to reclaim power is not without its challenges. It requires a significant amount of effort, dedication, and resources to make positive change happen. However, the potential benefits and impact are worth fighting for.

la unión hace la fuerza