ELECTRIC KILN

FRANK AUERBACH

EMMANUEL COOPER

LE CORBUSIER

PIERRE JEANNERET

LUCIE RIE

When I moved into Fonthill Pottery in 2014, I was acutely aware that I had stepped into a space alive with artistic memory. This was once the home and studio of Emmanuel Cooper: a place of making, of writing, of transformation. The electric kiln in the basement—since dismantled—had not only fired clay but ignited ideas. The house, like the man who lived and worked here, embodied a unique fusion of creativity, craft, activism, and intellect.

Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge has long been a source of inspiration and a creative stimulus behind the exhibitions at Fonthill Pottery. Having opened my home last year with an exhibition that juxtaposed my collection of furniture from Chandigarh— by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret—with works by artists and designers of South Asian heritage, it felt fitting this year to turn my attention to the history of the house and its surrounding neighbourhood.

I have always been drawn to the impastoed surfaces and landscapes of Frank Auerbach, who lived and worked just around the corner, perhaps because he so often depicted a landscape close to my own heart: Primrose Hill. Having frequently sought inspiration from architecture, I have also found deep resonance in the sculptural forms and poised clarity of Lucie Rie’s vessels. Rie, whose Albion Mews studio was located not far from here, has become a cornerstone of British studio pottery, bringing with her to London the spirit of fin-de-siècle Vienna.

To see Cooper’s works return to the rooms in which they were first conceived, coming ‘home’, Auerbach’s Mornington Crescent paintings and Primrose Hill sketches displayed just beyond the hill itself, and Rie’s elegant forms placed within a domestic setting rather than the glass cabinets of a white cube, has been a profound pleasure. When placed in dialogue with the works of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, they seem to come further to life.

These are works that, in their balance of function and form, echo the ethos of Rie and Cooper. The furniture, crafted for the utopian city of Chandigarh, now inhabits another kind of ideal space: a home that believes art and life should be inextricably interlinked. As David Horbury writes, we once thought the story of Fonthill Pottery had ended. And yet it continues, not as a reconstruction, but as a site of renewed creative dialogue.

I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to everyone who has been involved in bringing this exhibition to life.

– Rajan Bijlani

Electric Kiln – what a great title for an exhibition! As Chloe Redston explores in her essay the title is a touchstone for considering the work of three exceptional artists who lived and worked in London. One is a painter and two are potters. These descriptive words may appear absurdly reductive, yet Frank Auerbach, Emmanuel Cooper and Lucie Rie shared a fundamental respect for the limitless possibilities of paint and clay. All the works in this exhibition reflect a belief in the role of the artist as constantly experimenting — searching for what art can do. These paintings, drawings and pots blaze with life and have the potential, if we let them, to stop our world for a moment.

Looking at Frank Auerbach’s work is both to experience the physical reality of paint, charcoal, chalk or ink and to simultaneously be given a richness of colour and tone, an energy and expressiveness which together become a profound meditation on the nature of being, and of what it means to be free. Like Auerbach, Lucie Rie was also in exile from her home country. Her extraordinary body of work, so diverse in form, reflected an unrivalled inventiveness combined with astonishing skill. While Emmanuel Cooper, the acclaimed biographer of Rie, made outstanding pots which could only be handmade; their vibrant colours and surfaces a dynamic collaboration between maker and electric kiln.

To be able to see a terrific selection of pieces by these artists in a beautiful house, once the home and workshop of Emmanuel Cooper, is a unique opportunity. Even more so as they are placed among a remarkable collection of modernist design by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret. But the former Fonthill Pottery is still a home, not a museum. And for five weeks these artworks can speak to each other and to us.

– Andrew Nairne Director of Kettle’sYard

In the autumn of 1975 Emmanuel visited an exhibition in a gallery in Regent’s Park Road and afterwards, as he noted in his memoirs…

“I walked down Chalcot Road to the junction of Fitzroy Road and saw that number 38 …with its handsome shop,basementandtwo-storeymaisonettewasforsale. ImmediatelyIloveditandwantedit.Thestreetwaswide andairyanditwascentral,whichprovidedeasyaccessto CeramicReviewandtheWestEnd…Imanagedtoscrape together the sale price … and in April 1976 the Fonthill PotterymovedtoPrimroseHill.”1

Emmanuel was to live and work at the Fonthill Pottery for the rest of his life. Here he made and sold his pots; tested glazes; wrote his books and journalism; from here he would travel to the Ceramic Review office or to his various teaching jobs. When I joined him there in 1984 I was immediately struck by his extraordinary energy and creativity.

At the heart of that creativity were Emmanuel’s pots always inspired by where he lived and worked. ‘Ideas about pots’ he wrote, ‘come from the materials I use, the people I meet, from where I live and the gritty reality of urban life... Colours are those of roads, pavements and buildings.’2

It has been fascinating for me to witness some of those pots returning ‘home’ and to see them alongside the work of Lucie Rie and Frank Auerbach. Emmanuel knew Lucie well he wrote his acclaimed biography of her at the Fonthill Pottery, completing it only days before he died in January 2012. Auerbach he also admired they shared a love of Primrose Hil—a place where Emmanuel found inspiration looking out across the constantly changing city scape.

Like everyone else I had assumed that the story of Emmanuel at the Fonthill Pottery had come to an end the studio had been cleared, the pots packed up, his papers sorted and archived, the electric kiln dismantled.

And then... came Rajan Biljani.

1 David Horbury (Ed.),Making Emmanuel Cooper, Unicorn, 2019.

2 The Making: Interviewwith Emmanuel Cooper, 2008.

– David Horbury PartnerofEmmanuelCooper

It is natural to assess the entire career of an artist as a planned and intentional timeline of works that build, one on the next, to achieve a lifetime of continuous work. Obsessiveness can assume intent. What is essential is the approach, putting yourself in the studio and freeing one’s mind from any plan or preconception of what will happen that day. It is this spirit and context that unifies the work of Frank Auerbach, Lucie Rie and Emmanuel Cooper: intuitive faith in the artistic process and the energy of Northwest London in the postwar era.

Electric Kiln is a metaphor for the zeitgeist of North London in the second half of the twentieth century. Bombed-out buildings, upended lives, and reconstruction made for a creative environment and a firmament from which to draw creative outcomes. Auerbach, Rie and Cooper are artists who, one can imagine, would have been comfortable working in any time or place they had otherwise been born; however, they are eminently modern Londoners, urban artists of the 20th century. They are responsive to their environment and choose to use modern technology and contemporary subjects which are rendered with a timeless spirit.

There could have been no other painter who would resonate with the potters Lucie Rie and Emmanuel Cooper than Frank Auerbach. All three artists worked within a square mile of each other, and it is conceivable that Cooper threw his pots and wrote about Rie in his studio while Auerbach strolled by with a sketchbook in hand, en route to Primrose Hill. This unifying location, this point of elevated geology in the urban grid, proved to be the locus of creative innovation for the three artists of this exhibition. The physicality of North London is matched in the physical materiality of each of the artists: Auerbach’s paintings of urban life were layered as though time had built up mountains on a plain; Rie and Cooper mined the earth for clays that were magically spun into refined objects of pure modernity. Visceral surfaces and unconditional materiality grew out of each artist’s practice. There was never a plan upon entering their studios; work made work, and results would be determined by faith in the process of making. As the pressure and energy of London would produce exceptional experience for life, the same was true of placing pots in the electric kiln. The surprise upon opening the kiln after firing, or the delight in contemplating the results of a day’s painting in the studio, all created moments of pure artistic genius for Auerbach, Rie and Cooper.

Perseverance and an unwavering adherence to being uncompromising align all of the artists in Electric Kiln. This extends to the rigorous materiality of furniture by Le Corbusier and Jeanneret that serve as supporting actors in the interiors of Rajan Bijlani’s domestic spaces. Solid teak construction and simplified geometries form a complimentary backdrop to the delicate ceramic volumes by Rie and Cooper. Auerbach’s richly impastoed and earthy paintings find a resonance in the patinated teak surfaces of the furniture from Chandigarh. Both show the result of activity concentrated. Both are equally human and purposeful. The timelessness of each artist in the exhibition is the result of a deeply authentic practice which touches the core purpose of human existence. All of the artworks will be judged in the same way for centuries to come, and their alignment with what it is to be human will never lose its energy.

A life liberated from convention—Auerbach and Rie as refugees of the war, Cooper as a homosexual—play a crucial role in the genesis of the exhibition. One must carve their own path in an environment that can be hostile to that which is different. This extends to Rajan Bijlani himself. He is not conforming to art world norms, as a man of South Asian ancestry staging exhibitions that do not conform to the glare and austerity of the white box gallery or rules of the status quo. His tenacity and dedication match the spirit of the artists who now occupy the spaces of his home. As in the machine itself, Electric Kiln rewards the energy and creativity that enters it, and the results allow for unexpected resonance, beauty and magic to come out.

– Michael Jefferson CuratorandExpertin20th CenturyArt&Design

Taking place at Fonthill Pottery, the former home and studio of the late Emmanuel Cooper, Electric Kiln brings together the works of the potter Lucie Rie, the painter Frank Auerbach, and the potter, Cooper himself. Here, the electric kiln represents a site of metamorphosis, in which clay meets electrical current and tradition meets modernity, with often-unprecedented results. The spirit of alchemical transformation permeates the practices of all three artists. Each harnessed traditional mediums, which, charged with the electrical atmosphere of their time, they used to directly respond to their surroundings in London. Within this environment, the electric kiln becomes an extended metaphor: a symbol of transformation in which the raw materials of the city –its people, forms, and histories – are fired, tested, and ultimately reborn.

In 1965, Emmanuel Cooper (1938–2012), a butcher’s son from the small coal-mining village of Pilsley in north-east Derbyshire, set up his first pottery in the heart of London, marking the beginning of a career that fused working-class pragmatism with artistic innovation. Cooper’s initial contact with clay was at school, with ceramics being something of a humanising activity that was introduced into the state education system following the unprecedented destruction and loss of the Second World War. Despite his natural inclination towards the medium, Cooper began his career as an art teacher rather than a ceramicist, doubting its potential to earn him a living. It was a plan that offered not only financial security, independence and the possibility of moving through a still rigid class system, but – most importantly – it brought him to London.1 It was not until 1963, and after much deliberation, that he made the decision to give up full-time teaching to pursue pottery.2 Yet his dedication to education continued to influence his choice of work. As the author of almost thirty books, the cofounder and editor of Ceramic Review, and an LGBTQ activist, Cooper was as much a cultivator of thought and of community,

1 Moving to London had a profound impact on his development, both as artist and man; it gave him access to the thriving gay subculture, the possibility of meeting like-minded people, of finding support, connections and excitement. 2 In Cooper’s own words: ‘I remember thinking that my life was really beginning’: Emmanuel Cooper in: David Horbury (Ed.), Making Emmanuel Cooper, Unicorn, 2019, p. 117.

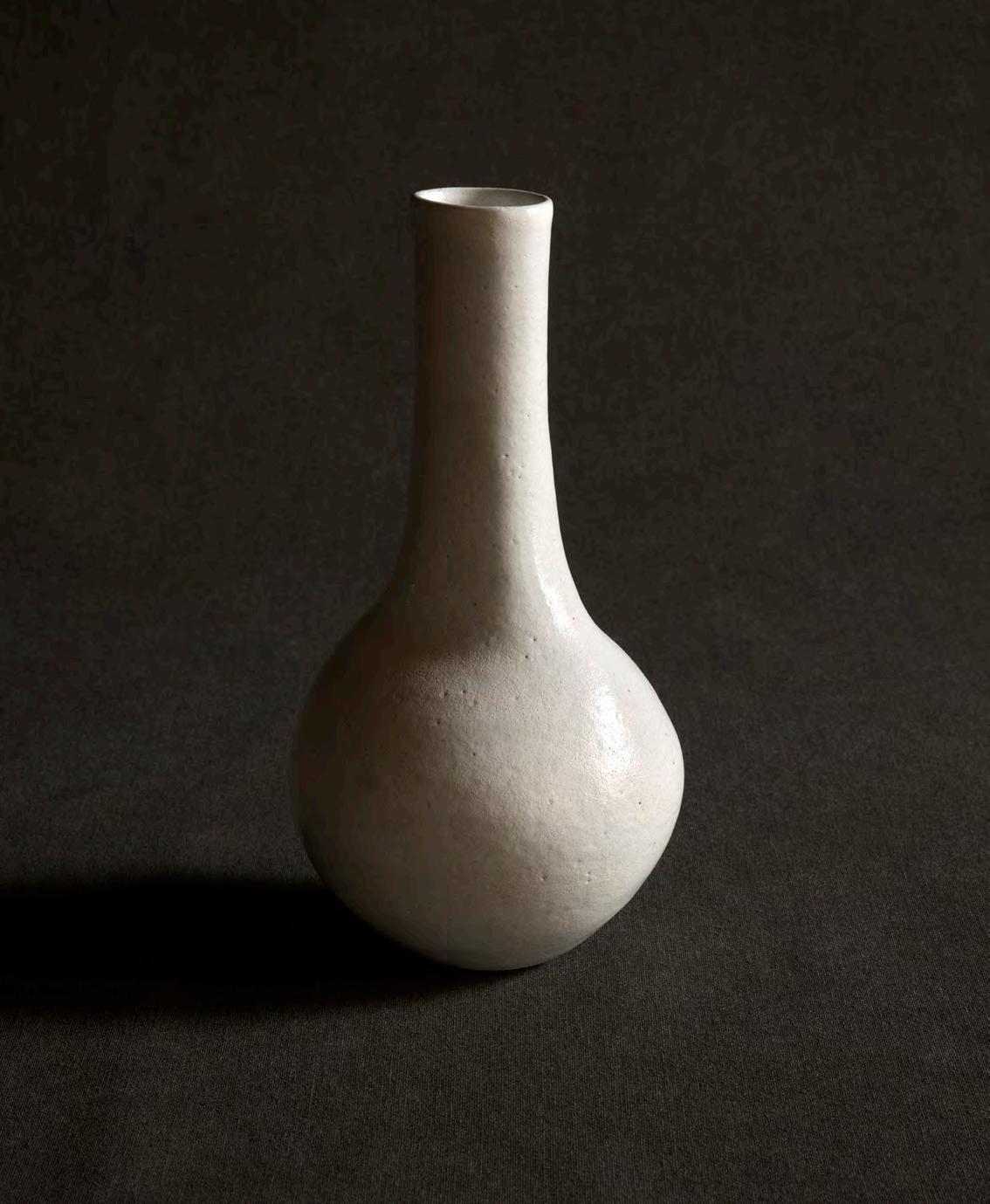

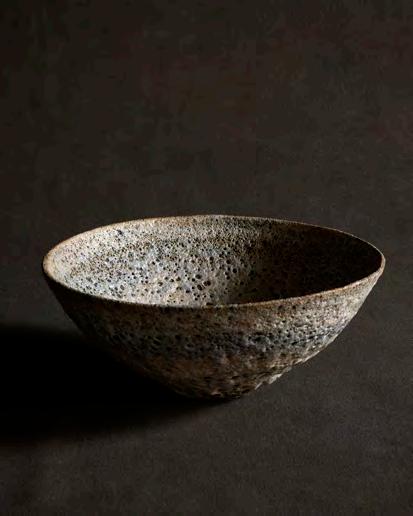

contemporary ceramicists4 – Cooper subverted the expectations of his medium,5 striving to create what he later referred to as an ‘electric kiln aesthetic.’6 This was a way of harnessing the so-called limitations of his environment, while simultaneously taking inspiration from it. Cooper’s glazes crackle with urban sensuality. In his own words: ‘If the textured stoneware could be seen as relating to road surfaces [see fig. 1], the porcelain reflected the brighter, more vibrant aspect of the city, whether in the colour of traffic lights or the illuminated signs of Piccadilly Circus [see fig. 2].’7 As De Waal observed, ‘his surfaces are baroque –pitted, crawled, as fierce as lava, with colours

4 These are: GlazesfortheStudioPotter, Batsford, 1978; The Potter’s Book of Glaze Recipes, Batsford, 1980; Electric Kiln Pottery, Batsford, 1982; Cooper’s BookofGlazeRecipes, Batsford, 1987. Many subsequent editions.

5 It is also worth noting that his importance in this field was such that, in 2008, Cooper was invited by the V&A to produce the glaze tests that were to form part of their permanent displays devoted to the ceramic process.

as of ceramic form. He founded Fonthill Pottery in Finsbury Park in 1973 and relocated to Primrose Hill in 1976, where he would live and work for the rest of his life.3 With only a small basement at his disposal, Cooper was unable to use a traditional fuel-burning kiln, which would produce fumes and require ventilation. Instead, he turned to the electric kiln and spent almost two decades exploring its possibilities.

There are many potters who say that their environs and personal histories influence their work. Few embodied this more vividly than Cooper. During the first half of the 20th century, studio pottery was often produced in woodfired kilns, which required space and natural resources; at that time, it was still largely synonymous with rural life. As a glaze pioneer – whose glaze recipe books continue to provide encyclopaedic insight for

6 The Making: Interview with Emmanuel Cooper, 2008.

7 Emmanuel Cooper for FineArt Society, London, 2003.

3 The original Fonthill Pottery (1973–76) was located in Fonthill Road, Finsbury Park.

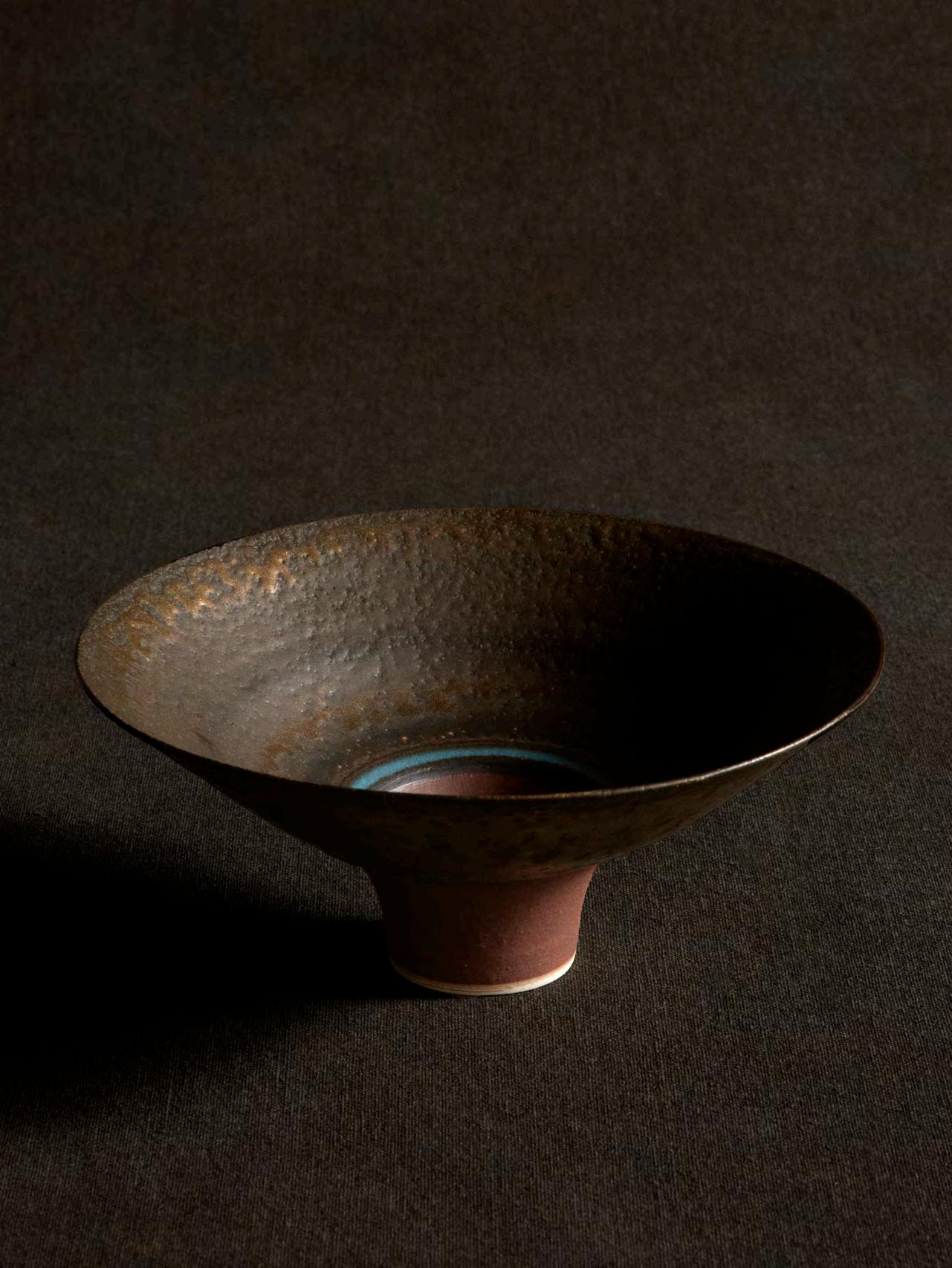

3 Detail: Emmanuel Cooper, footed bowl, c. 1990, porcelain footed bowl with dark matt glaze and gold lustre decoration to rim and centre, 8cm high, 20cm diameter. Underside impressed with maker’s mark.

as saturated as a Fauve, transgressing every barrier and boundary, every edict of the AngloOriental Pottery Tradition. Here is colour to start a fire.’8 The intensity of his palette and the visceral textures of his glazes embodied the vitality of the city itself, recasting the ceramic surface as a site of expressive energy rather than restraint.

Cooper ceased his production of tableware in the 1980s in part due to market trends, as restaurants increasingly favoured ‘the clinical lines of factory produced ware.’9 Functionality, however, remained a priority. As Sebastian Blackie observes, one senses he valued this aspect of potting as an expression of ‘unpretentious creativity that chimed with his working class roots and socialist views.’10 Of his many forms, perhaps those which he most favoured were that of the bowl and jug – universal archetypes for diverse potters.

While recalling the functionality of his earlier production ware, from the 1980s onwards, these forms also offered accessible interior and exterior surfaces on which to display nuance –where glaze might pool, run, or gather, always suggesting its liquid origins. These vessels carry the testimony of his hand, while their hues and cratered forms recall cracked tarmac, roadmarkings, or the sparkling lights of the London skyline. In this sense, they stand not only as objects of containment, but as vessels of lived urban experience. It is paradoxically within their apparent imperfections that we find meaning, marking Cooper’s departure from a more utilitarian tradition. Where he considered the crawling of a glaze to be excessive, he would sometimes repair it with a gold lustre spot after firing [as with fig. 3]. This act recalls the Japanese tradition of Kintsugi, whereby one simultaneously covers yet highlights the fault. In quoting the textures and tones of the metropolis, Cooper’s pots embody the material presence of London itself, the unpredictable nuances of his medium, and the idiosyncrasies of the hand and mind that made them.

Just a stone’s throw away from the former pottery, in Mornington Crescent, lies the studio of the late Frank Auerbach (1931–2024). Auerbach emigrated to Britain from Germany in 1939 as a refugee, without his parents and just seven years old; he would

8 Edmund de Waal, in: Emmanuel Cooper: Connections & Contrasts, Leach Pottery, 2015, p. 7.

9 Emmanuel Cooper, in: David Horbury (Ed.), Making Emmanuel Cooper, Unicorn, 2019, p. 251.

10 Sebastian Blackie, “To Live is to Leave Traces”, in: Emmanuel CooperOBE 1938-2012, Ruthin Craft Centre in association with the University of Derby, 2013, p. 29.

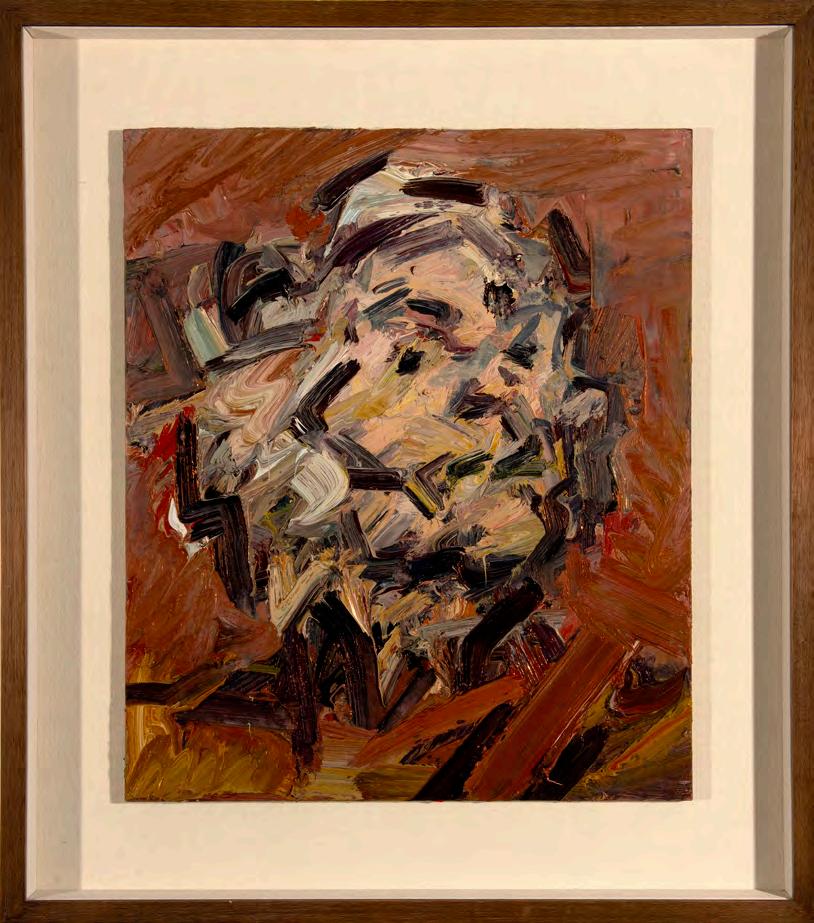

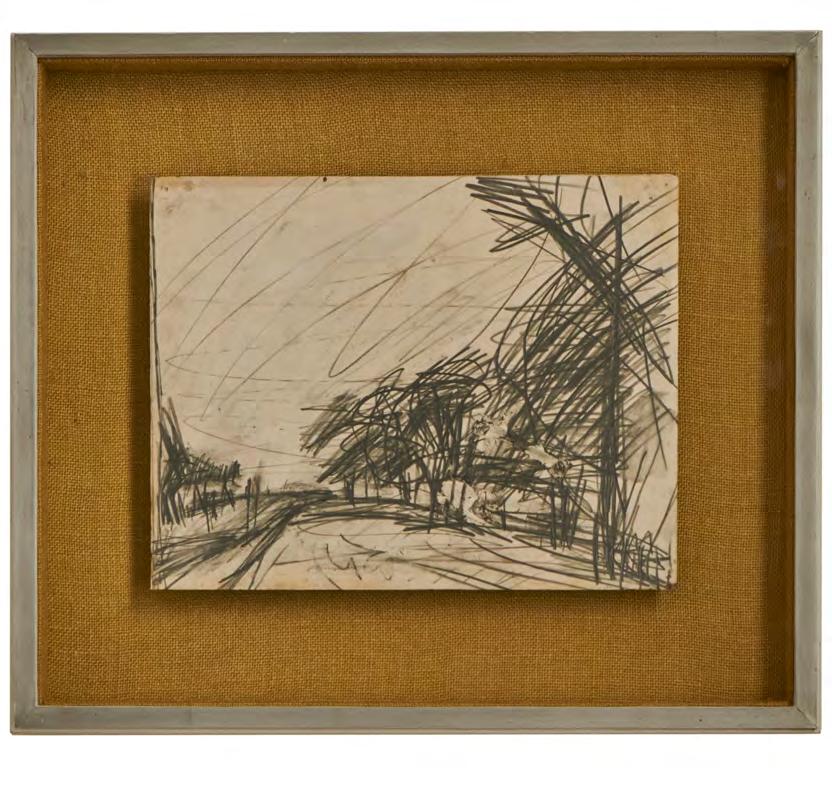

4 Frank Auerbach, StudyforPrimroseHill, c. 1960, graphite pencil on paper, 24 x 32 cm.

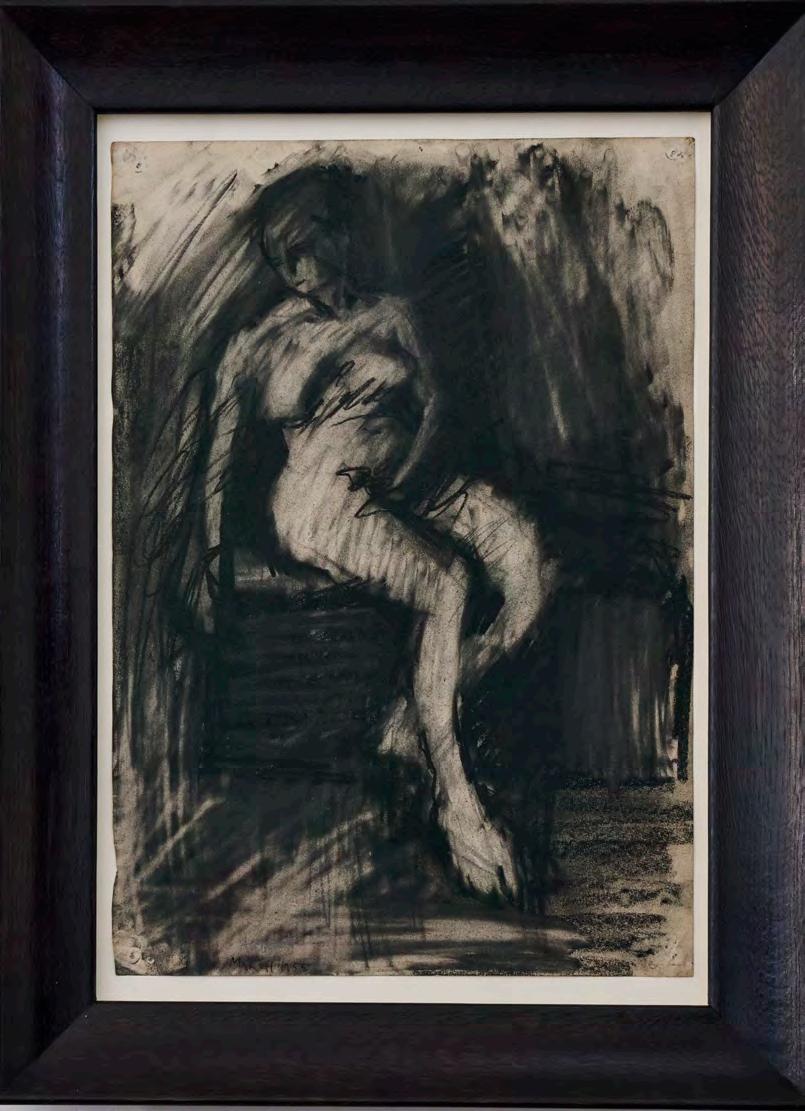

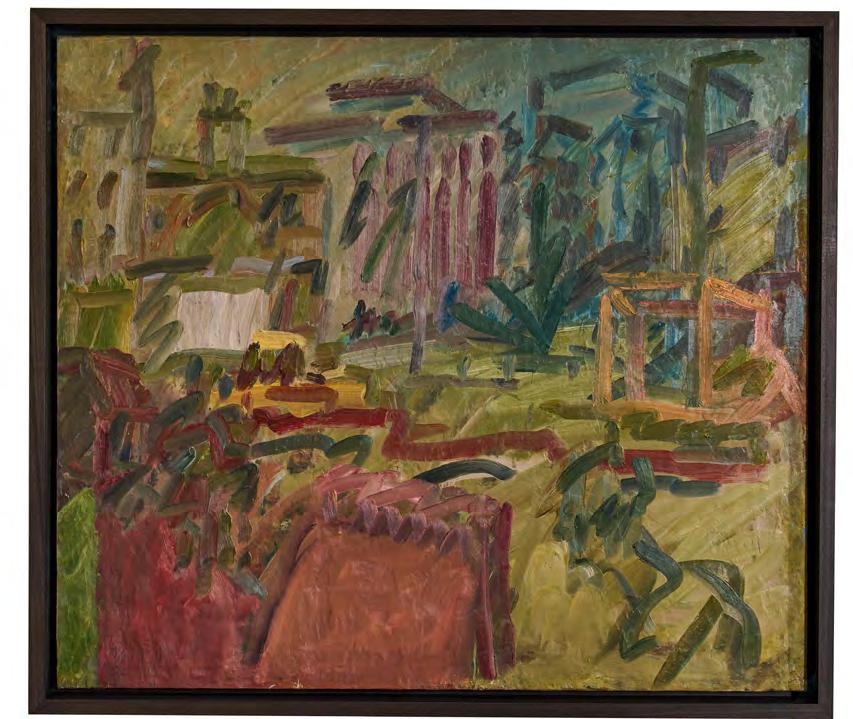

go on to become one of the most significant artists of the post-war generation. He moved to the capital in 1947 and would remain there for his entire career. Few artists have so fervently dedicated their practice to capturing London, season by season, year after year, as Auerbach. One of his most frequented locations was Primrose Hill [see fig. 4], which is visible from Fonthill Pottery. It is a subject he painted over forty times throughout his career.11 Like Cooper, Auerbach took inspiration from his urban surroundings. Speaking of his solitary teenage years in London, he commented: ‘My life was very much of the streets. I went around London; I took bus rides. This became one’s physical and mental terrain, which stimulated me to try and paint it, slightly impelled by the feeling that gradually it would be tidied up and disappear … On these planks, people wheeled wheelbarrows totally confidently; I would sit down and edge my way along them in order to do my drawings.’12 Immersed in and fascinated by the ever-evolving landscape of the city, his signature impasto technique lent itself to this topography of change: accumulations of thick paint, applied in gestural sweeps, appear to attack the canvas – the physicality of which not only recalls the bodily presence of the artist, but the controlled chaos of the rapidly growing urban landscape it depicts.

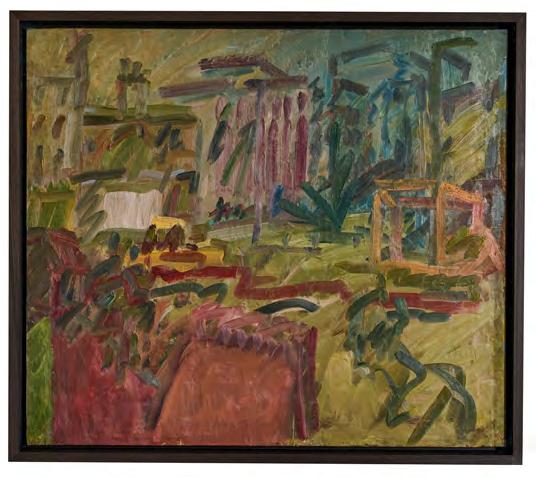

In Auerbach’s Christmas Tree at Mornington Crescent (2004-5) [see fig. 5], the paint surges with energy, as if echoing the bustle of city life or the markings of London’s streets. As Peter Ackroyd observes, ‘one senses both the exultation and the exaltation of an artist finding himself and his true subject within the immediate presence and energy of London … There are times when his vivid brushstrokes have the explosive vitality of the graffiti scrawled upon the walls around him, as if the perpetual anonymous voices of

5 Frank Auerbach, Christmas Tree at Mornington Crescent, 2004 – 5, oil on canvas, signed dated and titled twice on the stretcher, 133.4 x 155.6 cm.

Londoners had entered his paintings.’13 Formed through the arduous labour of daily repainting, Auerbach describes his method: ‘I actually find the landscapes … tremendous physical effort because that particular size and the way I work means putting up a whole image, and dismantling it and putting up another whole image, which is actually physically extremely strenuous, and I don’t think I’ve ever finished a landscape without a six or seven hour bout of work.’14 The very scale of the landscapes therefore becomes a visual analogue for the limits of the artist’s body. This labour produced surfaces that appear simultaneously grounded and shifting, perpetually dismantled and remade. In the words of his contemporary and friend, Lucian Freud: ‘It is the architecture that gives his paintings such authority. They dominate their given space: the space is always the size of the idea, while the composition is as right as walking down the street.’15 The three-dimensionality of his finished surfaces stands as a monument to construction – the embodiment of urban change – and situate

13 Peter Ackroyd, 1994, Frank Auerbach: Portraits of London, Outred & Waterman, 2024.

11 The same year that he became a naturalised British citizen.

12 Frank Auerbach, 2009 in: Frank Auerbach: PortraitsofLondon, Outred & Waterman, 2024 [emphasis author’s own].

14 Frank Auerbach, in: Catherine Lampert, Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting, London: Thames and Hudson, 1978, p. 62.

15 Lucian Freud, 1995, in: FrankAuerbach:Portraits of London, Outred & Waterman, 2024.

an interpretation of Auerbach’s work not only within the poetics of time, but also of space.

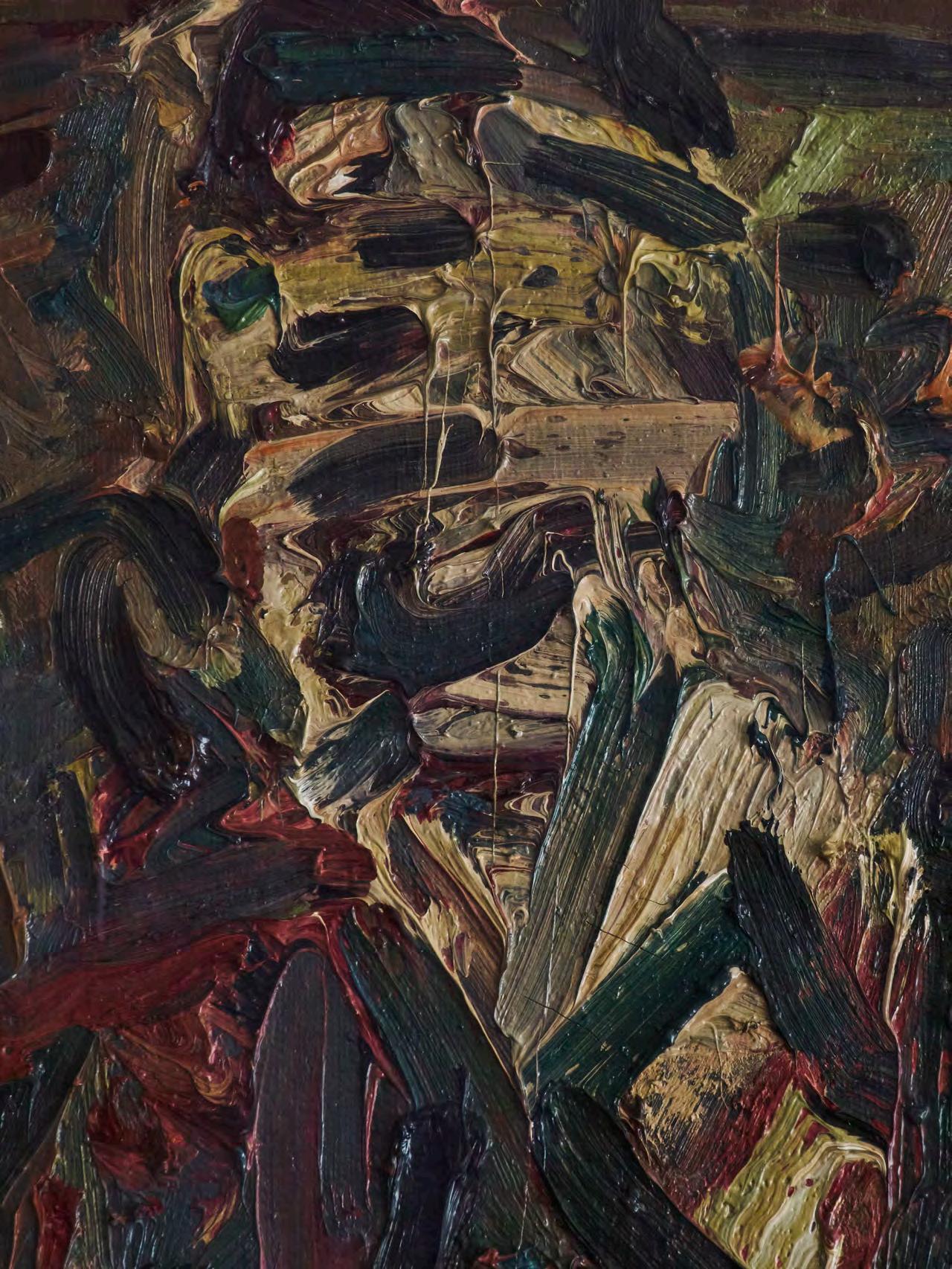

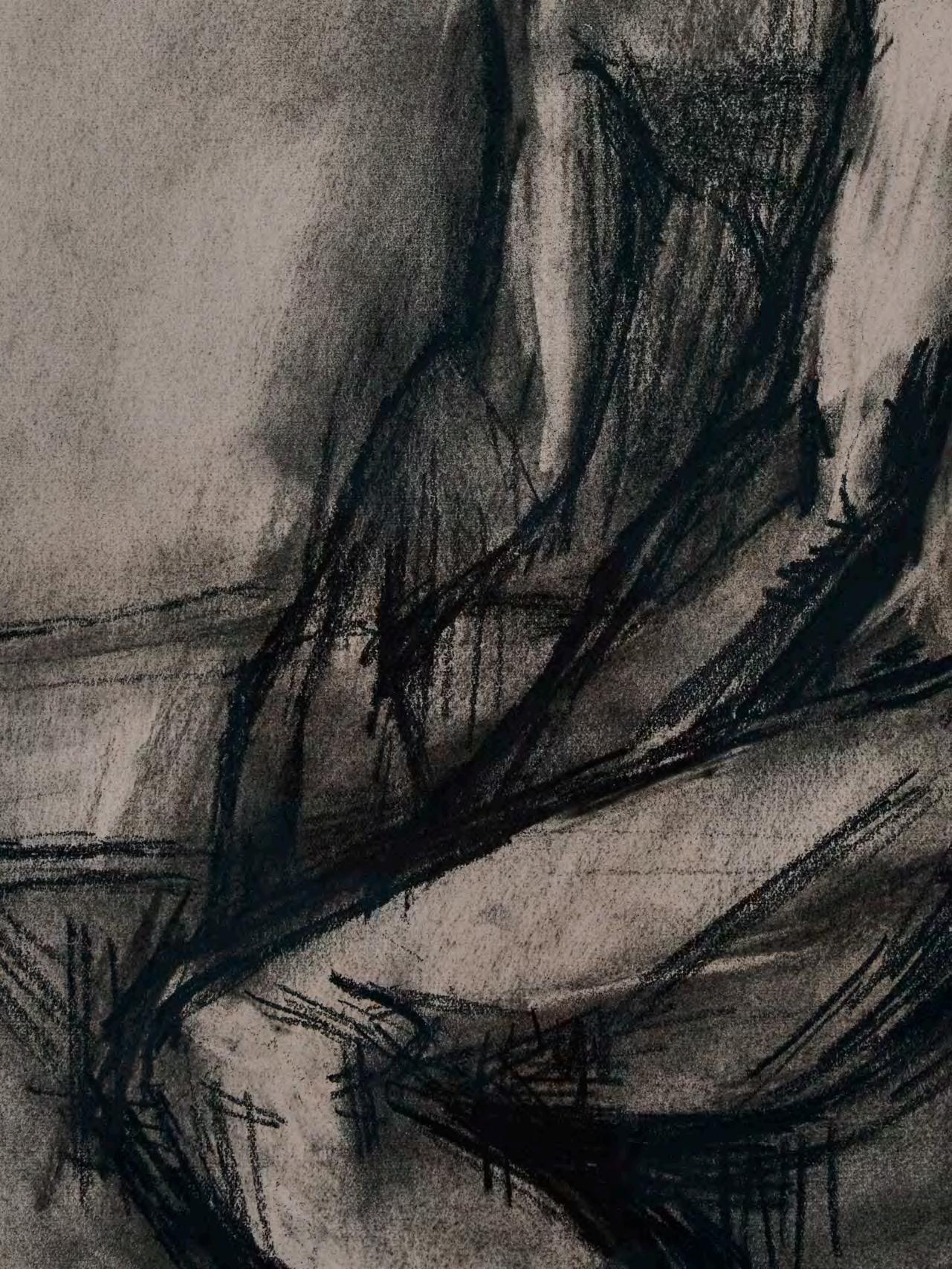

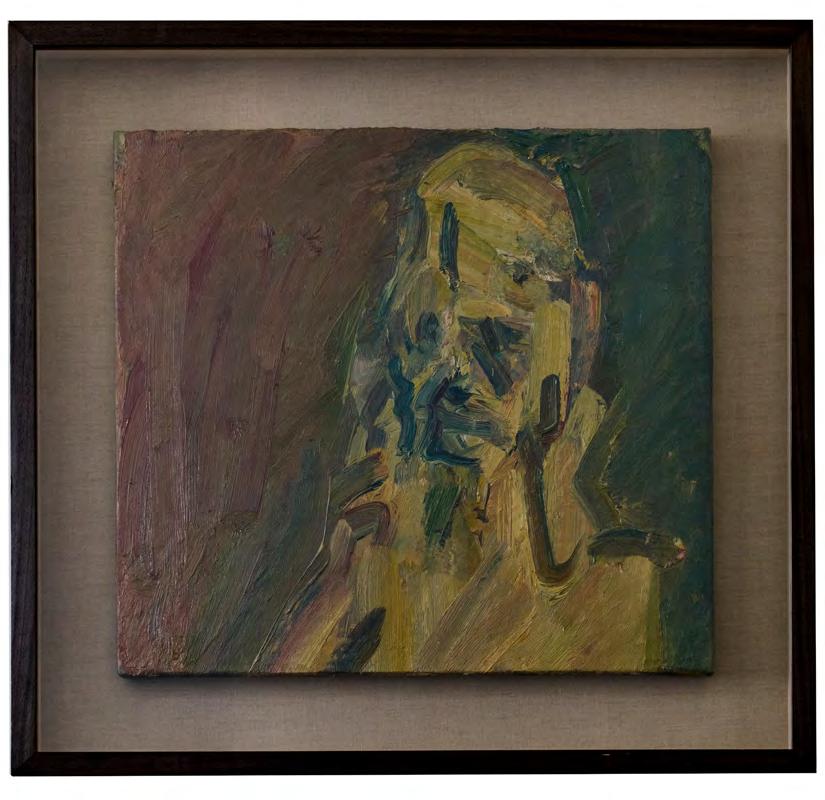

While his landscapes evoke the changing skyline of post-war London, Auerbach’s portraiture enacts a parallel excavation of the human psyche. Throughout his career Auerbach worked with a small circle of loyal sitters, among them, J.Y.M [see fig. 6], Catherine Lampert, and his wife, Julia, many of whom sat for him weekly over decades. Such sustained repetition was central to his method. Each work was constructed layer upon layer and scraped away if the artist was dissatisfied at the end of the day. As such, a tension was created between generative and erosive processes, one which mirrors, within his landscapes, the evolution and regeneration of bombed sites and within his portraiture, the complex psychological terrain of post-war London. Auerbach insisted that the sitter’s essence only emerged once the self-conscious mask of posing had dissolved: ‘When people first come and sit … they do things with their faces. It’s when they have become tired and stoical the essential head becomes clearer.’16 It is a process that not only solidifies the relationship, through a sustained dialogue, between artist and sitter,

but also inscribes the portrait with a layered record of their encounters. In turn, his marks seem to emerge from the very atmosphere they generate, so that the surface itself bears witness to both artistic struggle and human presence. Teetering on the edge of abstraction and figuration, Auerbach’s portraits possess a psychological impact that connects us to the tenor of their times, as lives were rebuilt post-war.17 Just as Cooper’s bowls carry the record of their maker, their pitted surfaces and cratered glazes sometimes repaired with gold lustre, Auerbach’s portraits bear the scars of their own revisions and the gestural bodily presence of their maker. But where Cooper’s gilded repairs recast imperfection as beauty, Auerbach monumentalises the very abrasions of his process, leaving erasure and repetition legible on the surface – a metaphor for the human experience.

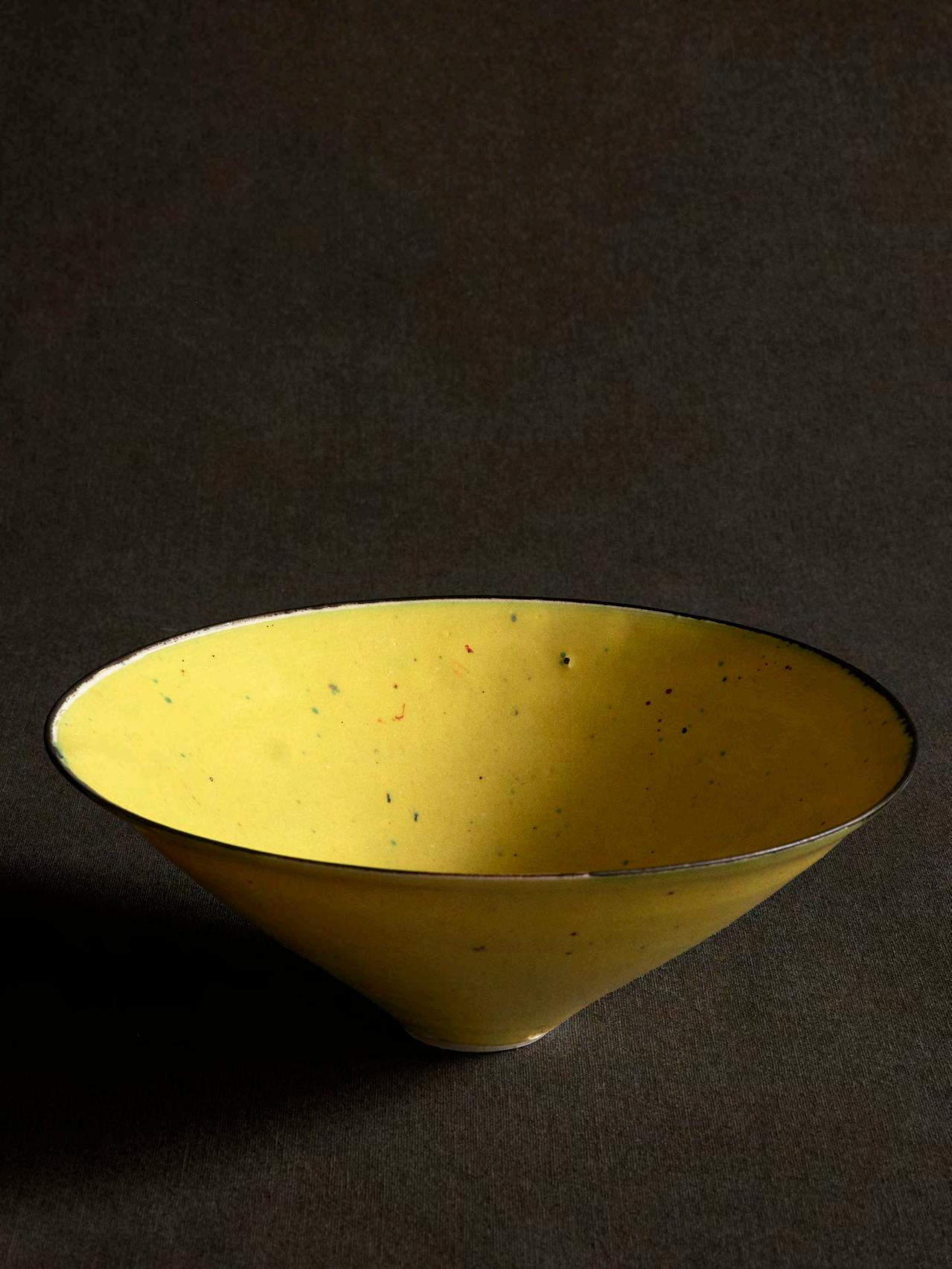

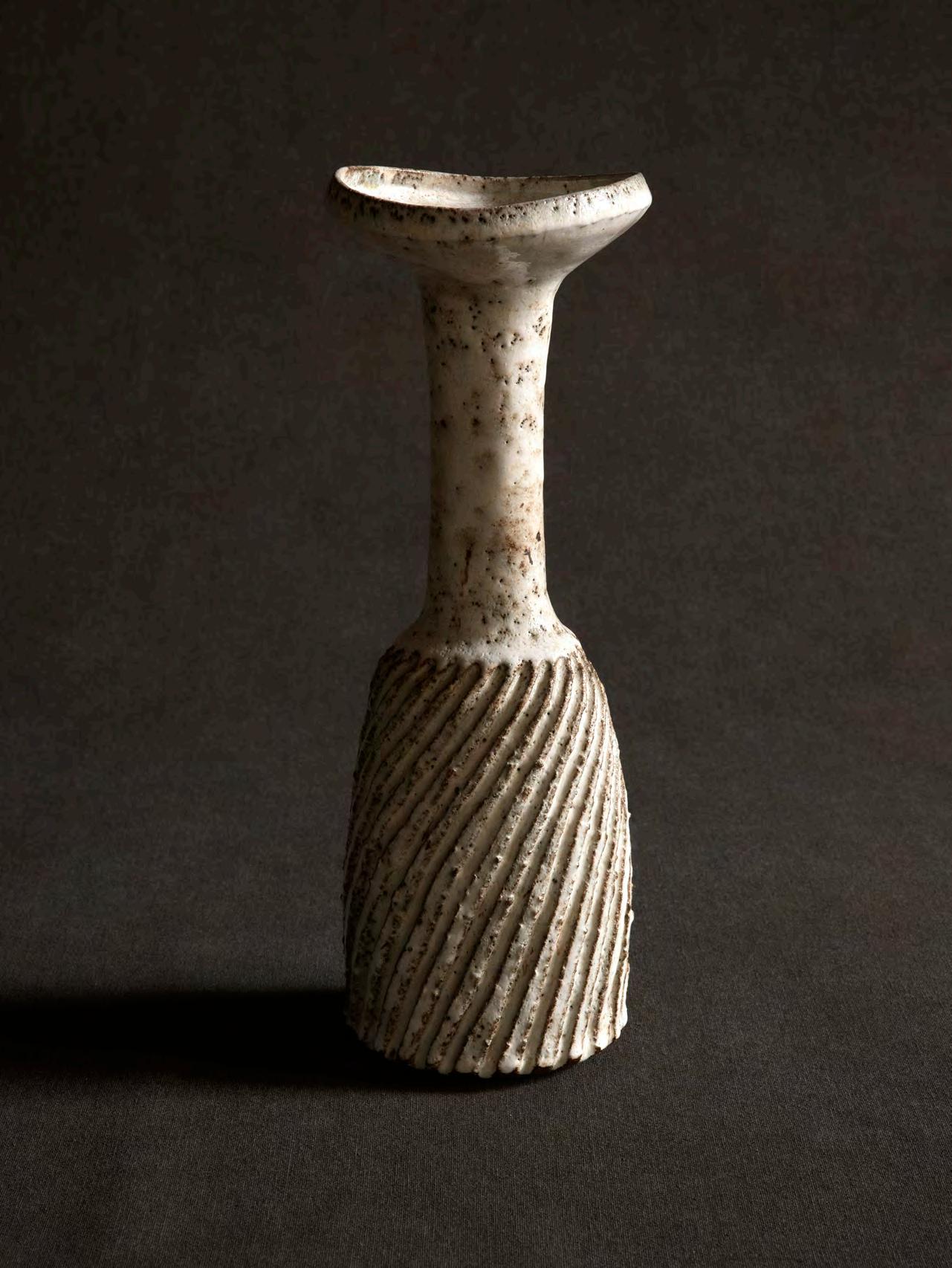

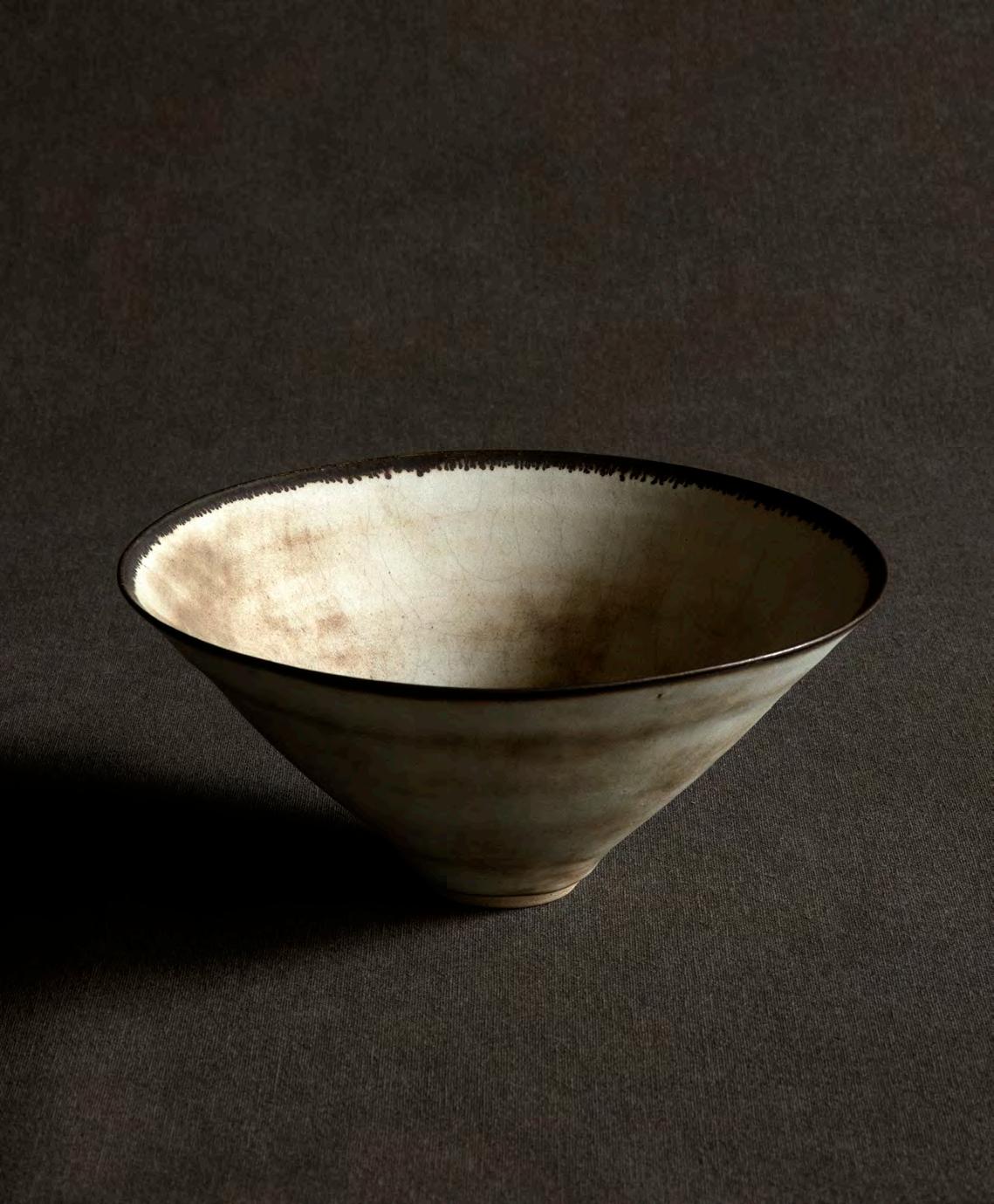

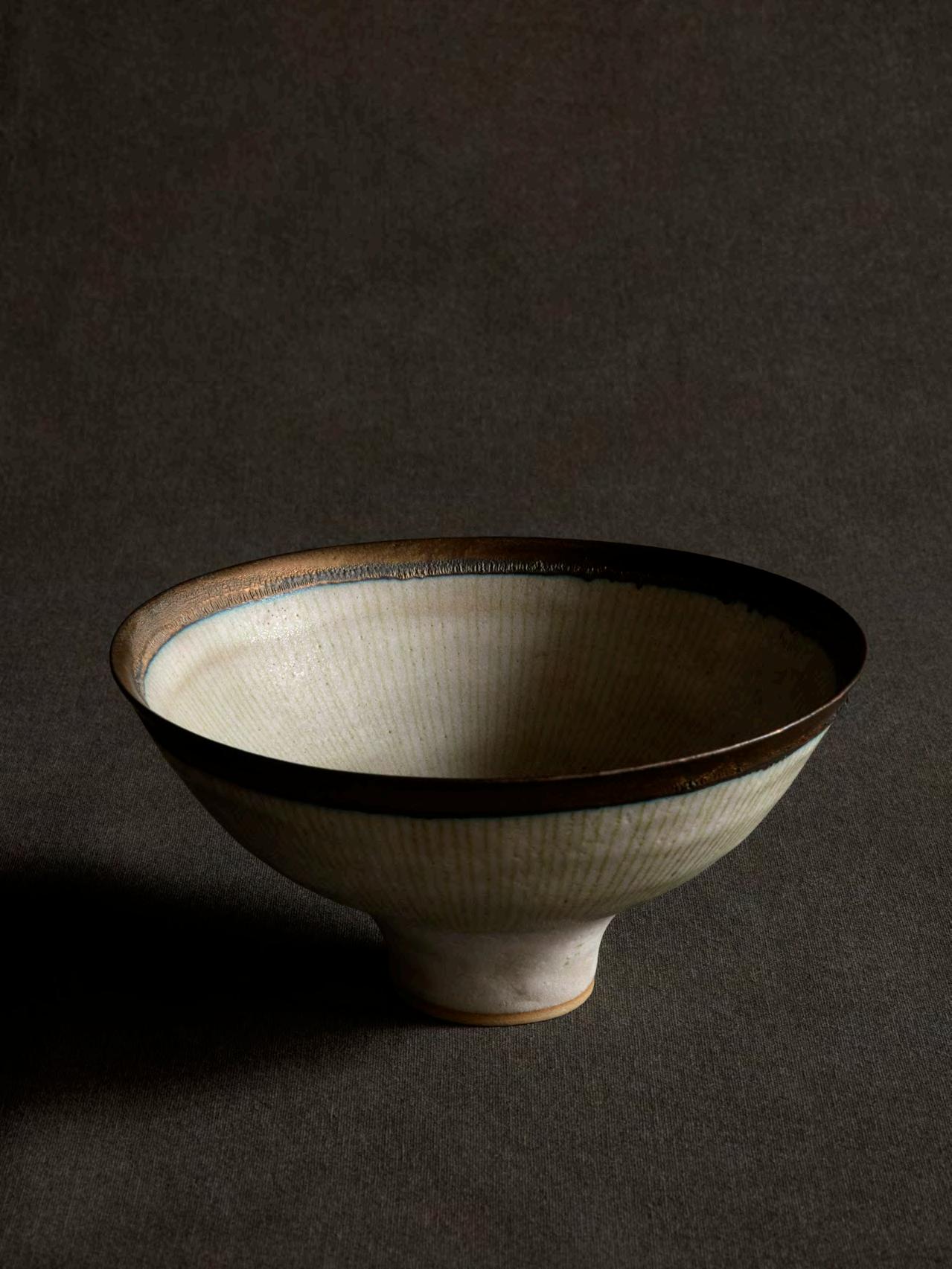

Just as Auerbach’s canvases bear the marks of their creation, ceramics by Lucie Rie (1902–95) possess the material trace of their maker; the surface of clay records the gestures and tools that produced them. Yet, unlike Auerbach’s dramatic mark-making, Rie often left her forms largely unadorned, allowing glazes to speak with quiet clarity. When she did intervene, her touch was restrained: delicately incised or inlaid rather than forceful or emphatic. Rie, like Cooper, favoured the electric kiln. When asked by David Attenborough in the 1982 BBC Omnibus interview, whether opening the kiln was a revelation, she replied: ‘Not a revelation, but a surprise,’ as she lifted what he referred to as ‘a small miracle’ from its chamber.18 It is a moment that captures the dual nature of her process: carefully considered, methodical, almost scientific, and yet still functioning somewhat within the realm of chance. It is a tension made visible in her treatment of glaze. In [fig. 7], despite the relative perfection of its form, the handling of the glaze on the interior of the vessel is idiosyncratic and perhaps more closely aligned with the drips and splashes

17 David Sylvester, “Young English Painting”, The Listener, 12 January 1956.

18 Lucie Rie & David Attenborough, BBC Omnibus Interview, 1982.

that one might expect from an abstract expressionist. Moreover, within her signature sgraffito technique [see fig. 8], incised lines cut through glaze establish the potter’s marks as both erosive and generative. This tension between incision and accretion situates her work within the same dialectic of process that defines Auerbach’s painting. Her vessels harness this process of discovery into one of poised clarity, balancing the uncertainty of the firing process with measured restraint. In both cases, however, the surface functions as testimony, carrying the history of its own becoming.

Rie’s contribution to post-war London extended beyond ceramic form and surface into the cultural fabric of the city itself. Having fled Vienna in 1938, she entered a milieu of émigré architects, writers and artists with similarly urbane, middle-European backgrounds. As Edmund de Waal notes, her chocolate-brownand-white tableware of the 1950s [fig. 9] – coffee pots, cups, jugs – was ‘in tune with the new optimism and formal clarity of the architecture and design of the period’, the ‘perfect kind of pot to sit in a modernist apartment … with a good abstract painting behind them.’19 Unlike Bernard Leach’s rural functionalism, Rie’s idiom bore ‘no counterpoint to the earthy traditions of British pottery’ but instead aligned ceramics with the urban modernism of London. The balance between pragmatism and modernist invention places Rie’s practice in dialogue not only with London’s post-war optimism but also with the cultural legacy of fin-de-siècle Vienna, a culture marked by what Kirk Varnedoe described as the ‘conquest of applied art by architecture.’20 It was this spirit of Gesamtkunstwerk, which framed design as part of a total work of art, that Rie transferred into her studio in Albion Mews, near Hyde Park.

For Rie, London was less an aesthetic muse than an enabling environment. Her experience

fig. 7 Detail: Lucie Rie, footed bowl, c. 1980, porcelain, bright golden manganese glaze, terracotta foot and well and a turquoise ring repeated inside and out, 8.6 cm high, 20 cm diameter. Underside impressed with artist’s seal.

fig. 8 Detail: Lucie Rie, Flaring footed bowl, c. 1978, porcelain, golden manganese glaze, radiating inlay and sgraffito design, 9.5 cm high, 22 cm diameter. Underside impressed with artist’s seal.

of the city was shaped as much by exile as by artistic choice: London offered safety, stability, and a supportive émigré community in which she could continue to experiment.21 Her adoption of the electric kiln reflected, on some level, as Phoebe Collings-James has noted, ‘a commitment to the future.’22 It was itself a

19 Edmund De Waal, “Modern Things”, in Lucie Rie: the Adventure of Pottery, Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard, 2023, p. 149.

20 Kirk Varnedoe, Vienna 1900, exh. cat., New York: MoMA, 1986, p. 82.

21 Cf. Tanya Harrod, “Lucie Rie in London” in Lucie Rie: the Adventure of Pottery, Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard, 2023.

22 Phoebe Collings-James, in: Ibid. p. 181.

fig. 9 Lucie Rie, tea set, c. 1960, teapot, jug, two cups and saucers and a sugar bowl, stoneware with a black shiny glaze, bamboo, the teapot is 21 cm high. Each with underside impressed with artist’s seal.

declaration of modernity, a commitment to invention. While Edmund de Waal sees in her pots ‘an affection for the city as a place to make,’ Eliza Spindel reminds us that her idiom cannot be reduced simply to the metropolitan: it ‘freely assimilated diverse sources.’23 Resonating beyond the urban, her inspirations were rooted more in the sense of the city – specifically London24 – representing a safe space for an exile to continue to experiment. Writing in 1951, Rie reflected that ‘the spirit of this country is a great influence – it is everywhere – in small things and in big things and it makes one feel very humble.’25 Such humility framed her consistent emphasis on functionality. Speaking of her 1950s tableware, she remarked: ‘I do not think I ever tried to make pots as pieces of decoration

23 Edmund De Waal, op. cit., p. 159; Eliza Spindel “Lucie Rie and the Natural World”, in: Ibid. p. 199.

24 As opposed to Nazi controlled Vienna.

25 Lucie Rie to J. A. Flint Wood, British Handicrafts Export Ltd, 22 May 1951, Lucie Rie Archive, CSC.

– I only wanted to make pots to be used’ and ones that ‘would look nice on the table.’26 Yet it was precisely this modesty that enabled her to reimagine ceramics as part of modern living. At Fonthill Pottery, her work finds particular resonance, not only as the former home and studio of Emmanuel Cooper – her ‘student’ and later biographer – but because this residential setting creates an immersive yet intimate atmosphere in which to experience the spirit of Gesamtkunstwerk 27

26 Ibid.

27 Cooper wrote the only major biography of Lucie Rie; I use the term ‘student’ here in the non-literal sense. Cooper was a long term admirer of Rie, and it is worth noting that while their ‘work shared some similar technical and aesthetic ground,’ the feeling of the work ‘is clearly of two very different artists each with their own distinct mature character’ – Sebastian Blackie, op. cit. p. 33..

Deriving its name from the tool so pivotal to both Rie and Cooper’s practices, Electric Kiln becomes an extended metaphor for the vivacity of London – the ever-evolving landscape of a city, continually dismantled and remade, yet always charged with creative possibility. In Auerbach’s impastoed canvases, in Rie’s poised modernist vessels, and in Cooper’s cratered bowls, surfaces carry the history of their making – marks of erosion, labour, and discovery. For Auerbach and Cooper, the city was both subject and material, a terrain to be painted or glazed. For Rie, London was above all an enabling environment, epitomising her commitment to invention and modernist renewal. At Fonthill Pottery, these convergences find a resonant home. Once the residence and studio of Emmanuel Cooper, it now houses an extensive collection of unique designs by architects Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret. The inclusion of these modernist furnishings within the exhibition extends the dialogue beyond ceramics and painting to encompass architecture and design – disciplines central to the mid-century pursuit of a total work of art. Their presence connects the practices of Rie, Cooper, and Auerbach to a broader ethos of synthesis between art, object, and environment. In this way, Electric Kiln not only situates these artists within a shared historical context but also activates Fonthill Pottery itself as a living expression of Gesamtkunstwerk – a space in which art, craft, and domestic design coalesce. Here, in the very rooms where Cooper experimented for decades, the works of three seminal artists are placed into dialogue, united not simply by place but by their lifelong pursuit of transformation: each finding in London the conditions to reimagine their medium, balance tradition with modernity, and look toward a new future.

RecliningHeadofJulia, 2007-08

55.9 x 55.9 cm

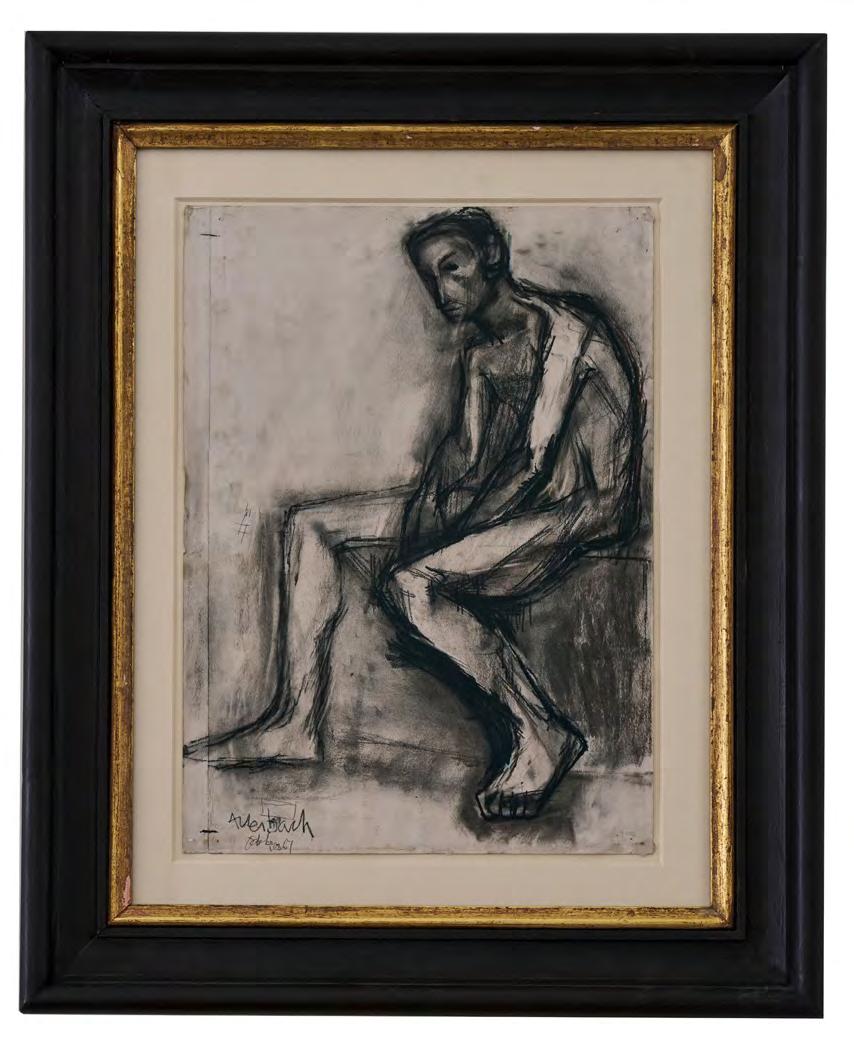

SeatedFigure, 1951

Charcoal on paper

55.5 x 40 cm

SeatedFigure, 1961

Charcoal and oil on paper, laid on board 97.8 x 66cm.

FRANK AUERBACH

StudyforPrimroseHill, c. 1960

Graphite pencil on paper

24 x 32 cm

SeatedFigure, 1955

Charcoal on paper

55.7 x 38.5 cm

ChristmasTreeatMorningtonCrescent, 2004 – 5

Oil on canvas

Signed dated and titled twice on the stretcher

133.4 x 155.6 cm

FRANK AUERBACH

21

21

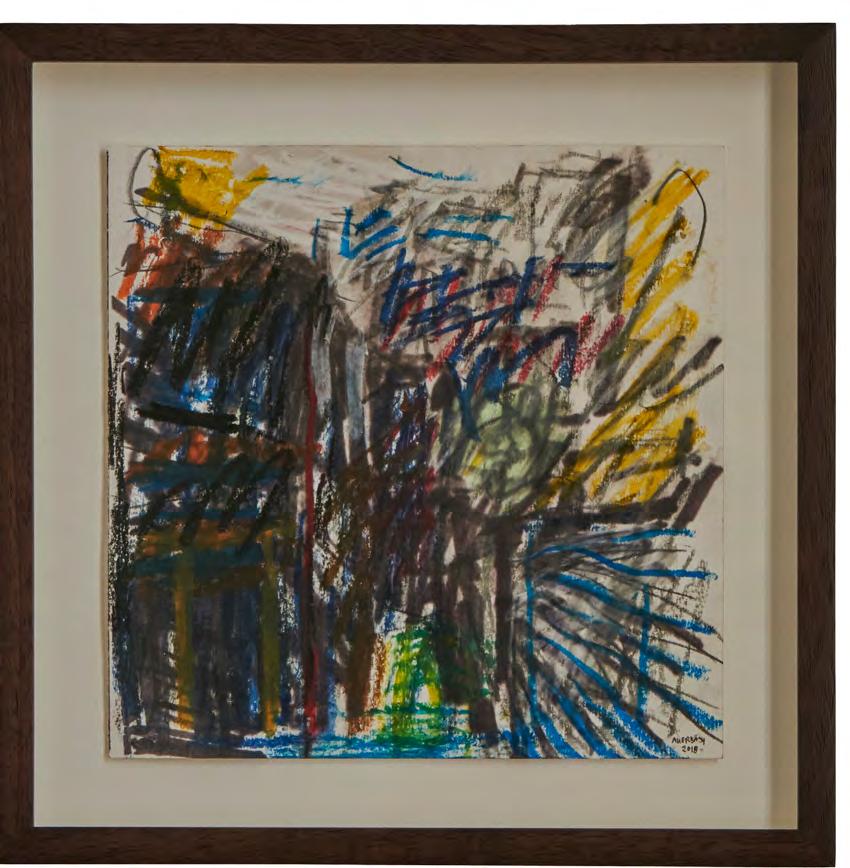

Fromthe Studio, 2018

Fromthe Studio, 2018

Porcelain footed bowl with dark matt glaze and gold lustre decoration to rim and centre

8cm high, 20cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

6cm

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Small conical bowl, c. 2005

Porcelain conical bowl with vivid yellow glaze, thin red band to rim, and lustre spot decoration

6.5cm high, 14cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Small bowl, c. 1980

Stoneware bowl with bands of white and brown glaze and torn rim

10cm high, 13cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Oval

15cm high, 15cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

10

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

10cm high, 17.5cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

‘None’, 2010

Porcelain hand-built ‘None’ with bright yellow glaze and lustre spot decoration

20cm high, 8cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

‘None’, 2010

Porcelain hand-built ‘None’ with white glaze and lustre spot decoration

18cm high, 13cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

10cm high, 26cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Small conical bowl, c.2002

Stoneware conical bowl with pink and white volcanic glaze over black slip 10cm high, 16cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Conical bowl, c.1990

Porcelain conical bowl with crackled light blue glaze and manganese rim

6cm high, 18cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

10cm high, 23cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Covered in a bronze manganese glaze with bright blue rim and well 11.5cm high

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

COOPER

Porcelain hand-built jug form with vivid yellow glaze and lustre spot decoration 15cm high, 19cm width, 3cm depth

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Small jug, 2010

Porcelain hand-built jug form with shiny white glaze and lustre spot decoration 13cm high, 15cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

22cm high, 10cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

EMMANUEL COOPER

Jug, c. 1997

Stoneware jug form with blue volcanic glaze over black slip

25cm high, 27cm width, 8cm depth

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

13cm

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Small jug, 2010

Porcelain hand-built jug form with light green crackled glaze and gold spot decoration 13cm high, 16cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

Small stoneware conical bowl with white volcanic glaze over black slip and gold decoration on the rim

6cm high, 16cm diameter

Underside impressed with maker’s mark

1887 - 1965

Executive Desk, 1954 Teak

LE CORBUSIER & PIERRE JEANNERET

HighCourtArmchair, 1960

89 x 72 x 69cm

HighCourtSofa, 1955

79 x 145 x 78cm

High Court, Chandigarh, India

HighCourtChair, 1955-6

76 x 56 x 67cm

High Court, Chandigarh, India

JEANNERET

Committee Chair, 1955-6

EasyCane‘Camping’Sofa(TwoSeater), 1955 - 56

80

Chandigarh, India

EasyChair, 1956

CrossEasyChair, 1955-6

FloatingBackOfficeChair(Black), 1956

77

VLegChair, 1958

86 x 44 x 52 cm

Punjab University, Chandigarh, India

Science Department, Punjab University, Chandigarh, India

6 x 3 MetalTable, 1960-61

78 x 183 x 91.5cm Mechanical

WorkingTable, 1960

Teak, zinc

75 x 92 x 62cm

Chandigarh, India

Architect’s Table, 1956

Teak

92.5 x 114 x 75cm

Architecture College, Chandigarh, India

RectangularCoffeeTablewithGlass, 1960

Teak, Glass

78 x 117 x 41cm

Chandigarh, India

Cabinet, 1957-8

Secreteriat, Chandigarh, India

Clerk Desk, 1957-8

Vase with fluted body and flaring lip, c. 1960

Stoneware with manganese speckle, pitted white glaze over diagonally fluted body

36.8 cm high

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

Underside

Underside impressed with artist’s seal and with applied label “LR 463”

Underside impressed with artist’s seal and with paper label “Lucie Rie/No. 2.”

Porcelain, unglazed with concentric inlaid lines, a manganese foot, lip and well

9.3 cm high, 19 cm diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

‘Knitted’ bowl, c. 1975

Stoneware, light grey with a black and gold inlaid radiating design, bands around the well, lip and foot

10.5 cm high, 24 cm diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

Porcelain, golden manganese glaze, radiating inlay and sgraffito design

9.5 cm high, 22 cm diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

10.4 cm high, 22.9 cm diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

Footed bowl, c. 1980

Porcelain, bright golden manganese glaze, terracotta foot and well and a turquoise ring repeated inside and out

8.6 cm high, 20 cm diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

Vase, c. 1980

Porcelain with golden manganese and copper glazes with sgraffito and inlaid lines to shoulder, neck, and rim

25.4 cm high, 10.8 diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

Vase with flaring lip, c. 1980

Porcelain, golden manganese glaze with terracotta bands crossed with sgraffito and inlaid blue lines to shoulder, neck and rim

26.2 cm high

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

11.5 cm high, 22.5 cm diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal and with applied label “19”

Underside

Large conical bowl, c. 1985

Stoneware, white feldspathic glaze over a mixed clay body producing a delicate blue spiral

13 cm high, 31.7 cm diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal and with applied label “LR/135.”

Tea set, c. 1960

Teapot, jug, two cups and saucers and a sugar bowl

Stoneware with a black shiny glaze, bamboo

The teapot is 21 cm high

Each with underside impressed with artist’s seal

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

Early vase, c. 1957

Porcelain, manganese glaze with sgraffito designs repeated inside and out of leaf designs

14 cm high, 9 cm diameter

Underside impressed with artist’s seal

Buttons & Brooches, c. 1948

Press-moulded or hand-modelled earthenware, glazes

Press-moulded or hand-modelled earthenware, glazes

designed

All artwork by Frank Auerbach © Frankie Rossi Art Projects

All artwork by Emmanuel Cooper © The Estate of Emmanuel Cooper

All artwork by Lucie Rie © The Estate of Lucie Rie