13 minute read

NEWS

STUDENTS WITH CHILDREN FACE UNIQUE CHALLENGES DURING THE PANDEMIC

Nontraditional students with children have found support through UO’s resources and connections with each other.

BY ERYN McGUIRE • TWITTER @ERYNMCGUIRE_

Moss St. is a program that is provided through the EMU. It aims to aid UO Faculty and students with a flexible daycare experience. Moss St. Children’s Center accommodates the needs of parents’ workloads when enrolled in University. (Maddie Stellingwerf/Emerald) The Children's Center is located on the corner of 17th Ave and Moss St. It accommodates the needs of parents’ workloads when enrolled at UO. (Maddie Stellingwerf/Emerald)

Throughout the academic year, navigating online classes has been more difficult for some than others. This is especially true for many students with children of their own who have faced the task of balancing their child’s Zoom learning with their own.

Danica Barrick, a UO public relations major and mother of an 11-year-old, has found support through the Nontraditional Student Union, a student-run organization dedicated to connecting these students to resources as well as each other.

“I can't say I connected with too many other undergrads that were outside of the Nontraditional Student Union, but when I got to meet other parents in the same situation as me, that's when I found my people,” she said. “I think that finding that community was imperative for me to feel accepted on campus.”

Barrick, 36, moved her family from southern california to Eugene to pursue a bachelor's degree after getting an associate’s degree at her local community college. Along with her 11-year-old son, she also has two stepsons, aged 21 and 20.

When all UO classes moved online due to COVID-19, Barrick was home with her son, helping him navigate fifth grade on Zoom. He suffers from test anxiety and had an especially hard time adjusting to taking exams at home with none of his classmates around, she said. She sometimes needed to miss class to be there to support him.

Barrick took online classes while studying for her associate’s degree, but it’s been a lot more difficult with a child at home, she said. She never gets the chance to turn off her “mom brain” and focus on her work. When her son is somewhere else, under someone else’s supervision, it’s easier to get work done, she said.

“Once you start reading and writing it's like you can't get on a roll because you’re getting interrupted all the time like: ‘Mom, I need help. Mom, I need to snack. Mom, I need to go to my friend's house,’” she said.

Barrick currently serves as co-director of the Nontraditional Student Union and works to connect student parents with resources for success. She also works with Maria Kalnbach, coordinator of nontraditional and veteran student success, who leads the Dean of Students-run Nontraditional Student program to plan events and help connect students to one another.

“If you're a student, parent or a nontraditional student that needs to work, study and be a parent, you're balancing and juggling a lot of things,” Kalnbach said. “We try to help them figure out how to manage all of that stuff without getting into too much stress.”

During spring term, NSP worked alongside the UO Women’s Center and University Housing on a children’s clothing swap, an annual event that was held for the first time since the pandemic started. Each year, NSP collaborates with the Student Rec Center to host a family recreation day during winter term. It’s also brought in tutoring center staff to teach students about speed reading and time management, as well as counseling center staff to talk about mental health resources at the university.

Moss Street Children’s Center, located at the south edge of campus, serves families with parents who either study or work at UO, with first priority given to students. At the start of the pandemic, the center closed until resuming limited in-person sessions in August. While shut down, it still offered virtual resources for parents, the center’s director Becky Lamoureux said.

“It’s great that we’re able to be open even though there are a lot of safety protocols to be followed,” she said. “We love seeing how much the children are getting out of being here and how much appreciation the parents have for us being open.”

Barrick said that she and her peers feel that the university does a good job of offering support to students with children, but there is always room for improvement. Many student parents would benefit from having a wider range of online classes year-round and having the ability to bring their children into buildings like the EMU, she said.

“I know that there are a lot of parents that have smaller children, and there's no way they can get to use our printing resources or to talk to anybody on campus without being able to bring our kids into the EMU,” she said.

Barrick is six classes away from graduating with a bachelor’s degree in public relations. Her son is now going to school in person for four hours each day, and she looks forward to the day when his classes are back to normal.

NEWS UO TO OFFER NATIVE AMERICAN UO TO OFFER NATIVE AMERICAN AND INDIGENOUS STUDIES MAJOR AND INDIGENOUS STUDIES MAJOR

Pending approval from state legislators, UO will extend the Native studies minor into an undergraduate major.

BY JOANNA MANN • TWITTER @JOANNA_MANN_

(Courtesy of Kirby Brown)

The Many Nations Longhouse, located on the University of Oregon campus, serves as a meeting place for Indigenous/Native American students at UO. The UO Senate and Board of Trustees have approved a new Native American and Indigenous studies major. (Will Geschke/Emerald)

The University of Oregon will offer an undergraduate degree in Native American and Indigenous studies starting in either fall 2021 or 2022. It will be the only undergraduate program on campus with “explicit commitments to serving Indigenous nations and communities,” according to Native American Studies Director Kirby Brown.

“The university has stated public commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion and has acknowledged that Indigenous and communities of color have been severely underrepresented, structurally and systemically,” Brown said. “Having a Native studies program on campus at the flagship institution in the state of Oregon, with nine federally recognized tribes, is an important symbolic but also intellectual gesture.”

UO is built on Kalapuya Ilihi land and has an Indigenous population 50% higher than the national average, with 0.7% of UO students identifying as Native American. A Native studies minor was created in 2013 and has grown steadily over the years, with an alltime high of 41 students currently enrolled in the minor. Over 80% of students in the minor identify as Native.

One of these students is UO senior Gwen Wolfe, who is a member of the Choctaw nation of Oklahoma and is an Indigenous, race and ethnic studies major. They are involved with the UO Native American Student Union and work with Native faculty at the Center for Multicultural Academic Excellence.

Wolfe said they have been advocating for a Native studies major since coming to UO in 2017. Had it existed a couple of years ago, Wolfe said they would have absolutely declared the major.

“Indigenous studies is my focus within the IRES [major],” they said. “There have been classes that I've had to take to fulfill my major requirements that have caused me to not be able to take Indigenous studies-related classes that I wanted, because I just didn't have the slots open.”

The major, an extension of the current Native studies minor, will be offered as a bachelor of arts and a bachelor of science. It will have an interdisciplinary track and a language track, both of which will require 56 credits. All students will take Intro to Native American Studies, Indigenous Peoples of Oregon, Native Feminisms and Indigenous Methodologies.

The program was approved by the UO Senate and Board of Trustees, and it now has to go through multiple levels of state approval. If completed over the summer, the major will begin in fall 2021. If not, it will start up the following year.

Brown said he wants the new major to be a place where Native students can see themselves represented in the curriculum and have their communities and experiences centered in the classroom. However, non-Native students are encouraged to take these courses as well.

“We believe that Native studies is for everyone, and we absolutely want every student who comes to the University of Oregon to have some exposure to Native American studies,” Brown said. “You can't really understand Oregon history or American history without understanding the relationship of Native peoples to that history and to the federal government.”

Students who are currently enrolled in the minor will be able to shift their credits over to the major. Additionally, undeclared students and other underclassmen will be able to declare the major along with incoming students.

Portland State University and Southern Oregon University already offer Native studies programs in their curriculum. Every course will be taught by faculty who currently work within the IRES department.

“The UO hasn't always had a reputation as a place that was welcoming for Native students,” Brown said. “I think that having a major curriculum that both Native and non-Native students can pursue at the university will be a pretty big draw for Native students who are considering higher education in the state of Oregon.”

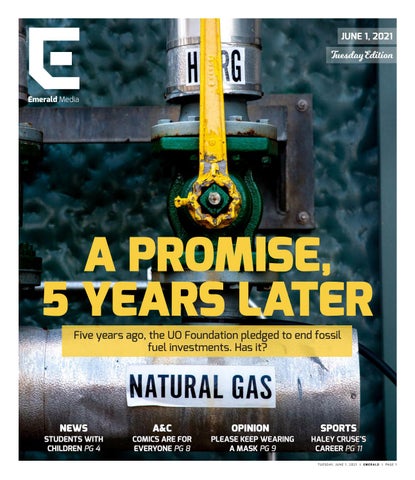

‘MONEY SPEAKS:’ THE UO FOUNDATION’S PROMISE TO END FOSSIL FUEL INVESTMENT, 5 YEARS LATER

UO Foundation president Paul Weinhold said the foundation has “absolutely honored” its commitment to let current contracts with fossil fuel extractors run out, but some climate change activists cast doubt on the organization’s transparency.

The University of Oregon Foundation, a charitable organization in charge of allocating private donations given to UO, has not made any new investments in fossil fuels since its 2016 promise to no longer financially support its extraction, UO Foundation president Paul Weinhold said. Weinhold and the UO Foundation said they won’t release current investments for independent verification.

“We explained at the time that sometimes the investments we make are long-term investments with private managers, and we will let those run out, and those are in the process of running out,” he said. “It’s literally a fraction of what we had in 2016, I believe. We’re absolutely honoring that commitment.”

The UO Foundation is a private organization separate from UO, which maintains confidential investment agreements with various investment managers. For that reason, the foundation does not share information publicly about which investments it holds and does not publish its investment catalogues.

Citing the confidential nature of some of its investments, the foundation declined to provide the Emerald with its current portfolio for the purposes of independently verifying when the existing contracts between itself and fossil fuel extraction corporations will expire. However, Weinhold said all of the foundation’s existing investments are set to run out within the next one to two years.

Mirjana Knepprath is a member of the Climate Justice League’s Divest UO campaign, which advocates for the UO Foundation and the university to fully divest from all fossil fuels. She said Divest UO is satisfied with the intentions behind the UO Foundation’s pledge, but “isn’t satisfied at all” in the way the foundation is trying to accomplish it.

The campaign’s main issue is with their members’ interactions with the foundation. Knepprath said that despite repeated attempts to get a clear answer about the status of the fossil fuel divestment, they haven’t been able to get one.

“They’ll say they’re divested from fossil fuels, but the problem is transparency,” she said. “We can’t look into their investments, and a lot of their investments are investments they can keep private for legal reasons.”

Unless the UO Foundation allows students to see their current investments, she said, students can’t know for sure whether it has divested fully or whether it has signed new contracts with fossil fuel extractors. Knepprath said the first thing that needs to happen is for the foundation to be completely transparent in its investments.

“I can’t know — and we can’t know — where they’re invested or even what new things we could be invested in without knowing what they’re currently invested in,” she said. “Everything starts with transparency.”

She acknowledged that the UO Foundation does have a legal obligation to abide by the confidential contracts it has signed but said that the contracts shouldn’t exist in the first place.

“Their first priority should be to the students and ensuring that the students have a transparent look into how the foundation operates and what they invest in,” Knepprath said.

Jay Mamyet, then-chief investment officer for the UO Foundation, highlighted in 2016 the foundation’s belief that initiatives like solar and wind power, as well as sustainable forestry and organic farming, would gradually replace the backing of fossil fuels.

“We intend to let those carbonbased investments — which were initiated many years ago — expire without renewal, ending our investment in carbon-based fuel sources,” Mamyet wrote.

Weinhold said that the decision to no longer invest in fossil fuels “hasn’t harmed us in any way,” given the foundation’s original position that fossil fuel extraction isn’t a good investment.

Grace Brahler is the Oregon climate action plan and policy manager for the local climate activism group Beyond Toxics. She said the board’s decision has huge implications.

“It’s all about power,” she said. “Fossil fuel divestment — especially by such a large and well publicized institution like the UO Foundation — really holds the fossil fuel industry accountable for its culpability in the climate crisis.”

Divesting from fossil fuels is a worldwide movement across multiple industries, including governments, faith-based institutions and philanthropic foundations. Nearly 1,400 institutions around the world have pledged to divest from fossil fuel extractions, according to 350. org’s Fossil Free, totaling an estimated $14.56 trillion value.

“Fossil fuel divestment, that movement, it can just break the hold that the fossil fuel industry has on our society and our government,” Brahler said. “And so this is a big signal that the public no longer wants to consent to the destruction caused by the fossil fuel industries and especially on those vulnerable communities.”

Brahler said the UO Foundation’s move to divest also highlights the moral dimensions of climate change, and that Beyond Toxic’s work centers those who are most seriously impacted by the climate crisis.

“We work to involve and center and highlight the impact on frontline communities, who have and will continue to experience the impact of climate change first and worst,” Brahler said.

Weinhold said the UO Foundation has a “very singular focus,” which is to grow the endowment for the university community.

“We take into consideration environmental and social and governance issues at all times, and that we care about the same things they care about,” he said, regarding what the UO community cares about. “But we do have a mandate, and that’s to maintain the purchasing power of the endowment for generations to come.”

Weinhold said that he appreciates students’ concern and input regarding the investments of the UO Foundation.

“Oftentimes, students can be very close to things that are happening in the world that maybe we’re not, so certainly we appreciate that feedback,” he said.

Weinhold said the UO Foundation takes the concerns of the Climate Justice League “very seriously,” calling them “a passionate group of students who care about the future of the planet.”

Knepprath said that it’s important for big investors like UO to more broadly divest from fossil fuels.

“Just generally, fossil fuel companies cannot continue their work without investors,” she said. “It’s important for all these other big foundations to divest on a larger scale, because if you can start small at a small university, this can happen at other universities.”

“Money speaks,” Brahler said, “and the sooner that our prominent institutions or foundations use their power to divert those funds away from the fossil fuel industry, the sooner much needed broad level systemic change can take place and we can actually begin to realize the future — the just future where our communities are healthy and thriving and supportive.”

BY DUNCAN BAUMGARTEN • TWITTER @DUNCANBAUMGART2

(Emerald Archives)